Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/26/06. The contractual start date was in October 2016. The draft report began editorial review in November 2020 and was accepted for publication in April 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Corrections

-

This article was corrected in August 2022. See Hopewell S, Keene DJ, Heine P, Marian IR, Dritsaki M, Cureton L, et al. Corrigendum: Progressive exercise compared with best-practice advice, with or without corticosteroid injection, for rotator cuff disorders: the GRASP factorial RCT. Health Technol Assess 2022;25(48):159–160. https://doi.org/10.3310/KTCG3040-c202208

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Hopewell et al. This work was produced by Hopewell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Hopewell et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

Problem and diagnosis

Shoulder pain is common. Annually, around 1% of adults aged > 45 years in primary care present with a new episode of shoulder pain, accounting for 2.4% of all general practitioner (GP) consultations in the UK. 1 This is most commonly attributed to the rotator cuff, which causes around 70% of cases. 2 The rotator cuff is a group of four muscles and their tendons/attachments. The rotator cuff actively moves and stabilises the shoulder joint, enabling a wide range of efficient movements at the shoulder. Disorders of the rotator cuff can be associated with substantial, persistent disability (e.g. being unable to dress independently) and pain. Rotator cuff disorders can persist for long periods. Up to half of those who present for treatment, particularly older people, continue to have pain and/or functional disturbance for up to 2 years. 3

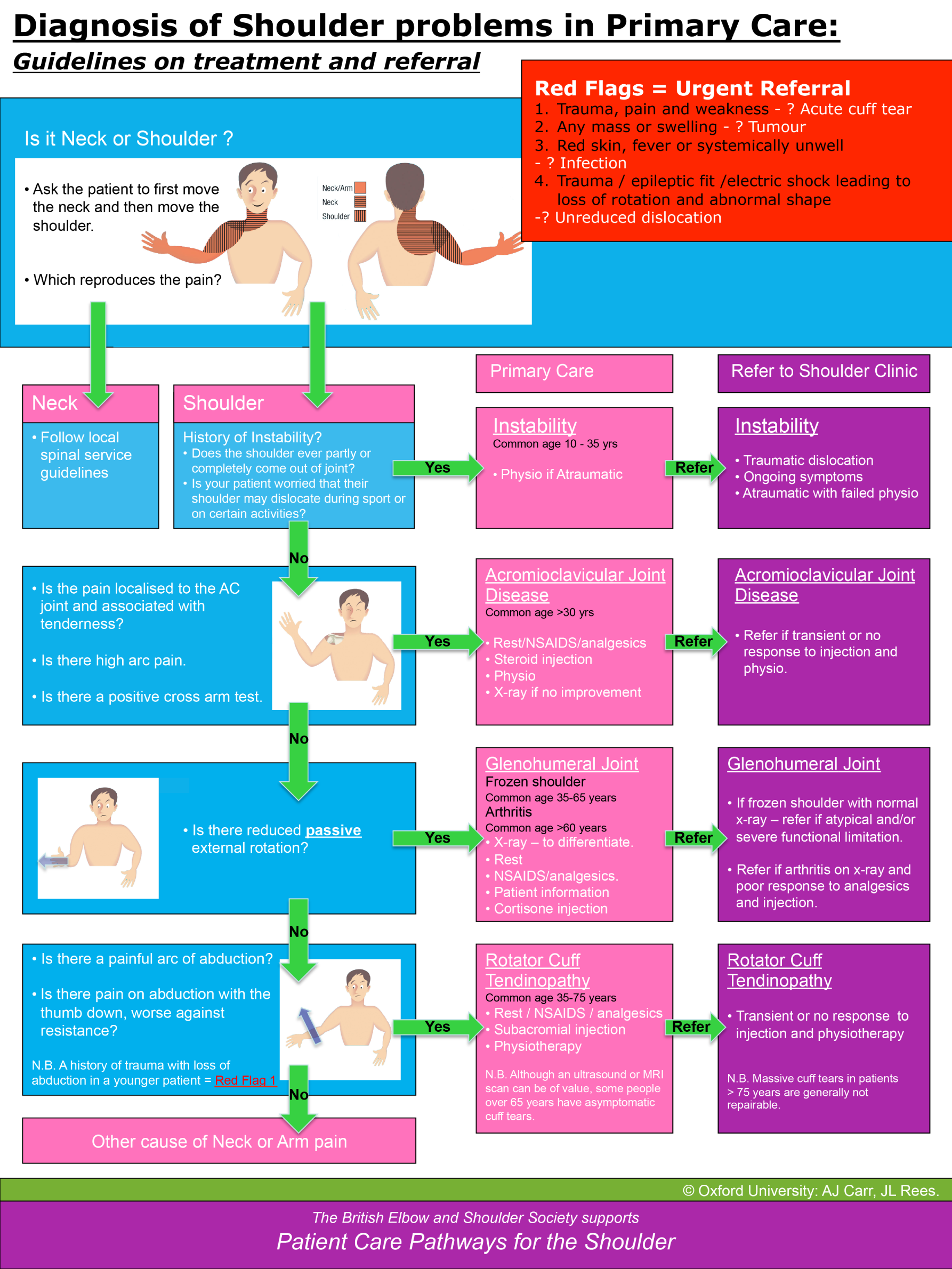

The majority of shoulder pain is managed in primary care or in musculoskeletal interface services by physiotherapists and GPs. Musculoskeletal interface services are led by specialist practitioners who manage patients with musculoskeletal disorders through assessment, treatment, investigation and by referring to appropriate health-care professionals. Musculoskeletal interface services aim to promote more community-based management options for patients, rather than traditional hospital-based secondary care, and provide a more efficient, cost-effective and sustainable model for dealing with high-volume conditions. Treatments for rotator cuff disorders aim to improve pain and function. Standard primary care options include rest, advice, analgesia, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, physiotherapy and corticosteroid injections. 4,5 However, usual care can be highly variable and there are no National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical guidelines.

A diagnostic algorithm2 has been developed as part of the NICE-accredited standards developed by the British Elbow & Shoulder Society (BESS) and other professional bodies (e.g. the Royal College of Surgeons, the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy and the British Orthopaedic Association) to confirm when a diagnosis of rotator cuff disorder is highly likely, based on a patient’s history and simple shoulder tests4 (see Appendix 1, Figure 13). The recommended tests have been selected with primary care application in mind,6 although they do require a reasonable degree of clinical skill. Imaging is not recommended in primary care because of the poor fit between structural change and symptomatic presentation. 7 We have used the BESS algorithm (see Appendix 1, Figure 13) to define the entry criteria for the GRASP (Getting it Right: Addressing Shoulder Pain) trial, thereby ensuring that the trial is consistent with national guidance.

Explanation of rationale

Problems associated with rotator cuff disorders can seriously affect patient health and well-being. The prevalence of shoulder complaints in the UK is estimated at around 14%,8 increasing with age1 and highest in those aged ≥ 60 years. Shoulder problems are a significant cause of morbidity and disability in the general population and have a significant socioeconomic burden, as they affect an individual’s capacity to work and ability to perform daily tasks and social activities. They have a significant impact on primary care services. The average cost per patient with a musculoskeletal condition in the NHS is £461.13 per head per year,9 with wide geographical variability. The estimated cost to the UK economy is £7.4B per year.

The NHS currently invests considerable amounts of money in unproven therapies and corticosteroid injections. One common treatment prescribed for rotator cuff disorders is corticosteroid injection, which typically costs £47–332, depending on the mode of delivery (the cheapest of which is by a physiotherapist without ultrasound guidance). In comparison, a set of six physiotherapy sessions costs approximately £206 and an assessment and advice session costs £45 (see Chapter 5). It is important for the NHS to develop cost-effective, pragmatic methods for dealing with high-volume conditions. Rotator cuff disorders may be self-limiting if they are managed effectively in primary care, as patients can regain function and pain can be reduced. However, the consequences of poor initial management are an increased likelihood of recurrent or persistent problems in older age and the need for surgical intervention. 4

We planned to conduct a large, well-powered randomised controlled trial, using a factorial design, to co-test two interventions commonly used in the management of rotator cuff disorders in primary care: (1) progressive exercise delivered by a physiotherapist and (2) corticosteroid injection. We used a best-practice advice session with a physiotherapist and no injection as the respective comparators. The interventions tested used current patient pathways for people with a rotator cuff disorder. We wanted to assess which of these interventions, or combination of interventions, are most clinically effective and cost-effective for the NHS. The primary outcome for the trial is shoulder pain and function, which is assessed using the well-validated Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI). 10,11 The SPADI is a tool that was developed to measure current shoulder pain and disability in an outpatient setting.

Choice of comparators

Exercise interventions

In designing the trial, we looked at existing evidence regarding the choice of comparator interventions. There is promising evidence from small, short-term trials that physiotherapist-prescribed exercise is effective. 12–14 However, there is a lack of evidence regarding its long-term clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness,12–14 despite the widespread provision of physiotherapy for these conditions. There is also uncertainty about which types of exercise and delivery mechanisms (e.g. supervised or home based) are associated with the best outcomes. 12,13,15–17 This evidence is limited by problems in study design and choice of comparators. 13 There are also competing ideologies around which exercise programmes should be considered to ensure a worthwhile trial. Resistance training to improve muscular strength, whether supervised or home based, has been identified as a core component of exercise for rotator cuff disorders, although there is no evidence that any specific programme is superior. 18,19 Manipulation of the exercise volume and intensity is achieved by varying the frequency, load, number of sets, repetitions and rest intervals. 20 A trial of strength training found that duration, specificity of exercises, progression criteria and individualisation (i.e. adjusting the programme to suit each participant) were also important. 21 We did not consider other forms of physiotherapy-led interventions, such as electrotherapy, acupuncture, soft tissue mobilisation, manipulation or stratified care, because of the lack of evidence of their efficacy. 22,23

Little attention has been paid to the need for behavioural frameworks to enhance adherence to advice and exercise programmes and to tackle pain beliefs and behaviour in this context. 24 Non-adherence to physiotherapy treatment is estimated to be up to 70%. 25 In a large trial of exercise for lower back pain that did not include a behavioural component to increase exercise adherence, only half of the participants attended the minimum number of treatment sessions. 26 Risk factors for low adherence include low levels of physical activity, low self-efficacy, depression, anxiety, poor social support and greater perceived barriers to exercise. 24 Some of these risk factors are modifiable in the context of a physiotherapy intervention. We have previous expertise in this area27 and planned to include a behavioural component as part of the progressive exercise intervention.

Corticosteroid injection

There is systematic review evidence that, in comparison with placebo, corticosteroid injections have a short-term benefit in the shoulder, as in other areas of the body. However, there are some concerns about the longer-term benefits and harms of corticosteroid injections. 28–30 The combination of injection and physiotherapy has intuitive appeal, with some evidence of an additive, but not interactive, effect in the short term (3–4 months). 30–33 The longer-term benefits of injections require further study. We planned to use a no-injection comparison, as finding an inert robust placebo is challenging and, given the existing evidence,28–30 we believed that it was unethical and undesirable to progress a placebo arm in a large Phase III trial. In our study based in NHS musculoskeletal services, extended-scope physiotherapists typically deliver the corticosteroid injections. This is increasingly common practice in the NHS, where therapists undertake additional post-registration training to deliver injections, working within a local Patient Group Direction and/or becoming qualified non-medical independent prescribers. 34 Although the use of ultrasound to guide injections in primary care has become increasingly common, evidence from the SUPPORT (SUbacromial imPingement syndrome and Pain: a randomised controlled trial Of exeRcise and injecTion) trial35 and other trials3 have demonstrated that it is no more effective than standard injection practice. Ultrasound guidance also substantially increases the cost and reduces the practicality of injection therapy. Therefore, we planned to deliver injections without the use of ultrasound guidance.

Objectives

The aim of the GRASP trial was to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of individually tailored progressive exercise compared with best-practice advice, with or without corticosteroid injection, in patients with a new episode of a rotator cuff disorder. The primary objectives were to assess the following:

-

whether or not an individually tailored progressive exercise programme, including behavioural change strategies and led by a physiotherapist, provides greater improvement in shoulder pain and function over the 12 months post randomisation compared with a best-practice advice session with a physiotherapist supported by high-quality materials

-

whether or not subacromial corticosteroid injection provides greater improvement in shoulder pain and function over the 12 months post randomisation compared with no injection.

The secondary objectives of the GRASP trial were to investigate if there were any differences at 8 weeks and at 6 and 12 months in shoulder pain, shoulder function, health-related quality of life, fear avoidance, pain self-efficacy, sleep disturbance, return to desired activities (RDA) (including work, social life and sport activities), patients’ global impression of change, adherence to exercises, use of medication (prescribed and over the counter), time off work, health resource use (consultation with primary and secondary care) and additional out-of-pocket expenses.

A parallel within-trial health economic analysis was also conducted.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Hopewell et al. 36 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Marian et al. 37 This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Trial design

The GRASP trial protocol36 and the statistical analysis plan (SAP) have been reported previously. 37

The GRASP trial is a 2 × 2 factorial trial, which was used to test the following four physiotherapy-led interventions:

-

Progressive exercise programme (i.e. an individually tailored, progressive, home exercise programme prescribed and supervised by a physiotherapist, involving up to six face-to-face sessions over 16 weeks).

-

best-practice advice (i.e. one face-to-face session with a physiotherapist and a home exercise programme supported by high-quality self-management materials).

-

Progressive exercise programme (as described above) preceded by a subacromial corticosteroid injection.

-

best-practice advice session (as described above) preceded by a subacromial corticosteroid injection.

A parallel within-trial health economic analysis was also conducted.

The factorial design allowed two primary comparisons, based on the assumption that there was no interaction effect: (1) progressive exercise programme compared with best-practice advice session and (2) subacromial corticosteroid injection compared with no injection.

Internal pilot

An internal pilot was included as an integral part of the GRASP trial design, which mirrored the procedures and logistics undertaken in the main GRASP trial. The purpose of the internal pilot was to test and refine the recruitment process and explore treatment acceptability. The decision to progress to the main trial was made in collaboration with the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme based on a predefined progression criterion: reaching the target recruitment rate (42 participants) within the specified time frame (4 months). Data from the internal pilot trial contributed to the final analysis, as there were no substantive changes in design or delivery of the trial interventions.

Study setting

The GRASP trial was conducted across 20 primary care-based musculoskeletal services and their related physiotherapy services in the NHS. These services treat people with a range of musculoskeletal conditions and are run by specialist practitioners, including extended-scope physiotherapists, GPs with a specialist interest in musculoskeletal conditions, clinical nurse specialists and, in some instances, rheumatologists and orthopaedic consultants. Sites were chosen so that they reflected a range of settings (urban and rural) and were able to deliver the trial interventions. The local principal investigator was responsible for the conduct of the research at their site.

Participants

Participants were recruited if referred by their GP or physiotherapist for treatment of a new, but not necessarily first, episode of shoulder pain attributable to a rotator cuff disorder. Participants were predominantly seeking treatment for one shoulder. People who self-referred directly to the musculoskeletal service were also assessed for eligibility, as the typical route of referral varied across services. The participants did not routinely undergo diagnostic imaging, such as magnetic resonance imaging or ultrasound, as a requirement of the trial, as this is generally not recommended in primary care.

Inclusion criteria

-

Men and women aged ≥ 18 years.

-

A new episode of shoulder pain (i.e. within the previous 6 months) attributable to a rotator cuff disorder (e.g. cuff tendonitis, impingement syndrome, tendinopathy or rotator cuff tear), using the diagnostic criteria set out in the BESS guidelines4 (see Appendix 1, Figure 13).

-

Not currently receiving physiotherapy.

-

Not being considered for surgery.

-

Able to understand spoken and written English.

Exclusion criteria

-

Participants with a history of recent significant shoulder trauma (e.g. dislocation, fracture or full-thickness tear requiring surgery).

-

Those with a neurological disease affecting the shoulder.

-

Those with other shoulder disorders (e.g. inflammatory arthritis, frozen shoulder or glenohumeral joint instability) or with red flags consistent with the criteria set out in the BESS guidelines. 4

-

Those who had received corticosteroid injection or physiotherapy for shoulder pain in the previous 6 months.

-

Those with contraindications to corticosteroid injections.

Recruitment

Recruitment of participants, screening and eligibility assessment

Potentially eligible participants were identified by clinicians in NHS musculoskeletal services. People attended their clinic appointments in accordance with standard NHS procedures. The treating practitioner in the musculoskeletal services undertook a clinical assessment according to their usual practice. If a patient fulfilled the criteria for a rotator cuff disorder, they were assessed to see whether or not they met the GRASP trial eligibility criteria. Patients were provided with a copy of the participant information sheet and asked if they wished to be considered for the trial. Those who met the eligibility criteria and wanted to participate were approached for informed consent. Participants who did not meet the eligibility criteria or who did not wish to participate received standard NHS treatment. We recorded anonymous information on the age and sex of those who declined to participate so that we could assess the generalisability of those recruited. Reasons for declining were also recorded.

Informed consent and baseline assessment

After participants had been assessed for eligibility, informed consent for participation in the GRASP trial was obtained by a research facilitator at the site who was trained in Good Clinical Practice (GCP). The following was explained to the participant: the exact nature of the study; what it would involve for the participant, including expectations that the participant would be willing and able to attend sessions to receive the study intervention; and any risks involved. The potential participant was provided with a patient information sheet and was given the opportunity to discuss issues and ask questions. In most cases, the process of obtaining informed consent took place during the initial musculoskeletal clinic appointment. Some participants required a second research appointment because they required more time to consider the study or because of local resources at site. Participants were then asked to complete a baseline assessment questionnaire that recorded simple demographic information and baseline measurements for the primary and secondary outcomes (Table 1).

| Outcome | Measurement | Time point |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic | Age, sex, height, weight, ethnicity, marital status, smoking, date of rotator cuff diagnosis, duration of symptoms, hand dominance, affected shoulder, current work status, level of education, place of residence, household income and state benefits | Baseline |

| Primary | ||

| Pain and function | SPADI10,11 13-item total scale | Baseline, 8 weeks, 6 months, 12 months |

| Secondary | ||

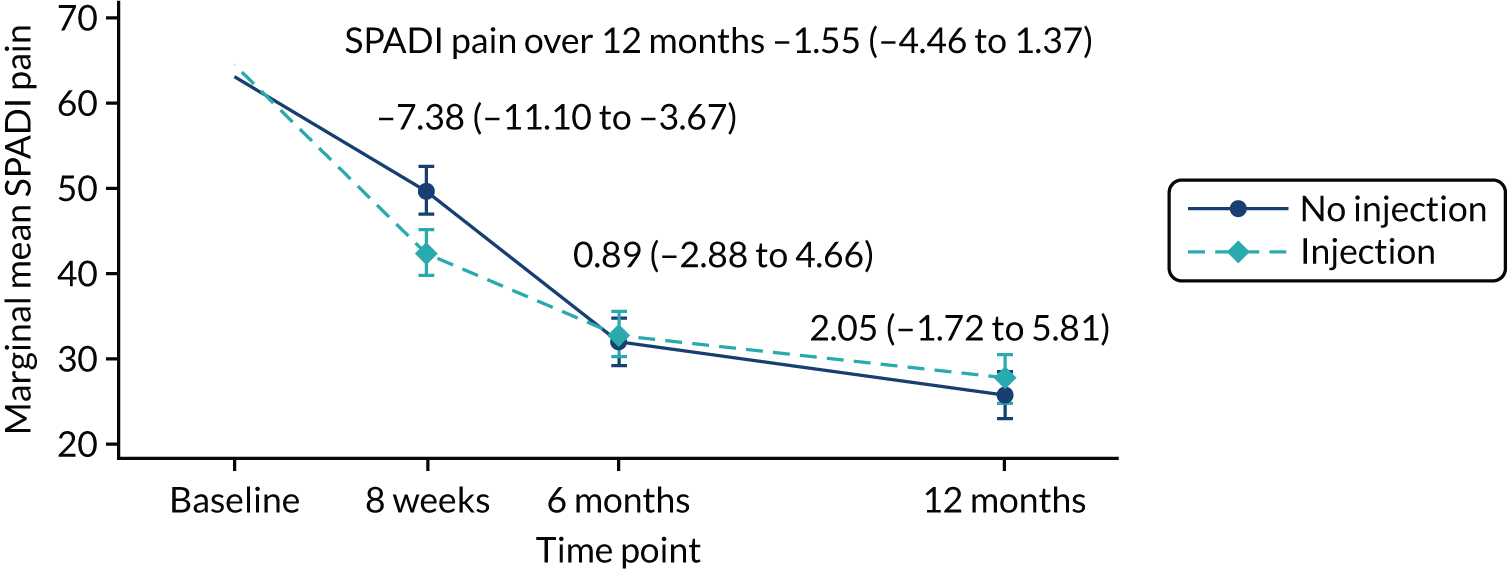

| Pain | SPADI10,11 five-item subscale | Baseline, 8 weeks, 6 months, 12 months |

| Function | SPADI10,11 eight-item subscale | Baseline, 8 weeks, 6 months, 12 months |

| Health-related quality life | EQ-5D-5L score38 | Baseline, 8 weeks, 6 months, 12 months |

| Psychological factors | FABQ-PA five-item subscale39 and PSEQ-240 | Baseline, 8 weeks, 6 months, 12 months |

| Sleep disturbance | ISI41 | Baseline, 8 weeks, 6 months, 12 months |

| GIT | Patient-rated Likert scale42 | 8 weeks, 6 months, 12 months |

| RDA | Patient-reported RDA, including work, social life and sport activities | Baseline, 8 weeks, 6 months, 12 months |

| Exercise adherence | Patient-reported adherence to exercise | 8 weeks, 6 months, 12 months |

| Medication usage | Prescribed and over-the-counter medications, additional steroid injection | 8 weeks, 6 months, 12 months |

| Work disability | Sick leave (days) | 8 weeks, 6 months, 12 months |

| Health-care use | NHS outpatient and community services (e.g. GP, additional physical therapy), NHS inpatient and day case (e.g. radiography, MRI) and private health-care services | 8 weeks, 6 months, 12 months |

| Out-of-pocket expenses | Patient-related out-of-pocket expenses recording form | 8 weeks, 6 months, 12 months |

Randomisation

Consented participants were randomised to one of the four physiotherapy-led intervention groups (1 : 1 : 1 : 1) (see Trial design), using a centralised computer randomisation service RRAMP (Registration/Randomisation and Management of Product; URL: https://rramp.octru.ox.ac.uk) provided by the Oxford Clinical Trials Research Unit (OCTRU). This was undertaken directly by the research facilitator at the site or by the research facilitator contacting the central randomisation centre by telephone, who then accessed the system on their behalf, depending on the facilities available at the study sites. Randomisation was computer generated and stratified by centre, age (18–35 years, > 35 years) and sex, using a variable block size to ensure that participants from each study site had an equal chance of receiving each intervention.

Blinding

Both the physiotherapists delivering the intervention and the study participants were informed of treatment allocation at the initial appointment. Because of the nature of the interventions being tested, it was not possible to blind them to the treatment allocation once treatment allocation was revealed. Where practical, team members were blinded until after data analysis was complete. Trial statisticians had access to treatment assignment during the study for the purposes of data monitoring and safety. Data entry personnel entered data from anonymised questionnaires, which included some details on treatments received.

Interventions

Full details of the exercise interventions are described in Chapter 3 and have been reported previously. 43 A summary is provided here for continuity.

Subacromial corticosteroid injection

The subacromial corticosteroid injection was delivered prior to the progressive-exercise or best-practice advice intervention. The injections were predominantly carried out by extended-scope physiotherapists with appropriate post-registration qualifications in injection therapy who worked within a local patient group directive or as non-medical independent prescribers. 34 This reflects an increasingly common practice in the NHS and ensured that the injections were delivered in the most cost-effective manner possible. The corticosteroid injection was given as per its marketing authorisation and in accordance with its normal indication and therapeutic dosage. 44

The corticosteroid and local anaesthetic were given together in one injection or separately in two injections, depending on local treatment protocols at sites. The corticosteroid injected was either methylprednisolone acetate (Depo-Medrone®, Pfizer Ltd, Walton Oaks, UK; up to 40 mg) or triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog™, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Mulhuddart, Ireland; up to 40 mg), as per local treatment protocols. These are the two routinely injected corticosteroids for shoulder pain. There is no clear evidence that either corticosteroid is more effective than the other. 30 The local anaesthetic was either 1% lidocaine (up to 5 ml) or 0.5% bupivacaine hydrochloride (up to 10 ml). We selected sites that adhered to these prescribing boundaries. The choice and dose of corticosteroid, local anaesthetic (including volume) and the injection site were recorded for each participant on a trial injection data collection form (see Appendix 2, Figure 14).

Participants were advised to take care and avoid heavy lifting for 24–48 hours after the injection. Appointments were co-ordinated so that participants typically received their injection within 10 days of randomisation. Very occasionally, a second injection was given after 6 weeks in accordance with the trial protocol (but within 16 weeks of the patient being randomised), but this injection was administered to only those patients who received good initial benefit from their first injection and who requested further pain relief to facilitate their exercises. Any participants who received a second injection had the dose, drug and date of administration recorded on a trial injection data collection form.

Progressive-exercise intervention

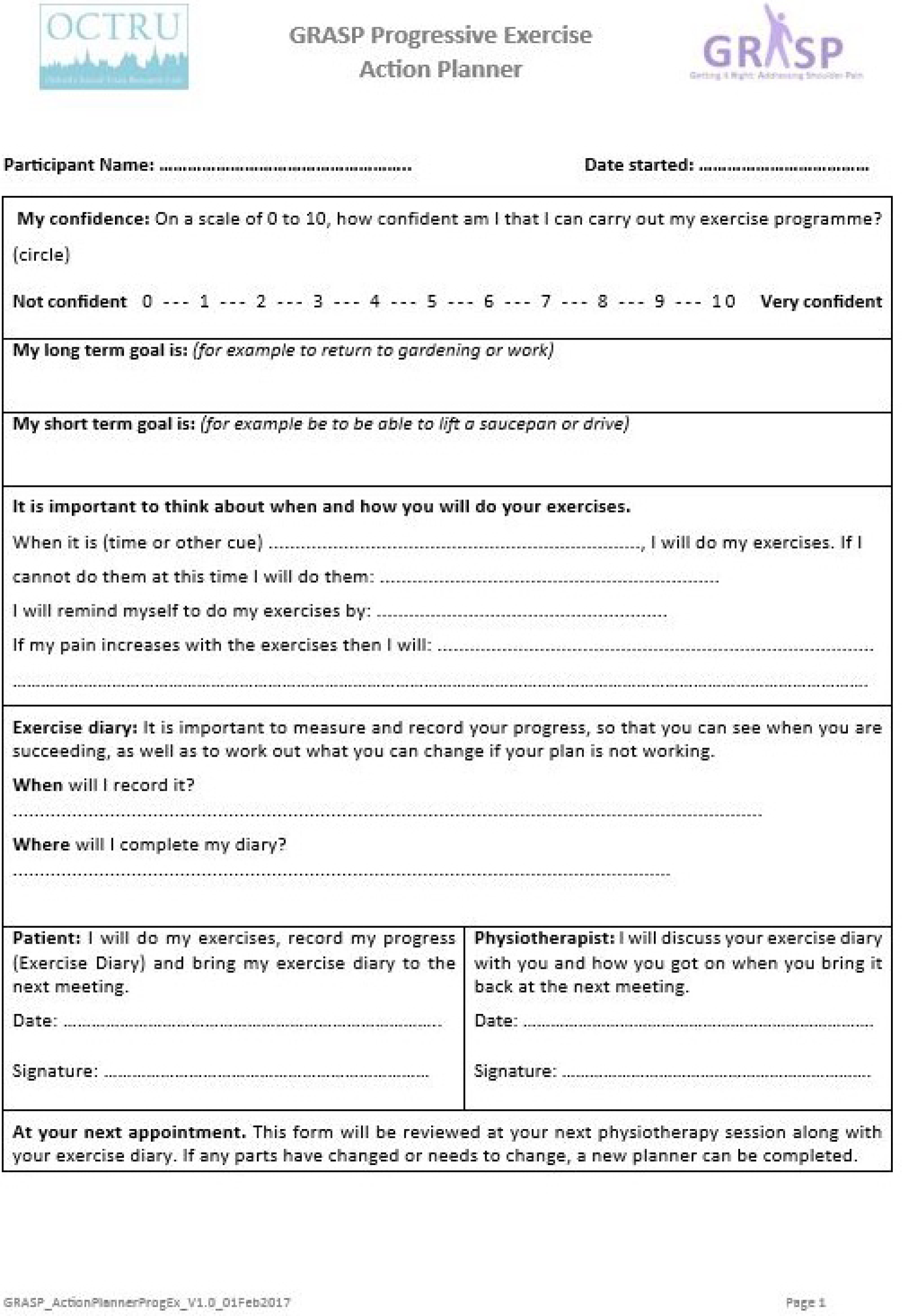

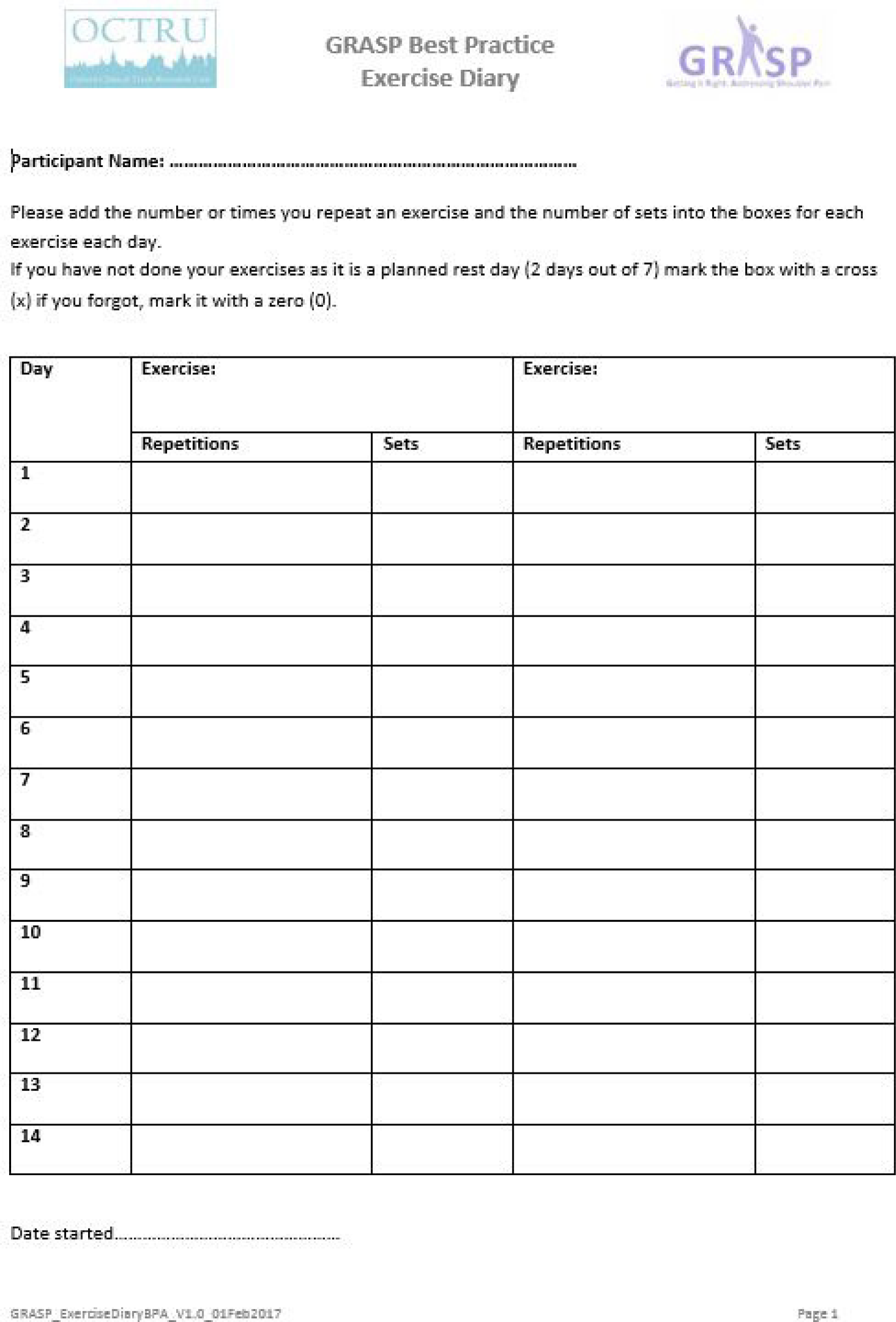

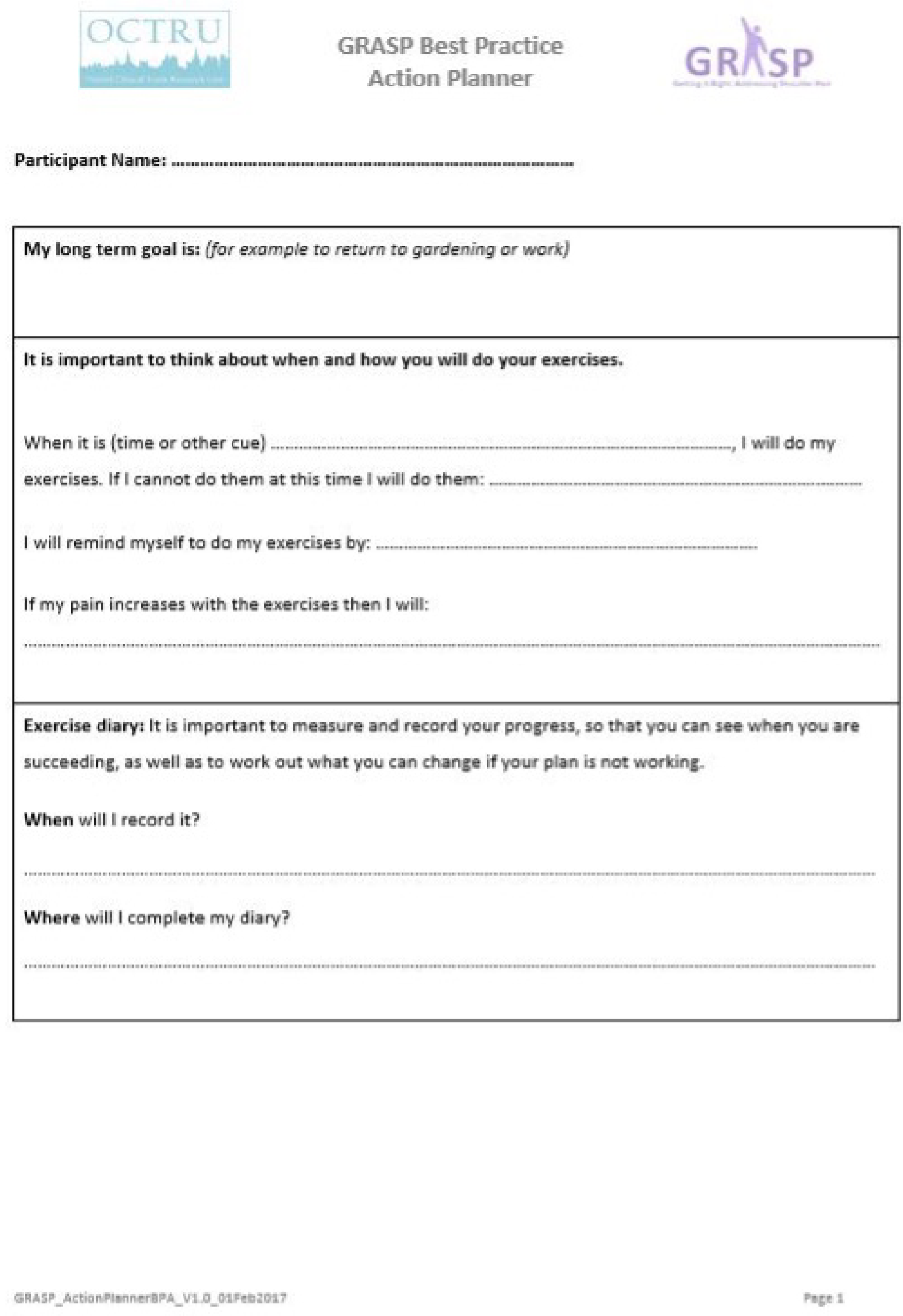

Participants randomised to the progressive-exercise intervention received up to six individual face-to-face sessions with a physiotherapist over 16 weeks. These sessions included a behavioural component to encourage adherence to the exercises. A similar rationale has been used to good effect in other trials. 21,45 We chose the number of sessions, spread over this time, to enable progression of the intensity of exercise and provide a sufficient amount of time for a physiological response in the neuromuscular system. 46 Appointments were co-ordinated so that participants typically started their first exercise session within 14–28 days of randomisation, as per local appointment availability. The initial session lasted up to 60 minutes for assessment and setting up the home exercise programme, followed by up to five 20- to 30-minute follow-up sessions. Participants were provided with a folder containing an advice booklet, an exercise action planner and diary, and instructions on their exercise programme set up in collaboration with their physiotherapist. A resistance band was issued as required. The physiotherapists recorded the number of treatment sessions attended by each participant. The intervention was designed to support participants through a progressive dose of exercises and optimise adherence to the home exercise plan. The progressive-exercise programme was highly structured, but could be tailored to the needs and preferences of participants, with the aim of helping them achieve their rehabilitation goals. Importantly, the intervention could be delivered within the current NHS commissioning paradigm. 47

Best-practice advice intervention

Participants randomised to the best-practice advice intervention received a single, individual face-to-face session with a physiotherapist, lasting up to 60 minutes. Again, appointments were co-ordinated so that participants typically started their exercise session within 14–28 days of randomisation, as per local appointment availability. After a comprehensive shoulder assessment, participants were given an advice booklet. The content of the advice in the booklet was the same as that provided for the progressive-exercise group, with the exception of the different exercise programme. An exercise diary was also provided, along with a simplified version of the exercise action planner (see Chapter 3). Tailored education, reassurance and self-management exercise advice, including advice on pain management and activity modification, was offered. Participants were also given a simple set of self-guided exercises, including at least one level of resistance band and an exercise video [available on a website and digital versatile disc (DVD)], which could be progressed and regressed, depending on their capability. The exercises were designed using similar concepts to those of the progressive-exercise intervention, such as increased resistance, but with a simpler range of exercise options that were not supervised.

The best-practice advice intervention was selected as the comparator because it is consistent with current clinical practice guidelines regarding the self-management advice that should be provided to people with rotator cuff disorders. 4,5 In addition, people may find a single advice session and DVD preferential to a course of face-to-face physiotherapy sessions, as they do not have to come back to the hospital or clinic, take time off work or make carer arrangements.

Concomitant care

All participants were advised that they could take over-the-counter analgesia as required (e.g. paracetamol with or without codeine, or an oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug) in accordance with the BESS guidelines. 4 Participants could seek other forms of treatment during the follow-up period, but were informed that they should use usual routes (predominantly NHS referral) to do so. Additional treatments, including contact with their GP or other health professional, changes in medication, use of physical treatment and alternative therapies, were recorded as a treatment outcome through the patient questionnaires at 8 weeks, 6 months and 12 months post randomisation.

Training and monitoring of intervention delivery

All physiotherapists delivering study interventions, progressive exercise and best-practice advice had access to a comprehensive intervention manual and were required to have undertaken trial-specific training by a GRASP trial research physiotherapist. A rigorous quality control programme was also conducted to ensure intervention fidelity (see Chapter 3).

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was shoulder pain and function over the 12 months post randomisation measured using the SPADI,10,11 which was developed to measure current (i.e. in the last week) shoulder pain and disability in an outpatient setting. The SPADI scale is based on 13 questions, all scored on a 0–10 scale, on which 10 is the worst score. In addition, the SPADI scale has a five-item pain subscale and an eight-item disability subscale. The subscale items are summed and converted to a 0–100 scale, where a higher value denotes more pain and/or disability. A systematic review of outcome measurement sets for shoulder pain trials showed that SPADI is the most commonly used measure to assess pain and disability. 48 The SPADI scale has good psychometric properties, is used widely in the field and can be completed using a postal questionnaire.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes (see Table 1) were subdomains of the SPADI, which are pain measured using the SPADI five-item pain subscale10,11 and function measured using the SPADI eight-item disability subscale;10,11 health-related quality of life, measured using the well-validated EuroQol 5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) score;38 psychological factors, measured using the Fear Avoidance Belief Questionnaire – Physical Activity (FABQ-PA) five-item subscale39 and the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire, two-item version (PSEQ-2);40 sleep disturbance, measured using the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI);41 patient global impression of change;42 RDA, including work, social life and sport activities; patient adherence to exercise; any serious adverse events (SAEs); health resource use, including consultation with primary and secondary care, prescribed and over-the-counter medication use, additional physiotherapy or injection use, and hospital admission; additional out-of-pocket expenses; and work absence (i.e. number of sickness days).

The EQ-5D-5L38 is a validated, generic health-related quality-of-life measure comprising five dimensions, each with a five-level answer possibility and a health thermometer scale. The EQ-5D-5L can be used to report health-related quality of life in each of the five dimensions and each combination of answers can be converted into a health utility score, where 1 represents perfect health and 0 indicates health states equal to death. The health thermometer scale (EuroQol visual analogue scale) takes values between 0 and 100, where 0 represents worst imaginable health and 100 best imaginable health. It has good test–retest reliability and gives a single preference-based index value for health status that can be used for broader cost-effectiveness comparative purposes.

The Fear Avoidance Belief Questionnaire (FABQ)39 is a validated measure of fear-avoidance behaviour. The FABQ-PA is a subscale of the FABQ that measures fear-avoidance beliefs about physical activity using five items scored on a 0 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree) scale. The total score range for FABQ-PA is 0–24, with higher scores representing greater levels of fear-avoidance behaviour.

The PSEQ40 is a well-established 10-item measure of pain self-efficacy (i.e. a belief in one’s ability to carry out activities despite pain). PSEQ-2 is a two-item, short measure of pain self-efficacy. 40 The two items reflect the confidence in ability to work and lead a normal life despite the pain, on a 0 (not at all confident) to 6 (completely confident) scoring scale. The total PSEQ-2 score is summed from the two items, giving a range from 0 to 12, with higher values representative of higher confidence levels despite the pain.

The ISI41 is a brief self-report measure of a patient’s perception of their insomnia, targeting the subjective symptoms and consequences of insomnia, as well as the degree of concerns or distress caused by those difficulties. The ISI has seven items rated on a 0–4 scale and the total score is a summation of these items, with a value ranging from 0 to 28. Higher scores are suggestive of more severe insomnia. A detailed interpretation of the ISI total score is as follows:

-

A score of 0–7 indicates no clinically significant insomnia.

-

A score of 8–14 indicates subthreshold insomnia.

-

A score of 15–21 indicates clinical insomnia of moderate severity.

-

A score of 22–28 indicates severe clinical insomnia.

The Global Impression of Treatment (GIT)42 is a simple method of measuring change in health status, with respect to shoulder problems, by charting self-assessed clinical progress on an 11-point scale that ranges from –5 (very much worse) to 5 (completely recovered). Psychometric properties include a minimum detectable change of 0.45 points and a minimally clinically important difference (MCID) of 2 points.

Return to desired activities is a self-reported outcome that aims to measure physical function during social life, recreational activities and work. RDA is an adapted version of the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (QuickDASH), using three questions with a five-point Likert scale answer option, with lower scores indicating better function.

Other secondary outcomes (including medication usage, work disability, health-care use and out-of-pocket expenses) are analysed separately as part of a health economics analysis (see Chapter 5).

Adverse events

Expected adverse events occurring as a result of the trial intervention(s) were not recorded as part of the trial. Participants were provided with information on the potential adverse events resulting from exercise and corticosteroid injection (if applicable) as part of their treatment, including what they should do if they experienced an adverse event, as would happen as part of standard NHS procedures. SAEs (defined as any medical occurrence that could result in death, is life-threatening or results in hospitalisation or incapacity) were considered highly unlikely to occur as a result of either the exercise or the corticosteroid injection therapy delivered in this trial. However, if a SAE arose in the period from the participant’s enrolment in the trial to their final visit for their allocated intervention, standard procedures for recording and reporting SAEs applied.

Follow-up data collection

Measurements for the primary and secondary outcomes were all patient reported and collected using postal questionnaires at 8 weeks, 6 months and 12 months after randomisation (see Table 1). Participants were asked to complete the questionnaire and return it to the GRASP study team in the prepaid envelope. For those who did not respond to the initial questionnaire, at least one postal reminder was sent. A web-based version of the questionnaire, and telephone and e-mail follow-up were used to contact those who did not respond to the postal questionnaire. Telephone and e-mail follow-up was also used to collect a core set of questionnaire items if these had not been fully completed on the returned questionnaire. To maximise response rates for the 12-month follow-up, a small monetary incentive (in the form of a gift voucher) was sent to all participants along with their 12-month follow-up questionnaire as a thank you for the time and effort involved.

Data management

All data were processed according to the General Data Protection Regulation 2018 and all documents were stored safely in confidential conditions. 49 All trial-specific documents, except for the signed consent form and follow-up contact details, referred to the participant using a unique study participant number/code and not by name. Participant identifiable data were stored separately from study data and in accordance with local procedures. All trial data were stored securely in offices that were accessible using a swipe card by the central co-ordinating team staff and authorised personnel only.

Statistical methods

Sample size

The target sample size for the trial was 704 randomised participants (176 in each treatment arm). This sample size was based on 90% power and 1% two-sided statistical significance to detect a minimally clinically important between-group difference of 8 points on the SPADI total scale,10 assuming a baseline standard deviation (SD) of 24.3 (chosen as representative of the patient population50). This difference is the equivalent of a standardised effect size of 0.33, which required a sample size of 550 participants [Power Analysis and Sample Size 13 NCSS Statistical Software Kaysville, UT, USA; URL: www.ncss.com (accessed 20 May 2021)]. Allowing for a potential loss to follow-up of 20% at 12 months inflated the sample size to 688. We further inflated the sample size to take into account the potential for a small clustering by physiotherapist effect in the progressive-exercise intervention group. We used an interclass correlation (ICC) of 0.001, based on our experience with individually tailored physiotherapy interventions51 and the expectation that each physiotherapist would treat approximately 20 participants in the progressive-exercise intervention group. This lead to an inflation of:

and increased the sample size to the total of 704 participants.

This sample size was based on the assumption that there was no interaction effect and was powered for the two main effect comparisons: (1) progressive exercise compared with best-practice advice and (2) corticosteroid injection compared with no injection. However, this number of participants also provided 80% power and 5% two-sided significance to detect an interaction standardised effect size of 0.35, if an interaction effect did exist. The interaction effect was tested before the main effect comparisons were undertaken. It should be noted that a non-significant interaction effect did not preclude a smaller interaction that this study was not powered to detect. We chose 90% power and 1% two-sided significance to provide more convincing evidence of any treatment effects discovered. No further adjustments to the sample size were made because of multiple testing. The Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) reviewed the sample size assumptions after 338 participants were recruited and no changes were made to the final sample size.

Statistical analysis

A separate SAP37 provides full details of all planned statistical analyses and was finalised prior to any primary outcome analysis. A summary is provided below.

The SAP was reviewed and received input from the TSC and DMEC. Any changes or deviations from the original SAP are described and justified in Chapter 4 and any additional publications, as appropriate. All statistical analyses were undertaken using Stata® (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

The primary statistical analysis was carried out on the basis of intention to treat (ITT), with all randomised participants included and analysed according to their allocated treatment group, irrespective of which treatment they actually received or their compliance with the proposed interventions. The two main effect comparisons for this 2 × 2 factorial trial were (1) progressive exercise compared with best-practice advice to determine the efficacy of progressive exercise [group A (progressive exercise) + group C (progressive exercise + injection) vs. group B (best-practice advice) + group D (best-practice advice + injection)] and (2) subacromial corticosteroid injection compared with no injection to determine the efficacy of subacromial corticosteroid injection (A + B vs. C + D). This ‘factorial analysis’ was conducted ‘at the margins’ of the table (Table 2). The sample size for this type of analysis was calculated under the assumption that there will be no intervention interaction effect (i.e. that progressive exercise would not interact with the steroid injection, such that it would work, work better or work worse only when used together rather than used alone). If a substantial interaction between the two interventions was present, the factorial analysis of the groups would lead to biased results and, therefore, the efficacy of each intervention would need to be drawn from comparisons within the intervention groups (i.e. ‘inside-the-table’ comparisons). Regardless of being able to detect a significant interaction effect, the results of the trial for the primary outcome, SPADI, meant that estimates were to be presented both ‘inside the table’ and ‘at the margins’, together with the size of the interaction. 52 The success or otherwise of the interventions would be evaluated from the analysis results conducted based on evidence for presence/absence of a treatment interaction.

| No corticosteroid injection | Corticosteroid injection | Effect of ProgEx intervention | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ProgEx intervention | Group A (ProgEx) | Group C (ProgEx + injection) | A + C vs. B + D |

| BPA intervention | Group B (BPA) | Group D (BPA + injection) | |

| Effect of corticosteroid injection | A + B vs C + D | ||

Interaction

An interaction between the two main effect comparisons was not expected, but the trial was powered to identify a moderate standardised interaction effect of 0.35. The presence of an interaction between the two interventions was formally investigated before testing their effects on the primary outcome. An initial regression model was fitted for the primary outcome to predict the outcome of interest and included the two effects of interest [i.e. (1) individually tailored progressive-exercise programme compared with best-practice advice and (2) subacromial corticosteroid injection compared with no injection] and their interaction.

In the presence of a non-statistically significant treatment interaction (i.e. p ≥ 0.05), a factorial analysis was planned to determine the success of the trial. The effects for the individually tailored progressive-exercise programme and corticosteroid injection were determined separately from this model as mean differences (MDs) with associated 99% confidence intervals (CIs), as appropriate, adjusted for the relevant covariates. The model used did not include an intervention interaction term.

If a statistically significant treatment interaction (i.e. p < 0.05) had been detected then the effect of the individually tailored progressive-exercise programme and corticosteroid injection would have been evaluated from comparisons within the intervention groups, referred to as ‘inside-the-table’ comparisons (i.e. group A vs. group B to test the effect of the individually tailored progressive exercise programme and group B vs. group D to test for the effect of the corticosteroid injection) (see Table 2). The main effects and their interaction terms would have been included in the analysis model, their regression coefficient with corresponding 95% CI for the interaction terms presented and the reduced statistical power of this model noted.

Primary outcome analysis

The difference in SPADI between the two intervention groups was estimated overall and at each data collection time point using a repeated measures linear mixed-effects regression model. 53 The model was adjusted for the fixed effects of age, sex and baseline SPADI, and random intercepts by centre and observations within participants. Robust standard errors (SEs) for treatment effects from all time points were reported. Clustering by physiotherapist in the progressive-exercise group was accounted for using cluster-robust SEs as part of the mixed-effects model. The final trial results were based on the adjusted model. A non-parametric statistical test (e.g. Mann–Whitney test for comparison of means) with no adjustment and medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) were reported where approximate normality for the model residual terms was not established. Statistical significance was set at the 1% level and corresponding 99% CIs were reported for the primary outcome. Flooring effects in the SPADI outcome over the 12 months were explored and reported for each treatment group.

Secondary outcome analyses

The intervention effects on secondary outcomes were analysed following the analysis method described for the primary outcome on the basis that the outcomes are clinically similar. If there was no statistically significant evidence of an interaction effect for the primary outcome, then no interaction effect would be assumed for the secondary outcomes. Likewise, if a statistically significant interaction effect was identified for the primary outcome, then the secondary outcomes would be analysed, assuming an interaction effect was present. Continuous secondary outcomes analyses were conducted following similar methods to the outline for the primary outcome analysis, using linear regression for continuous outcomes and logistic/multinomial logistic regression (i.e. logit, mlogit or ologit, as appropriate) for binary and ordinal outcomes. Statistical significance for secondary outcomes was set at 5% and 95% CIs were reported.

Missing data

Missing data were reported and summarised by treatment group. Item-level imputation for the primary outcome SPADI was carried out for items where no more than two out of five items in the pain subscale were missing and no more than three out of eight items in the function subscale were missing, given that no more than 10% of cases had missing data. 54,55 Missing continuous primary and secondary outcomes were handled as part of the likelihood-based estimation of the repeated measures mixed-effects model, assuming the data were missing at random. 56 This method took account of missing observations owing to missed visits or a participant leaving the study prematurely. The distribution of missing data was explored to assess the assumption of data being missing at random. Full details are provided in the SAP. 37

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were used to assess the robustness of the trial results in the light of the assumptions made about the underlying missing data mechanism. Most analyses assume data to be missing at random or missing completely at random. The sensitivity analysis, therefore, assumed missing not at random, such that missing outcomes were assumed to be worse or better than the observed outcomes.

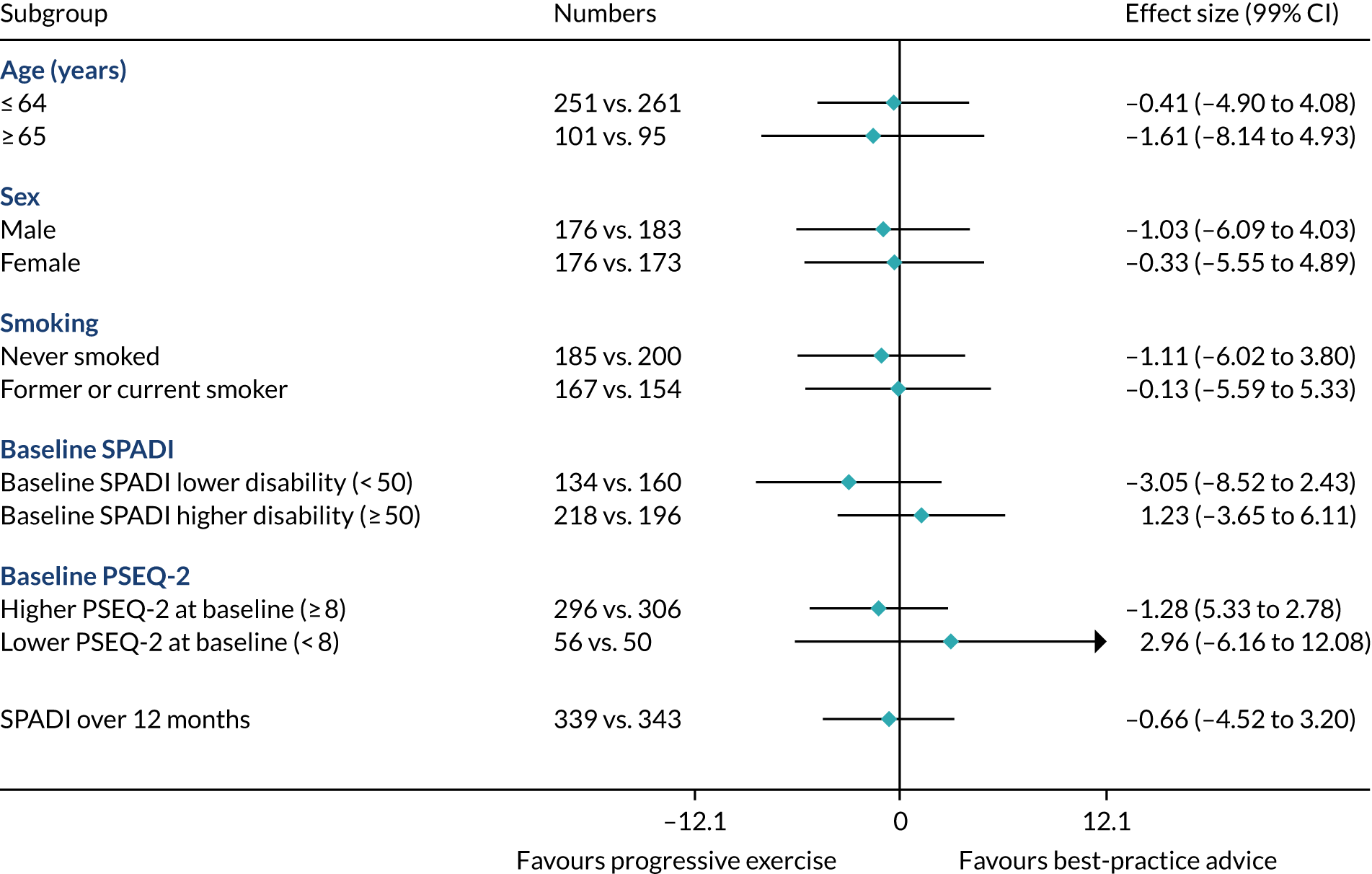

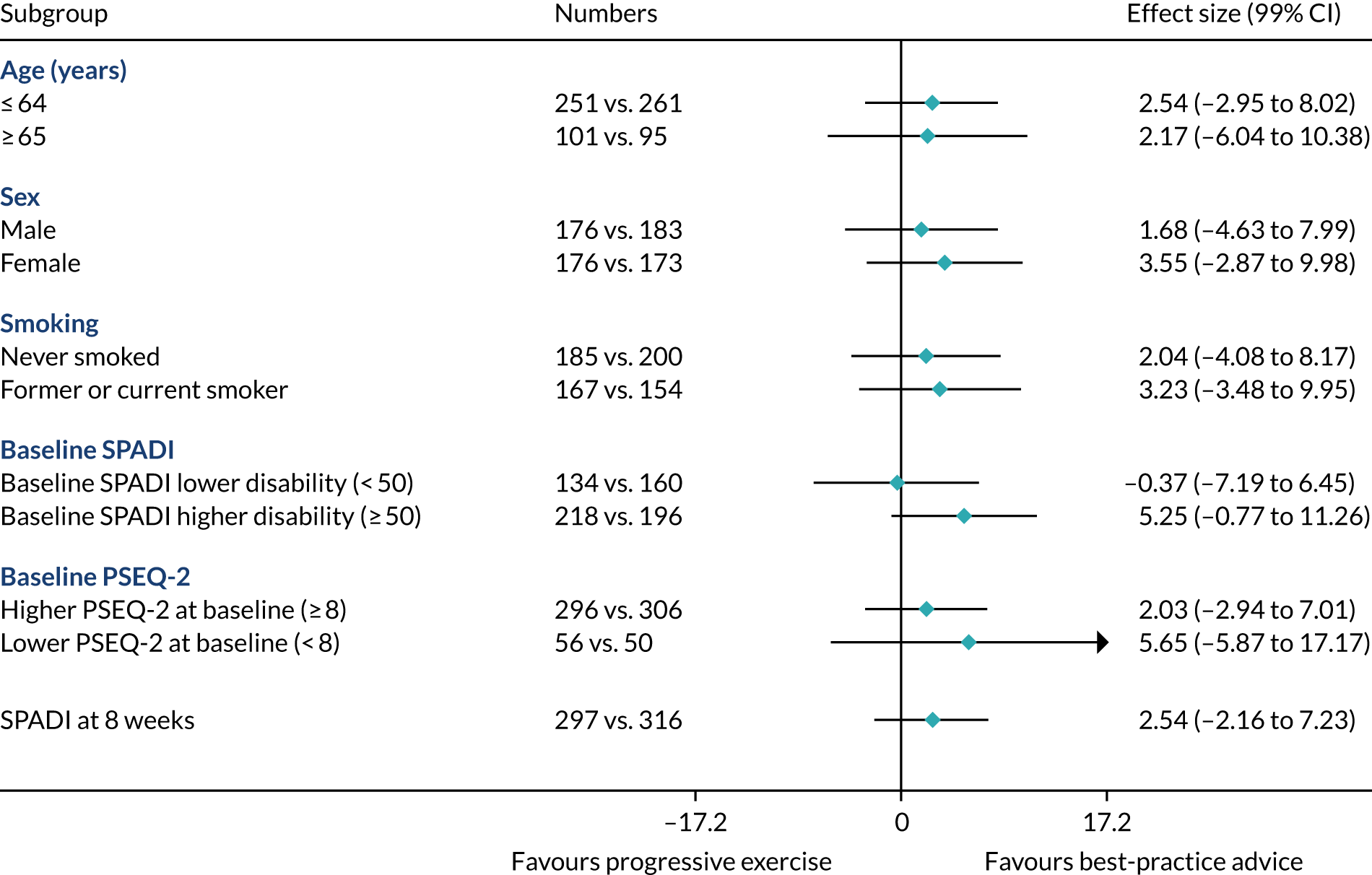

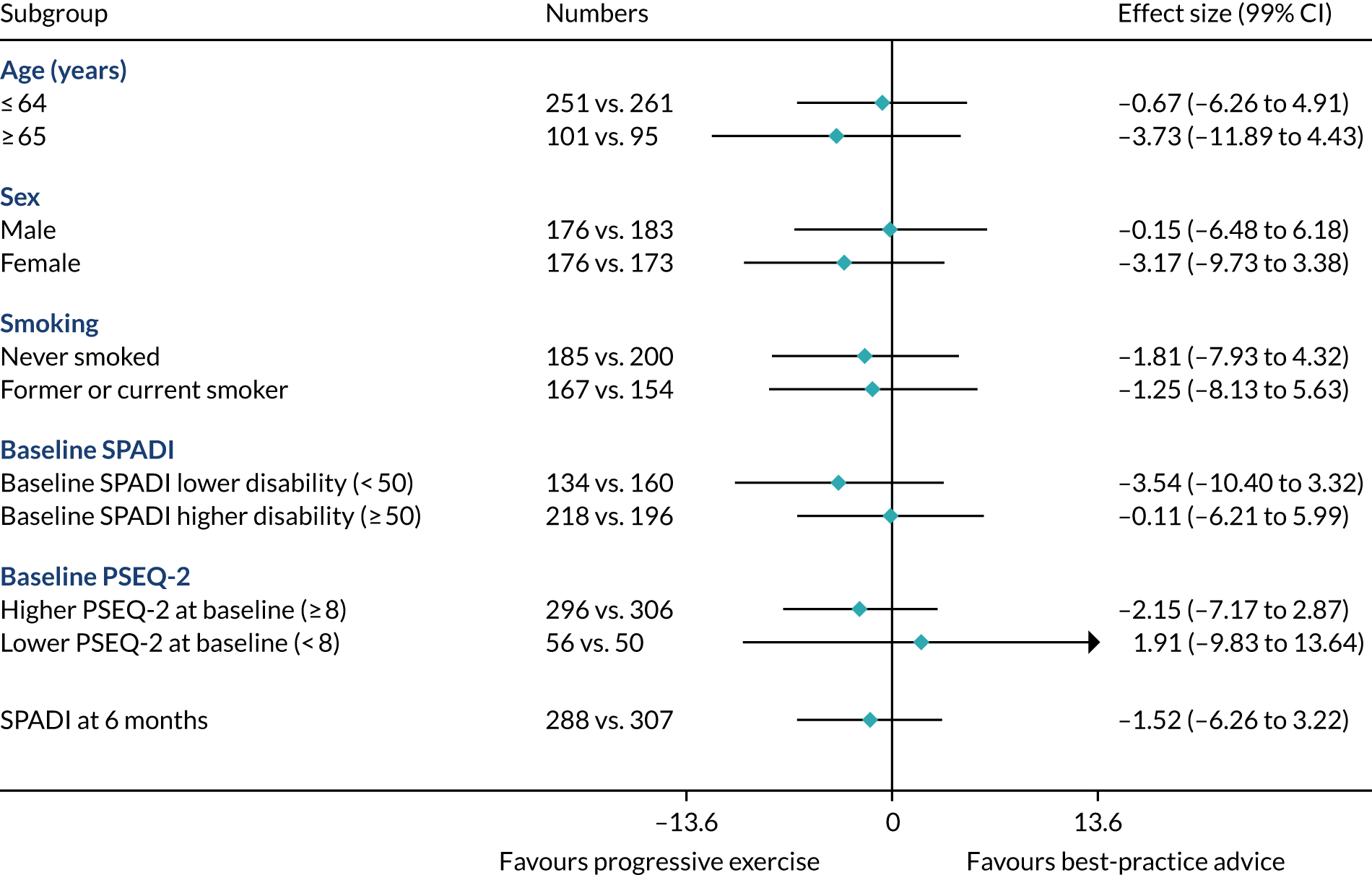

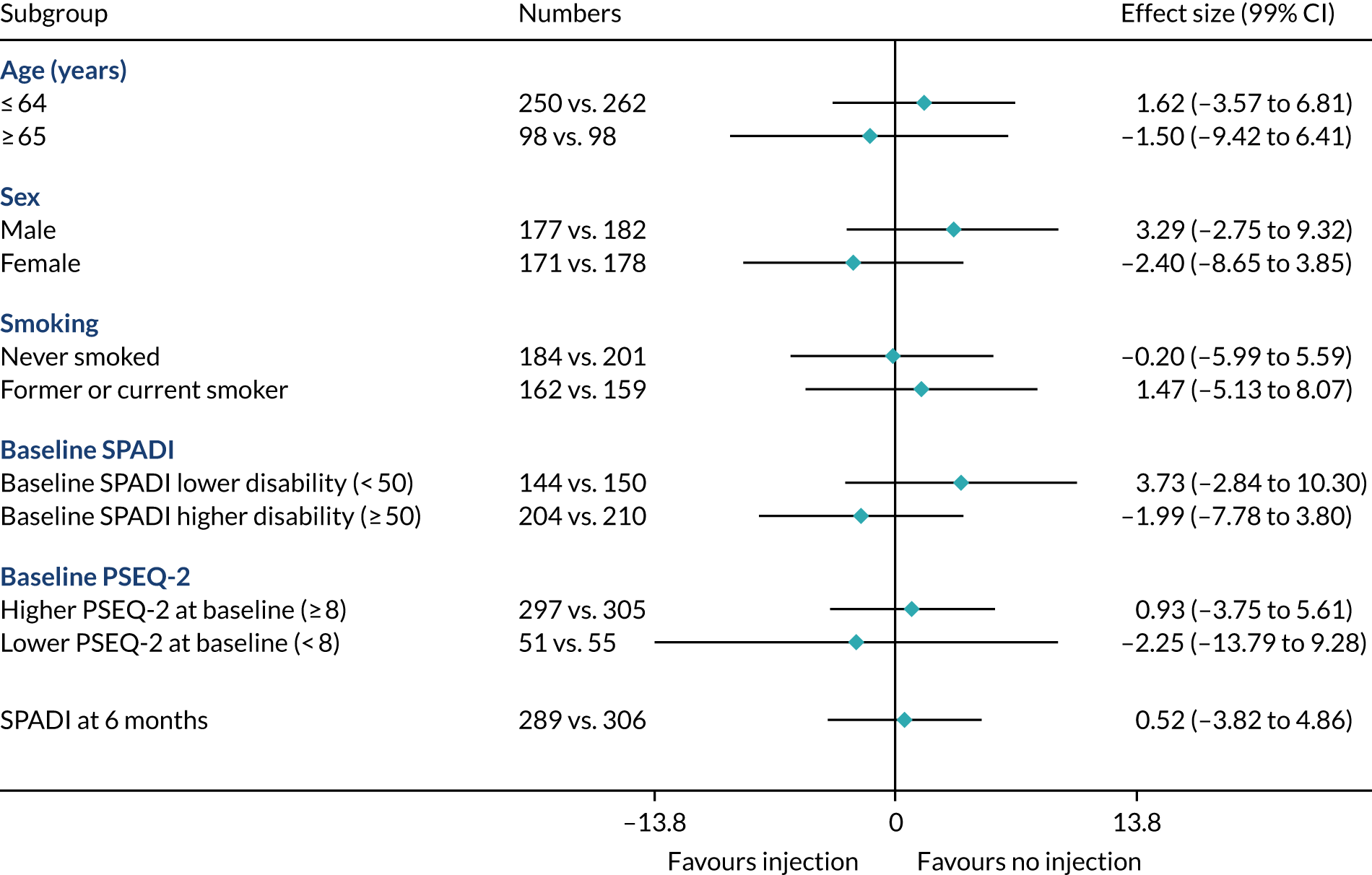

Prespecified subgroup analysis

Subgroup effects in the following prespecified subgroups were analysed for the primary outcome, utilising subgroup-by-treatment interactions:

-

Age: ≤ 64 years vs. ≥ 65 years. (Rationale: increasing age has been shown to be associated with poorer outcome. 57,58)

-

Sex: male vs. female. (Rationale: prevalence is higher in males than in females. 1)

-

Smoking status: never smoked vs. former smoker or current smoker. (Rationale: smoking has been shown to be associated with a negative effect on tendon healing. 59)

-

Higher SPADI score at baseline. (Rationale: higher pain and functional disability at baseline may be associated with poorer outcome. We defined a higher SPADI score as ≥ 50 at baseline when the SPADI is converted to the 0 to 100 scale. 19,57)

-

Higher pain self-efficacy (PSEQ-2) score at baseline. (Rationale: higher belief in one’s ability to carry out activities despite pain may be associated with better outcome. We define a higher PSEQ-2 score as ≥ 8 at baseline when the PSEQ-2 is converted to the 0–12 scale.)

Supplementary/additional analyses

A complier-average causal effect (CACE) analysis was used to investigate the role of compliance in the treatment effect, given the CACE assumptions described in the SAP. Compliance with intervention was defined in the SAP37 as follows. For the progressive exercise intervention, participants were considered compliant with treatment if they had been signed off for completing treatment or if they receive all six physiotherapy sessions. For corticosteroid injection intervention, participants were considered compliant if they received at least one injection. If no evidence of a statistically significant interaction between the two treatments was identified, then this analysis was planned to be conducted ‘at the margins’ and using a similar mixed-effects model. If a statistically significant treatment interaction for the primary outcome was identified, the CACE analysis would be conducted ‘inside the table’.

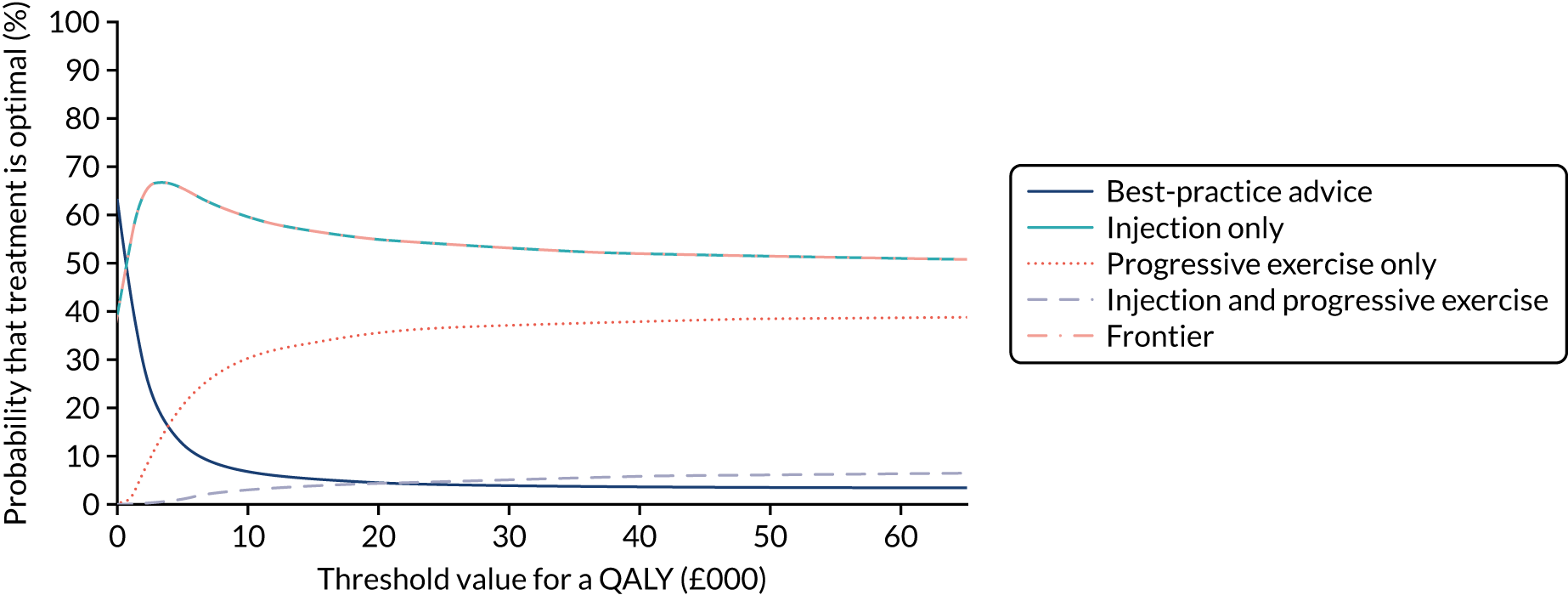

Cost-effectiveness analysis

An economic evaluation was integrated within the GRASP trial design. Full details are described in Chapter 5 and a summary is described here for continuity.

The economic evaluation, in the form of a cost–utility analysis, was conducted from the recommended NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) perspective. 60 Individual patient data on the use of health and social services were collected at 8 weeks, 6 months and 12 months post randomisation as part of the follow-up data collection process (see Table 1). The cost of delivering each intervention, including physiotherapists’ training, materials, delivery of the progressive exercise and advice sessions, and corticosteroid injections, were also estimated. Participants’ health-related quality of life was captured through the EQ-5D-5L at baseline and at 8 weeks, 6 months and 12 months post randomisation.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI) was central to the design of the GRASP trial and was maintained throughout the trial set-up, implementation and dissemination. PPI representatives were involved in a number of ways. First, as part of the initial trial design, we held a PPI study development meeting, supported by the Research Design Service South Central (Oxford, UK), where the proposed research was presented and discussed with attendees. The views expressed by the patients contributed to the trial design and subsequent trial protocol. In particular, an outcome looking at sleep disturbance was included, as this was deemed to be very important to patients. The PPI representatives also advised keeping the number of self-reported outcomes to a minimum to avoid an undue burden on the participants and recommended using diaries so that the patients could record and monitor their own progress.

Patient and public involvement representatives also attended the GRASP intervention development meeting (see Chapter 3) and provided valuable practical input regarding delivery and acceptability of the progressive-exercise and best-practice advice interventions. In addition, PPI representatives were involved in reviewing the participant information sheets and participant questionnaires to ensure that they were accessible and user-friendly. Two PPI representatives were formal members of the GRASP TSC and attended and actively contributed to these meetings, including the final results meeting where data were shared and interpreted. As part of the dissemination process, the PPI representatives also reviewed and advised on the wording of the letter to trial participants, advising them of the GRASP trial results.

Ethics approval and monitoring

Ethics committee approval

The GRASP trial protocol and all related documentation (e.g. informed consent forms, participant information leaflets, patient questionnaires and any proposed advertising material) was approved by the Berkshire B Research Ethics Committee (reference 16/SC/0508) and Integrated Research Application System (ID 199243). The trial was also approved by the UK competent authority the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, as it was classified as a clinical trial of an investigational medicinal product (EudraCT number 2016-002991-28). The trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki61 and the Medical Research Council’s GCP guidelines. 62

Trial Management Group

A Trial Management Group, consisting of the core trial team, chief investigator and co-applicants, was responsible for the day-to-day running of the trial and met monthly to report on progress and ensure that milestones were met. A trial manager oversaw all aspects of the day-to-day trial management.

Trial Steering Committee

A TSC was responsible for monitoring the trial’s progress and providing independent advice. The TSC comprised an independent clinician, two specialist physiotherapists, a statistician, a health economist and two patient representatives.

Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee

A DMEC was responsible for monitoring the trial’s progress and providing independent advice. It advised the chairperson of the TSC if, at any time, in its view, the trial should be stopped for ethics reasons, including concerns about participant safety. The DMEC comprised an independent clinician, health service researchers, a specialist physiotherapist and a statistician.

Chapter 3 Intervention description and rationale

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Keene et al. 43 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Developing the GRASP trial exercise interventions

The GRASP trial interventions were developed using Medical Research Council guidance for developing and evaluating complex interventions. 63 We took into account clinical guidelines, research evidence, current practice variation, deliverability in the NHS (in terms of staffing, resources and time), expert and patient opinion, acceptability to clinicians and patients, and the need to ensure consistency in delivery and reproducibility. The intervention development and descriptions have been reported previously. 43

Intervention development

In Chapter 1, the lack of evidence for particular exercises, treatment intensities or durations were outlined. With no clear evidence or clinical consensus, advice from clinicians, patient and public representatives and other experts was crucial to the development of the GRASP trial interventions. Twenty-six clinicians, researchers, patients and public representatives attended a GRASP intervention development meeting (June 2016). Delegates discussed and evaluated a comprehensive list of 22 exercise types commonly used in clinical practice and/or reported in trials of shoulder pain treatments (see Appendix 3, Table 26). The delegates categorised the exercises into essential exercises, optional exercises or exercises considered not important for managing rotator cuff disorders.

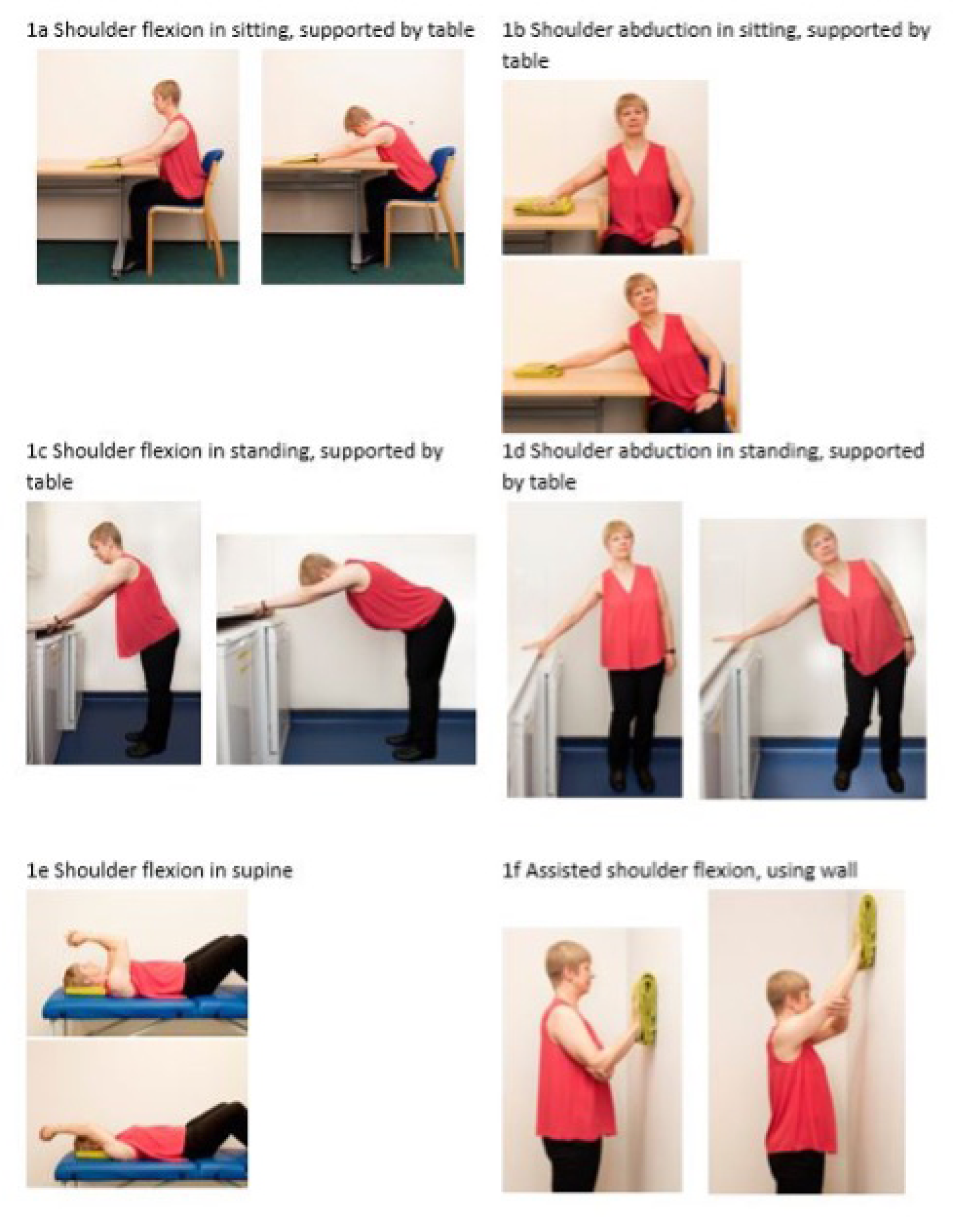

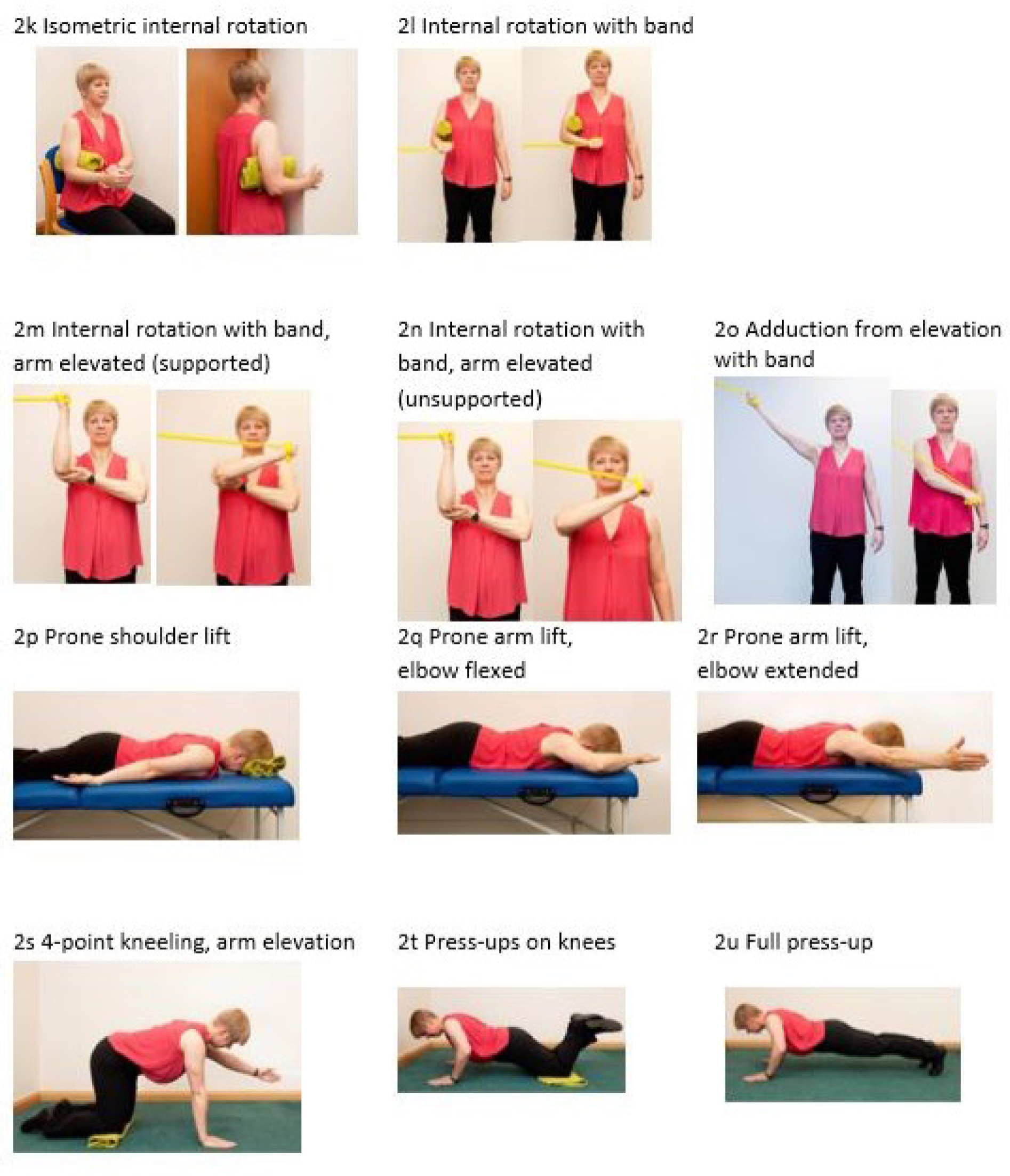

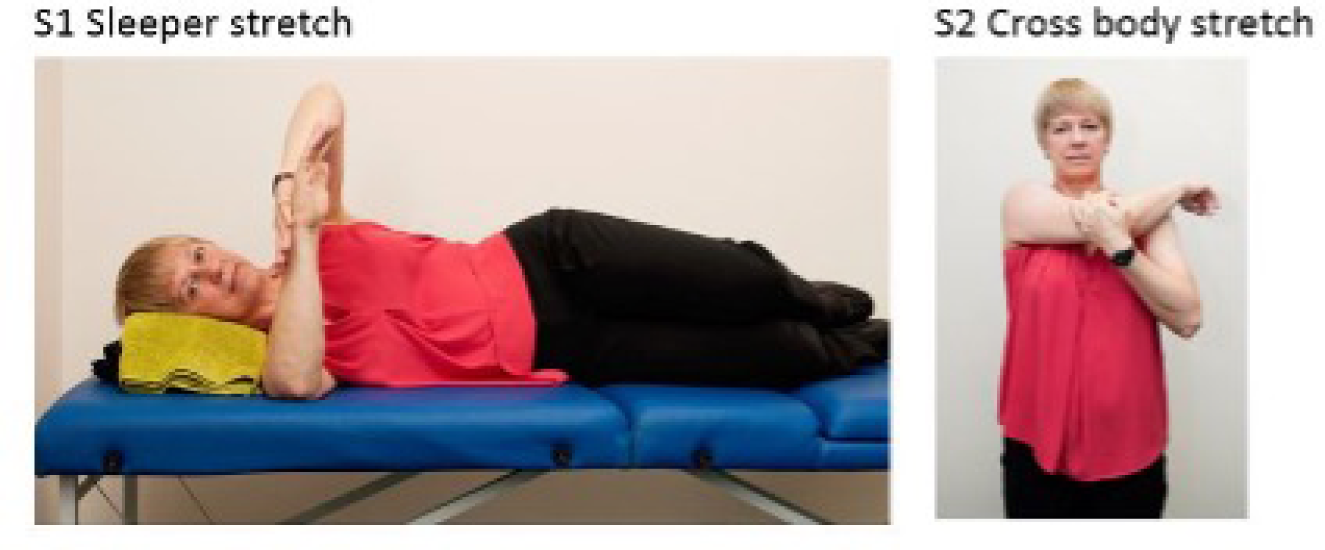

Those selected as essential exercises generally strengthen the posterior rotator cuff muscles (i.e. supraspinatus, infraspinatus and teres minor) and load the shoulder into an elevated position, consistent with current trial evidence. 17,64 The GRASP trial, therefore, included these exercise types as an essential component of both the progressive-exercise and best-practice advice exercise interventions. Delegates agreed that both exercise interventions should be as practical and simple as possible. Some exercises were considered important for patients with specific presentations or in particular circumstances. These were included as optional exercises in the progressive-exercise intervention. They were not incorporated into the best-practice advice intervention, which prioritised a simple, progressive set of exercises that were likely to benefit most patients and could be easily understood and performed at home without supervision.

Delegates agreed that stretching was not a priority target in rotator cuff disorders and that range of motion could be incorporated into other active exercises. A posterior capsule/soft tissue stretch for the shoulder was included as an option in the progressive-exercise intervention as we recognised that these stretches feature in many exercise programmes evaluated in other clinical trials. 14 Isolated exercises to correct posture towards a theoretical ideal were not included, as there is limited evidence for this approach. 65 Experts disagree on whether exercises can or should provoke symptoms or should be symptom-free. There is limited evidence for these alternatives, although evidence is building for the acceptability of mild-to-moderate pain symptoms during exercise. 66,67 The participant information booklet, which was included as part of the GRASP trial intervention materials, and treating physiotherapists advised participants that some pain during the exercises is acceptable, provided that they found it manageable and symptoms resolved to an acceptable level within a few hours.

After the meeting, we developed detailed intervention manuals for the treating physiotherapists that described the key components of the progressive-exercise and best-practice advice interventions. We also developed patient-facing materials, which were reviewed by patient representatives.

Internal pilot

As part of the GRASP trial, we ran an internal pilot from February to June 2017 at three sites, recruiting 42 participants. One of the aims of the internal pilot was to test and refine the recruitment process and explore treatment acceptability. The physiotherapists delivering the GRASP exercise interventions were also asked to provide feedback on the delivery of the intervention. The exercise intervention manuals and training materials were subsequently refined to clarify identified misconceptions. The interventions did not require significant modifications.

The GRASP trial interventions

Table 3 summarises the key components of the GRASP exercise interventions. The interventions were delivered face to face and one to one by UK-registered physiotherapists based at physiotherapy and musculoskeletal services across England.

| TIDieR items68 | Progressive exercise | Best-practice advice |

|---|---|---|

| Brief name | GRASP | |

| Why | Physiotherapy-led exercise and advice are commonly used to manage rotator cuff disorders; however, evidence is lacking in terms of how exactly it should be delivered and whether or not patients do better if they receive a corticosteroid injection before starting an exercise programme | |

| What | Home exercise and advice programme overseen by physiotherapist over six or fewer sessions within 16 weeks | Home exercise and advice programme initiated during a single face-to-face session with a physiotherapist, and then performed unsupervised by participant at home |

| Materials: participants |

Participant information booklet (see Table 4) and exercise instruction sheets with photos Action planner and exercise diary (see Appendix 3, Figure 15) Resistance bands (if applicable) |

Participant information booklet (see Table 4), incorporating exercise instructions with photos Action planner and exercise diary (see Appendix 3, Figure 22) Resistance bands Exercise instruction videos available on website or DVD |

| Materials: physiotherapists |

Therapist manuals detailing all aspects of the trial and the progressive-exercise intervention, and a quick reference guide for use in the clinic Training, including 1 full day (at least 4–5 hours) of face-to-face training delivered by GRASP trial research physiotherapists |

A therapist manual detailing all aspects of the trial and the best-practice advice intervention At least half a day of training |

| Procedures |

Initial appointment Assess participant as per normal physiotherapy practice Issue folder containing the progressive-exercise participant information booklet Agree level of exercise that is most appropriate for the participant initially (see Figures 1 and 2) Advice should address barriers to exercise identified during assessment Provide education regarding pain during and after exercise Help participant to complete exercise documentation (i.e. the exercise diary and action planner) Make follow-up appointment(s) Complete treatment log Appointments 2–6 Reassess as per normal physiotherapy practice Assist participant to progress/regress exercises Reassure the participant and reinforce key messages from the advice and education Review home exercise programme using the exercise diary Discuss return to functional activities Review action planner Complete treatment log (after every session) |

Single face-to-face appointment Assess participant as per normal physiotherapy practice Issue best-practice advice participant information booklet Explain exercise ladder (see Appendix 3, Figure 21) and agree with participant what level of the ladder is most appropriate initially Educate participants on how to progress and regress their exercises Ensure that the participant knows how to access the exercise videos online or issue DVD (or both) Advice should address barriers to exercise identified during assessment Provide education regarding pain during and after exercise Help participant to complete exercise documentation (i.e. the exercise diary and action planner) Strategies to encourage adherence to exercise were less extensive than in the progressive-exercise intervention, as they need to be feasible to deliver within a single session Discharge participant with advice/encouragement to continue with the self-management exercise programme for at least 16 weeks Complete treatment log |

| Who provides |

Physiotherapists already working in NHS musculoskeletal services who have attended the progressive-exercise intervention training The GRASP trial does not exclude physiotherapists based on number of years qualified or experience in treating shoulder conditions |

Physiotherapists already working in NHS musculoskeletal services who have attended the best-practice advice intervention training The GRASP trial does not exclude physiotherapists based on number of years qualified or experience treating shoulder conditions |

| How |

Participants receive up to six sessions with a physiotherapist over 16 weeks The initial session lasts up to 60 minutes for assessment. It is then followed by up to five 20- to 30-minute sessions |

Participants receive a single face-to-face session with a physiotherapist lasting up to 60 minutes |

| Where |

Physiotherapy sessions are in outpatient clinics based in the NHS The exercise programme is performed by the participant at home |

Same as progressive-exercise intervention |

| When and how much |

The initial appointment is co-ordinated within 14–28 days of randomisation, as per local appointment availability Up to five follow-up sessions arranged within 16 weeks Can be fewer than six sessions if participant has met rehabilitation goals and is self-managing condition Volume of exercise described in Figure 2 |

Same as progressive exercise, but without any follow-up appointments |

| Tailoring |

Education and advice Focus of education and advice are individualised and based on assessment Exercises Selection, manipulation of sets, repetitions and/or load is a joint decision-making process Range of motion and position may be modified to accommodate the patient’s comfort and preferences |

Education and advice Focus of education and advice are individualised and based on assessment Exercises The range of motion through which an exercise is performed, and the load and volume, may be increased or decreased |

| Modifications | Quick reference guides for each intervention were produced after the pilot phase and contained all key operational procedures for each intervention to supplement the comprehensive manuals | |

| Intervention fidelity | ||

| How well: training | All aspects of training delivery, content, structure, duration and therapists’ confidence to implement the intervention were evaluated using the post-training feedback forms that were completed anonymously | |

| How well: physiotherapists | Intervention fidelity is monitored centrally using treatment logs and during site monitoring and quality assurance visits. If performance is found to be below the required standard of protocol adherence, further measures (e.g. further training) will be instituted after discussion with the Trial Management Team and the site | |

| How well: participants |

Exercise adherence Physiotherapists review the exercise diary at each subsequent session Participants asked to report exercise frequency in postal follow-up questionnaires at 8 weeks, 6 months and 12 months |

Exercise adherence Participants asked to report exercise frequency in postal follow-up questionnaires at 8 weeks, 6 months and 12 months |

| How well: reporting | Intervention fidelity is reported with main trial results | |

Research physiotherapists from the GRASP trial team provided 1 full day (at least 4–5 hours) of face-to-face training on the progressive-exercise intervention and at least half a day of face-to-face training on the best-practice advice intervention to the relevant delivering physiotherapists. Details on who provided the interventions are provided in Chapter 4. Physiotherapists were trained to deliver either the progressive-exercise intervention or the best-practice advice intervention (not both) to reduce the risk of contamination. Training included the trial background, how to deliver the intervention, the exercises permitted within the trial protocol, behavioural techniques to improve adherence, trial reporting and paperwork, and practical examples using case studies. Physiotherapist manuals were provided, which detailed all aspects of the trial and interventions. GRASP trial team members were available post training to provide support and answer queries.

GRASP trial exercise interventions

Assessment and advice

Appointments were co-ordinated so that participants typically started their first exercise session within 14–28 days of randomisation. The physiotherapist carried out an initial assessment, as per their usual practice, to identify which shoulder movements, in relation to the rotator cuff, were particularly problematic in terms of pain, weakness and restriction, and the associated functional deficits. All GRASP trial participants received a participant information booklet, which contained education and advice relevant to people with a rotator cuff disorder (Table 4). All parts of the booklet contained the same information in the progressive-exercise and best-practice advice intervention groups, with the exception of the specifics of the exercise guidance. Advice included use of over-the-counter analgesia, as per BESS guidance. 69 The treating physiotherapist reinforced the education and advice aspects relevant to that participant. All participants were advised to perform the exercises for at least 4 months and to continue to do so for longer if they were still improving or finding them helpful. Physiotherapists delivering the interventions were trained in questioning techniques based on cognitive–behavioural models70 to elicit and address unhelpful beliefs about shoulder pain or exercise that can impede exercise adherence. 71

| Section | Content |

|---|---|

| Introduction | Summary of common treatments for rotator cuff disorders |

| What is the rotator cuff? | Description of rotator cuff muscles |

| What does the rotator cuff do? | Function of rotator cuff muscles |

| What can go wrong with the rotator cuff? | Possible mechanisms and common symptoms of rotator cuff disorders |

| What can I do to help my rotator cuff problem? | Introduction to role of self-management advice, includes simple pain education, pain management (including use of heat and cold, medication and pacing) |

| Maintaining physical fitness | Importance of staying active |

| Return to usual physical activities | Fear avoidance and deconditioning, and how to address these |

| Modifying activities | Modifying rather than avoiding activities |

| Work | Advice on returning to work activities |

| Sleeping | Sleep positions, pacing to lessen night-time pain |

| Looking after your mental well-being | Activities to maintain a positive mood and when to seek medical advice |

| Coping with flare-ups | Planning exercise and activity for times when pain is more severe |

| Exercise guide |

Benefits of exercise and how long to continue with exercise Pain during and after exercise Guidance on doing GRASP trial exercises with full instructions (e.g. colour photographs and text explaining technique and modifications that can be made) |

Progressive-exercise intervention

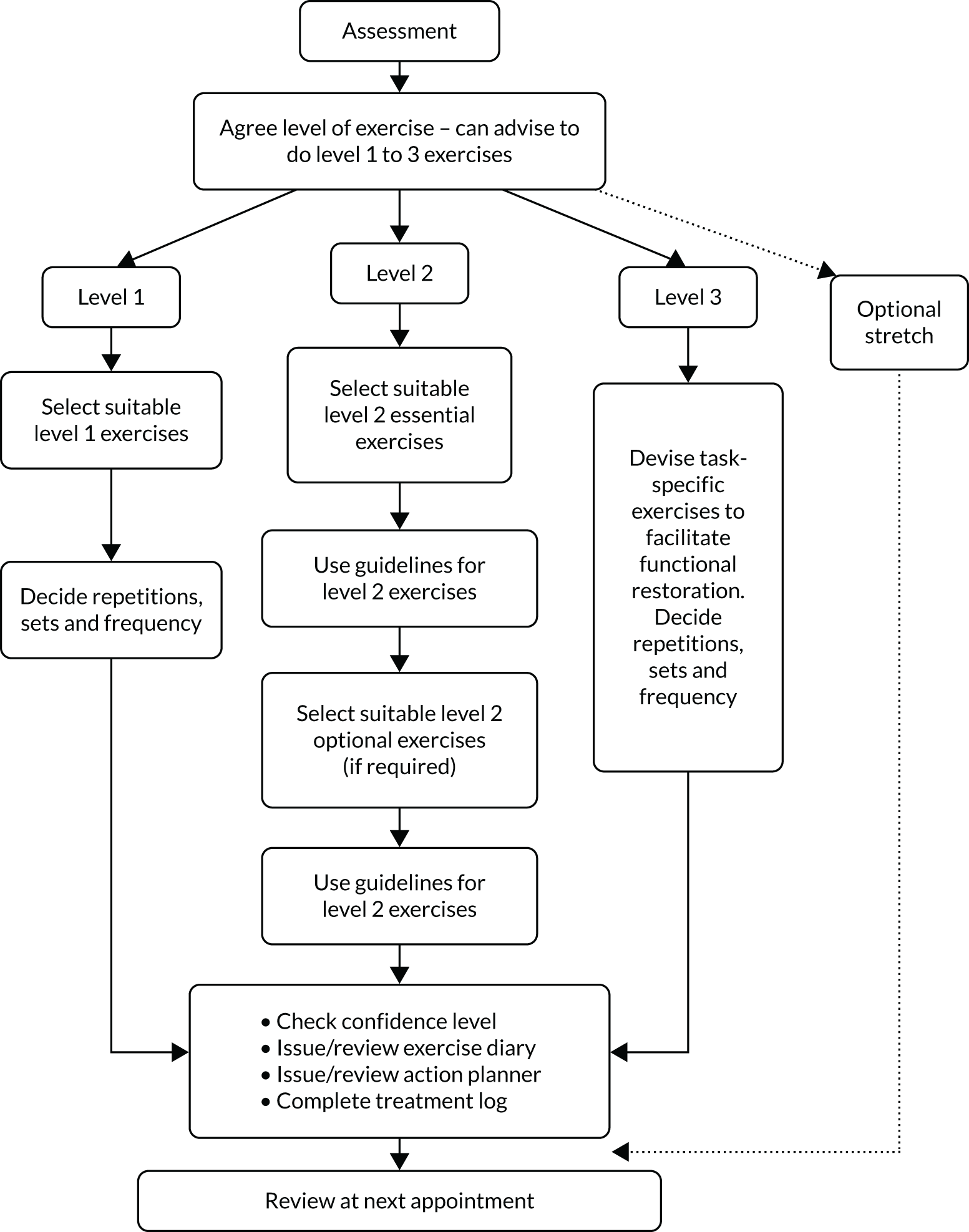

Participants received up to six sessions with a physiotherapist over 16 weeks. The initial session was set to last up to 60 minutes for assessment and treatment initiation, followed by up to five 20- to 30-minute follow-up sessions. The physiotherapist and participant decided how frequently to schedule the review appointments within the 16-week time frame. Six sessions over 16 weeks was set to allow the exercise intensity to be progressed and because it was a volume of physiotherapy within the range of feasible delivery in the NHS. It was also deemed to be a sufficient time for a physiological response in the neuromuscular system. 46 The participant information booklet was provided in a file so that instructions on the progressive exercises selected could be inserted, including detailed guidance and photos for each exercise. The physiotherapist and participant jointly chose one to three exercises to address the problems identified during the assessment (Figure 1). We anticipated participants presenting with different problems and pain irritability and, therefore, the exercises were categorised into three difficulty levels (level 1, 2 and 3 exercises), with progressions within each level and different aims and guidelines to match indications for use.

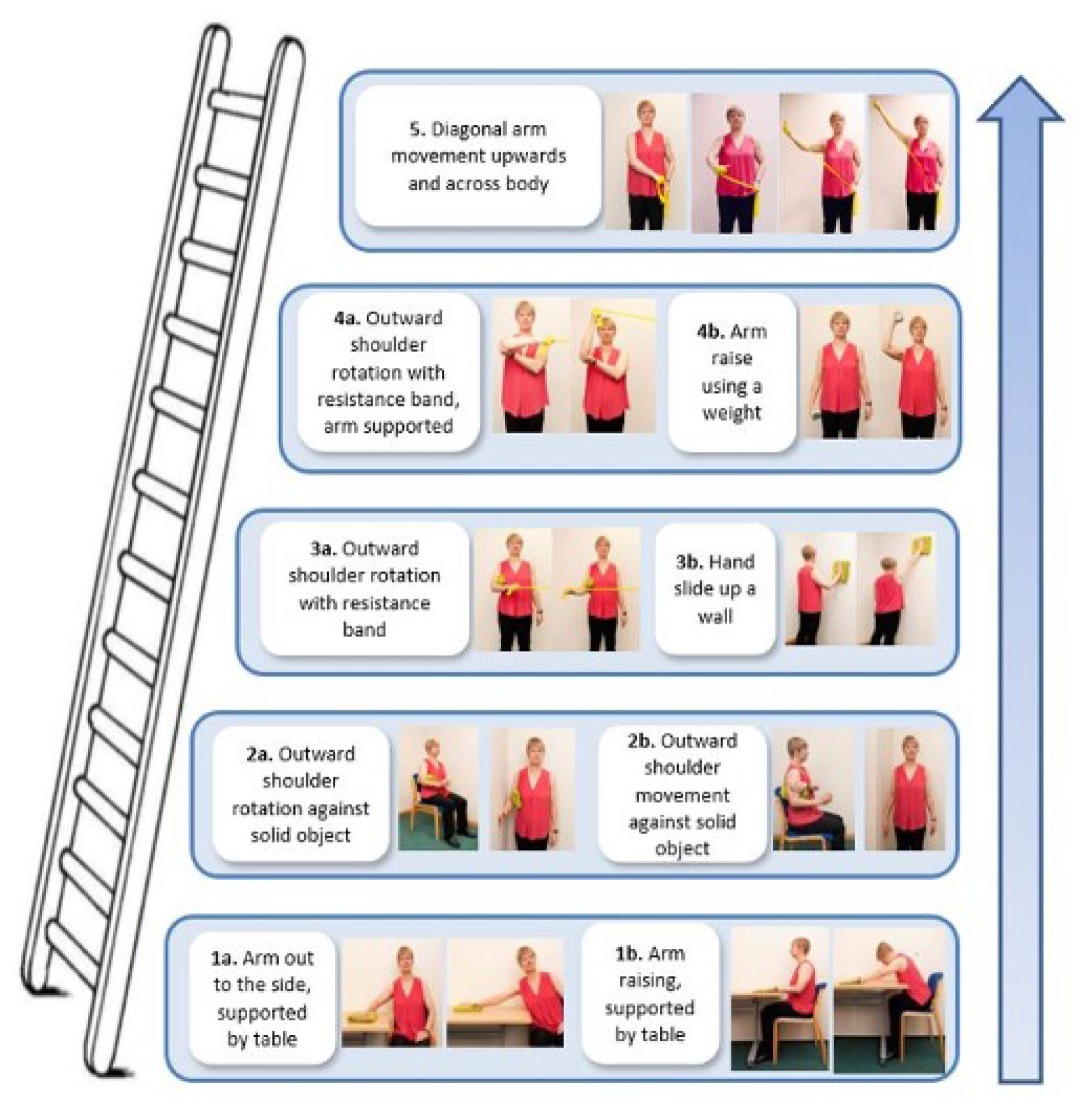

FIGURE 1.

Process map of the GRASP trial progressive exercise intervention.

Level 1 exercises: simple shoulder movements

Level 1 exercises aimed to reduce fear, encourage normal movement, improve shoulder mobility and build confidence in exercising independently at home (see Appendix 3, Figure 17). The exercises were considered appropriate for participants with irritable and/or severe shoulder pain and/or fear avoidance. The frequency and the number of sets and repetitions for each exercise were agreed between the physiotherapist and participant. Depending on symptom severity, it was recommended that some participants could reasonably move straight to level 2 exercises.

Level 2 exercises: progressive structured resistance training

Level 2 exercises included the essential exercises that target strengthening of the posterior rotator cuff muscles and other optional exercises (see Appendix 3, Figure 18). The essential exercises focused on movements commonly affected by a rotator cuff disorder (i.e. resisted external rotation, flexion and abduction of the shoulder). 64 Resistance exercises for other shoulder movements were optional. If participants were prescribed exercises at level 2, at least one had to be from the essential exercise category.

The American College of Sports Medicine guidance for progressive resistance training recommends two to three sessions of resistance training per week,20 whereas many studies of resistance training in patients with musculoskeletal disorders use daily exercise programmes. 21,72 We attempted to strike a balance, ensuring that the resistance training was effective, but also regular enough to address other aims, such as building confidence in moving the arm and re-learning motor skills. We asked GRASP trial participants to do their exercises 5 days per week, with 2 non-consecutive recovery days.

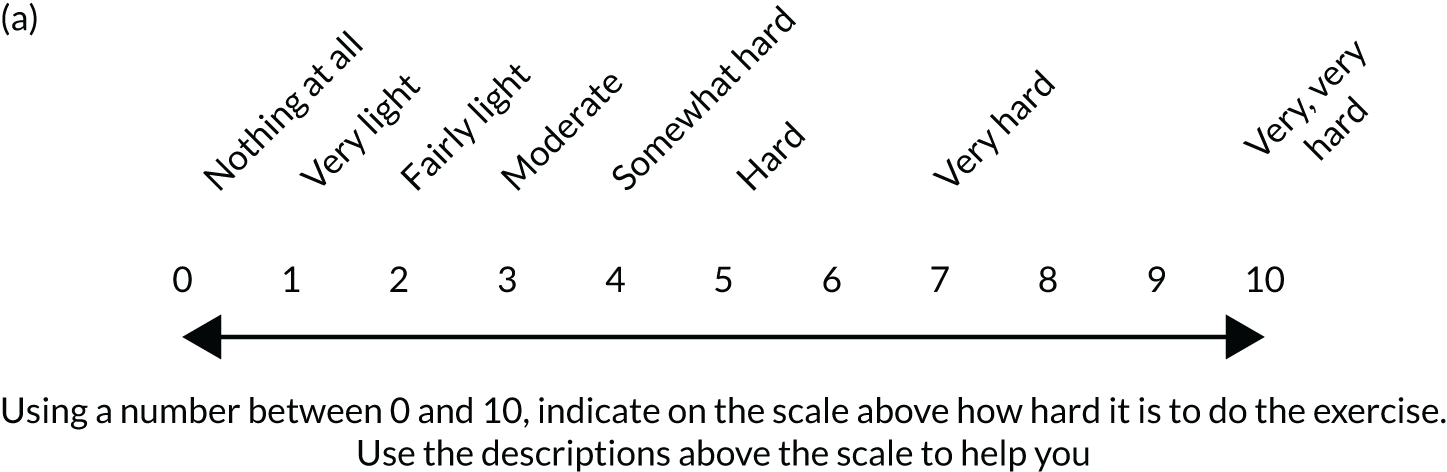

Physiotherapists were taught to regulate the exercise intensity using the modified Borg scale of perceived exertion, an 11-point version of the Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale,73 validated for quantifying the intensity of resistance exercise. 74 Participants started at a moderate load (3 or 4 on the Borg scale) to enhance motivation and adherence and reduce the likelihood of symptom flare-up. Figure 2 contains detailed guidance on the scale and how level 2 exercises were initiated, progressed and regressed. Where appropriate, resistance bands or hand weights were incorporated into the exercise, with the level of resistance recommended being guided by the RPE scale feedback from the participant.

FIGURE 2.

Guidance for setting level 2 resistance exercises in the GRASP trial. (a) Modified Borg scale; (b) setting the initial exercise; and (c) progression and regression decision guidance.

Level 3 exercise: patient-specific functional restoration

It was recommended that participants progress to level 3 when their initial problems (e.g. weakness) began to resolve. The physiotherapist altered the exercise programme to be more task specific (e.g. returning to sport) by devising a new exercise in consultation with the participant. Level 3 exercises aimed to modify the essential resistance-training exercises towards the specific movements required to achieve the participant’s individual functional goals. The exercise could be high or low load, using many or few repetitions, depending on the participant’s needs. It was recognised that not all GRASP trial participants would reach or need this stage of the programme. We anticipated that level 3 exercise instructions would be given face to face and reinforced with written guidance to aid recall.

Optional stretching exercise

Posterior capsule and/or soft tissue stretches of the shoulder (see Appendix 3, Figure 19) were included as optional exercises at any stage. We recommend selective use, generally for younger adults engaged in throwing or other overhead athletic or physical activities75 who have posterior capsule tightness. We anticipated these exercises to be suitable for participants with low irritability and if they did not provoke symptoms. Although discomfort and stretching sensations were considered acceptable during stretches, we did not anticipate provocation of anterior shoulder pain or reproduction of the participant’s specific symptoms. We advised holding stretches for 20–30 seconds, but the physiotherapist and participant decided the number of repetitions and frequency.

Exercise progression

During the physiotherapist training, emphasis was placed on the need to progress the exercise interventions as much as possible. To determine that this had in fact occurred, treatment logs completed for each session by the physiotherapists [detailing prescribed exercises, number of sets/repetitions (i.e. volume) and exercise intensity73] were analysed to allow an estimation of treatment progression for the progressive-exercise intervention (see Chapter 4). Exercises were categorised and ranked in order of difficulty level (1 = least difficult, 8 = most difficult) according to the following scale:

-

passive movements

-

isometric

-

active assisted

-

active (unassisted)

-

loaded exercises (isotonic) in neutral (0 °)

-

loaded exercises (isotonic) at 90 °(supported)

-

as for 6, but unsupported

-

as for 7, but through range.