Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/26/05. The contractual start date was in January 2014. The draft report began editorial review in December 2019 and was accepted for publication in May 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Rodgers et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Rodgers et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Parts of this chapter have also been reproduced from Rodgers et al. 2 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

In 2011, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme commissioned a call for proposals3 to determine the clinical effectiveness of robot-assisted training for upper limb recovery following a stroke: are robot-assisted training devices clinically effective for upper limb disability in post-stroke patients?

-

Technology: robotics or ‘electromechanical devices’. Researchers should justify the choice of machine, using the patient group and setting to inform their decision.

-

Patient group: post-stroke adults with moderate/severe paretic upper limb impairment. Researchers to define and justify which time point in the patient pathway.

-

Setting: community or hospital based.

-

Control or comparator treatment: treatment as usual (researchers to justify choice of control).

-

Design: three-arm efficacy randomised controlled trial (RCT): (1) treatment as usual, (2) enhanced physiotherapy and (3) robotic device. Researchers should undertake simple modelling of costs (comprehensive cost-effectiveness evaluation is not required).

-

Important outcomes: hand function, arm function and costs (including societal).

-

Other outcomes: rate of recovery, adverse events (pain or musculoskeletal injury), activities of daily living (ADL) and quality of life.

-

Minimum duration of follow-up: 6 months.

This report describes the findings of the Robot-Assisted Training for the Upper Limb after Stroke (RATULS) trial, which was commissioned to undertake this work.

Problems after stroke

Stroke is the commonest cause of complex disability in the UK. 4 The potential consequences of stroke are broad and include problems with mobility, arm and hand function, speech, cognition, vision, swallowing, continence, mood, pain and fatigue. 5 There are 1.2 million stroke survivors in the UK and > 100,000 people have a stroke each year. 6 Almost two-thirds of stroke survivors leave hospital with a disability. 6

Upper limb problems after stroke

Upper limb problems frequently occur following stroke, comprising loss of movement, co-ordination, sensation and dexterity, which lead to difficulties with everyday activities. Approximately 80% of people with acute stroke have upper limb motor impairment, and, of those with limited arm function early after stroke, 50% still experience problems after 4 years. 7 The strongest predictor of recovery is severity of initial neurological deficit; patients with severe initial upper limb impairment are unlikely to fully recover their arm function, with a clear impact on their quality of life. 8 Patients report that loss of arm function is one of the most distressing long-term consequences of stroke. Improving upper limb function has been identified as a research priority by stroke survivors, carers and clinicians. 9

Repetitive functional task practice to improve upper limb recovery

At the time of designing the RATULS trial, a systematic review7 reported that treatments that focused on increased intensity and repetitive task-specific practice showed promise for improving motor recovery. Since then, the body of evidence has increased, with a 2014 Cochrane overview of systematic reviews10 reporting moderate-quality Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation evidence showing that arm function following a stroke can be improved by the provision of at least 20 extra hours of repetitive task training. In addition, a 2016 Cochrane review11 found that repetitive functional task practice for stroke patients was associated with improved arm function [standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.25, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.01 to 0.49], hand function (SMD 0.25, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.51) and ADL (SMD 0.28, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.45).

Robot-assisted training for upper limb recovery

First proposed in the late 1980s, robot-assisted training enables stroke patients with moderate or severe upper limb impairment to perform repetitive tasks in a highly consistent manner, tailored to their motor abilities. At the time of designing the RATULS trial, the most recent (2008) Cochrane review12 of electromechanical and robot-assisted arm training after stroke reported outcomes from 328 patients who participated in 11 trials. The largest study had 55 participants13 and four of the 11 studies evaluated the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)-Manus robotic gym system (InMotion commercial version, Interactive Motion Technologies, Inc., Watertown, MA, USA). 13–16 The systematic review12 reported improvements with electromechanical and robot-assisted arm training in terms of arm motor function (SMD 0.68, 95% CI 0.24 to 1.11) and motor strength (SMD 1.03, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.78), but no improvement in ADL (SMD 0.29, 95% CI –0.47 to 1.06).

In 2010, the Veterans Affairs (VA) RCT was published evaluating the MIT-Manus in four centres in the USA. 17 This trial was the largest trial of robot-assisted training at the time, recruiting 127 patients with moderate or severe upper limb impairment who were ≥ 6 months after stroke. Participants were randomised to receive robot-assisted training, intensive comparison therapy or usual care. Robot-assisted training and intensive comparison therapy both consisted of 36 sessions, each lasting 1 hour, over 12 weeks. The trial found that robot-assisted training did not improve upper limb motor function at 12 weeks compared with intensive therapy or usual care (the primary outcome). However, participants who received robot-assisted training had significantly better results at 12 weeks on the Stroke Impact Scale (SIS) than those who received usual care. In secondary analyses, improvements were seen in motor function for those who received robot-assisted training compared with those who received usual care, but not compared with those who received intensive comparison therapy, at 36 weeks. The added costs of delivering robot-assisted training or intensive comparison therapy were compensated for by the fact that the health-care costs were lower than for usual care. 18

The Robot-Assisted Training for the Upper Limb after Stroke trial

The RATULS trial evaluated robot-assisted training using the MIT-Manus robotic gym system. This was compared with an upper limb therapy programme [named the enhanced upper limb therapy (EULT) programme] of the same frequency and duration, and with usual post-stroke care. Robot-assisted training and the EULT programme involved repetitive task practice and were provided in addition to usual care.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Rodgers et al. 2 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Trial aim and objectives

Aim

The aim was to determine whether or not robot-assisted training with the MIT-Manus robotic gym system improved upper limb function post stroke.

Objectives

-

To determine whether or not robot-assisted training improved upper limb function post stroke, compared with an EULT programme or usual care.

-

To determine whether or not robot-assisted training improved upper limb impairment, ADL and quality of life, compared with an EULT programme or usual care.

-

To model the costs of robot-assisted training, compared with an EULT programme or usual care.

-

To seek the views and experiences of patients and health service professionals about the upper limb rehabilitation that they received or provided, and about factors affecting the implementation of the trial.

-

To explore:

-

the time pattern of upper limb recovery of participants in each treatment group

-

the impact of the severity of baseline upper limb function and time since stroke on the effectiveness of the interventions.

-

Trial design

The RATULS trial was a three-group, pragmatic, observer-blind, multicentre RCT with an embedded economic analysis and a process evaluation. Participants were randomised to receive one of the following: robot-assisted training (in addition to usual NHS care), an EULT programme (in addition to usual NHS care) or usual NHS care in accordance with local clinical practice.

Trial setting

The trial was conducted in four NHS centres in the UK. Each centre comprised a hub site, which was a stroke service in an NHS hospital (Queen’s Hospital, Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Hospitals NHS Trust; Northwick Park Hospital, London North West University Healthcare NHS Trust; Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde; and North Tyneside General Hospital, Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust) with a MIT-Manus robotic gym system, plus several spoke sites (a total of 18), which were stroke services in adjacent NHS trusts and community services.

Participants who were randomised to receive robot-assisted training or EULT travelled to a hub stroke unit to receive these interventions. Participants who were randomised to usual care were treated by their local stroke service.

Trial participants

Adults with a first-ever stroke who fulfilled the following criteria were eligible to participate in the RATULS trial.

Inclusion criteria

-

Age ≥ 18 years.

-

Clinical diagnosis of stroke (cerebral infarction, primary intracerebral haemorrhage, subarachnoid haemorrhage).

-

Between 1 week and 5 years since stroke.

-

Moderate or severe upper limb functional limitation [i.e. Action Research Arm Test (ARAT) score of 0–39]19 due to stroke.

-

Able to provide consent to take part in the trial and to comply with the requirements of the protocol.

Exclusion criteria

-

More than one stroke (patients who had had a previous transient ischaemic attack could be invited to participate).

-

Other current significant impairment of the upper limb affected by stroke (e.g. fixed contracture, frozen shoulder, severe arthritis, recent fracture).

-

Diagnosis likely to interfere with rehabilitation or outcome assessments (e.g. registered blind).

-

Previous use of the MIT-Manus robotic gym system or other arm rehabilitation robot.

-

Current participation in a rehabilitation trial evaluating upper limb rehabilitation after stroke.

-

Previous enrolment in the RATULS trial.

Case ascertainment, recruitment and consent

Participants were recruited from both incident and prevalent stroke populations. Participants were sought from a number of settings in primary and secondary care, including stroke units, outpatient clinics, day hospitals, community rehabilitation services and general practices. The trial aimed to recruit similar numbers of participants within 3 months of stroke, > 3–12 months after stroke and > 12 months to 5 years after stroke.

Potential participants from secondary care

In secondary care, potential participants were identified by local clinicians and/or staff from the NIHR Local Clinical Research Network (LCRN). Staff approached potentially eligible patients, discussed the trial and provided a trial information leaflet. After allowing sufficient time for the information to be considered, staff asked the patient if they were potentially interested in taking part in the trial.

Potential participants were also identified from hospital stroke discharge summaries/clinic letters. If this method was used, potential participants were approached by letter. A short RATULS trial leaflet, a patient information sheet, a RATULS trial reply slip and a pre-paid envelope were enclosed with the letter. Interested patients could make contact by telephone or by return of the RATULS trial reply slip. Following a few short questions to confirm potential eligibility, a face-to-face appointment for further discussion was arranged, if appropriate.

Potential participants from primary care

To identify potential participants from primary care, general practices performed a database search using the trial inclusion/exclusion criteria. A general practitioner (GP) screened the list of potentially eligible participants to approve the issue of an invitation letter. This letter was accompanied by the same information that was sent to individuals identified from secondary care records. The invitation letter detailed the main trial eligibility criteria and asked interested patients to contact their trial centre for further information. Following a few short telephone questions to confirm potential eligibility, a face-to-face appointment for further discussion was arranged, if appropriate.

Potential participants from other sources

Local community stroke clubs and day centres were also given information about the trial. In addition, some individuals heard about the trial from press releases or saw information about the trial on a poster or a RATULS trial leaflet. Interested individuals were able to contact the trial centres directly for further information about the trial.

Consent

Individuals who were interested and potentially eligible to take part in the trial were given an appointment for further discussion and consent. This was conducted by a local trial co-ordinator or NIHR LCRN staff. Written informed consent was obtained if a patient wished to take part in the RATULS trial.

Screening assessment

Once informed consent was obtained, a screening assessment was performed by the local trial centre co-ordinator or NIHR LCRN staff. The following data were collected: demography, stroke details, comorbidity and upper limb function (ARAT score19,20). If a patient fulfilled the trial inclusion and exclusion criteria, the local trial co-ordinator/NIHR LCRN staff proceeded with the baseline assessment. If it was not possible to complete the baseline assessment on the same day as the screening assessment, eligibility for the trial was reconfirmed on the day of the baseline assessment.

Baseline assessment

The following baseline data were collected: stroke severity (measured using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale21), cognitive function (measured using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment22), language skills (measured using the Sheffield Screening Test for Acquired Language Disorders23), upper limb impairment [measured using the Fugl-Meyer Assessment (FMA)20,24 (motor and sensory arm sections)], ADL (measured using the Barthel ADL Index25), quality of life [measured using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)26], upper limb pain (measured using a numeric rating scale27) and current upper limb rehabilitation treatments.

In addition, patients were given a self-completion questionnaire containing pre-trial resource use questions [an adaption of the Client Services Receipt Inventory (CSRI)28–30].

Randomisation

Randomisation was conducted by the local trial co-ordinator/NIHR LCRN staff following completion of the baseline assessment. A central independent web-based service, hosted by Newcastle University Clinical Trials Unit, was used. Participants were stratified according to trial centre, time since stroke (< 3 months, 3–12 months, > 12 months) and severity of upper limb functional limitation (ARAT score categories:19 0–7, 8–13, 14–19 and 20–39), and randomised, using permuted block sequences, 1 : 1 : 1 to receive robot-assisted training, EULT or usual care. The sequences were prepared by an independent statistician prior to the start of enrolment.

Randomisation groups

Robot-assisted training using the MIT-Manus robotic gym system

This was delivered using the MIT-Manus robotic gym, which was specifically designed for clinical rehabilitation applications. 31–33

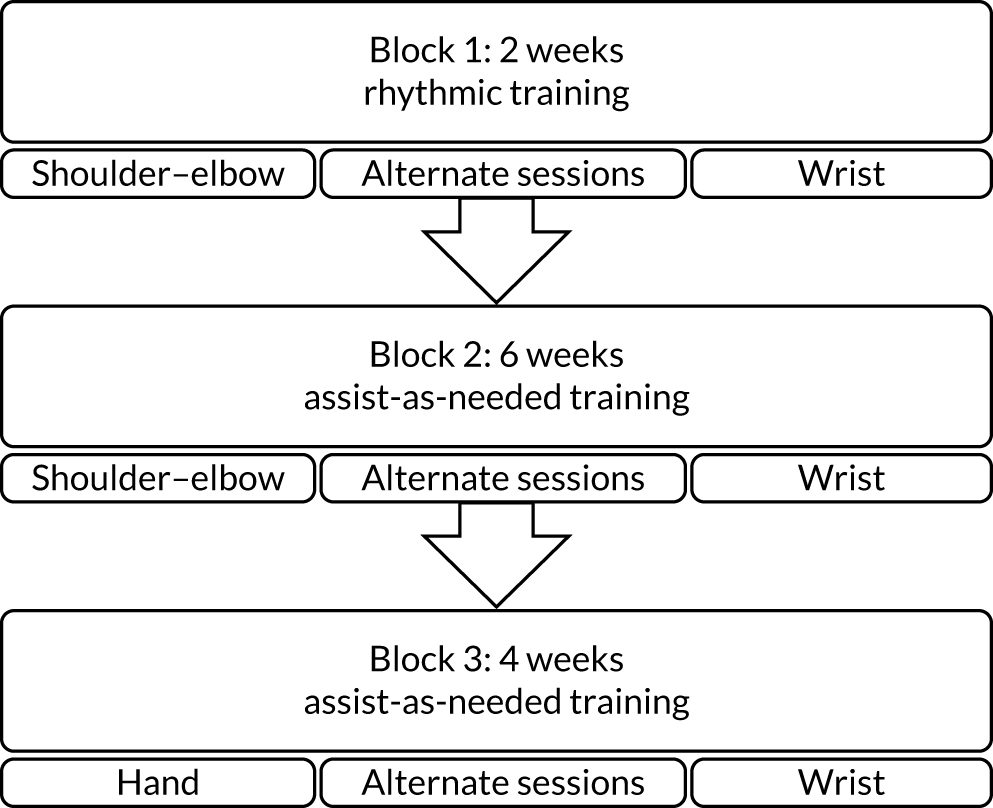

The robot-assisted training programme consisted of 45 minutes of face-to-face therapy during a 1-hour session, 3 days per week for 12 weeks, in addition to usual care. A detailed description of the robot-assisted training programme is provided in Chapter 4, and a completed Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist34 is provided in Appendix 1, Table 27. The MIT-Manus robotic gym recorded data on the robot-assisted training sessions content.

The enhanced upper limb therapy programme

The EULT programme aimed to match the frequency and duration of the robot-assisted training programme sessions. It was developed from the upper limb therapy programmes used in the NIHR HTA Botulinum Toxin for the Upper Limb after Stroke (BoTULS) trial35–37 and the Repetitive Arm Functional Tasks after Stroke (RAFTAS) project. 38 Using the principles of person-centred goal-setting and repetitive functional task practice, the EULT programme aimed to drive neuroplasticity and motor recovery after stroke.

The EULT programme consisted of 45 minutes of face-to-face therapy during a 1-hour session, 3 days per week for 12 weeks, in addition to usual care. A detailed description of the EULT programme is provided in Chapter 5, and a completed TIDieR checklist34 is provided in Appendix 1, Table 27. Therapists recorded data on the content of EULT sessions.

Usual care

Defining usual care is a challenge for any stroke rehabilitation trial. One of the current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) quality standards is that:

Patients with stroke should be offered a minimum of 45 minutes of each appropriate therapy that is required, for a minimum of five days a week, at a level that enables the patient to meet their rehabilitation goals for as long as they are continuing to benefit from therapy and as long as they are able to tolerate it.

NICE39

For most stroke services, this is aspirational, and the majority of patients do not receive this intensity, particularly after discharge from hospital or early supported discharge services. 40 Patients with chronic stroke are unlikely to receive ongoing rehabilitation in the longer term. Most services do not regularly review patients to address unmet rehabilitation needs beyond 1 year.

Participants in all three randomisation groups received a trial ‘arm rehabilitation therapy log’ in which they were asked to record any ‘usual’ upper limb rehabilitation that they received during the course of the trial. Periodic text messages were sent to remind participants about completion of the rehabilitation logs. In addition, participants in all three randomisation groups received regular trial newsletters, which included requests to complete the rehabilitation logs.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was upper limb functional recovery ‘success’ (assessed using ARAT)19 at 3 months post randomisation (at the end of intervention period). The ARAT assesses upper limb function by scoring the ability to complete a range of functional tasks. The scale is made up of 19 items in four subscales (grasp, grip, pinch and gross movement), which are rated on a four-point ordinal scale ranging from zero (can perform no part of the test) to three (performs test normally). 19

The definition of upper limb functional recovery ‘success’ differed depending on baseline severity:

-

ARAT baseline score of 0–7; ‘success’ is an improvement of ≥ 3 points

-

ARAT baseline score of 8–13; ‘success’ is an improvement of ≥ 4 points

-

ARAT baseline score of 14–19; ‘success’ is an improvement of ≥ 5 points

-

ARAT baseline score of 20–39; ‘success’ is an improvement of ≥ 6 points.

A stepped approach was used because, although the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for the ARAT is 10% of its range (6 points41), a smaller treatment effect may be clinically beneficial in those with severe initial upper limb functional limitation, who are likely to improve less than those with more moderate limitation.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes at 3 and 6 months were upper limb function (measured using the ARAT19) ‘success’ (at 6 months); total ARAT score; upper limb impairment (measured using the FMA24); ADL (measured using the Barthel ADL Index25); quality of life (measured using the SIS42 version 3.0); upper limb pain (measured using a numeric rating scale27); resource use costs (an adaptation of the CSRI28,43); and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), derived from the EQ-5D-5L. 26

Upper limb functional recovery ‘success’ at 6 months

The same success criteria based on the baseline ARAT19 score used at 3 months were used to define upper limb functional recovery ‘success’ at 6 months.

Total Action Research Arm Test score

A secondary analysis of ARAT used the numeric score, which ranges from 0 to 57. 19 A higher score indicates better upper limb function.

Action Research Arm Test subscales

The original plan was to analyse the subscales as numeric scores, and to compare means, but after database lock for the final data set, it was realised that the data distribution for subscales was U-shaped and almost binary, as participants mostly scored zero or full marks on each subscale. The clinical team felt that a better approach was to create a binary variable for each ARAT subscale. For this, if a participant scored 2 (‘completed test, but takes abnormally long time, or has great difficulty’) or 3 (‘performs test normally’) for any of the items in that subscale, that participant was classified as ‘could complete at least one task’ for that subscale. Conversely, if a participant scored 0 (‘can perform no part of the test’) or 1 (‘performs test partially’) for all parts of the subscale, that participant was classified as ‘could not complete one task’ for that subscale. The rationale was that a comparison should be made between participants who could complete a task fully and those who could not.

The Fugl-Meyer Assessment total upper-extremity score

The FMA total upper-extremity score (score 0–126) assesses upper limb impairment by incorporating the motor, sensory, range of motion and joint pain subscales. 24 Each item is scored on a 3-point ordinal scale (0–2 points per item):

-

Motor function. This has 24 items, which include scoring of the active movement of the shoulder, elbow, forearm, wrist and hand, and co-ordination and speed. The score for this subscale ranges from 0 to 66.

-

Sensation. This has six items and the score for this subscale ranges from 0 to 12.

-

Range of motion and joint pain. This has 12 items, which are scored for each range of motion and joint pain. The score for this subscale ranges from 0 to 48.

A higher FMA total upper-extremity score indicates less upper limb impairment.

Barthel Activities of Daily Living Index

The Barthel ADL Index consists of 10 items (bowels, bladder, grooming, toilet use, feeding, transfer, mobility, dressing, stairs and bathing), and is calculated by summing up the individual items and ranges from 0 to 20. 25 A higher score indicates a better ability to complete ADL independently.

The Stroke Impact Scale

The SIS is a self-completion stroke-specific questionnaire to measure quality of life. 42 There are 59 items investigating nine dimensions (strength, hand function, mobility, ADL, emotion, memory, communication, social participation and stroke recovery). Each item was scored on a 5-point scale (1–5). The dimension and domain scores range from 0 to 100. A higher score implies a better quality of life.

Upper limb pain

Upper limb pain was measured using a numeric rating scale on which participants were asked to rate their upper limb pain, with zero being no pain at all and 10 being ‘as painful as it could have been’. 27

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version, quality-adjusted life-years and resource use

Participant responses to the EQ-5D-5L44 questionnaire, completed at baseline and at 3 and 6 months, were used to derive QALYs. Utility values were estimated from the responses using health state utility scores based on the UK population tariff,45,46 and mapped back to the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version, valuation set. 47 Costs incurred by the NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) were collected via the adapted CSRI28–30 resource use questionnaires completed at baseline and at 6 months.

Undertaking outcome assessments

Outcomes were assessed at 3 months (± 7 days) and 6 months (± 7 days) following randomisation, and were undertaken in two stages.

Stage 1 was a self-completion postal questionnaire consisting of the SIS42 (at 3 and 6 months) and the adapted CSRI28–30 resource use questions (at 6 months only).

Stage 2 was a face-to-face assessment with a researcher who was masked to the randomisation group. The following data were collected: ARAT,19 FMA24 (total upper-extremity score), Barthel ADL Index,25 EQ-5D-5L,26 upper limb pain27 and adverse events. At the end of the 6-month stage 2 assessment, participants were given a further self-completion questionnaire and were asked to return this by post. This questionnaire contained time and travel resource use questions. 48,49

Staff training

All staff received trial-specific training at the start of their involvement, with refresher training provided throughout the trial. Staff performing trial assessments (screening, baseline, outcomes) and delivering trial interventions received training in these aspects. In addition, manuals describing delivery of the interventions and instructions on how to perform the assessments were provided. Video demonstrations of the ARAT and FMA were also prepared and made available for ongoing reference.

Masking

Owing to the nature of the interventions, it was not possible to mask participants or treating therapists to treatment allocation. It was intended that stage 2 outcome assessments would be conducted by a researcher masked to treatment allocation. At each outcome assessment, the researcher was asked to record whether or not they had unintentionally become aware of treatment allocation in conversation with a participant.

Trial withdrawal

No specific withdrawal criteria were preset. Participants could withdraw from the trial at any time and for any reason. A reason for withdrawal was sought, but participants could withdraw without providing an explanation.

Investigators, GPs, stroke physicians and therapists could also withdraw participants from the trial at any time if they felt that it was no longer in their interest to continue, for example because of intercurrent illness or adverse events. Participants were informed that data collected prior to withdrawal would be used in the trial analysis, unless consent for this was specifically withdrawn. Participants who wished to receive no further intervention were not withdrawn from trial follow-up unless they specifically requested this.

Safety evaluation

The safety of robot-assisted training, EULT and usual care was evaluated by examining the occurrence of all adverse events and serious adverse events (SAEs) in accordance with the National Research Ethics Service guidance for non-Clinical Trials of an Investigational Medicinal Product. 50

All adverse events were captured by including the following question in the outcome pro formas: ‘are there any new medical problems since the last study assessment?’.

Events considered to be SAEs were subsequently documented on a separate trial SAE form, and a causality and expectedness assessment was performed. As trial investigators or other members of the research team could become aware of SAEs at times other than at outcome assessment appointments, the SAE form was also used to directly capture these events.

The standard definition for a SAE was used. 51 A SAE is an untoward occurrence that:

-

results in death

-

is life-threatening

-

necessitates hospitalisation, or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

consists of a congenital anomaly or birth defect

-

is otherwise considered medically significant by the investigator.

Data management

Trial data were collected on trial-specific paper case record forms, and subsequently entered onto an online database by trial administrators at participating centres.

Sample size

The target sample size was 762 participants (254 participants per group). Responses from 216 participants in each randomisation group would provide 80% power (significance level of 1.7% because of multiple comparisons) to detect a 15% difference in upper limb function ‘success’ between each of the three pairs of treatments (robot-assisted training, EULT and usual care). The target was inflated for 15% attrition, subsequent to protocol publication. The baseline estimate of success was estimated as 30% from the BoTULS trial,35,36 and a difference of between 45% and 30% corresponds to an odds ratio of 1.9.

Statistical analysis of primary and secondary outcome data

Analysis populations

All analyses were done in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population of all participants, in the group to which they were assigned, who did not have missing data after simple imputation.

A secondary analysis comparing the primary outcome robot-assisted training and EULT was carried out on a per-protocol (PP) analysis set, which removed participants who did not receive at least 20 sessions of therapy. This was based on evidence that 20 hours of repetitive task training improves upper limb function. 10 No definition of PP could be made for the usual care group, so no comparisons were undertaken for this group.

The main analysis of the primary outcome was on all participants; however, we performed two sensitivity analyses. The first was based on participants who completed their assessment visits within 3 months ± 14 days and 6 months ± 28 days. We have taken 3 months to be 91 days, and 6 months to be 183 days, post randomisation date. The second sensitivity analysis excluded participants from the analysis if they had a zero ARAT score at baseline, as such patients have a poor prognosis for recovery of arm function. 52

Missing data in the measurement scales

The pattern and extent of missing observations in all scales was examined to investigate both the extent of missing data and whether it was missing at random or was informative. The number (percentage) of participants for whom a whole or partial measure was missing was reported by measure.

Apart from the SIS, for which we followed the specific scale developer’s rules,42 where no more than 20% of questions were missing or uninterpretable on specific scales, the score was calculated by using the median value of the respondent-specific completed responses on the rest of the scale to replace the missing items (i.e. simple imputation). 53

We planned that multiple imputation techniques would be considered if > 20% of participants had missing values for the primary outcome, but these techniques were not necessary.

Analysis of primary outcome

The primary outcome was ‘success’ at 3 months based on the ARAT score. 19

The primary outcome of ‘success’ at 3 months is reported descriptively by randomisation group and overall as a proportion.

Logistic regression was used to compare ‘success’ between the three randomisation groups at 3 months, adjusting for time since stroke, baseline upper limb function (ARAT score) and trial centre. A two-level logistic model (trial centre and participants) was used. We adjusted the coverage of the CIs to account for the three paired comparisons between the randomisation groups. Because the trial was powered on a significance level of 1.67%, we used 98.33% (100% – 1.67%) as the CI coverage. We considered the trial centre as a fixed effect. We explored the possibility that participants in a trial centre may be more alike in the treatment randomisation groups, owing to participants sharing therapists in the robot-assisted training and EULT groups, but not in the usual care group. This is called partial nesting, but accounting for this did not improve model fit; therefore, we did not include this in the models reported here. 54–56

Analysis of secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes included upper limb functional recovery ‘success’ at 6 months, the ARAT total score19 (numeric rather than ‘success’), ARAT subscales,19 upper limb impairment (FMA total upper-extremity score24), ADL (Barthel ADL Index25), quality of life (SIS42) and upper limb pain (numeric rating scale27) at 3 and 6 months.

The secondary outcome of ‘success’ at 6 months was analysed as described for the primary outcome, and similarly for the binary version of the ARAT subscales.

All numeric secondary outcomes are reported at baseline (if collected) and at 3 and 6 months descriptively by randomisation group as means and standard deviations (SDs). The secondary outcomes were analysed at 3 and 6 months using linear regression, adjusting for time since stroke, baseline score and trial centre. The baseline score used to adjust the analysis was the same scale; for example, the baseline ARAT score was used to adjust for baseline in the model for the ARAT. The SIS was not collected at baseline; therefore, no baseline score adjustment could be made. We adjusted the coverage of the CIs to account for the three paired comparisons between the randomisation groups. Because the trial was powered on a significance level of 1.67%, we have used 98.33% (100% – 1.67%) as the CI coverage. We presented bias-corrected and accelerated CIs (100,000 bootstrap intervals) because of the distribution of the data.

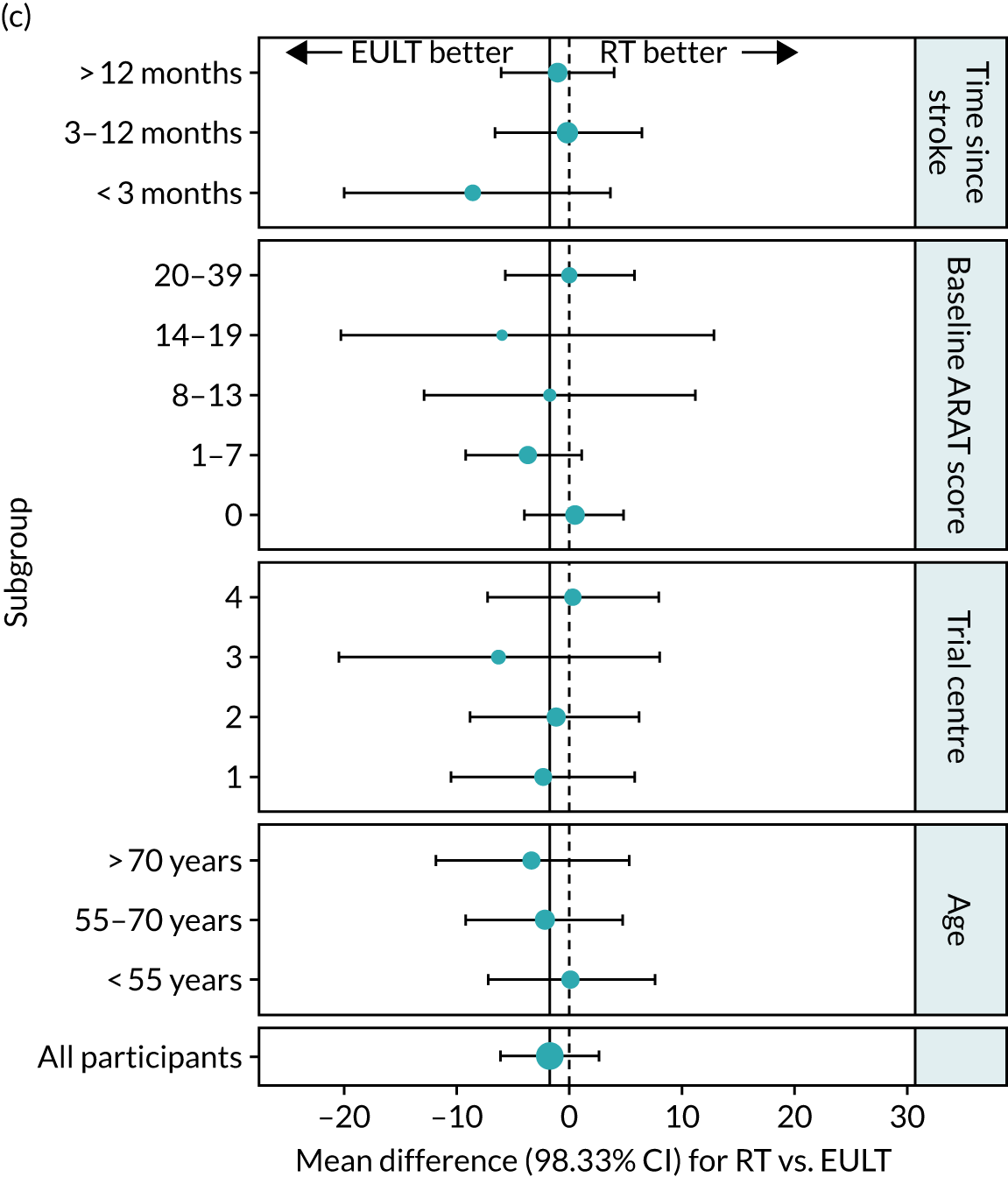

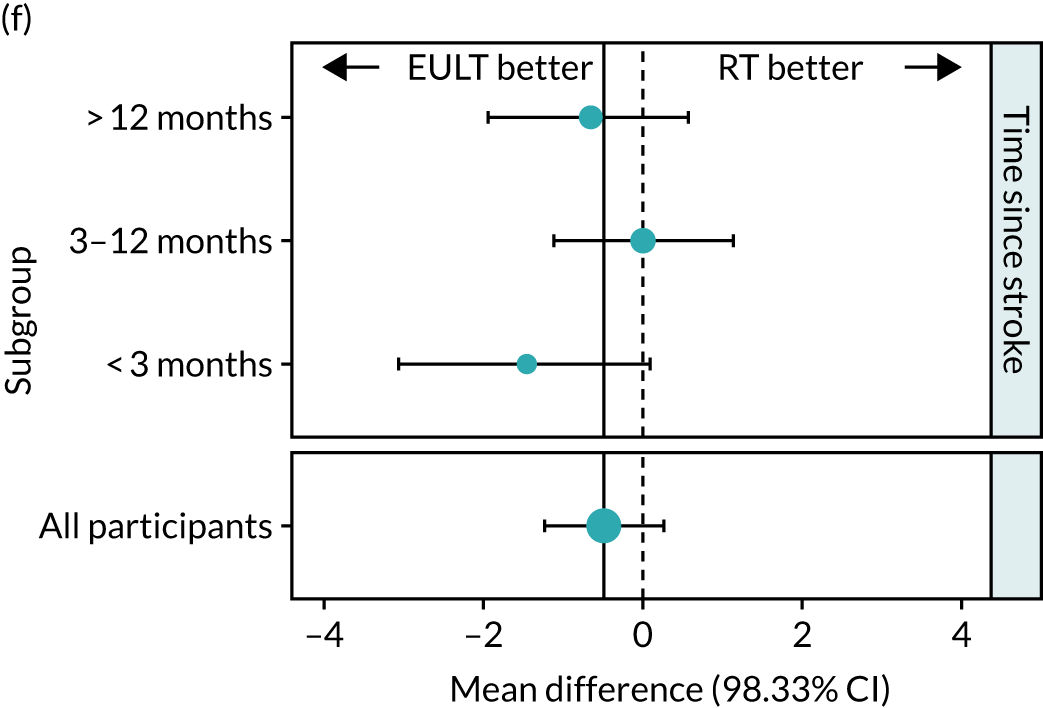

Exploratory subgroup analysis

The protocol included a subgroup analysis to consider the relationship between the severity of baseline upper limb functional limitation and time since stroke on the effectiveness of the interventions. The subgroup analyses examined trial centre and age, and are listed below. There was not sufficient power to perform any formal subgroup analyses, so all analyses must be considered exploratory.

We performed subgroup analysis for the numeric ARAT score at 3 months across the following subgroups:

-

time since stroke (< 3 months, 3–12 months, > 12 months)

-

baseline ARAT score (0, 1–7, 8–13, 14–19, 20–39, 40–57)

-

trial centre

-

age (< 55 years, 55–70 years, > 70 years).

When preparing the detailed statistical analysis plan, two further subgroup analyses were prespecified. These were for the FMA motor score and the Barthel ADL Index at 3 months, but only for the time since stroke categories. CIs were calculated using bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrap CIs (100,000 samples).

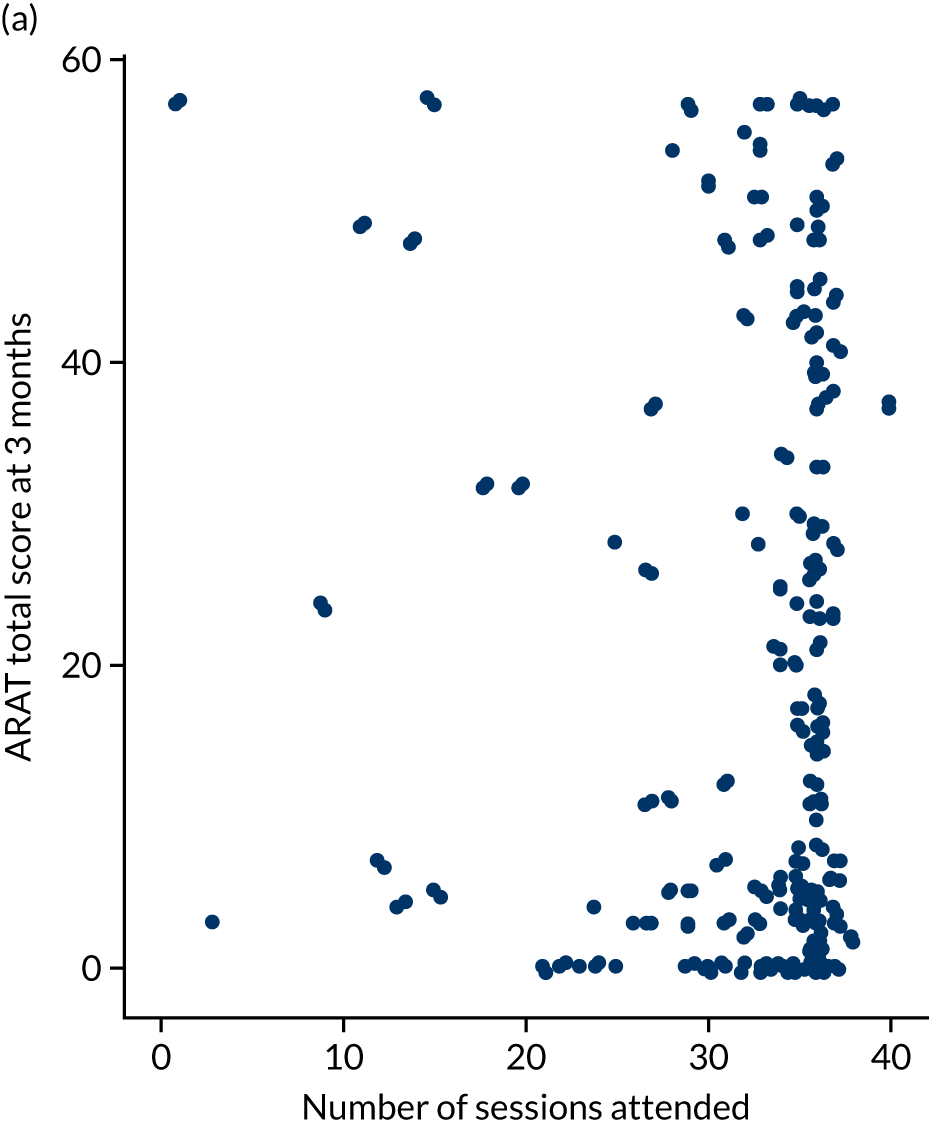

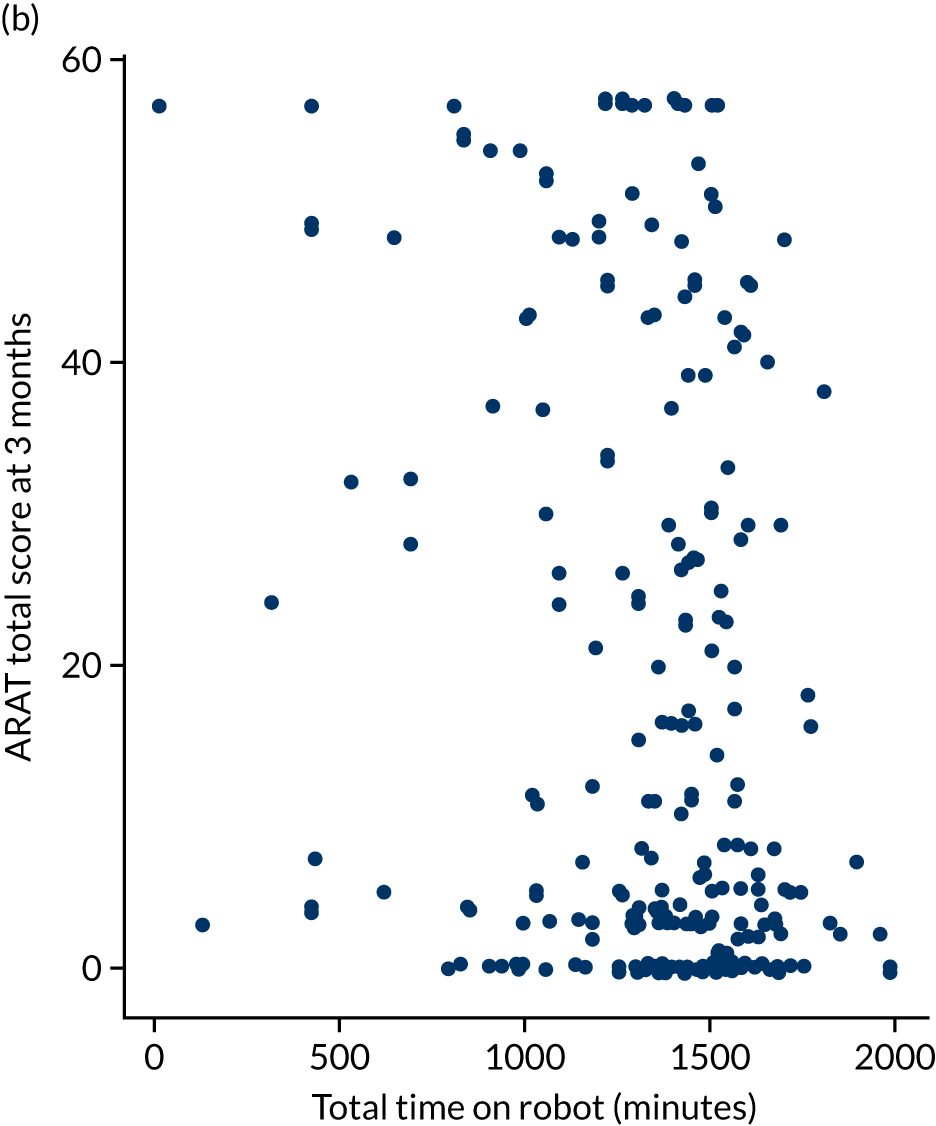

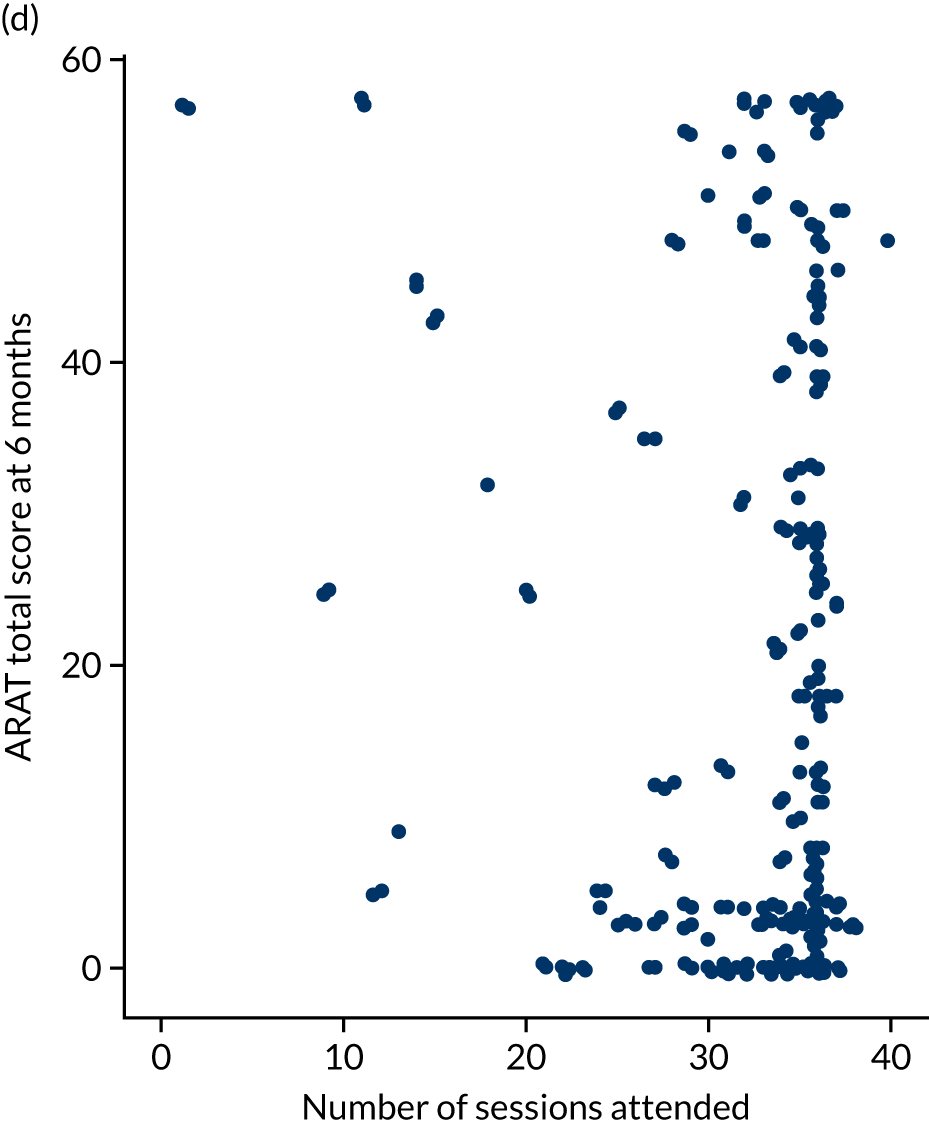

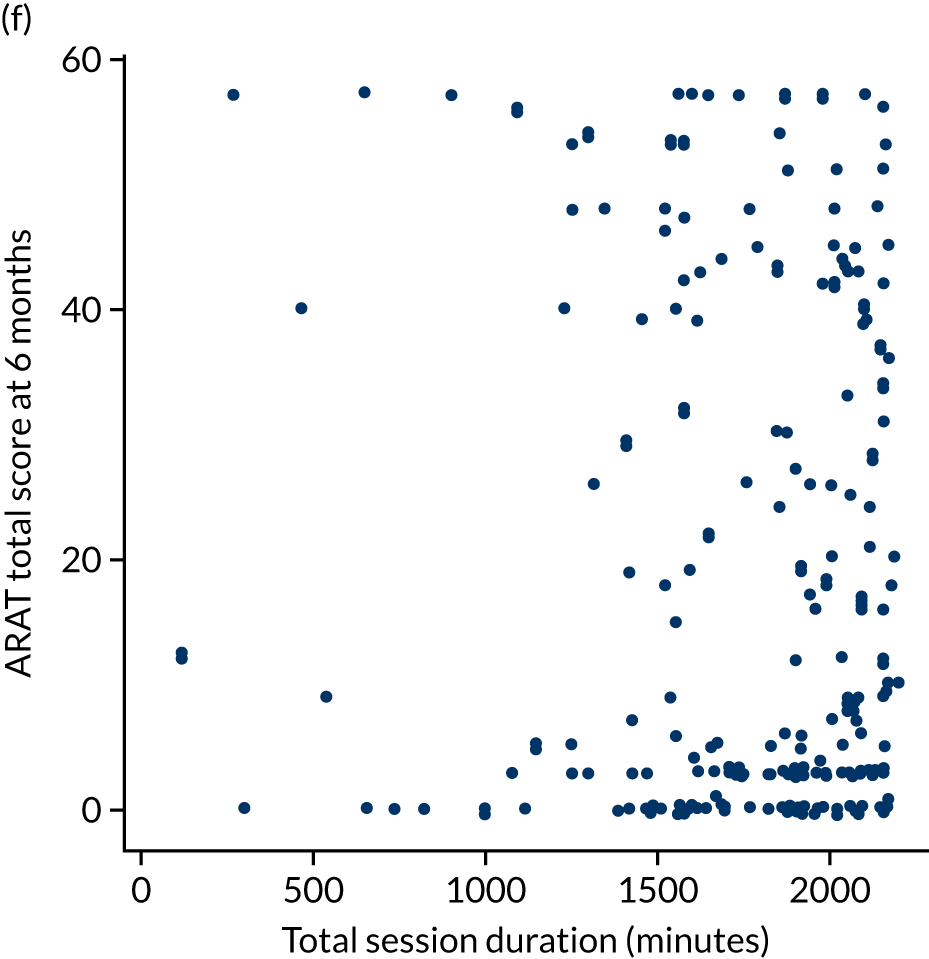

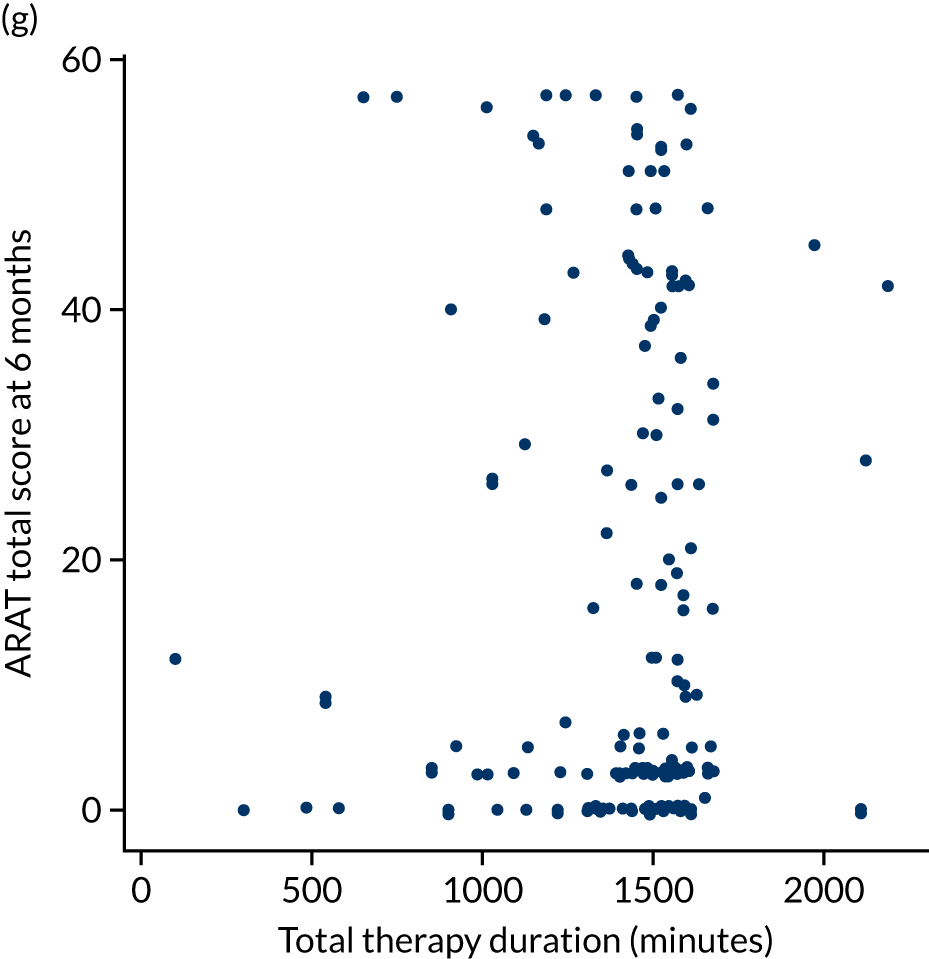

Descriptive analysis of the relationship between treatment received and total Action Research Arm Test score

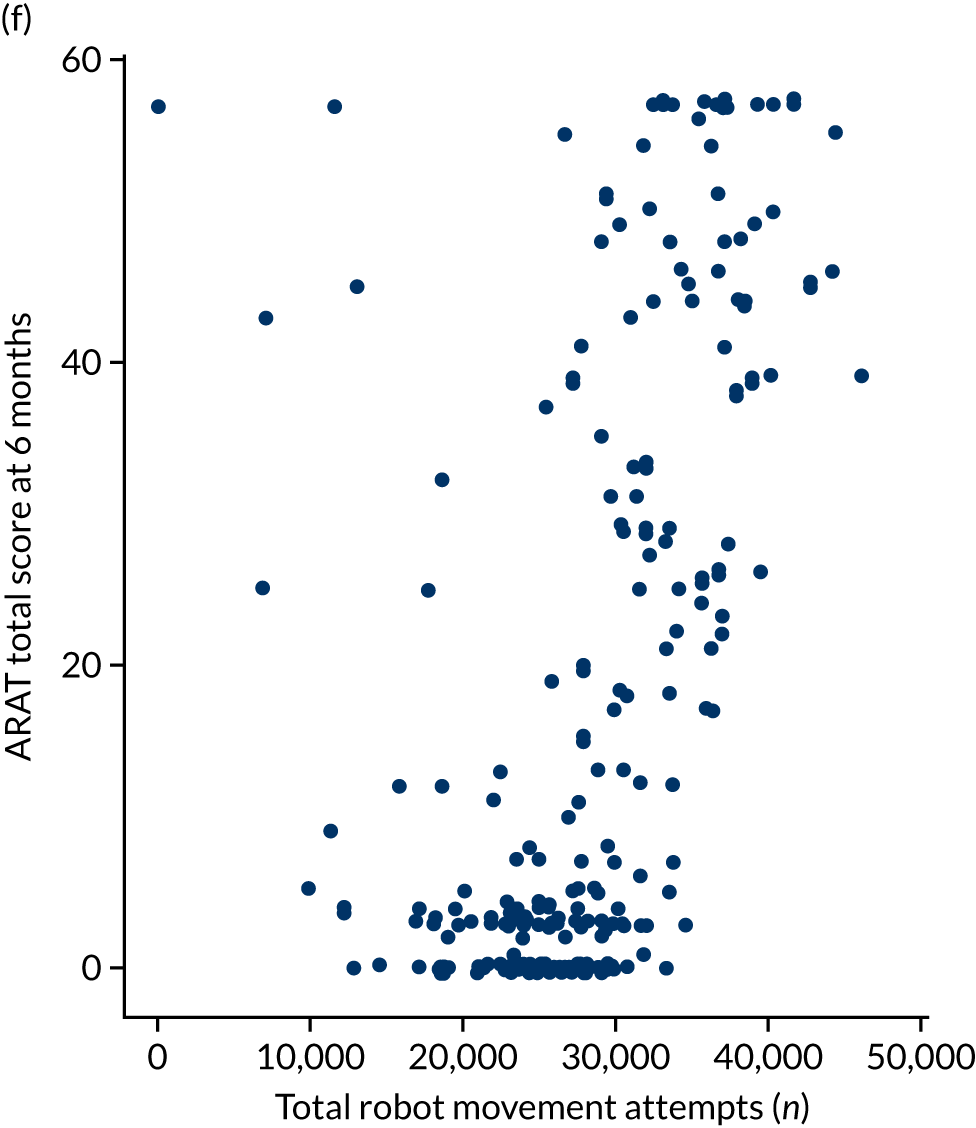

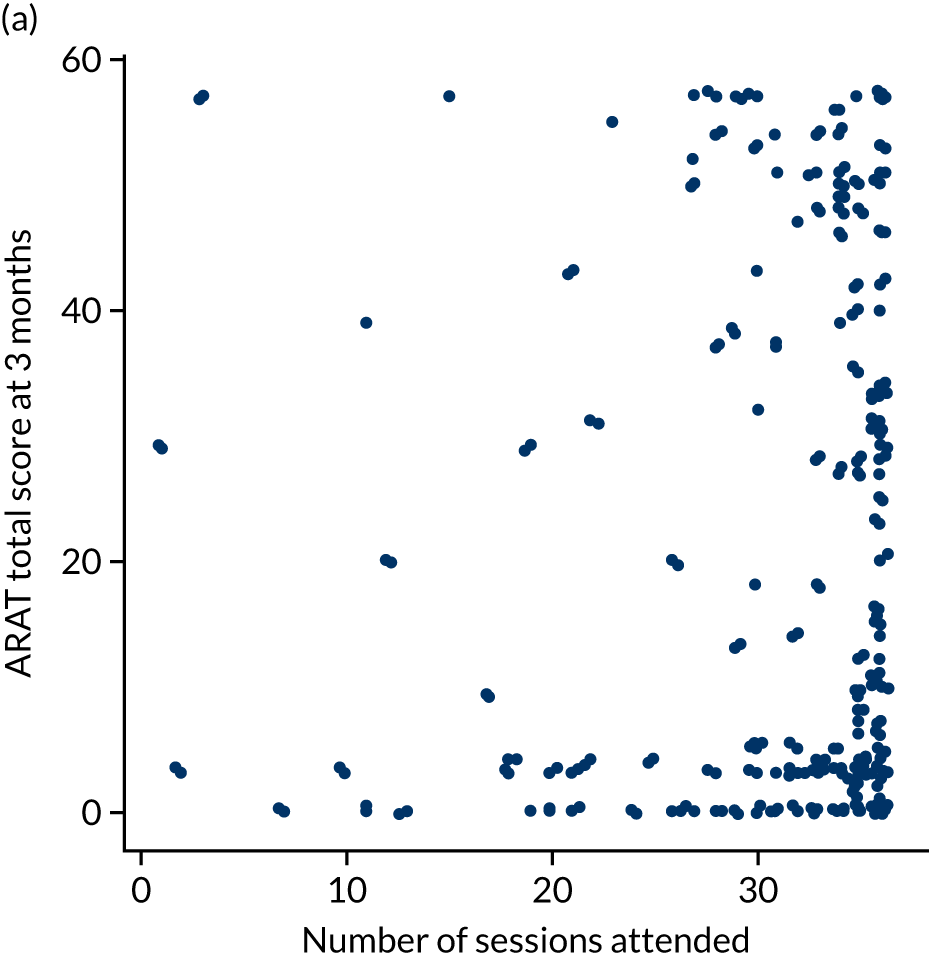

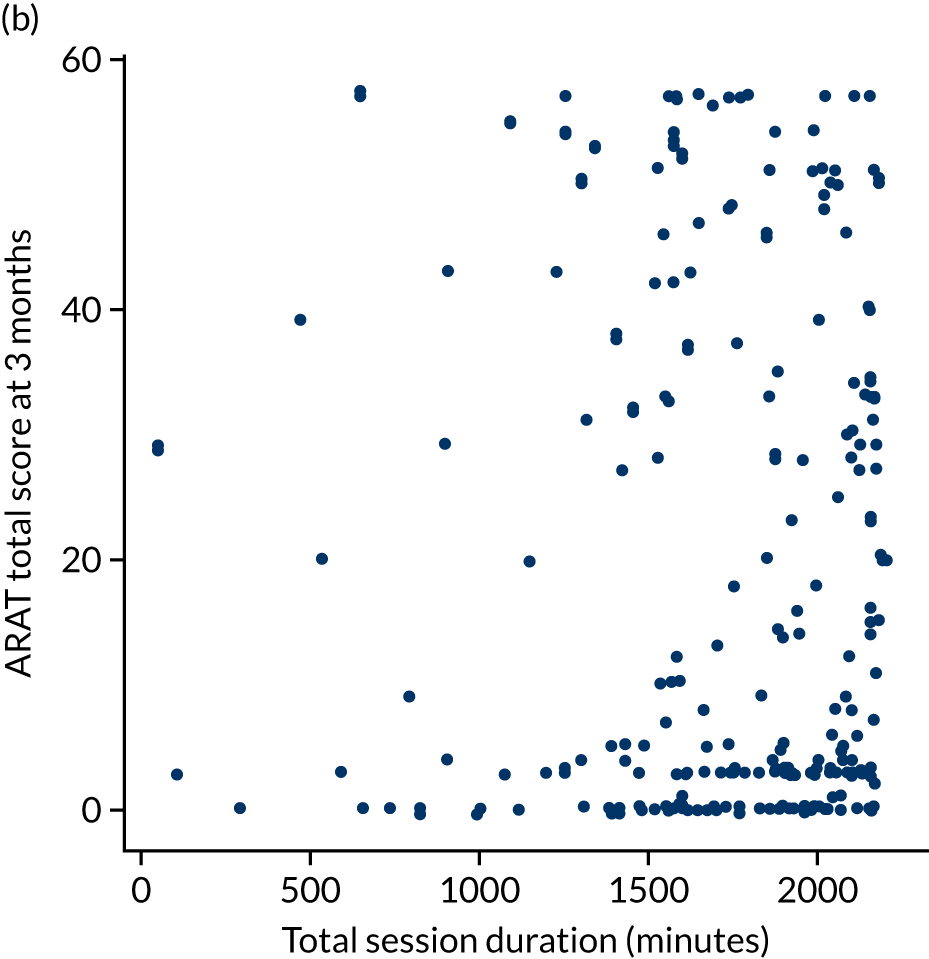

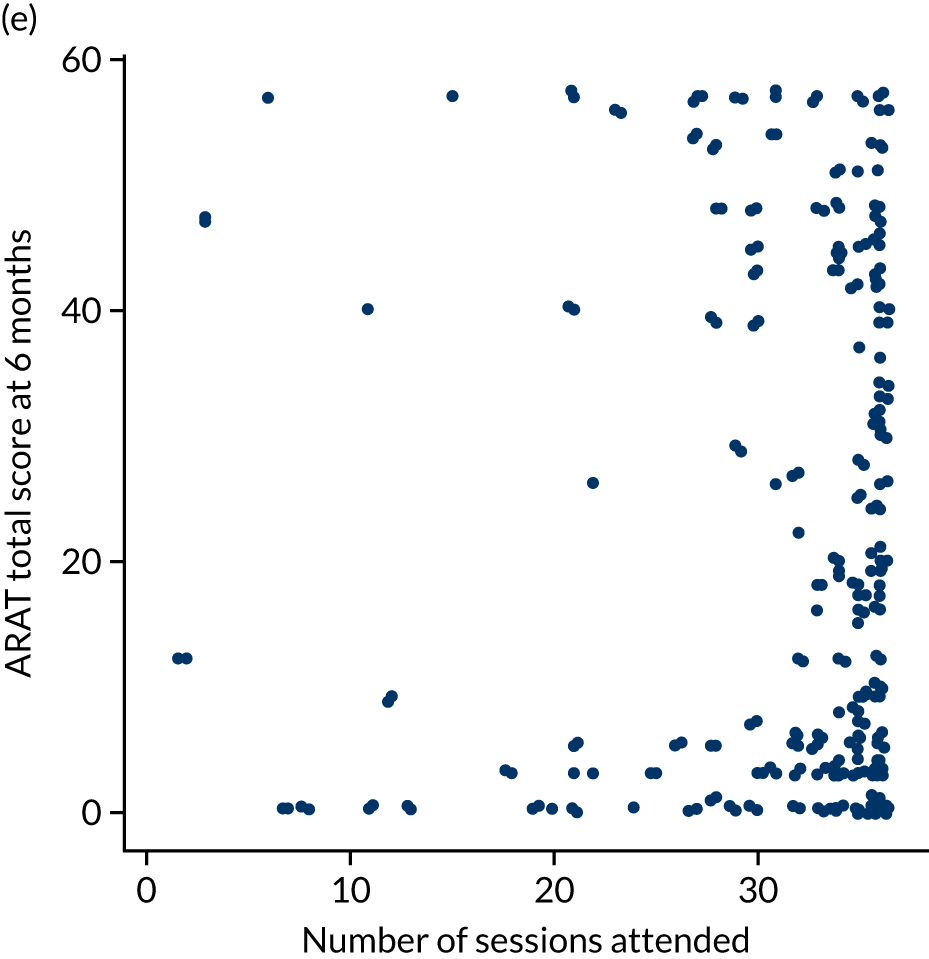

The total ARAT score at 3 and 6 months was plotted against the number of sessions attended, total duration of therapy received, total number of therapy repetitions (EULT group only) and total robot movement attempts (robot-assisted training group only) for the two intervention randomisation groups. Zero was assumed for duration, therapy task repetitions and movement attempts for participants who did not attend an appointment.

Safety

The proportion of participants with at least one SAE was reported by randomisation group and the difference in proportions (98.33% CI) was calculated. The median number of SAEs per participant was also calculated and the distribution of SAEs was compared across groups using the Mann–Whitney U-test. The above was also completed for adverse events at 3 and 6 months.

Economic analysis

The economic evaluation consisted of a microcosting analysis, a within-trial economic evaluation and a longer-term economic model. 57 Methods are described in Chapter 8.

Parallel process evaluation

A two-stage process evaluation was conducted to understand (1) participants’ and health service professionals’ experiences of robot-assisted training, EULT and usual care and (2) factors affecting the implementation of the trial within and across trial sites. Methods are described in Chapter 7.

Ethics and regulatory issues

The trial sponsor was Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. The trial was conducted in accordance with research governance framework for health and social care58 and good clinical practice. Ethics approval was granted by the National Research Ethics Committee Sunderland (reference number 13/NE/0274). Local NHS approvals were obtained from all participating NHS organisations. Monitoring of trial conduct and data collection was performed by regular visits to all participating trial centres. The trial was managed by a co-ordinating centre based at Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. An independent Data Monitoring Committee and Trial Steering Committee were in place for the duration of the project.

Amendments made to the trial after it commenced

-

Modification of the postal invitation procedure for potential participants by letter (from both primary and secondary care). When the trial commenced, potential participants who were invited by letter were asked to telephone their local trial team if they would like more information. The response rate to these invitations was low; it was suggested that this was because the letter and information sheet were too long, and that people may prefer to respond in writing initially. The letter was revised, a short summary leaflet designed and a postal reply slip created. These revised documents were then used for postal invitations. In addition, the option to re-contact potential participants who did not respond to the initial invitation letter was introduced. This was by follow-up letter or telephone call, according to local preference.

-

Introduction of reminders to complete the trial arm rehabilitation logs. To attempt to promote completion of the trial arm rehabilitation logs, regular reminders via text message were introduced.

-

Provision of trial newsletters. Regular newsletters were introduced for participants during their time in the trial. This was in response to noting that attrition was higher than anticipated, and aimed to encourage retention in the trial.

-

Modification of the parallel process evaluation. Several changes were made to the parallel process evaluation:

-

The initial protocol included interviewing a larger proportion of participants in the robot-assisted training group. However, the need for equal data collection in both the robot-assisted training and EULT groups became apparent, owing to their equivalent complexity. Therefore, the requirement to interview more robot-assisted training group participants was removed.

-

The participant interview time points for the second period of data collection (August 2016 to April 2017) were changed from twice during the first 3 months to once during the first 3 months and once at around 6 months. This change was informed by the analysis of data collected in the first period of data collection (February to June 2016). It allowed continued exploration of views and experiences of treatments, but also additional exploration of the impact of therapy following the end of treatment, plus participants’ experiences of trial participation (e.g. completing trial documentation and outcome assessments).

-

A review of the quantitative outcome assessment data (ARAT score at baseline and at 3 and 6 months) was added to the process evaluation for some participants. Comparison of quantitative data with participants’ subjective experiences captured in the interview data aimed to inform interpretation of the trial.

-

The range of health service professionals to be interviewed was broadened. Rather than interviewing only health service professionals who delivered therapy to RATULS trial participants (as per the original trial protocol), other staff who were involved in the trial were included in interviews. These included principal investigators, NIHR LCRN staff, local site trial co-ordinators and trial administrators. This allowed more information to be captured about factors affecting the implementation of the trial.

-

-

Revision of recruitment target. In the original trial protocol, the target sample size was 720 participants, which included 10% attrition for the primary outcome. As the trial proceeded, it became apparent that dropout was > 10%, and nearer to 15%. The target sample size was therefore increased to 762 participants, to allow for 15% attrition.

Chapter 3 Randomised controlled trial results

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Rodgers et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Participant recruitment and randomisation

Between 14 April 2014 and 30 April 2018, 770 participants were recruited from the four trial centres, and were randomised as follows: robot-assisted training, 257 participants; EULT, 259 participants; and usual care, 254 participants.

Original predicted, revised predicted and actual cumulative recruitment are shown in Figure 1. Recruitment predictions were revised in July 2016, when target recruitment was increased to 762 participants. Monthly recruitment by trial centre is tabulated in Appendix 2, Table 28.

FIGURE 1.

Predicted and actual cumulative recruitment. The initial recruitment target was 720 participants, to allow for 10% attrition, but the sample size was increased to 762 participants to allow for 15% attrition.

Participant retention and follow-up

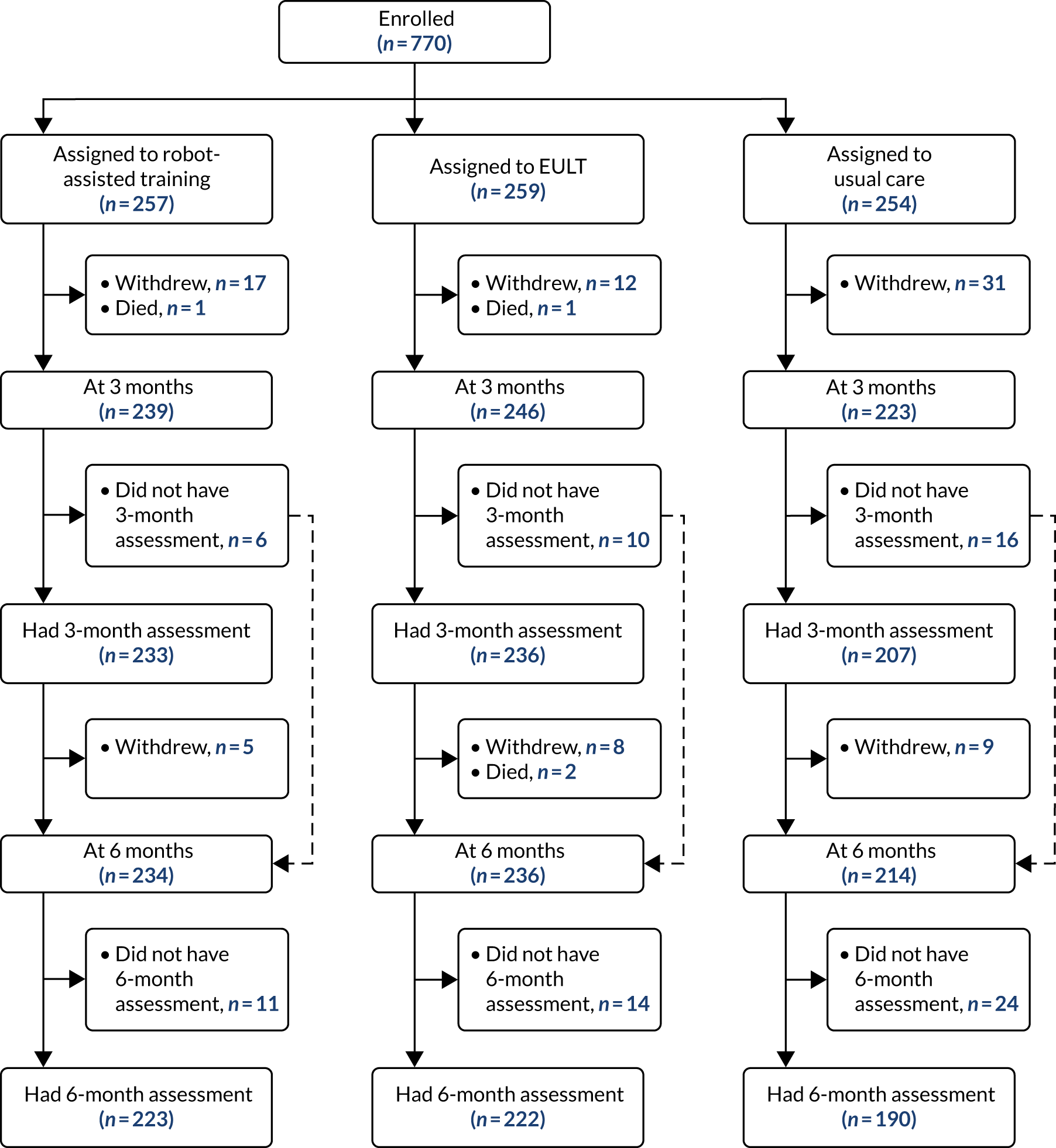

Participant flow through the trial is shown in a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT flow diagram.

Of the 257 participants randomised to robot-assisted training, 233 (91%) completed a 3-month assessment and 223 (87%) completed a 6-month assessment. Of the 259 participants randomised to EULT, 236 (91%) completed a 3-month assessment and 222 (86%) completed a 6-month assessment. Of the 254 participants randomised to usual care, 207 (81%) completed 3-month assessment and 190 (75%) completed a 6-month assessment. There was a lower follow-up rate in the usual care group and, therefore, differential attrition between randomisation groups. Seven participants did not complete the ARAT at their 3-month assessment, but remained in the trial.

The numbers of participants who did not have assessments, and the reasons why, are reported in Appendix 2, Table 29. There were 60 withdrawals by 3 months, and a further 22 withdrawals by 6 months. The main reasons given for withdrawal were not wanting to be randomised to usual care [19/60 (32%) by 3 months], the burden of participation [19/60 (32%) by 3 months and 4/22 (18%) by 6 months] and being unwell [10/60 (17%) by 3 months and 6/22 (27%) by 6 months]. There were two deaths before 3 months and a further two deaths before 6 months. Assessments were not conducted for a further 32 people at 3 months and 49 people at 6 months. The main reasons for this were non-response to attempts to arrange the assessment [14/32 (44%) at 3 months and 37/49 (76%) at 6 months], missing the assessment and non-response to attempts to re-arrange [6/32 (19%) at 3 months and 5/49 (10%) at 6 months], and being unwell and unable to complete the assessment [8/32 (25%) at 3 months and 4/49 (8%) at 6 months].

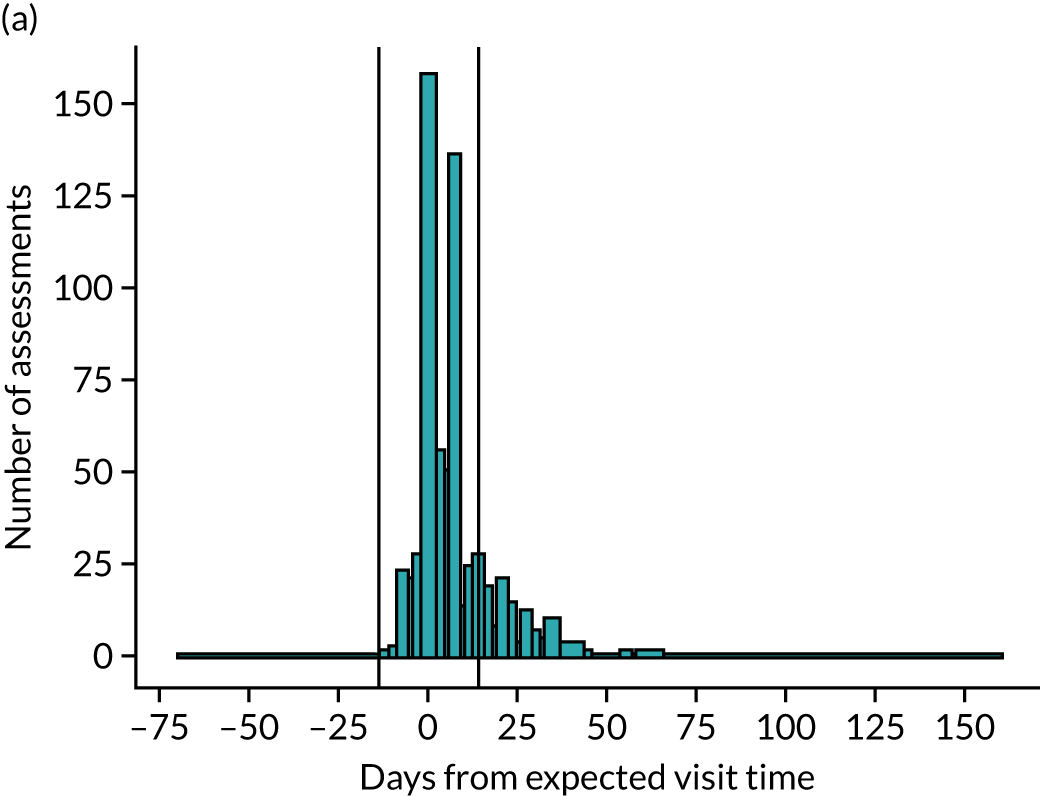

Timing of participant outcome assessments

Of the 676 assessments scheduled for 3 months, 545 (81%) were carried out at 3 months ± 14 days; the median time from randomisation was 96 days [interquartile range (IQR) 91–102 days]. Of the 635 assessments scheduled for 6 months, 575 (91%) were carried out at 6 months ± 28 days; the median time from randomisation was 187 days (IQR 182–193 days) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Compliance with time of assessments at (a) 3 months and (b) 6 months. The vertical lines indicate the allowable window of time within which the assessment could take place (± 14 days for 3 months and ± 28 days for 6 months).

Missing data in the measurement scales

There were very few data missing across the scales, and simple imputation did not add many participants to the analyses. For example, the ARAT total score was fully completed for 668 out of 708 (94%) of expected participants at 3 months; after simple imputation, only one more participant was included, as this participant was the only one with missing data who had < 20% of items missing. The number (percentage) of participants with no missing data on the measurement scales is reported by measure and time point in Appendix 2, Tables 30–32. These tables also show how many participants were included after simple imputation. As < 20% of participants were missing data on the primary outcome after simple imputation, multiple imputation techniques were not used.

Participant baseline characteristics

Baseline demographics and stroke characteristics are shown in Tables 1 and 2; they appear balanced across groups. The mean age of participants was 61 years (SD 13.5 years), and 468 out of 770 (60.8%) participants were men. Most participants had experienced a cerebral infarction [613/770 (79.6%)]. The median time from stroke to randomisation was 240 days (IQR 109–549 days), and participants had a mean ARAT score of 8.4 points (SD 11.8 points), a mean FMA motor score of 18.1 points (SD 13.7 points) and a mean Barthel ADL Index score of 14.4 points (SD 3.9 points). Typically, the ARAT score was low [median 3 points (IQR 0–11 points)] and the distribution was positively skewed. The upper limb rehabilitation treatments that were being received at baseline are given in Appendix 2, Table 33. A total of 409 out of 768 (53.3%) participants were receiving physiotherapy and/or occupational therapy at the time of randomisation.

| Characteristic | Robot-assisted training (N = 257) | EULT (N = 259) | Usual care (N = 254) | Total (N = 770) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 156 (60.7) | 159 (61.4) | 153 (60.2) | 468 (60.8) |

| Female | 101 (39.3) | 100 (38.6) | 101 (39.8) | 302 (39.2) |

| Age at randomisation (years), mean (SD) | 59.9 (13.5) | 59.4 (14.3) | 62.5 (12.5) | 60.6 (13.5) |

| Time from stroke to randomisation (days), median (IQR) | 233 (102–549) | 258 (115–546) | 242 (107–549) | 240 (109–549) |

| Time from stroke to randomisation (months), n (%) | ||||

| < 3 | 57 (22.2) | 46 (17.8) | 58 (22.8) | 161 (20.9) |

| 3–12 | 105 (40.9) | 117 (45.2) | 106 (41.7) | 328 (42.6) |

| > 12 | 95 (37.0) | 96 (37.1) | 90 (35.4) | 281 (36.5) |

| Arm affected by stroke, n (%) | ||||

| Right | 112 (43.6) | 116 (44.8) | 113 (44.5) | 341 (44.3) |

| Left | 145 (56.4) | 143 (55.2) | 141 (55.5) | 429 (55.7) |

| Stroke type, n (%) | ||||

| Cerebral infarction | 197 (76.7) | 202 (78.0) | 214 (84.3) | 613 (79.6) |

| Primary intracerebral haemorrhage | 58 (22.6) | 56 (21.6) | 38 (15.0) | 152 (19.7) |

| Subarachnoid haemorrhage | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.8) | 5 (0.6) |

| NIHSS total score (0–42) | n = 255 | n = 259 | n = 254 | n = 768 |

| Median (IQR) | 5.0 (3.0–7.0) | 5.0 (3.0–7.0) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | 5.0 (3.0–7.0) |

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment (0–30) | n = 248 | n = 250 | n = 242 | n = 740 |

| Median (IQR) | 24.0 (19.0–27.0) | 24.0 (19.0–27.0) | 24.0 (19.0–27.0) | 24.0 (19.0–27.0) |

| Sheffield Screening Test for Acquired Language Disorders | ||||

| Receptive skills score (0–11) | n = 255 | n = 258 | n = 254 | n = 767 |

| Median (IQR) | 8.0 (7.0–9.0) | 8.0 (7.0–9.0) | 8.0 (7.0–9.0) | 8.0 (7.0–9.0) |

| Expressive skills score (0–9) | n = 251 | n = 258 | n = 254 | n = 763 |

| Median (IQR) | 11.0 (9.0–11.0) | 11.0 (10.0–11.0) | 11.0 (9.0–11.0) | 11.0 (9.0–11.0) |

| Total score (0–20) | n = 251 | n = 258 | n = 254 | n = 763 |

| Median (IQR) | 19.0 (16.0–20.0) | 19.0 (17.0–20.0) | 19.0 (17.0–20.0) | 19.0 (17.0–20.0) |

| Handedness,a n (%) | n = 255 | n = 259 | n = 254 | n = 768 |

| Right | 221 (86.7) | 223 (86.1) | 228 (89.8) | 672 (87.5) |

| Left | 34 (13.3) | 35 (13.5) | 25 (9.8) | 94 (12.2) |

| Ambidextrous | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.3) |

| Dominant hand affected by stroke, n (%) | n = 255 | n = 259 | n = 254 | n = 768 |

| No (including ambidextrous) | 141 (55.3) | 131 (50.6) | 132 (52.0) | 404 (52.6) |

| Yes | 114 (44.7) | 128 (49.4) | 122 (48.0) | 364 (47.4) |

| Upper limb measure | Robot-assisted training (N = 257) | EULT (N = 259) | Usual care (N = 254) | Total (N = 770) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARAT (0–57) | n = 256 | n = 259 | n = 254 | n = 769 |

| ARAT total score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 8.5 (11.9) | 8.7 (11.9) | 8.1 (11.5) | 8.4 (11.8) |

| Median (IQR) | 3.0 (0–12) | 3.0 (0–13) | 3.0 (0–11) | 3.0 (0–11) |

| ARAT total score category (0–57), n (%) | n = 256 | n = 259 | n = 254 | n = 769 |

| 0–7 | 178 (69.5) | 175 (67.6) | 173 (68.1) | 526 (68.4) |

| 8–13 | 18 (7.0) | 22 (8.5) | 23 (9.1) | 63 (8.2) |

| 14–19 | 13 (5.1) | 9 (3.5) | 13 (5.1) | 35 (4.6) |

| 20–39 | 47 (18.4) | 53 (20.5) | 45 (17.7) | 145 (18.9) |

| FMA | ||||

| Motor function score (0–66) | n = 255 | n = 259 | n = 254 | n = 768 |

| Mean (SD) | 18.0 (13.1) | 18.2 (14.1) | 18.2 (13.9) | 18.1 (13.7) |

| Range of motion and joint pain score (0–48) | n = 254 | n = 259 | n = 254 | n = 767 |

| Mean (SD) | 41.5 (6.1) | 41.5 (6.2) | 41.0 (6.6) | 41.3 (6.3) |

| Sensation score (0–12) | n = 253 | n = 258 | n = 252 | n = 763 |

| Mean (SD) | 9.4 (3.2) | 9.4 (3.3) | 9.8 (2.9) | 9.5 (3.1) |

| Total upper extremity score (0–126) | n = 254 | n = 259 | n = 254 | n = 767 |

| Mean (SD) | 68.9 (16.5) | 69.0 (17.9) | 68.9 (17.4) | 68.9 (17.3) |

| Barthel ADL Index (0–20) | n = 255 | n = 259 | n = 254 | n = 768 |

| Mean (SD) | 14.5 (3.8) | 14.3 (4.0) | 14.4 (3.9) | 14.4 (3.9) |

| Numeric pain scale (0–10) | n = 253 | n = 259 | n = 254 | n = 766 |

| Mean (SD) | 2.9 (3.2) | 2.7 (3.0) | 2.6 (3.1) | 2.7 (3.1) |

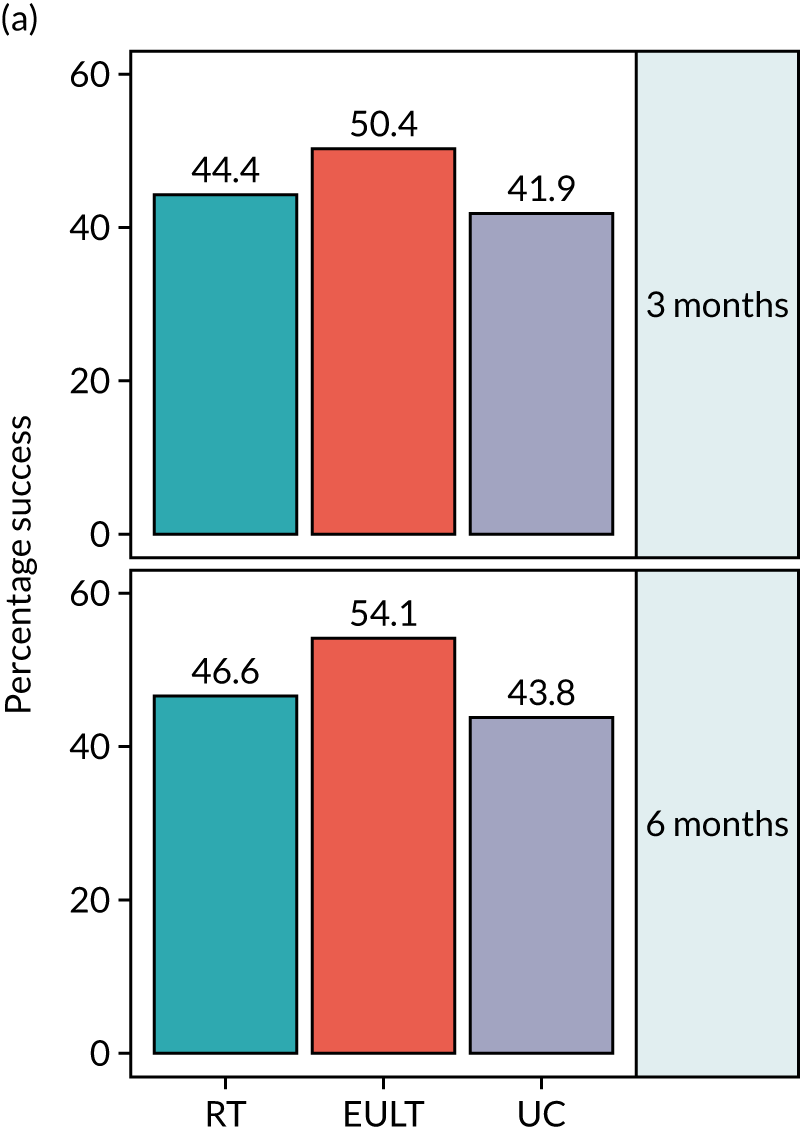

Primary outcome

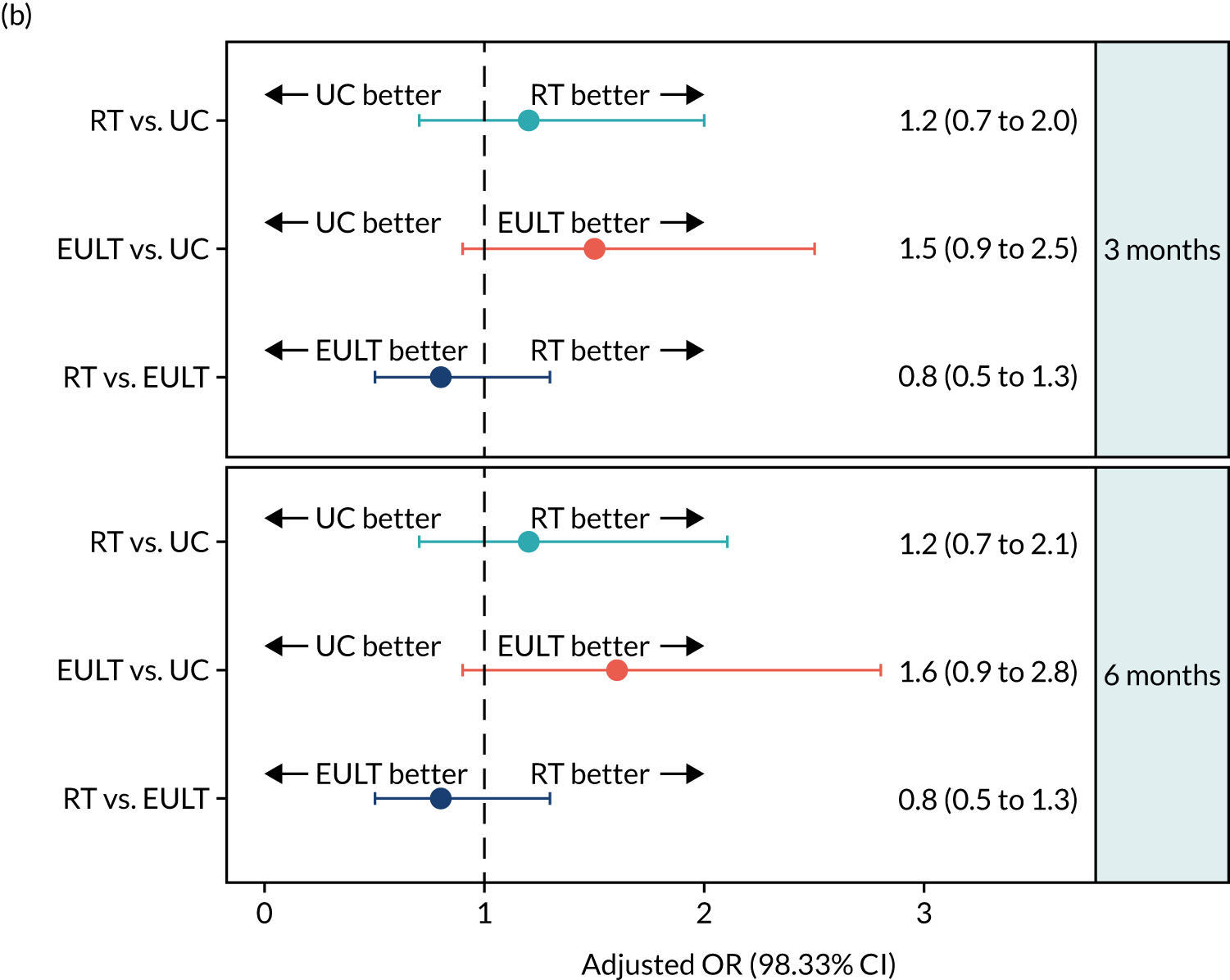

The proportion of participants who achieved upper limb functional recovery ‘success’ at 3 months in the ITT analysis was 103 out of 232 (44%) in the robot-assisted training group, 118 out of 234 (50%) in the EULT group and 85 out of 203 (42%) in the usual care group (Table 3 and Figure 4). There was little evidence of a statistically significant difference in the incidence of ‘success’ at 3 months when comparing the robot-assisted training group with the usual care group [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 1.2, 98.33% CI 0.7 to 2.0], the EULT group with the usual care group (aOR 1.5, 98.33% CI 0.9 to 2.5), or the robot-assisted training group with the EULT group (aOR 0.8, 98.33% CI 0.5 to 1.3). Although the unadjusted success rate was 8% higher in the EULT group than in the usual care group, the trial was powered to detect a difference of 15% in success rates between groups. The results of both sensitivity analyses and the PP analysis were consistent with the ITT analysis (see Table 3).

| Outcome | Robot-assisted training | EULT | Usual care | OR (98.33% CI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robot-assisted training vs. usual carea | EULT vs. usual carea | Robot-assisted training vs. EULTa | ||||||||||

| N | n (%) | N | n (%) | N | n (%) | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | |

| Primary outcome, 3 months | ||||||||||||

| ITT | 232 | 103 (44.4) | 234 | 118 (50.4) | 203 | 85 (41.9) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.8) | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.0) | 1.4 (0.9 to 2.2) | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.5) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.2) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.3) |

| Sensitivity analysis 1c | 197 | 89 (45.2) | 187 | 94 (50.3) | 157 | 66 (42.0) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.9) | 1.1 (0.6 to 2.0) | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.3) | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.4) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.3) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.4) |

| Sensitivity analysis 2d | 148 | 71 (48.0) | 145 | 81 (55.9) | 116 | 56 (48.3) | 1.0 (0.5 to 1.8) | 1.1 (0.6 to 2.2) | 1.4 (0.7 to 2.5) | 1.6 (0.8 to 3.1) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.3) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.4) |

| PP | 222 | 97 (43.7) | 219 | 112 (51.1) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.2) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.2) |

| Secondary outcomes, 6 months | ||||||||||||

| ITT | 221 | 103 (46.6) | 218 | 118 (54.1) | 185 | 81 (43.8) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.8) | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.1) | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.5) | 1.6 (0.9 to 2.8) | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.2) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.3) |

| Sensitivity analysis 1c | 200 | 91 (45.5) | 203 | 110 (54.2) | 163 | 71 (43.6) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.8) | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.2) | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.5) | 1.6 (0.9 to 2.9) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.1) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.3) |

| Sensitivity analysis 2d | 139 | 72 (51.8) | 136 | 84 (61.8) | 109 | 55 (50.5) | 1.1 (0.6 to 1.9) | 1.3 (0.6 to 2.8) | 1.6 (0.9 to 3.0) | 1.9 (0.9 to 4.1) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.2) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.4) |

| PP | 213 | 97 (45.5) | 206 | 113 (54.9) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.1) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.2) |

FIGURE 4.

Upper limb functional recovery ‘success’ at 3 and 6 months for robot-assisted training, EULT and usual care. (a) The proportion of participants achieving upper limb functional recovery ‘success’ by randomisation group; and (b) pairwise comparisons of group upper limb functional recovery ‘success’ presented as ORs (98.33% CIs) (ITT population). RT, robot-assisted training; UC, usual care.

The secondary outcome results of upper limb functional recovery ‘success’ at 6 months are shown in Table 3 and Figure 4. The number of participants who achieved upper limb functional recovery ‘success’ at 6 months in the ITT analysis was 103 out of 221 (47%) in the robot-assisted training group, 118 out of 218 (54%) in the EULT group and 81 out of 185 (44%) in the usual care group; all groups showed slight improvement from the 3-month assessment. The unadjusted success rate was 10% higher in the EULT group than in the usual care group, but there was little evidence of a difference in the incidence of ‘success’ at 6 months when comparing the robot-assisted training group with the usual care group (aOR 1.2, 98.33% CI 0.7 to 2.1), the EULT group with the usual care group (aOR 1.6, 98.33% CI 0.9 to 2.8) or the robot-assisted training group with the EULT group (aOR 0.8, 98.33% CI 0.5 to 1.3). The results of both sensitivity analyses and the PP analysis were consistent with the ITT analysis (see Table 3).

Secondary outcomes

Robot-assisted training versus usual care

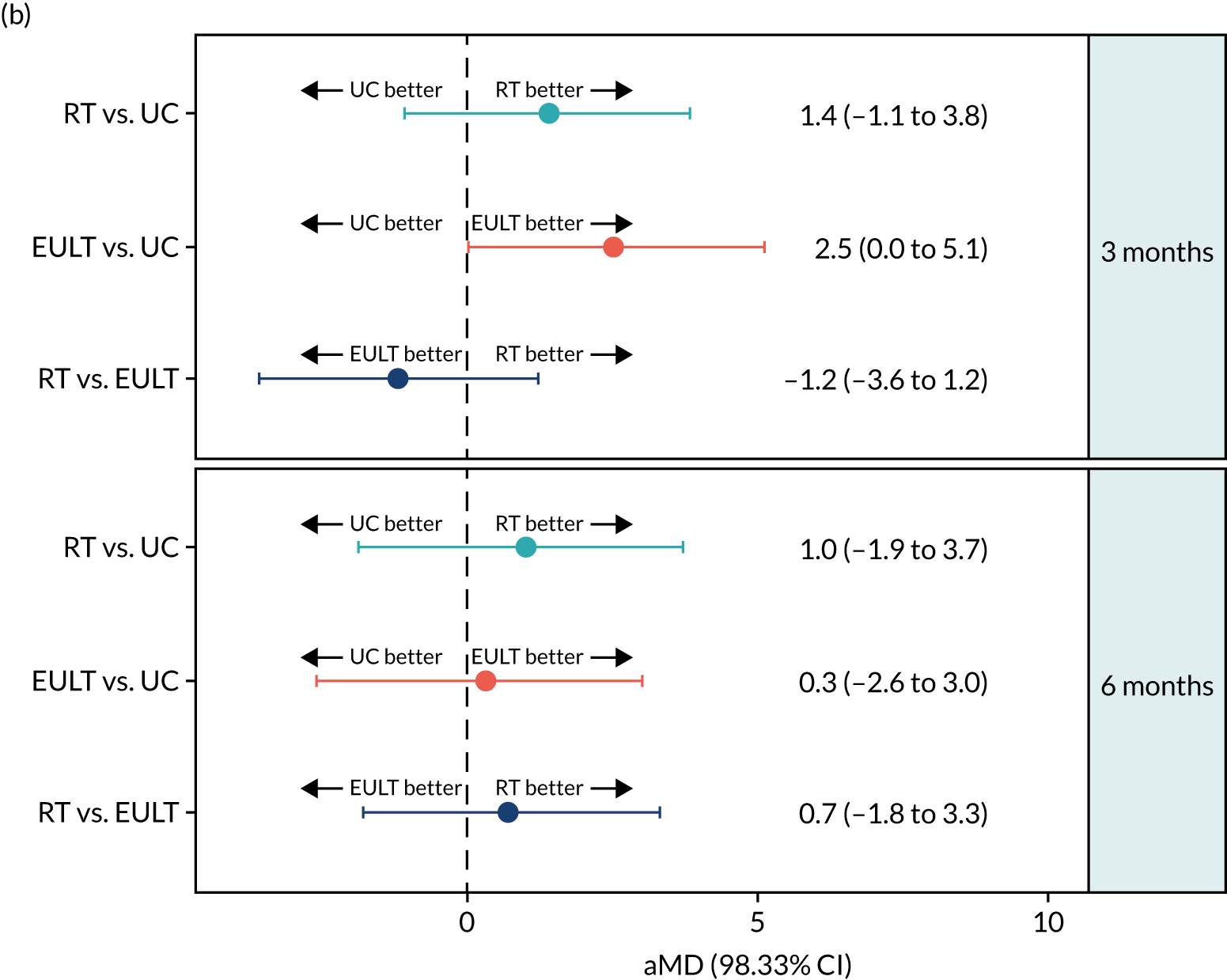

Action Research Arm Test total score

In the robot-assisted training group, the mean ARAT total scores were 8.5 points at baseline, 15.5 points at 3 months and 16.5 points at 6 months. For the usual care group, the mean ARAT total scores were 8.1 points at baseline, 14.2 points at 3 months and 16.4 points at 6 months. There was little evidence of a difference in the ARAT total score between these groups at 3 months [adjusted mean difference (aMD) 1.4, 98.33% CI –1.1 to 3.8] and 6 months (aMD 1.0, 98.33% CI –1.9 to 3.7) (Table 4 and Figure 5). The MCID for the ARAT total score is 6 points,59 so the changes in mean ARAT scores between baseline and 3 months were consistent with a clinically meaningful difference on this scale for both groups, but the differences between 3 and 6 months, and between groups at 3 and 6 months, were not. The results of the ARAT subscales are given in Appendix 3, Table 34.

| Time point | Robot-assisted training | EULT | Usual care | Mean difference (98.33% CI) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robot-assisted training – usual care | EULT – usual care | Robot-assisted training – EULT | |||||||||||||

| n | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | n | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | n | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |

| Baseline | 256 | 8.5 (11.9) | 3 (0–12) | 259 | 8.7 (11.9) | 3 (0–13) | 254 | 8.1 (11.5) | 3 (0–11) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 3 months | 232 | 15.5 (19.1) | 5 (0–28) | 234 | 17.3 (20.1) | 5 (1–33) | 203 | 14.2 (19.6) | 3 (0–22) | 1.2 (–3.3 to 5.7) | 1.4 (–1.1 to 3.8) | 3.0 (–1.6 to 7.5) | 2.5 (0.0b to 5.1) | –1.8 (–6.2 to 2.6) | –1.2 (–3.6 to 1.2) |

| 6 months | 221 | 16.5 (19.7) | 4 (0–29) | 218 | 17.2 (19.9) | 5 (0–36) | 185 | 16.4 (21.3) | 3 (0–34) | 0.1 (–4.8 to 5.0) | 1.0 (–1.9 to 3.7) | 0.8 (–4.3 to 5.6) | 0.3 (–2.6 to 3.0) | –0.6 (–5.2 to 3.9) | 0.7 (–1.8 to 3.3) |

FIGURE 5.

The ARAT total score at baseline and at 3 and 6 months for robot-assisted training, EULT and usual care. (a) The ARAT total score by randomisation group; and (b) pairwise comparisons of the ARAT total score presented as mean differences (98.33% CIs). RT, robot-assisted training; UC, usual care.

Fugl-Meyer Assessment total upper-extremity score

A similar pattern was seen in the mean FMA total upper-extremity scores, which were 68.9 points at baseline, 76.6 points at 3 months and 78.2 points at 6 months in the robot-assisted training group. By comparison, they were 68.9 points at baseline, 74.2 points at 3 months and 77.9 points at 6 months in the usual care group. There was little evidence of a difference between these groups on this scale at 3 months (aMD 3.1, 98.33% CI –0.0 to 6.5) or at 6 months (aMD 1.6, 98.33% CI –1.8 to 5.2) (Table 5). There is no published MCID for the FMA total upper-extremity score.

| FMA and time point | Robot-assisted training | EULT | Usual care | Mean difference (98.33% CI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robot-assisted training – usual care | EULT – usual care | Robot-assisted training – EULT | ||||||||||

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |

| Total upper-extremity score (0–126) | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 254 | 68.9 (16.5) | 259 | 69.0 (17.9) | 254 | 68.9 (17.4) | ||||||

| 3 months | 232 | 76.6 (22.1) | 234 | 77.8 (22.8) | 202 | 74.2 (23.6) | 2.4 (–2.9 to 7.6) | 3.1 (–0.0 to 6.5) | 3.6 (–1.8 to 8.9) | 3.7 (0.5 to 6.8) | –1.3 (–6.2 to 3.7) | –0.5 (–3.4 to 2.6) |

| 6 months | 221 | 78.2 (22.8) | 218 | 79.4 (24.1) | 186 | 77.9 (23.2) | 0.3 (–5.2 to 5.8) | 1.6 (–1.8 to 5.2) | 1.5 (–4.3 to 7.0) | 1.8 (–1.8 to 5.3) | –1.1 (–6.5 to 4.2) | –0.2 (–3.6 to 3.4) |

| Motor function (0–66) | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 255 | 18.0 (13.1) | 259 | 18.2 (14.1) | 254 | 18.2 (13.9) | ||||||

| 3 months | 232 | 26.2 (17.7) | 234 | 27.1 (18.3) | 202 | 24.2 (18.4) | 2.0 (–2.2 to 6.2) | 2.8 (0.7 to 5.0) | 2.9 (–1.3 to 7.1) | 3.0 (0.9 to 5.0) | –0.9 (–4.8 to 3.1) | –0.2 (–2.2 to 1.9) |

| 6 months | 221 | 27.2 (18.4) | 217 | 28.2 (19.3) | 186 | 26.3 (18.9) | 0.9 (–3.6 to 5.3) | 2.5 (0.1 to 5.1) | 1.9 (–2.7 to 6.4) | 2.4 (–0.2 to 4.8) | –1.0 (–5.3 to 3.3) | 0.1 (–2.3 to 2.7) |

| Range of motion and joint pain (0–48) | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 254 | 41.5 (6.1) | 259 | 41.5 (6.2) | 254 | 41.0 (6.6) | ||||||

| 3 months | 232 | 40.8 (6.8) | 234 | 41.2 (6.2) | 204 | 40.0 (8.0) | ||||||

| 6 months | 221 | 41.5 (6.1) | 218 | 41.6 (5.9) | 186 | 41.6 (6.2) | ||||||

| Sensation (0–12) | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 253 | 9.4 (3.2) | 258 | 9.4 (3.3) | 252 | 9.8 (2.9) | ||||||

| 3 months | 231 | 9.6 (3.1) | 234 | 9.5 (3.0) | 202 | 9.9 (2.9) | ||||||

| 6 months | 221 | 9.5 (3.0) | 218 | 9.6 (2.9) | 186 | 10.0 (2.7) | ||||||

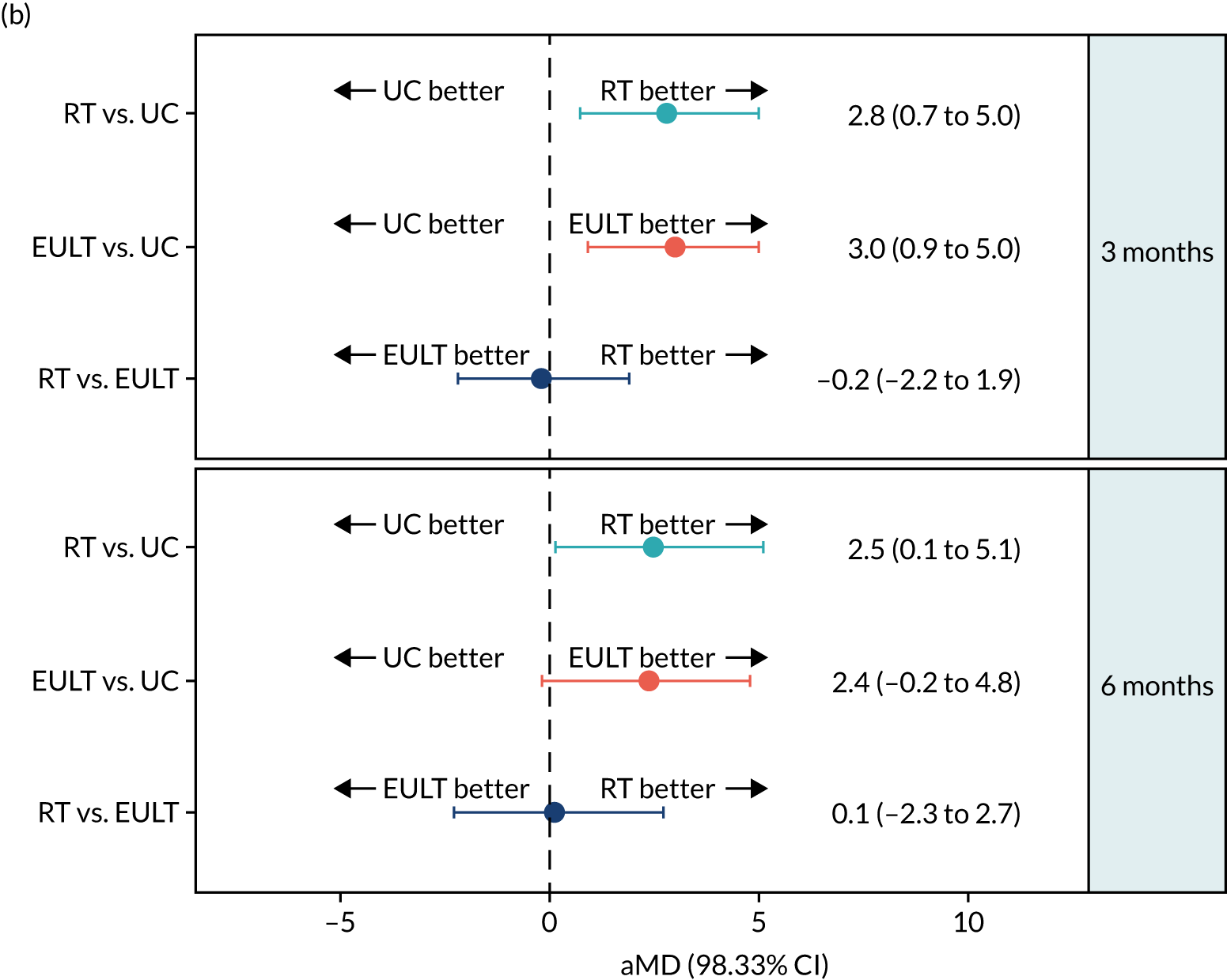

Fugl-Meyer Assessment motor function subscale

This pattern of improvement was also seen for the FMA motor function subscale. For the robot-assisted training group, the mean scores were 18.0 points at baseline, 26.2 points at 3 months and 27.2 points at 6 months. In comparison, for the usual care group the mean scores were 18.2 points at baseline, 24.2 points at 3 months and 26.3 points at 6 months. The robot-assisted training group had a higher average FMA motor function subscale score than the usual care group at 3 months (aMD 2.8, 98.33% CI 0.7 to 5.0), and this difference was maintained at 6 months (aMD 2.5, 98.33% CI 0.1 to 5.1) (Figure 6; see also Table 5). The MCID for this subscale is 4 points for acute stroke patients and 5.25 points for chronic stroke patients, which makes it difficult to interpret the results from a mixed patient group. 59 Further details and descriptive statistics for the ‘range of motion and joint pain’ and ‘sensation’ subscales are given in Table 5.

FIGURE 6.

The FMA motor function subscale score at baseline and at 3 and 6 months for robot-assisted training, EULT and usual care. (a) The FMA motor function subscale score by randomisation group; and (b) pairwise comparisons of the FMA motor function subscale score presented as mean differences (98.33% CIs). RT, robot-assisted training; UC, usual care.

Barthel Activities of Daily Living Index

There was little change in the Barthel ADL Index score over time. In the robot-assisted training group, the mean was 14.5, 15.5 and 15.6 points at baseline, 3 months and 6 months, respectively. This was similar to the usual care group, in which the mean was 14.4, 15.3 and 15.3 points at baseline, 3 months and 6 months, respectively. There was little evidence of a difference between these groups on this scale at 3 months (aMD 0.2, 98.33% CI –0.4 to 0.8) or at 6 months (aMD 0.5, 98.33% CI –0.1 to 1.1) (Table 6). The MCID on this scale is 1.85 units,59 and so the changes in the mean Barthel ADL Index scores between baseline, 3 months and 6 months were not large enough to be consistent with a clinically meaningful difference on this scale for both groups (i.e. robot-assisted training and usual care), nor were the comparisons between group means at 3 or 6 months.

| Time point | Robot-assisted training | EULT | Usual care | Mean difference (98.33% CI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robot-assisted training – usual care | EULT – usual care | Robot-assisted training – EULT | ||||||||||

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |

| Barthel ADL Index (0–20) | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 255 | 14.5 (3.8) | 259 | 14.3 (4.0) | 254 | 14.4 (3.9) | ||||||

| 3 months | 233 | 15.5 (3.4) | 236 | 15.9 (3.4) | 207 | 15.3 (3.8) | 0.2 (–0.6 to 1.0) | 0.2 (–0.4 to 0.8) | 0.6 (–0.2 to 1.5) | 0.7 (0.2 to 1.2) | –0.5 (–1.2 to 0.3) | –0.5 (–1.0 to –0.0) |

| 6 months | 223 | 15.6 (3.4) | 222 | 16.0 (3.5) | 190 | 15.3 (3.7) | 0.3 (–0.5 to 1.1) | 0.5 (–0.1 to 1.1) | 0.6 (–0.2 to 1.5) | 0.9 (0.3 to 1.5) | –0.4 (–1.2 to 0.4) | –0.4 (–1.0 to 0.1) |

Stroke Impact Scale

There was little change over time on any SIS subscale. The mean scores on the ADL subscale were 50.8 points at 3 months and 50.4 points at 6 months in the robot-assisted training group, but they were 50.8 and 51.9 points at 3 and 6 months, respectively, in the usual care group. The results were consistent with the Barthel ADL Index, in that they showed little evidence of a difference between these groups at 3 months (aMD 0.7, 98.33% CI –4.2 to 5.8) or at 6 months (aMD –0.6, 98.33% CI –5.6 to 4.5) (Table 7). The MCID on this SIS subscale is 5.9 units,59 so the differences between groups were not consistent with a clinically meaningful difference.

| SIS subscale and time point | Robot-assisted training | EULT | Usual care | Mean difference (98.33% CI) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robot-assisted training – usual care | EULT – usual care | Robot-assisted training – EULT | |||||||||||||

| n | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | n | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | n | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |

| ADL (0–100) | |||||||||||||||

| 3 months | 220 | 50.8 (22.5) | 48 (33–70) | 223 | 55.9 (19.8) | 55 (40–70) | 194 | 50.8 (21.1) | 50 (33–65) | 0.0b (–5.1 to 5.2) | 0.7 (–4.2 to 5.8) | 5.1 (0.3 to 9.9) | 5.6 (0.9 to 10.2) | –5.1 (–10.0 to –0.3) | –4.8 (–9.5 to –0.1) |

| 6 months | 212 | 50.4 (22.3) | 50 (33–68) | 216 | 52.5 (22.3) | 50 (38–68) | 179 | 51.9 (21.3) | 53 (35–70) | –1.4 (–6.7 to 3.9) | –0.6 (–5.6 to 4.5) | 0.6 (–4.7 to 5.8) | 1.1 (–3.9 to 6.1) | –2.0 (–7.2 to 3.1) | –1.7 (–6.7 to 3.3) |

| Hand function (0–100) | |||||||||||||||

| 3 months | 219 | 15.5 (24.4) | 0 (0–20) | 223 | 21.4 (27.9) | 5 (0–40) | 193 | 14.3 (22.9) | 0 (0–25) | 1.3 (–4.3 to 6.8) | 2.6 (–2.6 to 7.9) | 7.2 (1.1 to 13.1) | 7.9 (2.2 to 13.5) | –5.9 (–11.9 to 0.1) | –5.4 (–10.9 to 0.2) |

| 6 months | 213 | 15.7 (25.2) | 0 (0–25) | 216 | 18.4 (26.2) | 0 (0–35) | 179 | 14.8 (23.5) | 0 (0–25) | 0.9 (–5.0 to 6.8) | 1.9 (–3.6 to 7.5) | 3.6 (–2.4 to 9.5) | 3.9 (–1.8 to 9.6) | –2.7 (–8.6 to 3.3) | –2.0 (–7.4 to 3.6) |

| Mobility (0–100) | |||||||||||||||

| 3 months | 219 | 61.6 (25.1) | 64 (44–83) | 223 | 66.4 (23.2) | 69 (50–86) | 192 | 61.0 (24.6) | 61 (46–81) | 0.6 (–5.3 to 6.5) | 1.3 (–4.3 to 6.9) | 5.4 (–0.1 to 11.1) | 5.8 (0.4 to 11.2) | –4.8 (–10.4 to 0.7) | –4.5 (–9.9 to 0.9) |

| 6 months | 213 | 61.7 (24.8) | 64 (44–83) | 216 | 63.9 (23.7) | 68 (47–83) | 180 | 62.9 (23.8) | 65 (44–83) | –1.2 (–7.1 to 4.7) | –0.5 (–6.0 to 5.1) | 1.1 (–4.6 to 6.8) | 1.4 (–4.1 to 6.8) | –2.3 (–7.9 to 3.3) | –1.9 (–7.3 to 3.5) |

| Social participation (0–100) | |||||||||||||||

| 3 months | 217 | 47.7 (24.7) | 47 (29–66) | 221 | 51.7 (23.0) | 53 (38–69) | 193 | 47.1 (23.7) | 47 (31–63) | 0.6 (–5.1 to 6.3) | 0.5 (–5.2 to 6.2) | 4.6 (–0.9 to 10.1) | 4.7 (–0.7 to 10.1) | –4.0 (–9.5 to 1.5) | –4.2 (–9.6 to 1.3) |

| 6 months | 210 | 47.0 (25.9) | 44 (25–66) | 216 | 50.2 (24.4) | 50 (31–69) | 179 | 49.2 (23.8) | 50 (31–63) | –2.2 (–8.3 to 3.9) | –2.2 (–8.2 to 3.9) | 1.0 (–4.8 to 6.9) | 1.2 (–4.7 to 7.0) | –3.3 (–9.1 to 2.6) | –3.4 (–9.2 to 2.4) |

| Strength (0–100) | |||||||||||||||

| 3 months | 220 | 43.8 (20.4) | 44 (31–56) | 220 | 48.1 (22.2) | 50 (31–63) | 193 | 40.1 (19.1) | 38 (25–50) | ||||||

| 6 months | 213 | 40.9 (21.7) | 38 (25–56) | 216 | 44.3 (22.7) | 44 (25–63) | 176 | 40.3 (21.6) | 38 (25–56) | ||||||

| Emotion (0–100) | |||||||||||||||

| 3 months | 220 | 68.3 (18.2) | 69 (56–82) | 222 | 69.9 (16.5) | 69 (58–83) | 194 | 67.4 (20.5) | 67 (53–86) | ||||||

| 6 months | 211 | 66.9 (18.3) | 67 (53–81) | 216 | 68.3 (18.8) | 69 (56–83) | 179 | 67.4 (19.7) | 69 (56–83) | ||||||

| Memory (0–100) | |||||||||||||||

| 3 months | 219 | 76.0 (22.4) | 82 (61–96) | 222 | 80.3 (18.8) | 86 (68–96) | 194 | 76.8 (22.2) | 82 (61–96) | ||||||

| 6 months | 213 | 74.6 (22.7) | 79 (58–93) | 215 | 77.4 (21.2) | 82 (64–96) | 178 | 77.8 (23.4) | 86 (64–96) | ||||||

| Communication (0–100) | |||||||||||||||

| 3 months | 220 | 80.1 (23.4) | 89 (68–100) | 222 | 85.3 (20.5) | 96 (79–100) | 194 | 80.9 (24.3) | 93 (68–100) | ||||||

| 6 months | 213 | 79.3 (21.7) | 86 (68–100) | 216 | 83.7 (22.7) | 96 (75–100) | 179 | 82.2 (22.5) | 93 (71–100) | ||||||

| Stroke recovery (0–100) | |||||||||||||||

| 3 months | 217 | 47.9 (18.9) | 50 (30–60) | 223 | 50.3 (18.9) | 50 (40–60) | 190 | 45.2 (19.9) | 50 (30–60) | ||||||

| 6 months | 213 | 51.4 (20.4) | 50 (35–70) | 215 | 50.9 (21.5) | 50 (35–70) | 180 | 48.5 (20.3) | 50 (33–60) | ||||||

The mean scores on the SIS hand function subscale were 15.5 points at 3 months and 15.7 points at 6 months in the robot-assisted training group, but were 14.3 and 14.8 points at 3 and 6 months, respectively, in the usual care group. There was also little evidence of a difference in hand function between groups at 3 months (aMD 2.6, 98.33% CI –2.6 to 7.9) or 6 months (aMD 1.9, 98.33% CI –3.6 to 7.5). The MCID on this SIS subscale is 17.8 units,59 so the results were not consistent with a clinically meaningful difference.

The mean scores on the SIS mobility subscale were 61.6 points at 3 months and 61.7 points at 6 months in the robot-assisted training group, but were 61.0 and 62.9 points at 3 and 6 months, respectively, in the usual care group. As before, there was little evidence of a difference between groups for mobility at 3 months (aMD 1.3, 98.33% CI –4.3 to 6.9) or 6 months (aMD –0.5, 98.33% CI –6.0 to 5.1). However, the MCID on this SIS subscale is 4.5 units,59 which was included in these CIs, so a clinically meaningful difference between groups cannot be ruled out.

The mean scores on the SIS social participation subscale were 47.7 points at 3 months and 47.0 points at 6 months in the robot-assisted training group, but were 47.1 and 49.2 points at 3 and 6 months, respectively, in the usual care group. There was also little evidence of a difference at 3 months (aMD 0.5, 98.33% CI –5.2 to 6.2) or 6 months (aMD –2.2, 98.33% CI –8.2 to 3.9) between the robot-assisted training group and the usual care group, as measured by the SIS. More details and descriptive statistics for strength, emotion, memory, communication and stroke recovery are given in Table 7.

Robot-assisted training versus enhanced upper limb therapy

Action Research Arm Test total score

Both groups showed an improvement in ARAT total score from baseline to 3 months, but little improvement thereafter. In the robot-assisted training group, the mean ARAT total score was 8.5 points at baseline, 15.5 points at 3 months and 16.5 points at 6 months. In comparison, the mean ARAT total score for the EULT group was 8.7 points at baseline, 17.3 points at 3 months and 17.2 points at 6 months. There was little evidence of a difference in the ARAT total score between these groups at 3 months (aMD –1.2, 98.33% CI –3.6 to 1.2) or at 6 months (aMD 0.7, 98.33% CI –1.8 to 3.3) (see Table 4 and Figure 5). The MCID for ARAT total score is 6 points,59 so the changes in mean ARAT scores between baseline and 3 months were consistent with a clinically meaningful difference on this scale for both groups, but those between 3 and 6 months, and between groups at 3 and 6 months, were not. The results of the ARAT subscales are given in Appendix 3, Table 34.

Fugl-Meyer Assessment total upper-extremity score

There was a similar pattern in the FMA total upper-extremity score. The mean FMA total scores were 68.9 points at baseline, 76.6 points at 3 months and 78.2 points at 6 months in the robot-assisted training group, and were 69.0, 77.8 and 79.4 points at baseline, 3 months and 6 months, respectively, for the EULT group. There was little evidence of a difference between these groups on this scale at 3 months (aMD –0.5, 98.33% CI –3.4 to 2.6) or 6 months (aMD –0.2, 98.33% CI –3.6 to 3.4) (see Table 5). There is no published MCID for the FMA total upper-extremity score.

Fugl-Meyer Assessment motor function subscale

The FMA motor function subscale scores also showed a similar pattern. The mean score changed from 18.0 points at baseline to 26.2 points at 3 months and 27.2 points at 6 months in the robot-assisted training group, and was 18.2, 27.1 and 28.2 points at baseline, 3 months and 6 months, respectively, in the EULT group. There was little evidence of a difference in this subscale between the two groups at 3 months (aMD –0.2, 98.33% CI –2.2 to 1.9) or 6 months (aMD 0.1, 98.33% CI –2.3 to 2.7). The MCID for this subscale is 4 points for acute stroke patients and 5.25 points for chronic stroke patients59 (see Table 5 and Figure 6). Further details and descriptive statistics for ‘range of motion and joint pain’ and ‘sensation’ subscales are given in Table 5.

Barthel Activities of Daily Living Index

There was little change in the Barthel ADL Index score over time. In the robot-assisted training group, the mean score was 14.5 points at baseline, 15.5 points at 3 months and 15.6 points at 6 months. In comparison, the mean scores for the EULT group were 14.3, 15.9 and 16.0 points at baseline, 3 months and 6 months, respectively. There was limited evidence that the EULT group participants fared better than the robot-assisted training group participants when comparing ADL at 3 months (aMD –0.5, 98.33% CI –1.0 to –0.0), but there was no difference at 6 months (aMD –0.4, 98.33% CI –1.0 to 0.1) (see Table 6). The MCID on this scale is 1.85 units,59 and so the changes in mean Barthel ADL Index scores between baseline, 3 months and 6 months were not large enough to be consistent with a clinically meaningful difference on this scale for both groups, nor were the comparisons between group mean scores at 3 or 6 months.

Stroke Impact Scale

The mean scores on the SIS ADL subscale were 50.8 points at 3 months and 50.4 points at 6 months in the robot-assisted training group, but were 55.9 and 52.5 points at 3 and 6 months, respectively, in the EULT group. The scores of the ADL subscale of the SIS were consistent with the Barthel ADL Index scores, in that they showed evidence that EULT group participants fared better than the robot-assisted training group participants at 3 months (aMD –4.8, 98.33% CI –9.5 to –0.1), but there was no difference at 6 months (aMD –1.7, 98.33% CI –6.7 to 3.3) (see Table 7). The MCID on this scale is 5.9 units,59 which was included in the CI; therefore, a difference of this size cannot be ruled out at both time points.

The mean scores on the SIS hand function subscale were 15.5 points at 3 months and 15.7 points at 6 months in the robot-assisted training group, but were 21.4 and 18.4 points at 3 and 6 months, respectively, in the EULT group. There was little evidence of a difference between the robot-assisted training group and the EULT group in hand function at 3 months (aMD –5.4, 98.33% CI –10.9 to 0.2) or 6 months (aMD –2.0, 98.33% CI –7.4 to 3.6). The MCID on this scale is 17.8 units,59 so the results were not consistent with a clinically meaningful difference (see Table 7).

The mean scores on the SIS mobility subscale were 61.6 points at 3 months and 61.7 points at 6 months in the robot-assisted training group, but were 66.4 and 63.9 points at 3 and 6 months, respectively, in the EULT group. Similarly, there was little evidence of a difference in mobility at 3 months (aMD –4.5, 98.33% CI –9.9 to 0.9) or 6 months (aMD –1.9, 98.33% CI –7.3 to 3.5). The MCID on this scale is 4.5 units,59 which was included in these CIs, so a clinically meaningful difference cannot be ruled out.

Finally, the mean scores on the SIS social participation subscale were 47.7 points at 3 months and 47.0 points at 6 months in the robot-assisted training group, but were 51.7 and 50.2 points at 3 and 6 months, respectively, in the EULT group. There was little evidence of a difference in social participation scores at 3 months (aMD –4.2, 98.33% CI –9.6 to 1.3) or 6 months (aMD –3.4, 98.33% CI –9.2 to 2.4). More details and descriptive statistics for strength, emotion, memory, communication and stroke recovery subscales are given in Table 7.

Enhanced upper limb therapy versus usual care

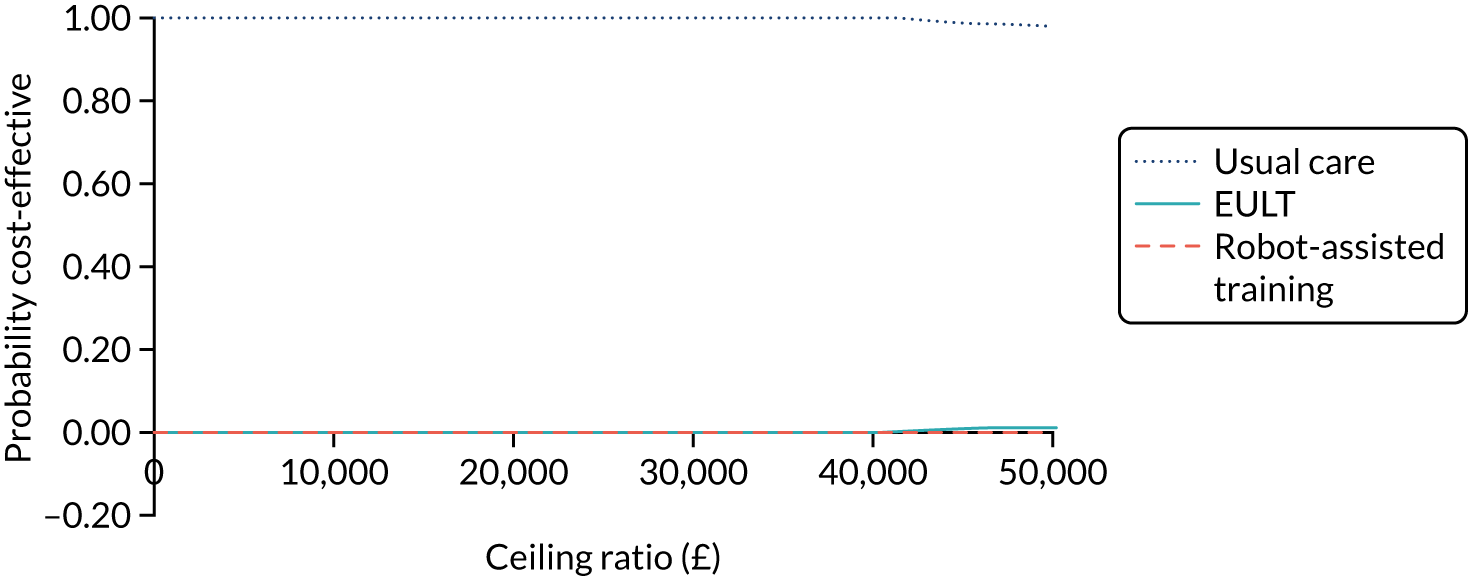

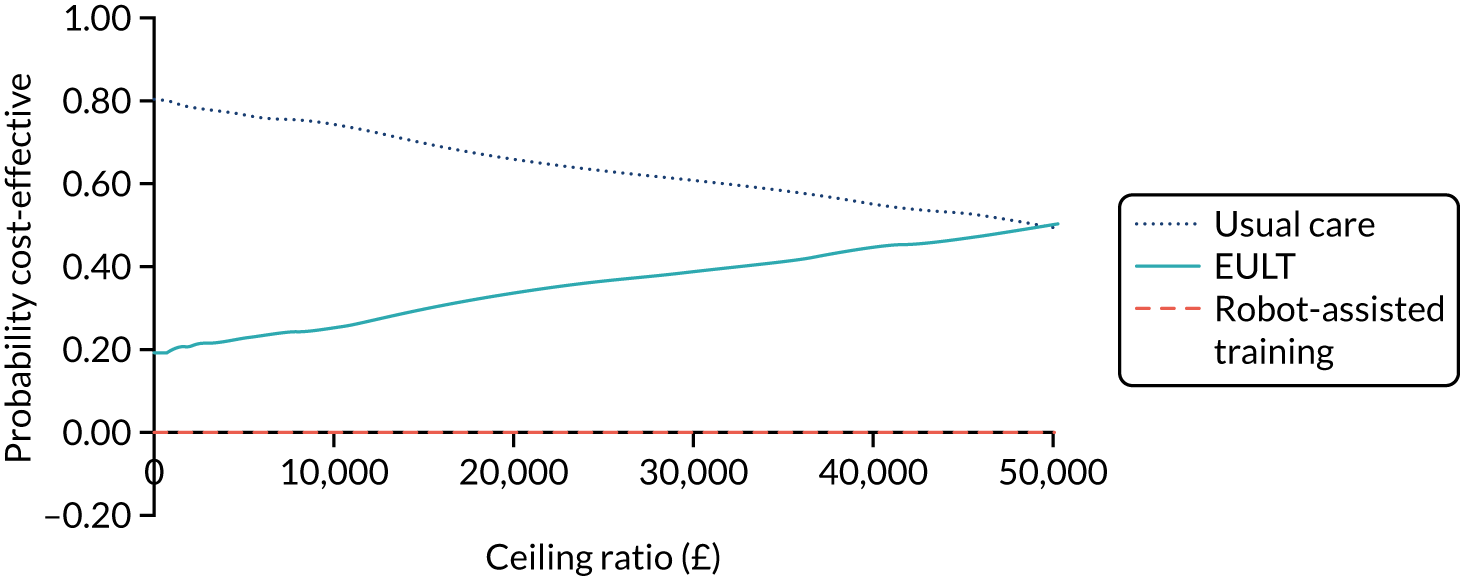

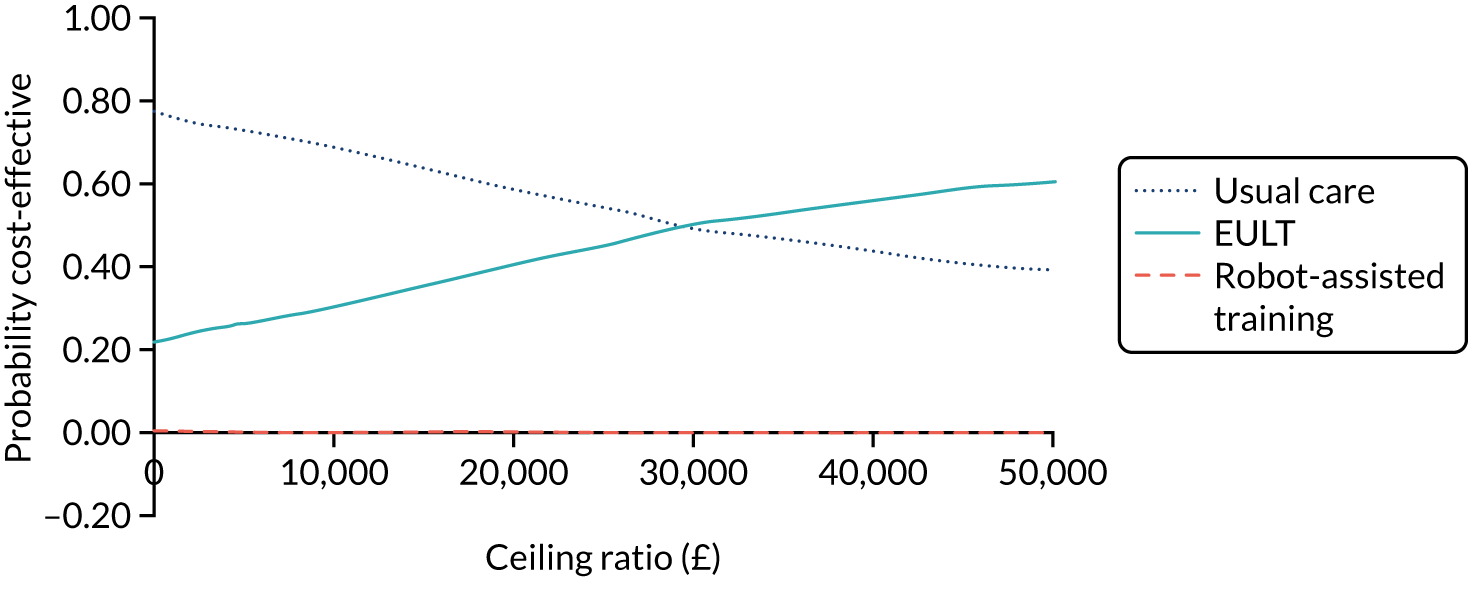

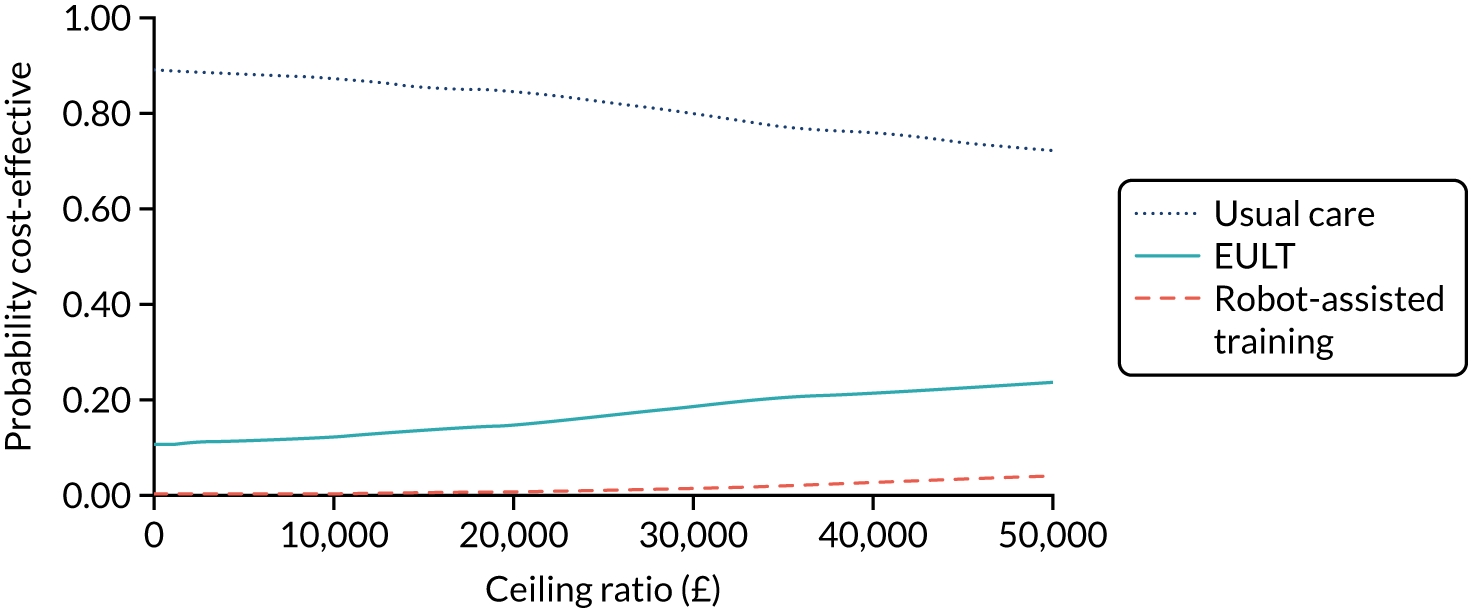

Action Research Arm Test total score