Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the Evidence Synthesis Programme on behalf of NICE as project number NIHR129932. The contractual start date was in October 2019. The draft report began editorial review in July 2020 and was accepted for publication in January 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Duarte et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Description of the health problem

Stable angina is a type of chest pain caused by insufficient blood supply to the heart, brought on by physical activity or emotional stress, which goes away with rest. It is the key symptom of coronary artery disease (CAD), which remains one of the main causes of morbidity and mortality in high-income countries. Complications include unstable angina, heart failure, myocardial infarction (MI) and sudden death.

To alleviate symptoms, patients may receive ‘revascularisation’ to open damaged, obstructed or blocked arteries. This most commonly consists of inserting a small tube or ‘stent’ into the artery to keep it open and allow blood flow. Patients who might need revascularisation undergo a number of tests to identify blocked arteries, including coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) and other non-invasive tests. If these tests are inconclusive, more invasive tests are needed, for example invasive coronary angiography (ICA), where a contrast medium is injected through a catheter into the coronary arteries and radiographic images (angiograms) are taken.

Angiograms have limited ability to differentiate between arteries with inadequate blood supply (which need revascularisation) and those with adequate supply that do not need treatment. To address this, the procedure may be combined with an invasive measurement of blood flow, such as invasive fractional flow reserve (FFR) assessment. During this procedure, the blood flow is measured by inserting a wire into the coronary arteries after the patient has taken drugs to dilate the artery. The procedure is invasive and, therefore, carries some risks and may have side effects.

The Health Survey for England 2017: Adult Social Care1 reported that the prevalence among adults of ever having ischaemic heart disease (including MI and angina) was 4%. The prevalence was higher among men (6%) than women (3%) and increased with age (3% in people aged 45–54 years, 16% in people aged > 75 years). Prevalence of angina and history of angina among all adults was 3%.

Description of the technologies under assessment

Non-invasive imaging tests have been proposed to precede or replace invasive FFR, by using the existing angiograms to determine blood flow, without inserting a wire.

QAngio XA 3D/QFR

QAngio® XA 3D/QFR® (three-dimensional/quantitative flow ratio) (Medis Medical Imaging Systems BV, Leiden, the Netherlands) imaging software is used to perform quantitative flow ratio (QFR) assessment of coronary artery obstructions. It is designed to be used with all ICA systems: biplane or monoplane. It uses two standard two-dimensional (2D) angiographic projections, taken at least 25° apart – ideally between 35° and 50° apart – to create a three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of a coronary artery; this shows the QFR values across the artery. QFR is an assessment (by frame count) of the pressure (blood flow velocity) drop over the artery, with a value of 1 representing a normally functioning artery with no pressure drop. A drop of ≥ 20 mmHg in blood pressure (QFR value of ≤ 0.8) is considered a significant obstruction where revascularisation should be considered. QAngio XA 3D/QFR software is installed on a laptop or workstation that is connected to the ICA system. The Digital Imaging and Communication in Medicine (DICOM) data from ICA projections are immediately uploaded and viewable on the connected workstation. The total time for data acquisition and analysis is about 4 to 5 minutes (as reported by the company).

AngioPLUS [Pulse Medical Imaging Technology (Shanghai) Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China] is an equivalent Conformité Européenne-marked version marketed in Asia.

The QAngio XA 3D/QFR software offers two different flow models to calculate QFR:

-

fixed-flow quantitative flow ratio (fQFR), using fixed-flow velocity

-

contrast-flow quantitative flow ratio (cQFR), using contrast frame count in an angiogram without hyperaemia.

Fixed-flow quantitative flow ratio is faster to compute, but may be less accurate than cQFR.

Furthermore, the QAngio XA 3D/QFR software provides four different QFR indices along the analysed coronary segment:

-

vessel quantitative flow ratio (vQFR): the QFR value at the distal location of the analysed vessel segment

-

index quantitative flow ratio (iQFR): a point that can be moved along the QFR pullback curve

-

lesion quantitative flow ratio (lQFR): the contribution to the QFR drop by the selected lesion alone

-

residual vQFR: an indication of the vQFR, if the selected lesion is resolved.

CAAS vFFR

The CAAS® vFFR® (vessel fractional flow reserve) (Pie Medical Imaging BV, Maastricht, the Netherlands) workflow builds a 3D reconstruction of a coronary artery based on two standard angiograms and assesses the pressure drop across the stenosis, and quantitative coronary arteriography (QCA) determines a vFFR value. It gives both anatomical and functional assessment of the stenosis and can be integrated into catheter laboratories. According to the company, the total time for analysis is approximately 2 minutes per artery.

All available versions of CAAS (i.e. 8.0, 8.1 and 8.2) use the same algorithm for calculating vFFR. The CAAS workstation provides various modules (e.g. QCA and left ventricular analysis), and the vFFR module can be added to the CAAS workstation. In addition to the vFFR, CAAS vFFR provides measurements at the end of the lesion and at a chosen position in the coronary artery.

Comparators

Invasive coronary angiography may differentiate between arteries with inadequate blood supply (which need revascularisation) and those with adequate supply that do not need treatment.

During an ICA procedure, a coronary diagnostic catheter is inserted into an artery and moved up the aorta and into the coronary arteries. A special type of dye called contrast medium is injected through the catheter into the coronary artery and angiograms are taken. Although providing valuable information on coronary artery anatomy, visual assessment of angiograms taken during ICA may have limited ability to differentiate between functionally significant (causing inadequate blood supply) and non-significant (not significantly affecting blood supply) coronary stenoses.

When ICA is inconclusive, it may be combined with the invasive measurement of FFR. In these procedures FFR is assessed invasively by advancing a pressure wire towards the stenosis and measuring the ratio in pressure between the two sides of the stenosis during maximum blood flow (induced by adenosine infusion). This is associated with risks related to the passage of a guide wire, side effects of adenosine and additional radiation exposure. The invasive FFR measurement is also associated with increased procedural time and costs compared with ICA alone. As an alternative to invasive FFR, the instantaneous wave-free ratio (iFR) may be used. This also uses inserted pressure wires to assess flow but does not require vasodilator drugs, such as adenosine.

Current service provision and care pathways

Patients who experience chest pain and may need revascularisation will be assessed for angina and other cardiovascular conditions. When clinical assessment alone is insufficient for a diagnosis, patients are referred for a 64-slice (or above) CCTA as the first-line diagnostic test.

Patients may go on to further diagnostic testing. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance2 recommends offering non-invasive functional imaging for myocardial ischaemia if a 64-slice (or above) CCTA has shown CAD of uncertain functional significance, or is non-diagnostic. This could include:

-

myocardial perfusion scintigraphy (MPS) with single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)

-

stress echocardiography

-

first-pass contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (MR) perfusion

-

MR imaging for stress-induced wall motion abnormalities.

In addition, NICE’s medical technologies guidance3 recommends that HeartFlow FFRCT (HeartFlow, Inc., Redwood City, CA, USA) should be considered as an option for patients with stable, recent-onset chest pain who are offered 64-slice (or above) CCTA. It provides both functional and anatomical assessment of coronary arteries and has better diagnostic performance than CCTA alone or other non-invasive or invasive tests. If these tests are also inconclusive, ICA is offered as a third-line diagnostic tool.

A diagnosis of stable angina is made when clinical symptoms are present and:

-

Significant CAD is found during ICA or 64-slice (or above) CCTA. This is usually defined as ≥ 70% diameter stenosis (DS) of at least one major epicardial artery segment, or ≥ 50% DS in the left main coronary artery.

-

Reversible myocardial ischaemia is found during non-invasive functional imaging.

Sometimes ICA is also used to guide treatment strategies for people with a confirmed diagnosis of stable angina whose symptoms are not satisfactorily controlled with optimal medical treatment (OMT), and so may require revascularisation. ICA may differentiate between arteries with inadequate blood supply (which need revascularisation) and those with adequate supply that do not need treatment. When ICA is used to determine the presence and severity of coronary stenosis and it is inconclusive, it may be combined with the invasive measurement of FFR using a pressure wire, as recommended by the European Society of Cardiology4 and American College of Cardiology. 5 Lesions with a FFR of ≤ 0.80 are functionally significant and revascularisation may be considered. Should iFR be used, a measure of ≤ 0.89 is considered functionally significant.

Invasive coronary angiography is performed either in diagnostic-only ICA laboratories or in interventional catheter laboratories as part of the initial stenosis assessment prior to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). In diagnostic-only laboratories, patients in whom ICA alone is inconclusive might be referred to an interventional laboratory for a FFR or iFR assessment. In interventional laboratories a FFR or iFR assessment can be performed immediately after ICA, if needed.

The British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS)’s audit reports that 244,332 ICA procedures took place in the UK in 2017/18 in NHS and private facilities, with 35,017 procedures performed in diagnostic-only catheter laboratories.

There is substantial regional variation in the diagnostic pathway for stable angina, due in part to the availability of imaging modalities at each centre, and experience (or preferences) of the cardiologists referring for the test. Clinical advisors noted that the pathway recommended by NICE is widely recognised as current best practice.

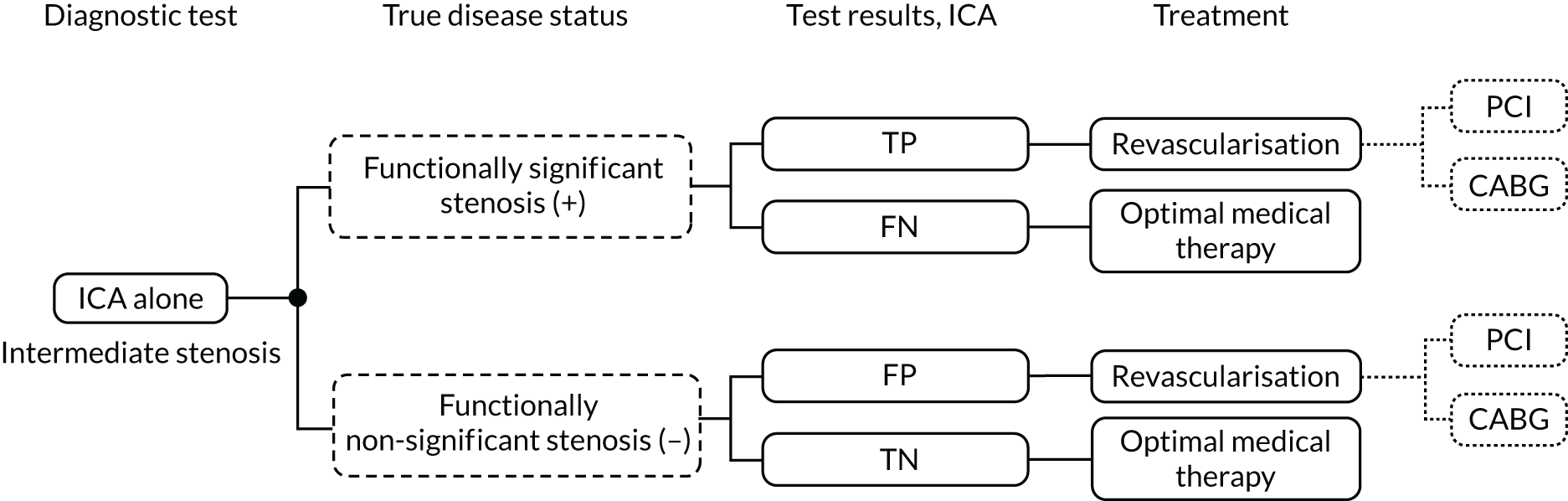

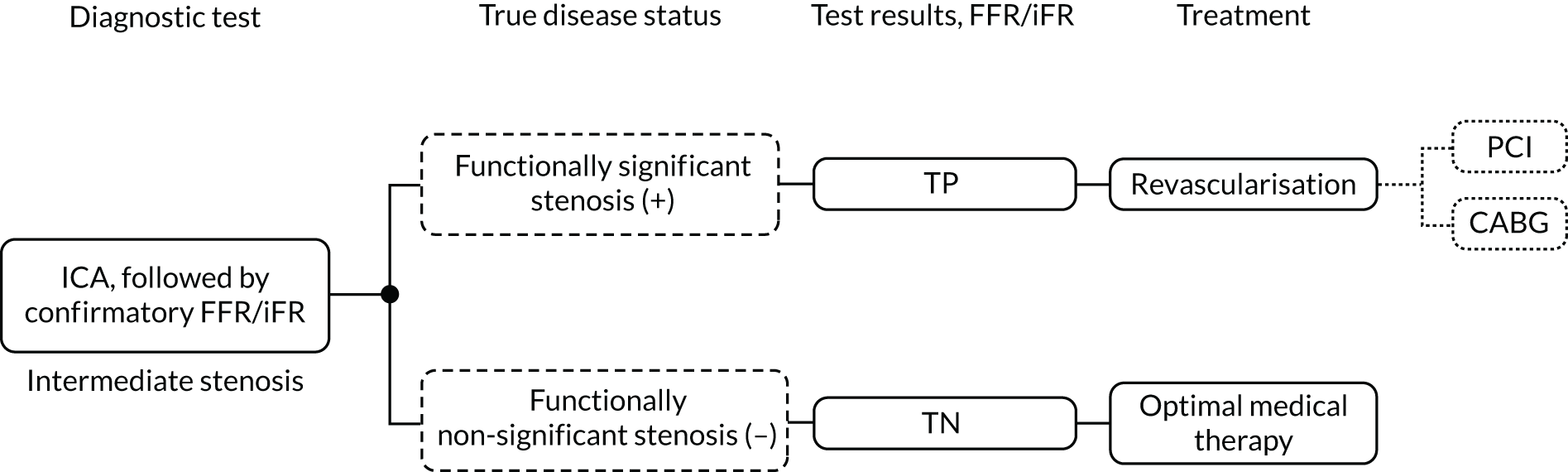

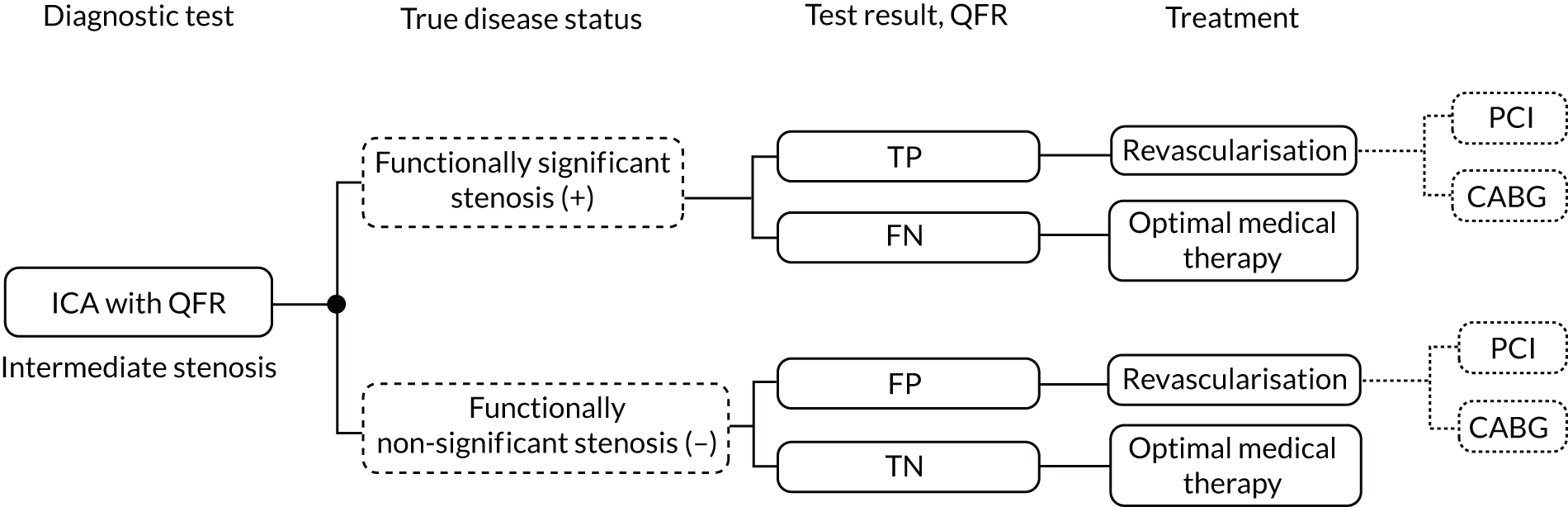

Position of the technology in the diagnostic pathway

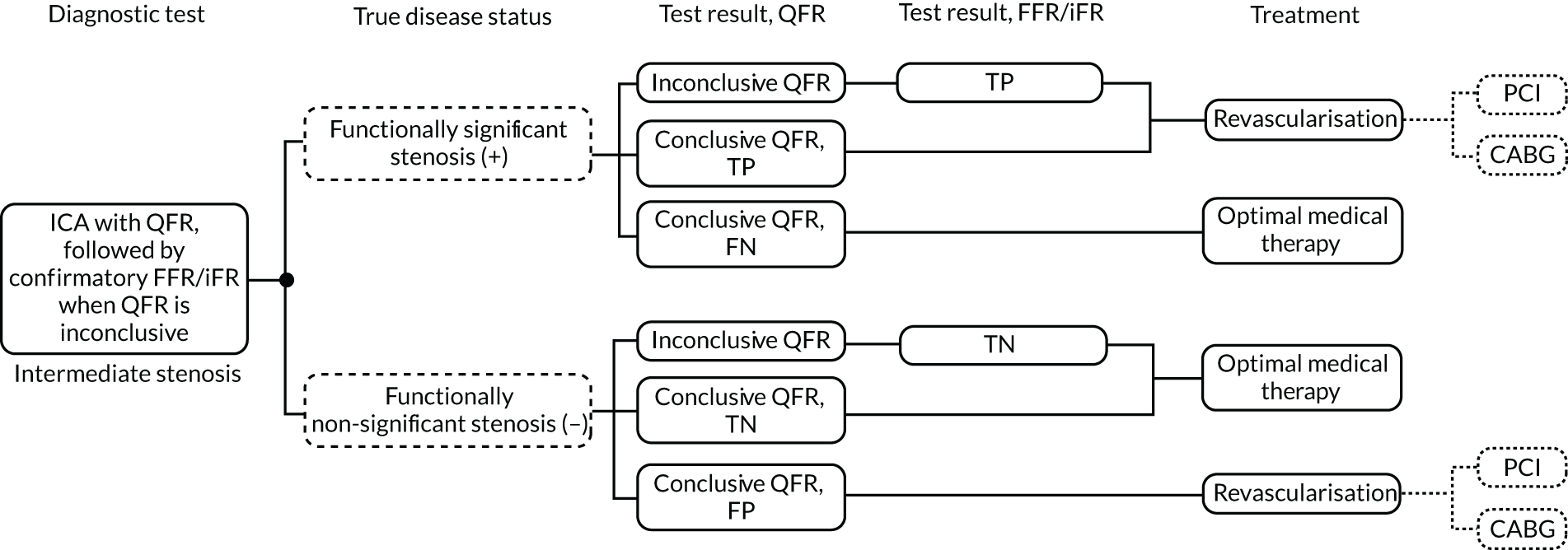

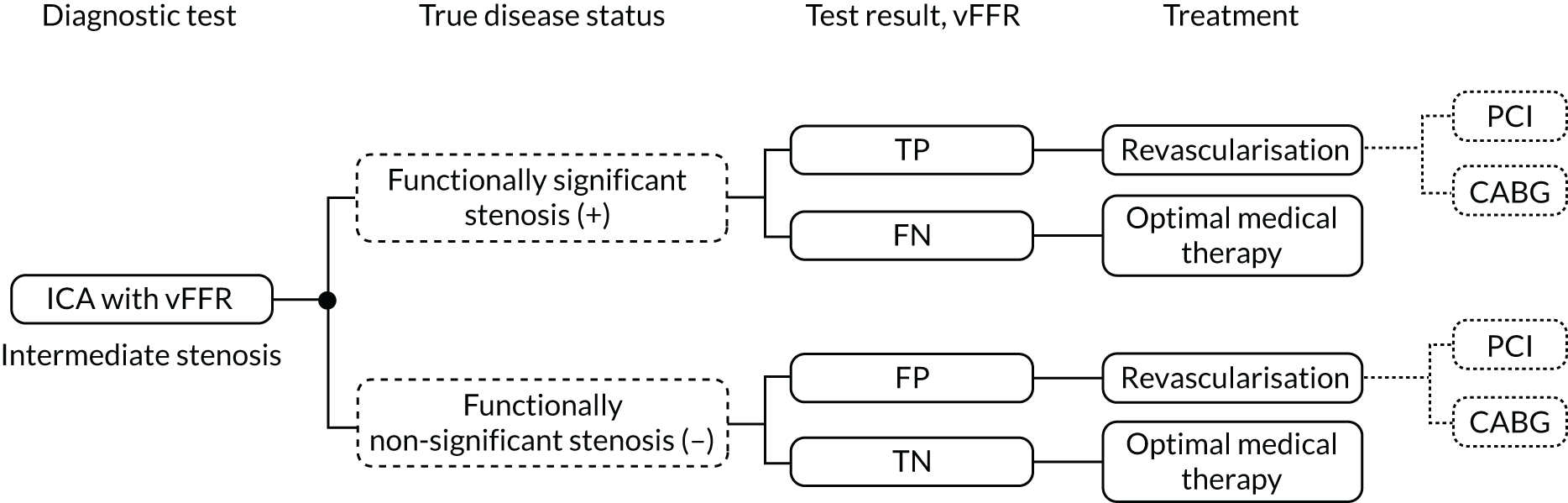

Either QFR or vFFR could potentially replace pressure wire FFR, or iFR, by providing a non-invasive means to assess FFR as part of an ICA assessment in people with stable chest pain of recent onset. Visual assessment of angiograms taken during ICA may be limited in its ability to differentiate between functionally significant (causing inadequate blood supply) and non-significant (not significantly affecting blood supply) coronary stenoses. Alternatively, they may be used as a precursor to invasive FFR, with the invasive procedure used when QFR or vFFR is inconclusive.

In addition, QFR may be used in other aspects of decision-making, including whether to stent more than one vessel or to select a stent type or other interventional device for revascularisation.

QAngio XA 3D/QFR and CAAS vFFR could also be used in diagnostic-only laboratories, possibly reducing the need for referrals to interventional laboratories.

The QAngio XA 3D/QFR instructions recommend the following approach:

-

QFR < 0.78 – treat the patient in the catheter laboratory

-

QFR > 0.84 – follow the patient medically

-

QFR 0.78–0.84 (grey zone) – verify by invasive FFR measurement.

Following request for clarification, Pie Medical Imaging stated that it recommends the same hybrid approach for CAAS vFFR.

The likely pathway leading to invasive FFR, and including the probable placement of QFR and vFFR, is summarised in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Diagnostic pathway for stable angina, including QFR or vFFR (from the NICE Diagnostics Assessment Programme 48 final scope). 6 a, Non-invasive functional imaging includes MPS with SPECT, stress echocardiography, first-pass contrast-enhanced MR perfusion and MR imaging for stress-induced wall motion abnormalities. © NICE [2019] QAngio XA 3D/ QFR and CAAS vFFR Imaging Software for Assessing the Functional Significance of Coronary Obstructions During Invasive Coronary Angiography. Final Scope. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/dg43/documents/final-scope All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication.

Chapter 2 Aims and objectives

The aim of the project is to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of non-invasive assessment of the functional significance of coronary stenoses, using QAngio XA 3D/QFR and CAAS vFFR imaging software.

To achieve this, the following objectives were set:

-

Clinical effectiveness –

-

To perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy and, where feasible, clinical efficacy of the QAngio XA 3D/QFR imaging software and CAAS vFFR software used during ICA for assessing the functional significance of coronary obstructions in people with stable chest pain whose angiograms show intermediate coronary stenosis.

-

To perform a narrative systematic review of the clinical efficacy and practical implementation of QAngio XA 3D/QFR and CAAS vFFR imaging software. This includes assessment of the associated revascularisation rates, mortality and morbidity, patient-centred outcomes, adverse events and acceptability to clinicians and patients.

-

-

Cost-effectiveness –

-

To perform a systematic review of published cost-effectiveness studies of the use of the QAngio XA 3D/QFR and CAAS vFFR imaging software for assessing the functional significance of coronary stenosis in people with stable chest pain whose angiograms show intermediate stenosis.

-

To develop a decision model to estimate the cost-effectiveness of the QAngio XA 3D/QFR and CAAS vFFR imaging software used during ICA to indicate whether or not coronary obstructions are functionally significant. Consideration will be given to differences in the cost-effectiveness of the technologies in diagnostic-only or in interventional catheter laboratories.

-

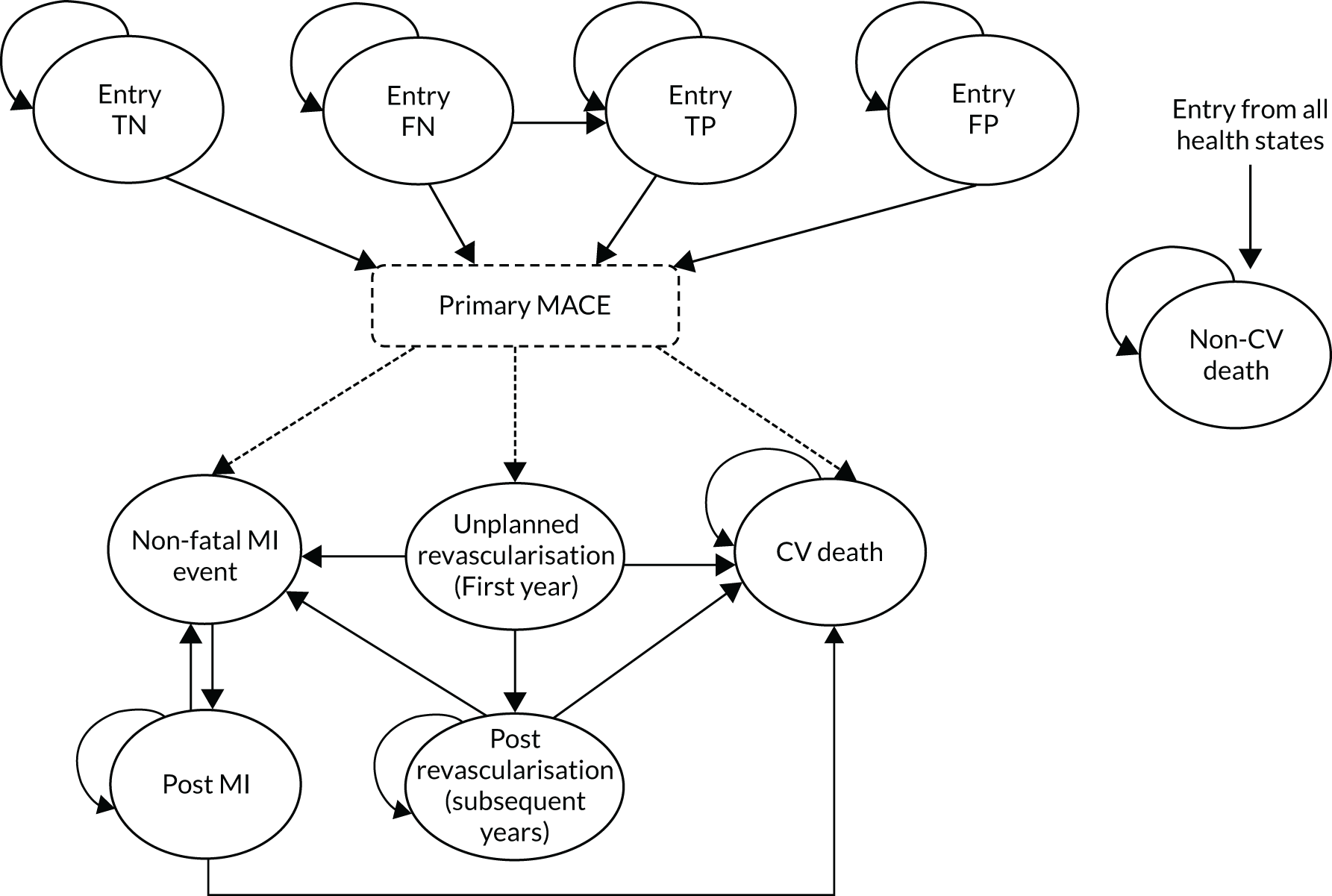

The decision model will link the diagnostic accuracy of QFR derived from the QAngio XA 3D/QFR imaging software, and vFFR derived from the CAAS vFFR software, to short-term costs and consequences (e.g. the impact on the number of revascularisations needed, the proportion of people who need invasive functional assessment of stenosis, time to test results, and associated risks of the diagnostic intervention). It will link the short-term consequences to potential longer-term costs and consequences (e.g. major cardiovascular events such as MI and sudden cardiac death, adverse events related to revascularisation and diagnosis, and mortality) using the best-available evidence.

-

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Methods for reviewing effectiveness

The systematic review was conducted following the general principles recommended in the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) guidance and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. 7

Searches

Comprehensive searches of the literature were conducted to systematically identify all studies relating to QAngio XA 3D/QFR and CAAS vFFR imaging software.

The searches were carried out during October 2019, with a further updated search undertaken on 2 January 2020. The following databases were searched: MEDLINE, PubMed, EMBASE™ (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), the Science Citation Index (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database and EconLit (American Economic Association, Nashville, TN, USA).

Ongoing and unpublished studies were identified by searches of ClinicalTrials.gov; Conference Proceedings Citation Index: Science (Clarivate Analytics); EU Clinical Trials Register; Open Access Theses and Dissertations; ProQuest® (ProQuest LLC, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) Dissertations & Theses A&I; PROSPERO; the World Health Organization’s International Clinical Trials Registry Platform portal; and manufacturer websites. Abstracts from any recent conferences that are thought to be relevant to the review were also consulted.

A search strategy for Ovid® (Wolters Kluwer, Alphen aan den Rijn, the Netherlands) MEDLINE is reported in Appendix 1. The MEDLINE strategy was translated to run appropriately on the other databases and resources. No language or date restrictions were applied to the searches. No study design search filters were used.

Reference lists of relevant recent reviews8 were checked to identify additional potentially relevant reports.

Database searches were carried out to identify cost-effectiveness studies where ICA (alone and/or with FFR) was one of the interventions under comparison. The following databases were searched: EconLit, EMBASE, HTA database, MEDLINE and NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED). The search strategies for EconLit, EMBASE and MEDLINE are reported in Appendix 1.

Pragmatic supplementary PubMed and Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) searches were carried out to identify studies of diagnostic data on ICA compared with FFR.

Contact with study authors and manufacturers and request for individual participant data

An individual participant data (IPD) meta-analysis of four studies that has previously been performed was eligible for this review. 8 The review authors contacted the study authors prior to commencing this assessment, and the study authors agreed, in principle, to share the collected IPD with the review authors for the purposes of this work. However, because of the slow response from the study authors, the IPD could not be supplied in time for this report, and the decision was made not to pursue an IPD analysis. Instead, published data and data presented in figures were used. Where possible, IPD-equivalent data were extracted from plots using a digitising software. See Data extraction for further detail.

Selection criteria

Two reviewers independently screened all titles and abstracts. Full papers of any titles and abstracts that were thought to be relevant were obtained where possible, and the relevance of each study assessed independently by two reviewers according to the criteria below. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus or by consulting a third reviewer. Conference abstracts were included where sufficient data were reported to confirm eligibility. Authors were contacted where insufficient data were reported to confirm inclusion (for instance, to clarify what index test was used in the study, or to provide complete 2 × 2 data) and where it was unclear whether or not the same diagnostic accuracy results were presented in more than one report (e.g. conference abstracts linked to a publication).

Diagnostic accuracy

Included were diagnostic accuracy and correlation studies in which QFR using any version of the QAngio® system (Medis Medical Imaging Systems BV) or CAAS vFFR were performed in addition to invasive FFR (or iFR) as a reference standard in the same patients. Only prospective and retrospective cohorts were included. Case–control studies, letters, editorials and reviews were excluded.

Clinical effectiveness/implementation

Included were observational studies where QFR or vFFR (with or without invasive FFR) have been used and that report relevant clinical outcomes as detailed. Relevant publications reporting issues related to implementation of, or practical advice for, QFR or vFFR and their use in clinical practice were also eligible. Case reports and studies focusing only on technical aspects of QFR or vFFR (such as technical descriptions of the testing process or specifications of machinery and software) were excluded.

Participants

Patients with intermediate stenosis (however defined) who are referred for ICA to assess coronary stenosis and the need for revascularisation were included. Although the main focus of this assessment was on patients with stable chest pain (either suspected stable angina or confirmed angina that is not adequately controlled by treatment), patients with all types of angina (including unstable, non-specific and atypical) were eligible for inclusion. Patients with acute MI [ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) < 72 hours] were also included provided QFR was performed in non-culprit vessels.

Interventions

All versions of QAngio XA 3D/QFR (including AngioPlus) and CAAS vFFR imaging software used in conjunction with ICA to allow simulation of FFR were included.

All submeasurements of QFR were eligible, including cQFR and fQFR. Eligible health-care settings were diagnostic-only and interventional catheter laboratories.

Reference standard

The reference standard was FFR assessed using an invasive pressure wire with or without adenosine. iFR, which was found to be non-inferior to FFR for predicting cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality,9 was also accepted as a reference standard.

Outcomes

The eligible outcome measures relating to diagnostic accuracy were:

-

sensitivity and specificity of QAngio XA 3D/QFR and CAAS vFFR

-

positive predictive values (PPVs) and negative predictive values (NPVs)

-

estimates of difference in measurements between QFR or vFFR and invasive FFR/iFR (including Bland–Altman assessments)

-

correlation between QFR or vFFR and invasive FFR/iFR measurements.

Some studies reported differences or concordance between QFR or vFFR and invasive FFR/iFR in numerous ways, including inter- and intra-rater differences in measurements, mean differences (MDs), correlation coefficients, sensitivity and specificity, or receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. All relevant outcome definitions and cut-off points were extracted and their applicability to the decision problem accounted for when presenting the results. Diagnostic accuracy results of ICA alone were considered if reported alongside QFR or CAAS vFFR.

In addition, the following clinical outcomes were eligible:

-

morbidity, mortality and major adverse cardiac events (MACEs) (e.g. MI, heart failure)

-

adverse events related to the diagnostic procedure (e.g. pressure wire damage, adenosine side effects, stroke)

-

adverse events related to revascularisation

-

distress, anxiety and similar harms caused by QAngio XA 3D/QFR, CAAS vFFR, invasive FFR or iFR

-

subsequent use of invasive pressure wire FFR or iFR

-

subsequent revascularisation procedures performed (including unscheduled revascularisations)

-

number of vessels with stent placements

-

health-related quality of life (HRQoL)

-

radiation exposure.

Eligible outcomes related to the implementation of the interventions of interest and related practical issues included:

-

acceptability of QFR, vFFR and invasive FFR (to clinicians and patients)

-

test failure rates

-

inconclusive test rates

-

inter-observer variability

-

timing of results from data acquisition

-

referral times

-

patient satisfaction

-

training requirements

-

uptake and compliance.

Data extraction

A standardised data extraction form was developed, piloted and finalised to data-extract both study and patient characteristics and eligible outcomes. For studies reporting diagnostic accuracy data, the number of true-positive (TP), true-negative (TN), false-positive (FP) and false-negative (FN) results were extracted for each index test evaluated in each study, along with sensitivity and specificity data, the area under the curve (AUC) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and PPVs and NPVs. Whether diagnostic accuracy was determined per patient, vessel or lesion was recorded.

Where not reported, sensitivity and specificity were calculated if data allowed. Further data were requested from study authors when required. Correlation and MD between QFR/vFFR and FFR were recorded along with reasons for any excluded, failed or inconclusive results and any other relevant clinical outcomes from the studies.

As IPD could not be supplied, digitised data were extracted using WebPlotDigitizer (Ankit Rohatg, Pacifica, CA, USA) software to approximately reconstruct the individual-level data from included studies. Data were extracted for all studies that presented a Bland–Altman or correlation plot. Bland–Altman plots were preferred for extraction, as these were found to be generally clearer and easier to extract. The extracted averages and differences between QFR and FFR were converted into QFR and corresponding FFR values for each study. For some studies, the quality of published figures was not sufficient to extract data.

Data were extracted by one reviewer using a standardised data extraction form and independently checked by a second reviewer. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion, with involvement of a third reviewer when necessary. Data from relevant studies with multiple publications were extracted and reported as a single study. The most recent or most complete publication was used in situations where we could not exclude the possibility of overlapping populations across separate study reports.

Critical appraisal

The quality of the diagnostic accuracy studies was assessed using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 (QUADAS-2) tool. The QUADAS-2 tool evaluates both risk of bias (associated with the population selection, index test, reference standard and patient flow) and study applicability (population selection, index test and reference standard) to the review question. The tool was piloted on a sample of studies. Signalling questions and criteria for decisions were finalised following piloting.

The quality assessments were performed by one reviewer and independently checked by a second reviewer. Disagreements were resolved through consensus and, when necessary, by consulting a third reviewer.

Methods of data synthesis

The results of data extraction were presented in structured tables and as a narrative summary, grouped by population and test characteristics. The diagnostic accuracy was calculated for each study based on extracted data, using the usual index test of QFR ≤ 0.8 and reference standard of FFR ≤ 0.8 as defining patients in need of stenting. Where sufficient clinically and statistically homogenous data were available, data were pooled using appropriate meta-analytic techniques. Studies that did not report sufficient information to derive 2 × 2 data (from tables, text or plots) were not included in the meta-analysis and were synthesised narratively.

Statistical analysis of diagnostic accuracy

Meta-analysis using 2 × 2 diagnostic data

The primary meta-analyses in this report were based on studies that reported 2 × 2 diagnostic data, or where data could be reconstructed from tables. Both univariate meta-analysis and bivariate meta-analysis of sensitivity and specificity10 were performed and compared, categorised according to ‘mode’ of QFR used: either fQFR, cQFR or non-specified QFR (referred to as QFR). These analyses included all patients, vessels and lesions. Results are reported in forest plots and summarised in tables and ROC plots.

Separate (univariate) meta-analyses were performed for each diagnostic outcome [sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV, diagnostic odds ratio (DOR), area under ROC curve, correlation between QFR and FFR, and MD between QFR and FFR] and presented in forest plots.

A hierarchical bivariate generalised linear mixed model, as described by Simmonds et al. ,11 was fitted to the data to calculate summary estimates of sensitivity and specificity and the associated 95% CIs. The same model was used to produce summary ROC curves, using the Rutter and Gatsonis formulation for the hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic (HSROC) curve. 11,12 Results are presented in ROC plots. Unless otherwise specified, all analyses used a cut-off point for the index test of QFR ≤ 0.8 and reference standard of FFR ≤ 0.8 as defining patients in need of revascularisation.

As some studies reported data on two or more tests (e.g. QFR and ICA or fQFR and cQFR), the bivariate model was extended to include diagnostic accuracy parameters for multiple tests, which allowed for formal comparison between models in terms of sensitivity and specificity. 11

Investigation of heterogeneity and subgroup analyses

For diagnostic accuracy data, we visually inspected the forest plots and ROC space to check for heterogeneity between study results. To assess the impact of patient factors, we performed meta-regressions of sensitivity, specificity and DOR against key patient parameters reported in papers. All meta-regressions were univariate analyses (i.e. one patient parameter per metaregression).

Where available, we considered the following factors as potential sources of heterogeneity:

-

type and severity of stenosis (e.g. high percentage DS)

-

multivessel CAD

-

diffuse CAD

-

multiple stenoses in one vessel

-

microvascular dysfunction (e.g. caused by diabetes)

-

chronic total occlusion

-

diabetes

-

sex

-

age

-

ethnicity (or study location as a proxy for ethnicity)

-

results of previous non-invasive tests

-

use of fQFR compared with cQFR (QAngio XA 3D/QFR)

-

previous MI.

For these analyses fQFR was not separated from cQFR; instead, one test per study (cQFR for preference) was analysed to maximise data. This was judged to be reasonable given that diagnostic accuracy did not appear to vary substantially according to the type of QFR used.

Where studies reported the factors of interest separately by subgroup, these subgroup results were compared; however, these were too sparsely reported to permit any meta-analysis. For patient factors where data did not allow for metaregression, a narrative synthesis of the impact of covariates has been provided.

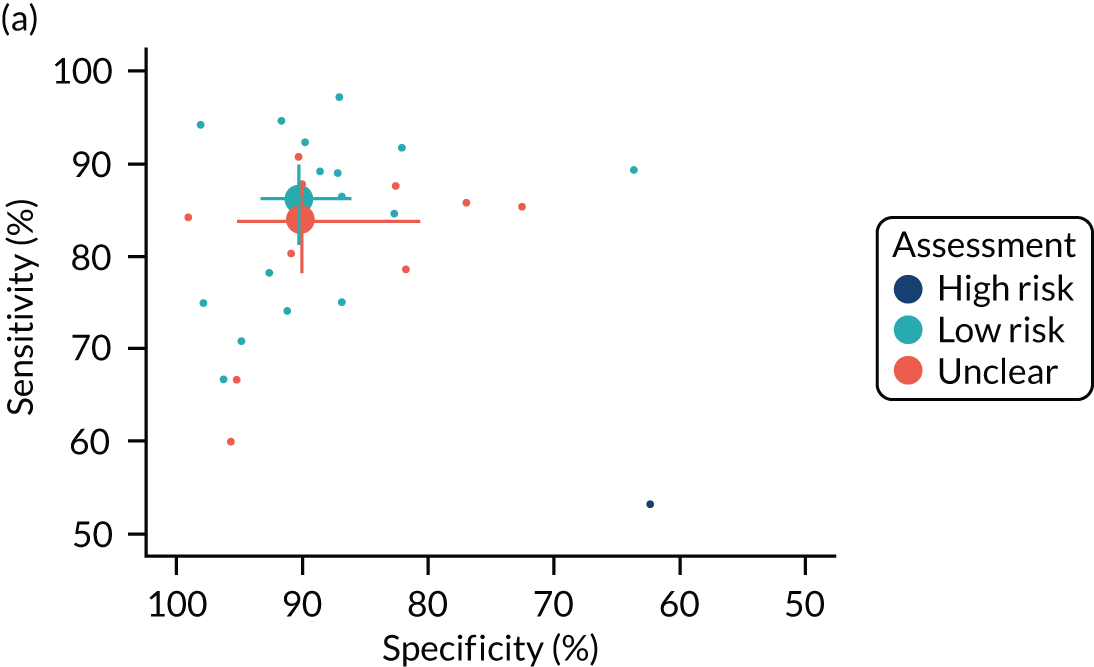

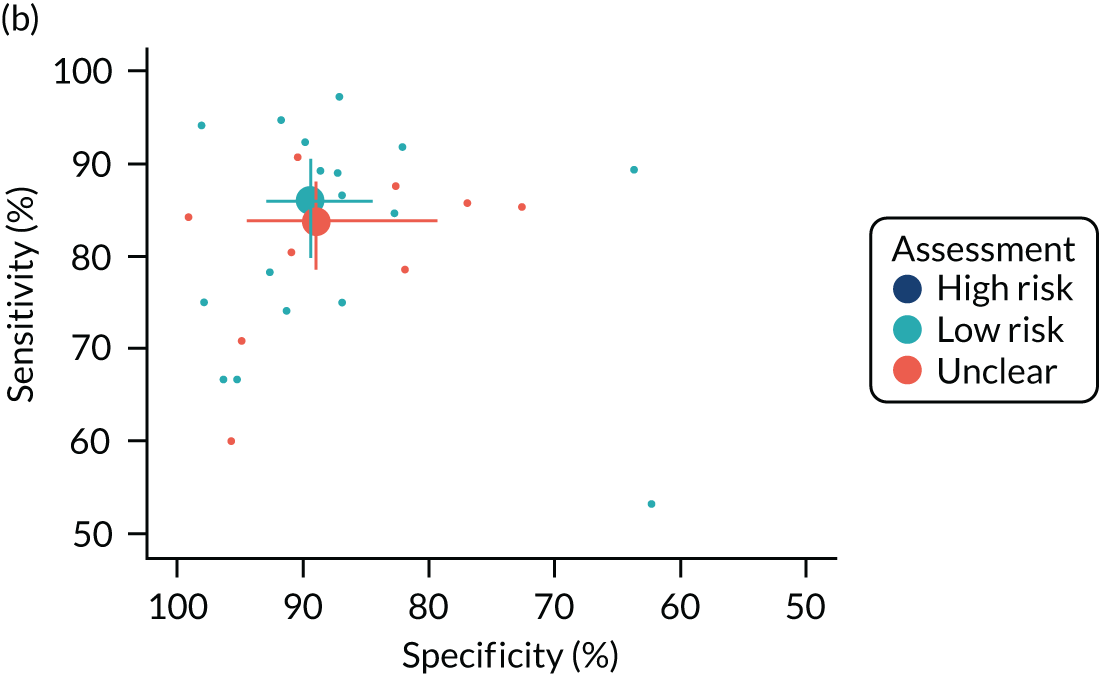

Sensitivity analyses

We conducted sensitivity analyses to explore the robustness of the results according to study quality based on QUADAS-2 domain results (e.g. risk of incorporation bias) and study design (e.g. in-procedure compared with retrospective evaluation of index test results) for diagnostic accuracy studies. ROC plots of sensitivity and specificity according to risk of bias were produced to visually assess possible bias. Where feasible, bivariate meta-analyses were repeated, subgrouped according to the assessed risk of bias.

Meta-analysis of data extracted from figures

Using data extracted from figures, estimates of sensitivity and specificity were calculated and presented on forest plots and in the ROC space to examine the variability in diagnostic test accuracy within and between studies. These were compared with the diagnostic accuracy results from 2 × 2 table to investigate whether or not the extracted data could be used for analysis. The bivariate meta-analyses performed using 2 × 2 data were repeated using the extracted figure data.

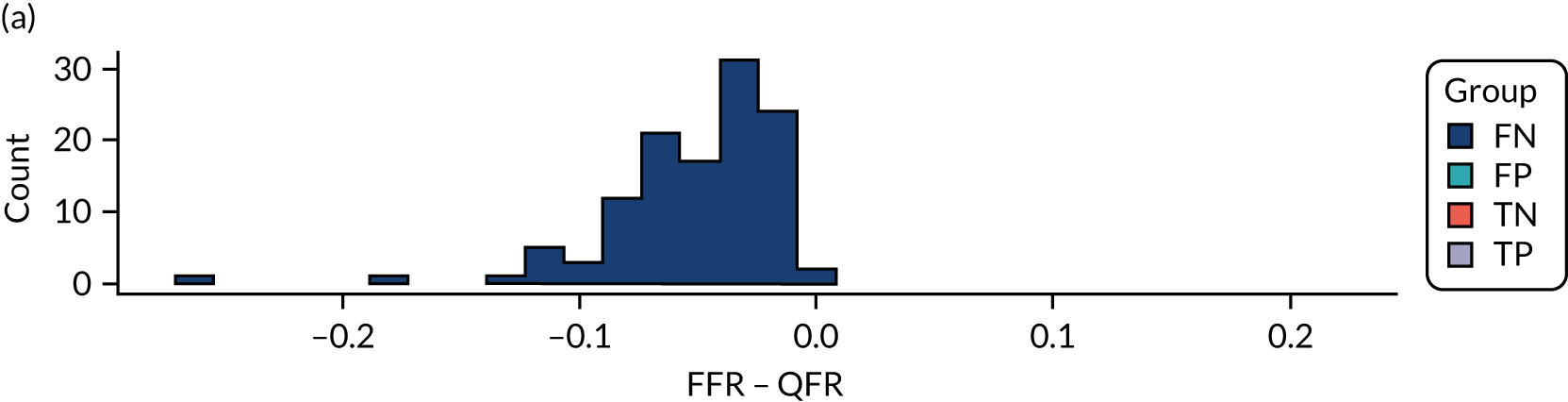

Grey-zone analysis

Extracted figure data were used to conduct an analysis where testing includes a grey zone of intermediate QFR values for which a FFR would be performed as a confirmatory test. The grey-zone diagnostic procedure considered, following the QAngio XA 3D/QFR instructions, was:

-

perform the QFR

-

if the QFR is > 0.84, continue without stenting/bypass (test negative)

-

if the QFR is ≤ 0.78, proceed to stenting/bypass (test positive)

-

if the QFR is between 0.78 and 0.84, perform a FFR test and proceed to stenting/bypass if the FFR ≤ 0.80 (the grey zone).

For the grey-zone analysis, it was assumed that anyone in the grey zone has perfect diagnostic accuracy (because all received a ‘gold standard’ FFR test); therefore, FPs and FNs are present only in patients outside the grey zone. The impact of using the grey zone on the diagnostic accuracy of QAngio XA 3D/QFR was assessed. The effect of using different FFR thresholds on the diagnostic accuracy of QAngio XA 3D/QFR was also assessed. Owing to the limited data on CAAS vFFR, no such analyses were performed for this technology.

Narrative synthesis

Evidence related to clinical effectiveness and implementation of QFR, vFFR and invasive FFR were too limited to allow meta-analysis. Results were tabulated and presented narratively. Conclusions of these studies suggested consequences for QFR and ICA and recommendations for practice, and suggested needs for further research were summarised.

Narrative summaries were used for any diagnostic accuracy outcomes where meta-analyses or other statistical analyses were not feasible. This included tabulating or plotting results as reported in studies, and narratively describing and comparing these results.

Statistical analysis of clinical effectiveness

The systematic review identified very few published data on the clinical impact of using QFR and QAngio screening. In particular, very few data were found on the impact that QFR (with or without a grey zone) might have on future incidence and prevention of coronary events. Therefore, to investigate what the clinical impact of using QFR testing might be, a simulation study was performed to identify the impact that QFR and invasive FFR assessment might have on the number of revascularisations performed, and on morbidity and mortality and other longer-term outcomes. This simulation used two key sources of data:

-

The data on FFR and QFR measurements extracted from published Bland–Altman figures were used as a representative population of patients with intermediate stenosis, with FFR and QFR measurements for each patient.

-

The IRIS-FFR study13 reported the association between FFR and coronary events in patients who are revascularised and in patients where revascularisation is deferred. These data were used to calculate the risk of coronary events, and then to simulate events for each patient in our sample population (from point 1), given their observed FFR measurement.

Combining these two data sources produced a simulated data set where each patient had the following data:

-

a FFR measurement

-

the associated QFR measurement

-

the risk of a coronary event if revascularisation were performed

-

the risk of a coronary event if revascularisation were deferred

-

whether or not the patient had a coronary event (if revascularised)

-

whether or not the patient had a coronary event (if deferred).

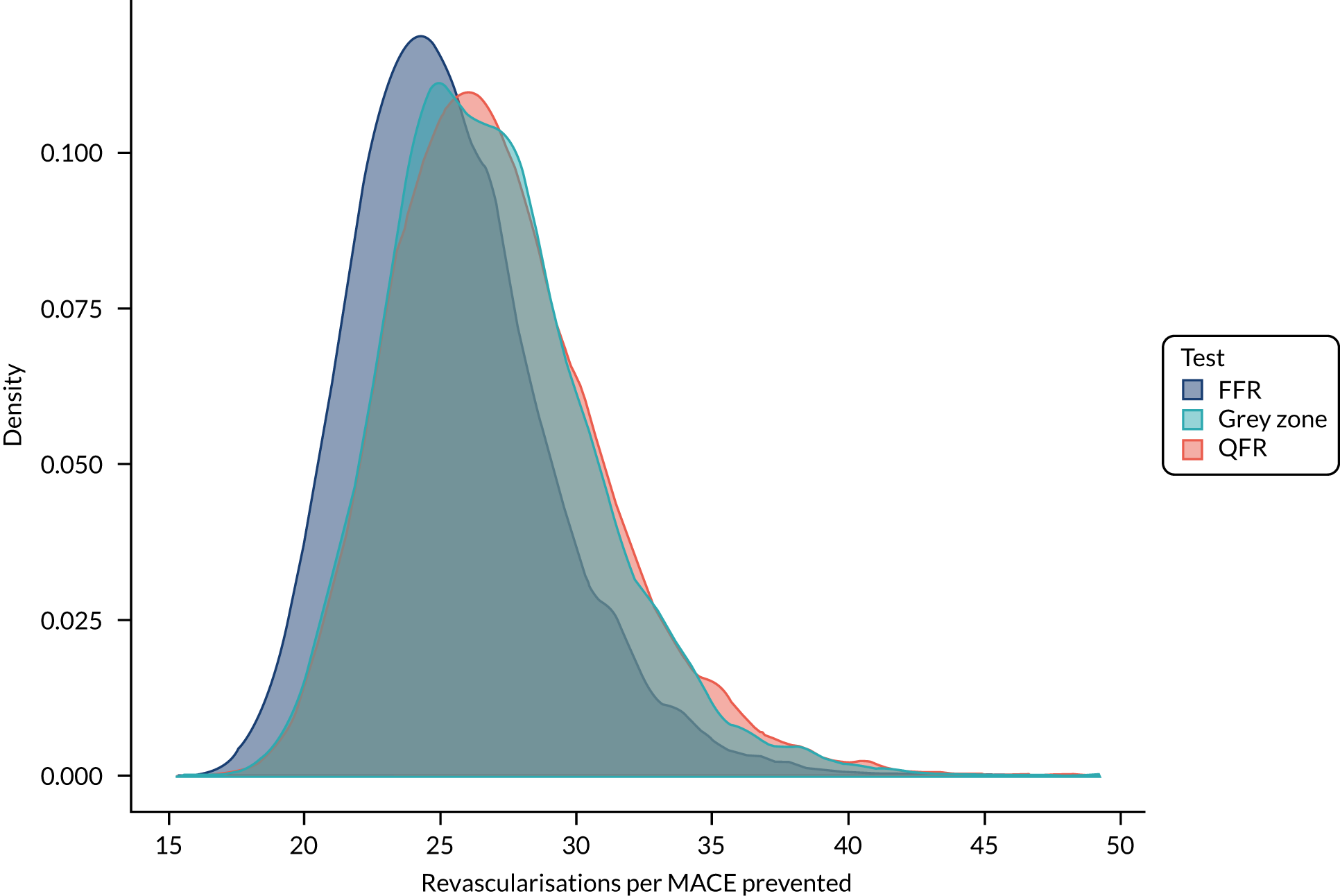

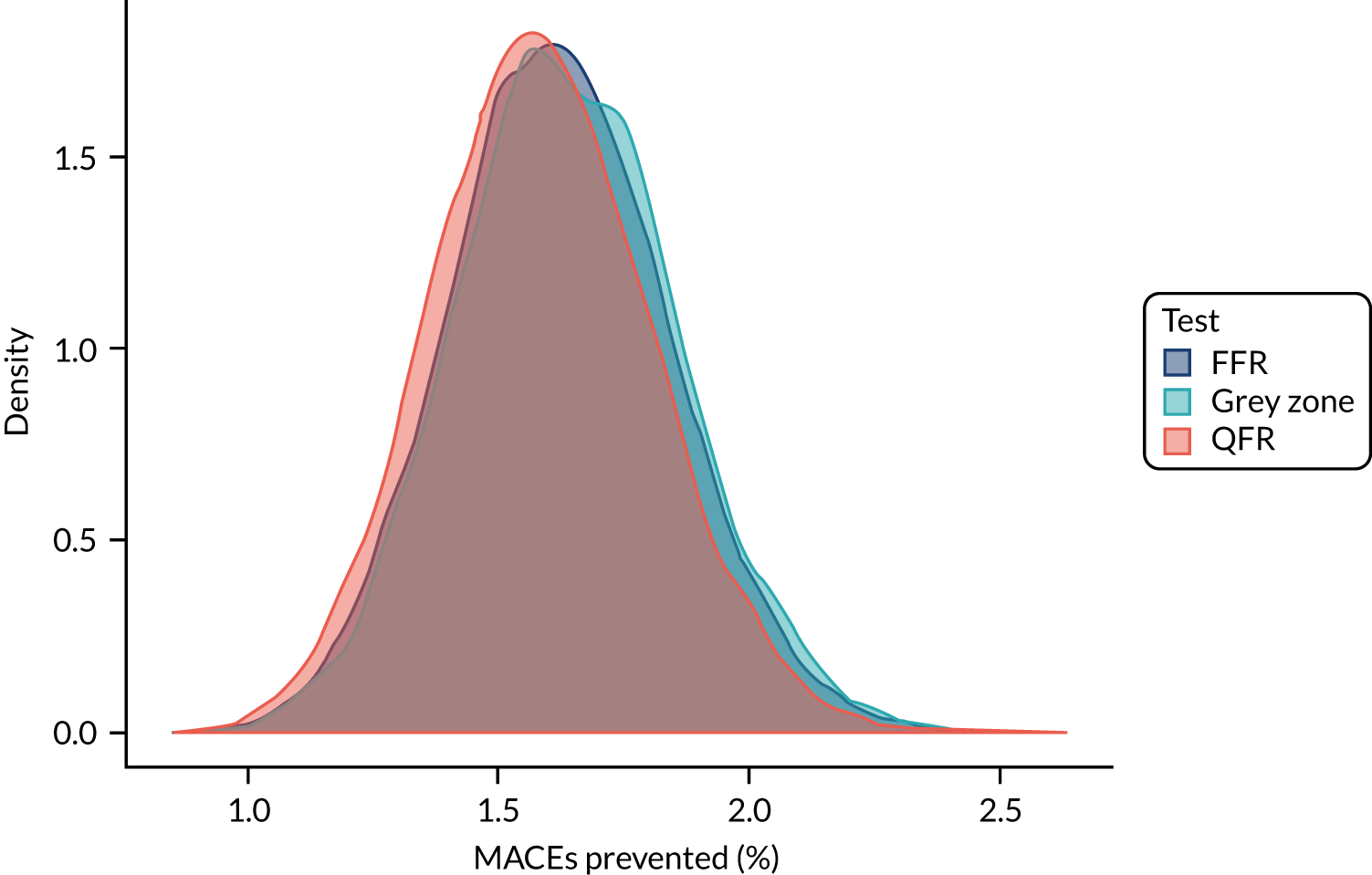

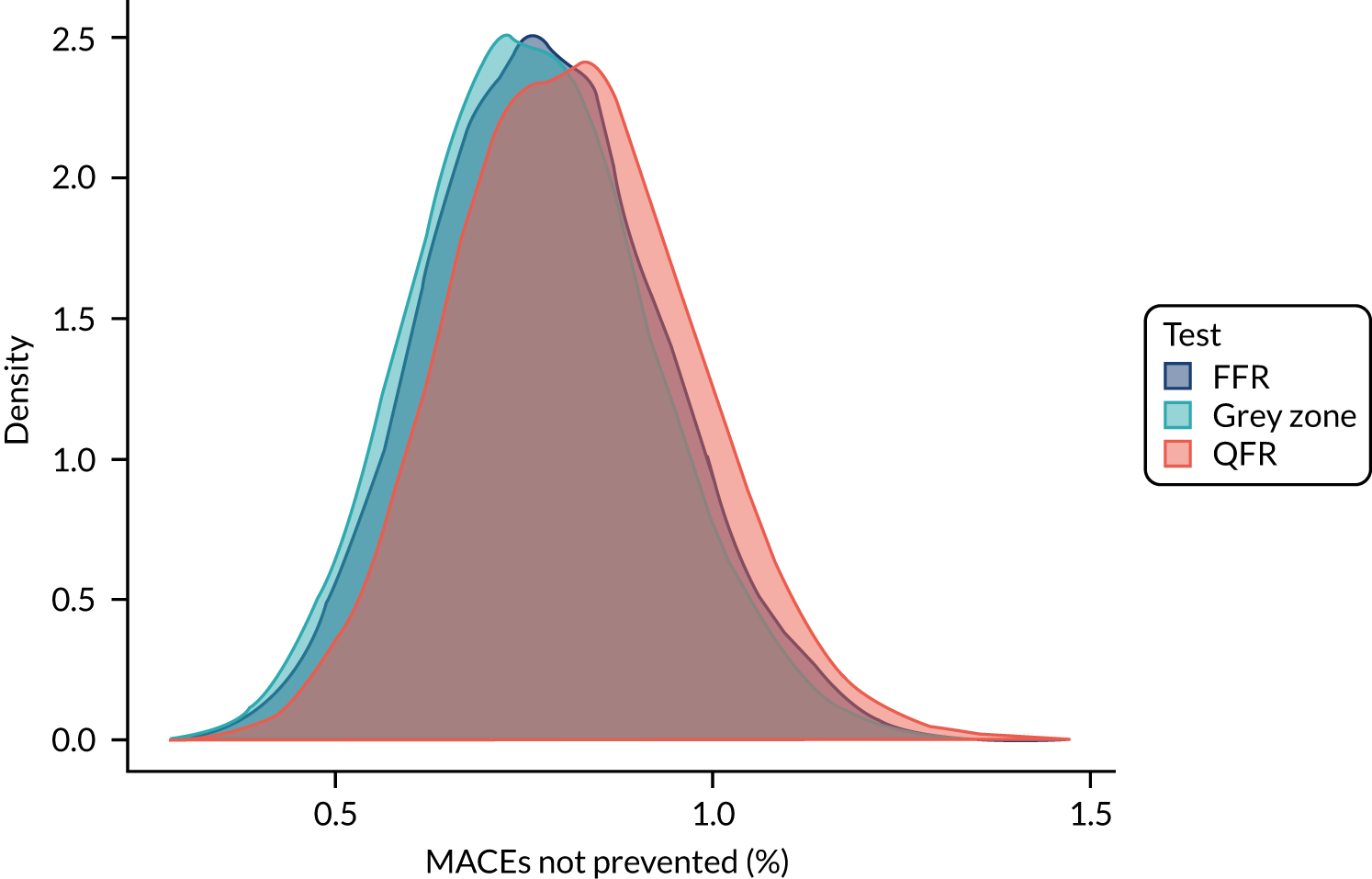

Three strategies for deciding on whether or not to revascularise were considered:

-

FFR only – perform FFR on all and revascularise if the FFR is ≤ 0.8

-

QFR only – perform QFR on all and revascularise if the QFR is ≤ 0.8, without FFR measurement

-

grey zone – perform a QFR and:

-

revascularise if the QFR is ≤ 0.78

-

defer if the QFR is > 0.84

-

if the QFR is between 0.78 and 0.84, perform FFR and revascularise if the FFR is ≤ 0.8.

-

Applying these strategies to the simulated data set, the following data were calculated for each strategy:

-

the proportion of patients who would be revascularised

-

the total number of coronary events

-

the proportion of patients who would undergo unnecessary revascularisation (i.e. revascularised, but would not have had an event if revascularisation were deferred)

-

the proportion of patients in whom revascularisation prevented an event (i.e. are revascularised, and would have had an event if revascularisation were deferred)

-

the proportion of patients in whom revascularisation caused an event (i.e. who would have an event after being revascularised, but would not have had an event if revascularisation were deferred).

These results were then compared across strategies to investigate how the differing strategies might alter the incidence of coronary events.

Detailed simulation methods

The sample population for the simulation was taken to be the data extracted from published Bland–Altman figures. For this analysis, fQFR data were excluded and only cQFR or non-specified QFR data were used, making a total of 3193 patients, each with a FFR measurement and its associated QFR measurement. As these data were extracted from figures, they may not be a perfect representation of the actual study patients (see Data extraction). The simulation did not differentiate between studies, so the patients were treated as if they came from a single ‘mega-study’.

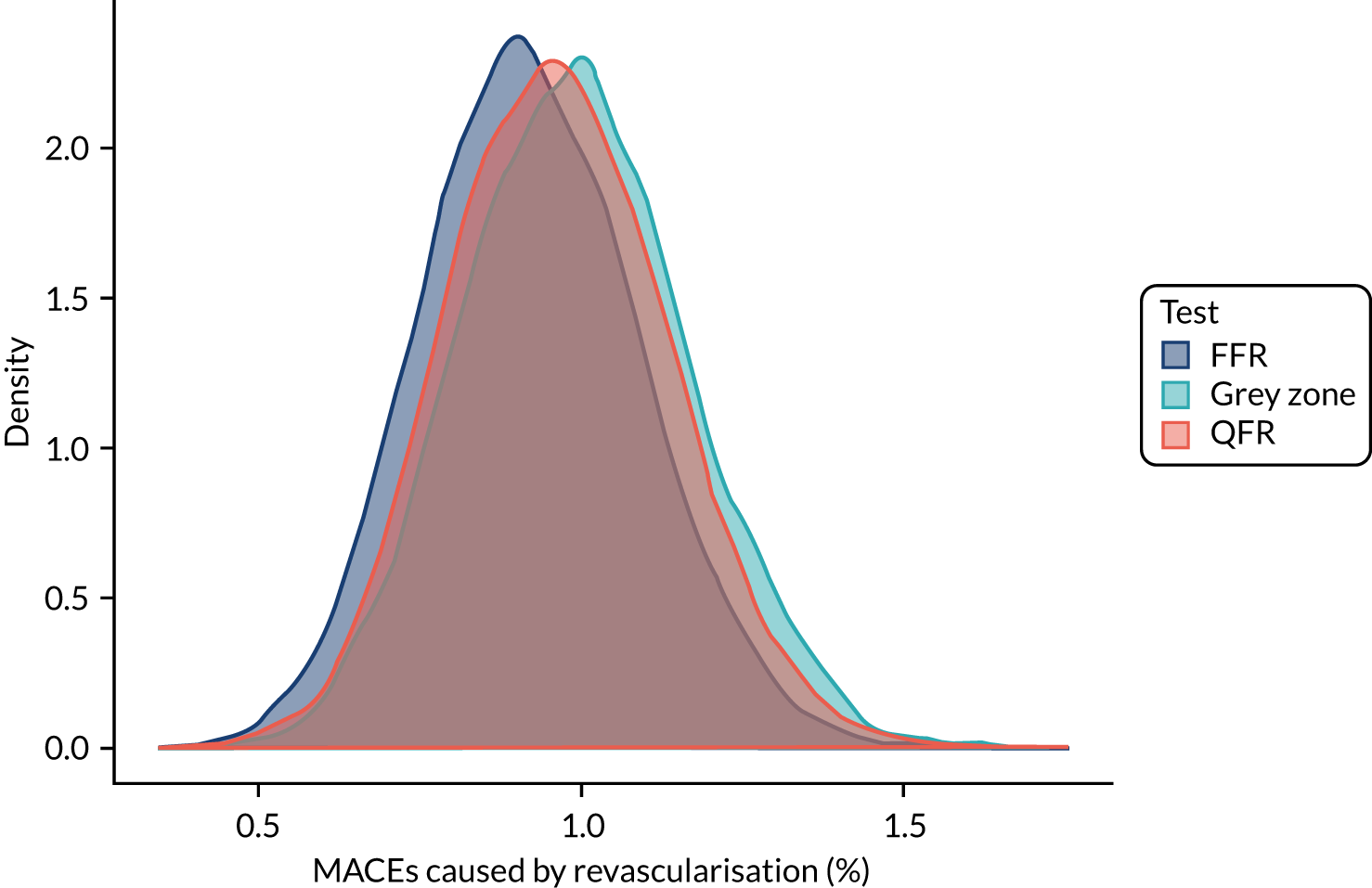

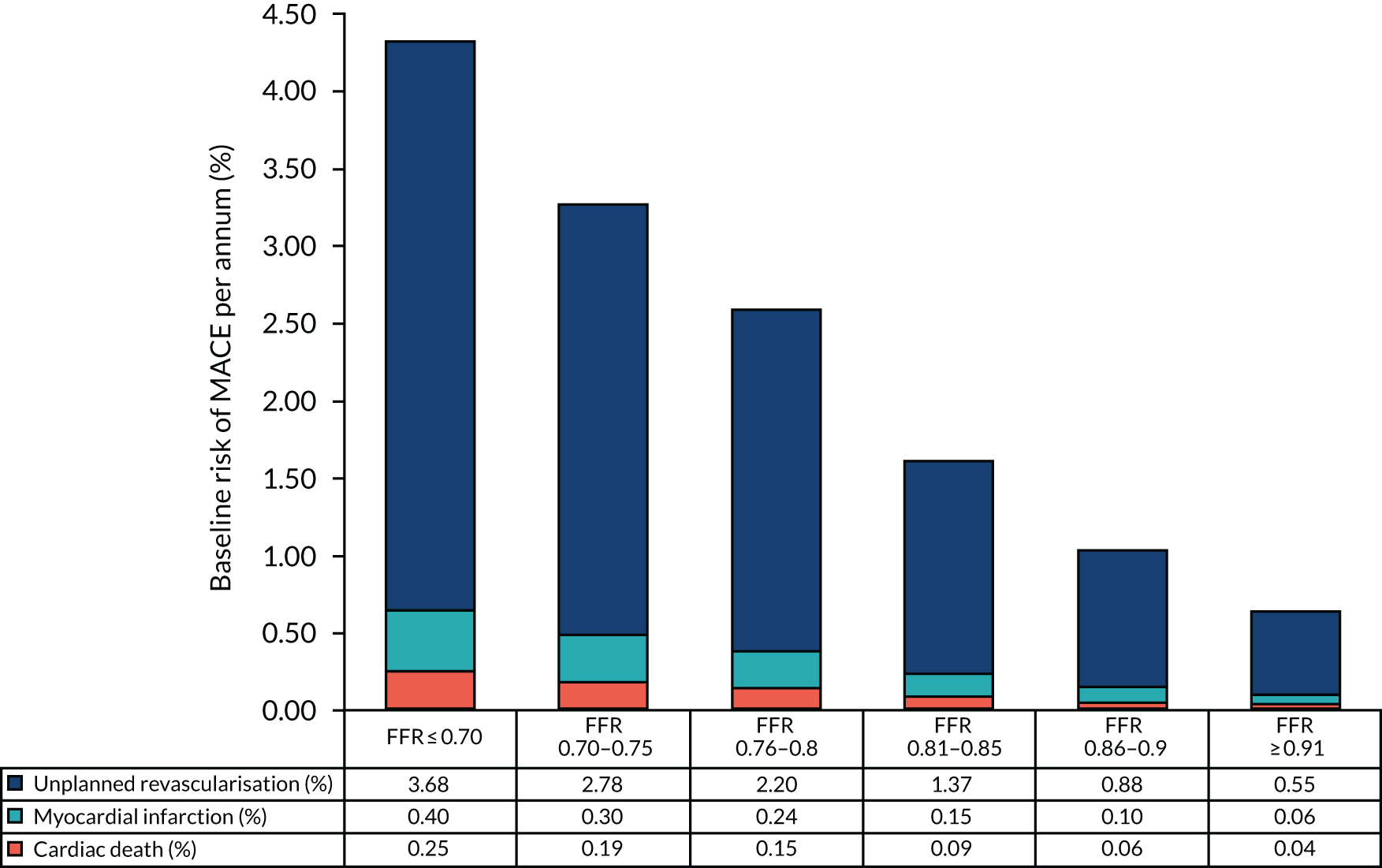

To predict coronary outcome in this sample population, the results of the recent IRIS-FFR registry report were used, representing 5846 patients who were either ‘revascularised’ (stent or bypass surgery) or ‘deferred’ (continued with current management without surgery) based on their measured FFR result. The IRIS-FFR study13 used major cardiovascular events (MACE, a composite of cardiac death, MI and repeated/emergency revascularisation) as its primary outcome. The mean incidence rate from MACE in deferred patients was 1.44 events per 100 lesion-years. For simplicity, it was assumed that each person has one lesion, equating to a 1.44% risk in 1 year. Based on data reported in the publication, this equated to a risk of 0.64% at a FFR of exactly 1. According to IRIS-FFR, most of these events are later revascularisations. The hazard ratio (HR) for MACE was estimated as 1.06 per 0.01 decrease in FFR. It was assumed that the 1-year relative risk (RR) is the same as this HR. In patients with revascularisations, the mean risk of MACE was 2.4% in 1 year, with a HR of 1 (so risk is the same regardless of FFR value).

Based on those risks, the predicted risk of MACE for every person in the sample population was calculated using their reported FFR measurement (this means that risk is not dependent on QFR). A risk of event if revascularised and a risk if deferred was calculated. A Monte Carlo simulation was then used to simulate whether or not each person had a MACE if they were ‘deferred’ or if they were revascularised, based on the calculated risks. Therefore, the incidence of simulated events is solely a function of FFR values and knowing that the QFR has no impact on risk of MACEs. The simulation process was repeated 10,000 times to produce a reasonable sample of plausible simulations.

For each simulated sample, who would and would not be revascularised was determined for each of the three strategies listed above. Given that, and the known MACE status for each patient, the five statistics in the list above were calculated. The results were pooled across simulations to find median values across simulations and to plot distributions across all simulations.

All statistical analyses were conducted in R software, version 3.6 or later (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Quantity and quality of evidence available

A total of 1248 unique references were screened for eligibility, and 41 unique studies were included in the systematic review. 14–54 A total of 39 studies evaluated QAngio XA 3D/QFR,14–17,20–55 and three studies evaluated CAAS vFFR. 18,19,26 One study directly compared CAAS vFFR with QAngio XA 3D/QFR. 26 Full lists of all included references, ongoing studies and studies excluded at full-text screening stage are presented in Appendix 2, Tables 33–35.

Two studies did not report diagnostic accuracy data, but included other eligible outcomes. 25,30 All other studies were included in the diagnostic accuracy review, of which 33 were included in a meta-analysis. 15–21,23,24,26–32,34,35,37,39–46,48–54 Seventeen were conference abstracts. 14,16,18,22,25–31,35,36,38,39,44,54 Figure 2 presents an overview of the study selection process.

FIGURE 2.

Study selection process: PRISMA flow diagram.

Characteristics of included studies

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review. Only seven studies used QFR prospectively as part of the ICA examination preceding FFR. 14,44,48–52 Fifteen studies were conducted in multiple centres. 15,22,24,26,34,37,38,41,45–47,50–52

| Main studies | Single/multicentre | Country | Population | Number of patients (vessels or lesions) | Age (years), mean (SD) | Male, % | Diabetes, % | Acute MI, % | FFR, mean (SD) or median (IQR) | Mean DS, % | Stable angina, % | Stable CAD, % | Previous MI, % | Previous PCI, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QAngio XA 3D/QFR studies | ||||||||||||||

| Cliff (2019),16 conference abstract | Single | Singapore | Acute MI and non-acute | 33 (41) | 59 (20) | 69 | 30 | 5 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Cortés et al. (2019)17 | Single | Spain | STEMI, > 50% DS in non-culprit arteries | 10 (12) | 70 (9) | 75 | NR | 100 | 0.87 (0.06) | NR | NR | 0 | NR | NR |

| Emori et al. (2018)20 | Single | Japan | Intermediate stenosis, prior/non-prior MI related | 75 (75) | 70 (9) | 77 | 47 | 0 | 0.79 (0.11)a/0.76 (0.13)a | 53 (14)a/54 (14)a | NR | NR | 50 | 51 |

| Emori et al. (2018)21 | Single | Japan | Intermediate stenosis | 100 (100) | 70 (10) | 71 | 48 | NR | 0.75 (0.10) | 55 (10) | NR | NR | 22 | NR |

| FAVOR II China: Xu et al. (2017)52 | Multi | China | CAD (suspected or known) | 308 (332) | 61 (10) | 74 | 86 | 14 | 0.82 (0.12) | 46.5 (11.3) | 23 | 34 | 48 | 65 |

| FAVOR II Europe–Japan: Westra et al. (2018)50 | Multi | Italy, the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, Spain, Japan, Denmark | Stable angina or secondary evaluation post MI | 272 (317) | 67 (10) | 72 | 29 | 2 | 0.83 (0.09) | 45 (10) | NR | NR | NR | 40 |

| FAVOR pilot: Tu et al. (2016)46 | Multi | Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands, Germany, China, Japan, USA | Stable angina, referred for ICA and FFR | 73 (84) | 66 (9) | 84 | 27 | 0 | 0.84 (0.08) | 64.5 (4.5) | 100 | 100 | 32 | 38 |

| Goto et al. (2019),22 conference abstract | Multi | Spain, Japan, the Republic of Korea | Intermediate left main stenosis | 62 (NR) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.76 (0.11) | 44.1 (13,331.1) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Hamaya et al. (2019)23 | Single | Japan | Stable CAD, three-vessel disease | NR (154) | 68 (10) | 76 | 38 | 0 | NR | 36.8 (14.4) | NR | 100 | 23 | NR |

| Hwang et al. (2019)24 | Multi | The Republic of Korea | Intermediate stenosis, stable angina or acute MI (NCLs) | 264 (358) | 61 (13) | 77 | 33 | 31 | 0.80 (0.13) | 0.531 | NR | 69 | 6 | NR |

| Kajita et al. (2019),27 conference abstract | Single | Brazil | Stable CAD, intermediate lesions | 24 (34) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Kameyama et al. (2016),28 conference abstract | Single | Japan | ACS, emergency ICA, NCLs | 25 (26) | NR | NR | NR | 100 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Kanno et al. (2019),29 conference abstract | Single | Japan | Intermediate stenosis | 95 (NR) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Kanno et al. (2019),30 conference abstract | Single | Japan | Intermediate stenosis, de novo, deferred revascularisation | 212 (NR) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.87 (0.84–0.90) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Kirigaya et al. (2019),31 conference abstract | Single | Japan | Stable CAD | 95 (NR) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Kołtowski et al. (2018)32 | Single | Poland | Stable CAD | 268 (306) | 66 (10) | 72 | 28 | 0 | 0.80 (0.10) | 51.3 (10.2) | NR | 100 | 48 | 59 |

| Kleczyński et al. (2019)33 | Single | Poland | Stable angina, intermediate stenosis | 50 (123) | 66 (9) | 72 | NR | 0 | 0.82 (0.10) | 44.2 (11.7) | 100 | 100 | NR | NR |

| Liontou et al. (2019)34 | Multi | Spain, Japan, the Republic of Korea | Intermediate in-stent restenosis | 73 (78) | 68 (11) | 81 | 30 | 6 | 0.79 (0.09) | 51 (9) | 69 | 69 | 58 | 100 |

| Liu et al. 2017,35 conference abstract | Single | The Netherlands | Stable angina | NR (45) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Mehta et al. (2019),36 conference abstract | Single | Australia | NR | NR (85) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.86 (0.09) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Mejia-Renteria et al. (2019)37 | Multi | Spain, the Republic of Korea, the Netherlands | Intermediate stenosis, stable angina and acute coronary syndrone (including MI patients, non-culprit arteries in staged procedure) | 248 (300) | 64 (10) | 76 | 38 | 17 | 0.80 (0.11) | 52 (12) | 70 | 70 | 14 | NR |

| Neylon et al. (2016), 38 conference abstract | Multi | France | NR | 36 (38) | 64 (18) | 66 | NR | NR | 0.88 (0.11) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Sato et al. (2018),39 conference abstract | Single | Japan | Intermediate stenosis | 68 (70) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Smit et al. (2019)40 | Single | The Netherlands | Referred for FFR following ICA in diagnostic-only setting | 290 (334) | 67 (9) | 69 | 24 | 0 | 0.85 (0.01) | 43.1 (8.5) | NR | NR | 16 | 33 |

| Spitaleri et al. (2018),41 reproducibility cohort | Multi | Italy | ACS, multivessel disease, staged procedure | 31 (34) | 64 (12) | 81 | 10 | 100 | NR | 59 (13) | NR | NR | 10 | 19 |

| Spitaleri et al. (2018),41 diagnostic accuracy cohort | Multi | Italy | STEMI, multivessel disease | 45 (49) | 62 (11) | 80 | 9 | 100 | 0.84 (0.11) | 66 (10) | NR | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Spitaleri et al. (2018),41 clinical outcomes cohort | Multi | Italy, Spain, the Netherlands | STEMI, multivessel disease | 110 (NR) | 64 (12) | 81 | 22 | 100 | NR | 62 (11) | NR | NR | 8 | 6 |

| Stähli et al. (2019)42 | Single | Germany | Intermediate and less severe stenosis (DS 40–70%), stable and unstable angina | 436 (516) | 72 | 68 | 23 | 4.1 (NSTEMI) | 0.88 (0.82–0.92) | 41 (median) | NR | 72 | 33 | 55 |

| SYNTAX II: Asano et al. (2019)15 | Multi | Belgium, the Netherlands, Spain, UK | Three-vessel disease | 386 (836) | 67 (10) | 93 | 32 | NR | 0.78 (0.73–0.84) | NR | NR | NR | 13 | NR |

| Ties et al. (2018)43 | Single | The Netherlands | Stable and unstable CAD | 96 (101) | 64 (10) | 60 | 25 | 16.7 (NSTEMI) | 0.87 (0.08) | 43.4 (8.4) | NR | 51 | NR | 24 |

| Toi et al. (2018),44 conference abstract | Single | Japan | Stable angina, intermediate stenosis | 50 (NR) | 69 (11) | 78 | 43 | NR | 0.81 (0.09) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Tu et al. (2014)45 | Multi | Belgium, Hungary, China | Stable and unstable CAD, intermediate stenosis, de novo lesions | 68 (77) | 62 (9) | 69 | 29 | 0 | 0.82 (0.11) | 46.6 (7.3) | 77 | 87 | NR | 32 |

| Van Diemen et al. (2019),47 conference abstract | Multi | The Netherlands, Canada, UK | NR | NR (286) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| van Rosendael et al. (2017)48 | Single | The Netherlands | Non-acute, eligible for FFR | NR (15) | 64 (11) | 71 | 6 | 0 | NR | 38.7 (8.6) | NR | 100 | 6 | 24 |

| Watari et al. (2019)49 | Single | Japan | Stable CAD, intermediate stenosis | 121 (150) | 71 (11) | 68 | 36 | 3 (NSTEMI/unstable angina) | 0.81 (0.12) | 49 (9) | 35 | 97 | 21 | 36 |

| WIFI II: Westra et al. (2018)51 | Multi | Denmark | CAD, Referred from CCTA | 172 (240) | 61 (8) | 67 | 10 | NR | 0.82 (0.11) | 50 (12) | 31 | NR | NR | NR |

| WIFI prototype study: Andersen et al. (2017),14 conference abstract | NR | Denmark (plus China and the Netherlands) | Stable angina and secondary evaluation after acute MI | 93 (NR) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.81 (0.09) | 47 (9) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Yazaki et al. (2017)53 | Single | Japan | Stable angina and asymptomatic CAD | 142 (151) | 73 (10) | 70 | 29 | 0.7 (NSTEMI/unstable angina) | 0.84 (0.08) | 48.8 (8.2) | 51 | 99 | 21 | 41 |

| Ziubryte et al. (2019),54 conference abstract | Single | Lithuania | Intermediate stenosis | 62 (69) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| CAAS vFFR studies | ||||||||||||||

| FAST-EXTEND: Daemen et al. (2019)18 | Single | The Netherlands | Stable or unstable angina or NSTEMI | 303 (NR) | 65 (11) | 67 | NR | NR | 0.84 (0.07) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| ILUMIEN I: Ely Pizzato et al. (2019)19 | Single | USA | Stable CAD, unstable angina and non-STEMI undergoing PCI. FFR measured pre and post PCI | 115 (115) | 65 (10) | 76 | 37 | 11 | 0.76 (0.12) | 53.3 (18.2) | 63 | 67 | 24 | NR |

| Jin et al. (2019),26 conference abstract | Multiple | China, UK | Intermediate stenosis | 82 (101) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

Most studies were conducted in Asia, including Japan (33 studies),20–24,26–53 China (five studies),14,26,45,46,52 the Republic of Korea22,24,34,37 and Singapore. 16

Twenty-one studies were conducted in Europe, including Belgium,15,45,46 Denmark,14,50,51 France,38 Germany,42,46,50 Hungary,45 Italy,41,46,50 Lithuania,54 the Netherlands,15,18,35,37,40,41,43,46–48,50 Poland,32,33,50 Spain15,22,34,37,41,50 and the UK. 15,26,47 Two studies were conducted in the USA,19,46 one in Brazil,27 one in Australia36 and one in Canada. 47 Eleven studies included an international cohort. 14,15,22,26,34,37,41,45–47,50

The QAngio XA 3D/QFR studies analysed a total of 5440 patients (over 6524 vessels or lesions), and CAAS vFFR studies analysed a total of 500 patients (over 519 vessels or lesions). Most studies included a mixed population of stable and unstable CAD, although 11 studies focused only on patients with stable CAD. 23,27,31–33,35,44,46,48,49,53 Three studies evaluated non-culprit vessels in patients with MI,17,28,41 two focused exclusively on patients with three-vessel disease,15,23 one study included only patients with intermediate left main stenosis (mostly left main bifurcation)22 and one focused specifically on in-stent restenosis. 34 Where reported, mean age ranged from 59.0 to 72.5 years, and most participants were male (60–93%). Patient history and stenosis severity varied widely across studies. The prevalence of diabetes ranged from 6% to 48%, rates of previous MI from 4% to 58%, and previous PCI 4% to 65% (not accounting for one study with 100% in-stent restenosis). 34 The mean/median FFR ranged from 0.75 to 0.88, and mean DS from 37% to 66%.

Quality of diagnostic accuracy studies

Table 2 summarises the results of the risk-of-bias and applicability assessment for QAngio XA 3D/QFR for the 24 diagnostic accuracy studies reported in a full-text manuscript, with further details reported in Appendix 3, Tables 36 and 37. The risk of bias from the 15 studies included in the diagnostic accuracy review that were reported only as conference abstracts was not formally assessed because of insufficient reporting. 14,16,18,22,25–31,35,36,38,39,44,54 Just as with FAST-EXTEND,18 the extension of the FAST study was reported as conference abstract only; only the quality of the earlier FAST study was assessed. 56

| Study | Risk of bias | Applicability | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient selection | Index test | Reference standard | Flow | Patient selection | Index test | Reference standard | |

| Cortés et al. (2019)17 | – | + | + | ? | – | – | + |

| Emori et al. (2018)20 | + | + | + | + | ? | – | + |

| Emori et al. (2018)21 | + | + | + | + | ? | – | + |

| FAVOR II China: Xu et al. (2017)52 | + | + | + | + | – | + | + |

| FAVOR II Europe–Japan: Westra et al. (2018)50 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| FAVOR pilot: Tu et al. (2016)46 | + | + | + | + | + | – | + |

| Hamaya et al. (2019)23 | – | + | + | + | + | – | + |

| Hwang et al. (2019)24 | – | + | + | + | – | – | + |

| Kleczyński et al. (2019)33 | + | – | + | + | + | – | + |

| Kołtowski et al. (2018)32 | – | + | + | + | + | – | + |

| Liontou et al. (2019)34 | ? | + | + | + | – | – | + |

| Mejia-Renteria et al. (2019)37 | + | + | + | + | + | – | + |

| Smit et al. (2019)40 | + | – | – | + | + | – | + |

| Spitaleri et al. (2018)41 (cohort B, diagnostic accuracy) | + | + | + | + | – | – | + |

| Stähli et al. (2019)42 | + | + | + | + | + | – | + |

| SYNTAX II: Asano et al. (2019)15 | + | + | + | – | – | – | + |

| Ties et al. (2018)43 | ? | + | + | + | – | – | + |

| Tu et al. (2014)45 | + | + | + | + | + | – | + |

| van Rosendael et al. (2017)48 | ? | – | – | ? | + | + | + |

| Watari et al. (2019)49 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| WIFI II: Westra et al. (2018)51 | + | + | + | + | – | + | + |

| Yazaki et al. (2017)53 | + | + | – | + | + | – | + |

| CAAS vFFR | |||||||

| ILUMEN I: Ely Pizzato et al. (2019)19 | – | + | + | + | + | – | + |

| FAST: Masdjedi et al. (2020)56 | – | + | + | + | + | – | + |

A total of 11 out of the 22 QAngio XA 3D/QFR studies were rated as being at low risk of bias across all domains. 20,21,37,41,42,45,46,49–52 The main source of bias was related to study participant selection; four studies were considered at high risk of patient selection bias because of high rates of patient exclusions or significant exclusion of potentially harder to diagnose patients,17,23,24,32 and three studies did not provide sufficient information on patient selection to assess risk of selection bias (unclear risk). 34,43,48 Exclusion rates and reasons are reported in Appendix 3, Table 37. Risk of bias was rated as being generally low for other domains, although three studies were rated as being at high risk of bias because of the conduct of the index test or reference standard (e.g. no reporting of blinding between QFR and FFR results),33,48,53 and one study was rated as being at high risk of bias because of patient flow concerns, as FFR was performed only in iFR grey-zone patients. 15

The ILUMIEN I19 trial was the only CAAS vFFR complete study with a full-text manuscript. The study was rated as being at high risk of bias because of the large percentage of lesions excluded from the study (65%). In an earlier published report of the FAST-EXTEND study, Masdjedi et al. 56 also reported a high rate of exclusions (54%). Although most of these failed tests appear to have been due to angiographic image processing issues rather than limitations inherent in CAAS vFFR (see Test failures: rates and reasons), the large exclusion rates reported mean that the risk of selection bias cannot be excluded.

Only three studies raised no concerns about their applicability to the review question. 48–50 The main concern about applicability related to QFR being used retrospectively (offline) rather than as part of the ICA examination and before FFR; only five studies (all of QAngio XA 3D/QFR) were conducted prospectively and raised no significant concerns regarding the applicability of the index test. 48–52 There were no significant concerns regarding the applicability of the reference standard in any of the studies. A total of 12 out of the 22 QAngio XA 3D/QFR studies did not raise significant concerns about the applicability of their population to the review question;23,32,33,37,40,42,45,46,48–50,53 concerns about study population applicability were primarily related to the under-representation of patients with stable CAD. We note that, because only patients with a FFR measurement could be included in the diagnostic accuracy review, a subset of patients with intermediate stenosis (including those examined in a diagnostic-only setting, or with a counter-indication to adenosine) are not represented in the included evidence.

Seven studies of QAngio XA 3D/QFR14,15,41,45,48,51,52 and one of CAAS vFFR18 reported a conflict of interest with their respective manufacturers.

Overview of the meta-analyses (QAngio XA 3D/QFR)

Meta-analysis of the included studies is focused on the diagnostic accuracy of QFR (measured using QAngio XA 3D/QFR) to detect lesions or vessels requiring intervention (defined as having a FFR ≤ 0.8). There were insufficient data to perform meta-analyses of any clinical outcomes; these are discussed in Clinical outcomes.

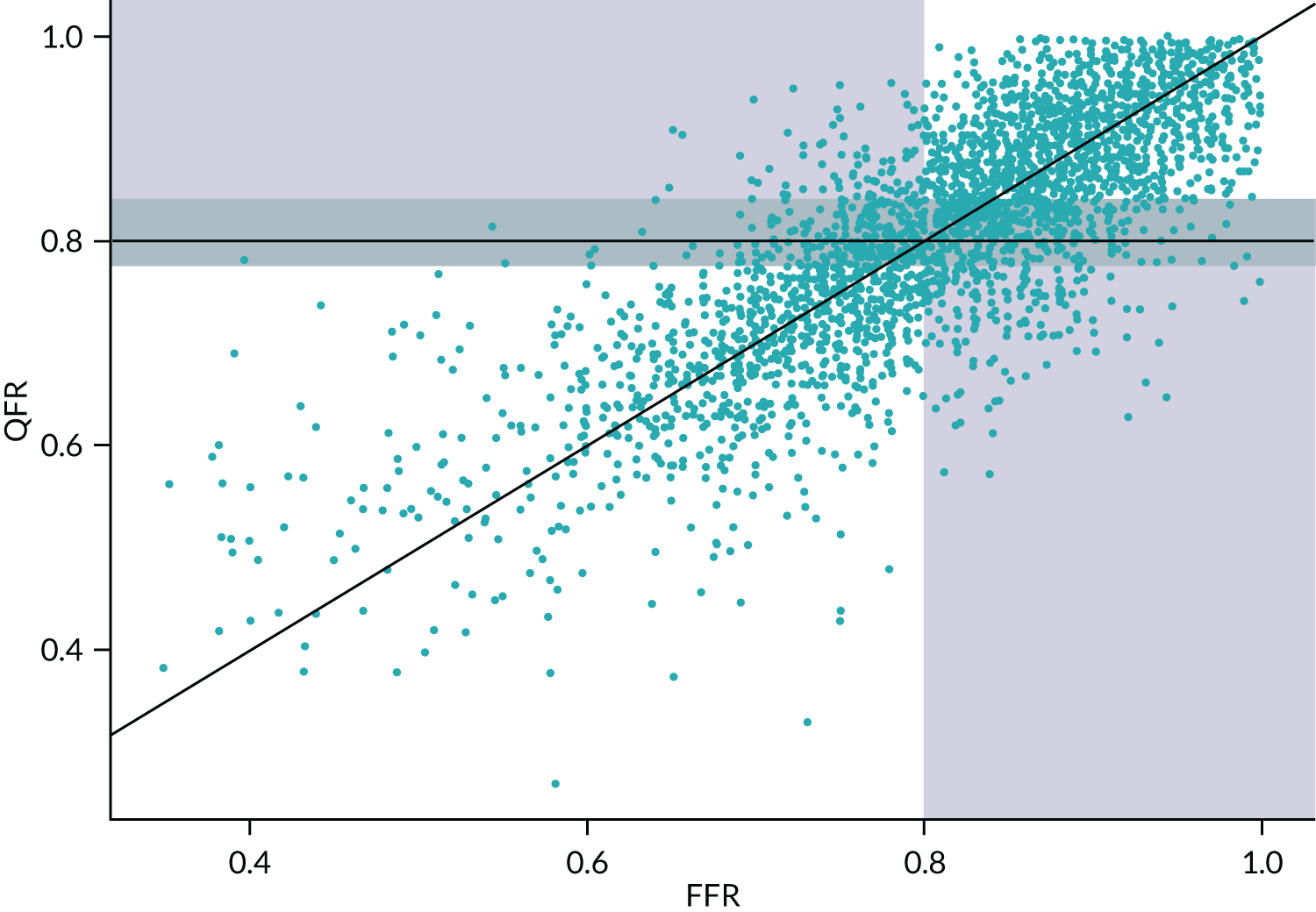

Diagnostic accuracy of QFR was analysed in two ways. The first, and primary, analysis consists of a meta-analysis of reported diagnostic accuracy data (TPs, TNs, FPs and FNs) in studies where these data were reported or could be derived from reported estimates of sensitivity and specificity. The second approach was to extract data on FFR and QFR values in each study from published Bland–Altman plots, or plots of FFR compared with QFR, and to use these to calculate diagnostic accuracy. This approach may be less accurate, because extracting data from figures is imperfect, but it allowed for a wider range of analyses, such as considering different QFR and FFR cut-off points, and the impact of using a grey zone where patients with intermediate QFR values go on to receive confirmatory FFR. This second approach is considered in Meta-analyses of data extracted from figures (QAngio XA 3D/QFR).

Of all the included studies of QAngio XA 3D/QFR, 26 reported sufficient diagnostic accuracy data to be included in the primary meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy (four studies23,34,44,48 were included only in analyses of data extracted from plots). These are divided into three ‘modes’ of QFR: fQFR, cQFR and studies where the type of QFR was not specified (listed as QFR or non-specified QFR). Most studies included in the primary analysis used FFR as the reference standard for determining whether or not intervention was required, all of these used a cut-off FFR point of 0.8. One study49 used iFR as the reference standard.

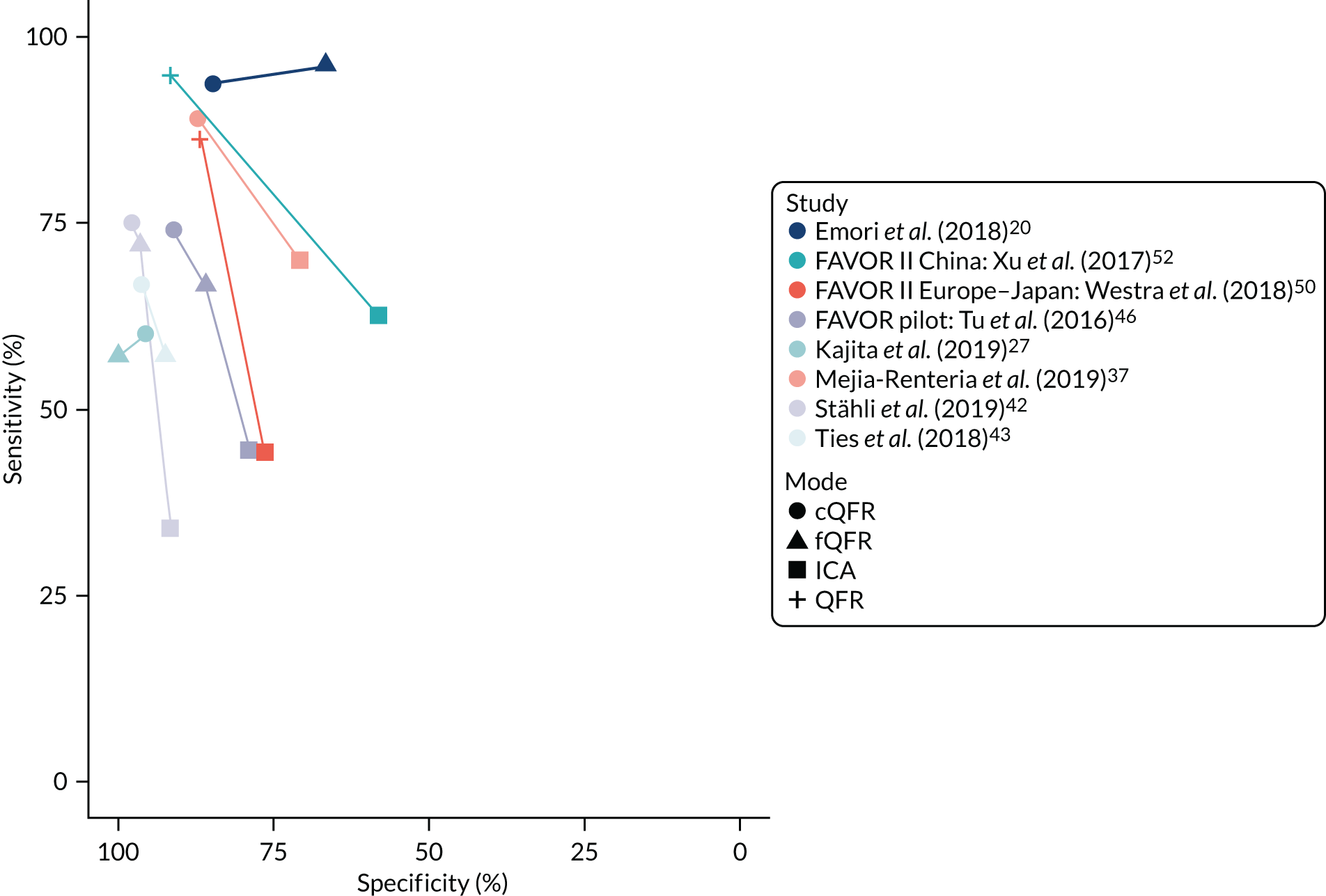

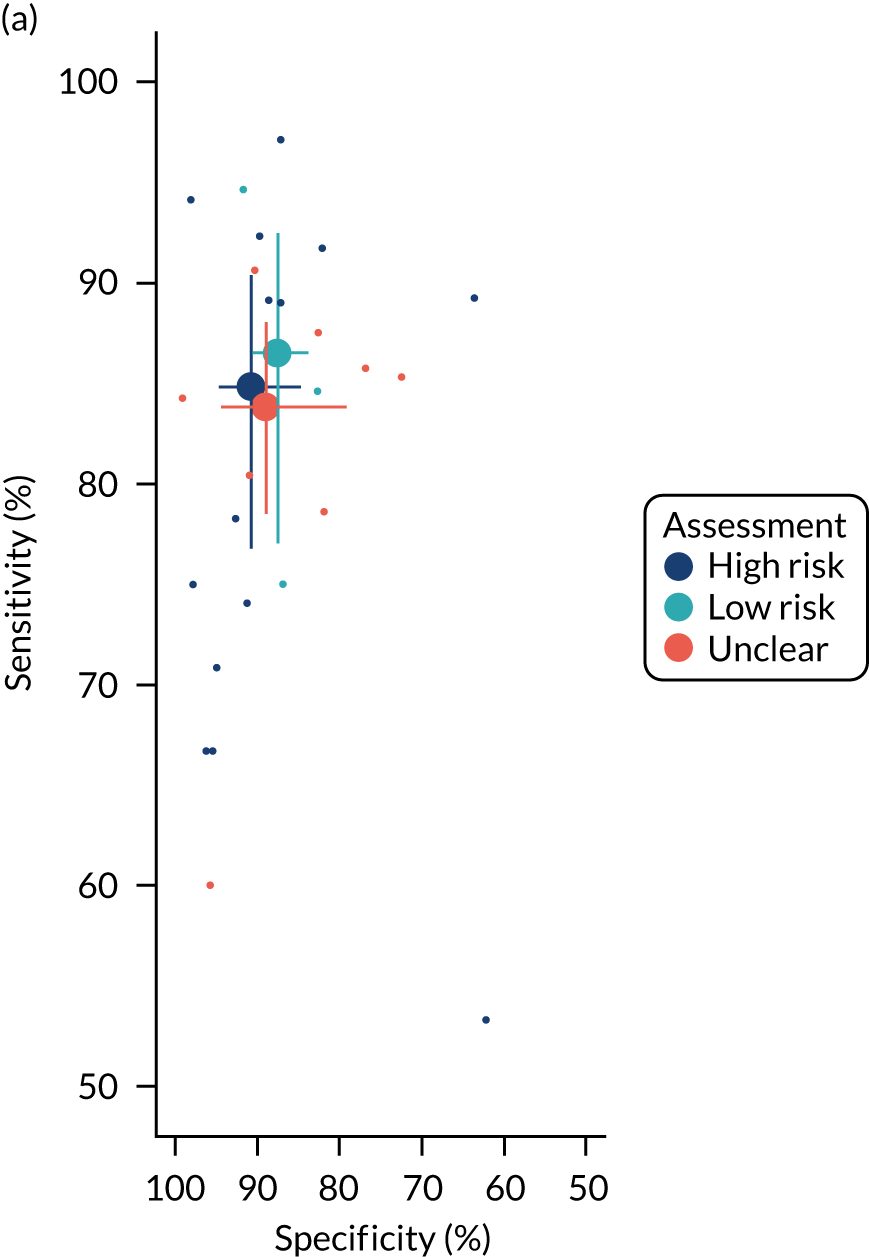

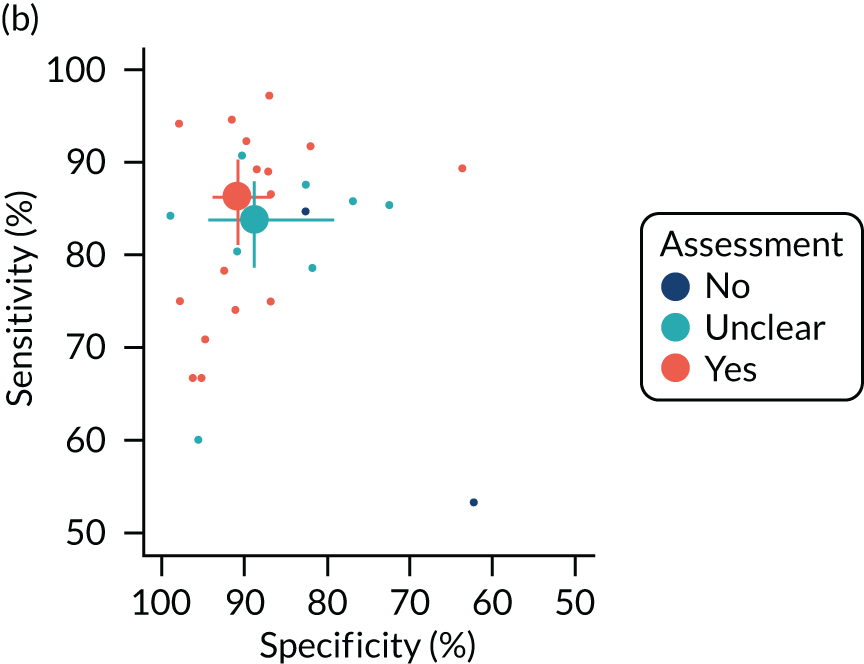

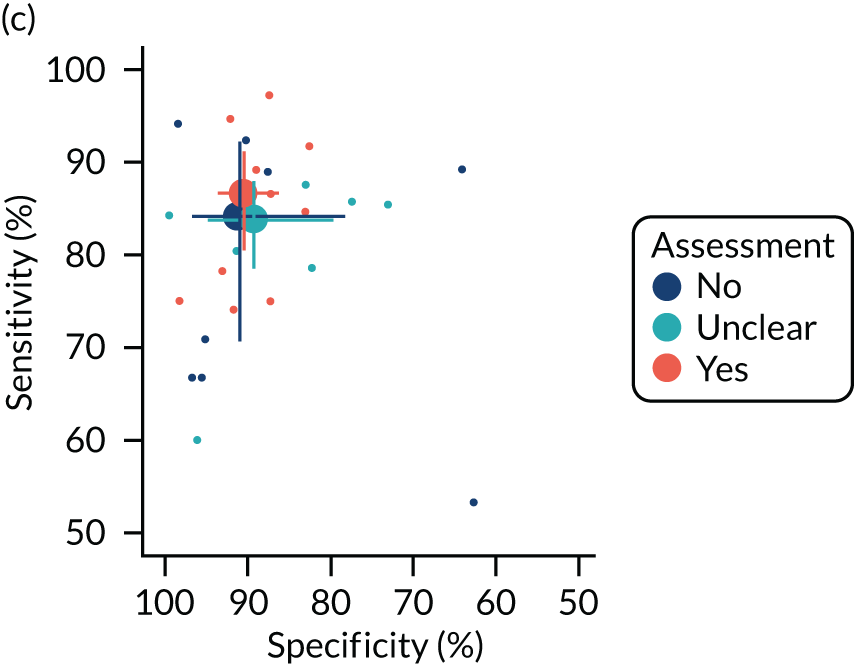

Figure 3 shows the general sensitivity and specificity estimates for each study, assuming an index test cut-off point of QFR ≤ 0.8 and a reference standard cut-off point of FFR ≤ 0.8. The results are plotted separately for each mode of QFR testing. This suggests that specificity is uniformly high and generally > 75% (except for two fQFR studies). Sensitivity is more heterogeneous, but is also > 75% in most studies (except for fQFR). There are no immediately apparent differences in accuracy between the three modes.

FIGURE 3.

Sensitivity and specificity estimates for each study, by mode of QFR: (a) cQFR; (b) fQFR; and (c) QFR.

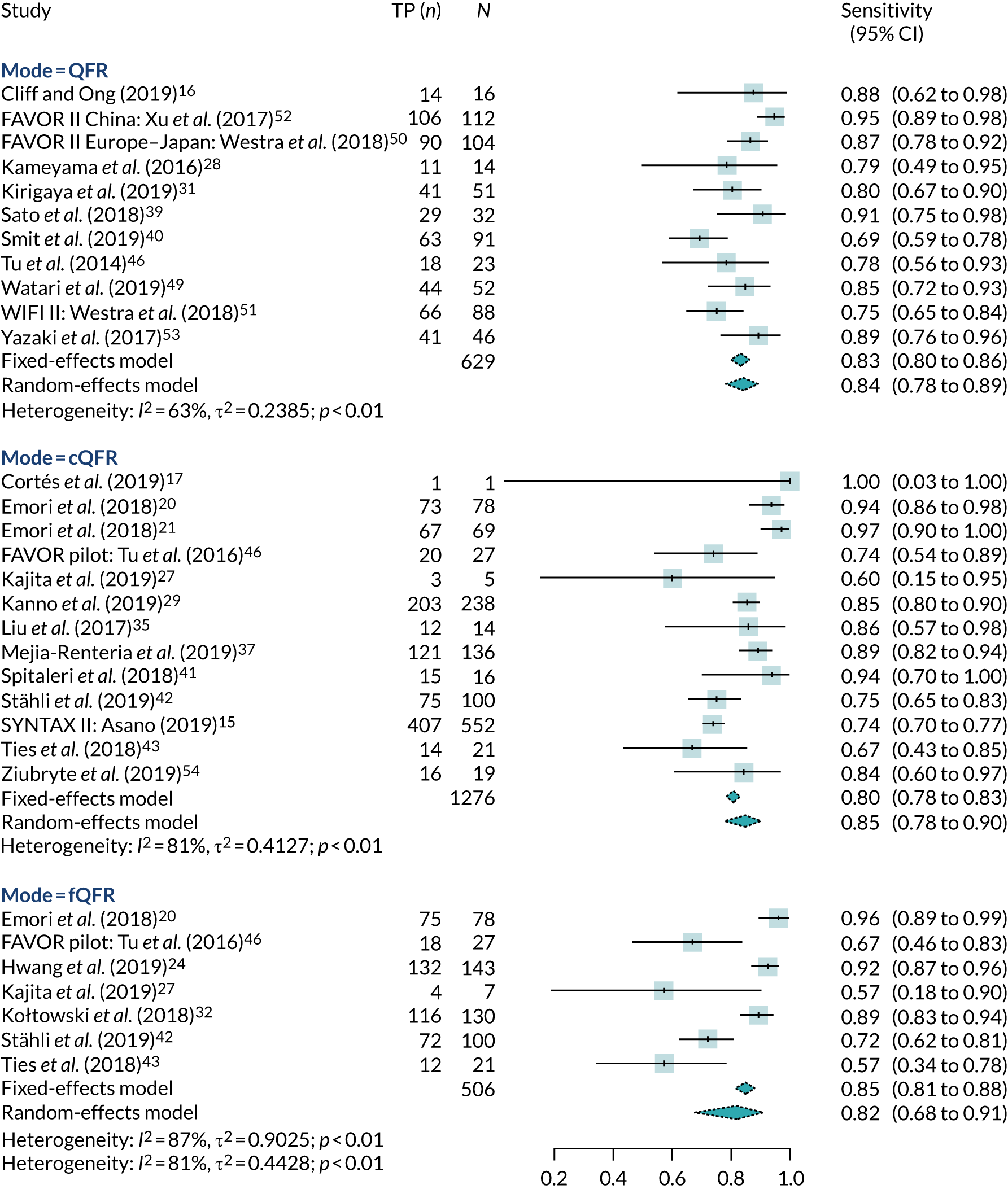

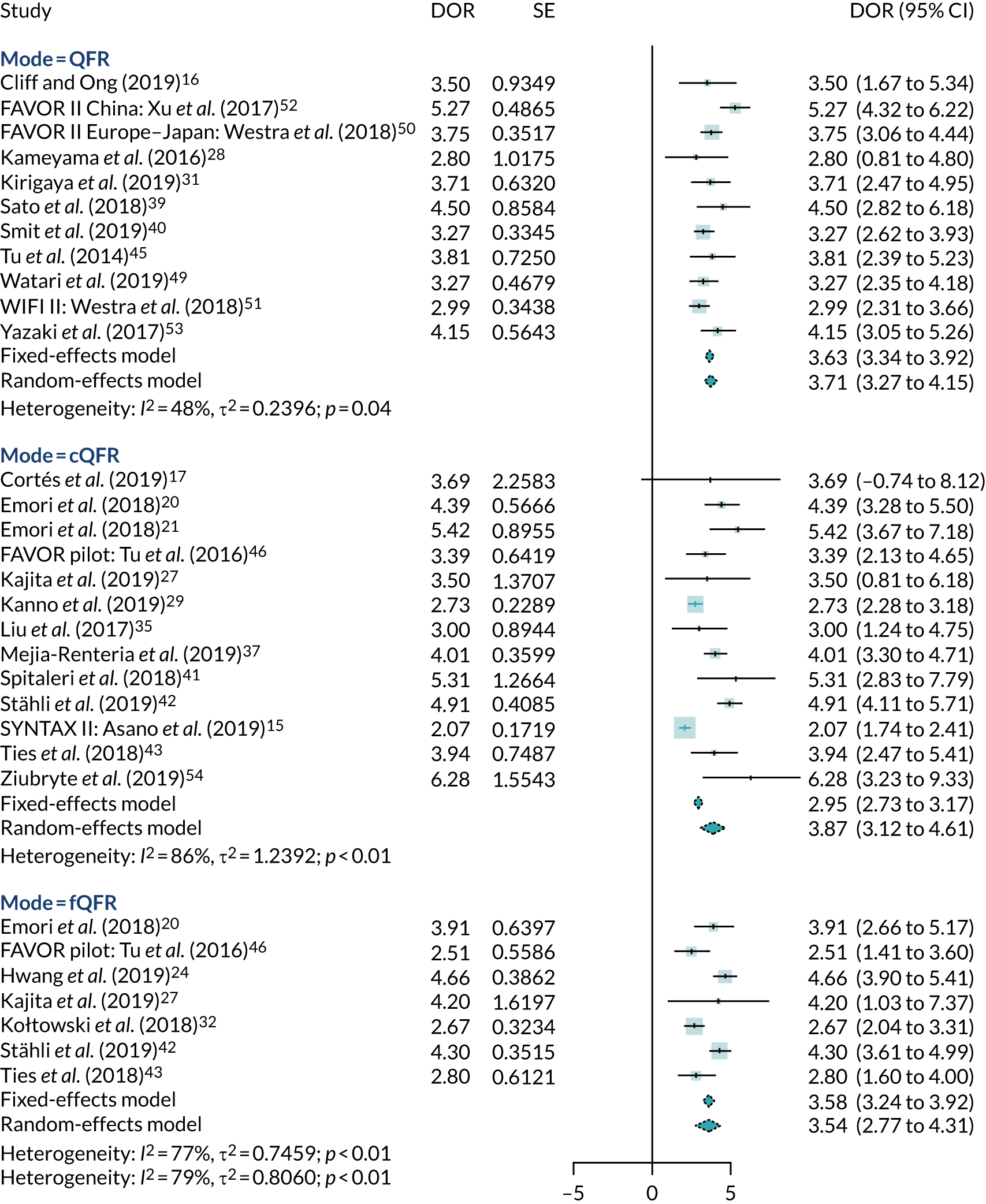

Univariate meta-analyses (QAngio XA 3D/QFR)

Figure 4 shows the forest plot for the univariate meta-analysis of sensitivity, and Figure 5 the same for specificity. For the random-effect analyses, these show high sensitivity (82–85%) and high specificity (89–91%) for all three models of QFR. cQFR had a sensitivity of 85% (95% CI 78% to 90%) and specificity of 91% (95% CI 85% to 95%); fQFR had a sensitivity of 82% (95% CI 68% to 91%) and specificity of 89% (95% CI 77% to 95%). Studies that did not specify the mode of QFR had a sensitivity of 84% (95% CI 78% to 89%) and specificity of 89% (95% CI 87% to 91%). Across-study heterogeneity was moderate to high (e.g. for cQFR sensitivity, I2 = 81%), but there does not appear to be any clear evidence that the mode of QFR (fQFR vs. cQFR) makes a difference to diagnostic accuracy.

FIGURE 4.

Univariate meta-analysis of sensitivity. FAVOR, Functional Assessment by Virtual Online Reconstruction; WIFI, wire-free invasive functional imaging.

FIGURE 5.

Univariate meta-analysis of specificity. FAVOR, Functional Assessment by Virtual Online Reconstruction; WIFI, wire-free invasive functional imaging.

Summary PPVs (see Appendix 4, Figure 18) were 77% (95% CI 69% to 83%) for fQFR, 85% (95% CI 80% to 89%) for cQFR and 80% (95% CI 76% to 84%) for non-specified QFR. Summary NPVs (see Appendix 4, Figure 19) were 92% (95% CI 89% to 94%) for fQFR, 91% (95% CI 85% to 94%) for cQFR and 91% (95% CI 87% to 93%) for non-specified QFR. It should be noted that PPV and NPV depend on the distribution of FFR in each study, so summary results may not represent PPV or NPV in an ‘average’ study.

Meta-analyses of AUCs and DORs were also performed (see Appendix 4, Figures 20 and 21). Summary AUCs were 87% (95% CI 83% to 92%) for cQFR, 89% (95% CI 86% to 92%) for fQFR and 92% (95% CI 90% to 94%) for non-specified QFR. Summary DORs were 3.51 (95% CI 2.71 to 4.30) for fQFR, 3.76 (95% CI 3.01 to 4.52) for cQFR and 3.71 (95% CI 3.27 to 4.15) for non-specified QFR.

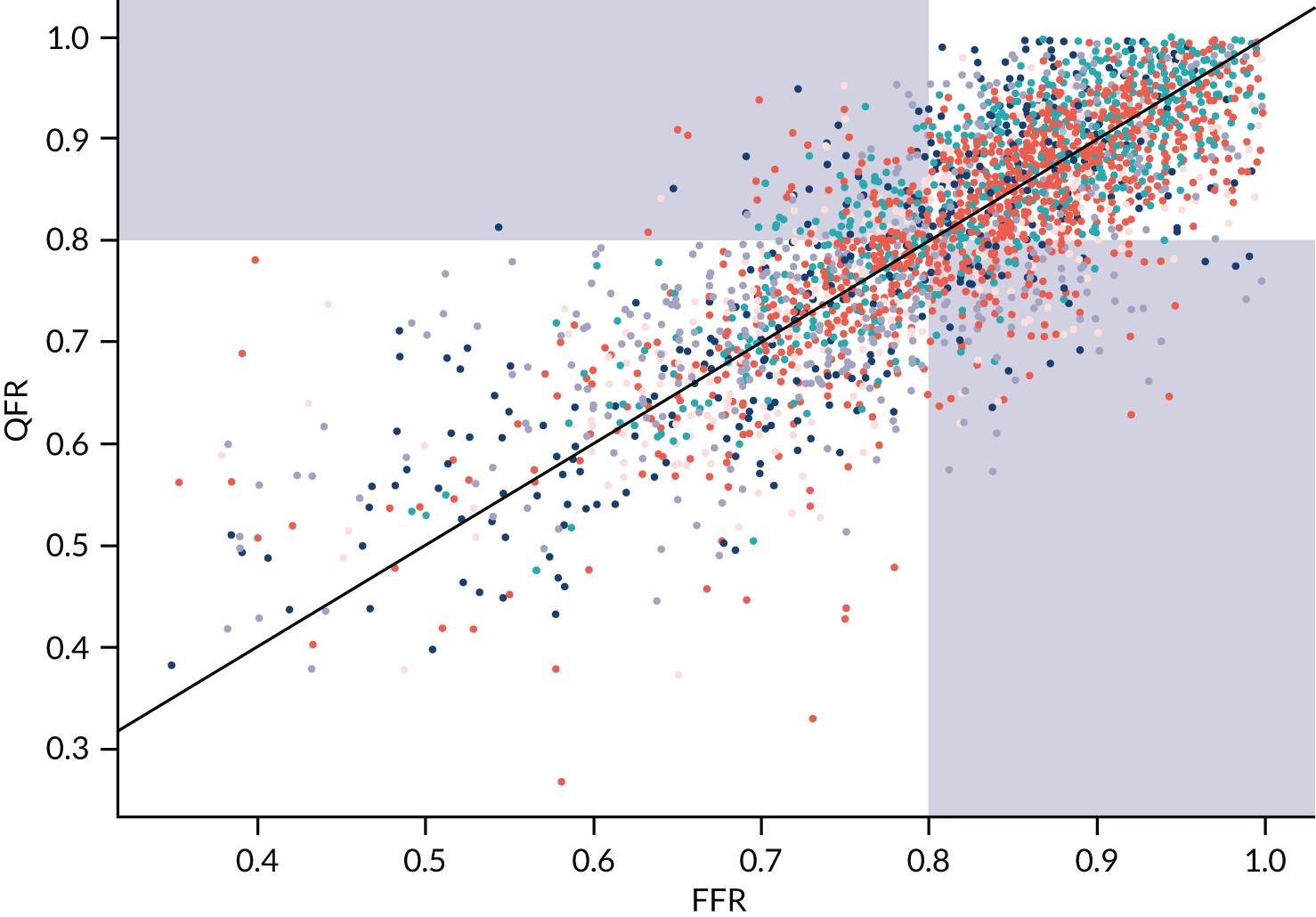

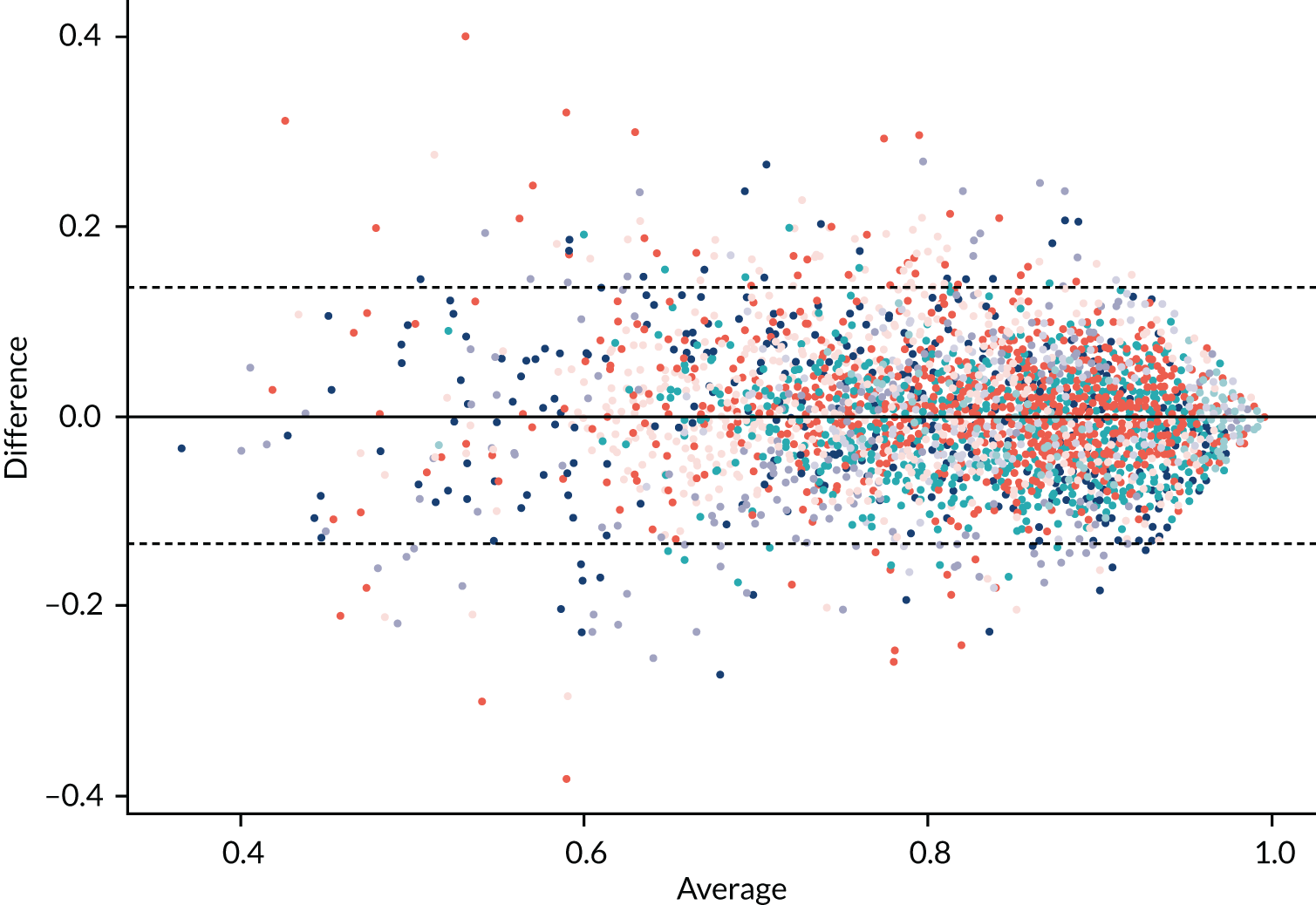

As both FFR and QFR are continuous measurements, it is also important to consider the agreement between FFR and QFR, in terms of the MD and variation between them, and their correlation. We meta-analysed reported MDs between FFR and QFR measurements and reported correlations. Where studies did not report the standard deviation (SD) of the MD, it was imputed by taking the average value from studies that did report SDs.

The MD between QFR and FFR was almost exactly zero for all three modes of QFR testing (see Appendix 4, Figure 22) [MD 0 (95% CI –0.05 to 0.06) for fQFR, –0.01 (95% CI –0.06 to 0.04) for cQFR; and MD 0.01 (95% CI –0.03 to 0.05) for non-specified QFR]. FFR and QFR were highly correlated in all studies (see Appendix 4, Figure 23): correlation coefficient 0.78 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.82) for fQFR, 0.78 (95% CI 0.70 to 0.85) for cQFR and 0.79 (95% CI 0.73 to 0.83) for non-specified QFR. We note that correlation coefficients are not a good measure of agreement between diagnostic tests; this meta-analysis is included here for information only.

Bivariate meta-analysis (QAngio XA 3D/QFR)

The results of the full bivariate meta-analysis are summarised in Table 3 and Appendix 4, Figure 24. The results are almost identical to the univariate analyses, with no evidence of differences between fQFR and cQFR.

| Mode | Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | Specificity (%) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| cQFR | 84.32 (77.29 to 89.48) | 91.40 (84.96 to 95.24) |

| fQFR | 81.61 (66.97 to 90.66) | 89.43 (77.58 to 95.38) |

| Non-specified QFR | 84.25 (78.51 to 88.68) | 88.95 (87.02 to 90.61) |

| cQFR or non-specified QFR | 84.34 (80.04 to 87.85) | 89.80 (86.36 to 92.45) |

To include all studies in a single meta-analysis, and given the similarity of results across modes of QFR, we performed a further bivariate meta-analysis that combined all studies using only a single ‘mode’ of QFR from each. In practice, this meant combining studies with cQFR results with studies not specifying how QFR was performed (and, as a result, excluding fQFR assessments). This might be expected to give the most ‘optimistic’ estimate of diagnostic accuracy because fQFR is excluded. The results for this combined analysis are also shown in Table 3. The results are, inevitably, very similar to those for cQFR or non-specified QFR, but with narrower CIs. We note that this arguably represents the best summary of the diagnostic accuracy of QFR, as it based on the maximum number of studies, but it is a post hoc analysis not specified in the protocol.

The summary results and HSROC curves in Appendix 4, Figure 24, demonstrate the high diagnostic accuracy of QFR and the similarity between the three analysed modes. The HSROC curve for fQFR lies consistently below that for cQFR, suggesting a possibility that fQFR may have slightly inferior diagnostic accuracy, but this difference is well within the bounds of uncertainty. This is in line with the expected use of QFR, where cQFR is calculated when the fQFR is in the range of 0.70–0.85.

Meta-analysis of invasive coronary angiography studies

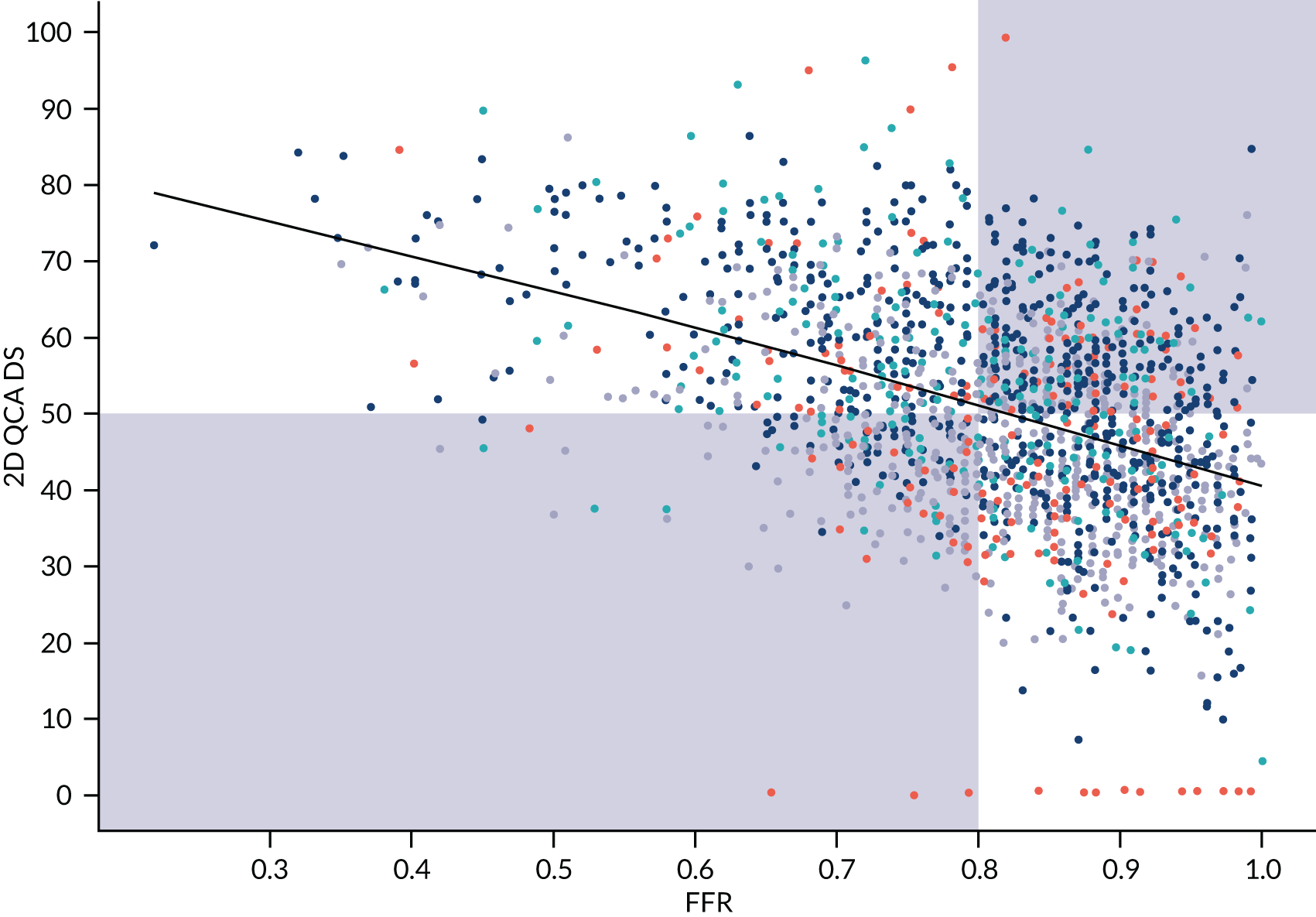

Five studies included in the meta-analysis also reported 2 × 2 table data on the diagnostic accuracy of using ICA alone, using 50% DS as the cut-off point with FFR < 0.8 as the reference standard. These five studies are summarised in Table 4. We note that reporting of diagnostic data on ICA may be subject to selection bias, as only a small subset of studies reported it, and they are likely to do so to demonstrate the superiority of using QFR over relying on ICA alone.

| Study | 2D or 3D | n | Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | Specificity (%) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAVOR II China: Xu et al. (2017)52 | 2D | 332 | 62.5 (53.5 to 71.5) | 58.2 (51.7 to 64.7) |

| FAVOR II Europe–Japan: Westra et al. (2018)50 | 2D | 317 | 44.2 (34.7 to 53.8) | 76.5 (70.8 to 82.2) |

| FAVOR pilot: Tu et al. (2016)46 | 3D | 84 | 44.4 (25.7 to 63.2) | 78.9 (68.4 to 89.5) |

| Mejia-Renteria et al. (2019)37 | 3D | 300 | 69.9 (62.1 to 77.6) | 70.7 (63.8 to 77.7) |

| Stähli et al. (2019)42 | 3D | 516 | 34.0 (24.7 to 43.3) | 91.6 (88.9 to 94.3) |

Given the limited number of studies, and because 2D and 3D ICAs may have very different performance levels, no bivariate meta-analysis of these data are presented here. Based on the results of individual studies, the diagnostic accuracy of ICA appears to be poorer than that of QFR.

Twelve included studies reported AUC estimates for diagnostic accuracy of using ICA alone. A meta-analysis of these studies gave a summary AUC for 3D ICA of 0.71 (95% CI 0.66 to 0.76). For 2D ICA, the summary AUC was 0.63 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.67). Both 2D and 3D ICA have lower AUC values than QFR, and it appears that 2D ICA may be inferior to 3D ICA.

Bivariate meta-analysis to compare tests

Eight studies in the meta-analysis compared two or more testing approaches: five of these compared using 2D or 3D ICA to QFR, and five compared fQFR to cQFR. A ROC plot of results from studies reporting two or more tests is shown in Appendix 4, Figure 25. In all five studies, ICA performed more poorly than QFR, with lower sensitivity and specificity. Differences between fQFR and cQFR were more mixed, with three studies suggesting that cQFR has slightly higher sensitivity than fQFR, but the other two were not consistent with this.

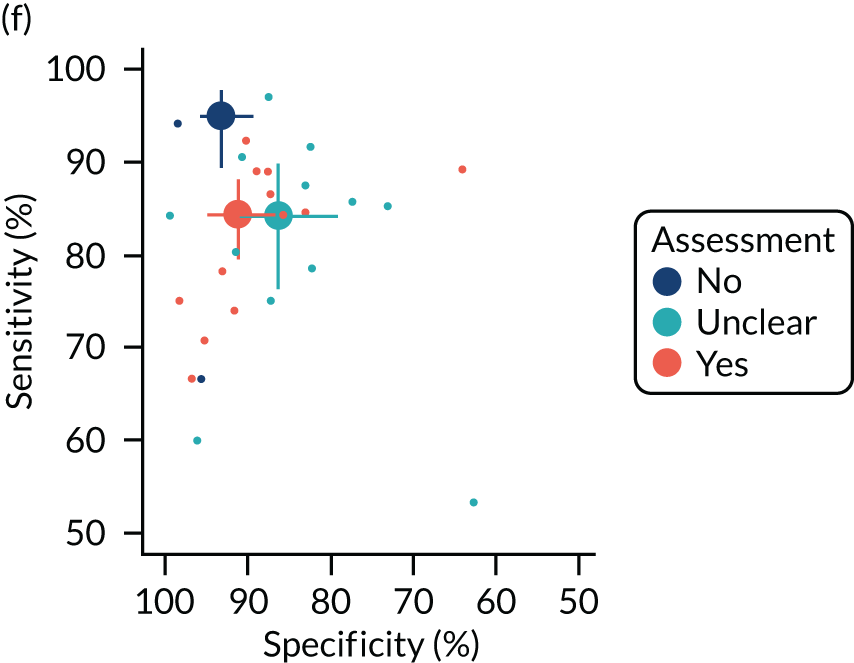

An indirect comparative bivariate meta-analysis accounting for these comparisons between studies is presented in Table 5 and Figure 6. These analyses show the clear inferiority of using ICA alone when compared with FFR as a reference standard. It is clearly inferior to using QFR in both sensitivity and specificity, with a sensitivity of only 51.2% and a specificity of 71.0%.

| Mode | Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | Specificity (%) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| cQFR | 83.97 (78.32 to 88.37) | 89.59 (85.15 to 92.82) |

| fQFR | 83.32 (76.42 to 88.50) | 83.91 (76.91 to 89.08) |

| QFR | 85.20 (79.76 to 89.38) | 90.09 (85.80 to 93.19) |

| ICA | 51.16 (41.86 to 60.38) | 70.99 (62.39 to 78.30) |

FIGURE 6.

A ROC plot of bivariate with comparisons of tests.

Unlike the earlier bivariate meta-analysis (see Appendix 4, Figure 24), the comparative analysis suggests that fQFR is slightly inferior to cQFR, mainly due to an inferior specificity (83.9% instead of 89.6%). This suggests that fQFR produces slightly too many FP results (where QFR ≤ 0.8 but FFR > 0.8). This might suggest that if an initial fQFR produces a result less than 0.8 it should be followed up by a confirmatory cQFR.

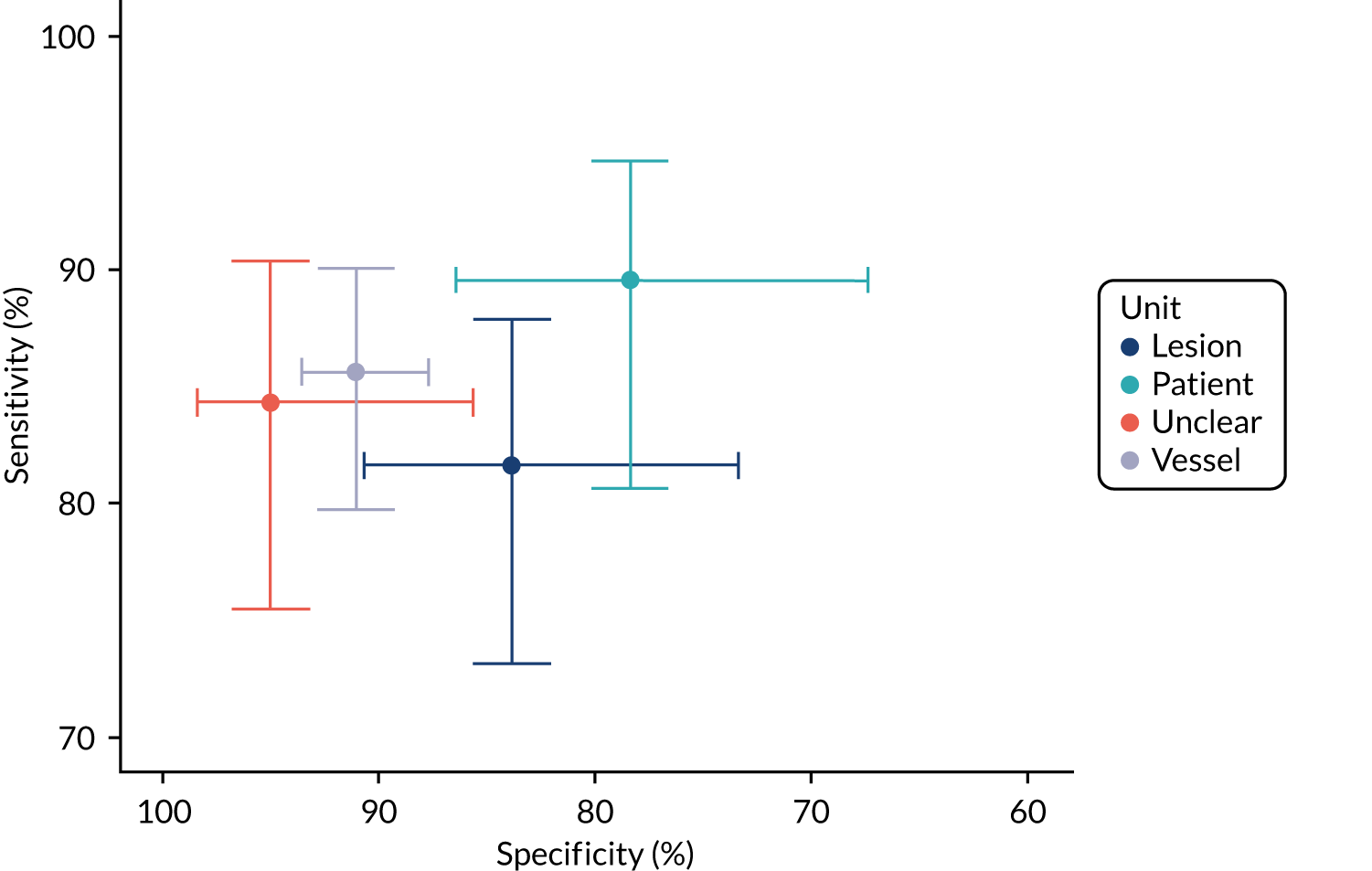

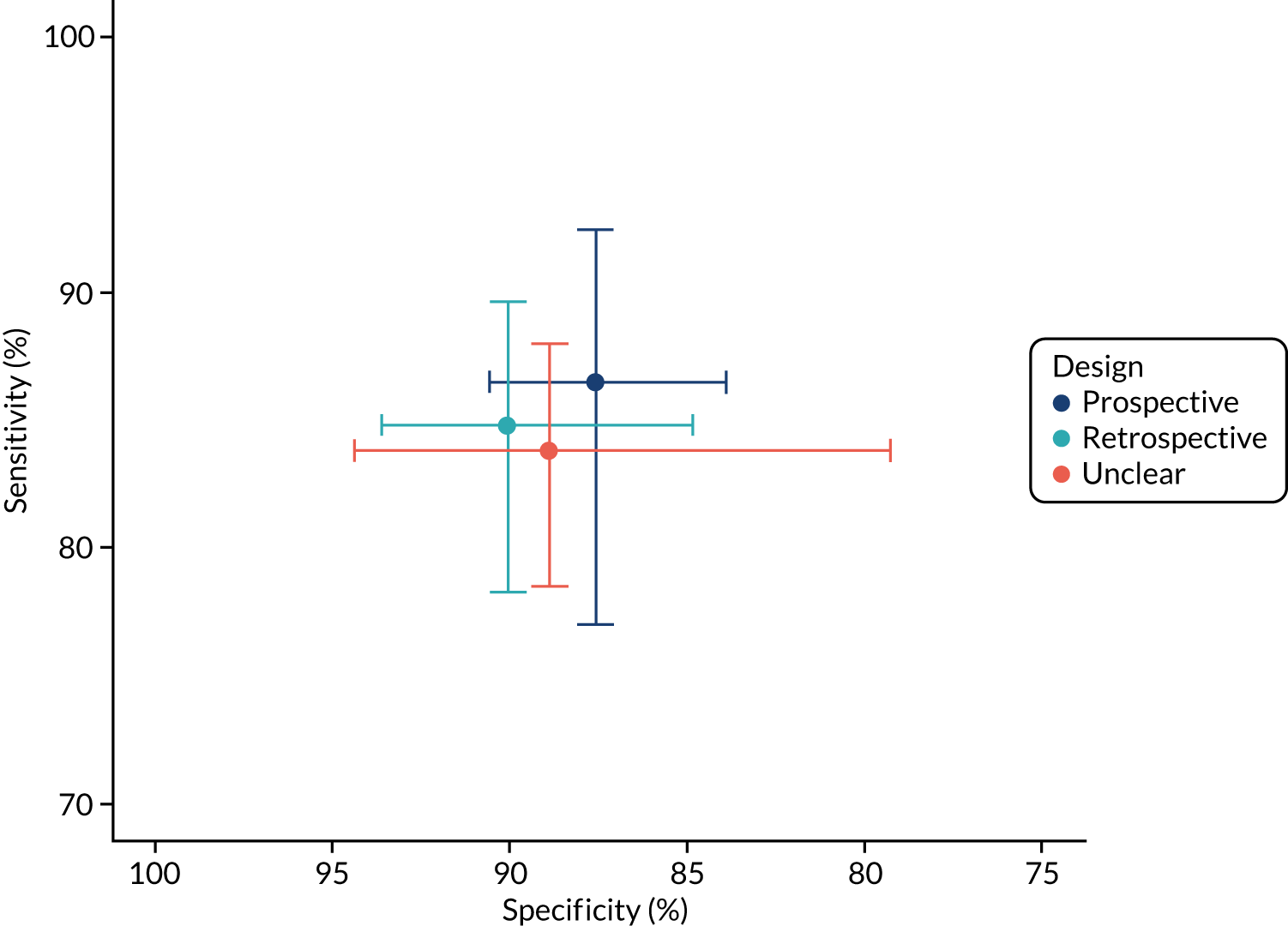

Impact of patient and study characteristics (QAngio XA 3D/QFR)

Impact of study characteristics

Receiver operating characteristic plots differentiating between studies reporting at patient, vessel or lesion level found no evidence that this affects diagnostic accuracy (see Appendix 4, Figure 26). There was also no evidence of any impact on diagnostic accuracy in studies where more than one approach was reported. We note that, where there was more than one lesion assessed, ‘by-patient’ and ‘by-vessel’ analyses selected a single lesion (either at random or based on clinical importance), so a lack of difference is unsurprising, as it would only arise if the choice of lesion was biased. It should also be noted that by-lesion analysis could be biased because of correlation between lesions within patients. Without full patient-level data, the impact this might have cannot be assessed.

There was no evidence of difference in diagnostic accuracy between prospective and retrospective analyses of QFR (see Appendix 4, Figure 27).

Impact of patient factors

Few studies reported diagnostic accuracy data in any form according to different patient characteristics (such as distinguishing between people with and without diabetes, or with and without multivessel disease). The limited evidence reported is discussed in Clinical outcomes.

Given this lack of evidence, to investigate the impact on diagnostic accuracy of key patient factors we have performed meta-regressions of sensitivity, specificity and DOR against the mean value of these factors, where reported in papers. These analyses are obviously limited by being meta-regressions of study-level proportions, rather than true analyses of patient-level data, and because of limited reporting of these factors across studies. For these analyses we did not separate fQFR from cQFR but used one test per study (cQFR for preference) to maximise data. This was considered reasonable given that diagnostic accuracy does not strongly depend on the mode of QFR used.

Appendix 4, Table 38, shows the regression parameter estimates (change in log-DOR, sensitivity or specificity per unit of the covariate), their 95% CIs and p-values from these metaregression analyses. For most parameters there is no evidence of any association with diagnostic accuracy. However, this may be due to a lack of data rather than no association.

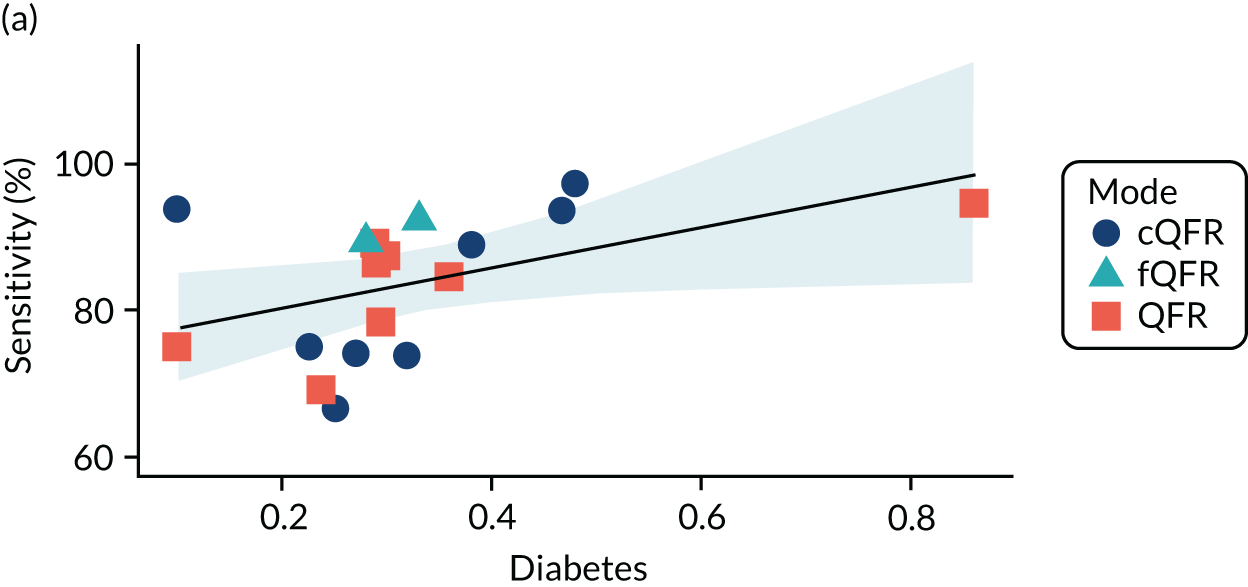

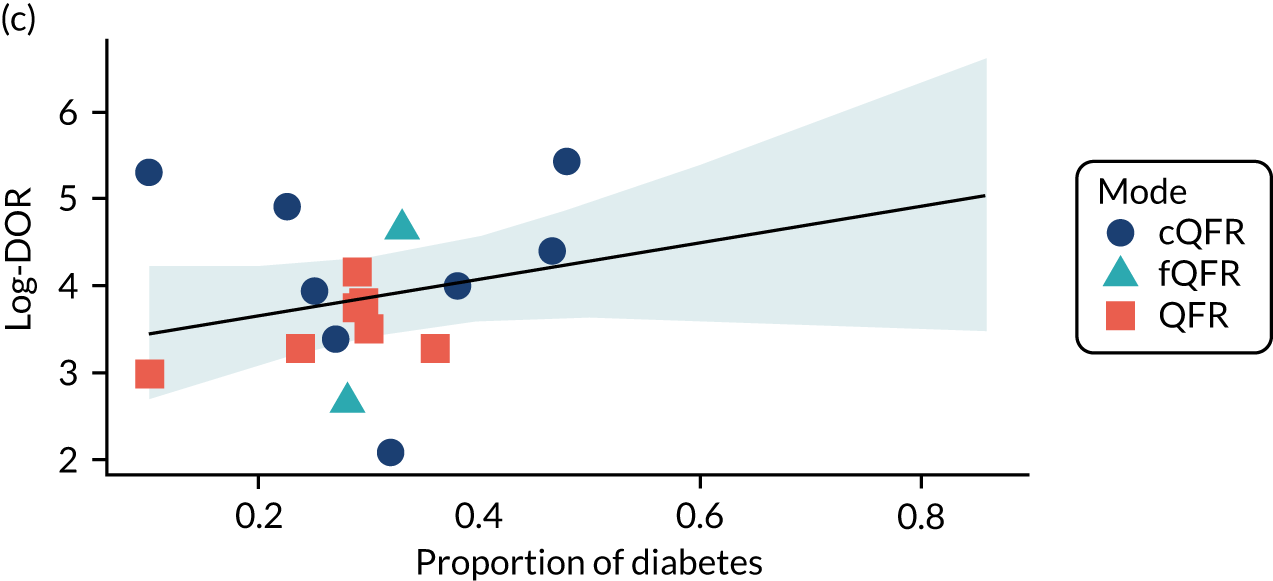

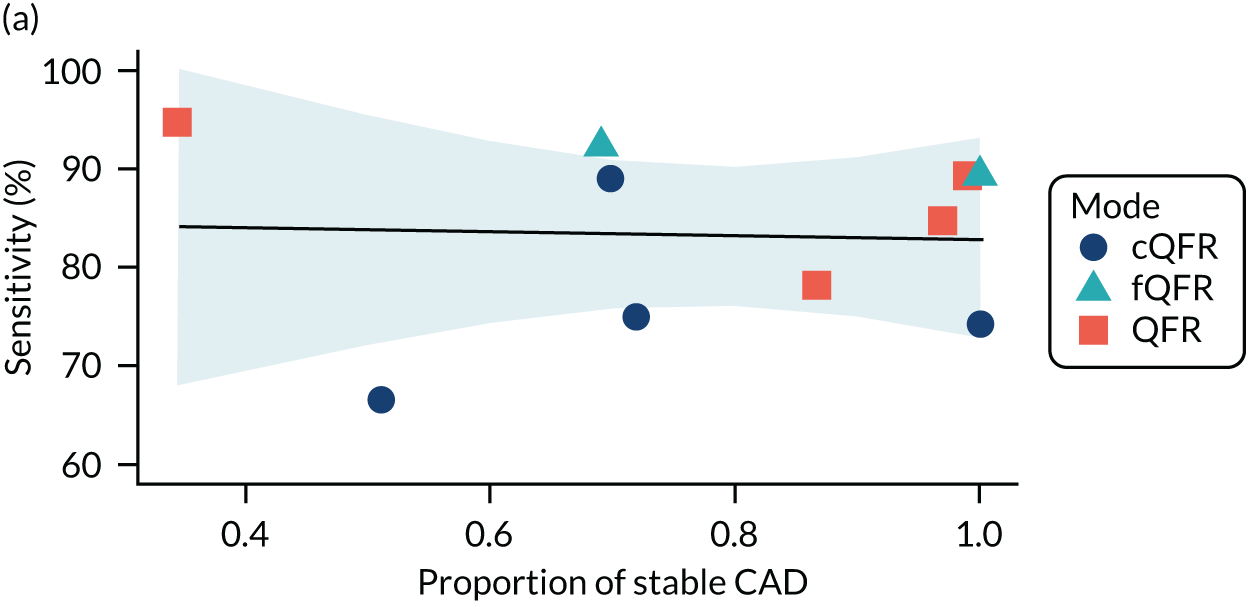

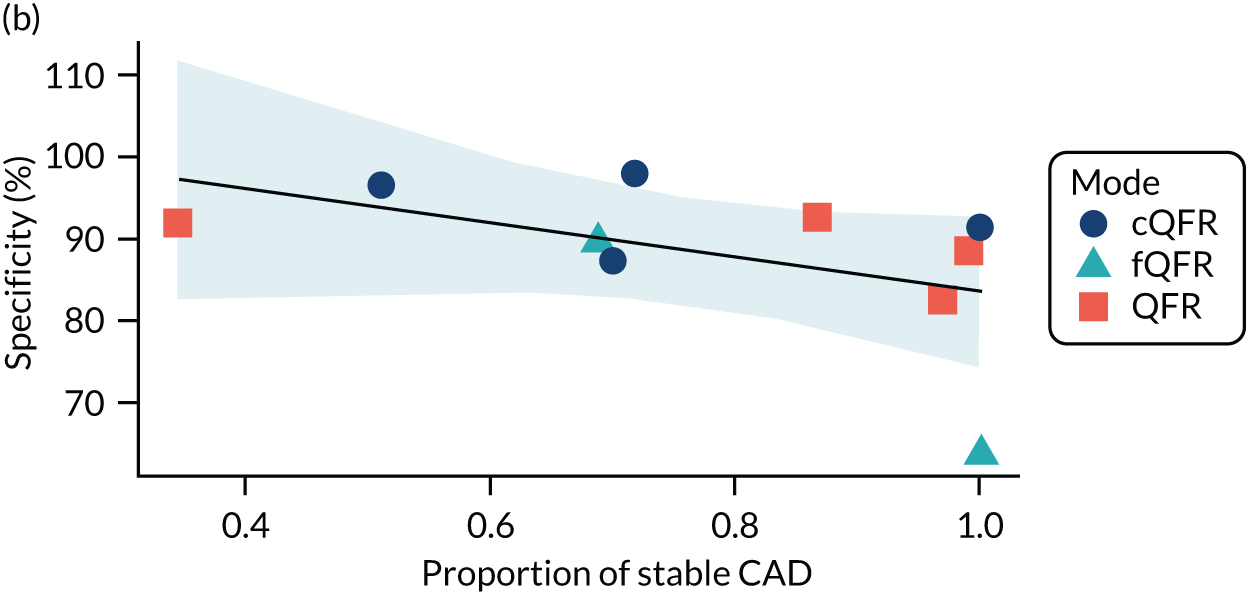

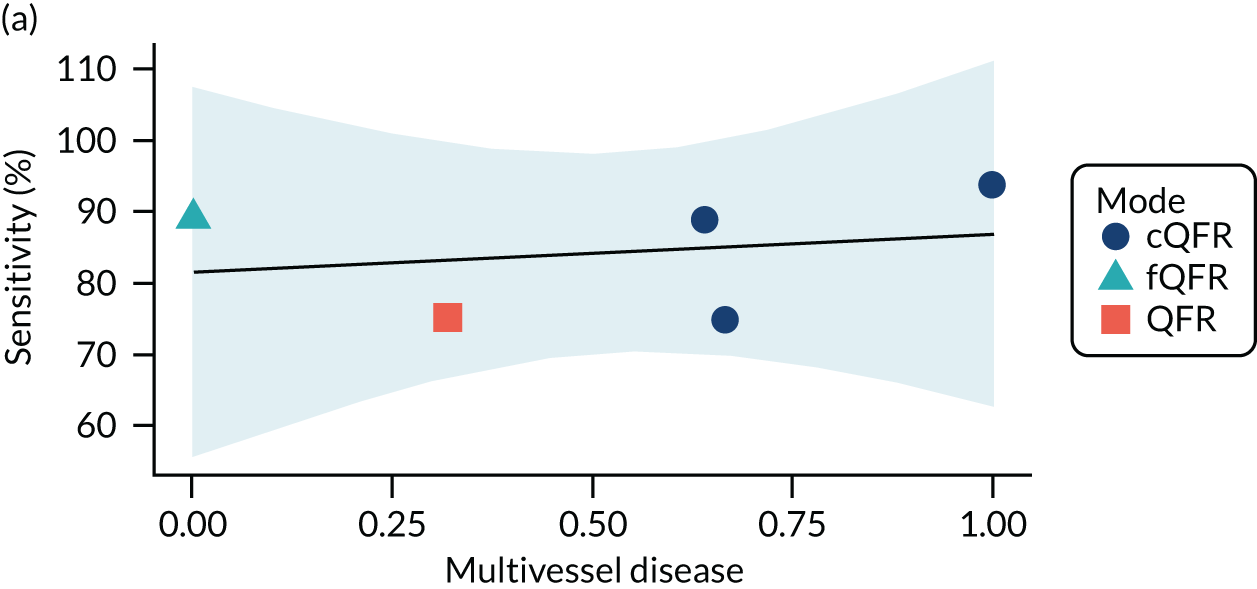

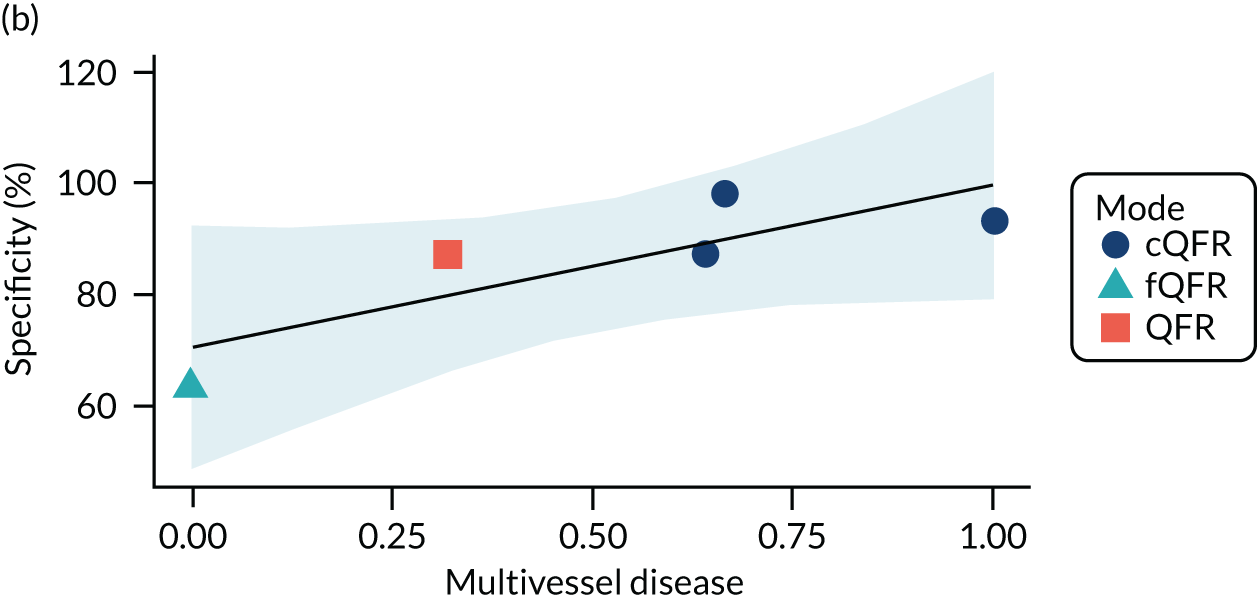

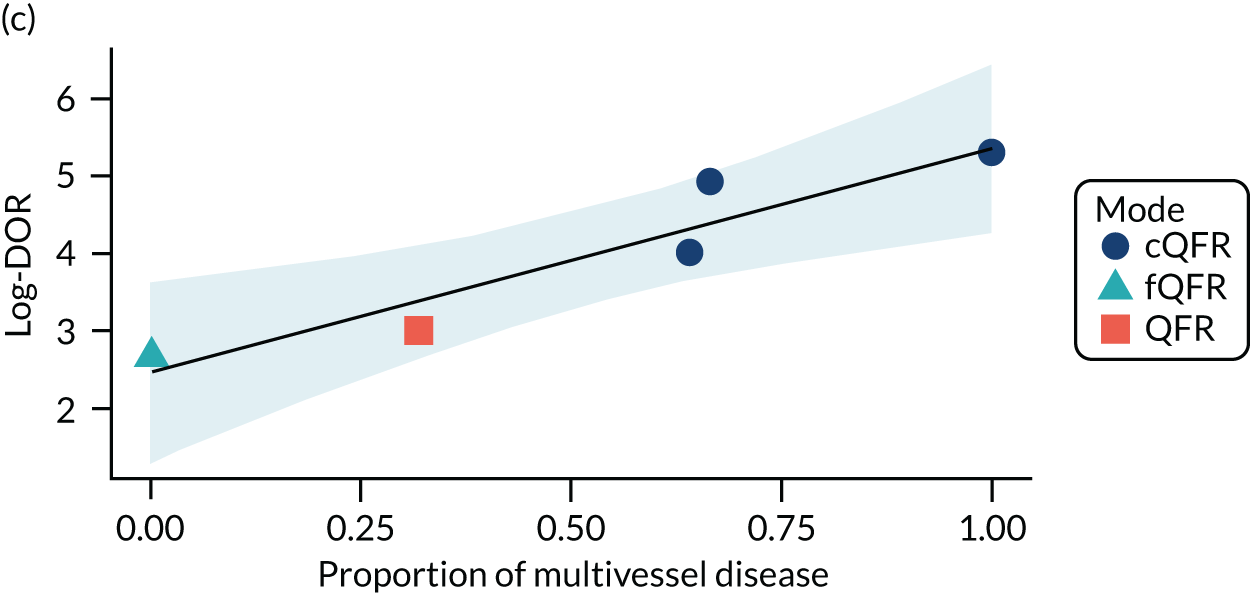

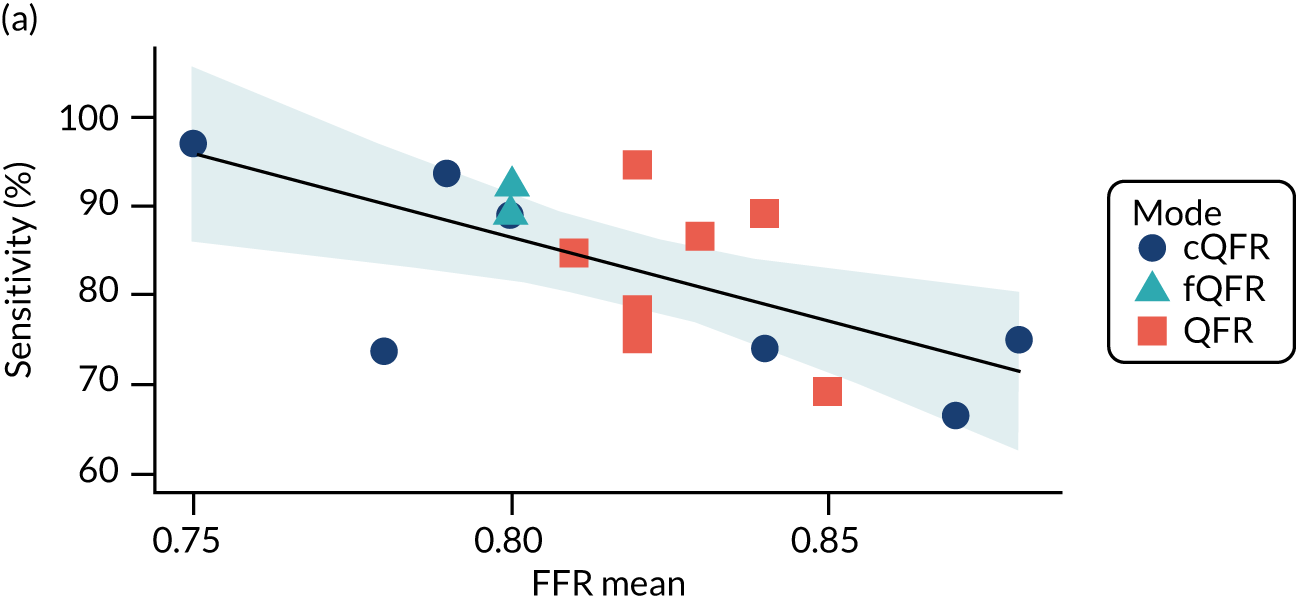

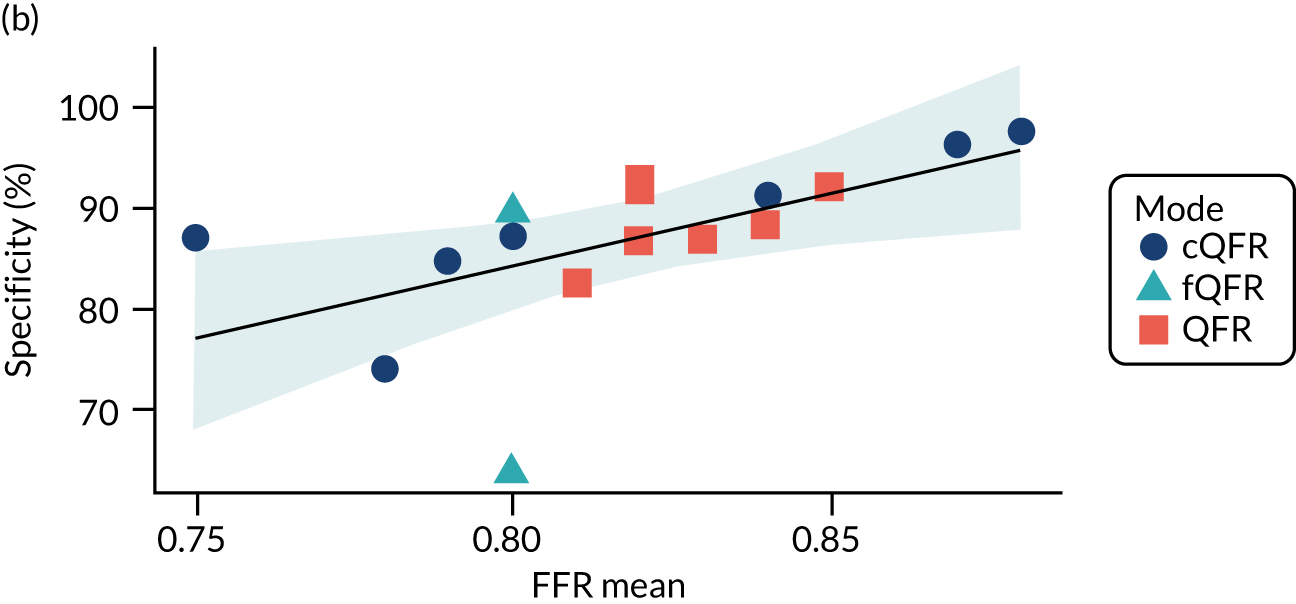

Four patient factors (i.e. diabetes, stable CAD, multivessel disease and mean FFR) suggest a possibility of association, as all have at least one p-value below 0.05. Plots of the proportions of patients with these factors, against estimated sensitivity, specificity and log-DOR are shown in Appendix 4, Figures 28–31.

The association between diabetes and diagnostic accuracy is partly driven by one study where nearly all patients had diabetes, but the trend for studies with more diabetic patients to have higher sensitivity and DOR remains even if that study is removed. There is a trend for specificity and DOR to decline as higher proportions of patients have stable CAD. Conversely, specificity and DOR increase as more patients have multivessel disease (although this is based on only five studies32,37,41,42,51).

There is evidence that the lower the average FFR in a study, the higher the sensitivity and the lower the specificity (but with no impact on the overall accuracy in terms of the DOR). We might therefore also expect some variation in diagnostic accuracy with any factor that lowers FFR (DS, medical history, etc.) but the data are too limited to confirm this.

Subgroup analyses

Eleven studies reported diagnostic accuracy results stratified by patient or vessel characteristics20,21,24,29,32,38,42,51,52,57,58 and four studies reported results of multivariate regression analyses of predictors of QFR/FFR discrepancies. 15,37,50,51 All studies were of QAngio XA 3D/QFR.

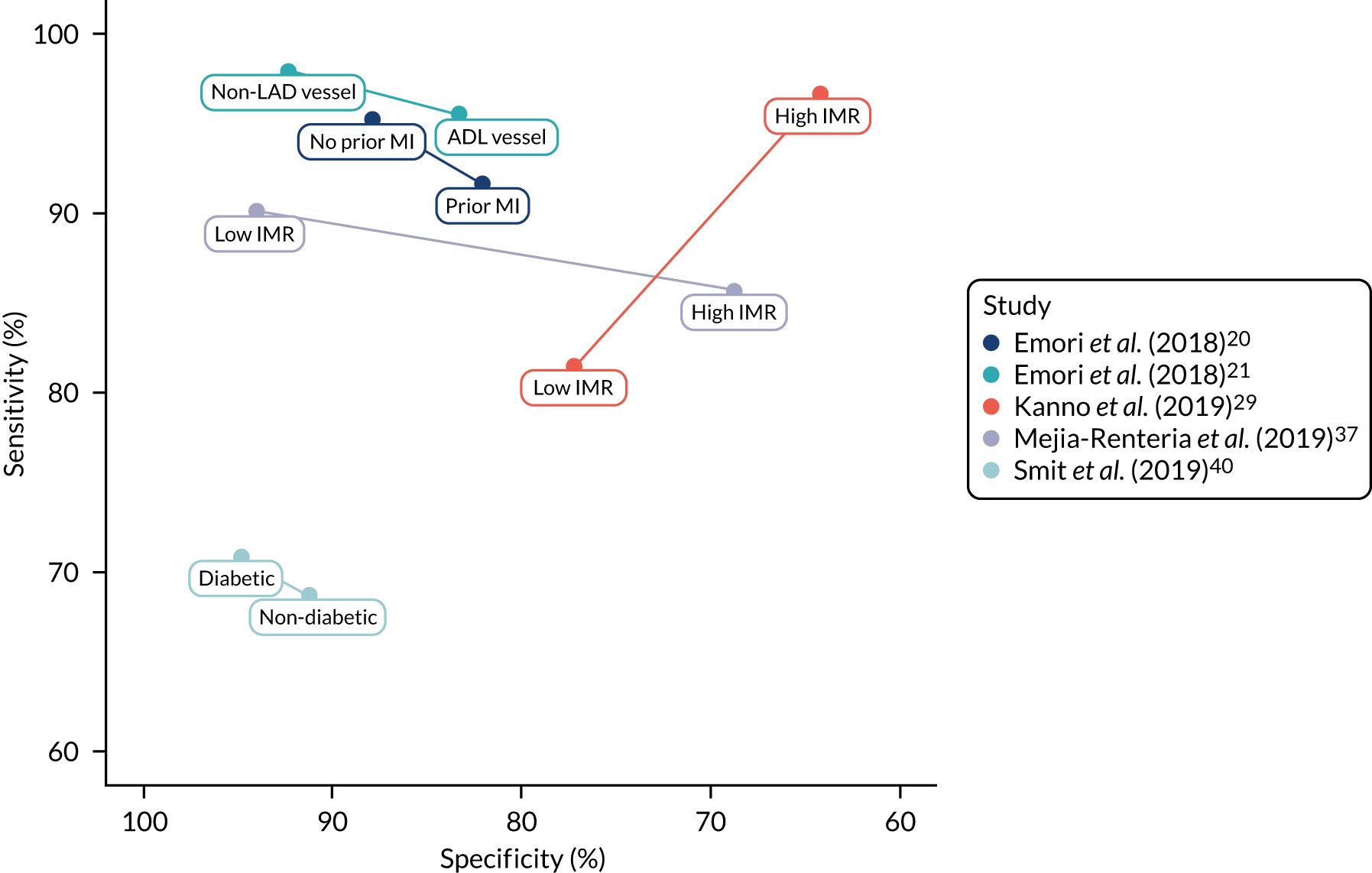

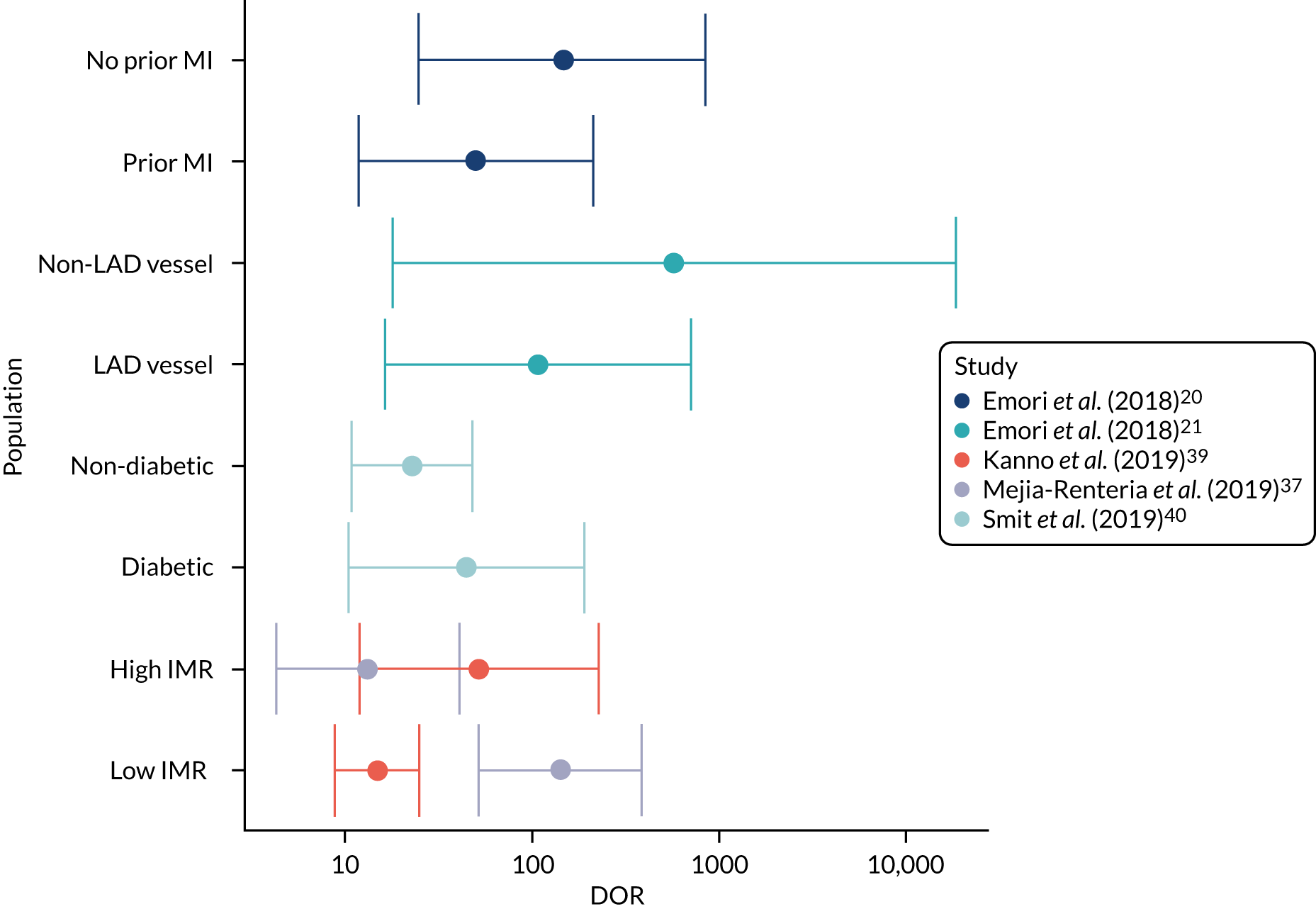

The number of subgroup analyses was too small to allow meta-analysis and results are summarised narratively, and in figures. None of the analyses reported in the included studies was prespecified in a prospectively registered protocol. All patient characteristics for which subgroup data were reported were specified in the review protocol [high/low index of microcirculatory resistance (IMR) small/non-small vessel diameter, multiple/single lesion, diabetes/no diabetes, MI history], except three [left anterior descending (LAD)/no LAD vessel, chronic kidney disease (CKD) and acute MI], which are presented for the sake of completion.

Appendix 4, Figure 32, shows a ROC plot for five studies reporting sensitivity and specificity by subgroups, and Appendix 4, Figure 33, shows the DORs for the same studies. The results of subgroup analyses reported in included diagnostic accuracy studies are summarised in Appendix 5, Tables 44 and 45.

Microcirculatory resistance

Two studies explored the effect of microcirculatory resistance on the accuracy of QAngio XA 3D/QFR and showed inconsistent results. 29,57 In both studies, patient populations were stratified according to microcirculatory status, defined by the IMR, the product of hyperemic Tmn and hyperemic distal arterial pressure and measured by pressure wire. Microcirculatory dysfunction was defined as ≥ 23 U (predefined as 75th centile of IMR values) in one study57 and as ≥ 25 U in the other. 29 Results differed significantly between the two studies. Although both found a statistically significant difference in diagnostic accuracy between high- and low-IMR groups, one study found that the accuracy of QAngio XA 3D/QFR was reduced in patients with high IMR compared with low IMR [sensitivity 86% vs. 90%, specificity 69% vs. 94%, AUC 0.88 vs. 0.96, odds ratio (OR) of misclassification 1.05 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.08)],57 whereas the other29 found that QAngio XA 3D/QFR had higher sensitivity but lower specificity in the high-IMR group (sensitivity 96.7% vs. 81.5%, specificity 64.2% vs. 77.2%).

Vessel characteristics and location

There was limited evidence that vessel characteristics and location were associated with different rates of QFR/FFR discrepancies, although two studies reported that vessels with bifurcation/trifurcation lesions were associated with poorer diagnostic accuracy than other vessels. The SYNTAX59 trial found that bifurcation/trifurcation were independent predictors for the increased incidence of FP QFR (OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.98), and one small study of 38 vessels reported that bifurcations lesions accounted for five out of six (83.3%) false measurements. 38 One study22 that included only patients with left main stenosis (85% left main bifurcation) had high sensitivity (84.8%) and moderate specificity (68.2%) (AUC 0.82, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.93). No other studies reported on the potential impact of left main stenosis on diagnostic accuracy.

Results from studies evaluating the effect of small vessel disease on diagnostic accuracy were mixed. One study found higher sensitivity and AUC for cQFR in patients with small-vessel disease (≤ 2.8 mm reference diameter), than in other patients [sensitivity 80.0% vs. 65.7%, specificity 98.5% vs. 97.2%, AUC 0.89 (95% CI 0.85 to 0.93) vs. 0.81 (95% CI 0.76 to 0.86)],60 whereas another study found that small-vessel disease (≤ 2.5 mm reference diameter) was associated with an increased incidence of FN QFR (OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.14 to 2.44) in a multivariate analysis. 15

One study found that found no significant differences in QAngio XA 3D/QFR accuracy between subgroups with LAD and non-LAD coronary arteries,21 although a multivariate analysis from SYNTAX II15 found a non-statistically significant trend suggesting LAD may be associated with a higher rate of FPs (OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.04), and that lesions located in side branches were associated with a higher rate of FP QFR (OR 2.07, 95% CI 1.14 to 3.76) and FNs (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.81).

One study found no significant difference in MDs between QFR and FFR per lesion in patients with single and multiple lesions,51 and multivessel disease was not a significant predictor of QFR/FFR discrepancy in a multivariate analysis conducted by another study. 37 Functional Assessment by Virtual Online Reconstruction (FAVOR) II-China52 found that the accuracy of QAngio XA 3D/QFR in patients with DS 40–80% did not differ from the whole study population results.

Comorbidities and other patient characteristics