Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/67/01. The contractual start date was in March 2013. The draft report began editorial review in April 2020 and was accepted for publication in December 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Wu et al. This work was produced by Wu et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Wu et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Cancer requiring chemotherapy is common. The National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service reported 169,000 patients receiving chemotherapy for years 2013 and 2014. 1 Although the frequency of administrations is not stated, based on data from 2009 it is likely to be approximately 500,000 chemotherapy deliveries per annum. When chemotherapy has to be administered intravenously, it can be given either through a peripheral cannula or short catheter (midline) into an arm vein or through a dedicated venous access device. These include a centrally inserted tunnelled catheters or Hickman-type devices (Hickman), peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) and centrally inserted totally implantable venous access device (PORTs). When the duration of the chemotherapy regime is over several months, these devices have the advantage that they all deliver the drug into a large high-flow central vein (superior vena cava). This avoids local problems from the irritant nature of many chemotherapeutic drugs, which can damage and rapidly occlude small peripheral arm veins and ulcerate the skin should they extravasate.

In 2012, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme released two commissioning calls to address the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of venous access devices for central delivery of chemotherapy:2 specifically, comparisons between (1) subcutaneously tunnelled central lines (i.e. Hickman) and PICCs, and (2) subcutaneously tunnelled central lines and implantable venous access PORTs. The following year, the Cancer And Venous Access (CAVA) trial was funded to address not only the two original research questions, but also the additional comparison of PICCs with PORTs.

The current decision-making processes behind device choice remain poorly understood. At the time of commissioning, Hickman were the most commonly used device in clinical practice. 3 Despite the lack of strong evidence on the relative effectiveness and safety of these devices, the use of PICCs has increased over the past decade as an alternative to the Hickman and PORTs. The reasons for this include perceived lower cost, alleged greater safety, reduced waiting times and ease of insertion (often by nursing teams) in that they do not require an operating theatre or expensive fluoroscopic imaging.

The existing evidence on the devices is heterogeneous and insufficient to inform decision-making. A systematic review evaluated the risk of infectious and non-infectious complications associated with the use of Hickman compared with PORTs. 4 Although the evidence base was heterogeneous, the overall evidence showed that Hickman were associated with greater risk complications than those of PORTs. A more recent systematic review evaluated the complications and costs of PICCs compared with those of PORTs. 5 Based on data from 15 cohort studies, the study showed an increased risk of complications, including thrombosis, occlusion, infection, malposition and accidental removal, with PICCs.

All three devices are currently used in the UK and are produced by several manufacturers. Currently, there is no prescriptive protocol as to how, where or by whom these devices should be placed. In general, clinical practice adheres to the evidence-based practice in infection control (epic) guidelines6 and the guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (clinical guideline). 7 These guidelines were both updated during the lifetime of this trial.

Aim and objectives

The aim of the CAVA trial was to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of venous access devices for the central delivery of chemotherapy.

The objectives were to determine:

-

whether or not PICCs are non-inferior to Hickman with regard to complication rates

-

whether or not PORTs are superior to Hickman with regard to complication rates

-

whether or not PORTs are superior to PICCs with regard to complication rates

-

the cost-effectiveness of Hickman, PICCs and PORTs

-

the acceptability of Hickman, PICCs and PORTs to patients and clinical staff.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

The CAVA trial was an open-label, multicentre, randomised controlled trial (RCT) to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of three routinely used central venous access devices (CVADs): centrally inserted tunnelled catheter (Hickman), PICCs and centrally inserted totally implantable venous access device (PORTs). Alongside the trial, pre- and post-trial qualitative research was also carried out to examine the acceptability of these devices to patients and clinical staff.

The trial was registered on 26 March 2013 as ISRCTN44504648 and the trial protocol was published in The Lancet. 8

Settings and locations

Initially, six recruiting sites were set up. However, during the course of the trial, a further 12 sites were included.

Original sites

-

Beatson West of Scotland Cancer Centre (BWoSCC), Glasgow (lead centre).

-

Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham, Birmingham.

-

Christie Hospital, Manchester.

-

Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne.

-

Guy’s Hospital, London.

-

St James’s University Hospital, Leeds.

Additional sites

-

University Hospital of North Durham, Durham.

-

Darlington Memorial Hospital, Darlington.

-

Northampton General Hospital, Northampton.

-

Weston Park Hospital, Sheffield.

-

Charing Cross Hospital, London.

-

Royal United Hospital, Bath.

-

Forth Valley Royal Hospital, Larbert.

-

Cumberland Infirmary, Carlisle.

-

Kent and Canterbury Hospital, Canterbury.

-

Royal Cornwall Hospital, Treliske.

-

Broomfield Hospital, Chelmsford.

-

Sunderland Royal Hospital, Sunderland.

-

Western General Hospital, Edinburgh.

Participants

All adult patients who were expected to receive chemotherapy over a long period of time to treat malignancy were eligible for enrolment if they met the following inclusion criteria:

-

aged ≥ 18 years

-

receiving or to receive anticancer intravenous therapy

-

duration of anticancer intravenous therapy of ≥ 12 weeks

-

intended duration of continuous device placement of ≥ 12 weeks with no temporary removal for surgery

-

clinical team uncertain as to which device is optimal for this indication

-

solid or haematological malignancy

-

suitable upper extremity vein for all the access devices to which the patient may be randomised

-

able to provide written informed consent.

Patients were excluded from the trial according to the following exclusion criteria:

-

life or treatment expectancy of < 3 months

-

previous venous access device removed as a result of complications within the last 2 weeks

-

patient has any evidence of active infection

-

requirement for high volume of flow rate (apheresis line)

-

requirement for catheter to be placed in a non-upper extremity vein.

Randomisation

The trial had four randomisation options for each eligible participant:

-

Hickman versus PICCs versus PORTs

-

PICCs versus Hickman

-

PORTs versus Hickman

-

PORTs versus PICCs.

This was to maximise recruitment by facilitating recruitment to the study in cases in which one device was not feasible to consider. For instance, a patient may have a strong dislike for one particular device, a patient may be considered to be unsuitable for a particular device or a particular device may be unavailable at the recruiting site. Clinicians could choose from any of the four randomisations depending on the individual patient and the practice at their individual site. Treatment allocations were obtained by contacting the Cancer Research UK (CRUK) Clinical Trials Unit (CTU), Glasgow. The three-way randomisation was initially set up with a 2 : 2 : 1 (Hickman–PICCs–PORT) ratio to over-recruit to the arms involved in the non-inferiority comparison, which required more patients. The numbers of patients assigned to each treatment arm in the three-way and two-way randomisations were monitored, with the plan to make adjustments to the three-way randomisation ratio as appropriate to ensure the required balance of arms; however, no adjustments were required. Randomisations were performed using a minimisation algorithm incorporating a random component. The stratification factors used in the minimisation were:

-

centre

-

body mass index (BMI) – < 20 kg/m2, 20 to < 30 kg/m2, 30 to < 40 kg/m2, ≥ 40 kg/m2

-

device history – patients with no prior devices fitted, patients having previously had at least one device fitted > 3 months prior to the study, patients having had devices fitted within 3 months of the study

-

type of disease – haematological malignancies, solid tumours

-

planned treatment mode – inpatient, outpatient.

Interventions

Subcutaneously tunnelled central catheter (Hickman)

Introduced in 1979, subcutaneously tunnelled central catheters are commonly known as Hickman and consist of a thin plastic tube that is inserted into a central vein in the neck or upper chest region. It is ‘tunnelled’ under the skin for a few centimetres before exiting and has a Dacron™ cuff (DuPont de Nemours, Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA) to improve stability and minimise the risk of infection. Ultrasound is used to target the vein. These catheters are inserted by a variety of specialists (nurse practitioners, interventional radiologists, anaesthetists and surgeons) but, currently, nursing experience in placement is limited. Maintenance involves regular dressing change and weekly line flushing. The cost of a Hickman lies between those of PICCs and PORTs. Removal requires simple dissection to free the Dacron cuff.

Peripherally inserted central catheters

Introduced in 1975, a PICC line is a thin plastic tube that is inserted into a peripheral vein in the upper arm. These catheters are commonly inserted by nurse practitioners, but also by interventional radiologists. Ultrasound is used to target the vein. Maintenance involves regular dressing change and weekly line flushing. It is the cheapest device to purchase and the simplest device to place. When it is no longer required, removal of the line is straightforward.

Implantable chest wall PORTs

Introduced in 1981, a chest wall port is a small, coin-sized device with a silicone membrane that is buried just under the skin in a subcutaneous pocket. It connects to a thin plastic tube similar to the other two devices. The entire device is completely implanted with nothing exiting the skin. Ultrasound is used to target the vein. The PORT has to be punctured via the skin with a special needle each time it is used. PORTs are inserted by a variety of specialists (nurse practitioners, interventional radiologists, anaesthetists and surgeons) but, currently, nursing experience in placement is limited. Given that PORTs are totally implanted, there is no dressing requirement and flushing is needed only monthly. PORTs are the most expensive of the three devices and the most complicated to insert and remove, requiring a minor surgical procedure.

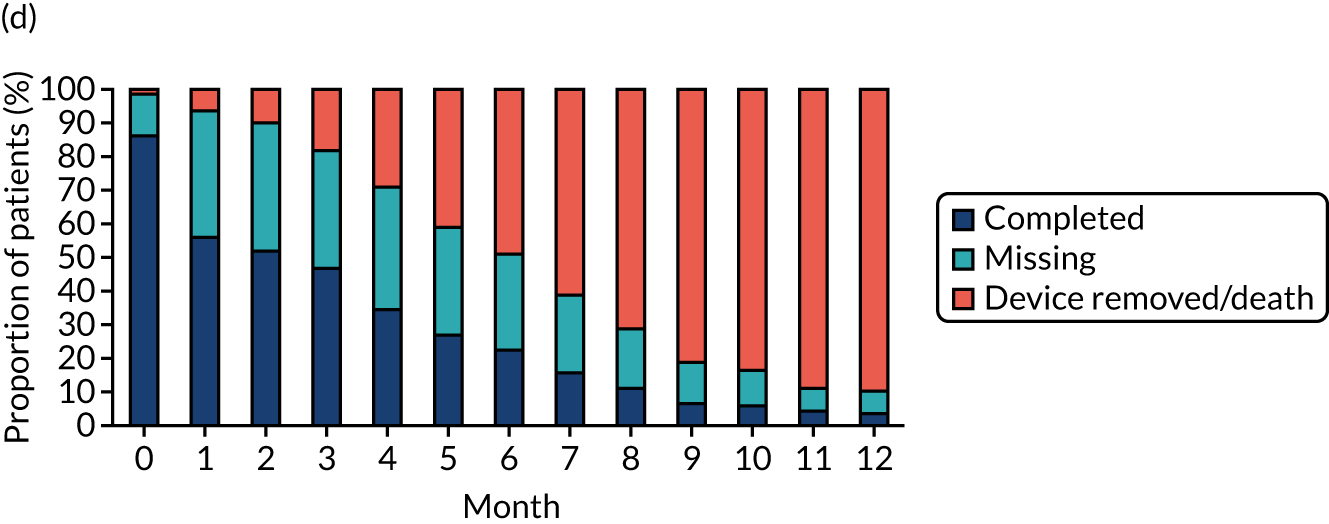

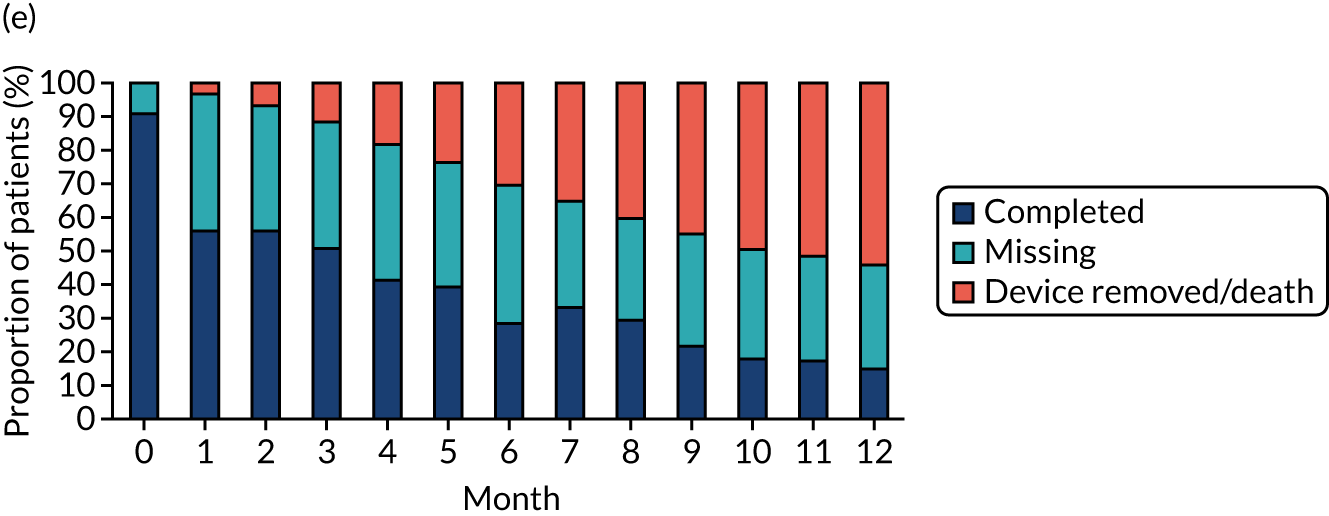

Outcomes measures

Complication and quality-of-life data were reported monthly until device removal or withdrawal up to a period of 12 months.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was complication rate, a composite of the inability to aspirate blood, infection associated with the device (suspected, confirmed or exit site), venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism related to the device, mechanical failure (line fracture, line separation from chest wall port, exposure of line cuff, exposure of chest wall PORT or breakdown of wound, chest wall port flip, line fallen out or line migration requiring intervention) and other complications.

Secondary outcome

The secondary outcome measures were:

-

Incidence of individual complications – inability to aspirate blood from the device, venous thrombosis related to the device, pulmonary embolism related to the device, laboratory-confirmed bloodstream infection, suspected catheter-related bloodstream infection, exit site infection, mechanical failure and other complications.

-

Complications per catheter-week – defined as the number of complications divided by the number of weeks that the device was in place.

-

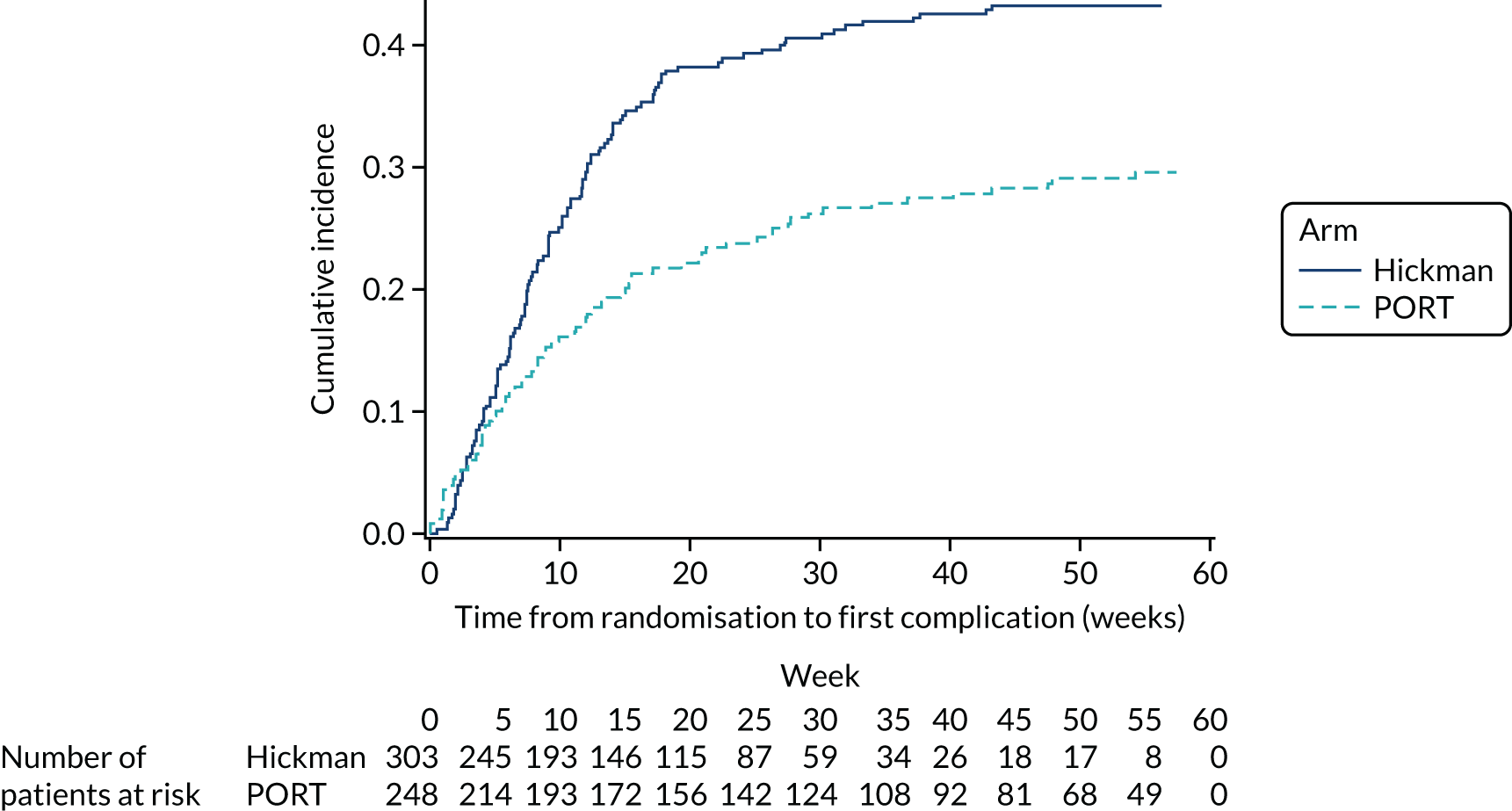

Time to first complication – defined as the time from randomisation to the first documented complication. Patients not experiencing a complication were censored at their device removal date or last available date (last chemotherapy date, last status assessment date or date of death) if the device was still in place at the end of the study.

-

Duration of chemotherapy treatment interruptions – overall and for each individual complication.

-

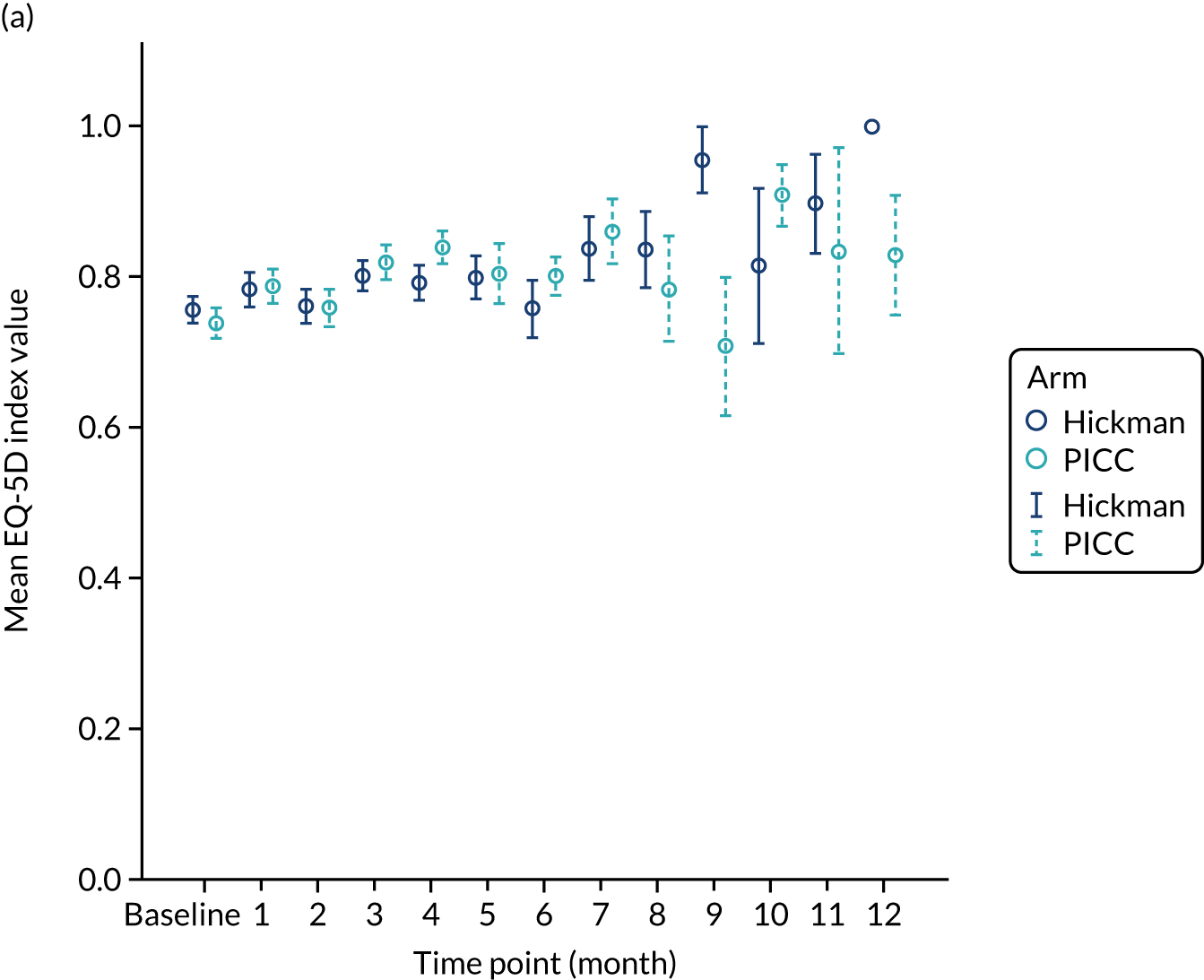

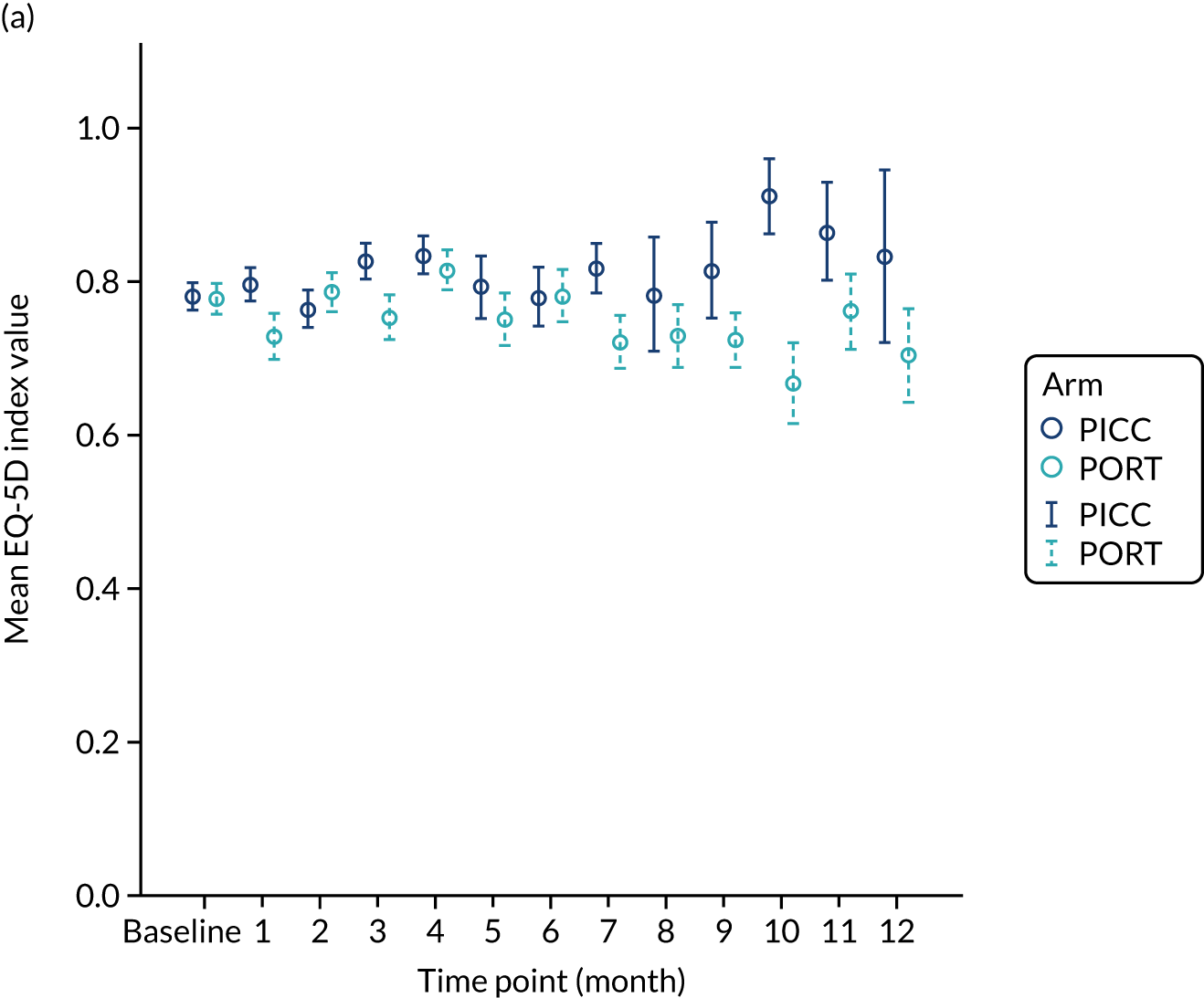

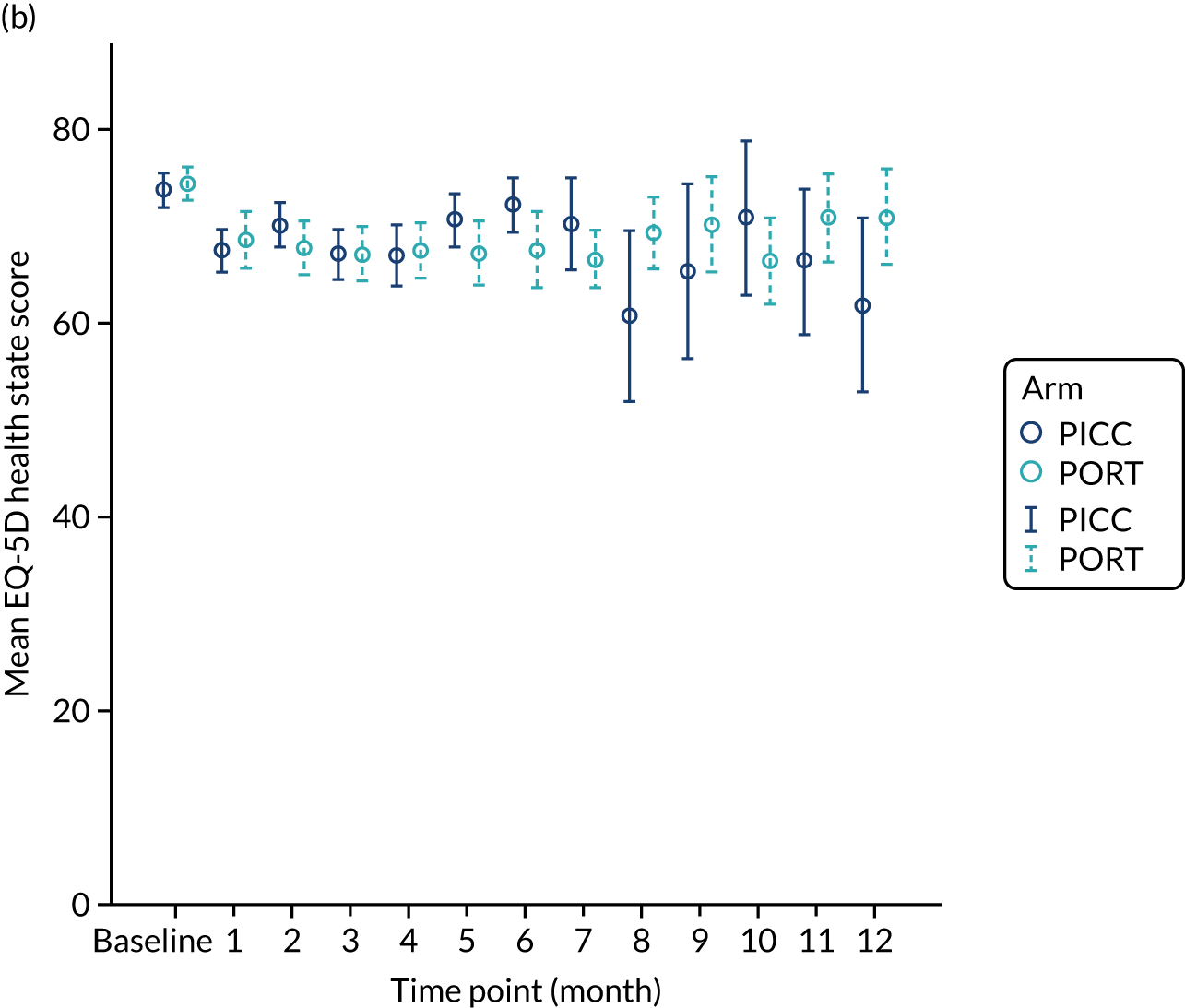

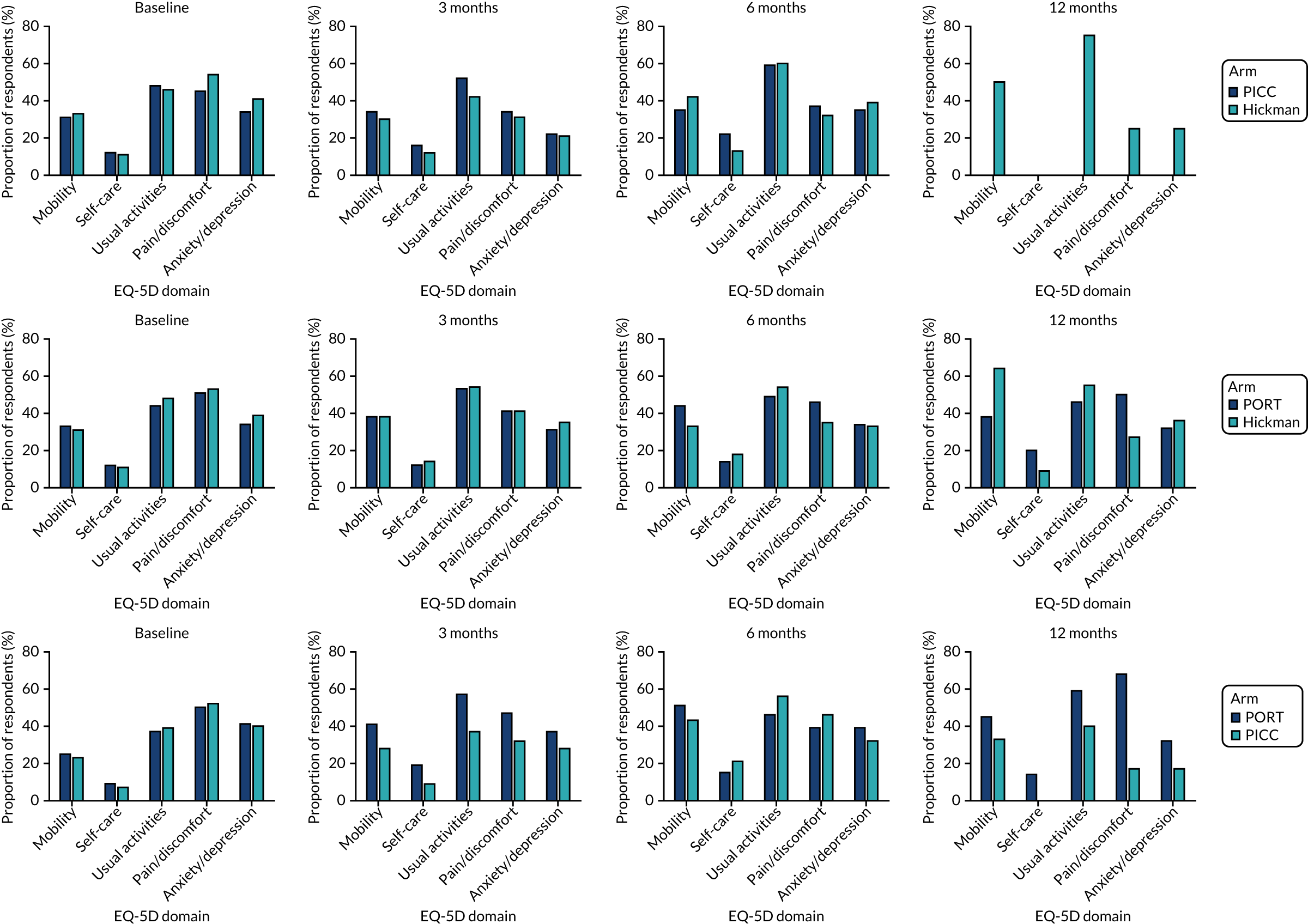

EuroQoL-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L) – a validated, generic, health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) measure comprising five dimensions (i.e. mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression). A value of 1 indicates perfect health, whereas a value of –0.594 indicates the worst health state (worse than dead). The visual analogue score for general health is reported on a scale of 0–100 (0 being the worst imaginable health state and 100 being the best).

-

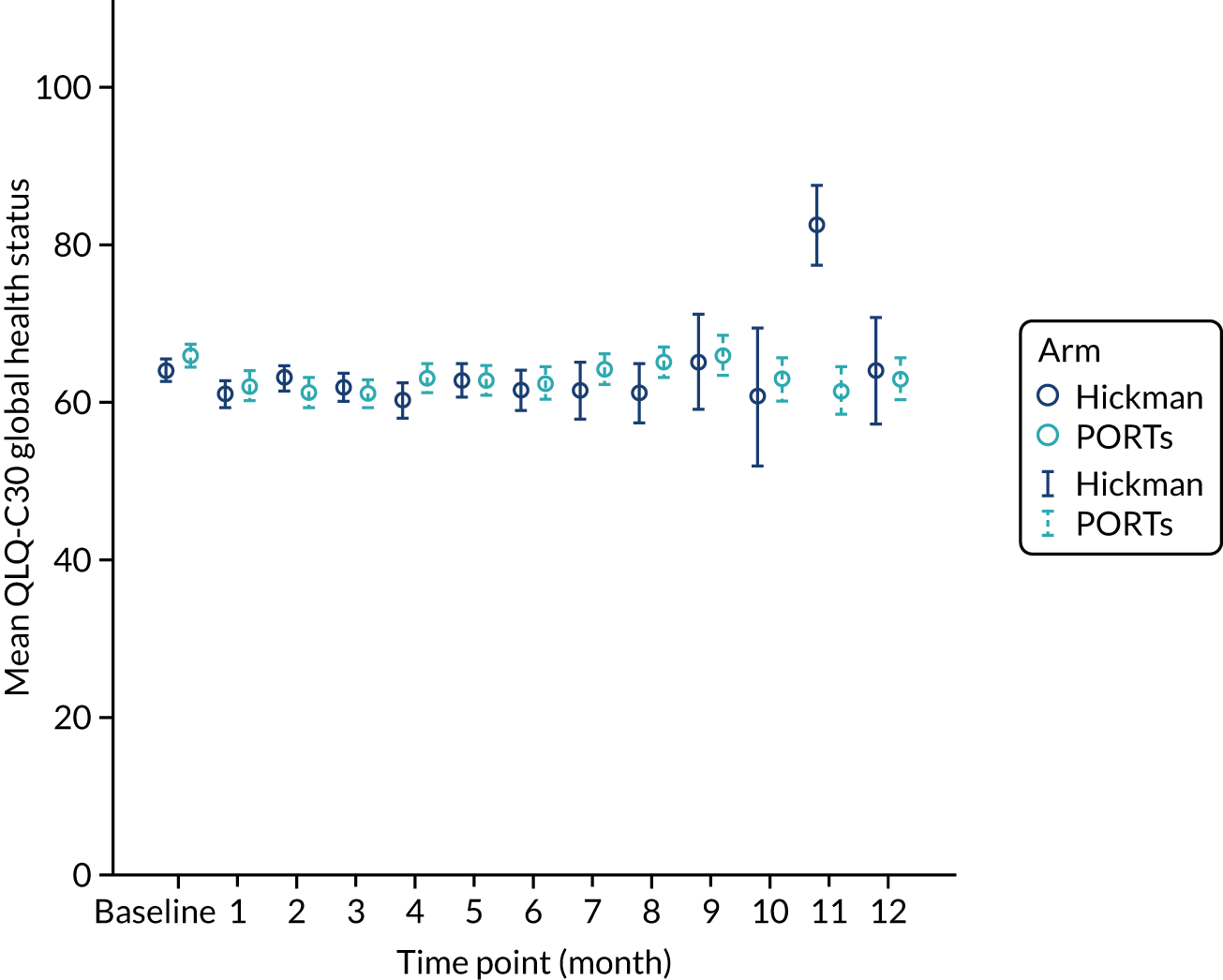

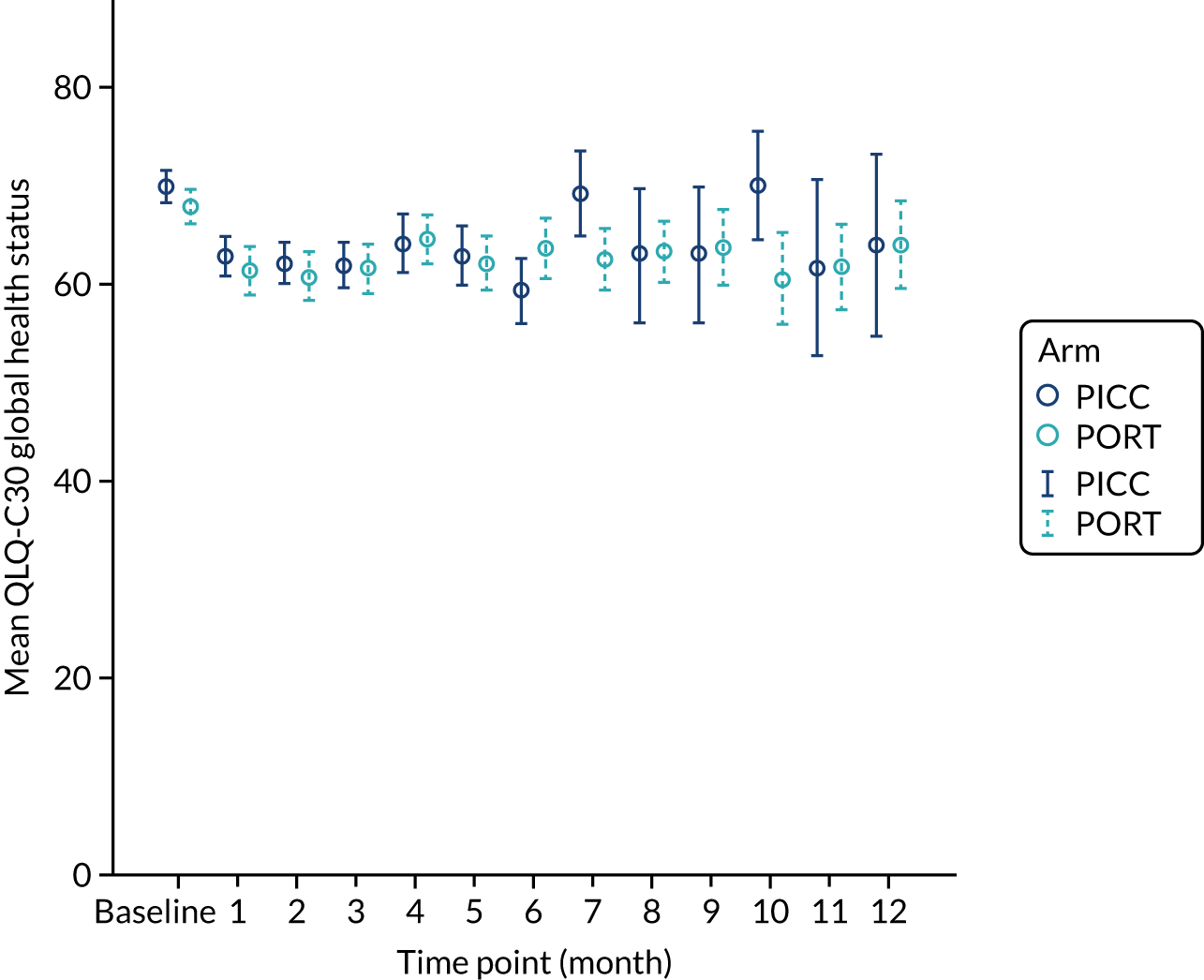

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire C30 (QLQ-C30) – comprising scores for the five functional scales (i.e. physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social), nine symptom scales (i.e. fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnoea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhoea and financial difficulties) and a global health status score, all on a scale of 0–100 (a high score represents a higher response level).

-

Venous Access Device Questionnaire (see Report Supplementary Material 1) – comprising 16 different questions (relating to continuing to drive, getting in and out of a car, using public transport, going shopping, eating, hygiene, sleeping, mobility, usual work, exercise, hobbies, feeling of self-consciousness). These items are assessed on a scale of 1–4 (not at all, a little, quite a bit, very much; as piloted in the Glasgow feasibility study). 3

Sample size

The sample size was based on the three hypotheses of interest.

Hypothesis 1: peripherally inserted central catheters are non-inferior to Hickman in terms of complication rate

Based on the assumption that the Hickman complication rate is 55%, PICCs would be considered non-inferior if their complication rate is no more than 10% higher (i.e. 65%). To rule out this difference with 80% power, and a one-sided significance level of 2.5% required 778 patients in total using a 1 : 1 randomisation.

Hypothesis 2: PORTs have a lower complication rate and are more cost-effective than Hickman

The minimum requirement here was to demonstrate that PORTs have a lower complication rate than Hickman. Based on the assumption that the Hickman complication rate is 55%, we aimed to detect at least a 15% reduction with PORTs. To detect this reduction with 95% power, and a two-sided significance level of 5% required 550 patients in total using a 1 : 1 randomisation.

Hypothesis 3: PORTs have a lower complication rate and are more cost-effective than peripherally inserted central catheters

The minimum requirement here was to demonstrate that PORTs have a lower complication rate than PICCs. Based on the assumption that the PICCs complication rate is 55%, we aimed to detect at least a 15% reduction with PORTs. To detect this reduction with 80% power, and a two-sided significance level of 5% required 341 patients in total using a 1 : 1 randomisation.

Statistical analysis

The analysis was performed separately for the three pairwise comparisons of interest. All analyses were based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, which was defined as all randomised patients, and study arms were based on the device that patients were assigned to at randomisation. Per-protocol sensitivity analyses were undertaken for the primary analysis of each comparison excluding patients who were not fitted with the device assigned at randomisation.

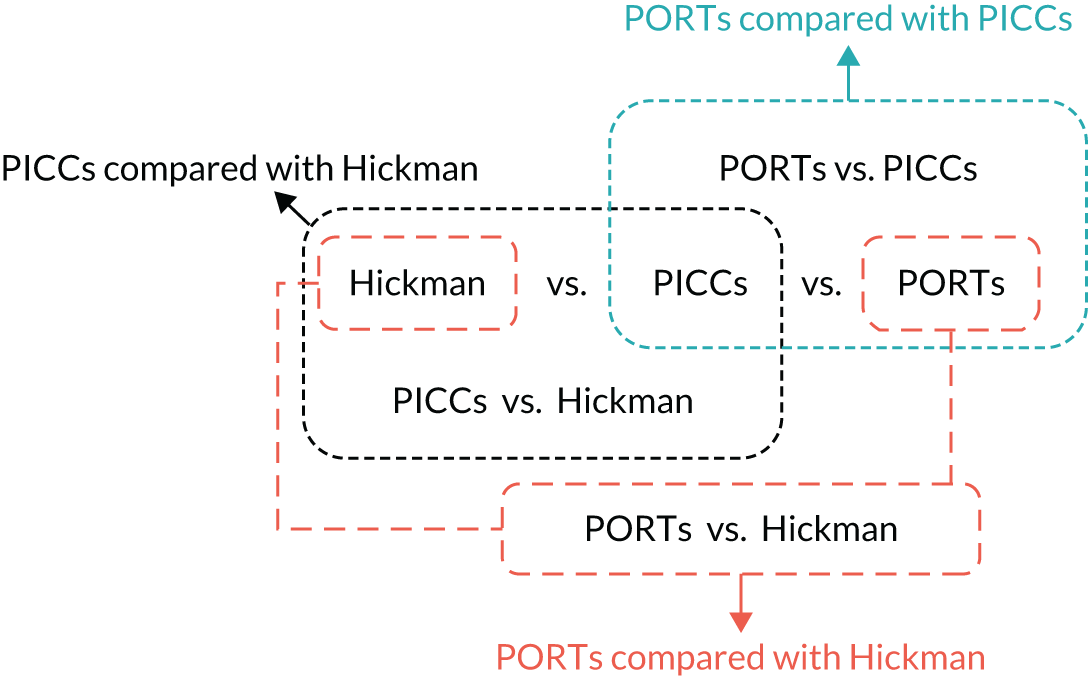

The primary outcome was complication rate. This was analysed using logistic regression, including terms for treatment arm, randomisation stratification factors and whether the data came from the relevant two-way or three-way randomisation (Figure 1). The incidence of venous thrombosis was compared using the same logistic regression approach as the primary analysis. The total durations of treatment interruptions were summarised and compared using Mann–Whitney U-tests for each complication and overall. The binary stratification factors of treatment mode and type of disease were excluded because of the small numbers of patients in one category across all comparisons (≤ 13% and ≤ 10%, respectively). BMI, device history and site were re-parameterised for the same reason. BMI was dichotomised into < 30 and ≥ 30 mg/kg2, device history was categorised as yes or no, and site retained the six sites with the highest recruitment (i.e. BWoSCC, Freeman Hospital, St James’s University Hospital, University Hospital of North Durham, Christie Hospital and Charing Cross Hospital) and combined the smaller sites into one ‘Other’ site.

FIGURE 1.

Four randomisations contributing to three comparisons.

For the PICCs versus Hickman comparison only, to judge non-inferiority in terms of an odds ratio (OR), the allowable 10% limit on the increase in complication rate (from 55% to 65%), as used in the sample size calculations, was converted to an OR. This 10% increase limit corresponds to an OR (PICCs/Hickman) limit of 1.519.

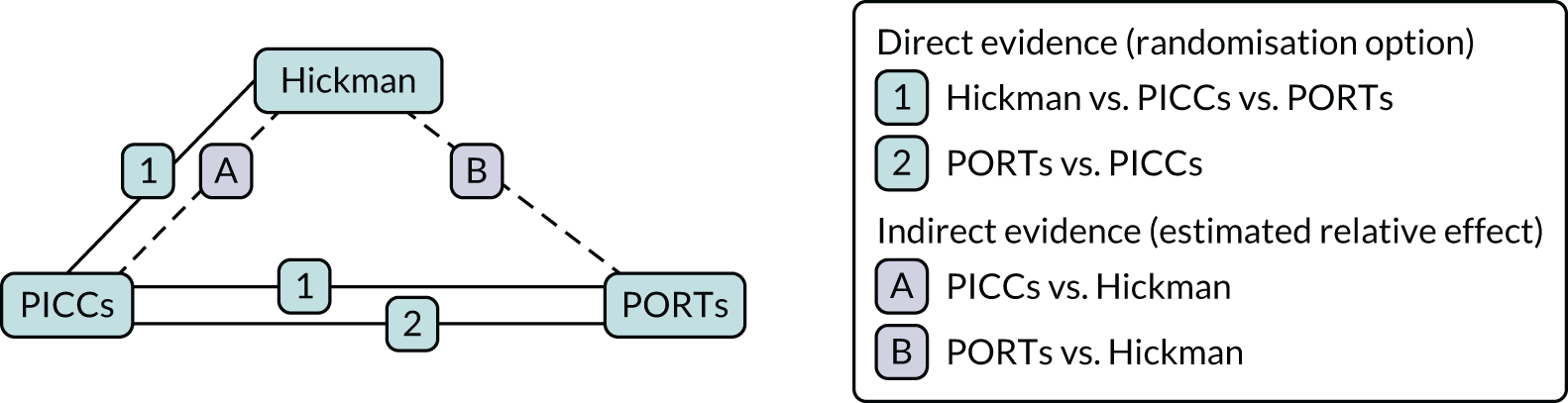

In addition, a network meta-analysis (NMA) of the four randomisation options was carried out. 9 The relative effects of each device compared with their comparator were estimated using both direct and indirect evidence, thereby generating a more precise estimate of the relative treatment effects. The direct evidence is based on the head-to-head randomisation options for each of the three comparisons. The indirect evidence was obtained omitting patients from the three-way randomisation and the final effect was estimated by augmenting the direct estimate with the indirect estimates using a fixed-effect estimates approach. The Q-statistic was used as a measure of heterogeneity between the direct and the indirect estimates to measure consistency to ensure that these could be appropriately combined for analysis. An illustration using the PORTs versus PICCs comparison is presented in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Direct and indirect evidence for estimating the effects of PORTs vs. PICCs.

Multiple imputation was applied to missing EuroQoL-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) data10 prior to calculating the index values; five imputed data sets were created. For each patient, the area under the curve (AUC) was estimated. 11 The AUCs described by the EQ-5D index score (both the original data and the imputed data) were standardised by the time spent in the study (from randomisation to device removal, withdrawal, death or a maximum of 12 months if the patient was still alive with the device in place). These standardised AUCs were adjusted by having the baseline value (value reported prior to the device being fitted) subtracted from them. These adjusted standardised AUC scores were compared between the arms; the five imputed data sets were analysed separately using the Mann–Whitney U-test before their results were combined to provide a single p-value for the difference between arms. The same approach was taken for the EQ-5D visual analogue scale for health. The resultant p-values for the individual scores were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate approach [calculated using the p. adjust function (FDR option) of the stats library in R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria); URL: www.r-project.org]. 12

The EORTC QLQ-C30 data were imputed and analysed as with the EQ-5D data, with the exception that the multiple imputation techniques were applied after the data had been scored in accordance with standard EORTC conventions. Unadjusted and adjusted p-values were obtained for the differences between arms for the five functional scales of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (i.e. physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social), nine symptom scales (i.e. fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnoea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhoea and financial difficulties) and the global health status score.

The worst responses for each question from the Venous Access Device Questionnaire were summarised and compared across arms via Mann–Whitney U-tests. The resultant p-values for the individual questions were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate approach, as with the EQ-5D data.

Changes to the study protocol

Substantial amendment 1 added the inclusion criterion of intended duration of continuous device placement of at least 12 weeks, with no temporary removal for surgery. This was in response to a site query regarding patients who have chemotherapy ahead of initial neo adjuvant surgery (if the line was expected to remain in situ during surgery then the patient was eligible and if it was expected to be removed the patient was ineligible).

Substantial amendment 2 amended the exclusion criterion for previous venous access device removal owing to complication from 3 months to 2 weeks. This was to maximise recruitment, as the 3-month exclusion was a barrier to recruitment. In addition, this amendment also added the exclusion criterion of any evidence of active infection to clarify the requirement that patients must not have an overt infection prior to study entry.

Substantial amendment 3 amended the sample size to 1300 patients following the results of the internal pilot study, which took place during the first 18 months of the recruitment period. The independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC) formally assessed the study progress against the following criteria:

-

At least 35% of the target recruitment for that time point met (individually for each of the three two-way comparisons).

-

If this milestone was not met for a particular comparison, the TSC would have considered stopping recruitment to that comparison, but this was not the case at the end of the pilot period.

Other amendments

-

In the protocol, the definition of the primary end point was a composite of infection associated with the device (suspected or confirmed) and/or mechanical failure only. This was amended as more complications were specified as the study developed. It was an error that the protocol was not updated accordingly.

-

The protocol incorrectly stated that the power for the PICCs versus Hickman comparison was intended to be 90%; this should have been corrected to state 80%.

-

An analysis was planned based on complication event rate data13 to estimate the relative effect of the devices on infections (laboratory-confirmed, suspected catheter related and exit site infections) versus non-infections (all other complications combined) to allow an assessment of the similarity of these effects over time via a likelihood ratio test. The test was to be conducted by comparing the likelihood of a standard joint frailty model [modelling complication (no distinction of type) and device removal rates simultaneously] with the likelihood of a multivariate joint frailty model [modelling the two complication types (infection and non-infection) and device removal rates simultaneously]. Unfortunately, no software could be found to apply the multivariate joint frailty model successfully to the CAVA trial data and the analysis was abandoned.

Economic evaluation

In line with the aim of the overall trial, to address the questions of the original NIHR commissioning brief, the objectives of the economic evaluation were to determine the cost-effectiveness of:

-

PICCs compared with Hickman

-

PORTs compared with Hickman

-

PORTs compared with PICCs.

An economic evaluation was undertaken from the perspective of the UK NHS. A within-trial analysis was conducted over the time horizon of 1 year (i.e. from randomisation to the end of CAVA trial follow-up period) to evaluate the three comparisons. Costs and outcomes were not discounted.

Resource use and costs

All health-care resource use data were collected by a research nurse involved in the delivery of care to patients in the CAVA trial. These include:

-

Procedure details relating to device insertion – staffing team (nurse, radiographer, anaesthesiologist, radiologist, doctor and surgeon), setting (theatre, treatment room, radiology department and bedside), type of anaesthesia and type of imaging. These components formed the basis of the intervention costs.

-

Device removal – device removal for any reason during the trial period.

-

Health-care resource use during follow-up period – number of admissions and length of stay, and outpatient visits. These were recorded monthly during the trial and formed the basis of the non-intervention costs.

Unit costs were based on national sources (Table 1). Where costs were not routinely available, resource use and unit costs were estimated through consultation with clinical experts. All unit costs were presented in Great British pounds for the price year 2017/18.

The total cost per patient was calculated by attaching relevant unit costs to the resource use data. In addition to the cost of the device, the cost associated with device insertion was calculated. This included the cost of the primary operator and any additional staff required for insertion, setting, imaging, anaesthesia and use of prophylactic antibiotics. Unit costs associated with staff and setting were applied to the time taken for device insertion based on data recorded within the trial. Similarly, unit costs for imaging, anaesthesia and the use of prophylactic antibiotics were applied to resource use data from the trial. The cost of device removal took into account staff time required to perform the procedure. The time required to remove each device was obtained from two separate clinical experts. Unplanned follow-up costs, including inpatient stays in hospital and outpatient visits recorded following device insertion (which were not part of the patient’s ongoing chemotherapy care), were collected. For the purposes of the analysis, device insertion costs (the device itself and device insertion costs) and unplanned follow-up costs (inpatient stay, outpatient visits, device removal and replacement costs) were also estimated alongside total costs.

| Resource | Unit | Unit cost (£) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Device cost | |||

| Hickman | Per device | 165 | Manufacturer (Vygon SA, Écouen, France) |

| PICC | Per device | 120 | Manufacturer (Vygon) |

| PORT | Per device | 340 | Manufacturer (Vygon) |

| Staff | |||

| Nurse | Per working hour | 55 | PSSRU 201914 |

| Radiographer | Per working hour | 109 | PSSRU 201914 |

| Anaesthesiologist | Per working hour | 109 | PSSRU 201914 |

| Radiologist | Per working hour | 109 | PSSRU 201914 |

| Doctor | Per working hour | 109 | PSSRU 201914 |

| Setting | |||

| Theatre | Per procedure | 571 | Walker and Todd15 |

| Treatment room | Per procedure | 286 | Expert clinical opinion |

| Radiology department | Per procedure | 571 | Walker and Todd15 |

| Beside | Per procedure | 14 | Expert clinical opinion |

| Imaging | |||

| Ultrasound | Per procedure | 168 | NHS Reference Costs (2017/18)16 |

| Fluoroscopy | Per procedure | 33 | NHS Reference Costs (2017/18)16 |

| Sherlock tracking | Per procedure | 60 | Taxbro et al. 202017 |

| X-ray | Per procedure | 11 | NHS Reference Costs (2017/18)16 |

| Anaesthesia | |||

| Local only | Per procedure | 11 | Calvert et al.18 |

| General anaesthesia | Per procedure | 35 | Calvert et al.18 |

| Other | |||

| Prophylactic antibiotics | Per procedure | 1.18 | Taxbro et al. 202017 |

| Device removal | |||

| Hickman | Per procedure | 483 | Expert clinical opiniona |

| PICC | Per procedure | 14 | Expert clinical opinionb |

| PORT | Per procedure | 501 | Expert clinical opinionc |

| Device replacement | |||

| Hickman | 1052 | Estimated from the CAVA trial data | |

| PICC | 484 | Estimated from the CAVA trial data | |

| PORT | 1135 | Estimated from the CAVA trial data | |

| Complications | |||

| Inpatient stay | Per day | 969 | ISD Scotland19 |

| Outpatient visit | Per visit | 136 | NHS Reference Costs (2017/18)16 |

Health-related quality of life

In accordance with NICE guidance on estimating cost-effectiveness,20 health outcomes were expressed as quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained. Data on HRQoL were collected using the EQ-5D-3L at baseline, and monthly thereafter until device removal, death or the end of follow-up at 12 months. The EQ-5D-3L assesses five health domains (i.e. mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression) according to three levels (i.e. no problems, some problems and extreme difficulty). Responses to EQ-5D-3L were converted into a single global measure of health utility for each time point. 21 For patients who had the device removed within the trial period, we did not collect data subsequent to device removal. Therefore, we estimated the quality-adjusted time spent on device per patient as a proxy for QALY gained. A baseline-adjusted AUC approach was used to estimate the QALYs gained in the trial, while adjusting for the life-years gained by the HRQoL experienced over the study period. 22

Missing data

Resource use data comprised data on inpatient stays and outpatient visits during the follow-up period. It was assumed that where a patient had no record of outpatient visits or inpatient admissions during the follow-up period, none had taken place. Therefore, we included resource use data only where they were reported and did not impute for missing resource use data.

Multiple imputation by chained equations was used to impute missing EQ-5D health–utility values. 23 For patients with missing values, health–utility values from all other available time points were used to predict missing values,24 while adjusting for the trial stratification factors (age, sex, BMI, device history and treatment arm).

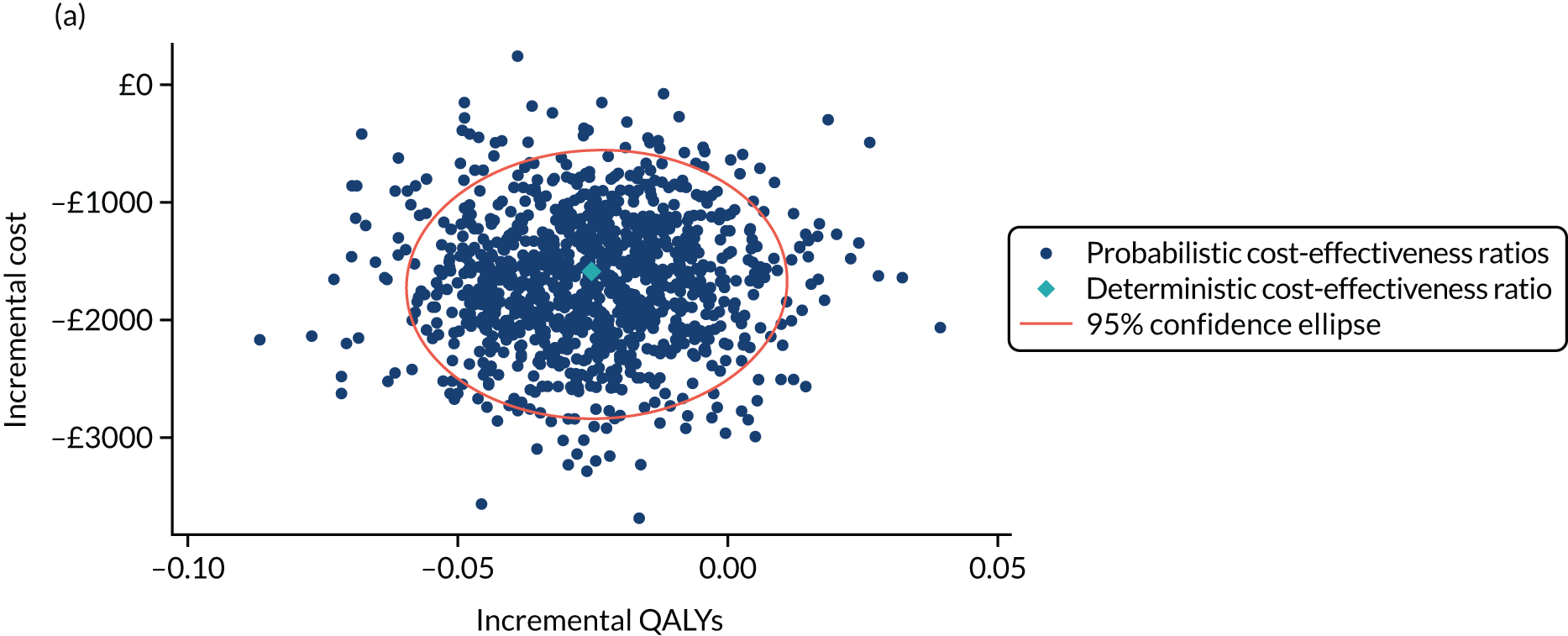

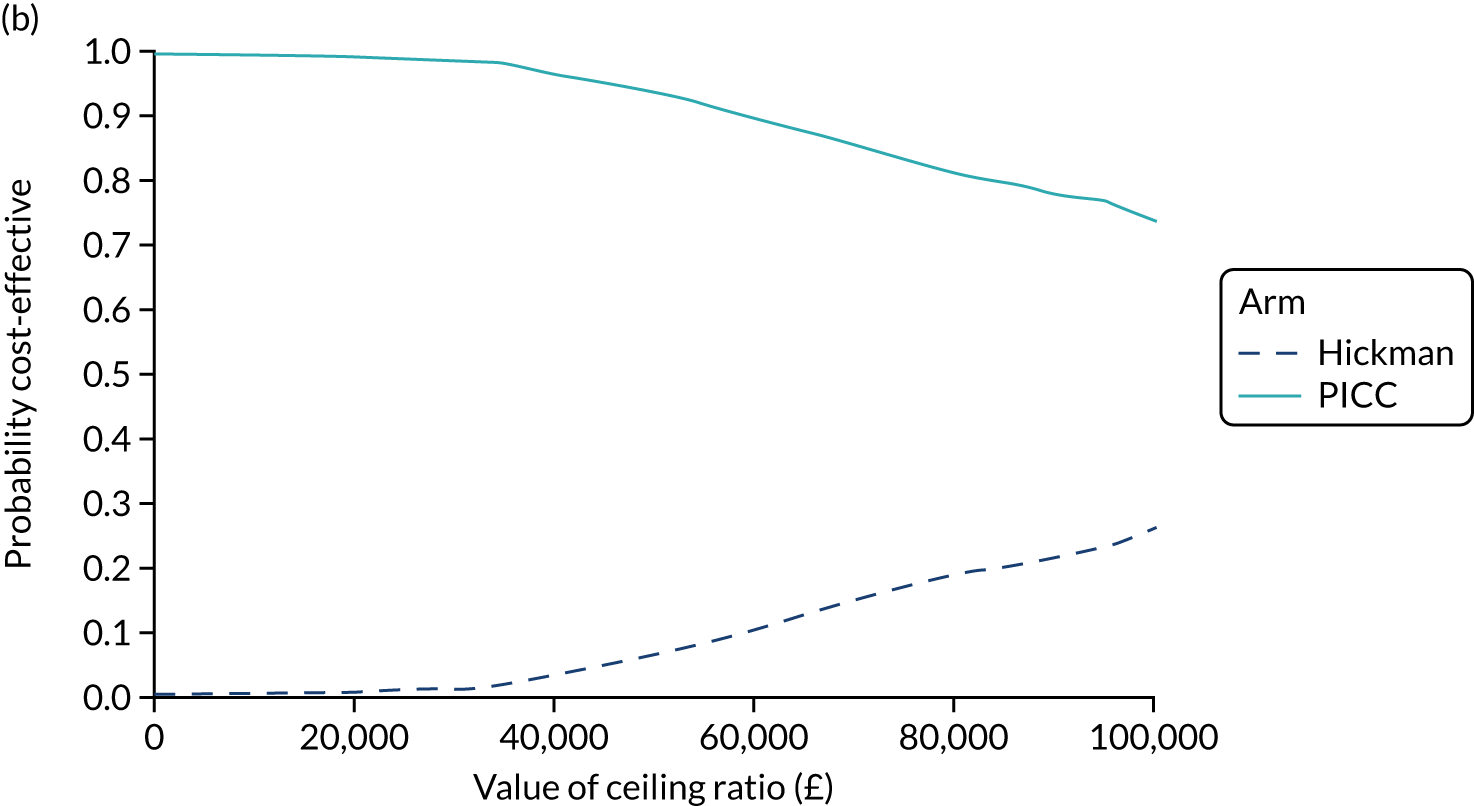

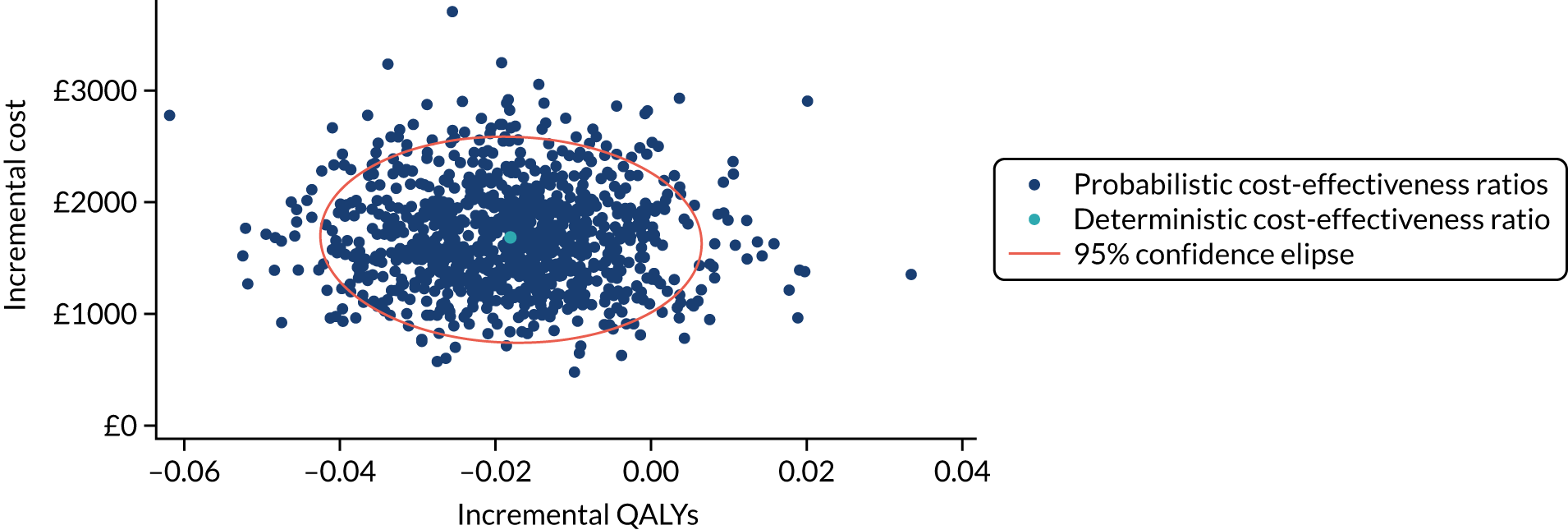

Cost-effectiveness analysis

The cost-effectiveness analysis was based on the imputed ITT patient population. The mean total costs and QALYs were estimated by fitting generalised linear models to the data and adjusting for age, sex, BMI, device history, treatment arm and baseline EQ-5D (QALY estimates only). The appropriate family for the generalised linear model was selected based on the results of the modified Park’s test. The final cost model was based on the log-link and gamma family; the final QALY model was based on the identity link and Gauss family. Based on the estimation of the final statistical model, the total cost and QALY difference between arms were based on the marginal prediction. All cost and QALY calculations were conducted in Stata® 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Non-parametric bootstrapping was used to explore uncertainty in our estimates of mean cost and QALYs and to describe how this uncertainty affects the model outcomes. A 1000-iteration bootstrap was undertaken to estimate the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for mean cost and QALYs for each device. The resultant distribution of mean costs and QALYs was then presented graphically on the cost-effectiveness plane.

Where appropriate, cost-effectiveness was expressed as incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs), calculated as the difference between devices in mean total costs divided by mean total QALYs. In addition, cost-effectiveness was also expressed as net monetary benefit (NMB) based on a willingness-to-pay threshold of £20,000. The NMB is a measure of the health benefit, expressed in monetary terms:

where E = effectiveness, WTP = willingness-to-pay threshold and C = cost.

When comparing two devices, a positive incremental NMB indicates that the device of interest is cost-effective compared with the alternative. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves were used to present the uncertainty in the decision regarding the most cost-effective option over a variety of monetary willingness-to-pay thresholds.

Sensitivity and scenario analyses

Several sensitivity and scenario analyses were undertaken to test the robustness of the cost-effectiveness estimates. These included:

-

Exploring the results at 3 and 6 months. There have been suggestions from the literature and from clinical practice that device-related complications typically occur within the first 6 months of device placement. The time to first complication was also investigated in the CAVA trial. A sensitivity analysis was conducted by restricting the analysis to 3 and 6 months of follow-up.

-

Exploring the results of patients with solid tumours only. The CAVA trial population included patients with solid tumours and haematological malignancies. There have been suggestions from the literature and from clinical practice that these patients are managed differently. This has also been reflected by the small number of patients with haematological malignancies being recruited into the trial. A sensitivity analysis was carried out by restricting the analysis to patients with solid tumours only.

-

Exploring a nurse-led model of care. There are variations across clinical practice in how care is provided for patients requiring venous access devices for chemotherapy, specifically with regard to device implantation, removal and replacement of PORTs. Where Hickman or PORTs devices are required, these are typically inserted in a theatre or radiology department by a radiologist. The associated resource requirements are greater than those for a PICC device. Furthermore, waiting times for theatre space and radiologist availability may also increase the time taken to start a patient on treatment. Personal communication with clinicians currently involved in the routine insertion of PORTs suggested that this procedure can be performed by a nurse-led service. A sensitivity analysis was carried out to examine this scenario. For such a nurse-led service, we assumed that three nurses would be required and that the procedure was undertaken in a treatment room (instead of in an ‘air handled’ room). We also included the cost of regular device maintenance required for Hickman and PICCs, delivered by a nurse in the community, which is currently standard practice but was not captured within the clinical trial. This involved a 30-minute visit per week from a district nurse.

Pre-trial qualitative study

The pre-trial qualitative study was carried out to explore patient and staff views about participation in a RCT, with the aim of maximising recruitment to the CAVA trial.

Sampling and recruitment

Following ethics approval of the study protocol, patients were approached in chemotherapy clinics and day care units and were invited to participate in the study. A patient information leaflet was sent out by post or handed out to interested patients. The research team followed up the initial contact with a telephone call to discuss any queries and to recruit participants. Initial plans to hold one focus group of 10 patients were modified when recruitment proved more difficult than anticipated. Barriers to recruitment included ill health, treatment schedules, travel issues, work commitments and a reluctance to join a group discussion. Therefore, following consultation with the CAVA project management group, the decision was taken to carry out three separate focus groups. A convenience sample of nine patients receiving treatment for cancer at the lead centre (BWoSCC, Glasgow) took part in three separate focus groups, each with three participants. Four male and five female patients participated. Participants’ ages ranged from 48 to 66 years. All participants had solid tumours, including two with metastatic disease. Three participants had experience of an implanted PORT, three participants had experience of a PICC line and two participants had experience of a tunnelled cuffed central catheter. One participant had experience of both a PICC and a tunnelled cuffed central catheter. Four participants had previously participated in a RCT.

Clinical staff were also invited to be interviewed because it was anticipated that there would be variations in attitudes regarding equipoise across specialties and roles, and differences in local practice, which may act as facilitators of and barriers to randomisation. One-to-one, semistructured interviews were conducted with 23 clinical staff (five nurse managers, four research nurses, four oncologists, six interventional radiologists, three haematologists and one anaesthetist) from six different centres (BWoSCC, Glasgow; Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham, Birmingham; St James’s University Hospital, Leeds; Christie Hospital, Manchester; Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne; University Hospital of North Durham, Durham). The research team made initial contact with the relevant individuals via the local principal investigator at each site and clinical staff information sheets were e-mailed to potential participants.

Procedure

Focus groups with patients took place in a private room at the lead centre and were facilitated by one of the authors (MS), who has received considerable training in qualitative research methodology and has a master of laws (medical law and health-care ethics), as well as a background in nursing. The moderator, who had no prior relationship with the participants, was accompanied by an assistant, but no one else was present during data collection. Signed consent to participation and to audio-recording of the discussion was obtained. A focus group guide was used (see Report Supplementary Material 2), which encompassed questions on participants’ attitudes, experiences and preferences relating to the three devices, and on participants’ understanding of the study design and willingness to participate in a randomised trial of the three devices. Learning aids included laminated photographs of the devices in situ, copies of the patient information sheet (PIS) for the trial and a demonstration of the three devices. Focus groups lasted approximately 1 hour and were digitally recorded.

The same qualitative researcher visited each centre to interview staff. Written consent to participation and to audio-recording of the interview was obtained prior to participation. A semistructured interview guide was used (see Report Supplementary Material 3) that aimed to elicit information on perceived barriers to and facilitators of recruitment, as well as the attitudes to the three devices and to RCTs. Feedback was obtained on trial materials including PISs and consent forms. All interviews were digitally recorded.

Analysis

All recordings, along with field notes taken during data collection, were transcribed verbatim, anonymised and thematically analysed. 25 The QSR NVivo10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) software program was used to facilitate data analysis. First, initial codes were identified, based on careful reading and re-reading of the data by two members of the research team independently. Second, these codes were sorted into potential themes. Finally, the themes were refined through repeated investigation of both similar and anomalous examples.

Post-trial qualitative study

The post-trial qualitative study sought to examine patient and staff acceptability of the three devices, as well as experiences of trial participation.

Sampling and recruitment

Forty-two patients enrolled in the CAVA trial participated in eight focus groups. Participants were purposively sampled from the CAVA trial’s six largest recruitment centres: BWoSCC, Glasgow; St James’s Hospital, Leeds; Christie Hospital, Manchester; Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne; University Hospital of North Durham, Durham; and Hammersmith Hospital, London. Three further participants who had agreed to participate were too unwell to attend, one each at Leeds, Durham and London. To include a range of perspectives and experiences, participants at each site were chosen for maximum variation in terms of age, sex, cancer diagnosis and device allocation, as well as positive and negative clinical experiences with CVADs. Eligible participants were initially contacted by local trial nurses with whom they had prior contact and who provided information sheets in person or by mail.

Originally, six focus groups (one at each centre) comprising participants with a mix of all three CAVA trial devices was planned. This plan was amended for two reasons. First, one site (Christie Hospital) had ceased recruitment at the time of focus group planning and only participants with PORT devices remained on the trial. Second, it was felt that, although mixed-device groups would be well suited to comparisons between devices, single-device groups could offer greater insight into attitudes and experiences of each device. The design was amended to include four large mixed-device groups (4–11 participants) and four smaller single-device groups (two PORTs only, one Hickman only, one PICC only; two or three participants). The two additional groups were sampled at the trial’s Glasgow site, which had higher recruitment rates than the other sites.

Clinical staff (nurses, oncologists, radiologists and anaesthetists) from each of the trial’s centres were contacted via e-mail by the research team, provided with copies of the information sheet and invited to be interviewed. The decision was made to also invite trial staff from non-clinical research backgrounds to take part, as it was felt that these staff could offer useful insights, particularly regarding the organisational and administrative aspects of the trial. Twenty-six one-to-one semistructured interviews with clinical staff from 13 centres were carried out.

Procedure

Focus groups took place on site at six CAVA trial centres in quiet meeting rooms and were moderated by one of the authors (CR), a female psychologist (PhD; Doctor of Philosophy) and an experienced qualitative researcher who had no prior relationship with the participants. A trial nurse attended part of one focus group (Leeds) to address patient queries; otherwise no other persons were present. Prior to each session, details about data collection, analysis and use were discussed, and written informed consent was obtained. The moderator started by explaining her own background and role in the trial. She then reminded participants about the purpose of the broader trial and current focus group, using A4 cards depicting each device type and reiterating current clinical equipoise. A focus group guide was used to ensure that all relevant topics would be addressed (see Report Supplementary Material 2). Topics included CAVA trial participation and day-to-day experiences relating to their device. To create a communication situation resembling a naturally occurring interaction, interference with the discussion was kept to a minimum. Focus group discussions lasted approximately 1 hour and were audio-recorded with participants’ permission. To assist with transcription and analysis, relevant field notes were compiled after each focus group.

Interviews with staff took place in person or by telephone by the same researcher. Face-to-face interviews took place in interviewees’ offices or in quiet rooms on site. As above, a semistructured interview guide was used to facilitate data collection (see Report Supplementary Material 3). Topics covered included the interviewee’s knowledge, experiences and opinions regarding the use of CVADs in the context of anticancer treatment, as well as their experience of participating in the CAVA trial. Interviews lasted, on average, 30 minutes and were audio-recorded using a digital voice recorder.

Analysis

All recordings, along with field notes taken during data collection, were transcribed verbatim, anonymised and uploaded to the QSR NVivo 10 qualitative software program. Data were analysed using thematic analysis, ‘a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data’. 25 Transcripts were read and re-read to ensure familiarity. A coding framework was developed based on patterns and repeated topics identified in the data. Data were coded, and coded chunks of data were grouped into initial themes. These processes were conducted by a single researcher in the first instance and reviewed by two further researchers at different stages. Data were then re-read and the appropriateness of themes interrogated. Particular attention was paid to similarities and differences across device types, and to discrepancies between developed themes and the data. As a final step, the specifics of each theme were refined, and clear definitions for each theme were formulated.

Chapter 3 Pre-trial qualitative results

The difficulties associated with recruitment, especially in multicentre RCTs, have been well documented. 26,27 Qualitative research methods have been shown to be successful in increasing rates of randomisation in RCTs, especially when undertaken at the feasibility stage of a trial or fully integrated into the design of the RCT. 28–30 The CAVA pre-trial qualitative study was informed by the Glasgow feasibility study and incorporated into the design of the Phase III study from conception. 31 The primary goal of the study was to explore patient and staff views about participation in the CAVA trial, with the aim of maximising recruitment.

Focus groups with patients

Four main themes were identified from the analysis of the focus group discussions with the patients: (1) taking part in RCTs, (2) views on randomisation, (3) study documentation and (4) familiarity with the devices. Each is discussed in turn below.

Taking part in randomised controlled trials

All participants were in favour of patients being invited to participate in clinical research. Factors influencing this were both self-benefiting and altruistic, while including an appreciation of the serious nature of cancer, a desire to help future patients and an understanding that progress and current practice is based on the results of previous clinical trials, together with a hope of being randomised to a device not currently available outside the study. As one of the participants said:

Well I think it is, because had I not taken part in the first clinical trial, then I wouldn’t be still here. It’s as simple as that. I think that clinical trials are absolutely essential.

Female, Hickman, prior experience of a RCT

Similarly, another patient with no previous experience of RCTs said:

I think for future care as well, em, the experiences of patients now helps to form better care for people coming along, you know, kind of after us if you like.

Female, PICC, no prior experience of a RCT

Views on randomisation

All patients expressed an understanding of the process and reasons for randomisation. The majority either had participated in or would be prepared to participate in a RCT, acknowledging that this is an informed decision. Yet, despite professing to understand the concept of RCTs, participants’ comments indicated a degree of confusion over common trial terms (e.g. ‘trial’ was equated with ‘experiment’ and ‘treatment arm’ with ‘chemotherapy regime’). One patient considered that there should be a degree of patient choice in device allocation, assuming that this would not affect the numbers required to be allocated to each device:

I think it’s an informed choice, you know, If you are prepared to go ahead with the trial, it is made very clear to you, you know, it is randomised, you’ve got a chance of having, you know, one of the three and if you’re happy with that then, you know, yeh, go ahead.

Female, PICC, no prior experience of a RCT

Other factors influencing this decision were the severity of illness and whether or not participation would have an impact on other issues, such as treatment schedules:

If I chose the Hickman or the PORT, it would delay my next chemotherapy by a week. And my last chemotherapy finished on my birthday and I was determined to get to that last one on that day.

Female, PICC, no prior experience of a RCT

Certain patients, however, stated that they would not want to take part in a randomised trial of the three devices, as they wished to retain an element of choice in relation to line type:

I can understand why you want to do it, ehm . . . but eh, I know that given the choice I wouldn’t want to be randomly selected for a Hickman line or one that is implanted . . .

Male, PICC, no prior experience of a RCT

Study documentation

Comments on the language used in the PIS varied between ‘straightforward’ and ‘jargon free’ and, by contrast, ‘patronising’. Similarly, views on the length of the PIS also varied. Although several participants were not concerned about the length of the information sheet, considering that this would be what was expected, other views were that it was too long and would be overwhelming for patients. One participant, in particular, felt strongly that the design and layout of the PIS could be significantly improved. He considered that, initially, patients should be provided with a summary sheet, that is, the ‘technical specification’. The opportunity to find out further information should then be in the form of frequently asked questions. This could also be supplemented by links to a website (that could be accessed while attending for treatment). The longer document could be retained for reference.

Familiarity with the devices

Patients were not neutral in their stance towards the three devices. Some had received more than one device over the course of their treatment and this experience had coloured their judgement. For instance, a patient who previously had a PICC mentioned:

Well, probably not the PICC, I wouldn’t want that . . . That looped inside you.

Male, Hickman, prior experience of a RCT

Others were influenced by family members’ and friends’ experiences of the devices:

My wife had the Hickman line and eh, she . . . got a lot of infections, she eventually at one stage got septicaemia. She was on holiday at the time and had to be airlifted off one of the islands so that was a bit of a trauma.

Male, PICC, no prior experience of a RCT

As in every area of medical care, the level of patients’ knowledge and understanding of the subject varied widely. Many had conducted their own internet research on the three devices before deciding whether or not to enter the study. However, other patients admitted to being reluctant to know too much about the disease or treatment, preferring information to be filtered or summarised by health-care professionals.

Clinical staff interviews

Analysis of staff interviews identified five main themes: (1) getting staff on board, (2) clinical staff perceptions and preferences, (3) logistics of device insertion, (4) lack of experience and training, and (5) attitudes towards trial materials.

Getting staff on board

It was clear that the CAVA trial would necessitate a relatively complex patient pathway crossing several different specialties, including oncology, haematology and radiology, as well as having implications for primary care staff. The need to have all staff informed, involved and committed to the study was a recurrent theme with both nursing and medical staff across all specialties and centres; this was acknowledged to be a priority and essential for effective recruitment and was frequently described as getting colleagues ‘on board’:

I have no concern, I mean I am absolutely confident that the staff, the nursing in particular, will be very supportive, but we need everybody to be absolutely onboard.

Oncologist, Glasgow

The CAVA champion was perceived to be instrumental in informing, advising and motivating staff at each centre, providing a point of contact for clinical and nursing staff and raising awareness of the study. Several initiatives were reported to be under way across centres to ensure that staff were kept up to date with the progress of study set-up, including sending out slides and flyers to advise of the study and holding meetings to introduce the study to relevant colleagues and visiting key clinicians and departments to raise awareness. The qualitative study, particularly the interviewing of clinical staff, also appeared to play a significant part in raising awareness of the study and stimulating discussion and debate.

The heavy workload typical of all departments treating patients with cancer, the number of RCTs carried out in cancer centres and the adverse impact that this can have on trial recruitment was not an unexpected finding and the need to ensure that staff are fully informed and motivated with regard to the study was reiterated. In addition, it became apparent that the oncology and haematology departments were much more familiar with drug trials than with device trials, raising the risk of a device trial being overlooked. The concept of ‘trial fatigue’ and the potential for a non-drug trial to be less visible was a valuable prompt to raise considerations of adequate notification of the study, particularly to those carrying out ongoing care, ensuring complete data collection and complications reporting. Initiatives to raise visibility of the study included colour coding patient-held diaries and case record forms, along with adding proformas to the front of case notes in clinics:

We are very busy, that can be the over-riding sort of factor in saying: ‘OK, fine, I’ll just get on with the standard work rather than spend another half an hour or an hour explaining a trial that the patient may or may not take up’.

Oncologist, Glasgow

Clinical staff perceptions and preferences

A significant finding of the pre-trial qualitative study was a lack of equipoise regarding the three devices for particular patient groups. Haematologists in all but one centre expressed concern regarding the suitability of PORTs in their patient subgroup. In addition to issues of staff inexperience with the device, concern was expressed over the risks posed by the more invasive nature of the procedure to insert and remove the device in thrombocytopenic and neutropenic patients. Consequently, in some centres there was a lack of engagement by haematologists in the study (Manchester and Durham). In Leeds, haematologists intended to randomise between PICCs and Hickman-type devices only, whereas in Glasgow concern was also expressed regarding the use of PICCs, which were considered to present difficulties in transfusing blood products and other supportive therapies required for acute leukaemic and transplant participants:

We are actually not familiar with the PORT in adult haematology or oncology really . . . It would be a major practical problem to be inserting it into our haematology patients in terms of the insertion itself, there is a possibility that the bleeding risk and the infection risk could create more problems for my type of patients, because these are acute leukaemia patients . . .

Haematologist, Leeds

Newcastle was the only centre where the haematologists were completely on board, willing to randomise between all three devices and to introduce PORTs for chemotherapy delivery in haematology patients.

With the exception of the issues discussed above, most clinicians and nursing staff interviewed seemed to be proactive in the conduct of RCTs and ostensibly at ease with introducing the concepts of equipoise and randomisation to cancer patients:

This is our, if you like, ‘bread and butter’. We are involved, myself and my colleagues . . . are involved in trials in general; Phase III trials, and randomisation is the core part of it. So, we do discuss randomisation with patients on a regular basis and I don’t see this as a complex trial at all, I think it is quite straightforward.

Oncologist, Glasgow

Logistics of device insertion

The logistics of the line insertion appointments was also a recurrent theme across clinical staff interviews. Several participants thought that the element of randomisation between devices could create an additional level of complexity in the process of commencing a patient on chemotherapy. This was particularly relevant in oncology and haematology, where the time from referral for line insertion to treatment can be short and any perceived potential delays to chemotherapy delivery may impact negatively on patient recruitment. Services at each centre varied significantly, and there was acknowledgement that there might be a scarcity of slots for PORT insertion in some centres. In others, PORT insertion for chemotherapy was in addition to existing workload:

I think, obviously you know kind of access to interventional radiology might be the decider here because if there is a waiting list to put a PORT in, what have you, then your treatment targets have to be met either for cancer waiting time target or from a clinical need target type of thing.

Oncologist, Newcastle

The introduction of PORTs for chemotherapy delivery also created a requirement for PORT removal appointments, either because of complications or because removal was requested by patients at the end of treatment. In many centres, this was in addition to current workload and, therefore, raised the issue of accommodating this requirement. Responses to this varied across centres; in one, this was not considered an appropriate use of interventional theatre time and arrangements were made for a surgical referral for PORT removal when necessary, whereas, in others, interventional radiologists were prepared to undertake line removal for study patients as required.

Lack of experience and training

Experience of PORTs varied widely between centres. In several centres, PORTs were already in use for chemotherapy delivery; however, in others experience was limited and the need for additional training was apparent. Staff interviews in Glasgow highlighted a lack of confidence and experience with PORTs as a major area of concern. Despite a programme of training, the learning curve generated by the new device resulted in additional referrals to interventional radiology for assistance with maintenance issues and additional hospital visits by patients for procedures normally carried out by the primary care team. The qualitative interviews did highlight, however, the nursing staff’s enthusiasm and commitment to developing the necessary skills:

So that’s a big buzz, eh, you know when we problem solve in a successful way. And I know that once we get used to PORTs, we’ll love them.

Oncology nurse, Glasgow

Attitudes towards trial materials

Clinical staff in all centres raised a few minor issues with trial materials, specifically the PIS. It was felt that illustrations were not as clear as they could be and that the inclusion of necklaces was distracting and did not demonstrate best practice. Some inconsistencies with local practice were raised, specifically the reference to pumps that were not universally used across all centres. It was felt that greater clarity was required in two areas: (1) that the radiation dose was less than that of a radiograph and (2) that monthly questionnaires did not involve a further hospital visit. Finally, two clinicians raised the point that the references to randomisation by ‘computer’ and ‘tossing a coin’ were considered not to be concepts that patients feel comfortable with in relation to decision-making. A summary of these points was forwarded to the project manager and the Trial Management Group for further discussion at a forthcoming Trial Management Group meeting, and the PIS was modified as appropriate.

Discussion

This qualitative study was one of a few fully integrated, qualitative studies in large multicentre RCTs. This integration has allowed the analysis, feedback and interventions to take place prior to the study opening to recruitment. Our findings showed that patients had a vested interest in the device used for the delivery of their chemotherapy and demonstrated a willingness to be involved in research on CVADs. The focus groups also raised awareness of the need for clarity around the concept of the RCT and, in particular, the process of randomisation. In addition, we found that clear information and education on the three devices was required to ensure fully informed consent. The main themes identified from the pre-trial clinical staff interviews, namely logistics and complexity of service delivery, the need for education and training, and, finally, the lack of equipoise, had the potential to present significant barriers to recruitment. Consequently, the remit of the funded role of the CAVA champion (i.e. a dedicated member of the study team at each centre) was developed to encompass not only recruitment and randomisation, but also co-ordination and facilitation of device insertion appointments, communication and liaison across specialties, and education and dissemination of knowledge (see Report Supplementary Material 4). Centres with a champion recruited well and the ability to move a champion from a centre with high recruitment to support one that was performing less well proved invaluable. In response to the need for training, The Implanted PORT Training Day, a 1-day workshop on PORT insertion and maintenance using cadavers, was devised by the chief investigator and has been held annually for clinicians, nurses and industry representatives. Furthermore, effective training models and manikins, sourced through industry, have been shared between centres. Additional meetings between the chief investigator and the haematologists were undertaken to address issues around equipoise, leading to some emerging support from haematologists for the use of PORTs as the study progressed. The above findings and measures were presented to the CAVA trial principal investigators and champions at a pre-recruitment meeting, at the Christie Hospital in Manchester, to maximise dissemination and with the aim of having a positive impact on recruitment.

Chapter 4 Recruitment

Target recruitment

Overall, 1061 participants were recruited from 18 UK sites. At each site, clinicians could choose any of the four randomisations depending on the individual patient and the practice at their individual site: (1) Hickman versus PICCs versus PORTs; (2) PICCs versus Hickman; (3) PORTs versus Hickman; and (4) PORTs versus PICCs. Recruitment commenced on 8 November 2013 and was originally planned to take place over a period of 3 years. The initial target sample size was a total of 1500 patients (Table 2).

| Sample size assumption | Comparison | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PICCs vs. Hickman | PORTs vs. Hickman | PORTs vs. PICCs | |

| Expected difference in complication rate | 10% (70% vs. 60%) | 20% (40% vs. 60%) | 20% (40% vs. 60%) |

| Power | 90% | 90% | 90% |

| Significance level | 2.5% | 5% | 5% |

| Target number of patients to recruit | 1000 | 250 | 250 |

An assessment on recruitment was prespecified at 18 months and was carried out in April 2015. If any of the comparisons had < 35% of the target sample size projected for this period, that comparison could be discontinued. The recruitment target was met for all of the comparisons; however, it was noted that the recruitment rate was below the predicted rate for the PICCs versus Hickman comparison and for the PORTs versus PICCs comparison. There were concerns that the target recruitment numbers could not be achieved within the remaining recruitment period. Furthermore, the results for the Glasgow feasibility study (PORTs vs. Hickman) became available at this time. The sample sizes and recruitment plan were re-estimated on the basis of these results and the observed recruitment (Table 3). This was approved by the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) in November 2015. Recruitment to randomisation to comparisons involving PICCs was challenging, with below-expected recruitment rates. In January 2017, a variation in contract was granted by the NIHR HTA programme to allow an additional 15 months of recruitment (until the end of February 2018).

| Sample size assumption | Comparison | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PICCs vs. Hickman | PORTs vs. Hickman | PORTs vs. PICCs | |

| Expected difference in complication rate | 10% (65% vs. 55%) | 15% (40% vs. 55%) | 15% (40% vs. 55%) |

| Power | 80% | 95% | 80% |

| Significance level | 2.5% | 5% | 5% |

| Target number of patients to recruit | 778 | 550 | 341 |

Recruitment by randomisation option

With the exception of one randomisation option, all randomisation options were open to recruitment until the end of the recruitment period. The randomisation option of PORTs versus Hickman was closed at the end of November 2015 given that it was clear that the required number of patients for the comparison would be achieved by the end of the study via the three-way comparison. The numbers of patients contributing to each of the comparisons of interest is shown in Table 4. Subsequently, these patients formed the population base for the three comparisons. The Hickman versus PORTs comparison had the highest recruitment; 42% of the recruited patients contributed to this comparison.

| Arm | Arm, n (%) | Total, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PORTs | PICCs | Hickman | ||

| Randomisation option | ||||

| PORTs vs. PICCs vs. Hickman | 53 (20.0) | 106 (40.0) | 106 (40.0) | 265 (100.0) |

| PICCs vs. Hickman | 0 (0.0) | 106 (50.0) | 106 (50.0) | 212 (100.0) |

| PORTs vs. Hickman | 200 (50.4) | 0 (0.0) | 197 (49.6) | 397 (100.0) |

| PORTs vs. PICCs | 94 (50.3) | 93 (49.7) | 0 (0.0) | 187 (100.0) |

| Total | 347 (32.7) | 305 (28.7) | 409 (38.5) | 1061 (100.0) |

| Comparison | ||||

| PICCs vs. Hickman | 0 (0.0) | 212 (50.0) | 212 (50.0) | 424 (100.0) |

| PORTs vs. Hickman | 253 (45.5) | 0 (0.0) | 303 (54.5) | 556 (100.0) |

| PORTs vs. PICCs | 147 (42.5) | 199 (57.5) | 0 (0.0) | 346 (100.0) |

| Total | 400 (30.2) | 411 (31.0) | 515 (38.8) | 1326 (100.0) |

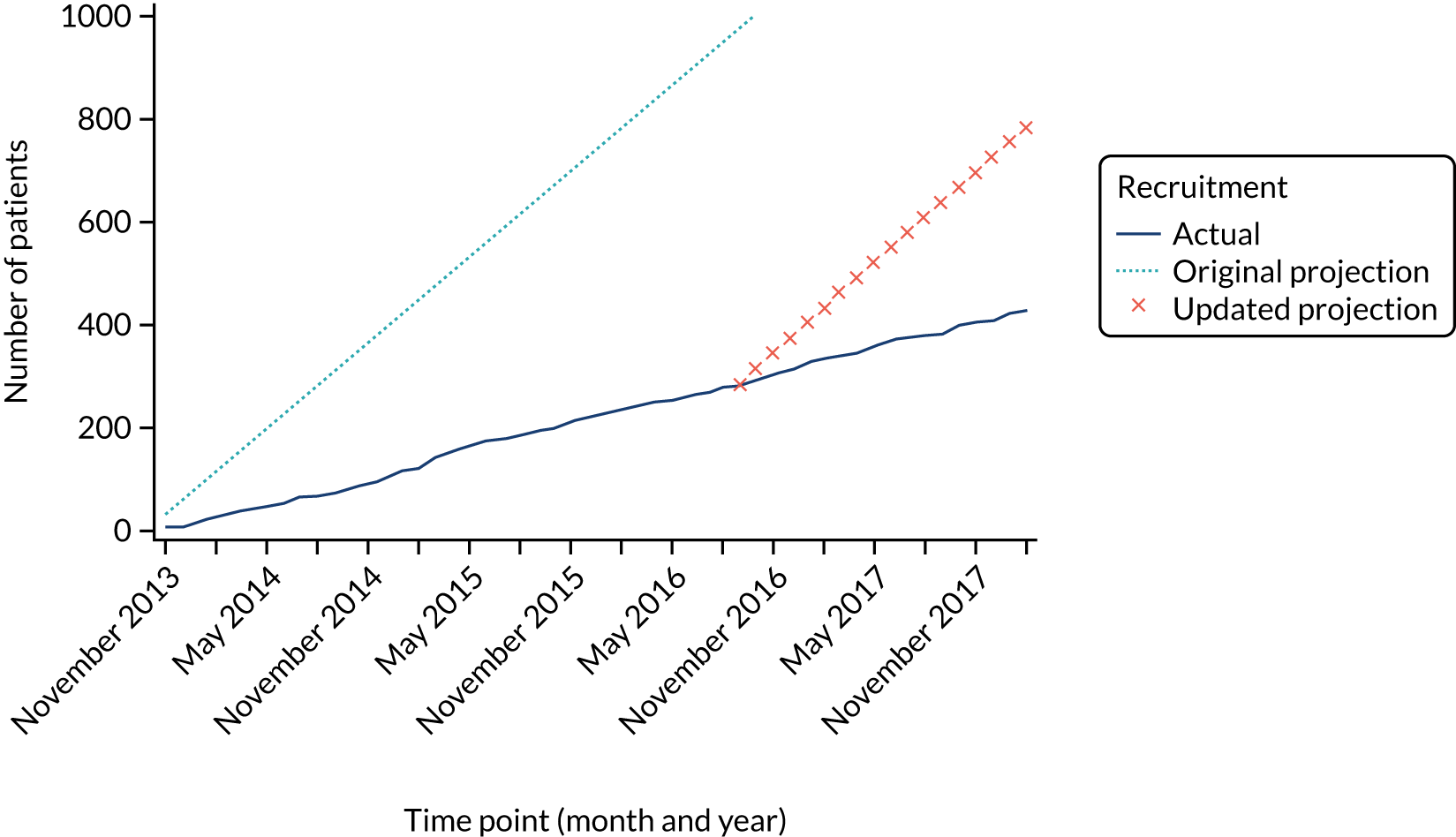

Hickman versus peripherally inserted central catheters comparison: recruitment

Recruitment to the Hickman versus PICCs comparison was challenging and was consistently below the target recruitment rate. The recruitment target was revised in April 2015, but overall recruitment remained below the target (Figure 3). In total, 424 patients from 15 sites contribute to the PICCs versus Hickman comparison (see Report Supplementary Material 5). This is notably less than the required 778 patients to ensure 80% power for our non-inferiority comparison. The resultant power of this comparison is 54%.

FIGURE 3.

Recruitment projections for the PICCs vs. Hickman comparison.

PORTs versus Hickman comparison: recruitment

Recruitment for the PORTs versus Hickman comparison was above the target recruitment rate (Figure 4). As a consequence, the two-way randomisation option for this comparison closed at the end of November 2015. However, patients continued to accrue to this comparison via the three-way randomisation until recruitment ended in February 2018. A target of 550 patients was required and a total of 556 patients were recruited from 10 sites (see Report Supplementary Material 5), which results in a final power for this comparison of 95%.

FIGURE 4.

Recruitment projections for the PORTs vs. Hickman comparison.

PORTs versus peripherally inserted central catheters comparison: recruitment

The initial recruitment rate for the PORTs versus PICCs comparison was lower than the expected rate. The recruitment rate was reassessed in April 2015 and a revised target was produced. Subsequently, the trial recruited to target for this comparison (Figure 5). A total of 341 patients were required from 11 sites for the PORTs versus PICCs comparison to ensure 80% power for the final comparison (see Report Supplementary Material 5).

FIGURE 5.

Recruitment projections for the PORTs vs. PICCs comparison.

Discussion

The estimation of target recruitment to the CAVA trial was complex. This was primarily because of the necessity of offering four randomisation options to accommodate the clinical services that recruiting sites can offer, as not all sites were able to deliver all three devices. Our recruitment target was 1500 patients. However, at the pre-planned interim assessment, it was clear that recruiting for the PICCs versus Hickman comparison was extremely challenging, and, to some extent, this was also the case for recruitment to the PORTs versus PICCs comparison. By contrast, we were able to over-recruit to the PORTs versus Hickman comparison. This is primarily as a result of the Hickman-type device no longer being the preferred device during this period and PICCs becoming the dominant strategy in clinical practice. Following the interim assessment, we were able to recruit to the revised target recruitment for the PORTs versus Hickman and PORTs versus PICCs comparisons. However, we were not able to do so for the PICCs versus Hickman comparison. As a result, the final power of this comparison was substantially reduced from 80% to 54%. We did not feel it appropriate to attempt to ‘artificially’ boost the power by modifying the significance level or the type of comparison from non-inferiority. We were able to increase the power (to 64%) of this comparison by borrowing strength from indirect estimates of the difference between the PICCs and Hickman-type devices from the other comparisons using a NMA approach. Despite this being less than the intended power, this is still the largest number of patients ever randomised into a trial comparing these devices.

Chapter 5 Results for the peripherally inserted central catheters versus Hickman comparison

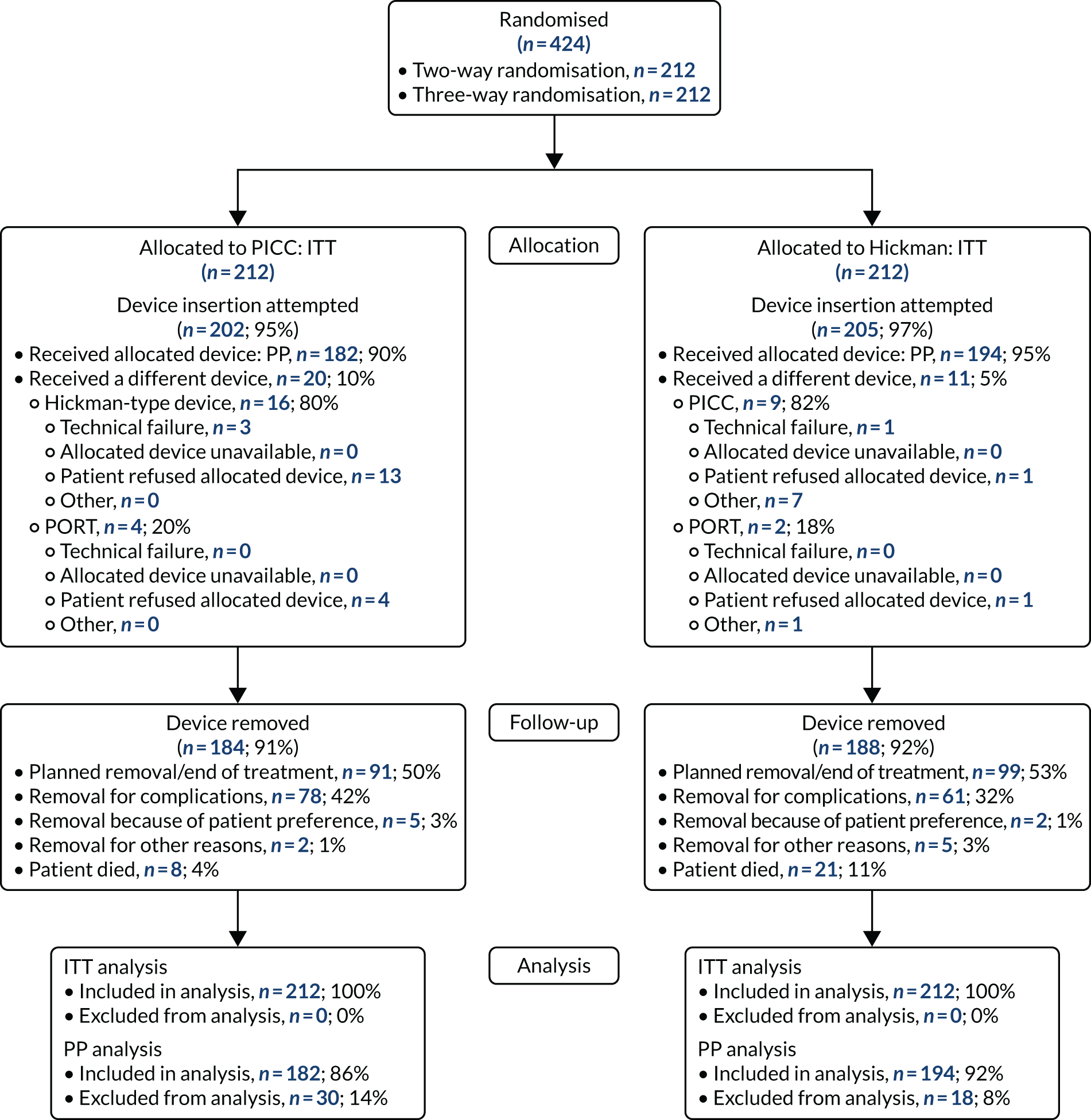

Study participants

Study participants were recruited from both two-way (Hickman vs. PICCs) and three-way (Hickman vs. PICCs vs. PORTs) randomisations. In total, 424 participants were included in the PICCs versus Hickman comparison (Figure 6). The two-way and the three-way randomisations both contributed equal numbers of participants to each arm. Of all of the patients who entered the trial, 212 were randomised to receive PICCs and 212 were randomised to receive Hickman-type devices. All patients were included in the ITT analysis. Device insertion was attempted with 95% (n = 202) and 97% (n = 205) of patients randomised to PICCs and Hickman, respectively. Of these patients, 10% (n = 20) in the PICCs arm and 5% (n = 11) in the Hickman arm received a different device from the one to which they were randomised. The per-protocol population consisted only of patients who received the device to which they were randomised: 194 patients in the Hickman arm and 182 patients in the PICCs arm. All patients were followed up monthly until device removal, death or to the end of the 12-month follow-up.

FIGURE 6.

The PICCs vs. Hickman comparison CONSORT flow diagram. PP, per protocol.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics were well balanced between the two arms (Table 5). There was no difference between the two arms with respect to age, sex, BMI and ethnicity. The mean age of participants was 61 ± 12 years. Over half of the participants (53%) were male. The majority of patients were white (98%) and had a BMI between 20 and 30 mg/kg2 (68%).

The majority (87%) of patients were solid tumour patients with metastatic disease; there was no difference between the two arms in respect of solid tumour and haematological malignancy. Among those with solid tumours, 61% of the patients had colorectal primary tumours, which included a greater proportion of the Hickman arm than the PICCs arm. The proportion of patients with pancreatic cancer was greater in the PICCs arm than in the Hickman arm (15% vs. 8%, respectively). Among those with haematological malignancies, the proportions varied across acute myeloid leukaemia, high-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and Hodgkin’s disease. Across the two arms, the majority of the participants had planned outpatient treatments (92%) and did not have any prior venous access device (85%). The mean EQ-5D-3L health–utility score was 0.7 ± 0.2; there were no differences across the two arms. Similar patterns were observed with the mean EQ-5D health state score and the mean QLQ-C30 quality-of-life score.

| Characteristic | Arm | Total, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PICCs | Hickman | ||

| Mean age (years) (SD, range) | 62 (11, 19–85) | 61 (12, 20–87) | 61 (12, 19–87) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 102 (48.1) | 96 (45.3) | 198 (46.7) |

| Male | 110 (51.9) | 116 (54.7) | 226 (53.3) |

| BMI (mg/kg2),a n (%) | |||

| < 20 | 10 (4.7) | 12 (5.7) | 22 (5.2) |

| 20 to < 30 | 145 (68.4) | 145 (68.4) | 290 (68.4) |

| 30 to < 40 | 51 (24.1) | 49 (23.1) | 100 (23.6) |

| ≥ 40 | 6 (2.8) | 6 (2.8) | 12 (2.8) |

| Ethnic origin, n (%) | |||

| White | 204 (96.2) | 210 (99.1) | 414 (97.6) |

| Asian | 3 (1.4) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (0.9) |

| Afro-Caribbean | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) |

| Missing | 4 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.9) |

| Type of disease,a n (%) | |||

| Solid tumour | 185 (87.3) | 184 (86.8) | 369 (87.0) |

| Colorectal | 104 (56.2) | 120 (65.2) | 224 (60.7) |

| Breast | 21 (11.4) | 21 (11.4) | 42 (11.4) |

| Pancreatic | 27 (14.6) | 15 (8.2) | 42 (11.4) |

| Other (two missing in PICCs) | 31 (16.8) | 28 (15.2) | 59 (16.0) |

| Haematological malignancy, n (%) | 27 (12.7) | 28 (13.2) | 55 (13.0) |

| Acute myeloid leukaemia | 7 (25.9) | 11 (39.3) | 18 (32.7) |

| High-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 5 (18.5) | 8 (28.6) | 13 (23.6) |

| Hodgkin’s disease | 4 (14.8) | 3 (10.7) | 7 (12.7) |

| Other (one missing in PICCs) | 10 (37.0) | 6 (21.4) | 16 (29.1) |

| Metastatic disease (solid tumour patients only), n (%) | |||

| Yes | 114 (61.6) | 108 (58.7) | 222 (60.2) |

| No | 68 (36.8) | 76 (41.3) | 144 (39.0) |

| Missing | 3 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.8) |

| Patients being administered 5-fluorouracil | 137 (64.6) | 143 (67.5) | 280 (66.0) |

| Planned treatment mode,a n (%) | |||

| Inpatient | 17 (8.0) | 19 (9.0) | 36 (8.5) |

| Outpatient | 195 (92.0) | 193 (91.0) | 388 (91.5) |

| Device historya | |||

| No prior device, n (%) | 181 (85.4) | 180 (84.9) | 361 (85.1) |

| ≥ 1 previous device inserted > 3 months before study entry, n (%) | 26 (12.3) | 26 (12.3) | 52 (12.3) |

| ≥ 1 previous device inserted ≤ 3 months before study entry, n (%) | 5 (2.4) | 6 (2.8) | 11 (2.6) |

| Baseline quality-of-life scores, mean (SD, range) | |||

| EQ-5D index value | 0.7 (0.3, –0.3 to 1.0) | 0.8 (0.2, –0.2 to 1.0) | 0.7 (0.2, –0.3 to 1.0) |

| EQ-5D health state score | 70.6 (20.7, 10.0 to 100.0) | 70.3 (18.6, 10.0 to 100.0) | 70.4 (19.6, 10.0 to 100.0) |

| QLQ-C30 global health status | 65.3 (22.6, 0.0 to 100.0) | 68.0 (21.1, 0.0 to 100.0) | 66.7 (21.9, 0.0 to 100.0) |

Device details

The majority (74%) of PICCs came from two manufacturers [Vygon and CR Bard Inc. (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA)], whereas Hickman-type devices were primarily from one manufacturer (Vygon) (see Appendix 1). In both arms, the majority of patients received single-lumen devices (86% in the PICCs arm and 73% in the Hickman arm). Antimicrobial coating was present in devices received by 11% of the patients in the PICCs arm and 3% of patients in the Hickman arm. Overall, 54% of PICCs were computerised tomography (CT) pump compatible, compared with 17% of Hickman-type devices. Valves were present in 36% of PICCs and 14% of Hickman-type devices.

Overall, the majority of the patients had their device fitted within 1 week of randomisation: median 7 days [interquartile range (IQR) 4–13 days] for patients in the PICCs arm and 6 days (IQR 3–11 days) for patients in the Hickman arm. The majority of PICCs were inserted by nurses (67%) in either a treatment room or a radiology department. Only 13% were placed by radiologists. In 76% of device fittings, the basilic or cephalic vein proximal to the elbow was used. Hickman-type devices were inserted by a variety of primary operators (radiologist 46%, nurse 23% and anaesthetist 20%) working in different environments using mainly the jugular vein (85%). Perioperative antibiotics were given to only 2% of patients in both arms. The majority of device insertions were completed within 30 minutes (55% PICCs vs. 72% Hickman), but, overall, the length of time for device insertion was longer with PICCs.

Complications and device removal