Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/71/03. The contractual start date was in September 2013. The draft report began editorial review in December 2018 and was accepted for publication in May 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Hagen et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background and current evidence base

There are various options for the management of female urinary incontinence (UI), including behavioural approaches, pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT), medication, surgery, nerve stimulation, injectable bulking agents, a botulinum toxin injection to the bladder wall, vaginal continence pessaries and the use of containment products, such as pads and catheters. These options may be used in combination.

Currently in the UK, supervised PFMT of at least 3 months’ duration is the first-line treatment for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and mixed urinary incontinence (MUI). 1 ‘Supervised PFMT’ refers to a course of treatment that involves one-to-one supervision by a health-care professional (usually a physiotherapist or nurse) who carries out a digital vaginal examination to ensure that the woman can correctly contract her pelvic floor muscles, and provides ongoing teaching, guidance and motivation relating to pelvic floor muscle exercises (PFMEs). The potential annual spend on PFMT is estimated at £38M (0.03% of the NHS budget of £106B), based on 0.8% of women aged ≥ 15 years being referred to UI services each year. 2 PFMT refers to the regular practice of repeated and progressive pelvic floor muscle contractions in order to produce a training effect on the muscles. The aim of a PFMT programme is to increase functionality of the pelvic floor through several mechanisms, detailed by Bo et al. 3

Adjuncts used with supervised PFMT in clinical practice include vaginal cones, electrical stimulation and biofeedback. Biofeedback is the technique by which information about a normally unconscious physiological process is presented to the patient and/or the therapist as a visual, auditory or tactile signal. 4 Electromyography (EMG) is the study of minute electrical potentials produced by depolarisation of muscle membrane. 5 In EMG biofeedback, which is the focus of this research, electrical activity arising from muscle activity (during exercise and voluntary effort) is recorded in microvolts and displayed as a visual and/or auditory signal for both the patient and therapist to view. In a PFMT programme, an internal vaginal or anal probe is used to record electrical information from pelvic floor muscles through surface recordings. The probe is connected by cables to a biofeedback unit. Handheld units, with a small visual display screen, are available for home use. The display provides a visual representation of the muscles contracting and relaxing, allowing monitoring of strength, endurance and repetitions.

Possible mechanisms for how biofeedback might improve continence

Biofeedback acts as a strong and specific training stimulus, which has the potential to markedly intensify a training programme. This effect is evidenced in the biofeedback and general exercise literature. 6 In this report, the exercise being referred to is PFME. In the context of supervised PFMT for treatment of UI, biofeedback contributes to:

-

teaching women the precise, correct muscle contraction in terms of technique, force and timing, and assisting the therapist in prescribing the correct exercise dose to ensure that appropriate physiological responses occur in the muscles

-

informing adjustments to the exercise prescribed by the therapist (modulating)

-

highlighting to women improvements in their muscle function (encouraging)7

-

increasing the quality of the interaction with the therapist (via biofeedback used in ways congruent with health behaviour change theory and practice)

-

change in women’s behaviour relating to home exercise, as biofeedback has been classified as a behaviour change technique (BCT) in a taxonomy of BCTs. 8

These features have the potential to increase a woman’s confidence (self-efficacy) in doing PFMT; self-efficacy for PFMT is a determinant of intention to adhere9 and adherence itself. 10,11 For PFMT to have an effect on UI, sufficient exercise must be carried out over a long enough period to strengthen (hypertrophy) the muscle. 12 Thus, maximising adherence to exercise is key to an intensive PFMT intervention. Intensive PFMT, which fosters PFMT self-efficacy, can potentially be achieved through the addition of biofeedback, leading to improvement in the quality and quantity of PFMT performed by women, and to more improvement in the severity of their UI than a less intensive programme.

Evidence for the effectiveness of biofeedback for female urinary incontinence

Both a Cochrane systematic review of biofeedback-assisted PFMT for women with UI7 and a Health Technology Assessment-funded systematic review of non-surgical treatments for women with SUI13 found that biofeedback-assisted PFMT appeared to offer benefit over basic PFMT alone. However, the Cochrane review,7 with its more restricted scope, conducted a more detailed analysis of the biofeedback trials and found that this effect may be confounded by the greater amount of health professional contact received by women in the biofeedback groups.

Rationale for research

Based on current evidence, it is not clear if the apparent benefit of biofeedback can be attributed to the biofeedback or to some other variable, such as additional health professional contact. Some of the trials in the Cochrane review7 had the same PFMT programme in both arms of the trial and the same amount of health professional contact. The results from these trials still favoured biofeedback, although the difference between groups was not statistically significant. A common problem in all these trials was the failure to clearly state the purpose of biofeedback, or to describe the intervention protocol. Thus, it was not clear if biofeedback could, theoretically or in practice, change the clinical effectiveness of the PFMT. Currently, the routine use of biofeedback as part of PFMT is not recommended and should be considered only for women who are unable to contract their pelvic floor muscles. 1 Despite this, we know that therapists use biofeedback in their clinical practice as an adjunct to a supervised PFMT programme when treating female UI. 14

Thus, a robust comparison of biofeedback-mediated intensive PFMT compared with basic PFMT, in which both groups have the same basic PFMT programme and the same amount of health professional contact, is imperative to establish whether or not biofeedback does add value and improve incontinence outcomes.

Aims and objectives

The overall aim of the Optimal Pelvic floor muscle training for Adherence Long-term (OPAL) trial was to carry out a randomised controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate a theoretically based biofeedback-intensified PFMT intervention to answer the primary research question: is biofeedback-mediated intensive PFMT, compared with basic PFMT, a clinically effective and cost-effective treatment for women with SUI or MUI (stress and urgency)?

The trial comprised the following components:

-

Development of biofeedback-mediated intensive PFMT and basic PFMT interventions based on health behaviour theory designed to treat SUI and MUI.

-

A RCT in which the use of biofeedback as an adjunct to basic PFMT (biofeedback PFMT) was compared with PFMT alone (basic PFMT), in terms of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

-

A process evaluation to identify and investigate the possible mediating factors that affect the effectiveness of the interventions (including fidelity to intervention delivery and uptake), how these mediating factors influence effectiveness and whether or not the factors differ between randomised groups.

-

A longitudinal qualitative case study to investigate women’s experiences of the trial interventions, to identify the barriers and facilitators that affect adherence, to explain the process through which they influence adherence and to identify whether or not these differ between randomised groups.

Development of the OPAL trial interventions

The OPAL trial interventions (including biofeedback-mediated intensive PFMT and basic PFMT protocols) were developed by Jean Hay-Smith, Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) (University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand); Sarah G Dean, PhD (University of Exeter, Exeter, UK); Doreen McClurg, PhD [Nursing, Midwifery and Allied Health Professions Research Unit (NMAHP RU) Research Unit, Glasgow Caledonian University (GCU), Glasgow, UK]; Suzanne Hagen, PhD (NMAHP RU, GCU, Glasgow UK); Carol Bugge, PhD (University of Stirling, Stirling, UK); and Joanne Booth, PhD (GCU, Glasgow, UK).

The OPAL trial interventions are essentially behavioural intervention (i.e. an intervention focusing on the adoption and maintenance of a PFMT programme, with or without use of biofeedback). PFMT adherence is problematic and often decreases over time. 15 PFMT interventions typically include a number of ‘active’ ingredients that ‘interact’ (e.g. in the OPAL trial, the exercise and biofeedback ingredients are presumed to interact to intensify PFMT) to produce an effect that is potentially greater than the sum of the parts. Thus, the OPAL interventions had two core characteristics (behavioural difficulty and interacting components) of a ‘complex’ intervention. 16 A further element of complexity was the tailoring components within the interventions, which allowed flexibility in delivery; these components have been called ‘optional’ in the intervention protocols.

Four sources were used to develop the intervention:

-

theory consistent with our objective of changing health behaviour: the information motivation behavioural skills (IMB) model17

-

existing qualitative evidence about women’s experiences of PFMT and why they did or did not adopt the behaviour to undertake PFMT18

-

the explicit use of BCTs to support adoption and maintenance of the behaviour8

-

the existing PFMT intervention from the Pelvic Organ Prolapse PhysiotherapY (POPPY) trial,19 which provided the outline for what therapists considered ‘basic’ PFMT in UK clinical practice.

Once developed, the intervention protocols to be delivered were detailed in the intervention manual, which was given to each therapist. Separate protocols were available for biofeedback-mediated intensive PFMT (referred to hereafter as biofeedback PFMT) and basic PFMT. In practice, the interventions were delivered over six appointments with a trial therapist, which the participant attended. Details of the desired content of each appointment were provided in the intervention manual and in checklist format in the therapist assessment form (TAF), completed by the therapist at each appointment. This is described in more detail in Chapter 3.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Trial design

The OPAL trial was designed to compare biofeedback PFMT with basic PFMT, in terms of long-term continence severity [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117103/#/ (accessed 29 July 2019)]. It included a superiority multicentre RCT comparing two treatment groups: (1) PFMT with EMG biofeedback in clinic and at home (biofeedback PFMT) and (2) PFMT alone (basic PFMT)20 (see Chapter 3).

The main trial was supplemented with a separate economic evaluation (see Chapter 4), a process evaluation (see Chapter 5) and a longitudinal qualitative case study (see Chapter 6). For a trial overview, see Appendix 1. A published protocol is available for the process evaluation and case study. 21

Ethics approval and research governance

Ethics approval for all aspects of the trial was granted by the West of Scotland Research Ethics Committee 4 on 13 March 2013 [reference number 13/WS/0048; see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117103/#/ (accessed 29 July 2019)]. Overall research and development (R&D) approval for the trial from NHS Research Scotland was granted on 24 January 2014 (reference number NRS13/UR13) and from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Co-ordinated System for gaining NHS permission on 2 April 2014 (reference number 120377). Local NHS R&D approval for the trial was granted by 16 different trusts in England, and six local health boards granted R&D approval for seven centres in Scotland. The trial sponsor was GCU and the OPAL trial office was based in the NMAHP RU at GCU. The OPAL trial is registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Register (ISRCTN57746448).

Management of the trial

A Project Management Group (PMG), made up of all co-applicants and research staff employed on the trial, met regularly, face to face or by teleconference, to review the trial’s progress. An independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) met at least yearly to review trial progress. Patient and public involvement in the trial was ensured by involvement in the development and delivery of the trial, and membership of the PMG, of a lay person who had experience of treatment for female UI. A second lay person was a member of the TSC.

Participants and setting

The trial recruited women with SUI or MUI from 23 centres across the UK, comprising hospital outpatient and community settings.

Inclusion criteria

The trial included women:

-

aged ≥ 18 years, presenting with a new episode of SUI or MUI.

Exclusion criteria

The trial excluded women:

-

with urgency UI alone

-

who had received formal instruction in PFMT in the previous year

-

not able to contract their pelvic floor muscles

-

who were pregnant or < 6 months postnatal

-

with a prolapse greater than stage II (i.e. > 1 cm below the hymen on valsalva)

-

receiving active treatment for pelvic cancer

-

with cognitive impairment affecting capacity to give informed consent

-

who had the following neurological diseases: multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, stroke, motor neurone disease, spinal cord injury

-

with a known nickel allergy or sensitivity

-

who were already participating in other research relating to UI.

Recruitment procedure

The research team at each centre was responsible for identifying potential participants from women newly presenting with UI, with urinary leakage as the presenting complaint. A pre-screening process was used to exclude women who were obviously not eligible and therefore not approached to be formally screened at a clinic appointment. Screening could take place either at the first clinical presentation or a separate appointment arranged to assess eligibility. During screening appointments, clinicians assessed women for a clinical diagnosis of SUI or MUI and performed a vaginal examination to assess other trial eligibility criteria. With ethics approval, these details, along with contact details, were recorded on the clinical assessment form [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117103/#/ (accessed 29 July 2019)]. Each potentially eligible woman was allocated a unique trial identity number that, if the woman was recruited, was used throughout the trial in all the woman’s trial materials. Centre trial staff discussed the trial with women who were eligible and willing to take part, provided a patient information leaflet [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117103/#/ (accessed 29 July 2019)], answered any questions and provided women with a consent form to complete [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117103/#/ (accessed 29 July 2019)].

Informed consent

Informed, written consent was sought after the women had received all trial information and after any questions about participating had been answered. Copies of the completed consent form were held (1) by the participating woman, (2) in their general practitioner’s (GP’s) notes, (3) at the centre and (4) at the trial office. Women were provided with information about the process evaluation audio-recordings and the linked case study [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117103/#/ (accessed 29 July 2019)] and given the option of being approached to take part in these additional aspects of the research (see Chapters 5 and 6).

Randomisation, concealment and blinding

Consenting participants were individually randomised to one of two groups: biofeedback PFMT or basic PFMT. Group allocation was generated by the web-based randomisation service provided by the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials (CHaRT), a UK Clinical Research Collaboration clinical trials unit, located in the Health Services Research Unit, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, UK. A woman’s group allocation was relayed by e-mail to the trial office and recruiting member of staff at the centre. Owing to the nature of the intervention, blinded allocation was not possible for the participants and therapists delivering the intervention. The data entry staff and statistician were not blinded, as some data collection forms were intentionally different between groups, and this would be apparent to those staff processing the data. However, clinicians performing the 6-month pelvic floor muscle assessments were blinded to group allocation. Group allocation used minimisation based on four variables: UI type (SUI or MUI), recruiting centre, age (< 50/≥ 50 years) and UI severity [International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI SF) score of < 13 or ≥ 13].

Therapist training

To ensure consistency of expertise, all therapists received face-to-face training in delivery of both interventions (biofeedback PFMT and basic PFMT, as described in Treatment group allocation) by OPAL trial staff. They were also supplied with the OPAL trial intervention manual, providing a background to the OPAL trial, and the OPAL intervention protocols, describing the health behaviour model adopted to maximise intervention adherence.

Treatment group allocation

Both trial groups (biofeedback PFMT and basic PFMT)

In both groups, participants completed the basic PFMT protocol over a 16-week period:22 six individual face-to-face appointments with a therapist were offered at weeks 0, 1, 3, 6, 10 and 15, based on a previous trial of PFMT. 19 At the first appointment the therapist performed a vaginal examination, including visual inspection and digital assessment of the pelvic floor muscles (the Oxford Classification,23 and the International Continence Society method24).

During this assessment, all participants were taught how to contract and relax their pelvic floor muscles and how to pre-contract their pelvic floor muscles prior to (and in expectation of) increases in abdominal pressure, such as coughing and sneezing (‘the Knack’25).

Based on the findings of the assessment, the therapist and participant agreed a PFMT programme, tailored according to the woman’s ability and lifestyle, which progressed over time. The PFMT programme focused on strength and endurance, aiming for three sets of contractions per day, progressed by increasing the number of repetitions, hold duration and body position modification on progression (i.e. lying, sitting, standing, squatting).

As per local practice, therapists provided participants with information to support good bladder management and methods of dealing with urgency and frequency. Therapists also used the BCTs that had been mapped to, and detailed in, the intervention protocols to encourage participants’ adherence to the PFMT programme. Participants recorded the PFMT they performed in a diary [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117103/#/ (accessed 29 July 2019)].

No EMG biofeedback equipment was used during appointments for the basic PFMT group. Verbal feedback based on digital vaginal palpation was, however, permitted.

Biofeedback PFMT

In addition to the basic PFMT protocol provided to both groups [see Both trial groups (biofeedback PFMT and basic PFMT)], women randomised to the biofeedback PFMT group received a biofeedback protocol during appointments and were provided with a biofeedback unit to use at home. Biofeedback units were provided by the trial office and the same type of unit was used during appointments and at home [NeuroTrac® Simplex single-channel EMG biofeedback unit (Verity Medical Ltd, Romsey, UK)]. The biofeedback unit displayed participants’ pelvic floor muscle activity, providing audio and visual feedback on muscle contraction and relaxation. Participants were instructed how to insert, use and clean the probe, operate the unit and interpret the biofeedback information. Therapists set the parameters of the biofeedback unit and agreed with participants the frequency for use at home. The units stored data on home usage and participants also recorded their home use (and PFMT practice) in a diary.

Data collection and management

Baseline characteristics were recorded for each participant, including age, body mass index, number of births and delivery mode (number of breech, caesarean, forceps, normal vaginal and vacuum deliveries) and type of UI and severity (normal, mild, moderate, severe). Participants also recorded their urinary leakage at baseline in a 3-day bladder diary [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117103/#/ (accessed 29 July 2019)].

Baseline and 6-, 12- and 24-month data were collected via questionnaire booklets completed by the participants, containing the primary and secondary outcome measures [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117103/#/ (accessed 29 July 2019)]. See Appendix 2 for an overview of the time points of when participant data were collected via questionnaires.

At each appointment, participants were given a diary to record the PFMT carried out (and biofeedback use, where appropriate), during the intervention period. Participants had the telephone number of their therapist written on their diary so they could make contact if there were any concerns about the home exercise programme.

At a participant’s first appointment, therapists recorded demographic information, medical history and pelvic floor assessment findings in the TAF. At each subsequent appointment the therapist used the TAF to record pelvic floor assessment findings, the treatment plan, the prescribed PFMT programme and the participant’s adherence.

Participants attended an appointment at 6 months for a further pelvic floor assessment. This was undertaken by an assessor who was blinded to the participant’s group allocation and had not been involved in treatment delivery. Blinding was achieved by instructing participants in their appointment letter not to discuss their allocated treatment group with the assessor until after the assessment was complete. Assessors were directed in a trial standard operating procedure to remind participants not to discuss their trial treatment until after the examination. Assessors also recorded whether or not they had been aware of a participant’s group when carrying out the examination and, if so, to provide details.

Researchers at the trial office entered the data described above into the trial database, developed by CHaRT.

Participant follow-up

The duration of follow-up was 24 months from date of randomisation. It is important to assess duration of effect; previous trials typically measured outcomes immediately post treatment or followed up participants for a maximum of only 1 year. Follow-up questionnaires were sent from the trial office by post or e-mail to participants, with postal, e-mail and telephone reminders. During telephone reminder calls, participants could verbally complete a shortened version of follow-up questionnaires, including ICIQ-UI SF, EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), and questions about PFMT adherence and UI treatment uptake [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117103/#/ (accessed 29 July 2019)].

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the ICIQ-UI SF score at 24 months. This met with the commissioning brief from the funder, which highlighted symptom severity as an important outcome and 2 years as the minimum duration of follow-up. The ICIQ-UI SF26 is a four-item questionnaire (total score ranging from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating greater severity), covering frequency of UI (never = 0, once a week = 1, two or three times a week = 2, once a day = 3, several times a day = 4, all the time = 5), amount of leakage (none = 0, small = 2, moderate = 4, large = 6), overall impact of UI (not at all = 0, a great deal = 10) and a diagnostic question to identify type of UI. Responses to the first three questions are summed to give the total score. The maximum score is 21; the higher the score, the more severe the UI, with a score of ≥ 13 rated as severe. 27

Secondary outcomes

Urinary outcomes

The number of women with UI cured and improved was derived from the ICIQ-UI SF (cured = negative response to both ‘how often do you leak urine?’ and ‘how much urine do you usually leak’; improved = a reduction in ICIQ-UI SF score of ≥ 3 points). 28 The Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I), which has been validated for use in females with UI,29 was completed to assess perceptions of improvement in UI. The PGI-I enabled participants to describe their UI at each time point compared with the start of the trial, using a 7-point scale from 1 (‘very much better’) to 7 (‘very much worse’). The International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire for Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (ICIQ-FLUTS)30 was completed to capture other urinary symptoms (nocturia, urgency, frequency, SUI, unexplained UI, bladder pain, diurnal frequency, hesitancy, straining, intermittency and enuresis), comprising 12 items, each scored 0–4, and three subscales [filling score (range 0–16), voiding score (range 0–12) and incontinence score (range 0–20)].

Participants completed questions assessing uptake of other treatment and use of services for UI: hospital admission, outpatient appointment, GP consultation, nurse appointment, physiotherapy appointment, surgery, medication and other treatment/medical advice.

Quality-of-life outcomes

Condition-specific quality of life was measured using the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire for Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Quality of Life (ICIQ-LUTSqol),31 which has 19 items, each scored from 1 to 4 (range 19–76). General health was measured using the EQ-5D-3L questionnaire32 (range –0.594 to 1) and the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) visual analogue score (range 0–100).

Pelvic floor-related outcomes

Pelvic floor outcomes were assessed using four different measurements: (1) the pelvic organ prolapse symptom score (POP-SS), a seven-item questionnaire measuring prolapse symptoms;33 (2) bowel symptoms were assessed via an unpublished early version of the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Bowel Short Form, comprising six items covering frequency and consistency of bowel movement; (3) the Oxford Classification23 was used by therapists to quantify pelvic floor muscle strength on a 6-point scale, as well as contraction endurance and repetitions; and (4) therapists also used the International Continence Society classification for muscle relaxation (absent, partial, complete) and contraction (absent, weak, normal, strong). 24

Self-efficacy for PFMT

Women’s self-efficacy for PFMT was assessed using the PFME self-efficacy scale,34 a 17-item self-report scale comprising two factors: (1) belief in PFME execution and its benefits (11 items); and (2) belief in performing PFME as scheduled and despite barriers (six items). Items are scored from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores are associated with a woman perceiving that she has greater confidence in her ability to perform PFMEs.

Adherence to PFMT

Adherence to performing PFMT and the use of biofeedback was captured through the number of appointments attended, participants completing PFMT diaries during the 16-week intervention period, information in the TAFs on whether or not the recommended intervention protocol had been followed and participants’ responses to questions in the follow-up questionnaires. Additional understanding of perceived outcomes, self-efficacy and adherence was gained through the process evaluation (see Chapter 5) and case study (see Chapter 6).

Economic-related outcomes

The primary health economic outcome measure of cost-effectiveness was incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) at 24 months, based on responses to the EQ-5D-3L. This incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was defined by the difference in cost between two trial interventions, divided by the difference in their effect.

Secondary outcomes were (1) the cost of resources used by participants, including the use of primary (GP services) and secondary (outpatient visits, inpatient stay, surgical interventions for incontinence) care services, and further referral for subsequent additional specialist management; (2) the personal costs to the participants, including costs of travelling to appointments and work/social restrictions; and (3) QALYs derived using the ICIQ-LUTSqol responses.

Full cost-effectiveness methods are described in detail in Chapter 4.

Adverse events

The interventions delivered in the trial are well established clinically; therefore, any adverse events (AEs) may commonly be found in women receiving PFMT and biofeedback. Expected AEs arising from the interventions were:

-

sore pelvic floor muscles

-

lower back pain

-

vaginal irritation or discomfort

-

thrush

-

urinary tract infection

-

spotting or staining (not linked to menstruation), potentially caused by biofeedback probe insertion

-

vaginal itchiness and discomfort (potentially linked to biofeedback probe if nickel sensitivity/allergy)

-

psychological distress from vaginal examination and/or use of biofeedback probe (e.g. as a result of previous abuse or distressing labour).

All AEs (for which the participant sought health-care professional interventions) and serious adverse events (SAEs) (an untoward medical occurrence in a participant, including death, life-threatening conditions, hospitalisation or prolonging of existing hospitalisation, persistent or significant disability or incapacity, a congenital anomaly or birth defect, and any event considered medically significant by the investigator) were assessed to determine cause, severity and relatedness, and were reported to the relevant regulatory bodies.

Serious adverse events were reported to the main Research Ethics Committee if they occurred within 30 days of the woman’s previous therapy appointment and were, in the opinion of the chief investigator or the chairperson of the DMEC, related to trial participation (resulted from the administration of any of the research procedures) and unexpected (not listed in the protocol as an expected occurrence). In additional, SAE forms were used to record deaths from any cause during the course of the trial.

Sample size

There were no published long-term outcome data for our primary outcome measure to inform our sample size calculation; thus, we referred to studies reporting baseline ICIQ-UI SF data for women with SUI/MUI. 35,36 These studies indicated a standard deviation (SD) of 5, but we expected that the SD at the 24-month time point in the trial could possibly be as high as 10. A minimal clinically important difference of 2.5 points on the ICIQ-UI SF score was assumed (a change in frequency of urine leakage of, e.g., ‘once a day’ to ‘never’), based on a study of older women available at the time. 37 On this basis, a sample size of 234 participants per group would detect this difference, with 90% power at a significance level of 0.05. Allowing for a 22% dropout, a target of 300 women per group was set.

Statistical methods

The analysis was based on an intention-to-treat (ITT) principle, in which participants were analysed according to their randomised group, regardless of the intervention received. All outcomes were described with the appropriate descriptive statistics: means and SDs for continuous outcomes, counts and percentages for dichotomous and categorical outcomes.

The analysis of the primary outcome estimated the mean difference [with 95% confidence intervals (CIs)] in the ICIQ-UI SF score at 24 months between the biofeedback PFMT group and the basic PFMT group, using a linear mixed model, adjusting for the minimisation covariates of therapist type (physiotherapist or other type of therapist) and baseline score. Recruiting centre was fitted as a random effect. Assumptions of linearity and normality of error distributions were examined by inspection of residual plots. Statistical significance was at the 5% level. Equivalent analyses were conducted for the ICIQ-UI SF score at 6 and 12 months.

The effect of missing ICIQ-UI SF data was investigated under various assumptions in a set of sensitivity analyses. Multiple imputation and repeated-measures models were analysed under a missing at random assumption. Pattern mixture models were then used under a missing not at random (MNAR) assumption. In these analyses, the imputed ICIQ-UI SF scores were first adjusted by adding 2.5 points (the minimal clinically important difference) and then by subtracting 2.5 points. These adjustments were then repeated in only one group and repeated again by applying the adjustments in only the other group. A further sensitivity analysis of the primary outcome was conducted, which took non-compliers into account, using a complier-average causal effect (CACE) model.

Secondary outcomes were analysed in a similar manner to the analysis of the ICIQ-UI SF, using appropriate generalised linear models (GLMs) (linear mixed models for continuous outcomes, binary logistic regression for dichotomous outcomes and ordinal logistic regression for ordered categorical outcomes). When ordinal models were fitted, the proportional odds assumption was examined using a Brant test. All models adjusted for minimisation variables, therapist type and, if measured, baseline score.

Subgroup analyses of the primary outcome by type of incontinence (SUI or MUI), type of therapist, participant age (< 50/≥ 50 years) and UI severity (ICIQ-UI SF score of < 13 or ≥ 13) were also conducted. A stricter level of statistical significance (1%) was set for the subgroup analyses, reflecting their exploratory nature. Heterogeneity of treatment effects among subgroups was tested for, using the appropriate subgroup by treatment group interactions.

The analysis of the trial data were conducted according to the statistical analysis plan [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117103/#/ (accessed 29 July 2019)], which was written by investigators blinded to accruing outcome data and agreed by the DMEC and the TSC. The DMEC reviewed confidential reports of accumulating data and a single main analysis was performed at the end of the trial when 24-month follow-up was complete and the database locked. We did not plan or conduct any interim analyses of outcome data, based on a decision made at the beginning of the trial and following discussion with the DMEC. Deviations from the statistical analysis plan are documented [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117103/#/ (accessed 29 July 2019)].

Important changes to the project protocol

The original protocol included the following exclusion criterion: women who were pregnant or were < 1 year postnatal. This was subsequently relaxed to women who were < 6 months postnatal. This recognised that any natural resolution of postnatal UI would occur within the first 6 months and, therefore, beyond this time point women should be eligible for inclusion. The original criteria: women who have had formal instruction in PFMT in the previous 3 years was changed to in the previous year. Memory of PFMT instruction given more than 1 year ago was thought likely to be poor; therefore, these women would be similar to women who had not received instruction before. Women taking antimuscarinic medication were originally excluded; however, this did not reflect current clinical practice, so inclusion criteria were changed to enable women using this medication to take part. Furthermore, an additional criterion was agreed, excluding women with a known nickel allergy or sensitivity, as such women, if randomised to the biofeedback PFMT group, might experience irritation due to the biofeedback probe. A nickel-free probe could have been sourced for these women, but they were not routinely stocked by the NHS and we did not procure them because of the cost.

The original protocol specified that participants would be asked to complete a 3-day bladder diary at 24 months to quantify urine leakage. This aspect of data collection was stopped because of a poor response rate and the observation that it was impeding responses to the 24-month questionnaire (which was sent to participants at the same time) and having a negative impact on the primary outcome data completeness.

All changes to the protocol were approved by the TSC and DMEC, when appropriate, and the Research Ethics Committee.

Chapter 3 Trial outcomes and results

This chapter reports the results of the trial analysis set out in the statistical analysis plan [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117103/#/ (accessed 29 July 2019)].

Participants

The OPAL trial recruited to target, with 600 participants randomised (300 to each group) between February 2014 and July 2016 (Figure 1). The trial had planned to recruit to target by November 2015, but the recruitment phase needed to be extended in order to randomise the required number of participants. Participants were recruited at 23 centres across the UK (see Appendix 3).

FIGURE 1.

Projected and actual recruitment.

A total of 687 women were formally screened for eligibility, of whom 87 were ineligible or declined to participate (see Appendix 4 for details of ineligibility). Of the eligible 629 women, 29 consented to participate but did not attend the subsequent appointment at which they would have been randomised. These women were therefore excluded from the trial, leaving 600 women who were randomised.

All outcome data were returned and entered by 4 June 2018, the date of agreed database lock.

Questionnaires were completed by 589 participants (98%) at baseline (292 in the biofeedback PFMT group and 297 in the basic PFMT group). Seven out of 600 participants withdrew consent to their data being used after randomisation, leaving 295 participants in the biofeedback PFMT group and 298 participants in the basic PFMT group included in the analysis (although the data for participants who withdrew are included in the summary of the baseline characteristics). At 6 months, 444 participants (74%) provided follow-up questionnaire data, rising to 504 participants (84%) at 12 months. At 24 months, the target of 468 responses (78%) set out in the sample size calculation was achieved, with 230 (77%) in the biofeedback PFMT group and 238 (79%) in the basic PFMT group. Of those women who were followed up, the proportions of participants who completed the full questionnaire (rather than a shortened version over the telephone) were 82%, 75% and 72% at 6, 12 and 24 months, respectively. The response rates were similar between the two groups at each follow-up time point, for both methods of response. No participants died during the course of the trial. The number of participants at each stage of the trial is summarised in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT flow diagram.

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 summarises the baseline characteristics of participants. The age of participants ranged from 20 to 83 years, with a mean age of 47 years (48.2 ± 11.6 years in the biofeedback PFMT group and 47.3 ± 11.4 years basic PFMT group); 61.3% of participants in each group had MUI (SUI and urgency UI).

| Variable | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|

| Biofeedback PFMT | Basic PFMT | |

| Age (years), n, mean (SD) | 300, 48.2 (11.6) | 300, 47.3 (11.4) |

| BMI (kg/m2), n, mean (SD) | 290, 28.6 (5.9) | 287, 28.3 (6.2) |

| Number of births, n/N (%) | ||

| 0 | 21/298 (7.0) | 12/289 (4.2) |

| 1 | 40/298 (13.4) | 60/289 (20.8) |

| 2 | 116/298 (38.9) | 122/289 (42.2) |

| 3 | 83/298 (27.9) | 63/289 (21.8) |

| ≥ 4 | 38/298 (12.8) | 32/289 (11.1) |

| Delivery mode history, n/N (%) | ||

| Vaginal deliveries only | 163/277 (58.8) | 164/266 (61.7) |

| Caesarean deliveries only | 11/277 (4.0) | 15/266 (5.6) |

| Vaginal and caesarean deliveries | 31/277 (11.2) | 17/266 (6.4) |

| Any forceps delivery | 52/277 (18.8) | 55/266 (20.7) |

| Any vacuum delivery (but no forceps) | 20/277 (7.2) | 15/266 (5.6) |

| Type of incontinence, n/N (%) | ||

| SUI | 116/300 (38.7) | 116/300 (38.7) |

| MUI | 184/300 (61.3) | 184/300 (61.3) |

Baseline UI measures are reported in Table 2. The ICIQ-UI SF score (the primary outcome measure) ranged from 0 to the maximum of 21. Approximately half of the participants (51%) had UI at baseline that could be classed as severe (ICIQ-UI SF score of ≥ 13). 27 For the Patient Global Impression of Severity (PGI-S) scale, 55% of participants reported a rating of moderate or severe. Baseline pelvic floor measures show that < 8% of participants had an Oxford Scale score of ≥ 4 for slow contraction strength (Table 3). The Oxford Scale is measured from 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating stronger muscle function. 23 The mean self-efficacy for PFMT score was 62 (measured on a scale from 17 to 85, with higher scores indicating stronger beliefs in ability to exercise)34 and 48% reported doing pelvic floor exercises at least one a week during the month prior to their participation in the trial.

| Variable | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|

| Biofeedback PFMT | Basic PFMT | |

| ICIQ-UI SF, n, mean (SD) | 291, 12.5 (4.1) | 294, 12.3 (3.7) |

| ICIQ-UI SF severity, n/N (%) | ||

| Mild/moderate (score of < 13) | 140/291 (48.1) | 149/294 (50.7) |

| Severe (score of ≥ 13) | 151/291 (51.9) | 145/294 (49.3) |

| ICIQ-FLUTS filling score, n, mean (SD) | 289, 5.0 (2.8) | 297, 4.8 (2.6) |

| ICIQ-FLUTS voiding score, n, mean (SD) | 292, 2.0 (2.0) | 294, 2.0 (2.1) |

| ICIQ-FLUTS incontinence score, n, mean (SD) | 290, 9.8 (3.6) | 294, 9.3 (3.4) |

| PGI-S scale, n/N (%) | ||

| Normal | 13/292 (4.5) | 23/294 (7.8) |

| Mild | 113/292 (38.7) | 115/294 (39.1) |

| Moderate | 137/292 (46.9) | 133/294 (45.2) |

| Severe | 29/292 (9.9) | 23/294 (7.8) |

| ICIQ-LUTSqol, n, mean (SD) | 292, 43.5 (12.3) | 297, 42.3 (12.1) |

| ICIQ-LUTSqol bother scale, n, mean (SD) | 288, 7.4 (2.6) | 288, 7.6 (2.5) |

| Variable | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|

| Biofeedback PFMT | Basic PFMT | |

| Prolapse symptoms: POP-SS, n, mean (SD) | 274, 6.4 (5.7) | 286, 6.7 (5.6) |

| Oxford Scale:a slow contraction strength, n/N (%) | ||

| 0 | 0/300 (0.0) | 0/300 (0.0) |

| 1 | 34/300 (11.3) | 31/300 (10.3) |

| 2 | 115/300 (38.3) | 111/300 (37.0) |

| 3 | 128/300 (42.7) | 134/300 (44.7) |

| 4 | 22/300 (7.3) | 24/300 (8.0) |

| 5 | 1/300 (0.3) | 0/300 (0.0) |

| Oxford Scale:a fast contraction strength, n/N (%) | ||

| 0 | 0/238 (0.0) | 0/220 (0.0) |

| 1 | 11/238 (4.6) | 14/220 (6.4) |

| 2 | 75/238 (31.5) | 73/220 (33.2) |

| 3 | 108/238 (45.4) | 102/220 (46.4) |

| 4 | 38/238 (16.0) | 28/220 (12.7) |

| 5 | 6/238 (2.5) | 3/220 (1.4) |

| Contraction endurance [length of hold (seconds)], n, mean (SD) | 264, 6.48 (3.00) | 250, 6.35 (3.13) |

| Number of repetitions slow, n, mean (SD) | 263, 6.03 (2.44) | 249, 5.77 (2.41) |

| Number of repetitions fast, n, mean (SD) | 248, 8.24 (2.50) | 239, 7.81 (2.64) |

| Self-efficacy scale for PFMT, n, mean (SD)b | 280, 62.7 (9.7) | 295, 62.2 (8.8) |

| Belief in PFMT execution | 280, 38.9 (7.1) | 295, 38.5 (6.3) |

| Belief in performing PFMT as scheduled | 282, 23.8 (3.8) | 294, 23.6 (3.8) |

| Frequency of PFMT in previous month, n/N (%) | ||

| None | 116/287 (40.4) | 119/295 (40.3) |

| Few times a month | 37/287 (12.9) | 32/295 (10.8) |

| Once a week | 21/287 (7.3) | 14/295 (4.7) |

| Few times a week | 52/287 (18.1) | 69/295 (23.4) |

| Once a day | 32/287 (11.1) | 32/295 (10.8) |

| Few times a day | 29/287 (10.1) | 29/295 (9.8) |

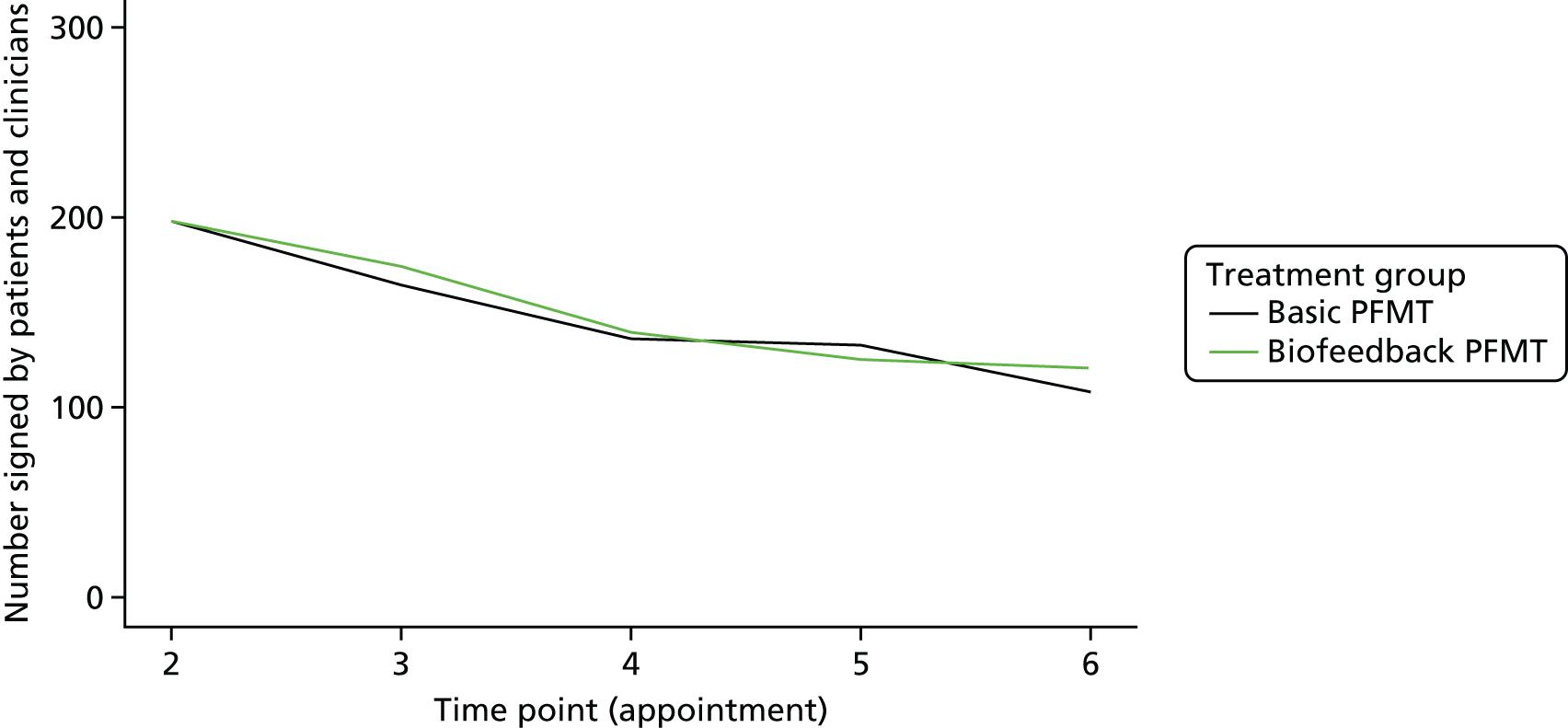

Intervention received

The proportion of participants attending the maximum number of six appointments was 36.9% in the biofeedback PFMT group and 35.6% in the basic PFMT group (Table 4). The mean number of appointments was 4.2 ± 1.9 (biofeedback PFMT) and 4.0 ± 2.1 (basic PFMT). Forty-nine out of 593 women (8.3%) did not attend any appointments [n = 16 (5.4%) biofeedback PFMT; n = 33 (11.1%) basic PFMT].

| Variable | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|

| Biofeedback PFMT | Basic PFMT | |

| Number of appointments attended, n/N (%) | ||

| 0 | 16/295 (5.4) | 33/298 (11.1) |

| 1 | 20/295 (6.8) | 18/298 (6.0) |

| 2 | 24/295 (8.1) | 22/298 (7.4) |

| 3 | 37/295 (12.5) | 33/298 (11.1) |

| 4 | 33/295 (11.2) | 22/298 (7.4) |

| 5 | 56/295 (19.0) | 64/298 (21.5) |

| 6 | 109/295 (36.9) | 106/298 (35.6) |

| Total number of appointments, n, mean (SD) | 295, 4.2 (1.9) | 298, 4.0 (2.1) |

| Type of therapist, n/N (%) | ||

| Physiotherapist | 256/295 (86.8) | 247/298 (82.9) |

| Nurse | 17/295 (5.8) | 11/298 (3.7) |

| Other and mixture | 6/295 (2.0) | 7/298 (2.3) |

| No therapist | 16/295 (5.4) | 33/298 (11.1) |

The majority of participants (84.8%) were treated by only physiotherapists (86.8% biofeedback PFMT, 82.9% basic PFMT), with the remainder mostly being treated by only nurses. In most cases, the participant was treated by the same therapist throughout. There were 13 participants whose therapist type is classified as ‘other and mixture’, which included participants treated either by a midwife, a consultant or a mixture of different therapist types. All therapists participating in the trial were female.

According to our a priori definition, participants were classed as receiving ‘treatment as allocated’ (i.e. compliant with protocol or ‘on-treatment’) if pelvic floor muscle contractions were taught and feedback was given (at the first appointment), and a recommended exercise programme was written in the home exercise diary and given to the participant (during at least one appointment). In addition, participants in the biofeedback PFMT group were required to be taught insertion and removal of the probe and placement of the electrode at the first appointment in order to be classed as having treatment as allocated. This protocol compliance rate was 74.4% (198/266) in the biofeedback PFMT group and 83.3% (230/276) in the basic PFMT group. In a post hoc analysis, the definition for the biofeedback PFMT group was relaxed to allow for training in the use of the biofeedback device during either the first or second appointment, which reflected more accurately the instructions provided to therapists. Mostly, this was because it was not always possible to fit everything into the first appointment, but sometimes it was a clinical judgement that it was not appropriate for the participant; thus, therapists were told that biofeedback could be initiated in the second appointment. This revised definition resulted in a protocol compliance rate of 83.5% (222/266) in the biofeedback PFMT group. There were some participants for whom compliance status could not be determined due to missing checklist items in the TAFs.

Four participants randomised to the biofeedback PFMT group were given basic PFMT from the outset (in error). Similarly, one participant was randomised to the basic PFMT group but received biofeedback PFMT.

The exercise programmes are summarised in Table 5. The mean recommended length of hold increased from 7.0 seconds in the biofeedback PFMT group and 6.8 seconds in the basic PFMT group to 10.4 seconds and 10.6 seconds, respectively, at the final appointment. The mean number of repetitions increased between the first and last appointment from 7.6 to 8.9 (biofeedback PFMT group) and 6.7 to 9.0 (basic PFMT group). Similarly, the mean number of fast contractions increased from 9.9 to 13.0 (biofeedback PFMT group) and 8.9 to 12.7 (basic PFMT group). The recommended levels for endurance and repetitions at the first appointment appear to be similar to the baseline levels summarised in Table 3. Table 5 also summarises the recommended daily frequency for carrying out the whole set of exercises, which ranged between three and four times a day in both groups.

| Variable | Appointment number | Treatment group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biofeedback PFMT | Basic PFMT | ||||||

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | ||

| Contraction endurance [length of hold (seconds)] | 1 | 262 | 7.0 | 3.9 | 257 | 6.8 | 3.5 |

| 2 | 238 | 7.7 | 4.0 | 230 | 7.8 | 4.9 | |

| 3 | 186 | 8.3 | 3.9 | 187 | 9.1 | 7.8 | |

| 4 | 181 | 9.5 | 4.5 | 172 | 9.6 | 5.6 | |

| 5 | 150 | 10.1 | 5.1 | 158 | 10.9 | 9.9 | |

| 6 | 176 | 10.4 | 6.3 | 172 | 10.6 | 6.8 | |

| Number of slow contractions (repetitions) | 1 | 261 | 7.6 | 6.6 | 256 | 6.7 | 2.6 |

| 2 | 237 | 7.9 | 2.6 | 228 | 7.5 | 2.9 | |

| 3 | 185 | 8.6 | 3.0 | 186 | 8.0 | 2.7 | |

| 4 | 180 | 9.0 | 3.4 | 172 | 8.4 | 2.6 | |

| 5 | 149 | 8.9 | 2.6 | 159 | 8.9 | 2.6 | |

| 6 | 177 | 8.9 | 2.9 | 173 | 9.0 | 2.5 | |

| Number of fast contractions (repetitions) | 1 | 251 | 9.9 | 5.8 | 251 | 8.9 | 4.2 |

| 2 | 226 | 10.7 | 6.2 | 220 | 10.3 | 5.0 | |

| 3 | 173 | 11.5 | 6.5 | 181 | 11.9 | 6.3 | |

| 4 | 176 | 12.5 | 9.3 | 164 | 12.6 | 7.0 | |

| 5 | 146 | 12.6 | 7.4 | 154 | 13.2 | 10.6 | |

| 6 | 174 | 13.0 | 10.1 | 167 | 12.7 | 6.6 | |

| Number of times per day | 1 | 257 | 3.2 | 1.3 | 255 | 3.7 | 1.4 |

| 2 | 232 | 3.2 | 1.3 | 227 | 3.7 | 1.0 | |

| 3 | 183 | 3.2 | 1.2 | 185 | 3.7 | 1.2 | |

| 4 | 177 | 3.1 | 1.1 | 171 | 3.6 | 1.0 | |

| 5 | 149 | 3.2 | 1.1 | 156 | 3.8 | 2.4 | |

| 6 | 174 | 3.2 | 2.1 | 172 | 3.2 | 1.3 | |

Primary outcome measure

The ICIQ-UI SF score at 24 months was the primary outcome measure in the trial (lower scores indicate lower symptom severity). In the biofeedback PFMT group, the mean score was 8.2 (SD 5.1) compared with 8.5 (SD 4.9) in the basic PFMT group, with a mean difference (adjusted for baseline score and minimisation covariates) of −0.09 (95% CI −0.92 to 0.75). There was therefore no evidence of a difference between the groups in terms of UI symptoms. Similar results of no difference between groups were found at the 6- and 12-month time points (Table 6).

| Time point | Treatment group | Mean difference | 95% CI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biofeedback PFMT | Basic PFMT | |||||||

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | |||

| Baseline | 291 | 12.5 | 4.1 | 294 | 12.3 | 3.7 | ||

| 6 months | 221 | 9.0 | 5.0 | 221 | 8.8 | 4.5 | 0.39 | –0.33 to 1.12 |

| 12 months | 249 | 9.1 | 4.9 | 252 | 8.7 | 5.0 | 0.57 | –0.17 to 1.31 |

| 24 months | 225 | 8.2 | 5.1 | 235 | 8.5 | 4.9 | –0.09 | –0.92 to 0.75 |

Sensitivity analyses

Analyses of the primary outcome to examine data under differing assumptions relating to non-compliance and missing data all showed very similar results to the primary ITT analysis (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Sensitivity analyses. MI, multiple imputation model; RMM, repeated-measures model. Reproduced with permission from Hagen et al. 38 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

The first sensitivity analysis, which tested non-compliance in a CACE analysis (CACE1), treated participants with an indeterminable compliance status as being compliant and the second analysis (CACE2) assumed these participants to be non-compliant. The results of these analyses estimated mean differences of −0.11 (95% CI −1.05 to 0.82) and −0.13 (95% CI −1.20 to 0.95), respectively (see Figure 3).

The multiple imputation and the repeated-measures models, which both treat missing data as missing at random, estimated mean differences of −0.11 (95% CI −0.95 to 0.74) and −0.08 (95% CI −0.86 to 0.70), respectively (see Figure 3). The repeated-measures model also provided estimates at the intermediate time points, which showed very similar results to the primary analysis: 0.28 (95% CI −0.51 to 1.07) at 6 months and 0.57 (95% CI −0.19 to 1.33) at 12 months. None of the sensitivity analyses performed under MNAR assumptions yielded results that contradicted the primary ITT analysis (see Appendix 5 and Figure 12).

An additional post hoc sensitivity analysis, in which therapist type was removed from the ITT analysis as a covariate in the model (to address the potential bias of including an independent variable that was measured post randomisation), gave a very similar result (mean difference −0.18, 95% CI −1.02 to 0.65).

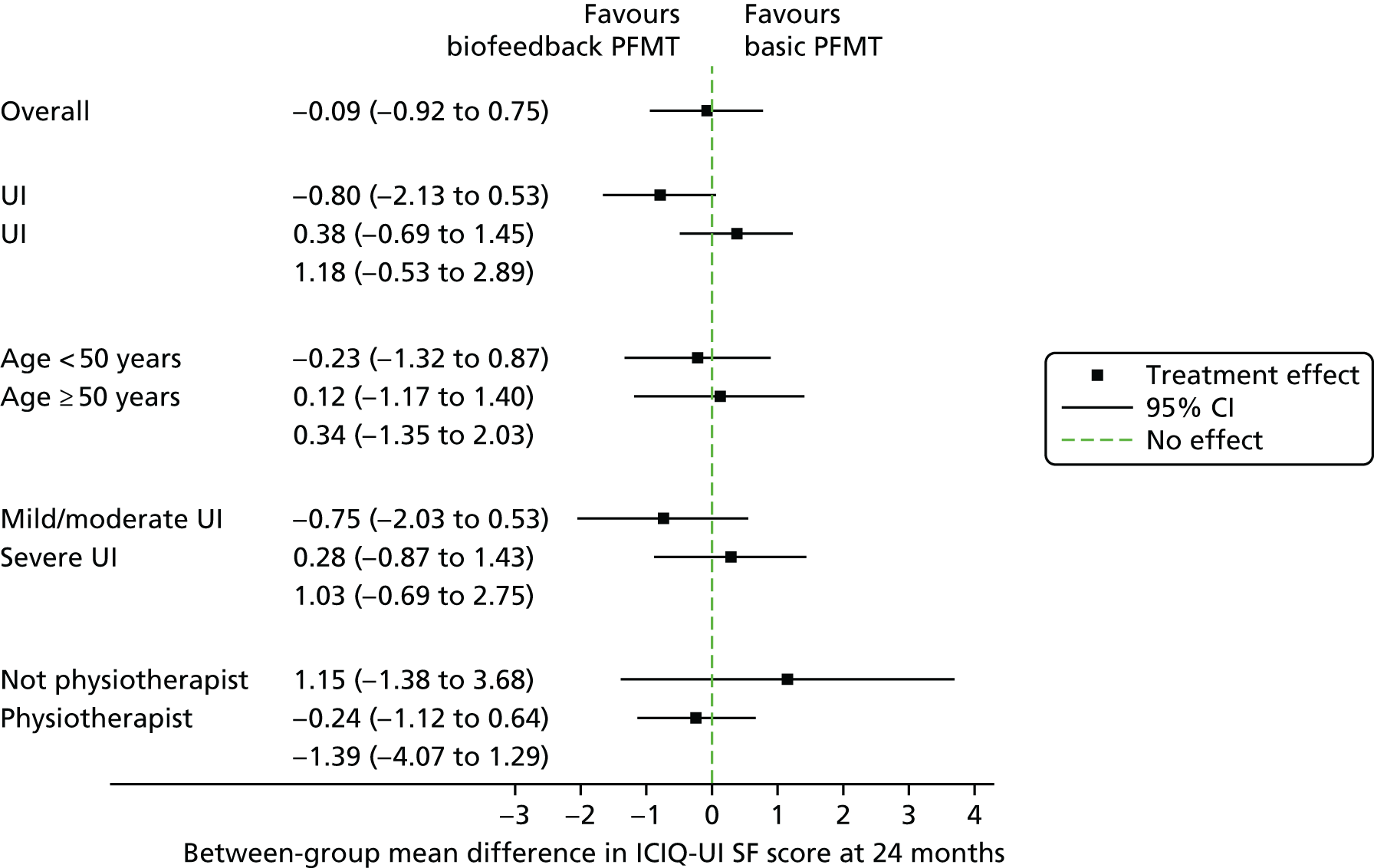

Subgroup analyses

The prespecified subgroup analyses of the primary outcome showed no significant treatment by subgroup interactions (Figure 4). Full results of the subgroup analysis are included in Appendix 6.

FIGURE 4.

Subgroup analyses. Reproduced with permission from Hagen et al. 38 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Urinary outcomes

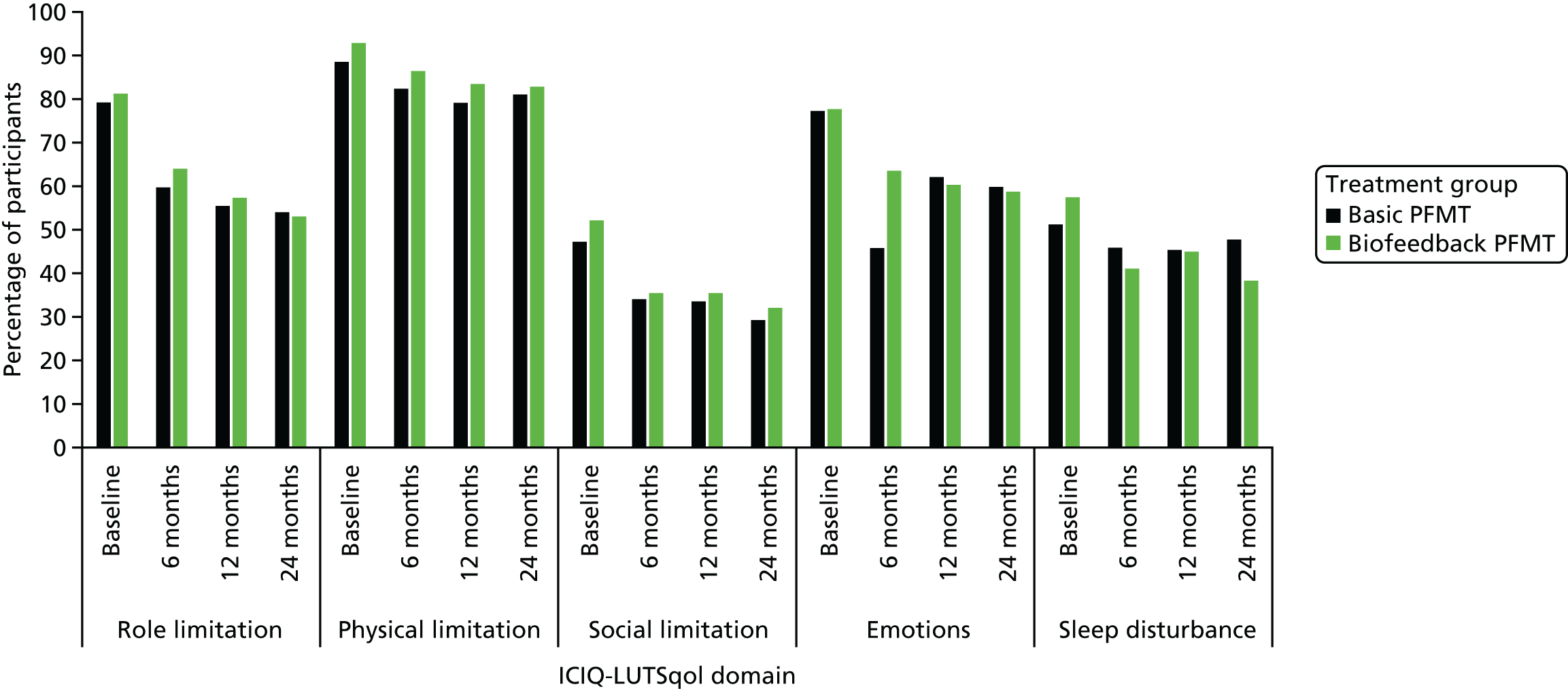

The results of the analysis of the lower urinary tract symptoms data are summarised in Table 7. The outcome measures used are all International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire measures,30,31 in which higher scores indicate greater symptom severity or impact on quality of life. There were no significant differences between the groups in any of the outcomes.

| Variable | Time point | Treatment group | Mean difference at 24 months | 95% CI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biofeedback PFMT | Basic PFMT | ||||||||

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | ||||

| ICIQ-FLUTS filling score | Baseline | 289 | 5.0 | 2.8 | 297 | 4.8 | 2.6 | ||

| 6 months | 183 | 3.7 | 2.7 | 176 | 3.4 | 2.3 | |||

| 12 months | 187 | 3.8 | 2.7 | 186 | 3.6 | 2.4 | |||

| 24 months | 167 | 3.4 | 2.6 | 168 | 3.5 | 2.3 | –0.19 | –0.61 to 0.24 | |

| ICIQ-FLUTS voiding score | Baseline | 292 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 294 | 2.0 | 2.1 | ||

| 6 months | 182 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 179 | 1.4 | 1.8 | |||

| 12 months | 188 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 186 | 1.5 | 1.8 | |||

| 24 months | 165 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 169 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 0.04 | –0.30 to 0.38 | |

| ICIQ-FLUTS incontinence score | Baseline | 290 | 9.8 | 3.6 | 294 | 9.3 | 3.4 | ||

| 6 months | 182 | 7.1 | 4.0 | 178 | 6.6 | 3.8 | |||

| 12 months | 188 | 7.1 | 3.9 | 182 | 6.6 | 4.1 | |||

| 24 months | 164 | 7.0 | 4.3 | 169 | 6.5 | 4.0 | 0.20 | –0.58 to 0.98 | |

| ICIQ-LUTSqol | Baseline | 292 | 43.5 | 12.3 | 297 | 42.3 | 12.1 | ||

| 6 months | 183 | 36.2 | 13.2 | 176 | 35.7 | 11.9 | |||

| 12 months | 189 | 35.7 | 13.3 | 184 | 34.7 | 12.1 | |||

| 24 months | 164 | 34.3 | 12.4 | 169 | 34.3 | 12.5 | –0.81 | –3.03 to 1.41 | |

| ICIQ-LUTSqol bother scale | Baseline | 288 | 7.4 | 2.6 | 288 | 7.6 | 2.5 | ||

| 6 months | 183 | 4.3 | 3.1 | 177 | 4.3 | 2.8 | |||

| 12 months | 189 | 4.0 | 3.1 | 184 | 3.9 | 3.0 | |||

| 24 months | 163 | 3.8 | 3.1 | 169 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 0.26 | –0.33 to 0.85 | |

Measures of cure and improvement are summarised in Table 8. We defined ‘cure’ as being asymptomatic, identified as a null response to the first two questions of the ICIQ-UI SF (amount and frequency of leakage). Using this definition, 7.9% of participants in the biofeedback PFMT group and 8.4% of participants in the basic PFMT group were asymptomatic at 24 months [odds ratio (OR) 0.90, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.78]. Three participants in the basic PFMT group were asymptomatic according to this definition at baseline, but they all reported non-zero scores on the ICIQ-UI SF scale for interference of UI with everyday life.

| Variable | Time point | Treatment group | OR | 95% CI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biofeedback PFMT | Basic PFMT | ||||||||

| n | N | % | n | N | % | ||||

| Asymptomatic (cure) | Baseline | 0 | 292 | 0.0 | 3 | 297 | 1.0 | ||

| 6 months | 12 | 221 | 5.4 | 13 | 223 | 5.8 | |||

| 12 months | 16 | 250 | 6.4 | 22 | 253 | 8.7 | |||

| 24 months | 18 | 229 | 7.9 | 20 | 238 | 8.4 | 0.90 | 0.46 to 1.78 | |

| Improvement in UI (≥ 3-point reduction in ICIQ-UI SF) | 6 months | 129 | 221 | 58.4 | 133 | 221 | 60.2 | ||

| 12 months | 148 | 249 | 59.4 | 163 | 252 | 64.7 | |||

| 24 months | 135 | 225 | 60.0 | 147 | 235 | 62.6 | 0.89 | 0.61 to 1.32 | |

| Very much better or much better (PGI-I) | 6 months | 96 | 219 | 43.8 | 85 | 221 | 38.5 | ||

| 12 months | 101 | 249 | 40.6 | 92 | 250 | 36.8 | |||

| 24 months | 93 | 227 | 41.0 | 90 | 236 | 38.1 | 1.12 | 0.76 to 1.63 | |

In terms of improvement, 60.0% of participants in the biofeedback PFMT group and 62.6% of participants in the basic PFMT group (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.32) had a reduction in their ICIQ-UI SF score between baseline and 24 months by a margin of ≥ 3 points (equivalent to the estimated minimum clinically important difference of ≥ 2.5 points). 28 Comparing the PGI-I in UI (ordinal scale)29 also shows no difference between groups at 24 months (OR 1.14, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.72). Full descriptive summaries of the PGI-I data are reported (see Appendix 7). As a post hoc analysis, data from a dichotomous version of this scale were compared between groups (see Table 8). At 24 months, 41.0% of participants in the biofeedback PFMT group and 38.1% of participants in the basic PFMT group reported being much better or very much better (OR 1.12, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.63), which resulted in a very similar effect estimate to the analysis of the full ordinal PGI-I data (OR 1.14, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.72). When tested, the proportional odds assumption held in the ordinal analysis.

Further treatment for urinary incontinence

Participants who accessed other treatments for UI (including surgery) were able to remain in the trial. Table 9 summarises the rates of surgical and non-surgical treatment for UI reported by participants. In the first 6 months post randomisation, 1.2% of women in the biofeedback PFMT group and 1.8% of women in the basic PFMT group had continence surgery (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.09 to 3.53). This increased to 3.9% and 5.2%, respectively, in the second 6 months (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.23 to 1.69) and to 5.2% and 7.4%, respectively, during the second year of follow-up (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.24 to 1.65). The cumulative rate for UI surgery over the whole 2 years was 12.3% in the biofeedback PFMT group and 9.3% in the basic PFMT group (OR 1.25, 95% CI 0.35 to 4.46).

| Treatment | Time point | Treatment group | OR | 95% CI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biofeedback PFMT | Basic PFMT | ||||||||

| n | N | % | n | N | % | ||||

| Surgery | 0–6 months | 2 | 172 | 1.2 | 3 | 164 | 1.8 | 0.56 | 0.09 to 3.53 |

| 6–12 months | 8 | 204 | 3.9 | 11 | 210 | 5.2 | 0.63 | 0.23 to 1.69 | |

| 12–24 months | 8 | 154 | 5.2 | 12 | 162 | 7.4 | 0.62 | 0.24 to 1.65 | |

| 0–24 months | 10 | 81 | 12.3 | 8 | 86 | 9.3 | 1.25 | 0.35 to 4.46 | |

| Non-surgical treatment | 0–6 months | 96 | 146 | 65.8 | 107 | 149 | 71.8 | 0.77 | 0.46 to 1.28 |

| 6–12 months | 70 | 164 | 42.7 | 74 | 159 | 46.5 | 0.90 | 0.56 to 1.42 | |

| 12–24 months | 40 | 105 | 38.1 | 42 | 119 | 35.3 | 0.65 | 0.65 to 2.03 | |

| 0–24 months | 49 | 60 | 81.7 | 55 | 69 | 79.7 | 1.35 | 0.54 to 3.41 | |

Rates of non-surgical treatments did not increase over the course of follow-up. There were high cumulative rates of uptake over the 2-year follow-up period in both groups (81.7%, biofeedback PFMT; 79.7%, basic PFMT, OR 1.35, 95% CI 0.54 to 3.41), although this measure includes a broad range of health-care use for the treatment of UI, some resources of which were accessed frequently. For example, appointments with either a continence nurse in secondary care or a physiotherapist were attended by 60.6% in the biofeedback PFMT group and 53.8% in the basic PFMT group (Table 10).

| Treatment | Time point | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biofeedback PFMT | Basic PFMT | ||

| Admitted to hospital, n/N (%) | 0–6 months | 3/180 (1.7) | 2/179 (1.1) |

| 6–12 months | 4/180 (2.2) | 4/175 (2.3) | |

| 12–24 months | 3/111 (2.7) | 1/130 (0.8) | |

| 0–24 months | 6/84 (7.1) | 3/94 (3.2) | |

| Number of nights in hospital, n, mean (SD) | 0–6 months | 180, 0.02 (0.13) | 179, 0.01 (0.11) |

| 6–12 months | 180, 0.06 (0.54) | 175, 0.03 (0.26) | |

| 12–24 months | 111, 0.04 (0.23) | 130, 0.01 (0.09) | |

| 0–24 months | 84, 0.16 (0.81) | 94, 0.05 (0.34) | |

| Hospital doctor appointment, n/N (%) | 0–6 months | 43/156 (27.6) | 46/163 (28.2) |

| 6–12 months | 27/185 (14.6) | 35/181 (19.3) | |

| 12–24 months | 18/124 (14.5) | 20/131 (15.3) | |

| 0–24 months | 35/83 (42.2) | 34/89 (38.2) | |

| GP appointment, n/N (%) | 0–6 months | 46/183 (25.1) | 65/183 (35.5) |

| 6–12 months | 32/187 (17.1) | 29/186 (15.6) | |

| 12–24 months | 18/125 (14.4) | 21/132 (15.9) | |

| 0–24 months | 37/99 (37.4) | 48/100 (48.0) | |

| GP nurse appointment, n/N (%) | 0–6 months | 13/180 (7.2) | 6/180 (3.3) |

| 6–12 months | 16/178 (9.0) | 11/183 (6.0) | |

| 12–24 months | 8/127 (6.3) | 6/128 (4.7) | |

| 0–24 months | 14/96 (14.6) | 10/94 (10.6) | |

| Hospital nurse/physiotherapist appointment, n/N (%) | 0–6 months | 62/177 (35.0) | 57/179 (31.8) |

| 6–12 months | 51/181 (28.2) | 49/181 (27.1) | |

| 12–24 months | 14/124 (11.3) | 21/129 (16.3) | |

| 0–24 months | 57/94 (60.6) | 50/93 (53.8) | |

| Medication, n/N (%) | 0–6 months | 32/209 (15.3) | 34/204 (16.7) |

| 6–12 months | 32/234 (13.7) | 38/232 (16.4) | |

| 12–24 months | 30/168 (17.9) | 28/174 (16.1) | |

| 0–24 months | 35/125 (28.0) | 36/128 (28.1) | |

| Other treatment/advice, n/N (%) | 0–6 months | 25/208 (12.0) | 29/201 (14.4) |

| 6–12 months | 22/229 (9.6) | 27/232 (11.6) | |

| 12–24 months | 12/208 (5.8) | 15/221 (6.8) | |

| 0–24 months | 35/157 (22.3) | 35/162 (21.6) | |

Pelvic floor outcomes

When self-efficacy for PFMT34 was compared, there was a small and statistically significant difference in favour of the biofeedback PFMT group in the overall score (mean difference 2.36, 95% CI 0.04 to 4.68) (Table 11). This difference appeared to be attributed more to the subscale for belief in PFMT and its execution, in which there was also a small and statistically significant difference (mean difference 1.54, 95% CI 0.03 to 3.06). There was no significant difference in the subscale for belief in performing PFMT as scheduled and despite barriers (mean difference 0.71, 95% CI −0.31 to 1.72).

| Subgroup | Time point | Treatment group | Mean difference | 95% CI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biofeedback PFMT | Basic PFMT | ||||||||

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | ||||

| Self-efficacy scale for PFMT | Baseline | 280 | 62.7 | 9.7 | 295 | 62.2 | 8.8 | ||

| 6 months | 172 | 65.6 | 10.2 | 165 | 65.7 | 10.1 | |||

| 12 months | 178 | 63.7 | 11.0 | 180 | 64.1 | 10.2 | |||

| 24 months | 154 | 63.1 | 11.6 | 161 | 60.9 | 12.0 | 2.36 | 0.04 to 4.68 | |

| Belief in PFMT execution subscale | Baseline | 280 | 38.9 | 7.1 | 295 | 38.5 | 6.3 | ||

| 6 months | 173 | 42.7 | 7.0 | 166 | 42.3 | 6.8 | |||

| 12 months | 179 | 41.7 | 7.3 | 180 | 41.6 | 6.6 | |||

| 24 months | 156 | 41.3 | 7.8 | 162 | 39.8 | 7.9 | 1.54 | 0.03 to 3.06 | |

| Belief in performing PFMT as scheduled subscale | Baseline | 282 | 23.8 | 3.8 | 294 | 23.6 | 3.8 | ||

| 6 months | 178 | 23.0 | 4.3 | 172 | 23.5 | 4.3 | |||

| 12 months | 183 | 21.9 | 4.9 | 179 | 22.6 | 4.8 | |||

| 24 months | 156 | 21.6 | 4.9 | 164 | 21.0 | 5.0 | 0.71 | –0.31 to 1.72 | |

The results from the 6-month blinded pelvic floor muscle assessment are summarised in Table 12. At baseline, there was only one participant who achieved the maximum score of 5 on the Oxford Scale for slow contraction strength. At 6 months, there were 13 participants (8.5%) in the biofeedback PFMT group and 10 (6.0%) in the basic PFMT group with a score of 5. There was no difference between the groups when the Oxford Scale at 6 months was compared (OR 1.28, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.89; p = 0.22). The proportional odds assumption, however, did not hold in this ordinal analysis.

| Variable | Time point | Score | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biofeedback PFMT | Basic PFMT | |||

| Oxford scale: slow contraction strength, n/N (%) | Baseline | 0 | 0/300 (0.0) | 0/300 (0.0) |

| 1 | 34/300 (11.3) | 31/300 (10.3) | ||

| 2 | 115/300 (38.3) | 111/300 (37.0) | ||

| 3 | 128/300 (42.7) | 134/300 (44.7) | ||

| 4 | 22/300 (7.3) | 24/300 (8.0) | ||

| 5 | 1/300 (0.3) | 0/300 (0.0) | ||

| 6 months | 0 | 0/153 (0.0) | 0/166 (0.0) | |

| 1 | 4/153 (2.6) | 3/166 (1.8) | ||

| 2 | 25/153 (16.3) | 23/166 (13.9) | ||

| 3 | 57/153 (37.3) | 74/166 (44.6) | ||

| 4 | 54/153 (35.3) | 56/166 (33.7) | ||

| 5 | 13/153 (8.5) | 10/166 (6.0) | ||

| Oxford scale: fast contraction strength, n/N (%) | Baseline | 0 | 0/238 (0.0) | 0/220 (0.0) |

| 1 | 11/238 (4.6) | 14/220 (6.4) | ||

| 2 | 75/238 (31.5) | 73/220 (33.2) | ||

| 3 | 108/238 (45.4) | 102/220 (46.4) | ||

| 4 | 38/238 (16.0) | 28/220 (12.7) | ||

| 5 | 6/238 (2.5) | 3/220 (1.4) | ||

| 6 months | 0 | 1/133 (0.8) | 0/152 (0.0) | |

| 1 | 2/133 (1.5) | 2/152 (1.3) | ||

| 2 | 30/133 (22.6) | 22/152 (14.5) | ||

| 3 | 49/133 (36.8) | 66/152 (43.4) | ||

| 4 | 39/133 (29.3) | 49/152 (32.2) | ||

| 5 | 12/133 (9.0) | 13/152 (8.6) | ||

| Contraction endurance [length of hold (seconds)], n, mean (SD) | Baseline | 264, 6.48 (3.00) | 250, 6.35 (3.13) | |

| 6 months | 152, 8.72 (2.26) | 166, 8.54 (2.48) | ||

| Number of slow contractions (repetitions), n, mean (SD) | Baseline | 263, 6.03 (2.44) | 249, 5.77 (2.41) | |

| 6 months | 151, 7.42 (2.62) | 165, 7.55 (2.59) | ||

| Number of fast contractions (repetitions), n, mean (SD) | Baseline | 248, 8.24 (2.50) | 239, 7.81 (2.64) | |

| 6 months | 149, 8.94 (2.14) | 164, 9.50 (1.50) | ||

For endurance and repetitions, the results at 6 months appear to be similar between groups and appear to be slightly higher than baseline in both groups, although it should be noted that nearly half of the participants did not attend the 6-month pelvic floor muscle appointment. Furthermore, at 6 months, the observed results for endurance and repetitions appear to be slightly lower than the prescribed programme at the end of the intervention period (see Tables 5 and 12).

Bowel and prolapse symptoms are summarised at each time point (see Appendix 8). No validated measure for bowel symptoms was available, but the results are summarised for each question asked individually (see Table 35). There was no evidence of any effect on prolapse symptoms with no difference between groups in the POP-SS (mean difference −0.60, 95% CI −1.51 to 0.30) (see Table 36).

Adherence

Our prespecified definitions for adherence are described in the statistical analysis plan [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117103/#/ (accessed 29 July 2019)]. Table 13 summarises the levels of adherence to separate aspects of the intervention; there were no differences between groups. Adherence to introductory teaching of PFMT and introduction to biofeedback (as appropriate) by the therapist was 88% in each group (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.33 to 1.42). Adherence to practising PFMT and biofeedback use during appointments was just under 80% in each group (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.25). Adherence by participants to the recommended programme at home between appointments was also around 80% in each group (OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.16). Table 13 also summarises the frequency of appointments with intervention adherence (subsequent to the first appointment) and the frequency of adherence at home (between appointments). There were some participants for whom adherence status could be determined, but the frequency of adherence could not be determined as a result of partially missing checklist data in the TAFs. There was also one participant in the biofeedback PFMT group and four in the basic PFMT group who, at 24 months, reported using a biofeedback device at home after the OPAL trial intervention had completed.

| Variable | Treatment group | OR | 95% CI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biofeedback PFMT | Basic PFMT | |||||||

| n | N | % | n | N | % | |||

| Adherence during clinic appointment | ||||||||

| Introductory teaching (as appropriate to group) | 254 | 288 | 88.2 | 259 | 293 | 88.4 | 0.69 | 0.33 to 1.42 |

| Any adherence in clinic | 231 | 290 | 79.7 | 231 | 292 | 79.1 | 0.89 | 0.63 to 1.25 |

| Frequency of adherence to intervention protocol at clinic appointments (subsequent to initial appointment) | ||||||||

| One appointment or more | 218 | 277 | 78.7 | 200 | 261 | 76.6 | ||

| Two appointments or more | 175 | 277 | 63.2 | 167 | 261 | 64.0 | ||

| Three appointments or more | 130 | 277 | 46.9 | 121 | 261 | 46.4 | ||

| Four appointments or more | 86 | 277 | 31.0 | 89 | 261 | 34.1 | ||

| All five appointments | 39 | 277 | 14.1 | 40 | 261 | 15.3 | ||

| Adherence at home | ||||||||

| Any adherence at home | 220 | 281 | 78.3 | 241 | 297 | 81.1 | 0.71 | 0.43 to 1.16 |

| Frequency of adherence to intervention protocol at home (number of appointments with adherence since previous appointment) | ||||||||

| Once or more | 196 | 257 | 76.3 | 177 | 233 | 76.0 | ||

| Twice or more | 155 | 257 | 60.3 | 156 | 233 | 67.0 | ||

| Three times or more | 115 | 257 | 44.7 | 125 | 233 | 53.6 | ||

| Four times or more | 75 | 257 | 29.2 | 105 | 233 | 45.1 | ||

| All five times | 34 | 257 | 13.2 | 52 | 233 | 22.3 | ||

The frequency of PFMT being undertaken, as reported by participants across the different post-intervention time points, is summarised in Table 14. At 24 months, the proportion of participants exercising at least once a week was 52.0% in the biofeedback PFMT group and 46.3% in the basic PFMT group.

| Time point | Time frame | Frequency | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biofeedback PFMT | Basic PFMT | |||

| At 6 months | Yesterday, n/N (%) | None | 47/167 (28.1) | 46/166 (27.7) |

| A little | 47/167 (28.1) | 42166 (25.3) | ||

| Now and then | 32/167 (19.2) | 17166 (10.2) | ||

| Regularly | 41/167 (24.6) | 61166 (36.7) | ||

| In previous 7 days, n, mean (SD) | Number of days | 168, 4.5 (2.0) | 167, 5 (2.0) | |

| Over previous month, n/N (%) | None | 19/183 (10.4) | 10/172 (5.8) | |

| A few times a month | 11/183 (6.0) | 10/172 (5.8) | ||

| Once a week | 12/183 (6.6) | 8/172 (4.7) | ||

| A few times a week | 36/183 (19.7) | 24/172 (14.0) | ||

| Once a day | 31/183 (16.9) | 39/172 (22.7) | ||

| A few times a day | 74/183 (40.4) | 81/172 (47.1) | ||

| At 12 months | Yesterday, n/N (%) | None | 59/147 (40.1) | 59/156 (37.8) |

| A little | 47/147 (32.0) | 51/156 (32.7) | ||

| Now and then | 19/147 (12.9) | 21/156 (13.5) | ||

| Regularly | 22/147 (15.0) | 25/156 (16.0) | ||

| In previous 7 days, n, mean (SD) | Number of days | 145, 4 (2.2) | 153, 4.1 (2.3) | |

| Over previous month, n/N (%) | None | 52/197 (26.4) | 40/195 (20.5) | |

| A few times a month | 20/197 (10.2) | 24/195 (12.3) | ||

| Once a week | 12/197 (6.1) | 11/195 (5.6) | ||

| A few times a week | 51/197 (25.9) | 41/195 (21.0) | ||

| Once a day | 27/197 (13.7) | 43/195 (22.1) | ||

| A few times a day | 35/197 (17.8) | 36/195 (18.5) | ||

| At 24 months | Yesterday, n/N (%) | None | 64/132 (48.5) | 70/128 (54.7) |

| A little | 39/132 (29.5) | 31/128 (24.2) | ||

| Now and then | 12/132 (9.1) | 10/128 (7.8) | ||

| Regularly | 17/132 (12.9) | 17/128 (13.3) | ||

| In previous 7 days, n, mean (SD) | Number of days | 133, 3.5 (2.3) | 129, 3.5 (2.4) | |

| Over previous month, n/N (%) | None | 47/173 (27.2) | 63/188 (33.5) | |

| A few times a month | 36/173 (20.8) | 38/188 (20.2) | ||

| Once a week | 5/173 (2.9) | 7/188 (3.7) | ||

| A few times a week | 45/173 (26.0) | 31/188 (16.5) | ||

| Once a day | 17/173 (9.8) | 27/188 (14.4) | ||

| A few times a day | 23/173 (13.3) | 22/188 (11.7) | ||

Adverse events

There were no suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions reported by participants in the trial. There were eight SAEs (six in the biofeedback PFMT group and two in the basic PFMT group), all of which were unrelated to the intervention received (e.g. two participants had atrial fibrillation).

In addition to the SAEs, there were 48 participants for whom at least one AE was reported (34 in the biofeedback PFMT group and 14 in the basic PFMT group), but none of these complications was classified as a SAE. Of these participants, 23 (21, biofeedback PFMT; 2, basic PFMT) had a complication related or possibly related to one of the interventions. Only one of these complications was definitely related to the intervention, when a participant randomised to the biofeedback PFMT group was found to have a nickel allergy and did not continue with the intervention.

Chapter 4 Health economic evaluation

Methods

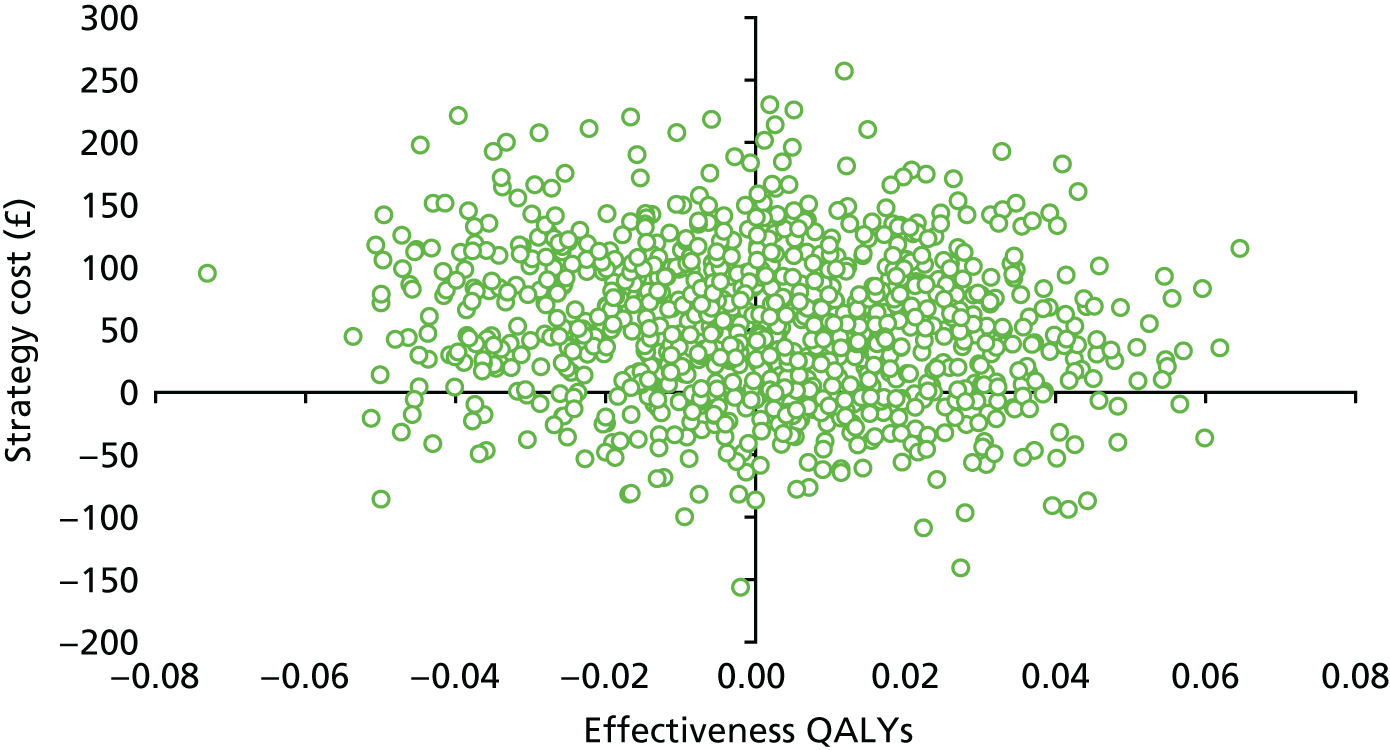

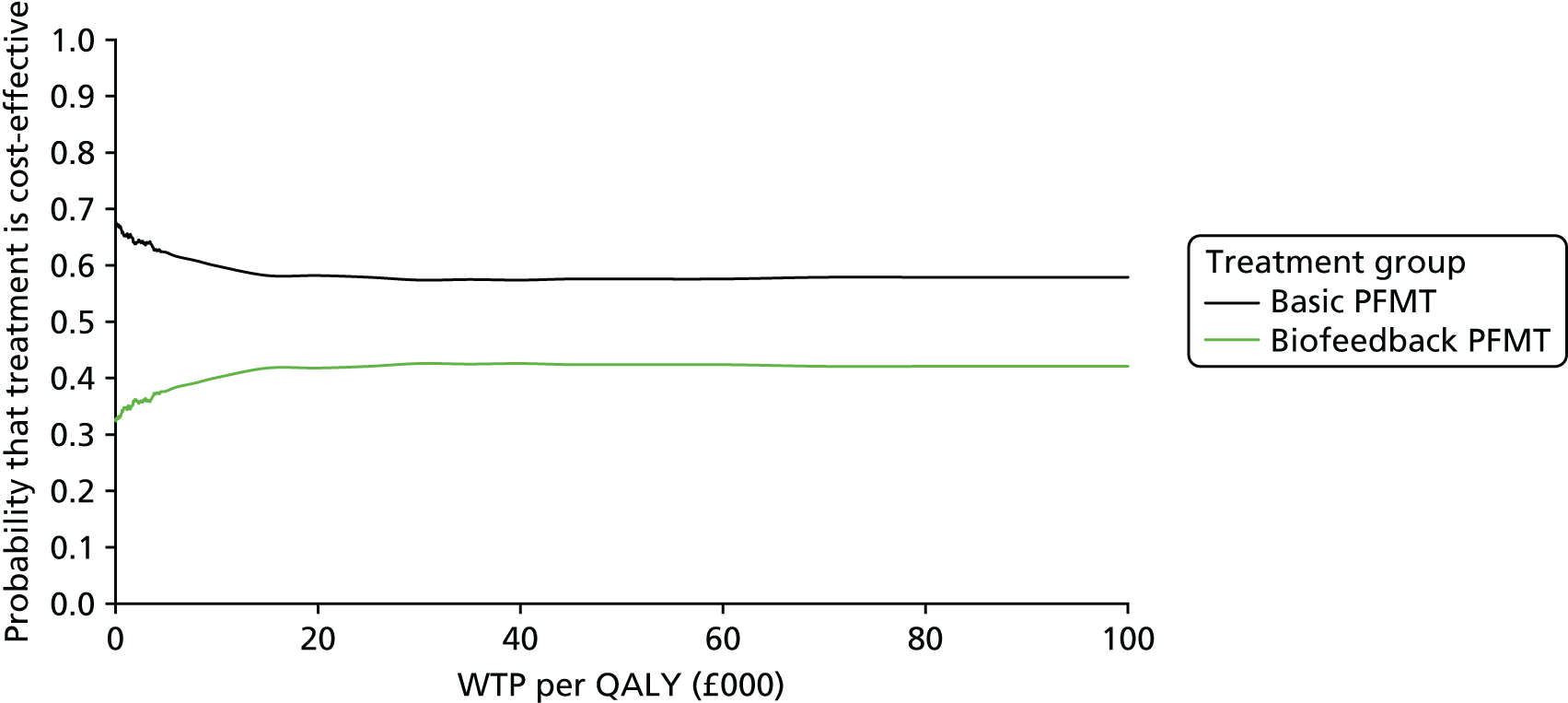

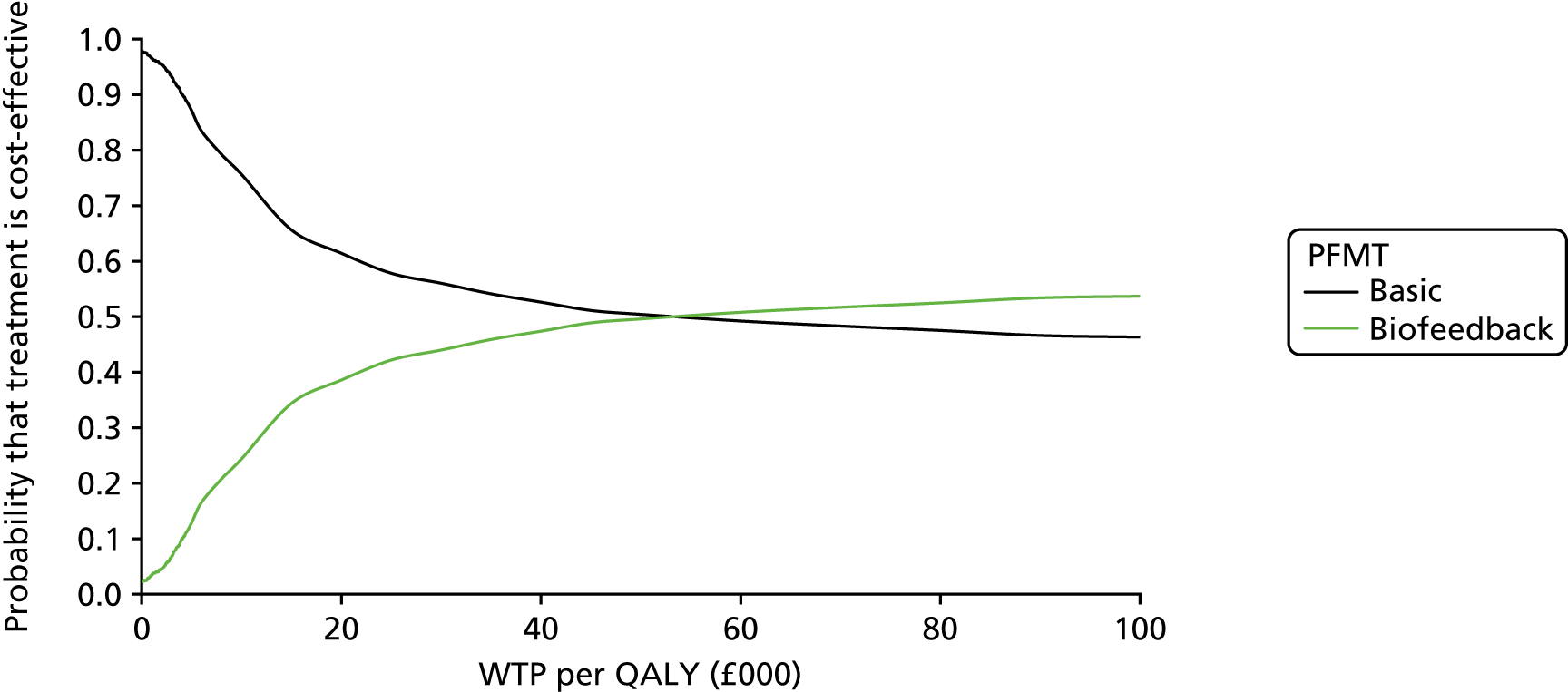

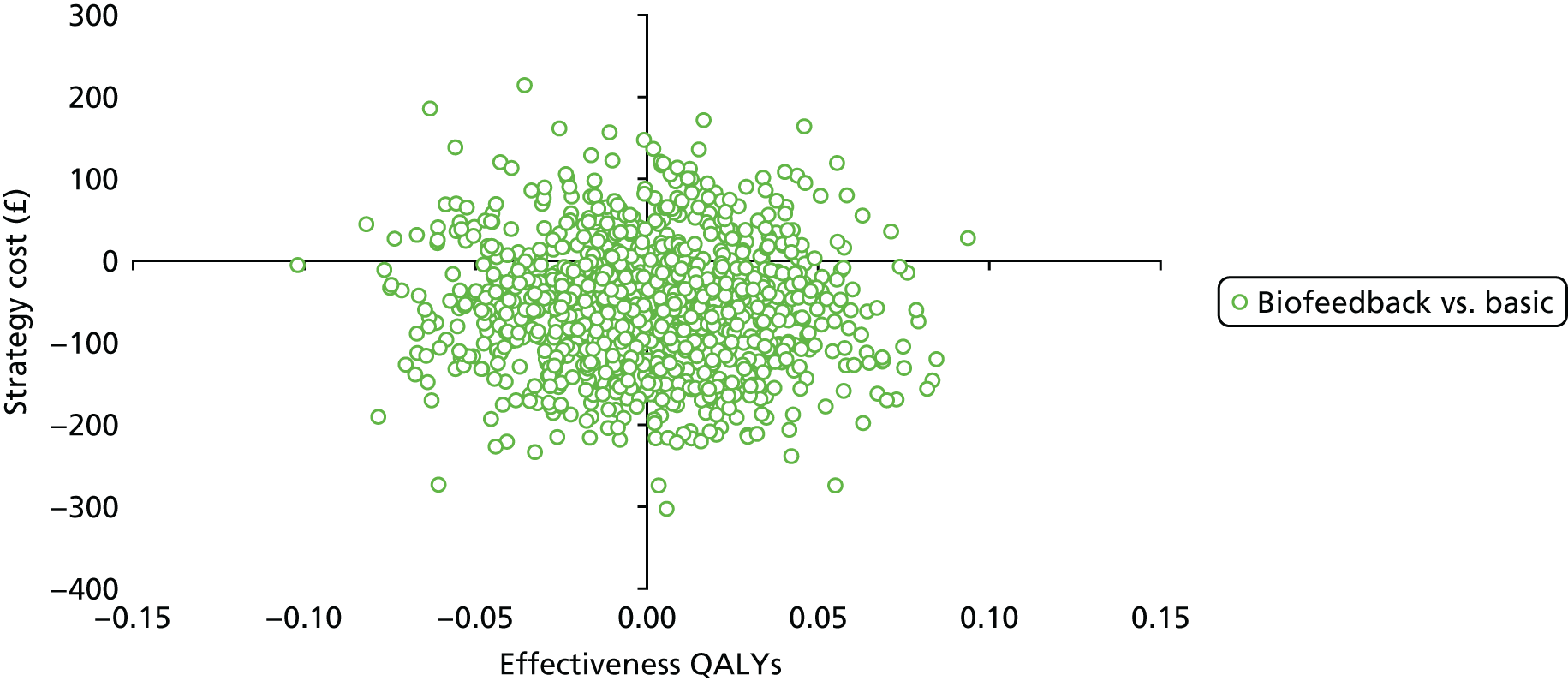

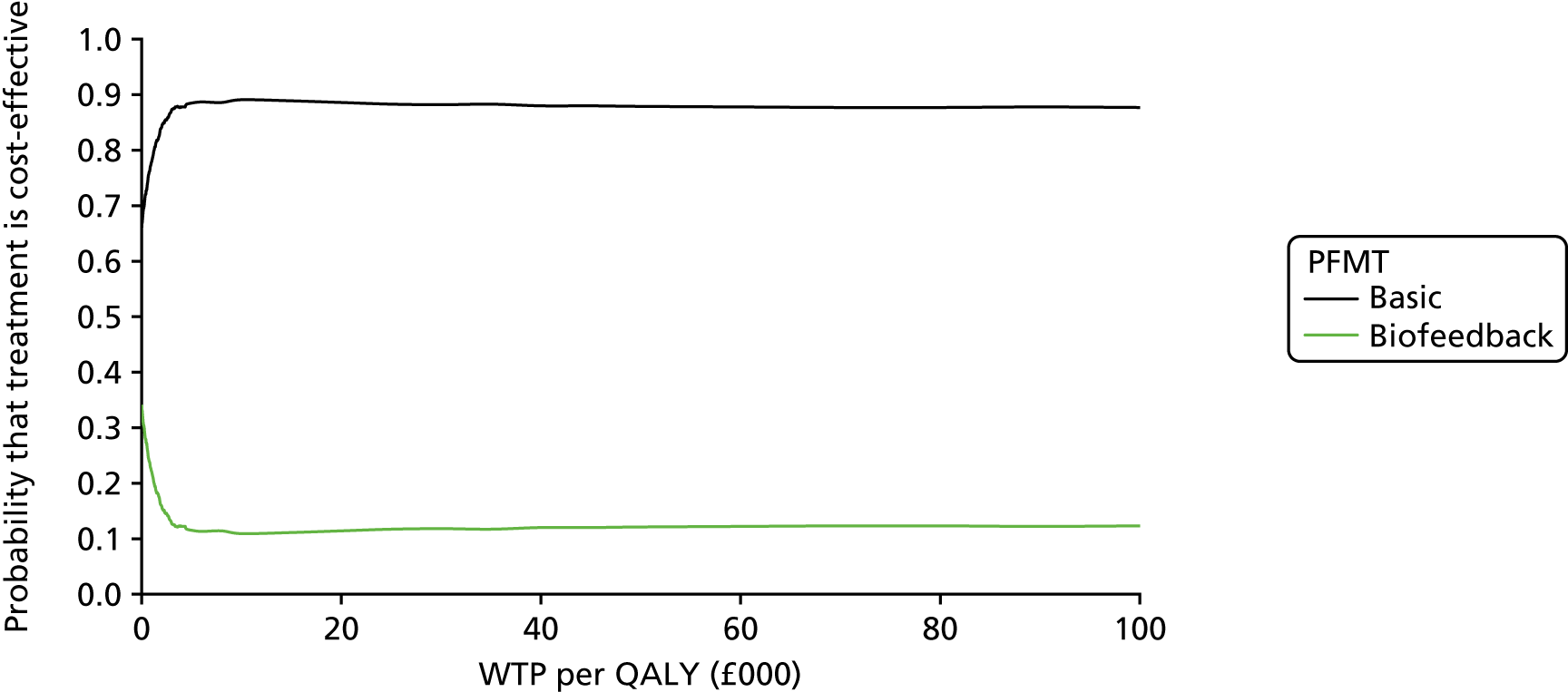

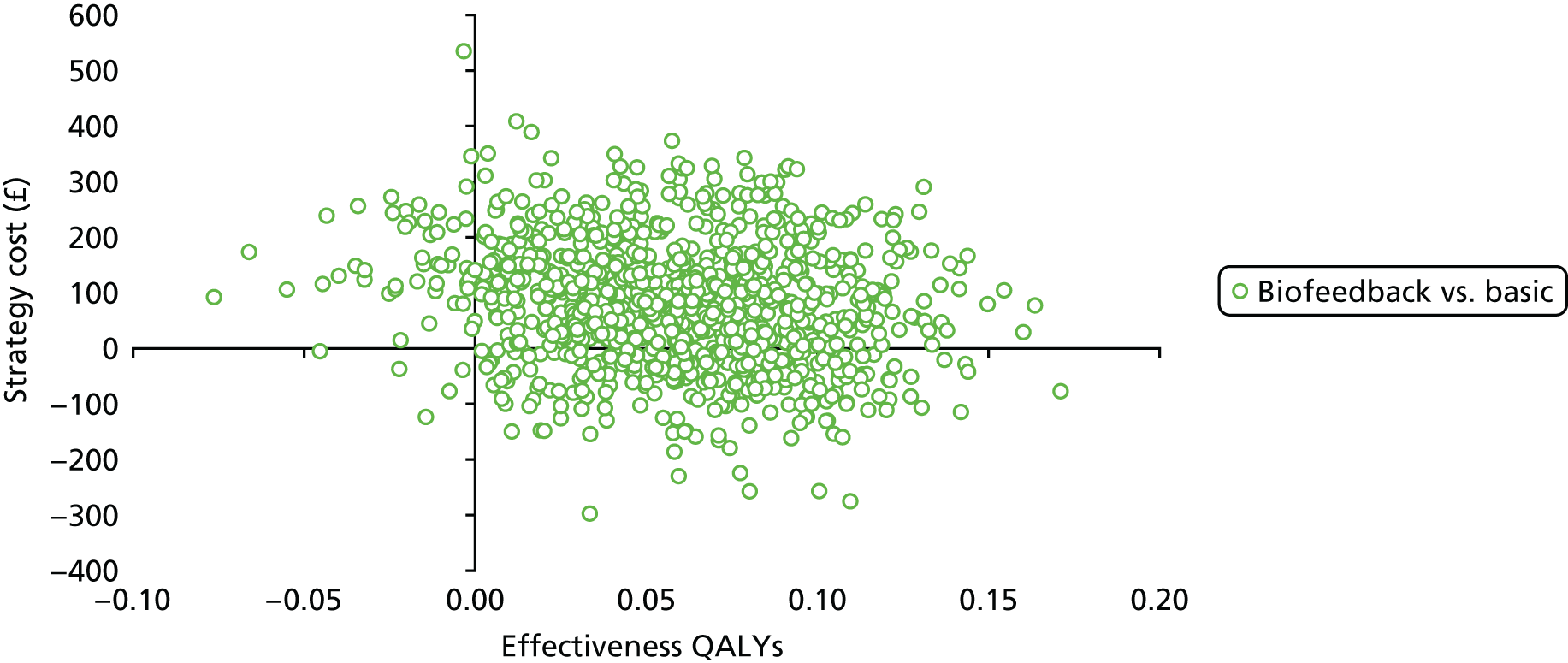

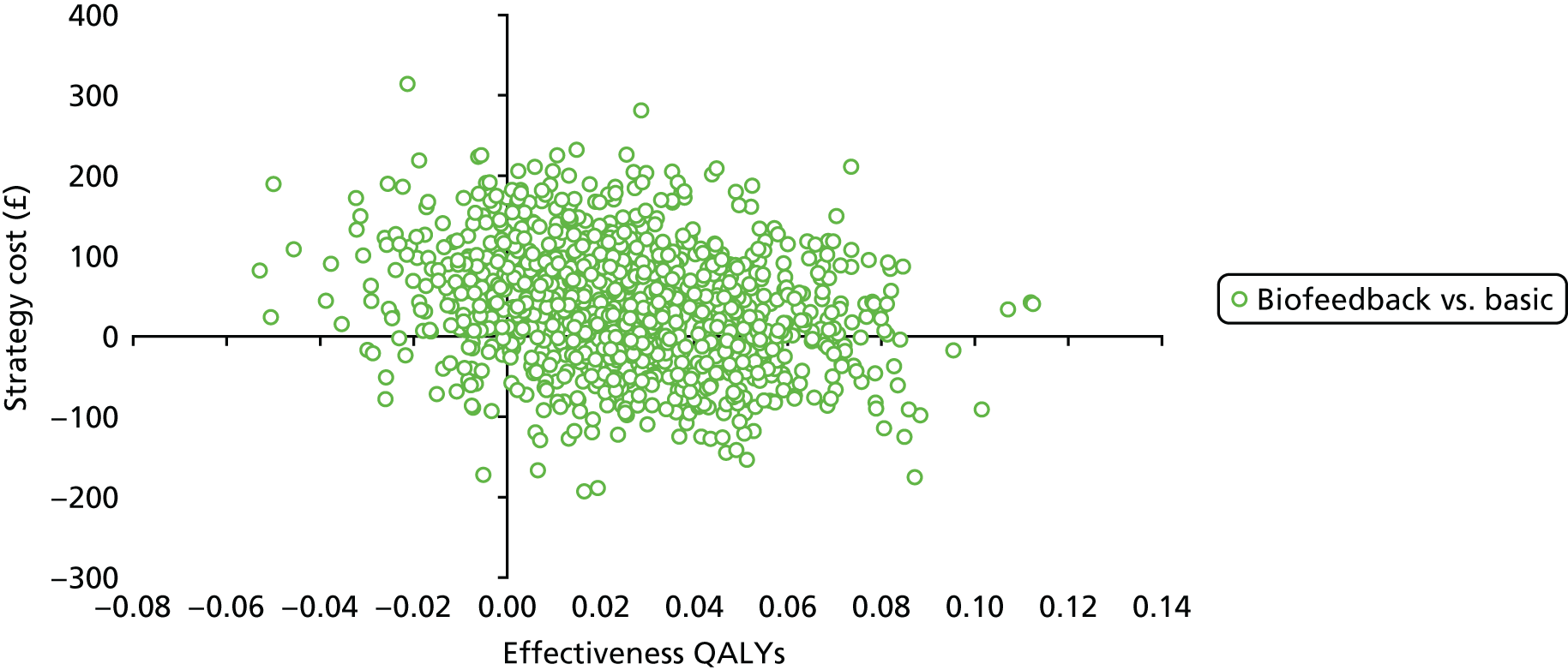

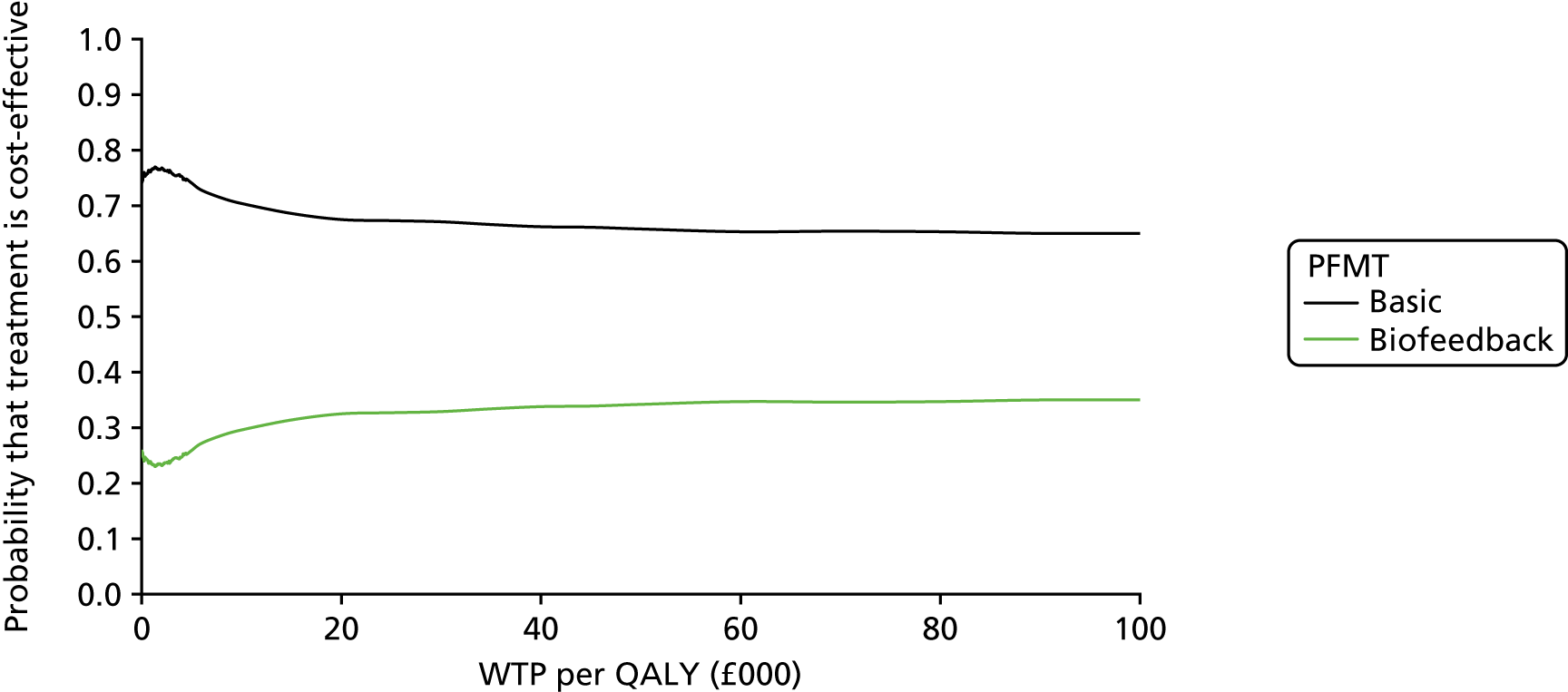

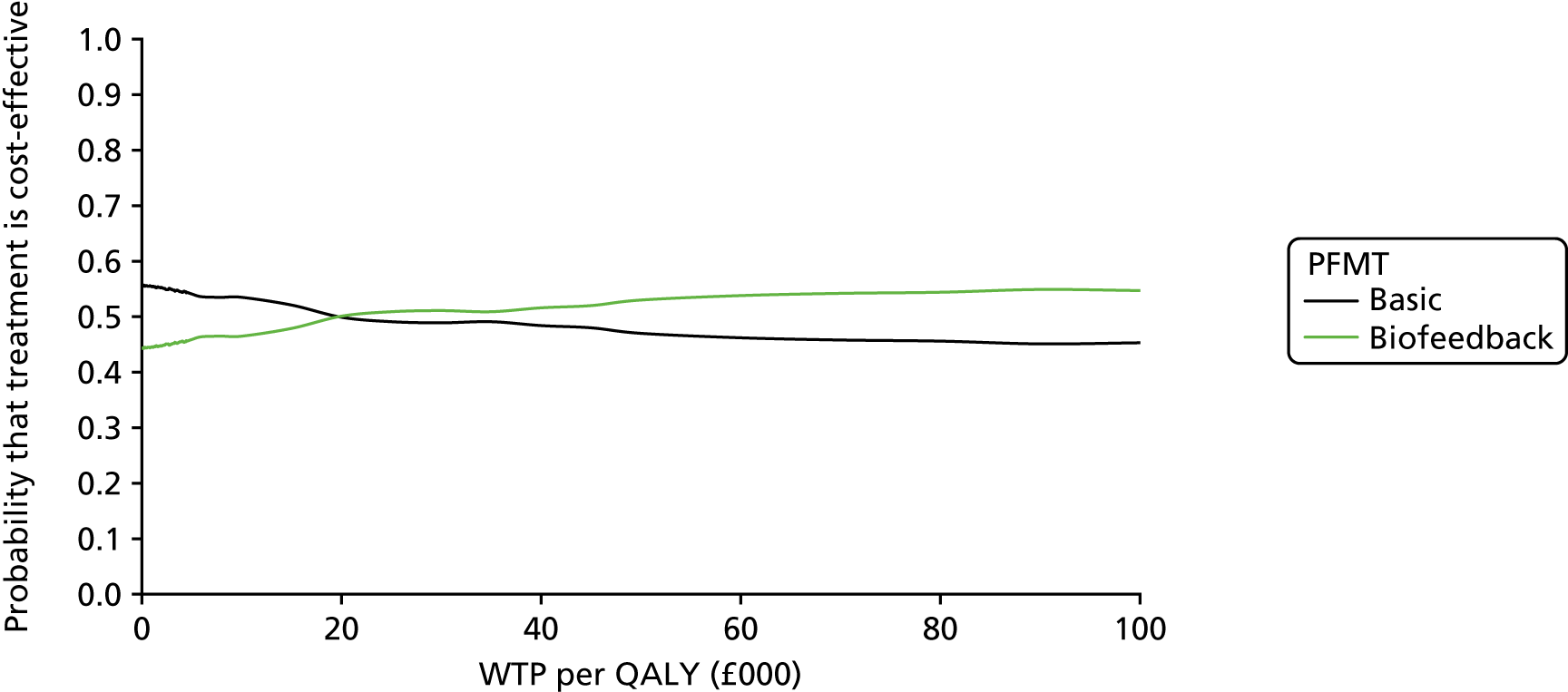

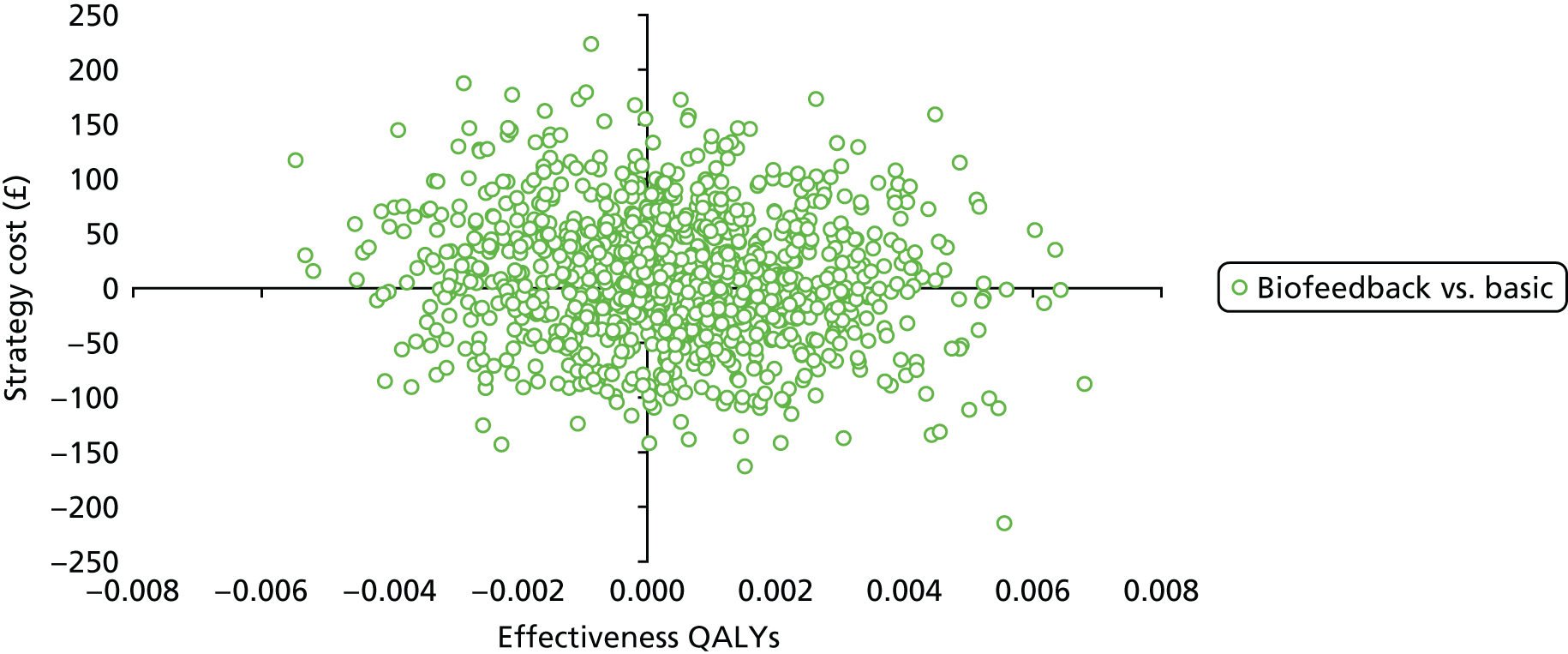

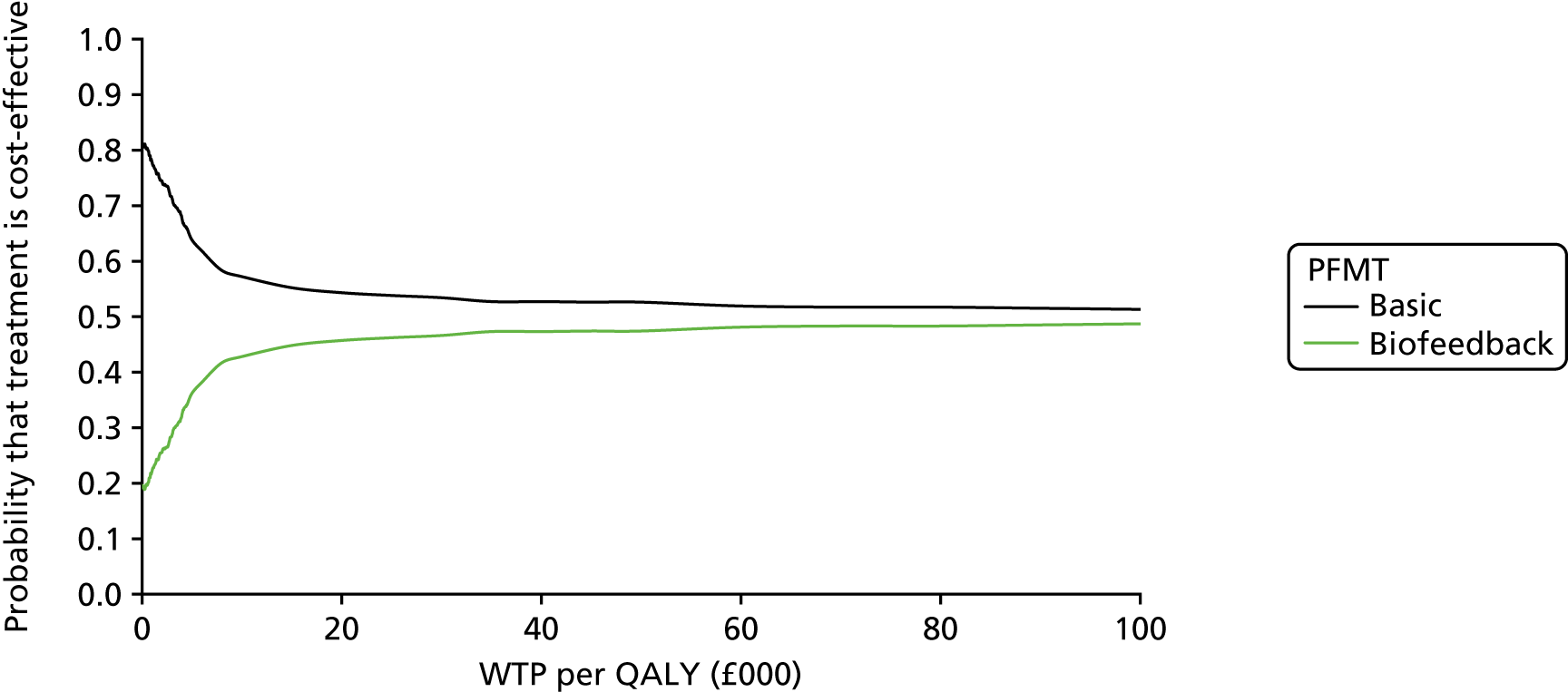

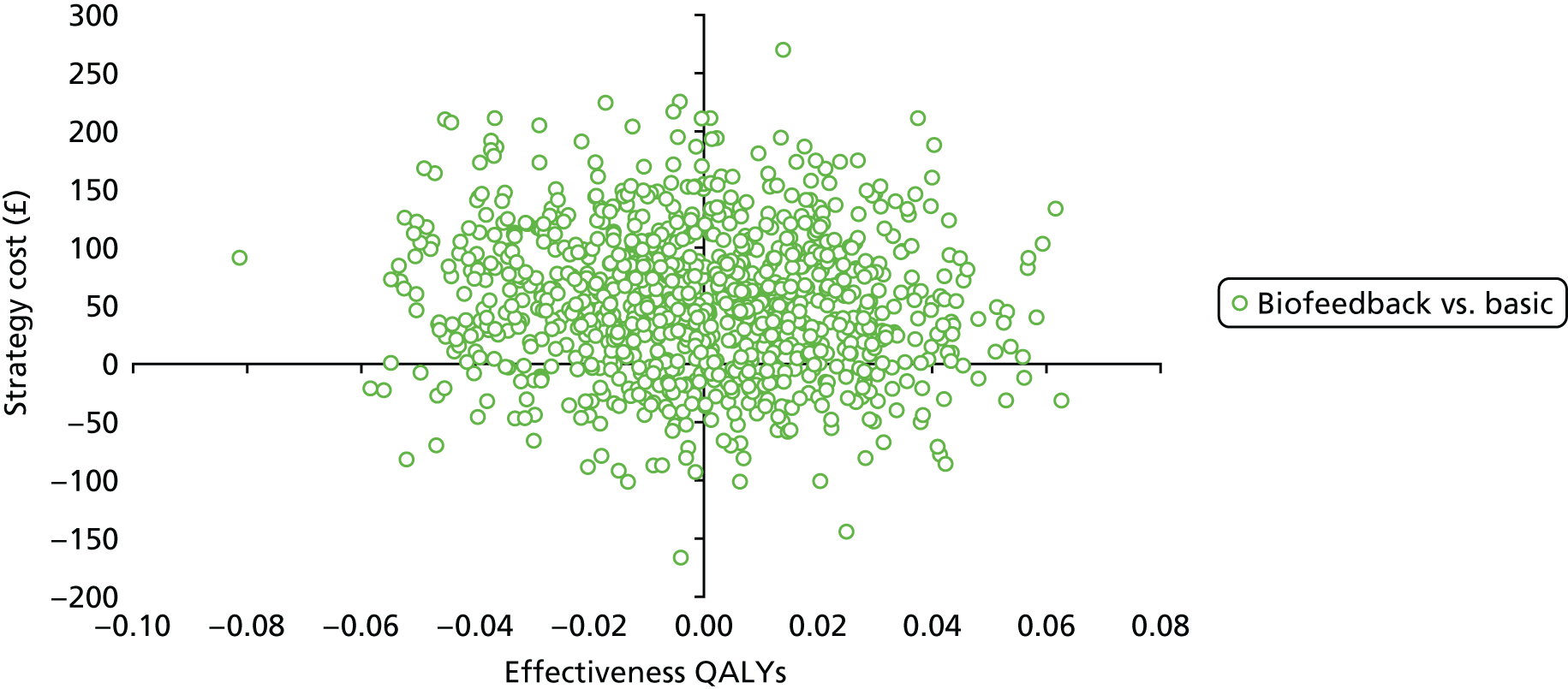

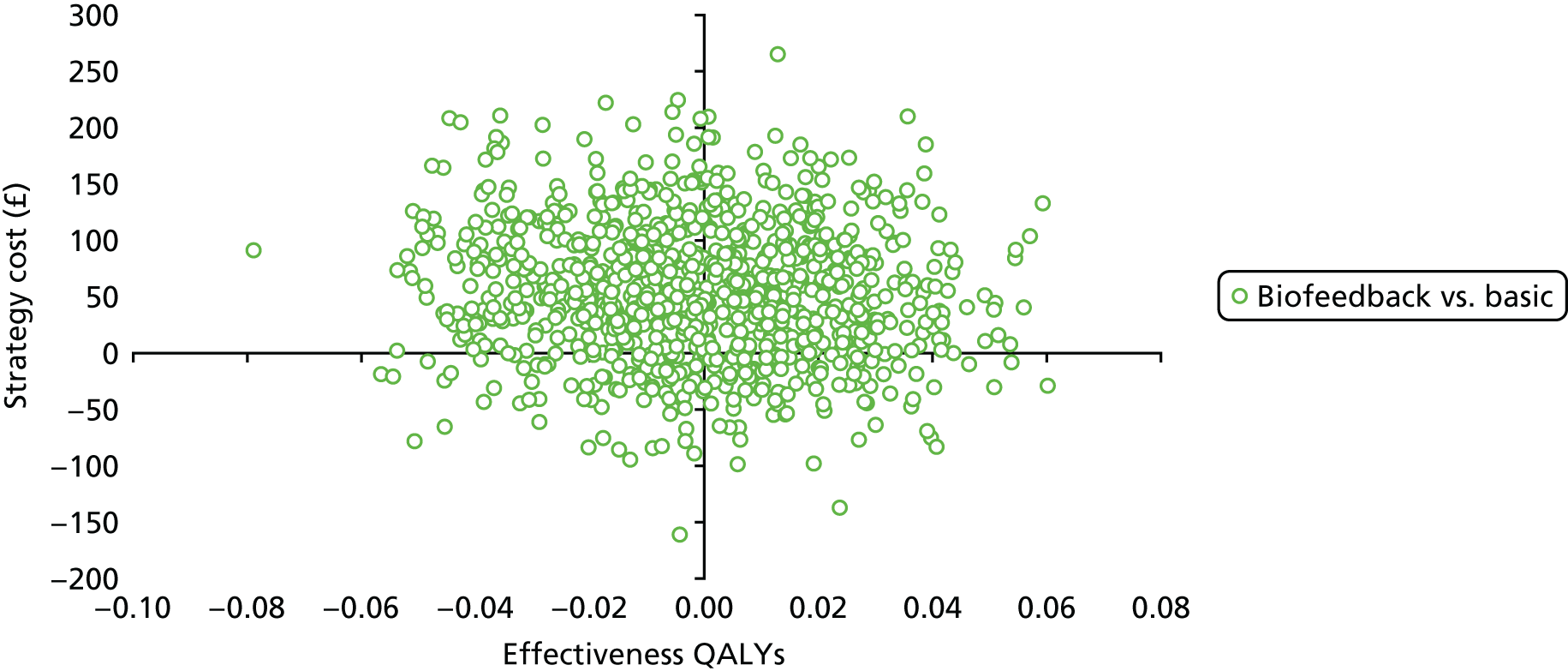

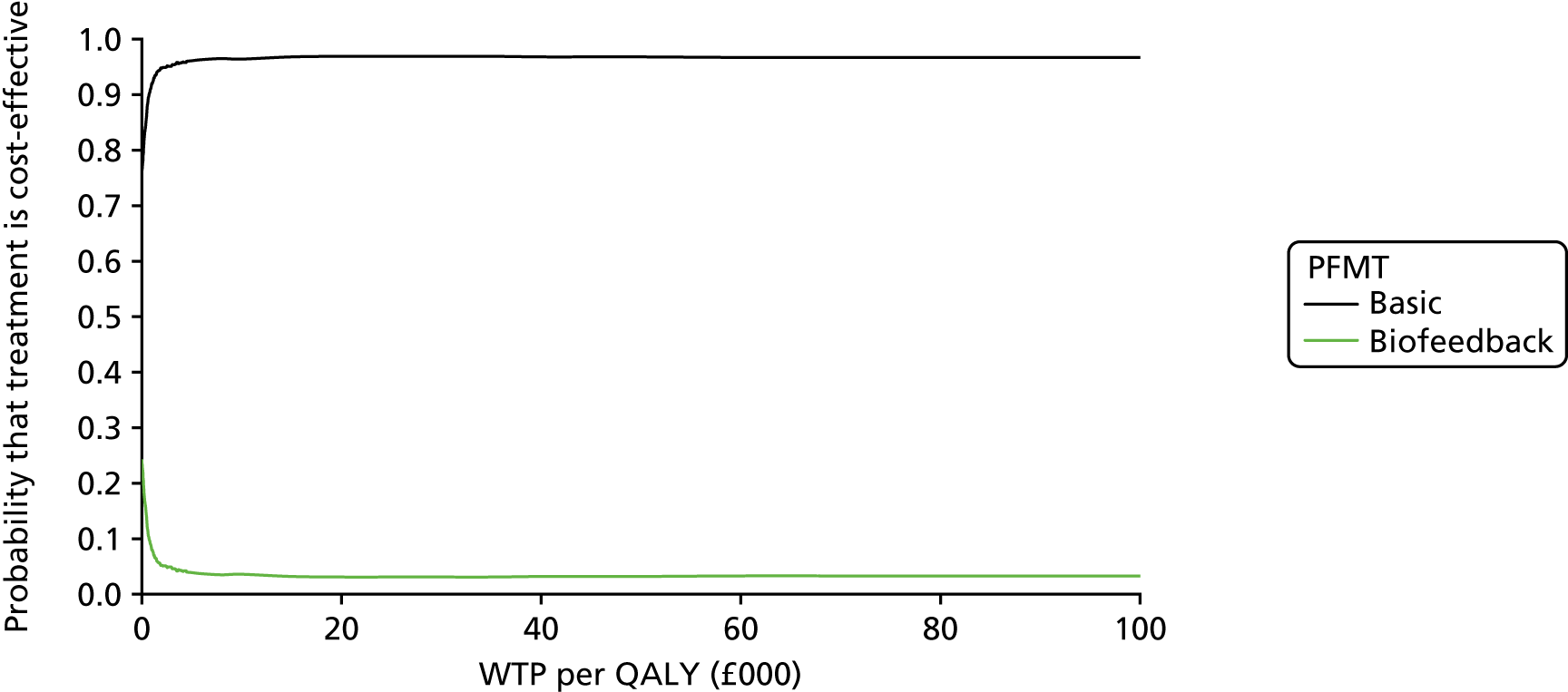

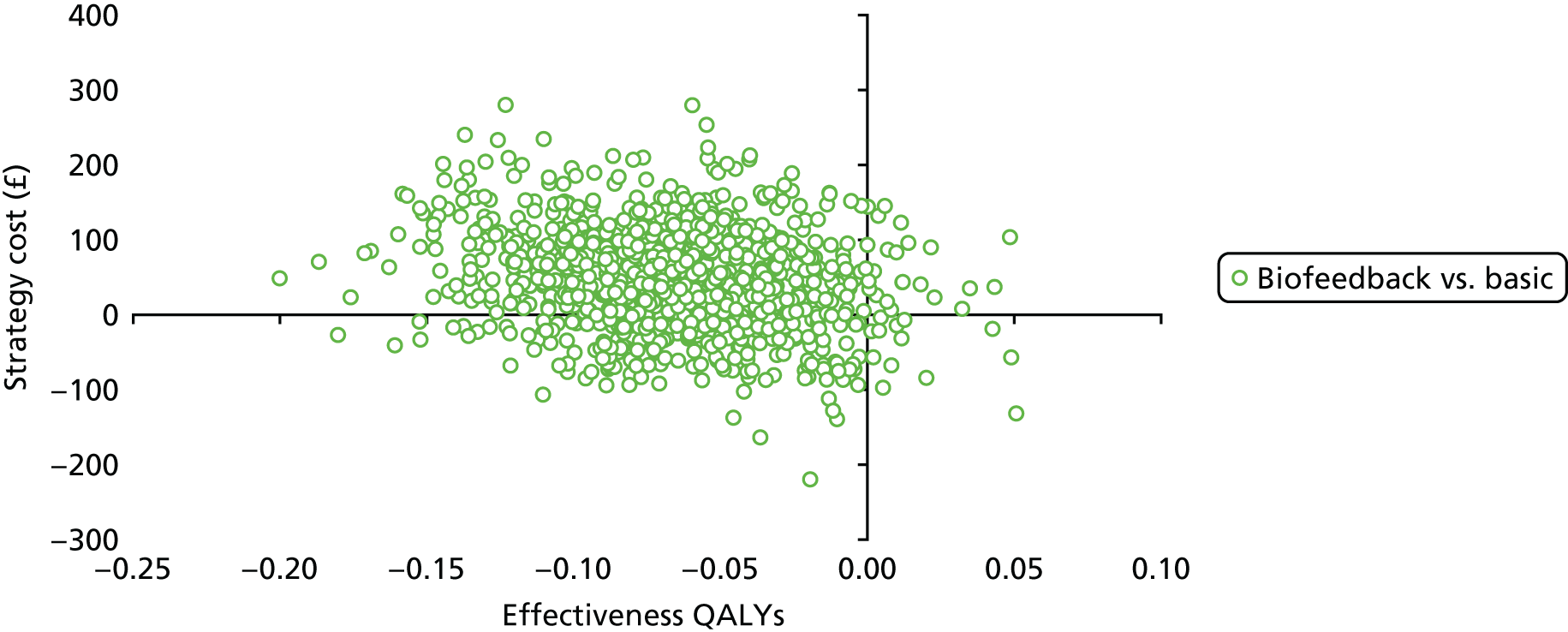

The principal research question being addressed in the economic analysis concerns the cost-effectiveness of a policy of biofeedback PFMT compared with basic PFMT. The main economic evaluation was based on data collected alongside the RCT. There was a plan to undertake an additional modelling analysis that considered a longer time horizon, to provide additional information for policy-makers, if relevant. However, the evidence indicated that there were no statistical or clinically meaningful differences in either the clinical or the economic outcomes to warrant further extrapolation of the data. Therefore, no modelling was conducted and this chapter focusses on the within-trial analysis. The trial population were women presenting with SUI or MUI. The base-case trial analysis assessed the costs and cost-effectiveness of the interventions from the perspective of the NHS. A further analysis included a societal perspective that considered the cost to the participants and their families. The costs were in Great British pounds (GBP) and the cost year was 2017. All analyses were prespecified in the health economic analysis plan [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/117103/#/ (accessed 29 July 2019)] and were reported following the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) recommendations [URL: www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/cheers/ (accessed 29 July 2019)]. The methods are summarised below.

Data collection