Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/107/02. The contractual start date was in September 2016. The draft report began editorial review in October 2019 and was accepted for publication in June 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Parsons et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale for the research

The NHS is the biggest employer in the UK, with NHS England alone employing more than 1 million full-time equivalent staff. 1 As a whole, the NHS performs relatively poorly across many measures of staff health and well-being, with sickness absence rates that are 27% higher than the UK public sector average and 46% higher than the average for all sectors. 2 In 2009, Department of Health and Social Care research estimated that NHS trusts in England could save an average of £350,590 per year by reducing sickness absence. 3 Financial considerations aside, there is an important link between the positive well-being of staff and better patient care. 3

In Britain, common mental health disorders (CMDs), including depression and anxiety, are the main causes of sickness absence in the working population,4 and poor mental health is estimated to account for more than one-quarter of staff sickness absence in the NHS. 3,5 The full cost of CMDs in NHS staff is hard to quantify because, as well as direct financial impacts on the NHS, individual staff members and their families incur losses, and there is a financial cost to society as a whole. While the majority of staff who go on sick leave with CMDs will eventually return to work (RTW), 15% of staff on long-term sick leave with a CMD never RTW. 4 It is generally recognised that sickness absence caused by CMDs involves a complex myriad of factors; as well as the severity of the condition, occupational and personal issues play an important role. Therefore, an intervention to improve RTW following sickness absence because of a CMD needs to address the biopsychosocial causes of the absence.

A recent Cochrane review of workplace interventions to improve capacity for work in people on sick leave found that the quality of evidence about the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of workplace interventions for workers with CMDs was low. 6 If an intervention for NHS workers who are on sick leave with CMD could, in a way that was cost-effective, accelerate return to useful work and prevent sickness absence extending beyond 6 months, there could be major benefits for the affected worker, their colleagues, their employers and NHS patients.

Existing literature and interventional studies

Previous work has indicated that interventions to reduce time away from work due to CMDs are most likely to be effective if they are multifaceted. 7–10 Systematic reviews suggest that an intervention should include:

-

identification of obstacles to RTW11

-

work-focused cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT)12

-

focused problem-solving13

-

optimisation of clinical treatment; goal-setting; and a step-wise, written RTW plan based on discussion between the participant and their manager14

-

both physical and mental health interventions15

-

consideration of workplace adjustments, including flexible working and graded RTW10,11

-

service co-ordination and communication of the RTW plan with other health-care professionals [general practitioners (GPs) in particular]. 16

Equally important is the maintenance of contact between the line manager and the sick-listed worker. 17 A comprehensive systematic literature search on RTW interventions specifically for workers with CMD produced similar results:9 it explored whether or not any of the interventions were specific to health-care, and found that most of the evidence concerned mixed groups of occupations and did not focus on a single sector.

Two important guidelines relevant to the management of workers on sick leave with CMDs have been published in the Netherlands and the UK. 8,18 The Dutch guideline8 is specific to CMDs. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline on managing sickness absence18 applies to all types of illness, and its implementation needs to be tailored to specific conditions and the local context. A few studies have evaluated the use of the Dutch guidelines. A randomised controlled trial (RCT) comparing the implementation of the first edition (published in 2000) with care as usual (CAU)19 showed a decrease in the time to RTW among workers with minor stress disorders but not in those with other CMDs. Similarly, a follow-up RCT evaluating the effectiveness of the 2007 Dutch guideline in improving RTW of workers with CMD,20 which compared its use by appropriately trained occupational physicians with management by others who have not received such training, showed that occupational physician adherence to the guidelines did not result in an improved RTW (either time to full RTW or time to first RTW) for workers with a CMD. It is important to note, however, that in the Netherlands each employee is required to have a rehabilitation consultation with an occupational physician when they take sick leave beyond a specified period. This is not the case in the UK, where NHS staff who take sick leave would possibly not see an occupational health (OH) professional at all and, if they do, would most likely see an OH nurse. Therefore, although we took the evidence about the Dutch guideline into account in planning our study, we could not assume that the evidence would be generalisable to NHS workers.

A Norwegian RCT21 demonstrated that work-focused CBT combined with individual job support for those on sick leave with CMD led to increased work participation compared with CAU, especially in those who had been on sick leave for longer than 12 months. However, the trial was not set in a workplace and the results are unlikely to be transferable to the UK, particularly because the Norwegian National Insurance Scheme provides 100% coverage for income lost from CMDs. Thus, these results may not be generalisable to the UK.

Collaborative care interventions such as case management and interventions focused on work-orientated problem-solving have been widely adopted and adapted for specific health conditions and areas, including occupational rehabilitation. 22–26 In essence, case managers (who are often specially trained, allied health professionals) work collaboratively with patients to address their care and treatment needs, usually within a biopsychosocial framework. In the health-care context, the focus is specifically on the biopsychosocial assessment of needs; co-ordination and engagement of services and support; case review, and follow-up. At the time of the production of this report, an ongoing RCT in Sweden is evaluating a new, work-orientated, problem-solving intervention delivered in primary care by specially trained rehabilitation co-ordinators for employees on sick leave with a CMD for a minimum of 14 days and a maximum of 13 weeks. 22

The importance of combining workplace and clinical interventions is reinforced by the findings of a recent Cochrane review of interventions to improve RTW in people on sick leave with depression,12 and also by a systematic review of characteristics of interventions that facilitate RTW after sickness absence. 27 Although there have been few interventional studies in the UK, one investigation carried out at an NHS trust in England suggested that an intervention could be cost-effective if it was based on multidisciplinary case management delivered by trained OH case managers (mainly OH nurses). 24 Another, the EASY (Early Access to Support for You) study,28 based in a Scottish health board, also used case management. In both studies a biopsychosocial approach to assessment was a key component of the intervention.

Proposed timing of the intervention

The NICE guidelines advise that RTW interventions should be delivered between 2 and 6 weeks (and a maximum of 12 weeks) into a period of sickness absence. 18 Other publications recommend that the interventions to facilitate RTW following sickness absence should be delivered between 4 and 6 weeks after work cessation. 14,29,30 Previous UK studies of interventions for all causes of sickness absence have intervened after workers have been absent for 4 weeks24 or 1 day. 28 Smedley et al. ’s24 choice was based on evidence from Waddell14 on the pattern of RTW, albeit for all causes of absence or musculoskeletal disorders.

The EASY study intervention at day 1 was by telephone and was based on the management of sickness absence in ‘commercially successful companies’. 28 The recommendations from Waddell,14 Black and Frost,29 and NICE18 were based on data relating to all causes of sickness absence, with the premise that most workers who are on sick leave RTW within 4 weeks without intervention. In contrast, the Dutch guidelines on RTW after absence due to CMDs8 recommend that the intervention should take place 2 weeks into the absence, and ongoing trials of interventions to improve RTW after sickness absence due to CMDs are intervening at ‘about two weeks’31 and before 3 months of sick leave (Professor Gunnar Bergström, University of Gävle, 2017, personal communication).

In considering the timing of the intervention for our study, we looked at two sets of data from NHS workers on sick leave with CMDs. The NHS electronic staff record (ESR) system has a code (S10) for sickness absence due to anxiety/stress/depression and CMDs. We obtained all staff sickness absence data for code S10 at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust for 2015 (which included three staff members whose sickness absence for CMDs commenced in 2014). The corresponding Kaplan–Meier curve showed that ≈ 30% of staff who were on sick leave with CMDs at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Trust between 1 January and 30 November 2015 returned to work within 1 week (Figure 1). At the time of this research, at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, there was no policy for intervention until day 27 of sickness absence.

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival estimate.

These data suggest that ≈ 25% of the trust staff who were off sick with a CMD returned to work within 1 week of absence and that about half of trust staff were still absent after 3 weeks.

We also obtained data from NHS Digital (Table 1).

| Duration (days) of sickness absence | Incidents of sickness absencea (%) | Days absentb (%) |

|---|---|---|

| All sickness absence | ||

| < 7 | 62.56 | 5.97 |

| 7–28 | 18.47 | 11.38 |

| > 28 | 18.97 | 82.65 |

| Selected attendance reasonsc | ||

| < 7 | 21.23 | 1.10 |

| 7–28 | 30.86 | 9.28 |

| > 28 | 47.91 | 89.62 |

These data indicate that 21% of absences for CMDs lasted less than 7 consecutive days. If we deliver an intervention too early, we risk intervening unnecessarily for the ≈ 20% of workers who are likely to RTW within a few days, making it less likely that any benefits will be cost-effective. Moreover, evidence from studies about early interventions in workers who go on sick leave because of back pain indicated that very early intervention may obstruct recovery, owing, in part, to labelling and attention effects, which may encourage illness behaviour. 32 In the UK, absences of ≤ 1 week are self-certificated, and fit notes provided by a GP are unlikely to be practically available as a method of case ascertainment in a hospital employment setting until the second week of absence at the earliest. Beyond 8 days, the curve outlined in Figure 1 becomes less steep. Moreover, a fit note with a written cause of absence should become available by day 8 of absence. Therefore, delivery of our intervention as soon as possible after 8 days seemed a suitable and pragmatic choice, and aligns with the evidence and commissioning brief.

Patient and public involvement

Four patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives informed our application. A NHS human resources (HR) manager who has used an OH service for management of his own depression strongly welcomed the proposal and advised that it should be feasible to deliver in the NHS. In addition, following advice from a community interest group providing consultancy for NHS OH services, we also included NHS Employers and the NHS Health at Work Network on the panel of stakeholders. Our main patient representative has a CMD and works full time. She has been involved as a PPI representative for research studies at University College London. Our PPI representatives were involved in the development of the final protocol and commented on the plain English summary. In addition, our main (patient) PPI representative, who had a history of CMD, attended the stakeholder meeting and was involved in the development of the intervention and protocol. We also invited our main (patient) PPI representative to comment on the participation sheets, consent forms and questionnaires. At the end of the study, the PPI representatives helped us deliberate on the study findings, lessons learned and recommendations for future development work.

Data collection tools

In the feasibility study, we developed and tested the acceptability and feasibility of data collection tools that we proposed for use in a full trial. This allowed us to generate information that could be used to refine the design of the full trial at the same time. The measures of interest included clinical and occupational outcomes, and prognostic and cost-effectiveness indicators. The data were obtained largely through participant self-completed questionnaires and case report forms completed by case managers and field workers, and also included electronic data collected by the ESR system at each participating trust. ESR is in use across all NHS trusts and health boards, and has a specific code (S10) for sickness absence due to anxiety/stress/depression and mental health.

There is no consensus on the best tools for collecting data on relevant occupational outcomes. Indeed, recently published NICE guidelines33 specifically call for more research on how the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of workplace health policies and programmes can be measured. We chose tools that had been used successfully in other studies and were considered feasible for use in this study.

Clinical outcomes

Clinical improvement in CMDs, such as a decrease in the number or severity of symptoms, can be captured using a range of well-established assessment tools. In this feasibility study we used the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9) and Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) because they are brief and designed to be completed by the patient, changes in their score accurately reflect changes in symptoms of depression and anxiety, and they are free to use. 7,34 Furthermore, PHQ-9 is used by GPs and practitioners involved in the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) initiative, providing an opportunity to compare the outcomes of this study directly with routine care in non-NHS workers. In addition, we collected information on adherence to and change in use of medication.

Occupational outcomes

We measured time to full RTW (defined in this study as working the same days or hours per week as before sickness absence in an identical or equivalent role for at least 4 weeks) and time to partial RTW (defined as working any number of hours in any role) through the ESR and self-completion questionnaires. A study examining a multistakeholder perspective on the definition of RTW after sickness absence due to CMD found that definitions of RTW based on working days and hours may not accurately reflect the priorities of all stakeholders. 35 Therefore, we selected the most appropriate questions and discussed these with our PPI representatives, who approved the final version for our study.

A number of instruments have been developed to measure presenteeism and workability, such as the Work Ability Index (WAI)36 (to explore the effect of physical co-morbidity on work ability) and the Work and Social Adjustment Scale37 (to measure global functioning). Initially, it was our intention to use both of these measures of occupational outcomes to allow us to compare the results from the measures and to recommend one or both for use in a full trial. However, we reviewed the use of these in the research team and with our two external, international experts (Professor Carel Hulshof and Dr Karen Nieuwenhuijsen). The Work and Social Adjustment Scale contains only one item on work: ‘Because of my problem, my ability to work is impaired’ (score 1–8). We considered this unsuitable as a robust work ability outcome for this study. We then compared the WAI with the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS)38 at the suggestion of our international experts. Although the WAI is widely used in rheumatology medicine in assessing RTW, its validity has not been assessed in mental health. The WHODAS appears to have more face validity in mental health and work research because it has two specific items relating to areas that are important functional modalities and are frequently impaired in workers with CMDs. These are learning a new task and concentrating on something for > 10 minutes. Both of these impairments are known to be associated with CMDs. The WHODAS has been used in mental health studies on RTW. 39

Prognostic indicators

At baseline, we collected demographic data about personal characteristics such as age, sex, job, previous sickness absence and history of CMD and physical ill health. We enquired about expectations of full RTW and self-efficacy with regard to RTW because both of these indicators are strongly associated with RTW outcomes. 40,41 Self-efficacy with regard to RTW was measured by the Return-to-Work Self-Efficacy (RTW-SE) scale,42 a self-report tool that has shown promising reliability and prediction of actual RTW within 3 months.

Cost-effectiveness measures

To assess cost-effectiveness in a future trial, we collected data on the health and social care services that may be used more or less as a result of the intervention.

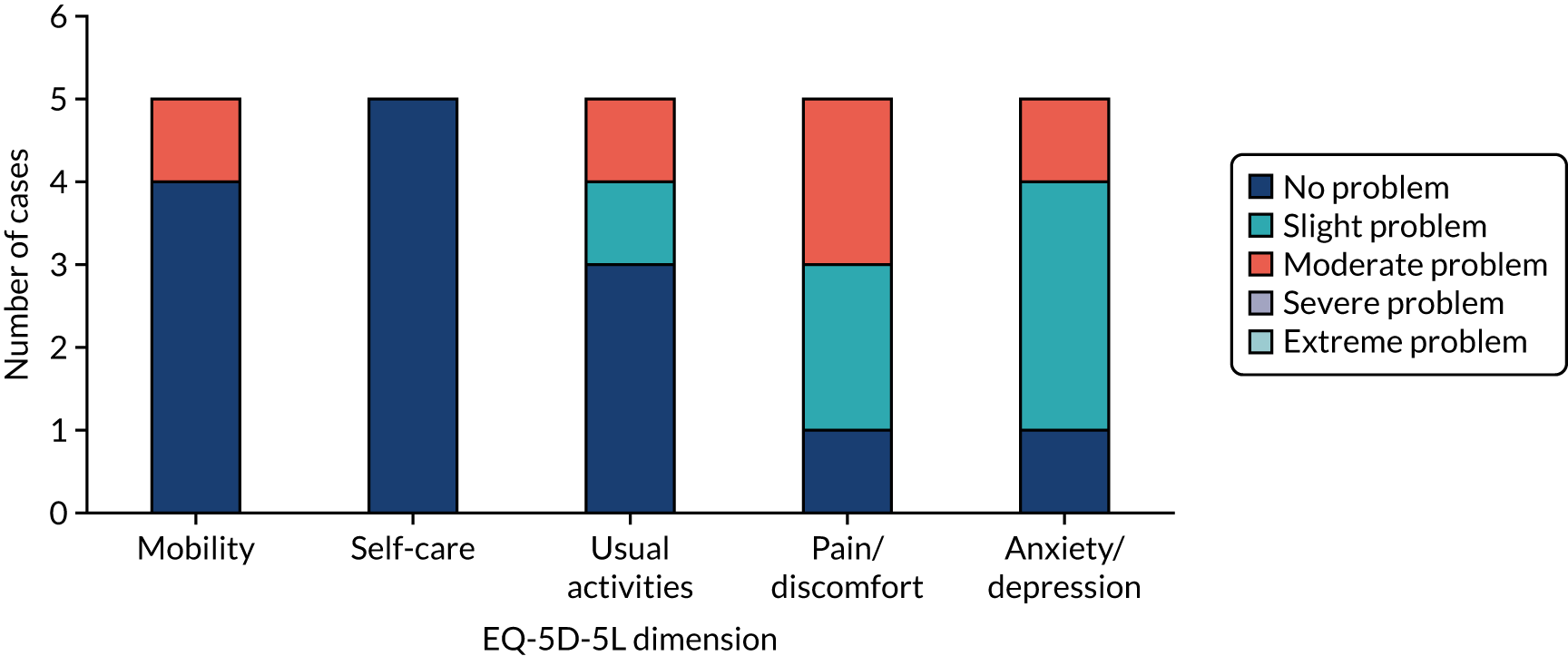

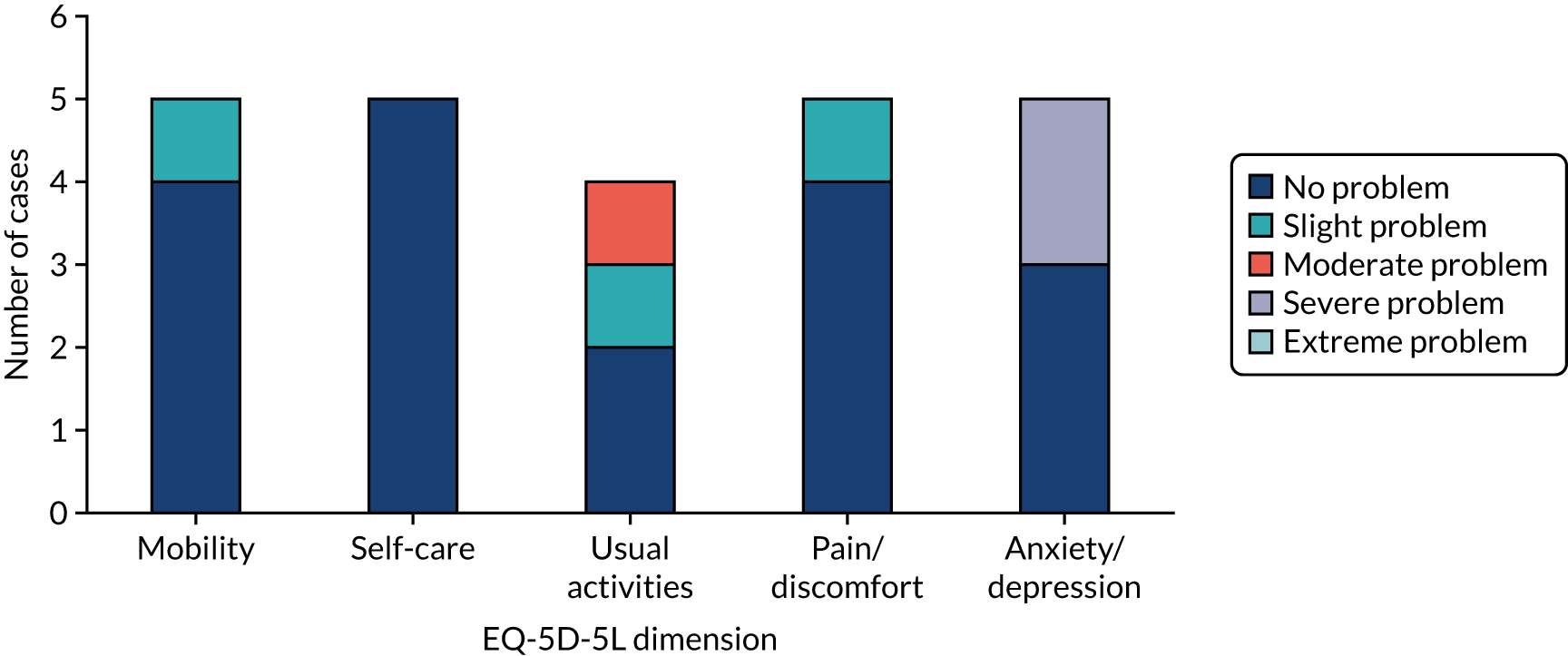

To this end, we used a short, self-completed version of the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI). 43 The objective was to determine which services were used during study follow-up and how often. Although the questionnaire was relatively short, the list of services was deliberately comprehensive; this list can be reduced as a result of the feasibility study. A full trial will involve linking costs for treatment and control arms with clinical outcomes and also quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). The most widely used measure for generating QALYs is the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D). 44 The EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), was used in the study, and the relationship between the utility weights derived from it and the clinical measures was explored. This indicated the appropriateness of the measure in a full study. Sensitivity of the utility weights to change in other measures was assessed using correlations and standardised mean responses. Costs of delivering the package of interventions, including OH nurse time, participant and manager time, and cost of training OH nurses in case management, were measured.

Other measures

In addition to the above, we collected information about rates of recruitment, adherence to the intervention in those allocated to receive it and the management of those allocated to CAU. In addition, we collected information on rates of follow-up, and participants’ referral to and uptake of IAPT services and the government’s Fit for Work service, in accordance with the funder’s commissioning brief.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Research questions

The feasibility study was undertaken to address the following research questions:

-

What is the most up-to-date evidence about the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of interventions to improve RTW in workers who go on sick leave with a CMD?

-

What is the current practice of NHS OH departments in managing staff who go on sick leave with a CMD?

-

What form of intervention is most likely to be cost-effective in promoting RTW in NHS staff who go on sick leave with a CMD, and how can this be manualised (written as an instruction manual) to meet individual and organisational needs in different OH settings?

-

What data collection tools should be used to assess changes in clinical state and occupational functioning as a consequence of such an intervention?

-

How feasible and acceptable is it to train OH nurses as case managers? What is the impact of the training on skill acquisition during the study period? How much additional training would case managers need to achieve established competency targets and prevent decay in skills?

-

How feasible and acceptable would it be to deliver such an intervention in different NHS settings? What rate of uptake could be expected, and how good would the adherence by OH staff and study participants be? What would be the resource implications of the intervention?

-

If a trial were conducted to test such an intervention, how well would methods of recruitment and data collection work in practice? What rates of recruitment and follow-up would be expected? What would be the likelihood of ‘contamination’ if, within the same OH department, the intervention were delivered to some staff and not to others?

The study was a 37-month mixed-methods project with four complementary work packages (WPs) to address the aims and objectives:

-

WP1 – the aim was to gather evidence and information to develop a practical and acceptable evidence-informed intervention.

-

WP2 – the aim was to gather information to develop a pragmatic protocol to evaluate the feasibility of the intervention.

-

WP3 – the aim was to test the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention in the NHS and to assess for contamination if the main trial were to be a RCT at departmental level.

-

WP4 – the aim was to inform the preparation for a future multisite trial in the UK.

The project addressed two elements of the development and evaluation process (i.e. developing the evidence base and feasibility) of the Medical Research Council (MRC)’s Framework for Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions. 45 WP1 took account of Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. 46

We used both qualitative and quantitative measures to allow an initial evaluation of process at this feasibility stage, particularly of the impact of context (NHS employment setting). We included both quantitative measures and more detailed qualitative analysis, with an iterative loop that allowed the basic assessment and development of fidelity and reach of the intervention during this feasibility stage. We anticipated that, should the intervention prove to be feasible, further process evaluation, including further work on fidelity, dose and mechanisms of impact, would be built in at the full trial stage.

Ethics approval and research governance

This study fell under the category of ‘research limited to the involvement of NHS or social care staff recruited as research participants by virtue of their professional role’ and, therefore, did not require ethics approval under the Governance Arrangements for Research Ethics Committee (GAfREC). Notwithstanding, approval to conduct the study within the NHS was granted from the Health Research Authority (IRAS reference 209317).

Data collection and follow-up

Outcomes were assessed using a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods.

Quantitative data

We collected the same data on all participants and participating trusts. Data from all groups (to which participants were allocated) were used to answer questions about rates of recruitment and follow-up, as well as the acceptability and performance of methods to assess possible outcome measures. Data from group A (intervention arm) and group D (intervention arm) provided information about the acceptability and costs of the intervention, as well as rates of adherence to the intervention. Data from group B (CAU arm) and group C (CAU arm) provided information about the distribution of possible outcome measures in the absence of the intervention (which would help in power calculations for a subsequent trial). Comparison of the management of participants in groups B and C gave an indication of the potential for major contamination. The follow-up period was 6 months from recruitment.

Before recruitment started, sites were advised on how to collect sickness absence data from their trust’s ESR. We assisted participating OH departments in liaising with their HR departments to ensure that the HR departments accurately recorded fit notes reporting CMD with the correct code (S10) in the ESR system.

Data on sickness absence for a CMD were collected at 6 months after the participant entered the study using data coded as S10 on the participating centre’s ESR and by self-report questionnaire. Additionally, we collected data about the distribution of possible outcome measures, including change in anxiety/depression, health-related quality of life, change in antidepressant use and RTW during the 6-month study period. Full and partial RTW was measured by total days of sickness absence before RTW (whether partial or full RTW). We collected information about participants’ referral to and uptake of IAPT services and the government’s Fit for Work Service.

Questionnaires were completed by study participants at the time of entry to the study and at 3 and 6 months after entry to the study. All participants in both arms completed the same baseline and intermediate questionnaires; however, responses provided in the intermediate questionnaire determined which version of the final questionnaire was used. Version 1 was used for participants back at work in any capacity for more than 4 weeks at the 3-month time point. Version 2 was administered to participants on sick leave due to a CMD at the intermediate questionnaire (including those who had not returned to sustained work) and those who did not return the intermediate questionnaire.

Participants were invited to complete hard-copy questionnaire booklets, and pre-paid envelopes were provided to facilitate return to the central research team. A series of reminders were used to encourage return of the study questionnaires. Reminders were sent as follows: one reminder via e-mail, one reminder via telephone and, finally, a second copy of the questionnaire booklet sent to the participants’ preferred postal address. This reminder strategy was used successfully in another OH study47 and was adopted for use in this study. Contact details were collected with the baseline questionnaire so that the follow-up questionnaires (and reminders, if needed) could be sent.

We recorded reasons for non-participation, baseline characteristics of those eligible for inclusion, adherence to the intervention in those allocated to receive it and the management of those who were not allocated to receive the intervention. We also recorded any protocol violations, reasons for not completing the intervention and any adverse events. Costs of delivering the package of interventions, including OH nurse time, participant and manager time, and cost of training OH nurses in case management, were also measured.

At the sponsor site (Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust), as well as at another non-participating NHS trust where a co-investigator was employed, additional exploratory work was completed to better understand the factors affecting the identification and referral of staff who were on sick leave with a CMD. Where appropriate and with relevant permissions, this included reviewing information on existing management referrals made to the OH department.

Qualitative data

Qualitative data collection was undertaken using semistructured focus groups and one-to-one interviews, once the quantitative data collection was complete. The qualitative work explored views and experiences in relation to:

-

strategies for screening and recruiting study participants, and for promoting the study across trusts (including barriers and enablers)

-

motivation for taking part in the study

-

RTW processes

-

communication pathways established during the study

-

use of study documentation and resources (usefulness and acceptability)

-

case manager training workshop (content, delivery and acceptability)

-

delivery of the case management intervention (how it worked in practice)

-

recommendations to consider for a future full trial.

Most of the interviews were conducted locally at each of the participating sites. Individual telephone interviews were conducted for those unable to attend in person. Purposive sampling was used to invite participants to take part in the focus group and interviews. Pilot interviews were carried out to assess comprehension, relevance and appropriateness of the interview schedule. We conducted one or two focus group sessions at each participating site, with the exception of Royal Papworth Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, which decided to withdraw from the study soon after participant recruitment commenced and chose not to participate in the follow-up interviews.

The central research team provided the local field workers with wording to promote and advertise upcoming focus group sessions, and requested that they promulgate this information via appropriate communication channels. Those interested in taking part were asked to contact the central research team so that further details (date/time/location) could be provided. Study participants (sick-listed workers participating in the study) were individually invited by e-mail to take part in a one-to-one interview. All participants in the focus groups and individual interviews were sent a participant information sheet at least 1 week before sessions were held and were given a chance to ask any questions that they may have in a telephone call with a member of the central research team. Prior to the commencement of each session, participants were asked to complete a consent form. For telephone interviews, verbal consent was taken and recorded on a paper consent form. Sessions took place in a quiet location and typically lasted 60–90 minutes. Most focus groups were facilitated by two members of the central research team (GG and VP) and one-to-one interviews were facilitated by one member of the central research team. Sessions were recorded on a digital audio-recorder and transcribed verbatim shortly after each session by a fully skilled medical secretary contracted by Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust. Audio-recordings were retained after transcription and will be kept for 20 years. No identifiable information was included during the transcription process. Transcripts were stored electronically using password protection. All transcriptions were uploaded onto NVivo version 8 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) to facilitate data management and coding.

Statistical methods

For the purpose of the intention-to-treat analysis, participants were considered as entered into the study on completion of the baseline questionnaire.

Quantitative analysis

In keeping with the objectives of this feasibility study, no formal statistical analysis beyond simple descriptive presentation of results was undertaken.

Rates of recruitment were calculated from the numbers of eligible participants and those who agreed to participate in the study. Characteristics of eligible participants were recorded at baseline and were summarised through means, medians, standard deviations (SDs) and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Outcome variables, including anxiety/depression scores, health-related quality of life scores and use of antidepressants, were summarised separately for baseline and follow-up. RTW time (full, partial or modified) was summarised and we compared data on RTW from participants’ self-report with data provided by case managers.

For each possible outcome measure, the prevalence of missing data was quantified. We calculated the proportion of participants who completed the intervention and the proportion of completed data sets.

Qualitative analysis

The interview and focus group transcripts were analysed using a thematic analysis approach as a guide. 48 This was chosen as the most suitable method to use on the basis that it is not aligned to any pre-existing theoretical or epistemological framework, and is widely considered a flexible and useful research tool. The qualitative components for the study, including the questions used in the interview schedules, were developed with the realist perspective in mind because we were interested in understanding the experiences and views of those who took part in the study (participants, OH case managers, line managers and HR personnel) as described in their own accounts.

The aim of the thematic analysis at this stage was to identify important and meaningful patterns in the data and to provide insights to account for the experiences and views of those involved in the study. As outlined in the study protocol, we initially planned to follow a six-phase, structured approach:

-

transcription of all interviews by a professional transcriber

-

familiarisation with text and creation of an initial list of emerging themes

-

coding of transcriptions uploaded to NVivo, a qualitative software package that allows data to be annotated as codes and cross-referencing of these codes

-

categorisation and interpretation through additional coding phases and development of representative themes and theoretical concepts emerging from analytical induction and cross-checking with an additional researcher on the team

-

identification of thematic frameworks in additional discussions with the team, which focused on further refinement through constant comparison within and between codes to ensure that the framework reflected the data

-

linking of findings with existing or newly generated theoretical concepts and models to provide context and confirm the relevance and robustness of the key findings of the study.

However, for pragmatic reasons we decided to adopt the following approach to the qualitative analysis. We initially created separate thematic coding frames in NVivo for each of the three qualitative data collection groups (focus groups, case managers and study participants). The final coding frame for each group can be found in Appendix 1. Most insights were derived primarily from research areas of specific interest included as topics in the interview guide (deductive analysis). These included site set-up, study promotion, participant recruitment, delivery of the intervention, stakeholder engagement and communication, and case manager training. In this regard, the analysis stopped short of developing overarching themes and subthemes (or a thematic map) because our focus was on addressing each of the specific research questions and objectives. As recommended by Braun and Clarke,48 we used this analytical approach, which did not occur in a linear fashion but rather reflected a process of going back and forth between different phases. A brief description of activities undertaken is given below.

Familiarisation of the data

Transcripts were read and re-read by two study team members (GG and VP). Where necessary, audio-recordings were listened to again to correct any minor discrepancies in the transcriptions. Importantly, this familiarisation with the qualitative data was enhanced by the involvement of the two study team members as facilitators of the focus group and individual interviews. In addition, this provided the two study members with an opportunity to develop and agree on, in consultation with the qualitative expert on the study (Stephani Hatch), the thematic coding frame to be used for the data analysis.

Generating initial codes and making annotations

Transcripts were coded (by either GG or VP) into NVivo using the thematic coding frame. This process enabled the data to be organised in a systematic and structured manner, ensuring that important and meaningful segments of data were extracted and applied to relevant codes (areas of interest), which allowed for additional codes (and nodes) to be created as new and emerging insights were revealed. Free-text annotations were also recorded next to relevant data extracts, allowing us to record our own interpretations of their significance during this phase.

Searching for themes

Once all transcripts had been coded into NVivo, the two researchers independently reviewed the collated extracts that had been coded to each code and deliberated on their significance and meaning (including the relationship between different codes) with the research questions and objectives in mind, until broad descriptions of the relevant codes were described in detail and supported by relevant verbatim quotations.

Rigour and trustworthiness

Several strategies were used during the study to demonstrate rigour and trustworthiness that were in keeping with fundamental principles of qualitative methods and analysis, for example collecting data using a variety of methods, constructing an audit trial to describe the approach used (including during the thematic analysis phase) and a peer review process to validate and question the analytic linkage being made between the data, coding framework and emerging insights.

A distress protocol was developed. The research team members who conducted the individual and focus group sessions were qualified health-care professionals and had experience providing counselling support. This allowed us to provide immediate support, if necessary, as well as providing the participant with information about local services and resources. In addition, the interviewers were supported by co-investigators with extensive clinical experience in occupational medicine and occupational psychiatry. We took a number of different measures to prevent and minimise upset; for example, participants were given the option to skip questions if they did not wish to provide an answer. Participants were also informed during the consent stages that they were free to withdraw from the study at any stage without giving a reason.

A further in-depth systematic thematic analysis exploring the broader myriad of issues (e.g. organisational, personal and cultural) relating to the provision of OH support for NHS staff with a CMD is proposed to be undertaken at a later time, with the emerging themes and subthemes published subsequently. At the time of writing this report, we have already progressed with a second independent rater, who was not involved in the formulation of the thematic coding frame and has not carried out any coding using the thematic coding frame, and who is now conducting an independent analysis of three random transcripts, one transcript from each study group. The purpose of this exercise is to compare and contrast relevant patterns in terms of insights that were identified by the two independent assessment approaches.

Economic analysis

Background

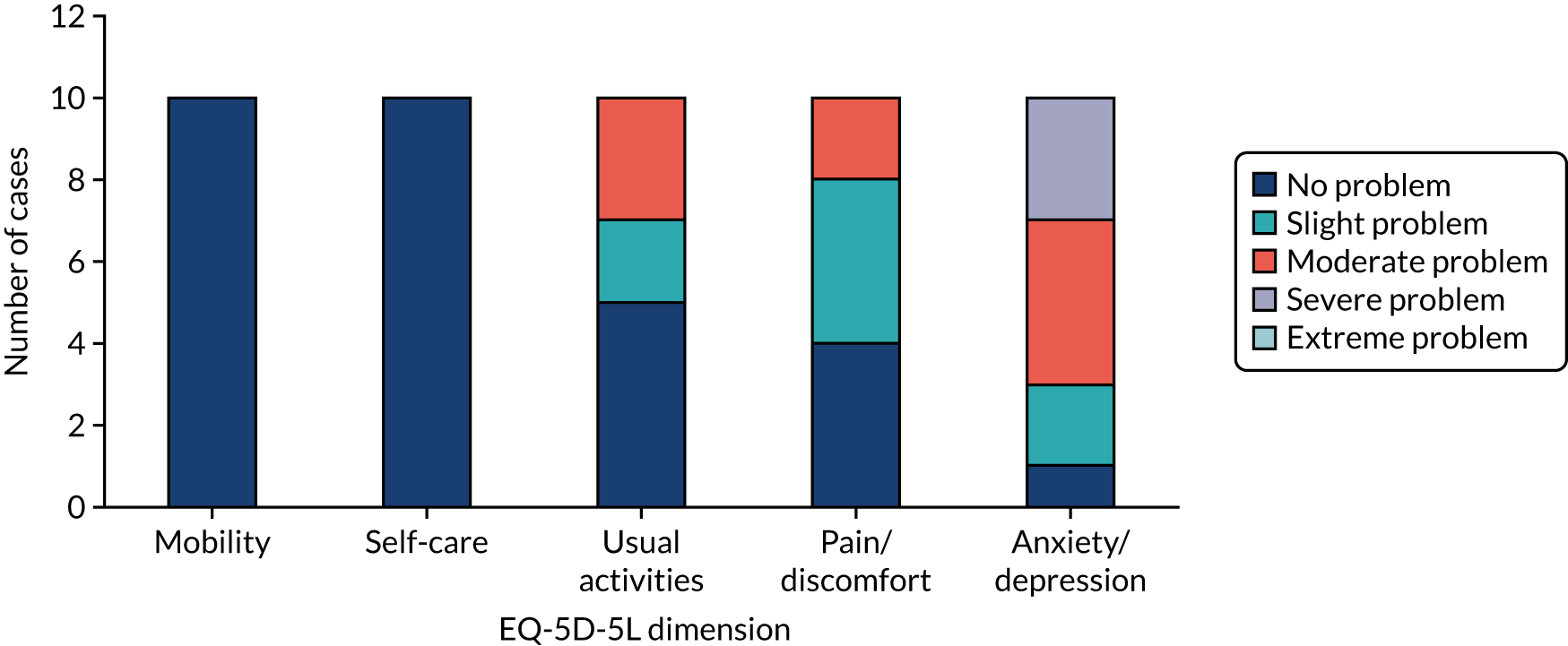

Establishing whether or not health-care resources are used in a way that represents value for money is necessary in a resource-constrained system. A full trial of this intervention would include a cost-effectiveness analysis in which health-care costs (including those of the intervention itself) would be combined with outcomes. This feasibility study explored the measurement of service use and health-related quality of life.

Aims and objectives

The objectives of the health economic component of the feasibility study were to (1) examine the feasibility of collecting service use data with the CSRI,43 (2) examine feasibility of collecting EQ-5D-5L data,49 (3) assess the appropriateness of the EQ-5D-5L in this population and (4) estimate intervention costs. Because this was a feasibility study, we did not focus on the costs of health services but rather their use, and we did not conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis. This would need to be done in a full trial.

Methods

The CSRI was developed in the 1980s and is a schedule commonly used to measure the use of services over a defined period. It is usually adapted for each study. We identified key services that we thought may be used by participants and asked participants at baseline and follow-up whether or not they had used these in the previous 3 months. We also asked for information on how many contacts were made. In the feasibility study we were particularly interested in the number of contacts made and what services were used.

The EQ-5D-5L is used to measure health-related quality of life. It consists of five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression). Each of these receives a score of 1 (no problem in that area) to 5 (extreme problems). The EQ-5D-5L is used to generate QALYs by attaching weights anchored at 1 (full health) and 0 (death) to the health states that can be derived from the EQ-5D-5L. Scores < 0 are also possible for states considered worse than death.

Intervention costs were calculated based on the cost of training time, materials and therapy time. This information was recorded centrally by the research team.

Chapter 3 Work package 1

To inform intervention development and delivery in WP2 and WP3, we gathered relevant evidence through a systematic review of the literature and established CAU. In addition, we developed the intervention and data collection tools through an iterative process. Specific details are outlined in this chapter.

Systematic review of the literature

The systematic review of the literature concerned research question 1: what is the most up-to-date evidence available on the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of interventions to improve RTW in workers who go on sick leave with a CMD?

Study design

This was a systematic review of the literature.

Key questions:

-

Which workplace-based interventions are effective in improving RTW outcomes for workers with a CMD?

-

What are the key elements of effective interventions?

-

Are any interventions specific to the health-care sector?

-

Are any interventions specific to the UK?

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

-

The inclusion criteria focused on interventions based in the workplace that have RTW or work absence as outcomes.

-

We excluded papers in which the results were not presented separately for workers with CMDs or a specified subset of CMDs.

Search strategy

A comprehensive systematic review by Pomaki et al. 9 on RTW/stay-at-work interventions for workers with CMDs included studies up to November 2009. We extended that review to cover the 7-year period from 1 November 2009 to the end of September 2016.

Search terms

We combined three groups of terms (‘worker’, ‘mental health’, ‘intervention’) using an AND strategy. We restricted our search to English-language papers because papers in other languages are less likely to be relevant to the UK health-care service setting. We searched for systematic reviews, meta-analyses and primary quantitative and qualitative studies in five electronic databases [MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycINFO and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews]. The electronic database searches were supplemented by including the results of two relevant active reviews that had been identified on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (an international database of prospectively registered systematic reviews in health and social care, welfare, public health, education, crime, justice and international development where there is a health-related outcome):

-

Lyssenko L, Hahn C, Kleindienst N, Bohus M, Ostermann M, Vonderlin R. A Systematic Review of Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Occupational Settings. PROSPERO 2015: CRD42015019282. 50

-

Fishta A, Weikert B, Wegewitz U. Return-to-Work (RTW) Interventions for Employees with Mental Disorders: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. PROSPERO 2015: CRD42015023496. 51

At the time of the production of this report, both reviews were ongoing (to be completed).

To inform the systematic review of the published scientific literature, two guideline documents relevant to the management of workers on sick leave also informed the intervention development phase: (1) the Dutch national guideline,8 which is specific to CMDs, and (2) the NICE guideline on managing sickness absence. 18 The existing literature suggested that an intervention should include identification of obstacles to RTW,11,52 work-focused CBT,12 focused problem-solving,13 a focus on participant engagement and motivational interviewing (MI) techniques, optimisation of clinical treatment, goal-setting, written RTW plans based on discussion between the participant and their manager,14 consideration of workplace adjustments including flexible working and graded RTW, regular review and communication of the RTW plan with other health-care professionals, in particular GPs who are treating participants,11,16 along with maintenance of contact between the line manager and the sick-listed worker. 17

Data extraction and appraisal

A data extraction template was developed, focusing on the population to which the intervention was delivered, the setting of the intervention, the components of the intervention, economic costs, outcome measures and effect sizes. We appraised the papers and guidelines, taking into account the methodological quality of each paper, biases and confounders, and the direction of bias and size of effect of interventions. For RCTs we used the Cochrane risk of bias tool to assess the methodological quality of the trial. 53 Two reviewers appraised all papers independently. Where agreement was not obtained, papers were referred to a third reviewer. A meta-analysis was not conducted because of the high degree of heterogeneity of the included studies.

Outputs

We reported the systematic review based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. 54

Results

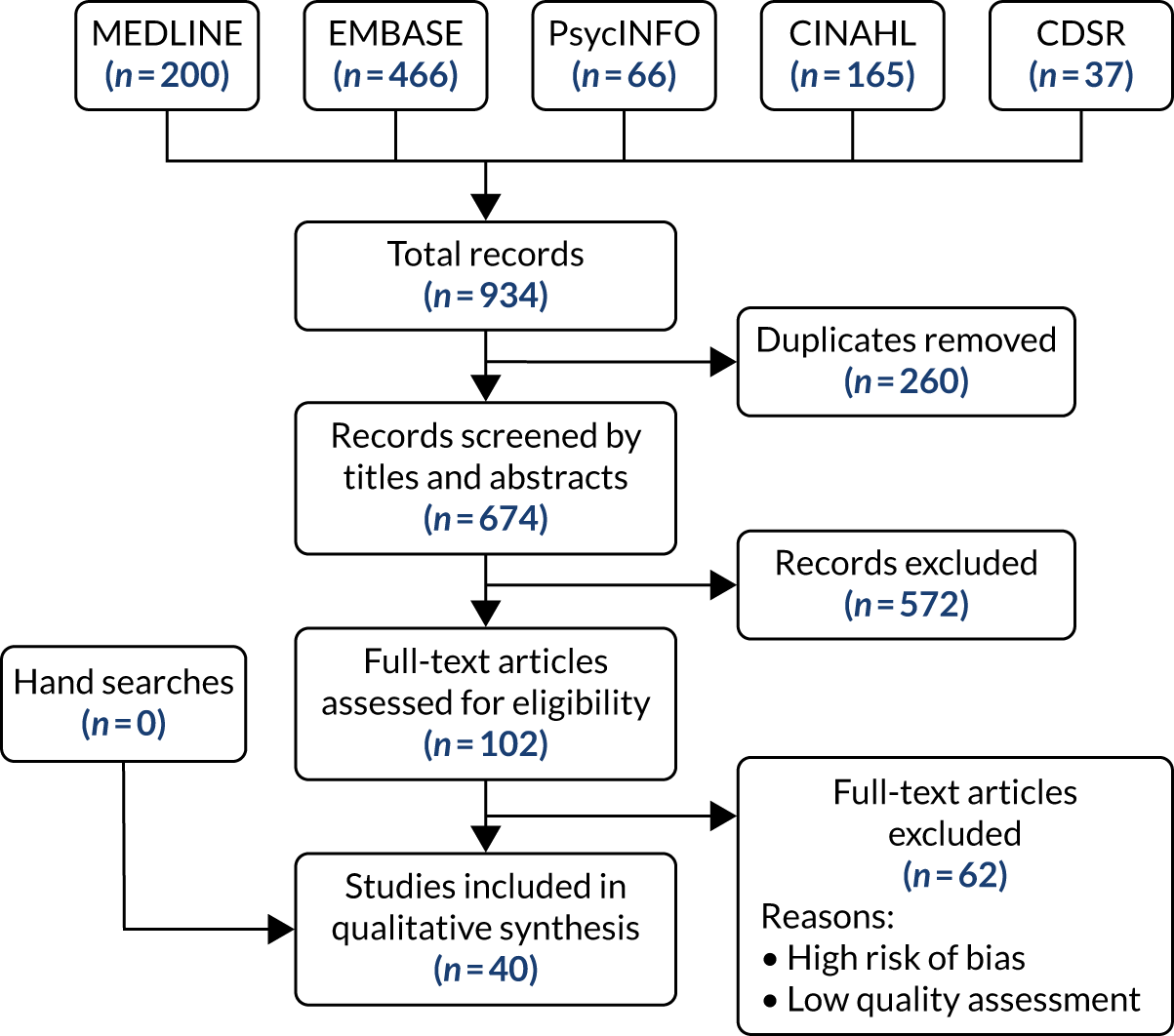

A total of 934 articles were retrieved from five databases (Figure 2). In total, 40 articles were included for qualitative synthesis and are listed in Table 2. Our search was sensitive because it included all CMDs. The majority of the 572 records excluded at the title/abstract stage were excluded because of studies not presenting results on CMDs.

FIGURE 2.

The PRISMA flow diagram of included studies. CDSR, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

| Number | Article |

|---|---|

| 1 | Netterstrom et al.55 |

| 2 | Bhui et al.56 |

| 3 | van der Feltz-Cornelis et al.57 |

| 4 | Cowls and Galloway58 |

| 5 | De Zeeuw et al.59 |

| 6 | Sahlin et al.60 |

| 7 | Eklund et al.61 |

| 8 | Evans-Lacko et al.62 |

| 9 | Falkenberg et al.63 |

| 10 | Grossi and Santell64 |

| 11 | Haraguchi et al.65 |

| 12 | Hees et al.66 |

| 13 | Hees et al.67 |

| 14 | Arends et al.68 |

| 15 | Jansson et al.69 |

| 16 | Joosen et al.70 |

| 17 | Joyce et al.71 |

| 18 | Reid et al.72 |

| 19 | Kroger et al.73 |

| 20 | Lagerveld et al.42 |

| 21 | Lagerveld et al.74 |

| 22 | Lemieux et al.75 |

| 23 | van Vilsteren et al.6 |

| 24 | Mackenzie et al.76 |

| 25 | Martin et al.77 |

| 26 | Nieuwenhuijsen et al.12 |

| 27 | Noordik et al.78 |

| 28 | Noordik et al.79 |

| 29 | Noordik et al.80 |

| 30 | Pomaki et al.81 |

| 31 | Rebergen et al.19 |

| 32 | Rebergen et al.82 |

| 33 | Reme et al.21 |

| 34 | Van Oostrom et al.83 |

| 35 | Van Oostrom et al.84 |

| 36 | Shippee et al.85 |

| 37 | Simpson et al.86 |

| 38 | Vlasveld et al.87 |

| 39 | Volker et al.88 |

| 40 | Hees et al.89 |

The following were key findings and recommendations from the systematic review and informed the development of the case management intervention; they relate to questions 1 (which workplace-based interventions are effective in improving RTW outcomes for workers with a CMD?) and 2 (what are the key elements of effective interventions?):

-

We found strong evidence suggesting that workplace-focused interventions significantly reduce the time until partial RTW, and low-quality evidence that they do not significantly reduce time to full RTW compared with no treatment.

-

The systematic review included four economic evaluations: two workplace-focused interventions were found to be cost saving from the perspective of the employer60,71 and two studies showed no economic benefit compared with CAU. 21,80

-

A review of qualitative studies58,69,78,86 that focused on the RTW process found that, from the employee perspective, the following considerations were prominent: (1) concerns about reduced working capacities, (2) difficulty setting limits in demanding work situations, (3) a sense of responsibility and a fear of being a burden to an employer, (4) recognition of exhaustion and (5) the need to control cognitions and behaviour such as perfectionism. An interesting finding was that most workers were able to describe solutions; however, few workers expressed an intention to implement or utilise the solutions in the workplace, with the exception being structural adaptations of work demands.

-

Several studies have demonstrated that a number of baseline characteristics appear predictive of a longer duration of sickness or poor RTW outcomes. These include a low level of education, a history of sickness absence, low self-esteem, low social functioning, older age and negative expectation regarding RTW.

-

Evidence suggests that different stakeholders have different perspectives regarding barriers to RTW. For example, employers tend to underestimate the importance of the work environment, whereas health-care professionals emphasise remaining at work, maintaining contact with employers and support in the work environment as important.

-

We found strong evidence that interventions should be based in the workplace and should involve problem-solving and an element of work-focused behavioural therapy.

For question 3, we found no interventions specific to the health-care sector.

For question 4, we found no interventions specific to the UK.

Collectively, the literature review suggested that our new intervention should include:

-

identifying obstacles to RTW11

-

work-focused CBT12

-

focused problem-solving13

-

focus on participant engagement and MI techniques, optimisation of clinical treatment, promoting sleep hygiene, goal-setting, written RTW plans based on discussion between participants and their manager14

-

workplace adjustments including flexible working and graded RTW, regular reviews, and communication of the RTW plan with other health-care professionals, in particular GPs who are treating participants11,16

-

maintenance of contact between the line manager and the sick-listed worker. 17

Discussion

The systematic review exercise was undertaken as an extension of the earlier review by Pomaki et al. ,81 and provided an important opportunity to incorporate updated information and learnings from the literature when developing our new case management intervention. We confirmed that interventions to improve RTW following sick leave with a CMD should be based in the workplace and based on work-focused behavioural changes. Although we undertook a comprehensive literature review, a more recent systematic review and meta-analysis52 exploring predictors of RTW for people on sick leave with CMDs was not completed during this present study, and so the findings and recommendations of this could not be taken into consideration when developing our case management intervention. 90–94 Another, concurrent review94 suggests that future interventions designed to facilitate RTW for people with CMD should attempt to ameliorate high workload issues. Our systematic review enabled us to identify key components of our proposed intervention.

Survey of care as usual

The survey of CAU concerned research question 2: what is the current practice of NHS OH departments in managing staff who go on sick leave with a CMD?

The published article relating to the survey of CAU95 can be found elsewhere.

Study design

This was a cross-sectional survey of OH departments providing OH services to NHS trusts and health boards.

Methods

We identified OH departments providing OH services to NHS trusts and health boards from two lists. Specifically, 122 providers of NHS OH services were identified from the NHS Health at Work Network and four providers were identified from the Commercial Occupational Health Providers Association. These 126 providers were invited to complete the survey of CAU.

We designed a 12-item electronic questionnaire that enquired about how OH providers currently manage NHS staff who go on sick leave with a CMD. We included questions on the type(s) of trust to which they provide OH services, who delivers the intervention, the nature of the intervention, how the line manager is involved, whether or not the workers have rapid access to mental health assessments or treatment (including CBT), and whether or not a worker’s treating health-care professional is involved.

The questionnaire was piloted among the 35 OH departments taking part in the SCIN (Skin Care Intervention in Nurses) trial. 96 We confirmed that nine OH departments were willing to take part in the feasibility study and use electronic OH data collection systems that would enable us to collect the data required for this study. We included OH departments that provide a service to acute and mental health trusts. NHS staff working in ambulance trusts have the highest sickness absence rates of all health-care workers, and the organisational structure of ambulance trusts is very different from that of acute trusts. In the light of this, we were keen to include an ambulance trust in our feasibility study. Because only one of the 35 centres we contacted provided OH care to an ambulance trust, we contacted one of the largest ambulance trusts in England (West Midlands Ambulance Service University NHS Foundation Trust). This trust completed the questionnaire and confirmed its willingness to participate in the feasibility study. Accordingly, we selected six NHS OH providers to take part in the feasibility study, with one as a reserve. The reserve site was intended to be opened if one of the existing sites withdrew at a very early stage during the study. Although Papworth Hospital NHS Foundation Trust subsequently withdrew from the study, it was not feasible because of time constraints to train an additional case manager from the reserve site.

Data analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarise the patterns of management of CMDs.

Outputs

The information we collected gave us a picture of usual management of NHS staff who go on sick leave with a CMD.

Results

A total of 49 out of 126 (39%) OH providers who were invited to complete the survey responded. We found that the majority (98%) of respondents reported that they had an organisational policy specifically relating to the management of sickness absence that also included triggers for referral for staff on sick leave with a CMD. In 63% of cases, referrals by line managers of sick-listed staff with a CMD to OH occurred between 8 and 28 days after commencement of sickness absence. A total of 10 respondents (20%) accepted referrals on the first day of absence and one respondent accepted referrals as soon as a fit note was received. Timely access to assessment by a psychiatrist or therapist was available to 82% of respondents, whereas early access to treatment by a mental health professional, through online CBT or via a counselling or employee assistance programme service, was available to 88% of respondents. Table 3 details the usual clinical aspects covered during the first consultation.

| Element | Never/sometimes, n (%) | Often/always, n (%) | Do not know, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exploration of typical symptoms of CMD | 0 (0) | 49 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Administration of standardised questionnaires | 20 (41) | 29 (59) | 0 (0) |

| Assessment of medication | 1 (2) | 48 (98) | 0 (0) |

| Assessment of non-pharmacological treatment | 4 (8) | 44 (90) | 1 (2) |

| Assessment of drug and alcohol misuse | 4 (8) | 45 (92) | 0 (0) |

| Assessment of risk to self (i.e. suicide and self-harm) | 3 (6) | 45 (92) | 1 (2) |

| Assessment of risk to colleagues and patients | 4 (8) | 45 (92) | 0 (0) |

| Assessment of support needs | 1 (2) | 48 (98) | 0 (0) |

| Signposting to support services (e.g. EAP) | 2 (4) | 46 (94) | 1 (2) |

| Identifying workplace barriers to RTW | 0 (0) | 49 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Identifying non-workplace barriers to RTW | 2 (4) | 47 (96) | 0 (0) |

| Problem-solving and goal-setting for RTW | 5 (10) | 43 (88) | 1 (2) |

| Consideration of workplace adjustments | 1 (2) | 48 (98) | 0 (0) |

| RTW planning with staff member and their manager | 4 (8) | 44 (90) | 1 (2) |

| Case management | 19 (39) | 29 (60) | 1 (2) |

| Arranging regular, timed reviews | 18 (37) | 31 (63) | 0 (0) |

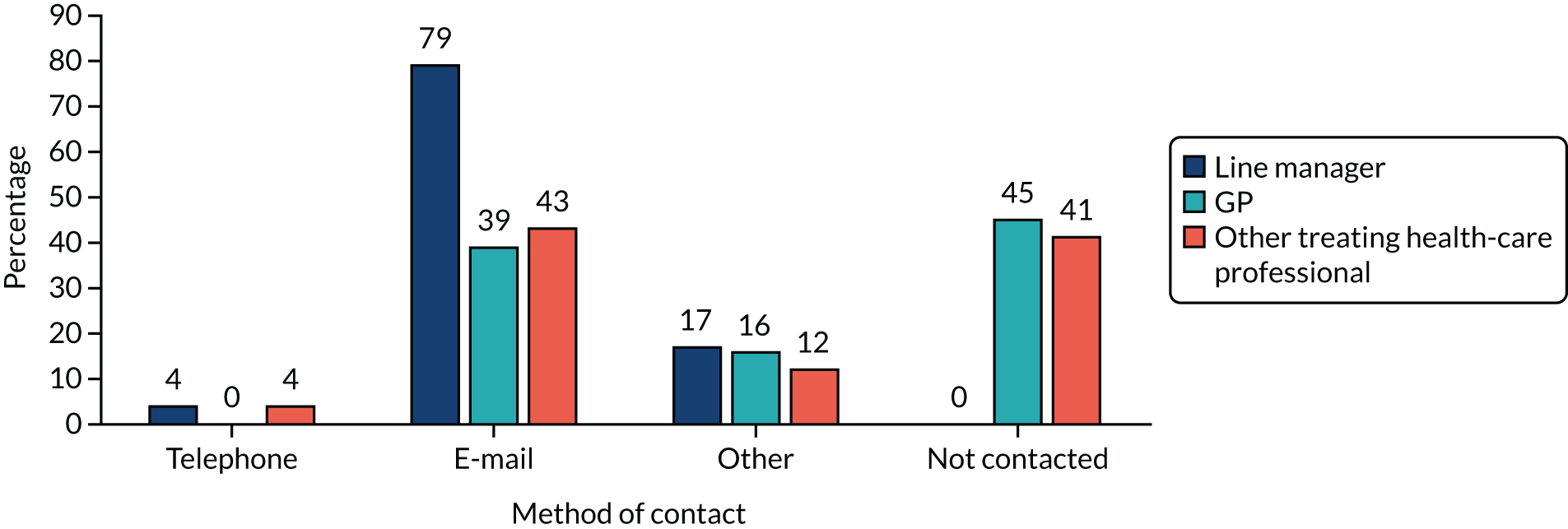

A key finding from the survey of CAU is that a large proportion of OH providers either do not deliver or only sometimes deliver a case management approach or regular, timed reviews (38.8% and 36.7%, respectively) for sick-listed workers with a CMD. Moreover, of those who reported that they do provide a form of case management or regular timed reviews, specific details with regard to the nature of both features were unknown. Forty-five OH providers (92% of responders) reported that a qualified OH professional, usually an OH nurse, undertook the first consultation. Seventeen (35%) OH providers always used face-to-face appointments for first consultations, while 22 (45%) OH providers used face-to-face consultations more than half of the time. The remainder predominantly used telephone consultations. All respondents provided contact and support for line managers of staff referred for CMDs. The most frequent advice provided was to maintain contact with sick-listed staff (86%). Most (80%) OH providers provided training for managers to better support staff with CMDs. The survey also found that some level of support or advice is provided by OH providers to line managers of NHS workers on sick leave with a CMD. Contact with the staff member’s GP or mental health professional was less consistent, and when this occurred contact was most commonly made by e-mail (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Methods of contact initiated between OH providers and other stakeholders.

Discussion

This was the first national survey to report on current OH management practices for NHS staff with a CMD. This survey found noteworthy variation in the elements comprising the first OH consultation for NHS workers who are on sick leave with a CMD, particularly with regard to the time between the commencement of sick leave (in response to a CMD) and initial OH consultation. Our survey of CAU capitalised on one of the stated outputs of the SCIN trial: ‘to establish a network of NHS OH departments which would be in a good position to deliver future studies’. 96 Because only 39% of OH providers participated in the survey, an important limitation was the potential impact of non-response bias. Therefore, it is reasonable to argue that OH providers that are able to deliver superior OH services may have been more motivated to respond to the survey and, therefore, the results from this survey may not reflect routine OH management practices for sick-listed staff with a CMD. With regard to the variation in the method of conducting first consultation (i.e. telephone vs. face-to-face), these differences could be due to variation in OH service delivery (e.g. in-house OH service vs. external, contracted OH service). The findings from the survey highlight a need to promote the standardised adoption of early case management practices in the provision of OH services, which may facilitate the early and sustained RTW for NHS staff with a CMD. Embedding a standardised approach to the management of NHS staff with a CMD will also enable future widespread evaluation of OH services.

Chapter 4 Work package 2

Development and refinement of the intervention

The development and refinement of the intervention concerned research question 3: what form of intervention is most likely to be cost-effective in promoting RTW in NHS staff who go on sick leave with a CMD, and how can this be manualised (written as an instruction manual) to meet individual and organisational needs in different OH settings?

Study design

This was a two-stage, iterative consultation based on methodology that the chief investigator (Ira Madan) and co-investigator (Julia Smedley) have used in the development of national evidence-based guidelines. 97 This section describes the various stages used during the intervention development phase.

Stage 1: mapping of evidence from the literature and expert feedback

Methods

In April 2017, we conducted a 1-day mapping meeting, with seven members of the multidisciplinary research team (IM, JS, MM, MH, DJ, VP and our work/patient representatives) each contributing their expertise from their respective professional disciplines, including occupational medicine, occupational psychiatry, psychology and general practice. The objectives of the mapping meeting were threefold:

-

To discuss and deliberate on the evidence and learnings derived from the systematic review, taking into account participants’ professional expertise and knowledge.

-

To consider its relevance in relation to the scope and intention of the proposed intervention.

-

To map the relevant aspects of the evidence onto the preliminary case management intervention and to develop additional therapeutic resources (sleep hygiene leaflet and RTW resource booklets) that would underpin the intervention. This process was further refined with additional features added to the intervention. A step-wise flow diagram was created describing the key components of the intervention.

When developing the work-directed case management intervention for this feasibility study, care was taken to interpret the evidence in the context of its relevance to NHS staff and the NHS work environment. The definition of case management adopted for this study was that of Hutt et al. ,98 who propose that case management is a process typically comprising core stages such as patient assessment and planning, co-ordination of services and support and reviewing care. The core components of case management approaches commonly comprise case identification, assessment, care planning, care co-ordination (which can include medical management, self-care support, advocacy and negotiation, psychological support, monitoring and review) and case closure or discharge, with the option of providing time-limited case reviews where clinically necessary. We also recognised that the steps involved are non-linear and repeat reviews or further assessments may be required, as previously highlighted by Ross et al. 99

An iterative approach was adopted for intervention development. A particular focus when developing the intervention was the question: What form of intervention is most likely to be cost-effective in promoting RTW in NHS staff who go on sick leave with a CMD, and how can this be manualised (written as an instruction manual) to meet individual and organisational needs in different OH settings? The formulation of the provisional intervention model took account of the volume, quality and consistency of the evidence. Well-conducted studies with negative findings and studies that report significant associations were given appropriate weight. Where possible, we looked at the size of the effect of the intervention and considered the applicability of each intervention to our target population.

Output

The output was a provisional evidence-based model of a complex intervention to improve RTW among NHS staff on sick leave with a CMD. This was represented in the form of a flow chart.

Stage 2: stakeholder workshop

Methods

In May 2017, a 1-day multidisciplinary stakeholder workshop was held with participation from key stakeholder groups. The group comprised two OH nurses and an OH matron delivering OH services in the NHS setting, an NHS HR representative, representatives from the NHS Health at Work Network and NHS Employers, a representative from a health-care union (UNISON, London, UK) and our PPI representatives. The session was also attended by members of the research team (including an OH physician, GP collaborator, psychiatrist collaborator and post-doctoral research fellows) and was facilitated by the chief investigator. The purpose of the follow-up multidisciplinary stakeholder meeting was to deliberate on the proposed preliminary case management intervention, with a particular focus on the timing of each component of the intervention (referral to OH provision of first and subsequent appointments), referral pathways into the study, signposting follow-up services, the procedure for delivering each component of the intervention, agreement on the role and responsibility of each worker (line manager, HR and OH staff), and deciding on appropriate supplementary resources to make available to sick-listed workers and their line managers. In the stakeholder session, we also considered the optimal methods and screening tools for identifying and screening potentially eligible participants. In this feasibility study, we included in the study questionnaires Whooley questions100 and the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 to screen for depression and anxiety as recommended by NICE. 7 The aims of the workshop were to:

-

refine the map of the intervention, timelines, responsibilities, referral routes and checks and balances for each component of the intervention

-

encourage understanding, buy-in and ownership of the intervention for some of the staff who operated the system.

Outputs

-

A manualised model of the intervention, which we considered would be acceptable and feasible to its intended participants, for testing in the feasibility study.

-

A procedure for recruitment and selection of participants to enter the feasibility study.

In addition to the stakeholder workshop, the chief investigator and study co-ordinator met with two international experts from the Netherlands (Karen Nieuwenhuijsen and Carel Hulshof) in 2018 to review the proposed intervention model and seek their experience- and evidence-based advice so that further refinements to the intervention could be made.

Results

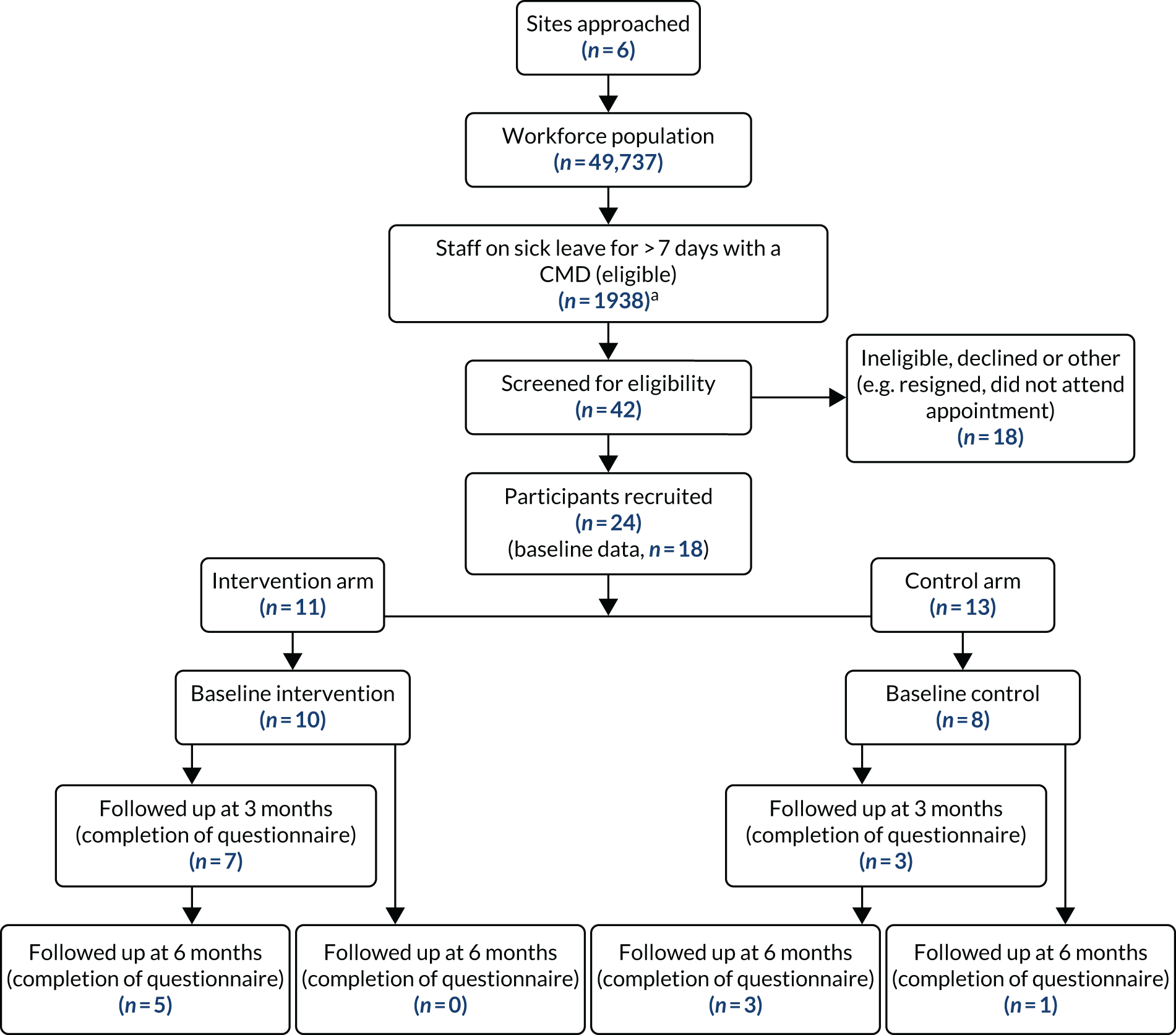

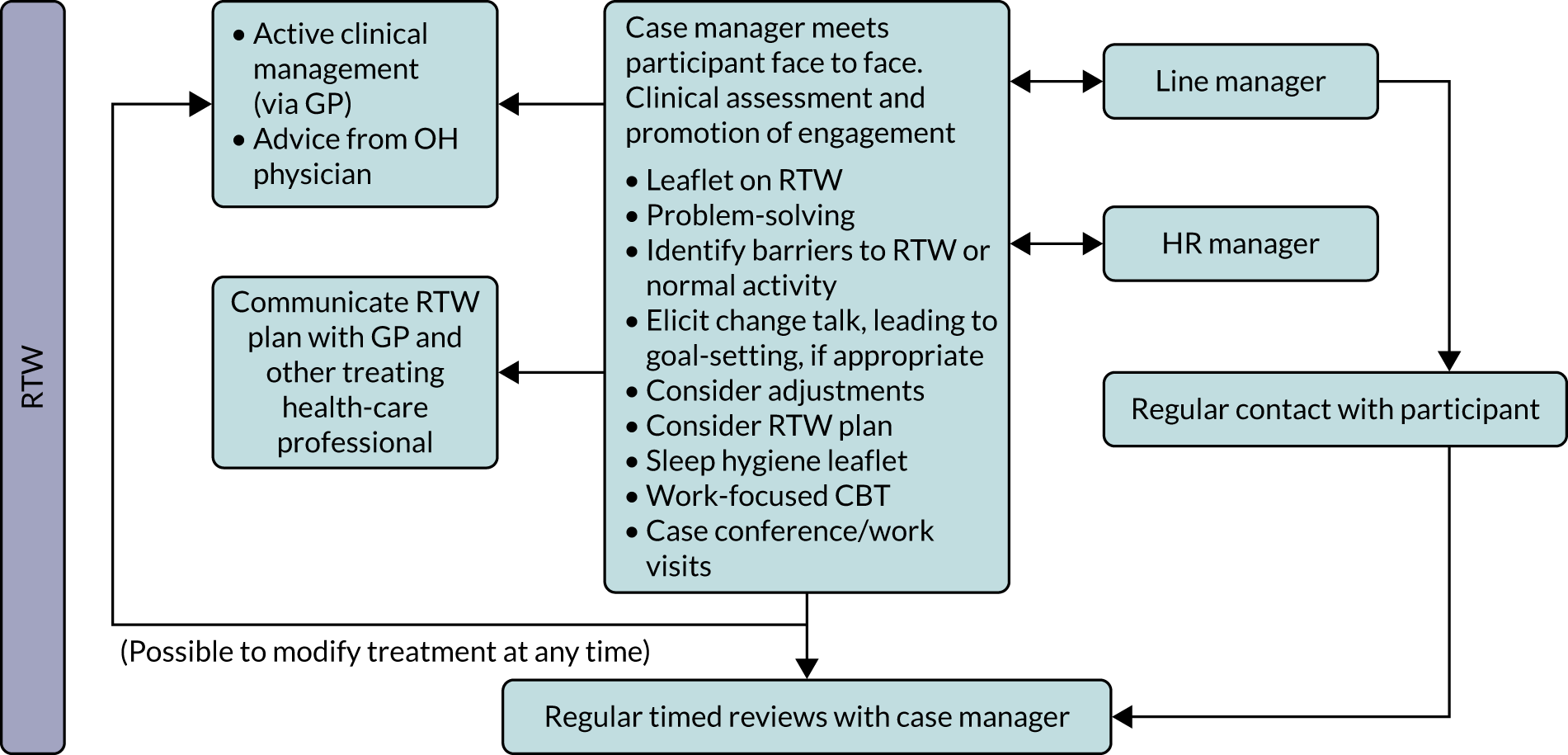

The preliminary case management intervention was developed using the iterative process (i.e. using results from the systematic review of the evidence on RTW and mental health, and mapping of the evidence onto the preliminary intervention) and was subsequently delivered in the feasibility study. As far as practicable, this is presented in keeping with the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) reporting requirements101 (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Manualised model of the intervention (including recruitment and CAU pathways). PIS, participant information sheet.

The intervention was based on a case management approach delivered by an OH nurse (case manager) trained in a CBT-based approach to problem-solving in the context of CMDs. The assessment of the worker on sick leave followed a biopsychosocial approach and the focus of the intervention was on the present (forward looking): the case manager encouraged and facilitated active engagement with the sick-listed workers rather than providing passive instruction. The intervention included identification of barriers to RTW; problem-solving by the participant and manager, as recommended by Arends et al. 13 and Waddell et al. ;11 work-focused CBT [via online programmes, e.g. the HeadGear smartphone application (app) (version 1.1.27, Black Dog Institute, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia), or face-to-face therapy, depending on local access] as recommended by Nieuwenhuijsen et al. ;12 two evidence-informed leaflets on RTW (one for managers and and one for employees); optimisation of clinical treatment, goal-setting, peer-support networking, a written RTW plan based on discussion between the participants and their manager, and workplace adjustments including flexible working and graded RTW in discussion with the participant’s manager, as recommended by Waddell et al. ;11 maintenance of contact between the line manager and the sick-listed worker as recommended by Nieuwenhuijsen et al. ;17 communication of the RTW plan with the treating health-care professionals, including the participant’s GP; regular timed reviews as recommended by Stern and Madan16 and Waddell et al. ;11 and referral to an occupational physician or secondary services, if required. The intervention was delivered on receipt of a fit note (or management/self-referral to OH) or soon after. Consultations between case managers and sick-listed staff occurred in person, although there was the option for case managers to maintain contact by telephone, if necessary.

We used evidence from the systematic review to develop a bespoke information leaflet for managers on how to communicate with the sick-listed employee. The leaflet would be given to the line manager by the case manager. The line manager had the option to ask the case manager for additional practical advice on how to initiate supportive communication with a sick-listed employee who has a CMD. The evidence from the systematic review also informed the design of a bespoke sleep hygiene leaflet, especially for NHS workers with a CMD, as well as a My Action Plan (MAP) template to record actions employees would take to tackle their identified problems.

Discussion

The stakeholder group played a vital role in developing the intervention and ensuring that it would be acceptable to participants (employees), case managers, line managers and employers, which is in keeping with recommendations published in guidelines on developing and evaluating complex interventions. 45 Based on participants’ advice, we refined the pathways and processes of the intervention to maximise the chances of its success.

Based on the findings from this feasibility study, the preliminary manualised case management intervention was modified and finalised (see Figure 4).

Development of data collection tools

The development of data collection tools concerned research question 4: what data collection tools should be used to assess changes in clinical state and occupational functioning as a consequence of such an intervention?

Method

We developed a series of data collection tools that included self-report participant questionnaires and site-level case report forms that were completed by field workers (case managers and independent assessors). The study questionnaires were shared and discussed with our PPI representatives to obtain their views on comprehension and acceptability, particularly on the appropriate questions to measure RTW outcomes that are important for workers. We did not undertake reliability analysis on the data collection tools; instead, the research team made a decision about their suitability based on a review of the completeness of the data collected at the end of the study coupled with feedback on acceptability from our PPI representatives, participants, case manager and local field workers. This allowed us to assess whether or not the proposed data collection tools would be of sufficient scope to reliably report on each of the outcome measures.

Output

The output was a series of data collection tools for use in the feasibility study, including suitable questionnaires.

Results

A series of data collection forms (case report forms) were produced to record specific data relating to clinical, occupational, prognostic and cost-effectiveness measures. Data collection forms included participant self-completed questionnaires (i.e. previously validated tools including the PHQ-9, GAD-7, WHODAS, Work and Social Adjustment Scale, RTW-SE scale, CSRI and alcohol-use tools) and tools for the collection of site-level data by local field workers (including tools to record screening and recruitment activity, provision of CAU interactions, delivery of case management interventions, consultation time duration and sickness absence duration). The data collection tools used in this study are given in Table 4.

| Data collection tool | Completion by |

|---|---|

| Audit form | Independent assessor |

| CAU data collection form | Field worker |

| Checklist for case managers (intervention arm) | Field worker |

| Clinical form for initial consultation (form 1) | Field worker |

| Decliners questionnaire | Field worker |

| Eligibility form | Field worker |

| Monthly audit of fit notes received per department | Field worker |

| MAP | Study participant |

| Participant sickness record: ESR data | Field worker |

| Questionnaire A (baseline) | Study participant |

| Questionnaire B (3 months) | Study participant |

| Questionnaire C (6 months: control arm – has not returned to work) | Study participant |

| Questionnaire C (6 months: control arm – has returned to work) | Study participant |

| Questionnaire C (6 months: intervention arm – has not returned to work) | Study participant |

| Questionnaire C (6 months: intervention arm – has returned to work) | Study participant |

| Screening log: NHS workers | Field worker |

| Withdrawal form | Field worker |

| Withdrawal questionnaire | Study participant |

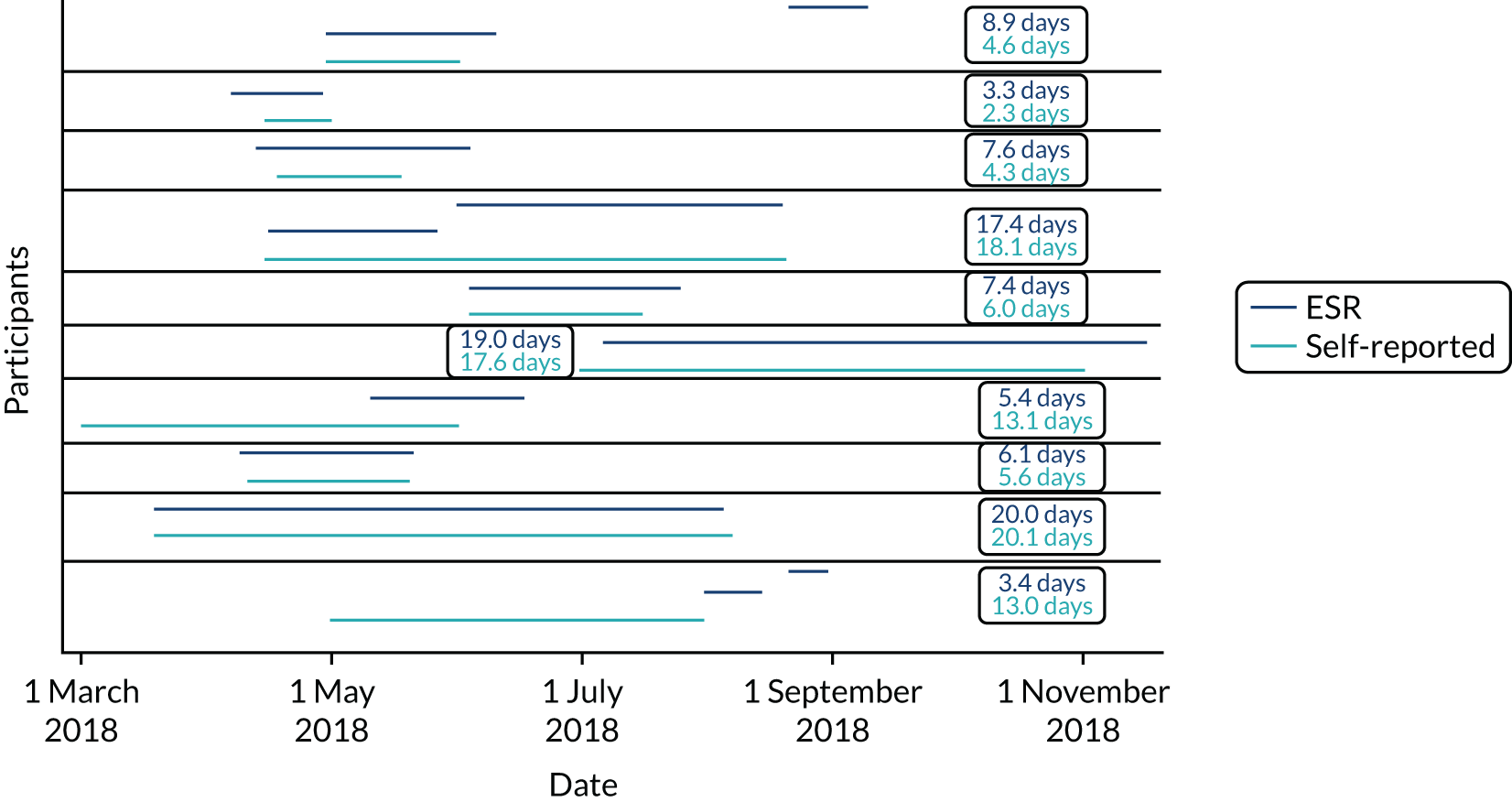

The site-level data collection tool capturing information on consultation time duration and number of follow-up consultations required was also suitable for use in the study. However, in relation to approaches for measuring time to RTW outcomes (partial or full), the results showed that there was poor agreement between the self-report and case manager feedback, and, unfortunately, this was consistent across the five possible outcomes (i.e. ‘RTW, any’, ‘RTW and stay continuously for > 4 weeks without any further sickness absence’, ‘returned to modified duties’, ‘returned to unmodified duties’, ‘returned to normal hours’). This observation reflects the accumulating evidence showing the inherent difficulty in reliably measuring RTW among sick-listed staff. 102

During the conduct of this study, researchers from the Netherlands undertook a project aimed at developing core outcome measures for sickness absence that can be used in research projects. In relation to measuring absenteeism (periods of sickness absence), the researchers recommended that recall of, at a maximum, 2 months could be collected by self-report from participants. Nevertheless, we found only modest consistency in the capacity of participants to accurately self-report ‘duration’ of recent episodes of sickness absence (i.e. during the study period) when these self-report data were compared with organisational sickness absence data (see Figure 9). Furthermore, we also found that not all participants were able to accurately recall each individual episode of sickness absence during the study period when we compared these self-report data with organisational data (although we also acknowledge that organisational sickness absence data are prone to inaccuracies). Collectively, this suggests that self-reported sickness absence is not a reliable measure to use alone.

A further complication with capturing RTW and sickness absence data from case managers and field workers during delivery of the case management intervention was the lack of access to trusts’ HR systems that record this information. In the light of these challenges, it is proposed that alternative, more reliable methods to capture RTW data are explored. One possible means would be to make use of short messaging service (SMS), sending texts to study participants on a regular basis (weekly/fortnightly) to request details of recent sickness absence periods. A notable advantage of this method is that it would help to minimise recall bias.

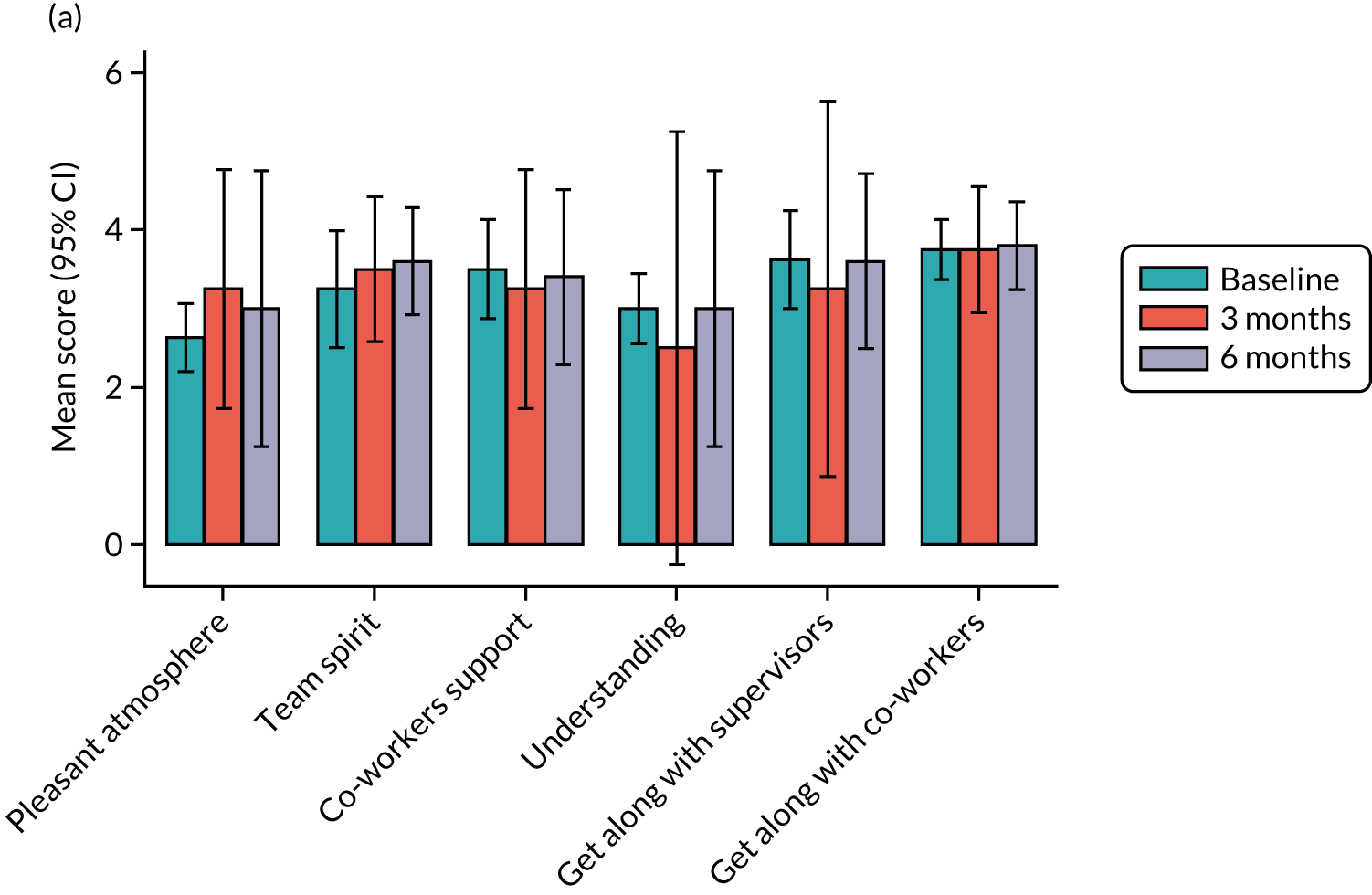

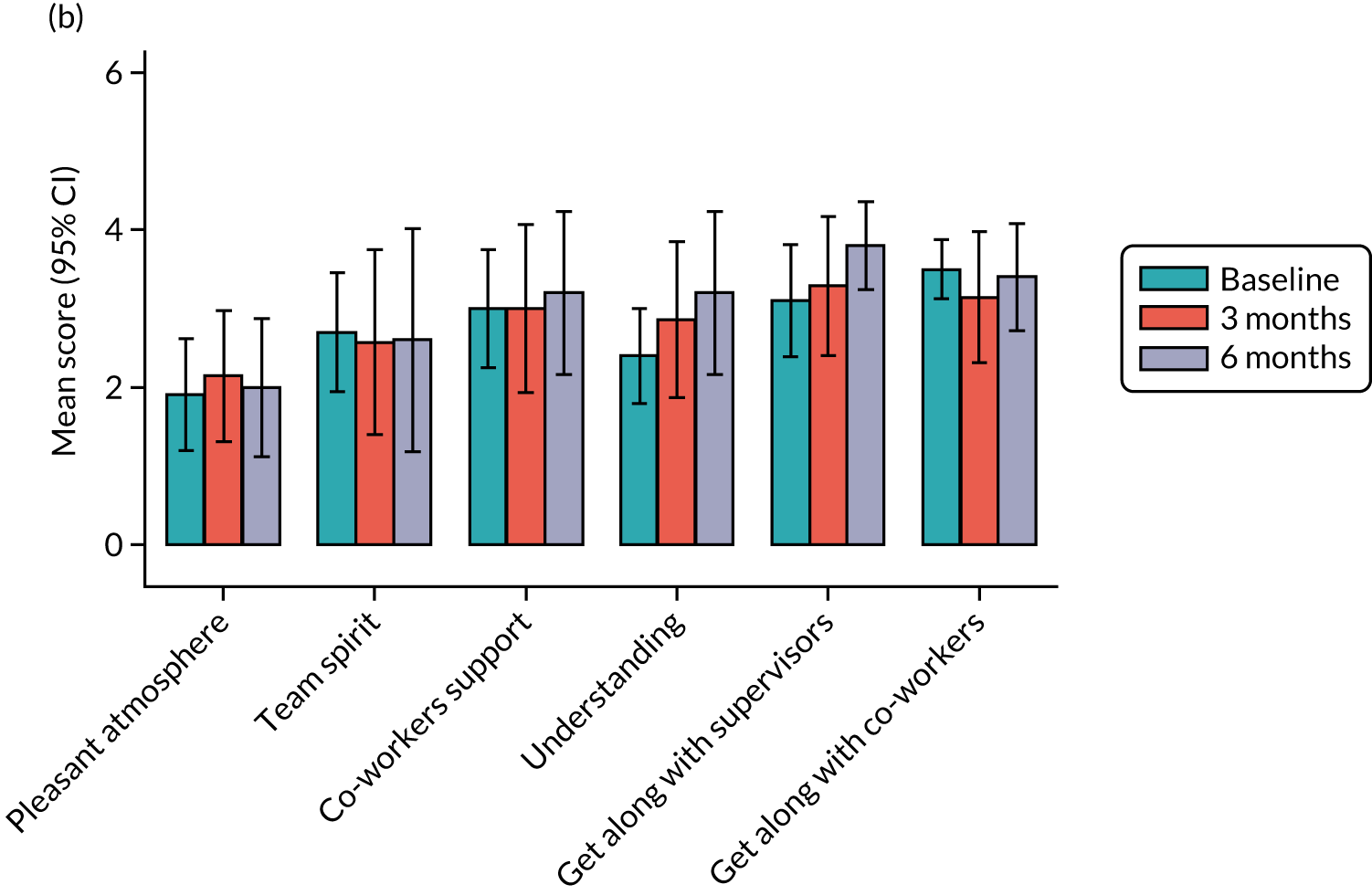

We also found that the site-level data collection tools (audit form and checklist form), as well as the participants’ study questionnaires, were reliable tools to measure intervention fidelity (uptake and adherence to individual components of the case management interventions). However, a notable shortcoming with the 6-month study questionnaire for participants in the intervention arm was that it did not capture important information on reasons for non-uptake of and non-adherence to the intervention. This additional source of information would have been helpful to gain a better understanding of the reasons why some participants chose not to engage with specific components of the intervention.