Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/35/07. The contractual start date was in January 2014. The draft report began editorial review in June 2019 and was accepted for publication in October 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Jayne et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Treatment options for faecal incontinence and rationale for SaFaRI clinical trial

Much of the text included in this chapter has been taken from the SaFaRI protocol. 1 The research team has previously published the protocol in the International Journal of Colorectal Disease. Reproduced with permission from Williams et al. 1 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

Faecal incontinence (FI) is a distressing condition that affects between 5% and 10% of the adult population. It is more common in female patients and with advancing age, and is the second most common cause of admission to a nursing home. It has an impact on social, physical and mental well-being and is a substantial burden on NHS resources.

Current treatment options

Current treatment strategies for adult FI are summarised in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 2014 guidance. 2 All patients should undergo a thorough history and physical examination to determine the nature and severity of the problem, and to identify a probable aetiological cause. Initial management consists of a combination of patient education, dietary modification and antidiarrhoeal medication. If this is unsuccessful, investigation in the form of endoscopic visualisation of the colorectum, anorectal manometry (pudendal nerve testing optional), and endoanal ultrasound is performed to further characterise the underlying disorder and inform treatment options.

Conservative therapies

Conservative therapies include pelvic floor retraining, with or without biofeedback therapy, and irrigation techniques (rectal or antegrade irrigation). Biofeedback therapy aims to increase the patient’s awareness of the muscles of continence and rectal sensation. Incontinent symptoms are improved in around 50% of patients, although there appears to be a significant placebo effect, with a marked decrease in efficacy on long-term follow-up. 3 Rectal irrigation, for example using the Peristeen® system (Coloplast, Humlebæk, Denmark), aims to clear the rectum and lower colon of faecal residue. In the short term it can have beneficial effects, but as a long-term solution patients frequently find it unacceptably time-consuming and inconvenient. Recently, there has been interest in the use of bulking agents to augment the anal sphincter. Data on the efficacy of these agents is limited, but they may have a role in controlling minor incontinence or ‘seepage’, or where an isolated sphincter defect is causing incomplete closure of the anal canal. 4

Surgical interventions

Surgical interventions are indicated for those patients with moderate to severe FI that is resistant to the conservative therapies listed in Conservative therapies.

Anterior sphincteroplasty, artificial bowel sphincter and dynamic graciloplasty

Anterior sphincteroplasty may be considered for patients with discrete sphincter defects, which occur typically as a result of obstetric injury. Through a perineal incision, the disrupted sphincter muscle is isolated and an overlapping sutured repair performed. Short-term results are reasonable, with 70% of patients reporting an improvement in continence; however, there is a drop-off in the longer term, with fewer than 50% of patients experiencing a benefit at 5 years. 5 Patients who do worse following anterior sphincteroplasty include those with coexistent pudendal neuropathy, multiple sphincter defects or sphincter atrophy, and irritable bowel syndrome. Because of the poor long-term results, there has been a move away from sphincter repair, except in well-defined cases, and an increased enthusiasm for sacral nerve stimulation (SNS).

Another surgical intervention which may be considered to treat FI is the artificial bowel sphincter (ABS). The ABS consists of (1) a fluid-filled silicone cuff placed around the anus, (2) a fluid-filled, pressure-regulating balloon positioned in the abdominal wall and (3) a manual pump connecting these components, placed in either the labia majora or the scrotum. When the cuff is inflated, the anal canal is sealed. The fluid is transferred to the balloon by the manual pump, deflating the cuff and opening the anal canal to allow defaecation. A successfully functioning device improves continence and quality of life (QoL); however, it is expensive, with the device alone costing around £4000. The main problem with the ABS is the high complication rate. Revisional surgery is needed in between 12.5% and 50% of cases, with explantation rates between 16.7% and 41.2%. 6 The majority of revisions are for cuff leaks that are thought to arise from microperforations caused by repeated cycles of inflation and deflation over a number of years. Most explantations are for infective complications. As a consequence, the ABS is not in common usage.

Dynamic graciloplasty involves mobilisation of the gracilis muscle from the inner thigh and wrapping around the anus to augment sphincter function. A neurostimulation device with an impulse generator is implanted to adapt the type II, fast-twitch muscle fibres to type I, slow twitch, fatigue-resistant fibres. The patient uses an external programming device to deactivate the electrical stimulation, relaxing the muscular contraction and enabling defaecation at a voluntary time. The success rate of the operation is between 40% and 60%. 7 Like the ABS, the main problem is the high complication (infections, 28%; device malfunction, 15%; and leg pain, 13%) and reintervention rates. The use of dynamic graciloplasty in the UK has largely been superseded by SNS.

Sacral nerve stimulation

Sacral nerve stimulation for FI was first described in 19958 and has grown in popularity, gaining NICE recognition as a minimally invasive treatment for moderate to severe FI. SNS works by a combination of anal sphincter augmentation and modulation of spinal/supraspinal pathways. It benefits from a two-stage procedure, which enables the patient to assess acceptability and the clinician to evaluate efficacy prior to commitment to a permanent and expensive implant. An initial percutaneous nerve evaluation, or temporary stimulation, is performed under local, regional or general anaesthetic as a day-case procedure. A fine needle is inserted percutaneously into the sacral foramina (S3 or S4) on both sides to determine the best response in terms of anal sphincter contraction and dorsiflexion of the great toe (S3 stimulation). Once a satisfactory response is obtained, the temporary electrode is inserted, secured to the skin and connected to an external test stimulator, allowing the patient to alter the stimulation voltage. The patient is asked to keep a bowel diary for the 2–3 weeks of stimulation, which allows the clinician to quantify the degree of response. A positive response is defined as a reduction in incontinence episodes or incontinence score of ≥ 50% during the stimulation period.

Around 70% of patients have a good response and proceed to a permanent implant. Of these, 10% never gain any significant improvement and 26% experience loss of efficacy, usually within the first year. 5,9–11 A further 2–5% suffer irresolvable complications and undergo explantation. Thus, from a decision-to-treat perspective, the long-term efficacy is around 45–50%. Overall, only 50% of patients thought to be eligible for SNS have a functioning device in the long term.

The reasons for loss of efficacy are not clear, but may relate to device malfunction or fibrosis of the stimulating electrode leading to loss of conduction. Pain or discomfort at the stimulator site, down the leg or into the vagina is another commonly reported complication, experienced by 38.1% of patients. Overall, only 58.5% of patients who have a permanent implant have a good or acceptable result in the medium term. 5

Although SNS is an effective treatment for FI, it is also very costly. The component costs alone (excluding other direct and indirect medical costs) are £200 for the test stimulation and £9393 for the permanent stimulator. 12 A European study has calculated the 5-year cumulative costs for SNS at €22,150 per patient, which compares with €33,996 for a colostomy and €3234 for conservative treatment. 13 Despite this, SNS has been shown to be cost-effective. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for SNS is £25,070 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained, which is within the £30,000 per QALY threshold recommended by NICE as an effective use of NHS resources.

NICE first issued its guidance on SNS for FI in 200414 and concluded that current evidence on safety and efficacy appeared to support its use, but that the procedure should only be performed in specialist units by clinicians with a particular interest in the condition. A systematic review at that time included six case series and 266 patients. In patients who had permanent implants, complete continence was achieved in 41 to 75%, while 75 to 100% of patients experienced a decrease of ≥ 50% in the number of incontinent episodes. Improvements were noted in both disease-specific and general QoL scores. The most recent review, including 13 studies and 929 patients, has confirmed the short-term efficacy of SNS. 15 Although the extent of the therapeutic effect varied between studies, a significantly beneficial effect was noted. Functional improvement was observed in 77% with idiopathic FI, 76% in sphincter rupture/episiotomy, 78% after anal repair, and 73% after neurological injury. The benefit was not restricted to improved continence, with several studies showing a significant improvement in QoL. 9,10,13

FENIX™ continence restoration system (FENIX™ magnetic sphincter augmentation)

The FENIX™ continence restoration system, or FENIX™ magnetic sphincter augmentation (MSA) (Torax Medical, Minneapolis, MN, USA), is a device that has been designed to reinforce the native sphincter for the treatment of FI that is resistant to conservative therapies. It consists of a ring of 14–20 titanium beads with magnetic cores that are linked together to form a structure to be surgically placed around the anal sphincter complex. To defecate, the patient strains in a normal way and the force generated separates the beads to open the anal canal. Continence is restored by means of passive attraction of the beads. Once implanted, the device does not require patient input to function.

The FENIX MSA costs £4000. Data on efficacy are limited, but they suggest a ≥ 50% improvement in continence in 70% of patients. Complications can occur in around 20% of patients, leading to explantation in around 10%.

Preliminary results are promising, with 70% of patients reporting a benefit; however, studies have been small and a more rigorous evaluation is required prior to its widespread adoption.

The device is manufactured in different lengths to accommodate variations in anal canal circumference, and has been CE (Conformité Européenne) marked since November 2011. FENIX MSA has been used in selected European and US centres to support a feasibility trial and was first used in the NHS in 2013.

The available evidence on safety and efficacy is limited but encouraging. Barussaud et al. 16 published data on a series of 24 patients who were implanted with FENIX between 2008 and 2012. All patients were female, with a mean age of 64 years (range 35–78 years) and the mean duration of FI being 8.8 years (range 1–40 years). The mean follow-up was 17.6 months. There was one immediate postoperative complication: cardiac arrest due to drug intolerance. The patient recovered without further sequelae. Two patients (8.7%) had the device explanted, one for device separation and one for perineal abscess at 6 months post implant. The procedure was considered a failure for five patients (21%) due to a lack of improvement in FI symptoms. Bowel diary results showed a significant improvement in the number of weekly FI episodes, decreasing from 32 to 8 in a 3-week diary. The mean Wexner score [Cleveland Clinic Incontinence Score (CCIS)] was reduced significantly from 16 points at baseline to 7 points, 8 points and 5 points at 12, 24 and 36 months, respectively. All four domains of the faecal incontinence quality-of-life (FIQoL) questionnaire scores significantly improved and remained stable postoperatively compared with the score at baseline.

A retrospective, case-matched comparison of the FENIX MSA with the ABS (Acticon® Neosphincter; American Medical Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) in 20 patients with severe FI17 showed that the FENIX MSA and ABS produced similar significant improvements in FI and QoL. Compared with the ABS, the FENIX MSA was associated with a significantly shorter operating time (FENIX MSA: 62 minutes vs. ABS: 97.5 minutes; p = 0.0273) and length of hospitalisation (FENIX MSA: 4.5 days vs. ABS: 10 days; p = 0.001). No difference was observed in postoperative complications. The ABS was associated with more explants/revisions (FENIX MSA: 1 vs. ABS: 4; p = 0.830), a greater incidence in postoperative constipation, and was more expensive.

Permanent stoma

For patients for whom the above surgical attempts fail to restore normal continence, the options are limited. A permanent stoma (usually colostomy) is often the last resort for patients with intractable FI. It is an effective strategy, but one that carries psychological and physical morbidity. Although most patients adapt to a permanent stoma, there is a continual fear of appliance leakage that can have an impact on social functioning. Around 50% of permanent stomas are complicated by parastomal herniation that may require surgical intervention. Moreover, a stoma is not a cheap intervention, with the 5-year cumulative costs estimated at £28,000. 13

Rationale for the SaFaRI trial

New technologies have often been introduced into clinical practice without rigorous evaluation of safety, efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Objective assessment has been overlooked because of the intrinsic appeal of new innovation, the need to be a part of a ‘pioneering group’ or, worse, because of the financial incentives from industry. Once introduced, low-grade observational evidence is often used to keep practices going. As a result, it has often been easier to ‘stop them starting’ than to ‘start them stopping.’18 Ideally, any new technology introduced into clinical practice should be simultaneously evaluated, and in most cases the best way of doing this is by randomised comparison with an already established technique. The National Institute for Health Research Horizon Scanning Centre (NIHR HSC) was established to ‘supply timely information to key health policy and decision-makers within the NHS about emerging health technologies that may have a significant impact on patients or the provision of health services in the near future.’19 In May 2012, the NIHR HSC reported on the FENIX Continence Restoration System (FENIX MSA) and concluded that ‘in order to determine its potential place in the pathway of care for FI larger long term studies of the safety, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of FENIX in comparison to existing treatments are needed.’20 Therefore, although FENIX MSA may have a role to play in the treatment of FI, the evidence was not robust enough to support its widespread adoption.

The SaFaRI trial was thus designed to undertake a rigorous, prospective assessment of the new FENIX MSA as it was adopted into the NHS. The aim was for reliable data, collected independently from commercial interests, to be made available on the safety and efficacy of the device. This would include information on safety, efficacy, QoL and cost-effectiveness. Important information would be gained on the costs associated with the device, enabling the ICER per QALY to be determined. This would allow health-care providers to make informed decisions about value for money and future provision of the technology.

Sacral nerve stimulation was chosen as the comparator to FENIX MSA as SNS is currently the preferred, and NICE-recommended,2 surgical intervention for FI that is resistant to conservative therapies; the NIHR HSC report19 from May 2012 also identified SNS as the preferred comparator for any randomised comparison with FENIX MSA.

Furthermore, the SaFaRI trial was designed to collect additional, important data about SNS. SNS is a costly yet effective treatment for FI; however, concerns have been expressed about the lack of efficacy when analysed on an intention-to-treat basis and the loss of efficacy on longer-term follow-up. The SaFaRI study provided an additional opportunity to clarify the indications for SNS and the indicators of success.

The opportunity also presented itself to comprehensively document, for the first time, the treatment and associated costs for patients for whom either SNS or FENIX MSA is not successful. In effect, these patients would provide comparative, longitudinal data of the patient pathway where FENIX MSA or SNS is either unsuitable or unavailable.

In addition to the costs detailed above, the health economics would provide data on the short- and long-term cost-effectiveness of FENIX MSA compared with SNS. Within the analyses, use of two measures of health-related QoL to produce QALYs, the Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12) together with the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D), would allow assessment of the sensitivity of the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) to detect changes in FI, which is to date unproven. The disease-specific questionnaire chosen to assess QoL, the FIQoL questionnaire, collects important information on many social and psychological aspects of FI (shame, depression, enjoyment, etc.). These aspects of FI have received little previous recognition in the literature and remain poorly defined.

Methods

Aim and objectives

The overall objectives of the study were to:

-

determine the short-term safety and efficacy of FENIX MSA and SNS in adult FI

-

assess FENIX MSA and SNS in terms of impact on QoL and cost-effectiveness.

Aim

The aim was to conduct a thorough evaluation of the FENIX MSA device, compared with SNS, for the treatment of adult FI.

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure was success, defined as device in use and ≥ 50% improvement in the participant-reported CCIS at 18 months post randomisation.

Secondary outcome measures

-

Length of hospital stay.

-

Complications.

-

Reinterventions.

-

Constipation.

-

QoL.

-

Cost-effectiveness.

Trial design

SaFaRI was a prospective, UK multisite, parallel-group, randomised clinical study investigating the safety and efficacy of the FENIX MSA for adult FI. The comparator was SNS, a preferred treatment recommended by NICE for the treatment of FI that is resistant to conservative therapies. 2 Participants were randomised on a 1 : 1 basis to receive either FENIX MSA or SNS.

Prior to randomising participants, all participating surgeons had to have performed a minimum of 10 permanent SNS implantations, observed a minimum of one FENIX MSA procedure and performed two FENIX MSA procedures under proctorship.

A registration phase was incorporated into the study design to enable surgeons without the required FENIX MSA experience prior to study participation to gain the relevant experience within the scope of the study. Within the registration phase, the first two eligible patients providing consent were registered to the study under the training surgeon’s name and received FENIX MSA implants (there was no randomisation in the registration phase); these two operations, which were performed under proctorship, were considered study training cases and were not included in the main study/main trial analysis. Once the required FENIX MSA experience had been obtained, the surgeon could progress to the randomisation phase.

The trial received national ethics approval in the UK. The trial conduct was overseen by an independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC). The trial had public and patient involvement during the trial design phase and throughout the course of the study. The trial was registered on the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) register (16077538).

Participants

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

aged ≥ 18 years

-

able to provide written informed consent

-

FI for > 6 months

-

incontinent episodes of ≥ 2 per week

-

suitable candidate for surgery, as judged by the operating surgeon

-

suitable for either FENIX MSA or SNS (unless the patient was being registered as a training case, in which event they only needed to be suitable for the FENIX MSA)

-

anal sphincter defect < 180° as documented on endoanal ultrasound scan

-

able and willing to comply with the terms of the protocol including QoL questionnaires.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

previous interventions for FI (i.e. SNS, FENIX MSA or ABS) (unless the patient was registered as a training case, in which event they could have had previous interventions for FI)

-

chronic gastrointestinal motility disorders causing incontinence due to diarrhoea

-

obstructed defaecation, defined as an inability to satisfactorily evacuate the rectum [it was recommended that the Obstructed Defecation Score (ODS) was calculated and was ≤ 8 for trial inclusion]

-

anal sphincter defect ≥ 180°, as documented on endoanal ultrasound scan

-

an electric or metallic implant within 10 cm of anal canal

-

co-existent systemic disease (e.g. scleroderma) affecting continence

-

active anorectal sepsis

-

diagnosis of colorectal or anal cancer within previous 2 years

-

external rectal prolapse

-

significant scarring of the anorectum that, as judged by the treating surgeon, would prohibit FENIX MSA implantation or put the patient at high risk of implant erosion

-

pregnancy (it was the local surgeon’s responsibility to assess pregnancy in women of childbearing potential)

-

immunocompromised, including haematological abnormalities and treatment with steroids or other immunomodulatory medicines

-

congenital spinal abnormalities, preventing SNS implantation

-

known requirement for future magnetic resonance imaging surveillance, which would be contraindicated in the presence of metallic implant

-

suspected or known allergies to titanium.

Interventions

Preoperative investigation and preparation were as per institutional protocol, which included, as standard practice, visualisation of the colorectum (flexible sigmoidoscopy as a minimum), anorectal manometry (pudendal nerve testing optional) and endoanal ultrasound.

Sacral nerve stimulation

Sacral nerve stimulation implantation was performed in accordance with each research site’s usual practice. SNS implantation is a two-stage procedure. As per standard care, a temporary device was implanted during a day-case procedure and the degree of response to the device recorded by the participant over the course of 2 weeks. Response was assessed in accordance with each research site’s usual practice. For the purposes of the trial, the CCIS was recorded at this time point regardless of how the response was assessed locally.

As per routine care, if the response was positive (defined as a ≥ 50% improvement in incontinence episodes or ≥ 50% improvement in CCIS), then a second day-case procedure was scheduled and a permanent SNS device was implanted. If the response was negative, the temporary device was removed and the participant did not receive any further study intervention but continued follow-up for the required 18-month period. Further treatment was as per standard practice but participants were not permitted to undergo FENIX MSA implantation during the 18-month post-randomisation follow-up period.

Postoperative care was as per routine care, but participants had to be reviewed at clinic for trial purposes 2 weeks postoperatively for both temporary and permanent device implants, and at 6, 12 and 18 months post randomisation as a minimum. Any further visits were according to local standard clinical practice, but were captured on the follow-up case report forms (CRFs).

FENIX magnetic sphincter augmentation

FENIX MSA implantation was usually performed during an in-patient stay (usually of 1–3 days). Participants for whom FENIX MSA failed were not permitted to undergo SNS during the 18-month follow-up period. No postoperative care was required above routine wound care, but participants had to be reviewed for trial purposes at 2 weeks postoperatively and at 6, 12 and 18 months post randomisation as a minimum. Any further visits were performed according to local standard clinical practice and were recorded on the follow-up CRFs.

Participant-completed questionnaires

Participants completed a number of questionnaires designed to capture FI symptoms prior to randomisation (baseline), at 2 weeks post operation and at 6, 12 and 18 months post randomisation:

-

The CCIS. 21 The CCIS assesses five parameters associated with incontinence – incontinence to solid, incontinence to liquid, incontinence to gas, use of pads, and lifestyle restriction. Each parameter is scored 0–4, with ‘0’ for never and ‘4’ for every day. The five parameters are added to give a total score out of 20.

-

The ODS. 22 The ODS consists of five items: excessive straining, incomplete rectal evacuation, use of enemas and/or laxatives, vaginal-anal-perineal digitations, and abdominal discomfort and/or pain. Each item is graded from 0 to 4 with a score ranging from 0 (no symptoms) to 20 (very severe symptoms).

-

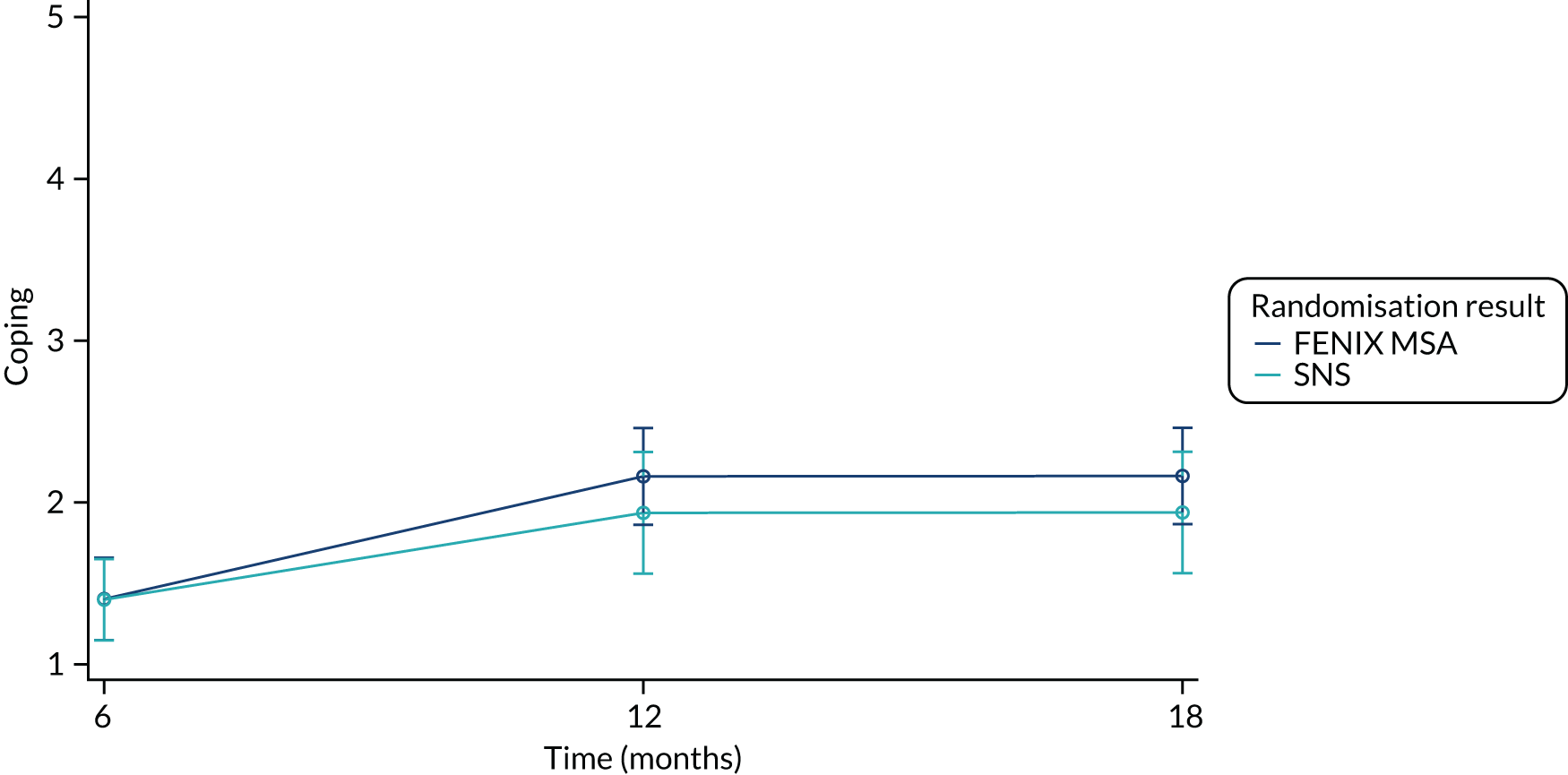

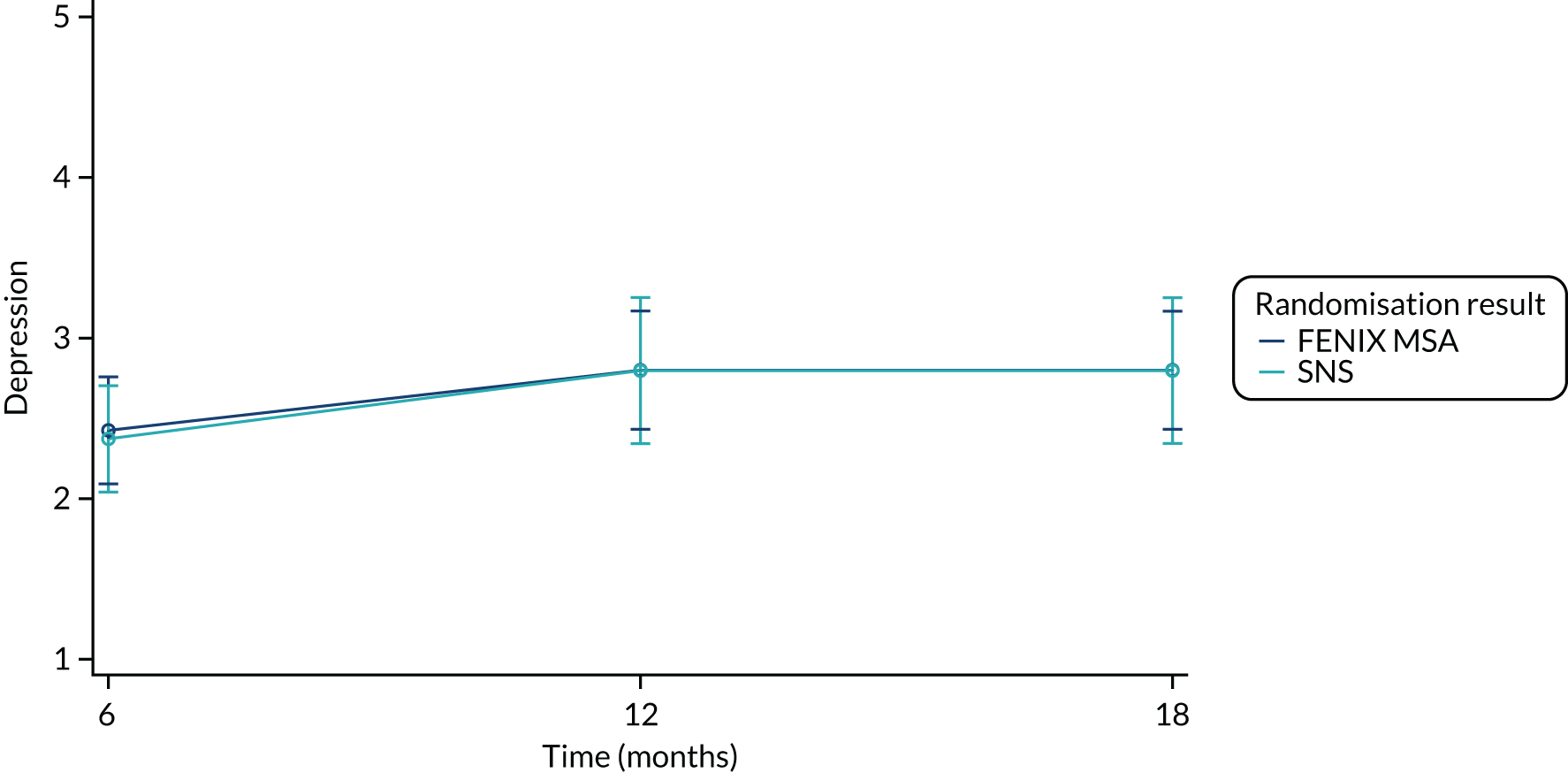

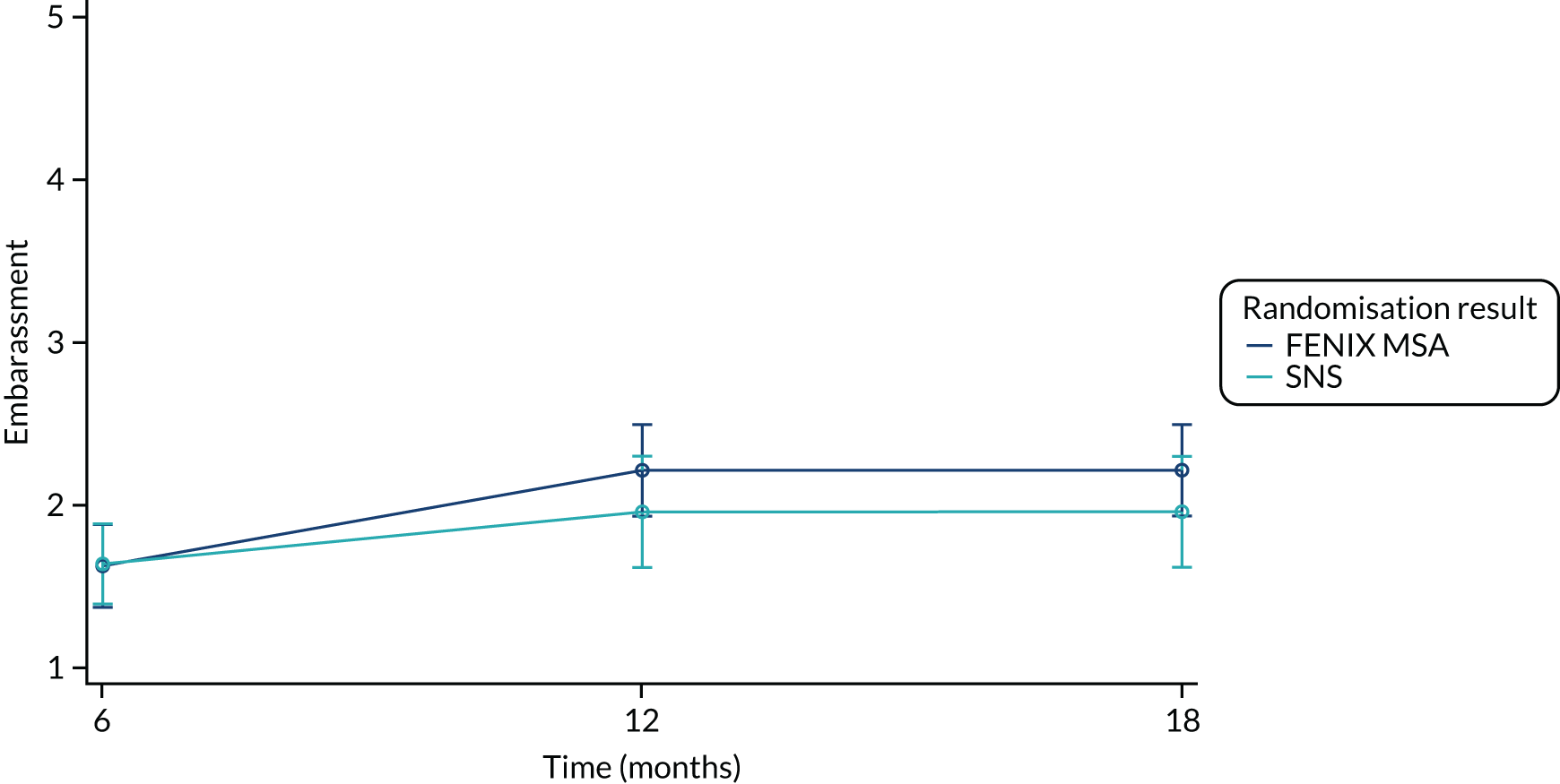

The FIQoL questionnaire. 23 This questionnaire is composed of 29 items that make up four scales: lifestyle (10 items), coping/behaviour (9 items), depression/self-perception (7 items) and embarrassment (3 items). Scoring is derived from a participant-completed questionnaire that assesses the impact of FI on four domains of QoL. Scales range from 1 to 5, with 1 indicating a lower functional QoL. Scale scores are derived by averaging the response to all items in the scale.

-

Health and Social Care Resource Use. The questionnaire is composed of questions related to contact with primary, community and social care services. The questionnaire consists primarily of ‘tick-box’ completion questions.

-

SF-12. 24 The SF-12 is a 12-item subset of the Short Form questionnaire-36 items version 2 that measures the same eight domains of health. It is a brief, reliable measure of overall health status. It is useful in large population health surveys and has been used extensively as a screening tool.

-

EQ-5D-5L. 25 This is a well-validated questionnaire used to assess generic QoL; it provides a simple descriptive profile and a single index value for health status.

Participants completed all of the above listed questionnaires at baseline and at 6, 12 and 18 months post randomisation. In addition to these time points, participants completed the CCIS and the Health and Social Care Resource Use questionnaire at 2 weeks postoperatively (for temporary SNS and FENIX MSA only). For the permanent SNS, participants completed the Health and Social Care Resource Use questionnaire at 2 weeks postoperatively.

Summary of protocol changes

A summary of all substantial amendments to the SaFaRI protocol can be found in Table 1.

| Version and date | Summary of changes |

|---|---|

| V1.0, 9 April 2014 | N/A: original protocol submitted for ethics review |

| V2.0, 10 October 2014 |

|

| V3.0, 30 April 2015 |

|

| V4.0, 7 March 2016 |

|

| V4.0, 7 March 2016 | No change to protocol. Substantial amendment submitted to formally notify the REC of the early trial closure owing to the withdrawal from the market of the FENIX MSA device |

Early trial closure

On 23 March 2017, the SaFaRI trial team received formal notice from Torax Medical (the manufacturer of the FENIX MSA device) that the decision had been made to suspend the commercial sale of the FENIX MSA device in the UK and other European countries for ‘strategic and business reasons’. As a result of this, recruitment into the SaFaRI trial, regrettably, had to cease with immediate effect.

Following the withdrawal of the FENIX MSA device and with approval from the Research Ethics Committee, all patients who had consented for the trial up to 23 March 2017, and had been randomised to the FENIX MSA arm but had not yet had surgery, were given the chance to have the FENIX MSA device implanted if they still wished to proceed with the operation as randomised. Any patients not wishing to undergo a FENIX MSA implantation, in the light of the fact that the device had been withdrawn, were offered alternative FI treatment as per local standard practice (this included the option of undergoing the alternative study intervention, SNS).

In total, 99 participants were randomised into the SaFaRI trial and 23 participants were registered as FENIX MSA training cases. A consequence of recruiting only 99 patients out of the target sample size of 350 is that the study is substantially underpowered to detect differences between the treatment arms, in particular with respect to the primary end point. Although the recruitment total was significantly less than the originally planned sample size of 350 participants, it was felt that continuing to follow up all randomised participants until the end of the planned follow-up period (i.e. 18 months post randomisation) would still provide valuable data that, at the very least, could provide some initial evidence; at the time of trial closure, SaFaRI was also the largest randomised trial of SNS to date.

The National Institute for Health Research was amenable to the trial team’s proposal to continue with the planned follow-up period, and, as a result, all patients who had been randomised into the SaFaRI trial continued to be followed up until 18 months post randomisation. The last participant’s final follow-up took place in September 2018.

End points

Primary end point

The primary end point was success, defined as device in use and ≥ 50% improvement (between the baseline and 18-month scores) in the participant-reported CCIS, at 18 months post randomisation.

Secondary end points

Secondary end points included:

-

the safety of FENIX MSA or SNS, as judged by explant rates, operative (this included those occurring during theatre time and post-surgery hospital stay) and postoperative (up to and including 12 months from the date of the last study surgery) complications

-

change from baseline in generic and disease-specific QoL as measured by CCIS, ODS, FIQoL, EQ-5D-5L and SF-12 at 6, 12 and 18 months post randomisation

-

cost-effectiveness

-

success at 6 and 12 months as defined in the primary end point.

Sample size

A total of 350 participants were required to detect at least a 20% difference in the percentage of successes at 18 months post randomisation (where success was defined as device in use and ≥ 50% CCIS improvement from baseline) between FENIX MSA and SNS at a 5% level of significance, with 90% power, assuming approximately 40% success in the SNS arm and allowing for 20% loss to follow-up. However, the number of patients recruited was 99.

Randomisation

Following confirmation of written informed consent and eligibility, patients were randomised into the trial by authorised members of staff at the trial sites. Randomisation was performed centrally using the Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU) automated 24-hour telephone randomisation system. Authorisation codes and personal identification numbers (PINs), provided by the CTRU, were required to access the randomisation system.

Participants were randomised on a 1 : 1 basis to receive either FENIX MSA or SNS, and were allocated a unique study number. A computer-generated minimisation programme that incorporated a random element was used with the following minimisation factors:

-

treating surgeon

-

participant sex (male or female)

-

severity of incontinence (CCIS)

-

mild to moderate: CCIS ≤ 10 points

-

moderate to severe: CCIS > 10 points.

-

-

degree of anal sphincter defect on endoanal ultrasound

-

no anal sphincter defect

-

anal sphincter defect ≤ 90°

-

> 90° anal sphincter defect < 180°.

-

Blinding

The study was not blinded to participants, medical staff or clinical trial staff because of the difference between the two devices being compared (SNS treatment requires a temporary implant followed by a permanent implant if successful and involves patient input to function).

Statistical methods

Unless otherwise stated, all analyses were prespecified and conducted on the intention-to-treat population (i.e. all randomised participants were categorised into treatment groups based on their randomisation regardless of what treatment they subsequently received). All hypothesis tests were two-sided and conducted at the 5% level of significance. Estimates and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values are presented for fixed effects. For all end points, missing outcome data were assumed to be missing at random, and the treatment effect was therefore estimated via maximum likelihood estimation using all participants with non-missing outcome data for non-longitudinal end points (this is referred to as a complete case analysis for the remainder of the report). All models were fitted using SAS® v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). (SAS and all other SAS Institute Inc. product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of SAS Institute Inc. in the USA and other countries. ® indicates USA registration.)

Primary end point: device in use and ≥ 50% improvement in CCIS at 18 months post randomisation

The primary analysis was a complete case analysis. Multilevel logistic regression was used to estimate the odds ratios between treatment groups for a ‘success’ in terms of the primary end point, adjusting for all minimisation factors. All minimisation factors were included as fixed effects, except randomising surgeon, which was included as a random effect. A random intercept model was fitted using maximum likelihood via adaptive quadrature, and all modelling was performed using the SAS v9.4 glimmix procedure.

A sensitivity analysis was performed to consider additional covariates in the primary analysis regression model that were thought to be related to patient outcome. These covariates were:

-

age (years)

-

body mass index (BMI)

-

American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade

-

aetiology of incontinence (obstetric trauma, idiopathic, iatrogenic, neurological conditions)

-

type of incontinence (urge predominant, passive predominant, mixed urge and passive)

-

ODS

-

FI medication.

Secondary end point: device in use and ≥ 50% improvement in CCIS at 6 months or 12 months post randomisation

Success at 6 or 12 months was analysed using a multilevel logistic regression model, adjusting for all of the minimisation factors, to estimate the odds ratios. All minimisation factors were included as fixed effects, except randomising surgeon, which was included as a random effect.

Secondary end point: intraoperative complications

Intraoperative complications were modelled using a multilevel logistic model to estimate the odds ratio between the treatment groups for whether or not participants had an intraoperative complication, adjusting for all minimisation factors. All minimisation factors were included as fixed effects, except randomising surgeon, which was included as a random effect with a random intercept.

Secondary end point: postoperative complications and reinterventions

Postoperative complications were modelled using a multilevel logistic model to estimate the odds ratio between the treatment groups for whether participants had a postoperative complication or not, adjusting for all minimisation factors. All minimisation factors were included as fixed effects, except randomising surgeon, which was included as a random effect with a random intercept and slope.

Secondary end point: device explants

The number of explants was analysed using a multilevel logistic regression model, adjusting for all of the minimisation factors, to estimate the odds ratios. All minimisation factors were included as fixed effects, except randomising surgeon, which was included as a random effect.

Quality-of-life end points

All QoL end points were modelled using a three-level multilevel model to account for the hierarchical nature of the repeated measures data and also for the clustering effect of the operating surgeon. All models were adjusted for the minimisation factors, with the minimisation factors included as fixed effects, except for the randomising surgeon, which was included as a random intercept.

Chapter 2 Results

Recruitment

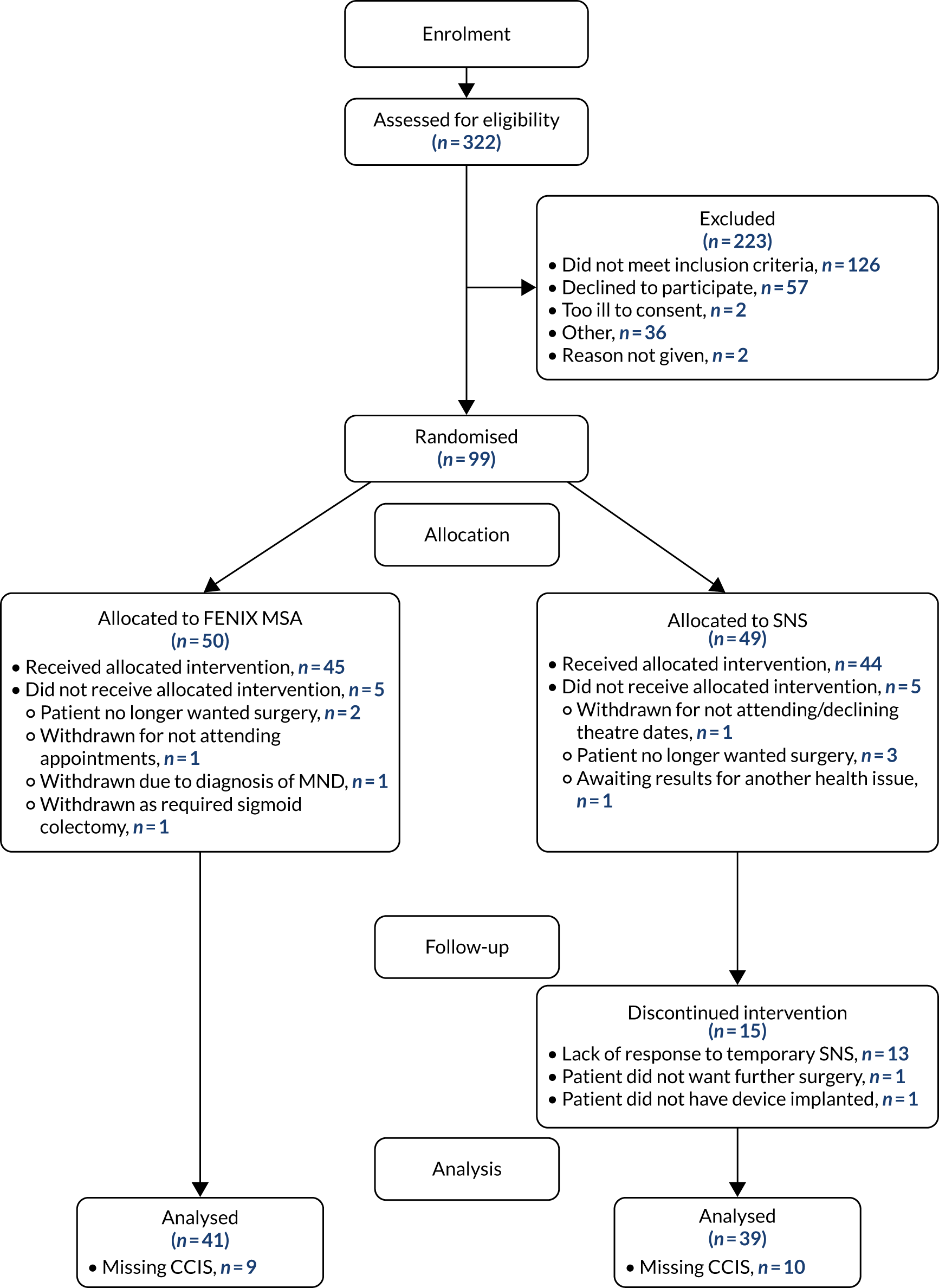

Between 30 October 2014 and 23 March 2017, 322 patients were assessed for eligibility across 18 sites. Ninety-nine of these patients were randomised into the SaFaRI study and 23 participants were registered as FENIX MSA training cases. Recruitment by site can be seen in Table 2. A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram showing all patients screened for eligibility can be seen in Figure 1.

| Site number | Site name | Randomised patients, n | Registered patients, n |

|---|---|---|---|

| 00050 | St James’s University Hospital | 45 | 1 |

| 00170 | University Hospital of North Durham | 4 | 1 |

| 00114 | Southampton General Hospital | 2 | 0 |

| 00232 | The Northern General Hospital | 14 | 0 |

| 00052 | St Peter’s Hospital | 5 | 0 |

| 00108 | Poole Hospital | 7 | 2 |

| 00002 | Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital | 3 | 0 |

| 00153 | The Churchill Hospital | 0 | 3 |

| 00172 | Wythenshawe Hospital | 4 | 0 |

| 00099 | Good Hope Hospital | 2 | 3 |

| 10908 | University College London Hospital | 0 | 2 |

| 00080 | Manchester Royal Infirmary | 4 | 0 |

| 00117 | Bristol Royal Infirmary | 4 | 2 |

| 00072 | Royal Victoria Infirmary | 2 | 2 |

| 00023 | Dewsbury District Hospital | 1 | 2 |

| 00317 | St Mark’s Hospital | 1 | 2 |

| 00031 | Leicester Royal Infirmary | 1 | 2 |

| 00118 | Derriford Hospital | 0 | 1 |

FIGURE 1.

The CONSORT flow diagram. MND, motor neuron disease.

Baseline data

The minimisation factors are summarised by treatment arm across all randomised patients in Table 3. Summaries of additional baseline characteristics are given in Table 4. All the minimisation factors and baseline characteristics are well balanced between the two treatment arms.

| Stratification factor | FENIX MSA, n (%) | SNS, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgeon ID | |||

| 2 | 10 (20.0) | 12 (24.5) | 22 (22.2) |

| 1 | 11 (22.0) | 8 (16.3) | 19 (19.2) |

| 3 | 6 (12.0) | 8 (16.3) | 14 (14.1) |

| 31 | 3 (6.0) | 4 (8.2) | 7 (7.1) |

| 26 | 2 (4.0) | 3 (6.1) | 5 (5.1) |

| 4 | 3 (6.0) | 1 (2.0) | 4 (4.0) |

| 12 | 3 (6.0) | 1 (2.0) | 4 (4.0) |

| 21 | 2 (4.0) | 2 (4.1) | 4 (4.0) |

| 30 | 2 (4.0) | 2 (4.1) | 4 (4.0) |

| 36 | 1 (2.0) | 3 (6.1) | 4 (4.0) |

| 32 | 2 (4.0) | 1 (2.0) | 3 (3.0) |

| 8 | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | 2 (2.0) |

| 15 | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | 2 (2.0) |

| 25 | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | 2 (2.0) |

| 5 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| 23 | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| 999 | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Total | 50 (100) | 49 (100) | 99 (100) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 49 (98.0) | 47 (95.9) | 96 (97.0) |

| Male | 1 (2.0) | 2 (4.1) | 3 (3.0) |

| Total | 50 (100) | 49 (100) | 99 (100) |

| CCIS | |||

| ≤ 10 points (mild to moderate) | 6 (12.0) | 5 (10.2) | 11 (11.1) |

| > 10 points (moderate to severe) | 44 (88.0) | 44 (89.8) | 88 (88.9) |

| Total | 50 (100) | 49 (100) | 99 (100) |

| Anal sphincter defect | |||

| No anal sphincter defect | 27 (54.0) | 27 (55.1) | 54 (54.5) |

| ≤ 90° | 19 (38.0) | 18 (36.7) | 37 (37.4) |

| > 90° to < 180° | 4 (8.0) | 4 (8.2) | 8 (8.1) |

| Total | 50 (100) | 49 (100) | 99 (100) |

| Characteristic | FENIX MSA | SNS | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 60.6 (13.1) | 60.8 (14.3) | 60.7 (13.7) |

| Median (range) | 61.5 (30.0–82.0) | 59.0 (35.0–90.0) | 59.0 (30.0–90.0) |

| IQR | 50.0–71.0 | 52.0–72.0 | 52.0–71.0 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| n | 50 | 49 | 99 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 47 (94.0) | 49 (100.0) | 96 (97.0) |

| Mixed | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Asian (Indian) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Black | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Total | 50 (100) | 49 (100) | 99 (100) |

| Incontinence type, n (%) | |||

| Mixed urge and passive | 16 (32.0) | 20 (40.8) | 36 (36.4) |

| Urge predominant | 13 (26.0) | 12 (24.5) | 25 (25.3) |

| Passive predominant | 8 (16.0) | 4 (8.2) | 12 (12.1) |

| Missing | 13 (26.0) | 13 (26.5) | 26 (26.3) |

| Total | 50 (100) | 49 (100) | 99 (100) |

| FI aetiology, n (%) | |||

| Obstetric trauma | 29 (58.0) | 26 (53.1) | 55 (55.6) |

| Idiopathic | 11 (22.0) | 15 (30.6) | 26 (26.3) |

| Iatrogenic | 5 (10.0) | 1 (2.0) | 6 (6.1) |

| Neurological conditions | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | 2 (2.0) |

| Other | 4 (8.0) | 6 (12.2) | 10 (10.1) |

| Total | 50 (100) | 49 (100) | 99 (100) |

| ASA grade, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 25 (50.0) | 23 (46.9) | 48 (48.5) |

| 2 | 24 (48.0) | 21 (42.9) | 45 (45.5) |

| 3 | 1 (2.0) | 5 (10.2) | 6 (6.1) |

| Total | 50 (100) | 49 (100) | 99 (100) |

| Length of time suffered FI (months) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 71.6 (64.6) | 89.9 (90.8) | 80.6 (78.6) |

| Median (range) | 60.0 (9.0–384) | 60.0 (12.0–480) | 60.0 (9.0–480) |

| IQR | 36.0–84.0 | 27.0–114 | 36.0–96.0 |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| n | 50 | 48 | 98 |

| Average number of episodes per week | |||

| Mean (SD) | 7.4 (6.95) | 7.0 (7.01) | 7.2 (6.94) |

| Median (range) | 5.0 (2.0–28.0) | 4.0 (1.5–30.0) | 4.3 (1.5–30.0) |

| IQR | 3.0–7.0 | 2.0–10.0 | 2.5–8.0 |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| n | 49 | 49 | 98 |

| Resting pressure (cmH20) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 52.4 (28.2) | 58.4 (29.2) | 55.4 (28.7) |

| Median (range) | 48.0 (10.0–120) | 53.0 (19.0–133) | 51.5 (10.0–133) |

| IQR | 33.0–73.0 | 35.0–77.5 | 34.0–75.0 |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| n | 50 | 48 | 98 |

| Squeeze pressure (cmH20) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 77.0 (50.0) | 84.8 (42.0) | 80.8 (46.2) |

| Median (range) | 69.5 (7.0–269) | 85.5 (22.0–199) | 71.0 (7.0–269) |

| IQR | 44.0–105 | 49.0–116 | 46.0–109 |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| n | 50 | 48 | 98 |

| Threshold volume (ml) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 57.6 (35.0) | 53.1 (39.3) | 55.5 (36.9) |

| Median (range) | 52.0 (14.0–180) | 46.0 (10.0–200) | 47.0 (10.0–200) |

| IQR | 32.5–79.0 | 30.0–60.0 | 30.0–74.0 |

| Missing | 10 | 15 | 25 |

| n | 40 | 34 | 74 |

| Maximum tolerated volume (ml) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 127 (60.6) | 137 (69.1) | 131 (64.4) |

| Median (range) | 112 (35.0–270) | 117 (37.0–292) | 114 (35.0–292) |

| IQR | 85.0–160 | 77.0–195 | 80.0–180 |

| Missing | 10 | 15 | 25 |

| n | 40 | 34 | 74 |

| Internal anal sphincter defect, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 8 (16.0) | 10 (20.4) | 18 (18.2) |

| No | 41 (82.0) | 39 (79.6) | 80 (80.8) |

| Missing | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Total | 50 (100) | 49 (100) | 99 (100) |

| External anal sphincter defect, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 20 (40.0) | 19 (38.8) | 39 (39.4) |

| No | 29 (58.0) | 30 (61.2) | 59 (59.6) |

| Missing | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Total | 50 (100) | 49 (100) | 99 (100) |

| ODS | |||

| Mean (SD) | 7.4 (3.78) | 7.1 (3.62) | 7.3 (3.68) |

| Median (range) | 7.0 (2.0–18.0) | 8.0 (2.0–17.0) | 7.0 (2.0–18.0) |

| Missing | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| n | 45 | 43 | 88 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 28.8 (5.59) | 28.9 (5.78) | 28.9 (5.65) |

| Median (range) | 28.8 (19.1–53.0) | 28.7 (19.2–45.0) | 28.7 (19.1–53.0) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| n | 49 | 49 | 98 |

| CCIS (points) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 14.4 (3.15) | 14.7 (2.95) | 14.6 (3.04) |

| Median (range) | 14.5 (6.0–20.0) | 15.0 (9.0–20.0) | 15.0 (6.0–20.0) |

| Missing | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| n | 46 | 46 | 92 |

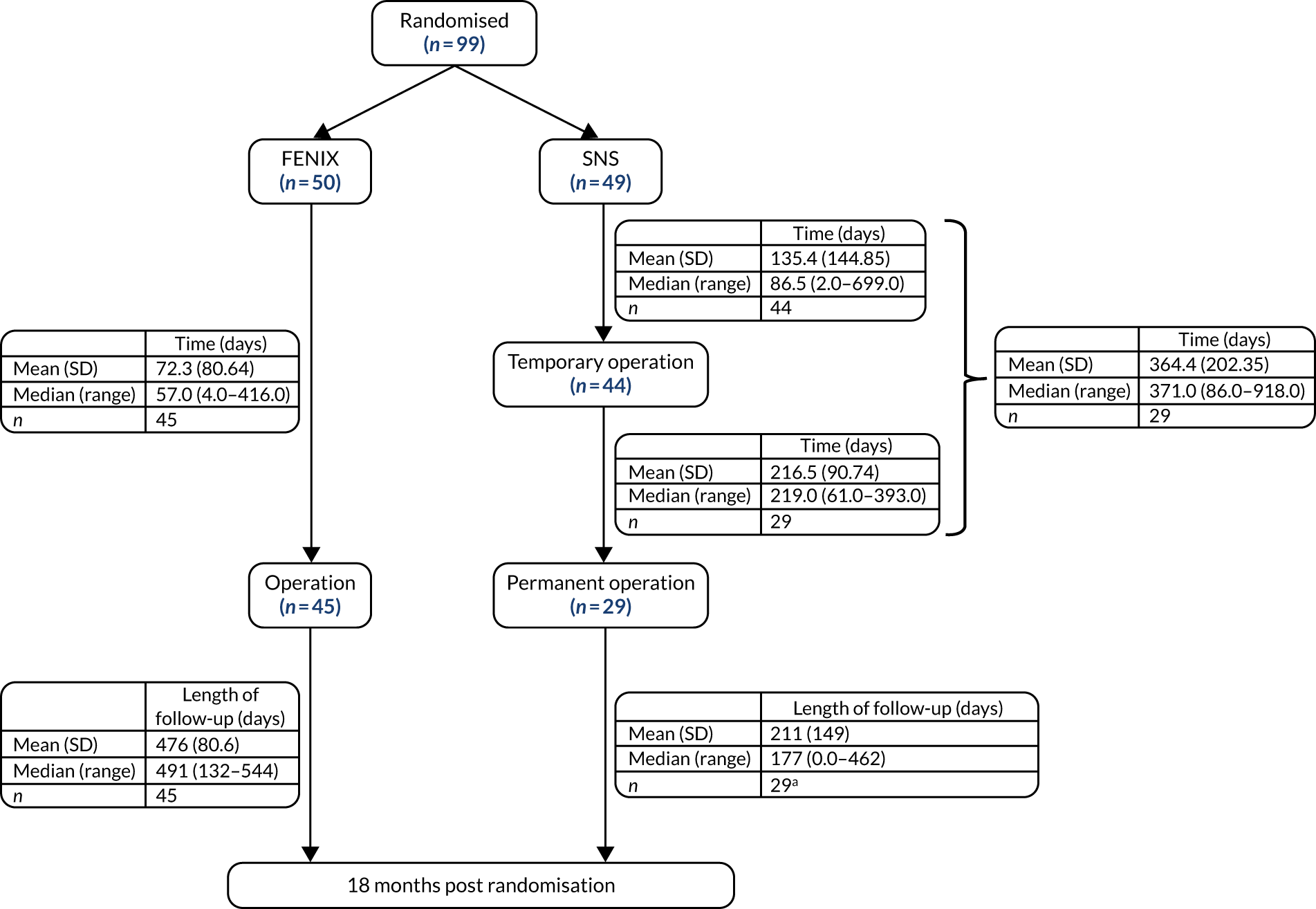

The time from randomisation to surgery can be seen in Figure 2. The time to implant of the permanent device was very different between the two treatment arms, with some SNS participants not receiving a permanent device until more than 18 months post randomisation. The reason for the delays in the SNS arm were mostly due to surgical capacity.

FIGURE 2.

Time from randomisation to surgery. a, Patients that received operation after 18 months’ follow-up have length of follow-up set to 0. SD, standard deviation.

Primary end point: device in use and ≥ 50% improvement in Cleveland Clinic Incontinence Score at 18 months post randomisation

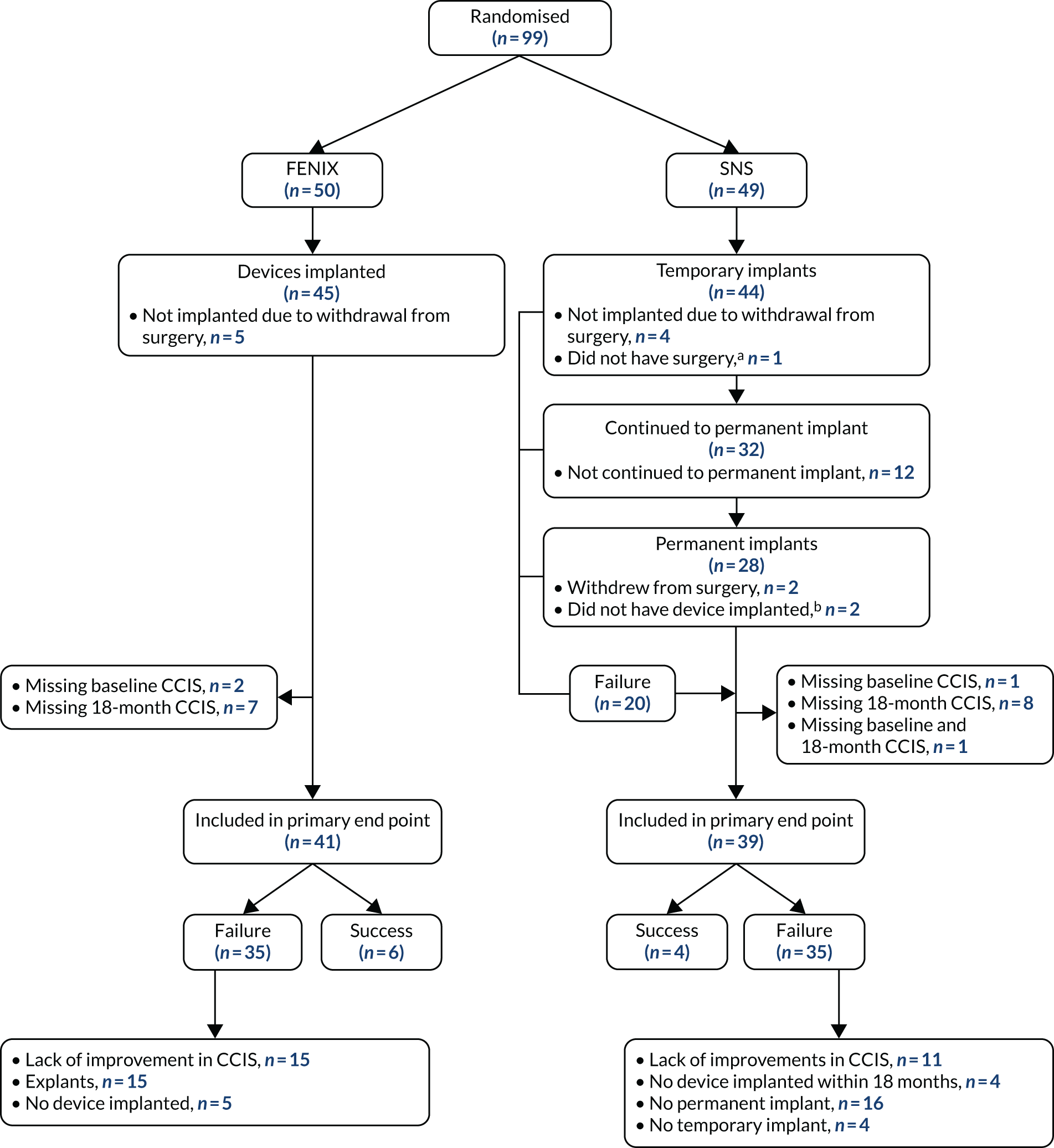

A total of 80 out of 99 (80.8%) participants were included in the primary analysis as 19 participants had missing primary outcome data. The pathway for participants in the primary analysis can be seen in Figure 3.

The characteristics for participants included in the primary analysis are presented in Table 5.

FIGURE 3.

Diagram of participants in primary analysis. a, Due to other health issues; b, due to complication during procedure.

| Variable | FENIX MSA | SNS | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCIS at baseline (points) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 14.2 (3.23) | 14.6 (3.05) | 14.4 (3.13) |

| Median (range) | 14.0 (6.0–20.0) | 14.5 (9.0–20.0) | 14.0 (6.0–20.0) |

| Missing, n | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| n | 39 | 38 | 77 |

| CCIS at 18 months (points) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 11.3 (4.42) | 12.0 (4.57) | 11.7 (4.48) |

| Median (range) | 11.5 (3.0–17.0) | 12.0 (1.0–19.0) | 12.0 (1.0–19.0) |

| Missing, n | 13 | 6 | 19 |

| n | 28 | 33 | 61 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 1 (2.4) | 2 (5.1) | 3 (3.8) |

| Female | 40 (97.6) | 37 (94.9) | 77 (96.3) |

| Total | 41 (100) | 39 (100) | 80 (100) |

| CCIS stratification factor, n (%) | |||

| ≤ 10 points (mild to moderate) | 6 (14.6) | 5 (12.8) | 11 (13.8) |

| > 10 points (moderate to severe) | 35 (85.4) | 34 (87.2) | 69 (86.3) |

| Total | 41 (100) | 39 (100) | 80 (100) |

| Anal sphincter defect, n (%) | |||

| No anal sphincter defect | 22 (53.7) | 22 (56.4) | 44 (55.0) |

| ≤ 90° | 16 (39.0) | 13 (33.3) | 29 (36.3) |

| > 90° to < 180° | 3 (7.3) | 4 (10.3) | 7 (8.8) |

| Total | 41 (100) | 39 (100) | 80 (100) |

| Randomising surgeon, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 10 (24.4) | 6 (15.4) | 16 (20.0) |

| 2 | 10 (24.4) | 10 (25.6) | 20 (25.0) |

| 3 | 5 (12.2) | 6 (15.4) | 11 (13.8) |

| 4 | 3 (7.3) | 1 (2.6) | 4 (5.0) |

| 5 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (1.3) |

| 8 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (1.3) |

| 12 | 2 (4.9) | 1 (2.6) | 3 (3.8) |

| 15 | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (2.5) |

| 21 | 2 (4.9) | 2 (5.1) | 4 (5.0) |

| 23 | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.3) |

| 25 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (1.3) |

| 26 | 1 (2.4) | 2 (5.1) | 3 (3.8) |

| 30 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (1.3) |

| 31 | 3 (7.3) | 2 (5.1) | 5 (6.3) |

| 32 | 2 (4.9) | 1 (2.6) | 3 (3.8) |

| Other | 1 (2.4) | 3 (7.7) | 4 (5.0) |

| Total | 41 (100) | 39 (100) | 80 (100) |

The primary end point was not evaluable for 19 out of 99 randomised patients: 9 out of 50 patients randomised to FENIX MSA and 10 out of 49 patients randomised to SNS (see Figure 3). For the remaining 80 out of 99 patients with an evaluable primary end point, the rate of ‘success’ was 10 out of 80 (12.5%) patients overall: 6 out of 41 (14.6%) patients in the FENIX MSA arm and 4 out of 39 (10.3%) patients in the SNS arm (Table 6). The unadjusted odds ratio was 1.50 (95% CI 0.39 to 5.78; p = 0.56).

| Success | FENIX MSA | SNS | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18 months post randomisation, n (%) | |||

| Unsuccessful | 35 (85.4) | 35 (89.7) | 70 (87.5) |

| Successful | 6 (14.6) | 4 (10.3) | 10 (12.5) |

| Total | 41 (100) | 39 (100) | 80 (100) |

Summaries of the two individual components of the primary end point have been provided in Appendix 1, Tables 30–33.

The odds ratio adjusting for the minimisation factors was 1.45 (95% CI 0.36 to 5.83; p = 0.59).

The adjusted estimates of odds ratios and 95% CIs are presented in Table 7. The model shows no statistically significant differences between any of the minimisation factors, although this would be expected owing to the small number of patients recruited, which has led to large standard errors (SEs) of the estimates (i.e. wide CIs and underpowered hypothesis tests).

| Effect | Odds ratio | Odds ratio 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| FENIX MSA (vs. SNS) | 1.453 | 0.362 to 5.827 | 0.5926 |

| Male (vs. female) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 to infinity | 0.9957 |

| Baseline CCIS > 10 points (vs. baseline CCIS ≤ 10 points) | 0.631 | 0.110 to 3.614 | 0.5993 |

| Anal sphincter defect ≤ 90° (vs. no defect) | 1.108 | 0.260 to 4.723 | 0.8883 |

| Anal sphincter defect > 90° to < 180° (vs. no defect) | 1.238 | 0.115 to 13.298 | 0.8579 |

The estimated random effects with respect to surgeons were equal to 0. The SE was not estimable owing to the low numbers of patients operated on by each surgeon (see Table 5).

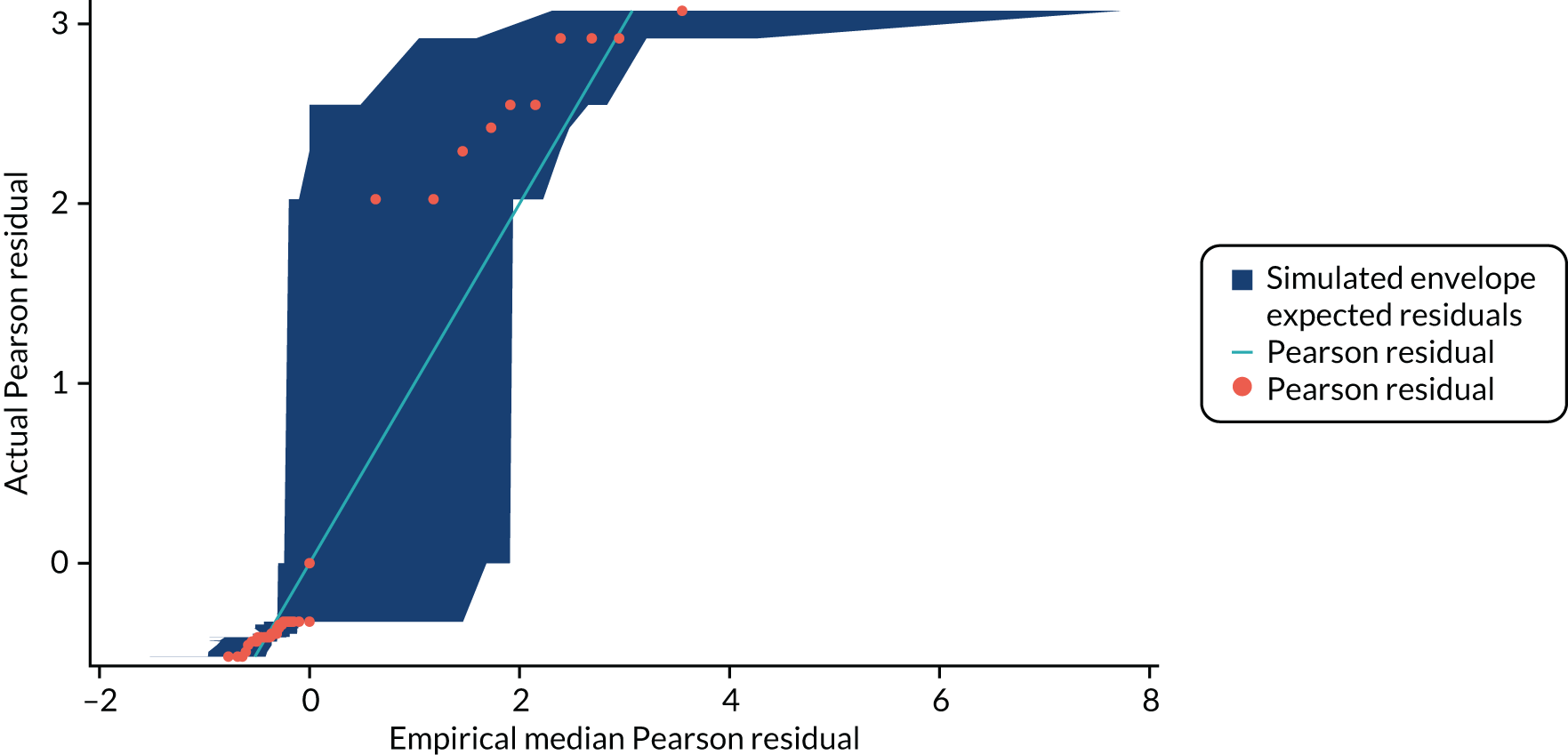

In Appendix 1, Figure 30 shows the empirical probability plot for the primary analysis model, which can be used to compare actual Pearson residuals with expected Pearson residuals. The y-axis is the actual Pearson residual value, the x-axis is the empirical median Pearson residual expected under our fitted model assumptions. Each dot represents the actual Pearson residual for an individual patient. If the model fitted perfectly, we would expect all of the dots to lie on the reference line. The band in Appendix 1, Figure 30, represents the interval between the empirical 2.5th percentile and 97.5th percentile empirical Pearson residual. There are some areas where the reference line is outside the band, meaning that the model may not fit the data too well, but this is due to the small sample size and the rarity of successful outcomes.

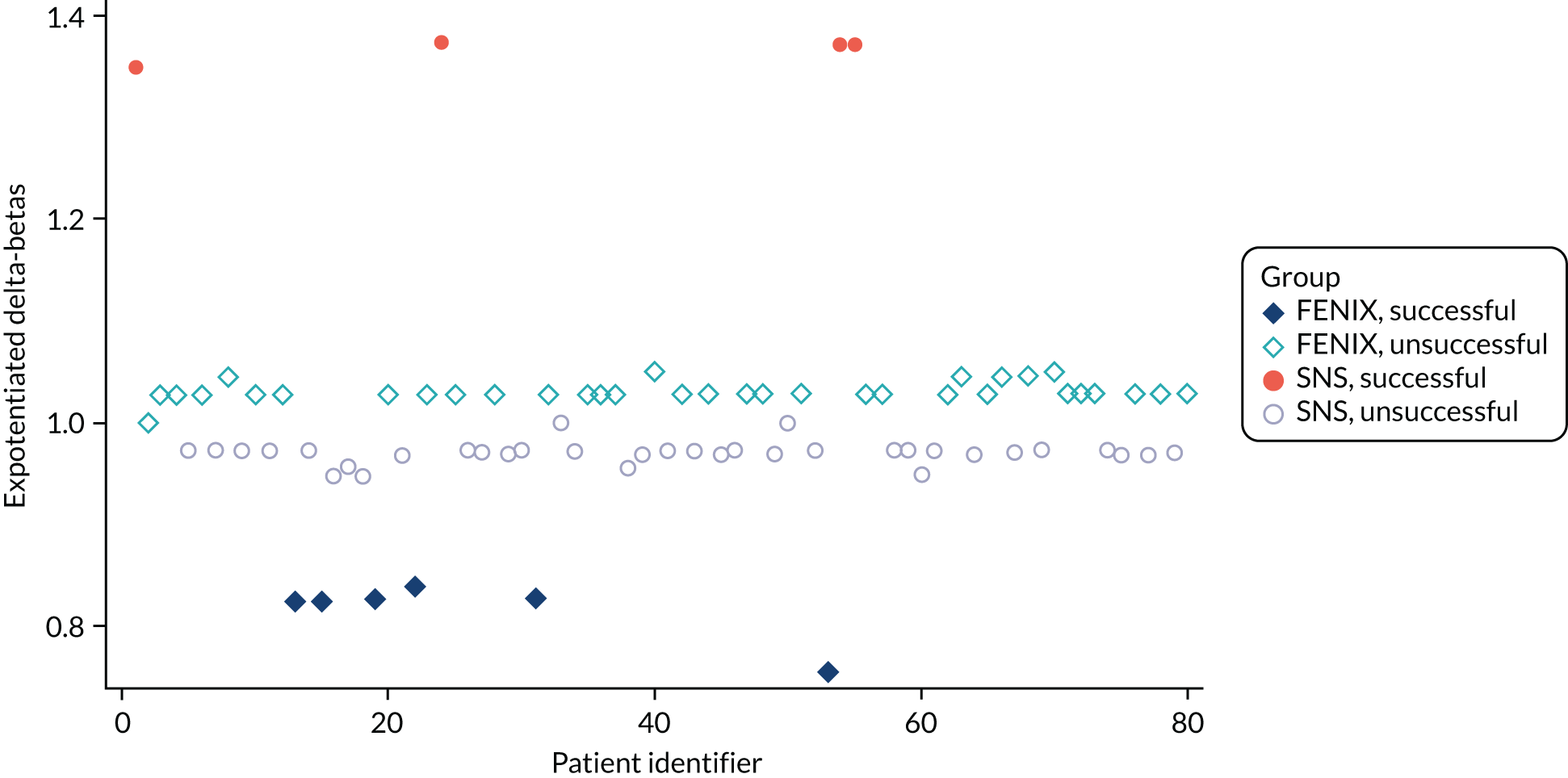

In Appendix 1, Figure 31 presents the plot of exponentiated delta-betas (y-axis) versus patient identifier. Exponentiated delta-betas further from 1 indicate greater influence of the observation on the estimated treatment effect. Patients with a success for the primary end point are more influential than patients without success for the primary end point, which may be expected given that success was an uncommon occurrence. There does not appear to be any other observations with a large influence on the model.

Sensitivity analysis: additional covariates

Owing to the small number of ‘successes’, performing the sensitivity analysis with additional covariates that was described in the analysis plan was inappropriate.

Longitudinal analysis

As the primary end point was measured at 6, 12 and 18 months post randomisation, a longitudinal analysis using the data at each time point was performed. The model did not adjust for the stratification factors because of the added complexity and the number of missing data. In addition, the stratification factors caused the model to fail to converge.

The fixed effects of the model can be seen in Table 8. The estimated random effect caused by the operating surgeon was 1.52 (SE 0.99) and the estimated random effect caused by within patient measurements was 1.19. The model does not show a significant difference between the treatment arms (p = 0.20) or in change over time (p = 0.17), although, again, it is worth noting that the estimates have large SEs due to the small sample size.

| Effect | Estimate | Estimate 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| FENIX MSA (vs. SNS) | 1.429 | 0.281 to 7.261 | 0.20 |

| Time (months) | 1.039 | 0.914 to 1.180 | 0.17 |

| Time and treatment interaction | 1.278 | 0.902 to 1.812 | 0.27 |

The model results can be seen in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Longitudinal model results.

Secondary end point: device in use and ≥ 50% improvement in Cleveland Clinic Incontinence Score at 12 months post randomisation

Success at 12 months post randomisation was evaluable for 67 out of 99 (67.7%) participants. Thirteen patients (1 FENIX and 12 SNS) were not included in this analysis as they had not had a permanent device fitted within 12 months of randomisation because of surgical capacity in the trial sites. The other 19 patients were not included because of missing CCIS at baseline, at 12 months post randomisation, or at both time points.

A total of 4 out of 27 (14.8%) patients did not have a temporary SNS device fitted (and therefore did not have a permanent device implanted) because they withdrew from surgery before the temporary SNS operation. A total of 4 out of 40 (10%) patients in the FENIX arm did not have a FENIX device implanted as a result of withdrawing from surgery. Seventeen out of 27 (63%) patients did not have a permanent SNS device implanted because of either withdrawal (n = 5) or the lack of success of the temporary device (n = 12). Ten out of 40 (25%) patients who were randomised to FENIX had the device explanted; there were no explants in the SNS arm. The number of successes is summarised in Table 9. Owing to the small number of successes at 12 months, the models fitted were not meaningful and so are not presented.

| Success | FENIX MSA | SNS | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 months post randomisation, n (%) | |||

| Unsuccessful | 35 (87.5) | 26 (96.3) | 61 (91.0) |

| Successful | 5 (12.5) | 1 (3.7) | 6 (9.0) |

| Total | 40 (100) | 27 (100) | 67 (100) |

Secondary end point: device in use and ≥ 50% improvement in Cleveland Clinic Incontinence Score at 6 months post randomisation

Success at 6 months post randomisation was evaluable for 56 out of 99 (56.6%) patients. Twenty-three patients (3 FENIX and 20 SNS) were not included in this analysis because they had not had a permanent device fitted within 6 months of randomisation owing to surgical capacity at trial sites. The other 20 patients were not included because of missing CCIS at baseline, 6 months post randomisation, or at both time points.

A total of 3 out of 18 (16.7%) patients did not have a temporary SNS device implanted (and therefore no permanent SNS device was implanted) because of withdrawal from surgery. Two out of 38 (5.3%) of patients randomised to FENIX did not have a permanent device implanted because of withdrawal from surgery. Thirteen out of 18 (72.2%) patients did not have a permanent device fitted because of withdrawal (n = 4) or the lack of efficacy of the temporary SNS device (n = 9). Nine patients in the FENIX arm (76.3%) had the device explanted within 6 months of randomisation and there were no explants in the SNS arm. The number of successes in each arm is summarised in Table 10. Owing to the small number of successes at 6 months, the models fitted did not converge and so are not presented.

| Success | FENIX MSA | SNS | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months post randomisation, n (%) | |||

| Unsuccessful | 33 (86.8) | 18 (100.0) | 51 (91.1) |

| Successful | 5 (13.2) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (8.9) |

| Total | 38 (100) | 18 (100) | 56 (100) |

Secondary end point: intraoperative complications

In total, 89 out of 99 patients (89.9%) had intraoperative complication data; 45 patients received an operation in the FENIX arm and 44 patients received an operation in the SNS arm.

There were four intraoperative complications in four patients; 3 out of 45 patients (6.7%) who were randomised to FENIX and received the operation had an intraoperative complication, and 1 out of 44 patients (2.3%) who were randomised to SNS and received at least one operation had an intraoperative complication, giving an overall complication rate of 4.5% (4/89) in randomised patients.

The complication in the SNS arm was an unexpected serious complication (USC). The details are as follows:

-

USC – anaphylaxis

-

Clavien–Dindo grade – IVb

-

USC description – patient became tachycardic, hypotensive and flushed following administration of Teicoplanin (Targocid, Sanofi, Paris, France) prior to their anaesthetic for insertion of SNS

-

Outcome – recovered.

There were three intraoperative complications in the FENIX arm, none of which was serious. The complications were bleeding, cyst found in recto vaginal septum, and rectal perforation.

Secondary end point: postoperative complications

A total of 85 out of 99 patients (85.9%) were included in the analysis of postoperative complications; 10 patients were not included due to not receiving an operation and four patients were not included due to missing follow-up forms. There were 42 out of 85 (49.4%) patients who experienced at least one postoperative complication: 33 out of 45 patients (73.3%) in the FENIX MSA arm and 9 out of 40 patients (22.5%) in the SNS arm (Table 11). The unadjusted odds ratio of having a complication in the FENIX MSA arm was 7.77 (95% CI 3.0 to 20.0; p < 0.001).

| Did patient experience a postoperative complication?, n (%) | FENIX MSA | SNS | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 33 (73.3) | 9 (22.5) | 42 (49.4) |

| No | 12 (26.7) | 31 (77.5) | 43 (50.6) |

| Total | 45 (100) | 40 (100) | 99 (100) |

Figure 2 shows the time from randomisation to operation and Table 12 shows the time from randomisation to first complication. Complications data were collected at 6, 12 and 18 months’ post-randomisation follow-up visits; therefore, patients who had their SNS devices fitted more than 18 months post randomisation will not have any complications recorded. There were five complications from the temporary SNS operation: (1) neurological, (2) haemorrhoid discomfort, (3) intermittent flare of eczema at SNS dressing site, (4) lack or loss of efficiency, and (5) device failure/separation. There were eight complications from the permanent SNS operation: (1) lead migration/fragmentation, (2) pain at battery site, (3) lack or loss of efficiency, (4) transient anal/rectal pain, (5) rectal/anal pain on defaecation, (6) neurological, (7) cardiorespiratory and (8) device reoperation: replacement of SNS wire. There were 88 complications across 33 patients in the FENIX MSA arm (Table 13).

| Parameter | FENIX MSA | SNS | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) (days) | 80.0 (148.72) | 79.3 (123.87) | 79.8 (142.33) |

| Median (range) (days) | 12.0 (0.0–540.0) | 15.0 (0.0–355.0) | 13.0 (0.0–540.0) |

| Participants, n | 33 | 9 | 42 |

| Complication | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Worsening constipation/obstructed defecation | 18 (20.5) |

| Othera | 17 (19.3) |

| Transient anal/rectal pain | 14 (15.9) |

| Device erosion | 8 (9.1) |

| Wound infection | 7 (8.0) |

| Device explant/reoperation | 7 (8.0) |

| Implant infection | 5 (5.7) |

| Bleeding/wound haematoma | 4 (4.5) |

| Neurological | 3 (3.4) |

| Lack or loss of efficiency | 3 (3.4) |

| Urinary retention | 1 (1.1) |

| Device failure/separation | 1 (1.1) |

| Total | 88 (100) |

The adjusted model odds ratios can be seen in Table 14. The model results show a statistically significant difference in the odds of a complication between the two treatment arms, with an adjusted odds ratio of 12.91 (95% CI 2.75 to 60.68; p = 0.004). The random effect with respect to surgeon (i.e. the ‘random intercept’) was 0.79 (SE 1.38), and the random effect with respect to the interaction between surgeon and the difference between treatments (i.e. the ‘random slope’) was < 0.0001 (SE 2.17).

| Effect | Odds ratio | Odds ratio 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| FENIX MSA (vs. SNS) | 12.91 | 2.75 to 60.68 | 0.0042 |

| Male (vs. female) | 1.04 | 0.03 to 36.87 | 0.98 |

| Baseline CCIS > 10 points (vs. baseline CCIS ≤ 10 points) | 0.79 | 0.11 to 5.59 | 0.81 |

| Anal sphincter defect ≤ 90° (vs. no defect) | 1.43 | 0.44 to 4.68 | 0.55 |

| Anal sphincter defect > 90° to ≤ 180° (vs. no defect) | 0.41 | 0.03 to 6.78 | 0.53 |

The time from randomisation to operation is presented in Figure 2. There is a large difference between the arms, with four patients in the SNS arm not having a permanent operation within 18 months of randomisation; therefore, the model results may be biased against the FENIX MSA arm as patients in this arm will have had longer postoperative follow-up and, therefore, longer exposure to the risk of postoperative complication within the trial follow-up period. However, Table 12 shows the number of days from operation to first complication and this shows that most complications occurred within 3 months, with some happening a long time after the operation. As seen in Figure 2, most SNS patients were followed up for > 3 months post randomisation.

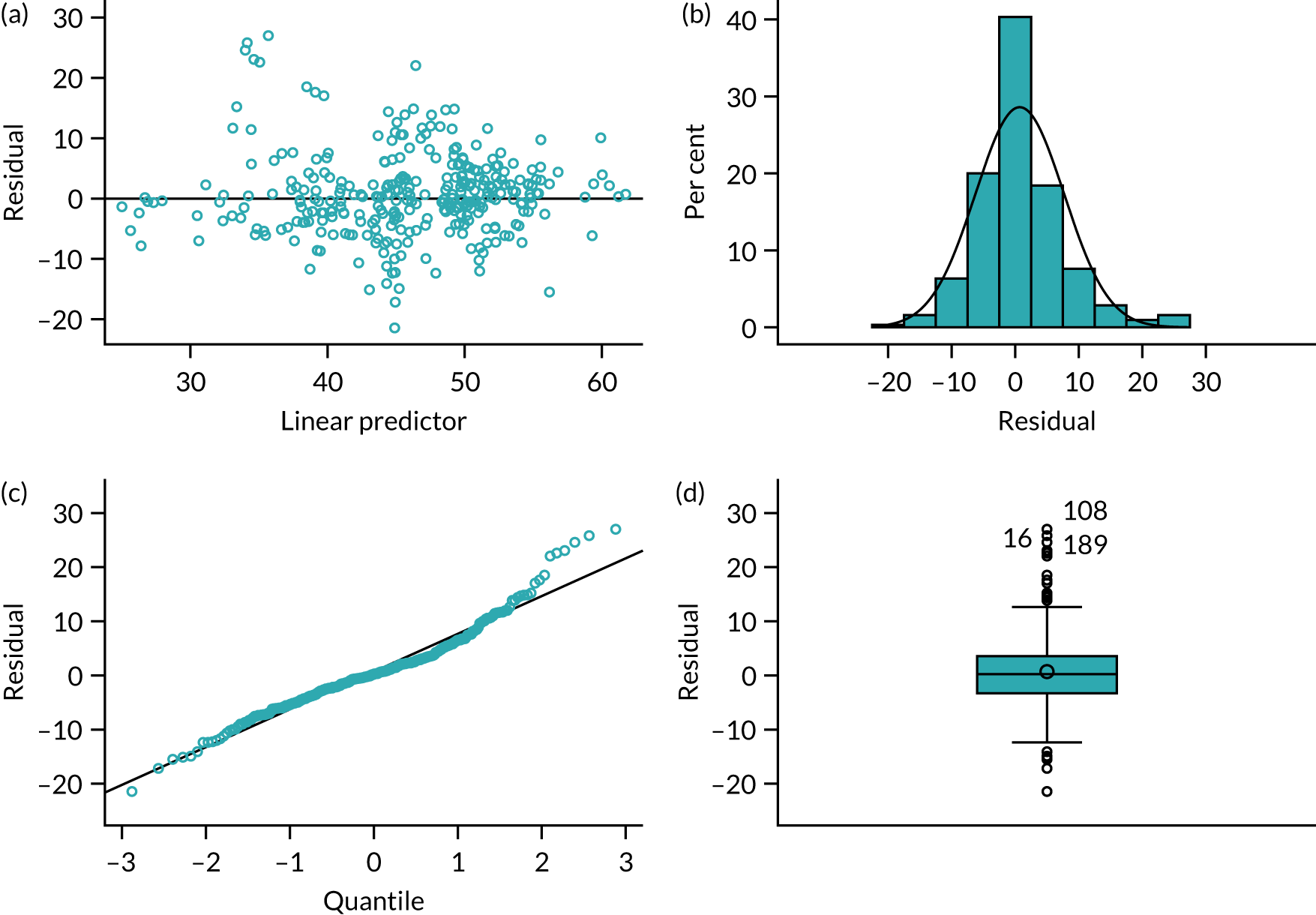

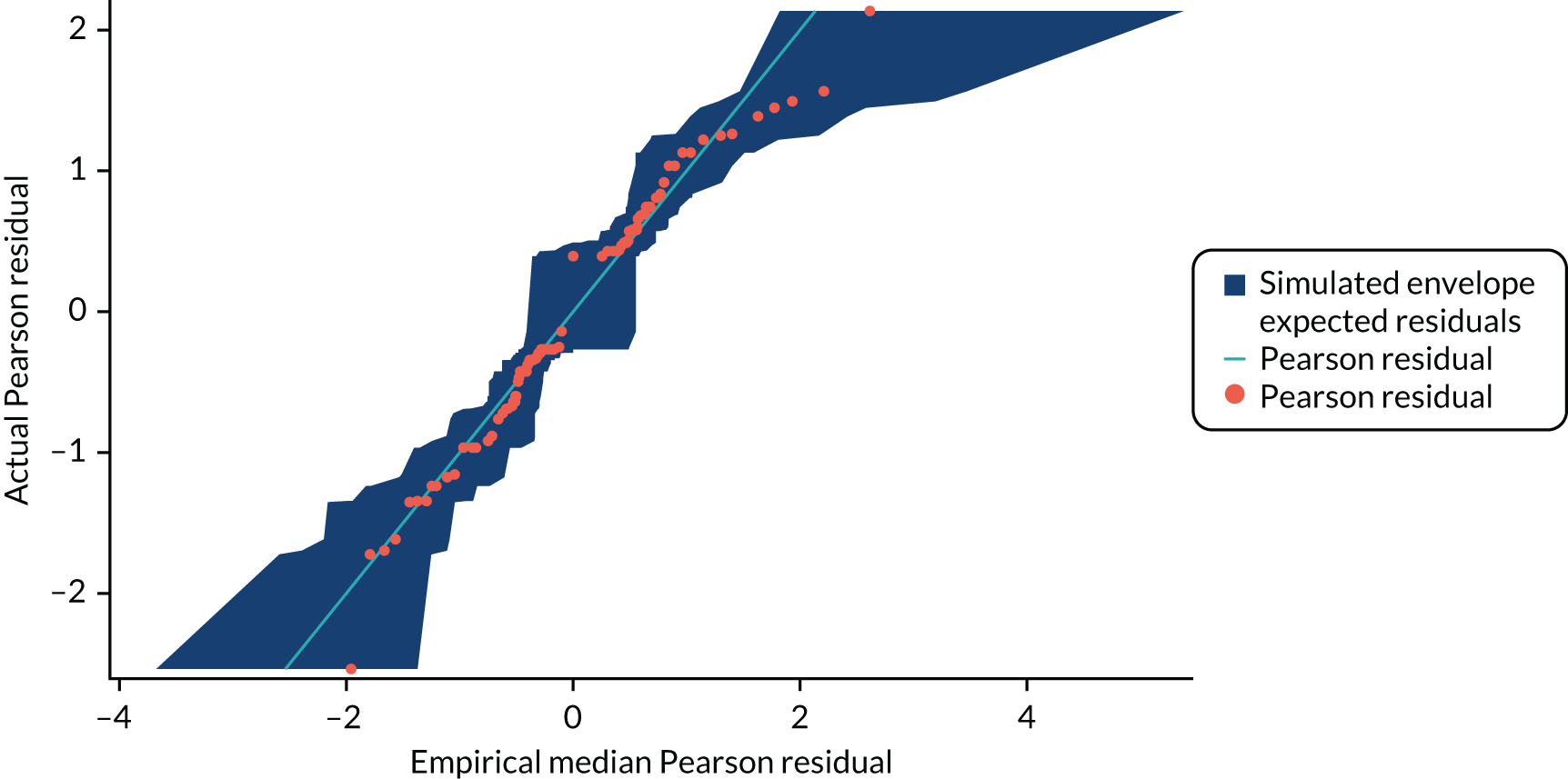

Appendix 1, Figure 32, shows the empirical probability plot for the postoperative complications model, which can be used to compare actual Pearson residuals with expected Pearson residuals. The y-axis is the actual Pearson residual value, the x-axis is the empirical median Pearson residual expected under our fitted model assumptions. Each dot represents the actual Pearson residual for an individual patient. If the model fitted perfectly we would expect all of the dots to lie on the reference line. The band in Figure 32 represents the interval between the empirical 2.5th percentile and 97.5th percentile empirical Pearson residual. No values lie outside this region, indicating that we do not have any substantial outliers.

Appendix 1, Figure 33, presents the plot of exponentiated delta-betas (y-axis) versus patient identifier. Exponentiated delta-betas further from 1 indicate greater influence of the observation on the estimated treatment effect. There does not appear to be any unusually influential observations in the delta-beta plot.

Secondary end point: device explants

The number of devices in situ and explanted within 18 months of randomisation can be seen in Table 15. The mean number of days from device implant to explant was 164 (SD 168) and the median number of days was 112 (range 0–449).

| Device status | FENIX MSA, n (%) | SNS, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Device in situ | 30 (60.0) | 24 (49.0) | 54 (54.5) |

| Device explanted | 15 (30.0) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (15.2) |

| No device fitted | 5 (10.0) | 21 (42.9) | 26 (26.3) |

| Device implanted more than 18 months post randomisation | 0 (0.0) | 4 (8.2) | 4 (4.0) |

| Total | 50 (100) | 49 (100) | 99 (100) |

Figure 5 shows the periods of time (measured from randomisation) for which each patient had a permanent device in situ. The mean number of days from implant to explant was 164 (SD = 168) and the median number of days was 112 (range 0–449). As there were no explants in the SNS arm, the device explants end point has not been modelled because any regression models would not converge.

FIGURE 5.

Time to explant: (a) FENIX MSA; and (b) SNS. Dashed line indicates that patient had device explanted.

The reasons for explant are given in Table 16 and include participant intolerance (n = 4), device erosion/migration and infection, implant infected and visible through the skin, device eroded, infection/erosion (n = 3), rectal perforation the device was removed/no implant, chronic sinus infection, participant did not have adequate response, and device malfunction.

| Reason | Days from randomisation to explant |

|---|---|

| Participant intolerance | 257 |

| Device erosion/migration + infection | 16 |

| Implant infected and is visible through the skin | 154 |

| Participant did not have adequate response | 399 |

| Device eroded | 350 |

| Infection/erosion of FENIX beads SAE | 14 |

| Rectal perforation the device was removed/no implant | 0 |

| Infection and erosion, device explanted | 7 |

| Infection erosion | 69 |

| Chronic sinus infection | 169 |

| Participant did not have adequate response | 409 |

| Device malfunction | 449 |

Secondary end point: Cleveland Clinic Incontinence Score

The CCIS assesses five parameters associated with incontinence: incontinence to solid, incontinence to liquid, incontinence to gas, use of pads and lifestyle restrictions. Each parameter is scored 0–4 with ‘0’ for never and ‘4’ for every day. The five parameters are added to give a total score out of 20, with a lower score indicating a better QoL.

Summary measures of the CCIS split by time point and treatment arm are given in Table 17.

| CCIS (points) | FENIX MSA | SNS | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| Mean (SD) | 14.4 (3.15) | 14.7 (2.95) | 14.6 (3.04) |

| Median (range) | 14.5 (6.0–20.0) | 15.0 (9.0–20.0) | 15.0 (6.0–20.0) |

| Missing | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| n | 46 | 46 | 92 |

| 6 months post randomisation | |||

| Mean (SD) | 11.7 (4.61) | 13.8 (3.45) | 12.8 (4.16) |

| Median (range) | 12.0 (2.0–20.0) | 14.0 (7.0–20.0) | 13.0 (2.0–20.0) |

| Missing | 15 | 10 | 25 |

| n | 35 | 39 | 74 |

| 12 months post randomisation | |||

| Mean (SD) | 11.8 (4.86) | 12.9 (3.78) | 12.3 (4.37) |

| Median (range) | 12.0 (3.0–20.0) | 13.0 (5.0–20.0) | 12.0 (3.0–20.0) |

| Missing | 15 | 15 | 30 |

| n | 35 | 34 | 69 |

| 18 months post randomisation | |||

| Mean (SD) | 11.1 (4.35) | 12.1 (4.55) | 11.6 (4.45) |

| Median (range) | 11.0 (3.0–17.0) | 12.5 (1.0–19.0) | 12.0 (1.0–19.0) |

| Missing | 20 | 15 | 35 |

| n | 30 | 34 | 64 |

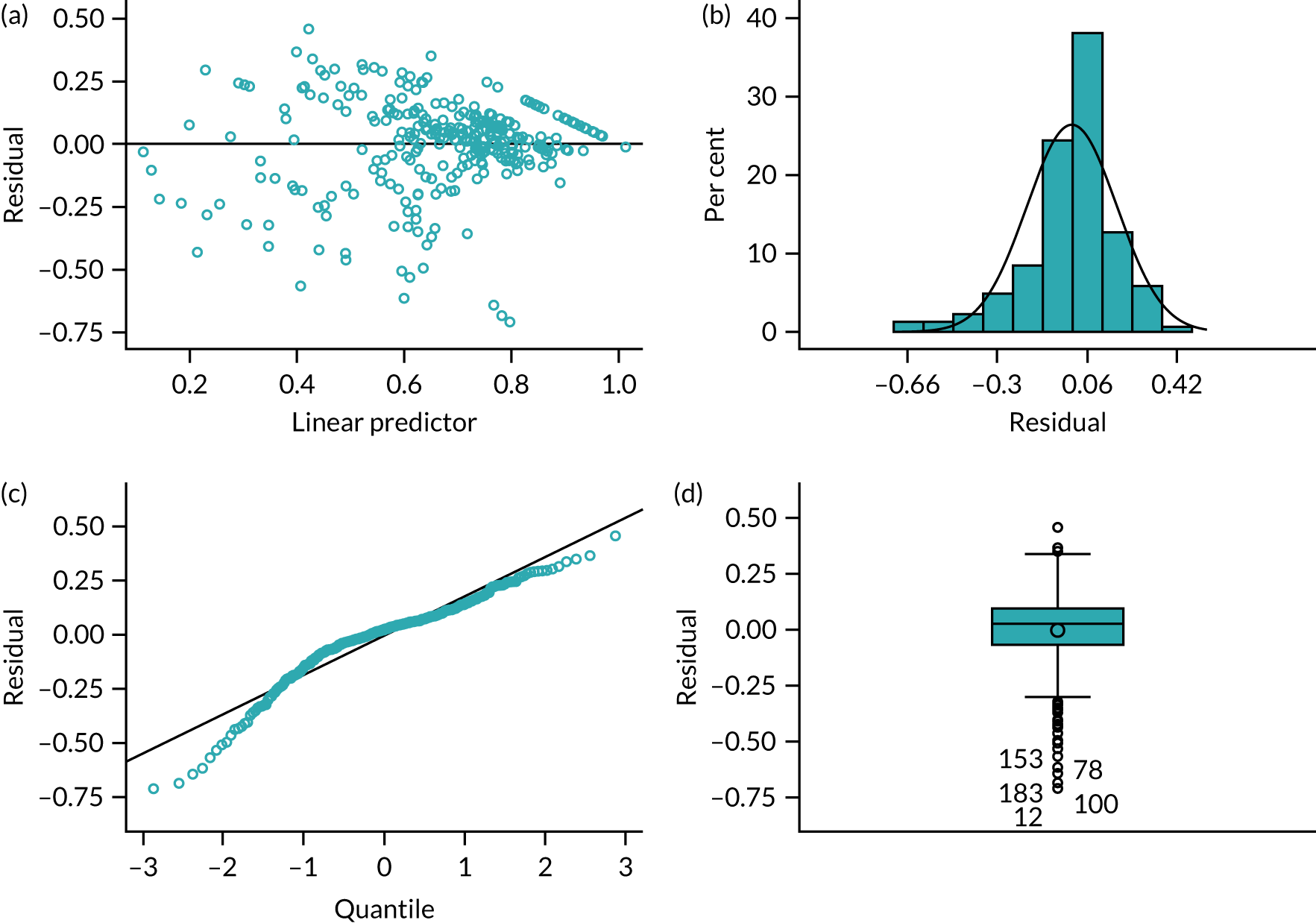

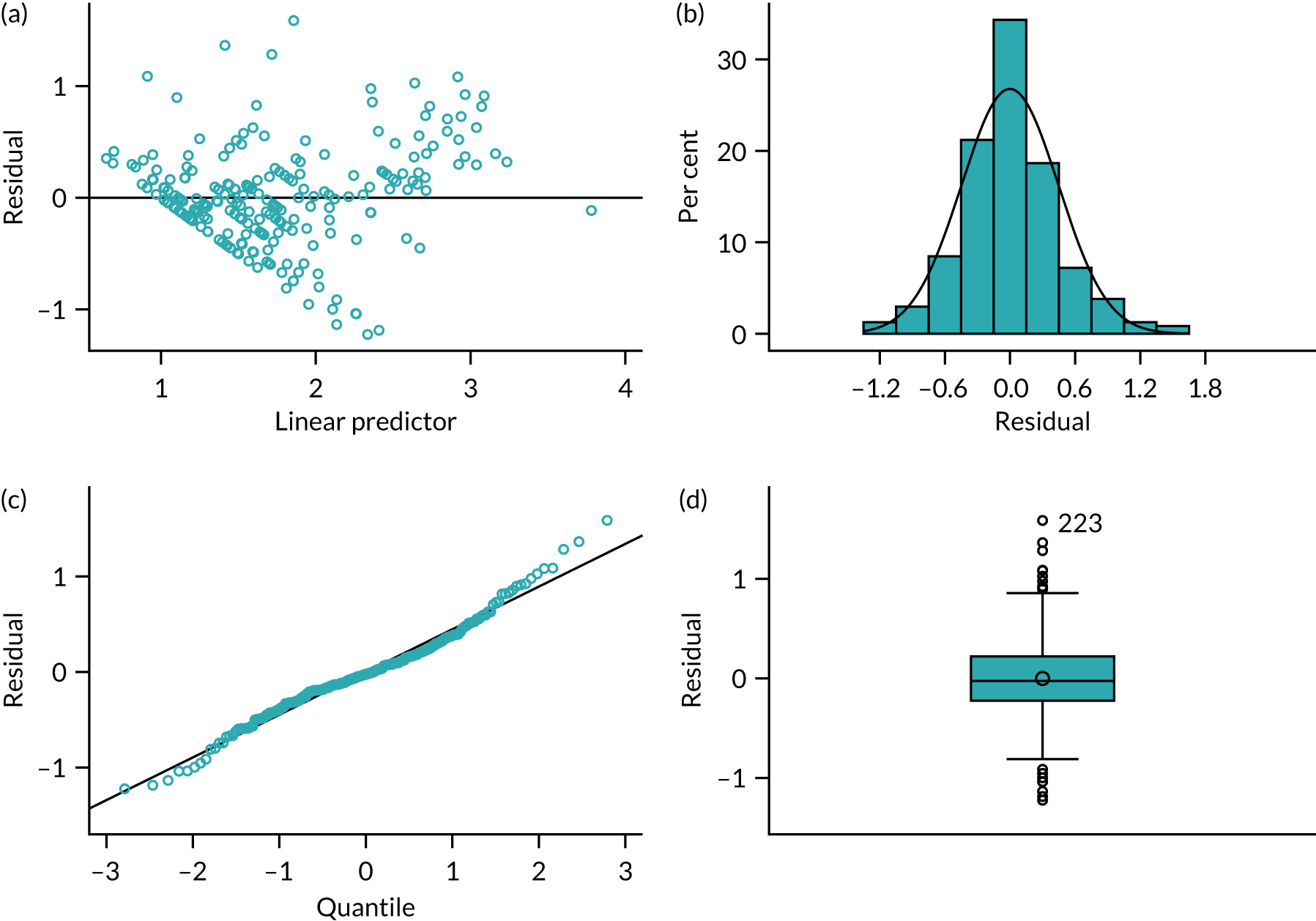

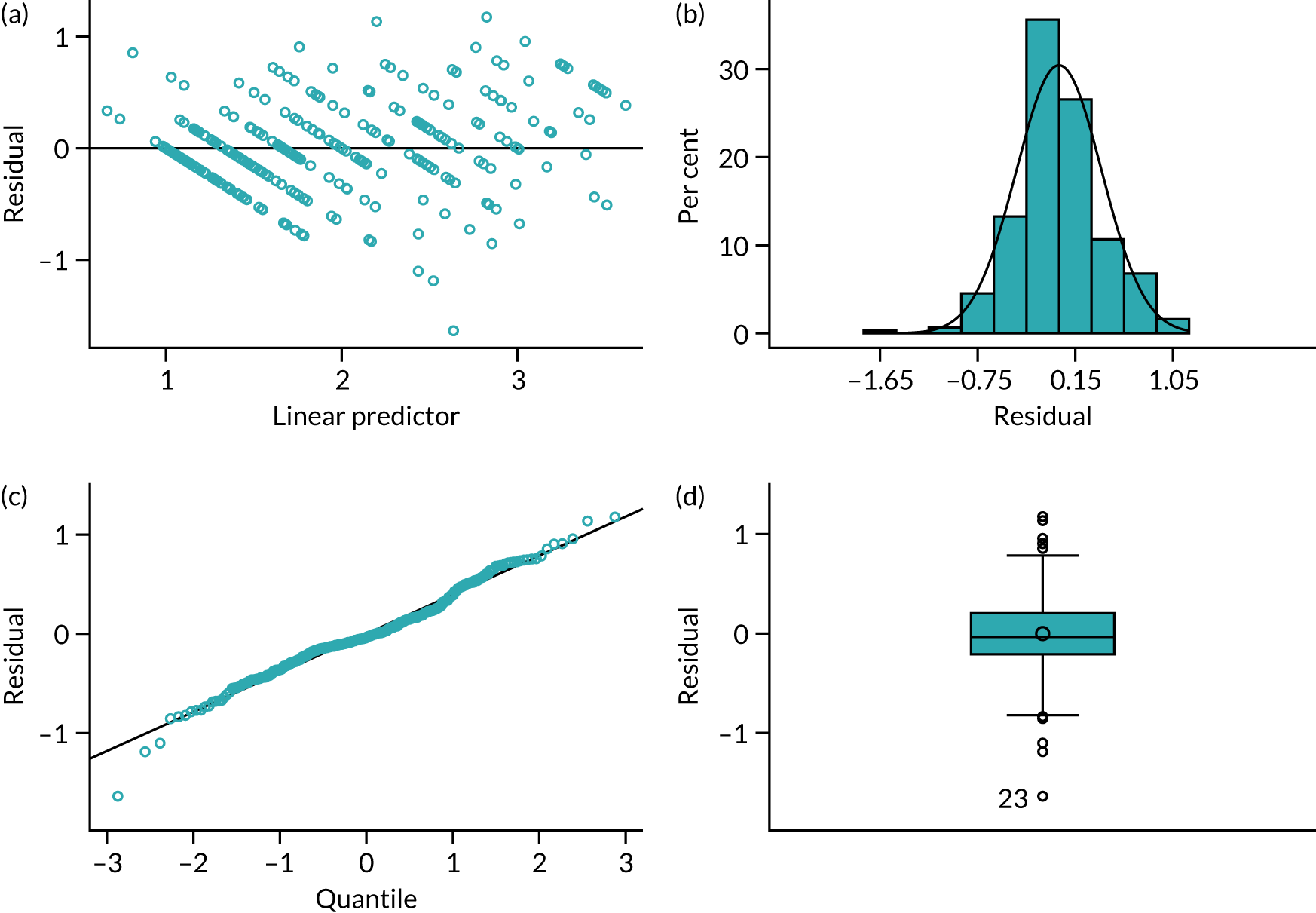

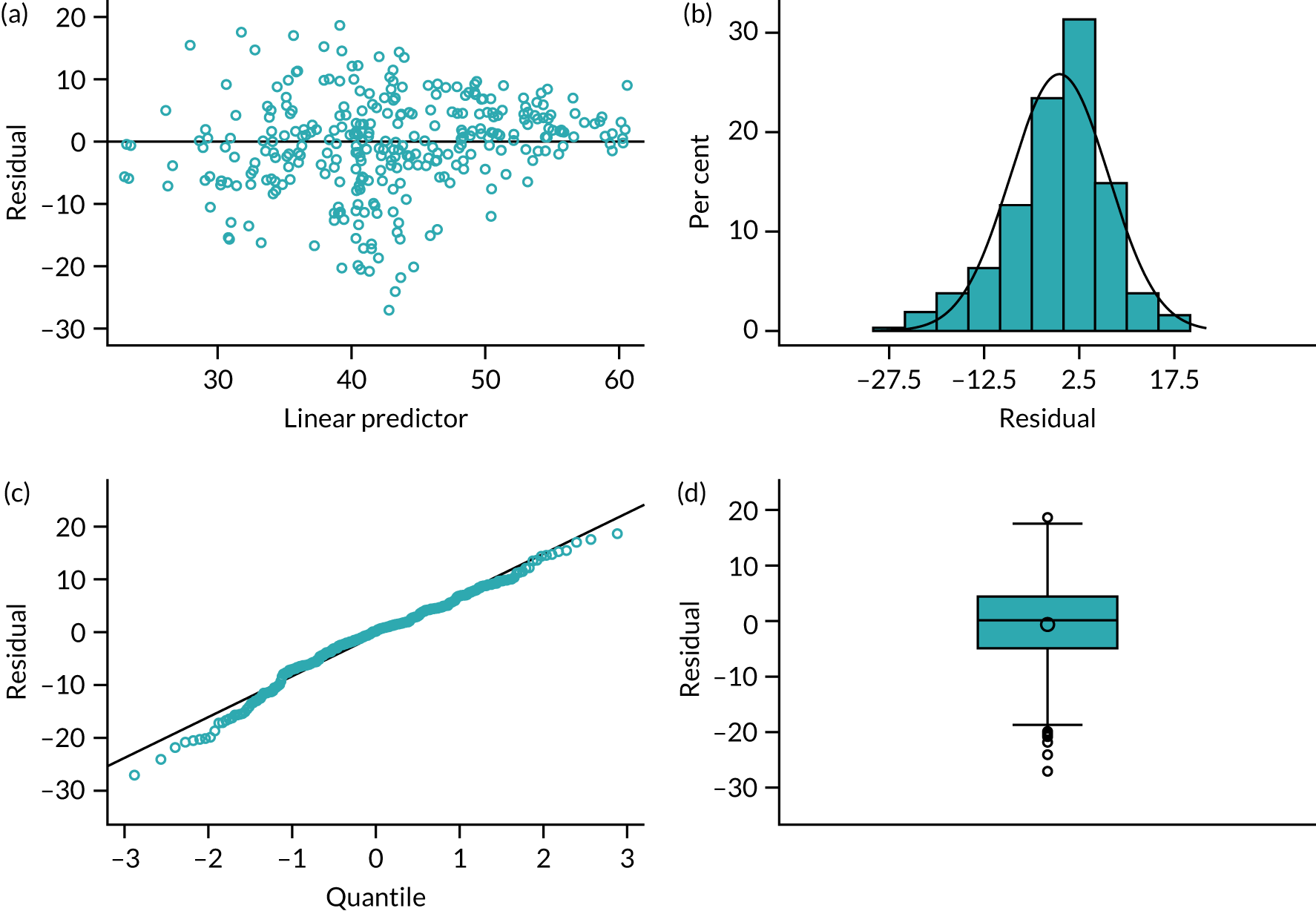

The model diagnostics can be seen in Appendix 1, Figure 34.

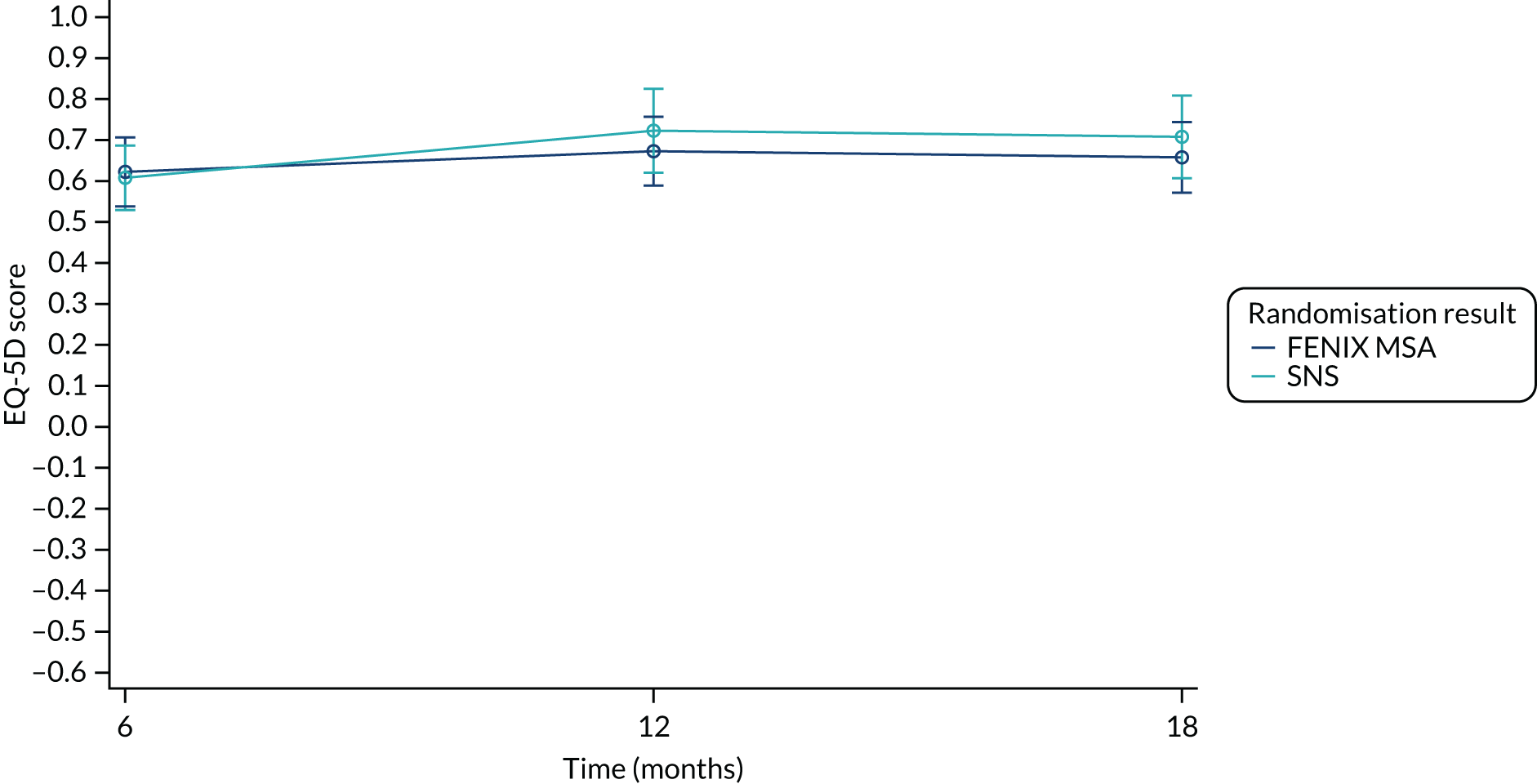

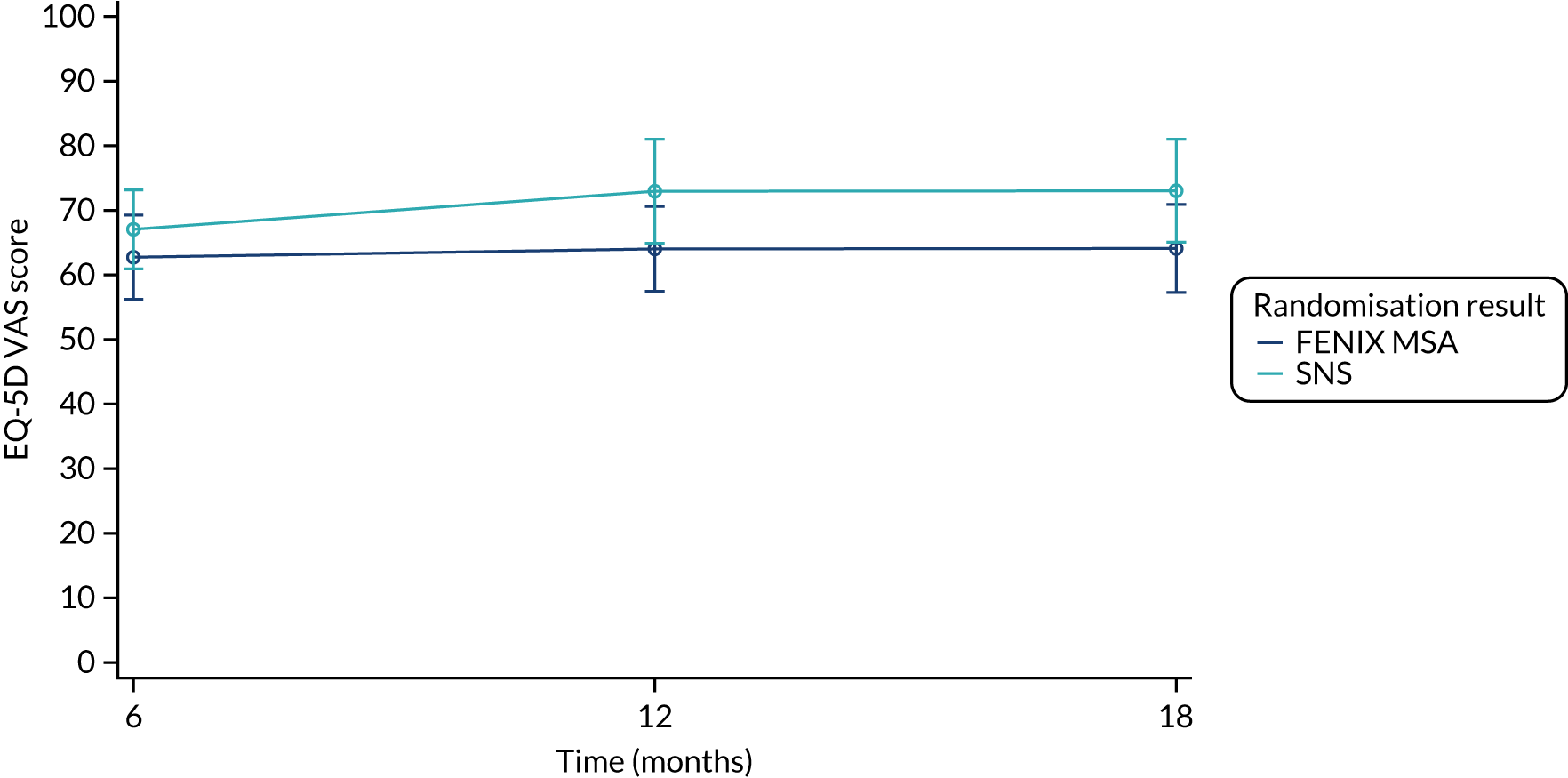

Secondary end point: EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version

The EQ-5D-5L is made up of 5 dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression), each of which has 5 levels (no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems and extreme problems). These levels can be combined to calculate an index value, which ranges from 1 (best possible health), through 0 (death) to –0.594 (worse than death).

Summary measures of the EQ-5D-5L index values, and the EQ-5D-5L Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) scores, split by time point and treatment arm, are given in Table 18.

| Variable | FENIX MSA | SNS | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D-5L score | |||

| Baseline | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.666 (0.256) | 0.647 (0.261) | 0.657 (0.257) |

| Median (range) | 0.740 (–0.02–1.00) | 0.736 (–0.05–1.00) | 0.736 (–0.05–1.00) |

| Missing | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| n | 46 | 46 | 92 |

| 6 months post randomisation | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.687 (0.225) | 0.639 (0.295) | 0.662 (0.263) |

| Median (range) | 0.736 (–0.02–1.00) | 0.732 (–0.22–1.00) | 0.736 (–0.22–1.00) |

| Missing | 12 | 7 | 19 |

| n | 38 | 42 | 80 |

| 12 months post randomisation | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.684 (0.258) | 0.673 (0.263) | 0.679 (0.259) |

| Median (range) | 0.750 (–0.06–1.00) | 0.752 (00.023–1.00) | 0.750 (–0.06–1.00) |

| Missing | 13 | 13 | 26 |

| n | 37 | 36 | 73 |

| 18 months post randomisation | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.660 (0.258) | 0.683 (0.255) | 0.672 (0.255) |

| Median (range) | 0.732 (0.054–1.00) | 0.743 (–0.05–1.00) | 0.735 (–0.05–1.00) |

| Missing | 20 | 17 | 37 |

| n | 30 | 32 | 62 |

| EQ-5D-5L VAS score | |||

| Baseline | |||

| Mean (SD) | 65.7 (20.3) | 66.8 (24.8) | 66.2 (22.5) |

| Median (range) | 70.0 (0.00–95.0) | 70.0 (5.00–100) | 70.0 (0.00–100) |

| Missing | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| n | 48 | 45 | 93 |

| 6 months post randomisation | |||

| Mean (SD) | 66.9 (19.6) | 72.7 (19.3) | 69.9 (19.5) |

| Median (range) | 70.0 (30.0–95.0) | 75.0 (15.0–95.0) | 75.0 (15.0–95.0) |

| Missing | 11 | 7 | 18 |

| n | 39 | 42 | 81 |

| 12 months post randomisation | |||

| Mean (SD) | 65.5 (21.1) | 73.2 (19.7) | 69.4 (20.6) |

| Median (range) | 70.0 (10.0–96.0) | 75.0 (20.0–100) | 72.5 (10.0–100) |

| Missing | 14 | 13 | 27 |

| n | 36 | 36 | 72 |

| 18 months post randomisation | |||

| Mean (SD) | 66.0 (19.6) | 72.1 (14.0) | 69.2 (17.0) |

| Median (range) | 67.5 (20.0–95.0) | 70.0 (33.0–100) | 70.0 (20.0–100) |

| Missing | 20 | 16 | 36 |

| n | 30 | 33 | 63 |

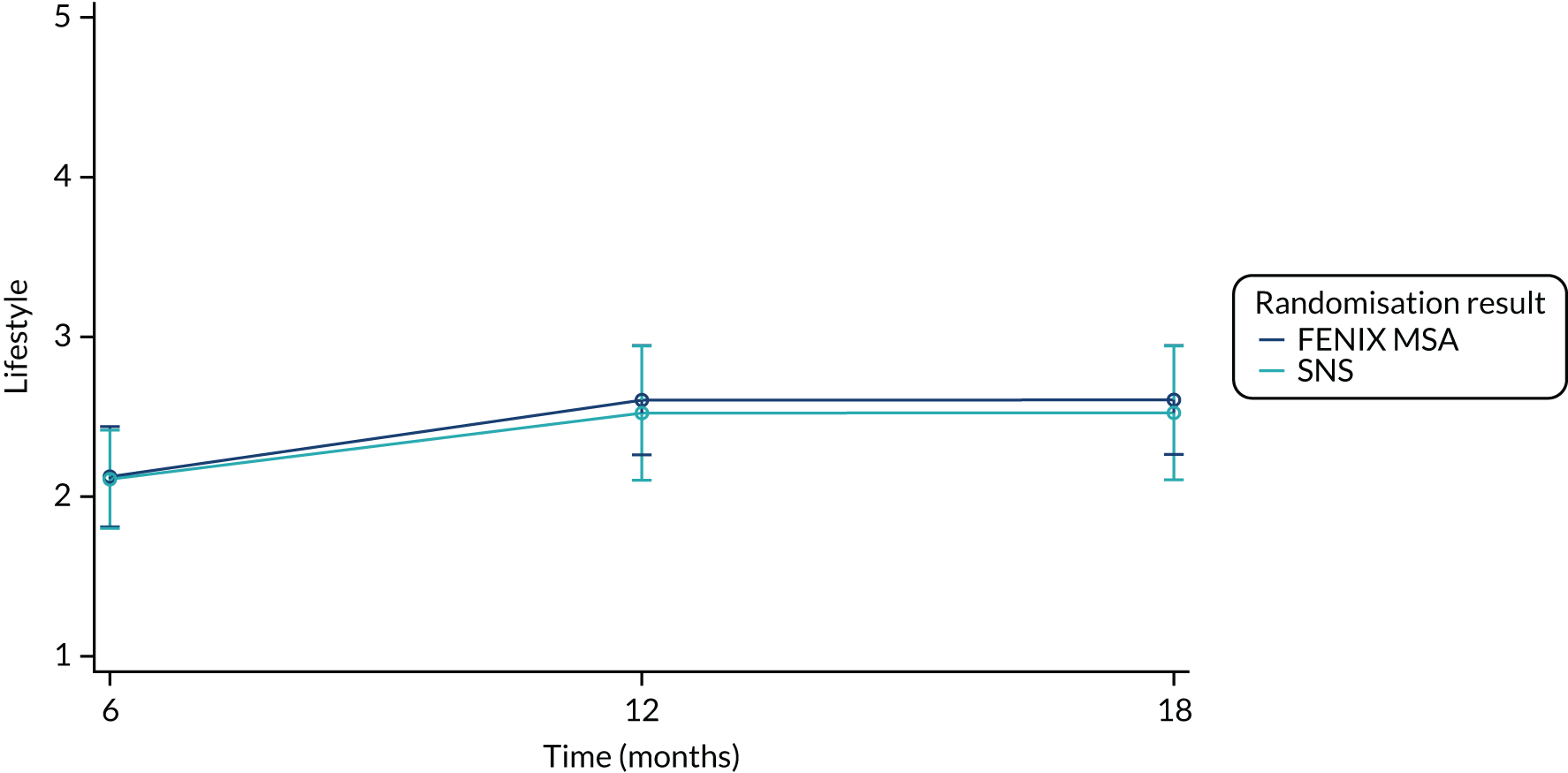

Secondary end point: faecal incontinence quality of life

The FIQoL questionnaire is composed of 29 items that make up four scales: lifestyle (10 items), coping/behaviour (9 items), depression/self-perception (7 items) and embarrassment (3 items). Scales range from 1 to 5 and scale scores are derived by averaging the response to all items in the scale. A lower score indicates a lower functional QoL.

Summary measures of the four FIQoL domains split by time point and treatment arm are provided in Table 19.

| FIQoL domain | FENIX MSA | SNS | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lifestyle (baseline) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.17 (0.864) | 2.12 (0.887) | 2.15 (0.871) |

| Median (range) | 2.00 (1.00–3.80) | 2.00 (1.00–3.90) | 2.00 (1.00–3.90) |

| Missing | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| n | 45 | 44 | 89 |

| Lifestyle (6 months post randomisation) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.64 (1.09) | 2.39 (0.918) | 2.51 (1.01) |

| Median (range) | 2.70 (1.00–4.00) | 2.30 (1.00–4.00) | 2.50 (1.00–4.00) |

| Missing | 13 | 11 | 24 |

| n | 37 | 38 | 75 |

| Lifestyle (12 months post randomisation) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.74 (1.08) | 2.35 (1.03) | 2.56 (1.06) |

| Median (range) | 3.05 (1.00–4.00) | 2.30 (1.00–3.90) | 2.75 (1.00–4.00) |

| Missing | 14 | 17 | 31 |

| n | 36 | 32 | 68 |

| Lifestyle (18 months post randomisation) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.73 (1.03) | 2.62 (1.02) | 2.68 (1.02) |

| Median (range) | 2.90 (1.00–4.00) | 2.90 (1.00–4.00) | 2.90 (1.00–4.00) |

| Missing | 21 | 22 | 43 |

| n | 29 | 27 | 56 |

| Coping (baseline) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.44 (0.534) | 1.50 (0.616) | 1.47 (0.573) |

| Median (range) | 1.33 (1.00–3.67) | 1.33 (1.00–3.44) | 1.33 (1.00–3.67) |

| Missing | 9 | 9 | 18 |

| n | 41 | 40 | 81 |

| Coping (6 months post randomisation) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.04 (0.984) | 1.63 (0.610) | 1.81 (0.818) |

| Median (range) | 1.67 (1.00–4.00) | 1.56 (1.00–3.22) | 1.56 (1.00–4.00) |

| Missing | 23 | 16 | 39 |

| n | 27 | 33 | 60 |

| Coping (12 months post randomisation) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.24 (1.02) | 1.57 (0.671) | 1.91 (0.923) |

| Median (range) | 2.11 (1.00–4.00) | 1.44 (1.00–3.22) | 1.56 (1.00–4.00) |

| Missing | 23 | 22 | 45 |

| n | 27 | 27 | 54 |

| Coping (18 months post randomisation) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.94 (0.895) | 1.97 (0.820) | 1.96 (0.847) |

| Median (range) | 1.67 (1.00–3.89) | 2.11 (1.00–3.44) | 1.89 (1.00–3.89) |

| Missing | 30 | 28 | 58 |

| n | 20 | 21 | 41 |

| Depression (baseline) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.52 (0.956) | 2.33 (0.864) | 2.43 (0.911) |

| Median (range) | 2.14 (1.14–4.29) | 2.29 (1.00–4.29) | 2.14 (1.00–4.29) |

| Missing | 11 | 11 | 22 |

| n | 39 | 38 | 77 |

| Depression (6 months post randomisation) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.74 (1.07) | 2.48 (0.891) | 2.60 (0.978) |

| Median (range) | 2.36 (1.43–4.43) | 2.43 (1.14–4.14) | 2.43 (1.14–4.43) |

| Missing | 24 | 19 | 43 |

| n | 26 | 30 | 56 |

| Depression (12 months post randomisation) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.70 (1.11) | 2.57 (0.898) | 2.64 (1.01) |

| Median (range) | 2.29 (1.14–4.29) | 2.64 (1.29–4.00) | 2.43 (1.14–4.29) |

| Missing | 20 | 21 | 41 |

| n | 30 | 28 | 58 |

| Depression (18 months post randomisation) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.53 (1.01) | 2.89 (0.948) | 2.72 (0.981) |

| Median (range) | 2.43 (1.29–4.43) | 3.00 (1.43–4.43) | 2.57 (1.29–4.43) |

| Missing | 29 | 25 | 54 |

| n | 21 | 24 | 45 |

| Embarrassment (baseline) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.74 (0.699) | 1.64 (0.640) | 1.69 (0.668) |

| Median (range) | 1.67 (1.00–3.33) | 1.33 (1.00–3.33) | 1.67 (1.00–3.33) |

| Missing | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| n | 46 | 47 | 93 |

| Embarrassment (6 months post randomisation) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.12 (0.996) | 1.87 (0.789) | 1.99 (0.897) |

| Median (range) | 1.67 (1.00–4.00) | 1.67 (1.00–4.00) | 1.67 (1.00–4.00) |

| Missing | 11 | 7 | 18 |

| n | 39 | 42 | 81 |

| Embarrassment (12 months post randomisation) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.20 (0.970) | 1.87 (0.791) | 2.04 (0.894) |

| Median (range) | 2.33 (1.00–4.00) | 1.67 (1.00–3.67) | 1.83 (1.00–4.00) |

| Missing | 13 | 12 | 25 |

| n | 37 | 37 | 74 |

| Embarrassment (18 months post randomisation) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.24 (1.02) | 1.99 (0.827) | 2.11 (0.926) |

| Median (range) | 2.33 (1.00–4.00) | 1.83 (1.00–4.00) | 2.00 (1.00–4.00) |

| Missing | 21 | 17 | 38 |

| n | 29 | 32 | 61 |

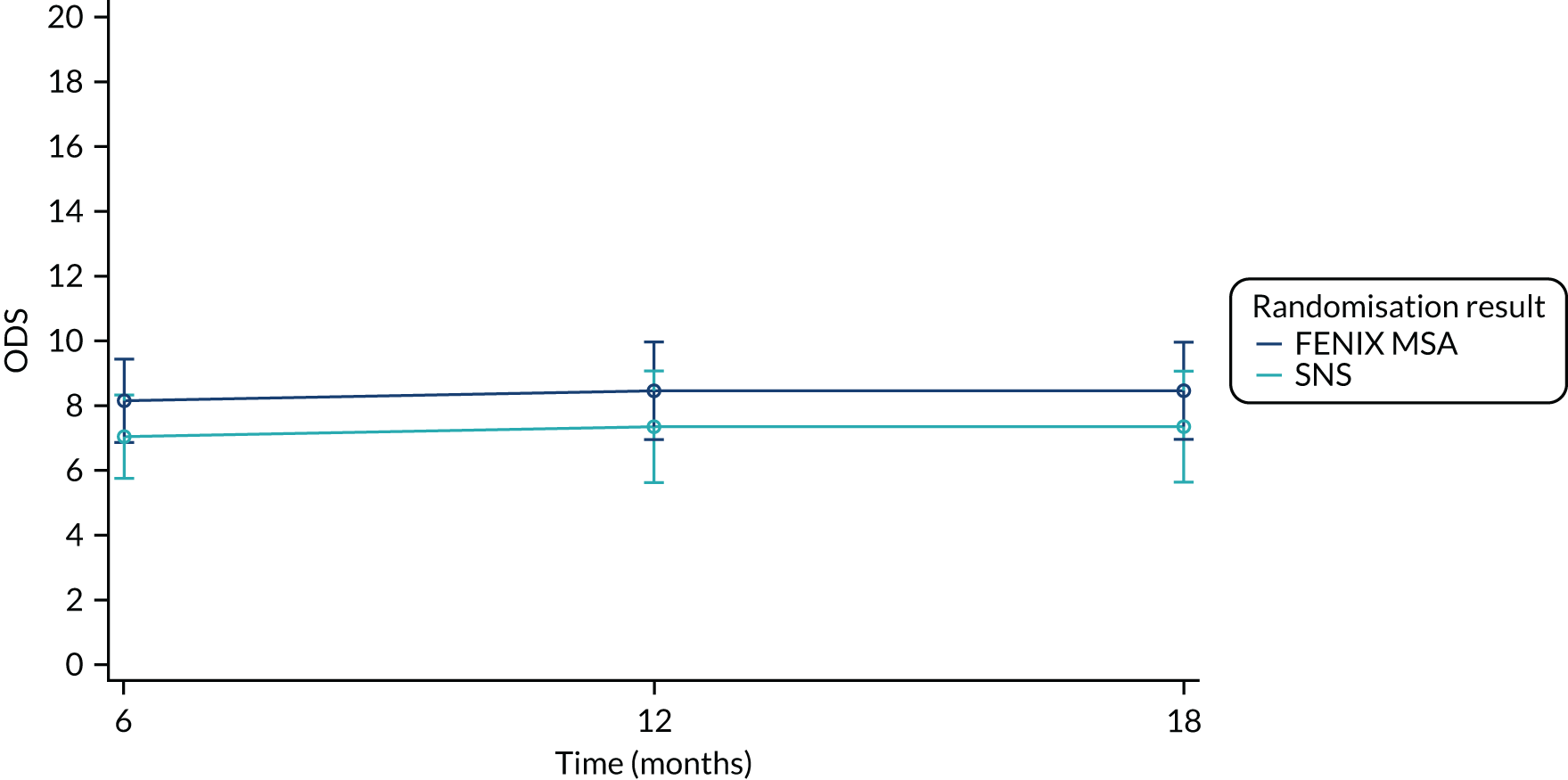

Secondary end point: Obstructed Defecation Score

The ODS consists of five items: excessive straining, incomplete rectal evacuation, use of enemas and/or laxatives, vaginal-anal-perineal digitations, and abdominal discomfort and/or pain. Each item is graded from 0 to 4, with scores ranging from 0 (no symptoms) to 20 (very severe symptoms), meaning that a lower score indicates better QoL.

Summary measures of the total ODS split by time point and treatment arm are presented in Table 20.

| ODS | FENIX MSA | SNS | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| Mean (SD) | 7.44 (3.78) | 7.09 (3.62) | 7.27 (3.68) |

| Median (range) | 7.00 (2.00–18.0) | 8.00 (2.00–17.0) | 7.00 (2.00–18.0) |

| Missing | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| n | 45 | 43 | 88 |

| 6 months post randomisation | |||

| Mean (SD) | 9.10 (4.83) | 7.53 (3.48) | 8.40 (4.33) |

| Median (range) | 8.00 (0.000–20.0) | 7.00 (0.000–16.0) | 8.00 (0.000–20.0) |

| Missing | 10 | 17 | 27 |

| n | 40 | 32 | 72 |

| 12 months post randomisation | |||

| Mean (SD) | 8.34 (4.86) | 7.52 (3.75) | 7.94 (4.34) |

| Median (range) | 8.00 (1.00–20.0) | 8.00 (2.00–15.0) | 8.00 (1.00–20.0) |

| Missing | 15 | 16 | 31 |

| n | 35 | 33 | 68 |

| 18 months post randomisation | |||

| Mean (SD) | 8.58 (4.77) | 6.90 (4.34) | 7.67 (4.58) |

| Median (range) | 8.00 (0.000–18.0) | 6.00 (0.000–16.0) | 7.00 (0.000–18.0) |

| Missing | 24 | 18 | 42 |

| n | 26 | 31 | 57 |

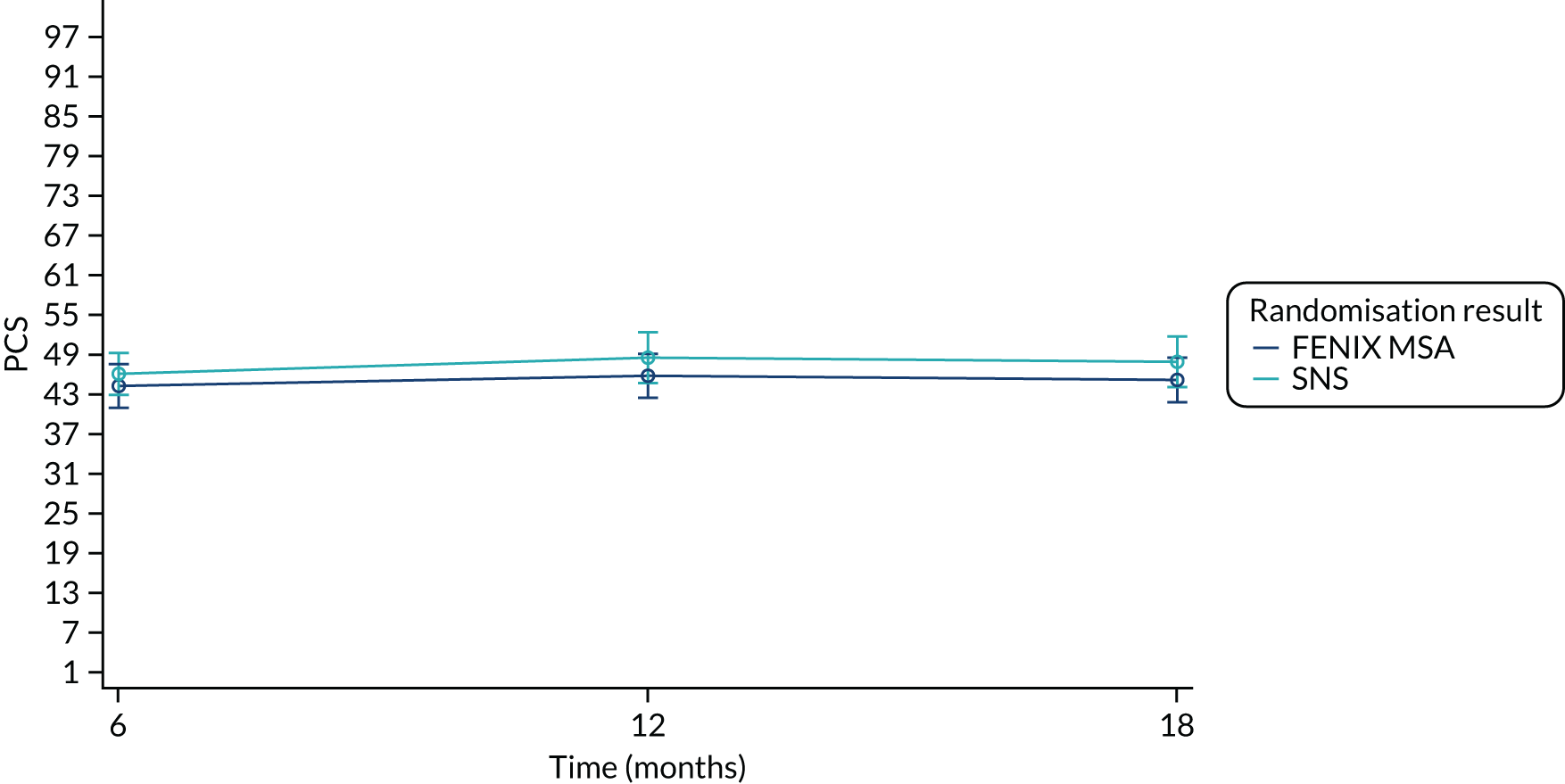

Secondary end point: Short Form questionnaire-12 items

The SF-12 version 2 is a generic health survey that measures eight health domains: physical functioning, role – physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role – emotional and mental health. The Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS) measures are calculated using a combination of the eight domains. Scores are calibrated so that the mean score is 50 with a standard deviation (SD) of 10 in the 2009 general US population. All scores range from 0 to 100, with a higher value indicating better functioning and well-being.

Summary measures of the SF-12 PCS and MCS components split by time point and treatment arm are presented in Table 21.

| SF-12 component | FENIX MSA | SNS | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCS (baseline) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 44.9 (9.36) | 46.9 (10.2) | 45.9 (9.78) |

| Median (range) | 46.5 (18.6–61.2) | 47.3 (23.6–64.0) | 47.3 (18.6–64.0) |

| Missing | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| n | 47 | 48 | 95 |

| PCS (6 months post randomisation) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 46.2 (9.96) | 47.7 (9.71) | 47.0 (9.80) |

| Median (range) | 45.6 (27.6–68.5) | 48.7 (23.9–70.0) | 47.1 (23.9–70.0) |

| Missing | 11 | 7 | 18 |

| n | 39 | 42 | 81 |

| PCS (12 months post randomisation) | |||