Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/140/61. The contractual start date was in December 2015. The draft report began editorial review in December 2019 and was accepted for publication in July 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. This report has been published following a shortened production process and, therefore, did not undergo the usual number of proof stages and opportunities for correction. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Shalhoub et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background venous thromboembolism aetiology and prevention

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a common condition in which a blood clot forms in a vein. If a clot forms in the deep veins of the leg or groin, this is known as a deep-vein thrombosis (DVT). The clot, or part of the clot, can break free from the vein wall and travel to the lungs, where it may block some of the blood supply; this is known as a pulmonary embolism (PE). VTE is the collective term for both DVT and PE.

Venous thromboembolism is a significant cause of mortality and long-term disability owing to chronic venous insufficiency, which can, in turn, cause venous ulceration and development of a post-thrombotic limb (characterised by chronic pain, swelling and skin changes). It is estimated that VTE occurs at an annual incidence of approximately 1 per 1000 adults, increasing to between 2 and 7 per 1000 adults among those aged ≥ 70 years. 1,2 Treatment of non-fatal symptomatic VTE and related long-term morbidities is associated with a considerable cost to the health service, consuming 2% of the annual NHS budget, and has a significant impact on patients’ quality of life. 3

The graduated compression as an adjunct to thromboprophylaxis in surgery (GAPS) trial focused on hospital-acquired thrombosis (HAT), a term encompassing any new episode of VTE diagnosed during hospital admission or within 90 days of discharge. Hospital patients are at an increased risk of VTE as a result of decreased mobility, blood vessel trauma because of surgery or other serious injury. More than half of all VTE events are associated with prior hospitalisation, and it remains a common cause of in-hospital mortality. 4 At least two-thirds of HAT cases are preventable through VTE risk assessment and the administration of appropriate thromboprophylaxis. 5 Since the introduction of the National VTE Prevention Programme in 2010, reducing the number of HAT cases has been a key patient safety priority for both health-care commissioners and local hospitals across the UK.

Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis

Thromboprophylaxis is available in both pharmacological and mechanical form. There is a huge body of evidence demonstrating that the provision of suitable thromboprophylaxis for at-risk inpatients significantly reduces VTE by 30–65%. 6–9

Pharmacological thromboprophylaxis

The choice of prophylaxis for surgical patients depends on the procedure performed, patient suitability and local policy. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline (NG89)4 states that pharmacological thromboprophylaxis, in most cases, should start as soon as possible or within 14 hours of patient admission. The group of anticoagulants known as low-molecular-weight heparins (LWMHs) are safe and effective for use in patients undergoing most surgical procedures, and are usually preferred for a more predictable anticoagulant response over unfractionated heparin. 10 Patients who have risk factors for bleeding (e.g. acute stroke, thrombocytopenia and acquired or untreated inherited bleeding disorders) should receive only pharmacological prophylaxis when their risk of VTE outweighs their risk of bleeding. 4

Mechanical thromboprophylaxis: graduated compression stockings

Graduated compression stockings (GCS) are offered as knee-length or thigh-length garments to inpatients at risk of VTE. They are presumed to work by improving the velocity of venous flow towards the heart, minimising reflux to the foot or laterally into the superficial veins. 11 They are designed to offer graduated pressure to the leg, with the greatest degree of pressure exerted at the ankle and gradually decreasing towards the knee or thigh. The optimal gradient of pressure to improve venous flow has previously been shown to be 18 mmHg at the ankle, 14 mmHg at the calf and 10 mmHg at the knee. 12 For inpatients, the 2018 NICE guidance4 recommends that GCS should be worn day and night until the patient is sufficiently mobile and should not be offered to patients admitted with acute stroke or those with conditions such as peripheral arterial disease, peripheral neuropathy, severe leg oedema, or local conditions such as gangrene and dermatitis. 4

Cost, complications and compliance

Although GCS are generally regarded as safe, patients often report associated complications including skin breaks, ulceration, peripheral neuropathy and difficulties with application. The Clots in Legs Or sTockings after Stroke (CLOTS) 1 trial13 reported a higher incidence of skin breaks, ulcers, blisters and skin necrosis in patients allocated to GCS than in those allocated to avoid GCS. As a result, their use has already been limited in certain contexts. Over the past 6 years, Salisbury District Hospital has adopted a pharmacological prophylaxis policy (without GCS) for high-risk surgical patients. In Salisbury, the incidence of hospital-acquired thrombosis is 1.3–2.9 per 1000 admissions,14 which is comparable to centres elsewhere in the UK (King’s College Hospital: 3.83 per 1000 admissions). 15 The non-compliance rate for GCS has been reported to be between 30% and 65%. 16–18

A 2008 audit at one hospital in the UK19 showed that 54% of patients across 16 mixed-surgical specialty wards were not wearing GCS at the time of audit. For those wearing GCS, approximately one-third of patients (wearing above-knee garments) had them applied incorrectly. 19 Commonly cited reasons for non-compliance with GCS include pain and discomfort, difficulties in application, perceived ineffectiveness, erythema, skin irritation, prescription cost and cosmesis. 11,16,20,21

Patients undergoing surgical procedures that require prolonged admission or patients prescribed stockings beyond discharge may require more than one pair of stockings. In addition, there are further staff costs related to training in the use of GCS and the regular application and removal in immobile patients. In the UK, the unit cost of GCS is £6.36 for one pair. 22 In other countries, the cost of stockings is much higher. At 2014 rates, the cost of 10 minutes of hospital nursing contact time with a patient was £14 (£84 per hour). 23 Therefore, the cost of purchasing and applying GCS to surgical inpatients assessed as being at a moderate or high risk of VTE in England is estimated at £63.1M per year. 24 This estimate does not include the further cost and time implications related to the identification and management of complications related to GCS and more serious problems associated with poor application and fitting, such as leg ulceration.

UK national guidelines for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis

In 2005, the House of Commons produced a select committee report, The Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism in Hospitalised Patients,5 that reported the scale of the problem and promoted awareness about the risk and management of VTE. The report commissioned NICE to produce a set of clinical guidelines (CGs) and make VTE prevention an NHS priority.

In 2007, NICE produced a CG (CG46)25 that specified that a mandatory documented risk assessment should be performed on all hospitalised patients to deliver appropriate preventative treatment. Surgical patients identified as being at a moderate or high risk of VTE should be offered both mechanical thromboprophylaxis and pharmacological thromboprophylaxis. In England, a comprehensive approach to VTE prevention was launched in 2010 and NICE’s CG [CG92] was updated, extending the scope to medical as well as surgical patients. In 2012, new evidence was found that supported the use of GCS in surgical patients with or without other methods of thromboprophylaxis,26 which is in line with current recommendations in CG92. 3 The evidence update stated that the review was not able to answer the question of the efficacy of high-length versus knee-length GCS.

Existing research

Cochrane review: graduated compression stockings for prevention of deep-vein thrombosis

The aim of the Cochrane review by Sachdeva et al. 26 was to determine the magnitude of the effectiveness of GCS in preventing DVT in various groups of hospitalised patients. The authors included 20 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of both medical and surgical patients, with and without background pharmacological prophylaxis for VTE. Eight RCTs compared GCS alone with no GCS. The incidence of DVT was statistically significantly lower in the GCS group than in the no GCS group.

There are, however, limitations to the Cochrane review. 26 Nineteen of these trials were conducted before the year 2000, and it is now recognised that the rates of VTE have fallen over the last 50 years. This is because of not only improved thromboprophylaxis but also changes in clinical practice;27 thus, the utility of GCS in modern medicine is uncertain. The authors also excluded two large trials on the basis that they were too specific or pragmatic: the CLOTS 1 trial in 2518 stroke patients13 and one trial in 874 orthopaedic patients. 28 Both trials did not support the use of GCS. Six of the included trials obtained funding or support from pharmaceutical companies or stocking manufacturers.

The CLOTS 1 randomised controlled trial

The CLOTS 1 trial (ISRCTN28163533)13 aimed to evaluate the risks and benefits of external compression in patients with acute stroke. A total of 2518 patients who were admitted to hospital within 1 week of an acute stroke and who were immobile were enrolled from 64 centres in the UK, Italy and Australia. Randomisation was 1 : 1 to either routine care plus thigh-length GCS (n = 1256) or routine care plus avoidance of GCS (n = 1262). The CLOTS 1 trial found no significant difference in symptomatic or asymptomatic femoropopliteal DVT in individuals admitted to hospital with acute stroke (10.0% in the group allocated GCS compared with 10.5% in the group allocated to avoid GCS). In addition, the use of GCS was associated with an increase in adverse events, including skin breaks on the legs. The authors suggested that the CLOTS 1 data do not lend support to the use of thigh-length GCS in patients admitted to hospital with acute stroke.

Meta-analysis: randomised trials for prevention of venous thromboembolism after surgery

A 2014 meta-analysis7 considered VTE rates in surgical patients receiving pharmaco-thromboprophylaxis and GCS compared with either modality alone. Although the trial had a number of methodological shortcomings, the authors concluded that evidence concerning ‘adding compression to anticoagulation reduces VTE risk is of low quality’7 and was undermined by publication bias. To address some of the shortcomings, a systematic review24 was conducted that aimed to summarise and assess the quality of existing evidence specifically concerning the benefits of GCS, in addition to prophylactic-dose pharmaco-thromboprophylaxis for elective surgical inpatients, including orthopaedics. Inclusion criteria were RCTs published within the last 10 years, surgical inpatients, a study arm examining prophylactic dose pharmacological thromboprophylaxis alone [LMWH, fondaparinux (Arixtra®, Glaxosmith Klein) or unfractionated heparin], a study arm examining prophylactic dose pharmacological thromboprophylaxis in conjunction with GCS, and an outcome of VTE.

A heterogeneity analysis was conducted to look at the variation in VTE rates between the included study arms. In total, 1025 articles were screened and 27 RCTs were included. Six RCT study arms treated participants with GCS in conjunction with prophylactic dose pharmaco-thromboprophylaxis. Twenty-two RCT study arms treated participants with prophylactic dose pharmaco-thromboprophylaxis alone. One RCT included both of its randomised study arms in the systematic review. In total, 12,481 participants across the included studies received prophylactic pharmaco-thromboprophylaxis alone. Of these patients, 1292 (10.4%) had VTE. The total number of participants randomised to GCS in conjunction with prophylactic pharmaco-thromboprophylaxis was 1283, 75 of whom had VTE (5.8%). A heterogeneity analysis showed that the results of the included study arms were significantly heterogeneous, and for this reason prevented the authors calculating the usual meta-analytic summary estimates.

This systematic review demonstrated that the additional benefit of GCS to pharmaco-thromboprophylaxis in surgical inpatients is undetermined based on the existing available data. Based on this, the authors decided that there was sufficient uncertainty to conduct a trial to examine whether or not GCS provide any adjuvant benefit in reducing the rate of VTE in surgical patients receiving a prophylactic dose of LMWH.

Rationale for the GAPS trial

Despite NICE’s recommendations for the use of GCS for the prevention of VTE in the UK the evidence base has been challenged,29,30 with data suggesting that there is sufficient uncertainty of the adjuvant benefit offered by GCS in addition to pharmaco-thromboprophylaxis for patients at risk of VTE.

It is also recognised that the rates of VTE have fallen over the past 50 years not only because of thromboprophylaxis but also because of improved surgery and anaesthesia, earlier mobilisation and shorter hospital stays. 31 Thus, the utility of GCS in modern practice is uncertain. If GCS were found not to offer additional reductions in VTE risk in individuals given prophylactic dose LMWH, this would negate the need for GCS in this patient group, namely moderate-risk and high-risk surgical patients receiving LMWH. 22 This would also eliminate the side effects of this treatment and reduce the cost burden of GCS in surgical NHS patients. The GAPS trial aimed to determine the following: in surgical inpatients determined to be at moderate or high risk for VTE, is low-dose LMWH alone non-inferior to low-dose LMWH in combination with GCS?

Chapter 2 Methods

Primary objectives

The primary clinical objective was to compare the venous thromboembolism rate in elective surgical inpatients receiving GCS and LMWH (control) with those receiving LMWH alone (intervention).

Secondary objectives

Other objectives included:

-

compliance with GCS during admission

-

compliance with LMWH during admission

-

profile the adverse effects of GCS and LMWH anticoagulation in this context

-

quality of life – change in EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), (a validated generic quality-of-life tool) score over 90 days from baseline

-

support future guidance and policy in VTE prevention.

Trial design

A multicentre, prospective, non-inferiority, group sequential randomised clinical trial to compare VTE outcomes in surgical inpatients assessed as being at moderate or high risk of VTE. Participants were randomised 1 : 1 to either:

-

LMWH and GCS (standard care)

-

LMWH alone (intervention).

Changes to the trial design

Under the null hypothesis it was expected that 134 events would be recorded in a maximum sample size of 2236 participants. The first interim analysis was scheduled at 25% of these events (i.e. 34 events). The independent Data Monitoring Committee (iDMC) was unable to meet according to the planned schedule because the number of events was substantially smaller than expected given the assumptions of the power calculation. This prompted investigation by the senior statistician, which resulted in a report being produced based on blinded interim data to understand what was happening and presented modifications to the design as possible solutions. This report was presented to the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), iDMC and study funders. The Trial Management Group (TMG) simultaneously launched an investigation into whether or not events might be being missed, but no flaws in the identification or recording process were uncovered. The TMG also asked sites to check participant VTE status against general practitioner (GP) records in case an event had occurred and had been missed by the study team. Recruitment continued as planned and approached a steady-state target of around 100 participants per month.

In December 2017, as part of the senior statisticians report, four distinct subpopulations of risk recruited to the study were identified:

-

subpopulation 1 – participants aged < 65 years at moderate risk of VTE

-

subpopulation 2 – participants aged < 65 years at high risk of VTE

-

subpopulation 3 – participants aged ≥ 65 years at moderate risk of VTE

-

subpopulation 4 – participants aged ≥ 65 years at high risk of VTE.

The TMG proposed to immediately stop recruitment of subpopulations 1–3; following agreement from the REC, sponsor, TSC and iDMC, recruitment was stopped on 20 December 2017. A letter was issued to all seven sites requesting immediate cessation of the recruitment of participants to subpopulations 1–3 and for continuation of recruitment to subpopulation 4 only.

In April 2018, the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme approved a 12-month time-only extension (no additional funds) that enabled sites to continue to exclusively recruit and follow-up participants to subpopulation 4 until April 2019.

See the GAPS protocol, version 3.0 December 2018, on the project web page: https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/14/140/61 (accessed January 2020). This describes the impact of emerging blinded data on the study and explains the rationale for changes made to the protocol and statistical analysis plan. See the statistical analysis plan version 1.0, March 2016, this relates to protocol version 2.1, March 2016, including a group sequential design for a single unified population. Version 2.0, April 2019, of the statistical analysis plan relates to protocol version 3.0, December 2018, and presents the analysis plans for four distinct subpopulations of the original population, with the group sequential analysis abandoned in favour of a fixed single analysis. These changes were made to the design in December 2017 as a result of a lower than expected event rate (assessed blind to the randomised group).

Amendments to the protocol

Substantial amendments to the trial protocol were submitted after initial approval to clarify statistical changes and make terminology consistent throughout the document:

-

Version 2.0, dated 4 February 2016 – changes were made from version 1.0 to submit to the REC for approval.

-

Version 2.1, dated 17 March 2016 – the wording was amended from ‘post-randomisation’ to ‘post-surgery’ to provide clarity to follow-up schedules.

-

Version 3.0, dated 3 December 2018 – an amendment was made to make terminology consistent throughout the document; the ‘trial co-ordination centre’ refers to Imperial College London and the ‘Clinical Trials Unit’ refers to The Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials (CHaRT) Aberdeen. ‘Moderate risk’ replaced all instances of ‘medium or intermediate risk’ throughout the document. The flow chart shown in Appendix 3 was updated to add secondary outcome text, ‘overall mortality’, that was not included in the original flow diagram. Section 7.4 was updated to reflect changes to the statistical analysis that were based on the small number of events recorded during the study. Wording was added to explain that a time-only, no-cost extension of 12 months was approved by the funder. The term ‘composite outcome’ was removed to tighten the terminology and accurately reflect the outcome measure being used. A sentence was added to say that data collected by the trial team for the duplex ultrasound scan outside the 14–21 day window would be recorded by the trial co-ordinating centre and analysed. A summary of the rationale for the statistical changes made to the study was included in the protocol (see the project web page for further details; URL: https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/14/140/61; accessed January 2020).

Ethics and research and development approvals

A favourable ethics opinion was given by the National Research Ethics Service Committee London – City Road and Hampstead on 8 February 2016 (reference number 16/LO/0015).

Study-wide governance review was undertaken by the North-West London Clinical Research Network (CRN) in February 2016. Research and development NHS approvals were granted at participating sites between March and July 2016. The study was granted the new Health Research Authority approval in June 2016.

Sponsorship

The trial was sponsored by Imperial College London, London, UK.

Study management

Trial Management Group

The Trial Management Group comprised Professor Alun Davies (as chief investigator), Mr Joseph Shalhoub (as co-investigator), Ms Rebecca Lawton (as trial manager), Ms Jemma Hudson (as statistician), Professor John Norrie (as senior statistician), Mrs Alison MacDonald (as senior trial manager) and Mr Mark Forrest (as senior programme developer).

Trial Steering Committee

In line with the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) governance guidelines, an independent TSC was established to oversee the conduct of the trial. The committee comprised four independent members (see Acknowledgements), as well as the chief investigator, trial manager, study statistician and lay patient co-applicant. The committee met every 6 months or more regularly if required, as decided by the committee. See Appendix 2 for the meeting dates.

Independent Data Monitoring Committee

The iDMC was established as per the HTA iDMC terms of reference to monitor study data and safety. The committee comprised three independent members (see Acknowledgements). The members met once prior to the start of the trial to agree the iDMC charter, and then on a 6-monthly basis to review recruitment, retention and unblinded comparative data.

Interim analyses were planned (see the project web page for statistical analysis plan, version 1.0; https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/14/140/61; accessed January 2020) but subsequently abandoned, and the trial statistician was the only member of the direct study team to have access to the unblinded data. Following each meeting, the iDMC recommended continuation of the trial to the TSC with no change to the protocol. See Appendix 2 for the meeting dates.

Participants

All patients aged ≥ 18 years who were assessed as being at moderate or high risk of VTE according to the widely-used NHS England VTE risk assessment tool32 and undergoing an elective surgical procedure as an inpatient were eligible to be included in the trial.

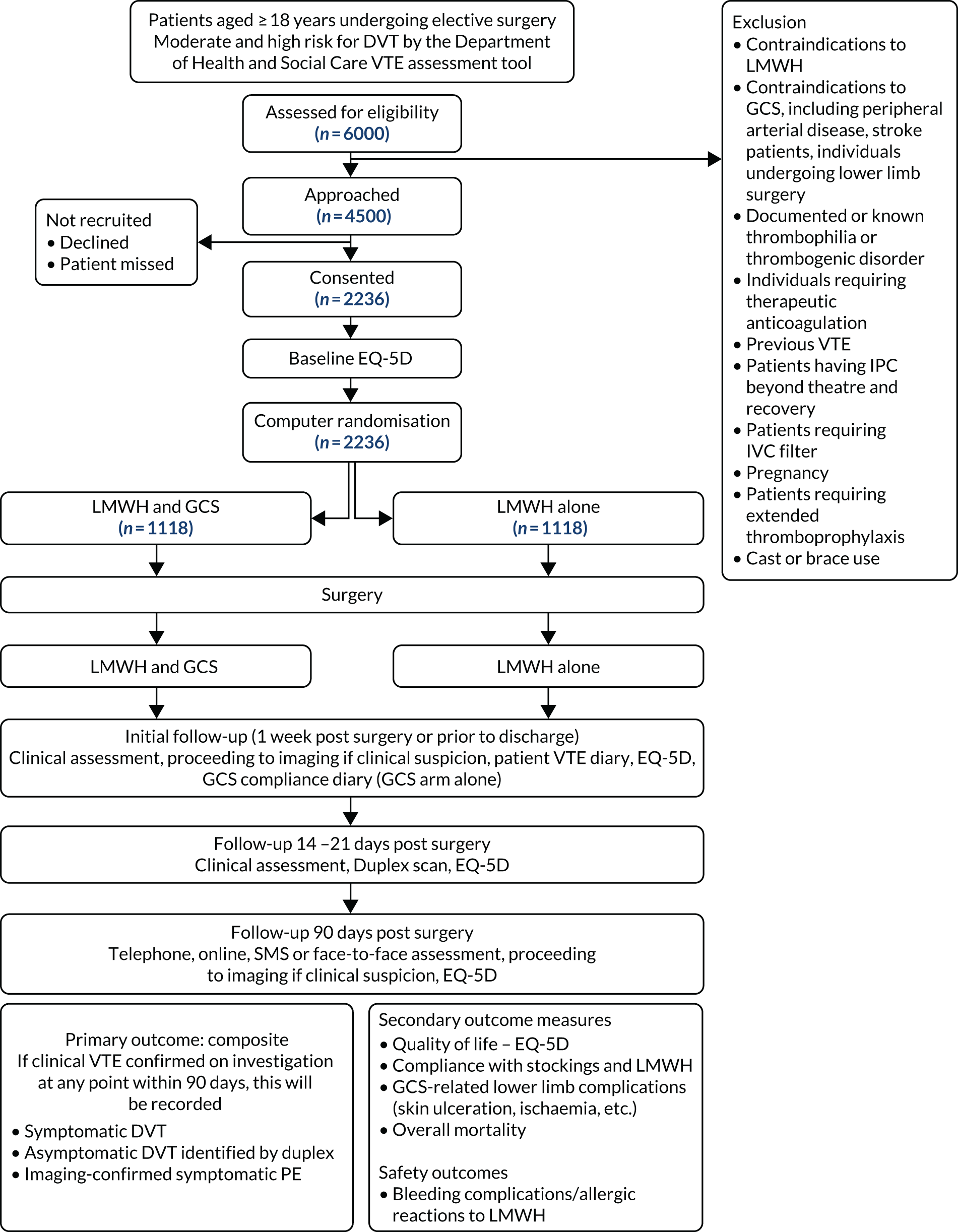

Intervention

Participants in both arms were given thromboprophylactic doses of LMWH for the period of inpatient admission in line with NICE guideline CG46, which was updated to NG89 in 2018. 4 Patients in the standard of care (control) arm received above- or below-knee GCS in addition to thromboprophylactic doses of LMWH, and were asked to wear the stockings for the duration of their hospital admission. GCS could be fitted at the time of admission or immediately post operatively in accordance to local practice and to facilitate pragmatism (Figure 1). Patients received either below-knee or above-knee GCS, which was determined at a local level. A variety of brands were used including FITLEGS™ (Griffiths and Nielsen Ltd, Horsham, UK), Medtronic (MEDLINE Industries Inc., Northfield, IL, USA), Covidien TED™ stockings (Mansfield, MA, USA) and Carolon Cap stockings (Rural Hall, NC, USA). Participants randomised to the intervention arm were required to refrain from wearing any kind of compression stockings for up to 90 days after surgery.

FIGURE 1.

Research nurse Vernisha Ali applying GCS to a patient. This photo has been used with permission from the photo subject.

Inclusion criteria

For a full list of inclusion criteria see the Scientific summary.

Patients who could not speak/understand English were eligible for inclusion as long as informed consent could be obtained with assistance from translation services as per standard clinical practice. In view of the lack of cross-cultural validation for quality-of-life tools, it was decided that only VTE outcome data would be collected for such participants.

Exclusion criteria

For a full list of exclusion criteria see the Scientific summary.

Sample size

With a one-sided test at a 2.5% level of significance (equivalent to a two-sided test at a 5% level of significance) the trial has 90% power to conclude that the single pharmacological intervention is non-inferior to the combined intervention (pharmacology and GCS), assuming an event rate of 6% of VTE at 90 days in the combined treatment arm and a non-inferiority margin of 3.5%, and a conservative loss to follow-up (i.e. non-evaluable for the primary outcome) rate of 10%. The maximum sample size required under this group sequential design, including allowance for loss to follow-up, is a total of 2236 participants. 22 (Reprinted from European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, Vol 53, Issue 6, Shalhoub J, Norrie J, Baker C, Bradbury AW, Dhillon K, Everington T, et al., Graduated Compression Stockings as an Adjunct to Low Dose Low Molecular Weight Heparin in Venous Thromboembolism Prevention in Surgery: A Multicentre Randomised Controlled Trial, 880–5, 2017, with permission from Elsevier.)

Interim analyses

In the original study design we adopted a group sequential approach, giving four equally spaced formal interim analyses for efficacy (at 25%, 50%, 75% and a final analysis at 100% of the information) and one formal interim analysis for futility at 50% of the information. The flexibility to stop early on either efficacy or futility marginally increased the maximum sample size to 2012 [4% increase, using East 6.3 (Cytel Corporation,Waltham, MA, USA)], a flexibility that is useful given the quality, relevance and uncertainty of the evidence base informing the sample size assumptions.

At full size, the trial expected to observe approximately 134 VTE episodes at 90 days under the null hypothesis (that the single intervention is not non-inferior to the combined) and approximately 121 events under the alternative hypothesis (that the single intervention is non-inferior to the combined); therefore, in information time the interim looks will be scheduled to around 35 (25%), 70 (50%, including the single futility look as well) and 105 (75%) events recorded. 22

Revised sample size

Owing to the observed low-event rate it was decided to abandon the group sequential design. It was clear from the blinded (aggregate) data that the overall population, which was subdivided by risk of primary outcome into four subpopulations (i.e. subpopulation 1: ≤ 65 years at moderate risk of VTE; subpopulation 2: ≤ 65 years at high risk of VTE; subpopulation 3: ≥ 65 years at moderate risk of VTE; subpopulation 4 ≥ 65 years at high risk of VTE) [with around 250 participants randomised in subpopulation 1 with zero expected events (zero events observed from the first 180 randomised to December 2017); very few events in subpopulation 2 (around 750 randomised by December 2017, observed event 3/510 or 0.6% in the first 510 randomised); virtually no-one randomised in subpopulation 3 (only 12 randomised to Dec 2017; this subpopulation will be reported descriptively with no further consideration of formal sample size or inference) and for subpopulation 4, 750 in subpopulation 4 (306 randomised to Dec 2017 with 11 events observed)], that the study would not observe sufficient events in total or specifically in subpopulation 4 (the only subpopulation still open to recruitment) to make a re-application of the sequential design sensible.

In December 2017, the senior blinded statistician considered the implications of the sample sizes of the four subpopulations; Table 1 gives the detectable non-inferiority margins for indicative sample sizes (at 90% power and a one-sided level of significance of 2.5%).

| Subpopulation | Subpopulation number | Expected number of participants randomised | Assumed event rate | Detectable non-inferiority margin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aged < 65 years at moderate risk of VTE | 1 | 258 | 0.1% | 1.30% |

| Aged < 65 years at high risk of VTE | 2 | 733 | 0.6% | 1.85% |

| Aged ≥ 65 years at moderate risk of VTE | 3 | 12 | N/A | N/A |

| Aged ≥ 65 years at high risk of VTE | 4 | 912 | 3.6% | 4.0% |

Note that these revised sample size calculations do not adjust for multiple comparisons and do not adjust for the original group sequential alpha spending (given that no interim analyses took place). See the project web page for GAPS protocol version 3.0, for the rationale for statistical changes for further detail (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1414061/#/; accessed January 2020).

In April 2018, the funder agreed to the revised sample size of 912 participants in subpopulation 4. The other three subpopulations (1–3) were closed to any further recruitment at this time, and we stated a plan to analyse all available data in these three subpopulations.

Randomisation and treatment allocation

Consenting participants were registered on the web-based data entry system that was maintained by CHaRT (NIHR-registered Clinical Trials Unit #7, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen). Randomisation was web-based and was hosted at CHaRT; a minimisation algorithm was used that incorporated centre, moderate or high risk of VTE and sex, as well as a random element. Once eligibility was confirmed, randomisation was performed at the local hospital site by the research nurse prior to the patient undergoing surgery.

Blinding

Owing to the nature of the intervention it was impossible to blind the research nurse or patient to the study allocation, and a sham stocking was deemed both impractical and difficult to administer. Vascular scientists/technologists performing the 14- to 21-day bilateral duplex ultrasound scan were blinded to the patient’s treatment allocation. If patients were scanned early because of clinical suspicion they were asked by the research nurse to remove their stockings prior to the scan. The senior statistician also remained blinded throughout the study.

Settings and location

The majority of participants were recruited from the pre-assessment clinics of seven secondary care NHS trusts throughout England: Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust; University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust (formerly Heart of England NHS Trust); Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust; Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust; University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust; and Portsmouth Hospitals University NHS Trust. For a list of participating hospitals see Acknowledgements, Local research teams.

Sites were selected based on their ability to recruit to the trial, the range of surgical procedures performed, the willingness of the principal investigator (PI) to randomise into the trial and their proven track record in research.

Screening and participant identification

Adult patients presenting to pre-assessment clinics prior to surgery, or admitted to surgical wards for elective surgery, were screened for eligibility at recruiting centres. The trial was pragmatic and included ‘all comers’ in terms of surgical specialty and operation type, ensuring that the results of the trial were maximally generalisable and externally valid.

At pre-assessment clinics, or on admission for elective surgery, patients were risk assessed for VTE by the doctor or nurse in accordance with NICE guidelines4 using the national, mandated, NHS England VTE risk assessment tool33 or the trust equivalent. Risk assessment identifies patients as ‘low risk’ or ‘not low risk’ for VTE.

Patients who were identified as ‘not low risk’ for VTE were further reviewed against the VTE risk factors listed on the assessment sheet. 34 Risk factors are not exhaustive, and clinicians may consider additional risks in individual patients. One tick for VTE risk on the tool confers a status of ‘at moderate risk of VTE’ and more than one tick on the form confers a status of ‘at high risk of VTE’. Any box ticked for thrombosis risk should prompt prescription of thromboprophylaxis in accordance with NICE guidance. The risk of bleeding is then judged by the clinician who considers if it is sufficient to preclude pharmacological intervention. Patients identified as ‘not low risk’ for VTE and ‘not at high risk’ for bleeding (i.e. can safely receive LMWH) were flagged by the clinical team to the research nurse who then approached the patient and offered them an information leaflet about the trial. Patients were given appropriate time to consider participation before consenting procedures took place.

Information about the study could also be sent by post or given to potential participants (e.g. in outpatient clinics) by the direct care team prior to admission. This allowed potential participants to consider being involved in the study prior to their admission for surgery and maximised their opportunity to ask questions. This information highlighted that eligibility for the trial would be assessed following a documented VTE risk assessment. Participants who did not agree to participate in the trial were recorded on the screening log along with a minimum data set of age, sex, surgical procedure, admitting specialty and reason(s) for non-inclusion.

Recruiting sites also displayed posters and leaflets describing the study at pre-assessment clinics, and the study was presented at many surgical multidisciplinary team meetings to promote awareness among staff.

Informed consent

Most patients were approached at pre-assessment clinics, and if they expressed an interest in the study they were directed to see the research nurse who provided them with a GAPS leaflet and patient information sheet to consider the trial with family or any other medical professional.

If participants agreed to participate at the pre-assessment appointment, all baseline questionnaires could be completed at that visit prior to surgery. If patients consented on the day of surgery, all of the baseline assessments were completed prior to surgery and randomisation.

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant at the baseline visit. The patient information sheet and the consent form (see Report Supplementary Material 1) both refer to the possibility of long-term follow-up and access to the patient’s NHS records for these purposes. With consent, a letter was also sent to the participant’s GP (see Report Supplementary Material 2). A copy of the consent form and the patient information sheet were filed in the participant’s hospital notes and the local research file, and a copy was given to the participant.

All trial documentation contained the contact details of the local PI, the GAPS chief investigator and the trial manager to enable participants to contact members of the wider study team if necessary.

Baseline assessment

Once written informed consent was obtained from the participant, baseline data could be collected by the research nurse using the case report form (see Report Supplementary Material 3). Recorded assessments included the following.

Patient demographic and contact details

Demographic details were obtained including age, sex, ethnicity and working status. Women of child-bearing potential were required to take pregnancy tests to ensure that they did not breach the exclusion criteria.

Caprini risk assessment model

A second VTE risk assessment was performed using the Caprini tool,34 a validated risk assessment model used primarily in the USA. The factors considered in the Caprini tool mirror those in the NHS England VTE risk assessment tool. 32 A score is provided by summing individual risk factors on the tool, placing patients into four categories by weighted risk stratification: ‘low risk’ (0 or 1 points), ‘moderate risk’ (2 points), ‘high risk’ (3 or 4 points) and ‘highest risk’ (≥ 5 points).

Vital signs and lifestyle

Weight and height were recorded, and the database auto-calculated body mass index (BMI). Lifestyle details were recorded including smoking status, alcohol consumption, diet and physical activity level.

Medications and medical history

Significant medical history and current medications were recorded.

Surgery details

Details of the patient’s surgical procedure, the anaesthetic used during surgery (local, regional or general) and whether above- or below-knee stockings were prescribed (if randomised to the control arm) were recorded.

EuroQol-5 dimensions, five-level version, questionnaire

Patient-reported quality of life was assessed at baseline, prior to randomisation. EQ-5D-5L is a widely recognised, generic tool to measure health-related quality of life. It consists of two parts: a descriptive system and a visual analogue scale, EuroQol-visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS). The first part, the descriptive system, assesses the participant’s mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression levels. Respondents select the option that most closely matches their health state: no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems and extreme problems. The EQ-VAS records the participant’s self-rated health on a vertical scale with ‘the best health you can imagine’ and ‘the worst health you can imagine’ at opposite ends of the scale. Participants are required to ‘mark an X on the scale to indicate how your health is TODAY’. The information recorded from the EQ-VAS can be used as a quantitative measure of health.

On completion of all baseline assessments, eligible participants could then be randomised via the trial website 1 : 1 into the intervention or control arm of the study. Participants were then given further materials including:

-

a resource use diary to capture any instance of contact with health-care providers or carers

-

a stocking compliance diary (control arm alone) to record how much time they wore their stockings and any reasons for non-adherence

-

a wallet card reminder indicating their treatment allocation, contact details of the research nurse and a message requesting that they not inform the vascular technologists to which arm of the trial they had been randomised to.

Adverse events

The research nurse collected occurrences of adverse events during the patients’ hospital admission, in person, via the telephone or via hospital notes, and at each follow-up in instances where the patient had been discharged with GCS or LMWH. Only adverse events deemed by the local PI to be related to GCS or LMWH were recorded. Risks associated with the interventions were judged to be very small and generally predictable. Adverse events expected to be related to the interventions are summarised in Table 2.

| Effect | Related to GCS | Related to LMWH |

|---|---|---|

| Systemic | Allergic reaction | |

| Abnormal liver enzyme tests | ||

| Local | Discomfort in legs | Rash |

| Skin breaks | Skin change | |

| Skin ulcers | Thrombocytopenia | |

| Skin necrosis | Bleeding complications during admission or within 24 hours of discharge | |

| Blistering of the skin | ||

| Rash | ||

| Limb ischaemia |

Adverse events were reviewed and categorised by the trial manager and chief investigator.

Serious adverse events

As per the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) good clinical practice (GCP) guidelines,35 serious adverse events (SAEs) were defined as those adverse events that result in death; are life-threatening; require inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation; result in persistent or significant disability or incapacity; result in congenital anomaly or birth defect; are cancer; or are other important medical events in the opinion of the responsible investigator (i.e. not life-threatening or resulting in hospitalisation, but may jeopardise the participant or require intervention to prevent one or more of the outcomes described previously). All SAEs were collected whether or not they were deemed by the local PI to be related to GCS or LMWH.

The research nurse collected data regarding the occurrence of all SAEs at each follow-up visit or via clinical or surgical notes and hospital admission records. SAEs were reported to the trial co-ordinating centre via the web-based data capture system within 24 hours of the nurse becoming aware of the event, and were reviewed by the chief investigator.

All SAEs were also reported by the trial manager to the sponsor and were reviewed by the iDMC. SAEs were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) Version 21.0. (URL: www.meddra.org; accessed 1 August 2019). MedDRA® is a clinically validated international medical terminology dictionary (and thesaurus) developed under the auspices of ICH GCP and used by regulatory authorities in the pharmaceutical industry during regulatory processes.

Follow-up

All randomised participants were followed up until completion of the trial, which was defined as:

-

90 days after surgery

-

withdrawal from the trial

-

death.

Seven days or discharge assessment

Participants in both treatment arms were followed up at 7 days after surgery or at discharge, whichever was earlier. Assessments at this time point included:

-

Review of hospital records for any diagnosis of VTE (anonymised copies of any duplexes were forwarded to the trial co-ordinating centre).

-

Any symptoms or signs of VTE (if there was clinical suspicion identified by the research nurse that was not identified by the clinical team, the research nurse informed the clinical team who proceeded to imaging if appropriate).

-

EQ-5D-5L generic quality-of-life assessment.

-

Review of participant resource use diary.

-

Collection of stocking compliance diary.

-

Collection of adverse events or SAEs.

-

Review of prescription and adherence with LMWH from the drug chart. Where known, reasons for non-adherence were recorded.

At this time point, the patient was booked to attend a bilateral duplex ultrasound scan between 14 and 21 days after surgery.

Duplex assessment between 14 and 21 days after surgery

The aim of the second follow-up visit was to detect DVT. We expected to capture > 95% of VTE given that the average time point for DVT is 7 days and for PE is 21 days, with vast majority of events being DVT. Participants in both treatment arms underwent a routine bilateral full lower-limb duplex ultrasound scan between 14 and 21 days post surgery or earlier if there was clinical suspicion of DVT. We later amended the protocol to promote adherence to this visit and widened the availability of scanning slots by accepting scans performed outside this window up to 90 days after surgery. This was undertaken to minimise losses to follow-up that, if unequal between the two treatment arms, could bias the results of the trial. Vascular scanning departments followed local protocols for the detection of DVT, but we asked that the whole limb of both legs was scanned as this is not always performed in routine clinical practice. Once the scan was reviewed by local treating clinicians (blinded to the study allocation) an anonymised copy of the scan report was sent to the trial co-ordinating centre for source data verification. We did not carry out central clinical verification of negative scans because meaningful verification of clinical reports is difficult. If definite above-knee or below-knee DVT was detected prior to the 14–21 day duplex ultrasound scan, a second research scan was no longer required. When complications occurred post surgery or when participants were unable to attend hospital for the duplex ultrasound scan between days 14 and 21, the randomising person made their best effort to arrange a scan for as close to the follow-up time point as possible.

Management of deep-vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism

If the clinician was satisfied that a patient had DVT or PE, the patient was anticoagulated using subcutaneous heparin/LMWH or warfarin in accordance with local protocols, as long as there was no contraindication. The primary outcome was reported by the research nurse on a VTE form and the trial co-ordinating centre was informed.

Participant communications

Participants were kept updated on trial progress via the GAPS trial web page (the homepage of the database; https://w3.abdn.ac.uk/hsru/GAPS/), Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; www.facebook.com) and Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; www.twitter.com) accounts. A newsletter summarising the main results from the GAPS trial was also sent to non-withdrawn participants.

Statistical methods

The primary trial analysis was carried out in accordance with the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle (all participants remained in the treatment arm allocated at randomisation) but, as a non-inferiority design, a per-protocol (PP) analysis that included only participants who received the intervention to which they were randomised to was carried out and presented. Participants were excluded from all analyses if they did not undergo surgery.

The primary outcome (confirmed VTE up to 90 days after surgery) was analysed using a generalised linear model that adjusted for sex, and a cluster robust error was added for centre. A non-inferiority p-value was calculated. A sensitivity analysis looked at including only participants who had a duplex ultrasound scan and including the post-randomisation exclusions. For the four subpopulations a similar analysis was performed unless there was a zero event rate in each arm, for which a one-sided absolute incidence confidence interval (CI) was reported. As there were no missing data in the primary outcome, there was no need for a missing data analysis.

Complications with LMWH and GCS-related complications were summarised using appropriate summary statistics. All other secondary outcomes were analysed in a similar way to the primary outcome with generalised linear models appropriate for the distribution of the outcome.

The EQ-5D-5L data were analysed using a mixed-effects repeated-measures model adjusted for baseline score, VTE risk, sex and a random effect for centre. Non-parametric bounds for the average causal effect were performed for the compliance outcomes. GCS-related complications, adverse reactions to LMWH, bleeding complications and overall mortality were summarised descriptively, and no formal analyses were planned. Data for these outcomes were summarised as randomised and by treatment received. The four subpopulations were analysed in a similar way.

A post hoc analysis of the Caprini risk score was performed using a generalised linear model that was adjusted for sex, and a cluster robust error was added for centre. Owing to the small number of participants in some of the categories, the Caprini risk score was recategorised as lowest (i.e. a score of < 5 points) and highest (i.e. a score ≥ 5 points). All analyses were undertaken using Stata® 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Chapter 3 Results

Study recruitment

Recruitment commenced in May 2016 and ceased at the end of January 2019. In total, 1905 participants were recruited from seven study centres. Table 3 shows the total number of participants recruited per centre. Figure 2 shows the trajectory of recruitment over the study period. At trial commencement, the monthly recruitment target was 24 participants per month across the seven study centres. Following changes to the study design, this was reduced to six participants per month per centre.

| Centre | Treatment arm, n (%) | Total (N = 1905) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LMWH (N = 954) | LMWH and GCS (N = 951) | ||

| Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust | 176 (18.4) | 175 (18.4) | 351 (18.4) |

| Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 137 (14.4) | 135 (14.2) | 272 (14.3) |

| University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust | 125 (13.1) | 125 (13.1) | 250 (13.1) |

| Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust | 74 (7.8) | 73 (7.7) | 147 (7.7) |

| Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust | 163 (17.1) | 161 (16.9) | 324 (17.0) |

| University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust | 127 (13.3) | 131 (13.8) | 258 (13.5) |

| Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth | 152 (15.9) | 151 (15.9) | 303 (15.9) |

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment graph.

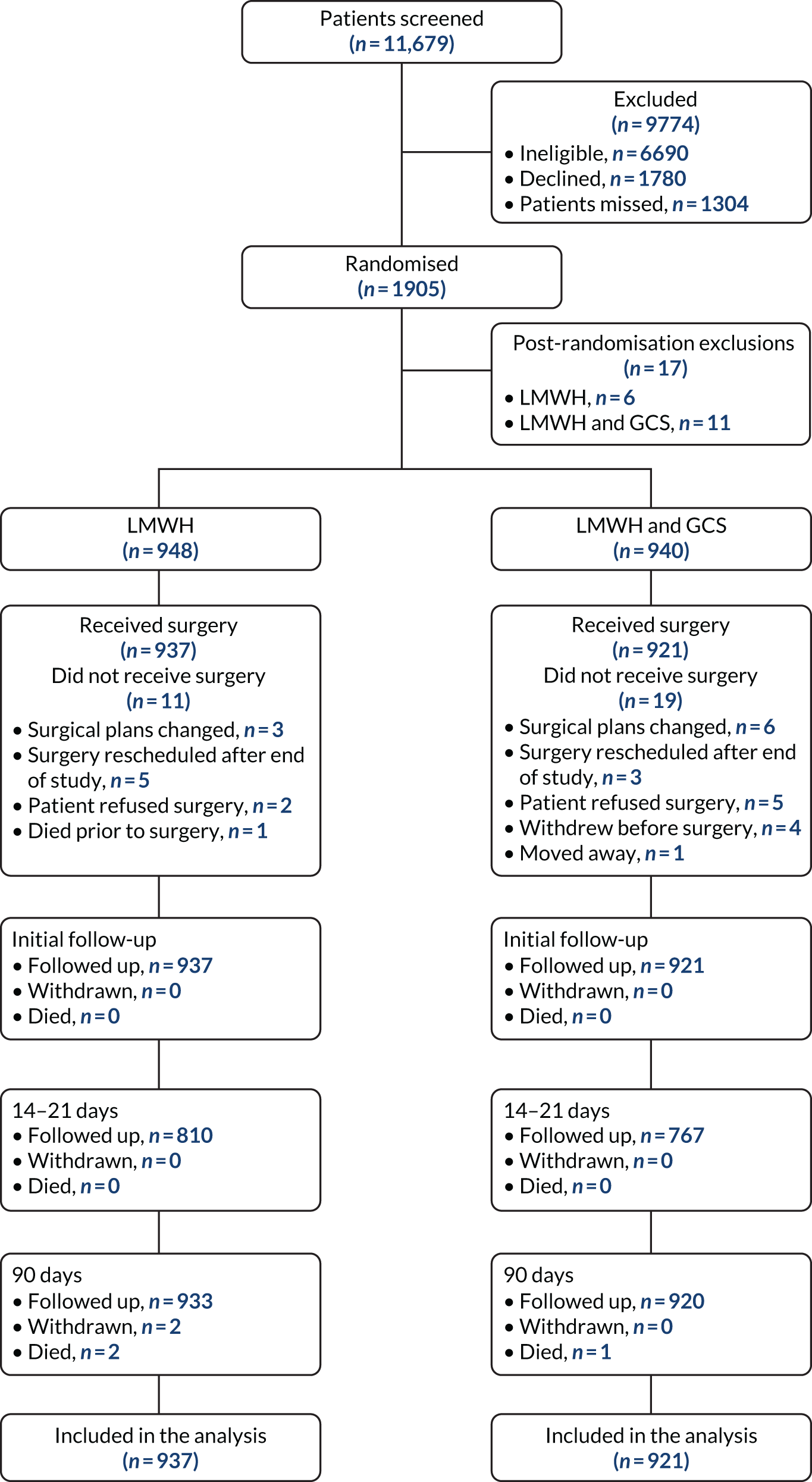

Participant flow

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram of the trial population is shown in Figure 3; the numbers of participants who had withdrawn, died or been lost to follow-up by each time point are presented. There were 11,679 patients assessed for eligibility. Of these, 9774 participants were excluded: 6690 did not meet the eligibility criteria, 1780 declined and 1304 were missed from being approached about participation in the study (Table 4). In total, 1905 participants were randomised and 17 were excluded post randomisations. The reasons for exclusion were that the participant was to receive extended thromboprophylaxis (LMWH-alone arm, n = 4; LMWH and GCS arm, n = 6), had a pre-existing peripheral vascular disease (LMWH and GCS arm, n = 2), was taking an anticoagulant at baseline (LMWH-alone arm, n = 1; LMWH and GCS arm, n = 1), was not for LMWH (LMWH and GCS arm, n = 1), had a thrombogenic disorder (LMWH and GCS arm, n = 1) and was reclassified to no risk of VTE prior to surgery (LMWH-alone arm, n = 1).

FIGURE 3.

The CONSORT flow diagram of the trial population.

| Reason | Total number of participants |

|---|---|

| Ineligiblea | 6690 |

| Day case | 2427 |

| Patients requiring thromboprophylaxis to be extended beyond discharge | 1270 |

| Patients having intermittent pneumatic compression beyond theatre and recovery | 682 |

| Contraindications to low LMWH | 679 |

| Individuals requiring therapeutic anticoagulation | 643 |

| Contraindications to GCS | 345 |

| Previous VTE | 331 |

| Lack of capacity | 290 |

| Not 65 years of age and not at high risk of VTEb | 244 |

| Clinical team did not give agreement | 168 |

| Surgery cancelled | 134 |

| Documented or known thrombophilia or thrombogenic disorder | 110 |

| Contraindications to LMWH: high risk of bleeding | 21 |

| Aged < 18 years | 14 |

| Pregnant | 7 |

| Application of a cast or brace in theatre | 7 |

| Patients requiring inferior vena cava filter | 6 |

| Unknown | 23 |

| Declined | 1780 |

| No reason given | 784 |

| Attending clinic | 567 |

| Participant wanted stockings | 289 |

| Not interested | 92 |

| Family declined | 25 |

| Did not want to wear stockings | 18 |

| Did not want to receive LMWH | 5 |

In total, 948 participants in the LMWH-alone arm were randomised and included in the study compared with 940 participants in the LMWH and GCS arm. In the LMWH-alone arm a total of 937 participants received surgery, and in the LMWH and GCS arm 921 participants received surgery.

Table 5 shows the number of participants randomised for the four subpopulations. Among participants aged < 65 years with a moderate risk of VTE, 280 participants were randomised. Among participants aged < 65 years with a high risk of VTE, 765 participants were randomised. Among participants aged ≥ 65 years with a moderate risk of VTE, 21 were randomised. Among participants aged ≥ 65 years with a high risk of VTE, 822 were randomised.

| Subpopulation | Treatment arm, n (%) | Total (N = 1888) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LMWH (N = 948) | LMWH and GCS (N = 940) | ||

| Aged < 65 years with moderate risk of VTE | 139 (14.7) | 141 (15.0) | 280 (14.8) |

| Aged < 65 years with high risk of VTE | 362 (38.2) | 403 (42.9) | 765 (40.5) |

| Aged ≥ 65 years with moderate risk of VTE | 12 (1.3) | 9 (1.0) | 21 (1.1) |

| Aged ≥ 65 years with high risk of VTE | 435 (45.9) | 387 (41.2) | 822 (43.6) |

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics for the overall population are shown in Table 6. The mean age in the LMWH-alone arm was 59 years, and in the LMWH and GCS arm this was 58 years; 63% of participants were female in both arms. The mean BMI was 29 kg/m2 (overweight), 84% were at high risk of VTE, 3% had one or more risk factor for bleeding and 68% had the highest Caprini risk score (i.e. ≥ 5 points). The mean EQ-5D-5L was similar between both arms at baseline (0.825 in the LMWH and 0.817 in LMWH and GCS arm). See Appendix 5, Tables 26–29, for baseline characteristics of the four subpopulations.

| Characteristic | Treatment arm | |

|---|---|---|

| LMWH (N = 948) | LMWH and GCS (N = 940) | |

| Age (years), n; mean (SD) | 948; 59.3 (15.2) | 940; 58.1 (14.9) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 347 (36.6) | 346 (36.8) |

| Female | 601 (63.4) | 594 (63.2) |

| BMI (kg/m2), n; mean (SD) | 948; 28.7 (5.9) | 940; 29.0 (6.1) |

| VTE risk | ||

| Moderate | 151 (15.9) | 150 (16.0) |

| High | 797 (84.1) | 790 (84.0) |

| Bleeding risk | ||

| No bleeding risk | 918 (96.8) | 911 (96.9) |

| One or more risk factors | 30 (3.2) | 29 (3.1) |

| Caprini risk score | ||

| Low (0 or 1 points) | 4 (0.4) | 5 (0.5) |

| Moderate (2 points) | 23 (2.4) | 28 (3.0) |

| High (3 or 4 points) | 275 (29.0) | 267 (28.4) |

| Highest (≥ 5 points) | 646 (68.1) | 640 (68.1) |

| EQ-5D-5L, n; mean (SD) | 942; 0.825 (0.185) | 926; 0.817 (0.192) |

| EQ-5D-VAS, n; mean (SD) | 941; 76.9 (17.5) | 923; 77.0 (18.1) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White British | 811 (85.5) | 817 (86.9) |

| White Irish | 14 (1.5) | 14 (1.5) |

| White other | 35 (3.7) | 27 (2.9) |

| White and black Caribbean | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) |

| White and black African | 0 (0) | 2 (0.2) |

| White Asian | 3 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) |

| Other mixed background | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) |

| Indian | 15 (1.6) | 6 (0.6) |

| Pakistani | 15 (1.6) | 9 (1.0) |

| Bangladeshi | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) |

| Other Asian background | 6 (0.6) | 5 (0.5) |

| Caribbean | 10 (1.1) | 17 (1.8) |

| African | 13 (1.4) | 15 (1.6) |

| Black other | 5 (0.5) | 1 (0.1) |

| Chinese | 2 (0.2) | 4 (0.4) |

| Other | 16 (1.7) | 18 (1.9) |

| Smoker | ||

| Never | 476 (50.2) | 465 (49.5) |

| Ex-smoker | 56 (5.9) | 58 (6.2) |

| Ex-smoker for < 1 year | 25 (2.6) | 35 (3.7) |

| Ex-smoker for < 5 years | 52 (5.5) | 28 (3.0) |

| Ex-smoker for > 5 years | 222 (23.4) | 237 (25.2) |

| Current smoker | 117 (12.3) | 117 (12.4) |

| Alcohol consumption | ||

| Never | 238 (25.1) | 217 (23.1) |

| Ex-drinker | 144 (15.2) | 132 (14.0) |

| Current drinker | 566 (59.7) | 591 (62.9) |

| Diet | ||

| Vegetarian | 47 (5.0) | 39 (4.1) |

| Low-meat diet | 630 (66.5) | 633 (67.3) |

| High-meat diet (> 90 g per day) | 271 (28.6) | 268 (28.5) |

| Physical activity level | ||

| Low | 294 (31.0) | 305 (32.4) |

| Moderate | 562 (59.3) | 544 (57.9) |

| Vigorous | 92 (9.7) | 91 (9.7) |

| Occupation | ||

| Worker | 133 (14.0) | 136 (14.5) |

| Employee | 211 (22.3) | 221 (23.5) |

| Self-employed | 63 (6.6) | 66 (7.0) |

| Contractor | 8 (0.8) | 5 (0.5) |

| Director | 8 (0.8) | 6 (0.6) |

| Office holder | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Unemployed | 62 (6.5) | 77 (8.2) |

| Student | 4 (0.4) | 5 (0.5) |

| Retired | 458 (48.3) | 423 (45.0) |

| Medication | ||

| Oral contraceptives (women only) | ||

| Yes | 16/601 (2.7) | 24/594 (4.0) |

| No | 584/601 (97.2) | 570/594 (96.0) |

| Missing | 1/601 (0.2) | 0/594 (0) |

| Hormone replacement therapy | ||

| Yes | 35/601 (5.8) | 39/594 (6.6) |

| No | 565/601 (94.0) | 555/594 (93.4) |

| Missing | 1/601 (0.2) | 0/594 (0) |

| Anti-inflammatory | 70 (7.4) | 87 (9.3) |

| Statins | 207 (21.8) | 185 (19.7) |

| Antiplatelet therapy | ||

| None | 894 (94.3) | 885 (94.1) |

| Single | 52 (5.5) | 53 (5.6) |

| Dual | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) |

| Triple | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) |

| History of malignancy | 213 (22.5) | 197 (21.0) |

| Past surgical history | 809 (85.3) | 802 (85.3) |

| Medical historya | ||

| Previous myocardial infarction | 10 (1.1) | 15 (1.6) |

| Previous stroke | 5 (0.5) | 9 (1.0) |

| Treated hypertension | 270 (28.5) | 257 (27.3) |

| Other medical history | 488 (51.5) | 503 (53.5) |

| No past medical history | 324 (34.2) | 321 (34.1) |

| Previous pregnancies | ||

| Yes | 485 (51.2) | 475 (50.5) |

| No | 461 (48.6) | 464 (49.4) |

| Missing | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) |

Treatment received

Overall, 937 (98.8%) participants in the LMWH-alone arm and 921 (98.0%) participants in the LMWH and GCS arm had surgery. Reasons for participants not having surgery post randomisation are shown in Table 7. Of the participants who had surgery, 758 (80.9%) in the LMWH-alone arm and 750 (81.4%) in the LMWH and GCS arm received their allocated treatment. Details of the treatment received are shown in Table 7. Overall, 795 (84.8%) participants in the LMWH-alone arm and 771 (83.7%) in LMWH and GCS arm received LMWH. Reasons for LMWH not being given are shown in Table 7. The main reasons were patients being discharged early (LMWH: n = 54, 38.0%; LMWH and GCS: n = 58, 38.7%), LMWH not being prescribed (LMWH: n = 48, 33.8%; LMWH and GCS: n = 50, 33.3%) and LMWH not being given owing to clinical reasons (LMWH: n = 25, 17.6%; LMWH and GCS, n = 25, 16.7%). In the LMWH-alone arm, 55 (5.9%) participants were given GCS, and in the LMWH and GCS arm 892 (96.9%) participants were given GCS (as allocated). Neither treatment, LMWH or GCS, was given for 124 (13.2%) participants in the LMWH-alone arm and eight (0.9%) in the LMWH and GCS arm. In the LMWH and GCS arm, 95.7% of participants were prescribed below-knee garments (see Table 7). Table 7 provides a description of the surgical procedures patients underwent at baseline, with the majority being within general (upper gastrointestinal) and obstetrics and gynaecology specialties.

| Surgical status | Treatment arm, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| LMWH (N = 948) | LMWH and GCS (N = 940) | |

| Received surgery | 937 (98.8) | 921 (98.0) |

| Did not receive surgery | 11 (1.2) | 19 (2.0) |

| Did not receive surgery | ||

| Surgical plans changed, not for surgery | 3 (27.3) | 6 (31.6) |

| Surgery rescheduled after the end of the trial | 5 (45.5) | 3 (15.8) |

| Patient refused surgery | 2 (18.2) | 5 (26.3) |

| Withdrew prior to surgery | 0 (0) | 4 (21.1) |

| Moved away | 0 (0) | 1 (5.3) |

| Died prior to surgery | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0) |

| Received surgery | ||

| Anaesthetic used | ||

| General | 914 (97.5) | 899 (97.6) |

| Regional | 15 (1.6) | 19 (2.1) |

| Both | 8 (0.9) | 3 (0.3) |

| Treatment received | ||

| Received allocated treatment | 758 (80.9) | 750 (81.4) |

| Details of treatment received | ||

| LMWH and GCS | 37 (3.9) | 750 (81.4) |

| LMWH alone | 758 (80.9) | 21 (2.3) |

| GCS alone | 18 (1.9) | 142 (15.4) |

| Neither LMWH nor GCS | 124 (13.2) | 8 (0.9) |

| Reasons for LMWH not given | N = 142 | N = 150 |

| Patient discharged early | 54 (38.0) | 58 (38.7) |

| Not prescribed | 48 (33.8) | 50 (33.3) |

| Clinical | 25 (17.6) | 25 (16.7) |

| Missed | 4 (2.8) | 6 (4.0) |

| No reason | 8 (5.6) | 7 (4.7) |

| Patient declined | 2 (1.4) | 1 (0.7) |

| Procedure abandoned in theatre | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.3) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) |

| Type of GCS | N = 55 | N = 892 |

| Above the knee | 2 (3.6) | 38 (4.3) |

| Below the knee | 5 (9.1) | 854 (95.7) |

| Not recorded | 48 (87.3) | 0 (0) |

| Surgical procedure | ||

| General: upper gastrointestinal | 293 (31.3) | 289 (31.4) |

| Obstetrics and gynaecology | 160 (17.1) | 163 (17.7) |

| General: lower gastrointestinal | 106 (11.3) | 116 (12.6) |

| Urology | 86 (9.2) | 79 (8.6) |

| General | 50 (5.3) | 54 (5.9) |

| General: breast | 54 (5.8) | 50 (5.4) |

| Ear, nose and throat | 44 (4.7) | 43 (4.7) |

| Neurosurgery | 36 (3.8) | 26 (2.8) |

| Plastics | 18 (1.9) | 21 (2.3) |

| Orthopaedics | 11 (1.2) | 17 (1.8) |

| Cardiothoracic | 3 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) |

| Vascular | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) |

| Other | 74 (7.9) | 61 (6.6) |

For the subpopulation aged < 65 years with moderate risk of VTE, see Appendix 5, Table 16, for surgery details and treatment received. In the LMWH-alone arm, 137 out of 139 (98.6%) participants received surgery compared with 140 out of 141 (99.3%) participants in the LMWH and GCS arm. Of these participants, 108 (78.8%) in the LMWH-alone arm and 106 (75.7%) in the LMWH and GCS arm received their allocated treatment. For the subpopulation aged < 65 years with high risk of VTE, see Appendix 5, Table 17, for surgery details and treatment received. In the LMWH-alone arm, 360 out of 362 (99.4%) participants received surgery compared with 395 out of 403 (98.0%) participants in the LMWH and GCS arm. In total, 82% of participants received their allocated treatment. Of the participants aged ≥ 65 years with moderate risk of VTE (see Appendix 5, Table 18), 11 out of 12 (91.7%) in the LMWH-alone arm and 9 out of 9 (100.0%) in the LMWH and GCS arm received surgery. Of the participants who were aged ≥ 65 years with high risk of VTE, 429 out of 435 (98.6%) in the LMWH-alone arm and 377 out of 387 (97.4%) in the LMWH and GCS arm received surgery (see Appendix 5, Table 19). Of these participants, 347 (80.9%) in the LMWH-alone arm and 311 (82.5%) in the LMWH and GCS arm received their allocated intervention.

Follow-up

Primary outcome

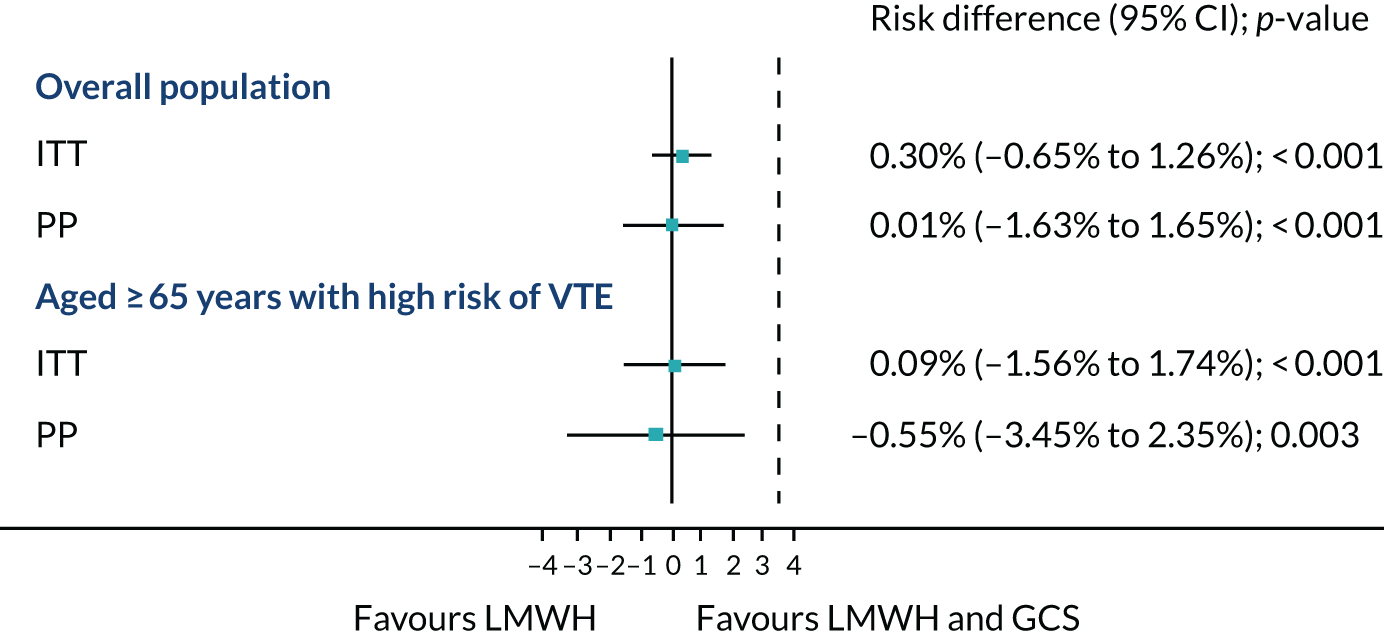

In the ITT analysis, VTE occurred in 16 out of 937 (1.7%) patients in the LMWH-alone arm compared with 13 out of 921 (1.4%) in the LMWH and GCS arm. The risk difference between the LMWH-alone arm and the LMWH and GCS arm was 0.3% (95% CI –0.65% to 1.26%; p < 0.001) (Figure 4). Given that the 95% CI did not cross the non-inferiority margin of 3.5%, non-inferiority of LMWH alone was shown. The PP analysis showed similar results. A sensitivity analysis was carried out including the participants who were excluded post randomisation, as well as those who had a duplex ultrasound scan. Overall, the results were similar (Table 8).

FIGURE 4.

Venous thromboembolism rates for the overall population and the subpopulation of those aged ≥ 65 years with high risk of VTE. Data are risk difference in percentages. Dashed line is the non-inferiority margin (3.5%).

| Analysis | Treatment arm, n/N (%) | RD (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMWH | LMWH and GCS | |||

| Including post-randomisation exclusions | 16/943 (1.7) | 13/932 (1.4) | 0.35% (–0.72% to 1.43%) | < 0.001 |

| Including those who had a duplex ultrasound scan | 16/810 (2.0) | 13/767 (1.7) | 0.30% (–0.95% to 1.54%) | < 0.001 |

Among the subpopulation aged ≥ 65 years with high risk of VTE, 14 out of 429 (3.3%) in the LMWH-alone arm and 12 out of 377 (3.2%) in the LMWH and GCS arm had a VTE. The risk difference was 0.09% (95% CI –1.56% to 1.74%; p < 0.001) (see Figure 4), which again showed non-inferiority. The PP analysis showed a similar result.

Table 9 shows the results for the other subpopulations. No VTE was confirmed for the subpopulation aged < 65 years with moderate risk of VTE, with an exact 95% CI (0 to 0.01) for the ITT analysis as well as for the PP analysis. For the subpopulation aged< 65 years with a high risk of VTE, 2 out of 360 (0.6%) participants in the LMWH-alone arm and 1 out of 395 (0.3%) in the LMWH plus GCS arm had a VTE, with an exact odds ratio of 2.20 and exact 95% CI (0.11 to 130.18). No VTE was confirmed for the subpopulation aged ≥ 65 years with moderate risk of VTE, with an exact 95% CI (0 to 0.14) for the ITT analysis and an exact 95% CI (0 to 0.15) for the PP analysis.

| Subpopulation | Treatment arm, n/N (%) | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LMWH | LMWH and GCS | ||

| < 65 years with moderate risk of VTE | |||

| ITT analysis | 0/137 (0) | 0/140 (0) | 0% to 1% |

| PP analysis | 0/108 (0) | 0/106 (0) | 0% to 1% |

| < 65 years with high risk of VTE | |||

| ITT analysis | 2/360 (0.6) | 1/395 (0.3) | –0.62% to 1.06% |

| PP analysis | 2/294 (0.7) | 1/324 (0.3) | –0.75% to 1.26% |

| ≥ 65 years with moderate risk of VTE | |||

| ITT analysis | 0/11 (0) | 0/9 (0) | 0% to 14% |

| PP analysis | 0/9 (0) | 0/9 (0) | 0% to 15% |

Breakdown of venous thromboembolism

Pulmonary embolism occurred in 2 out of 16 (12.5%) participants in the LMWH-alone arm compared with 1 out of 13 (7.7%) participants in the LMWH and GCS arm. DVT occurred in 12 out of 16 (75.0%) participants in the LMWH-alone arm compared with 11 out of 13 (84.6%) participants in the LMWH and GCS arm. Table 10 shows further details of the location of the VTE. Appendix 5, Tables 20 and 21, shows details of VTE for the subpopulations.

| Type of VTE | Treatment arm, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| LMWH (N = 948) | LMWH and GCS (N = 940) | |

| Received surgery | 937 | 921 |

| VTE within 90 days | 16 (1.7) | 13 (1.4) |

| Type of VTE | ||

| Symptomatic DVT | 2 (12.5) | 1 (7.7) |

| Asymptomatic DVT identified by duplex ultrasound scan | 12 (75.0) | 11 (84.6) |

| Imaging-confirmed symptomatic PE | 2 (12.5) | 1 (7.7) |

| VTE in right leg | 5 (31.3) | 2 (15.4) |

| Location | ||

| Below knee | 4 | 3 |

| Single calf vessel | 3 | 0 |

| More than one calf vessel | 0 | 2 |

| Distal popliteal vein | 1 | 0 |

| Above knee (femoral/proximal popliteal) | 0 | 1 |

| VTE in left leg | 8 (50.0) | 7 (53.8) |

| Location | ||

| Below knee | 7 | 4 |

| Single calf vessel | 3 | 3 |

| More than one calf vessel | 2 | 1 |

| Distal popliteal vein | 1 | 1 |

| Above knee (femoral/proximal popliteal) | 2 | 1 |

| VTE in both legs | 1 (6.3) | 2 (15.4) |

| Location | ||

| Below knee | 1 | 1 |

| Single calf vessel | 1 | 1 |

| More than one calf vessel | 0 | 1 |

| Location unknown | 2 (12.5) | 2 (15.4) |

Secondary outcomes

For the EQ-5D-5L and EQ-5D-VAS, there is no evidence of a difference between the two treatment arms over the follow-up time points for the overall population (Table 11). For compliance with GCS (see Table 11), defined as wearing the prescribed stockings for ≥ 75% of the total admission time, 1 out of 37 (2.7%) participants had a VTE in the LMWH-alone arm, and 12 out of 750 (1.6%) participants had a VTE in the LMWH and GCS arm. In total, 13 out of 768 (1.7%) participants had a VTE in the LMWH-alone arm, and 10 out of 755 (1.3%) participants had a VTE in the LMWH and GCS arm. For partial compliance (received > 50% of prescribed doses), 13 out of 779 (1.7%) participants had a VTE in the LMWH-alone arm and 10 out of 762 (1.3%) in the LMWH and GCS arm.

| Variable | Treatment arm | Mean difference (95% CI)a | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMWH (N = 948) | LMWH and GCS (N = 940) | |||

| Received surgery (n) | 937 | 921 | ||

| EQ-5D-5L, n; mean (SD) | ||||

| Baseline | 933; 0.825 (0.185) | 910; 0.818 (0.192) | ||

| 1 week/discharge | 874; 0.648 (0.232) | 839; 0.627 (0.244) | 0.015 (–0.004 to 0.033) | 0.118 |

| Between 14 and 21 days | 846; 0.788 (0.202) | 820; 0.773 (0.206) | 0.011 (–0.008 to 0.030) | 0.249 |

| 90 days | 774; 0.856 (0.192) | 743; 0.843 (0.197) | 0.011 (–0.009 to 0.031) | 0.272 |

| EQ-5D-VAS | ||||

| Baseline, n; mean (SD) | 932; 77.0 (17.4) | 907; 77.0 (18.2) | ||

| 1 week/discharge, n; mean (SD) | 873; 68.2 (19.5) | 837; 67.8 (20.1) | 0.23 (–1.32 to 1.79) | 0.770 |

| Between 14 and 21 days, n; mean (SD) | 846; 77.4 (17.4) | 819; 77.2 (17.0) | –0.04 (–1.62 to 1.54) | 0.958 |

| 90 days, n; mean (SD) | 773; 80.2 (17.9) | 743; 80.7 (18.2) | –0.29 (–1.94 to 1.37) | 0.732 |

| Compliance with GCS,b n (%) | 37 (4.0) | 750 (81.4) | (–0.18 to 0.04) | |

| Compliance with LMWH, n (%) | ||||

| Received all prescribed LMWH doses | 768 (82.0) | 755 (82.0) | (–0.18 to 0.18) | |

| Received ≥ 50% of prescribed doses | 779 (83.1) | 762 (82.7) | (–0.17 to 0.17) | |

The EQ-5D-5L, EQ-5D-VAS and compliance for the subpopulations are shown in Appendix 5, Tables 22–25.

Complications and overall mortality by treatment received are shown in Table 12. In the LMWH-alone arm, 2 out of 779 (0.3%) participants had a stocking-related complication (however, these participants wore stockings for < 1 hour so they did not fulfil the definition of compliance and were not included in the analysis). In the LMWH and GCS arm, 50 out of 787 (6.4%) participants had a stocking-related complication, as did 5 out of 160 (3.1%) participants who received only GCS. In the group of participants who were classified as receiving neither treatment, 1 out of 132 (0.8%) experienced a stocking-related complication; this was not formally classified as the patient did not meet the compliance criteria. For adverse reactions to LMWH, 6 out of 779 (0.8%) participants had a reaction in the LMWH-alone arm compared with 2 out of 787 (0.3%) in the LMWH and GCS arm. In the LMWH-alone arm, 5 out of 779 (0.6%) participants had a bleeding complication compared with 4 out of 787 (0.5%) in the LMWH and GCS arm. There were two deaths in the LMWH-alone arm, both because of cancer. There was one death in the group of participants who received neither treatment; this was because of a cardiac disorder. See Appendix 5, Tables 30–32, for complications and overall mortality for the subpopulations, apart from the subpopulation of ≥ 65 years with moderate risk of VTE for which there were no events.

| Complications | Treatment received, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMWH (N = 779) | LMWH and GCS (N = 787) | GCS (N = 160) | Neither (N = 132) | |

| GCS-related complicationsa | 2 (0.3)a | 50 (6.4) | 5 (3.1) | 1 (0.8)b |

| Discomfort | 2 | 41 | 4 | 1 |

| Skin break/ulcer | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Skin rash | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 0 | 21 | 1 | 0 |

| Adverse reactions to LMWHa | 6 (0.8) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Abnormal liver enzyme | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Bleeding complications | 5 (0.6) | 4 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Overall mortality | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.8) |

Serious adverse events

Table 13 shows the SAEs for the overall population categorised by the treatment received. SAEs (n = 239) were reported in 210 patients, with eight events being considered possibly or probably related to LMWH. The number of SAEs was in 92 (11.8%) in the LMWH-alone arm, 103 (13.1%) in the LMWH and GCS arm, five (3.1%) in those who received only GCS and 10 (7.6%) in those who received neither treatment. Most of the events required hospitalisation, and the main primary system organ class (SOC) term for the SAEs was gastrointestinal disorders. For SAE details for the four subpopulations see Appendix 5, Tables 33–36, for results by as treated.

| Variable | Treatment received, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMWH (N = 779) | LMWH and GCS (N = 787) | GCS (N = 160) | Neither (N = 132) | |

| Number of participants with a SAE | 92 (11.8) | 103 (13.1) | 5 (3.1) | 10 (7.6) |

| Total number of SAEs | 110 | 112 | 5 | 12 |

| Serious reason | ||||

| Death | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Life-threatening | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Required hospitalisation | 72 | 74 | 3 | 11 |

| Required prolonged hospitalisation | 30 | 29 | 2 | 0 |

| Resulted in persistent or significant disability | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Frequency | ||||

| Single episode | 87 | 92 | 5 | 9 |

| Intermittent | 4 | 4 | 0 | 2 |

| Frequent | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Continuous | 16 | 14 | 0 | 1 |

| Unknown | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Severity | ||||

| Mild (aware of it easily tolerated) | 21 | 13 | 1 | 0 |

| Moderate (discomfort/interference with usual activity) | 28 | 40 | 1 | 4 |

| Severe (inability to carry out normal activity) | 53 | 51 | 3 | 7 |

| Life-threatening or disabling | 8 | 8 | 0 | 1 |

| Relationship to LMWH or GCS | ||||

| Not related | 94 | 102 | 5 | 9 |

| Unlikely | 10 | 8 | 0 | 3 |

| Possible | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Probable | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Primary SOC term | ||||

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 33 | 28 | 0 | 3 |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | 25 | 20 | 1 | 2 |

| Infections and infestations | 15 | 13 | 0 | 2 |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 7 | 13 | 1 | 0 |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 3 | 9 | 1 | 1 |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 6 | 4 | 0 | 1 |

| Surgical and medical procedures | 3 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Vascular disorders | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Investigations | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Cardiac disorders | 1 | 4 | 0 | 1 |

| Hepatobiliary disorders | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Nervous system disorders | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Neoplasms benign, malignant and unspecified (including cysts and polyps) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Eye disorders | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Product issues | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Post hoc analyses

A post hoc analysis with the Caprini risk score was performed to provide comparison with published studies in the USA. 34 For this analysis, the Caprini risk score was categorised as low–high (score of < 5 points) and highest (score of ≥ 5 points) owing to the small number of participants in some of the categories (Table 14). For the ITT analysis, 14 out of 640 (2.2%) VTE episodes in the LMWH-alone arm and 12 out of 625 (1.9%) VTE episodes in the LMWH and GCS arm were in the highest risk group (score of ≥ 5 points) (risk difference 0.27%, 95% CI –1.09% to 1.64%; p < 0.001 for non-inferiority).

| Caprini subpopulation | Treatment arm, n/N (%) | Estimatea (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMWH | LMWH and GCS | |||

| Low–high | ||||

| ITT | 2/297 (0.7) | 1/296 (0.3) | 2.00 (0.10 to 118.39) | |

| PP | 2/236 (0.9) | 1/238 (0.4) | 2.02 (0.10 to 120.0) | |

| Highest | ||||

| ITT | 14/640 (2.2) | 12/625 (1.9) | 0.27% (–1.09% to 1.64%) | < 0.001 |

| PP | 10/522 (1.9) | 11/512 (2.23) | –0.19% (–2.35% to 1.96%) | < 0.001 |

Chapter 4 Discussion

Interpretation of results

The GAPS trial is the first multicentre, pragmatic randomised trial to investigate the adjuvant benefit of GCS in elective surgical patients receiving appropriate pharmaco-thromboprophylaxis. The results show that LMWH alone is non-inferior compared with LMWH and GCS in elective surgical patients assessed as being at moderate or high risk of VTE. This finding was sustained when examining subgroups based on age (< 65 years or ≥ 65 years) and baseline VTE risk (assessed as being at moderate or high risk).

Our findings are also supported by data from a single centre, Salisbury District Hospital, in which local policy has been to omit GCS in surgical patients receiving appropriate thromboprophylaxis in the form of LMWH. VTE outcomes at this centre are comparable to national figures. 14

The results of this study add to a growing body of evidence that does not support the use of GCS when pharmaco-thromboprophylaxis is not contraindicated. 13,29 This is likely to have impact on the prescription of GCS for elective surgical patients and, as a result, a potentially significant reduction in NHS costs, which, if scaled globally and on a recurring basis, are likely to have a positive financial impact on hospital health-care systems. Many of the DVTs identified by duplex ultrasonography were located within the deep veins of the calf, the clinical significance of which is a subject of debate and controversy. 36 An isolated calf DVT, if left untreated, can propagate to involve the more cephalad veins in up to one-fifth of cases in which they become more clinically important; this largely occurs within 1 week. 36 We also note that 80% of participants enrolled in the trial received the treatment that they were allocated to and the number or participants who did not were similar across both treatment arms.