Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/108/02. The contractual start date was in January 2017. The draft report began editorial review in January 2020 and was accepted for publication in July 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Linaker et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background and rationale for the research

Chronic pain is that which troubles a person all or most of the time over months/years and is defined as pain that persists beyond the normal period of healing, usually taken as 3 months (with a 6-month cut-off point used for research purposes). It is a major public health problem associated with mental illness, job loss, impaired function and poor quality of life. Epidemiological studies suggest that 31% of men and 37% of women have chronic pain at any point in time and that prevalence increases with age. 1 Chronic pain is more common and more severe among those with poorer socioeconomic status. Mental illness, including depression and anxiety, is significantly increased among people with chronic pain, with prevalence rates as high as 70% among those with more severe pain. Between 20% and 27% of people of working age with chronic pain are unable to participate in their usual activities, including work, because of their pain. 2 Health-care costs associated with chronic pain are high. It has been estimated that chronic pain patients consult their general practitioner (GP) up to five times more frequently than other patients, with almost 5 million GP appointments annually. 3 The costs of chronic back pain, for example, have been estimated at £12.3B per year. 4 In addition to direct medical costs, it has been estimated that as much as 48–88% of the total cost burden of chronic pain can be attributed to indirect costs arising from restricted productivity, sick leave, disability benefits and other aspects of work disability. 5 Importantly, 3 of the top 10 conditions that impact productivity are painful disorders (e.g. back/neck pain, other chronic pain and arthritic conditions). 1 In a national audit, as many as 40% of people attending UK pain clinics were prevented from working (paid or voluntary) by pain. 5

Prolonged unemployment, for any reason, causes additional health problems. 6 Those who lose their job suffer from worse mental health,7 have poorer life expectancy,8 attend health-care consultations more frequently with physical symptoms and report higher levels of pain. 9 Moreover, these effects transfer to the next generation, such that the children of unemployed people also have poorer mental health and themselves experience higher rates of unemployment. 10 Taken together, these findings illustrate the potential public health impact of rehabilitating people with chronic pain back into work.

There have been calls in the UK for improved services for chronic pain. For example, chronic pain was a focus of the Chief Medical Officer’s Annual Report 2008,2 which emphasised the need for improved holistic pain services. In addition, the Royal College of General Practitioners named chronic pain a clinical priority area in 2011–14. 11 A particular area of need highlighted by patient representative groups12 was the poor availability of information and support from health-care professionals regarding employment.

Chronic pain is one of the major causes of health-related incapacity for work in the UK, with marked impact on the individual, their family, health-care providers and society. There is little evidence showing effectiveness of traditional ‘train and place’ rehabilitation interventions for chronic pain patients in the UK, partly because return to work (RTW) is rarely the principal outcome. The results of one published study suggested that occupational rehabilitation can be integrated with pain management programmes, producing a 38% RTW rate at 6 months,13 and showed that those already unemployed need a different approach from that used for those currently in work.

People unemployed with chronic pain have a number of compounding problems, including diminished self-esteem and confidence; progressive loss of fitness and stamina through inactivity; outdated vocational skills; lack of suitable, sustainable employment opportunities; poor availability of ‘tailored’ job-seeking and occupational advice; and potential prejudice from employers against people with poor sickness records. These problems exactly parallel those faced by people with severe mental illnesses, in whom rates of unemployment as high as 95% have been reported. 14 Among people with severe mental illness, the traditional ‘train and place’ model of rehabilitation has been shown to have little success, with many patients obtaining employment in sheltered workshops only. Being in paid work, as compared with being in supported work, is associated with higher self-esteem and higher levels of hope and optimism among people with mental illness, and is clearly the outcome of choice. 15 Therefore, a new approach was developed in the USA in which the emphasis was on direct job placements, plus support to patient and employer, the so-called ‘place-and-train’ model. The model of ‘place-and-train’ that has been researched most intensively is individualised placement and support (IPS). 13,16–23 IPS is a systematic approach to helping people with severe mental illness obtain competitive employment. It involves the allocation of carefully trained vocational advisers to people who wish to RTW and equipping them with skills and health support as required. It relies on eight principles: (1) it aims towards competitive employment; (2) it is open to all those who want to work; (3) it tries to find jobs consistent with people’s preferences; (4) it works quickly; (5) it brings employment specialists into clinical teams; (6) employment specialists develop relationships with employers based on a person’s work preferences; (7) it provides time-unlimited, individualised support for the person and their employer; and (8) benefits counselling is included. 13 Although originally developed and tested in the USA, IPS has since been shown to be effective in European countries,16 despite very different systems of welfare and diverse job markets. It has been shown to translate to mental health patients in the UK,16,23 provided that it is implemented effectively23 and a high rate of adherence to the fidelity principles is achieved. 24 Pooled data from a 2012 systematic review suggest that up to 47% of those unemployed in Europe because of severe mental illness can be returned to meaningful employment using IPS. 23

Given its success for severe mental illness, IPS might work for chronic pain patients who suffer similar disability, social isolation and rates of unemployment, and for those who have high levels of psychological comorbidity. Indeed, in an uncontrolled pilot study performed by members of our research team, IPS was offered through Remploy (Leicester, UK) to 17 patients attending the local pain clinic. The results showed excellent employment rates and high rates of patient satisfaction, with a social return on investment of between £5.01 and £6.77 for every £1 invested. 25 However, long-term funding for this service could not be secured after the pilot study because of a lack of evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and insufficient data on cost-effectiveness to justify its widespread adoption.

Individualised placement and support programmes are already being offered patchily in the UK by private sector and local authority schemes. Given that IPS was manualised for a different patient group, providers will be approaching adaptation in different ways, particularly in relation to integration with pain management services. Although IPS is, in the main, a set of practical interventions in support of people seeking work, it may be that some people in pain are not ready for behavioural change, in terms of psychological and/or systemic factors. In this respect, IPS may be supported by well-evidenced psychological interventions that centre around engaging people in the process of change. Two such interventions are motivational interviewing26 and values-based work (which is described in the context of contextual cognitive–behavioural therapy). 27 The research process allows for the development of the IPS intervention to include those components that are associated with cognitive and behavioural change, and establish a basis for integration of pain management.

It is important that IPS be evaluated for chronic pain patients and that the validity of the fidelity principles for people with chronic pain be explored, given that high levels of adherence to these principles is associated with better outcomes in severe mental illness. Crucially, a high-quality clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness analysis is needed if we are to justify the widespread adoption of this approach in this prevalent group of patients.

This research aimed to test the feasibility of adopting IPS for people unemployed with chronic pain to lay the groundwork for a definitive RCT.

Patient and public involvement

Prior to submission of our funding application, 20 patient and public representatives participated in three workshops to review and inform our proposal. Participants were male and female, aged 20–86 years and all were diagnosed with chronic pain conditions. They included individuals who were currently working, retired from professional/managerial work, not working on the grounds of ill health and currently signed off sick from work, in addition to those actively seeking work/voluntary work. The public and patient involvement (PPI) representatives were involved in the development of the final protocol and commented on the Plain English summary.

A further two workshops were held, which included eight patient and public representatives, during the first phase of the research [alongside work packages (WPs) 1–3]. These groups reviewed all aspects of WPs 1–4 and commented on all patient-facing documentation, including the invitation letter, patient information leaflets, consent form and questionnaires. The groups iteratively helped the research management team to develop and improve procedures for recruitment and to devise the treatment-as-usual (TAU) booklet. With their proactive support, the TAU booklets were designed to be patient friendly and informative, with up-to-date information about local services for pain and employment (see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1510802/#/documentation; accessed January 2021).

At the end of the study, two further PPI groups were held, involving six people with chronic pain (people who were employed, unemployed, retired through ill-health and retired not for health reasons) to reflect on the study findings, lessons learned and recommendations for future development work.

Lay co-applicant

Our application included a lay co-applicant who was a former local small business employer, as well as an adviser to local health charities. He proved invaluable throughout the process of the research, from original application to this report. He provided continuity by attending the Trial Management Group meetings and participating as a lay representative to the Trial Steering Committee (TSC).

Data collection tools

During this research, we piloted the use of questionnaires at baseline and follow-up, which were developed from a range of potentially suitable validated tools for evaluating an employment intervention on pain, function and quality of life. Their acceptability was evaluated qualitatively and quantitatively, and, based on our findings, they will be suitable for adaptation for any future definitive trial.

Treatment-as-usual booklet

Together with our PPI representatives, we developed and piloted a TAU booklet, which was found highly acceptable by participants and the Research Ethics Committee. Although specific to the location of this research, these would make a good prototype to be adapted for any larger-scale trial.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Objectives

The specific objectives were to answer questions in the following areas.

Recruitment/retention

-

Can patients who are unemployed with chronic pain be identified efficiently from primary care?

-

Would sufficient numbers of eligible participants consent to take part in a trial?

-

What rates of dropout occur during follow-up?

-

How acceptable would such patients find randomisation?

-

What are the barriers to patients’ and health-care providers’ participation in a future RCT (e.g. practical, financial, motivational)?

-

What would be the risk of ‘contamination’ if individual-level randomisation were used?

Intervention

-

In practice, what is needed to manualise IPS for chronic pain patients?

-

What adaptations are needed?

-

How do the fidelity principles perform and can they be translated across to IPS for chronic pain patients?

-

What training/support is needed for employment support workers (ESWs) to integrate with pain services?

-

How feasible is it that this complex intervention can be delivered within the NHS?

Comparator

-

What is TAU?

-

What information should be in a booklet provided to ‘control’ subjects?

Outcomes

-

What should be the primary outcome measure in a definitive trial (e.g. employment, health related or economic)?

-

In addition to competitive employment outcomes, which in trials of IPS for severe mental health conditions have consistently found to have been improved, what do:

-

patients think are the important outcome measures?

-

employers think are the most important outcomes measures?

-

-

What is the distribution of the relevant outcome measures to calculate power for the trial?

The research was carried out over 39 months and was led by a multidisciplinary team (that included expertise in chronic pain management, delivering a programme of IPS, epidemiology, occupational medicine, research methods, primary care, public health, health economics, qualitative psychological research and local employment circumstances). The research involved mixed methods and comprised six WPs, which aimed to pave the way for a definitive RCT of IPS by addressing the below objectives.

Work package 1

Work package 1 involved qualitative work with a group of individuals with long-term health conditions and at least 24 months’ unemployment who had recently engaged with IPS [as part of the 2-year funded Solent Jobs Programme (SJP) in the cities of Southampton and Portsmouth]. We aimed to understand their views about participating in research (specifically in a trial involving IPS), whether or not they thought people would wish to, and would be able to, take part in a trial, and their individual experience of undertaking the IPS programme.

Work package 2

Work package 2 involved qualitative research with local ESWs, who were delivering IPS as part of the local SJP, to gain insight into their experiences of IPS. In addition, we enquired about their knowledge of and attitudes to people with chronic pain and their specific learning needs to implement IPS tailored to such individuals.

Work package 3

In WP 3, we undertook focus groups with primary care-based health-care professionals (PCPs) to understand their views about a trial of IPS for people with chronic pain and gain their insight as to how to develop recruitment strategies to identify people who are unemployed and have chronic pain within primary care. Furthermore, we sought their views about the acceptability of a trial of this nature and what the most important relevant outcome measures would be, and asked them to comment on the development of study materials (e.g. the TAU booklet) for WP 4.

Work package 4

Work package 4 involved a pilot primary care-based longitudinal study [i.e. the Individualised Support To Employment Participation (InSTEP) trial] to develop the RCT protocol in a small sample of individuals to:

-

test methods of recruitment and evaluate the acceptability of procedures for consent and randomisation to the IPS intervention or TAU

-

develop and ultimately manualise IPS for people with chronic pain by developing training for ESWs, creating shared documentation and integrating pain management planning by a pain specialist in conjunction with the ESWs

-

measure adherence to the study protocol and rates of attrition with follow-up of all participants using postal questionnaires at 3, 6 and 12 months

-

evaluate the acceptability of questionnaires in terms of whether or not participants can and do complete them as intended

-

inform the choice of primary outcome measures (e.g. competitive employment, quality of life, health and health economics) for a definitive trial.

In doing this, we aimed to assess any unforeseen impact on the NHS from trying to place chronic pain patients back into employment to gain an indication of the success levels and what should be measured in a definitive trial, so as to ensure that a more efficient, cost-effective trial to fully test the intervention might be ultimately conducted.

Work package 5

Work package 5 involved qualitative work to evaluate the experience and views of all stakeholders (i.e. ESWs, participants, employers and PCPs) during the pilot trial and to identify barriers to a definitive trial. From the participants, we wished to assess their motivation for participation and their perceptions of the benefits that they experienced and how those benefits might best be captured as outcome measures. In addition, we wanted to seek their views about participation in any future trial and any perceived barriers. From the ESWs, we wished to seek views about the IPS service, about integration with pain services and about important outcome measures. In addition, we hoped to understand what further training needs they perceived for working with chronic pain patients and to facilitate integration of IPS with pain management planning. From employers, we wished to understand opinions about the IPS service, providing a placement and employing someone with chronic pain and what they regarded as important outcome measures. For PCPs, we wished to evaluate the ease and success of identification and referral of people with chronic pain from primary care, and also their capacity to develop effective health plans to support these individuals. We explored the risks of contamination and any barriers to being involved with a trial. We also asked PCPs for suggestions to refine and optimise the protocol for a future trial.

Work package 6

In WP 6 we aimed to manualise the IPS intervention for chronic pain patients and review fidelity principles, in addition to refining the study protocol for a definitive trial.

Ethics approval and research governance

Ethics approval to conduct WPs 1–3 was granted by the University of Southampton Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee on 19 December 2016 (Integrated Research Application System ID 215081) and Health Research Authority approval was given on 11 January 2017 (reference 17/HRA/0035). Approval to conduct WPs 4–6 was granted by the South Central-Hampshire Area Research Ethics Committee on 22 September 2017 (Integrated Research Application System ID 226125) and Health Research Authority approval was given on 9 October 2017 (reference 17/SC/0398).

Methods

Work packages 1–3

Common methodological elements

In these WPs, qualitative interviews were carried out by one of two trained interviewers who were research assistants in psychology and who had prior qualitative research experience. All participants gave written, informed consent to be interviewed, for the interview to be recorded and transcribed, and for the analysis of their comments. All were made aware that their comments were confidential and would be non-attributable. In each WP, the interviewers followed a semistructured topic guide (Table 1) to allow participants to tell the story of their own experiences. 28,29 Neither interviewer had any prior relationship with any of the participants. Questions and prompts were developed in advance to aid the interviewer, but the topic guide was intentionally flexible to allow for natural discussion throughout the process. Interviews were recorded and field notes were made by the interviewer during and immediately after data collection.

| Clients | ESWs | PCPs |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Data analysis

Recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim by the interviewers and all text was entered into NVivo qualitative data analysis software version 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) for analysis. The data were analysed thematically and independently by both researchers as an iterative process alongside data collection. 30

-

All data were coded inductively by both researchers.

-

Codes were examined for patterns and refined.

-

Relationships and refined patterns between initial codes were identified and themes were developed into higher-level categories following discussion between both researchers.

-

Themes were described with representative data that supported each theme. This methodology enabled thorough exploration and detailed description of clients’ views. 31,32 Quotations were selected from the arising themes to best describe the findings, with non-identifiable identification numbers allocated to participants. The study findings were reported in accordance with the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ). 33

Participants and recruitment to work packages 1–3

Work package 1

Work package 1 involved a sample of people with chronic health conditions (including pain) who had been unemployed for at least 24 months and had been, therefore, recruited for and attended the SJP IPS intervention in the cities of Portsmouth and Southampton in the preceding 12 months.

Clients who were potentially eligible to take part were identified by the ESWs and managers of the IPS service in the city councils. We provided the ESWs with a participant information sheet that explained the nature and purpose of our research. The leaflet explained that we were seeking willing volunteers to take part in qualitative research, what was required of participants, that their expressed views would be confidential, anonymised and non-attributable, and that they could withdraw their consent at any time. Individuals who expressed interest in participating were asked to give consent for their contact information to be passed to the qualitative researchers. Potential participants were then contacted via telephone by the researchers to arrange an interview. Interviews were conducted at a time that suited the clients and they were offered the choice of an interview by telephone or face to face (arranged in their local job centre). It was explained to each client that the interviewer was independent of the IPS programme and that they were part of a research team investigating whether or not high-quality employment services could be of benefit to people who were unemployed and affected by long-term health conditions. Clients were assured that their comments would be strictly confidential and no one from the SJP IPS programme would be present during the interview. Travel expenses incurred by the clients were remunerated and participants were sent a high street shopping voucher after their interview to thank them for their assistance.

Work package 2

Work package 2 involved ESWs currently working in the SJP IPS intervention in the cities of Portsmouth and Southampton.

All eight ESWs involved in the SJP IPS intervention in the cities of Portsmouth and Southampton were eligible to participate. Eligible individuals were given a written information sheet by their managers, which explained the purpose of the study, emphasising that participation was voluntary and that comments would be confidential, anonymised and non-attributable, and that they could withdraw their consent at any time. Semistructured interviews were arranged at the convenience of the ESW at their place of work and travel expenses incurred by ESWs were remunerated. Written, informed consent was obtained from ESWs to record their interview and for the analysis of their views.

Work package 3

Work package 3 involved qualitative focus groups with members of the primary health-care team who were familiar with chronic pain patients (i.e. PCPs). PCPs were contacted via the local Clinical Research Network, which advertised the study to research-active general practices. Practices that expressed interest in the study were then provided with written information about the purpose of the study and what was required. Any member of the practice team involved in the care of chronic pain patients was eligible to participate.

Practices that expressed interest were contacted by a member of the research team by telephone to explain what was involved in the research and, if agreeable, a suitable time was arranged to conduct a focus group within the practice premises. Focus groups were chosen to facilitate interaction between participants and enable them to bounce ideas off each other,34 and also for convenience to minimise the total clinical time of the PCPs taken up by the research. It was emphasised that all expressed views would be confidential, anonymised and non-attributable, and that they could withdraw their consent at any time. Written, informed consent to participate, for recording and for the analysis of their views was obtained from all PCPs prior to the start of the focus group. Participating general practices were remunerated so that they could backfill the time required.

Results

Work packages 1–3

Data collection for all three WPs took place in 2017. The following sections describe those who participated.

Work package 1: participants in the Solent Jobs Programme individualised placement and support

In 2017, approximately 50 people per month were referred to the SJP IPS programme, of whom just under half agreed to participate. A total of 20 potential clients were identified and registered their interest to participate in our qualitative research. However, five clients proved uncontactable by telephone and six failed to attend an interview at an agreed time. Ultimately, a total of nine clients were interviewed. In each case, the interviews lasted a maximum of 45 minutes.

Work package 2: employment support workers

All ESWs at the two SJP IPS sites in Portsmouth and Southampton were given written information about the research. Six ESWs expressed interest in participating. However, because of work commitments, one was unable to do so. A total of five interviews were conducted and all lasted a maximum of 45 minutes.

Work package 3: health-care professionals in primary care

A total of 11 PCPs from two general practices took part in two focus groups. The PCPs included four GPs, an advanced nurse practitioner, three practice nurses, a health-care assistant, a practice manager and a medicines manager. Focus groups were arranged to make the groups as inclusive and accessible as possible, and lasted a maximum of 1 hour.

Themes identified

Quotations have been selected from the arising themes to best describe the findings, with non-identifiable identification numbers allocated. The results are presented under the key themes.

Undertaking a research trial involving individualised placement and support

The PCPs were extremely positive about the idea of a trial of an employment intervention for people unemployed with chronic pain:

I think the intentions are brilliant.

PCP1

Likewise, all ESWs were very positive about the SJP IPS programme and enthusiastic about research to show its benefits. They were keen to share success stories and highlight the benefits of the intervention that they had observed.

Primary care-based health-care professionals stated that they had observed patients who were trying to RTW and find employment, and that such individuals would be interested and engaged in a trial. However, they voiced concern that some individuals might not wish to RTW and that differences in motivation might prove problematic in terms of study trial recruitment:

And it’s the individuals, there are some people who actually like to work as we would like to see that, but there are those who just wanna get the money and the money is just easier if you are just sitting on your backside sometimes.

PCP1

The PCPs expressed concern that some patients may not want to seek employment and that it would be important to identify and measure motivation as part of the study.

One client saw the benefit of conducting the proposed research trial but, similarly, expressed concerns about the purpose and how that purpose would be communicated (e.g. about the wording of the information sheet that stated that the research aim was to ‘improve the health of people who are unemployed through long-term health problems’). She felt that this could be considered derogatory, feeling that she was not ‘unemployed’ but ‘unable to work’. At the end of the interview, she voiced apprehensions about the future research being used to force individuals to work even if they were unable to do so:

I think this is a really interesting study. I think that, it’s important, but I also think in the wrong hands, it could be used to be malicious and force people with pain into work.

C5

Overall, clients were very positive about the SJP IPS programme with which they were engaged. However, we found that they had difficulty in discussing a potential research trial that is distinct from their own personal experiences of their IPS programme. Even after clarification, some clients found the concept of a research trial difficult to understand and their answers were inherently linked to their individual experience of IPS. For example, clients seemed anxious that recruitment to a trial would mean an increased workload for their ESWs, who, they perceived, already had limited time available, without them being further burdened by new clients in a research trial:

I mean at the end of the day they’ve got 25–30, erm, clients, and you’ve only got four advisors maybe five advisors. And to be totally honest, they are also doing more interviews at the job centre in [location] and [location] and that to get more people on this course. So you are limited to the amount of time you can have with them.

C2

Recruitment to a randomised controlled trial of individualised placement and support

One client expressed concern about recruitment in health-care settings:

I don’t think . . . if I got a letter like that from my GP, I think I would just shove it in the bin. Or I would . . . I wouldn’t be very happy.

C5

In contrast, other clients felt that this method of recruitment could be a positive way to identify people who might benefit from the intervention:

That sounds like a good idea, because in a way when I was put on my antidepressants the doctor who gave me the antidepressants and telling me what to do, he told me that I needed to be part of a support programme, you are not gonna be able to do this alone, you’ve got your church, you’ve got your wife but you are gonna need more than that. You need someone to steer you in the right direction, which I have done and I continue to do.

C4

One of the core precepts of IPS is that participation is voluntary and dictated by client choice. Even so, our interviewees appeared confused about whether their enrolment in the SJP IPS programme was voluntary or mandatory. Although the ESWs explained at the outset that the programme was completely voluntary, some clients stated that they did not feel they had a choice about participation, particularly if they were referred by the job centre (which was the case for the SJP, but would not be the case in the planned pilot study). This uncertainty about their freedom of choice regarding employment services was particularly unhelpful when trying to elicit their engagement with employment-related research and when explaining the voluntary nature of research participation:

Even the advisors say it’s ‘voluntary’ it’s not voluntary . . . when you go to see the advisor at the job centre they said ‘you’re on the work activity group, you must be doing something’ so they put you on [IPS programme]. And then when you come here, they say it’s all voluntary. But it’s not voluntary; the job centre put you on this course for a reason.

C3

Clients also commented on the large volume of paperwork that arose from participation in the programme and evaluations of the IPS (i.e. evaluations of the SJP and unrelated to the current research) and that the need for this was not apparently explained to them. One client did not understand the purpose of the volume and content of questions asked in evaluations:

Yeah it’s like these [consent forms and information sheets]. Tick this thing on the computer. Tick, tick, tick. One question was did you have school dinners as a child? Yeah what’s that about?

C3

One ESW hypothesised that individuals recruited in different settings may differ from the clients who were currently being offered IPS:

. . . the referral would be different, it would be interesting to see those clients coming from a doctor’s surgery that are told to speak to someone, ’cause their mentality might be different, to people that are in the process of referrals coming often from the job centre.

ESW5

Primary care-based health-care professionals discussed recruiting eligible patients from health-care settings. They felt that it would be possible to undertake database searches using the Read codes. Read codes are the standard clinical terminology system used in general practice in the UK. 35 They provide a hierarchical clinical coding system for the purpose of reporting research decision-making and allow data to be shared reliably between different computer systems. They have been used previously for chronic pain. 36 However, the PCPs recognised that currently no Read code for unemployment exists, and so searches would identify patients with pain and certified sickness absence, but not unemployment. PCPs suggested that Read codes for chronic pain conditions could be used in conjunction with medication codes (e.g. opioids or gabapentinoids) to identify potential participants.

The PCPs also believed that they could personally identify individuals who would benefit from the programme based on regular contact through primary care services.

About the nature of the individualised placement and support intervention

Employment support workers were in agreement with offering IPS after only 3 months of unemployment, which they thought would be particularly beneficial. The clients made the same point, suggesting that the sooner after losing their job someone could enter the programme, the better it would be:

Because everybody needs that helping hand, if you think about it, if somebody’s just come out of work, for 3 months and they’ve got nothing, that’s where they’re starting to lose the point, ‘I’m unemployed, I’m signing on, I’ve gotta do this, I’ve gotta do that . . . you know where do I go next?’ We don’t want that person to go 3 months after that, 6 months unemployed and still going nowhere, they need to be somewhere where they get the support, yeah I totally agree with that.

C4

Likewise, the PCPs emphasised the importance of early intervention after unemployment:

I think the sooner you can get someone back to work, the better.

PCP4

The ESWs felt that IPS should continue to be available for longer than 1 year, as the process of preparing someone for work and securing employment could be lengthy. Clients, likewise, reported that it could take time to get someone ready for employment and into the workplace.

The pivotal role of their individual ESW in successful IPS was emphasised by the clients and, in their view, this relationship was crucial in finding clients suitable employment. On the other hand, some clients described a lack of continuity in the programme and felt that they had not developed a relationship with a single ESW, having met multiple different ones, which had negatively affected their experience of the programme:

I’ve just been moved from one advisor to another advisor, to a new one.

C2

Clients reported that ESWs asked about their potential needs and barriers to creating an individualised plan. One client recalled that the specific details of her condition had not been considered, but rather a very general discussion of her disability and illness:

So, for people with chronic pain, or anybody with mental health, or, you know, or anything that’s specific, I think what would improve this service is having an advisor who specialised in that condition. Or in a couple of things. It’s having that understanding, it bridges that gap.

C5

It seemed to the clients that personalised advice and a holistic approach were key features of the IPS intervention. Likewise, ESWs discussed the importance of tailoring IPS to each individual client. This was usually achieved by discussion with clients, as the ESW had limited knowledge about the impact and management of specific conditions:

. . . you should have advisers that have training around chronic pain and there should be a fully comprehensive directory of signposting people.

ESW4

Clients were aware of the existence of other employment interventions available for unemployed people. However, IPS was felt to be the best approach for patients with chronic pain, as other employment interventions were seen as not appropriate for individuals with complex issues:

. . . the other programme, they understood my problems but they didn’t do anything about it.

C4

The ‘control’ intervention was mentioned by the PCPs. The PCPs reviewed the draft TAU booklet that would be provided to all subjects. They reviewed the booklet positively and, in particular, highlighted the vernacular language used throughout and the reader-friendly style in which it addressed commonly asked questions without overwhelming the reader with excessive information:

I think it’s very useful, I think it will help people . . . I think patients will find it quite useful.

PCP8

The PCPs reported willingness to randomise patients to both the IPS and control interventions. One PCP explained that in previous studies participants had been unhappy if they had been randomised to a control group, and felt that it would be important to explain the benefit of both interventions:

I tend to . . . not sell it if it’s a non-intervention or control, but actually saying . . . you are actually really important in this study as well. They are part of it and they are helping. If we get to the actually nitty gritty and we are actually recruiting patients, then they’ve got that far, and we’ve talked about it, and we’ve consented them, then hopefully they are still on board.

PCP4

Outcomes to be assessed in a future trial

Participants appreciated that the outcome of the programme would be entry to employment, although they indicated that a client may well not have found employment within the relatively short length of the proposed intervention (i.e. 6–12 months). At the time of interview, none of the clients on the SJP IPS programme had secured paid employment, but all were keen to discuss the progress they had made. They highlighted the skills they had gained from the programme that made them qualified for employment, with ‘job-readiness’ seen as a potential outcome for a future study:

I feel a lot better about starting now, I don’t expect anything to happen until I’ve been here a few months or so, one thing at a time, I need some solid ground to stand on.

C7

Some clients also described a boost in their confidence since starting the programme and reported that they were being more active in daily life:

. . . it gets me out of the house and that you know what I mean, well . . . I’m out and about every day.

C6

Employment support workers recognised that the likely principal outcome of IPS would be entry to employment. However, they also recognised the probability that clients may not yet have secured employment by the end of the intervention. ESWs were keen to talk about the success stories of the IPS programme, notably client improvement in several quality-of-life domains.

The ESWs highlighted the skills that clients had acquired from the programme, which had enabled them to consider a work placement in the future. ‘Job-readiness’ was therefore proposed as a potential outcome for a future study. The importance of building clients’ confidence was also noted:

The knee jerk reaction, which throws up the barriers in the first place. So you’ve got to get those down. And by doing that, when people talk about it, when you are chatting with the client and I’ll say ‘but if you are doing that, why don’t you take it. it’s the same thing but you are on a different’, and they go ‘ohhh right’. Erm, so you are getting those kind of barriers down. At the same time as doing that, ’cause you actually understand, it builds their confidence. And ‘maybe I could do that, maybe I could plan’.

ESW3

Similar to the ESWs, PCPs speculated about the importance of the intervention in building clients’ confidence. Participants also discussed changing clients’ attitudes and views about work.

The PCPs postulated a number of benefits of employment for individuals with chronic pain. For example, they suggested that employment could increase physical activity, which in turn might reduce pain levels. In addition, they highlighted the link between chronic pain and mental health, stating that improving social interaction and sense of achievement through work could improve depression. It was thought that employment could improve patients’ overall quality of life:

So then at least these sort of work based programmes are starting to tackle that, helping people to get out of the house regularly, introducing some sort of ‘maybe I could do something’, a degree of hopefulness, where there is a degree of hopelessness.

PCP8

A summary of all of the barriers to and facilitators of a future trial of IPS for people unemployed with chronic pain that were identified from WPs 1–3 is shown in Table 2.

| Specifics of trial design | Barrier | Facilitator |

|---|---|---|

| Doing a trial | Is it voluntary to take part or compulsory?Client | This is a good thing to test. It is importantClient, PCP, ESW |

| Recruitment to a trial | Recruitment might be challenging in primary care as our GPs do not know that we are employed/not employedClientI would not be happy if my GP wrote to me about a job interventionClientThere is a risk of sending a lot of letters to people with chronic pain who currently are in workPCP | Lots of opportunities to find unemployed people with chronic pain: job centre, from other employment programmes, chronic pain services, physiotherapists, rheumatologists, support groups, community groups, librariesClientI would be more likely to consider this if my GP recommended it for meClientWe can find people using Read code searches of the primary care database. Although no code for ‘unemployed’, we can use chronic pain and medications (e.g. opioids)PCPWe know who these patients are personallyPCPRecruiting from places other than the Job centres might bring in people who are different and perhaps better motivatedESW |

| Acceptability of the intervention | It needs to be clear that it is a choice to go on the programme that it is not mandatory and that you are not being ‘forced’ into work by anybodyClientClients need to be motivated to want to work for this intervention to be possibleESWClients sometimes need more than 12 months’ support to be ready to apply for competitive employmentESW | A trial offering this support earlier after you have lost your job would be likely to be much better for people before they have lost confidence, etc.Client |

| Delivering the intervention | ESWs would need extra training in chronic painClientWe would need to know more about chronic pain and chronic pain services and management to do thisESW | The relationship with the ESW is crucial for this and it works best when you have continuity and build a relationshipClient |

| Process | There is a lot of paperwork already involved in IPS assessmentsClient | |

| Acceptability of the TAU | The booklet provided for treatment as usual is brilliantClient, PCP, ESWI think it would be very helpful and would be happy to recommend patients if they could have this or the treatmentPCP | |

| Outcomes that are important | Motivation to work will be an in important factor determining outcomePCP | Although your main reason for attending is to get a job, you get so much more out of it, for example confidence, increased social interactionClientThe benefits will include less pain, more exercise, less depression, better quality of life, not just a jobPCPThe clients develop over time; they are not all ‘ready’ for a job at the same stage but you see them benefiting in other ways to begin with. ‘Readiness for work’ could be an important outcomeESW |

Discussion work packages 1–3

In general, all three groups were enthusiastic about the proposal of a future trial of IPS for people unemployed with chronic pain. Compared with other employment interventions, both clients and ESWs favoured the choice of IPS because of its personalised approach. Everybody thought that employment could pose future health benefits. Clients and ESWs felt that they would need additional training to enable them to provide IPS for people with chronic pain. It was viewed as important that motivation to work was measured and that clients should feel that they have the choice to participate. The importance of a longer-term relationship with the ESW was emphasised by clients, something previously reported from another qualitative study undertaken among mental health IPS patients in a RCT. 37 Early intervention shortly after unemployment was thought to be key. Likewise, it was considered important that the duration of intervention could be flexible, as not everyone will achieve employment within a fixed time. Finally, although employment rates were an essential outcome, the parties all identified a number of other relevant and important outcomes that could be modified by this intervention, including confidence, mental health, increased physical activity and quality of life.

The opportunity for the current research arose from the existing SJP-funded pilot of IPS available through local job centres for anyone who was unemployed ≥ 2 years with a long-term health condition. Therefore, the clients had all experienced very long-term unemployment. It is insightful and interesting that clients pointed to the importance of offering IPS early after unemployment and they were extremely positive about the InSTEP pilot study recruiting after just 3 months’ unemployment. Re-employment rates are known to be considerably lower after prolonged unemployment because of a complex array of factors, including physical and mental health impacts, loss of confidence and self-efficacy, de-skilling and financial dependence on welfare benefits. 37–42 There may also be a strong selection effect (i.e. those best able to RTW will tend to do so sooner). It is important in planning any trial to consider how to best time the intervention to provide the greatest benefit. The views expressed by our interviewees reinforce our own view that consideration needs to be given to offering IPS as soon as possible after unemployment. Notably, there is a Norwegian trial currently underway that is recruiting individuals with more than 2 years' unemployment. 43

Clients were positive about the relevance and importance of a future trial that would recruit unemployed individuals with chronic pain. However, we encountered challenges framing research in this field to clients who struggled to comment on a hypothetical trial without referencing it to their own IPS engagement. In particular, we found that recent SJP clients were uncertain as to how voluntary the nature of their engagement in the IPS programme was, and this appeared to lead to further confusion when the concept of research was introduced. Our findings highlighted that trial participants may need additional support and explanation of the purpose of the research and their rights to give or withhold consent to participate, including withdrawing their consent at any time. Clients appeared to feel that they were compelled to engage in the IPS programme, fearing that if they did not they would be at risk of compromising their welfare benefit payments. Perhaps because of cultural differences, or differences in national health and welfare systems, no such problems were reported in the recent Norwegian pilot study. 43 In developing a UK trial, researchers will need to be sensitive to this complexity, and make every effort to ensure that participants have understood the voluntary nature of participation in IPS and research about IPS. This issue will also need careful consideration when defining the content of the patient information leaflet and will need taking into account in a situation where IPS is not widely available (i.e. deciding whether or not it is ethical to offer IPS to only those who give consent to take part in the trial).

A key challenge identified was the lack of employment status information in existing UK health-care databases and a lack of availability of linkage between health-care databases and employment databases. PCPs saw this as having important implications in terms of future trial design (i.e. a lower level of recruitment and higher attrition than might be observed in a different population, and the need to consider specific strategies to enable ongoing participation both with the IPS intervention and with the research trial).

The study highlighted an important challenge for a future definitive trial in terms of obtaining and maintaining engagement with this client group. To try to maximise participation, a choice of a face-to-face interview or a telephone interview was offered. Despite this, we found that a number of those who had agreed to participate were unavailable at the agreed time and place. This may be because individuals with chronic pain frequently have complex problems, including low self-efficacy, poor organisational or health literacy, unpredictable symptoms and comorbid conditions (e.g. depression and anxiety44). It was interesting that the PCPs also alluded to potential difficulties in undertaking research with this population because of their complex problems. These issues, however, are very similar among people with severe mental health conditions, for whom IPS has shown excellent efficacy. Therefore, design of any trial will need to take account of these issues, perhaps predicting a lower level of recruitment and a poorer rate of retention than that seen in other client groups. The design should also consider specific strategies to enable ongoing participation, both with regard to the intervention and the research. Interestingly, however, such challenges may not differ markedly from those reported in a trial of IPS for people with serious mental illness. 45

The findings do need to be considered alongside some limitations. First, although care was taken not to provide too detailed an explanation about the research aims to the ESWs who identified possible client participants, it is possible that clients who agreed to take part in WP 1 differed from other clients, and may have been more positively disposed to research and derived more benefit from the SJP IPS intervention compared with those who declined an interview. Unfortunately, the study design did not provide the opportunity to explore the views of those who did not wish to participate. Second, the views of the PCPs were elicited from two general practices that had volunteered to take part. There is therefore the possibility that the views expressed by the PCPs were generally more positive about our research aims than those of a wider sample of PCPs.

In conclusion, WPs 1–3 identified a number of barriers to and facilitators of a future trial of IPS for people unemployed with chronic pain. The insights from clients, ESWs and PCPs fed directly into the design of WP 4, the questionnaires at baseline and follow-up, and the design of the intervention and the pilot trial.

Work package 4: the InSTEP pilot trial

Study design

Work package 4 was a pilot primary care-based longitudinal study (i.e. the InSTEP pilot trial), which tested the feasibility of a RCT, with follow-up at 3, 6 and 12 months.

Research question

The research question was:

-

Among people of working age who are unemployed for > 3 months with chronic pain but wish to work, how feasible is it to undertake a RCT to test the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of IPS compared with a control, and what should be the outcome for a definitive trial?

The study aimed to:

-

test methods of recruitment and evaluate the acceptability of procedures for consent and randomisation to the IPS intervention or TAU

-

develop and ultimately manualise IPS for people with chronic pain by developing training for ESWs, creating shared documentation and integrating pain management planning by a pain specialist in conjunction with the ESWs

-

measure adherence to the study protocol and rates of attrition with follow-up of all participants using postal questionnaires at 3, 6 and 12 months

-

evaluate the acceptability of questionnaires in terms of whether or not participants can and do complete them as intended

-

inform the choice of primary outcome measures (e.g. competitive employment, quality of life, health and health economics) for a definitive trial.

In doing this, we aimed to assess any unforeseen impact on the NHS from trying to place chronic pain patients back into employment to gain an indication of the success levels and what should be measured in a definitive trial, so as to ensure that a more efficient, cost-effective trial to fully test the intervention might be ultimately conducted.

Study process

Supported by the Clinical Research Network, we advertised the research to identify practices willing to recruit for the study. Interested practices were asked to test the different methods of recruitment we had devised from WPs 1–3, including displaying posters for self-referral, Read code searches followed by a mailshot to those identified, opportunistic recruitment during appointments and opportunistic screening after hand-searching records.

All potential participants identified by any strategy were sent a study pack provided by the research team. The pack comprised a personalised invitation letter, an information sheet explaining the purpose of the study, a reply slip and a pre-paid envelope in which to return the reply slip to the study co-ordinator. Interested individuals were offered a number of ways by which they might contact the research study co-ordinator (i.e. telephone, e-mail or by completing and posting a reply slip in the pre-paid envelope).

Pre-assessment screening

All individuals who returned a reply slip were subsequently telephoned by the study co-ordinator at their convenience. This provided the opportunity to discuss the study and address any questions that the individual might have had. If agreeable, the study co-ordinator completed a brief eligibility screening form with the individual over the telephone to confirm that they:

-

were able to provide written, informed consent

-

had not previously been referred to, or had taken part in, the IPS programme via Southampton or Portsmouth city councils

-

had chronic pain (i.e. pain continuing for > 3 months)

-

had completed the diagnostic pathway for their chronic pain

-

did not anticipate recovery within the coming 12 months

-

wished to RTW.

Following satisfactory completion of the screening form, the individual was asked to give verbal consent to randomisation by the study co-ordinator. If agreeable, the participant was then randomly allocated by computer-generated algorithm (block 1 : 1) to either the active IPS intervention arm of the study or the TAU control arm.

Finally, the study co-ordinator informed the participant regarding the next (baseline visit) stage of the study. If randomised to the TAU arm, the research co-ordinator herself telephoned to make the baseline appointment at their general practice. If randomised to the intervention, the local ESW telephoned the participant to arrange the baseline appointment at the local city council premises.

Treatment as usual/control arm

There was no evidence-based NHS alternative to IPS available and suitable for use as a ‘control’ for the pilot trial. However, a number of services are available and are provided by the Department for Work and Pensions, local government and the voluntary sector, and individuals may self-refer to these services or can be referred by health-care professionals. Although the nature and type of services varies widely by region in the UK. It is not known what proportion of patients with chronic pain discuss their employment status with their GP or other member of the primary care team. It is also not known how comprehensively the PCPs keep themselves up to date about the availability of appropriate services in their area. A significant hindrance for this patient group is that they frequently lack confidence, skills and self-efficacy as a result of their chronic pain and comorbidities, such as depression and anxiety. Therefore, for the pilot trial, NHS TAU was supplemented with a standardised booklet to signpost participants to local employment and health-care services. We chose this approach both for ethical reasons and to encourage participation.

Two booklets were co-designed with our PPI group (i.e. one for each city involved). The resultant booklets were professional looking, informative and tailored to the particular location (i.e. Portsmouth or Southampton), with specific information about local services for pain management and job support, including voluntary and third-sector organisations and health-related advice. The PPI group suggested that pages should be included for participants to make their own notes and to construct a list of goals that was structured towards ultimately enabling gainful employment. The booklets also promoted positive messages about self-efficacy and the value of employment in enhancing health and well-being. It was envisaged that the booklet might be an appropriate vehicle to facilitate discussion with their GP about enhancing their health sufficiently for them to RTW using existing services, and provide clear guidance about local services that might help them seek employment.

Participants randomised to TAU were contacted and offered an appointment, at their convenience, with the study co-ordinator (who had a background as a health-care professional, but had no formal occupational rehabilitation training). At the appointment, any questions about the research were answered, written, informed consent for participation was obtained and the baseline questionnaire was completed (taking approximately 20 minutes). Subsequently, the study co-ordinator spent approximately 10 minutes guiding the participant through the booklet and encouraged them to take it home and read it at their leisure. Travel costs incurred were reimbursed. No further appointments were made.

Individualised placement and support intervention/active arm

Participants allocated to the active arm of the study attended a baseline appointment with the council-employed ESW at the local city council premises, which lasted approximately 1 hour. The ESW confirmed with the individual that they were willing to participate, addressed any further questions that they might have and then obtained their written, informed consent to take part in the study and in IPS. The participant was asked to complete the baseline questionnaire (which took approximately 20 minutes) and was also given a copy of the TAU booklet. The participant was encouraged to take the booklet home and read it at their leisure. Travel costs incurred by participants were reimbursed.

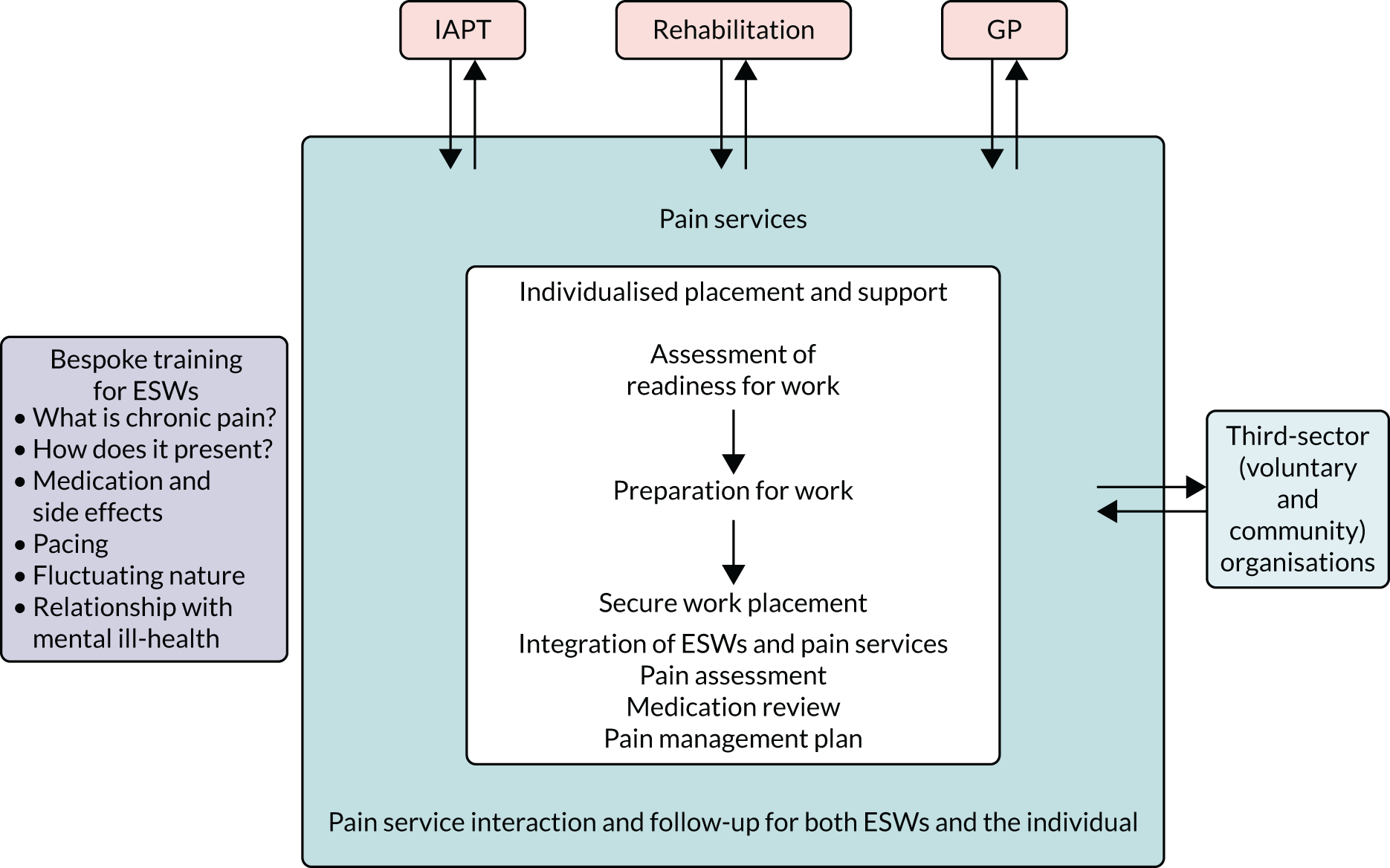

Adapting individualised placement and support for chronic pain patients

Based on the results of WP 3, the ESWs were provided with initial training by the specialist pain team before recruitment commenced. The content of this training focused on what chronic pain is, how it presents in practice, the types of medication used to manage the pain (and their side effects) and common approaches to enable functioning used by pain experts.

Furthermore, all participants recruited to the trial and randomised to IPS were seen by their assigned ESW and the community pain occupational therapist (OT) together for one of their initial appointments. Some standardised integrated documentation was developed, including those domains that both parties usually covered in their initial consultations, which it was agreed would be shared subsequently with the study team. The focus of these joint appointments was on assessment of the participants’ pain and current pain management strategies, with the possibility of specific counselling and support from the OT, signposting to other relevant services or follow-up by the pain team. The ESWs were invited to integrate as much as possible with the local pain services and attend multidisciplinary team meetings, and follow-up pain service use was available to any participant.

Active arm: individualised placement and support (subsequent follow-up appointments)

Following local procedures for IPS, and alongside people participating in the SJP, pilot trial participants met with the ESW as frequently as required to support and develop their employment plans. Fundamentally, this process fell into three stages: (1) assessing preparedness for work, (2) preparing for work and (3) choice of and allocation to, a competitive paid work placement.

Questionnaires

Questionnaires were developed for baseline and reassessment at 3, 6 and 12 months of the pilot trial. The baseline questionnaire was completed with the support of the ESWs or study co-ordinator (during attendance at the baseline visit). The three follow-up questionnaires were posted to allow participants to complete and return the form at their leisure. A pre-paid envelope accompanied the questionnaire. If no response was received after 4 weeks, a reminder letter and a further copy of the questionnaire were sent. On receipt of each completed questionnaire, a £10 shopping voucher was sent to the participant to thank them for their assistance.

Analysis

Our analysis focused on the acceptability of the questionnaire, and the rates of missing data in returned questionnaires and the attrition of participants in both arms. Another aim was to scope the most suitable outcome measures for a definitive trial and define the size of change to carry out power calculations. The questionnaires therefore asked about demographics, past employment history, current employment aims, comorbidities, health-care utilisation and health literacy. The validated tools that were included were the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), health-care utilisation, the Return-to-Work Self-Efficacy Scale, the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS), Waddell’s Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9), self-rated health and Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale. At follow-up, we additionally asked about interviews that the participants may have had for jobs and any new employment that they had taken up.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the:

-

proportion of people identified in primary care who were eligible for the study

-

proportion who agreed to take part

-

rates of attrition in each arm of the trial

-

rates of satisfactory completion of questionnaires in each arm

-

distribution of potential outcome measures through analysis of the questionnaire responses among participants in the control arm.

These data informed the choice of primary and secondary outcome measures for a future RCT. Time-specific differences in self-efficacy measures between the two trial arms were explored using t-tests. Changes over time were explored using random intercept linear and logistic regression modelling for continuous and binary outcomes, respectively, after adjusting for intervention arm. Analyses were carried out using Stata® version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Changes over time in self-rated health were explored using random intercept logistic regression modelling after adjusting for intervention arm.

Results

Recruitment

Our original estimate was that four general practices would be needed to recruit a maximum of 80 pilot study patients. However, to recruit the final sample, we needed to widen our sampling frame to include nine general practices in Southampton and Portsmouth (covering an estimated 200,000 people).

We trialled all of the approaches to primary care recruitment suggested in WPs 1–3 to understand (1) which was most effective and (2) which was most efficient. Table 3 summarises the outcomes of the approaches we made to patients identified through the different recruitment methods.

| Recruitment method | Number approached | Number identified but ineligible | Number recruited |

|---|---|---|---|

| Database search (GP) | 1017 | 31 | 26 |

| Hand-searching records | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Posters in general practices | Unknown | 2 | 0a |

| Opportunistic (GP) | 5 | 5 | |

| Opportunistic (pain services) | 13 | 13 | |

| Total | 50 |

Read code database searches were undertaken by all nine of the participating practices (Box 1). Once they had been carried out, GPs were asked to review the generated lists to exclude anybody who they felt should not be contacted (e.g. because of recent bereavement or terminal illness). After screening, the practice mailed study packs to all those identified to ensure patient privacy and to minimise any concerns a participant may have about disclosure to others.

Exclusions: cancer, palliative, severe enduring mental health condition (as these are eligible for IPS through mental health services).

Drugs search strategyA prescription over the past 3 years, including one or more than one of tricyclics, gabapentinoids or analgesics.

(Rationale for restriction: chronic pain may have resolved if not active prescription drug users.)

Exclude-

Acute migraine treatment.

-

Analgesics: buprenorphine hydrochloride; naloxone hydrochloride (SUBOXONE® (Indivior UK Ltd, Hull, UK)) or methadone, fentanyl > 50 µg, buprenorphine (TRANSTEC®; Napp Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Cambridge, UK) > 70 mg and morphine sulfate (Zomorph®, Ethypharm UK Ltd, High Wycombe, UK) > 120 mg (on grounds upper limits of safe dosing).

-

Neuropathic pain medications: ketamine, sodium valproate (used largely in palliative care) and phenytoin sodium (rarely used in chronic pain patients).

Study information packs were posted by each practice between November 2017 and September 2018. In total, 1017 packs were mailed. In response, 57 patients made contact with the research team after receiving a pack, of whom more than half did not meet the eligibility criteria (e.g. retired, already in paid work, no longer had chronic pain). Great interest in the study was shown by those who made contact and disappointment was expressed by those who were not eligible to participate. In particular, a number of people who made contact with us reported that they were currently working but having difficulties caused by their pain and were keen to have employment support (n = 10). Unfortunately, we were not able to offer this type of support within the terms of the current research project. A further five individuals expressed interest by returning a reply slip to the research team, but were not contactable (this was because an incorrect contact number was provided or messages were left by the study co-ordinator, but no response could be obtained, despite multiple attempts).

Opportunistic screening was carried out through hand-searching of GP records (in one practice) or during GP appointments (at another practice). Using these approaches, those identified were 100% eligible and were all recruited. However, this approach proved to be slow and resource intensive (e.g. the hand-searching took approximately 2 weeks of research nurse time to yield the final six recruited patients).

Posters advertising the study were displayed in all nine practices involved, but yielded only two telephone calls from patients, both of which unfortunately came after recruitment closed.

Despite all efforts, recruitment via primary care was proving challenging and very slow; therefore, with the approval of the TSC, we approached the community pain services in April 2018 to enlist their assistance with recruitment. A targeted face-to-face opportunistic approach was again found to yield a high rate of eligible participants who went on to be successfully recruited (n = 13), but these participants were recruited over a total of 5 months, showing that even with such a personalised approach, the number of patients suitable for the trial was relatively small per head of patient attending pain services.

Ultimately, a total of 50 individuals were successfully recruited to the study using all the different approaches described. Personalised approaches were the most successful and, during the pilot trial, this was achieved most efficiently in community pain services.

Randomisation

Given the delays experienced with recruitment from primary care, block randomisation was compromised by the availability of the IPS intervention until a fixed time point (i.e. until the end of September 2019 and so the final recruit to the active arm was required by September 2018 to achieve the 12-month follow-up). Therefore, after random allocation initially, we subsequently allocated as many of the earlier recruits as possible to IPS until it was no longer available, and the remainder were thereafter allocated to TAU. Importantly, all those recruited from one large practice early on (n = 13) were randomly allocated 1 : 1 so that an assessment of the risk of contamination could be made. In all cases, the participants were recruited to a RCT and gave written informed consent to be allocated randomly to either arm. Nobody in either trial arm expressed dissatisfaction with randomisation or their allocation, and nobody dropped out after allocation or before their first appointment.

Contamination

Although the number of participants involved was small, the risk of contamination was assessed to be low, given that study participants viewed their employment as of limited relevance to their health care and held the same belief about the interest of their GP. GPs were not directly involved with any aspect of the trial and all trial information (including the TAU booklets) was provided by the study team directly and not distributed by practice staff members.

Characteristics of study participants from baseline questionnaires

Table 4 describes the baseline characteristics of those recruited to the pilot study, overall and by allocation. More women than men were recruited and participants were mostly white. A relatively high proportion were single/divorced (n = 21/50). The mean age at which participants left school was 16 years and approximately half attended further education or university. A small minority (n = 4) had university degrees and more than half (n = 30) had vocational qualifications. Interestingly, three participants had never held a paid job. Of the remainder, all had previously stopped working in a paid job, mainly or partly because of their health. When asked to indicate the type of health condition that had led to job loss, responses included chronic pain, but comorbid mental health/stress and ‘other’ diagnoses were also described by participants. Comorbidities were well reported by participants and revealed very high levels of anxiety/depression (n = 33 ‘yes’; n = 3 ‘not sure’). Most of those recruited (n = 41) were looking for part-time rather than full-time work and wanted to work < 24 hours per week.

| Characteristic | All | Trial arm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IPS | TAU | ||

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 20 (40) | 10 (45) | 10 (36) |

| Female | 30 (60) | 12 (54) | 18 (64) |

| Ethnic origin, n (%) | |||

| White | 46 (92) | 20 (91) | 26 (93) |

| Black Caribbean | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Black African | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Black other | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Indian | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (7) |

| Pakistani | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Bangladeshi | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Chinese | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Married | 27 (54) | 8 (36) | 19 (68) |

| Single | 13 (26) | 10 (45) | 3 (11) |

| Civil partnership | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Widowed | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Divorced | 8 (16) | 3 (14) | 5 (18) |

| Living with a partner | 2 (4) | 1 (5) | 1 (4) |

| Age (years) left school (two missing values) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 16.0 (1.1) | 15.9 (1.3) | 16.1 (1.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 16 (15.5–16) | 16 (15–16) | 16 (16–16) |

| Further education/university, n (%) | |||

| No | 24 (48) | 10 (45) | 14 (50) |

| Yes | 26 (52) | 12 (55) | 14 (50) |

| Educational level, n (%) | |||

| O levels/GCSEs (or equivalents) | 38 (76) | 15 (68) | 23 (82) |

| A levels (or equivalents) | 9 (18) | 3 (14) | 6 (21) |

| Vocational training certificate(s) | 30 (60) | 10 (45) | 20 (71) |

| University degree(s) or HND | 4 (8) | 2 (9) | 2 (7) |

| Higher professional qualifications | 4 (8) | 1 (5) | 3 (11) |

| Ever in paid job, n (%) | |||

| No | 2 (4) | 1 (5) | 1 (4) |

| Yes | 48 (96) | 21 (95) | 27 (96) |

| Time (years) since last in paid work | |||

| Median (IQR) | 3.0 (1.3–5.5) | 2.8 (1.3–4.1) | 3.2 (1.3–16.1) |

| Missing, n | 11 | 4 | 7 |

| Leaving job because of health, n (%) | |||

| No | 3 (6) | 1 (5) | 2 (7) |

| Yes, mainly because of health | 34 (68) | 16 (73) | 18 (64) |

| Yes, partly because of health | 11 (22) | 4 (18) | 7 (25) |

| Missing | 2 (4) | 1 (5) | 1 (4) |

| HRJL (type of health problem), n (%) | |||

| Chronic pain | 24 (48) | 14 (64) | 10 (36) |

| Back, neck, arm, shoulder or leg | 34 (68) | 13 (59) | 21 (75) |

| Mental health problem or stress | 15 (30) | 5 (23) | 10 (36) |

| Heart or lungs | 2 (4) | 1 (5) | 1 (4) |

| Other | 6 (12) | 3 (14) | 3 (11) |

| N/A (no HRJL) | 3 (6) | 1 (5) | 2 (7) |

| Future work prospect, n (%) | |||

| Part time | 41 (82) | 17 (77) | 24 (86) |

| Full time | 9 (18) | 5 (23) | 4 (14) |

| Hours wanted in part-time future job, n (%) | |||

| 0–8 | 10 (20) | 5 (23) | 5 (18) |

| 9–15 | 13 (26) | 4 (18) | 9 (32) |

| 16–24 | 13 (26) | 6 (27) | 7 (25) |

| > 25 | 3 (6) | 2 (9) | 1 (4) |

| N/A | 9 (18) | 5 (23) | 4 (14) |

| Missing | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (7) |

| Comorbidities reported, n (%) | |||

| High blood pressure | |||

| No | 36 (72) | ||

| Yes | 9 (18) | ||

| Not sure | 5 (10) | ||

| Heart problems | |||

| No | 47 (94) | ||

| Yes | 3 (6) | ||

| Not sure | 0 (0) | ||

| Diabetes | |||

| No | 46 (92) | ||

| Yes | 4 (8) | ||

| Not sure | 0 (0) | ||

| Kidney disease | |||

| No | 49 (98) | ||

| Yes | 1 (2) | ||

| Not sure | 0 (0) | ||

| Previous stroke or TIA | |||

| No | 48 (96) | ||

| Yes | 2 (4) | ||

| Not sure | 0 (0) | ||

| Arthritis | |||

| No | 27 (54) | ||

| Yes | 19 (38) | ||

| Not sure | 3 (6) | ||

| Missing | 1 (2) | ||

| Asthma or other lung problems | |||

| No | 37 (74) | ||

| Yes | 12 (24) | ||

| Not sure | 1 (2) | ||

| Anxiety or depression | |||

| No | 14 (28) | ||

| Yes | 33 (66) | ||

| Not sure | 3 (6) | ||

| GI or other stomach problems | |||

| No | 37 (74) | ||

| Yes | 10 (20) | ||

| Not sure | 3 (6) | ||