Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/04/33. The contractual start date was in October 2014. The draft report began editorial review in January 2020 and was accepted for publication in October 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2021 O’Farrelly et al. This work was produced by O’Farrelly et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 O’Farrelly et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Behaviour problems and their impact on health and development

Behaviour problems are among the most common mental health problems in young children, affecting an estimated 5–10% of children. 1,2 These disorders typically include attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder,3 and are a key concern for the NHS. According to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE),4 ≈ 30% of a typical general practitioner’s (GP’s) child consultations are for behaviour problems and 45% of community child health referrals are for behaviour disturbances. Behaviour problems are also one of the most common reasons for children to be referred to mental health services. 4,5

Behaviour problems are distinct in having one of the earliest onsets of mental health problems, with increasing research indicating that early symptoms can be identified in children aged 1 and 2 years. 6 Where problems endure over time, they can give rise to poorer educational attainment and physical health, as well as elevated risk of psychiatric disorders, substance misuse, antisocial behaviour and criminality. 2,5,7,8 In addition to the distress caused to individuals and families, there is a considerable cost to society through the health-care, social care and criminal justice systems. 9 Recent estimates put the lifetime costs of support for a child with conduct disorder at £280,000. 10

Interventions for behaviour problems

The quality of the early parental care that children experience has been causally linked to the development of behaviour problems. Where children experience low levels of sensitive parenting behaviour and greater use of harsh discipline, they are at a high risk of developing behaviour problems. 11 Consequently, these parenting behaviours, sensitivity and discipline, represent the key targets of most early intervention programmes in the UK, based on attachment theory and social learning theory, respectively. 12,13

There is an established evidence base demonstrating positive effects of parenting interventions for preschool- and school-aged children’s behaviour. An umbrella meta-analysis14 of 26 meta-analyses identified 411 studies of parenting interventions for children with externalising behaviours. The authors found that those studies that reported on externalising behaviour showed evidence of moderate positive effects. A recent meta-analysis15 of 154 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) also found a moderate positive effect of parenting interventions on children’s behaviour. The authors also reported an individual participant data meta-analysis of 13 RCTs of a specific parenting intervention, Incredible Years, which showed similar positive effects on conduct problems and ADHD symptoms. 15 Estimates of the cost savings associated with such programmes suggest that parenting interventions could provide savings of approximately £16,425 per family over 25 years. 16 As most programmes target preschool- (aged 3 or 4 years) and school-aged children, we know less about the effectiveness of programmes delivered in infancy and toddlerhood. Intervening earlier in childhood could be more effective both clinically and economically, provided that there is reliable identification of children at risk, as there is increased opportunity to intercept psychopathology before it becomes embedded and to reduce the burden of suffering experienced by families. 17

An evidence-based programme that can be delivered from aged 12 months is the Video-feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting and Sensitive Discipline (VIPP-SD) programme. 18,19 VIPP-SD represents a powerful combination of social learning theory and attachment theory, and targets the two key parenting behaviours: sensitivity and discipline. The goal of the intervention is to promote parents’ sensitivity (i.e. their capacity to identify their child’s attachment cues and exploratory behaviour, and respond to them appropriately) and sensitive discipline, which involves a consistent but non-harsh response to challenging behaviour. The VIPP-SD programme has been developed systematically and has been tested in 12 RCTs20–31 in a range of clinical and non-clinical populations. A recent meta-analysis32 of these trials demonstrated combined positive effects on caregivers’ sensitivity and children’s behaviour problems. However, VIPP-SD has yet to be tested in a routine health service context in the UK.

Rationale for the research

Early intervention has the potential to improve behaviour problems before they become established, which could yield cascading benefits for children’s outcomes across their life course. Indeed, early intervention has become a key priority of global and domestic policy. 33–35 However, there are few effective early psychological interventions that target behaviour problems in very young children. 36 The literature also demonstrates that no single programme or service delivery method has been shown to be a panacea for the varied challenges that families face. 37 Rather, effective early intervention for children at risk of behaviour problems is likely to require the identification of a range of efficient and repeated interventions at different developmental stages. 38 This is in keeping with global policy recommendations on the importance of staged and developmentally informed intervention across early childhood that is grounded in nurturing caregiving. 39 Successful early intervention, therefore, first requires effective programmes that can target behaviour problems at their earliest onset in children aged 1 and 2 years. The Healthy Start, Happy Start study was designed to address this gap by testing whether or not a brief parenting intervention (VIPP-SD) could be effective in preventing enduring behaviour problems in children aged 1 and 2 years in a pragmatic health service context.

Aims and objectives

The aim of the Healthy Start, Happy Start study was to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a brief early parenting intervention to prevent enduring behaviour problems in young children aged 12–36 months.

The objectives were to:

-

undertake a RCT to evaluate whether or not a brief parenting intervention (VIPP-SD) leads to lower levels of behaviour problems in young children who are at high risk of developing these problems, compared with usual care in the NHS

-

undertake an economic evaluation to assess the cost-effectiveness of the intervention compared with usual care.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design

The Healthy Start, Happy Start study was a pragmatic, assessor-blinded, multisite, two-arm, parallel-group RCT, to test the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a brief parenting intervention (VIPP-SD) for parents of young children (aged 12–36 months) at risk of behaviour difficulties. VIPP-SD was predominantly delivered by trained therapists through NHS health visiting teams and was compared with receiving usual care alone.

Ethics and governance

Ethics approval for the study was given by Riverside Research Ethics Committee (14/LO/2071), which is part of the NHS Research Ethics Service. The trial was registered with the Integrated Research Approval System (IRAS) under the reference number 160786 and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network (CRN) Portfolio under the reference number 18423. The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) registry as number ISRCTN58327365. Approval for the study to be conducted within participating NHS sites was obtained from the NHS Health Research Authority (HRA). Local NHS permissions were also given for each recruitment site. The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki,40 UK Policy Framework for Health and Social Care Research41 and Imperial Clinical Trials Unit (ICTU) standard operating procedures.

Participants

Participants were children aged 12–36 months who demonstrated behaviour problems and their caregiver(s).

Inclusion criteria

To be eligible to participate, families had to meet the following inclusion criteria:

-

participating caregivers were aged ≥ 18 years

-

child was aged between 12 and 36 months

-

child scored in the top 20% of population norms for behaviour problems on the parent-reported Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

-

written informed parental consent from participating caregivers.

Exclusion criteria

Participants were not eligible to participate if any of the following criteria were met:

-

child or parent had severe sensory impairment, learning disability or language limitation that was sufficient to preclude participation in the trial

-

a sibling was already participating in the trial

-

family was participating in active family court proceedings

-

parent was participating in another closely related research trial and/or was receiving an individual video-feedback-based intervention.

Setting

Recruitment for the study was conducted in six UK NHS trusts: Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust, Whittington Health NHS Trust, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, North East London NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust, and Hertfordshire Community NHS Trust. Recruitment efforts were predominantly targeted across seven areas within these trusts: the London Boroughs of Camden, Hillingdon, Islington, and Barking and Dagenham, as well as Oxfordshire, Peterborough and Hertfordshire. Research assessments were carried out in participants’ homes or in another setting if the participant preferred (e.g. a private room in a children’s centre).

Recruitment procedure

There were two stages of recruitment in the study. In stage 1, potential participants in participating NHS sites were screened for behaviour difficulties using the parent-reported SDQ. 42 The principal pathway for recruitment was through health visiting services, with health visitors screening families using a study screening pack during routine 12- and 24-month child health reviews. This was supplemented by direct screening undertaken by members of the research team and CRN support staff in the waiting room of these clinics and children’s centres. Health visiting services also posted screening information to families with children within the target age range, and advertisements for the study were placed in health visiting centres and GP surgeries. Participants were also recruited through wider community services including nurseries, libraries, and through social media advertisements in local and community forums. Recruitment advertisements included the questions ‘[I]s your child’s behaviour sometimes a challenge?’ and ‘[A]re you interested in finding out more about your child’s behaviour?’.

In stage 2 of recruitment, the research team contacted caregivers by telephone if their children met the eligibility criteria based on their scores on the SDQ questionnaire (i.e. scoring in the top 20% of population norms). During this telephone call, the family’s full eligibility and interest in participating in stage 2 of the study were assessed. Researchers also enquired as to whether or not there were two parents/caregivers in the family and, if so, if both would be willing and available to participate in the study. Interested participants were sent an information pack for stage 2 of the study by e-mail or post, and a date to meet with them at their home for the baseline assessment visit was scheduled.

Informed consent

Participating parents/caregivers provided written informed consent for each stage of the study. All participant resources were ethics approved [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/130433/#/documentation (accessed January 2021) for participant information sheets (PISs) and consent forms used through both stages of the trial, as well as template letters used to inform GPs and health visitors of families’ study participation]. In stage 1, potential participants were given screening packs containing an information leaflet and the stage 1 PIS and consent form, alongside the screening questionnaire. Parents/caregivers were able to provide written or electronic consent to complete the screening stage of the study. Consent for stage 2 of the study was not provided at this point.

Participants who were eligible for and interested in the second stage of the study, the full RCT, were sent the stage 2 PIS either by e-mail or by post following a telephone call from the research team and ahead of their scheduled baseline assessment. The PIS and the clauses of the consent form were then fully explained in person to participants by a trained researcher at the beginning of the research assessment. Participants’ right to withdraw from the trial at any point was explained. Participants were given the opportunity to ask any questions that they had.

Baseline assessment

Baseline assessments were carried out in participants’ homes (or, in a very small number of cases, in private rooms of children’s centres close to participants’ homes). At baseline, trained researchers obtained written informed consent and collected family demographic information. Parent demographic information included parents’ sex, age, ethnicity, education level, employment status and relationship status. Child demographic data included children’s sex, age and ethnicity. Measures administered during the baseline assessment can be seen in Table 1.

| Data | Measure | Source | Timing of data collection | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 5-month follow-up | 24-month follow-up | |||

| Demographicsa | Parents’ and children’s sex, age, and ethnicity; parent education level, employment status and relationship status | Interview | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Primary outcome | PPACS | Interview | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Secondary outcomes | CBCL | Questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| SDQ (parent report) | Questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| SDQ (teacher report) | Questionnaire | ✗ | |||

| PHQ-9 | Questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| GAD-7 | Questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Parenting Scale | Questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| RDAS | Questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Economic data | CA-SUS | Interview | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Implementation data | Participant feedback questionnairea,b | Questionnaire | ✗ | ||

| Intervention fidelity | Audio recordings | ✗ | |||

The baseline visits took between 2 and 2.5 hours to complete (depending on the number of caregivers participating). All baseline assessments were conducted between July 2015 and July 2017.

Follow-up

Follow-up visits took place at two time points. The first was a post-treatment assessment (i.e. after the VIPP-SD intervention for those in the treatment group), approximately 5 months post randomisation, whereas the second was scheduled for 24 months post randomisation, when the children were aged 3–5 years. These assessment points were timed to allow for an initial post-intervention assessment when treatment would have usually been completed (5-month assessment) and to assess for longer-term outcomes (24 months). To assess whether or not the intervention had clinically significant effects on child behaviour problems, the measures of child behaviour collected at baseline were also administered at both follow-up visits. Similarly, measures of self-reported parenting practices, as well as parent mental health measures, and couple functioning, where appropriate, were also repeated at follow-up time points. Families were also asked to complete a structured interview of service use at both follow-up time points to assess cost-effectiveness. Administration of all trial measures is outlined in Table 1.

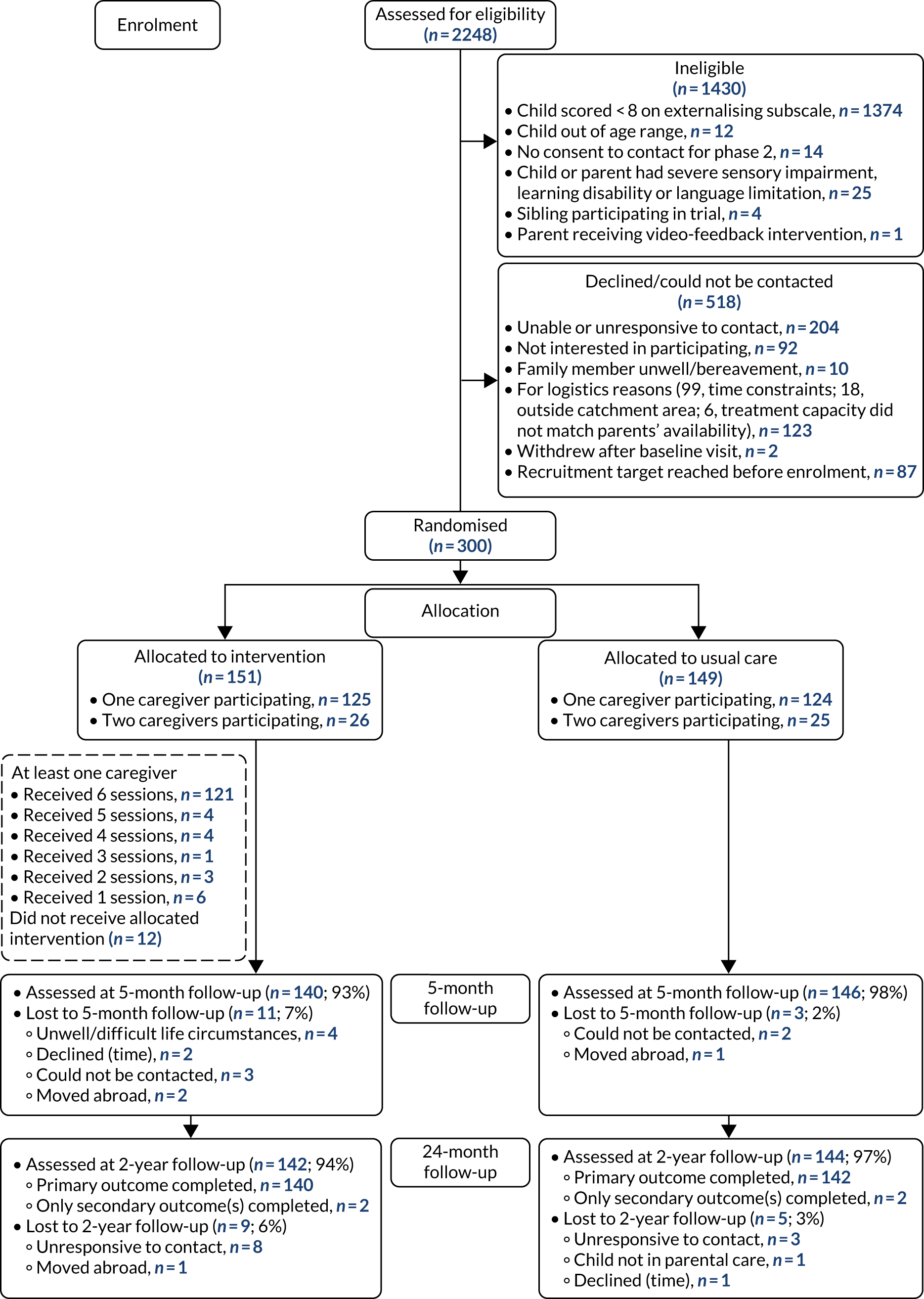

The follow-up visits took between 2 and 2.5 hours to complete. All follow-up data were collected between December 2015 and July 2019. Figure 1 shows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram outlining participant recruitment and retention during the study.

FIGURE 1.

The CONSORT flow diagram for the Healthy Start, Happy Start RCT.

Intervention

Video-feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting and Sensitive Discipline is a manualised, home-based intervention developed by Juffer, Bakermans-Kranenburg and van IJzendoorn and based on attachment theory and social learning theory. 18 The goal of the intervention is to promote parents’ sensitivity (i.e. their capacity to identify their child’s attachment cues and exploratory behaviour, and respond to them appropriately), as well as sensitive discipline, which involves a consistent but non-harsh response to challenging behaviour. VIPP-SD was delivered by trained therapists over six sessions, lasting 1–2 hours, at approximately fortnightly intervals. The role of the therapist was to develop a trusting and empathetic relationship with the parent(s) and to deliver the six sessions (four core sessions and two booster sessions) in line with the manual.

The first half of each session involved the therapist filming the parent with their child during interactions that aimed to reflect everyday situations, such as reading a book together, playing with toys and a mealtime. Following the session, the therapist used the video-recorded interactions to write a feedback script based on an appraisal of the parent’s interaction profile needs, the guidelines of the protocol, and the sensitivity and discipline themes for that session. The parent and therapist spent the second half of each session reviewing the interactions filmed in the previous visit, with the therapist frequently pausing the video to deliver feedback based on the script they had prepared following the last session. The content and focus of each session were manualised, but the feedback was delivered in an individualised way, as feedback is unique to each parent and child in that moment. A modified version of VIPP-SD, Video-feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting for Co-parents (VIPP-Co),43 was delivered when two caregivers in the family were participating. The content and themes of the VIPP-Co intervention broadly mirrored the VIPP-SD manual, with additional emphasis on interactions involving both caregivers together with the child and on positive co-parenting. In the first three sessions, feedback was delivered separately to each caregiver (as in VIPP-SD) and, from session 4 onwards, feedback was delivered to both caregivers together. The intervention was delivered by 40 trained therapists, the majority of whom were health visitors, community nursery nurses and clinical psychologists, as well as a small number of professionals from other backgrounds, such as family and child therapy, psychology and psychiatry.

Fidelity

Each therapist delivering the intervention undertook 4 days of VIPP-SD training, as well as an additional day of training on delivering the intervention to two caregivers and on the study protocol. Therapists undertook supervised clinical practice with a practice case before becoming a therapist on the trial and received regular clinical supervision throughout the trial. Therapists audio-recorded the feedback of sessions and reported on fidelity in terms of the delivery of key components of the treatment, as well as reporting on global adherence to the manual. We randomly selected 10% of audio-recordings to allow two assessors trained in the intervention to rate the quality of sessions and adherence to the VIPP-SD manual.

Usual care

Participants in both groups continued to receive their usual care, which was minimal in most cases (there are no standard care pathways in the NHS for early-onset behaviour problems). Some participants received support and advice from a health visitor or GP, referral to early intervention mental health services linked to a children’s centre, or parenting advice and support sessions. Data were collected on concurrent use of health and social care services and are presented in Chapter 4.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome for the trial was the assessment of the severity of behaviour problems at 5 months post randomisation, measured using a modified version of the Preschool Parental Account of Children’s Symptoms (PPACS)44,45 (see Appendix 1). The PPACS is a semistructured interview administered by trained researchers and conducted with the child’s primary caregiver. Interview measures are considered the gold standard outcome measure as they can circumvent potential biases related to parent-reported outcomes. 46 We made minor adaptations to the measure for use in the current study to ensure its suitability for use with children in the sample’s age range.

During the PPACS interview, the primary caregiver is asked to recall and describe detailed examples of their child’s typical behaviour over the past week in a range of settings (e.g. in the home, with friends, in public). The objective of this approach is to allow the interviewer to rate the child’s behaviour based on real examples, rather than caregivers’ global impressions or judgements of whether or not the behaviour is normal. To ensure that the example given is characteristic of the child, caregivers are asked how representative the described behaviour is of the child in the last 4 months. The researcher rates the severity and frequency of the child’s symptoms based on professional judgement, following training, guided by written definitions and thresholds of each of the scored behaviours. The interview is used to score the children on two subscales; the first measures ADHD/hyperkinesis, whereas the second measures conduct problems.

This measure has high inter-rater reliability and good construct validity, and has been used as an outcome measure in a number of other clinical trials assessing intervention effects on child behaviour. 47–49 Thirty interviews were randomly selected by the study statistician to be double-scored by another trained researcher to ensure inter-rater reliability in the current study. One-way, single-measurement, absolute agreement intraclass correlation coefficients were calculated for each time point and indicated high levels of inter-rater reliability among researchers (with intraclass correlation coefficients as follows: baseline – total score, 97; conduct subscale, 93; hyperactivity subscale, 97; 5-month follow-up – total score, 96; conduct subscale, 95; hyperactivity subscale, 95; and 24-month follow-up – total, 92; conduct subscale, 72; and hyperactivity subscale, 98).

Key secondary outcomes

Based on prespecified hypotheses in the trial protocol, there were two key secondary outcomes measuring child behaviour.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

The SDQ42 was used to measure behaviour problems as it is routinely used in both research and practice settings the UK. Participating caregivers were asked to complete this questionnaire. At the 24-month follow-up, the child’s nursery or school was also asked to complete the questionnaire, if parental consent was given. The measure comprises 25 items that respondents rate on a three-point scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat true or 2 = certainly true). The items are divided between five subscales: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer relationship problems and prosocial behaviour. Scores on the conduct problems and hyperactivity scales can be combined to provide an overall externalising behaviour score. The preschool version of the SDQ (for children aged 2–4 years) was used. The psychometric properties and utility of this version have been established in children aged 2 and 3 years. 50,51

Child Behaviour Checklist

Behaviour problems were also measured using the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL). 52 The CBCL is a 100-item questionnaire that asks parents to rate how true the behaviour is of their child over the last 2 months on a three-point scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat true or 2 = very true or often true). The measure gives a total score, an externalising score and an internalising score. The externalising score is made up of two syndrome subscales for attention problems and aggressive behaviours. The internalising score is made up of items from the emotionally reactive, anxious/depressed, somatic complaints and withdrawn syndrome subscales. The CBCL was selected for use as well as the SDQ because it has been validated in children as young as aged 12 months and is widely used in research studies. 53

Other secondary outcomes

Parenting scale

Parenting practices were assessed using the self-reported Parenting Scale,54 which is a measure of dysfunctional discipline practices in parents. The Parenting Scale is a 30-item questionnaire that asks parents to rate how they would respond to various behaviour problems, with each item receiving a score of 1–7 (effective to ineffective strategies).

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

Self-reported depression severity and symptomatology were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). 55 The PHQ-9 is a nine-item questionnaire, with each statement corresponding to one of the nine criteria for depression outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV). 56 Each statement is scored for the frequency in which the parent has experienced each problem over the last 2 weeks. Scores range from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), with a total score obtained by summing all items of the questionnaire.

Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7

Parental anxiety was assessed using the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). 57 The GAD-7 is a seven-item questionnaire that asks respondents how often they have experienced each problem in the last 2 weeks. Each statement is scored from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), with a total score obtained by summing all items of the questionnaire.

Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale

Relationship adjustment was measured using the Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale (RDAS). 58 The RDAS is a 14-item questionnaire consisting of three subscales: dyadic consensus, dyadic satisfaction and dyadic cohesion. Scores range from 0 to 69, where higher scores indicate greater relationship satisfaction and lower scores suggest greater relationship distress.

Child and Adolescent Service-Use Schedule

Information on the use of health and social care services was recorded in an interview using a modified version of the Child and Adolescent Service Use Schedule (CA-SUS). 59 Modifications to the CA-SUS were based on a review of recent literature and clinical feedback. This is an interview measure conducted with the child’s primary caregiver that asks parents to recall use (number and duration of appointments/sessions) of key services. Data were collected on the use of accommodation services (e.g. foster care, supported housing), hospital services (e.g. inpatient stays, outpatient contacts, accident and emergency attendances), community-based health and social care services (e.g. contacts with GPs, clinical psychologists) and all prescribed medication. Parents/caregivers were interviewed at baseline and asked about their child’s use of services and/or their use of services in relation to their child’s needs in the previous 3 months. At subsequent follow-up points (5 and 24 months), service use was recorded for the period since the previous interview to ensure that the entire duration of the trial had been captured.

Feedback questionnaire

Parents who were allocated to the intervention group were also asked to complete a feedback questionnaire [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/130433/#/documentation (accessed January 2021)] following the 5-month follow-up assessment visit to explore their satisfaction with and experiences of the VIPP-SD programme. The questions were related to their perceived impact of the programme (in terms of their relationship with their child and their child’s communication and behaviour) and their satisfaction with the home-based delivery format.

Serious adverse events

Serious adverse events (SAEs) were defined as ‘an adverse event that results in death, is life-threatening, requires hospitalisation or prolongation of existing inpatient’s hospitalisation, results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity’ [reproduced with permission from the European Medicines Association. Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6(R2)60]. The occurrence of SAEs was collected at the 5- and 24-month follow-up assessments. Child hospitalisation data were collected using the CA-SUS. Owing to the low-risk nature of this trial, non-serious adverse events were not collected.

Sample size

A sample size of 300 children and their caregiver/parent(s) was selected to provide between 80% and 90% power to detect standardised effect sizes of 0.36 and 0.42, respectively, on the primary outcome, at a 5% level of statistical significance, and assuming a 20% attrition rate. The analysis was adjusted for baseline behaviour score, time from randomisation to follow-up, recruitment site, age of child at recruitment, and caregiver involvement (one vs. two participating caregivers) as fixed effects. This is likely to have increased power to > 90% as such adjustment, especially for baseline scores of the same variable, will have reduced the residual error variance in our model.

Randomisation and blinding

The randomisation list was prepared by an independent statistician using block sizes of two, four and six (varying at random) and 1 : 1 allocation to either VIPP-SD or usual care. The randomisation list was uploaded to the study electronic data capture system before the trial commenced. Randomisation was performed using a web-based randomisation system linked to the trial database following enrolment by the researcher who conducted the baseline assessment and who was blind to all treatment allocations. Eligible participants were allocated online to the next available treatment code in the appropriate stratum. Randomisation was stratified by recruitment site and the number of caregivers participating (one vs. two). Access to the allocation sequence was restricted to an independent statistician and appropriate members of the InForm™ (version 4.6) technical support team (Imperial College London, London, UK) to maintain allocation concealment.

Following randomisation, the trial manager informed participants of their allocated groups and matched participants to therapists for treatment according to the availability of both the therapists and the parents. All assessors remained blind to treatment allocation for the duration of the study. Participants were reminded of the importance of researchers remaining blinded to group allocation by the trial manager or administrative assistant at each contact when scheduling their follow-up assessments. Researchers also reminded parents of the importance of blinding in person at the start of the follow-up visits to ensure that researchers stayed blinded to group allocation during the assessment. In cases where unblinding did occur, the primary outcome (PPACS) was re-scored by a blinded trained assessor.

Data collection and data management

The trial’s source data included paper forms, questionnaires, written interview notes, scoring from researchers’ research assessments, and feedback notes and log books from trial therapists’ intervention sessions. Source data were collected and stored securely in accordance with the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) good clinical practice (GCP),61 the Data Protection Act62 and the UK Policy Framework for Health and Social Care Research. 41 Following the assessments/intervention visits, data were entered on an electronic Case Report Form (eCRF) developed in InForm™, an electronic data capture system built around an Oracle database. The InForm system includes automated range checks and validation rules for data entry to help ensure data accuracy. A computer-generated audit trail is in place that records the date, time, operator, operation and previous value of all manipulation of clinical data.

InForm storage and management were undertaken by the Imperial College Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) team. InForm sits on a server behind a firewall connected to the College Storage Area Network (SAN). The data are backed up regularly to removable media, which allows for disaster recovery. In addition to the College backup facility, every 20 minutes, the activity logs for the trial are moved to another server in a different location to facilitate rapid recovery of data should it become necessary (e.g. in a disaster recovery scenario). Access to the system was restricted to trained staff with unique password-protected accounts. Identifiable data were not recorded in the eCRF and participants were identified by a unique trial identifier only.

All data monitoring and cleaning were also completed on InForm. Predefined data ranges were included in the eCRF, which raised automated queries if data outside the expected range were entered. In addition to the automated queries, the trial data were reviewed on a regular basis by the trial manager and trial statistician for discrepancies and errors. Data cleaning was performed prior to each Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) meeting and prior to database lock. Final data checks were performed by the statistician once the database had been soft locked and before hard lock was complete. All outstanding queries were resolved prior to the database hard lock.

Quality assurance and monitoring

Quality assurance (QA) and monitoring were performed in accordance with ICTU standard operating procedures (SOPs). A risk assessment was conducted by the ICTU QA manager prior to the start of the study, which assigned a risk category of ‘low risk’ to the trial. A monitoring plan was developed in accordance with the risk assessment to define how monitoring procedures would be carried out and the level of source data verification required for the study.

In accordance with the monitoring plan, 100% of participant consent forms and SAEs were source-verified. Further to this, 20% of key trial data were also source-verified against the original paper records, which included the primary outcome (PPACS); two of the secondary outcomes (i.e. CBCL and SDQ); and 10% of demographics, therapist logbooks and all other outcomes (Parenting Scale, PHQ-9, GAD-7, RDAS and CA-SUS).

Discrepancies noted between the paper records and trial database were queried and corrected in the trial database. Monitoring was carried out centrally by the research team, ensuring that the member of staff carrying out source data verification was not the same person who had performed data entry in each case. Participant data to be monitored were identified by the trial statistician through random selection.

Data analysis

A comprehensive statistical analysis plan was produced before undertaking the analysis and agreed with the Project Management Group (PMG), Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and DMEC. Primary analyses were conducted on an intention to treat (ITT) basis.

Multiple linear regression was used to assess the primary outcome measure, the difference in PPACS score between the trial groups at 5 and 24 months post randomisation. The PPACS score at the 5-month follow-up was the dependent variable, whereas trial group, PPACS score at baseline, time since randomisation, recruitment centre, age of the child at recruitment and number of parents/caregivers participating (one or two) were included as independent variables. Separate models were fitted at 24 months (adjusting for the baseline measurements, but not the 5-month measurements). These were distinct from the models fitted at 5 months (which, again, were adjusted for baseline measurements). Similar models, with adjustment for the appropriate baseline score, were used to assess the difference in CBCL and SDQ scores between the trial groups at the 5-month follow-up.

Regression residuals were plotted to assess their fit to the normal distribution using probability plots. PPACS scores (total and subscales) were normally distributed at 5 months and close to normal at 24 months. Inspection of residuals plots suggested assumption of homoscedasticity and of linearity were also reasonably well met. Visual inspection of the residuals from the regression analyses of secondary outcomes at 5 and 24 months suggested that they were close to normally distributed. Repeating the regression models using bootstrap methods (that allow for departure from normality) produced very similar results. For consistency, the results based on linear regression only are presented.

Secondary outcomes that were completed by each participating caregiver were analysed separately by sex. Standardised effect sizes (also known as d) were calculated by dividing the differences in means by the standard deviation in the usual-care group at follow-up.

Missing answers to individual questions in the PPACS were imputed. Unrateable or missing items in the attention/hyperactivity scale occurred most often when children did not regularly undertake an activity required for scoring (e.g. watching television or playing with a sibling/friend on the same activity). This assumption of ‘missing at random’ inherent in the multiple imputation analysis seems reasonable here. This implies assessing attention based on the activities that the child regularly undertakes (e.g. playing alone and eating a meal), by imputing values for activities that the child does not regularly undertake (e.g. watching television and/or playing with a friend or sibling). There were negligible missing data in the conduct disorder scale. The level, pattern and likely causes of any missingness in the baseline variables and primary outcome were investigated. Multiple imputation was of individual missing items in the PPACS interview when it was partially completed (because this always implied that at least 50% of items in the scale had been completed). Multiple imputation of the whole score was performed if the entire scale was missing. At the 5- and 24-month follow-ups, imputation was based on randomised group, sex of child, age of child at the 5- and 24-month assessments and baseline score, utilising information from both the baseline and 5- and 24-month PPACS interviews. Imputation at baseline was based on randomised group, sex of child, age of child at baseline and information from the baseline PPACS questionnaire.

Missing items in the other secondary outcome scales (child behaviour as assessed by the CBCL and SDQ; and self-reported parental discipline behaviour, mood, anxiety and couple functioning) were dealt with by scaling up. Thus, the sum of the maximum possible scores for non-missing items in each scale was divided by the maximum possible total score for a fully completed scale to give the proportion of the scale that had been completed (inflation factor). Scaling up was achieved by dividing the observed total score for each scale by the inflation factor. The proportion of missing items was generally negligible. See Appendix 2 for additional information on multiple imputation.

Analysis of the primary outcome was repeated without adjustment for time since randomisation and using complete cases after multiple imputation of missing items only. Analysis was also repeated assuming that those who did not have PPACS follow-up data available had better than anticipated results and then worse than anticipated results (anticipated by multiple imputation, better and worse by one standard deviation of the difference between PPACS scores at follow-up and at baseline). In further analyses, unrateable items within PPACS were filled in as the best possible scores and then as the worst possible scores. Analysis of primary and secondary child behaviour outcomes was repeated for each domain separately. Complier-average causal effects (CACE) analysis was performed, using two-stage least squares regression analysis, to determine the effect of receiving the intervention, rather than just being randomised to receive it. Compliance was defined as receipt of the four core VIPP-SD visits.

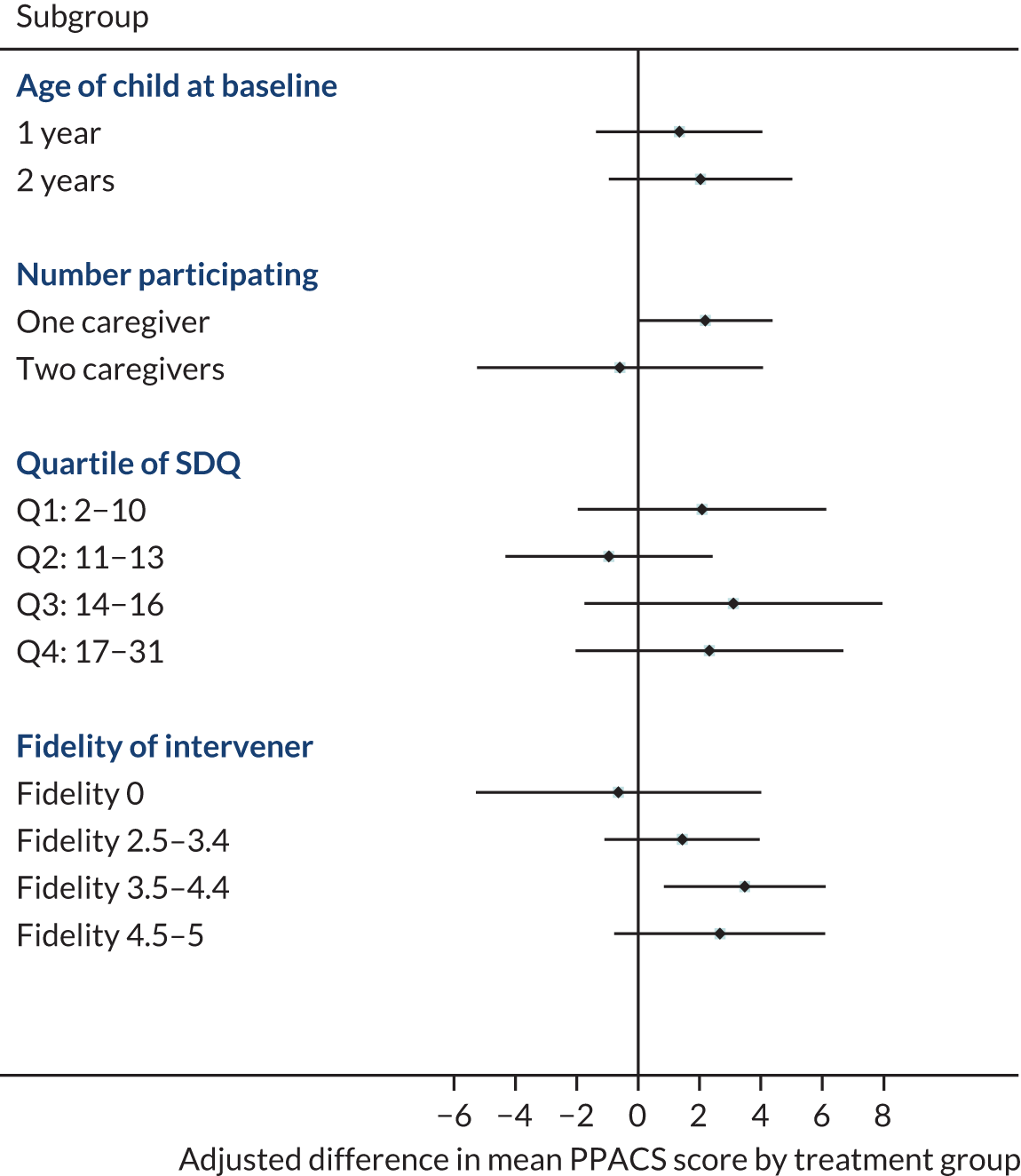

Planned subgroup analyses of the primary outcome were of the effects of child age at baseline (12–23 months compared with 24–36 months) and of the number of parents participating (one vs. two). We also undertook an ad hoc subgroup analysis to assess the effect of quartiles of severity of child behaviour problems at baseline and of fidelity of the intervention in those randomised to VIPP-SD. The magnitude of the treatment effect was estimated by repeating analysis of the primary outcome for each subgroup separately (and for each fidelity group compared with all patients allocated to the usual-care group).

All analyses were conducted using Stata® (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) software (versions 13.0 and 15.0).

Trial organisation and management

Trial management

The trial was managed by the UK Clinical Research Collaboration registered ICTU, including statistics, operations, database development and QA. The trial manager was based with the chief investigator at the Division of Psychiatry in Imperial College London, working in collaboration with the ICTU.

The trial was overseen by three main oversight committees: (1) TSC, (2) PMG and (3) DMEC. A patient and public involvement (PPI) group was also convened.

Trial Steering Committee

The TSC provided overall supervision of the trial, monitoring the progress of the study, ensuring that there were no major protocol deviations and providing advice to the trial investigators. The TSC comprised an independent chairperson, two members of the PPI group and, in general, four additional independent members, as well as non-independent members, including the chief investigator, the trial and operations managers and the senior study statistician. Membership of the TSC was approved by the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme prior to convening the committee. The TSC met prior to the commencement of the study, every 6 months during recruitment (2015–17) and annually during follow-up. The TSC agreed on a charter, in line with NIHR guidelines,63 outlining its responsibilities at the first meeting.

Project Management Group

The PMG was responsible for overseeing the management of the study and operational issues. The PMG met every 2 months during the set-up phase of the trial and quarterly thereafter. Members of the PMG included the chief investigator, investigators, the trial and operations managers, and the trial statistician.

Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee

The independent DMEC was responsible for overseeing the safety and data quality of the trial and met annually during the trial. The committee monitored and reviewed trial recruitment, adherence to the protocol, SAEs and interim outcome data presented by the trial statisticians. The NIHR HTA programme approved and invited all members of the committee. The DMEC agreed on a charter outlining its roles and responsibilities at the first meeting. The charter was prepared in line with the Data Monitoring Committees: Lessons, Ethics, Statistics (DAMOCLES) charter64 and NIHR guidelines. 63

Patient and public involvement group

Our PPI group was composed of seven representatives and included members of the pilot study, as well as those identified through community and health-care services. Group members were mothers and fathers of young children and/or educational/child care professionals. The PPI group contributed to the study’s progress throughout the trial and provided significant and important input on the design and management of the study. The group met annually from the start of the trial in 2015 until the end of the trial in 2019, with an average of four members attending each meeting.

Public involvement was a key element in the study’s success, with the PPI group providing ideas, advice and feedback that were integral to the study’s recruitment processes, participant retention, data collection procedures and dissemination of study findings. Specifically, the group was able to advise and offer feedback on the optimal settings and services needed to be targeted for trial recruitment, especially for populations, such as fathers, that previous studies have often struggled to engage and accommodate. The PPI group also helped to produce and develop a brief, informative video for use in recruitment purposes. The video outlined what participation in the trial would involve and was provided to families alongside the PIS. A study within a trial (SWAT) aimed to explore whether or not the addition of this video aided the consent process.

A key study success was sustaining high levels of participant retention across the 2-year follow-up period (95% and 94% retention at the 5- and 24-month follow-ups, respectively). The PPI group was, again, integral to this process and advised on the key engagement strategies implemented by the study team. These included the creation of a study website for caregivers to visit, a welcome pack for families, the use of certificates and visit trackers for the children following each assessment, the sending of birthday cards to the children, a thank-you toy to acknowledge children’s participation, and the sharing of sample clips from the visits as a keepsake. Regular newsletters sent to participating families by e-mail were also a key initiative of the PPI process. The newsletters provided an update on the study, informed participants about what was coming next and constituted a pathway for families to easily update the study team with any changes in contact details. This meant that the study team was able to communicate more efficiently and effectively with families when it came to arranging follow-up assessments. The PPI group was also involved in decisions around how to communicate and explain the study findings to participants. The group recommended considering a range of different dissemination materials, including an animation, a brief newsletter, an infographic, and an example story to illustrate the study and its outcomes in a more personal way.

The PPI members were highly engaged and motivated throughout the project. At the start of each meeting, a study summary was provided, as well as a recap on how the group’s suggestions and feedback (from the previous meeting) had been implemented in the wider project. Two members of the PPI group were also full members of the TSC and participated in the piloting of baseline and follow-up assessments. All PPI members were reimbursed for incurred travel expenses and were offered a voucher following each meeting in keeping with the INVOLVE guidelines.

Amendments to protocol

-

We changed the eligibility criteria so that participants who had previously received individualised video-feedback programmes were no longer excluded. We also extended the eligibility criteria to exclude parents who had a sensory impairment or learning disability that precluded their participation in the trial.

-

Timing of the primary outcome was extended from 4 to 5 months post randomisation because of scheduling difficulties in completing the treatment in the allocated time for the intervention group of the trial. This was to reduce the likelihood of systematic differences in the timing of the follow-up assessments between the trial groups.

-

Reporting of outcomes in the current report is confined to those that were funded as part of this project and were included in the prespecified statistical analysis plan. Following an ethics amendment, we amended the protocol to include one secondary and five exploratory outcomes. As a secondary outcome, parent–child interaction data were collected across all three time points to allow for the measurement of parental sensitivity, which was a target of the intervention. This measure may be instructive in better understanding the mechanisms of this intervention. Exploratory outcomes were also added at the 24-month time point. These measures included direct assessment of children’s executive functions, emotion regulation, delay of gratification and narrative representations during dolls house play, as well as genetic variance (through buccal swabs) and parental involvement. Analyses of these variables is yet to be undertaken and findings will be published once available.

Chapter 3 Clinical results

Participant flow and retention

Between 30 July 2015 and 26 July 2017, a total of 2248 families were assessed for eligibility. Of these families, 1430 were ineligible, 518 did not progress to the trial (declined/could not be contacted) and 300 were randomised to stage 2 of the trial. In total, 151 participants (50%) were randomly allocated to the VIPP-SD group and 149 participants (50%) to the usual-care group. We recruited to target (n = 300; see Appendix 3 for the study’s recruitment graph), with the majority of participants recruited from health visiting services (30% face to face and 25% through posting screening information to families with children in the target age range) and children’s centres (30%). The remaining participants were recruited largely from other community venues and online adverts (Table 2 shows a full outline of recruitment pathways). Participants were recruited across seven NHS sites (Table 3). Follow-up data were collected between December 2015 and July 2019. Follow-up data were analysed for 286 (VIPP-SD, n = 140; usual care, n = 146) participants and 282 (VIPP-SD, n = 140; usual care, n = 142) participants at 5 and 24 months, respectively. See Figure 1 for the CONSORT flow diagram summarising the eligibility, trial group allocation and subsequent progress of randomised participants. Approximately one-third of children who were screened were eligible to take part in the study, which was higher than the anticipated 20%. It is possible that families with children with elevated problems self-selected into the study and/or that health visitors were more likely to complete screening with families who they thought may be more likely to be eligible based on the child’s behaviour.

| Recruitment route at screening | Trial group, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| VIPP-SD (N = 151) | Usual care (N = 149) | All (N = 300) | |

| Routine developmental review/clinic by health visitors | 47 (31) | 44 (30) | 91 (30) |

| Health visiting service posting screening information | 34 (23) | 40 (27) | 74 (25) |

| Children’s centre | 46 (30) | 45 (30) | 91 (30) |

| Other clinic/community venues | 12 (8) | 11 (7) | 23 (8) |

| Online advert | 9 (6) | 5 (3) | 14 (5) |

| Word of mouth | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Other | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Recruitment site | Family recruited into RCT, n (%) | Family had two participating caregivers, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Barking and Dagenham | 14 (5) | 1 (2) |

| Camden | 83 (28) | 13 (25) |

| Hertfordshire | 7 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Hillingdon | 22 (7) | 5 (10) |

| Islington | 105 (35) | 23 (45) |

| Oxford | 43 (14) | 5 (10) |

| Peterborough | 26 (9) | 4 (8) |

| Total | 300 (100) | 51 (100) |

Baseline participant characteristics

Participant characteristics at baseline were well balanced between groups. Table 4 shows the baseline characteristics of participating children and primary caregivers. The participating children had a mean age of 23 months [standard deviation (SD) 6.7 months]; 54% were male and 65% were recorded as being of white ethnicity. Participating primary caregivers were predominantly female (96%), with a mean age of 34.2 years (SD 5.8 years). Most primary caregivers were married or cohabiting (85%), were of white ethnicity (72%), had a graduate-level qualification (64%) and were in some form of employment or on paid parental leave (59%). There were more male children in the usual-care group (58%) than in the VIPP-SD group (50%), and the usual-care group was also more diverse in terms of primary caregiver and children’s ethnicity. Appendix 4, Table 24, shows the baseline characteristics of participating secondary caregivers.

| Characteristic | Trial group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| VIPP-SD (N = 151) | Usual care (N = 149) | All (N = 300) | |

| Child characteristic | |||

| Sex (male), n (%) | 76 (50) | 87 (58) | 163 (54) |

| Age (months), mean (SD) | 22.8 (6.8) | 23.2 (6.5) | 23 (6.7) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Asian | 9 (6) | 8 (5) | 17 (6) |

| Black | 3 (2) | 15 (10) | 18 (6) |

| Mixed ethnicity | 36 (24) | 25 (17) | 61 (20) |

| White | 100 (66) | 94 (63) | 194 (65) |

| Other | 3 (2) | 7 (5) | 10 (3) |

| Primary caregiver characteristic | |||

| Sex (male), n (%) | 8 (5) | 5 (3) | 13 (4) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 33.7 (5.6) | 34.7 (5.9) | 34.2 (5.8) |

| Parental status, n (%) | |||

| Parent (including step or adoptive) | 151 (100) | 149 (100) | 300 (100) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Asian | 15 (10) | 16 (11) | 31 (10) |

| Black | 3 (2) | 15 (10) | 18 (6) |

| Mixed ethnicity | 11 (7) | 11 (7) | 22 (7) |

| White | 114 (75) | 103 (69) | 217 (72) |

| Other | 8 (5) | 4 (3) | 12 (4) |

| Relationship status, n (%) | |||

| Married/civil partnership/cohabiting | 128 (85) | 127 (85) | 255 (85) |

| Divorced/widowed/legally separated | 1 (1) | 4 (3) | 5 (2) |

| Single and none of the above | 12 (8) | 17 (11) | 29 (10) |

| In a relationship but not cohabiting | 10 (7) | 1 (1) | 11 (4) |

| Employment status, n (%) | |||

| Employed | 66 (44) | 64 (43) | 130 (43) |

| Paid parental leave | 6 (4) | 10 (7) | 16 (5) |

| Self-employed | 20 (13) | 12 (8) | 32 (11) |

| Full-time student | 3 (2) | 7 (5) | 10 (3) |

| Looking after home and children | 56 (37) | 56 (38) | 112 (37) |

| Highest qualification, n (%) | |||

| GCSE or lower | 17 (11) | 14 (9) | 31 (10) |

| A level/NVQ/BTEC | 42 (28) | 36 (24) | 78 (26) |

| Graduate | 92 (61) | 99 (66) | 191 (64) |

Delivery of intervention

Therapists

Forty trained therapists delivered any amount of VIPP-SD (median three participants each; range 1–12 participants each). Therapists had a mean of 13 years’ experience (SD 12 years’ experience) post-training in NHS services. Table 5 shows a full overview of therapist professions.

| Profession/training background | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Health visitor | 10 (25) |

| Community nursery nurse | 8 (20) |

| Clinical psychologist | 7 (17) |

| Trainee clinical psychologist | 4 (10) |

| Researcher | 4 (10) |

| Psychotherapist | 3 (8) |

| Research nurse | 2 (5) |

| Psychiatrist | 2 (5) |

| Total | 40 (100) |

Intervention dosage

Of the 151 participants randomised to the VIPP-SD group, 129 participants (85%) completed at least four sessions (the compliance cut-off point for treatment adherence), with 121 of these participants (80%) receiving all six sessions. Twelve participants (8%) received no intervention, with a further 10 participants (7%) completing one, two or three visits only.

Intervention fidelity

Treatment fidelity was assessed against the VIPP-SD manual and was found to be acceptable in the majority of the sessions. 18 Two assessors trained in the intervention rated audio-recordings using a global scale of adherence to the manual on a five-point scale (1 = did not follow the manual at all; 2 = adapted most of the material, did not follow the manual closely; 3 = sometimes adapted the material, followed manual somewhat; 4 = adapted only minor elements, followed the manual quite closely; and 5 = followed the manual very closely and delivered the session as specified). A score of 3 was set as the acceptable fidelity threshold as to receive this score most core components of the intervention needed to be identified as present in the feedback. Following piloting of the scale, the assessors double-scored a subset of 10 sessions (comprising 31 scripts) and established an acceptable level of reliability [intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) 0.69]. The fidelity assessment determined that 94% (72/77 randomly selected audio-recordings of therapy sessions) met the minimum threshold (score of ≥ 3) of adherence to the manual. The mean sum score of adherence across sessions was 3.66 (SD 0.60, range 3.4–4.0).

Primary outcome: Preschool Parental Account of Children’s Symptoms score at the 5- and 24-month follow-ups

We present the primary outcome (total PPACS score) and its subscale scores at the 5-month (primary time point) and 24-month follow-ups in Table 6. The group mean difference in PPACS score was modelled using linear regression adjusted for baseline scores, treatment centre, randomised group, length of follow-up, age of the child and the number of participating caregivers. At the post-treatment 5-month follow-up, the mean scores of child behaviour problems on the PPACS were found to have decreased from 33.5 (SD 9.0) to 28.8 (SD 9.2) in the VIPP-SD group and from 32.4 (SD 10.6) to 30.3 (SD 9.9) in the usual-care group. This represents a significant difference in reduction of problems favouring the VIPP-SD group [adjusted mean difference, VIPP-SD vs. usual care 2.03, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.06 to 4.01; p = 0.04]. The adjusted standardised effect size was Cohen’s d = 0.20 (95% CI 0.01 to 0.40). VIPP-SD was also found to be superior to usual care, in particular, on the conduct problems subscale of the primary outcome [adjusted mean difference 1.61, 95% CI 0.44 to 2.78; p = 0.007 (d = 0.30, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.51)], but not the hyperactivity subscale [adjusted mean difference 0.29, 95% CI –1.06 to 1.65; p = 0.67 (d = 0.05, 95% CI –0.17 to 0.27)].

| Outcome | Trial group | Mean differencea (95% CI) | Effect sizeb (95% CI) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIPP-SD | Usual care | ||||||

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | ||||

| PPACSc total score – primary analysis at 5 months | |||||||

| Baseline | 151 | 33.5 (9.0) | 149 | 32.4 (10.6) | |||

| 5 months | 140 | 28.8 (9.2) | 146 | 30.3 (9.9) | 2.03 (0.06 to 4.01) | 0.20 (0.01 to 0.40) | 0.04 |

| 24 months | 140 | 23.1 (8.2) | 142 | 24.7 (9.9) | 1.73 (–0.24 to 3.71) | 0.17 (–0.02 to 0.37) | 0.08 |

| PPACSc conduct scale | |||||||

| Baseline | 151 | 16.0 (5.8) | 149 | 15.5 (6.4) | |||

| 5 months | 140 | 14.8 (5.1) | 146 | 15.8 (5.4) | 1.61 (0.44 to 2.78) | 0.30 (0.08 to 0.51) | 0.007 |

| 24 months | 140 | 13.4 (4.8) | 142 | 14.4 (5.3) | 1.07 (–0.06 to 2.2) | 0.20 (–0.01 to 0.42) | 0.06 |

| PPACSc ADHD scale | |||||||

| Baseline | 151 | 17.5 (5.8) | 149 | 16.9 (6.6) | |||

| 5 months | 140 | 14.0 (6.1) | 146 | 14.5 (6.2) | 0.29 (–1.06 to 1.65) | 0.05 (–0.17 to 0.27) | 0.67 |

| 24 months | 140 | 9.7 (5.1) | 142 | 10.3 (6.1) | 0.62 (–0.60 to 1.84) | 0.10 (–0.10 to 0.30) | 0.32 |

At the 24-month follow-up, the adjusted mean difference on the total PPACS score remained about the same, with a decrease in effect size of d = 0.03 [VIPP-SD vs. usual care 1.73, 95% CI –0.24 to 3.71; p = 0.08 (d = 0.17, 95% CI –0.02 to 0.37)]. The adjusted mean difference on the conduct subscale continued to favour the VIPP-SD group [VIPP-SD vs. usual care 1.07, 95% CI –0.06 to 2.2; p = 0.06 (d = 0.20, 95% CI –0.01 to 0.42)]. There was no evidence of the superiority of VIPP-SD over usual care on the hyperactivity subscale [difference 0.62, 95% CI –0.60 to 1.84; p = 0.32 (d = 0.10, 95% CI –0.10 to 0.30)].

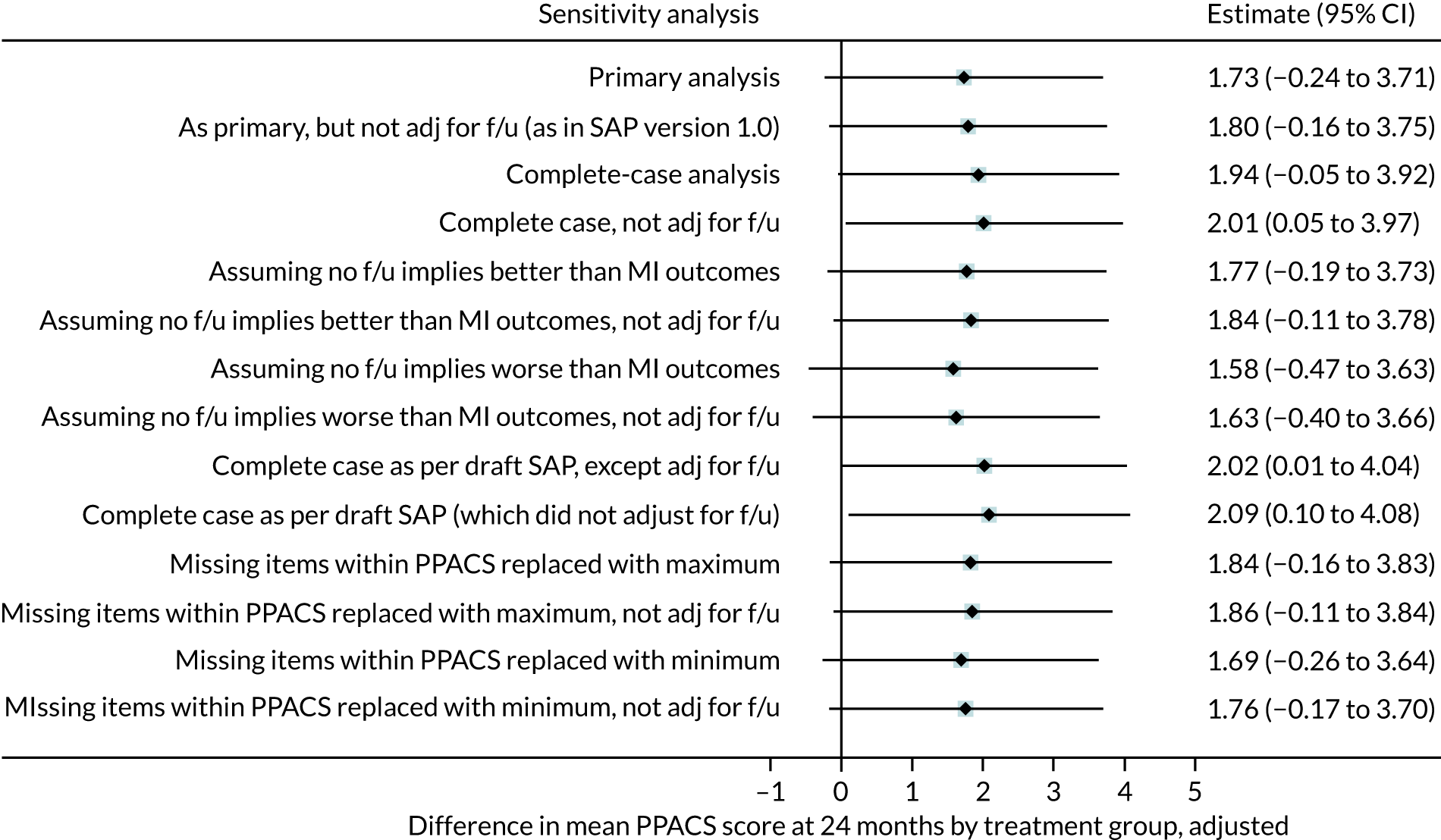

The positive effect of VIPP-SD on the PPACS total score at the 5-month follow-up was robust to sensitivity analyses, which estimated the impact of varying the assumptions made in respect of missing data and adjustment for length of follow-up (see Appendix 5, Table 28). Figures 2 and 3 present the forest plots for the sensitivity analyses of the 5-month and 24-month follow-up PPACS scores, respectively. Appendix 5 details the profiles of families with and without missing PPACS data (see Appendix 5, Table 29) and reports descriptive outcome data for those with and without PPACS scores at the 5- and 24-month follow-ups (see Appendix 5, Table 30).

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot for sensitivity analysis at the 5-month follow-up. adj, adjusted; f/u, follow-up.

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot for sensitivity analysis at the 24-month follow-up. adj, adjusted; f/u, follow-up.

The primary analyses included multiple imputation (MI) for unrateable items on the PPACS scales, MI for PPACS total scores in those who did not complete their 5-month follow-up assessment and adjustment for length of follow-up. Sensitivity analyses included lack of adjustment for length of follow-up (combined with other assumptions). Complete-case analyses are then reported (using MI solely for unrateable items on the PPACS scale and excluding those who did not complete their 5-month follow-up). Further analyses assume better PPACS scores and then worse PPACS scores (than predicted by MI by one standard deviation of the mean change in PPACS scores between the baseline and 5-month follow-up assessment) in those who did not complete their 5-month follow-up. The final analyses assume that unrateable PPACS items were replaced with the highest possible score and then the lowest possible score.

Sensitivity analyses were completed at the 24-month follow-up in the same way as in the 5-month follow-up sensitivity analyses. This included lack of adjustment for length of follow-up (combined with other assumptions). Complete-case analyses are then reported (using MI solely for unrateable items on the PPACS scale and excluding those who did not complete their 24-month follow-up). Further analyses assume better PPACS scores and then worse PPACS scores (than predicted by MI by one SD of the mean change in PPACS scores between the baseline and 24-month follow-up assessment) in those who did not complete their 24-month follow-up. The final analyses assume that unrateable PPACS items were replaced with the highest possible score and then the lowest possible score.

Secondary outcomes: parent-reported measures of child behaviour at the 5- and 24-month follow-ups

On the key secondary outcomes, parent-reported questionnaire measures of children’s behaviour (total scores of the CBCL and SDQ), the results indicate a positive direction of effect favouring the VIPP-SD group at the 5-month follow-up, yet indicate little evidence of a sustained effect at the 24-month follow-up (Table 7). At the 5-month follow-up, the VIPP-SD group had lower CBCL scores [adjusted mean difference 3.24, 95% CI –0.06 to 6.54; p = 0.05 (d = 0.15, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.31)] and SDQ scores [adjusted mean difference 0.93, 95% CI –0.03 to 1.90; p = 0.06 (d = 0.18, 95% CI –0.01 to 0.36)] than the usual-care group. At the 24-month follow-up, although the VIPP-SD group continued to have lower behaviour scores than the usual-care group, these differences had diminished somewhat and there was little evidence of sustained effects of VIPP-SD on the CBCL (adjusted mean difference 2.82, 95% CI –1.82 to 7.45; p = 0.23) and SDQ (adjusted mean difference 0.35, 95% CI –0.78 to 1.47; p = 0.54). There was no evidence of superiority of VIPP-SD over usual care on the teacher-reported total score for the SDQ at the 24-month follow-up (difference 0.54, 95% CI –1.00 to 2.08; p = 0.49).

| Outcome | Trial group | Mean differencea (95% CI) | Effect sizeb (95% CI) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIPP-SD | Usual care | ||||||

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | ||||

| CBCLc total score (primary caregiver report) | |||||||

| Baseline | 151 | 40.7 (21.7) | 149 | 42.7 (21.1) | |||

| 5 months | 140 | 32.5 (20.6) | 145 | 37.2 (21.0) | 3.24 (–0.06 to 6.54) | 0.15 (0.00 to 0.31) | 0.05 |

| 24 months | 141 | 30.6 (23.4) | 144 | 35.3 (23.7) | 2.82 (–1.82 to 7.45) | 0.12 (–0.08 to 0.31) | 0.23 |

| SDQc total score (primary caregiver report) | |||||||

| Baseline | 150 | 13.8 (4.8) | 149 | 14.0 (4.7) | |||

| 5 months | 140 | 11.3 (5.1) | 145 | 12.2 (5.2) | 0.93 (–0.03 to 1.9) | 0.18 (–0.01 to 0.36) | 0.06 |

| 24 months | 141 | 10.4 (5.4) | 144 | 10.9 (5.8) | 0.35 (–0.78 to 1.47) | 0.06 (–0.13 to 0.25) | 0.54 |

| SDQc,d total score (teacher report) | |||||||

| 24 months | 106 | 7.1 (6.0) | 104 | 7.8 (5.7) | 0.54 (–1.00 to 2.08) | 0.10 (–0.18 to 0.37) | 0.49 |

Table 8 shows the adjusted group differences on the subscale scores for the secondary behaviour outcomes (CBCL and SDQ) at the 5- and 24-month follow-ups. At the 5-month follow-up, there was evidence of an effect favouring the VIPP-SD group over the usual-care group on the SDQ externalising subscale [adjusted mean difference 0.68, 95% CI 0.00 to 1.37; p = 0.05 (d = 0.18, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.37)] as well as weaker evidence favouring the VIPP-SD group over the usual-care group on the CBCL internalising scale [adjusted mean difference 1.03, 95% CI –0.10 to 2.16; p = 0.07 (d = 0.15, 95% CI –0.01 to 0.32)]. There was no strong evidence of group differences on the remaining subscales. In general, differences on the subscales had attenuated at the 24-month follow-up and there was little evidence of sustained effects on these measures. On the teacher-reported SDQ, although teachers tend to report lower behaviour problems for the VIPP-SD group than for the usual-care group on key subscales, there was only weak evidence of group differences on these subscales: conduct [adjusted mean difference 0.38, 95% CI –0.16 to 0.92; p = 0.17 (d = 0.18, 95% CI –0.08 to 0.45)], hyperactivity [adjusted mean difference 0.46, 95% CI –0.25 to 1.16; p = 0.20 (d = 0.17, 95% CI –0.09 to 0.43)] and externalising [adjusted mean difference 0.81, 95% CI –0.29 to 1.92; p = 0.15 (d = 0.19, 95% CI –0.07 to 0.45)] subscales.

| Outcome | Trial group | Mean differencea (95% CI) | Effect sizeb (95% CI) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIPP-SD | Usual care | ||||||

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | ||||

| CBCLc externalising subscale | |||||||

| Baseline | 151 | 16.5 (8.1) | 149 | 17.5 (8.3) | |||

| 5 months | 140 | 13.3 (8.3) | 145 | 15.2 (8.5) | 1.15 (–0.32 to 2.63) | 0.14 (–0.04 to 0.31) | 0.12 |

| 24 months | 141 | 11.6 (8.8) | 144 | 13.4 (9.6) | 0.81 (–1.02 to 2.65) | 0.09 (–0.11 to 0.28) | 0.38 |

| CBCLc internalising subscale | |||||||

| Baseline | 151 | 8.9 (7.2) | 149 | 9.7 (7.5) | |||

| 5 months | 140 | 7.1 (6.5) | 145 | 8.5 (6.8) | 1.03 (–0.10 to 2.16) | 0.15 (–0.01 to 0.32) | 0.07 |

| 24 months | 141 | 8.1 (8.2) | 144 | 9.0 (7.6) | 0.44 (–1.16 to 2.04) | 0.06 (–0.15 to 0.27) | 0.59 |

| CBCLc attention subscale | |||||||

| Baseline | 151 | 3.8 (2.0) | 149 | 4.2 (2.3) | |||

| 5 months | 140 | 2.9 (2.1) | 145 | 3.5 (2.2) | 0.25 (–0.18 to 0.68) | 0.11 (–0.08 to 0.30) | 0.26 |

| 24 months | 141 | 2.2 (2.0) | 144 | 2.7 (2.2) | 0.27 (–0.18 to 0.71) | 0.12 (–0.08 to 0.31) | 0.24 |

| CBCLc aggression subscale | |||||||

| Baseline | 151 | 12.7 (6.9) | 149 | 13.3 (7.0) | |||

| 5 months | 140 | 10.4 (6.8) | 145 | 11.8 (6.9) | 0.98 (–0.25 to 2.22) | 0.14 (–0.04 to 0.32) | 0.12 |

| 24 months | 141 | 9.4 (7.4) | 144 | 10.7 (7.9) | 0.63 (–0.90 to 2.16) | 0.08 (–0.11 to 0.27) | 0.42 |

| SDQd,e externalising subscale | |||||||

| Baseline | 150 | 9.4 (3.0) | 149 | 9.4 (3.5) | |||

| 5 months | 140 | 7.6 (3.4) | 145 | 8.2 (3.7) | 0.68 (0.00 to 1.37) | 0.18 (0.00 to 0.37) | 0.05 |

| 24 months | 141 | 7.0 (3.6) | 144 | 7.4 (4.1) | 0.39 (–0.38 to 1.16) | 0.10 (–0.09 to 0.29) | 0.32 |

| 24 months (teacher-report) | 106 | 4.1 (4.2) | 104 | 4.9 (4.3) | 0.81 (–0.29 to 1.92) | 0.19 (–0.07 to 0.45) | 0.15 |

| SDQd,e conduct subscale | |||||||

| Baseline | 150 | 3.6 (2.0) | 149 | 3.4 (2.1) | |||

| 5 months | 140 | 3.1 (1.9) | 145 | 3.1 (2.0) | 0.27 (–0.14 to 0.67) | 0.13 (–0.07 to 0.33) | 0.20 |

| 24 months | 141 | 2.9 (2.0) | 144 | 3.1 (2.3) | 0.34 (–0.11 to 0.79) | 0.15 (–0.05 to 0.35) | 0.14 |

| 24 months (teacher-report) | 106 | 1.2 (2.0) | 104 | 1.6 (2.1) | 0.38 (–0.16 to 0.92) | 0.18 (–0.08 to 0.45) | 0.17 |

| SDQd,e hyperactivity subscale | |||||||

| Baseline | 150 | 5.9 (1.9) | 149 | 6.1 (2.2) | |||

| 5 months | 140 | 4.5 (2.1) | 145 | 5.1 (2.3) | 0.37 (–0.08 to 0.81) | 0.16 (–0.03 to 0.35) | 0.11 |

| 24 months | 141 | 4.1 (2.2) | 144 | 4.3 (2.4) | 0.07 (–0.40 to 0.53) | 0.03 (–0.17 to 0.22) | 0.78 |

| 24 months (teacher-report) | 106 | 2.9 (2.6) | 104 | 3.4 (2.7) | 0.46 (–0.25 to 1.16) | 0.17 (–0.09 to 0.43) | 0.20 |

| SDQd,e emotional problems subscale | |||||||

| Baseline | 150 | 1.4 (1.5) | 149 | 1.6 (1.5) | |||

| 5 months | 140 | 1.4 (1.7) | 145 | 1.4 (1.5) | 0.01 (–0.32 to 0.33) | 0.01 (–0.21 to 0.22) | 0.96 |

| 24 months | 141 | 1.8 (1.8) | 144 | 1.7 (1.8) | –0.18 (–0.56 to 0.21) | –0.10 (–0.30 to 0.11) | 0.37 |

| 24 months (teacher-report) | 106 | 1.4 (1.8) | 104 | 1.2 (1.7) | –0.21 (–0.68 to 0.27) | –0.12 (–0.40 to 0.16) | 0.39 |

| SDQd,e peer problems subscale | |||||||

| Baseline | 150 | 3.0 (1.9) | 149 | 3.0 (1.8) | |||

| 5 months | 140 | 2.3 (1.9) | 145 | 2.5 (2.0) | 0.23 (–0.19 to 0.64) | 0.12 (–0.10 to 0.33) | 0.29 |

| 24 months | 141 | 1.6 (1.6) | 144 | 1.8 (1.9) | 0.15 (–0.24 to 0.53) | 0.08 (–0.12 to 0.28) | 0.44 |

| 24 months (teacher-report) | 106 | 1.6 (1.9) | 104 | 1.6 (2.0) | –0.06 (–0.59 to 0.47) | –0.03 (–0.30 to 0.24) | 0.82 |

| SDQd,e prosocial scale | |||||||

| Baseline | 150 | 5.7 (2.3) | 149 | 5.4 (2.2) | |||

| 5 months | 140 | 6.6 (2.0) | 145 | 6.3 (2.2) | –0.07 (–0.47 to 0.34) | –0.03 (–0.22 to 0.16) | 0.75 |

| 24 months | 141 | 7.7 (1.8) | 144 | 7.3 (1.9) | –0.19 (–0.59 to 0.21) | –0.10 (–0.31 to 0.11) | 0.36 |

| 24 months (teacher-report) | 106 | 7.1 (2.5) | 104 | 6.7 (2.3) | –0.31 (–0.94 to 0.33) | –0.13 (–0.41 to 0.14) | 0.34 |

Table 9 shows the results of the secondary CACE analysis estimating the effects of receiving the intervention (defined as at least four VIPP-SD sessions), rather than merely being randomised to it. The CACE analysis was completed on the primary and secondary behaviour outcome measures (PPACS, CBCL and SDQ). For the PPACS scores, the results showed a larger adjusted mean difference favouring the VIPP-SD group at the 5-month follow-up when accounting for treatment adherence [difference 2.59, 95% CI 0.24 to 4.94; p = 0.03 (d = 0.26, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.50)] than in the ITT analysis [difference 2.03, 95% CI 0.06 to 4.01; p = 0.04 (d = 0.20, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.40)]. At the 24-month follow-up, the difference remains in the same range, similar to the outcome in the ITT analysis, although the adjusted group difference and effect size tends to be larger in the CACE analysis [difference 1.96, 95% CI –0.30 to 4.23; p = 0.09 (d = 0.20, 95% CI –0.03 to 0.43)]. A similar pattern is observed on the CBCL [adjusted mean difference 3.56, 95% CI 0.04 to 7.09; p = 0.05 (d = 0.17, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.34)] and SDQ [adjusted mean difference 1.03, 95% CI –0.01 to 2.06; p = 0.05 (d = 0.20, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.39)] at the 5-month follow-up, such that both outcomes show slightly larger adjusted mean differences and effect sizes, and stronger evidence of group differences in the CACE analysis than in the ITT analysis. As with the ITT analysis, there is little evidence of a sustained group difference on the secondary behaviour outcomes (CBCL and SDQ) at the 24-month follow-up in the CACE analysis. Tables 25–27 in Appendix 4 show the analysis of the secondary behaviour outcomes as reported by secondary participating caregivers.

| Outcome | Trial group | Mean differenceb (95% CI) | Effect sizec (95% CI) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIPP-SD | Usual care | ||||||

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | ||||

| PPACSd | |||||||

| Baseline | 151 | 33.5 (9.0) | 149 | 32.4 (10.6) | |||

| 5 months | 140 | 28.8 (9.2) | 146 | 30.3 (9.9) | 2.59 (0.24 to 4.94) | 0.26 (0.02 to 0.5) | 0.03 |

| 24 months | 140 | 23.1 (8.2) | 142 | 24.7 (9.9) | 1.96 (–0.30 to 4.23) | 0.20 (–0.03 to 0.43) | 0.09 |

| CBCLe | |||||||

| Baseline | 151 | 40.7 (21.7) | 149 | 42.7 (21.1) | |||

| 5 months | 140 | 32.5 (20.6) | 145 | 37.2 (21.0) | 3.56 (0.04 to 7.09) | 0.17 (0.00 to 0.34) | 0.05 |

| 24 months | 141 | 30.6 (23.4) | 144 | 35.3 (23.7) | 2.90 (–2.19 to 7.98) | 0.12 (–0.09 to 0.34) | 0.26 |

| SDQe – primary caregiver reported | |||||||

| Baseline | 150 | 13.8 (4.8) | 149 | 14.0 (4.7) | |||

| 5 months | 140 | 11.3 (5.1) | 145 | 12.2 (5.2) | 1.03 (–0.01 to 2.06) | 0.20 (0.00 to 0.39) | 0.05 |

| 24 months | 141 | 10.4 (5.4) | 144 | 10.9 (5.8) | 0.32 (–0.91 to 1.56) | 0.06 (–0.16 to 0.27) | 0.61 |

| SDQe – teacher report | |||||||

| 24 months | 106 | 7.1 (6) | 104 | 7.8 (5.7) | 0.61 (–1.06 to 2.27) | 0.11 (–0.19 to 0.40) | 0.48 |

Table 10 shows the ITT analysis for secondary outcomes relating to participating caregivers’ reported parenting practices, mood, anxiety and couple functioning, disaggregated by sex of the reporting caregiver. There was no evidence of group differences on these secondary outcomes (p-values = 0.15–0.95).

| Outcome | Trial group | Mean differencea (95% CI) | Effect sizeb (95% CI) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIPP-SD | Usual care | ||||||

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | ||||

| Female caregiversc | |||||||

| Parenting Scaled | |||||||

| Baseline | 146 | 2.96 (0.52) | 147 | 2.95 (0.58) | |||

| 5 months | 135 | 2.90 (0.50) | 143 | 2.90 (0.60) | 0.06 (–0.22 to 1.23) | 0.11 (–0.37 to 2.06) | 0.22 |

| 24 months | 136 | 3.02 (0.53) | 142 | 3.02 (0.57) | 0.03 (–0.07 to 0.13) | 0.06 (–0.12 to 0.23) | 0.51 |

| PHQ-9e | |||||||

| Baseline | 145 | 4.34 (4.00) | 147 | 4.28 (4.35) | |||

| 5 months | 135 | 3.99 (4.49) | 144 | 4.20 (4.71) | 0.25 (–0.69 to 1.20) | 0.05 (–0.15 to 0.25) | 0.60 |

| 24 months | 136 | 3.99 (4.60) | 141 | 4.02 (4.22) | 0.05 (–0.86 to 0.97) | 0.01 (–0.20 to 0.23) | 0.91 |

| GAD-7e | |||||||

| Baseline | 145 | 4.89 (4.33) | 147 | 4.73 (4.22) | |||

| 5 months | 134 | 4.29 (4.46) | 144 | 3.92 (4.00) | 0.05 (–0.85 to 0.95) | 0.01 (–0.21 to 0.24) | 0.91 |

| 24 months | 136 | 4.12 (4.64) | 141 | 4.20 (4.09) | 0.16 (–0.76 to 1.07) | 0.04 (–0.19 to 0.26) | 0.74 |

| RDASf | |||||||

| Baseline | 130 | 49.18 (8.36) | 126 | 50.50 (9.22) | |||

| 5 months | 118 | 49.19 (9.32) | 120 | 49.92 (9.59) | 0.20 (–1.44 to 1.83) | 0.02 (–0.15 to 0.19) | 0.81 |

| 24 months | 120 | 50.01 (8.15) | 115 | 50.59 (6.96) | –0.40 (–1.78 to 0.99) | –0.06 (–0.26 to 0.14) | 0.57 |

| Male caregiversg | |||||||

| Parenting Scaled | |||||||

| Baseline | 31 | 2.98 (0.54) | 25 | 2.78 (0.48) | |||

| 5 months | 29 | 2.90 (0.50) | 24 | 2.89 (0.41) | 0.10 (–0.13 to 0.33) | 0.24 (–0.32 to 0.8) | 0.39 |

| 24 months | 28 | 2.9 (0.49) | 24 | 2.95 (0.45) | 0.15 (–0.06 to 0.36) | 0.34 (–0.13 to 0.82) | 0.15 |

| PHQ-9e | |||||||

| Baseline | 31 | 3.03 (2.64) | 25 | 2.56 (2.96) | |||

| 5 months | 29 | 2.48 (2.34) | 24 | 3.25 (3.57) | 0.63 (–0.86 to 2.12) | 0.18 (–0.24 to 0.6) | 0.40 |

| 24 months | 28 | 2.64 (2.15) | 24 | 2.54 (3.08) | 0.11 (–1.21 to 1.42) | 0.03 (–0.39 to 0.46) | 0.87 |

| GAD-7e | |||||||

| Baseline | 31 | 2.35 (2.69) | 25 | 2.84 (2.98) | |||

| 5 months | 29 | 2.21 (2.32) | 24 | 3.21 (3.66) | –0.04 (–1.54 to 1.45) | –0.01 (–0.42 to 0.40) | 0.95 |

| 24 months | 28 | 2.54 (2.32) | 24 | 2.50 (2.70) | –0.51 (–1.59 to 0.57) | –0.19 (–0.59 to 0.21) | 0.35 |

| RDASf | |||||||

| Baseline | 31 | 50.56 (5.20) | 25 | 50.23 (6.51) | |||

| 5 months | 29 | 50.38 (6.42) | 24 | 48.31 (8.80) | 0.11 (–3.42 to 3.65) | 0.01 (–0.39 to 0.41) | 0.95 |

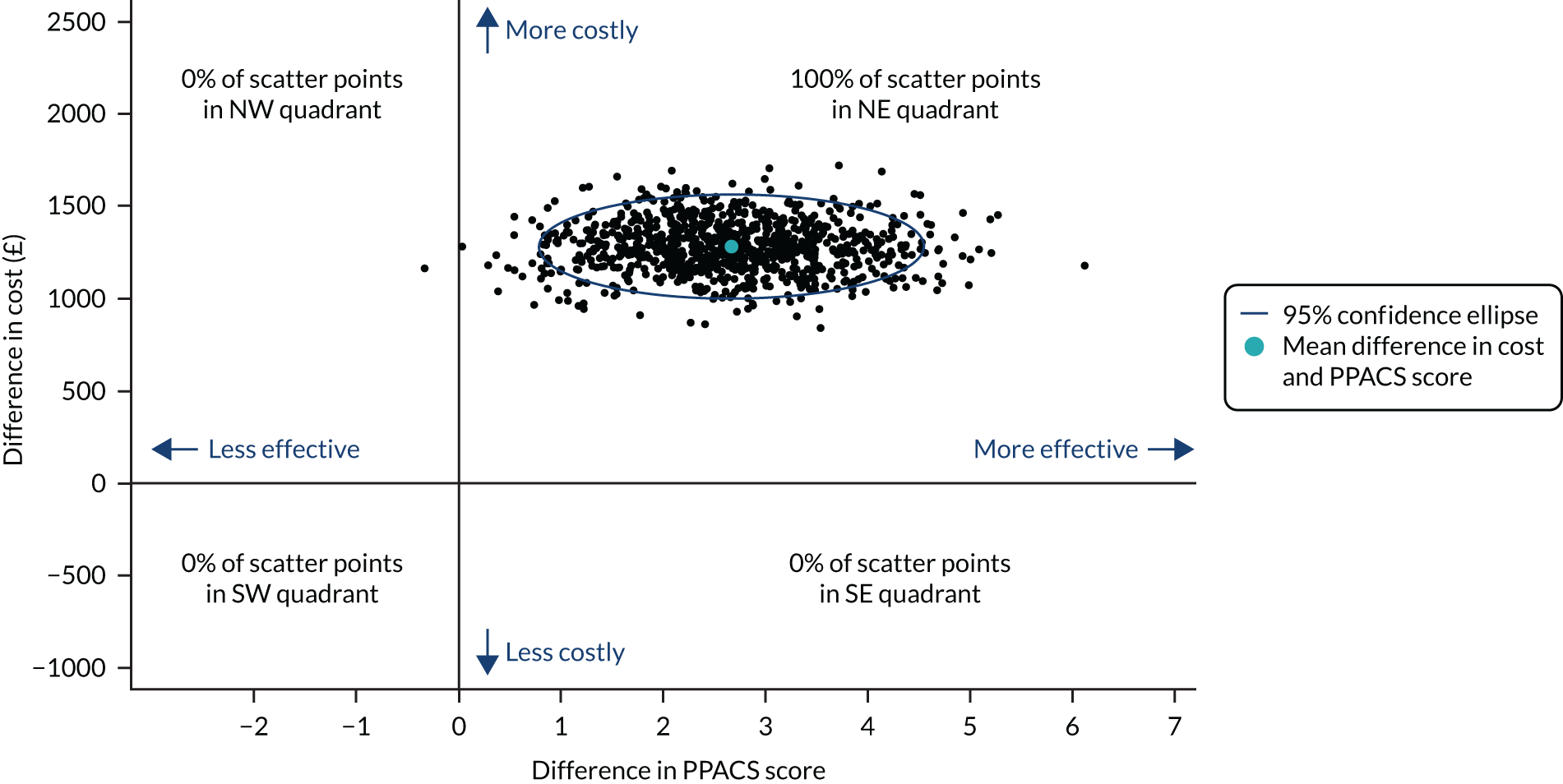

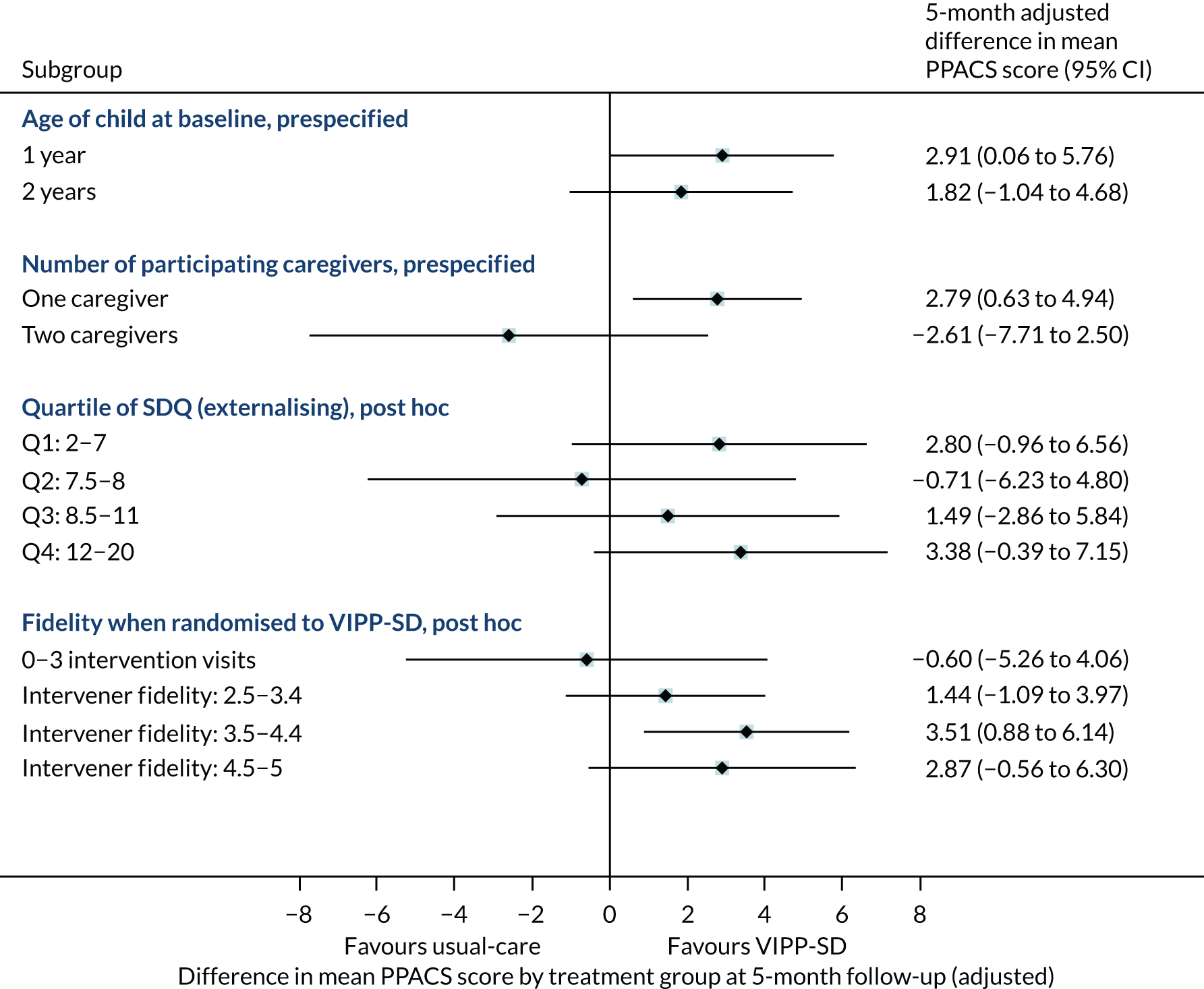

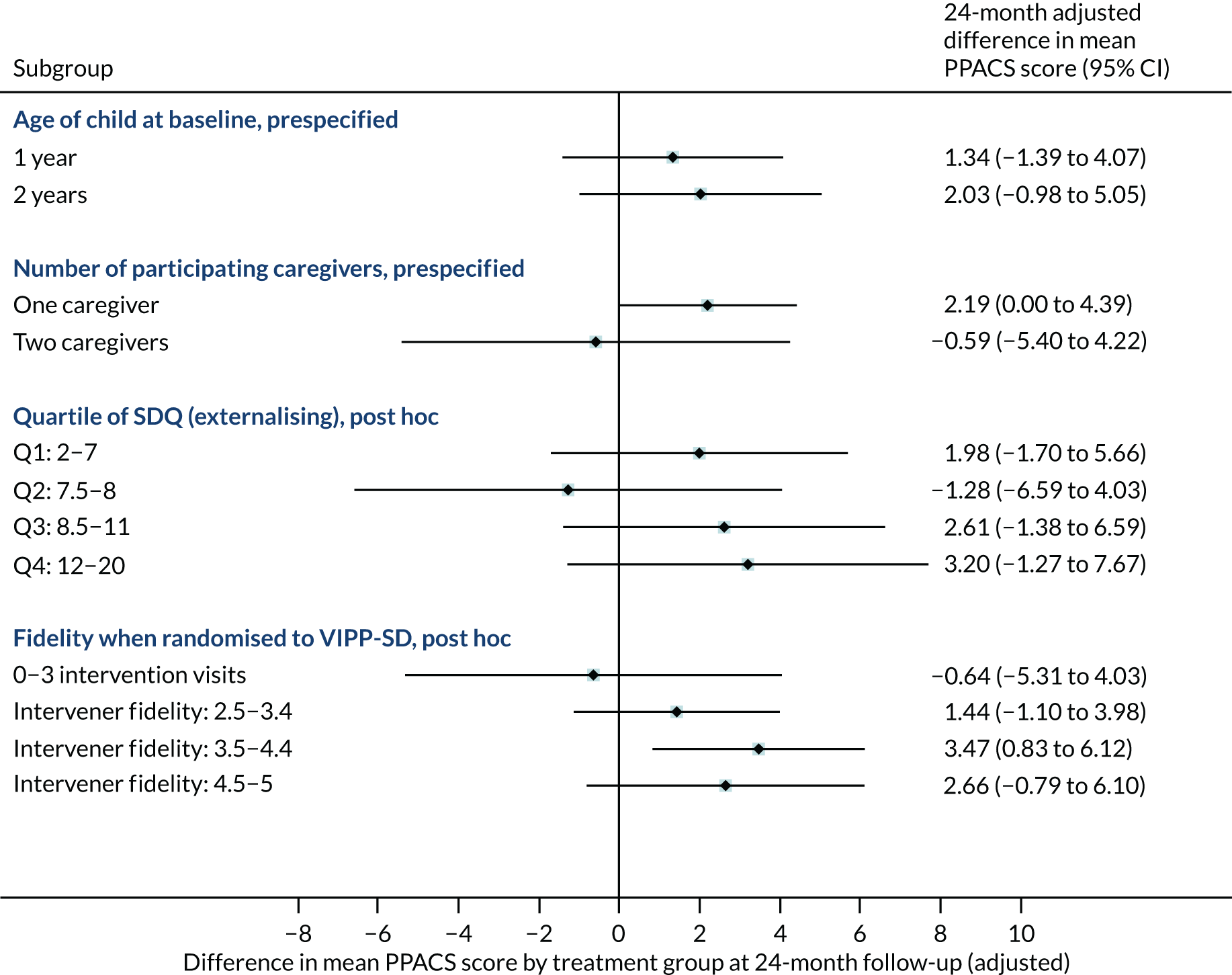

| 24 months | 27 | 51.37 (4.87) | 24 | 48.82 (6.78) | –1.27 (–3.97 to 1.42) | –0.19 (–0.59 to 0.21) | 0.35 |