Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 17/98/01. The contractual start date was in April 2019. The final report began editorial review in October 2022 and was accepted for publication in March 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Ingram et al. This work was produced by Ingram et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Ingram et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that can have a profound impact on quality of life due to pain, suppuration of pus and scarring. 1,2 It is characterised by inflammatory nodules, abscesses and skin tunnels occurring in flexural skin regions such as the axilla, groin and perineum, often leading to scarring. 3 At least 1% of the UK population is affected;4,5 however, the prevalence may be higher due to undiagnosed cases resulting from a typical diagnostic delay of 7 years. 6 Onset of HS is usually at or soon after puberty, so HS affects young adults, with major impact on relationships and careers, producing cumulative life course impairment. 1 The aetiology of HS remains uncertain, with genetics, microbiological, immune dysregulation, lifestyle and endocrine factors thought to contribute. 7

The management goals for HS are to prevent and treat flares of inflammatory skin lesions and the avoidance of scarring. Medical (drug) treatments for HS are intended to improve and prevent disease flares, while surgery and other non-drug therapies are required to treat scarring once it has occurred. Holistic management of HS therefore requires integration of medical and surgical treatment pathways. 8

Existing evidence

A 2015 Cochrane review of interventions for HS found a relative lack of randomised controlled trials (RCTs), identifying only 12 RCTs involving a total of 615 participants, despite HS being such a common condition. 9,10 Since 2015, few RCTs have been performed and so the UK, European and North American guidelines for HS management continue to rely on expert consensus to a large extent. 8,11–13 Trials of biological therapies for HS sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry are now under way; however, the evidence base for current HS systemic treatments continues to rely mainly on retrospective case series/cohort evidence.

Surveys investigating current HS management in the UK, undertaken to inform the Treatment of Hidradenitis Suppurativa Evaluation Study (THESEUS), demonstrated substantial variation in HS care among dermatologists, surgeons and general practitioners (GPs). 14–16 It is likely that the variance produces inequalities of care and poorer outcomes for some people with HS depending on their UK location.

Rationale for the Treatment of Hidradenitis Suppurativa Evaluation Study

Prioritisation of the research question

A James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership (PSP) for HS produced a top 10 list of research questions in 2014, following a prioritisation exercise involving people with HS and their clinicians. 17 THESEUS was designed to improve the evidence base for several of the top 10 priorities including: what is the most effective and safe group of oral treatments in treating HS (ranked number one priority); what is the impact of HS and the treatments on people with HS (ranked third) and what is the best surgical procedure to perform in treating HS (ranked sixth).

The design of THESEUS was also guided by the funding call from the UK National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme, which posed the question: ‘What are the best management options for HS when first line treatments fail?’

The aims of THESEUS are to understand how HS treatments are currently used in the UK and to inform the design of future RCTs in HS.

Introduction of deroofing and laser treatment for hidradenitis suppurativa into the UK

Deroofing is a tissue-sparing procedure, usually performed under local anaesthetic, which removes the subcutaneous linear channels known as skin tunnels (also known as sinus tracts or fistulae) that form in HS. 18 It is routinely performed in some countries, such as the Netherlands and USA, but is rarely performed in the UK. The advantage of deroofing compared with conventional surgery is that blunt probing of tunnels ensures that all subcutaneous branches are removed while avoiding excision of unaffected skin. By including deroofing as one of the treatment options within THESEUS, the intention was to upskill several centres in the UK to perform deroofing for HS as part of the IDEAL Collaborative’s stage 2b of surgical innovation.

Several small RCTs suggest benefit from laser treatment targeting the hair follicle in HS. Access to laser treatment for HS is limited in the UK, with seemingly unwarranted variation. This is despite it being included in some HS management guidelines. 8 Including laser therapy as an intervention within THESEUS would help to understand the desirability of this treatment to patients, upskill recruiting sites ready for any future RCT involving laser therapy for HS and gather initial data on likely treatment effectiveness.

Validation of HiSTORIC core outcomes set instruments

A systematic review of outcome measure instruments (OMIs) included in the HS Cochrane review demonstrated substantial heterogeneity, with 30 different OMIs used in the 12 RCTs. 19 This finding led to the creation of the Hidradenitis SuppuraTiva cORe outcomes set International Collaboration (HiSTORIC), with the aim of developing a core outcomes set for HS. 20 The six domains of the set have been established by consensus and HiSTORIC is now developing and validating OMIs for each domain. 21,22 THESEUS has the opportunity to contribute to HiSTORIC OMI validation, in particular providing evidence for feasibility and interpretation of the OMIs, including evaluation of minimum important difference.

Nested process evaluation studies

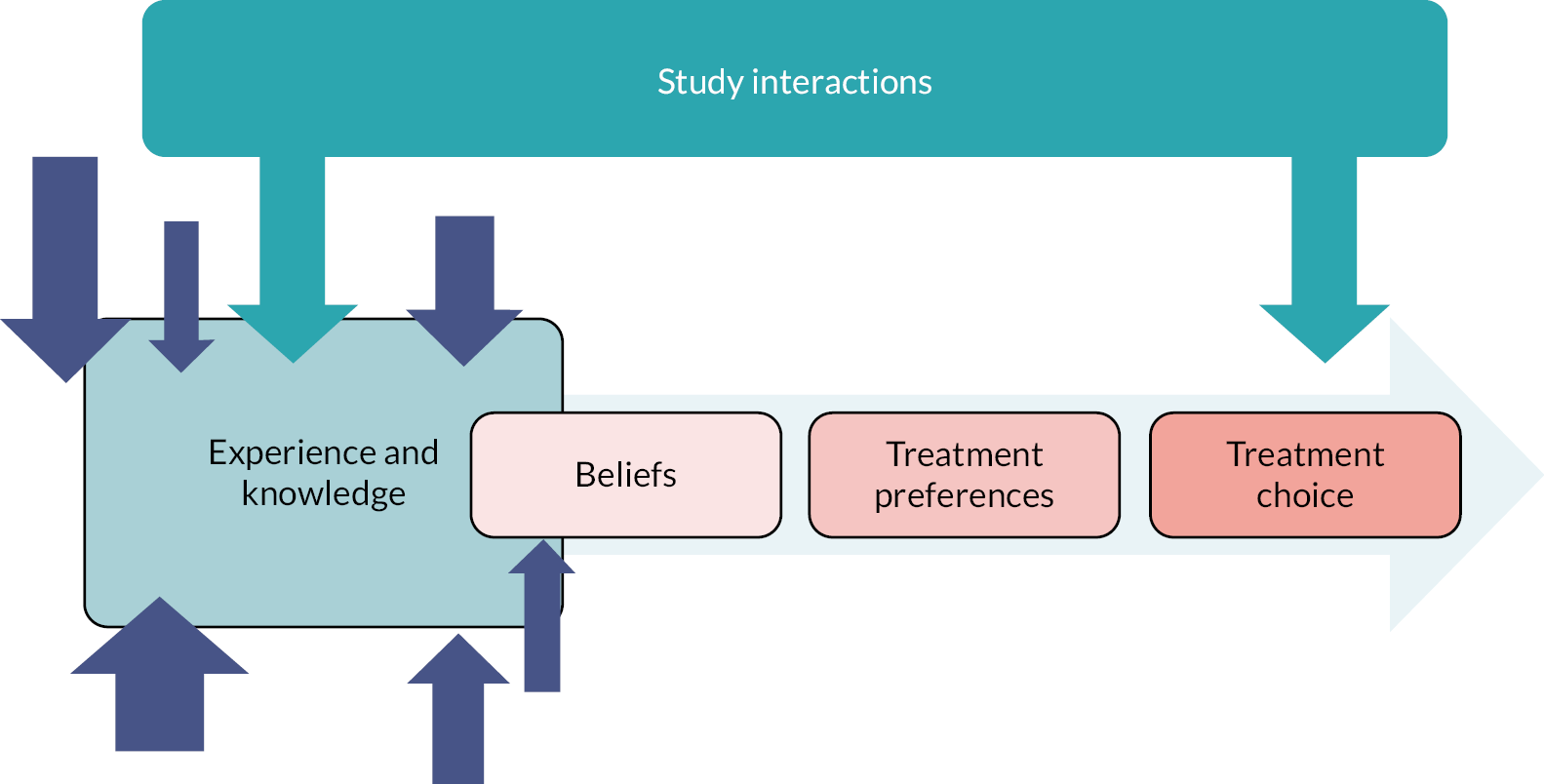

Qualitative studies were nested within THESEUS to gain a deeper understanding of the processes involved in HS clinical trials and to inform the design of future RCTs. The aims were as follows:

-

to characterise current conventional surgical procedures and document best practice for laser and deroofing interventions;

-

to understand the factors influencing choice of intervention from the perspectives of patients and clinicians;

-

to identify barriers and facilitators to recruitment into future RCTs.

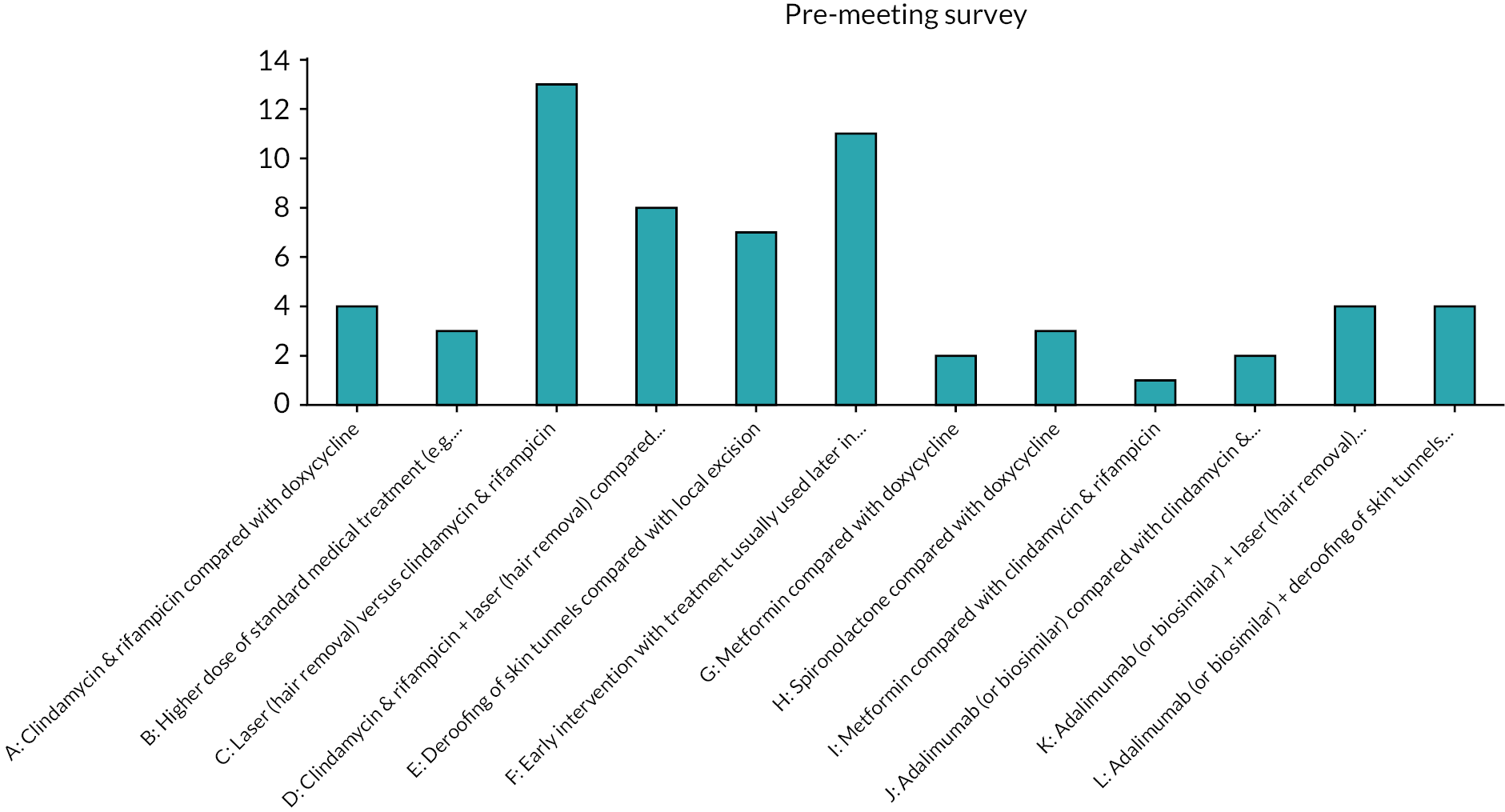

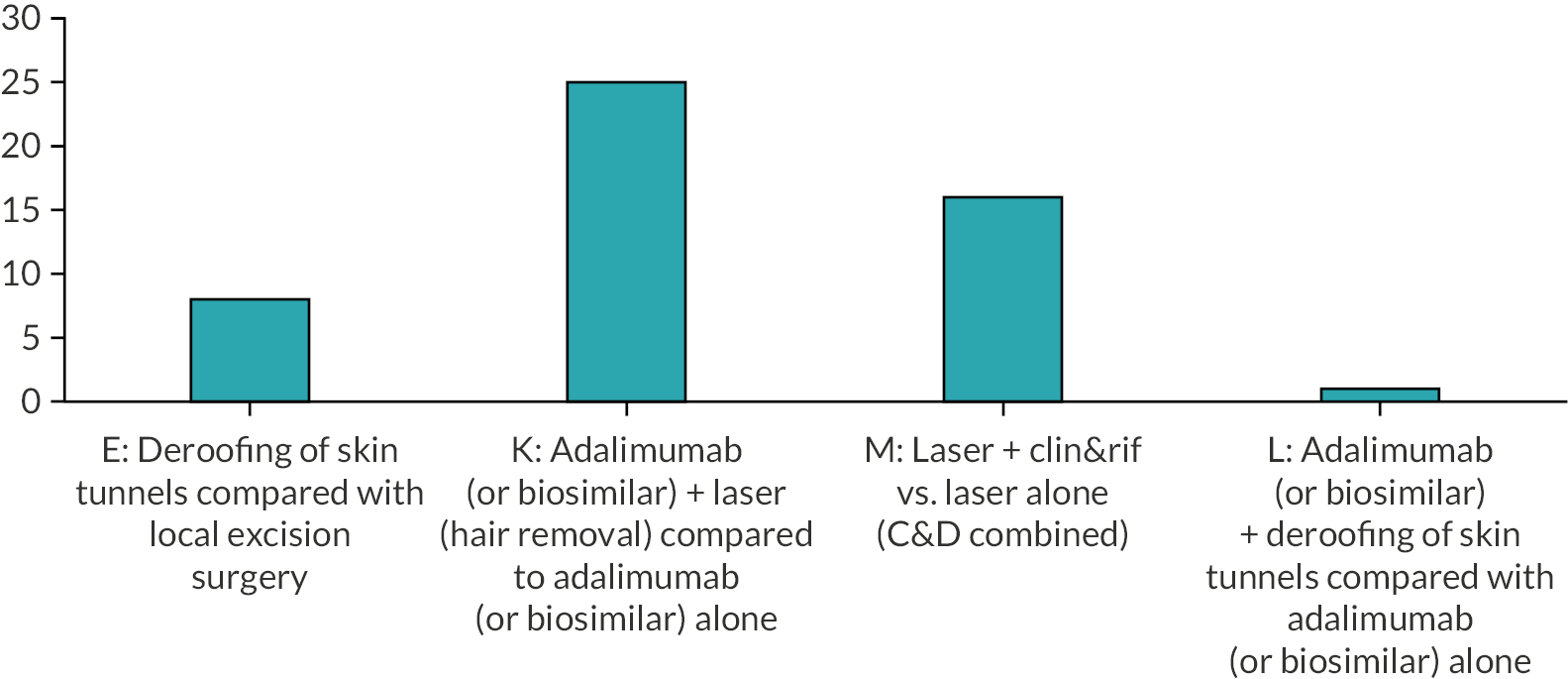

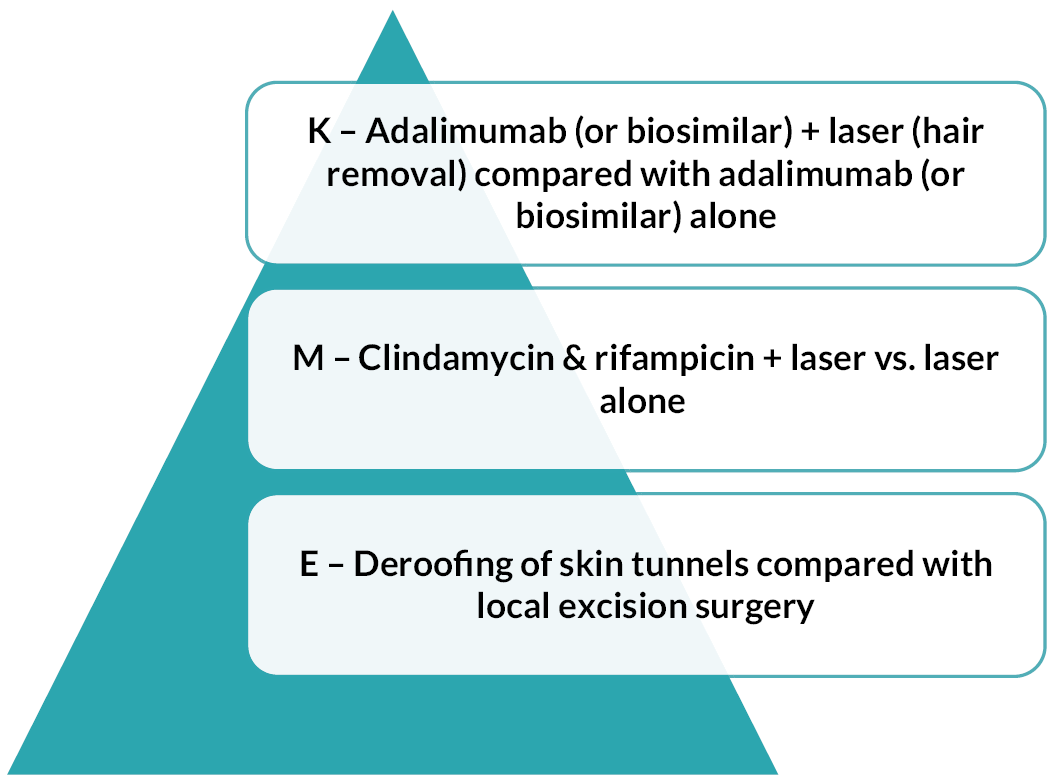

Consensus workshop

To inform the design of future HS RCTs, the final aim of THESEUS was to host a consensus workshop attended by study participants, HS patient advocates, clinicians, methodologists and researchers. Objectives of the workshop were to identify the highest priorities for future HS RCTs in terms of participants, interventions, comparators and outcomes.

Chapter 2 Methods for the THESEUS observation cohort study

Study design

The THESEUS study was a prospective observational cohort study, with a nested process evaluation, of individuals living with HS, for which the protocol has been published. 23 Study participants were patients receiving treatment for their HS recruited from secondary care. Following recruitment, and after undergoing a clinical examination and baseline data collection, participants were asked to indicate their willingness to receive the five treatment options detailed below and to rank them from most preferred to least preferred, with the help of a THESEUS treatment decision grid (see Chapter 6). The participant’s clinician provided guidance regarding treatment eligibility and together the participant and their clinician agreed to the final treatment selection. This was a pragmatic, non-randomised study with the aim to understand and explore current practices around HS management and care pathways for those living with HS and to inform the design of future HS RCTs. Described below are the primary and secondary objectives and the outcome measures.

The THESEUS study was informed by surveys of patients (n = 358), dermatologists (n = 57), plastic and general surgeons (n = 225) and GPs (n = 133). 14–16 The surveys provided insight into current HS treatment pathways, gaps in treatment provision and willingness of respondents to take part in a HS clinical trial.

Patient and public involvement (THESEUS patient research partners)

A patient research partner (PRP) and founder of the HS Trust patient support group was a co-applicant for the THESEUS grant application. A further two PRPs joined the THESEUS study management group (SMG), attending regular meetings and contributing to all aspects of the conduct of the study. The THESEUS PRPs also made substantial contributions to the management and implementation of the THESEUS consensus workshop, through preworkshop results dissemination, facilitation of group discussions involving study participants and collating feedback from the discussions. Another PRP was a member of the study steering group.

Ethical approval and governance

The Wales Research Ethics Committee 4 provided ethical approval for THESEUS on 26 September 2019, reference number 19/WA/0263. Cardiff University acted as sponsor for the study. All sites received local research and development approvals. Prospective trial registration on the ISRCTN Registry was obtained on 9 August 2019 (ISRCTN69985145). Study oversight was provided by a combined study steering committee and independent data monitoring committee. There were four independent members of the committee: a chairperson experienced in the conduct of clinical trials, an academic, a biostatistician and a patient representative. The study was conducted in accordance with the Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care, principles of good clinical practice, General Data Protection Regulation and Cardiff University Centre of Trials Research standard operating procedures.

THESEUS study interventions

Participants recruited into the study had to be eligible and willing to receive at least one of the five THESEUS interventions offered: (1) oral doxycycline; (2) oral clindamycin and rifampicin; (3) laser treatment; (4) deroofing of skin tunnels; and (5) conventional surgery. The choice and dose of the THESEUS treatments were informed by the results of the stakeholder surveys.

If the participant’s first treatment choice carried a long waiting time, the participant was offered an alternative treatment to cover the interim period, based on a joint decision between the clinician and the participant. Using one of the study treatments in the interim period was preferred; however, other treatments were permitted, depending on clinician judgement. Participants could opt to switch treatments to another THESEUS intervention, or a combination of interventions, once they had been on their chosen intervention for 6 months.

Option 1: oral doxycycline

Oral doxycycline was offered at a dose of 200 mg once daily.

Option 2: oral clindamycin and rifampicin

Oral clindamycin and rifampicin were each taken at a dose of 300 mg twice daily as a combined course for 10 weeks initially, with the option to continue up to 6 months. Prior to commencing treatment, participants were required to have safety blood tests (full blood count, renal function, liver function) at baseline and repeated 4 weeks after starting the treatment, as per usual care.

Option 3: laser treatment

Laser treatment targeting the hair follicle was specified in the protocol with Nd-YAG laser (skin types 2–6) or alexandrite/diode laser (skin types 1–3). This treatment option was scheduled to be administered on four occasions, each 1 month apart.

Laser hair removal treatment was performed by healthcare professionals (HCPs) trained and certified in the use of medical lasers. Training in laser treatment is already formalised as part of medical laser training and certification was required for practitioners to be insurable. THESEUS did not provide study-specific training in laser treatment; however, a laser protocol was provided.

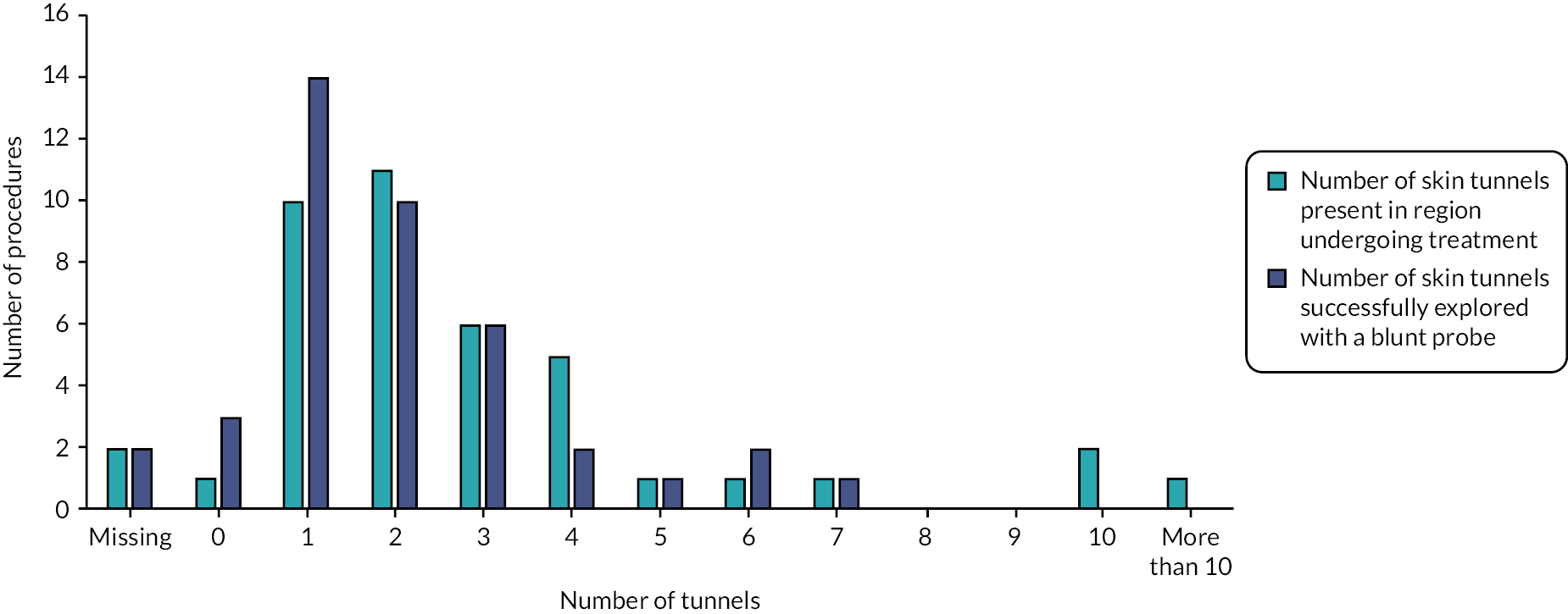

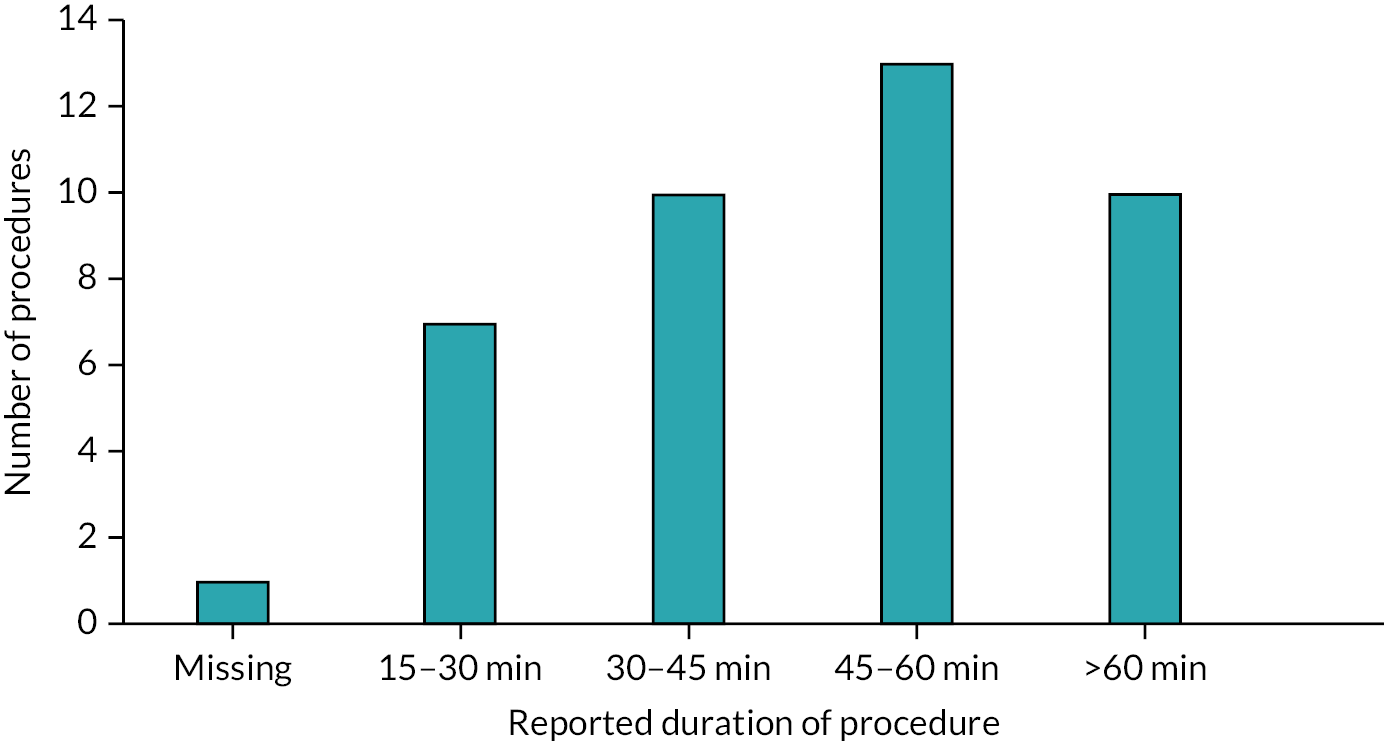

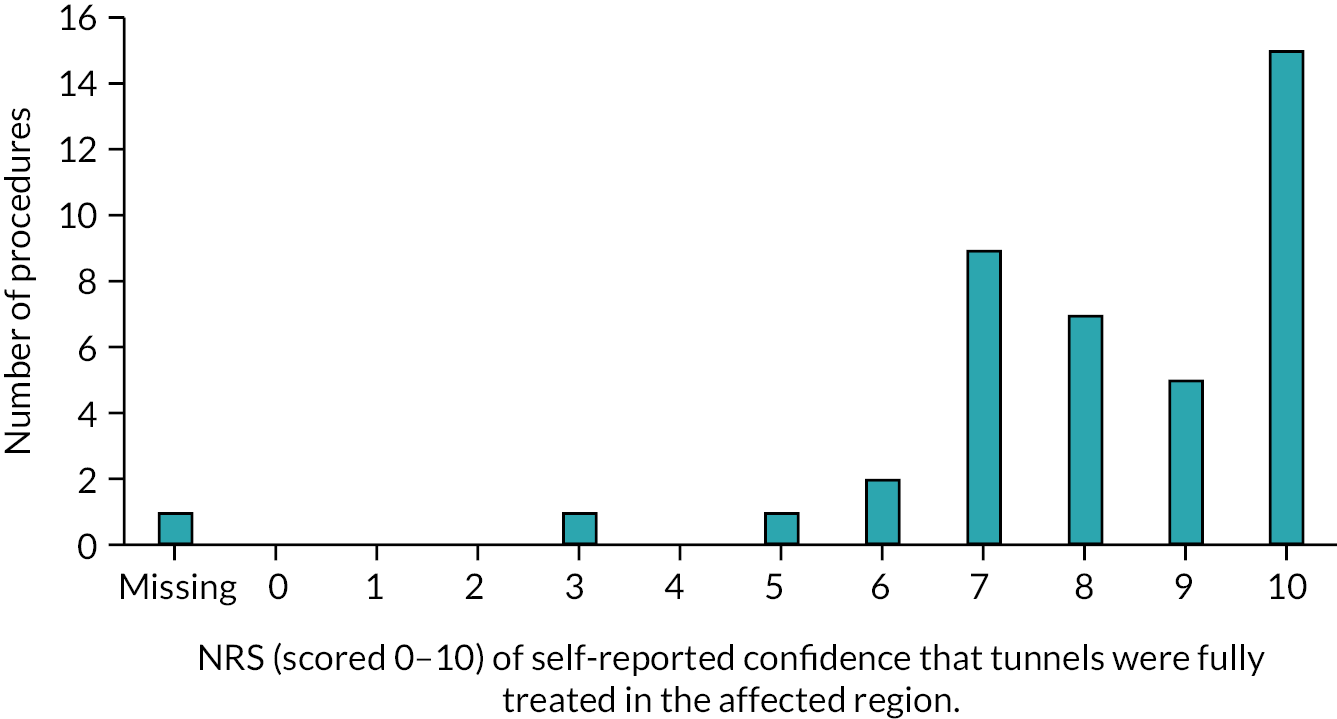

Option 4: deroofing of skin tunnels

Deroofing of skin tunnels was carried out using electrocautery and details of the procedure performed were documented in a clinical report form.

A protocol and training video was developed by the study team to guide HCPs (including dermatologists, plastic surgeons and other surgeons) through the deroofing procedure. HCPs wishing to use the procedure HCPs were invited to attend an in-person training event. The training video and an information video for participants were made available on the publicly accessible THESEUS study website (https://www.cardiff.ac.uk/centre-for-trials-research/research/studies-and-trials/view/theseus).

Deroofing procedures were performed under local anaesthetic in most cases and could be repeated if required. Details of the procedure were recorded in a clinical report form in each case. The total area treated at one time was limited by the volume of local anaesthetic needed and expected degree of impairment of activities of daily living during recovery. Wound healing took place by secondary intention healing over a period of a few weeks.

Option 5: conventional surgery

Participants selecting the conventional surgery option were assessed as to the most appropriate excision margins (narrow or wide). Skin closure following excision could also vary depending on which method the clinician felt most appropriate.

No formal training was provided for conventional surgical options because one of the objectives of THESEUS was to document current practice and assess any variability. A protocol was provided to surgeons, which contained some basic parameters, allowing for wide variation in practice. The surgical technique used for each procedure was documented using an online questionnaire.

Study objectives and outcome measures

Study objectives

The primary objective of the THESEUS study was to understand how HS treatments are currently used and to inform the design of future HS RCTs.

The secondary objectives of the study were to determine the feasibility of recruiting individuals with HS; to test the feasibility and responsiveness of OMIs; to understand current patient pathways and what influences patients’ and clinicians’ treatment choices; to fully characterise the study interventions (dose of medication, type of surgical techniques used); and to explore consensus-agreed recommendations for future RCT study designs.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome of THESEUS was to determine the proportion of participants who were eligible, and hypothetically willing, to use the different THESEUS treatment options.

The secondary outcomes included the proportion of participants choosing each of the study interventions, with reasons for their choices; the proportion of participants who switch treatments, with reasons for switch; study treatment fidelity; the loss to follow-up rates during the study; treatment efficacy outcome estimates after 6 months of follow-up, and to inform OMI responsiveness.

Setting and participants

Site selection

Clinical sites were selected for participant recruitment based on their clinical services and experience in HS management. Sites with the following expertise were selected: (1) those that offered a multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach integrating HS medical and surgical care; (2) sites with experience in HS surgery; (3) dermatology departments that were experienced in HS medical management. Additionally, study sites had to offer at least four of the five THESEUS interventions.

Clinical site set-up

Between November 2019 and May 2021, 11 secondary care sites were identified to carry out participant recruitment. Ten sites actually opened to recruitment as one site had to be withdrawn because it was unable to provide capacity and capability approvals following the restart period during the COVID-19 pandemic. Site set-up and recruitment were staggered due to the pandemic, and not all 10 sites were open to recruitment simultaneously. Dermatologists or surgeons took the role of principal investigator in 9 of the 10 sites, and a GP working in a dermatology department undertook the role in 1 site. The local investigating team comprised research nurses, dermatologists, surgeons, specialist nurses and trial co-ordinators. Training was delivered to the principal investigators and the site research team in one site set-up session, usually via teleconference. THESEUS was a low-risk study following usual clinical practice. A risk-based approach to study monitoring was adopted and outlined in the study risk assessment document. The study was monitored centrally and there were no preplanned site monitoring visits.

Participant eligibility

Individuals could be included in the study if they met all of the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria. Individuals had to be at least 18 years of age with active HS of any severity and not adequately controlled by current treatment; their HS diagnosis had to meet the disease definition (i.e. a lifetime history of at least five flexural skin boils or two flexural skin boils in the past 6 months) and the disease had to be confirmed by a recruiting clinician with experience of HS care. Individuals also had to be eligible and willing to receive at least one of the five THESEUS study interventions.

Individuals were excluded if they were unable or unwilling to provide informed consent and if they were pregnant or breastfeeding. Most of the study questionnaires were only validated in English, so individuals who were not sufficiently fluent in English were also excluded.

Participant recruitment

Assessment of eligibility was undertaken by a medically qualified clinician. Informed consent to take part in the study was obtained by an appropriately trained local researcher at the study site. After completing the consent process, baseline data collection was undertaken.

The research team recommended that the recruitment/baseline appointment should be carried out in person; however, for patients who were well known to the local investigating team, the recruitment/baseline appointment could be conducted remotely via telephone or videoconference. Patients who were not known to local investigators were required to attend a recruiting clinic in-person to ensure study eligibility and assess disease severity. Exceptions to in-person attendance could be made if the patient’s HS skin involvement was limited to non-intimate sites and could be assessed remotely. The inclusion of remote appointments was included in the study protocol as an amendment during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data collection

Data were collected with the participant at the hospital-based clinic. Data were also collected with the participant over the telephone or via video- or teleconferencing if preferred. Data were collected electronically via a bespoke Cardiff Centre for Trials Research-built online database, with paper copies as a backup. All data collected on paper were later entered electronically into the database by local researchers at the site. Data were added to the database using a secure electronic device.

The database had in-built ranges, checks and validation rules, with incomplete fields and data outliers flagged at the time of entry. Data queries and missing data were referred back to the site. Once participants had completed data collection at the relevant time point the data manager would note completion of the data collection on a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet. The schedule of interventions and assessments is shown in Table 1.

| Review number | –1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planned month | –1 | Baseline | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 |

| Screening | X | X | ||||

| Eligibility assessment | X | X | ||||

| Demographics and consent | X | |||||

| Clinical examination including Hurley stage | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Interventions for which participant is potentially eligible | X | |||||

| Intervention received, with reasons for choice (including treatments switched after baseline) | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Outcomes | ||||||

| Hidradenitis Suppurativa Quality of Life (HiSQOL) | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) | X | X | X | X | X | |

| European Quality of Life 5 dimension 5 level questionnaire | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Pain numerical rating scale (NRS) | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Pain score (via text message) | 12 weeks from start of intervention | |||||

| Need for dressings | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Patient Global Assessment (PtGA) | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Anchor question for change in severity | X | X | X | X | ||

| Flare frequency | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Assessment of HS physical signs | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Adverse effects of study treatment | X | X | X | X | ||

| Treatment fidelity | X | X | X | X | ||

| End-of-study questionnaire (participants and clinicians) | X | |||||

| Surgeon questionnaires/pro forma | After each surgery | |||||

| Structured interview (subset of participants) | Single interview | |||||

| Consensus workshop (subset of participants, clinicians and researchers) | Single workshop | |||||

While the majority of clinical data and questionnaire data were added to the bespoke online database, THESEUS also used the ‘Online Surveys’ platform (https://www.onlinesurveys.ac.uk) to enter and hold the THESEUS clinician questionnaire data. Data were manually entered into the platform by the THESEUS clinician at the time of data collection. Additionally, a telecommunications provider (Esendex, Commify UK Limited, Nottingham, UK) was used to send text messages to the participants asking for their daily pain scores. Data returned from participants via text messages were stored on Esendex servers. All data, including sensitive and personal data, were handled in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation 2016.

Data were extracted from all databases on completion of data cleaning and supplied to the statistician or qualitative researchers for analysis. As per Cardiff University’s procedures, data will be retained for 15 years following study closure.

Baseline review

Baseline data and contact details were collected immediately following participant recruitment.

The baseline appointment entailed a clinical examination to assess baseline severity of disease (measured by Hurley staging and refined Hurley staging). 24,25 The participant’s smoking status, body mass index (BMI) and other demographics were recorded. Details of their past medication history and history of surgery relating specifically to their HS were collected.

The participant was asked to complete questionnaires about their HS and its impact on functioning and quality of life. Outcome measures included the six core domains recommended by the HiSTORIC core outcomes set initiative for HS (pain, HS-specific quality of life, global assessment, disease progression, physical signs and symptoms)22 as measured by pain numerical rating scale (NRS), HS quality of life questionnaire (HiSQOL),26 Patient Global Assessment (PtGA),27 number of patient-reported HS flares, a count of inflammatory HS lesions, the use of dressings and fatigue severity. 28 Dermatology life quality index (DLQI)29 and general health-related quality of life [EuroQoL 5 dimension 5 level (EQ5D-5L)] questionnaires were also administered. The baseline appointment concluded with a clinical assessment of participant eligibility for each of the THESEUS treatments, with the participant finally choosing a THESEUS treatment that they were eligible to receive (and available at the recruiting site) in consultation with their clinician.

Follow-up data collection

Follow-up data collection included daily pain data returned by text message for 12 weeks after the chosen intervention was first received by the participant, as well as face-to-face or telephone follow-up review appointments at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months after the baseline appointment. Clinicians who undertook the THESEUS non-medical interventions (laser, deroofing or conventional surgery) were asked to complete a questionnaire providing details of the procedure performed in each case. Members of the local investigating team who had been involved in THESUS recruitment, data collection or procedure delivery were also asked to complete a questionnaire about their experience of carrying out the THESEUS study.

Pain score collected via text message

The feasibility of collecting daily pain data using short messaging service (SMS) text messages was trialled in the THESEUS study. When a participant commenced their treatment, or first received their procedure, they were sent a text message asking the magnitude of their current pain, using the pain 0–10 NRS instrument. The messages would be sent to the participant for up to 12 weeks. The text to the participants read:

Hello. This a text message from the THESEUS study. Please indicate the level of pain you are CURRENTLY experiencing due to your HS. The scale is from 0–10. ‘0’ means no pain and ‘10’ means pain as severe as it could be. You have until 02.00 am tomorrow morning to return today’s pain score. If you no longer wish to receive these messages please text STOP to [telephone number]

The participant receiving the messages could withdraw from participation in the text messaging by texting ‘STOP’ directly to the message. They were not charged for the withdrawal text message.

The messages were sent by Esendex, a telecommunications service provider. This was an automated process whereby Esendex was instructed to send the same message to the participant at the same time, 6 p.m., each day, with responses accepted until 2 a.m. the following day. The series of messages were triggered by the addition of data/dates into the intervention case report form within the online database. The responses from the text messages were held securely within the Esendex servers.

Once text message data collection was concluded a command was issued from the THESEUS server to query the Esendex application programming interface and request the inbound participant responses (as SMS messages).

Three-, six- and nine-month follow-up reviews

Reviews 1, 2 and 3 took place 3, 6 and 9 months after recruitment, respectively. Sites were encouraged to collect data within a window of 2 weeks either side of the intended follow-up date.

Reviews 1, 2 and 3 included a clinical examination of the disease stage using Hurley Staging24 and a HS skin lesion count, documenting the number of inflamed nodules, abscesses and draining skin tunnels. The patient reported outcome measures collected at baseline were repeated at Reviews 1, 2, and 3, as described in Table 1.

Participants were asked questions related to the THESEUS intervention they had selected. If the participant had chosen one of the THESEUS procedures (laser, deroofing, surgery), questions would focus on receipt of the procedures and whether the participant was content to continue with the course of treatment. If the participant had selected one of the THESEUS antibiotics options, then questions would centre around adherence to the chosen medication and whether they would be continuing with the treatment.

Twelve-month follow-up review

The final review (review 4) took place 12 months after recruitment. Review 4 repeated the assessments performed at the previous reviews, including information about receipt of the intervention, fidelity of procedure delivery and treatment adherence, as well as the clinician- and patient-reported outcome measures. In addition, participants were asked to complete an end-of-study questionnaire, which contained multiple choice and free text responses aimed at understanding their experience of taking part in the THESEUS study, and their recommendations around future HS-based research.

Follow-up adaptations as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic limited the capacity for THESEUS sites to follow up participants in person and so a study amendment was submitted and approved to permit remote follow-up. Remote assessment was carried out by video call or telephone call. In the case of telephone calls, participants could send photographs of skin regions affected by HS by secure e-mail. In the absence of photographs, participants were permitted to provide their own count of active HS skin lesions, supported by guidance from their investigator during the telephone call. The method of lesion count assessment was recorded in each case.

Adverse events

THESEUS was a low-risk observational study, and the adverse event reporting procedure was developed to reflect this. As such, adverse events that were not deemed to be related to any of the study interventions were not reported. Local investigators were encouraged to follow their usual processes for reporting adverse events (e.g. yellow card reporting) when required.

Adverse events that were, or could be, related to the study procedures or treatments were recorded in the THESEUS adverse event reporting form or in the Intervention case report forms at the routine review appointments. The adverse event was described in a free text box in the case report forms.

Study withdrawal

Participants could withdraw from any aspect of the study, at any time, without giving an explanation. If a participant wished to withdraw from the study a withdrawal form was available on the THESEUS online database. The participant could also withdraw from text messages directly by texting ‘STOP’. Using the online form, the participant could withdraw from the following elements of the study: THESEUS treatment(s), text message pain scores, study data collection (choice of complete or partial withdrawal), withdrawal from being contacted about the interview study and consensus workshop.

Statistical methods

Sample size

A sample size of 150 participants, permits estimation of the proportion of participants who are hypothetically willing and eligible to be randomised in a clinical study to within a 95% confidence interval (CI) of ±7%. We also wished to identify the case mix of patients for each of the possible treatment options. From our patient survey, the least favoured treatment option (13%) was minor surgical procedures. A total of 150 patients would provide us with 20 patients opting for each of the non-medical interventions, which is sufficient to explore delivery in an IDEAL 2b evaluation. The IDEAL 2b framework for the evaluation of surgical interventions outlines a process of innovation, development, exploration, assessment and long-term study. 30 Stage 2b refers to the exploration stage in evaluating new surgical techniques.

Statistical methods/analysis plan

The analysis and reporting of this study is in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) extension for randomised pilot and feasibility trials guidelines and the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines. The THESEUS study was not powered to test hypotheses. Most analyses are descriptive in nature. Continuous data are reported as means and standard deviations (SDs), or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), as appropriate, and categorical data reported as frequencies and proportions. The analyses and presentation of this study are based on the participants’ final treatment selection. All statistical analysis was carried out using Stata version 16.1 (Timberlake Consultants Ltd, Richmond upon Thames, UK).

Participation in the study (screened, eligible, recruited, withdrawals) and completeness of follow-up at each time point (3, 6, 9 and 12 months) was illustrated by a CONSORT flow diagram and table. Reasons for not being eligible and for not being recruited are described. We characterised participants recruited to the study by their demographics, clinical history and severity of HS.

The willingness of participants (participant preference) to receive each of the five treatment options was described along with the number of treatments participants were willing to receive. For individuals not willing to receive a particular intervention, reasons were reported. We characterised willingness to use treatment options, using selective baseline demographics and clinical examination data. We also examined the clinicians’ assessment of their eligibility and described the number and characteristics of individuals eligible/not eligible for each treatment option to help inform future RCTs. For the primary outcome, the willingness and eligibility data were combined for each treatment option. We also described the final treatment decision for each participant and reasons for selection. We characterised the group membership of the final intervention choice to determine the drivers of treatment choice. For participants choosing non-medical interventions, we also described where participants chose another treatment during the waiting period. Where a participant switched initial intervention within 6 months, we reported the reasons for this and explored the characteristics of switching (including intervention type, site and other baseline demographics). Treatment fidelity (concordance) was measured by self-reported adherence at each review time point. During the study period, we reported whether participants continued with and adhered to their chosen intervention or whether they switched to alternative HS interventions during the study period. Reasons for discontinuing or switching intervention were reported.

Efficacy outcome measures covering the six core domains recommended by the HiSTORIC core outcome set initiative for HS were examined:

-

HS quality of life questionnaire (HiSQOL)26 score (17 items);

-

PtGA28 – ‘In the past 7 days how much has your HS influenced your quality of life? (select one option from 0 to 10 where 10 is maximum influence)’;

-

progression of course:

-

number of flares in the last month;

-

change in disease severity – ‘Overall, has there been any change in your HS disease severity since you were last seen for the THESEUS study? Please select one option where “0” represents no change in disease severity, “–7” represents a very great deal worse, and “7” represents a very great deal better’;

-

refined Hurley stage. 5

-

-

physical signs:

-

symptoms:

-

drainage and need for dressings;

-

Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS). 28

-

-

pain NRS;

plus generic measures of quality of life:

-

DLQI score;29

-

EQ5D-5L score (5 items);

-

EQ5D health today (score 0–100).

Outcomes were described at each time point (baseline, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months). Owing to the skewed nature of the data and small numbers in each treatment group, the median and IQR was reported for each outcome. Effect over time, from baseline to 6 months, was estimated for each efficacy outcome for each treatment group again using median (IQR) change. As THESEUS is a feasibility study and not powered to detect differences between arms, a decision was made by the SMG to not perform any mixed-effect modelling to examine the effect of outcomes over time by treatment group.

The pattern of missingness of daily pain scores over the 12-week period was examined to determine whether concordance reduced over time or on specific days (proportion of valid texts received of an expected 84). We modelled the predictors of adherence using the demographic, clinical data and baseline scores using time to event analysis. We described the mean NRS score over the 12-week period and computed the standard errors of the mean scores over time to use them for the calculation of 95% CI around the mean score to produce a graphical display of the estimates over time. A generalisability theory analysis33 was performed to examine if efficient and consistent results of the NRS score are produced if different time windows such as weekly, fortnightly or monthly for the self-reported measures of NRS scale were to be used in a future study. This analysis was performed using linear mixed-effects regression model for the NRS scores within the framework of generalised linear mixed-effect modelling techniques to account for an appropriate structure of the within person correlations over time. Initially, the model included the random effects of patients, time, treatment selection, ‘reports/no reports of NRS scale’ and centres as well as their interaction terms as independent variables. In addition, the model allowed us to adjust for the fixed effects of other baseline potential confounders (such as age, gender, ethnicity, HiSQOL) if required.

Chapter 3 Prospective observational cohort results

Recruitment and follow-up rates

The first participant was recruited on 18 February 2020 and the last on 28 July 2021. Recruitment was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and there were two substantial pauses which mirrored the two main waves of the pandemic in the UK, in the spring and summer of 2020 and the beginning of 2021 (Figure 1). The flow of participants through the trial is represented in Figure 2.

FIGURE 1.

THESEUS cumulative recruitment.

FIGURE 2.

Study flow diagram. Oral clind. and rif. = oral clindamycin and rifampicin; conventional surg. = conventional surgery.

A total of 291 patients with HS were assessed for eligibility, with 151 (51.9%) recruited into the study over a period of 18 months; 81 (27.8%) patients were ineligible, 59 (20.3%) were eligible but not recruited. Reasons for patients’ ineligibility and for not taking part when eligible are reported in Table 2. Of the 151 recruited, one participant’s data were removed due to a lack of consent (and did not complete baseline). One individual completed baseline data collection twice; in the first instance they withdrew soon after choosing their intervention but were re-recruited and their latest data retained for analysis. The number of participants included in this study was 149, 51.2% of those assessed for eligibility. Follow-up rates (participants with at least one field recorded at review) at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months were 89% (n = 132), 83% (n = 123), 70% (n = 104) and 42% (n = 63), respectively, of those recruited. The 12-month follow-up rate was affected by recruitment delays that prevented complete follow-up of some participants due to closure of the study to adhere to study timelines; this accounted for 26 of the 35 participants who were lost to follow-up. Seventeen withdrawals were observed, two from the doxycycline arm, three from the clindamycin and rifampicin arm, eight from laser treatment, one from deroofing and three from conventional surgery.

| Patients n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Patients ineligible: | 81 (27.8)a |

| 0 of the 5 study interventions appropriate | 27 (33.3) |

| HS adequately controlled by current treatment | 18 (22.2) |

| Diagnosis did not meet disease definition | 13 (16.0) |

| Unable or unwilling to give informed consent | 10 (12.3) |

| Pregnant or breastfeeding | 8 (9.9) |

| Not fluent in English | 3 (3.7) |

| Age <18 years with active HS of any severity | 2 (2.5) |

| Patients eligible but not recruited: | 59 (20.3)a |

| Declined to take part | 46 (78.0) |

| Unable to arrange appointment/uncontactable | 13 (22.0) |

| Eligible participants recruited | 151 (51.9)a |

| Participant data removed due to lack of consent | 1 (0.3)a |

| Patients who were eligible and recruited: participated | 150 (51.5)a |

| Individual re-recruited after initial withdrawal (excluded initial record) | 1 |

| Participants included in the analysis at baseline | 149 (51.2)a |

| Participants followed up at:b | |

| 3 months | 132 (88.6) |

| 6 months | 123 (82.6) |

| 9 months | 104 (69.8) |

| 12 months | 65 (43.6) |

| Did not complete due to shortened follow-up period | 23 (15.4) |

Study sites

Ten sites across the UK recruited 149 participants, including one site in Scotland and one in Wales (Table 3). Two sites, Salford and Sussex, were initiated towards the end of the recruitment period. A total of 64 of the participants were recruited from six dermatology-led sites, 50 were recruited from two surgery-led sites and 35 from two sites that already had an integrated medical and surgical HS MDT approach. Six of the sites offered laser treatment.

| Sites | Participants recruited (n) |

|---|---|

| Dermatology-led: | 64 |

| NHS Forth Valley | 15 |

| Oxford University Hospitala | 16 |

| Newcastle Upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trusta | 14 |

| Barnsley Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | 5 |

| Salford NHS Foundation Trust | 4 |

| University Hospital Sussex | 10 |

| Surgery-led: | 50 |

| Buckinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trusta | 37 |

| Mid Essex Hospital Servicesa | 13 |

| Pre-established multidisciplinary service: | 35 |

| Guy’s and St Thomas NHS Foundation Trusta | 10 |

| Cardiff and Vale University Health Boarda | 25 |

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the participants recruited to the study by their demographics, clinical history, medications and severity of HS are reported in Table 4. Participants were on average 36 years (range: 18.2–67.1 years), 81% were female, and 86% had a raised BMI. Just over 20% had non-white ethnicity and Fitzpatrick skin photo type from IV to VI. Two-thirds of the participants were either current (43%) or ex-smokers (22%), and smokers on average smoked 10 cigarettes per day. There was balanced representation across the quintiles of deprivation apart from a lower proportion in the least deprived quintile.

| Demographics | Descriptive statistics |

|---|---|

| Age (years) Mean (SD) | 36.1 (10.5) |

| Sex: Female n (%) | 121 (81.2) |

| Ethnic group or background n (%) | |

| White | 118 (79.7) |

| Mixed/Multiple ethnic groups | 8 (5.4) |

| Asian/Asian British | 9 (6.1) |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British | 11 (7.4) |

| Other ethnic background | 2 (1.4) |

| Fitzpatrick scale n (%) | |

| I – very fair; always burns, cannot tan | 17 (11.5) |

| II – fair; usually burns, sometimes tans | 50 (33.8) |

| III – medium; sometimes burns, usually tans | 46 (31.1) |

| IV – olive; rarely burns, always tans | 13 (8.8) |

| V – brown; rarely burns, tans easily | 16 (10.8) |

| VI – dark brown; never burns, always tans | 6 (4.1) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | N = 143 |

| BMI mean (SD) | 33.0 (7.9) |

| Healthy weight (BMI ≥ 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2), n (%) | 20 (14.0) |

| Overweight (BMI ≥ 25.0 to 29.9 kg/m2), n (%) | 40 (28.0) |

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30.0 to 39.9 kg/m2), n (%) | 54 (37.8) |

| Severely obese (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2), n (%) | 29 (20.3) |

| Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) quintiles n (%): | |

| 5----- least deprived | 15 (10.1) |

| 4---- | 29 (19.5) |

| 3--- | 31 (20.8) |

| 2-- | 37 (24.8) |

| 1- most deprived | 37 (24.8) |

| Type of study site n (%): | |

| Dermatology-led (6 sites) | 64 (43.0) |

| Surgery-led (2 sites) | 50 (33.5) |

| Pre-established multidisciplinary service (2 sites) | 35 (23.5) |

| Smoking n (%): | |

| Non-smoker | 53 (35.8) |

| Ex-smoker | 32 (21.6) |

| Current smoker | 63 (42.6) |

| For smokers, number cigarettes smoked per day, median (IQR) | 10.0 (5.0 to 11.0) |

| Nicotine replacement therapy n (%) | 21 (14.3) |

In the previous 12 months, around two-thirds of participants had previously been treated by a GP or dermatologist (70.1% and 64.6%, respectively) with just under one-third being treated by a surgeon (30.6%), while 20% reported seeing a doctor in the emergency department. The groin and axilla were the most common skin regions affected. On average, participants had four inflammatory nodules, one abscess and one draining or inflamed skin tunnel at baseline. Hurley stage at baseline was I (mild) in 13%, II (moderate) in 68% and III (severe) in 19% of the participants. Components of the refined Hurley stage are listed in Table 5, the greatest proportion of participants being stage IIC (30%), with a range from IA to III.

| Baseline variables | Descriptive statisticsa | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical history | ||

| Participants’ HS recently treated by n (%): | ||

| GP | 103 | (70.1) |

| Dermatologist | 95 | (64.6) |

| Surgeon | 45 | (30.6) |

| Doctor in emergency department | 29 | (19.7) |

| Nurse (community/primary care) | 29 | (19.7) |

| Anybody else (others) | 12 | (8.1) |

| Severity of HS | ||

| Skin region affected: n (%) | ||

| Axilla | 102 | (68.5) |

| Groin | 114 | (76.5) |

| Perineum | 47 | (31.8) |

| Buttocks | 58 | (38.9) |

| Chest | 46 | (30.9) |

| Other | 45 | (30.4) |

| Total number of inflammatory nodules, median (IQR) | 4 | (1.0–8.5) |

| Total number of abscesses, median (IQR) | 1 | (0–3) |

| Total number of draining or inflamed skin tunnels, median (IQR) | 1 | (0–2) |

| IHS4,a median (IQR) | 11 | (4–21) |

| Number of HS flares in the last month, median (IQR) | 4 | (2–10) |

| Drainage of pus, blood, other fluid due to HS,b median (IQR) | 3.5 | (0–6) |

| Magnitude of skin odour,b median (IQR) | 3.5 | (0–7) |

| Hurley stage (most severely affected region) n (%) | ||

| H-I: mild; individual, non-scarring lesions | 19 | (12.8) |

| H-II: moderate; multiple scarring lesions separated by normal skin | 102 | (68.5) |

| H-III: severe; lesions coalescing into inflammatory plaques | 28 | (18.8) |

| Skin lesions fixed in location or migratory, n (%): | ||

| Fixed | 94 | (63.5) |

| Migratory | 54 | (36.5) |

| Draining skin tunnels due to HS present in any skin region n (%) | 86 | (58.1) |

| Three or more body regions with draining skin tunnels n (%) | 27 | (18.1) |

| Skin regions across body with at least 1% interconnected draining tunnels, n (%) | 15 | (10.1) |

| Refined Hurley stage for HS severity, n (%): | ||

| Hurley IA | 13 | (8.7) |

| Hurley IB | 32 | (21.5) |

| Hurley IC | 18 | (12.1) |

| Hurley IIA | 12 | (8.1) |

| Hurley IIB | 14 | (9.4) |

| Hurley IIC | 45 | (30.2) |

| Hurley III | 15 | (10.1) |

| How lesion count was assessed for the purposes of this review, n (%)c | ||

| By a health professional in person | 47 | (69.1) |

| By the patient self-reported | 21 | (30.9) |

Patients were not required to discontinue current HS therapy before entering the study.

Table 6 reports recent HS interventions received prior to study entry. In the case of non-biological medical therapies, including topical and oral therapy, results relate to the 1-month period prior to THESEUS recruitment. For biological therapy, details are provided for the preceding 3-month period and for surgical and laser therapy information was collected for the previous 12-month period.

| Baseline variables | Descriptive statisticsa | |

|---|---|---|

| Topical and oral therapy in previous month: | ||

| Chlorhexidine solution | 48 | 32.2 |

| Antiseptic | 37 | 25.0 |

| Clindamycin 1% | 29 | 19.5 |

| Other antibiotic | 11 | 7.4 |

| Corticosteroid | 9 | 6.1 |

| Non-biological treatment in previous month: | ||

| Tetracycline | 39 | 26.4 |

| Clindamycin | 19 | 12.8 |

| Rifampicin | 16 | 10.8 |

| Other oral antibiotic | 47 | 32.0 |

| Dapsone | 1 | 0.7 |

| Isotretinoin | 3 | 2.0 |

| Metformin | 13 | 8.7 |

| Spironolactone | 4 | 2.7 |

| Prednisolone | 2 | 1.3 |

| Zinc | 7 | 4.7 |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug | 50 | 34.0 |

| Paracetamol | 94 | 63.5 |

| Codeine | 35 | 23.6 |

| Morphine | 5 | 3.4 |

| Oral contraceptive | 17 | 11.6 |

| Finasteride | 1 | 0.7 |

| Botulinum toxin injections | 1 | 0.7 |

| Steroid injection into acute HS lesion(s) | 1 | 0.7 |

| Phototherapy | 1 | 0.7 |

| IV antibiotic | 5 | 3.4 |

| Other HS treatment | 8 | 5.4 |

| Biological medication use in previous 3 months: | ||

| Adalimumab | 9 | 6.0 |

| Etanercept | 1 | 0.7 |

| Infliximab | 1 | 0.7 |

| Anakinra | 1 | 0.7 |

| Other biologic | 1 | 0.7 |

| Incision and drainage under local anaesthetic | 23 | 15.6 |

| Lesion removed surgically and wound closed with stitches | 11 | 7.5 |

| Skin tunnel laid open and allowed to heal naturally | 15 | 10.2 |

| Wider area of skin removed | 4 | 2.7 |

| Method of wound healing: | ||

| Skin graft | 1 | 0.7 |

| Secondary intention | 3 | 2.1 |

| Laser treatmentb | 4 | 2.8 |

| Other surgical treatmentb | 5 | 3.4 |

Participants’ willingness to use the different THESEUS treatment options

Participants were asked to report their willingness to receive the five available treatment options, while clinicians assessed their eligibility for each of the treatment options (Table 7). Participant willingness to receive treatment was highest for laser (79.2%), deroofing of skin tunnels (66.4%) and conventional surgery (64.2%), and lower for the oral antibiotic treatments. The most common reason for unwillingness to receive oral doxycycline and oral clindamycin and rifampicin was ‘had the treatment before and was not effective’ (see Table 7). Some participants were unwilling to receive laser or deroofing due to anticipation of insufficient benefit. Some 41% of patients ranked laser treatment as the most preferred followed by 21% for deroofing treatment.

| Doxycycline | Clindamycin and rifampicin | Laser | Deroofing | Conventional surgery | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Willingness | ||||||||||

| Participant willing to receive treatment | 63 | (42.3) | 76 | (51.0) | 118 | (79.2) | 99 | (66.4) | 95 | (63.8) |

| Reasons for unwillingness: | ||||||||||

| Will not provide enough benefit | 14 | (9.4) | 12 | (8.1) | 18 | (12.1) | 23 | (15.4) | 19 | (12.8) |

| Potential side effects/complications | 11 | (7.4) | 12 | (8.1) | 1 | (0.7) | 5 | (3.4) | 13 | (8.8) |

| Had this before – not effective | 40 | (26.8) | 29 | (19.5) | 1 | (0.7) | 4 | (2.7) | 3 | (2.0) |

| Had this before – experienced side effects | 15 | (10.1) | 14 | (9.4) | 1 | (0.7) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Information from other sources | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.7) | 1 | (0.7) | 2 | (1.3) |

| Other reason | 6 | (4.0) | 6 | (4.0) | 9 | (6.0) | 17 | (11.4) | 16 | (10.7) |

| Patient ranked 1 (most preferred) | 17 | (14.3) | 19 | (15.8) | 52 | (40.6) | 26 | (20.8) | 15 | (12.0) |

| Clinician assessed eligibility | ||||||||||

| Clinically appropriate | 88 | (59.5) | 96 | (64.4) | 89 | (59.7) | 100 | (67.1) | 94 | (63.1) |

| Eligible but treatment not available at the site | na | na | 22 | (14.8) | na | na | ||||

Clinician-assessed eligibility for the different THESEUS treatment options

Overall, clinician-assessed eligibility was highest for laser treatment, with a total of 74.5% of participants being suitable, factoring in 14.8% in whom laser was clinically appropriate but not available at the study centre (see Table 7). The second highest proportion was for deroofing, with 67% of participants deemed eligible for the treatment.

Primary outcome: participants who are eligible, and hypothetically willing, to use the different THESEUS treatment options

Table 8 provides details of the THESEUS primary outcome, the proportion of participants who were both clinically eligible and willing to receive the intervention. The highest proportion was for laser treatment (68.5%) followed by deroofing (57.7%) and then conventional surgery (53.7%).

| Primary outcome: patients willing and eligible for study interventiona | Patients | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Doxycycline | 55 | 36.9 |

| Clindamycin and rifampicin | 65 | 43.6 |

| Laser | 102 | 68.5 |

| Deroofing | 86 | 57.7 |

| Conventional surgery | 80 | 53.7 |

Secondary outcome: participants’ final intervention choice

The participants’ final intervention choice is provided in Table 9. Laser was the most frequently chosen intervention, followed by deroofing, the oral antibiotic options and then conventional surgery. The most frequent reason for the intervention choice (59%) was ‘My doctor recommended it’, followed by ‘I wanted to try something new’ (19% of participants; Table 10). For both antibiotic options and also for deroofing, the main reason underpinning the participant’s choice was that their doctor had recommended it, while for laser, 27% wanted to try something new (see Table 10). Some 33% chose conventional surgery because they had received it before, while 17% based their choice on the information read on the THESEUS website. Participants’ first ranked treatment preference was often the same as their final treatment choice, ranging from 70% for doxycycline to 92% for conventional surgery (see Table 8).

| Final intervention choice,a n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | Clindamycin and rifampicin | Laser | Deroofing | Conventional surgery | |

| Patients, n (%) | 23 (15.4) | 23 (15.4) | 56 (37.6) | 35 (23.5) | 12 (8.1) |

| Patients’ ranking of treatment | |||||

| 1 = most preferred | 16 (70%) | 19 (83%) | 51 (91%) | 25 (71%) | 11 (92%) |

| 2 | 1 (2%) | 1 (3%) | |||

| 3 | 1 (4%) | 1 (3%) | |||

| 4 | 1 (4%) | 3 (13%) | |||

| 5 = least preferred | |||||

| Missing | 5 (22%) | 1 (4%) | 4 (7%) | 8 (23%) | 1 (8%) |

| Reason for deciding on the final treatment | Final choice of treatment, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | Clindamycin and rifampicin | Laser | Deroofing | Conventional surgery | |

| n = 23 | n = 22 | n = 55 | n = 35 | n = 12 | |

| My doctor recommended it | 15 (65.2) | 15 (68.2) | 27 (49.1) | 27 (77.1) | 3 (25.0) |

| I wanted to try something new | 5 (21.7) | 5 (22.7) | 15 (27.3) | 2 (5.7) | 1 (8.3) |

| I’ve used it before | 1 (4.4) | 1 (4.6) | 0 | 0 | 4 (33.3) |

| Based on | |||||

| Information read in THESEUS information sheet | 2 (8.7) | 0 | 5 (9.1) | 2 (5.7) | 0 |

| Information read on website(s) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.8) | 1 (2.9) | 2 (16.7) |

| Information read in THESEUS decision grid | 0 | 1 (4.6) | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 0 |

| My preferred option was not available | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.8) | 1 (2.9) | 0 |

| Other reason | 0 | 0 | 5 (9.1) | 2 (5.7) | 2 (16.7) |

Characterisation of ineligibility to receive the intervention options

Table 11 describes the number and characteristics of individuals not eligible for each treatment option to understand clinicians’ treatment choices and why individuals were not suitable, to inform a future trial’s eligibility criteria and target group. Individuals with migratory skin lesions were more likely to be deemed as ineligible for both deroofing and conventional surgery compared with those with fixed skin lesions as were those without skin tunnels. Age was a factor for non-eligibility for laser treatment, with older participants more likely to be unsuitable (average age = 41.2 years) compared with eligible patients aged 33.3 years on average (see Table 11). Older patients were slightly more likely to be eligible for oral antibiotics (doxycycline and clindamycin and rifampicin). Female patients were more likely to be ineligible for oral doxycycline and clindamycin and rifampicin (19 and 17 percentage points higher than male patients, respectively) and laser treatment (10 percentage points higher than male patients). Sex does not appear to drive differences in deroofing eligibility. Participants with obesity/severe obesity were more likely to be ineligible for deroofing (43%/41%, respectively). Participants of other ethnic background were more likely to be eligible for oral antibiotics or laser intervention.

| Baseline characteristics | Doxycycline | Clindamycin and rifampicin | Laser | Deroofing | Conventional surgery | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ineligible to receive intervention | 60 (40.5) | 52 (35.1) | 38 (25.5) | 49 (32.9) | 55 (36.9) | |

| Eligible to receive intervention | 88 (59.5) | 96 (64.9) | 89 (59.7) | 100 (67.1) | 94 (63.1) | |

| Participant eligible but intervention not available | na | na | 22 (14.8) | na | na | |

| Age (years) Mean (SD) | N = 148 | |||||

| Ineligible | 33.4 (8.4) | 34.0 (10.0) | 41.2 (12.5) | 36.8 (11.9) | 35.4 (10.2) | |

| Eligible | 38.0 (11.5) | 37.3 (10.7) | 33.3 (8.7) | 35.8 (9.8) | 36.5 (10.7) | |

| Participant eligible but intervention not available | na | na | 38.6 (10.0) | na | na | |

| Ineligible for intervention, n (%) | ||||||

| Sex: | ||||||

| Male | 28 | 7 (25.0) | 6 (21.4) | 5 (17.9) | 9 (32.1) | 9 (32.1) |

| Female | 120 | 53 (44.2) | 46 (38.3) | 33 (27.3) | 40 (33.1) | 46 (38.0) |

| BMI: | ||||||

| Healthy weight | 20 | 11 (55.0) | 7 (35.0) | 9 (45.0) | 7 (35.0) | 7 (35.0) |

| Overweight | 40 | 14 (35.0) | 14 (35.0) | 8 (20.0) | 10 (25.0) | 12 (30.0) |

| Obese | 54 | 23 (42.6) | 19 (35.2) | 10 (18.5) | 19 (35.2) | 23 (42.6) |

| Severely obese | 29 | 10/28 (35.7) | 9/28 (32.1) | 11 (37.9) | 13 (44.8) | 12 (41.4) |

| Smoking status: | ||||||

| Non-smoker | 53 | 22 (41.5) | 17 (32.1) | 14 (26.4) | 19 (35.8) | 19 (35.8) |

| Current smoker | 62 | 24 (38.7) | 21 (33.9) | 16 (25.4) | 18 (28.6) | 21 (33.3) |

| Ex-smoker | 32 | 14 (43.8) | 14 (43.8) | 8 (25.0) | 12 (37.5) | 14 (43.8) |

| Ethnicity: | ||||||

| White | 118 | 49/117 (41.9) | 46/117 (39.3) | 34 (28.8) | 38 (32.2) | 43 (36.4) |

| Other ethnic background | 30 | 11 (30.4) | 6 (20.0) | 4 (13.3) | 11 (36.7) | 12 (40.0) |

| IMD quintiles | ||||||

| 5----- least deprived | 15 | 4 (46.7) | 8 (53.3) | 4 (26.7) | 3 (20.0) | 5 (33.3) |

| 4---- | 29 | 13 (44.8) | 10 (34.5) | 6 (20.7) | 4 (13.8) | 13 (44.8) |

| 3--- | 31 | 9 (29.0) | 9 (29.0) | 10 (32.3) | 12 (38.7) | 10 (32.3) |

| 2-- | 36 | 13 (36.1) | 13 (36.1) | 8 (21.6) | 12 (32.4) | 12 (32.4) |

| 1- most deprived | 37 | 18 (48.6) | 12 (32.4) | 10 (27.0) | 18 (48.6) | 15 (40.5) |

| Skin lesions: | ||||||

| Fixed | 93 | 40 (43.0) | 34 (36.6) | 27 (28.7) | 26 (27.7) | 30 (31.9) |

| Migratory | 54 | 20 (37.0) | 18 (33.3) | 11 (20.4) | 23 (42.6) | 24 (44.4) |

| Skin tunnels present: | ||||||

| No | 62 | 24 (38.7) | 26 (41.9) | 13 (21.0) | 27 (43.5) | 27 (43.5) |

| Yes, n (%) | 85 | 35 (41.2) | 26 (30.6) | 25 (29.1) | 21 (24.4) | 27 (31.4) |

| Hurley stage for HS, n (%): | ||||||

| H-I: mild | 19 | 4 (21.1) | 8 (42.1) | 5 (26.3) | 8 (42.1) | 8 (42.1) |

| H-II: moderate | 102 | 47 (46.1) | 34 (33.3) | 29 (28.4) | 34 (33.3) | 39 (38.2) |

| H-III: severe | 27 | 9 (33.3) | 10 (37.0) | 4 (14.3) | 7 (25.0) | 8 (28.6) |

Characterisation of participants’ willingness to receive interventions

Table 12 characterises participant willingness to receive each intervention in terms of demographic and disease factors. Those willing to receive antibiotics were older than those who were unwilling, while younger people were more likely to be willing to undergo laser treatment. As expected, participants with skin tunnels and fixed skin lesions were more willing to receive deroofing, while participants with migratory lesions were more willing to receive laser treatment. Severe HS predicted willingness to receive laser, deroofing or conventional surgery.

| Baseline characteristics | Total | Doxycycline | Clindamycin and rifampicin | Laser | Deroofing | Conventional surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients willing to receive treatment, n (%) | 149 | 63 (42.3) | 76 (51.0) | 118 (79.2) | 99 (66.4) | 95 (64.2) |

| Age (years), mean (SD): | ||||||

| Willing | 39.5 (10.8) | 38.1 (10.7) | 35.0 (10.2) | 36.0 (10.5) | 36.4 (10.6) | |

| Not willing | 33.6 (9.6) | 34.0 (9.9) | 40.2 (10.6) | 36.3 (10.7) | 35.6 (10.6) | |

| Sex: | ||||||

| Male | 28 | 17 (60.7) | 20 (71.4) | 22 (78.6) | 18 (64.3) | 19 (67.9) |

| Female | 121 | 46 (38.0) | 56 (46.3) | 96 (79.3) | 81 (66.9) | 76 (62.8) |

| BMI (kg/m2): | ||||||

| Healthy weight | 20 | 4 (20.0) | 11(55.0) | 17 (85.0) | 14 (70.0) | 14 (70.0) |

| Overweight | 40 | 20 (50.0) | 21 (52.5) | 32 (80.0) | 25 (62.5) | 23 (57.5) |

| Obese | 54 | 24 (44.4) | 29 (53.7) | 44 (81.5) | 35 (64.8) | 36 (66.7) |

| Severely obese | 29 | 12 (41.4) | 13 (44.8) | 19 (65.5) | 19 (65.5) | 17 (58.6) |

| Smoking status: | ||||||

| Non-smoker | 53 | 18 (34.0) | 28 (52.8) | 42 (79.3) | 32 (60.4) | 35 (66.0) |

| Current smoker | 63 | 32 (50.8) | 31 (49.2) | 50 (79.4) | 50 (79.4) | 42 (66.7) |

| Ex-smoker | 32 | 13 (40.6) | 17 (53.1) | 25 (78.1) | 17 (53.1) | 18 (56.3) |

| Ethnicity: | ||||||

| White | 118 | 53 (44.9) | 60 (50.9) | 92 (78.0) | 82 (69.5) | 76 (64.4) |

| Other ethnic backgrounda | 30 | 10 (33.3) | 15 (50.0) | 25 (83.3) | 16 (53.3) | 18 (60.0) |

| IMD quintiles | ||||||

| 5----- least deprived | 15 | 5 (33.3) | 4 (26.7) | 14 (93.3) | 11 (73.3) | 12 (80) |

| 4---- | 29 | 10 (34.5) | 12 (41.4) | 24 (82.8) | 23 (79.3) | 20 (69.0) |

| 3--- | 31 | 18 (58.1) | 21 (67.7) | 26 (83.9) | 19 (61.3) | 19 (61.3) |

| 2-- | 37 | 11 (29.7) | 18 (48.7) | 26 (70.3) | 24 (64.9) | 22 (59.5) |

| 1- most deprived | 37 | 19 (51.4) | 21 (56.8) | 28 (75.7) | 22 (59.5) | 22 (59.5) |

| Skin lesions: | ||||||

| Fixed in one region | 94 | 37 (39.4) | 46 (48.9) | 70 (74.5) | 67 (71.3) | 63 (67.0) |

| Migratory | 54 | 26 (48.2) | 30 (55.6) | 47 (87.0) | 32 (59.3) | 32 (59.3) |

| Skin tunnels present: | ||||||

| No | 62 | 30 (48.4) | 36 (58.1) | 53 (85.5) | 34 (54.8) | 35 (56.5) |

| Yes | 86 | 33 (38.4) | 39 (45.4) | 64 (74.4) | 65 (75.6) | 59 (68.6) |

| Hurley stage for HS: | ||||||

| H-I: mild | 19 | 10 (52.6) | 10 (52.6) | 15 (79.0) | 11 (57.9) | 12 (63.2) |

| H-II: moderate | 102 | 41 (40.2) | 53 (52.0) | 78 (76.5) | 68 (66.7) | 62 (60.8) |

| H-III: severe | 28 | 12 (42.9) | 13 (46.4) | 25 (89.3) | 20 (71.4) | 21 (75.0) |

Characterisation of participants by final treatment choice

Regarding participants’ final treatment choice, a higher proportion of female patients chose laser and deroofing (Table 13). Laser was favoured by a younger group of patients while doxycycline was selected by older patients. Current smokers favoured doxycycline and deroofing over other treatments while a higher proportion from ethnic minority backgrounds favoured laser treatment.

| Baseline characteristics | Final treatment choice | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | Clindamycin and rifampicin | Laser | Deroofing | Conventional surgery | |

| n (%) | n = 23 | n = 23 | n = 56 | n = 35 | n = 12 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 8 (34.8) | 5 (21.7) | 7 (12.5) | 5 (14.3) | 3 (25.0) |

| Female | 15 (65.2) | 18 (78.3) | 49 (87.5) | 30 (85.7) | 9 (75.0) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 40.2 (13.2) | 38.1 (10.4) | 33.1 (8.9) | 37.0 (10.7) | 36.2(8.8) |

| BMI groups | |||||

| Healthy weight | 2 (8.7) | 5 (21.7) | 6 (11.1) | 7 (21.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Overweight | 4 (17.4) | 4 (17.4) | 19 (35.2) | 9 (28.1) | 4 (36.4) |

| Obese | 11 (47.8) | 9 (39.1) | 18 (33.3) | 10 (31.3) | 6 (54.5) |

| Severely obese | 6 (26.1) | 5 (21.7) | 11 (20.4) | 6 (18.8) | 1 (9.1) |

| Smoking | |||||

| Non-smoker | 5 (21.7) | 9 (39.1) | 26 (47.3) | 10 (28.6) | 3 (25.0) |

| Current smoker | 14 (60.9) | 9 (39.1) | 15 (27.3) | 20 (57.1) | 5 (41.7) |

| Ex-smoker | 4 (17.4) | 5 (21.7) | 14 (25.5) | 5 (14.3) | 4 (33.3) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 21 (91.3) | 18 (78.3) | 40 (72.7) | 29 (82.9) | 10 (83.3) |

| Other ethnic backgrounda | 2 (8.7) | 5 (21.7) | 16 (27.3) | 6 (17.1) | 2 (16.7) |

| IMD quintiles | |||||

| 5----- Least deprived | 3 (13.0) | 1 (4.4) | 6 (10.7) | 4 (11.4) | 1 (8.3) |

| 4---- | 4 (17.4) | 5 (21.7) | 10 (17.9) | 9 (25.7) | 1 (8.3) |

| 3--- | 7 (30.4) | 4 (17.4) | 14 (25.0) | 4 (11.4) | 2 (16.7) |

| 2-- | 5 (21.7) | 6 (26.1) | 10 (17.9) | 11 (31.4) | 5 (41.7) |

| 1- Most deprived | 4 (17.4) | 7 (30.4) | 16 (28.6) | 7 (20.0) | 3 (25.0) |

| Skin lesions | |||||

| Fixed in one region | 11 (47.8) | 14 (60.9) | 37 (67.3) | 26 (74.3) | 6 (50.0) |

| Migratory | 12 (52.2) | 9 (39.1) | 19 (32.7) | 9 (25.7) | 6 (50.0) |

| Skin tunnels present (% yes) | |||||

| No | |||||

| Yes | 12 (52.2) | 12 (52.2) | 24 (43.6) | 29 (82.9) | 9 (75.0) |

| Hurley stage for HS | |||||

| H-I: mild; individual | 5 (21.7) | 2 (8.7) | 7 (12.5) | 4 (11.4) | 1 (8.3) |

| H-II: moderate; multi | 14 (60.9) | 20 (87.0) | 38 (67.9) | 24 (68.6) | 6 (50.0) |

| H-III: severe; lesion | 4 (17.4) | 1 (4.4) | 11 (19.6) | 7 (20.0) | 5 (41.7) |

Treatment fidelity

We summarised the treatment fidelity for each treatment option in Tables 14–18. Regarding fidelity to doxycycline, at the 3-month review, 52% of participants were still receiving doxycycline, a proportion which was maintained at 6 months and dropped to 26% after 9 months (Table 14). At 9 months, 65% did not provide fidelity data which could indicate that use of doxycycline had ceased. However, the expectation would be for patients to continue with doxycycline if it was still effective and well tolerated. The most common participant reasons for treatment discontinuation were lack of effectiveness, opting to try an alternative intervention, and adverse effects.

| Review 1, 3-month follow-up, n (%) | Review 2, 6-month follow-up, n (%) | Review 3, 9-month follow-up, n (%) | Review 4, 12-month follow-up, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final treatment choice at baseline review = doxycycline | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 |

| Still receiving doxycycline? | ||||

| Yes | 12 (52.2) | 13 (56.5) | 6 (26.1) | 4 (17.4) |

| If yes, self-reported adherence | ||||

| Very well | 8 | 10 | 3 | 3 |

| Somewhat well | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Not at all | – | 1 | 1 | – |

| No | 8 (34.8) | 5 (21.7) | 2 (8.7) | 1 (4.3) |

| If no, reason why? | ||||

| Participant chose different treatmenta | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Clinician chose different treatmenta | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Treatment delay | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Missing/No review (na) | 3 (13.0) | 5 (21.7) | 15 (65.2) | 18 (78.3) |

| Continuing with doxycycline? | ||||

| Yes | 12 (52.2) | 8 (34.8) | 6 (26.1) | 4 (17.4) |

| No | 8 (34.8) | 10 (43.5) | 2 (8.7) | 1 (4.3) |

| If no, reason why?b | ||||

| Opted to try alternative treatment | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Did not find treatment effective | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Adverse effects | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Other reason | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Missing/No review (na) | 3 (13.0) | 5 (21.7) | 15 (27.7) | 18 (78.3) |

Of the 23 participants that chose clindamycin and rifampicin, at 3 months post recruitment 30% were still receiving treatment, all of whom self-reported that they were adhering somewhat or very well to therapy (Table 15). In some cases, treatment discontinuation was due to the review being after the scheduled finish for the 10 weeks of therapy, while adverse effects and treatment ineffectiveness were also reasons for not continuing with the intervention.

| Review 1, 3-month follow-up, n (%) | Review 2, 6-month follow-up, n (%) | Review 3, 9-month follow-up, n (%) | Review 4, 12-month follow-up, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final treatment choice at baseline review = clindamycin and rifampicin | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 |

| Still receiving clindamycin and rifampicin? | ||||

| Yes | 7 (30.4) | 1 (4.3) | 1 (4.3) | 0 |

| If yes, self-reported adherence: | ||||

| Very well | 5 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Somewhat well | 2 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Not at all | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| No | 12 (52.2) | 10 (43.5) | 9 (39.1) | 4 (17.4) |

| If no, reason why? | ||||

| Participant chose different treatmenta | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Clinician chose different treatmenta | 4 | 5 | 4 | 0 |

| Treatment delay | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| Missing/No review (na) | 4 (17.4) | 12 (52.2) | 13 (56.5) | 19 (82.6) |

| Continuing with clindamycin and rifampicin? | ||||

| Yes | 7 (36.8) | 7 (58.3) | 3 (30.0) | 1 (25.0) |

| No | 12 (63.2) | 5 (41.7) | 7 (70.0) | 3 (75.0) |

| If no, reason why?b | ||||

| Opted to try alternative treatment | 4 | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| Did not find treatment effective | 5 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Adverse effects | 5 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Other reason | 2 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Missing/No review (na) | 4 | 11 | 13 | 19 |

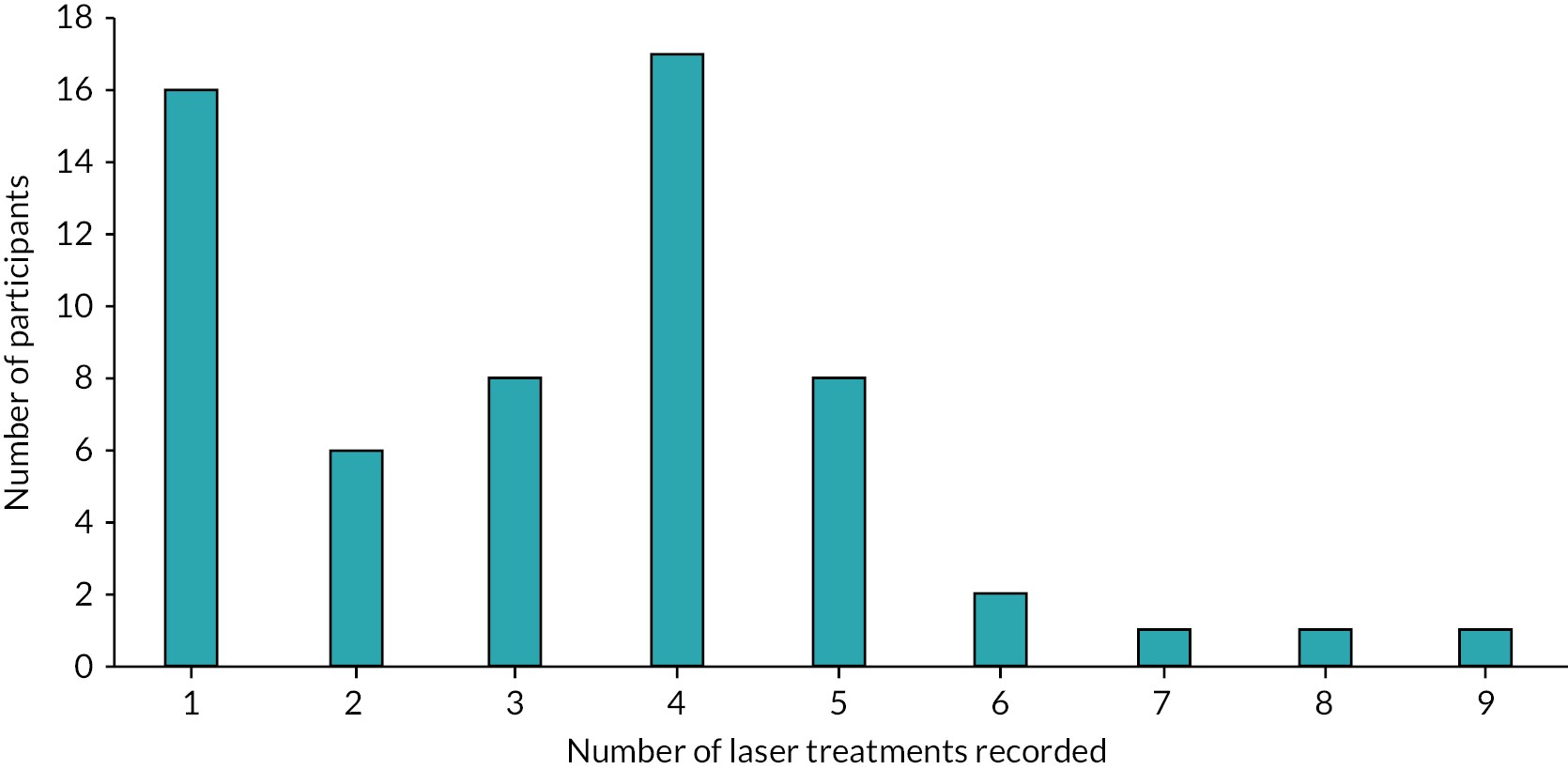

Of the 56 participants who chose laser as their intervention, only 43% started treatment (received at least one treatment session) at the 3-month review (Table 16). This relates to delays receiving treatment due to waiting times that were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, with THESEUS being an observational study. The figure rose to 64% by 6 months, 77% at 9 months and 79% by 12 months. Treatment delay was reported by 23, 8, 4 and 3 participants at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months, respectively. Only three reports of switching the treatment were observed at follow-ups.

| Review 1, 3-month follow-up, n (%) | Review 2, 6-month follow-up, n (%) | Review 3, 9-months follow-up, n (%) | Review 4, 12-month follow-up, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final treatment choice at baseline review = laser | 56 | 56 | 56 | 56 |

| Did the participant receive first laser treatment? | ||||

| Yes | 21 (37.5) | 31 (55.4) | 36 (64.3) | 39 (69.6) |

| Partially | 3 (5.4) | 5 (8.9) | 7 (12.5) | 5 (8.9) |

| Missing/No review (na) | 8 (14.2) | 11 (19.6) | 9 (16.1) | 9 (10.7) |

| No | 24 (42.9) | 9 (16.1) | 4 (7.1) | 3 (5.4) |

| If no, reason why? | ||||

| Participant chose different treatmenta | ||||

| Clinician chose different treatmenta | ||||

| Treatment delay | 23 | 8 | 4 | 3 |

| Participant did not attend their procedure appointment | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Continuing with laser treatment? | ||||

| Yes | 48 (85.7) | 43 (76.8) | 31 (55.4) | 14 (25.0) |

| No | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| If no, reason why?b | ||||

| Opted to try alternative treatment | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Other reason | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Time between recruitment and the first procedure (days), median (IQR) | N = 59 105 (53–172) |

|||

Of the 35 participants who chose deroofing as their final treatment, only 25% received their procedure after 3 months of follow-up (Table 17). Some 43% reported receipt of their first deroofing at 6 months of follow-up, 54% after 9 months and 63% after 12 months. The majority of participants who provided follow-up information preferred to continue deroofing. Deroofing delay was reported by 21, 14, 8 and 5 participants at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months, respectively. During follow-up, there were only three reports of switching treatment to a different intervention.

| Review 1, 3-month follow-up, n (%) | Review 2, 6-month follow-up, n (%) | Review 3, 9-month follow-up, n (%) | Review 4, 12-month follow-up, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final treatment choice at baseline review = deroofing | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 |

| Did the participant receive first deroofing? | ||||

| Yes | 9 (25.7) | 15 (42.9) | 19 (54.3) | 22 (62.9) |

| Missing/No review (na) | 5 (14.3) | 6 (17.1) | 7 (20.0) | 7 (20.0) |

| No | 21 (60.0) | 14 (40.0) | 9 (25.7) | 6 (17.1) |

| If no, reason why? | ||||

| Participant chose different treatmenta | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Clinician chose different treatmenta | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Treatment delay | 21 | 14 | 8 | 5 |

| Participant did not attend their procedure appointment | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Continuing with deroofing treatment? | ||||

| Yes | 28 (80.0) | 24 (68.5) | 17 (48.6) | 12 (34.3) |

| No | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| If no, reason why?b | ||||

| Opted to try alternative treatment | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Other reason | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Time between recruitment and the first procedure [days, median (IQR)] | N = 31 116 (71–245) |

|||

Conventional surgery was substantially delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic and only one participant reported receiving surgery by 3 months (Table 18) and six (50%) by the end of the study. Delay in surgery was reported by eight and five participants at the 3- and 6-month follow-up reviews, respectively. Overall, three participants chose to switch to an alternative intervention.

| Review 1, 3-month follow-up, n (%) | Review 2, 6-month follow-up, n (%) | Review 3, 9-month follow-up, n (%) | Review 4, 12-month follow-up, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final treatment choice at baseline review = conventional surgery | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Did the participant receive first surgery? | ||||

| Yes | 1 (8.3) | 3 (25.0) | 6 (50.0) | 6 (50.0) |

| Missing/No review (na) | 3 (25.0) | 3 (25.0) | 6 (50.0) | 6 (50.0) |

| No | 8 (66.7) | 6 (50.0) | 0 | 0 |

| If no, reason why? | ||||

| Participant chose different treatmenta | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Clinician chose different treatmenta | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Treatment delay | 8 | 5 | ||

| Participant did not attend their procedure appointment | ||||

| Continuing with conventional surgery? | ||||

| Yes | 8 (66.7) | 7 (58.3) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (8.3) |

| No | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| If no, reason why?b | ||||

| Opted to try alternative treatment | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Other reason | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Time between recruitment and the first procedure (days), median (IQR) | N = 8 175 (129.5–214) |

|||

Efficacy outcome estimates

Clinical outcomes over time have been described using medians alongside IQRs at each time point (baseline, 3, 6 and 9 months) and by each treatment group (Table 19). Interpretation of the change in outcome measures over time was hindered by the fact that individuals especially in the surgical interventions may not have received their treatment by the 6-month review. For example, of the 56 participants who chose laser surgery, 32 (57.1%) had received their first treatment before the 6-month review, 9 (16.1%) had not and 7 (12.5%) had received partial treatment (8 missing information by 6 months). Of the 36 that chose deroofing, 15 (41.7%) had received their first treatment by the 6-month review and 14 (38.9%) had not (7 missing information by 6 months). Of the 12 that chose conventional surgery, 3 (25.0%) had received their procedure by the 6-month review and 6 (50.0%) had not (3 missing information by 6 months).

| Baseline | Review 1, 3-month follow-up | Review 2, 6-month follow-up | Review 3, 9-month follow-up | Review 4, 12-month follow-up | Change, median (IQR) (baseline to 6 months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLQI score: sum of the responses to all 10 DLQI items ranging from 0 to 30, with a higher score corresponding to worse quality of life | ||||||

| Doxycycline | n = 23 | n = 20 | n = 19 | n = 13 | n = 7 | n = 19 |

| 6.0 (4.0, 13.0) | 3.5 (1.5, 8.0) | 4.0 (1.0, 7.0) | 4.0 (3.0, 11.0) | 3.0 (2.0, 7.0) | –2.0 (–6.0, 0.0) | |

| Clindamycin and rifampicin | n = 23 | n = 18 | 18 | n = 15 | n = 10 | n = 18 |

| 14.0 (9.0, 18.0) | 10.5 (4.0, 13.0) | 8.5 (2.0, 12.0) | 12.0 (4.0, 16.0) | 6.0 (4.0, 15.0) | –6.5 (–1.0, −2.0) | |

| Laser | n = 56 | n = 45 | n = 43 | n = 41 | n = 19 | n = 43 |

| 15.0 (10.5, 9.0) | 11.0 (7.0, 16.0) | 11.0 (4.0, 15.0) | 10.0 (6.0, 19.0) | 6.0 (4.0, 12.0) | –3.0 (–11.0, 0.0) | |

| Deroofing | n = 35 | n = 32 | n = 31 | n = 27 | n = 23 | n = 31 |

| 12.0 (8.0, 18.0) | 11.5 (5.5, 16.0) | 10.0 (3.0, 18.0) | 7.0 (2.0, 16.0) | 7.0 (2.0, 13.0) | 0.0 (–7.0, 2.0) | |

| Conventional surgery | n = 12 | n = 11 | n = 8 | n = 7 | n = 4 | n = 8 |

| 16.0 (10.0, 21.0) | 13.0 (8.0, 22.0) | 11.5 (10.5, 6.5) | 15.0 (7.0, 8.0) | 12.5 (6.5, 4.0) | –2.5 (–9.0, 0.0) | |

| EQ5D-5L score: health-related quality of life index where 1 = best possible health, through 0 = death to –0.59 = worse than death | ||||||

| Doxycycline | n = 21 | n = 20 | n = 18 | n = 13 | n = 7 | n = 17 |

| 0.71 (0.50, 0.90) | 0.80 (0.50, 0.90) | 0.80 (0.70, 0.90) | 0.72 (0.50, 0.80) | 0.77 (0.20, 1.00) | 0 (–0.18, 0.15) | |

| Clindamycin and rifampicin | n = 23 | n = 17 | n = 16 | n = 14 | n = 9 | n = 16 |

| 0.69 (0.50, 0.90) | 0.77 (0.50, 0.80) | 0.67 (0.50, 0.90) | 0.72 (0.60, 0.80) | 0.80 (0.60, 1.00) | 0.06 (–0.16, 0.33) | |

| Laser | n = 50 | n = 34 | n = 40 | n = 36 | n = 17 | n = 38 |

| 0.69 (0.50, 0.80) | 0.70 (0.50, 0.80) | 0.69 (0.50, 0.80) | 0.70 (0.60, 0.80) | 0.72 (0.60, 0.80) | 0 (–0.12, 0.10) | |

| Deroofing | n = 33 | n = 31 | n = 31 | n = 27 | n = 22 | n = 30 |

| 0.64 (0.60, 0.80) | 0.70 (0.60, 0.80) | 0.73 (0.60, 0.80) | 0.83 (0.50, 1.00) | 0.77 (0.60, 0.90) | 0 (–0.12, 0.16) | |