Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/29/01. The contractual start date was in January 2016. The draft report began editorial review in March 2019 and was accepted for publication in March 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Abel et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Extent of the problem

Better care means that people of reproductive age who suffer from a mental illness are more likely to start families and become parents. 1 Consequently, the number of children and adolescents living with experience of significant parental mental illness may be increasing. Population data from the UK seem to bear this out. Abel et al. 2 report a significant increase in the prevalence of children and adolescents living with serious parental mental illness (CAPRI) in the last 30 years. In 2007, the number of children in the UK exposed to a mother with a mental illness diagnosed in primary care was 22.2%. By 2017, this figure had increased to 25.1%. Over the same period, the proportion of children exposed to maternal non-affective psychotic disorder such as schizophrenia increased from 0.16% to 0.20%, and the proportion living with maternal affective psychotic disorders increased by 50% (from 0.25% to 0.37%). Currently, by the time a child reaches the age of 16 years, there is a 53% chance that their mother will have experienced a mental illness that has come to services’ attention. 2

These findings suggest that parental mental illness is an increasingly common factor in the lives of children in the UK (note that these figures exclude paternal mental disorder burden). Therefore, given the scope and magnitude of the problem, and with similar estimates reported elsewhere (e.g. Australia,3 the USA,4 Canada5), the need for better information and more resources to support these young people has never been greater.

Improving the lives of CAPRI has become an urgent public health priority. 6,7 This vulnerable group is likely to experience significant difficulties on a daily basis and throughout their lives,8–10 as a result of which they are likely to suffer a poorer quality of life and utilise services more than children living with ‘healthy’ parents. 11,12 Recent epidemiological data13 show that CAPRI average one more general practitioner (GP) or nurse consultation per year than their peers, and the excess health utilisation cost to the NHS has been estimated at £652M per year. These combined facts present a strong public health argument for better early and preventative care.

Mechanisms of risk

As a group, CAPRI have, overall, been reported to show poorer outcomes than their peers across a range of domains. 14 Mechanisms of this effect vary depending on the outcome, but include social influences of multiple deprivation and life stressors,14 lack of parental support15 and parental difficulties in combining the management of their own mental health with caregiving for their children. 16,17 Such environmental effects interact with genetics,18 as well as with in utero19 and obstetric events;20 consistent reports find an association between prenatal maternal conditions, including psychopathology, and offspring neurodevelopmental abnormalities. 21 Direct effects of parental mental illness may vary and may be less detrimental than the social adversities associated with mental illness, such as poverty, multiple deprivations, living in a single-parent family and repeated parent–child separations. 22,23 Greater exposure to family discord and parental hostility is also reported to increase risk;24 one study25 reports that children of depressed mothers with antisocial personalities fare much worse than children of mothers with depression alone. Other important factors, such as parentification, neglect, maltreatment and domestic violence, compound unmet developmental needs. 6,26

Although it remains unclear how age interacts with CAPRI risks, timing of parental mental illness and associated adversity across a child’s life is likely to be important; early exposure may mean that children are exposed for longer, whereas exposure during adolescence may influence critical developmental periods. Evidence suggests that vulnerability exists during pregnancy,27 infancy,28 throughout childhood and adolescence24,29 and into adulthood. 30,31 This means that CAPRI may be exposed to a clustering of multiple adverse influences over time22,26,32 and, in many cases, effects are additive or interactive with independent direct effects of parental mental illness. 25,33,34 But the well-being of these young people should not be seen as corresponding to ‘the ebb and flow of parental mental health’, as child difficulties may persist long after parental symptoms abate,24 although risk heightens when the parent experiences hospitalisation or an acute phase of illness. 35 This especially affects children who do not have another parent or relative to look after them when this occurs. 3,35,36

Most research on the relationship between parental mental illness and adverse child outcomes revolves around the mentally ill mother,37 but evidence on the independent effects of paternal psychopathology is increasing. 38,39 For example, in their early years, children with depressive fathers are twice as likely as unaffected children to develop behavioural and emotional problems. 40 In adolescence, the effect of having a father with depression either parallels41 or outstrips the effect of having a mother with the same condition, the latter being more influential earlier on in terms of shaping child outcomes. 42

It should be noted that, even with this evidence, we cannot assume that all the same factors act as promoters or protectors in relation to all outcomes in all individuals. Rather, it is likely that many individuals show resilience across a range of circumstances and across a range of outcomes, whereas some show little resilience in few and not in all circumstances (for further discussion see Rutter,43,44 and Cicchetti and Curtis45).

Implications for CAPRI lives

With these caveats in mind, evidence suggests that CAPRI do less well across a range of life outcomes than their peers. 7 These outcomes include poorer physical health46–49 and more behavioural and emotional difficulties,9,10 which also contribute to poorer educational outcomes. 50–52 Entering adulthood, there is greater susceptibility to socioeconomic difficulties, alcohol/substance misuse and premature death. 31,53 Health care and mental health service utilisation is significantly higher among CAPRI. 11,12 Whether this always reflects greater ill health or more need for support by parents is unclear.

Living with parental mental illness also places a demonstrable strain on quality of life. CAPRI frequently grow up in environments of high family conflict,54 stress,55 and maltreatment and neglect,6,26 all of which amplify risks for impaired social functioning. 56 Several studies demonstrate that CAPRI experience more severe interpersonal difficulties than their peers, including rejection, victimisation and not being liked. 30,31,57 This vulnerable group is reported to show higher levels of internalisation of problems (manifesting as, for example, anxiety, crying, withdrawal or quietness) that make socialisation difficult and can lead to stigmatisation or bullying by other children. 56,58 In addition, CAPRI suffer socially because of parents’ potential inability (or unwillingness) to support their child’s engagement in social activities. This may deprive children of opportunities not only to make friends, but also to take part in school/afterschool activities or sports teams that would improve their interpersonal skills. 56,59,60 CAPRI may assimilate maladaptive social parental behaviours, which influence interactions with their peers outside the home. 61 Higher rates of autism62 and other neurodevelopmental disorders63 may also contribute to the social problems that they experience. Social difficulties experienced by CAPRI are neither specific nor exclusive to their parental mental illness exposure and are similarly associated with parental physical illness, parental incarceration and premature parental death. 24 Notwithstanding, the particular stigma of having a parent with mental illness is specific and may lead children and adolescents to fear developing a mental illness themselves.

But risk and resilience cannot be viewed as constant general traits among children exposed to parental mental illness. Resilience following adversity may be found for one outcome but not every outcome, or indeed any outcome of relevance to children themselves. 43,44 Thus, our approach to improving health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is based on the following premises: first, that we must ask CAPRI themselves what their needs are in relation to HRQoL; second, all CAPRI (including those not expressing risks such as mental illness or behavioural problem as detailed in literature) will benefit from such a CAPRI-informed intervention to improve HRQoL; and, third, such an intervention requires a public health approach that is scalable to all in the risk subset (i.e. all children with parental mental illness).

In summary, most CAPRI will not develop a mental illness; many will perform well in school and sustain relationships,8,15 and not all children living in the same affected family will be influenced in the same way. 64 However, multiple factors contribute to variance in risk versus resilience for a range of outcomes in individual children;65 for example, the availability of alternative familial, social, health and cognitive resources appears to benefit children. 66 The severity and duration of parental mental illness are consistently strong predictors of outcomes; children of parents with enduring and severe disorders exhibit the highest risks expression. 10,24 Children are less likely to experience problems if they have access to a healthy parent, one who acts as a ‘buffer’ between the child and the behavioural and emotional difficulties of the ill parent. 67 Mental health literacy, social connectedness and self-efficacy also equip children with internal resources to manage difficulties associated with parental mental illness on a day-to-day basis. 66

Thus, the evidence paints a picture of CAPRI as vulnerable, but with a heterogeneous set of needs that vary widely between individuals, between circumstances and over time, which means that some children require significantly more help than others. Services must understand such heterogeneity and variation in the planning of their response to unmet needs. For more complex interventions to be effective and cost-efficient, such understanding and targeting is essential. 18 No interventions currently target quality of life (QoL) in CAPRI and virtually none has been child, as opposed to parent or family, centred. 68 Currently, poorer intervention efficacy/cost-effectiveness is attributed to limited resources, budgetary restraints and skill limitations among practitioners, whereas inadequate screening and assessment processes are likely to contribute significantly. 26 Importantly for future planning, lack of multiagency collaboration between adult mental health services, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS), social care and child protection services means that support lacks co-ordination and leadership. 17,68

Although many parents want to consult with professionals about their children,69 some are reluctant to do so because they fear that they may be judged or lose their children to care. 70 Such factors are likely to mean that CAPRI remain hidden because, unless they come forward themselves, they may not be identified as having a need by services whose focus remains the ill parent/parents. 17 We agree that a ‘fundamental paradigm shift is required at all levels of service development, delivery and policy’71 lest the needs of these children remain unmet. However, unlike these writers, our perspective is specifically focused on prevention for non-clinical unmet need and aligned with enhancing daily HRQoL across childhood for all CAPRI and not simply those at highest risk.

Background and rationale for the Young SMILES programme

The European Union’s (EU) Child and Adolescent Mental Health in Enlarged Europe initiative urged a change in political systems, legislative systems and health and social care systems to acknowledge and attend to the needs of CAPRI. 72 This initiative also called for better information on CAPRI and how to target vulnerable groups before their life trajectories are disrupted. 72 However, in spite of adequate policy guidance50,73 and a strong case for early intervention to support these young people,74 little reliable or child-centred evidence for intervention was available to take the process forward. 68,75 Therefore, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme posted call 14/29, which posed the following question to researchers:

Is it possible to develop a community-based intervention to enhance the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of children who live with a primary carer with serious mental illness, and would it be suitable for a future trial?

This report examines whether or not the Young Simplifying Mental Illness plus Life Enhancement Skills (SMILES) programme achieved its primary aim to answer that question.

The 14/29 call for interventions aimed at enhancing HRQoL among CAPRI derived, in part, from our HTA-funded systematic review. 68 This had shown that there is little or no community-based provision for CAPRI, let alone any high-quality evidence or child-centred approaches to HRQoL. The likelihood of these young people developing mental illness, although greater than that of their unexposed peers, is outweighed by the likely influence on QoL of daily hardship and multiple deprivation. 7 Thus, the rationale for creating and piloting a novel intervention to improve CAPRI HRQoL was driven by this understanding alongside the knowledge of the significant and growing numbers of exposed and vulnerable young people in the UK today. 7 In the UK and the wider EU, we were aware of only two models aimed at supporting CAPRI directly, as opposed to supporting their parents. 76 Our task, therefore, was to create, with stakeholders, a viable approach to a significant public health problem with a view to improving resilience and reducing long-term effects of poor HRQoL in children and adolescents with serious parental mental illness.

The 2014 NIHR HTA programme call drew broadly on our own HTA systematic review of interventions for CAPRI. 68 This review had been widely informed by three focus groups with 19 different stakeholders: eight representatives from the children’s charities Barnardo’s, Young Minds, the National Children’s Bureau, the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) and the Fairbridge Trust; five independent parents (four mothers and one father); and six CAPRI. 6,68,76 Key elements specified in the original HTA call were that the intervention should be community based and delivered to children across the age range living with severe parental mental illness with the express intention of improving HRQoL.

Quality of life in CAPRI

As suggested above, the HRQoL model may reflect the needs and priorities of CAPRI better than other health-related outcomes, such as mental and behavioural disorders. It is increasingly recognised that ‘well-being’ refers to more than absence of disease, with QoL being increasingly seen as a valid clinical outcome for services. 77 With recent UK50,73 and European72 policies highlighting the need for clinicians to consider young people’s perceptions of their own life experience within the context of their personal goals, expectations and priorities, a HRQoL model is anchored in the lived realities of children, rather than being service driven with disease-specific outcome measures. 6 Bee et al. 68 highlight five core life domains in QoL measures for children: (1) physical health, (2) emotional health, (3) social function, (4) material well-being and (5) environmental well-being. However, evidence is needed for a HRQoL that specifically captures the experiences of children living with a mentally ill parent. 74

Evidence for interventions to improve health-related quality of life in CAPRI

Existing interventions concerned with parental mental illness usually target the affected parent. 68 They include various modes of service delivery, including individual support78 and peer support groups,78 online courses79 and psychoeducational programmes. 80 The aim of these interventions is to enhance protective behaviours in the parent, usually the mother. 68 Recently, there has been a shift away from parent-based interventions to interventions centring on the needs and preferences of the family. 68,76 Numerous interventions with a family-centric model of delivery report positive outcomes for child well-being. 9,58,81,82 Although encouraging, such evidence should be treated with circumspection as studies reporting the largest effect sizes are invariably poorest in quality. 75 High-quality studies are still in the minority, but also consistently report modest effect sizes. Furthermore, only few studies contain any analyses of longitudinal effects, making it difficult to monitor effectiveness over time. 75,83

Reliable data on the efficacy of child-centred interventions are conspicuously lacking. 68 Most data derive from small, biased samples reporting effects too small to enable them to be considered cost-effective. 75 Efficacy might be underestimated or go undetected by aggregating effects produced by interventions across at-risk and resilient children18 (i.e. high- and low-risk individuals within the risk subset). Furthermore, most follow-up in studies is limited to < 1 year from baseline; monitoring effects over extended periods allows ascertainment of whether or not an intervention is acting to prevent difficulties in children who are at risk. 84 Potential effect moderators need to be explored; adequately powered samples might then identify which subgroups will be more responsive or sensitive to an intervention. Such moderators may include a child’s sex, age, parental diagnosis, and socioeconomic status. 84,85

Similar methodological problems apply to interventions aiming to improve the HRQoL in CAPRI. Bee et al. 68 demonstrated a lack of reliable evidence to support the effectiveness of any existing interventions. Many included studies were conducted over 20 years ago, mainly outside UK or European settings, which limits their generalisability to the NHS. Furthermore, most studies focused on parents with mild to moderate (postnatal) depression; only three considered parental serious mental illness (SMI). Interventions were not child centred and did not consider young people’s QoL; all focused exclusively on parental outcomes. 68

The review concluded that further work is needed to develop and evaluate child-centred interventions that improve HRQoL in these young people. 68 However, the challenges implicit in this recommendation are numerous and complex. One such challenge is deciding when, where and how best to intervene, while demonstrating clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and the potential for non-stigmatising and non-threatening delivery of specific interventions for CAPRI. In our view, interventions should place emphasis on mental health promotion and early intervention (i.e. public health approaches), while putting young people’s preferences and priorities at the centre of service delivery. 6,17,68,76 Such preventative and early interventions should use models that are strength based and focus on resilience and, as such, better reflect CAPRI’s short- and long-term goals. Delivery should take place within community settings, such as schools, community centres, the home and other venues embedded within the child’s routine. 76

Developing the model for Young SMILES

We considered the two existing models of working with families with parental mental illness, KidsTime and Family SMILES, not only because of their suitability for adaptation, but also to take account of expert reviewer and HTA Board comments from the original grant proposal, and because of the 3-year time scale of the proposed call. We knew that both of these group-based interventions ran successfully with CAPRI families in community settings but that neither had been evaluated and that they were not designed explicitly to enhance CAPRI HRQoL. Consultation with stakeholders and NSPCC collaborators provided us with permission to adapt Family SMILES to focus on a more child-centred approach and to work alongside the NSPCC to develop a non-NHS platform of delivery through the third sector. This was important for us because we recognised that the need for a new service fell into a preventative rather than direct health care domain and, therefore, potentially sat outside a CAMHS or NHS remit. This meant that the feasibility study needed to consider willingness to pay for, arguably, a public mental health approach in an increasingly large group of children and adolescents, most of whom, at least from a mental health perspective, would remain well. We were asked to test the suitability of the new intervention for a future trial. This meant that the intervention we developed needed to be manualised, staff needed to be trained, participants needed to be randomised with a control group and, where possible, assessors needed to be blinded. With an eye to future cost-effectiveness and sustainability in community settings, which we anticipated would not be traditional NHS settings, it was agreed that the established national network of family centres offered by our NSPCC collaborators represented an ideal setting to fulfil the brief of the 14/29 call.

We saw the need to design an intervention that responded to the changing shape of service provision and stood a chance of sustainability and scalability in economically stringent environments. To this end, we determined that delivering an intervention in different community settings and to different age groups would best be achieved by partnering with established third-sector community providers and with NHS Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT), which was beginning to broaden its remit to work with children and families.

Chapter 2 provides an overview of the policy landscape behind a drive towards better HRQoL for CAPRI and, in this context, sets out the aims and objectives of the final Young SMILES programme against which we report.

Chapter 2 Aims and objectives of the feasibility study

Current policy and initiatives

As far back as 1999, the Department of Health and Social Care made perinatal mental health a priority in the NHS Plan; in the recent Implementing the Five Year Forward View for Mental Health paper,86 NHS England included perinatal mental health as the only element of focus on women’s mental health. As a result, resources have been directed to support adults with mental illness in their parenting roles, particularly women with postnatal mental illness. 87 In addition, an increase in whole-family assessments and recovery plans stems from national outcome strategies that tackle mental health across the lifespan as well as the transgenerational transmission of psychiatric morbidities. 88,89 And deeper integration between child and adult mental health services is now advocated, alongside earlier interventions for troubled families. 87,90,91

Despite this, CAPRI are neglected by social and health care services. 50,92 For a range of reasons, parents with mental illness experience greater exclusion from general health and social care services, restricting the monitoring and support available to their children. 50,93 Collectively, extant publications outline the roles and responsibilities services should take when supporting CAPRI in their daily lives. 17

Thus, in 2015, the Department of Health and Social Care and NHS England published Future in Mind,94 outlining a 5-year strategy to make it easier for children and young people (CYP) to access high-quality mental health services in recognition of the treatment gap of around 25–35% among children and young people with a diagnosable mental health condition. It proposed a step change from a ‘tiered model of care’ (i.e. a system defined in terms of what services organisations provide) to one that responds to the needs of CYP as well as their families’ needs. Greater flexibility and leadership at a more regional level was recommended to allow different services to develop to suit local needs. Developing a ‘better offer’ for the most vulnerable children was also proposed,94 contributing to a growing body of literature highlighting the importance and gaps in provision identifying and supporting at-risk children. 95

In Addressing Adversity: Prioritising Adversity and Trauma-informed Care for Children and Young People in England,96 Young Minds recommended investment in trauma-informed models of care with development of a common framework to identify at-risk children, reducing heterogeneity in how ‘vulnerable’ is defined across services, and proposed that adverse childhood experiences (ACE)/childhood adversity become a local commissioning priority. In response, new legislative requirements have been placed on local authorities, Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), schools, police, and other organisations and agencies to work collaboratively to provide early identification and help for vulnerable young people, specifically mentioning children exposed to parental mental illness. 97

Thus, successive policy reflects a gradual understanding that CAPRI are unlikely to get the help they need simply as a by-product of their parents’ care, and recognition across different countries that a framework of responses dedicated to them is required (Table 1).

| Publication | Year | Author |

|---|---|---|

| Child and Adolescent Mental Health in Enlarged Europe98 | 2007 | The EU |

| Child Welfare Act99 | 2007 | Ministry of Social Affairs and Health (Finland) |

| NSW Children of Parents with a Mental Illness (COPMI) Framework for Mental Health Services 2010–2015 100 | 2010 | Department of Health (Australia) |

| Social and Emotional Wellbeing for Children and Young People 73 | 2011 | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK) |

| Think Child, Think Parent, Think Family: A Guide to Parental Mental Health and Child Welfare 50 | 2011 | Social Care Institute for Excellence (UK) |

| Children First: National Guidance for the Protection and Welfare of Children 101 | 2011 | Department of Children and Young People (Ireland) |

| Working with Troubled Families: A Guide to the Evidence and Good Practice 88 | 2012 | Department for Communities and Local Government (UK) |

| Future In Mind94 (guidance outlining aims for transforming how CAMHS services are delivered nationally) | 2015 | Department of Health and Social Care (UK) |

| Children’s and Young People’s Strategy 2017–2027 102 | 2016 | Department of Education (Northern Ireland) |

Although mental health services are becoming more accessible to CYP,103 CAPRI are often not mentally ill. Instead, they are in need of recognition for the challenges they face day-to-day, of monitoring and of recourse to non-stigmatised help when they need it. 6,15,68

One possible avenue for such provision is the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies for Children and Young People service or IAPT-CYP. 104 NHS England aims to upskill these and other workforces involved in the care of CYP and to strengthen the collaboration between existing services. IAPT-CYP also promotes more evidence-based practice and robust outcome monitoring in routine services. 103,104 However, there remain challenges to increasing the accessibility of a service for CYP who commonly do not have a mental health problem when CAMHS is being prioritised, hence the need to consider other supports within non-clinical settings.

Aims and objectives of the feasibility study

This research responded to the 2014 NIHR HTA programme call to answer the related questions of whether or not (1) it is possible to develop a community-based intervention to enhance the HRQoL of children and adolescents who live with a primary carer with SMI, and (2) such an intervention is suitable for a future trial.

The initial study protocol set out our aim and preliminary objectives [available on the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/142901/#/ (accessed 1 March 2020)]. These objectives were revised prior to commencing recruitment and published in our updated protocol paper. 105

For clarity, Table 2 presents the original preliminary objectives, the subsequently revised objectives from that paper and the rationale for any changes alongside each.

| Preliminary objectives (HTA, 2014) | Revised objectives105 | Justification for change |

|---|---|---|

| A. To randomise children, adolescents and their parents to the intervention or treatment as usual pathways in a wait-list control design | 1. Using a feasibility RCT comparing the intervention developed in our earlier work with usual care to determine uptake, adherence and follow-up rates | Waiting list control was mooted as a comparator in much earlier versions of the protocol as requested by reviewers. However, it was rejected because study sites were not able to deliver twice the number of Young SMILES groups – once for the intervention group and once for the control group – within the given time frame and costs. Thus, the comparator was always usual care and not waiting list, as stated in objective A. In objective B, the comparator is stated as usual care |

| B. To estimate uptake, intervention adherence and retention to follow-up rates in a RCT comparing the intervention with usual care | Preliminary objective B was merged with objective A to make a revised objective 1 | |

| C. To determine which child/adolescent self-completed outcome measures are able to capture the effects of the intervention over time, especially in the primary outcome measures identified as important by the stakeholders | 2. To determine, from a battery of outcome measures, the most appropriate primary outcomes with which to assess any effects of the intervention over time, considering the areas identified as important by the stakeholders | The preliminary and revised objectives are the same |

| D. To obtain estimates of intervention effects and measures of variability on the selected outcome measures to inform sample size calculations for a definitive trial | Preliminary objective D was removed as inappropriate because in our feasibility trial we are not powered to estimate intervention effects | |

| E. To optimise and pilot a data collection tool to capture the most relevant aspects of families’ resource utilisation (including Young SMILES) over time | 3. To develop and pilot a data collection tool relevant to family resource use over time | Preliminary objective E and revised objective 3 remained the same |

| 4. To determine if the intervention is acceptable to CAPRI, their parents and the practitioners delivering the intervention | Objective 4 was added as part of the revised objectives (there was no corresponding one in the preliminary objectives). This is because assessing the intervention’s acceptability via qualitative work was a major aspect of the feasibility study and the preliminary objectives did not reflect this | |

| 5. To establish if the intervention can be implemented successfully within third-sector and NHS settings | Objective 5 was added as part of the revised objectives (there was no corresponding preliminary objectives). This is because the study had two distinct implementation models (NHS and third sector) and the preliminary objectives did not reflect this |

This report includes a set of final objectives, which are reproduced with permission from Gellatly et al. 105 (This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text), and are worded differently to help with the presentation of our results across the report, our ability to make judgements about whether or not we have delivered against these objectives and, furthermore, whether or not a full randomised controlled trial (RCT) is feasible.

Table 3 presents the final objectives for this report and maps them on to our published objectives. 105

| Final objectives in HTA report | Mapping onto Gellatly et al.105 objectives |

|---|---|

| A. To co-produce (with stakeholders) an intervention that was acceptable to families and feasible to deliver in the NHS and in the community with support from health and non-health professionals | This objective captures the primary aim of the study (as stated in the original 14/29 HTA call) and also incorporates published objectives 4 and 5 |

| 4. To determine if the intervention is acceptable to CAPRI, their parents and the practitioners delivering the intervention | |

| 5. To establish if the intervention can be implemented successfully within third-sector and NHS settings | |

| B. To determine the rates of intervention uptake and adherence, and of completed follow-up measures | This is the same as published objective 1 |

| 1. Using a feasibility RCT to compare the intervention developed in our earlier work with usual care to determine uptake, adherence and follow-up rates | |

| C. To identify appropriate outcome measures and estimate their data missingness | This is a revised version of objective 2. We cannot assess intervention effects on specific outcomes in a feasibility study. Therefore, we describe our objective more accurately here in terms of feasibility of completion of outcome collection at baseline and follow-up (assessed by data missingness) |

| 2. To determine, from a battery of outcome measures, the most appropriate primary outcomes with which to assess any effects of the intervention over time, considering the areas identified as important by the stakeholders | |

| D. To develop a child resource utilisation questionnaire and estimate its data missingness | This is the same as objective 3 below, revised to include ‘data missingness’ as a more accurate objective of feasibility for data collection. The final objective also specifies that resource utilisation refers to the child and not the family |

| 3. To develop and pilot a data collection tool relevant to family resource use over time | |

| E. To capture the experiences of children and parents who participated in the intervention and of professionals who referred or supported families to participate in the intervention | This is an objective that maps onto objectives 4 and 5 of Gellatly et al.105 that conveys the qualitative work that was a large part of this study to determine acceptability and feasibility |

| 4. To determine if the intervention is acceptable to CAPRI, their parents and the practitioners delivering the intervention | |

| 5. To establish if the intervention can be implemented successfully within third-sector and NHS settings |

Report roadmap

The final objectives, which we address in this report, remain focused on the basic feasibility criteria of being able to recruit and randomise participants (CAPRI and their parents) to the newly co-created Young SMILES intervention, as well as to be able to maintain participation of recruited individuals up to, and including, follow-up data collection. The final objectives place greater emphasis on participant and staff experiences as indicators of acceptability of Young SMILES and of its deliverability inside and outside the NHS.

These objectives can be broadly divided across the quantitative and qualitative aspects of the research report. The first 18 months of work is described in Chapter 3. It included study set-up and recruitment of sites, a process delayed significantly by coinciding with the newly formed Health Research Authority and by changes in the organisation of our NSPCC partner, as described in detail in Appendix 1. Subsequently, development, manualisation and training of NHS and non-NHS staff in the new, child-centred intervention (i.e. Young SMILES) was completed with significant input from children, young people and their parents. Chapter 3 describes the development and manualisation of the intervention with stakeholders over a 12-month period. Training was undertaken across three sites in Warrington, Coventry and Newcastle.

The feasibility study, testing our ability to deliver the new intervention, is described in Chapters 4–6 and constituted the second part of the 3-year study of two halves. However, the fact that the original timeline for recruitment was foreshortened by 11 months as a result of delays beyond the study team’s control (and described in detail in Appendix 1, Table 31) is, in our view, central to our final reporting of results and our recommendations about what future research activity should look like (i.e. the feasibility of a future trial).

Of note, progression criteria were not a part of the current study design.

Chapter 8 uses a matrix to present the study’s findings and to make a judgement as to whether or not a future full RCT is feasible based on established norms of uptake, adherence and follow-up rates, and also based on the reported experiences of children, parents and staff.

Chapter 3 discusses the modelling phase of an intervention called Young SMILES, which drew on qualitative and co-production methods to put children’s HRQoL needs at the centre of service delivery considerations.

Chapter 3 Intervention development

Phase 1 of the feasibility trial entailed the development of the intervention through an iterative process of integrating the existing evidence base with stakeholder consultation. This is in line with the developmental stage of the MRC Complex Intervention Framework. 106 What follows is a summary of an article published in Frontiers Psychiatry by Gellatly et al. 107 that describes the generation and co-development of the intervention. Copyright © 2019 Gellatly, Bee, Kolade, Hunter, Gega, Callender, Hope and Abel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

Current evidence provides a compelling case for the theoretical development, delivery and evaluation of effective interventions that support CAPRI’s HRQoL. In view of this, we co-developed an intervention called Young SMILES during the modelling stage (Phase I) of the feasibility trial. This intervention builds on the NSPCC’s existing intervention Family SMILES, which was based on the Australian Simplifying Mental Illness plus Life Enhancement Skills (SMILES) programme. Family SMILES targeted families affected by parental mental illness. The intervention demonstrated potential to reach broader demographics in the context of the NHS, with a more clinical focus on CYP’s QoL.

Using a ‘bottom-up approach’, we explored the primary development foundations of such an intervention by utilising qualitative and co-production methods. Our aim was to put children and adolescent’s HRQoL needs at the forefront of co-refinement and co-development work, underlining the primacy of their voice by considering avenues to support CAPRI directly, and separately, from the experiences and needs of their parents. We anticipated that this evaluative process would culminate in an acceptable and feasible child-centred, community-based intervention that improves CAPRI’s HRQoL.

Methods

Semistructured interviews and focus groups were conducted with CYP (n = 14), parents (n = 7), and practitioners from social, educational and health-related sectors (n = 31), considering five key areas: (1) experiences of previous support, (2) unmet needs, (3) barriers to and facilitators of receiving/delivering support, (4) gaps in current provision and (5) what an ideal intervention would look like. Every interview was transcribed and subsequently thematically analysed. Thereafter, key findings and a summation of current evidence were presented to stakeholders, which informed a consensus exercise to underpin the preferred structure and primary components of the intervention.

Key findings

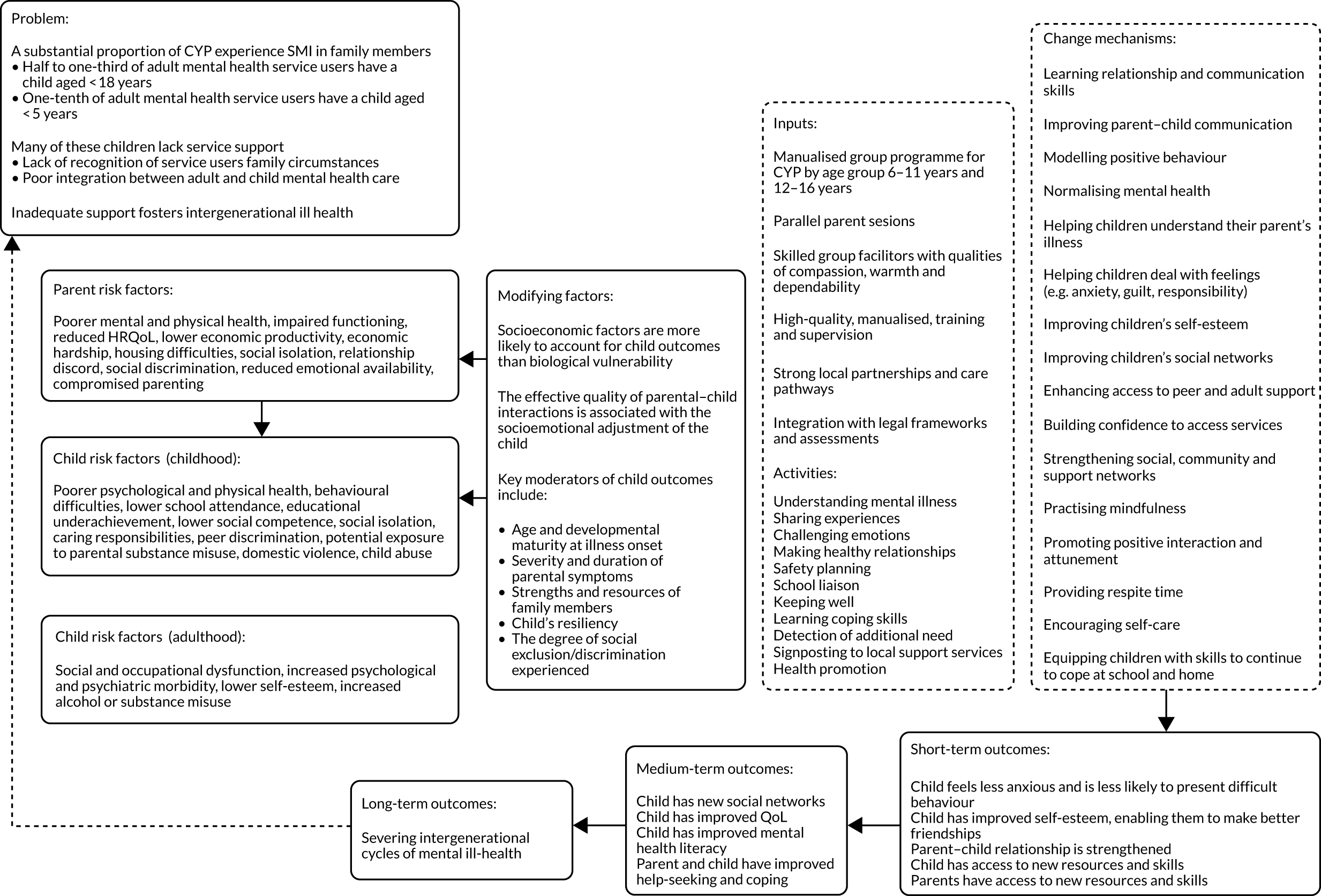

There was some consensus between parents and professional stakeholders about the perceived needs of CYP, but neither went into detail about specific requirements or their need for routine care on a daily basis. Mental health literacy, communication and problem-solving skills emerged as common themes throughout the qualitative work; however, CAPRI frequently disclosed a need for more peer-focused support, as well as more advice on how to better understand and respond to their parent’s difficulties in their own space (i.e. separate from their parents). Isolation was a recurrent problem reported by CAPRI, which was furthered by a lack of understanding from schools about their situation. Sensitively helping parents make sense of how and when their difficulties detrimentally affect their children was a need that was also identified (see Figure 1 for more details). All views were discussed at the consensus exercise and discrepancies were dealt with in group discussion. All views were taken into account but focus was specifically paid to those that did not diverge from the aims and objectives of Young SMILES (i.e. those highlighting the needs of CYP and opportunities to improve their HRQoL).

Young SMILES

These findings informed the co-development of a manualised intervention for CYP aged 6–16 years and their parents called Young SMILES. The intervention was developed within an existing delivery framework and lasted 8 weeks. Additional training materials for professionals were also included. Sessions were delivered on a weekly basis by two highly trained facilitators, each lasting 2 hours. They were group based and peer focused, including fun activities and snack times with parents. There were two age groups: children aged 6–11 years in one group and young people aged 12–16 years in another. Sessions were designed to be delivered in small groups of four to six CYP. Parents’ sessions were delivered separately from the child sessions, commencing after the fourth week of the intervention. For both the parent and the child sessions, although each had its own distinct learning objective, they were all informed by common themes of mental health literacy, communication and problem-solving skills. The venue was located within the community, which was accessible and acceptable to the child and the parent. Referral pathways were embedded within NHS and voluntary sector organisations, which identified potential families. Children’s services, mental health services, schools and voluntary organisations also supported the referral pathway.

Theory of change

A theory of change developed through consultation and consensus-building work is presented in Appendix 2, Figure 2. Primarily, this conceptualises Young SMILES in view of the problems faced by CAPRI, Young SMILES inputs and change mechanisms, primary outcome(s) for children and the impact that this has on associated risk of negative outcomes.

Conclusion

Through consultation with professional stakeholders, children and their parents, we identified a need for a more child-centred, community-based approach towards supporting CAPRI in their daily lives. In response, we have co-developed an intervention that accommodates a diversity of need for CAPRI, which can be validated with quantifiable child-centred outcome measures. This is the first multicontext intervention to improve the HRQoL among this vulnerable group in the UK.

Chapter 4 Trial design and methods

Trial design

Young SMILES is a two-arm, pragmatic, randomised controlled feasibility trial, with a 2 : 1 allocation ratio. Randomisation was considered the most appropriate response to the original NIHR HTA programme 14/29 call that specified having two arms, a control arm and an intervention arm, and that the study design followed the Medical Research Council (MRC) Complex Intervention Guidance. The MRC Complex Intervention Guidance states that ‘Experimental designs are preferred to observational designs in most circumstances’. 106 Therefore, consenting families with CYP aged 6–16 years and a parent/carer with a SMI were randomised to receive either:

-

Young SMILES – a manualised, 8-week intervention for CYP with concurrent 5-week parent sessions adapted from the Family SMILES intervention, which was developed and evaluated by the NSPCC. If eligible, families were given an initial baseline assessment prior to randomisation. Then 4- and 6-month follow-up appointments were completed with an optional feedback interview. Families referred to the NSPCC were also assessed for safeguarding concerns and suitability for the programme.

-

Treatment as usual (TAU) – families continue to use the same services as before, while receiving the baseline, 4- and 6-month assessments.

Protocol changes

Throughout the feasibility process, a number of protocol changes were made. Applications to the Research Ethics Committee (REC)/Health Research Authority (HRA) were made and the following changes were approved for all changes outlined:

-

Primary outcome point – there was a change from a 3-month to a 4-month primary outcome point, without altering the 6- and 12-month time points. This was to assist with family availability and referral rates and to ensure that the number of ‘useful data’ was maximised.

-

Data collection – a demographic questionnaire for referrers was subsequently produced to capture the variety of professional backgrounds involved in the referral process.

-

Randomisation – the ratio was altered from 1 : 1 to 2 : 1 randomisation allocation procedures (two Young SMILES intervention to one control) to expedite the formation of intervention groups. This amendment took place 8 months into recruitment, which, after numerous recruitment difficulties, expedited the start of the intervention in the two sites where most referrals were received: Newcastle (32 families referred) and Warrington (16 families referred).

-

Randomisation method – there was a change from using the Sealed Envelope system (www.sealedenvelope.com) to online randomisation software [www.randomisation.com (accessed 1 March 2020)], as the former system would not meet our requirements in relation to sample size and the ability to stratify by age and site without incurring costs.

-

Inclusion of siblings – it was initially agreed that inclusion of siblings within the same group may have a negative effect on the group dynamics. After further consideration, this was changed to allow siblings within the same group (if in the same age band), which would also expedite the formation of groups.

-

Travel – some families preferred the young person to travel to the group alone. For safeguarding, a travel consent form was developed for parents/carers to consent to the child/adolescent travelling to the intervention venue alone.

-

Participant communication – following participant feedback, we simplified the participant information sheets to enable a better understanding of the aims and objectives of the trial.

Participant eligibility

Families were considered eligible if they met the following criteria:

-

Children and adolescents aged 6–16 years whose parent had serious mental illness.

-

Parents/carers with SMI and their partners, the latter of whom may or may not have had any mental health problems. SMI is defined as a severe psychiatric disorder that requires intervention, hospitalisation or ongoing treatment; parents with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or related disorder, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, severe recurrent unipolar depression, psychotic depression, severe anxiety, obsessive–compulsive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder were sought. Parents with a current diagnosis of a severe psychiatric disorder with a minimum requirement of scheduled follow-up with secondary care services were eligible for study inclusion. The focus of our project was the children and adolescents and their outcomes, rather than the parents. Therefore, we did not intend to carry out full clinical interviews with the parents or to report diagnostic codes. We accepted the primary and secondary diagnoses reported by a key health professional, such as the GP, care co-ordinator and key worker, as most of these parents were likely to receive secondary care or be monitored in primary care. This could be gleaned during professional referral into the study or, in the case of a self-referral by the parent, we obtained the diagnosis by contacting the parent’s appropriate care co-ordinator (e.g. GP or community psychiatric nurse) after gaining the parent’s permission to do so.

-

Children and adolescents had to have at least 10 hours of contact per week with the parent/carer with SMI. (The child/adolescent did not have to live with a mentally ill parent necessarily.)

-

The parents/carers/guardians understood the purpose and remit of the intervention for themselves and their child/adolescent and consented to their attendance and completion of outcome measures and interviews.

-

Children/adolescents had to have some awareness of the parent’s mental illness, as confirmed by the parent and/or the appropriate care co-ordinator. If they had no awareness of the parent’s illness, we discussed how the parent and care co-ordinator could prepare the children/adolescents before they started group work.

Families were excluded if they exhibited the following criteria:

-

Children/adolescents of parents diagnosed with common mental health problems (e.g. mild–moderate depression) or with primary substance misuse, rather than with a primary diagnosis of SMI as defined in inclusion criterion 2, above.

-

The children/adolescents had significant cognitive impairment or a learning disability or major mental illness or behavioural problems (as verified by their GP or other health professionals involved in the family’s care) that made it impossible or unsafe for them to participate in group work.

-

The parent was extremely mentally ill at the time of eligibility assessment, which made it difficult or unsafe for them to participate in group or individual work. (It was acknowledged that these children/adolescents might be those especially in need of support and therefore this was judged on a case-by-case basis by experienced practitioners.)

-

The children/adolescents had already participated in Family SMILES (which is not applicable in the north-east of England, where Family SMILES is not available).

Trial sites

The study was conducted at the following sites:

-

North East – Northumberland Tyne and Wear (NTW) Trust, conducted by the local Family Therapy Service and the Barnardo’s Young Carer’s team for Newcastle upon Tyne.

-

North West – NSPCC Warrington, delivered by NSPCC practitioners at the Peace Centre, Warrington. The facilitators came mainly from a social work background and had significant experience of working with vulnerable CYP.

A third locality in NSPCC Coventry had been identified to provide Young SMILES groups; however, there were recruitment problems and so no groups were run in this area (see Appendix 1, Table 31).

Recruitment and consent

Families were identified through practitioners working in CYP services, CAMHS, Adult Mental Health services and education services. Referral sources were broadened by close co-operation with NHS practitioners and services. The NIHR’s Clinical Research Network was used to assist with recruitment and identification of suitable families via GP registers, community mental health and inpatient teams, and rehabilitation units. Posters and flyers were distributed to relevant NHS and third-sector organisations and schools. In addition, practitioners working in the community were informed of the study to assist with direct opportunistic referrals.

Two methods of identifying families were deployed:

-

Recruitment gatekeepers (e.g. community nurses, care co-ordinators and young carer’s workers) identified people from their caseload who may be eligible for the trial.

-

A member of the trial team acquired permission from the gatekeeper to screen their caseload for eligible families first, and provided a list of families to the gatekeeper.

In each case, the gatekeeper gave the potential family a study information pack (an invitation letter, information sheet and consent-to-contact form). Separate packs containing the same information were provided to CYP and parents. If a family was interested in participating, they returned the consent-to-contact form, detailing their preferred method(s) of contact. Alternatively, the family could provide verbal consent to be contacted to the gatekeeper, who would then inform the study team. Here, a verbal consent-to-contact form was completed by the gatekeeper to confirm that they had received consent.

All families that were on the caseload of the services involved in the delivery of the trial were considered to be potential participants. In addition, caseloads of services within NTW Trust were also screened for participants with the permission of the professional holding the caseload.

After gaining consent to contact, the research team contacted the family, determined eligibility and received confirmation of desire to participate, which was usually received from the mentally ill parent, but could also be from the healthy parent. If the latter, the only additional factor that had to be ascertained was that the child had at least 10 hours per week of contact with the mentally ill parent. This number was considered to be an appropriate and readily measurable amount of time to ensure that the ill parent could be fully informed about what was happening and be able to support the child.

If eligible, families were informed that they would be contacted at a later stage to arrange to complete a face-to-face baseline interview. Dates for baseline interviews were contingent on the research team receiving enough referrals from the same age group at one site (based on the minimum feasible group size of four children). Families were telephoned fortnightly during the waiting period by the research team. They were informed of progress in organising groups and given an opportunity to ask any additional questions. A one-off home visit to discuss the study was also offered.

When multiple children were recruited from the same family, for the main analysis we identified an index child and included data from only that child in the analysis. We asked the parents to nominate the index child, which was always determined by which child experienced the most difficulties in responding to parental mental illness.

At baseline, the family were given the opportunity to ask any further questions and written consent was taken. The CYP were asked to give assent to participate. Consent from their parents/carers was also obtained in support of their child’s participation. Separate consent was obtained for parents/carers. It was clarified to both that they could withdraw at any point without detriment to their care. If a parent was to withdraw, their child/children could still participate with their consent. If the parent had more than one child, all children in the family were eligible to participate but were not required to do so.

After obtaining consent, family members were asked to complete the baseline measures. All measures are standardised and designed as self-complete, with the researcher present to offer assistance. Outcome measure booklets were age-dependent. Families received a total of £50 of shopping vouchers over the data collection time points for their participation in the study (£20 at baseline and £15 for each of the 4- and 6-month follow-ups). On every visit, trial researchers identified if any adverse events had occurred and reported these as per the agreed procedures. Outcome measure visits took place at a time/location convenient for the participant, which was invariably at the family’s home.

Intervention design

Comparator: treatment as usual

The control group received TAU. This was defined as access to any services or resources to which CYP and their families would usually be referred or have access. Participation in the trial did not preclude access to these services.

At the NSPCC site, there were no other services that would be a natural alternative to Young SMILES. The two other services that were on offer at the same time as the Young SMILES study were a therapeutic service for children who have been sexually abused and an assessment and a treatment programme for children who display harmful sexual behaviour.

At the NHS site, the type of TAU offered to the children depended on how they were recruited. Some children received usual family therapy support (in the form of home visits by a systemic practitioner), some received assessment and advice relevant to their role as ‘young carers’ (by practitioners in Barnardo’s) and others did not receive any specific intervention as they were children of parents who were looked after by a care co-ordinator in a community mental health team (CMHT) (these teams focus on the parent with SMI with no routine provision for their children).

Intervention: Young SMILES

Young SMILES is an 8-week group programme (four to six CYP per group) delivered by two trained practitioners. Age groups were 6–11 years or 12–16 years. At week 4, five parallel sessions were offered to the parent/carer. CYP and parent sessions lasted 2 hours each, including time for a short break and refreshments during and after the group session. Where possible, the sessions were held in non-stigmatising venues, such as a community-based location. Hospital clinics or schools were, therefore, avoided.

In Newcastle, groups were delivered in an NHS organisation, utilising a co-delivery model where one facilitator was from the NHS (Family Therapy Service) and the other was from a third-sector organisation (Barnardo’s). Third-sector organisation facilitators had a mix of professional backgrounds, which included social work, children’s services and occupational therapy.

In Warrington, the intervention was delivered by NSPCC practitioners at the Peace Centre, which is an accessible, award-winning venue embedded within the local community. The facilitators came mainly from a social work background and had significant experience of working with vulnerable CYP.

The training manual for facilitators provided an overview of the feasibility trial and development of Young SMILES. It incorporated details about service and intervention delivery. It provided a manual to support trainers to ‘teach’ practitioners aspects of the model and how it should be delivered, as well as an ongoing guide/reference for practitioners who delivered the service.

Children and young people’s group sessions

Every session had specific aims and objectives, which for both age groups remained consistent throughout (Table 4). However, activities and communication style varied depending on the abilities of the CYP. Adapting to the learning styles of the CYP in the group was also an important role of the facilitators. The themes traversing all sessions were mental health literacy, communication and problem-solving skills. The outcome of each session was facilitated through the creation of an ‘imaginary family’ for younger children (made from cardboard cut-outs/cartoon characters created electronically and printed) and a ‘graffiti wall family’ for older children. A normal session included a ‘getting to know you’ (first session)/’welcome back’ and a ‘check-in’ on previous week, ‘ice-breaker’ activity, activities based on the session aims and snack time. A ‘weekly challenge’ at the end of each session was included to orientate and tether the CYP to the next session in order to optimise engagement.

| Session | Objectives |

|---|---|

| 1: Welcome to Young SMILES | Understand the aims of the group and introduce key themes (e.g. the fictitious family) |

| 2: All about me | Understand a sense of self, and identify personal strengths and qualities |

| 3: What happens in my family? | Understand mental illness and the impact that it can have on a young person’s family |

| 4: Things we worry about | Identify the sources of feelings and understand healthy and unhealthy responses to them |

| 5: Our world | Identify the key sources of stress and the building blocks needed for a foundation of feeling good |

| 6: Where do I go when I need help? | Identify support networks and learn how to access help from professionals |

| 7: Enjoying being me | Understand personal strengths and aspirations, recognise which aspirations they can shape |

| 8: Moving on together | Celebrate progress, consolidate relationships and plan for the future |

Parent/carer group sessions

The focus of the parent/carer sessions was determined during the CYP session in the previous week (Table 5). This was to retain the child-centred basis of the intervention. CYP and parents came together in the final ‘Moving on together’ session to review progress and for the last few activities that focus on hopes and fears, achievements and moving forward. Activities for each session were standardised, but not prescriptive. As long as they met the overall objectives of the sessions and were consistent with the ethos of the Young SMILES programme the facilitator was afforded the freedom of action to change their approach to better suit the different needs and learning styles within the group.

| Session | Objectives |

|---|---|

| 1: Welcome | General introduction and welcome parents |

| 2: What our children do well | Develop insights into how parents/carers can (and do) encourage and support their children to do well and feel good about themselves |

| 3: What our children worry about | Identify sources of stress in their children and understand healthy and unhealthy responses |

| 4: How we support our children | Identify obstacles to successful family communication and identify support networks |

| 5: Moving on together | Celebrate progress, consolidate relationships and plan for the future |

Practitioner training

The Development and Impact Manager from NSPCC Children’s Services held a 2-day Young SMILES intervention training event, which was held in Newcastle (1 and 2 March 2017) for NTW NHS Foundation Trust and Barnardo’s Newcastle practitioners, and in Warrington (20 and 21 March 2017) for NSPCC Warrington and NSPCC Coventry practitioners. The training provided practitioners with the following: the study context, the feasibility study, intervention format and guidance, delivery location context and referral pathways, the incorporation of the imaginary family and problem-solving.

Four half-day sessions were also arranged to work through the intervention activities (11, 12 and 18 July 2017 and 5 September 2017), ensuring that practitioners felt confident supporting CYP and their parents/carers. Practitioners also identified the need to gain more of an understanding about SMI in adults. This was covered in the training in Newcastle and additionally in two sessions for Warrington and Coventry NSPCC staff (5 and 6 July 2017).

Outcome assessment

A list of the primary and secondary outcomes and tools used can be found in Table 6. A description of each measure and how scores were calculated can be located in Appendix 3. Although measures were available for all ages, some CYP experienced difficulties completing certain measures. In this instance, researchers were responsive to the CYP’s needs, supporting the CYP to ensure completion of the self-report measures. The following demographic details were also collected: age, sex, sexual identity (if aged ≥ 16 years), ethnicity, nationality, religion, education, employment and current living arrangements.

| Outcome | Measured by/using |

|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |

| HRQoL | PedsQL108 |

| KIDSCREEN™109 | |

| Secondary outcomes | |

| Child psychopathology and prosocial behaviour | SDQ110 |

| Symptoms of common mental health problems | RCADS111 |

| Knowledge and perceptions about SMI (mental health literacy) | MHLq112,113 |

| Parenting competencies | Arnold–O’Leary Parenting Scale114 |

| Degree and cause of stress in parent–child relationships | PSI-SF115 |

| Incremental health gain in quality-adjusted life-years | CHU-9D116 |

| Resource use | Child and Adolescent Service Use Schedule [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/142901/#/ (accessed 1 March 2020)] |

| CYP, parent, facilitator acceptability | Qualitative interviews |

Outcome measures

Outcome measures are summarised by trial arm at baseline and follow-up. As efficacy is not within the scope of a feasibility trial, estimated effect sizes are not presented. Completeness and variability of the outcome measures will be used to inform future trial design. In cases where multiple children were recruited from the same family, parents were asked to nominate an index child for inclusion in the main analysis. Other sibling(s) were still offered the opportunity to attend Young SMILES (if their family was randomised to the intervention group). Parents were not present for any data collection from their child/children. The number of families with multiple children is presented and summaries of demographics are presented for index children and all children.

Resource utilisation

Collection of child resource utilisation data was piloted using the Child and Adolescent Service Use Schedule (CA-SUS). We aimed to develop a resource use collection tool that captures the most important aspects of resource utilisation and assess the feasibility of collecting child resource utilisation.

The CA-SUS was adapted for our study setting in consultation with Professor Sarah Byford, the designer of the CA-SUS questionnaire. This adaptation involved removing the sections on out-of-pocket expenses and employment, removing the question on education type, removing the follow-on questions asking name of hospital for the hospital service use questions, removing complementary therapist (e.g. homeopath) from the list of community services, adding NHS walk-in services and NHS Direct to the list of community services, and simplifying the questions in the criminal justice services section. A copy of the CA-SUS version used for data collection was submitted alongside this report [see project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/142901/#/documentation (accessed April 2020)].

Resource utilisation data were collected retrospectively using participant recall. The adapted version of the CA-SUS records resource use in the following categories: accommodation, education, hospital services, community services, medication and criminal justice services. Resource utilisation data were collected at three time points: baseline (recalling use over the previous 6 months), 4-month follow-up (recalling use since baseline) and 6-month follow-up (recalling use since the last interview).

As the aim was to assess the feasibility of collecting resource utilisation data to inform data collection methods in a future trial, reporting of results is purely descriptive. No statistical testing was performed.

Qualitative interviews

Acceptability is a key priority in the design, implementation and evaluation phases of complex interventions. 117 It is perceived as a necessary but not sufficient condition concerning the effectiveness of an intervention. Broadly speaking, acceptability is a construct that examines the degree to which an intervention is accepted by those delivering and/or receiving it. 117,118 Definitions have varied considerably, depending on what theoretical perspective the researcher adopts. For example, two studies119,120 investigate acceptability in the terms of patient attitude or satisfaction, whereas other work121,122 conflates the construct with patient behaviours, such as engagement and adherence to treatment. This lack of consensus has served to undermine the credibility of acceptability as a valid assessment instrument. 117

A post-intervention qualitative evaluation of Young SMILES was conducted with CYP, parents/carers and eligible referrers. This was to determine acceptability among those that received the intervention, as well as to assess how practitioners and potential referrers were able to deliver the intervention. These studies (four in total) took place after the primary outcome point. Interviews with CYP and parents/carers focused on, inter alia, barriers to and facilitators of attending, what they liked and disliked, and if they thought Young SMILES helped their family. Referrer and practitioner interviews explored which factors facilitated or hindered the implementation of Young SMILES (see Chapters 5 and 6 for a description of the methods and analysis). 123

Sample size in all of the qualitative studies conducted was governed by the numbers of eligible participants referring, delivering or taking part in the intervention, rather than by traditional concepts of data saturation. In qualitative research, saturation is reported as a criterion for achieving an adequate sample size, and thus no additional information is expected to enhance or change the findings. However, this is an inappropriate quality marker where sample sizes are limited by other factors, including trial participation. In such studies, information power is a more appropriate concept,123 with the final sampling frame guided by the study aim. A less extensive sample is needed when participants taking part are targeted because of their characteristics that are aligned with the study aim, in this case trial (and intervention) participation. Recruitment ceased when all intervention facilitators and participants had been invited for interview. Data analysis in the context of this feasibility study was focused on achieving key insights that contributed to or challenged current understandings of intervention acceptability.

Sample size

Formal power calculations for between-group effects were not conducted as is appropriate for a feasibility study, which is primarily aimed at developing and piloting a new intervention and training package. The study that was piloted examined the feasibility of the Young SMILES intervention training and the acceptability of delivering this to young people in a RCT design in two different settings. The original sample size proposed at the outset was 60 randomised families (30 per group, as recommended for pilot studies124). This was deemed sufficient to facilitate the main study aims [e.g. determining feasibility of recruitment and estimating standard deviations (SDs) of the outcome measures to perform a future power calculation]. The aim was to run a minimum of three sets of CYP groups, alongside three parallel parent groups in the two recruitment sites during the recruitment period. The new target sample size was 35–40 families, following challenges during the study that significantly restricted our recruitment and follow-up periods (see Appendix 1, Table 31).

Randomisation

The randomisation ratio for the final three groups was 2 : 1. Randomisation lists were stratified by age group and site, prepared using Stata® 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) by an independent statistician with the command ralloc, using random blocks of size 3 and 6.

Blinding

Randomisation was conducted by the study co-ordinator to maintain blinding of the statistician and research team, thereby reducing detection bias. To facilitate blinding, the research team adhered to the following: (1) that families knew that they could contact the study co-ordinator should they have any queries about their allocation or Young SMILES arrangements and (2) the researcher conducting the data collection visits reminded families to refrain from revealing their allocation during follow-up visits. Should a researcher become aware of any allocations, this was recorded and reported.

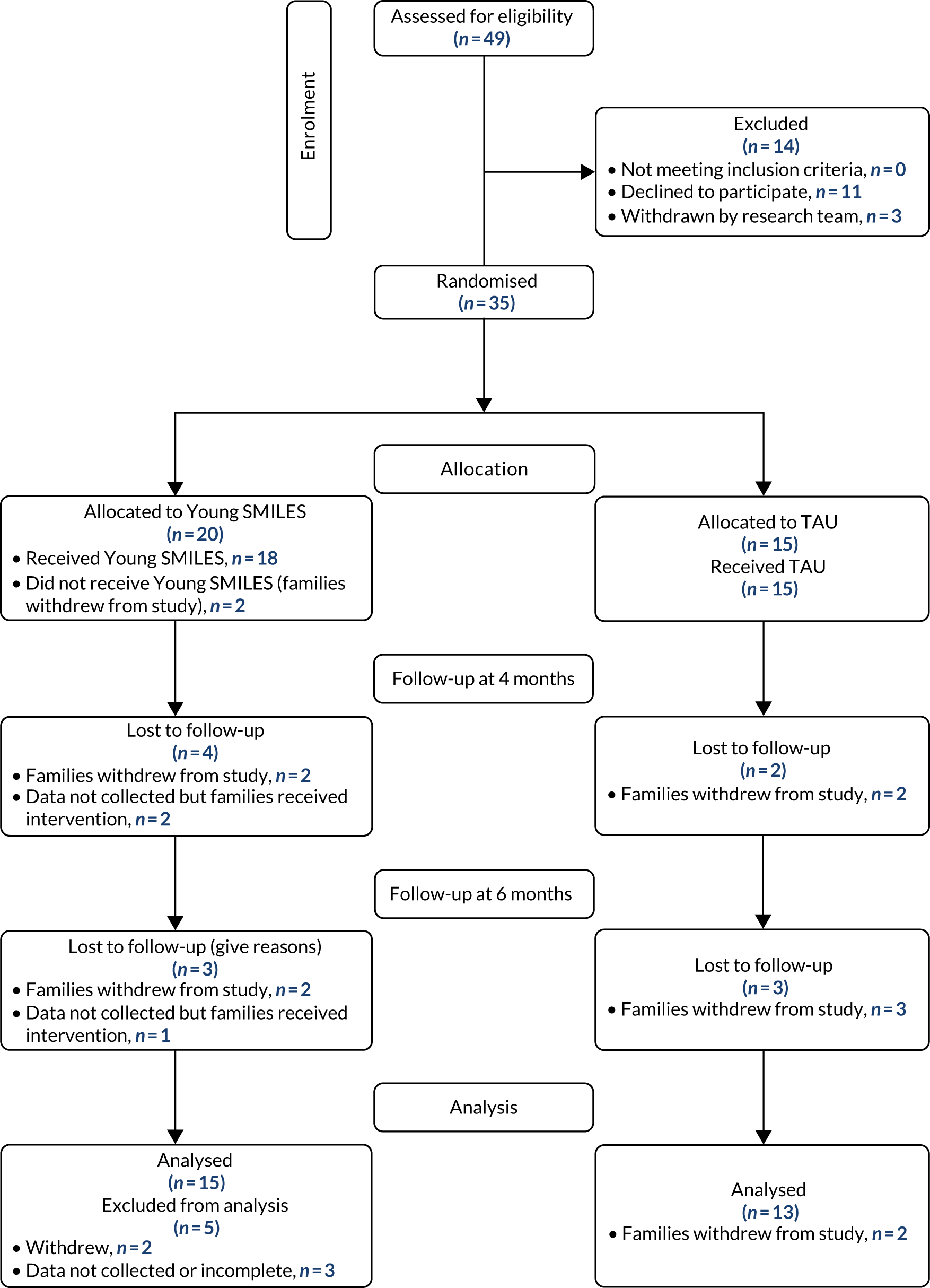

Statistics

The overall focus is on summaries of the key indicators of success of the study: recruitment and participant flow. Data are reported in line with the feasibility and pilot extension of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement. 125 The numbers of participants who dropped out from the intervention, withdrew their consent and did not provide follow-up outcome data are also reported.

Adverse events

During the baseline and subsequent follow-up visits, trial researchers identified if any adverse events occurred and reported, as per standard operating procedures (SOPs) [see additional files (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/142901/#/documentation; accessed April 2020)]. The Trial Steering Committee monitored participant safety during the trial and was responsible for reviewing any serious adverse events occurring as part of the trial.

Public involvement

The research team actively consulted with young people and practitioners about what the intervention would comprise. This included the structure of the group and the activities within the groups. Young people and practitioners were also consulted on the outcome measures that would be used to calculate the time taken to complete the outcome measure booklets.

Young people, parents/carers, referrers and practitioners were all interviewed to provide feedback on the trial recruitment procedures, their experience in the group and what effect the Young SMILES intervention had on experiences outside the group.

Chapter 5 Quantitative results

This chapter examines and reports data on the feasibility of the recruitment of CAPRI and the delivery of the Young SMILES intervention. This entails reporting the number of families approached, the number of eligible children within the approached group, the number that were recruited from that eligible population and the number finally randomised and who took part. This chapter will also report on the number of children in each group (randomised to Young SMILES or to TAU) who completed data collection at each follow-up time point. Thereafter, as evidence of feasibility of delivery, we report on how many children and adolescents randomised to Young SMILES (as opposed to TAU) adhered to the intervention and how many sessions they completed.

In addition, we provide evidence on the feasibility of collecting data from children of all age groups (6–16 years) and their parents, using the chosen measures within the protocol. We present data that help to assess whether or not the chosen measures can capture change in the population over the time periods of use. The Young SMILES protocol and study design is neither tasked nor designed to estimate the effect of our intervention. As a result, we shall not make between-group comparisons in the chosen measures over the time periods of data collection. Such an examination will be undertaken in an appropriately powered and designed efficacy study.

Participant flow

The first pathway of recruitment into the study relied on NHS staff identifying eligible families through screening their patient caseloads and patient records within adult community mental health NHS teams, as well as contacting relevant care co-ordinators of patients with a diagnosis of severe mental illness who had children aged 6–16 years. Care co-ordinators were asked to contact their patients to pass on information about the study. Once their patient has confirmed their interest in the study, the care co-ordinator would either complete a verbal-consent-to-contact form and send it to the address of the research team, or encourage the patient to complete and send a consent-to-contact form to the same address. Adult community mental health services in the NHS routinely focus on adults. They are therefore not concerned with their children, unless there is a risk of harm to the child or a mental illness diagnosed for the child.