Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/92/03. The contractual start date was in June 2014. The draft report began editorial review in August 2019 and was accepted for publication in June 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Hykin et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Retinal vein occlusion (RVO) is the second most common retinal vascular disorder,1,2 after diabetic retinopathy, and comprises branch RVO, hemiretinal vein occlusion and central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO). CRVO has a prevalence of 0.08–0.41%3–5 and a 15-year cumulative incidence rate of 0.5%. 6,7 Approximately 6860 people develop CRVO every year in England and Wales, of these, 5150 develop visual impairment due to macula oedema (MO), which is unlikely to improve spontaneously8–11 and is therefore potentially eligible for treatment, according to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 12,13

Central retinal vein occlusion is characterised by retinal haemorrhages, venous dilatation and tortuosity in all four quadrants of the retina. 1,7 An increase in hydrostatic pressure at the venous end of the retinal capillary network reduces retinal perfusion, upregulating the production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which, in turn, increases retinal capillary permeability and is probably the major cause of MO,14 although the raised hydrostatic pressure per se probably plays a part. 7 VEGF promotes iris and retinal neovascularisation in severe cases. The characteristic presentation of CRVO is sudden painless unilateral decrease in vision due to MO. 8 In severe cases, vision is affected by macular ischaemia or the development of iris neovascularisation and, subsequently, neovascular glaucoma with elevated intraocular pressure, pain, redness and visual loss if the condition is left untreated. CRVO may be bilateral in 5% of cases, and the risk of developing RVO in the contralateral eye within 12 months is approximately 5%. 7,8

Central retinal vein occlusion has two distinct clinical subtypes. 7,8 Non-ischaemic CRVO is characterised by a visual acuity of ≥ 6/30, no relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD), mild to moderate retinal venous dilatation and tortuosity, and intraretinal haemorrhage and MO. Ischaemic CRVO is characterised by a visual acuity of ≤ 6/36, the presence of a RAPD, and intraretinal haemorrhage with venous dilatation and tortuosity greater than the Central Vein Occlusion Study (CVOS) standard photograph,15 with complications that include MO, macular ischaemia, retinal ischaemia, iris and retinal neovascularisation and neovascular glaucoma. 16 Optical coherence tomography (OCT) confirms and characterises the MO, and fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) confirms and characterises the extent of macular and retinal ischaemia and the presence of retinal neovascularisation; both investigations guide management. 7,8 Novel morphological OCT biomarkers for CRVO have been identified that may provide important diagnostic and prognostic information, although, to our knowledge, none has been utilised in a large prospective clinical trial to date. 17–19 Conventional seven-field FFA is semiquantitative and, if the total area of angiographic non-perfusion is at least 10 disc areas in size, the prognosis is less good than for the non-ischaemic subtype. 20,21 More recently, wide-angled FFA has allowed a greater proportion of the peripheral retina to be imaged, although the exact amount and distribution of non-perfusion that characterises the subtypes of CRVO have not been well defined. 22,23 Eyes with larger areas of retinal ischaemia on conventional FFA are more prone to neovascular complications. 20 Approximately 15–20% of cases present with ischaemic CRVO, and in 25–34% of cases non-ischaemic CRVO converts to the ischaemic subtype within 3 years. 20,24 Neovascular complications such as iris neovascularisation are typically managed using a combination of retinal laser therapy and anti-VEGF therapy. 7,8

In non-inferiority ophthalmology clinical trials, the primary outcome has typically been a visual acuity difference of –5 Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) letters. This is thought to represent a meaningful difference between two treatments, based on the following:

-

Most patients in a busy clinic setting can reliably distinguish an 8-letter (1.5-line) difference on an ETDRS visual acuity chart, but they may perform better than this in a clinical trial setting. 25

-

A 5-letter (1-line) improvement in mean visual acuity in retinal studies typically results in a 50% increase in the number of patients gaining 15-letter (3-line) improvement in visual acuity, suggesting that this is a meaningful difference. 26

-

The choice of a 5-letter margin was 32% higher than the available estimated 12-month placebo-controlled effect of 6.6 letters for ranibizumab (0.5 mg/0.05 ml Lucentis®; Novartis International AG, Basel, Switzerland), the standard (comparator) treatment in this multicentre, double-masked, randomised controlled non-inferiority trial comparing the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of intravitreal therapy with ranibizumab (Lucentis) versus aflibercept (Eylea) versus bevacizumab (Avastin) for macular oedema due to central retinal Vein Occlusion (LEAVO). This margin choice was, therefore, consistent with maintaining assay sensitivity sufficiently to be able to declare non-inferiority [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/119203/#/documentation (accessed 14 July 2020)].

-

This margin was accepted by the funder.

Although a 4-letter change has been used as a non-inferiority margin, this was not common practice at the time LEAVO was designed, and we wanted to ensure that LEAVO would be as similar as possible to alternative comparable studies of anti-VEGF therapy in CRVO [e.g. Study of Comparative Treatments for Retinal Vein Occlusion 2 (SCORE2)27].

Central retinal vein occlusion-related macular oedema and antivascular endothelial growth factor therapy

Visual impairment in CRVO is primarily due to MO; it is typically significant, resolution is likely to occur in only the mildest non-ischaemic cases24 and the anatomical improvement of MO may not result in a corresponding improvement in visual acuity. 8 Presenting visual acuity is typically a good predictor of final visual outcome: patients who present with an initial visual acuity of ≥ 6/12 will probably retain good vision, whereas 80% of those who present with a visual acuity of ≤ 6/60 do not improve to > 6/60. 20 The natural history arm of the CVOS showed no change in mean baseline visual acuity over 3 years;20 this finding is supported by the sham arms in the Ranibizumab for the Treatment of Macular Edema after Central Retinal Vein OcclUsIon Study: Evaluation of Efficacy and Safety (CRUISE),9 GALILEO28–30 and COPERNICUS10,28,30,31 licensing trials for ranibizumab and aflibercept (2 mg/0.05 ml Eylea®; Bayer AG, Leverkusen, Germany), in which patients who were initiated on treatment 6 months after randomisation to sham did not achieve as large visual gains as participants randomised to prompt therapy. Therefore, prompt treatment is typically recommended to maximise visual outcomes.

First-line therapy for MO is repeated intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF agents to block the action of VEGF, thereby reducing capillary permeability. 9,32–38 Early studies excluded patients with ischaemic CRVO33,39 as it was questionable whether or not a significant improvement in vision would result from anti-VEGF therapy. More recent (2017) studies40 did not exclude such patients, and this is the approach we adopted in LEAVO to ensure that our study population fully reflected a general UK population likely to present for treatment.

To date, three anti-VEGF agents have been used in the treatment of MO due to CRVO:

-

Ranibizumab is a humanised, affinity-matured VEGF antibody fragment that binds to and neutralises all isoforms of VEGF-A. Ranibizumab was the first anti-VEGF therapy to demonstrate improved visual outcomes in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nvAMD),41,42 and in 2012 it was licensed by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for MO due to CRVO. This was based on the CRUISE data9 that showed that monthly intraocular ranibizumab therapy improved the mean best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) by +15 ETDRS letters at 6 months and a pro re nata regimen with monthly monitoring improved the mean BCVA by +14 ETDRS letters by 12 months. 9 In an open-label extension [An Open-Label, Multicentre Extension Study to Evaluate the Safety and Tolerability of Ranibizumab in Subjects with Choroidal Neovascularization Secondary to Age-Related Macular Degeneration or Macular Oedema Secondary to Retinal Vein Occlusion Who Have Completed a Genentech-Sponsored Ranibizumab study (HORIZON)] from months 12 to 24, the mean visual acuity in CRVO only patients reduced by 4.1 letters with an average of 3.5 injections in 12 months. Ranibizumab was well tolerated: 6.5% of patients had some degree of cataract after 2 years and < 1% had a rise in intraocular pressure. 38

-

Aflibercept is a fusion protein of the key domains of VEGF receptors 1 and 2 and human IgG Fc that blocks all VEGF-A isoforms and placental growth factor. In 2014, it was licensed by the FDA and the EMA for CRVO based on the GALILEO and COPERNICUS studies, which showed a mean gain of +16.2 letters in BVCA at 12 months and a mean gain of +13.0 letters in BCVA at 24 months, with 60% gaining ≥ 15 letters at 12 months and 49.1% gaining ≥ 15 letters at 24 months. 29–31 Despite these results, and the fact that it was non-inferior to ranibizumab when given every 8 weeks after a loading phase in nvAMD, suggesting improved cost-effectiveness,43 no clinical trial had been undertaken to directly compare aflibercept with ranibizumab or bevacizumab (1.25 mg/0.05 ml Avastin®; F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG, Basel, Switzerland), even though NICE recommended aflibercept for MO due to CRVO [NICE technology appraisal (TA) guidance 30512]. Cumulative safety data have not, to date, shown an increased risk of any ocular or systemic adverse events (AEs) with aflibercept compared with other drugs used for these indications.

-

Bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody that also inhibits VEGF; it is licensed by the EMA for the treatment of cancer but is used off-label for treatment in the eye. However, it was crucial to fully assess bevacizumab’s suitability for intraocular use because (1) it is substantially cheaper than ranibizumb and aflibercept when divided by a compounding pharmacy into multiple doses from a single 4-ml vial; (2) it was found by the Decision Support Unit44 to be used in NHS trusts across the UK for nvAMD, diabetic macula oedema (DMO), RVO and other less common indications, such as choroidal neovascularisation due to myopia and retinal dystrophies; (3) it is widely used in UK private practice; and (4) there have been concerns about possible systemic side effects following intraocular injection of bevacizumab. 45 Bevacizumab was found to be non-inferior to ranibizumab in terms of macular dysfunction and final visual acuity over 2 years in two large clinical trials: the Inhibit VEGF in Age-related choroidal Neovascularisation (IVAN)45 trial and the Comparison of Age-related macular degeneration Treatments Trials (CATT). 46 These trials also found no increased risk of local or systemic side effects with bevacizumab compared with ranibizumab; although more patients receiving bevacizumab were hospitalised due to serious adverse events (SAEs), the investigators thought that these SAEs were unrelated to bevacizumab. 47

Two independent reviews48,49 had previously suggested an increase in bevacizumab-related side effects, increasing the need to compare the safety of bevacizumab directly with that of ranibizumab. NICE Technology appraisal (TA) 28313 (on ranibizumab) and NICE TA30512 (on aflibercept) for MO secondary to CRVO recommended that additional head-to-head trials including bevacizumab were needed for RVO to carefully examine clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Therefore, it was proposed that LEAVO be conducted in MO due to CRVO to (1) compare the clinical effectiveness of ranibizumab, aflibercept and bevacizumab in a pragmatic trial over 24 months that followed up patients over the natural history of the disease, (2) compare the cost-effectiveness of the agents in a trial that closely resembled clinical practice and (3) describe the safety profile of each agent in terms of ocular and systemic AEs over 24 months.

Evidence update post LEAVO initiation

Ranibizumab, aflibercept and bevacizumab continue to be used in many countries for multiple retinal diseases, with bevacizumab the most frequently given anti-VEGF agent worldwide, as the licensed alternatives remain too costly. Despite convincing case series and early trials employing bevacizumab, full-scale randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were commissioned and completed by the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and the US National Institutes of Health to compare bevacizumab with ranibizumab in nvAMD45,46 prior to the licensing of aflibercept. To our knowledge, no RCTs have compared all three agents for nvAMD. Nevertheless, after a review of all the available evidence, the NICE Guideline Committee reported that all three agents were of equivalent efficacy and had similar side effects,50 and systematic reviews found no differences in the risk of vision-threatening complications or systemic AEs. 51,52

Despite this, bevacizumab has not achieved widespread use in the UK. The reasons for this include no clear position on the issue from NHS England or the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA); likely conflicts of interest among key stakeholders, including physicians; and the belief in some quarters that bevacizumab is an unlicensed medication, rather than a licensed medication being used in an off-label indication. Most recently, a UK judicial review (the Whipple judgement, September 2018), brought by the manufacturers of aflibercept and ranibizumab against north of England Clinical Commissioning Groups that had adopted a policy that off-label bevacizumab should be the preferred option for the treatment of nvAMD, ruled that this was lawful. 53 However, this outcome is now subject to appeal by the manufacturers and the uncertainty continues, which is frustrating as the economic case for bevacizumab is overwhelming. The only retinal condition for which the three anti-VEGF agents have been compared is DMO. The visual gains at 2 years in eyes with moderate and severe visual loss (visual acuity of ≤ 20/50) occurred earlier and were greater in eyes receiving aflibercept therapy. However, among patients with mild initial visual impairment, visual gains were similar across treatment arms, suggesting that bevacizumab could be used for these patients. 54

Robust data remain lacking on long-term comparisons of outcomes with anti-VEGF agents for MO due to CRVO. After the initiation of LEAVO, the secondary outcomes of the randomised, double-masked, Phase III licensing trials of aflibercept for CRVO, the COPERNICUS and GALILEO studies, became available. These showed that the visual and anatomic improvements after fixed monthly dosing through to week 24 and continued pro re nata dosing with monthly monitoring from week 24 to week 52 were largely maintained up to 100 weeks if monitored every 8 weeks, and diminished if monitored quarterly from week 52 to week 100. 29–31 The 12-month single-arm study of an individualised dosing regimen of ranibizumab driven by stabilisation criteria in 357 patients with CRVO also resulted in significant gain in visual acuity (CRYSTAL). 55 The mean number of injections by 12 months was 8.8, with better outcomes in eyes with CRVO of < 3 months’ duration and lower baseline visual acuity. The visual outcomes were similar in eyes with and eyes without baseline macular ischaemia. The study also showed that visual acuity could be stabilised with visual acuity-guided re-treatment criteria up to 100 weeks. 56

Although these trials compared each anti-VEGF agent with sham treatment for MO due to CRVO, RCTs comparing these agents over a longer term have been limited. A RCT comparing aflibercept and ranibizumab on a treat-and-extend regimen over 18 months showed that the frequency of injections was significantly lower in the aflibercept arm than in the ranibizumab arm. 57 The SCORE2 study group randomised 362 patients with MO due to CRVO or hemiretinal vein occlusion 1 : 1 to receive monthly aflibercept or bevacizumab for 6 months, and reported that intravitreal bevacizumab was non-inferior to aflibercept with respect to visual acuity. 27 The participants who responded well to monthly aflibercept and those who responded well to bevacizumab for 6 months in SCORE2 were further randomised to receive either monthly injections or treat-and-extend regimens of aflibercept (for those who responded well to aflibercept) and bevacizumab (for those who responded well to bevacizumab). The 12-month outcome showed that the treat-and-extend arm of each anti-VEGF agent required up to two fewer injections from 6 to 12 months than the monthly mandated treatment arms, although the difference in visual outcomes showed significant variability. 58 A RCT comparing aflibercept and bevacizumab on a one plus pro re nata basis found that those in the aflibercept arm required fewer injections at 12 months. 59

The COMRADE-C trial was a Phase IIIb, multicentre, double-masked, randomised clinical trial that compared a ranibizumab loading phase followed by pro re nata dosing with 0.7 mg of dexamethasone, given only at baseline, for MO due to CRVO, and showed a favourable outcome with ranibizumab. 60 A 2019 systematic review61 evaluating the effectiveness and adverse effects of ranibizumab, aflibercept and bevacizumab in three common retinal conditions, including RVO, reported that none of the 17 included studies showed a clinically important difference (i.e. ≥ 5 letters) in visual acuity gains between agents. There was insufficient evidence to compare bevacizumab and ranibizumab in RVO. Overall, the authors reported that no agent had a clear advantage over another in effectiveness or safety, but in two trials61 both aflibercept and ranibizumab were significantly less cost-effective than repackaged bevacizumab. 61

Another systematic review and network analysis of 11 RCTs of the three anti-VEGF agents for RVO found no statistically significant differences in the proportion of patients who gained at least 15 letters in BCVA, in the mean change from baseline in BCVA, or in the mean change from baseline in central macular thickness at 6 months. 62 However, to date, no RCTs have compared all three anti-VEGF agents for treating this condition over the at least 2-year duration of the disease.

To our knowledge, the LEAVO trial is the first RCT evaluating the comparative clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and relative safety of these three anti-VEGF agents for CRVO-related MO over 100 weeks. In summary, if bevacizumab was shown in LEAVO to be non-inferior to ranibizumab, and aflibercept was non-inferior to ranibizumab, with no new safety concerns, it could be considered for NHS use in MO due to CRVO. In addition, this would provide evidence of its equivalence to the licensed medications in multiple indications and lend substantial support to the case for using bevacizumab in the treatment of nvAMD and other retinal diseases.

Clinical trial objective

The objective of the trial was to compare the relative clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the anti-VEGF agents bevacizumab (investigational treatment), aflibercept (investigational treatment) and ranibizumab (standard care) in MO due to CRVO over 100 weeks. The trial was intended to determine if bevacizumab or aflibercept was as effective as ranibizumab in reducing visual loss from MO due to CRVO, whether or not they had an equivalent side-effect profile and whether or not either could be considered or recommended for NHS treatment based on non-inferior clinical effectiveness and superior cost-effectiveness.

Primary objectives

-

To determine whether or not bevacizumab is non-inferior to ranibizumab in treating visual loss due to MO secondary to CRVO.

-

To determine whether or not aflibercept is non-inferior to ranibizumab in treating visual loss due to MO secondary to CRVO.

Secondary objectives

-

To determine the difference between arms in terms of mean change in BCVA at 52 weeks.

-

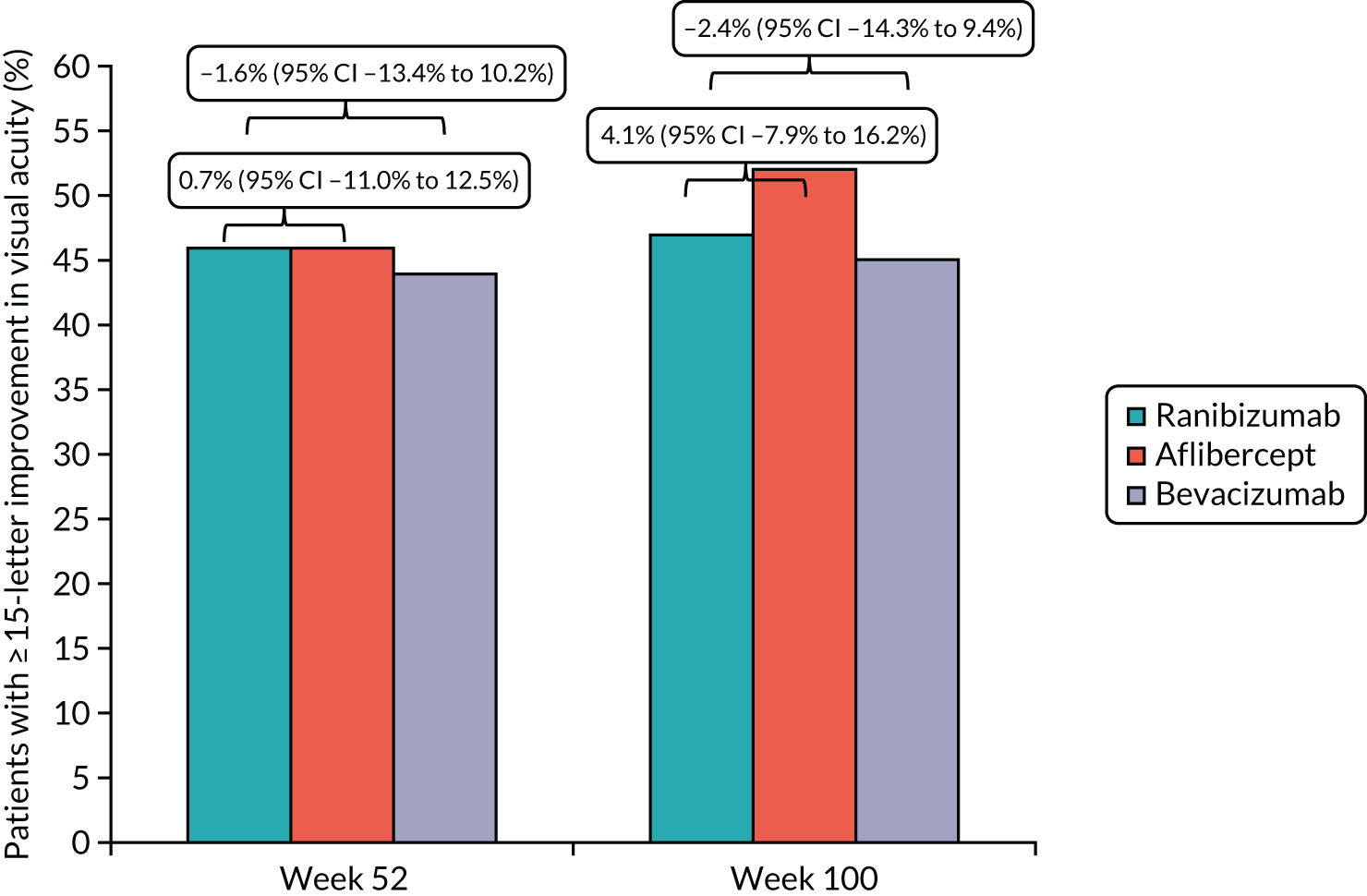

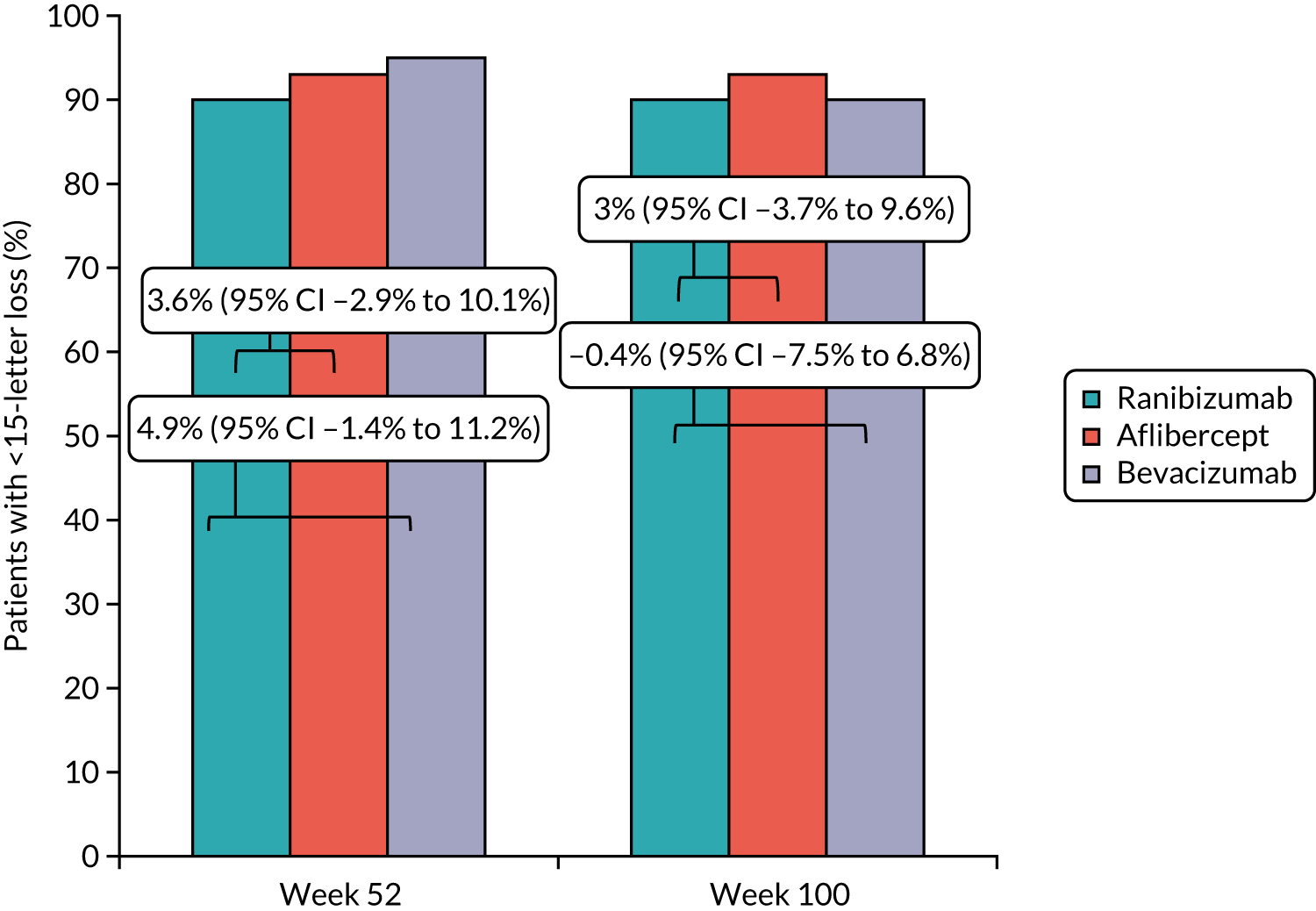

To determine the difference between arms in the proportion of participants with ≥ 15 ETDRS letter improvement (appreciable visual gain), ≥ 10-letter improvement, < 15-letter loss and ≥ 30-letter loss (severe visual loss) at 52 and 100 weeks.

-

To determine the difference between arms in the proportion of participants with ≥ 73 ETDRS letters or > 6/12 Snellen equivalent (i.e. approximate driving visual acuity), ≤ 58 ETDRS letters (≤ 6/24) and ≤ 19 letters (≤ 3/60) [Certificate of Vision Impairment (CVI) partial and severe visual impairment] at 52 and 100 weeks.

-

To determine the difference between arms in the mean change in OCT central subfield thickness (CST) and macular volume at 52 and 100 weeks.

-

To determine the difference between arms in the proportion of participants with an OCT CST of < 320 µm [as measured with the Spectralis® (Heidelberg Engineering, Inc., Franklin, MA, USA) or equivalent] at 52 and 100 weeks (key guide to subsequent NHS clinical practice).

-

To determine the differences between arms in the mean number of intravitreal injections given to each participant at 100 weeks.

-

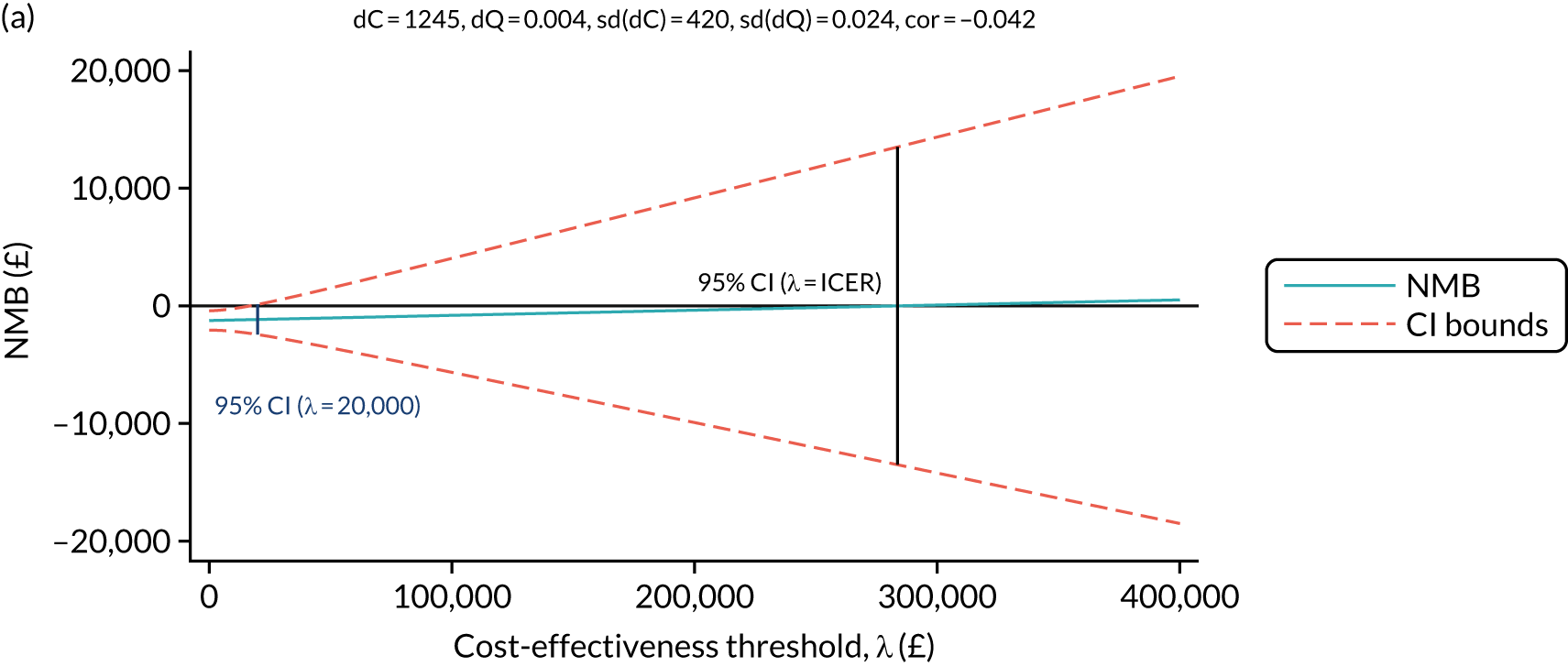

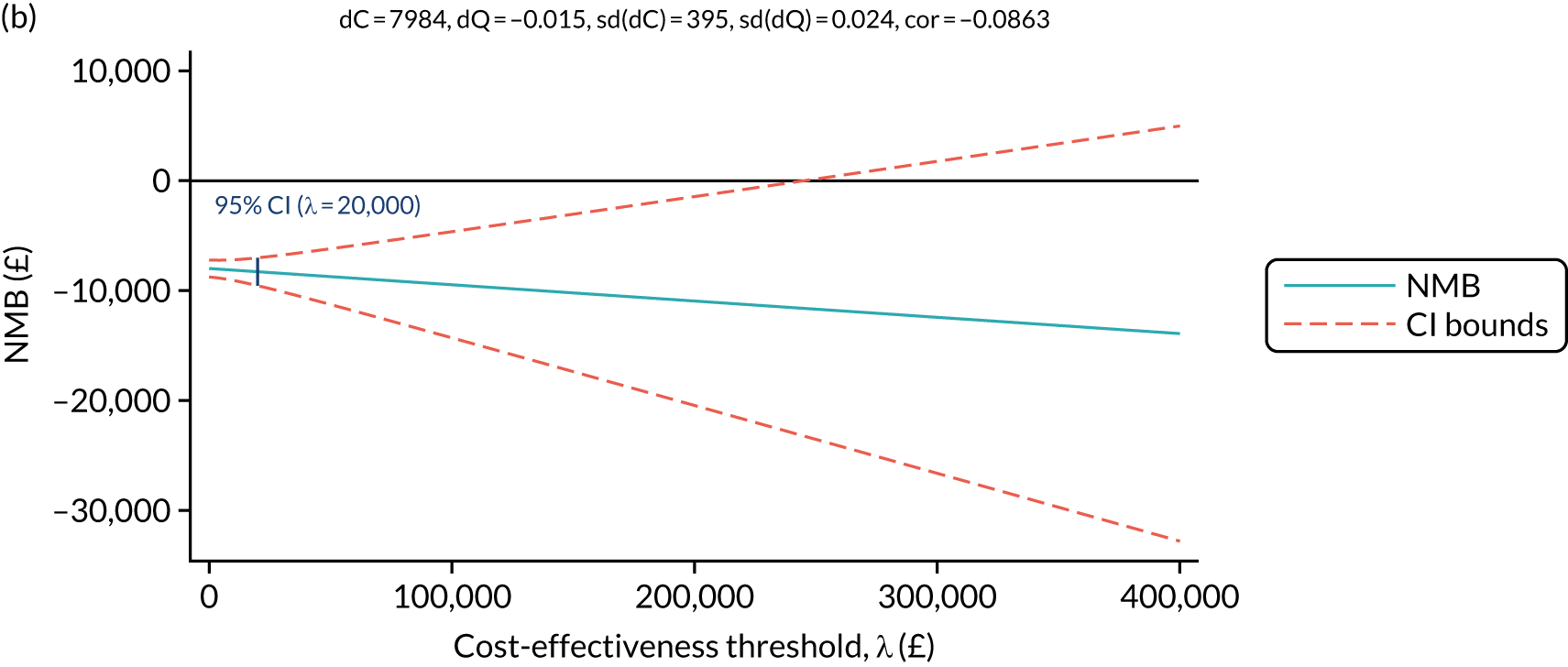

To determine any differences in the relative effectiveness of the investigational treatments and comparator on quality of life and resource use, reported as incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs), at 52 and 100 weeks.

-

To detect any differences in the prevalence of local and systemic side effects at 100 weeks.

-

To determine the differences between arms at 100 weeks in the proportion of (1) persistent non-responders who develop a change in retinal non-perfusion, compared with screening, and (2) participants who develop anterior and posterior segment neovascularisation.

-

To determine the differences between arms in terms of mean change in BCVA at 100 weeks.

-

To determine the differences between arms in changes in area of non-perfusion at 100 weeks and OCT anatomical features from baseline to 100 weeks.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

LEAVO was a Phase III, randomised, controlled, double-masked, non-inferiority clinical trial conducted to evaluate the relative clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of intravitreal bevacizumab and aflibercept, compared with ranibizumab, for MO due to CRVO. The intention was to randomise 459 participants with MO due to CRVO in at least one eye in a ratio of 1 : 1 : 1 to ranibizumab (0.5 mg/0.05 ml), aflibercept (2.0 mg/0.05 ml) and bevacizumab (1.25 mg/0.05 ml), all of which would be administered by repeated intravitreal injection, and to follow up these participants for 100 weeks. The study was conducted in the UK NHS across 44 ophthalmology centres that had staff with expertise in retinal disorders and a proven track record of effectiveness research. 2

Participants

The trial population, from which the trial sample was drawn, was adults aged ≥ 18 years with MO secondary to CRVO of < 12 months’ duration who attended one of the 44 NHS ophthalmology centres. The complete inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in the following sections.

Selection of participants

Inclusion criteria

-

Subjects of either sex aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Clinical diagnosis of centre-involving MO due to CRVO.

-

Central retinal vein occlusion of ≤ 12 months’ duration.

-

Best corrected visual acuity ETDRS letter score in the trial eye of between 78 (approximate Snellen equivalent: 20/32) and 19 (approximate Snellen equivalent: 20/400).

-

Optical coherence tomography CST of > 320 µm (as measured with the Spectralis) (or equivalent with an alternative OCT device) predominantly due to MO secondary to CRVO in the trial eye.

-

Media clarity, pupillary dilatation and subject co-operation sufficient for adequate fundus imaging of the trial eye.

-

Best corrected visual acuity ETDRS letter score in the non-trial eye of ≥ 14 (approximate Snellen equivalent: 20/600).

Exclusion criteria

The following applied to the trial eye only, unless specifically stated otherwise:

-

Macular oedema considered to be caused by a condition other than CRVO (e.g. DMO, Irvine–Gass syndrome).

-

An ocular condition present that, in the opinion of the investigator, might have affected MO or altered visual acuity during the trial (e.g. vitreomacular traction).

-

Any diabetic retinopathy or DMO on baseline clinical examination of the trial eye.

-

Moderate or severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy or quiescent, treated or active proliferative diabetic retinopathy or MO in the non-trial eye. Note that mild non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy only was permissible in the non-trial eye.

-

History of treatment for MO due to CRVO in the previous 90 days with intravitreal or peribulbar corticosteroids or in the previous 60 days with anti-VEGF drugs or more than six prior anti-VEGF treatments in the previous 12 months.

-

Active iris or angle neovascularisation, neovascular glaucoma, untreated neovascularisation disc (NVD), neovascularisation elsewhere (NVE) and vitreous haemorrhage or treatment for these conditions in the previous month.

-

Uncontrolled glaucoma (i.e. eye pressure of > 30 mmHg) either untreated or being treated with antiglaucoma medication at screening.

-

Any active periocular or intraocular infection or inflammation (e.g. conjunctivitis, keratitis, scleritis, uveitis, endophthalmitis).

Systemic exclusion criteria

-

Uncontrolled blood pressure, defined as a systolic value of > 170 mmHg and a diastolic value of > 110 mmHg.

-

Myocardial infarction, stroke, transient ischaemic attack, acute congestive cardiac failure or any acute coronary event < 3 months before randomisation.

-

Women of childbearing potential, unless they were using an effective method of contraception during the trial and for 6 months after their last injection for the trial. Effective contraception was defined as one of the following:63

-

Barrier method – condoms or occlusive cap with spermicides.

-

True abstinence – when in line with the preferred and usual lifestyle of the subject. Periodic abstinence (e.g. calendar, ovulation, symptothermal, post-ovulation methods) and withdrawal were not acceptable methods of contraception.

-

Tubal ligation or bilateral oophorectomy (with or without hysterectomy).

-

Male partner sterilisation. The vasectomised male partner should be the only partner of the female participant.

-

Use of established oral, injected or implanted hormonal methods of contraception and intrauterine device.

-

-

Pregnant or lactating women.

-

Men who did not agree to an effective form of contraception for the duration of the trial and for 6 months after their last injection for the trial.

-

Hypersensitivity to the active ingredients of aflibercept, bevacizumab or ranibizumab, or to any of the excipients of these drugs.

-

Hypersensitivity to Chinese hamster ovary cell products or other recombinant human or humanised antibodies.

-

A condition that, in the opinion of the investigator, would preclude participation in the trial.

-

Participation in an investigational trial involving an investigational medicinal product within 90 days of randomisation.

Rescreening of patients2

Patients could be rescreened in the following circumstances:

-

Patients who did not meet the BCVA or OCT CST inclusion criteria could be rescreened a minimum of 4 weeks after their last screening visit if they were thought to meet the eligibility criteria.

-

Individuals who did not meet other modifiable inclusion criteria, for example blood pressure, could be rescreened a minimum of 2 weeks after the last screening visit.

All assessments performed at the initial screening visit were repeated during the rescreening visit, except FFA if the rescreening visit was within 10 weeks of the original screening visit. If a patient was found to be eligible on rescreening and was randomised, their initial entry on the electronic case report form (eCRF) system was updated, rather a ‘new’ patient being created on the system. This avoided such patients being incorrectly counted twice in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram.

Recruitment

The trial recruited participants from 44 UK ophthalmology centres over 24 months. Recruitment was competitive; however, each site was allocated a minimum target number of participants to recruit and was encouraged to exceed this if possible. Sites were set up strategically: larger sites with greater capacity were initiated first to maximise early recruitment and to ensure that the recruitment period was fully utilised. Eligible patients were invited to participate via their local clinics, or in an invitation letter. At each site, participants were identified from subspecialty retinal, general and eye casualty clinics. Once identified, potential participants underwent a clinical examination, followed by discussion of the trial with an experienced trial clinician, and were provided with the patient information sheet. 2

Trial procedures

Informed consent procedure

The principal investigator or designated subinvestigator was responsible for ensuring that a patient was fully consented after being provided with an adequate explanation of the aims, methods, anticipated benefits and potential hazards of the trial. Patients were advised that any data collected would be held and used in accordance with the Data Protection Act 1998. 64 Patients were given at least 24 hours after receiving the patient information sheet to consider taking part. The principal investigator or designee recorded in the medical notes the date when the patient information sheet was given to the patient and the facts that patients were under no obligation to enter the trial and that they could withdraw at any time without giving a reason. No clinical trial procedures were conducted before consent was taken from a participant; consent denoted enrolment in the trial. A copy of the signed informed consent form was given to the participant. The original signed form was retained at the trial site and a copy was placed in the medical notes. If new safety information resulted in significant changes in the risk/benefit assessment, or if there were significant changes to the protocol or patient information sheet, participants were consented again as appropriate.

Randomisation

Only one eye of each participant was randomised to the trial. In 95% of cases, one eye was affected by CRVO and so was the ‘worse-seeing eye’ and was randomised. On rare occasions, participants had bilateral CRVO that met the eligibility criteria. In these cases, the worse-seeing eye was randomised unless the participant opted for randomisation of the ‘better-seeing eye’. The plan was to recruit 459 adult participants with MO due to CRVO and to randomise them 1 : 1 : 1 at the level of the individual using the method of minimisation incorporating a random element. The three stratifying factors were (1) visual acuity, stratified by screening BCVA letter score [of ≤ 38 (approximate Snellen equivalent: ≤ 6/60), 39–58 (approximate Snellen equivalent: 6/48 to 6/24) or ≥ 59 (approximate Snellen equivalent: ≥ 6/18)]; (2) duration of disease, from date of CRVO diagnosis to commencement of therapy (< 3, 3–6 or > 6 months); and (3) treatment naive versus previous treatment. Each participant was randomised to one of three arms: bevacizumab, aflibercept or ranibizumab. 2

A patient identification number (PIN) was generated by registering a patient on the MACRO eCRF system (InferMed Macro; Elsevier Ltd, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), after consent had been obtained. Randomisation was carried out in a bespoke web-based randomisation system hosted at the King’s Clinical Trials Unit (KCTU). A unique PIN was generated in the MACRO program; this was recorded on all source data worksheets and was used to identify a participant throughout the trial. 2,63 The trial manager allocated all authorised site staff a username and password for the randomisation system. All authorised staff members, who were typically the principal investigator or designee, logged in to the randomisation system and entered a participant’s details, including the unique PIN. Once a participant had been randomised, the system automatically generated e-mails to key staff in the trial. Unmasked e-mails sent to site pharmacies alerted them to a participant’s treatment arm: ranibizumab, aflibercept or bevacizumab. The pharmacy department used the e-mail to cross-check the trial prescription to ensure that the correct medication was dispensed for the correct participant. Additional masked e-mails were generated from the randomisation system and sent to key trial site staff,63 and unmasked e-mails were sent to the emergency unmasking service (ESMS Global Ltd, London, UK) and unmasked trial management staff. 2

Masking of treatment allocation

In randomisation process, only the pharmacy at a local trial site was informed by e-mail of a subject’s treatment allocation; a copy of the e-mail was sent to the emergency unmasking service (ESMS Global Ltd) and to unmasked trial management staff. The trial drug that a participant received was transferred to the dedicated injection room in an opaque masking bag designed to securely and safely transport medication. A unique seal was attached to the bag before it left the pharmacy. The bag had a safe zipped compartment containing a printed form detailing a participant’s unique PIN, their date of birth, the date the drug was dispensed and the injection batch number. Before a participant entered the injection room, the unmasked injector broke the seal and took the drug out of the masking bag. Bevacizumab was provided in a prefilled syringe, but ranibizumab and aflibercept were provided in a vial and drawn into a syringe by the unmasked injector. The syringe was placed on the injection trolley out of view of the participant, who was then invited into the room and asked to lie on the bed, and then received the injection. During the trial the manufacturer of ranibizumab began to provide the drug, in a unique prefilled syringe and vials ceased to be available. In this situation, the unmasked injector took care not to allow the participant to see the syringe either before or after the injection had been given. This was achieved by administering the injection while the participant was lying down and the injection was given via the pars plana in any quadrant of the eye, with the syringe brought to and taken away from the injection site via a participant’s inferotemporal field of vision so that it did not pass across their line of sight. The unmasked injector signed the source notes to the effect that the treatment in the masked bag had been administered to the participant, without specifying the treatment, and also signed the printed form that was in the masking bag. The empty syringe with needle and vial were disposed of in the injection room. The masking bag and completed printed form were returned to the pharmacy. The outer packaging of the drug was disposed of in the injection room. 2

The clinical assessment team, including the site principal investigator, optometrist (i.e. assessor of the primary outcome), site trial co-ordinator, clinical investigator, clinical assessment trial nurse and ophthalmic technician, remained masked throughout the trial, as there was no record of a participant’s treatment arm in the source notes or the case report form (CRF). Similarly, co-ordinators or administrators completing questionnaires with participants in person (or, in extreme circumstances, only over the telephone at specific time points) had details of a participant’s PIN only. If, at any time, information regarding treatment allocation was shared with the outcome assessors, this was recorded in the trial master file, and the person(s) involved met with the site principal investigator to ensure that no repetition occurred and undertook not to convey this information either to the participant or to others involved in the project. Certain secondary outcomes (e.g. interpretation of FFA) occurred at the remote Network of Ophthalmic Reading Centres (NetwORC) UK (Belfast, UK), where the assessors were masked to the treatment allocation. These masking procedures avoided both performance and detection bias. We have described the completeness of outcome data for each outcome, including any unmasking in error, reasons for attrition and exclusions from the analysis. 2 The trial statisticians had access to the accumulating outcome data that were required for reporting to the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC). Both trial statisticians attended both the open and the closed DMEC meetings.

Screening and baseline assessment

A patient had to receive the patient information sheet not later than 24 hours before the screening assessment. The screening and baseline visits could be undertaken on the same day, provided that all test results were available. A patient could return within 10 days of screening for the baseline assessment, at which point the screening procedures were still valid and were not repeated at baseline (see Appendix 3, Table 29).

Milestone and non-milestone visits

Trial milestone assessments, when key research data were collected, occurred at baseline and at weeks 12, 24, 52, 76 and 100. These visits, as well as treatment visits at weeks 4 and 8, were calculated and agreed with a participant prior to randomisation (with flexibility of 0 to 14 days for weeks 4, 8 and 12, and of –14 to 14 days for weeks 24, 52, 76 and 100, from the date of randomisation). It was mandatory for all participants to attend all milestone visits, even if a milestone visit fell < 4 weeks after a treatment visit or if a participant was being followed up every 8 weeks and the next milestone visit fell during the 8-week interval. The intervening trial treatment visits were deliberately flexible to allow normal clinical practice treatment follow-up to be accommodated. All data from the trial milestone visits were entered into the eCRF. For regular treatment visits, only the following information was entered into the eCRF: BCVA; OCT CST; whether or not an injection was given; and, if no injection was given, the reason why. At milestone visits, refracted visual acuity was tested and health economic questionnaires were completed; colour photography was undertaken at baseline and at weeks 52 and 100; and FFA was undertaken at baseline and at week 100, in addition to the clinical examination and OCT tests performed at all other trial visits (see Appendix 3, Table 29).

Trial assessments and methods

Participant demographics, medical and ophthalmic history

This information was retrieved from the participant, from hospital medical records or from a general practitioner. Data included age, sex and ethnic background. Data were also collected on clinically relevant medical history and management in the preceding 24 months, and on any ocular history and treatment. 2

Visual acuity tests

Visual acuity tests were performed by a certified optometrist in a certified visual acuity testing lane using validated ETDRS vision charts and standard operating procedures. 65,66 Refracted visual acuity was carried out in both eyes at screening,63 at weeks 12, 24, 52, 76 and 100, and at the point of withdrawal. For all other visits, the visual acuity was tested with the previous most recent protocol refraction. Visual acuity examiners were masked to the treatment. The visual acuity scores were recorded in the eCRF2 (see Appendix 4).

Standard ophthalmic examination

A standard ophthalmic examination using slit-lamp biomicroscopy included an undilated examination for neovascularisation of the iris (NVI), RAPD and tonometry in both eyes at all visits. Dilated fundus examination was performed in both eyes at all milestone visits (i.e. at screening, at baseline, at weeks 12, 24, 52, 76 and 100, and at the point of withdrawal). At all other visits, dilated fundus examination was performed in the trial eye and, at the discretion of the investigator, in the non-trial eye. Gonioscopy, if indicated, was carried out prior to dilatation at any visit. 2

Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography

The CST and total macular volume in both eyes were recorded in the eCRF from the spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) thickness map at every visit, and, if applicable, at the point of withdrawal. 63 Any SD-OCT machine could be used for the trial, but the same model of SD-OCT machine had to be used for each individual throughout the period of the trial. SD-OCT images at screening and at weeks 52 and 100 only were transferred to and read by masked graders at the independent NetwORC UK. NetwORC UK provided each site with a trial imaging protocol on how to acquire SD-OCT images, colour fundus photographs and fundus fluorescein angiographs and how to transfer these to NetwORC UK to them. Initial grading of all OCT images at baseline and at weeks 52 and 100 was performed by NetwORC UK. The grading took into account intraretinal oedema, classified as diffuse, cystic or mixed; determined subretinal fluid as being present or absent; and determined vitreoretinal interface abnormalities as being present (as either an epiretinal membrane or vitreomacular traction) or absent. Following the contract variation, additional grading parameters were assessed at NetwORC UK in collaboration with specialised retinal graders at Moorfields Eye Hospital, utilising additional definitions and analyses that had been developed while the trial was in progress. 1,67,68 Only images captured using a Spectralis OCT machine had sufficient detail to support the enhanced grading definitions. Retinal morphology was assessed using the Spectralis® Heidelberg Macular Raster OCT device (Heidelberg Engineering, Inc.) of 31 line scans, 30 × 25 mm in size, at an interscan distance of 240 µm or the equivalent for alternative devices. MO was graded using the entire line-scan series and the central 1500 µm, that is seven scans were employed for vitreomacular interface abnormality and subretinal detachment or equivalent. The remaining parameters were graded using the central 1000 µm only, that is central five-line scans only. A magnification of 300% was used to assess the ellipsoid zone (EZ), disorganisation of the retinal inner layers (DRIL)67,68 and hyperreflective foci (HRF),69,70 with 100% magnification for the remaining parameters. HRF, external limiting membrane (ELM), EZ and cone outer segment tips (COSTs) were graded as positive only if the foveal line showed involvement of the foveal depression such that it was distorted, lessened or absent. 2 For the grading of normal and abnormal individual morphological features, see Appendix 5, Specific grading of individual morphological optical coherence tomography features, and Figures 22 and 23.

Colour fundus photography

Non-stereo, seven-field conventional or wide-angle colour fundus photography (CFP) was performed at screening and at weeks 52 and 100 in the trial eye. CFP confirmed the diagnosis of CRVO and assisted interpretation of features identified by FFA, for example to differentiate between non-perfusion and masking due to haemorrhage. If applicable, CFP was also performed at the point of withdrawal, and at any other trial visit, as per investigator discretion. Colour fundus photographs were transferred to and read by masked graders at the independent NetwORC UK. Either a colour camera capable of taking seven-field colour fundus photographs or a wide-angle system was used, but the same model of camera was used for each individual throughout the trial. The colour photographs were graded by the NetwORC UK. 2

Fundus fluorescein angiography

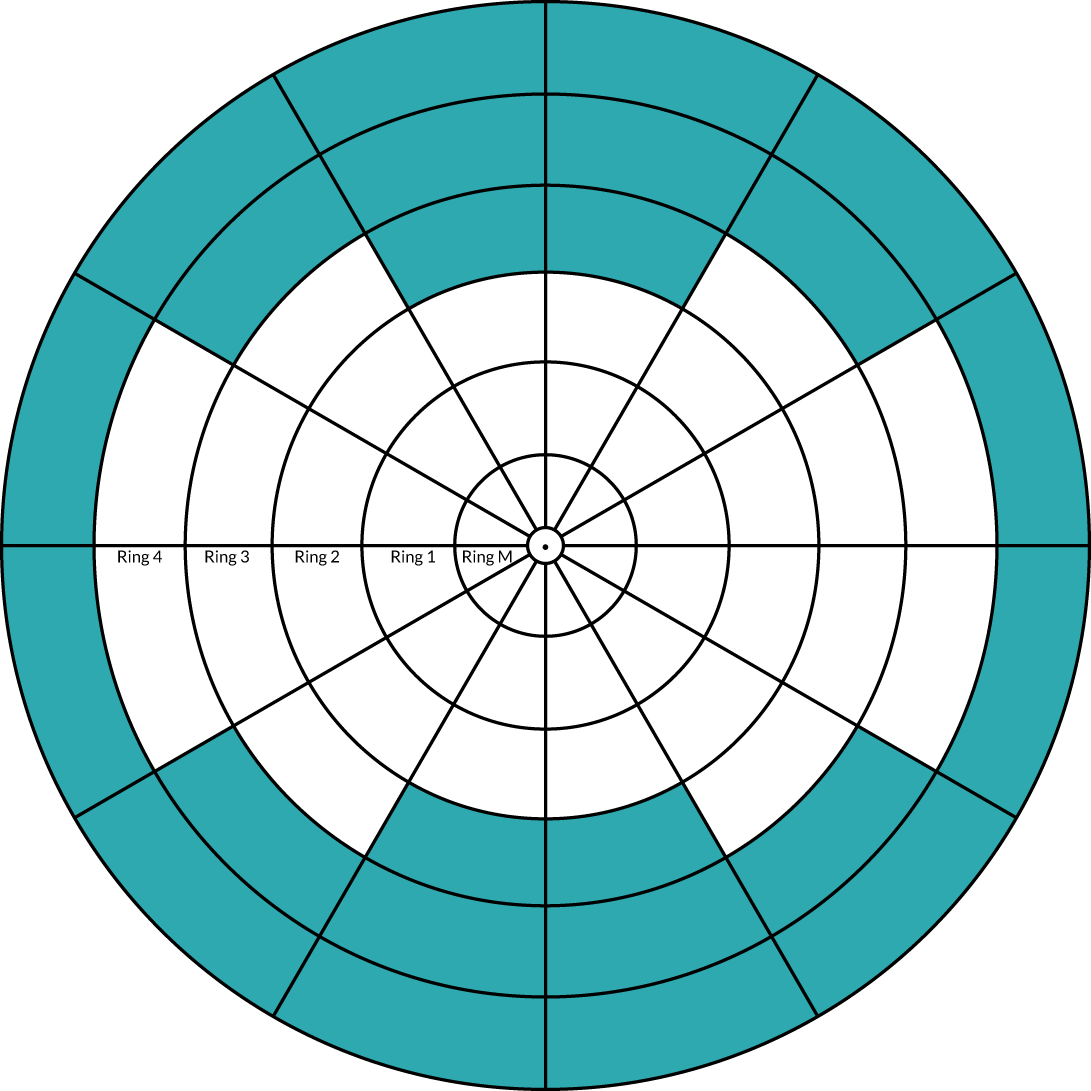

Non-stereo, seven-field conventional or wide-angle FFA was performed at screening and at week 100 in the trial eye. Any FFA system capable of taking seven-field FFA pictures or a wide-angle system was allowed, but the same system had to be used in the same individual throughout the trial. 2 FFA was used to quantify the degree of retinal ischaemia and for identification of retinal neovascularisation (see Appendix 5, Fundus fluorescein angiography grading). Pseudo-anonymised FFA images were transferred to NetwORC UK, where the standard NetwORC UK 13-sector grid (see Appendix 5, Figure 24) was applied over the wide-angle or montaged seven-field angiography pictures at baseline and at 100 weeks. The first 100 gradings were double-graded. Discrepancies were adjudicated. Subsequently, one in every eight gradings was double-graded. Kappa values for key fields (e.g. detection of new vessels on the disc and new vessels elsewhere) were required to be > 0.8. Any graders who did not achieve this were required to undergo additional training. Each sector in the grid was semiquantified in terms of percentage of non-perfusion (nil, 1–25%, 26–50%, 51–75% and 76–100%), and all available sets of images were analysed to identify how many participants in each arm had experienced a two-step increase (e.g. zero to 26–50%, or 26–50% to 76–100%) in one to five or more sectors (see Appendix 5, Figure 24). This technique was used in preference to the ischaemic index, which estimates the ratio of ischaemic to total retinal area but is very susceptible to image quality and is applicable to wide-angled images only. 22 Therefore, during the trial we used the concentric rings method, which displays superimposed concentric circles, centred on the fovea. 23,71,72 The innermost circle was 1 disc diameter (DD) in size, and is not graded as it represents the foveal avascular zone. The second circle, representing the macular ring (ring M), has a radius of 2.5 DD. Each of the subsequent rings (rings 1, 2, 3 and 4) is placed at increments of 2.5 DD in radius from the foveal centre. Each of these rings is subdivided into 12 equal segments. 23 To calculate the size of the concentric rings required, we assumed that the mean axial length was 24 mm, and excluded 2 mm from this to account for the cornea and part of the anterior chamber. In the model eye, the radius was 11 mm (diameter 22 mm); therefore, the full circumference would have been 69.1 mm (π = 3.142). The wide-angled imaging system (Optos®; Optos, Inc., Marlborough, MA, USA) was able to image 200 degrees of the retina; we used this to calculate the average diameter of retina obtained in a single central image. This was calculated to be 38.4 mm. Using the DD of 1.8 mm, this meant that the diameter of the image was 21.3 DD. A diameter of 21.3 DD resulted in the need for a macular ring plus three/four further rings. 23 Based on our validation study, we identified that ring 4 was gradable, but the superior and inferior segments of rings 3 and 4 were ungradable because the ultra-wide field image had better clarity in the horizontal meridian. For details of this method, see Appendix 5, Figure 25.

Health economic questionnaires

The following quality-of-life and resource use questionnaires were administered at baseline, at 12, 24, 52, 76 and 100 weeks, and at the point of withdrawal: the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire-25 items (VFQ-25), EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D), EuroQol-5 Dimensions with vision bolt-on (EQ-5D-V), and a bespoke resource use questionnaire [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/119203/#/documentation (accessed 14 July 2020)].

Treatment allocation guess form

Participants and masked optometrists were asked to complete a treatment allocation guess form at week 100, or at the point of withdrawal, to assess how well participant and assessor masking worked in the trial. 2

Definition of the end of the trial

Participants were enrolled in the trial for approximately 100 weeks from the point of randomisation. The end of the trial was defined as the last participant’s last trial visit.

Treatment procedures

Treatment schedule

After mandated administration in all three trial arms at baseline and at 4, 8 and 12 weeks, further pro re nata intervention was administered at weeks 16 and 20 if re-treatment criteria were met and if visual acuity was ≤ 83 letters.

Regardless of whether a treatment was given, the participant was reviewed in 4 weeks. From weeks 24 to 96, the interval was initially 4 weeks (with a visit window of –14 to 14 days), with the potential for the interval to increase to 8 weeks (with a visit window of –14 to 14 days) if criteria for ‘stability’ were achieved. ‘Stability’ was defined as three successive visits from week 16 onwards at which treatment criteria were not met, and so the first time at which treatment could be deferred for 8 weeks was week 24.

Similarly, ‘success’ was defined as an ETDRS letter score of > 83 letters, and if this was present at any re-treatment visit from week 16 onwards, treatment was not given at that visit and the participant was reviewed subsequently. The review occurred 4 weeks later if the initial visit was at 16 weeks, 20 weeks or any other visit if treatment had been given at this or the preceding visit. If no treatment had been given at these two visits, the participant was reviewed 8 weeks later. If, at any subsequent visit, re-treatment criteria were met and BCVA was ≤ 83 ETDRS letters, then re-treatment was commenced (Figure 1). At each visit between weeks 24 and 96 inclusive, ‘non-responder treatment suspension’ criteria could be met. If so, the principal investigator, or their designee, at their discretion, could suspend treatment to prevent therapy in a participant who had not responded to at least their last three injections. If the criteria for restarting therapy after ‘non-responder treatment suspension’ were met, then the participant had to resume therapy. If re-treatment criteria were met at one of the visits that took place every 8 weeks or at an unscheduled visit, then visits every 4 weeks were resumed. Treatment could be ‘deferred’ in certain circumstances, but the participant was asked to still attend the milestone visits.

FIGURE 1.

Re-treatment algorithm for weeks 24–96 of the trial.

Re-treatment criteria

Criteria were met if one or more of the following was present:

-

a decrease in visual acuity of ≥ 6 letters between the current and most recent visit, attributed to an increase in OCT CST

-

an increase in visual acuity of ≥ 6 letters between the current and most recent visit

-

OCT CST of > 320 µm (on Spectralis, or of > 300 µm on other machines) because of intraretinal or subretinal fluid

-

an OCT CST increase of > 50 µm from the lowest previous measurement.

Investigational medicinal products

Comparator: ranibizumab (0.5 mg/0.05 ml)

Ranibizumab is a humanised recombinant monoclonal antibody fragment that binds to VEGF A, preventing receptor interaction and blocking downstream action of VEGF, that is increased vascular permeability, leading to MO in CRVO. It is licensed by the EMA, and NICE has recommended it for use in the treatment of nvAMD, DMO and RVO. NICE TA28313 for MO due to RVO was issued in May 2013. Ranibizumab has been the mainstay of routine clinical care for this condition since the third quarter of 2013 and was the comparator in this trial. It was supplied to each site hospital pharmacy directly from the manufacturer as a part of routine hospital stock. 2

Intervention: aflibercept (2.0 mg/0.05 ml)

Aflibercept is a fusion protein that includes the key binding domains of human VEGF receptors 1 and 2 with human IgG Fc and acts as a dummy receptor for all VEGF isoforms and placental growth factor, preventing increased permeability and MO in CRVO. At initiation of this trial, it was licensed by the EMA, and NICE has recommended it for nvAMD. NICE TA30512 was published in February 2014; NICE recommends this drug as first-line use for CRVO-related MO. Aflibercept was supplied in a glass vial to each site hospital pharmacy directly from the manufacturer as part of routine hospital stock. 2

Intervention: bevacizumab (1.25 mg/0.05 ml)

Bevacizumab is a full-length humanised monoclonal antibody that binds to VEGF A, forming a protein complex incapable of binding to the VEGF receptor, thus blocking downstream VEGF action. In this trial, bevacizumab was supplied in a prefilled plastic syringe in a sealed package to each trial site pharmacy from the Liverpool and Broadgreen Pharmacy Aseptic Unit, Royal Liverpool University Hospital, Liverpool, UK. 2

Site pharmacy storage, ordering and handling procedures of investigational medicinal products

A trial medication dispensing and return log was maintained by the trial site pharmacies. Administration records from these sites were retained by the pharmacy and monitored by the trial manager to ensure that accurate CRF data were recorded. The randomisation system was linked to the investigational medicinal product (IMP) supply. Each site pharmacy was also responsible for appropriate storage, dispensing, disposal, and recall and destruction logs, in accordance with good manufacturing practice73 and good clinical practice,74 and the site hospital pharmacy’s approved policies for IMP accountability and management. Furthermore, each site pharmacy maintained a record of trial drug administration, based on the pre-printed form signed by the unmasked investigator that was returned to the pharmacy at each centre. 2

Investigational medicinal product accountability

Used and unused trial study medication and study medication accountability

Each masking bag contained a pre-printed form that listed the details of the participant’s unique PIN, date of birth, date the drug was dispensed and injection batch number. After performing the intravitreal injection, the unmasked injector signed this form to confirm that the drug had been given to the allocated patient, and they then returned it in the masking bag to the pharmacy. All used drug vials and syringes were disposed of in the injection room and not returned to the pharmacy. Pharmacies in each site maintained a trial medication dispensing log, including date dispensed, batch number, expiry date and return log. The return log was compiled from the form signed by the unmasked injector. In addition, the trial-specific prescriptions were maintained in the pharmacy file for audit purposes. Any administration errors were reported to the chief investigator and trial statistician. In the event that an injection was not given as scheduled, the reason was documented in the participant’s notes and the CRF. The trial monitor checked the pharmacy records against the eCRF. All records were reconciled with the investigator site file at the end of the trial. 2

Description and justification of route of administration and dosage of investigational medicinal product

The approved route of administration (i.e. by intravitreal injection through the pars plana of the eye) was used in all cases under sterile conditions in a designated treatment area in accordance with the guidelines75 for intravitreal injection of the Royal College of Ophthalmologists and any approved procedures at the individual site hospital. The injection could be performed by the unmasked injector(s) only, who was (were) on the hospital site LEAVO delegation log and was (were) experienced in intravitreal injection procedures. The dosages of ranibizumab (0.5 mg/0.05 ml) and aflibercept (2.0 mg/0.05 ml) used in this trial were approved by the EMA, and NICE recommends these doses of these agents for intraocular use. 12,13 The dosage of bevacizumab (1.25 mg/0.05 ml) was the dosage used in the IVAN clinical trial and the CATT of treating wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD), and the standard dose used in clinical practice. Post-injection checks were conducted in accordance with local hospital policy and included a visual acuity, intraocular pressure or optic nerve head perfusion check, or a combination of these. The interval between two doses of all three drugs was not recommended to be less than 4 weeks. 2

Management of complications

Complications, such as the development of ischaemic CRVO, neovascularisation of the angle, NVI, neovascular glaucoma (NVG), NVE and NVD, in the trial eye were recorded as AEs. The diagnosis and management of these complications of CRVO in the trial were at investigator discretion and based on local practice. Laser therapy formed the mainstay of therapy and was recorded as a concomitant procedure. 7,8

Recording and reporting of adverse events and reactions

Routine reporting

The MHRA definitions of AEs and SAEs were adopted for this trial. AEs were reported by the site in the AEs log in the eCRF. All SAEs, serious adverse reactions and suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSARs) were recorded and reported on the SAE form to the chief investigator/delegate within 24 hours of learning of their occurrence. A record of this notification (including date of notification) was clearly documented to provide an audit trail. In the case of incomplete information at the time of initial reporting, a follow-up report was provided as soon as the information became available. The sites responded promptly to any queries raised by the chief investigator/delegate. The principal investigator/delegate, who had to be a clinician at the site, assessed the relationship of the SAE to any of the trial interventions. The chief investigator was responsible for assessing the expected or unexpected nature of all serious adverse reactions. The chief investigator/delegate, with the support of the KCTU, ensured that Moorfields Eye Hospital, as sponsor, was made aware of any SUSARs and serious adverse reactions that occurred. The chief investigator/delegate, in conjunction with the sponsor, was responsible for reporting all SUSARs to the MHRA and relevant ethics committee within the appropriate time frame.

All principal investigators were informed of all SAEs that were assessed as fulfilling the criteria for a SUSAR (i.e. possibly, probably or definitely related to any trial intervention, and unexpected as per the summary of product characteristics or the protocol). 2

Planned ‘hospitalisations’, non-emergency procedures and adverse event reporting

Some AEs met the definition of serious but did not need to be reported on a SAE report form. Common ophthalmology- and non-ophthalmology-related events that resulted in planned, non-emergency hospital admissions for the investigation or treatment of those events and that were not possibly, probably or definitely related to the IMPs did not need to be reported on a SAE report form. These events were recorded on the AE form and the investigation and treatment of ophthalmology-related events were recorded on the ophthalmology-related concomitant procedure forms. All concomitant medications were recorded on the concomitant medication form. These forms were updated following each trial visit to ensure that the independent DMEC received accurate reports of the occurrence and treatment of AEs. 2

Pregnancy

In the event that a female participant became pregnant, this was reported to the KCTU on a pregnancy form sent by fax or e-mail as soon as the investigator became aware of it. The pregnancy was monitored to determine outcome. Any information related to the pregnancy following the initial report was reported on a follow-up pregnancy form. 2

Data management

Confidentiality

Data were handled, computerised and stored in accordance with the Data Protection Act 1998. 64 Participants were identified via a unique PIN, their date of birth and their initials. Identifiable information was stored in the eCRF and did not leave the site. Any participant contact information was stored in the site on password-protected computers or in secured locations with restricted access.

Data collection tools and source document identification

Written informed consent was obtained before screening and other trial-specific procedures were performed. SAE data were collected on paper SAE report forms and e-mailed or faxed to the KCTU. Summary details of SAEs were transcribed to the AE section of the eCRF. For all other data collected, source data worksheets were used for each patient and data were entered onto the eCRF database. Source data worksheets were reconciled at the end of the trial with a patient’s NHS medical notes in the recruiting site. During the trial, critical clinical information was written in the medical notes to ensure that informed medical decisions could be made in the absence of the trial team. Trial-related clinical letters were copied to the medical notes during the trial. It was the responsibility of the principal investigator and his/her team to ensure that the accuracy of all data entered in the worksheets and the eCRF was in accordance with good clinical practice. The delegation log identified all those personnel with responsibilities for data collection and handling, including those who had access to the trial database. The principal investigator was responsible for ensuring that source data worksheets were filed in a suitably secure location so that source data verification could be undertaken throughout the trial. 2

Data handling and analysis

All trial data and site files were kept on site in a secure location with restricted access.

The trial used an eCRF created using the InferMed MACRO database system. Data were managed using this system. The eCRF was created in collaboration with the trial statistician and the chief investigator and maintained by the KCTU. It was hosted on a dedicated secure server in King’s College London. This system is regulatory compliant; has a full audit trail, data discrepancy functionality and database lock functionality; and supports real-time data cleaning and reporting. The trial manager was responsible for providing usernames and passwords to permitted local trial personnel. Only those authorised by the trial manager were able to use the system. 2,63

Quality assurance

The trial incorporated a range of data management quality assurance functions. The eCRF system contained a range of validations defined by the trial team that alerted sites to inconsistencies in the data being entered, which were monitored by the trial manager. The trial manager provided trial training and ongoing trial support, and conducted regular monitoring visits at each site, checking source data for transcription errors. Any necessary alterations to entered data were date- and time-stamped in the eCRF. A detailed monitoring plan and data management plan was developed and updated as the trial progressed, detailing the quality control and quality assurance checks to be undertaken. 2

Database lock and record-keeping

Prior to database lock, the trial manager reviewed any outstanding warnings on the eCRF and resolved or closed these, as appropriate. Local trial personnel resolved any queries that arose. Once all queries were resolved, no further changes were made to the database unless specifically requested by the trial office in response to the statistician’s data checks. The trial principal investigator reviewed all of the data for each participant and provided e-mail sign-off to verify that all data were complete and correct. At this point, all data were formally locked for analysis. At the end of the trial, each site was supplied with a CD-ROM containing the eCRF data for their site. This was filed locally for any future regulatory inspection or internal audit. The chief investigator is the custodian for the data generated from the trial and is responsible for archiving the original data. All data will be archived for at least 5 years from the end of the trial and will be archived in accordance with sponsor’s and regulatory requirements. Principal investigators were responsible for securely archiving local data generated, essential documents and source data in accordance with local requirements, but for at least 5 years from the end of the trial. 2

Statistical considerations

Sample size calculation

Bevacizumab and aflibercept were hypothesised to be substantially inferior to ranibizumab if, in each case, the mean of the primary outcome (i.e. change in BCVA ETDRS letter score) was worse by a margin of 5 letters, a previously used non-inferiority margin,26,76 representing the minimum visual acuity change that a patient may distinguish. A similar CRVO population9 reported a standard deviation (SD) of 14.3 letters in the ranibizumab (0.5 mg) arm; the 12-month rate of those lost to follow-up was 8.4% in the ranibizumab arms (0.5 mg and 0.3 mg). In the absence of 24-month data, we assumed a comparable SD of 14.3 letters at 100 weeks, and allowed for 15% dropout. The two null hypotheses, that bevacizumab was substantially inferior to ranibizumab, and that aflibercept was substantially inferior to ranibizumab, were each planned to be rejected if the estimated 95% confidence interval (CI) for the difference in treatment means was wholly above the 5-letter margin in each case. Assuming equal efficacy, there was 80% power to reject each null hypothesis and to declare non-inferiority, with 130 followed-up patients analysed per arm. Allowing for 15% missing data at 100 weeks, 459 patients were planned to be randomised to the three arms (equal allocation ratio of 153 participants per arm). Sample size calculations were performed using nQuery Advisor version 4.0 (Statistical Solutions, Saugus, MA, USA). The primary method of analysis was a linear mixed-effects (LME) model with adjustment for baseline, which was expected, other things being equal, to increase the power to detect non-inferiority. The primary method of analysis included all available refracted data of the primary outcome up to and including 100 weeks, including data from the 15% of participants who we anticipated could miss the 100-week primary outcome end point. 2

Statistical considerations

The trial statisticians were responsible for all statistical aspects of the trial, from design through to analysis and dissemination. 2 A detailed statistical analysis plan was completed before the start of the trial; it was commented on by the DMEC and approved by the Trial Steering Committee (TSC). The plan was accompanied by a health economics analysis plan, and was updated and re-approved by the TSC when the protocol was amended.

Target population

The target population, to which inferences from the end of this trial were intended to generalise, was adult patients with MO due to CRVO.

Trial population

The trial population, from which the trial sample was drawn, was further defined to be adults aged ≥ 18 years, with visual impairment due to CRVO-related MO of < 12 months’ duration, who attended one of the 44 ophthalmology centres in the UK that had staff with expertise in retinal disorders and a proven track record of effective research. Only one eye per participant was included in the trial.

Hypotheses

The hypotheses refer to the populations of relevant patients, rather than to trial subjects:

-

The working hypothesis – the so-called ‘working hypothesis’ was the hypothesis that motivated the trial, which the trial results may or may not support. It was that the change in BCVA is non-inferior in patients treated with either aflibercept or bevacizumab, compared with patients treated with ranibizumab.

-

The statistical null hypothesis 1 – bevacizumab is inferior to ranibizumab in eyes with MO due to CRVO at 100 weeks.

-

The statistical null hypothesis 2 – aflibercept is inferior to ranibizumab in eyes with MO due to CRVO at 100 weeks.

-

Statistical alternative hypothesis 1 – bevacizumab is non-inferior to ranibizumab in eyes with MO due to CRVO at 100 weeks.

-

Statistical alternative hypothesis 2 – aflibercept is non-inferior to ranibizumab in eyes with MO due to CRVO at 100 weeks.

Treatment arms

The trial was randomised with equal allocation of participants in a 1 : 1 : 1 ratio to the three arms (see Chapter 2, Randomisation).

Trial samples

Intention to treat

The achieved trial sample comprised those patients who consented to participate and were actually randomised to the trial. 63 These patients were the trial subjects. This randomised trial sample was also the trial intention-to-treat (ITT) population. The ITT principle states that every subject will be analysed according to the treatment group to which they are randomised. In this trial, subjects’ data were analysed according to the ITT strategy,77 under which at least one analysis is recommended to be based on the ITT population. The trial ITT population comprised all randomised participants, regardless of whether there was an error in their eligibility (inclusion/exclusion), whether they had withdrawn post randomisation and whether the correct trial treatments or other interventions were received. 63

Per protocol

A per-protocol set of subjects was also included. These were defined as the subset found to be eligible at entry and who had minimal sufficient exposure to the treatment regimen, defined as four treatments correctly assessed and received during the first six visits up to week 20. For each of the first four visits, a correct treatment was defined as receiving the injection. For the fifth and sixth visits, a correctly assessed and received treatment was defined to be the receipt of an injection if this was indicated to be required by the re-treatment criteria, or the non-receipt of an injection if this was indicated by the re-treatment criteria.

The main reason for having a per-protocol set was that this was a non-inferiority trial, and so the use of the full analysis set would not generally be conservative [see the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) guidance, E9, section 5.2.378]. As Lesaffre79 states, ‘dropouts and a poor conduct of the study might direct the results of the two arms towards each other’. Although this can be interpreted as an indication that the per-protocol analysis is the conservative choice for non-inferiority studies, Garrett80 states that ‘The perceived conservative nature of the PP [per protocol] population appears to be much more a reflection of reduced patient numbers than the presence of bias, while bias can be in either direction depending on the pattern of violations’. Moreover, with two active treatments, it may be more likely that any bias affecting both treatments is reduced, in comparison with a placebo-controlled trial. 63

Prominence

Non-inferiority was declared only if both the ITT and the per-protocol analyses supported a non-inferiority conclusion. The Committee on Proprietary Medical Products Points-to-Consider and several other papers support this. 63 The requirement to declare non-inferiority in both the ITT and the per-protocol analyses emphasised the adherence to treatment protocol and the minimisation of exclusions, maintaining power.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was BCVA in the trial eye, measured in ETDRS letter score at 4 m at 100 weeks. Measurements of BCVA at milestone visits were included in the analysis of the primary outcome. Any BCVA measurement was excluded from the analysis if it is was > 3 SDs below the mean at that time point (including all measurements) and taken within 3 months of the occurrence of a vitreous haemorrhage, or was from another cause unrelated to maculopathy secondary to CRVO (e.g. NVG).

Secondary outcomes

The secondary efficacy outcome measures are listed in the following sections according to their type of variable. They were formally analysed at 52 and 100 weeks, but also measured at other time points.

Continuous outcome variables

-

Visual acuity and clinical outcomes:

-

change from baseline in ETDRS letter score measured at 4 m at 52 weeks

-

change from baseline in mean OCT CST at 52 and 100 weeks

-

change from baseline in macular volume at 52 and 100 weeks

-

number of injections performed in the trial eye by 100 weeks

-

change in retinal non-perfusion as assessed by mean disc area of non-perfusion at 100 weeks.

-

-

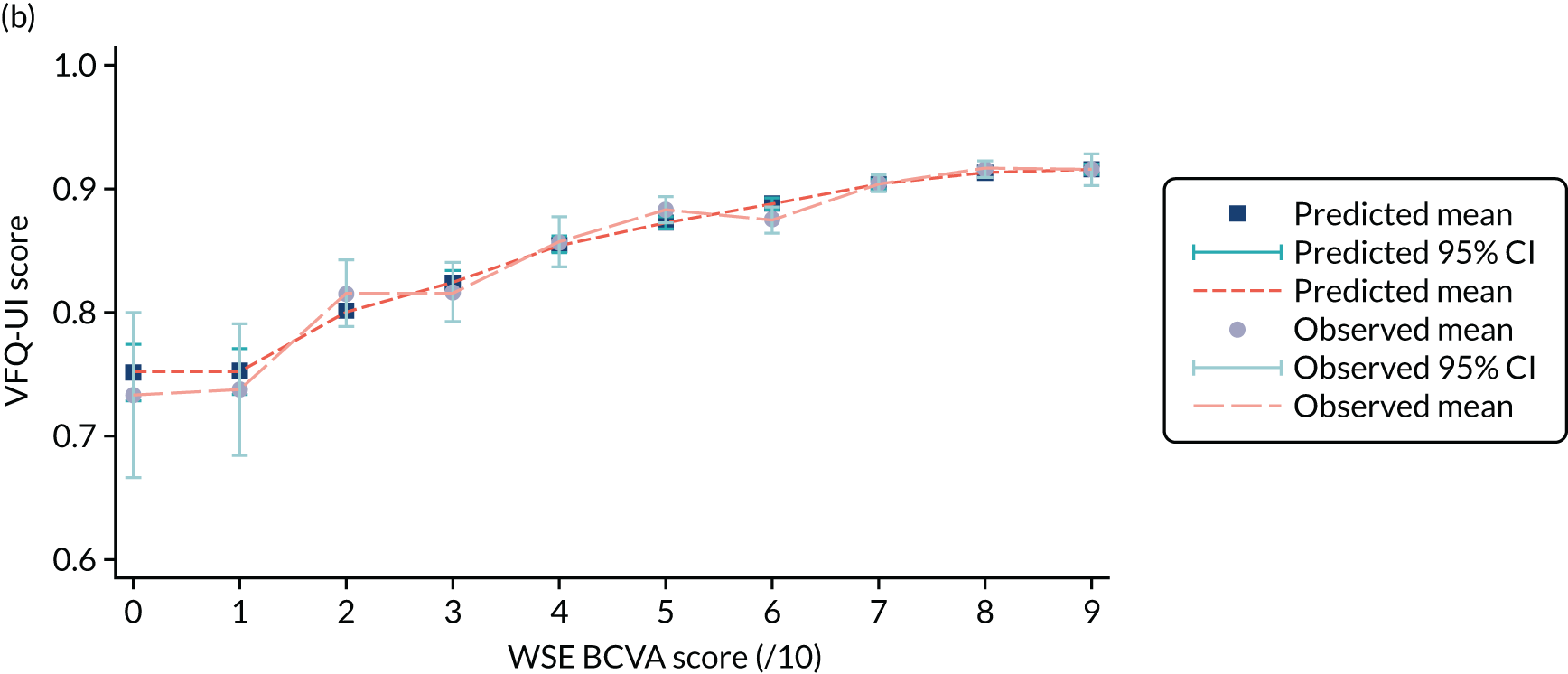

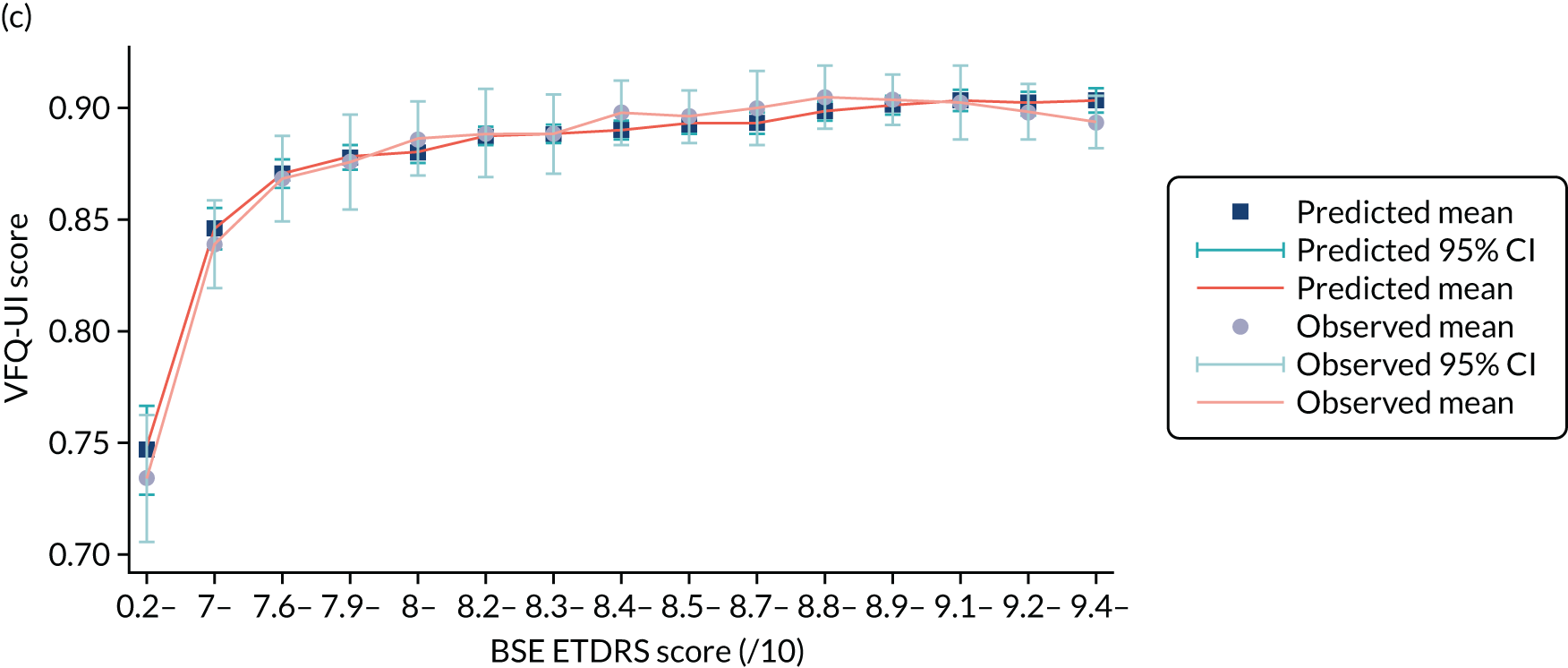

Patient-reported outcomes:

-

National Eye Institute VFQ-25 composite score, distance and near subscales at 52 and 100 weeks.

-

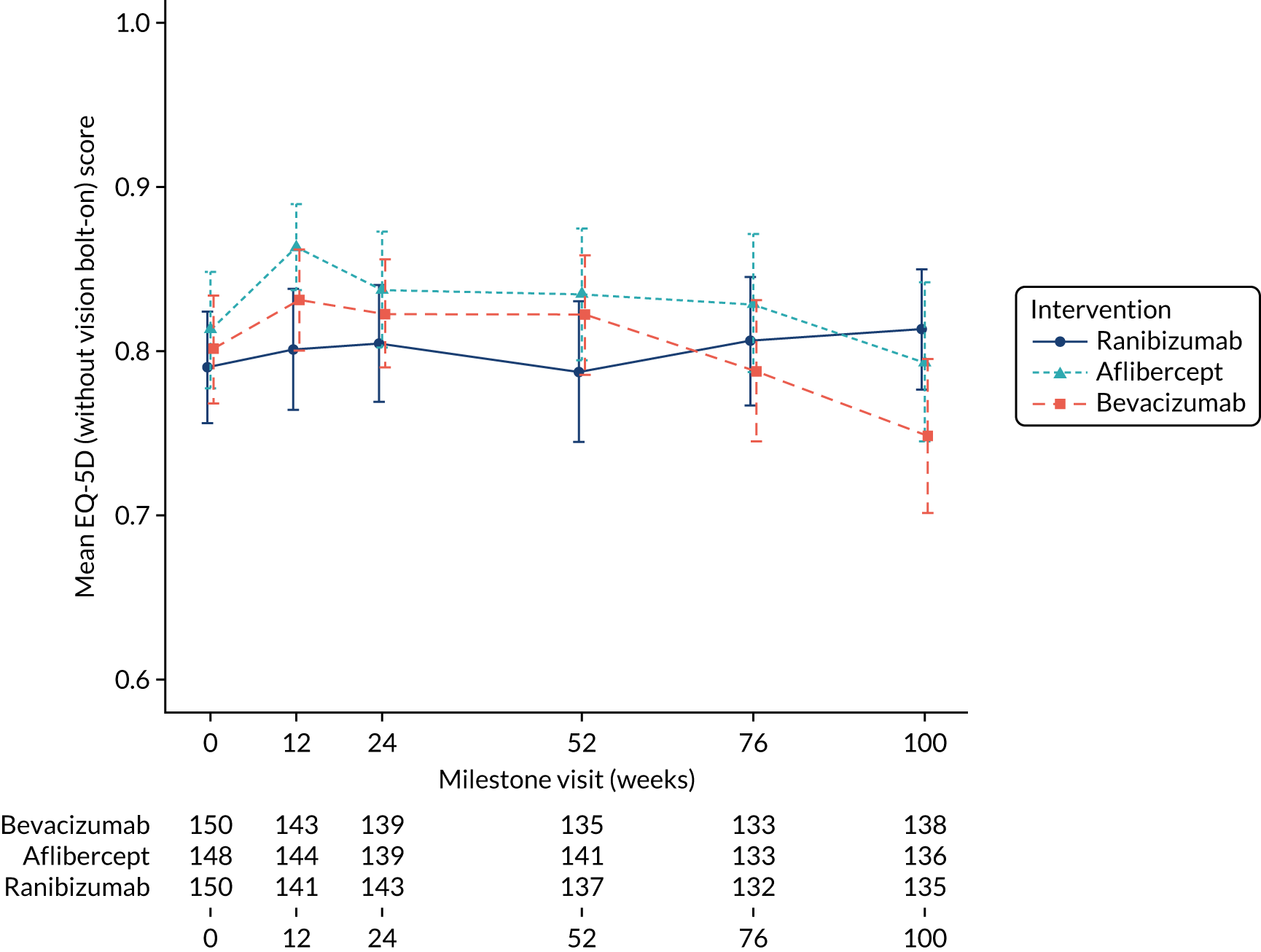

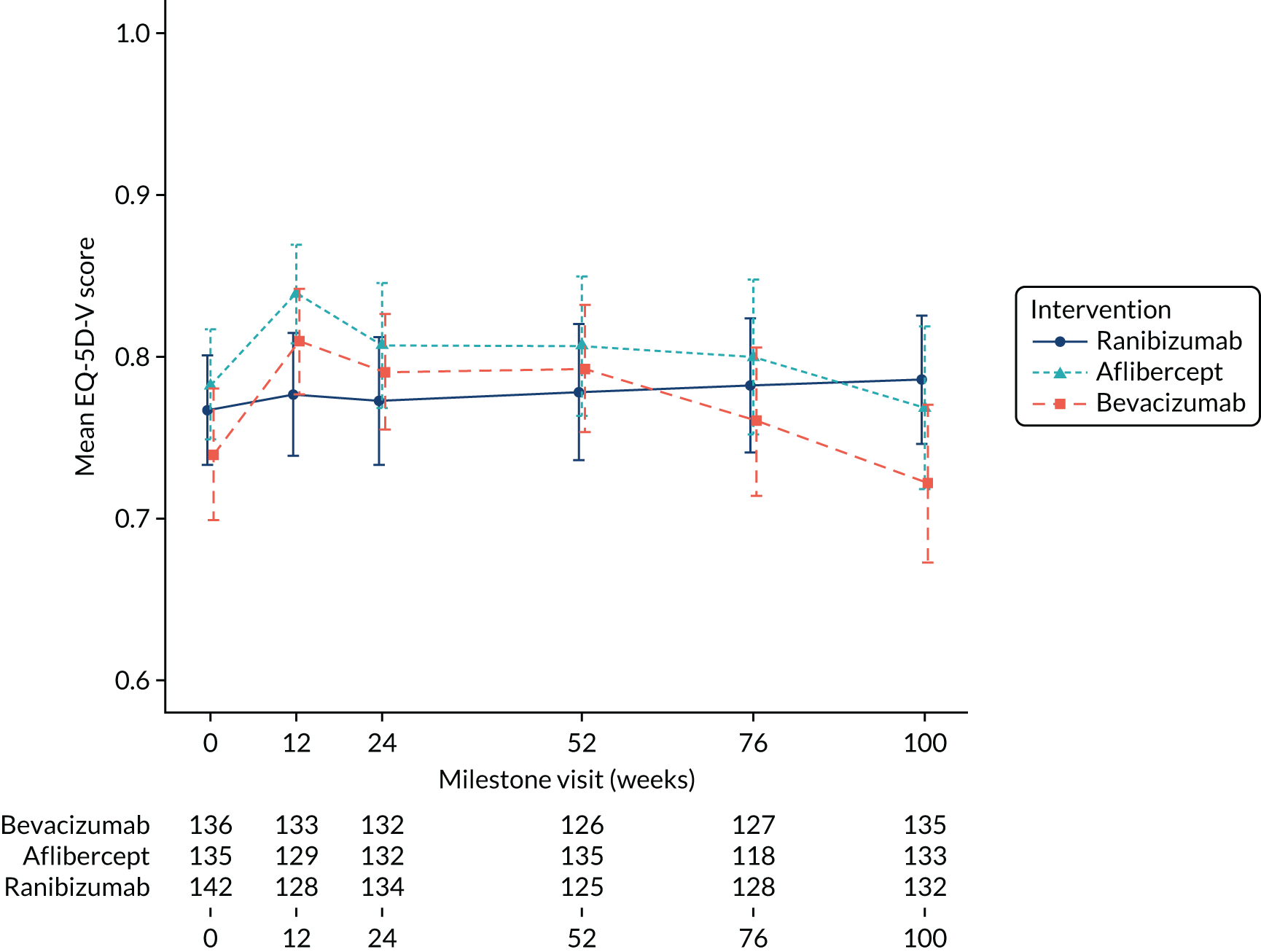

quality of life (measured using the EQ-5D and the EQ-5D-V) at 52 and 100 weeks.

-

-

Economic reported outcomes (detailed in the health economics analysis plan):

-

quality-of-life scales (measured using the VFQ-25, the EQ-5D and the EQ-5D-V) at 0, 12, 24, 52, 76 and 100 weeks.

-

resource use at 0, 12, 24, 52, 76 and 100 weeks.

-

Categorical outcome variables

-

Visual acuity and clinical outcomes:

-

participants with ≥ 15 ETDRS letter improvement (appreciable visual gain), ≥ 10-letter improvement, < 15-letter loss and ≥ 30-letter loss (severe visual loss) at 52 and 100 weeks

-

participants with ≥ 73 ETDRS letters, or > 6/12 Snellen equivalent (i.e. approximate driving visual acuity), ≤ 58 letters (≤ 6/24 Snellen equivalent) and ≤ 19 letters (≤ 3/60 Snellen equivalent) (CVI partial and severe visual impairment) at 52 and 100 weeks

-

participants with OCT CST of < 320 µm (on the Spectralis, or of < 300 µm on other machines) at 52 and 100 weeks (key guide to subsequent NHS clinical practice)

-

participants with the anatomical OCT features of diffuse intraretinal oedema, intraretinal cystic change, subretinal fluid or vitreomacular interface abnormality (either vitreomacular traction or epiretinal membrane) over time and at 100 weeks

-

participants with a change in retinal non-perfusion at 100 weeks.

-

-

Safety and tolerability:

-

prevalence of local and systemic side effects at 100 weeks

-

participants who were persistent non-responders and who developed anterior and posterior segment neovascularisation at 100 weeks.

-

Subgroup variables

Three subgroup variables were considered: (1) baseline visual acuity (low, moderate and high: ≤ 38 letters, 39–58 letters and 59–78 letters, respectively), (2) disease duration (< 3 months or ≥ 3 months) and (3) ischaemic compared with non-ischaemic. These variables were based on the fact that the visual gain in the worse-vision group may be higher than that achieved by the better-vision group, and this effect may differ between arms. The shorter the duration of disease, the better the visual acuity outcomes, and this may have varied between treatment arms.

Outcomes requiring derivation

The VFQ-25 is a validated tool for assessing vision-related quality of life. It consists of a base set of 25 vision-targeted questions, representing 11 vision-related subscales, plus an additional single-item question rating general health. The overall composite score is computed as the simple average of the vision-targeted subscale scores, excluding the general health rating question. The overall score can range from 0 (worst possible score) to 100 (best possible score).

The EQ-5D and the EQ-5D-V

The EQ-5D is a generic instrument for describing and valuing health. It is based on a descriptive system that defines health in terms of five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression). Each dimension [in the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)] has five response categories corresponding to ‘no problems’, ‘slight problems’, ‘moderate problems’, ‘severe problems’ and ‘unable to/extreme problems’. A preference-based score ranges from states worse than dead (< 0) to 1 (full health), anchoring dead at 0. In addition, the EQ-5D includes a visual analogue scale, which records a respondent’s self-rated health on a vertical scale where the end points are labelled ‘best imaginable health state’ (marked as 100) and ‘worst imaginable health state’ (marked as 0). The EQ-5D-V is similar to the EQ-5D-5L, but with another dimension (vision) added to overcome perceived inadequacies in a particular population.

More information is given in Chapter 4, Health-related quality-of-life measures.

Defining outliers

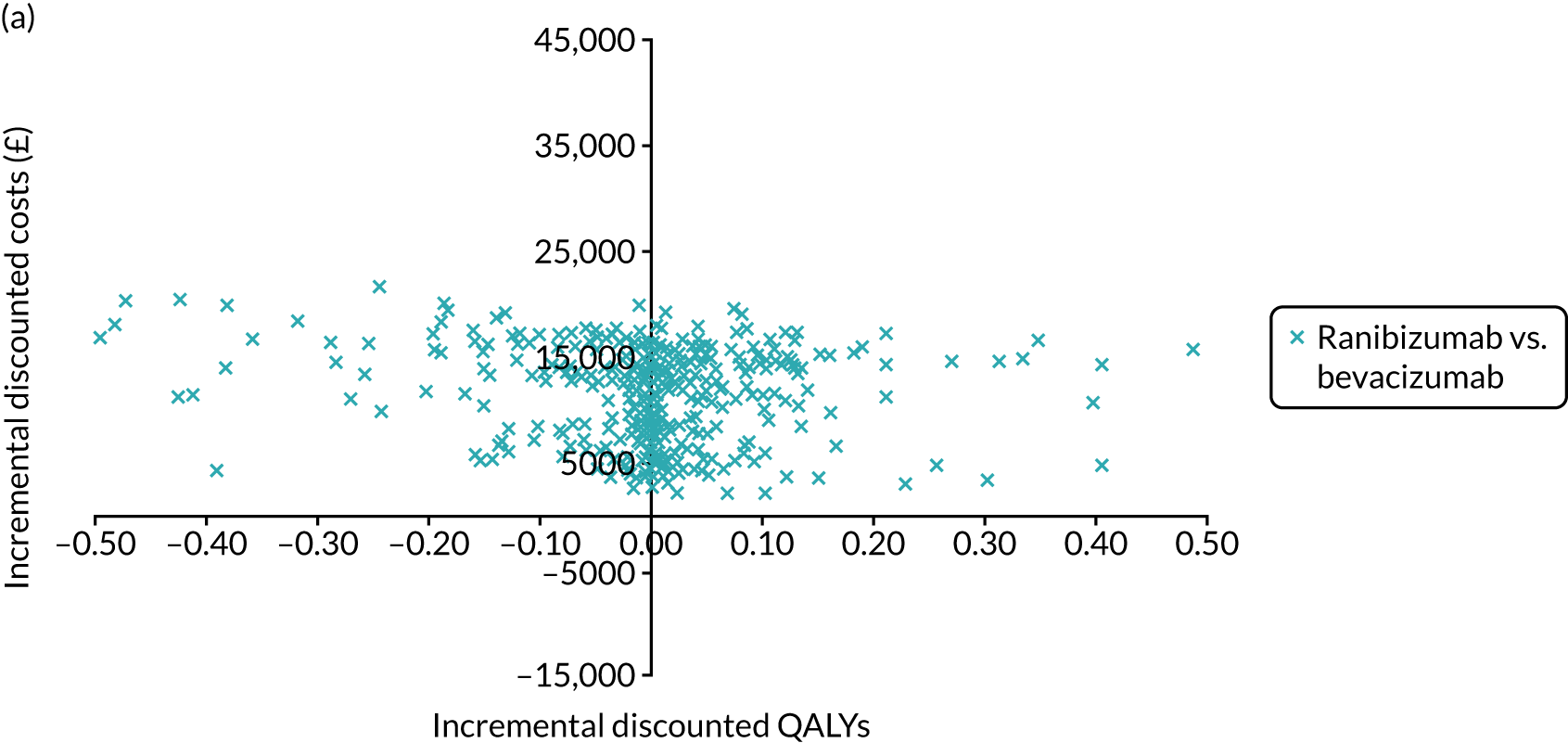

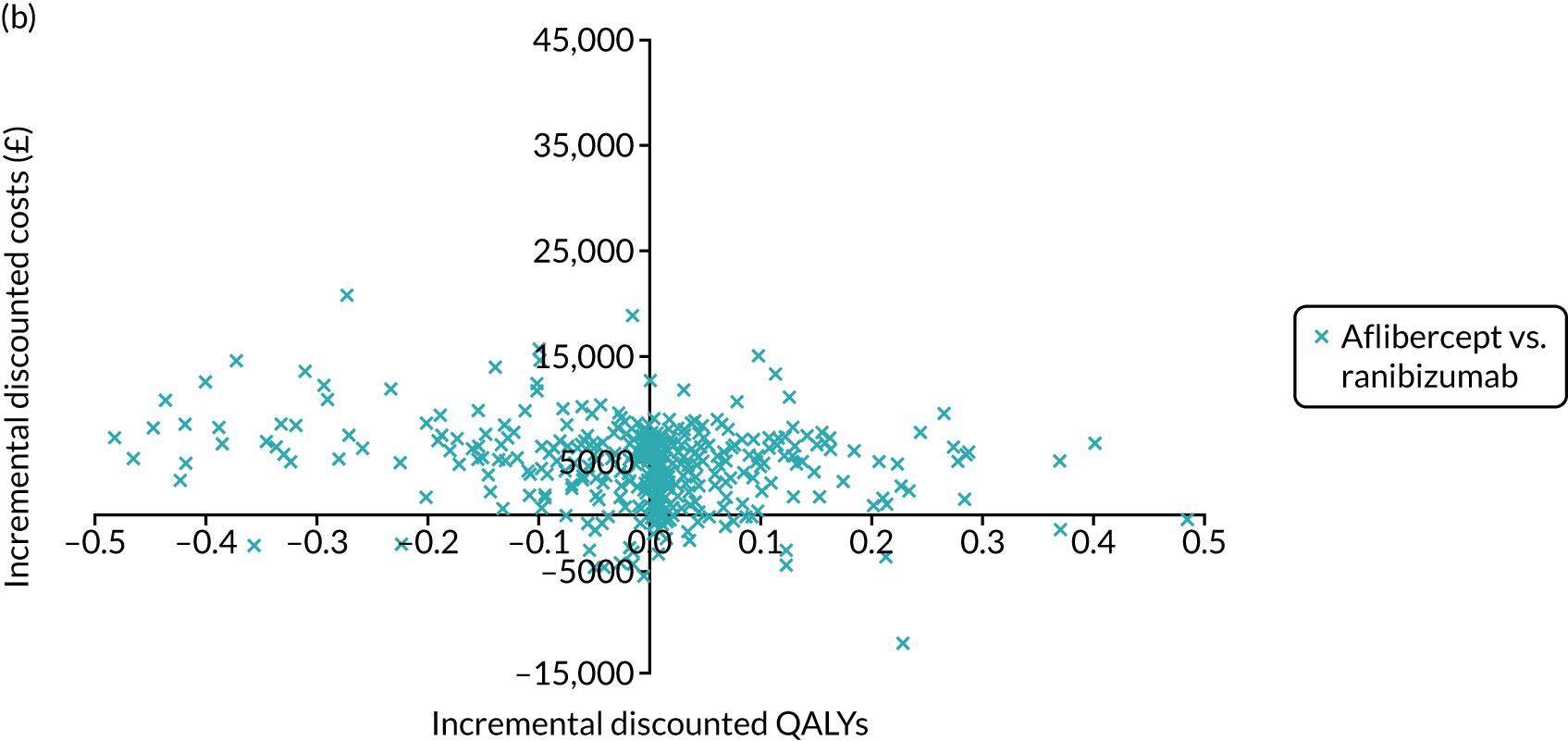

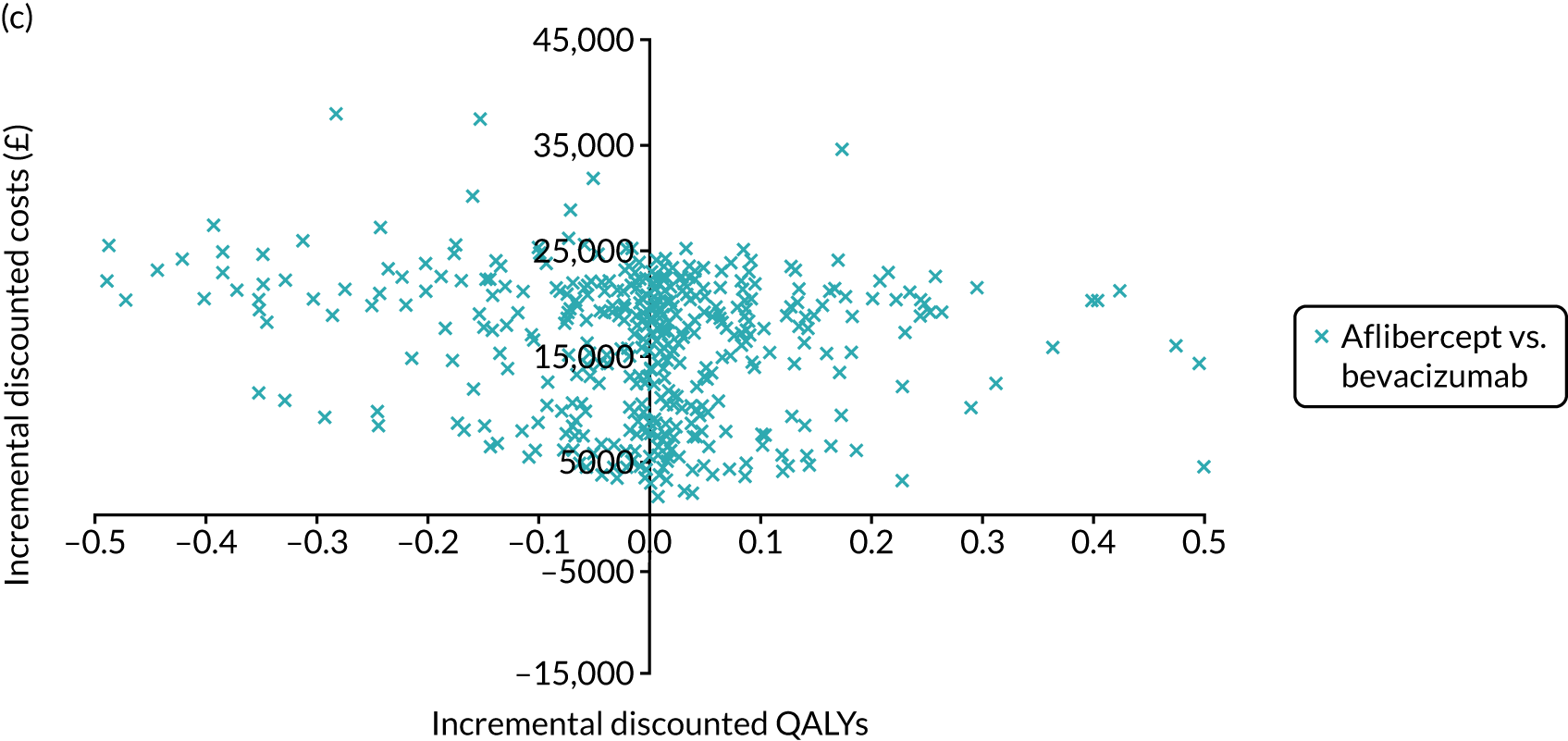

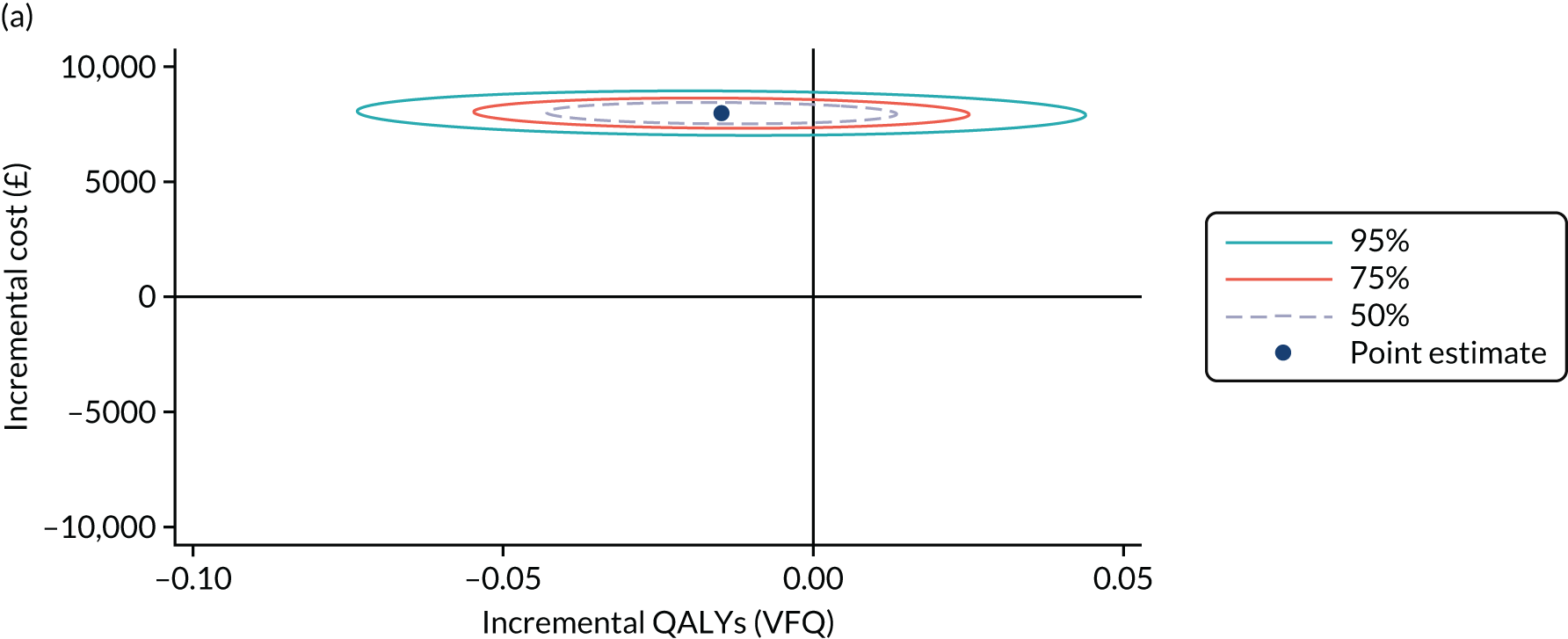

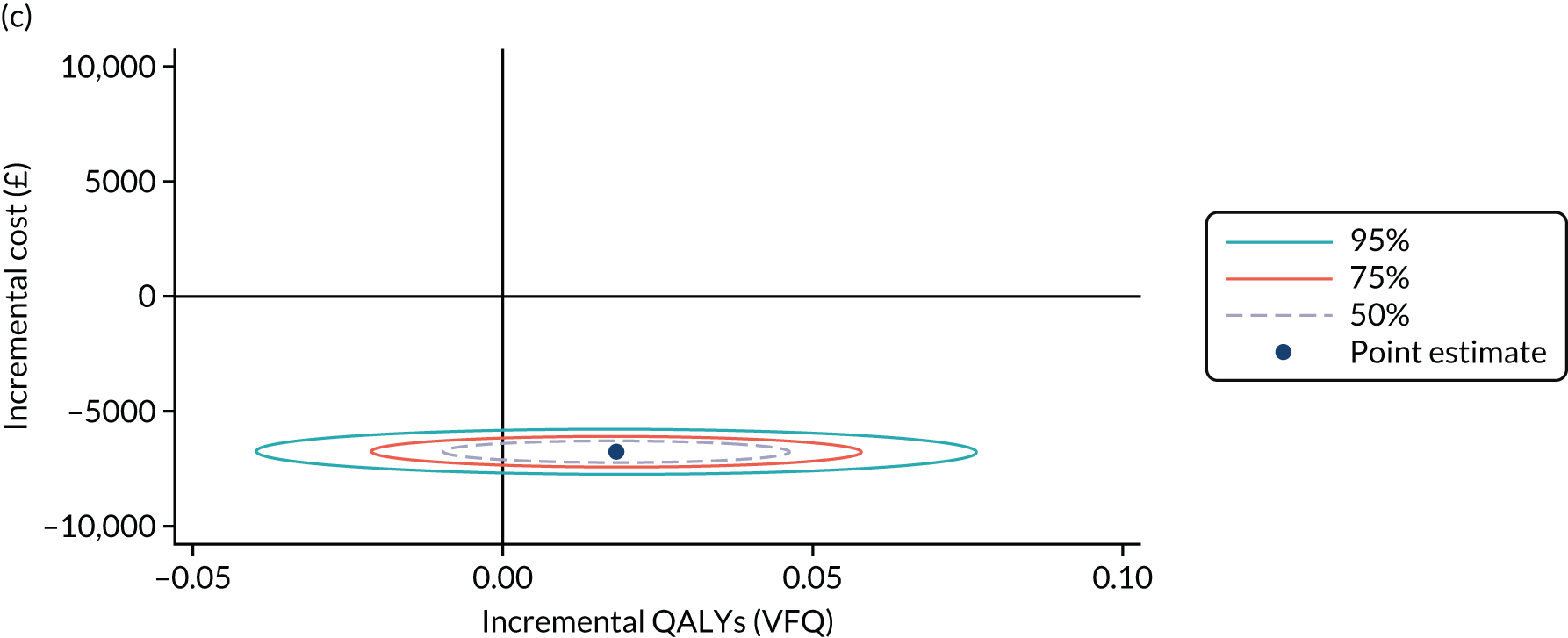

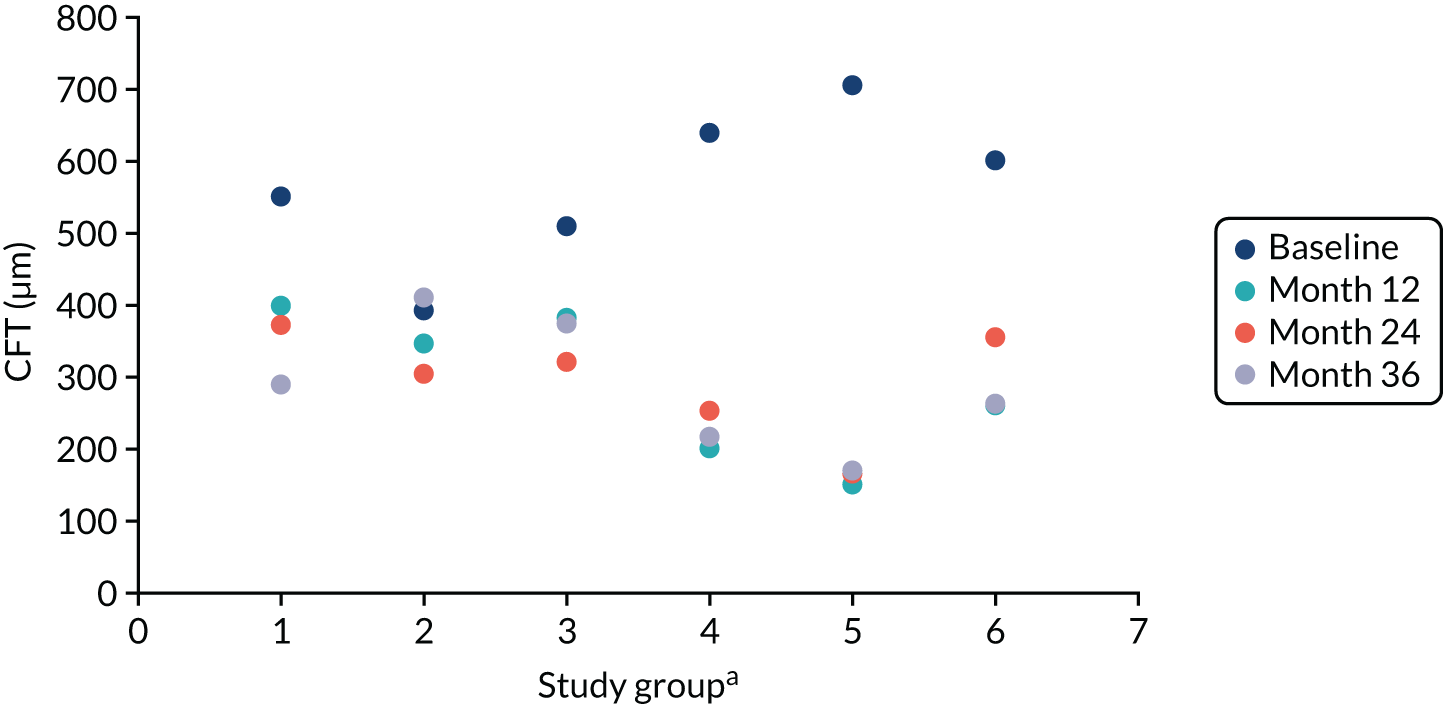

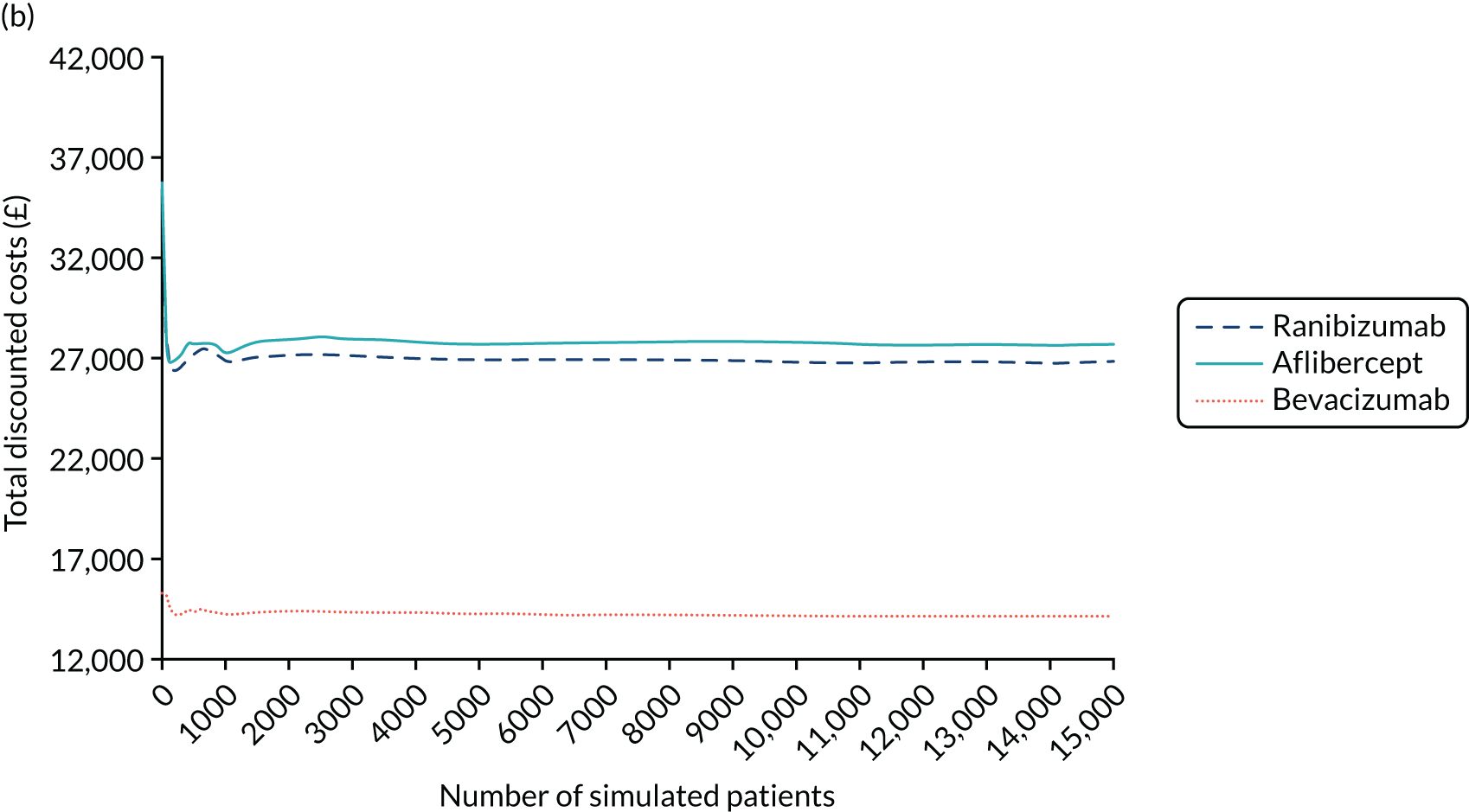

Outliers are observations that have extreme values relative to other observations under the same conditions. An outlier was defined as a data point at least 4 SDs from the mean of its distribution of values observed across other participants. A ‘bivariate outlier’ for checking was defined as a pair of successive serial data points of the same measure for a participant whose difference was at least 4 SDs from the mean of all participants’ such differences. Simple plots of successive pairs of serial measures were used throughout the 24-month period to help identify outliers for data-checking. 63