Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/113/01. The contractual start date was in April 2017. The draft report began editorial review in July 2020 and was accepted for publication in January 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Cameron et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Unintended pregnancy is a major public health problem. Despite having one of the highest rates of modern contraceptive use worldwide, the UK has among the highest abortion rates in Europe. 1 In 2018, almost 200,000 pregnancies ended in induced abortion. 2,3 Unintended pregnancy also ends in childbirth. Around 10% of UK births are unintended and 25% are mistimed. 4 Unintended pregnancy is costly to the NHS5 and distressing for women. Unintended pregnancies are over-represented in young women from deprived backgrounds. Unintended childbirth can have both socioeconomic consequences for women and their families, and mental health consequences. 6

Emergency contraception (EC) prevents pregnancy in individual women following unprotected sex or contraceptive accidents (e.g. burst condom). Approval of EC from pharmacies and making it free of charge to all women in Scotland and Wales, and free to many women in England, has increased use and EC is now largely obtained from pharmacies. 7 However, although trials have shown that facilitating access to EC increases use of EC, these trials have failed to show an effect on unintended pregnancy rates. 8

Emergency contraception [containing levonorgestrel (LNG)] is only effective if taken within 72 hours of unprotected sex. It does not prevent conceptions from subsequent sex. The risk of pregnancy is increased up to threefold among women who have further unprotected sex in the same menstrual cycle after using EC. 9 An effective method of contraception should therefore be started as soon as possible – known as ‘quick starting’. 10 However, the only contraceptives available from pharmacies without prescription are condoms, which have high failure rates. 11 To start an effective contraceptive (i.e. hormonal or intrauterine contraception) women must visit a general practitioner (GP) or attend a sexual and reproductive health (SRH) clinic. It may take time to get an appointment and many women may lose the motivation to seek contraception, leading to an unintended pregnancy. In addition, in some UK studies, fewer than half of pharmacists gave advice about ongoing contraception after EC. 12,13

There is a lack of evidence on interventions to increase uptake of effective contraception after EC. We conducted a literature search of PubMed English-language articles from 2000 to March 2020 using search terms (((bridging) OR bridge)) AND (emergency contracept*) and identified only two relevant articles. One was a cluster randomised trial14 from Jamaica, in which women seeking EC were offered a voucher that gave them a discount on the cost of contraceptive pills. This study reported no effect of the intervention on subsequent contraceptive use. The other article15 was a pilot study of 12 pharmacies in Edinburgh, with 168 women presenting for EC randomised to receive 1 month of a progestogen-only pill (POP), rapid access to a local SRH clinic or standard care. Participants were contacted by telephone 6–8 weeks later to determine which method of contraception they were using. In the POP arm, 35 out of 39 (90%) women used the pills provided and 9 out of 28 (32%) women in the rapid-access arm attended the SRH clinic. Compared with standard care, the proportion of women using effective contraception after EC was statistically significantly greater in both the POP arm (56% vs. 16%; p = 0.001) and the rapid-access arm (52% vs. 16%; p = 0.027). The study concluded that a 1-month supply of POP after EC or rapid access to a SRH service might increase short-term uptake of effective contraception following EC, but that a high-quality, adequately powered randomised trial was needed.

Rationale for study

Unintended pregnancy remains a public health problem in the UK. Guidance from the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare of the Royal College of the Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (London, UK) stresses the need to ‘quick-start’ ongoing contraception after EC. 10 In 2014, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance on contraceptive services for young people endorsed this recommendation. 16 In some parts of the UK, pharmacies are offering women supplies of contraceptive pills after EC use,17 despite the lack of evidence that this is an effective intervention or is cost-effective. We must show that the intervention is effective before we can recommend adoption of this approach. A recent cost-effectiveness analysis of EC estimated that, in 2011, unintended pregnancies cost the NHS over £1B. 5 It is possible that even these costs are an underestimate of the ‘real costs’, as they did not include the cost of managing medical complications of pregnancy or account for the additional costs associated with teenage pregnancy. If a community pharmacy-based intervention could be designed that was effective in reducing unintended pregnancies and was shown to be cost-effective, then this would result in savings for the health systems, which could be invested elsewhere. Women who present for EC should be given the best chance to prevent an unintended pregnancy.

Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), which includes the implant, intrauterine contraception and injectable contraception, has been shown to be the most effective reversible method of contraception for preventing pregnancy. 18 In recognition of the effectiveness of LARC, national initiatives in the UK to increase uptake have been encouraged. 16,18 Rapid referral of women using EC to SRH services capable of initiating LARC immediately (as in this study) could do much to improve LARC uptake among women at risk of unintended pregnancy.

We therefore conducted the ‘Bridge-It’ study: a robust trial to determine whether or not a pharmacy-based intervention designed to facilitate the uptake of effective contraception after EC increases use of effective contraceptive methods, compared with standard care alone. For the Bridge-it study, we used a composite intervention of a small ‘bridging’ supply of the POP and the offer of rapid access to a participating SRH clinic. This combined both temporary contraception (giving women time to arrange an appointment with their usual contraceptive provider) with facilitated access to a specialist contraceptive service (i.e. the SRH clinic) where all methods of contraception, including the most effective LARC methods, are provided.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

The Bridge-it study was a pragmatic cluster randomised cohort crossover trial of community pharmacies in three regions of the UK [London (south and central), Lothian (Edinburgh and region) and Tayside (Dundee and region)]. 19 With this design, the order in which each community pharmacy provided intervention or control was randomised. There was an intervening period of at least 2 weeks (during which recruitment halted) before the pharmacy switched to the other recruitment phase. 19 The cluster design was chosen as our pilot study15 findings indicated that an individual randomised trial would not recruit sufficient numbers of women. The crossover was chosen for efficiency, with each cluster acting as its own control and fewer pharmacies required. The washout period between recruitment periods minimised any contamination effect of pharmacists between recruitment periods.

Pharmacies were chosen to be a mixture of large commercial chain stores and small independent stores. Each pharmacy had to have a sufficient volume of EC dispensing (at least 30 ECs per month) to participate.

Women receiving LNG EC from a study pharmacy were considered for study participation. The LNG EC was given in the appropriate dose (1.5 mg or 3 mg) for the woman’s weight. 10

The intervention was a composite intervention. Women received 3 months worth of the POP (75 µg of desogestrel/day) at no cost (as is the norm in the NHS) and the offer to attend a local participating SRH service to discuss and provide ongoing effective contraception, including the most effective LARC methods (i.e. intrauterine contraceptive methods and contraceptive implants). 18 The three packets of POP provide women with 3 months within which they could attend a contraceptive provider for ongoing contraception. The POP has very few absolute contraindications,20 making it safer for pharmacy provision than the combined oral contraceptive pill. The desogestrel POP was chosen as it is the market leader, the most effective POP (as it has high rates of ovulation inhibition) and is inexpensive (£9 for 3 months of the generic version). 21 Community pharmacists provided the POP using locally approved patient group directions (PGDs) (i.e. strict criteria to permit provision of specified medicines by non-prescribers). 21,22 Participating pharmacists were trained on the study protocol and use of the PGD for the POP, including information about medical contraindications to POP, potential drug interactions and ‘missed pill’ guidance. Pharmacists advised women to start the POP the day after the EC. Women in the intervention group also received a rapid-access card that on presentation to the local SRH clinic would help them to be seen as a walk-in patient to discuss contraception and obtain their preferred ongoing method. The card provided information about the location of the SRH clinic and the opening hours. The clinics (three in London, one in Lothian and two in Tayside) were located within 5 miles of the community pharmacies.

In the control group, women received standard care with the EC (i.e. usual advice about ongoing contraception). Mystery shopper visits with simulated patients12,13 were conducted in the pharmacies just before recruitment started in the control group to document the content of the standard care EC consultations (see Chapter 4).

Participants

Pharmacists assessed women’s eligibility for the study, invited them to participate, obtained written informed consent for the study (including access to SRH clinic records and data linkage with the national abortion registries) and provided a patient information sheet. Participants completed a baseline questionnaire that included demographic details, reproductive history and previous methods of contraception used, including ECs (see Appendix 3). To maximise retention in the study, participants received an online shopping voucher of £10 following recruitment. 23

Procedures

Participants in both groups of the study had a single follow-up at 4 months: either a telephone interview with a research nurse or a self-administered web-based questionnaire, according to participant preference (see Appendices 4 and 5). In addition to contraceptive use, women were asked about their interaction with the pharmacist and use of the rapid-access card (intervention group only). Participants reporting pregnancy also completed the London Measure of Unplanned Pregnancy, which is a validated questionnaire to measure the intendedness of the index pregnancy. 24,25 Serious adverse events since recruitment were also recorded.

The participating SRH clinics also searched their clinic record systems for data on if and for what reason participants in both arms of the study had used their service during the 4 months following recruitment.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was self-reported use of effective contraception (hormonal or intrauterine) at 4 months. Secondary outcomes were incidence of abortion in the 12 months following recruitment and an economic evaluation of the intervention. Both secondary outcomes will be reported later [as per agreement with the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)].

A multimethod process evaluation was also conducted to assess implementation, mechanisms of change and context,19 and included qualitative interviews with participants, pharmacists and staff at SRH clinics. The process evaluation is reported separately in this report (see Chapter 5).

Sample size

An original power calculation for the study was based on two co-primary outcomes: (1) abortion rates at 12 months and (2) use of effective contraception at 4 months. For the abortion outcome, we required > 2000 women to be randomised in at least 26 pharmacies to have 90% power at 2.5% level of significance to detect a relative reduction of around 50. During the study, it became evident that recruiting this number of women was not feasible within the available time frame and resources. The independent oversight committees [the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring Committee (DMC)] and the funder (NIHR Health Technology Assessment programme) agreed to repower the study on a single primary outcome (i.e. use of effective contraception at 4 months). To have 90% power at a 5% level of significance and to demonstrate an increase from around 30% to 45% (absolute change 15%, relative increase 50%), the study required between 626 and 737 women, depending on the intraclass correlations (within period and between periods), which were not observable within the study at the time this change was made. 26 The sample size calculation assumed that we would not have the 4-month primary outcome data for 25% of participants and that there would be 25 participating pharmacies. For the intracluster correlations, the within-cluster, within-period correlation was 0.032 and the between-period, within-cluster correlation was also 0.032. The observed correlation between the two outcomes in the same cluster period compared with the two outcomes from different periods in the same cluster was effectively zero (< 0.00001).

Randomisation

The order of delivery of intervention or control for each pharmacy was generated using a computer software algorithm. This randomly allocated permuted blocks of size two, four and six, and blocking was used to ensure a balanced order. The randomisation file was prepared by the study statistician at the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials, University of Aberdeen (Aberdeen, UK), using SAS® 6.4 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Pharmacists were informed of the randomisation allocation by the study trial manager. The study was not blinded.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics of participants and 4-month follow-up data were summarised using mean [standard deviation (SD)] or median (interquartile range) for continuous variables. Discrete variables were summarised with numbers and percentages. The published study protocol19 specified a hierarchical mixed-effects logistic regression on individual data for the analysis of reported use of effective contraception at 4 months, and this represented our analysis intentions at the time of submission of the study protocol. However, we revised this primary analysis in the final statistical analysis plan (accepted 5 November 2019, before any unblinded data had been seen) to use a linear model on the unweighted proportion (expressed as a percentage) at site level, following methodological guidance from Morgan et al. ,27 and we used the hierarchical mixed-effects logistic regression as a sensitivity-type analysis. Although the linear model on percentages at site level makes less use of the available information, it can be more robust, with fewer assumptions, and expresses the treatment effect as a percentage difference in proportion rather than as an odds ratio.

Ideally, the design would generate equal contributions in each time period and each site would contribute equal numbers. However, we knew from the aggregated accruing data on the database, returned to date, that sites were quite different in size and also returning different numbers in each period. Therefore, and guided by the Morgan et al. 27 paper, which indicated that the simple approach of modelling the percentages by site had the best properties in terms of control of type 1 error, we took the unusual decision to prefer the simpler approach to the more complex hierarchical approach. This resulted in forgoing the potential increase in power traded against the possibility of model misspecification, as the model assumptions (regarding the several decompositions of within and between cluster correlation, the influence of missing data, and the influence of very different sizes by period and site) might have been violated. We felt that the hierarchical approach could still usefully be reported as a sensitivity-type analysis and, as it happened, it does seem to support the simpler analysis of proportions, giving similar estimates, but with the expected increase in precision.

For the primary outcome, the percentage of women reporting use of effective contraception in each cluster period was analysed using linear regression, adjusting for period, treatment arm and centre, and with centre as a fixed effect. 27 Prespecified baseline covariates (i.e. mean age, percentage of participants currently in a sexual relationship and percentage of participants who had previously used effective contraceptive methods) were included as an additional analysis. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

For the primary outcome, prespecified subgroup analysis for LARC use18 was performed using a stricter level of statistical significance (two-sided 1% significance level) and 99% confidence intervals (CIs).

The sensitivities of treatment effect estimate to missing outcome data were undertaken using multiple imputation. The missing primary outcome (i.e. uptake of effective contraception) was imputed using all baseline characteristics as predictors, except for ‘previous ectopic pregnancy’ (because of small numbers). Stata® version 16 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used to impute 40 data sets.

Summary of changes to the protocol

Owing to resource and time constraints, the study was repowered on a single primary outcome (i.e. effective contraception use at 7 months). For the same reasons, the planned follow-up of participants at 12 months was removed. Abortion rates at 12 months will still be collected and these and the cost-effectiveness model will be reported separately (because of a later study end date than anticipated). A summary of changes to the protocol can be found in Box 1. The final and previous versions of the protocol can be found on the NIHR Journals Library [URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1511301/#/ (accessed 15 February 2021)].

Changes were requested to the exclusion criteria and how identifiable data would be handled. The protocol was updated to version 2, 16 June 2017.

Approved.

Non-substantial amendment to protocol Protocol version 3, 16 April 2018There was a minor clarification to the wording on page 14 of the protocol to explain the time frame for the two phases of the study:

Each pharmacy will recruit on average 80 women to provide around 60 evaluable women at 12 months. 30 women will be recruited to the intervention arm and 30 women will receive standard care. In order for each pharmacy to recruit on average 80 women, pharmacies will recruit for approximately two months in each intervention or standard care phase; some pharmacies will recruit for a shorter or longer duration depending on the recruitment rate at the pharmacy and the size of the pharmacy. However, there will be a minimum break (wash-out period) of two weeks in between the two recruitment periods.

Approved.

Substantial amendment to the protocolIn December 2018, a substantial amendment was submitted to the REC.

Protocol version 4, 12 November 2018The primary and secondary end points were updated and the sample size was reduced to 626–737 participants. The trial team also requested a 6-month no-cost extension. The changes to the sample size and extension were reviewed and approved by both the TSC and the trial funder (i.e. NIHR Health Technology Assessment programme). The end date of the study was changed from 30 September 2019 to 31 March 2020.

Protocol version 5, 8 January 2019The REC reviewed this in January 2019 and requested further changes to protocol to clarify at what time GPs would be contacted.

Approved.

REC, Research Ethics Committee.

Ethics

Ethics approval was obtained from South East Scotland Research Ethics Committee in June 2017. Approvals were also obtained from NHS Research Scotland (Clydebank, UK) and Health Research Authority (London, UK).

Chapter 3 Results

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Cameron et al. 28 in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Recruitment and participant flow

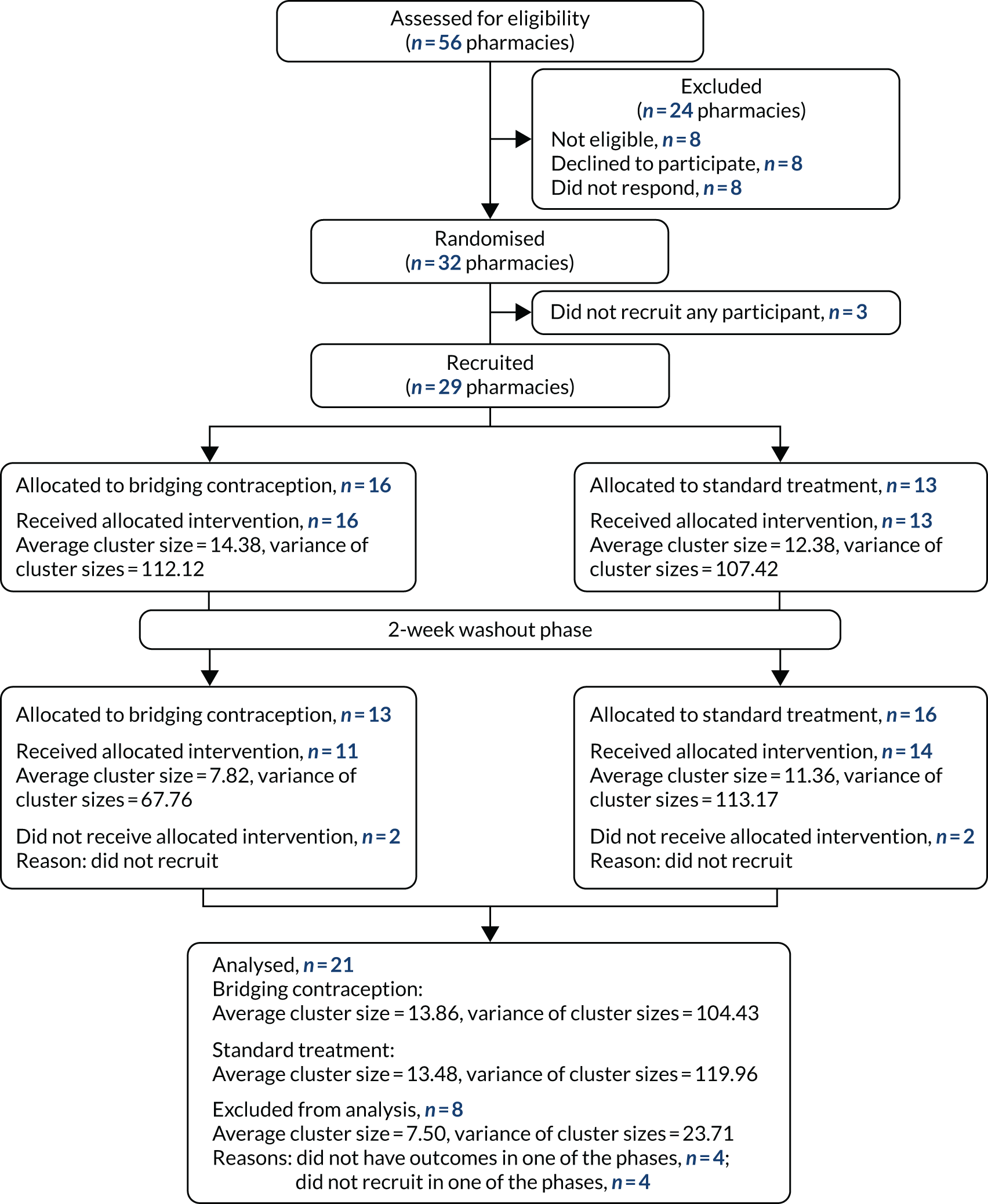

Fifty-six pharmacies were approached to participate and 32 agreed to take part in the trial (Figure 1). Twenty-nine out of the 32 pharmacies recruited participants (14 in London, 12 in Lothian and three in Tayside). Participants were recruited between 19 December 2017 and 26 June 2019. A total of 1252 participants were screened, of whom 762 were eligible and 636 consented and were randomised. Box 2 shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow chart.

Eligible for LNG EC confirmed.

Able to give informed consent to participate in and adhere to trial requirements.

Aged ≥ 16 years.

Willing to give contact details and be contacted at 4 months by telephone, SMS, e-mail or post.

Willing to give identifying data sufficient to allow data linkage with NHS registries.

Exclusion criteriaContraindications to POPs.

Taking medication that interacts with POPs.

Already using hormonal contraception.

Requires interpreting services.

Pharmacist has concerns about non-consensual sex.

SMS, short message service.

Table 1 shows reasons for ineligibility and Figure 2 shows participant flow. The number of participants recruited per pharmacy ranged from 2–35 in the pharmacies’ first recruitment period and from 0–38 in the second period.

| Reason | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Does not require EC | 93 (19.0) |

| Lacks capacity to give informed consent | 64 (13.1) |

| Aged < 16 years | 10 (2.0) |

| Unwilling to give contact details and be contacted for follow-up | 264 (53.9) |

| Unwilling to give identifying data sufficient to allow data linkage with NHS registries | 262 (53.5) |

| Contraindication to POPs | 15 (3.1) |

| Medication that interacts with POPs | 5 (1.0) |

| Already using hormonal contraception | 156 (31.8) |

| Needs an interpreter | 10 (2.0) |

| Pharmacist concerns about non-consensual sex | 2 (0.4) |

FIGURE 2.

Participant flow chart. n, number of women who returned a 4-month questionnaire; N, number of women recruited; P, number of pharmacies.

Table 2 summarises the baseline characteristics of participants by randomised group and recruitment period. The mean age of participants was 22.7 (SD 5.7) years and 22.6 (SD 5.1) years in the intervention and control groups, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences between groups.

| Baseline characteristic | Intervention | Control | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period 1 (N = 229) | Period 2 (N = 86) | Period 1 (N = 161) | Period 2 (N = 155) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 23.2 (6.0) | 21.4 (4.8) | 22.2 (4.4) | 22.9 (5.8) |

| Methods of contraception ever used, n (%) | ||||

| Combined hormonal contraception | 114 (49.8) | 41 (47.7) | 99 (61.5) | 94 (59.9) |

| POP | 39 (17.0) | 19 (22.1) | 35 (21.7) | 32 (20.4) |

| Male condom | 189 (82.5) | 66 (76.7) | 117 (72.7) | 135 (86.0) |

| Progestogen-only injectable | 14 (6.1) | 6 (7.0) | 10 (6.2) | 18 (11.5) |

| Progestogen-only implant | 29 (12.7) | 10 (11.6) | 23 (14.3) | 19 (12.1) |

| Cu-IUD | 6 (2.6) | 0 | 4 (2.5) | 4 (2.5) |

| LNG-IUS | 0 | 1 (1.2) | 4 (2.5) | 2 (1.3) |

| Withdrawal method | 65 (28.4) | 28 (32.6) | 52 (32.3) | 67 (42.7) |

| Other methodsa | 10 (4.4) | 6 (7.0) | 7 (4.3) | 9 (5.7) |

| Never used any method | 8 (3.5) | 4 (4.7) | 10 (6.2) | 2 (1.3) |

| Past birth: yes, n (%) | 30 (13.1) | 5 (5.8) | 7 (4.3) | 13 (8.3) |

| Past termination: yes, n (%) | 38 (16.6) | 6 (7.0) | 22 (13.7) | 27 (17.2) |

| Past miscarriage: yes, n (%) | 17 (7.4) | 5 (5.8) | 10 (6.2) | 6 (3.8) |

| Current sexual relationship: yes, n (%) | 176 (76.9) | 55 (64.0) | 104 (64.6) | 111 (70.7) |

| First time ever use of EC: yes, n (%) | 52 (22.7) | 22 (25.6) | 28 (17.4) | 32 (20.4) |

| Number of times used EC in the last 12 months | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.4 (1.4) | 1.5 (1.5) | 1.5 (1.2) | 1.7 (2.0) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 1.0 (0.0, 2.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) |

| Minimum, maximum | 0.0, 8.0 | 0.0, 9.0 | 0.0, 6.0 | 0.0, 20.0 |

| Ethnic background, n (%) | ||||

| White | 157 (68.6) | 60 (69.8) | 98 (60.9) | 114 (72.6) |

| Asian or Asian British | 21 (9.2) | 6 (7.0) | 8 (5.0) | 21 (13.4) |

| Black or black British | 29 (12.7) | 12 (14.0) | 36 (22.4) | 15 (9.6) |

| Mixed or other | 19 (8.3) | 6 (7.0) | 17 (10.6) | 6 (3.8) |

| Missing | 3 (1.3) | 2 (2.3) | 2 (1.2) | 1 (0.6) |

Four-month follow-up

Follow-up data at 4 months were available for 198 out of 315 (62.9%) women and 208 out of 318 (65.4%) women in the intervention and control groups, respectively. Follow-up rates did not differ statistically between groups nor between those recruited in the first and second recruitment periods of pharmacies. There were no substantial differences in any baseline characteristics between responders and non-responders (Table 3). No significant adverse events were reported.

| Characteristic (at baseline) | Non-responders (N = 227) | Responders (N = 406) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 22.3 (5.0) | 22.8 (5.7) |

| Methods of contraception ever used, n (%) | ||

| Combined hormonal contraception | 118 (52.0) | 230 (56.7) |

| POP | 46 (20.3) | 79 (19.5) |

| Male condom | 157 (69.2) | 350 (86.2) |

| Progestogen-only injectable | 19 (8.4) | 29 (7.1) |

| Progestogen-only implant | 29 (12.8) | 52 (12.8) |

| Cu-IUD | 3 (1.3) | 11 (2.7) |

| LNG-IUS | 2 (0.9) | 5 (1.2) |

| Female condom | 0 | 3 (0.7) |

| Cap/diaphragm | 0 | 6 (1.5) |

| Vasectomy | 1 (0.4) | 3 (0.7) |

| Withdrawal method | 62 (27.3) | 150 (36.9) |

| Natural family planning | 7 (3.1) | 13 (3.2) |

| Other method | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.5) |

| Never used any method | 11 (4.8) | 13 (3.2) |

| Past birth: yes, n (%) | 16 (7.0) | 39 (9.6) |

| Past abortion: yes, n (%) | 36 (15.9) | 57 (14.0) |

| Past miscarriage: yes, n (%) | 16 (7.0) | 22 (5.4) |

| Current sexual relationship: yes, n (%) | 154 (67.8) | 292 (71.9) |

| First time ever use of EC: yes, n (%) | 44 (19.4) | 90 (22.2) |

| Number of times used EC in the last 12 months | ||

| Mean (SD) | 1.5 (1.2) | 1.5 (1.7) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) |

| Minimum, maximum | 0.0, 6.0 | 0.0, 20.0 |

| Ethnic background, n (%) | ||

| White | 134 (59.0) | 295 (72.7) |

| Asian or Asian British | 25 (11.0) | 31 (7.6) |

| Black or black British | 42 (18.5) | 50 (12.3) |

| Mixed or other | 23 (10.1) | 25 (6.2) |

| Missing | 3 (1.3) | 5 (1.2) |

Primary outcome: effective contraception use at 4 months

The proportion of women using effective contraception (hormonal and intrauterine contraception) was 20.1% greater (95% CI 5.2% to 35.0%) in the intervention group (58.4%, SD 21.6) than in the control group (40.5%, SD 23.8) (adjusted for recruitment period, treatment arm and centre; p = 0.011) (Table 4).

| Analysis | Intervention, n; mean (SD) | Control, n; mean (SD) | Estimate | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcomea | 21; 58.4 (21.6) | 21; 40.5 (23.8) | 20.1 | 5.2 to 35.0 | 0.011 |

| Primary outcome adjustedb | 21; 58.4 (21.6) | 21; 40.5 (23.8) | 14.5 | 0.9 to 28.2 | 0.038 |

Use of effective contraception remained statistically significantly higher in the intervention group when adjusted for recruitment period, treatment group, study centre, age, whether or not currently in a sexual relationship and history of past use of effective contraception, and was robust to the missing data (Tables 4–6) using a multiple imputation approach under an assumption of missing at random.

| Sensitivity analysisa | Intervention, n; mean (SD) | Control, n; mean (SD) | Estimate | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omit cluster with fewer than three responses | 14; 60.2 (19.7) | 14; 42.9 (13.8) | 15.2 | 2.3 to 28.1 | 0.026 |

| Omit cluster with > 30% individuals with missing data (excluded centre from the model) | 5; 58.5 (14.4) | 5; 44.1 (6.6) | 14.7 | 1.1 to 28.2 | 0.040 |

| Including percentage missing and number of responders in the model | 21; 58.4 (21.6) | 21; 40.5 (23.8) | 15.3 | –0.1 to 30.6 | 0.051 |

| Including percentage missing in the model | 21; 58.4 (21.6) | 21; 40.5 (23.8) | 15.0 | 0.3 to 29.7 | 0.046 |

| Including number of responders in the model | 21; 58.4 (21.6) | 21; 40.5 (23.8) | 15.0 | 0.6 to 29.4 | 0.042 |

| Multiple imputation | 15.0 | –2.0 to 32.0 | 0.076 |

| Analysisa | Intervention, n/N (%) | Control, n/N (%) | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects for cluster | 112/198 (56.6) | 85/208 (40.9) | 1.93 | 1.21 to 3.09 | 0.006 |

Contraceptive use and long-acting reversible contraception use at 4 months

The methods of contraception used at 4 months after EC are shown in Table 7. The most common methods used were oral contraceptive pills (POPs in the intervention group and the combined hormonal contraceptive pills in the control group). There were no sterilisations or women relying on vasectomy. Use of LARC methods (e.g. implant, intrauterine and injectable) did not differ between the intervention group (13/198, 6.6%) and control group (23/208, 11.1%) (95% CI –10.04% to 1.05%; p = 0.112).

| Variable | Intervention (N = 198), n/N (%) | Control (N = 208), n/N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Methods of contraception used nowa | ||

| Combined hormonal contraception | 28/198 (14.1) | 47/208 (22.6) |

| POP | 71/198 (35.9) | 15/208 (7.2) |

| Male condom | 31/198 (15.7) | 63/208 (30.3) |

| Progestogen-only injectable | 4/198 (2.0) | 4/208 (1.9) |

| Progestogen-only implant | 3/198 (1.5) | 11/208 (5.3) |

| Cu-IUD | 3/198 (1.5) | 4/208 (1.9) |

| LNG-IUS | 3/198 (1.5) | 4/208 (1.9) |

| Other method | 0 | 1/208 (0.5) |

| Not using any method | 57/198 (28.8) | 62/208 (29.8) |

| LARCb | 13/198 (6.5) | 23/208 (11.1) |

| When did they start using this method? | ||

| Same day as EC | 18/141 (12.8) | 14/146 (9.6) |

| Day after EC | 38/141 (27.0) | 7/146 (4.8) |

| With start of period after EC | 13/141 (9.2) | 23/146 (15.8) |

| Other | 48/141 (34.0) | 62/146 (42.5) |

| Missing | 24/141 (17.0) | 40/146 (27.4) |

| Where did they get contraception from? | ||

| GP clinic | 74/141 (52.5) | 53/146 (36.3) |

| SRH clinic | 34/141 (24.1) | 35/146 (24.0) |

| Other | 21/141 (14.9) | 40/146 (27.4) |

The most common reason given by respondents for not using effective contraception at 4 months was that they were not currently sexually active (Table 8). Significantly fewer women in the intervention group than in the control group had used EC again since recruitment [20/198 (10.1%) vs. 37/208 (17.8%)] (95% CI –15.38% to –1.48%; p = 0.018) (see Table 8).

| Reasons for not using effective contraception | Intervention (N = 57), n/N (%) | Control (N = 62), n/N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Not currently sexually active | 27/57 (47.4) | 28/62 (45.2) |

| Worried about side effects with contraception | 12/57 (21.1) | 21/62 (33.9) |

| Medical reasons | 1/57 (1.8) | 2/62 (3.2) |

| Not decided on method to be used | 9/57 (15.8) | 11/62 (17.7) |

| Difficult to get appointment | 8/57 (14.0) | 4/62 (6.5) |

| Difficult to find time to get to GP or SRH clinic | 6/57 (10.5) | 4/62 (6.5) |

| Trying for baby | 1/57 (1.8) | 0 |

| Other | 8/57 (14.0) | 5/62 (8.1) |

| Further use of EC: yes | 20/198 (10.1) | 37/208 (17.8) |

A significantly larger proportion of women in the intervention group reported that the pharmacist had advised them about starting ongoing contraception (98% vs. 75.5%; p < 0.001) (Table 9).

| Contraceptive advice | Intervention (N = 198), n (%) | Control (N = 208), n (%) | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Did pharmacist provide information about starting contraception? | |||

| No | 2 (1.0) | 46 (22.1) | 0.216 (0.156 to 0.277); p < 0.001 |

| Yes | 194 (98.0) | 157 (75.5) | |

| Missing | 2 (1.0) | 5 (2.4) | |

| Did pharmacist provide information about where to get contraception? | |||

| No | 19 (9.6) | 67 (32.2) | 0.237 (0.159 to 0.315); p < 0.001 |

| Yes | 178 (89.9) | 134 (64.4) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) | 7 (3.4) | |

A total of 158 out of 198 (79.8%) respondents in the intervention group reported that they used some of the study POP that the pharmacist provided. Table 10 provides data on when women started the POP, the number of packets of POPs used and reasons for non-use or discontinuation of the POP.

| Use of POP | Intervention (N = 198), n/N (%) |

|---|---|

| Used any of the POPs that pharmacist provided? | |

| Yes | 158/198 (79.8) |

| No | 35/198 (17.7) |

| Missing | 5/198 (2.5) |

| If not, why?a | |

| Not a regular partner | 8/35 (22.9) |

| Not requiring regular contraception | 7/35 (20.0) |

| Worried regarding side effects | 10/35 (28.6) |

| Did not understand how to use it | 1/35 (2.9) |

| Preferred another contraceptive | 6/35 (17.1) |

| Used POP in the past and it did not agree | 1/35 (2.9) |

| Preferred to see GP for contraception | 2/35 (5.7) |

| Other | 10/35 (28.6) |

| When did they start POPs? | |

| Same day as EC | 27/158 (17.1) |

| Day after EC | 93/158 (58.9) |

| With start of period after EC | 19/158 (12.0) |

| Other | 16/158 (10.1) |

| Missing | 3/158 (1.9) |

| Number of packets of POPs used | |

| Less than one | 15/158 (9.5) |

| One | 17/158 (10.8) |

| Less than two | 13/158 (8.2) |

| Two | 8/158 (5.1) |

| Less than three | 10/158 (6.3) |

| Three | 70/158 (44.3) |

| Still taking POP | 22/158 (13.9) |

| Missing | 3/158 (1.9) |

| Main reason for stopping POPs before the supply ran out | |

| Side effects | 40/158 (25.3) |

| Started another method | 6/158 (3.8) |

| Other | 22/158 (13.9) |

| Missing | 90/158 (57.0) |

Rapid-access card and sexual and reproductive health clinic utilisation

At the 4-month follow-up interview, 137 out of 198 (69.2%) respondents in the intervention group could recall receiving the rapid-access card, but only 31 respondents (15.6%) reported that they attended the SRH clinic. Only two respondents used the rapid-access card within 1 month of recruitment. Four out of 31 respondents (12.9%) received a LARC method at the SRH clinic (Table 11).

| Variable | Period 1 (N = 147), n/N (%) | Period 2 (N = 51), n/N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Did pharmacist provide a rapid-access card? | ||

| Yes | 105/147 (71.4) | 32/51 (62.7) |

| No | 25/147 (17.0) | 5/51 (9.8) |

| I cannot remember | 12/147 (8.2) | 12/51 (23.5) |

| Missing | 5/147 (3.4) | 2/51 (3.9) |

| Did they attend the SRH clinic? | ||

| Yes | 25/117 (21.4) | 6/44 (13.6) |

| No | 90/117 (76.9) | 35/44 (79.5) |

| Missing | 2/117 (1.7) | 3/44 (6.8) |

| If no, why?a | ||

| Not requiring contraception | 19/90 (21.1) | 9/35 (25.7) |

| Preferred to see a GP for contraception | 45/90 (50.0) | 17/35 (48.6) |

| Preferred to attend another SRH clinic for contraception | 5/90 (5.6) | 0 |

| Other | 22/90 (24.4) | 8/35 (22.9) |

| When did they attend the SRH clinic? | ||

| Same day as EC | 1/25 (4.0) | 0 |

| < 1 month after EC | 1/25 (4.0) | 0 |

| 1–2 months after EC | 2/25 (8.0) | 1/6 (16.7) |

| 2–3 months after EC | 12/25 (48.0) | 3/6 (50.0) |

| 3–4 months after EC | 4/25 (16.0) | 1/6 (16.7) |

| Other | 4/25 (16.0) | 0 |

| Missing | 1/25 (4.0) | 1/6 (16.7) |

| Did they remember to take rapid-access card to the SRH clinic? | ||

| Yes | 14/25 (56.0) | 3/6 (50.0) |

| No | 11/25 (44.0) | 2/6 (33.3) |

| Missing | 0 | 1/6 (16.7) |

| If no rapid-access card, were they refused an appointment? | ||

| Yes | 1/11 (9.1) | 0 |

| No | 10/11 (90.9) | 2/2 (100.0) |

| How long did they wait at the SRH clinic? | ||

| < 30 minutes | 8/25 (32.0) | 3/6 (50.0) |

| < 1 hour | 7/25 (28.0) | 1/6 (16.7) |

| 1–2 hours | 8/25 (32.0) | 1/6 (16.7) |

| Other | 2/25 (8.0) | 0 |

| Missing | 0 | 1/6 (16.7) |

| Did the SRH clinic provide a method of contraception? | ||

| Yes | 19/25 (76.0) | 5/6 (83.3) |

| No | 6/25 (24.0) | 0 |

| Missing | 0 | 1/6 (16.7) |

| Did the SRH clinic provide the participant’s preferred method? | ||

| Yes | 16/25 (64.0) | 5/6 (83.3) |

| No | 8/25 (32.0) | 0 |

| Missing | 1/25 (4.0) | 1/6 (16.7) |

| If no, why?a | ||

| Not enough staff or time | 2/8 (25.0) | 0 |

| Risk of pregnancy | 1/8 (12.5) | 0 |

| Other | 6/8 (75.0) | 0 |

| Method of contraception received | ||

| Progestogen-only implant | 1/25 (4.0) | 0 |

| Progestogen-only injectable | 0 | 0 |

| Cu-IUD | 1/25 (4.0) | 0 |

| LNG-IUS | 2/25 (8.0) | 1/6 (16.7) |

| Combined hormonal contraception | 3/25 (12.0) | 0 |

| POP | 12/25 (48.0) | 4/6 (66.7) |

| Male condom | 2/25 (8.0) | 0 |

| Experience of the rapid access to study SRH clinic | ||

| Smooth | 16/25 (64.0) | 3/6 (50.0) |

| Neither/nor | 6/25 (24.0) | 2/6 (33.3) |

| Problematic | 1/25 (4.0) | 0 |

| Missing | 2/25 (8.0) | 1/6 (16.7) |

Data obtained from the SRH clinic databases showed that similar proportions of participants in both the intervention and control groups actually attended the SRH clinics within 4 months of recruitment [52/305 (17%) intervention group vs. 43/309 (13.9%) control group, 95% CI –2.60% to 8.87%; p = 0.284]. A total of 41 out of 95 (43.1%) attendees received contraception and the methods supplied are shown in Table 12. There was no statistically significant difference in LARC provision to women in each group.

| Variable | Intervention (N = 305), n/N (%) | Control (N = 309), n/N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Attended the SRH clinic? | ||

| No | 253/305 (83.0) | 266/309 (86.1) |

| Yes | 52/305 (17.0) | 43/309 (13.9) |

| Method of contraception provided at this visit? | ||

| Yes | 26/52 (50.0) | 15/43 (34.9) |

| Method provided | ||

| Progestogen-only implant | 2/26 (7.7) | 3/15 (20.0) |

| Cu-IUD | 1/26 (3.8) | 4/15 (26.7) |

| LNG-IUS | 1/26 (3.8) | 3/15 (20.0) |

| Progestogen-only injectable | 0 | 0 |

| Combined hormonal contraception | 3/26 (11.5) | 1/15 (6.7) |

| POP | 16/26 (61.5) | 2/15 (13.3) |

| Male condom | 3/26 (11.5) | 3/15 (20.0) |

| Other method | 1/26 (3.8) | 0 |

A total of 75 women both attended the SRH clinic and provided data at the 4-month interview. For 34 of these women, the SRH clinic provided a contraceptive method. Thirty out of 34 (88%) women reported using the same method of contraception at 4 months as the method provided by the SRH clinic.

Pregnancies in the 4 months since emergency contraception

Nineteen respondents (4.7%) (intervention, n = 9; control, n = 10) reported that they had been pregnant (n = 17) or were currently pregnant (n = 2). The outcome of the pregnancies that had ended were abortion in 10 women (58.8%) and miscarriage in six women (35.3%); this information was unknown for one woman (5.9%). Based on the London Measure of Unintended Pregnancy24,25 scores from the questionnaire, 15 out of 19 pregnancies (78.9%) had been unintended (seven in the intervention group and eight in the control group).

Chapter 4 Mystery shopper exercise

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Glasier et al. 13 in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Mystery shopper exercise

Pharmacists were advised that one or two mystery shopper visits would take place before the control group of the study started, but they were not told when these would occur. Visits took place between April 2018 and January 2019. Research nurses recruited female volunteers (aged ≥ 16 years) to be mystery shoppers and instructed them on the aims of the exercise, the scenario to be followed and the data to be collected. The members of the patient and public involvement (PPI) group for the study assisted in identifying potential mystery shoppers. The shoppers received £20 for each completed visit. They followed a scenario (a single episode of unprotected sex within 72 hours) relating to a request for EC. The scenario had been approved by the PPI group. Immediately after leaving the pharmacy, shoppers completed a data collection pro forma, recording the time of arriving and leaving the pharmacy, duration of the consultation and where the consultation about EC took place. They also noted any information provided by the pharmacist, including advice on ongoing contraception. Data from the proforma were entered into an Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) database and descriptive statistics were conducted for each question.

Results

A total of 55 mystery shopper visits were conducted at the 30 study pharmacies participating in this part of the trial. The mean total time reported spent in the pharmacy was 12 (range 1–47) minutes. The median reported duration of the consultation with the pharmacist was 6 (range 1–18) minutes. Consultations took place in a private room with 34 women (62%) and the remaining consultations took place at the counter.

Eleven mystery shoppers (20%) were unable to get EC from the pharmacy. Seven mystery shoppers reported that they were told that no trained pharmacist was available to provide EC. Four mystery shoppers were told that EC was not in stock. Two of the latter women were aged 16 years and visited the same pharmacy on the same day and both were advised to return 90 minutes later. A further two mystery shoppers were advised that a copper intrauterine device would be more effective and were directed to a SRH clinic for insertion, but neither was offered oral EC as an interim measure. Eight mystery shoppers were told that they had to swallow the EC tablets in the pharmacy and seven mystery shoppers (in London) were told that the pharmacy could not offer free EC. Three mystery shoppers were asked to provide proof of identity and age to get free EC. Table 13 shows the results for information provided by the pharmacist around EC or ongoing contraception.

| Information provided or discussed | Yes (n) | No (n) | Not completed (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reason for needing EC | 43 | 12 | |

| Information about accessing ongoing contraception | 30 | 25 | |

| Oral information on importance of ongoing contraception | 27 | 27 | 1 |

| Oral advice to conduct a pregnancy test in 3 weeks | 22 | 32 | 1 |

| Written information on importance of ongoing contraception | 5 | 50 | |

| Written advice to conduct a pregnancy test in 3 weeks | 2 | 53 |

A total of 27 out of 55 (49%) mystery shoppers received advice (oral or written) about ongoing contraception. Forty-eight of the mystery shoppers made comments about their experience. Analysis of the free-text comments showed four common themes: (1) the manner of the pharmacist, (2) being requested to take the EC on the premises, (3) pharmacy not able to provide EC and (4) concerns about privacy. Examples are shown in Box 3.

He did however request for me to take the pill in front of him to make sure it is for me and not someone else. He said this is required legally. I then stated that I am uncomfortable with it, apologised for any inconvenience and left the pharmacy.

Mystery shopper B

They made me wait for a while and then fill out a form, which they kept. I was then told that they only had one EC pill and they needed to give me two because the law had changed so I should go elsewhere. I don’t think I spoke to a pharmacist at all, just a man who worked there?

Mystery shopper C

Initially asked at counter and the lady said to wait for the pharmacist. Had to repeat to pharmacist that I needed EC. Quite a few people around.

Mystery shopper D

Discussion

The mystery shopper exercise was undertaken to describe ‘standard care’ for the control group regarding the request for EC at a community pharmacy. The exercise showed that, although pharmacists were generally helpful, getting EC (for which all of the women were eligible) was not always easy (1/5 did not get EC). In addition, waiting times were sometimes long, consultations short and privacy was not always guaranteed. In a few cases, women were asked for proof of identity/age, which was not a requirement of the local PGD in place for supplying EC. In addition, fewer than half of pharmacists in the mystery shopper exercise gave any advice about ongoing contraception. These findings are similar to a previous mystery shopper study from Edinburgh, published 10 years ago. 12 Although the current mystery shopper exercise was conducted in only 30 UK pharmacies and may therefore not be fully representative of care across the UK, all participating pharmacists had recently undergone training for the Bridge-it study and so one might have expected that the performance of these pharmacies regarding advice around ongoing contraception would have been higher.

These findings suggest that opportunities to provide EC to women and to prevent unintended pregnancy are currently being missed in community pharmacies across the UK. Furthermore, opportunities for pharmacists to discuss ongoing contraception with women provided with EC are also being missed.

This adds to the debate of whether or not EC should be available on the general sales list (i.e. available without the need for a consultation and purchasable from a range of outlets). According to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (London, UK), the general sales list is appropriate for medicines that can, with reasonable safety, be sold or supplied in ways other than by or under the supervision of a pharmacist. 29 The term ‘with reasonable safety’ has been defined as ‘where the hazard to health, the risk of misuse, or the need to take special precautions in handling is small and where wider sale would be a convenience to the purchaser’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0. URL: https://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/). 29

It is now more than 20 years since EC was first approved as a pharmacy medicine in the UK. 7 There is abundant evidence to demonstrate that it does not present a hazard to health, nor is it widely misused, and does not need special precautions. If ECs were a general sales list medicine, then there would be more opportunities to obtain it, which would benefit women and, possibly, public health.

Chapter 5 Process evaluation

The Bridge-it study included a multimethod process evaluation to assess implementation, mechanisms of change and context to better understand the effectiveness of the trial (see Table 14). This chapter will report the methods employed and key findings relating to the following:

-

Implementation – was the intervention implemented as planned?

-

Mechanisms of change – how did the delivered intervention produce change in and impact on contraceptive practices?

-

Context – how did the local and broader context affect implementation and outcomes?

Findings are common across trial sites, unless indicated otherwise. Throughout the chapter, we highlight those findings that are pertinent to future implementation of POP provision with EC.

Methods: data sources and analysis

We employed a range of quantitative and qualitative methods, including qualitative interviews with providers (pharmacists and SRH staff) and participants, monitoring of pharmacy selection and training observations, analysis of relevant data from the 4-month follow-up questionnaire and monitoring of contemporaneous events (e.g. relevant media coverage). Further details on each data collection method and analysis approach are provided in Appendix 1, Table 16. Collection of such data allowed us to assess the role of our critical assumptions, mediators of change and intermediate outcomes that could impact on the effectiveness of the intervention.

All process data were analysed independently from the outcome data and documented before the outcomes were known. The process evaluation team (SP and LMcD) discussed the progress of data collection and analysis on a regular basis, allowing any issues that were encountered to be resolved (Table 14).

| Measure | Questions to be answered | Method/source |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation | Fidelity:

|

Qualitative interviews with pharmacists SRH providers and participants Observation of pharmacist training Monitoring and screening logs Notes from TMG and TSC meetings |

| Mechanisms of impact | Experiences of the intervention:

|

4-month intervention questionnaire Qualitative interviews with pharmacists, SRH providers and participants |

| Context | How did the local and broader context affect implementation and outcomes?

|

Qualitative interviews with pharmacists, SRH providers and participants Monitoring of contemporaneous events Notes from TMG and TSC meeting |

Qualitative interviews with pharmacists, sexual and reproductive health providers and participants

Qualitative interviews were conducted with those responsible for delivering the study (i.e. pharmacists and SRH providers) and those receiving the intervention (i.e. Bridge-it Study participants). The breakdown of recruitment by site is detailed in Figure 3. Specific details about sampling, recruitment, topics covered and analysis for each group is detailed below.

FIGURE 3.

Process evaluation flow chart.

Semistructured qualitative telephone interviews were conducted with pharmacists and SRH providers to explore the acceptability of the intervention and training received (pharmacists), the perceptions of barriers to and facilitators of implementation, and existing contextual challenges within their services (see Appendix 2). In total, 22 pharmacists were interviewed (12 from Lothian, three from Tayside and seven from London-based pharmacies). The aim had been to interview one pharmacist from each participating pharmacy in the study. The main pharmacies not represented (n = 7) are based in London (south), as it had not been possible to conduct interviews before the study was discontinued. Interviews were conducted between July 2018 and July 2019, with most interviews taking place once recruitment had ended in their pharmacy.

As well as interviewing pharmacists involved in the study, we interviewed five SRH providers in three out of four participating NHS sites (two in Lothian, two in Tayside and one in London) between May and October 2019. Our original aim had been to interview three or four staff members from each service; however, recruitment was challenging, particularly because of low Bridge-it study participant attendance at SRH clinics. Interviews were conducted 4–6 months after study recruitment had ended to allow time for SRH staff to have experience of participants attending their service.

Qualitative interviews were also conducted with a purposive sample of 36 intervention participants (24 participants in Lothian, nine participants in London and three participants in Tayside) to explore intervention acceptability, experiences of bridging from EC to effective contraception, facilitators of and barriers to continued uptake and the wider context of their contraceptive experiences. Unintended consequences were documented through the process evaluation, including asking participants whether or not they perceived any unintended negative outcomes resulting from participation in the trial. Research nurses asked participants for consent to be contacted by the process evaluation research assistant for a qualitative interview at the end of the 4-month follow-up questionnaire, and interviews were conducted between November 2018 and October 2019. Purposive sampling was employed to recruit a representative and diverse sample, with participants sampled by area, age, use of the study POP and attendance at a SRH clinic. The characteristics of the participants who were interviewed are shown in Table 15.

| Characteristic | Participants (n) |

|---|---|

| Age group (years) | |

| 18–19 | 9 |

| 20–24 | 14 |

| 25–29 | 5 |

| 30–37 | 8 |

| Location | |

| Lothian | 24 |

| Tayside | 3 |

| London | 9 |

| Contraceptive use at time of interview | |

| POP | 10 |

| Combined pill | 4 |

| Intrauterine contraception | 1 |

| Implant | 1 |

| None | 20 |

| Contraceptive service attendeda | |

| GP | 14 |

| SRH clinic | 5 |

| No service attended | 13 |

| Unknown | 6 |

| Previous effective contraceptive use | |

| Yes | 22 |

| No | 13 |

| Missing | 1 |

All provider and participant interview data were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and anonymised. Data management was assisted by ethnographic software (NVivo 10, QSR International, Warrington, UK). Transcription and analysis (proceeding case by case) began with the first interview and was ongoing during data collection, allowing emergent themes to be identified and explored in future interviews. Data analysis was undertaken using ‘framework analysis’, which is a method of proven validity and reliability in which data are coded, indexed and charted systematically, then organised using a matrix or framework. 30 Such a method helps to ensure systematic thematic analysis and facilitates the synthesis of key themes across the data set. Constant comparison was carried out to ensure that the analysis represents all perspectives and negative (‘deviant’) cases.

Monitoring of pharmacy selection and observations of training

To evaluate reach and recruitment, pharmacy selection was recorded using a standardised template format. Study team members responsible for recruiting pharmacies routinely recorded decision-making that contributed to pharmacy selection, including number of contacts made, responses from potential pharmacies, rationales for inclusion/exclusion and reasons for acceptance/refusal.

To shed a light on intervention fidelity and delivery, and the potential impact of contextual factors, all intervention and training materials were reviewed and observations of training sessions were conducted by the process evaluation research assistant, where feasible. A standardised training observation form was used to guide observations, with a particular focus on the way key processes of the intervention were presented to and understood by pharmacists. In total, 13 training sessions were observed by the process evaluation research assistant in Scotland. In London, the study trainers completed the observation forms after each training session. Written observational data were transcribed into Microsoft Word, thematic analysis was conducted and descriptive summaries were written.

Monitoring of contemporaneous events

To monitor local, national and international contemporaneous events that could have an impact on contraceptive use and behaviour over the course of the study, high-coverage media stories relating to contraception were monitored and recorded over the study period (i.e. July 2017–December 2019). Weekly Google Alerts (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) were set up using relevant search terms (e.g. ‘contraception’ and ‘morning-after pill’) and key information was recorded in a Microsoft Excel workbook (e.g. date of publication, news source, headline and topic focus). Relevance was assessed primarily through the scale of coverage and source of publication. Articles were included if they were published by a mainstream media source, such as widely read print/online titles (e.g. the Daily Mail, the Guardian and the Metro), popular magazines (e.g. Time and Cosmopolitan), popular social media news sources (e.g. HuffPost, LADbible and BuzzFeed) and other relevant and widely used internet sources (e.g. BBC news website, Google News and Ofcom). Over the period of the study, 736 articles were identified from mainstream media sources in the UK and were organised into key topic areas (e.g. negative focus, personal stories, emerging contraceptive methods, accessibility of contraception, contraceptive behaviour trends and general informative pieces). Descriptive summaries of key topics identified and scale of coverage were created in Microsoft Word.

Quantitative data collected as part of the main study

Data from the pharmacist eligibility screening logs (n = 599) and relevant data from the 4-month follow-up surveys (n = 406) were drawn on as part of the process evaluation to shed a further light on acceptability, fidelity of implementation, barriers to participation and the uptake of routine contraception. As part of the study, pharmacists were asked to screen all of those attending for EC and to fill out a standardised screening form detailing reasons for ineligibility. Relevant data collected from the 4-month follow-up survey included participation in the intervention (e.g. if the woman used EC/POP, accessed a SRH service, started effective contraception, and if not then why not), delivery of key mechanisms by pharmacists and SRH providers (e.g. information provided on where to access further contraception, rapid-access card received and length of time at SRH service) and changes in circumstances that could influence contraceptive use (e.g. change of partner or pregnancy). Data were entered into statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics and descriptive analysis conducted.

Researcher field notes and meeting minutes

Throughout the study, researcher field notes and reflections were documented, and meeting minutes were analysed to record factors that may have influenced the consistency or quality of data, and contextual factors that may have had an impact on implementation.

Synthesis of multiple data sources

After independent analysis of each data strand was completed, the findings from the multisource process evaluation were integrated to shed a light on implementation, mechanisms of change and the role of contextual factors on implementation and outcomes. To achieve this, key findings from each stage of data collection were synthesised in an analytical integration table. The table was organised to allow consideration of findings from each stage, with each strand being positioned in a single matrix for each PE component (e.g. implementation, mechanisms and context) (see Appendix 1). This method facilitated the systematic synthesis of the process data, drawing out synergistic interpretations to reveal a broader holistic perspective on how the intervention worked in practice.

Implementation

Pharmacist and sexual and reproductive health provider acceptability of the intervention

The majority of pharmacists and SRH providers were very positive about the premise of the intervention and the role of pharmacy in developing and improving contraceptive services. Bridging in community pharmacies was seen as an important way to improve access to contraception and to reduce repeat EC use and unwanted pregnancies:

. . . it shows that people are taking the issue of unwanted pregnancy seriously and they’re trying to improve, you know, the accessibility of services to women . . . and the choice that’s available to them.

Pharmacist 18, Lothian

As well as the pharmacy setting being viewed favourably, the EC consultation was seen as a particularly suitable and opportune time to offer access to routine contraception:

I also think it’s quite an opportune time when somebody comes in for emergency contraception, to pick up on, you know, sort of routine contraception. You know, the fact that they need emergency contraception, obviously something has gone wrong, so it’s a good time to be able to kind of go, well actually, have you had a think about this, or how can you deal with this kind of thing?

SRH worker 1, Lothian

It was suggested that approaching women in this way could break down some barriers (e.g. lack of time, difficulties accessing contraceptive appointments and avoidance) to accessing routine contraception at critical times.

Acceptability of taking part in a research study

Figure 4 shows the pharmacist support and training that was provided for delivering the Bridge-it study. During training sessions, the majority of pharmacists seemed enthusiastic and motivated to take part in the study and often reflected on this in interviews, expressing a desire to take part in more research:

I’m kind of like, I’d love to be involved in more things so I’m always welcome . . . you know, I’m welcome to do more kind of projects like this.

Pharmacist 20, London

FIGURE 4.

A flow chart of pharmacist training and support for delivering the Bridge-it study.

In particular, pharmacists who had been involved in the earlier pilot study15 or who had previous experience of pharmacy-based interventions were particularly enthused and seemed to be more accepting of the pharmacist role in the study, potentially because of familiarity with the kinds of processes and documentation required for trials. It is important to note that pharmacists who were particularly enthusiastic about the benefits of bridging through community pharmacies for patients, and about taking part in the study, were those who tended to recruit the most participants, perhaps highlighting the importance of ‘buy-in’ to the premise of the intervention.

Although most pharmacists reflected positively on the premise of the intervention and on taking part in research to expand contraceptive services, some concerns were raised during training. Pharmacists’ concerns typically focused on worries relating to managing the additional time and workload pressures of taking part in a research study (rather than of delivering POP per se), scepticism that additional time would be set aside to accommodate this, and concerns about how the study would fit with existing practices and changing guidelines relating to EC. These concerns are detailed in The impact of context on the Bridge-it study implementation and outcomes and focus on facilitators of and barriers to delivery and implementation in practice.

Pharmacist and sexual and reproductive health provider awareness of the study and preparedness to deliver

Pharmacists’ perceptions of and satisfaction with training

Observation of training demonstrated fidelity across sites, with sessions typically delivered as per the training guidance, covering all components and being consistent in content. Adaptations to training typically related to the time spent on particular components, fuelled by contextual factors such as lack of time. The majority of pharmacists were positive about the training received for the Bridge-it study and described the study as ‘informative’, ‘concise’, ‘well-designed’ and ‘convenient’. Pharmacists typically described being satisfied with the training staff:

. . . it was good, they were very clear, lovely manner the ladies had, so you didn’t feel daft asking a number of questions . . .

Pharmacist 8, Tayside

The venue, composition and timing of training also seemed to be acceptable to the majority of pharmacists, with different options available, small-group learning-facilitating dialogue and well-timed training encouraging confidence:

I think it was good. It wasn’t a particularly large group of us doing it. I think there were about sort of 8–10 so we were able to ask questions and chat and things which was quite good .

Pharmacist 11, London

I think it worked really well, I could start it straight away and it would be fresh in my mind because the training was a week before they would launch it, so it was good.

Pharmacist 2, Lothian

Pharmacists were also generally satisfied with the content of training and the study resources provided:

. . . the training was pretty good, pretty informative. And I think the material provided . . . stuff that they provided for reading was pretty informative as well.

Pharmacist 18, Lothian

The majority of pharmacists that were interviewed indicated that the training provided prepared them to deliver the intervention as planned, but acknowledged that time and practice were necessary to be fully prepared:

Obviously just with any of the new services it does take you just a . . . to get into a rhythm of like filling in all the paperwork and things like that.

Pharmacist 6, Lothian

However, some ways in which the training could have been improved to bolster preparedness were highlighted, including through drawing on pharmacists’ expertise in designing the training, increasing practice-based and role-play learning, and providing formalised refresher training between phases.

Awareness in sexual and reproductive health centres

Sexual and reproductive health providers were made aware of the study through management in their services. SRH providers interviewed described a lack of familiarity with their role in the study and a general lack of awareness of the study in their service:

I’m aware of a lot of studies but I wasn’t really aware of this one too much. I never saw any of the signs. You know? I never saw anything.

SRH provider 5, London

Most SRH providers indicated awareness of the study waning over time and stressed the need for reminders and easy and accessible study information to be available for all staff (including front-line reception staff).

Fidelity of intervention delivery

Experiences of delivery in participating pharmacies

Pharmacists’ descriptions of delivery and women’s accounts of their experiences in participating pharmacies suggest that fidelity of delivery was, on the whole, achieved. Although pharmacists’ descriptions of the recruitment process suggested adherence to the training protocol, there was some evidence of fatigue with research procedures, with failure to complete screening paperwork or enter data into the database relatively common across sites. Therefore, the added burden of the research context was apparent, typically extending EC consultations by approximately 15–20 minutes:

It’s a time-consuming process. So sometimes you need to manage your time really, really well and be very tight with time to fit it all in.

Pharmacist 1, Lothian

Research nurses from all sites reported having to spend a substantial amount of effort on the ground to encourage pharmacists to recruit and to assist with paperwork and database entry. Such experiences suggest the need for a more streamlined process with less paperwork and repetition, and the need for a high level of in-person support during implementation. However, the nurses noted that most of this related to taking part in a research study rather than the provision of POP as a bridging method itself. The impact of the pharmacy context on implementation is described in more detail in The impact of context on the Bridge-it study implementation and outcomes.

Women typically discussed positive and informative experiences in participating pharmacies:

. . . the lady who gave me all the advice on it, she was really, really thorough at explaining everything. She helped me out with the forms as well.

Participant 15, London

Data from the 4-month follow-up survey demonstrated that 90% (n = 178) of intervention participants recalled being given information about accessing further contraception during the EC consultation, in contrast to 64% (n = 134) of control participants. Most of the participants interviewed recalled being advised to access further contraception through either the participating SRH clinic (with rapid-access card) or their GP, typified here by participant 1, Lothian:

. . . so he said that I could either go into the clinic, and he gave me one of the ticket things [rapid-access card] to hand them [ . . . ] and he also said that if I told my GP about the study and what pill it was, they’d be able to give it to me as well.

Therefore, participants’ accounts highlighted that information around further access to contraception was predominantly accurate, consistent and clear, and may have contributed to many going on to successfully access further contraception. It is important to note that most women accessed further contraception through their GP (74/141) rather than a SRH clinic (21/141), and there was no difference in the proportion of women in either the intervention group or the control group who accessed the SRH service.

Although the majority of participants described being satisfied with the information provided in the pharmacy context, some inconsistencies in information provision emerged. Some indicated that they would have benefited from more in-depth information about the study and process involved:

I wouldn’t say from the initial chat with the pharmacist that I got a totally clear picture.

Participant 12, Lothian

It was not uncommon for participants to think that the aim of the study was to test out a new contraceptive pill, rather than about increasing access to further routine contraception:

It would be because you’re testing out a new drug to give out at pharmacies and GPs [ . . . ] and there was loads of girls getting asked to be part of the project to do statistics and see how it was affecting certain people.

Participant 10, Lothian

This framing of the intervention and lack of understanding about the aim may have had an impact on decision-making around accessing further contraception and motivations to do so. Around one-quarter of intervention participants (n = 54) could not recall being given a rapid-access card, typified by participant 35:

Do you remember if you were given a study card?

No, I don’t have a study card.

Were you told where to go if you had any issues with the contraception or if you wanted to get more?

Yes, he said that I could go there [pharmacy] and get my card and then obviously keep getting the pill but he wasn’t there when I last went so . . .

Such accounts highlight that there were some inconsistencies in information provided to participants in participating pharmacies, which resulted in confusion and, in some cases, trouble accessing further contraception.

Experiences within participating sexual and reproductive health clinics

As already highlighted, the SRH providers interviewed described a general lack of awareness of the study in their services, and few SRH providers interviewed described encountering Bridge-it study participants. In contrast to participants’ reflections on experiences in participating pharmacies, those who attended participating SRH clinics as part of the rapid-access component of the intervention reported less positive experiences, with a general lack of awareness among SRH staff encountered:

I think I spoke to someone who didn’t know what I was talking about, because when I went over and was like, can I have these . . . I was like, I’m with the study, can I please get some more contraceptive? And I don’t think she really knew, she was like, oh make an appointment with your GP.

Participant 5, Lothian

Such an experience was not uncommon, with four out of the five interviewed participants who attended their local SRH centre reporting difficulties accessing an appointment for further routine contraception in this way. Two participants were unable to access rapid appointments because the services were too busy. Although one participant overcame the time-related barriers and returned on another day, another participant was asked to wait for 2–3 hours and was unable to, and thus failed to access further contraception:

So waiting for 2 hours and being a working individual where clinics aren’t open 24 hours either, I just think, you know, some things you just have to bite your tongue with. So to cut a long story short, I’m pregnant.

Participant 23, London

Barriers to recruitment

During the Bridge-it study period, recruitment was slow and initial recruitment targets were not met, both for recruiting pharmacies and participants to take part in the study. This section describes the challenges of recruiting pharmacies and explore barriers to participation in the study that may have implications for wider implementation of bridging as a service in pharmacies.

Branches of large chain pharmacies and smaller independent pharmacies were approached to take part in the study because of their proximity to the participating SRH services, large footfall and high EC dispensing rates. Initially, it was decided to approach only those pharmacies with a dispensing rate of > 30 ECs per month, which ruled out many of the smaller independent pharmacies that appeared to be easier to set up. However, because of delays with setting up some of the larger chain pharmacies, the pharmacy recruitment strategy was adapted (September 2017) to allow consideration of pharmacies with lower EC dispensing rates. In total, 21 pharmacies that were initially approached were excluded or refused to take part. Barriers to pharmacy selection and recruitment included low EC distribution, charging for EC, already being commissioned to give out oral contraception after EC, lack of interest/enthusiasm and pharmacy environment/workload (e.g. too busy, understaffed and other disruptions).

Barriers to participation

Analysis of screening log data and pharmacist accounts in interviews indicated a variety of barriers to participation. In screening logs, pharmacists most commonly recorded unwillingness to give contact details for follow-up (n = 264) or data linkage (n = 262); in qualitative interviews, pharmacists expanded on these research-related barriers to participation, highlighting the time-consuming nature of paperwork and worries relating to confidentiality of data:

. . . lots of them were concerned about confidentiality, they were scared that I could just share the data with the GP.

Pharmacist 3, Lothian

Uncertainty around bridging as a new practice was also highlighted as a barrier to participation:

I mean, a lot of people were a little bit . . . they weren’t too sure about it I suppose, but they’re usually going to their doctor, so there was maybe issues there that they were just a little bit uncertain about the process of getting this through the pharmacy.

Pharmacist 5, Lothian

It seemed that the unfamiliar nature of this practice acted as a deterrent to some. Some thought that these particular barriers to participation would be overcome if bridging became an established pharmacy service, with less paperwork and greater advertising and awareness of the service:

I mean, if it was more widely known and became a more accepted pharmacy service, you would see more people.

Pharmacist 5, Lothian

Pharmacists talked about greater awareness resulting in more people participating, having time to decide whether or not to participate and visiting pharmacies specifically for longer-term contraception.

As well as research-related barriers, pharmacists drew attention to some barriers to participation that may impact on uptake if bridging were widely implemented as a service in this format, which therefore require consideration. Narratives of resistance to take POP specifically or hormonal contraception generally were commonly raised by pharmacists as a barrier to participation:

Do you think there’s anything that prevented people from participating?

Erm, well I’d say, the choice of it only being one pill, would definitely have been one. A lot of people didn’t like the fact that it was the progestogen-only one.

As well as a lack of choice of contraceptive bridging options available, pharmacists commonly described lack of time and a sense of rush as being common to EC consultations and a barrier to further discussion:

. . . the main problem is people are in a rush every time they come in to get the morning after pill.

Pharmacist 15, London