Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/26/08. The contractual start date was in September 2015. The draft report began editorial review in August 2017 and was accepted for publication in June 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Rona Moss-Morris has published papers that met the criteria for inclusion in the review, and she was previously an advisor to the NHS Improving Access to Psychological Therapies programme. Peter White does consultancy work for a re-insurance company. He also is a member of the Independent Medical Experts Group, a non-departmental body, which advises the UK Ministry of Defence regarding the Armed Forces Compensation Fund. Peter White was also an unpaid chairperson of One Health between 2002 and 2010. One Health is a not-for-profit company that was set up to promote the British Psychological Society model within medicine. Andrew Booth is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Complex Reviews Advisory Board, the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research Funding Board and the NIHR Systematic Review Advisory Group.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Leaviss et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Definition of medically unexplained symptoms

The term ‘medically unexplained symptoms’ (MUS) is used to describe a wide range of persistent bodily complaints for which adequate examination does not reveal sufficient explanatory structural or other specified pathology (reproduced with permission from the Royal College of General Practitioners). 1 Henningsen et al. 2 describe three main types of MUS: pain in different locations, for example headache, back pain, non-cardiac chest pain; functional disturbance of organ systems; and complaints of fatigue or exhaustion. The term MUS may be applied to patients presenting with single symptoms, multiple symptoms or clusters of symptoms that are related to one another and are specific to a certain organ system or medical specialty; for example, chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or fibromyalgia. CFS, IBS or fibromyalgia are often referred to as functional somatic syndromes (FSSs). 3 For patients reporting multiple symptoms, these may vary in range and type. MUS may also vary in terms of reported severity (i.e. number/duration of symptoms) and their effects on functional disability or quality of life.

The term MUS is controversial, and debate regarding its use is ongoing. To many patients with symptoms that are not readily explainable by disease, a diagnostic label is important, but the label ‘MUS’ can be regarded as offensive. 4 Creed et al. 5 suggest that the use of the term ‘MUS’ is a barrier to improved care and, presented a review of the challenges associated with terminology in this area. They suggested alternative terms, such as functional or persistent symptoms. ‘MUS’ is a portfolio term covering a wide range of presentations. The term ‘medically unexplained’ does not exclude physical pathology.

The debate surrounding an appropriate alternative to ‘MUS’ is ongoing and the current review does not seek to contribute to this, nor to address ‘causes’ of MUS.

Classification and diagnosis of medically unexplained symptoms

Diagnostic criteria for MUS are varied. Most of the FSSs are diagnosed according to published diagnostic criteria that include specified symptom criteria alongside the exclusion of medical and/or psychiatric conditions that may mimic similar symptoms [e.g. CFS may be diagnosed by the Fukuda Diagnostic Criteria,6 functional gastrointestinal disorders may be diagnosed by the Rome 111 Diagnostic Criteria,7 fibromyalgia may be diagnosed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 2010 Diagnostic Criteria8]. Patients visiting their general practitioner (GP) frequently with unexplained symptoms are not necessarily offered a formal diagnosis. Where diagnosis of MUS is made, this may be either by use of a validated instrument, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) 15,9 Screening for Somatoform Symptoms (SOMS),10 the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI),11 or by clinical judgement, usually by a GP. Hoedeman et al. 12 describe a continuum of severity for MUS, ranging from short term or incidental to persisting and recurrent. Fink et al. 13 argue that research into the FSSs and related disorders and their treatment is restricted by the lack of a valid and reliable diagnostic classification. There is overlap between the diagnostic categories of functional somatic disorders and, therefore, patients with similar symptoms and clinical presentations may receive different diagnostic labels. Fink et al. 13 have gone on to describe ‘bodily distress syndrome’ as an alternative to MUS.

The presence of MUS is also a key feature of a range of somatoform disorders. These include somatisation disorder, somatoform pain disorder, undifferentiated somatoform disorder and unspecified somatisation disorder. Diagnosis of any of the somatoform disorders is made by clinical structured interview, with patients meeting diagnostic criteria according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV,14 or V15 or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-916 or 10. 17 Although the DSM-IV specifically refers to symptoms being medically unexplained, the DSM-V classification no longer has a requirement that symptoms should lack an explanation. Somatic symptom disorder in the DSM-V is characterised by ‘the presence of one or more distressing and disabling somatic symptoms that disrupt daily functioning’. 18 Significant, moderate to severe somatic symptoms are required to be present, accompanied by excessive, illness-related thoughts, feelings or behaviours. Criticism of the DSM-V definition of somatic symptom disorder centres around the removal of the requirement for symptoms to be ‘unexplained’, and the focus on ‘excessive responses’. As the DSM-V classifies mental disorders, it is argued that this extended scope risks mislabelling many people with physical conditions, such as cancer, heart disease, IBS or fibromyalgia, as mentally ill. 19 Frances20 raises concerns that mislabelling a patient with somatic symptom disorder causes harms (e.g. missed diagnosis of underlying medical causes), subjecting patients to stigma, inappropriate drugs, psychotherapy and iatrogenic disease, and that it may also cause patients to be disadvantaged with regard to employment, education and health care. The 2016 Rome IV guidelines suggest removing the term ‘functional’ from gastrointestinal disorders such as IBS and replacing them with terminology relating to ‘brain–gut interaction’. 21,22 Smith and Dwamena23 propose a clinical spectrum of severity for MUS, from normal/mild, featuring few, minor transient symptoms and little accompanying depression/anxiety, to very severe, which includes the somatoform disorders. Other acknowledged somatoform disorders that have their own diagnostic criteria include bodily distress syndrome, bodily distress disorder and complex somatic symptom disorder.

The current review uses a broad definition of MUS, which encompasses all of the above definitions, so that the term MUS will be used to refer to any of the following definitions: (1) the occurrence of physical symptoms in the absence of clear physical pathology, (2) to FSSs, such as CFS, IBS or fibromyalgia, (3) the DSM-IV (and more recently V) somatoform disorders and (4) somatoform disorders that have their own diagnostic criteria (e.g. bodily distress syndrome). The rationale behind this broad definition is that there is clear overlap between these groups and as yet no consensus as to the validity of one syndrome (i.e. MUS) versus many (i.e. the various FSSs). Whether patients are diagnosed with MUS as opposed to a more specific diagnosis can be an artefact of clinician or researcher preference rather a defining feature of the included patients. 3,24 A final point about classification of MUS is that there is preliminary evidence that several single FSSs are in fact themselves composed of multiple different conditions, united only by common symptoms, which may complicate our understanding of whether or not interventions work for MUS.

Clinical guidelines for MUS (Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health 201725) encourage a philosophy of care where physical and mental health are integrated. A recognition that MUS are ‘mind–body problems’ is also encouraged. Some authors have suggested that the biopsychosocial model itself is responsible for dissatisfaction and harm in patients with CFS,26 arguing that its application is biased towards the psychological, framing patients as mentally ill. It is argued that this risks distraction from research into the biological aetiology of symptoms and syndromes, for example Ghoshal and Gwee,21 de Vega et al. 27 and Gur and Oktayoglu. 28 Imposing the biopsychosocial model on patients, it is argued, can lead to ‘disputes over diagnosis, rejection of psychiatric diagnosis, as well as doctors being dismissive, sceptical and lacking in knowledge about the condition’. 29 The alternative view is that the biopsychosocial model allows the inclusion and integration of biological, psychological and social factors in understanding and treatment particularly of chronic conditions. 30

Prevalence and costs of medically unexplained symptoms

A range of prevalence rates of MUS have been estimated. Edwards et al. 31 report worldwide prevalence rates of primary care patients presenting with MUS of 25–50%. In the UK, Taylor et al. 32 report a MUS prevalence rate of 18% of consecutive attenders to UK GP practices. It is estimated that this creates an annual cost to the UK NHS in excess of £3.1B. 33,34 Taking into account quality of life and sickness absence, wider costs to the economy were estimated at over £14B. 33 The inappropriate management of MUS may result in patients undergoing invasive and potentially harmful tests and treatments. Some patients with MUS have comorbid depression/anxiety. 35 Health-care utilisation varies between patients with MUS due to the wide variability in symptom experience. Collin et al. 36 used a case–control study of nearly 8000 matched pairs to show that GP consultation rates for patients with CFS were 50% higher in adult cases than in the controls 11–15 years before diagnosis, and 56% higher 6–10 years after diagnosis, with a peak difference of more than twofold higher in the year of diagnosis. Similarly, a study of health-care resource use for patients with fibromyalgia37 found that patients had considerably higher resource use at least 10 years prior to their diagnosis of fibromyalgia. At the time of diagnosis, patients recorded an average of 25 visits per year compared with 12 visits for the matched controls. For IBS, health-care visits are considerably lower, with one study estimating one extra visit to primary care per year compared with controls. 38

A systematic review of the course and prognosis of MUS and somatoform disorders39 suggested that the prognosis for patients with MUS is influenced by the severity of the condition at baseline and by the number of symptoms. Creed et al. 40 showed, in a large epidemiological study, that symptom count predicted later quality of life. It has been estimated that between 50% and 75% of patients with MUS will improve, whereas between 10% and 30% will see their condition deteriorate. 39

Interventions for medically unexplained symptoms

A wide range of interventions has been implemented in the treatment of MUS. Pharmacological interventions (e.g. antidepressants) are sometimes used. Reviews of pharmacological interventions have shown these to produce some improvement in responsive patients in terms of symptom severity and functioning,12,41,42 but significant heterogeneity of efficacy between different FSSs.

Psychological therapies

Several types of psychological therapies have been implicated. Cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) for treatment of MUS is based on the model of CBT proposed by Beck43 and is one of the most common interventions used for this group of patients. CBT for MUS focuses on the perpetuating cycle that maintains symptoms, distress and disability. This type of therapy targets the relationship between cognitive, behavioural and physiological responses that are proposed to maintain symptoms. 44 Reattribution for MUS, although no longer commonly delivered, was designed to be delivered by GPs and is based on providing a psychological explanation for somatised mental disorders. Patients are encouraged to reattribute their symptoms and relate them to psychosocial problems. The three stages of therapy are feeling understood, changing the agenda and making the link. 45 Behaviour therapy may be delivered to MUS patients. In these cases, therapy aims to modify behaviours such as increased vigilance in detecting physical symptoms, or reducing inappropriate coping behaviours such as reassurance-seeking or inactivity. 46 Relaxation therapies may be used as treatments for MUS – these include biofeedback,47,48 meditation-based stress reduction49 and qigong. 49 Third-wave CBTs include mindfulness and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), which focuses on psychological flexibility, self-regulation of attention and acceptance. 50 Other psychological therapies such psychodynamic therapy have also been adopted for the treatment of MUS. 51

Physical therapies

A further category of interventions for MUS are physical therapies. Such physical therapies include graded exercise therapy (GET), whereby exercise is started gradually and increased over time, and may incorporate the psychological component of graded exposure to exercise alongside a range of aerobic or non-aerobic exercise, such as walking, pool-based exercise or strength training. 52–56 More physiologically based physical activity interventions include aerobic exercises or non-aerobic exercise (e.g. yoga/qigong), which may also be offered to patients with MUS. 57–59 Our review distinguishes between graded and other physical activity interventions, with the former defined as exercise with a defined behavioural model and the latter defined as exercise with a physiological rationale. Physiotherapy-based exercise interventions were considered provided they included an element of active behavioural participation. Manual therapies were not considered for inclusion if they were predominantly passive.

Other therapies

Other therapies that have been adopted for the treatment of MUS include alternative therapies such as hypnotherapy60 or acupuncture. 61 These are usually passive therapies and were not included in the review.

Not all of these treatments are available on the NHS and, therefore, some patients with MUS may pay to access treatments that they perceive to improve their own symptoms, and where they feel they have more time to express their concerns without the pressure of a time-limited GP consultation.

Setting

Interventions for MUS may be delivered in primary care settings, or after referral to secondary care (e.g. to one or more specialists, such as general physicians, immunologists, neurologists, haematologists, or psychiatrists). 62 In primary care, GPs may deliver behavioural modification interventions to MUS patients as part of enhanced care (encompassing techniques including CBT, reattribution or reframing). Alternatively, patients with MUS may receive collaborative care, where for example a psychologist may deliver CBT within the primary care setting. Delivering interventions in a primary care setting may offer additional benefits, for example patients with MUS may refuse referral to services outside the primary care setting. 63

Evidence for the effectiveness of interventions for medically unexplained symptoms

To our knowledge, there are currently no published systematic reviews that specifically evaluate behavioural modification interventions for patients fulfilling the broad definition of MUS patients as outlined above, within a primary care setting. However, a number of reviews have been conducted for specific subgroups of interventions or patients. Reviews of evidence for the effectiveness of interventions for MUS in general are less common than reviews of individual FSS. Reviews of FSSs have shown that, in the case of CFS, CBT and GET can improve symptom severity and functioning following treatment and are acceptable to patients. 64–67 In the case of fibromyalgia, CBT has been shown to improve physical symptoms and functioning,68 as have exercise therapies69,70 and multicomponent therapy. 71 In the case of IBS, psychological therapies have been shown to reduce symptoms as effectively as pharmacological therapies,42 whereas Zijdenbos et al. 72 found psychological interventions to be slightly superior to usual care or waiting list controls. For other conditions, Aggarwal et al. 73 found only weak evidence of effectiveness of psychosocial interventions including CBT and biofeedback for patients with chronic orofacial pain. Champaneria et al. 74 found psychological interventions improved pain scores for patients with chronic pelvic pain compared with no psychological intervention. van Dessel et al. 75 conducted a review of all non-pharmacological interventions for somatoform disorders and MUS but identified only studies of psychological interventions. The authors found that compared with usual care, treatment resulted in less severe symptoms at the end of treatment. The evidence for CBT was similar to other psychotherapies.

Primary care reviews

The majority of studies included in these reviews were conducted within secondary care. Fewer reviews addressed the effects of interventions in a primary care setting. A review of psychological interventions for MUS76 found that short-term psychotherapy demonstrated small effects for the improvement of physical symptoms in patients with medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS), with type and mode of therapy and profession of the therapist moderating the results (e.g. inpatient therapy was more effective, as was therapy delivered by mental health professionals). However, GP-delivered interventions were found to be more effective at reducing health-care utilisation. Rosendal et al. 77 reviewed enhanced care delivered by generalists for patients with functional somatic symptoms and concluded that the current evidence does not answer the question of whether or not there is an effect for these types of interventions. Gerger et al. 78 reviewed psychological therapies for MUS and compared the effectiveness of such interventions when delivered by GPs versus psychologists. They found a small effect for psychological therapies at the end of treatment for physical symptoms, physical functioning and psychological functioning. This effect was moderated by the provider, with delivery by a psychologist found to be more effective, but only for physical symptoms. There was no robust evidence for any long-term effects. Metaregression also showed moderating effects for the number of sessions, with more sessions being more effective. There was no moderating effect of severity of symptoms, although exploratory analyses indicated that psychological intervention delivered by a GP was more effective for more patients with more severe symptoms. Garcia-Campayo et al. 79 reported that psychological interventions may be no less effective in primary care than when conducted in secondary care settings. Edwards et al. 31 provide a narrative review of the literature on the treatment of MUS in primary care, which outlines some of the issues related to the delivery of interventions in a primary care setting, for example the importance of the doctor–patient relationship, involving family members in interventions and the importance of cultural considerations. The authors concluded that no single approach would effectively treat all MUS patients in primary care, and that care must be taken to investigate which intervention is appropriate for individual patients. Our qualitative review and realist synthesis will add to these findings.

Definitions of behavioural modification interventions

As evidenced by the existing literature and described above, interventions for MUS are, in general, based around pharmacological, psychological or physical therapeutic models. Our review will focus specifically on interventions that aim to promote behavioural change. Although there are a number of theoretical models of behavioural change, attempting to assign interventions designed for patients with MUS to any of these theoretical frameworks presents difficulties. For example, for psychological therapies, there may be little behaviour modification theory or practice in ‘pure’ cognitive therapies but it has been shown empirically that in practice not many therapists will practice pure cognitive therapy – most will incorporate behavioural elements. 80 Similarly, for physical therapies, if an intervention is based around a model of physical fitness rather than behaviour re-engagement, then it could be argued that this no longer meets the criteria of a behavioural modification intervention. Many physical fitness methods involve predetermined goals based on a patient’s physiology, which are set by the physiologist or sport scientist and may not be considered as ‘therapy’, although they still constitute an intervention. We will therefore adopt a liberal definition of ‘behavioural modification interventions’ as ‘interventions aimed to achieve behavioural change’. Interventions will include ‘named’ behavioural interventions such as CBT, behavioural therapy and GET (GET incorporates principles of systematic desensitisation and behaviour modification with the aim of gradually increasing physical activity, see, for example, Bagnall et al. 62). However, we will also include any intervention that meets the criteria described above. Owing to wide variation in these interventions, we will categorise them by subtype rather than attempt to treat them as one homogeneous intervention type.

Modifying effects

Results of existing reviews suggest that the effectiveness of treatments for MUS may be modified by a number of factors and that treatment may depend on how MUS is defined. There is currently no consensus on whether or not to use a generic intervention protocol, where all patients with MUS receive the same treatment protocol regardless of key presenting symptoms and/or level of disability versus the use of a very specific protocol, developed for patients with a defined functional somatic or DSM syndrome. There is some suggestion from previous reviews that more specific protocols may have larger treatment effects but this has yet to be investigated systematically. 76

Furthermore, the type of control condition used in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) may influence an intervention’s effectiveness. Some studies have shown that patients with IBS respond well to placebo,72 whereas patients with CFS do not respond well. 81 This highlights the importance of recognising differences in the design and conduct of control conditions. Where the control condition is inactive (e.g. waiting list or treatment as usual), good effect sizes for the experimental intervention have been found, whereas trials with active control interventions have shown small effect sizes. 82 Our review will take account of these issues by extracting information from individual studies for a number of potential modifiers, including mode of delivery of the intervention, MUS population (e.g. diagnosed FSSs), multiple MUS, and chronic unexplained pain as described in Chapter 3, Description of the evidence. Potential modifying effects for intervention type will be explored by categorising by broad type of behavioural modification intervention (e.g. CBT, GET, behaviour therapy). Details of all types of controls will be synthesised for all included trials.

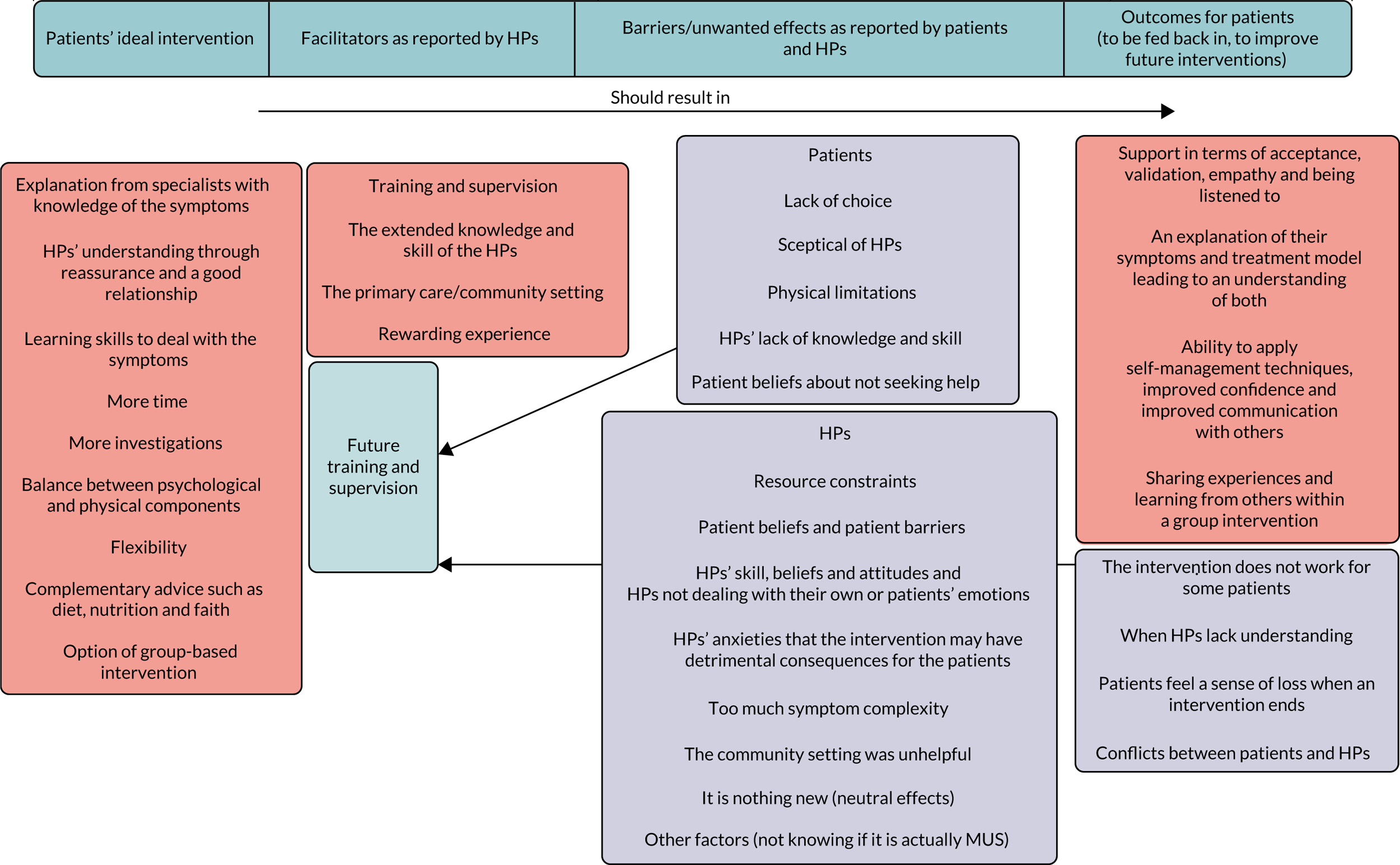

Acceptability of primary care interventions for medically unexplained symptoms

Several authors suggest that the relationship between service users and service providers is key to the success of primary care interventions. 83–85 Poor communication between the GP and the patient as well as lack of emotional and practical support are suggested as barriers to effective treatment of MUS. Creating a safe, therapeutic environment, and the importance of offering effective reassurance, are highlighted as important enabling factors for effective treatment of MUS. 84 Therefore, the current review aims to add greater depth to the clinical effectiveness data by retrieving qualitative data relating to potential barriers to and facilitators of effectiveness and conducting realist synthesis of these data. This is of particular importance as a good proportion of these patients hold strong views about the biological nature of their condition and view the suggestion of a more psychosocial approach to treatment as invalidating their symptoms. 86 Understanding ways in which to make behavioural approaches more acceptable may increase their uptake.

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem

The assessment addressed the question: what is the clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and acceptability of behavioural modification interventions for MUS in primary care or community-based settings?

Intervention

Interventions that aimed to modify behaviour were sought. These included explicit behavioural interventions such as CBT, behaviour therapy and GET. Where the intervention was not explicitly named as a behavioural modification intervention (i.e. one of the above), a broad definition of behavioural change interventions was adopted. Interventions therefore included but were not exclusive to a range of psychotherapies, for example CBT, behavioural therapy, psychodynamic therapy, mindfulness and reattribution. Interventions also included other physical therapies, such as aerobic exercise and strengthening or stretching exercises. Interventions with multiple components were included where one of the components was considered a behavioural modification technique as defined by the above criteria. Individual and group interventions were noted as separate interventions; however, because of the limited number of studies per intervention type, both group and individual interventions of the same type were considered together for the purposes of the network meta-analyses, and sensitivity analyses conducted where possible. Interventions were also considered where primary care practitioners were trained to communicate a ‘behavioural’ message to patients during their consultations. In these cases, interventions required a stated explicit aim to train GPs to adopt a behavioural or biopsychosocial approach towards consultations with patients with MUS.

Population and relevant subgroups

Studies of populations meeting the criteria for MUS, MUPS, and somatoform disorders were included. Populations with defined FSSs were also included. Diagnostic/inclusion criteria used are discussed in more detail in Chapter 5, Scope the primary literature.

Relevant comparators

Any comparator was considered. Comparators are described in greater detail in Chapter 5, Scope the primary literature.

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

Research aim

This project evaluated the clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and acceptability of behavioural modification interventions for MUS in primary care or community-based settings. The purpose of the project was to provide a comprehensive systematic review of both quantitative and qualitative studies, using rigorous methods for reviewing, evidence synthesis and cost-effectiveness modelling to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of these interventions.

Research objectives

-

To determine the clinical effectiveness of behavioural modification interventions for MUS in primary care and community-based settings, by undertaking a full systematic review of quantitative literature.

-

To evaluate the barriers to and facilitators of effectiveness and acceptability of behavioural modification interventions for MUS from the perspective of both patients and service providers, by undertaking a realist synthesis following a systematic review of the available qualitative research literature.

-

To undertake a meta-analysis of the available evidence on clinical effectiveness, including a network meta-analysis (NMA) to allow simultaneous comparison of all identified intervention types where appropriate.

-

To identify and synthesise evidence on health economic outcomes such as health-care resource use (e.g. GP appointments), and health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) data from the studies included in the clinical effectiveness review.

-

To provide new evidence on the cost-effectiveness of behavioural modification interventions for MUS conducted in a primary care or community setting, by conducting a systematic review of existing economic analyses and undertaking a de novo model-based evaluation where there is an absence of high-quality published analyses which are directly applicable to our research question.

-

To explain which circumstances influence the effects of behavioural interventions for MUS patients (via realist synthesis).

Patient and public involvement

Patients were involved throughout the review process. Two members of the public with a history of MUS contributed to the writing of the review protocol. They, along with a person with experience of fibromyalgia, went on to be active members of our Expert Advisory Group. The Expert Advisory Group was made up of subject experts, clinicians and our patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives (experts by experience). There were two whole-group meetings: the project team and one of the Expert Advisory Group, held at the School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR) but with an independent chairperson. These were at the beginning of the review to discuss plans and potential issues before the review got started, and at the end of the review to report the results of the review. Between these meetings, the Expert Advisory Group were e-mailed at key stages in the project to receive updates on progress and to be invited to contribute any feedback.

In addition to the two whole-group meetings, a meeting with JL, AS and MB was held in London solely for the PPI representatives. The purpose of this meeting was to allow a more informal discussion of the project, in particular the qualitative and quantitative reviews, with a focus on a patient point of view. The PPI representatives were also given a booklet containing plain English information on the systematic review process.

All of the PPI representatives made substantial and valuable contributions to the project. Providing a patient perspective at each stage of the review enabled the project team to gain a deeper understanding of the issues arising from the literature, and kept the importance of patient perceptions of their symptoms and health-care provision in focus.

One patient with MUS wrote:

Being involved with this review has opened up my understanding of how important it is when one has ‘unexplained symptoms’ to take part in one’s own recovery and health and how difficult it must be for doctors to have patients who look to them as saviours, not to be able to diagnose and then treat. I thoroughly enjoyed having an insight into both doctors’ and patients’ point of view into the frustrating world of MUS! It also gave me hope seeing the differing and varied interventions available. It was encouraging to see that nearly all symptoms under the various headings seemed to respond to CBT. It has been a great pleasure to be involved with this study and review. The team were brilliant in making a very complex subject accessible and interesting to a lay person.

The other patient with MUS wrote:

It has been a fascinating experience being a small part of a very carefully thought out and thorough review. Credit should go to the team that managed to filter through all of the studies and create a model that allowed for some conclusions to be made. While the review didn’t perhaps reach the clear conclusions it aimed for, there were a lot of interesting observations: From a patient-perspective, the fact that there were few significant effects for any GP intervention, i.e. reattribution, GP led CBT, or GP MUS management, is quite worrying. It is useful knowledge that multimodal and CBT interventions have an impact on the majority of MUS. These findings are something that should be embraced and addressed by the NHS (although it’s interesting to see that there is little evidence supporting the impact on long-term health). It seems that patient caution and stigma can still be attached to CBT and similar therapies so I would be interested to find how this problem could be tackled in the future. It’s also a pity that little could be found that would benefit patients with ‘somatisation and generic physical symptoms’. I’ve really enjoyed working on this project and would be happy to contribute to any further studies.

The person with experience of fibromyalgia wrote:

My experience of being part of the stakeholder group: It was an enormous piece of research that was undertaken and I observed that it was done with great care. I always felt that my opinions, written and oral, were taken seriously and followed-up. I am not sure how valuable my contributions were. I do know that I tried my best to look at all the information and paid attention to the details as much as I tried to look at the bigger picture. I do think that having patient representatives helps to keep the research grounded in the real world. I was astounded by some of the outcomes, as they seemed counter to generally held beliefs. This only shows how important it was to collate this evidence. I do hope that the report will help many people with pain and other unexplained symptoms to reach relief that they have not yet achieved.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Methods for reviewing effectiveness

A systematic review of the literature and (network) meta-analysis (where appropriate) was undertaken to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of behavioural modification interventions for MUS, in a primary care or community setting. The review of the clinical evidence was undertaken in accordance with the general principles recommended in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.

Identification of studies

Searches were undertaken to identify relevant studies regarding clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and acceptability (qualitative studies). The search strategies are reported separately for each below. Methods of searching for studies included in the realist synthesis are described in Chapter 7.

Screening and eligibility

A two-stage sifting process for inclusion of studies (title/abstract then full-paper sift) was undertaken. Titles and abstracts were scrutinised by one systematic reviewer (JL) according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. There was no exclusion on the basis of quality. All studies identified for inclusion using the abstract alone, plus any study in which a decision on inclusion was not possible only from the abstract, were retrieved for more detailed appraisal. Agreement on inclusion at title/abstract sift was checked by a second systematic reviewer (CGC) for 20% of the total electronic search results. Further sifting processes were developed as it became apparent that there were many studies where inclusion/exclusion was unclear. A sifting meeting was held with all subject experts present to discuss general sifting issues and specific individual cases. A common issue was whether or not interventions met the primary care/community-based criteria. To address this issue, operational sifting criteria were developed in order to aid decision-making. Data were extracted regarding where diagnosis, recruitment and referral (to the study) took place and where the intervention took place, and outcomes were assessed. Inclusion was decided based on a combination of these factors and, where there was doubt, judgements were made via discussion among the review team. Inclusion of studies on setting was kept broad. Appendix 2, Table 40, shows the sifting criteria considered for setting for each included study. Another common issue was the nature of the symptoms meeting the ‘unexplained’ criteria. Studies were included if symptoms were explicitly described as ‘medically unexplained’, as were studies that explicitly stated that they included patients with ‘MUS’. Studies of populations with FSSs were included without a need for further reference to medical explanation. Inclusion issues became apparent in studies of patients with chronic pain but no description of whether or not the pain had a known organic cause. To address this issue, a sample of study authors of these papers were contacted to request further information about their populations. None of the studies of those who responded had lack of ‘medical explanation’ as a criterion for inclusion. Therefore, it would be impossible to determine whether the populations contained a mix of patients with chronic pain with known cause, for example arthritis, and patients with pain without known cause. Specifically, an explanation of the cause of pain was not deemed necessary in these studies, nor was it necessary for pain to be a target for the interventions. It was therefore decided to keep this inclusion criterion narrow, and to include only studies of patients with chronic pain that deliberately targeted pain of unknown or ‘unexplained’ origin.

Clinical effectiveness searches

A systematic search strategy was developed in consultation with the review team, to identify systematic reviews and RCTs relating to the defined population. The focus was on identifying studies in primary care or community-based settings; therefore, population terms were combined with terms to define the setting. A combination of free-text terms and thesaurus searching was used. Published methodological search filters to limit the study type (systematic review or RCT) were used where available. No other search limits were applied. Reference sections of included studies were scrutinised for additional potential studies to include, as were reference lists from relevant reviews.

Searches were conducted in the following sources:

-

MEDLINE via OvidSP (1946–20 November 2015)

-

MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations & Epub Ahead of Print & MEDLINE® without Revisions via OvidSP (2013–20 November 2015)

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) via EBSCOhost (1981–3 December 2015)

-

PsycINFO via OvidSP (1967–3 December 2015)

-

EMBASE via Ovid SP (1974–4 December 2015)

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) via the Cochrane Library (2005–4 December 2015)

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) via the Cochrane Library (1994–April 2015 – no longer updated, archive only searched 4 December 2015)

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) via the Cochrane Library (1898–4 December 2015)

-

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Database via the Cochrane Library (1989–4 December 2015)

-

Science Citation Index via Web of Science (1900–7 December 2015)

-

Social Sciences Citation Index via Web of Science (1956–7 December 2015).

Searches for systematic reviews and RCTs were conducted between 20 November and 7 December 2015. Detailed search strategies are provided in Appendix 1.

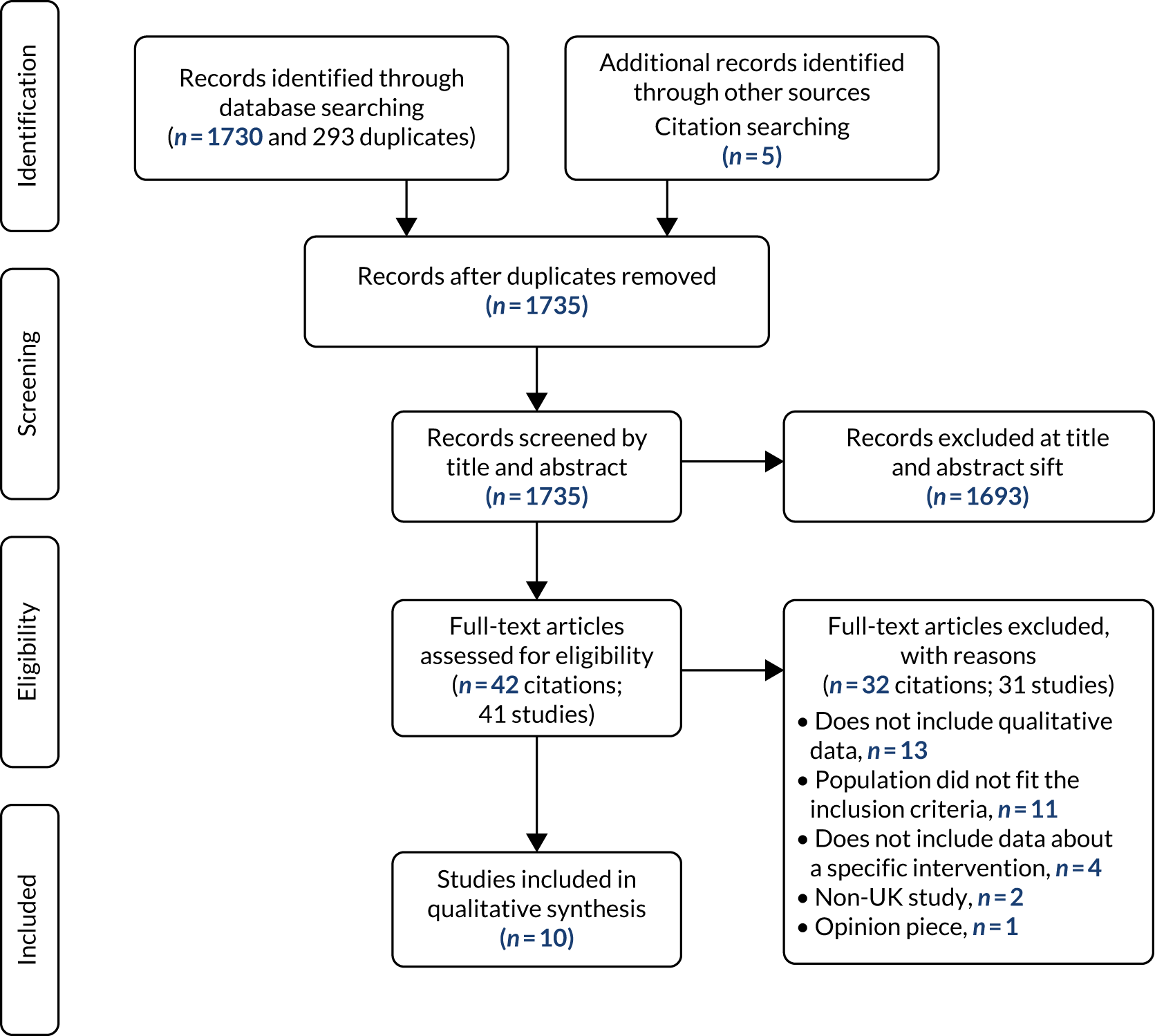

Qualitative searches

A systematic search strategy was developed in consultation with the review team to identify qualitative research relating to the defined population. The focus was on identifying studies in primary care or community-based settings; therefore, population terms were combined with terms to define the setting. A combination of free-text terms and thesaurus searching was used. Published methodological search filters to limit to study type (qualitative) were used where available. The qualitative research filter was combined with a geographic filter to identify UK studies only. No other search limits were applied.

Searches were conducted in the following sources:

-

MEDLINE via OvidSP (1946–4 July 2016)

-

MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations & Epub Ahead of Print & MEDLINE without Revisions via OvidSP (2013–4 July 2016)

-

EMBASE via Ovid SP (1974–4 July 2016)

-

CINAHL via EBSCOhost (1981–4 July 2016)

-

PsycINFO via OvidSP (1967–4 July 2016)

-

Science Citation Index via Web of Science (1900–4 July 2016)

-

Social Sciences Citation Index via Web of Science (1956–4 July 2016).

Searches for qualitative research were conducted on 4 July 2016. Detailed search strategies are provided in Appendix 1.

Economic searches

A systematic search strategy was developed in consultation with the review team to identify economic evaluations relating to the defined population. The focus was on identifying studies in primary care or community-based settings; therefore, population terms were combined with terms to define the setting. A combination of free-text terms and thesaurus searching was used. Published methodological search filters to limit to study type (economic evaluation) were used where available. No other search limits were applied.

Searches were conducted in the following sources:

-

MEDLINE via OvidSP (1946–15 August 2016)

-

MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations & Epub Ahead of Print & MEDLINE without Revisions via OvidSP (2013–15 August 2016)

-

EMBASE via Ovid SP (1974–25 August 2016)

-

CINAHL via EBSCOhost (1981–25 August 2016)

-

PsycINFO via OvidSP (1967–25 August 2016)

-

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) via the Cochrane Library (1968–April 2015 – no longer updated, archive only searched 25 August 2015)

-

Science Citation Index via Web of Science (1900–25 August 2015)

-

Social Sciences Citation Index via Web of Science (1956–25 August 2015).

Searches for economic evaluations were conducted between 15 and 25 August 2016. The search results were imported into EndNote [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA] and subsequently filtered to identify UK studies, using terms from line 29 of the EU economies search filter to search the EndNote library for potentially relevant references. Detailed search strategies are provided in Appendix 1.

Clinical effectiveness review

Details of the qualitative and cost-effectiveness review methods are detailed in Chapters 4–6.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Study design

Only RCTs were included as these represent the optimal study design for assessing intervention effectiveness. Scoping of the review indicated the availability of a substantial number of published RCTs. No minimum duration of follow-up was applied.

Intervention

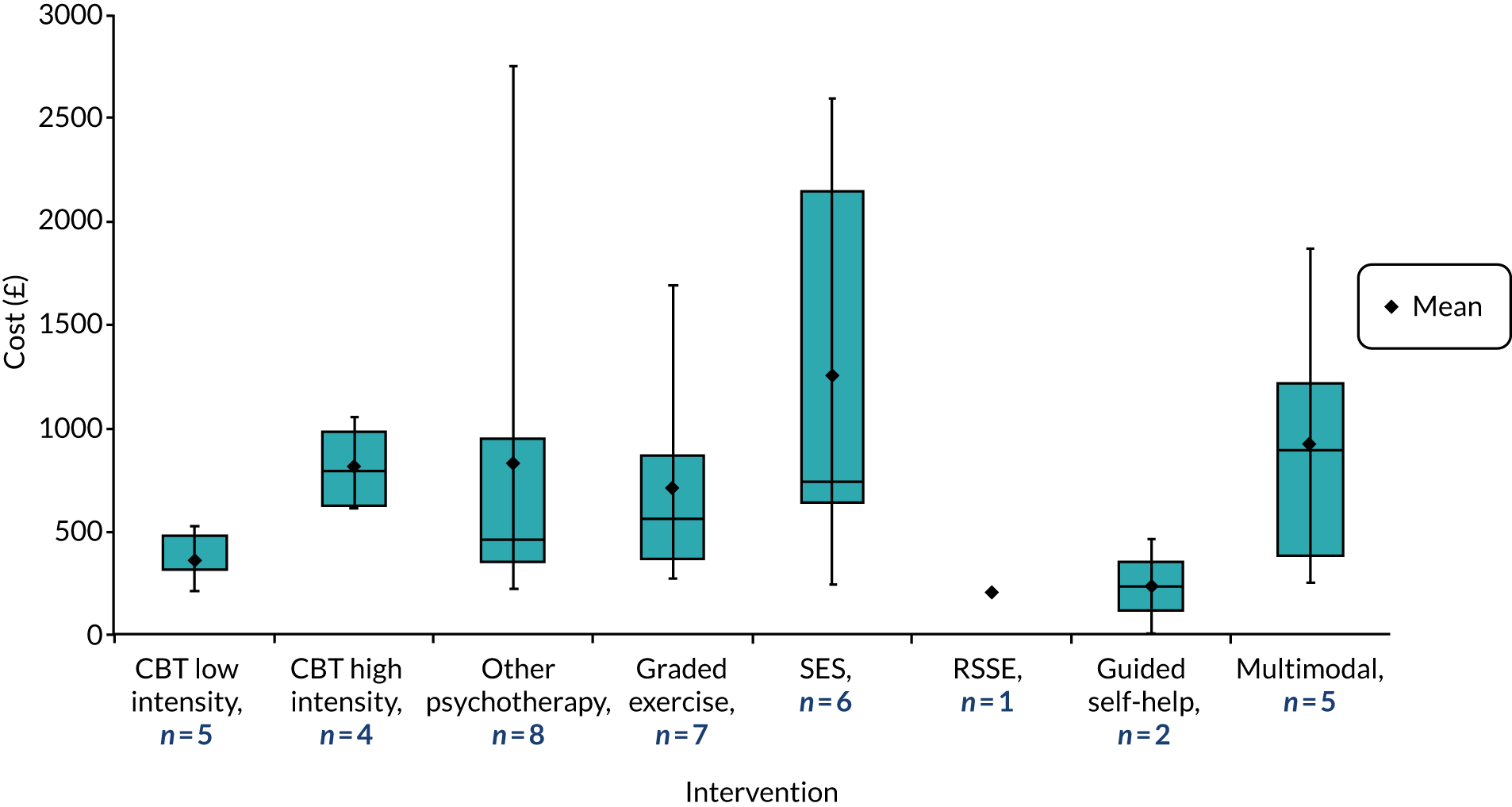

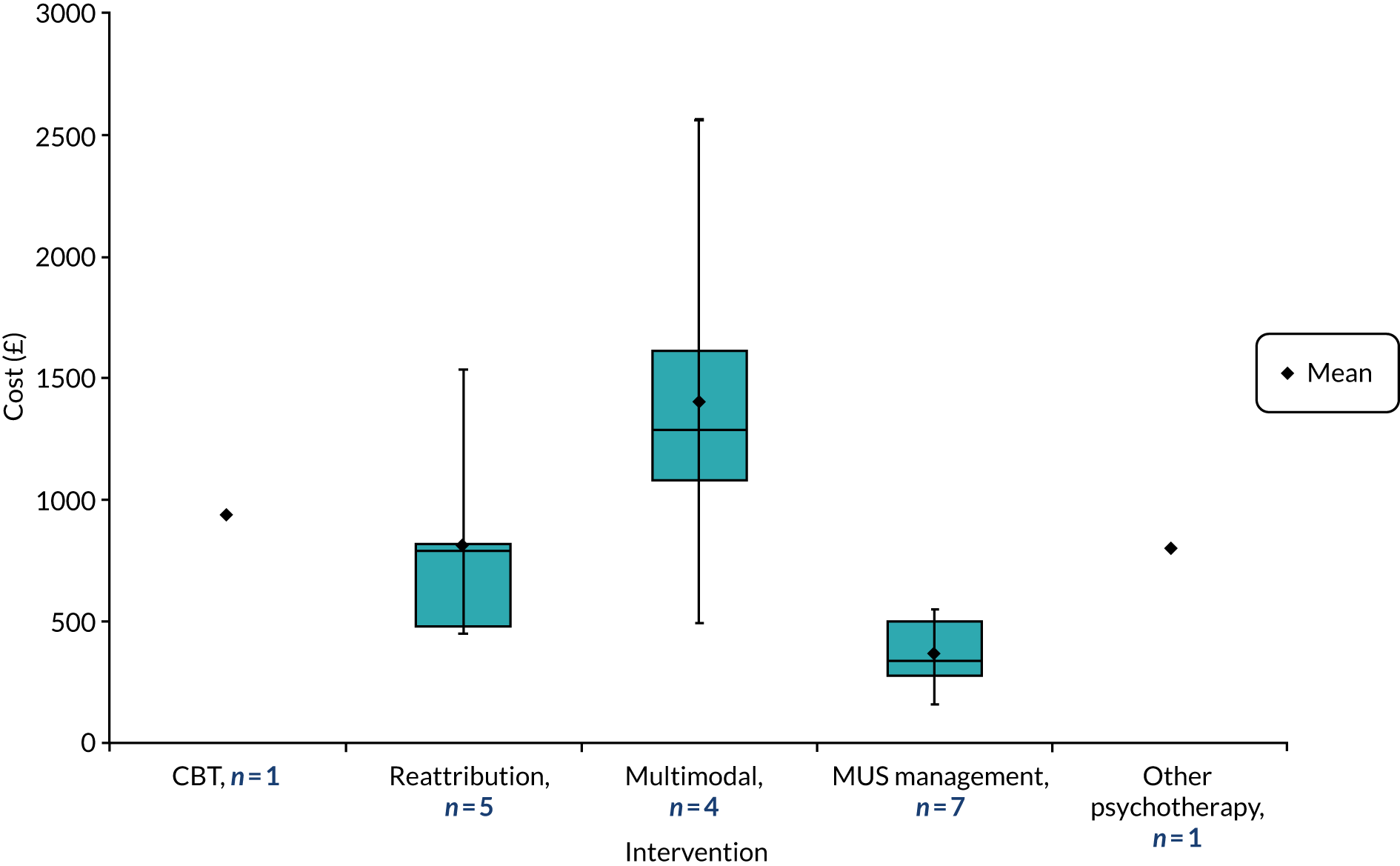

A diverse range of interventions that met with our definition of behavioural interventions were identified. Interventions were subsequently ‘grouped’ by type. Definitions of intervention groups were created following review team discussions. These are presented in Table 1. Two reviewers initially grouped each included intervention into these groups. Where there were difficulties or disagreements, subject experts were consulted.

| Intervention group | Description |

|---|---|

| CBT – high intensity | CBT, delivered by a trained clinical specialist, ≥ 6 hours’ contact |

| CBT – low intensity | CBT, either delivered by a trained clinical specialist but < 6 hours’ contact time, or delivered by a non-specialist (may be > 6 contact hours) |

| Other psychotherapy | Any other psychotherapy (e.g. expressive, psychoanalytic) |

| Graded activity or exercise therapy | Exercise with a defined behavioural model |

| Strength, endurance, sport | Exercise with a physiological model (e.g. aerobic, strengthening) |

| Relaxation, stretching, social support/emotional support | Interventions designed to encourage relaxation or stress relief, general MUS-focused support, stretching |

| Guided self-help | Educational support, including information or self-management materials; visual presentations |

| Multimodal | An intervention that incorporates components from more than one category or was conceptualised as ‘multimodal’ by the study authors |

| GP interventions | |

| GP – reattribution | GP trained in reattribution according to Goldberg principles45 or modified reattribution |

| GP – CBT | GP trained in and delivered CBT |

| GP – other psychotherapy | GP trained in and delivered any other type of psychotherapy as described in general ‘other psychotherapy’ category |

| GP – MUS management | GP trained in the management of MUS. Must be focused on management using behavioural/biopsychosocial principles |

| GP – other | GP intervention consisting of multiple components, does not fit with any other category |

| Non-behavioural comparator interventions | |

| Medication | Any medication prescribed specifically as a comparator intervention (i.e. above patients’ usual regimen) |

| Usual care | Care as usual, also incorporates waiting list or treatment as usual |

| Usual care plus | Enhanced usual care or usual care with minor addition (e.g. a leaflet) |

Appendix 2, Table 28, describes the interventions at a study level, with a brief description, with their designated intervention groupings.

Population

Adults aged ≥ 18 years with MUS, MUPS or somatoform disorders were included. Diagnosis of MUS or MUPS could be either by validated instrument (e.g. PHQ-15, SOMS, BSI) or by clinician judgement. Diagnosis was not restricted by duration (except in the case of chronic pain the duration of which should be > 3 months) or severity (e.g. number of symptoms). Patients with single symptoms were included. Populations with FSSs were included (e.g. IBS, CFS, fibromyalgia). For somatoform disorders, diagnosis should have been made by formal clinical interview and should meet DSM-IV or DSM-V, or ICD-9 or ICD-10 criteria. Somatoform disorders included somatisation disorder, somatoform disorders, somatoform pain disorders, persistent physical symptoms, bodily distress syndrome, bodily distress disorder, FSS, medically unexplained syndrome.

Appendix 2, Tables 29–36, shows diagnostic/inclusion criteria used by condition for individual studies.

Comparator

Studies where ‘usual care’ was the comparator were included. Owing to variation in terminology, studies where the comparator is ‘treatment as usual’ or ‘waiting list’ ’were also included as usual care’. A ‘medication’ control group was included for studies where a comparator arm consisted of a specific medication regimen. Trials with a ‘placebo’ control (e.g. which control for time and attention) were also included. As a number of high-quality head-to-head trials of two or more experimental interventions were identified during scoping searches, head-to-head trials were also included where at least one intervention arm met the definitions outlined above.

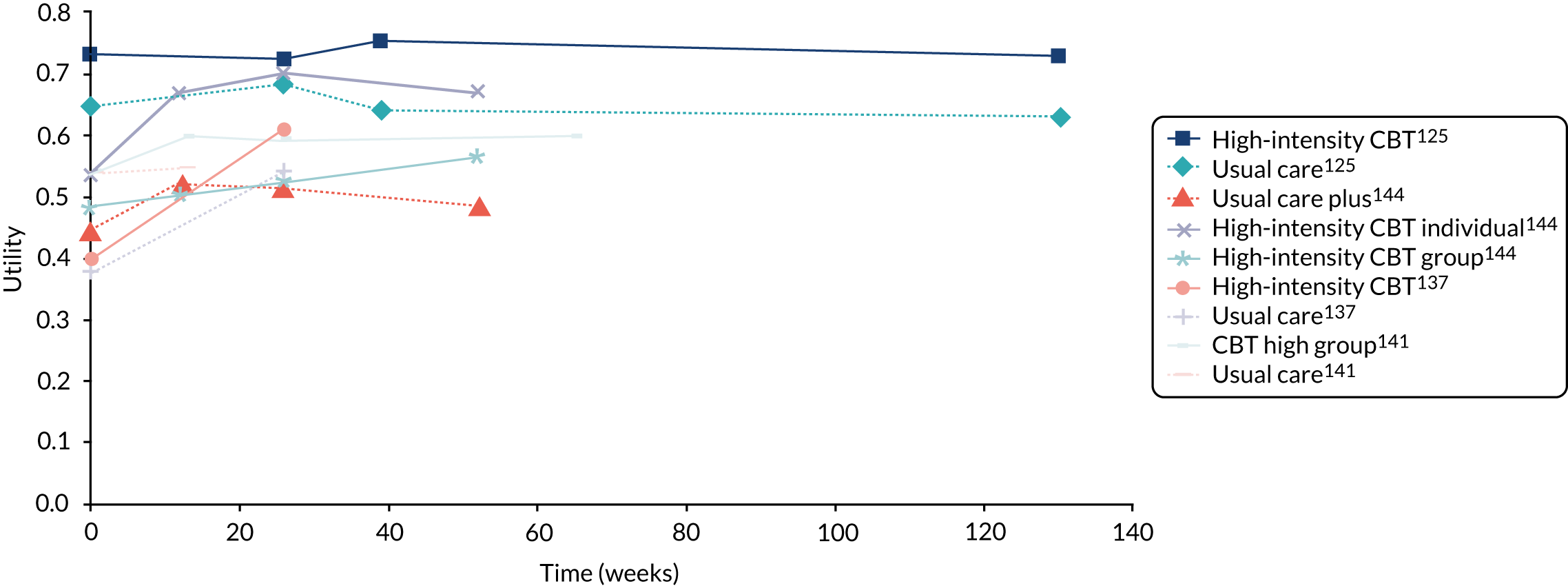

Outcomes

Appendix 2, Table 37, presents information on primary and secondary outcomes measured in each study, with an indication of the scale used.

Primary outcomes

Patient level: improvement in symptoms, functioning and/or health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Measures of symptom improvement could be through assessment of severity or frequency and must have been assessed using a generic or symptom-specific validated instrument, for example EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)/Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) for HRQoL, symptom checklist for symptom severity and PHQ-15.

Health-care level: use of health-care resources (e.g. frequency of GP visits, diagnostic outpatient procedures, hospital admissions, emergency department attendances). Costs are reviewed in detail in the cost-effectiveness review Chapter 6.

Secondary outcomes

Emotional distress, including depression and anxiety as diagnosed by a validated instrument [e.g. Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) or Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)] or a composite measure, such as the mental health component from the SF-36; satisfaction with care; attrition (persistence and adherence).

Studies were diverse and, because of the differences in populations, types of symptoms measured were varied. Scales used to measure similar constructs (e.g. depression, quality of life) differed between studies. Appendix 2, Table 37, lists all the primary and secondary outcomes measured, with scales used, for all included studies. Outcome data for individual studies were extracted and commonalities were sought. Ten key outcomes were considered to have sufficiently similar data to be included in meta-analyses. These were individual physical symptoms: pain, fatigue and bowel symptoms; somatisation; composite measures of emotional distress; physical functioning; depression; anxiety; impact of symptoms on daily activities (including disability); and generic physical symptoms (e.g. severity of ‘main’ symptom, where no particular symptom is specified). In addition, data were extracted regarding satisfaction/adherence, adverse events and health-care utilisation. These outcomes were considered too heterogeneous to consider meta-analysis and are reported as a narrative synthesis only.

Outcome measurement time points

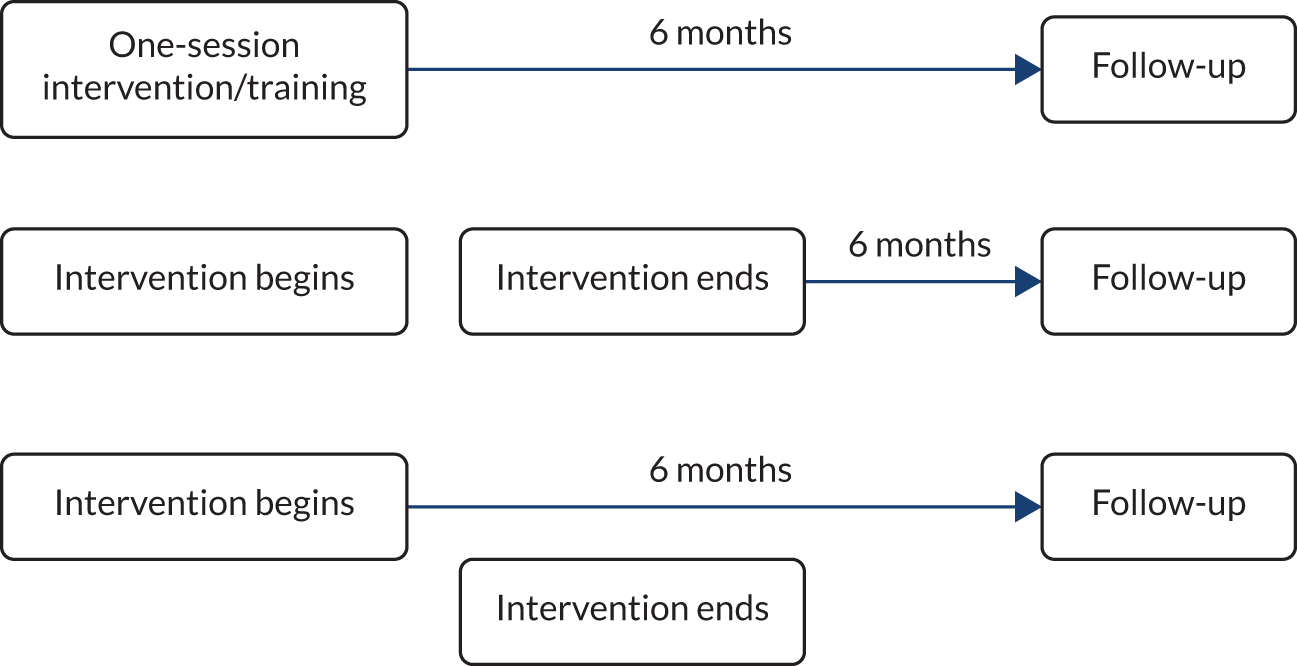

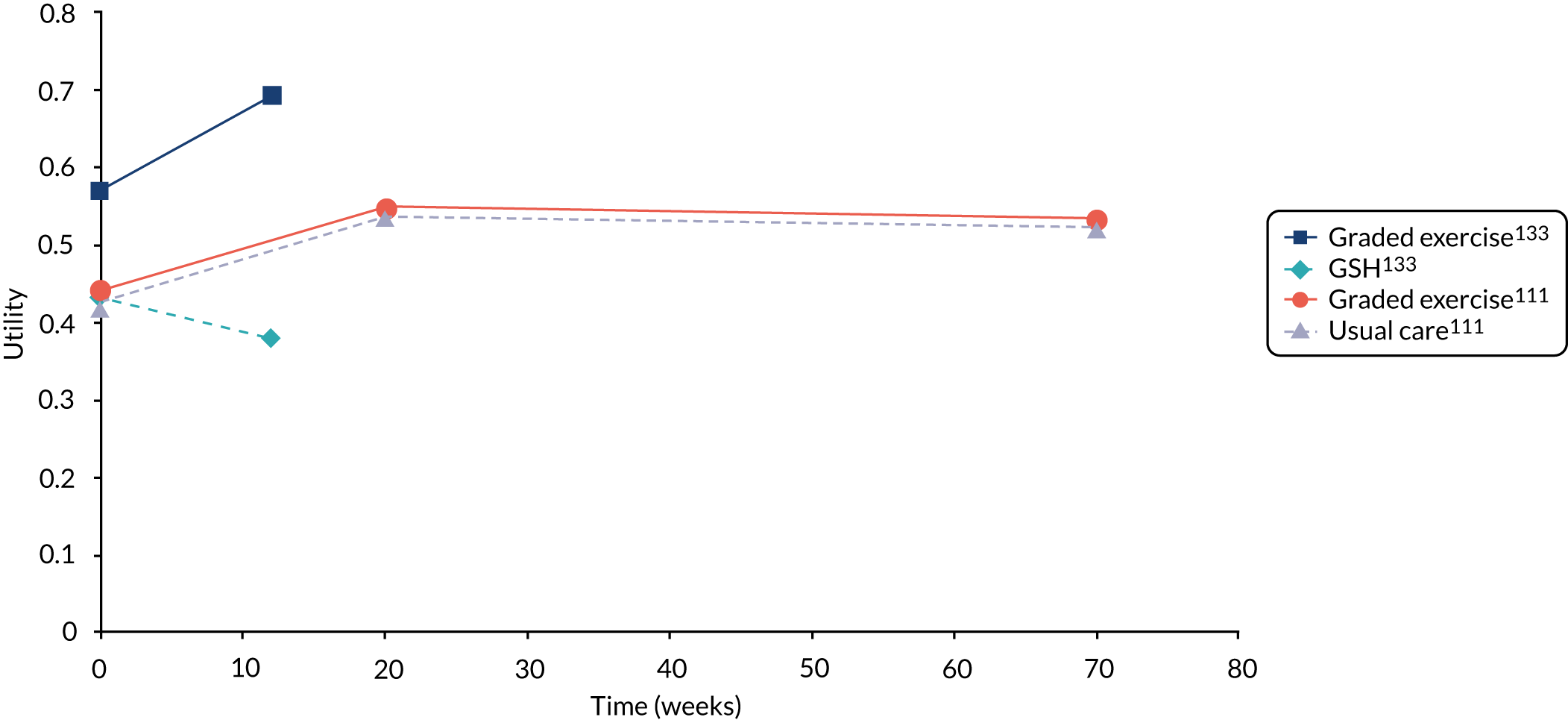

Studies measured outcomes at a range of time points. As well as variation in follow-up times (e.g. 3 months, 6 months, 1 year), there was variation in the definitions of these time points. As an example, Figure 1 shows three different ways of defining ‘6 months’ follow-up’.

FIGURE 1.

Variation in definitions of follow-up.

Although all of these variations may be described in individual studies as ‘6 months’ follow-up’, 6 months may refer to the time since one-off treatment, to the time since the end of treatment, to the time since the GP received training, or to the time since baseline (pre-treatment). As previous studies have shown that intervention effects can diminish once treatment has ended, time since end of treatment was considered important. Time points used in the meta-analyses were extracted as baseline, end of treatment (i.e. corresponding to duration of treatment), short-term follow-up (time since end of treatment < 6 months) or long-term follow-up (time since end of treatment ≥ 6 months). The longest follow-up time point within these categories was chosen where possible. Where studies did not explicitly report end-of-treatment time, this was calculated by subtracting duration from follow-up since baseline. Weeks were converted to months using a conversion of 1 week = 0.230137 months. Assessment time points as reported in individual studies are reported in the table of basic study design characteristics in Appendix 2, Table 42. Converted or calculated time points are reported for individual studies in Appendix 2, Table 39.

Settings

Studies in primary care or community-based settings were included. To be considered a primary care setting, interventions must have been conducted within a primary care or community-based setting, but they could have been delivered by any health-care discipline within that setting. Interventions could be face to face or delivered at a distance (e.g. via the internet or telephone), and may include computer-assisted interventions. However, to be considered primary care, a degree of involvement with primary health professionals (HPs) was necessary. Therefore studies of e-health, telephone interventions or self-help that were conducted by university research teams with no primary care practitioner involvement were excluded. For interventions delivered by a therapist (e.g. a psychologist or physiotherapist – not by the GP or primary care practice staff), these could have been delivered by the therapist while the patient was still regarded as a ‘primary care patient’, but not once the patient had been referred to secondary or tertiary care. Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) interventions were included if delivered in a primary care or community-based setting.

Data extraction strategy

Data extraction was performed by one reviewer into a standardised data extraction form and independently checked for accuracy by a second. The extraction form was designed using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) Checklist as a guide. Intervention information regarding setting, duration, provider (e.g. qualifications and training) and number of sessions, etc., was extracted. Basic demographic information for participants was also extracted. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers and, if agreement could not be reached, then a third reviewer was consulted.

Critical appraisal strategy

The quality assessment of included RCTs was performed by one reviewer (JL) using Higgins’ risk-of-bias tool87 for RCTs, and 20% of completed checklists were independently checked for accuracy by a second reviewer (AS). Discrepancies were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers and, if agreement could not be reached, then a third reviewer was consulted.

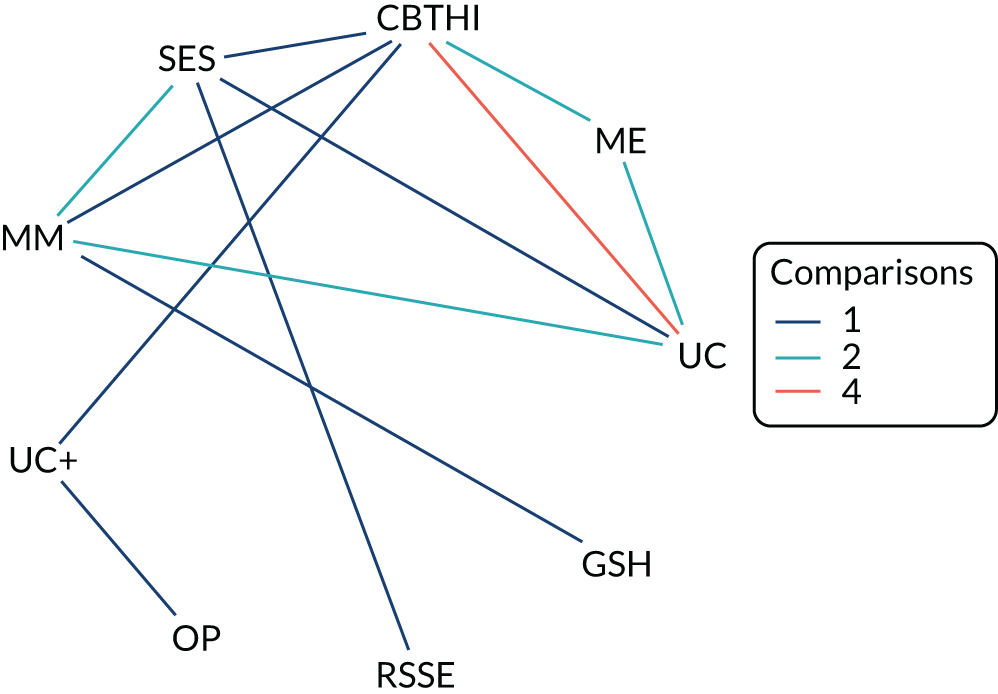

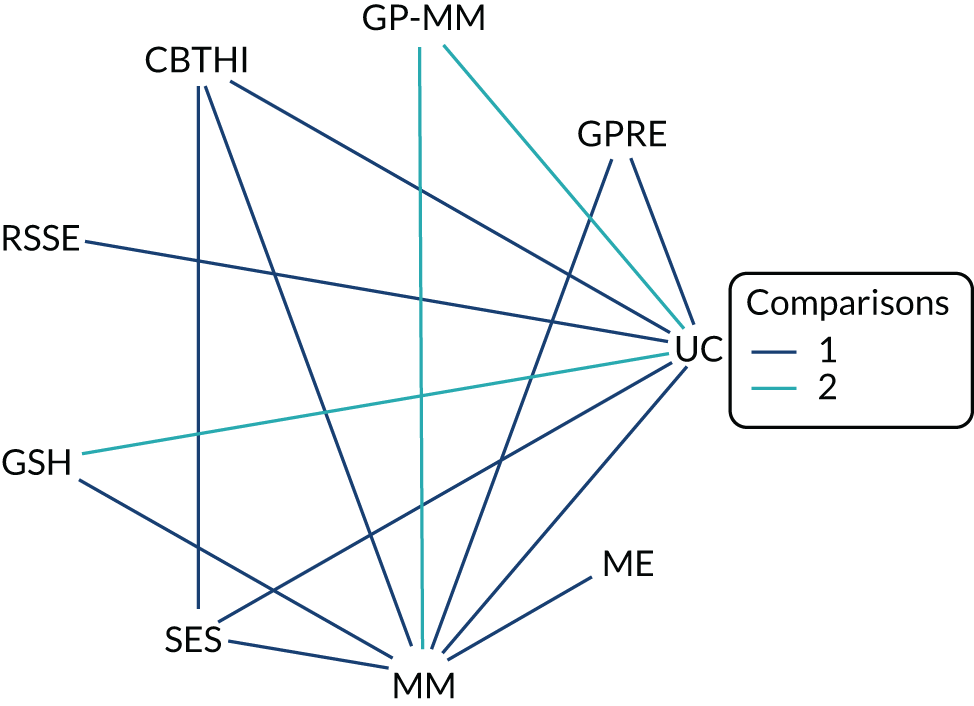

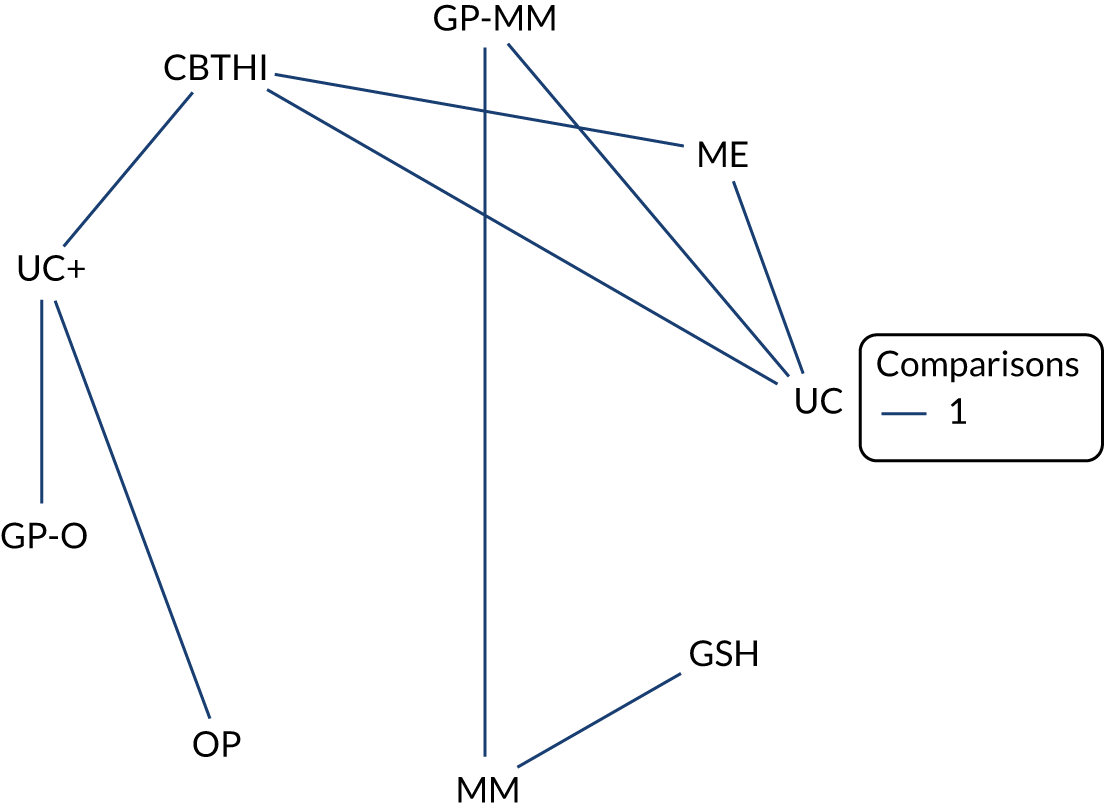

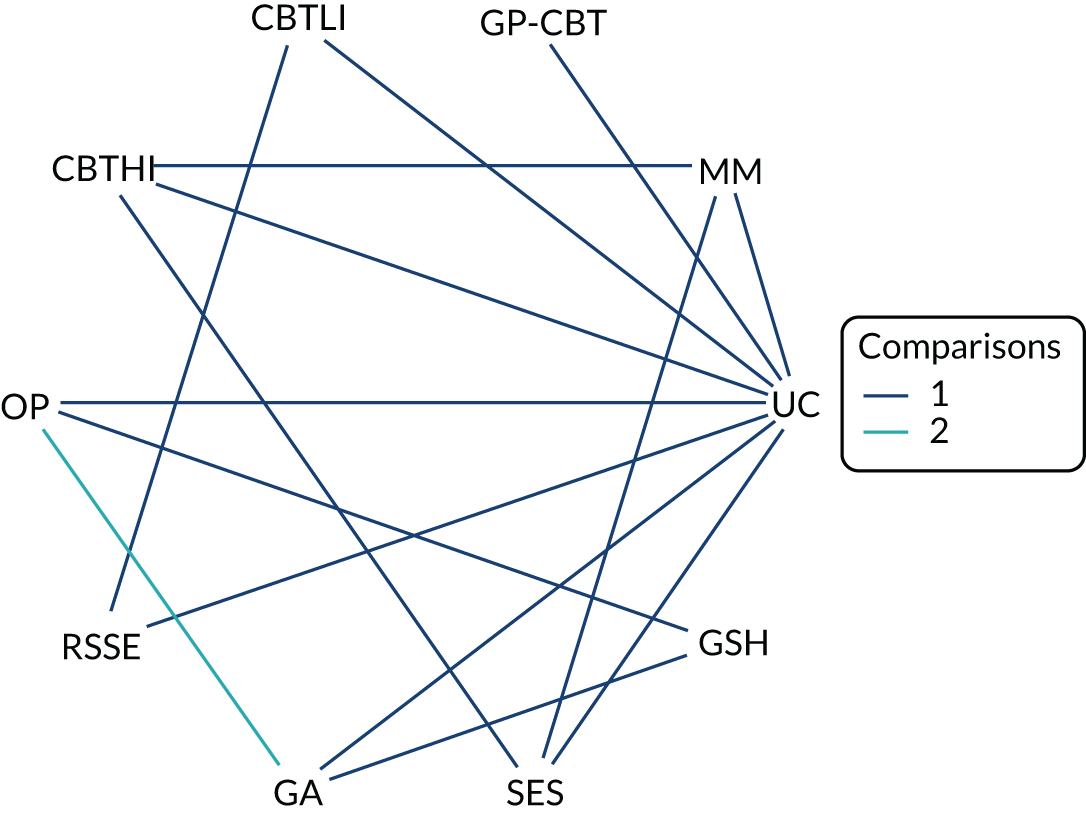

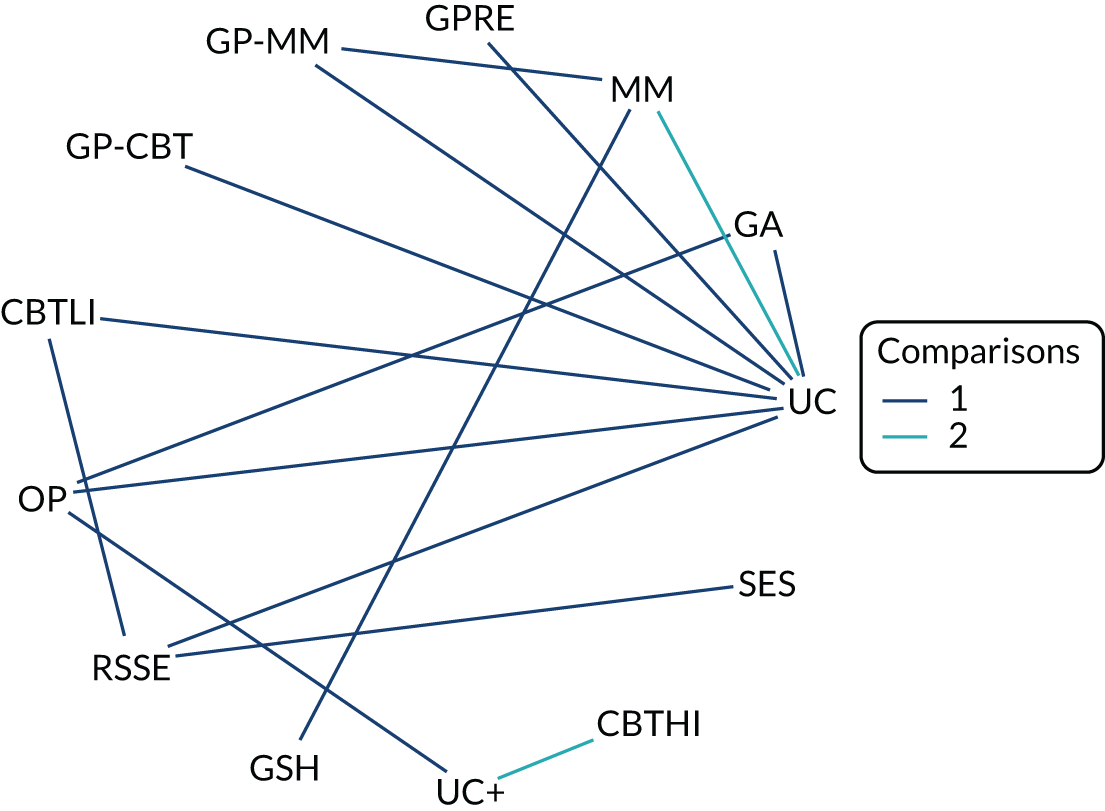

Methods of data synthesis

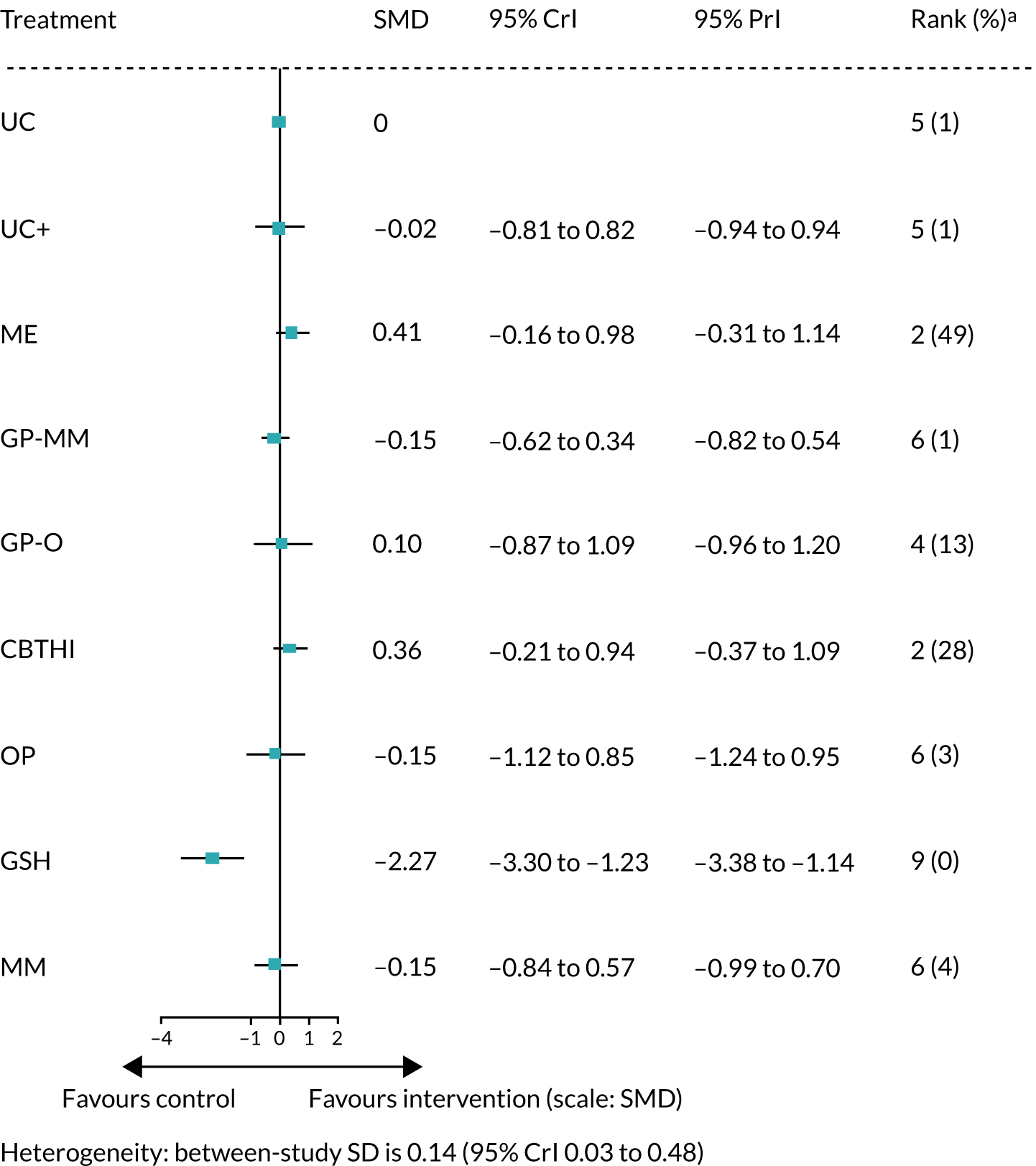

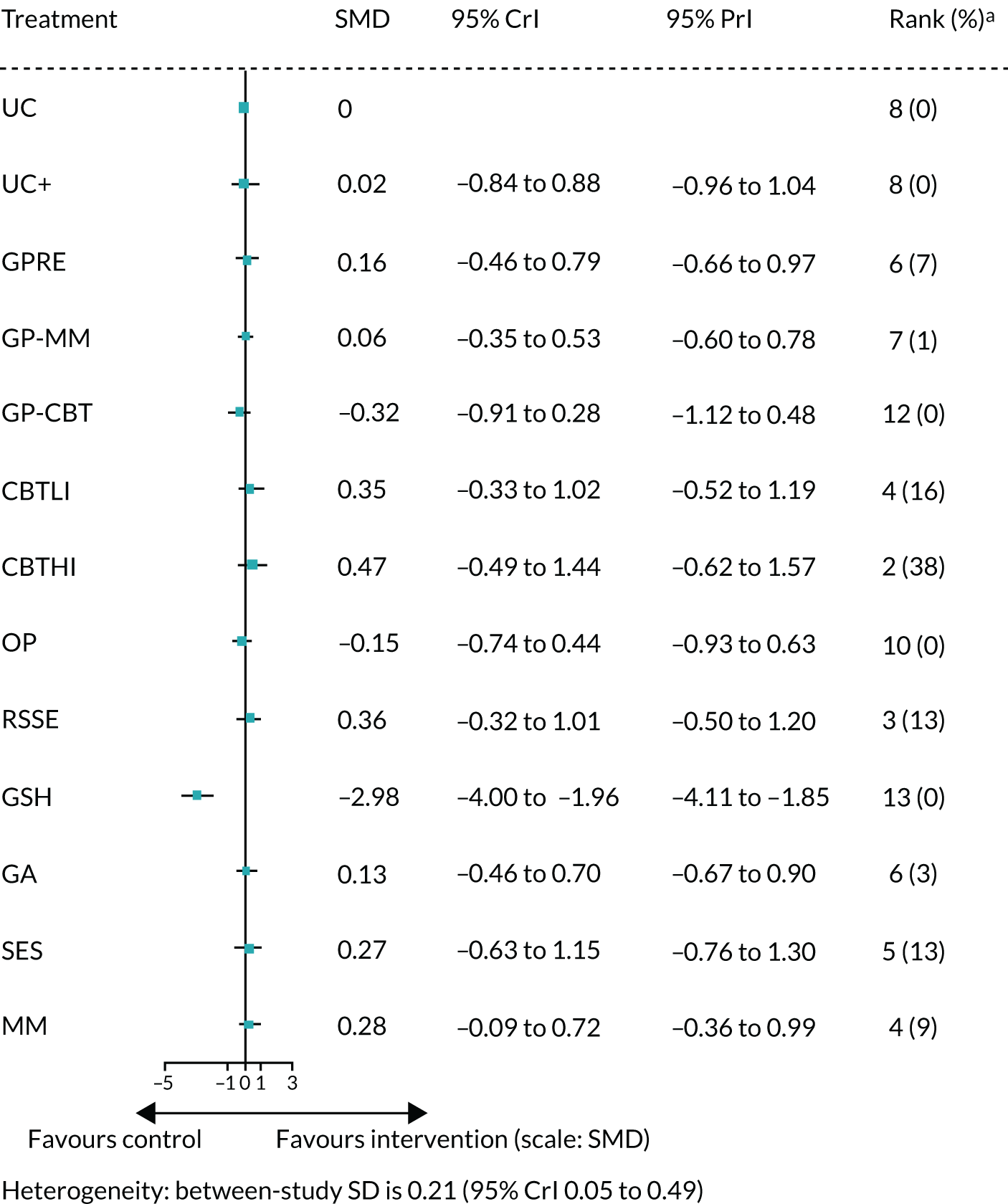

Comparative effectiveness was evaluated using a NMA to allow a comprehensive synthesis of all evidence on all relevant interventions. NMA is an extension of pairwise meta-analysis and it can be used to combine direct and indirect evidence about treatment effects across studies to provide an internally consistent set of intervention effects while respecting the randomisation used in individual studies. 88 The NMAs were conducted using a Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo approach88 on the following outcomes: pain, fatigue, bowel symptoms, somatisation, generic physical symptoms, physical functioning, impact of illness on daily activities, anxiety, depression and emotional distress. This assumed a random-effects model to allow for heterogeneity in treatment effects across studies. Separate NMAs were performed for the three time points: immediately post treatment, short term (up to 6 months post treatment) and long term (> 6 months post treatment).

Definition of treatment effect (continuous outcome measures)

For each outcome of interest, the individual studies may have used one of several different (continuous) measurement scales (see Appendix 2, Table 38). To allow studies using different measurement scales to be included in a single NMA, standardised mean differences (SMDs) were computed for each study. The use of SMDs stems from the concept that the different reported measures are essentially quantifying the same effect and can be placed on a common scale by dividing the mean difference between the intervention and control arms in each study by the standard deviation (SD). Raw reported data, in the form of mean/median, SD/standard error (SE)/confidence interval (CI)/interquartile range (IQR), were used to calculate the SMD for each study using Hedges’ (corrected) g. 87 The SMD was computed based on absolute values at the end of follow-up rather than mean difference from baseline, as the within-study correlation would be needed for the latter and was not reported. All of the scales were transferred to be consistent across the scales used in the included studies so that a positive SMD indicates beneficial effect of a treatment in the intervention group when compared with the treatment in the control group.

Synthesis population

The synthesis population was defined following the inclusion criteria as all MUS. Condition groupings within MUS have been defined as chronic fatigue, chronic pain single site, chronic pain multiple sites, IBS or MUS/somatoform disorders. All condition groupings were synthesised in a single integrated analysis. Ideally, differential responses within each condition grouping would be explored through metaregression; however, the networks were too sparse to allow this.

Statistical model for the network meta-analysis

Let yik denote the observed SMD of arm k of trial i (i = 1 . . . ns, k = 1 . . . na), with variance Vik. We assume that the treatment effects are normally distributed such that:

The parameters of interest, θik, are modelled using the identity link function:

A random-effects model was assumed, so that the trial-specific treatment effects, δi,1k, are assumed to arise from a common population distribution with mean treatment effect relative to the reference treatment such that:

where dti1tik represents the mean effect of the treatment in arm k of study i (tik) compared with the treatment in arm 1 of study i (ti1) and τ2 represents the between-study variance in treatment effects (heterogeneity), which is assumed to be the same for all treatments.

Parameters were estimated in a Bayesian framework. Where there was sufficient sample data, conventional reference prior distributions were used:

-

between-study SD of treatment effects, τ ∼ U(0,1.1)

-

mean of treatment effects dti1tik∼N(0,1002).

In the case of there being relatively few studies, an informative prior distribution was assumed for the between-study SD. Rhodes et al. 89 proposed a t-distribution for log of the heterogeneity parameter for the SMD scale. The prior proposed by Rhodes et al. 89 still has probabilities of extremely high heterogeneity, which is implausible in the context that we are working on. For example, this prior represents the belief that the heterogeneity will be low, moderate, high or extremely high with probabilities of 22%, 41%, 16% or 20%, respectively. It has about 20% of the odds ratio in one study would be > 50 times greater than in another. Hence, the prior prosed by Ren et al. 90 is used, which is a truncated Turner et al. 91 prior [a log-normal (–2.56, 1.742)]. The truncation is based on the judgement that the odds ratio in one study would not be ≥ 50 times greater than in another. The resulting prior represents the belief that the heterogeneity will be low, moderate, high or extremely high with probabilities of 15%, 66%, 19% or 0%, respectively.

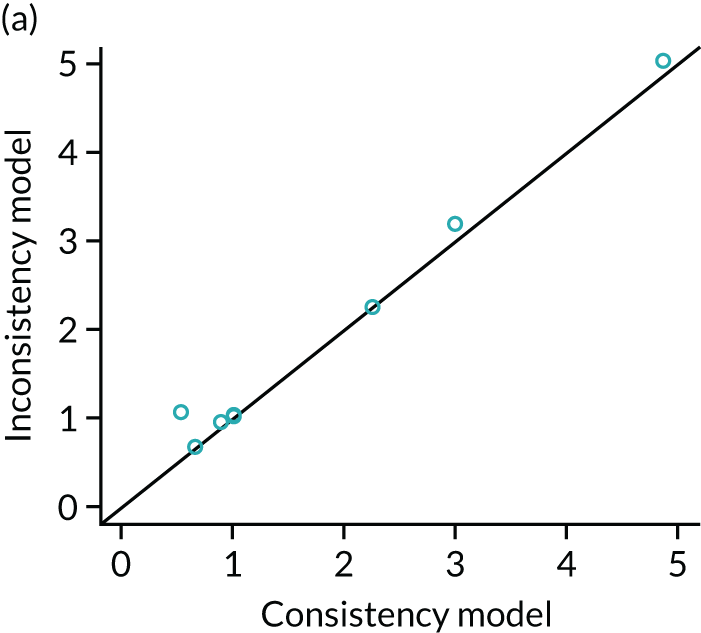

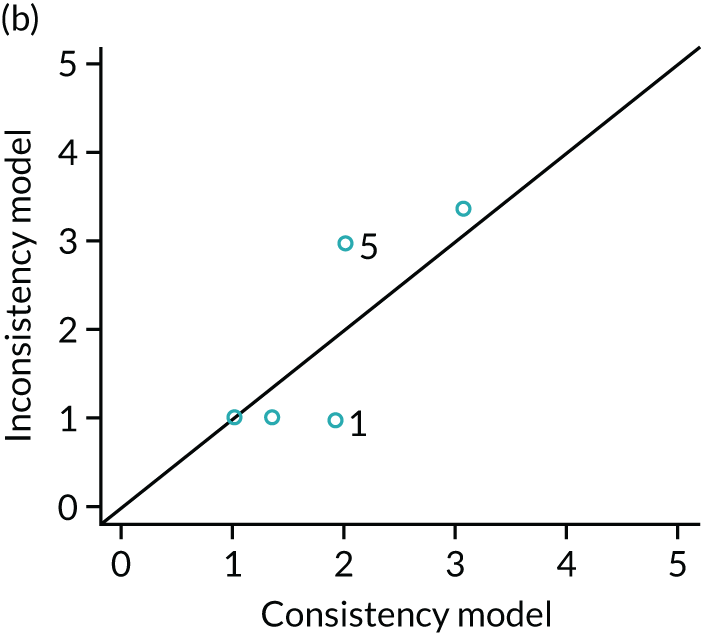

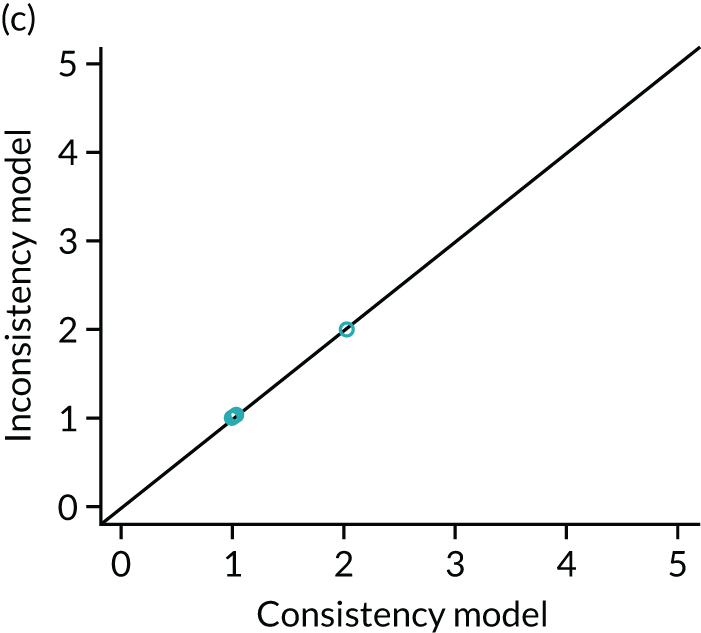

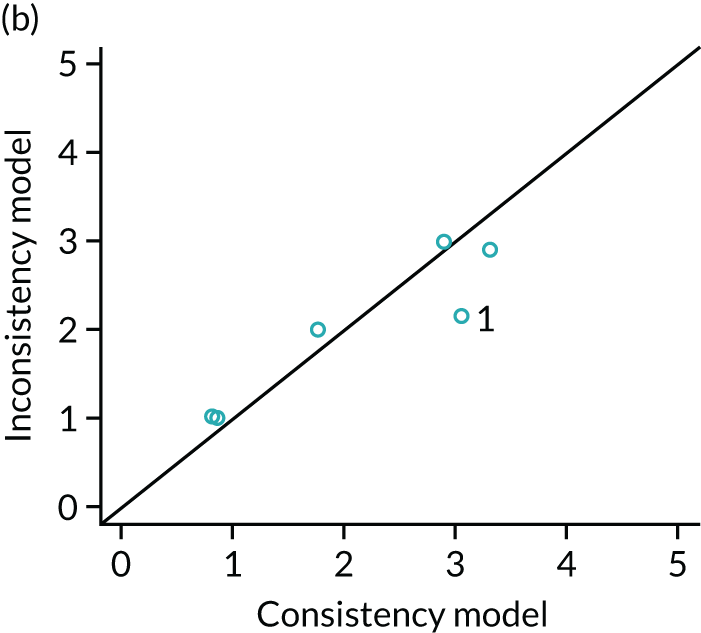

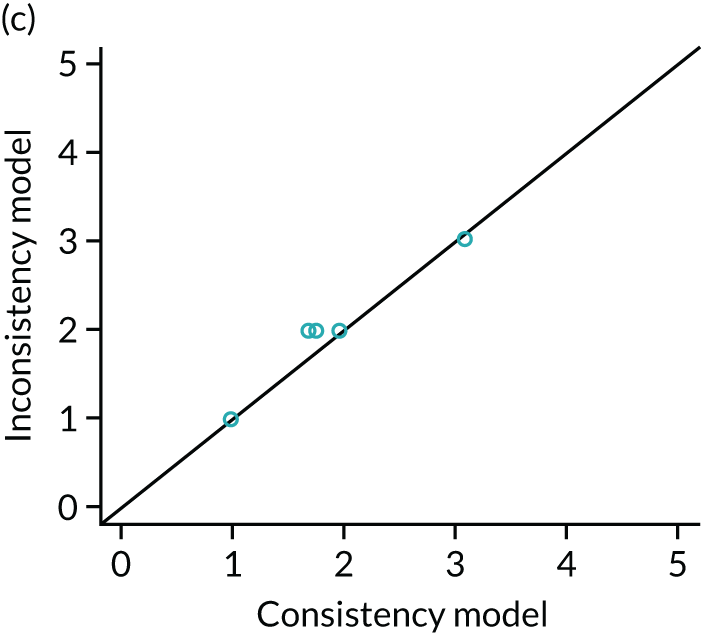

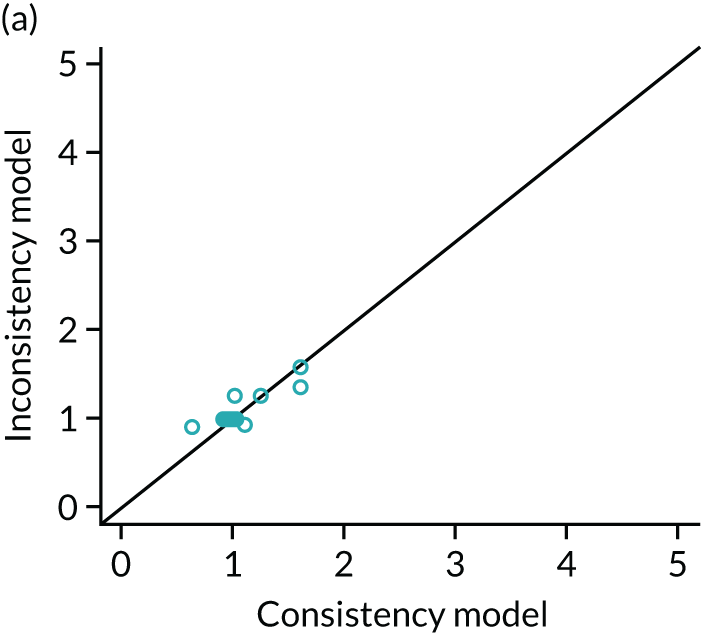

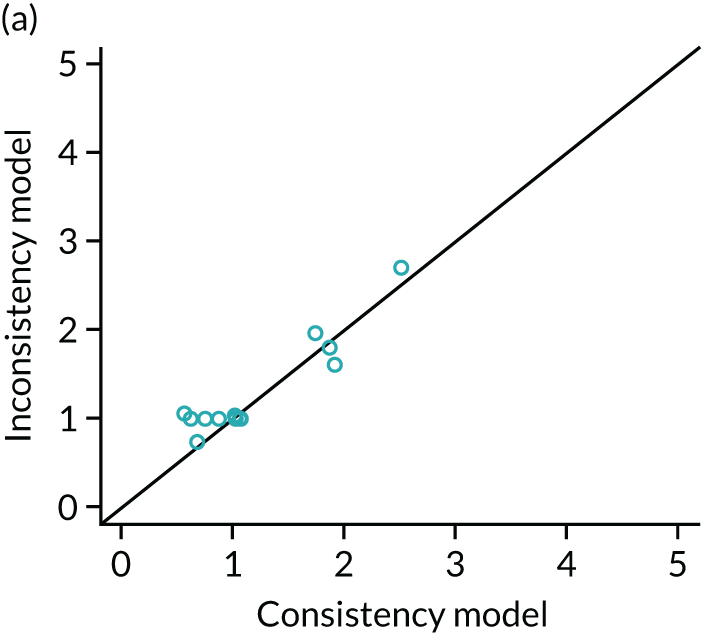

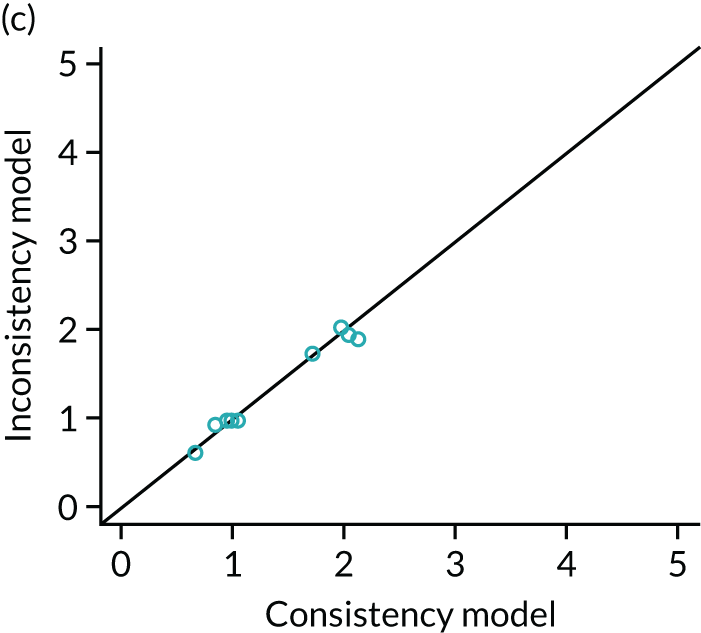

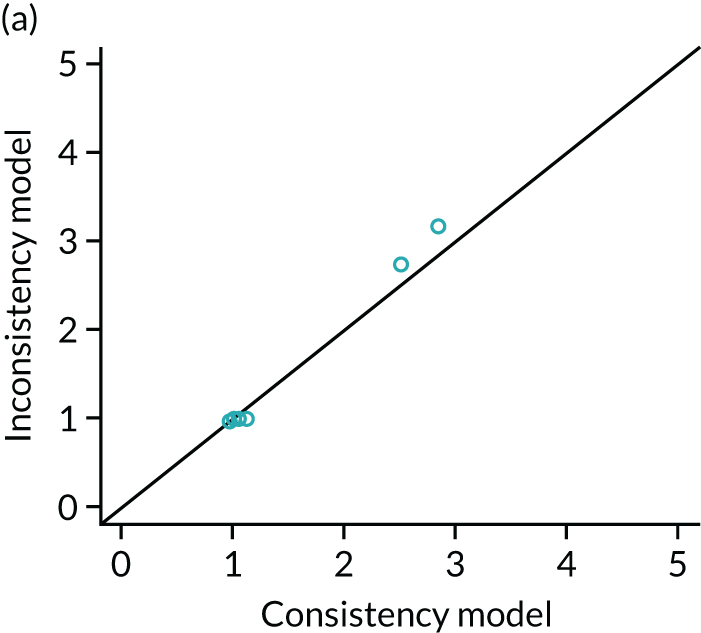

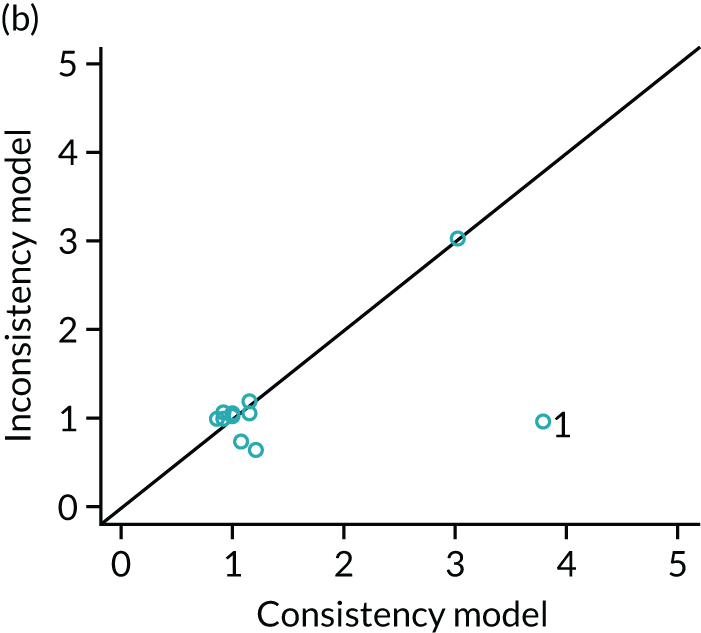

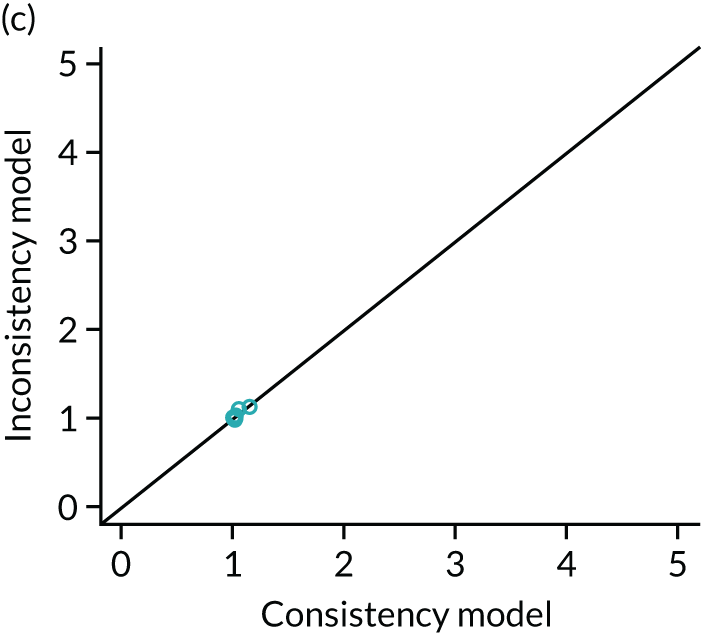

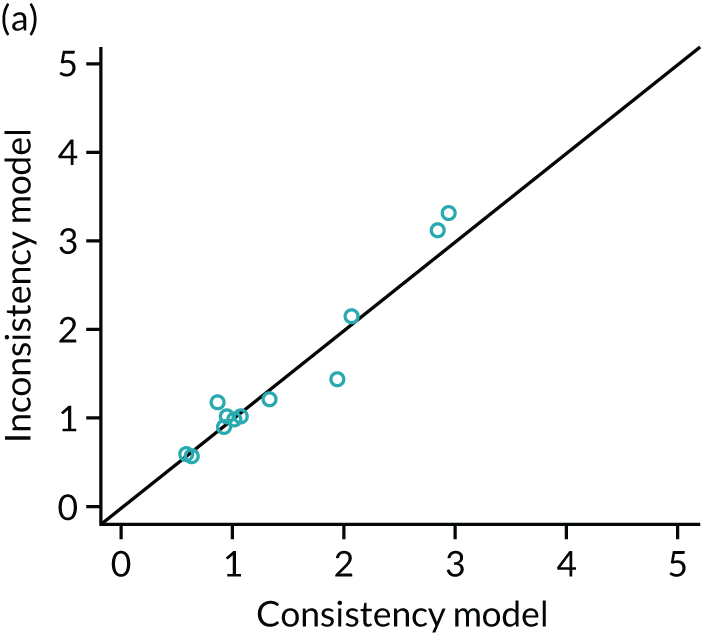

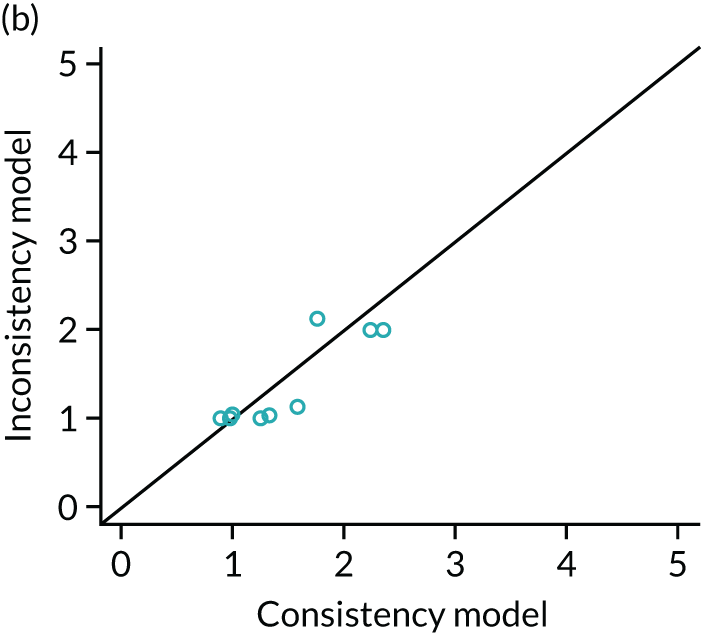

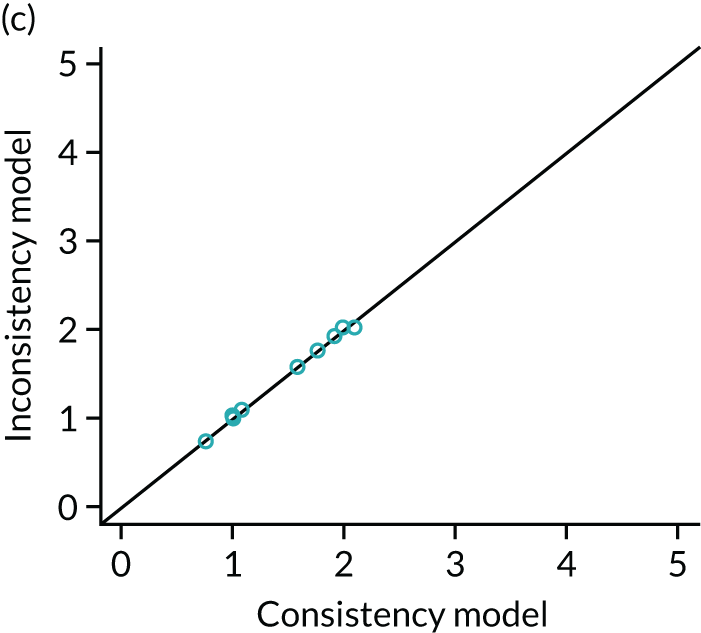

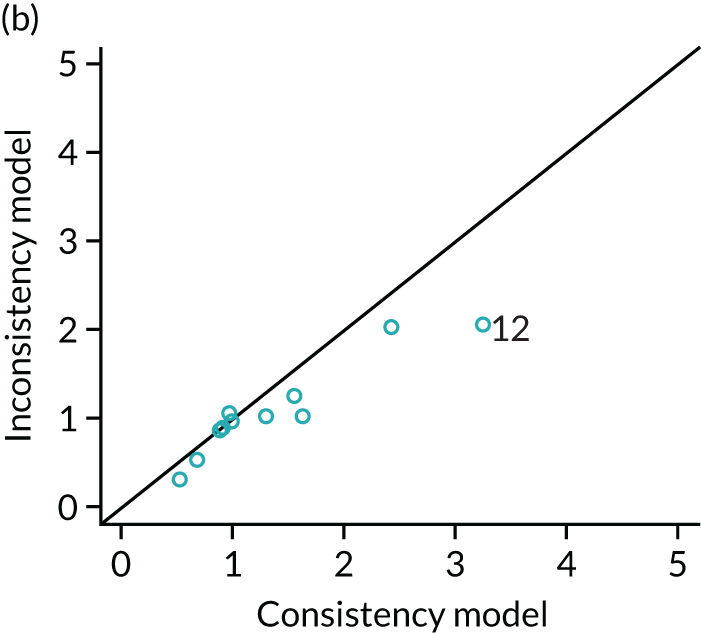

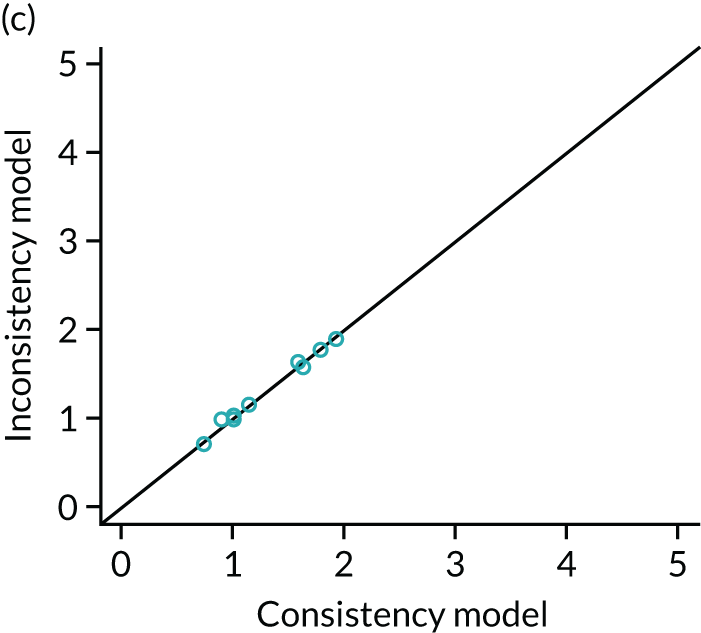

Inconsistency checking was performed by comparing the standard NMA consistency model with an inconsistency model. 92 In the inconsistency model, no consistency is assumed; that is, each of the pairwise comparisons represents an unrelated parameter to be estimated. The deviance information criteria (DIC) for both models are compared, as are the contributions to the deviance for both models, to determine if there is evidence to suggest inconsistency in the network.

All analyses were conducted in the freely available software packages WinBUGS93 (MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK) and R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using the R2Winbugs interface package. 94 Convergence to the target posterior distributions was assessed using the Gelman–Rubin statistic. 95 The chains converged within 18,000 iterations so a burn-in of 18,000 iterations was used. We retained a further 20,000 iterations of the Markov chain to estimate parameters using one chain. The absolute goodness of fit was checked by comparing the total residual deviance with the total number of data points included in an analysis.

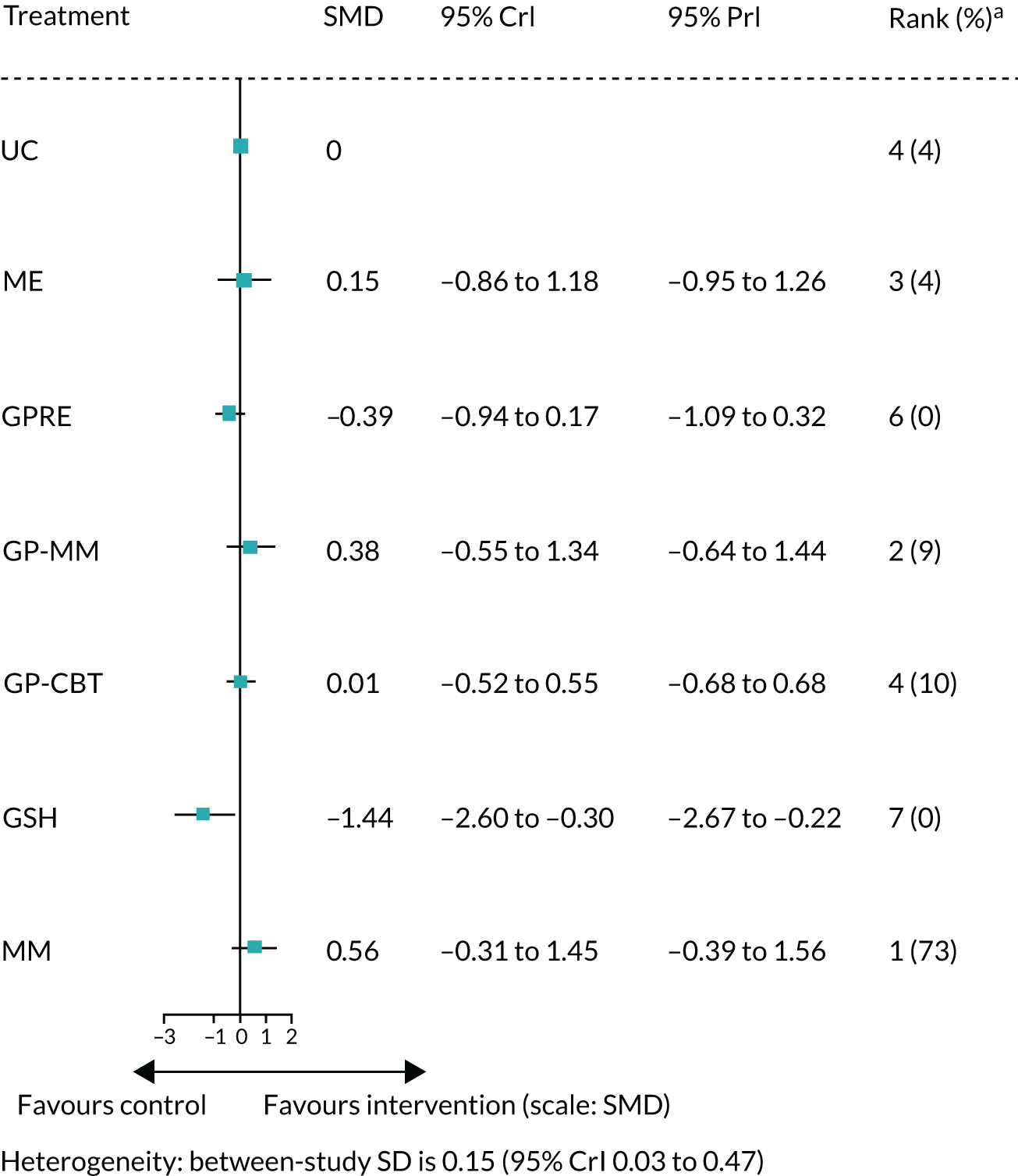

Results are presented using the posterior median treatment effects, 95% credible intervals (CrIs) and 95% prediction interval (PrI). The 95% PrI indicates the extent of between-study heterogeneity by illustrating the range of SMDs that might be expected in a future study. The PrI is calculated based on the predictive distribution of the mean treatment effect. In a Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo setting, the predictive distribution is obtained by sampling from the distribution of effects N(d,τ2). Probabilities of treatment rankings were computed by counting the proportion of iterations of the Markov chain in which each intervention had each rank. Median treatment rankings and the probabilities of being the best treatment are presented.

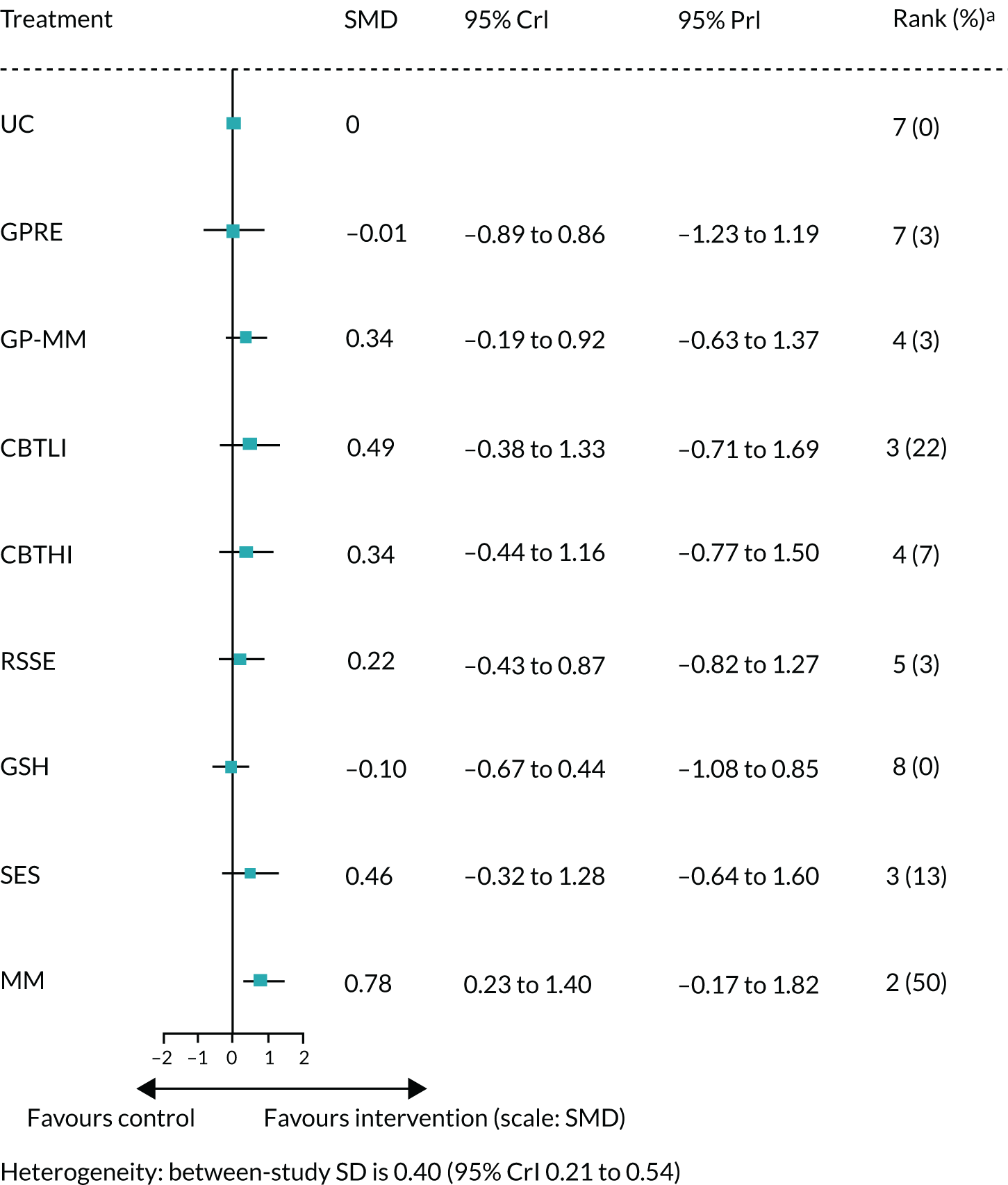

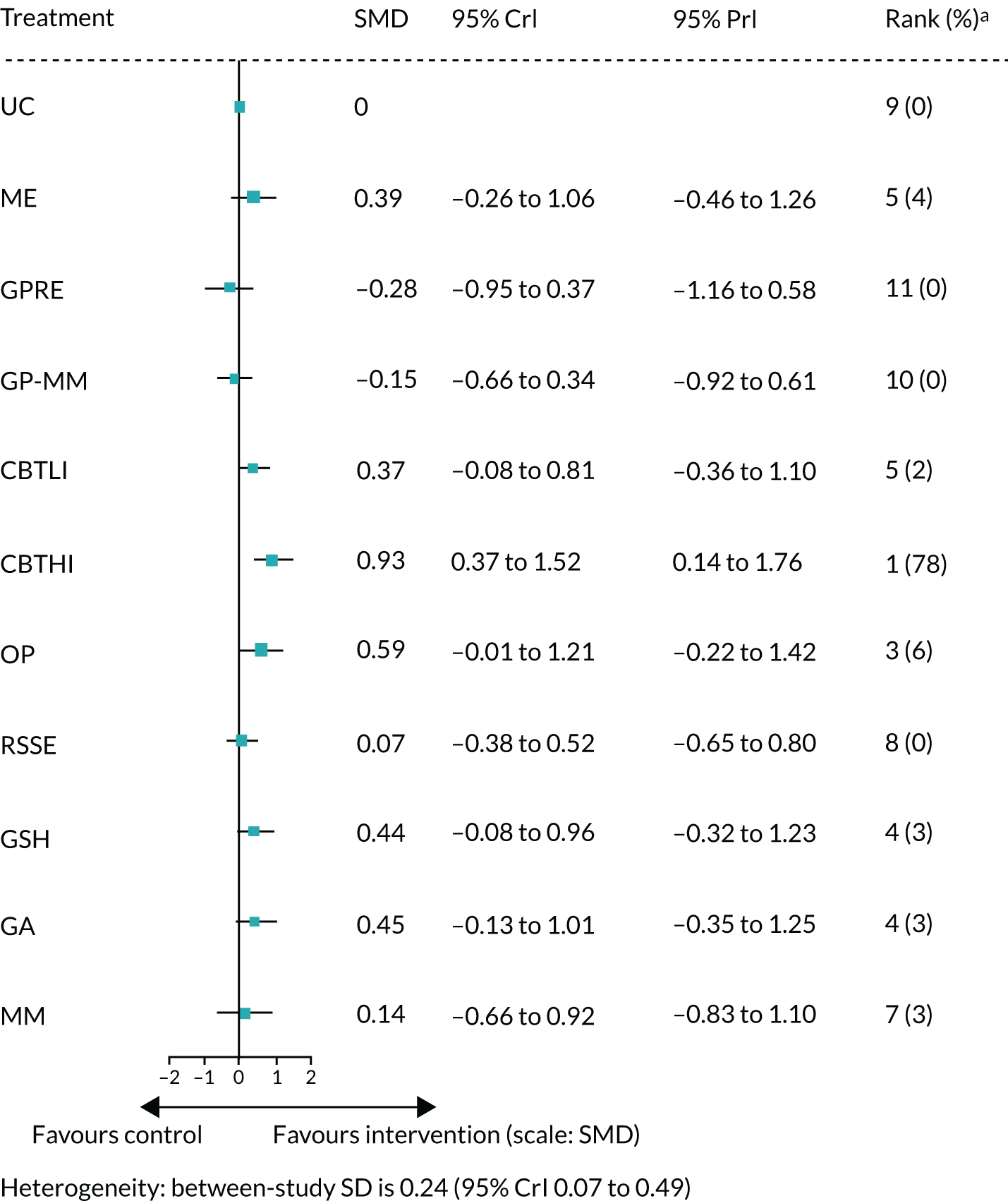

Results

Quantity of research available

Characteristics of included studies

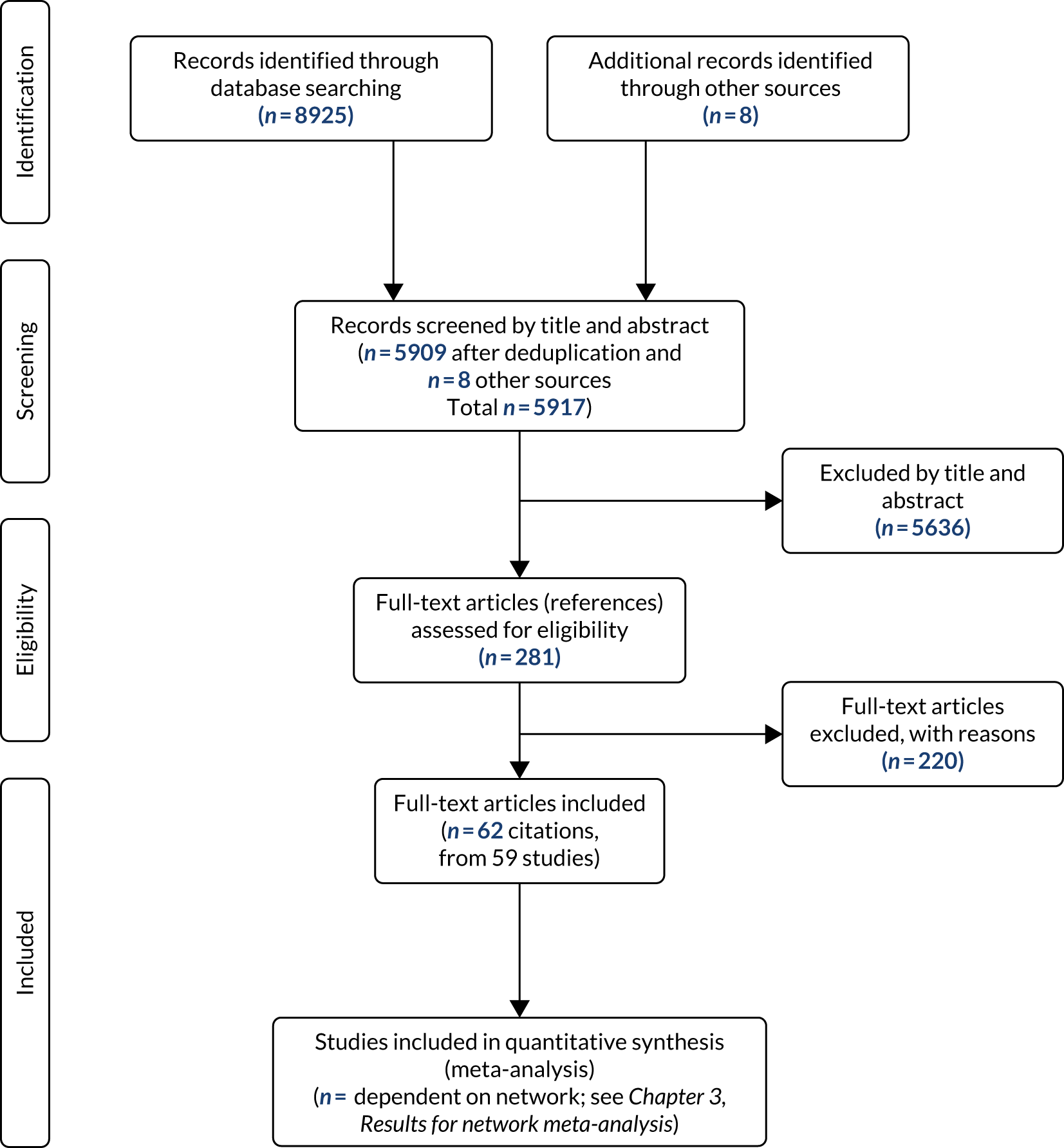

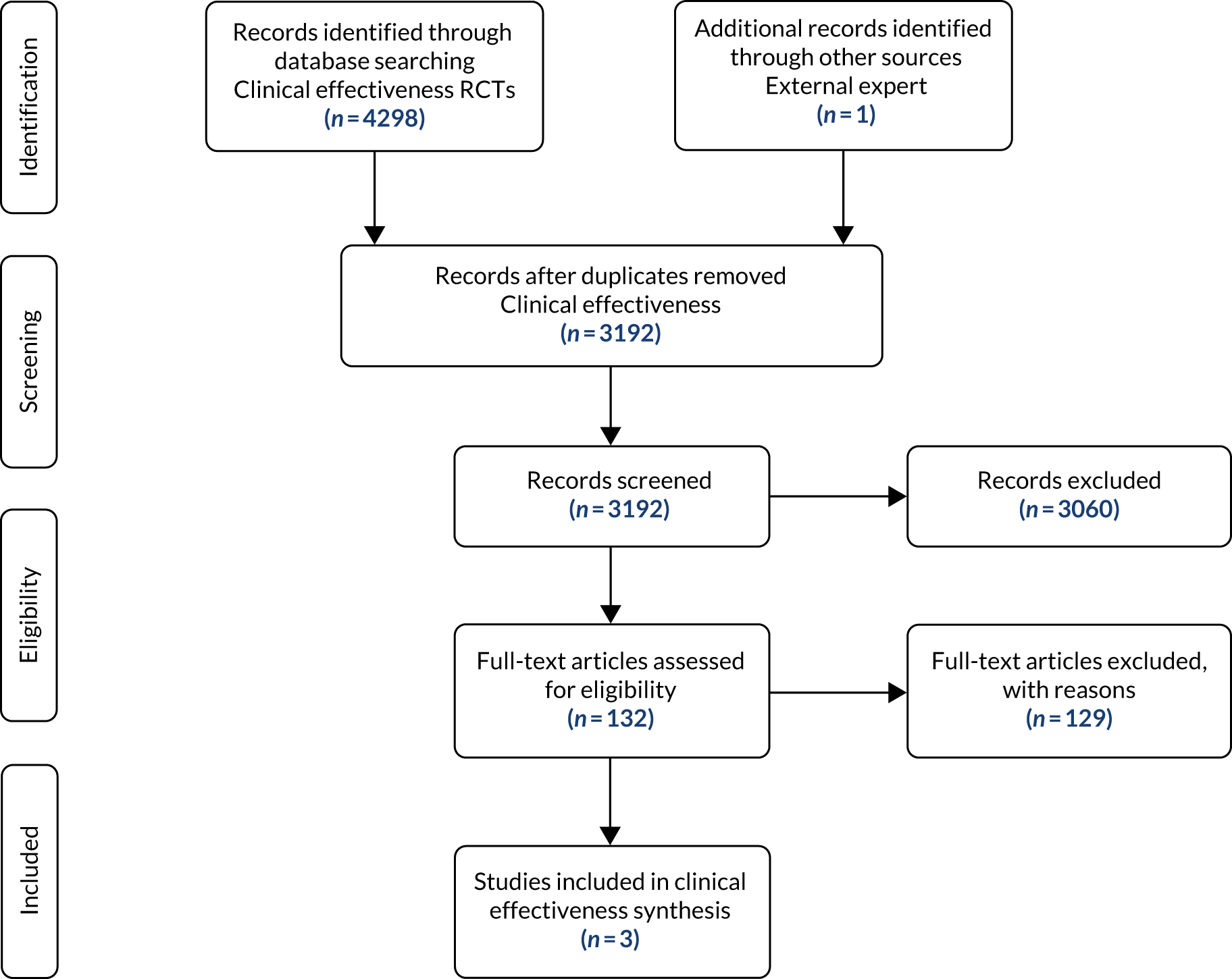

The searches identified 8925 citations for RCTs and 2929 citations for reviews. After deduplication, there were 5909 unique citations for RCTs and 2464 for reviews. For the RCTs, 281 full papers were retrieved as being potentially relevant. A total of 220 of these papers were excluded for at least one of the following reasons: pain was acute or subacute; symptoms did not meet the pre-defined review criteria for ‘unexplained’ as described above; pain was mixed explained/unexplained but populations could not be distinguished from one another in the results; setting was not primary care or insufficient primary care involvement; outcomes were not relevant; conference abstracts or dissertations; or not RCTs. Figure 2 shows the PRISMA flow chart. Studies excluded at full-paper stage are presented with reasons in Appendix 4.

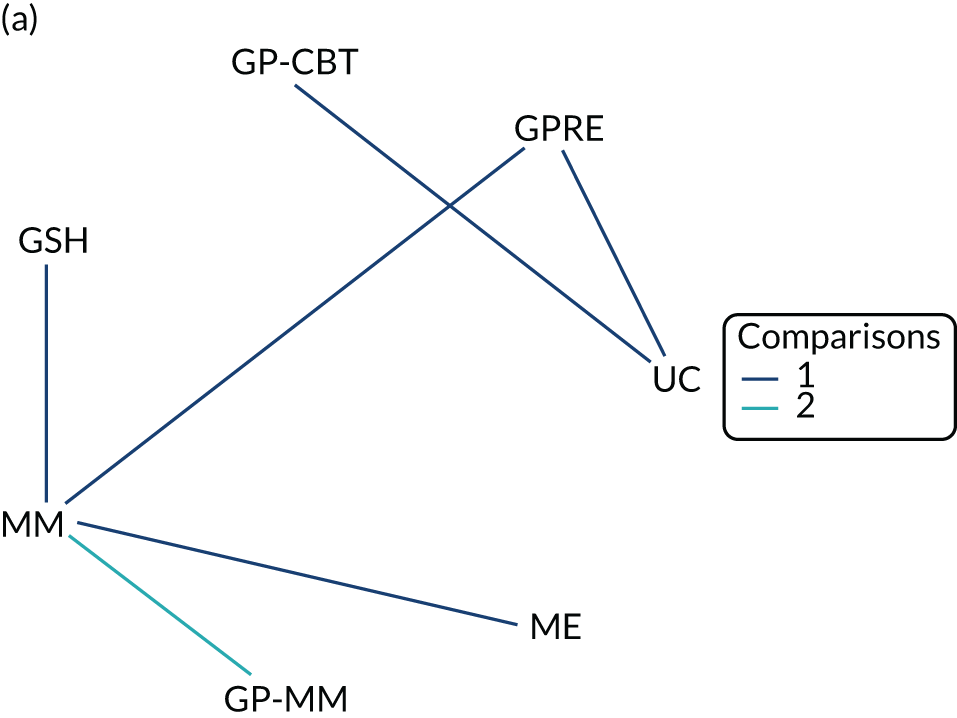

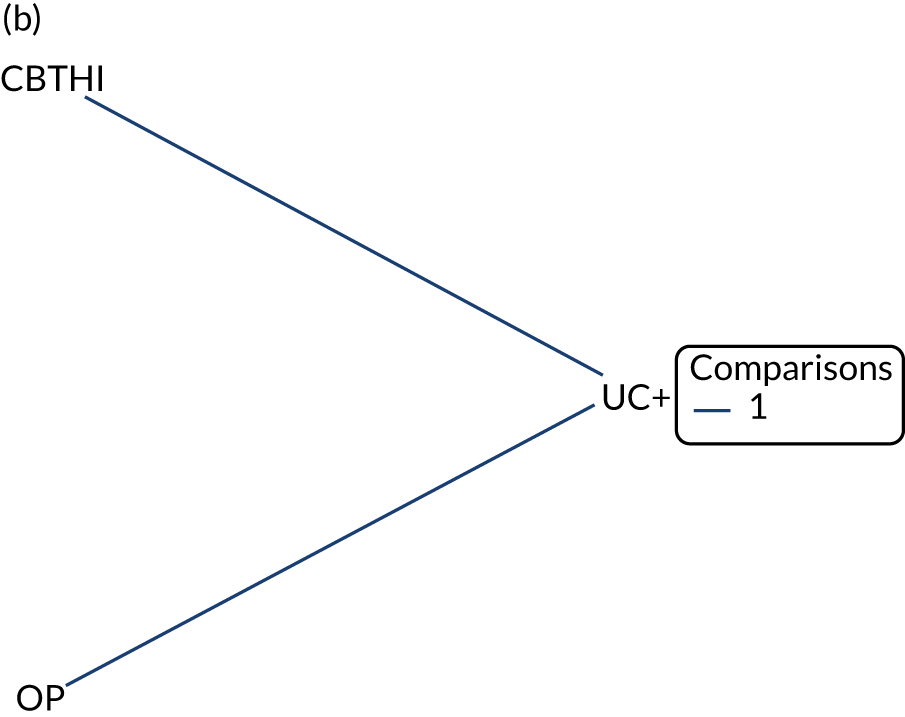

FIGURE 2.

The PRISMA flow diagram.

Sixty-two papers provided data from 59 trials. There were a total of 9077 participants across all trials that randomised numbers in each arm. The number of participants in a single trial ranged from 1096 to 524. 97 Owing to the nature of some of the interventions (i.e. where GPs received training to deliver treatment of MUS), some studies were cluster randomised, whereas the rest were randomised at patient level. Basic study characteristics are presented in Appendix 2, Table 42.

Description of the evidence

Study characteristics

Population

Appendix 2, Tables 29–36, shows the population inclusion criteria for individual studies by condition grouping. Condition groupings were MUS/somatoform disorder (including single MUS or mixed MUS), chronic fatigue (including but not exclusive to CFS), chronic pain (single site), chronic pain (multisite, including fibromyalgia) and IBS.

Of 59 studies that met the inclusion criteria, 29 studied either ‘MUS’ or ‘somatoform disorder’. Approximately half of these studies required participants to meet the diagnostic criteria for either somatoform disorder (DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, ICD-9, or ICD-10) or abridged somatisation disorder. 98 The remaining studies included populations of patients with ‘MUS’. Criteria for inclusion were varied, from number of unexplained symptoms within a set time (e.g. two or more within the past 6 months,99 lifetime history of 6–12 unexplained symptoms,100 five or more symptoms meeting the definition of unexplained during past 6 months101) to more general criteria (e.g. ‘multiple unexplained symptoms’,102 ‘symptoms rated by the GP as psychosomatic in origin’,103 ‘GP confirmed medically unexplained nature of symptoms’104 or ‘primary care providers had recognised that emotional status may have been related to their patient’s symptoms’105). The remaining studies set duration of unexplained symptoms as their inclusion criteria (e.g. duration of unexplained complaints of at least 12 months,106 no documented organic disease to explain symptoms of at least 6 months’ duration107 and ≥ 3 months’ physical symptoms not explained by physical pathology108).

One of the 59 studies109 had a population of mixed diagnoses that included any functional disorders, and one further study included participants with a single MUS: medically unexplained vaginal discharge. 110

Twelve of the 59 studies were of participants with chronic fatigue, and 7 of these 12 included populations meeting diagnostic criteria for CFS. Most of these used the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria for CFS,6 but one study used the Oxford criteria. 111 Two of the 12 studies included participants who either met US CDC criteria for CFS or scored ≥ 4 on the Chalder Fatigue Scale. 112,113 The remaining three studies did not include participants with CFS, with two requiring a score of ≥ 4 on the Chalder Fatigue Scale,114,115 and one requiring a score of ≥ 35 on the fatigue subscale of the Dutch Checklist of Individual Strength. 116,117

Six of the 59 studies were of chronic pain at a single site on the body. Four of these were of back pain,118–121 one was of headache122 and one was of neck pain. 123 All required the duration of pain to be ≥ 3 months, apart from Loew et al. ,122 in which the requirement was for ≥ 12 months’ duration.

Seven of the 59 studies were of chronic pain at multiple sites of the body. Four of these studies were of participants with fibromyalgia, and these used the 1990 ACR diagnostic criteria as their inclusion criteria. 124 The remaining three studies were of chronic widespread pain125,126 or mixed chronic multisite pain, for example chronic generalised or regional pain where organic explanation had been ruled out. 127,128

The remaining three studies were of IBS. Inclusion criteria were that patients met the Rome I diagnostic criteria129 or Rome I and II diagnostic criteria. 130 The third IBS study required a diagnosis of functional gastrointestinal symptoms diagnosed as IBS, but participants did not necessarily have to meet Rome criteria. 131

Setting

Fifty-six of the included studies were defined as ‘primary care’, with the remaining three studies defined as ‘community based’. Appendix 2, Table 40, shows that there was considerable heterogeneity in the details of the setting of the studies. Studies varied in the primary care involvement, although all were designed for primary care patients rather than patients already in tertiary care or who self-referred to a university-based study without co-ordination with a primary care practitioner. Variation in setting detail included study designs where:

-

Patients were recruited and treated by their own GP at their own GP practice.

-

Patients were recruited by their GP, but treated by another health-care professional at their own GP practice.

-

Patients were recruited and assessed by their GP, but treated by another health-care professional at an outside facility; for example a gymnasium or park.

-

Patients were recruited and co-ordinated by their GP, but treatment was self-directed (e.g. home-based exercises).

-

Non-UK studies where the organisation of primary care may differ from the UK health-care system (e.g. ‘primary care physiotherapy clinic’). These clinics are described as working in close co-operation with ordinary primary health systems.

Studies where the intervention itself was not delivered within the primary care practice tended to be sport- or exercise-based interventions, or use of self-help materials. Community-based interventions were included only if the study was explicit in its description and aim of the intervention as being community based. Appendix 2, Table 40, shows setting details for individual studies.

Interventions

Intervention arms were coded into one of the 13 pre-defined intervention groupings. Appendix 2, Table 28, reports the detail of the intervention arms for each study, as described by the authors, and the intervention grouping that the arm has been coded into. Control arms that were active rather than passive were coded into one of the intervention groupings, therefore the numbers reported below for each intervention group add up to greater than the number of studies. Passive control arms were coded either as medication or as usual care/usual care plus. There were a total of 127 intervention arms. Of these, 80 were active intervention arms (or were categorised as such by the review team; for example, where an education booklet/presentation was called usual care by the authors, this was categorised as guided self-help and, therefore, an active intervention) and 47 were passive control arms. There was considerable heterogeneity both between and within groupings. Numbers for types of intervention groups are listed below. Appendix 2, Table 41, presents a summary of intervention groupings for each study arm.

Active intervention arms:

-

GP reattribution (including modified), n = 5

-

GP MUS management, n = 6

-

GP-CBT, n = 1

-

GP other psychotherapy, n = 1

-

GP other, n = 1

-

CBT high intensity, n = 8

-

CBT low intensity, n = 7

-

other psychotherapy, n = 11

-

graded activity (GA), n = 7

-

strength/endurance/sport (SES), n = 7

-

relaxation, stretching, social support, emotional support (RSSE), n = 8

-

guided self-help, n = 6

-

multimodal, n = 12.

Passive control arms:

-

medication, n = 3

-

usual care, n = 39

-

usual care plus, n = 5.

The most common active intervention was multimodal therapy. There was wide variation in the nature of the multimodal interventions, with various combinations of the individual interventions represented. These may be specifically defined in the paper as ‘multimodal’ (e.g. Smith et al. 107) or may consist of components from different groups (e.g. van der Roer et al. 120 sport/exercise + education + behavioural programme; McBeth et al. 125 CBT + sport/exercise). Not only did the RSSE group encompass a wide range of different types of intervention, but these types of intervention were also commonly used as active controls (or were classed as active controls by the review team), as were guided self-help interventions, which were often a self-management information/education booklet. There was an element of overlap between some of the guided self-help interventions and low-intensity CBT (CBTLI), with the latter providing more structure and support than the guided self-help interventions. Other psychotherapy was the next most common intervention, with high-intensity CBT (CBTHI) and CBTLI being the third and fourth most common. Graded activity and sport/exercise interventions were equally represented, with seven arms each. Some interventions were conducted in groups and some were conducted individually. Some were conducted face to face whereas others were conducted at a distance, either by telephone or by e-mail. Appendix 2, Table 41, presents these details by arm for each study.

For most interventions, treatment was directed at patients, in a set number of sessions, for a recommended duration. However, some interventions were directed primarily at the GP. GPs would receive training in methods of treating patients with MUS. This training aimed to enable the GP to communicate a behavioural/biopsychosocial approach to unexplained symptoms to their patients. In these cases, a set study period was usually specified, during which time the GP would conduct consultations with patients in their usual distribution of surgeries rather than at a set number of GP/patient sessions. This study period could last up to 2 years. 97

There was also heterogeneity within intervention groups. Appendix 2, Tables 43 and 44, presents details of planned duration of treatment sessions for each arm, and Table 44 presents details of planned duration of the treatment period. Greater detail by intervention arm for actual mean sessions/duration for each arm is reported in the cost analysis in Chapter 6. There was no typical treatment duration, either between or within intervention groups. Treatment sessions ranged from 1 × 10- to 15-minute session with a HP followed by self-management114 to 10 × 90-minute sessions of treatment plus booster sessions. 132 The shortest treatment periods were around 6–8 weeks (e.g. McCleod et al. ,105 LeFort128 – 6 weeks; Macedo et al. ,119 Moss-Morris et al. 130 – 8 weeks), with a mid-range of 12 weeks (e.g. Marques et al. 133 and Ridsdale et al. 112). Longer-term treatment periods ranged up to 1 year (e.g. Kocken et al. 103 and Smith et al. 107).

Differences in intervention provider and the contact time spent with patients are shown in Appendix 2, Table 45. Interventions were delivered by a range of health-care professionals (e.g. GPs, psychologists, practice nurses, physiotherapists, psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses and health educators). There was little consistency in contact time between provider and patient across the studies.

Most usual-care arms were not specific in their descriptions of care received – this probably varies between individual patients in response to their particular needs, but may consist of giving information leaflets/medication. Some controls defined as ‘usual care’ by the study authors were categorised into active intervention groups. For example, an active study intervention ‘self-help’ consisting of a self-management booklet and minimal contact with a HP114 is categorised as guided self-help. The same booklet is used as a part of a ‘usual-care’ control arm in another study115 but, for the purposes of the review, has been categorised as guided self-help.

Outcomes

All primary and secondary outcomes assessed in each study, together with the scales used for assessment, are reported in Appendix 2, Table 37. Owing to differences in populations, outcomes varied between studies. Key outcomes across studies were identified and are presented in Appendix 2, Table 38. Condition-specific symptoms were measured, for example bowel symptoms for IBS studies, fatigue for chronic fatigue studies, and pain for chronic pain studies. Some of these condition-specific symptoms were also recorded for studies of ‘MUS’ patients, most commonly for pain, but never for bowel symptoms. Pain was most frequently measured using a visual analogue scale (VAS) or numerical rating scale (NRS) in studies of chronic pain populations, whereas, for studies of MUS patients, the SF-36 bodily pain subscale was more frequently used. Fatigue was almost always assessed using the Chalder Fatigue Scale. Psychological symptoms, most commonly anxiety and depression, were measured across all condition groups. For depression, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Depression (HADS-D), BDI, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) and Symptom Checklist-90 – Depression (SCL-90-D) were the most frequently used scales. For anxiety, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Anxiety (HADS-A), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) and Symptom Checklist-90 – Anxiety (SCL-90-A) were the most frequently used scales. Composite measures of emotional distress were also reported, most commonly using the SF-36 mental health subscale, but also HADS total scores, or the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-30). For ‘MUS/somatoform’ studies, ‘somatisation’ was commonly measured to assess symptom load, using a number of scales but most commonly the SOMS or PHQ-15 or Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI). Severity of main symptoms or number of symptoms was also measured (generic physical symptoms) in a minority of studies, with severity VAS or number of symptoms used as methods of assessment. Physical function was measured in studies of all conditions, almost always using the Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12) or SF-36 physical functioning subscale. Finally, illness impact on daily activities was measured across conditions, using disability scales such as the Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), the Neck Disability Index or Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), or, for fibromyalgia, the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) total.

Quality of the evidence

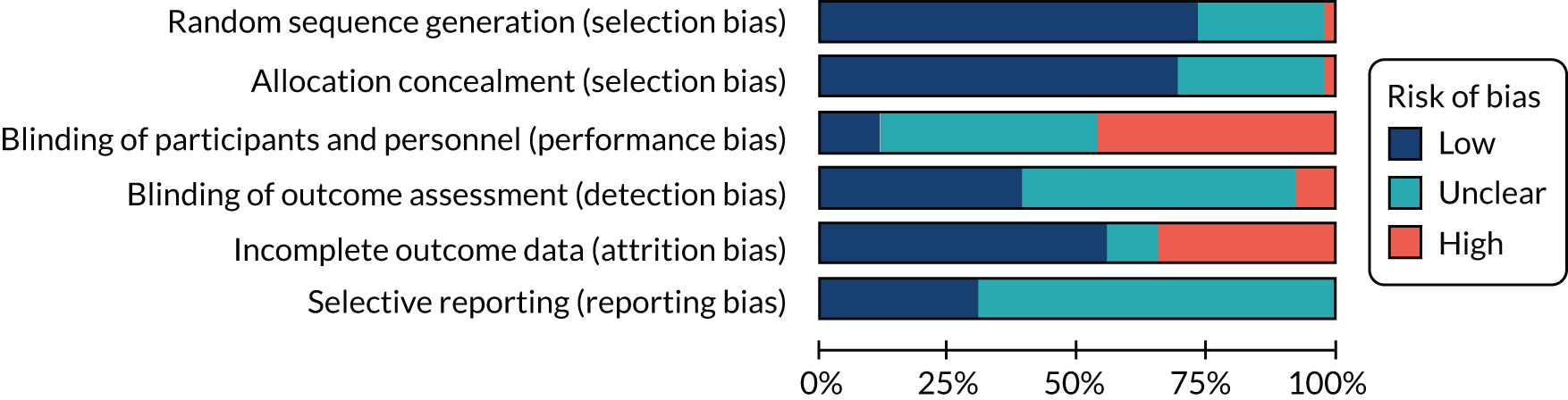

Individual risk-of-bias extractions and summary tables can be found in Appendix 3. The quality of individual studies ranged from low to high. Most commonly, studies were found to be at high risk of performance bias, with patients and intervention providers frequently not blinded because of the nature of the interventions and comparators. Over 25% of studies were at high risk of attrition bias, but over 50% of studies were found to be at low risk of attrition bias using the 20% cut-off point. 134 Reporting bias was assessed by reference to study protocols. Study protocols were sought using a number of methods and these are described, with success rates, in a separate paper. 135 Figure 3 shows the summary table for risk-of-bias assessments.

FIGURE 3.

Summary table of risk-of-bias assessments.

Study results

Raw data extracted from individual studies (means, SD/SE by outcome) can be found in Appendix 4. For the following reasons, studies do not contribute data to all outcomes in the NMA:

-

as is seen in Appendix 2, Table 38, key outcomes vary by study

-

as is seen in Appendix 2, Table 39, follow-up time points are not consistent between studies

-

studies could not be included in the NMA where both intervention arms were grouped into the same intervention category; for example, Aiarzeguena et al. 136 where both arms were grouped as GP reattribution (one arm being modified reattribution) or where both arms were GA (one arm being symptom contingent and one arm being time contingent)

-

data could not be included where no variance was given

-

data could not be included when only provided in graphical format

-

studies could not be included where no raw data were provided for non-significant outcomes.

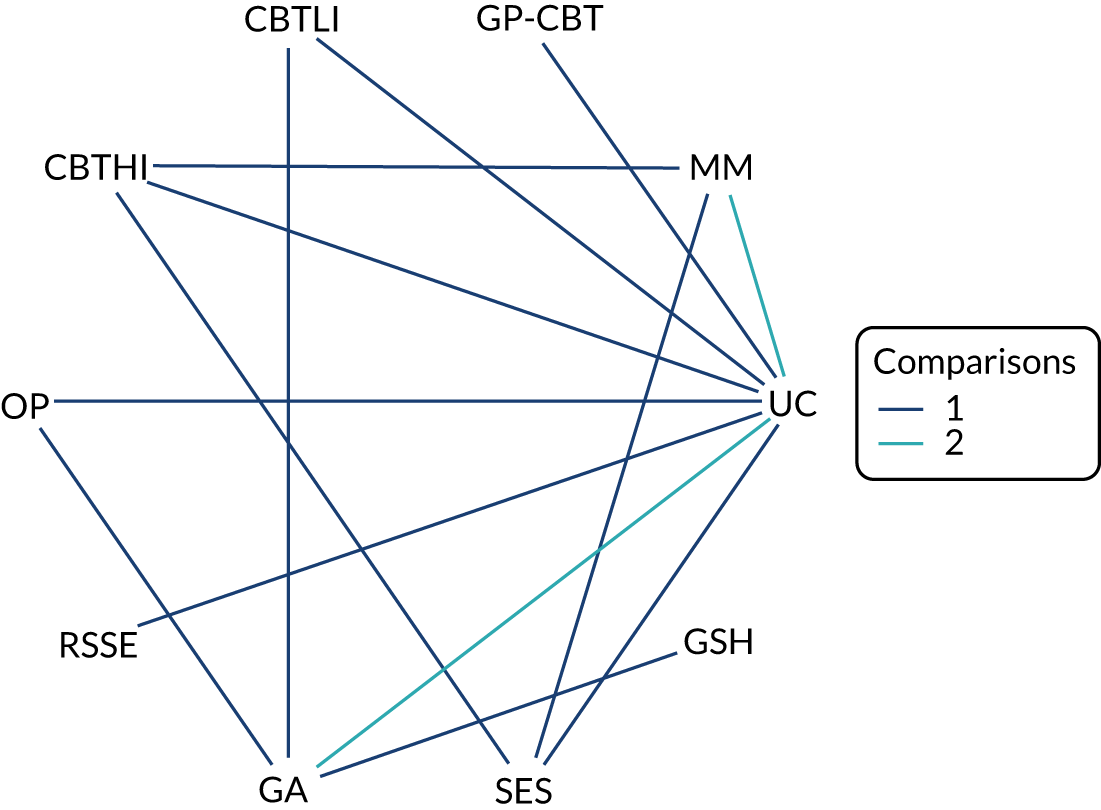

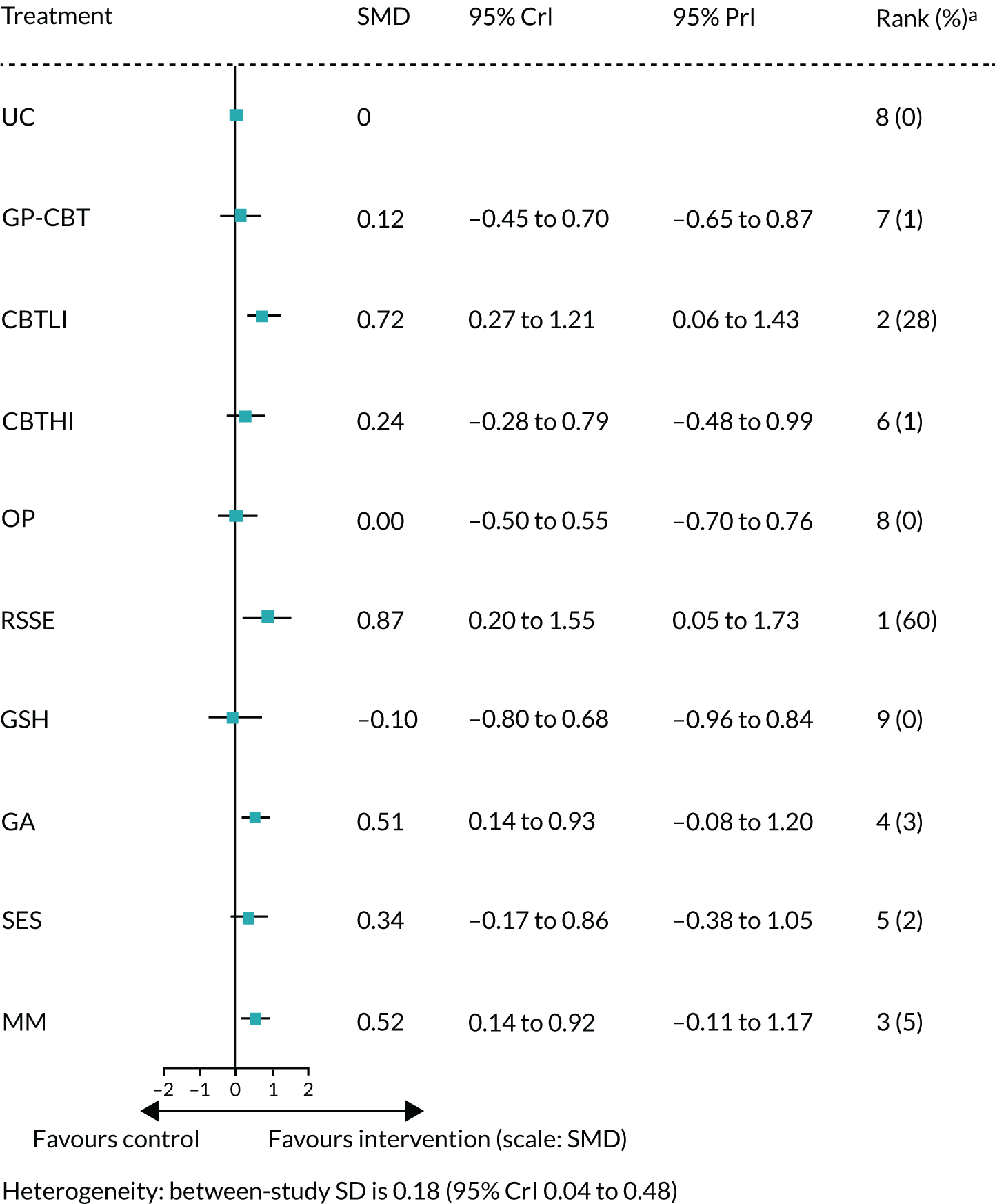

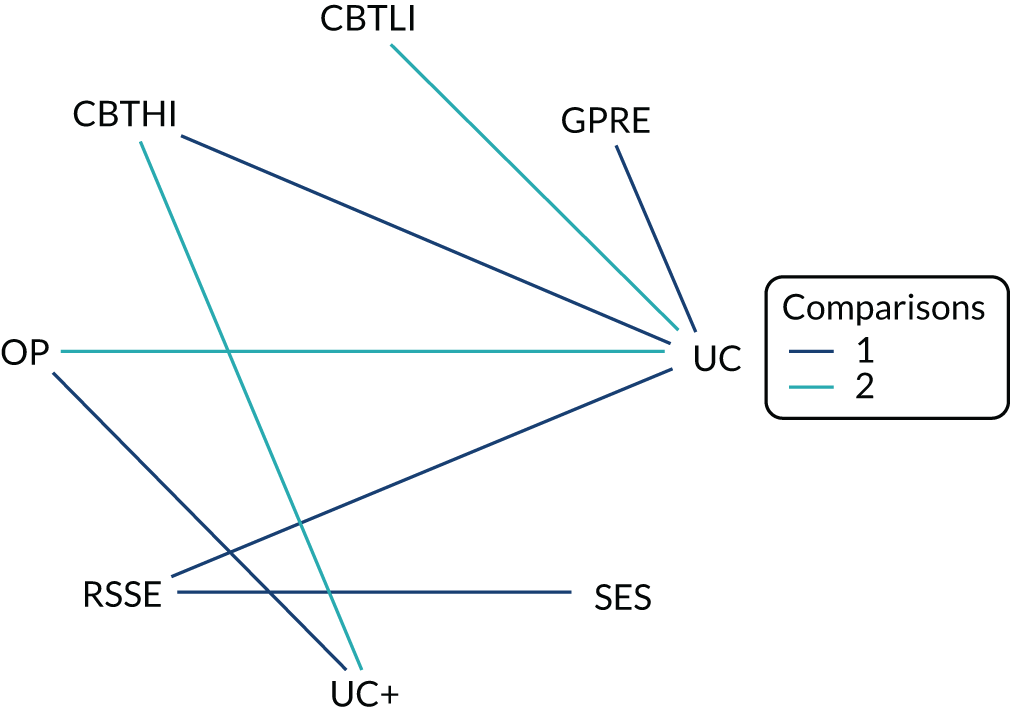

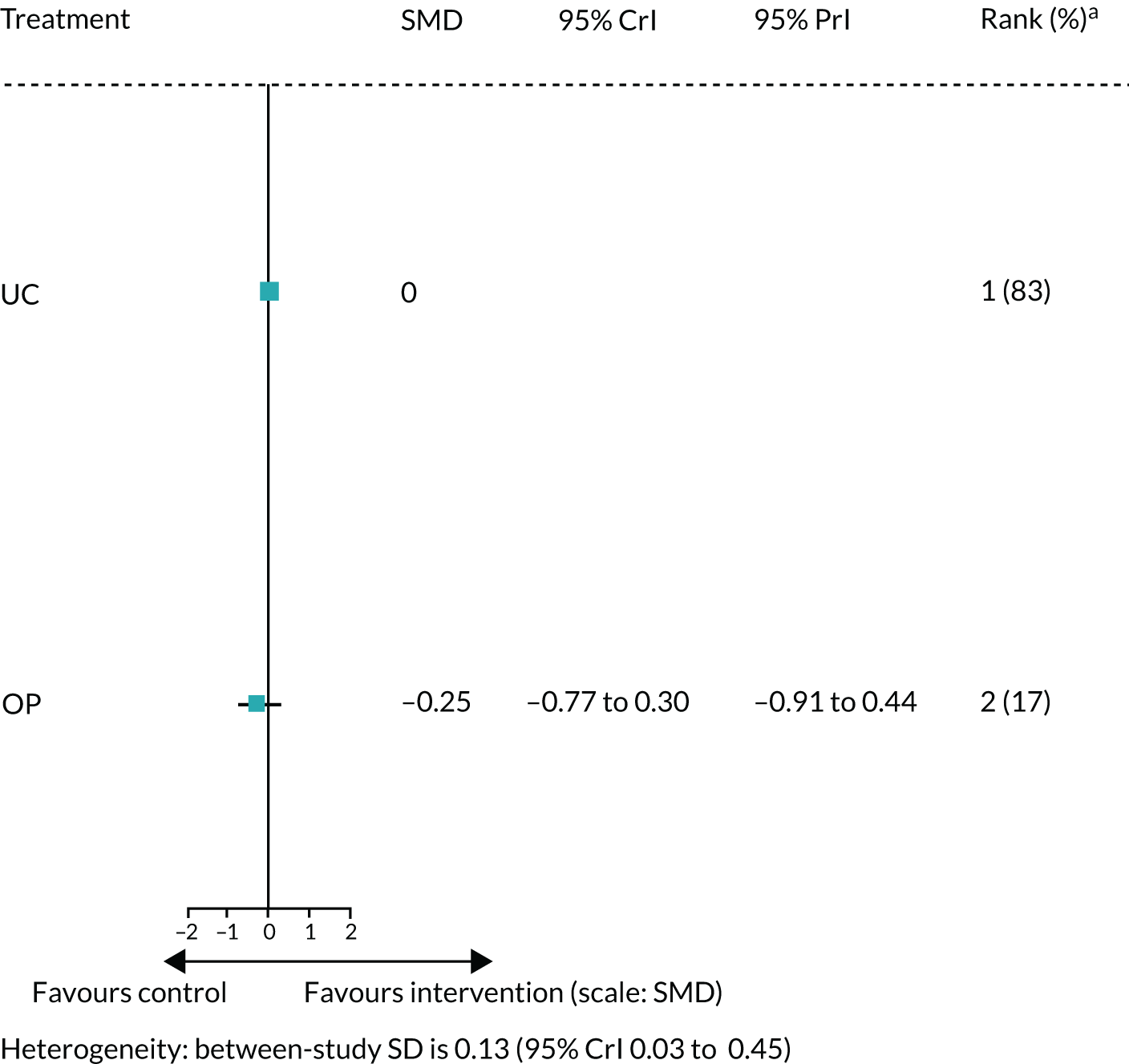

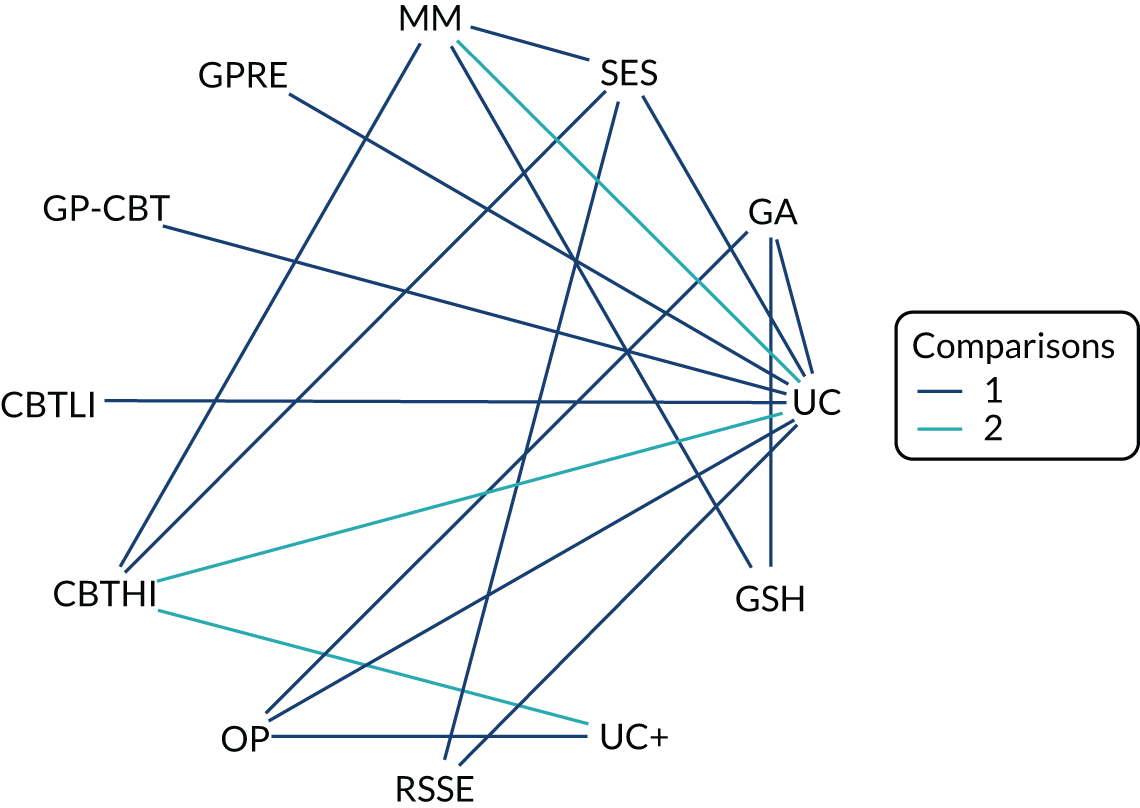

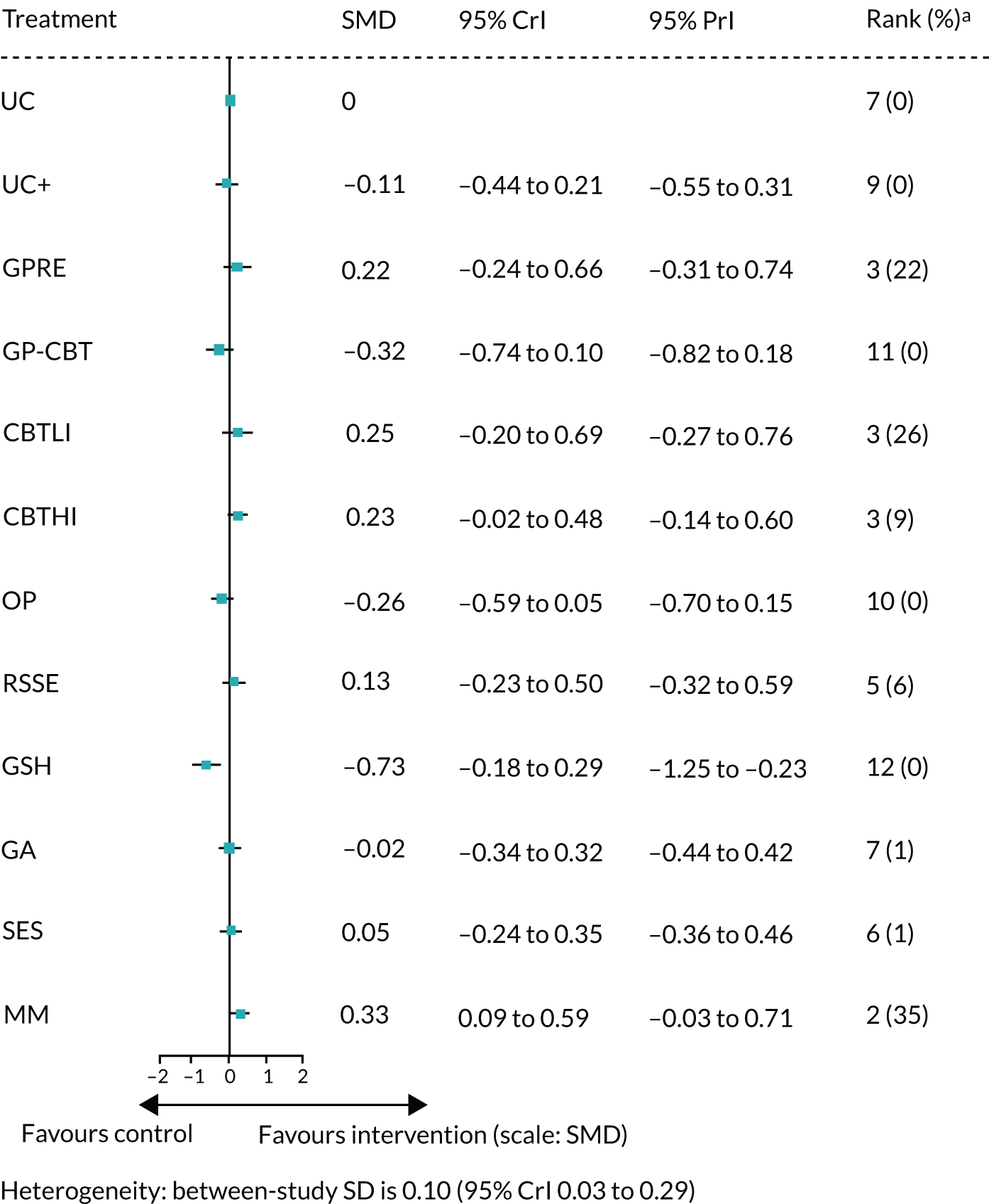

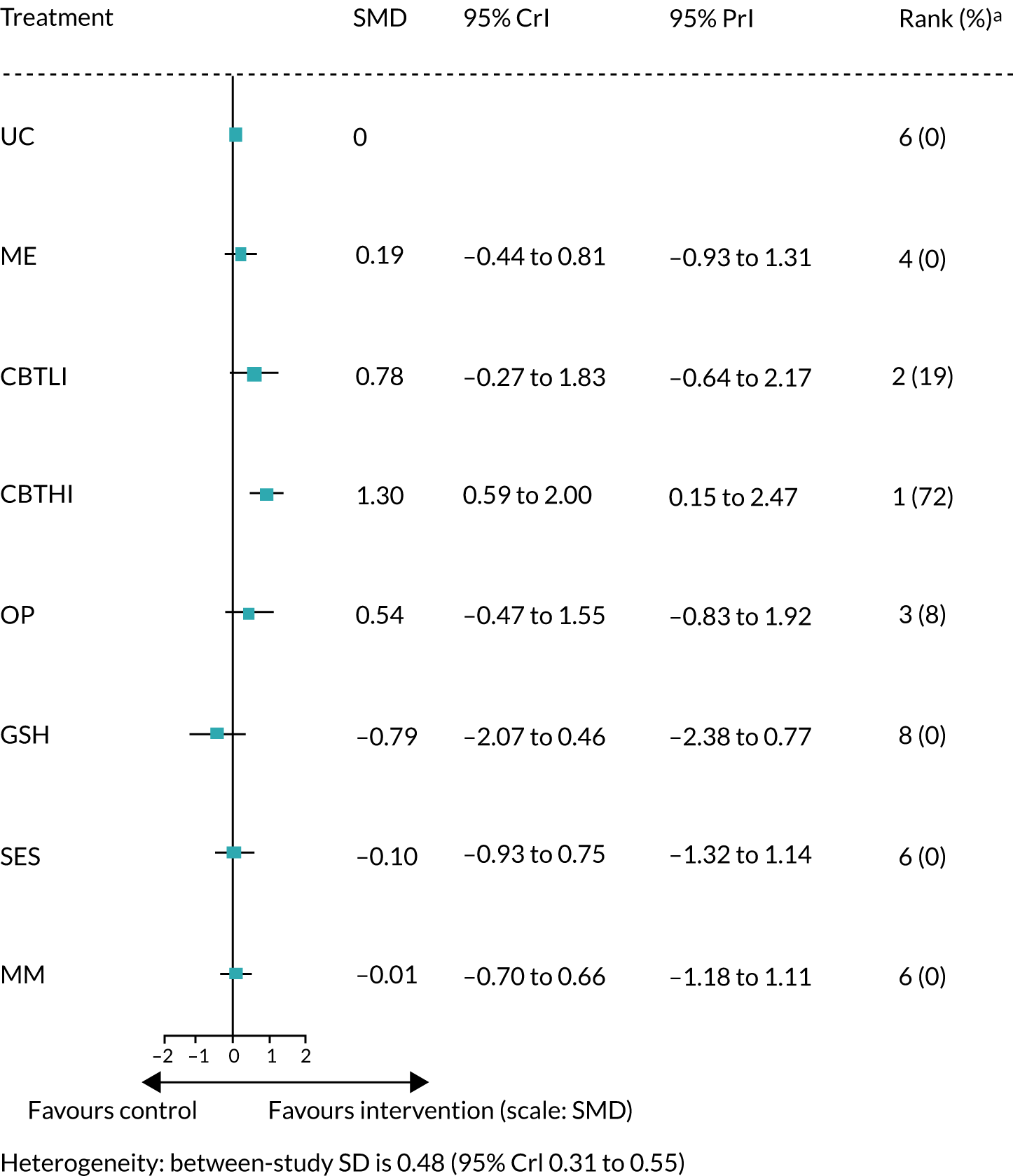

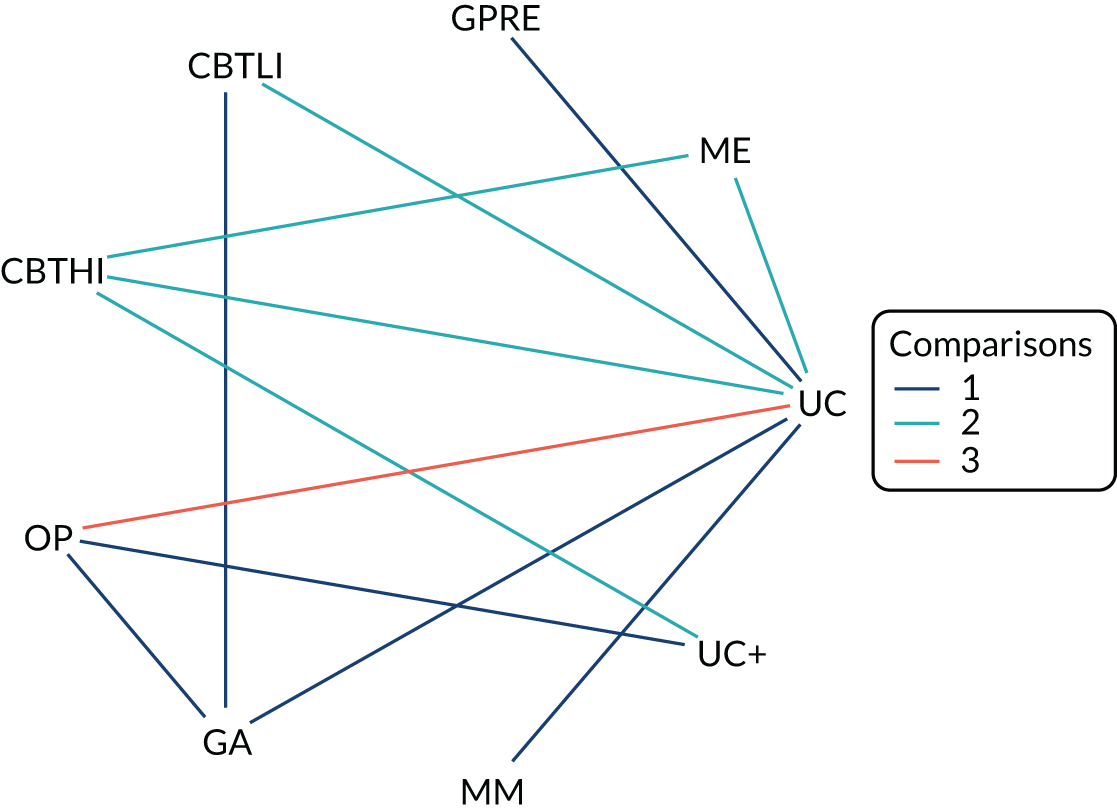

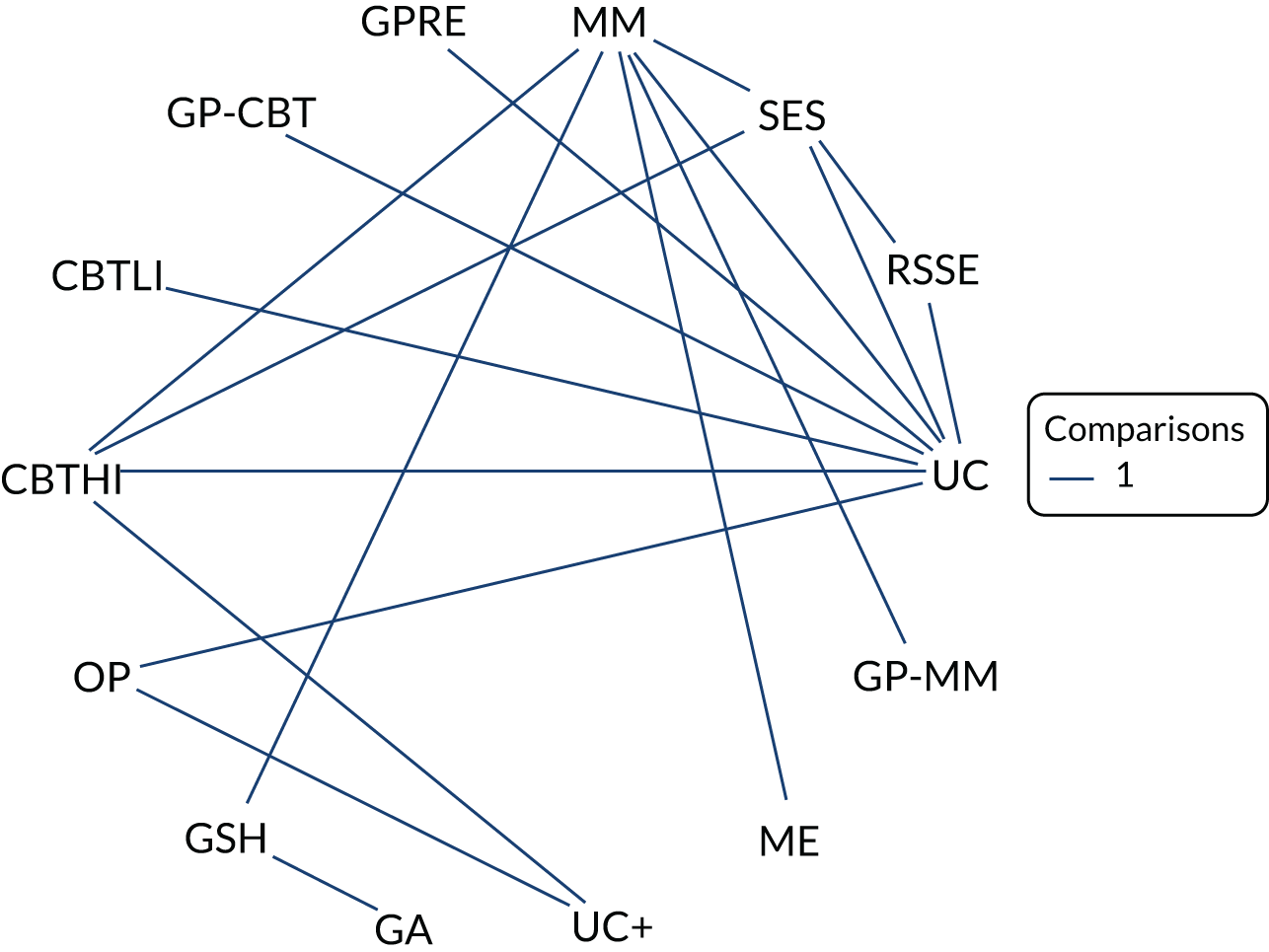

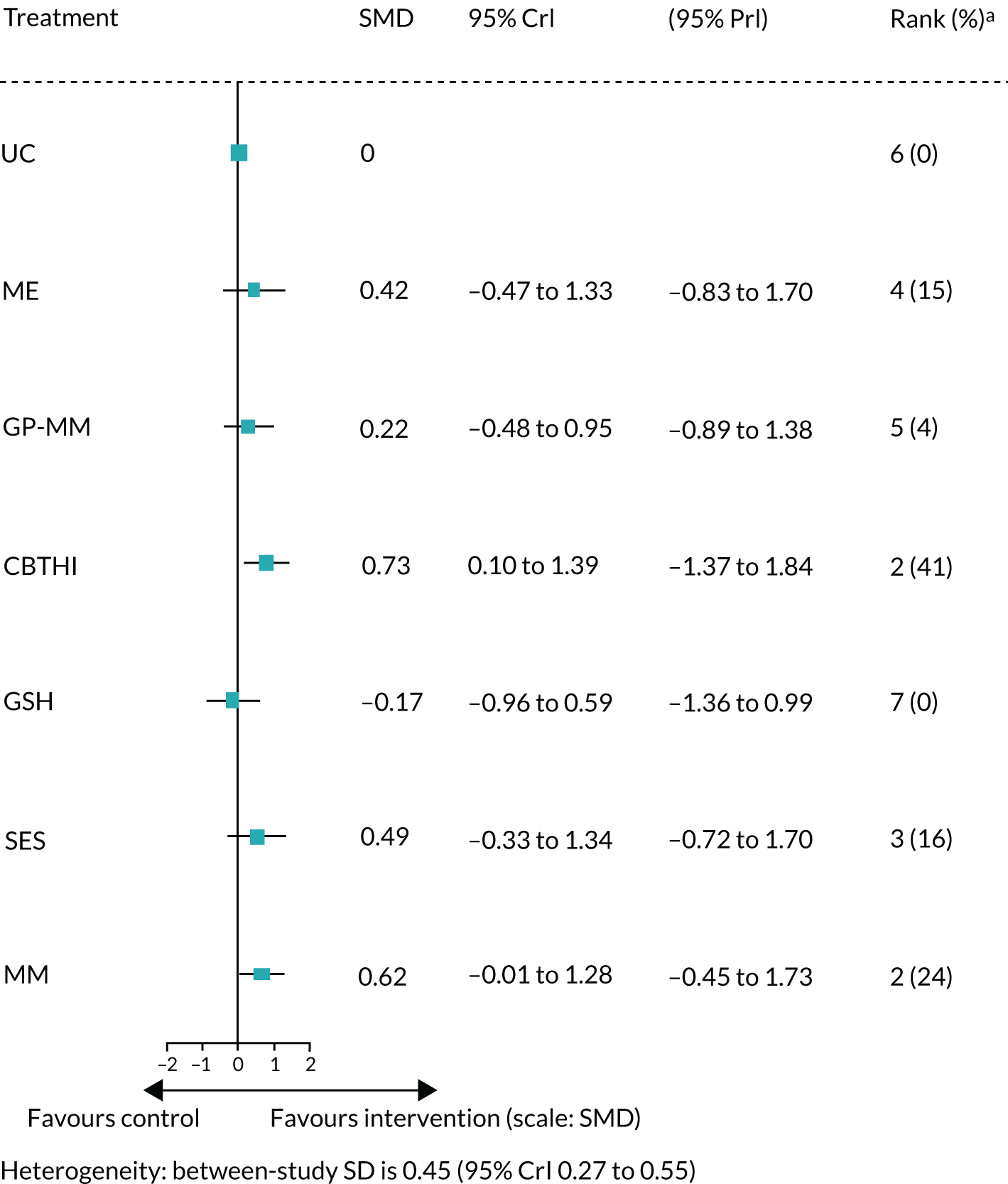

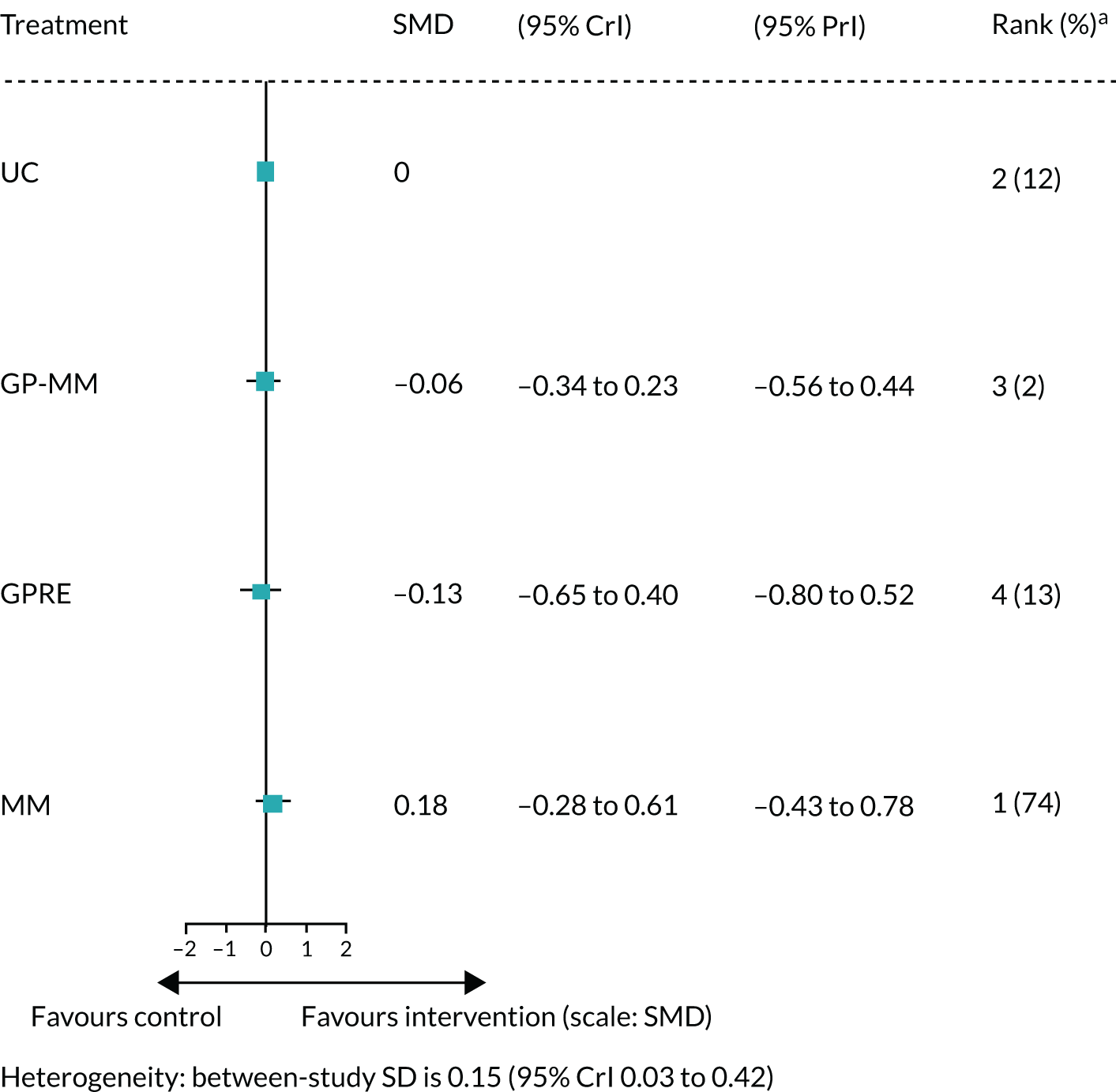

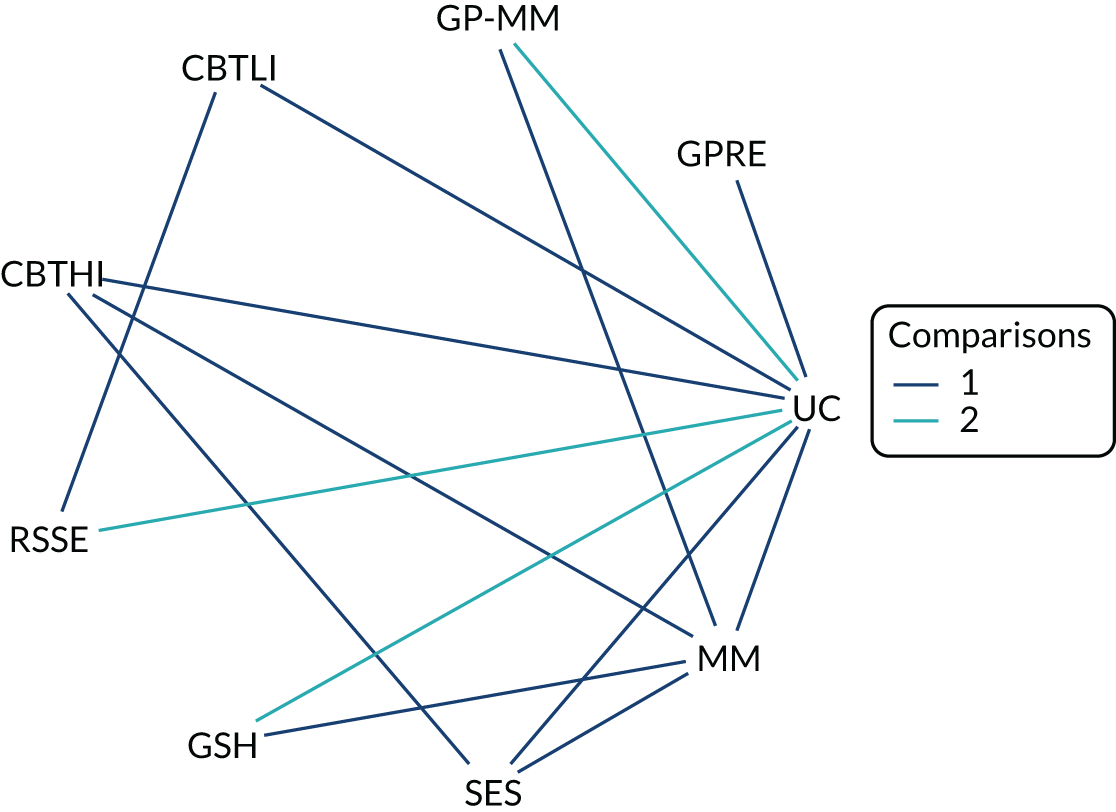

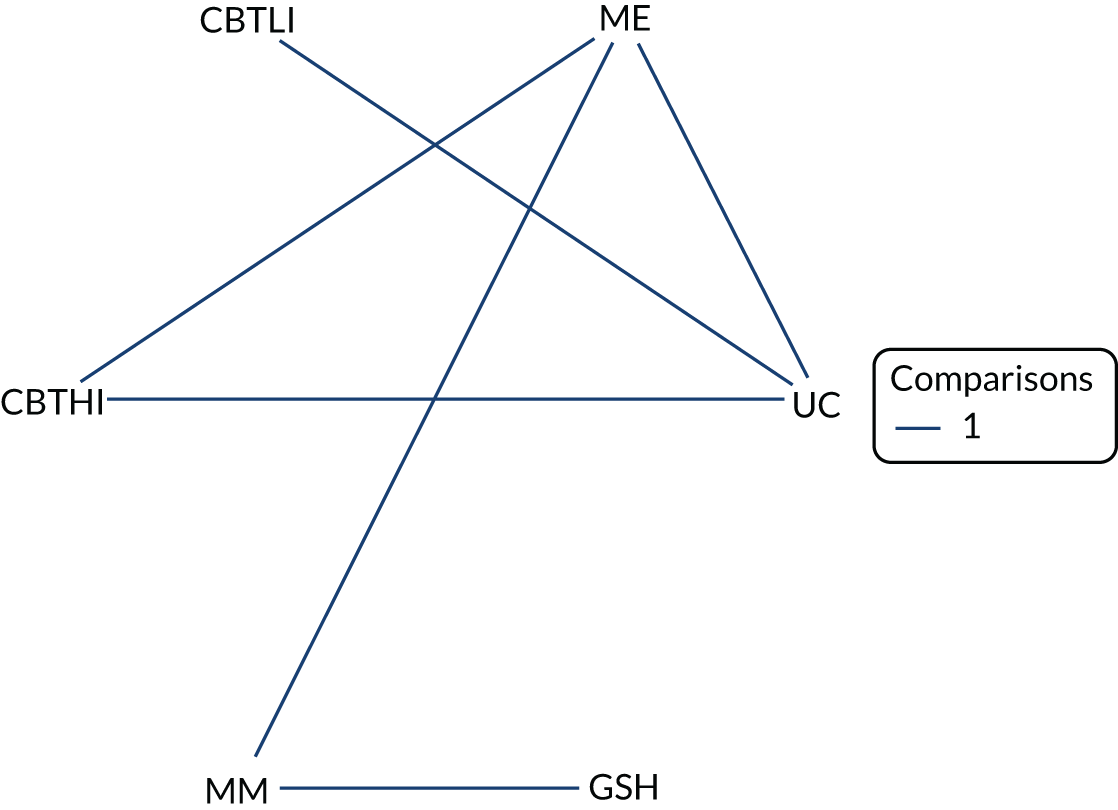

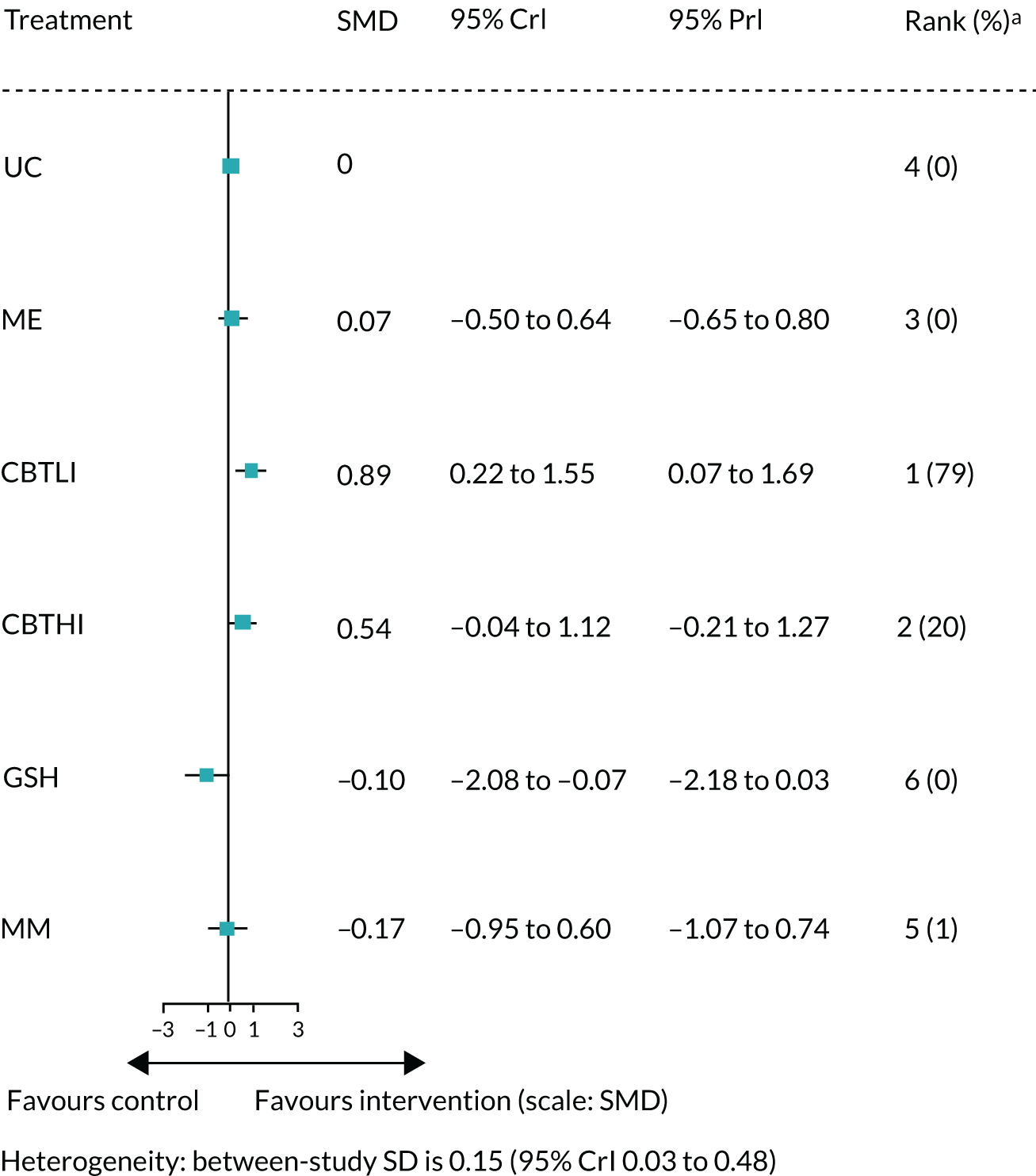

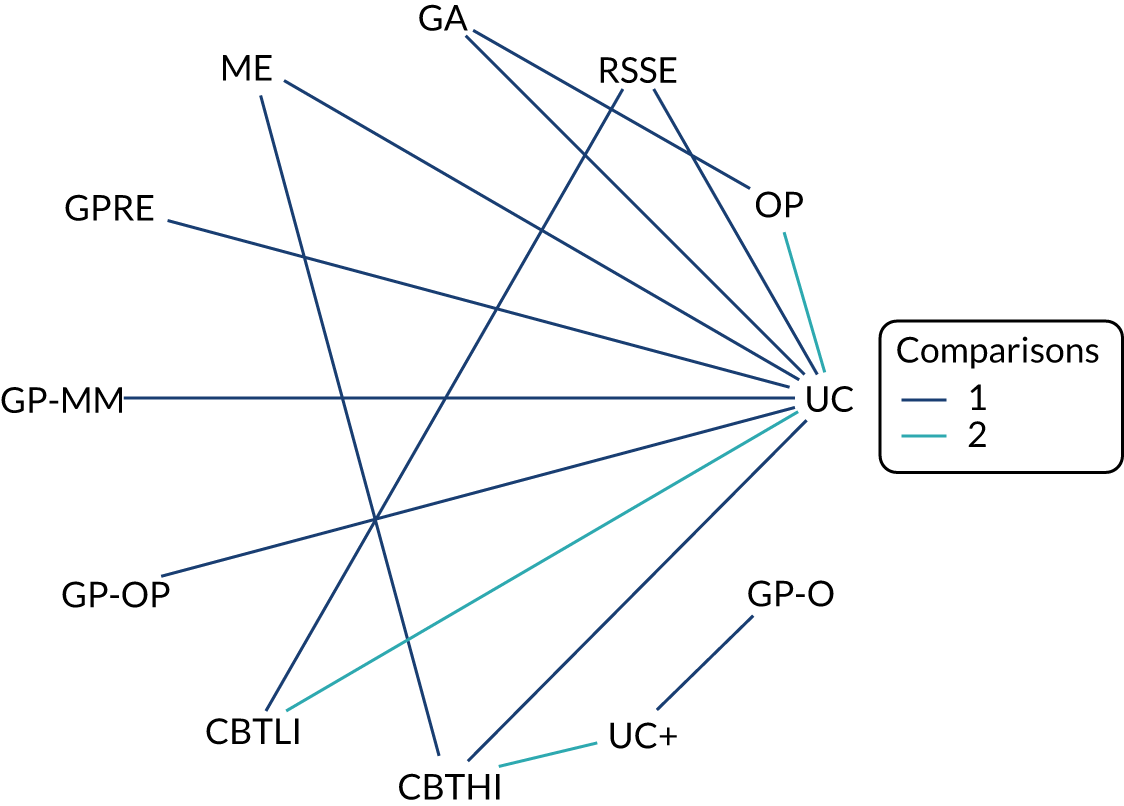

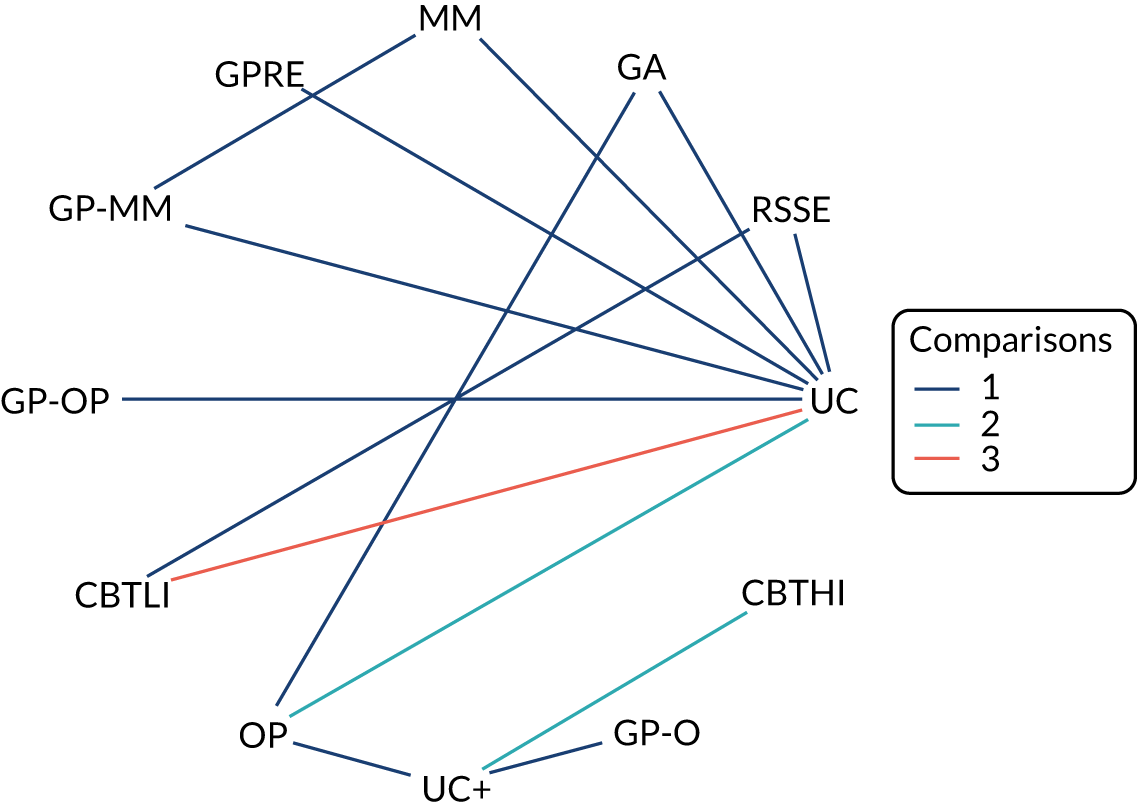

For these reasons, results of the NMA should be interpreted with caution, and considered within the context of the narrative summaries of results from individual studies. Appendix 2, Tables 46–76, presents narrative summaries of results for key outcomes for individual studies.