Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/196/08. The contractual start date was in August 2014. The draft report began editorial review in January 2020 and was accepted for publication in June 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. This report has been published following a shortened production process and, therefore, did not undergo the usual number of proof stages and opportunities for correction. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Barker et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

The COmmunity based Rehabilitation after Knee Arthroplasty (CORKA) trial was commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme to address the question ‘What is the clinical and cost-effectiveness of intensive rehabilitation programmes following knee joint replacement for chronic osteoarthritis?’. 1 The commissioning brief specified that the intervention should be intensive rehabilitation that is likely to bridge between hospital and home and should target older adults who have undergone elective knee arthroplasty (KA) who are considered to be at risk of poorer functional outcomes.

The CORKA trial compared the effect of two rehabilitation approaches on a range of functional outcomes: traditional clinic-based therapy and a rehabilitation package delivered by rehabilitation assistants supported by qualified therapists in participants’ homes. This chapter provides background information on KA and rehabilitation approaches.

Background to the problem

Knee osteoarthritis is a common musculoskeletal condition that causes pain and loss of function. It is the most common cause of disability in older people,2 with painful osteoarthritis affecting 18.2% of people over the age of 45 years in the UK. 3 The use of KA for end-stage knee osteoarthritis is an established and effective treatment for patients who have already completed all non-surgical options but continue to experience significant pain and decreased function.

The number of KA operations taking place in the UK is continuing to rise. The 15th Annual National Joint Registry Report (2018)4 showed that over 100,000 KA operations were performed in the UK in 2017. This is an increase of over 3% from 2010. Part of the reason for this increase is that KA is increasingly performed for patients who are older and who have other health conditions in addition to their osteoarthritis. A further change relates to the increasing use of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA). Approximately 90% of KAs are a total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and 10% are a UKA or partial KA. In TKA, the entire tibiofemoral joint is replaced, whereas in UKA the affected medial or lateral side of the tibiofemoral joint is replaced only. National outcome data have revealed that patients’ age and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification grades are increasing. In the 15th National Joint Registry Report of 2018,4 15% of patients were aged 80–89 years and 1% were over 90 years of age. The average ASA classification grade is also increasing, with 19% reported as ASA classification grade 3 (severe systemic disease that limits activity). 4

Age should not be a barrier to a good KA outcome, with reports of successful outcomes in patients aged over 80 years. 5,6

Data from patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) have shown that most patients achieve a satisfactory outcome following KA. However, between 15% and 30% of patients are unsatisfied or report little or no improvement after KA. 7 We do not yet know how to identify these patients or target rehabilitation to improve their outcomes.

Predicting which patients will have poor outcomes

The existing literature has demonstrated that it is difficult to predict who will do well after KA. Any prediction is complex and extends far beyond a simple linear relationship with factors such as age or presurgical function. A number of studies have explored the influence of pre-operative predictors on post-operative KA outcomes and have generally agreed that patients who have a higher pre-operative status, such as better pre-operative function or less pain, tend to have better post-operative outcomes. 8–12 However, no screening tool that can accurately identify and predict who is at risk of a poor post-operative outcome currently exists, despite much previous work exploring this subject. 13–15

Rehabilitation pathway

Many hospitals follow an accelerated or enhanced recovery protocol, mobilising patients for the first time in the first 4 hours after surgery. Bohl et al. 16 and Okamoto et al. 17 demonstrated that early mobilisation within the first 24 hours after surgery shortened length of stay, but did not affect longer-term outcomes. Most hospitals have discharge criteria governing when patients are discharged from hospital that are based on safe mobilisation, ability to perform self-care and attainment of a minimum amount of knee flexion (commonly set at 90 degrees). Patients will have reached a minimal level of function at discharge, but will continue to have rehabilitation needs to help restore muscle strength and endurance, range of motion, walking distance and performance of higher-level functional activities.

Patients are commonly referred for further physiotherapy in an outpatient setting to assist with these issues. The timing of this referral varies, with some hospitals advocating immediate commencement of therapy after discharge from hospital and others waiting until the first post-operative review at around 6 weeks before considering referral. The type of therapy also differs, with some sites using self-directed home exercise and others advocating for more formal outpatient treatment using manual therapy, individually progressed exercises and functional activities in an individual or group setting.

Outpatient rehabilitation approaches

We conducted a systematic review evaluating the effectiveness of exercise after KA. We found that functional physiotherapy exercise interventions following discharge after elective primary TKA offered short-term benefit. 18 We found a small to moderate standardised effect size [0.33, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.08 to 0.58] in favour of functional exercise at 3–4 months post operatively, which included small to moderate weighted mean differences of 2.90° (95% CI 0.61° to 5.20°) for range of motion and 1.70 (95% CI –1.00 to 4.30) for quality of life, in favour of functional exercise. However, the post-treatment benefits faded and were not carried through to 1 year post operation.

The review revealed the complexity that is involved in deciding the best rehabilitation after arthroplasty. A growing number of studies have chosen to apply an intervention later in the rehabilitation pathway (often between 6 weeks and 6 months after surgery), which suggests that a delay in starting the intervention avoids the period of early post-operative pain, swelling and limited motion. 19–21 Similarly, assessing outcomes after arthroplasty is known to be complex and multifaceted. 22,23 The lack of certainty about what constitutes best physiotherapy practice has been recognised internationally, with considerable variation in the post-operative rehabilitation protocols used. A recent Australian survey of physiotherapy practice24 and an observational cohort study of US rehabilitation services25 have started to address this knowledge gap. However, there are no published randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of occupational therapy after KA. Other studies do not allow the occupational therapy input to be disaggregated from the overarching rehabilitation package to assess its contribution.

Patients in the UK usually receive a short course of between four and six sessions of post-operative physiotherapy after their surgery, usually in a physiotherapy outpatient clinic setting. Concern has been raised that many exercise programmes lack adequate intensity to lead to optimal recovery. 24,26 Internationally, where much longer courses of physiotherapy are often provided, research has indicated that 12–18 hours of physiotherapy21 or a mean of 17 visits27 may be needed to produce benefit. These levels of care are substantially higher than those provided in the UK and, in the current economic climate, may be more than the NHS can afford given the rising number of KA operations that are performed each year. Patients are likely to have an occupational therapy assessment before surgery to identify any potential issues on discharge, such as home layout. However, it is not usual for patients to have further input from occupational therapists unless they have particular problems.

Given the rising number of KA operations, the relatively limited therapy resources available and the increasing age and frailty of patients receiving this surgery, it is important that we concentrate our rehabilitation resources on those patients who need the most help to achieve a good outcome. It is important that exercise and functional rehabilitation is linked to demonstrable increases in function and participation levels. Not all patients need physiotherapy to help them recover, and some patients will recover fully using self-directed rehabilitation. 28–31 It is, thus, pertinent to focus our resources on those who are most likely to be at risk of a poor outcome, least likely to be able to engage with a self-management approach and able to benefit from rehabilitation input.

It is clear that current rehabilitation strategies do not meet the needs of all patients, particularly those who are socially isolated, do not have easy access to transport and are frail. This is a particular concern given both the projected increased need for joint arthroplasty over the next decade to accommodate an ageing population and the pressure of potential reductions in NHS funding. Evaluating the value of treatment modalities offered to these patients is crucial because many more patients are being discharged home earlier from the acute setting. There is less time available for acute physical recovery, rehabilitation and education in hospital, which increases the potential burden of care for these patients and their families.

Rationale for the CORKA trial

There is considerable variation in the quantity and content of rehabilitation received by patients after KA. Previous evidence has shown that some patients do well with minimal input or self-directed exercise programmes,30–33 but that many patients continue to experience pain and poor function after their surgery and report dissatisfaction with the rehabilitation that they have received.

In the CORKA trial, we aimed to evaluate a different approach designed to cater to the needs of an older, frailer population. We evaluated two strategies of rehabilitation after KA: a traditional outpatient clinic-based model and a rehabilitation programme delivered in participants’ homes by rehabilitation assistants supported by qualified therapists.

The programmes were designed to be acceptable to NHS physiotherapists and occupational therapists, based on current available evidence, and affordable to UK commissioners. A parallel economic study enabled conclusions to be made about cost-effectiveness. A nested qualitative study assessed the acceptability of the interventions to participants and the therapists who delivered them.

Research objectives

The CORKA research objectives were published in the protocol paper in Trials in 2016:34

-

to design a prognostic screening tool based on an analysis of factors associated with poor outcomes following KA to guide patient selection for the trial

-

to evaluate if a multicomponent rehabilitation programme delivered in patients’ homes could improve their outcomes compared with those receiving standard outpatient rehabilitation over 12 months

-

to undertake a nested qualitative study exploring patients’ and clinicians’ perceptions of the community-based rehabilitation programme

-

to undertake an economic analysis to compare the cost-effectiveness of the interventions.

Chapter 2 Methods

The protocol for the RCT was published in Trials in 2016. 34 The trial was delivered as published with no changes to the protocol.

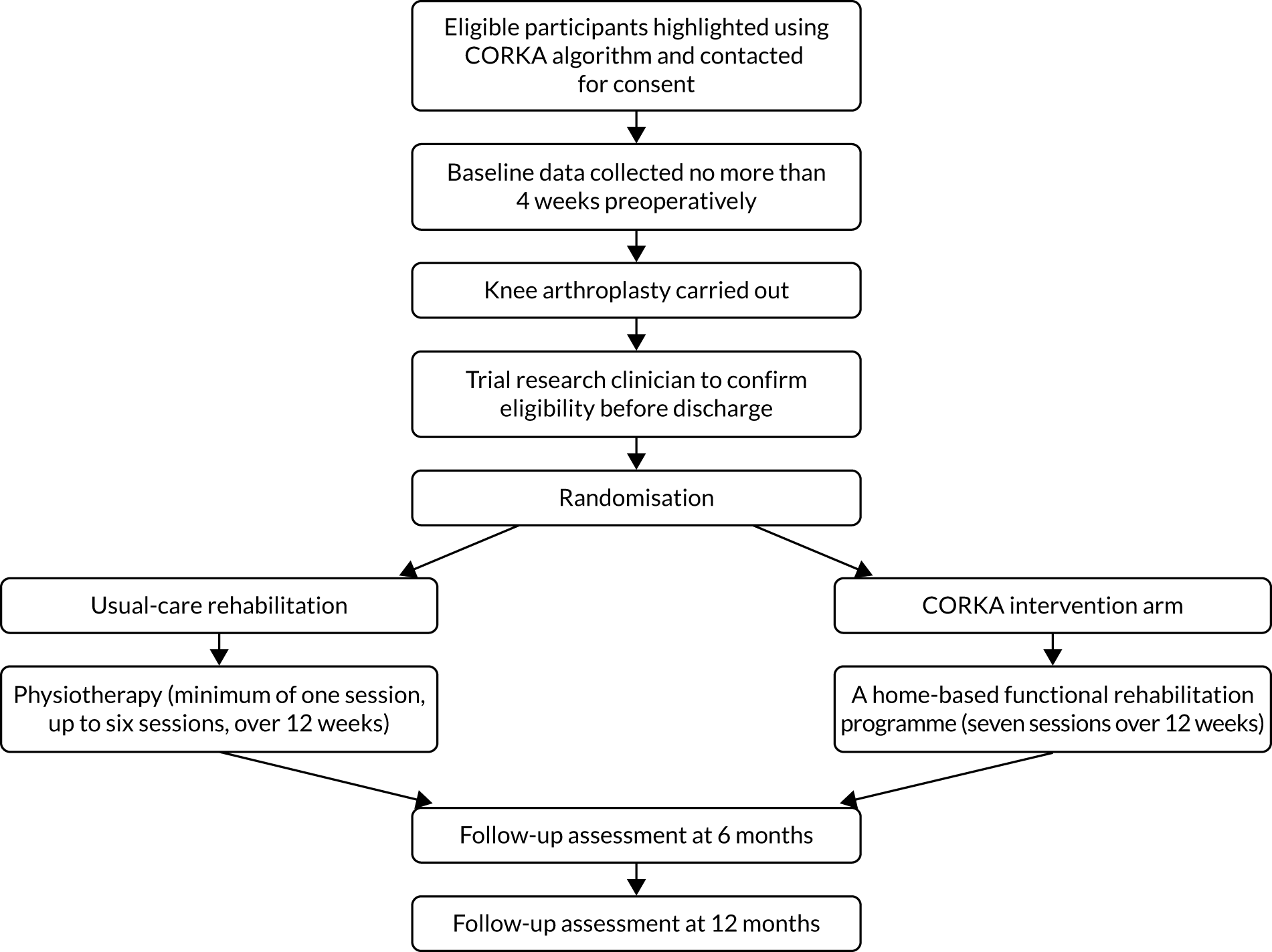

Trial design

The CORKA trial was a prospective, individually randomised, two-arm controlled trial with blinded outcome assessment for the clinical outcomes at baseline, 6 months and 12 months. It aimed to determine if a multicomponent rehabilitation programme provided to participants who were deemed at risk of a poor outcome following KA by the CORKA screening tool (see Chapter 7) was better than usual care. The trial took place in 14 NHS hospitals across the UK. The design included a parallel health economic evaluation and a nested qualitative study. Figure 1 gives an overview of the flow of participants through the trial and the timing of assessment procedures.

FIGURE 1.

Flow of participants through the trial.

Randomised controlled trial

During the trial, people undergoing KA were screened for suitability during their pre-operative assessment clinic appointment using the screening tool that had been developed for the trial. Once informed consent was gained, participants were enrolled in the trial and baseline data were collected. After surgery, participants’ eligibility was confirmed and randomisation took place. Participants were allocated to receive one of two rehabilitation options: ‘usual care’ or the ‘home-based intervention’. Both participants and those delivering the rehabilitation were aware of the treatment allocation owing to the nature of the interventions.

Participants remained in the trial until data relating to their 12-month follow-up were collected. The trial had two follow-up time points: 6 and 12 months after randomisation. The physiotherapists carrying out the follow-ups remained blinded to the participants’ allocation.

Economic analysis

Once all participants completed their 12-month follow-up appointment, an economic analysis comparing the community-based rehabilitation programme with usual care was conducted (described in Chapter 5).

Qualitative study

As part of the main study, a nested qualitative study was conducted with 10 participants who undertook the community-based rehabilitation programme and 11 clinical staff who provided the treatment (five therapists and six rehabilitation assistants). We conducted one-to-one interviews with these participants to obtain their in-depth views about the intervention and how it was delivered (described in Chapter 6).

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Participants were included in the trial if they met all of the following inclusion criteria:

-

was willing and able to give informed consent for participation in the trial

-

was male or female, aged ≥ 55 years

-

was scheduled to have a primary UKA procedure

-

was deemed by the study screening tool to be at risk of a poor outcome

-

was willing to allow therapists to visit their home to deliver the community-based rehabilitation programme if randomised to the intervention arm.

Exclusion criteria

Participants were excluded from the study if they met any of the following exclusion criteria:

-

had any absolute contraindications to exercise

-

had severe cardiovascular or pulmonary disease (New York Heart Association III-IV)35

-

had severe dementia, assessed using the hospital dementia screening tool

-

had rheumatoid arthritis

-

had further lower limb surgery planned within 12 months

-

had serious perioperative complications.

Screening and recruitment

Patients were initially identified from clinic lists. Those who were scheduled to receive a KA were sent the CORKA participant invitation letter and participant information sheet. This pack was sent out by a member of the patient’s usual-care team before they attended their pre-operative assessment clinic appointment. Patients who had been sent the information were approached during their pre-operative assessment clinic appointment to determine if they were interested in the trial, and were given the opportunity to discuss the trial further and ask any questions. If the patient indicated that they were interested in taking part, the CORKA screening tool was used to identify if they were at risk of a poor outcome. They were also then checked for eligibility into the trial. Once they were deemed eligible, an appointment was made to gain informed consent and collect baseline outcome data with a member of the research team. This baseline appointment took place either in the hospital or in the patient’s own home no more than 4 weeks before the date of surgery.

Patients were not formally recruited into the trial or randomised until their eligibility had been re-checked on day three after surgery. Patients with serious peri-operative complications were excluded, as they would not be able to complete routine post-operative rehabilitation. Those participants who were still eligible were then asked to confirm their consent verbally to a member of the research team before being enrolled into the trial and randomised (described in Intervention monitoring and support).

Settings and locations

The trial was run in 14 NHS sites (names correct at time of participation):

-

Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

-

Horton Hospital – Banbury

-

The Royal Orthopaedic Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

-

Ashford and St Peter’s Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

-

Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust

-

Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust

-

Dorset County Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

-

Dorset Healthcare University NHS Foundation Trust

-

Royal United Hospitals Bath NHS Foundation Trust

-

Countess of Chester Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

-

Central Manchester NHS Foundation Trust

-

Medway NHS Foundation Trust

-

Medway Community Healthcare

-

Epsom and St Helier University Hospitals NHS Trust.

Interventions

Full details of the interventions are provided in Chapter 3, but are described briefly here. This trial tested physiotherapy and occupational therapy in a multicomponent package of rehabilitation that was delivered by a generic rehabilitation therapist. The occupational therapy element focused on assessment of and adaptations to participants’ homes to enable a safe environment for home exercise and everyday functional tasks. The physiotherapy element included a home-based intervention with an emphasis on functional, activity-based rehabilitation. We tested whether or not the intervention could be delivered by generic rehabilitation assistants rather than uni-professionally.

Usual care can vary geographically, including the number of sessions of physiotherapy given post discharge. 36 To standardise the usual-care arm without changing it significantly, we set a minimum and maximum number of sessions allowed for usual care. Participants were expected to attend at least one and a maximum of six sessions of outpatient physiotherapy.

Data collection

Baseline assessments: pre surgery

Baseline data were collected on paper questionnaires and most measures were participant reported. Baseline assessments were carried out either in the participant’s home or in the hospital. Wherever the baseline assessment took place, the 6- and 12-month follow-ups were conducted in the same location. All sites were given a research clinician manual that gave detailed instructions on how to complete all baseline and follow-up measures.

In addition to the battery of primary and secondary outcome measures, the following data were collected at baseline: name, contact details, age, surgery, ASA classification rating, review of medical notes and Functional Co-morbidities Index. The Functional Co-morbidities Index is a measure of comorbidity and was completed because comorbidities affecting physical outcome are likely to be present in this more frail population. 35 Table 1 shows the measures collected at each time point.

| Measure | Baseline | 6 months | 12 months |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ✗ | ||

| Medical history | ✗ | ||

| Late Life Function and Disability Instrument | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Oxford Knee Score | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Quality-of-life subscale of the Knee Osteoarthritis Outcome Score | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Health economics using EQ-5D-5L | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| 30-Second Chair Stand Test | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Figure-of-8 Walk Test | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Single Leg Stance test | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Participant diarya | ✗ | ✗ |

Follow-up visits

The trial had two follow-up time points at 6 and 12 months post randomisation. Local site staff organised follow-up and liaised directly with the participants to organise home-based follow-ups. In addition to the outcome measures, the following data were collected at the two follow-up time points:

-

complications/adverse events, including any apparent KA-related complications since discharge

-

falls, including time to first fall.

Outcomes

Follow-up data collection was carried out at face-to-face clinical assessments at 6 and 12 months following randomisation. Where face-to-face assessment was not possible, postal and telephone data collection methods were used to obtain self-reported core data. Table 1 shows the measures collected at each time point.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the Late Life Function and Disability Instrument (LLFDI) overall function score. This outcome instrument was developed specifically for community-dwelling older adults. It assesses and responds to meaningful change in two distinct outcomes: a person’s ability to do discrete actions or activities (function) and a person’s performance of socially-defined life tasks (disability). 37 The overall function score consists of 32 items. Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better function. The summary of the outcomes measured has previously been published in the protocol paper by the authors. 34

Secondary outcomes

-

LLFDI disability frequency and limitation total dimension scores. These scores each consist of 16 items. They have a total score ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating higher frequency and better capability of participation in life tasks.

-

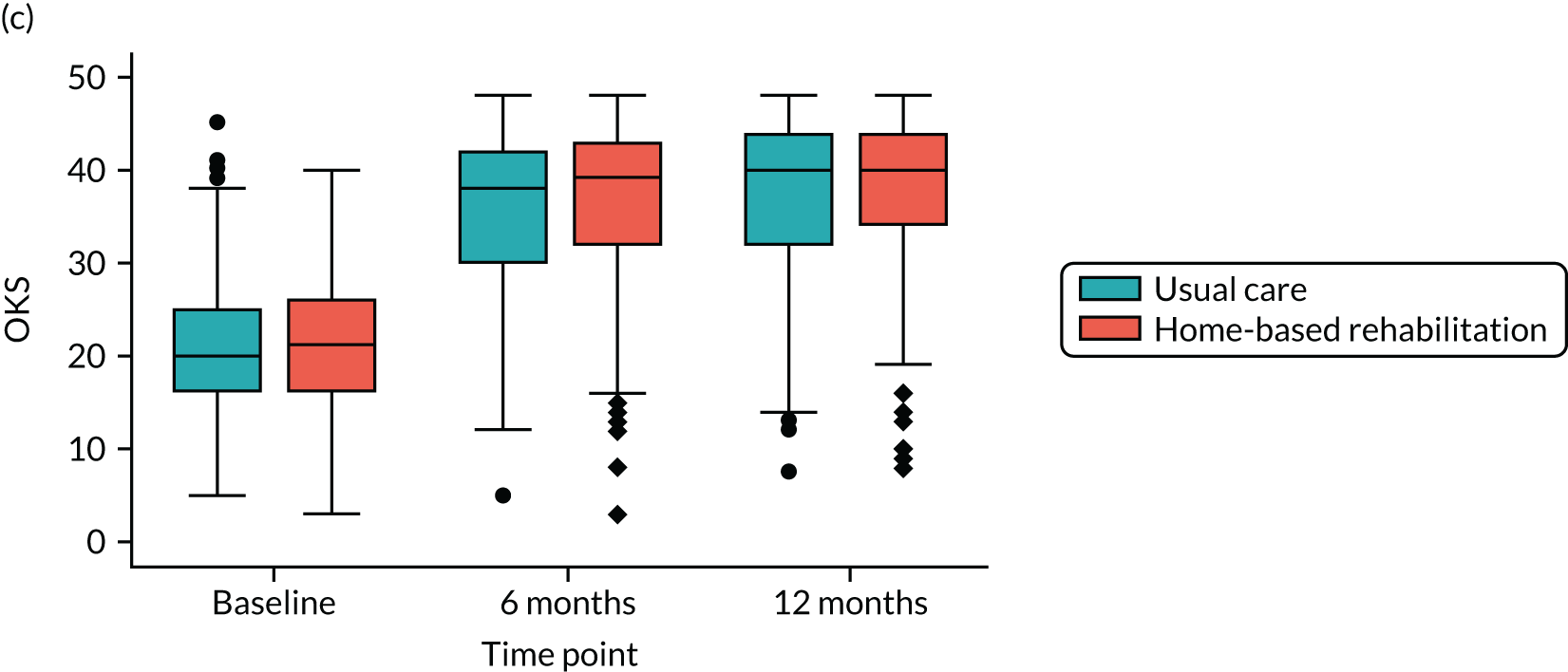

Oxford Knee Score (OKS). The OKS is a disease-specific measure to assess function and allow comparison with data from large epidemiological cohort studies. It is a 12-item PROM that is designed to measure pain and function after KA surgery. 38 Each item is scored from 0 to 4, and total scores are calculated as a sum across the individual items. Scores range from 0 (least severe symptoms) to 48 (most severe symptoms).

-

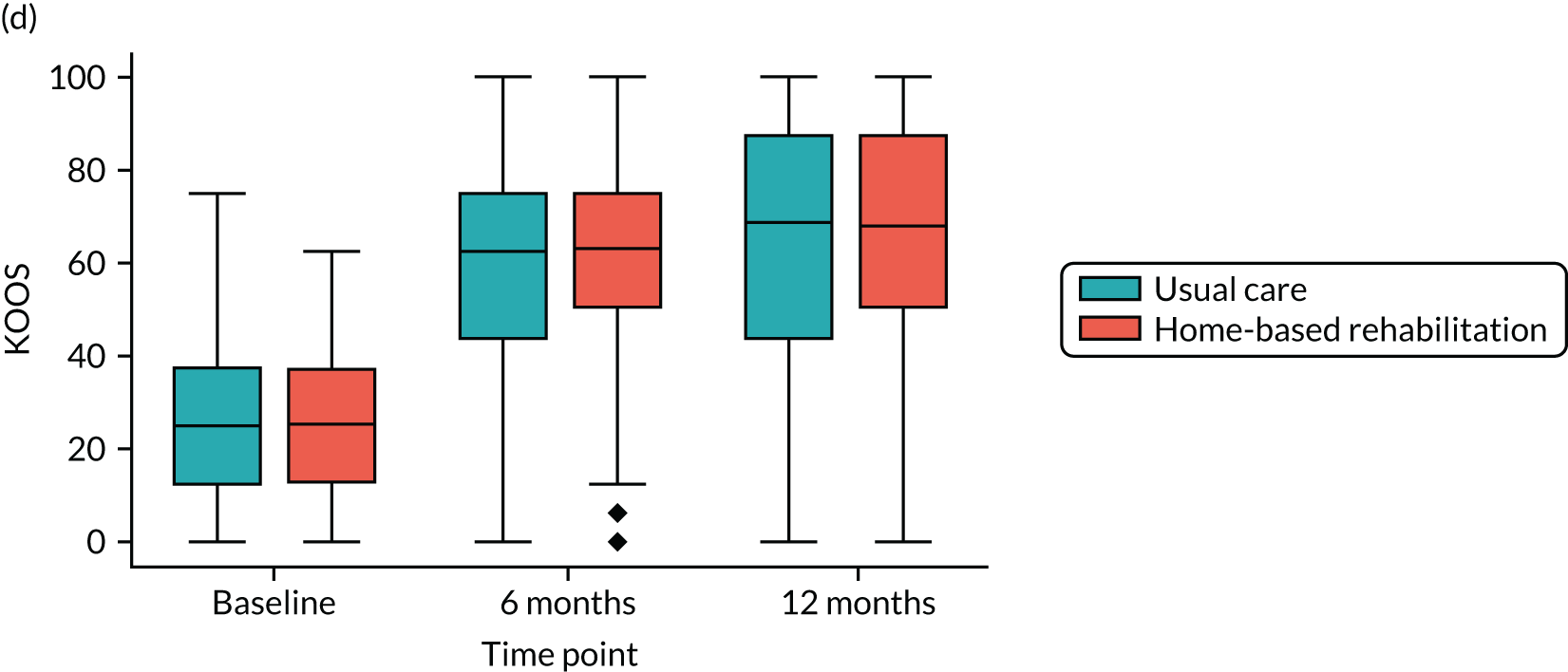

Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) – Quality of Life subscale. This is a specific instrument for knee osteoarthritis, which can also be analysed to calculate the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC). It is a self-reported questionnaire consisting of five subscales: pain, other symptoms, function in daily living, function in sport and recreation, and knee-related quality of life (QoL). The quality-of-life subscale of KOOS consists of four self-reported questions. 39 Total scores range from 0 (extreme problems) to 100 (no problems).

-

Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) questionnaire. This is a self-reported scale designed to measure the physical activity level of those aged ≥ 65 years. It consists of three subscales: leisure time activity, household activity and work-related activity. It is a short, self-administered questionnaire to assess activity in the past week. 40 Time spent participating in each activity is weighted by the difficulty of that activity to calculate a total score. Higher scores indicate greater levels of physical activity.

-

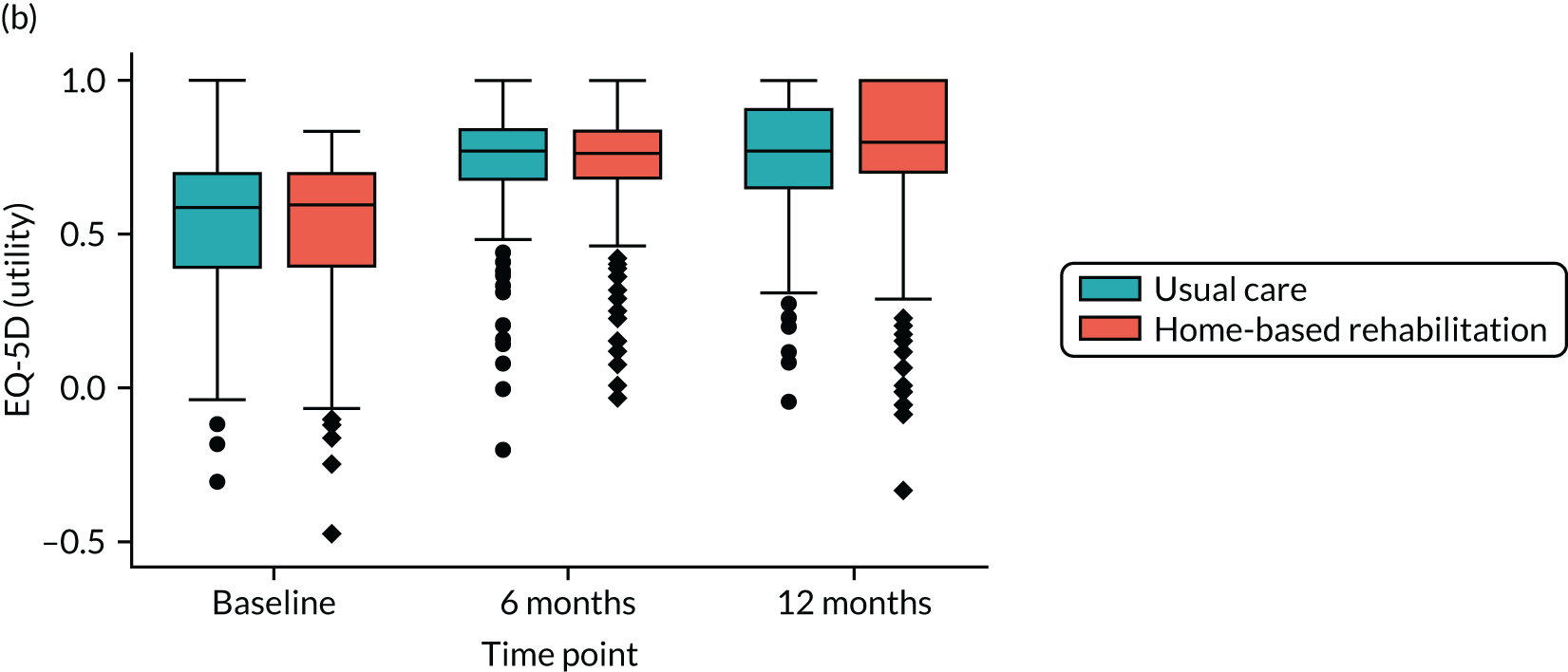

Health economics using EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L). This is a self-reported outcome measure consisting of five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activity, pain and discomfort, and anxiety and depression. Each dimension has five categories of response. It is designed to provide a generic measure of health status for clinical and/or economic evaluation. 41 Responses are converted into multi-attribute utility scores, where 1 represents perfect health, 0 represents death and scores < 0 represent a QoL worse than death.

-

Physical measures. Physical measures included measures of balance, mobility and physical activity, which are all affected by KA. Each test is reliable and valid, has been used with older, community-dwelling adults and has been shown to be responsive in previous rehabilitation studies. Physical function was measured by three physical performance tasks:42–44

-

Figure of 8 Walk Test (F8WT). In the F8WT, participants are asked to walk in a figure of eight around two cones. Their walk is timed, the number of steps taken counted and their accuracy in performing the task (ability to stay within the test boundary) recorded.

-

30-Second Chair Stand Test (30SCST). The participant starts in a seated position on a chair with a seat height of 17 inches. They are asked to complete as many full stands in 30 seconds as possible, sitting down after each stand. The number of full stands they can complete is recorded.

-

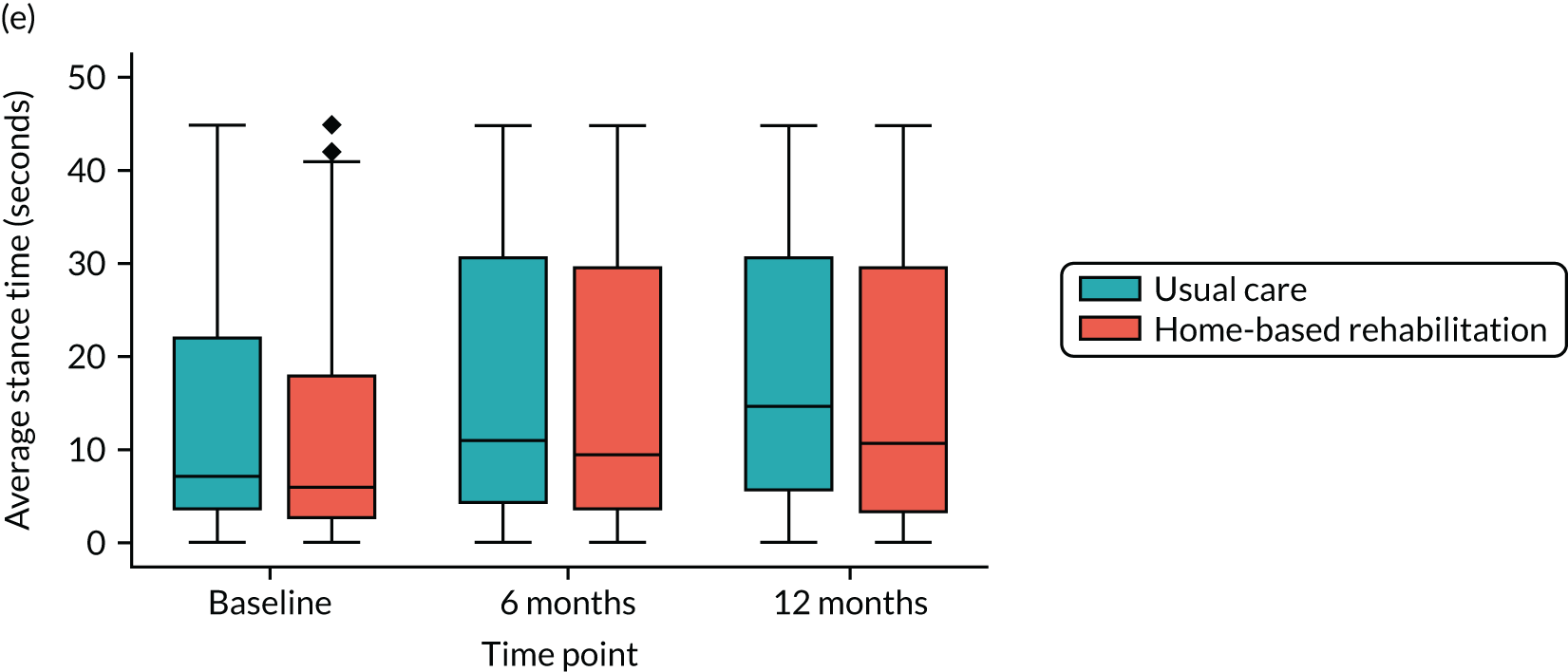

Single Leg Stance (SLS). The participant is asked to stand and lift one leg off of the ground without using any other support. They are timed standing on one leg. The participant stands with a chair in front of them should they require support. They are timed three times on each leg, for a maximum of 45 seconds for each trial.

-

-

Health resource diary. On discharge, participants were given a diary to regularly record:

-

daily exercises undertaken (completed daily for 6 weeks and weekly thereafter)

-

medication taken, including dose and frequency

-

use of health-care services and personnel

-

falls

-

adverse events.

-

Intervention monitoring and support

Quality assurance checks took place at all CORKA research sites. They included fidelity checks, during which assessment and treatment delivery were observed. All aspects of the intervention were checked against a predefined fidelity checklist that was created in line with the study protocol. Following checks, feedback was given and any training needs or action points identified. The investigator site file was also reviewed and any necessary changes were recorded. Staff at research sites were assured that support could be provided as required, not just during a monitoring visit. Staff were encouraged to contact the central CORKA trial team in Oxford if they had any questions or concerns about any aspect of the trial.

Randomisation

Randomisation took place using the Registration/Randomisation and Management of Product website provided by the Oxford Clinical Trials Research Unit randomisation service.

Allocation

Participants were randomly allocated by a computer-generated system to either ‘usual care’ or ‘home-based exercise programme’ in a 1 : 1 ratio. Randomisation using permuted blocks of various sizes (2, 4 and 6) in a 1 : 2 : 1 ratio was stratified by recruitment site to account for any site effects.

Blinding

Participants and those delivering the rehabilitation were aware of the treatment allocation owing to the nature of the intervention. The therapists who carried out the follow-up visits remained blinded.

Sample size

We chose the LLFDI as the primary outcome using the overall function subscore at 1 year. The sample size calculation was based on a moderately small standardised effect size of 0.275. This standardised effect size is, for example, equivalent to detecting a three-point difference between treatment arms on the LLFDI overall function score, assuming a standard deviation (SD) of 10.91 and no clustering effect across sites. 45

A total of 558 participants (279 per arm) would be required to detect a standardised effect size of 0.275, with 90% power and 5% (two-sided) significance. A 10% loss to follow-up was chosen based on previous experience of trials in a similar population, which resulted in the planned sample size of 620 participants (310 per arm).

An internal pilot study was conducted at one site (Oxford) to review recruitment feasibility and confirm the intervention package. Fifteen participants were randomised during this pilot study. These participants are included in the final analysis, as the interventions were not changed between the pilot and the main trial.

Data analysis

General analysis principles

Two analysis populations were considered: the intention-to-treat (ITT) population and the per-protocol (PP) population. The ITT population, which was the primary analysis set, included all randomised participants who were analysed according to their allocated intervention. Analyses of the primary and key secondary outcomes were repeated for the PP population, which included participants who received at least one session of their allocated intervention, did not receive more treatment than intended (more than six sessions of usual care or seven sessions of home-based rehabilitation) and provided follow-up data. The statistical significance level used throughout was 0.05, and 95% CIs are reported. All analyses were undertaken using Stata® 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

The statistical analysis plan for this trial was prespecified and was approved by the trial Data Safety Monitoring Committee and the Trial Steering Committee in October 2017. The agreed statistical analysis plan was then published in Trials. 46

Descriptive analyses and availability of data

The flow of participants through the trial from screening, through randomisation, allocation and follow-up, to analysis was summarised using a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) patient-reported outcomes extension flow chart (see Figure 4). 47 The baseline comparability of the two treatment groups was summarised using numbers with percentages for binary and categorical variables, and means and SDs or medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables, as appropriate, in terms of (1) risk factors for a poor outcome after KA according to the CORKA screening tool,48 (2) baseline characteristics and (3) primary and secondary outcomes. Losses to follow-up and withdrawals before 6-month follow-up and 12-month follow-up were reported by intervention arm with reasons. Absolute risk differences were tested to ensure that there were no differential losses between the two groups. The availability of all primary and secondary outcomes from baseline to 12 months post randomisation was also summarised by intervention arm.

Treatment

Compliance with home-based rehabilitation was defined as completing at least four treatment sessions, and with usual care as completing at least one treatment session. The number and percentage of compliers in each treatment group was calculated. The average (median and IQR) number of treatment sessions received in each treatment group was summarised overall and by site. Details of what the treatment sessions involved were also summarised by treatment site for each intervention.

Analysis of the primary outcome

The LLFDI function scores at 6 and 12 months post randomisation were summarised by treatment group and were analysed using a linear mixed-effects model with repeated measures adjusted for baseline score and recruiting site (stratification factor). Time was treated as categorical and an interaction between the outcome measurement time point and the randomised group was included so that the treatment effect at each time point could be estimated, reported as the adjusted mean difference in LLFDI between groups with 95% CI and associated p-value. The underlying assumptions of this model were assessed. The primary time point was 12 months post randomisation. The primary analysis was performed for the ITT population using multiple imputation to impute missing data. The multiple imputation model included type of KA (TKA or UKA), gender, whether or not the participant had had previous lower limb surgery, Charnley Classification score49 (whether the participant had single knee arthropathy, bilateral knee arthropathy or multiple joint disease), whether or not a walking aid was currently used, recruiting site and baseline score. Imputation was performed separately for each treatment group, and 10 data sets were imputed (approximately equal to the percentage of missing data).

To examine the robustness of conclusions of different assumptions about missing data and departure from randomised allocation, this analysis was repeated for the ITT population using available cases only and for the PP population using available cases. A complier-average causal effect analysis was undertaken using an instrumental variable approach. 50,51

Analysis of secondary outcomes

Linear mixed-effects models with repeated measures, similar to those described for the primary outcome, were used to analyse each of the secondary PROMs (LLFDI disability limitation, LLFDI disability frequency, OKS, KOOS QoL, PASE, EQ-5D-5L utility and visual analogue scale), 30SCST (number of stands) and F8WT (time and steps). These analyses were performed for the ITT population using available cases only.

For the key secondary outcomes (LLFDI disability limitation, LLFDI disability frequency, OKS and KOOS QoL), these analyses were repeated for the ITT population using multiple imputation (imputation model as outlined for the primary outcome) and the PP population using available cases. A complier-average causal effect analysis was also undertaken.

Average SLS test times were summarised using medians and IQRs for each treatment group at each time point. Differences between the two groups were tested using a Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and p-values were reported owing to the substantial floor and ceiling effects observed in this outcome. These analyses were unadjusted and carried out separately at each time point.

Analysis of safety data

The number of adverse events and the number and percentage of participants experiencing adverse events up to 6 months post randomisation, and between 6 and 12 months post randomisation, were reported by treatment group. The number of participants with an adverse event was compared across treatment groups using risk differences. Similar methods were used to analyse serious adverse events.

Monitoring and approvals

Formal approvals

The CORKA trial was approved by the National Research Ethics Service Committee South Central – Oxford B in February 2015 (Research Ethics Committee reference 15/SC/0019) and by the Research and Development department of each participating site. The Clinical Trials and Research Governance office at the University of Oxford confirmed sponsorship in December 2014.

The first substantial amendment was submitted and approved in August 2015, in which the sample size was recalculated using a consistent description of the clinically important standardised mean difference, a 45-minute travel inclusion zone was added and the KOOS was added to the questionnaire pack. A second substantial amendment was granted in December 2015, which added the internal pilot participants to the sample size, increasing the sample size from 620 to 635, and sought approval to send appointment reminder letters to participants. A third substantial amendment was requested in February 2017 to reduce the sample size back to 620.

Trial Steering Committee

A Trial Steering Committee was responsible for monitoring and supervising the progress of the CORKA trial throughout its duration. The committee consisted of three independent experts, a lay member and leading members of the trial management group.

Data Safety Monitoring Committee

The Data Safety Monitoring Committee was independent of the trial and was tasked with monitoring progress, conduct, participant safety and data integrity. The trial statistician provided data and analyses requested by the committee at each meeting.

Trial management group

A trial management group was responsible for the day-to-day management of the trial, consisting of the chief investigator, research physiotherapist, statistician and trial manager. They ensured the overall integrity of the trial, compliance with the protocols, welfare of all participants and appropriate reporting of the trial.

Chapter 3 Intervention development

This chapter describes the steps taken by the CORKA trial team to produce the CORKA home-based intervention. It describes the development process and each component of the intervention. The CORKA home-based intervention was developed with consideration of the Medical Research Council’s guidelines for developing and evaluating complex interventions52 and the Template for Intervention Description and Replication checklist. 53 A recent systematic review54 of intervention development approaches has categorised differing approaches in a taxonomy. Although the CORKA home-based intervention was developed before this taxonomy was published, we can classify the development approach as a combined approach, with parts of the development aligning with the ‘target population centred’, ‘theory and evidence-based’, and ‘intervention-specific’ taxonomy categories.

Overview of the development process

The CORKA home-based intervention development drew on a number of sources, including reviewing the relevant evidence base on post-arthroplasty rehabilitation, identifying appropriate exercise guidelines and seeking the views of relevant stakeholders. An intervention development day was organised that was attended by research staff, physiotherapists and occupational therapists. During the day, potential intervention approaches were discussed and refined, and factors associated with the design, content and intervention delivery were discussed. A draft intervention was presented.

The draft intervention was reviewed and refined, then tested in a clinical NHS setting as part of a pilot phase, which included participant and clinician feedback.

The development steps are outlined below and are represented in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Intervention development considerations.

Health Technology Assessment programme brief

The first step in developing the CORKA home-based intervention was considering the HTA commissioning brief. This brief called for an intensive and, if possible, multidisciplinary rehabilitation intervention in the community setting that was designed for older adults who were at risk of poorer functional outcomes following elective knee joint arthroplasty surgery that could be compared with usual care.

Evidence base

Before designing a draft intervention, we undertook a systematic search of the literature on rehabilitation post-KA, and a wider search on the field of rehabilitation following arthroplasty. This process identified a number of papers that were used in the design of the intervention. These papers are outlined in Table 2 and are described in more detail in the following section on the rationale underlying the CORKA home-based intervention.

| Authors and year of publication | Design | Conclusion or key considerations | Relevant intervention component |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bade et al. 201055 | Cohort | Impairments can persist 6 months after TKA. More intensive therapeutic approaches may be needed | Functional task practice |

| Bade and Stevens-Lapsley 201156 | Cohort | High-intensity early rehabilitation after TKA may lead to better functional performance | Strengthening |

| Bade and Stevens-Lapsley 201257 | Review | Higher-intensity rehabilitation programmes using progressive resistance strengthening produce long-term strength and functional gains | Functional task practice |

| Strengthening | |||

| Bhave et al. 200558 | Cohort | Functional limitations can be present after knee replacement. A structured programme may be needed | Range of movement exercises |

| Functional task practice | |||

| Bruun-Olsen et al. 201320 | RCT | Improvements in the 6-minute walk test were demonstrated after a walking skills programme | Gait skills |

| Graduated walking programme | |||

| Coulter et al. 200959 | Cohort | Strengthening exercises delivered during one-to-one physiotherapy or class-based physiotherapy after joint replacement showed no difference in WOMAC scores | Strengthening |

| Fitzsimmons et al. 201060 | Systematic review | Stiffness is a common problem after total knee replacement | Range of movement exercises |

| Harmer et al. 200961 | RCT | Similar outcomes were demonstrated with land-based and water-based rehabilitation after TKA | Graduated walking programme |

| Heiberg et al. 201062 | Cohort | Difficulty can be experienced with strenuous activities, including walking long distances, after TKA | Gait skill |

| Graduated walking programme | |||

| Kearns et al. 200863 | Cohort | Falling was reported by 78 out of 1341 consecutive patients after TKA | Balance |

| Knoop et al. 201164 | Narrative review | People with knee osteoarthritis have decreased knee proprioception | Balance |

| Lee et al. 201465 | Cross-section | Lower-limb strength and the Y-balance test were weakly correlated | Strength |

| Balance | |||

| Liao et al. 201366 | RCT | Significant changes in the 10-metre walk test and the Timed Up and Go Test were observed after balance training | Balance |

| Mandeville et al. 200867 | Cohort | Gait stability can be affected by total knee replacement surgery | Balance |

| Gait skills | |||

| McClelland et al. 200768 | Systematic review | Altered gait patterns are observed following TKA | Gait skills |

| Meier et al. 200869 | Review | Quadriceps muscle impairment can contribute to functional limitations after total knee replacement | Functional task practice |

| Strengthening | |||

| Minns Lowe et al. 200718 | Systematic review | Functional physiotherapy exercises resulted in short-term benefit after total knee replacement | Functional task practice |

| Mizner et al. 200570 | Cohort | Functional performance was highly correlated with quadriceps strength | Strengthening |

| Moffet et al. 200421 | RCT | Short- and mid-term functional ability was improved by intensive functional rehabilitation | Strengthening |

| Naylor and Ko 201271 | Mixed methods study (nested within a RCT) | Patients were able to exercise at moderately hard-intensity levels after total knee replacement | Graduated walking programme |

| Strengthening | |||

| Noble et al. 200572 | Cross-section | Significant functional impairments were experienced by TKA patients | Functional task practice |

| Pandy et al. 201073 | Review | The muscles of the hip and calf play a significant role in gait | Strengthening |

| Gait skills | |||

| Philbin et al. 199574 | Cross-section | Those with end-stage osteoarthritis of the lower extremity can be severely deconditioned | Graduated walking programme |

| Piva et al. 201019 | Pilot RCT | Balance training after TKA is feasible, as supported by high adherence and a low dropout rate | Balance |

| Piva et al. 201175 | Cross-section | Physical function after arthroplasty can be influenced by hip abduction strength | Strengthening |

| Pozzi et al. 201376 | Systematic review | Strengthening and intensive functional exercises should be included in optimal physiotherapy programmes | Strengthening |

| Functional task practice | |||

| Ries et al. 199677 | Cohort | There can be improvements in cardiovascular fitness at 1 or 2 years after TKA | Graduated walking programme |

| Rowe et al. 200078 | Cohort | A suitable goal for knee rehabilitation is to reach 110° of knee flexion | Range of movement exercises |

| Stratford et al. 201079 | Cohort | The first 12 weeks post arthroplasty is when the greatest range of movement improvements took place | Range of movement exercises |

| Stevens et al. 200380 | Cohort | Reduced quadriceps strength was observed in those with knee osteoarthritis. This weakness persisted post surgery | Strengthening |

| Su et al. 201081 | Review | Stiffness is a frequent complication after TKA | Range of movement exercises |

| Turcot et al. 201382 | Cohort | Gait parameters can affect patient satisfaction after TKA | Gait skills |

| Graduated walking programme | |||

| Walsh et al. 199883 | Cohort | Physical impairments and functional limitations may persist at 1 year after TKA | Strengthening |

| Wiik et al. 201384 | Cohort | Gait parameters were much closer to normal after unicompartmental knee replacement than total knee replacement patients, but were not as good as control participants | Gait skills |

| Graduated walking programme |

Rationale underlying the CORKA intervention

The different components of the CORKA home-based intervention were informed by a review of existing trials. The intervention primarily consists of a functional exercise programme. The rationale for the following sections of this exercise programme is given below:

-

range of movement exercises

-

strengthening exercises

-

balance exercises

-

gait and aerobic exercise

-

functional exercise.

Range of movement

Both flexion and extension can be limited after KA surgery. 58,79 Stiffness is a common complication after surgery,78 with as many as 60% of those undergoing KA experiencing stiffness. 73 Many functional activities require a knee joint range of 0–110°,80 and a significant proportion of this range is likely to be attained within the first 12 weeks after surgery. 79 A number of studies have, therefore, included range of movement exercises in their post-arthroplasty interventions. 56,66,75

Strengthening

Decreased quadricep strength is a common finding in people with knee osteoarthritis,80 and these strength deficits can persist for a long time after KA. 76 One year after arthroplasty, both knee flexor and extensor peak muscle torque are lower in those who have undergone surgery than age-matched controls. 83 As there is a close link between muscle strength and functional performance, strength is an important consideration for the population in question. For example, the ability to change position from sitting to standing and the ability climb stairs have been linked to quadriceps strength. 70 The ability to get up from a chair, climb-up stairs, walk and change direction have been linked with hip abduction strength. 75 Hip and calf strength also perform a significant role in gait and balance. 65,73 Strengthening exercises have formed part of previous interventions following lower limb arthroplasty, targeting muscle groups such as the quadriceps, hamstrings, hip abductors and calf muscles. 21,56,59,75

Balance

As KA surgery can affect gait, balance and stability,67 it is not surprising that falling has been reported as a problem after KA. 63 In a pilot study, Piva et al. 19 gave participants functional training or functional training enhanced by a balance training programme after KA. The pilot study’s design was underpowered to detect changes between groups but showed that the balance training group had high adherence, had a low dropout rate and reported no adverse events. A RCT66 that investigated the effect of adding a balance programme to functional training after KA reported that those in the balance training group had significantly better outcomes, including on the Timed Up and Go, 10-metre walk, 30SCST and Stair Climb tests.

Gait skills and aerobic exercise

McClelland et al. 68 conducted a systematic review that studied gait analysis following KA and concluded that patients exhibit altered gait patterns after surgery. Gait problems after KA include specific gait deficits linked to underlying problems, such as reduced range of movement or pain, and general problems, such as decreased walking speed and endurance. 62,68,83 Such gait problems may continue to persist 1 year after surgery. Patients undergoing UKA are more likely to exhibit a gait pattern closer to normal than patients undergoing TKA. 84 It is important to consider gait in patients who have undergone KA, as gait outcomes influence patient satisfaction. 82

Bruun-Olsen et al. 20 undertook a RCT comparing a walking skills intervention with usual physiotherapy. They reported that the walking skills group demonstrated better short-term and long-term functional mobility. Walking can also be considered from a wider cardiovascular perspective. People with end-stage lower limb osteoarthritis are likely to be physically deconditioned,74,77 which can be exacerbated immediately after surgery owing to reduced mobility. Naylor and Ko71 found that moderate-intensity exercise was tolerable and safe following KA. Later studies have included aerobic exercise using cycling on a static bike or walking on a treadmill. 59,61

Functional exercise

Functional limitations can persist after the immediate post-operative period following KA. 57,69 One year post KA surgery, it is common for patients to be significantly slower with activities, such as walking or stair climbing, and have more functional impairments with tasks that involve kneeling or squatting than matched controls. 72,83 Measurements of function, such as the Timed Up and Go, 6-minute walk, Stair Climb and SLS tests, have been found to be worse in participants following KA at 1, 3 and 6 months after surgery than in healthy participants. 55 A 2007 systematic review18 investigating the effectiveness of post-KA exercise advocated for the use of functional physiotherapy exercise interventions to achieve short-term benefits. It found that the interventions had a small to moderate effect on functional outcomes, QoL and joint range of movement at 3 to 4 months after surgery; however, these benefits were not found 1 year after surgery. A later study explored function after KA57 and a 2013 systematic review76 of exercise after KA recommended that physiotherapy interventions include strengthening and functional exercise.

Guidelines

Currently, there are no specific exercise guidelines for patients after KA. We considered two relevant guidelines for patients following KA when developing the CORKA home-based intervention:

-

Physical activity and public health in older adults: recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. 85

-

Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. 86

These guidelines cover exercise guidelines for adults aged 65 years or older and aged 50–64 years with functional limitations or a chronic condition,85 and apparently healthy adults of all ages. 86 On the basis of these guidelines, it is recommended that participants accumulate five sessions of 30 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week, which is accumulated in at least 10-minute bouts.

Intervention development day and workshop

An intervention development day was attended by researchers, physiotherapists and occupational therapists. A draft intervention developed using the evidence base and guidelines outlined above was presented at the workshop. The proposed intervention programme, strategies for exercise progression and patient materials were discussed and reviewed. Feedback was given on all aspects of the proposed intervention, leading to changes in the content of the intervention and patient materials.

Pilot phase

Following the workshop, a final version of the CORKA home-based intervention was compiled. It was then tested in a pilot phase with 15 participants. Three participants and two clinicians were interviewed after the participants had completed their treatment sessions to get feedback on the intervention content and the mode of delivery. As a result, changes were made to the participant materials and intervention procedures. These modifications included retaking some of the photographs used in the participant exercise sheets to make them brighter and more vibrant, and providing a space on the sheets for participants to make comments.

The CORKA intervention arms

The CORKA trial had two intervention arms:

-

usual care

-

the CORKA home-based intervention.

The intervention arms are described in the following sections.

Usual care

Those who were allocated to the usual-care arm received standard post-operative physiotherapy, as offered by their local physiotherapy department. It was recognised that usual care after KA could vary considerably across the trial’s UK locations. 36 However, there was a reasonable likelihood that it would include some of the following: one to six sessions of physiotherapy in an outpatient setting, class-based setting or hydrotherapy; written advice on home exercise at discharge from hospital; and an assessment of any potential home requirements and barriers to discharge by an occupational therapist. To standardise usual care as much as possible, participants were expected to attend at least one and no more than six sessions of usual-care physiotherapy.

The CORKA home-based intervention

The CORKA home-based intervention was an individually tailored, multicomponent rehabilitation programme that could be adapted for each participant. The intervention’s aim was to improve the function and participation of participants who were at risk of a poor outcome post KA. The primary component was an individually adapted exercise programme that was conducted in the participant’s own home, with additional components consisting of functional task practice, appropriate adherence approaches and, if required, the provision of appropriate aids and equipment.

The CORKA home-based intervention started within 4 weeks of surgery. It comprised an initial home assessment appointment, followed by up to six follow-up sessions. It was designed to be delivered by a mixture of qualified occupational therapy and physiotherapy staff, and rehabilitation assistants. The CORKA home-based intervention is outlined further in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Components of the CORKA home-based intervention exercise programme. ROM, range of movement.

Home exercise programme

The CORKA home-based intervention exercise programme comprised groups of possible exercises that were arranged into the following categories:

-

knee flexion range of movement

-

knee extension range of movement

-

basic quadriceps strengthening

-

strengthening – quadriceps

-

strengthening – hamstrings

-

strengthening – hip abductors

-

strengthening – calf

-

balance

-

gait skills.

The programme included a range of exercises in each category, and at least one exercise from each category was to be selected for a participant’s exercise programme. This allowed the intervention to cover a range of exercises and be tailored to each participant.

Functional task practice

A functional task practice component was also included. During a participant’s first appointment, the therapist focused on tasks that the participant had identified as being potentially problematic. The exercise programme was, therefore, tailored to the specific needs, goals and functional problems of the individual. As necessary, different techniques were used as part of a problem-solving approach, including breaking the task down and identifying any specific components for practice. Each task could also be demonstrated and practised during the intervention sessions. To reinforce the importance of practising the selected tasks during their daily life, participants were encouraged to follow the written advice in the exercise diary.

Graduated walking programme

The graduated walking programme was included as it was deemed the most practical and relevant method to increase walking endurance and include moderate-intensity aerobic exercise within the exercise programme. It was considered likely that participants would have a wide range of mobility levels at entry into the trial. The aim of the graduated walking programme was to increase walking distance and/or time. During session 3 of the CORKA home-based intervention, participants were asked about their walking and how far or how long they were currently able to walk. They were then asked to gradually increase this distance and/or time, giving consideration to any pain or swelling. Walking was reviewed at subsequent follow-up sessions.

Prescription and progression

Therapists and assistants were asked to use treatment algorithms and decision aids to prescribe and progress participants’ exercises, which are outlined and described in Table 3. The Rating of Perceived Exertion scale87 that is mentioned is an 11-point scale that allows participants to rate how hard they feel they are working during exercise.

| Exercise type | Repetitions and sets | Decrease intensity/difficulty | Maintain intensity/difficulty | Increase intensity/difficulty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strengthening exercises |

|

|

|

|

| Balance exercises |

|

|

|

|

| Range of movement exercises |

|

|

|

|

| Gait skills |

|

|

|

|

| Walking |

|

|

|

|

| Task practice |

|

|

|

|

Exercise duration and frequency

It was envisaged that the whole exercise programme would take 15–25 minutes to complete. Participants were advised that their exercise programme could be performed as one block or spread throughout the day. They were asked to perform the exercise programme daily, although it was recognised that this would not be possible for everyone.

Modifications

The therapists and rehabilitation assistants delivering the CORKA home-based intervention were encouraged to use their clinical reasoning skills when assessing and treating participants. If at any time they felt that it would be unsafe or inappropriate to give a participant an exercise from one or more of the intervention’s categories, then they were advised not to do so. If they decided that a participant needed additional exercises from an intervention category, for example if they felt that a participant had a particular problem with knee flexion and needed to be given more than one exercise from the knee flexion range of movement category, then they were encouraged to do so. Clinicians were asked to record any modifications that they made on the treatment logs that were returned to the central CORKA trial team.

Information booklet

Participants were given an information booklet that contained information about topics relevant to patients after KA, such as wound management, pain and swelling, expected symptoms, scar massage, walking, slips, trips and falls, kneeling, stairs, driving, returning to work, and returning to leisure activities or sports.

Adherence approaches

A number of adherence strategies were used within the intervention to encourage participants to adhere to their exercise programme, including an exercise diary, a behavioural contract and goal-setting. Participants recorded their exercises, repetitions and sets in an exercise diary so that they could monitor their own progress.

The CORKA trial participant materials included a behavioural contract. Participants were asked when they would be able to perform their exercises, whether or not there was a specific location where they could perform their exercises and if there was anyone who could help them undertake their exercise programme. The therapists and participant signed this contract to encourage adherence.

The therapist and participant took time to discuss the goals that were important to the participant. These goals were written in the appropriate section in the participant materials, along with the steps that the participant would follow to meet the goals: (1) practice tasks related to the goals, (2) undertake their tailored exercise programme and (3) record their exercise progress in the exercise diary provided. Each participant was given opportunities to review and set new goals as required in follow-up treatment sessions.

Intervention materials

Trial sites were given at least one copy of the treating therapists’ manual. This manual gave a detailed overview of the intervention and a point-by-point guide for each intervention session, including how to select the initial exercise level for each section of the exercise programme. It also included copies of all of the paperwork needed for the intervention and the contact details for the central CORKA team.

The CORKA website (https://corka.octru.ox.ac.uk/) was a further resource for staff at research sites. It contained a section for site staff that sites gained access to once they had signed up for the trial. This section included digital copies of all trial documents needed for that site.

Intervention providers and setting

The CORKA home-based intervention was undertaken using qualified therapists and rehabilitation assistants. The initial appointment consisted of a home assessment that was conducted by a therapist and a rehabilitation assistant. Subsequent rehabilitation sessions were undertaken by the rehabilitation assistant, except for one session midway through the treatment that was undertaken by the qualified therapist. Clear channels of communication were encouraged, and rehabilitation assistants were asked to feed back to the qualified staff member after all treatment sessions. All of the therapists that delivered the intervention were UK-registered physiotherapists or occupational therapists, with NHS banding ranging from 5 to 7. The rehabilitation assistants were NHS bands 3 or 4.

Training

All members of staff who were involved in delivering the CORKA home-based intervention received a 2- to 3-hour training session that was delivered by the central CORKA trial team. The training included instructions on how to assess and treat CORKA participants, prescribe and progress the different categories within the exercise programme, and complete the trial paperwork, in line with the trial protocol. None of the intervention components was beyond the normal scope of practice for the staff who delivered the intervention.

Safety and serious adverse events

The safety of participants and therapists was paramount and was considered as part of the CORKA home-based intervention. All trial site staff members delivering the intervention were encouraged to consider their and their patients’ safety. One of the significant considerations for a community-based trial like CORKA is that staff are by themselves when visiting participants in their homes. All staff members at all sites were, thus, asked to adhere to their organisation’s lone-working policy. They were also asked to report anything that they felt might constitute a serious adverse event. To make this process as easy as possible for clinicians involved in the treatment sessions, they were encouraged to discuss any questions or concerns with the central CORKA team in Oxford.

Chapter 4 Results

Study participants

The trial opened for recruitment on 17 March 2015, and the first participant was randomised on 27 March 2015. As recruitment was slower than predicted in the first year, the funder (HTA programme) requested a recovery plan be put in place. The recovery plan was reviewed by the Trial Steering Committee on 16 June 2016 and submitted to the HTA programme on 8 July 2016. In February 2017, a funding extension was agreed with the HTA programme with a revised trial end date of 31 December 2019.

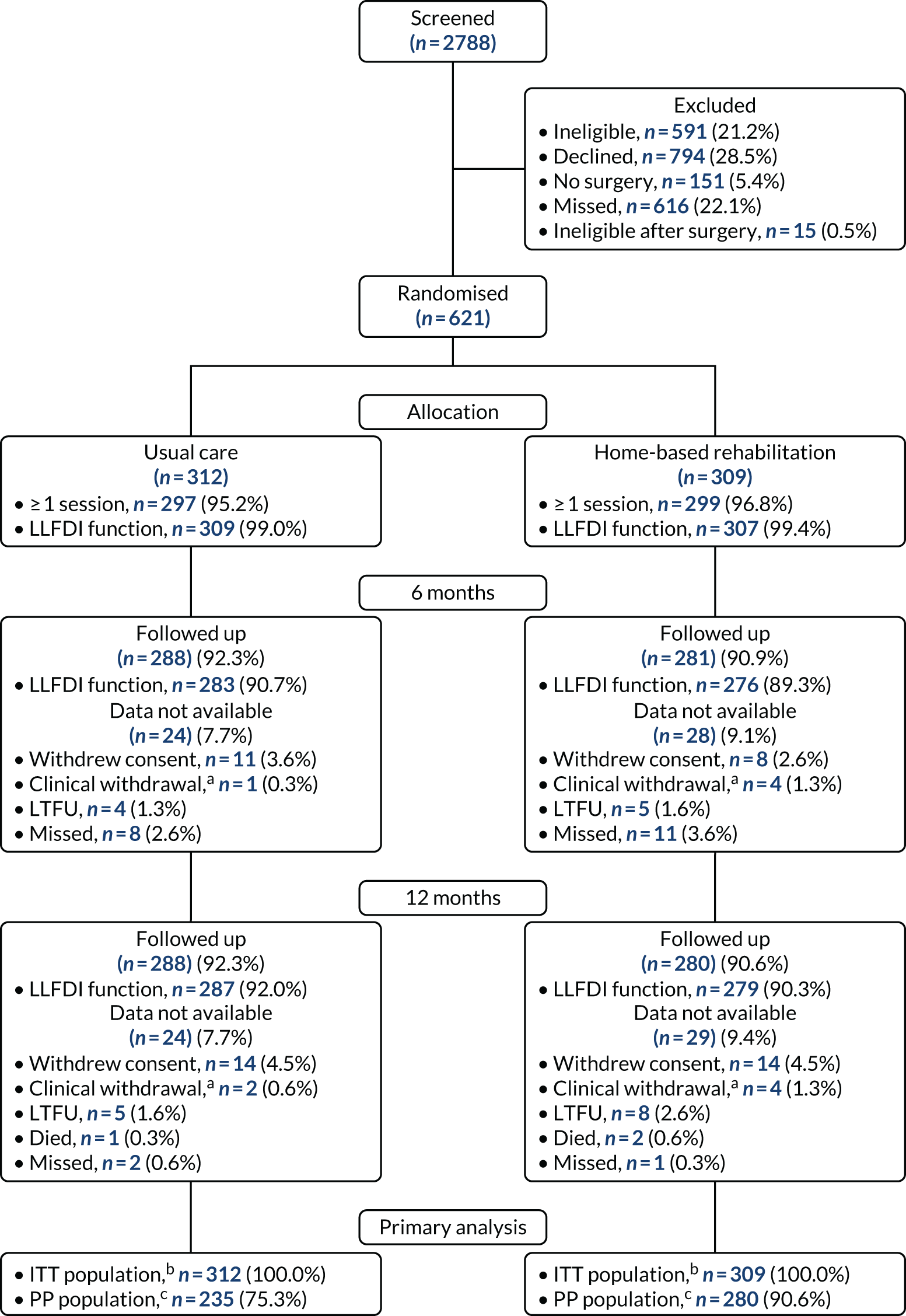

The final randomisation took place on 26 January 2018. In total, 2788 patients were screened and 621 participants were recruited to the trial. The 12-month follow-up was completed in February 2019. The CONSORT flow chart (Figure 4) summarises the flow of participants through the trial, including details of the number of participants randomised and the numbers allocated to and receiving at least one session of each treatment. The number of participants followed up at 6 and 12 months and providing the primary outcome measure is summarised by treatment group. Reasons why participants were not followed up are also included. The numbers of participants included in the ITT and PP populations are summarised by treatment group.

FIGURE 4.

The CONSORT flow chart. LTFU, lost to follow-up. a, Clinical withdrawals include those who withdrew owing to an adverse event, serious adverse event or medical contraindication; b, missing follow-up data in the ITT population were imputed using multiple imputation for the primary outcome analysis; c, analysis of the PP population was based on available data only.

Available data

The data available at baseline and at each follow-up time point (6 and 12 months) are summarised by treatment group in Table 4. These data include which participants returned a case report form (CRF) at each time point and which participants returned a questionnaire. Reasons for data not being available are also summarised. The proportion of available data is high at both 6 and 12 months; approximately 90% for each treatment group. There were no significant differences in data availability between the two groups (Table 5).

| Data | Usual care (N = 312), n (%) | Home-based rehabilitation (N = 309), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||

| Data available | 312 (100.0) | 309 (100.0) |

| Completed CRF | 312 (100.0) | 309 (100.0) |

| Completed questionnaire | 312 (100.0) | 309 (100.0) |

| 6 months | ||

| Data available | 288 (92.3) | 281 (90.9) |

| Completed CRF | 280 (89.7) | 276 (89.3) |

| Completed questionnaire | 284 (91.0) | 278 (90.0) |

| Data not available | 24 (7.7) | 28 (9.1) |

| Withdrawna | 12 (2.8) | 12 (3.9) |

| Missingb | 12 (3.8) | 16 (5.2) |

| 12 months | ||

| Data available | 288 (92.3) | 280 (90.6) |

| Completed CRF | 282 (90.4) | 276 (89.3) |

| Completed questionnaire | 287 (92.0) | 279 (90.3) |

| Data not available | 24 (7.7) | 29 (9.4) |

| Withdrawna | 16 (5.1) | 18 (5.8) |

| Missingb | 7 (2.2) | 9 (2.9) |

| Died | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) |

| Time point | Risk difference (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| 6 months | –0.01 (–0.06 to 0.03) | 0.54 |

| 12 months | –0.02 (–0.06 to 0.03) | 0.45 |

Withdrawals

Thirty-four participants (5.5%) withdrew from follow-up during the course of the trial. Most withdrawals were because of participants withdrawing their consent (n = 28), with the rest a result of a clinical decision (n = 6). Most of the withdrawals happened before the 6-month follow-up (n = 24) and the remainder happened between the 6-month and the 12-month follow-up (n = 10). Three participants died between the 6-month and the 12-month follow-up.

Baseline characteristics

Randomisation in the CORKA trial was stratified by recruiting site. The number and proportion of participants randomised to each treatment group at each site are summarised in Table 6. Participants were well balanced between the two groups at each site.

| Trial site | Usual care (N = 312), n (%) | Home-based rehabilitation (N = 309), n (%) | Total (N = 621), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | 33 (10.6) | 34 (11.0) | 67 (10.8) |

| Site 2 | 38 (12.2) | 38 (12.3) | 76 (12.2) |

| Site 3 | 4 (1.3) | 4 (1.3) | 8 (1.3) |

| Site 4 | 8 (2.6) | 7 (2.3) | 15 (2.4) |

| Site 5 | 8 (2.6) | 7 (2.3) | 15 (2.4) |

| Site 6 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) |

| Site 7 | 3 (1.0) | 2 (0.6) | 5 (0.8) |

| Site 8 | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | 3 (0.5) |

| Site 9 | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) | 4 (0.6) |

| Site 10 | 15 (4.8) | 14 (4.5) | 29 (4.7) |

| Site 11 | 30 (9.6) | 30 (9.7) | 60 (9.7) |

| Site 12 | 99 (31.7) | 100 (32.4) | 199 (32.0) |

| Site 13 | 65 (20.8) | 63 (20.4) | 128 (20.6) |

| Site 14 | 5 (1.6) | 5 (1.6) | 10 (1.6) |

A screening tool was used to identify participants at higher risk of a poor outcome following KA for inclusion in the CORKA trial (see Chapter 7). The key features of the screening tool were body mass index (BMI), pain, health status and anxiety or depression.

Table 7 summarises the number and proportion of people satisfying each of the criteria, which combine to give the total screening tool score. These appear well balanced across the two treatment groups. The slight apparent imbalance in BMI may have been because this variable was treated as categorical (see Table 8). Table 7 also included the contribution of each characteristic to the total score, the number of participants with each score and the constituent parts that make up that score. All participants met the moderate to severe usual pain from the knee criteria, which was usually combined with a high BMI.

| Screening tool details | Usual care (N = 312), n (%) | Home-based rehabilitation (N = 309), n (%) | Total (N = 621), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | |||

| Normal (0) | 11 (3.5) | 7 (2.3) | 18 (2.9) |

| Overweight (1) | 121 (38.8) | 138 (44.7) | 259 (41.7) |

| Obese (2) | 180 (57.7) | 164 (53.1) | 344 (55.4) |

| Usual pain from knee | |||

| Moderate or severe (4) | 312 (100.0) | 309 (100.0) | 621 (100.0) |

| Health status | |||

| Fit and healthy (0) | 296 (94.9) | 298 (96.4) | 594 (95.7) |

| Severe systemic disease (2) | 16 (5.1) | 11 (3.6) | 27 (4.3) |

| Limited | |||

| None, a little or some of the time (0) | 248 (79.5) | 248 (80.3) | 496 (79.9) |

| Most or all of the time (2) | 64 (20.5) | 61 (19.7) | 125 (20.1) |

| Screening tool scores and constituent parts | |||

| 5 – Overweight | 87 (27.9) | 104 (33.7) | 191 (30.8) |

| 6 – Obese | 150 (48.1) | 135 (43.7) | 285 (45.9) |

| 6 – Severe systemic disease | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| 6 – Limited most/all of the time | 10 (3.2) | 7 (2.3) | 17 (2.7) |

| 7 – Overweight and severe systemic disease | 4 (1.3) | 6 (1.9) | 10 (1.6) |

| 7 – Overweight and limited most/all of the time | 26 (8.3) | 27 (8.7) | 53 (8.5) |

| 8 – Obese and severe systemic disease | 6 (1.9) | 3 (1.0) | 9 (1.4) |

| 8 – Obese and limited most/all of the time | 23 (7.4) | 25 (8.1) | 48 (7.7) |

| 9 – Overweight and severe systemic disease and limited most/all of the time | 4 (1.3) | 1 (0.3) | 5 (0.8) |

| 10 – Obese and severe systemic disease and limited most/all of the time | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) |

The descriptive characteristics of all randomised participants are summarised by treatment group, and overall, in Table 8. These values are presented as numbers and percentages for binary and categorical factors, and as means and SDs or medians and IQRs, as appropriate, for continuous variables. These variables appear well balanced across the two treatment groups.

| Characteristic | Usual care (N = 312) | Home-based rehabilitation (N = 309) | Total (N = 621) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 125 (40.1) | 125 (40.5) | 250 (40.3) |

| Female | 187 (59.9) | 184 (59.5) | 371 (59.7) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 70.18 (8.14) | 70.67 (8.01) | 70.42 (8.07) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 31.65 (4.99) | 31.34 (4.48) | 31.50 (4.74) |

| Side of operation, n (%) | |||

| Right | 169 (54.2) | 169 (54.7) | 338 (54.4) |

| Left | 142 (45.5) | 139 (45.0) | 281 (45.2) |

| Not recorded | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) |

| Knee arthroplasty type, n (%) | |||

| TKA | 229 (73.4) | 231 (74.8) | 460 (74.1) |

| UKA | 82 (26.3) | 77 (24.9) | 159 (25.6) |

| Not recorded | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) |

| ASA classification grade, n (%) | |||

| Healthy | 38 (12.2) | 55 (17.8) | 93 (15.0) |

| Mild systemic disease | 218 (69.9) | 202 (65.4) | 420 (67.6) |

| Severe systemic disease | 43 (13.8) | 44 (14.2) | 87 (14.0) |

| Not recorded | 13 (4.2) | 8 (2.6) | 21 (3.4) |

| Falls in the last year | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 77 (24.7) | 89 (28.8) | 166 (26.7) |

| No, n (%) | 235 (75.3) | 220 (71.2) | 455 (73.3) |

| If yes, number of falls, median (IQR) | 1 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 3) |

| Previous lower limb surgery, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 200 (64.1) | 189 (61.2) | 389 (62.6) |

| No | 112 (35.9) | 120 (38.8) | 232 (37.4) |

| Screening tool score, median (IQR) | 6 (5, 6) | 6 (5, 6) | 6 (5, 6) |

| Charnley ABC, n (%) | |||

| A: single KA | 134 (42.9) | 138 (44.7) | 272 (43.8) |

| B: both knees affected | 140 (44.9) | 145 (46.9) | 285 (45.9) |

| C: multiple joint disease/other disability | 38 (12.2) | 26 (8.4) | 64 (10.3) |

| Stairs mobility, n (%) | |||

| Normal | 19 (6.1) | 19 (6.1) | 38 (6.1) |

| One step at a time | 34 (10.9) | 39 (12.6) | 73 (11.8) |

| Down with rail | 18 (5.8) | 19 (6.1) | 37 (6.0) |

| Up/down with rail | 225 (72.1) | 216 (69.9) | 441 (71.0) |

| Unable down | 2 (0.6) | 3 (1.0) | 5 (0.8) |

| Unable | 14 (4.5) | 12 (3.9) | 26 (4.2) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) |

| Support mobility, n (%) | |||

| None | 178 (57.1) | 178 (57.6) | 356 (57.3) |

| Stick outdoors | 83 (26.6) | 78 (25.2) | 161 (25.9) |

| Stick always | 34 (10.9) | 31 (10.0) | 65 (10.5) |

| Two sticks | 6 (1.9) | 7 (2.3) | 13 (2.1) |

| Two crutches | 5 (1.6) | 7 (2.3) | 12 (1.9) |

| Walking frame | 6 (1.9) | 8 (2.6) | 14 (2.3) |

| Functional comorbidity index,a n (%) | |||

| 0 | 189 (60.6) | 176 (57.0) | 365 (58.8) |

| 1–3 | 112 (35.9) | 125 (40.5) | 237 (38.2) |

| 4–6 | 8 (2.6) | 6 (1.9) | 14 (2.3) |

| 7 or more | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | 3 (0.5) |

The PROMs and physical measure baseline values are summarised by treatment group, and overall, in Table 9, and are all similar across the two treatment groups.

| Outcome | Usual care (N = 312) | Home-based rehabilitation (N = 309) | Total (N = 621) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LLFDI function, mean (SD) | 51.21 (7.09) | 51.68 (7.17) | 51.45 (7.13) |

| LLFDI disability (frequency), mean (SD) | 51.28 (7.25) | 51.55 (7.46) | 51.42 (7.35) |

| LLFDI disability (limitation), mean (SD) | 66.26 (11.96) | 66.25 (12.48) | 66.26 (12.21) |

| EQ-5D-5L utility, median (IQR) | 0.59 (0.39, 0.70) | 0.59 (0.39, 0.70) | 0.59 (0.39, 0.70) |

| EQ-5D-5L VAS, median (IQR) | 70.0 (58.0, 80.0) | 75.0 (55.0, 80.0) | 70.0 (55.0, 80.0) |

| OKS,a mean (SD) | 20.59 (7.50) | 20.81 (7.31) | 20.70 (7.40) |

| PASE, median (IQR) | 114.4 (62.2, 160.0) | 98.5 (62.2, 149.6) | 108.2 (62.2, 157.4) |

| KOOS, median (IQR) | 25.0 (12.5, 37.5) | 25.0 (12.5, 37.5) | 25.0 (12.5, 37.5) |

| 30SCST number of stands, median (IQR) | 8 (6, 10) | 8 (6, 11) | 8 (6, 10) |

| 30SCST adaptations, n (%) | |||

| None | 211 (67.6) | 214 (69.3) | 425 (68.4) |

| Uses hands on legs | 94 (30.1) | 90 (29.1) | 184 (29.6) |

| Uses walking aid | 2 (0.6) | 4 (1.3) | 6 (1.0) |

| Not tested: unable | 5 (1.6) | 1 (0.3) | 6 (1.0) |

| F8WT | |||

| Time (seconds), median (IQR) | 10.3 (8.6, 13.0) | 10.9 (9.0, 14.0) | 10.6 (8.8, 13.5) |

| Steps, median (IQR) | 16.0 (13.0, 19.0) | 16.0 (14.0, 19.0) | 16.0 (14.0, 19.0) |

| Stayed within cones, n (%) | 303 (97.1) | 304 (98.4) | 607 (97.7) |

| F8WT smoothness score, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 9 (2.9) | 11 (3.6) | 20 (3.2) |

| 1 | 73 (23.4) | 87 (28.2) | 160 (25.8) |

| 2 | 50 (16.0) | 56 (18.1) | 106 (17.1) |

| 3 | 180 (57.7) | 155 (50.2) | 335 (53.9) |

| SLS test average time (seconds), median (IQR) | |||

| KA side | 5.3 (2.6, 13.0) | 4.5 (1.9, 14.5) | 5.1 (2.2, 14.0) |

| Other side | 7.2 (3.6, 22.0) | 6.3 (2.6, 18.0) | 6.9 (3.2, 19.8) |

Treatment compliance

Participants were defined as complying with usual-care if they attended at least one treatment session. Compliance with home-based rehabilitation was defined as receiving at least four treatment sessions. Table 10 summarises the number and percentage of compliers in each treatment group, the number of participants who attended no sessions and the average number of treatment sessions received.

| Treatment details | Usual care (N = 312) | Home-based rehabilitation (N = 309) |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum number of sessions for compliance | 1 | 4 |

| Compliers, n (%) | 297 (95.2) | 269 (87.1) |

| Participants with no treatment logs, n (%) | 12 (3.8) | 10 (3.2) |

| Number of sessions, median (IQR) | 4 (2, 6) | 5 (4, 7) |

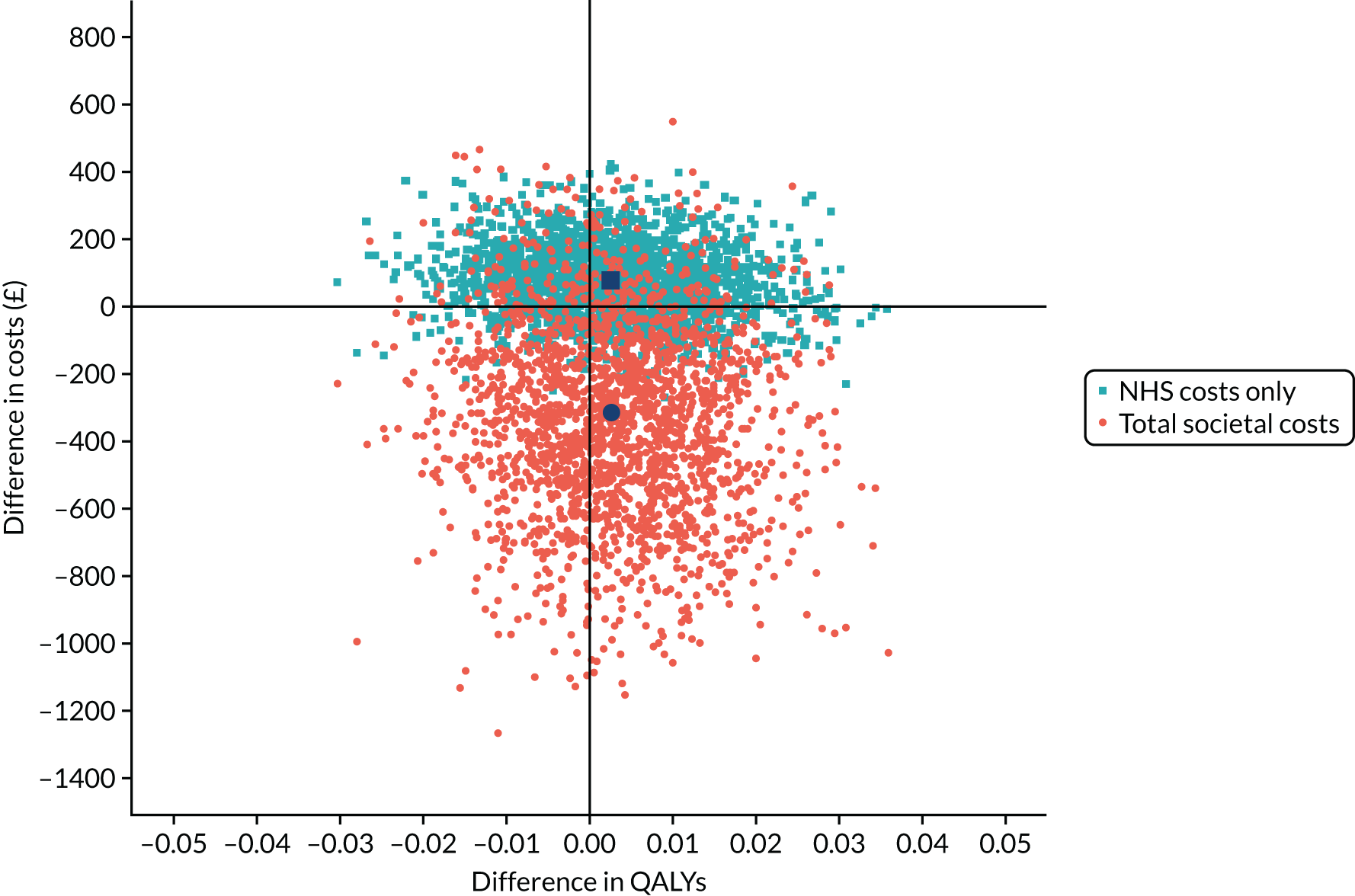

| Number of sessions (minimum, maximum) | (0, 27) | (0, 8) |