Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/79/09. The contractual start date was in October 2015. The draft report began editorial review in February 2019 and was accepted for publication in November 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Stephenson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Control of fertility is crucial to the health and well-being of women, but unintended pregnancy remains common and costly for both health services and individuals. In the UK, despite a range of freely available effective contraceptive methods, abortion rates have changed little over two decades (at around 190,000 per year for women resident in England and Wales). 1 Despite a national teenage pregnancy strategy and recent fall in conceptions among those aged < 18 years, England still has the highest rate of teenage pregnancy in western Europe. A key report on the economics of sexual health concluded that it should be feasible to improve contraception and abortion services in ways that better meet the preferences of service users and that this could lead to a net saving (largely from fewer unintended pregnancies and reduced delay in abortion) of up to £1B over 15 years. 2

Although avoidance of unintended pregnancy may be viewed as a shared responsibility between sexual partners, the burden of decision and action more often remains with women. Preventing unintended pregnancy involves many processes, including timely education, awareness and socially patterned behaviours that lead women to seek, choose and use contraception consistently and correctly. Health services have a key role in supporting women to choose and use an appropriate method that best meets their needs. However, many women are still not aware of the range of different methods available to them. There are widespread myths about contraception (e.g. fears about impact on future fertility, weight gain or the significance of amenorrhoea). The combined oral contraceptive pill and condoms are well known and widely used – by around half of all women using contraception – but they are not the most effective contraceptive methods.

Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) methods, including copper intrauterine devices, progestogen-only intrauterine systems, progestogen-only injectable contraceptives and progestogen-only subdermal implants, offer women the most effective protection against pregnancy. Women who use oral contraceptive pills, the contraceptive patch or vaginal ring have a 20 times higher failure rate than women who use LARC methods. 3 More than a decade ago, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) concluded that increasing uptake of LARC is more cost-effective in reducing unintended pregnancy than the contraceptive pill or condoms, even at 1 year. 4 At that time (2005), estimated uptake of LARC in the UK was low, at 8% (2003/4 data), compared with 25% for the oral contraceptive pill and 23% for male condoms. Since then, uptake of LARC has increased, to 12% in the population in 2008/9 and to 41% by 2013, in women attending community contraceptive clinics. 5 Even in specialist community services, younger women are less likely to use LARC (24% in those aged < 30 years) than older women.

There are multiple pathways by which women get information about contraception and choose a method. The main sources of information are the internet, family and friends, school relationships and sex education, general practitioners (GPs), community pharmacies, and sexual and reproductive health services. However, not all of these sources provide information on LARC and uptake of LARC is limited by the number of appropriately trained doctors or nurses to fit them. It is understood that many general practices, which are the source most commonly used by women for contraception,6 have little or no capacity for fitting and therefore rely on referral to specialist contraceptive services. Effective interventions are needed that expand women’s choice of more effective methods of contraception, and increase uptake in a variety of settings.

Current standard care pathways for contraception vary considerably within and between different settings. Some services provide leaflets (e.g. the Family Planning Association) explaining the different methods, but the extent to which such leaflets are read, understood or help women reach an informed decision about contraceptive method is unclear. The quality of face-to-face consultation varies widely between different health-care providers with different skills, competencies and experience. The evidence base for improving contraceptive uptake and adherence through better face-to-face consultations is slim and mostly disappointing;7–9 our population-based study (funded by the UK Medical Research Council) of why women stop or switch contraceptive methods concluded that traditional consultation with a doctor or nurse in clinic has only modest influence on women’s contraceptive decisions.

Health care in the UK is undergoing a health informatics revolution. The vast majority of young people have access to digital technology, which offers huge potential for health promotion. Recent data from the Office for National Statistics indicate that 99% of 16- to 24-year-olds have accessed the internet and 88% use it daily. 10 We know that younger women are likely to turn to digital resources for information on contraception. 11 For the proposed study, we therefore explored the use of interactive digital interventions (IDIs) that provide information and decision support for contraceptive choices. 12–15 IDIs may be available directly to users for self-guided use, or available with remote or face-to-face human support. They may be delivered by any digital medium, including the internet, mobile phone and handheld computers. Access can be private and self-paced, and programmes can be tailored according to individual characteristics. Digital interventions are effective at increasing knowledge of emergency contraception16 and there is evidence of effect on sexual behaviour,12 contraceptive choice and adherence. 13–15 However, we are not aware of any services in the UK that currently provide IDIs to support women’s contraceptive decision-making.

Study aims and objectives

The original aim of the study was to develop (Phase I) and test the feasibility (Phase II) of an intervention to increase the uptake of LARC methods in young women. LARC methods include intrauterine devices, intrauterine systems, subdermal implants and injectable contraception.

Phase I objectives

-

To systematically review evidence on individual-level education or decision aid interventions relating to acceptability, uptake and adherence to LARC, including underpinning theories and user and provider views [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/137909/#/ (accessed January 2020)].

-

To obtain the views of contraceptive service users and providers in five settings (general practice, sexual and reproductive health services, abortion services, maternity services and community pharmacies) relating to access, acceptability and uptake of LARC.

-

To apply the information from objectives 1 and 2 to identify the key design issues and content for an IDI.

-

To co-design the IDI with young women and health-care professionals.

Phase II objectives (including transition from a feasibility trial to an efficacy trial)

The original objectives were:

-

To conduct a randomised feasibility trial of the IDI in five different service settings (general practice, sexual and reproductive health services, abortion services, maternity services and community pharmacies).

-

To assess, through qualitative process evaluation, the acceptability of the trial procedures, women’s views of the intervention itself and NHS implementation considerations.

-

To write a protocol for a definitive trial of an IDI to improve informed choice of contraception and the acceptability, uptake and adherence to LARC methods in young women.

However, when we presented the website at conferences and seminars, the response from colleagues working in sexual and reproductive health was overwhelmingly positive. Service providers wanted to direct clients to the Contraception Choices website right away. The immediate demand for the website convinced us that definitive testing in a subsequent efficacy trial, which would take years to complete, would be unwise and arguably unethical. Moreover, one site [the Margaret Pyke Centre (MPC)] wanted to promote the Contraception Choices website through its routine online system for booking clinic appointments. In response to this situation, we revised the feasibility trial protocol into an efficacy (Phase III) trial to examine the effect of the intervention on two clinical outcomes that were originally secondary outcomes in the feasibility trial: (1) use of a LARC method of contraception and (2) satisfaction with method of contraception at 6 months. The expansion in recruitment was achieved rapidly by recruiting women online (rather than in clinic) via the online booking system of the MPC (see below).

By changing from a feasibility trial to an efficacy trial, we completed the trial referred to in objective 7 [see Phase II objectives (including transition from a feasibility trial to an efficacy trial)], rather than writing a protocol for it.

Study setting

The five main service providers of contraceptive advice and supplies provide the setting for the study: general practice, sexual and reproductive health services, community pharmacies, maternity services and abortion services. Together, these settings provide contraceptive care for the great majority of women in the UK. They include services that provide care for women at highest risk of unintended pregnancy (i.e. those who attend abortion services or seek emergency contraception through community pharmacies). These settings also provide care for different demographic subgroups within the population. Four out of five women go through childbirth, many of whom will require postpartum contraception to avoid an unintended pregnancy. Around 60% of women aged 16–44 years in Britain access contraception through general practice, whereas 23% of women attend community (sexual and reproductive health) clinics each year for contraception. 6

Chapter 2 Phase I: design and development of the website

Overview of methods

We conducted three systematic reviews of the literature: (1) a review of reviews of factors influencing contraception choice and use, (2) a review of IDIs for contraception and (3) a review of face-to-face interventions for contraception and theoretical approaches to contraception decision-making.

We conducted six focus groups and 25 individual interviews to explore the views of 74 young women relating to contraception (access, acceptability, barriers and concerns), the design and content of the IDI (website) that we wished to develop, and their views on a future randomised controlled trial of such a website. We also reviewed 35 YouTube (YouTube, LLC, San Bruno, CA, USA) videos of women talking about contraception, including views expressed in video comment threads.

We synthesised the findings from the systematic reviews, women’s views on YouTube and qualitative research with women and health professionals, and held an expert workshop to develop a trial-ready, self-guided website that presents a number of contraceptive options in response to input of women’s preferences and concerns.

Objective 1 (systematic reviews)

Systematic review 1: factors influencing contraception choice, uptake and use – a meta-synthesis of systematic reviews

We synthesised the findings of 18 systematic reviews that were mostly of moderate or high quality [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/137909/#/ (accessed January 2020)]. Factors affecting contraception use are remarkably similar among women in very different cultures and settings globally. Use of contraception is influenced by the perceived likelihood and appeal of pregnancy, and relationship status. Contraception choice and uptake is influenced by women’s knowledge, beliefs and perceptions of side effects and health risks. Male partners have a strong influence on contraception uptake, as do the views and experiences of peers, and family members’ expectations. Lack of education and poverty are linked with low contraception use, and social and cultural norms influence contraception and expectations of family size and timing. Contraception use also depends on the availability of methods, the accessibility, confidentiality and costs of health services, and attitudes, behaviour and skills of health-care personnel.

It is clear that contraception has remarkably far-reaching benefits and is highly cost-effective. However, our synthesis shows that women worldwide lack sufficient knowledge, capability and opportunity to make reproductive choices, and health-care systems often fail to provide access and informed choice. Urgent action is needed at many levels, involving a range of stakeholders, to enable informed family planning choice, and enhance the life chances of women and their families.

Systematic review 2: effectiveness of interactive digital interventions for contraception choice, uptake and use

We completed a review of IDIs for contraception [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/137909/#/ (accessed January 2020)]. Our extensive search using Cochrane Collaboration systematic review methods found five randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of IDIs for contraception and one cost-effectiveness analysis. One RCT demonstrated a statistically significant impact of an IDI plus a tailored printout in comparison with a generic contraception leaflet on uptake of an effective birth control method [155/206 (75.2%) vs. 318/490 (64.9%); p = 0.008]. The same trial showed no difference between tailored and generic printouts of IDI results. It was not possible to combine any of the RCT results because of the risk of bias, or too few trials in each analytic group. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a facilitated IDI predicted eight fewer births per 100 women at an unadjusted cost of US$18,672 per prevented repeated birth.

We concluded that IDIs for contraception choice and use are feasible, and one high-quality RCT demonstrated a statistically significant impact on contraception choice. Access to, and information about, contraception is crucial to women’s health and well-being. IDI could play an important role in providing convenient, reliable and tailored information about contraception and support for choice of method.

Systematic review 3: effectiveness of face-to-face interventions for contraception and review of theoretical approaches to contraception decision-making

We synthesised the findings of 21 systematic reviews of interventions for contraceptive choice and use. A meta-analysis of eight RCTs found that motivational interviewing significantly increased effective contraceptive use up to 4 months post intervention, but without a later reduction in pregnancy. 17 A synthesis of eight trials of educational interventions (including written materials, audiotapes, videotapes, interactive computer games, contraceptive decision aid and feedback from a provider) found that they are effective for knowledge acquisition, but not for change in attitudes or behaviour. 18 Multiple interventions (combining educational and contraceptive-promoting interventions) significantly lowered the risk of unintended pregnancy among adolescents. 19

Contraception interventions based on theoretical constructs appear to be more effective than those not using theory. 20 Evidence suggests that the most effective behaviour change interventions are those that use multiple strategies to achieve multiple goals, including, for example, awareness, information transmission, skill development and supportive environments. Goal-setting and self-monitoring are important elements of many successful interventions. Behavioural interventions should be sensitive to audience and contextual factors, and recognise that most behaviour change is incremental and that maintenance of change usually requires continued and focused efforts.

Objective 2 (views of contraceptive service users and providers)

Recruitment

We invited young women to share their views on computer-based interventions for sexual health via focus groups and interviews [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/137909/#/ (accessed January 2020)]. Before recruiting from the five clinics involved in the project (a community pharmacy, a general practice, two sexual health centres, an abortion clinic and a maternity clinic), we first piloted the study materials with women who were students at University College London to make sure that the questions made sense and to test out the topic guide. Initially, we held a practice focus group with six students recruited from University College London to test the topic guide, make sure that women understood the questions and to make sure that the questions were suitable. Following this, recruitment started in each of the clinic sites. We placed posters [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/137909/#/ (accessed January 2020)] in each clinic waiting room and leaflets (reduced-size poster) were handed out by reception staff and a researcher, inviting women to take part. Eligibility criteria included being aged 15–30 years, having the ability to converse in English language and give informed consent, and having an interest in taking part in contraceptive research.

Six focus groups were conducted with 44 women recruited from a sexual health clinic, a general practice and a pharmacy. In addition, individual interviews were conducted with five women recruited from a maternity hospital, 12 women from an abortion clinic and eight women from a young person’s sexual health service. Individual interviews were preferred by women attending these clinics for the following reasons: women from the maternity hospital found it inconvenient to return to a focus group, women from the abortion clinic did not want to be identified in the focus group as having had an abortion and women recruited from the young person’s service were doubtful about returning for a focus group. The focus groups were conducted in university offices and the interviews were conducted in private rooms in each clinic. Each participant received a participant information sheet and provided written consent. Participants were offered £20 for taking part in the research, as a token of appreciation. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed, with participant permission.

Topic guide

At each interview and focus group, women were made aware of the nature of the research and the confidentiality of their data. Ground rules for focus groups were also agreed at the outset. Questions on the topic guide centred around (1) views relating to access, acceptability, uptake and adherence to contraception; (2) views on proposed research design of a future RCT; and (3) design and content of an IDI for contraception decision-making [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/137909/#/ (accessed January 2020)].

Analysis of qualitative data

Thematic analysis was used to identify patterns and links within the qualitative data. The data were coded and categorised by theme and relationships between different elements of the text were identified. There was discussion of the findings and coding decisions within the team. The data set was analysed as a whole, seeking consistency or contradiction in themes within and across transcripts. Data were interpreted in the light of the context they were collected.

Key findings

-

The most commonly expressed concern about contraception was the ‘unnaturalness’ of hormones contained in hormonal contraceptive methods.

-

Other commonly expressed concerns or anxiety about contraception related to infertility, irregular bleeding, having no periods, risk of cancer and side effects.

-

Many women think that it is unhealthy to skip periods.

-

Many women think that their bodies need a break from contraception.

-

Women do not have a good understanding of contraceptive side effects.

-

There is a strong tendency to underestimate contraceptive benefits and to overestimate contraceptive side effects.

-

Partners’ views are important to women.

-

Women like seeing honest videos of other women talking about their experiences of contraception.

-

Women dislike seeing a lot of text on a website and would prefer to have options to view more information if they wish to know more.

Views of health-care providers

Each site had a project lead who was recruited for interview. Other members of staff were recruited and interviewed on the suggestion of the leads. Fourteen health-care professionals were interviewed in total: three specialist (sexual and reproductive health) doctors, two GPs, two pharmacists, five nurses, one midwife and one receptionist. The interviews with health-care professionals gave rise to all the same issues raised by women themselves in relation to contraceptive knowledge, concerns and misperceptions. Other issues explored in interviews with health-care professionals were practical ones relating to the feasibility trial design and the practicalities of recruiting in clinics, such as access to Wi-Fi [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/137909/#/ (accessed January 2020)].

Objective 2 (review of YouTube videos)

As noted in Chapter 1, women increasingly turn to digital sources for information on health care, and contraception is no exception. The social media platform YouTube provides a source of ‘raw’ opinions that can include misperceptions about contraception. We therefore examined the views and concerns expressed by women on YouTube in order to identify common misperceptions that would need to be addressed through the Contraception Choices website.

A qualitative thematic analysis was conducted on contraceptive myths and misperceptions of 35 YouTube video clips and the video comment threads. The search terms used to locate videos were ‘birth control story’, ‘birth control experience’, ‘contraception story’, ‘contraception experience’, ‘contraceptive pill’, ‘hormonal pill’, ‘combined pill’, ‘intrauterine device’, ‘IUD’, ‘intrauterine system’, ‘IUS’, ‘patch’, ‘birth control patch’, ‘contraceptive patch’, ‘depo injection’, ‘depo-provera’, ‘implant’, ‘contraceptive implant’, ‘nuvaring’ and ‘natural family planning’. Thirty-five video clips matched the search terms; these had been posted up to a maximum of 5 years before carrying out this analysis (i.e. from November 2010 onwards) and all comments used for analysis had been posted within the last 24 months (i.e. from November 2013 onwards). Data analysis was completed once data saturation was reached.

The most common myths and misperceptions featured on YouTube included a fear of hormones, weight gain, needing a break from contraception, cancer, infertility, whether or not contraception causes moodiness and whether or not it is natural to have periods. Analysis of comments also revealed women’s concerns about what happens during appointments with clinicians, their fear of asking questions that might be considered ‘stupid’ and men’s views with regard to women’s contraceptive choices, which are rarely discussed in the published literature.

Objective 3 (applying the information from objectives 1 and 2 to identify the key design issues and content for an interactive website)

Website aims

The Contraception Choices website is designed to help women (and male partners) decide which method of contraception might suit them best, aiming to increase women’s satisfaction with choice of contraception and to encourage uptake of more effective contraceptive methods. The website aims to facilitate informed decision-making, which was conceptualised as a voluntary, well-considered decision that an individual makes on the basis of information and understanding about the advantages and disadvantages of possible courses of action, made in accordance with the individual’s beliefs. 21 Enacting a decision for contraception use will depend on factors outside women’s control (e.g. access to health care, availability of a chosen method, and attitudes of partners and others).

Contraception Choices takes as a starting point the concerns that influence women’s choices, and aims to provide honest information on the advantages and disadvantages of a range of contraception methods, featuring a decision-making tool from which tailored suggestions are presented, based on individual users’ priorities and preferences.

Guiding principles underpinning the Contraception Choices website

The website content is written from a sexual and reproductive rights perspective (i.e. people have a right to honest, straightforward information and freedom of choice regarding contraception, reproductive decisions and sexual well-being). The team believe that it is a woman’s choice if and when they get pregnant (acknowledging that there are many influences on this choice, including partners, family, community and religion). We also believe that it is up to women to decide which method of contraception suits them, and that health professionals’ role is to facilitate an informed choice without pressure or judgement. 22

Understanding the context and complexity of contraceptive decision-making

To understand the context and complexity of contraception decisions, we conducted systematic literature reviews, carried out qualitative fieldwork with the target website user group (women aged 15–30 years) and held an expert (health professional) website content workshop. The whole process is described in the following sections.

Literature review 1: factors influencing contraception choice, uptake and use

Findings

We synthesised the findings of 18 systematic reviews, which showed that pathways to successful contraception choice and use are complex, and strongly shaped by factors that are often outside individual women’s control. Use of contraception is influenced by the perceived likelihood and appeal of pregnancy, relationship status, knowledge, beliefs, and perceptions of side effects and health risks. Male partners have a strong influence on contraception uptake, as do the views and experiences of peers and family members’ expectations. Lack of education and poverty are linked with low contraception use, and social and cultural norms influence expectations of family size and timing. Contraception use also depends on the availability of methods, the accessibility, confidentiality and costs of health services, and attitudes, behaviour and skills of health-care personnel.

Implications for Contraception Choices website design

The website addresses women’s concerns in several different ways: succinct text (‘Contraceptive Methods’), question and answer format (‘Frequently Asked Questions’), videos (‘Video’) and an interactive decision aid (‘What’s Right for Me?’). Most of the content addresses women’s concerns and priorities, rather than the wider influences on women’s decisions. However, a section for male partners addresses men’s concerns about women’s use of contraception (‘Did you Know? For Men’). Two infographics acknowledge the complexity of factors that influence contraception choice, including method benefits and side effects, women’s priorities, partner views, friends, family, the media, wider society and experiences with health-care professionals (‘Challenges’ and ‘What Matters to Women?’).

Literature review 2: effectiveness of interactive digital interventions for contraception choice, uptake and use

Findings

We located five RCTs and one health economic analysis of IDI for contraception choice. 13–15,23–25 One RCT13 demonstrated a statistically significant impact of an IDI plus a tailored printout on uptake of an effective birth control method and another26 showed a statistically significant impact in preventing unintended pregnancy. The other trials were small and of low quality.

Implications for Contraception Choices website design

This review shows that digital interventions for contraception are feasible and promising, and that offering access in the waiting rooms of health-care facilities is appropriate. We incorporated a feature on the Contraception Choices website that allows users to export the personalised results of the What’s Right for Me? decision tool via e-mail or text message for later reference.

Literature review 3: effectiveness of face-to-face interventions for contraception and review of theoretical approaches to contraception decision-making

Findings

We synthesised the findings of 21 systematic reviews of interventions for contraceptive choice and use. A meta-analysis of eight RCTs found that motivational interviewing significantly increased effective contraceptive use up to 4 months post intervention, but without a later reduction in pregnancy. 17 A synthesis of eight trials of educational interventions (including written materials, audiotapes, videotapes, interactive computer games, contraceptive decision aid and feedback from a provider) found that they are effective for knowledge acquisition, but not for change in attitudes or behaviour. 18 Multiple interventions (combining educational and contraceptive-promoting interventions) significantly lowered the risk of unintended pregnancy among adolescents. 19

Contraception interventions based on theoretical constructs appear to be more effective than those not using theory. 20 Evidence suggests that the most effective behaviour change interventions are those that use multiple strategies to achieve multiple goals, including, for example, awareness, information transmission, skill development and supportive environments. Goal-setting and self-monitoring are important elements of many successful interventions. Behavioural interventions should be sensitive to audience and contextual factors, and recognise that most behaviour change is incremental and that maintenance of change usually requires continued and focused efforts.

Implications for Contraception Choices website design

The website content draws on several different theoretical models to prompt active, informed choice of contraceptive method (see Table 1). A key feature of motivational interviewing is that counselling starts with people’s own perspectives and seeks to help people find their own motivations for change. Young women’s perspectives and concerns are integral to the Contraception Choices website design and content, and advice is offered in a way that does not judge or blame women for their choices or situations.

| Issue to address | Website section or feature | Intended outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Need for accurate, balanced information on contraceptive method choices; concerns about side effects or harms; myths and misperceptions | Clearly presented information on 12 contraception methods, explaining pros and cons, benefits and mode of action [URL: www.contraceptionchoices.org/contraceptive-methods (accessed January 2020)] |

Accurate knowledge to support informed choice Less worry about potential side effects or harms |

| Inaccurate perceptions of the effectiveness of different contraceptive methods | Interactive infographic showing the likelihood of pregnancy with each method [URL: www.contraceptionchoices.org/infographic (accessed January 2020)] | Accurate portrayal of risk of pregnancy in a form that people can understand, to support informed choice |

| There are many contraception methods and it is difficult to retain comparative information | ‘Compare all’ contraception methods table with extra explanation on hovering [URL: www.contraceptionchoices.org/whats-right-for-me/table (accessed January 2020)] | Better ability to assess pros and cons of methods, to support informed choice by allowing easy comparison of method attributes |

| Peer views and experiences influence women’s contraception choices. Many women seek peer views online. Women have mixed experiences and trust in clinicians | Videos featuring young women and clinicians: personal experiences of young women who had used a variety of contraceptive methods; health-care professional responses to women’s concerns within the same video | To acknowledge women’s concerns through voices they trust (peers and clinicians) and to show how concerns might be addressed. Less worry about potential side effects or harms |

| Little knowledge or faith in the potential benefits of contraception. Disproportionate worry about side effects or harms | ‘Did you Know?’ [URL: www.contraceptionchoices.org/did-you-know (accessed January 2020)] and ‘Frequently Asked Questions’ [URL: www.contraceptionchoices.org/faqs (accessed January 2020)] sections. Honest information regarding benefits and concerns about contraception, to acknowledge and address women’s concerns and to showcase benefits of different methods | Accurate knowledge. Less worry about potential side effects or harms |

| Choosing and using contraception can be complex and difficult, and can be out of women’s immediate control |

‘Challenges’ infographic [URL: www.contraceptionchoices.org/did-you-know/challenges (accessed January 2020)] and ‘What Matters to Women’ infographic [URL: www.contraceptionchoices.org/did-you-know/how-body-works (accessed January 2020)] Infographics that acknowledge key factors that influence contraception choice and use: women’s priorities, method attributes, partner influence, friends, family, media, culture and experience in clinics |

Acknowledging that choosing and using contraception can be difficult. To draw attention to wider factors that may be influencing women’s decisions |

| Half-hearted use or non-use of contraception (through lack of access to informed choice) | What’s Right for Me? decision tool. Tailored decision aid, for users to input their preferences in terms of contraception attributes. Three ‘best-fit’ options are offered and compared side by side | Decision-aid to simplify the complex process of weighing up multiple pros and cons, offering information that is personally relevant. Increased motivation to seek a more suitable method |

| To provide a personalised record of contraception choice suggestions | Top three contraceptive method suggestions. Three top choices of method compared side by side and e-mailed or texted, if wanted | To facilitate recall of choices, and as a prompt for more informed discussions with clinicians |

| Most contraception methods need to be prescribed or fitted by clinicians | Clinic finder. Information on abortion services and support for domestic abuse | To support the next steps in acquiring a contraceptive method (i.e. clinic attendance). Resources for women seeking abortion or support with intimate partner abuse |

Qualitative fieldwork

As described above, our qualitative fieldwork focused on exploring women’s views and experiences of contraception, to understand their concerns, beliefs, myths and misperceptions, and views on how to harness the potential benefits of different contraceptive methods. We conducted interviews and focus groups with 74 young women and reviewed 35 YouTube videos and discussion threads (see Key findings).

Implications for Contraception Choices website design

All of these themes were reflected in the website content and design, addressing women’s beliefs, concerns, myths, misperceptions, contraception benefits and women’s views on design options, including section titles, colours, logo and interactive features. The website offers information using written, video-recorded and pictorial methods (including infographics) to address different preferences for communication of information and literacy. Text was presented in small chunks wherever possible (e.g. bullet points), with more information available as wanted.

Hypothesised mechanisms of change

The main issue addressed by the website is the risk of unwanted or unplanned pregnancy. Our logic model shows how the website content addresses factors that contribute to this, including a lack of accurate knowledge on contraceptive method choices; worry about side effects or harms; misperceptions about methods and their use; and little knowledge of or faith in the potential benefits of contraception [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/137909/#/ (accessed January 2020)]. The website aims to present relevant information; to address worry about procedures or side effects; to facilitate women’s ability to weigh up pros and cons of different methods (or no method); and to increase motivation to find (and obtain) a suitable method.

A key step in obtaining most contraception methods is to consult a health-care professional (either in person or online). The website exports a record of the three personal contraceptive method suggestions by e-mail or by text message to users’ mobile phones, if wanted. This is to facilitate recall and can be used as a prompt for conversations with clinicians. It was hypothesised that interaction with the Contraception Choices website before a clinical encounter could result in more informed discussions with clinicians, and shared decision-making, leading to contraception choices that are more likely to be effective and more likely to be satisfactory (if women are more actively involved in making choices). The website offers a clinic finder.

Objective 4 (co-developing the website with young women and professionals)

Expert (health professional) intervention content workshop

We held an expert workshop, inviting sexual health clinicians, researchers and e-health experts to contribute their views on the design of an IDI to help young women make contraceptive choices. Participants, who included Contraception Choices research team members and other experts in the field, were asked to propose and debate design features of a digital intervention, to try to reach a consensus [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/137909/#/ (accessed January 2020)]. We summarised debates on a Microsoft Excel® worksheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) to assess the pros and cons of each design decision. Decisions were made by the research team on the basis of congruence with the intervention aims, practicality and/or resources needed (for intervention development or for future maintenance). User views were sought for website design and content once draft ideas had been conceptualised.

Clinical content of the website

Information about individual contraceptive methods derives from guidelines produced by the UK Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare27 and textbooks. 22,28 The website authors (Julia V Bailey and Lisa Walton) are sexual health professionals who have extensive experience of prescribing contraception and addressing women’s concerns and queries in clinic settings.

Website development process

We recruited a software company, Moore-Wilson (Salisbury, UK), following a competitive tendering process. Moore-Wilson drew up website design ideas (wireframes) following team discussions about possible options. Front-running designs were discussed and refined by women in focus groups run by Anasztazia Gubijer, with design and content also discussed via an e-mail user group. Website content was written by Julia V Bailey and Lisa Walton first in Microsoft Word documents (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and/or directly into the website content management system. For each content feature, there were several design iterations involving the software company, the research team and target users.

For the video section, we sought freely available YouTube videos that provided accurate information about different contraception methods. We did not find suitable videos for every method, or for all of women’s main concerns, so we shot our own films in a digital media studio. We filmed individual interviews with six young women who described their own experiences of using contraception. Julia V Bailey then noted the exact time codes for each topic discussed (i.e. specific benefit or problem with a method). Selected interview excerpts were then played back to clinicians who were filmed responding to each concern with advice from their clinical experience.

A scoring algorithm was developed by Julia V Bailey for the ‘What’s right for me?’ decision aid, based on evidence of the likelihood of experiencing a particular effect or side effect with each contraception method, in terms of amenorrhoea or regular periods, lighter or less painful periods, impact on acne or premenstrual syndrome, effort involved in remembering a method, presence of hormones and immediate reversibility. If methods scored exactly the same following women’s choices within the tool, scores were weighted so that the more effective methods were displayed first.

To see the final Contraception Choices website please visit www.contraceptionchoices.org (accessed January 2020).

Information on contraceptive methods

The ‘Contraceptive Methods’ section features information on pros and cons of methods presented in bullet points, with more information available on benefits and side effects, and tips on how to use each method.

The ‘Effectiveness’ infographic is interactive, displaying the risk of pregnancy for ‘typical use’ of each contraceptive method and comparing with risk of pregnancy if using no contraception.

The ‘Video’ section features educational YouTube videos and short films of young women expressing their views and experiences of contraception, followed by clinician explanations on specific topics.

The ‘Did you Know?’ section addresses women’s most common concerns about contraception.

The ‘Frequently Asked Questions’ section is organised as answers to questions, which show which methods have specific benefits (e.g. lighter, less painful periods).

Interactive tailored decision aid

The ‘What’s Right for Me?’ tailored decision aid takes into account women’s priorities concerning contraception attributes and potential benefits to suggest three methods of contraception to suit their preferences. Hovering over the image of each method offers a very succinct summary of method attributes, and the tool allows users to see the effect of their choices after each question. For example, selecting ‘regular periods’ highlights the methods that are compatible with regular periods and fades out the methods that can alter the menstrual cycle. The top three results are presented side by side, allowing comparison of the main contraception attributes. If a suggested method is ‘binned’, the next in the list will be displayed. Results can be exported by e-mail or by text message if a user wishes.

Further information section

Under the tab ‘COVID-19’, the Contraception Choices website features links to several other websites, such as Find a Sexual Health Service on the NHS website [www.nhs.uk/service-search/other-services/Sexual-health-information-and-support/LocationSearch/734 (accessed 18 June 2020)].

Additional evaluation of Contraception Choices

In parallel with the Phase II study, a further formative evaluation of Contraception Choices was conducted by a Master of Science (MSc) student, Xia Zhou, who was studying human–computer interaction. This study showed that Contraception Choices compared favourably (on qualitative measures) with other web-based tools that support contraception decision-making and highlighted a few areas in which the interaction design could potentially be improved. However, as this was a small-scale study, the findings need further validation, which was outside the scope of this project. See https://uclic.ucl.ac.uk/content/2-study/4-current-taught-course/1-distinction-projects/1-17/zhou_xia_2017.pdf (accessed 18 June 2020) [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/137909/#/ (accessed January 2020)].

The findings from the following sources of evidence therefore informed the Contraception Choices website content (Table 1):

-

systematic literature reviews

-

women’s priorities and concerns (YouTube study and qualitative fieldwork)

-

user design preferences

-

clinical evidence and guidelines: UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (www.fsrh.org/ukmec/) and Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare clinical guidelines (www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/current-clinical-guidance/)

-

clinical expertise.

Chapter 3 Phase II: evaluation trial of the website

Methods

Original feasibility trial design (objectives 5 and 6)

This was an individually randomised, parallel-group trial.

Setting

Study sites were recruited to represent the health-care settings that provide the great majority of contraceptive care in the UK (Table 2).

| Category | Name | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Sexual and reproductive health service | MPC | Capper Street, London, UK |

| Sexual and reproductive health service for young people | Brook | Brook clinic, Euston, London, UK |

| Abortion service | BPAS | Romford Road, Stratford, London, UK |

| Community pharmacy | Green Light Pharmacy (Shepherd’s Bush) | Uxbridge Road, London, UK |

| Maternity service | Ashford and St Peter’s Hospitals NHS Foundation Trusta | St Peter’s Hospital, Guildford Road, Chertsey, Surrey, UK |

| General practice | General practice (Camden and Islington) | Clerkenwell Medical Practice, Finsbury Health Centre, Pine Street, London, UK |

Inclusion criteria

Women were included if they were aged 15–30 years with a need for current or future contraception, were attending one of the study sites, were able to read English, and had an active e-mail account and access to the internet.

Exclusion criteria

Women were excluded if they were unable to provide informed consent (e.g. severe learning difficulties) or if they needed a language advocate to understand English, as the intervention content was intended to be accessed in private.

The intervention

At the end of Phase I, using evidence from systematic reviews, women’s views on social media, an expert workshop, and interviews with women and health professionals, we had created a trial-ready, self-guided website that presents a number of contraceptive options in response to input of women’s preferences and concerns. The website has four main components: (1) general information on contraception and method-specific information, including contraceptive benefits, side effects and other common concerns; (2) an interactive tool to help women choose a method of contraception, which provides individually tailored results; (3) videos of women and health professionals discussing contraceptive experiences, concerns and misperceptions; and (4) a page offering a link to NHS clinic finders and other useful resources, such as further information on sexual health, and websites offering support and advice about sexual abuse.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

-

Follow-up rate at 6 months.

Secondary outcomes: quantitative

-

Recruitment rate. Measured via the trial website as the time taken to recruit (up to 80) women at each site.

-

Effectiveness of contraceptive method in use at 6 months. Measured by response to study outcome questionnaire and grouped as follows: from least to most effective; no method; withdrawal or natural method; condoms or diaphragm; pill, patch or ring; LARC or sterilisation.

-

Change in method between baseline and 6 months, indicating whether any change is to a method of greater, lesser or similar effectiveness (based on grouping above).

-

Pregnancy by 6 months. Measured at 3 and 6 months by response to study outcome questionnaire.

-

Sexually transmitted infection diagnosis by 6 months. Measured at 3 and 6 months by response to study outcome questionnaire.

-

Health service and out-of-pocket costs for contraception and other sexual health services. Measured at 3 and 6 months by response to study outcome questionnaire.

Secondary outcomes: qualitative

-

Patient views and experience of the intervention and trial procedures, assessed through qualitative interviews at 2 weeks after randomisation with five women at each study site (total 25 interviews [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/137909/#/ (accessed January 2020)]. The questions explored included:

-

Are the online trial procedures acceptable to participants? For example, the process of online registration and consent, the receipt of incentives, completing online questionnaires, contact and follow-up by e-mail and text?

-

What are women’s views of the intervention?

-

How might trial procedures be improved to optimise retention in a full-scale trial?

-

-

Provider views about impacts on the service and trial procedures, assessed through qualitative interviews with up to 15 key staff (up to three per site), sampling those who have roles in facilitating the study in each setting (e.g. receptionists, practice managers, nurses, midwives, doctors and pharmacists) [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/137909/#/ (accessed January 2020)]. The areas explored included:

-

Are recruitment procedures acceptable to staff?

-

How might recruitment procedures be improved to optimise recruitment to a full-scale trial?

-

Staff views on the feasibility and usefulness of a contraception decision website in each clinic setting?

-

Sample size

The original target sample size of 80 participants in each of the settings was based on estimating an expected follow-up rate at 6 months (primary outcome) of 70%, to within 10% precision [95% confidence interval (CI) 60% to 80%], for each setting. This sample size also provided 80% power to detect a statistically significant difference (at the 5% level) in the follow-up rate between two settings if the true difference is 22% (e.g. 59% vs. 81%). By pooling data across settings, this sample size would also provide 80% power to detect a statistically significant difference (at the 5% level) in the follow-up rate between the intervention and standard arms if the true difference is 15% (e.g. 62.5% vs. 77.5%). The expected follow-up rate was based on a previous sexual health study that recruited and followed up the participants online (Sexunzipped29).

Baseline survey

Participants were asked to complete a short questionnaire at baseline before randomisation [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/137909/#/ (accessed January 2020)]. This included:

-

demographic data (age, ethnicity, highest completed level of education) and whether or not English was their first language

-

current use of contraception, or reasons for non-use, including being pregnant, type of method [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/137909/#/ (accessed January 2020)], from where the method was obtained, including whether or not obtained online and if paid for

-

satisfaction with current contraception (very satisfied, satisfied, neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, dissatisfied and very dissatisfied)

-

if ever used different methods (same list as current use)

-

diagnosed sexually transmitted infections in the last 3 months [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/137909/#/ (accessed January 2020)].

Follow-up surveys

At follow-up, at 3 and 6 months, participants were asked what method of contraception they were using (including none) and how satisfied they were with the method; whether or not they had had a pregnancy and, if so, the outcome of the pregnancy (ongoing, gave birth, miscarried, terminated, or prefer not to say); and if they had a diagnosed sexually transmitted infection.

All participants were asked whether or not they had visited the website (control participants were asked to assess ‘contamination’) and if being in the study had resulted any good or bad effects on their life.

Intervention group participants only were asked how helpful the website was for getting useful information about contraception and how helpful it was for finding a method of contraception that is right for them; whether or not they had discussed the website with anyone, including a doctor or nurse, pharmacist, partner, family or friends; and what they liked or disliked about the website.

Procedures: recruitment in clinics

Recruitment, completion of the baseline survey and randomisation were all accomplished online using bespoke trial software, but the process was initiated while the participant was attending one of the study clinics. Participants randomised to the intervention group were immediately given access to the website, whereas women randomised to the control group were thanked for their participation and then received standard contraceptive care only. All women in both intervention and control groups were asked by automated e-mail to complete the same outcome questionnaires online at 3 and 6 months. The control group was offered access to the intervention website at the end of the study (after 6 months’ follow-up).

On arrival at each study site, women were given a flyer about the trial by the reception or research staff with very brief information about the study, indicating the inclusion criteria. The same information was available on posters in waiting rooms and clinic rooms [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/137909/#/ (accessed January 2020)]. Clinic staff were asked to direct women who were interested in the study to a member of research staff or directly to the tablet device.

In the feasibility trial, the website was displayed on a tablet computer as it was designed to be available in clinic and integrated into the clinic pathway, as well as being accessible online at any time. It is accessible on mobile phones as well as desktop computers. The trial software was set up to allow participants to go through the steps of screening, consent, automatic randomisation, data collection and intervention viewing without assistance from the staff, although in practice this process was nearly always guided by the researcher. We did not use individual identifications or passwords, as recruitment in a previous study of sexual health websites had been hampered by enrolment procedures that patients found onerous and time-consuming. Consequently, we streamlined the online trial software as much as possible and minimised the number of questions asked at baseline and follow-up [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/137909/#/ (accessed January 2020)].

Participants who agreed to participate gave their contact details (compulsory e-mail address and optional telephone number and postal address) for follow-up surveys. They were given electronic vouchers for completing follow-up surveys (£5 for the survey at 3 months and £15 for the survey at 6 months). All follow-up e-mails included a link to allow participants to withdraw from the study, including one sent immediately after enrolment.

Randomisation procedures

A randomisation list was generated by a random number-based algorithm in the computer software Stata® (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and incorporated into the trial software program to allocate all participants to either the intervention group or the control group. The randomisation list was stratified by setting and using varying block sizes. Allocation was immediate (online) and concealed.

Participants allocated to the intervention condition were directed straight away to the Contraception Choices website. Those allocated to the control condition were notified that they had not been selected to view the website until the end of the trial. All participants were reminded that they would be contacted again in 3 and 6 months to gather follow-up data.

Follow-up procedures

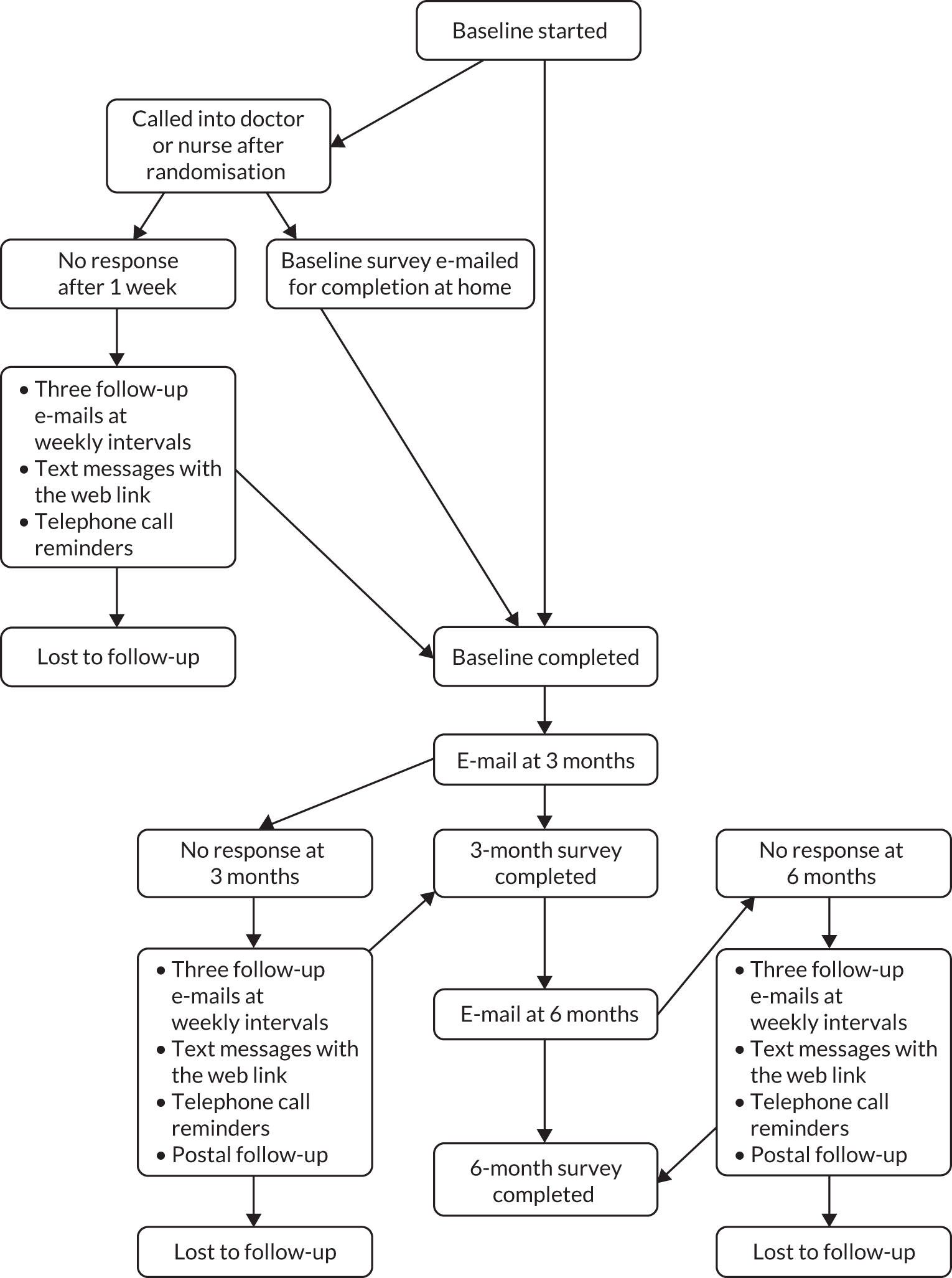

As described in Figure 1, follow-up was automated through e-mail and text messages. If there was no response to e-mails or texts, the researcher telephoned participants to remind them to complete the follow-up surveys:

-

automated e-mail, with three further follow-up e-mails at weekly intervals

-

two text messages (if mobile phone number supplied) at the same time as the last two e-mails

-

three telephone calls (if mobile phone number supplied) in 1-week intervals after the final e-mail.

FIGURE 1.

Follow-up procedures in feasibility trial.

Study timeline

The planned duration of the feasibility trial was 15 months [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/137909/#/ (accessed January 2020)]:

-

6 months’ recruitment (based on the large number of patients attending each of the study sites, and an estimated proportion of 20–30% agreeing to take part, given previous experience of similar studies and the financial incentives offered)

-

6 months’ follow-up

-

3 months’ analysis of quantitative and qualitative data.

Phase I took longer than anticipated, largely because of the lengthy process of obtaining research permissions. During Phase II, we were awarded a 6-month no-cost extension when the feasibility trial changed to an efficacy trial.

Trial process evaluation

In addition to obtaining women’s views on the website itself, we assessed women’s experiences of taking part in an online study of contraception. This formed an early part of the feasibility study and the findings were intended to inform the subsequent feasibility trial.

Aim

To explore women’s experiences of taking part in an online study of a contraception website and to use the information to improve the subsequent trial design as appropriate.

Methods (trial procedures, rapid follow-up, then interviews)

We recruited 18 women from all the clinic sites to take part in an ‘expedited’ study of the website, followed by an interview to explore their experiences. Unlike the subsequent recruits, who were randomised to the intervention or control group, all of the early participants were assigned to the Contraception Choices website and followed up by e-mail 1 week after recruitment, rather than 3 and 6 months later. This method enabled us to gain information about the website and the trial procedures in a short time, so that we could make any necessary changes before starting the main recruitment. It also meant that participants had a shorter time period over which to recall their experiences, which should enhance the reliability of their recollections. As these early participants were not randomly allocated to the intervention or control group, they were not included in the randomised trial.

Findings

The main reason for agreeing to take part was an interest in finding out more about contraception. Participants found registering for the study on the tablet computer ‘quick’ and ‘easy’ and the information provided ‘clearly written’ so that they understood what the study was about and what they were agreeing to. Most participants felt that it was appropriate and acceptable to be approached about the study in a clinic waiting room. When asked what they felt about the topic of contraception and pregnancy, women commented that they were:

Open to it . . . like being in the clinic anyway, you kind of expect to, to talk about it . . . it’s quite comfortable . . . it wasn’t really that weird to talk about it.

One participant recruited from the abortion service felt ‘mixed’ about being asked about contraception and pregnancy at the time:

I don’t really know I think I was quite mixed there because I was definitely like not, well I guess I was just like cursing myself at the time I was like this is something I should have thought about before.

In general, participants did not have concerns about providing their contact details (telephone number and e-mail address) and understood that they were giving them so the research team could send them the follow-up questionnaire and contact them to arrange an interview. Once recruited, participants found it convenient to be contacted about the study by e-mail, text and telephone.

All participants, when asked, reported that they would take part in the study again.

Conclusions for the trial

Given the overall positive findings from these early recruits, we concluded that there was no need to make changes to the feasibility trial design.

Transition from feasibility to efficacy trial (modified objective 7)

As noted above, the immediate popularity of the Contraception Choices website with young women and contraception providers convinced us to ‘expand’ the feasibility trial into an efficacy trial. To achieve this, we increased the recruitment target and changed the primary outcome from a feasibility measure (6-month follow-up rate) to clinical outcomes that were originally secondary outcomes in the feasibility trial, resulting in two primary outcomes: (1) use of LARC at 6 months and (2) satisfaction with contraceptive method at 6 months.

In addition to the 400 women recruited to the feasibility trial, we planned to recruit another 530 women from one site only, the MPC, via its routine online booking system. We estimated that a total of 930 participants would be sufficient to detect an (82% power) increase in uptake of long-acting methods from 35% to 47%, assuming a follow-up rate of 70%. No formal calculation was made for the other primary outcome – satisfaction with method.

When women request an appointment for contraception at MPC, they are routinely directed to the trust website to book their appointment. Once an appointment is booked, the patient receives a text message confirming the date and time of their appointment. For the efficacy trial, we inserted into the routine text an invitation to take part in contraception research by clicking on a hyperlink. Clicking on the hyperlink took women to the trial recruitment home page from where all procedures were the same as those described above.

Statistical analysis

For the efficacy trial, the analysis focused on the effect size for the key clinical outcomes that became primary outcomes: use of a LARC method at 6 months and satisfaction with contraceptive method at 6 months.

The primary analysis is by modified intention to treat, basing analysis on those who complete at least one follow-up outcome questionnaire. For each outcome listed above, we present the percentage of participants if the outcome is binary (e.g. use of LARC) or ordinal (e.g. effectiveness of method, satisfaction with method) together with a 95% CI. These percentages and means are reported separately by intervention and standard care arm.

To formally assess differences between arms, we use logistic regression (for binary outcomes) or ordinal logistic regression (for ordinal outcomes), reporting adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs.

The primary outcome of LARC use at 6 months is analysed among women in need of contraception (not pregnant or currently trying to become pregnant) and the primary outcome of satisfaction with method is analysed among women who are using a method at 6 months. The primary outcome of LARC use at 6 months is analysed stratified by LARC use at baseline, leading to three intervention effects: (1) the effect in baseline LARC users, (2) the effect in baseline non-users and (3) the overall effect adjusted for baseline LARC use. Assuming that < 90% of baseline LARC users in the control arm are using a LARC method at 6 months, the primary effect measure is the overall adjusted intervention effect. If, conversely, > 90% of baseline LARC users in the control arm are using a LARC method at 6 months, the primary effect measure is the intervention effect in women not using a LARC method at baseline, because there would be little possibility of increasing LARC use through the intervention in baseline LARC users. Besides adjustment for baseline LARC use, analysis of both primary outcomes is also adjusted for satisfaction with method at baseline and setting. A further subgroup analysis is also presented for both primary outcomes to assess, based on testing an interaction term, whether or not the effect of the intervention varies by setting.

Primary comparisons for the primary outcomes between arms are based on multiple imputation, for which the primary outcomes at 6 months are imputed based on the outcomes at 3 months for those participants who completed the 3-month outcome questionnaire but failed to complete the questionnaire at 6 months. Imputation was conducted using the chained equations approach and implemented using the mi impute function in Stata; 20 imputed data sets were generated.

A post hoc decision was made to conduct a ‘per-protocol’ analysis for the primary outcomes based on a comparison of intervention arm participants who reported seeing the Contraception Choices website with all control arm participants.

Costs of contraception and budget impact analysis

The primary analysis is a budget impact analysis of the website and contraception reporting the total costs to each payer [NHS (primary care vs. secondary care), local government, private and out of pocket]. This will be reported as the total cost of contraception and pregnancy outcomes for a range of different population sizes. The analysis conforms to the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) good practice guidelines for budget impact analysis. 30

Costs include the cost of contraception (NHS and out-of-pocket costs), including the cost of LARC, sexual health service use, sexual health-related primary and acute care use, and the cost of pregnancy-related outcomes. Resource use collected as part of the trial is costed based on published sources including Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) reference costs31 and the British National Formulary. 32 Details for unit costs are reported in Table 3. For contraception, when there is more than one option, for example the different types of the combined pill, the lowest-cost option of (1) the option recommended by the NHS or, if not available, (2) the most commonly taken was used to determine the cost used. Out-of-pocket costs are costed at the same value as publicly financed costs except in the case of condoms, in which case it is assumed that three are given out by the NHS or other community sexual health services, but that people buy a pack of 24 if bought out of pocket. All costs are reported in 2016/17 Great British pounds.

| Resource | Unit cost (for 3 months for medication) (£) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| General practice | 31.00 | PSSRU31 |

| Sexual health clinic | 121.12 | Reference costs34 |

| Young persons’ clinic (assume NHS band 5 nurse) | 12.00 | PSSRU31 |

| Pharmacy | 8.80 | PSNC35 |

| Gynaecology | 140.93 | Reference costs34 |

| Combined or unknown pill [ethinylestradiol with norgestimate (Cilest)] | 7.16 | BNF32 |

| Mini pill [desogestrel (Cerazette)] | 2.75 | BNF32 |

| Contraceptive patch [ethinylestradiol with norelgestromin (EVRA)] | 19.51 | BNF32 |

| Vaginal ring [ethinylestradiol with etonogestrel (NuvaRing)] | 29.70 | BNF32 |

| Pack of condoms (24 pack) | 11.99 | Boots36 |

| Condoms (three free per 3 months) | 2.29 | Boots36 |

| Female condoms (pack of five) | 5.99 | Amazon37 |

| Emergency contraception [ulipristal acetate (EllaOne)] | 14.05 | BNF32 |

| Diaphragm | 10.21 | BNF32 |

| Injectable contraception [medroxyprogesterone acetate (Provera)] | 6.01 | BNF32 |

| Implant [etonogestrel (Nexplanon)] | 83.43 | BNF32 |

| Intrauterine system [levonorgestrel (Mirena)] | 83.43 | BNF32 |

| Intrauterine device: copper | 8.95 | BNF32 |

| Vasectomy | 829.57 | Reference costs34 |

| Female sterilisation | 2416.00 | Reference costs34 |

At 6 months, participants were asked if they had become pregnant in the past 6 months and the outcome of the pregnancy. The cost of termination is costed as the weighted costs for all terminations in the NHS (£840 reference costs). The cost per miscarriage and cost per full-term pregnancy were taken from Public Health England33 contraception return on investment analysis at £653 and £5735 per pregnancy, respectively.

The cost of the website includes ongoing maintenance costs and how these might be incurred by organisations that wish to use the website in the future. This cost is reported for a range of different population sizes.

In addition to the budget impact analysis of total cost for each payer, we report descriptive statistics for each cost type. We calculated the average total health-care cost of contraception per participant for the website compared with current practice at baseline and 6 months. The 95% CIs for each analysis are reported based on linear regression adjusting for baseline and site and bootstrapping with bias-corrected adjustment.

As there is limited information available on the number of free condoms that women obtain from the NHS every 3 months, we assumed cost containment and the minimum number per pack (three condoms). We have included a sensitivity analysis in which this number is increased to 12 every 3 months, the number available on a condom card, at a cost of £9.99 every 3 months.

Ethics issues

In describing the ethical issues to the Research Ethics Committee, we included the following points:

-

We did not foresee major ethical issues or risks associated with asking individual participants or groups of women (focus group discussions) about access, acceptability and adherence to different methods of contraception, or the likely features of an IDI that might help them make better contraceptive choices. Nonetheless, all interviews and focus groups were facilitated in a sensitive manner by experienced researchers, setting out ground rules at the start for mutual respect and non-judgemental stances about lifestyle or behaviour choices.

-

It is important to include women aged 15 years, as around one-fifth to one-third of women have had sexual intercourse before the age of 16 years and the intention was to help inform young women’s first thoughts and choices about contraception. A substantial proportion of women attending community pharmacy and specialist contraceptive services, in particular, are aged 15 years.

-

We assessed capacity to consent to the research by offering written study information and by answering any queries about the research. Young women wishing to discuss this with parents or others first were encouraged to do so. We did not require parental consent, as young women may be excluded from the research if parental consent was required.

The study was approved by London – Camden & King’s Cross Research Ethics Committee and by the Health Research Authority, including substantial amendments (reference 17/LO/0112).

Chapter 4 Trial results

Recruitment

The first participant was randomised on 4 July 2017 and the last on 22 December 2017.

The first recruitment through the MPC online central booking service was on 31 October 2017 and the last on 22 December 2017.

Recruitment online was much faster than in the clinics. It took approximately 6 months to recruit 400 women from the clinic sites, as originally planned; we recruited 530 women via the online booking system in just over 7 weeks.

Follow-up

The last follow-up survey was completed on 16 August 2018.

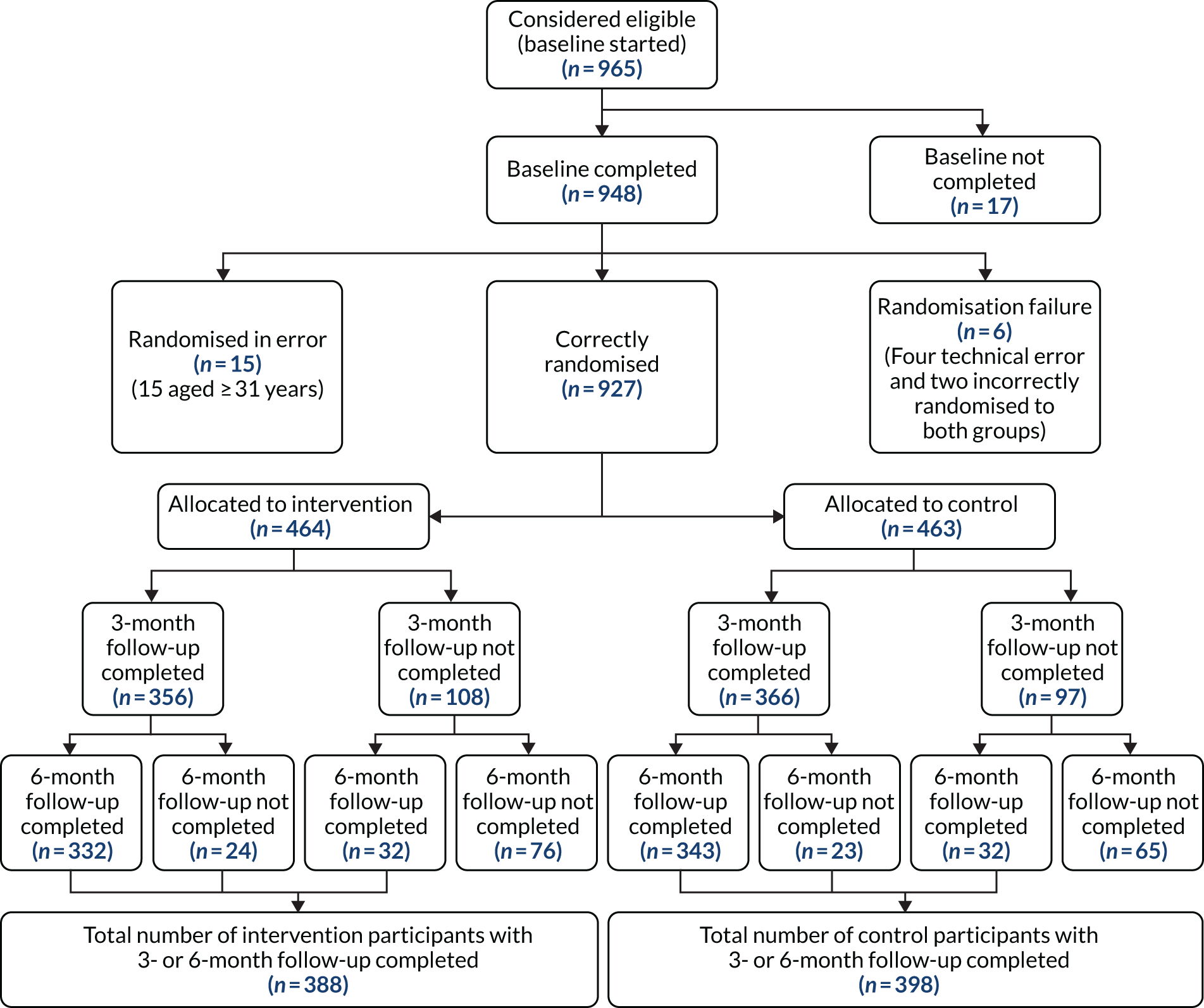

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram (Figure 2) details the flow of participants through the trial.

FIGURE 2.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram. Reproduced with permission from Stephenson et al. 38 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) which permits any use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages (https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage). The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

In total, 927 women were randomised to the website (n = 464) or to the control group (n = 463), of whom 739 (80%) provided follow-up data at 6 months and 786 (86%) provided data at 3 and/or 6 months for analysis of primary outcomes with imputation.

Follow-up rates were similar across all sites (data not shown), except the British Pregnancy Advisory Service (BPAS), for which the follow-up rate was only 50%. Women often gave incorrect contact details that prevented follow-up.

The quality of the survey data collected was exceptionally high, with nearly 100% of women responding to the follow-up questionnaires providing the primary outcome data.

A total of 19 women (2%) withdrew from the trial: 11 from the intervention group and 7 from the control group. They did not offer reasons for withdrawing.

Qualitative findings

Over four-fifths of participants in the intervention group provided free-text comments in the follow-up surveys at 3 and 6 months. All free-text comments were coded and analysed using thematic analysis. Comments about the website were overwhelmingly positive, with a few neutral comments from women who were already well informed. The only negative comments were from women with medical conditions, such as polycystic ovary syndrome, who did not find information specific to their condition.

The following themes and subthemes emerged.

Information/website content

Evidenced-based and trustworthy information

As a trainee GP myself I would definitely sign post people to this website in the future when discussing contraception.

Increased knowledge and awareness about contraception

I feel very well educated thanks to the website – I wish someone had explained about all the different choices years ago.

Honest information about pros and cons

It’s nice to get an overview of all contraception options out there, the pros and cons, so you can review them in your own time.

Tailored information

This website ensures girls can get the best contraception for THEM and only them.

Informative after having a baby

I have just had a baby, however, in the next few months I believe that I will be looking at contraception and it [website] will be useful.

Website improvement suggestions

I wish it had more tips on dealing with difficult conversations that can happen or knowing your rights (like what to do if your GP won’t allow you to have the method you want, or tries to convince you that one type is better because it’s cheaper) [sic].

Design and format

Visual aesthetics

The interface is easy to use and aesthetically pleasing.

User-friendly

I love the simplicity of the website. It’s easy to find the method of contraception you’re interested in. It’s informative and it’s very quick finding what you need.

Easy to understand

The language is clear and simple, which is very helpful when English is not your first language.

Accessible at any time

I like that I can research safe and comfortable with reliable information from my own home.

Health professional interaction

Women felt more empowered to speak to their health professionals

It has made me feel more confident. Prior I didn’t really have anyone to speak to about contraception and I didn’t feel comfortable discussing it with my doctors so this bridged the gap.

Aiding appointments

[Using the website at home meant] more time to consider options without feeling pressure to pick something that might not be the best option.

Reported impacts of the Contraception Choices website

Changing or considering swapping to a new contraceptive method

I think it’s [the website] got me thinking more about which contraception I should use. I’m quite happy with my pill and currently not sexually active, but I do think I would like to switch to a LARC if I am in a relationship again.

Changing behaviour due to having misperceptions addressed

It’s cleared up some of my doubts and things I worried about (probably unconsciously!) about hormonal contraception.

Reminders to act

If anything the e-mails have been a helpful reminder to sort a more permanent solution for my contraception needs.

Discussing the website with others

It’s [the website] helped me be more open about contraception and discuss it with friends. It’s become less of a taboo.

Health service barriers to accessing contraception

Lack of appointments/long waiting times

Long waiting times. GP did not offer the services to get implant fitted. Lack of sexual health clinics in my area means very long waiting times.

Lack of services offering long-acting contraception methods

Very difficult to find an appointment to have an implant replaced due to GPs no longer offering this service. Spent 2 full days off work waiting in clinics but was not seen. Implant was 1 month out of date before I was able to book an appointment.

I wanted the coil but I found it difficult to find someone to fit it in London.

Being part of the study