Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/170/02. The contractual start date was in March 2017. The draft report began editorial review in July 2020 and was accepted for publication in December 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research, or similar, and contains language which may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Gidlow et al. This work was produced by Gidlow et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Gidlow et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Gidlow et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Cardiovascular disease and NHS Health Check

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) accounts for over one-quarter of UK deaths and costs the NHS around £9B annually. 2 Given that CVD mortality has decreased in the UK (68% reduction between 1980 and 2013), the number of people living with CVD remains large. 3 Therefore, prevention, for which the NHS Health Check (NHSHC) programme plays an important part, remains a priority. 4,5 NHSHC aims to assess the CVD risk of adults in England aged 40–74 years who are not known to have certain cardiovascular-related diseases. 6 It is the largest CVD risk identification and management programme of its kind globally. NHSHCs have been linked to some increases in the detection of risk factors and chronic disease, and in statin prescriptions,7,8 but there are gaps in the evidence for long-term benefits for CVD risk, morbidity and mortality,9–14 and mixed predictions of future benefit from microsimulation studies. 15,16

Health check consultations typically take place in primary care with a health-care assistant (HCA) or practice nurse (PN), and comprise (1) assessing patients’ CVD risk and (2) communicating CVD risk, which should inform (3) the discussion of CVD risk management through lifestyle, or subsequent medical appointments or referrals. Public Health England (PHE)’s best practice guidance17 specifies that those attending a health check ‘must be told their BMI, cholesterol level, blood pressure and AUDIT score as well as their cardiovascular risk score’ (p. 14; contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v2.0.). However, this guidance document primarily focuses on legal requirements for local authorities delivering health checks, processes for risk assessment and clinical pathways. The associated competence framework for practitioners who deliver health checks, both the version available at the time of data collection18 and the updated version,19 are more explicit in the role of CVD risk communication and expectations of practitioners. They make clear that it is important that practitioners understand CVD risk information and are able to communicate it so that patients understand, and the need to involve patients in strategies to manage their risk (Box 1).

The use of a risk engine together with clinical judgement and observations/discussions during the assessment, to calculate the individual’s risk of developing cardiovascular disease. Thereafter, understanding the results that must be communicated to them.

Communication of risk

All healthcare professionals involved with delivering the NHS Health Check should be trained in communicating the risk score and results to the client. It is important to understand that sharing information about risk with people may not necessarily motivate them to change.

Therefore, the use of behaviour change methods, such as motivational interviewing techniques, should engage clients in person-centred conversations about their own reasons for change.

Risk should be communicated in everyday, jargon free language, so the client understands their level of risk. Advice should be tailored to the client’s values and beliefs for better health outcomes, and the impact of the wider social determinates of health should also be considered.

Brief intervention/signposting/referral

These competences enable the effective and appropriate signposting of clients to the range of locally available interventions in a supportive manner. It requires more than a simple communication of information; the person signposting must be able to engage the client in the choice and communicate in a manner that will maximise the potential that the client will take up the agreed action and sustain it.

Some material has been reproduced from Public Health England,20 which contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government License v2.0 (www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/2/).

Despite a growing body of evidence on NHSHC, little is known at present about the nature or content of health check consultations. What we know about what takes place in the consultations is limited to qualitative data from retrospective interviews with patients and practitioners, who are asked to recall and reflect on their experiences. 21 Although these data have value, they do not present a complete understanding of the dynamics and interactions that may influence the outcomes of a health check.

Cardiovascular disease risk communication

Practitioner–patient interactions are complex,22 and communicating risk is challenging. 23 For health checks to promote health-protective behaviours that reduce CVD risk, risk information must be effectively communicated and understood, such that the patient leaves the consultation with the knowledge and intention to act.

A review of 70 risk-scoring methods concluded that there is no single ‘correct’ approach. The appropriate method depends on individual preferences and understanding, which differs with education, numeracy and personality traits, such as optimism. 24 The emotional response to the communication of risk, how and by whom the information is conveyed, presentation of risk and the influence on health behaviour, differs greatly between patients. 25–28 Poor communication of risk can cause patients anxiety and reduce their confidence in health professionals who use risk communication techniques. 29 However, if risk communication is delivered effectively, it can enhance knowledge, aid decision-making about treatment, empower and create autonomy. 30 Wells et al. 31 assessed whether or not an electronic CVD risk visualisation tool facilitated explanation of CVD risk to primary care patients. They found that watching a video about the communication of risk increased associated practitioner confidence and understanding, which led to greater efficiency. Researchers who interviewed general practitioners (GPs) indicated that the GPs vary their strategy for communicating CVD risk depending on factors such as patient’s perception of risk, motivation and anxiety, and recommended that clinicians should have alternative ways to explain absolute risk to improve how the metrics were used in practice. 32

Cardiovascular disease risk communication in health checks

For CVD risk assessment in NHSHC, QRISK® (QRISK®2 and, more recently, QRISK®3) is the mandated CVD risk calculator. 17,33 QRISK provides a percentage risk of a CVD event in the next 10 years, and this must be communicated to patients for the health check to be considered ‘complete’. It is integrated within the general practice electronic medical record software, so can be calculated from pre-populated and new data. The score is then saved directly to the patient’s record. However, there are limitations to the QRISK score and how it is used. First, 10-year risk estimates, such as those presented by QRISK, have been criticised for being heavily influenced by age and sex, thereby underestimating risk in younger adults and women, and not accounting for risk from other diseases as effectively as long-term (lifetime) estimates. 34,35 Second, qualitative studies indicate limited practitioner and patient understanding of percentage CVD risk. 21 Practitioners report difficulties in explaining percentage CVD risk. 26,36–38 In turn, patients attending health checks have been unable to recall being provided with a risk score or have found it confusing. 21

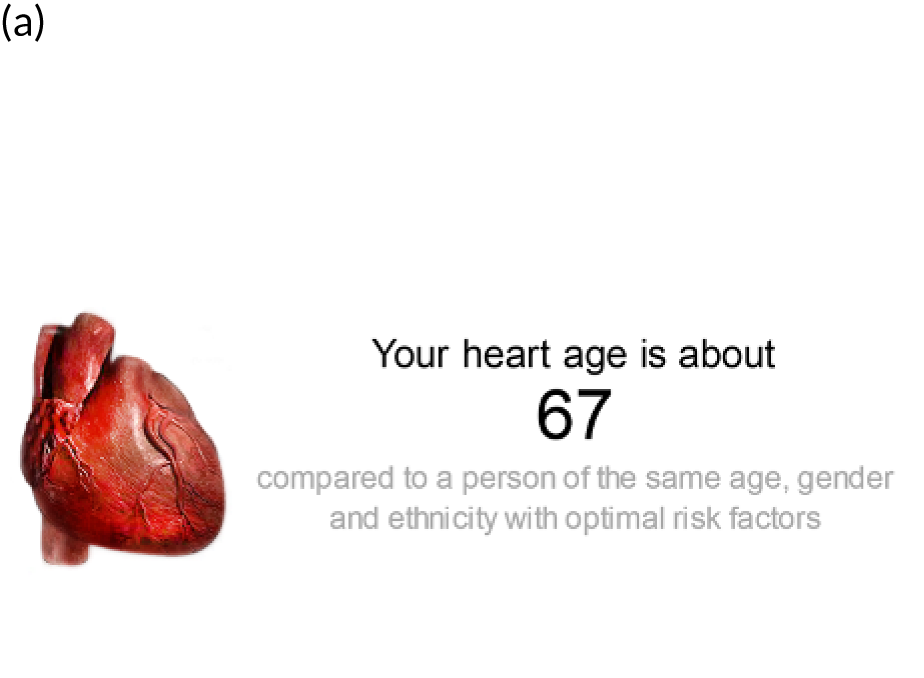

In 2014, the Joint British Societies (JBS) launched the JBS3 risk calculator. JBS3 has a primary focus on lifetime risk,34 which can address some of the limitations of short-term risk estimates and identify raised CVD risk that would not be picked up through conventional 10-year risk estimates. 39 JBS3 has a range of features (Figure 1):

-

Heart age. This is the estimated age of someone of the same sex and ethnicity, and with the same annual risk of an event, but with all other risk factors at ‘optimal’ levels (see Figure 1a); for example, an individual with a heart age of 67 years has the same CVD risk at someone aged 67 years, of the same sex and ethnic group, who has optimal levels of risk factors. Those with an ‘old’ heart age should be motivated towards risk-reducing behaviours to bring their heart age back to their real chronological age. There is evidence that heart age is more easily communicated to, and understood and recalled by, patients. 41,42 A recent review concluded that randomised controlled trials testing the effects of CVD risk communication using heart age have reported improvements in some risk factors (cholesterol and blood pressure) and intentions to improve lifestyle compared with usual care or alternative risk scores. 43

-

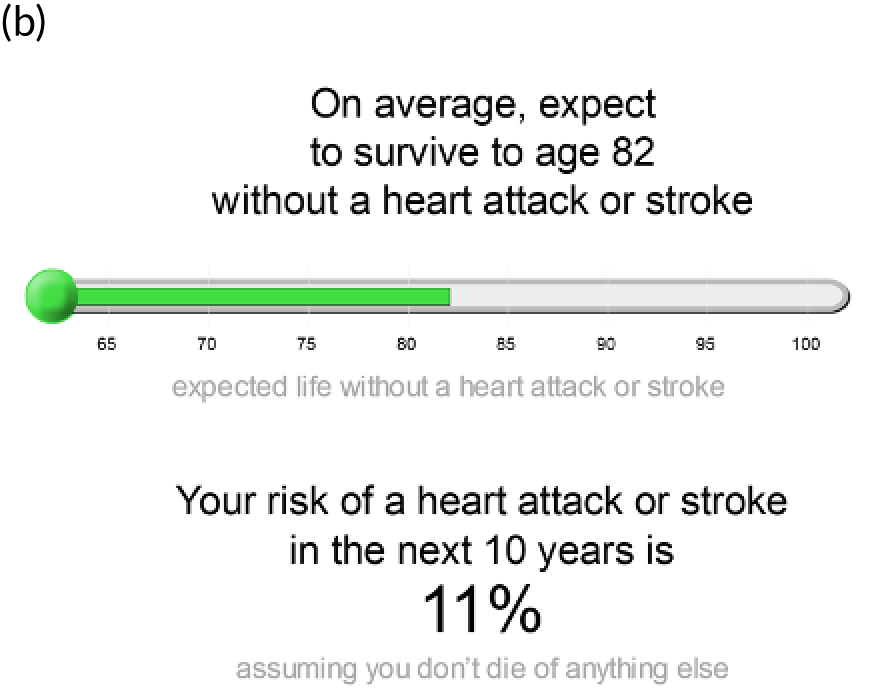

Event-free survival. This is the age by which an individual might expect, based on their current risk profile, to sustain their first CVD event. This is presented on a visual analogue scale that indicates the average expected age of a cardiac event for an individual (based on demographic and risk factor profile; see Figure 1b).

-

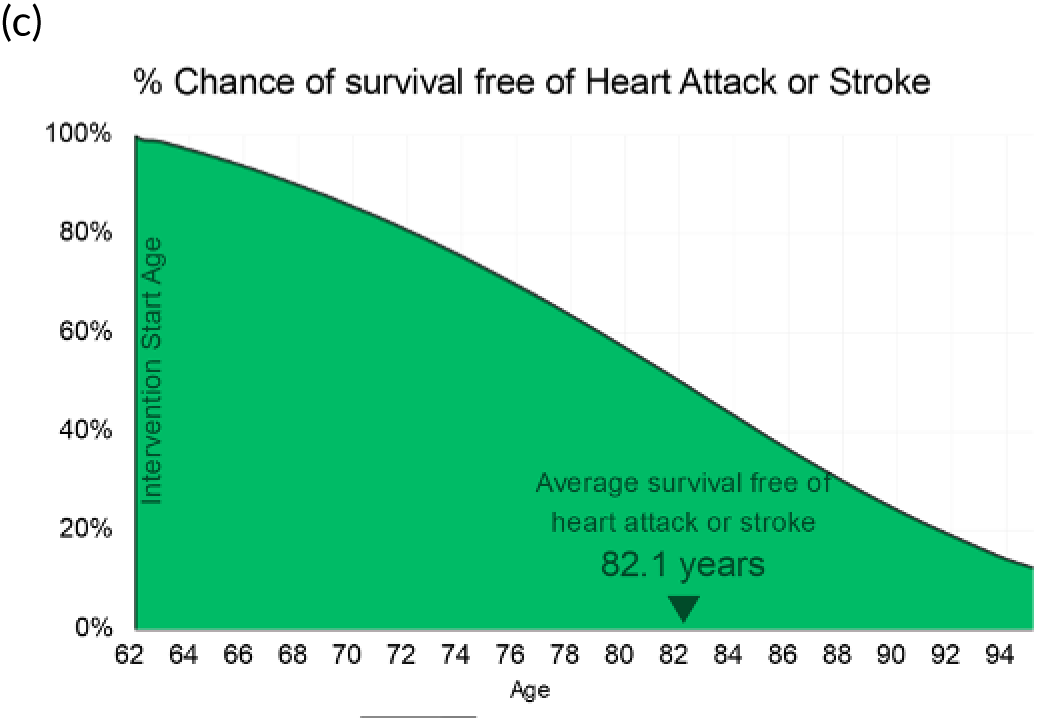

Percentage chance of survival free of heart attack or stroke, by age. This is presented as a survival curve, showing the reduction in the percentage chance of being free of heart attack or stroke as age increases (see Figure 1c).

-

A range of visual displays. Lifetime risk scores are presented using a range of images, including icon array or Cates’ plots, an image of a heart for heart age, visual analogue scales and a survival curve. This variety aims to accommodate a range of preferences23 and can be preferable for promoting risk-reducing behaviour. 44

-

Risk score manipulation. Risk factors can be modified (e.g. altering smoking status or reducing blood pressure or cholesterol level) to show the beneficial effect of effective intervention on risk scores (see Figure 1d). This ability to interact with graphics has the potential benefit of engaging the individual with the information and promoting their understanding and retention. 23,45

FIGURE 1.

Example JBS3 outputs. (a) Heart age; (b) event-free survival age; (c) percentage change of survival free of CVD event; (d) risk score manipulation (showing the effect on event-free survival of reducing blood pressure and cholesterol). Source: JBS3 risk Calculator 201440 [reproduced with permission from British Cardiovascular Society for the prevention of CVD, personal communication, 2020 (Copyright© UoC/BCS. All rights reserved)].

Collectively, these attributes of JBS3 might accommodate a range of patients and facilitate practitioner communication that allows patients to understand and retain their CVD risk, and perhaps foster intentions towards risk-reducing behaviour. 23,31 Yet, to our knowledge, a comparison of the relative benefits JBS3 and QRISK2 for communicating CVD risk in health checks has not been undertaken.

The most effective way to address CVD risk during health checks is to involve the patient in a discussion of their risk and allow them to identify strategies that they could adopt to manage that risk. This is preferable to a didactic consultation, in which practitioners are providers of information and patients are the passive recipients. Studies of clinician–patient interactions have identified that short, clinician-dominated (or ‘paternalistic’) consultations are less patient centred and are linked with low patient and clinician satisfaction,46–49 which, in turn, have been linked with poorer patient outcomes, such as poor adherence to clinical recommendations and failure to adopt health-promoting behaviour. 50 As noted in the competence framework (see Box 1), CVD risk management should be negotiated through a mutual exchange between practitioner and patient (i.e. a person-centred approach) that places the individual at the centre of their own care, service or treatment, as part of a shared decision-making process. 51 At present, there is no evidence regarding the practitioner–patient balance during health checks, particularly the extent to which patients are engaged in discussion of their CVD risk and its management.

Patient outcomes from health checks will depend on patients’ actions, and the support and interventions available to them following their consultation (e.g. referral to effective lifestyle support programmes or appropriate specialist referrals). There is evidence that patient outcomes from primary care consultations are influenced by patients’ experience; hence, there is a need to understand more about the dynamics of the health check event. If delivery of the health check consultation does not create a positive experience for patients, their engagement with and effectiveness of the subsequent risk management actions could be undermined. To optimise the efficacy of health checks in laying the foundations for the management of identified risks, a better understanding of what is already occurring during health check consultations and identification of areas requiring improvement are necessary.

In summary, the NHSHC programme aims to assess CVD risk and prompt patients and practitioners to undertake risk management behaviours. At present, there is insufficient knowledge about how they are conducted, the nature and adequacy of CVD risk communication, and the potential benefit of using alternative CVD risk calculators, such as JBS3. Knowing which approach best delivers the information that patients need to foster intentions for risk-reducing behaviour (or actual behaviour change) could inform decisions about practitioner training and resource allocation.

Research objectives

RIsk COmmunication in NHS Health Check (RICO) was a qualitative study and quantitative process evaluation that aimed to explore practitioner and patient perceptions and understanding of CVD risk when using the JBS3 lifetime risk calculator or the QRISK2 10-year risk calculator, the associated advice or treatment offered by the practitioner and the response of the patient.

Specific study objectives were to:

-

explore how practitioners use QRISK2 and JBS3 to communicate CVD risk during the consultation

-

explore how patients respond to the risk information

-

explore how QRISK2 and JBS3 promote patient and practitioner understanding and perception of CVD risk

-

explore patient intentions with respect to health-protective behaviours

-

explore mechanisms by which intentions for health-protective behaviours are elicited

-

make recommendations regarding use of QRISK2 or JBS3 during health checks.

Theoretical basis

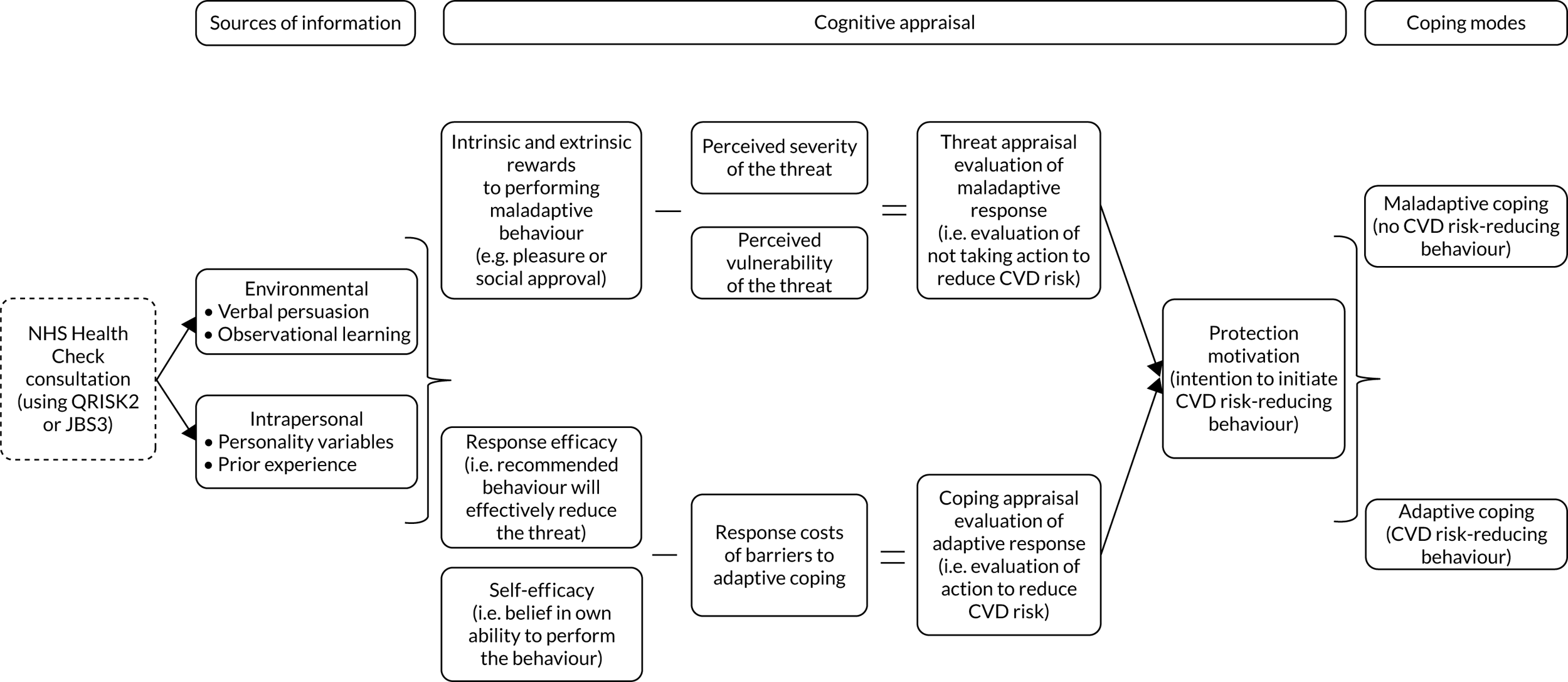

Given the complexity of practitioner–patient interactions52,53 and the translation of risk information into health-protective behaviour,54 we used a theoretical framework based on the revised protection motivation theory (PMT). 55 In PMT, ‘protection motivation’ refers to the intention to undertake health-protective behaviour resulting from the cognitive appraisals (or internal assessments). CVD risk communication could be a key source of information feeding into such appraisals (Figure 2).

Protection motivation theory is informed by fear-driven models, which recognise that behaviour change can be prompted by fear-inducing communications that motivate action to reduce the perceived threat (or risk). 54,56 However, protection motivation is influenced by two cognitive appraisals: appraisals of the threat (risk of CVD) and coping (consequences of undertaking positive behaviour change). Threat appraisal evaluates maladaptive responses (i.e. not initiating positive behaviours in response to recognising an elevated CVD risk). This considers the source of the threat (i.e. practitioner/health check), intrinsic rewards (e.g. enjoyment associated with health risk behaviour) and extrinsic rewards (e.g. social approval), and the perception of the threat (i.e. perceived severity and personal vulnerability). Coping appraisal evaluates the adaptive response to cope with the threat (i.e. CVD risk), and considers the likelihood that positive behaviour change (adaptive response) will reduce the patient’s risk (response efficacy), the patient’s own ability to make the necessary changes (self-efficacy), and the burdens of, or barriers to, making the change (response costs). 54,55,57,58 Threat and coping appraisals are influenced by both environmental aspects (e.g. persuasive communication and observational learning) and intrapersonal variables [e.g. personality and feedback from prior experience of both positive (adaptive) and negative (maladaptive) behaviours]. 54 In the context of this study, PMT emphasises the key role of practitioners in providing information on CVD risk (severity and vulnerability) and incorporating a patient’s beliefs, priorities and experiences into strategies to reduce this risk so that patients feel they can achieve adaptive behaviours55 and subsequent health outcomes.

Protection motivation theory is particularly pertinent to the study of the relative merits of different CVD risk calculators and the mechanisms by which they might promote positive behaviour change for several reasons. First, it was initially developed to examine intention to adopt behaviours relating to disease prevention. 59 Second, it does not assume rationality in behaviour choices,54,60 that is people will undertake unhealthy behaviours because they serve other purposes, for example enjoyment or social integration. Third, its components have been associated with (intention for) behaviour change in relevant contexts (e.g. smoking cessation and exercise). 55,57 Finally, it provides an understanding of why attitudes and behaviour can change when people are confronted with threats (i.e. the mechanisms). 54

Chapter 2 Methodology

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Gidlow et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Design and setting

This qualitative study, with quantitative process evaluation, was undertaken in 12 general practices in the West Midlands of England that were already delivering NHSHCs. Six practice pairs, which were approximately matched on level of deprivation,61 were randomly assigned to one of two groups: the QRISK2 (usual practice) group, in which practitioners continue to use QRISK2 to communicate CVD risk, or the JBS3 (intervention) group, in which practitioners use the JBS3 CVD risk calculator to communicate CVD risk following brief introductory training about the platform. Participating practices were asked to video-record NHSHCs using the allocated CVD risk calculator until 20 useable consultations were recorded. Data collection took place from January 2017 to February 2019 and comprised (1) video-recording NHSHC consultations; (2) post-consultation video-stimulated recall (VSR) interviews with patients within 4 weeks of their health check, using excerpts from recorded health checks to facilitate recall and reflection; (3) VSR interviews with practitioners after their final recorded health check; and (4) patient medical record reviews 12 weeks post health check to determine subsequent action (e.g. GP appointment, lifestyle referrals, lifestyle referral and statin prescription).

Sample

General practices

General practices were recruited if they met the following criteria:

-

were delivering NHSHCs

-

were already using the QRISK2 percentage risk score during health checks

-

were already delivering (or were willing to deliver) health checks in specific clinics to facilitate data collection

-

had signed up to the ‘incentive scheme’ implemented by the Clinical Research Network (CRN) to ensure that the practice is ‘research ready’

-

were willing to participate.

Postcodes were used to stratify general practices into the bottom or top 50% based on national deprivation rankings,62 as a proxy for the typical socioeconomic status of the local population (Table 1).

| Age (years) | Sex (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | |

| 40–54 | 4 (3 white British/1 ethnic minority) | 4 (3 white British/1 ethnic minority) |

| 55–64 | 3 (2 white British/1 ethnic minority) | 3 (2 white British/1 ethnic minority) |

| 65–74 | 3 (2 white British/1 ethnic minority) | 3 (2 white British/1 ethnic minority) |

Patients

The patient population were those eligible for NHSHCs based on national criteria. These criteria excluded people who:

-

were outside the target age range of 40–74 years

-

had existing diagnoses for certain cardiovascular-related chronic conditions

-

were taking statins

-

had attended an NHSHC in the last 5 years

-

were known to be at high risk of CVD (i.e. had a 10-year CVD risk score of ≥ 20%). 17

Practitioners

Participating practitioners were health-care professionals who usually delivered health checks in participating practices and who were willing to participate (usually one or two PNs or HCAs per practice).

Recruitment

Practice sampling

The CRN facilitated practice sampling. Briefly, this involved an initial e-mail inviting expressions of interest, followed up with telephone calls and subsequent practice visits. Practice participation was incentivised through financial reimbursement of service support costs and additional remuneration for completing all parts of the study. Following practice-level consent, practice pairs that were matched on level of deprivation (bottom vs. top 50% of national deprivation rankings), were randomly assigned to the QRISK2 or the JBS3 group using a random number generator in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). After randomisation, the research team completed initiation meetings at practices to provide further information and basic training for staff involved.

Patient and practitioner sampling

There were three levels of patient sampling:

-

Total sample (target, n = 240) – to achieve the 144 recorded consultations suitable for qualitative analysis (12 recorded consultations per practice allowing for non-attendances and consultations with no/minimal discussion of CVD risk), the aim was that health check clinics were recorded until 20 recordings per practice (240 total) were complete. In each practice, the patient database was searched to identify eligible patients, who were then stratified by age, sex and ethnicity to ensure that there was representation from different demographic groups (see Table 1).

Invitation letters, information sheets and consent forms were sent out to eligible patients (up to 400 per practice depending on the size of the eligible cohort), asking them to contact the CRN for more information or to arrange their video-recorded health check. Those who did not respond were contacted by telephone by the general practice staff.

-

Qualitative analysis (target, n = 144) – video-recordings were quantitatively coded soon after the health check to identify those for qualitative analysis (target of 12 video-recordings per practice) and VSR interview (target of four VSR interviews per practice). Where risk was not discussed by patient or practitioner, the patient’s data were not used for either.

-

VSR interviews (target, n = 48) – VSR interviews were conducted with patients (target, n = 24 VSR interviews per group) sampled from the 144 recorded health checks. The aim was to stratify by sex, age and CVD risk (Table 2), although issues with recruitment meant that this could not be strictly adhered to and, in some under-recruiting practices, all those who consented were asked to take part.

| Age (years) | CVD riska (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Low (< 10%) | Medium–high (≥ 10%) | |

| 40–54 | 2 males/2 females | 2 males/2 females |

| 55–64 | 2 males /2 females | 2 males/2 females |

| 65–74 | 2 males/2 females | 2 males/2 females |

The target of 144 recorded consultations (12 per practice) was comparable to other studies using audio-recordings of similar consultations to explore CVD risk communication in patients with psoriasis (e.g. n = 130 in 10 practices),63 while the targets of 48 patient VSR interviews and 18 practitioner VSR interviews were in alignment with the number of interviews carried out in other VSR studies (n = 9–39). 52,64

All practitioners who delivered the video-recorded health check were asked to participate in VSR interviews.

Groups

General practices were randomly assigned to one of two groups:

-

QRISK2 group (usual practice) – practitioners delivered health checks using the QRISK2 risk calculator as per usual practice.

-

JBS3 group (intervention) – practitioners delivered health checks using the JBS3 risk calculator. 40 An introductory session with practitioners established the minimum requirements to use:

-

the first two output screens, which show heart age and healthy years (event-free survival age)

-

risk score manipulation to show the effects of intervention through modifying one of those risk factors (e.g. lowering blood pressure, smoking cessation) (see Figure 1).

-

Practitioners were also asked to practise using JBS3 in at least two health checks prior to the video-recorded clinics and could seek further clarification from the research team should they wish. During these introductory sessions, practitioners were provided with a verbal explanation of the tool, given written materials to support data entry and given a digital versatile disc (DVD) and link to an online training video (www.youtube.com/watch?v=idecGzlwIc4%26feature=youtu.be; accessed June 2021), which was also played to them during the introductory session. As a requirement of the NHSHC programme, patients in the JBS3 group were also told their QRISK2 10-year risk.

Data collection procedures

Video-recorded health checks

Digital camcorders were positioned in health check clinic rooms to provide an audio-visual record of consultations. Informed by patient and public involvement (PPI) and pilot work, cameras were positioned to capture both the patient and the practitioner, but prioritising the view of the patient. Video-recordings were screened soon after the health check. If there was no discussion of CVD risk, this was noted and the file retained. In the case of consultations that involved discussion of CVD risk and were eligible for qualitative analysis, the audio-recording was separated from the visual recording [using Adobe® Premiere Pro (Adobe Systems Incorporated, San Jose, CA, USA)] for transcription and qualitative analysis.

Semistructured video-stimulated recall interviews with patients and practitioners

Semistructured one-to-one VSR interviews with patients were conducted at the patients’ home or their general practice (depending on patient preference) within 4 weeks of their health check. VSR interviews with practitioners were conducted at the general practice within 2 weeks of their final recorded health check. No others (i.e. non-participants) were present in the room during interviews. After each clinic, the recorded heath checks were watched to identify sections of the consultation to use in VSR interviews that related to discussion of the CVD risk score, modification of the risk score (in the JBS3 group) and practitioner advice, recommendations and interventions. During their VSR interviews, practitioners were shown excerpts of video consultations with some of their patients who had subsequently been selected for VSR interview. Semistructured VSR interviews followed a pre-piloted process and topic guide, with variation depending on whether the patient/practitioner was in the QRISK2 group or the JBS3 group. All VSR interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis.

Patient medical record review

Data from the 12 weeks following the health check were extracted from patient medical records. Data were processed by the principal investigator (CJG), with verification by a GP co-investigator (EC), to identify any relevant recorded activity or prescriptions that occurred as a result of the health check. Classifications were data driven, as detailed in Appendix 1, Tables 11 and 12. Where possible, these were based on Read codes/terms, but also included uncoded additional text.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement activities informed study development and were used throughout. There were three PPI strategies. First, we engaged with Patient Participation Groups (PPGs) by attending meetings at three general practices on two occasions to gather opinion on the study concept and overall design and, subsequently, the methods and protocols. This initial engagement had an impact through validating the study as being important and the acceptability of video-recording methods, while making important links for ongoing PPI. One PPG facilitated the completion of four mock health checks (with the PN and four PPG members) to allow testing of protocols including camera placement, video-recording quality, participant consent and debrief processes, development of the quantitative and qualitative coding frameworks, post processing of the video for VSR excerpts and development of the VSR topic guide and protocols. This had an important impact on all of our data collection processes, and the mock health check data allowed development of coding processes. Second, two patient representatives sat on the Programme Advisory Board, which was important to ensure that the patient voice was considered at the level of project management, as well as at the operational and process levels. Third, a virtual study patient group was established using a closed Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; www.facebook.com) group. This novel approach had an impact throughout data collection by allowing engagement with a large number of patients and members of the public (membership reached over 270), who provided rapid feedback that further informed study processes (e.g. consent forms, participant information sheets, camera placement) and how we responded to problems with recruitment.

Data processing and analysis

Qualitative and quantitative data were analysed to inform the quantitative process evaluation, qualitative outcomes and case studies. The processes are summarised by data source.

Qualitative data: recorded health check consultations

Qualitative data were analysed using deductive thematic analysis,65 following the six-stage process described by Braun and Clarke66 (Table 3). A coding template was developed around PMT. 56 Use of this framework (see Figure 2) was considered appropriate to investigate the use of the two CVD risk assessment tools given the complexity of patient–practitioner interactions52,53 and the translation of risk information into health-protective behaviour. 54

| Phase | Summary |

|---|---|

| 1. Familiarisation | Analysis started with a period of familiarisation involving watching and re-watching the video-recorded consultation (or listening to audio-records in the cases of interviews), noting initial thoughts in the transcript |

| 2. Initial coding | For deductive analysis, codes from the PMT template were applied to the transcript independently by two researchers (where possible); for inductive analysis, codes were generated based on interesting features and recurrent patterns in the data. For both inductive and deductive analysis, the researchers checked their own codes, before discussion to verify and agree final codes |

| 3. Searching for themes | Agreed codes were collated into potential themes, gathering all data relevant to each potential theme |

| 4. Reviewing themes | Constant comparison was used to check themes by revisiting data to ensure that they were representative |

| 5. Defining and naming themes | Ongoing analysis was used to refine the specifics of each theme, and the overall story, generating clear definitions and names for each theme |

| 6. Reporting | Illustrative extracts were selected to include in a narrative that tells the overall story |

Each transcript was uploaded to NVivo version 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) qualitative data analysis software. 67 This allowed the interpretation of how QRISK2 and JBS3 were used to communicate risk in the context of PMT components (e.g. verbal persuasion, influencing patient prior beliefs and priorities, and how patients respond, which will reflect the nature of their appraisal within the consultation).

Initially, 14 transcripts were inductively coded independently by Lisa Cowap and Victoria Riley. This was to check the application of PMT to health check consultations and agree coding between the researchers. Following inductive coding, 13 new codes were added to the framework (e.g. medical history, clarification of results). The final version of the coding template, including examples for each code from health check consultations, is provided in Appendices 3 and 4. The remaining 114 transcripts were individually coded by Lisa Cowap and Victoria Riley; 2 out of every 20 transcripts were independently dual coded to check their reliability using kappa coefficients for each node in the PMT framework. Reliability ranged from 0.48 to 0.71 over the five reliability checks conducted, indicating fair to good reliability. 68 Data saturation was considered to have been reached at the point of completion of coding.

Subsequent analysis of codes was led by Sophia Fedorowicz (qualitative researcher and doctoral student, Staffordshire University) (supported by SG, CJG, NE and VR) to identify codes for key elements of the PMT model, splitting health checks into two groups (QRISK2 and JBS3). Specific parts of transcripts that illustrated the practitioner communicating CVD risk to the patient, and the patient responses, were identified. These related to cognitive appraisal (threat appraisal and coping appraisal) and coping modes (adaptive and maladaptive).

Qualitative data: semistructured video-stimulated recall interviews with patients and practitioners

Patient VSR interview transcripts were analysed using inductive thematic analysis, with codes and themes generated from data based on individual reflections, perceptions and experiences. In the case of patient VSR interviews, line-by-line coding and preliminary theme development were undertaken by Lisa Cowap. Themes were discussed with Victoria Riley and Sarah Grogan, before reviewing and agreeing final themes.

Practitioner VSR interviews were line-by-line coded by Naomi J Ellis and Sarah Grogan (see Acknowledgements). Sian Calvert led theme development and was supported by Victoria Riley and Christopher J Gidlow, who reviewed and agreed the final themes.

Quantitative: content of health check consultations (process evaluation)

Recorded health checks were viewed by two authors (LC and VR) and the content of the consultations was characterised using a second-by-second coding framework developed specifically for this study. The framework comprised 36 items grouped into six categories: patient–practitioner communication, health check general (e.g. collecting and inputting data), risk dialogue (e.g. overall discussion of risk, 10-year risk reference, heart age, patient question on CVD risk), causal CVD risk factors (e.g. medical, lifestyle), risk management (lifestyle intervention or medical intervention) (see Appendix 2). This allowed derivation of aggregate indicators for each consultation to allow between-group comparisons of:

-

length of health check

-

time (absolute and proportion of consultation) discussing CVD risk, CVD risk factors (overall, lifestyle, medical) and risk management (lifestyle, medical)

-

practitioner–patient communication balance (proportion of health check time for which practitioners and patients spoke, ratio of practitioner to patient speaking time)

-

number and proportion of patients asking questions about CVD risk

-

use of heart age, healthy years (event-free survival age) and risk score manipulation (as fidelity check in the JBS3 group).

As noted in a previous paper,1 the coding process and framework development was iterative, using four mock health checks that were video-recorded as part of PPI. To reach consistency in approach, Naomi J Ellis and Lisa Cowap coded mock health checks by consensus. Victoria Riley then coded the same four consultations independently and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) demonstrated excellent inter-rater reliability (ICCs from 0.968 to 0.995). Once data collection had started, health checks were coded by authors Lisa Cowap and Victoria Riley, with verification of 10% (2 out of every 20 independently coded) to mitigate the risk of coder drift. ICCs ranged from 0.992 to 0.999, indicating excellent inter-rater reliability.

Data on patient sex, age, ethnic background (classified as white British or ethnic minority) and lower-layer super output area (which was used to derive deprivation decile)62 were also extracted from patient medical records.

Following checks for normal distributions, QRISK2 and JBS3 groups were compared using key variables. To take into account the nature of the sampling, which was in clusters, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated; as usual, where the CIs of the two groups do not overlap then the groups can be considered to differ significantly. Data processing and analysis were performed in SPSS version 26 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Quantitative: patient medical record review (process evaluation)

Activities extracted from the patient medical records were classified as relating to further assessment of CVD risk (or QRISK), weight, blood pressure, cholesterol level, diabetes, other tests (e.g. liver function test, kidney function test, echocardiography), lifestyle, lifestyle referral and new diagnoses. Relevant medications that were prescribed following the health check were grouped as statin/lipid lowering, anticoagulants, cardiovascular or diabetes. The specific composition of each category is shown in Appendix 1, Tables 11 and 12.

Between-group comparisons were explored, but were somewhat limited by the relatively small number of patients with relevant recorded activity or prescriptions in their medical records.

Case studies

A subsample of 10 patients were selected for within-case analysis. Selection was on the basis of evidence of positive patient intentions and/or behaviours to reduce their CVD risk following the health check, and to provide coverage across general practices. The aim was to further explore apparent mechanisms by which the risk calculators may lead to changes in patient or practitioner behaviour. A data extraction template was created to bring together data from all sources (see Appendix 6, Table 13).

Quantitative data

-

Patient medical records: age, sex, ethnicity, deprivation level of home neighbourhood and 10-year CVD risk recorded in the health check, and relevant activities, diagnoses and prescriptions recorded in the 12 weeks following the health check.

-

Quantitative coding of health checks: total duration (in minutes), practitioner–patient communication balance (ratio of practitioner to patient minutes), practitioner speaking (as percentage of total health check), patient speaking (as percentage of total health check), no speaking (as percentage of total health check) and total minutes discussing CVD risk.

-

Non-verbal patient engagement: non-verbal communication during sections of the health checks in which CVD was discussed, was assessed independently by two researchers. As detailed in Appendix 6, a Likert scale was derived and piloted, informed by existing measures of non-verbal communication. Results for each case study patient are presented in Appendix 7.

Qualitative data

Transcripts of recorded health checks and VSR interviews with the patients and the corresponding practitioners were revisited, and excerpts were extracted to provide information on:

-

the patient (e.g. current lifestyle, awareness and perceptions of NHSHC)

-

the practitioner (e.g. role, experience, training)

-

how the NHSHC was conducted

-

the use, understanding and perceptions of QRISK2, heart age, event-free survival age and risk score manipulation

-

risk management (recommendations and subsequent intentions or action)

Christopher J Gidlow, Victoria Riley and Naomi J Ellis extracted all data and drafted case studies, with support from a GP co-investigator, Elizabeth Cottrell.

Sample size

A priori determination of sample sizes for qualitative research is a point of contention. 69,70 In the present study, it was necessary to estimate requirements for the patient VSR interviews and use this to inform the total number of recorded health checks required per practice. The target of 48 VSR patient interviews (24 per group, four per practice) was chosen to allow patient sampling stratified by sex, age and CVD risk (see Table 2), and to compare favourably with studies using VSR or audio-recordings of primary care consultations (ranging from 9 to 44). 63,64 These 48 recorded health checks were to be selected (with stratification) from 144 (72 per group, 12 per practice) recorded health checks that were subject to deductive qualitative analysis (i.e. 12 per practice was deemed sufficient to allow stratified sampling of four patients per practice). To obtain the 144 recorded health checks suitable for qualitative analysis, we aimed to record 240 health checks (120 per group, 20 per practice).

This oversampling aimed to serve two purposes. First, it would allow for exclusions owing to non-attendance, technical issues and health checks that contained little or no discussion of CVD risk. Second, a sample size calculation undertaken for the target between-group quantitative comparison estimated that 120 consultations per group, six clusters (practices) per group with a two-tailed probability and an alpha of 0.05, would provide statistical power of 0.8 to detect an effect size (r) of 0.24 (small to medium effect). The overall number of eligible practices from which the clusters were chosen was 625 (in the absence of a definitive estimate of how many West Midlands general practices conducted health checks, the total number of general practices in the region was used). 71

Chapter 3 Results 1: quantitative analysis of NHS Health Check consultations and medical record reviews (process evaluation)

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Gidlow et al. 72 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

General practice characteristics

General practices were recruited in matched pairs, based on the level of deprivation [Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) deciles 1–5 vs. deciles 6–10],62 and randomly assigned to the QRISK2 group or the JBS3 group (Table 4). Practices were located across eight CCG areas in the West Midlands. Variation in practice size was not used for stratification. Many large modern practices are aggregations of smaller practices, such that the total list size is large but the operation of individual surgeries within them would be more aligned to ‘small’ practices. The proportion of ethnic minority patients averaged 13.5%, but this figure ranged from 1.5% to 63.7%.

| Practice ID | Practice characteristic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVD risk calculator | Deprivation decilea (1 = most deprived; 10 = least deprived) | Practice size (nearest 1000) | Health check practitioners | Blood test procedures | NHSHC appointment time (minutes) | QOF achievementb (%) | Patients with positive experiencec (%) | Ethnic minorityd (%) | Number of patients recruited for the RICOe study | |

| 1 | JBS3f | 6 | 13,000 | 1 HCA, 1 PN | PoC | 30 | 98.4 | 96.2 | 2.0 | 12 |

| 2 | QRISK®2+f | 6 | 9000 | 1 HCA | PoC | 25 | 98.4 | 90.2 | 1.9 | 22 |

| 3 | QRISK2 | 1 | 4000 | 1 HCA | Prior | 20 | 78.1 | 88.9 | 31.6 | 14 |

| 4 | JBS3 | 4 | 45,000 | 1 HCA | PoC | 20 | 98.5 | 67.4 | 6.4 | 29 |

| 5 | JBS3 | 2 | 5000 | 1PN | Prior | 30 | 99.6 | 75.9 | 3.9 | 7 |

| 6 | QRISK2 | 9 | 4000 | 2 PN | Prior | 30 | 98.6 | 74.8 | 2.5 | 17 |

| 7 | JBS3f | 10 | 8000 | 1 HCA | PoC | 30 | 99.6 | 95.0 | 2.4 | 20 |

| 8 | JBS3 | 6 | 4000 | 1 HCA, 1 PN | Prior | 30 | 98.7 | 95.5 | 2.5 | 24 |

| 9 | QRISK2 | 4 | 7000 | 1 HCA | PoC | 30 | 82.4 | 95.3 | 16.5 | 5 |

| 10 | QRISK2 | 2 | 3000 | 1 PN | Prior | 15 | 100.0 | 85.8 | 26.6 | 3 |

| 11 | JBS3 | 2 | 5000 | 1 HCA | Prior | 25 | 99.4 | 49.9 | 63.7 | 8 |

| 12 | QRISK2+f | 6 | 8000 | 1 PN | PoC | 30 | 100.0 | 83.0 | 1.5 | 12 |

Half of the practices used point-of-care (PoC) testing to measure cholesterol levels during the health check and half required patients to have blood tests in advance. Four practices (two in each group) routinely used Informatica74 during health checks, an additional software embedded into the health check template that has some JBS functionalities, such as heart age and risk manipulation. The two practices (2 and 12) that were assigned to the QRISK2 group were asked to continue with their usual practice (i.e. QRISK2 plus Informatica). For those assigned to JBS3 (practices 1 and 7), JBS3 was used instead.

As proxies for practice quality, data from the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) were retrieved for overall QOF achievement and patients reporting positive experiences. These showed some variation, with three practices scoring markedly lower on patient experience (practices 4, 6 and 11; two JBS3, one QRISK2).

There was marked variation in the success of patient recruitment. Each practice was asked to continue with recruitment until 20 useable recorded health checks had been completed. This was achieved in only four practices, but each practice exhausted its list of eligible patients. When recruitment was more successful, there was some over-recruitment of patients to boost the overall sample size. The varied success of recruitment across practices created an imbalance of patients across the QRISK2 and the JBS3 groups.

There was a trend towards practices in the most deprived 50% of areas (based on the IMD), on average, recruiting fewer patients and allocating shorter appointment slots to health checks than those in the least deprived 50% of areas (mean recruitment 11.0 ± 9.6 vs. 17.8 ± 5.1 patients; mean appointment allocation 23.3.0 ± 6.1 vs. 29.2 ± 2.0 minutes). This vindicated sampling of practices stratified by level of deprivation.

Practitioner characteristics

Practitioners (n = 15) all worked within primary care (nine HCAs, six PNs; Table 5) and all were female. Thirteen were classified as white British and two were of Asian British ethnic background. On average, the practitioners had been delivering health checks for 4.7 ± 2.4 years, ranging from 9 months to 9 years. Where training in health checks was reported (n = 9), it tended to be focused on general delivery and health check processes. Six practitioners had received no training.

| Practice | Practitioner characteristic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk calculator | PID | Role | Sex | Ethnicity | Time delivering NHSHCs | NHSHC training | Number of recorded NHSHCs | |

| 1 | JBS3 | 1.1 | PN | Female | WBRI | 9 years | No formal training | 7 |

| 1.2 | HCA | Female | WBR | 6 years | Generic training, PoC training | 5 | ||

| 2 | QRISK2 | 2.1 | HCA | Female | WBRI | 2.5 years | Generic training | 22 |

| 3 | QRISK2 | 3.1 | HCA | Female | WBRI | 2.5 years | No formal training (at time of study) | 14 |

| 4 | JBS3 | 4.1 | HCA | Female | EM | 2 years | No formal training | 29 |

| 5 | JBS3 | 5.1 | PN | Female | WBRI | 8 years | Generic training × 2 | 7 |

| 6 | QRISK2 | 6.1 | PN | Female | WBRI | 2 years | No formal training | 6 |

| 6.2 | PN | Female | WBRI | 6 years | Generic training, lifestyle advice and referrals | 11 | ||

| 7 | JBS3 | 7.1 | HCA | Female | WBRI | 5 years | Generic training, PoC training (could not recall details) | 20 |

| 8 | JBS3 | 8.1 | HCA | Female | WBRI | 5 years | Generic training | 11 |

| 8.2 | PN | Female | WBRI | 9 months | No formal training | 13 | ||

| 9 | QRISK2 | 9.1 | HCA | Female | WBRI | 6 years | Generic training (could not recall details) | 5 |

| 10 | QRISK2 | 10.1 | PN | Female | WBRI | 3 years | No formal training | 3 |

| 11 | JBS3 | 11.1 | HCA | Female | EM | 8 years | Generic training × 2 (8 and 1 years earlier) | 8 |

| 12 | QRISK2 | 12.1 | PN | Female | WBRI | 4 years | Generic training (4 years earlier) | 12 |

Patient characteristics

A total of 175 video-recorded health checks were completed, of which 173 were included in the analysis (QRISK, n = 73; JBS3, n = 100). Two were excluded because practitioner process error invalidated the consultation. The sample comprised approximately equivalent proportions of males and females (Table 6). The proportion of patients who were white British or from ethnic minorities was approximately representative of the general practice populations from which they were drawn (see Table 4). There was a spread of deprivation levels in both study groups, with a trend towards more participants from the JBS3 group residing in more deprived areas (but with a relatively small effect size; see Table 6). The average age was higher in the JBS3 group (mean 60.87 years, 95% CI 58.91 to 62.83 years) than in the QRISK2 group (mean 54.70 years, 95% CI 51.66 to 57.70 years), while 10-year CVD risk was slightly higher in the JBS3 group (mean 9.71, 95% CI 7.85 to 11.57) than in the QRISK2 group (mean 8.69, 95% CI 5.56 to 11.81).

| Characteristic | Total | Study group | Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JBS3 | QRISK | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | r a | |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 40–54 | 60 | 34.68 | 24 | 24.00 | 36 | 49.32 | 0.32 |

| 55–64 | 54 | 31.21 | 30 | 30.00 | 24 | 32.88 | |

| 65–74 | 59 | 34.10 | 46 | 46.00 | 13 | 17.81 | |

| Total | 173 | 100 | 73 | ||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 86 | 49.71 | 49 | 49.00 | 37 | 50.68 | 0.05 |

| Female | 87 | 50.29 | 51 | 51.00 | 36 | 49.32 | |

| Total | 173 | 100 | 73 | ||||

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| White British | 144 | 83.24 | 81 | 81.00 | 63 | 86.30 | 0.07 |

| Ethnic minority | 29 | 16.76 | 19 | 19.00 | 10 | 13.70 | |

| Total | 173 | 100 | 73 | ||||

| Deprivation quintileb | |||||||

| 1 | 32 | 18.50 | 16 | 16.00 | 16 | 21.92 | 0.13 |

| 2 | 33 | 19.08 | 16 | 16.00 | 17 | 23.29 | |

| 3 | 37 | 21.39 | 22 | 22.00 | 15 | 20.55 | |

| 4 | 34 | 19.65 | 22 | 22.00 | 12 | 16.44 | |

| 5 | 37 | 21.39 | 24 | 24.00 | 13 | 17.81 | |

| Total | 173 | 100 | 73 | ||||

| CVD risk categoryc | |||||||

| Low | 104 | 60.12 | 57 | 57.00 | 47 | 64.38 | 0.06 |

| Medium–high | 67 | 38.73 | 41 | 41.00 | 26 | 35.62 | |

| Total | 171 | 98 | 73 | ||||

Headline findings from the process evaluation

-

Health check duration varied greatly, but most lasted < 20 minutes.

-

Health checks were often verbally dominated by practitioners.

-

There was little discussion of CVD risk overall (< 2 minutes per health check, on average).

-

Compared with health checks using QRISK2, in those using JBS3:

-

there was more discussion of CVD risk

-

consultations were less verbally dominated by practitioners

-

more patients asked questions about CVD risk.

-

-

At 12 weeks post health check, relevant follow-up activity was recorded for fewer than one-third of patients, < 9% had received prescriptions as a result and there were 10 new diagnoses. There were no corresponding statistical differences between the QRISK2 group and the JBS3 group.

Quantitatively coded health checks

Length of NHS Health Check consultations

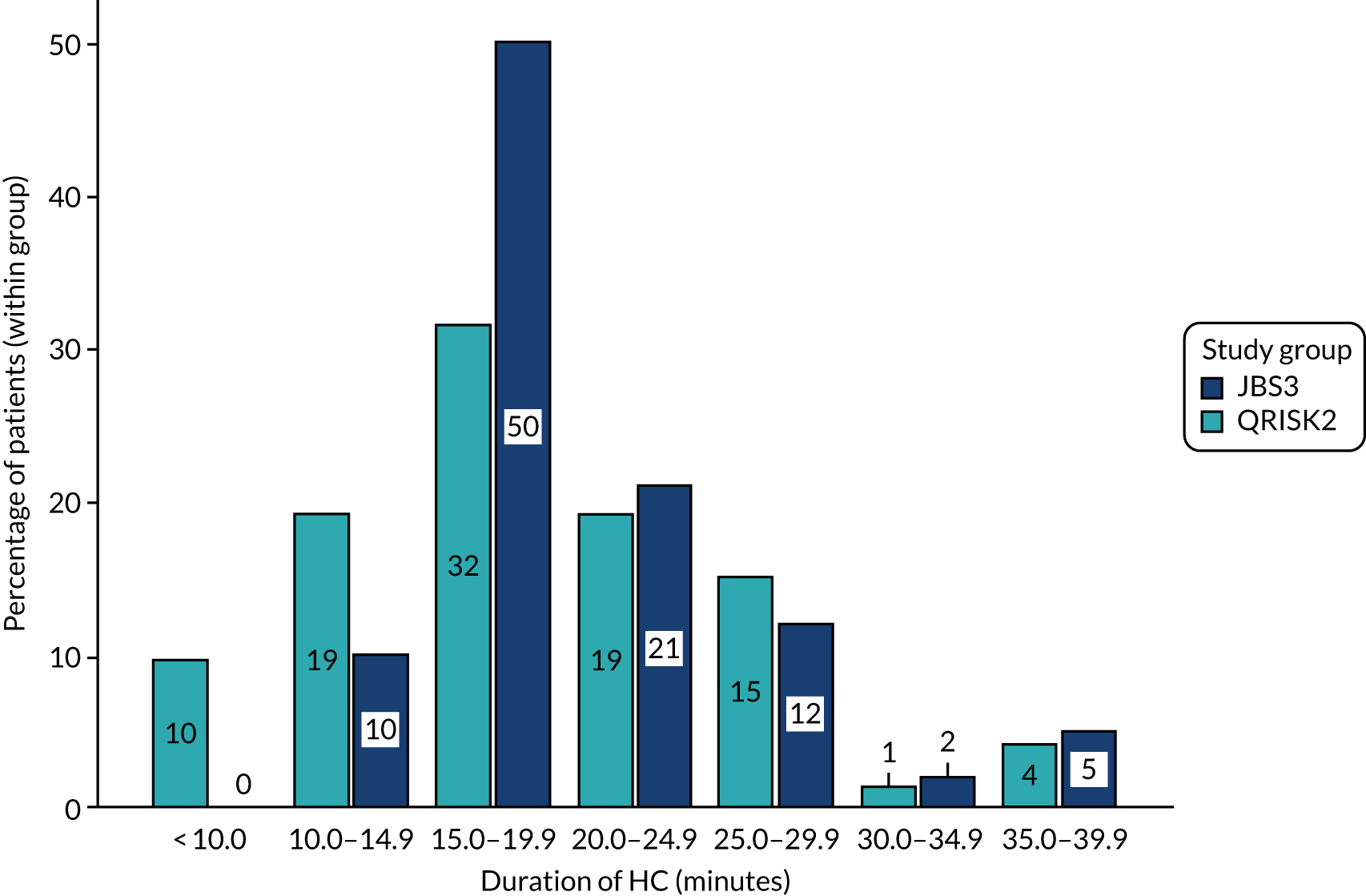

Table 7 summarises the characteristics of health check consultations by study group and overall. Consultation duration varied widely (range 6.8 to > 38 minutes), but the majority of consultations lasted between 15 and 20 minutes, with most consultations (60%) lasting < 20 minutes (Figure 3). Consultations were only slightly shorter, on average, in the QRISK2 group than in the JBS3 group (with a relatively small effect size of 0.13).

| Outcome | Total | Study group | Differencea (QRISK2 vs. JBS3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JBS3 | QRISK2 | ||||||

| Mean (95% CI) | SD | Mean (95% CI) | SD | Mean (95% CI) | SD | r | |

| Duration (minutes) | 20.06 (18.87 to 21.24) | 6.21 | 20.66 (18.89 to 22.42) | 5.65 | 19.24 (15.28 to 23.19) | 6.84 | 0.13 |

| Verbal dominance | |||||||

| Percentage of total time practitioner speaking | 50.07 (45.90 to 54.24) | 9.55 | 46.60 (41.36 to 51.84) | 8.79 | 54.82 (50.00 to 59.64) | 8.48 | 0.42 |

| Percentage of total time patient speaking | 23.37 (19.87 to 26.87) | 10.62 | 24.67 (20.47 to 28.87) | 10.53 | 21.6 (15.71 to 27.43) | 10.56 | 0.15 |

| Verbal dominance ratiob | 2.70 (2.23 to 3.19) | 1.50 | 2.35 (1.89 to 2.81) | 1.31 | 3.21 (2.44 to 3.97) | 1.62 | 0.27 |

| Percentage of total health check time | |||||||

| Discussing CVD risk | 9.06 (7.36 to 10.76) | 4.30 | 10.24 (8.01 to 12.48) | 4.07 | 7.44 (5.29 to 9.58) | 4.08 | –0.32 |

| Discussing risk factors | |||||||

| Total | 37.54 (32.92 to 42.17) | 12.96 | 35.33 (27.76 to 42.90) | 13.29 | 40.58 (36.20 to 44.96) | 11.91 | 0.22 |

| Medicalc | 21.34 (18.35 to 24.33) | 9.41 | 20.13 (15.33 to 24.94) | 9.38 | 22.98 (19.96 to 26.31) | 9.26 | 0.16 |

| Lifestyled | 16.11 (13.79 to 18.44) | 7.03 | 15.08 (11.87 to 18.30) | 6.49 | 17.52 (14.16 to 20.88) | 7.53 | 0.16 |

| Discussing risk management | |||||||

| Total | 19.64 (16.48 to 22.81) | 11.37 | 18.82 (13.92 to 23.73) | 11.12 | 20.77 (16.59 to 24.94) | 11.69 | 0.08 |

| Lifestyle | 16.59 (13.44 to 19.74) | 10.2 | 15.94 (11.27 to 20.62) | 10.04 | 17.48 (12.95 to 22.01) | 10.41 | 0.08 |

| Medicale | 63% | 58% | 69.9% | –0.12 | |||

FIGURE 3.

Duration of health check consultation by CVD risk calculator group.

Discussion of cardiovascular disease risk

Overall, < 10% (9.1% ± 4.3%) of consultation time was devoted to CVD risk discussion, which equated to 1.7 ± 0.83 minutes. A higher proportion of consultation time was spent discussing CVD risk when using JBS3 (equivalent to 2.1 ± 0.82 minutes) than when using QRISK2 (equivalent to 1.31 ± 0.63 minutes), with a medium effect size. Nearly all health checks in both groups included reference to the 10-year percentage CVD risk score (94% vs. 94.5%; r = 0.01). The proportion of patients asking questions about CVD risk was higher in the JBS3 group than in the QRISK2 group (32.0% vs. 12.3%; r = 0.23).

In the JBS3 group, nearly all health checks included discussion of heart age (100%) and event-free survival age (97%), and manipulation of the risk score(s) to show the potential effect of intervention on risk (92%). This showed fidelity to the requested minimum use of JBS3 outputs. Use of heart age and risk manipulation was also evident in 52.1% and 21.9% of QRISK2 consultations, respectively. This is a result of two general practices in the QRISK2 group using Informatica (a software addition that offers some JBS3 functionalities), and because heart age and risk manipulation are possible (but not main features) in QRISK2.

Discussion of cardiovascular disease risk factors and risk management

Over one-third of total health check time was spent discussing causal CVD risk factors. This was slightly higher in health checks using QRISK2 than in those using JBS3 (small to medium effect size), but with wide variation within groups (see Table 7).

Interventions to manage risk were discussed for approximately one-fifth of total consultation time and predominantly related to lifestyle rather than medical intervention, which was not discussed at all in over 30% of QRISK2-informed and 42% of JBS3-informed health checks (r = –0.12).

Verbal dominance

Practitioners spoke for just over half of the total time in QRISK2 consultations and just under half in JBS3 consultations (compared with ≈ 23% for patients) (Figure 4). There was an indication of higher practitioner verbal dominance in health checks using QRISK2 than in those using JBS3 (r = 0.27).

FIGURE 4.

Mean percentage of total health check time with speaking by practitioner or patient. Error bars: 95% CI.

Patient medical records: activity and prescriptions 12 weeks post health check

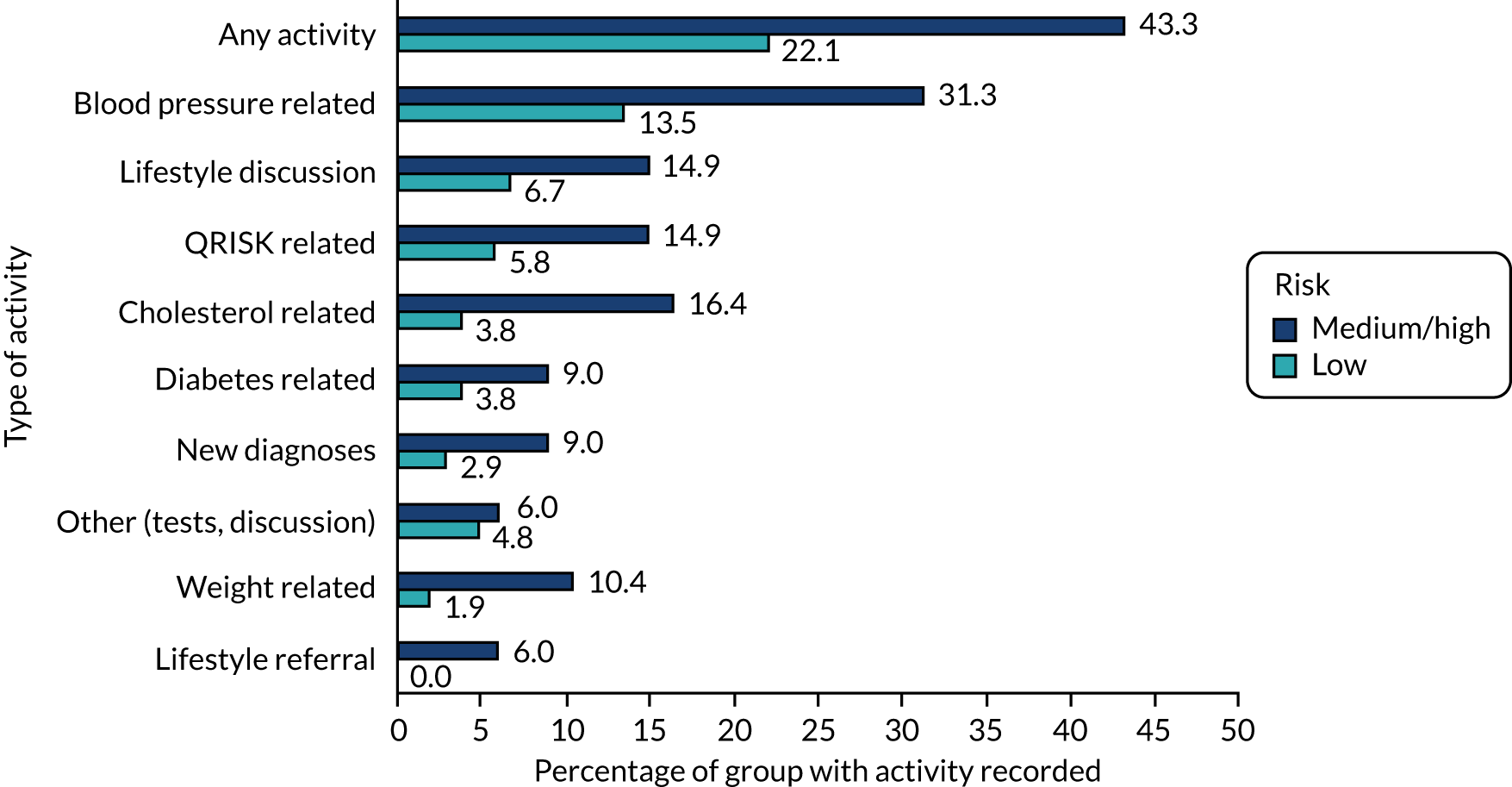

Fewer than one-third of all patients had resulting activity (30.1%) and 8.7% had prescriptions logged in their medical records in the 12 weeks following their health check. Figures 5 and 6 show the between-group comparisons. Chi-squared tests confirmed that there were no statistical differences between risk calculator groups (all had p-values > 0.05).

FIGURE 5.

Proportion of patients in each risk calculator group with relevant activity within 12 weeks of their health check. Data from all patients (n = 173).

FIGURE 6.

Proportion of patients in each risk calculator group with relevant prescriptions within 12 weeks of their health check. Data from all patients (n = 173).

The most common follow-up activities were related to blood pressure measurement or discussion (20.2%), followed by lifestyle discussion (9.8%), CVD risk assessment or discussion (9.2%) and cholesterol measurement or discussion (8.7%). Among the 173 patients, there were 10 new diagnoses (three pre-diabetes, three diabetes, two hypertension and two hyperlipidaemia).

Just 5% of all patients received prescriptions for lipid-lowering or cardiovascular medication, with 1% receiving prescriptions for anticoagulants or diabetes medication.

Figures 7 and 8 show that, as expected, the proportion of patients in whom relevant follow-up activity or prescriptions were recorded was higher among those at medium risk (with a QRISK2 score of 10–19.9%) or high risk of CVD (with a QRISK2 score of ≥ 20%) than among those at low risk (with a QRISK2 score of < 10%). Despite the relatively small numbers, differences between low- and medium-/high-risk groups reached significance for any medication (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.028) and statin/lipid-lowering medication (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.006), and for a number of relevant follow-up activities (Fisher’s exact tests: any activity, p = 0.004; weight related, p = 0.029; blood pressure related, p = 0.006; cholesterol related, p = 0.010; lifestyle referral, p = 0.022).

FIGURE 7.

Proportion of patients at low or medium/high risk of CVD with relevant activity within 12 weeks of their health check. Data from 171 patients (CVD risk missing for two patients in JBS3 group).

FIGURE 8.

Proportion of patients at low or medium/high risk of CVD with relevant prescriptions within 12 weeks of their health check. Data from 171 patients (CVD risk missing for two patients in JBS3 group).

Summary

Second-by-second quantitative coding of 173 video-recorded health checks (JBS3, n = 100; QRISK2, n = 73) and a review of patient medical records 12 weeks after their health check revealed a number of key findings.

-

Health check duration varied greatly (6.8–38.0 minutes), with most consultations lasting < 20 minutes. During this time, practitioners are expected to complete a range of clinical and administrative tasks, such as CVD risk assessment, involving measurement of (and data entry for) weight, blood pressure and, sometimes, cholesterol level through PoC testing; assessment of lifestyle (physical activity, alcohol, diet); explaining to patients their CVD risk score(s) and what it means; and patient-centred discussion of risk management to prompt risk-reducing behaviours.

-

There was evidence of practitioner verbal dominance because, on average, practitioners spoke for half of the total consultation time. This suggests more information provision than patient-centred, two-way interaction (see Chapter 4).

-

On average, CVD risk was discussed for < 2 minutes (9.1% ± 4.3% of the consultation time). Discussion of causal risk factors accounted for the largest proportion of total health check time.

-

There were indications that, compared with health checks using QRISK2, those using JBS3 involved more CVD risk discussion and were less verbally dominated by practitioners.

-

One in three patients (32%) in JBS3 consultations asked questions about their CVD risk, compared with one in eight patients (12%) in QRISK2 consultations, suggesting that there is better engagement with JBS3 than with QRISK2.

-

Fewer than one-third of all patients (30.1%) had relevant activity logged in their medical records in the 12 weeks following their health check, and just 8.7% received prescriptions as a result. Among the 173 patients, there were 10 new diagnoses. There was a trend for follow-up activities and prescriptions to be more frequent in patients at medium/high risk of CVD than among those at low risk, and for the number of prescriptions issued to be higher following health checks using QRISK2 than those using JBS3.

Chapter 4 Results 2: qualitative analysis of NHS Health Check consultations

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Riley et al. 76 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Headline findings from deductive thematic analysis of recorded health checks

-

There was little discussion of CVD risk, particularly in health checks using QRISK2.

-

Practitioners often relayed the risk score without discussing the implications or risk management.

-

Patients offered minimal responses to the risk information (e.g. single-word acknowledgement).

-

Practitioners frequently missed cues from patients who were unclear about their risk score.

-

For QRISK2, it was unclear whether or not the patient understood 10-year percentage risk, or trusted its credibility or relevance.

-

JBS3’s visual presentations of risk and heart age appeared more impactful and better understood (than 10-year risk in QRISK2).

-

JBS3’s event-free survival age lifetime risk was often misunderstood (patients and practitioners).

-

JBS3 may provide more opportunities to initiate risk factor and management discussion than QRISK2.

-

Positive responses were more evident when practitioners checked patient understanding, made risk meaningful to the patient, and asked for patient feedback around the CVD risk score.

Participant characteristics

To define the sample for the qualitative analysis, a further 19 of the 173 recorded health checks (included in the quantitative analysis) were excluded for reasons including communication of projected (not actual) risk score (n = 7), no discussion of risk (n = 2), no communication of lifetime risk (n = 4), incorrect use of JBS3 (n = 4) and insufficient use of the English language (n = 2). Of the remaining sample (n = 154), 64 health checks included communication of CVD risk using QRISK2. Therefore, 64 health checks using JBS3 were identified, matched on patients’ sex, CVD risk score and ethnicity, giving a sample of 128 for analysis (Table 8).

| Characteristic | Total | Study group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JBS3 | QRISK2 | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Total | 128 | 64 | 64 | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 64 | 50.00 | 32 | 50.00 | 32 | 50.00 |

| Male | 64 | 50.00 | 32 | 50.00 | 32 | 50.00 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 40–54 | 55 | 42.97 | 21 | 32.81 | 34 | 53.13 |

| 55–64 | 37 | 28.91 | 20 | 31.25 | 17 | 26.56 |

| 65–74 | 36 | 28.13 | 23 | 35.94 | 13 | 20.31 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| White British | 114 | 89.06 | 56 | 87.50 | 58 | 90.63 |

| Ethnic minority | 14 | 10.94 | 8 | 12.50 | 6 | 9.38 |

| CVD risk categorya | ||||||

| Low | 86 | 67.19 | 43 | 67.19 | 43 | 67.19 |

| Medium–high | 42 | 32.81 | 21 | 32.81 | 21 | 32.81 |

The results of deductive thematic analysis demonstrate how practitioners communicated risk using either QRISK2 or JBS3, and patient responses, to explore similarities and differences between the two calculators. The analysis, therefore, focused on parts of the health checks in which CVD risk was discussed. As noted in Chapter 3, this accounted for < 10% of consultation time, on average, and most patients said little in response to CVD risk information. Therefore, where there was evidence of two-way dialogue around CVD risk, we present quotations that best illustrate risk communication and subsequent patient response. Each quotation is labelled to denote which risk calculator was used (using QRISK®2+ where Informatica was used), the consultation identifier, patient sex and age. Where dialogue is reported, ‘P’ denotes the patient’s contribution and ‘HP’ denotes the health professional’s contribution (i.e. the practitioner).

Theme 1: cognitive appraisal

Threat appraisal

Threat appraisal focuses on the source of a threat (CVD risk) and factors that increase or decrease the probability of maladaptive responses (i.e. behaviours that inhibit patients’ ability to adjust to the threat). This theme is central to the health check. It focuses on the discussion of risk as it relates to patients’ perceived severity of CVD risk, the consequences of CVD, the perceived vulnerability to future CVD, and the intrinsic and extrinsic rewards for not addressing CVD risk [i.e. perceived benefits of not acting to manage or reduce risk (maladaptive response)]. Threat appraisal was the most commonly identified element of the PMT model. It was observed in all health checks, although less frequently in those using JBS3 (coded 584 times; average 9 times per consultation) than those using QRISK2 (coded 634 times; average 10 times per consultation).

Patients, when presented with their 10-year risk, generally acknowledged it, but the extent of their understanding was often unclear. For example, one asked ‘Is that percentage of risk alright?’. Most often, the risk score was acknowledged with a single-word response, such as ‘yeah’ or ‘OK’, limiting practitioners’ ability to gauge the patient’s understanding and classification of response for this analysis. Heart age in JBS3 aided patient understanding of CVD risk, resulting in questions such as ‘. . . so really what can I do about that? I mean I know it is all estimated’. Such questions reflected a level of understanding of the score and intention towards risk-reducing behaviour. Several patients expressed surprise at their risk. The patient in the extract below appeared to question how the score was calculated because he perceived himself to be healthier than the outcome suggested, leading to some mistrust. They also made two references to being ‘fitter’ than the risk score indicated, which was not addressed by the practitioner:

I thought I was fitter than that though.

[Laughter] You are doing good exercises.

But I was fitter than that though . . .

OK, so the health years, so on average expect to survive is 80 for yourself without a heart attack or a stroke, yeah? And then your risk of a heart attack or stroke in the next 10 years is 15%, so you do need to look after yourself, because we would say that is a medium risk.

Yes.

So wouldn’t say it is too high or low, but a medium to high.

OK.

OK, and then that’s what it looks like so from now until there, that’s the last one the chance of surviving without a heart attack.

That’s estimated?

This is estimated, we don’t know what’s going to happen you might be even longer.

So about 94 I might snuff it?

JBS3, 11_028, male, 58

Because the practitioner appeared to ignore the patient’s surprise, continuing to focus on the process of the health check, the patient switched off briefly, until presented with his event-free survival age. Moreover, there was evidence of misunderstanding among some patients and practitioners who interpreted event-free survival age as estimated age of survival (i.e. age of death).

Practitioners provided little follow-up explanation of risk scores when using QRISK2 or JBS3:

Right, this is the screening I was telling you about. I will just print that out for you. So your risk of any heart disease is 15%.

Yeah, which is not very high.

It does increase with age. If it is above 10% we then pass it on for them to have a look at it and they will be able to decide when to have your next health check, which should be 3 years or 1 year. Obviously next time you come in any results you’ve got in the red tend to up your risk and they tend to up your heart age as well. So when you come in next time if your blood pressure is back down, and obviously it could be less so . . . Your heart age has come up as 66.

Well I am 66 this year.

Yes, yes, so it is quite near isn’t it? Yes. So, for example, if you were a smoker and that was in the red that would put your heart age at 75. So the only one we have got in the red really is that one cholesterol . . .

It’s only marginal though isn’t it?

QRISK2+, 2_016, male, 65

The patient quoted above was identified as medium–high risk, but the practitioner did not elaborate on the severity or implications, leaving the patient’s interpretation of his risk score as ‘not very high’. This was compounded when the patient received his heart age. The practitioner did not address the patient’s misinterpretation of the severity of his risk nor explain why his results were conflicting (i.e. percentage risk score is age and sex dependent, heart age is not), again perhaps focusing on the consultation process more than the patient. This led the patient to dismiss his elevated cholesterol as ‘only marginal’. The absence of active listening skills was recurrent across both groups, making it difficult to gauge patient understanding, and lends support to the apparent imbalance between patient and practitioner contributions (see Chapter 3).

There was evidence, albeit still limited, that patient engagement in conversations about the threat of CVD was greater in the JBS3 group, prompted by risk score manipulation (e.g. practitioners visually showed patients that a reduction in blood pressure could lower their heart age):

. . . so obviously your blood pressure is not too bad, that is fine where it is at 128, but your cholesterol, so ideally we like that to be below 5. So if you could get it below 5, so let’s put it down to 4.8, you can see that automatically that it brings your risk down to 1.8%.

Oh, I see, yes.

. . . improves your life expectancy slightly, and probably brings your heart age down a year. So it is just, you know, showing that it can and, obviously, the lower you can keep these factors that you influence, for longer, the better quality of life and life expectancy there is . . . your risk is going to increase slightly with age. So it is about trying to moderate those other factors.

So what impact does exercise have on that?

It has quite a significant impact on your cholesterol, it does help your cholesterol a lot. We know that it helps because that increases your good cholesterol, which can help increase the balance so, that can help with it as well.

So what’s the normal range that is seen for HDL cholesterol?

HDL can be anything from sort of 1.1 to about 2.5, you don’t get much over, I can’t say I have seen many, I have seen a few. But your cholesterol could be anything down to you know 3.5.

OK and really bad would be?

6 or 7s, so would be sort of . . .

Oh, OK – so 5.6 is yeah it is edging up, isn’t it?

JBS3, 7_020, male, 45

The patient evaluated the threat and sought information to facilitate their appraisal. Although positive, this exchange again demonstrated misunderstanding of CVD event-free survival age as expected survival age, this time on the part of the practitioner. The visual impact of demonstrating how CVD risk can be reduced through risk factor modification (e.g. cholesterol, smoking status) appeared to aid patient understanding and realistic threat appraisal. There were fewer examples of active engagement during discussion of the CVD risk score during QRISK2 consultations, which may be because of the inability to show risk factor modification when using the calculator.

Coping appraisal

Coping appraisal focuses on the coping responses available to the individual to deal with a health threat (i.e. evaluation of ways to reduce CVD risk). This included patients’ perceptions of self-efficacy to engage in adaptive coping, practitioners’ promotion of self-efficacy through individualisation, the perceived response efficacy of adaptive coping and the response cost of adaptive coping (see Figure 2). References to coping appraisal were more common in JBS3 (n = 60, 94%) than QRISK2 health checks (n = 55, 86%). The communication of risk in JBS3 consultations was not observed in the same way as in those using QRISK2; most such consultations focused on facilitators of adaptive coping (i.e. risk-reducing changes that patients could make):

Erm and then this gives you your healthy years outlook [event-free survival age]. So based on your current lifestyle your risk of a heart attack or a stroke in the next 10 years is coming out at 2.4%. We aim for people’s risk to be below 10% so that’s . . .

Yeah.

. . . absolutely fine and on average you expected to survive to an age of 84 without a heart attack or stroke, so brilliant. So as I say, your blood pressure pretty good as it is, you not going get that much lower.

No.

Diet-wise would you say you got a pretty good diet do you know the sorts of . . .

We sort of grow our own vegetables and fruit and stuff like that . . .

Yeah.

. . . so, erm, I mean we eat reasonably healthy.

JBS3, 7_044, female, 54

Following communication of the risk score, the practitioner moved on to ways that the patient could maintain a low risk through dietary behaviours. This suggested that, although practitioners (from both groups) spent little time talking about the CVD risk score, the additional risk information in JBS3 may have helped to facilitate more risk factor discussion between the patient and the practitioner (than if using QRISK2).

Discussions around response costs for adaptive coping (i.e. perceived costs associated with a recommended behaviour) related to the use of statins or blood pressure medication, and were only observed in seven JBS3 consultations (11%) and none of the QRISK2 consultations. Data are limited, but may offer some evidence to suggest that JBS3 was more likely than QRISK2 to promote discussion around adaptive coping:

Obviously we’ve tried them, and they haven’t agreed with you.

I tried the [medication name] statin.

Yeah, and there are other statins we can discuss and obviously benefits of those they can reduce your cholesterol obviously and we can reduce your risk of cardiovascular disease so it might be worth having a think about and if you want to just discuss that further or a different type of statin . . .

All they did was it affected my reflux and it made the reflux worse.

Yeah.

So.

Yeah.

I was on that and an aspirin – I did the aspirin first and then . . .