Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/35/38. The contractual start date was in January 2014. The draft report began editorial review in February 2020 and was accepted for publication in December 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 King et al. This work was produced by King et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 King et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from King et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Background

Glaucoma is a pressure-related optic neuropathy that results in progressive visual field (VF) deterioration. The World Health Organization estimates that, in 2010, 4.5 million people were blind because of glaucoma,2 which accounts for 12.3% of global blindness. Glaucoma is estimated to affect around 2% of the UK population aged > 40 years, and this percentage increases with age,3–7 with as many as 10% of those in their 80s affected. Glaucoma is the second most common cause of registration as being visually impaired in the UK, accounting for 8.4–11.6% of registrations in those aged > 65 years. 8,9 However, this is likely to be an underestimate. 10

In England, there are over 1 million glaucoma-related visits to the NHS per year. The management of glaucoma patients constitutes a major part of ophthalmologists’ workload, accounting for 23% of all follow-up attendances to the UK hospital eye service11 and 13% of all new referrals. 12 The number of patients with glaucoma is predicted to increase substantially as the result of an ageing population. 13 There is currently no effective screening strategy in the UK for the early identification of all patients with glaucoma. 14

Sight loss from glaucoma is preventable; the Public Health Outcomes Framework for England 2013–1615 has made reducing the number of people living with preventable sight loss a priority. However, people are unaware of the onset of glaucoma because it is typically asymptomatic in the early stages and, as a consequence, between 10% and 39% of patients with glaucoma in the UK present with advanced disease in at least one eye. 16–20 In the most recent study, more than one-third of patients presenting to secondary care had severe disease in at least one eye. 18 Those most at risk include the socially disadvantaged with no family history of glaucoma, those with high intraocular pressure (IOP) and those who do not attend an optometrist regularly. 18,20–22

Advanced glaucoma at presentation: a risk factor for blindness

Presentation with advanced VF loss increases the risk of further progression and blindness. 23–28 Odberg et al. 23 noted in a cohort of patients with advanced glaucoma that 70% of the affected eyes had progressed after a mean of 7.6 years despite treatment. Grant and Burke25 found that eyes with a VF defect at the beginning of treatment were more likely to progress to blindness than eyes in which treatment was started when there was no VF loss. Wilson et al. 26 found that initial VF loss was the strongest determinant of the rate of further VF loss. The rate of deterioration was 11.7 times faster in eyes with more advanced VF loss at presentation. Mikelberg et al. 24 found that, when scotoma mass was small (i.e. early glaucoma), the rate of VF loss was slow, but, when scotoma mass was large (i.e. severe glaucoma), rapid linear progression of VF loss occurred. Oliver et al. 29 found that unilateral blindness owing to glaucoma more than doubled the risk of bilateral blindness.

Current treatment options

Reducing IOP is currently the only effective treatment for glaucoma. 30–33 Better control of IOP at an early stage reduces the risk of progression to blindness. The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS) demonstrated that the extent of lowering of IOP was related to the progression of VF loss over an 8-year period, showing that progression was least when IOP was maintained below 18 mmHg at all follow-up visits. 34

The primary treatment options in the UK for advanced glaucoma are mainly medical or surgical interventions. Currently, most ophthalmologists treat patients medically, starting with topical drop monotherapy followed by escalating the number of drop therapies until the maximum tolerated combination therapy is achieved. 35 All frequently used eye drops (i.e. prostaglandin analogues, beta-blockers, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, alpha-agonists and anticholinergic miotics) are now available in generic form and, therefore, cost less. In patients whose glaucoma continues to progress despite eye drop treatment or in whom the target IOP is not achieved, clinicians may opt for surgical intervention, most frequently trabeculectomy. 30–33,36 Patients have indicated that they are not concerned about the treatment that they receive as long as it is effective in the prevention of further visual loss. 37

Recently published National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines suggest that patients presenting with advanced disease should be offered augmented trabeculectomy as a primary intervention and should be offered medical management only if surgery is declined, but point out that the evidence to support this recommendation is of poor quality. 38 By using eye drops as a first-line treatment instead of surgery and by operating on patients only in whom drop therapy fails, NHS resources could be saved in the short term; however, the long-term effects on visual outcome are uncertain. Modern glaucoma eye drops lower IOP significantly more and have fewer side effects than those previously used, which may or may not reduce the need for surgery. Social resources may be saved by avoiding the need to support those becoming blind. A survey of consultant ophthalmologists indicated that most do not follow NICE guidance and prefer medical management because of the poor evidence base and concern regarding surgery complications. 35

Compared with surgery, primary eye drop treatment would save upfront surgery costs and may save other NHS costs in the short term, such as intensive follow-up, and reduce the number of patients requiring cataract surgery to restore visual function. Avoiding surgery could improve patient health and quality of life (QoL) in the short term; however, in the long term, insufficient IOP control may produce more VF loss and poorer health outcomes. A head-to-head trial of these two primary treatments is, therefore, required.

Rationale for this study

There is uncertainty about how best to manage patients diagnosed with advanced glaucoma. Such individuals have a high risk of blindness, and effective treatment is required to minimise the chances of disease progression. Currently, NICE guidelines recommend initial surgery but acknowledge the lack of evidence to support this recommendation. Surgery may be more effective in the long term but is associated with potential adverse events (AEs) and increased costs at the time of surgery. Current medical therapies (e.g. eye drops) may be able to control the disease in a proportion of patients with advanced glaucoma. Within the Treatment of Advanced Glaucoma Study (TAGS), we considered whether or not primary medical management is clinically effective and cost-effective for the management of newly diagnosed advanced glaucoma compared with the NICE-recommended treatment of augmented trabeculectomy (glaucoma surgery).

A recent Cochrane systematic review30 comparing primary medical management with surgical treatment for open-angle glaucoma (OAG) identified four relevant studies. 31,39–41 Despite methodological weaknesses and non-standard treatments, the review authors concluded that in severe OAG evidence suggested, that medication was associated with more progressive VF loss and less IOP lowering than surgery. The authors also reported that ‘risk of treatment failure was greater with medication than trabeculectomy [odds ratio (OR) 3.90, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.60 to 9.53; hazard ratio (HR) 7.27, 95% CI 2.23 to 25.71]’. 30 Three of these four trials are now obsolete because new types of medical management have since been introduced, and the most recent study did not include patients with advanced disease.

The authors30 concluded that surgery lowers IOP more than medication; however, none of these trials specifically addressed the management of those presenting with advanced glaucoma or used modern glaucoma medications that are more effective at lowering IOP and have fewer side effects than previous generations of eye drops. The authors recommended that further randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing current medical managements with modern glaucoma surgery be carried out in people with advanced OAG. 30

This uncertainty has subsequently been added to the UK Database of Uncertainties about the Effects of Treatments (UK-DUETS) as an important question requiring further investigation: https://jla.nihr.ac.uk/news-and-publications/downloads/2007–2008-DUETs-Development-Report.pdf (accessed in 2014).

No previous RCT has explored the best treatment options for patients presenting with advanced glaucoma. The AGIS, for example, did not compare primary medical and surgical interventions and did not explore primary treatment options, as all patients had failed on maximum medical management prior to entry. 42 In addition, it included patients with mild glaucoma. The USA-based Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study (CIGTS), although comparing the outcomes of primary medical with primary surgical treatment in newly diagnosed patients with glaucoma, enrolled patients presenting with mild disease (CIGTS score of 4.6 ± 4.2). 31 A recent update from the CIGTS suggests that, in a subgroup of patients presenting with more advanced disease [mean difference (MD) < –10 dB], VF progression was slower in those in whom the primary intervention was surgical. 43

We aimed to reduce the uncertainty identified by the Cochrane review,30 UK-DUETS and NICE38 by undertaking a pragmatic RCT of current best medical care in the NHS (a stepped approach of medications) compared with primary surgery. In addition, we aimed to address the concerns of the Public Health Outcomes Framework for England 2013–1615 by identifying the best treatment approach to minimise preventable sight loss in this group of vulnerable patients.

Patient and public involvement

The research topic was identified in a review of primary medical management compared with primary surgical treatment in glaucoma and was subsequently adopted by UK-DUETS. Patients fulfilling the eligibility criteria for the proposed trial agreed to participate in a focus group discussion to identify concerns that they had about the value of such a trial and their participation. Several themes were identified: patients were concerned about the real need for such a trial, that if they participated in a trial they may be going against the judgement of their clinician and that they may be randomised to the wrong group. 44 Discussion of these points in the focus group setting reassured patients both that the trial itself was important and necessary and that, currently, clinicians do not possess the evidence required to recommend one treatment above the other. Several of the patients who contributed to the focus group discussions agreed to form a patient group to develop patient-related material for the trial, particularly in relation to the consenting process, and one was a member of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC). In addition, a patient representative organisation the International Glaucoma Association (IGA) endorsed this study and its chairperson sat on the TSC (until retirement in 2018, when he continued to participate as a lay representative but not representing the IGA).

A patient representative was an active member of the Project Management Group (PMG) and, as part of this role, contributed to the development of trial materials and processes. He participated in the focus group discussions and, therefore, had insight into the experience and concerns of other glaucoma sufferers. In addition to this representative, several other patients with glaucoma who participated in the focus group discussions agreed to form a patient representative group that advised the study team on the development of patient-related study material. This was primarily aimed at the development of the patient information leaflet to provide patients with all of the information that they required to make a decision when asked to participate in the study, specifically regarding concerns about surgery.

Aims of the trial

Primary objective

The primary objective of this trial was to compare primary medical management with primary augmented trabeculectomy (glaucoma surgery) for patients presenting with advanced glaucoma [Hodapp–Parrish–Anderson (HPA) Classification severe] in terms of patient-reported health status using the National Eye Institute’s Visual Function Questionnaire-25 (VFQ-25). 45–54

Secondary objectives

-

To compare generic and vision- and glaucoma-specific patient-reported health and experiences in the short and medium term.

-

To compare the costs and benefits [quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained] of surgery and medication at 2 years based on responses to the (1) EQ-5D-5L, (2) the Health Utilities Index version 3 (HUI-3) and (3) the Glaucoma Utility Index (GUI). 55

-

To compare clinical outcomes (VFMD changes, logMAR visual acuity changes, IOP, Esterman VF for driving vision, registered visual impairment).

-

To compare the need for additional cataract surgery.

-

To compare safety by comparing AEs arising from both surgical and medical interventions.

-

To employ an existing discrete choice experiment (DCE) among participants with advanced glaucoma to generate a revised scoring system for the GUI that is more sensitive and specific for those with advanced disease.

-

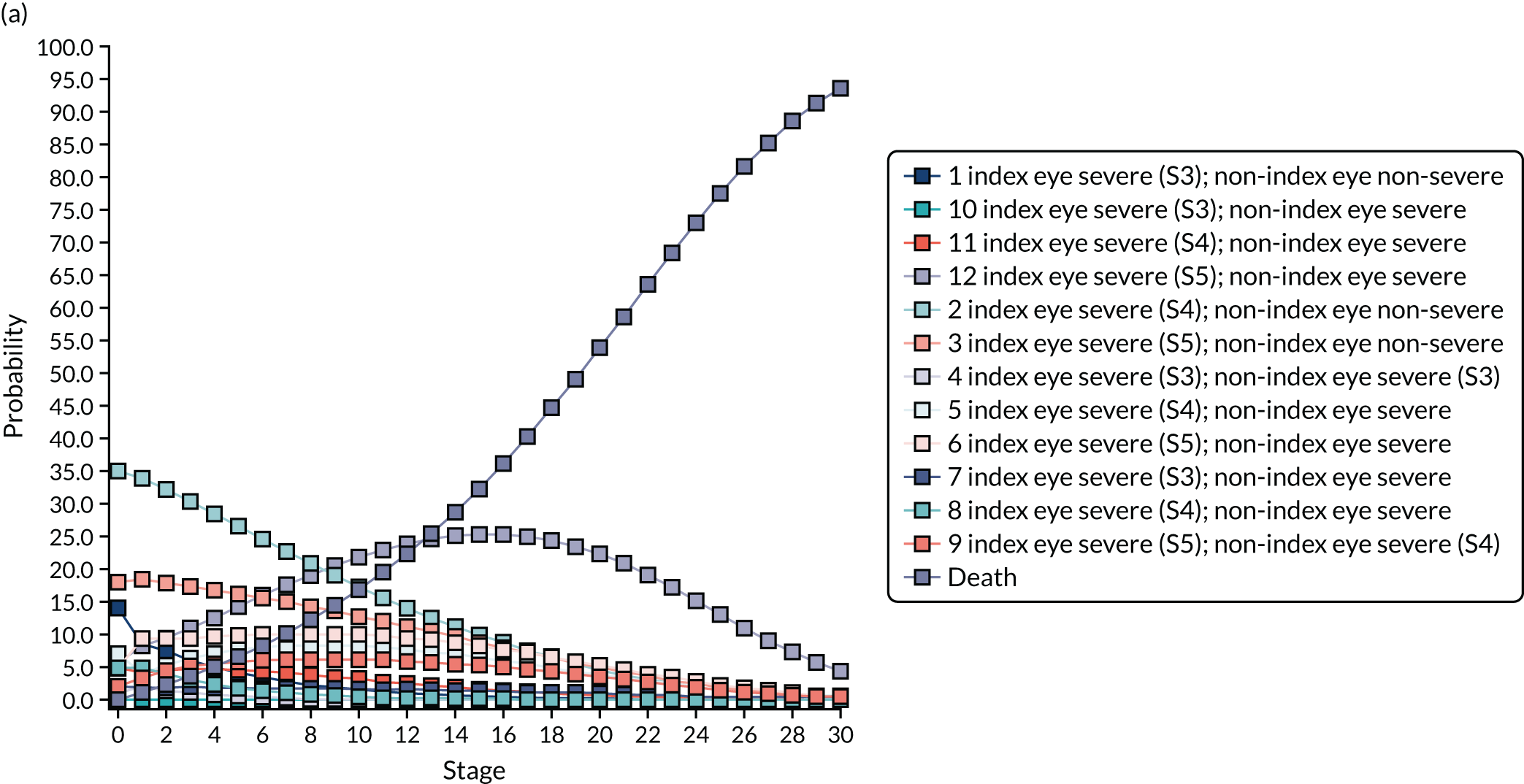

To compare long-term costs and benefits through a modelling evaluation.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter contains material reproduced with permission from King et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Some of the material in this chapter is also reproduced with permission from King AJ, Hudson J, Fernie G, Burr J, Azuara-Blanco A, Sparrow JM, et al. Baseline characteristics of participants in the Treatment of Advanced Glaucoma Study: a multicenter randomised controlled trial. Am J Ophthal 2020;213:186–94. 56

Study design

The TAGS is a pragmatic,57 two-arm, parallel-arm multicentre RCT comparing primary medical management with primary augmented trabeculectomy (standard care) (see Appendix 1). Participants were randomised to medical management or augmented trabeculectomy (1 : 1 allocation, minimised by centre and bilateral disease).

The perspective of this study was that of the NHS and the patient, with the economic perspective also reflecting Personal Social Services (PSS) and a wider perspective including patients and their families. The framework of the study was an integrated clinical and economic evaluation of the patient outcomes, costs and cost-effectiveness of the two alternative established methods of management of patients presenting with advanced glaucoma. Both treatment strategies currently have been evaluated to assess efficacy and safety. 58–63 The study protocol was published in 2017. 1

Setting

Clinical centres

Twenty-seven secondary care centres with at least one consultant who subspecialises in glaucoma recruited patients for the study.

Population

Adults with advanced (severe) glaucoma in at least one eye defined as severe according to the HPA grading64 for VF loss severity were invited to participate in the study.

Participants

Disease was classified as advanced if it met the criteria for ‘severe’ VF loss according to the HPA classification of glaucoma severity64 (the presence of any of the following):

-

VFMD < –12.00 dB

-

> 50% of points depressed below the 5% level on the pattern deviation probability plot

-

> 20 points depressed below the 1% level on the pattern deviation probability plot

-

one point in the central 5° has a sensitivity of 0 dB

-

points within 5° of fixation under 15 dB sensitivity in both upper and lower hemifields.

Consent to participate

Potential participants who were likely to be eligible for the RCT were identified at their initial consultation for glaucoma by a member of the clinical assessment team. In centres in which it was possible to vet clinic referrals prior to the patient’s attendance at clinic, potentially eligible subjects were identified from their referral letters. At the initial consultation, the consultant, research nurse or another delegated individual introduced the study and, if potential interest was expressed, provided further details of the study by means of the patient information leaflet. The contact details of all interested patients were passed on to the recruitment centre’s study research team if they were not part of the initial consultation. If the patient agreed in principle to the study, then arrangements were made for assessment and consent to be taken. This may have been at a separate appointment or at the initial visit if the patient consented to participate at that visit. Arrangements were individualised for each centre. Eligible patients were asked for their signed informed consent before being randomised. Both the patient information leaflet and the consent form referred to the possibility of long-term follow-up.

We included people who:

-

had severe glaucomatous VF loss (HPA classification)64 in one or both eyes at presentation

-

had OAG, including pigment dispersion glaucoma, pseudoexfoliative glaucoma and normal tension glaucoma

-

were willing to participate in a trial

-

were able to provide informed consent

-

were aged ≥ 18 years

-

agreed, if female and of childbearing potential, to ensure that they used effective contraception during the study and for 3 months thereafter (a negative urine pregnancy test for females of childbearing potential was required prior to randomisation).

We excluded people who:

-

were unable to undergo incisional surgery owing to an inability to lie flat or unsuitable for anaesthetic

-

had a high risk of trabeculectomy failure, such as previous conjunctival surgery or complicated cataract surgery

-

had secondary glaucomas and primary angle-closure glaucoma

-

were pregnant, nursing or planning a pregnancy, or were of childbearing potential not using a reliable method of contraception (a woman was considered to be of childbearing potential unless she was without a uterus or was post-menopausal and had been amenorrhoeic for at least 12 consecutive months).

Health technologies compared

The intervention was either primary medical management or augmented trabeculectomy. Both interventions are established and well-documented approaches to the management of glaucoma. 65 Following randomisation, care for both treatment arms followed NICE guideline recommendations. 65

Primary medical management: escalating medical therapy

Participants randomised to medical management could be prescribed a variety of licensed glaucoma medications (eye drops). These eye drops were used in accordance with NICE guidelines. 65 Escalating medical management was defined as follows: study participants may be started on one or more medications at their initial visit depending upon the judgement of the treating clinician. When monotherapy is initiated this should be with a prostaglandin analogue as directed by NICE guidelines. Subsequent addition of medications was based on clinician judgement/preference. When drops failed to control IOP adequately oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitors may be used.

Primary trabeculectomy: standard trabeculectomy augmented with mitomycin C

Standard trabeculectomy was defined as the creation of a ‘guarded fistula’ by making a small hole in the eye that is covered by a flap of partial-thickness sclera, which allows aqueous humour to egress from the eye into the subconjunctival space. The operation could be performed under either local or general anaesthetic. The dose of mitomycin C in terms of exposure time and concentration was left to the discretion of the operating surgeon and decided on a case-by-case basis.

The protocol specified that all surgery be undertaken within 3 months of randomisation by a consultant who subspecialises in glaucoma or a glaucoma fellow who has performed at least 30 trabeculectomies. Where both eyes were eligible for the study, the eye with better VFMD was allocated as the index eye. An amendment to the protocol allowed the decision about which eye would undergo trabeculectomy first to be made locally when subjects were allocated to the trabeculectomy arm. 1

To ensure that recognised standard trabeculectomy procedures66,67 were being followed by all participating glaucoma surgeons, all potential surgeons completed a questionnaire about their surgical technique that was reviewed and signed off by the chief investigator. No feedback was given because all surgeons were essentially conducting the same operation.

Compliance with study treatment

We designed TAGS as a pragmatic trial and compliance with study treatment was monitored as it would be in routine clinical practice – by asking the patient if they are using their eye drops. There is currently no practical and effective method for monitoring compliance in patients taking glaucoma medications. 68 The degree of compliance feeds into the outcome measurements, as poor compliance for medications is likely to lead to further disease progression. There was no requirement for participants to return any unused eye drops.

Accountability of the study treatment

The local clinical team used a standard hospital prescription form or asked patients’ general practitioners (GPs) to prescribe the medications required in line with standard practice for that team, pragmatically reflecting standard NHS practice.

Concomitant medication

Medications as required for normal clinical care were prescribed for the participants irrespective of their randomised allocation. Throughout the study, investigators could prescribe any concomitant medications or treatments deemed necessary to provide adequate supportive care.

Treatment allocation

All participants who agreed to enter the study were logged with the central trial office and given a unique study number. Randomisation utilised the existing proven remote automated computer randomisation application at the central trial office in the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials (CHaRT) (a fully registered UK Clinical Research Network clinical trials unit) in the Health Services Research Unit (HSRU), University of Aberdeen. This randomisation application was available as a telephone-based interactive voice response system and as an internet-based service.

Randomisation was computer allocated, minimised by centre and bilateral disease status. The unit of randomisation was the participant (not the eye). Participants with both eyes affected by advanced glaucoma and eligible were expected to undergo the same treatment in both eyes following randomisation. For those participants with both eyes eligible, an index eye was selected for evaluating clinical outcomes. The eye with better MD value (less severe VF damage) was nominated as the index eye.

For those randomised to the trabeculectomy arm with both eyes eligible, a period of 2–3 months would normally be allowed between operations (but this was at the discretion of the treating clinician). Prior to surgery, IOP was controlled using temporary medical management.

Study outcome measures and schedule of assessment

The TAGS outcomes and schedule of measurement are detailed in Table 1.

| Outcomes | Time point | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post randomisation (months) | |||||||

| 1 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 12 | 18 | 24 | ||

| Patient outcomes | ||||||||

| VFQ-25 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| EQ-5D-5L | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| HUI-3a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| GUIa | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Patient experience questions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Clinical outcomes | ||||||||

| Medical history | ✓ | |||||||

| VFMD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Esterman VF | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| LogMAR VA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| IOP | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Standard clinical examination | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Health economicsb,c | ||||||||

| Health-care utilisation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Participant cost | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Participant time and traveld | ✓ | |||||||

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was a vision-specific patient-reported outcome QoL measurement, the vision-specific health profile (VFQ-25), which was evaluated at 24 months. The VFQ-25 is a validated questionnaire that has been widely used to evaluate visual outcomes in glaucoma. 47,69–71 In addition to eliciting information about general health and vision, it specifically addresses difficulty with near vision, distance vision, driving and the effect of light conditions on vision.

Secondary outcomes

Patient centred

Patient-centred data were mainly collected through patient-completed questionnaires. The VFQ-25 was completed at baseline and 4, 12 and 24 months post randomisation. The EQ-5D-5L, HUI-3 and GUI responses were converted into health state utility values. These questionnaires were completed at baseline and at 1, 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months post randomisation and immediately prior to trabeculectomy.

Clinical

Visual field mean deviation

Visual field mean deviation (VFMD), a global measure of the VF, represents the amount of vision loss occurring because of glaucoma during the study period. It is a routinely measured parameter in standard care of glaucoma patients and it is the primary clinical measure on which management decisions for glaucoma are made, in accordance with NICE guidelines. 65 VF damage is the major measure of the functional impact of glaucoma with direct relevance to QoL measures. 69,72–74 The Humphrey Visual Fields test [24–2 Swedish Interactive Threshold Algorithm (SITA standard)] was performed in all participants. All VF tests were performed by VF technicians or nurses trained to carry out VF tests. VF tests eligible for analysis had to achieve predefined reliability criteria (false positives < 15%). If the VF tests were not reliable, they were repeated at the clinicians’ discretion in accordance with local clinical practice. Two baseline VF tests (24–2 SITA standard) were performed prior to randomisation to confirm eligibility. If the second VF test did not fulfil the criteria for ‘severe defect’ by the HPA criteria, a third VF test was undertaken prior to randomisation and the result of this was deemed to define whether or not the patient was eligible. These were performed at the same baseline clinic evaluation or at a separate evaluation, but had to be completed prior to randomisation. At 24 months, two reliable 24–2 SITA standard VF tests were performed and used to establish the VF outcome VFMD. In addition, a reliable Esterman VF test was performed and was used to assess driving eligibility. An independent VF reading centre assessed all the VF tests. The reading centre was masked to the treatment received by the study participant.

Intraocular pressure

Intraocular pressure was measured by Goldman tonometry at baseline and at 4, 12 and 24 months. The unit of IOP measurement is mmHg. The measurement was undertaken by two observers, and the first observer interacted directly with the patient. Without looking at the measurement dial, the investigator applied the Goldman tonometer to the eye and reached the end point for the measurement value of IOP. The second observer then recorded the values from the measurement dial. This process was repeated and both measures were recorded. If the difference between the first and the second measurements was > 3 mmHg, a third measurement was undertaken.

Visual acuity

Best-corrected log-median angle of resolution (logMAR) visual acuity (VA) was measured at baseline and at 4, 12 and 24 months post randomisation.

Ability to drive

The retention of the ability to drive is one of the most important issues to patients with glaucoma who drive. 37 All patients diagnosed with glaucoma are obliged to inform the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) of their diagnosis. Visual standards for driving are assessed on the basis of VF and VA levels. This assessment is arranged at regular intervals by the DVLA. To evaluate visual standard for driving, all participants had an Esterman VF test performed (on the Humphrey VF Analyser) at baseline and at the final visit at 24 months. Registration as visually impaired was based on VA and VF criteria. The consultant ophthalmologists were responsible for registering patients as visually disabled on the basis of these criteria. If a participant has been registered as visually impaired or severely visually impaired, this was recorded along with the date of registration in the study case report form (CRF) at 24 months.

The complications of surgery, the need for cataract surgery and therapy changes were captured from the participants’ case records. All clinical outcomes were recorded on a trial-specific CRF.

Clinical data were collected and entered onto the TAGS secure web database at the participating sites.

Economic

The objective of the economic analysis was to determine the relative cost-effectiveness of augmented trabeculectomy compared with medical management (usual care) over the trial follow-up period and extrapolated over the participant’s lifetime. Economic outcomes were:

-

incremental costs to the NHS, PSS and participants

-

incremental QALYs (based on responses to the EQ-5D-5L, HUI-3 and glaucoma utility index).

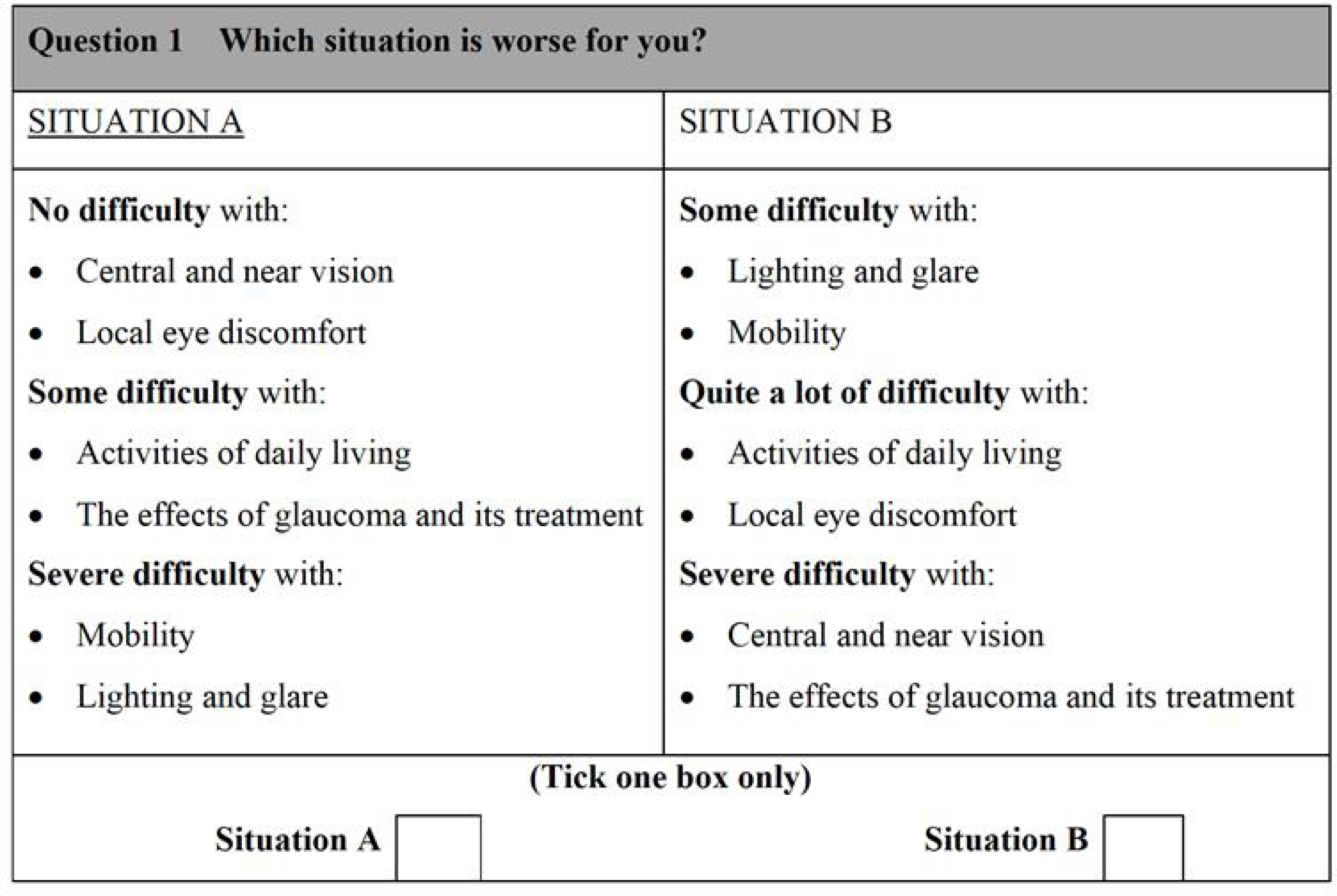

In addition, an existing DCE questionnaire with an updated design was administered to trial participants to estimate the value that individuals with advanced glaucoma place on different health states associated with glaucoma and to obtain utility scores for these health states in a population with advanced glaucoma. 55 These data were used to score the GUI responses and were incorporated into the economic evaluation reported in Chapter 6.

Details of the DCE are reported in Chapter 5, and the economic evaluation is reported in Chapter 6.

Safety reporting

We defined AEs as those events that occurred after randomisation and within the 24-month follow-up period of the trial. To be considered as an AE, an event had to be categorised as related to participation in the trial or related to glaucoma. Thus, we excluded a continuous and persistent disease or symptom, present before the trial, which failed to progress and signs or symptoms of the disease being studied (except where they deteriorated sufficiently to be considered serious).

We identified potentially expected AEs linked to medical management and trabeculectomy (with mitomycin C) as:

-

Medical management – redness, stinging, itching, transient blurred vision, eye watering, ocular discomfort, allergy, eyelash growth, change in skin colour around eye, change in iris colour, shortness of breath, unpleasant taste in mouth, dry mouth, fatigue, kidney stones, skin rash, cataract formation and retinal detachment. In some cases, some of these symptoms may have been because of preservatives in the eye drops and, if this was the case, preservative-free eye drops were used.

-

Trabeculectomy with mitomycin C – discomfort, blurred vision, corneal epithelial defect, conjunctival button hole, flap dehiscence, IOP too low, transient choroidal effusion, suprachoroidal haemorrhage, hyphaema, early bleb leak, shallow anterior chamber (grades 1–3), iris incarceration, persistent uveitis, transient or permanent ptosis, macular oedema, malignant glaucoma, corneal decompensation, cataract formation and retinal detachment, late bleb leak, bleb infection, bleb-related endophthalmitis, permanent severe loss of vision at time of surgery (< 1/500), bleeding in the eye, broad complex tachycardia while under general anaesthetic and post-operative dizziness.

In addition, a VA AE was defined as any of the following:

-

irreversible loss of 10 Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) letters of logMAR VA

-

loss of two or more stages of categorical VA measurement (count fingers, hand motion, light perception, no light perception)

-

any loss to no light perception.

These definitions were based on knowledge of AEs associated with augmented trabeculectomy and the relevant product information documented in the summary of product characteristics for eye drops. The latest online version of the appropriate summary of product characteristics was considered in the assessment of an AE.

We adhered to the standard definition of serious adverse events (SAEs) as those leading to death, hospitalisation (or prolongation of existing hospitalisation), persistent or significant disability or incapacity, congenital anomaly or birth defect, as well as an event that was considered life-threatening or otherwise considered medically significant.

Pregnancy was not considered an AE or SAE; however, we put in place processes (see the trial protocol for details1) to collect pregnancy information for participants who became pregnant while participating in the study (defined as while taking or within 3 months of ceasing to take study medications).

Masking

Given that TAGS investigated medical versus surgical management, neither the participants nor the local clinical team could be masked to the randomised treatment allocation. The only masked aspect was the evaluation of VFs at the end of the study, which was undertaken by an independent reading centre masked to the allocation: Central Angiographic Resource Facility (CARF), Queen’s University Belfast.

Methods to protect against sources of bias

The allocation to treatment arms was concealed by using a central randomisation service that could be accessed only by clinical trials unit programming staff.

The evaluation of VFs collected during the study period was by CARF masked to the participant intervention. IOP was measured by two observers: one taking the reading and the other reading the IOP value to minimise the risk of measurement bias.

The expected attrition rate was low based on a previous glaucoma treatment RCT,75 but we allowed for a potential attrition rate of 13.5% over 24 months to accommodate this.

External validity was maximised by recruiting from multiple centres and participants were treated by multiple clinicians.

Statistical analysis

Ground rules for statistical analysis

The trial analysis followed a statistical analysis plan (see Report Supplementary Material 2), which was agreed in advance by the TSC. The main analyses were based on the intention-to-treat (i.e. analyse as randomised) principle and took place after the 24-month follow-up. Baseline and follow-up data were summarised using appropriate statistics and graphical summaries. Statistical significance was at the two-sided 5% level with corresponding CIs derived. All analyses were carried out using Stata® version 16 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Sample size

The primary patient-reported outcome was the health status measured by the VFQ-25 assessment at 24 months. A study with 190 participants in each arm would have 90% power at a two-sided 5% significance level to detect a difference in means of 0.33 of a standard deviation (SD), which translates to 6 points on the VFQ-25 assuming a common SD of 18 points observed in previous work that has a clinically relevant effect size in patients with advanced glaucoma. 76,77 Seven points is a likely minimally important difference based on our pilot work on VFQ-25 scores in patients with glaucoma,77 but there is uncertainty, and so we opted for a more conservative 6-point difference, which is supported by the literature for another chronic eye disease, macular degeneration. 78 Assuming a drop-out rate of 13.5% as a result of declining further follow-up and death, we had to randomise a total of 440 participants to detect this difference.

For the secondary clinical outcome (VFMD), TAGS had 90% power at 5% significance to detect a 1.3 dB difference in VFMD. This is derived from a subgroup of patients with advanced glaucoma and is a clinically significant difference in the context of advanced glaucoma and predictive further visual disability. 30,43

Centres that had a throughput of at least 20 eligible patients annually were approached to participate in the trial. This enabled the development of a recruitment projection based on 20 sites recruiting approximately 9–11 patients per year, with a staggered start of recruiting sites, and allowed 440 participants to be recruited over 3 years (assuming a reduced rate during the first month of each site set-up and 50% reduction during the holiday months of August and December).

Primary/secondary outcome analysis

The primary outcome, VFQ-25 assessed at 24 months, was analysed using a heteroscedastic partially nested repeated-measures mixed-effects linear model correcting for baseline score and bilateral disease, and time as a fixed effect. 79 The repeated measures were VFQ-25 assessed at 4, 12 and 24 months. Treatment effects were estimated from time-by-treatment interactions at each time point; the primary time of interest was 24 months. This approach uses participant data from all of the time points and incorporates a random effect for centre and surgeon using restricted maximum likelihood. We used this approach to account for the potential lack of independence of outcome data for patients treated by the same surgeon. This is known as clustering or the surgeon effect, and occurs in the trabeculectomy arm only (hence the ‘nested’ approach) in TAGS. We also adjusted for heteroscedastic errors because the residuals compared with the fitted values showed evidence that the variance of errors were different between treatment arms. We did not carry out any sensitivity analysis for missing data because < 10% of VFQ-25 data were missing. Given the pragmatic nature of TAGS, there was the potential for participants to cross over from one intervention to the other. To estimate the treatment effect in the subgroup of participants who complied with allocated treatment, we used complier-average causal effect (CACE) methods using instrumental variable regression80 and a per-protocol analysis.

For the secondary outcomes, EQ-5D-5L, HUI-3, GUI, IOP and logMAR VA, VFs were analysed following the same method as the primary outcome. The utility values for the GUI were derived from the results of the DCE (which are presented in Chapter 5). For the IOP, logMAR VA and VF tests, a sensitivity analysis was performed using data from all eligible eyes by also including a random effect at the participant level to reflect the lack of independence of eyes within participants. In addition, for the VFs a further two sensitivity analyses were performed: the first included only the VF tests performed in accordance with SITA standard and the second removed participants who had only one VF test or in whom the false positive standard was > 15%. The post hoc Dunnett’s multiplicity p-values were presented for IOP and logMAR VA. Patient experience (glaucoma getting worse) was analysed using a repeated-measures mixed-effects Poisson model adjusting for bilateral disease and including a random effect for surgeon and treatment. The need for cataract surgery, visual standards for driving and safety outcomes were analysed using the same modelling approach. Given that the number of events for patients registered as sight impaired was small, we used Fisher’s exact test. Data missing at baseline were reported as such, and for the primary/secondary outcomes continuous data were imputed using the centre-specific mean of that variable.

Subgroup analyses

Planned subgroup analyses explored the potential treatment effect moderation of sex, age (< 65 years vs. ≥ 65 years), one or both eyes affected with advanced glaucoma, Index of Multiple Deprivation (quintile) and extent of VF loss at baseline (–20 dB, ≥ –20 dB) on the primary outcome. The subgroup-by-treatment interaction was assessed by including interaction terms in the models outlined above. We used a stricter level of statistical significance (two-sided 1% significance level) and 99% CIs to reflect the exploratory nature of these analyses. A post hoc subgroup analysis of IOP at diagnosis (< 21 mmHg vs. ≥ 21 mmHg) was also explored following the same analysis method as the planned subgroup analysis.

Criteria for the termination of the trial

Owing to the staggered nature of recruitment and, therefore, the measurement of the primary outcome at 24 months, we did not anticipate that the trial would be terminated early for benefit. We proposed one main effectiveness analysis at the end of the trial. During the trial, safety and other data were monitored by reports prepared for the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC). The DMC decided to meet every 6 months until June 2018.

Economic evaluation

In this study both a ‘within-trial’ and a model-based economic evaluation were conducted. These are described in detail in Chapter 6.

Research ethics and regulatory approvals

TAGS received favourable ethics opinion from the East Midlands – Derby Research Ethics Committee (REC) on 12 December 2013 (REC reference number 13/EM/0395).

Changes to the protocol

The main changes to the protocol (see Appendix 8) since original ethics approval include the addition of further follow-up assessments (at 3, 4 and 5 years) and a genetics substudy. All amendments were reviewed by the sponsor and the independent TSC on behalf of the funder before being submitted to, and then approved by, the REC. The results of these studies are not reported in this monograph.

Management of the trial

The trial management team, based within CHaRT, University of Aberdeen, provided day-to-day support for the recruiting centres and was led by a local principal investigator (PI). The PIs, in most cases supported by research nurses, trial co-ordinators or dedicated staff, were responsible for all aspects of local organisation, including the recruitment of participants, delivery of the interventions and notification of any problems or unexpected developments during the study period.

Study oversight committees

Study Management Group

The Study Management Group (SMG) was responsible for the day-to-day management of the trial. This group consisted of the chief investigator, trial manager, senior trial manager, data co-ordinator, statistician and a sponsor representative. Members of the SMG are listed in the Acknowledgements.

Project Management Group

The Project Management Group (PMG) was responsible for overseeing the management of the trial. This group consisted of the SMG plus grant applicants, a public and patient involvement (PPI) representative and a senior programmer. Members of the PMG are listed in the Acknowledgements.

Trial Steering Committee

The Trial Steering Committee (TSC) was responsible for monitoring and supervising the progress of TAGS. The committee met seven times between April 2014 and December 2019 at agreed intervals. The TSC consisted of independent experts, a PPI member, the chief investigator and key members of the PMG. Members of the TSC are listed in the Acknowledgements.

Data Monitoring Committee

The DMC was independent of the trial and was responsible for monitoring safety and data integrity. The committee met eight times between April 2014 and August 2018, approximately every 6 months at intervals agreed by the committee. The trial statistician provided the data and analyses requested by the DMC prior to each meeting. The committee consisted of three independent experts. Members of the DMC are listed in the Acknowledgements.

Chapter 3 Participant baseline characteristics

Trial recruitment

Between 3 June 2014 and 21 May 2017, we recruited 453 participants from 27 centres (Table 2): 227 were randomised to the trabeculectomy arm and 226 to the medical management arm. The trajectory of recruitment from all centres is shown in Figure 1.

| Centre | All (N = 453), n (%) | Treatment arm, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trabeculectomy (N = 227) | Medical management (N = 226) | ||

| Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth | 52 (11.5) | 26 (11.5) | 26 (11.5) |

| Queen’s Medical Centre, Nottingham | 46 (10.2) | 24 (10.6) | 22 (9.7) |

| Guy’s and St Thomas’, London | 36 (7.9) | 18 (7.9) | 18 (8.0) |

| Moorfields Eye Hospital, London | 26 (5.7) | 12 (5.3) | 14 (6.2) |

| Bristol Eye Hospital, Bristol | 26 (5.7) | 14 (6.2) | 12 (5.3) |

| Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital, Norwich | 24 (5.3) | 12 (5.3) | 12 (5.3) |

| Manchester Royal Eye Hospital, Manchester | 21 (4.6) | 10 (4.4) | 11 (4.9) |

| York Hospital, York | 19 (4.2) | 9 (4.0) | 10 (4.4) |

| Princess Alexandra Eye Hospital, Edinburgh | 17 (3.8) | 8 (3.5) | 9 (4.0) |

| Hinchingbrooke Hospital, Huntingdon | 17 (3.8) | 9 (4.0) | 8 (3.5) |

| Western Eye Hospital, Imperial, London | 16 (3.5) | 9 (4.0) | 7 (3.1) |

| Sunderland Eye Infirmary, Sunderland | 16 (3.5) | 8 (3.5) | 8 (3.5) |

| Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast Health and Social Care Trust, Belfast | 15 (3.3) | 7 (3.1) | 8 (3.5) |

| Maidstone Hospital, Maidstone | 14 (3.1) | 7 (3.1) | 7 (3.1) |

| Royal Derby Hospital, Derby | 13 (2.9) | 6 (2.6) | 7 (3.1) |

| Warrington Hospital, Warrington | 13 (2.9) | 6 (2.6) | 7 (3.1) |

| James Paget Hospital, Great Yarmouth | 13 (2.9) | 7 (3.1) | 6 (2.7) |

| Birmingham and Midland Eye Centre, Birmingham | 12 (2.6) | 7 (3.1) | 5 (2.2) |

| Birmingham Heartlands Hospital, Birmingham | 12 (2.6) | 6 (2.6) | 6 (2.7) |

| University Hospital Coventry, Coventry | 10 (2.2) | 6 (2.6) | 4 (1.8) |

| Queen Margaret Hospital, Dunfermline | 9 (2.0) | 4 (1.8) | 5 (2.2) |

| Cheltenham General Hospital, Cheltenham | 8 (1.8) | 4 (1.8) | 4 (1.8) |

| Harrogate District Hospital, Harrogate | 6 (1.3) | 3 (1.3) | 3 (1.3) |

| Ninewells Hospital, Dundee | 4 (0.9) | 2 (0.9) | 2 (0.9) |

| Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.9) |

| Hairmyres Hospital, Lanarkshire | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.9) |

| Gartnavel General Hospital, Glasgow | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) |

FIGURE 1.

Recruitment over time.

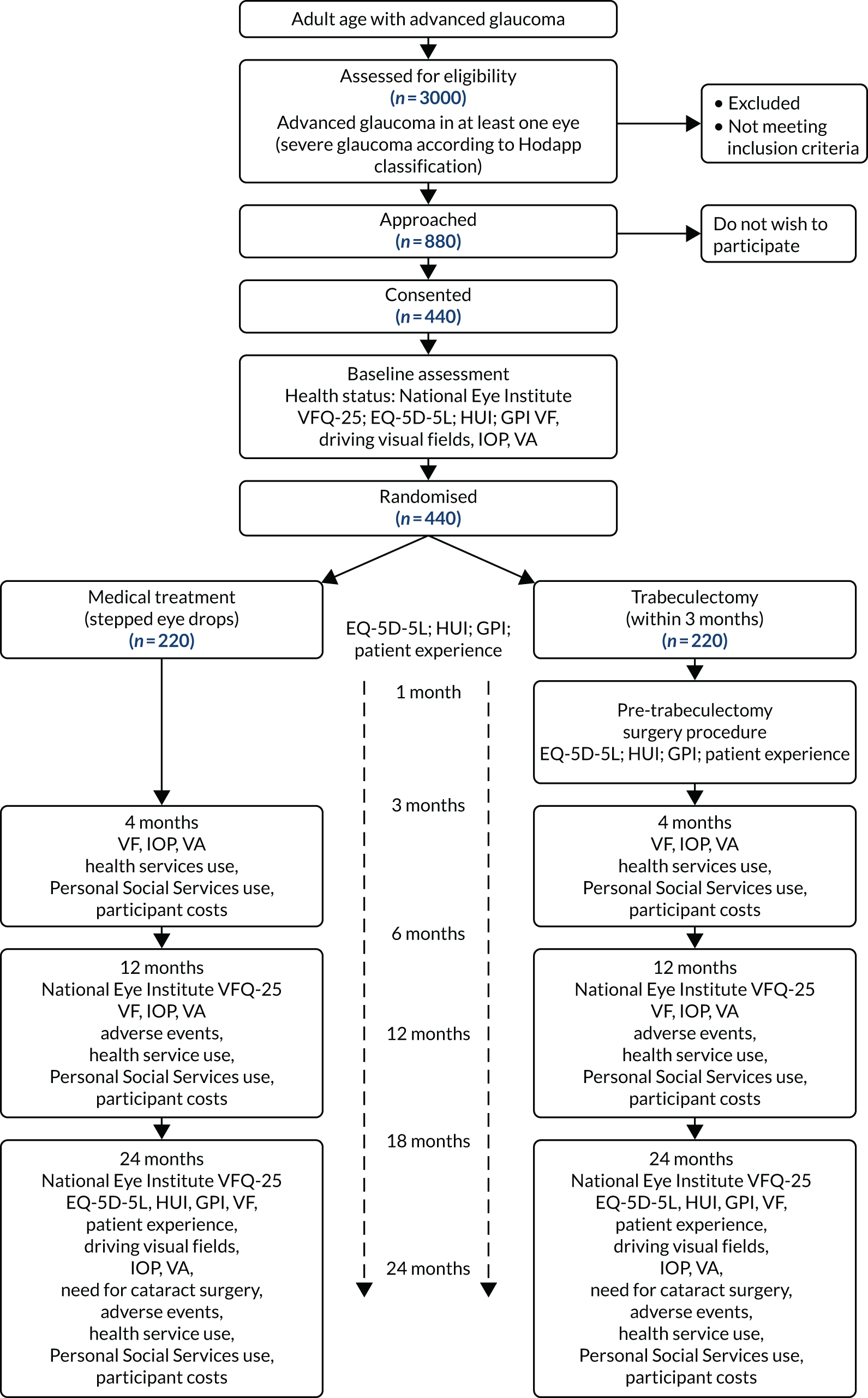

Participant flow

Figure 2 shows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram for TAGS. A total of 962 potentially eligible patients were screened, of whom 509 were excluded: 233 because they were ineligible and 276 because they declined to participate. The main reasons for ineligibility were that VFs did not meet the inclusion criteria (24%) and that patients could not be randomised within 3 months of diagnosis (22.7%). Those who declined either did not give a reason (27.9%) or did not want surgery (19.6%). Further details on reasons why patients were excluded can be found in Appendix 2, Table 23.

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT flow diagram presenting participant flow in the trial.

All of the participants attended a baseline clinical assessment, but one participant in the trabeculectomy arm and two participants in the medical management arm did not provide baseline VFQ-25 (primary outcome). A total of 11 participants declined further questionnaires and clinical follow-up (not including treatment clinics) from the study, and nine deaths were reported, none of which was caused by a study intervention. In the trabeculectomy arm, 201 (88.5%) participants underwent trabeculectomy in their index eye: trabeculectomy was performed within 3 months of randomisation in 151 (66.5%) participants and after 3 months in 49 (21.2%) participants. For one participant, the timing of trabeculectomy was unknown (see Figure 2). There were 16 (7.0%) participants who declined trabeculectomy, two (0.9%) died before they could receive a trabeculectomy and eight (3.5%) did not receive trabeculectomy in their index eye. Further details about the treatment received are described later in this chapter. At the 24-month follow-up, 207 (91.2%) participants in the trabeculectomy arm and 205 (90.7%) participants in the medical management arm provided primary outcome data.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 3 and the treatment arms were well balanced. The mean age of the participants was 67 years in the trabeculectomy arm and 68 years in the medical management arm. Over 65% of participants were male and over 80% were white. In total, the percentage of participants who had bilateral disease was 19.4% in the trabeculectomy arm and 19.5% in the medical management arm, and over 90% in both arms had primary OAG. The mean VFQ-25 was 87.1 in both arms and the mean VFMD (dB) was –14.9 and –15.3 in the trabeculectomy arm and the medical management arm, respectively. The baseline characteristics for the non-index eye and the HPA classification of glaucoma severity are shown in Appendix 2, Tables 24 and 25, respectively.

| Characteristic | Treatment arm | |

|---|---|---|

| Trabeculectomy (N = 227) | Medical management (N = 226) | |

| Age (years), n; mean (SD) | 227; 67 (12.2) | 226; 68 (12.4) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 156 (68.7) | 147 (65.0) |

| Female | 71 (31.3) | 79 (35.0) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White | 182 (80.2) | 191 (84.5) |

| Afro-Caribbean | 32 (14.1) | 27 (11.9) |

| Asian – India/Pakistan/Bangladesh | 8 (3.5) | 4 (1.8) |

| Asian – Oriental | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0) |

| Mixed | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Other | 3 (1.3) | 2 (0.9) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Advanced glaucoma in both eyes, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 44 (19.4) | 44 (19.5) |

| No | 183 (80.6) | 182 (80.5) |

| Glaucoma in both eyes, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 178 (78.4) | 169 (74.8) |

| No | 49 (21.6) | 57 (25.2) |

| Eligible to be registered as sight impaired, n (%) | ||

| No | 214 (94.3) | 212 (93.8) |

| Sight impaired | 10 (4.4) | 12 (5.3) |

| Severely sight impaired | 3 (1.3) | 2 (0.9) |

| Glaucoma diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Primary OAG (including NTG) | 219 (96.5) | 220 (97.3) |

| Pigment dispersion syndrome | 5 (2.2) | 4 (1.8) |

| Pseudoexfoliation syndrome | 3 (1.3) | 2 (0.9) |

| Lens status, n (%) | ||

| Phakic | 212 (93.4) | 209 (92.5) |

| Pseudophakic | 15 (6.6) | 17 (7.5) |

| Central corneal thickness (µm), n; mean (SD) | 226; 539.4 (35.7) | 223; 541.4 (35.7) |

| Glaucoma eye drops, n (%) | ||

| Prostaglandin analogue | 186 (81.9) | 182 (80.5) |

| Beta-blocker | 52 (22.9) | 52 (23.0) |

| Carbonic anhydrase inhibitor | 45 (19.8) | 33 (14.6) |

| α-agonist | 7 (3.1) | 4 (1.8) |

| Diamoxa | 6 (2.6) | 2 (0.9) |

| Family history of glaucoma, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 63 (27.8) | 79 (35.0) |

| No | 152 (67.0) | 131 (58.0) |

| Missing | 12 (5.3) | 16 (7.1) |

| Number of times visited the optician in the last 10 years, n; median (IQR) | 214; 5 (2–6) | 209; 5 (3–8) |

| Index of Multiple Deprivation, n (%) | ||

| First quintile (most deprived) | 54 (23.8) | 52 (23.0) |

| Second quintile | 30 (13.2) | 37 (16.4) |

| Third quintile | 45 (19.8) | 43 (19.0) |

| Fourth quintile | 50 (22.0) | 43 (19.0) |

| Fifth quintile (least deprived) | 47 (20.7) | 49 (21.7) |

| Missing | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.9) |

| Ocular comorbidity, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 50 (22.0) | 50 (22.1) |

| No | 177 (78.0) | 176 (77.9) |

| Ocular comorbidity details,b n (%) | ||

| AMD | 6 (12.0) | 4 (8.0) |

| Cataract | 42 (84.0) | 42 (84.0) |

| Vascular occlusion | 2 (4.0) | 1 (2.0) |

| Diabetic retinopathy | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) |

| Other | 9 (18.0) | 6 (12.0) |

| VFQ-25, n; mean (SD) | 226; 87.1 (13.6) | 224; 87.1 (13.4) |

| VFQ-25 subscales, n; mean (SD) | ||

| Near activities | 225; 84.2 (18.5) | 224; 84.4 (16.9) |

| Distance activities | 226; 88.5 (16.1) | 224; 89.7 (14.4) |

| Dependency | 226; 94.0 (17.3) | 222; 94.9 (15.7) |

| Driving | 171; 85.9 (26.7) | 158; 84.8 (26.2) |

| General health | 225; 63.6 (23.4) | 223; 60.9 (22.6) |

| Role difficulties | 226; 87.1 (19.8) | 222; 87.4 (20.8) |

| Mental health | 226; 81.1 (21.2) | 224; 81.8 (19.9) |

| General vision | 223; 74.9 (14.5) | 223; 72.8 (14.2) |

| Social function | 225; 95.2 (11.9) | 224; 94.9 (12.1) |

| Colour vision | 223; 96.9 (10.9) | 222; 96.6 (11.1) |

| Peripheral vision | 224; 86.6 (20.8) | 224; 87.2 (20.2) |

| Ocular pain | 225; 84.7 (19.0) | 224; 83.9 (17.2) |

| VFMD (dB), n; mean (SD) | 227; –14.91 (6.36) | 226; –15.26 (6.34) |

| LogMAR VA, n; mean (SD) | 227; 0.15 (0.25) | 223; 0.17 (0.26) |

| Intraocular pressure (mmHg), n; mean (SD) | ||

| Diagnosis | 226; 26.9 (9.1) | 223; 25.9 (8.4) |

| Baseline | 222; 19.4 (6.2) | 221; 19.0 (5.7) |

| EQ-5D-5L, n; mean (SD) | 222; 0.844 (0.185) | 222; 0.837 (0.176) |

| HUI-3, n; mean (SD) | 214; 0.814 (0.202) | 214; 0.809 (0.208) |

| GUI, n; mean (SD) | 219; 0.884 (0.131) | 222; 0.863 (0.130) |

| Participant experience (glaucoma getting worse), n (%) | ||

| Yes | 95 (41.9) | 76 (33.6) |

| No | 113 (49.8) | 133 (58.8) |

| Missing | 19 (8.4) | 17 (7.5) |

| Visual standards for driving, n (%) | ||

| Pass | 187 (82.4) | 196 (86.7) |

| Fail | 27 (11.9) | 21 (9.3) |

| Missing | 13 (5.7) | 9 (4.0) |

Treatment received

In the trabeculectomy arm, 201 (88.5%) participants received surgery in their index eye. Of the remaining 26 participants, four had surgery in their non-index-eye only, 16 declined surgery, two died prior to having surgery and four had yet to receive surgery. Thirty-four (15.0%) participants underwent trabeculectomy in their non-index eye, of whom four did not undergo trabeculectomy in their index eye (see Appendix 3, Table 27). In the medical management arm, 39 (17.3%) participants underwent trabeculectomy (Table 4). The median time to trabeculectomy was 8.9 weeks in the trabeculectomy arm. Among the 27 participants in the medical management arm for whom the date of surgery was known, the median time to surgery was 47.7 weeks post randomisation, and in 15 cases was more than 12 months post randomisation. At the time of surgery, the mean number of eye drop agents that the patient had received pre-operatively was 1.4 (SD 1.1) in the trabeculectomy arm and 1.9 (SD 1.1) in the medical management arm (see Table 4 for the classes of eye drops prescribed.) At the time of surgery, the mean pre-operative IOP was 19.3 mmHg in the trabeculectomy arm and 21.1 mmHg in the medical management arm. Appendix 3, Table 26, gives further details of the trabeculectomy procedure. Appendix 3, Table 27, shows the results for the non-index eye.

| Trabeculectomy details | Treatment arm | |

|---|---|---|

| Trabeculectomy | Medical management | |

| Received surgery in their index eye, n/N (%) | 201/227 (88.5) | 39/226 (17.3) |

| Time to trabeculectomy (weeks), n; median (IQR) | 200; 8.9 (5.3–11.9) | 39; 47.4 (23.0–63.1) |

| Reasons for trabeculectomy,a n (%) | ||

| Uncontrolled IOP | 23 (60.5) | |

| VF progression | 6 (15.8) | |

| Drop intolerance | 4 (10.5) | |

| Missing | 11 (28.9) | |

| Trabeculectomy clinical report form provided (n) | 199 | 27 |

| Number of different types of eye drops received pre-operatively, mean (SD) | 1.4 (1.1) | 1.9 (1.1) |

| Type of pre-operative eye drop, n (%) | ||

| Carbonic anhydrase inhibitor | 57 (28.6) | 14 (51.9) |

| Prostaglandin analogue | 148 (74.4) | 21 (77.8) |

| Beta-blocker | 56 (28.1) | 12 (44.4) |

| α-agonist | 9 (4.5) | 4 (14.8) |

| Parasympathomimetic | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0) |

| Diamox, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 3 (1.5) | 1 (3.7) |

| No | 192 (96.5) | 26 (96.3) |

| Missing | 4 (2.0) | 0 (0) |

| Pre-operative IOP (mmHg), n; mean (SD) | 179; 19.3 (6.0) | 26; 21.1 (4.0) |

At the 24-month follow-up, 9 out of 181 (5.0%) participants in the trabeculectomy arm had been added to a waiting list to have a trabeculectomy in their non-index eye. In their medical management arm, 14 out of 204 (6.9%) participants had been added to a waiting list to have a trabeculectomy, in 11 of whom trabeculectomy was planned for the index eye.

Chapter 4 Trial results

Primary outcome

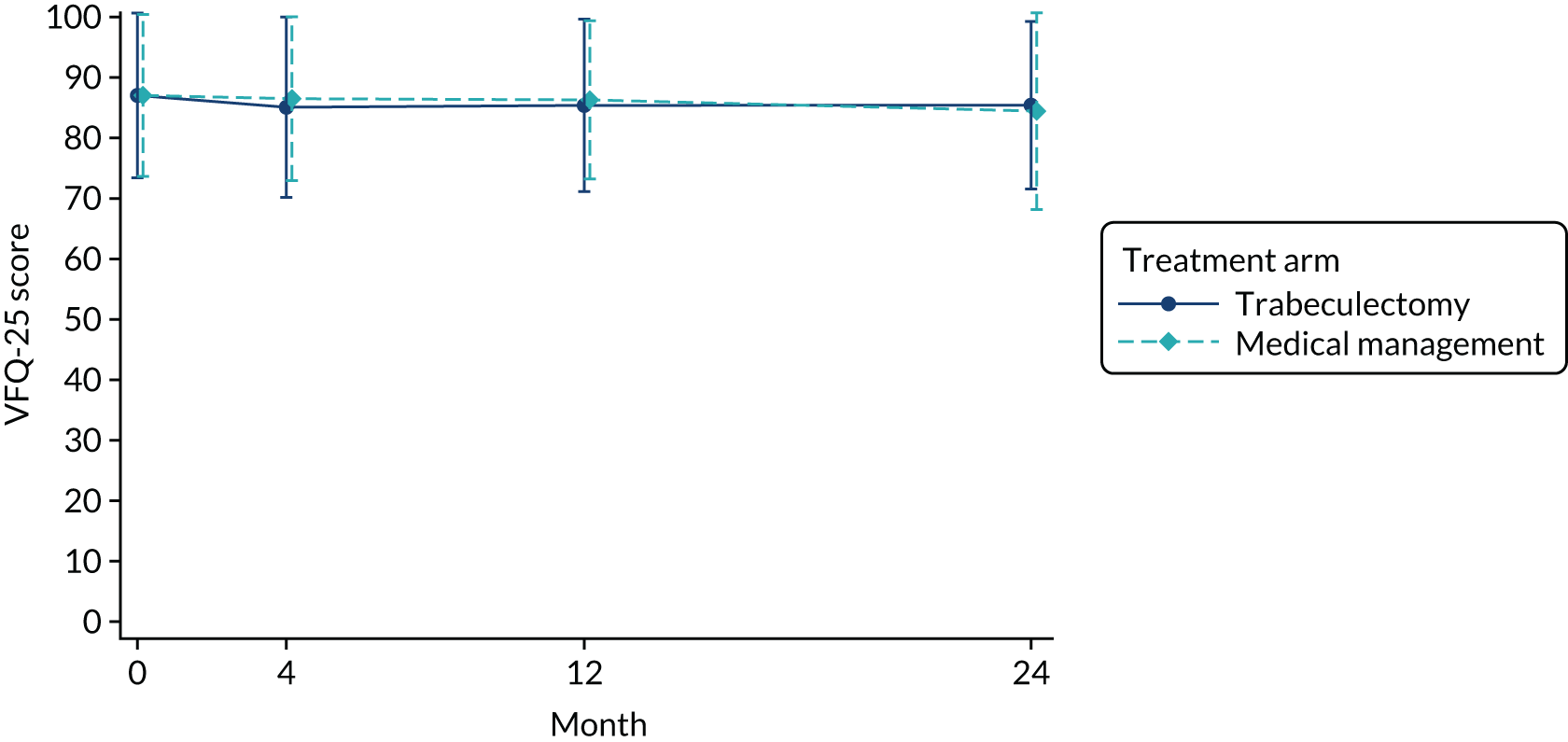

The mean VFQ-25 score in the trabeculectomy arm and the medical management arm at baseline was 87.1 (Table 5). Figure 3 shows the mean (SD) VFQ-25 score over time. At 24 months, the difference between arms was 1.06 (95% CI –1.32 to 3.43; p = 0.383). The results were similar at all other time points (see Table 5). The VFQ-25 subscales are presented in Table 5. The per-protocol analysis (see Appendix 3, Table 28) showed similar results across all time points; at 24 months, the adjusted MD was 0.95 (95% CI –1.54 to 3.45; p = 0.454). The per-protocol analysis for VFQ-25 subscales is also presented in Appendix 3, Table 28. The CACE results for VFQ-25 score were also similar at 24 months (MD 1.52, 95% CI –1.27 to 4.30; p = 0.286) (see Appendix 3, Table 29).

| Measure | Treatment arm, n; mean (SD) | Adjusted MD | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trabeculectomy (N = 227) | Medical management (N = 226) | ||||

| VFQ-25 | |||||

| Baseline | 226; 87.1 (13.6) | 224; 87.1 (13.4) | |||

| 4 months | 212; 85.1 (14.9) | 216; 86.5 (13.6) | –1.24 | –3.58 to 1.11 | 0.301 |

| 12 months | 214; 85.4 (14.3) | 209; 86.3 (13.1) | –0.64 | –3.00 to 1.72 | 0.595 |

| 24 months | 207; 85.4 (13.8) | 205; 84.5 (16.3) | 1.06 | –1.32 to 3.43 | 0.383 |

| VFQ-25 subscales | |||||

| Near activities | |||||

| Baseline | 225; 84.2 (18.5) | 224; 84.4 (16.9) | |||

| 4 months | 211; 83.9 (18.0) | 214; 84.9 (17.1) | –0.56 | –4.12 to 3.01 | |

| 12 months | 214; 84.1 (18.6) | 209; 84.7 (18.4) | –0.06 | –3.63 to 3.52 | |

| 24 months | 205; 82.8 (18.4) | 204; 82.3 (19.9) | 1.11 | –2.50 to 4.73 | |

| Distance activities | |||||

| Baseline | 226; 88.5 (16.1) | 224; 89.7 (14.4) | |||

| 4 months | 211; 87.8 (16.8) | 216; 89.0 (15.4) | 0.10 | –2.92 to 3.13 | |

| 12 months | 214; 88.2 (16.3) | 209; 88.6 (15.7) | 0.94 | –2.10 to 3.99 | |

| 24 months | 207; 88.0 (15.9) | 204; 86.2 (18.9) | 2.89 | –0.18 to 5.96 | |

| Dependency | |||||

| Baseline | 226; 94.0 (17.3) | 222; 94.9 (15.7) | |||

| 4 months | 211; 91.2 (20.2) | 216; 93.4 (17.5) | –1.67 | –4.97 to 1.62 | |

| 12 months | 213; 92.1 (19.6) | 209; 94.3 (14.5) | –1.40 | –4.71 to 1.90 | |

| 24 months | 206; 93.6 (15.6) | 203; 92.7 (17.7) | 2.00 | –1.34 to 5.35 | |

| Driving | |||||

| Baseline | 171; 85.9 (26.7) | 158; 84.8 (26.2) | |||

| 4 months | 151; 82.1 (30.6) | 155; 83.0 (27.4) | –0.10 | –7.00 to 6.80 | |

| 12 months | 152; 81.3 (28.9) | 149; 79.9 (29.8) | 0.63 | –6.33 to 7.59 | |

| 24 months | 143; 81.1 (29.3) | 138; 79.9 (28.7) | 1.88 | –5.18 to 8.94 | |

| General health | |||||

| Baseline | 225; 63.6 (23.4) | 223; 60.9 (22.6) | |||

| 4 months | 211; 66.0 (23.4) | 215; 64.8 (20.9) | –0.07 | –4.68 to 4.54 | |

| 12 monthsa | 214; 66.1 (23.8) | 208; 60.5 (22.4) | 4.86 | 0.23 to 9.49 | |

| 24 months | 206; 63.3 (25.5) | 205; 59.9 (23.5) | 2.44 | –2.22 to 7.09 | |

| Role difficulties | |||||

| Baseline | 226; 87.1 (19.8) | 222; 87.4 (20.8) | |||

| 4 monthsa | 212; 82.5 (24.5) | 216; 86.3 (21.7) | –4.60 | –8.70 to –0.50 | |

| 12 months | 213; 83.2 (23.2) | 209; 84.8 (21.1) | –2.07 | –6.19 to 2.06 | |

| 24 months | 207; 83.0 (22.7) | 203; 83.4 (23.4) | –0.80 | –4.97 to 3.37 | |

| Mental health | |||||

| Baseline | 226; 81.1 (21.2) | 224; 81.8 (19.9) | |||

| 4 months | 212; 79.5 (23.3) | 216; 83.5 (19.6) | –3.76 | –7.55 to 0.02 | |

| 12 months | 214; 79.6 (22.4) | 209; 83.2 (19.7) | –3.26 | –7.06 to 0.54 | |

| 24 months | 207; 80.8 (20.7) | 205; 81.4 (21.6) | –0.55 | –4.38 to 3.28 | |

| General vision | |||||

| Baseline | 223; 74.9 (14.5) | 223; 72.8 (14.2) | |||

| 4 monthsa | 211; 71.7 (14.4) | 215; 74.0 (12.5) | –3.17 | –6.03 to –0.32 | |

| 12 months | 213; 73.1 (14.6) | 208; 73.8 (13.9) | –1.70 | –4.57 to 1.17 | |

| 24 months | 206; 73.3 (13.4) | 203; 72.2 (14.6) | –0.03 | –2.92 to 2.87 | |

| Social function | |||||

| Baseline | 225; 95.2 (11.9) | 224; 94.9 (12.1) | |||

| 4 months | 211; 95.1 (12.0) | 216; 94.6 (11.9) | 0.33 | –2.29 to 2.95 | |

| 12 months | 214; 94.3 (13.5) | 208; 94.5 (11.8) | –0.34 | –2.98 to 2.29 | |

| 24 months | 206; 95.0 (12.2) | 205; 93.2 (16.1) | 1.47 | –1.18 to 4.13 | |

| Colour vision | |||||

| Baseline | 223; 96.9 (10.9) | 222; 96.6 (11.1) | |||

| 4 months | 209; 97.4 (8.8) | 214; 96.8 (10.2) | 0.44 | –1.40 to 2.28 | |

| 12 months | 212; 96.1 (11.1) | 205; 97.4 (8.7) | –1.37 | –3.22 to 0.49 | |

| 24 months | 206; 95.6 (13.9) | 204; 95.0 (15.2) | 0.70 | –1.17 to 2.57 | |

| Peripheral vision | |||||

| Baseline | 224; 86.6 (20.8) | 224; 87.2 (20.2) | |||

| 4 months | 210; 85.4 (21.1) | 214; 85.6 (20.4) | –0.43 | –4.59 to 3.74 | |

| 12 months | 214; 86.4 (20.8) | 207; 85.6 (20.2) | 0.87 | –3.31 to 5.06 | |

| 24 months | 205; 85.1 (19.6) | 204; 83.8 (22.4) | 0.86 | –3.35 to 5.08 | |

| Ocular pain | |||||

| Baseline | 225; 84.7 (19.0) | 224; 83.9 (17.2) | |||

| 4 months | 212; 81.3 (19.2) | 216; 80.5 (18.9) | 0.22 | –2.96 to 3.40 | |

| 12 months | 214; 81.6 (20.0) | 209; 81.9 (16.3) | –0.61 | –3.80 to 2.59 | |

| 24 months | 207; 81.6 (19.7) | 205; 80.5 (18.7) | 0.98 | –2.25 to 4.21 | |

FIGURE 3.

Mean (SD) VFQ-25 by arm over time.

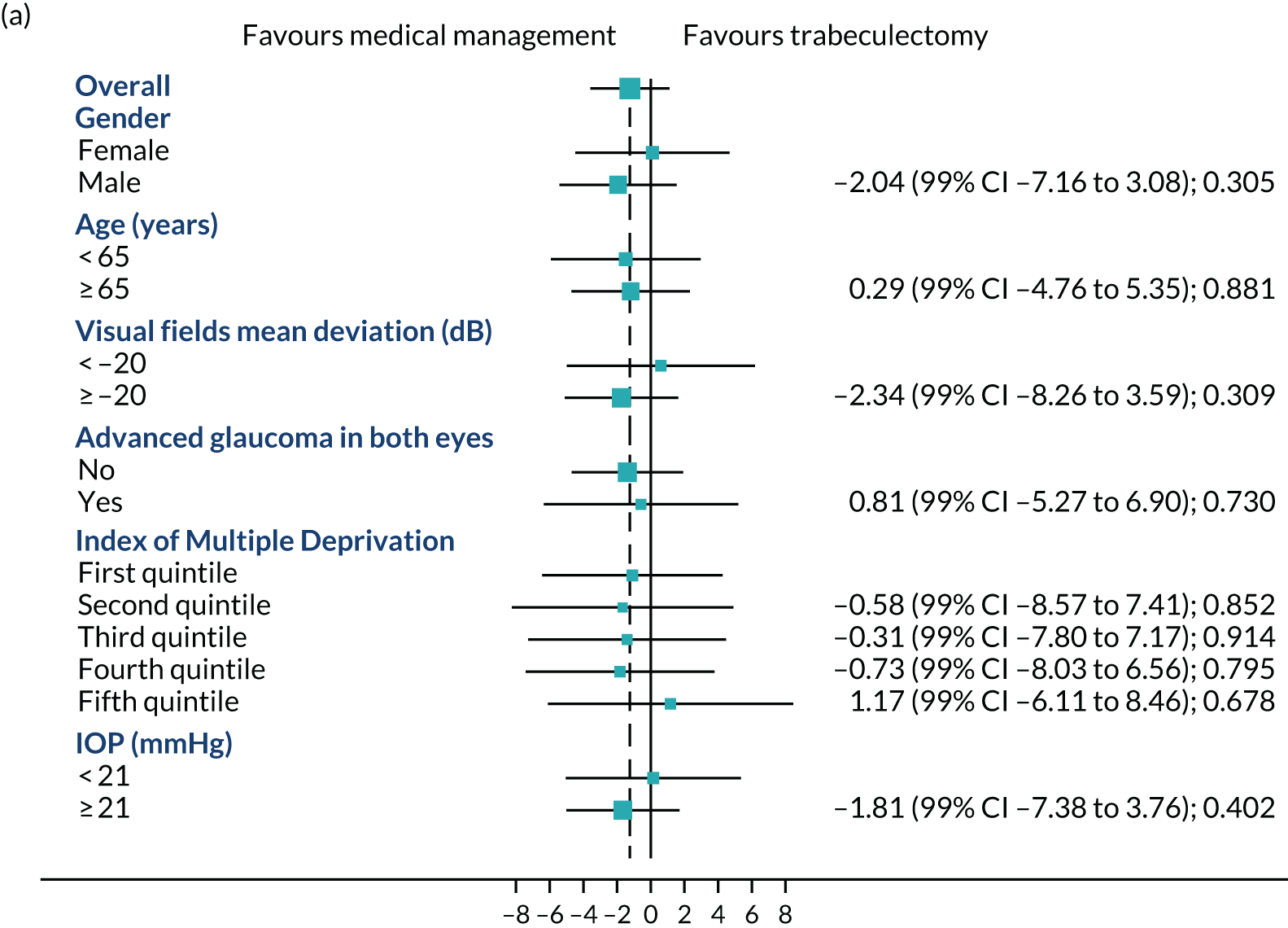

Subgroup analysis

Figures 4a–c show the prespecified subgroup analyses at 4, 12 and 24 months for VFQ-25 score, sex, age (< 65 vs. ≥ 65 years), VFs (–20 dB vs. ≥ –20 dB), advanced glaucoma in both eyes, Index Multiple Deprivation quintile (most deprived to least deprived) and IOP at diagnosis (< 21 mmHg vs. ≥ 21 mmHg). There was no evidence of any treatment effect heterogeneity at 4 or 12 months. At 24 months, a potential moderating effect of age is emerging; however, there is considerable uncertainty around the estimate of the interaction effect.

FIGURE 4.

Subgroups for trabeculectomy vs. medical management: (a) 4 months, (b) 12 months and (c) 24 months. First quintile, most deprived; fifth quintile, least deprived. Boxes indicate mean differences. Solid black line indicates 99% CI. Solid vertical line indicates no effect. Dashed vertical line indicates overall effect.

Secondary outcomes

EQ-5D-5L

The mean baseline EQ-5D-5L score was 0.844 in the trabeculectomy arm and 0.837 in the medical management arm. At the follow-up time points, there was no evidence of a difference in the mean EQ-5D-5L score, and at 24 months the MD was 0.016 (95% CI –0.021 to 0.053; p = 0.405) (Table 6).

| Measure | Treatment arm | Estimatea | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trabeculectomy (N = 227) | Medical management (N = 226) | ||||

| EQ-5D-5L, n; mean (SD) | |||||

| Baseline | 222; 0.844 (0.185) | 222; 0.837 (0.176) | |||

| 1 month | 194; 0.838 (0.185) | 203; 0.808 (0.203) | 0.025 | –0.012 to 0.062 | 0.189 |

| 3 months | 186; 0.836 (0.167) | 179; 0.814 (0.195) | 0.015 | –0.024 to 0.053 | 0.455 |

| 6 months | 186; 0.850 (0.184) | 195; 0.822 (0.204) | 0.016 | –0.021 to 0.054 | 0.391 |

| 12 months | 211; 0.837 (0.177) | 209; 0.823 (0.164) | 0.014 | –0.022 to 0.051 | 0.442 |

| 18 months | 181; 0.828 (0.185) | 184; 0.791 (0.219) | 0.023 | –0.016 to 0.061 | 0.244 |

| 24 months | 206; 0.810 (0.179) | 203; 0.796 (0.191) | 0.016 | –0.021 to 0.053 | 0.405 |

| HUI-3, n; mean (SD) | |||||

| Baseline | 214; 0.814 (0.202) | 214; 0.809 (0.208) | |||

| 1 month | 184; 0.791 (0.232) | 193; 0.786 (0.230) | –0.000 | –0.043 to 0.043 | 1.000 |

| 3 months | 180; 0.796 (0.223) | 179; 0.779 (0.222) | 0.007 | –0.036 to 0.051 | 0.741 |

| 6 months | 180; 0.805 (0.216) | 182; 0.782 (0.224) | 0.020 | –0.024 to 0.063 | 0.376 |

| 12 months | 204; 0.829 (0.193) | 196; 0.798 (0.199) | 0.024 | –0.018 to 0.066 | 0.262 |

| 18 months | 169; 0.802 (0.212) | 174; 0.749 (0.258) | 0.022 | –0.022 to 0.066 | 0.324 |

| 24 months | 198; 0.786 (0.227) | 193; 0.751 (0.246) | 0.036 | –0.006 to 0.078 | 0.094 |

| GUI, n; mean (SD) | |||||

| Baseline | 219; 0.884 (0.131) | 222; 0.863 (0.130) | |||

| 1 month | 194; 0.862 (0.138) | 205; 0.853 (0.156) | –0.000 | –0.028 to 0.028 | 0.984 |

| 3 months | 187; 0.849 (0.130) | 190; 0.844 (0.156) | –0.008 | –0.036 to 0.021 | 0.589 |

| 6 months | 186; 0.839 (0.159) | 191; 0.853 (0.135) | –0.024 | –0.052 to 0.005 | 0.105 |

| 12 months | 209; 0.857 (0.139) | 204; 0.860 (0.143) | –0.012 | –0.039 to 0.016 | 0.403 |

| 18 months | 181; 0.851 (0.144) | 184; 0.832 (0.157) | 0.003 | –0.026 to 0.032 | 0.832 |

| 24 months | 205; 0.849 (0.152) | 202; 0.830 (0.184) | 0.011 | –0.017 to 0.039 | 0.434 |

| Patient experience (glaucoma getting worse), n/N (%) | |||||

| Baseline | 95/208 (45.7) | 76/209 (36.4) | |||

| 1 month | 60/188 (31.9) | 50/201 (24.9) | 1.19 | 0.79 to 1.80 | 0.392 |

| 3 months | 37/182 (20.3) | 40/185 (21.6) | 0.88 | 0.55 to 1.41 | 0.591 |

| 6 months | 30/182 (16.5) | 40/189 (21.2) | 0.74 | 0.45 to 1.21 | 0.229 |

| 12 months | 38/207 (18.4) | 57/199 (28.6) | 0.59 | 0.38 to 0.91 | 0.018 |

| 18 months | 40/180 (22.2) | 38/181 (21.0) | 0.99 | 0.62 to 1.59 | 0.979 |

| 24 months | 44/196 (22.4) | 57/194 (29.4) | 0.70 | 0.46 to 1.07 | 0.099 |

| IOP (mmHg), n; mean (SD) | |||||

| Baseline | 222; 19.40 (6.15) | 221; 19.05 (5.73) | |||

| 4 months | 217; 12.39 (5.73) | 220; 16.40 (4.12) | –4.11 | –5.18 to –3.05 | < 0.001 |

| 12 months | 215; 11.90 (4.48) | 209; 16.12 (4.54) | –4.25 | –5.33 to –3.18 | < 0.001 |

| 24 months | 206; 12.40 (4.71) | 202; 15.07 (4.80) | –2.75 | –3.84 to –1.66 | < 0.001 |

| LogMAR VA, n; mean (SD) | |||||

| Baseline | 227; 0.15 (0.25) | 223; 0.17 (0.26) | |||

| 4 months | 210; 0.25 (0.31) | 217; 0.16 (0.24) | 0.10 | 0.05 to 0.14 | < 0.001 |

| 12 months | 212; 0.18 (0.23) | 209; 0.16 (0.26) | 0.03 | –0.02 to 0.08 | 0.198 |

| 24 months | 199; 0.21 (0.28) | 201; 0.16 (0.26) | 0.07 | 0.02 to 0.11 | 0.006 |

| VFMD (dB) | |||||

| Baseline, n; mean (SD) | 227; –14.91 (6.36) | 226; –15.26 (6.34) | |||

| 4 months, n; mean (SD) | 211; –14.35 (6.78) | 217; –14.84 (6.52) | –0.05 | –0.79 to 0.70 | 0.897 |

| 12 months, n; mean (SD) | 214; –14.76 (6.92) | 209; –14.95 (6.53) | 0.03 | –0.72 to 0.78 | 0.939 |

| 24 months, n; mean (SD) | 202; –15.15 (6.63) | 200; –15.42 (6.39) | 0.18 | –0.58 to 0.94 | 0.645 |

| Need for cataract surgery | |||||

| Yes, n/N (%) | 28/222 (12.6) | 27/221 (12.2) | 0.98 | 0.50 to 1.95 | 0.963 |

| Visual standards for driving (pass/no defects), n/N (%) | |||||

| Baseline | 187/214 (87.4) | 196/217 (90.3) | |||

| 24 months | 167/187 (89.3) | 168/188 (89.4) | 1.01 | 0.81 to 1.25 | 0.951 |

| Registered as sight impaired at 24 months, n/N (%) | |||||

| No | 182/186 (97.8) | 184/184 (100.0) | 0.123 | ||

| Sight impaired | 4/186 (2.2) | 0/184 (0) | |||

| Eligible to be registered at 24 months, n/N (%) | |||||

| No | 188/199 (94.5) | 187/196 (95.4) | |||

| Sight impaired | 8/199 (4.0) | 7/196 (3.6) | |||

| Severe sight impaired | 3/199 (1.5) | 2/196 (1.0) | |||

Health Utility Index version 3

The mean baseline HUI-3 score was 0.814 in the trabeculectomy arm and 0.809 in the medical management arm, with no evidence of a difference at the follow-up time points. At 24 months, the mean score was 0.786 in the trabeculectomy arm and 0.751 in the medical management arm, with a MD of 0.036 (95% CI –0.006 to 0.078; p = 0.094) (see Table 6).

Glaucoma Utility Index

The baseline mean GUI score was 0.884 in the trabeculectomy arm and 0.863 in the medical management arm. These mean scores decreased in both arms over the course of the study, but there was no evidence of a difference at any time point. At 24 months, the mean score was 0.849 in the trabeculectomy arm and 0.830 in the medical management arm, with a mean difference of 0.011 (95% CI –0.017 to 0.039; p = 0.434) (see Table 6).

Patient perception: glaucoma getting worse

At baseline, 95 out of 208 (45.7%) participants in the trabeculectomy arm and 76 out of 209 (36.4%) participants in the medical management arm perceived that their glaucoma was getting worse. At the later follow-up time points, this proportion decreased in both study arms. At 12 months, 38 out of 207 (18.4%) participants in the trabeculectomy arm and 57 out of 199 (27.3%) participants in the medical management arm perceived that their glaucoma was getting worse [relative risk (RR) 0.59, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.91; p = 0.018]. At 24 months, the RR was 0.70 (95% CI 0.46 to 1.07; p = 0.099) (see Table 6).

Intraocular pressure

At baseline, the mean IOP was 19.40 mmHg in the trabeculectomy arm and 19.05 mmHg in the medical management arm. At later time points, the mean IOP decreased, with lower IOP in the trabeculectomy arm at all follow-up time points. Figure 5 shows the mean and SD over time. At 24 months, the mean IOP was 12.40 mmHg in the trabeculectomy arm and 15.07 mmHg in the medical management arm (mean difference –2.75, 95% CI –3.84 to –1.66; p < 0.001) (see Table 6). The Dunnett’s multiplicity p-value was also < 0.001 for all time points The sensitivity analysis incorporating data from the non-index eye for participants with bilateral disease (see Appendix 3, Table 30) showed similar results.

FIGURE 5.

Mean (SD) IOP by arm over time. The SD values are at the end point of the vertical lines.

LogMAR visual acuity

At 4 and 24 months, there was evidence of a difference in logMAR VA in favour of medical management (MD at 24 months 0.07, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.11; p = 0.006) (see Table 6). The Dunnett’s multiplicity p-value was 0.002 for 4 months, 0.483 for 12 months and 0.061 for 24 months. The sensitivity analysis incorporating data from the non-index eye for participants with bilateral disease showed similar results (see Appendix 3, Table 30).

Visual fields mean deviation

At 24 months, the mean VFMD was –15.15 in the trabeculectomy arm and –15.42 in the medical management arm, with no evidence of a difference between arms [mean difference 0.18, 95% CI –0.58 to 0.94; p = 0.645) (see Table 6). Two sensitivity analyses were carried out. The first included only SITA standard VF (excluding SITA fast) and the second removed participants who had only one VF or for whom the false positive standard was > 15% required for reliability. Overall, the results were similar (see Appendix 3, Table 31). The sensitivity analysis incorporating data from the non-index eye for participants with bilateral disease showed similar results (see Appendix 3, Table 30).

Need for cataract surgery

Over the course of the trial, 28 out of 222 participants (12.6%) in the trabeculectomy arm and 27 out of 221 participants (12.2%) in the medical management arm needed cataract surgery, with no evidence of a difference between arms (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.95; p = 0.963) at 24 months (see Table 6).

Visual standards for driving (pass/no defects)

At 24 months, 167 out of 187 participants (89.3%) in the trabeculectomy arm and 168 out of 188 participants (89.4%) in the medical management arm passed the visual driving standards, with no evidence of a difference between arms (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.25; p = 0.951) (see Table 6).

Registered as sight impaired at 24 months

At 24 months, 4 out of 186 participants (2.2%) in the trabeculectomy arm and 0 out of 184 participants (0%) in the medical management arm were registered as sight impaired, with the difference between the arms having a p-value of 0.123 (see Table 6). In addition, we also recorded whether or not participants were eligible to be registered (see Table 6 and Appendix 3, Table 32, for baseline data). At baseline, 10 participants (94.3%) in the trabeculectomy arm were sight impaired and three participants (1.3%) were severely sight impaired. In the medical management arm, 12 participants (5.3%) were sight impaired at baseline and two participants (0.9%) were severely sight impaired. At 24 months, the results were similar.

Safety

A safety event is defined as either a SAE or an AE.

By allocation

The number of participants who experienced a safety event during the 24-month follow-up was 88 (38.8%) in the trabeculectomy arm and 100 (44.2%) in the medical management arm (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.17; p = 0.366). The number of participants who experienced a SAE was 12 out of 226 (5.3%) participants in the trabeculectomy arm and 8 out of 226 (3.5%) participants in the medical management arm. One participant in the trabeculectomy arm had two SAEs. Table 7 provides further details of the safety events throughout the follow-up period. Appendix 3, Table 34, shows details for the non-index eye.

| Measure | Treatment arm | |

|---|---|---|

| Trabeculectomy (N = 227) | Medical management (N = 226) | |

| Number of participants with a safety event, n (%) | 88 (38.8), adjusted risk ratio 0.88 | 100 (44.2), 95% CI 0.66 to 1.17; p = 0.366 |

| SAE | ||

| Number of participants, n/N (%) | 12/226 (5.3) | 8/226 (3.5) |

| Number of events (n) | 13 | 8 |

| Details (n) | ||

| Death | 5 | 4 |

| Life-threatening | – | 1 |

| Hospitalisation | 3 | 4 |

| Significant disability | 2 | – |

| Important condition | 3 | 1 |

| Expected event | 3 | 2 |

| Classification (n) | ||

| General medical (death) | 2 | 4 |

| Unclassified (death) | 3 | – |

| General medical | 2 | 3 |

| Related to glaucoma surgery | 3 | 1 |

| General ophthalmology | 1 | – |

| Non-glaucoma vision loss | 1 | – |

| Glaucoma progression despite treatment | 1 | – |

| 4 months | ||

| Number of participants, n/N (%) | 49/217 (22.6) | 45/220 (20.5) |

| Number of events (n) | 63 | 54 |

| Details (n) | ||

| Shallow anterior chamber | 3 | – |

| Early bleb leak | 10 | – |

| Corneal epithelial defect | 2 | – |

| Conjunctival buttonhole | 2 | – |

| Hyphaema | 4 | – |

| Choroidal effusion | 6 | – |

| Suprachoroidal haemorrhage | 1 | – |

| Hypotony requiring intervention | 6 | – |

| Late bleb leak | 1 | – |

| Ptosis | 2 | – |

| Drop related | 9 | 39 |

| Ocular surface related | 9 | 11 |

| Potential AE related to surgery | 1 | – |

| Non-specific | 6 | 3 |

| Glaucoma progression | 1 | 1 |

| 12 months | ||

| Number of participants, n/N (%) | 35/216 (16.2) | 43/211 (20.4) |

| Number of events (n) | 43 | 48 |

| Details (n) | ||

| Irreversible loss of ≥ 10 ETDRS lettersa | 1 | – |

| Shallow anterior chamber | 3 | – |

| Early bleb leak | 1 | 2 |

| Persistent uveitis | 1 | – |

| Conjunctival button hole | 1 | – |

| Choroidal effusion | 2 | – |

| Suprachoroidal haemorrhage | 1 | – |

| Hypotony requiring intervention | 3 | 1 |

| Late bleb leak | 1 | – |

| Blebitis | 1 | – |

| Ptosis | 3 | – |

| Non-specific unrelated uveitis | 1 | – |

| Drop related | 4 | 29 |

| Ocular surface related | 12 | 11 |

| Potential AE | 2 | – |

| Non-specific | 5 | 4 |

| Cataract | 1 | 1 |

| 24 months | ||

| Number of participants, n/N (%) | 30/211 (14.2) | 41/208 (19.7) |

| Number of events (n) | 33 | 53 |

| Details (n) | ||

| Irreversible loss of ≥ 10 ETDRS lettersa | 2 | – |

| Shallow anterior chamber | 1 | 2 |

| Early bleb leak | 1 | 1 |

| Corneal epithelial defect | 1 | – |

| Macular oedema | – | 1 |

| Choroidal effusion | 1 | 2 |

| Hypotony requiring intervention | 2 | 2 |

| Late bleb leak | 2 | – |

| Blebitis | 1 | – |

| Endophthalmitisa – endogenous | 1 | – |

| Endophthalmitisa – bled related | – | 1 |

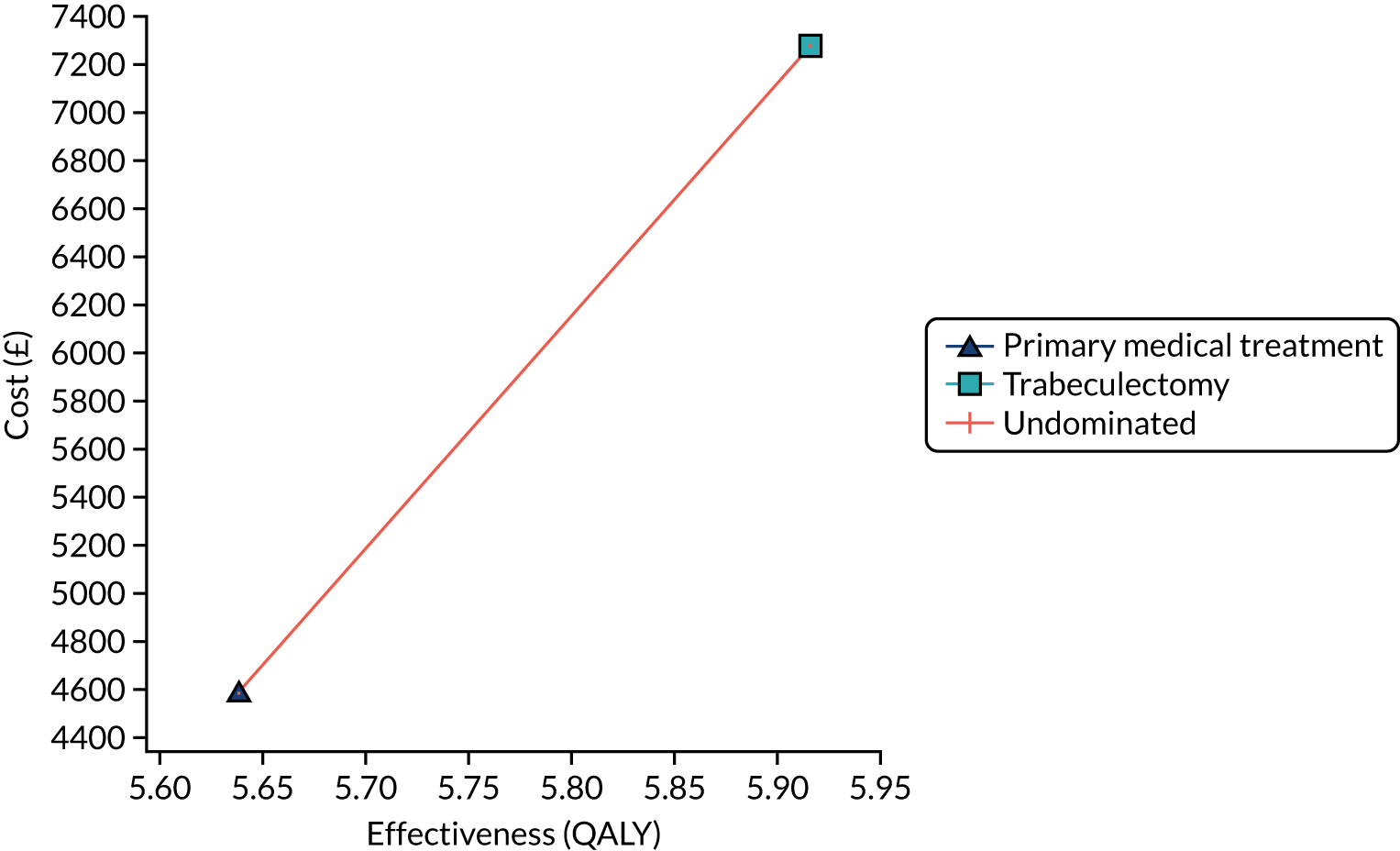

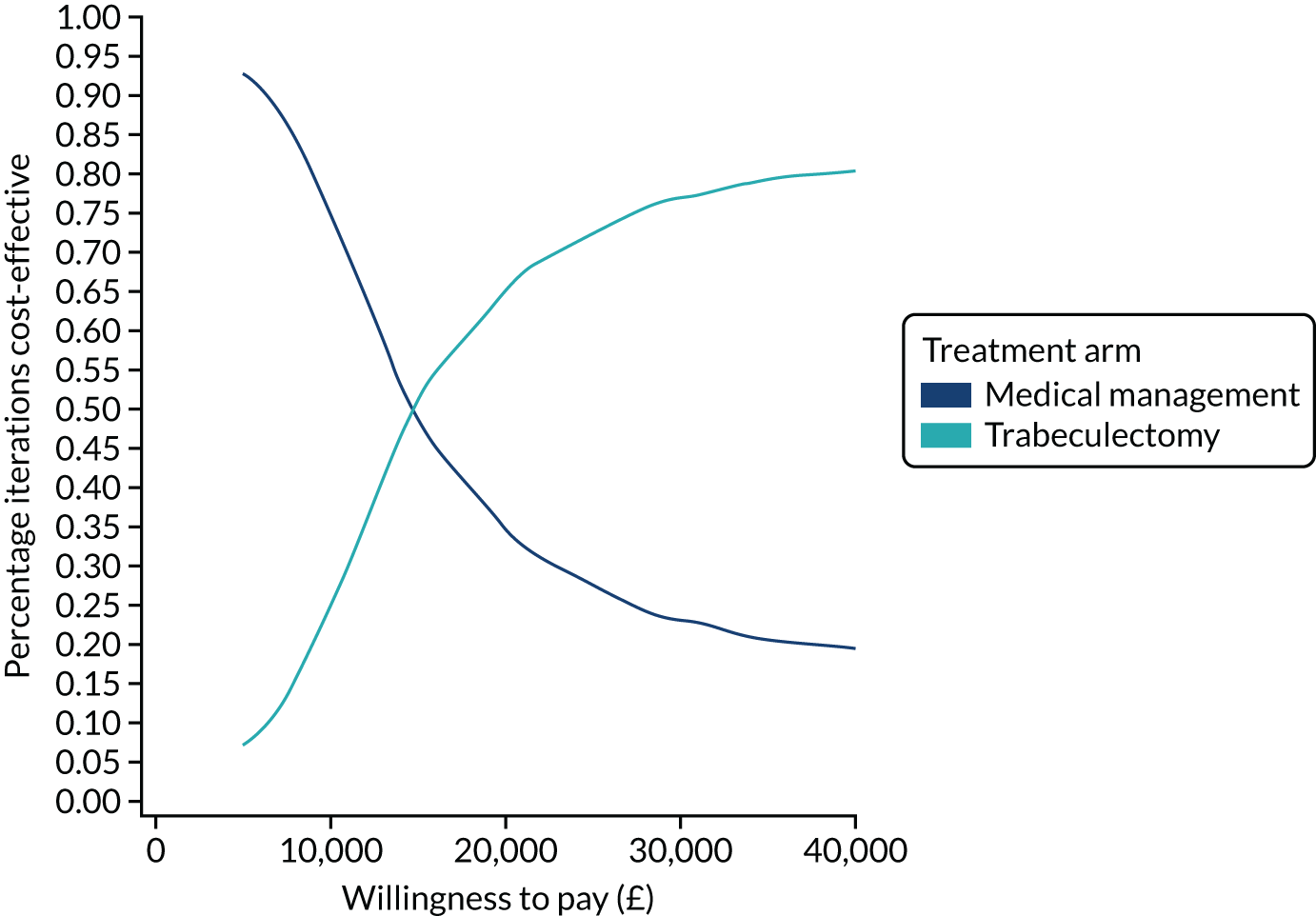

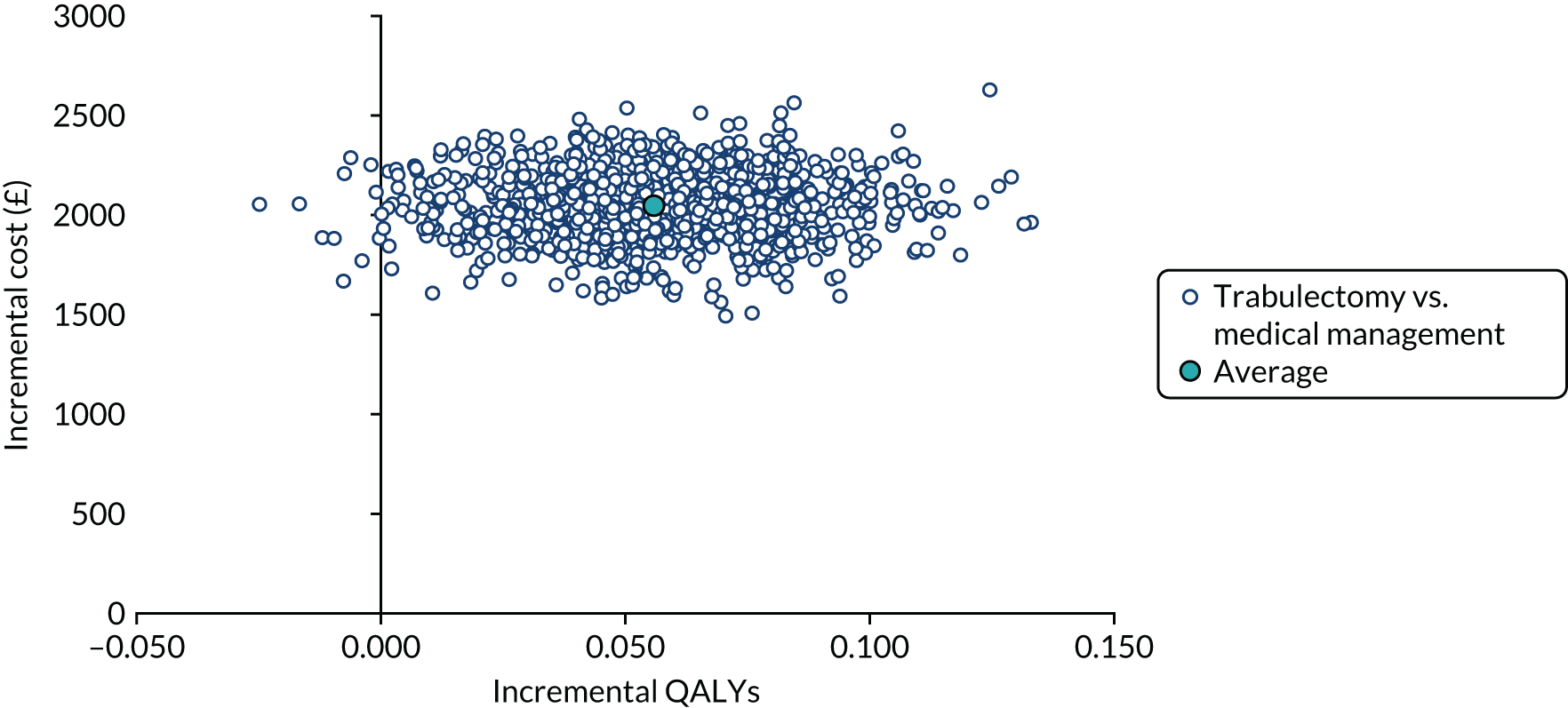

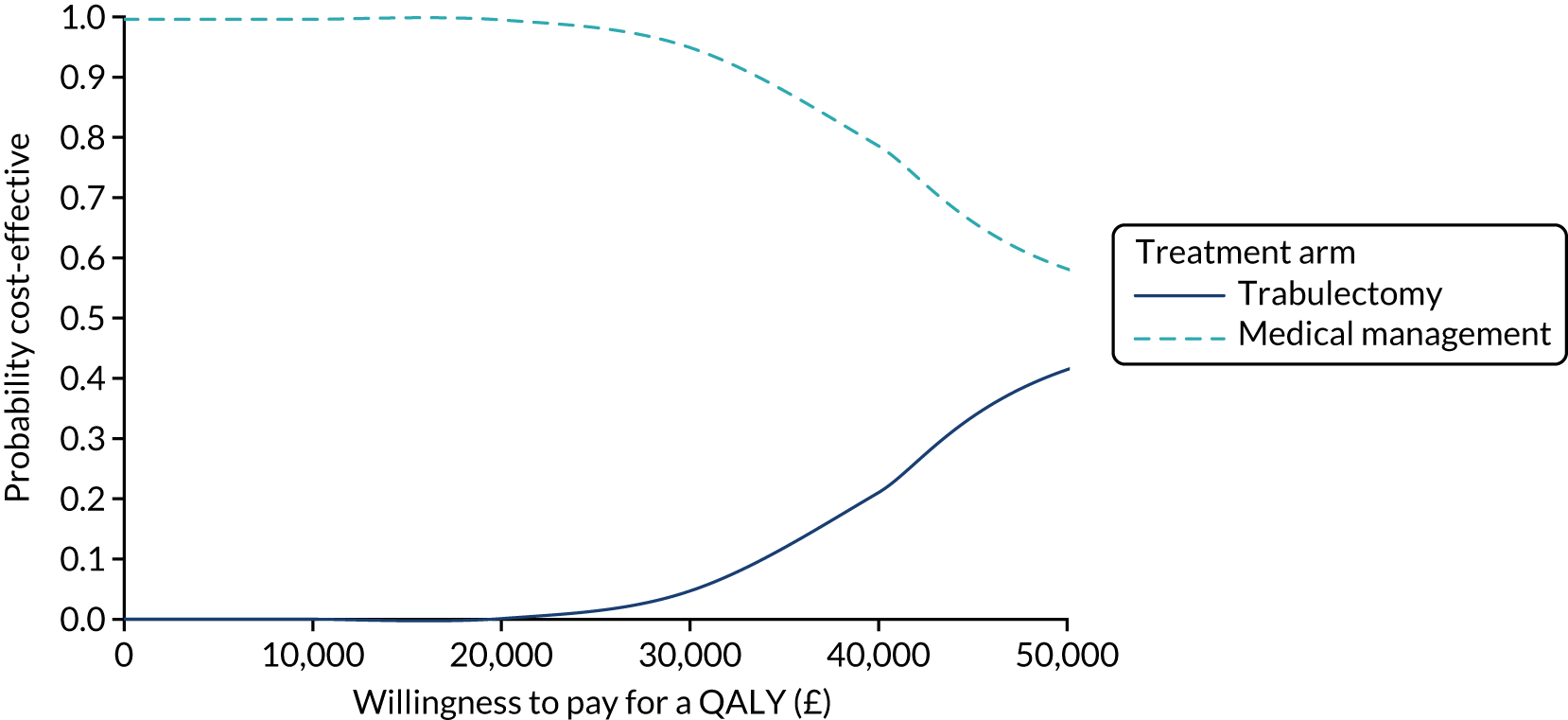

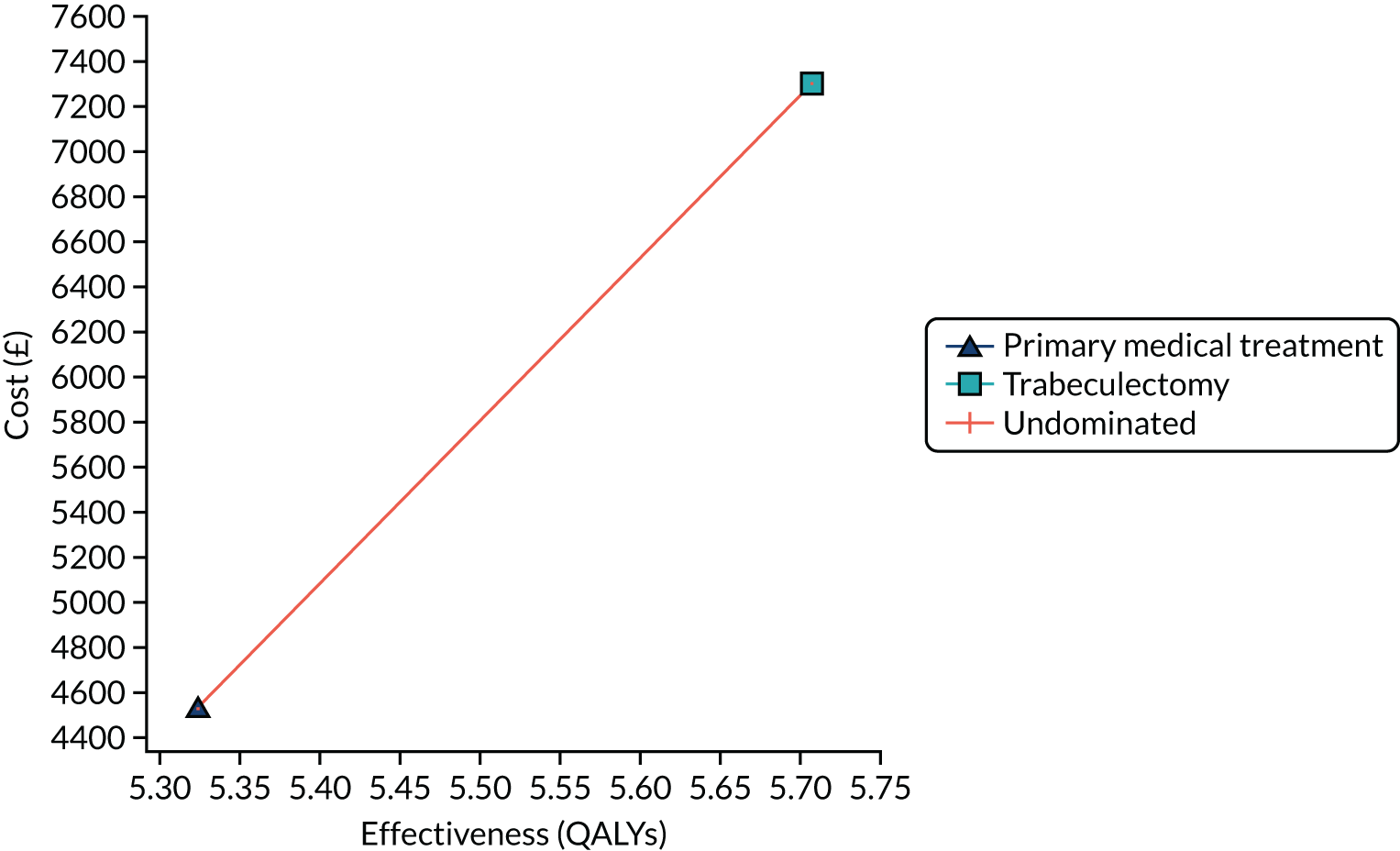

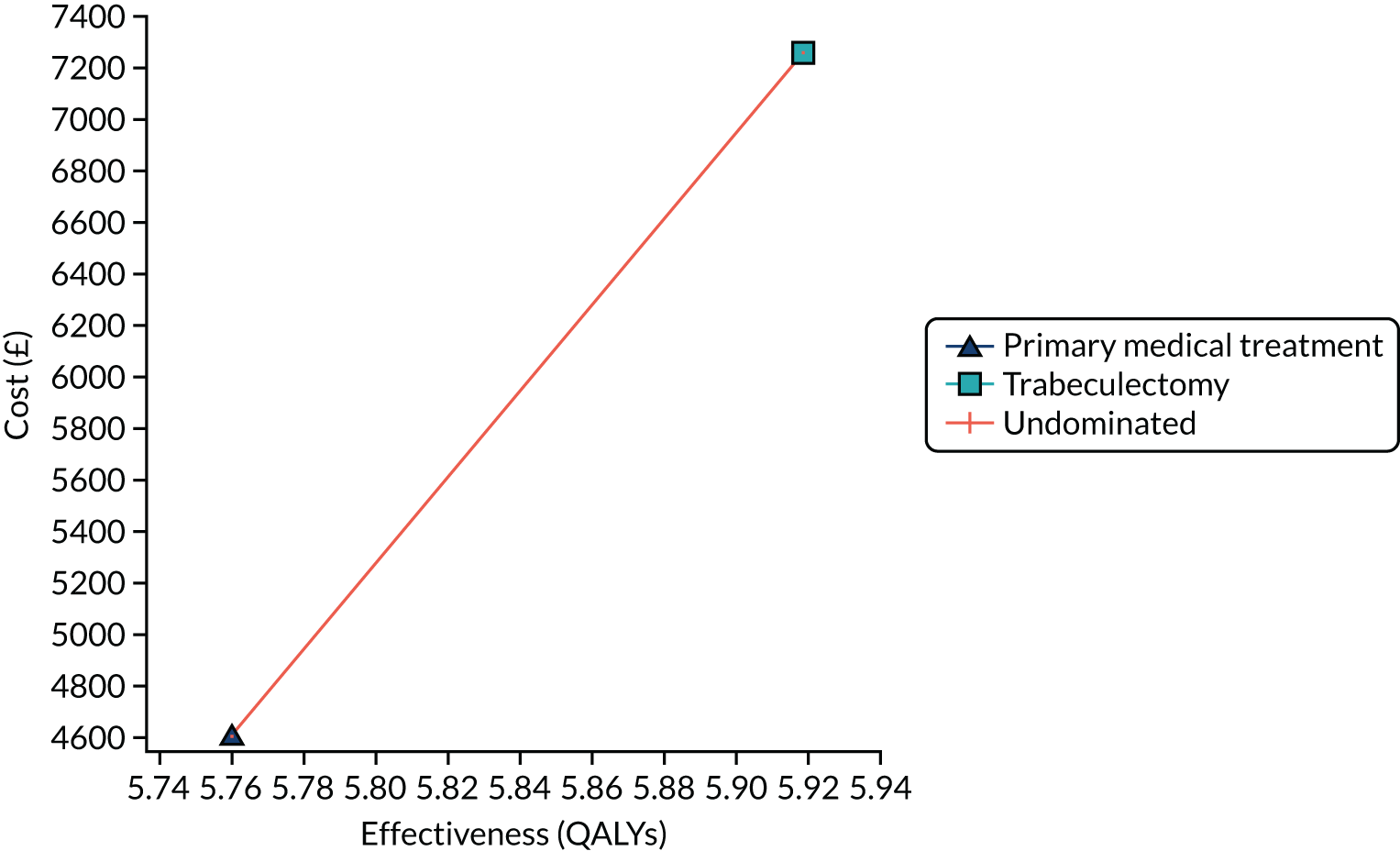

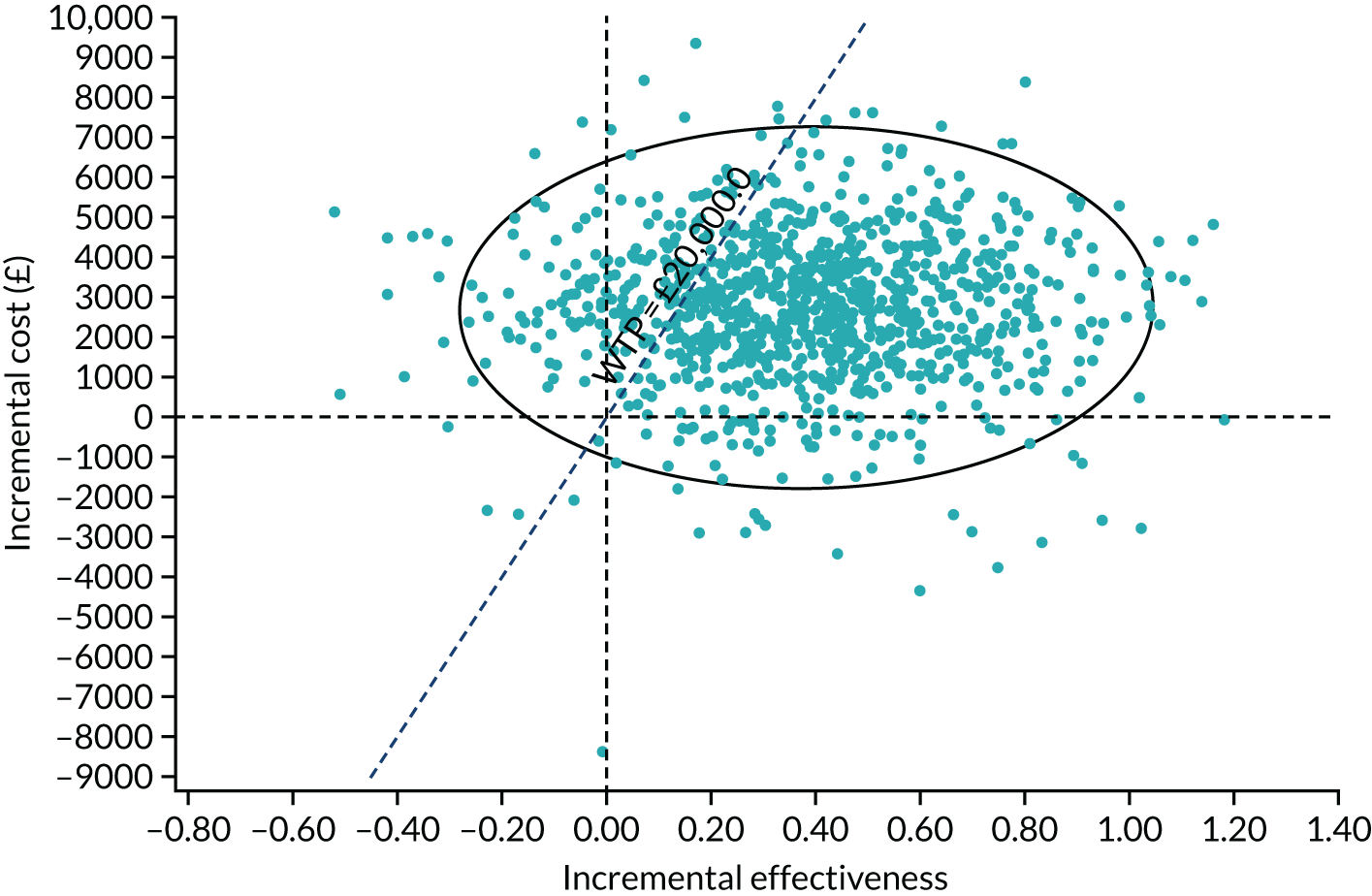

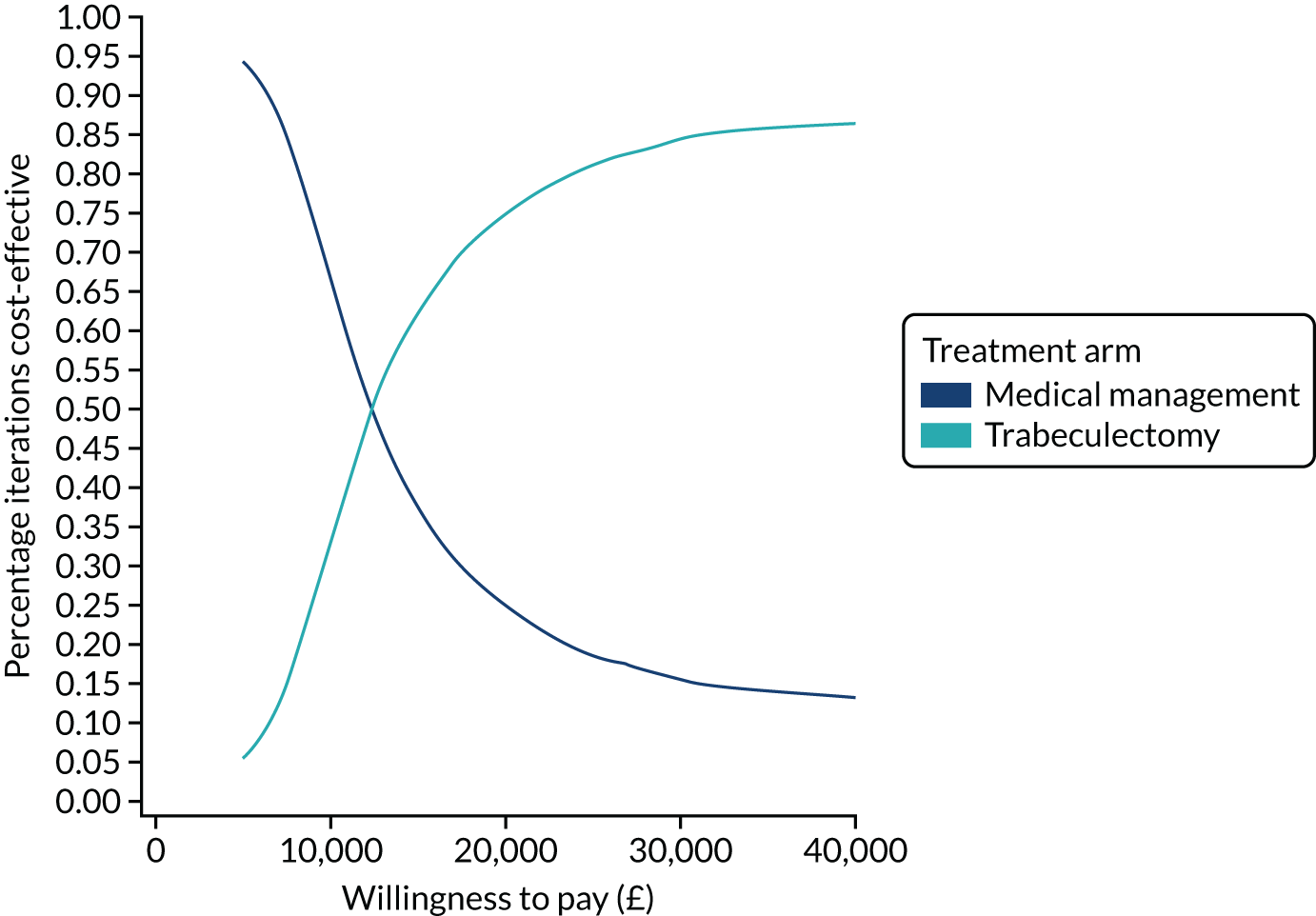

| Ptosis | – | 1 |