Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 17/109/19. The protocol was agreed in March 2019. The assessment report began editorial review in September 2019 and was accepted for publication in January 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Jai Patel attended a product training course for using TheraSphere™ [BTG Ltd, London, UK (now Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA)] in Essen, Germany, in 2016, which was sponsored by Biocompatibles UK Ltd (Farnham, UK) [acquired by BTG Ltd], and is a member of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Medical Technologies Advisory Committee (June 2015 to present). Ian Rowe reports personal fees from AbbVie Inc. (North Chicago, IL, USA) and personal fees from Norgine BV (Amsterdam, the Netherlands), outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Walton et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

This report contains reference to confidential information provided as part of the NICE appraisal process. This information has been removed from the report and the results, discussions and conclusions of the report do not include the confidential information. These sections are clearly marked in the report.

Description of health problem

Liver cancer is the fifth most common cancer and the second most frequent cause of cancer-related death globally. 1 Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of liver cancer, representing around 90% of primary liver cancers. 1 Around 90% of HCCs are associated with a known underlying aetiology, most frequently chronic viral hepatitis B or C, or overconsumption of alcohol (alcoholic liver disease). Long periods of chronic liver disease, characterised by hepatic inflammation, fibrosis and aberrant hepatocyte regeneration, can cause scarring of the liver (cirrhosis). 2 One-third of patients with cirrhosis will develop HCC during their lifetime. 1

In the UK, the underlying aetiology of HCC is commonly alcoholic liver disease and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, with 50% of cases attributable to these factors. Hepatitis infection (hepatitis B or C) is also a common cause in the UK but, in contrast with non-Western populations, represents only 15% of cases. Viral hepatitis is the primary cause of HCC in non-Western populations, with up to 90% of cases directly attributable to the hepatitis B and C virus. 3

Underlying liver cirrhosis and the burden of a growing tumour results in an often substantially reduced liver function in HCC patients, with consequences for morbidity and mortality. Liver dysfunction associated with chronic liver disease is commonly assessed using the Child–Pugh scoring system, which classifies patients into three groups: A, B or C (least severe disease, moderate liver disease and severe/end-stage liver disease). Treatment options available to HCC patients are in part dictated by liver function, with choices becoming more limited with increasing liver dysfunction. The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system is used to establish prognosis and enable the selection of appropriate treatment based on both the underlying liver dysfunction and the cancer stage. 1 A modified version of the BCLC staging system is presented in Table 1. The BCLC staging system classifies patients into five stages (0, A, B, C and D) according to tumour burden, liver function and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status,4 which must all be considered when selecting appropriate treatment. 1

| Prognostic stage | Tumour burden | Liver function | Performance status | Recommended treatment | Survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very early stage (BCLC 0) | Single < 2-cm nodule | Preserved liver function | 0 | Ablation or resection | > 5 years |

| Early stage (BCLC A) | 1–3 nodules of < 3 cm in size | Preserved liver function | 0 | Ablation, resection or transplant | > 5 years |

| Intermediate stage (BCLC B) | Multinodular, unresectable | Preserved liver function | 0–1 | Conventional transarterial therapies (TAE, TACE and DEB-TACE) | > 2.5 years |

| Advanced stage (BCLC C) | PVI/extrahepatic spread | Preserved liver function | 0–2 | Systemic therapy [sorafenib,a lenvatinibb or regorafenibc (for patients who have previously had sorafenib)] | ≥ 10 months |

| Terminal stage (BCLC D) | Non-transplantable HCC | End-stage liver function | 3–4 | Best supportive care | 3 months |

Epidemiology

The incidence of HCC is higher in men than in women, with 2128 men and 586 women diagnosed with HCC in England in 2017. 5 The majority of cases occur in adults aged > 60 years. 5 The average age of patients at HCC diagnosis is 66 years, reflecting the long-term nature of most chronic liver disease underlying HCC. 6 Approximately 30% of European patients are diagnosed with early-stage (BCLC stage 0 or A) HCC, approximately 10% are diagnosed with intermediate-stage (BCLC stage B) HCC, approximately 50% are diagnosed with advanced-stage (BCLC stage C) HCC and approximately 10% are diagnosed with terminal (BCLC stage D) HCC. 7 The majority of patients are, therefore, diagnosed with advanced disease, for which treatment options are more limited (see Current service provision).

Prognosis

Prognosis of patients with HCC is heavily dependent on the stage of disease, and is summarised in Table 1. In very early-stage and early-stage disease, a range of potentially curative treatment options are typically available and, thus, the long-term prognosis of these patients can be good. In very early-stage disease, 5-year survival is between 70% and 90%, and it is between 50% and 70% in early-stage disease. 8 In intermediate- and advanced-stage disease, treatment options are more limited and are primarily delivered to prolong survival and reduce the burden of symptoms. Length of survival is, therefore, significantly shorter; prognosis in patients with advanced disease is particularly poor, with a median survival of < 12 months. 8

Current service provision

Clinical management of HCC is complex. There are a range of treatment options available, which depend on the location and stage of the cancer and liver function. Clinical practice guidelines published by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) summarise treatment recommendations according to BCLC classification. 1 These recommendations are presented in Table 1, with some modifications, reflecting entry criteria to pivotal clinical trials.

The primary aim of therapy in patients diagnosed with early-stage HCC is typically curative, and there are a number of available treatment options with curative potential. These include radiofrequency ablation (which uses the heat generated by alternating currents to destroy solid tumour tissue), resection (in which the tumour-containing portions of the liver are removed) and liver transplantation. 1 Owing to the limited availability of suitable donors, liver transplant is typically reserved for patients with a poor prognosis owing to impaired liver function, and in whom resection is inappropriate, for example in patients with multifocal tumours. Suitability for transplant is assessed against the Milan criteria,9 which require patients to have a single lesion of < 5 cm, or up to three lesions of < 3 cm each, without macroscopic vascular invasion (MVI). 1 Typically, patients not meeting these criteria are ineligible for a transplant, but increasingly patients whose disease has been ‘downstaged’ may be considered for transplant. Downstaging is when patients whose tumours fall outside the limits permitted by the Milan criteria9 are brought within the criteria, typically through the use of conventional transarterial therapies (CTTs) (see below) to reduce tumour burden. Patients waiting for a transplant may also receive CTT as a ‘bridging therapy’, in which the intent is to control the progression of disease to keep patients within the Milan criteria. 9 However, as transplant waiting times in the UK are typically relatively short, with a median time for HCC patients of approximately 50 days, the use of bridging therapy is limited.

Conventional transarterial therapies are the standard care in intermediate HCC if resection or other curative treatment modalities are unsuitable. CTT includes transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE), drug-eluting bead transarterial chemoembolisation (DEB-TACE) and transarterial embolisation (TAE) without chemotherapy. Blood is primarily supplied to the liver via the hepatic portal vein, whereas most tumours are supplied by the hepatic artery. All three forms of CTT work by administering an embolising agent into the hepatic artery to block blood vessels feeding the tumours within the liver. This process preferentially interrupts the blood supply to the tumours, while allowing blood to continue to reach the remaining healthy tissue. In the case of TACE, Lipiodol® (Guerbet, Villepinte, France) is combined with a chemotherapy agent, typically doxorubicin or cisplatin, which is administered directly to the tumour, allowing for much higher concentrations of the drug to be achieved than could be tolerated systemically. In DEB-TACE, drug-eluting beads typically bound with doxorubicin or epirubicin are administered to the tumour via the hepatic artery. This allows the release of the chemotherapeutic agent over a prolonged period of time, thereby reducing systemic concentrations (and thus any side effects) compared with TACE. 10 TAE, or bland TACE, involves only the physical occlusion of blood vessels, with no addition of chemotherapy. Because the primary therapeutic effect of CTT is the embolisation of the hepatic artery, the use of these techniques is typically limited to patients with good portal vein flow, so as to maintain a good blood supply to the liver. Therefore, patients with portal vein thrombosis (PVT) or tumour invasion of the portal vein are typically considered contraindicated to CTT.

In patients who have advanced HCC, or for whom CTT has previously failed, the current standard of care consists of systemic chemotherapy. Current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance in this population recommends sorafenib (Nexavar®; Bayer plc, Leverkusen, Germany) as an option for people with Child–Pugh class A liver impairment (TA474). 11 Lenvatinib (Kisplyx®, Eisai Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) is also recommended as an option for people with Child–Pugh class A liver impairment and an ECOG performance status of 0 or 1 (TA551). 12 A recent technology appraisal on regorafenib (Stivarga®; Bayer plc, Leverkusen, Germany) for treating advanced unresectable HCC (TA555)13 recommends regorafenib as an option for people who have previously been treated with sorafenib and have Child–Pugh class A liver impairment and an ECOG performance status of 0 or 1. Best supportive care (BSC) is offered to patients when CTTs or systemic therapy are not available or appropriate, including patients with terminal-stage disease.

Description of the technology under assessment

Selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT), also known as transarterial radioembolisation (TARE), is a complex intervention that delivers radiation directly to liver tumours via microspheres that are injected into the hepatic artery via a catheter inserted into the femoral artery. The most likely position for SIRT in the HCC treatment pathway is for patients with intermediate-stage (BCLC stage B) or advanced-stage (BCLC stage C) HCC as a non-curative option, as the use of SIRT is not precluded by reduced liver function as strictly as CTTs. However, SIRT is unlikely to be suitable for patients with more limited liver function (Child–Pugh class ≥ B8) or extrahepatic tumour spread. There may also be a role for SIRT as a bridging therapy for BCLC stage A patients awaiting transplant (see Current service provision) as an alternative to CTTs.

The NICE interventional procedures guidance 46014 states that current evidence on the efficacy and safety of SIRT for primary HCC was adequate to permit routine use of the technology. However, significant uncertainties remain about its comparative effectiveness relative to conventional transarterial and systemic therapeutic options. 14 Clinicians have been encouraged by NICE to enter eligible patients into trials comparing the procedure against other forms of treatment and to enrol all patients into the UK SIRT registry (launched in 2013). 14

The present appraisal concerns three SIRTs: SIR-Spheres® (Sirtex Medical Ltd, Woburn, MA, USA), TheraSphere™ [BTG Ltd, London, UK (now Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA)] and QuiremSpheres® (Quirem Medical BV, Deventer, the Netherlands). SIR-Spheres [manufactured by Sirtex Medical Ltd (hereafter Sirtex)] is a Conformité Européenne (CE)-marked class III active medical device comprising resin microspheres containing yttrium-90; SIR-Spheres is indicated for the treatment of inoperable liver tumours. TheraSphere [manufactured by BTG Ltd (hereafter BTG)] is a CE-marked class III active medical device comprising glass microspheres containing yttrium-90; TheraSphere is indicated for the treatment of hepatic neoplasia. QuiremSpheres [manufactured by Quirem Medical BV and distributed by Terumo Europe NV (Leuven, Belgium)] is a CE-marked class III active medical device comprising poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) microspheres containing holmium-166; QuiremSpheres is indicated for the treatment of unresectable liver tumours.

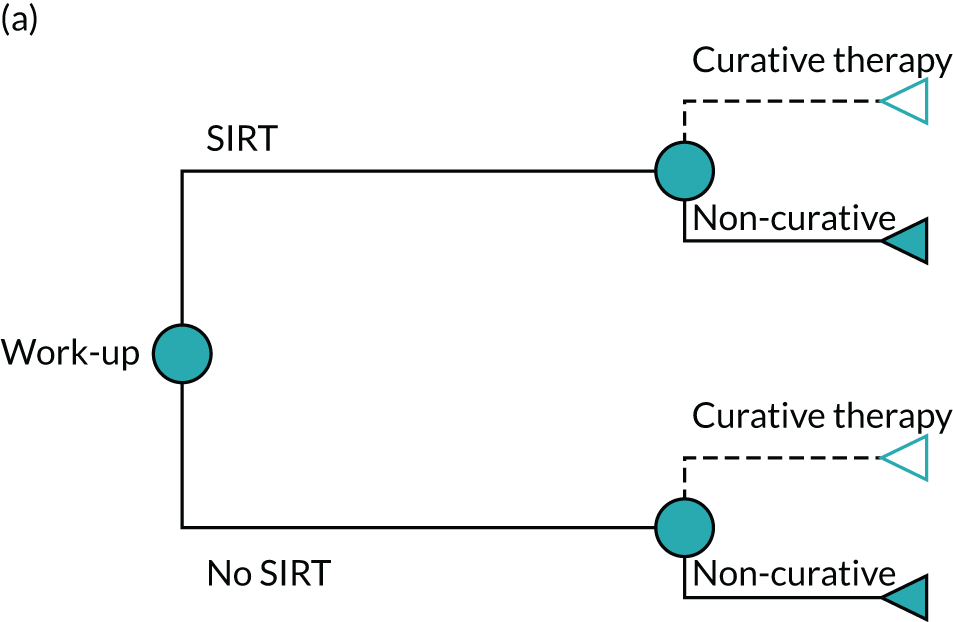

In preparation for SIRT, patients undergo preliminary angiography of the hepatic artery, and protective coiling of extrahepatic branches to reduce extrahepatic radiation uptake. For TheraSphere and SIR-Spheres, technetium-99m-macroaggregated albumin is used as an imaging surrogate and injected into the hepatic artery using the same catheter position chosen for the scheduled SIRT session. Calculation of the radiation dose to the tumour and adjacent liver, hepatopulmonary shunt fraction and tracer distribution are evaluated with single-photon emission computerised tomography (SPECT) imaging. This is known as the ‘work-up’ procedure, and is ultimately what decides whether or not patients are eligible to receive SIRT. A high level of lung shunt or extrahepatic uptake contraindicate the SIRT procedure. When SIRT is not contraindicated following work-up, patients are later readmitted for the SIRT procedure, which is performed in a lobar, sectorial or segmental approach according to tumour size and location. 1 When tumours are present in both lobes, patients may receive a separate administration of SIRT to each lobe on separate occasions (often several weeks apart), to allow clinicians to monitor the liver’s response to radiation and prevent damage.

The work-up procedure for QuiremSpheres exploits the properties of holmium-166 microspheres, which, unlike yttrium-90, can be visualised with SPECT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) even at low concentrations. Therefore, a lower dose of holmium-166 is used for evaluating dose distribution [known as QuiremScout® (Quirem Medical BV)], rather than a surrogate, which may allow for a more accurate assessment of radiation distribution and dosimetry.

Table 2 presents an overview of the main characteristics of each therapy.

| Technique | SIR-Spheres | TheraSphere | QuiremSpheres |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radioactive isotope | Yttrium-90 | Yttrium-90 | Holmium-166 |

| Microsphere material | Resin | Glass | PLLA |

| Therapeutic mode of action | Beta radiation | Beta radiation | Beta radiation |

| Mean diameter of the microsphere (µm) | 32.5 | 20–30 | 30 |

| Half-life of the radioactive isotope (hours) | 64.1 | 64.1 | 26.8 |

| Specific activity per microsphere (Bq) | 50 | 2500 | 350 |

| Typical administered activity (GBq) | 1.4–2.0 | – | – |

| Typical number of microspheres administered (millions) | 30–40 | 4 | 20–30 |

| Time for 90% of dose to be deposited (days) | 11 | 11 | 4 |

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

The decision problem in terms of participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, study design and other key issues

The decision problem relates to the use of the three SIRTs, TheraSphere, SIR-Spheres and QuiremSpheres, within their approved indications for the treatment of HCC. Relevant comparators are each other, CTTs (i.e. TAE, TACE and DEB-TACE) or, for people for whom any transarterial therapies are inappropriate, established clinical management without SIRT, such as systemic therapy (sorafenib, lenvatinib or regorafenib) or BSC.

Overall aims and objectives of the assessment

This appraisal will assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the SIRT (TheraSphere, SIR-Spheres and QuiremSpheres) for treating HCC.

The objectives of the assessment are to evaluate the:

-

clinical effectiveness of each intervention

-

adverse effect profile of each intervention

-

incremental cost-effectiveness of each intervention compared with (1) each other, (2) CTTs, (3) systemic therapy and (4) BSC.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Methods for reviewing clinical effectiveness

A systematic review of the clinical effectiveness evidence on SIRT was undertaken following the general principles outlined in the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD)’s guidance on undertaking systematic reviews15 and reported in accordance with the general principles of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. 16 The research protocol is registered on PROSPERO, the international prospective register of systematic reviews in health and social care (registration number CRD42019128383).

Search strategy

A comprehensive search was undertaken to systematically identify clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness literature relating to TheraSphere, SIR-Spheres and QuiremSpheres for HCC. In addition, a search for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of comparator therapies was undertaken to strengthen the network of evidence on SIRT.

Search strategy for selective internal radiation therapy studies

A search strategy was developed in Ovid MEDLINE by an information specialist (MH), with input from the review team. The strategy consisted of a set of terms for HCC combined with terms for SIRT, and was limited to studies from 2000 onwards. The 2000 date limit was applied as scoping searches had identified controlled studies of SIR-Spheres and TheraSphere published after the year 2000; earlier studies were preliminary uncontrolled studies so have limited value for addressing the decision problem. In addition, clinical advice confirmed that the treatment environment for patients with HCC was different prior to 2000 in terms of comparator treatment options. The searches were not limited by language or study design. The MEDLINE strategy was adapted for use in all other resources searched.

The following databases were searched on 28 January 2019:

-

MEDLINE (all) (via Ovid)

-

EMBASE (via Ovid)

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Plus

-

Science Citation Index (via Web of Science)

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (via Wiley)

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (via Wiley)

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (via CRD databases)

-

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database (via CRD databases)

-

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) (via CRD databases)

-

EconLit (via Ovid).

In addition, information on studies in progress, unpublished research or research reported in grey literature was sought by searching a range of relevant resources:

-

ClinicalTrials.gov

-

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry portal

-

European Union Clinical Trials Register

-

PROSPERO

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (via Web of Science)

-

ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I (via ProQuest).

A search of the NICE website and NHS Evidence for relevant guidelines was undertaken on 8 May 2019.

Company submissions and relevant systematic reviews were also hand-searched to identify further relevant studies. Clinical advisors were consulted for any additional studies.

Search results were imported into EndNote X9 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and de-duplicated. Full search strategies can be found in Appendix 1.

Search strategy for comparator therapies

A search for RCTs of comparator therapies was undertaken to strengthen the network of evidence on SIRT. In view of time and resource limitations, it was decided to identify RCTs of CTTs (i.e. TAE, TACE and DEB-TACE) by searching existing relevant systematic reviews and meta-analyses and undertaking update searches if necessary.

Evidence on systemic therapies for HCC was identified from the recent NICE single technology appraisals of sorafenib,11 lenvatinib12 and regorafenib. 13

The search strategy for systematic reviews and meta-analyses of CTTs was developed in Ovid MEDLINE by an information specialist (MH), with input from the review team. The strategy consisted of a set of terms for HCC combined with terms for embolisation or chemoembolisation, and was limited to studies from 2010 onwards to identify the most recent reviews. A search strategy to limit retrieval to systematic reviews or meta-analyses was added in MEDLINE and EMBASE. 17 The MEDLINE strategy was adapted for use in all resources searched.

The following databases were searched on 7 May 2019:

-

MEDLINE (all) (via Ovid)

-

EMBASE (via Ovid)

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (via Wiley)

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (via CRD databases)

-

HTA database (via CRD databases).

In addition, PROSPERO was searched to identify any unpublished or ongoing systematic reviews or meta-analyses.

Search results were imported into EndNote X9 and de-duplicated. Full search strategies can be found in Appendix 2.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were defined in line with the final scope provided by NICE and are outlined below. Studies were initially assessed for relevance using titles and abstracts. One reviewer examined titles and abstracts, with a second reviewer checking 10% of records. Full manuscripts of any titles/abstracts that appeared to be relevant were obtained if possible and the relevance of each study was assessed independently by two reviewers in accordance with the criteria outlined in the following sections. Any discrepancies were resolved through consensus and, if necessary, a third reviewer was consulted. Relevant foreign-language studies were translated and assessed for inclusion in the review. Studies available only as abstracts were included and attempts were made to contact authors for further data.

Study design

Randomised controlled trials were eligible for inclusion in the clinical effectiveness review. However, where RCT evidence was insufficient to address the decision problem, non-randomised comparative studies (including retrospective studies) and non-comparative studies of SIRT were considered for inclusion. The evidence was scoped before deciding what level of evidence would be included for data extraction and quality assessment.

Participants

Studies of people with early-stage HCC in whom curative treatment is contraindicated (BCLC stage A), and with intermediate-stage (BCLC stage B) or advanced-stage (BCLC stage C) HCC, with or without PVT/portal vein invasion (PVI), were included in the review. Studies of people with secondary liver metastases or other types of liver cancer (such as cholangiocarcinoma) were not included unless they also included people with primary HCC, and results were reported separately for people with HCC.

Interventions

The interventions under consideration were the selective internal radiation therapies TheraSphere, SIR-Spheres and QuiremSpheres. Studies in which more than one type of SIRT was used were included only if results were reported separately for the different types of SIRT. Where studies did not state which type of SIRT or radioembolisation technology was used, authors were contacted to identify the specific technology used.

Evidence on combined treatments (e.g. SIRT plus sorafenib) was also considered for inclusion, and evidence was scoped before deciding which trials would be included for data extraction and quality assessment.

Comparators

Relevant comparators were:

-

alternative SIRT interventions (i.e. TheraSphere, SIR-Spheres and QuiremSpheres)

-

conventional transarterial therapies (i.e. TAE, TACE and DEB-TACE)

-

established clinical management without SIRT, such as systemic therapy (i.e. sorafenib, lenvatinib and regorafenib) or BSC, for people for whom any TAE therapies are inappropriate.

To strengthen the network of evidence on SIRT, we considered undertaking comparisons of CTTs (i.e. TAE, TACE and DEB-TACE), systemic therapies (i.e. sorafenib, lenvatinib and regorafenib) and BSC, using RCT evidence. The evidence was scoped and criteria for inclusion were developed. Relevant RCTs were assessed for quality and key outcome data were extracted, based on requirements for the model.

Outcomes

The outcome measures to be considered included:

-

overall survival (OS)

-

progression-free survival (PFS)

-

time to progression (TTP)

-

response rates

-

rates of liver transplant or surgical resection

-

adverse effects of treatment

-

health-related quality of life (HRQoL)

-

time on treatment/number of treatments provided.

Data extraction

Data were extracted by one reviewer using a standardised data extraction form and independently checked for accuracy by a second reviewer. Disagreements were resolved through consensus and, if necessary, a third reviewer was consulted. If multiple publications of the same study were identified, data were extracted and reported as a single study.

Critical appraisal

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using criteria relevant to the study design. RCTs were assessed using the most recent version of the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool. 18 Quality-assessment tools for other study designs were developed using relevant criteria, such as those outlined in the CRD’s guidance on undertaking systematic reviews. 15 Quality assessment was undertaken by one reviewer and independently checked by a second reviewer. Any disagreements were resolved through consensus and, if necessary, a third reviewer was consulted. Details of the quality of the included studies are presented in descriptive tables and their impact on the reliability of results is discussed.

Methods of data analysis/synthesis

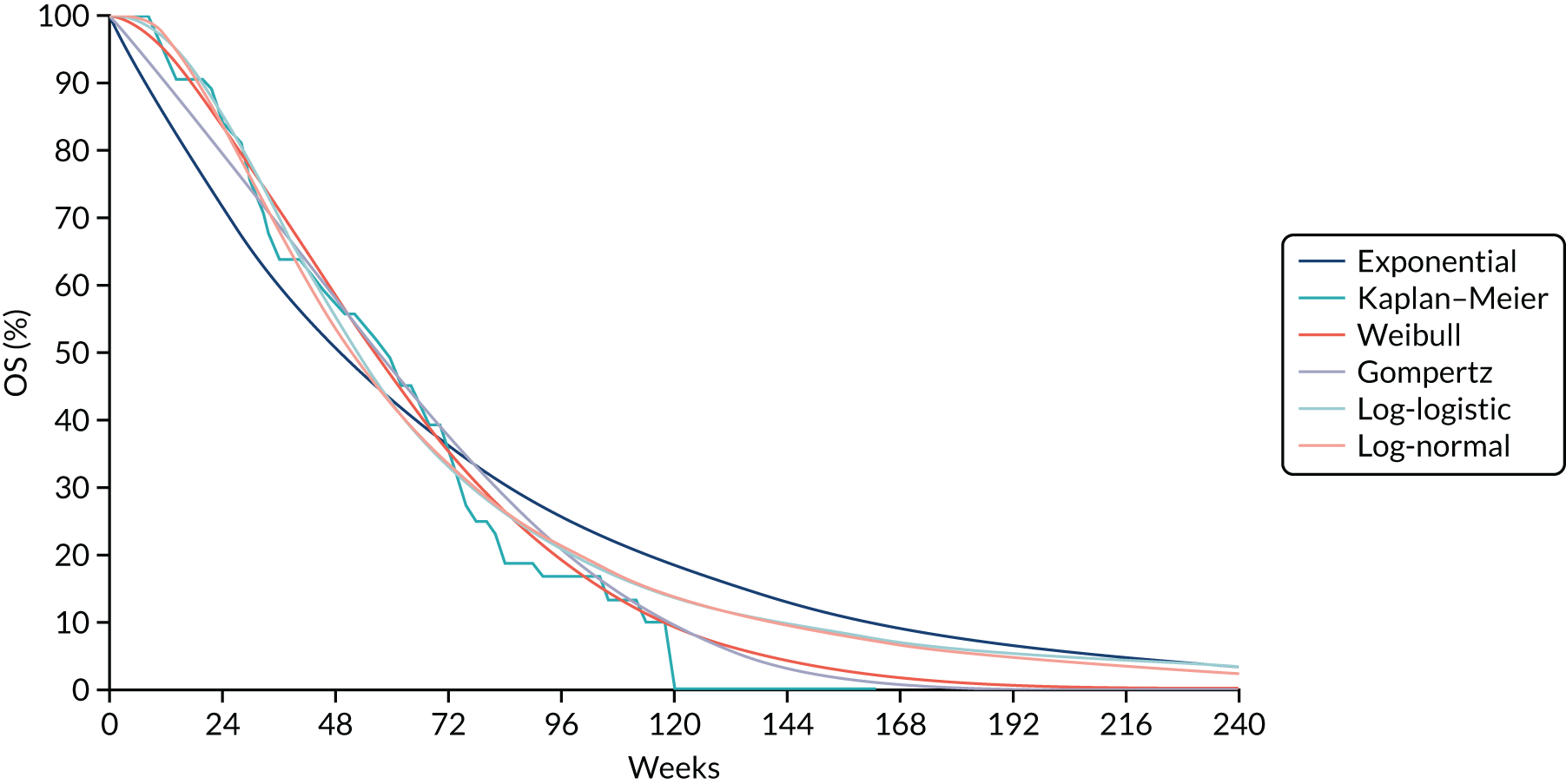

Characteristics of the included SIRT studies (such as participant and intervention characteristics, results and trial quality) were tabulated and described in a narrative synthesis. Where sufficient clinically and statistically homogenous data were available, data were pooled using appropriate meta-analytic techniques using WinBUGS software (Medical Research Council Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK). Clinical, methodological and statistical heterogeneity were investigated, with sensitivity or subgroup analyses undertaken where appropriate and where available data permitted.

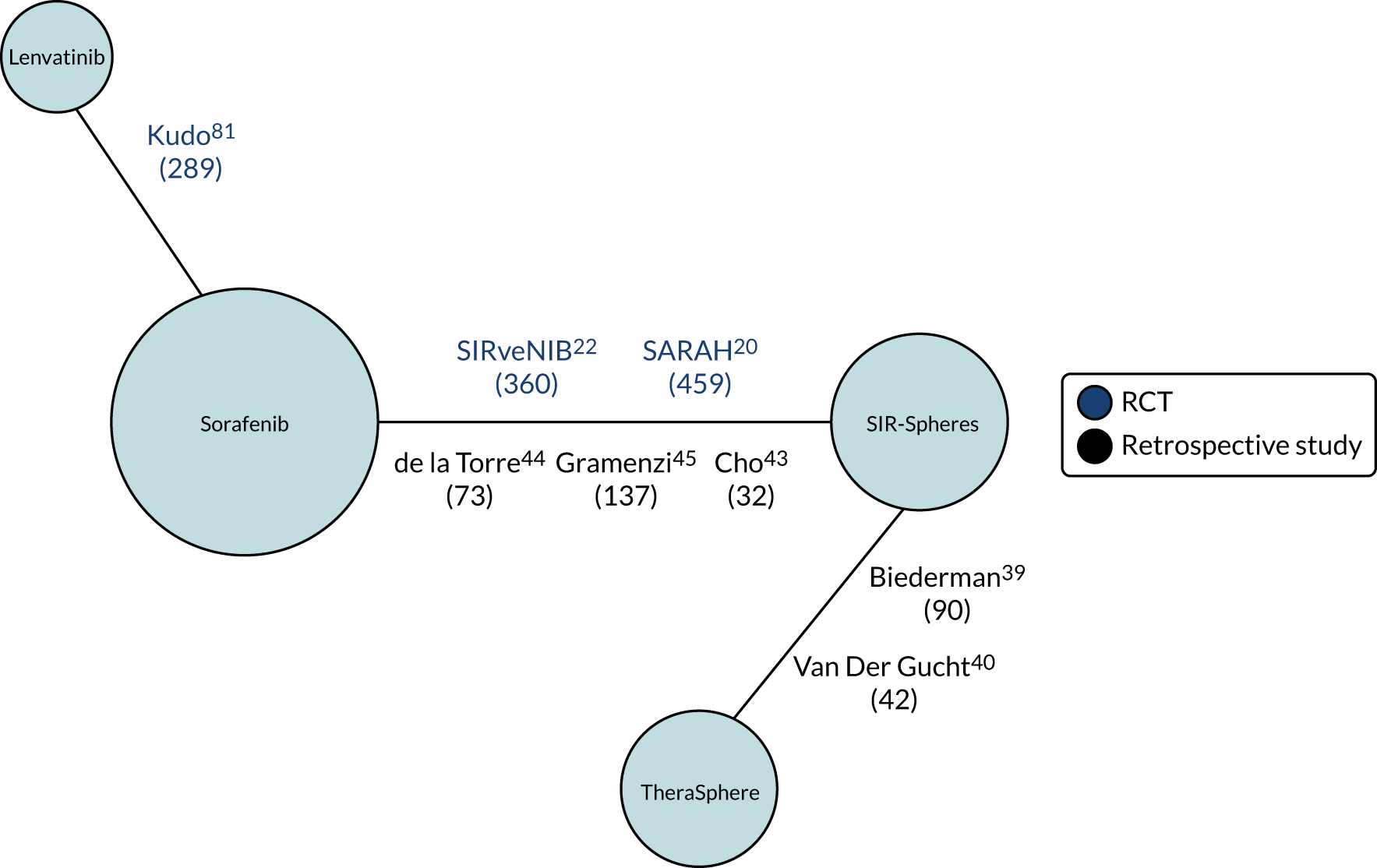

Where the data allowed, a network meta-analysis (NMA) using Bayesian statistical methods with WinBUGS software was undertaken to estimate the relative effectiveness of the different treatments. Results are summarised using point estimates and 95% credible intervals (CrIs) of the effect of each treatment relative to the reference treatment. Where possible, consistency between direct and indirect estimates of treatment effect in the NMA was assessed. The results of the NMA are described in Chapter 4 of this report and were used in the economic model described in Chapter 7.

Clinical effectiveness results

Quantity and quality of research available

Studies of selective internal radiation therapy

The electronic searches for clinical effectiveness evidence on SIRT interventions (i.e. TheraSphere, SIR-Spheres and QuiremSpheres) identified a total of 4755 records (after de-duplication between databases). The 4755 records were inserted into an EndNote library. Reviewer 1 (RW) screened 2615 titles and abstracts, and reviewer 2 (SS) screened 2617 titles and abstracts. A total of 477 records (10% of the library) were double-screened; discrepancies were resolved through consensus or in consultation with a third reviewer (AE).

Of the 4755 records in the library, 3670 were excluded from the clinical effectiveness review after title and abstract screening as they did not include patients with unresectable HCC, did not assess TheraSphere, SIR-Spheres or QuiremSpheres, did not report relevant patient outcomes or were not a primary study. A total of 1085 records appeared to meet the study selection criteria based on title and abstract (where an abstract was available).

In view of the large number of potentially eligible records, the evidence was scoped before deciding which studies to order for full-paper screening. Records were coded, using titles and abstracts (where available), in terms of the intervention (type of SIRT and whether the study focused on the delivery of SIRT or the work-up procedure), the study design (prospective or retrospective, comparative or not) and the number of HCC patients included in the study. A large number of records were conference/meeting abstracts (n = 603) rather than full publications (n = 482); reviewer 1 (RW) coded the full publications and reviewer 2 (SS) coded the conference/meeting abstracts. Studies marked as a ‘RCT’ (n = 47; 43 full publications and four conference/meeting abstracts) or as ‘prospective comparative’ (n = 26; 18 full publications and eight conference/meeting abstracts) or ‘retrospective comparative’ (n = 103; 61 full publications and 42 conference/meeting abstracts) studies were ordered for full-paper screening as comparative studies (total n = 176) were prioritised over non-comparative studies. However, it was clear that there were no comparative studies of QuiremSpheres; therefore, all studies considered to relate to QuiremSpheres (referring to holmium as the intervention) were ordered for full-paper screening (n = 11). In addition, large non-comparative studies that included > 500 patients were also ordered for full-paper screening (n = 6). One additional non-comparative study, in which BCLC subgroups and subsequent treatments were reported and which was considered to be particularly relevant for the economic model, was ordered. Therefore, a total of 194 records were ordered for full-paper screening.

Of the 194 records ordered, 130 were excluded based on full-paper screening and 64 were considered to be potentially relevant records to be included in the clinical effectiveness review and/or NMA (55 studies plus nine associated publications).

A total of 130 records were coded at the title and abstract stage as systematic reviews. Reviewer 1 (RW) screened systematic reviews from 2015 onwards for relevance; there were 25 relevant systematic reviews (plus one associated erratum). The reference lists of these systematic reviews were screened to check for additional potentially relevant studies; no additional studies were identified.

Separate searches of guideline databases (the NICE website and NHS Evidence), conducted in May 2019, identified a total of 23 records after de-duplication against the original library, none of which were considered relevant for inclusion in the systematic review. The reference lists of relevant guidelines were screened to check for additional potentially relevant studies; no additional studies were identified.

Clinical advisors were not aware of any additional studies other than those already identified from electronic searches.

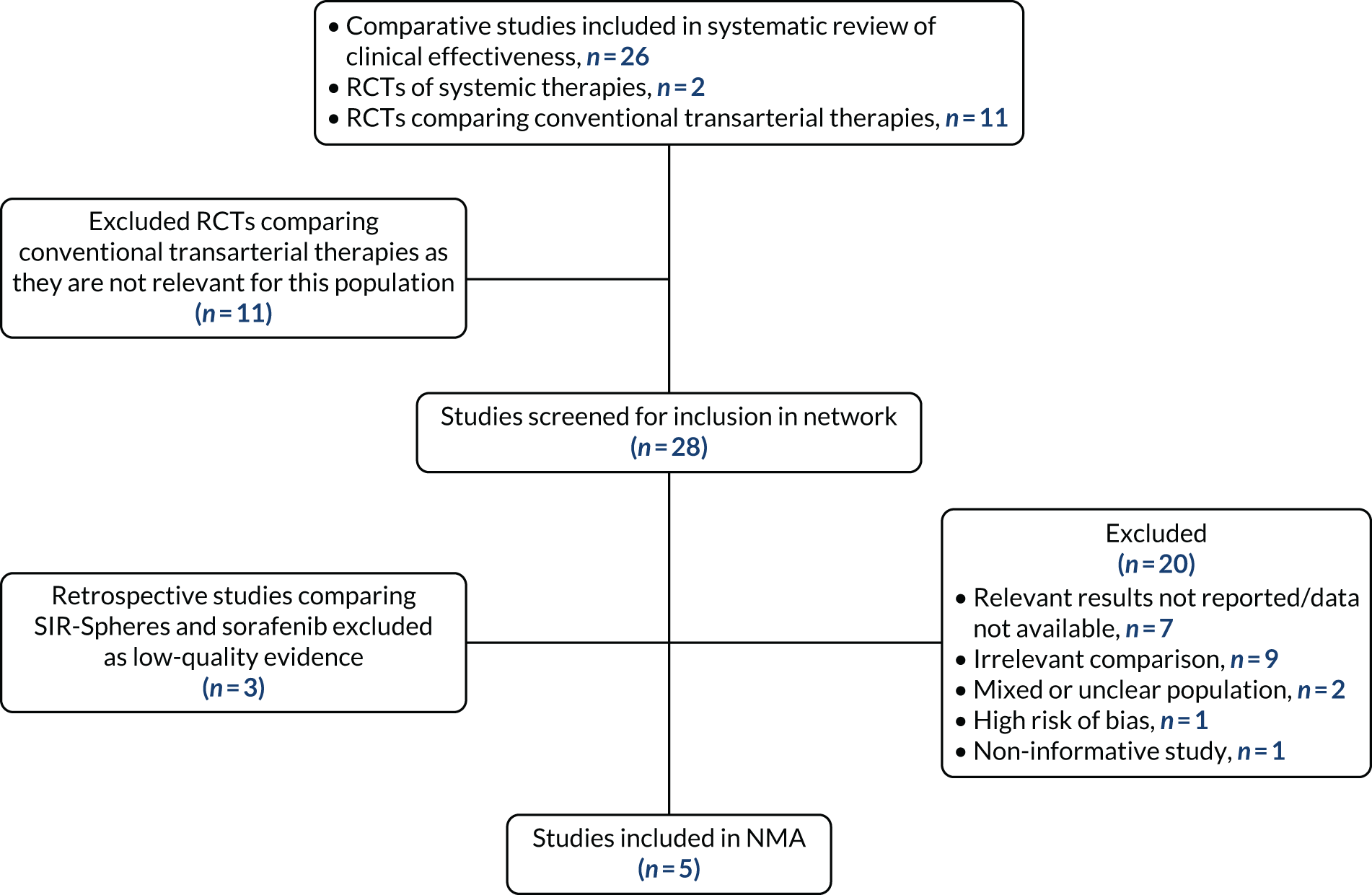

A PRISMA flow diagram is presented in Figure 1. In total, 27 of the 55 studies were prioritised for data extraction, as they were considered to be the most relevant for the assessment of clinical effectiveness and/or the proposed NMAs; these studies are summarised in Table 3. One non-comparative study was included in the clinical effectiveness review because this was the only study of QuiremSpheres;51 the other 26 studies were comparative studies.

FIGURE 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process for the clinical effectiveness review.

| Study (first author and year) | Intervention | Comparator | Location | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCTs of SIR-Spheres (n = 5) | ||||

|

Vilgrain 201719 and Bouattour 201720 SARAH |

SIR-Spheres | Sorafenib | France | Adults with locally advanced HCC (BCLC C) or new HCC not eligible for surgical resection, transplant or thermal ablation after a previously cured HCC (cured by surgery or thermoablative therapy) or HCC with two unsuccessful rounds of TACE |

|

Chow 201821 SIRveNIB |

SIR-Spheres | Sorafenib | Asia-Pacific region | Adults with locally advanced HCC (BCLC B or C) not amenable to curative treatment |

|

Kolligs 201522 SIRTACE |

SIR-Spheres | TACE | Germany and Spain | Adults with unresectable liver-only HCC (without portal vein occlusion) |

| Pitton 201523 | SIR-Spheres | DEB-TACE | Germany | Adults with unresectable N0, M0 HCC (BCLC stage B) |

|

Ricke 201524 SORAMIC |

SIR-Spheres plus sorafenib | Sorafenib alone | Germany | Adults with unresectable intermediate or advanced HCC (BCLC stage B or C), with preserved liver function (Child–Pugh class ≤ B7) and ECOG < 2, who were poor candidates for TACE (including those failing TACE) |

| RCTs of TheraSphere (n = 2) | ||||

|

Salem 2016,25 Gabr 201726 and Gordon 201627 PREMIERE |

TheraSphere | TACE | USA | Adults with BCLC stage A/B unablatable/unresectable HCC with no vascular invasion, Child–Pugh class A/B |

| Kulik 2014,28 Lewandowski 201629 and Vouche 201330 | TheraSphere | TheraSphere plus sorafenib | USA | Adults with Child–Pugh class ≤ B8 and potential candidates for orthotopic liver transplant |

| Prospective comparative studies of TheraSphere (n = 7) | ||||

| Kirchner 201931 | TheraSphere | TACE/DEB-TACE | Germany | Adults with unresectable HCC |

| El Fouly 201532 | TheraSphere | TACE | Germany and Egypt | Adults with intermediate-stage (BCLC B) unresectable HCC and good liver function (Child–Pugh class < B7) |

| Salem 201333 | TheraSphere | TACE | USA | Adults with treatment-naive HCC with ECOG 0–2 |

| Memon 201334 | TheraSphere | TACE | USA | Adults with HCC that progressed after intra-arterial locoregional therapies (TACE and SIRT) |

| Hickey 201635 | TheraSphere | TACE | USA | Adults with unresectable HCC and bilirubin ≤ 3.0 mg/dl |

| Maccauro 201436 | TheraSphere plus sorafenib | TheraSphere alone | Italy | Adults with unresectable HCC (Child–Pugh class A) |

| Woodall 200937 | TheraSphere | BSC | USA | Adults with unresectable HCC (including both patients with and patients without PVT) |

| Retrospective comparative studies of SIR-Spheres vs. TheraSphere (n = 5) | ||||

| Biederman 201538 | SIR-Spheres | TheraSphere | USA | Adults with HCC with PVT |

| Biederman 201639 | SIR-Spheres | TheraSphere | USA | Adults with HCC with PVI |

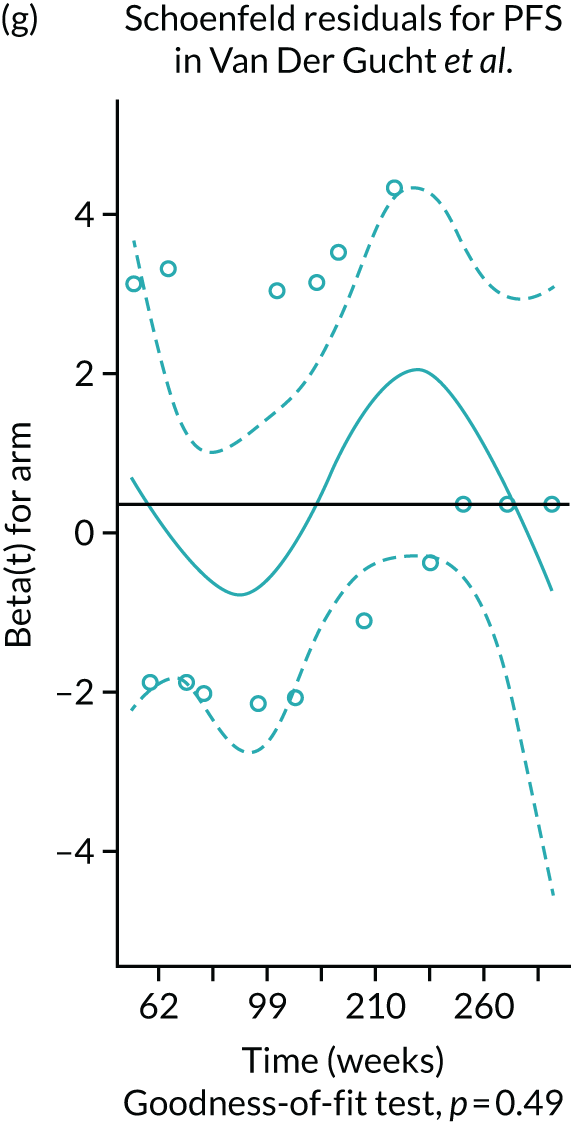

| Van Der Gucht 201740 | SIR-Spheres | TheraSphere | Switzerland | Adults with unresectable HCC |

| Bhangoo 201541 | TheraSphere | SIR-Spheres | USA | Adults with unresectable HCC |

| d’Abadie 201842 | SIR-Spheres | TheraSphere | Belgium | Adults with HCC |

| Retrospective comparative studies of SIR-Spheres (n = 4) | ||||

| Cho 201643 | SIR-Spheres | Sorafenib | Korea | Adults with BCLC stage C HCC with PVT |

| de la Torre 201644 | SIR-Spheres | Sorafenib | Spain | Adults with HCC with PVI |

| Gramenzi 201545 | SIR-Spheres | Sorafenib | Italy | Adults with HCC unfit for other effective therapies, Child–Pugh class A/B, performance status ≤ 1, no metastases and no previous systemic chemotherapy |

| Soydal 201646 | TACE | SIR-Spheres | Turkey | Adults with BCLC B or C HCC |

| Retrospective comparative studies of TheraSphere (n = 3) | ||||

| Salem 201147 | TheraSphere | TACE | USA | Adults with unresectable HCC and bilirubin 3.0 mg/dl |

| Moreno-Luna 201348 | TheraSphere | TACE | USA | Adults with unresectable HCC |

| Akinwande 201649,50 | TheraSphere | DEB-TACE | USA | Adults with unresectable HCC (with or without PVT) |

| Non-comparative studies of QuiremSpheres (n = 1) | ||||

| Radosa 201951 | QuiremSpheres | N/A | Germany | Adults with HCC |

The 28 lower-priority studies are summarised in Appendix 7 along with the reason for not including them in the systematic review of clinical effectiveness or the proposed NMAs (e.g. consultation with clinical advisors confirmed that the comparators used were not applicable to current UK practice). 52–55

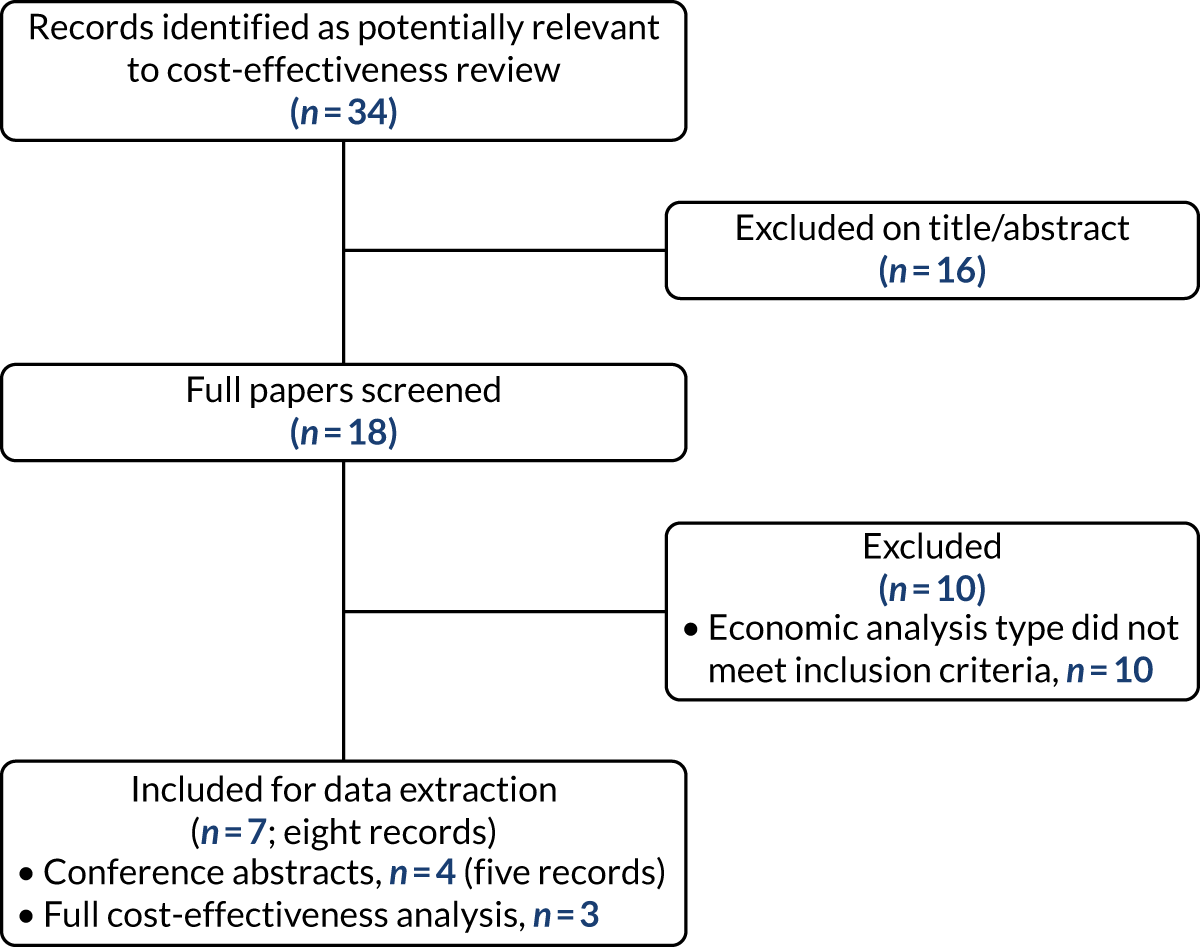

Thirty-four records were coded at the title and abstract stage as potentially relevant economic studies (seven of which were also coded as includes for the clinical effectiveness review). A separate flow diagram of the study selection process for these economic studies is presented (see Figure 7).

Studies of comparator therapies

Randomised controlled trials of comparator therapies were sought to strengthen the network of evidence on SIRT (see Chapter 5). The search for systematic reviews and meta-analyses of CTTs (TAE, TACE and DEB-TACE) identified 989 records. The records were inserted into an EndNote library and one reviewer (RW) screened the titles and abstracts. Records were put in reverse date order and screened started at the year 2019 and worked backwards until no new relevant RCTs were identified from the reviews and meta-analyses. A total of 319 records were screened, published between 2017 and 2019. Twenty-four of the 319 records were relevant systematic reviews or meta-analyses; full papers were obtained and reference lists were checked for RCTs comparing TAE, TACE or DEB-TACE with each other. Eleven relevant RCTs (reported in 12 publications) were identified, which are summarised in Table 4. In view of the recency of the relevant systematic reviews and meta-analyses and the age of the RCTs of CTTs (published between 1992 and 2016), it was decided that update searches were not necessary.

| Study (first author and year) | Intervention | Comparator | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

|

PRECISION V |

DEB-TACE | TACE | Adults with HCC unsuitable for resection or percutaneous ablation (BCLC A/B without portal invasion or extrahepatic spread) |

| Golfieri 201458 | DEB-TACE | TACE | Adults with HCC unsuitable for curative treatment or had failed/recurred after resection/ablation |

| Sacco 201159 | DEB-TACE | TACE | Adults with previously untreated unresectable HCC not suitable for ablative treatment, Child–Pugh class A or B and ECOG score of 0/1, absence of PVT and extrahepatic metastases |

| van Malenstein 201160 | DEB-TACE | TACE | Adults with HCC who were not candidates for curative treatments, Child–Pugh class A or B cirrhosis and an ECOG score of 0 or ECOG score of < 3 if the restriction in status was not because of the HCC |

| Llovet 200261 | TACE | TAE | White patients with unresectable HCC not suitable for curative treatment, or Child–Pugh class A or B and Okuda stage I or II |

| Kawai 199262 | TACE | TAE | HCC patients |

| Chang 199463 | TACE | TAE | Untreated patients with inoperable HCC |

| Meyer 201364 | TACE | TAE | Patients aged ≥ 16 years with HCC not eligible for surgical resection |

| Yu 201465 | TACE | TAE | Unresectable HCC |

| Malagari 201066 | DEB-TACE | TAE | HCC patients unsuitable for curative treatments, with potentially resectable lesions but at high risk for surgery and patients with HCC suitable for RFA but of high risk because of location |

| Brown 201667 | DEB-TACE | TAE | Adults with HCC with ECOG score of 0 to 1 and Okuda stage I or II |

Evidence on systemic therapies for HCC was identified from the recent NICE single technology appraisals of sorafenib,11 lenvatinib12 and regorafenib. 13

Assessment of clinical effectiveness

This section describes the seven RCTs and seven prospective comparative studies of SIR-Spheres and TheraSphere, the five retrospective comparative studies comparing SIR-Spheres with TheraSphere and the non-comparative case series of QuiremSpheres. The additional seven retrospective comparative studies of SIR-Spheres or TheraSphere (see Table 3) and studies of comparator therapies (see Table 4) that were selected, as they were considered to be potentially relevant for the NMAs, are described in Chapter 5.

Risk of bias

Results of the risk-of-bias judgements are presented in Appendix 5.

The SorAfenib versus Radioembolization in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma (SARAH) and Selective Internal Radiation Therapy Versus Sorafenib in Locally Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma (SIRveNIB) RCTs were both rated as having a low overall risk of bias. 19–21 There were some concerns regarding bias for the trials undertaken by Pitton et al. 23 and Kulik et al. 28 Concerns related to the randomisation process for the study by Pitton et al. 23 There were concerns related to the randomisation process, potential deviations from the intended interventions and measurement of the outcome for the study by Kulik et al. 28 The SIRTACE,22 SORAMIC24 and Prospective Randomized study of chEmoeMbolization versus radIoEmbolization for the tReatment of hEpatocellular carcinoma (PREMIERE)25–27 trials were all rated as being at a high overall risk of bias; the SIRTACE trial was rated as being at a high risk of bias arising from the randomisation process, missing outcome data and measurement of the outcome,22 the SORAMIC trial was rated as being at a high risk of bias in relation to deviations from the intended interventions as well as some concerns arising from the randomisation process,24 and the PREMIERE trial was rated as being at a high risk of bias arising from the randomisation process and concerns arising from deviations from the intended interventions. 25–27

The prospective comparative studies were all rated as being at a high risk of bias. 31–37 In particular, allocation to treatment groups was either inadequately described or inappropriate, resulting in differences in prognostic factors between treatment groups at baseline. Outcome assessors do not appear to have been blinded in any of the prospective comparative studies.

Four of the retrospective comparative studies were rated as being at a high risk of bias. 38–40,42 The two studies by Biederman et al. 38,39 appear to have included many of the same patients, although one of the studies was reported only as a conference abstract, with very limited study details. 38 Each of the studies rated as being at a high risk of bias appeared to include patients with different prognostic characteristics at baseline in the two different treatment groups. It was unclear whether or not outcome assessors were blinded in any of the studies. The study by Bhangoo et al. 41 was rated as being at an unclear risk of bias; it was unclear whether or not treatment groups were similar at baseline, whether or not outcome assessors were blinded and whether or not missing outcome data were balanced across treatment groups.

The small case series undertaken by Radosa et al. 51 should be considered to be at a high risk of bias; it is unclear whether or not patients were representative of all those who would be eligible for SIRT in clinical practice, outcome assessors were not blinded to the participants’ intervention and outcome measures were not consistently assessed.

Efficacy and safety of SIR-Spheres

As discussed in Study design, RCTs were eligible for inclusion in the clinical effectiveness review, with non-randomised comparative studies and non-comparative studies considered for inclusion, in the absence of sufficient RCT evidence. Five RCTs of SIR-Spheres were identified, comparing SIR-Spheres with established therapies available to patients with intermediate (TACE/DEB-TACE) and advanced (sorafenib) HCC. Other studies of SIR-Spheres identified also compared with sorafenib or TACE (see Table 3); therefore, they were not included in the review.

This section focuses on the two large good-quality RCTs (SARAH and SIRveNIB) and also presents a brief summary of the three lower-quality RCTs of SIR-Spheres.

The SARAH and SIRveNIB randomised controlled trials

Two large RCTs compared SIR-Spheres with sorafenib in patients who were not suitable for curative treatments: the SARAH trial was conducted in France19,20 and the SIRveNIB trial was conducted in the Asia-Pacific region. 21 Both trials were considered to have a low overall risk of bias (see Appendix 5). Further details of these trials are presented in Table 5.

| Characteristic | SARAH19 | SIRveNIB21 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial characteristic | ||||

| Study design | Multicentre open-label RCT | Multicentre open-label RCT | ||

| Location | France (25 centres) | Asia-Pacific region (11 countries) | ||

| Source of funding | Sirtex | Sirtex | ||

| Inclusion criteria | Locally advanced HCC (BCLC stage C) or new HCC not eligible for surgery/ablation after previously cured HCC (cured by surgery or thermoablative therapy) or HCC with two unsuccessful rounds of TACE. Life expectancy of > 3 months, ECOG performance status 0 or 1, Child–Pugh class A or B score of ≤ 7 | Locally advanced HCC (BCLC stage B or C without extrahepatic disease) with or without PVT, not amenable to curative treatment modalities | ||

| Intervention |

SIR-Spheres (n = 237) Patients underwent angiography, protective coiling and MAA-SPECT/computerised tomography scan and were readmitted for SIRT 1 or 2 weeks later. In bilobar tumours, the first treatment was delivered to the hemiliver with the greatest tumour burden and the contralateral hemiliver was scheduled for treatment 30–60 days after the first treatment. If the tumour progressed, SIRT could be repeated 184/237 patients received SIR-Spheres:53/237 (22%) patients did not receive SIRT |

SIR-Spheres (n = 182) Patients underwent angiographic and MAA assessment of suitability for SIRT. Eligible patients received a single delivery of SIRT 52/182 (28.6%) patients did not receive SIRT |

||

| Comparator |

Sorafenib (n = 222) Continuous oral sorafenib (400 mg twice daily) |

Sorafenib (n = 178) Continuous oral sorafenib (400 mg twice daily) |

||

| Primary outcome | OS | OS | ||

| Secondary outcomes |

|

|

||

| Baseline patient characteristic (ITT population) | ||||

| SIR-Spheres | Sorafenib | SIR-Spheres | Sorafenib | |

| Number of patients |

237 (ITT) 174 (per protocol) |

222 (ITT) 206 (per protocol) |

182 (ITT) 130 (per protocol) |

178 (ITT) 162 (per protocol) |

| Median/mean age (years) | 66 (IQR 60–72) | 65 (IQR 58–73) | 59.5 (SD 12.9) | 57.7 (SD 10.6) |

| Proportion male (%) | 89 | 91 | 80.8 | 84.8 |

| Cirrhosis present, n (%) | 211 (89) | 201 (91) | NR | NR |

| Cause of HCC, n (%) | ||||

| Alcohol | 147 (62)a | 124 (56)a | NR | NR |

| Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis | 49 (21)a | 60 (27)a | NR | NR |

| Hepatitis B | 13 (5)a | 15 (7)a | 93 (51.1) | 104 (58.4) |

| Hepatitis C | 55 (23)a | 49 (22)a | 26 (14.3) | 19 (10.7) |

| Hepatitis B and C | NR | NR | 4 (2.2) | 5 (2.8) |

| Other/unknown | 45 (19)a | 41 (18)a | NR | NR |

| BCLC classification, n (%) | ||||

| Stage A | 9 (4) | 12 (5) | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| Stage B | 66 (28) | 61 (27) | 93 (51.1) | 97 (54.5) |

| Stage C | 162 (68) | 149 (67) | 88 (48.4) | 80 (44.9) |

| Child–Pugh classification, n (%) |

A5 + A6: 196 (83) B7: 39 (16) Unknown: 2 (1) |

A5 + A6: 187 (84) B7: 35 (16) Unknown: 0 (0) |

A: 165 (90.7) B: 14 (7.7) |

A: 160 (89.9) B: 16 (9.0) |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 145 (61) | 139 (63) | 135 (74.2) | 141 (79.2) |

| 1 | 92 (39) | 83 (37) | 47 (25.8) | 37 (20.8) |

| Tumours, n (%) | ||||

| Single | 110 (46) | 96 (43) | NR | NR |

| Multiple | 127 (54) | 126 (57) | ||

| Tumour involvement, n (%) | ||||

| Unilobar | 187 (79) | 187 (84) | NR | NR |

| Bilobar | 50 (21) | 35 (16) | ||

| MVI, n (%) | 149 (63) | 128 (58) | NR | NR |

| PVT, n (%) | NR | NR | 56 (30.8) | 54 (30.3) |

| Portal venous invasion, n/N (%) | ||||

| Main portal vein | 49/143 (34) | 38/118 (32) | NR | NR |

| Main portal branch (right or left) | 65/143 (46) | 59/118 (50) | ||

| Segmental | 29/143 (20) | 21/118 (18) | ||

| Portal vein occlusion, n/N (%) | ||||

| Complete | 18/48 (38) | 18/38 (47) | NR | NR |

| Incomplete | 30/48 (62) | 20/38 (53) | ||

| Previously received TACE, n (%) | 106/237 (45) | 94/222 (42) | NR | NR |

| Trial results | ||||

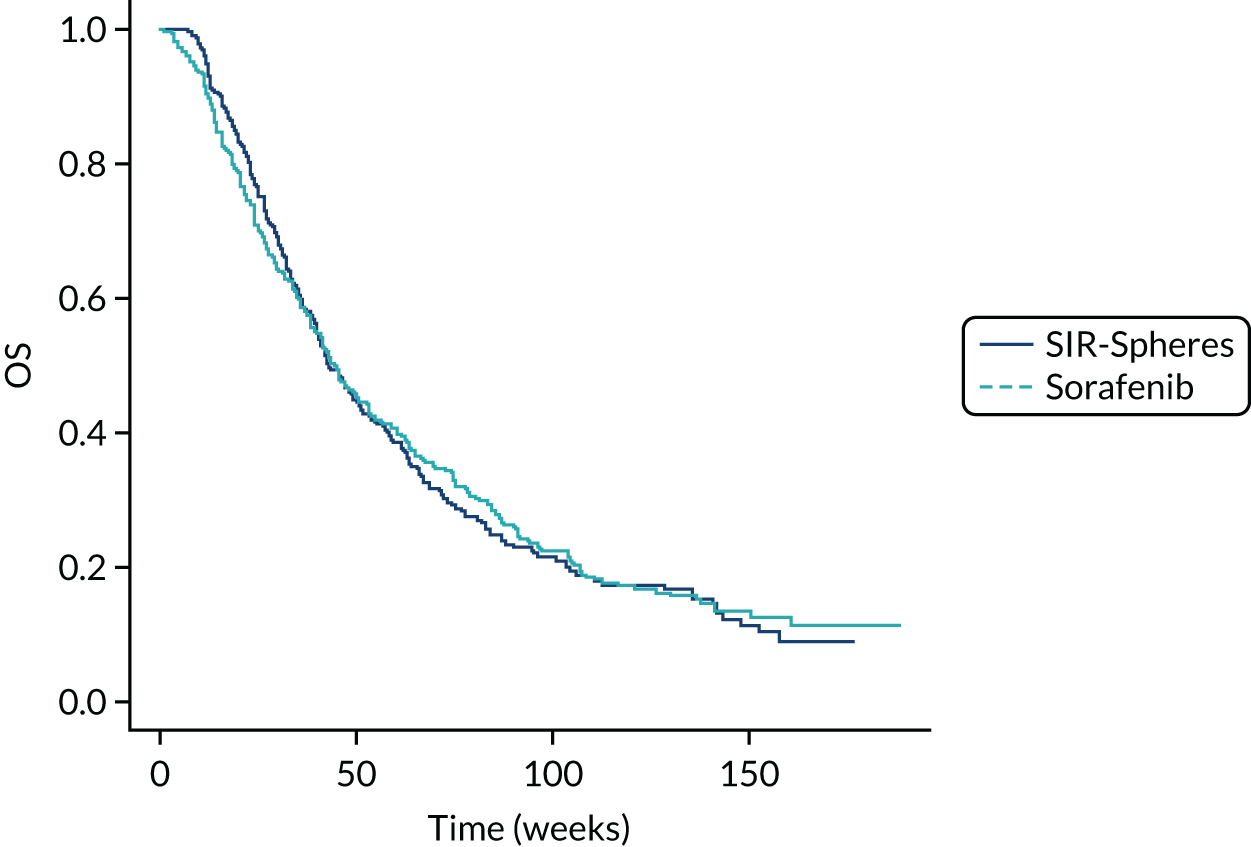

| Median OS (months) | 8.0 (95% CI 6.7 to 9.9) | 9.9 (95% CI 8.7 to 11.4) | 8.8 | 10.0 |

|

HR 1.15, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.41; p = 0.18 (ITT) HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.24 (per protocol) |

HR 1.12, 95% CI 0.9 to 1.4; p = 0.36 (ITT) HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.7 to 1.1; p = 0.27 (per protocol) |

|||

| Median PFS (months) | 4.1 (95% CI 3.8 to 4.6) | 3.7 (95% CI 3.3 to 5.4) | 5.8 | 5.1 |

| HR 1.03, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.25; p = 0.76 (ITT) |

HR 0.89, 95% CI 0.7 to 1.1; p = 0.31 (ITT) HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.6 to 0.9; p = 0.0128 (per protocol) |

|||

| TTP (months) | NR | 6.1 | 5.4 | |

| Tumour response rate | 36/190 (19%) evaluable patients achieved a complete (n = 5) or partial (n = 31) response | 23/198 (12%) evaluable patients achieved a complete (n = 2) or partial (n = 21) response | 16.5% (all partial response, 0% achieved a complete response) | 1.7% (all partial response, 0% achieved a complete response) |

| Rates of subsequent liver transplantation or resection |

6/237 (2.5%) had tumour ablationb 3/237 (1.3%) had liver surgeryb 2/237 (0.8%) had liver transplantation |

2/222 (0.9%) had tumour ablation 1/222 (0.5) had liver transplantation |

1/182 (0.5%) had radiofrequency ablation 2/182 (1.1%) had surgery |

2/178 (1.1%) had radiofrequency ablation 1/178 (0.6%) had surgery |

| HRQoLc | Global health status subscore was significantly better in the SIRT group than in the sorafenib group (group effect p = 0.0048; time effect p < 0.0001) and the between-group difference tended to increase with time (group × time interaction p = 0.0447) | There were no statistically significant differences in the EQ-5D index between the SIRT and sorafenib groups throughout the study in either the ITT or the per-protocol populations | ||

| Number of patients reporting treatment-related adverse events, n/N (%) | 173/226 (77) | 203/216 (94) | 78/130 (60) | 137/162 (84.6) |

| Number of patients reporting grade ≥ 3 adverse events, n/N (%) | 92/226 (41) | 136/216 (63) | 36/130 (27.7) | 82/162 (50.6) |

As shown in Table 5, there were methodological differences between the SARAH and the SIRveNIB trials. In the SIRveNIB trial, patients could receive only one SIRT delivery, whereas in the SARAH trial patients could receive more than one delivery of SIRT; 69 out of 184 (37.5%) patients who received SIRT received more than one delivery to either the ipsilateral or the contralateral lobe.

The SARAH trial was conducted in France and the SIRveNIB trial was conducted in the Asia-Pacific region. This has implications for the generalisability of the SIRveNIB trial results to the UK population. HCC in European patients is more likely to be caused by alcohol or hepatitis C, whereas in Asia it is more likely to be caused by hepatitis B. The natural history of these diseases is different. Treatment options are also different, as hepatitis B-related liver disease is often less advanced than in alcohol-related or hepatitis C-related disease; therefore, patients may have had more treatment prior to receiving systemic therapy.

The Sirtex submission stated that patient selection in the SARAH trial did not reflect UK clinical practice, as the trial included patients with a poor survival prognosis who would be considered for only systemic therapy or BSC [e.g. because of a high tumour burden, main PVT or impaired liver function (Child–Pugh class B)]. Therefore, this has implications for the generalisability of the SARAH trial results to the UK population who would be eligible for SIRT in clinical practice.

In both trials, patients were assessed for suitability of SIRT after randomisation. In the SARAH trial, 53 out of 237 (22.4%) patients allocated to SIR-Spheres did not receive SIRT, 26 of whom were treated with sorafenib. In the SIRveNIB trial, 52 out of 182 (28.6%) patients allocated to SIR-Spheres did not receive SIRT, three of whom were treated with sorafenib (where reported; subsequent treatments were not reported for 31/52 patients). Results were presented for both the intention-to-treat (ITT) and the per-protocol populations; patients who did not receive their allocated treatment were excluded from the per-protocol analysis (those who received sorafenib instead of SIRT were not included in the sorafenib arm in the per-protocol analysis).

The SARAH and SIRveNIB trial publications reported baseline characteristics for both the ITT and the per-protocol populations. 19,21 The SIR-Spheres and sorafenib groups were generally similar at baseline in the ITT populations (see Table 5). However, in the per-protocol population, patients in the sorafenib arm appeared to have slightly worse disease characteristics than those in the SIR-Spheres arm in the SARAH trial (BCLC stage C: 69.4% vs. 65.5%; Child–Pugh class B7: 14.6% vs. 11.5%; median tumour burden: 20% vs. 12.5%, respectively) and in the SIRveNIB trial (BCLC stage C: 45.1% vs. 38.5%; PVT: 29.6% vs. 23.1%; tumour size > 50% of liver: 21.6% vs. 17.7%, respectively).

Neither trial found a statistically significant difference in OS between SIR-Spheres and sorafenib in either the ITT or the per-protocol analyses, as shown in Table 5.

Both trials undertook subgroup analyses according to baseline characteristics. The SIRveNIB trial reported a statistically significant difference in OS favouring SIR-Spheres in the subgroup of patients with BCLC stage C disease in the per-protocol analysis [median 9.2 vs. 5.8 months, hazard ratio (HR) 0.67, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.4 to 1.0; p = 0.0475]. The SARAH trial demonstrated a statistically significant difference in OS favouring sorafenib in the subgroup of patients with complete occlusion in the main portal vein in the per-protocol analysis (HR 2.44, 95% CI 1.01 to 5.88); however, the number of patients included in this subgroup analysis was very small, so the result should be interpreted with caution.

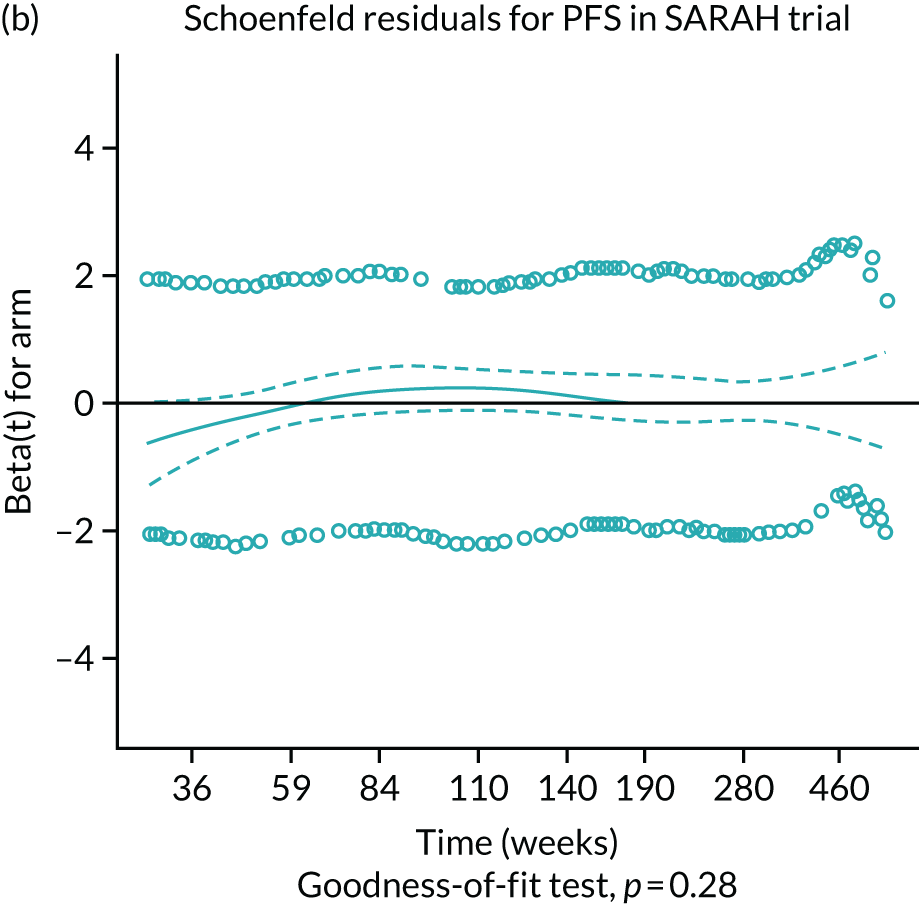

In the SARAH trial, PFS was defined as the time from the closest date of radiological examination before first administration of study treatment to disease progression, in accordance with Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) 1.1 criteria,68 or death. In the SIRveNIB trial, PFS was defined as the time from the date of randomisation to tumour progression at any site in the body, or death, whichever is earlier. Tumour progression was assessed in accordance with RECIST 1.1 criteria. 68

Progression-free survival was not statistically significantly different between treatment groups in the ITT analyses of either the SARAH or the SIRveNIB trials. However, in the SIRveNIB trial, PFS was statistically significantly improved with SIR-Spheres in the per-protocol analysis (HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.6 to 0.9; p = 0.0128).

Tumour response was statistically significantly greater in the SIR-Spheres arm than in the sorafenib arm in both the SARAH and the SIRveNIB trials (SARAH: 19% vs. 12%, p = 0.0421; SIRveNIB: 16.5% vs. 1.7%, p < 0.001). However, in the SARAH trial, only 190 SIR-Spheres patients and 198 sorafenib patients were evaluable and included in the analysis.

A very small proportion of patients in both treatment arms of the SARAH and the SIRveNIB trials went on to have subsequent liver transplantation (< 1%), liver surgery (0.6–1.3%) or tumour ablation (0.5–2.5%).

The SARAH trial reported statistically significantly better HRQoL in the SIR-Spheres treatment group than in the sorafenib group for both the ITT and the per-protocol populations, assessed using the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ)-C30. However, the proportion of patients who completed questionnaires was 71% in the SIR-Spheres group (169/237) and 84% (186/222) in the sorafenib group at baseline, reducing with time to only 29% (26/90 patients at risk) in the SIR-Spheres group and 32% (29/92 patients at risk) in the sorafenib group at 12-month follow-up. There was no statistically significant difference in HRQoL between the treatment groups in the SIRveNIB trial, assessed using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) index.

The proportion of patients reporting at least one treatment-related adverse event (TRAE) and the proportion reporting at least one grade ≥ 3 adverse event (AE) was higher in the sorafenib group than in the SIR-Spheres group in both trials, as shown in Table 5.

In the SARAH trial, the most frequent grade ≥ 3 AEs were fatigue (SIR-Spheres 9% vs. sorafenib 19%), liver dysfunction (11% vs. 13%), increased laboratory liver values (9% vs. 7%), haematological abnormalities (10% vs. 14%), diarrhoea (1% vs. 14%), abdominal pain (3% vs. 6%), increased creatinine (2% vs. 6%) and hand–foot skin reaction (< 1% vs. 6%).

In the SIRveNIB trial, the most frequent grade ≥ 3 AEs of interest were anaemia (SIR-Spheres 0% vs. sorafenib 2.5%), fatigue (0% vs. 3.7%), diarrhoea (0% vs. 3.7%), abdominal pain (2.3% vs. 1.2%), ascites (3.8% vs. 2.5%), hypertension (0% vs. 1.2%), upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage (0.8% vs. 1.9%), jaundice (0.8% vs. 1.2%), radiation hepatitis (1.5% vs. 0%) and hand–foot skin reaction (0% vs. 16.7%).

The AE profiles of SIRT and sorafenib are very different. Sorafenib is a continuous treatment, whereas most patients receive only one delivery of SIRT [37.5% patients in the SARAH trial received more than one delivery, either to the ipsilateral or to the contralateral lobe (primarily because of bilobar tumours or a large central tumour requiring bilateral treatment), whereas in the SIRveNIB trial patients received only one delivery]. AE rates were not reported separately for patients who received more than one delivery of SIRT; therefore, it is not possible to compare AE rates for patients who received one delivery with those who received more than one delivery. In the SARAH trial, patients with bilobar tumours received the first treatment in the hemiliver with the greatest tumour burden, and treatment of the contralateral hemiliver was scheduled 30–60 days after the first treatment. No patient had a whole-liver treatment approach in one session. Clinical advisors confirmed that this is reflective of their experience; patients would not receive whole-liver treatment in one session to reduce the risk of radioembolisation-induced liver disease (REILD). However, the Sirtex submission states that SIR-Spheres can be administered to both lobes of the liver during the same procedure [based on observational data in which 95.9% patients in the European Network on Radioembolisation with Yttrium-90 Resin Microspheres (ENRY) register received whole-liver treatments in a single session69]; neither the SARAH trial nor the SIRveNIB trial administered SIR-Spheres to both lobes during the same procedure. This variance is probably because of the clinical indication for SIRT; the ENRY register is likely to include a majority of patients with colorectal cancer liver metastases, who do not have underlying cirrhosis, whereas in HCC patients the cirrhotic liver is likely to be more susceptible to REILD.

A relatively large proportion of patients who undergo work-up for SIRT, to assess their suitability for the procedure, are unable to receive SIRT (e.g. owing to liver-to-lung shunting or unfavourable hepatic arterial anatomy) [42/226 (18.6%) in SARAH and 37/182 (20.3%) in SIRveNIB]. The work-up of patients who are unable to undergo SIRT delivery has cost implications.

The SARAH randomised controlled trial subgroup analysis (low tumour burden/low albumin–bilirubin grade)

The Sirtex company submission selected a subgroup of patients from the SARAH trial with ≤ 25% tumour burden and albumin–bilirubin (ALBI) 1 for their base-case analysis in the economic model; the company stated that these patients are considered the most appropriate candidates for SIR-Spheres in clinical practice, as they are the most likely to benefit from SIRT. This is not a clinically recognised subgroup and was based on a post hoc analysis; therefore, these results should be prospectively validated before being considered relevant for clinical practice.

This subgroup included 37 (16%) patients in the SIRT group and 48 (22%) patients in the sorafenib group; 92% of those allocated to SIRT received treatment after work-up. Baseline characteristics were relatively well balanced between treatment groups, although more patients in the SIRT arm had BCLC stage B disease, single tumours and received previous TACE (these patients generally have a better prognosis than patients who are diagnosed at a later stage and are not eligible for TACE) than in the sorafenib arm. More patients in the sorafenib arm had an ECOG performance status of 0 and unilobar liver involvement. Table 6 presents the baseline characteristics and results for the full ITT population and the low tumour burden/low ALBI grade subgroup of the SARAH trial.

| Characteristic | ITT population | Low tumour burden/low ALBI grade subgroup | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIR-Spheres | Sorafenib | SIR-Spheres | Sorafenib | |

| Baseline patient characteristic | ||||

| Number of patients | 237 | 222 | 37 | 48 |

| Median age (years) | 66 | 65 | NR | NR |

| Age group (years) (%) | ||||

| ≥ 65 | NR | NR | 43 | 48 |

| < 65 | NR | NR | 57 | 52 |

| BCLC classification (%) | ||||

| Stage A | 4 | 5 | 3 | 6 |

| Stage B | 28 | 27 | 43 | 35 |

| Stage C | 68 | 67 | 54 | 58 |

| Child–Pugh classification (%) |

A5 + A6: 83 B7: 16 Unknown: 1 |

A5 + A6: 84 B7: 16 Unknown: 0 |

A: 95 B: 5 |

A: 98 B: 2 |

| ECOG performance status (%) | ||||

| 0 | 61 | 63 | 62 | 79 |

| 1 | 39 | 37 | 38 | 21 |

| Tumours (%) | ||||

| Single | 46 | 43 | 43 | 33 |

| Multiple | 54 | 57 | 57 | 67 |

| Tumour involvement (%) | ||||

| Unilobar | 79 | 84 | 76 | 85 |

| Bilobar | 21 | 16 | 24 | 15 |

| MVI (%) | 63 | 58 | 54 | 52 |

| Portal venous invasion, n/N (%) | ||||

| Main portal vein | 49/143 (34) | 38/118 (32) | 11 | 10 |

| Main portal branch | 65/143 (46) | 59/118 (50) | ||

| Segmental | 29/143 (20) | 21/118 (18) | ||

| Previously received TACE (%) | 45 | 42 | 51 | 44 |

| Trial results | ||||

| Median OS (months) | 8.0 (95% CI 6.7 to 9.9) | 9.9 (95% CI 8.7 to 11.4) | 21.9 (95% CI 15.2 to 32.5) | 17.0 (95% CI 11.6 to 20.8) |

| HR 1.15, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.41; p = 0.18 | HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.21; p = 0.22 | |||

| Median PFS (months) | 4.1 (95% CI 3.8 to 4.6) | 3.7 (95% CI 3.3 to 5.4) | NR | NR |

| HR 1.03, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.25; p = 0.76 | HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.41 to 1.02; p = 0.06 | |||

| Tumour response rate | 36/190 (19%) evaluable patients achieved a complete (n = 5) or partial (n = 31) response | 23/198 (12%) evaluable patients achieved a complete (n = 2) or partial (n = 21) response | NR | NR |

| Rates of subsequent liver transplantation or resection |

6/237 (2.5%) had tumour ablationa 3/237 (1.3%) had liver surgerya 2/237 (0.8%) had liver transplantation |

2/222 (0.9%) had tumour ablation 1/222 (0.5%) had liver transplantation |

14% (subsequent curative therapy) | 2% (subsequent curative therapy) |

| HRQoLb | Global health status subscore was significantly better in the SIRT group than in the sorafenib group (group effect p = 0.0048; time effect p < 0.0001) and the between-group difference tended to increase with time (group*time interaction p = 0.0447) | NR | ||

| Number of patients reporting TRAEs, n/N (%) | 173/226 (77) | 203/216 (94) | NR | NR |

| Number of patients reporting grade ≥ 3 AEs, n/N (%) | 92/226 (41) | 136/216 (63) | NR | NR |

As shown in Table 6, median OS and PFS appeared to be better in the SIR-Spheres arm than in the sorafenib arm in the post hoc subgroup analysis, although the difference between treatment groups was not statistically significant. The proportion of patients who went on to have potentially curative therapy was higher in the SIR-Spheres arm than in the sorafenib arm, although numbers were very low (five and one patients, respectively). Tumour response rate, HRQoL and AEs were not reported separately for the low tumour burden/low ALBI grade subgroup.

Prespecified and post hoc subgroup analysis results were presented in the SARAH trial publication for OS. 19 Tumour burden was included as a post hoc subgroup. However, neither the ALBI grade nor the combination of low tumour burden and low ALBI grade was presented.

The SIRveNIB trial did not report subgroup analysis results for the subgroup of low tumour burden/low ALBI grade patients. However, ALBI grade was included in the OS subgroup analysis. Results favoured SIR-Spheres in the subgroup of ALBI 1 patients (HR 0.89, 95% CI 0.6 to 1.4; p = 0.58), whereas results favoured sorafenib for the subgroup of patients with ALBI 2/3 (HR 1.24, 95% CI 0.9 to 1.7; p = 0.14).

Other randomised controlled trials of SIR-Spheres

The SIRTACE is a small RCT rated as being at a high risk of bias that compared SIR-Spheres (n = 13) with TACE (n = 15) in patients with unresectable HCC without portal vein occlusion. 22 A higher proportion of patients in the SIRT group had BCLC stage A disease (38.5% vs. 26.7%) and Child–Pugh liver function class A (92.3% vs. 86.7%) than in the TACE group. The average number of tumour nodules was higher in the TACE group (5.0 vs. 3.5). Therefore, patients in the SIR-Spheres treatment arm had a better prognosis than those in the TACE arm.

At 6 months, 69.2% of SIRT patients and 86.7% of TACE patients were still alive. At 12 months, 46.2% of SIRT patients and 66.7% of TACE patients were still alive. PFS, disease control rate and the proportion of patients who went on to have potentially curative therapy were similar between treatment groups. The proportion of patients with a partial response was higher in the SIRT group than in the TACE group (30.8% vs. 13.3%), although patient numbers were very small.

There were no statistically significant differences between treatment groups in HRQoL by week 12, despite Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Hepatobiliary-Pancreatic Symptom Index (FACT-Hep) scores being lower in the SIRT group at baseline (indicating lower quality of life). However, 10 out of 28 patients had missing baseline data and were excluded from HRQoL analyses. The proportion of patients reporting TRAEs was higher in the TACE group than in the SIRT group (33.3% vs. 23.1%), although the proportion of patients reporting at least one AE was higher in the SIRT group (92.3% vs. 66.7%), as was the number of patients with grade ≥ 3 AEs (three vs. two patients) and serious AEs requiring hospitalisation (seven vs. five patients).

A small RCT by Pitton et al. ,23 with some concerns regarding bias, compared SIR-Spheres (n = 12) with DEB-TACE (n = 12) in patients with unresectable intermediate (BCLC stage B) HCC with preserved liver function (Child–Pugh class A–B7). Treatment groups appeared reasonably similar at baseline, although more patients in the SIRT group had received prior local ablation (four vs. one) and more patients in the DEB-TACE group had received prior resection (five vs. three). Median OS and PFS were longer in the DEB-TACE arm than in the SIR-Spheres arm (788 days vs. 592 days and 216 days vs. 180 days, respectively), although the difference between groups was not statistically significant. Median TTP was 371 days in the SIRT arm and 336 days in the DEB-TACE arm. AEs were not reported.

The SORAMIC RCT compared SIR-Spheres followed by sorafenib with sorafenib alone in patients with unresectable intermediate or advanced (BCLC stage B or C) HCC with preserved liver function (Child–Pugh class ≤ B7) and ECOG performance status of < 2, who were poor candidates for TACE. Only safety and tolerability data for the first 40 patients have been published to date, rated as being at a high risk of bias. 24 More patients in the sorafenib-alone group had PVT (35% vs. 15%) and BCLC stage C disease (70% vs. 60%), indicating poorer prognosis in this group. There were 196 treatment-emergent AEs reported in the SIRT plus sorafenib arm and 222 events in the sorafenib-alone arm, of which 21.9% and 21.2%, respectively, were considered to be grade ≥ 3. The most common grade 3 or 4 AEs (hypertension, hand–foot skin reaction and diarrhoea) were reported in a similar number of patients in both treatment arms. Grade 3 or 4 fatigue appeared more common in patients receiving SIRT plus sorafenib (20% vs. 10%). Grade 3 or 4 infection and anorexia appeared more common in patients receiving sorafenib alone (20% vs. 5% and 0% vs. 10%, respectively). Grade 3 or 4 laboratory-related events were more common in patients receiving sorafenib alone (elevated gamma-glutamyltransferase level 45% vs. 30%, elevated aspartate aminotransferase level 15% vs. 0% and elevated alanine aminotransferase level 10% vs. 0%). One patient experienced a grade 3 gastric ulcer that was probably (but not proven to be) related to SIRT microspheres deposition.

Further details of each of these trials are presented in Appendix 6.

Ongoing studies

There are three ongoing studies of SIR-Spheres including patients with HCC: the Austrian Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe Registry for SIR-Spheres Therapy (CIRT),70 the RESIN tumour registry in the USA71 and the RESIN tumour registry in Taiwan. 72 The CIRT study was completed in January 2020, the RESIN tumour registry study in the USA is due to be completed in August 2022 and the RESIN tumour registry study in Taiwan was due to be completed in December 2019.

There is also an ongoing individual patient data prospective meta-analysis of patients from the SIRveNIB and SARAH trials: VESPRO. 73

Efficacy and safety of TheraSphere

As discussed in Study design, RCTs were eligible for inclusion in the clinical effectiveness review. Non-randomised comparative studies (including retrospective studies) and non-comparative studies were considered for inclusion in the absence of sufficient RCT evidence. Only two small RCTs of TheraSphere were identified. Therefore, prospective non-randomised comparative studies were also included in the clinical effectiveness review; seven non-RCTs were included, most of which compared TheraSphere with TACE/DEB-TACE. The retrospective comparative studies of TheraSphere that were identified also compared against TACE/DEB-TACE (see Table 3); therefore, they were not included in the review as they were considered to be lower quality than the prospective comparative studies.

One small RCT rated as being at a high risk of bias (PREMIERE) compared TheraSphere (n = 24) with TACE (n = 21) as a bridge to transplant in patients with BCLC stage A or B unresectable HCC with no vascular invasion and Child–Pugh liver function class A or B. 25–27 The proportion of patients with Child–Pugh class A was much higher in the TACE arm than in the TheraSphere arm (71% vs. 50%) and the proportion of patients with portal hypertension was much lower in the TACE arm (52% vs. 83%), suggesting better prognosis in the TACE arm. OS was slightly longer in the TheraSphere arm (18.6 months vs. 17.7 months) and the rate of liver transplant/resection was also higher in the TheraSphere arm (87% vs. 70% of ‘listed patients’), although time to transplant/resection was slightly longer in the TheraSphere arm (8.8 months vs. 7.6 months). TTP was significantly longer in the TheraSphere arm: overall median TTP was not reached in the TheraSphere arm (> 26 months) and was 6.8 months in the TACE arm (HR 0.112, 95% CI 0.027 to 0.557; p = 0.007); TTP in the non-transplanted patients was also significantly longer in the TheraSphere arm (median > 26 months vs. 4.8 months). AEs and HRQoL were not reported.

One small RCT by Kulik et al. ,28–30 which caused some concerns regarding bias, compared TheraSphere plus sorafenib (n = 10) with sorafenib alone (n = 10) as a bridge to transplant in patients with Child–Pugh liver function class ≤ B8 HCC who were potential candidates for liver transplant. A higher proportion of patients in the TheraSphere plus sorafenib arm were male (80% vs. 50%) and had BCLC stage A disease (70% vs. 50%), with more patients in the TheraSphere-alone arm having BCLC stage C disease (40% vs. 20%). More patients in the TheraSphere plus sorafenib arm had ECOG performance status 0 (80% vs. 60%) and Child–Pugh liver function class A (80% vs. 60%). Three patients died in the TheraSphere arm, compared with two patients in the TheraSphere plus sorafenib arm. The proportion of patients receiving liver transplant or resection was 90% in each treatment arm. Most AEs were more common in the TheraSphere-alone arm (fatigue 90% vs. 40%, diarrhoea 20% vs. 10%, pain 50% vs. 0%, nausea 70% vs. 20% and vomiting 20% vs. 0%), although grade ≥ 3 hand–foot skin reaction was more common in the TheraSphere plus sorafenib arm (20% vs. 0%).

Five prospective comparative studies, all rated as being at a high risk of bias, compared TheraSphere with TACE/DEB-TACE in patients with HCC. 31–35 Two studies assessed OS. In one small study (n = 86), OS appeared slightly longer with TACE than with TheraSphere in patients with intermediate-stage disease (median 18 months vs. 16.4 months). 32 In a much larger study (n = 765) in which survival outcomes were stratified by BCLC stage and Child–Pugh liver function class, survival was longer in the TACE arm for patients with early- and intermediate-stage disease but longer in the TheraSphere arm for patients with advanced-stage disease. 35 Two small studies (n = 86 and n = 96) assessed TTP, which was longer with TheraSphere than with TACE (median 13.3 months vs. 6.8 months and median 13.3 months vs. 8.4 months). 32,34 Two small studies (n = 67 and n = 86) assessed complete or partial response rate; results were conflicting, with one study31 favouring TACE (2.3% vs. 0%, using RECIST criteria68) and the other32 favouring TheraSphere (75% vs. 50%, using modified RECIST criteria68). Two small studies (n = 67 and n = 56) assessed HRQoL, both favouring TheraSphere. 31,33 Only one study (n = 86) reported AEs; the most commonly reported AE (unspecific abdominal pain) was more frequent in TACE patients than in SIRT patients (83% vs. 5%). 32

One small prospective matched case–control study by Maccauro et al. ,36 rated as being at a high risk of bias, compared TheraSphere plus sorafenib (n = 15) with TheraSphere alone (n = 30) in patients with predominantly BCLC stage C (due to PVT) unresectable HCC with Child–Pugh liver function class A. The study was published only as a conference abstract; therefore, very limited data are available. Results were similar between treatment groups for OS (median 10 months in each treatment arm), PFS (median 6 months vs. 7 months in the TheraSphere plus sorafenib and TheraSphere-alone arms, respectively) and response rate, using modified RECIST criteria68 (45.5% vs. 42.8%). However, response rate using EASL criteria1 was better in the TheraSphere-alone arm (40% vs. 10%).

One small prospective comparative study by Woodall et al. ,37 rated as being at a high risk of bias, compared TheraSphere in HCC patients without PVT (n = 20) with TheraSphere in HCC patients with PVT (n = 15) and a no-treatment control (BSC) in HCC patients who were not eligible for SIRT owing to substantial extrahepatic disease or hepatopulmonary shunt or underlying liver insufficiency (n = 17). OS was significantly longer in patients without PVT who received TheraSphere (median 13.9 months) than in patients with PVT who received TheraSphere (median 3.2 months) and patients who received BSC (median 5.2 months). AEs were more common in TheraSphere patients who had PVT than in those who did not have PVT (33% vs. 25%). No other outcomes were reported.

Further details of each of these studies are presented in Appendix 6.

Ongoing studies

There is one ongoing RCT of TheraSphere in patients with HCC: STOP-HCC, which has an estimated study completion date of February 2020; final results are not anticipated before at least December 2020. 74

The BTG submission presents 12 additional ongoing or planned studies of TheraSphere.

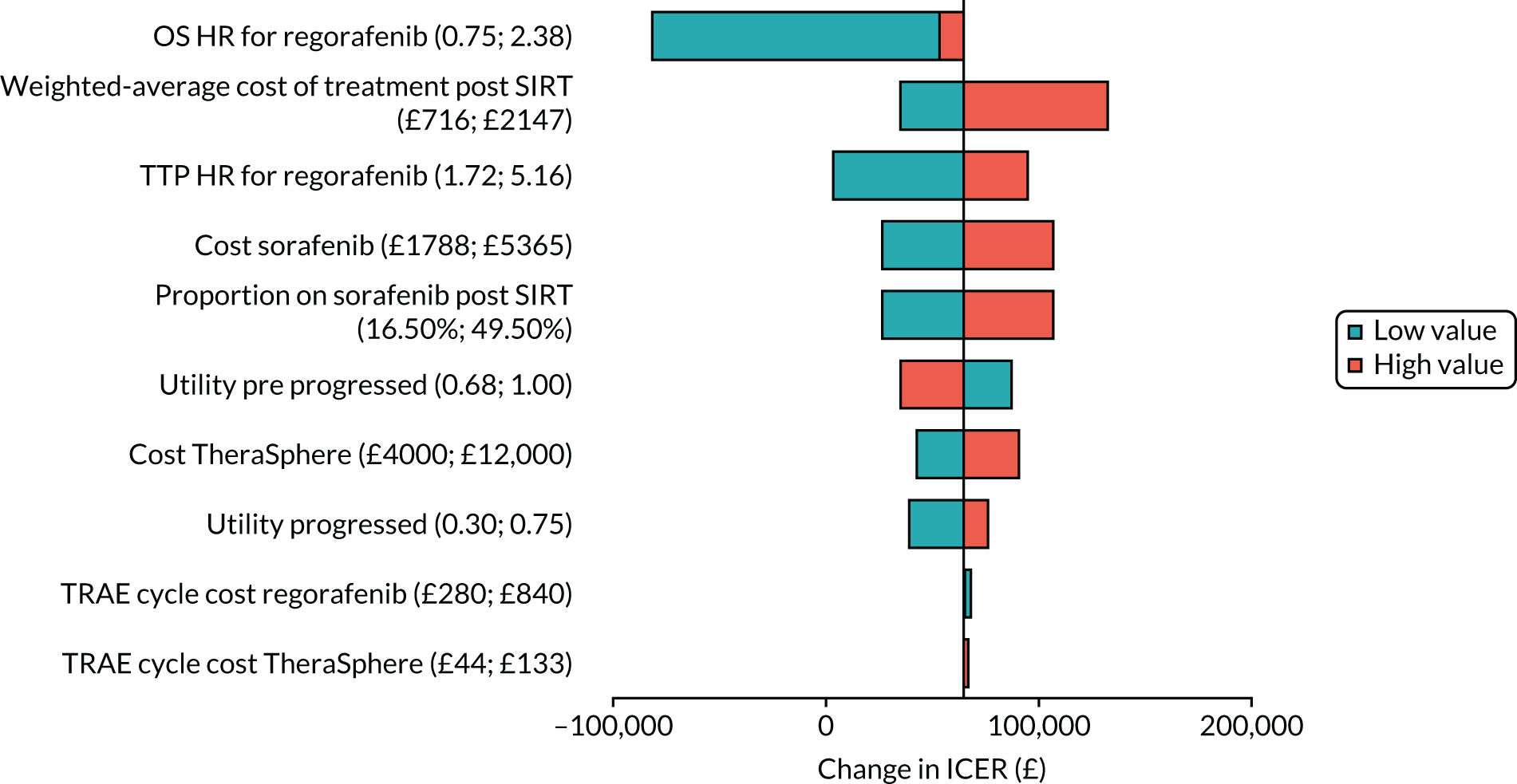

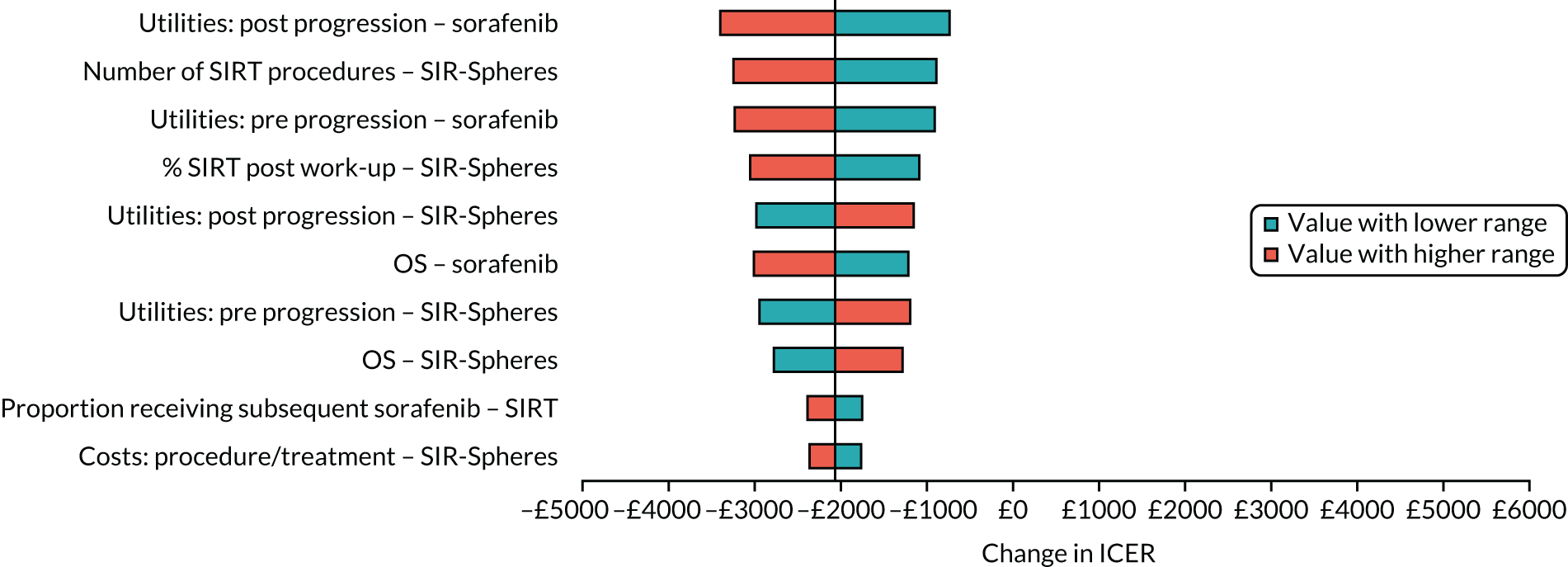

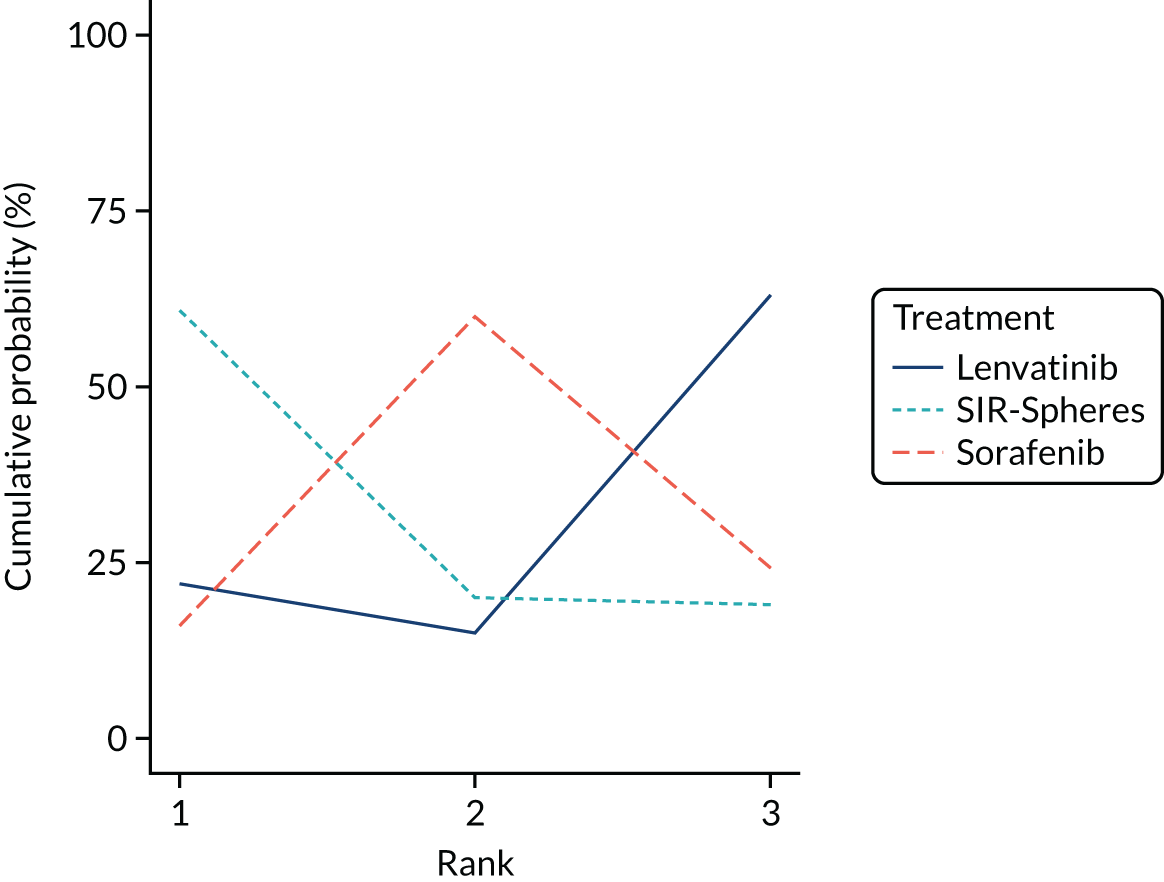

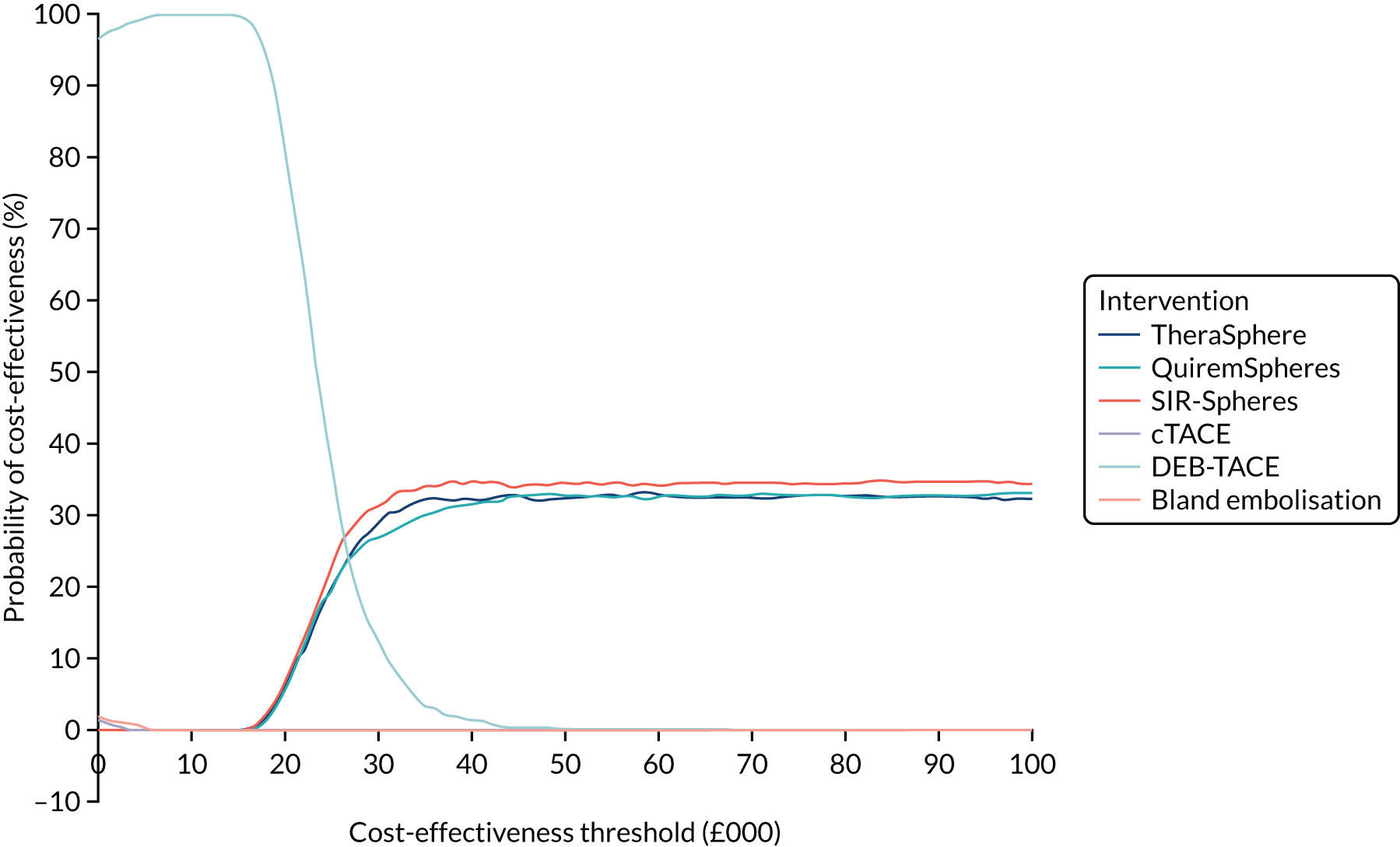

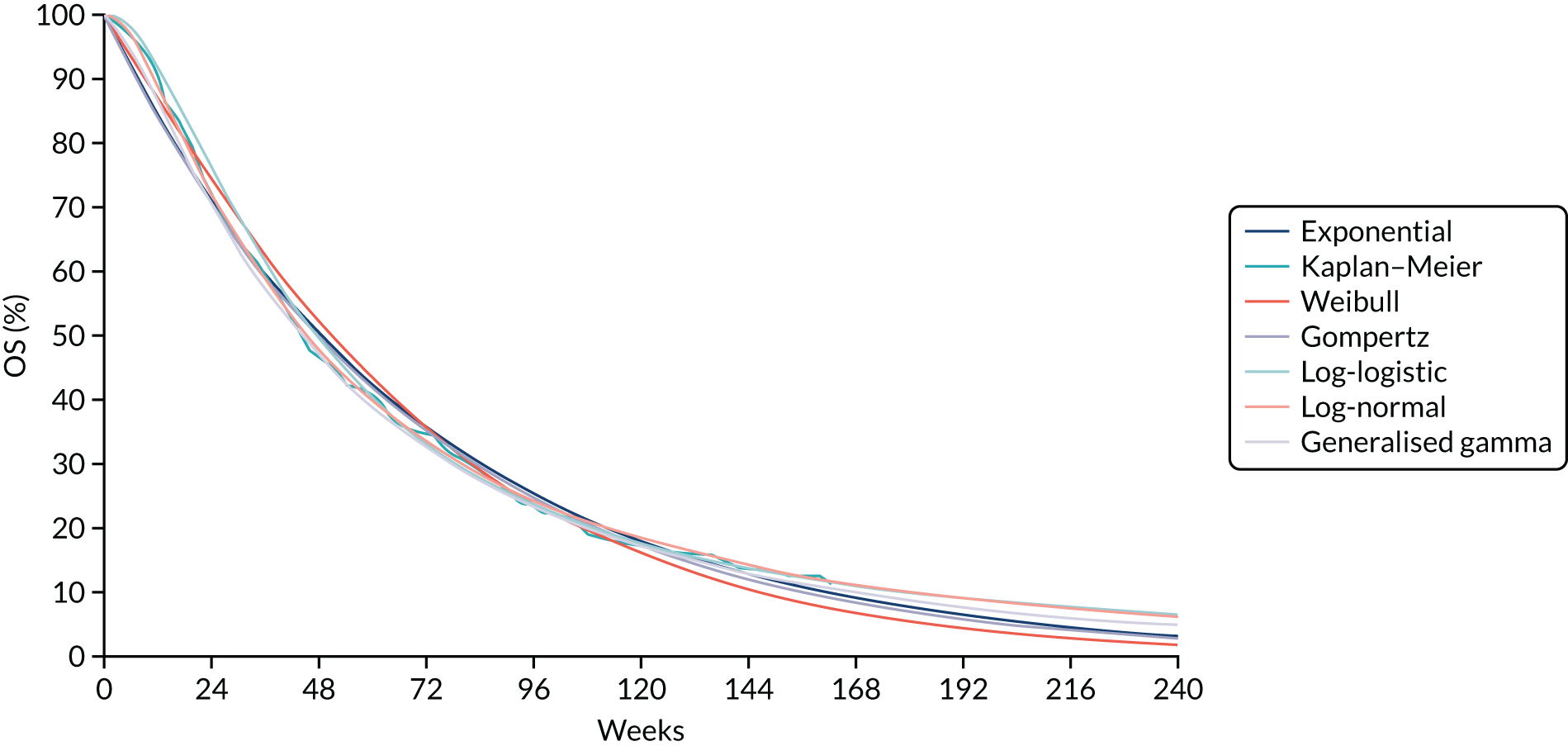

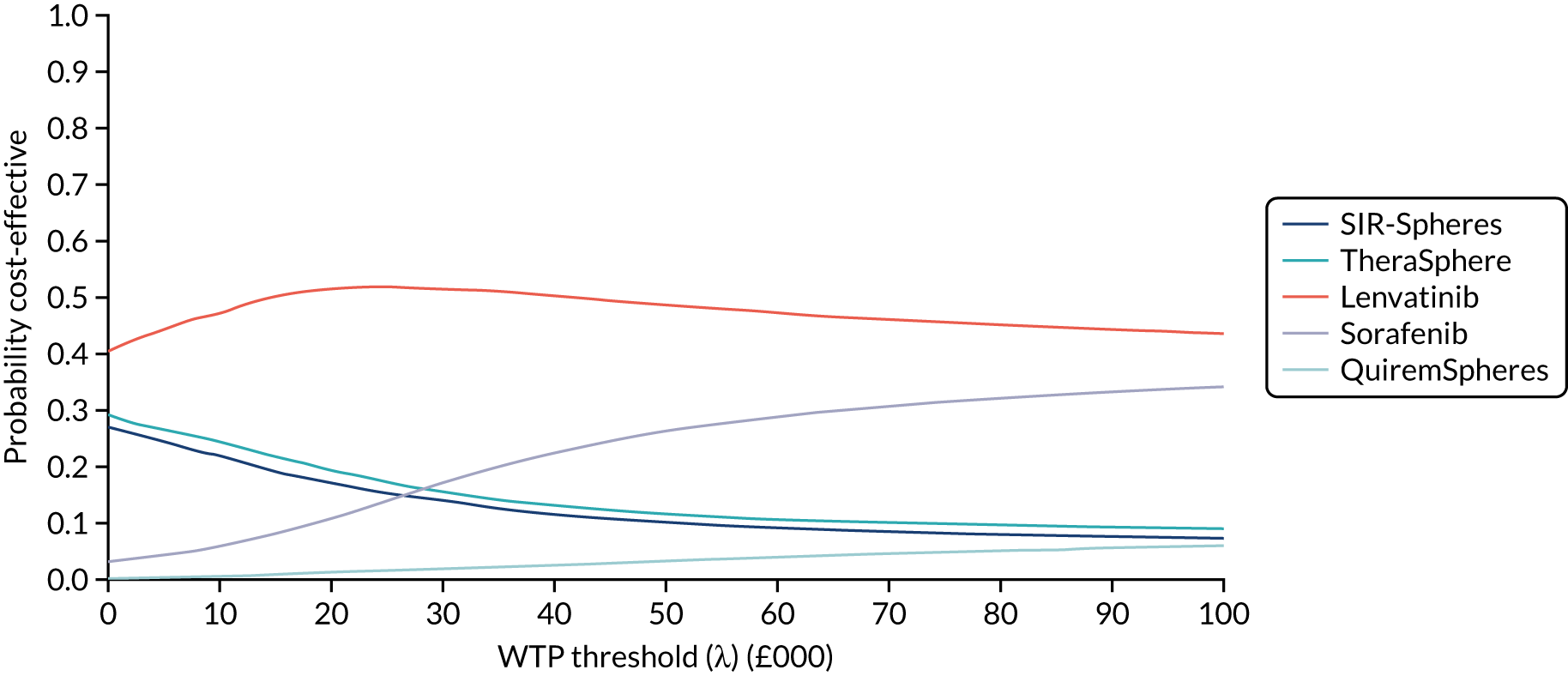

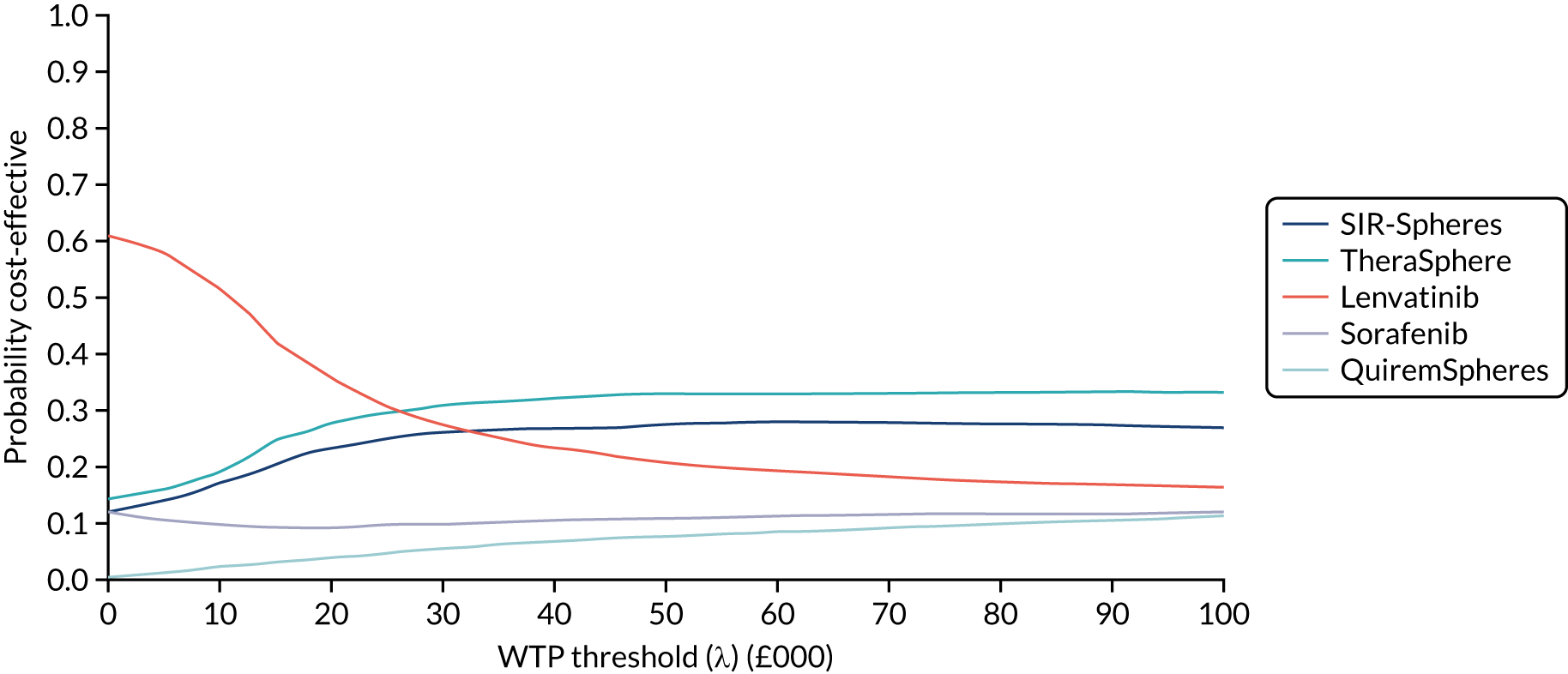

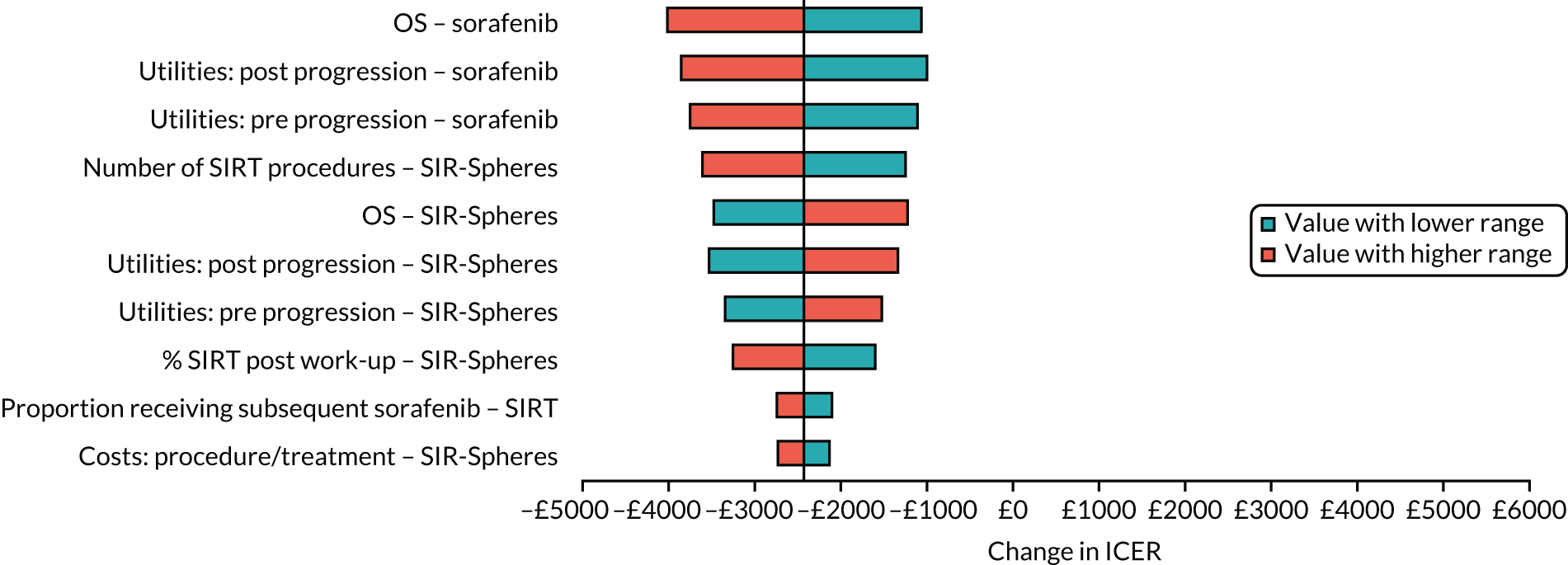

Efficacy and safety of QuiremSpheres