Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number 17/21/06. The contractual start date was in November 2018. The draft report began editorial review in April 2022 and was accepted for publication in January 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Scholefield et al. This work was produced by Scholefield et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Scholefield et al.

Chapter 1 Phase 1a: scoping review of literature

Introduction

This review aimed to evaluate early mobilisation and rehabilitation (ERM) within paediatric intensive care as reported within the published literature. We characterised the evidence base using a narrative synthesis approach to understand features of ERM associated with effectiveness and successful implementation within paediatric intensive care units (PICU).

Study management

The work package was led by BRS. The study management group was responsible for defining and reviewing scope of search. JYT performed searches, data extraction, risk of bias assessment, evidence synthesis and first draft of chapter. Second screening of articles, data extraction and risk of bias performed by Dr Olivia Craw, JMc and JMen. Methodological expertise provided by DM and BRS.

Objectives

Our primary objective was to summarise the types and effectiveness of ERM interventions and outcome measures delivered to children admitted to PICUs.

Our secondary objective was to thematically identify subpopulations (if any) that benefit most from ERM or experience associated adverse or clinical events, and any patterns or gaps during implementation.

Methods

Search strategy

Searches were conducted in the bibliographic databases [Excerpta Medica Database (Embase) (via OVID), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (via EBSCO), MEDLINE (via OVID), PEDro, Open grey or Cochrane CENTRAL)]. Original search was from inception to 12 October 2019 and an updated search was performed 1 November 2021, using strategies that combined, where relevant, free text and index terms for:

-

children and young people (CYP);

-

admitted to paediatric critical care settings;

-

receiving early (within 7 days) rehabilitation and mobilisation.

The search strategy was developed in MEDLINE (via OVID) (see Appendix 2) and adapted for other databases.

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, National Health Service (NHS) Economic Evaluation Database and Health Technology Assessment database (all via Centre for Reviews and Dissemination) were searched for relevant systematic reviews to identify primary studies for the review. These were supplemented by relevant websites using hand-searching for mobilization-network.org and search terms for clinicaltrials.gov or Chinese clinical trial registry, checking reference lists of relevant studies, and forward citation-checking of included studies in Web of Science. We screened reference lists to identify relevant primary studies and contacted primary authors to find full texts of incomplete records.

Eligibility criteria

We included all completed studies published in English that met the following criteria:

-

Study participants: critically ill infants, children or young people aged ≤18 years, admitted to PICUs, who received an intervention described as rehabilitation or mobilisation delivered by any health professional within ≤7 days after admission. Rehabilitation or mobilisation interventions could include but were not limited to physiotherapy (PT), occupational therapy, speech and language therapy (SLT) and bundled interventions; these included ABCDEFH bundles (spontaneous awakening and breathing trials; choice of sedation and analgesia, delirium prevention, surveillance and management; early mobilisation and exercise programmes with or without adjuncts; family engagement and empowerment; proper nutrition and humanism) so long as their application was considered within the first 7 days of admission; AND

-

Outcome: at least one outcome was related to participants’ health and well-being, health service utilisation, feasibility, acceptability or intervention implementation.

-

Study design: primary research studies of any designs, with >10 participants to synthesise evidence on intervention effectiveness. Case reports, case series with ≤10 patients, qualitative studies and systematic reviews were excluded if relevant primary studies were not identified in the references. Abstracts or ongoing studies identified from clinical trial registries were used to highlight the presence of future emerging research.

Screening and selection

Records identified were imported into a bibliographic referencing software programme (EndNote X9, Thomson Reuters, San Francisco, CA, USA), and duplicates were removed. One PT researcher (JT) and one clinical academic (BS or JMen) independently screened titles and abstracts for relevance against the eligibility criteria within Rayyan systematic review software. 1 The full texts of relevant articles were obtained and assessed against the selection criteria by two reviewers independently (JT, Dr Olivia Craw). A wider range of publication types (abstracts and full texts) were selected to identify all possible lists of ERM interventions but were not analysed to summarise types of ERM. Reasons for exclusion were noted. Discrepancies were discussed via consensus meeting with a third author (JMc).

Data extraction

Data were extracted using a standardised, piloted data-extraction form in Excel. Information within the following domains was extracted:

-

Study – author, year of publication, country, study design using an algorithm for classifying studies. 2

-

Patient demographics – age, sex, admission diagnosis, the severity of illness and, comorbidity using established criteria3 or paediatric scoring tools such as Pediatric risk of mortality (PRISM III), the Pediatric logistic organ dysfunction (PELOD), the Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category (PCPC) and the Pediatric Overall Performance Category (POPC). We also considered the following prognostic factors when assessing non-randomised studies: age, sex, weight or body mass index (BMI) in percentile, baseline severity, comorbidities and admission diagnosis on the intervention.

-

Intervention details – definition of ERM, type of interventions, the volume of ERM (time-to-initiation, duration, number of sessions), implementation strategies such as safety and progression criteria, involvement of health professionals or availability of organisational support.

-

Study comparators and outcome – components of usual care, primary and secondary outcomes (where specified) and assessment time points. When outcome measures were not specified or reported, the outcomes most proximal to the health domain were considered the primary outcome.

Data were extracted (JT) and independently verified by co-authors (Dr Olivia Craw, JMc and JMen). We used all eligible studies, abstracts or full texts that reported any intervention to summarise types of interventions. We only included full-text reports where ERM was initiated within the first 7 days of admission to PICU to synthesise ERM outcomes.

Quality assessment of individual studies

Risk of bias was assessed in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) the using Cochrane Risk of Bias tool version 24 and in non-randomised studies using the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies – of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool. 5 One reviewer (JT) assessed the methodological quality of studies and this was independently verified by a second (Dr Olivia Craw, JMc).

We evaluated the reporting quality of studies using the Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT). 6 Due to the nature of the study interventions included in this review, participants, providers and assessors were aware of the intervention, which can affect compliance, outcome assessment or intervention fidelity. To understand implementation, we grouped studies that provided information on different aspects of delivering ERM, such as core content of ERM, who commonly delivers it, mode, timing, frequency of delivery, and the adaptation process for tailoring ERM.

Data synthesis

A narrative synthesis of all included studies was undertaken. Due to the heterogeneous nature of paediatric populations and interventions, meta-analysis was not appropriate. All outcomes were grouped as short-term (≤6 months post-discharge) or intermediate-term (≥6 months post-discharge) outcomes.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

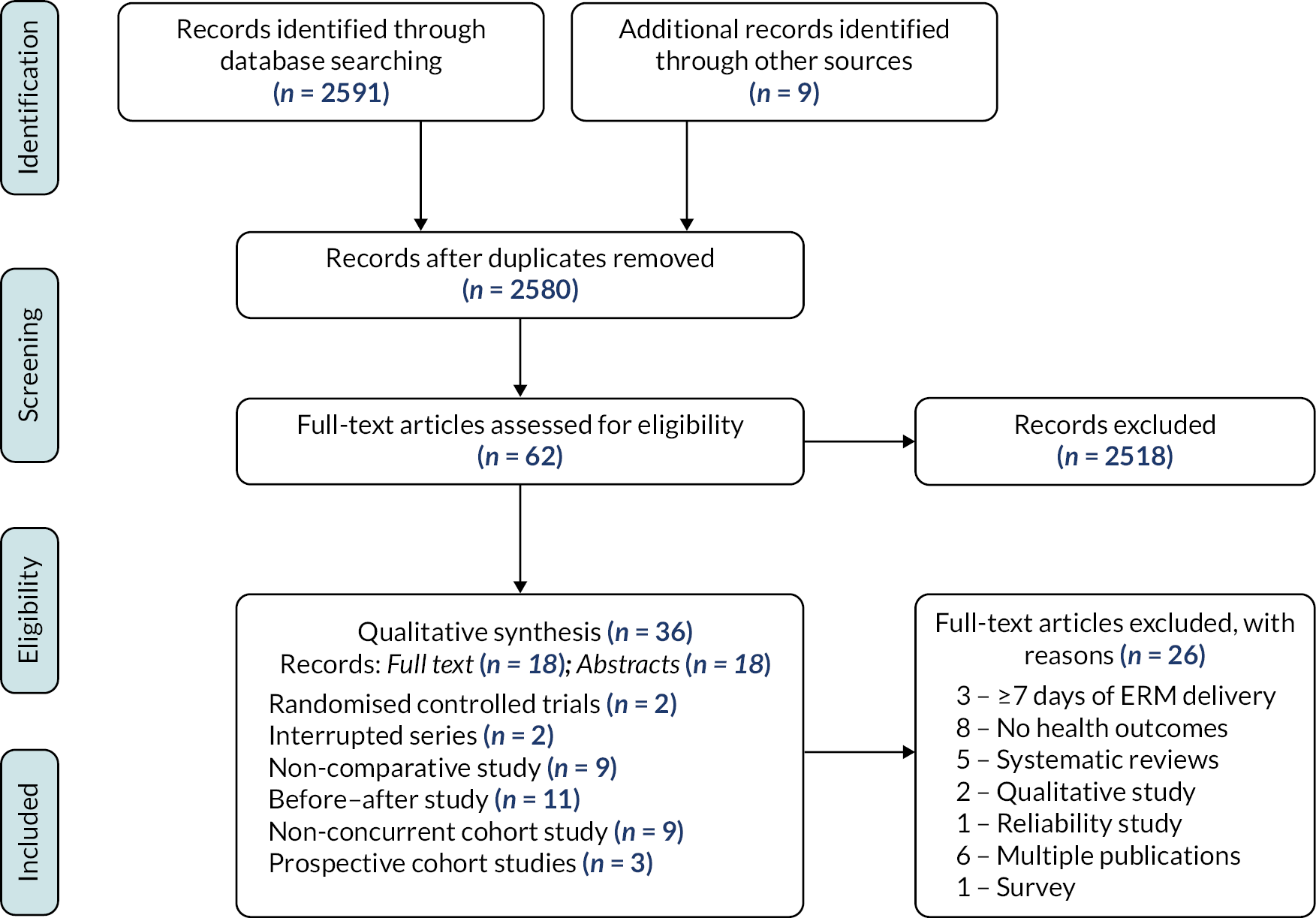

As shown in Figure 1, 2580 unique records were screened for relevance, and 62 relevant full-text articles were assessed for inclusion. Twenty-six of these were excluded, mainly due to the ineligibility of the study design or outcomes. Eighteen of the 36 studies that met the eligibility criteria were abstracts, and 18 had full-text reports. Most were conducted in North America,7–25 Australia,26 Belgium,27,28 Brazil,29,30 Italy,31 Japan,32–34 the Netherlands,35 Turkey36,37 and the UK. 38–41 One study was conducted across 15 countries in Europe42 (see Appendix 2, Table 32).

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA diagram.

Five studies15,18,21,22,24 were conducted across multiple PICUs, and two studies15,43 used controlled designs. Three studies were prospective cohorts,24,41,42 2 were interrupted-time series,7,27 9 non-comparative studies,8,10,13,22,30,31,34,36,40 11 before–after studies9,11,12,17,23,25,32,33,35,38,44 and 9 non-concurrent cohort studies. 14,16,18,19,21,26,28,37,45

Types of interventions identified

Of the 36 studies that evaluated PICU rehabilitation, we identified two broad categories of early rehabilitation or mobilisation (ERM): non-mobility and mobility interventions. Non-mobility interventions mentioned in included studies were pain and agitation assessment,23 sleep hygiene/delirium screening,17,22,23,35 ERM screening checklist,26 cuddles,18,40 SLT8,12,15,21 and chest PT. 21 The majority were mobility interventions and included mobility goals/orders,22,23,35,40,41 out-of-bed exercises,15,17 in-bed cycling,11,19,20,46 edge-of-bed mobility,40 bed-mobility exercises,15,17,21,32 interactive boxing,7 physical therapy8,10,12–16,18,21,30,32 and OT. 8,10,12–16,18,21,30 When usual care15,20,24 was used as a comparison, it consisted of positioning,

Interventions were commonly administered from 24 to 72 hours after PICU admission. The volume of sessions varied widely, but most sessions were delivered twice daily. In some situations,32 information on initiating ERM delivery was unavailable. Five studies7,11,19,26,43 used single-component interventions. One study13 reported the number of encounters or admissions but provided no information about patient characteristics. Multicomponent interventions (12/16 studies) consisting of PT, OT and SLT were more commonly explored.

Patient and study characteristics

Out of the 36 studies that met our eligibility criteria, 18 full-text records evaluated at least one ERM outcome (as defined by the study authors) within 7 days after admission; the results reported here are for these 18 full-text publications. The study population consisted of day-old children to ≤18 years, with sample sizes of 12–722 participants. In almost all studies (n = 17/18), patients were admitted with a mixture of medical and surgical diagnoses – respiratory, neurological and cardiac conditions.

Outcomes

Among 18 studies that evaluated ERM, the feasibility and safety of ERM alongside process outcomes were the most frequent outcomes considered. See Appendix 2, Table 32.

Adverse events

Fifteen studies7,10–14,17–19,24,25,32,36,42,43 provided information on adverse events (AEs). The most common event was tachycardia/desaturation. 13,14,24,42 Three studies reported haemodynamic changes7,15,42 or tube removals. 7,10,42 Other events mentioned include pain,7 fall,7 behavioural changes,24 excessive secretions24 and discontinuation of therapy. 14,15,43

Evaluation of early rehabilitation and mobilisation interventions

Feasibility in randomised controlled designs

Only two studies used randomised controlled designs, both judged as having a moderate risk of bias. 15,43 These studies15,43 evaluated the feasibility of ERM as a primary outcome. The consent rates were 60%15 and 94%. 43 One RCT, in 58 children aged 3–17 years with brain injury, showed that physical therapy was delivered 80% of the time in the usual-care arm and 100% among patients receiving early protocolised ERM. 15 In addition, patients receiving early protocolised rehabilitation received less post-PICU rehabilitation, but there were no differences in functional or quality of life (QoL) outcomes at 6 months. 15

In a pilot randomised trial with 30 children aged 3–17 years,43 the primary end point was feasibility defined as (1) the ability to enrol at least 75% of eligible patients, (2) an accrual rate of 1–2 patients a month and (3) a 30-day follow-up of >75%. The consent rate was 94%, and the 30-day follow-up rate was 87%. The median time from randomisation to delivery of mobility PT was not different between patients in the control standard mobilisation group [2.3 hours, interquartile range (IQR) 1–20] and standard mobilisation plus in-bed cycling (2.5 hours, IQR 0.9–11 hours). In this study,43 the authors found no difference between arms (0.17, IQR −0.01–0.36) among 24/30 patients (80%) who developed new functional difficulties in PICU [Paediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory-Computer Adaptive test (PEDI-CAT)]. In the usual-care arm 7/10 (70%) did with median of 0.4 (IQR: 0.3–0.6), compared with 17/20 (85%) in the cycling arm (median: 0.6, IQR: 0.4–0.7). Overall, only 10% of these patients fully recovered functional ability at 1 month, and mobility was the slowest to return. 43 No differences were identified for other outcomes evaluated in these studies. 15,43

Feasibility/prevalence of early rehabilitation and mobilisation in observational prospective and retrospective studies

Single-centre studies

Most studies (n = 16) reported improvements in early mobilisation rates, demonstrating the feasibility of ERM. One study completed enrolment 1 month earlier than anticipated with an 85% consent rate. 19 Another study12 reported more PT and OT ERM consultations. Betters et al. 10 also reported higher ERM consultations (median 30, IQR 29–45 minutes). Alqaqaa et al. 8 reported higher mobilisation rates among non-ventilated patients (mean difference of a day) compared to no change for mechanically ventilated patients. In another study,17 mobilisation and OT consultation rates increased, but this change was not significantly different for PT consultations.

Choong and colleagues11 showed higher lower-limb activity during in-bed cycling [mean ± standard deviation (SD) 266.47 ± 166.12] versus during non-intervention times (mean ± SD 20.94 ± 15.26, counts/20 minutes, p < 0.001) different to baseline. In another study,21 the median time to mobilisation was 2 days (IQR 1–6) compared to 1 day for non-mobility interventions (IQR 1–3). Likewise, the frequency of physical therapy improved in another study,32 with more patients achieving their rehabilitation goals.

Multicentre studies

In a multicountry study,42 the prevalence of PT- and/or OT-provided mobility was 39% [95% confidence interval (CI) 34.7 to 43.9%] and did not differ according to baseline neurodevelopmental function level (PCPC ≤ 2.22% vs. PCPC ≥ 3.26%, p = 0.331), while PT or OT consultations were higher in a different study, ordered in 68/128 (49.6%) within 2 days (1–5 days) after PICU admission. 24 The prevalence of out-of-bed mobility was nearly two-thirds (87/110; 63.5%), passive range-of-motion 13.9% and no activity 19.7%. Out-of-bed mobility was common among non-mechanically ventilated children (48/56; 85.7%) and those under 3 years (71/100; 71%), while older children (18/37; 48.6%) were commonly not actively mobilised. 24 Similarly, consultations for all admissions were increased from 25% pre-implementation to 56% (p < 0.001) post implementation,25 while consultations within 2 days increased from 34% to 67% (p < 0.001) and within 3 days, from 21% to 30% (p = 0.02) for at least one PT and/or OT mobility or 29% to 35% (p = 0.29) for mobilisations.

In another multicentre study, ~70% of children18 received at least one mobilisation intervention. For children on mechanical ventilation (MV), one-third of those <3 years and ~50% of those ≥3 years were mobilised using passive range of movement (ROM) (72%). 18 Out-of-bed mobility was achieved 70% of the time, but less frequently among mechanically ventilated children, 47% (95% CI 44% to 49%).

Secondary or clinical outcomes in observational prospective and retrospective studies

Single-centre studies

Choong et al. 19 found improved functional ability measured using PEDI among 28% and 42% of participants at 3 and 6 months. Only 22% of those with a pre-existing chronic condition and 14% with functional limitations returned to baseline levels at 6 months. In comparison, 60% of previously healthy children and 58% of children with normal baseline function regained full functional abilities. The overall mortality rate was 3/33 (9%), and 19/33 (63%) were readmitted within 6 months after PICU discharge. 19

Alqaqaa et al. 16 reported small improvements in length of stay [LOS; average LOS pre-WeeMove = 6.25 days vs. post-WeeMove LOS = 5.23 days] and time spent intubated (pre-WeeMove was 27.86 hours, post-WeeMove = 25.09 hours). 16 In contrast, Abdulsatar and co-authors7 noted that PCPC scores were worse (mean ± SD change of 1.08 ± 1.0, p = 0.02) among two-thirds of patients who received ERM. 7 There was no improvement in grip strength or physiological status, despite increased activity levels (mean ± SD, upper-limb (UL) activity pre: 9.36 ± 4.12 vs. post: 57.12 ± 46.60 counts) and higher carer satisfaction. 7

Colwell and co-authors reported higher adherence among younger patients (p = 0.04), with higher baseline severity of illness (p < 0.001) when mobilisation sessions were goal-directed (p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences in mobilisation rates (pre: mean = 0.86 vs. post: = 0.84) or AEs 14/560 (2.5%, p = 0.18). 13 In the study by Wieczorek et al., nearly half of the children (48/100) received at least one ERM intervention by day 3 of admission, and the proportion of children receiving at least one in-bed activity increased by 18% from post intervention (p < 0.001). 17 However, there was no change in passive ROM, only an increase in active interventions (57% vs. 26%; p < 0.001), especially among children ≥3 years. There was also a slight increase from 0% (0/39) ambulation while orally intubated to 10% (4/40) post intervention. 17

Multicentre observational studies

Studies described a lower amount of mobilisation among younger patients with higher baseline disability13,17,18 or severity of illness on admission. 13,18 One study21 showed that older, less sick children admitted during the winter who were not mechanically ventilated, sedated or receiving neuromuscular blockade were more likely to receive mobility interventions. Similarly, consultations within 3 days were higher among males, older children and those with lower baseline function, without an indwelling endotracheal tube (ETT) or urinary catheter, who had adequate family support. 18

Predictors of early rehabilitation and mobilisation

Three studies evaluated predictors of ERM using multivariate analysis. 18,24,42 The adjusted odds ratio (aOR) for out-of-bed mobility was negatively associated with the presence of an ETT (aOR, 0.13; 95% CI 0.08 to 0.2), a urinary catheter (aOR, 0.28; 95% CI 0.14 to 0.57), opioid infusion (0.42; 95% CI 0.24 to 0.73) and severe baseline disability (PCPC 4 vs. 1) (aOR, 0.59; 95% CI 0.4 to 0.87). Longer PICU LOS and lower nurse-to-patient ratio (1.82; 95% CI 1.2 to 2.8) increase the odds of out-of-bed mobilisation. For children <3 years old, family presence was associated with out-of-bed mobility (aOR, 4.55; 95% CI 3.1 to 6.6) while being older predicted PT or OT (aOR, 3.1; 95% CI 2.01 to 4.79). 18 In another study,24 the presence of ETT or infusion among children ≤3 years reduced the likelihood of receiving therapist-provided out-of-bed mobility [odds ratio (OR) 3.62; 95% CI 1.49 to 8.82]. However, this improved when the family were present. 24

Ista and colleagues42 showed that older age (2.28, 95% CI 1.23 to 4.22), moderate baseline disability (defined as PCPC: 3 vs. 1) (2.12, 95% CI 1.02 to 4.56), severe baseline disability (PCPC: 4 vs. 1) (2.24, 95% CI 1.14 to 4.40), having a central venous line (CVC) in place (aOR 1.63, 95% CI 1.02 to 2.62) and family presence (aOR 5.13, 95% CI 2.55 to 10.32) increased the odds of receiving a mobility session. However, the presence of a urinary catheter reduced the chance of mobilisation (aOR 0.46, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.92). MV through an ETT (aOR 0.29, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.68), being admitted for a surgical reason (aOR 0.58, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.95) and the presence of a urinary catheter (aOR 0.39, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.81) reduced odds of out-of-bed mobility, but this improved with family presence (aOR 7.83, 95% CI 3.09 to 19.79). 42

Quality assessment

Controlled trials

Two studies15,43 randomly assigned participants into groups and were assessed using RoB v2. One study43 ensured allocation concealment using a computer-generated sequence and reported adequate sample size considerations. In the other study,43 sample size calculations were not applicable; consequently, outcomes were possibly underpowered. We did not identify attrition bias for both studies, outcomes assessment was similar at baseline, and co-interventions were similar across groups.

Prospective and retrospective studies

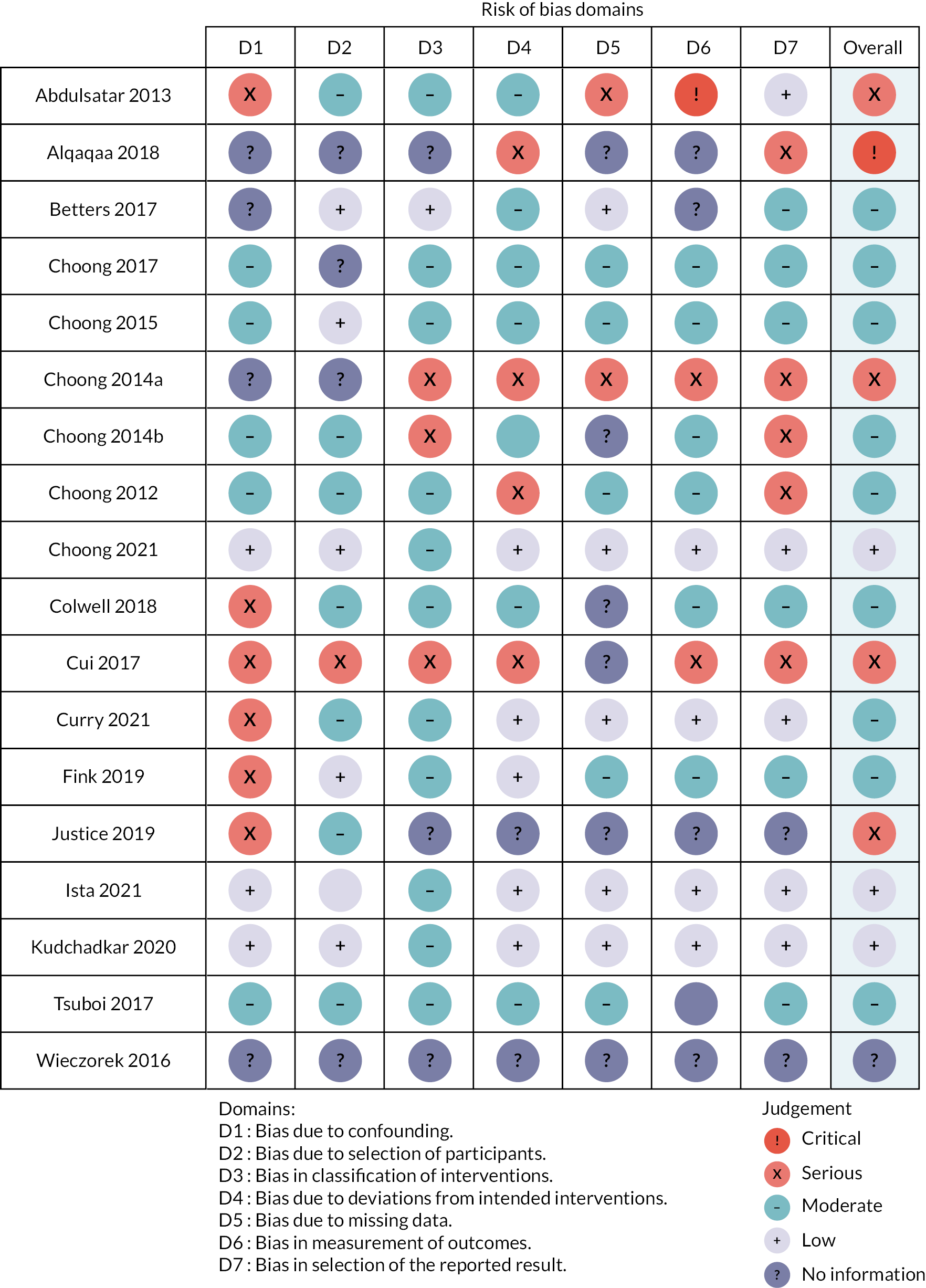

We used the ROBINS-I tool to assess the quality of observational studies (see Appendix 2, Table 33). Overall, most studies were judged to have a serious or critical risk of bias. Three studies (3/18)18,24,42 were judged to have a low risk of bias. Nine10,12,13,15,19–21,25,32 were judged to be at moderate risk of bias, while in four there was serious risk. 11,14,16,31 In some studies bias was judged as critical,8 or information reported was insufficient17 and could not be assessed (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Pictorial presentation of quality assessment using ROBINS-I.

The primary reason for downgrading studies was bias due to blinding or poor consideration of baseline confounding. There was no indication of selection bias during enrolment; studies were judged as adequate except in three retrospective studies. 14,17,31 The lack of a clear definition of ERM hierarchy limited the evaluation of demonstrable effects on objective clinical outcome measures. This made it challenging to determine intervention superiority. Broadly, intervention categories of non-mobility and mobility were consistent across studies, which were judged to be at risk of misclassification bias half of the time (9/18). We assessed the impact of bias due to deviations from the intended response as adequate in most studies. In some studies,7,8,10,11,13,14,16,17,21,32 the technique for handling missing data was unclear or not reported. We did not identify any evidence of selective outcome reporting or errors due to outcome measurements. Most studies demonstrated congruence between previously defined analyses and outcomes reported. However, none of the studies published a protocol. Overall, most studies did not provide definitive evidence of the effects of the intervention. However, consistent evidence across all studies supports the feasibility of ERM as an intervention in PICU, while physical therapy was the most common intervention considered.

Quality of consensus on exercise reporting

We described techniques considered during intervention design and excluded items not relevant to this review. These items included item no. 3 (descriptions of individual or group exercises), item no. 9 (use of home equipment; discharge interventions were not considered) and item no. 12 (setting of exercise delivery; all studies were conducted in PICUs). See Appendix 2, Table 34 for details.

Quality of consensus on exercise reporting reporting

Most studies (12/18)7,10,16–18,20,21,24,25,31,32,42 provided details on the type of ERM intervention to aid replication. Some studies (4/18)18,21,25,32 provided training or engaged multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) to facilitate ERM delivery. Organisational strategies were sometimes applied across MDTs to facilitate PICU culture change. Some studies (12/18) explicitly mentioned using qualified providers such as physiotherapists, nurses or other therapists to supervise sessions and ensure intervention fidelity. 10,11,13–15,17,18,21,24,25,42,43 However, the detail provided was insufficient to explain how differences in experience levels, treatment approaches and therapists’ behaviour in these circumstances influence outcomes.

Intervention components were generally tailored and not standardised. Sometimes, it was unclear what aspects of the interventions were usual practice or complementary during ERM delivery. In most studies, information on how deviations from study protocols were handled (i.e. regression or progression) and how these events may have affected outcomes was unavailable. Personalising the volume of ERM was a common concept across studies used to improve compliance. However, since interventions were tailored to tolerance levels, we did not assess intervention fidelity. Some studies provided a detailed description of how compliance or adherence was measured. Strategies mentioned include rehabilitation sheets11,19,20,32 and electronic records during PICU ward rounds. 17,18 Two studies7,11 used an objective outcome to measure compliance – ACTi-graph accelerometers. This outcome measure can be used as a benchmark for future studies, incorporating routinely collected outcomes to increase transferability. 47 Labour-intensive or ad hoc approaches for determining adherence or compliance, such as caregiver verbal confirmation following direct observation, charts or checklists, may limit the implementation of rehabilitation and future attempts at service evaluation.

Early rehabilitation and mobilisation change techniques

No study provided explicit details about applying complex intervention theories when designing interventions, while details on the implementation processes were inconsistently reported. Therefore, it is unclear to what extent interactions between intervention volume of ERM and health systems produce positive effects. It is not impossible to envisage a situation where contextual factors such as how the intervention works, for example the presence of a local champion or an ERM enthusiast, staff turnover, population demographics, or existing PICU culture, affect outcomes, either positively or negatively. No study provided details on motivation strategies or precise details on how interventions were personalised. Safety guidelines (underpinned by clinical stability), verbal feedback and tolerance levels to determine progression were commonly used across studies. Eight studies10,14,17,18,21,24,25,42 provided information to enable replication. Hence, these studies can be used as a springboard to undertake detailed intervention mapping when designing ERM manuals. Overall, key aspects of intervention delivery were poorly reported, such as co-interventions, strategies for tailoring interventions and motivating patients.

Discussion

This review aimed to summarise evidence on the effectiveness of ERM research within PICUs. We narratively synthesised evidence to improve interpretation of effectiveness given variation in ERM implementation. We identified a broad range of activities, categorised as non-mobility and mobility interventions. Other interventions identified but not considered in this review include undefined ERM,48–50 music therapy51 and neuro-psychological training. 52 This review suggests that interdisciplinary multicomponent interventions, sometimes delivered as a bundle, are feasible, safe, acceptable and possibly beneficial to patients. The programmes mainly were designed using safety criteria, were goal-directed and tailored. Although the rate of intervention-related AE reporting across all studies was low, we cannot rule out selective reporting as none of the included studies had published their statistical analysis plan a priori.

Given the limited description of interventions, intervention manuals and process data would be essential to understand the complexity of ERM. There are also organisational factors that need to be considered when implementing ERM. What remains unclear is the number of organisational levels that should be targeted and how. Other issues to consider include mechanisms of effect (moderators – participants’ responses to and interactions with the intervention and mediators that affect intervention outcomes in unexpected ways). Administering staff training was a common feature we identified across studies to ensure consistency. However, nursing capacity required to deliver the intervention and family involvement need to be carefully considered. Family involvement is crucial when considering non-mobility ERM for children under 3 years old.

Evidence

We found that children under 3 years of age admitted to PICU tend to be given passive and active in-bed activities. Children 3 years and older were primarily involved in out-of-bed activities when this was considered safe. In addition, one study18 reported higher ERM incidence among male children, but this finding was not consistent across studies. Hence, it is unclear what interventions should be administered to these age groups and whether certain combinations of interventions are superior to those given to their older counterparts.

We found equivocal evidence suggesting that other factors such as time to admission, tube presence, MV, or sedation also influenced developmental or mobility goals. Only four studies13,18,24,42 evaluated baseline severity of illness (measured using validated tools) and comorbidities that affected clinical and functional outcomes in multivariate models. Consequently, the effect of residual confounding or chance on the estimated intervention effect remains unknown. Overall, the evidence about subgroup effectiveness was indicative of clinical pragmatism but otherwise inconclusive.

Comparison with the broader literature

Our findings reflect the evidence in previous systematic reviews of ERM interventions within adult and paediatric PICU. 53–56 The evidence emerged from North American PICU contexts, and its transferability to the UK settings remains uncertain. 38,39,46,57 Besides variation in practice, interactions within complex health systems have additional issues. As an additional complexity, due to the nature of interventions considered in this review, it is difficult to determine if intervention effects are additive, multiplicative (biologically plausible) when combined or neutralise each other and plateau.

Most outcomes of feasibility or acceptability were exploratory findings, and the strength of the evidence for objective clinical or functional outcomes remains unclear. Nevertheless, PT and OT, sometimes with SLT, were frequently implicated in the exposure-mechanism-outcome pathway. Furthermore, barriers reported reflect previous literature and support the need for activity orders.

Summary of findings to inform the paediatric early rehabilitation and mobilisation during intensive care study

-

Optimal aspects of intervention delivery – timing, content, active ingredients, dose–response relationships, progression and implementation strategies – have yet to be established.

-

Improvements in functional independence (though small and sometimes inconsistent) have not been matched with improved PICU-acquired weakness or survival measures. ERM appears safe but requires long-term studies.

-

Standardised definitions for ERM, safety and core outcome measures will improve comparability across studies. Authors should consider the effect of an intervention on core outcome sets recommended for paediatric critical care. These include four domains: global cognition, emotional, physical and overall health. Four child-specific outcomes of health-related QoL, pain, survival and communication have also been recommended. 47 Benefits so far indicate some improvement in QoL.

-

ERM has been demonstrated to be feasible and acceptable within PICU. There are still uncertainties about the effectiveness of ERM interventions; only two studies used randomised designs. The evidence uncertainty is worse for objective outcomes such as PICU LOS. Overall, non-mobility rather than mobility interventions seem to be preferred in children 3 years and younger compared to their older counterparts.

-

The lack of a well-defined ERM protocol is a significant barrier to ERM implementation. There is no clear evidence on the impact of bundles of care or behavioural interventions incorporated with ERM. We identified several studies that evaluated the feasibility of ERM in PICU, some of which report improved QoL as a longer-term outcome. However, the evidence for effectiveness is inconsistent, uncertain and needs further testing. Most studies were quality-improvement studies, which may be the best methodology for evaluating ERM within PICU until a better consensus on intervention components is achieved. As an alternative, nested controlled trials embedded within longitudinal studies or routine data collection can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions. Data from such studies might also enable mediation analysis to understand key intervention components and mechanisms of action.

Chapter 2 Phase 1b: national survey to establish standard practice

Introduction

This study involved a national electronic web-based survey for paediatric intensive care healthcare professionals to understand the context and professional perspectives of delivering early rehabilitation and mobilisation (ERM) within UK PICUs.

Study management

The work package was led by BRS. JYT co-ordinated survey responses and developed the on-line tool. The study management group provided input into survey questions and designs. The study was piloted in Birmingham and Nottingham by JYT, Emily Brush and Francesca Ryde. Statistical analysis of the full survey was undertaken by JYT, BRS, JMen, JMan and JMc. Qualitative analysis of the free-text responses was undertaken by JYT.

Aims and objectives

To explore how healthcare professionals describe ERM, identify current ERM practice and understand perceived barriers and facilitators of ERM.

Methods

A web-based survey (administered through www.smartsurvey.co.uk) was developed that included 25 questions that related to the study aims. The survey was piloted with multidisciplinary teams of health professionals (n = 40) at two PICUs to assess acceptability and comprehensiveness. Minor changes to improve question clarity were made. Pilot responses were excluded from main survey analysis.

The University of Birmingham granted institutional ethical approval on 5 February 2019 (reference ERN_18-1134). Consent was implied through survey completion.

The survey was administered using a chain-referral method. A UK Paediatric Critical Care Society Study Group (PCCS-SG) member from each UK PICU (n = 29) was contacted via e-mail and requested to identify and cascade an invitation e-mail to members of their local MDT (including at least one physiotherapist, doctor and nurse). Participating PICUs were sent a survey link between May and August 2019 to distribute. Three follow-up reminders were sent at weekly intervals to PICUs that had not responded.

Statistical analysis was performed using R version x64 3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Data were analysed using descriptive statistics, with categorical responses expressed as numbers (percentage), with Likert scales (median IQR) used to express the frequency of practice or level of agreement. Ranking of perceived ERM benefits was calculated using the sum of ranked scores of respondents’ top five important benefits (five points for first, reducing to one point for fifth placed).

Free-text data from the open-ended responses were analysed using a qualitative content analysis approach. 58 Two researchers independently familiarised themselves with the data and conducted open-coding, utilising NVivo™ (QSR International, Warrington, UK) software for data management. Codes were then discussed, summarised and organised. 59,60 Anonymised, free-text quotes from respondents are used in the reporting of this analysis to add context and clarity. 61

Results

Demographics

We received responses from PCCS-SG link members in 26/29 (90%) UK PICUs. A total of 191 health-care professionals opened the survey link with 124 (65%) submitting responses, with a median of 4.5 participants (IQR 3–6) per PICU.

Most respondents were nurses (n = 34, 27%), physiotherapists (n = 28, 23%) and doctors (n = 22, 18%) (see Appendix 3, Table 36). Respondents also included occupational therapists (OT) (n = 19, 15%), play therapists (n = 7, 6%), psychologists (n = 7, 6%), dieticians (n = 6, 5%) and SLTs (n = 1, 1%). Almost three-quarters of health professionals had ≥5 years’ experience, with 48 (39%) ≥15 years.

Description of early rehabilitation and mobilisation

We invited participants to describe ERM in their own terms, with 104 (84%) responding. Participant definitions of ERM aligned to four categories, ‘Activity-focused’, ‘Tailored’, ‘Promote recovery’ and ‘Timing of ERM’ (Table 1). Overall ERM was an individualised package of graded interventions, based on an activity-focused programme, to reduce the sequelae of critical illness or injury. However, responses differed for when ERM should be initiated, often emphasising the need for individualisation.

| Category | Subcategories | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Activity-focused ERM is activity-focused, with consideration of seating and equipment, primarily delivered by nursing and allied healthcare professionals with optimised sedation management to promote patient engagement. There is a lack of consensus on what is routine care compared with purposeful ERM activity |

Activity – mobilising, positioning, stretching | ‘ERM provided includes – passive movements of limbs, periodic change of position, use of splints on extremities and if stable in the long-term patients – sitting up in tumble form chair and mobilising out of bed.’ (Doctor, 67) ‘We aim to get the children sitting upright, either over the edge of the bed or in appropriate seating as soon as possible.’ (OT, 001) ‘Nursing staff are taught the importance of regular position changes for patient … and positioning to maintain ranges of movement and prevent foot drop.’ (Nurse, 017) |

| Core healthcare professional involvement – physiotherapist, nurse, OT | ‘We try and mobilise patients as soon as able when not invasively ventilated – physio led.’ (Doctor, 058) ‘As physiotherapists, we work with the OT and nursing staff to either re-position, sit up in bed, sit on the edge of the bed or stand whilst on the ventilators.’ (Physiotherapist, 069) |

|

| Additional healthcare professional involvement – psychology, dietician, play therapist, SLTs | ‘Speech and language therapy become involved usually when nursing or medical staff identify a need for referral.’ (Doctor, 003) ‘We have a Play Specialist on PICU, who assists with communication tools/toys.’ (Nurse, 082) |

|

| Seating and equipment | ‘Specialist seating need – linking in with OT to ensure appropriate seating available.’ (Physiotherapist, 019) ‘We have also in the past asked adult (services) to use their moto-med bike and used this with teenagers, but this can be a challenge as it is very far from PICU and it is often in use.’ (Physiotherapist, 014) |

|

| Sedation management | ‘Working with the medics to wean sedation as quickly as possible. This promotes faster ability to mobilise and progress in their rehabilitation.’ (Nurse, 034) | |

| ‘Routine care’ vs. ‘purposeful ERM package’ | ‘Some centres define ERM as passive range of movement, repositioning or providing splints. We would deem this as essential core cares rather than ERM; the large majority of our patients will have positioning and movement plan from day 1 of admission.’ (Physiotherapist, 111) | |

| Tailored Following the assessment of needs and patient and family preference, ERM activities are personalised to the individual patient |

Assessment of need | ‘We have a programme where patients are categorised to one of 3 levels. Each level provides nursing and therapy staff with activities aligned to the acuity of the patient.’ (Nurse, 040) |

| Individual preference | ‘Parents will tell us what their child enjoys doing and make suggestions, often provide toys/games from home.’ (Nurse, 076) ‘Discuss with parents what patient enjoys doing, watching etc. Discuss options regarding taking patients “out” where possible if long-term patients.’ (Nurse, 015) |

|

| Promote recovery The purpose of ERM is to normalise the PICU environment, to create an environment that addresses holistic needs, sustains or promotes development and supports recovery from critical illness |

Normalising PICU environment | ‘Provide activities they would use for their enjoyment. This enables them to be more relaxed and less aware of what is going on with/around them.’ (Play specialist, 102) ‘Being in PICU can be a frightening experience. Not only is a child/young person away from home, but also away from their usual environment, family and friends. There are unfamiliar sounds, smells, equipment and people. The play specialist can help to make the stay much more enjoyable and children/young people to cope and understand.’ (Play specialist, 055) |

| Sustain/promote child development | ‘Encouraging the patient to regain or further their development in a therapeutic fun manner.’ (Play therapist,102) | |

| Restoration/recovery | ‘Interventions aim to promote physical recovery – movement, and ability to engage in activities and psychological recovery – orientation, speech, ability to play and attend school.’ (Nurse, 021) | |

| Timing of ERM The optimal timing of ERM initiation is challenging for healthcare professionals to define, although likelihood perceived to increase with increased LOS. Influenced by the perceived stability of patients and the balance of risk to benefit |

‘Early’ poorly defined | ‘I like to think we consider it within 2–3 days we have a better idea of the patients’ PICU journey and how long they are going to stay. The reality is it’s usually longer … usually week 2 of admission if they are still on the unit.’ (Physiotherapist, 090) ‘There is no formal plan for who decides if a patient should start ERM and when …. Currently the delivery of ERM is fairly ad hoc, based on what is highlighted from daily handover each morning.’ (Physiotherapist, 083) ‘We provide ERM as a structured programme … every patient after 24 hours of admission is considered for ERM.’ (Doctor, 012) |

| Patient stability, risk and benefit | ‘Members of the PICU team with less experience of early rehab can deem ERM “unsafe” which can occasionally act as a barrier.’ (Physiotherapist, 016) ‘Usually ERM activity is not considered until patients can physiologically tolerate movement and are stable with observations.’ (Nurse, 008) |

|

| ‘Long-stay’ | ‘ERM is often thought about as a patient comes up to extubation or has failed extubation, and we feel that the reason for failure may be because of critical care weakness.’ (Physiotherapist, 031) ‘We provide very little ERM on PICU, other than for long-term patients, which is often, in my opinion, delayed.’ (Nurse, 007) |

Most respondents considered ERM to be a priority, either crucial 15 (12%), very important 67 (55%) or important 35 (29%) in the care of PICU patients (see Appendix 3, Table 37).

Availability of established early rehabilitation and mobilisation protocols

Respondents were asked to describe the content of established ERM protocols within their PICU. Only 12 (10%) participants from 5/26 PICUs reported having an established ERM protocol. The most common components of ERM protocols were ‘physical therapy not requiring additional equipment’ (9/12, 75%) and ‘OT interventions’ (8/12, 67%). Only 4/12 (33%) referred to play therapy or SLT, and no ERM protocol specified input from psychologists or psychiatrists.

All participants were asked about the content of non-ERM protocols in their PICU. Only 18/124 (15%) participants reported that guidance for physical or OT activities existed in other, non-ERM protocols that were used in the PICU setting (see Appendix 2, Table 35).

Recipients of early rehabilitation and mobilisation

Despite the paucity of ERM protocols, 51 (41%) respondents reported that all PICU patients ‘always’ or ‘very often’ received ERM (Table 2). ERM was reported to be more likely to be delivered to patients when PICU LOS exceeded 28 days. Patients admitted for 28 days or more were more likely (91, 75%) to ‘always’ or ‘very often’ receive ERM in comparison to only 17 (13%) of those reported to stay fewer than 3 days. Participants reported that patients with acquired brain injury (75, 60%) and severe developmental delay (54, 44%) were ‘always’ or ‘very often’ likely to receive ERM.

| By age group | Always, n, (%) |

Very often, n, (%) |

Sometimes, n, (%) |

Seldom, n, (%) |

Never, n, (%) |

Don’t know, n, (%) |

Not applicable,b n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All PICU patients (any age) | 6 (5) | 45 (36) | 48 (39) | 14 (11) | 0 (0) | 11 (9) | 0 |

| >10–18 years old | 18 (15) | 40 (32) | 43 (35) | 8 (6) | 1 (1) | 14 (11) | 0 |

| >4–10 years old | 16 (13) | 42 (34) | 41 (33) | 10 (8) | 1 (1) | 14 (11) | 0 |

| 1–4 years old | 13 (10) | 42 (34) | 39 (31) | 13 (10) | 1 (1) | 16 (13) | 0 |

| Infants and <1 year old | 6 (5) | 47 (38) | 32 (26) | 20 (16) | 3 (2) | 16 (13) | 0 |

| By LOS in PICU | |||||||

| PICU > 28 days | 43 (35) | 48 (39) | 14 (11) | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | 15 (12) | 0 |

| PICU > 7–28 days | 27 (22) | 46 (37) | 26 (21) | 8 (6) | 0 (0) | 17 (14) | 0 |

| PICU 3–7 days | 12 (10) | 32 (26) | 40 (32) | 19 (15) | 5 (4) | 16 (13) | 0 |

| PICU < 3 days | 3 (2) | 14 (11) | 39 (31) | 33 (27) | 17 (14) | 18 (15) | 0 |

| By diagnostic category | |||||||

| Acquired brain injury | 36 (29) | 39 (31) | 16 (13) | 11 (9) | 4 (3) | 18 (15) | 0 |

| Severe developmental delay | 11 (9) | 43 (35) | 39 (31) | 12 (10) | 3 (2) | 16 (13) | 0 |

| Cancer | 11 (9) | 24 (19) | 36 (29) | 14 (11) | 4 (3) | 35 (28) | 0 |

| Pre-existing physical morbidity | 9 (7) | 38 (31) | 44 (35) | 12 (10) | 4 (3) | 17 (14) | 0 |

| Mechanically ventilated | 9 (7) | 38 (31) | 39 (31) | 18 (15) | 5 (4) | 15 (12) | 0 |

| Congenital heart disease | 9 (7) | 24 (19) | 39 (31) | 15 (12) | 6 (5) | 31 (25) | 0 |

| Respiratory illness | 7 (6) | 35 (28) | 39 (31) | 22 (18) | 3 (2) | 18 (15) | 0 |

| Sepsis | 7 (6) | 28 (23) | 44 (35) | 20 (16) | 5 (4) | 20 (16) | 0 |

| Multiorgan failure | 5 (4) | 14 (11) | 32 (26) | 35 (28) | 12 (10) | 26 (21) | 0 |

| Mechanically supported (e.g. extracorporeal life support) | 4 (3) | 8 (6) | 14 (11) | 13 (10) | 47 (38) | 38 (31) | 0 |

| Healthcare professional team members and parent or family member(s) involvement in ERM (when applicableb) | |||||||

| Physiotherapist | 86 (70) | 27 (22) | 4 (3) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 4 (3) | 1 |

| Nurse | 54 (44) | 49 (40) | 9 (7) | 5 (4) | 0 (0) | 6 (5) | 1 |

| Parent or family member | 36 (29) | 56 (46) | 19 (15) | 7 (6) | 1 (1) | 4 (3) | 1 |

| OT | 23 (19) | 34 (29) | 29 (24) | 20 (17) | 6 (5) | 7 (6) | 5 |

| Doctor | 22 (18) | 20 (16) | 26 (21) | 30 (24) | 13 (11) | 12 (10) | 1 |

| Play therapist | 12 (10) | 24 (21) | 39 (34) | 26 (23) | 9 (8) | 5 (4) | 9 |

| Dietician | 10 (8) | 20 (17) | 12 (10) | 29 (24) | 37 (31) | 13 (11) | 3 |

| SLT | 4 (3) | 11 (9) | 40 (33) | 35 (29) | 20 (17) | 10 (8) | 4 |

| Psychologist | 3 (3) | 11 (10) | 24 (23) | 32 (30) | 30 (28) | 6 (6) | 18 |

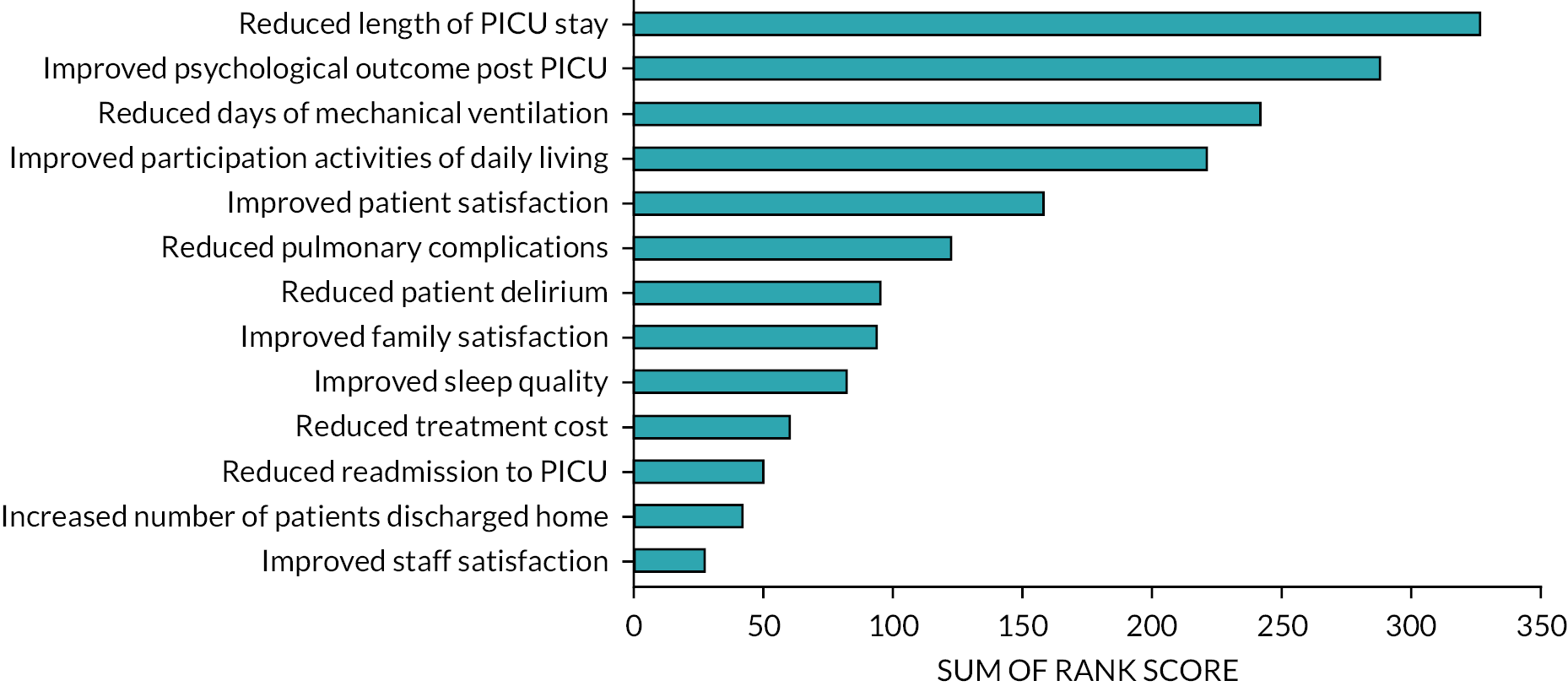

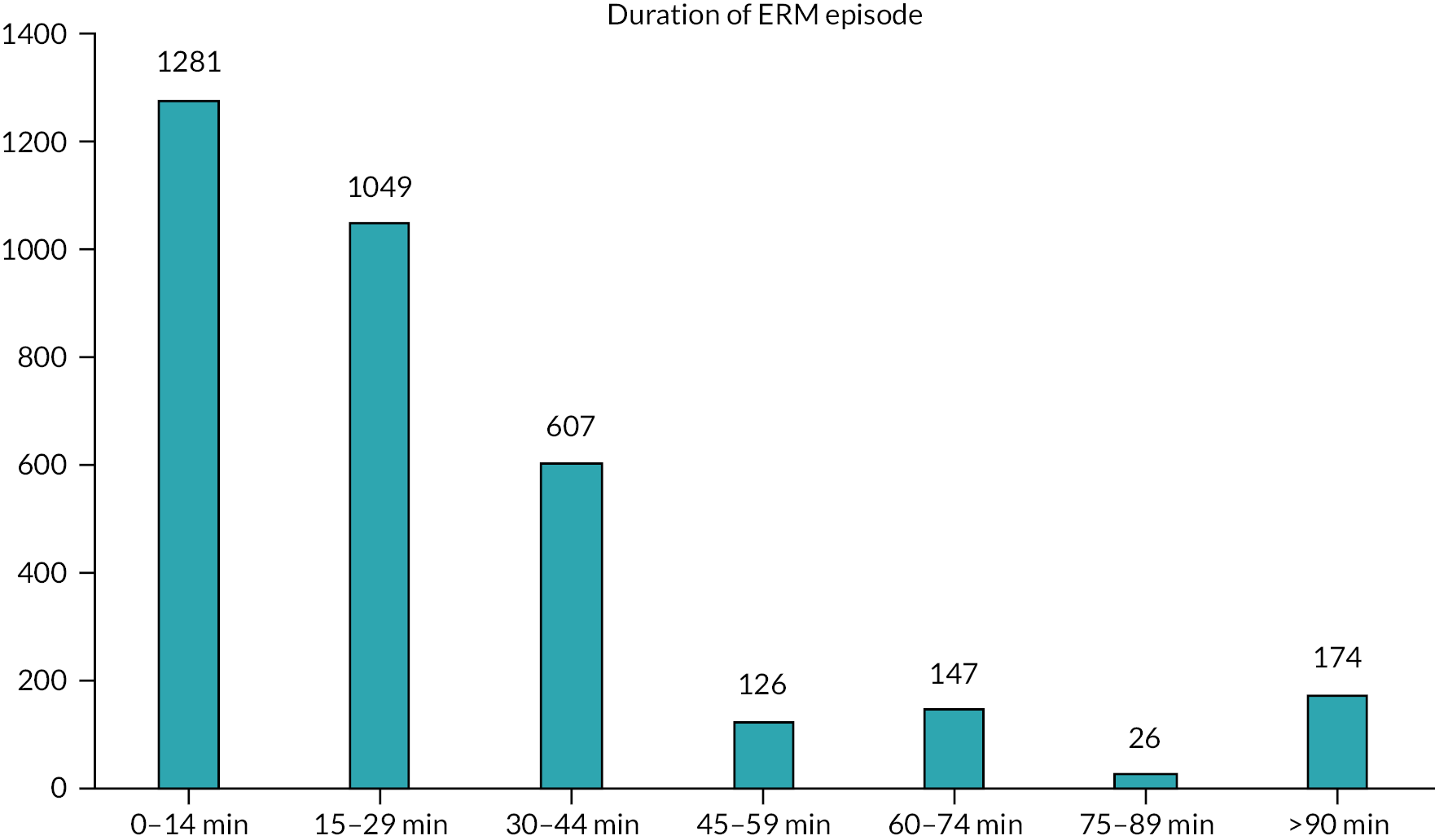

Perceived benefits of early rehabilitation and mobilisation

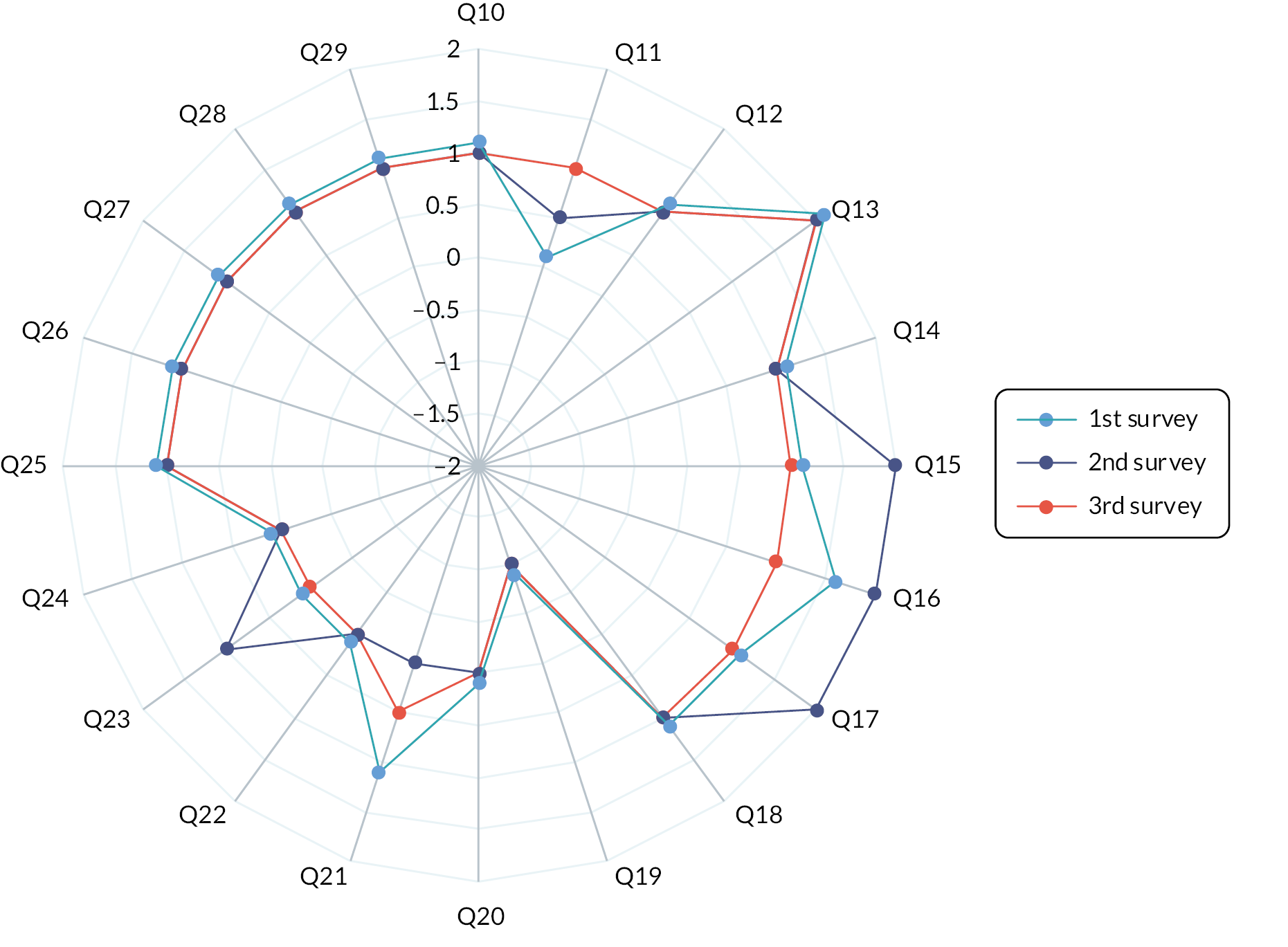

Participants ranked the 5 most important potential benefits of ERM out of 13 options (Figure 3). The most important outcomes identified were: (1) reduced PICU LOS, (2) improved psychological outcomes for patients after PICU, (3) reduced days of MV, (4) improved participation in activities of daily living and (5) improved patient satisfaction.

FIGURE 3.

Perceived benefits of ERM. Ranking of participants’ potential top five perceived benefits of delivering ERM within PICUs. Sum of rank score: ranking of top five (1–5) (first-placed rank scored five points to fifth placed scored one point). Ranked scores of 121/124 (98%) participants.

Initiation and delivery of early rehabilitation and mobilisation

The decision for ERM initiation was perceived by respondents to be primarily led by physiotherapists (96, 77%), doctors (92, 74%) and bedside nurses (64, 52%). Parents were felt to initiate ERM by only 24 (19%) of respondents (see Appendix 3, Table 38).

Factors that influenced ERM initiation included patient stability (69, 56%) and LOS, specifically within 3 days of admission (31, 25%). Five (4%) respondents reported they would not consider ERM at all. The influence of perceived clinical stability is demonstrated in respondents’ free-text comments:

We are involved as early as required depending on the child/young person medical stability and their rehabilitation needs.

(OT, 033)

Usually, ERM activity is not considered until patients can physiologically tolerate movement and are cardio-vascularly stable.

(Nurse, 008)

Assessment of patient stability and tolerance of ERM were less well described. Most respondents (98, 79%) provided subjective cues or informal clinical criteria. These included monitoring of vital signs, physiological changes, observation of behavioural changes and documentation of AEs.

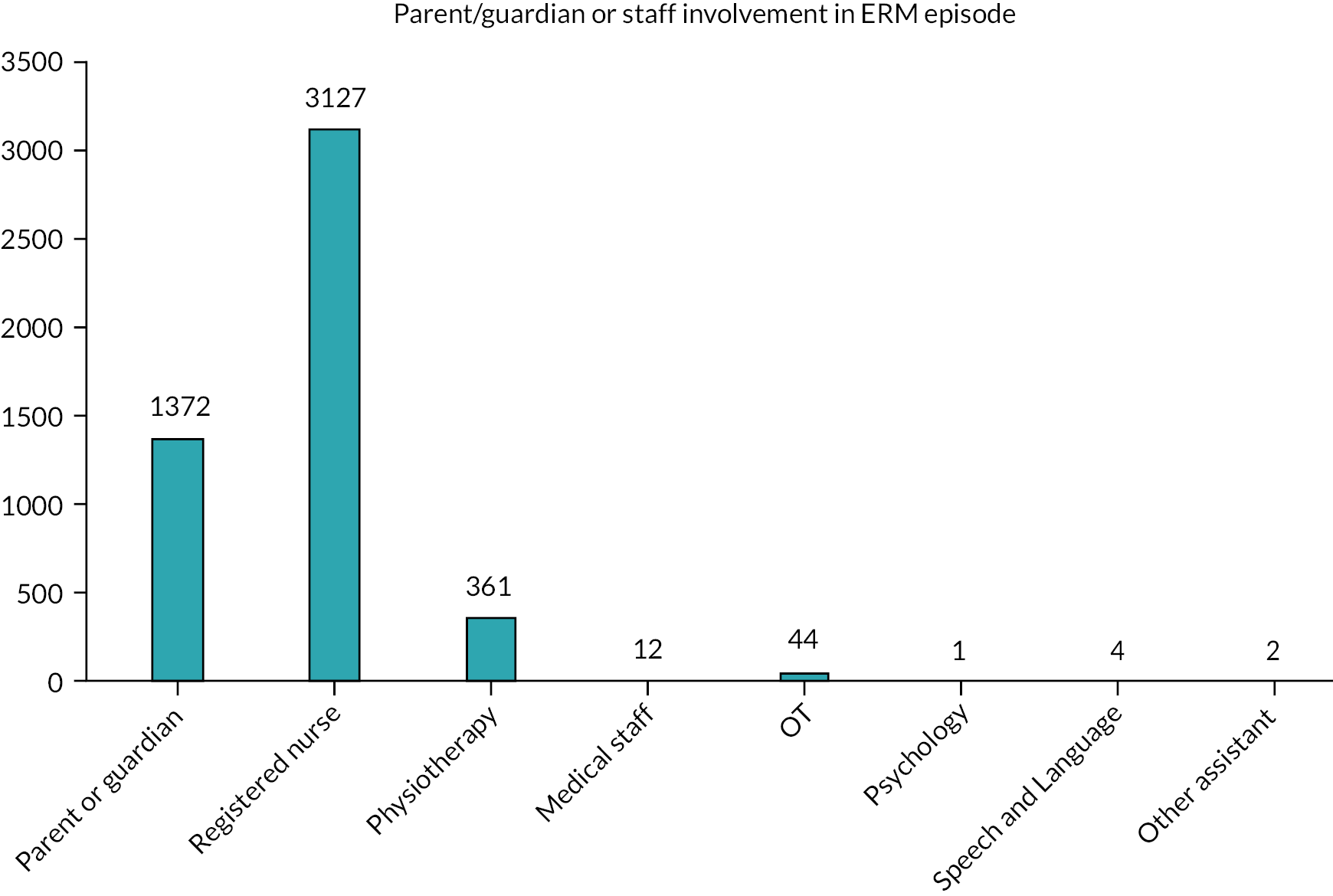

Physiotherapists (113, 92%), nurses (103, 84%) and parents or family members (92, 75%) were ‘always’ or ‘very often’ involved in the ongoing delivery of ERM, with less frequent input from other members of the MDTs (see Table 2).

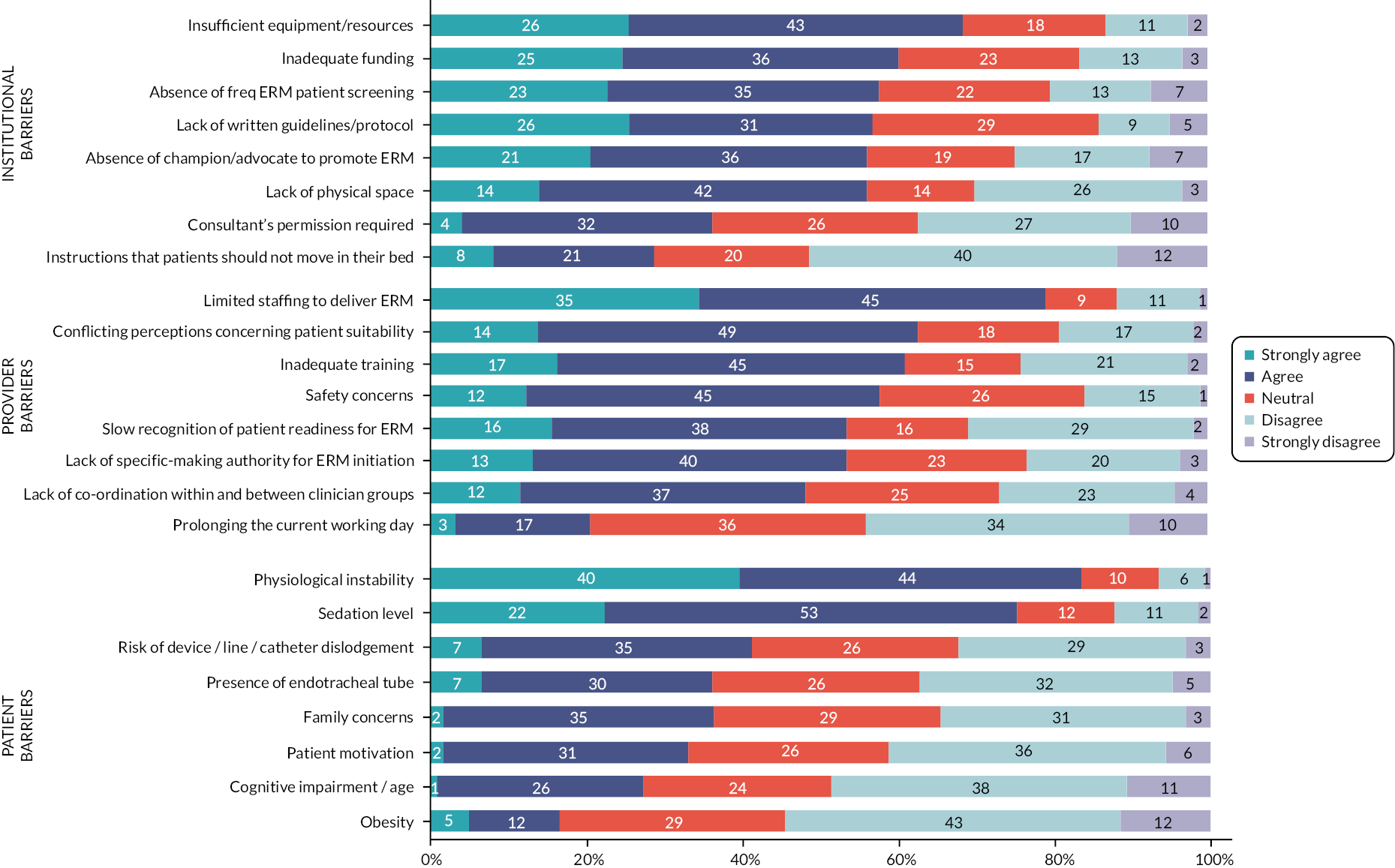

Barriers to early rehabilitation and mobilisation implementation

Figure 4 presents the perceived barriers of ERM. The most significant factors identified as barriers at the institutional levels were insufficient resources/equipment (83, 69%) and inadequate funding (73, 61%). Participants provided examples of resources having to be shared across organisations or having to be specially ordered to deliver ERM to patients.

FIGURE 4.

Perceived barriers of ERM.

All equipment shared with the whole therapy department at present, therefore dependent on availability.

(OT, 010)

Most PICUs had access to standard lifting 22/26 (85%) and specialist static seating equipment 25/26 (96%). However, bedside or in-bed cycling machines were only available in 10 (38%) of PICUs (see Appendix 3, Table 39).

A lack of established protocols (69, 57%), ERM champions (68, 57%), space (68, 56%) and robust patient-screening processes (63, 58%) were also issues identified by respondents.

Limited staffing was the most frequently reported barrier to ERM being delivered (101, 79%). Approximately half of the respondents agreed issues such as training, patient safety, lack of decision-making authority and delays in recognition of patients’ ERM needs were barriers to ERM initiation. However, only 25 (21%) identified that the impact of ERM potentially prolonging the working day was a barrier.

At the patient level, the two most frequently reported barriers to delivering ERM were physiological instability (101, 81%) and sedation (91, 73%).

Institutional, patients and provider barriers to ERM

Table 2 shows the percentage of responses for the categories strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree and strongly disagree. Responses ranked on the cumulative score of percentage ‘strongly agree and agree’.

Summary of findings to inform the PERMIT study

-

This national survey of healthcare practitioners (HCPs) from UK PICUs identified the importance of ERM as an intervention which participants believe can improve the physical, psychological and cognitive recovery of critically ill or injured infants and children across all ages.

-

Our findings indicate support for ERM, but highlight uncertainty with suitability, variability with the definition of this complex intervention, variation in timing of initiating and which patient groups should receive ERM.

-

Key barriers to ERM delivery were identified (e.g. funding and staffing) and potential clinical (e.g. improved psychological outcomes) and economic (e.g. reduced PICU LOS) benefits to patients and PICUs.

-

Our results indicate uncertainty and wide variation in time to start ERM (24 hours to over 7 days), increasing agreement for ERM to be considered after longer periods on PICU, and support for the concept of ‘as early as the patient’s clinical condition allows’, which may be much longer.

-

The uncertainty of the content of ERM also adds to the challenge for healthcare professionals to appreciate when ERM could be delivered. Understandably, normal bedside nursing care (e.g. functional positioning) may be considered acceptable earlier than more advanced physical therapies requiring multiple staff (e.g. sitting a ventilated child out of bed or in-bed cycling).

-

Our survey identified that clinical stability is the most influential patient factor for initiation.

-

The reported lack of ERM protocols in most (21/26) UK PICUs reinforces a strong requirement for evidence-based standardised protocols with optimal timing, intensity, frequency and duration of ERM. There is a need for flexible protocols to allow for tailoring rather than prescription.

-

ERM was more likely to be delivered to patients admitted for >28 days, among patients with acquired brain injury or severe developmental delay across all age ranges. Most published ERM intervention studies to date have excluded patients <3 years of age. 20,15 However, this represents 60% of the UK PICU patient population,62 and this age group was as likely to receive ERM as older children in our study. Future ERM trials should include all PICU age groups to ensure ERM content and efficacy are assessed across all potential patients.

-

Our results show that within the UK NHS setting, doctors, physiotherapists and nurses have an equally significant role in the decision to initiate ERM.

-

Nurses’ and parent’s roles are also important in both initiation and delivery of ERM. In our study, 91% felt ‘involved’ in delivery of ERM. However, parents were reported to be the least likely group to initiate ERM (19%), although becoming influential in its ongoing delivery.

-

The key barriers to ERM practice were (1) at institutional level: insufficient resources, equipment and funding; (2) at provider level: limited staffing, training, protocols and slow recognition of readiness for ERM; and (3) at patient level: physiological instability, risk of ETT dislodgement and amount of sedation.

Chapter 3 Phase 1c: observational study

Introduction

This chapter describes the observational study to ascertain current ERM practices, as well as barriers and facilitators to ERM delivery, within the PICU setting. Following the scoping review and survey (see Chapters 1 and 2), we were interested in the concept of early ERM occurring by day 3 and over the following 7 days of PICU admission, and ERM to include the broad category of any rehabilitation or mobilisation, including both mobility and non-mobility activities. We directly observed current ERM practices within UK PICUs, identify patients who do and do not receive ERM and describe variation between PICUs and factors associated with ERM practices.

Study management

The work package was led by BRS. The study management group provided input into protocol and ethics design. JYT was study co-ordinator and piloted and developed the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database. Statistical analysis was undertaken by JYT, BRS and James Martin. Data interpretation was by BRS, JYT, JMan and JMen with input from all study management group.

Objectives

-

Observe and describe current ERM practice, including barriers and facilitators, in UK PICUs.

-

Assess the capability of UK PICUs to deliver ERM.

-

Establish and model how many/which CYP may be suitable for ERM in the PICU population using routinely collected data.

Method

Study design

A multicentre prospective observational study.

Target population/setting

All CYP (0 to <16 years) admitted to PICU and remaining on PICU by 9 a.m. on day 3 after PICU admission were eligible to participate. The exclusion criteria included a local decision by PI or treating clinical team not to include patients (e.g. receiving end-of-life care) and parents or guardians who choose to opt out. The broad study inclusion criteria allowed for the observation of all types of patients admitted for PICU care (e.g. planned and unplanned admissions), and all age ranges.

Site and patient selection

The Paediatric Early Rehabilitation and Mobilisation during InTensive care (PERMIT) study was an observational study conducted in 15 UK PICUs across two 21-day periods: (1) 26 November–16 December 2019 and (2) 14 January–3 February 2020. PICUs were identified from the PERMIT survey (see Chapter 2). The PICUs selected were of varying sizes (n = 6 large: >800 admissions/year, n = 5 medium: 500–800 admissions/year, n = 3 small: <500 admissions/year) and reported ERM activity of differing levels in the survey.

This study was conducted in two separate time periods to maximise efficiency, overcome recruitment hurdles and meet the target. Ten sites recruited and collected data during period 1, with a further five sites in period 2. Patients were observed on study day 1–14 with a further week to complete follow-up (study day 15–21). Individual patient data collection and observations took place for up to 7 days after patients were recruited or until PICU discharge, whichever was sooner.

Recruitment/enrolment

The study protocol, manual of operation, checklists and case report forms (CRFs) provided details on the study procedures. Staff at participating sites received remote training on research conduct before, and ongoing support sessions during, the study period.

Research staff screened patients admitted to PICU for the PERMIT study using a bespoke study screening log. The daily screening process ensured patients becoming eligible (e.g. the day before their third day) were identified. Designated research co-ordinators entered data on ERM activities recorded by clinical staff in clinical notes on the study proformas. Data were transferred to a secure electronic database (REDCap™), with scanned copies uploaded for data validation. Data were pseudo-anonymised at the local site before secure transfer to the PERMIT trials office.

Consent

As the study was observational, Regional Ethics Committee (REC) approved data collection without seeking prior consent from parents/legal representatives. In addition, this avoided unnecessary burden for parents/legal guardians in approaching consent during a very sensitive time. Information about the study was provided to all eligible patients’ families and was displayed within public areas of participating PICUs. This explained the study to parents, family, friends and children who were able to make autonomous decisions. Parents/legal guardians were able to opt the child’s data out of the study at any time and were aware that the future care their child would receive would not be affected.

Study procedure and data collection

Site staff collected demographic data on the third day of admission. Clinical and ERM data were collected from enrolment until discharge at the end of the study period. Data were collected twice, between 09.00 and 10.00 and between 14.00 and 15.00, each day.

Patient-level data

Patient characteristics collected at PICU admission included age (in categories); reason for admission; primary diagnosis; the severity of illness using Pediatric Index of Mortality (PIM3) score, with clinical function being assessed at baseline (pre-PICU state) and admission via the PCPC and POPC, which scores from 1 to 6 (1: normal, 2: mild disability, 3: moderate disability, 4: severe disability, 5: vegetative state or coma and 6: death). 63 PICU LOS was also recorded.

Clinical data

Data collected during PICU stay included healthcare interventions; requirement for MV; sedation and level of consciousness; presence of delirium; critical care interventions; indicators of physiological status; and individual patient PICU resource use. We calculated PELOD score (PELOD-2),64 which is a measure to describe the severity of organ dysfunction/illness in critically ill CYP, daily at 9 a.m.

Observed early rehabilitation and mobilisation active interaction

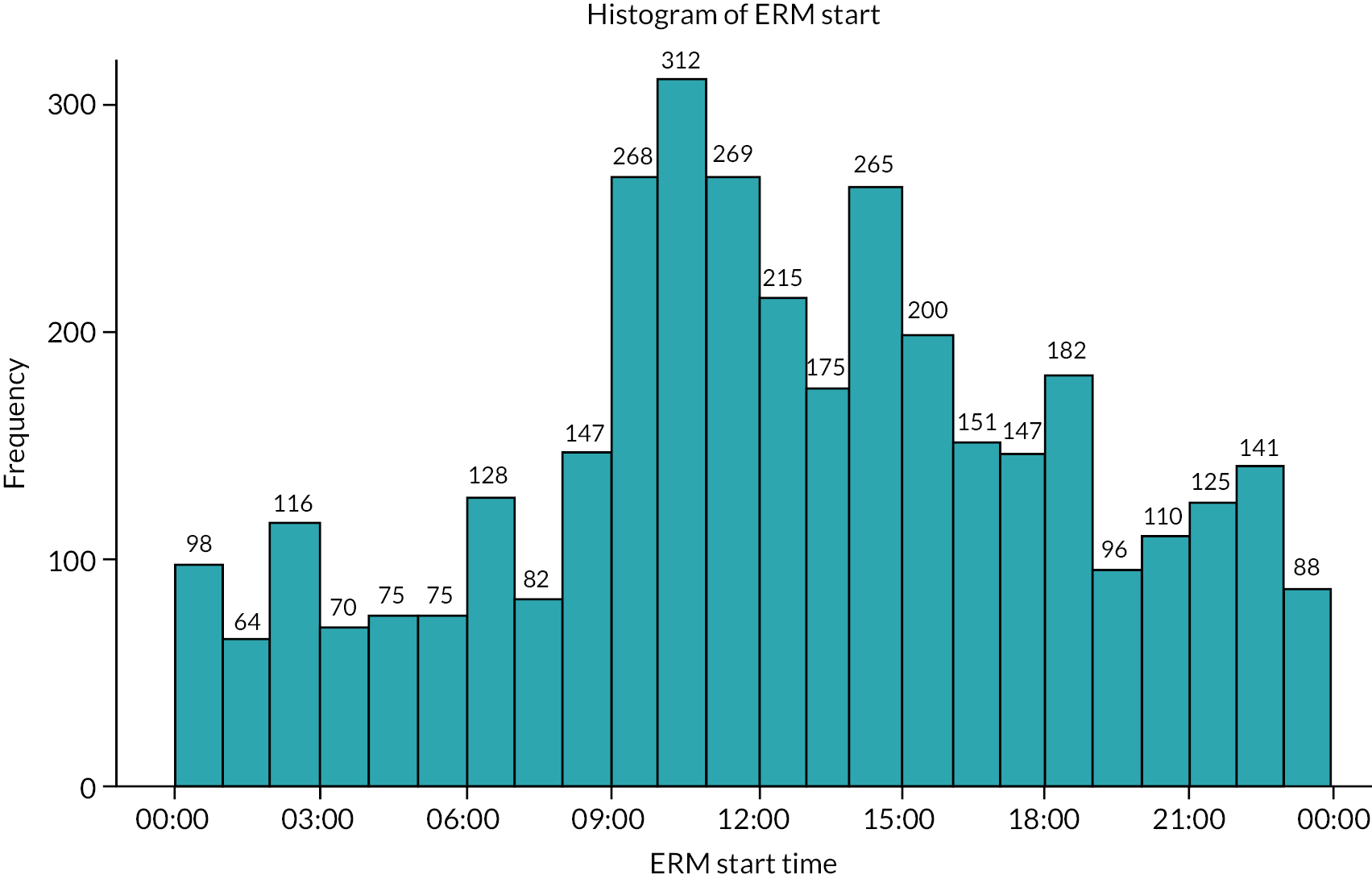

Clinical staff performing ERM activities were instructed to record the planned and delivered ERM activity duration in medical records. A research nurse or co-ordinator used these data to complete the bespoke active interaction CRF, which was submitted to the PERMIT study office. CRFs were completed hourly between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. by the local site research nurse. A retrospective review of clinical case records of ERM activities that occurred overnight was carried out, with CRFs completed accordingly. Overnight ERM interventions were defined as the time from the end of the observed active interaction period 17.01 until 08.59 before the start of the next period.

We defined a priori ERM as (1) any ERM activity, (2) any mobility ERM activity and (3) mobility activity out of bed, informed by scoping review and survey (see full breakdown of ERM activities, ERM group and level of ERM detailed in Appendix 3, Table 40). We excluded chest PT, tracheal tube suctioning and routine nursing ‘cares’ (such as mouth and eye cleaning).

Patients were defined as receiving any ERM intervention if any ERM was recorded on study day. Details on interventions such as type of ERM activity (mobility, non-mobility, out-of-bed, passive, active and psychological) and safety events (such as changes in heart rate, oxygen saturation, removal of tubes or falls) were recorded.

Primary outcome

-

the delivery of any ERM activity on day 3 post admission (study day 1).

Secondary outcomes

-

the delivery of any ERM activity on days 4–10 post admission (study day 1–7);

-

the delivery of ERM involving any mobility activity and out-of-bed mobility ERM on days 3–10;

-

the number, type and duration (e.g. dose) of ERM delivered on each day;

-

predictive factors related to the delivery of ERM on day 3 post admission.

Data analysis

We reviewed data for errors: missing data, duplicated records and outliers. Extreme values were set to missing if they were deemed impossible, based on their validity range. Continuous variables were reported as mean and SD or median and IQR based on data distribution. Categorical variables were described in numbers and/or percentages.

The prevalence and scope of ERM were described as the proportion of patients provided with any ‘active interaction’ of any ERM on day 3 post admission. Proportions of eligible patients receiving ERM interventions were analysed for each day. Rate ratios of patients receiving an ERM intervention during the study period were analysed using a Poisson regression model.

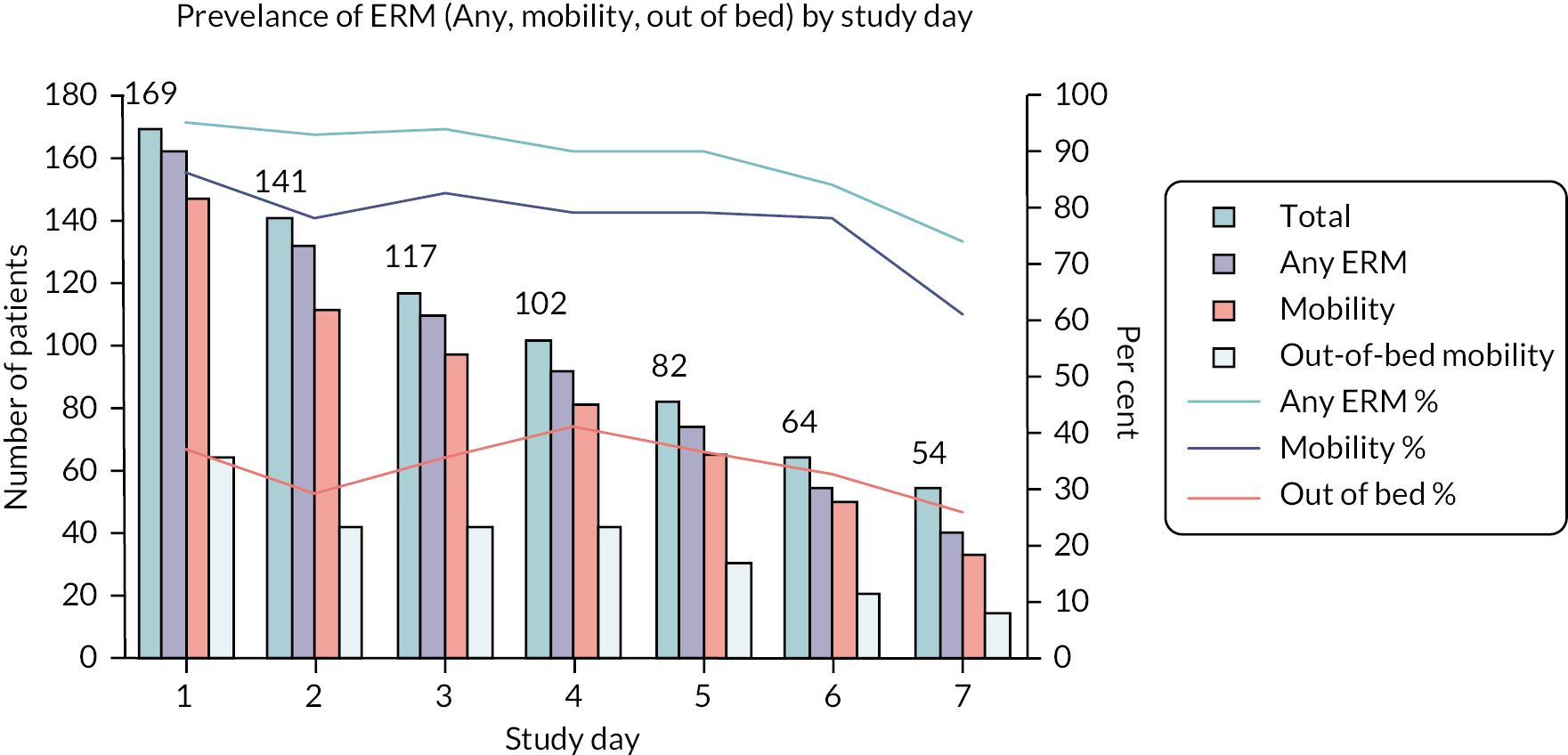

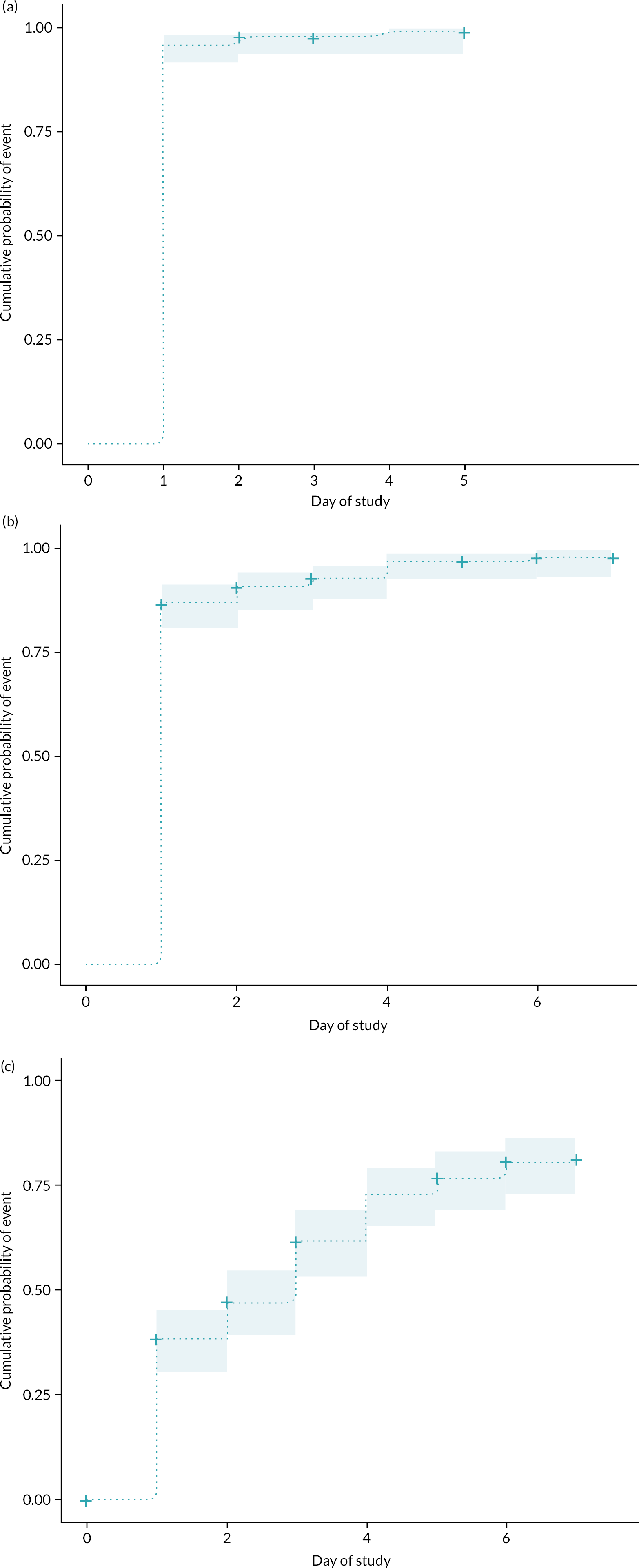

Cumulative prevalence for each day in PICU after day 3 up to day 10 post admission was calculated. Cumulative proportion of patients receiving ERM interventions as per prespecified categories during the study period was described graphically using Kaplan–Meier estimation and event rate plots.

We undertook further analysis to understand potential predictive factors associated with ERM and the incidence of ERM. We performed multivariable logistic regression to evaluate predictive factors of ERM provided on day 3. Factors of interest were established following the PERMIT survey and expert group consensus. These included age; baseline PCPC score; unplanned versus emergency admission; ventilation status; requirement of vasoactive infusion, sedative infusion, or neuromuscular blocking drugs; presence of urinary catheter, CVC or arterial line; family member present or participating in ERM activity; and presence of PICU protocol.

We calculated level of mobility activity using a modified progression score previously described in the EU-PACK (European Prevalence of Acute Rehabilitation for Kids in the PICU) study42 – Level 1: passive ROM, 2: sitting and exercise in bed, 3: sitting edge of bed, 4: held by parent or nurse (cuddle), 5: transfer to chair, 6: mat play, 7: standing, 8: walking in room/PICU, 9: walking out of PICU (see Appendix 3, Table 40). Further post hoc categorisation of ERM activities as enrichment, passive and active activities was also applied.

Adverse events rates were calculated per ERM activity. For zero rate observed AEs, the upper 95% CI are presented using Hanley’s formula. 65

Patient and public involvement and engagement

For an overview of the approach to patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) adopted throughout the study, please see Chapter 8. With this element of the study, we explored the potential consent model, especially the acceptability of an ‘opt out’ approach to consent. There was a study recruiting at the time on PICU with an ‘opt out’ approach – the Sedation AND Weaning In Children trial (SANDWICH) trial. 66 At the time, the SANDWICH trial had recruited over 700 patients at Birmingham Children’s Hospital (BCH), with only three families choosing to opt out of their child’s data being collected. It was therefore regarded as a highly successful approach to consenting.

For the SANDWICH trial, parents were given a leaflet outlining that data collection was taking place on data routinely collected as part of ‘normal care’ which goes to the national PICU audit. 67 They were told that the SANDWICH team would have access to some of this information. In addition, the research team would also collect information from the child’s medical notes and charts. All the data were anonymised and there were no interventions (at the individual level), just data collection. Parents were not asked for their informed consent. They received the Participant Information Sheet (PIS). If they did not want to take part, they then spoke to the clinical staff, who informed the research staff, and this was documented as an ‘opt out’.

We spoke to families who had received the information to ask how they had experienced the process of approach for the SANDWICH study. In addition, we approached families who were participating in other research studies known to the PPIE lead (JMen) and whose children had recently been discharged from hospital. We spoke to six parents of four children (aged 0.3–6 years) who had experienced one or more PICU admission(s) and had experience of their child being recruited to research. We also spoke to three young people (aged 17–20) naive to PICU to participate as PPIE participants. Different models of consent were discussed and where there was no intervention then an opt-out model of consent was universally popular (Table 3). We also discussed the PISs and poster to inform parents about the observational study with them and they suggested a number of changes to the language, graphics and layout of them.

| Aspect | PPIE feedback | Impact/changes made |

|---|---|---|

| Consent model | Opt-out consent acceptable Informed consent model also acceptable but adds burden at a difficult time |

Opt-out consent approach used. Well received with no negative feedback from the 15 sites that participated and no queries or amendments from REC |

| Participant-facing information | Language: current draft was understandable and clear but few suggestions to change phrasing and shorten sentence length Graphics: would like to see pictures of what was meant by early rehabilitation activities and feedback about the selection of figures used Layout: need larger font, better spacing, figures to break up text |

PIS and poster both amended. No negative feedback from the REC or the 15 sites that participated. Used as a template for Phase 3 work |

Results

Eligibility and enrolment

A total of 169 patients were enrolled into the study from 15 PICUs, with each PICU enrolling a median (IQR) of 10.0 (9.5–15.3) patients.

During the 14-day enrolment period, the median census on each PICUs was 10.5 patients (IQR 7.0–17.0; range 3–26). Overall, there was a median (IQR) of 1 patient (0–2) eligible per PICU per study day of whom 1 patient (0–1) was enrolled into the study per PICU per study day. This identified 203/2447 (8.7%) patients within each PICU eligible, of whom 158/203 (77.8%) were enrolled over the 14-day enrolment period (enrolment data were missing from 1 unit which recruited 11 patients). Ineligible patients had either not reached day 3 or had already reached day 4 or greater on day of screening. Table 4 shows PICU patient census, eligibility and enrolment proportion. During days 8–14, some sites reported not enrolling as they had already reached their target of 10 patients. Enrolment rate in study days 1–7 was 98/108 [90.7% (95% CI 83.6% to 95.4%)].

| Study day | Patients in PICUa | Eligible, n |

Eligible (%) | Enrolled, n |

Enrolled (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 174 | 11 | 6 | 11 | 100 |

| 2 | 183 | 15 | 8 | 14 | 93 |

| 3 | 183 | 14 | 8 | 12 | 86 |

| 4 | 183 | 20 | 11 | 18 | 90 |

| 5 | 178 | 16 | 9 | 14 | 88 |

| 6 | 171 | 15 | 9 | 14 | 93 |

| 7 | 169 | 17 | 10 | 15 | 88 |

| 8 | 189 | 16 | 8 | 13 | 81 |

| 9 | 182 | 12 | 7 | 7 | 58 |

| 10 | 183 | 19 | 10 | 13 | 68 |

| 11 | 177 | 9 | 5 | 6 | 67 |

| 12 | 163 | 15 | 9 | 9 | 60 |

| 13 | 157 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 56 |

| 14 | 155 | 15 | 10 | 7 | 47 |

Demographics

Of the 169 patients, 59.2% were male; median age was 4.5 months (IQR 1.1–37.9). The majority (81%) were <4 years with 62.7% <1 year. Only 48 (28.4%) were ambulatory prior to PICU admission (key demographics at admission are in Table 5).

| Factor | All | No ERM | Any ERM activity | No mobility ERM | Mobility ERM | Not out-of-bed | Out-of-bed ERM | Missing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 169 | 7 | 162 | 22 | 147 | 105 | 64 | |

| Age (days), median (IQR) | 135 (34–1137) | 207 (51–680) | 134 (33–1169) | 49.5 (10–283) | 183 (40–1299) | 260 (47–1169) | 92.5 (25–734.5) | 0 |

| Patient age group | ||||||||

| <1 month | 34 (20.1) | 0 (0.0) | 34 (21.0) | 6 (27.3) | 28 (19.0) | 18 (17.1) | 16 (25.0) | 0 |

| 1–3 months | 46 (27.2) | 3 (42.9) | 43 (26.5) | 7 (31.8) | 39 (26.5) | 26 (24.8) | 20 (31.3) | |

| 4–6 months | 11 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (6.8) | 1 (4.5) | 10 (6.8) | 6 (5.7) | 5 (7.8) | |

| 7–11 months | 14 (8.3) | 2 (28.6) | 12 (7.4) | 4 (18.2) | 10 (6.8) | 9 (8.6) | 5 (7.8) | |

| 1–4 years | 31 (18.3) | 1 (14.3) | 30 (18.5) | 1 (4.5) | 30 (20.4) | 26 (24.8) | 5 (7.8) | |

| 5–8 years | 6 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (4.1) | 2 (1.9) | 4 (6.3) | |

| 9–13 years | 13 (7.7) | 1 (14.3) | 12 (7.4) | 1 (4.5) | 12 (8.2) | 10 (9.5) | 3 (4.7) | |

| 13–17.9 years | 14 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (8.6) | 2 (9.1) | 12 (8.2) | 8 (7.6) | 6 (9.4) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 93 (55.0) | 5 (71.4) | 88 (54.3) | 14 (63.6) | 79 (53.7) | 56 (53.3) | 37 (57.8) | 22 |

| Mixed | 4 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.7) | 2 (1.9) | 2 (3.1) | |

| Asian | 18 (10.7) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (12.2) | 11 (10.5) | 7 (10.9) | |

| Black | 12 (7.1) | 2 (28.6) | 10 (6.2) | 3 (13.6) | 9 (6.1) | 10 (9.5) | 2 (3.1) | |

| Other | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) | 2 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Not stated | 18 (10.7) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (11.1) | 1 (4.5) | 17 (11.6) | 11 (10.5) | 7 (10.9) | |

| Reason for admission | ||||||||

| Post surgery: neurology | 5 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (3.4) | 4 (3.8) | 1 (1.6) | 1 |

| Post cardiac surgery | 16 (9.5) | 1 (14.3) | 15 (9.3) | 5 (22.7) | 11 (7.5) | 9 (8.6) | 7 (10.9) | |

| Other surgery | 21 (12.4) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (13.0) | 1 (4.5) | 20 (13.6) | 13 (12.4) | 8 (12.5) | |

| Haematology/oncology | 4 (2.4) | 1 (14.3) | 3 (1.9) | 1 (4.5) | 3 (2.0) | 2 (1.9) | 2 (3.1) | |

| Cardiac (medical) | 16 (9.5) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (9.9) | 1 (4.5) | 15 (10.2) | 7 (6.7) | 9 (14.1) | |

| Infectious | 5 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (3.4) | 3 (2.9) | 2 (3.1) | |

| Neurology | 9 (5.3) | 1 (14.3) | 8 (4.9) | 3 (13.6) | 6 (4.1) | 6 (5.7) | 3 (4.7) | |

| Renal | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Respiratory | 80 (47.3) | 4 (57.1) | 76 (46.9) | 10 (45.5) | 70 (47.6) | 51 (48.6) | 29 (45.3) | |

| Trauma | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other medical | 9 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (5.6) | 1 (4.5) | 8 (5.4) | 7 (6.7) | 2 (3.1) | |

| POPC | ||||||||

| 1. Good | 85 (50.3) | 5 (71.4) | 80 (49.4) | 13 (59.1) | 72 (49.0) | 49 (46.7) | 36 (56.3) | 1 |

| 2. Mild disability | 41 (24.3) | 1 (14.3) | 40 (24.7) | 6 (27.3) | 35 (23.8) | 23 (21.9) | 18 (28.1) | |

| 3. Moderate disability | 20 (11.8) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (12.3) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (13.6) | 12 (11.4) | 8 (12.5) | |

| 4. Severe disability | 21 (12.4) | 1 (14.3) | 20 (12.3) | 2 (9.1) | 19 (12.9) | 19 (18.1) | 2 (3.1) | |

| 5. Coma/vegetative state | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| PCPC | ||||||||

| 1. Good | 113 (66.9) | 6 (85.7) | 107 (66.0) | 16 (72.7) | 97 (66.0) | 64 (61.0) | 49 (76.6) | 3 |

| 2. Mild disability | 21 (12.4) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (13.0) | 2 (9.1) | 19 (12.9) | 11 (10.5) | 10 (15.6) | |

| 3. Moderate disability | 14 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (8.6) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (9.5) | 11 (10.5) | 3 (4.7) | |

| 4. Severe disability | 17 (10.1) | 1 (14.3) | 16 (9.9) | 2 (9.1) | 15 (10.2) | 16 (15.2) | 1 (1.6) | |

| 5. Coma/vegetative state | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

The most common admission diagnosis was bronchiolitis in 55 (32.5%). Eighty-four (49.7%) were admitted from another hospital, requiring retrieval into PICU. There were 127 (75.1%) emergency admissions, 150 (89.3%) required invasive ventilation at admission, 5 (3%) extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and 60 (35.5%) required cubicle isolation. Prior to admission, 66% had a PCPC score of 1 or 2 and 50% a POPC score 1 or 2, indicating a high proportion with moderate to severe disability pre-PICU. Admission predicted probability of mortality, as measured by PIM3, was median 1.2% (0.5–4.4%) and 68 (40.2%) children were enrolled in a PICU with an existing ERM protocol (as reported in the PERMIT survey – Chapter 2).

Patient clinical status on day 3 of admission (study day 1)

Between PICU admission and study day 1, 12 (7.1%) had surgery, 1 had a cardiac arrest. Most (119; 70%) remained ventilated by an ETT, 40 (23.7%) required vasoactive infusions and 3 remained on ECMO (Table 6).

| Factor n(%) or median (IQR) |

All | No ERM | Any ERM activity | No mobility ERM | Mobility ERM activity | Not out-of-bed | Out-of-bed ERM activity | Missing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = | 169 | 7 | 162 | 23 | 146 | 105 | 64 | |

| PELOD 2 score median (IQR) | 4 (2–6) (n = 169) | 5 (1.5–6) (n = 8) | 4 (2–6) (n = 161) | 5 (4–7) (n = 23) | 4 (1–5) (n = 146) | 5 (3–6) (n = 105) | 2.5 (0–5) (n = 64) | |

| Type of ventilation | ||||||||

| No oxygen support | 19 (11.2) | 1 (12.5) | 18 (11.2) | 2 (8.7) | 17 (11.6) | 6 (5.7) | 13 (20.3) | |

| High-frequency oscillator | 5 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (3.1) | 1 (4.3) | 4 (2.7) | 5 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Conventional ventilation | 114 (67.5) | 6 (75.0) | 108 (67.1) | 19 (82.6) | 95 (65.1) | 86 (81.9) | 28 (43.8) | |

| Non-invasive (CPAP/BiPAP) | 15 (8.9) | 1 (12.5) | 14 (8.7) | 1 (4.3) | 14 (9.6) | 6 (5.7) | 9 (14.1) | |

| High-flow oxygen | 10 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (6.2) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (6.8) | 1 (1.0) | 9 (14.1) | |

| Supplemental oxygen only | 6 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (4.1) | 1 (1.0) | 5 (7.8) | |

| Vasoactive infusions | 40 (23.7) | 3 (37.5) | 37 (23.0) | 7 (30.4) | 33 (22.6) | 27 (25.7) | 13 (20.3) | 1 |

| Neuromuscular blocking drugs | 26 (15.4) | 4 (50.0) | 22 (13.7) | 8 (34.8) | 18 (12.3) | 23 (21.9) | 3 (4.7) | 1 |

| Sedation medication | 108 (63.9) | 6 (75.0) | 102 (63.4) | 20 (87.0) | 88 (60.3) | 82 (78.1) | 26 (40.6) | 1 |

| Screened for delirium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| ETT | ||||||||

| Oral | 82 (48.5) | 3 (37.5) | 79 (49.1) | 12 (52.2) | 70 (47.9) | 63 (60.0) | 19 (29.7) | |

| Nasal | 44 (26.0) | 3 (37.5) | 41 (25.5) | 8 (34.8) | 36 (24.7) | 30 (28.6) | 14 (21.9) | |

| No tube | 43 (25.4) | 2 (25.0) | 41 (25.5) | 3 (13.0) | 40 (27.4) | 12 (11.4) | 31 (48.4) | |