Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/170/01. The contractual start date was in March 2016. The draft report began editorial review in November 2018 and was accepted for publication in April 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Creswell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is characterised by a persistent and disproportionate fear of social situations. It is the third most frequent of all mental health disorders, with a lifetime prevalence of up to 13%. 1,2 The age at onset is typically during adolescence (median 13 years),3,4 with most people developing the condition before they reach their twenties. Indeed, studies that have focused on young people between the ages of 11 and 17 years have estimated that 0.7% and 10.9%5 of young people meet diagnostic criteria at SAD at any one point in time, with European studies (in Germany and Finland) identifying prevalence rates between 1.4% and 3.2%. 6–8

Social anxiety disorder is differentiated from normal shyness by the marked disability and interference caused in day-to-day life. For example, among adults it often has a negative impact on social relationships (e.g. friendships,9 marriages and children8) and is associated with more days off work,10 receipt of state benefits11 and more outpatient medical visits than the general population. 12 SAD is also associated with an increased risk of other mental health problems, including other anxiety and mood disorders, substance abuse and psychosis,2,13,14 and has the lowest natural recovery rate of all anxiety disorders. 15 Several of the handicaps that result from having the condition in adolescence (e.g. missed opportunities for social learning and poor educational achievement)16 cannot be overcome by treatment when the person reaches adulthood. These factors highlight the need for effective treatment for SAD in adolescence.

Currently, the most commonly delivered treatment approach for adolescents with SAD is a generic cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) anxiety programme that is used across a range of anxiety disorders. Unfortunately, in recent studies, young people with SAD have had significantly poorer outcomes than those with other anxiety disorders (e.g. for 7- to 17-year-olds, remission rates of 40.6% for SAD vs. 72% for other anxiety disorders). 17 However, among adults, a focused form of cognitive therapy for SAD (CT-SAD), which targets key psychological mechanisms that are known to maintain the disorder,18 achieves much higher recovery rates of up to 84% in randomised controlled trials (RCTs). 19–21 Among adults, it has also been shown to be superior (in terms of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness) to traditional group CBT, guided CBT self-help, exposure therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, psychodynamic psychotherapy and medication (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors),22,23 and is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) as a first-line intervention for SAD in adults. 24

There is recent evidence that the same psychological mechanisms maintain SAD in adults and adolescents. 25–28 Therefore, adapting CT-SAD so that it is suitable for use with adolescents may significantly enhance treatment efficacy. NICE guidance also highlights that treatment for SAD in adolescents should address the need to create treatment supporting environments, by working with parents, teachers and/or peers as appropriate. 24

A recent case series in which cognitive therapy for SAD was adapted for use with adolescents (CT-SAD-A) reported excellent outcomes. 29 All adolescents (n = 5; 11–17 years) had severe SAD and achieved excellent outcomes after receiving CT-SAD-A, with overall reductions in social anxiety symptoms that were greater than the average reductions achieved with adults. Of note, all the adolescents were free of their primary diagnosis of SAD as well as comorbid mental health diagnoses post treatment. Promising findings have also come from a RCT which compared individual cognitive therapy to group CBT and an attentional control. 30 The individual cognitive therapy condition was associated with significantly greater reductions in symptoms and impairment than group CBT and the attentional control, which did not differ from each other. Notably, the cognitive therapy programme applied within this trial included a number of important departures from the Clark and Wells’ approach,31 including a focus on psychoeducation and developing a generic formulation for anxiety maintenance over the first four sessions. Nonetheless, given this evidence, it seems possible that CT-SAD-A may improve treatment outcomes for adolescents with SAD over the generic forms of CBT that are often applied. As SAD presents a risk for ongoing mental health problems, impaired educational performance, restricted employment and productivity, and increased medical needs, the successful development of a highly effective treatment for adolescent SAD also has the potential to bring direct benefits to the NHS and child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS), as well as adult mental health services and society more broadly, by disrupting this negative trajectory.

Objective 1

This study initially set out to determine the feasibility of a RCT in routine NHS CAMHS to compare CT-SAD-A with the C.A.T. Project (a CBT programme that has been developed for adolescents with a range of anxiety disorders and that is already in use in CAMHS) for adolescents with SAD. Specifically, our aims were to train NHS CAMHS therapists to deliver the adapted treatment and assess therapist competency and young people’s outcomes; identify appropriate clinical outcome and economic measures for a subsequent definitive trial; and examine whether or not a definitive trial can be conducted on the basis of a feasibility trial that would:

-

explore the acceptability of the treatments and trial procedures

-

establish likely recruitment rates

-

establish the likely rate of treatment drop out

-

establish likely retention to research assessments post treatment and (in a subset of participants) at 3-month follow-up

-

establish if adapted CT-SAD-A can be delivered so that it is clearly distinct from the C.A.T. Project, with high levels of fidelity by practitioners and credibility with patients in both arms;

-

conduct exploratory analyses of possible outcomes for the two treatments, including changes in social anxiety symptoms and diagnostic status, depression, social functioning, school attendance, concentration in class, quality of life, health-care resource use and other outcomes identified through patient and public involvement (PPI)

-

describe negative impacts of the treatments and the trial procedures (to patients, their parents and therapists).

Objective 2

Unfortunately, during the training phase of the study, it became clear that the proposed trial would not be feasible within routine CAMHS (see Chapter 4) and, on the basis of liaison with the Study Steering Committee (SSC) and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), the study aims were adapted to examine the training in and delivery of CT-SAD-A in routine NHS CAMHS, in terms of therapists’ ability to deliver CT-SAD-A, young people’s outcomes, and the experiences of both participating families (young people and their parents/carers) and the therapists involved (both therapists delivering the treatment and their service managers) within a CAMHS setting. Specifically, the aims were to:

-

train NHS CAMHS therapists to deliver the adapted treatment and assess therapist competency (an independent rater is currently rating therapist competency, and these outcomes will be reported in a later publication) and young people’s outcomes

-

estimate the cost of delivering CT-SAD-A within an NHS CAMHS setting

-

understand the experience of receiving CT-SAD-A and participating in a research study within a CAMHS setting among young people and their parents

-

understand the experience of CAMHS therapists receiving training in and delivering CT-SAD-A and their experience of being part of a research study

-

understand the experiences of the CAMHS service managers in relation to supporting the training and delivery of CT-SAD-A and the accompanying research procedures within their services.

Chapter 2 Methods

Participants

Participating therapists were identified within the participating NHS trusts on the basis of meeting the following inclusion criteria:

-

currently in clinical practice within participating CAMHS

-

willing to be randomly allocated to deliver either (1) the C.A.T. project, or (2) CT-SAD-A, and to receive training and supervision for the allocated treatment approach

-

have at least 2 years’ experience of using CBT as their main treatment approach, receiving regular CBT supervision during this time

-

a minimum of 2 years working clinically with children and young people

-

have treated at least two adolescent/adult social anxiety disorder cases and 10 anxiety cases using CBT.

Young people were referred to CAMHS in the participating trusts through usual routes (e.g. by general practitioners, school nurses) for treatment of anxiety or mood disorders. Adolescents and their parents completed the NICE screening questions24 (see Appendix 1) and the Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS) to identify potential SAD within a routine CAMHS assessment. Where adolescents ‘screened positive’, they were invited to take part in the research. An initial assessment included a structured diagnostic interview with the young person and carer [Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, child and parent version (ADIS-C/P)]32 to establish whether or not the young person met the following criteria:

Inclusion criteria

-

Young people (aged 11–17.5 years at intake) whose primary presenting disorder was a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), diagnosis of SAD.

-

If young people had been prescribed psychotropic medication, the dosage must have been stable for 2 months.

Exclusion criteria

-

Young people who had previously received CBT for SAD were excluded if they had received more than four sessions in which key procedures of CT-SAD-A had been used (i.e. video feedback, attention training, memory work and multiple behavioural experiments).

-

Young people with established autistic spectrum disorders [or suspected on the basis of Social Cognitions Questionnaire (SCQ)18; see Measures], learning disabilities, suicidal intent or recurrent self-harm (i.e. comorbid conditions that are likely to interfere with treatment delivery).

-

Young people with a primary presenting disorder other than SAD.

The managers/clinical leads who were involved in managing the participating therapists on a day-to-day basis were invited to take part in qualitative interviews.

Procedures

Ethics review

The study was approved by the NHS South Central – Oxford B Research Ethics Committee (REC reference: 16/SC/0315) and the University of Reading Research Ethics Committee (UREC 16/43).

Therapist training

CAMHS therapists were provided with a detailed treatment manual ahead of the training. They were also given a memory stick loaded with short video clips demonstrating many of the key steps in CT-SAD-A. Finally, they received a pack containing all worksheets needed to support CT-SAD-A. The training materials that were used in this study are freely available here: https://oxcadatresources.com.

Participating therapists completed a training programme comprising an initial 2-day workshop, focusing on the CT-SAD-A model and the key procedures involved in the first stage of therapy. Therapists were offered 6 months of weekly case supervision via Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) or telephone and a further 1-day workshop, which covered the key procedures used later in the therapy in more detail.

Supervision sessions involved a review of questionnaire measures, a detailed discussion of the previous treatment session, a discussion of any problems that had arisen and step-by-step planning for the next session. Videotaped treatment sessions were discussed on a regular basis in the supervision sessions.

Intervention: cognitive therapy for social anxiety disorder in adolescents

All young people received CT-SAD-A. Treatment was delivered in the CAMHS clinic in which the therapists usually worked, with behavioural experiments conducted in different environments, as required (e.g. in a shopping centre or a café). This therapy is based on Clark and Wells’ model of the maintenance of the disorder. 31 The treatment programme consists of 14 weekly sessions, each lasting 90 minutes, plus 2-monthly booster sessions and focuses on changing social anxiety-related beliefs and behaviours, with a particular emphasis on the four maintenance processes specified in the model. 31 These are (1) increased self-focused attention and observation (self-consciousness) and an associated decrease in observation of other people and their responses, (2) use of internal information (feelings and images) to make excessively negative inferences about how one appears to others, (3) use of overt and covert safety behaviours that prevent patients from discovering that their fears are unrealistic and interfere with the initiation and flow of social interactions, and (d) pre- and post-event processing (e.g. anticipatory worry and rumination). Given this, CT-SAD-A involves a number of components:33 (1) the development of a personalised cognitive model including the patient’s negative thoughts, self-images, focus of attention, safety behaviours and anxiety symptoms; (2) an experiential exercise to demonstrate the adverse effects of self-focused attention and safety behaviours; (3) video (and still photograph) feedback to correct negative self-imagery; (4) training in externally focused attention; (5) behavioural experiments to test patients’ negative beliefs by dropping safety behaviours and focusing attention externally on social situations and by also purposefully displaying feared behaviours or signs of anxiety (decatastrophising); (5) surveys to discover other people’s views of feared outcomes; (6) memory work (discrimination training and memory rescripting) to reduce the impact of social trauma experiences. The components of CT-SAD-A were well received by the adolescents in the case series. 29

Key adaptations were made to CT-SAD for working specifically with adolescents on the basis of previous experience from a development case series. 29 These were as follows: (1) working with peer victimisation (which is likely to involve school liaison) and (2) working with parents/carers. The degree of parental involvement varied from case to case. Typically, parents are involved at the start of treatment to learn about social anxiety and cognitive therapy and at the end of therapy to learn about their child’s relapse prevention plan and their role in supporting their child to stay well. Some parents will bring their child to sessions and will help to ensure that they complete their weekly measures. In some cases, therapists may speak with parents individually to identify and work with parental social beliefs that may interfere with their child’s progress in therapy. As described in Chapter 3, our PPI co-applicant and young people with relevant lived experience also gave feedback on their experiences of treatment, the treatment manual and the reviewed treatment materials to ensure it was appropriate and acceptable for adolescents with SAD.

Measures

Young people and their primary caregivers completed measures (1) prior to treatment, (2) at each treatment session, both to guide treatment and so that data from the last weekly session that was attended could be used to assess outcomes at the end of treatment, and (3) after the last booster session (1.16–4.63 months after the final weekly session). These time points will be referred to as ‘pre’, ‘sessional’ and ‘follow-up’, respectively, in the descriptions below. Each participant (young people, parents, therapists and service managers) who took part in the qualitative interviews was compensated for their time (£20 each).

Initial screening measures

The screening questions proposed in the NICE guideline on the identification, assessment and treatment of SAD24 were used to screen participants for social anxiety symptoms in the absence of any validated brief screening measures. The young person and their parents/carers were asked whether or not the young person gets scared about doing things with other people, whether or not they find it difficult to do things when others are watching and whether or not they ever feel they cannot do these things or try to avoid them (see Appendix 1).

The Social Communication Questionnaire (SComQ) was used to identify young people with an undiagnosed autism spectrum disorder (ASD). This is a 40-item, parent-report measure based on the Autism Diagnostic Interview Revised. It requires a ‘yes/no’ response to 19 items assessing behaviours occurring at any time throughout the young person’s life and 21 items assessing behaviours between the ages of 4 and 5 years. The questionnaire consists of three subscales: reciprocal social interaction (13 items), communication (8 items) and repetitive, restrictive behaviours and interests (RRBI) (6 items). A score above the cut-off point of 15 indicates a possible diagnosis of ASD. Therefore, young people scoring ≥ 15 were excluded from the study.

Outcome measures

The young person self-report version of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale for Children and Adolescents (LSAS-CA-SR)34 was administered to assess the adolescents’ self-reported social anxiety symptom severity (at all time points: pre, sessional and follow-up). The LSAS-CA includes 24 items, rated on a scale from ‘none’ (0) to ‘severe’ (3), to assess fear and avoidance of social interaction and performance (range 0–144). The LSAS-CA has well-established psychometric properties when administered to children and young people from 7 to 18 years of age. 35 Reliable improvement in the LSAS-CA-SR is defined as a drop of 16.13 points, calculated using internal consistency data over the course of treatment. 35

Symptoms of broader anxiety disorders and depression were assessed using the Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS),36 which is routinely collected within CAMHS as part of the Children and Young People’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapies programme (CYP IAPT) initiative. The RCADS is a 47-item child report scale that assesses symptoms of separation anxiety disorder, SAD, generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder and major depressive disorder (MDD). Responders rate how often each item applies on a scale of 0 (‘never’) to 3 (‘always’). T-scores can be calculated according to a child’s age and sex. The RCADS has been shown to have robust psychometric properties in children and young people from 7 to 18 years of age. 37 We focused on the social anxiety subscale and the depression and GAD subscales, as these are the most common co-occurring difficulties. The RCADS was administered at all time points (pre, sessional and follow-up).

The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule – child and parent report (ADIS-C/P)38 is a structured diagnostic interview used to determine whether or not the young person meets diagnostic criteria for SAD and other comorbid anxiety, mood and behavioural disorders and to establish clinical severity ratings (CSR) for each disorder. The ADIS-C/P was administered to young people and their parents by research assistants (psychology graduates) trained to a high level of inter-rater reliability through observation, role play and ongoing supervision. All diagnostic interviews were discussed with an independent experienced therapist, who also assigned diagnoses and ratings. Agreement (kappa/intraclass correlation) was > 0.85 for diagnoses and CSRs across all anxiety disorders and for SAD specifically. The ADIS-C/P was used at two time points: pre and follow-up.

Concentration in class scale – young person report was used to measure the young person’s self-reported concentration in class, administered at all time points (pre, sessional and follow-up). This is a single-item self-report scale on which the young person indicates from 0 (‘not at all’) to 100 (‘totally’) how well they have been able to concentrate on what the teacher is saying and what they have been learning in class in the preceding week. This scale has been used in the recent (2016) pilot work by DC/EL, and respondents have found it to be a relevant indicator of change. 29

The CYP IAPT goals progress scale is a simple 10-point rating scale on which a young person rates the extent to which they have made progress towards their therapy goals. This scale is routinely used in both participating NHS trusts as part of the CYP IAPT initiative, and it was also administered at every therapy session (sessional time point).

Social functioning was examined using an 18 item self-report measure of social participation and social satisfaction, developed by Alden and Taylor39 for use with adults with SAD. Respondents indicate on a seven-point scale how often they have engaged in different social activities and how satisfied they have felt with their relationships with different types of people. This scale has been used in the recent pilot work by DC/EL, and young people have found it to be a relevant indicator of change. 29 It was administered at pre and follow-up and also as a mid-treatment measure at session 7.

The Outcome Rating Scale (ORS)40 comprises four simple rating scales on which the young person/parent rates how they (or their son/daughter) have been feeling over the last week (individually, interpersonally, socially and overall). This scale is routinely used in both participating NHS trusts, as part of the CYP IAPT initiative, and was administered at all time points (pre, sessional and follow-up).

Measures of treatment mechanisms

Social cognitions and attitudes were measured using the SCQ18 and the Social Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ),18 both of which were adapted for children and adolescents. The SCQ is a 22-item questionnaire assessing SAD-related negative automatic thoughts. Each thought is rated twice. First, the respondent rates the frequency with which the thought occurred in the last week when he/she was ‘nervous or frightened’. The frequency rating scale is as follows: 1 = ’thought never occurs’, 2 = ’thought rarely occurs’, 3 = ’thought occurs during half of the times when I am anxious’, 4 = ’thought usually occurs’, 5 = ’thought always occurs when I am anxious’. Second, the respondent rates the extent to which the thought was considered to be true. The belief rating scale runs from 0 = ’I do not believe this thought’ to 100 = ’I am completely convinced this thought is true’. The SCQ has high internal consistency and discriminant validity in adults. 18 It was adapted for use with children and adolescents on the basis of PPI consultation, in that the wording was amended to be more developmentally appropriate in seven items, and a further seven items were added (specifically: ‘I will embarrass myself’; ‘People will be angry with me’; ‘I will wet myself/have diarrhoea’; ‘I will get picked on/teased’; ‘I will look stupid’; ‘I will be forced to do things I don’t want to do’; ‘People will laugh at me’). The SCQ was administered at all time points (pre, sessional and follow-up).

The SAQ is a 50-item scale that assesses beliefs that are thought to make an individual vulnerable to SAD. The beliefs were intended to fit into three broad categories: ‘excessively high performance standards’, ‘conditional beliefs’ and ‘unconditional beliefs’. However, item selection was based more on clinical experience than on an attempt to sample each category in a comprehensive manner. Each item is rated on a scale that ranges from 1 to 7: 1 = ’totally agree’, 2 = ‘agree very much’, 3 = ’agree slightly’, 4 = ’neutral’, 5 = ’disagree slightly’, 6 = ’disagree very much’, 7 = ’totally disagree’. Respondents are asked to choose the rating that ‘Best describes how you think’. The SAQ has high internal consistency and discriminant validity in adults. 18 For children and adolescents, two further items were included (‘If I make a mistake in a social situation people will laugh at me or be angry with me’; ‘If people see I am anxious I will be forced to do things I don’t want to do’) and the language was changed to be more developmentally appropriate on the basis of PPI consultation. The SAQ was administered at pre and follow-up and also as a mid-treatment measure at session 7.

Safety behaviours associated with SAD were measured using the Social Behaviours Questionnaire (SBQ)18 – adapted for children and adolescents. The SBQ is a 28-item scale assessing the use of social phobia-related safety behaviours when respondents are anxious or in a social situation. Each behaviour is rated on a four-point scale ranging from 0 to 3: 0 = ’never’, 1 = ’sometimes’, 2 = ’often’ and 3 = ’always’. The SBQ has good psychometrics properties in adults. 18 It was adapted for use with children and adolescents through the addition of four further questions (‘Wear clothes so I blend in’; ‘Seek reassurance from my friends and family’; Get other people to speak for me or do things for me’; ‘Have an excuse or ‘get out’ of planned activities’) and through changes to the wording in four other items, to be more developmentally appropriate on the basis of PPI consultation. The SBQ was administered at pre assessment and follow-up and also as a mid-treatment measure at session 7.

The final versions of the SCQ, SAQ and SBQ that were adapted for use with adolescents can be found at https://oxcadatresources.com (accessed 7 February 2019).

Participant acceptability rating

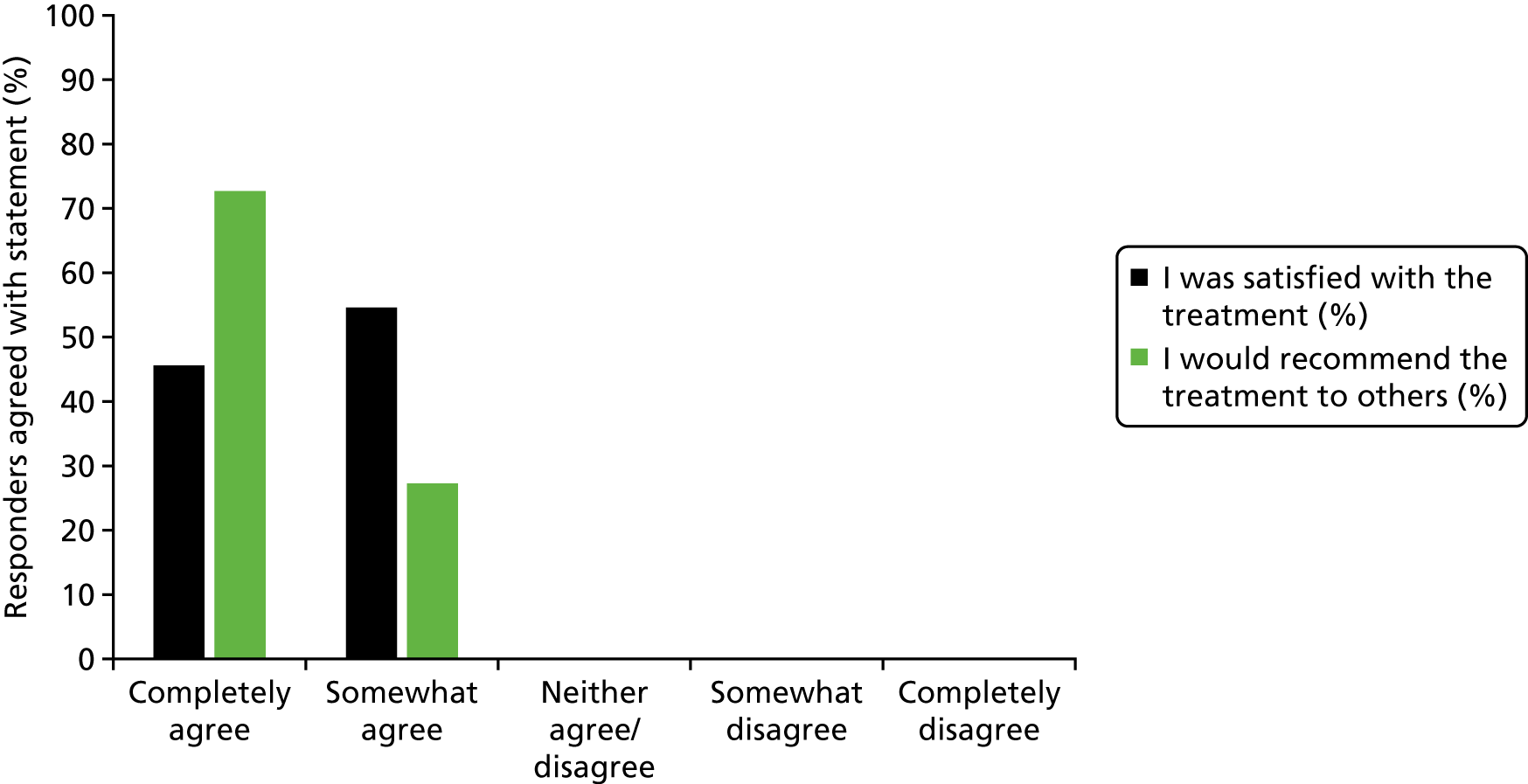

At the end of treatment (follow-up), participants rated how acceptable they found the treatment. 41 Young people were specifically asked to report on the extent to which they agreed with the two statements ‘I was satisfied with the treatment’ and ‘I would recommend the treatment to others’ on a five-point scale from ‘completely agree’ to ‘completely disagree’. They also had the opportunity to complete a free-text box to comment on the treatment.

Other adolescent self-report measures

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) is a nine-item measure assessing the presence of the main symptoms of major depression on a four-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) over the last 2 weeks. This is followed by one item asking young people to rate how difficult these problems have made it for them to work, take care of things at home or get along with other people on a four-point scale from ‘not at all difficult’ to ‘extremely difficult’. This measure is widely used and has robust psychometric properties when used with young people. 42 This measure was added (after the study had started) to ensure that suicidal ideation was routinely monitored within sessions. Because the data were incomplete and the measure was included (at pre and follow-up time points) for clinical management purposes, we have not included this as an outcome measure.

Health economic records

Clinician’s logs were designed to capture the amount of health-care resources (i.e. qualified staff time) necessary to implement the CT-SAD-A treatment within a CAMHS setting. They were completed by both supervisors and therapists who recorded, as applicable, the amount of time spent in activities related to the CT-SAD-A treatment, including training, supervision, preparation and delivery (i.e. contact with client) of the CT-SAD-A treatment. Data recorded in the clinician’s logs were used to calculate the total mean amount of qualified staff time used by the NHS per adolescent treated. Results were stratified by type of staff time use (i.e. time spent in training, supervision, preparation and delivery of the CT-SAD-A treatment).

Qualitative interviews

Interviews were conducted with young people, parents, therapists and their managers/clinical leads to explore their experiences of the intervention and the research study. The approach and design of the qualitative work is described in full in Chapter 7.

Chapter 3 Patient and public involvement

We have described PPI in line with the GRIPP2-SF reporting checklist. 43 We have also provided specific examples of PPI activity to illustrate our adherence with the NIHR INVOLVE National Standards for Public Involvement (Table 1). 44

| Standard number and title | Example of what we did to meet the standard |

|---|---|

| Standard 1: inclusive opportunities |

|

| Standard 2: working together |

|

| Standard 3: support and learning |

|

| Standard 4: communications |

|

| Standard 5: impact |

|

| Standard 6: governance |

|

Aim

To collaboratively involve patients as research partners at all stages of the project.

Methods

-

An expert by experience (GS) was a co-investigator on the project and, as such, had a leadership role at all stages of the project, including the following:GS represented PPI views at the study management group to ensure that:In addition, GS attended all SSC meetings to express his own views and to also ensure that the young person member of the SSC was able to fully contribute. GS was involved in drafting the patient information sheets, the qualitative topic guide and theme development within the qualitative analysis. GS also co-wrote this PPI section of the final report and contributed to drafting all other sections.

-

Development of the research question – the study was a NIHR commissioned call, so the research questions were prespecified; however, they were based on one of the research recommendations of the 2013 NICE guideline on the identification, assessment and treatment of SAD. 24 GS was a patient representative on this NICE guideline and, as such, contributed to the development of research recommendations.

-

Development of the application – as an applicant, GS contributed to the development of all aspects of the application, in particular how to use PPI effectively throughout the study. Examples of specific proposals that came from his involvement include the following: (1) GS would jointly facilitate PPI panel meetings, bringing benefits from his personal and professional experience; (2) online materials would be produced for patients and the public about SAD in adolescence and its treatment (this aspect of the work was discontinued, as we did not progress to the trial).

-

Conduct of the study – as a co-applicant and member of the study management group, GS oversaw all aspects of the study.

-

the adapted treatment was appropriate and acceptable for adolescents with SAD

-

the clinical outcome and health economic measures that are meaningful to patients and carers were determined

-

recruitment and retention of trial participants were maximised by keeping participants’ needs in mind

-

patients’ experiences of the adapted treatment and the trial procedures were considered appropriately

-

dissemination to potential patients was delivered effectively.

-

-

A young person who had received treatment for SAD within CAMHS was a member of the SSC. She attended SSC meetings and, as such, contributed to decisions made about all aspects of the study. She also consulted on the drafting of the qualitative topic guide.

-

A group of four young people who had received CT-SAD-A within a pilot phase of work consulted on their experience of treatment, the adaptation of measures, and the development of the therapist manual and materials for young people. GS provided oversight of and input into this PPI work.

-

The Anxiety and Depression in Young People Research Advisors Group (AnDY RAG) at the University of Reading comprises young people who have had experience of anxiety and/or depression and parents/carers. They consulted on the drafting of all patient information sheets and the qualitative topic guide.

Results

The broad approach to PPI meant that patients’ views and experiences were incorporated at all stages of the study. Particular examples of how the study changed because of PPI are listed below; however, it is important to emphasise that these are a set of discrete examples that do not do justice to the overall influence of PPI input throughout the study.

-

After the initial SSC meeting, GS proposed changes to the structure of the agenda to ensure that PPI input was a standing item so that if the PPI member of the SSC had not felt able to participate at particular points in the discussion she would always have sufficient opportunities to express her views. We have maintained this agenda structure in all subsequent SSC meetings, for this study and others.

-

GS encouraged the inclusion of a general goals measure, with the aim of measuring the relevance of treatment to patients’ lives in their own terms, rather than through the use of clinical measures focused on specific elements of the cognitive model of social anxiety or specific symptoms.

-

A number of changes were made to the questionnaires measuring psychological mechanisms targeted in the treatment (the SCQ, SBQ and SAQ) on the basis of feedback from young people with SAD who had experience of the measures as part of treatment, AnDY RAG and the community population. Their feedback led to changes that made the language more developmentally appropriate (e.g. on the cognition measure ‘I am inadequate’ changed to ‘I am not good enough’) and the addition of items relevant to young people with SAD (e.g. on the measure of safety behaviours, ‘Seek reassurance from my friends and family’).

-

A number of changes were made to how CT-SAD-A treatment materials were formatted, worded and administered, based on feedback from young people who had had experience of it. Young people also reported generally preferring to complete worksheets by hand rather than using technology, as they found this helped them remember key points. A number of edits were made to paper worksheets to address issues raised by the group.

-

Young people and parents/carers in the AnDY RAG provided feedback on all patient information sheets. They made a large number of suggestions to change wording and formatting to clarify the aims and procedures of the study. Parents particularly emphasised the importance of providing greater clarity regarding the fact that the study was taking place alongside ‘usual NHS care’ and that participants would continue to be CAMHS patients. This was a particular concern for many families who had had experience of long waits and ‘battles’ to get seen within CAMHS. Young people also highlighted the importance of the information sheets having an ‘NHS-look’ about them so that they did not raise concerns that researchers were ‘experimenting on’ them. Changes were made to the wording and the design of the leaflet to show that it was fully integrated within NHS CAMHS and to address the other issues raised by the group.

-

The qualitative topic guide was developed with PPI input to take into account particular difficulties that young people with SAD may have interacting with an unfamiliar researcher in an interview setting. Emphasis was put on the use of visual materials, to increase clarity and remove demands for eye contact with the researcher, and on the importance of ensuring a clear message that there were no ‘wrong answers’ throughout. A number of specific items were also suggested, including questions relating to the impact of the treatment on the young person’s relationship with their parent(s). Notably, GS also highlighted areas in which further PPI input from young people was not needed, that is, regarding whether or not young people should be consulted about key terminology used within treatment, as this was not relevant to the experience or success of the treatment.

-

PPI input was used in the qualitative analysis to ensure that patients’ feedback on their experience of treatment was not inadvertently misunderstood.

A further outcome that is important to note is that the PPI representative on the SSC wrote to the principal investigator (PI) at the end of the study to express her thanks for having had the opportunity to participate. She stated not only that it had been an interesting experience that had helped her with her university applications, but that she also felt that it had played an important role in her recovery from SAD. This was in line with GS’s previous experience on the NICE Guideline Development Group in which he had the opportunity to contribute to a daunting social situation (large group, academic demands), but in which there was a supportive environment and his anxiety was acknowledged and accepted.

Discussion and conclusions

The PPI in this study was very effective and influenced important aspects of the study, as highlighted above. This might have been related to several factors. First, the PPI co-investigator had received training in relevant research methods and had extensive experience of representing patients’ views through his previous experience on a NICE Guideline Development Group. Second, the PPI member of the SSC also had experience of contributing to research through previous involvement in the AnDY RAG. Third, the researchers were experienced at involving patient partners in their research, for example through facilitation of the AnDY RAG for over 2 years as well as involving PPI representatives in specific studies.

GS was involved from the beginning of the study, allowing him to help shape the study from the start and ensure that the right procedures for PPI were in place. Successful involvement of patients in this study was also facilitated by pre-existing relationships between some of the PPI representatives and members of the research team, the collaborative approach taken by the team, funding to finance PPI time, and a supportive attitude of PPI involvement from the SSC.

Some limitations should also be noted. Because the PPI co-investigator role was a part-time (low % full time-equivalent) role, GS had to accommodate the role around his main occupation. He managed this very effectively, attending meetings in person on most occasions and, when necessary, remotely, for example by telephone or Skype. However, it was not possible to time the AnDY RAG meetings and the meetings with four young people who had experience of CT-SAD-A at times when the relevant researchers, young people and GS were available within the time frame needed to keep the study on track. Going forward, having more substantial PPI roles might help enable the flexible timing required to make full use of PPI co-investigators. A further limitation was that, because of often tight time frames, on occasion papers for meetings were sent to PPI members quite close to the time of the meetings. More time would have been useful to allow PPI members to understand the materials and ask questions about relevant terminology, which was necessary to be able to fully understand and digest the documents and prepare PPI feedback. Finally, though it is not particular to this study, despite their sometimes extensive relevant experience (such as GS’s involvement with the NICE Guideline Development), PPI participants may have only been involved in PPI with certain teams, which means that they may not have always been able to identify and be involved in how to use PPI input creatively and as far as possible. A specifically designed training course in PPI input and research methodology may be a useful resource to help address this challenge in which PPI representatives can become aware of a range of different examples of how successful PPI can be achieved.

Reflections/critical perspective

The PPI in the study was embedded as far as possible at every level.

A strength of the study was the combination of dedicated expert PPI, who knew the project well through close involvement, and the observations and contributions from the young person PPI representative on the SSC, the young people who had previously received CT-SAD-A, and the AnDY RAG who had a more distanced take on the study and was thus able to make unique contributions.

Patient and public involvement members also fed back that they felt supported and listened to, and that their feedback was treated as important and valuable at all times. This was especially important owing to the nature of SAD, and it enabled them to contribute effectively.

Future studies would benefit from costing more substantial PPI time to allow greater flexibility, consistent provision of papers, etc. at least 2 weeks ahead of all meetings and dedicated training to help PPI co-applicants in leading the development of creative and effective mechanisms to get the most out of PPI contributions.

Chapter 4 Results 1: feasibility in routine child and adolescent mental health services – recruiting and retaining therapists and young people

Recruiting and retaining therapists

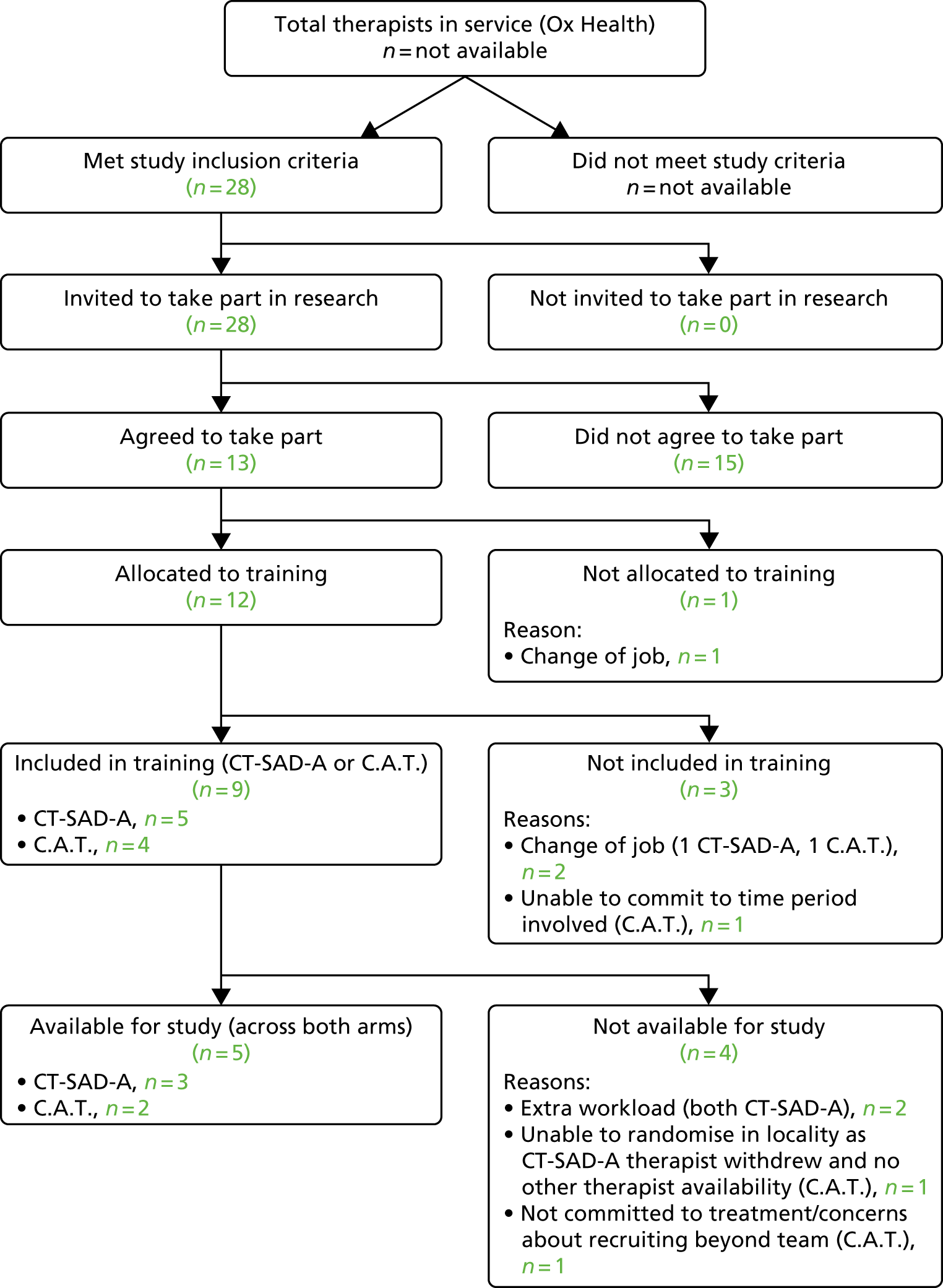

The initial protocol included a feasibility RCT to compare CT-SAD-A with a CBT programme that can be applied across different types of anxiety disorders and is commonly used in child and adolescent mental health settings (‘The C.A.T. Project’). 45 To ensure that we had enough trained therapists to deliver treatment within each arm (n = 3), we set out to identify 10–12 therapists to allow for a potential loss of trained therapists. In line with our plans, we initially identified 12 CAMHS therapists within the participating services who met our study inclusion criteria and who were willing to take part. Within the early stages of the study, five therapists withdrew from the project (Figures 1 and 2) after being allocated to training but prior to attending the workshop, the ‘not included in training’ box. This meant that we had to engage therapists from additional CAMHS teams within the participating NHS trusts and ensure that there would be therapist representation across both study arms in each of the five teams (as therapists were not able to work across teams). In total, 20 therapists were recruited to the study and 19 were allocated to treatment arms. In total, 10 of those therapists withdrew from the study (including the five therapists mentioned above) and one went on maternity leave towards the end of the training phase. In addition, one therapist resigned from her NHS role but agreed to continue to participate in the study. Figures 1 and 2 show therapist recruitment and retention to the study, and also reasons for therapist withdrawal. The final distribution of therapists across clinical teams is shown in Table 2, with their core professional training detailed in Table 3. As can be seen, in many locations there was only one therapist trained in each of the two therapies, which left the study extremely vulnerable to any further therapist loss.

FIGURE 1.

Therapist recruitment and retention to the study (Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust). BHFT, Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust.

FIGURE 2.

Therapist recruitment and retention to the study (Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust). Ox Health, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust.

| NHS trust | Attended training workshops | Available for study (and completed training cases for CT-SAD-A) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT-SAD-A | C.A.T. Project | CT-SAD-A | C.A.T. Project | |

| Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust | ||||

| Team 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1a |

| Team 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1a |

| Team 3 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Team 4 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust | ||||

| Team 1 | 2 (+ 1 on maternity leave) | 2 | 2 (+ 1) | 1a |

| Core professional training | Number of years since qualification (at consent) | |

|---|---|---|

| CT-SAD-A therapists | Clinical psychologist | 18 |

| Clinical psychologist | 1 | |

| Clinical psychologist | 5 | |

| Social worker | 5 | |

| Social worker/CYP IAPT | 4/same year | |

| CBT therapist (via IAPT CBT adult mental health training) | 2 | |

| C.A.T. therapists | Clinical psychologist | 1 |

| Clinical psychologist | 21 | |

| Clinical psychologist | 5 |

Owing to high service demand and staff vacancies in all participating CAMHS teams, all service managers placed restrictions on the amount of time (and, hence, the number of trial cases) that the participating therapists could spend on the study (meaning only one or two patient contacts per week were possible). Although we secured excess treatment costs (ETC) to reimburse teams for the additional therapist time taken by the trial, this was of limited help to them, as they all had unfilled vacancies and so there was no scope to backfill existing staff (particularly as ETCs are paid in arrears). As a result, with the therapists available, we would have been able to recruit a maximum of n = 26 (13 per arm), rather than n = 48 as initially planned to test the feasibility of a RCT. This was likely to be an optimistic figure based on therapists being able to seamlessly pick up new trial patients immediately after completing therapy with a previous patient. Although there was one further therapist in Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust (BHFT) who was available and willing to take part in the study, none of the sites across Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust (OxHealth) was able to provide additional therapists due to the high demand on services and there being a number of unfilled vacancies/staff on maternity leave across all sites. Given this, it was not possible to secure sufficient CAMHS therapist time to be able to run the feasibility trial within the participating NHS trusts.

Recruiting and retaining young people with social anxiety disorder

We found that some of the participating CAMHS teams identified few young people with a primary SAD, as activity was increasingly dominated by risk management. Given this, some of the participating sites struggled to identify suitable participants for the trial, recruitment of training cases was slow, and therapists were not always able to work at their full allocated capacity. For example, between July and December 2017, only one training case was recruited on a site in which there were three therapists participating in the study. To overcome this, we had to reach out beyond the services to identify suitable training cases (e.g. to neighbouring services and to local schools’ hubs). However, this created challenges for services who were already struggling to meet the existing demand.

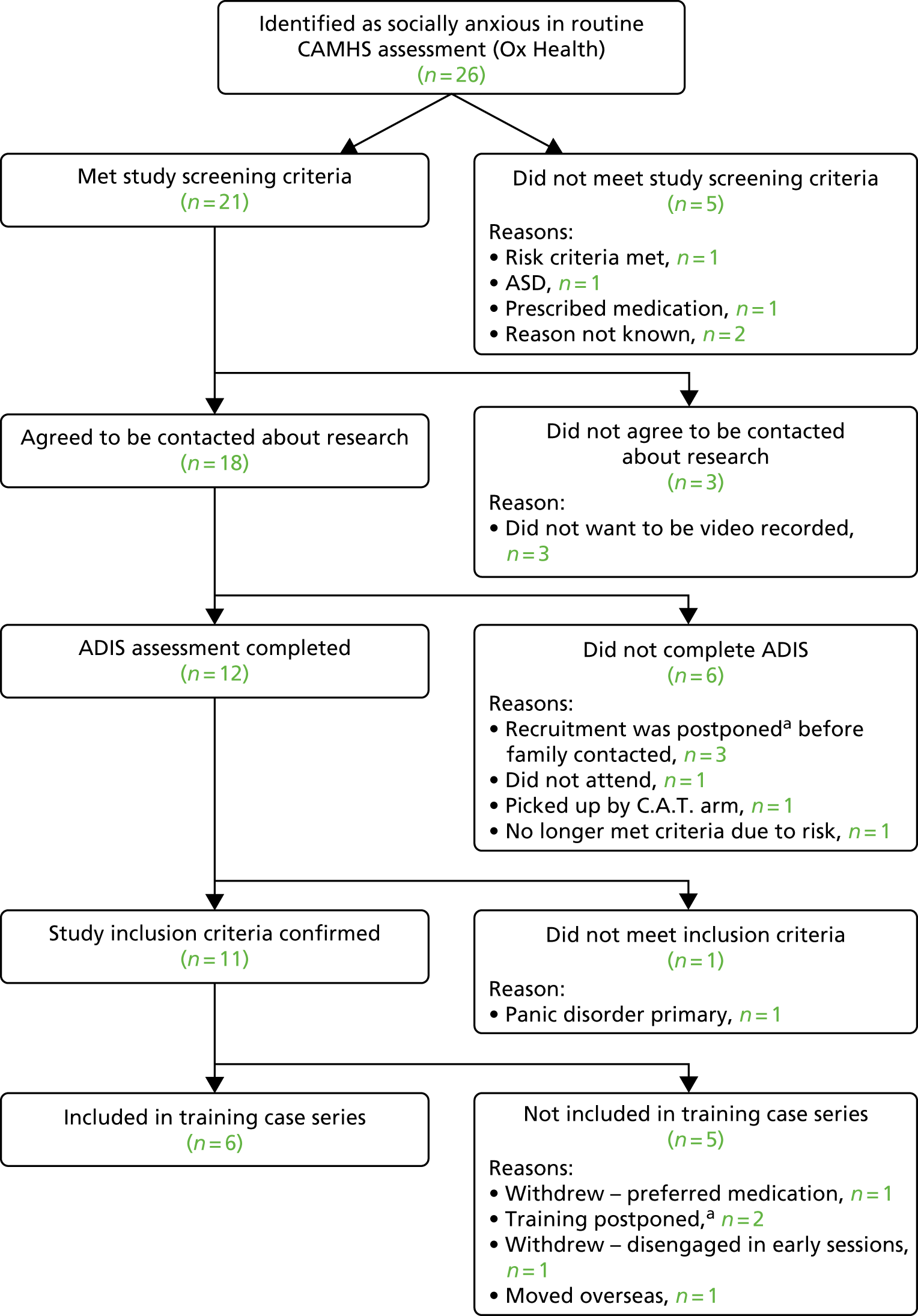

Figures 3 and 4 show patient participant recruitment and retention to the study. Of those young people identified as potentially eligible for the study, less than one-quarter ended up participating in the training series for a broad range of reasons. Notably, when potential participants were assessed and confirmed as eligible for the study, uptake and retention was high. In total, 26 out of 35 (74%) young people who were contacted by the research team participated in the study, 12 out of 14 (86%) were retained throughout treatment and 11 of these 12 (92%) completed the follow-up assessment.

FIGURE 3.

Patient recruitment and retention to the CT-SAD-A training phase (Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust). a, Training was postponed from September 2016 to June 2017 while the primary supervisor was on maternity leave.

FIGURE 4.

Patient recruitment and retention to the CT-SAD-A training phase (Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust). a, Training was postponed from September 2016 to June 2017 while the primary supervisor was on maternity leave.

Action taken

In response to the difficulties that we experienced with recruiting and retaining CAMHS therapists and identifying eligible young people within CAMHS, we considered extending recruitment to other NHS trusts. However, after extensive consultation with representatives from a range of CAMHS teams, it was clear that this was not going to be possible, because (1) a substantial increase in costs would be required to be able to conduct the required diagnostic assessments across a wider geographical area and/or (2) other NHS CAMHS teams reported having similar problems with staffing (i.e. unfilled posts and a rapid turnover of staff) and caseloads that were increasingly dominated by high levels of risk. As a result of the difficulties with therapist retention and participant identification, we concluded that the feasibility question that we set out to address had been answered and that the proposed RCT would not be feasible in the current CAMHS context. Given this, we felt that it was not a responsible use of NIHR funds to proceed to the RCT phase of the study. To maximise the learning from the work and investment that had taken place, we proposed the following next steps:

-

We would complete CT-SAD-A treatment and post-treatment assessments with all the training cases to report on an extended case series of application of the novel treatment (CT-SAD-A) in routine CAMHS (including costs of treatment delivery).

-

We would move forward qualitative work that had been planned alongside the RCT phase of the original proposal to learn about young people and parents’ experiences of receiving this novel treatment within a CAMHS setting to inform future work about how best to deliver specialist psychological treatments in CAMHS.

-

We would extend the proposed qualitative work to include therapists and service managers to learn from their experiences of (1) delivering CT-SAD-A within routine CAMHS and (2) participating in psychological therapies research in routine CAMHS, to learn both about the application of specialist psychological treatments in CAMHS and about what needs to happen to enable CAMHS to participate in research.

This proposal was agreed by the SSC and the NIHR HTA programme. The following chapters report on the outcomes of the revised programme of work.

Chapter 5 Results 2: training case series – clinical outcomes

Patient and therapy characteristics

The 10 females and two males included in the case series had an average age of 15.17 years (SD 1.80 years; range 12–17 years). The sample was predominantly white British (10/12), which was representative of the participating trust areas. None of the patients reported being prescribed psychotropic medication.

As shown in Table 4, seven patients received the planned 14 weekly therapy sessions, two patients received 10 weekly sessions and three patients received 11 sessions, 12 sessions, and 17 sessions, respectively. Four patients received the planned two booster sessions, one received three boosters, two received one booster and the remaining five did not receive a booster session. The follow-up assessment was carried out, on average, 2.88 months (SD 1.15 months, range 1.16–4.63 months) after the final weekly therapy session. Outcomes are presented graphically for each case below.

| ID | Young person’s sex | Young person’s age (years) at initial assessment | No. of weekly sessions | No. of booster sessions | Diagnostic profile of young person at initial assessment (diagnosis yes/no and CSR) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAD | Specific phobia 1 | Specific phobia 2 | Panic disorder without agoraphobia | GAD | PTSD | Dysthymia | MDD | |||||||||||||

| 1 | Female | 16 | 14 | 2 | Yes | 6 | No | – | No | – | No | – | Yes | 4 | No | – | No | – | No | – |

| 2 | Male | 17 | 14 | 2 | Yes | 6 | Yes | 4 | No | – | Yes | 5 | Yes | 4 | No | – | No | – | No | – |

| 3 | Female | 12 | 14 | 3 | Yes | 7 | No | – | No | – | No | – | No | – | No | – | No | – | Yes | 6 |

| 4 | Female | 15 | 14 | 2 | Yes | 6 | No | – | No | – | No | – | Yes | 5 | No | – | No | – | No | – |

| 5 | Female | 17 | 14 | 1 | Yes | 7 | Yes | 4 | No | – | No | – | Yes | 6 | No | – | Yes | 6 | No | – |

| 6 | Female | 13 | 14 | 2 | Yes | 4 | No | – | No | – | No | – | No | – | No | – | No | – | No | – |

| 7 | Male | 13 | 10 | 1 | Yes | 5 | No | – | No | – | No | – | Yes | 4 | No | – | No | – | No | – |

| 8 | Female | 17 | 12 | 0 | Yes | 7 | No | – | No | – | No | – | Yes | 5 | No | – | No | – | No | – |

| 9 | Female | 15 | 11 | 0 | Yes | 5 | No | – | No | – | No | – | No | – | No | – | No | – | No | – |

| 10 | Female | 17 | 14 | 0 | Yes | 7 | Yes | 6 | No | – | No | – | Yes | 5 | Yes | 6 | No | – | Yes | 5 |

| 11a | Female | 14 | 10 | 0 | Yes | 7 | No | – | No | – | No | – | Yes | 5 | No | – | No | – | No | – |

| 12 | Female | 16 | 17 | 0 | Yes | 7 | Yes | 5 | Yes | 5 | No | – | No | – | No | – | No | – | No | – |

Patient outcomes

The mean and median pre-treatment and follow-up data are presented in Table 5. Given the small sample size and the non-normal distribution of a number of the variables, pre-treatment and follow-up comparisons were made with non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. The z-statistic is presented in Table 5, with associated p-values and effect size estimates (r).

| Measure | n | Time point | Wilcoxon | p | r a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre treatment | Follow-up | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | Median (Q1, Q3) | Mean (SD) | Median (Q1, Q3) | Test statistic | ||||

| LSAS-CA-SR | 12 |

97.41 (26.02) |

100.09 (79.50, 119.50) |

36.18 (38.31) |

24.50 (3.50, 75.25) |

z = –3.06 | 0.002* | 0.62 |

| RCADS social anxiety T-score | 12 |

74.26 (21.93) |

70.29 (59.46, 78.19) |

44.00 (15.58) |

41.89 (30.61, 55.13) |

z = –2.93 | 0.003* | 0.60 |

| ADIS-C/P SAD CSR score | 11 |

6.09 (1.04) |

6.50 (5.00, 7.00) |

2.45 (3.11) |

0.00 (0.00, 5.00) |

z = –2.21 | 0.021* | 0.47 |

| RCADS depression T-score | 11 |

68.46 (16.84) |

67.17 (55.93, 85.91) |

47.35 (15.18) |

44.70 (37.96, 62.67) |

z = –2.94 | 0.003* | 0.63 |

| RCADS GAD T-score | 11 |

57.46 (9.18) |

56.77 (51.37, 64.49) |

38.04 (8.07) |

37.56 (29.81, 46.28) |

z = –3.02 | 0.003* | 0.64 |

| Parent RCADS social anxiety T-score | 11 |

76.57 (14.45) |

81.16 (60.23, 90.30) |

58.00 (15.37) |

52.97 (46.31, 72.03) |

z = –2.80 | 0.005* | 0.60 |

| Parent RCADS depression T-score | 11 |

75.34 (18.68) |

81.08 (54.15, 86.80) |

60.21 (18.23) |

59.32 (48.22, 69.21) |

z = –2.05 | 0.041* | 0.44 |

| Parent RCADS GAD T-score | 11 |

66.76 (13.62) |

81.08 (54.15, 86.80) |

50.84 (11.15) |

45.17 (42.28, 64.21) |

z = –2.49 | 0.013* | 0.53 |

| Social participation | 12 | 39.58 (15.46) |

41.50 (24.00, 51.75) |

60.35 (19.38) |

59.00 (42.50, 80.75) |

z = –2.90 | 0.004* | 0.59 |

| Social satisfaction | 12 | 14.83 (4.97) |

14.50 (10.50, 19.75) |

18.75 (6.69) |

20.50 (10.75, 24.75) |

z = –1.96 | 0.050 | 0.40 |

| Concentration | 12 |

53.33 (24.71) |

55.00 (35.00, 73.75) |

64.17 (28.73) |

65.00 (42.50, 91.25) |

z = –1.49 | 0.137 | 0.30 |

| ORS – individual | 12 |

39.05 (36.91) |

32.50 (3.16, 76.00) |

49.33 (38.65) |

46.50 (7.00, 90.75) |

z = –0.89 | 0.374 | 0.18 |

| ORS – interpersonal | 12 |

40.61 (38.75) |

22.15 (6.24, 84.50) |

55.55 (39.07) |

70.00 (8.13, 90.25) |

z = –0.86 | 0.388 | 0.18 |

| ORS – social | 12 |

24.55 (28.37) |

10.65 (1.90, 45.75) |

46.83 (42.19) |

48.00 (3.15, 93.25) |

z = –1.73 | 0.084 | 0.35 |

| ORS – overall | 12 |

28.14 (28.21) |

23.00 (3.98, 43.78) |

50.85 (39.43) |

50.00 (7.38, 94.50) |

z = –1.96 | 0.050 | 0.40 |

| CYP IAPT goal 1 | 7 |

1.57 (7.71) |

1 (1, 2) |

7.71 (1.98) |

8 (7, 9) |

z = –2.38 | 0.018* | 0.64 |

| SCQ – belief | 12 |

61.91 (23.18) |

68.69 (46.29, 81.17) |

13.61 (20.32) |

3.55 (1.46, 26.93) |

z = –3.06 | 0.002* | 0.62 |

| SBQ | 12 |

1.63 (0.50) |

1.71 (1.29, 1.96) |

0.64 (0.59) |

0.45 (0.24, 0.79) |

z = –2.85 | 0.004* | 0.58 |

| SAQ | 12 |

4.46 (1.22) |

4.84 (3.13, 4.99) |

2.86 (0.93) |

2.89 (2.50, 3.69) |

z = –2.67 | 0.008* | –0.55 |

Social anxiety symptom scales

Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale for Children and Adolescents: self-report version

The Wilcoxon paired rank-sum test revealed a significant difference in LSAS-CA-SR scores from pre treatment to follow-up, with a large effect size. Scores dropped on average 66.80% over time, ranging from 3% to 100% (Figure 5). Ten participants, 83% of the sample, made a reliable improvement in their LSAS-CA-SR scores. Nine participants made a reliable and clinically significant improvement, based on a pre-treatment to follow-up change of at least 2 SDs from the original mean (a drop of 48.75 points).

FIGURE 5.

Individual patient LSAS-CA-SR scores at the following measurement points: pre assessment, mid-treatment, at the end of weekly sessions and at the follow-up assessment.

Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale: social anxiety subscale

RCADS social anxiety T-scores showed a significant and large decrease over the course of treatment. Before treatment, eight patients were on the borderline or in the clinical range based on their age and sex (T-score of > 65), whereas only one patient remained in the clinical range at follow-up (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Individual patient RCADS social anxiety T-scores at the following measurement points: pre assessment, mid-treatment, at the end of weekly sessions and at the follow-up assessment.

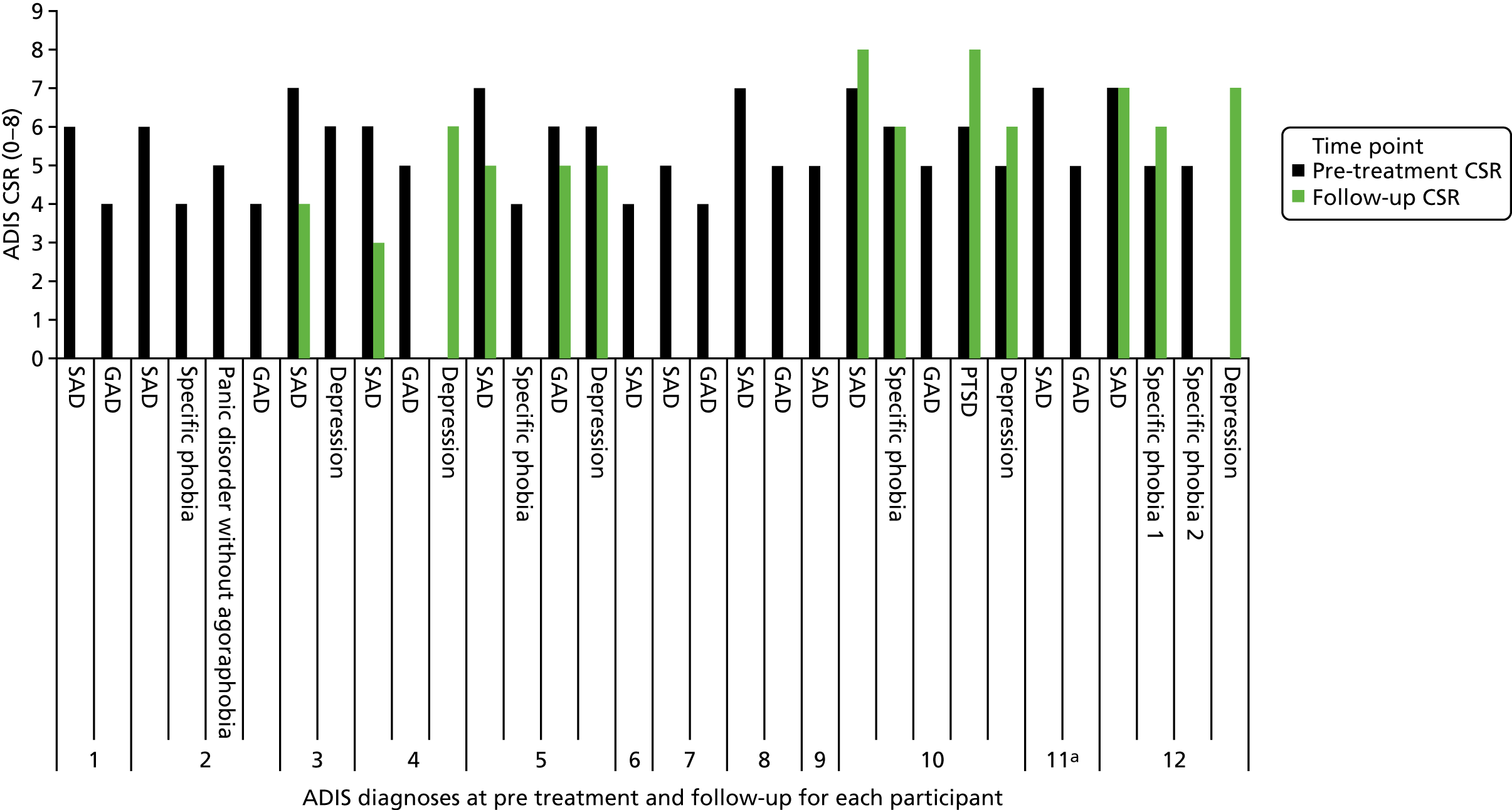

Diagnostic profile

Table 6 shows the presence of diagnoses measured using the ADIS-C/P pre treatment and at follow-up for each participant. CSRs for SAD diagnosis at both time points are given in Table 5. CSRs for all other diagnoses are shown in Figure 7. Follow-up diagnostic data were missing for ID 11 and, therefore, they are not included in the following discussion (i.e. N = 11 for below).

| Time point | Social anxiety | GAD | Specific phobia | Panic disorder without agoraphobia | Depression | PTSD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre (n) | 11 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Follow-up (n) | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

FIGURE 7.

The ADIS CSR pre treatment and at follow-up scores. Scores of ≥ 4 indicate a positive diagnosis. a, Follow-up ADIS data missing for ID 11.

At pre treatment, all patients had a diagnosis of SAD. Only two patients had no comorbid diagnoses; GAD was present in eight patients and depression (either MDD or dysthymia) was present in three young people. There were five diagnoses of specific phobia pre treatment across four patients, with one patient diagnosed with two specific phobias. One patient had a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and one had a diagnosis of panic disorder. (This is detailed in Table 4. )

At follow-up, seven patients (63.64%) had lost their primary diagnosis of SAD. These same seven patients are also those patients who fell below the LSAS-CA-SR clinical cut-off at follow-up. Six patients lost their diagnosis of GAD, and three diagnoses of specific phobia were lost (one patient had two phobias at pre treatment and lost one of these at follow-up).

The number of depressive disorders in the sample increased from three to four by follow-up. Of the four patients who retained their diagnosis of SAD at follow-up, one had lost their diagnosis of depression, two had retained their diagnosis of depression and one had acquired a new diagnosis of depression. One patient lost their diagnosis of SAD, but had become depressed at follow-up.

Related clinical outcomes

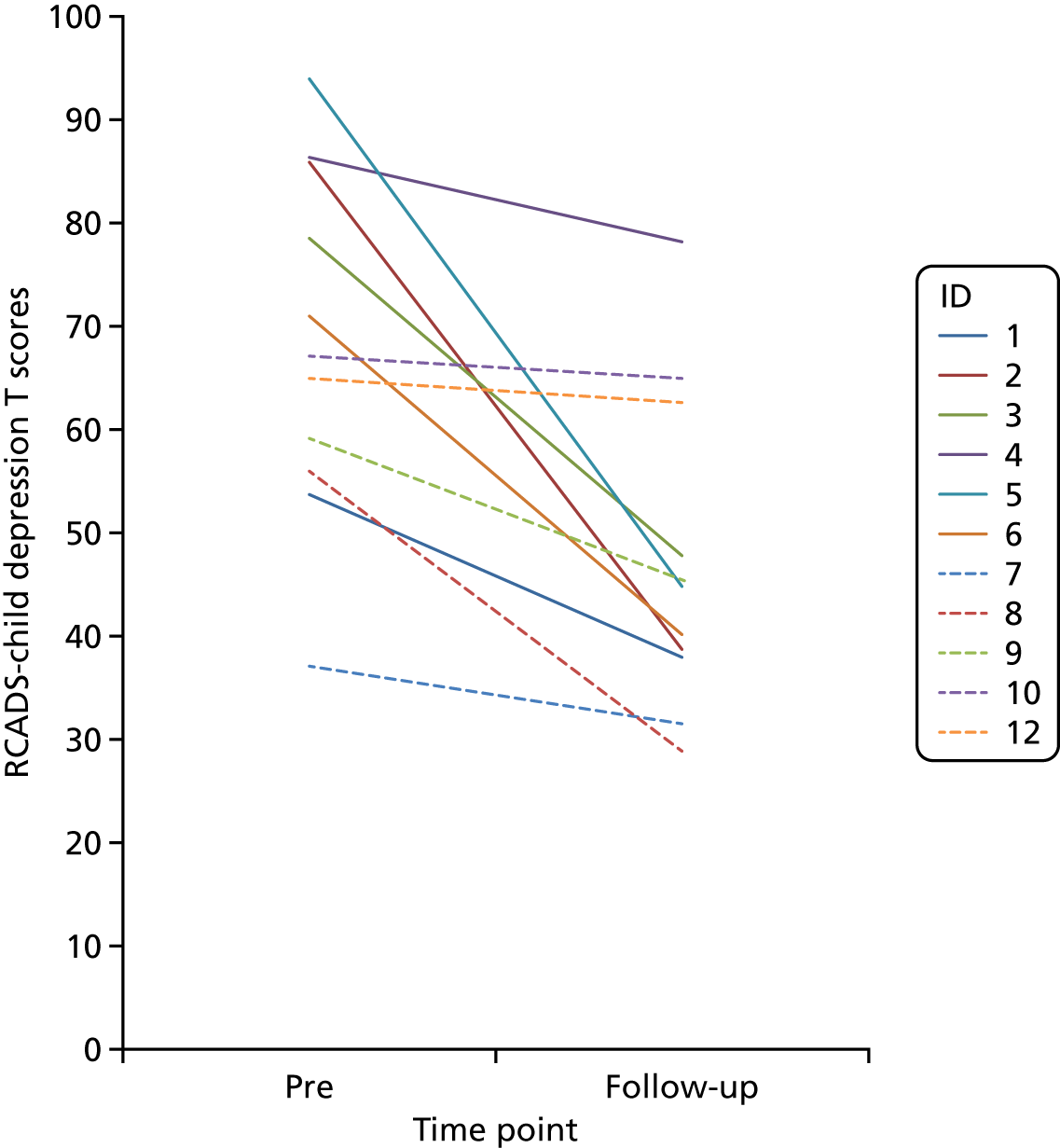

Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale depression scores

There was a large and significant drop in RCADS depression subscale scores over time (Figure 8). For nine patients, depression scores were below the suggested threshold (T < 65) at follow-up. ID 4 continued to show elevated symptoms of depression at follow-up and also developed a new diagnosis of depression over the course of treatment (see ADIS data in Table 6) while losing their SAD diagnosis.

FIGURE 8.

Individual patient RCADS depression T-scores at pre assessment and at the follow-up assessment.

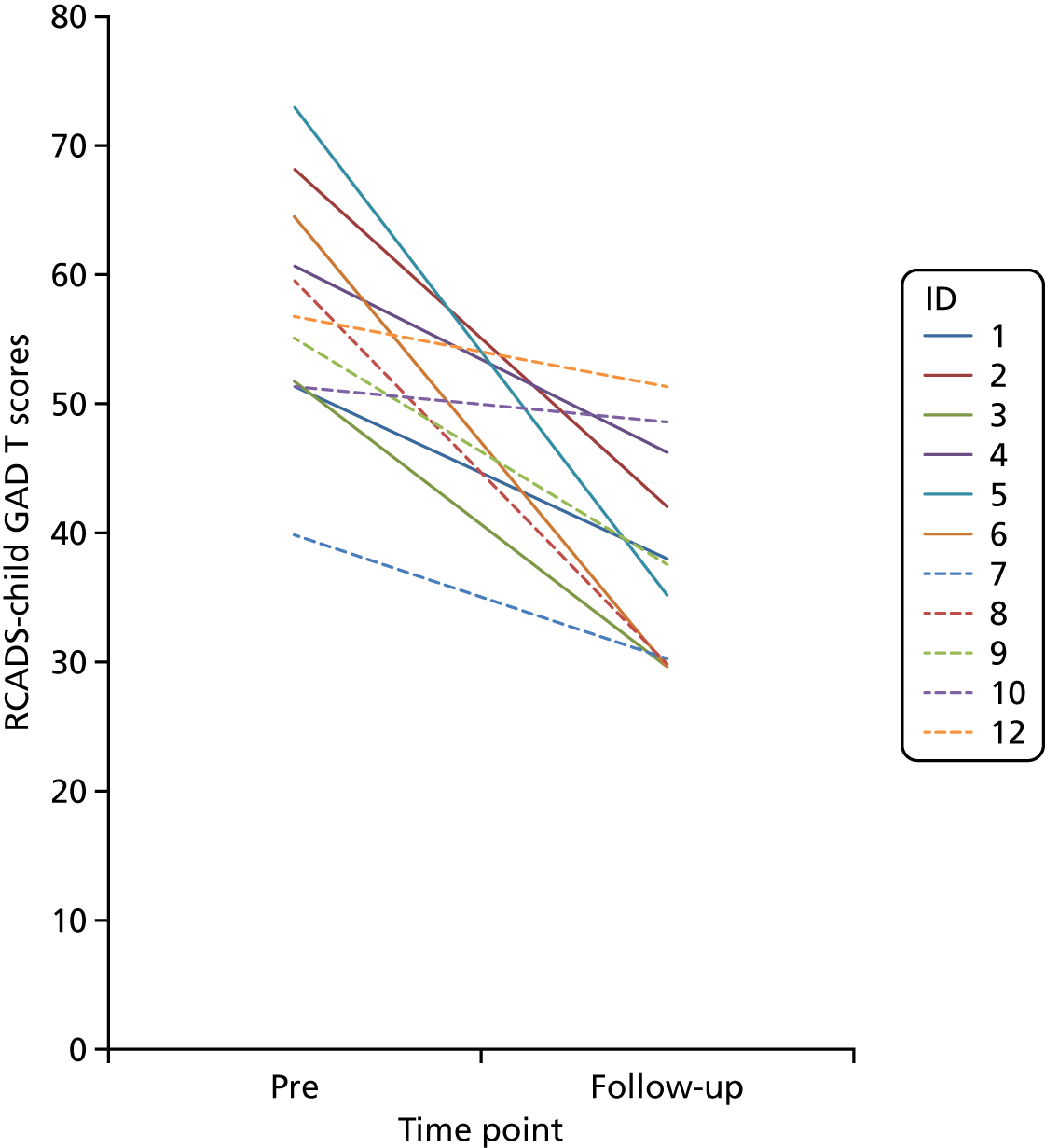

Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale generalised anxiety disorder scores

There was a large and significant drop in GAD scores over the course of treatment, with all patients scoring below threshold at follow-up (Figure 9).

FIGURE 9.

Individual patient RCADS GAD T-scores at pre assessment and at the follow-up assessment.

Parent-reported Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale

For the group as a whole (n = 11), parent ratings on the social anxiety, depression and GAD subscales of the parent RCADS were initially elevated (see Table 5) and reduced significantly by follow-up. Individual data for RCADS social anxiety subscale T-scores are presented in Figure 10. This indicates that all parents except ID 12 rated their child as making at least some improvement in their social anxiety symptoms.

FIGURE 10.

Parent RCADS social anxiety subscale T-scores pre treatment and at follow-up.

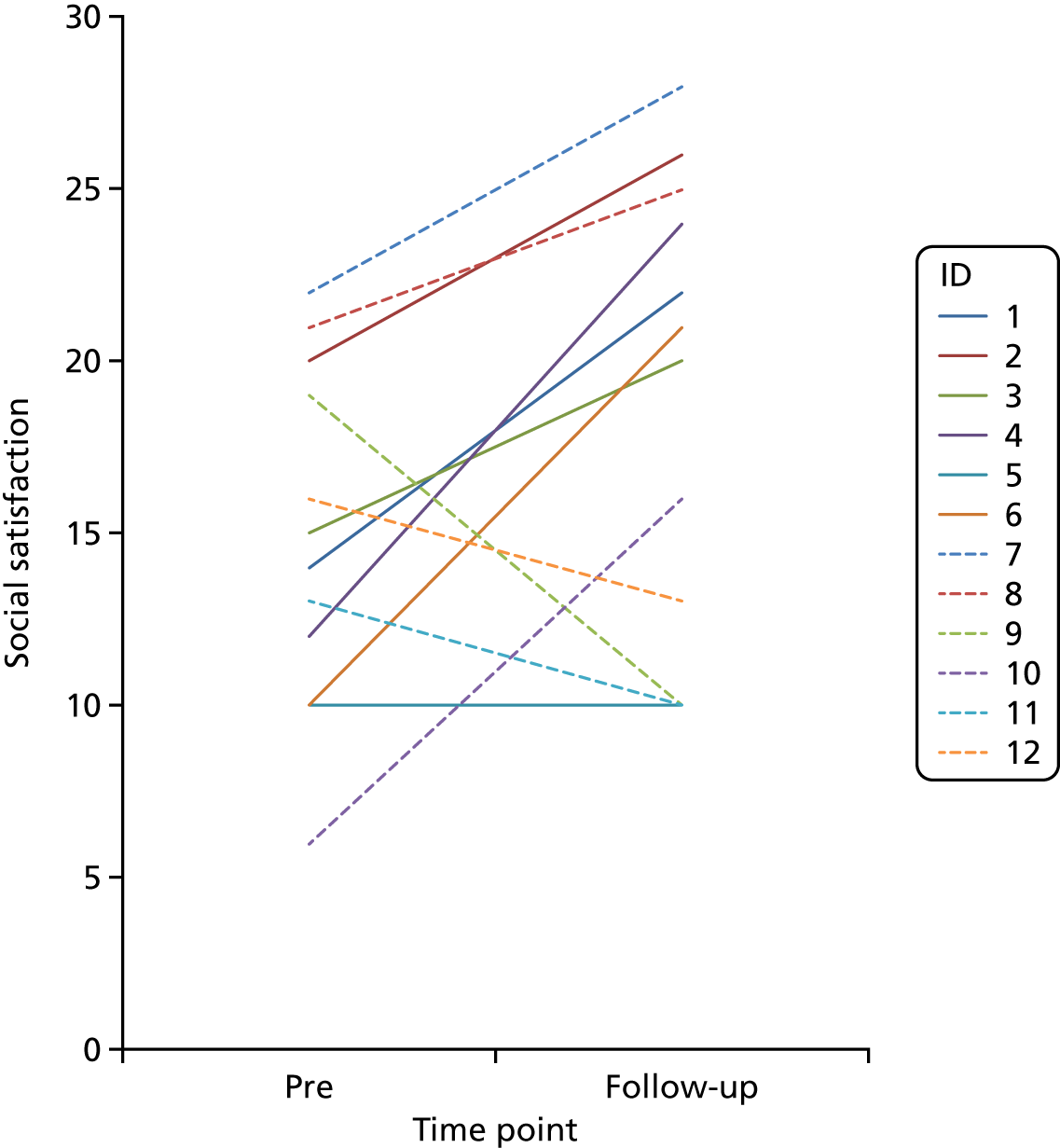

Social participation and satisfaction

The group as a whole showed large and significant improvements in their social participation (Figure 11). There was an improvement at trend level in ratings of social satisfaction for the group as a whole (Figure 12).

FIGURE 11.

Individual patient social participation scores at pre assessment and at the follow-up assessments.

FIGURE 12.

Individual patient social satisfaction scores at pre assessment and at the follow-up assessments.

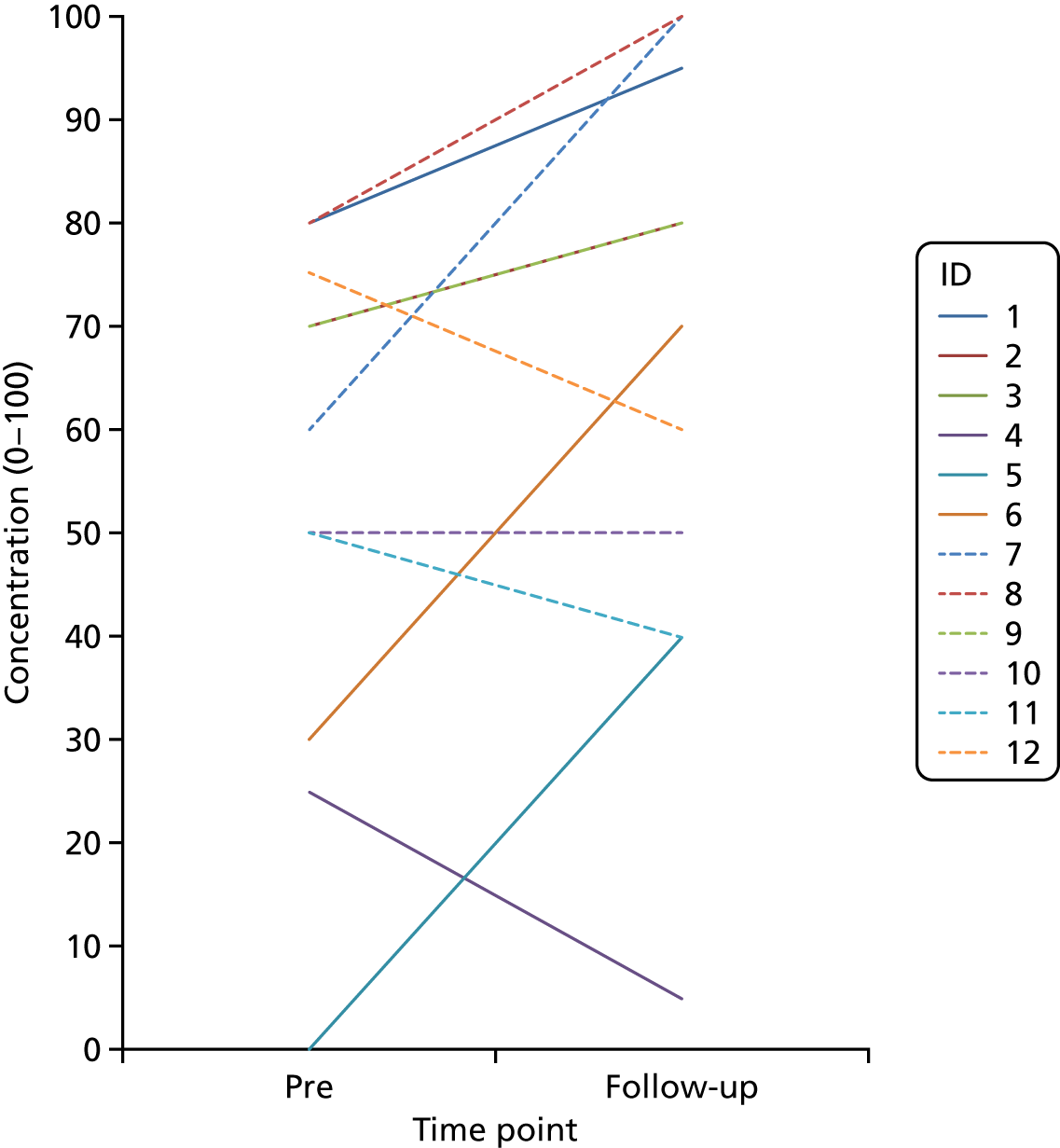

Concentration in class

The group as a whole showed a small to medium improvement in self-reported classroom concentration from pre treatment to follow-up, although this was non-significant. As shown in Figure 13, four young people showed either no change (ID 10) or a deterioration in their concentration (IDs 4, 11 and 12). Patients ID 10, 11 and 12 are those young people who did not show a clinically significant improvement on the LSAS-CA-SR and, while ID 4 lost their diagnosis of SAD, they developed a new diagnosis of depression during treatment.

FIGURE 13.

Self-reported concentration in class at pre assessment and at the follow-up assessment.

Outcome rating scales

Although no significant improvements were detected on the ORS, a small effect (at trend level) was observed on the overall scale and social scale. The overall and social subscale ratings for each individual at pre treatment and follow-up are shown in Figures 14 and 15.

FIGURE 14.

Individual patient ORS: overall subscale scores at pre assessment and follow-up.

FIGURE 15.

Individual patient ORS: social subscale scores at pre assessment and follow-up.

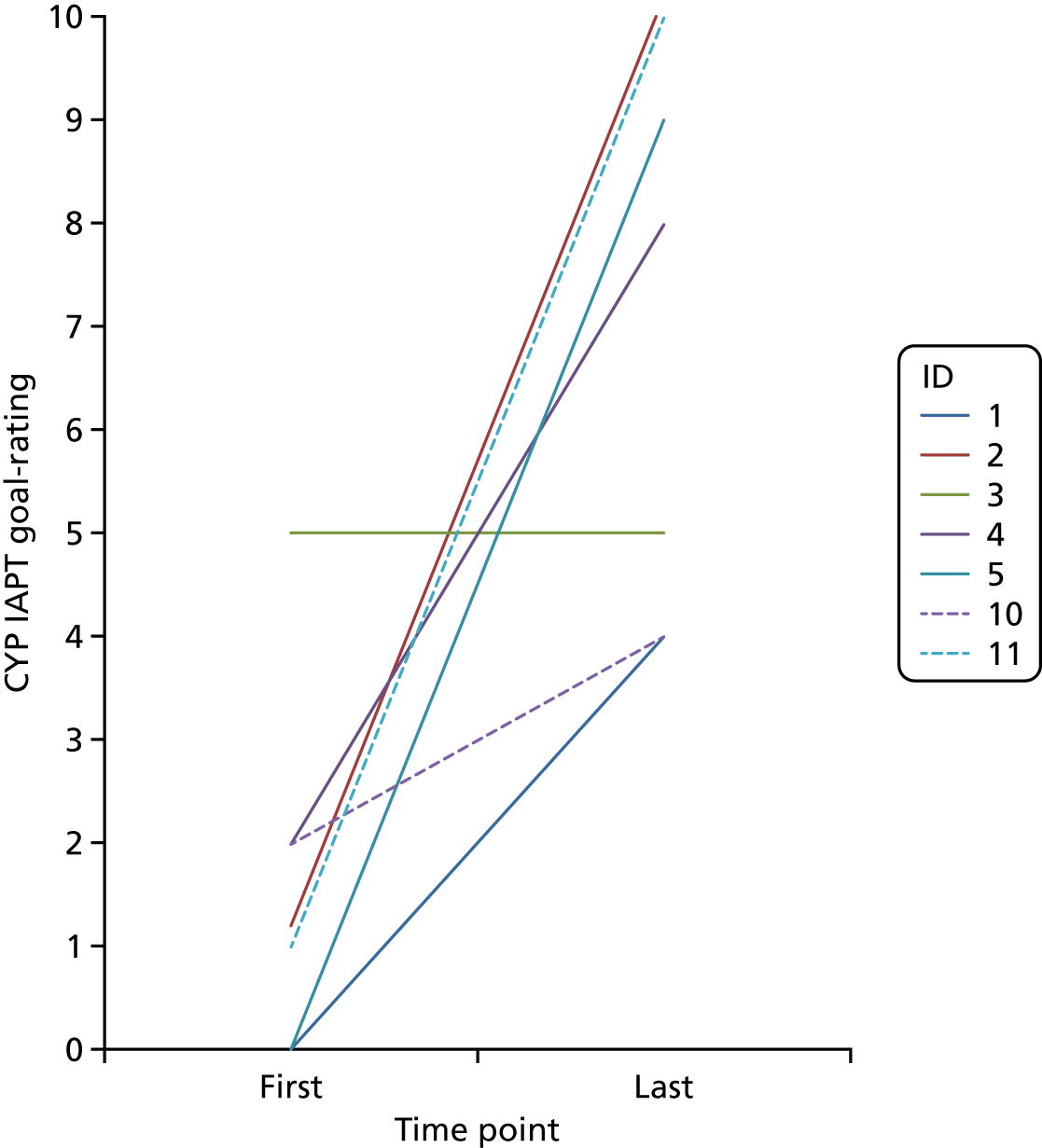

Children and Young People’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapies programme goal-rating

Therapists were expected to ask patients to identify their key goals and rate the extent to which they had reached those goals from 0–10 every session. There was wide variability in the collection and recording of these data, with data from two time points available for only 8 out of 12 participants. For one of these participants, there were only two time points at weeks 6 and 7, so these data have not been presented, as they do not accurately reflect initial and final progress. Data for the remaining seven patients’ primary goal are presented in Figure 16. Initial goals data were collected between sessions 1 and 3 for these participants. The last time this was collected was between sessions 8 and 14. Six patients rated themselves as closer to attaining their main goal at the last assessment point, while the remaining patient’s rating was the same at both the initial and final assessment points, although it did increase at points during the treatment.

FIGURE 16.

Individual patient data for first and last available CYP IAPT goal-ratings made by patients for their primary goal in therapy.

Psychological process measures

Social Cognitions Questionnaire

Social Cognitions Questionnaire – belief

All patients reported some reduction in ratings of belief in their social cognitions, and the group as a whole showed a large and significant reduction in belief ratings on the SCQ (Figure 17). For all but three patients, these reductions were substantial (belief rating reduced by 88–100%). The same nine patients who showed these large reductions in the SCQ also showed a clinically significant improvement on the LSAS-CA-SR, as indexed by a drop of 48.75 points on the scale.

FIGURE 17.

Individual patient SCQ mean belief scores at pre assessment and at the follow-up assessment.

Social Behaviour Questionnaire

All but three patients reported substantial reductions in their use of safety behaviours at follow-up, as indexed by scores of 0.55 or below on the SBQ (range 0–3) (Figure 18). The same nine patients who showed large reductions in the SBQ also showed a clinically significant improvement on the LSAS-CA-SR, as indexed by a drop of 48.75 points on the scale.

FIGURE 18.

Individual patient SBQ scores at pre assessment at the follow-up assessment.

Social Attitudes Questionnaire

For the group as a whole, there was a large and significant reduction in negative social attitudes (mean SAQ) from pre treatment to follow-up (Figure 19). Only one patient (ID 10) showed a strengthening of their negative social attitudes, and they also retained their SAD diagnosis at follow-up.

FIGURE 19.

Individual patient mean SAQ scores at pre assessment and at the follow-up assessment.

Treatment acceptability

Eleven young people completed the treatment acceptability scale at the follow-up assessment. All of them somewhat or completely agreed with the statements ‘I was satisfied with the treatment’ and ‘I would recommend the treatment to others’ (Figure 20).

FIGURE 20.

Treatment acceptability.

Chapter 6 Results 3: costs of treatment delivery in routine child and adolescent mental health services

Aim

The aim of the economic analysis was to estimate the cost of training therapists to deliver CT-SAD-A as well as the cost per adolescent treated from the perspective of the NHS.

Methods

Clinician’s logs (see Chapter 2, Health economics records) were completed by both supervisors and therapists. Data recorded in the logs were used to calculate the cost of training therapists to deliver CT-SAD-A and the mean total amount and cost of qualified staff time used by the NHS per adolescent treated. Results were stratified by type of staff (i.e. supervisor and therapist) time use (i.e. time spent in training, supervision, preparation and delivery of CT-SAD-A). Time spent by supervisors training and supervising therapists, as well as time spent by the therapists being trained and supervised, were attributed pro-rata to each patient treated. For each study participant, all components of treatment costs, stratified by category of resource use, were computed by multiplying units of resource use by their unit costs. Values were expressed in 2016/17 UK GBP (£). Unit costs used and their sources are summarised in Table 7. Results were reported in terms of total amount of qualified staff time and associated cost for training and supervision as well as in terms of mean values of qualified staff time and associated cost per patient treated, with variability around the mean measured by SDs. Percentage of missing values were reported. As missing data occurred exclusively on the time spent on face-to-face therapist contact with the young person and were highly deterministic (i.e. readily identifiable and standardised given observed practice), a conditional imputation method was conducted whereby missing data were estimated as an average of known durations for that patient. For patients for whom all information was missing, the average duration across all patients was used. Analyses were conducted using Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), and Stata® statistical software, release 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

| Item | Cost | Source | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinicians – therapists | £42/hour | Curtis and Burns47 | Table 12.647 – generic single-disciplinary CAMHS team |

| Clinicians – supervisors | £62/hour | Curtis and Burns47 |

Table 947 – scientific and professional staff Cost per working hour for community-based scientific and professional staff, band 8a |

Results

Data completeness

Supervisor-completed economic logs, which included information on time spent by supervisors and therapists in workshops and weekly case supervision practice, had a 100% completion rate. Therapist-completed economic logs, which included time spent in delivering CT-SAD-A to patients and associated activities (e.g. preparation time), had rates of missing values that ranged from 50% to 67% for various treatment sessions across all patients. No data were recorded for any of the treatment sessions throughout the whole treatment programme for 4 out of the 12 patients.

Qualified supervisors’ and therapists’ time and costs

Three supervisors provided training and supervision to therapists during the training phase of the study. Day-long (7 hours) workshop training was usually delivered by two supervisors. Five day-long workshops were conducted during the duration of the study, because new therapists had to be recruited partway through the project. Weekly case supervision was generally led by only one supervisor who was occasionally helped by a second supervisor for part of the session. Sixty-two weeks of active case supervision were reported during the study. The time between case supervision weeks could be longer than a temporal week. Case supervision sessions were intended to be delivered to groups of four therapists at a time but, because new therapists were recruited at different times throughout the programme, multiple supervision sessions were delivered to a less than optimal number of therapists, and, on several occasions, a one-to-one case supervision session had to be offered. The mean number of therapists attending weekly supervision sessions was 2.8 (SD 1.27).

Table 8 shows that, during the whole training phase of the study, supervisors spent overall 4740 minutes (around 79 hours) on preparation and delivery of all of the training workshops, which would cost the NHS £4898. The mean time and cost per workshop were 948 minutes (SD 50.20 minutes) and £980 (SD £51.87), respectively. For the whole case supervision, supervisors spent overall 8621 minutes (around 144 hours) on preparation and delivery of all of the case supervision. As supervisors reported overall preparation and delivery time per week of active supervision (even if more than one supervision session may have occurred in a week), the mean time and cost of qualified supervisor time per supervision week were 139 minutes (SD 71 minutes) and £144 (SD £74), respectively.

| Activity | Total timea (minutes) | Total costa (£) | Time (minutes), meanb (SD) | Cost (£), mean a (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training workshops | ||||

| Preparation | 540 | 558 | 108 (50.20) | 111.6 (51.87) |

| Delivery | 4200 | 4340 | 840 (0.00) | 868 (0.00) |

| Total | 4740 | 4898 | 948 (50.20) | 979.6 (51.87) |

| Total timec (minutes) | Total costc (£) | Time (minutes), meand (SD) | Cost (£), meand (SD) | |

| Case supervision | ||||

| Preparation | 2350 | 2428 | 37.90 (20.60) | 39.17 (21.28) |

| Delivery | 6271 | 6480 | 101.15 (54.20) | 104.52 (56.00) |

| Total | 8621 | 8908 | 139.05 (71.25) | 143.68 (73.63) |

Table 9 reports the mean time and cost of supervisor input per therapist attending each workshop and case supervision week. Results are stratified by time used for preparation and time used for delivery. Supervisors devoted on average 278 minutes (SD 157 minutes) (around 4.6 hours) to each therapist during the workshop training phase, which would cost the NHS £287 (SD £162) per therapist. The large cost was due to the long duration of each workshop (7 hours per day) and the relatively small number of therapists attending each workshop (two to six therapists per workshop day). The amount of qualified supervisor time per therapist was, on average, 50 minutes (SD 14 minutes) throughout the duration of the case supervision of the programme. The associated cost to the NHS would be £51.5 (SD £14.6) per therapist.

| Activity | Time (minutes), meana (SD) | Cost (£), meana (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Training workshops | ||

| Preparation | 26 (5.48) | 26.87 (5.66) |

| Delivery | 252 (153.36) | 260.4 (158.47) |

| Total | 278 (157.07) | 287.27 (162.30) |

| Time (minutes), meanb (SD) | Cost (£), meanb (SD) | |

| Case supervision | ||

| Preparation | 13.7 (6.71) | 14.18 (6.93) |

| Delivery | 36.12 (9.91) | 37.32 (10.24) |

| Total | 49.84 (14.09) | 51.50 (14.56) |

There were five full-day workshops; the mean number of therapists participating in each workshop was 4.4, the number of weeks of active supervision was 62, and the average number of therapists participating in each supervision week was 2.8.

To have an estimate of the overall cost to the NHS of training therapists to deliver CT-SAD-A, the amount of therapist time spent being trained and the associated cost needed to be estimated. Overall, 9240 minutes (around 154 hours) of therapists’ time was spent on workshop training (five full-day workshops to train a total of eight therapists), which would equate to a total cost to the NHS of £6468. Each therapist spent on average 420 minutes (SD 0 minutes) (7 hours) at each workshop for an NHS cost per workshop attended by a therapist equal to £294 (SD £0).

Table 10 presents descriptive statistics referring to therapists’ time and cost of participating in the weekly case supervision phase of their training. A total of 62 case supervision weeks were recorded, as often weekly case supervision occurred with more than one therapist. On average, each therapist participated in 24 (SD 12) case supervision sessions.

| Therapists | Number of supervision sessions attended | Total time (minutes) spent being supervised | Cost (£) of total time spent being supervised | Time (minutes) per supervision session attended, mean (SD) | Cost (£) per supervision session attended, mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapist 1 | 32 | 2680 | 1876 | 83.75 (37.48) | 58.63 (26.24) |

| Therapist 2 | 38 | 2885 | 2019.50 | 75.92 (38.97) | 53.14 (27.28) |

| Therapist 3 | 29 | 2405 | 1683.50 | 82.93 (38.53) | 58.05 (26.97) |

| Therapist 4 | 34 | 2710 | 1897 | 79.71 (39.25) | 55.79 (27.48) |

| Therapist 5 | 3 | 480 | 336 | 160.00 (34.64) | 112.00 (24.25) |

| Therapist 6 | 19 | 750 | 525 | 39.47 (13.43) | 27.63 (9.40) |

| Therapist 7 | 16 | 630 | 441 | 39.38 (13.28) | 27.56 (9.29) |

|

All – mean (SD) |

24.43 (12.34) |

1791.43 (1107.48) |

1254 (775.23) |

73.33 (39.93) |

51.33 (27.95) |

Overall, 12,540 minutes (around 209 hours) of therapists’ time was spent on case supervision sessions, which would equate to a total cost to the NHS of £8778. Each therapist spent in total 1791 minutes (SD 1107 minutes) (around 30 hours) on the whole case supervision sessions, which would equate to a cost to the NHS of £1254 (SD £775) per therapist. Each therapist spent on average 73 minutes (SD 40 minutes) at each case supervision session; the average NHS cost for a therapist to attend a supervision session would equate to £51 (SD £28).

Qualified clinician time and cost per adolescent treated

Tables 11 and 12 summarise the mean qualified therapists’ time per patient for each of the 14 treatment sessions and the two booster sessions, stratified by type of activity associated with each session, as reported by therapists. Data were reported for only half, or less than half, of the patients. Data on the associated costs are reported in Tables 13 and 14.

| Type of contact | Mean duration (minutes) per therapy session | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Session 1 (n = 6) | Session 2 (n = 5) | Session 3 (n = 5) | Session 4 (n = 4) | Session 5 (n = 6) | Session 6 (n = 6) | Session 7 (n = 4) | Session 8 (n = 4) | |||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| CT-SAD-A: face to face (with young person only) | 78.33 | 8.16 | 85.00 | 8.66 | 86.00 | 6.52 | 90.00 | 0.00 | 55.00 | 44.16 | 80.83 | 11.58 | 85.00 | 7.07 | 85.00 | 10.00 |