Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/04/46. The contractual start date was in September 2014. The draft report began editorial review in January 2020 and was accepted for publication in July 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Day et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this text have been reproduced with permission from Day et al. 1,2 © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd and Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Cataract surgery is one of the most commonly performed operations in the Western world, with almost half a million procedures performed per year in the UK3 alone. The current standard method, phacoemulsification cataract surgery (PCS) (using ultrasound), was introduced > 50 years ago. 4

Complications can affect recovery, and some complications are serious and associated with long-term poor outcomes [e.g. posterior capsule rupture (PCR)/vitreous loss was reported to occur in 1.4% cases in the recent UK National Ophthalmology Database audit for the period 2016–17]. 5 Among patients who experience serious outcomes, one-third have complaints about their eye and vision 3.5 years after surgery. 6 One in five patients requires further surgery7 and they are at a risk of retinal detachment within 3 years that is 15 times higher than in those who do not have further surgery. 8 The surgical learning curve is associated with complications, with a 1.6 to 3.7 times higher risk of PCR for surgeries performed by non-consultant-grade doctors. 9 Other complications, the majority of which are less serious, may mean a longer operation duration and delayed healing, as well as additional appointments and the need to use eye drops. Patients can be devastated when suffering a complication and, because of the importance of vision for daily activities, can find even minor complications very distressing.

Femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery (FLACS) first became commercially available almost 10 years ago. The reported advantages include more accurate positioning, the shape and size of the capsulotomy when compared with a capsulorrhexis,10–12 and less intraocular lens (IOL) tilt13 with fewer higher-order aberrations. 14 In addition, by using a laser to fragment the crystalline lens, less ultrasound energy is required to complete the lens removal and reductions of 70–96% of effective phacoemulsification time (ultrasound power) have been reported,15–17 with zero effective phacoemulsification time being possible in 30% of operations in a recent series. 15 This study15 also reported a 36% lower endothelial cell loss in the laser-assisted procedures than when using manual phacoemulsification.

When introduced, laser cataract surgery platforms were marketed as bringing a stepwise improvement in surgical technique and were used as a differentiating factor between cataract surgery providers.

The timing of FACT (Femtosecond laser-Assisted Cataract Trial) was critical because FLACS was being rapidly adopted worldwide, despite the absence of any randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing its safety and efficacy with that of PCS. Although its potential advantages may be attractive to patients and surgeons, laser-assisted surgery is expensive and there are logistical and practical issues that need to be understood. The absence of good evidence for any advantage of laser-assisted surgery was highlighted in a 2013 review article by Trikha et al. 18 and also by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Horizon Scanning Centre. 19 The topic was identified as a research priority by the national James Lind Alliance Sight Loss and Vision Priority Setting Partnership (see www.fightforsight.org.uk/sightlosspsp; accessed 1 January 2013).

The 2016 Cochrane review20 of FLACS compared with PCS concluded that there was limited evidence to determine equivalence or superiority and that large, adequately powered RCTs were needed. Three meta-analyses have been published;21–23 one found superior refractive outcomes with FLACS,23 whereas the others21,22 found no statistically significant differences in terms of patient-reported visual, refractive and complications. Two large RCTs have recently been completed, namely the French FEMCAT (FEMtosecond laser-assisted versus phacoemulsification CATaract surgery) trial,24 which found no difference in visual or refractive outcomes or complications between arms, and a UK trial of 400 eyes that found similar visual outcomes between treatment arms and a statistically significantly lower posterior capsule tear rate in the FLACS arm. 25

Overall, it was thought that the potential advantages of FLACS were broad and would translate to greater safety and better visual outcomes through greater precision and reproducibility. These systems are expensive but costs may potentially be mitigated by greater efficiency (faster surgery), fewer complications, less repeat surgery and better outcomes. At the time of funding FACT, there was already a demand for FLACS among NHS patients, and some NHS trusts, were tendering for FLACS platforms.

Currently, the cost of FLACS still remains high, which reflects the high development costs. For example, Alcon (Geneva, Switzerland) took over LenSx for US$744M in 201026 and Abbott Medical Optics (Abbott Park, IL, USA) purchased OptiMedicaCorp. for up to US$400M in 2013. 27

FACT will answer important questions about the potential introduction of laser cataract surgery platforms into NHS practice, and will also benchmark current surgical standards.

Aims and objectives

The aim of this trial is to determine if FLACS is as good as or better than PCS in NHS cataract surgical units. The proposed advantages were assessed by evaluating the following at 3 and 12 months post surgery:

-

visual acuity – uncorrected distance visual acuity (UDVA) (primary outcome at 3 months) and corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA) (secondary outcome) in the study eye, measured using the ETDRS (Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study) chart at a distance of 4 m

-

patient-reported outcome measures – vision health status using Catquest-9SF questionnaires

-

ocular complications

-

cost-effectiveness.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design and patients

FACT was a pragmatic, multicentre, single-masked, randomised controlled non-inferiority trial carried out at three hospitals in the UK to compare FLACS with PCS. 28 The three trial sites were high-volume NHS day care surgery units (Moorfields at St Ann’s Hospital, Tottenham; Sussex Eye Hospital, Brighton; and New Cross Hospital, Wolverhampton). The trial received ethics approval from the National Research Ethics Service Committee London – City Road and Hampstead (6 February 2015, reference 14/LO/1937). The design of the trial is detailed in full in the published protocol,28,29 and the final version (i.e. version 4.0) is available (https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/13/04/46; accessed 5 October 2020). The trial adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. 30

All patients were screened and recruited from routine cataract clinics between May 2015 and September 2017. In summary, adults aged ≥ 18 years with age-related cataract with expected postoperative refractive target within ± 0.5 dioptre of emmetropia (i.e. good distance vision) were eligible for participation. All patients provided written informed consent before participation. The patient inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed below, and there were no changes to these after trial commencement.

Participant inclusion criteria

-

Adults aged ≥ 18 years with visually symptomatic cataract in one or both eyes.

-

Patients must be willing to attend for follow-ups at 3 and 12 months following surgery in the study eye.

-

Patients must be sufficiently fluent in English for informed consent and completion of the health state questionnaires.

-

Postoperative intended refractive target in the study eye is within ± 0.5 dioptre of emmetropia.

Participant exclusion criteria

-

Eyes with corneal ring and/or inlay implant(s), or severe corneal opacities, corneal abnormalities, significant corneal oedema or diminished aqueous clarity that are likely to obscure optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging of the anterior lens capsule.

-

Descemetocele with impending corneal rupture.

-

Poor pupil dilatation that is expected to require surgical iris manipulation.

-

Subluxed crystalline lens.

-

Patient unable to give consent or unable to attend follow-up assessment.

-

Patient unable to be positioned for surgery.

-

Patient scheduled to undergo combined surgery (e.g. cataract and trabeculectomy).

-

Any contraindications to cataract surgery.

-

Any clinical condition that the investigator considers would make the patient unsuitable for the trial, including pregnancy.

Randomisation and masking

Participants were randomly assigned in a 1 : 1 ratio to undergo FLACS or PCS. Randomisation was performed on the day of surgery using a web-based online system (Sealed Envelope™, Sealed Envelope Ltd, London, UK; www.sealedenvelope.com) that used treatment centre, surgeon and one or both eyes eligible as minimisation stratifiers. For participants who required bilateral cataract surgery, the same intervention (i.e. FLACS or PCS) was offered when the patient returned for their second eye surgery, unless the patient wished otherwise. When possible, the second eye was operated on within 8 weeks of the first. Owing to the nature of the intervention, surgeon and participant masking was not possible. All trial follow-ups were performed by optometrists who were masked to the trial intervention.

Procedures

All participants underwent dilated slit-lamp examination prior to being listed for cataract surgery by an ophthalmologist. Patients were treated identically whether they had one or two eligible eyes. All participants underwent either PCS or FLACS with the CATALYS® femtosecond laser (Johnson & Johnson Inc., New Brunswick, NJ, USA) or Femto LDV Z8 (Ziemer Ophthalmic Systems AG, Port, Switzerland) while under topical or local anaesthesia. Trial surgeons were ophthalmologists who routinely performed cataract surgery at their trial sites and who had completed at least 10 supervised FLACS operations and had been certified by the CATALYS or Ziemer manufacturer. In FLACS, the laser was used to perform the capsulotomy and lens fragmentation. Laser arcuate keratotomy could be performed using the CATALYS laser at the surgeon’s discretion. Detailed descriptions of the use of CATALYS31,32 and Femto LDV Z833,34 for cataract surgery have previously been published. All patients had planned implantation of a monofocal IOL. Standard phacoemulsification was performed as per local practice. Management of astigmatism was at the treating ophthalmologist’s discretion. Prior to randomisation, the surgeon indicated if they would use a toric lens if local NHS funding arrangements permitted, a limbal relaxing incision for a PCS patient or an astigmatic keratotomy for a FLACS patient.

Postoperative care, including eye drops, was as per standard unit practice for cataract surgery. If the FLACS laser treatment could not be performed for any reason (e.g. unable to dock, laser machine fault) after a patient was randomised to this arm, the patient underwent PCS.

Follow-up assessments

Patients attended a follow-up visit at 3 and 12 months post surgery to undergo assessment of all end points and to complete all relevant trial questionnaires. If a patient was unable to attend the 3-month visit, they continued to be included in the trial and were encouraged to attend the 12-month follow-up visit. The majority of patients attended a check-up at 6 weeks post surgery (not part of the trial assessments schedule) as a routine part of cataract surgery care. Visual acuity data from this visit were obtained and are reported with the trial results.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was UDVA [measured using a ETDRS logMAR (logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution) chart at a starting distance of 4 m]35 in the study eye at the 3-month follow-up.

Secondary outcomes were CDVA at 3 months in the study eye, safety measures including intraoperative and postoperative complications and corneal endothelial cell count change, and refractive error (spherical equivalent) within 0.5 dioptre and within 1.0 dioptre of intended refractive outcomes. Health-related quality of life was assessed using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), questionnaire plus the vision bolt-on question36 at 6 weeks and 3 months, and patient-reported vision health status was assessed using Catquest-9SF37 (a Rasch-validated instrument) at 6 weeks and 3 months. No changes were made to the trial outcomes after trial commencement.

Outcome measures are detailed in Table 1 and also in the trial protocol (version 4.0, 27 September 2016). For participants without complete postal questionnaire data, a telephone interview was carried out for additional clarification and the completion of missing items. Staff measuring outcomes were all trained in doing so and masked to the trial arm for trial postoperative assessments, including visual acuity, subjective refraction, corneal measurements and endothelial cell count. After these measures had been completed, complications data were collected by reviewing the patient medical notes (masking to this was not possible). Additional secondary outcomes were collected at 12 months postoperatively, including UDVA, CDVA, patient-reported health, safety outcomes and data for a health economic analysis.

| Visit | Time point | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard pre-assessment | Baseline | Randomisation | Follow-up | |||||

| Surgical pre-assessment visit | Randomisation and surgery | Standard non-study post-operation appointment | 6 weeks post surgery (postal) | First trial appointment: 3 months post surgery | 6 months post surgery (postal) | Second trial appointment: 12 months post surgery | ||

| 1 | 1 or later | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| Medical and ocular history | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| Consent for cataract surgery | ✗ | |||||||

| Informed consent and eligibility screening | ✗ | |||||||

| Identification of study eye | ✗ | |||||||

| Visual acuity: UDVA (logMAR), pinhole, with/without glasses (Snellen), each eye | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| Visual acuity: UDVAa and CDVAb (logMAR) each eye and binocular | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| Visual acuity (logMAR) with usual method of correction | ✗c | |||||||

| Subjective refraction | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| Ocular biometry | ✗ | |||||||

| Pentacam® (OCULUS Optikgeräte GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) corneal topography | ✗d | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| OCTe | ✗d | ✗f | ✗d | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria | ✗ | |||||||

| Catquest-9SF questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| EQ-5D vision bolt-on | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Client Service Receipt Inventoryg | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Endothelial cell count measurement | ✗d | ✗f | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Surgery | ✗ | |||||||

| Adverse event collection | ✗ | ✗ | ✗h | ✗ | ||||

Sample size

FACT was designed as a non-inferiority trial to demonstrate that visual acuity following FLACS is not inferior to that achieved following PCS. The non-inferiority margin was based on a difference in mean UDVA of 0.1 logMAR (5 letters or one line measured using a standard ETDRS chart at a starting distance of 4 m) in the study eye at 3 months, which was considered to be clinically important to patients and ophthalmologists based on prior patient and public input to the trial design.

Interpretation of the trial results is based on the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the difference between FLACS and PCS. If the 95% CI for the difference lies wholly to the left of the non-inferiority margin, then we can conclude that FLACS is not inferior to PCS. If the 95% CI for the difference lies wholly to the left of zero (i.e. the 95% CI excludes zero), then we can conclude that FLACS is superior to PCS. We performed sequential testing of the non-inferiority and superiority hypotheses.

If there is truly no difference in mean logMAR between the two treatment arms, then 432 patients (216 per arm) would provide 90% power to be sure that a 95% two-sided CI would exclude the non-inferiority limit of 0.1 logMAR, assuming a common standard deviation (SD) of 0.32. 38 However, although treatment was delivered to patients individually, each patient could not be assumed to generate independent information because patients were clustered within surgeons. To take account of clustering by surgeon (i.e. the variation between surgeons in the treatment effect) the sample size was increased by an inflation factor:

Assuming that a total of 16 surgeons contributed an average cluster size (m) of 50 patients and an estimated intracluster correlation coefficient (ρ) of 0.012 gives an f of 1.59. Having a total of 688 patients (344 per arm) enabled the trial to take account of clustering by surgeon. To allow for an anticipated 15% dropout rate (the median age of patients undergoing cataract surgery in the UK is 77 years38 and many have significant systemic comorbidities), the total sample size required was 808 patients.

Statistical analysis

All primary and secondary analyses were carried out on an intention-to-treat basis, such that all consented randomised participants who had attended the follow-up visits were included in the analysis set in their allocated treatment group, regardless of the treatment that they received. All analysis models included information on the site and on the number of eyes eligible as covariates; surgeon identifier was included in the analysis models as random effects. The model for the primary outcome was also adjusted for baseline habitual logMAR visual acuity values, and similar adjustments were made for any continuous secondary outcomes if a baseline value was recorded. Astigmatism at baseline (as measured by keratometry readings from Pentacam corneal topography) was incorporated as an adjustment factor in the analyses of visual acuity outcomes. Adjusted treatment effect estimates, two-sided 95% CIs and two-sided p-values were reported for each outcome measure.

In a pragmatic clinical trial in a predominantly elderly patient group, some patients are inevitably lost to follow-up. Outcomes for such patients were therefore not fully observed. This could lead to biased estimates and standard errors, which could potentially mask or artificially augment any treatment effect. To reduce any potential impact of bias, multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) was used to impute data for any missing 3-month follow-up visits. Missing data were assumed to be missing at random conditional on all variables included in the imputation model and so to be independent of the values of the unobserved data themselves.

Enough imputed data were generated that the Monte Carlo error of the treatment effects estimated in the multiple imputation analysis was acceptably small (15 sets). The following (fully observed) variables were included in the imputation model: treatment arm, site, sex, age, ethnicity, astigmatism, prior ocular co-pathology, the number of eyes that were eligible for surgery, ocular complications and intraoperative complications. All available outcomes were included in the imputation model (UDVA, CDVA, central retinal thickness and spherical equivalent refraction index). In addition, postoperative visual acuity at 6 weeks, collected as part of NHS standard care, was included in the multiple imputation model.

For all continuous outcomes, including the primary outcome, of UDVA at 3 months, mixed-effects linear regression models were fitted to estimate the difference in outcomes between the two treatments (FLACS – PCS), together with a two-sided 95% CI, adjusting for baseline habitual logMAR visual acuity and the randomisation stratifiers (centre, surgeon and whether patients had one or two eligible eyes). Surgeon was included in the models as a random effect (random intercept) to account for clustering by surgeons. The effects were estimated using restricted maximum likelihood, and the results were presented using the mean difference with its corresponding 95% CI. For the primary outcome, if the upper end of the 95% CI for the difference between treatment means does not cross the non-inferiority limit of 0.1 logMAR, then FLACS is regarded as non-inferior. If the mean difference is negative and its 95% CI lies wholly to the left of zero, then we can conclude that FLACS cataract surgery is superior to PCS. Further supportive analyses of the primary outcome were also carried out, including a per-protocol analysis and a complete-case analysis. Binary secondary outcomes were analysed using mixed-effects logistic regression models, adjusting for stratification variables as above and baseline values as above.

The study eye is defined as the first eye to undergo cataract surgery and is chosen by the patient in discussion with the surgeon. For patients having surgery on both eyes, the fellow eye will also receive the allocated intervention unless the patient expresses a wish not to receive the same intervention. The fellow eye refers to fellow eyes eligible for trial surgery that received surgery after the study eye and within 3 months of study eye surgery. Note that where both eyes were eligible for surgery, there is no guarantee that the fellow eye received the same intervention as the study eye (as patients could express their wish not to receive the same intervention in the fellow eye). Given the observational nature of data on fellow eyes, outcomes are presented by treatment received and for the subgroup of patients who underwent surgery in the fellow eye within 3 months of surgery in the study eye.

Health economic analysis

The aim of the economic evaluation was to conduct a within-trial analysis of the mean incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained by FLACS compared with that gained by PCS over 12 months from a health and social care cost perspective. A secondary analysis from a societal cost perspective was also conducted.

Questionnaires

The following outcome measures were used for the trial-based component of the economic evaluation:

-

Study case report form (CRF) – a researcher completed the pro forma that included information on the surgery. It included timings for the FLACS patients and details on anaesthesia, consumables, intraoperative adverse events and postoperative adverse events for patients in both arms.

-

FACT costing study – this was a time-and-motion study of a sample of FLACS and PCS surgeries carried out by a trial research associate. This includes specific information on the timings of patient movements and the seniority of staff who were involved in the procedures.

-

Client Service Receipt Inventory39 – this is participant-completed questionnaire asking about health and social care resource use, the impact on employment, out-of-pocket costs and about the use of help from unpaid carers in the past 3 months at baseline and at 3 and 6 months post-surgery follow-up, and over the past 6 months at the 12-month follow-up.

-

EQ-5D-3L – this is a five-item, three-level questionnaire, scored from 1 (no problem) to 3 (extreme problems). Value sets corresponding to participants’ responses to the items are available from EuroQoL and the paper published by Dolan. 40 These value sets are used to calculate utility scores used in the QALY calculation. The EQ-5D-3L also includes a 100-point visual analogue scale, anchored at 0, the worst health imaginable, and 100, the best health imaginable. Participants mark how they feel on the day that they complete the measure. The vision bolt-on for the EQ-5D-3L was also completed, which has an associated utility tariff. 41

Costs of FLACS and PCS

The incremental cost of FLACS compared with PCS was calculated using bottom-up microcosting based on data collected from sites and trial CRFs. Table 2 lists all of the cost components used to cost FLACS and PCS and the details of how this costing was conducted; the costs of the components are based on standardised items used to cost the use of operating theatres. 46 The mean surgery time, including laser, for each patient was calculated using data from the FACT surgery CRF. Observational data were collected for 12 patients (FLACS arm, n = 7; PCS arm, n = 5) to assess if there were any key differences in how FLACS and PCS were delivered with regard to pre-surgery assessments and staffing, and to determine what model of delivery for FLACS was being used. Staffing levels were those recommended by the Association for Perioperative Practice. 46 Both FLACS and PCS had the same level of staffing except for a health-care assistant for the FLACS during that specific component of the surgery time only.

| Cost component | Trial data source | Costing source and calculation |

|---|---|---|

| Capital cost of laser | Hospital finance data | Annualised per-patient cost, including depreciation in FLACS arm only42 |

| Single-use patient interface for FLACS (‘click fee’) | Hospital finance data | Per-patient cost in FLACS arm only |

| Maintenance cost of laser | Hospital finance data | Per-patient cost in FLACS arm only |

| Surgeon training | Professional opinion (Alexander C Day, UCL, personal communication) | PSSRU43 for surgeon costs |

| Preparing the patient and theatre before surgery | Assumed to be the same in both arms | |

| Anaesthetist | FACT surgery CRF | Duration of surgery multiplied by the cost of anaesthetist time (from PSSRU)43 |

| Anaesthetic drugs | FACT surgery CRF | Costed if different between arms; British National Formulary44 |

| Nurse cost | FACT surgery CRF for the duration of surgery | Duration of preparation plus duration of surgery multiplied by weighted cost (accounting for different bands from PSSRU43) |

| Surgeon | FACT surgery CRF for the duration of surgery | Duration of surgery multiplied by cost from PSSRU43 |

| Health-care assistant for laser | FACT surgery CRF for the duration of FLACS laser | In FLACS arm only. Duration of laser multiplied by cost from PSSRU43 |

| Consumables | FACT surgery CRF | Costed if different between the two treatment arms; costs from hospital finance data |

| Cleaning up after theatre | Assumed to be the same in both treatment arms | |

| Recovery of patient | Assumed to be the same in both treatment arms | |

| Medication following surgery | FACT surgery CRF | British National Formulary 44 |

| Adverse events | FACT surgery CRF | NHS Reference Costs 2017–2018 45 |

| Overhead activity | FACT surgery CRF for the duration of surgery | PSSRU43 for overhead costs |

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to evaluate the impact of using an alternative model of delivery47 whereby two theatres are used for FLACS at the same time. In this model, the level of staffing is the same, other than only one anaesthetist is needed across the two theatres.

A previous study by Roberts et al. 47 found no difference in consumable and anaesthetic costs between FLACS and PCS. As a result, consumables and anaesthetics were costed only if there were any significant differences in their use between the trial arms. The means, SDs and ranges were reported for each component.

Health, social care and societal costs

Health, social care and societal resource use was collected using a modified version of the Client Service Receipt Inventory39 at baseline and at 3, 6 and 12 months, which asked about the past 3 months at baseline and at 3 and 6 months and about the past 6 months at 12 months. Health and social care resource use was costed using the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU)43 and NHS Reference Costs 2017–201845 (Table 3). Private and out-of-pocket costs were assumed to be the same as publicly funded costs given that the quality of data on out-of-pocket costs was poor (this information was missing in the majority of cases). Household adaptations were costed from the PSSRU43 and NRS Healthcare. 48 Participants were asked the number of hours of unpaid help they received from family and friends each week over the previous 3 or 6 months. This was then multiplied by the number of weeks (13 weeks for 3 months and 26 weeks for 6 months) and the cost per hour or unpaid carer time, costed the same as home help, at £28 per hour. 43 Lost earnings were costed as the mean hourly earnings in the UK in 2017/18 of £16.16 per hour. 49

| Resource use | Unit cost (£) (per contact) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| GP: surgery | 28 | PSSRU43 |

| GP: home visit | 64 | PSSRU43 |

| GP: telephone | 21 | PSSRU43 |

| Primary care nurse: telephone | 9 | PSSRU43 |

| Primary care nurse: clinic | 12 | PSSRU43 |

| District nurse | 49 | PSSRU43 |

| Occupational therapist: home | 99 | PSSRU43 |

| Occupational therapist: surgery | 78 | PSSRU43 |

| Physiotherapist: home | 63 | PSSRU43 |

| Physiotherapist: surgery | 54 | PSSRU43 |

| Clinical nurse specialist | 19 | PSSRU43 |

| Acute hospital day case | 745 | PSSRU43 |

| Inpatient: one night | 626 | PSSRU43 |

| Inpatient: more than one night | 337 (per night) | NHS Reference Costs 2017–2018 45 |

| A&E attendance | 160 | NHS Reference Costs 2017–2018 45 |

| Outpatient | 134 | PSSRU43 |

| Home help | 14 | PSSRU43 |

| Social worker | 31 | PSSRU43 |

The means and SDs of each unit cost are reported for complete cases at each follow-up time point. The adjusted total difference in mean costs at 12 months for complete cases across all time points was calculated using linear regression and adjusting for baseline costs, site and number of eligible eyes and with surgeon as a random effect. All costs are reported in 2017/18 Great British pounds.

Quality-adjusted life-years

The primary measure used to calculate QALYs was the EQ-5D-3L. QALYs were calculated as the area under the curve50 using the EQ-5D-3L utility values for the UK40 at baseline and at 3, 6 and 12 months for complete cases at each time point. For the FLACS arm compared with the PCS arm, the mean utility values are reported at each time point, and the mean unadjusted QALYs are reported from baseline to 12 months for complete cases. The adjusted total difference in mean QALYs at 12 months for complete cases across all time points was calculated using linear regression, adjusting for baseline utilities, site and the number of eligible eyes and with surgeon as a random effect.

A recently developed vision bolt-on question increases the sensitivity of the instrument to those populations whose primary condition is vision related. 36 As there is no agreed method for incorporating the vision tariff into QALY calculations, and to maintain consistency with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines,51 the primary analysis was based on the EQ-5D-3L without the additional vision question. A secondary analysis was conducted to calculate QALYs as the area under the curve using the vision tariff in addition to the EQ-5D-3L tariff to calculate the mean utility values at each time point for FLACS compared with PCS. The adjusted differences for total QALYs at 12 months were also reported.

Missing resource use or utilities data

The primary analysis was intention to treat. Assuming that the data are missing at random, MICE was used to impute missing costs and utilities at 3, 6 and 12 months, with age and ethnicity found to be predictors of missingness. A total of 60% of patients had missing resource use or utilities data for at least one follow-up point, and hence 60 imputed data sets were created.

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was defined as the mean incremental cost of FLACS compared with PCS divided by the mean incremental QALYs of FLACS compared with PCS. The mean incremental differences were adjusted for baseline values, site and the number of eligible eyes. To account for the correlation between costs and QALYs, seemingly unrelated regression was used to calculate the numerator and denominator of the ICER. ICERs are reported for total health and social care costs, using the EQ-5D-5L to calculate QALYs in the primary analysis and using total societal costs and the vision bolt-on question to calculate QALYs in secondary analyses. The final results for total costs and QALYs are based on imputed data, as described above, and the missing at random methodology described in Leurent et al. 52 is used for calculating cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) using bootstrapping and MICE for 100 draws of each of the 60 imputed data sets for 6000 replications in total.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves and cost-effectiveness planes

The CEACs were calculated for each bootstrap imputed analysis to calculate the probability that FLACS is cost-effective compared with PCS at a range of values of willingness to pay (WTP) for a QALY gained. Cost-effectiveness planes have also been reported for each bootstrapped, imputed, analysis.

Secondary and sensitivity analyses

Secondary analyses were conducted (1) using the EQ-5D-3L vision bolt-on to calculate QALYs and (2) to calculate costs from a societal cost perspective.

For sensitivity analyses, we evaluated the impact of an alternative model of FLACS delivery with two theatres, as described above, as well as a threshold analysis to determine how much FLACS would need to cost either to be no longer cost-effective or to be cost-effective.

Patient and public involvement: lay advisory group

Cataract patients and relatives of patients with cataracts were invited from clinics at Moorfields Eye Hospital and formed our lay advisory group, who were consulted on trial design, choice of outcome measures, trial recruitment and treatment acceptability. The lay advisory group contributed directly to the tailored trial information leaflets and consent forms.

As required by the NHS, and by INVOLVE guidelines and UK Clinical Research Collaboration policy, the results of this trial are being communicated to patients via NHS Choices and the findings will be published in open-access media.

Chapter 3 Results

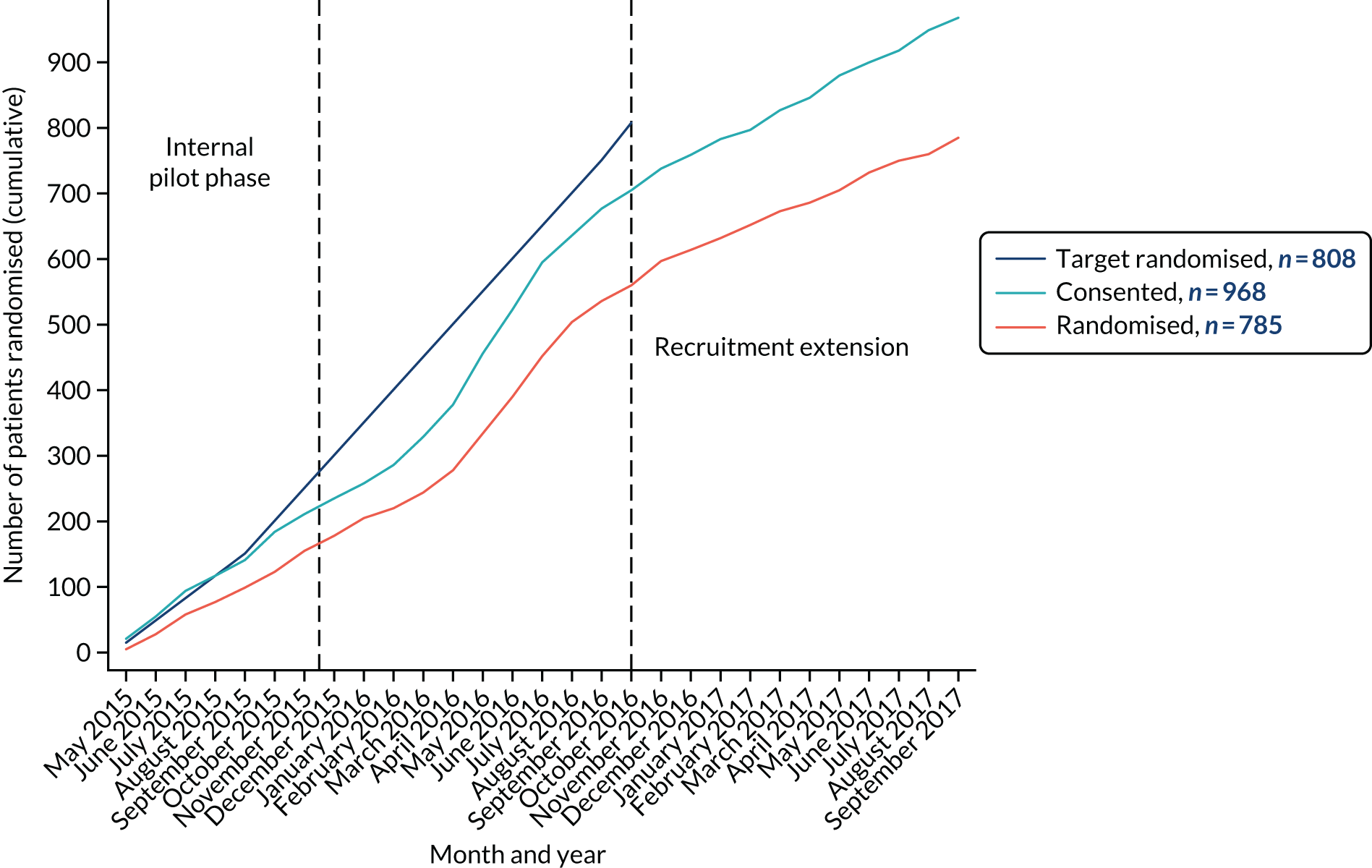

Participant enrolment

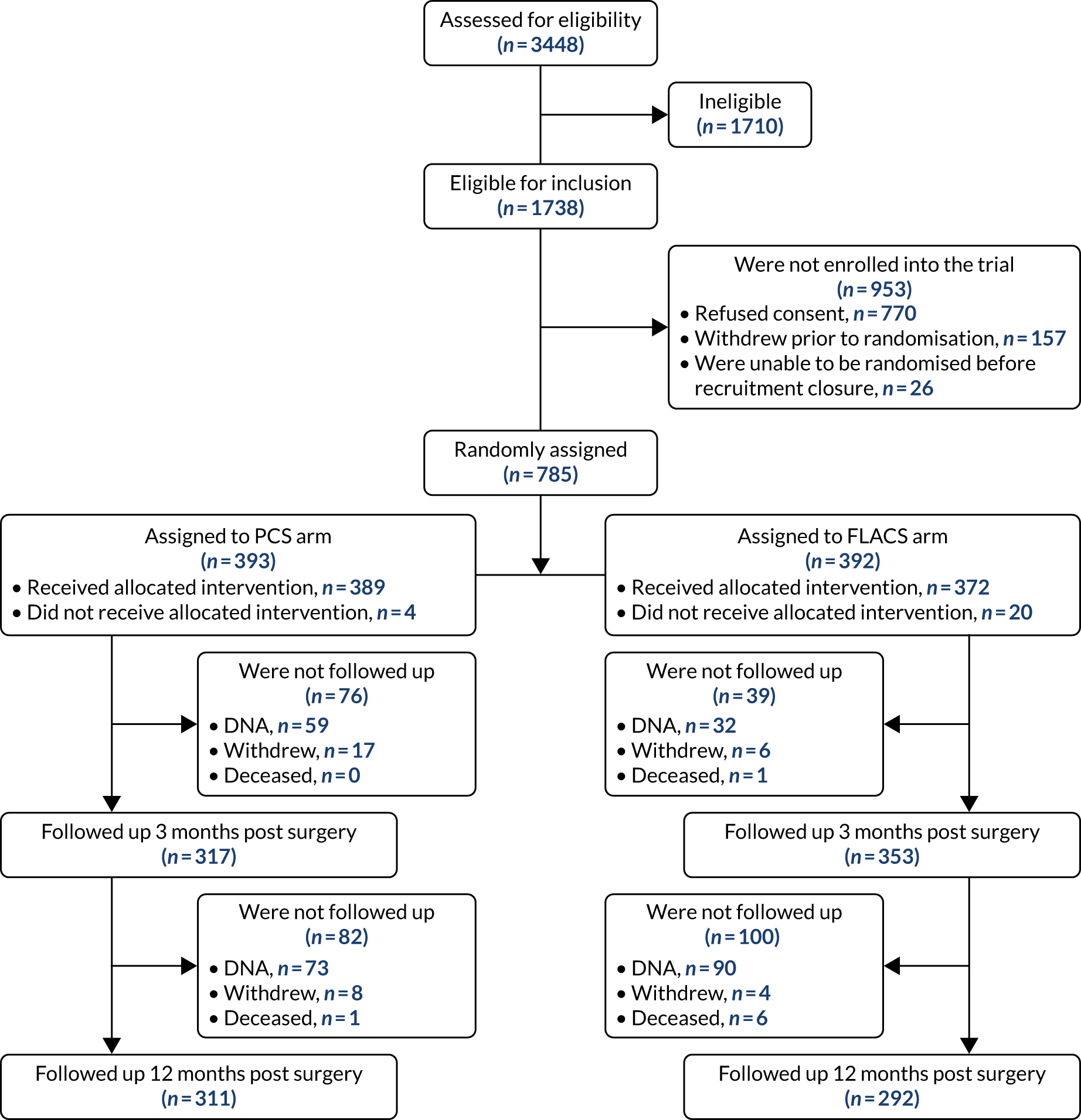

Of the 3448 patients assessed, 785 participants were enrolled between May 2015 and September 2017 and 392 were randomly assigned to the FLACS arm and 393 were randomly assigned to the PCS arm (Figure 1). Of these 785 participants, 653 were enrolled from Moorfields St Ann’s, 100 were enrolled from New Cross Hospital and 32 were enrolled from Sussex Eye Hospital.

FIGURE 1.

The trial profile. DNA, did not attend. Reproduced from Day et al. 1,2 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

The main reasons participants were excluded (n = 1710) were not being sufficiently fluent in English for informed consent and trial questionnaire completion (n = 564), postoperative refractive target being outside ± 0.5 dioptre of emmetropia (n = 180), having poor pupil dilatation (n = 176) and not being willing to attend follow-up (n = 155). Of the 1738 patients eligible to participate, 770 declined to take part, 157 withdrew prior to randomisation and 26 were awaiting randomisation at recruitment closure.

Protocol deviations

Forty major protocol deviations were identified: not receiving treatment according to randomisation [25 participants (5.1%): 21 allocated to FLACS and four allocated to PCS]; and not fulfilling refractive target eligibility criteria (15 participants: 10 allocated to FLACS and five allocated to PCS (see Appendix 1). Overall, 352 out of 392 (90%) participants allocated to the FLACS arm and 317 out of 393 (81%) participants allocated to the PCS arm attended their follow-up visit at 3 months. Figure 1 shows the trial profile.

Table 4 shows the trial population baseline characteristics by treatment arm. The participant demographics and preoperative ocular biometric characteristics in both arms were similar.

| Characteristic | Treatment arm | |

|---|---|---|

| FLACS (N = 392) | PCS (N = 393) | |

| Sex (male/female), n (%) | 182 (46)/210 (54) | 192 (49)/201 (51) |

| Previous cataract surgery (second eye cataract surgery in trial), n (%) | 82 (21) | 72 (18) |

| Right eye/left eye, n (%) | 206 (53)/186 (47) | 226 (57)/167 (43) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 68 (10) | 68 (10) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White | 281 (72) | 272 (69) |

| Mixed | 3 (0.8) | 7 (2) |

| Asian or Asian British | 33 (8) | 46 (12) |

| Black or black British | 57 (15) | 52 (13) |

| Other ethnic group | 18 (5) | 15 (4) |

| Not declared | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Anterior chamber depth (mm), mean (SD) | 3.22 (0.41) | 3.21 (0.39) |

| Axial length (mm), mean (SD) | 24.00 (1.49) | 23.97 (1.47) |

| Preoperative corneal astigmatism, n (%) | ||

| < 0.75 dioptre | 194 (49) | 177 (45) |

| 0.75 to < 2.0 dioptre | 163 (42) | 184 (47) |

| ≥ 2.0 dioptre | 34 (8.7) | 29 (7.4) |

| Endothelial cell count (cells/mm2), mean (SD) | 2640 (334) | 2604 (348) |

| Macular thickness (µm), mean (SD) | 249 (42) | 249 (41) |

| Ocular co-pathology, n (%) | 128 (33) | 140 (36) |

| Habitual UDVA logMAR, mean (SD) | 0.61 (0.46) | 0.68 (0.50) |

| Catquest-9SF score, mean (SD) | 0.62 (1.7) | 0.52 (1.7) |

| EQ-5D-3L, mean (SD) | 0.79 (0.24) | 0.78 (0.25) |

| EQ-5D-3L VAS, mean (SD) | 77.8 (18) | 77.3 (18) |

| EQ-5D-3L: vision bolt-on, n (%) | ||

| I have no problems seeing | 149 (38) | 137 (35) |

| I have some problems seeing | 127 (32) | 114 (29) |

| I have extreme problems seeing | 6 (1.5) | 5 (1.3) |

| Missing, n (%) | 110 (28) | 137 (35) |

The 3-month outcomes

Overall, 353 out of 392 (90%) participants allocated to the FLACS arm and 317 out of 393 (81%) participants allocated to the PCS arm attended their follow-up visit at 3 months. Table 5 shows the postoperative results at 3 months by treatment arm for selected outcomes. The trial primary outcome was UDVA (logMAR). Additional outcomes for the study eye and all outcomes for the fellow eye can be found in Appendix 2.

| Outcome | Treatment arm | FLACS vs. PCS effect (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLACS (N = 392)a | PCS (N = 393) | |||

| Primary outcome: UDVA logMAR, imputed, mean (SD); n | 0.13 (0.23); 392 | 0.14 (0.27); 393 | –0.01 (–0.05 to 0.03) | 0.63 |

| UDVA logMAR, complete case, mean (SD); n | 0.13 (0.23); 352 | 0.14 (0.26); 317 | –0.01 (–0.04 to 0.03) | 0.70 |

| UDVA logMAR, per protocol, mean (SD); n | 0.13 (0.22); 334 | 0.14 (0.26); 317 | –0.01 (–0.05 to 0.02) | 0.54 |

| CDVA logMAR mean (SD); n | –0.01 (0.19); 352 | 0.01 (0.21); 317 | –0.01 (–0.05 to 0.02) | 0.34 |

| SE refraction within ± 0.5 dioptre of target, n (%) | 250/352 (71) | 224/316 (71) | 1.01 (0.72 to 1.41) | 0.95 |

| SE refraction within ± 1.0 dioptre of target, n (%) | 327/352 (93) | 292/316 (92) | 1.08 (0.60 to 1.94) | 0.80 |

| Change in endothelial cell count (cells/mm2): mean loss (SD); n | 242 (416); 345 | 200 (369); 308 | 47 (–3 to 97) | 0.06 |

| Catquest 9-SF score, mean (SD); n | 2.30 (1.31); 283 | 2.27 (1.30); 253 | 0.07 (–0.13 to 0.28) | 0.49 |

| EQ-5D-3L index score, mean (SD); n | 0.84 (0.23); 351 | 0.82 (0.25); 323 | 0.0002 (–0.03 to 0.03) | 0.88 |

| I have no problems seeing, n (%) | 235 (67) | 220 (68) | – | – |

| I have some problems seeing, n (%) | 114 (32) | 100 (31) | – | – |

| I have extreme problems seeing, n (%) | 3 (0.9) | 3 (0.9) | – | – |

Table 6 shows the intraoperative complications in the study eye by treatment arm.

| Complication | Treatment arm (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| FLACS | PCS | |

| Anterior capsule tear | 3 | 2 |

| Posterior capsule tear with vitreous loss | 0 | 0 |

| Posterior capsule tear with no vitreous loss | 0 | 2 |

| Intraoperative pupil constriction needing intervention | 3 | 1 |

| Zonular dialysis with or without vitreous loss | 1 | 0 |

| Dropped lens fragments | 0 | 0 |

| Suprachoroidal haemorrhage | 0 | 0 |

| Incomplete laser capsulotomy | 4 | n/a |

Table 7 shows the postoperative complications in the study eye by treatment arm.

| Complication | Treatment arm, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| FLACS | PCS | |

| Postoperative anterior uveitis | 34 (9.7) | 32 (8.2) |

| Endophthalmitis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Vitreous to wound | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Steroid response ocular hypertension | 4 (1.0) | 3 (0.8) |

| Macular oedema | 8 (2.0) | 7 (1.8) |

| Retinal tear or detachment | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Medication allergy or intolerance | 4 (1.0) | 3 (0.8) |

| Corneal oedema | 4 (1.0) | 2 (0.5) |

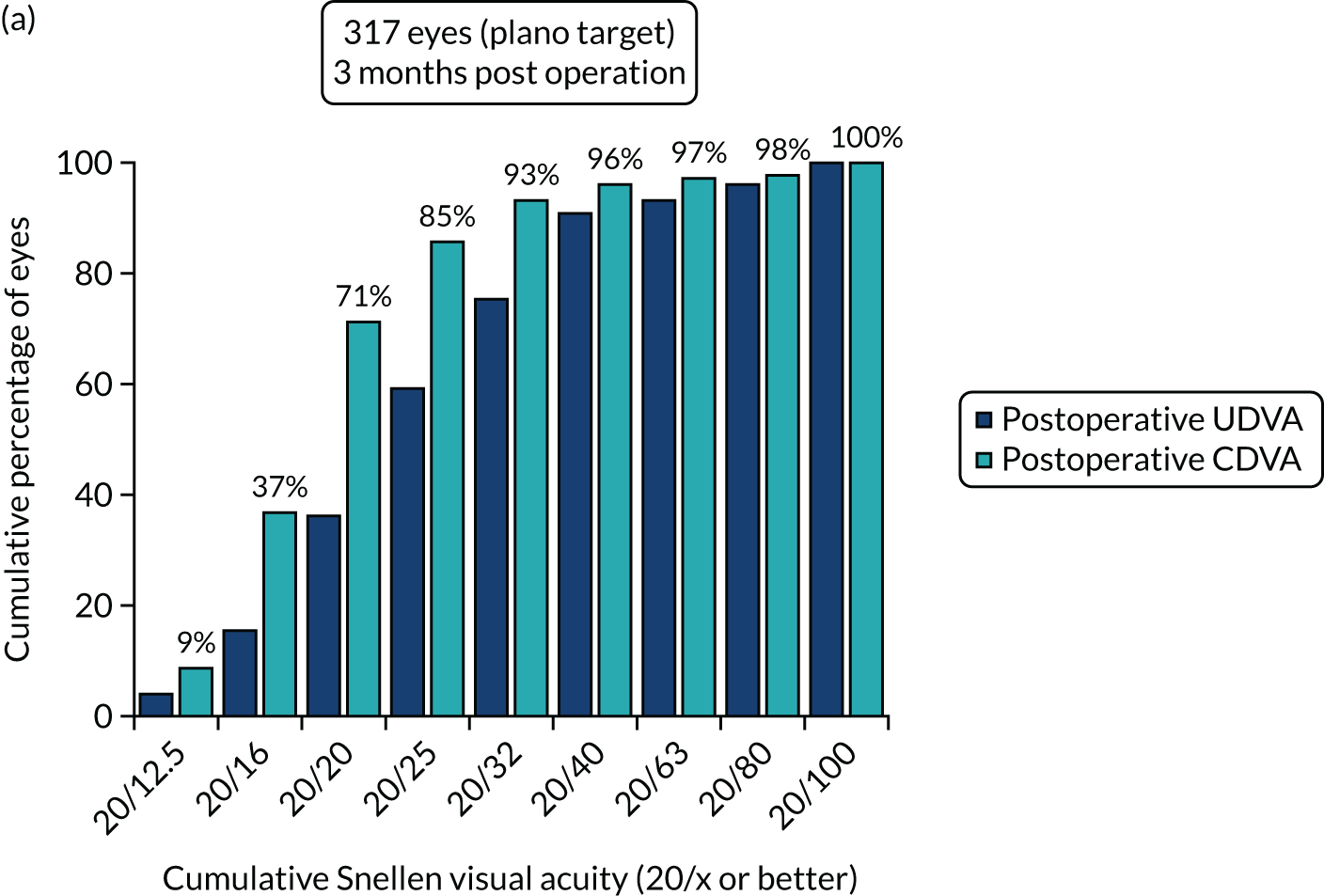

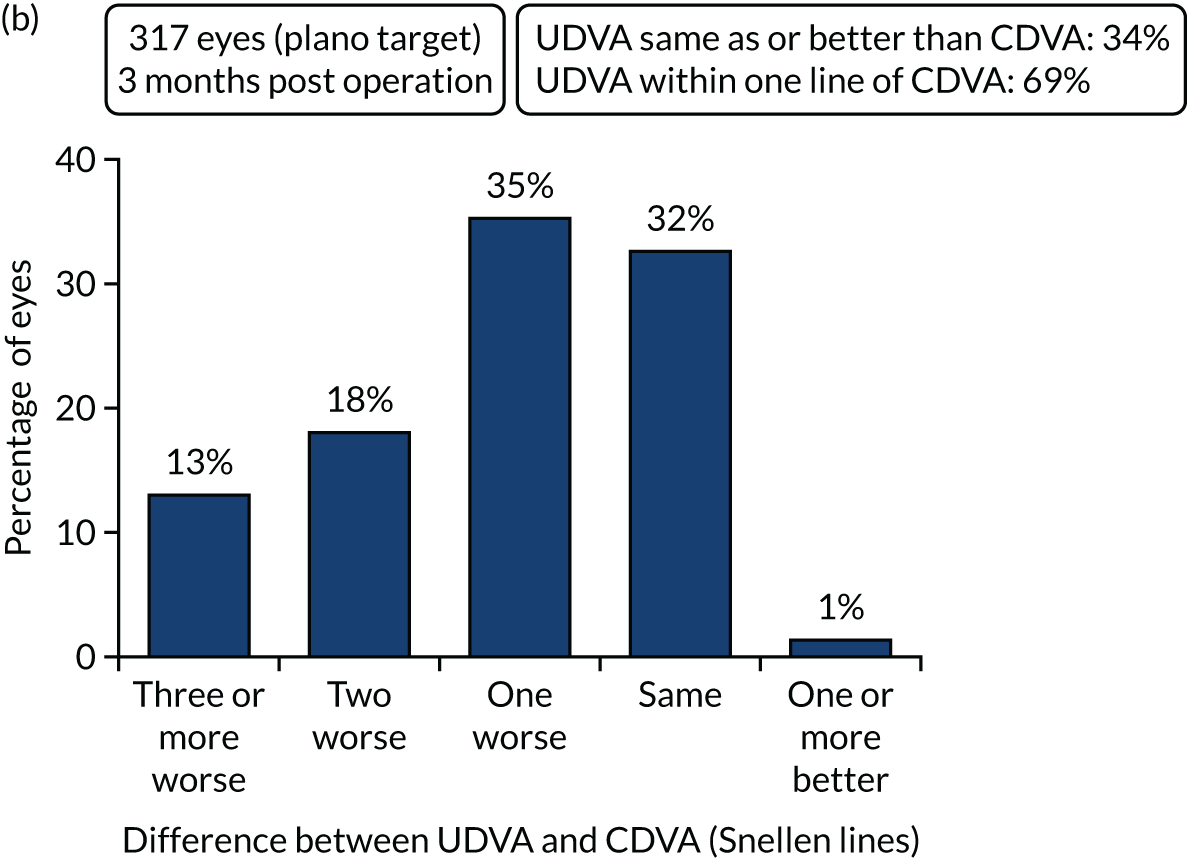

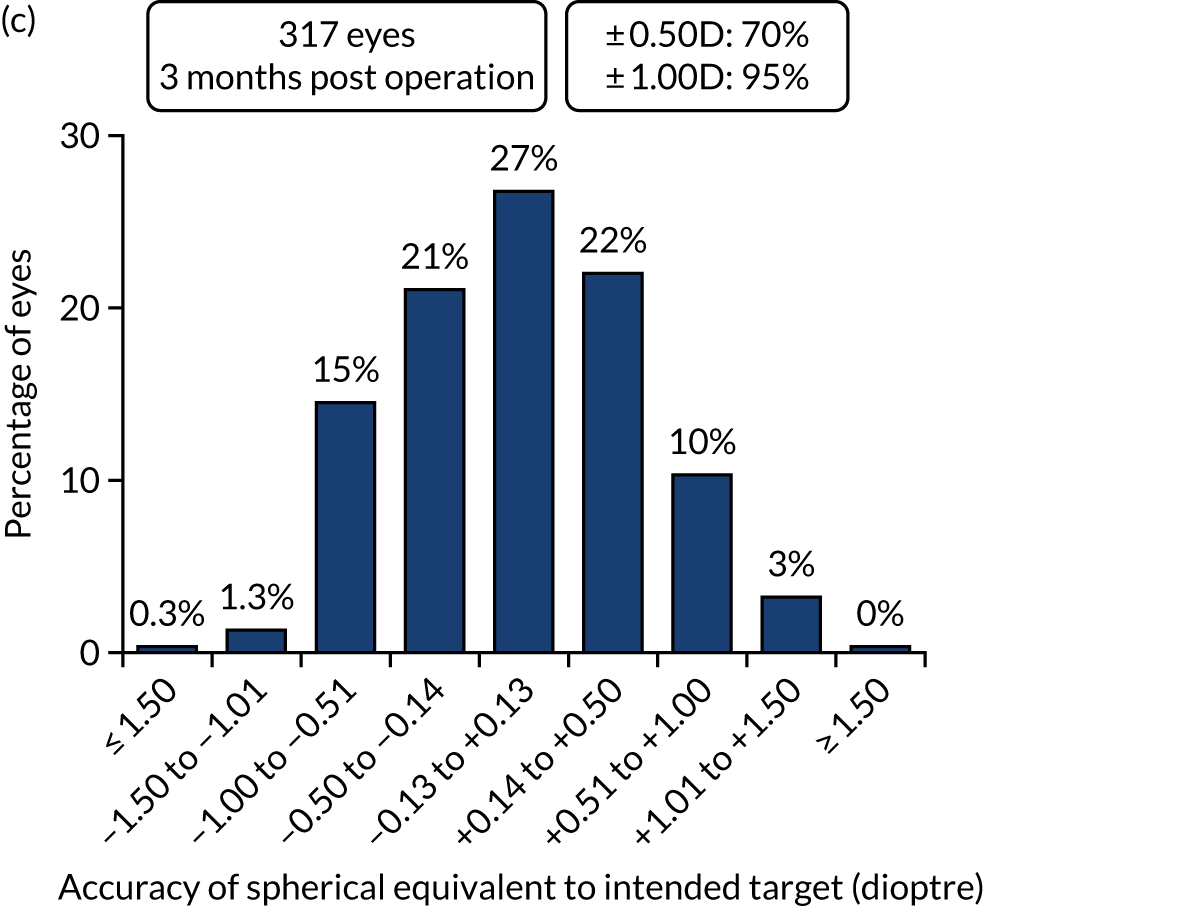

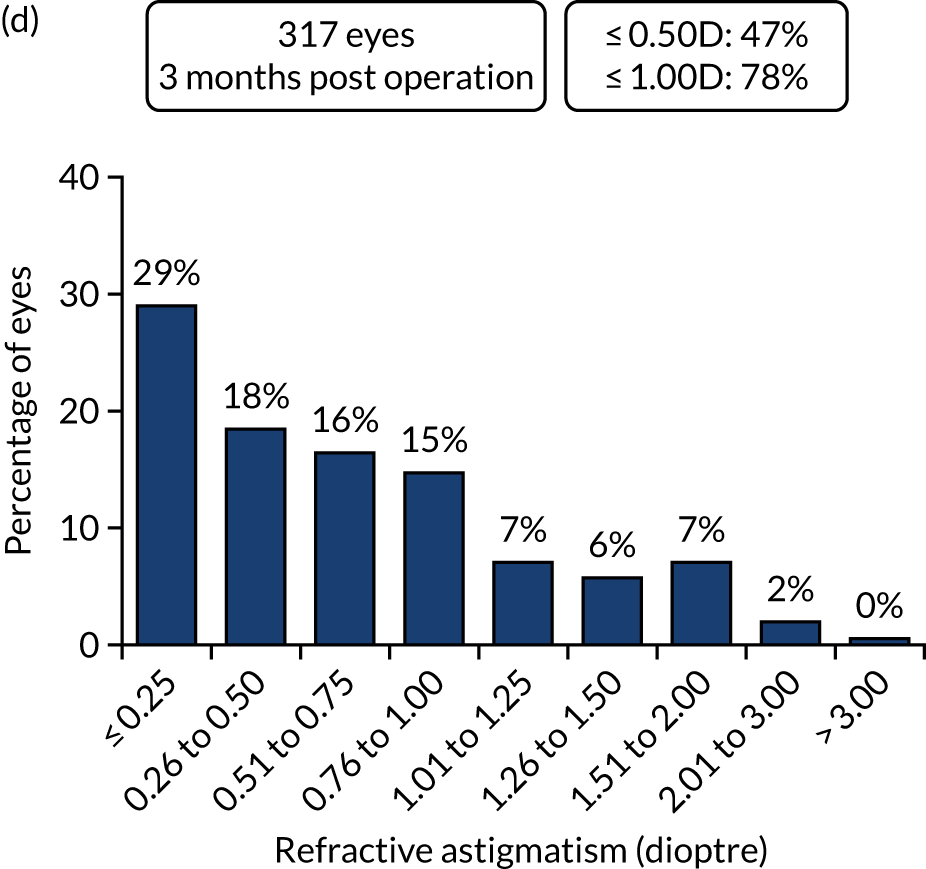

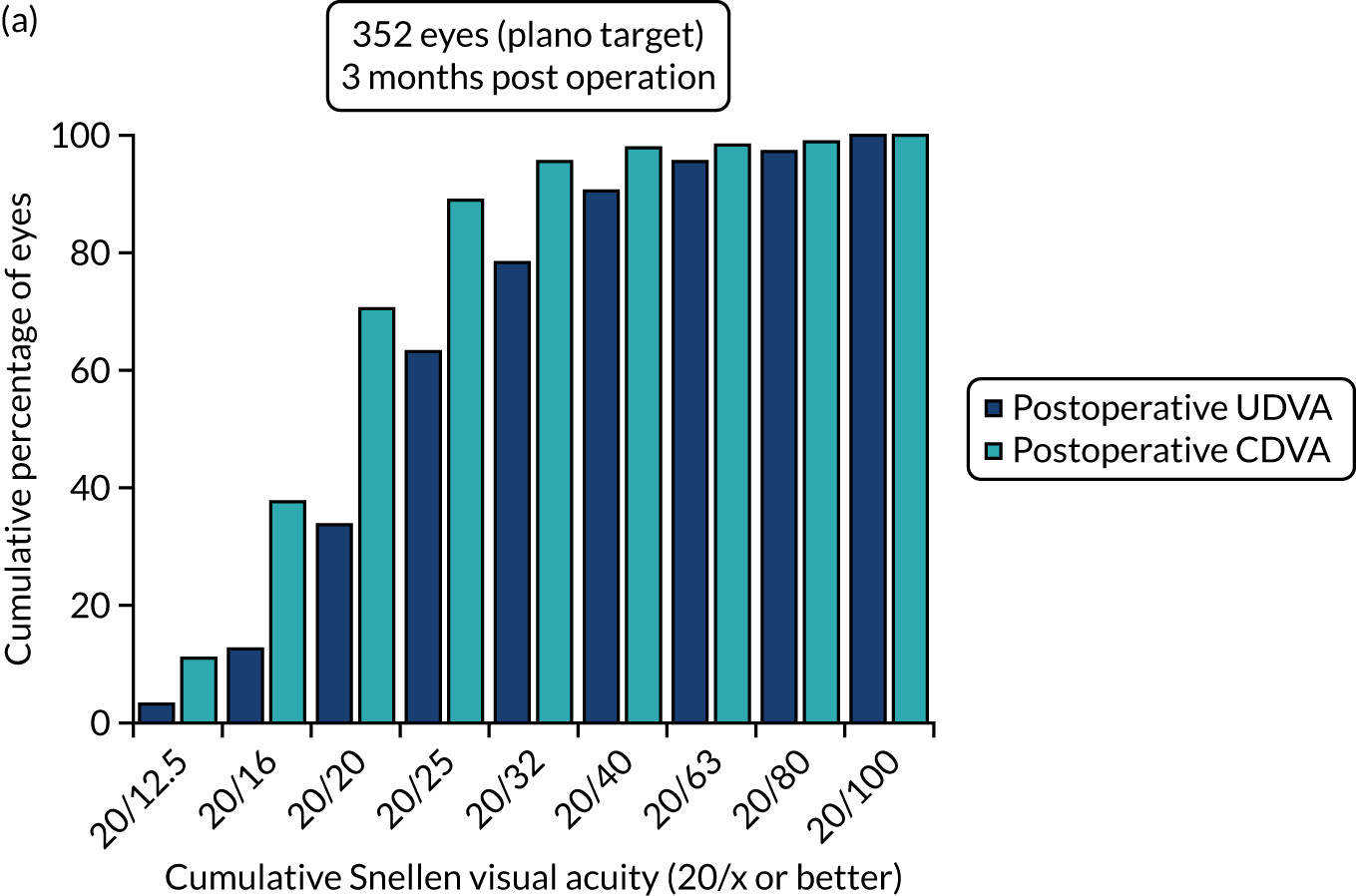

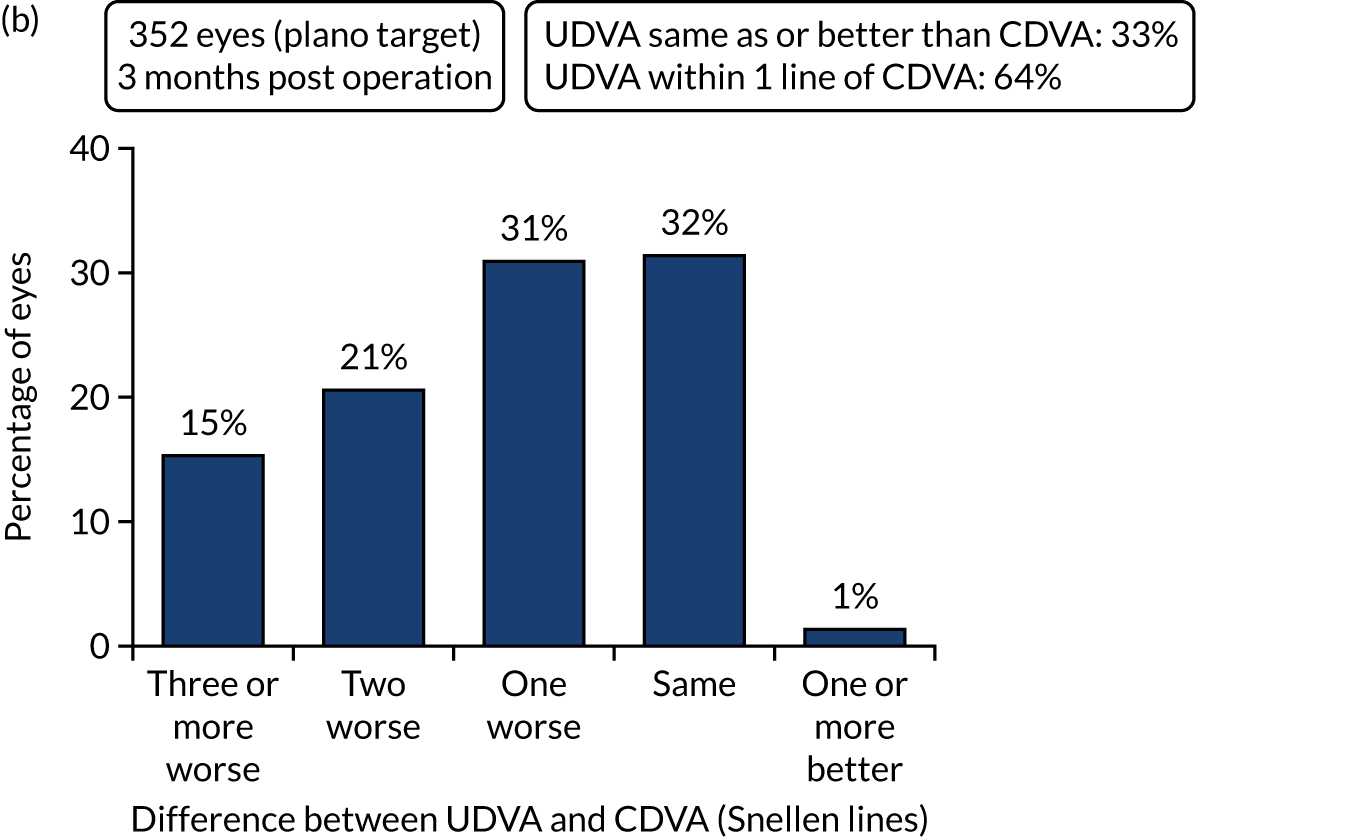

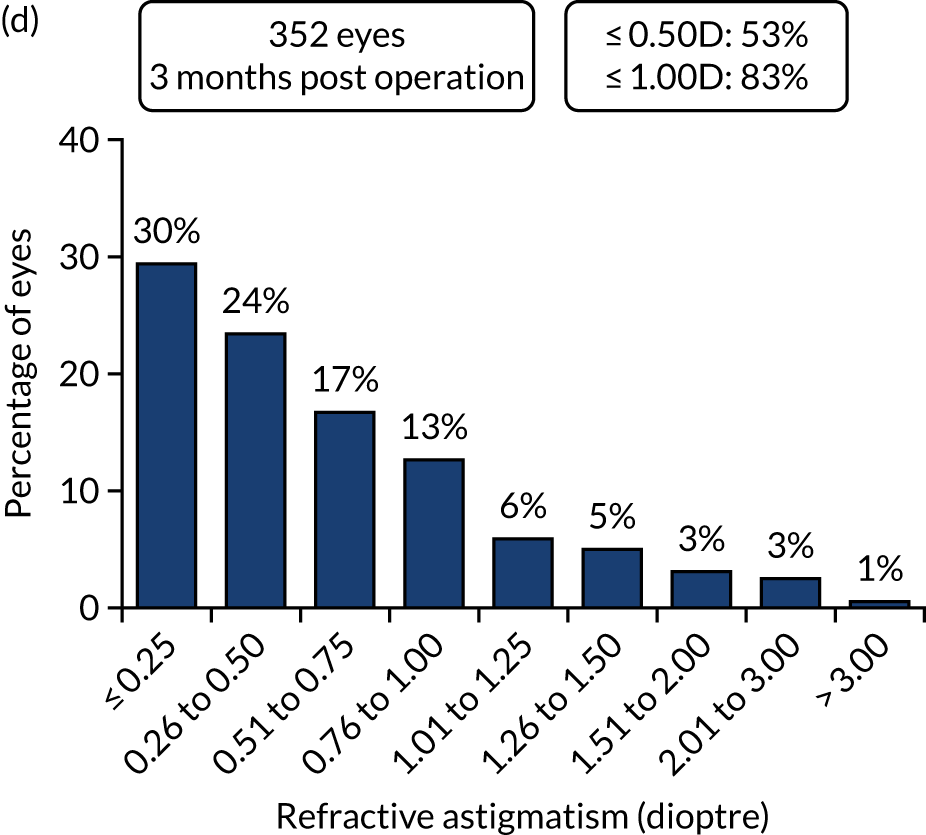

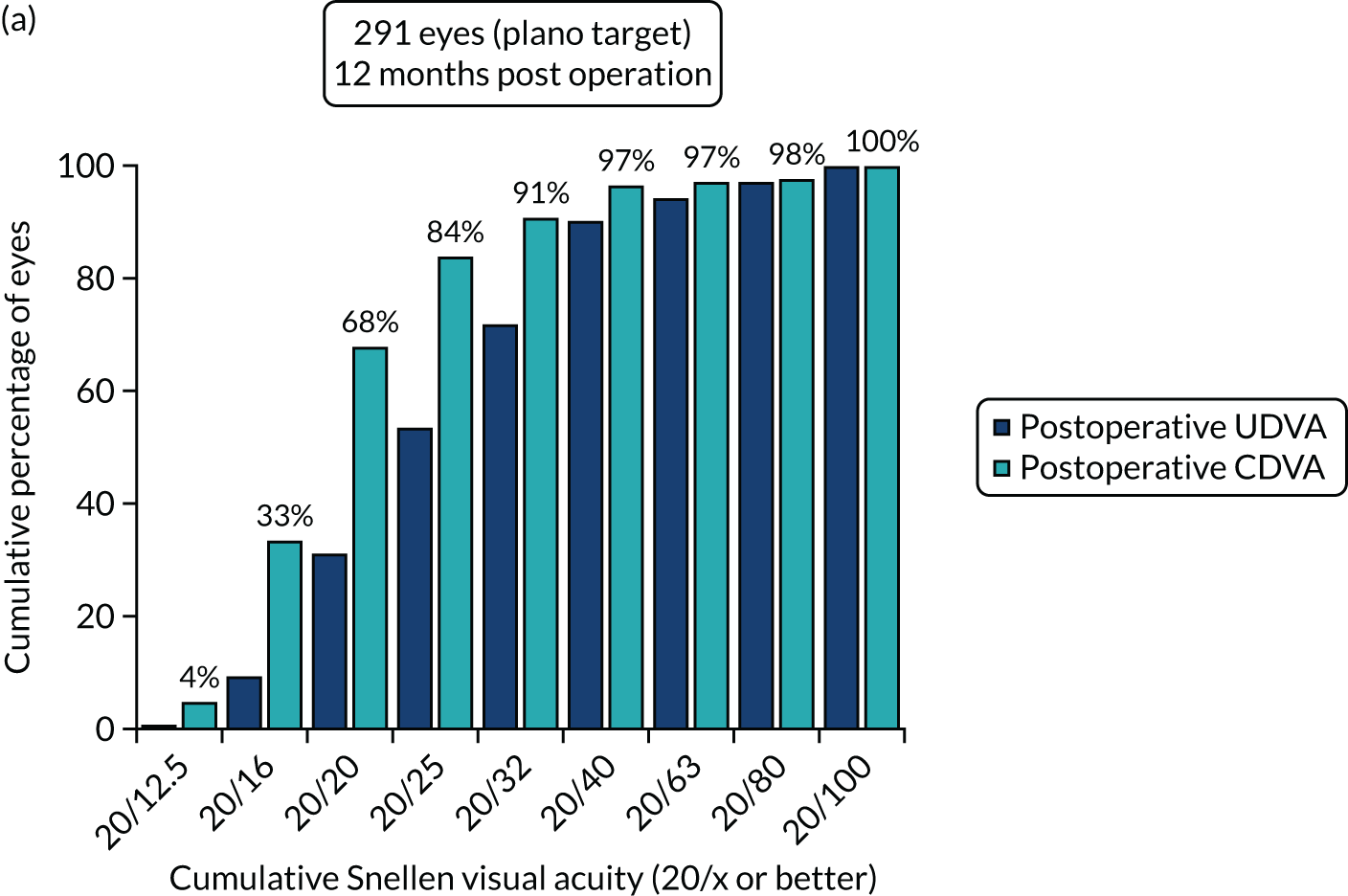

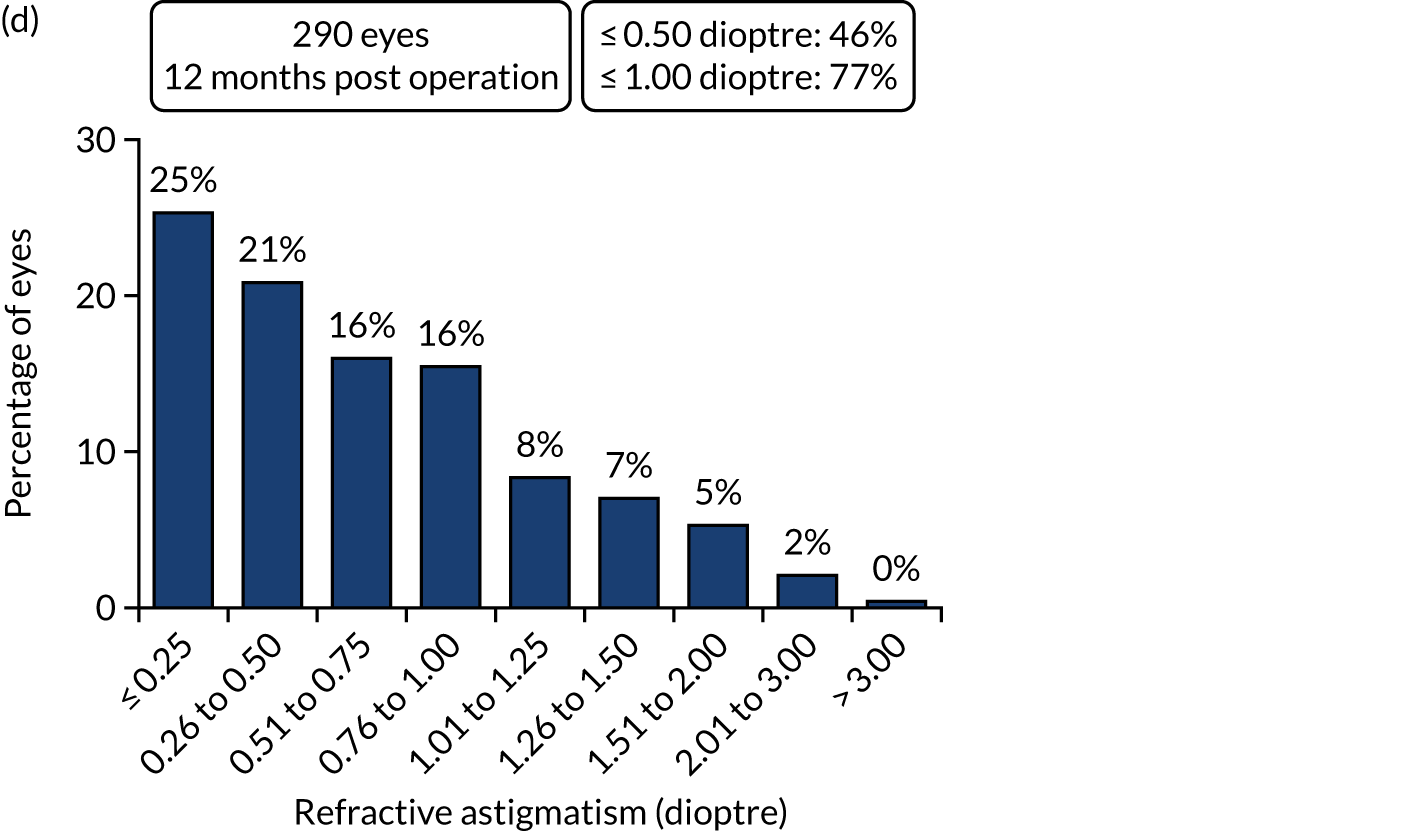

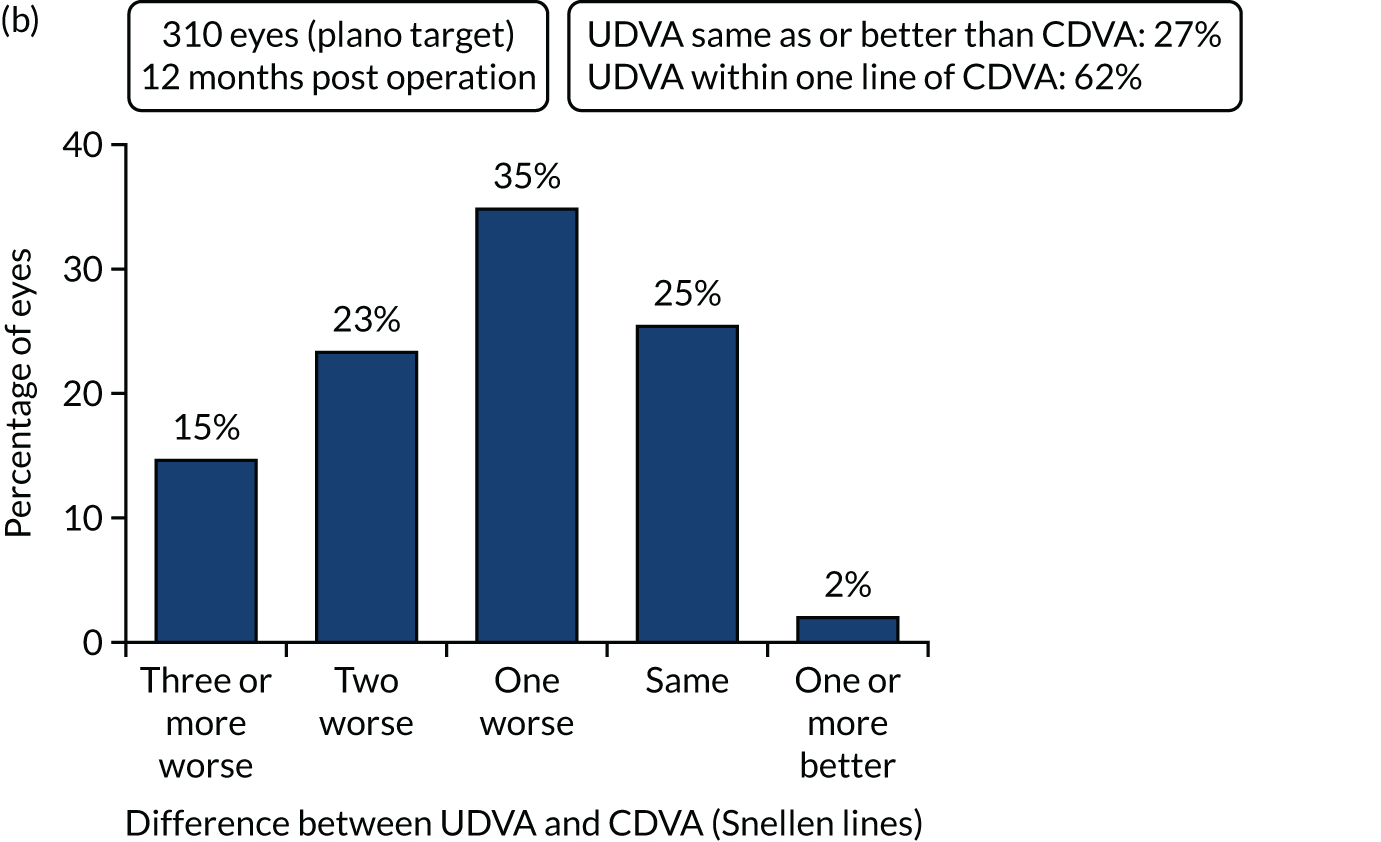

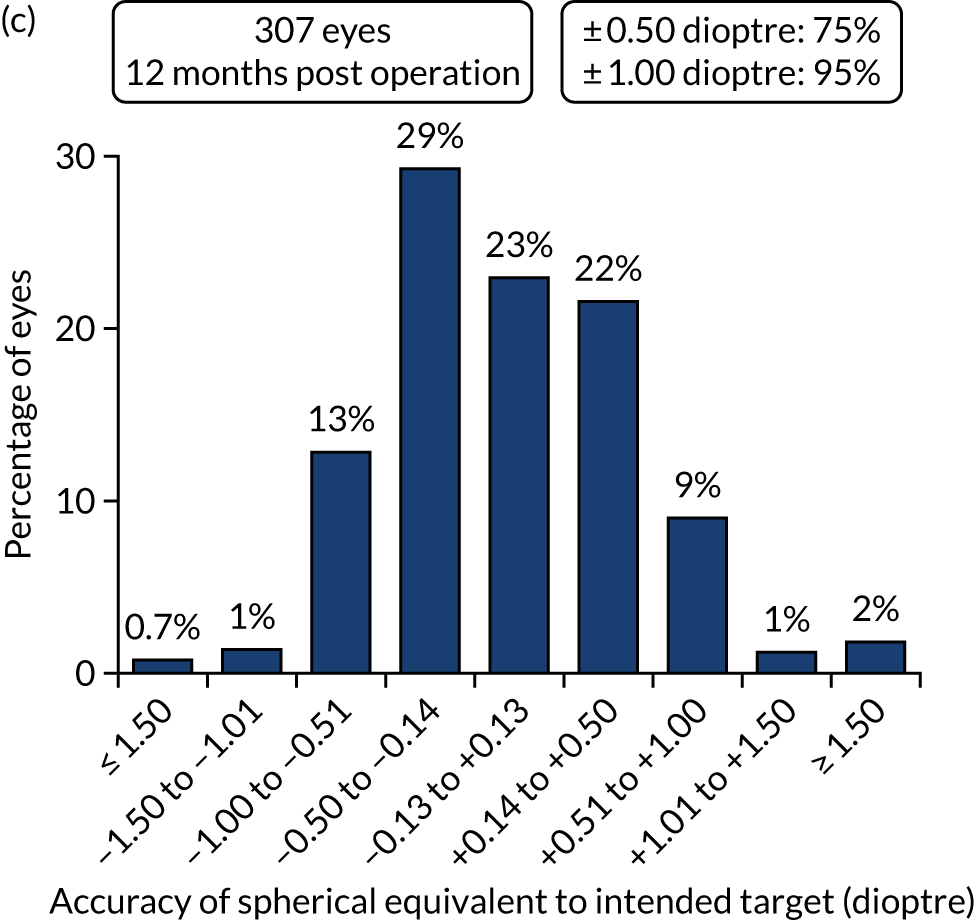

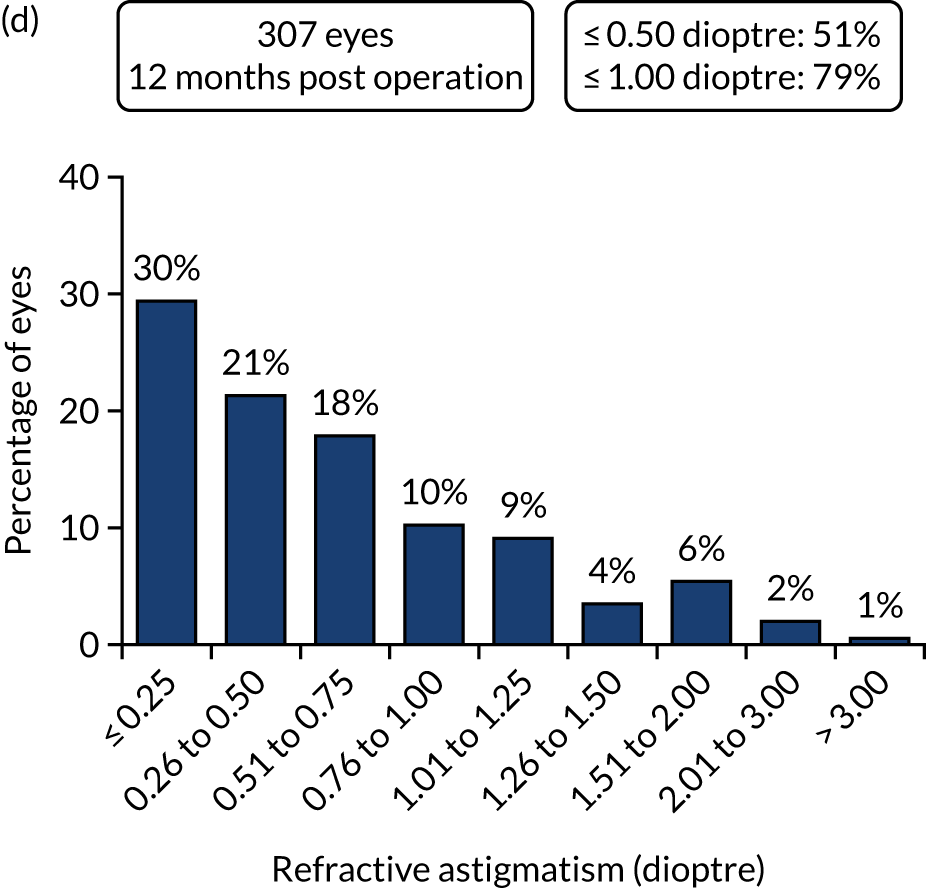

Figures 2 and 3 show the standardised graphs for reporting the outcomes of IOL surgery. 53

FIGURE 2.

Outcomes of IOL surgery: PCS arm. (a) UDVA and CDVA; (b) difference between UDVA and CDVA; (c) accuracy of spherical equivalent refraction to target; and (d) refractive astigmatism.

FIGURE 3.

Outcomes of IOL surgery: FLACS arm. (a) UDVA; (b) UDVA vs. CDVA; (c) spherical equivalent refraction accuracy; and (d) refractive astigmatism.

The 12-month outcomes

Overall, 311 out of 392 (79%) participants allocated to the FLACS arm and 292 out of 393 (74%) participants allocated to the PCS arm attended their follow-up visit at 12 months.

The analysis of toric IOL use by arm showed that 22 toric lens were used in the FLACS arm (369 monofocal, one with data missing) and 19 toric lens were used in the PCS arm (370 monofocal, four with data missing). Table 8 shows the postoperative visual and refractive outcomes at 12 months. Borderline statistical significance was met for CDVA both eyes open, with a mean CDVA difference of –0.02 logMAR (95% CI –0.05 to –0.002; p = 0.036) favouring the FLACS arm. There were no significant differences between the arms for any other outcome. Additional outcomes for the study eye and all outcomes for the fellow eye can be found in Appendix 3.

| Outcome | Treatment arm | FLACS vs. PCS effect (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLACS (N = 311) | PCS (N = 292) | |||

| UDVA logMAR, study eye, mean (SD); n | 0.14 (0.22); 310 | 0.17 (0.25); 291 | –0.03 (–0.06 to 0.01) | 0.17 |

| UDVA logMAR, both eyes open, mean (SD); n | 0.05 (0.16); 310 | 0.07 (0.20); 292 | –0.03 (–0.05 to 0.003) | 0.08 |

| CDVA logMAR, study eye, mean (SD); n | 0.003 (0.18); 311 | 0.03 (0.23); 292 | –0.03 (–0.06 to 0.01) | 0.11 |

| CDVA logMAR, both eyes, mean (SD) | –0.05 (0.11); 310 | –0.03 (0.17); 291 | –0.02 (–0.05 to 0.002) | 0.036 |

| SE refraction within ± 0.5 dioptre of target, n (%) | 230/307 (75) | 218/290 (75) | 0.99 (0.68 to 1.43) | 0.94 |

| SE refraction within ± 1.0 dioptre of target, n (%) | 292/307 (95) | 279/290 (96) | 0.76 (0.34 to 1.69) | 0.50 |

| Catquest 9-SF score, mean (SD); n | 2.94 (1.05); 318 | 2.96 (1.09); 300 | 0.01 (–0.15 to 0.17) | 0.91 |

| EQ-5D-3L index score, mean (SD); n | 0.83 (0.23); 318 | 0.82 (0.25); 299 | 0.001 (–0.03 to 0.03) | 0.95 |

| I have no problems seeing, n (%) | 242 (76) | 231 (77) | – | – |

| I have some problems seeing, n (%) | 70 (22) | 62 (21) | – | – |

| I have extreme problems seeing, n (%) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | – | – |

Figures 4 and 5 show the standardised graphs for reporting the outcomes of IOL surgery. 53

FIGURE 4.

Standardised graphs: PCS arm at 12 months. (a) UDVA; (b) UDVA vs. CDVA; (c) spherical equivalent refraction; and (d) refractive cylinder. Reproduced from Day et al. 1,2 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

FIGURE 5.

Standardised graphs: FLACS arm at 12 months. (a) UDVA; (b) UDVA vs. CDVA; (c) spherical equivalent refraction; and (d) refractive cylinder. Reproduced from Day et al. 1,2 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Table 9 shows the postoperative complications at 12 months.

| Complications | Treatment arm, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| FLACS | PCS | |

| Postoperative anterior uveitis | 38 (9.7) | 33 (8.4) |

| Endophthalmitis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Vitreous to wound | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Steroid response ocular hypertension | 7 (1.8) | 3 (0.8) |

| Macular oedema | 9 (2.3) | 14 (3.6) |

| Posterior vitreous detachment | 3 (0.8) | 2 (0.5) |

| Retinal tear or detachment | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.8) |

| Medication allergy or intolerance | 4 (1.0) | 3 (0.8) |

| Corneal oedema | 8 (2.0) | 2 (0.5) |

| Posterior capsule opacification | 4 (1.0) | 6 (1.5) |

Table 10 shows the corneal endothelial cell measures at 12 months. There was no significant difference between the arms.

| Corneal endothelial cell count (cells/mm2) | Treatment arm, mean (SD); n | FLACS vs. PCS effect (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLACS (N = 307) | PCS (N = 286) | |||

| Corneal endothelial cell count | 2404 (434); 307 | 2412 (406); 286 | 40 (–8 to 89) | 0.10 |

| Change in endothelial cell count, mean loss | 228 (353); 304 | 175 (312); 284 | 40 (–8 to 89) | 0.10 |

Health economic results

Cost of the FLACS and PCS interventions

Based on the Association for Perioperative Practice guidance and evidence from the observational study,46 the following staff were involved in delivering both the FLACS and PCS interventions:

-

two nurses (one band 5 and one band 6)

-

one operating department practitioner

-

one health-care assistant

-

one surgeon

-

one anaesthetist.

A technician was also present when patients were allocated to the FLACS arm, but only for the duration of the actual FLACS treatment. The total staff and overhead cost per minute was £9.59 per minute in the FLACS arm during the actual FLACS treatment and £9.02 per minute in the FLACS and PCS arms during the time in the operating theatre.

In the FLACS arm, surgery took a mean of 17.1 minutes (SD 7.4 minutes). FLACS laser took an additional 3.9 minutes (SD 3.5 minutes), with a total time of 20.8 minutes (SD 8.2 minutes). In the PCS arm, surgery took 17.8 minutes (SD 8.0 minutes).

At a cost of £232,500 for the machine, and an annual maintenance cost of £16,221, the cost per patient for the machine, annuitising for a 5-year lifespan, is £26 if one assumes that each site sees 3000 patients per year for cataract surgery and 90.5% of patients are able to receive FLACS based on the exclusion criteria seen in the trial. There is also a per-patient cost of £130 for the patient interface, with a total machine cost per patient for FLACS of £156. If an 8-year lifespan is assumed, the cost per patient for the machine is £18, with a total cost per patient of £148 including the patient interface.

There was no significant difference in the use of anaesthetic drugs or consumables between treatment arms except for VisionBlue® [D.O.R.C. (Dutch Ophthalmic Research Center) (International) B.V., Zuidland, the Netherlands; used for staining the anterior capsule to increase visibility, 43 patients in the PCS arm compared with three patients in the FLACS arm] at a cost per vial of £8.65.

Surgeon training for FLACS comprised 10 sessions of using the laser. At a cost per minute of £1.80 for surgeon time and an average time of using the lasert in FLACS of 4 minutes, the total cost of training per surgeon is £70. Given a caseload of approximately 1000 cataracts per year (from professional opinion), the cost of training is very close to zero and hence has been excluded from the total cost.

The average total patient cost of surgery was £363.21 (95% CI £347.65 to £378.77) in the FLACS arm, compared with £174.58 (95% CI £163.24 to £185.92) in the PCS arm (Table 11). The analysis is intention to treat, in line with the analysis plan. As a result, it includes 20 patients who were randomised to the FLACS arm but received standard cataract surgery and so are costed as PCS. Five patients had missing surgery data and, therefore, are not included in the analysis. Details on adverse events are also reported in Table 11.

| Cost | Treatment arm, mean cost (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| FLACS (n = 391) | PCS (n = 389) | |

| Surgery staff cost | 199.70 (78.38) | 160.95 (72.26) |

| FLACS machine | 146.70 (35.95) | 0 |

| Consumables: VisionBlue | 0.11 (0.97) | 0.90 (2.65) |

| Adverse events | 14.12 (112.06) | 8.90 (77.13) |

| Surgery medication | 3.72 (1.41) | 3.82 (1.80) |

| Total per patient | 363.21 (156.5) | 174.58 (113.78) |

Health, social care and societal costs

Complete-case health and social care and societal costs and MICE total costs are reported in Tables 12 and 13. There were no significant differences between the two arms in any health and social care or societal costs. For societal costs, missing carer costs were imputed as zero because otherwise the missing data created issues in the analysis, as a patient who was missing data at multiple time points had skewed carer costs. The carer costs should be interpreted with caution as they are calculated from a single question: ‘How many hours per week on average did [friends or relatives] help you over the last 3 months?’

| Cost | Treatment arm | Adjusteda mean difference | 95% CI | p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLACS | PCS | ||||||||

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | ||||

| GP | |||||||||

| Baseline | 383 | 45 | 61 | 375 | 48 | 57 | |||

| 3 months | 354 | 28 | 37 | 323 | 31 | 44 | |||

| 6 months | 265 | 35 | 44 | 242 | 42 | 65 | |||

| 12 months | 318 | 31 | 40 | 298 | 32 | 46 | |||

| Total cost | 220 | 86 | 84 | 196 | 100 | 124 | –0.080 | –21.823 to 21.663 | 0.994 |

| Community nurse | |||||||||

| Baseline | 383 | 6 | 21 | 374 | 10 | 55 | |||

| 3 months | 353 | 7 | 57 | 323 | 23 | 274 | |||

| 6 months | 266 | 5 | 14 | 242 | 10 | 49 | |||

| 12 months | 318 | 8 | 35 | 298 | 6 | 30 | |||

| Total cost | 221 | 21 | 84 | 195 | 20 | 50 | 1.637 | –8.729 to 12.002 | 0.748 |

| Occupational therapist | |||||||||

| Baseline | 382 | 14 | 187 | 374 | 3 | 25 | |||

| 3 months | 353 | 1 | 16 | 323 | 4 | 27 | |||

| 6 months | 265 | 2 | 18 | 242 | 4 | 36 | |||

| 12 months | 318 | 3 | 24 | 298 | 5 | 34 | |||

| Total cost | 220 | 6 | 39 | 195 | 11 | 57 | –8.215 | –17.578 to 1.147 | 0.083 |

| Physiotherapist | |||||||||

| Baseline | 381 | 14 | 127 | 375 | 8 | 48 | |||

| 3 months | 353 | 9 | 47 | 323 | 8 | 43 | |||

| 6 months | 265 | 4 | 28 | 242 | 9 | 41 | |||

| 12 months | 318 | 17 | 155 | 298 | 20 | 96 | |||

| Total cost | 220 | 29 | 96 | 195 | 28 | 82 | 0.389321 | –15.015 to 15.794 | 0.959 |

| Other community | |||||||||

| Baseline | 382 | 57 | 482 | 374 | 27 | 247 | |||

| 3 months | 352 | 8 | 63 | 322 | 38 | 460 | |||

| 6 months | 263 | 24 | 124 | 240 | 26 | 169 | |||

| 12 months | 318 | 9 | 72 | 298 | 24 | 198 | |||

| Total cost | 218 | 36 | 123 | 193 | 121 | 716 | –70.747 | –156.78 to 15.286 | 0.103 |

| Total community | |||||||||

| Baseline | 383 | 135 | 589 | 375 | 95 | 283 | |||

| 3 months | 354 | 53 | 111 | 323 | 103 | 548 | |||

| 6 months | 266 | 69 | 141 | 243 | 89 | 234 | |||

| 12 months | 318 | 67 | 189 | 298 | 87 | 236 | |||

| Total cost | 221 | 177 | 253 | 196 | 278 | 773 | –89.789 | –185.006 to 5.429 | 0.063 |

| A&E | |||||||||

| Baseline | 383 | 18 | 64 | 374 | 9 | 47 | |||

| 3 months | 354 | 20 | 61 | 323 | 22 | 69 | |||

| 6 months | 262 | 13 | 62 | 241 | 14 | 61 | |||

| 12 months | 318 | 14 | 50 | 298 | 15 | 77 | |||

| Total cost | 217 | 41 | 101 | 193 | 45 | 118 | –7.047 | –26.578 to 12.48 | 0.464 |

| Outpatient | |||||||||

| Baseline | 383 | 65 | 176 | 374 | 98 | 321 | |||

| 3 months | 354 | 63 | 270 | 323 | 55 | 179 | |||

| 6 months | 262 | 63 | 163 | 241 | 68 | 160 | |||

| 12 months | 318 | 88 | 211 | 298 | 100 | 280 | |||

| Total cost | 217 | 209 | 445 | 193 | 235 | 446 | –22.879 | –110.509 to 64.751 | 0.596 |

| Inpatient | |||||||||

| Baseline | 383 | 40 | 320 | 375 | 37 | 236 | |||

| 3 months | 354 | 72 | 518 | 323 | 45 | 418 | |||

| 6 months | 265 | 51 | 383 | 243 | 73 | 519 | |||

| 12 months | 318 | 104 | 757 | 298 | 89 | 422 | |||

| Total cost | 219 | 248 | 1204 | 195 | 198 | 783 | 97.360 | –86.520 to 281.250 | 0.286 |

| Social care | |||||||||

| Baseline | 382 | 3 | 44 | 375 | 3 | 34 | |||

| 3 months | 354 | 5 | 4 | 323 | 11 | 154 | |||

| 6 months | 267 | 2 | 27 | 244 | 4 | 38 | |||

| 12 months | 319 | 2 | 24 | 298 | 2 | 18 | |||

| Total cost | 222 | 6 | 45 | 196 | 20 | 201 | –16.578 | –46.287 to 13.130 | 0.261 |

| Total NHS and social care | |||||||||

| Baseline | 383 | 262 | 750 | 375 | 289 | 958 | |||

| 3 months | 354 | 215 | 757 | 323 | 239 | 751 | |||

| 6 months | 267 | 201 | 495 | 244 | 262 | 743 | |||

| 12 months | 319 | 365 | 1444 | 298 | 304 | 641 | |||

| Total cost | 222 | 750 | 1970 | 196 | 807 | 1477 | –28.743 | –290.488 to 233.002 | 0.823 |

| MICE NHS and social care | |||||||||

| n | Mean | SE | n | Mean | SE | ||||

| 3 months (MICE) | 383 | 215 | 43 | 375 | 226 | 40 | |||

| 6 months (MICE) | 383 | 196 | 29 | 375 | 210 | 34 | |||

| 12 months (MICE) | 383 | 312 | 60 | 375 | 304 | 37 | |||

| Total cost | 383 | 723 | 88 | 375 | 741 | 74 | –10.890 | –234.124 to 212.344 | 0.924 |

| Cost | Treatment arm | Adjusteda mean difference | 95% CI | p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLACS | PCS | ||||||||

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | ||||

| Home help private | |||||||||

| Baseline | 382 | 0.69 | 8.47 | 375 | 0.21 | 2.56 | |||

| 3 months | 354 | 0.23 | 2.9 | 323 | 0.17 | 3.06 | |||

| 6 months | 266 | 0.42 | 5.5 | 244 | 0.25 | 3.93 | |||

| 12 months | 318 | 0.2 | 2.86 | 298 | 1.11 | 14.48 | |||

| Total cost | 220 | 0.68 | 6.88 | 196 | 1.92 | 25.85 | –1.75055 | –6.19982 to 2.698725 | 0.425405 |

| Unpaid carers | |||||||||

| Baseline | 381 | 703 | 3834 | 373 | 667 | 2484 | |||

| 3 months | 353 | 623 | 2557 | 321 | 761 | 3799 | |||

| 6 months | 263 | 448 | 1857 | 239 | 755 | 2469 | |||

| 12 months | 319 | 669 | 3831 | 298 | 824 | 4485 | |||

| Total cost | 373 | 1477 | 5732 | 357 | 1878 | 6911 | –559.751 | –1394.57 to 275.0671 | 0.179873 |

| Reducing hours | |||||||||

| Baseline | 383 | 11.18 | 66.81 | 375 | 8.58 | 54.47 | |||

| 3 months | 354 | 5.84 | 40.19 | 323 | 5.85 | 46.31 | |||

| 6 months | 266 | 0.3 | 4.95 | 244 | |||||

| 12 months | 319 | 299 | 1.08 | 18.69 | |||||

| Total cost | 221 | 4.83 | 41 | 197 | 6.32 | 50.83 | –1.41168 | –12.1063 to 9.282926 | 0.787964 |

| All societal | |||||||||

| Baseline | 383 | 711 | 3830 | 375 | 672 | 2478 | |||

| 3 months | 354 | 627 | 2556 | 323 | 762 | 3787 | |||

| 6 months | 267 | 442 | 1845 | 244 | 740 | 2446 | |||

| 12 months | 319 | 669 | 3831 | 299 | 824 | 4478 | |||

| Total cost | 374 | 1480 | 5726 | 358 | 1880 | 6901 | –566.077 | –1342.95 to 210.7933 | 0.146231 |

| MICE all societal costs | |||||||||

| 3 months | 383 | 587 | 131 | 375 | 700 | 193 | |||

| 6 months | 383 | 337 | 85 | 375 | 824 | 154 | |||

| 12 months | 383 | 612 | 193 | 375 | 754 | 223 | |||

| Total cost | 383 | 1537 | 308 | 375 | 2279 | 423 | –761.396 | –1783.597 to 260.804 | 0.144 |

Quality-adjusted life-years

There were no significant differences between the FLACS and PCS arms for the complete-case analysis of QALYs (Table 14) or for the MICE analysis of QALYs (Table 15).

| EQ-5D | Treatment arm | Adjusted mean difference | 95% CI | p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLACS | PCS | ||||||||

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | ||||

| EQ-5D-3L | |||||||||

| Baseline | 380 | 0.795 | 0.236 | 373 | 0.783 | 0.25 | |||

| 6 weeks | 280 | 0.81 | 0.271 | 254 | 0.813 | 0.253 | |||

| 3 months | 351 | 0.835 | 0.23 | 323 | 0.822 | 0.245 | |||

| 6 months | 262 | 0.824 | 0.26 | 234 | 0.812 | 0.255 | |||

| 12 months | 318 | 0.833 | 0.231 | 299 | 0.819 | 0.253 | |||

| QALYs | 179 | 0.825 | 0.206 | 143 | 0.832 | 0.165 | –0.011 | –0.037 to 0.016 | 0.416 |

| EQ-5D-3L vision bolt-on | |||||||||

| Baseline | 380 | 0.769 | 0.249 | 373 | 0.759 | 0.26 | |||

| 6 weeks | 280 | 0.801 | 0.279 | 254 | 0.805 | 0.26 | |||

| 3 months | 351 | 0.829 | 0.232 | 323 | 0.816 | 0.25 | |||

| 6 months | 262 | 0.818 | 0.265 | 234 | 0.805 | 0.26 | |||

| 12 months | 318 | 0.828 | 0.233 | 299 | 0.814 | 0.257 | |||

| QALYs | 179 | 0.819 | 0.209 | 143 | 0.826 | 0.169 | –0.012 | –0.038 to 0.014 | 0.360 |

| EQ-5D | Treatment arm | Adjusted mean difference | 95% CI | p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLACS | PCS | ||||||||

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | ||||

| EQ-5D-3L | |||||||||

| 6 weeks | 380 | 0.819 | 0.015 | 373 | 0.827 | 0.014 | |||

| 3 months | 380 | 0.844 | 0.012 | 373 | 0.835 | 0.013 | |||

| 6 months | 380 | 0.828 | 0.015 | 373 | 0.827 | 0.014 | |||

| 12 months | 380 | 0.839 | 0.012 | 373 | 0.827 | 0.014 | |||

| QALYs | 380 | 0.815 | 0.010 | 373 | 0.810 | 0.001 | 0.0004 | –0.022 to 0.023 | 0.974 |

| EQ-5D-3L vision bolt-on | |||||||||

| 6 weeks | 380 | 0.810 | 0.015 | 373 | 0.818 | 0.014 | |||

| 3 months | 380 | 0.838 | 0.013 | 373 | 0.830 | 0.013 | |||

| 6 months | 380 | 0.822 | 0.015 | 373 | 0.822 | 0.014 | |||

| 12 months | 380 | 0.834 | 0.013 | 373 | 0.821 | 0.015 | |||

| QALYs | 380 | 0.811 | 0.012 | 373 | 0.804 | 0.011 | –0.004 | –0.0284 to 0.0203 | 0.744 |

Primary economic evaluation

The primary economic evaluation was a within-trial cost-effectiveness analysis over 12 months from a health and social care cost perspective using the EQ-5D-3L to calculate QALYs and using MICE for missing cost and utility data. Seemingly unrelated regression was used to account for correlation between costs and outcomes, with adjustment for baseline, site and the number of eyes that were eligible.

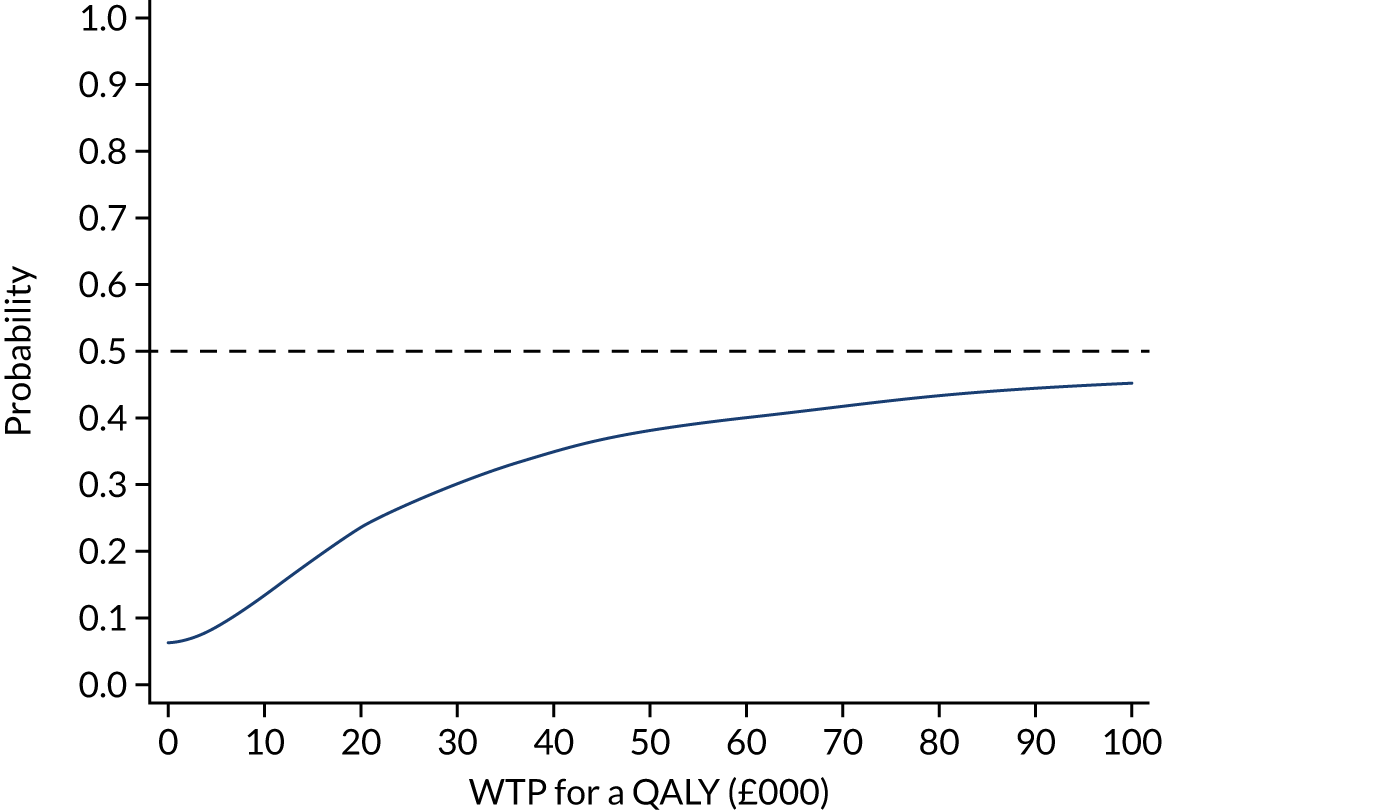

The mean cost difference (FLACS minus PCS) for the imputed, bootstrapped, adjusted data was £167.62 per patient (95% of iterations between -£14.12 and £341.67). The mean QALY difference (FLACS minus PCS) was 0.001 (95% of iterations between –0.011 and 0.015). This equates to an ICER (cost difference divided by QALY difference) of £167,620. The CEAC and cost-effectiveness planes are reported in Figures 6 and 7, respectively. There is a 24% probability that FLACS is cost-effective compared with PCS at a WTP threshold of £20,000 for a QALY gained and 30% probability at a £30,000 WTP threshold. As shown in Figure 7, the incremental mean cost of FLACS is greater than that of PCS for 97% of iterations, and in 53% of iterations FLACS has greater incremental mean QALYs.

FIGURE 6.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve of FLACS compared with PCS from a health and social care cost perspective: bootstrapped, adjusted with MICE.

FIGURE 7.

Cost-effectiveness plane of FLACS compared with PCS from a health and social care cost perspective: bootstrapped, adjusted with MICE.

Secondary and sensitivity analyses

Using the 3-month data only to calculate cost-effectiveness, in the MICE, bootstrapped and adjusted analysis, FLACS is dominated by PCS (mean cost difference of £171.70, 95% CI £57.59 to £285.80; mean QALY difference of –0.001, 95% CI –0.006 to 0.004).

When the vision bolt-on is included in the MICE, bootstrapped, adjusted results, PCS dominates FLACS, in that there is a mean cost difference of £234.94 (95% of iterations between £56.44 and £455.83) and the mean QALY difference is –0.003 (95% of iterations between –0.016 and 0.011). There is an 11% probability that FLACS is cost-effective compared with PCS at a WTP threshold of £20,000 for a QALY gained and a 16% probability at a £30,000 WTP threshold.

If two theatres are used at the same time, as opposed to just one, in the MICE, bootstrapped, adjusted results the ICER is £149,830, in that there is mean cost difference of £149.83 (95% of iterations between –£31.64 and £232.80) and the mean QALY difference is –0.001 (95% of iterations between –0.011 and 0.015). There is a 26% probability that FLACS is cost-effective compared with PCS at a WTP threshold of £20,000 for a QALY gained and a 32% probability at a £30,000 threshold.

In the societal analysis using MICE for missing data, and with the bootstrapped adjusted results, FLACS dominates PCS, with a mean cost saving of £623.53 per patient (95% of iterations between –£1431.27 and £203.24) and a mean QALY difference of 0.0004 (95% of iterations between –0.013 and 0.015). There is an 87% probability that FLACS is cost-effective compared with PCS at a £20,000 WTP for a QALY gained and an 86% probability at a £30,000 WTP threshold (Figure 8). The downwards slope of the CEAC is because of the very small number of additional negative incremental QALYs compared with positive incremental QALYs (50.2% vs. 49.8%, respectively).

FIGURE 8.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve of FLACS compared with conventional cataract surgery from a societal cost perspective: bootstrapped, adjusted with MICE.

For the threshold analysis from a health and social care cost perspective, assuming that FLACS results in an additional 0.001 QALYs per patient, FLACS needs to cost £138 less than it currently does to potentially be cost-effective at a WTP threshold of £30,000 for a QALY gained.

Chapter 4 Discussion

The result of FACT is that FLACS is not inferior to PCS for UDVA 3 months postoperatively (the primary outcome). In addition, we found no significant difference in any of our secondary outcome measures by treatment arm with follow-up to 12 months, with the exception of binocular CDVA, which, although statistically significant, was not clinically significant.

Overall, our complication rates were lower than or comparable to previously published data from big data sets on cataract surgery outcomes. 38 Specifically, the PCR rates were 0.0% for FLACS and 0.5% for PCS, compared with a reported UK benchmark rate of 2.0%. 38 Reported PCR rates in the FEMCAT study were 1.4% for FLACS compared with 1.6% for PCS. 24 A RCT of 400 eyes of 400 patients from St Thomas’ Hospital (London, UK) undergoing either FLACS or PCS found a statistically significantly lower PCR rate in the FLACS than in the PCS arm (0.0% vs. 3.0%). 25 Previously, there had been some concern over possible higher anterior capsule tear rates with FLACS because of the ‘postage-stamp’ edge pattern following laser capsulotomy creation, with rates of 1.9% reported for laser capsulotomy compared with 0.1% for standard capsulorrhexis in a comparative case series of 1626 surgeries. 54 In our trial, anterior capsule tear rates were 0.8% (3/392) for laser capsulotomy compared with 0.5% (2/393) for standard capsulorrhexis, and this difference did not reach statistical significance. In the St Thomas’ laser cataract RCT,25 the anterior capsule tear rate was 3.0% for FLACS cases and 1.5% for PCS, which did not reach statistical significance. In view of the low event rates of posterior capsule tears and anterior capsule tears, a meta-analysis of RCT outcomes is required to investigate this further.

For refractive outcomes, 75% of both FLACS and PCS cases were within ± 0.5 dioptre target, and 95% of FLACS cases and 96% of PCS cases within ± 1.0 dioptre target at 1 year, compared with 73% and 93% of eyes being within ± 0.5 dioptre and ± 1.0 dioptre target in a recent large EUREQUO (European Registry of Quality Outcomes for Cataract and Refractive Surgery) analysis of 282,811 cataract surgeries. 55 Comparative values from another recent large RCT of FLACS compared with standard PCS were 71% and 77% of eyes, respectively, within ± 0.5 dioptre, and 94% and 95% of eyes, respectively, within ± 1.0 dioptre. 25

This trial was designed to have adequate power to detect important differences in vision and to minimise possible bias. It was publicly funded and designed to be representative of the publicly funded NHS in the UK. Masking the operating surgeon was not possible because of the surgery methodology, and, although trial participants were not masked to their allocated arm, we do not believe that this was a significant source of bias in the outcome measures. Interestingly, we did observe a small difference in the 3-month follow-up rates for those who underwent FLACS compared with those who underwent PCS, with 90% of FLACS patients attending follow-up compared with 80% of PCS patients. Participants who did not attend were contacted by identical methods to rebook within trial timescales and an additional sensitivity analysis does not suggest a difference in the characteristics of those who were lost to follow-up. A surgical learning curve effect is possible for FLACS, as all trial surgeons had performed hundreds to thousands of PCS compared with a minimum of 10 FLACS to meet trial surgeon eligibility. We have previously published data on the learning curve for FLACS and found that complications attributable to FLACS tend to occur in the first few patients,56 but correspondence suggests that the learning curve may include the first 100 patients undergoing FLACS. 57 Even if the FLACS learning curve is 100 patients, the complication rate in the FLACS arm is low and so it is difficult to see how this would materially affect our findings. Another limitation is that the majority of patients were recruited from a high-volume cataract day surgery unit (St Ann’s, Moorfields Eye Hospital, London, UK) and this may not be fully representative of the set-up in other areas of the UK. Trial recruitment (785 participants) was slightly below the planned 808 total; however, based on the pre-recruitment power calculation, the 95% CI for the difference in visual acuity (95% CI –0.05 to 0.03 logMAR) did not include our non-inferiority margin of 0.1 logMAR that was considered to be appropriate for cataract drug efficacy trials. 58 FACT was not powered to identify differences in complications such as PCR that happen infrequently, and an additional meta-analysis of the available evidence is required to investigate possible differences in rare events.

FLACS automates cataract surgery steps, including capsulorrhexis, which can typically take < 1 minute to complete. This is a key step in surgical training, and delegating this step to a machine may have an impact on training, potentially affecting surgical cases that are unsuitable for FLACS and, therefore, by definition, technically more complex. In FACT, eligible surgeons were those who had completed 10 or more FLACS cases, and, although the trial was open to surgeons of all grades, we found that, anecdotally, specialist trainees were often not keen to take part as this would give them less experience of all the steps completed by hand in PCS.

The within-trial analysis conducted as part of FACT provides the best evidence that we are aware of to date of the cost-effectiveness of FLACS compared with PCS. Given that FLACS costs £216 more than PCS (£168 when any potential cost benefits from health and social care costs are included) and that the study has found no evidence of any additional benefit as a result of FLACS, there is a low probability that implementing FLACS is cost-effective for the NHS.

Based on the threshold analysis, FLACS would need to cost at least £138 less than it currently does to potentially be cost-effectiveness at a WTP threshold of £30,000 for a QALY gained (£168 if the non-significant difference in QALYs is not included). This cost is very close to that of the FLACS patient user interface. Even with a more efficient use of theatres, using two theatres at the same time, and hence saving some cost on staff that can work across theatres, FLACS has a 26% probability of being cost-effective at the upper NICE WTP threshold of £30,000 per QALY gained. Similar conclusions have been drawn by Roberts et al. ,47 who explored how FLACS could be implemented in the NHS so that it is cost neutral, using the model of two theatres functioning in parallel and staff working between the two. They came to the conclusion that either theatres would need to increase their list size by 100% or the cost of the patient interface would need to decrease by 70% for FLACS to approach cost saving. Based on the results of a decision model, Abell et al. 59 came to the conclusion that FLACS would need to significantly improve patient outcomes to be cost-effective in an Australian setting. The recent FEMCAT study concluded that FLACS was not cost-effective for the French health-care system. 24

There was some evidence that FLACS is potentially cost-effective from a societal perspective. However, this result is predicated on the single question about time spent caring for a partner and, hence, should be interpreted with caution. There is a slight possibility that this question captured an impact on patients that is not captured elsewhere in the analysis, but there is limited evidence for this. Any future health economic evaluations in this area should continue to measure the impact on carers but should ensure that this is done using a validated measure of carer time, such as iMTA Valuation of Informal Care Questionnaire (iVICQ),60 to ensure a more robust analysis. We may have underestimated the FLACS and PCS costs of surgeons for FLACS and PCS as these are based on the PSSRU44 cost per hour, including overheads, but do not include an adjustment for additional activities conducted outside face-to-face time with patients.

Although the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) is generally not recommended in trials involving eyes because it has been found to be unreliable at capturing changes in vision,36 we included the vision bolt-on in an attempt to overcome this. The QALYs for the vision bolt-on are not significantly different from those for the EQ-5D-3L, although the mean is in a different direction (negative mean QALYs for the vision bolt-on compared with positive mean QALYs for the standard EQ-5D-3L). Given the results reported elsewhere in this report, it is unlikely that a condition-specific measure would have detected a change that the EQ-5D-3L and its vision bolt-on have failed to capture. We have not explored the cost-effectiveness for any of the other outcomes in the trial because there were no significant differences between arms and hence these analyses would have provided limited additional information.

Chapter 5 Conclusions

In summary, the results of FACT showed that FLACS is not inferior to PCS. The methods appear to be similar in terms of vision, patient-reported health and safety outcomes after 12 months’ follow-up. FLACS is not cost-effective. Additional RCT data and meta-analyses are required to further investigate possible differences between the surgical methods due to the low complication rates and apparently similar efficacy.

Implications for health care

The results of this RCT provide the current best available evidence, to our knowledge, that is generalisable to the UK NHS. We did not find evidence for a change in practice to adopt FLACS in preference to PCS.

Acknowledgements

The trial was funded by the NIHR Health Technology Assessment programme (project reference number 13/04/46) and was sponsored by University College London (UCL).

We thank the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust for supporting the trial and Moorfields Eye Charity (grant references GR000233 and GR000449 for the endothelial cell counter and femtosecond laser used). Alexander C Day was supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre based at Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology. Catey Bunce is part funded/supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London.

We thank the patient panel at Moorfields Eye Hospital who contributed to the design of the trial, and also all FACT participants and recruiting sites.

We are also grateful to the following.

Members of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC):

-

TSC: chairperson Professor David Spalton, Mr Andrew Elders, Mr Larry Benjamin and Mr Horace Cheung.

Independent members of the Data Monitoring Committee:

-

Independent Data Monitoring Committee: chairperson Dr Chris Rogers, Miss Emma Hollick and Professor Augusto Azuara-Blanco.

-

Non-independent TSC member: Professor Anne Schilder.

Collaborators on behalf of the FACT group:

-

Francesco Aiello, Muna Ali, Walter Andreatta, Bruce Allan, Hayley Boston, Torsten Chandler, Sandeep Dhallu, Matthew Edmunds, Ahmed Elkarmouty, Joanna Gambell, Felicia Ikeji, Balasubramaniam Ilango, Emma Jones, Gemma Jones, John Koshy, Nicola Lau, Vincenzo Maurino, Victoria McCudden, Kirithika Muthusamy, Anna Quartilo, Gary Rubin, Jeffrey Round, Jasmin Singh, Yvonne Sylvestre, Richard Wormald and Yit Yang.

Staff facilitating recruitment and data collection:

-

Moorfields Eye Hospital –

-

Ahmed Al Maskari, Ahmed Elkarmouty, Alex Day, Alexa King, Aljazy Jaber, Bruce Allan, Chameen Samarawickrama, Chrysostomos Dimitriou, Darlene Catalan, Deborah Horney, Eme Chan, Emma Jones, Farah Mawji, Fransesco Alello, Giovanni Cillino, Harendra Thillaiampalam, Hayley Boston, James Byers, Jasmin Singh, John Koshy, Kareemah Adiatu, Konstantina Prapa, Krithika Muthusamy, Lena Potiwal, Marcus Ang, Mark Wilkins, Mohammed Ziaei, Muna Ali, Nick Taylor, Nicola Lau, Oluwatoyin Adenuga, Qasiem Nasser, Rajesh Deshmukh, Rasha Jorany, Rima Hussain, Samiul Rahman, Sandeep Dhallu, Sanjina Kathwiria, Sara Maio, Satvir Hansi, Scott Robbie, Sharona Hattersley, Simranjit Mehta, Steve Tuft, Tulsi Parekh, Victoria Grayson, Vincenzo Maurino, Vito Romano, William Kabanda and Yoganand Jeetun.

-

-

Sussex Eye Hospital staff –

-

Alfonso V Perez, Andrew Simpson, Campbell Keir, Carla Henrique, Carlos Garcia, Catherine Offer, Florence Winterflood, Jennifer Reid, Lisa Taylor, Lorraine Bennett, Luke Bromilow, Mayank Nanavaty, Nicola Sabokbar, Paul Frattarolli and Steven Borkum.

-

-

New Cross Hospital staff –

-

Balasubramaniam Ilango, Bhogal S Bhogal, Caz Ranford-Law, Claire Parkes, Donna Butler, Donna Jones, Gemma Edwards, Hafsa Iqbal, Imogen Hawthorne, Jas Purewal, Jose Maya, Kamaljit Balaggan, Matthew Edmunds, Meena Karpoor, Nick Denyer, Niro Narendran, Richard Webb, Sara Simmons, Sharon Hughes, Susan Massey, Walter Andreatta, Yit Yang, Jennie Green and Ian Bowen.

-

-

UCL Comprehensive Clinical Trials Unit staff –

-

Ana Quartilho, Caroline Doré, Emilia Caverly, Felicia Ikeji, Gemma Jones, Jade Dyer, Jeff Round, Kate Bennett, Michelle Tetlow, Philip Bakobaki, Pranitha Veeramalla, Rachael Hunter, Sophie Connor, Steve Hibbert, Tabassum Khan, Tola Erinle, Torsten Chandler, Victoria McCudden, Yvonne Sylvestre, Zainib Shabir and Gemma Jones.

-

Contributions of authors

Alexander C Day (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2099-8870) led the initial conception and design of the trial, led the writing of the protocol, acquired the funding and ethics approval, had complete involvement and oversight of the trial, provided clinical expertise and was the major contributor to manuscript writing.