Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/130/73. The contractual start date was in July 2017. The draft report began editorial review in July 2020 and was accepted for publication in January 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Booth et al. This work was produced by Booth et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Booth et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Some material throughout this chapter has been reproduced with permission from Booth et al. 1 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Scientific background and current evidence base

Urinary incontinence in care homes

Urinary incontinence (UI) is defined by the International Continence Society as ‘any involuntary loss of urine’. 2 Prevalence of UI increases with age,3 with the highest prevalence found in older adults living in residential or nursing care homes. 3 Adults living with dementia are three times more likely to have UI than individuals of equivalent age and characteristics who do not have dementia,4 with the development of UI often being a catalyst for individuals requiring full-time care. 5,6 The most common type of UI in the care home population is mixed UI,3 in which symptoms of urgency UI and stress UI occur together, and are often accompanied by additional functional leakage due to physical and cognitive frailty. Mixed UI is considered the most challenging form of incontinence to manage as it includes symptoms of both of the common types of UI (urgency and stress) and is often resistant to intervention. 7

Burden of urinary incontinence

The burden of UI is significant, and is increasing for older adults and care services. 8 It is a distressing condition for older adults, which has a negative impact on their dignity and quality of life. 9 UI is associated with cognitive and physical impairment,8,10 increased risk of falls and fractures,11 sleep disturbance,9 hygiene problems and tissue viability problems. 12 It also has a significant impact on social participation, which can lead to isolation and clinical depression. 13,14 Although the personal costs associated with reduced quality of life and social withdrawal are not quantifiable, the cost of treatment and management of UI remains high. The NHS currently spends upwards of £80M per year on absorbent pads alone for the purpose of containing UI,15 which excludes the costs of associated care needed to manage use of absorbent pads in older, frailer individuals or those living with dementia. With the number of such individuals predicted to increase rapidly as the population ages, the cost of managing UI is also set to increase, with significant implications for future care provision. 16

Management of continence in care homes

Urinary incontinence is viewed as a generic condition in care homes: assessment and identification of specific types of UI or bladder problems is not routine, and interventions targeted towards treatment of specific UI types, such as mixed or urgency UI, have not been extensively demonstrated in this setting. The most common management option for bladder and bowel incontinence in care homes is the use of absorbent products to contain the leakage, combined with scheduled toileting. 17,18 Other conservative, non-pharmacological options to aid management of UI, such as individualised voiding programmes, bladder training or pelvic floor muscle exercise programmes, are often considered unsuitable for care home environments because they are labour intensive and require a degree of co-operation and engagement, which may not be suitable for those with cognitive impairment or dementia. Antimuscarinic drugs may be prescribed for the management of urgency UI or overactive bladder problems; however, their use is associated with significant adverse effects in frail older people and may counteract the functional benefits of anticholinesterase inhibitors used in the treatment of dementia. 19,20 Active treatment of UI or the promotion of continence in care homes is rare and a containment approach predominates. 18

Use of transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation to treat urinary incontinence and possible mechanism of effect

Transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation (TPTNS) is a form of non-invasive neuromodulation used to treat the symptoms of an overactive bladder (OAB), including urgency UI and mixed UI. TPTNS uses surface electrodes applied behind the medial malleolus to electrically stimulate the tibial nerve. A full treatment programme is delivered in 30-minute bouts, twice per week over a 6-week period. Although the exact mechanism of action is yet to be fully understood, TPTNS is believed to restore the balance between excitatory and inhibitory bladder functioning by modulating the signal traffic to and from the bladder through the sacral plexus. 21 Current understanding suggests that stimulating afferent sacral nerves in the lower leg increases inhibition of the efferent pelvic nerve activity, which reduces detrusor contractility and increases bladder capacity. 21–23 By these means, TPTNS reduces the sensation of urgency and the frequency of voiding demanded, thus enabling improved bladder control. These mechanisms may also reduce the volume of urine retained in the bladder after voiding. 23 For the care home population, TPTNS may reduce the sudden urge to urinate, allowing residents more time to reach a toilet, and because the bladder capacity may increase the frequency of daily voiding may also reduce. In turn these changes may enable more appropriate use of the toilet to void, rather than relying on containment of leakage by absorbent products.

A treatment approach, as opposed to a containment approach, engenders respect for the person’s right to use a toilet. Treatment using TPTNS is distinctive because, unlike commonly used behavioural interventions, there is no requirement for the recipient to engage with the treatment. Therefore, it is highly suited to individuals who are frail and/or living with dementia, and the stimulation site at the tibial nerve in the ankle ensures that the person’s dignity and comfort are maintained.

Evidence for effectiveness of transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation

There is evidence that TPTNS can be effective at reducing symptoms of urgency or mixed UI in women, and in adults with neurogenic bladder dysfunction. 24–27 A systematic review of TPTNS for the treatment of UI using Cochrane methodology identified 10 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), with a total of 472 participants. 24 Improvements were reported in all studies in terms of bladder symptoms and/or UI-related quality of life. Although the studies had small sample sizes and contained methodological weaknesses [Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) score gave ‘low quality’ ratings], the results indicated that TPTNS showed promise as a safe, low-cost intervention for UI. 28 One small-scale feasibility study has been undertaken in care homes29 and indicated that TPTNS had the potential to be a safe, acceptable and effective treatment for UI in this population. However, definitive evidence on the effectiveness of TPTNS is required before it can be recommended for routine practice in a care home context.

Rationale for research

Current evidence24 to date has been generated from studies based on women only, or on both men and women adult populations. The participants in these studies had both physical and cognitive capacity, and the studies were conducted in outpatient health-care contexts. One small pilot study has shown the safety and acceptability of using TPTNS in care homes,29 but no other research in this care setting has been undertaken. Given the complexity of need, and the physical and mental dependence of care home residents, and the particular challenges of UI and its management in care homes there is a need for definitive evidence on the effectiveness of TPTNS before it can be recommended for routine practice in the care home context.

Aims and objectives

Aim

The aim of the ELECTRIC (ELECtric Tibial nerve stimulation to Reduce Incontinence in Care homes) trial was to determine the clinical effectiveness of a programme of TPTNS to treat UI in care home residents, and the associated costs and consequences.

Objectives

-

To establish whether or not TPTNS is more effective than sham stimulation for reducing the volume of UI at 6, 12 and 18 weeks in care home residents.

-

To investigate mediating factors that have an impact on the effectiveness of TPTNS in a mixed-methods process evaluation involving fidelity, implementation support and qualitative components.

-

To undertake an economic evaluation of TPTNS in care homes assessing the costs of providing the programme and presenting these costs alongside the key primary and secondary outcomes in a cost–consequences analysis.

-

To explore in an interview study the experiences of TPTNS from the perspectives of care home residents, family carers, care home staff (nurses, carers and senior carers), and care home managers.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Study design

The ELECTRIC trial was designed to evaluate TPTNS, an intervention to treat UI, in care home residents. It was a multicentre, pragmatic, participant and outcome assessor-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of TPTNS with sham stimulation to reduce the volume of UI in care home residents. The main trial was supplemented by an economic evaluation comparing TPTNS with the usual continence care pathway using a cost–consequences analysis (see Chapter 4). A mixed-methods process evaluation explored the adherence to intervention delivery and the acceptability of the intervention and support. A qualitative study was also undertaken, which explored views and experiences with TPTNS among care home residents, their families and care home staff, and is presented in Chapter 5. An internal pilot study was conducted with 97 participants. All stop/go criteria were met, allowing progression to the full trial.

The trial was designed in accordance with the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) checklist30 and the ELECTRIC trial protocol was published in an open access journal. 1

Ethics approval and research governance

Version 1.0 of the ELECTRIC trial protocol was approved by the Yorkshire and Humber Bradford Leeds Research Ethics Committee (REC) [reference 17/YH/0328, integrated research application system (IRAS) ID 233879 – see Report Supplementary Material 1) for English care home sites and by the Scotland A REC (reference 17/SS/0117, IRAS ID 224515 – see Report Supplementary Material 2) for Scottish care home sites. Ethics approval was also granted by Glasgow City Health and Social Care Partnership for involvement of care homes run by Glasgow City Council on 14 September 2018. The trial sponsor was Glasgow Caledonian University (GCU) and the ELECTRIC trial office was established at GCU. The trial was prospectively registered with Clinical Trials.gov under the registration number NCT03248362 (August 2017), and with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Register (ISRCTN) under the reference number 98415244 (April 2018). A summary of the changes made to the protocol, which were approved by both RECs, is provided in Appendix 1.

Participants

The trial recruited older adults, including those with cognitive impairment, residing in nursing or residential care homes in England and Scotland who experienced UI at least weekly.

Eligibility criteria

The care home residents were eligible for inclusion if they:

-

had self- or staff-reported UI more than once per week

-

used the toilet or a toilet aid for bladder emptying, with or without assistance

-

wore absorbent pads to contain urine.

Exclusion criteria included care home residents:

-

with an indwelling urinary catheter

-

with a symptomatic urinary tract infection (UTI)

-

with a post void residual urine volume (PVRU) > 300 ml

-

with a cardiac pacemaker

-

with epilepsy that was being treated

-

with bilateral leg ulcers

-

with pelvic cancer (current)

-

with palliative care status

-

who were non-English speakers.

Recruitment procedure

Identification and informed consent

One person in each care home (usually the care home manager or a senior nurse) was assigned as the local principal investigator (PI) for that site. The PI was responsible for identifying potentially eligible participants in the care home based on the aforementioned criteria (see Report Supplementary Material 9). However, the process for recruitment differed based on the location of the care home, in accordance with statutory requirements on capacity to provide informed consent to participate in research in Scotland and England (see below). All consent procedures were approved by RECs with responsibility for reviewing applications for research involving adults who lack capacity.

Recruitment in Scotland

The PI compiled a log of potentially eligible residents in the care homes based on the trial eligibility criteria, then provided trial information to the resident if appropriate (depending on capacity), and sought permission for the trial team to contact them with the purpose of providing more detailed information about the trial and answering any questions. An aphasia-friendly version of the participant information sheet was made available when appropriate. This approach was made by the regional research assistant (RRA), who was a registered nurse working as part of the trial team. Under the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000,31 when a resident had a certificate of incapacity the local PI would identify and provide the study information to the resident’s welfare attorney (if one was appointed) or their nearest relative. If there was no welfare attorney identified or the resident did not have a relative who could be consulted then they were considered ineligible to participate in the study. The local PI would seek agreement from the welfare attorney/nearest relative for the RRA to speak to the resident. Following confirmation from the local PI of permission to approach the resident or welfare attorney/nearest relative, the RRA would arrange to meet them (or telephone them if a meeting was not possible) to provide a full explanation of the trial, ensure eligibility (see Report Supplementary Material 10) and seek written consent for the resident to participate. In accordance with the principles of the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000,31 verbal consent or assent was sought at every research contact (to ensure ongoing consent to participate) and welfare attorneys/nearest relatives could withdraw consent for the resident at any time.

Recruitment in England

In England, the PI compiled a log of potentially eligible residents and approached residents with capacity similar to the procedure described for Scotland. In accordance with the Mental Capacity Act (MCA) 2005,32 if the local PI believed a resident’s capacity was in question, they would identify and provide the information to the resident’s personal consultee (usually a family member or friend) or, if one was not available, a nominated consultee identified by the care home study team, and would seek their agreement for an approach from the RRA. The RRA then provided a full explanation of the study, ensured eligibility and sought the consultee’s advice on what they felt that the resident’s wishes would have been about taking part in the trial, if they had had capacity. The consultee would sign a declaration form if they believed that the resident would have chosen to agree to participate. Similar to Scotland, verbal consent or assent was sought at every research contact and consultees could withdraw consent for the resident at any time if they felt that the resident’s wishes had changed.

Recruitment of family carers and care home staff

In both Scotland and England, written consent to answer questions about residents was sought from family carers and care home staff by the RRAs. In addition, the qualitative researcher identified and approached a sample of residents, family members and staff to take part in the process evaluation interviews and focus groups. When not previously given, written consent was obtained prior to the interview taking part.

Baseline visit

After informed consent was obtained from the resident or relevant person, the RRA performed a bladder scan for the final assessment of eligibility (PVRU < 300 ml) at the baseline visit. Data were collected for baseline measures (see Data collection) and a 24-hour pad collection was scheduled with care home staff (see Report Supplementary Material 11).

Randomisation, allocation and blinding

Following successful completion of baseline measures, including 24-hour pad weight test (PWT) (see Data collection), remote randomisation was initiated by the RRA. Residents were randomised to one of two groups: TPTNS or sham stimulation. Randomisation was computer allocated on a one-to-one basis in random permuted blocks of two, four or six individuals, with minimisation by sex – male/female; UI severity – mild (0–200 ml per 24 hours), moderate (201–400 ml per 24 hours), severe (> 400 ml per 24 hours); centre (care home).

Information required to perform the randomisation was submitted by the RRA to a web-based randomisation system created and managed by the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials (CHaRT) Unit at the University of Aberdeen, which ensured allocation was concealed from both participants and RRAs. The randomisation results, along with a unique study identification number, were automatically generated and emailed to the trial office, which in turn emailed these to the relevant local PI. The local PI recorded the allocation group in a separate file and informed the care home staff of which intervention to deliver.

The RRAs (who collected the data) were blinded to the allocation group. To ensure that the participant and their relatives/carers were also blinded to the allocation group, those in the control group received sham stimulation, rather than a no treatment comparator.

Intervention

Transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation utilises peripheral neuromodulation to improve bladder function. A portable electrical stimulation machine (Neurotrac Continence,™ Verity Medical Ltd, Tagoat, Ireland) and two surface electrodes were used to electrically stimulate the tibial nerve, which runs close to the skin surface behind the medial malleolus of the ankle.

In the treatment group, one electrode (the cathode) was placed behind the medial malleolus and the other (the anode) was placed 10 cm cephalad to it (two or three fingers above and slightly towards the back of the calf) – Figure 1 shows the correct positioning. Standardised stimulation parameters were applied of 10-Hz frequency, 200-µs–1 pulse width, in continuous stimulation mode. The machines were ‘locked’ prior to use so that the only adjustable parameter was the intensity of stimulation. The intensity (mA) was adjusted according to the tolerance level of the participant, keeping the intensity as high and close to the person’s motor threshold as possible, while still remaining comfortable throughout the session.

FIGURE 1.

Positioning of electrodes for TPTNS.

Comparison

In the sham group, the electrodes were placed on the lateral aspect of the ankle so as to avoid the tibial nerve. The cathode electrode was placed behind the lateral malleolus and the anode electrode 10 cm cephalad to it – Figure 2 shows the correct positioning. The same stimulation parameters as the treatment group were applied: 10-Hz frequency, 200-µs–1 pulse width, in continuous stimulation mode and the machines were locked prior to use. The intensity of stimulation was increased until the participant was aware of the sensation of electrical stimulation and then reduced to a low-intensity, subclinical stimulation of 4 mA for the duration of the session. The participant was informed that it was quite normal not to feel any sensation from the stimulation.

FIGURE 2.

Positioning of electrodes for sham stimulation.

Treatment delivery

Participants in both the treatment and sham groups received an electrical stimulation programme comprising 12 sessions of 30 minutes’ duration each, delivered twice per week over 6 weeks. The programme was delivered by care home staff who received specific training and support. A proposed schedule for each participant was suggested at the start of the intervention, but there was flexibility around where, how and when the sessions were delivered. Stimulations delivered were logged by care home staff on a stimulation diary for each participant (see Report Supplementary Material 12).

Each stimulation session was recorded by care home staff in a stimulation diary, showing the date, time of day, intensity of stimulation and any relevant comments, such as where the session was given or what the participant was doing at the time. The stimulation (TPTNS or sham) was offered to the participant a maximum of two times in any 24-hour period and if the stimulation was refused when first offered (verbally or by non-verbal behaviour), it was postponed by at least 1 hour and then offered one further time. Records of acceptance and refusals were documented in the stimulation diary.

Training

Regional research assistant training

The RRAs were trained by the chief investigator and trial managers in the following tasks: assessing eligibility, taking consent, collecting data, completing the case report form (CRF), recording adverse events (AEs)/change of status, randomisation procedures and using the trial database. This training was accompanied by a detailed standard operating procedure (SOP) for the RRAs. Each RRA underwent good clinical practice (GCP) training and 2-yearly updates as required.

Implementation support facilitator training

The implementation support facilitators (ISFs) received training from the chief investigator and trial managers on administering TPTNS in both the treatment and sham groups (to check correct use by care home staff), checking adherence and reporting AEs/change of status. A detailed SOP was developed for ISFs. The ISFs also underwent GCP training and 2-yearly updates as required.

Care home staff training

A bespoke training programme for care home staff on how to administer the intervention was developed and delivered to small groups in each home by the chief investigator and trial managers. The half-day theory and practice-based training course included:

-

a background presentation, including the purpose of the study, participants’ individual roles, education about UI in care home residents, usual management strategies, common challenges to continence promotion, theory of TPTNS and how to implement it in care

-

an informal discussion about what the staff found difficult and challenging around UI, what they believe ‘works’ when supporting people with dementia and how this would help implement TPTNS in usual-care pathways

-

a practical demonstration of application, initiation and removal of TPTNS/sham intervention

-

experiential learning, during which all staff were provided with an electrical stimulator to become familiar with the equipment and practise administering TPTNS/sham intervention to each other under supervision of the chief investigator and trial managers.

A SOP was developed for care home staff and a signed Certificate of Competence was awarded to staff who completed the ELECTRIC trial training and achieved competency in delivering the intervention.

Following the training session(s), the ISF worked with the care home staff in a period of facilitated support to build their confidence and help them implement their learning in practice. This was followed by an individual staff competency assessment during the first 1–2 weeks of the intervention, during which the ISF corrected any errors in delivery of the intervention (TPTNS or sham), provided any remedial training and issued a further Certificate of Competence.

Care home principal investigator training

The PI in each care home underwent similar training to care home staff (described above), with additional training on identifying potential participants and completing the site screening log, reporting AEs/change of status and storing trial paperwork. A SOP was developed to provide support to PIs in this role.

Training handbook and digital versatile disc

As part of the training programme, a training handbook (see Report Supplementary Material 3) and digital versatile disc (DVD) were developed to ensure that care home staff were knowledgeable and competent to administer the intervention. These resources were available electronically and were presented to staff during training.

Adherence monitoring

Records of stimulations delivered (sham and treatment) were kept by care home staff using individual stimulation diaries for each participant. Date, time, intensity and length of stimulation were recorded, and this log was compared with data recorded automatically by the locked electrical stimulator machines at three time points (approximately once every 2 weeks) during the 6-week intervention period (see Report Supplementary Material 13). Any discrepancies between the two records were flagged and, when appropriate, additional training provided to care home staff to correct for future stimulations (e.g. if the intensity of sham stimulation was found to be higher than 4 mA, staff were advised to lower the intensity to 4 mA in future stimulations). These adherence checks were initially performed by local PIs, who were also asked to ensure correct electrode positioning (i.e. how they would be positioned during the treatment) photographically. However, during the pilot study it emerged that this was too great a burden for local PIs and adherence checks were being missed. Taking photographs of electrode positioning was also found to be problematic because the person conducting the adherence monitoring was not always present at the time of the stimulation, thus they were subsequently unable to identify participants from the photograph. Following discussions with the project management group (PMG) and approval from both RECs, the role of adherence monitoring was passed to the ISFs, who were already visiting care homes to independently witness that stimulations were being delivered according to the protocol and address additional training needs. They were thus able to directly observe electrode positioning. In addition, a field was added to the stimulation diary for care home staff to record electrode positioning as the internal or external ankle site. In the case of the final adherence check being made at the end of the stimulation period with no further stimulations due, the last adherence check was made by the trial managers in the trial office (Scottish care homes only). The ISF based in England performed all three adherence checks.

Using data from the three checks, adherence was assessed as follows:

-

Time was judged to be correct if the time on the stimulation diary was within 1 hour of that recorded on the electrical stimulator (which was only able to record in intervals of whole hours).

-

Intensity was judged to be correct for participants in the treatment group if the average measurement recorded by the electrical stimulator was higher than 10 mA and within 10 mA of that recorded in the diary.

-

Intensity was judged to be correct for participants in the sham group if the average recorded by the electrical stimulator and stimulation diary was lower than 10 mA.

-

Position was judged to be correct if the local PI/ISF witnessed electrodes positioned correctly for the group to which the participant was allocated (i.e. medial side of ankle for those in the treatment group, lateral side of ankle for those in the sham group). Position was also judged to be correct if the position field on the stimulation diary was correctly completed.

An adherence check (of which there were three) was judged to be correct if the criteria for time, intensity and position were all assessed as correct. Overall adherence was deemed to be correct for a participant if two or more adherence checks were correct.

Data collection

Baseline and outcome data were collected by the RRAs during face-to-face visits to the care homes and from accessing care home medical records. To ensure consistency, the RRAs followed a SOP for data collection. The data were entered by the data co-ordinator into a database created and managed by CHaRT, University of Aberdeen. Randomisation occurred following the baseline visit and outcomes were measured at 6, 12 and 18 weeks post randomisation.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the volume of urine leaked in 24 hours at 6 weeks post randomisation, measured using a 24-hour PWT. This test is based on the premise that 1 g of fluid weight is equal to 1 ml of urine and is thus an objective measure of urine leakage. To carry out a PWT, the participant (with the help of staff if required) emptied their bladder, applied a clean, dry pad at an agreed set time and then retained all used pads for the following 24 hours. Individual pads were sealed in a small plastic bag and then collected in a larger resealable bag to prevent evaporation. The RRA collected and weighed the large bag as close to the end of the 24-hour pad collection period as possible, and the dry weight of an equivalent number of pads to those collected was deducted from the total weight of the bag, to provide the 24-hour volume of urine passed as a result of UI.

Secondary outcomes

Urinary outcomes

-

The 24-hour PWT was repeated at 12 and 18 weeks to assess the sustainability of any effect of TPTNS.

-

The number of pads used in 24 hours was measured at 6, 12 and 18 weeks post randomisation and recorded by care home staff in a bladder diary.

-

The PVRU was measured at 6, 12 and 18 weeks post randomisation using a portable ultrasound bladder scanner to assess if there was any impact of TPTNS on urinary retention.

-

The Perception of Bladder Condition (PBC)33 was assessed at 6, 12 and 18 weeks post randomisation. This is a single-question global patient-reported outcome measure of perceived bladder condition, and was adapted for use with family carers and staff as well as participants.

-

The Minnesota Toileting Skills Questionnaire (MTSQ)34 was administered at 6, 12 and 18 weeks post randomisation. This is a five-question patient-reported outcome measure of degree of difficulty relating to skills necessary to use the toilet and was completed by the participant and a staff member separately.

Quality-of-life outcomes

-

Dementia Quality of Life (DEMQOL)35 was assessed at 6 and 18 weeks post randomisation. This was completed by the participant and/or an identified proxy (using DEMQOL-PROXY) for that participant. DEMQOL measures health-related quality of life in people with dementia.

Economic outcomes

-

A resource use questionnaire (RUQ) incorporated into the CRFs was administered by the RRAs at baseline, and then at 6 and 18 weeks post randomisation (see Report Supplementary Material 4–7). This recorded the participant’s usual continence care pathway, including details on aids and devices for managing incontinence, medication relating to continence and, if appropriate, how many staff were required to help with toileting.

-

Staff grades and the time required for delivering the intervention were recorded by each care home and costed using the appropriate pay scales for each site, alongside cost estimates for training materials, the trainer and training time, based on the market rates for these items. Care provided by health professionals external to the care home as a result of UI was also recorded in the CRF, along with unit costs attached to these resources using standard sources including NHS Reference Costs,36 Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 201937 and the British National Formulary. 38

Qualitative data collection

See Chapter 5 for further details.

Resident/family members

Face-to-face interviews were conducted with a sample of care home residents and/or family members at 6 weeks (i.e. immediately following the intervention) and 12 weeks to explore perspectives relating to the intervention and any noted impact on continence status and quality of life.

Care home staff

Focus group and individual interviews were conducted with care home staff who had received the ELECTRIC trial training and were involved in the direct delivery of the TPTNS/sham intervention to elicit views about the treatment, care home practices and the research processes.

Care home managers

Individual interviews with care home managers, with a range of working backgrounds and years of experience, were completed at 18 weeks, when the study concluded.

Internal pilot study

An internal pilot study was undertaken to assess the feasibility of recruitment and retention, adherence to the allocated stimulation programme and completion of the primary outcome measure. Data were collected and assessed against four preset criteria during the first 6 months of the recruitment phase (months 6–12) and reviewed by the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and funders in month 13 to determine whether or not the ELECTRIC trial should progress to full trial. Data for each of the four criteria were categorised using a traffic light system of green (to indicate ‘continue’), amber (to indicate the need to ‘implement contingency measures’) and red (to indicate the need to ‘pause’ the trial and investigate the possibility of discontinuing the trial). Table 1 outlines the four criteria and preset thresholds for traffic light categories.

| Criterion | Target | Green: continue | Amber: implement contingency measures | Red: pause trial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Recruitment | 100 residents during pilot | > 90 residents recruited | 76–90 residents recruited | ≤ 75 residents recruited |

| 2. Adherence to stimulation | At least 8 out of 12 stimulation sessions received by each participant | > 70% of participants receive ≥ 8 stimulation sessions | 50–70% of participants receive ≥ 8 stimulation sessions | < 50% of participants receive ≥ 8 stimulation sessions |

| 3. Completeness of 24-hour PWT at 6 weeks | A complete PWT for all randomised participants (no missing data) | > 70% of participants with complete 6-week PWT | 50–70% of participants with complete 6-week PWT | < 50% of participants with complete 6-week PWT |

| 4. Fidelity to allocated intervention | All residents remaining in trial to receive the intervention protocol associated with the group to which they were allocated, in terms of duration, intensity and correct ankle position | > 70% of participants correctly receive ≥ 8 stimulation sessions | 50–70% of participants correctly receive ≥ 8 stimulation sessions | < 50% of participants correctly receive ≥ 8 stimulation sessions |

Participant withdrawal

Participants who withdrew from the treatment/sham intervention could still participate in all other follow-up outcome data if they wished, for example questionnaires or interviews. Those who were unable to participate in some 6- or 12-week data collection measures (e.g. if they were hospitalised or too unwell) could still be followed up at subsequent visits.

Sample size

Original sample size justification

The original recruitment target was calculated to be 500 care home residents, based on a sample size of 344 needed to detect important clinical differences of 200 ml per 24 hours of urine leakage, with 90% power at the two-sided 5% alpha level, including an inflated attrition estimate of 30% to account for loss owing to death and other types of loss to follow-up. The standard deviation (SD) used in the original calculation came from a small, single-centre trial with a selected population in which the reported SD was 450 ml. 39 A 95% confidence interval (CI) was put around the SD estimate and the upper CI bound (570 ml) was used as a conservative measure for the sample size calculation to account for recruiting to a pragmatic multicentre trial.

Revised recruitment target

Following 1 year of recruitment to the ELECTRIC trial, a data cut was performed by CHaRT, University of Aberdeen, and the recruitment target was reviewed. Kieser and Friede40 recommend re-estimating the sample variance from observed data using the whole trial cohort and calculating the one-sample variance, and also an adjusted estimate to account for potential bias in the one-sample variance, under the alternative hypothesis. The required sample size was then recalculated without penalty to the type I error rate. The SDs using these two methods were 427 and 415, which indicated sample sizes of 194 and 184, respectively. Choosing the more conservative of these and applying the increase for 30% attrition gave a total of 278 participants randomised for 90% power to detect a 200 ml difference in the primary outcome. The observed attrition after 1 year of recruitment to the ELECTRIC trial was 15%, suggesting 278 participants to be a conservative upper bound estimate of the required sample size. However, to account for potential differences in variability and missingness of data at the beginning and end of the trial it was concluded that recruitment should continue for the duration of the planned recruitment period (18 months), with the aim of exceeding the minimum requirement of 278 randomised participants. Three blinded independent statisticians, the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC), the TSC, the PMG and the funders all agreed with the revision to the sample size and recruitment target.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were prespecified in a statistical analysis plan (SAP) (see Report Supplementary Material 8) approved by the PMG, TSC and DMEC in advance of the analysis. A 5% two-sided significance level was used to denote statistical significance throughout, with any estimates displayed with 95% CIs and p-values. Statistical analysis was undertaken according to the intention-to-treat principle based on all participants who were randomised. All analyses were undertaken in Stata® version 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Primary outcome

The primary outcome, total volume of urine leaked in 24 hours at 6 weeks post randomisation, was analysed using linear regression correcting for baseline 24-hour PWTs and the design covariates [severity of UI (mild/moderate/severe) and sex (male/female)]. Potential care home clustering was controlled for using a random-effects robust variance. In addition, the effects of adherence to treatment (duration, intensity and position) were explored using randomisation as the instrumental variable in a complier-average causal effect (CACE) model40 (using two-stage least squares). Compliance was determined for both the TPTNS and sham groups individually (see Figure 3). However, for the CACE analysis, compliance is defined as being compliant to the intervention (i.e. TPTNS). Consequently, in the modelling, compliance for the sham group is set to zero to reflect that the sham group is not compliant to TPTNS.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were analysed using a similar strategy, but with models suitable for each outcome. In addition, these utilised all available follow-up data from all randomised participants using a standard time interaction model to incorporate repeated measures. These were estimated using generalised linear model linear regression for continuous data; although outcomes may be skewed, the use of baseline information as a covariate will satisfy the normal assumptions. For binary outcomes, Poisson regression models were used with a log-link function summarising the treatment effects as adjusted risk differences and adjusted relative risk ratios. All models were adjusted as described above.

All model assumptions were assessed by means of the summary statistics and/or graphical plots.

Patient-reported outcome measures

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) collected using validated questionnaires were combined into an overall score and missing items were imputed using the strategies described in appendix B of the SAP (see Report Supplementary Material 8), and taking into account the level of missingness overall and within a person.

Subgroup analyses

Predefined subgroups were reported as the magnitude of the subgroup effect estimates along with their 95% CIs, and interpreted in an exploratory manner and broadly to provide recommendations for further investigations. Predefined subgroups were tested using interactions for the following:

-

sex (male/female)

-

UI severity [mild (0–200 ml per 24 hours); moderate (201–400 ml per 24 hours); severe (> 400 ml per 24 hours)]

-

functional dependency –

-

total Barthel Index score

-

Barthel Index Mobility score (immobile, wheelchair independent, walks with help of one person, independent)

-

Barthel Toilet Use score (dependent; occasional accident; continent)

-

-

clinical frailty scale – (≤ 5, 6, 7 or more)

-

on anticholinergics for incontinence (or not)

-

falls status in last 6 months

-

number residents who, at baseline, have fallen in the last 6 months [n (%)]

-

number of falls: ≤ 6 falls, > 6.

-

For identified post hoc subgroups, forest plots were used to illustrate possible effects of the following:

-

size of the centre

-

functional mobility

-

restricted communication

-

need for help to use the toilet

-

number of helpers needed to use the toilet

-

urinary urgency symptoms.

Economic evaluation

A cost–consequences analysis (CCA) approach was used to incorporate the range of costs and benefits of the TPTNS intervention (see Chapter 4). The conclusions of economic analysis were presented in a disaggregated ‘balance sheet’ form, presenting costs of providing the intervention alongside the key primary and secondary outcomes. Health-related quality of life was assessed using Dementia Quality of Life - utility index (DEMQOL-U) and Dementia Quality of Life Proxy - utility index (DEMQOL-PROXY-U) with a UK tariff. 41 Full details on how unit costs were attached to resource use are presented in Chapter 4.

Breaches

Only one protocol breach was documented during the trial (see Appendix 3). This involved the unblinding of a participant’s relative by a member of care home staff at the 12-week follow-up, who subsequently unintentionally unblinded the RRA. The incident was reported to the chief investigator, who took the decision that the RRA should continue to collect 12- and 18-week follow-up data as their ability to influence outcome measures was minimal.

Public and patient involvement

To involve users and carers in the set-up and delivery of the ELECTRIC trial, a stakeholder and public involvement group (SPIG) was established to meet every 6–9 months during the trial, undertaking the following roles:

-

advising on information and documentation, for example consent and information forms

-

assessing the acceptability of intervention and data collection processes

-

assisting with the interpretation of finding and results

-

assisting with the development and distribution of lay summaries.

Members of the SPIG included an older adult with experience of receiving TPTNS, a family carer with extensive experience of developing practice in care homes, a Scottish Care Inspectorate Health Improvement Advisor with a special interest in promoting continence, representatives from Age Scotland (Edinburgh, UK) and Alzheimer Scotland (Edinburgh, UK), an NHS Continence Service Manager, and a care home manager and senior clinical nurse with extensive educational experience. One of the members of the SPIG was invited to be a study co-applicant and joined the PMG, and another member (with experience of TPTNS) agreed to join the TSC to enable patient and public involvement (PPI) representation in these groups.

Our original research proposal included a Care Home Reference Group (CHRG), comprising residents and staff of a single BUPA UK (London, UK) care home, that was consulted during proposal development about elements of our proposed plans, particularly the outcome measures. However, because of the BUPA UK decision to close their care homes in Scotland, our planned study partnership was unable to progress.

Trial oversight

The ELECTRIC trial was managed by a PMG comprising all co-investigators and representatives from the trial office and the CHaRT trial team. The PMG met regularly face to face or by teleconference to review and direct study progress. A TSC with independent members, including PPI, oversaw the conduct and progress of the trial. The DMEC oversaw the safety of participants within the trial.

Chapter 3 Trial outcomes and results

This chapter describes the recruitment, baseline characteristics and other data on participants and the care homes that they were recruited from, and reports the results of the trial analysis as described in the SAP (see Report Supplementary Material 8).

Care home and participant recruitment

A total of 44 care homes agreed to participate in the ELECTRIC trial. Of these, 37 care homes recruited at least one resident (see Appendix 2). Between January 2018 and July 2019, 714 residents were screened for inclusion, of which 410 were eligible to be randomised.

Figure 3 shows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram for the trial from care home identification, through resident eligibility screening and randomisation to outcomes data collection at the three follow-up time points. Reasons for declining to participate, ineligibility and withdrawal/attrition at each outcome assessment are presented. Two residents were excluded following consent, but before randomisation, because a baseline 24-hour PWT was not available.

FIGURE 3.

A CONSORT flow diagram of care homes and participants through the ELECTRIC trial. PO, patient outcome; REL, resident eligibility log. a, Resident/welfare guardian/attorney; b, for CACE adherence to sham protocol is zero – see Primary outcome and Intervention received.

We randomised 408 participants, but two participants were classified as post-randomisation exclusions and none of their data (baseline or otherwise) is included in any tables. Both participants were in the TPTNS group, had pacemakers and were randomised in error. Both received some TPNS treatment (six and two sessions, respectively) but this was stopped immediately on discovery of the pacemaker. Neither participant experienced any AE related to receiving TPTNS. In total, 406 residents were included in the trial: 197 allocated to the TPTNS group and 209 to the sham stimulation group. Resident recruitment was completed by the end of July 2019 and all follow-up data was collected by January 2020.

Baseline characteristics

Table 2 summarises the participants’ general baseline characteristics. The two groups were comparable at baseline. Resident age ranged from 58 to 107 years and the mean age was 85 years (SD 8 years). The majority of residents in both groups were female (76.6% in the TPTNS group; 78.5% in the sham group) with moderate cognitive impairment [mean Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score 12.8 (SD 9.3) in the TPTNS group and 13.4 (SD 8.9) in the sham group]. Participants had similar levels of high physical dependency [mean Barthel score 7.2 (SD 3.9) in the TPTNS group and 7.9 (SD 4.0) in the sham group] and, in both groups, the majority were severely or very severely frail (54.3% in the TPTNS group; 51.2% in the sham group).

| Variable | TPTNS (N = 197) | Sham (N = 209) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | |

| Female, n (%) | 151 (76.6) | 164 (78.5) | ||||

| Age (years) | 85 | 8 | 85 | 8 | ||

| MMSE total score | 119 | 12.8 | 9.3 | 133 | 13.4 | 8.9 |

| Length of stay prior to randomisation (weeks) | 194 | 109 | 93 | 206 | 115 | 125 |

| DEMQOL | 70 | 84.6 | 14.1 | 80 | 88.7 | 14.9 |

| DEMQOL-PROXY | 193 | 98.2 | 15.2 | 208 | 99.1 | 13.7 |

| Barthel score | 188 | 7.2 | 3.9 | 197 | 7.9 | 4 |

| Clinical frailty categories, n (%) | ||||||

| Managing well | 5 (2.5) | 14 (6.7) | ||||

| Vulnerable | 12 (6.1) | 9 (4.3) | ||||

| Mildly frail | 15 (7.6) | 26 (12.4) | ||||

| Moderately frail | 58 (29.4) | 53 (25.4) | ||||

| Severely frail | 107 (54.3) | 104 (49.8) | ||||

| Very severely frail | – | 3 (1.4) | ||||

| Falls in the last 6 months | ||||||

| Number of residents who have fallen, n (%) | 91 (46.2) | 102 (48.8) | ||||

| Number of falls per resident | 197 | 1.8 | 5.5 | 208 | 1.1 | 1.8 |

Table 3 summarises the residents’ continence status at baseline and shows that UI was a chronic condition, being present for at least 18 months in the TPTNS group and 20 months in the sham group. The majority of residents (59.4% in the TPTNS group; 55.5% in the sham group) experienced severe UI of > 400 ml leakage in 24 hours and all apart from one resident in the TPTNS group wore absorbent pads continuously to contain the leakage. The number of pads used in a 24-hour period was similar for both groups. The PVRUs were relatively small (approximately 80 ml, which is within normal limits), as was the number of residents taking anticholinergic medication to treat UI. The mean total volume of urine leaked in 24 hours (the primary outcome measure) at baseline was similar between the two groups (536 ml in the TPTNS group; 560 ml in the sham group) but the SDs indicate greater variability of leakage in the sham group (370 ml in the TPTNS group; 469 ml in the sham group).

| Variable | TPTNS (N = 197) | Sham (N = 209) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | |

| Base UI severity, n (%) | ||||||

| Mild (0–200 ml per 24 hours) | 44 (22.3) | 54 (25.8) | ||||

| Moderate (201–400 ml per 24 hours) | 36 (18.3) | 39 (18.7) | ||||

| Severe (> 400 ml per 24 hours) | 117 (59.4) | 116 (55.5) | ||||

| Total volume of urine (ml) in 24 hours | 197 | 536.0 | 369.6 | 209 | 560.4 | 468.7 |

| Duration of UI (months) | 63 | 17.7 | 18.1 | 75 | 20 | 31.5 |

| Pads used (24 hours) | 197 | 3.9 | 1.5 | 209 | 3.8 | 1.7 |

| PVRU (ml) | 177 | 75.5 | 65.1 | 183 | 80.8 | 70.3 |

| UTIs treated (antibiotics) | 197 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 207 | 0.3 | 0.7 |

| Wear pad continuously, N; n (%) | 194; 193 (99.5) | 207; 207 (100.0) | ||||

| On anticholinergics to treat UI, N; n (%) | 197; 8 (4.1) | 209; 7 (3.3) | ||||

| Toilet access restrictions, n (%) | ||||||

| Mobility | 168 (85.3) | 162 (77.5) | ||||

| Problems communicating need | 86 (43.7) | 85 (40.7) | ||||

| Problems locating toilet | 54 (27.4) | 67 (32.1) | ||||

| Does not try to get to toilet | 20 (10.2) | 34 (16.3) | ||||

| Other | 16 (8.1) | 24 (11.5) | ||||

| MTSQ (resident) | 82 | 6.7 | 7.8 | 94 | 5.1 | 7.1 |

| MTSQ (staff) | 194 | 13.7 | 6.8 | 203 | 12.7 | 7 |

| PBC (resident) | 87 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 99 | 2.2 | 1.6 |

| PBC (carer) | 53 | 3.5 | 1.1 | 57 | 3.6 | 1.2 |

| PBC (staff) | 193 | 3.3 | 1.5 | 206 | 3.3 | 1.4 |

Restricted access to independent toilet use as a result of mobility problems was found for more than three-quarters of residents (85% in the TPTNS group; 78% in the sham group) and communicating need to use the toilet was an issue for > 40% of residents in both groups (44% in the TPTNS group; 41% in the sham group). Functional skills for independent toilet use were similar in both groups for the resident-reported and the staff-reported MTSQ; however, staff reported more severe functional deficits than residents (scores range from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating more difficulty). Ratings of PBC by each of the three respondent groups (residents, family carers and staff) were similar for the TPTNS and the sham groups; however, residents rated their PBC as less severe [mean score 2.4 (minor problems to some moderate problems)] than staff (mean score 3.3) and family carers [mean score 3.6 (some moderate problems to severe problems)].

Flow of participants through the trial

At the primary outcome time point of 6 weeks, there were 7 (3.6%) and 4 (1.9%) deaths in the TPTNS and sham groups, respectively (see Figure 3). There were also 23 (11.7%) and 27 (12.9%) participants, respectively, with missing pad weight data at 6 weeks. We do not have detailed reasons for missing pad weights. There were 167 (84.8%) participants in the TPTNS group and 178 (85.2%) participants in the sham group who provided pad weight data and were included in the primary outcome analysis. Detailed information on deaths and missing pad weight data at other time points is included in Figure 3.

Intervention received

A description of the stimulation that residents received in both arms of the trial is presented in Table 4. Full details of the stimulation protocol are in Chapter 2 but are repeated here briefly. The intervention comprised a programme of 12 sessions of stimulation of 30 minutes’ duration, delivered twice per week for 6 weeks. We defined adherence in terms of intensity of stimulation, position of electrodes, duration of stimulation and number of sessions, confirmed by a minimum of two correct adherence checks made by the ISF during the 6-week intervention programme. This meant that for each group the participants received their allocated stimulation at the correct intensity [resident-directed that for comfort above 10 mA (TPTNS) or 4 mA (sham)], delivered in the correct position [medial malleolus (TPTNS) or lateral malleolus (sham)] for the correct duration (≥ 15 minutes) for the correct number of times (fidelity ≥ 8 sessions; full stimulation programme = 12 sessions). The ISF reported adherence to the allocated protocol for 154 (78.2%) participants in the TPTNS group and 149 (71.3%) participants in the sham group.

| Number of stimulation sessions | TPTNS (N = 197), n (%) | Sham (N = 209), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 8 (4) | 17 (8) |

| 1–4 | 11 (6) | 17 (8) |

| 5–7 | 17 (9) | 17 (8) |

| ≥ 8 | 161 (82) | 158 (76) |

| Adherent to allocated protocol | 154 (78) | 149 (71) |

In the primary outcome CACE analysis (see Chapter 2), the proportion in the TPNS arm classed as adherent to allocated intervention and for whom a 24-hour pad weight was available was 142 out of 167 (85.0%). Our fidelity checks confirmed that no participants in the sham arm received TPTNS.

Primary outcome results

Data on the primary outcome, volume of urine loss (ml) per 24 hours at the 6-week follow-up, is described in Table 5. The results of the intention-to-treat complete-case analysis show that the adjusted mean (SD) reduction in urine leakage was –5 ml (362 ml) in the TPTNS group and –66 ml (394 ml) in the sham group. The difference between the groups (adjusted for baseline leakage and covariates) was 68 ml (95% CI 0 to 136 ml; p = 0.05 ml) in favour of the sham intervention.

| Descriptive data | TPTNS (N = 197) | Sham (N = 209) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | |

| Baseline volume (ml) | 536 | 370 | 197 | 560 | 469 | 209 |

| 6-week volume (ml) | 566 | 382 | 167 | 498 | 400 | 178 |

| Change from baseline (ml) | –5 | 362 | 167 | –66 | 394 | 178 |

| Model | Estimate of treatment effect (ml) | 95% CI (ml) | p-value (ml) | |||

| Complete-case ITT | 68 | 0 to 136 | 0.050 | |||

| Multiple imputation | 65 | –3 to 133 | 0.060 | |||

| Adjusted for non-compliance | 81 | 2 to 160 | 0.044 | |||

| Multiple imputation adjusted for non-compliance | 79 | –2 to 159 | 0.057 | |||

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis to assess the robustness of the treatment effect to missing data and non-compliance to the TPTNS gave similar results to the complete-case intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis.

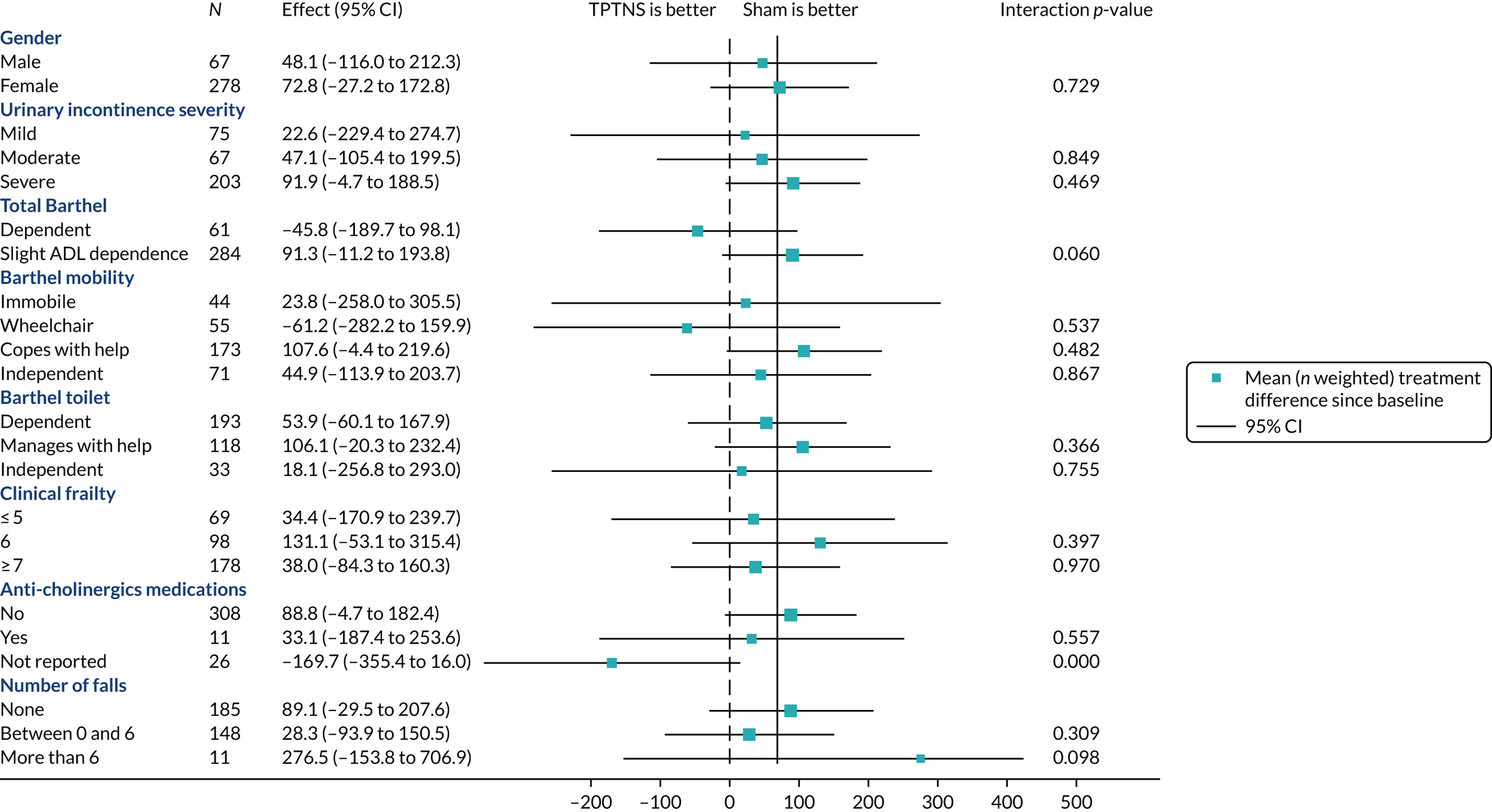

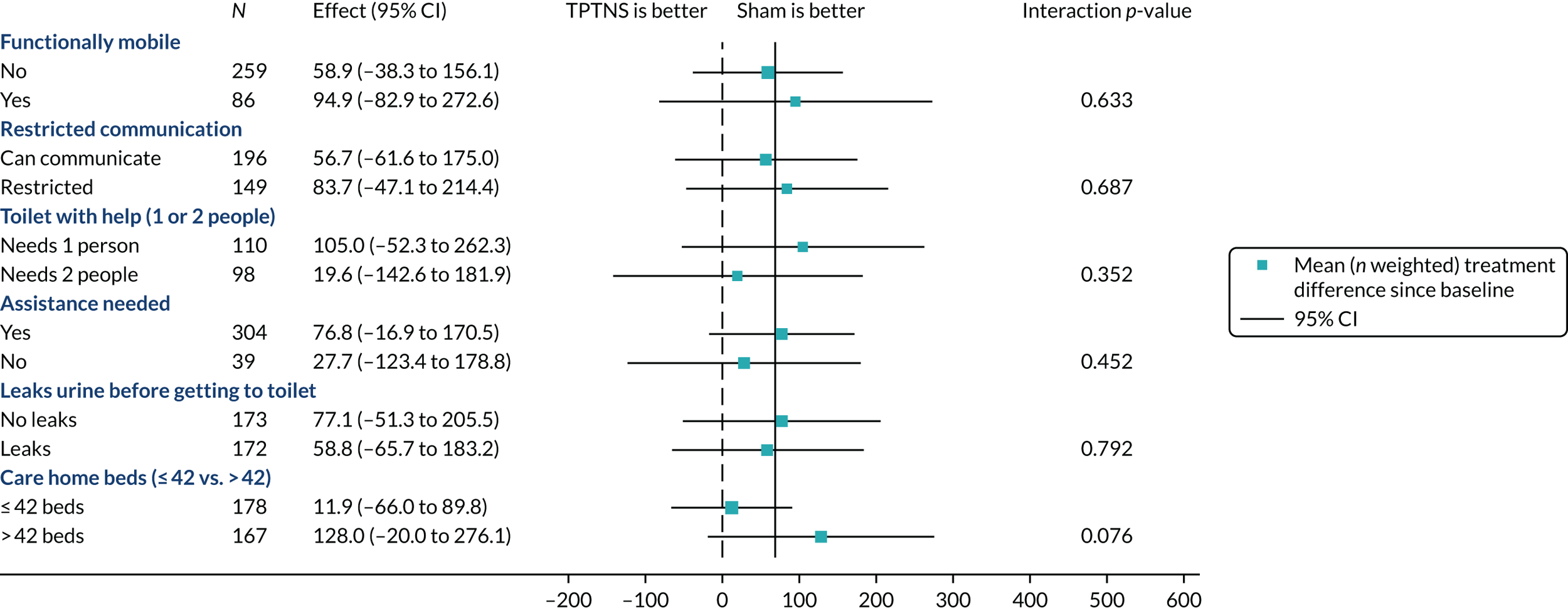

Subgroup analysis

Figure 4 summarises the prespecified subgroup analyses and Figure 5 presents the post hoc subgroup analyses. There were no modifying effects on the treatment effect in a subgroup analysis.

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot of subgroup analysis for the primary outcome. Clinical frailty: ≤ 5, very fit to mildly frail; 6, moderately frail; ≥ 7, severely or very severely frail. ADL, activities of daily living.

FIGURE 5.

Forest plot of post hoc subgroup analysis for the primary outcome. Effect size of total urine leaked (after 6 weeks).

Table 6 describes total urine leakage over time. Treatment effect estimates were fairly consistent over time: incompatible with a worthwhile reduction in urine volume when receiving TPTNS. It should be noted that the treatment effect estimate at 6 weeks differs from the figure in Table 5, reflecting the longitudinal model. Secondary clinical outcomes are reported in Table 7; pad use and PVRU were similar between groups at all time points, confirming that TPTNS does not increase urinary retention in this population.

| Time | TPTNS, mean (SD); n | Sham, mean (SD); n | Estimate of treatment effect (ml) | 95% CI (ml) | p-value (ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 536 (370); 197 | 560 (469); 209 | |||

| 6 weeks | 566 (382); 167 | 498 (400); 178 | 53 | –22 to 128 | 0.164 |

| 12 weeks | 585 (438); 152 | 520 (411); 157 | 70 | –9 to 148 | 0.081 |

| 18 weeks | 555 (400); 133 | 547 (454); 156 | 21 | –60 to 102 | 0.605 |

| Outcome | TPTNS, mean (SD); n | Sham, mean (SD); n | Estimate of treatment effect | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pads used (24 hours) | |||||

| Baseline | 3.5 (1.6); 197 | 3.4 (1.8); 209 | |||

| 6 weeks | 3.5 (1.6); 166 | 3.4 (1.7); 178 | 0.1 | –0.2 to 0.4 | 0.47 |

| 12 weeks | 3.2 (1.7); 152 | 3.1 (1.5); 156 | 0.1 | –0.2 to 0.5 | 0.54 |

| 18 weeks | 3.1 (1.5); 133 | 3.0 (1.6); 156 | 0.1 | –0.3 to 0.4 | 0.71 |

| PVRU (ml) | |||||

| Baseline | 76 (65); 177 | 81 (70) 183 | |||

| 6 weeks | 92 (81); 112 | 86 (83); 124 | 1.4 | –18 to 21 | 0.89 |

| 12 weeks | 81 (89); 83 | 86 (84); 99 | –3.5 | –25 to 18 | 0.75 |

| 18 weeks | 84 (88); 80 | 79 (76); 99 | 0.5 | –22 to 23 | 0.96 |

Resident- and staff-reported outcomes and treatment effect estimates are summarised in Table 8. Perception of bladder control was measured using the single item PBC (by residents, their family and care home staff). The rating was fairly constant over time (between minor and moderate problems) for residents and staff; CIs around treatment effects generally rule out any difference of more than one point on the item in either direction. The family ratings are few and should be interpreted with care.

| Assessment | TPTNS, mean (SD); n | Sham, mean (SD); n | Estimate of treatment effect | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient PBC | |||||

| Baseline | 2.6 (1.6); 87 | 2.2 (1.6); 99 | |||

| 6 weeks | 2.3 (1.5); 69 | 2.0 (1.4); 81 | 0.2 | –0.7 to 1.1 | 0.63 |

| 12 weeks | 2.2 (1.6); 53 | 2.0 (1.4); 72 | 0.0 | –1.0 to 1.0 | 0.94 |

| 18 weeks | 2.2 (1.5); 43 | 1.9 (1.2); 58 | 0.1 | –1.0 to 1.2 | 0.84 |

| Family PBC | |||||

| Baseline | 3.5 (1.1); 53 | 3.6 (1.2); 57 | |||

| 6 weeks | 2.9 (1.7); 12 | 2.6 (1.7); 11 | 0.1 | –2.2 to 2.4 | 0.92 |

| 12 weeks | 2.0 (1.0); 3 | 2.4 (1.3); 7 | 0.1 | –3.0 to 3.2 | 0.95 |

| 18 weeks | 3.3 (0.6); 3 | 3.7 (0.6); 3 | –3.2 | –8.7 to 2.4 | 0.26 |

| Staff PBC | |||||

| Baseline | 3.3 (1.5); 193 | 3.3 (1.4); 206 | |||

| 6 weeks | 2.9 (1.4); 166 | 3.2 (1.4); 177 | –0.5 | –1.0 to -0.1 | 0.024 |

| 12 weeks | 3.2 (1.3); 147 | 3.2 (1.4); 161 | 0.0 | –0.5 to 0.4 | 0.85 |

| 18 weeks | 3.1 (1.6); 137 | 3.0 (1.5); 155 | 0.1 | –0.4 to 0.6 | 0.59 |

| MTSQ (resident) | |||||

| Baseline | 6.7 (7.8); 82 | 5.1 (7.1); 94 | |||

| 6 weeks | 6.4 (7.0); 66 | 5.4 (7.4); 78 | 0.3 | –1.5 to 2.0 | 0.78 |

| 12 weeks | 6.8 (7.4); 46 | 5.3 (7.2); 66 | 0.6 | –1.5 to 2.6 | 0.59 |

| 18 weeks | 8.7 (7.9); 41 | 5.0 (6.6); 56 | 1.0 | –1.1 to 3.1 | 0.37 |

| MTSQ (staff) | |||||

| Baseline | 13.7 (6.8); 194 | 12.7 (7.0); 203 | |||

| 6 weeks | 14.2 (6.8); 166 | 12.5 (7.4); 179 | 1.2 | 0.2 to 2.2 | 0.017 |

| 12 weeks | 14.8 (6.4); 152 | 13.6 (6.8); 166 | 0.6 | –0.5 to 1.6 | 0.30 |

| 18 weeks | 15.6 (6.0); 138 | 13.7 (6.8); 151 | 1.2 | 0.2 to 2.3 | 0.024 |

| DEMQOL | |||||

| Baseline | 84.6 (14.0); 70 | 88.7 (14.9); 80 | |||

| 6 weeks | 87.0 (15.3); 51 | 89.7 (10.9); 61 | –0.6 | –4.6 to 3.5 | 0.78 |

| 18 weeks | 85.8 (13.1); 28 | 90.3 (11.1); 42 | 0.4 | –4.7 to 5.4 | 0.89 |

| DEMQOL-PROXY | |||||

| Baseline | 98.2 (15.2); 193 | 99.1 (13.7); 208 | |||

| 6 weeks | 100.8 (11.7); 162 | 98.2 (12.9); 172 | 2.3 | –0.1 to 4.7 | 0.055 |

| 18 weeks | 103.5 (11.6); 132 | 102.2 (12.6); 152 | 1.0 | –1.6 to 3.5 | 0.46 |

The MTSQ scores range from 0 (no difficulties) to 20 (cannot do), rated by both residents and staff at the care home. For both outcomes at each time point there were small differences favouring the sham intervention.

Fewer than 40% of residents in each arm were able to complete the DEMQOL health-related quality-of-life questionnaire at baseline. The proxy version of the score was completed by a family member or a member of care home staff at both 6 and 18 weeks. There was a small difference (about 0.2 SD) in favour of the TPTNS treatment at 6 weeks.

Safety

Adverse events are summarised in Table 9.

| Adverse events | TPTNS (N = 197), n (%) | Sham (N = 209), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| UTI | 8 (4.1) | 4 (1.9) |

| UTI and chest infection | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.4) |

| Leg pain/heavy sensationa | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.0) |

| Reduced kidney function | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Blood on absorbent pad | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) |

| Participant became agitateda | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) |

| Episodes – suspected seizure (not confirmed) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) |

| Total | 9 (4.6) | 12 (5.7) |

Serious adverse events

There were four serious adverse events (SAEs) that required residents to be admitted to hospital: three in the sham group (one for a kidney infection, one for a chest infection and a UTI, and one for vomiting and irregular heart rhythm); and one in the TPTNS group (for a UTI and pulmonary oedema). All four events occurred during the 6-week intervention programme; none of the events was classified as being related to the trial interventions (see Appendix 4).

Non-serious adverse events

There were a total of 21 participants who had a non-SAE, mainly a UTI (15/21), three of whom also had a potential chest infection. All non-SAEs were judged to be unrelated to the intervention, other than two in the sham group: one participant withdrew because their leg felt ‘heavy’ and they felt dizzy; one participant became agitated and distressed, with no impact on intervention delivery as the contingency plan to offer the intervention at alternative times was implemented successfully (see Appendix 4).

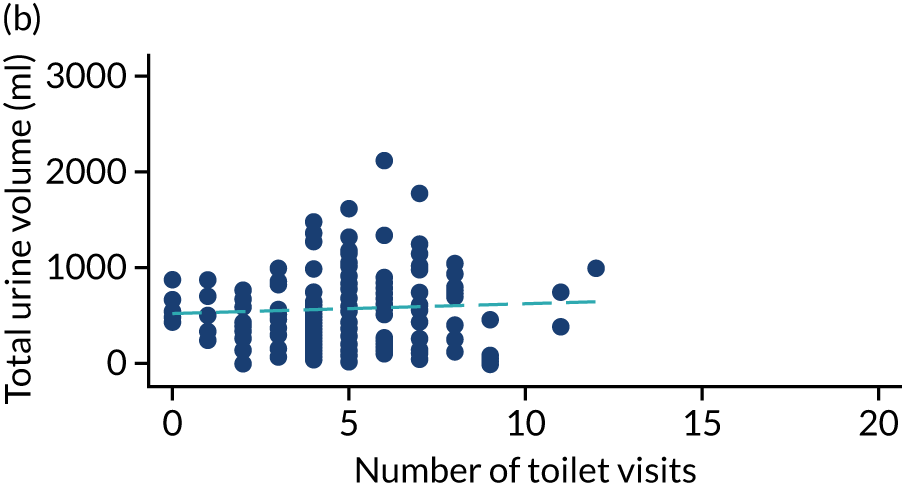

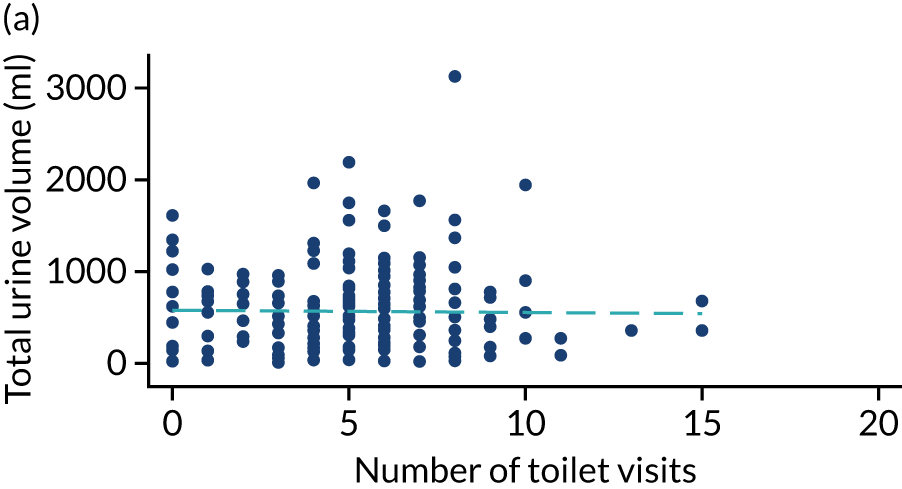

Routine toileting practice

Post hoc analysis of any changes in routine toileting practices in care homes across the four time points are shown in Figures 6 and 7. The expected increase in the number of visits to the toilet at 6 weeks, associated with a reduced volume of urine leaked in the pads and increased use of the toilet to void, is not demonstrated. Routine toileting practices remained similar across the time points for both the TPTNS and sham groups.

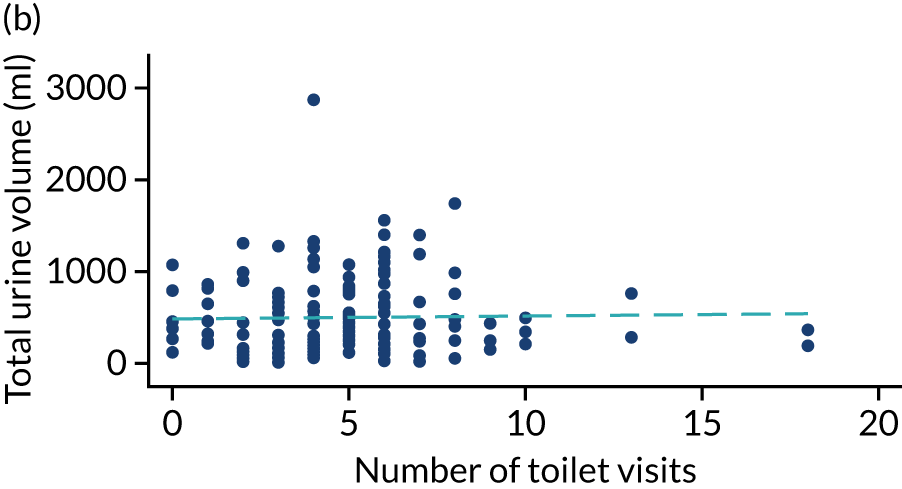

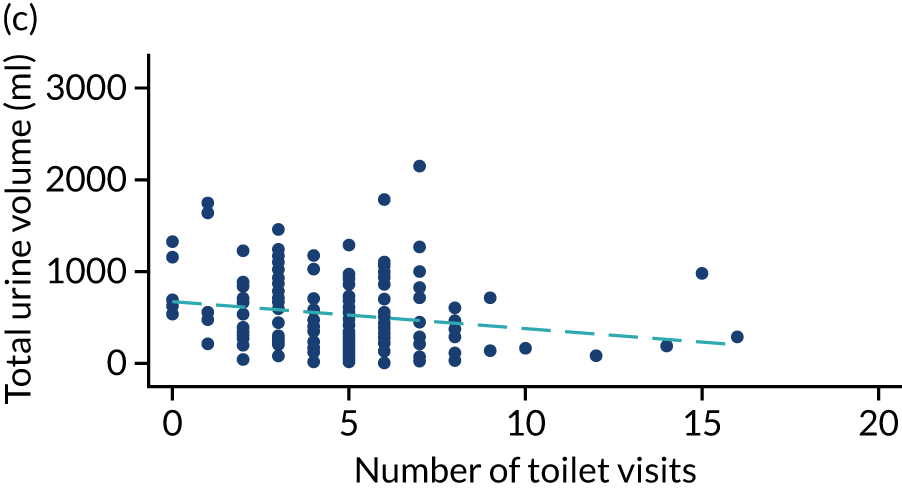

FIGURE 6.

Urine leaked in pads (ml) against number of toilet visits in the TPTNS group over time. (a) Baseline: rho = –0.164; p = 0.022; (b) 6 weeks: rho = 0.050; p = 0.524; (c) 12 weeks: rho = 0.114; p = 0.180; and (d) 18 weeks: rho = –0.092; p = 0.303. Dashed blue line represents the line of fit.

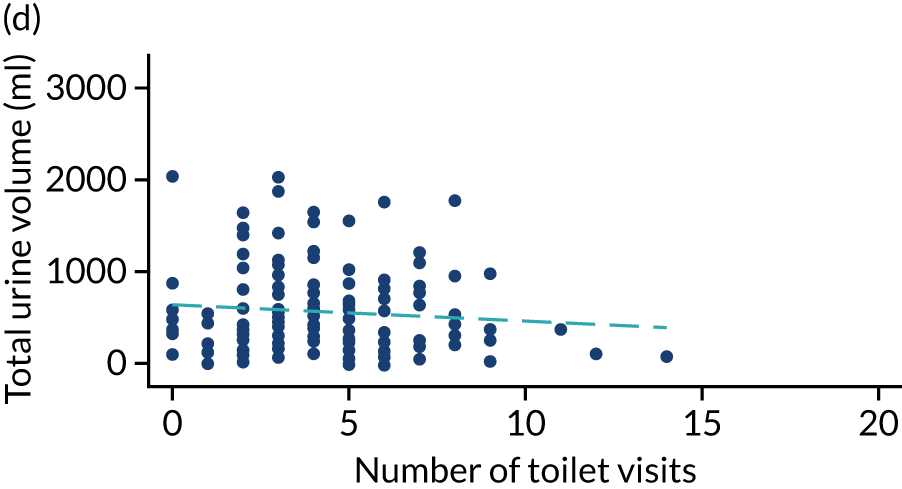

FIGURE 7.

Urine leaked in pads (ml) against number of toilet visits in the sham group over time. (a) Baseline: rho = –0.006; p = 0.930; (b) 6 weeks: rho = 0.069; p = 0.367; (c) 12 weeks: rho = –0.199; p = 0.015; and (d) 18 weeks: rho = –0.047; p = 0.572. Dashed blue line represents the line of fit.

Summary of effectiveness results

We randomised 406 care home residents recruited from 37 care homes to receive TPTNS or sham stimulation. The majority had severe UI (> 400 ml per 24 hours), all wore absorbent pads, and the two groups were comparable at baseline with regard to age, sex, and cognitive and physical impairment levels. We found no evidence of any clinically relevant reductions in 24-hour urine leakage at any time point after treatment with TPTNS. Given the challenges of undertaking research in this population, our compliance with allocated treatment was high and the number of missing data was small; furthermore, results from sensitivity analyses were consistent with the primary complete case ITT analysis, reinforcing our findings. There were no safety concerns related to TPTNS.

Chapter 4 Economic evaluation

Introduction

This chapter describes the economic evaluation that was undertaken alongside the trial. The aim of the analysis was to assess the costs of providing a programme of TPTNS, compared with the costs of providing sham treatment. The TPTNS intervention, an electrical stimulation programme comprising 12 sessions of 30 minutes’ duration each, provided twice per week over 6 weeks, was delivered by care home staff who received a specific package of training and support. To make the best use of the evidence generated during the trial and to incorporate the range of costs and benefits of the TPTNS intervention, a CCA approach was used. This presented costs of providing the programme alongside the key primary and secondary outcomes. This was conducted instead of a cost-effectiveness analysis because there was more than one multidimensional outcome of importance that was considered useful to capture. An original intention had been to complement the CCA with a further synthesis of costs and benefits between the groups in the trial using a cost-effectiveness analysis. However, as no difference was found between the two groups in DEMQOL or DEMQOL-PROXY, and no difference was found between groups in costs, none of the constituent parts indicated that this would be useful.

Methods

Economic evaluation

A CCA approach was used. 42 This involves a descriptive presentation of the range of costs and benefits of an intervention. Outcomes are reported in natural units, such as the use of incontinence products or the impact on continence care pathways, which should resonate with those involved in the planning and delivery of continence care in care homes. It also enables costs and benefits to be reflected where there is a known direction of change, but insufficient data is available to quantify that change. The use of a ‘balance sheet’ reporting approach allows the reader to form their own opinion on the relevance and relative importance of the findings to their decision-making context. 42 Disaggregated costs and benefits were descriptively presented and outcomes reported in natural units.

Perspective

A public sector payer perspective (in the UK, this is the central government Treasury), specifically in terms of NHS costs and local authority costs for care homes, was used to provide a practical assessment of resource implications and consequences of interest for those involved in care home service provision and funding decisions.

Discounting

Reporting of economic analysis was in 2018–19 Great British pounds (GBP). The time horizon for the trial was 18 weeks. As costs did not extend beyond 1 year, discounting was not required.

Quality-of-life health outcomes

Data about quality of life were collected using the DEMQOL and DEMQOL-PROXY (titled DEMQOL-Carer) questionnaires. These are condition-specific measures of health-related quality of life designed specifically for use with individuals experiencing cognitive decline and dementia. 35,43 The raw scores from each of these can be used to generate health state utility values for use in economic evaluation through conversion to DEMQOL-U and DEMQOL-PROXY-U, respectively. 41,44 DEMQOL-U consists of five domains: positive emotion, memory, relationship, negative emotion and loneliness. Four possible levels of response relating to severity are available for each domain. DEMQOL-PROXY-U consists of four domains: positive emotion, memory, appearance and negative emotion. As with DEMQOL-U, each has four possible levels of response relating to severity. DEMQOL was administered at baseline and at the 6- and 18-week follow-ups, and completed by the participant. DEMQOL-PROXY was administered at baseline and at the 6- and 18-week follow-ups, and completed with a proxy resident perspective by a single, named proxy. This could be a different proxy at each time point. Individual raw scores were converted to health state utility values using the scoring algorithm for the UK. 41

Resource use

Resources to deliver the TPTNS intervention, details about the use of absorbent pads (number and type) and other equipment, and (if appropriate) the number of staff required to assist residents to use the toilet were measured. Data on resource use were collated from the RUQ designed for this study and from data collected as part of the main trial (see Report Supplementary Material 4–7). The RUQ consisted of three questions related to medication prescribed for incontinence, resources required for toilet assistance, and aids and devices for managing incontinence. In addition, at the 6- and at 18-week follow-ups, questions about the use of primary care in the preceding 6-week period were included. Information on all consultations with health-care professionals external to the care home as a result of their UI was categorised according to who the consultation was with [general practitioner (GP), nurse, physiotherapist, etc.] and where the consultation took place (in the surgery or in the care home). Stimulation diary records were used to determine the average time taken by care home staff to complete stimulations [over 12 sessions in a 6-week period (minutes)] and the staff grade of the stimulation administrator. This was recorded on the RUQ. The RUQ was administered at baseline to establish the usual continence care pathway and completed by the RRA. The RRA was a registered nurse working in trial regions in Scotland and England. The RUQ was used again at the 6- and 18-week follow-ups.

Unit costs

The unit costs and sources used to estimate total cost per participant are given in Appendix 5. Unit costs were attached to the individual resources identified in the RUQ. Unit costs were identified using Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 201937 for staff for primary care, and British National Formulary38 for prescribed medication. Incontinence products’ market prices were identified from supplier direct websites or large chain shops with an online presence. Direct costs of interest included expenditure on absorbent pads and expenditure on other protection products to manage UI.

Intervention costs

Intervention costs included staff training (training time using staff roles reported for delivery of TPTNS/sham intervention), the trainer and the materials (TPTNS electrical stimulator machines, skin electrodes, handbook and training DVD). Costs were based on the market rates for these items. The costs of developing the handbook and DVD were not included. Cost of training facilities was not included. (It was assumed that training would not be expected to be delivered off site in normal working practice.) Equipment to deliver the intervention [cost of TPTNS Neurotrac machine, consumables (skin electrodes, wipes, batteries)] were also based on market rates for these items. Time to deliver the intervention was costed using staff time.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to assess the number of each item of resource used by participants in each group. The total cost per participant was estimated by combining the number of each item of resource used with the unit cost of that item. This provided an estimate of mean cost per participant by treatment group. Differences in mean costs associated with UI products, staff time for toilet assistance and other health-care resource use (e.g. GP visits) during routine follow-up were assessed. Independent samples t-tests were used to compare the groups at each time point for resource use. Utility change scores from baseline to 6 weeks, and from baseline to 18 weeks, were calculated and tested using the parametric paired t-test for statistically significant difference in health-related quality-of-life scores before and after TPTNS. Treatment groups were compared using independent t-tests. Although an original intention had been to estimate quality-adjusted life-year gain, this was not conducted as no differences were observed in benefits or costs. To maximise transparency and aid interpretation of results all available data were used, when possible.

Missing data

Missing data can preclude calculation of utilities for DEMQOL-U and DEMQOL-PROXY-U. No imputation was conducted. When resource use was missing for health-care NHS contacts, the participant was assumed not to have used the resource category.

Results

Intervention costs

Seventy-two bespoke training courses were delivered to 425 care home staff at care home venues. Each staff member received an online handbook and DVD to support their skills development. A total of 148 participants also received a follow-up individual staff competency assessment in their workplace. The average cost of the training and support package per staff member was estimated to be £121.03, based on the assumption that normal practice would be to make use of local trainers [10-mile radius (travel time of 30 minutes and 20-mile round-trip mileage reimbursement per person)] and excluding economic cost of venue. Although this reflects trial costs for training conducted in care homes in Scotland, it should be noted that additional costs were incurred by travel and subsistence reimbursements for training conducted in care homes in England because distances to care homes were greater.

Delivery of the intervention required one staff member for each of the 12 times that the stimulation was delivered during the trial. An average salary of £38.06 per hour was used to value staff time. This was estimated from staff roles reported in trial stimulation diary records (66% care assistants, 13% care leaders, 20% nurses). Staff did not need to be present during stimulation. Data for time to set up and take off the machine for each stimulation event was available for 92% of stimulation events. Data were missing for 8% (345/4127) stimulation events. Time to set up and take off the machine took ≤ 5 minutes for 94% (3536/3782) of stimulations, with 80% of stimulations (3042/3782) taking ≤ 3 minutes. The cost of delivery of TPTNS (excluding training) in the trial was estimated to be £81.20 per participant (Table 10).

| Item | Unit cost (£) | Numbera | Total cost (£) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TPTNS training and support package | |||

| Handbook and DVD | 11.20 | 425 | 4760.00 |

| Training events | 143.00 | 72 | 10,296.00 |

| Carer hours for intervention training | 28.00 | 170 × 2 hours | 9520.00 |

| Care leader hours for intervention training | 40.00 | 210 × 2 hours | 16,800.00 |

| Nurse hours for intervention training | 60.00 | 45 × 2 hours | 5400.00 |

| Individual staff competency assessment | 31.50 | 148 | 4662.00 |

| Average training cost per staff (n = 425) | 121.03 | ||

| TPTNS intervention | |||

| Neurotrac machine (branded) | 74.49 | 172 | 12,812.28 |

| Skin electrode pads (single use) | 2.98 | 4130 | 12,307.40 |

| Time to set up and take off the machine (per resident per stimulation event) | 38.06 | 4127 × 3 minutes (206 hours) | 7840.98 |

| Average intervention cost per participant (n = 406) | 81.20 | ||

Dementia Quality of Life and Dementia Quality of Life Proxy