Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/127/126. The contractual start date was in March 2014. The draft report began editorial review in August 2019 and was accepted for publication in July 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Perkins et al. This work was produced by Perkins et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Perkins et al

Chapter 1 Introduction

Description of condition

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is defined as the loss of functional cardiac mechanical activity, in association with an absence of systemic circulation, occurring outside a hospital setting. 1

The majority of OHCA events result from cardiac causes such as ischaemic heart disease, myocardial infarction and rhythm disturbances. Other causes of OHCA include trauma, submersion, drug overdose, asphyxia, exsanguination or other medical causes such as stroke or pulmonary embolism. 2,3

Cardiac arrest occurs through three different mechanisms: (1) lethal arrhythmias [ventricular fibrillation (VF) or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT)] leading to loss of cardiac output, (2) insufficient myocardial contraction to produce cardiac output [pulseless electrical activity (PEA)] and (3) complete failure of the electrical conduction system of the heart (asystole).

Manifestation of OHCA is dramatic: blood supply to the brain and vital organs ceases within seconds, the patient loses consciousness and the process of cell death commences. The window of opportunity to achieve return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) is very narrow: a matter of minutes. Delays in attempts to restart the heart have catastrophic consequences, increasing the likelihood of death or severe neurological injury. Prolonged duration of resuscitation attempts is associated with poor outcomes.

The Department of Health and Social Care’s Cardiovascular Disease Outcomes Strategy: Improving Outcomes for People With or at Risk of Cardiovascular Disease,4 published in 2013, estimated that an increase in the survival rate from OHCA in England of between 10% and 11% could save > 1000 lives each year. Resuscitation to Recovery: A National Framework to Improve Care of People with Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest (OHCA) in England,5 was published in 2017, providing a consensus on the optimal pathway for OHCA in England. Research to improve understanding of resuscitation from OHCA was identified as a national priority. Similar initiatives have been published in the devolved nations. 6–8

Chain of survival

The chain of survival9 concept (Figure 1) is recognised internationally and summarises the key components of the response to OHCA to optimise the chances of survival. The links in the chain are discussed in more detail in the following sections.

FIGURE 1.

The chain of survival. 9 CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Reprinted from Resuscitation, Vol. 71, Nolan J, Soar J, Eikeland H, The chain of survival, pp. 270–1, Copyright 2006, with permission from Elsevier.

Early access

The first link in the chain highlights that it is important to identify a patient at risk of cardiac arrest (e.g. someone with an acute coronary syndrome) or a patient who has suffered a cardiac arrest (signs of which are loss of consciousness and absence of normal breathing). Rapid identification and calling for help early allow the ambulance service to send a trained advanced life support team to them as quickly as possible.

Raising public awareness of OHCA and the steps members of the public can take to increase chances of survival [calling 999 immediately and commencing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)] are the subject of major campaigns led by the British Heart Foundation and Resuscitation Council (UK), voluntary aid societies such as St John Ambulance and British Red Cross, and NHS ambulance services. World ‘Restart a Heart’ Day is an annual initiative that aims to train as many people as possible in CPR in 1 day. 10 NHS England has led work on improving ambulance call-taker’s recognition of life-threatening emergencies such as cardiac arrest, based on information provided by the person calling 999/111, as a component of the Ambulance Response Programme. 11 Ambulance telephone triage using NHS Pathways to identify OHCA accurately identifies 75% of adult OHCA {sensitivity 0.759 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.473 to 0.773], specificity 0.986 (95% CI 0.9858 to 0.98647), positive predictive value 26.80% (95% CI 25.88 to 27.73)}. 12 This facilitates despatch of an ambulance response with the highest priority, and the provision of advice and support to the caller on how to perform CPR pending arrival of trained personnel. In other countries, such as Singapore, a comprehensive programme of ambulance dispatcher telephone support was associated with a doubling in bystander CPR rates. 13 When the ambulance service is aware of a nearby defibrillator, there is an opportunity to direct the caller and/or another responder to retrieve this, provided this does not delay or interrupt bystander CPR (see High-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation).

High-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation is the combination of chest compressions and ventilations, and is optimally started by those initially at the scene of the collapse (bystander CPR). Bystander CPR increases the odds of survival by 1.23 (95% CI 0.71 to 2.11) in the studies with the highest baseline survival rates, to 5.01 (95% CI 2.57 to 9.78) in the studies with the lowest baseline rates. 14 When the emergency medical services (EMS) arrive on scene, they will take over CPR. Current resuscitation guidelines highlight the importance of high-quality CPR for ensuring optimal outcomes from cardiac arrest. 15 High-quality CPR is CPR that ensures an adequate chest compression depth is achieved (5–6 cm), that the compression rate is 100–120 per minute, that interruptions are minimised (for rhythm check/defibrillation and during extrication) and that the chest is allowed to recoil between chest compressions.

There are no randomised trials evaluating different compression parameters. Nevertheless, high-quality CPR appears to be important for outcomes. 16 Experimental studies show a linear increase in cardiac output and coronary perfusion pressure with increasing compression depths. 17,18 Observational studies in humans found improved defibrillator shock success19 and trends towards better ROSC rates and long-term survival with deeper chest compressions. 20 Faster chest compression rates (> 100 per minute) are associated with improved survival21,22 and ensuring that the chest is allowed to recoil between sequential chest compressions also appears to be important. 23

Interruptions in CPR are harmful. 24 A particularly critical time to minimise interruptions to CPR is around the time of attempted defibrillation. Prolonged pre-shock and peri-shock interruptions in CPR reduce the chances of shock success19 and survival. 25

Mechanical chest compression has not been shown in randomised trials to improve the outcome of OHCA. 26

Early defibrillation

Approximately one-quarter of OHCAs in the UK are due to an arrhythmia either VF or pulseless VT. These rhythms are referred to as shockable rhythms, as the arrhythmias may be terminated and cardiac function restored by the successful delivery of defibrillator shocks. The time from the onset of VF/VT to the delivery of a shock is critical to shock success and the chances of survival. For every 60–90 seconds that a shock is delayed, the chances of survival fall by approximately 10%. 27

If a defibrillator is immediately available at the scene of a cardiac arrest, defibrillation should be attempted without delay. When there is a delay in applying a defibrillator, there is a theoretical rationale that providing CPR before a shock improves coronary perfusion and, therefore, the chances of achieving sustained ROSC. 28

This concept was evaluated by the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium (ROC) in a cluster randomised trial comparing early analysis (30–60 seconds of EMS-administered CPR before initial rhythm analysis) with later analysis (180 seconds of CPR before the initial electrocardiographic analysis). 29 The primary outcome was survival to hospital discharge with satisfactory functional status [a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of ≤ 3, on a scale of 0–6, with higher scores indicating greater disability]. The trial enrolled 9933 patients (5290 to early analysis and 4643 to late analysis) but found no difference in outcomes (cluster-adjusted difference of –0.2%, 95% CI –1.1% to 0.7%).

Public access defibrillation (PAD) has the potential to improve outcomes of OHCA. A national scheme led by the Department of Health and Social Care was launched in England in 1999 and was focused on busy public places such as railway stations. 30 ROSC was reported for 170 out of 437 (39%) patients, and hospital discharge was reported for 113 out of 437 (26%) patients. 31 A systematic review of observational studies reported an overall median survival of 40% (range 9–83.3%) in OHCA patients treated by PAD, with defibrillation by bystanders associated with median survival rates of 53% (range 26–72%). 32 In a further systematic review, bystander automated external defibrillator (AED) use was associated with survival to hospital discharge [odds ratio (OR) 1.66, 95% CI 1.54 to 1.79] and favourable neurological outcome (OR 2.37, 95% CI 1.58 to 3.57) in patients with shockable rhythms. However, the quality of the evidence quality was deemed to be low to very low. 33

Public access defibrillators are underutilised in OHCA. A retrospective review of OHCA in Hampshire reported that callers had access to an AED in 44 (4.2%) OHCA cases, and that AEDs were used before ambulance arrival in only 18 (1.7%) cases. 34 A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of PADs identified a range of themes, including knowledge and awareness, willingness to use, acquisition and maintenance, availability and accessibility, training issues, registration and regulation, medicolegal issues, EMS dispatch-assisted use of AEDs, AED locator systems, demographic factors, and other behavioural factors. The quality of the evidence was deemed to be very low. 35 Deakin et al. 36 recently mapped 4012 OHCAs to 2076 AEDs known to the South Central Ambulance Service, and reported that only 5.9% of the AEDs were within a 100 m radius of OHCA locations during daytime, falling to 1.59% during out of hours.

Adrenaline

Treatment with adrenaline has been an integral component of advanced life support from the birth of modern CPR in the early 1960s. In guidelines written originally in 1961, Safar37 recommended the use of adrenaline: 1 mg intravenously or 0.5 mg intracardiac. Adrenaline has been recommended in successive guidelines from around the world. An analysis of drug use across 264 EMS agencies in the USA and Canada reported that 81% (range 57–98%) of patients experiencing an OHCA received adrenaline. 38 The Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Outcomes (OHCAO) registry reported that 77.5% of patients in England and Wales received adrenaline as part of their treatment for OHCA. 39

Animal studies show that injection of adrenaline during cardiac arrest increases aortic tone, thereby augmenting coronary blood flow. 40,41 However, there are limited reliable data to assess the effects of adrenaline on long-term outcomes after cardiac arrest. The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) synthesised the available evidence for adrenaline in 2010 (also reassessed in October 2012) and noted that, although adrenaline may improve the rate of ROSC and short-term survival, there is insufficient evidence to suggest that adrenaline improves survival to discharge from hospital and neurological outcome. ILCOR stated that placebo-controlled trials to evaluate the use of any vasopressor in adult and paediatric cardiac arrest are needed. 42

Post-resuscitation care

The ROSC marks the start of the post-resuscitation care phase of treatment. 43 Unless the arrest has been relatively brief, most patients who achieve ROSC will have an obtunded consciousness level, necessitating admission to intensive care. The focus of the post-resuscitation care phase of treatment is stabilising cardiac function to prevent further cardiac arrest and minimising the consequences of the cardiac arrest on neurological outcome. This involves the use of targeted temperature management, the avoidance of hyperglycaemia and coronary angiography to guide coronary reperfusion, if required. Post-resuscitation care treatments are initiated by ambulance clinicians and continue after the patient’s arrival in the emergency department (ED) and in the intensive care unit (ICU). Patients with ROSC who have evidence of ST-segment elevation on a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) are transferred directly to the cardiac catheter laboratory for urgent angiography revascularisation, if appropriate, in accordance with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance. 44 A recent randomised clinical trial suggested no benefit for urgent angiography in post-cardiac arrest patients without ST-segment elevation on a 12-lead ECG,45 but other trials evaluating the role of urgent coronary angiography in these patients are ongoing. 46–51

Incidence and burden of disease

The societal burden of OHCA has been described as equal to or greater than that of other leading causes of death. 52 Each year, an estimated 275,000 people in Europe experience an OHCA, with < 30,000 surviving to hospital discharge. 53 The UK OHCA outcome project, a prospective observational study involving all UK NHS ambulance services, reported that 28,729 patients were treated for OHCA by the 10 ambulance services in England in 2014 (53/100,000 population), with 7.9% surviving to hospital discharge. 2 Globally, estimates of OHCA outcomes vary across countries, with survival to hospital discharge rates of 7.6% in Europe, 6.8% in North America, 3% in Asia and 9.7% in Australia. 54

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest exerts a major burden on NHS resources (ambulance response, emergency treatment, post-resuscitation care, rehabilitation) and years of life lost, but treatment currently has a low chance of success.

Existing evidence

A Cochrane review55 identified a single randomised, placebo-controlled trial of intravenous (i.v.) adrenaline in OHCA (the search was conducted in December 2012). The Pre-hospital Adrenaline for Cardiac Arrest (PACA) trial,56 conducted by our co-investigators Judith Finn and Ian G Jacobs, was undertaken in Western Australia. The study aimed to enrol 5000 patients, but, at the time the study closed, only 601 patients had been randomised. The relatively small numbers led to the results having large uncertainty. The rate of ROSC (short-term survival) was higher in those receiving adrenaline [64/272 (23.5%) vs. 22/262 (8.4%) patients; OR 3.4, 95% CI 2.0 to 5.6], but there was no clear evidence of a benefit in survival to hospital discharge (long-term survival) [adrenaline arm, 11 (4.0%) patients, vs. placebo arm, 5 (1.9%) patients; OR 2.2, 95% CI 0.7 to 6.3]. Two of the survivors in the adrenaline arm, but none in the placebo arm, had a poor neurological outcome. In addition to the trial’s imprecision, interpretation of the findings is limited by a large number of post-randomisation exclusions (n = 67, 11%).

A second randomised study, conducted in Oslo, Norway, compared i.v. cannulation and injection of drugs (including adrenaline) with no i.v. cannula or drugs among 851 patients experiencing an OHCA. 57 The patients in the i.v. arm had better short-term survival rates [ROSC: i.v. arm, 165/418 (40%), vs. no i.v. arm, 107/433 (25%); OR 1.99, 95% CI 1.48 to 2.67]; however, there was no clear difference between arms in long-term survival outcomes {survival to hospital discharge: i.v. arm, 44/418 (10.5%), vs. no i.v. arm, 40/433 (9.2%); OR 1.16, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.82; favourable neurological outcome [measured using the Cerebral Performance Category (CPC) 1 or 2]: i.v. arm, 9.8%, vs. no i.v. arm, 8.1%; OR 1.24, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.98}. The increase in the rate of ROSC was seen mainly in the patients with initial non-shockable rhythms (asystole and PEA): 29% in the i.v. arm versus 11% in the no i.v. arm. The rate of ROSC was 59% in the i.v. arm, compared with 53% in the no i.v. arm, in those patients with an initial rhythm of VF/VT.

In the post hoc analysis of the i.v. versus no-i.v. trial, outcomes were examined according to whether or not a patient had actually received adrenaline. 58 Treatment with adrenaline (n = 367) was associated with a greater chance of being admitted to hospital (OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.9 to 3.4). However, long-term survival outcomes were worse, with reduced survival to hospital discharge [adrenaline arm, 24/367 (7%), vs. no adrenaline arm, 60/481 (13%); OR 0.5, 95% CI 0.3 to 0.8] and reduced neurologically intact (CPC 1 or 2) survival [adrenaline arm, 19/367 (5%), vs. no adrenaline arm, 57/481 (11%); OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.2 to 0.7]. These effects persisted after adjustment for confounding factors (VF, response interval, witnessed arrest, sex, age and tracheal intubation).

At the time of developing the Pre-hospital Assessment of the Role of Adrenaline Measuring the Effectiveness of Drug administration In Cardiac arrest 2 (PARAMEDIC2) trial, three large observational studies59–61 suggested that adrenaline may cause worse long-term outcomes. The largest observational study of adrenaline use in cardiac arrest involves 417,188 OHCAs in Japan. 59 In propensity-matched patients, use of adrenaline was associated with an increased rate of ROSC [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 2.51, 95% CI 2.24 to 2.80], but was also associated with a 1-month survival rate of approximately half that achieved among those not given adrenaline (aOR 0.54, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.68). In another observational study from the Osaka group in Japan,60 1013 (32.0%) of 3161 patients who were analysed received adrenaline. Those patients receiving adrenaline had a significantly lower rate of neurologically intact (CPC 1 or 2) 1-month survival than those not receiving adrenaline (4.1% vs. 6.1%, respectively; OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.98).

An analysis of registry data had shown reduced survival in those who received adrenaline; The North American ROC Epistry (n = 16,000) found an inverse association between adrenaline dose and survival to discharge (survival was > 20% for those not requiring adrenaline, and fell to < 5% for those requiring more than two doses). This finding persisted after adjustment for age, sex, EMS-witnessed arrest, bystander-witnessed arrest, bystander CPR, shockable initial rhythm, time from 911 call to EMS arrival, the duration of OHCA and study site. 38 This was similar to a previous analysis of the Swedish Registry (n = 10,000 patients; OR of long-term survival 0.43, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.66). 61

This creates the paradox of better short-term survival at the cost of worse long-term outcomes, in other words a ‘double-edged sword’. 62 However, observational studies are limited by the influence of confounding variables that may introduce bias, in particular the phenomenon known as resuscitation time bias, whereby an exposure is more likely to occur the longer the cardiac arrest continues. Because duration of resuscitation is strongly associated with worse outcome, this will bias the results towards a harmful effect of the exposure. 63 The importance of differences in analytical approaches and the way they control for resuscitation time bias is illustrated by the discordant findings from the analysis of the same data set, whereby one study shows benefit64 and the other demonstrates harm. 59

Mechanisms by which adrenaline may cause harm

There are a number of mechanisms by which adrenaline may cause harm. These can be considered under the following headings.

Reduced microvascular blood flow and exacerbation of cerebral injury

In animal models of cardiac arrest, adrenaline increases coronary perfusion pressure (which predicts restarting the heart), but impairs macrovascular and microvascular cerebral blood flow. Specifically, adrenaline was noted to reduce carotid blood flow65 and microvascular blood flow,29 causing worsening cerebral ischaemia. 66

Cardiovascular toxicity

In a further analysis of the Norwegian i.v. versus no i.v. trial,57 adrenaline increased the frequency of transitions from PEA to ROSC and extended the time window for ROSC, but at a cost of greater cardiovascular instability after ROSC, with a higher rate of re-arresting. These observations were consistent with other studies that linked adrenaline with ventricular arrhythmias and increased post-ROSC myocardial dysfunction. 67 In human studies with patients with sepsis68 or acute lung injury,69 beta-agonist stimulation was similarly linked to cardiovascular instability and reduced survival. 70 A systematic review of beta-blocker treatment in animal models of cardiac arrest found that fewer shocks were required for defibrillation; that myocardial oxygen demand was reduced; and that post-resuscitation myocardial stability improved, with less arrhythmia and improved survival. 71

Metabolic effects

Adrenaline causes lactic acidosis,72 which is associated with poor outcomes after cardiac arrest. 73,74 It also induces stress hyperglycaemia, which is also associated with poorer outcomes. 75

Immunomodulation and predisposition to infection

Infective complications, including bacteraemia and early-onset pneumonia, are common after OHCA, and are associated with worse outcomes. 76 The immune-modulatory effects of beta agonists have been well characterised and may reduce host defence against infection,77 which may contribute to an increased susceptibility to post-resuscitation sepsis.

Summary of effects

Use of adrenaline in cardiac arrest increases short-term survival (i.e. ROSC), but doubt remained about whether or not this translated into better long-term outcomes.

Rationale for intervention

Whether or not the practice of giving adrenaline is effective remained an important question that needed to be answered. Uncertainty about adrenaline has been raised by recent evidence59–61 suggesting that it may be harmful. Resolving this uncertainty was urgent, as adrenaline is used widely to treat cardiac arrests, and, if harmful, may be responsible for many avoidable deaths. There have been several precedents whereby treatments have been evaluated after years or decades of use and had been found to be ineffective or harmful, including pulmonary artery catheters in intensive care,78 beta agonists for acute respiratory distress syndrome69 and corticosteroids for head injury. 79 It was therefore possible that adrenaline for cardiac arrest might be a similar case.

The ILCOR appraised the evidence surrounding adrenaline use for OHCA in 201042 and again in October 2012. It concluded that there was an urgent need for randomised, placebo-controlled trials of adrenaline.

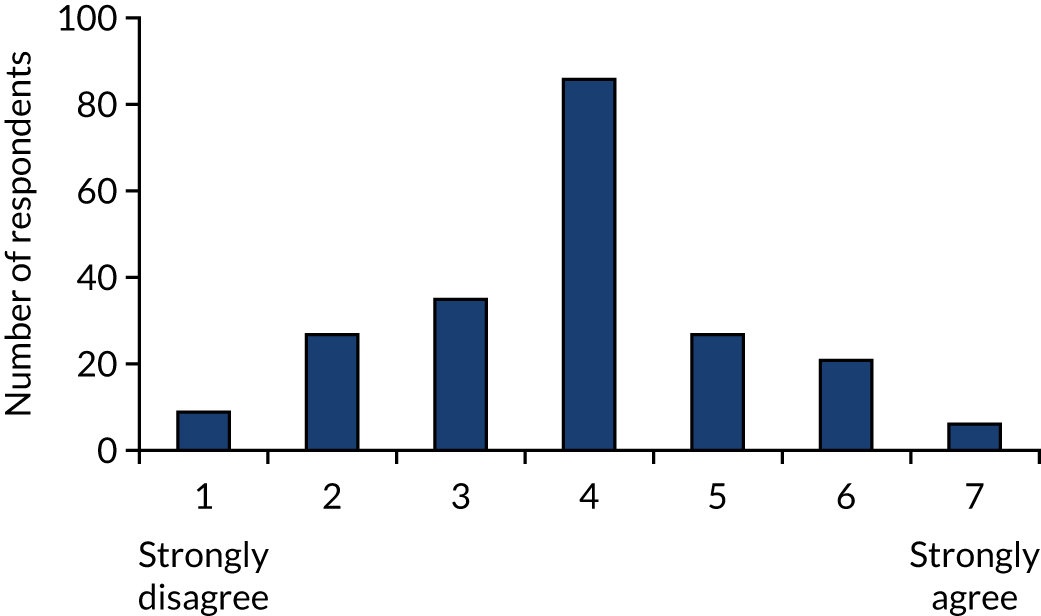

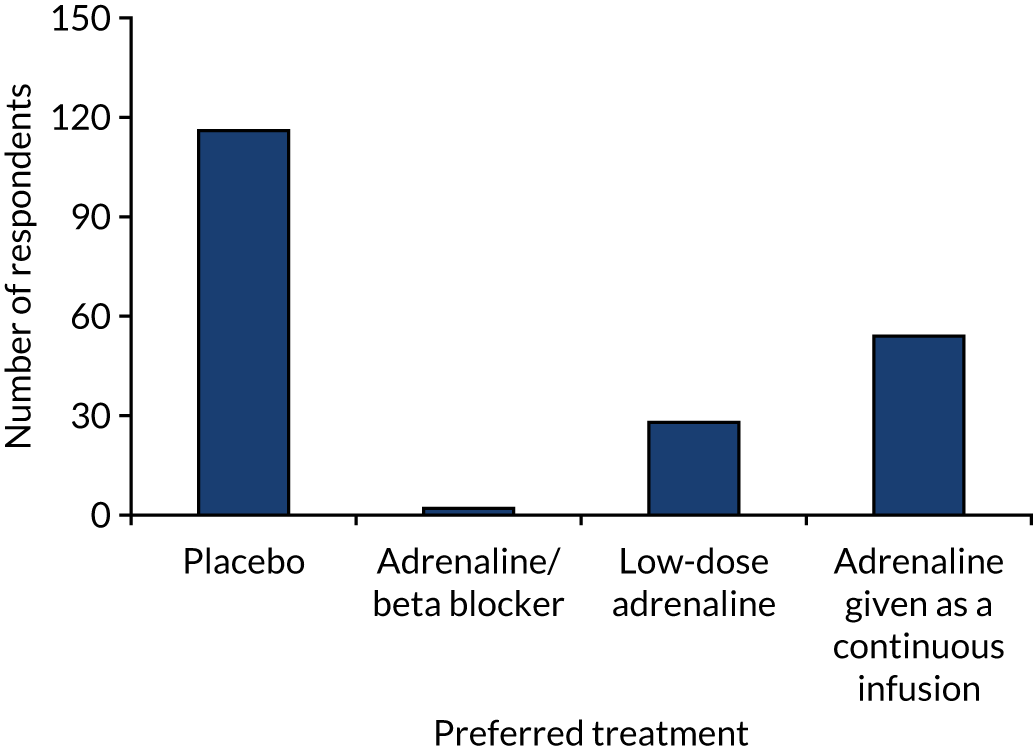

We conducted a written survey of 213 attendees (doctors, nurses, paramedics) of the Resuscitation Council (UK) Annual Scientific Symposium in September 2012 to assess the scientific and clinical communities’ current perspectives on the role of adrenaline in the treatment of cardiac arrest. Respondents expressed their agreement to a series of statements on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Respondents reported that adrenaline increased short-term survival [median score 6, interquartile range (IQR) 6–7], but disagreed that it improved long-term outcomes [median score 2 (IQR 2–3)]. The greatest uncertainty was around the balance of risks and the benefits of i.v. adrenaline (Figure 2). Respondents felt that the most pressing future research need for the NHS was a trial comparing adrenaline with placebo (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Perspectives of the UK clinical community on the role of adrenaline for the treatment of cardiac arrest. 80 Reprinted from Resuscitation, Vol. 108, Perkins GD, Quinn T, Deakin CD, Nolan JP, Lall R, Slowther A, et al. , Pre-hospital Assessment of the Role of Adrenaline Measuring the Effectiveness of Drug administration In Cardiac arrest (PARAMEDIC-2): trial protocol, pp. 75–81, Copyright 2016, with permission from Elsevier.

FIGURE 3.

Preferences of the UK clinical community. 80 Reprinted from Resuscitation, Vol. 108, Perkins GD, Quinn T, Deakin CD, Nolan JP, Lall R, Slowther A, et al. , Pre-hospital Assessment of the Role of Adrenaline Measuring the Effectiveness of Drug administration In Cardiac arrest (PARAMEDIC-2): trial protocol, pp. 75–81, Copyright 2016, with permission from Elsevier.

A trial addressing this question was timely, because of the recent publication of studies questioning the effectiveness of adrenaline, and calls for a large-scale randomised controlled trials to resolve this issue. There were no other completed, ongoing or planned trials in the ClinicalTrials.gov [https://clinicaltrials.gov/ (1 January 2012)] or controlled-trials.com (accessed 2012) databases. Moreover, research projects [e.g. the Prehospital Randomised Assessment of a Mechanical compression Device In Cardiac arrest (PaRAMeDIC) trial81 in 2010] had shown the feasibility of conducting large-scale OHCA trials in the UK. The learning from the PaRAMeDIC trial,81 undertaken by this group, helped to ensure efficient and successful recruitment.

The emerging data suggested that a number of experimental strategies could be considered, including comparing adrenaline with alpha 2 agonists, comparing adrenaline with beta blockade, lower-dose adrenaline or adrenaline as a continuous infusion. Preferences of the clinical community are summarised in Figure 3. The timing of adrenaline administration may also be important; however, this was primarily dependent on ambulance response times, which were difficult to control for in a randomised trial. We suggested that the most pressing need was for a definitive trial comparing standard-dose adrenaline (1 mg every 3–5 minutes) with placebo. Until there was clarity about the effect of adrenaline on long-term outcomes, the best comparator agent (placebo or standard-dose adrenaline) for trials of other agents remained unknown.

This randomised controlled trial of adrenaline had the support of key stakeholders, such as patient representatives, the College of Paramedics, the National Ambulance Services Medical Directors’ Group, the Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC), the Resuscitation Council (UK) and the British Heart Foundation.

Objectives

Primary objective

The primary objective of this trial was to determine the clinical effectiveness of adrenaline in the treatment of OHCA, measured as a primary outcome of 30-day survival.

Secondary objective

The secondary objectives of the trial were to evaluate the effects of adrenaline on survival and on the cognitive and neurological outcomes of survivors, and to establish the cost-effectiveness of using adrenaline.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

This was a pragmatic, randomised, allocation-concealed, placebo-controlled, parallel-group superiority trial and economic evaluation. Participants were randomised to either adrenaline (intervention) or placebo (control) in a 1 : 1 allocation ratio. Randomisation took place when a trial-trained paramedic opened an Investigational Medicinal Product (IMP) pack, which contained either 10 syringes of adrenaline (1 mg) or a matching placebo (0.9% saline). The primary outcome was survival to 30 days. Secondary outcomes focused on patient, clinical, resource and economic outcomes. Patients, clinical teams and those assessing patient outcomes were masked to the treatment allocation.

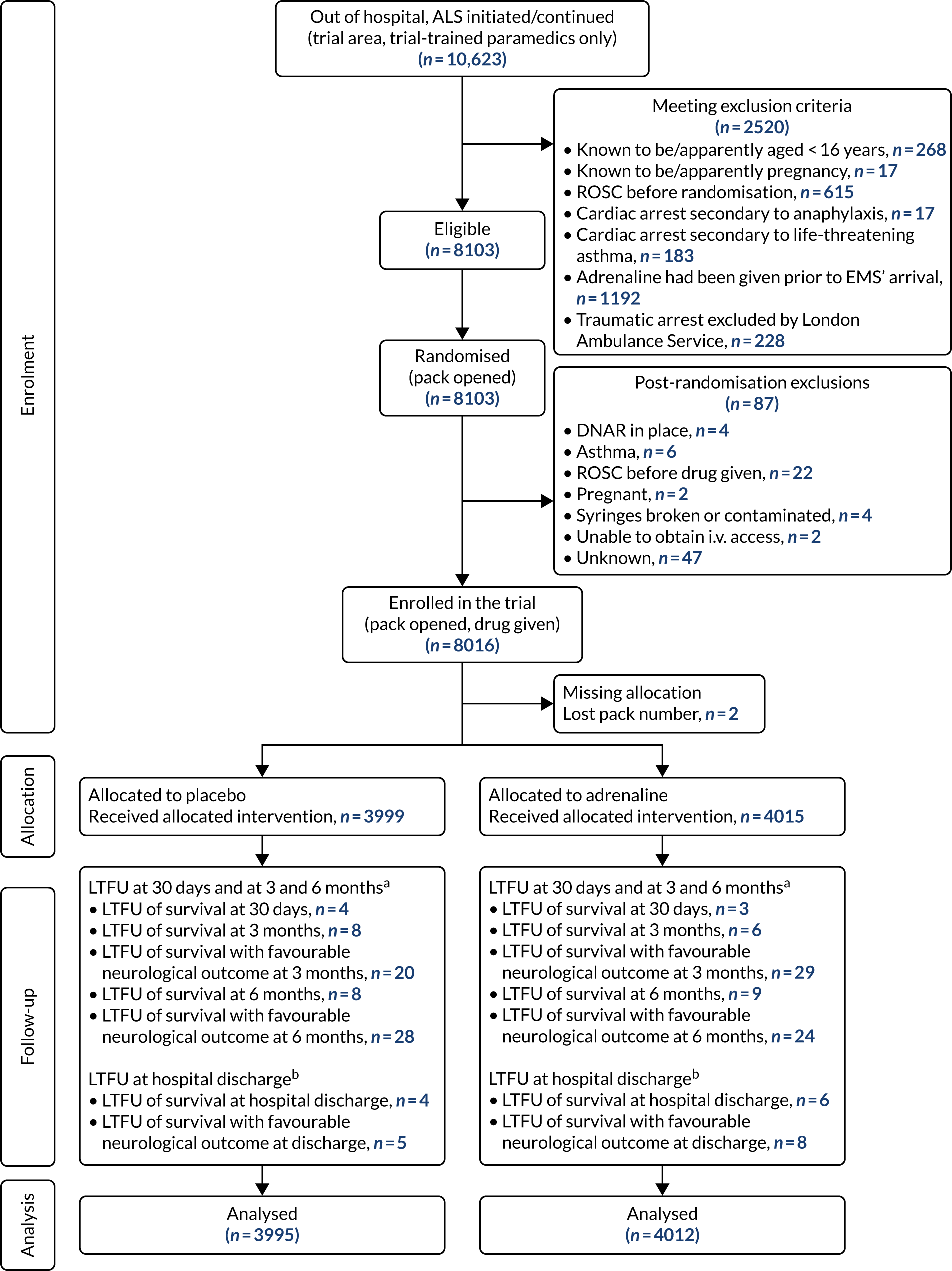

Figure 4 shows the planned flow of participants through the trial.

FIGURE 4.

Flow chart for PARAMEDIC-2 trial. 80 LTFU, lost to follow-up. Reprinted from Resuscitation, Vol. 108, Perkins GD, Quinn T, Deakin CD, Nolan JP, Lall R, Slowther A, et al. , Pre-hospital Assessment of the Role of Adrenaline Measuring the Effectiveness of Drug administration In Cardiac arrest (PARAMEDIC-2): trial protocol, pp. 75–81, Copyright 2016, with permission from Elsevier.

Pilot trial

An internal pilot was run to test that the components of this trial worked together. This pilot ran for 6 months. The data from this were included in the main trial. During the pilot, we measured recruitment rate and compliance with the allocated intervention, and checked that the approach to data collection and follow-up worked effectively. The pilot phase ran seamlessly into the main trial. The results of the pilot trial were reviewed with the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) and representatives from the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme, specifically considering the achievement of the following targets:

-

25% of ambulance staff trained [i.e. the majority (80%) of participating staff at 25% of stations]

-

181 patients recruited within 6 months of first randomisation

-

data available on primary outcome – > 98%

-

proportion of patients who are alive agreeing to follow–up – > 75%

-

reconcile IMP packs with participants enrolled in the trial

-

review of the approach to inform patients and relatives of trial participation

-

review of feasibility to collect secondary outcomes.

All pilot objectives were achieved, and the TSC approved continuation to the main phase of the trial on 7 May 2015.

Changes to trial design

There were no substantial changes to the trial design. Table 1 lists all amendments to the trial and details of the changes made. Reasons for changes to the trial design describes the reason for the change in exclusion criteria (amendment 6).

| Date of amendment | Number | Document(s) affected | Changes | New version number; date | Date approved by MHRA | Date approved by REC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 August 2018 | 21 | Unblinding response form | Unblinding response form updated | v2.0; 7 August 2018 | N/A | 14 August 2018 |

| Unblinding information sheet | Unblinding information sheet updated and separated into three versions (non-survivor, survivor with poor neurological outcome, and survivor with good neurological outcome) | v2.0; 2 August 2018 | ||||

| 25 July 2018 | 20 | Protocol |

|

v6.0; 25 July 2018 | N/A | 13 November 2018 |

| 26 March 2018 | 19 | Protocol |

|

v5.0; 28 March 2018 | N/A | 3 April 2018 |

| Unblinding information sheet | New document to be able to respond to requests for unblinding | v1.0; 28 March 2018 | ||||

| Unblinding response form | New document to be able to respond to requests for unblinding | v1.0; 28 March 2018 | ||||

| Unblinding cover letter for response form | New document to be able to respond to requests for unblinding | v1.0; 28 March 2018 | ||||

| Confirmation of treatment letter | New document to be able to respond to requests for unblinding | v1.0; 28 March 2018 | ||||

| 28 February 2018 | 18 | Protocol | Section 2.6.15.1 added to describe the process for responding to trial participation enquiries | v4.0; 28 February 2018 | N/A | 28 February 2018 |

| Cover letter (patient enrolled) | New document produced to be able to respond to trial participation enquiries | v1.0; 28 February 2018 | ||||

| Cover letter (patient not enrolled) | New document produced to be able to respond to trial participation enquiries | v1.0; 28 February 2018 | ||||

| Trial participation information sheet | New document produced to be able to respond to trial participation enquiries | v1.0; 28 February 2018 | ||||

| 13 March 2017 | 17 | N/A | Addition of hospital (Medway) | N/A | N/A | 17 March 2017 |

| 23 January 2017 | 16 | N/A | Addition of general practice surgeries as sites to allow mRS data collection under HRA approval | N/A | N/A | 23 January 2017 |

| 13 December 2016 | 15 | N/A | Addition of two hospital sites (Luton and Dunstable, and Bedford) | N/A | N/A | 20 December 2016 |

| 24 November 2016 | 14 | N/A | Translations and back translations of patient information sheet, consent forms and cover letters into Arabic, Gujarati, Hindi, Polish, Punjabi, Urdu and Welsh | N/A | N/A | 14 December 2016 |

| 2 November 2016 | 13 | GP letter (mRS) | New letters for GPs to collect mRS data (two versions – one for consent and one for passive follow-up) | v1.0; 1 November 2016 | N/A | 18 November 2016 |

| 21 October 2016 | 12 | Protocol | Addition of quality of CPR data collection | v3.0; 12 October 2016 | 27 October 2016 | 31 October 2016 |

| 1 June 2016 | 11 | Protocol |

|

v2.0; 4 May 2016 | N/A | 20 June 2016 |

| Patient information sheets |

|

v2.0; 8 April 2016 | ||||

| Patient information sheets cover letters | Separate versions created for patient and legal representative and approach in hospital or after hospital discharge | v2.0; 8 April 2016 | ||||

| Consent forms | Wording updated to include reference to Health and Social Care Information Centre (former name of NHS Digital) and Office for National Statistics | v2.0; 8 April 2016 (note that the legal representative consent form was amended to v2.1 because of a typographical error) | ||||

| 28 October 2015 | 10 | N/A | Addition of four hospitals (Burton Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Western Sussex Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust, and Countess of Chester Hospital NHS Foundation Trust) | N/A | N/A | 6 November 2015 |

| 28 October 2015 | 9 | GP letter | GP letter about survival and mRS scores for non-responders | v1.0; October 2015 | N/A | 9 November 2015 |

| 8 September 2015 | 8 | IMP dossier | Revision of IMP dossier to extend IMP shelf life to 12 months | 4.0 | 15 October 2015 | 9 November 2015 |

| 10 July 2015 | 7 | N/A | Addition of Royal Surrey County Hospital | N/A | N/A | 23 July 2014 |

| 24 June 2015 | 6 | Protocol | Addition of ‘cardiac arrest secondary to life-threatening asthma’ as exclusion criterion | 1.1; 24 June 2015 | 13 July 2015 | 8 July 2015 |

| 11 May 2015 | 5 | Poster for public ‘10 Facts about the PARAMEDIC2 trial’ | New document to raise public awareness of trial | 1.0; 12 May 2015 | N/A | 22 May 2015 |

| Leaflet for general practice surgeries | New document to raise public awareness of trial | 1.0; 12 May 2015 | ||||

| Communication strategy | Revised document | 11 May 2015 | ||||

| 3 December 2014 | 4 | N/A | Clarification that prisoners would not be excluded from the trial | N/A | N/A | 4 December 2014 |

| 8 October 2014 | 3 | N/A | Addition of English hospitals | N/A | N/A | 8 October 2014 |

| 4 September 2014 | 2 | N/A | Addition of Welsh hospitals: Bronglais General Hospital, Glan Clwyd Hospital, Glangwili General Hospital, Morriston Hospital, Nevill Hall Hospital, Prince Charles Hospital, Princess of Wales Hospital, Prince Philip Hospital, Royal Glamorgan Hospital, Royal Gwent Hospital, University Hospital of Wales, Withybush General Hospital, Wrexham Maelor Hospital, Ysbyty Gwynedd, Singleton Hospital, West Wales General Hospital and Llandough Hospital | N/A | N/A | 9 September 2014 |

| 27 August 2014 | 1 | Patient information sheet | Updated following feedback from CAG |

|

N/A | 10 October 2014 |

| Consent forms (patient and legal representative) | Updated following feedback from CAG |

|

||||

| Cover letter (patient and legal representative) | Updated following feedback from CAG |

|

||||

| Poster for public ‘OK to Ask’ | New document to raise public awareness of trial |

|

||||

| REC form Part C | WAST principal investigator corrected to Nigel Rees | N/A |

Reasons for changes to the trial design

Amendment 4

This amendment updated the Research Ethics Committee (REC) application to confirm that participants who were prisoners or young offenders in the custody of Her Majesty’s Prison Service or who were offenders supervised by the probation service in England or Wales would be included in the trial. The rationale for not excluding prisoners was as follows:

-

There may be practical difficulties in identifying a prisoner in an emergency situation.

-

Attempting to establish if someone is a prisoner may lead to confusion and delay of treatment, which may cause harm.

-

Prisoners are not being recruited to the trial because of their position as prisoners, they are being recruited because of their interaction with the NHS in a cardiac arrest situation.

-

It would be unethical to deny prisoners the rights to the potential benefits of the trial.

Amendment 6

Cardiac arrest secondary to life-threatening asthma was added as a trial exclusion criterion following amendment 6 on 24 June 2015. Although the published literature points to there being equipoise about the use of i.v. adrenaline in asthma,82–85 there is evidence that adrenaline may be beneficial for patients with anaphylaxis. The rationale for the change was that, during the pilot trial, ambulance staff were concerned about potential overlap between the presentation of asthma and anaphylaxis (both may present with bronchospasm). Therefore, the Trial Management Group (TMG) felt that the safest option was to extend the exclusion for anaphylaxis to include cardiac arrests suspected to have been caused by asthma.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Patients were eligible if both the following criteria were met:

-

cardiac arrest in an out-of-hospital environment

-

advanced life support initiated and/or continued by an ambulance service clinician.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria at the time of arrest were as follows:

-

known or apparent pregnancy

-

known to be or apparently aged < 16 years

-

cardiac arrest caused by anaphylaxis or life-threatening asthma

-

adrenaline given prior to arrival of ambulance service clinician.

In London Ambulance Service, traumatic cardiac arrests were also excluded, in accordance with local protocols.

Trial setting

Recruitment took place in five NHS ambulance services in the UK (London Ambulance Service NHS Trust, North East Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust, South Central Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust, West Midlands Ambulance Service University NHS Foundation Trust and Welsh Ambulance Service NHS Trust). These ambulance services serve a mix of urban and rural locations in England and Wales, covering a population of 24 million people. They collectively attend ≈32,000 cases of cardiac arrest each year; resuscitation is attempted or continued by ambulance staff in approximately 45% of these cases.

The ambulance services are activated through a central emergency call number (999, 112 or 111), which directs the caller to the geographically relevant emergency operations and dispatch centre. Calls are received and processed by trained NHS ambulance dispatch staff. Dispatch staff use one of two dispatch support systems: NHS Pathways or Advanced Medical Priority Dispatch System. Cases identified as a cardiac arrest are assigned the highest priority response. At the time of the trial, ambulance services were expected to provide a defibrillation-capable response within 8 minutes for 75% of these cases. There was an expectation of having an ambulance on scene within 19 minutes in 95% of cases. A typical first response could be a community first responder, a rapid response vehicle (e.g. car, motorbike or bicycle) or an air/land ambulance. Clinically trained staff, such as paramedics or emergency medical technicians, typically attend cardiac arrests. They are often supported by emergency care assistants. Paramedics can deliver advanced life support (ALS) interventions (including advanced airway management and i.v. drugs) and, after trial-specific training, were able to recruit patients to the trial. Technicians, emergency care assistants and many community responders dispatched by the NHS ambulance service can deliver CPR and defibrillation, and some use supraglottic airways. When ambulance staff arrive at a cardiac arrest, one of the first steps is for them to assess the appropriateness of a full resuscitation attempt. If there is unequivocal evidence of death (major traumatic injuries, putrefaction, rigour mortis, post-mortem staining, etc.) NHS guidelines86 allow resuscitation to be withheld. Other situations in which resuscitation may be withheld are when a patient has a ‘do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation’ instruction, if the patient is in asystole, if no bystander CPR has been performed or if > 15 minutes have elapsed since the time of collapse. 87 Ambulance services follow common national guidelines for resuscitation from the Resuscitation Council UK guidelines,86 which follow those provided by the European Resuscitation Council. 88 The overall UK rate of survival to discharge for all cases of OHCA for which resuscitation is attempted is 7.9%. 89

Trial intervention

Patients were enrolled in the trial by the attending ambulance service clinicians, who determined whether or not a resuscitation attempt was appropriate (according to the JRCALC guidelines87), and, if it was, whether or not the patient was eligible. Patients who met the eligibility criteria were randomised to the trial.

Patients received resuscitation according to the Resuscitation Council (UK) and JRCALC ALS guidelines. 86 All standard ALS interventions were provided, including chest compression, defibrillation and advanced airway management, as required, with the exception that standard adrenaline was substituted with trial IMP drawn from a single trial treatment pack. Vehicles also carried their standard supply of adrenaline, for use only with ineligible patients.

If the patient reached the point in the resuscitation protocol where pharmacological treatments were indicated, they were randomly assigned to receive either parenteral adrenaline or saline placebo by the opening of a trial drug pack. Each treatment pack contained 10 × 3-ml prefilled syringes, with each syringe containing either 1 mg of adrenaline (intervention) or 0.9% saline (control). All trial drug packs were labelled with a unique trial pack number and in accordance with EudraLex Volume 4 Annex 13 requirements. 90 The adrenaline and placebo packs and syringes were identical in appearance; therefore, clinicians, patients and trial personnel were unaware of whether any specific pack contained adrenaline or placebo.

Single doses of adrenaline or saline were administered every 3–5 minutes by an i.v. or intraosseous route. Clinicians were instructed to use only one treatment pack per patient (10 × 3-ml syringes). Treatments were continued until a sustained pulse was achieved, resuscitation was discontinued or care was handed over to the clinician at the receiving hospital.

Treatment after admission to hospital was not specified in the trial protocol, but was informed by national guidelines,91 which covered targeted temperature management, haemodynamic and ventilator criteria and prognostication.

Randomisation

As recruitment took place in an emergency situation, telephone or internet randomisation was impractical; therefore, the trial used a system of pre-randomised treatment packs. The trial IMP was packaged in numbered treatment packs. The pre-randomised sequence was prepared by the programmers at the Warwick Clinical Trials Unit (WCTU). The randomisation sequence was computer generated by the stratified randomisation method with concealed assignment, using ambulance service as a strata, with an allocation ratio of 1 : 1.

Treatment packs were supplied to each ambulance service in a central location, and were distributed from there to participating ambulance stations and vehicles. When ambulance service personnel identified an eligible patient, randomisation was achieved by opening one of the packs carried in the vehicle attending the arrest.

Post-randomisation withdrawals and exclusions

There were three main sources of post-randomisation withdrawal and exclusions. The first was when, between randomisation (opening the drug pack) and administering the trial intervention, a patient was identified as ineligible. Examples of this include when a patient achieved ROSC, when a patient was confirmed to have died or when a trial exclusion became known to the ambulance clinicians before drug administration. This group would not receive vasopressor drugs in clinical practice. No follow-up data were collected on this group of patients and they were identified in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram as post-randomisation exclusions.

The second situation is when, after drug administration, it subsequently became known that the patient was ineligible for the trial. An example of this would be discovering in hospital that the cause of the cardiac arrest was anaphylaxis. This group of patients would be exposed to the vasopressor drugs in clinical practice, as it is not until after drug administration that the exclusion is discovered. This group of patients were followed up in the normal manner and included in the intention-to-treat analysis.

The third scenario is when a patient or their legal representative withdrew their consent for ongoing data collection. This group of patients were eligible for and received the trial intervention, but incomplete data were obtained on their long-term outcomes. This group of patients were included in the intention-to-treat analysis, up until the point of withdrawal. The information sheet explained the trial and the data that were collected. The consent form separated out the different data that were collected, and gave the patient the option to decline. NHS records were continually used unless the patient explicitly refused permission for this, as were tracking of the patients via NHS Digital to determine survival to 12 months post cardiac arrest.

In the rare situation in which a patient had neither consented to nor refused follow-up, they were not included in the face-to-face follow-up, but data collection from NHS records and in-hospital data sets continued.

Blinding

Methods for ensuring blinding

The packaging and the labelling of the IMP packs did not reveal which IMP was being used; therefore, the patient, attending clinicians, hospital treating team, research paramedics and trial administration team were masked to treatment allocation. Only the statistician was able to link the IMP pack number to the allocation of adrenaline or placebo.

Methods for unblinding the trial

The chief investigator retained the right to break the code for serious adverse events (SAEs) that were unexpected and suspected to be causally related to an investigational product, and that potentially required expedited reporting to regulatory authorities. The chief investigator unblinded if requested to do so by a coroner as part of a death enquiry. In exceptional circumstances, the chief investigator also considered requests for unblinding from patients or, if they lacked capacity, family members/next of kin. In this scenario, the trial statisticians made the unblinding on the chief investigator’s request and the chief investigator was informed accordingly of the allocation. This occurred only if the request was made after the benefits and harms of disclosing this information to them had been discussed. Otherwise, treatment codes (IMP pack number) were broken only for the planned interim analyses of data by the statistician at the request of the DMC.

Methods for unblinding the trial: after trial completion

Requests for unblinding of treatment allocation were received (either from survivors or from the next of kin of trial participants who were deceased) after completion of the trial. When these requests were received, the PARAMEDIC2 trial office sent the enquirer (on behalf of the ambulance services) an information sheet about unblinding and a response form for completion if they wished to continue with unblinding after having read the information provided. Once a completed response form was received, requesting unblinding, the PARAMEDIC2 trial office responded, once checks had been performed to verify the case details, to confirm the treatment allocation on behalf of the ambulance services, with ambulance service contact details for further queries.

Outcome measures

Efficacy

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was survival to 30 days post cardiac arrest.

Secondary outcomes

-

Survived event (sustained ROSC, with spontaneous circulation until admission and transfer of care to medical staff at the receiving hospital).

-

Survival to hospital discharge (the point at which the patient is discharged from the hospital acute care unit, regardless of neurological status, outcome or destination) and to 3, 6 and 12 months.

-

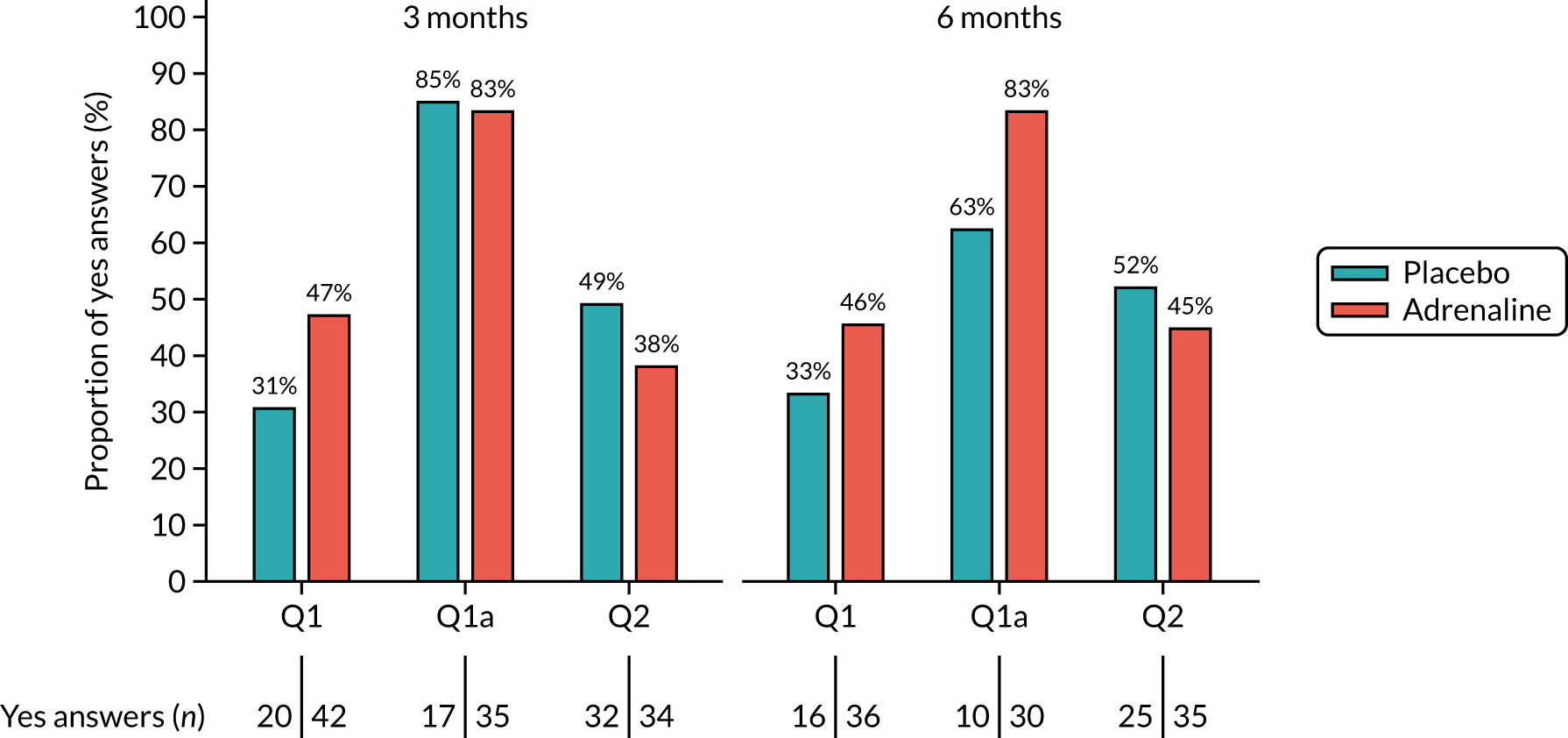

Neurological outcome (mRS) at hospital discharge and at 3 and 6 months [assessed at discharge using the Rankin Focused Assessment (RFA), and completed at 3 and 6 months via the simplified modified Rankin Scale questionnaire (smRSq)].

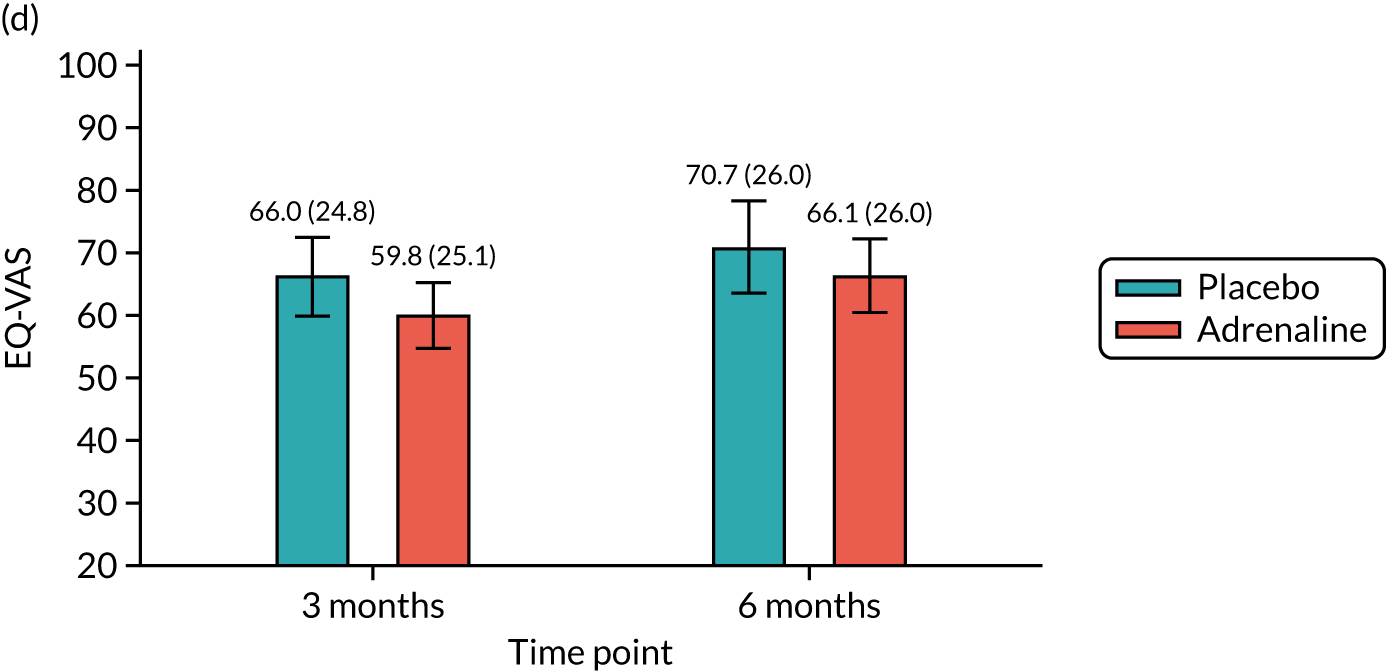

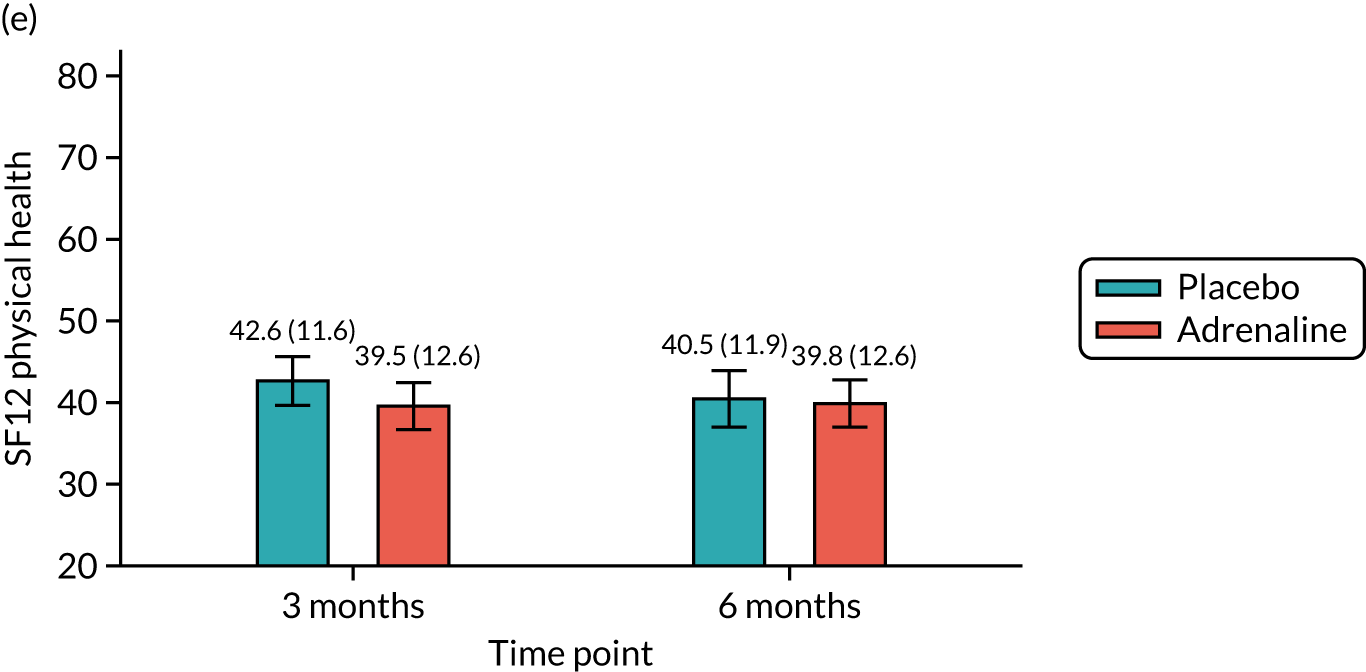

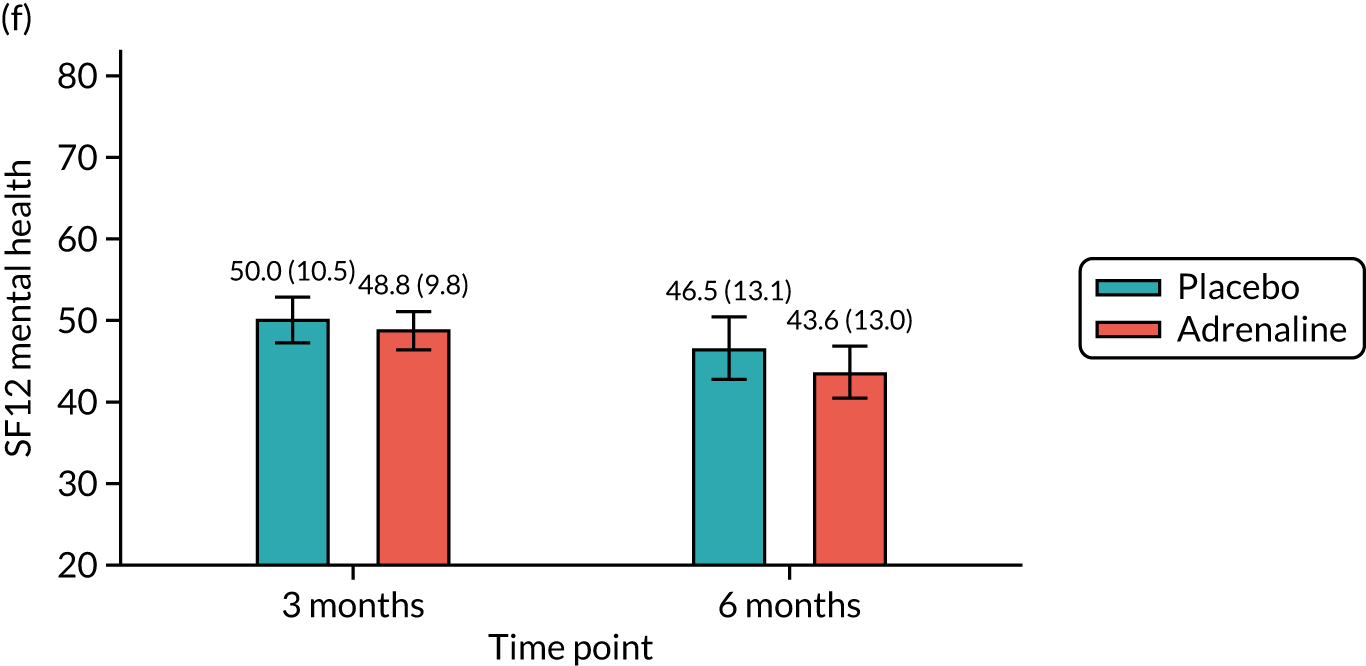

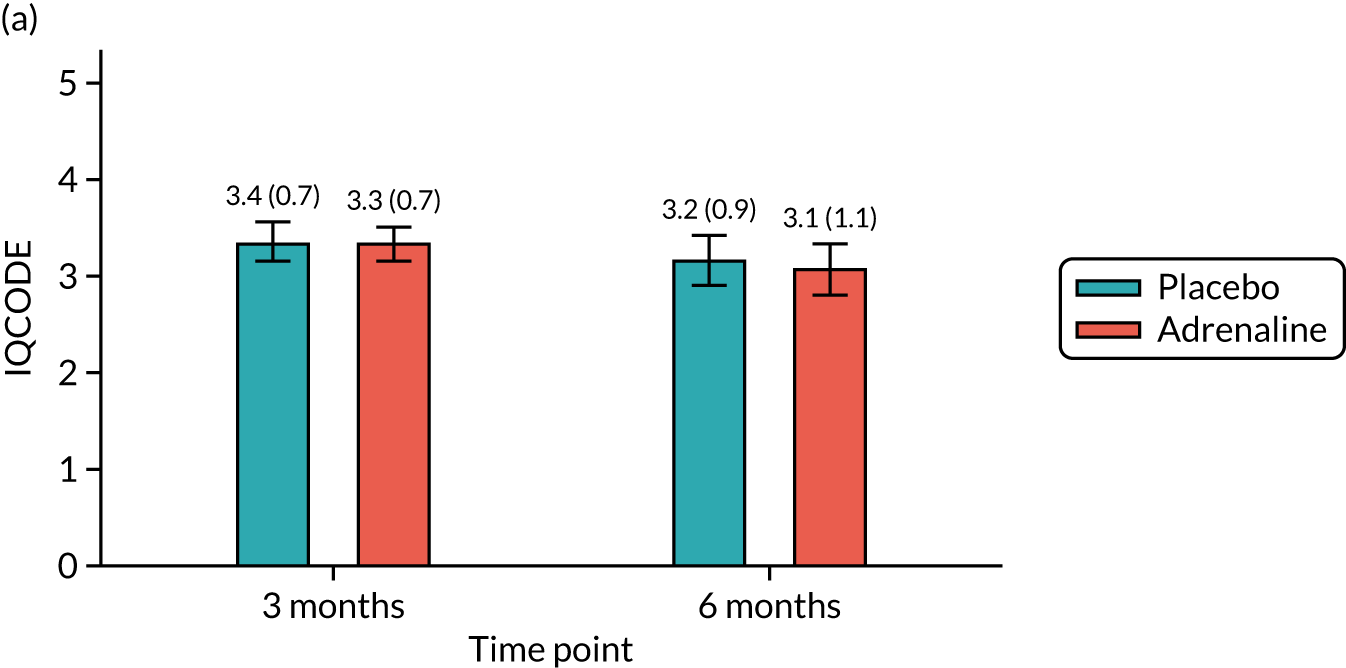

-

Neurological outcomes [assessed using the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) and ‘Two Simple Questions’] at 3 and 6 months.

-

Health-related quality of life at 3 and 6 months [assessed using the Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12) and the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)].

-

Cognitive outcome at 3 months [assessed using the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)].

-

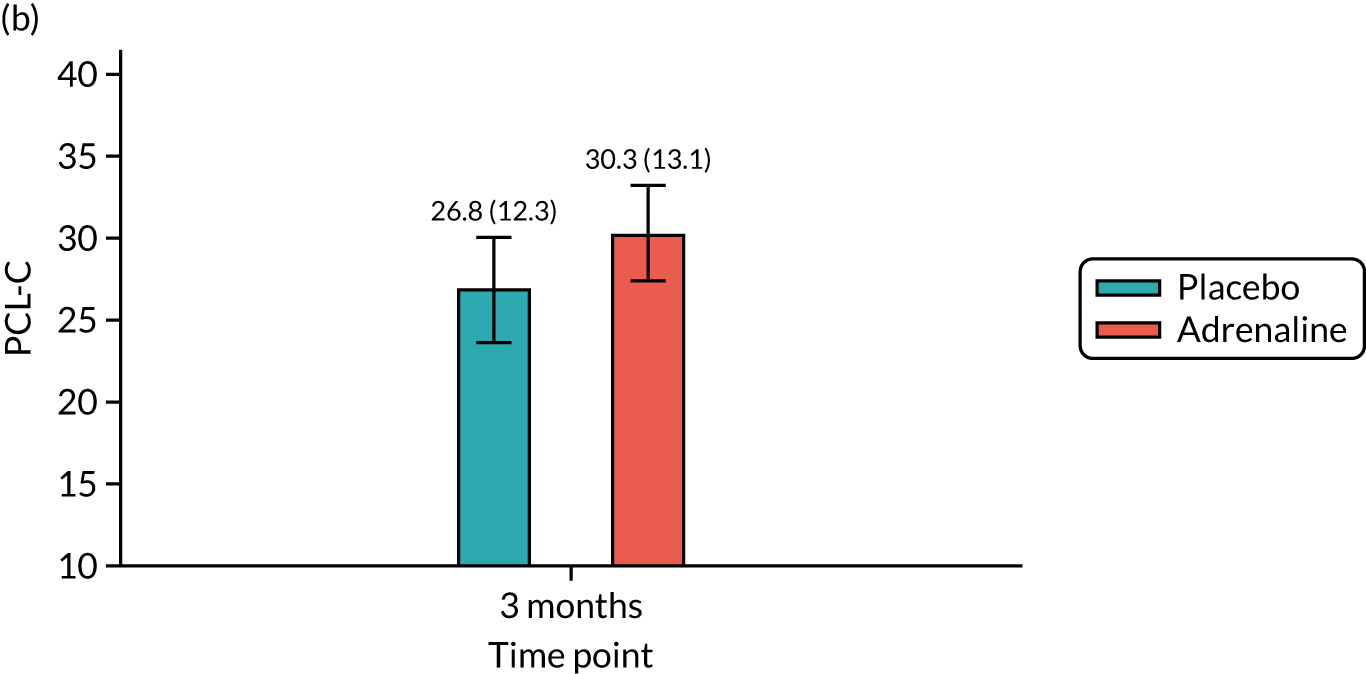

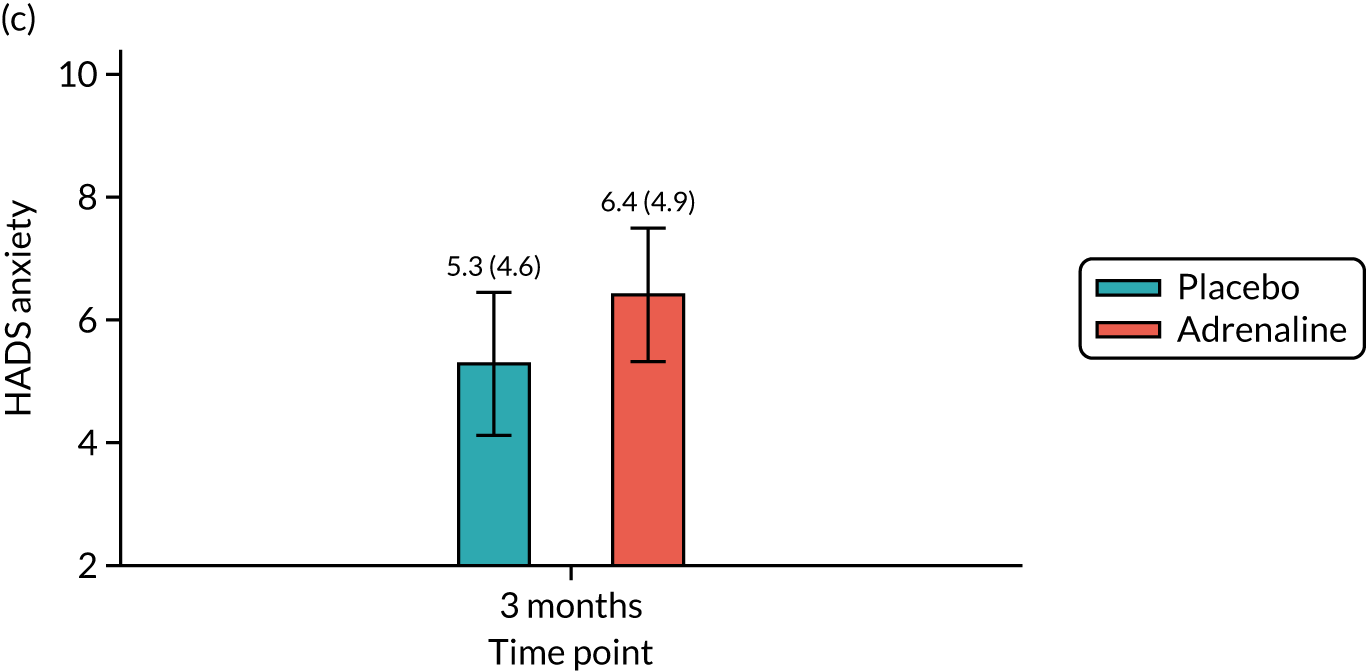

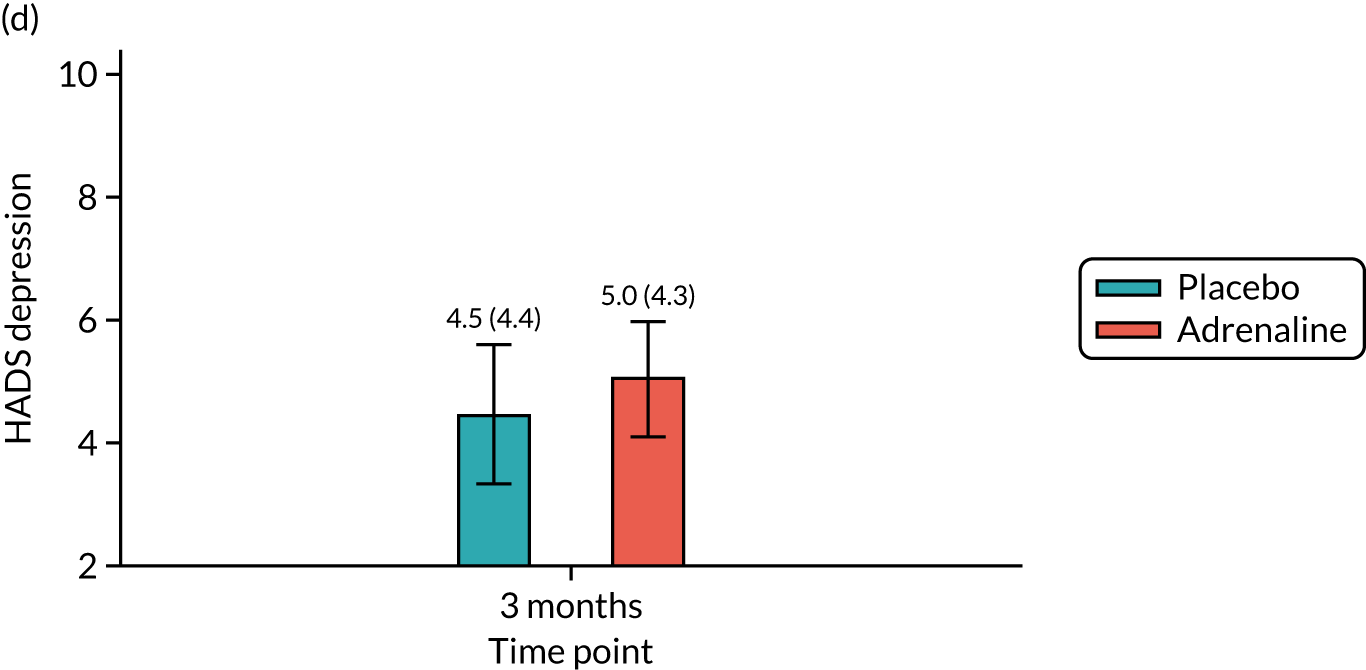

Anxiety and depression at 3 months [assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)].

-

Post-traumatic stress at 3 months [Post-traumatic stress disorder Checklist – Civilian Version (PCL-C).

-

Hospital length of stay.

-

Intensive care unit length of stay.

The outcomes defined by the Utstein convention for reporting outcomes from cardiac arrest92 were reported.

Rationale for outcome measures

The mRS was administered at hospital discharge and at 3 and 6 months. The mRS was selected instead of the CPC as it is more sensitive to detecting mild cognitive impairment. It can be reliably extracted from medical records and is a predictor of long-term survival. There was emerging international consensus (Utstein 2012/1393) that the mRS should be the primary measure of neurological outcome in cardiac arrest trials. The mRS is a seven-point scale ranging from mRS 0 (no symptoms) to 6 (dead). The RFA was chosen as a framework for assessing the mRS score at discharge, as this could be completed using a variety of sources of information, such as a patient assessment, via relatives or hospital staff or using hospital notes, and has been shown to have high inter-rater reliability. 94 The smRSq95 was used to collect the mRS score at 3 and 6 months, as this could be easily self-completed by the patient or legal representative. The spectrum of impairment of health-related quality of life following cardiac arrest includes memory and cognitive dysfunction, affective disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). 96 The SF-12 is a standard quality-of-life measure that is short and easy to complete. In addition, the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire was used as a health utility measure for the health economic analysis. Cognitive function was assessed using the MMSE. 97 The IQCODE and the ‘Two Simple Questions’ tool98 formed supplementary assessments of cognitive function. The PCL-C99 is a 17-item self-administered questionnaire measuring the risk of developing PTSD and had been used in previous studies as a good surrogate for the clinical diagnosis of PTSD, which requires a face-to-face interview by a suitably trained professional. The HADS is a 14-item self-administered questionnaire that had been previously used successfully to measure affective disorders in cardiac arrest survivors. 100 Two of these measures (PCL-C and HADS) were used as part of a multicentre follow-up for people surviving a critical illness (Intensive Care Outcome Network study);101 the people from this study were used as a reference population.

Health economics

Primary economic outcome

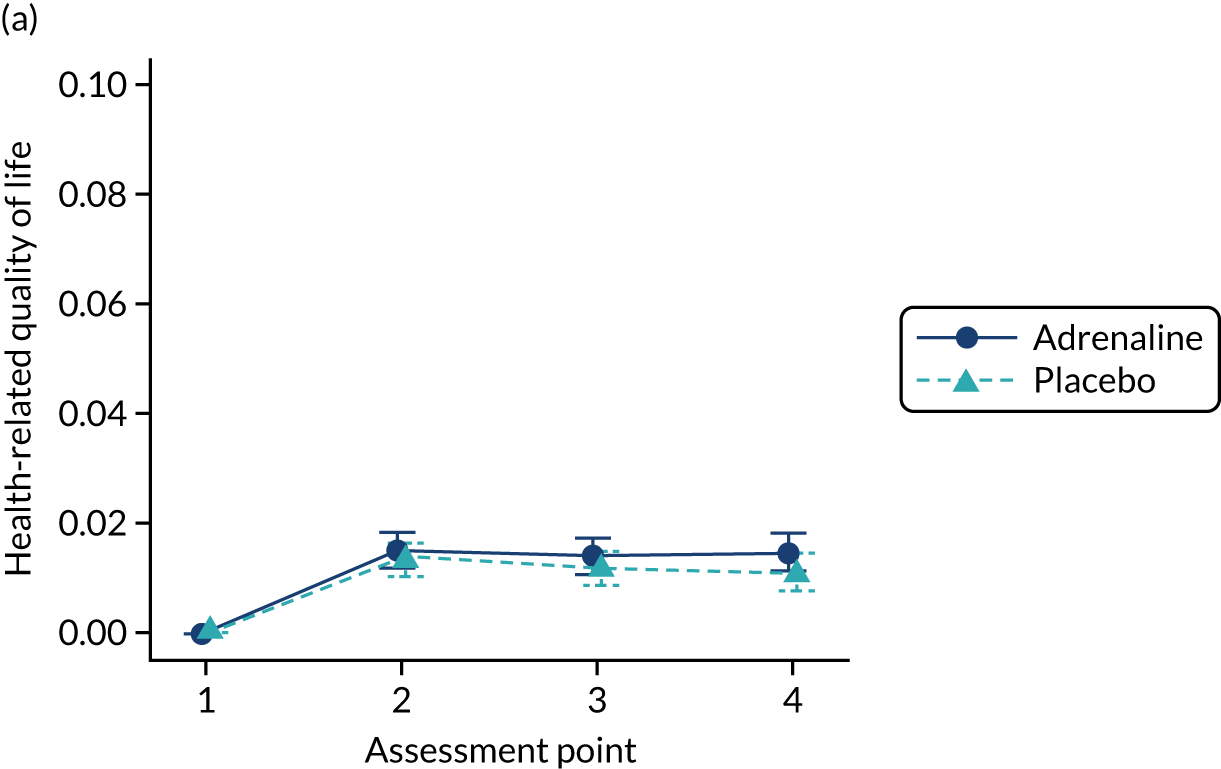

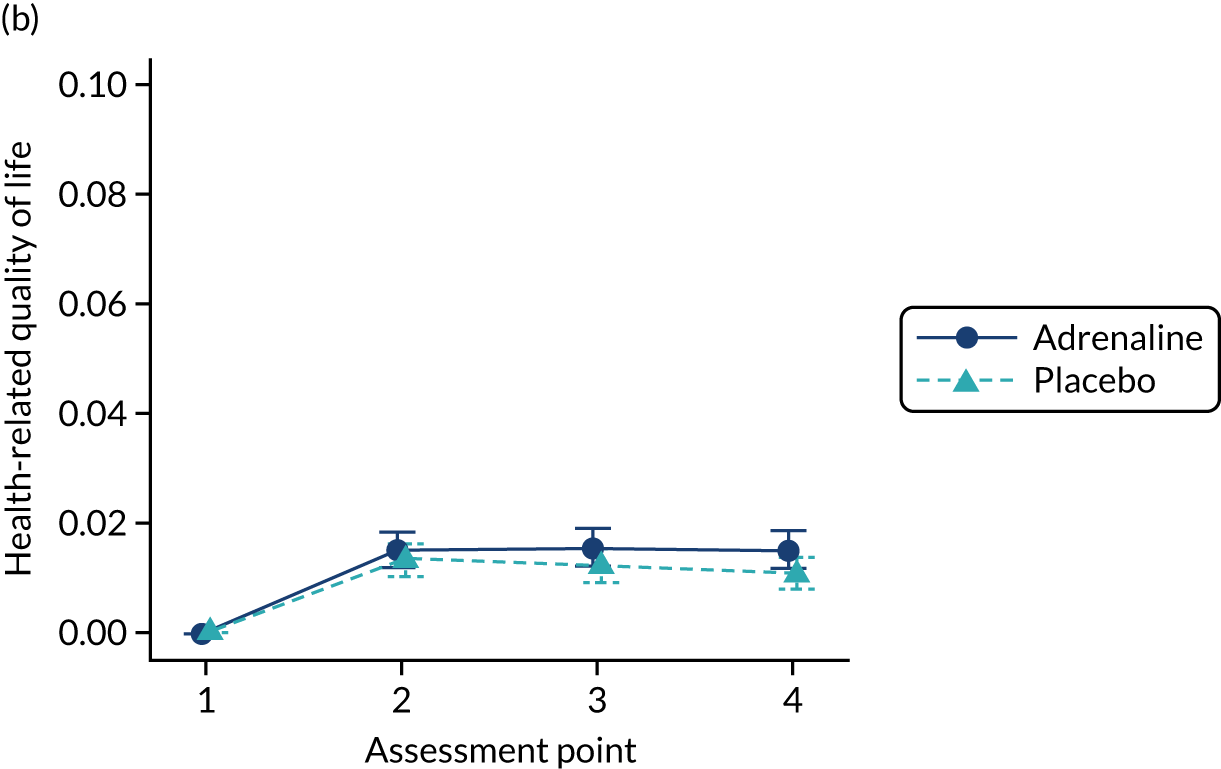

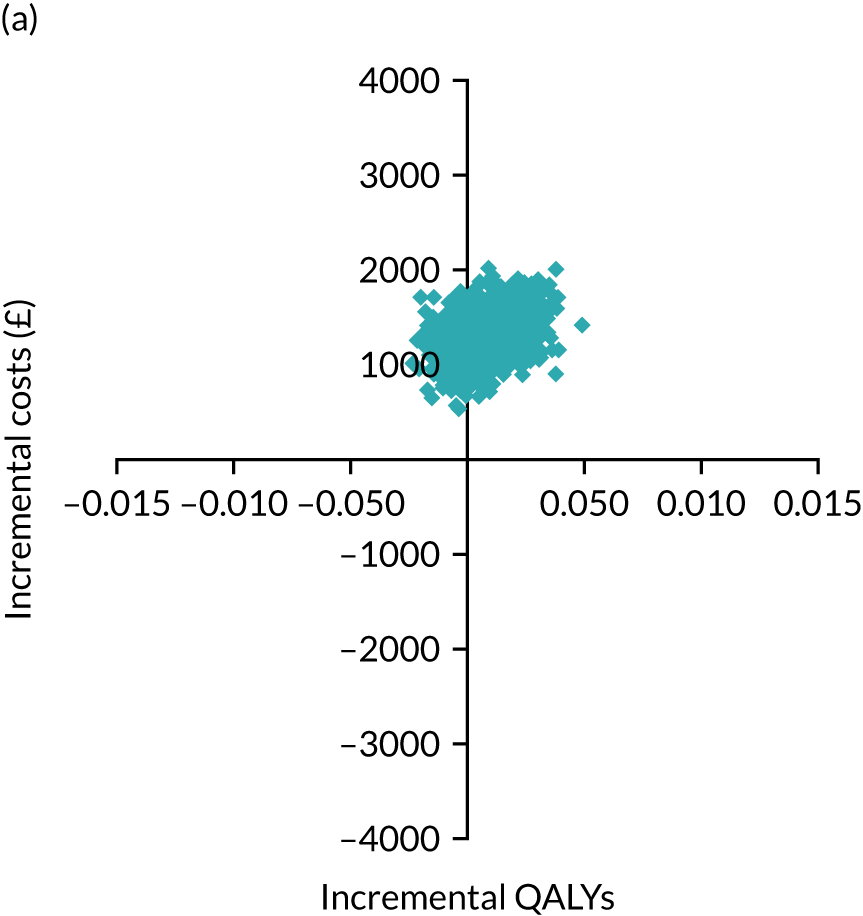

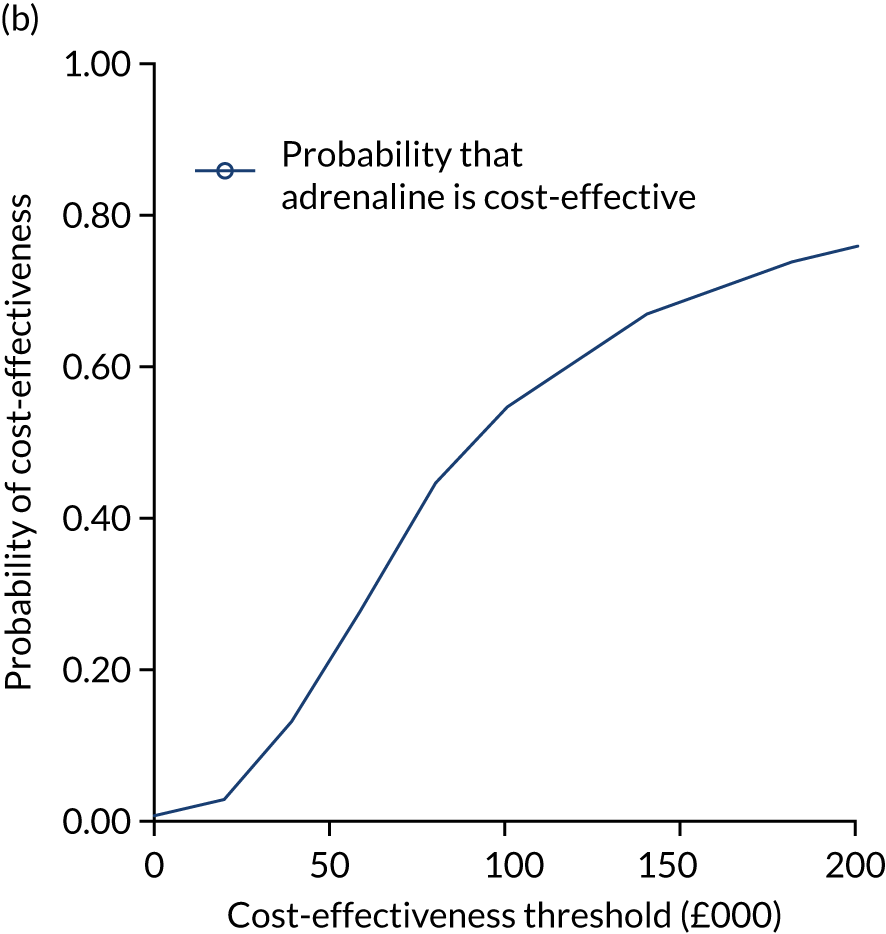

The primary economic outcome was the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained with use of adrenaline compared with the incremental cost per QALY gained with use of placebo from the perspective of the NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) over a 6-month time horizon. QALYs were calculated using area-under-the-curve methods, assuming linear interpolation between baseline utility (set to zero) and utility values derived from a combination of mRS and EQ-5D-5L assessments at hospital discharge and at 3 and 6 months post randomisation.

Secondary economic outcomes

-

Incremental cost per QALY gained from the perspective of the NHS and PSS with 1-year and lifetime (via decision-analytic modelling) time horizons.

-

Incremental cost per unit increase in the proportion surviving to 6 months post cardiac arrest, estimated from an NHS/PSS perspective.

-

Incremental cost per unit increase in the proportion surviving with good neurological outcome at 6 months post cardiac arrest, estimated from an NHS/PSS perspective.

-

Cost of critical care stay, cost of hospital stay, use of NHS and PSS resources after discharge and broader resource use after discharge. Resource use and costs were estimated over the 6-month period from randomisation/cardiac arrest event onwards.

Sample size

Incidence of primary outcome

Most existing data refer to survival to hospital discharge rather than survival to 30 days, but as most mortality will occur in the first few days after cardiac arrest, we expect these two measures to be very similar. Estimates of long-term survival of patients who receive adrenaline during a resuscitation attempt vary between about 3.5% and 12%. From national data for England, overall survival to hospital discharge of patients for whom resuscitation is attempted is 7%. 89 However, this will include a small number of patients who achieve ROSC immediately and would not receive adrenaline, and hence would not be recruited to the trial. As these patients have much better outcomes, we expected that the survival among the trial population would be slightly lower. Estimates from the Norwegian trial of i.v. drugs and the Australian trial of adrenaline were 9%57 and 4%,56 respectively. We therefore expected a rate of survival to 30 days of ≈ 6% in the adrenaline group.

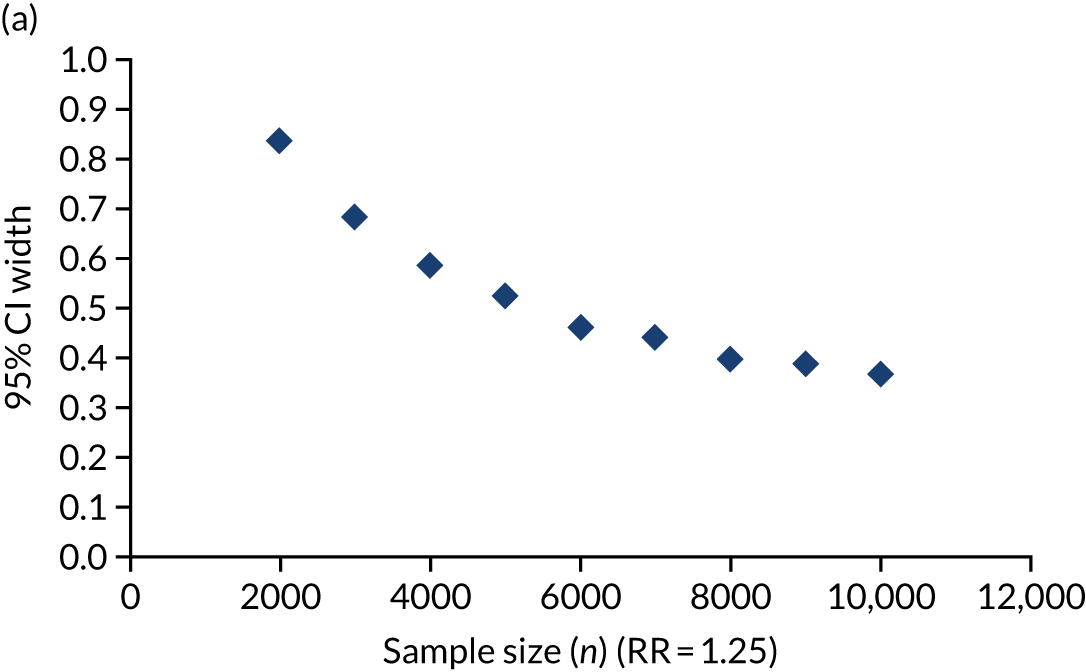

The trial’s primary aim was to estimate the treatment effect of adrenaline and the uncertainty around this; we therefore based the target sample size primarily on the precision of the estimate of the risk ratio (RR). 40 Figure 5 shows the precision that is achievable (width of the 95% CI for the RR) with different total sample sizes, for RRs (placebo vs. adrenaline) of 1.25 and 1.00. A RR of 1.25 corresponds to an increase in 30-day survival from 6% in the adrenaline group to 7.5% in the placebo group.

FIGURE 5.

Width of 95% CI for the RR against sample size. (a) RR 1.25; and (b) RR 1.0, with 6% survival in the adrenaline arm.

Sample size

The target sample size was 8000 participants, which was expected to give a width of the 95% CI for the RR of approximately 0.4 or slightly less; for a RR of 1.25, the 95% CI would be 1.07 to 1.46, and for a RR of 1.0 the 95% CI would be 0.84 to 1.19. There was a trade-off between precision and practicality in setting a target sample size at > 8000, there was only a small improvement in precision, but the difficulty and time needed to recruit this number increased significantly. We expected a very small number of missing data for survival outcomes. In the PaRAMeDIC trial,102 we ascertained survival status for > 99% of randomised patients; therefore, we have not adjusted the sample size estimates to account for missing data.

Using a conventional sample size calculation based on a significance test, a sample size of 8000 would have 93% power to achieve a statistically significant (p < 0.05) result if the true treatment difference is a RR of 1.33 (increase from 6% in the adrenaline group to 8% in the placebo group), or 75% power if the true treatment difference is a RR of 1.25 (increase from 6% in the adrenaline group to 7.5% in the placebo group).

Reconsideration of sample size after low survival rate

In July 2016, the DMC raised concerns regarding a lower than anticipated survival rate. We explored additional data sources and the current literature to assess if the original assumption was correct. Since the inception of the trial, we had access to two contemporary sources of information for the epidemiology and outcome of this patient group in the UK.

The first was a secondary analysis of the PaRAMeDIC trial. 102 The PaRAMeDIC trial102 enrolled adult patients experiencing OHCA in three English and the Welsh ambulance service regions. Patients were eligible for enrolment if they had an OHCA attended by a trial vehicle and resuscitation was continued by the EMS team. Patients who were pregnant or who sustained a traumatic cardiac arrest were excluded. We collected information on whether or not a patient received i.v. cardiac arrest medications per se, rather than specifically adrenaline. As resuscitation algorithms recommend that adrenaline and amiodarone (the only other recommended i.v. drug for cardiac arrest) are given together, we believed that this was a reasonable surrogate to the patient requiring i.v. adrenaline. For the PaRAMeDIC trial,102 this group comprised 3621 patients, with an overall 30-day survival rate of 2.8%.

The second source of data was the national OCHA registry (OHCAO) hosted by the University of Warwick. 103 This registry collects process and outcome information from all English ambulance services. Data were available covering the period from 2013 to 2015. These data were analysed for patients aged > 16 years who were given i.v. adrenaline (n = 28,939). In this group, 3.1% survived to discharge.

We extended the initial review of the literature to include studies that included standard-dose adrenaline as control, rather than limiting to intervention. Table 2 gives a brief detail of these studies, together with the percentage rates for survival to discharge for patients receiving standard-dose adrenaline (1 mg). This identified 10 studies in which high-dose adrenaline or vasopressin were given as comparator. In one trial, placebo was given as comparator. 56 The median rate of survival to discharge was 2.8%, and the weighted mean was 3.5%.

| Study | Number of survivors (n) | Participants receiving intervention (n) | Survival to discharge (%) | Comparator | Population | Setting | VF (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown et al.104 1992 | 26 | 632 | 4.1 | High-dose adrenaline | Adults | OHCA | 49 |

| Callaham et al.105 1992 | 3 | 270 | 1.1 | High-dose adrenaline | Adults | OHCA (non-trauma) | 21 |

| Gueugniaud et al.106 1998 | 46 | 1650 | 2.8 | High-dose adrenaline | Adults | OHCA (non-trauma) | 16 |

| Sherman et al.107 1997 | 0 | 62 | 0.0 | High-dose adrenaline | Adults | OHCA (non-trauma), on arrival ED | 16 |

| Steill et al.108 1992 | 2 | 165 | 1.2 | High-dose adrenaline | Adults | IHCA/OHCA | 43 |

| Jacobs et al.56 2011 | 11 | 272 | 4.0 | Placebo | Adults | OHCA | 43 |

| Ducros et al.109 2011 | 2 | 16 | 12.5 | Vaso/Epi | Adults | Witnessed OHCA | 0 |

| Gueugniaud et al.110 2008 | 33 | 1452 | 2.3 | Vasopressin/epinephrine | Adults | OHCA (non-trauma) | 9 |

| Lindner et al.111 1997 | 3 | 20 | 15.0 | Vasopressin/epinephrine | Adults | OHCA, refractory VF | 100 |

| Ong et al.112 2012 | 8 | 353 | 2.3 | Vasopressin/epinephrine | Adults | ED | 8 |

| Wenzel et al.113 2004 | 58 | 597 | 9.7 | Vasopressin/epinephrine | Adults | OHCA (non-trauma) | 41 |

Considering this information and the survival outcomes for PARAMEDIC2 at the time of our review, we concluded, as a trial team, that our initial estimates of survival to discharge/30-day survival, as detailed in the protocol, were overly optimistic. An adjusted sample size calculation based on the collected data indicated that, if we assumed a rate of survival to 30 days of 2% in the control arm, we would need > 24,000 patients for a RR of 1.33 at 90% power.

In addition, we estimated treatment effects detected by the sample size of 8000, as seen in Table 3.

| Power (%) | Proportion on control (%) | Proportion on intervention (%) | ARR (%) | RR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80 | 2 | 2.98 | 0.98 | 1.49 |

| 90 | 2 | 3.15 | 1.15 | 1.57 |

| 93 | 2 | 3.23 | 1.23 | 1.62 |

We believed that revising the sample size to 24,000 was unachievable (and unaffordable) at that point in the trial.

We noted that the Jacobs et al. 56 trial showed an OR of 2.2 in the survival to discharge outcome, but with wide CIs (95% CI 0.7 to 6.3). Furthermore, a threshold of 1% in absolute risk reduction for outcomes has been used widely in resuscitation science as the threshold that defines the minimal clinically important difference. 114,115 We therefore believed that the trial would still yield valuable information about the safety and effectiveness of adrenaline if the observed survival rates continued to the end of the trial.

Consent

Obtaining consent

The ambulance service research teams received training on informed consent and assessing capacity, good clinical practice (GCP) guidelines, relevant legislation, and the trial-related procedures around consent.

Informing the patient about participation in the trial

For all patients who were transported to hospital for further treatment, ambulance service research teams conducted checks with local hospitals to determine whether or not a patient had survived. The first attempt to contact the patient and inform them of their enrolment in the trial was during their stay in hospital. The ambulance service research paramedics made contact with the patient as soon as practicable after the initial emergency had passed, taking the utmost care and sensitivity in doing so. Following our experience from an OHCA study of 4400 patients (PaRAMeDIC trial),81 and from discussions with fellow researchers from the REVIVE AIRWAYS cardiac arrest study116 and discussions with patient and public representatives, we believed that the earliest practicable time to approach patients and relatives was once the patient was discharged from the ICU and was on a hospital ward. This allowed sufficient time for the research team to be made aware of enrolment, to identify who the patient was, to check which hospital the patient was transferred to and whether or not they were still alive and to verify with the hospital team where the patient was in the hospital. Transfer to a ward indicated that the initial emergency had passed and the patient’s condition had stabilised. It was also considered more likely that the patient had regained consciousness and it would avoid any confusion or additional distress of making an approach while the patient remained critically ill in intensive care.

For patients or legal representatives who did not speak English, patient information sheets and consent forms were translated into some common languages. When printed translations were not available in the required language, Language Line Services (now known as LanguageLine Solutions, Monterey, CA, USA) was used to translate the patient information sheets and consent forms for the patient or their legal representative.

Procedure for taking consent

The research paramedic assessed if the patient had capacity to consent, with advice from the hospital team. If the patient had capacity, they were provided with the information sheet explaining the trial and the options for their involvement. The patient was allowed time to consider the information provided and had the opportunity to ask questions and discuss with others. The research paramedic or hospital team then asked when the patient would like someone to come back to discuss participation further and potentially take consent. The patient could decide that it was not an appropriate time to discuss the trial or they could decide that they did not want to be involved, in which case their feelings were respected and their decision about continuing in the trial was recorded.

The consent form listed the different sorts of information that were collected. Specific consent was not sought to use the data already collected. If the patient did not want the trial team to continue to collect data about survival, or to access the patient’s health records, then they indicated this on the consent form by not initialling the corresponding boxes or told the trial team verbally.

Research paramedics confirmed with the patient or legal representative their willingness to continue with the trial at each contact point.

In the event that a patient lacked capacity to consent, the research paramedic worked with the hospital team to identify a legal representative, defined as:

-

personal legal representative – a person independent of the trial, who, by virtue of their relationship with the potential study participant, is suitable to act as their legal representative for the purposes of that trial, and who is available and willing to so act for those purposes.

Or, if there is no such person:

-

professional legal representative – a person independent of the trial, who is the doctor primarily responsible for the medical treatment provided to that adult

-

a person nominated by the relevant health-care provider.

The legal representative was approached and provided with the information sheet explaining the trial and the options for their and the patient’s involvement, including the need for them to give consent on behalf of the patient and complete questionnaires on behalf of the patient. The legal representative was given time to consider the information provided. The research paramedic or hospital team then asked when the legal representative would like someone to come back to discuss participation further and potentially take consent.

The legal representative could decide that it was not an appropriate time to discuss the trial or they could decide that the patient would not want to take part, in which case their feelings were respected and their decision about taking part was recorded.

In exceptional circumstances, if consent was not obtained during the hospital stay, the patient or their legal representative was sent an invitation letter by post and written consent was taken at the 3-month follow-up visit, if the patient or legal representative agreed.

It is possible that the patient could have regained capacity by the time the 3-month visit was due. When contacting the legal representative to arrange the 3-month visit, the ambulance service research team asked if they could speak with the patient. If, on assessment of the patient, either on the telephone or at the visit, it was found that the patient still lacked capacity, the legal representative was asked to complete the questionnaires on behalf of the patient. If the patient had regained capacity, then information was provided about the trial and consent for further data collection was sought.

General information about the trial and contact details for further information was made freely available throughout the trial. Information about the trial was placed on ambulance trust and University of Warwick websites, ambulance service public newsletters, posters and information leaflets were shared with general practices, pharmacies, hospital accident and EDs and waiting areas, totalling 6500 mail-outs, which included 2356 general practices and 3181 pharmacies. Prior to the start of the trial, a press release was issued providing information about the trial. This was followed by periodic regional press releases as the trial progressed. The trial website was updated with information throughout the trial [www.warwick.ac.uk/paramedic2 (accessed 1 August 2019)], and was accessed > 178,000 times during the trial.

Although not required by the relevant regulations, the trial team developed a system to allow a patient to decline participation in the trial in the event that they sustained a cardiac arrest.

Requests not to participate were sent to and managed by the WCTU trial team. An online form could be completed on the website or the team could be contacted by telephone or e-mail. A stainless steel ‘No Study’ bracelet was issued to the person’s home address and, with the person’s permission, their home address was passed to the ambulance service to register the person’s wishes by placing an address flag on dispatcher systems. Those requesting a ‘No Study’ bracelet were also told to tell those close to them their wishes and told that those wishes would be respected by the treating paramedics. Paramedics were trained to look for the bracelet when attending a cardiac arrest.

Enquiries regarding trial participation

The following process was introduced at the end of the trial to deal with trial participation enquiries from members of the public.

If a member of the public enquired as to whether or not their next of kin was enrolled in the PARAMEDIC2 trial, they completed a trial participation enquiry form. On receipt of a completed trial participation enquiry form, the PARAMEDIC2 trial office worked with the appropriate site to check whether or not the next of kin of the enquirer was enrolled in the PARAMEDIC2 trial. Once it was confirmed, a letter was sent from the appropriate ambulance service to confirm whether or not the enquirer’s next of kin was enrolled in the trial, along with an information sheet about the trial, which included contact details for the PARAMEDIC2 trial office.

Serious adverse events

Events that were related to cardiac arrest and that were expected in patients undergoing attempted resuscitation were not reported. These included:

-

death

-

hospitalisation

-

persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

organ failure.

All events categorised as serious [SAE/serious adverse reaction (SAR)/suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction (SUSAR)] were required to be reported to the WCTU within 24 hours of becoming aware of the event. All reports of SAEs/SARs/SUSARs were reviewed on receipt by the chief investigators or delegated clinical members of the TMG; the main REC, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and the sponsor were notified within 7 or 15 days of receipt of those that were considered to satisfy the criteria for being related to the IMP and unexpected, in accordance with regulatory requirements. Reports of SAEs/SARs/SUSARs were also reviewed by the DMC at its regular meetings, or more frequently if requested by the DMC chairperson.

Procedures in case of pregnancy

Known pregnancy at the time of the cardiac arrest was an exclusion criterion for this trial. However, should the patient later be known to have been pregnant at the time of cardiac arrest and trial intervention, the protocol specified that the outcome of the pregnancy would be followed up and documented, even if the subject was discontinued from the trial. All reports of congenital abnormalities or birth defects were to be reported and followed up as a SAE.

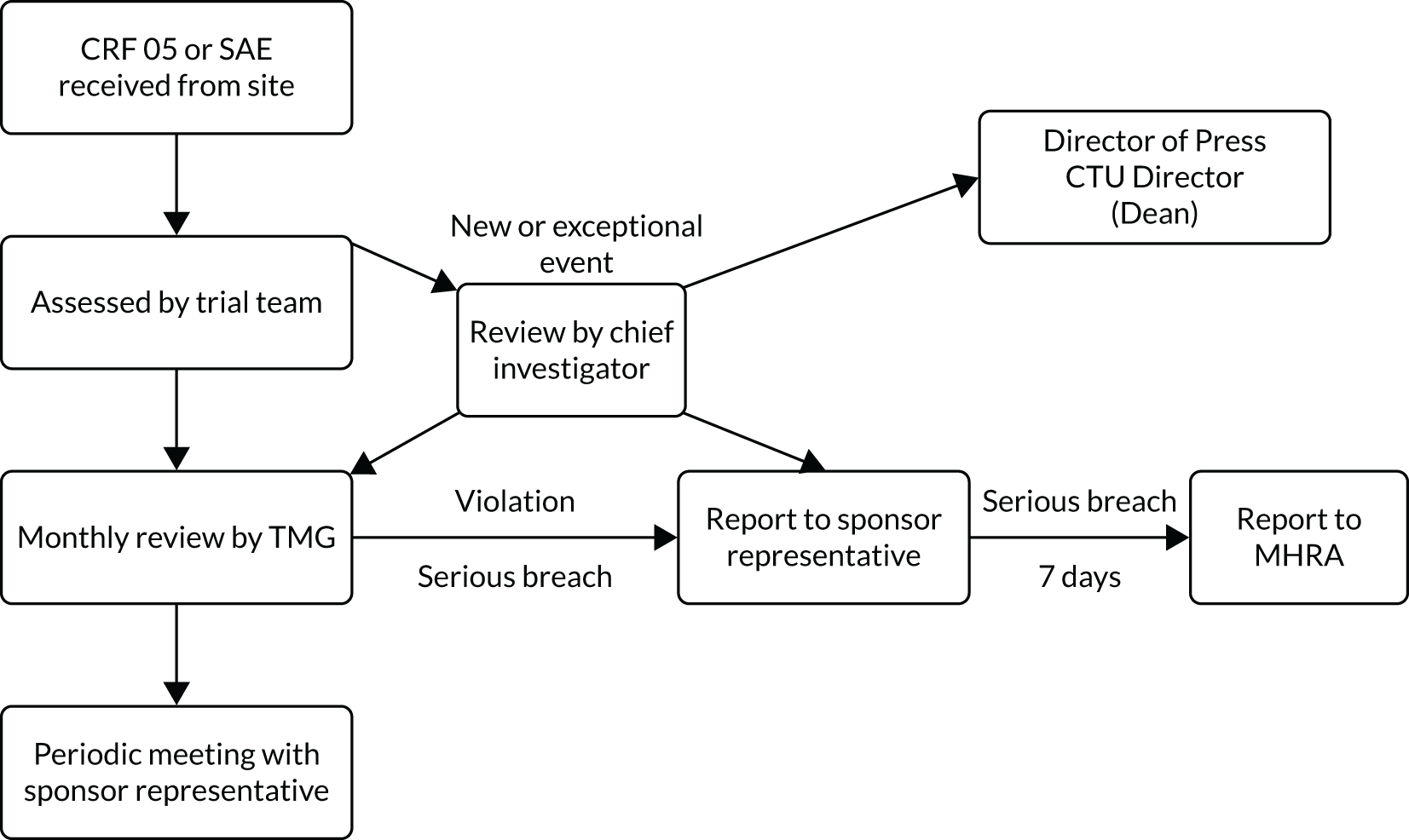

Protocol non-compliances

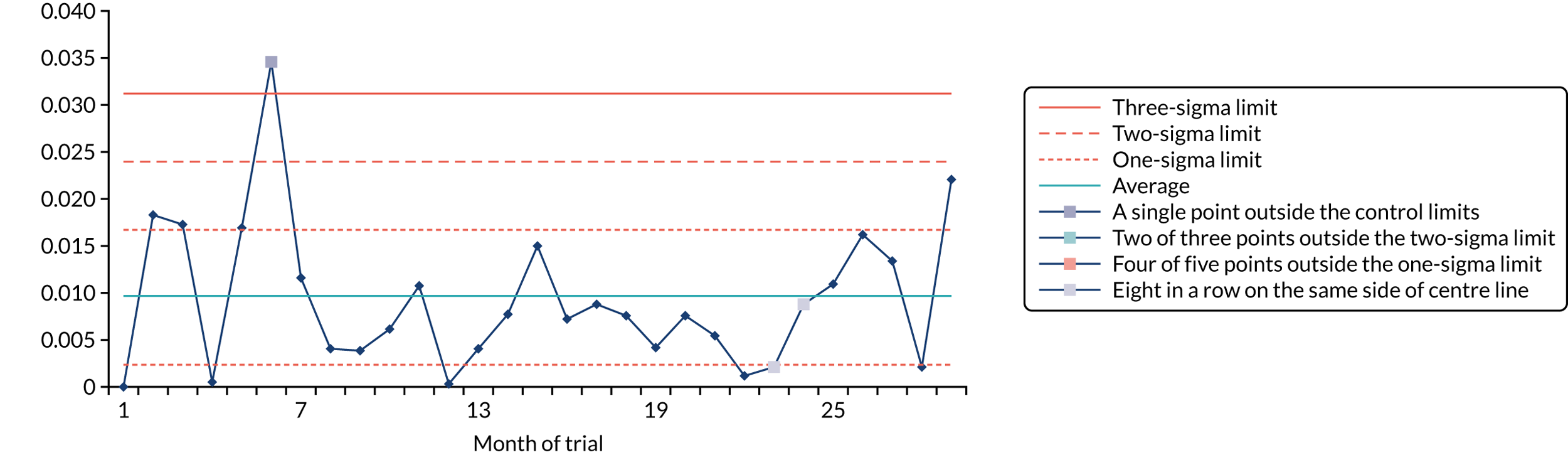

Any deviations from or violations of the trial protocol or GCP were reported to the WCTU trial team promptly via a paper case report form (CRF) or an electronic case report form (eCRF). Any reports were assessed by the trial team on the day of receipt, or the following working day if received on a weekend, and escalated to the chief investigator (or their delegate), the quality assurance team and the WCTU manager if the non-compliance was a new or an exceptional event. All non-compliances, including cumulative numbers, trends and frequency over time, were reviewed at monthly trial management meetings. All violations and serious breaches were reported to the sponsor, and serious breaches were reported to the MHRA within 7 days (Figure 6). The ambulance service trial teams put in place corrective and preventative actions to mitigate the risk, and these actions were reviewed by the WCTU trial team to ensure that all had been completed.

FIGURE 6.

Process for receipt of a non-compliance report. CTU, Clinical Trials Unit.

A protocol deviation was defined as a change or departure from the clinical trial protocol and/or GCP that did not result in harm to the trial participants or significantly affect the scientific value of the reported results of the trial.

A protocol violation was defined as a serious non-compliance with the approved protocol resulting from error, fraud or misconduct.

A serious breach was defined as a breach (deviation or violation) that was likely to affect, to a significant degree, either the safety or physical or mental integrity of the participants of the trial, or the scientific value of the trial.

Data collection

Screening data

Data were collected on a screening log of all cardiac arrests, which were attended by a trial-trained paramedic in the trial areas. These data consisted of the case identifier, the age and sex of the patient and the reason why the patient was not enrolled in the trial. This allowed assessment of the proportion of missed enrolments and the reasons, to ensure that the trial sample was representative of the trial population. The reasons for missed enrolments were established either from reviewing the patient’s clinical record, or from speaking to the attending clinician. Several strategies were used during the trial to reinforce the message that all eligible patients should be enrolled in the trial, and data on the numbers and reasons for missed enrolments were reviewed throughout the trial and fed back to sites.

Patient enrolment

All cardiac arrests for which a trial pack was opened were reported to the ambulance service trial teams by the recruiting clinician. The method for notification of enrolled patients was specific to each research site, but was usually done via telephone to the control centre or to a dedicated telephone number. Once ambulance service research teams were notified of an enrolled patient, the patient details were registered promptly on the trial database via an online web application hosted by the University of Warwick.

Baseline cardiac arrest data

Baseline cardiac arrest data were obtained retrospectively from ambulance service clinical records and the OHCAO registry (University of Warwick) and transcribed directly onto eCRFs via the PARAMEDIC2 web application. All ambulance service staff were trained on how to collect and enter trial data, and all data definitions followed Utstein recommendations. 92 Follow-up data were then obtained from hospitals, general practitioner (GP) surgeries, NHS Personal Demographics Service and patient follow-up questionnaires and were entered into the PARAMEDIC2 web application as they became available.

Hospital

Patients were taken to any hospital in the trial regions. Although hospital clinicians did not have a role in delivering the trial interventions, they were informed about the trial and were provided with information about the trial for any clinicians or patients who needed it.

Hospitals were contacted initially to ascertain survival of patients handed over from ambulance services to the ED. If the patient had survived, the research paramedics liaised with the hospital clinicians to visit the patient and seek consent for continuation in the trial (see Consent).

For any patient taken to hospital, data were collected on survival, length of stay in hospital and ICU, targeted temperature management, adrenaline use and mRS score at discharge, as well as discharge address and GP details. As some patients were found in a public place without any identifiers, or only part of their details were known to the ambulance service at the time of arrest, hospitals also, when necessary, provided missing information such as name, address and date of birth.

Survival checks

Survival checks were completed by the ambulance service research teams or the WCTU trial team using a variety of sources:

-

hospital data

-

Summary Care Record/Welsh Demographic Service

-

GP surgeries.

Follow-up

Survivors willing to take part were followed up approximately 3 months and 6 months after their cardiac arrest, as per Figure 4. Whenever possible, the 3-month assessments were a home visit, but, if the patient preferred postal questionnaires or to go through the questionnaires over the telephone, this was arranged, although the MMSE was not completed over the telephone. Questionnaires at the 6-month time point were sent by the WCTU and returned by post.

Following the approach to the patient, in the unlikely event that we had not obtained a response from the patient, the WCTU trial team approached the patient’s GP or hospital or ambulance service for information on their mRS score as close to the 3- and 6-month time points as possible. If the 3-month booklet had not been completed by the time the 6-month visit was due, the patient was sent the 3-month booklet to complete instead, so that outcomes that are only collected at 3 months were not missed.

Data linkage with other data sets