Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/21/01. The contractual start date was in January 2014. The draft report began editorial review in July 2018 and was accepted for publication in October 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

All authors declare financial support from The Tavistock Trust for Aphasia. Rebecca Palmer was a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)/Higher Education Funding Council for England-funded senior clinical academic lecturer until June 2017. She has current funding from the Stroke Association for a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) student conducting work on fidelity to the intervention. The Stroke Association had previously funded early development work on the software used in the intervention but she was not involved in that. She was author of the intervention manual. Nicholas Latimer is supported by the NIHR (Post-doctoral Fellowship, reference PDF-2015-08-022) and is currently supported by Yorkshire Cancer Research (award S406NL). Pam Enderby has a patent on the Therapy Outcome Measures (2015) used in this trial from which she receives royalties. Audrey Bowen is funded by the Stroke Association and the NIHR Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care Greater Manchester. She co-authored the Communication Outcome after Stroke (COAST) and Carer COAST tools, which are patented. Madeleine Harrison receives PhD fellowship funding from the Stroke Association. Esther Herbert received a NIHR Research Methods Fellowship, outside the submitted work. Cindy Cooper sits on the NIHR Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) Standing Advisory Committee (2016 to present) and the UK Clinical Research Collaboration Registered CTU Network Executive Group (2015 to present).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Palmer et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Post-stroke aphasia

Aphasia is the most common language disorder acquired post stroke, affecting a person’s ability to speak, read, write or understand language. One-third of stroke survivors are affected by aphasia and 30–43% of them will remain significantly affected in the long term. 1 Aphasia has an impact on everyday activity including the ability to have conversations, make telephone calls, listen to the radio, write letters, e-mails and text messages and read for pleasure, information or work. It therefore restricts the ability to carry out pre-stroke roles at work, in the family and in the community, often leading to withdrawal from participation in usual activities and reduced social networks. These changes affect the wellbeing of both the person with aphasia and their family/carer, with increased frustration, misunderstandings and breakdown of/strain on relationships. Consequently, people with aphasia are highly susceptible to depression. 2

Evidence for speech and language therapy

Speech and language therapy is provided for people with aphasia. It aims to improve the language impairment and the ability to communicate and participate in daily activities. Neuroplasticity is the process by which the brain can form new connections and pathways to enable a person to relearn a skill, such as language, previously controlled by an area of the brain now affected by the stroke. Impairment-focused speech and language therapy aims to promote experience-dependent neuroplasticity for language. Key principles of experience-dependent neuroplasticity underpinning therapy according to Kleim and Jones3 include ‘use it or lose it’, ‘use it and improve it’, specificity matters (the nature of the therapy dictates the nature of the plasticity, i.e. you get better at doing what you practice doing), salience matters (therapy must be meaningful to induce plasticity) and repetition matters (induction of plasticity requires sufficient repetition).

In a Cochrane review of aphasia therapy for people with aphasia post stroke, Brady et al. 4 showed that speech and language therapy was more effective than no treatment, resulting in clinically and statistically significant benefits to patients’ functional communication, reading, writing and expressive language. They found no evidence of one type of therapy being superior to another and there is no current evidence of long-term effects of therapy. 4 Medical instability, fatigue and confusion may reduce full engagement with language therapy in the early weeks post stroke, reducing the opportunity for some people to engage in therapy; however, some stroke survivors may tolerate speech and language therapy later post stroke.

Traditionally, it was thought that language recovery can reach a ‘plateau’ after 6 months or more, leading to speech and language therapy services being delivered predominantly in the first few months after stroke. However, in a systematic review of 21 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), Allen et al. 5 found evidence to support the provision of speech and language therapy for more than 6 months after the onset of post-stroke aphasia. In a recently published RCT of speech and language therapy for aphasia in the chronic stage post stroke (> 6 months), Breitenstein et al. 6 randomised 156 patients with aphasia to either speech and language therapy or waiting list control in 18 rehabilitation centres in Germany and showed significant statistical and clinical functional language (activity) benefit of speech and language therapy. The therapy was delivered in clinical settings for ≥ 10 hours per week for at least 3 weeks (minimum dose of 30 hours) and combined one-to-one speech and language therapy, group therapy with a speech and language therapist (SLT) and self-managed computer therapy or pencil-and-paper linguistic exercises prescribed by a SLT. 6

Delivery of therapy for persistent aphasia: the clinical problem

Despite evidence of benefit, treatment of aphasia that persists beyond the first few months after stroke is often not available through NHS services,7 as ongoing therapy is costly through face-to-face speech and language therapy and places greater demands on already-limited resources, which are predominantly targeted in the earlier months following stroke. If people with aphasia are to be able to reach their recovery potential, lower-cost options for the support of repetitive practice in the longer term are urgently needed to enable access to therapy at a time that is best for each individual, and for as long as the individual is able to benefit.

Potential solutions to increasing the amount of tailored therapy delivered for persistent aphasia without increasing demand on speech and language therapy resources

There is evidence that non-speech and language therapy professionals can be employed successfully to support therapy activity and the Cochrane review found little indication of a difference in the effectiveness of therapy facilitated by volunteers trained by a SLT and the effectiveness of therapy delivered by a SLT directly. 4,8,9 Computer technology can also provide the potential for supporting treatment in the long term. Computer programs developed for the treatment of aphasia have been reported to be useful in the provision of targeted language practice and provide opportunities for independent home practice as part of a self-managed approach to maximise repetitive practice,10–12 improving outcomes for reading, spelling, word-finding and expressive language. 11,13–15 Computer-based tasks can be tailored to the individual’s needs, accounting for personal context and language ability levels, potentially helping to motivate independent practice. Self-managed practice schedules can also account for personal needs, such as fatigue, ability to travel and fitting practice around other commitments. Bespoke software and applications (apps) are available for self-managed aphasia therapy practice. In addition to personal computers (PCs), Stark and Warburton16 showed the feasibility of using iPads (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) to deliver app-based aphasia therapy. In a systematic review of computer therapy for aphasia, Zheng et al. 17 concluded that therapy delivered using a computer is more effective than no therapy, and potentially as effective as therapy delivered by a SLT. The meta-analysis carried out in the Cochrane review4 similarly concluded that there was no evidence of a difference between therapy delivered on a computer and one-to-one therapy from a SLT. Both studies acknowledge the low quality of this evidence, with only five small RCTs (the largest having 55 participants) reported to date (2016). Only one of these five studies considered impact on functional communication, indicating that the majority of the evidence is for impairment-based outcomes rather than functional or activity-based outcomes. No a priori sample size calculations were reported. Computer-based services for long-term management of aphasia therapy have the potential to provide a low-cost therapy option. However, the actual cost-effectiveness has not been investigated until recently in the Clinical and cost-effectiveness of aphasia computer treatment versus usual stimulation or attention control long term post-stroke (CACTUS) pilot study. 18 There is therefore a pressing need for fully powered, well-designed RCTs of both the clinical effectiveness and the cost-effectiveness of self-managed computer aphasia therapy approaches for aphasia.

Intervention aimed at addressing delivery of long-term speech and language therapy for persistent aphasia investigated in the Big CACTUS trial: self-managed, computer aphasia therapy approach for persistent aphasia

The computerised approach to long-term aphasia therapy used in the Big CACTUS project [see Chapter 2, Self-managed computerised therapy intervention for word-finding (computerised speech and language therapy)] combines current theory and evidence underpinning language therapy with practical considerations for treatment delivery. As word-finding is a common difficulty for people with aphasia, this intervention focuses on the treatment of word-finding specifically. The approach has four main components:

-

Access to specialist speech and language therapy software.

-

Skills of a qualified SLT used to select individually targeted therapy exercises (specificity) to practice retrieval of words of personal relevance to each individual with aphasia (salience).

-

Regular self-managed practice of the therapy exercises (20–30 minutes per day over 6 months is recommended as shown to be manageable in the pilot study). 18

-

Volunteers/speech and language therapy assistants (SLTAs) support use of the computer exercises and generalisation of the newly acquired vocabulary in conversation. 19

The intervention was predominantly focused on improving the word-finding impairment, with support from volunteers or SLTAs designed to assist with generalisation of words learned to functional use.

The computer software package used within this trial is called StepByStep© version 5.0 (Steps Consulting Ltd, Acton Turville, UK),20 and is marketed by Steps Consulting Ltd at a cost of £250 for an individual lifetime licence to be purchased for a patient to put on their own computer, or £550 for a clinician licence owned by the NHS and installed on an NHS computer. The Stroke Association funded the initial development of the first version of StepByStep in the early 2000s. Since that time, it has been iteratively developed and marketed by Steps Consulting Ltd. Version 5 was used in the Big CACTUS trial. The approach described above is based on a similar approach used in therapy by Steps Consulting Ltd as an independent therapy provider. The software is intended to be tailored by SLTs with practice supported by a non-SLT specialist, often a carer or relative. The approach has been adapted for use in the NHS, particularly recognising that not everyone who accesses NHS services has a carer/relative able to provide support and therefore a training programme for volunteers and SLTAs was developed. Steps Consulting Ltd was not a collaborator on the project and therefore was not involved in project design, delivery or analysis. It did, however, support therapists on the trial with software use as it would for any therapist who purchased the software independently of the trial. For rationale for the choice of StepByStep, see Chapter 2, Self-managed computerised therapy intervention for word-finding (computerised speech and language therapy).

We carried out a pilot study evaluating the approach described above with 34 people with persistent aphasia. 21 They were randomly assigned to using the computer therapy approach or usual long-term care (most frequently this was social support). On average, people with aphasia practised their speech exercises on the computer independently for 25 hours over 5 months. The therapy significantly improved people’s ability to use spoken words when compared with usual care (UC). The mean improvement in word-finding was 19.8% [95% confidence interval (CI) 4.4% to 35.2%; p = 0.014]. The results indicated that self-managed computer therapy supported by volunteers (total of 4 hours’ support over 5 months on average) could help people with chronic aphasia to continue to practise, improving their vocabulary and confidence when speaking. 21 Patients and carers found it an acceptable alternative to face-to-face therapy. 22 The pilot study also showed, through qualitative interviews, that self-managed computer therapy could potentially improve the quality of life of people with persistent aphasia,22 at a relatively low cost to the NHS and society, but that a full economic evaluation with a larger sample was still required to reduce uncertainty in estimates of cost-effectiveness. 18

Research rationale and objectives

The literature shows that people with persistent aphasia can improve their communication with sufficient amounts of speech and language therapy. This can be difficult to provide face to face with limited resources. Consequently, the use of specialist computer software for self-managed repetitive practice with volunteer support has been explored as a potential option for the provision of effective speech and language therapy to people with persistent aphasia, providing the opportunity for people with aphasia to receive greater quantities of therapy over a longer period than would be possible face to face. The aim of the Big CACTUS trial was to provide definitive evidence of whether or not targeted, speech and language impairment based therapy intervention for word-finding through self-managed computer exercises for persisting post-stroke aphasia in addition to currently available face-to-face speech and language therapy was clinically effective and cost-effective, when compared with currently available speech and language therapy alone. This built on the successful 3-year Research for Patient Benefit-funded pilot RCT conducted by this team, which informed possible effects, measures, feasibility, recruitment rates, compliance, cost-effectiveness analysis and a power calculation. Results demonstrating feasibility were published by Palmer et al. 21

The World Health Organization recommends use of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)23 to describe and evaluate the impact of health problems on a person’s life. As the intervention in Big CACTUS predominantly targeted word-finding impairment anticipating carry-over to functional activity, both impairment and activity were relevant to evaluate, along with participation. The first three research objectives therefore sought to identify the effect of the Big CACTUS approach to self-managed computer treatment for persisting aphasia supplementing UC (for a definition of UC in this trial, see Chapter 2, Usual-care control group), compared with UC alone or activity/attention control (AC) plus UC on the ICF dimensions of impairment, activity and participation:

The main research objectives were to:

-

establish whether or not self-managed computerised speech and language therapy (CSLT) for word-finding increases the ability of people with aphasia to retrieve vocabulary of personal importance (impairment)

-

establish whether or not self-managed CSLT for word-finding improves functional communication ability in conversation (activity)

-

investigate whether or not patients receiving self-managed CSLT perceive greater changes in social participation in daily activities and quality of life (participation)

-

establish whether or not self-managed CSLT is cost-effective for persistent aphasia post stroke

-

identify whether or not any effects of the intervention are evident 12 months after therapy has begun.

Additional research objectives include investigating the generalisation of treatment to retrieval of untreated words (impairment); the generalisation of treated words to functional use in conversation; carers’ perception of communication effectiveness (participation) and the impact on carers’ quality of life; and identification of any possible negative effects. Consistent with our objectives, we selected assessments to measure impairment, activity and participation (see Chapter 2 for details). Since our trial was designed, the international aphasia research community has developed a consensus statement about the importance of measuring these ICF dimensions and has identified recommended measures. 24

Patient, carer and public involvement

The CACTUS pilot study had a strong patient, carer and public involvement (PCPI) group, which acted as an independent advisory group made up of people with aphasia and carers. This group was refreshed at the beginning of the Big CACTUS trial, with four members (two people with aphasia and two carers) providing continuity from the pilot study and three new members (two people with aphasia and one carer) joining the group to provide a fresh perspective. Members were recruited via a stroke patient and public involvement (PPI) database held by the University of Sheffield. The work of the group has been reported throughout this report using the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public 2 (GRIPP2).

The aims of the group were to:

-

facilitate the recruitment and inclusion of people with aphasia in the trial

-

ensure that trial materials and processes were accessible to people with aphasia

-

ensure that the interventions and trial procedures were appropriate and manageable for people with aphasia

-

ensure that dissemination of trial results reached a broad audience in accessible formats.

The group met with members of the research team and was predominantly facilitated by the chief investigator, Rebecca Palmer, who is a qualified SLT. Involving people with language difficulties presents additional challenges for PCPI collaboration. Standard supportive techniques used included having an aphasia-friendly agenda at each meeting (see study documentation at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/122101/#/), using practical activities with pictures and keywords to support discussions, and, for key decisions, members of the research team worked with each member with aphasia independently to facilitate inclusion of their perspectives. The clinically trained members of the research team worked with those members with the most limited language ability. The group members met when their advice or help with decision-making or production of materials was required and therefore the frequency of meetings varied. Fifteen meetings took place during the project.

The level of involvement was collaborative. Activities included development of the plain English summary for the original application; assisting with style and content of information sheets for people with different severities of aphasia; assisting with the design and evaluation of the consent support tool used in recruitment; advising on recruitment; informing the design of an aphasia-friendly adapted EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L); making decisions about the materials used in the AC group; identifying key facts from the results that need to be particularly highlighted for people with aphasia; driving the dissemination plans; and stimulating and co-producing a film and accessible booklet of the trial results. The contribution of the PCPI group has been further detailed in Chapter 2. The impact of the PCPI activity has been considered in the discussion section (see Chapter 6). The group was awarded a PCPI prize at the UK Stroke Forum 2016 in recognition of their contribution to the Big CACTUS project.

In addition, a person with aphasia and his wife were members of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC).

Chapter 2 Methods

This report is concordant with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines for individually randomised parallel-group trials25 (including non-pharmacological treatments,26 pragmatic27 and harms28 extensions) and the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist. 29

Trial design

The trial used a pragmatic, superiority, individually randomised, single-blind (blinded outcome assessors), parallel-group, randomised controlled adjunct trial design. All participants received UC, and outcomes were compared for people with persistent aphasia 4 months or more post stroke who were randomly allocated to one of the following groups:

-

UC

-

self-managed CSLT in addition to UC

-

AC in addition to UC.

Participants were randomised to one of the three groups using a 1 : 1 : 1 allocation ratio. Randomisation was stratified by the NHS speech and language therapy department (site) providing the interventions and severity of the patient’s word-finding difficulty.

Important changes to methods after trial commencement

The planned sample size was 285 participants. We extended the recruitment period by 1 month to increase recruitment as it was slightly short of the target owing to the recruitment rate slowing down towards the end of the recruitment period. The reduction in recruitment rate is likely to be caused by the fact that recruitment was from current and past patient lists and by the end of recruitment past patient lists had been exhausted. After an extra month of recruitment, the trial team, in discussion with the Trial Steering Committee and the trial statistician, made a decision to stop recruitment at 278 participants, seven participants short of the planned target, as the withdrawal rate was lower (9%) than that estimated in the sample size calculation (15%) and therefore sufficient numbers had been recruited to address research objectives with the intended statistical power.

The original funded trial did not include measurement of fidelity, beyond that of participant adherence to the interventions. Fidelity measurement of additional components of CSLT (i.e. delivery by SLTs and support from volunteers or SLTAs) was later funded by the Stroke Association as part of a postgraduate research [Doctor of Philosophy (PhD)] fellowship awarded to one of the Big CACTUS research associates, Madeleine Harrison, who was supervised by two of the Big CACTUS collaborators, Rebecca Palmer and Cindy Cooper. The methods for the fidelity assessment were added to the Big CACTUS protocol version 4.0, dated 17 July 2015, 8 months after recruitment commenced.

Important protocol changes since version 1.0

In the original protocol, the co-primary outcome ‘conversation’ was measured using two assessments. These were the Therapy Outcome Measures (TOMs) and the number of target words used in conversation. The trial was originally powered on only the TOMs and the other co-primary outcome, ‘word-finding ability’. It was not possible to power the trial also on ‘number of words used in conversation’ as there was no prior information to inform a sample size calculation. Prior to the trial starting and publication of the protocol, it was recognised that there was not adequate information to combine the two measures of the co-primary outcome of ‘conversation’ into one outcome. Therefore the validated, published measure, TOMs, was kept as the co-primary outcome and number of words used in conversation was moved to be a secondary outcome before recruitment began.

An additional ‘per-protocol’ definition for intervention use was added for clarity during the recruitment period but before data lock and analysis: ‘across at least a 4 month period will be considered per protocol’.

An inter-rater and intrarater reliability testing protocol for raters of the practice videos in the primary outcome measure was added prior to evaluation of the videoed conversations.

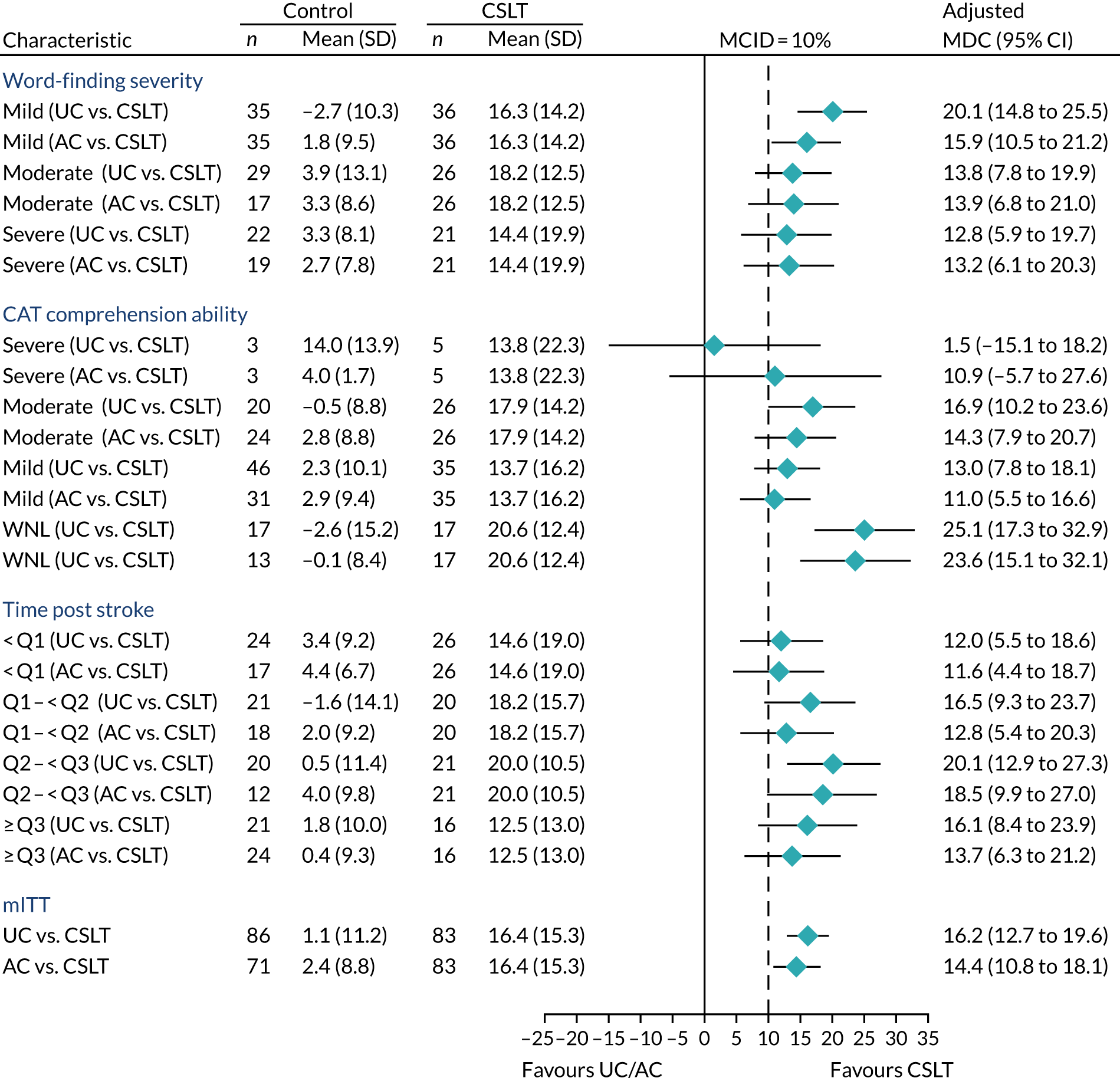

Details of key subgroup analyses were added during development of the statistical analysis plan (SAP) prior to data lock: severity of word-finding difficulty, length of time post stroke and baseline comprehension ability.

Participants and eligibility criteria

Participants were included if:

-

They were aged ≥ 18 years.

-

They were diagnosed with stroke(s). Studies often limit inclusion to first stroke. As this is a pragmatic trial, and patients with multiple strokes are typically treated, inclusion was not limited to patients with a first stroke.

-

Their onset of stroke was at least 4 months prior to randomisation (to ensure that aphasia was persistent).

-

They had been diagnosed with aphasia, subsequent to stroke, confirmed by a trained SLT.

-

They scored 5–43 out of 48 on the Comprehensive Aphasia Test (CAT) Naming Objects30 (mild is 31–43, moderate is 18–30 and severe is 5–17; participants scoring < 5 were excluded as the pilot study showed no benefit for participants who were able to retrieve < 10% of words).

-

They were able to perform a simple matching task in StepByStep with at least 50% accuracy (score of at least 5/10; this was a pragmatic method that may be used clinically to confirm sufficient visual and cognitive ability to use the computer exercises).

-

They were able to repeat at least 50% of words in a simple word-repetition task in the StepByStep program (score of at least 5/10). Significant difficulty with repeating words is an indication of apraxia of speech, which would require a different intervention.

Participants were excluded from the trial if they:

-

Had another premorbid speech and language disorder caused by a neurological deficit other than stroke. A formal diagnosis could be reported by the participant or relatives and confirmed by the recruiting SLT.

-

Required treatment for a language other than English (as the software is currently only available in English).

-

Were currently using the StepByStep computer program or other computer speech therapy aimed at word retrieval/naming to avoid similarity between groups.

Eligibility of providers

NHS speech and language therapy departments were eligible to participate if they routinely provided community services for people with aphasia post stroke. Treating clinicians were eligible if they were qualified SLTs with experience of treating post-stroke aphasia. Speech and language therapy or generic rehabilitation assistants were eligible if they routinely carried out work under the supervision of a qualified SLT. Services were invited to use volunteers to provide the same support as assistants if they routinely used volunteers to support speech and language therapy work.

Settings and locations where the data were collected

Participant identification

Participants were recruited from 21 speech and language therapy departments in 20 NHS trusts (see Appendix 1) across the UK, from both current and past patient records, speech and language therapy colleagues and contacts with longer-term voluntary support groups. Identification from past patient records and voluntary support groups was aimed at including participants who may have finished their speech and language therapy intervention based on currently available services. However, these potential participants would be eligible for additional/extended therapy if the Big CACTUS approach to providing more therapy through self-managed computer exercise was to be implemented in the future if found to be clinically effective and cost-effective. Speech and language therapy departments agreeing to participate in the project were asked to identify potential participants. Potential participants unknown to speech and language therapy departments and voluntary groups, who found the trial on the website, were able to self-present by contacting the central trial team who put them in touch with their nearest local NHS speech and language therapy departments in the trial where possible. Potential participants (those identified as having had a stroke, and a diagnosis of aphasia, at least 4 months post stroke, aged ≥ 18 years) were contacted by the research SLT in each participating NHS trust. This person was a member of the local clinical team who was appointed to take responsibility for the running of the trial and the trial intervention in their NHS trust. The participant was sent project summary information and followed up by a telephone call 1 to 2 weeks later to establish whether or not they were interested in the trial. If they were, the research SLT made an appointment to visit them at home. All trial procedures, including recruitment, intervention and outcome measures, were conducted in the participants’ own homes.

A screening log was completed by the therapist who identified potentially eligible patients from patient records, speech and language therapy colleagues or voluntary groups. Data recorded and sent back to the clinical trials research unit (CTRU) included unidentifiable information including initials, gender and age. The reason, if given, for not arranging an appointment was recorded.

Screening for eligibility

At the first visit to the potential participant, before providing detailed trial information, the research SLT determined whether or not the person was eligible. They requested verbal consent to undertake the naming test of the CAT,30 which is used in routine practice and can establish the severity of a person’s word-finding deficit. If the word-finding score was < 5 (10%) or > 43 (90%) (out of 48), an explanation was given to the patient that this type of computer therapy was not suitable for them. If they were still interested in computer-based therapies, they were directed to the aphasia software finder (www.aphasiasoftwarefinder.org; accessed 20 June 2018) developed to help patients with aphasia to identify software that would be most suitable for them. If the potential participant had eligible word-finding scores, the research SLT asked them to attempt a simple matching task on the computer to confirm ability to see the screen and perform simple tasks.

Recruitment

The level of support required to enable a person with aphasia to provide informed consent is dependent on the severity and profile of the aphasia. Considerable attention was given to the recruitment of participants with aphasia to ensure informed consent. In order to provide information in a format consistent with each individual’s language ability, the Consent Support Tool was used. 31 The research SLT at each site requested verbal consent from the potential participant to carry out part A of the Consent Support Tool (language screening test of 5–10 minutes). The result indicated which style of information would best support their understanding of the trial. Three different styles of information sheet were available to enable as many participants as possible to make their own decision regarding whether or not to consent to participation in this trial. The consent support tool, carer information sheets and consent forms can be accessed online (see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/122101/#/related-articles), as can aphasia-friendly/accessible information sheets and videos (see www.sheffield.ac.uk/scharr/sections/dts/ctru/bigcactus). Patient information sheet 1 was in large font with keywords emboldened for those who could understand written paragraphs. Patient information sheet 2 was for those who could read simple sentences but not full paragraphs. It followed standard aphasia-friendly principles with one idea presented per page in short simple sentences of large font. Keywords were emboldened and each idea was represented by a picture. Patient information sheet 3 was for those who could understand with significant support. Each idea/sentence was presented on a Microsoft PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) slide with simple text, keywords emboldened and picture support. Research SLTs were instructed to present each point in turn, read aloud to the potential participant and support with gestures, objects and drawings. The next sentence was then presented. All participants were given sufficient time to consider their participation before informed consent was taken by the research SLT. Participants providing their own informed consent were asked to sign an aphasia-friendly consent form.

The Consent Support Tool also identified individuals who did not have the mental capacity to consent for themselves owing to the severity of their language difficulty (those with severe aphasia who find it difficult to understand information, even with the support of adapted/pictorial information formats). These individuals receive speech and language therapy treatment in practice and may benefit from the trial intervention; therefore, it was important to include them. These potential participants were shown a short video clip of the computer program being used and of someone being assessed to show what was involved. If potential participants with severe aphasia who lacked capacity to consent indicated an interest, a relative (in Scotland, the person’s legal representative or nearest relative) was asked to read the full information sheet and a covering letter detailing their responsibility, and to sign a carer declaration that they believed that their relative wished to take part (in Scotland, they were asked to sign a consent form). At the request of the PCPI group, all patients were given a copy of either the standard information sheet or the aphasia-friendly information booklet and a picture summary on one side of A4 paper.

For those participants with a carer, the carer was asked if they were willing to complete outcome measures related to their own quality of life and perception of their relative’s communication ability. They were provided with the carer information sheet and were asked to sign a consent form.

Interventions

Following the TIDieR checklist,29 the three trial interventions are described below.

Usual-care control group

Usual care for people with long-standing aphasia following stroke varies across the country in terms of type, frequency and length of provision, and is dependent on available resources in each locality. To accurately describe UC provided to people with aphasia > 4 months post stroke, patients, carers and therapists were asked what therapy they had received in the 3 months before they were randomised. Therapy notes were then consulted to record the dates of therapy sessions, therapy goals, length of sessions, personnel providing therapy and the mode of therapy delivery. The UC received prior to randomisation is reported here based on the 244 participants who were at least 4 months post stroke at the start of the observation period. These data can be considered as a trial result. However, as describing UC was not a research objective, and as the data describe one of the trial interventions, the information has been reported in this section.

What?

Of the people with aphasia at least 4 months post stroke in the 3 months prior to randomisation, 40% were in receipt of speech and language therapy and 60% were not. People with aphasia were more likely to receive therapy than not if they were < 12 months post stroke, but they were less likely to receive therapy if they were > 12 months post stroke. A lower proportion of people with mild word-finding difficulties (32%) received therapy than those with moderate (52%) and severe (40%) word-finding difficulties. Forty-eight per cent of the participants attended voluntary or social support groups. Twenty-three per cent of participants were in receipt of therapy but did not attend voluntary or social support groups, 32% attended support groups but did not receive therapy, 29% had neither and 16% had both.

Therapy aims or goals recorded for each therapy session in speech and language therapy notes were analysed using a quantitative content analysis by two SLTs (RP and HW). The goal categories, descriptions and examples in Table 1 show the range of speech and language therapy activity forming UC. Approximately 50% of therapy goals in UC focused on rehabilitation of the language impairment. Twenty-three per cent of goals focused on enabling the person to communicate, often with compensatory strategies. Time was also spent on providing support, in addition to assessment and reviewing progress. More than 5 years after stroke, enabling goals were more prevalent than rehabilitation goals.

| Goal category (level 1) and goal description (level 2) | Example (as described in the patient notes from which data were collected) | Number of goals | Percentage of goals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | Assess higher level language functions | 44 | 4.8 |

| Review | Review progress made in therapy | 49 | 5.2 |

| Rehabilitation (improving impairment) | 4628 | 49.8 | |

| Comprehension | Improve auditory comprehension | 21 | 2.3 |

| Expressive language | To produce longer/more complete verbal sentences | 87 | 9.4 |

| Intelligibility | Clearer speech | 15 | 1.6 |

| Money skills | Money handling skills | 14 | 1.5 |

| Number skills | Number recognition | 10 | 1.1 |

| Phonological skills | Phonological therapy | 32 | 3.5 |

| Reading | Identify functional written words | 81 | 8.8 |

| Semantic skills | Semantic categorisation of concrete items | 44 | 4.7 |

| Word-finding | To be able to find words in conversation with more ease | 107 | 11.5 |

| Writing | To be able to write short clear emails | 51 | 5.5 |

| Enabling | 211 | 22.7 | |

| Augmentative and alternative communication | Functional communication using low tech AAC | 29 | 3.1 |

| Conversation support | Supported conversation using technology | 82 | 8.8 |

| Participation in social conversation/activities | Speak more fluently with golf friends | 18 | 1.9 |

| Total communication strategies | Alternative ways to get message across | 19 | 2.1 |

| Using everyday technology | Use of spell check | 40 | 4.3 |

| Word-finding/self-cueing strategies | Functional and compensatory strategies for word-finding | 23 | 2.5 |

| Supportive | 36 | 3.9 | |

| Emotional support | Exploring loss and gain | 8 | 0.9 |

| Improve mood | To improve mood | 1 | 0.1 |

| Increase confidence in communicating | To improve confidence in talking in group setting | 6 | 0.7 |

| Managing frustration | Frustration levels | 1 | 0.1 |

| Providing information | To advise patient and family about impact and recovery from aphasia | 13 | 1.4 |

| Support communication with other professionals/form completion | Form filling support | 3 | 0.3 |

| Support for family | Communication support for family | 1 | 0.1 |

| Vocational support | Attend ‘fit for work’ interview | 3 | 0.3 |

| Activity to support therapy | 39 | 4.2 | |

| Discussing discharge | Discharge planning | 5 | 0.5 |

| Expert patient training | Expert patient training | 2 | 0.2 |

| Goal-setting | To set goals for occupational therapy and speech therapy | 16 | 1.7 |

| Handover | Handover to new SLT | 4 | 0.4 |

| Liaison with other staff/family | Liaison with social workerTo demonstrate laptop comprehension tasks to family | 4 | 0.4 |

| Preparing/monitoring homework | Set up home exercises | 2 | 0.2 |

| Therapy planning | Establish motivation for therapy | 6 | 0.7 |

| Insufficient information | 86 | 9.3 | |

| Goal not sufficiently described | Activity practiceTo achieve 90% on tasks | 74 | 8.0 |

| No goal recorded | 12 | 1.3 | |

| Not communication therapy | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Total | 928 | 100.0 | |

Who?

Usual speech and language therapy was predominantly provided by qualified SLTs at Agenda for Change bands 6 and 7. Some therapy sessions were provided by SLTAs on Agenda for Change bands 2 and 3.

How?

Usual speech and language therapy was predominantly provided face to face, with 87% of sessions delivered one to one and 12% of sessions delivered to a group of patients. Overall, five telephone calls were recorded as being used to provide therapeutic intervention and one instance of the use of telehealth was recorded.

Where?

Therapy was predominantly provided in patients’ own homes when one to one, and in outpatient/community health-care settings when provided in a group.

When and how?

The median therapy time received was 5 hours and 20 minutes, delivered in 1-hour sessions once every 2 weeks (median averages). The total time and number of sessions reduced with length of time post stroke, from 8 hours delivered in 1-hour sessions 0.67 times per week for people between 4 and 6 months post stroke to only 2 hours and 45 minutes delivered in 45-minute sessions once per month for people > 5 years post stroke (median averages).

Tailoring

Usual-care goals were tailored depending on a participant’s interests and clinical decisions regarding their needs.

Modifications

As this was a pragmatic trial, UC varied between sites and participants according to usual practices. No attempt was made to standardise the UC received. Consequently, there were no planned modifications to UC during the trial.

Fidelity/measurement of how well usual care was delivered

Amounts of therapy time were recorded for UC throughout the trial to assess whether or not this stayed constant between trial groups. Fidelity to UC is reported in the trial results [see Chapter 4, Usual-care speech and language therapy offered (fidelity/adherence to provision of usual care)].

Self-managed computerised therapy intervention for word-finding (computerised speech and language therapy)

Why?

The intervention targeted word retrieval as it is one of the challenges most frequently experienced by people with aphasia, restricting their communication. The intervention was designed by SLTs specialising in aphasia and use of computer software for its treatment. The components of the intervention were designed to incorporate key factors that neuroplasticity principles and research suggest positively influence aphasia therapy outcomes combined with practical considerations: exercises tailored to the difficulty experienced by the individual with aphasia (specificity); content of therapy tailored to personal interests (salience); use of computer software to enable independent practice and therefore increased amounts of practice for a duration longer than that achievable through face-to-face therapy alone; and practical support and motivation for use of the software.

The four key components of the intervention are summarised below:

-

StepByStep software (version 5) – specialist aphasia software designed by SLTs and commercially available.

-

Qualified SLT assessment of the participant’s language profile to tailor computer exercises using StepByStep so that they target the specific language deficit identified. Creation of exercises using target words of personal relevance to the participant.

-

Daily independent word-finding practice with the tailored computer exercises by the participant for 6 months.

-

Volunteer/SLTA support to enhance adherence to the computer exercises and to encourage transfer of new words into functional daily situations.

The TIDieR items ‘what?’, ‘who?’, ‘how?’, ‘where?’, ‘when?’, ‘how much?’ and ‘tailoring’ are described within each of the four components of the intervention in the following sections.

StepByStep software

What?

StepByStep software was chosen as it focuses on word-finding, allows for exercises to be tailored to individual need, enables personalisation through the addition of photographs (e.g. their spouse’s) and provides feedback to the person with aphasia on practice frequency and duration and progress to aid motivation for repetitive practice. All of these features support the principles of experience-dependent neuroplasticity. The software was purchased by each NHS trust and provided to participants randomised to the computer therapy group of the trial. If participants had their own laptop/desktop or tablet computer, a home licence was installed by the SLT (for additional information on devices and microphone recommendations, refer to the Therapy manual: Big CACTUS StepByStep computer therapy approach at www.sheffield.ac.uk/scharr/sections/dts/ctru/bigcactus). If the participant did not own their own device, or their device could not run the software, a laptop or tablet computer owned by the NHS trust was loaned with a clinician licence of the software installed (for more than one user) for a period of 6 months. Participants with a home licence installed on their own computer kept this after the 6-month period. The combination of loaning devices for set periods of time and provision of home-user licences enabled equity of intervention provision, and reflected pragmatic decisions required for delivery of such interventions in clinical practice.

Qualified speech and language therapist assessment, tailoring of exercises and monitoring

Who?

A qualified SLT (one at each site) with experience of treating aphasia post stroke as part of the clinical team at that site.

What and tailoring

The SLT-tailored computer exercises to the individual using 100 words of personal relevance chosen by the participant. The word sets were standardised to 100 for each participant to allow sufficient words to maintain interest and motivation to practice for the long intervention period (up to 6 months). A meta-analysis of numbers of words used in word-finding therapy and outcome showed that people with all severities of aphasia could manage large word sets. 32 There is a large bank of photographs within the StepByStep computer program from which to select personally relevant vocabulary and if something extra was required (e.g. a picture of a grandchild or favourite football team) it was photographed digitally and added by the SLT. The computer software20 enabled the SLT to select exercises using these words; the exercises follow steps in the therapy process that the therapist would take if delivering word-finding therapy face to face. The SLTs based the selection of exercises on language skills demonstrated in the initial language assessments and therefore ensured that word-finding cues were useful and exercises were set at a level of difficulty with which the participant could experience success before moving on to more challenging exercises (see Therapy manual: Big CACTUS StepByStep computer therapy approach for the NHS, for instructions on how to modify exercises according to assessment results, at www.sheffield.ac.uk/scharr/sections/dts/ctru/bigcactus). The SLT provided an initial demonstration of the software exercises and spent time checking that the individual was able to use the software and monitoring the appropriateness of the tailored exercises. The SLT also reviewed the need for additional pieces of hardware, such as tracker balls, in order to make it physically possible for participants to use the computer.

Where?

The SLT carried out both assessment of and introduction to the computer exercises in the participants’ own homes.

Regular self-managed practice

How, where, when and how much?

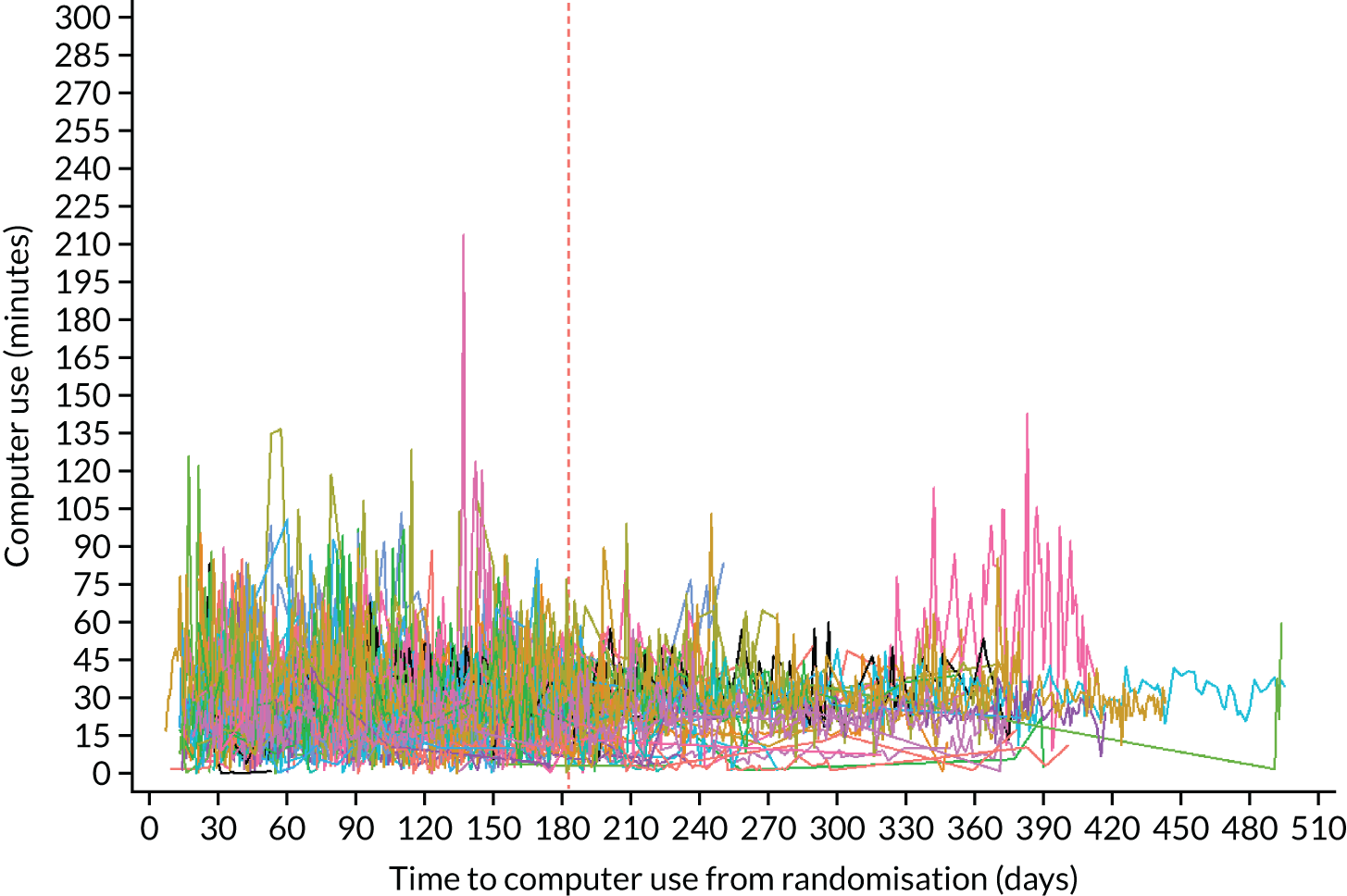

The participant was then asked to work through the exercises on the computer, with the aim that they would practise each day for 20–30 minutes. Participants were given a 6-month period to work through the therapy material on the computer at home and to practise using the new vocabulary in their daily lives. Practice with the computer for a minimum of 20 minutes three times per week at home on average across at least a 4-month period was considered per protocol. This accounted for periods of illness and holiday expected to occur in a 6-month period. The amount of practice was captured automatically by the computer program. Those participants who had the software installed on their own computers were not prevented from continuing to practise if they wished (with no prescribed support) following the 6-month supported intervention time. If computers were loaned, they were taken back after 6 months or when a new participant needed to borrow a computer (as permanent loan of equipment would be unusual in practice).

Volunteer or speech and language therapy assistant support with treatment adherence and carry-over into daily activity

Who?

To support use of the computer exercises, the SLT provided training to local volunteers who already had a working relationship with the speech and language therapy department (based in NHS trusts, local voluntary organisations or student SLTs) or SLTAs based in their department. This variation aimed to allow for consistency with the current mechanisms for providing therapy support in each NHS trust.

What, when, where, and how much?

The training programme and instruction book developed and evaluated during the pilot study was used (see Big CACTUS volunteer/assistant handbook at www.sheffield.ac.uk/scharr/sections/dts/ctru/bigcactus). The volunteer was asked to visit the participant at home for a minimum of 4 hours (once a month for 1 hour, or every 2 weeks for half an hour to suit the participant), carrying out the following tasks:

-

provide technical assistance

-

observe and encourage use of computer exercises

-

check results and discuss difficulties

-

assist the participant to move on to harder tasks in the therapy process pre-programmed by the SLT

-

encourage the use of new words in everyday situations through conversation and discussions with family about how to encourage use

-

set up new vocabulary sets if all 100 words had been completed.

Further advice provided to the volunteers/assistants on how to support the participant is detailed in the volunteer handbook (see www.sheffield.ac.uk/scharr/sections/dts/ctru/bigcactus). The participants were able to contact the volunteer/SLTA by telephone for technical advice on computer use between planned visits if necessary. The volunteer/assistant was introduced to the participant by the SLT on a joint home visit, and the volunteer was shown the exercises that had been set up. After each planned visit to the participant, the volunteer/assistant completed a feedback form for the SLT on what they did in the session and any issues/questions. The volunteer could contact the SLT by e-mail or telephone between support sessions to report any concerns/difficulties.

The computer intervention was delivered in addition to UC (see Usual-care control group).

Modifications

In response to feedback from the first four therapists providing the intervention to their first participants, the handbook was modified to explain that not all available cues needed to be tailored, only those assessed as being useful for the individual. Provision was also made for therapists to provide the words to the participant over more than one session, to add cues for a subset of words and to review the usefulness of the cue before adding to all 100 words.

Fidelity/measurement of how well the intervention was delivered

The aim was to measure the effectiveness of the intervention as it would be delivered in clinical practice. The SLTs delivering the intervention attended 1 day of training on how to use the StepByStep software; training was provided by SLTs in the central Big CACTUS team based on training available to SLTs from Steps Consulting Ltd. They received a therapy manual (see www.sheffield.ac.uk/scharr/sections/dts/ctru/bigcactus).

The volunteers/assistants and SLTs were to support participants’ adherence to computer practice as part of the intervention. However, no additional strategies were used to maintain or improve fidelity that could not be used in routine clinical practice.

Fidelity measures of the four key components of the intervention are outlined in the following sections.

StepByStep software

The proportion of participants allocated to the computer therapy group who had access to the StepByStep therapy software (the coverage of the intervention) was indicated by the completion of forms by the SLT to confirm that access had been given.

Assessment and tailoring of software by the speech and language therapist

Following training on how to set up the software and deliver the intervention, quality of delivery of the intervention was evaluated using a quiz of SLT knowledge about the intervention and a therapy planning form that SLTs completed each time they tailored the StepByStep software that captured their reasoning for the prompts and cues selected. SLTs delivering the intervention completed the quiz 5, 10 and 15 months after randomising their first participant. In addition, SLTs delivering the intervention were asked to complete therapy planning forms for an independent SLT to judge the extent to which exercises chosen were consistent with the language assessment results. For each SLT delivering the intervention, one therapy planning form was appraised by a StepByStep approach expert (RP, the Big CACTUS chief investigator, author of the therapy manual and a SLT experienced in delivering the StepByStep approach in clinical practice). Scores of 2 (reasonable rationale for tailored steps), 1 (partial rationale) or 0 (no or inexplicable rationale) were used. The time spent on each of the activities involved in delivering the intervention described in the manual was recorded by the SLTs delivering the intervention.

Practice of exercises by the participant

Adherence to exercise practice on the computer was captured automatically by the software and the total practice time was reported over the 6-month intervention period and compared with predefined per-protocol definitions (see Chapter 3, Per-protocol sets).

Volunteer/assistant support

The volunteers/SLTAs kept logs of the amount of time spent with each participant, including the number of sessions, duration of each session and session content.

The original Big CACTUS protocol funded by the Health Technology Assessment programme did not incorporate fidelity assessment. Measurement of fidelity to all components of the intervention was managed by a Big CACTUS research associate (MH) under the supervision of the chief investigator (RP) and co-investigator (CC) as part of a PhD funded by the Stroke Association. The results of the fidelity assessment described above are reported in the clinical results section of this report (see Chapter 4, Fidelity to computerised speech and language therapy: adherence to practice and quality of intervention delivery). A more-detailed evaluation of the fidelity to the intervention described within this trial will be available on completion of the PhD.

Attention control group

Why?

To control for the potential impact of elements of the computer intervention, which, of themselves, do not provide or require specific speech and language intervention.

What?

Participants were provided with generalised activities to carry out and general attention in addition to UC. On allocation to this group, the SLT conducting baseline assessments provided books of standard puzzles that could be purchased from most supermarkets or from high-street shops. Each book contained enough activities for one to be carried out each day for at least 1 month. Examples of puzzles include ‘spot the difference’, noughts and crosses, and word searches. The PCPI group advised on types of puzzle book that may be of interest and practical factors, such as size of the text.

Who?

The SLT provided age-appropriate puzzle books that matched the participant’s linguistic and cognitive ability as indicated by the baseline assessments. Puzzle books were colour coded into levels of easy, medium and hard by the clinicians on the research team centrally with support from the PCPI group and a leaflet was provided to give SLTs guidance on skills required for each level.

Who, how, where, when and how much?

A member of the research team contacted the participant or their carer by telephone or e-mail (whichever was preferred by the participant) once a month for the duration of the 6-month intervention period to mimic the attention provided by volunteers in the intervention group. Participants were asked if they were enjoying the activities, how many they managed to do at home, whether or not they would like a new puzzle book sent to them for the coming month and whether or not it needed to be the same level of difficulty, or easier or harder. The participants also had access to contact details of the research team to enable them to ask for easier or harder books at any time if necessary, mimicking the access to the volunteers/SLTAs and type of attention available in CSLT.

Modifications

No modifications were made to AC during the course of the trial.

Fidelity/measurement of how well the intervention was delivered

The number of puzzle books sent out and the number of contacts made by the research team were used as a proxy measure of adherence to AC. A puzzle book was sent out if a participant or carer reported completing the previous one. A minimum of six puzzle books and four contacts was used as a measure of adherence to the intervention.

Outcomes

Primary outcome measures

Research objective 1: to establish whether or not self-managed computerised speech and language therapy for word-finding increases the ability of people with aphasia to use vocabulary of personal importance (impairment)

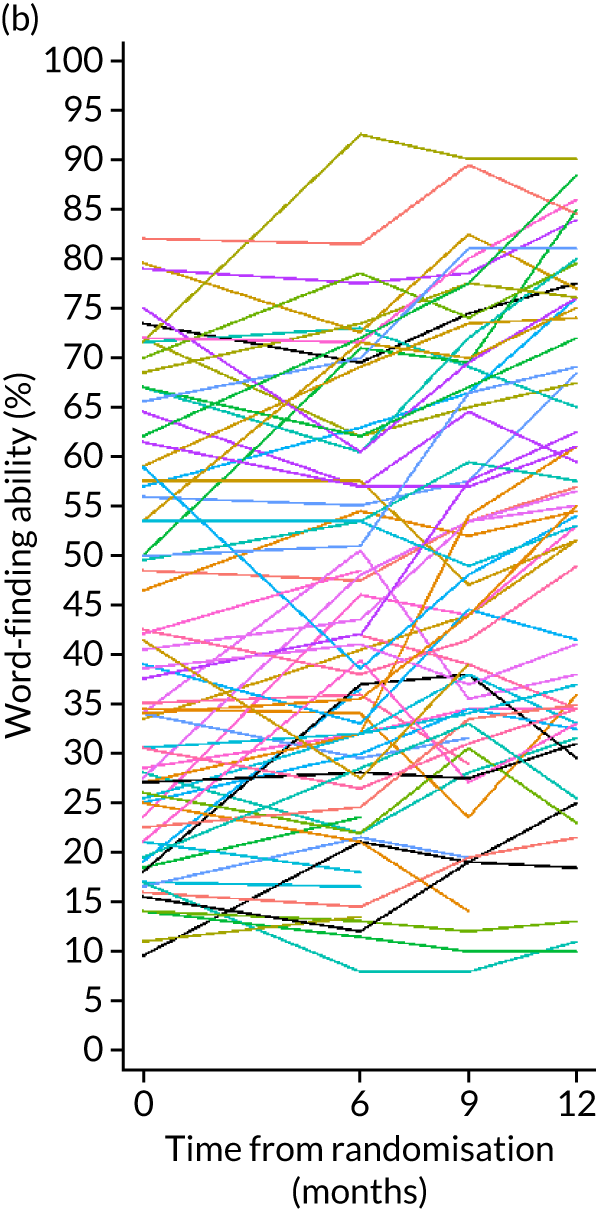

The change in word-finding ability, between baseline and 6 months, of words personally relevant to the participant was measured by a picture-naming task (100 words with a maximum of 2 points each). The word-finding score was expressed as a percentage of the total score, and change in the percentage 6 months from baseline was calculated. This is a measure of the change in the impairment and was considered to be of interest to SLTs as it indicates whether or not word-finding treatment for persistent aphasia (i.e. beyond the acute and subacute phase) is effective for improving retrieval of words.

The pictures were presented within an assessment module of the StepByStep programme by the research SLT at baseline at the NHS trust from which the participant was recruited.

The research SLT was trained on how to score the word-finding test and was provided with written instructions in the outcome measure therapists’ handbook (see www.sheffield.ac.uk/scharr/sections/dts/ctru/bigcactus). The research SLT was given two videos of people with aphasia carrying out word-finding tests for practice and this was reviewed by a speech and language therapy trainer from the central project team who provided feedback to the research therapist. The same test was performed 6 months after randomisation by an outcome measure therapist (a qualified SLT). This therapist was trained to score the test through webinar training from the central trial team. The scores derived from the two practice videos were compared with the scores of the research SLT in the same NHS trust to check for inter-rater reliability between raters within each trust. When there was a discrepancy, the research SLT and outcome measure therapist were encouraged to discuss differences and rate a third video.

Research objective 2: to establish whether or not self-managed computerised speech and language therapy for word-finding improves functional communication ability in conversation (activity)

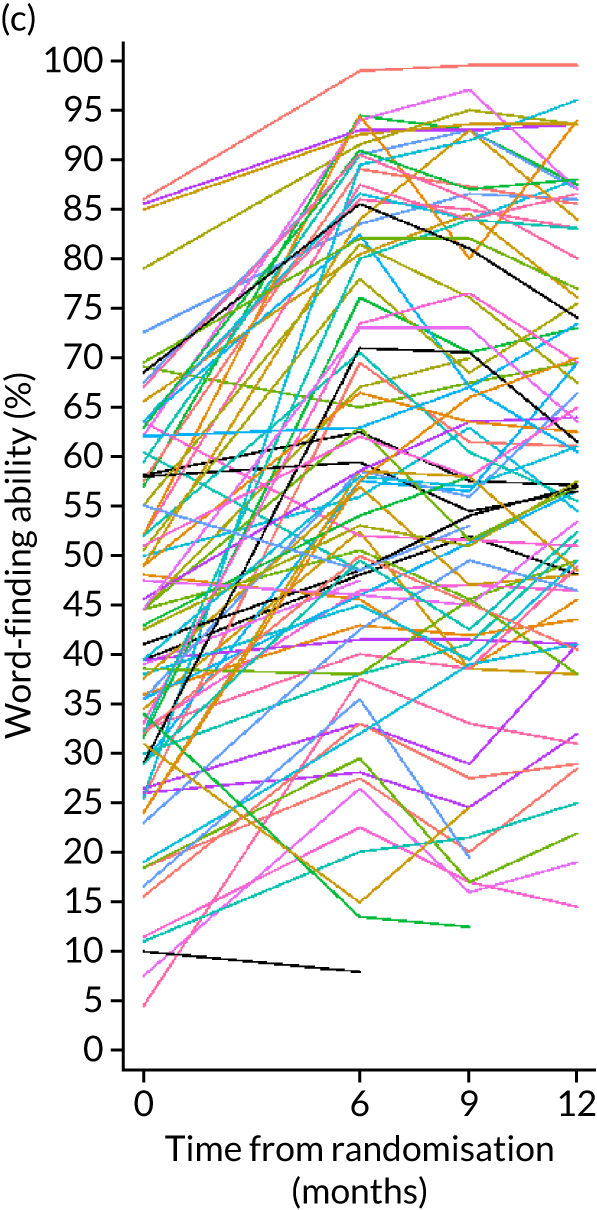

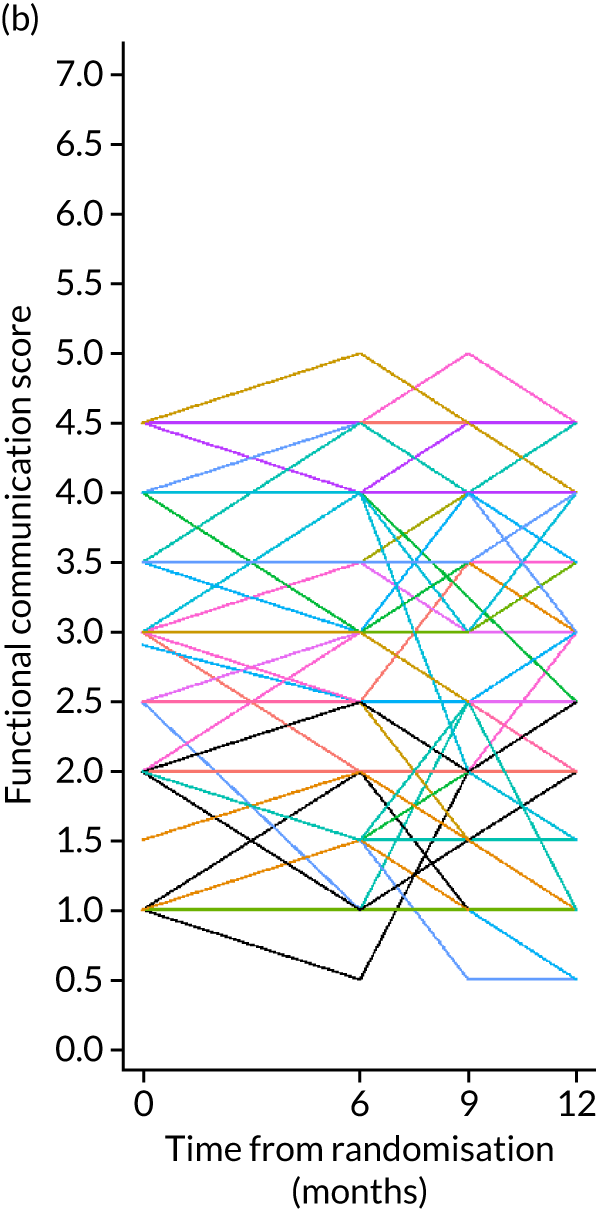

Change in functional communication between baseline and 6 months was measured by blinded ratings of 10-minute video-recorded conversations between a SLT (research SLT at baseline and outcome measures SLT at outcome) and participants, using the activity scale of the TOMs. 33 Conversations were structured around topics of personal relevance to the participants by the SLT performing baseline measures, based on the 100 words they selected. The same conversation topic guide was followed by SLTs performing outcome measures. Independent SLTs blinded to treatment allocation and measurement time point rated the videoed conversations at the project co-ordinating centre. This measure of functional communication ability was used to indicate whether or not the word-finding intervention had any impact on the ability to communicate in conversation. TOMs were chosen as a primary outcome measure of this ability as they have been standardised, shown to be reliable and have been used to rate videoed conversations in a previous RCT of aphasia intervention [Assessing Communication Therapy in the North West (ACT NoW)8] with good reliability.

A benchmarking session using the TOMs was conducted with potential raters to get consensus on the application of the TOMs in this project, followed by inter-rater and intrarater reliability tests at least 6 weeks apart using 10 practice videos. Scoring instructions were provided following consensus during the benchmarking session (see Appendix 2). The consensus was that pairs of videos were easier to rate for each individual rather than isolated videos for each participant. The 14 raters selected for final rating of all participant videos had intrarater reliability of at least 70% (7/10) of practice videos rated within 0.5 between rating at time 1 and time 2, and inter-rater reliability of at least 70% (14/20) of videos rated within 0.5 of the median scores from all raters at both time points. In total, 86% (240) of the 20 ratings made by each of the 14 reviewers (total 280 ratings) were within 0.5 of the median score, and 88% (123/140 ratings) were within 0.5 between time 1 and time 2. A slight upwards trend was noted in scoring between time 1 and time 2; therefore, the pairs were presented in random order. For further detail of the process for selection of TOMs raters and the scoring procedure, see Appendix 2.

Key secondary outcome measure

Research objective 3: to investigate whether or not patients receiving self-managed computerised speech and language therapy perceive greater changes in social participation in daily activities and quality of life (participation)

Improvement in patient perception of communication between baseline and 6 months was measured using the Communication Outcome after Stroke (COAST) scale, a patient-reported measure of communication, participation and quality of life validated for evaluating speech and language therapy interventions in the Health Technology Assessment ACT NoW project. 8 This measure was used to provide SLTs with quantitative information on participant perceptions of the effects of the intervention on their life to complement the qualitative information collected through patient interviews in the pilot study. The COAST was administered face to face by the research SLT at each participating NHS trust at baseline and by outcome measures therapists at 6 months.

Secondary outcome measures

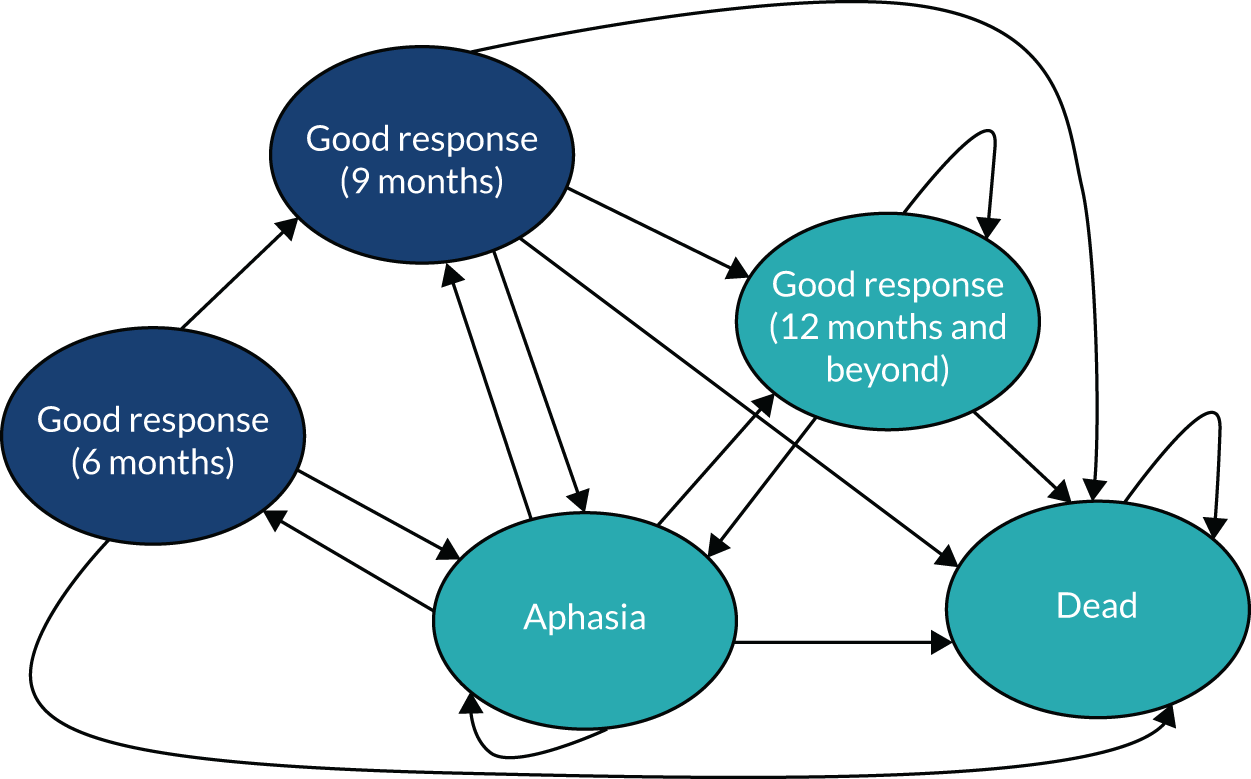

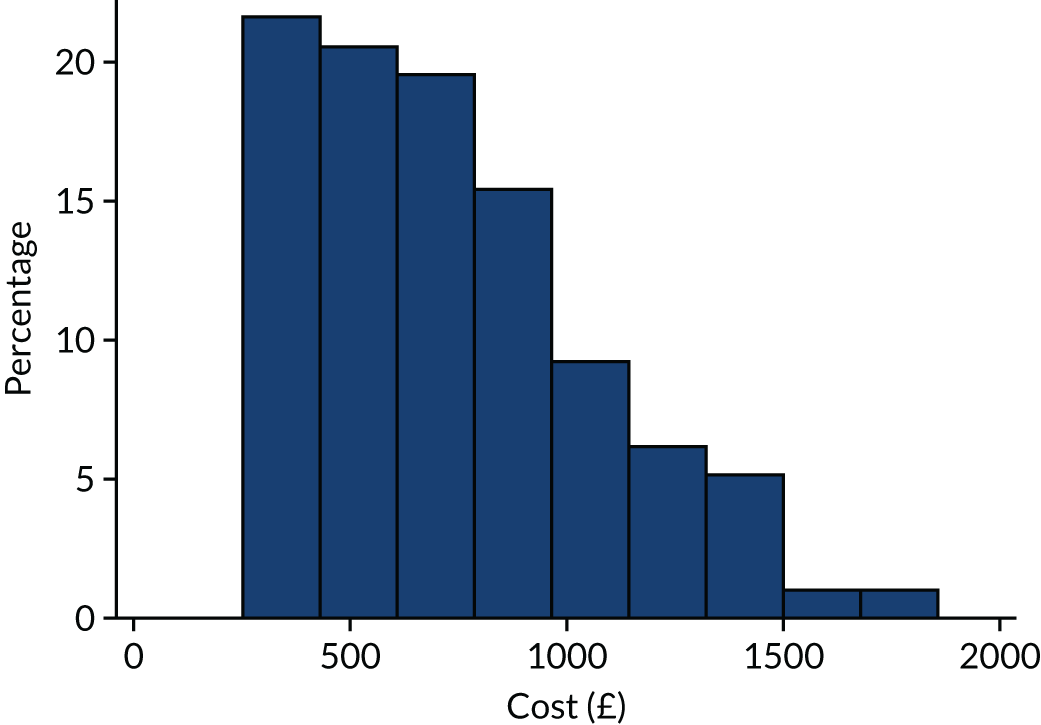

Research objective 4: to establish whether or not self-managed computerised speech and language therapy is cost-effective for persistent aphasia post stroke

A cost–utility analysis was undertaken from a NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) perspective. The cost-effectiveness outcome was the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), where effectiveness was measured in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). The incremental analysis included all three of the trial groups. Resource costs were estimated for patients, including intervention software and hardware, and SLT and assistant input time, combined with standard costing sources. Volunteer time was also recorded and costed for inclusion in a supplementary analysis taking a broader perspective. SLTs were asked to complete therapy activity forms for each contact with each participant, detailing their Agenda for Change pay band, time spent setting up the computer therapy or in face-to-face support, or support/training of the volunteer/assistant, and travel mileage. Assistants and volunteers were also asked to complete activity forms with information on their Agenda for Change pay grade if applicable, time spent face to face or indirectly with the participant, activity conducted with the participant and mileage.

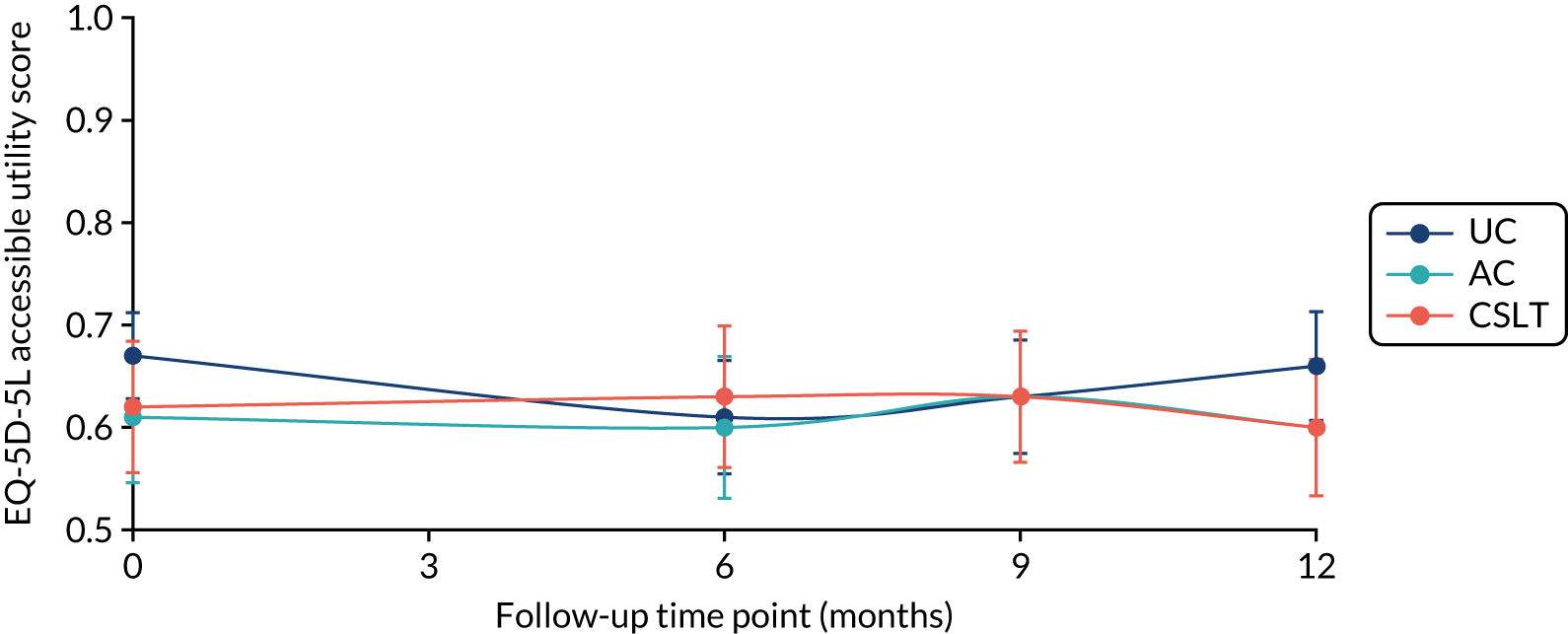

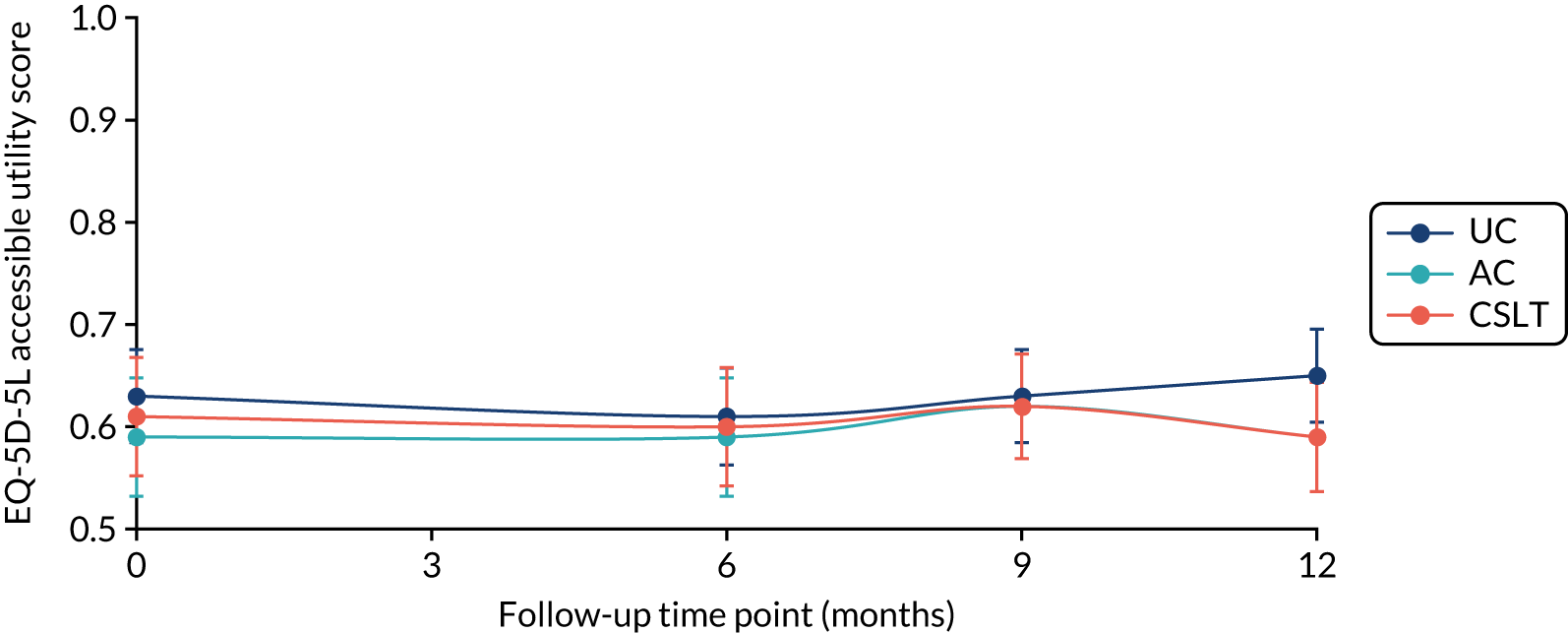

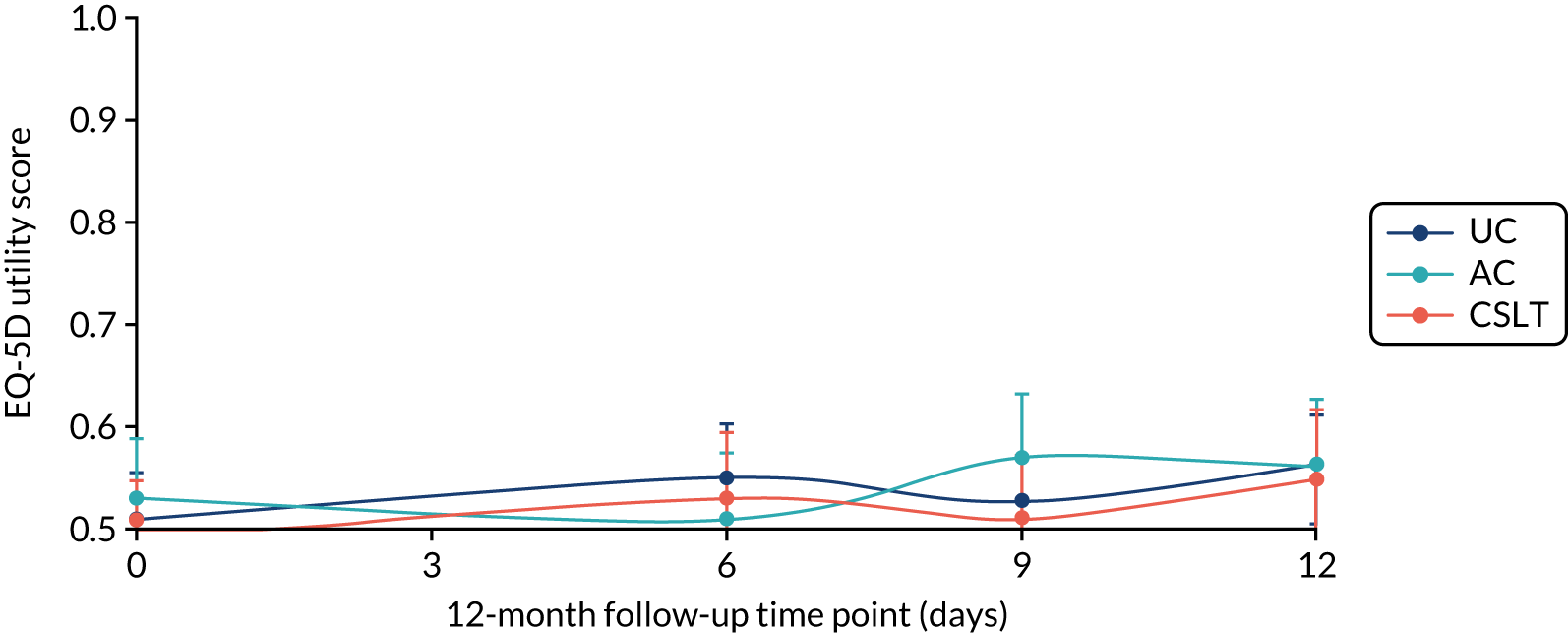

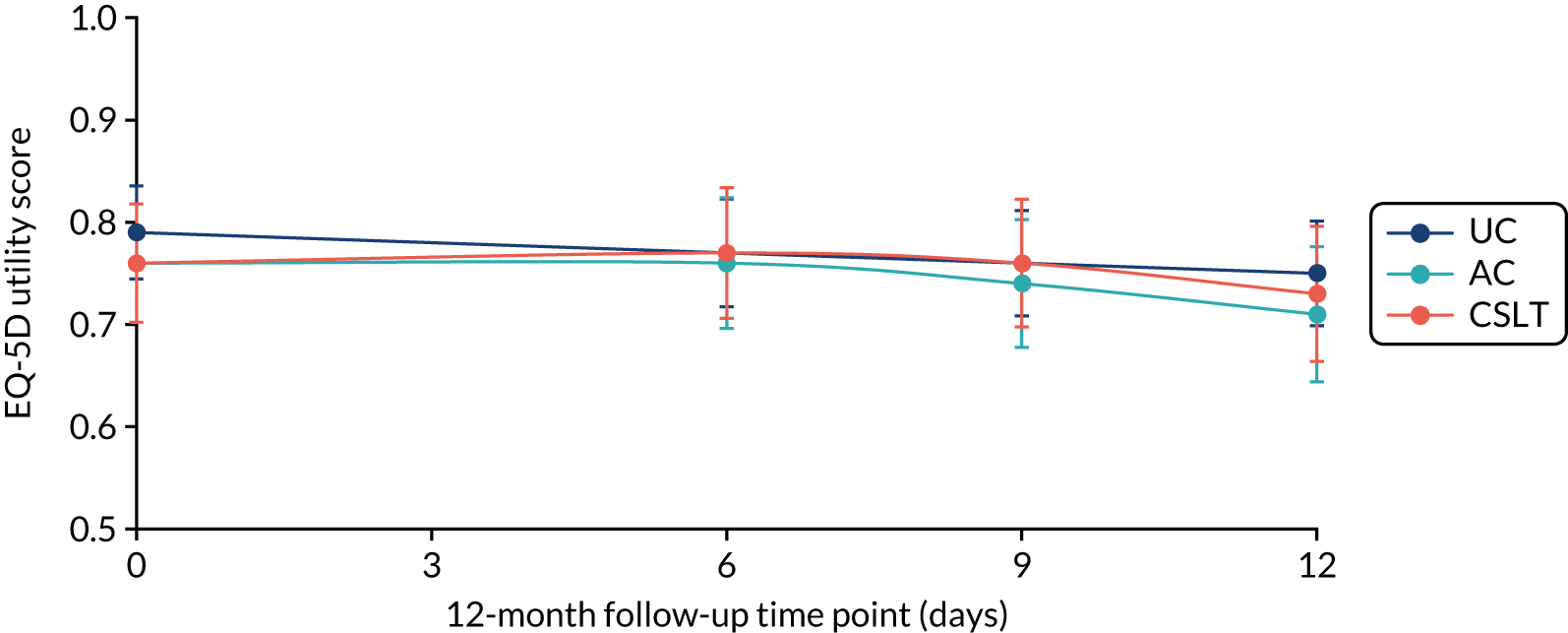

The EQ-5D-5L questionnaire was administered at all time points and combined with standard valuation sources to measure QALYs gained in each treatment group. An accessible version of the EQ-5D-5L designed by the PCPI group for people with aphasia was completed by participants. An accessible version of the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), had been tested in the pilot study. 18 The carers (if available) completed the standard version by proxy. Carers also completed the EQ-5D-5L for themselves. For more detail about the use of EQ-5D-5L in this trial, see Chapter 5, Health-related quality of life.

Information on cost-effectiveness was important to inform commissioners of speech and language therapy services as well as providers to assist with decisions regarding funding such an intervention.

Research objective 5: to identify whether or not any effects of the intervention are evident 12 months after therapy has begun

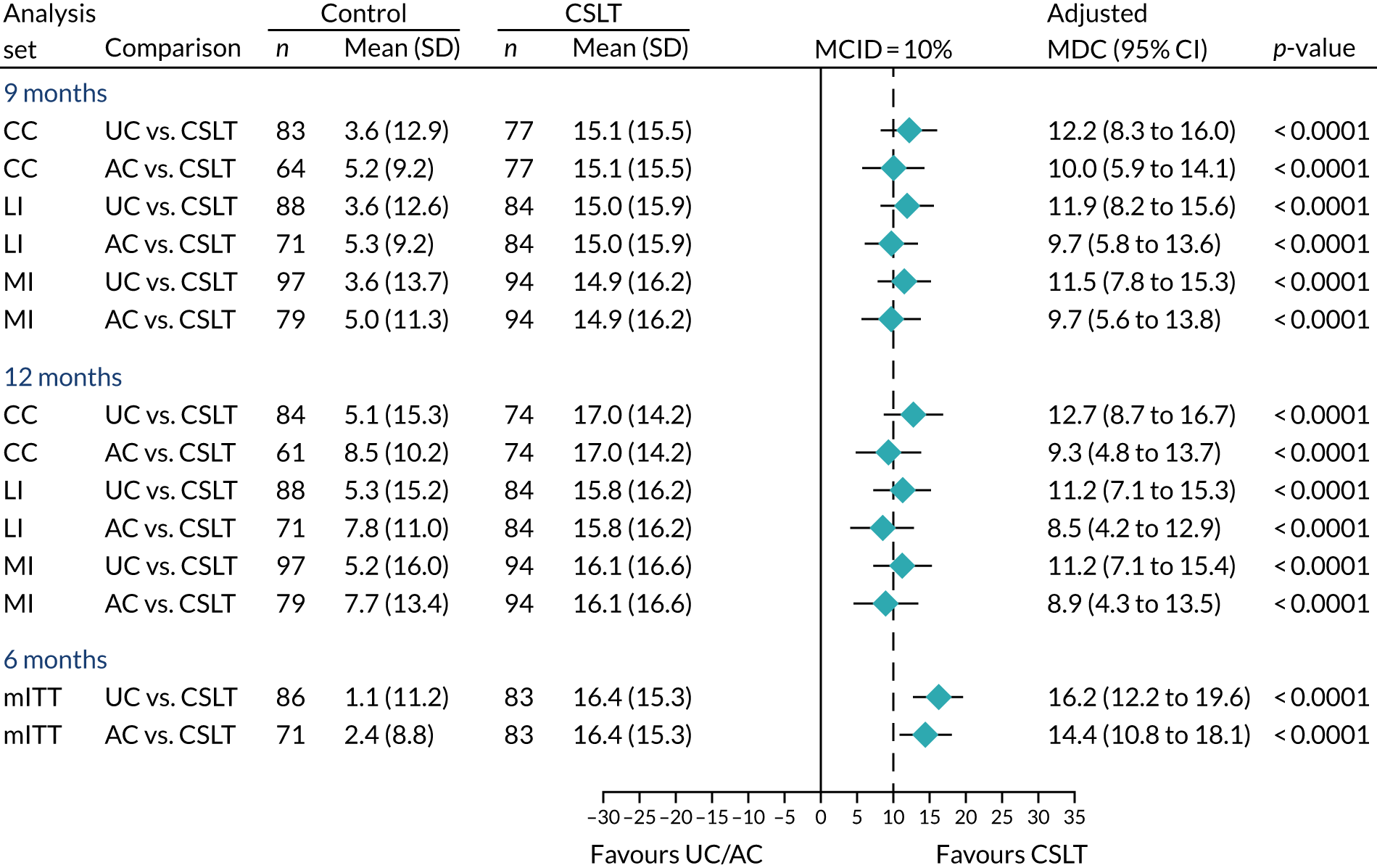

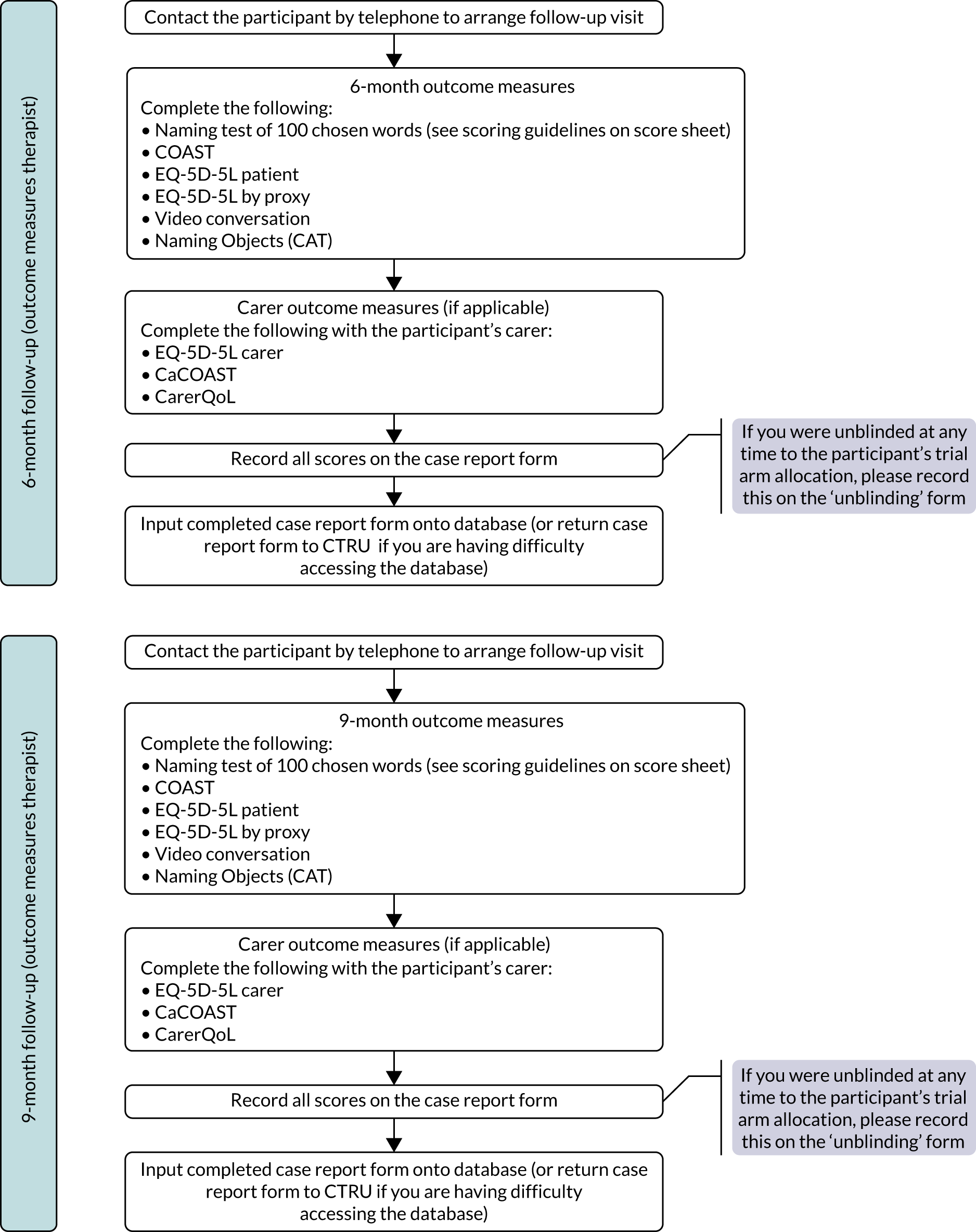

Evidence of treatment effect was measured by repeating all outcome measures at 9 and 12 months from baseline in addition to the primary end point of 6 months. The 9-month time point was included as an interim measure as withdrawal from the trial was found to increase over time in the pilot study. Follow-up measurements were important to provide information to SLTs, commissioners and providers about the long-term impact of the intervention.

Additional secondary outcome measures

The first primary outcome measure identified improvement in the ability to retrieve words practised in therapy and the second primary outcome measure identified any improvement in conversation using the standard descriptors provided by the activity scale of the TOMs33 to try to detect generalisation of any impairment level improvement to the level of activity. As an intermediate and potentially more sensitive measure of generalisation, use of words practised in therapy in the context of conversation was measured by two research members of the central trial team who watched each videoed conversation and identified how many words practised in therapy were used during the structured conversation on related topics. The researchers ticked the word on a checklist if it was heard and scored the total number of practice words heard. Intrarater and inter-rater reliability was established for the researchers. They both rated the same set of 10 videos twice, a minimum of 6 weeks apart. Inter-rater reliability was 80% (8/10) at both time 1 and time 2. Intrarater reliability was 100% (10/10) for rater Kathryn McKellar and 90% (9/10) for rater Ellen Bradley. The researchers were blind to the time point at which each video was made.

Generalisation of treatment to retrieval of untreated words was measured using the object naming test from the CAT. 30 This measure was used to show whether or not generalisation occurs from treated to untreated words. This is important to SLTs so they know whether or not careful selection of vocabulary for their treatment of word-finding is important.

Carer perception of communication effectiveness was measured using the Carer COAST (CaCOAST). 34

The last five items of the CaCOAST and responses to the Care-related Quality of Life instrument (CarerQol) were collected to indicate any impact of the intervention on the carers’ quality of life.

As self-managed computer use for speech and language therapy is relatively new and, by nature, unsupervised, any negative effects specifically felt to be related to computer use were collected using a negative effects questionnaire (see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/122101/#/related-articles) that was sent to the participants in the CSLT group every month. This asked participants whether the computer practice made them feel overtired, affected their eyes, gave them headaches or made them feel anxious or worried. They were also asked to list any other problems experienced as a consequence of using the computer therapy. In addition, adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported by the research therapists on discovery or following a telephone call to the participant or carer at 6, 9 and 12 months (see Appendix 3 for definitions of AEs and SAEs for the population in this trial).

For the method for calculating scores for all of the above outcome measures, see Chapter 3, Computation of summary outcome scores for analysis.

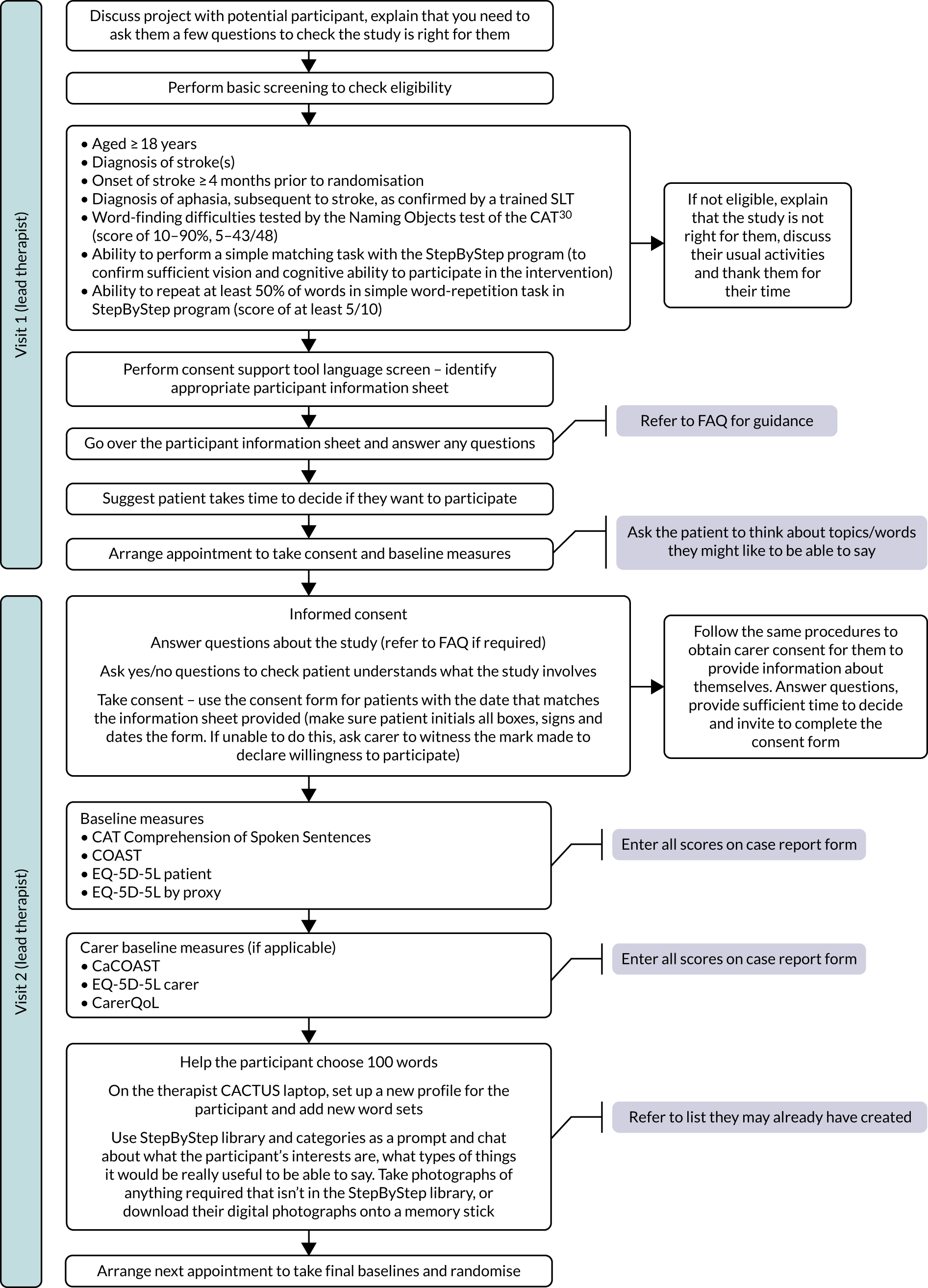

Staff training for delivery of outcome measures

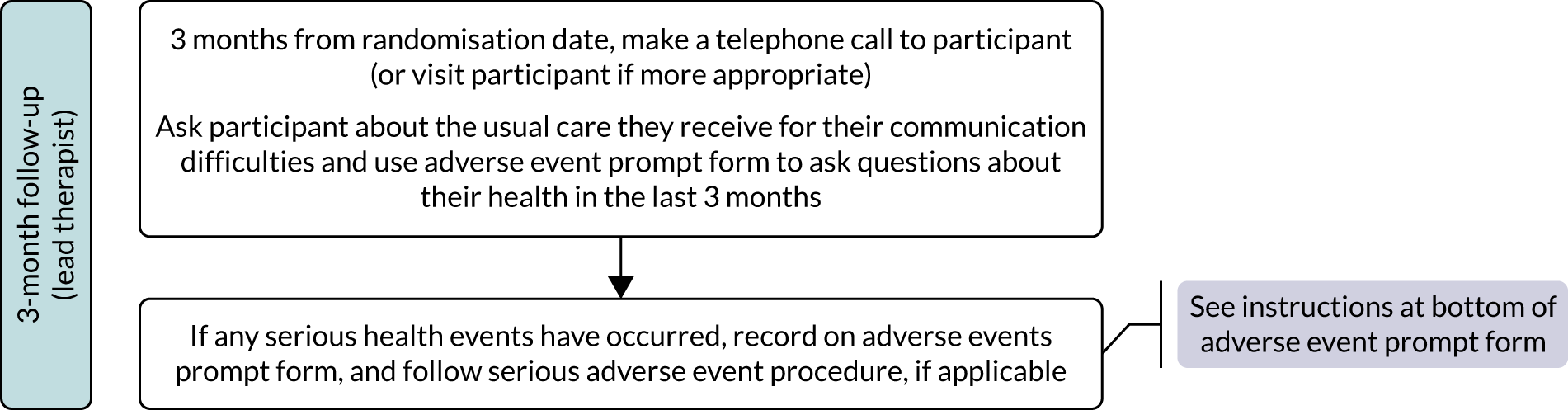

All research SLTs attended a 1-day training course delivered by the central research team to ensure understanding of the protocol and trial procedures including how and when to administer outcome measures. It was understood that some participants may need more than one visit to complete the assessments. The flow of participants through the trial was the responsibility of the research SLTs (principal investigators) at each participating NHS trust. A flow diagram of activity was provided to assist with this (see Appendix 4).

Therapists responsible for carrying out assessments at all follow-up time points (6, 9 and 12 months) were trained in their responsibilities, the importance of blinding and how to administer outcome measures. Training was in small groups via a webinar delivered by the trial manager and the central team speech and language therapy researcher. It was recommended that they conduct each outcome measure visit within 1 month of each time point to ensure that outcome measure visits were spaced sufficiently to avoid presenting a burden to participants.

Collection of demographic data

Initial assessment was undertaken by the research SLT at each participating NHS trust. The initial assessment visit included collection of demographic data: aphasia type, age, gender, time post onset of stroke, and type and location of stroke (if known).

Recording of usual care

The research SLT at each NHS trust was asked to record UC provided to each participant throughout the trial to provide a description of UC and also to ensure that UC did not change once participants were randomised to the trial. UC included care provided by both the NHS and the voluntary sector. In addition, the research SLTs were asked to record UC provided in the 3 months prior to randomisation from participant and carer reports and from SLT notes. For each session, they were asked to report the therapy goal, length of session, mode of delivery of session, Agenda for Change band of staff delivering the session and distance travelled. This information was sought every 3 months via telephone calls with the participants and carers and from inspection of participant notes if they were made aware that therapy had been received.

Sample size

The trial aimed to recruit a maximum of 285 participants (95 per group) across 20–24 speech and language therapy sites to preserve 90% power for a 5% two-sided test to address both co-primary objectives relating to word-finding of personally selected words and functional communication outcomes. We adjusted for a 15% drop-out rate observed in an external pilot trial. 21 For the change in word-finding, based on consensus of the therapists on the trial team and the aphasia PPI group, we assumed a 10% mean difference as clinically worthwhile to detect and a standard deviation (SD) of 17.38% estimated from an external pilot trial21 based on an analysis-of-covariance model.

We inflated the sample sizes by 1.14 to account for the fact that the variance was estimated from a pilot trial. 35,36 For the change in functional communication (TOMs activity scale), we sought an effect size of 0.45 of the SD as clinically worthwhile and a 0.5 correlation between baseline and outcome observed in the ACT NoW study (Professor Andy Vail, University of Manchester, 2013, personal communication).

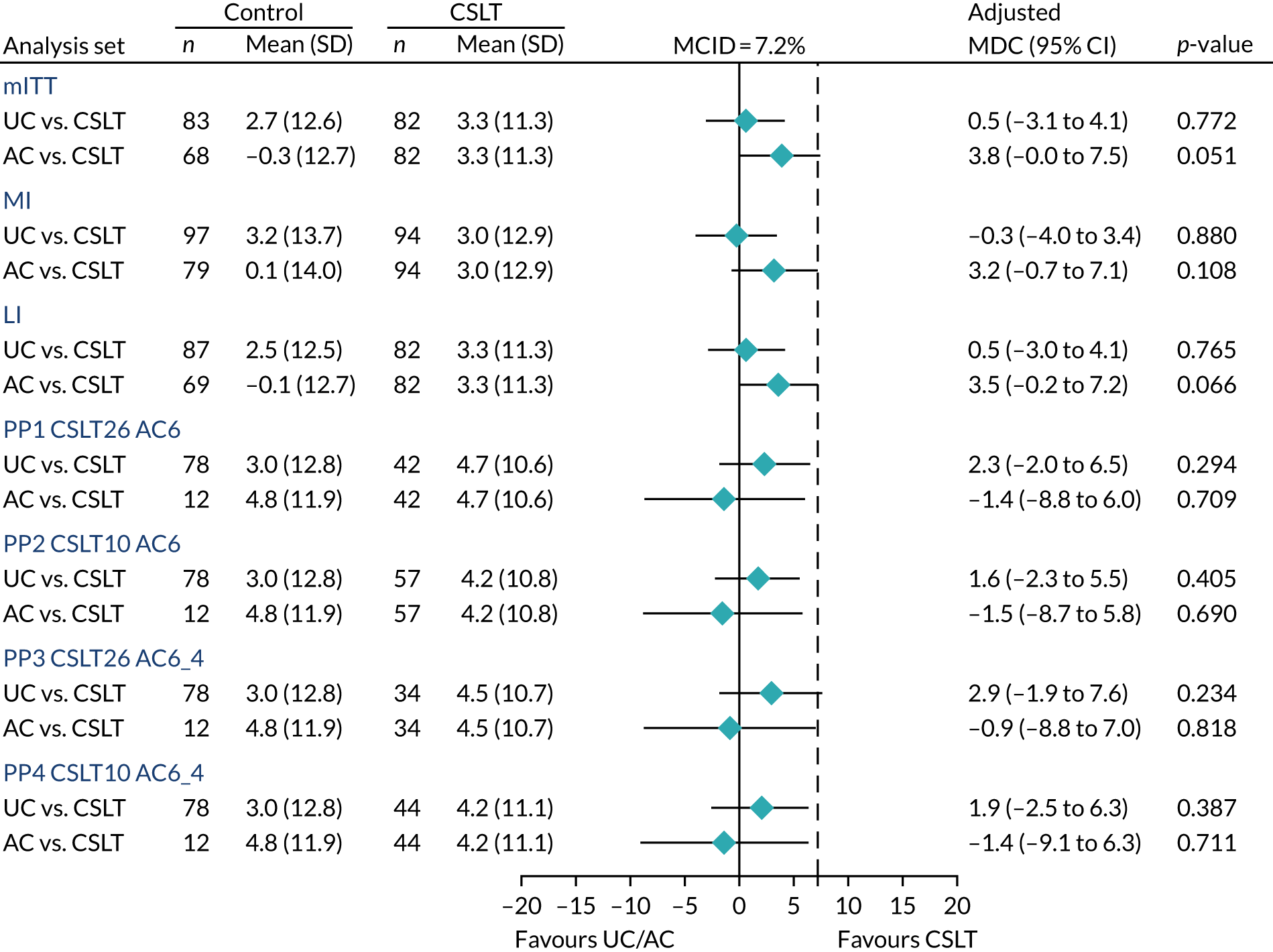

For the change in COAST, a key secondary outcome measure, we sought a 7.2% clinically worthwhile effect to detect and a SD of 18% based on externally supplied data and we assumed a 0.5 correlation between baseline and outcome. For a sample size of 285 (95 per group), the trial had 83% power for the COAST. The observed overall drop-out rate was about 9%, versus the planned 15%; as a result, further recruitment was terminated at 278 participants because the trial had the desired statistical power to address co-primary and key secondary outcomes.

Interim analyses and stopping guidelines

The initial phase of the trial was conducted as an internal pilot trial and included clear criteria to inform decisions about progression and the feasibility of the full trial only. No interim analysis for efficacy, futility or stopping early for safety was planned. Data from the internal pilot are included in the final analysis.

The internal pilot trial was limited to six sites (> 25% of the total). However, during this phase we recruited and commenced set-up processes for all of the intended sites to avoid a delay in the event that the trial continued. In accordance with the guidance on progression rules for Health Technology Assessment internal pilot trials, the lag phase expected before recruitment reached the target rate was excluded. For the substantive study, the lag phase included the period for obtaining approvals, site recruitment and staff training. The progression criteria were reviewed 8 months from site set-up of the sixth site.

Based on recruitment rates from the previously published pilot study,21 we aimed to recruit participants at an average rate of one participant per site per month. At the end of the internal pilot trial phase, the six pilot trial sites had been recruiting for a minimum of 8 months. The progression of the trial was based on achieving the following criteria.

Numbers recruited

The overall target for the six sites was 36 participants. The overall progression target for numbers recruited from the six sites was 30. This was equivalent to the number recruited in total in our previous pilot study and enabled comparison with previous recruitment rates to confirm whether or not our projections for the substantive study were accurate. There was also information available from other sites that had completed set-up and started to recruit; therefore, we expected at least 40 participants to have been recruited by the end of the internal pilot phase in total.

Recruitment as a percentage of the full-study recruitment targets

At the end of the internal pilot trial, progression depended on having recruited 30 participants (i.e. 10% of the total population recruited from 25% of the sites; this was midway through the recruitment phase for these sites). If we achieved this number, we would be on track to recruit only 80% of the sample size within the study period. We would then have to bring in the additional four contingency sites included in the costs to raise the recruitment to the sample size. If we did not meet this number, it would indicate that the larger study was unlikely to be feasible.

Retention to first outcome measure time point at 6 months (primary outcome)

The sample size calculation was based on an attrition rate of 15% at 90% power for the co-primary outcomes. The progression criterion for retention was set to ensure a minimum power of 80%. This would be achievable with a retention rate of 65%, which would still ensure that the results were generalisable.

Identification and retention of volunteers

Sites could provide support to patients in the intervention group of the trial from paid SLTAs or volunteers. Use of volunteers was reviewed at the end of the internal pilot phase. Progression criteria for continued use of volunteer support were set at 80% of participants having been offered a volunteer and 70% of participants continuing to be supported by the same volunteer for their 6-month treatment period. If these progression criteria were not achieved, continuation of the study would be with paid assistant support only.

Summary

In summary, 8 months after set-up of the sixth site, our progression criteria indicating feasibility of the full trial were:

-

recruitment of no fewer than 30 participants (10% of the target for the full trial)

-

a minimum retention rate of 65%.

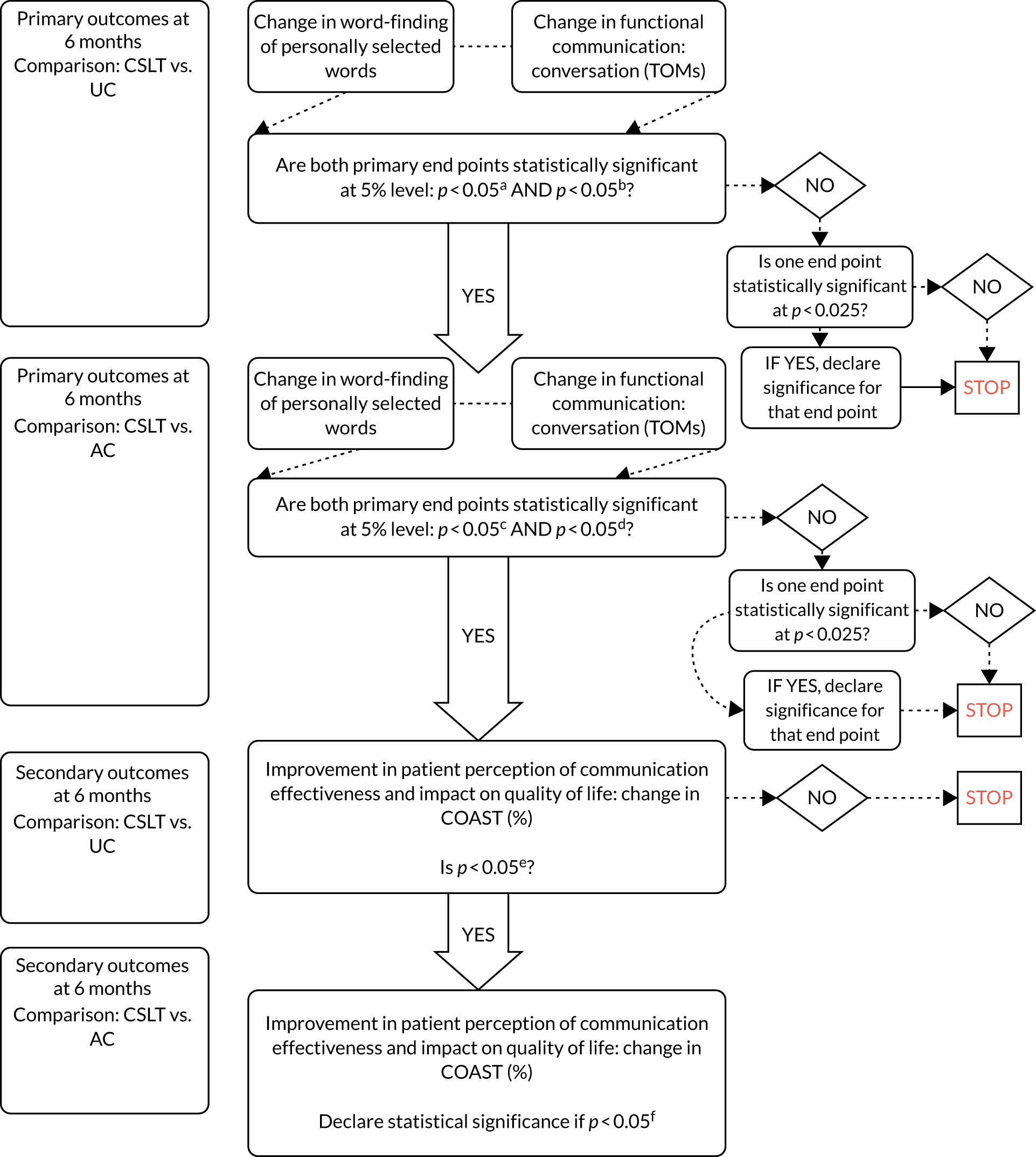

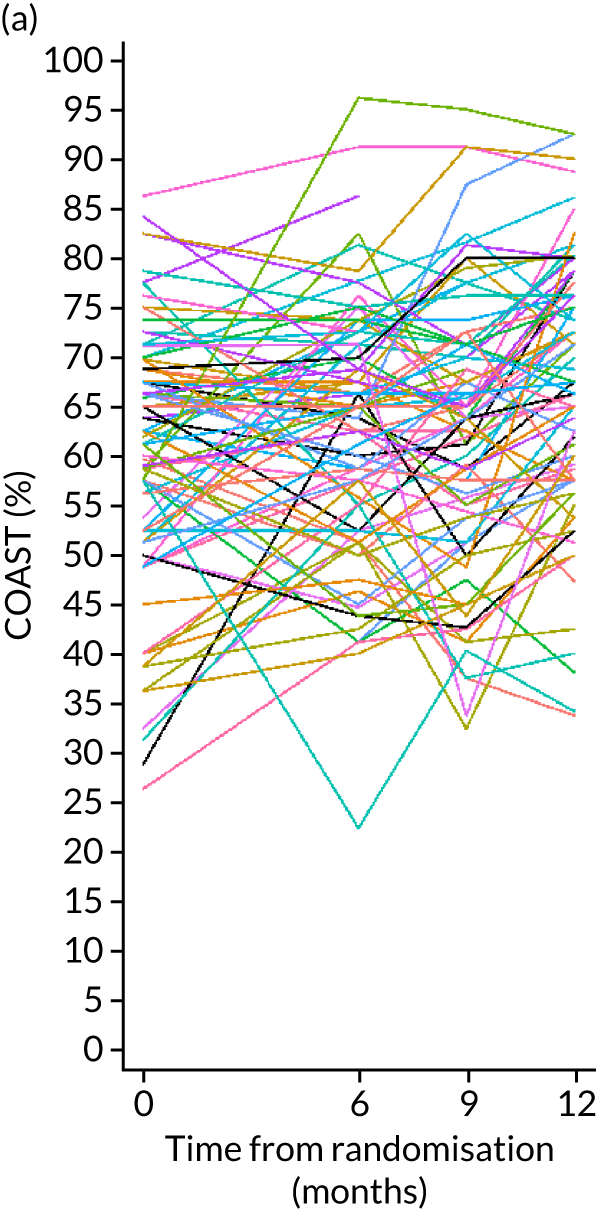

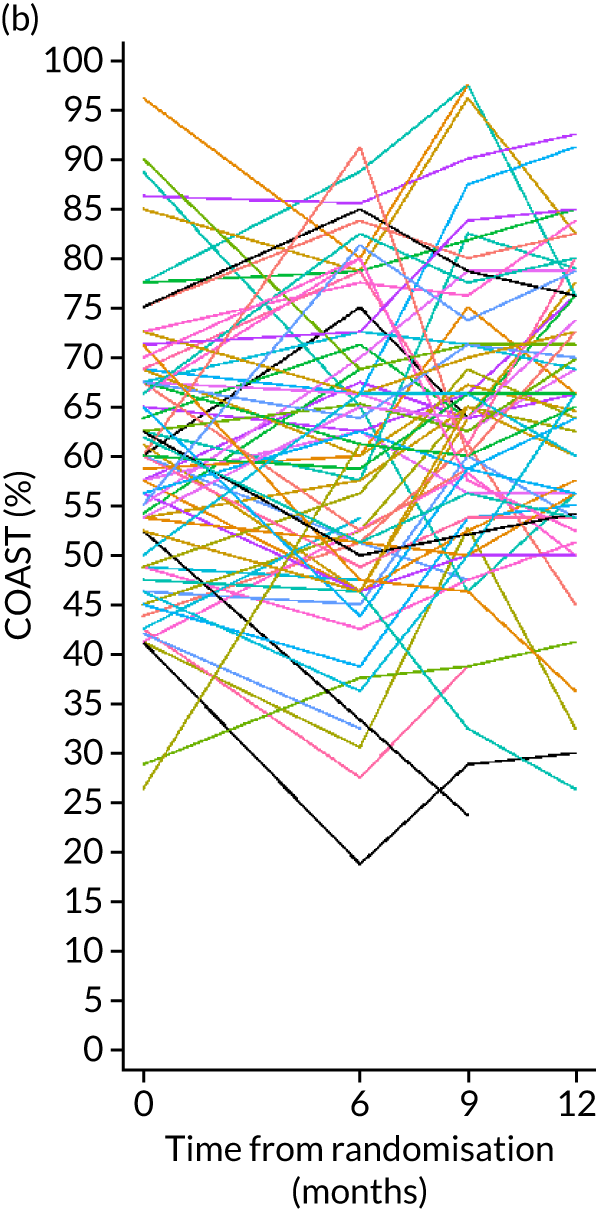

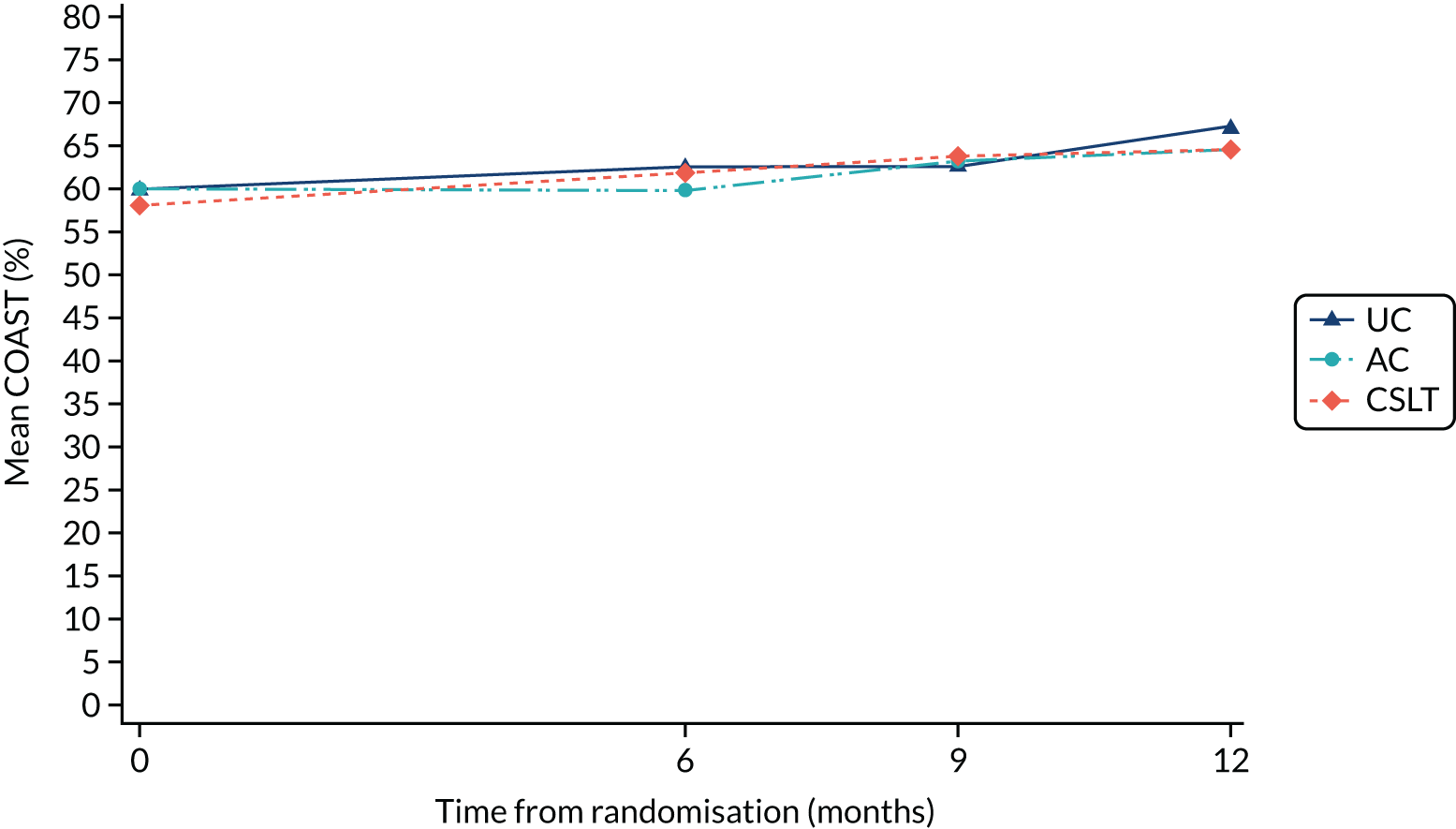

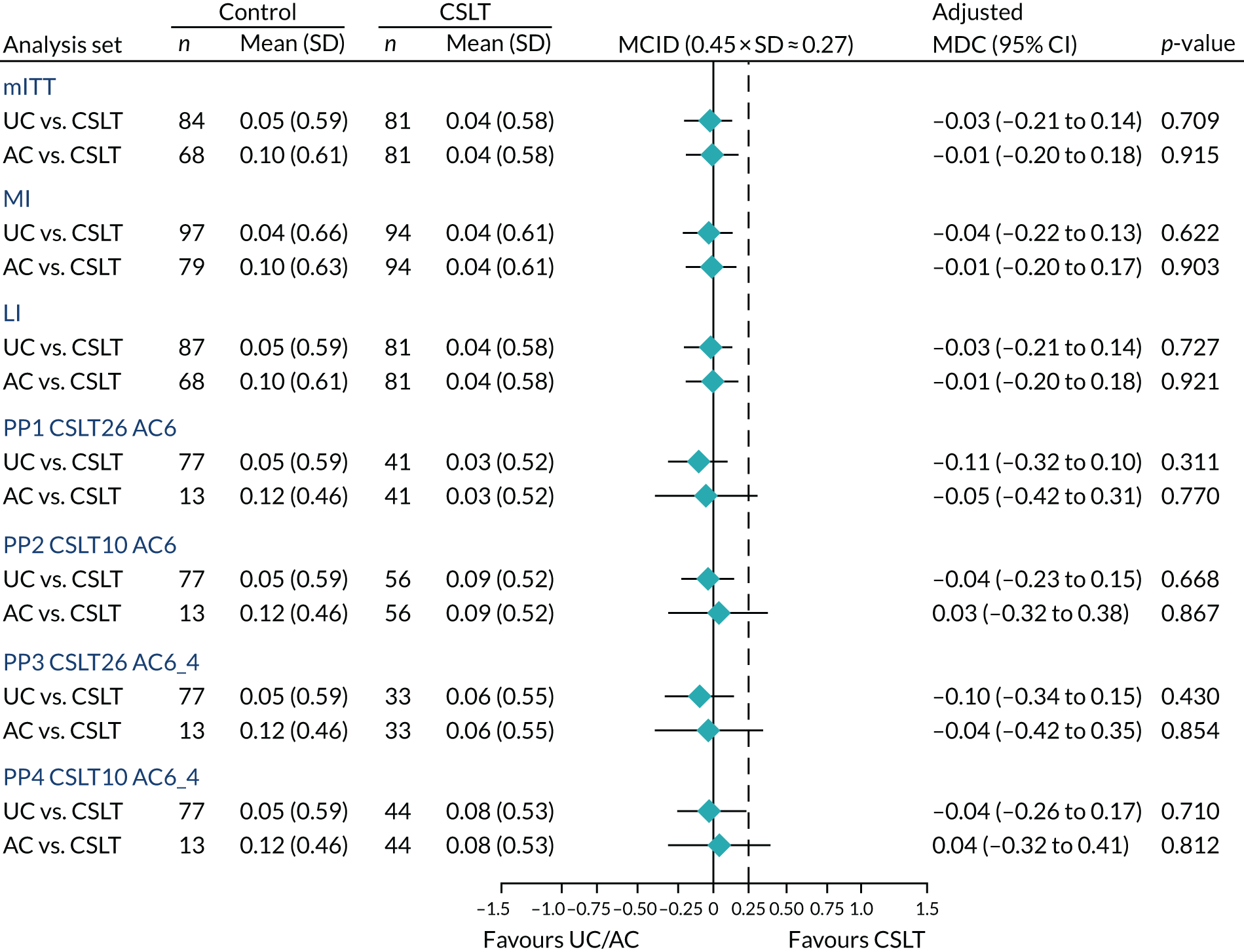

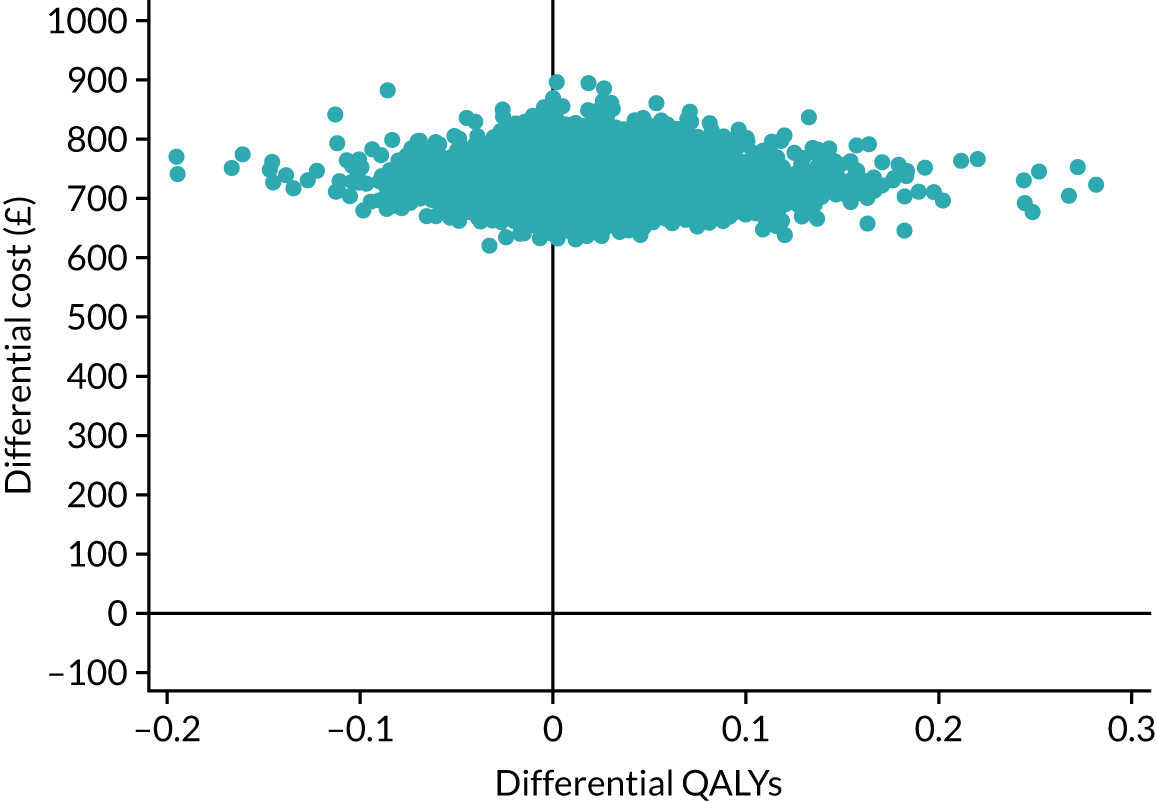

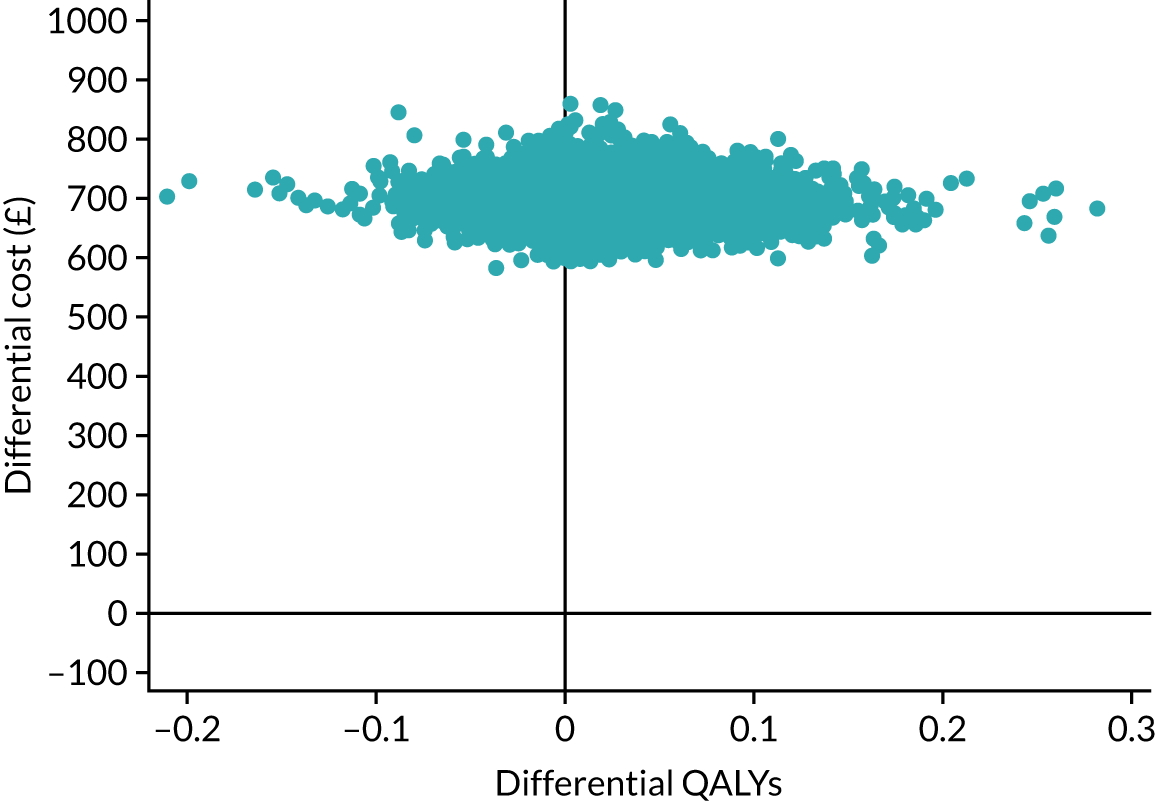

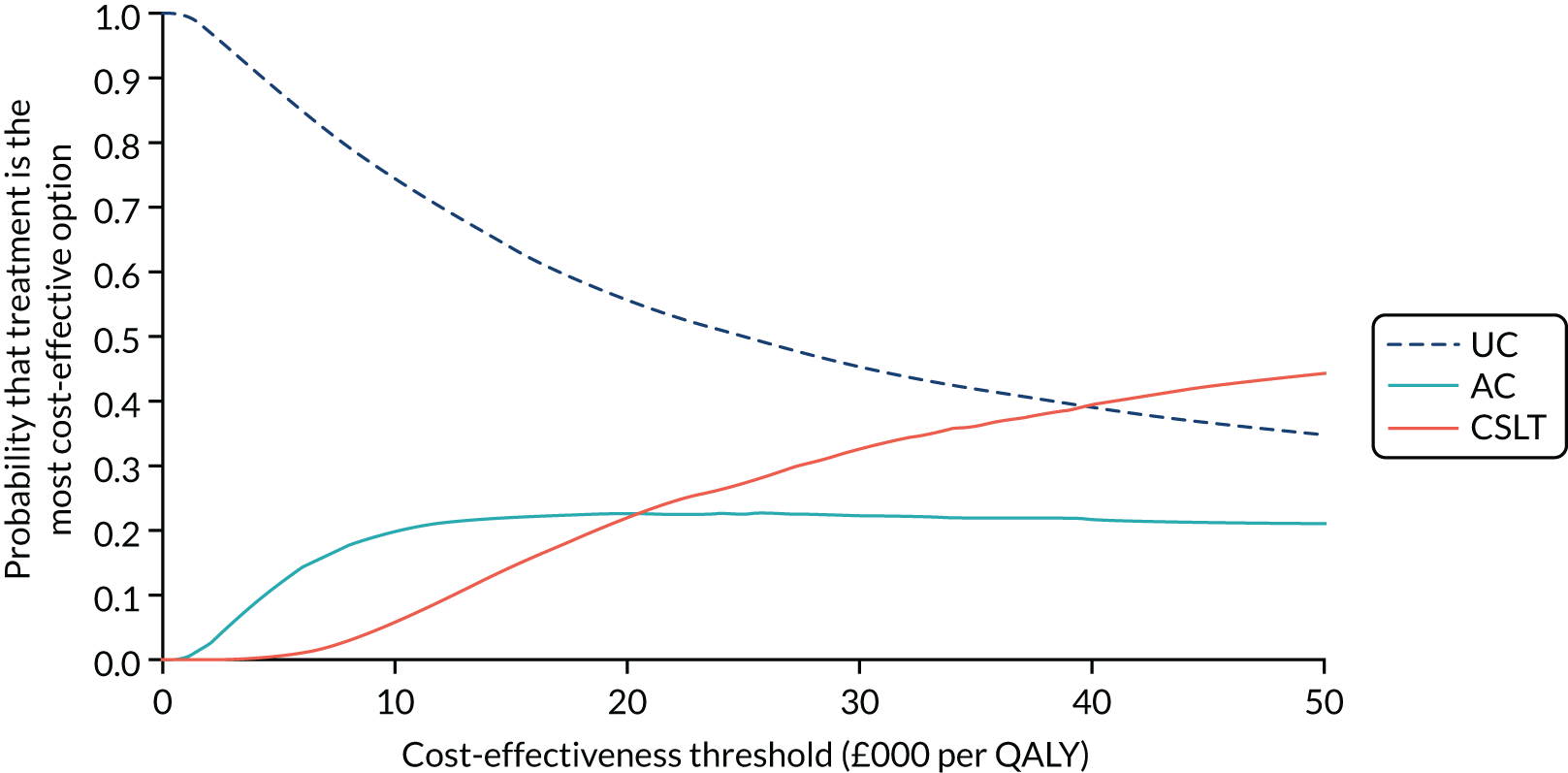

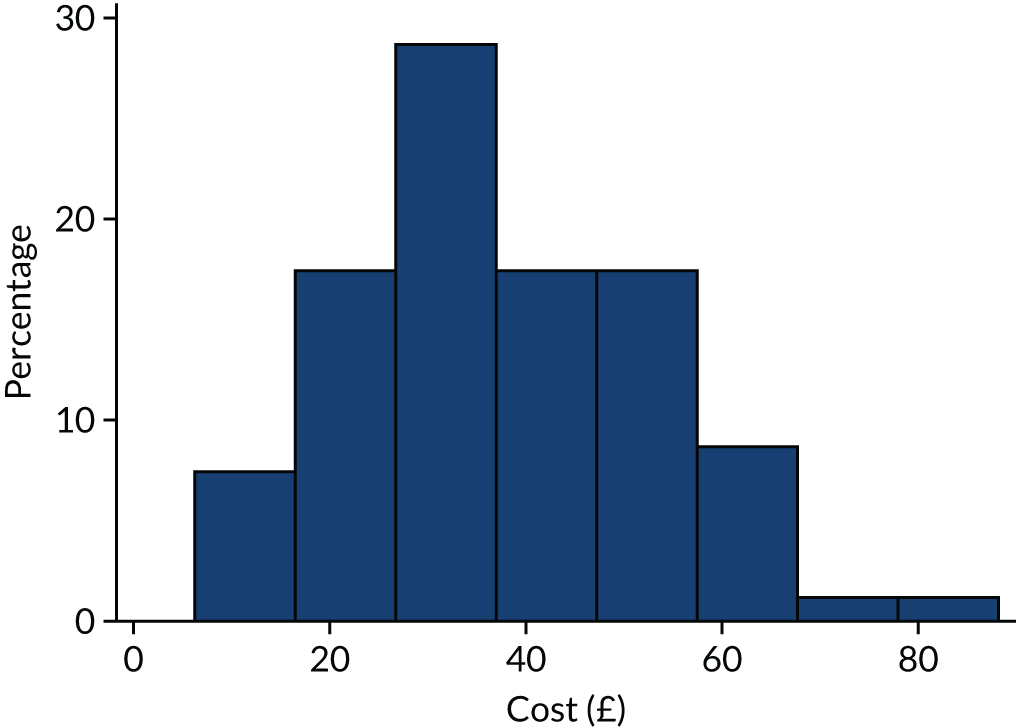

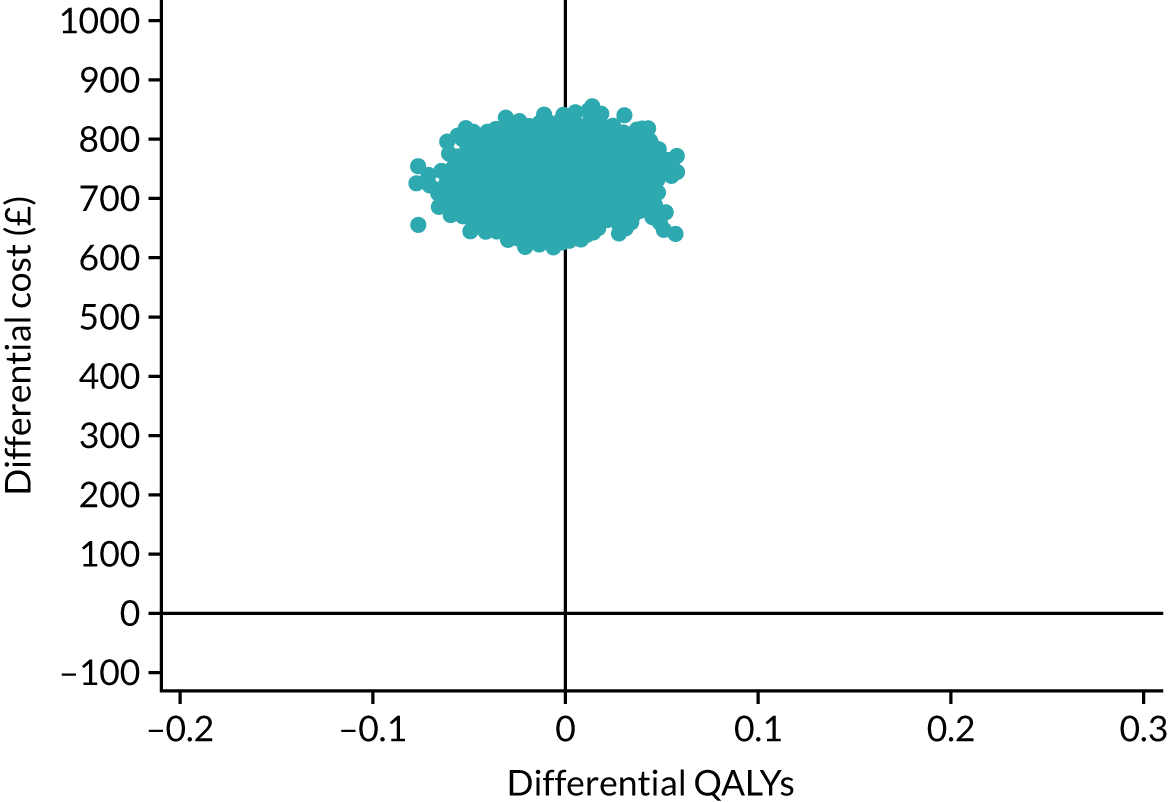

Randomisation and concealment