Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/26/01. The contractual start date was in June 2014. The draft report began editorial review in April 2020 and was accepted for publication in August 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Goldstein et al. This work was produced by Goldstein et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Goldstein et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background to this project

In 2012, a call was issued by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme for a multicentre, two-arm randomised controlled trial (RCT) to answer the question ‘What is the clinical and cost-effectiveness of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) for psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNESs)?’ (see Appendix 1). The call specified that the CBT should be tailored for adult PNES patients whose condition persisted beyond diagnosis by a neurologist or neuropsychiatrist. The trial would be conducted in outpatient or community healthcare settings.

The decision to include patients with comorbid epilepsy would be considered by the applicants; consideration would also be given to psychiatric comorbidities. CBT would be compared with standard medical care, which was to be defined by the research team; however, it was recognised that this might include a patient information leaflet. Potentially important outcomes were identified as seizure frequency and severity, as well as duration of seizure freedom. Other outcomes identified were psychiatric symptomatology, psychosocial functioning, quality of life, healthcare utilisation, cost-effectiveness and socioeconomic factors (i.e. disability and return to work). The minimum follow-up duration was set as 1 year post randomisation.

The call acknowledged that although psychotherapy is deemed the first-line intervention for PNESs, there is limited evidence of its effectiveness, despite reports that CBT has been shown to be successful in treating other somatoform conditions. A pilot RCT demonstrated that a version of CBT designed specifically for patients with PNESs was able to reduce seizure frequency over standard care. 1 The call highlighted the requirement for a fully powered RCT to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of CBT tailored for PNESs. The current study is a response to the call made by NIHR, proposing the expansion of the earlier pilot1 into a multicentre RCT recruiting patients from neurology services. The call recognised that PNESs are often referred to by other names. We adopted the term dissociative seizures (DSs) for reasons discussed in the next section (see Dissociative seizures). The trial was subsequently named ‘COgnitive behavioural therapy vs. standardised medical care for adults with Dissociative non-Epileptic Seizures: a multicentre randomised controlled trial (CODES)’.

Dissociative seizures

Dissociative seizures are paroxysmal behavioural events that resemble epileptic seizures or syncope; they are, however, not a result of epilepsy or any other medical condition. They are widely understood as involuntary episodes that arise via dissociative mechanisms and as a disorder sitting at the interface between neurology and psychiatry. 1–3 DSs are currently classified as conversion (functional neurological symptom) disorder4 and as a dissociative neurological symptom disorder. 5 For the purposes of the current study, DSs were defined as events leading to a transient loss of consciousness or apparent altered responsiveness. Such episodes would be clinically incompatible with recognised neurological or general medical conditions, and not better explained by another physical or psychiatric disorder. Symptoms or deficits would also cause significant distress, psychosocial impairment or warrant medical evaluation.

Dissociative seizures are also referred to as ‘pseudoseizures’, ‘functional seizures’, ‘psychogenic non-epileptic seizures’, ‘non-epileptic events/spells’ or ‘non-epileptic attack disorder’ among other names. Currently, the most prominent term used is PNESs, although it may have negative connotations for some patients,6,7 with the term ‘psychogenic’ potentially implying that the attacks are ‘deliberate’ or ‘imagined’ despite the intentions of healthcare professionals (HCPs). We chose the term ‘dissociative seizures’ in line with the International Classification of Diseases and Related Problems, Tenth Revision, classification that was current at the time that the project started,8 as it encourages a positive diagnosis and discussion of an aetiological mechanism.

The prevalence of DSs is estimated as 2–33 per 100,000 people,9 although more recent assessments place this estimate closer to 50 per 100,000 people. 10 A recent UK study2 documented the incidence rate as 4.9 per 100,000 people per year. Women form around three-quarters of all patients with DSs,11 with onset typically occurring in the late teens/twenties,12 although DSs can occur in both the old and the young. 13–15 It is thought that around 12–20% of patients presenting at epilepsy clinics may have DSs. 16

Video electroencephalography (EEG) is the gold standard diagnostic technique for DSs, with the key signs17 being the absence of typical epileptic EEG abnormalities and the presence of an intact alpha rhythm. However, a careful history alone should usually provide sufficient grounds to suspect DSs. 18 It is estimated that about 22% of DS patients have comorbid epileptic seizures,19 which may create problems in diagnosis and management. 18

Up to 80% of patients with DSs have a history of other functional somatic symptoms and disorders, including other functional neurological symptoms. 20 There are high levels of psychiatric comorbidity in patients with DSs,21–23 including maladaptive personality traits, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety and depression, with patients demonstrating less adaptive coping styles. 24,25 It has also been reported that patients with DSs might have a slightly higher risk of mortality; however, this is not directly related to the seizures. 26

A recent meta-analysis has shown a clear association between the presence of childhood stressors and the presence of adulthood stressors in patients with DSs, with an odds ratio of 3.1 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.7 to 5.6]. 27 In addition, the perceived impact of traumatic events appears greater. 28 Individual studies have shown an association between history of trauma and DSs, with 44–100% of patients reporting a history of trauma and 23–77% of patients reporting being physically and/or sexually abused. 29 This suggests that these experiences may be potential risk factors for DSs for a significant proportion of patients. The frequency of childhood sexual abuse is higher among females with DSs,30 and it has been reported that, for example, in one DS population studied, 41% of females had suffered from sexual abuse. 31 This is a much higher rate than the estimated rate of sexual abuse (15–25%) in the general female population. 32 Reports of sexual abuse increase the likelihood of a diagnosis of DSs by approximately threefold. 28,33 Importantly, however, a diagnosis of DSs is not dependent on a history of abuse. 22 In addition, patients with DSs report more life events than those with epilepsy and motor conversion disorder in the 12 months prior to DS onset,34,35 and it has been considered that repeated adverse experiences over the longer term may be as relevant as acute life events in the development of DSs. 22

In addition to trauma, two-thirds of patients with DSs report significant problems in family and social environments. 31 When compared with patients with epilepsy, marital and family problems have been reported to be more prevalent in patients with DSs. 36 Individuals with DSs have reported viewing their family as having a dysfunctional communication style,37 which may contribute to DS symptomology through distress, criticism and a tendency to somatise. 38 As a result, individuals with DSs sometimes perceive their families as lacking in commitment and support. 36

Quality of life in individuals with DSs is lower than in those who are diagnosed with epilepsy,39 which may in part be because of the association between quality of life and depression, dissociation, somatic symptoms, escape–avoidance coping strategies and family dysfunction. 40 Patients with DSs can experience very restricted lives and demonstrate high levels of avoidance behaviour41–43 owing to fears of having a seizure. Individuals with DSs may also experience high levels of stigma related to their seizures,44 which can lead to individuals isolating themselves to avoid any adverse social reactions. 45,46 In addition, family members can influence quality of life in patients with DSs. Those who have a family environment characterised by high levels of criticism and lack of interest and support have lower health-related quality of life (HRQoL). 47

In a study of longer-term outcome of 50 patients that was undertaken by retrospective analysis after an average of 2 years, over half of the patients were found to be in either a poor or a very poor state because of a combination of physical, psychological and social issues. 48 In addition to a potentially low quality of life, around 70% of individuals with DSs have poor long-term outcomes, including chronic disability and welfare dependence. 49 Studies suggest that around half of patients are receiving or dependent on disability/state benefits during follow-up. 49,50 In conjunction with this, it has been surmised51 that the societal costs of having DSs can be considerable and can, as a result of rates of unemployment and disability, approximate the costs associated with intractable epilepsy. There is also some evidence that disability and welfare dependence can continue even if patients become seizure free. 52,53

The most consistent predictive factor of poor outcome, defined in different ways in different studies, for people with DSs appears to be the duration of the symptoms: the longer the duration, the more likely the negative outcome. 48,54,55 Further factors that negatively predict outcomes include receiving social security benefits;56 the presence of previous psychiatric diagnoses,56 with evidence specifically relating to the presence of depression56,57 and anxiety;56 poor psychopathology inventory scores;49 and a difficulty in forming relationships. 58 Personality factors may also be associated with different patterns of outcome. 49,57,59 Factors predictive of good outcomes have variously been found to include employment;2,60 higher educational achievement49,61 and intelligence quotient;62 low somatisation scores;49 and being accompanied to the first clinic visit. 61 There have also been indications, of varying strength, that hyperkinetic DS semiology is associated with a less good outcome than hypokinetic DS semiology. 48,49,54,61

Health economic aspects of dissociative seizures

There is a lack of research investigating the healthcare costs incurred by people with DSs. However, the literature often refers to the prevalence of unnecessary tests and treatments that patients can undergo that are expensive and potentially harmful. 63 A study in the USA64 reported the pre-diagnosis cost of this patient group (excluding diagnostic tests) as potentially exceeding US$25,000 per patient, based on an average of 6 years to arrive at the correct diagnosis. A similar investigation in Ireland65 reported an annual pre-diagnosis cost of €5429.30, assuming that it takes an average of 5 years to reach a DS diagnosis. A correct diagnosis of DSs appears to lead to a decrease in health service use and a subsequent reduction in costs. 66,67 Although it is possible that patients with DSs may later develop other medically unexplained symptoms,20 which may also have financial implications, there is no evidence to predict whether or not this likelihood is reduced by psychological interventions.

Treatment for dissociative seizures

Although some research in the last 10 years has investigated pharmacological treatment for DSs using antidepressants,68,69 the treatment of choice in both clinical and research settings remains psychotherapy. 70,71 There has been some research on the beneficial use of psychodynamic therapy,72,73 group psychotherapy74 and psychoeducational approaches. 75,76 However, CBT has the most substantial body of data suggesting effectiveness in treating a range of somatoform disorders,77,78 although effect sizes have been noted to be small to medium. 78 More specifically, with respect to treating patients with DSs, the evidence for DS reduction comes from small, open-label studies and pilot RCTs. 79,80 Carlson and Nicholson Perry79 reviewed 13 studies of mixed quality and somewhat differing interventions that demonstrated that 47% of patients were reported to be seizure free at the end of the psychological intervention; they also reported that, considering data available from 10 studies, 82% of patients had shown at least a 50% reduction in DS occurrence at the end of the intervention.

Martlew et al. 80 reviewed data from eight open-label studies and four RCTs, and concluded that the strongest evidence for DS reduction at that point came from a pilot RCT. 1 This RCT, based on a previous single case study81 and an open-label study,82 was undertaken at just one clinical site and compared a manualised CBT treatment for DSs plus standard medical care with standard medical care alone. Standard medical care was provided within a specialist tertiary neuropsychiatry service. A total of 66 patients were allocated at random to two equally sized treatment arms. Patients who were allocated to receive CBT plus standard medical care were offered 12 sessions of DS-specific CBT (plus up to two booster sessions), including handouts supporting the session content. The structure of the treatment package was described. 1,83,84 Intention-to-treat analyses showed a significant reduction in DSs within the CBT arm at the end of treatment; at follow-up, the CBT arm tended to have fewer seizures than the arm receiving standard medical care only. In addition, at follow-up the CBT arm tended to be more likely to be seizure free for the last 3 months of the study than the standard medical care arm. Both trial arms showed a degree of improvement in some measures of health service use, as well as on the Work and Social Adjustment Scale; however, anxiety, depression and employment status showed no change. Although this study provided preliminary evidence of the efficacy of CBT for this patient group, it lacked independent outcome assessors and demonstration of effectiveness across multiple sites and practitioners.

Additional evidence for the efficacy of a largely CBT-informed approach in the treatment of DSs has been found within a small, four-arm, pilot RCT. 68 Thirty-eight patients (of whom 34 provided outcome data) from three sites were randomised to four treatment arms: 12 sessions of CBT-informed psychotherapy (CBT-ip) (n = 9), 12 sessions of CBT-ip plus flexible low-dose sertraline (n = 9), sertraline alone (n = 9) and treatment as usual (n = 7). CBT-ip was heavily informed by principles of CBT but also included other therapeutic techniques derived from mindfulness, dialectical behaviour therapy and psychodynamic approaches. The study was not powered to allow between-condition comparisons for the primary outcome of DS frequency; therefore, comparisons were made within treatment allocation. The two treatment arms incorporating CBT-ip demonstrated significant seizure reduction and improvement in functioning and scores on symptom scales, whereas the sertraline-alone arm showed a trend towards DS reduction but no change in secondary outcomes. No significant changes were found in the treatment-as-usual arm. There were also significant reductions in clusters of DSs in the two trial arms delivering CBT-ip, although the extent of the reduction depended on how clusters were defined. 85

Nonetheless, despite showing potential efficacy of a CBT approach to the reduction of DS occurrence, neither pilot RCT was an adequately powered effectiveness study that provided a sufficiently robust evidence base on which to make treatment recommendations.

Although the literature seems to suggest that psychotherapy (and, potentially, specifically CBT) should be the treatment of choice for patients with DSs, there is no uniform, recommended care pathway for these patients in the UK. 71 Furthermore, the availability of psychiatric and psychological services for the assessment, diagnosis and management of DSs is highly variable, despite the potential impact of DSs on patients, their families and society. 70 Mayor et al. 71 found that 15% of HCPs who responded to their survey indicated that they had nowhere to refer their patients; only one-third indicated that they would be able to refer patients with DSs for psychotherapy. Such psychotherapy might be further limited, given that these professionals reported that under half of their patients would be offered at least one psychotherapy session. Thus, although evidence exists for the benefit of psychotherapeutic input, the lack of an evidence-based care pathway and of evidence from larger robust treatment trials means that many patients may not be funded by their Clinical Commissioning Groups to receive psychotherapy. In addition, the geographical distribution of the patients means that in outside specialist centres there may be limited knowledge or willingness to enable these patients to be seen, resulting in inequalities in healthcare provision. A stronger evidence base would provide the basis on which policy changes to the service provision for DS patients could be made. This need is highlighted by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence86 and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network,87 which indicate the need for psychiatric and psychological input for DS patients. In addition, the International League Against Epilepsy,88 US National Institutes of Health89 and the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke90 have all identified the need to develop effective methods for treating DSs.

Summary and methodological rationale

The CODES trial was designed to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of CBT for DSs within a care pathway involving neurology, neuropsychiatry and psychotherapy. It offers a potential template for future services and the commissioning of DS treatment. In addition, it can form the basis for the more extensive training of therapists to work with patients with DSs and support the importance of psychiatrists in treating this patient group, who often present with complex mental health needs. 70 Preliminary evidence of efficacy had been obtained through a proof of principle RCT1 and, therefore, this study was the next step in examining the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness and generalisability of CBT as an intervention for DSs through a pragmatic, adequately powered, multicentre RCT.

Research objectives

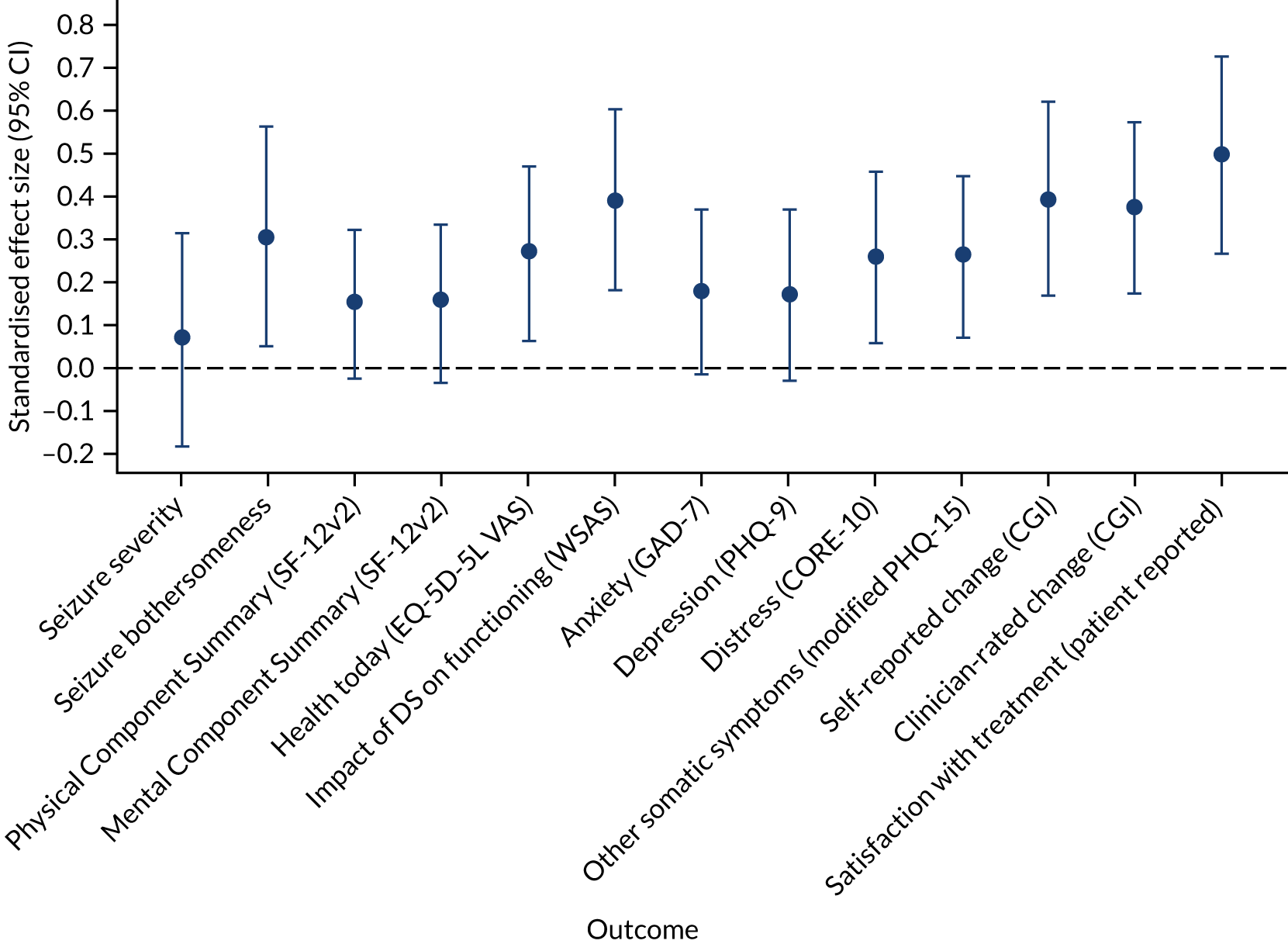

The main aim of this research, as determined by the NIHR HTA programme commissioning brief, was to evaluate the effectiveness of a psychological intervention (DS-specific CBT) plus standardised medical care (SMC) (i.e. CBT + SMC) compared with SMC alone in improving DS control and a range of psychosocial outcomes and in reducing health service use and costs.

The primary objective was to assess the effectiveness of CBT + SMC compared with SMC alone in reducing monthly DS frequency at 12 months post randomisation.

Secondary objectives were to assess the effectiveness of CBT + SMC compared with SMC alone at 12 months post randomisation in relation to:

-

reductions in DS severity

-

improvements in seizure freedom, psychosocial and psychological well-being and HRQoL

-

participants’ global clinical improvement [Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGI)]

-

participants’ satisfaction with treatment

-

reductions in health service use

-

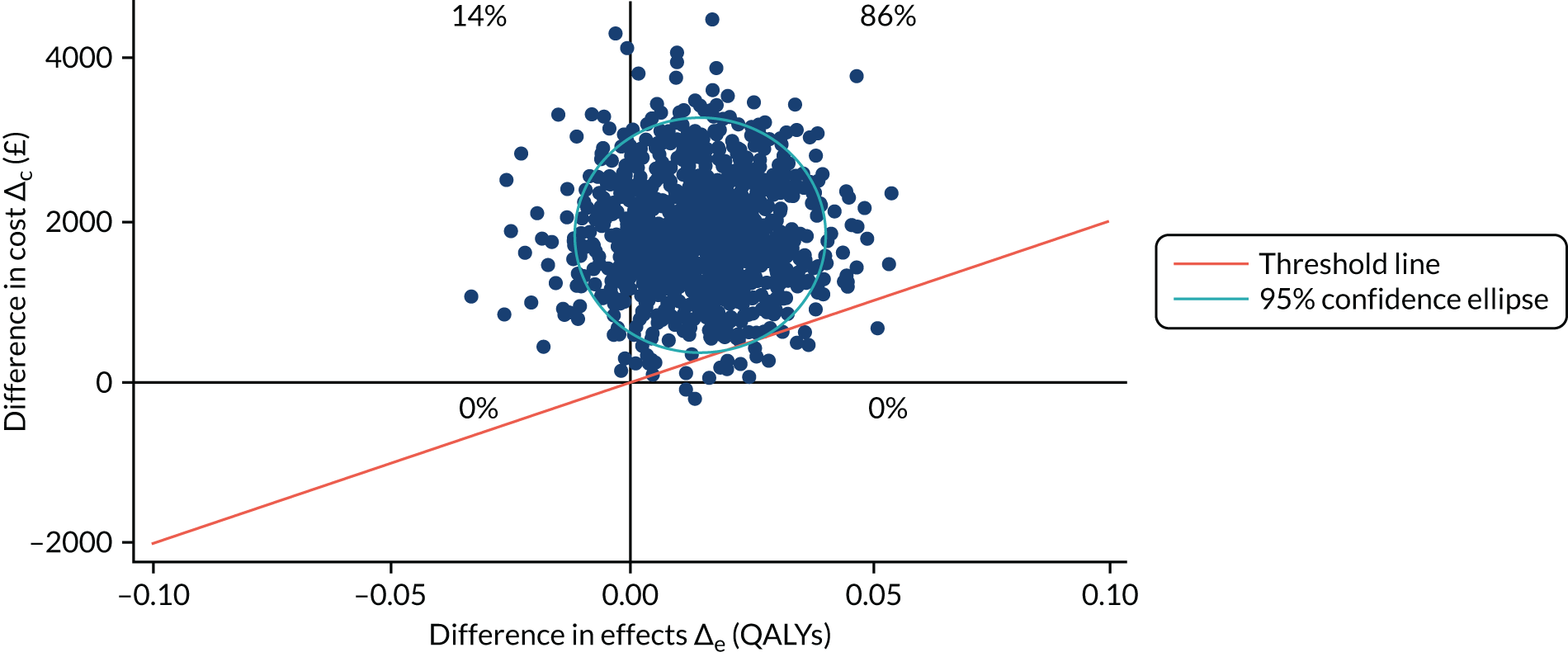

cost-effectiveness of CBT + SMC compared with SMC alone.

In addition, we sought to characterise:

-

patients’ subjective experiences of either the CBT or SMC treatment

-

subjective experiences of HCPs (neurologists, psychiatrists and CBT therapists) when delivering SMC or CBT (as relevant)

-

treatment fidelity of the manualised CBT treatment and the implications for roll-out in the NHS.

The completion of the CODES trial involved a number of stages in accordance with Medical Research Council guidelines,91 and these included our earlier work. 1,81,82 We refined our CBT manual and patient handouts based on our experience from our previous RCT. 1 We then trained CBT therapists) to deliver the intervention. We also developed our protocol and materials for neurologists and psychiatrists involved in diagnosing and treating patients in the study, with service user (SU) input into patient materials, and trained the research workers who would assess participants. At an early stage in the project we developed and published both our protocol for this complex intervention study84 and our statistical analysis plan (SAP)92 prior to undertaking any data analysis. We described the participants initially recruited to the study in neurology/specialist epilepsy services and then those participating in the RCT. We undertook an analysis of the fidelity with which the CBT was delivered, and conducted process analyses in the form of in-depth qualitative interviews with patients in both treatment arms. We also explored the experiences of neurologists, psychiatrists and CBT therapists delivering care during the study. We collected and analysed clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness follow-up data for both trial arms, with a view to disseminating the results and implications of the analyses once the study had been completed.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Patient and public involvement

We incorporated patient and public involvement (PPI) throughout the course of the study, with the aim of including PPI at the stages of study design, management and dissemination.

When we were developing the project in response to the HTA commissioned call, we presented our research questions to and consulted with the local NIHR Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) Service User Research Enterprise Advisory Group (SUAG) and SUs with DSs from our clinical service at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. Information was also sought via a postal/online survey, for which we contacted SUs from the SUAG and our clinical service. SUs confirmed the importance of this research.

Suggestions made by SUs with DSs were used to guide how we explained the study to potential recruits and the methods used to facilitate retention in the study. These included, for example, regular reminders to record seizure frequency; updates on study progress; a project team member to contact to discuss attendance difficulties; reimbursing transport and parking costs; flexible use of paper/electronic methods to collect seizure data; limiting the length of outcome measure completion time; offering a voucher for follow-up data completion; and providing feedback for participants at the study end as part of dissemination. SUs commented on and informed our choice of outcome measures. We consulted further with SUs with DSs prior to the submission of a full application and to guide our responses to feedback/queries from the HTA Board. SUs provided feedback on the information leaflets to be provided in the neurology and psychiatry clinics.

Subsequently, we identified four people (one from the SUAG and three SU representatives), three of whom had a diagnosis of DSs. Two became members of our Trial Management Group (TMG) and two joined our Trial Steering Committee (TSC). We provided a training session in June 2014 for all four people as the study commenced. This was facilitated by a former staff member from Epilepsy Action (Leeds, UK), which is a user-led organisation that had an active training programme and had committed to offering such training.

The chief investigator and the trial manager also held an interim face-to-face meeting with one SU representative from each committee in September 2017 to review their experiences in the study committees and to consider the challenges that they felt in participating in the study and how we might address these. The PPI representatives on each committee received all relevant trial paperwork and were given their own standing agenda item where they could comment on trial matters if they had not already done so as part of the meeting. They provided feedback on relevant paperwork and, early in the project, on our trial website. The trial manager acted as the main point of contact and would discuss with them the agenda and arising issues before or after the meetings, as appropriate.

Our SU representatives have taken an active role in advising on study progress and on means to improve follow-up rates, and supported our earlier need to extend recruitment and follow-up periods. They have made contributions to dissemination and commented on our communications with participants about study progress. They have advised on the wording of study outputs (e.g. papers and feedback to study participants) and two are co-authors on this report. We have been very fortunate to maintain the active input of all four individuals who initially joined our TMG and TSC (allowing for any times when their own circumstances made this difficult), and we feel that their willingness to give clear opinions on what we have been doing has benefited the study considerably.

We have also shared our experience of PPI within our institution. One of the SU members of the TSC worked with the CODES trial manager and a research associate in the NIHR Maudsley BRC to develop new guidelines for SU involvement on steering and advisory committees for clinical trials and other research projects. These are now available for researchers on the NIHR Maudsley BRC website (www.maudsleybrc.nihr.ac.uk/patients-public/support-for-researchers/involvement-guidelines/; accessed 10 January 2021). This SU member also gave a presentation to the NIHR BRC’s SUAG about her experience on the CODES TSC to encourage other SU representatives to become involved in committees for future clinical trials.

Study design

The CODES study consisted of two phases: an observational screening phase that lasted approximately 3 months after patients had initially been recruited in neurology/specialist epilepsy clinics and then, for eligible and willing patients, an intervention phase, namely a multicentre, pragmatic, two-arm RCT with assessor (research worker and statistician) blinding. The observational phase was to allow for patients who experienced rapid spontaneous remission following diagnosis, as well as to allow time for psychiatric assessments to be scheduled. Patients with DSs can show early remission after communication of the diagnosis alone,93 and we did not want to confound our evaluations by including people whose DSs remitted quickly. Participants were randomised at the beginning of the intervention phase using a 1 : 1 ratio, stratified by site, into two treatment arms. One treatment arm consisted of CBT plus SMC (CBT + SMC) and the other treatment arm consisted of SMC alone. SMC was standardised across the trial and was not simply the treatment that would usually be delivered at a particular centre. Although some demographic data were collected at the initial recruitment into the screening phase, further measures were collected at baseline (prior to randomisation) and at two follow-up assessments (at 6 and 12 months post randomisation).

Trial approval and monitoring

The trial was approved by London – Camberwell St Giles Research Ethics Committee (REC) (REC reference 13/LO/1595). It was also approved by local research and development departments at each NHS trust. The trial was monitored by the TSC and the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC). Both committees met at least once per year and at most twice per year during trial set-up, recruitment and follow-up. The DMEC monitored all serious adverse events (SAEs) within the RCT as they were reported. The TMG (comprising the chief investigator, co-investigators, PPI representatives and the junior statistician and junior health economist) met at regular intervals during the study to review ongoing progress and other relevant issues such as funding and dissemination.

Study settings and care pathway adopted in the study

The trial was run from the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, with the chief investigator, trial manager and some research workers based at this location. Research workers were also located at the University of Edinburgh and the University of Sheffield.

Our study design was based on a care pathway incorporating neurology and liaison/neuropsychiatry settings. After an initial assessment with a neurologist who established the diagnosis of DSs and provided the patient with an explanation for their DSs, the patient was referred to a psychiatrist, who carried out a detailed clinical assessment. The purpose of this was to review the diagnosis, establish a formulation of the patient’s problems, determine the existence of any psychiatric comorbidities and establish eligibility for the RCT. In some cases, pharmacological treatment of anxiety and/or depression was considered. We decided that the psychiatrists would be best placed to provide SMC follow-up sessions given that, in many settings, neurologists discharge patients following DS diagnosis, although SMC provision by neurologists was not proscribed. Most sites that were involved provided only neurology or only psychiatry input, but a small number of sites had both services within the same NHS trust (Table 1). Where sites comprised neurology services only, they referred patients on to designated psychiatry services, either following normal commissioning routes or following agreement for the study.

| Site location | Study phase | |

|---|---|---|

| Screening: neurology service | Intervention: psychiatry service | |

| Barts Health NHS Trust | ✗ | |

| Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust | ✗ | |

| Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | |

| Chesterfield Royal Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | |

| Croydon Health Services NHS Trust | ✗ | |

| Dartford and Gravesham NHS Trust | ✗ | |

| East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | |

| East Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust | ✗ | |

| Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | |

| Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust | ✗ | |

| King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | |

| Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust | ✗ | |

| Lewisham and Greenwich NHS Trust | ✗ | |

| Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust | ✗ | |

| Medway NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | |

| Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | |

| Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | |

| Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | |

| St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | |

| University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | |

| Western Sussex Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | |

| Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | |

| Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | |

| Derbyshire Community Health Services NHS Foundation Trust | a | |

| Derbyshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | |

| East London NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | |

| Kent and Medway NHS and Social Care Partnership Trust | ✗ | |

| Leeds and York Partnership NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | |

| Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | |

| Sheffield Health and Social Care NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | |

| South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | |

| South West London and St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust | ✗ | |

| Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | |

| West London Mental Health NHS Trust | ✗ | |

| Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | ✗ |

| Cardiff and Vale University Health Board | ✗ | ✗ |

| NHS Lothian | ✗ | ✗ |

| Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | b |

| University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | ✗ |

| University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust | ✗ | ✗ |

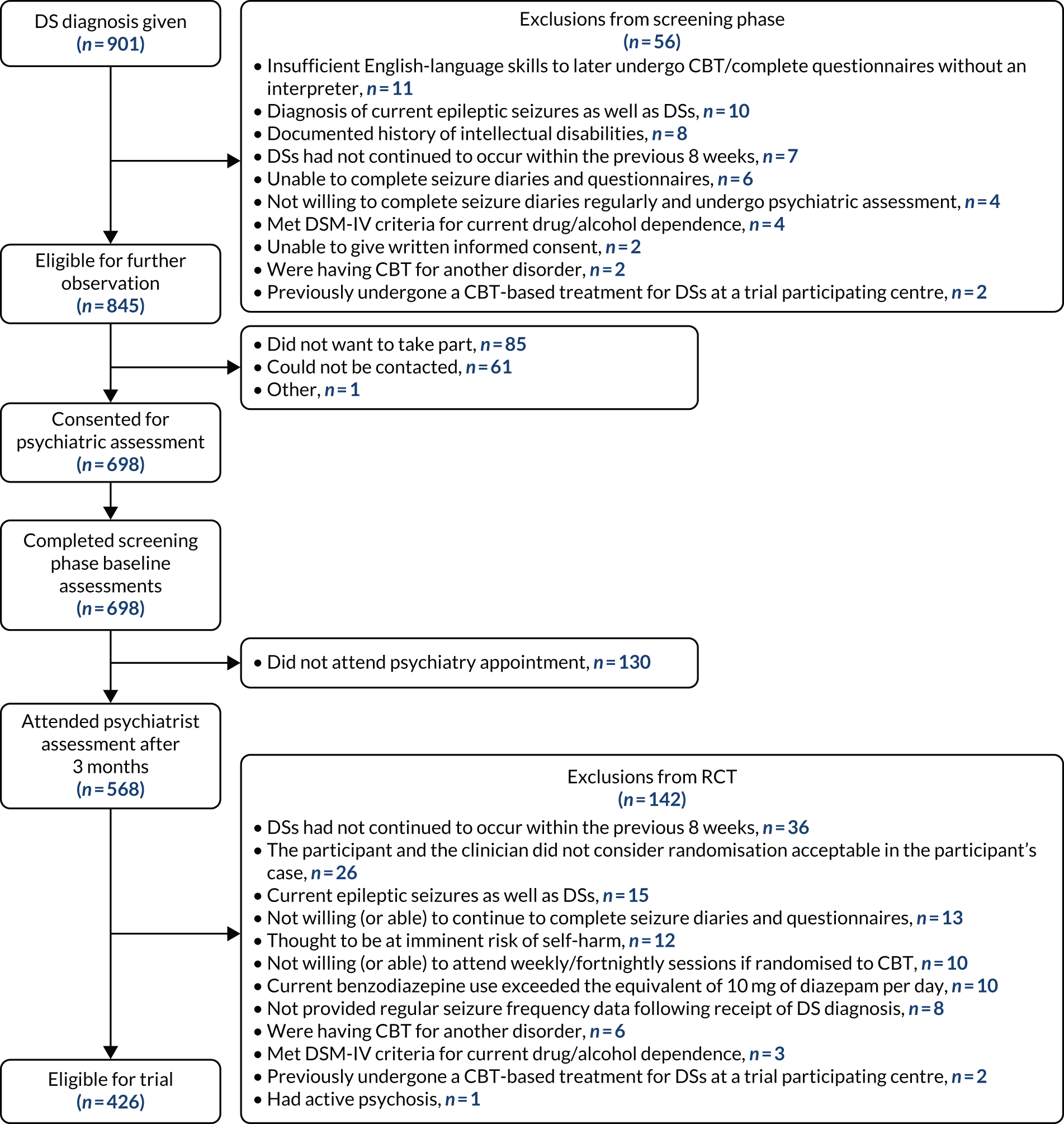

Screening and recruitment

Eligibility for the trial was ascertained at two stages. Participants were initially consented into the screening phase on the basis that the RCT was to be conducted on patients whose seizures persisted beyond diagnosis, and we judged this in relation to receipt of diagnosis by the neurologists. At the time of trial set-up, research indicated that only ≈ 14% of DS patients were likely to achieve seizure freedom 3 months after diagnosis. 93 Sufficient time before entering the RCT was, therefore, built into the protocol to ensure that patients continued to experience DSs before being randomised to a treatment arm within the RCT, as well as to allow sufficient time for appointments to be arranged with psychiatrists.

Screening phase

Participants were initially identified in neurology/specialist epilepsy outpatient clinics. Neurologists would make and explain the DS diagnosis (see Neurologists’ delivery of standardised medical care) and give the patient a booklet with further information about their condition (downloadable from www.codestrial.org/information-booklets/4579871164; accessed 10 January 2021). A protocol was developed for this process, as follows. If patients met the eligibility criteria and were interested in participating, the patient consented to the neurologist forwarding their contact details to the CODES team. A research worker would then contact the participant, explain the trial in more depth and cover the material in the participant information sheet (see Report Supplementary Material 1). If the patient was interested in proceeding, the research worker confirmed eligibility and obtained informed consent. This was carried out mostly in person but occasionally by post. Basic demographic information and a very brief medical history pertaining to the patient’s condition were obtained, and the patient was instructed how to keep seizure diaries. Patients were referred to the designated liaison/neuropsychiatry service by the neurologist. During this intervening period, a research worker contacted the participant fortnightly by telephone, text message or e-mail (based on participants’ preferences) to obtain seizure diary data, comprising the number of seizures experienced per week and how many were severe.

Intervention phase

A liaison or neuropsychiatrist assessed the patient approximately 3 months after their initial neurology diagnosis. This appointment was used in part to undertake further screening for eligibility for the RCT. The appointments included a reiteration of diagnostic points, provision of a more in-depth booklet about DSs (downloadable from www.codestrial.org/information-booklets/4579871164; accessed 10 January 2021) and a detailed clinical psychiatric assessment. A guide was written for the psychiatrist to facilitate consistency and good communication. If the patient met the eligibility criteria and was interested in participating in the RCT, with the patient’s consent, the psychiatrist informed the research worker, who then contacted the participant to explain the RCT further. If the participant still wished to participate, the research worker met with them and covered the material in the participant information sheet for the RCT (see Report Supplementary Material 2). The research worker confirmed eligibility, obtained informed consent and completed the baseline assessments with the patient. Participants were then randomised to one of the two treatment conditions. Enrolled patients were asked to consent to the research team contacting a carer/informant who could provide their own perspective on the participant’s DS frequency at the follow-up stages. If they agreed to this, carers/informants received a participant information sheet (see Report Supplementary Material 3) and, if they agreed to participate, they completed a consent form either at a face-to-face meeting or by post.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria (screening phase)

-

Adults aged at least 18 years old who had experienced DSs within the previous 8-week period and whose diagnosis was corroborated by either video EEG or if not available, clinical consensus (see Neurologists’ delivery of standardised medical care).

-

No recorded history of intellectual disability.

-

Had the ability to keep seizure diaries and fill out questionnaires.

-

Showed readiness to keep seizure diaries on a regular basis and attend a psychiatric assessment 3 months following receipt of their DS diagnosis in the study.

-

Were able to provide informed consent.

Exclusion criteria (screening phase)

-

A diagnosis of currently occurring epileptic seizures in addition to DSs (‘current’ is characterised as an epileptic seizure occurring in the prior year).

-

Lacking the ability to independently maintain seizure records or fill out questionnaires.

-

Met criteria for current alcohol or drug dependency in line with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)94 criteria since this might, among other things, make attendance and symptom reporting less reliable.

-

Insufficient fluency in English to complete questionnaires or later undergo CBT without an interpreter.

-

Currently undergoing CBT for another diagnosis, if this intervention would still be ongoing by the time the psychiatry assessment takes place.

-

Having previously had a CBT-based treatment for DSs at one of the trial participating centres.

Inclusion criteria for randomised controlled trial (intervention phase)

-

Adults aged at least 18 years old who had been recruited into the study in the screening phase following their diagnosis.

-

Indicated willingness to continue filling out seizure diaries and complete questionnaires.

-

Had given the research team data about their seizure occurrence on a regular basis since receiving their diagnosis of DSs in the screening phase.

-

Indicated that if they were allocated to CBT, they would be willing to attend weekly or biweekly therapy sessions.

-

Both the participant and their clinician believed that randomisation was acceptable.

-

Ability to provide written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria for randomised controlled trial (intervention phase)

-

Was currently experiencing epileptic seizures in addition to DSs.

-

DS had not been experienced during the 8-week period leading up to the psychiatry assessment.

-

Had previously had a CBT-based intervention for DSs at one of the centres taking part in the RCT.

-

Was currently undergoing a CBT intervention for another condition.

-

Was experiencing active psychosis.

-

Met criteria for current alcohol or drug dependence according to DSM-IV criteria since, in addition to making symptom recording and session attendance less reliable, it might be used to reduce anxiety and would reduce the impact of exposure during CBT, and have possible impact on patients’ memory for sessions.

-

Evidence of current use of benzodiazepines that exceeded the equivalent dose of 10 mg of diazepam per day, for reasons similar to those for alcohol or drug dependence.

-

Was at high risk of imminent self-harm, following the psychiatry assessment or according to the results of the structured psychiatric assessment [the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.)] administered by the research worker, subsequently followed up by a discussion with the relevant psychiatrist.

-

Had received a diagnosis of factitious disorder.

Randomisation

Randomisation took place following participants’ consent and completion of baseline assessments. Participants were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio between the SMC-alone treatment arm and the CBT + SMC treatment arm, using randomly varying block sizes and stratified by site. This was intended to ensure a 1 : 1 allocation in each location in which patients were recruited. Participants were enrolled by research workers and randomised using the online randomisation system at the King’s Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience. For each participant, the relevant research worker entered participant information into the randomisation system that then generated confirmation of randomisation e-mails. Research workers received blinded confirmation and the trial manager and chief investigator received unblinded confirmation with the participants’ treatment allocation. The chief investigator was unblinded for practical and administrative reasons.

Blinding and protection from bias

To protect from bias, research workers collecting outcome data and the trial statisticians were kept blind to participant treatment allocation throughout the trial. In addition to the chief investigator, the trial manager was unblinded so that they could contact participants to inform them of their treatment allocation and inform therapists about which participants to contact to arrange CBT appointments. Participants were asked not to inform research workers of their treatment allocation when completing follow-up assessments. If participants had a treatment-related question, they would contact the trial manager. To evaluate whether or not the research workers remained blind, they completed a ‘treatment guess’ form at the 12-month follow-up or point of withdrawal. If for any reason a research worker became unblinded to a participant’s treatment allocation, they reported this to the trial manager so that the outcome assessments could be completed by a blinded research worker. Participating clinicians and patients were not blinded to treatment allocations.

Interventions

The intervention was DS-specific CBT plus SMC, or SMC alone. SMC is described below from initial diagnosis with the neurologist to the end of the trial and, as both trial arms received this, it is described first.

Control intervention

Across the UK, medical and psychological care for DSs is variable, with different specialties contributing in specific ways. 71 To produce a broadly consistent treatment environment across the trial, key approaches were employed to create what we termed ‘standardised medical care’ for patients with DSs. This included providing briefing sessions to the clinicians (e.g. at site initiation visits), a detailed leaflet about how they might explain the diagnosis to patients, crib sheets containing the essential information that they should provide to patients during sessions (see, for example, Appendix 2 for the crib sheet for psychiatrists) and sets of frequently asked questions for clinicians providing SMC (see Report Supplementary Material 4–8 for the remainder of these materials). These are techniques that have been found to be acceptable in other studies. 93 It was intended that SMC would be provided by both neurologists and psychiatrists, and would start from the initial meeting with the neurologist at diagnosis. There was no mandatory number of SMC sessions; however, after the initial neurology and psychiatry assessment, we estimated that there would be up to two SMC sessions with the neurologist and three to four sessions with the psychiatrist. However, owing to local service procedures and clinical need, we could not be prescriptive about this.

One important component of SMC was the provision of information. We created two information booklets about DSs to be given at different stages of SMC to supplement the information given to patients by their medical clinicians. These booklets were devised by the clinical members of the project team, with input from SUs with DSs and a hospital information officer. The two booklets were:

-

Dissociative seizures factsheet (neurology). This was to be given to patients by their neurologists when the diagnosis of DSs was first communicated. It was also downloadable from www.codestrial.org/information-booklets/4579871164 (accessed 10 January 2021).

-

Dissociative seizures factsheet (psychiatry). This included content from the neurology leaflet but also provided more extensive information that could help provide further details relevant to psychiatric assessment and treatment. This was to be given to patients when they attended their psychiatric assessment. It has subsequently been made available at www.codestrial.org/information-booklets/4579871164 (accessed 10 January 2021).

When research workers contacted patients about potential participation in the study phases, they asked whether or not these factsheets had been provided; if not, they ensured that participants received the relevant factsheet.

Neurologists’ delivery of standardised medical care

The key elements of SMC provided by neurologists included making a firm diagnosis and explaining it, giving the patient the factsheet on DSs and referring the patient to the study psychiatrist. When making the diagnosis of DSs, neurologists were asked to undertake their usual assessments to clarify the nature of their patient’s seizure disorder to establish the diagnosis. We acknowledged that neurologists may sometimes make the patient’s diagnosis based on clinical history, physical assessment and information provided by informants. In some cases, this had been supplemented by mobile phone recordings of seizures but also by EEG or video encephalographic data. Although video EEG is the ‘gold standard’ for diagnosing DSs, yielding least diagnostic uncertainty,17 we acknowledged that this was not always readily available to a clinical service or deemed cost-effective when other clinical information led to a high level of diagnostic certainty. Thus, video EEG was not essential in the study. If video EEG was not undertaken, a diagnostic consensus was required either between two neurologists in the patient’s clinical service pathway or between the patient’s neurologist and a neurologist in the study team, who reviewed the patient’s clinical records and all relevant investigations. We anticipated that neuroimaging would be conducted only when clinically necessary.

Neurologists were asked to explain the disorder to the patient using the guidelines provided in a crib sheet (see Report Supplementary Material 4 and 6) and explained in detail elsewhere. 84 A key aspect of the neurologist’s role at this stage was to explain the referral to psychiatry and why this was appropriate, including the potential benefits of being seen by a psychiatrist. 84 Additional information given to patients by the neurologists that was likely to be tailored to the individual included explaining (1) that anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) are not effective in treating DSs; (2) that talking therapies might be helpful, although there is currently insufficient evidence and this is why the trial was being undertaken; (3) the disorder to significant others, and how to best respond to the DSs; and (4) driving regulations. They might also possibly discuss distraction techniques in general. Although neurologists were not expected to undertake the equivalent of a psychiatric assessment, if risks relating to self-harm, harm of others or psychosis were identified they were expected to refer patients to relevant services or instruct the patient’s general practitioner (GP) to do so if necessary.

After the initial diagnosis session, it was recommended that neurologists offer a minimum of one follow-up appointment at which any of the following might be included:

-

assessment of patient progress

-

reviewing the patient’s understanding of their diagnosis and, if necessary, going through this again

-

if appropriate, supervising the withdrawal of AEDs

-

managing comorbid physical disorders that required interventions

-

re-evaluating major psychiatric risks that might require interventions

-

consideration of the value of prescribing antidepressant or anti-anxiety medication where this was indicated on clinical grounds

-

completing any forms required by government departments if required.

However, given service and clinical limitations, this follow-up did not always occur.

Psychiatrists’ delivery of standardised medical care

The psychiatrists’ delivery of SMC was scheduled to begin with a clinical psychiatric assessment approximately 3 months following the neurological assessment and diagnosis. Where patients did not attend the first scheduled appointment, attempts were made to reschedule appoints as often as possible, allowing for service regulations regarding non-attendances and discharge.

This pre-randomisation assessment was intended to perform a partly educational function and cover several important aspects. Psychiatrists were asked to follow specific communication guidelines (see Report Supplementary Material 5 and Appendix 2); restate the points covered by the neurologist to reinforce and further explain the diagnosis; provide patients with a more detailed booklet on DSs (as indicated above); and acknowledge any fears that patients might have about being given a psychiatric diagnosis. The assessment would include a clinical assessment of relevant Axis I and Axis II psychiatric diagnoses and an assessment for risks related to self-harm and suicide; active suicidality would require exclusion from the trial and urgent treatment. It was anticipated that psychiatrists would explain and treat any other psychiatric or other functional somatic symptoms (using psychopharmacological approaches or referral to physiotherapy where relevant), and discuss any factors of possible aetiological significance that were elicited from the clinical history. Other components could include:

-

providing information concerning DS warning symptoms and the possibility of distraction without providing specific interventional techniques

-

liaising with other mental health clinicians involved in the provision of the patient’s care without referring for psychotherapy, instead focusing on psychoeducation and management of comorbid psychiatric conditions, as would normally be undertaken

-

encouraging the person to engage in or resume social activities and/or return to college/work where relevant, and liaising with the appropriate settings to facilitate this

-

involving family or friends in these areas as appropriate

-

completing forms for government departments as necessary.

Further follow-up appointments with the psychiatrist were intended to include general review and support, considering any psychiatric comorbidities and pharmacological treatment according to clinical need. Psychiatrists were instructed that no additional CBT techniques should be employed during the delivery of SMC.

Cognitive–behavioural therapy for dissociative seizures

Cognitive–behavioural interventions have generally now been shown to have positive benefits for a range of medically unexplained symptoms, as reported in a number of systematic reviews;78,95–99 however, these are not specifically studies of DSs and have not adopted specific models to underpin treatment of DSs. Although mechanisms of change have been studied in adults with medically unexplained symptoms,100 this work has not included adults with DSs. Recent conceptualisations of factors giving rise to DSs have, nonetheless, been developed and include an integrative cognitive model that seeks to explain DSs as automatic activations of a central representation of seizures (referred to as a seizure scaffold) in the context of dysfunction of inhibitory processing. 101 The seizure representation may be shaped by different factors that are relevant to seizures in the person’s life and yet further factors, such as chronic stress and arousal, may compromise adequate inhibitory processing. This and other conceptualisations of DSs (e.g. ‘panic without panic’43) offer the possibility of employing cognitive–behavioural interventions to address DS occurrence.

However, although acknowledging the richness of relatively recent models,101 the development of our CBT approach, which predates such models, stems from a single case study81 and was further refined in an open-label study82 and then in our pilot RCT. 1 A further description of the approach is given elsewhere. 83 A finding of increased symptoms of autonomic arousal as relevant to the concept of ‘panic without panic’43 is not in conflict with the approach taken in these studies.

Our cognitive–behavioural model incorporated the fear escape–avoidance model. 102,103 We considered DSs to represent a dissociative response to heightened arousal accompanying cognitive/emotional/physiological or environmental cues that may or may not be associated with previous/current distressing or life-threatening experiences. Alternatively, DSs may have occurred after events, such as panic attacks or syncope. All of these events may previously have led to unbearable feelings of distress and/or fear.

The treatment broadly consisted of engagement and rationale giving; helping the patient develop and use seizure control techniques; helping the person reduce avoidance behaviours via exposure; helping the person tackle maladaptive cognitions associated with seizure occurrence and facilitate emotional processing; dealing with trauma; and planning for relapse prevention. The key elements of the conceptualisation of the disorder and the treatment elements incorporated in the approach used here are illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Model showing responses associated with DSs and the CBT techniques used to target these in our DS-specific CBT. ABC, antecedents, behaviours, consequences.

Cognitive–behavioural therapy was intended to be delivered in 12 sessions (plus one booster session) informed by a treatment manual. This number of sessions was based on our previous work1,82 that we were seeking to extend here; in our 2010 pilot RCT1 that provided preliminary evidence for efficacy, not all patients attended both booster sessions so, for easier implementation for the therapists, we limited this to one booster session. The DS-specific CBT was designed to help facilitate the patient to:

-

develop an understanding of their seizure disorder

-

develop an understanding of how cognitive, emotional, physiological and behavioural aspects of their DSs are related

-

understand factors that led to the persistence of their DSs

-

learn how to prevent DSs by interrupting behaviours, cognitions or physiological responses occurring before or at the start of their DSs

-

improve their lifestyle by undertaking previously avoided activities

-

address thought patterns and attributions about their disorder that act to maintain their DSs

-

address and deal with previous traumas, poor mood, anxiety or reduced self-esteem, where relevant

-

increase their levels of independence and help them to comprehend the contribution of significant others to their disorder.

The CBT sessions included usual CBT components, such as session agendas and planning and reviewing homework activities, but also required patients to complete seizure diaries and undertake activities designed to help with seizure control. Although treatment was manualised, there was room for flexibility, allowing individual formulations. Participants receiving CBT were given a booklet (the ‘Manual for Patients Attending CBT’) that contained written material to supplement the therapy sessions and included pages for making notes. The titles of the individual topics covered in this manual were Introduction to cognitive behaviour therapy and dissociative seizures; A guide for other people; Distraction and re-focusing techniques; Progressive muscle relaxation exercises; Breathing exercises; Graded exposure; Trauma in the context of dissociative seizures; Identifying negative automatic thoughts; Alternatives to negative thoughts; Preparing for the future; and Discharge plan.

Intervention training

Before treating any patients, CBT therapists who had been identified as potentially delivering therapy to trial patients attended a 3-day workshop. The therapists were provided with information relating to the administration and running of the trial, including reporting any SAEs. We asked therapists to report suicidal ideation, suicide attempts and new deliberate self-harm. The workshop also included teaching on DSs and dissociation; a cognitive–behavioural model of DSs; eliciting information about DS occurrence/triggers/perpetuating factors; coping behaviours and avoidance; how to convey the rationale for treatment and engagement of patients; how to deal with DSs occurring in sessions; developing seizure control techniques; using graded exposure to deal with avoided activities; challenging unhelpful thoughts; dealing with trauma and facilitating emotional processing; and ending therapy.

Teaching was supplemented by Microsoft PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) slides and academic papers relating to the content of the treatment and our group’s prior work in this area. Skills specific to DSs were role-played. Three sets of workshops were held: 5–7 November 2014, 14–16 January 2015 and 14–16 October 2015. A total of 59 therapists attended these workshops. The first workshop was video-recorded in its entirety; the videos and accompanying Microsoft PowerPoint slides were edited to be viewable in manageable sections and were made available to all therapists via secure internet links as a means of reviewing the course content. This material was also made available to four additional therapists who joined later at different times during the study and for whom it was not possible to arrange full workshops. They watched the videos and had discussion sessions with the chief investigator, the lead for the intervention (Trudie Chalder) and the trial manager.

During the trial, therapists received group (and occasionally individual) supervision every 4–6 weeks. The supervisors were three senior therapists who were experienced in delivering the treatment model to patients with DSs (median experience 10 years; range 10–30 years). We expected that therapists would receive general service-related supervision in their workplace and supervision specifically related to trial patients from trial supervisors. Part of this supervision involved using recordings of therapy sessions to provide feedback to therapists and to ensure that they were adhering to the treatment model. A therapist rating scale based on the University College London CBT Competency Framework104 was used to rate one session from the initial patient for each therapist (focusing on the treatment rationale). The supervisors scored the therapists and fed back whether or not they were within the predetermined competency levels on the scale. Regular supervision allowed therapist competence and adherence to the manualised therapy to be monitored throughout the trial.

Intervention delivery

The CBT was planned to be delivered as an outpatient service at clinical centres, although occasional telephone sessions were utilised where necessary; we did not set out to evaluate the impact of telephone sessions on outcome, but telephone delivery has been shown to be feasible and effective in other disorders. 105,106 Session delivery was recorded in therapy logs. It was intended that the 12 sessions of CBT would be scheduled to occur over 4–5 months, with a further booster session being offered at approximately 9 months after randomisation. Therapists recorded and monitored attendance; reasons for rescheduling and non-attendances; disruption of therapy or injuries owing to DSs; and participants’ completion of homework and adherence to the therapeutic model on a session-by-session basis in a therapy log. We collected demographic details of those therapists who delivered the therapy. Each therapist was allocated a therapist identification number via the MACRO randomisation system (MACRO electronic data capture system, version 4, Elsevier) that was used on the therapy logs to ensure anonymity.

The treatment manual given to therapists was used as a guide, as treatment needed to be individually tailored to recognise that not all elements may be applicable to all participants and different participants may progress through the stages at different speeds or, if necessary, in a different order. The manual outlined what could potentially be covered within each session.

Completion of follow-ups

Follow-up collections of measures were conducted at 6 and 12 months post randomisation. The 6-month follow-up, undertaken to maintain participant involvement in the study and to improve data modelling, was usually conducted by post, and the 12-month follow-up was generally completed in person; a flexible approach was employed to ensure retention and ease for the participant. Efforts were made to minimise dropout rates. A large part of this was the regular contact attempted with participants throughout the trial; we also used procedures that have improved response rates when posting questionnaires, such as enclosing a personalised letter, providing a Freepost envelope for its return and using colour printing for the 6-month questionnaire packs. 107 Participants were contacted before the 6-month follow-up to inform them that packs would be arriving by post. The 12-month follow-ups were scheduled well in advance of the required time point wherever possible. Researchers also phoned participants to confirm receipt of posted questionnaire packs and to offer assistance completing the questionnaires. Participants received a £10 ‘Thank you’ shopping voucher for completing the 6-month follow-up questionnaires and a £15 shopping voucher for completing the 12-month follow-up questionnaires.

Remuneration

In addition to the ‘thank you’ shopping vouchers for completing the follow-up measures, we offered participants a maximum of £25 towards the cost of travel to the initial psychiatric assessment, towards attendance at each CBT session and towards any travel incurred in the follow-up (i.e. data collection) assessments.

Adverse event reporting and serious deterioration in health

Information regarding adverse events (AEs) that may have arisen during the intervention was collected over the entire 12 months following randomisation. If a participant indicated a change to health status, the research worker, research nurse or clinical studies officer would ask for further information to determine if the event met the criteria for an AE. Although we may have been made aware of AEs throughout participants’ time in the study, given the frequent contact with participants owing to seizure diary collection, research workers specifically asked at the 6- and 12-month follow-ups about changes in health and these were all self-reported by the participant.

An AE was defined as any health event reported by a participant that was a change from baseline but did not fulfil the criteria for a SAE. This included events where the participant consulted their GP or another medical advisor or took medication. Any AEs that were fatal, life-threatening or disabling, required hospitalisation or prolongation of hospitalisation, jeopardised the participant in a way that may result in one of the above outcomes without medical or surgical intervention or were new episodes of deliberate self-harm or suicidal ideation or a suicide attempt were classed as SAEs.

Seizures were specifically excluded from AE reporting, except where other criteria, such as hospitalisation, were met. Clinicians also reported AEs. During the treatment phase of the trial, any event reported in CBT sessions or during a SMC session was ultimately reported by the SMC doctor. This was to ensure accurate reporting, but also to maintain the blinding of the research workers and the statisticians by removing mentions of CBT. All AEs and SAEs were reported to the trial manager. They were reviewed by the chief investigator and the DMEC. The latter reviewed all SAEs in the treatment phase individually, but remotely, and they were unblinded to treatment arm after reviewing the incident.

To provide an independent assessment of AEs/SAEs in the study, we recruited three clinicians who were experienced in working with patients with DSs to review the AEs; they were initially blinded to treatment allocation. The three clinicians (two consultant neurologists and one consultant psychiatrist who had not been involved in recruiting or treating any study patients) were sent spreadsheets of accounts of entirely anonymised AEs, including information about events, the phase of the study in which these events had occurred, the body system involved and whether or not these events were DS related. They were asked to judge whether or not these met the criteria for SAEs and to rate the severity (mild, moderate or severe) of each event. For both AEs and SAEs, the raters were sent information about the treatment allocation and the initial assessment of relatedness to the intervention. They were then asked to rate the AEs/SAEs for relatedness to the treatment intervention. In undertaking the ratings, the independent clinicians were asked to consider whether or not the event met the protocol definition of ‘serious’ because, if not, the event would be classified as an AE. They were also asked to consider whether or not any SAEs needed to be upgraded to serious adverse reactions (SARs)/suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSARs) and whether or not any SARs/SUSARs needed to be downgraded to SAEs. Majority decisions were adopted with discussion if there was disagreement over the ratings of severity and relatedness.

We defined a serious deterioration in health as the occurrence of any of the following outcomes: (1) a decrease of 20 points [i.e. a drop by two standard deviations (SDs)] in the Short Form questionnaire-12 items, version 2 (SF-12v2), Physical Component Summary score between baseline and both the 6-month and the 12-month follow-up assessments; (2) participant-rated scores of ‘much worse’ or ‘very much worse’ on the CGI scale; or (3) a SAR.

Evaluation of treatment fidelity

With participants’ consent, CBT sessions were recorded using high-quality digital voice recorders and uploaded remotely onto a secure password-controlled audio-upload system housed by King’s CTU. Recordings were then deleted from the voice recorders following successful upload.

We had initially anticipated that around 15 therapists would treat the study patients. 84 Eventually, given local service differences in how therapists participated in the RCT and the overall increase in the number of participants (see Summary of changes to the project protocol), 39 CBT therapists were allocated patients in the RCT. Thus, the independent raters were asked to evaluate one session from each therapist from whom we had usable recordings (not all patients gave their consent to record sessions and some recordings were not uploaded owing to recording errors). We finally had usable recordings from 36 therapists. For each therapist, we chose one patient at random (where the therapist had treated more than one patient) and then chose, on a pseudorandom basis, one of two randomly selected sessions (the third or seventh session) to be rated by each independent rater, so that an equal number of the two sessions were assessed. Sessions were stratified according to whether they had occurred earlier or later in the trial’s progression. If the specific session was missing and at least one other patient’s recordings existed for that therapist, we looked to rate the same session from either the other patient or another randomly selected patient seen by that therapist.

Two independent and experienced CBT practitioners undertook ratings of the integrity of treatment delivery from a sample of these recordings. They were asked to rate the extent to which specific CBT skills were used in the context of working with patients with DSs; whether or not therapists adhered to the therapy, as described in the treatment manual, and were seen to be delivering CBT; and the quality of therapeutic alliance. The individual items rated for each selected therapy session are shown in Appendix 3.

An initial training session was held with the two raters, the chief investigator, the trial manager and Trudie Chalder. The raters listened to and rated a randomly selected session (not included in the main rating exercise), discussed the items and clarified their meanings with the other team members. The ratings were then piloted on four randomly selected sessions and a discussion of the ratings was held to further identify difficulties in ratings and further clarify the meaning of individual items to improve the clarity of coding rules, and achieve rating scores from each rater that fell within one scale point of each other. Further discussions were held after sets of 10 recordings to enable recalibration and to prevent rater drift; discussions were held when item scores differed by more than one scale point.

Raters were blind to the identity of the patient, the treating HCP and the trial outcome. Ratings were made independently; raters were asked to avoid using mid scores as far as possible. Scores were then converted to standardised scores out of 100. For the single-item subscales (i.e. overall therapist adherence, therapeutic alliance and overall CBT delivery), scores were calculated by dividing the score by 7 and multiplying by 100. For the specific DS skills scale (i.e. DS skill items 3–6 in Appendix 3), scores were totalled and then divided by [7 × number of relevant (‘yes’ rated) items scored] × 100 to generate standardised scores.

Summary of changes to the project protocol

At an early stage, we sought ethics approval to complete initial consents into the screening phase of the study by post or telephone if it was difficult to arrange face-to-face visits. At the 6-month follow-up assessments occurring early in the study, it became apparent that not all of the participants were willing to complete the questionnaire pack and return it by post or complete it by telephone; thus, we obtained approval to offer face-to-face data completion. Similarly, we gained approval for completion of 12-month follow-ups by post or telephone where it proved difficult to arrange a face-to-face appointment with the participant.

As the study progressed, we found that our clinical colleagues requested clarification of certain inclusion and exclusion criteria.

In particular, clinicians in the different services asked for further clarity over the length of DS freedom before patients became ineligible for the first phase of the study. We therefore changed our first inclusion criterion to indicate that the person should have been having DSs in the previous 8 weeks. In addition, it was considered more appropriate to exclude patients from the first phase of the study if it was already known that they had previously experienced a CBT-based treatment for DSs at a trial participating centre, rather than applying this criterion immediately prior to consenting to the second phase of the study. Similarly, it was considered more appropriate to exclude patients from the first phase of the study if they were known to be undergoing CBT for another condition (unless this would have finished by the time of the psychiatric assessment, when eligibility for the RCT would be considered).

Finally, we amended a previous exclusion criterion concerning the patient being thought to be at ‘imminent risk of self-harm, after (neuro)psychiatric assessment or structured psychiatric assessment by the research worker with the M.I.N.I.’; in practice, if the psychiatrist felt that the patient was at imminent risk of self-harm the patient would not be considered to be eligible and so would not be assessed on the M.I.N.I. by the research worker, so both conditions would not occur. Instead, we changed this criterion to read ‘the patient is thought to be at imminent risk of self-harm, after (neuro)psychiatric assessment or structured psychiatric assessment by the research worker with the M.I.N.I., followed by consultation with the psychiatrist’. In this way, if the patient reported a high risk of self-harm on the M.I.N.I. to the research worker, the research worker would then consult the psychiatrist about the patient’s suitability for the study.

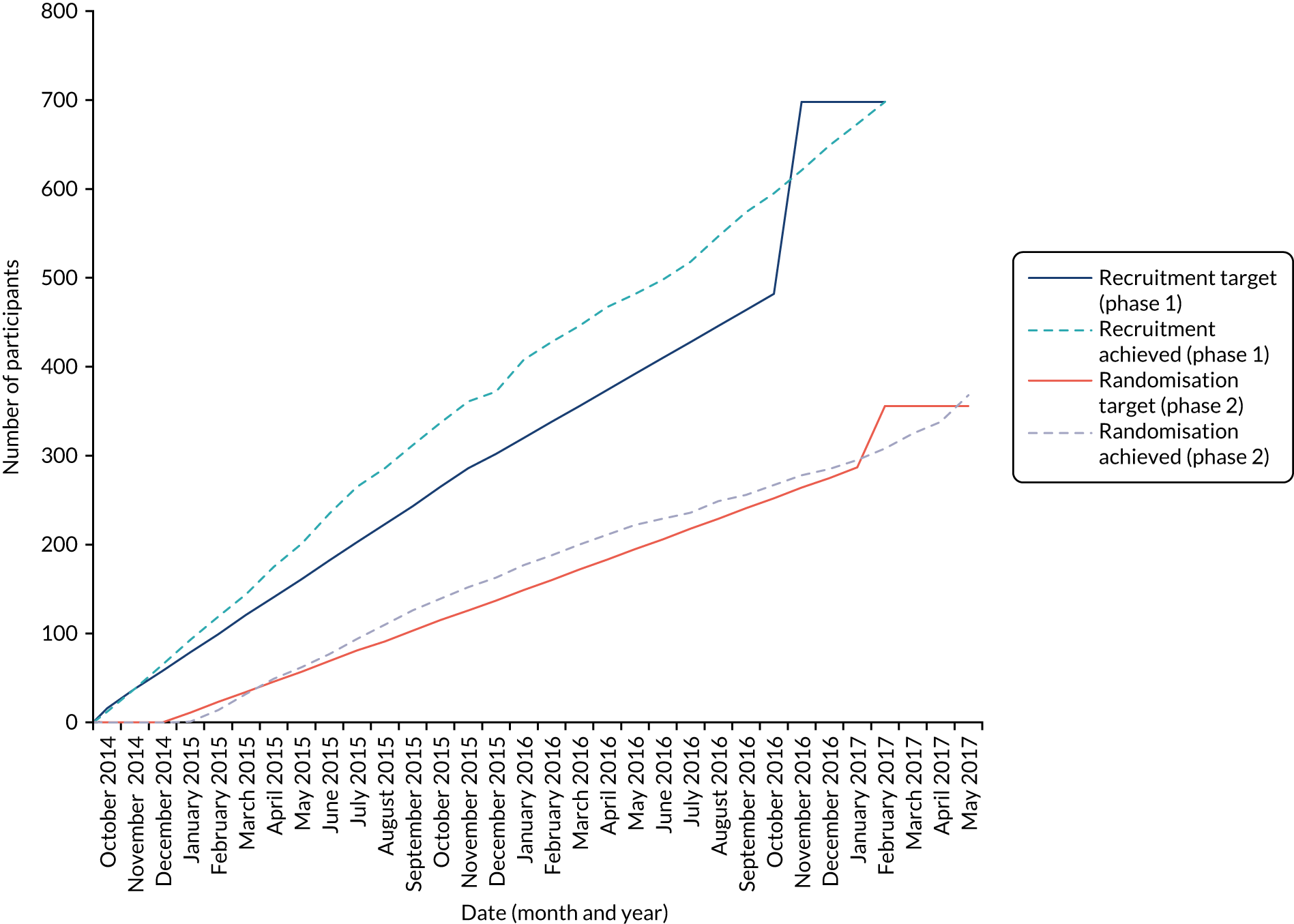

In the early stages of the 6-month follow-up data collection, it appeared that follow-up rates might be lower than estimated. We, therefore, sought HTA and ethics approval to extend our sample sizes in both stages of the study. This was also necessary because, although we had anticipated that approximately 60% of patients in the screening phase would subsequently enter the RCT, the figure consistently hovered around 51%. We gained permission to recruit 698 (rather than 501) participants into the screening phase to take into account a lower than expected rate of participants progressing from phase 1 to phase 2 (≈51% instead of ≈60%) and to randomise 356 (rather than 298) into the RCT to allow for the initially larger loss to follow-up at 6 months than expected (a conservative estimate of ≈30% rather than the expected ≈17%).

We initially intended that our nested qualitative study would focus on participants in the RCT only. With ethics approval, we extended this qualitative work to include a sample of CBT therapists delivering therapy in the RCT as well as a sample of liaison/neuropsychiatrists delivering SMC. We also obtained approval to undertake an online survey of the neurologists participating in the study.

Although we had considered obtaining Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data for not only baseline but the full post-randomisation period84 (and as suggested in our initial trial registration on ClinicalTrials.gov), we subsequently obtained ethics approval to obtain these data for baseline and for only the last 6 months of the follow-up period for practical reasons (these data are reported in Chapter 4).

Measures

Clinical and demographic information

We collected the following clinical and demographic information: date of birth, gender, ethnicity, living arrangements, marital status, dependants, attained qualifications, employment status, receipt of disability benefit, previous epilepsy diagnosis, prescription of AEDs, age at first seizure and whether or not the person had previously sought medical help for a mental health concern. Postcodes were collected from all participants to derive an Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), which provides a score that is indicative of the level of deprivation in a specific area. The separate databases for England (IMD), Scotland (Scottish IMD) and Wales (Welsh IMD) were published in different years and were based on slightly differing numbers of domains used to derive the scores. We used the versions in use at the time of the first recruitment into the study108–110 and, for consistency, we used the same versions throughout the study. We allocated IMD scores to quintiles ordered across the three databases so that the lowest quintile reflected the least deprivation.

At recruitment to the screening phase, participants rated how strongly they believed that they had been given the correct diagnosis (0 = not at all, 10 = extremely strongly). At recruitment into the intervention phase, self-report information was collected on other medical conditions with which participants were currently diagnosed, along with their treatment preference for CBT + SMC or SMC alone or whether they had no preference. In addition, expectation of the outcome of treatment was assessed by questions on how logical treatment seemed and how confident they were that the treatment would help them when considering CBT, being seen by a neurologist and being seen by a psychiatrist (see Appendix 4).

As well as demographic data, at recruitment into the intervention stage psychiatric comorbidities were assessed using a structured screening instrument (the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; M.I.N.I. v6.0)111 and a screening measure of personality [the Standardised Assessment of Personality Abbreviated Scale, Self-Report (SAPAS-SR)]. 112 We included a measure of personality in the light of accounts of personality disorder or personality clusters in people with DSs49,57 and to allow potential future examination of the effect of personality in moderating outcome.

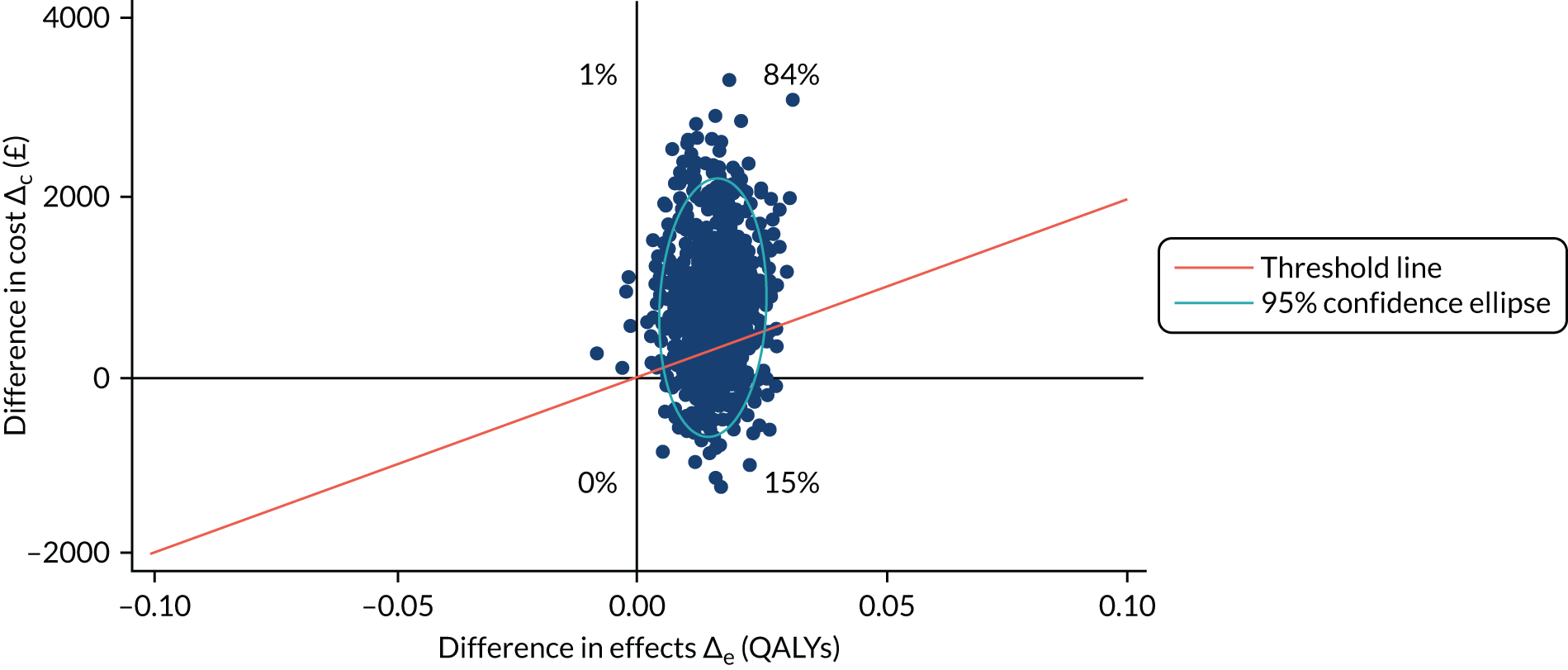

The M.I.N.I. is a commonly used, structured, psychiatric diagnostic interview and is divided into modules that correspond to diagnostic categories including major depressive episode; suicidality; manic and hypomanic episodes; panic disorder; agoraphobia; social phobia; obsessive–compulsive disorder; PTSD; alcohol dependence/abuse; substance dependence/abuse; psychotic disorders and mood disorder with psychotic features; anorexia nervosa; bulimia nervosa; generalised anxiety disorder; and antisocial personality disorder. Research staff who administered the M.I.N.I. attended a 1-day training event that was led by one of the psychiatrists in the project team (Nick Medford). In addition to didactic teaching, role plays were held. Follow-up consultations with Nick Medford were arranged to address administration/scoring difficulties.