Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/38/04. The contractual start date was in July 2016. The draft report began editorial review in April 2021 and was accepted for publication in September 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Wright et al. This work was produced by Wright et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Wright et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Wright et al. 1 © 2022 The Authors. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health. This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Wang et al. 2 Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Background and rationale

A specific phobia is an intense, enduring fear of an identifiable object or situation (e.g. dogs, heights or injections) that leads to anxiety, distress and avoidance,3 and is one of the most common mental health difficulties. 4 It is estimated that between 5% and 10% of children and young people (CYP) have a specific phobia that is severe enough to affect their everyday functioning,5 and that the average duration of their phobia is 20 years. 6 Specific phobias are, therefore, common in the population, are persistent over time and can have significant impacts on health and well-being. For example, specific phobias are associated with poorer health-related quality of life (HRQoL),7 considerable academic difficulties8 and distress and interference with day-to-day activities,9 and may predict a range of future mental health difficulties. 10,11 Consequently, it is important that CYP have access to effective treatments for specific phobias so that both the immediate and the possible future impacts can be mitigated. However, the proportion of CYP with phobias who receive treatment for phobia is small, at around 10%,6 and those who do seek treatment are likely to meet barriers and challenges to accessing timely, evidence-based support. 12–15

Current treatment approaches for specific phobia

Interventions based on the principles of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) remain the dominant model of delivery of therapy for specific phobias in the Children and Young People’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (CYP-IAPT) programme. 16,17 Indeed, CBT for specific phobias and for wider anxiety difficulties is effective and has a robust evidence base. 18–20 For example, Hudson et al. 21 reported that CBT in children with specific phobias resulted in significant reductions in clinician-rated phobia severity, as well as in both parent-reported and child-reported severity, and a significant increase in specific phobia diagnosis remission at follow-up. However, there are limitations to the provision of CBT. For example, face-to-face CBT is time-consuming22,23 and requires specially trained therapists,24,25 and, therefore, is often offered at high cost and with limited availability. 26,27 Furthermore, CBT is often offered over multiple sessions that can take many weeks and months to complete. Given that this requires CYP to be out of school, or the family to travel to receive therapy over many weeks and months, therapy provision can become a burden,28 which might contribute to the relatively high drop-out rate in CBT for CYP. 29,30 There is a need for brief, evidenced-based alternative treatments that can be offered in a more time- and cost-efficient manner for CYP living with specific phobias, as well as their families, and the clinical services providing care. One such option, with the potential to offer a brief and clinically effective treatment, is one-session treatment (OST).

One-session treatment: a brief and effective treatment for specific phobia

One-session treatment typically involves a combination of treatment techniques, including exposure, participant modelling, reinforcement, cognitive restructuring and skills training. At the core of OST is gradual exposure to the phobic stimulus, a process directed by the therapist using behavioural experiments. 31 Indeed, OST shares many of the same principles as CBT; however, unlike CBT, OST does not require an extensive treatment period. Instead, OST takes place over two sessions: (1) an initial assessment and planning session lasting around 1 hour and (2) one treatment session involving multiple graduated exposures lasting up to 3 hours, a procedure that has been shown to be clinically efficacious in CYP. 32–35 For example, in one of the largest randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of OST to date, conducted in the USA and Sweden, Ollendick et al. 33 randomised 196 CYP (aged 7–16 years) to one of three groups: (1) an OST group, (2) an education support group and (3) a waiting list control group. The authors reported that OST demonstrated superiority over both the education support group and the waiting list control group in terms of clinician-rated phobia severity, percentage of participants who were diagnosis free, and child ratings of anxiety and treatment satisfaction as reported by the children and their parents post intervention and at a 6-month follow-up point. OST, therefore, could offer a tool that can be used to reduce demands on therapist time, reduce the associated costs, prevent therapeutic drift and ultimately help CYP to recover more quickly from phobia.

Opportunities for advancement

Cognitive–behavioural therapy is the gold standard treatment for specific phobia and represents the dominant model of treatment provision; however, CBT is time-consuming and costly and has limited availability. Although the evidence base to date suggests that OST is a clinically efficacious treatment for phobia, there remain several areas of uncertainty that the present research aims to address. First, extant literature has tended to focus on the efficacy of OST, that is examining the performance of OST under more ‘ideal’ circumstances or in settings that do not reflect the ‘real world’. 36 For example, previous trials have tended to exclude participants based on specific characteristics that might influence treatment outcome if OST were to be implemented in clinical services, such as the presence of comorbid mental health difficulties,33 concurrent treatment for other difficulties33 or a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). 37 Consequently, it is unclear how well OST would perform in a more ‘real-world’ setting, such as Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS), where therapists are not always able to exclude CYP from therapy based on characteristics that might make treatment delivery more difficult (e.g. psychiatric comorbidity). 38,39 Second, to our knowledge, OST has not been compared with routinely delivered CBT with exposure (i.e. the gold standard treatment) in a RCT. Consequently, how OST performs against a much more active treatment, such as CBT, is unclear. Finally, although the consolidated, brief format of OST lends itself to being a more cost-effective tool than multisession CBT, to our knowledge, no study has performed an economic analysis to quantify any (potential) savings. Consequently, the cost-effectiveness of OST relative to CBT is unclear.

Research question, aims and objectives

The present research aims to address the gaps described above by conducting a pragmatic RCT of OST compared with multisession CBT for specific phobias experienced by CYP aged 7–16 years. Specifically, the primary aim of ASPECT (Alleviating Specific Phobias Experienced by Children Trial) is to investigate the non-inferiority of OST compared with multisession CBT for treating specific phobias experienced by CYP at a 6-month follow-up point. Non-inferiority would be demonstrated if OST was shown to produce similar, or improved, effects on the target specific phobia, as assessed using an in vivo exposure assessment tool: the Behavioural Avoidance Task (BAT) (i.e. the primary outcome). 40 In addition to the primary aims of ASPECT, several secondary aims are proposed. First, we aim to examine the cost-effectiveness of OST relative to CBT, with the resulting hypothesis being that OST will demonstrate superior cost-effectiveness relative to CBT. Second, the present research aims to investigate not only the effect of OST compared with CBT on the specific phobia itself, but also the impact on a wide range of associated outcomes, including broader mental health, quality of life (QoL), and school and social life. Finally, the present research aims to qualitatively investigate the acceptability of OST to the CYP receiving it, to their parents/guardians and to the clinicians administering OST. In conclusion, we believe that the present research has the potential to provide strong, high-quality evidence from which to base recommendations on not only the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of OST in real-world clinical settings, but also the perceived acceptability and feasibility of OST to CYP, their guardians and the clinicians responsible for providing care.

Chapter 2 Methods

Some text in this chapter has been reproduced from Wright et al. 41 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Wright et al. 1 © 2022 The Authors. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health. This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Hayward et al. 42 © 2022 Hayward et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Wang et al. 2 Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Main trial methods

This report is concordant with the 2010 Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement. 43

Trial design

The study was a two-arm, pragmatic, multicentre, non-inferiority RCT with an internal pilot to compare the clinical effectiveness of OST with that of multisession CBT. An economic evaluation of both OST and CBT and a qualitative investigation of the perceptions and acceptability of OST were nested within the study.

Important changes to methods after trial commencement

ASPECT received Health Research Authority and Research Ethics Committee (REC) approval from the North East – York Ethics Research Committee (17/NE/0012) in February 2017, with recruitment commencing on 30 June 2017. A series of amendments were submitted in response to observations made during the recruitment period. Several amendments resulted in changes to the protocol (see Appendix 1, Table 29), with all substantial amendments presented in Table 1. The trial protocol was published in BMJ Open in August 2018. 41

| Amendment number: date | Details | Protocol version number |

|---|---|---|

| 1: July 2017 | Approval was sought to display a poster in NHS trust locations to supplement recruitment | v1: as original approval |

| 2: November 2017 | Approval was sought to recruit from participant identification centres to increase recruitment | Not required |

| 3: January 2018 |

As the qualitative interviews (see Qualitative methods) were due at least 6 months post baseline, obtaining additional consent was deemed necessary for individuals to make an informed choice about participation Additional trial promotion methods were added to the study protocol. These included using social media accounts to promote the trial to internal staff and potential participants, the use of local media to promote the trial to stakeholders and the use of a recruitment poster displayed in NHS trust locations (linked with substantial amendment 1) Two study documents were amended: a school letter sent to head teachers to inform them of the study and request their participation (see School recruitment) was shortened to enhance readability, and the parent/guardian consent form was amended to explicitly state that therapy sessions might be recorded |

Now protocol v4: 8 January 2018a |

| 4: July 2018 | Permission was sought to provide those participating in qualitative interviews with an additional £10 voucher as a thank you for their time | Not required |

| 5: December 2019 | An additional case report form was added to the study. This collected information pertaining to additional diagnoses of ASD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and learning disabilities that participants may have had and any additional phobia treatments they had received, alongside trial treatment | Now protocol v5: 2 December 2019 |

Participants and eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Participants were CYP aged between 7 and 16 years experiencing a specific phobia, as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V), criteria. These criteria are:

-

Marked and out-of-proportion fear of a specific object or situation.

-

Exposure provokes immediate anxiety.

-

The phobic situation(s) is avoided where possible.

-

The avoidance or distress interferes with the person’s routine or functioning (e.g. learning, sleep and social activities).

-

Present for ≥ 6 months.

Participant eligibility was first assessed by research assistants using a telephone screening tool (see Report Supplementary Material 1) developed by the research team and completed with the CYP’s parent/guardian. The tool was based on the Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule (ADIS) and comprised five ‘yes’ or ‘no’ questions mapping directly onto the DSM-V, criteria for specific phobia. Parents/guardians needed to answer ‘yes’ to all questions to be considered eligible and, if they did, were invited to attend a face-to-face interview with the research assistant. At the interview, eligibility was further confirmed, with both the CYP and their parent/guardian completing the relevant versions of the ADIS (see Secondary outcome measures) to confirm that all five DSM-V criteria were met.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusions (pre randomisation) and withdrawals (post randomisation) were considered on a case-by-case basis. Reasons for exclusion or withdrawal were:

-

Exposure to the stimulus had the potential to be unsafe or cause harm (e.g. stimulus could not be safely produced or simulated).

-

A clinician decided, when referring or delivering treatment, that exposure therapy would not be the best first-line or best-available treatment option for the CYP (e.g. they had other needs that could make the therapy unsuitable, such as psychosis, severe learning disability, suicidality and severe conduct disorder).

Research settings

The sponsor, Leeds and York Partnership NHS Foundation Trust (LYPFT), in collaboration with the University of Sheffield Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU), coordinated the study nationally. Participants were identified through two main routes: (1) health-care and social care pathways and (2) schools.

Health-care and social care pathway recruitment

Given the trial’s pragmatic nature, recruitment took place within the services in which specific phobias were most likely to be seen. This included 12 NHS trusts comprising 26 CAMHS, three third-sector/voluntary services and one university-based CYP’s well-being service.

For the most part, participants were identified by therapists within these services at a range of different points within the care pathway, including at first contact with the services, during initial meetings with therapists to discuss needs, when on waiting lists to access support and following allocation to a therapist to receive therapy. Participants may have accessed the service specifically for their phobia, or were seeking support for a comorbidity and their specific phobia was identified.

Potentially eligible participants were given information about the study and an expression of interest form. The parents/guardians of interested participants were asked to return this form to the research team either directly or via a clinician. The research assistant then contacted the parent/guardian, discussed the study in detail and completed the initial telephone assessment (see Participants and eligibility criteria). If deemed eligible, a baseline visit was arranged.

During study recruitment, it became apparent that some CYP with specific phobias did not meet CAMHS acceptance criteria and were, therefore, unable to access the trial. To address this, a training clinic was set up by the study sponsor in one locality (York). This was staffed by clinicians who volunteered their time to offer therapeutic interventions. CAMHS clinicians referred CYP to the training clinic, and these clinics operated the same recruitment processes as those outlined above.

School recruitment

With previous experience recruiting from schools,44,45 the research team had established links to education services. Initially, a database of schools was compiled for each area linked to the study with the intention of identifying participants via an invitation pack posted out to families. However, this recruitment method proved unsuccessful, with few schools responding and many of those who did being unable/unwilling to distribute recruitment packs. Focus was, therefore, placed on recruiting via newly emerged school-based mental health and well-being services (see Chapter 3). A single school-based service took part, with schools within the service sent study information and invited to participate. When a school agreed, school nurses and the well-being service clinicians identified potential participants and gave them study information. Aligning to recruitment in CAMHS, the parents/guardians of interested participants were asked to return an expression of interest form to the research team either directly or via their school. Research assistants then contacted the family to discuss the study, ascertain eligibility and arrange a baseline visit.

Outcome measures

During ASPECT, outcome measures were completed by CYP and their parent/guardian. The assessments and their timings are presented in Table 2.

| Measure | Time points completed | Delivery method | Completed by |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening checklist | Screening | Telephone interview | Parent/guardian |

| Demographics | Screening | Telephone interview | Parent/guardian |

| Baseline | Face to face | Parent/guardian | |

| Baseline | Face to face | Participant | |

| BAT | Baseline | Face to face | Participant |

| 6 months after randomisation | Face to face | Participant | |

| ADIS-P | Baseline | Face to face | Parent/guardian |

| 6 months after randomisation | Face to face | Parent/guardian | |

| ADIS-C | Baseline | Face to face | Participant |

| 6 months after randomisation | Face to face | Participant | |

| CAIS-P | Baseline | Face to face | Parent/guardian |

| 6 months after randomisation | Face to face | Parent/guardian | |

| CAIS-C | Baseline | Face to face | Participant |

| 6 months after randomisation | Face to face | Participant | |

| RCADS-P | Baseline | Face to face | Parent/guardian |

| 6 months after randomisation | Face to face | Parent/guardian | |

| RCADS-C | Baseline | Face to face | Participant |

| 6 months after randomisation | Face to face | Participant | |

| Goal-based outcome | Baseline | Face to face | Participant |

| 6 months after randomisation | Face to face | Participant | |

| CHU-9D | Baseline | Face to face | Participant |

| 6 months after randomisation | Face to face | Participant | |

| EQ-5D-Y | Baseline | Face to face | Participant |

| 6 months after randomisation | Face to face | Participant | |

| Resource use | Baseline | Face to face | Parent/guardian |

| 6 months after randomisation | Face to face | Parent/guardian | |

| Therapist logs | Ongoing over intervention | N/A | Therapist/clinician |

| OST integrity scale | Ongoing over intervention | N/A | Clinical supervisor |

| CBT fidelity scale | Ongoing over intervention | N/A | Clinical supervisor |

Data collection methods: children and young people and parents/guardians

Children and young people and their parents/guardians completed several outcome measures with a trained research assistant at baseline, following consent but before randomisation, and at 6 months post randomisation. These meetings were held where the intervention delivery was due to take place/had taken place or at a mutually convenient location. Where follow-up assessments were due for completion during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Chapter 3), information was collected remotely via telephone or video conferencing. Administering the ADIS over the telephone has been examined elsewhere and has demonstrated good to excellent agreement with in-person delivery. 46 At baseline, demographic information (e.g. age, sex and ethnicity) was collected. As part of a subgroup analysis, CYP were also asked whether or not they had a treatment preference prior to randomisation, but this did not affect therapy allocation. On some occasions, particularly when younger participants were involved, the collection of measures was completed over two meetings. The following measures were completed at baseline and repeated at 6 months’ follow-up.

Primary outcome measure

Behavioural Avoidance Task

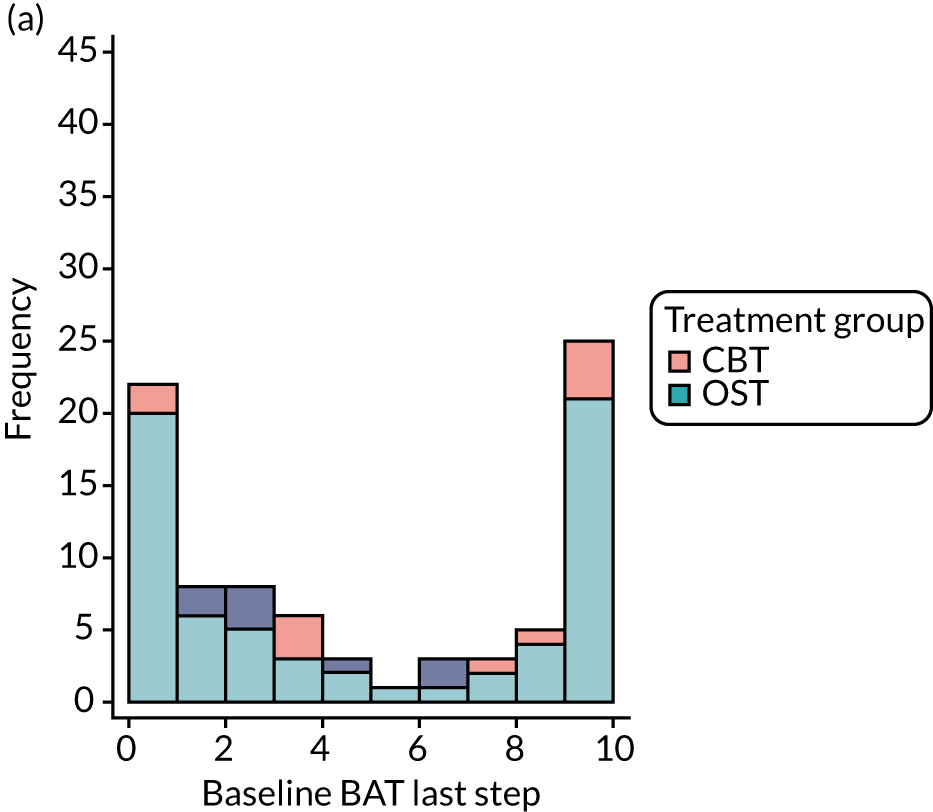

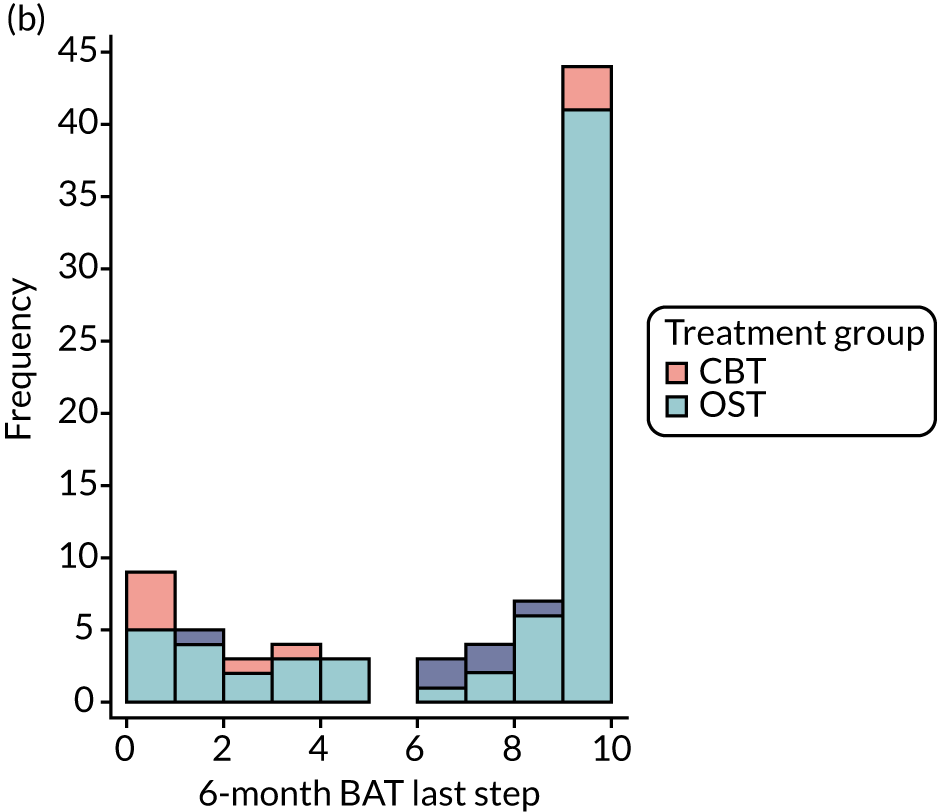

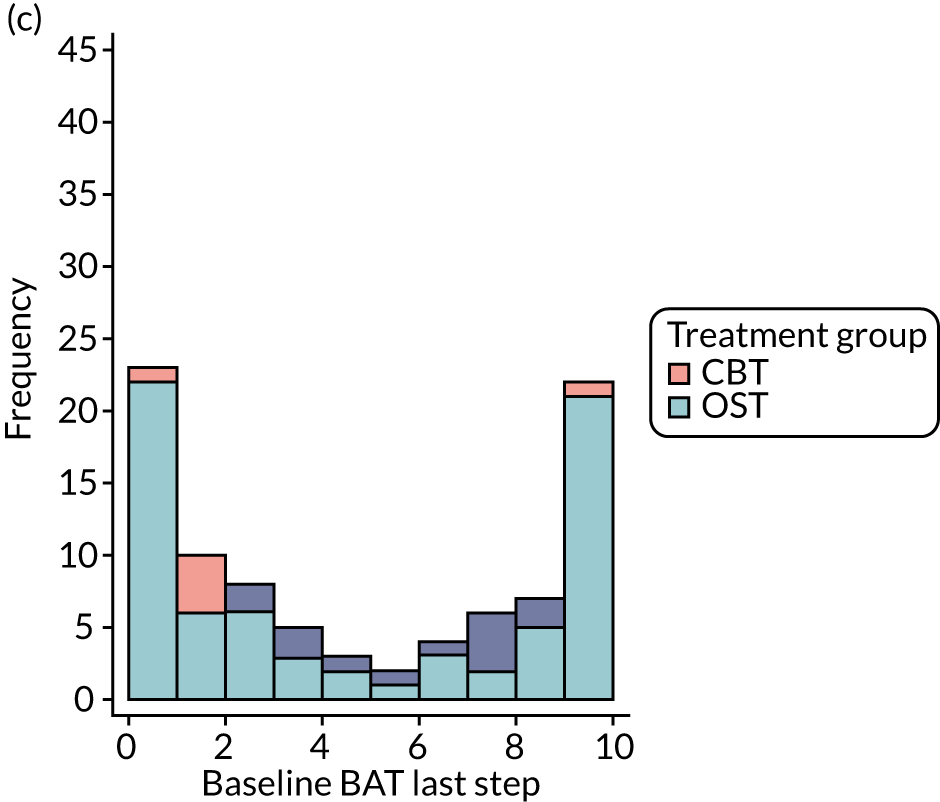

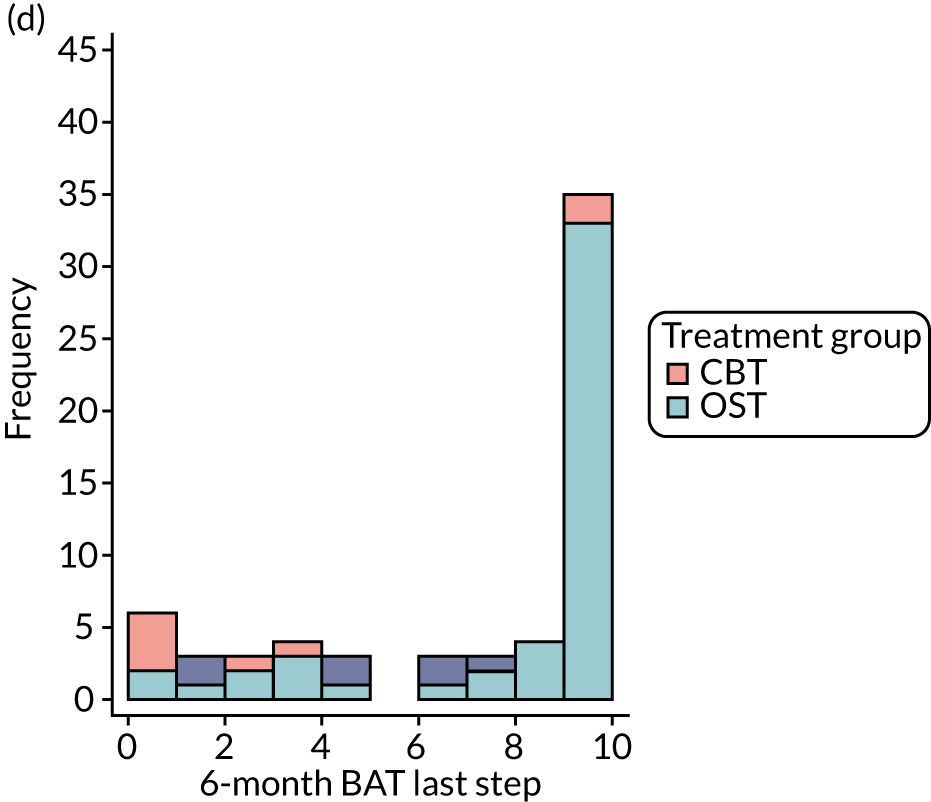

The BAT33 (Dr T Davis III, Louisiana State University, 2017, personal communication) is a widely used behavioural outcome measure for assessing phobias in children9,34,40 and is specific enough to distinguish between multiple phobias. BAT completion involved gradually exposing participants to their phobic stimulus over 10 predefined steps that increased in difficulty each time. For example, CYP with a dog phobia would start at step zero, which would involve standing outside a room in which there was a dog. Subsequent steps would involve moving closer to the dog, with step 10 (the final step) involving stroking the dog for a specified period of time. The number of steps taken, determined by the research assistant, was the main unit of measurement; a smaller number of steps indicated a higher severity of phobia. The BAT also includes a measure of subjective units of distress (SUDS) whereby participants indicated their level of fear both at the start of the BAT and at the last step completed, ranging from 0 (no fear at all) to 8 (very, very much fear).

Secondary outcome measures

Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule

The ADIS47 is a semistructured interview and a routinely used diagnostic tool in CYP phobia research. 48 The specific phobia subsection of the ADIS was used to assess full eligibility by obtaining information relating to the presence and type of specific phobias alongside the level of associated fear, avoidance and interference with daily life. During ADIS completion, both parents and CYP used rating scales ranging from 0 (not at all) to 8 (very, very much) to provide information about the level of fear and interference resulting from the specific phobia. Following guidance from the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), the research assistant selected the highest interference score between those provided by the parent and child or young person and used this to determine a composite clinical severity rating (CSR). Where a composite CSR score was ≥ 4, a child or young person was deemed eligible for study entry.

Child Anxiety Impact Scale

The Child Anxiety Impact Scale (CAIS)49 is a 27-item parent and child self-report questionnaire that is designed to measure anxiety-related functional impairment across three subdomains: school activities, social life and home/family life. 50 Participants used a four-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very much) to describe their agreement with each statement. Both the parent and the child versions of the CAIS were completed.

The Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale

The Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS)51 is a 47-item, self-report scale that is used to capture mental health information relating to CYP across six subdomains: separation anxiety disorder, social phobia, generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder and major depressive disorder. Participants used a four-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (always) to describe the frequency with which several statements related to them. Both the parent and the child versions of the RCADS were completed.

Goal-based outcome measure

A goal-based outcome measure, based on recent guidelines,52 was used to compare how far a child or young person felt that they had moved towards attaining specific goals set prior to treatment. At baseline, CYP set three goals, with progress towards meeting these assessed at the 6-month follow-up using an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (goal not met) to 10 (goal reached). For a dog phobia, goals may have included being able to stroke a dog, feed a dog or visit a place where a dog might be present.

EuroQol-5 Dimensions Youth version

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions Youth version (EQ-5D-Y)53 measures QoL in CYP on five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression). Individuals classify their health relative to these dimensions using a three-point scale (1, no problems; 2, some problems; 3, a lot of problems). A visual analogue scale is used by participants to indicate their overall health status from 0 (worst imaginable state) to 100 (best imaginable state). The EQ-5D-Y can provide utility values for cost–utility analysis. The EQ-5D-Y was completed by the CYP only.

Child Health Utility 9D

The Child Health Utility 9D (CHU-9D),54 a child-completed, nine-item questionnaire, measures HRQoL for CYP. Participants describe their feelings in relation to several constructs (worried, sad, pain, tired, annoyed, schoolwork/homework, sleep, daily routine and activities) by selecting one of five sentences. The CHU-9D also provides utility values, allowing the calculation of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) for use in cost–utility analysis.

Resource use

Tailored questionnaires were used to collect resource utilisation information for CYP with specific phobias and for delivering interventions. The questionnaires were specifically designed for ASPECT and were based on previous studies focusing on CYP and CYP with mental health issues. 55–57 The questionnaire for service use was completed by the parent/guardian whereas the resource use questionnaire for intervention delivery was completed by the trial research team.

Outcome measures: scoring and interpretation

The ADIS CSR was scored on a scale of 0 to 8, with high scores suggesting the phobia is more disturbing for the child/young person. The CAIS score was calculated by summing scores for each question if no more than three items were missing, and ranges from 0 to 81, with higher scores representing greater impact on psychological function. RCADS domain scores were calculated if no more than two items in that domain were missing by summing the relevant question scores. RCADS total anxiety was calculated by summing contributing domain scores if all were available. RCADS total anxiety ranges from 0 to 111, with higher scores representing more anxiety symptoms. Value sets for the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version,58 were used to score the ED-5D-Y; the score ranges from –0.594 to 1 (0 means death, 1 is full health and a negative score is a state worse than death). The CHU-9D utility score was calculated by assigning utility values to each response and then summing these values59 if all questions were completed. The CHU-9D utility score ranges from 0.33 to 1, where higher scores represent greater HRQoL. Any missing items on any outcome measure were imputed with the mean of completed items for that scale.

Interventions

Following completion of all baseline measures, participants were randomised to either the intervention group (OST) or the control group receiving usual care (CBT). In all centres, usual care was multisession CBT (no sites were routinely offering OST). Most interventions were delivered in the location at which the CYP had been identified for study inclusion. For the research clinic, suitable spaces in the participant’s locality were identified and used for intervention delivery. As this was a pragmatic trial, the presence or absence of the parent/carer in the session was a clinical decision based on the age and needs of the child and the assessment of the parent/carer–child dyad, and was not considered a confound for analysis given that two previous studies found no clear signal of difference with or without a parent. 34,37

One-session treatment

One-session treatment uses many of the same techniques as CBT (e.g. exposure, participant modelling, reinforcement, cognitive restructuring and skills training). However, instead of being delivered over weekly 1-hour sessions, it takes a more condensed and intensive approach, with delivery comprising two sessions: an initial 1-hour functional assessment followed by a separate treatment session (lasting up to 3 hours) with graduated exposure.

The functional assessment session aims to assess maintaining factors for the phobia, collect information about the CYP’s catastrophic thoughts and generate a fear hierarchy. This session is also used to develop an understanding of the onset and course of the phobia as well as to build a rapport between the clinician, CYP and their parents. The session concludes with focus placed on the treatment rationale and a discussion about what will happen during the subsequent 3-hour exposure session. The therapist reiterates to the CYP that nothing will happen without their permission and, as all therapy tasks are graded, they will not move on to the next one until they have agreed to do so.

The aim of the exposure session is for the CYP to gradually confront and remain in each feared situation on the hierarchy until their anxiety and fear subsides by at least 50%. Participant modelling helps the CYP to approach their feared stimulus slowly and gradually through the therapist first discussing and then demonstrating how to interact with the object/situation and supporting the CYP to do so (an example of participant modelling for dog phobia is the therapist stroking the dog, the child placing their hand on the therapist’s shoulder, then on the therapist’s arm, then over the therapist’s hand, then stroking the dog themselves). Exposure tasks can be used to actively elicit, challenge and test catastrophic thoughts and beliefs associated with the feared object or situation. The CYP are encouraged to maintain their gains from the session by practising self-directed exposure tasks at home (e.g. refraining from avoiding/escaping the feared object/situation and trying to expose themselves to their feared stimulus daily). The main treatment session requires considerable organisation of materials for sequential exposure experiments (e.g. two or three different dogs over the 3-hour session).

Cognitive–behavioural therapy-based interventions

Cognitive–behavioural therapy uses cognitive and behavioural techniques to support people to change unhelpful behaviours and thought patterns that may occur in response to situations. Interventions based on the principles of CBT are the most common model of therapy delivery for specific phobias and are supported by a robust evidence base. 16–20,60,61 CBT for specific phobias aims to help CYP to:

-

recognise anxious feelings and bodily reactions to anxiety

-

gradually confront feared situations until anxiety subsides

-

capture and challenge anxious or scary thoughts when faced with a phobic situation or object, helping to adjust unhelpful or incorrect beliefs

-

develop coping strategies and use anxiety management techniques, especially if distress and physical symptoms become overwhelming and the CYP cannot stay in the feared situation for the purposes of therapy.

Cognitive–behavioural therapy-based interventions for phobias are typically delivered in weekly hour-long sessions comprising the usual practices of building a fear hierarchy, exposure and cognitive restructuring. Each session has a specific objective for the CYP to achieve, supplemented by homework tasks between sessions. Therapists providing CBT as part of ASPECT were asked to deliver their service’s usual CBT multisession treatment approach. There is currently no recommended number of CBT sessions for specific phobias; however, CYP would usually receive 6–12 sessions.

Therapist training

ASPECT therapists received OST training in a 1-day workshop (see Chapter 3, Intervention training and delivery). Some senior practitioners also attended a ‘train the trainer’ session that enabled them to train other therapists in the delivery of OST at their site. Although OST delivery followed a treatment protocol used in previous research,62 CBT delivery did not. However, a manual, co-written by several study principal investigators with extensive experience of delivering CBT to CYP was developed to support therapists.

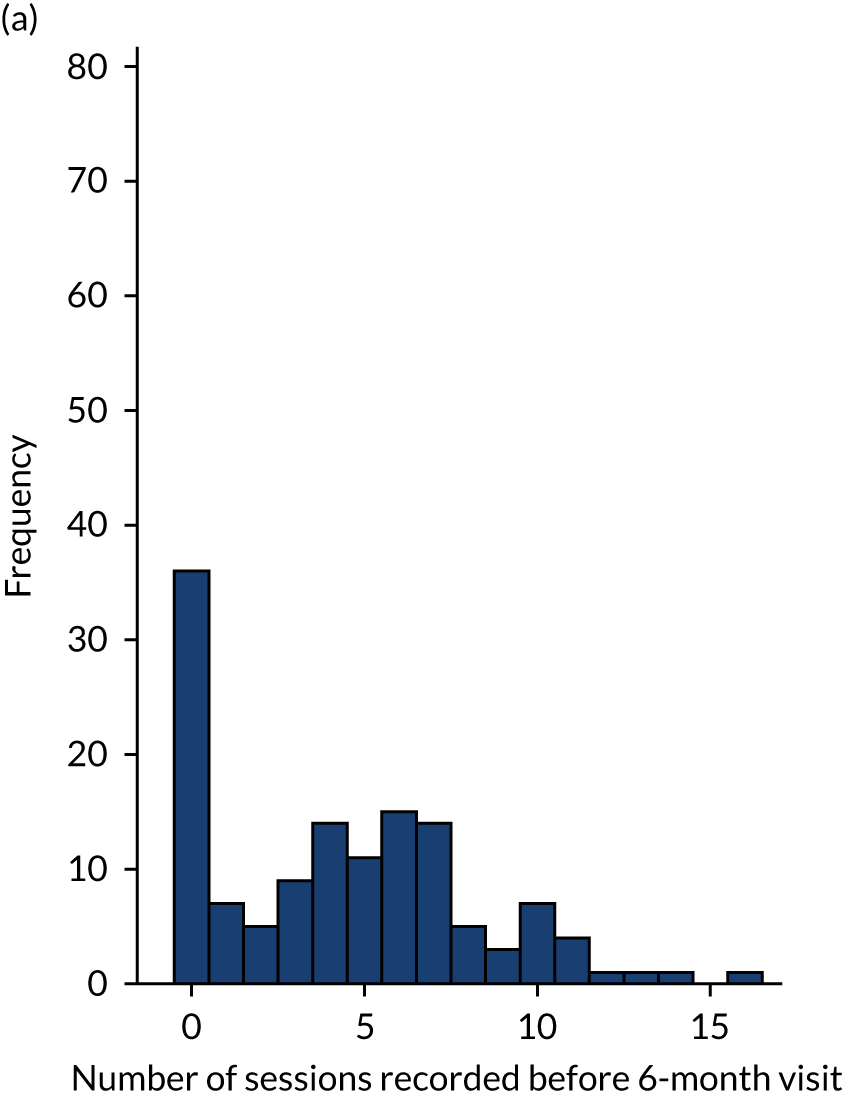

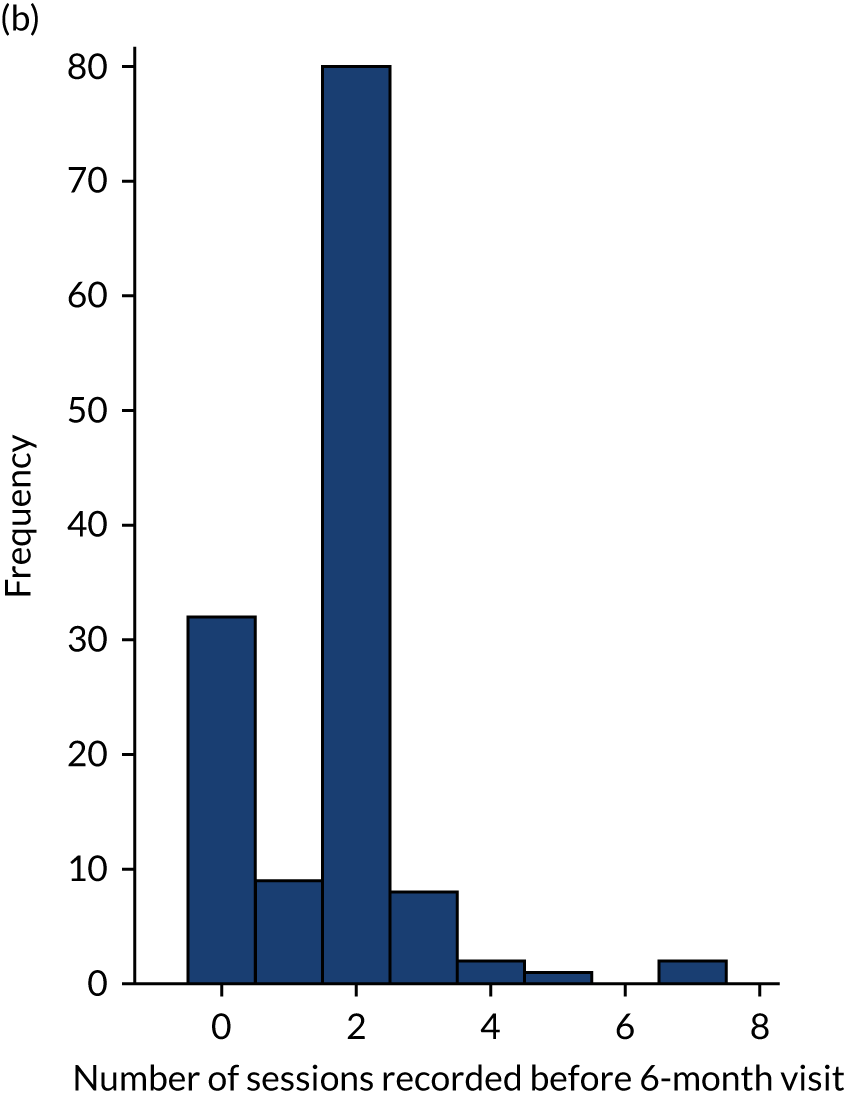

Study therapists and data collection

All therapists involved in ASPECT were asked to provide some basic information about their professional experience (role, grade, organisation, years of experience and qualifications) before delivering any study treatments. Therapist preference between OST and CBT was also ascertained prior to randomisation. As part of the fidelity (see Assessment of fidelity) and economic evaluations (see Health economic methods) conducted, all therapists were asked to keep a log of the sessions that they delivered (see Chapter 4, Cognitive–behavioural therapy and one-session treatment intervention summaries; see also Table 7). Information was collected pertaining to session number, duration and frequency alongside the strategies employed, the resources required and the number of individuals in attendance at therapy sessions (i.e. whether or not a parent attended). Therapists were also asked to report all contact they had with study participants, any adverse events (AEs) (see Chapter 4, Safety and harms; see Table 16) and any instances where participants withdrew from treatment.

Assessment of fidelity

Therapists were asked to audio-record all treatment sessions, where possible, following informed consent from the CYP and their parents/guardians. To ensure that CBT principles were delivered in both treatment arms, five expert clinical members of the ASPECT team independently rated a random sample of the therapy session recordings (CBT and/or OST). Allocation of session recordings was determined using a randomising formula in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Prior to assessment, the clinicians each assessed the same two session recordings (one CBT and one OST) for comparison to ensure inter-rater reliability. Recorded sessions were scored using the criteria in the session recording forms and one of the following measures relative to the treatment delivered.

The Cognitive Behaviour Therapy Scale for Children and Young People

The Cognitive Behaviour Therapy Scale for Children and Young People (CBTS-CYP)63 is a measure used with CYP to assess fidelity to CBT delivery that is based on the Cognitive Therapy Scale – Revised (CTS-R),64 which is the most widely used tool for measuring CBT competence with adults. Like the CTS-R, the CBTS-CYP utilises a 7-point Likert scale to assess competence over 14 items relating to the use of goals and assessments, behavioural technique use, cognitive technique use and the ability to facilitate self-discovery and child engagement. Scores range from 0 (incompetent) to 6 (expert) and there are two pass criteria: no single item is scored lower than 2 and the total score exceeds 50%. The measure has demonstrated high face validity, internal reliability and robust convergent validity with the CTS-R. 63

The One-Session Treatment Rating Scale

To assess the fidelity to the principles of OST delivery the One-Session Treatment Rating Scale, developed in a previous RCT of OST with CYP,37 was employed. A scale of 0 (not at all) to 6 (excellent) is used to indicate how well a therapist delivering OST adheres to the core principles of the approach over 13 items. Item examples include the extent to which the therapist ‘created a good and therapeutic relationship with the child’ and how well they ‘guided the child in the exposure procedure’. We used the same pass and fail criteria as for the CBT competence assessment (i.e. no single item is scored less than 2 and the total score exceeds 50%).

Fidelity was classified using established criteria to describe the extent of observed fidelity of delivery;65 if < 50% of intended content is delivered, this is classified as ‘low’ fidelity, 51–79% as ‘moderate’ fidelity and 80–100% as ‘high’ fidelity.

Sample size calculations

To our knowledge, no systematic review had examined the effect of CBT on specific phobias as measured using the BAT in CYP. Consequently, the assumptions for the proposed sample size and non-inferiority margin were based on two separate Cochrane reviews66,67 investigating the effects of psychotherapy for those experiencing anxiety. Wolitzky-Taylor et al. 66 conducted a review on studies that used both behavioural measures and self-report questionnaires on adults with specific phobias and reported an overall large effect size of d = 0.81. However, as the treatment may have a different effect on children, the review by Reynolds et al. 67 was also examined. This review was conducted on studies of children with specific phobias but used self-report questionnaires rather than the BAT. This review also reported a large effect size (d = 0.85) for multisession CBT.

As prior meta-analyses suggest that a standardised mean difference of around 0.8 on the BAT is clinically important, the non-inferiority margin was set to be half of this, at 0.4. 68 Assuming a correlation of 0.5 between baseline and final BAT measures, 200 participants (100 per arm) would have been required to have 90% power with a 2.5% one-sided significance level to demonstrate non-inferiority of OST compared with CBT. It was assumed that therapy would be delivered by therapists who would each see approximately 15 patients and therefore a weak therapist effect [intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) = 0.01] was expected. This clustering was anticipated to result in a design effect of 1.14, which increased the number of participants required per arm to 114. We further assumed a 20% dropout rate, concluding that 286 (143 per arm) would need to be recruited to demonstrate non-inferiority of OST to CBT.

Sample size recalculation

In April 2019, a 7-month extension was requested from the funders in response to lower than expected recruitment, and the sample size was recalculated. As of 27 March 2019, data completeness on the primary end point was 64/88 (72.7%), which translated to a dropout rate of 27.3% (95% CI 18.3% to 37.8%). Based on this and the original timelines, this would have resulted in about 136 (68 per group) participants with 6-month primary outcome data.

We observed a correlation of 0.7 between baseline and 6-month primary outcome measures. We also observed that a therapist was expected to treat five CYP (instead of 15). If the original assumption made about the ICC (of 0.01) was accurate, then the design effect was 1.04 (instead of the planned 1.14). Given these observations, had ASPECT been extended to recruit the original sample size of 286 participants (143 per group), it would have had a power of 97.7% (0.7 correlation, 27.3% dropout rate, five CYP per therapist). Based on a conservative correlation of 0.6, observed dropout rate of 27.3%, each therapist treating an average of five CYP and an ICC of 0.01, a total of 246 participants (123 per group) was required to preserve a power of ≈ 90% for a one-sided 2.5% test with a standardised non-inferiority margin of 0.4. This resulted in 178 participants (89 per group) with primary outcome data for analysis. The decision to recalculate the sample size was presented to and supported by the TSC and the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC).

Stop/go criteria

The internal pilot embedded within ASPECT was due to last for 9 months before it was determined if the trial would need to be terminated against stop/go criteria. In response to delays in setting up some recruitment sites and in conjunction with TSC recommendations, this assessment was postponed by 4 months and was moved from March 2018 to July 2018. However, the original stop/go criteria targets for March 2018 were retained.

The stop/go criteria were based on the feasibility of both recruitment and retention alongside safety outcomes. Based on an anticipated recruitment rate of 12 participants per month, the overall stopping criteria of 75% of the target (n = 81) and 70% retention for those eligible for a 6-month follow-up (n = 25) were set. The safety of the trial was also reviewed by the DMEC.

Randomisation

The randomisation of eligible participants was conducted remotely through a secure web-based system developed by Sheffield CTRU. The randomisation sequence was generated prior to the start of the study by the trial statistician. Participants were randomised 1 : 1 to receive either OST or CBT. Randomisation was stratified according to both age (7–11 vs. 12–16 years) and phobia symptom severity [ADIS clinician’s severity rating (CSR) mild/moderate (scoring 4/5) vs. severe (scoring 6/7/8)] and restricted using randomly permuted blocks of size 4 and 6.

Parent/guardians and the designated therapist were informed of treatment allocation by an unblinded member of the research team. A letter was also sent to the participant’s general practitioner (GP) to inform them of study involvement and treatment allocation.

Allocation concealment and blinding

To reduce sources of bias, the research assistants responsible for conducting baseline and follow-up assessments remained blind to treatment allocation until the completion of all 6-month follow-up measures. Thus, the research assistants were not involved in the allocation procedure, had no involvement in organising therapy sessions and had only limited access to the study database. Furthermore, participants, their parents and therapists were explicitly reminded not to disclose their treatment allocation to the research assistant. All study tasks requiring knowledge of randomisation (e.g. organising therapies) were completed by unblinded members of the research team.

In the event that a research assistant who was responsible for collecting 6-month follow-up data was unblinded, arrangements were made for a different outcome assessor where possible. Information was collected pertaining to the unblinding incident; research assistants were asked about the suspected allocation, date, source and method of unblinding.

The trial statisticians and health economists were blind to treatment allocation while the trial was ongoing. To maintain blinding, the reports presented to the TSC and Trial Management Group (TMG) did not report treatment allocations.

Analysis populations

The intention-to-treat (ITT) population included all consented and randomised participants according to the randomised treatment assignment with complete primary outcome data. This excludes participants who withdrew before randomisation and includes participants who were found to be ineligible post randomisation. 69 The per-protocol (PP) population is a subset of ITT who receive their intervention in accordance with the protocol.

In ASPECT, participants in the OST group were defined as PP if, by the 6-month follow-up, they had attended:

-

one assessment session

-

one main exposure session

-

an optional extra session.

And all of the following had taken place during the therapy:

-

an assessment

-

establishment of a fear hierarchy

-

exposure.

Any participant who attended more than the maximum three sessions outlined above, before their 6-month follow-up occurred, was not classed as PP.

A participant in the CBT group was defined as PP if they had:

-

attended at least four CBT sessions.

If a participant was still undergoing therapy at the time of their 6-month follow-up assessment, only sessions conducted before the follow-up counted towards the PP assessment. An extended ITT population was used for participants who had secondary but not primary outcome data (owing to the COVID-19 pandemic) in the secondary outcome analysis.

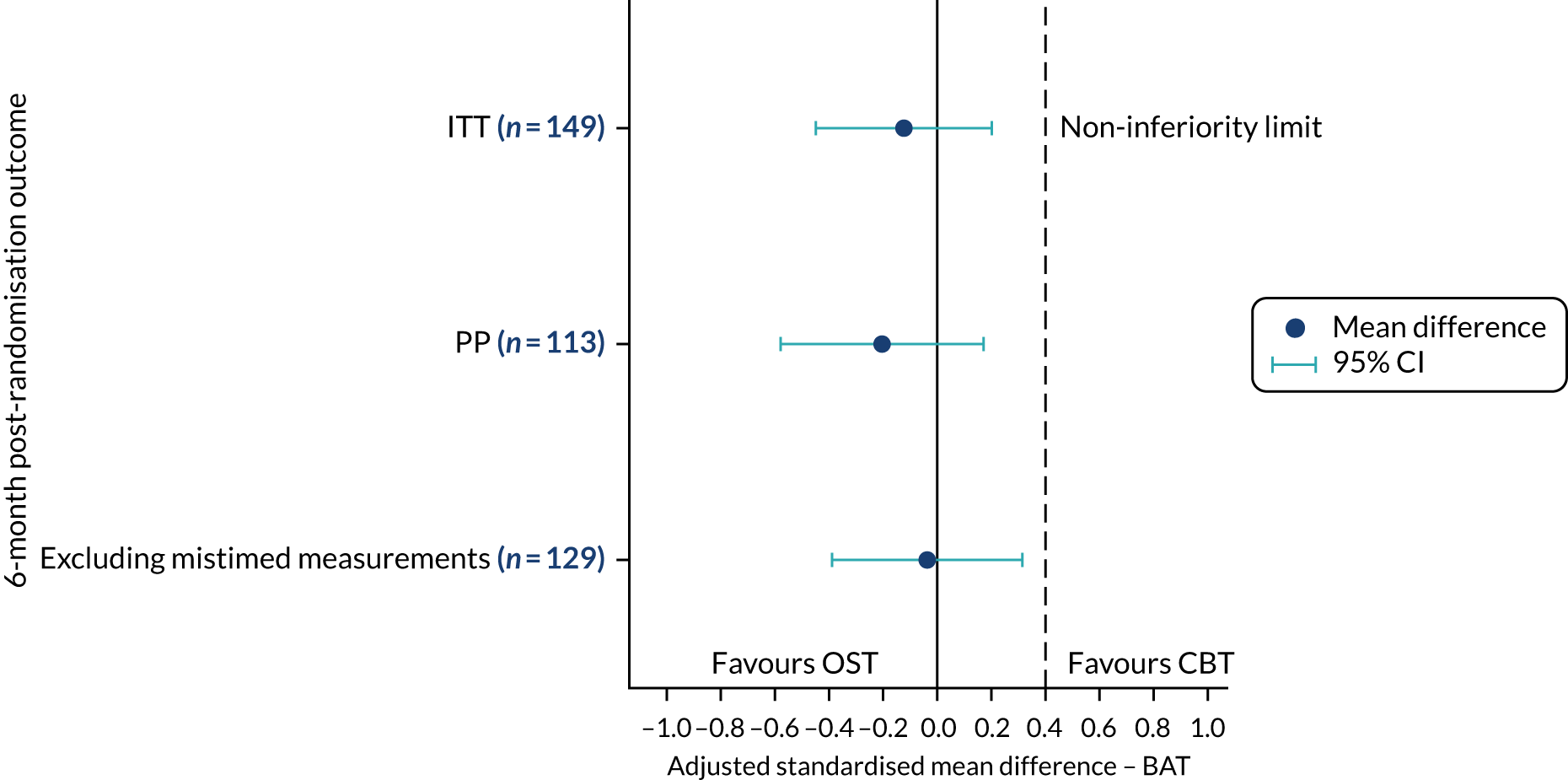

Owing to the non-inferiority research question, the main analysis on the primary outcome (BAT score at 6 months post randomisation) was prespecified to be PP with sensitivity analysis on the ITT population. 68,70 We required both the PP and the ITT analyses to demonstrate statistically significant evidence of non-inferiority to declare that the treatment was non-inferior. If the results of the analysis were discrepant (e.g. the ITT rejected the null of inferiority but the PP analysis did not, or vice versa) then the conflicting results from both analyses would be reported, highlighting the inconclusive nature of the results.

Statistical methods

General considerations

All statistical analyses were performed in Stata® version 16 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) statistical software. A comprehensive statistical analysis plan was developed while the statistician was blinded to treatment allocation. Data were reported and presented in accordance with the revised CONSORT statement43 and the non-inferiority trials CONSORT extension. 70

Analyses were conducted on the primary outcome (BAT score at 6 months) using all analysis sets (ITT, PP and sensitivity analysis). For all secondary outcomes, the analysis was reported on the ITT population unless there were important differences between results based on the ITT and PP sets. As a guideline, any difference in treatment effect, between ITT and PP populations, of more than 0.1 standard deviation (SD) on any inventory was assessed further.

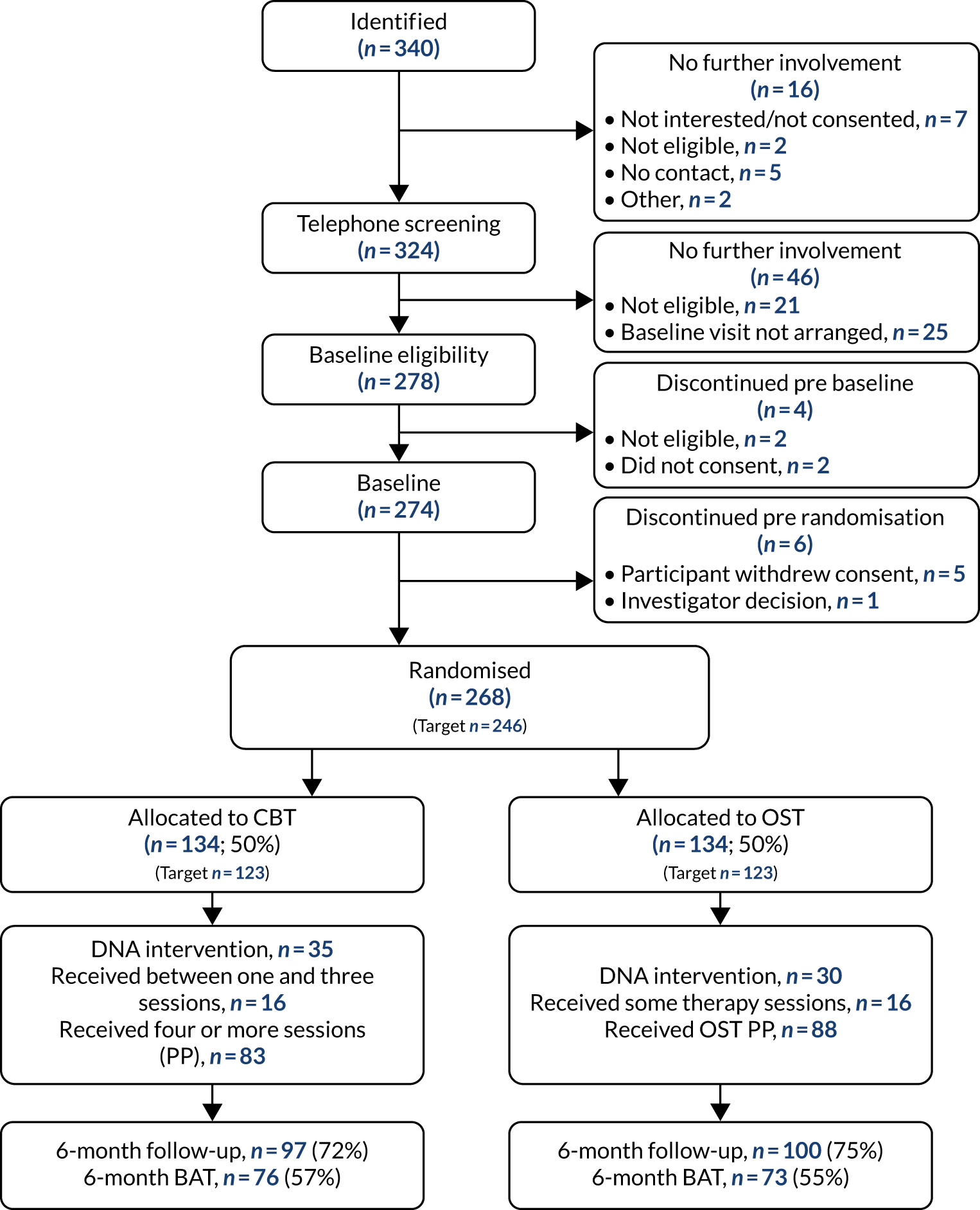

Data completeness

A CONSORT flow diagram was used to display data completeness and participant throughput from first contact to final follow-up.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics, assessments and QoL data for participants and parents/guardians were summarised and assessed for comparability between the treatment groups. No statistical significance testing was conducted to test imbalances between the treatment groups but any noted differences are reported descriptively.

Primary outcome analysis

The primary outcome (BAT score at 6 months) was compared between groups using mixed-effects linear regression with robust standard errors and exchangeable correlation to allow for the clustering of outcomes within therapist. The mixed-effects regression was adjusted for baseline BAT score, site and stratifying variables (age and baseline phobia severity) as fixed effects. The null hypothesis of inferiority would have been rejected if the lower limit of the two-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) for the standardised difference was wholly below 0.4 (the range of clinical non-inferiority). The standardised difference was calculated using Hedges’ correction factor and the CI was calculated using the true standard error. 71 The standardised non-inferiority limit of 0.4 was back-transformed to the raw scale using pooled SD from baseline data for analyses presented on the raw scale.

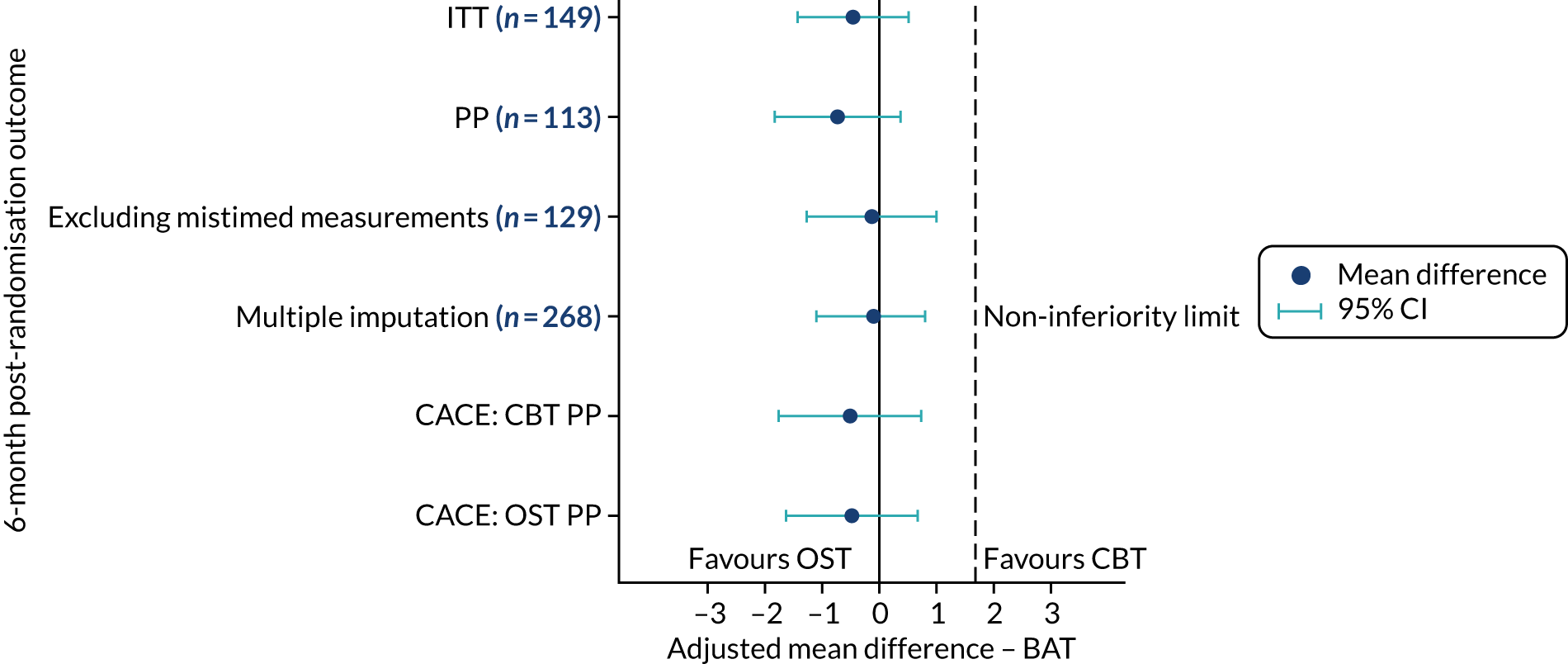

Sensitivity analysis

The following pre-planned sensitivity analyses were undertaken on the primary outcome and displayed alongside the ITT and PP analyses.

To truly implement ITT analysis, multiple imputation was used to include all patients who were consented and randomised, including those with missing BAT outcome data. Participants’ baseline characteristics were summarised and compared between participants with and participants without 6-month primary outcome data. Multiple imputation imputed missing outcome data using chained equations (regression) with 100 imputations using baseline BAT score, age, ethnicity, treatment preference, ADIS CSR, sex and site, and 6-month CAIS, RCADS total anxiety and EQ-5D-Y as covariates in the imputation equation, and excluding treatment group. The model described in the primary outcome analysis was applied to the multiply imputed data.

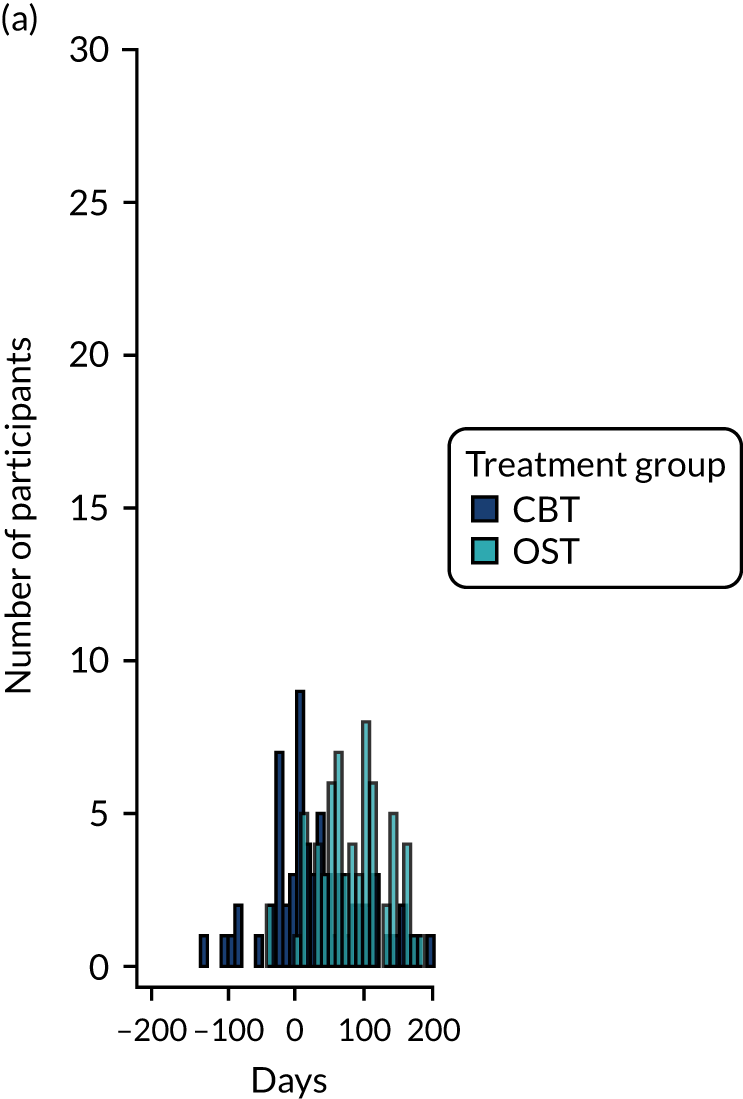

A sensitivity analysis on the primary outcome was conducted (excluding participants with data collected more than 4 weeks pre and 6 weeks post the 6-month follow-up date).

Further analysis of outcomes in relation to OST and CBT compliance consisted of complier-average causal effect (CACE) analysis72 using a two-stage least squares regression (excluding clustering adjustment) but including site and baseline covariates (age, phobia severity, EQ-5D-Y and BAT). The endogenous variable (treatment receipt) was regressed on the instrumental variable (random treatment allocation) and baseline covariates, generating a prediction of the endogenous variable. The primary analysis model was then fitted after replacing treatment with this prediction. CACE analysis was conducted for both CBT and OST. Compliance was defined using the PP definition for each group (see Analysis populations). Exploratory descriptive analysis compared compliers and non-compliers with respect to baseline data.

Secondary outcomes analysis

Secondary continuous outcomes were analysed using a mixed-effects regression model as for the primary outcome, including the baseline measurement of the respective outcome as a covariate. Secondary binary outcomes were analysed using a mixed-effects logistic regression model adjusted for age, site, phobia severity and therapist as the random effect.

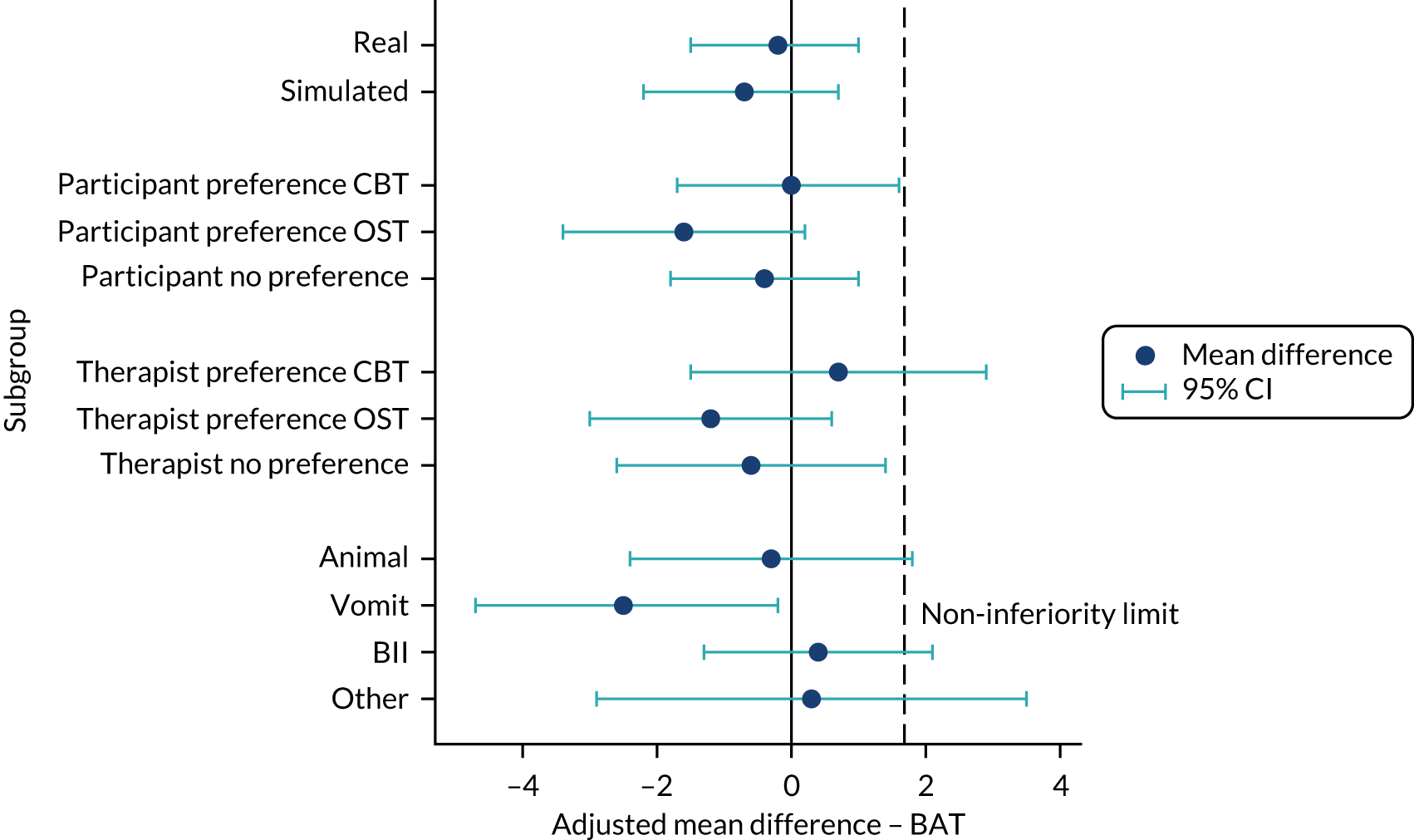

Subgroup analyses

Pre-planned subgroup analyses were undertaken and regarded as exploratory. The following subgroups were investigated:

-

BAT stimulus set-up (simulated vs. real stimuli)

-

participant treatment preference (OST vs. CBT vs. no preference)

-

therapist treatment preference (OST vs. CBT vs. no preference)

-

phobia type [animal vs. vomit vs. blood injection injury (BII) vs. other].

The subgroup analysis used mixed-effects linear regression with BAT scores at 6 months as the response. The model included the main effects of treatment and subgroup and an interaction term between subgroup and was adjusted for covariates as in the primary analysis model. The evidence for treatment effect varying between subgroup was investigated using a statistical test for interaction between the randomised intervention group and the subgroup.

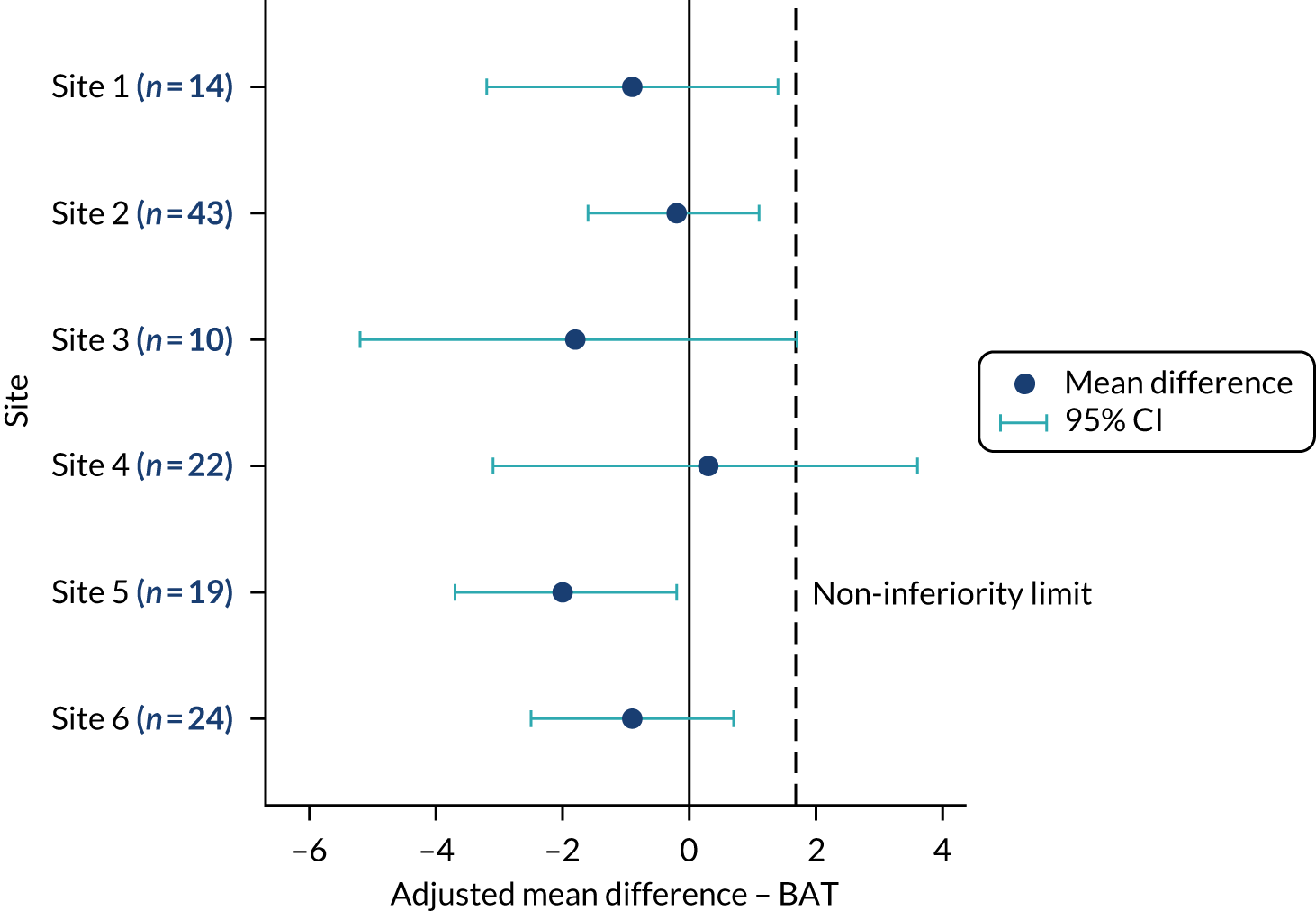

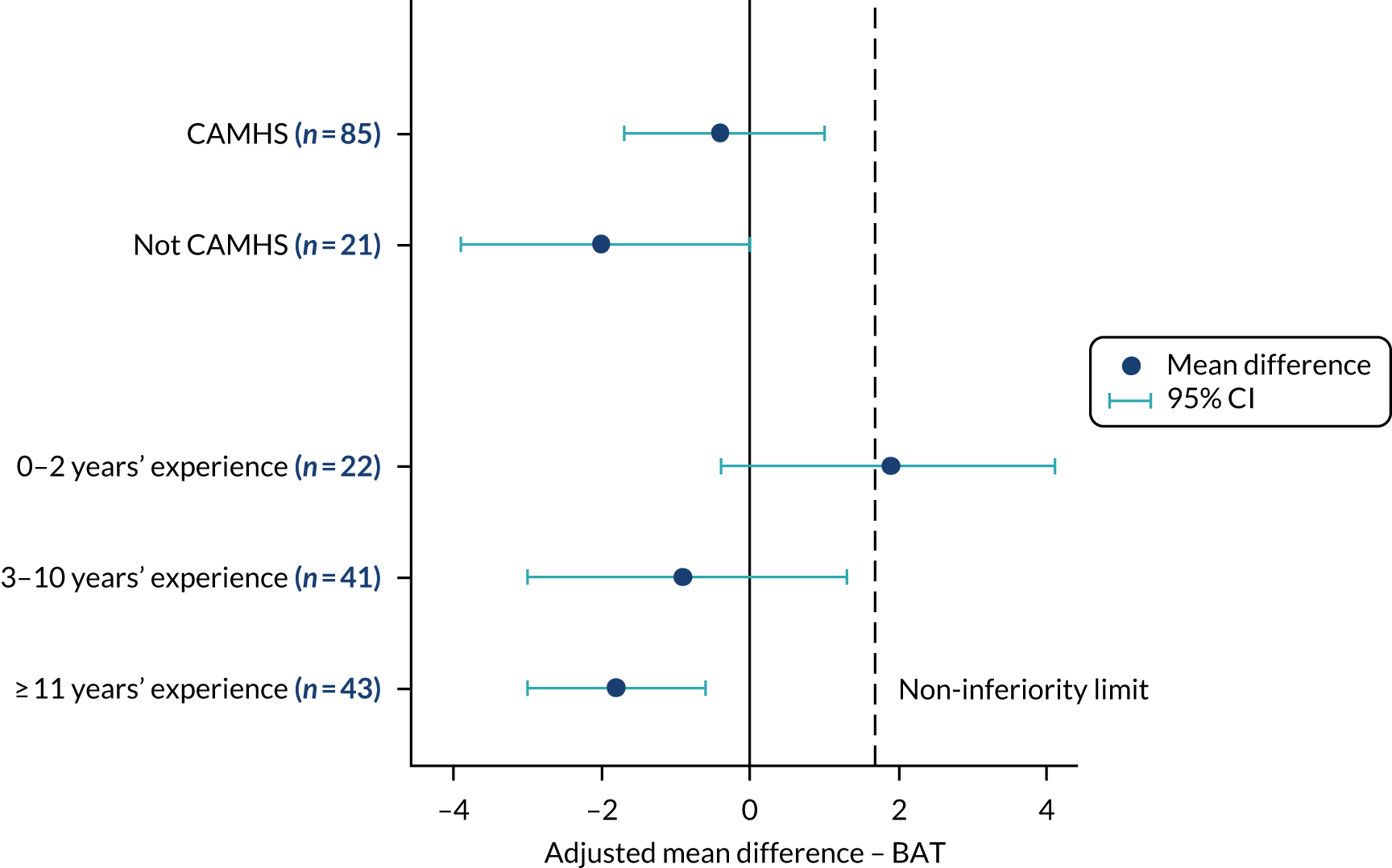

The impact of site and therapist on treatment difference was also investigated using the same methods. Sites were included in a subgroup analysis if at least five participants per group had primary outcome data for that site. The following therapist characteristics were analysed as subgroups:

-

setting (CAMHS vs. not CAMHS)

-

years of experience (0–2 vs. 3–10 vs. ≥ 11 years).

Additional pre-planned sensitivity analyses

To investigate the impact of differing time between the last session of treatment and the 6-month outcomes being collected in the two treatment groups, the following sensitivity analyses were conducted:

-

including a covariate of days between last session (prior to the 6-month outcome) and the 6-month outcome date in the primary analysis model

-

including the above covariate and an interaction term between treatment and the number of days between the last session and the 6-month outcome data being taken.

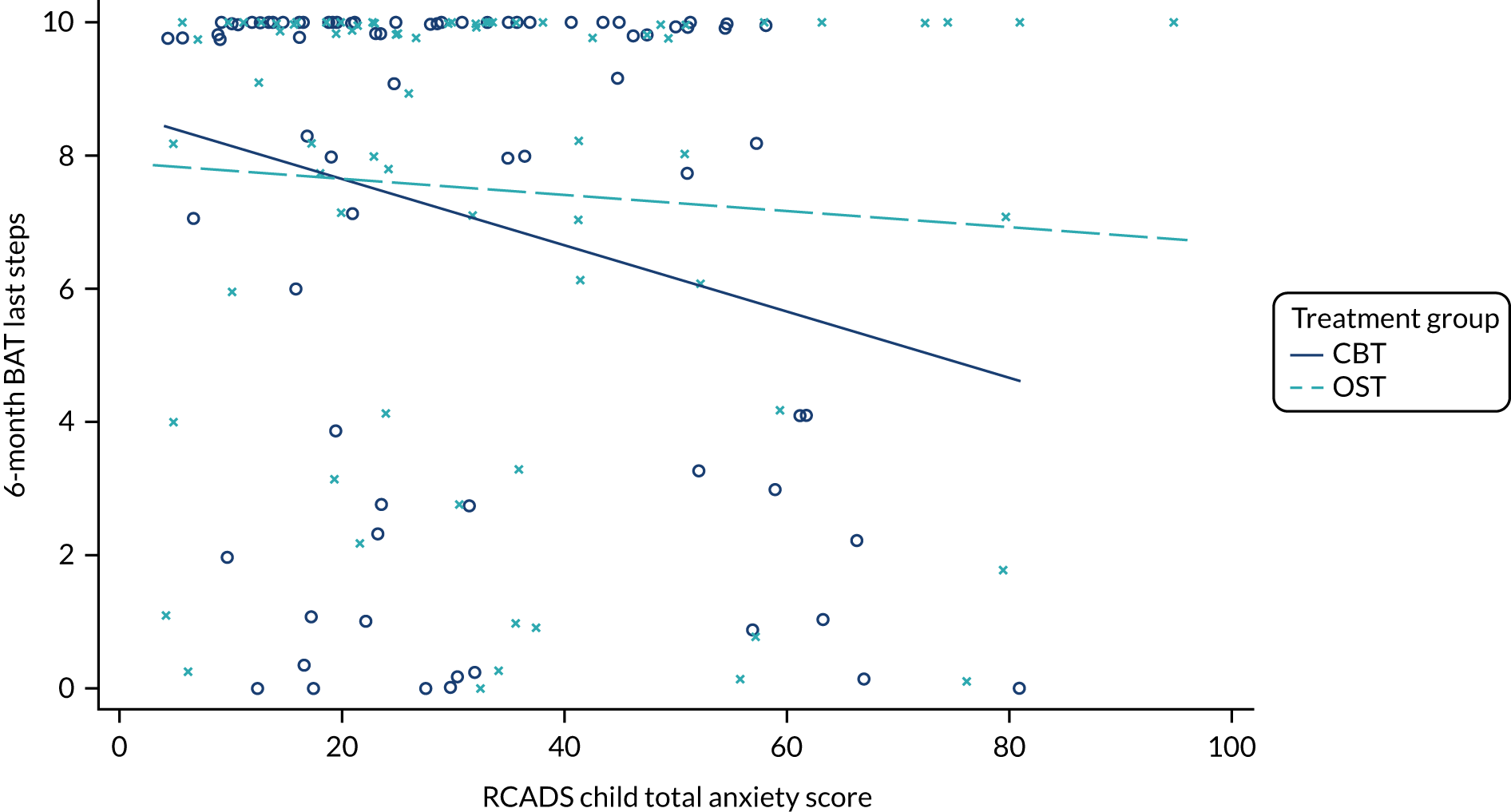

To investigate the moderating effect of baseline anxiety and depression, the primary analysis was repeated with a covariate of baseline RCADS and an interaction term of RCADS and treatment group. This was performed for RCADS child major depression domain and RCADS total anxiety score.

Safety and harms analysis

Adverse events and serious adverse events (SAEs) were summarised and assessed for similarity between treatment groups. Safety data were reported on an ITT basis for randomised participants only.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public representatives were actively involved at all stages of this research. The original research was developed in consultation with the phobia charity ‘Triumph Over Phobia’ with their development manager named as a co-applicant. This co-applicant was also part of the TMG and provided advice throughout study completion.

In the development phase of ASPECT, the York Youth Council (a group of approximately 15 people aged 11–18 years who work to make a positive difference to young people living in York) were consulted. In addition to commenting on the study documentation, detailed feedback was received from the Youth Council regarding the methodology and the potential impact of the study in the community. This feedback was incorporated to ensure that the study methods and documentation were suitable for the target population

One member of the independent TSC was an individual with lived experience of phobia and provided advice regarding study oversight throughout trial implementation.

A patient and public involvement (PPI) group meeting was held after completion of the qualitative analysis. It was attended by an individual with lived experience of phobia, a therapist who had delivered OST for ASPECT and TB, with the aim of providing a sensibility check for the qualitative findings. The group were consulted on whether or not they felt that the main points and quotations selected were reasonable, and their recommendations were considered.

Health economic methods

Background

To investigate the cost-effectiveness of OST compared with CBT in CYP with specific phobias, an economic evaluation taking the form of a within-trial cost–utility analysis from the UK NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) perspective was conducted.

Effectiveness

Effectiveness for the health economic analysis was measured using the EQ-5D-Y (see Secondary outcome measures) and the CHU-9D (see Secondary outcome measures) instruments. The measured utilities at baseline and follow-up were further joined through time, and the area under the curve approach was used to calculate QALYs for further cost–utility analyses. 73

Resource use and costs

All the resource use incurred during the 6-month follow-up was considered, including both intervention and all-cause service use required by CYP with specific phobias.

The resources required to train the professionals and to deliver the interventions were measured by the time spent by professionals as well as other resources used (including second therapist and phobic stimulus acquisition, e.g. animal hire). The relevant training and intervention delivery information was collected using the tailored questionnaire (see Secondary outcome measures) completed by the study team and therapists, respectively.

Children and young people’s service use included parent-reported use of primary and secondary health care, as well as social care. Other additional therapies and services received in either group during the trial period were recorded. Data on productivity loss due to absenteeism from work to care for the CYP were also collected. All resource use data were collected using tailored resource utilisation questionnaires (see Secondary outcome measures) completed by parents/guardians.

All the service use data were further multiplied by corresponding unit cost to arrive at a total cost in each arm using the bottom-up costing approach. Unit costs of health and social service use were obtained from the UK national database of National Cost Collection (previously called Reference Costs)74 and the Unit Costs of Health and Social Care report produced by the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU). 75 Unit costs of medication were based on the most recent version of the Prescription Cost Analysis – England. 76 Parental productivity costs were valued according to national average wage rates.

Economic analysis

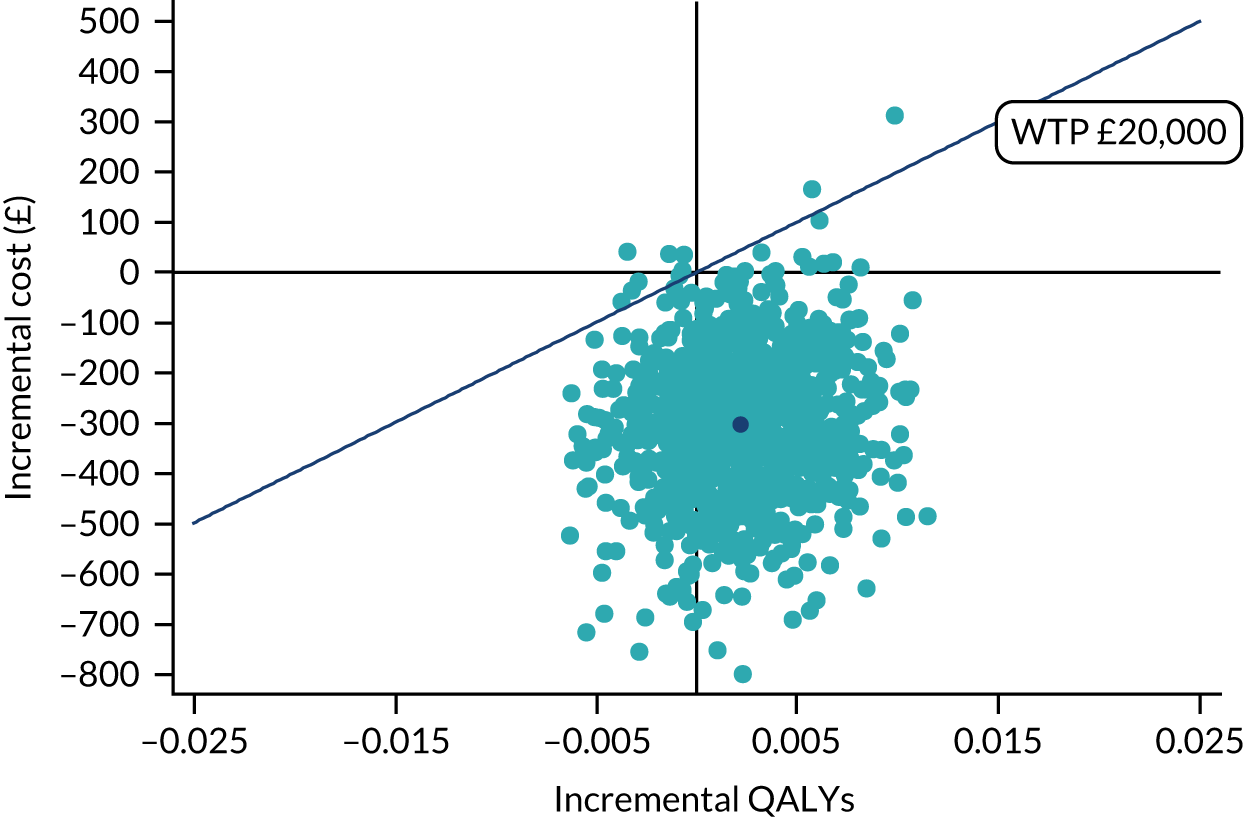

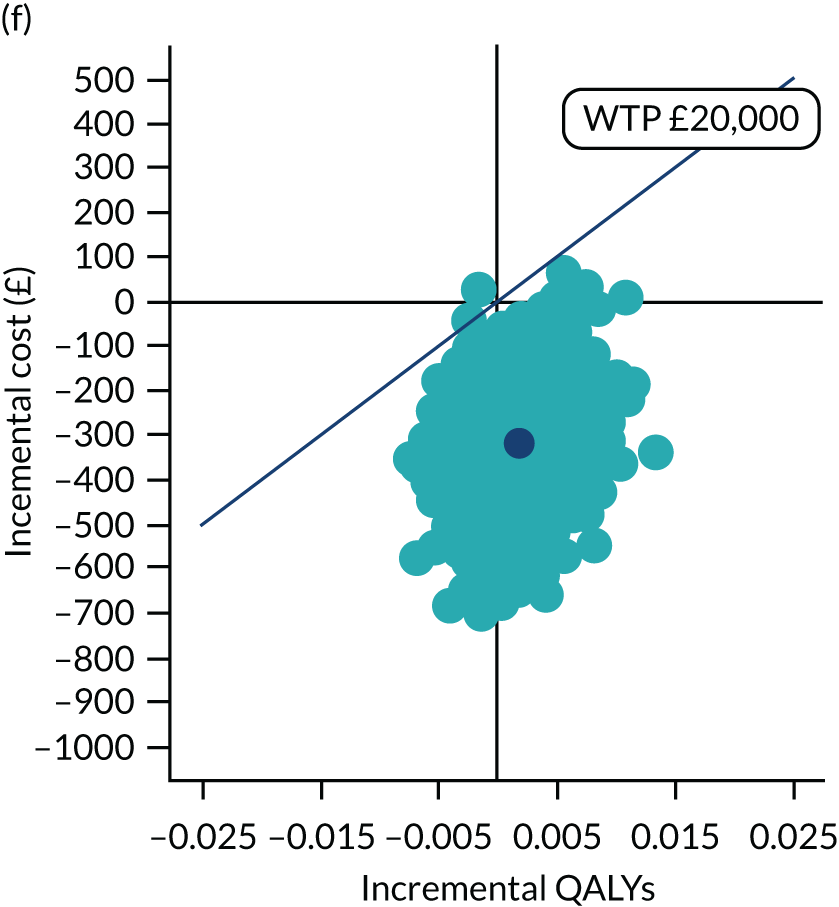

The within-trial cost–utility analysis from a UK NHS and PSS perspective was conducted in line with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)77 recommendations to compare costs and QALYs of OST and CBT interventions for CYP with specific phobias. Costs were measured using tailored service use questionnaires, and health outcomes (QALYs) were measured using the EQ-5D-Y. Discounting was not applied because of the short-term nature of the trial.

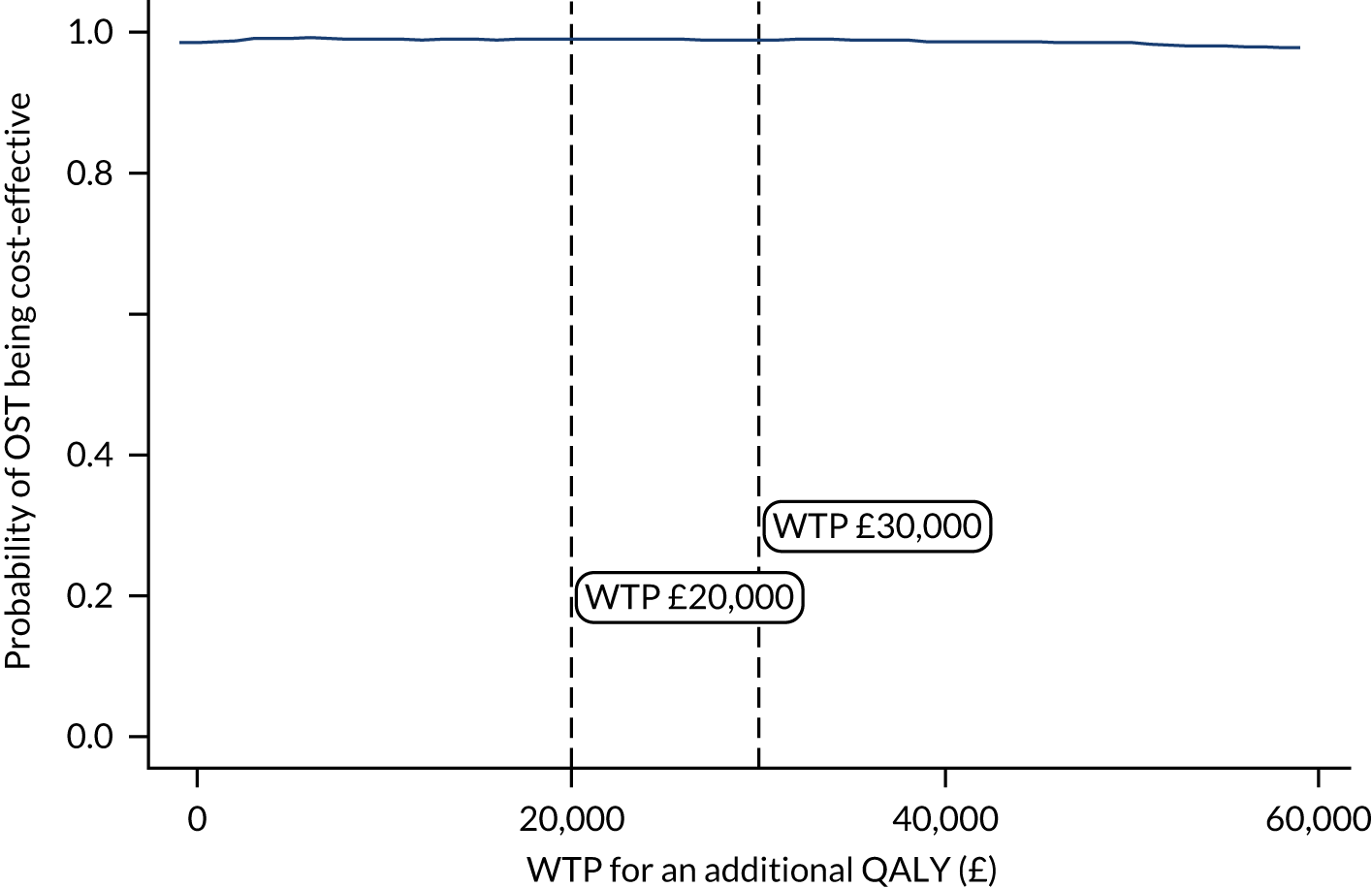

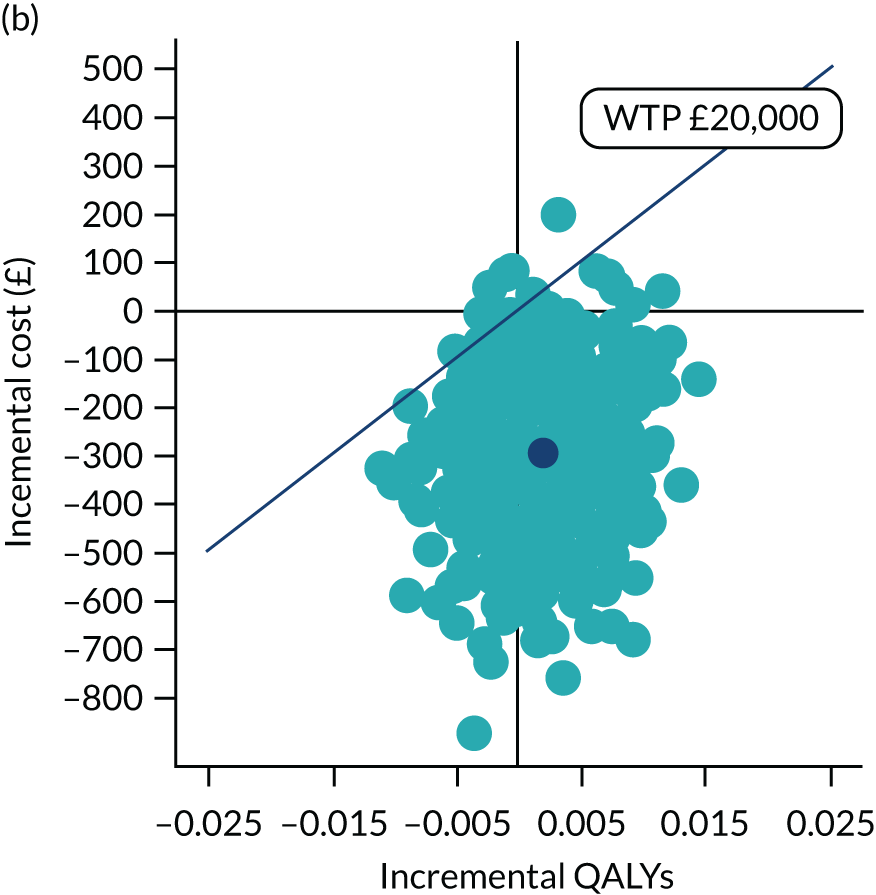

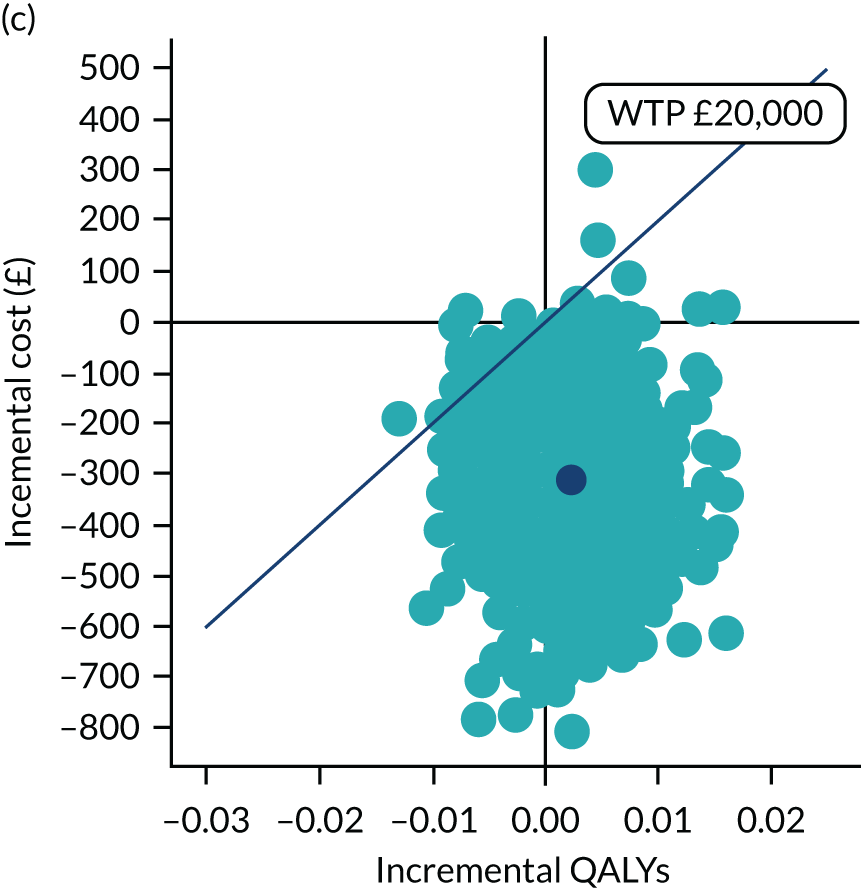

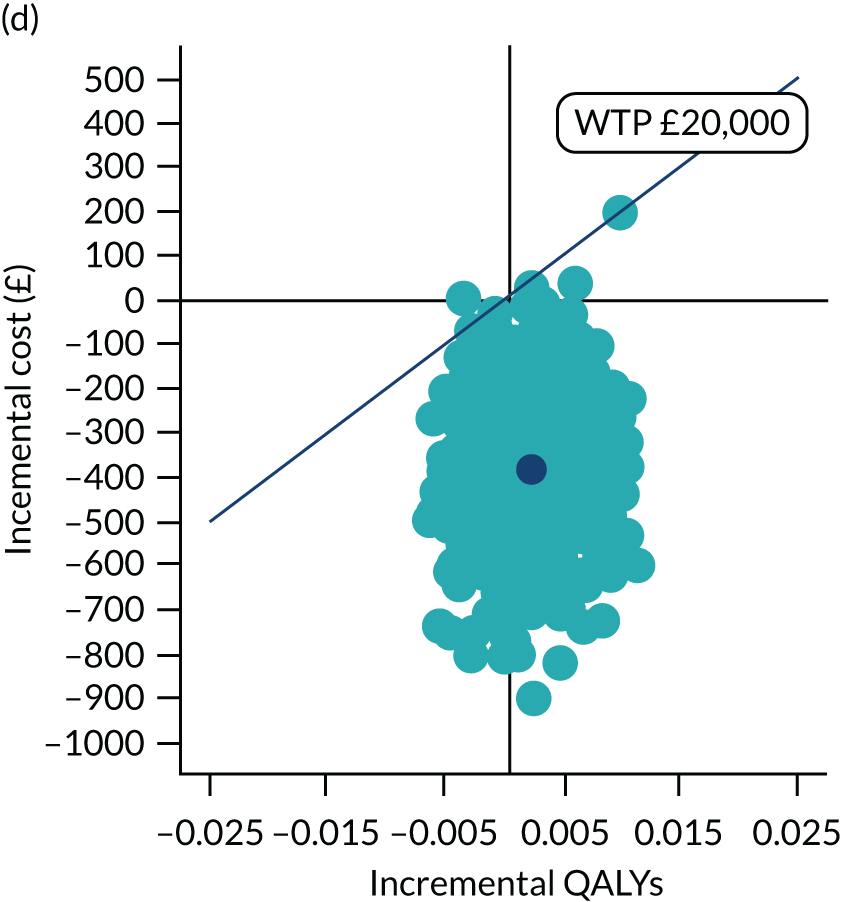

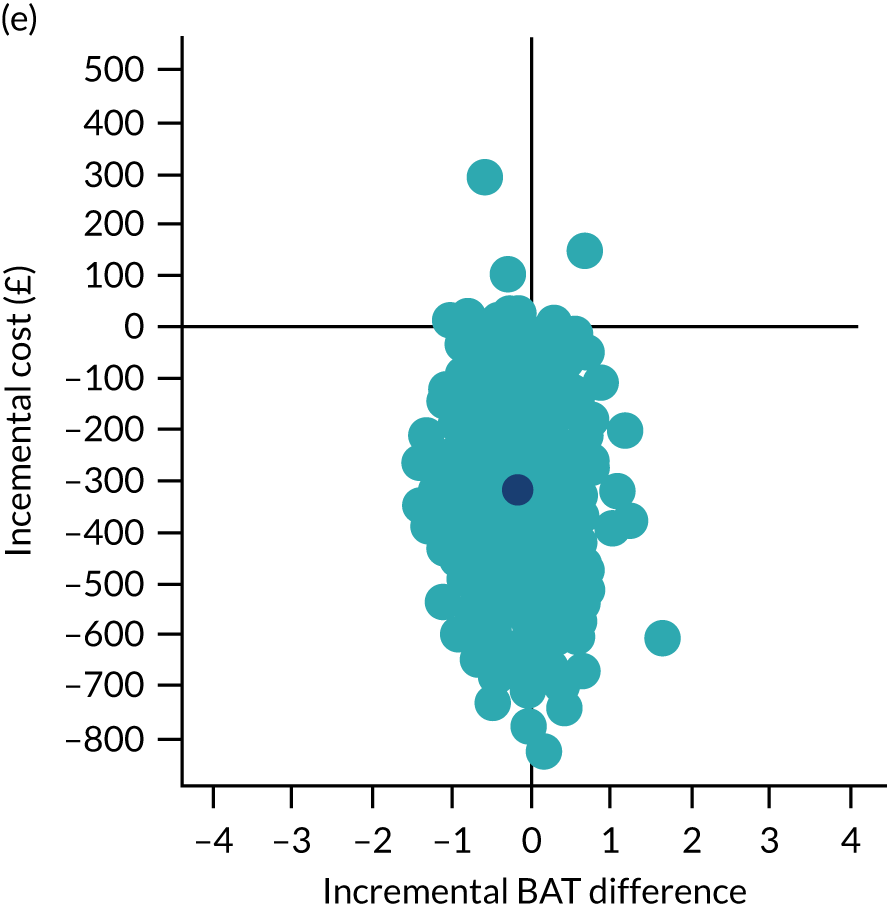

The primary analysis was based on a UK NHS and PSS perspective to calculate the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), which was then compared with the national willingness-to-pay threshold of £20,000–30,000 per QALY gained to assess the cost-effectiveness of the OST intervention following the NICE recommendations. 77 A set of sensitivity analyses were conducted to account for the uncertainty.

Descriptive analysis

Total costs, including intervention and service utilisation costs, and QALYs were compared between the OST and the CBT groups using appropriate descriptive analyses

Handling missing data

Missing data existed in both service use and health outcome data. For service use, data were deemed as missing when all questions under a particular section were left blank. If one of these questions was answered, the others were assumed to be zero. For EQ-5D-Y, the whole section was considered missing if any of the five questions were not answered. The identified missing data were further imputed using Rubin’s multiple imputation method. 78

Regression analysis and bootstrapping

Regression models were used to compare mean costs and QALYs based on an ITT approach. The regression analyses were controlled for baseline differences in utility,79 cost, age, sex, site, phobia type and ADIS highest CSR score at baseline. The model specifications followed the approach recommended by Glick et al. ,80 which considers the distribution of the dependent variable as well as any correlation between the cost and the QALY outcomes. The ICER was then calculated based on the regression coefficients on intervention, as they represented the difference in mean cost and mean QALYs between the two groups. To take uncertainty into consideration, a non-parametric bootstrap resampling method on the basis of 5000 iterations was used to produce CIs for the ICERs. This was done because of the likely skewness in the distribution of regression residuals,81 and the number of 5000 iterations was chosen because it was considered to be sufficient to generate robust estimates of standard errors82 and is widely used in trial-based cost-effectiveness analyses for mental illness. 83–85

The bootstrapped results were presented in the conventional form of a cost-effectiveness plane and a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC). The uncertainty based on the outcomes of the 5000 bootstrap iterations was represented graphically on the cost-effectiveness plane. The CEAC presented the probability of the intervention being cost-effective over a range of willingness-to-pay thresholds per QALY. 86

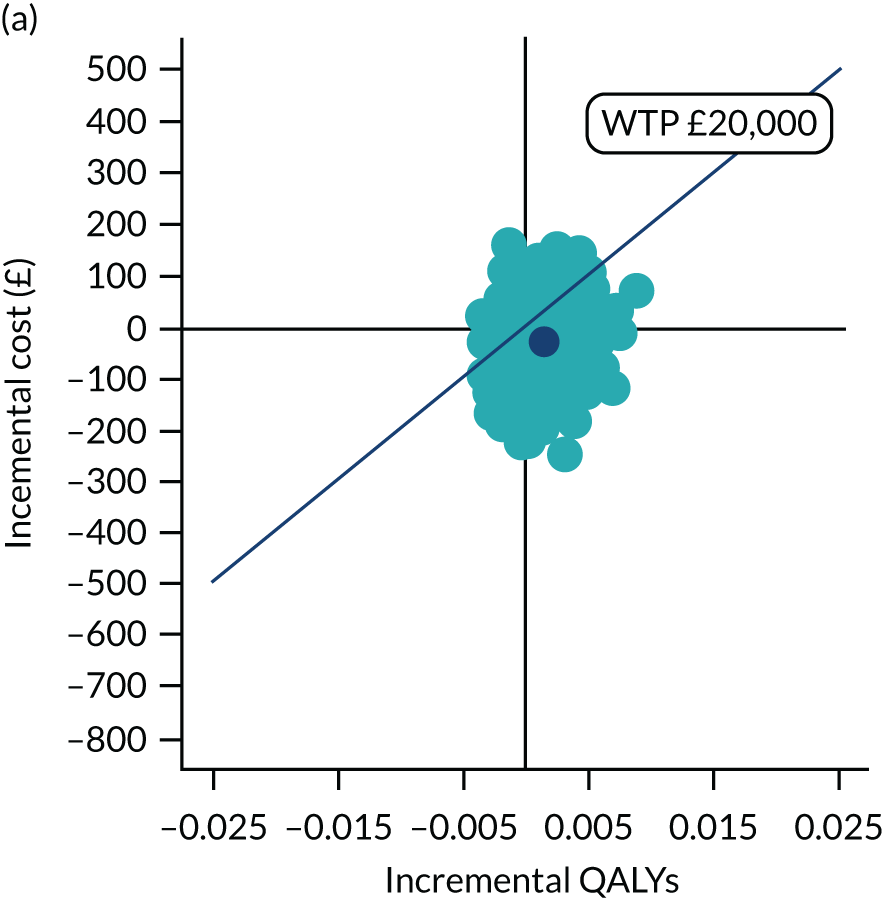

Sensitivity analysis

The following sensitivity analyses were conducted to test assumptions made in the primary analysis:

-

the impact of missing data, considered using the data from the complete case

-

the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, considered using the data from those who received at least one intervention within the follow-up period

-

the impact of using CHU-9D instead of EQ-5D-Y to measure QALYs

-

the impact of taking a societal perspective, considered including parental productivity costs to account for the economic impact outside the NHS/PSS perspective

-

the impact of outcome measurement, considered using the phobia-specific measure of BAT score instead of a utility-based measure

-

the impact of OST training costs, considered excluding the one-off OST training costs to account for the economic impact once the OST is rolled out.

Qualitative methods

Introduction

Alongside examining the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of OST relative to quantitative outcomes, it was also important to examine its feasibility and acceptability from the perspectives of multiple stakeholders. Through obtaining a greater understanding from those receiving the treatment, their parents/guardians and those delivering OST, it was hoped that additional information to aid the interpretation of quantitative trial results would be gained. Furthermore, this information could be used to facilitate intervention refinement and, should OST show non-inferiority to CBT, optimise its implementation into service and clinical practice.

Aims and objectives

The ASPECT process evaluation aimed to establish the acceptability of OST to the CYP participating in the trial, their parents/guardians and the therapists administering OST.

Methods

Recruitment and sampling

Interviews were conducted with three participant groups: (1) CYP who had received OST, (2) parents/guardians of CYP receiving OST and (3) therapists delivering OST. Maximum variation sampling ensured a spread of participant characteristics, including age, sex, geographical location and phobia type. The final sample size was determined by data saturation (i.e. the point where no new themes, ideas and/or concepts emerge from the interviews). Based on previous nested qualitative research examining patient acceptability with brief psychological interventions,87 it was estimated that a maximum of 25–30 parent, 25–30 CYP and 15 therapist interviews would be required.

Children and young people who had received OST, their parents/guardians and therapists who had delivered OST during the trial were eligible to attend an interview if they provided consent to do so. Eligible participants were invited to take part via telephone or e-mail.

Interviewers

Interviews were conducted by research assistants working on ASPECT (JL, HE, AB, EH, JH and AS). Participants may have been familiar with interviewers from meeting during data collection visits, but did not know the interviewers personally. Five interviewers were female and one was male. All had Bachelor of Science (BSc) qualifications. All interviewers had previous experience of working with CYP, parents/guardians and clinicians, and were trained prior to the interviews being conducted. Interviewers did not have any access to emerging trial findings.

Interview timings and settings

All interviews with CYP and their parents/guardians were conducted after participants had completed the final outcome measures at the 6-month follow-up point. Interviews with therapists took place as soon as their involvement in the trial was complete. Parent interviews and interviews with older children (≥ 13 years) were conducted face to face or by telephone, depending on participant preference. Interviews with younger children (≤ 12 years) were all conducted face to face. Face-to-face interviews were conducted at mutually convenient locations, generally in participant’s homes or treatment settings. Interviews with CYP and parents/guardians were completed separately. There were some occasions where the parents/guardians were present during CYP’s interviews, but in these instances parents were instructed not to speak during the interview.

Therapist interviews were due to take place in clinic settings or by telephone. However, at the point when these interviews could convene, government restrictions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic were in place and therefore all therapist interviews were conducted by telephone.

Obtaining informed consent

Initially, at the baseline assessment, CYP and their parent/guardian were asked to provide informed consent to be approached for interview as part of the qualitative phase. Where consent to be approached had been given and the CYP had received OST, they and their parent/guardian were asked again if they would like to participate in a qualitative interview at the end of their 6-month follow-up visit. The parent/guardian and the CYP were given information outlining the qualitative research and had the opportunity to discuss this in more detail with the research assistant, who explained the study procedures and answered any questions. Informed consent was taken in person and in writing using age-specific consent forms. Parents/guardians were asked to provide separate consent for both themselves and the CYP to be interviewed. CYP were asked to provide assent to participate with parental consent required alongside.

For therapist interviews, consent was sought using an ethically approved form available in paper and electronic formats.

Interview content and structure

All interviews were semistructured and based on topic guides developed by the research team (see Appendix 2). These guides were endorsed by York Youth Council, whose members checked them and provided useful feedback on how they could be improved. Interviews with parents/guardians focused on phobia experiences, personal and family impact, perceived treatment need, treatment expectations, and treatment engagement and acceptability (e.g. content, delivery mode, format, setting and facilitation). Interviews with CYP focused on the same topics, adapted for age and developmental maturity. Face-to-face interviews with younger participants drew on the principles of ‘draw and write’ techniques, whereby they were offered an opportunity to draw a picture relating to their experiences as a prompt to initiate more in-depth discussion. 88,89 CYP interviews lasted up to 30 minutes and parent/guardian interviews lasted up to 60 minutes.

Therapist interviews lasted up to 60 minutes and focused on their experiences and views of delivering OST, barriers to and enablers of its implementation and roll-out, the individual, team and organisational-level supports required and the perceived suitability of OST for the identified client group.

All interviews were conducted by study research assistants who received training on the methodologies used in the interviews.

Data analysis

All interviews were digitally recorded using an encrypted digital recorder and transcribed verbatim with participant consent. No notes were taken during the interviews. Analysis followed a qualitative framework approach,90 a widely used method of analysing primary qualitative data pertaining to health-care practices with policy relevance. 91 Framework analysis permits both deductive and inductive coding, enabling potentially important themes or concepts that have been identified a priori to be combined with additional themes emerging de novo. A priori themes were determined by the literature and through discussion with the ASPECT team. Data coding was undertaken independently by trained researchers.

Five coders met regularly (fortnightly) to develop a shared coding manual and to ensure that all emerging codes remained grounded in the original data. NVivo version 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) software supported the coding of the transcripts, and an Excel spreadsheet was developed that incorporated preliminary framework themes as column headings and the demographic information related to participants who provided data under each theme. As the constant comparison of new data occurred and the coding team’s understandings of the themes under consideration developed, the framework was amended and reshaped to enable the introduction of new codes and/or the deletion of redundant, similar or otherwise compromised codes. In this way, a final framework was achieved that was considered representative of the entire data set. Data from each stakeholder group (CYP, parents/guardians and therapists) were coded separately. The final coding manuals, with example entries, were presented to the TMG and TSC to confirm validity, coherence and conceptual relevance. Co-applicant PB supervised the qualitative study and analysis.

Owing to ethics limitations, participants were not recontacted to discuss their transcripts, or study findings. Instead, coding trees and interim analyses were reviewed and discussed with a PPI panel.

Ethics considerations

Prior to the qualitative study, several ethical and practical issues were considered, with plans made to address them if required. If a participant became distressed during an interview, the researchers were well briefed about what to do, and had access to a specific protocol to follow [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/153804/#/documentation (accessed 10 January 2022)]. Possible responses included encouraging the participant to take a break from answering questions, reiterating to participants that they did not have to answer anything that they did not want to and offering the participant the opportunity to stop the interview.

During the interviews there was the potential that the researchers could have become upset from listening to potentially distressing experiences. Regular contact between team members ensured the opportunity to seek support where necessary. A team approach to risk management was adopted and any concerns were communicated to the qualitative lead (PB) in the first instance.

Given that interviews could be conducted in participants’ homes, the trial sponsor’s lone worker policy was followed during all interviews to ensure the safety of research staff. Furthermore, any researcher conducting interviews in a participant’s home adhered to a ‘buddy system’, which ensured that their whereabouts were known to other team members who could inform the relevant people/authorities if contact with the researcher was lost.

Chapter 3 Challenges to the implementation and delivery of ASPECT

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Tindall et al. 92 © 2022 Tindall, Scott, Biggs, Hayward, Wilson, Cooper, Hargate, Wright and Gega. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

This section of the report provides a narrative summary of the challenges faced in implementing and delivering ASPECT. We describe the key challenges the study team faced (along with our approach to mitigation), including problems with (1) site set-up, (2) participant identification and recruitment, (3) data collection, (4) intervention training and delivery, and (5) COVID-19.

Setting up recruiting sites

Commissioning and service delivery restructuring

Recruitment to ASPECT coincided with the reorganisation of CAMHS by NHS clinical commissioning groups in response to the government papers Future in Mind93 and the Child Mental Health Green Paper. 94 In parallel, there were also large reductions in local authority and NHS child mental health service funding, which occurred against a backdrop of large increases in child mental health referral rates across England. Consequently, many CAMHS underwent significant restructuring alongside a reduction in staff. Moreover, in some cases CAMHS that the trial team had set up to recruit and deliver treatment disbanded completely, or merged with other NHS trusts, further complicating trial implementation.

This restructuring lead to widespread service reprioritisation of the types of mental health difficulties experienced by CYP so that already limited) resources could be available to CYP who needed it the most. This often meant that specific phobias were deemed lower priority, with many CAMHS ceasing to provide usual phobia support (i.e. CBT). In some areas specific phobia cases were passed to school-based services that were still under development within the care pathway, and unable to offer multisession CBT as required by the ASPECT protocol. Furthermore, in some CAMHS where treatments for specific phobias were still delivered, mental health problem severity thresholds for service acceptance were often set at high levels, with many accepting CYP with a specific phobia only if they had a mental health comorbidity severe enough to reach this threshold. These commissioning and service delivery changes led to challenges, both in terms of trial set up and intervention delivery; for example, given that specific phobias were given lower priority, and often referred to other school-based services, gaps in service provision emerged and there were far fewer participants with phobias available to be recruited than was initially planned.

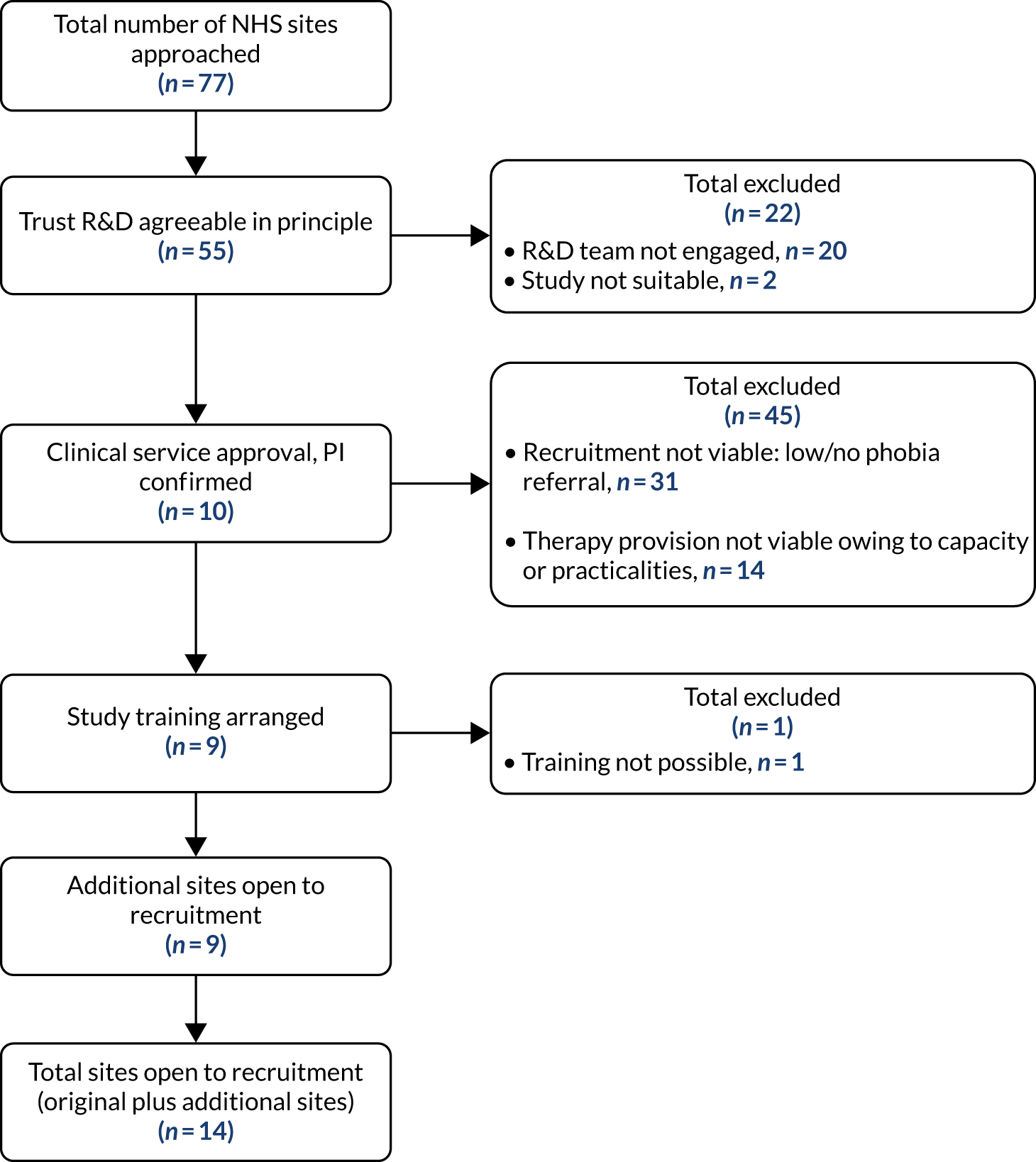

Solutions: adding new recruiting sites

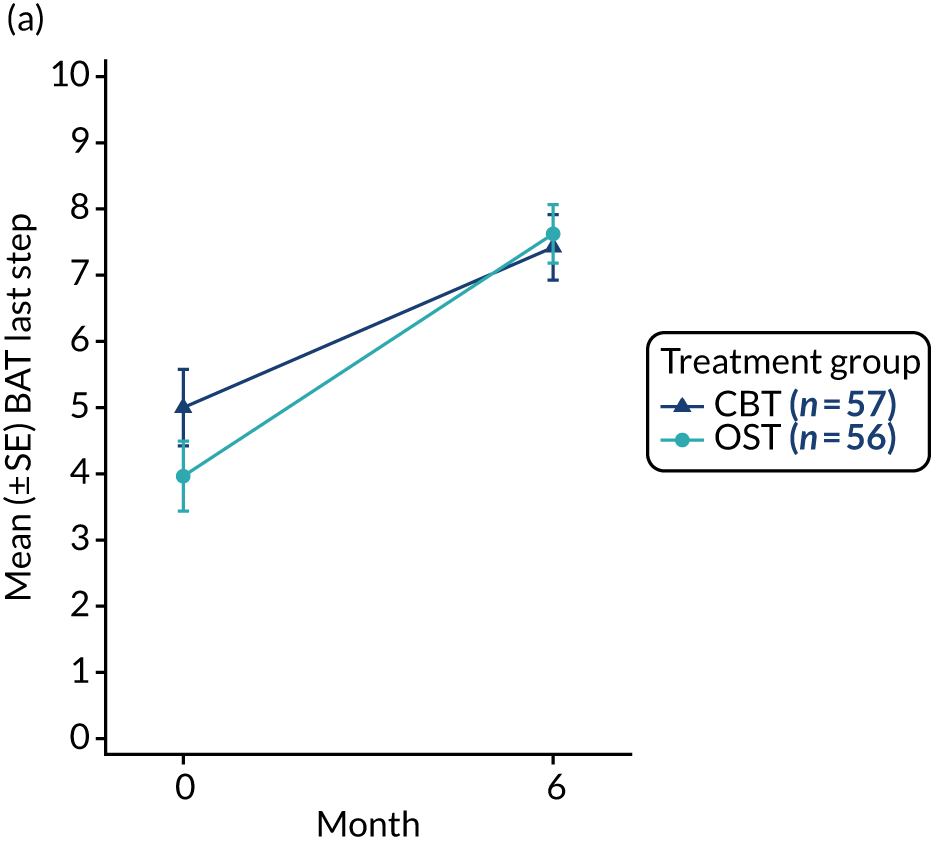

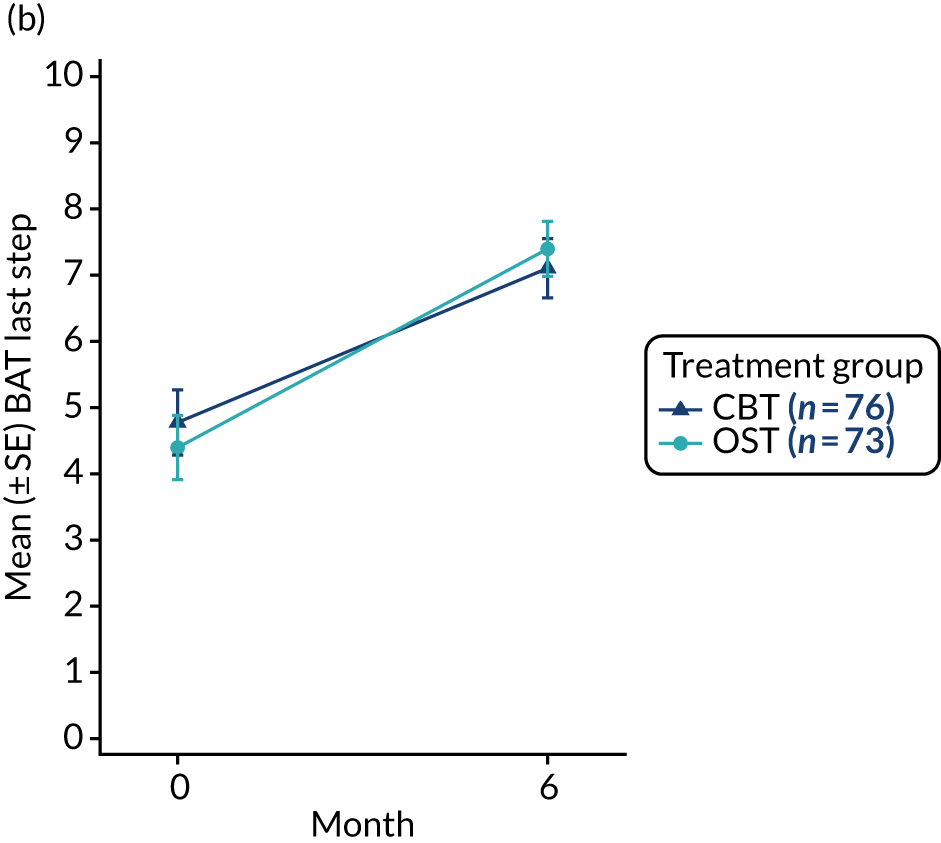

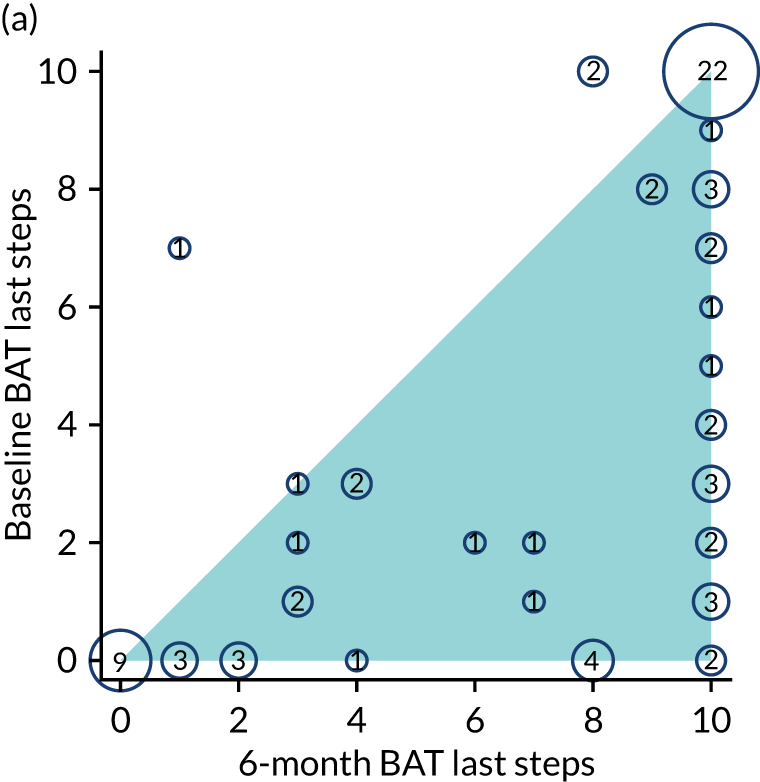

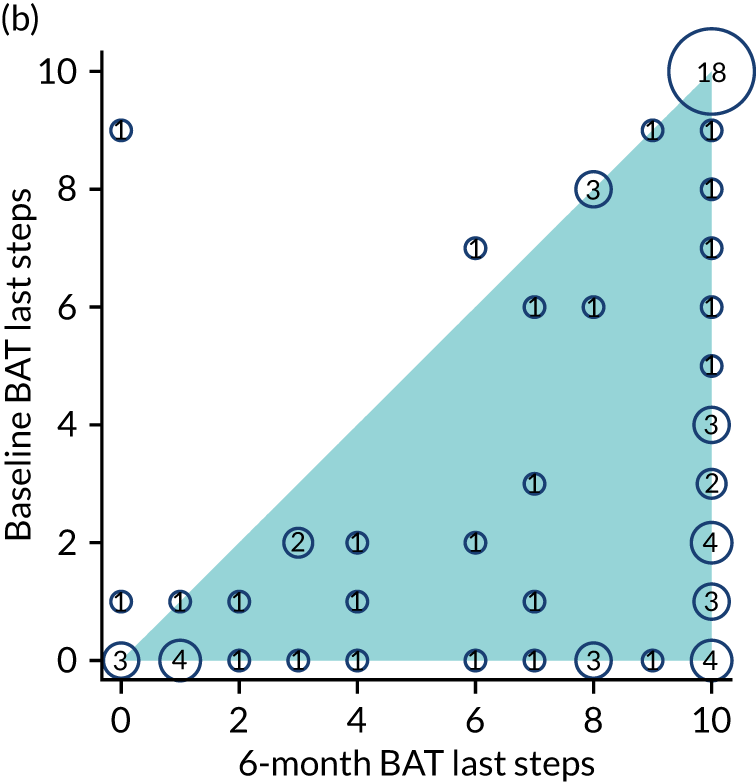

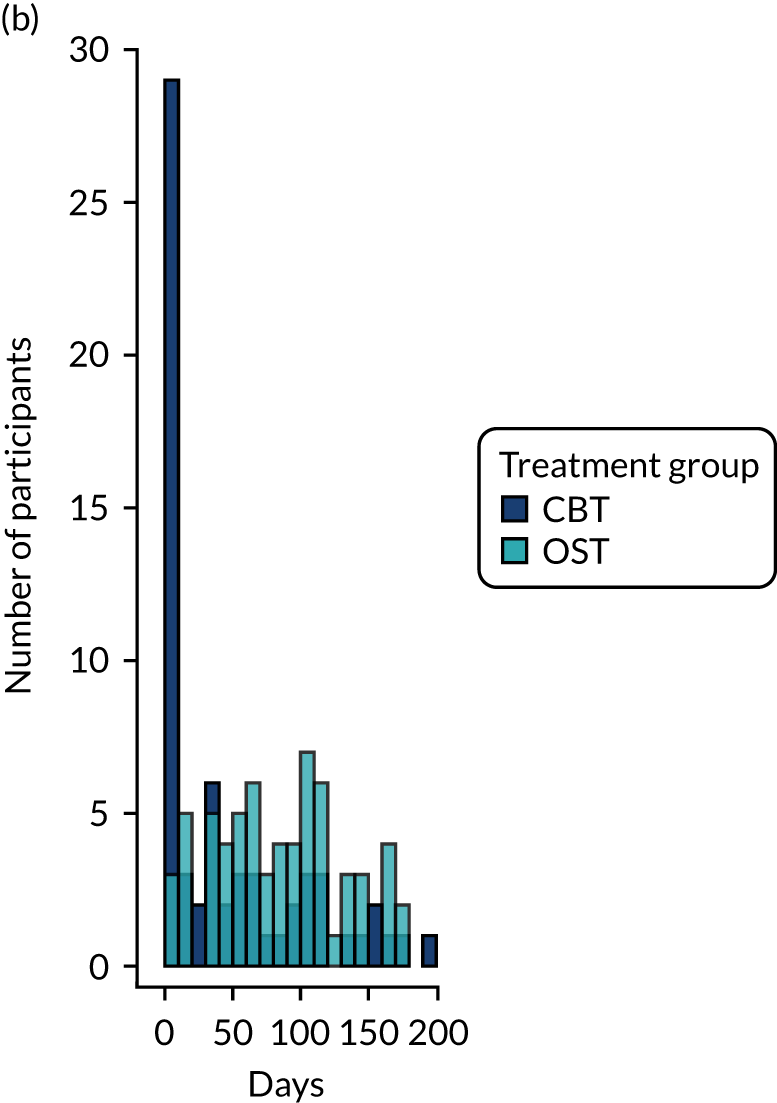

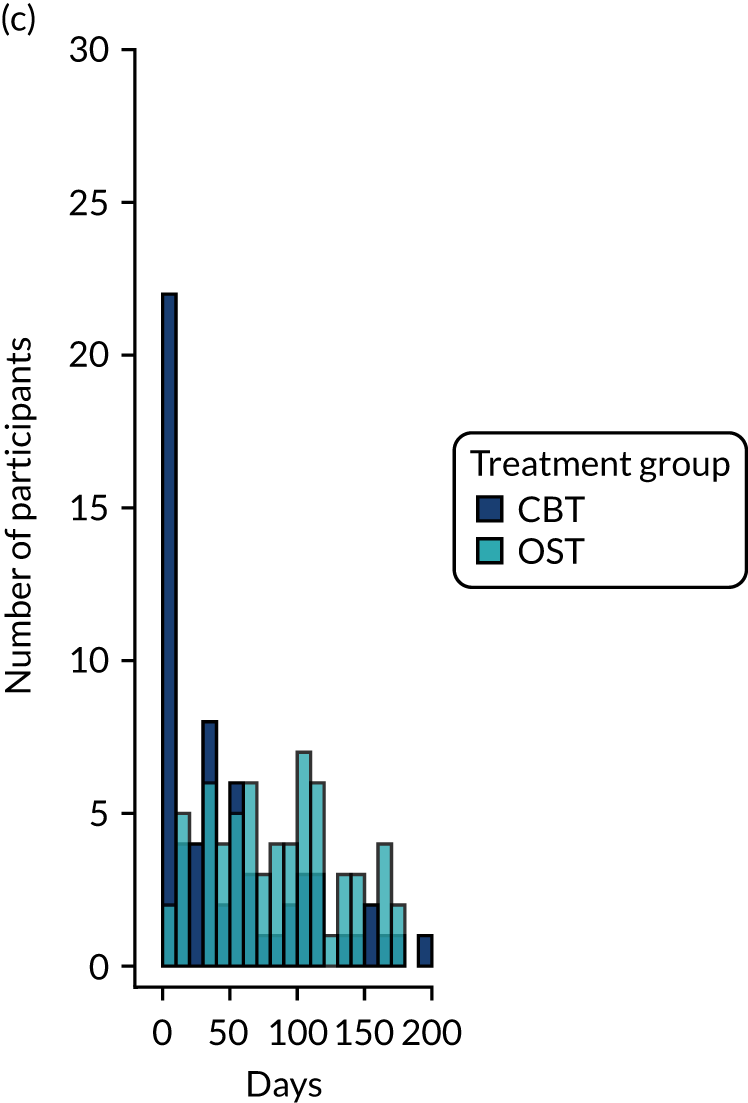

The ASPECT team implemented a number of strategies to mitigate the impact of commissioning and service delivery changes on recruitment and intervention delivery. The most impactful strategy was to substantially increase the number of recruiting sites from the five that had been originally planned to 12 NHS trusts. Over the course of the trial, study recruitment was conducted in 14 geographical regions across England encompassing 12 NHS trusts comprising 26 CAMHS, three third-sector/voluntary services, one university-based CYP’s well-being service and a research clinic.