Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 16/78/04. The contractual start date was in May 2018. The draft report began editorial review in November 2020 and was accepted for publication in May 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Jones et al. This work was produced by Jones et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Jones et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background context

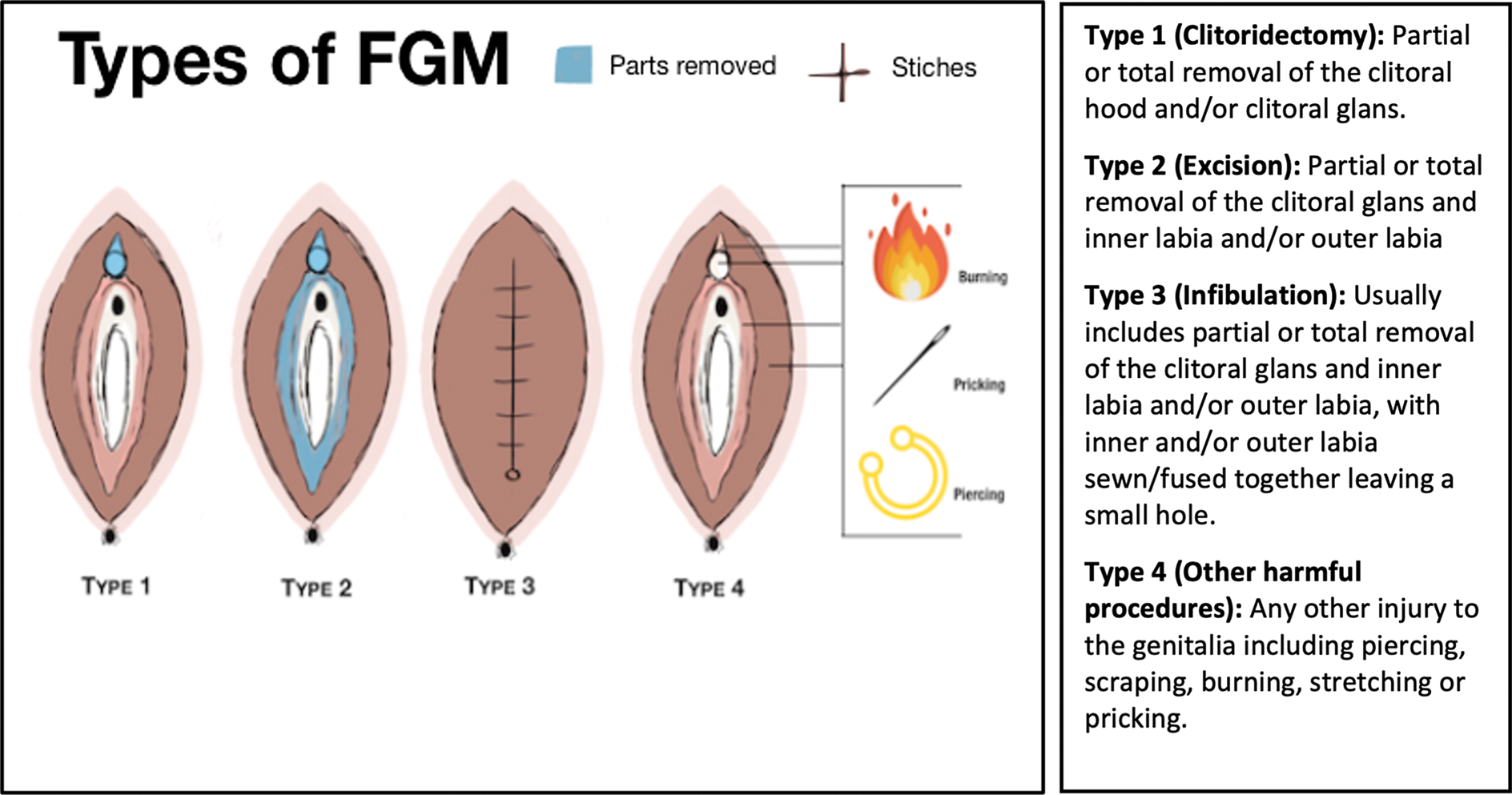

Defining female genital mutilation

Female genital mutilation (FGM) involves the partial or total removal of or any other injury to the female genitalia for non-medical reasons. 1 Since 1997, FGM has been classified into four distinct types (types 1–4; Figure 1), ratified by a joint statement from the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the United Nations Population Fund (formerly the United Nations Fund for Population Activities; UNFPA). 4 The FGM typology has since been strengthened by the inclusion of a further seven subtypes to capture variations of the practice. 4,5 Generally, the extent of tissue removed increases from type 1 to type 3, with type 3 (infibulation) being the most extensive and often requiring surgical intervention (deinfibulation). 6 Nevertheless, there may still be some difficulty with classification of FGM since traditional cutters who perform the practice do so based on the culture of the community rather than conforming to a specific typology. 7

Although the WHO definitions are most widely used when describing FGM typology, further definitions have emerged from a social and political perspective that may reflect the impact of FGM on the survivor and their family. For example, FGM is a violation of the human rights of women and girls,8 a form of child abuse9 and a severe form of violence against women and girls (VAWG). 10,11 The practice is deeply entrenched in gender inequalities and discrimination. 12,13 The term female genital mutilation and the acronym FGM emerged following an ethnographic study14 presented to the WHO in 1979. Although the term was conceived by an outsider of the practice and the report was deemed to be demeaning to communities that believed FGM to be an important part of cultural heritage (see the Glossary for explanations of the terms used and justification of their choice in this report),15 the WHO ratified the use of the term given that it clearly describes the harmfulness of the act, makes it clear that it is a violation of human rights and differentiates it from male circumcision. 1 Although there has been some controversy surrounding the use of the term FGM,16 it is the most widely known term to describe cultural, non-medical alteration of the female genitalia and will therefore be used throughout this report. However, it is important to recognise that FGM is a dynamic practice, with ongoing and context specific changes to the practice globally. 17 FGM has been, and continues to be, a divisive issue between activists and academics, reflecting a wide range of discourses around and worldviews on the practice. 17

Global prevalence of FGM

The origins of FGM remain obscure; however, it is likely that FGM has been performed for millennia, and there is some evidence that it has been practised in Egypt since as early as the fifth century BC. 18 In 2020, UNICEF published a report highlighting that FGM is now practised across 31 (predominantly African) countries;19 however, Cappa et al. 20 have found evidence of the practice in as many as 50 countries, including Eastern Europe, Latin America, South-East Asia and the Middle East. Although it can be problematic to accurately estimate the prevalence of FGM because of the lack of representative data, an estimated 200 million women and girls have experienced FGM, which equates to approximately 5% of the global female population. 21 Approximately 1 in 10 of these women and girls will have experienced type 3 FGM. 12 An estimated 3 million women and girls are at risk of FGM each year, with most being cut aged < 15 years. 13 Without sustained and effective measures to eradicate FGM, it is anticipated that, given the projected rise in the global population over the next 15 years, the number of women and girls who experience FGM will also increase. 19,22 The eradication of FGM by 2030 is a Sustainable Development Goal 5 target. 23 To meet this target, UNICEF has posited that, even in the countries where the prevalence of FGM is reducing, progress would need to be at least 10 times higher than the current rate. 19 In some countries where the practice was historically almost universal (e.g. Egypt and The Sudan), there is some evidence of a reduction in prevalence; however, in other countries (e.g. Somalia and Guinea) there has been little, if any, change in the prevalence of FGM over the last 30 years. 19

UK prevalence of FGM

In 2015, a report using census data estimated that, on the basis of the country of their birth, 137,000 women and girls with FGM were permanent residents in England and Wales in 2011. 24 A further study, again using 2011 census data, reported that 178,781 women and girls aged > 10 years with FGM were resident in the United Kingdom (UK) at that time. 25 Although it remains challenging to accurately estimate the prevalence of FGM in the diaspora living in the UK,26,27 MacFarlane and Dorkenoo’s24 research highlighted that women and girls with FGM lived in every local authority in England and Wales.

To better inform FGM prevalence estimates and to support service-planning and provision in England,28 NHS Digital has attempted to collect FGM-related data from English NHS acute trusts, mental health trusts and general practices using the Female Genital Mutilation Enhanced Data set (FGMED) since 2015. 29 Between 2015 and 2019, 40,030 health-care attendances related to FGM and 20,470 previously unidentified cases of FGM in England were recorded via the FGMED. 26 A report published in early 2020 showed that between April 2019 and March 2020 there were a total of 11,895 attendances where FGM was identified: 6590 of these attendances were recorded as individual attendances. 30 A total of 88% (n = 5815) of these survivors were of child-bearing age (aged 18–40 years), with only 0.5% (n = 35) of survivors being aged < 18 years. 30 FGM type was known/recorded in 60% (n = 3965) of individual women and girls. Of the women and girls that had a known FGM type, 21% (n = 825) were reported as having type 3; 2% (n = 90) had a history of type 3 (that is, they had type 3 but have since been deinfibulated); and 1.5% (n = 60) were type 3 where reinfibulation had been identified. 30

However, Karlsen et al. 26,27 argue that these data should be interpreted with caution given, for example, that only a minority of general practices (≈ 2%) and not all NHS trusts (≈ 62%) have submitted data to the FGMED since it was initiated. Moreover, these data are reliant on FGM survivors accessing health and social care services, and they do not take into account FGM survivors who have not accessed health care. In addition, census data do not account for FGM survivors who have entered the UK as asylum seekers or those who have entered the UK illegally. Hence, FGM prevalence estimates in the UK may be significantly higher than the current statistics suggest.

Reasons why FGM is practised

To provide some context to the views around FGM, it is useful to explore the rationale for the practice. Since the mid-twentieth century, a number of reasons have been reported in the literature, and these vary between affected communities and cultures. 1,13 Six core themes or reasons for FGM have been identified: sociological, tradition and cultural; socioeconomic; psychosocial; hygiene, aesthetic and femininity; marriageability; and religious reasons. 1,12 Burrage31 reports that religion, culture and tradition are the most commonly cited reasons for the practice. In Western society, some have argued that there is no religious connotation or mandate for practising FGM,32 but evidence suggests that there is a strong belief in a religious rationale among some communities that perpetuate the practice. 33

Although culture and tradition are dominant reasons given for the practice of FGM, the cultural connotations are widely regarded as being under the control of women. For example, in a qualitative study exploring Egyptian men’s views of FGM, it was reported that men considered FGM to be the responsibility of mothers and grandmothers, but both men and women believed that FGM prevented women becoming ‘oversexed’, thus affecting marital stability. 34

Nevertheless, FGM has been described as an important cultural practice that has endured the colonial period and signifies the transition from childhood to adulthood. 35 In parallel, anti-FGM campaigns have been described as constructs of colonialism, with African nations labelled as a ‘land of torture’ whereas the West is described as the lands of ‘freedom and liberty’. 36 Therefore, while the knowledge and understanding of FGM in Western society appears to be polarised from FGM-practising communities, which are predominantly in the East, there is further evidence of polarisation within and between affected communities. However, we do recognise that there may be pockets of Westernisation in some of the countries that practise FGM.

Consequences of FGM

The WHO suggests that all women and girls are likely to report physical and/or psychological consequences as a result of their FGM. 1 There are no physical health benefits, and women and girls with more extensive forms of FGM, such as type 3, report more severe complications. 6,37 The physical health impacts of FGM are wide-ranging, and the large number of consequences identified in the literature can be subdivided into immediate, short- and long-term consequences. 1 Immediately and shortly after FGM, women and girls are typically at risk of more than one health complication. 38 Immediate complications include severe pain; haemorrhage and haemorrhagic shock; acute urine retention; urinary, vaginal and uterine infections; septicaemia; trauma to adjacent tissues; transmission of blood-borne viruses [e.g. human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)]; fracture of bones from being held down; and, potentially, even death. 1,3,38–40 Shorter-term complications include delayed wound healing, scarring/keloid formation, pelvic infection, epidermoid cysts/abscesses and/or neuroma. 1,3,39,40 Longer-term impacts include reproductive tract infections, haematocolpos (impaired flow of menstrual blood), dysmenorrhoea (painful menstruation), dysuria (painful and difficult urination), dyspareunia (difficult or painful sexual intercourse), morbidity and mortality during pregnancy and childbirth, pelvic inflammatory disease/infertility, increased risk of HIV transmission or death. 1,39–45 Pregnant survivors are also at increased obstetric risks, including of prolonged and difficult labour, perineal tearing, episiotomy, instrumental delivery, caesarean section, post-partum haemorrhage and a longer maternal hospital stay. 1,6,41,42,45 Babies who are born to women who have undergone FGM also have an increased risk of stillbirth, early neonatal death and needing to be resuscitated at birth. 1

The consequences of FGM are broader than just physical health impacts, with evidence that FGM can have psychological, psychosexual, social and economic impacts for survivors and their communities. 6,39,40,42,46–52 Although there is less evidence for this than for the physical health outcomes of FGM, a recent systematic review has shown an association between FGM and adverse mental health outcomes. 37 For example, survivors are at an increased risk of developing conditions such as low self-esteem, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), compared with women who have not experienced FGM. 51,52

Compared with women without FGM, survivors report impaired sexual function, including experiencing pain during sex, problems becoming stimulated and low sexual desire and satisfaction. 51,52 There is a significant economic burden of FGM at the individual, societal and governmental levels. 53 In 2020, the WHO estimated that the global annual financial cost for health care for survivors was US$1.4B. 54 If the practice of FGM is not abandoned, then these costs could increase by 50% by 2050. 54 In 2016, the annual cost of NHS care for FGM survivors in the UK was estimated at £100M. 55 Given the increasing migration of the FGM diaspora to the UK, this cost is likely to escalate going forward.

Deinfibulation for type 3 FGM survivors

Type 3 FGM (infibulation) involves the most extensive tissue removal from the female genitalia and has the most significant physical health impact. 12 Generally, type 3 FGM is carried out in the east of Africa and is most prevalent in Somalia, The Sudan and Djibouti. 12,22 Deinfibulation is a procedure to surgically release the narrowed vaginal introitus in women and girls with type 3 FGM. 56 The WHO has reported56 that deinfibulation is associated with improved health and well-being, as well as allowing sexual intercourse and childbirth. However, currently, there is only limited direct evidence to support this statement. For example, a recent systematic review reported no evidence that deinfibulation improved urological complications. 57 There is, however, stronger observational evidence, albeit of very low quality, to suggest that deinfibulation is associated with improved gynaecological and obstetric outcomes. 58 Deinfibulated women were at a significantly lower risk of undergoing a caesarean section [odds ratio (OR) 0.19, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.09 to 0.39; two studies] and post-partum haemorrhage (OR 0.31, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.83; one study) than those women with type 3 FGM without deinfibulation. 58 Compared with women without FGM, deinfibulated women were at a similar risk of episiotomy (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.02; two studies), caesarean delivery (OR 0.60, 95% CI 0.33 to 1.10; one study), vaginal lacerations (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.65; one study), post-partum haemorrhage (OR 2.52, 95% CI 0.49 to 13.07; one study) and volume of blood loss at vaginal delivery (ml) [mean difference (MD) 9.50, 95% CI –15.47 to 34.47; one study]. They also had similar length of second stage of labour (hours) (MD –0.18, 95% CI –2.47 to 2.10; two studies) and length of hospital stay (days) (MD –0.30, 95% CI –0.69 to 0.09; one study). 58

Evidence around preferences for timing of deinfibulation for type 3 FGM survivors

The development of evidence-based care to improve outcomes for FGM survivors, in particular regarding the optimal or preferred timing of deinfibulation, has been limited to date, with expert opinion and low-quality evidence typically informing recommendations. 1,39,56,58–60

Two recently published qualitative evidence syntheses have explored survivors’ experiences of accessing and receiving FGM health care61 and the factors that influence provision of FGM health care from the perspective of health-care professionals (HCPs). 62 These reviews61,62 and the associated full study report63 explored experiences, communication, timing and outcomes of deinfibulation. In line with preventative health care, the review62 highlighted that HCPs identified ‘compelling’ reasons for antenatal deinfibulation, such as the availability of outpatient care and local anaesthetic, the assurance of professionals who were competent and confident in the deinfibulation procedure and the potential for reduced costs through the avoidance of associated emergencies during intrapartum care. 62 However, much of this evidence was weak, and preventative health care such as antenatal deinfibulation was outside the cultural norms of FGM survivors. 62 HCPs reported that they believed that FGM survivors preferred labour deinfibulation so that they experienced only one procedure, but there was limited evidence to support this interpretation. In addition, the review highlighted that, despite participating in training, HCPs were anxious about deinfibulation, an anxiety that was rooted in a lack of awareness and understanding of the procedure itself. Evidence also suggested that there were inconsistent practices around deinfibulation, guidelines lacked consistency and HCPs were influenced by cultural stereotypes, which reflected cultural dissonance and ethnocentric views.

In the review exploring survivors’ views,61 there were strong cultural imperatives to avoid deinfibulation prior to marriage and pregnancy. A survivor’s family (prior to marriage) and her husband (after marriage) were particularly influential in decision-making around deinfibulation, with evidence to suggest that some women felt the need to seek permission to undergo the procedure outside childbirth. The majority of studies included in the review reported that survivors preferred intrapartum deinfibulation to avoid undergoing two procedures. However, there was evidence that women could ‘be persuaded’ towards the HCPs preferred option of antenatal deinfibulation following discussion and where there was a ‘trusted’ relationship between the survivor and the HCP. Overall, the review61 highlighted that women with type 3 FGM would benefit from more discussion, information and advice throughout their life, as well as both prior to and after deinfibulation.

Current guidance on the timing of deinfibulation for type 3 FGM survivors

Deinfibulation can be undertaken at any point during a survivor’s life; however, the main times suggested in the literature are ‘outside of or during pregnancy’. 1,59 There is considerable variation between and within clinical guidance around the optimal time for deinfibulation. 60,63 For example, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) guidelines9 recommend that deinfibulation should be offered prior to pregnancy and preferably before first sexual intercourse. However, these guidelines also state that deinfibulation can be performed antenatally, in the first stage of labour, at the time of delivery or during a caesarean section. The Royal College of Nursing (RCN) FGM guidance64 does not provide a clear indication on the optimal timing of deinfibulation, with one statement indicating that the procedure is best performed when the woman is not pregnant and another statement suggesting that deinfibulation is best undertaken before or at least during the second trimester of pregnancy. The WHO guidelines on the management of FGM56 recommend either antepartum or intrapartum deinfibulation, with the caveat of a suggestion that timing should be based on wider contextual factors, including patient preference, access to health-care facilities, place of delivery and the skill level of the HCP. In addition to a lack of consensus about when deinfibulation should be performed, there is also debate about whether or not timing affects outcomes, with some studies suggesting that obstetric risks increase the later that deinfibulation is undertaken. 65,66 However, these findings were not substantiated in a systemic review of low-quality observational evidence comparing childbirth outcomes between antepartum and intrapartum deinfibulation. 59

In 2016, the Department for Education and the Department of Health and Social Care in collaboration with the Home Office issued Multi-Agency Statutory Guidance on Female Genital Mutilation for those working in England and Wales. 67 The multiagency guidance has three key functions: to provide (1) information on FGM, (2) strategic guidance on FGM and (3) advice and support to front-line professionals. 67 Interestingly, other than a definition, deinfibulation is not discussed within this guidance.

Legal aspects of FGM

The practice of FGM is illegal in at least 59 countries, including the UK. 12 FGM has been illegal in the UK since 1985 as a result of the Prohibition of Female Circumcision Act 1985. 68 The 1985 Act was replaced in England, Wales and Northern Ireland in 2003 by the Female Genital Mutilation Act 200369 and in Scotland in 2005 by the Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation (Scotland) Act 2005. 70 In 2015, Section 70(1) of the Serious Crime Act 201571 amended section 4 of the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003 in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. In 2020, Scotland introduced the Female Genital Mutilation (Protection and Guidance) (Scotland) Act 2020,72 which amended and added to the Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation (Scotland) Act 2005. Despite increasing legal frameworks and growing political support to end FGM, FGM remains a global issue with little enforcement of legislation, even in countries such as the UK. For example, despite being illegal in the UK for > 35 years, as of October 2020, only five people have been prosecuted for FGM-related offences, with only one leading to a conviction. 73,74

Legislation around FGM has strong associations with practice guidelines, both clinical and social. For example, the RCOG published guidelines with the clinical remit of managing FGM survivors’ care. 9 Although the guideline encompasses clinical care, there are specific recommendations that relate to the legal implications of FGM. 9 As such, when RCOG guidance on FGM informs or benchmarks local clinical guidance on FGM, there is a possibility that the recommendations relating to legal implications are transferred into local guidelines. This has the potential to lead to the discussions between HCPs and survivors being overly focused or framed around the legal aspects of FGM, rather than on the provision of respectful, person-centred and culturally appropriate care. 63

Education and training for health-care professionals around FGM

The care provided to FGM survivors depends on the knowledge and awareness of HCPs, the foundation of which is derived from health-care education. An online FGM educational programme has been developed by NHS Health Education England, in partnership with key stakeholders, and is available for free to NHS health and social care professionals. 75 Other professionals are able to gain access to FGM training using the eIntegrity platform76 or through a Home Office learning package. 77 The Health Education England training covers topics including (1) communication skills, (2) legal and safeguarding issues, (3) management of FGM with children and young women, (4) management with women during pregnancy and (5) psychological impact. 75 This training recommends that deinfibulation should take place around the twentieth week of pregnancy. However, there is no current evidence to substantiate this, with recommendations for the timing of deinfibulation in clinical guidance being based on clinician opinion only. 1,9,64 Although the Health Education England training package is aimed at HCPs, the Home Office training is aimed at a multiagency audience. 77 Nevertheless, there are similar notions throughout the Home Office training; for instance, there is a strong victimisation of survivors depicted, with the word ‘victim’ being used on several occasions in audio excerpts. There is a parallel with the Health Education England training package in that there is a lack of the survivor’s voice inherent in the training. Furthermore, negative ‘power’ words are used; for instance, there is a statement that points out that professionals should ‘not fear being branded racist or discriminatory’. The wider evidence base suggests that HCPs would benefit from additional training in relation to FGM and, in particular, deinfibulation;63 however, the current training packages lack the voices of survivors, are not based on best evidence and potentially victimise those from FGM-affected communities.

FGM service provision

Services for FGM survivors across the UK still appear to be sporadic and suboptimal. 62 The Foundation for Women’s Health Research and Development (FORWARD) has identified 21 clinics that currently provide services specifically for FGM survivors. 78 Yet the majority of these services are attached to NHS maternity services and they are concentrated in inner-city NHS trusts. As a result, many women may not access these services or be aware of their existence until pregnancy. In an attempt to alleviate this issue, in 2019, NHS England commissioned eight community clinics for FGM survivors. The clinics accept referrals from general practitioners (GPs) and other HCPs, as well as FGM survivors’ self-referrals and walk-in appointments. 79 However, this service provision is concentrated in the Greater London area, with only three clinics currently serving the rest of England.

Study justification

FGM remains a significant global health concern that is an important health-care challenge in the UK as a result of the increase in the diaspora from countries where FGM is practised. 22 The NHS will be required to provide culturally acceptable and safe evidence-based care to growing numbers of FGM survivors. There is evidence to suggest that current care provided to FGM survivors may be not culturally sensitive or appropriate. 63

Current estimates of the prevalence of FGM in the UK diaspora potentially underestimate the true burden of FGM given the sensitive nature of disclosure, a perceived lack of clinical and cultural competence among HCPs, language barriers and the often limited engagement of FGM survivors with health-care services. 63 This lack of engagement with FGM services is likely to reflect a complex picture, including the fact that there may be an absence of FGM service provision in some areas of the UK and, where there is provision, services may be disjointed and invisible to survivors.

Type 3 FGM is associated with significant health, psychological, sexual and economic consequences that have an impact on girls, women and men. 1 The WHO has suggested that deinfibulation is beneficial for the health and well-being of girls and women and that it reduces the risk of negative outcomes in childbirth. 56 Currently, however, there is no clear preference for the timing of deinfibulation for type 3 FGM survivors. 56,59,60,63 Recommendations for future FGM research suggest that ‘there is an urgent need for well-designed research to inform evidence-based guidelines, and to improve the health care of women and girls with FGM’. 60 In addition, there is a specific need to focus on exploring preferences for the timing of deinfibulation, involving a diverse range of FGM survivors, men and HCPs, across multiple centres. 60,63,80 At present, there is a lack of robust qualitative evidence of UK-based deinfibulation experiences from the perspective of FGM survivors, HCPs and, in particular, men.

Health services in the UK have increasingly sought to develop patient-centred care. 81 Qualitative research actively seeking a diversity of experiences from those who are recipients of care can provide richer insights to direct quality improvement. 82 Barker82 argues that methodologically robust qualitative research has an ‘increasingly important role to play’ in health service design and delivery, and when a diversity of patients’ voices are heard, the benefits can be gained by all stakeholders.

Research aims and objectives

The overarching aim of the FGM Sister Study was to explore and understand the views of FGM survivors, men and HCPs on the timing of deinfibulation and how NHS services can best be delivered to meet the needs of FGM survivors and their families. This overarching aim was addressed through two work packages (WPs).

Work package 1

The aim of WP1 was to qualitatively explore and understand the timing preferences for deinfibulation and how NHS FGM services could be improved for type 3 FGM survivors (WP1a), men (WP1b) and HCPs (WP1c). This was achieved through the following objectives:

-

to explore knowledge, awareness and understanding of FGM and deinfibulation (WP1a, b and c)

-

to elicit views on preferences for the timing of deinfibulation and the rationale for these views (WPs 1a, b and c)

-

to explore perspectives on the decision-making process around deinfibulation (WPs 1a and b)

-

to explore knowledge, awareness and experiences of FGM services and support (WPs 1a, b and c)

-

to understand the enablers of, motivators of and barriers to FGM care-seeking behaviours (WP1s a and b)

-

to explore how HCPs describe, explain and reason about their care provision for FGM survivors and their families (WP1c)

-

to understand how FGM care provision could be improved to best meet the needs of FGM survivors, their families and HCPs who support them in their local context (WPs 1a, b and c).

Work package 2

The aim of WP2 was to use established techniques to synthesise the qualitative research findings, inform best practice and policy recommendations around the timing of deinfibulation and FGM care provision, and identify future actions. This was achieved through the following objectives:

-

to explore views and reflections on the trustworthiness of our interpretation of the data and the conclusions drawn (WPs 2a and b)

-

to establish if there is a consensus on the optimal timing of deinfibulation (WPs 2a and b)

-

to identify the key recommendations to inform NHS FGM care provision (WPs 2a and b)

-

to explore the facilitators of and barriers to implementation of changes to NHS FGM care provision (WP2b)

-

to explore views on the requirements for future FGM research (e.g. randomised trials) (WP2b).

Structure of the report

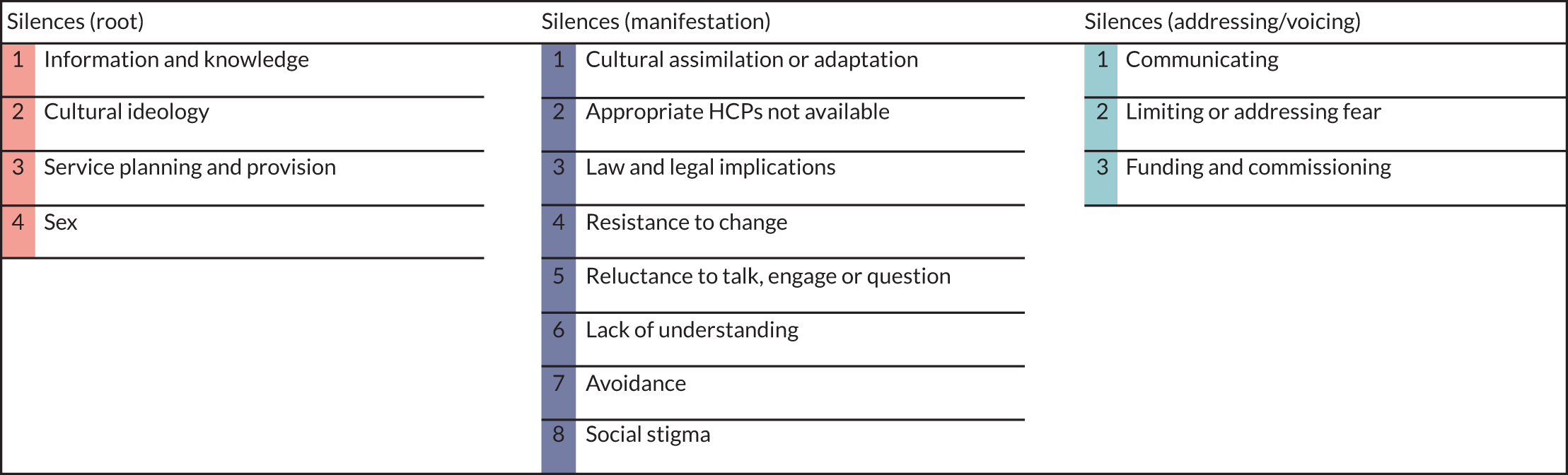

Chapter 2 presents the methodology and methods, including the theoretical foundation of the study; the conceptual framework used to underpin the methods, sampling, data collection and analysis; and ethics considerations. Changes to the protocol are also documented in Chapter 2. Chapter 3 presents the thematic results interpreted from the synthesised and analysed data. Chapter 4 presents the interpreted roots and manifestations of silences. Chapter 5 presents the address of silences, discussion of the interpreted results situated within the context of the wider literature, discussion of the robustness of the results, the limitations of the research and findings and makes recommendations for further research, as well as implications and recommendations for health-care provision as a result of this study. Chapter 6 presents the conclusions of the study.

Chapter 2 Methodology and methods

Introduction

This chapter presents an overview of the methodology and methods of the study. The study protocol has been published83 and the study was prospectively registered as International Standard Registered Clinical/soCial sTudy Number (ISRCTN) 14710507. 84 This study has been reported against the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) guidelines. 85 As highlighted in Chapter 1, the aim of the FGM Sister Study was to explore and understand the views of FGM survivors, men and HCPs on the timing of deinfibulation and how NHS services can best be delivered to meet the needs of FGM survivors and their families. This overarching aim was addressed through two WPs. WP1 was undertaken by the research team and WP2 was a collaboration between the research team and our charity partner – the National FGM Centre (Ilford, UK).

Study design and underpinning framework

The methods of this qualitative study were structured around the Sound of Silence framework (SSF). 86 The SSF is underpinned by broader theoretical approaches that accept that reality (or truth) is not objective; rather, the social world is influenced by people in a particular society at a particular point in time. 87 Truth is influenced by subjective individual and group interpretations of events and experiences, and the social and personal contexts in which these occur. 86 The SSF is aligned with philosophical approaches, including feminist, ethnic and criticalist viewpoints that recognise that interpretations of lived experiences, for example through qualitative research, are subjective and inherently influenced by particular social and political viewpoints. 86

‘Silences’ define areas of research and experiences that are little researched or understood or are unheard,86,88 and are useful for researching sensitive issues and/or the health-care needs and perspectives of marginalised populations. 86 Within the context of this study, although FGM is a contemporary issue that has increasingly become the subject of political and media interest, it remains a sensitive issue prevalent among marginalised populations and one that is under-researched. The nature of this study, namely working with potentially marginalised groups on a sensitive issue, needed to be accounted for in our methodology and methods. Using an appropriate framework was important to ensure that the perspectives of such marginalised groups were respected and at the forefront of the research, and that the needs of such marginalised groups were identified in relation to their requirements.

Sound of Silence framework

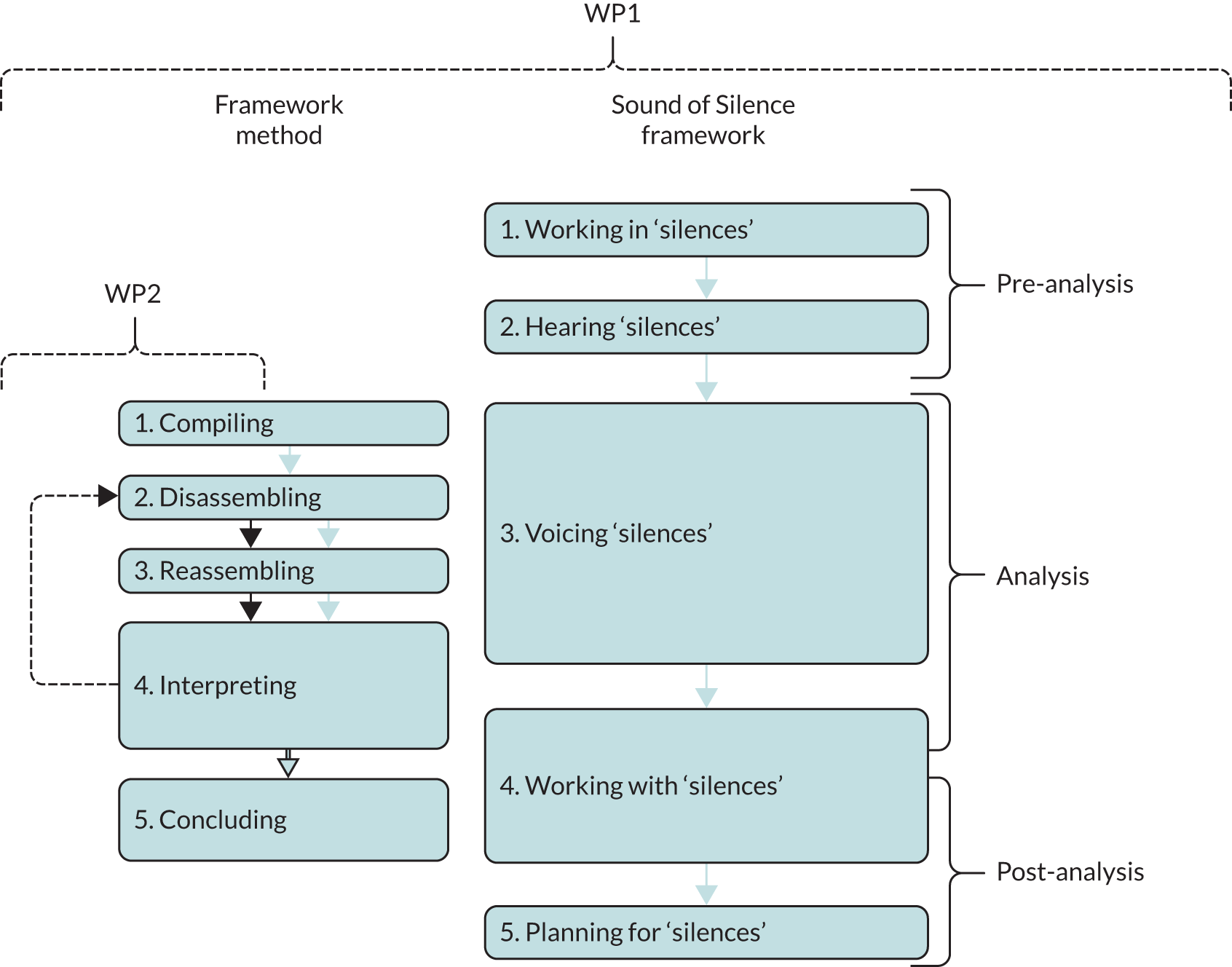

Next is a brief overview of the salient features of the five stages outlined in the SSF86 and how the FGM Sister Study aligned with each stage. This is supplemented by Figure 2, which provides a schematic overview of the SSF.

FIGURE 2.

The Sound of Silence Framework (adapted from Serrant-Green86). Serrant-Green L, Journal of Research and Nursing 16(4), pp. 347–60, copyright © 2011 by SAGE Publications. Reprinted by permission of SAGE Publications.

Sound of Silence framework stage 1: working in silences

Stage 1 provided the context for the research through a critical review of the existing literature on FGM. Stage 1 aims to ascertain preliminary answers to some initial key questions, including what is currently known, what is evident, whether or not silence already exists by exploring what appears to be unreported and how things currently are in relation to knowledge and practice. This stage is important for helping to expose the real world in which the research will take place,86 which facilitates contextual understanding and a basis for the research. This stage (see Chapter 1) has already helped shape the research study and the published protocol. 83

Sound of Silence framework stage 2: hearing silences

Stage 2 identified the silences inherent in conducting the research study, by researcher A at time X and with marginalised group/individual B. This was an important step in ensuring that the researchers were aware of what they as individuals brought to the research, for instance their preconceived ideas and biases at a particular place/time. The researchers were the primary vehicle through which silences were heard86 and so they had to be open to and reflexive in identifying and exploring silences related to their role in the research. This stage, therefore, recognised that different researchers may hear different silences and participants may identify/experience different silences. This stage outlined the methodological importance of reflexivity, whereby the researcher is reflexive with respect to reporting on and exploring participants’ or listeners’ identification of screaming silences.

Sound of Silence framework stage 3: voicing silences

Stage 3 explored the data that were collected from the participants to attempt to identify ‘silences’ in the context and from the perspectives of survivors, family (e.g. the partners of survivors) and care providers (e.g. HCPs). Importantly, this stage involved ‘transferring power to the participants, thus ensuring that their experiences [and preferences] count as valuable and ensuring their voices [are] not further silenced’. 89

Sound of Silence framework stage 4: working with silences

Stage 4 aimed to ensure that the aims and objectives of the research had been met, and facilitated a critical reflection on the contribution of the research by looking at how the researcher and collective voices have had an impact on the research. It sought to develop recommendations across a number of relevant domains, including informing clinical practice.

Sound of Silence framework stage 5: planning for silences

This stage sought to develop recommendations for future research, explore the implications of the findings and offer mechanisms for planning for and alleviating current and future silences.

Study setting

Survivors live in every local authority in England and Wales,24 so the study was undertaken across multiple regions, settings and services in the UK. However, census and NHS data suggest that larger populations of FGM survivors generally reside in inner-city areas. 24,90 For example, the following regions have some of the highest prevalence rates of FGM survivors: London (21.0 per 1000 people), Birmingham (12.4 per 1000) and Manchester (16.2 per 1000). 24 Moreover, Birmingham and Manchester have large FGM diaspora from countries that almost universally practise type 3 FGM, and practitioners anecdotally reported that London has a more transient FGM population: survivors were more likely to be type 3 and present in labour/at the point of delivery, without previously having accessed care. Therefore, these three regions offered a range of potentially different realities to explore and we purposively sought to recruit survivors and men in these locations. Given the significant variation in FGM service provision, we sought to identify HCPs and wider stakeholders from diverse regions and settings (including those with high and low prevalence) across the UK.

Eligibility

Work packages 1 and 2

WP1a and WP2a used the same inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria for these WPs were FGM survivors who were:

-

aged ≥ 18 years

-

resident in the UK

-

able to speak fluent English, Somali, Arabic and/or French

-

willing and able to provide voluntary informed consent (written, electronically completed or verbal).

The exclusion criterion was:

-

FGM survivors who experienced psychological distress related to FGM that prevented them from consenting and/or participating in the study.

For WP1b, the inclusion criteria were male participants who:

-

were aged ≥ 18 years

-

were resident in the UK

-

were able to speak fluent English, Somali, Arabic and/or French

-

were willing and able to provide voluntary informed consent (written, electronically completed or verbal)

-

had a partner/spouse or family member who had experienced FGM.

Recruitment for WP1b included snowballing from WP1a, so there was one exclusion criterion for this cohort:

-

Partner/spouse does not consent to their participation (if identified through a WP1a participant).

WP1c comprised HCPs who were providing care to FGM survivors and their families or who had provided care within the last 5 years. As such, the inclusion criteria were being:

-

aged ≥ 18 years

-

able to speak fluent English

-

willing and able to provide voluntary informed consent (written, electronically completed or verbal)

-

a HCP (including, but not limited to, GPs, practice nurses, midwives, obstetrics and gynaecology clinicians, genitourinary clinicians and sexual health specialists) who was currently or recently (within the last 5 years) involved in the delivery of care to FGM survivors and their families in the UK.

There were no exclusion criteria for this cohort.

WP2b comprised stakeholders in FGM care and the delivery of services. The inclusion criteria for this group were being:

-

aged ≥ 18 years

-

able to speak fluent English

-

willing and able to provide voluntary informed consent (written, electronically completed or verbal)

-

a key FGM stakeholder, such as HCPs (see WP1c inclusion criteria), policy-makers, FGM-specialist researchers/academics, health economists, commissioners and representatives from third-sector organisations (e.g. charity and advocacy groups), who was currently or recently (within the last 5 years) involved in the planning and delivery of care to FGM survivors and their families in the UK.

There were no exclusion criteria for this cohort.

Sampling and recruitment

There were four core target cohorts of participants (survivors, men, HCPs and FGM stakeholders). The following section presents the methods used for the sampling and recruitment of each of these core participant groups.

Work package 1a sampling

The sample of women targeted for this study were FGM survivors resident in the UK. Although the focus of the study pertains to type 3 FGM survivors, during consultation it was acknowledged by patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives and specialist FGM clinicians that FGM typology is usually diagnosed during health-care episodes, particularly maternity care episodes. Women who were recruited through non-NHS organisations may not be aware of FGM typology; hence, survivors who had experienced types of FGM other than type 3 were not specifically excluded. Pregnant and non-pregnant women were purposively sampled91 to give a broad range of experiences and views on service provision. This sample was inclusive of women who had (1) not had a deinfibulation procedure, (2) a deinfibulation procedure for health and/or personal reasons, (3) a deinfibulation procedure antenatally and (4) a deinfibulation procedure during labour or at the point of birth. To maximise the diversity of the sample,92 women from a range of locations, ages, education levels and FGM-affected communities were included.

Work package 1a recruitment

There was significant discussion and consultation with the study team’s specialist clinicians and PPI survivor group regarding advertising the study for recruitment. Evidence suggests that women from hard-to-reach communities, such as FGM-affected communities, may not relate to language used in recruitment, mistrust the research process and/or believe that the research will not be beneficial to their community, as well as that it could potentially cause harm. 93 Therefore, recruitment was primarily through trusted networks and advocates, such as midwives who facilitated FGM-specialist clinics and community support workers. This was supplemented with discrete advertising in clinics, community settings, social media and through culturally sensitive snowballing. 94 A range of advertising material was developed with support from our PPI survivor group to provide study information and aid recruitment, with participant information leaflets (PILs) containing more detailed information (see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/167804/#/documentation; accessed 25 August 2021). We trained potential recruiters (e.g. at site initiation visits) to approach survivors to participate in the study. Survivors were approached, in the first instance, by a member of their usual care team or by a trusted advocate in community organisations. Advocates briefly screened survivors for eligibility and introduced the study. Survivors who responded positively to study participation were then asked to complete and sign a contact detail form that gave permission for us to contact them to discuss the study further. A researcher then contacted the survivor (supported by an interpreter, as needed) to check her eligibility, discuss the study further, answer any questions she might have and arrange a mutually convenient time and location for the interview. At the end of the interview women were asked if their male partner and other survivors that they knew would wish to participate in the study. When survivors responded positively, our contact details were provided and the men/other survivors were asked to contact us directly.

Work package 1b sampling and recruitment

The sample of men targeted for this study were predominantly identified through their female partners who took part in WP1a, as well as community and third-sector organisations and social media.

Work packages 1a and 1b for speakers of other languages

Because English is not the first language in the regions where FGM is predominantly practised, potential participants may not have been fluent English speakers. Language diversity and inclusion was one of the primary considerations during the preliminary study design stage. UNICEF has identified > 30 countries where FGM is highly prevalent,22 with potentially > 1500 languages spoken across these countries. 95 It was identified that Arabic and Somali are the most widely spoken languages in these countries; however, because of historical colonisation, English and French are also widely spoken. 96 In addition, we sought the advice of the specialist clinicians in each of the three main recruiting regions to ascertain if Arabic, English, French and Somali are common languages of the survivors that they see in practice to ensure that these were the most appropriate languages to use. All participant-facing documents were available in Arabic, English, French and Somali. These were developed in English and then forward- and back-translated by native speakers of each language. The focus was on cross-cultural and conceptual translation, rather than linguistic or literal equivalence,97 to ensure that appropriate terminology and phrasing were used, and to facilitate fluency of the text in the translated versions.

Work package 1c sampling

Health-care professionals were purposively recruited from a diverse range of groups, including GPs, midwives, obstetricians and gynaecologists, genitourinary clinicians and sexual health specialists. Allied health professionals (i.e. physiotherapists, psychotherapists and psychologists) who met inclusion criteria were also recruited.

Work package 1c recruitment

Multiple recruitment pathways were employed as the target population for WP1c was UK-wide and dependent on the profession of HCPs. For example, NHS maternity units were contacted to invite midwives, obstetricians and gynaecologists to participate, whereas general practice surgeries were contacted with the view of inviting GPs and practice nurses to take part. Depending on the commissioning stream of FGM services, these were contacted either through NHS maternity services or directly (if they were stand-alone services); some of these maternity services were contacted through our personal networks. The study was also advertised on social media platforms, including Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; URL www.twitter.com) and Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; URL www.facebook.com), as well as contacting professional bodies such as the Royal College of Midwives (RCM) and the RCOG to advertise the study on our behalf. To obtain a wide range of views and experiences of providing care for FGM survivors, recruitment took place in both high- and low-prevalence areas. Snowballing from potential HCP participants was also used,94 particularly in FGM services where other allied health professionals were involved in the provision of care to survivors as part of holistic care delivery. HCPs were asked to contact us directly if they were interested in taking part. Following contact, they were screened for eligibility, provided with further study information, given time to answer questions and then a mutually convenient time and location for the interview was arranged.

Work package 2a sampling and recruitment

FGM survivors who took part in WP1a and had expressed an interest in participating in WP2a were contacted by the research team. Recruitment was further supplemented through the same pathways as identified for WP1a and with support from our charity partners at the National FGM Centre, who advertised the study through their networks, community support workers and snowballing through trusted advocates in their community outreach groups. Potential participants were provided with information about the study and were able to liaise with us and the National FGM Centre team, as needed, ahead of the events.

Work package 2b sampling and recruitment

We recontacted each HCP who participated in WP1c and had responded positively to participating in WP2b. This was supplemented using the same pathways as described for WP1c. Other key stakeholders (see Eligibility) were identified through our and the National FGM Centre networks and collaborators, advertising on social media and snowballing. 94 Potential participants were provided with information about the study and were able to liaise with us and the National FGM Centre team, as needed, ahead of the event.

Consent

The method of consent for WP1a and WP1b was a two-stage process that commenced with the potential participant providing their consent for the research team to establish contact (for copies of consent forms, see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/167804/#/documentation; accessed 25 August 2021). Their contact details were passed to the research team through a live telephone conversation and recorded directly in the secure study database. We then attempted to contact each potential participant using their preferred method. When contact was not established on initial telephone call or there was no response within approximately 1 week, where permission had been given, alternative mechanisms of contact were attempted using an interpreter as necessary. Alternative contact mechanisms, up to a maximum of three attempts, and associated dates were documented in the secure study database. If, after three contact attempts, contact was not established in any form then a failed contact was documented.

In some cases, more than three attempted contacts were made when contact was deemed to have failed, but the potential participant contacted the study team after three contacts expressing their wish to participate.

On successful contact with a favourable response from the potential participant, the contacting member of the study team discussed the study in detail and provided options for voluntary informed consent to participate in the study. The options included:

-

consent form posted to the participant by postal mail, signed with wet ink and returned to the study team using a provided stamped addressed envelope

-

consent form posted to the participant by postal mail or sent by e-mail, printed and signed with wet ink, electronically scanned and sent to the research team by e-mail

-

consent form posted to the participant by postal mail or sent by e-mail, printed and signed with wet ink, photographed and sent back to the research team by e-mail

-

consent form posted to the participant by postal mail or sent by e-mail and completed at the time of face-to-face interview with a member of the research team

-

consent form sent by e-mail, completed electronically by the participant and e-mailed back to the study team

-

consent form posted to the participant by postal mail or sent by e-mail, completed verbally and recorded at the commencement of audio-recording of the interview during telephone interviews.

The last two methods of consent were added to mitigate against poor recruitment. The target population for this study was considered to be hard to reach and the consent process appeared to be a contributory factor to the disengagement of potential participants. Following discussion with the study management group (SMG) and the Study Steering Group (SSG), a substantial amendment to the protocol was incorporated to provide some flexibility in the consent process (FGM Sister Study Protocol v2.0). Although written informed consent was sought wherever possible, this flexibility resulted in improved engagement and increased recruitment. This was the only substantial amendment to the protocol during the course of the study.

The purpose of the informed consent was to gain permission for agreement to participate in the study, to collect demographic data in a background questionnaire (for copies of the background questionnaires, see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/167804/#/documentation; accessed 25 August 2021) and to audio-record the dialogue of the interview discussion (or event). At commencement of audio-recording of the data collection episode, all participants were asked to reconfirm their consent to participate. When verbal consent was gained, the audio-recording was started and each statement from the consent form was read out by the interviewing member of the research team. If a participant did not consent to any of the statements, the interview was terminated. Consent forms were available in all languages and verbal consent at the start of the interview was supported by an interpreter as necessary.

The consent processes for the other WPs were the same, aside from the fact that there was no consent to contact form. All participants were reassured that participation in the study was voluntary and that they were free to withdraw up to 2 weeks after the data collection event without providing a reason.

Anticipated sample sizes

Work package 1

We sought to recruit up to a total of 110 participants:

-

up to 50 women who are FGM survivors

-

up to 10 male partners

-

up to 50 HCPs.

Work package 2

We sought to recruit up to a total of 60 participants:

-

20–25 FGM survivors for the community engagement event

-

30–35 stakeholders for the national stakeholder event.

However, numbers remained flexible, and the adequacy of the final sample size was carefully monitored during the research process to ensure that the overall sample and associated data had sufficient information power to develop new knowledge in relation to the research questions. 98

Data collection

Work package 1

Data collection and analysis was undertaken in stage 3, ‘Voicing Silences’, of the SSF and was informed by stage 1, ‘Working in Silences’. Semistructured interviews were used as the data collection method during WP1, as these have been identified as one of the most appropriate methods for facilitating an in-depth exploration of participants’ experiences that may involve sensitive and traumatic events. 99 Following PPI feedback, we added focus groups to the protocol (prior to receiving ethics permission, thus this was not a substantial amendment) as an alternative method of data collection, but none of the participants expressed a preference for discussing their experiences as part of a group.

Each interview was conducted by a trained qualitative researcher who was independent of the participant. Two researchers conducted the majority of the interviews, with support from four others. Professional interpreters, who we had trained, supported data collection where necessary. Discussion guides (for copies of the discussion guides, see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/167804/#/documentation; accessed 25 August 2021), informed by the aims and objectives of the study, our critical review of the literature and discussion with our PPI group, were used to help guide WP1 interviews. Discussion guides were developed iteratively based on interviewer field notes and reflections and regular discussion across the research team. Interview audio files were transcribed by a specialist external transcription company.

Work package 2

Work package 2 consisted of two community engagement events and one national stakeholder event. Staff from the National FGM Centre facilitated the community engagement events and the national stakeholder event was hosted by the National FGM Centre, but facilitated by five members of the research team. At the beginning of each event, a brief overview of the study was presented to the group. Discussions focused on the credibility of our interpretation of the data and the findings of WP1, and whether or not it was possible to establish consensus regarding findings and conclusions.

The way the events were run differed slightly between WP2a and WP2b because of the number of participants. We initially planned to run one community event only; however, as a result of small numbers in the first event, a second event using the same facilitator was undertaken. For the community events, given the small numbers, the discussions were facilitated as a whole group. However, WP2b consisted of a larger number of participants and so the group was divided into four smaller ‘table’ groups that considered the homogeneity and inclusivity100 to create a safe space where participants felt empowered to share their views and question the views of others. The results of the smaller group discussions were then shared as part of the facilitated whole group discussion to establish whether preferences for deinfibulation and recommendations for service improvement were ratified, refuted and/or challenged to inform policy, practice and education. Small and whole group discussions were audio-recorded and the audio files were transcribed by a specialist external transcription company.

Development of the discussion guides for work package 2

The discussion guides (for copies of the discussion guides, see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/167804/#/documentation; accessed 25 August 2021) for WP2 were derived from the interpretation of findings from WP1, as the purpose of WP2 was to ratify, refute and/or challenge the initial findings. As such, the discussion guides used in WP2 differed slightly from those used in WP1. However, the focus remained the same: experiences of care and preferences for deinfibulation.

In parallel with the discussion guides, various quotations were selected from the data collected in WP1 to explore the credibility of the research team’s interpretation of the data. This method was also used in WP2a and WP2b. However, as the data collection tool was constructed from the initial findings, there were occasional subtle differences in the responses from event participants compared with the responses in WP1, albeit there were different stakeholders present in WP2b. Although these differences were categorised as ‘new data’, they did not generate new subthemes and/or overarching themes/silences. Instead, the new data supported the interpretation of subthemes and, subsequently, the overarching themes and silences (see Analysis).

Use of interpreters

During the planning stage of the study, it was acknowledged that there was a potential need for interpreters to facilitate communication between the participant and researcher to support recruitment and data collection through interviews. FGM is not openly discussed among the communities101 and, therefore, lay or peer interpretation was not appropriate. The PPI survivor group advised against the use of community members and/or peers of potential participants for interpretation; they explained that the potential stigma attached to FGM within the community may discourage participation and/or affect the information provided by the participant, as well as the accuracy of interpretation. As such, professional interpreters were employed to provide real-time interpretation during the recruitment, consent and interview processes. We trained interpreters on FGM, study processes (including taking consent) and how the interviews needed to be interpreted with a focus on conceptual equivalence, rather than word-for-word or literal translation. 97

Analysis

The framework method and alignment justification

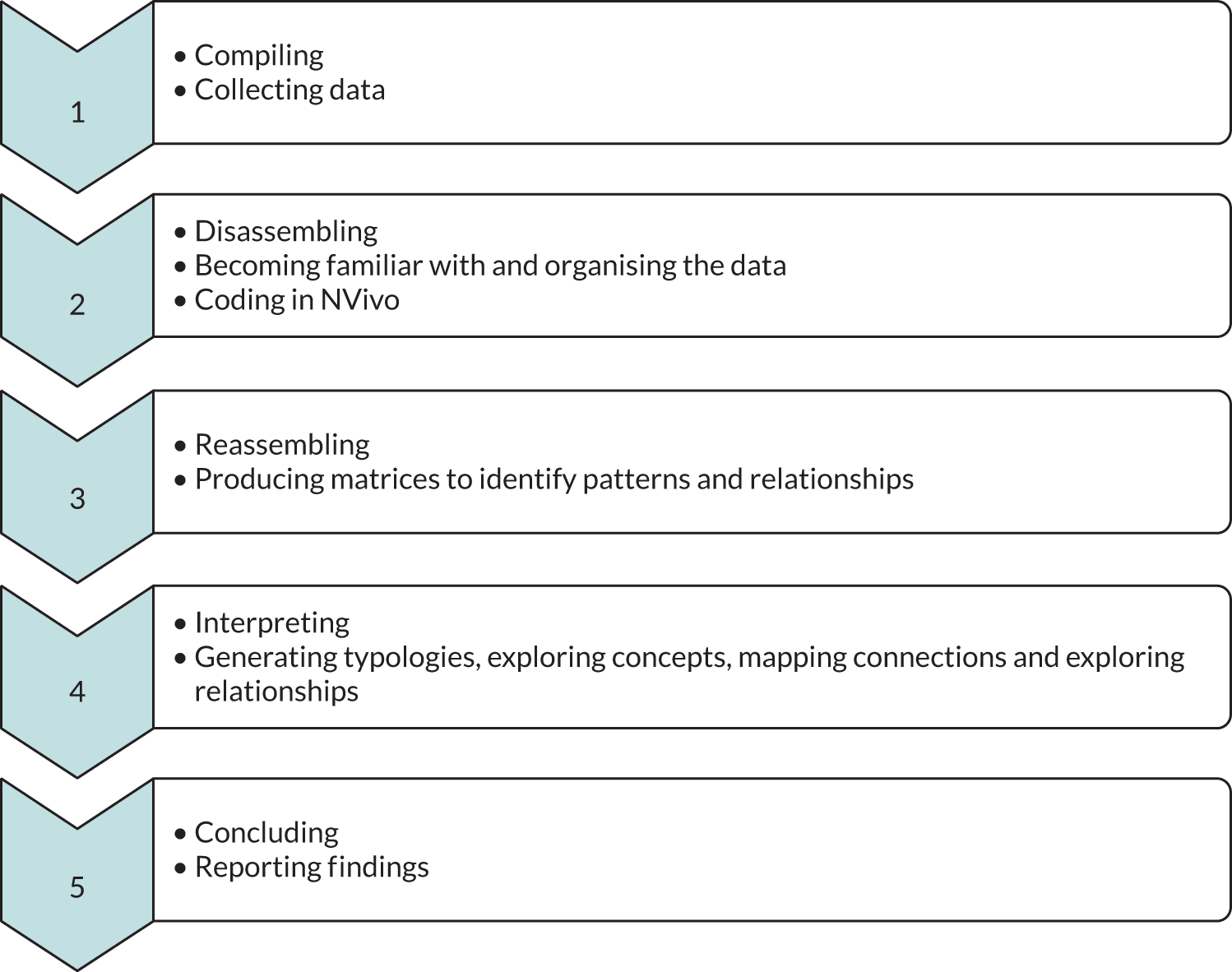

The framework method (FM) is a ‘systematic and flexible approach’ to qualitative analysis in multidisciplinary research, including applied health research. 102 The FM requires researchers to take a staged approach to research to facilitate the collection, interpretation and analysis of data. Although the FM is usually understood as a seven-stage method,102 more recent methodologists have refined the number of stages. 103 We have used the five-stage FM outlined by Castleberry and Nolen (Figure 3). 103

FIGURE 3.

Five-step model of the framework method (informed by Castleberry and Nolen103). Reprinted from Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, Vol. 10, Castleberry A and Nolen A, Thematic analysis of qualitative research data: is it as easy as it sounds? pp. 807–15, (2018) with permission from Elsevier. Coding in step 2 was performed using NVivo software, version 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK).

The alignment of the SSF and the FM in a hybrid framework method (HFM) is important, as the framework utilised during research must (1) clearly answer the ‘what’ question,104 namely ‘what is the purpose of the study?’ and (2) provide adequate and project-relevant philosophical underpinnings for the research study. 105 However, the FM on its own does not provide (1) or (2); the FM provides a method for the management and analysis of qualitative data only. 102 In short, the FM requires supplementation, with a framework that addresses (1) and (2). We utilised the robustness of the FM and its effectiveness in multidisciplinary research by transposing the core features of the method onto the SSF, as this is appropriate to the research questions, the marginalised participants and the sensitive topics that we engaged with as part of the research.

The hybrid framework method: aligning the framework method and the Sound of Silence framework

Figures 4 and 5 provide outlines and descriptions of our HFM. The HFM is not in itself a discrete method, but rather a placeholder term used to describe and contain the alignment of the FM and the SSF. The HFM is divided into three categories: pre analysis, analysis and post analysis. This categorisation places the process of analysis at the heart of the method. Further details of stage alignment can be found in Appendix 1.

FIGURE 4.

The HFM.

FIGURE 5.

Alignment of the HFM with the FM and SSF.

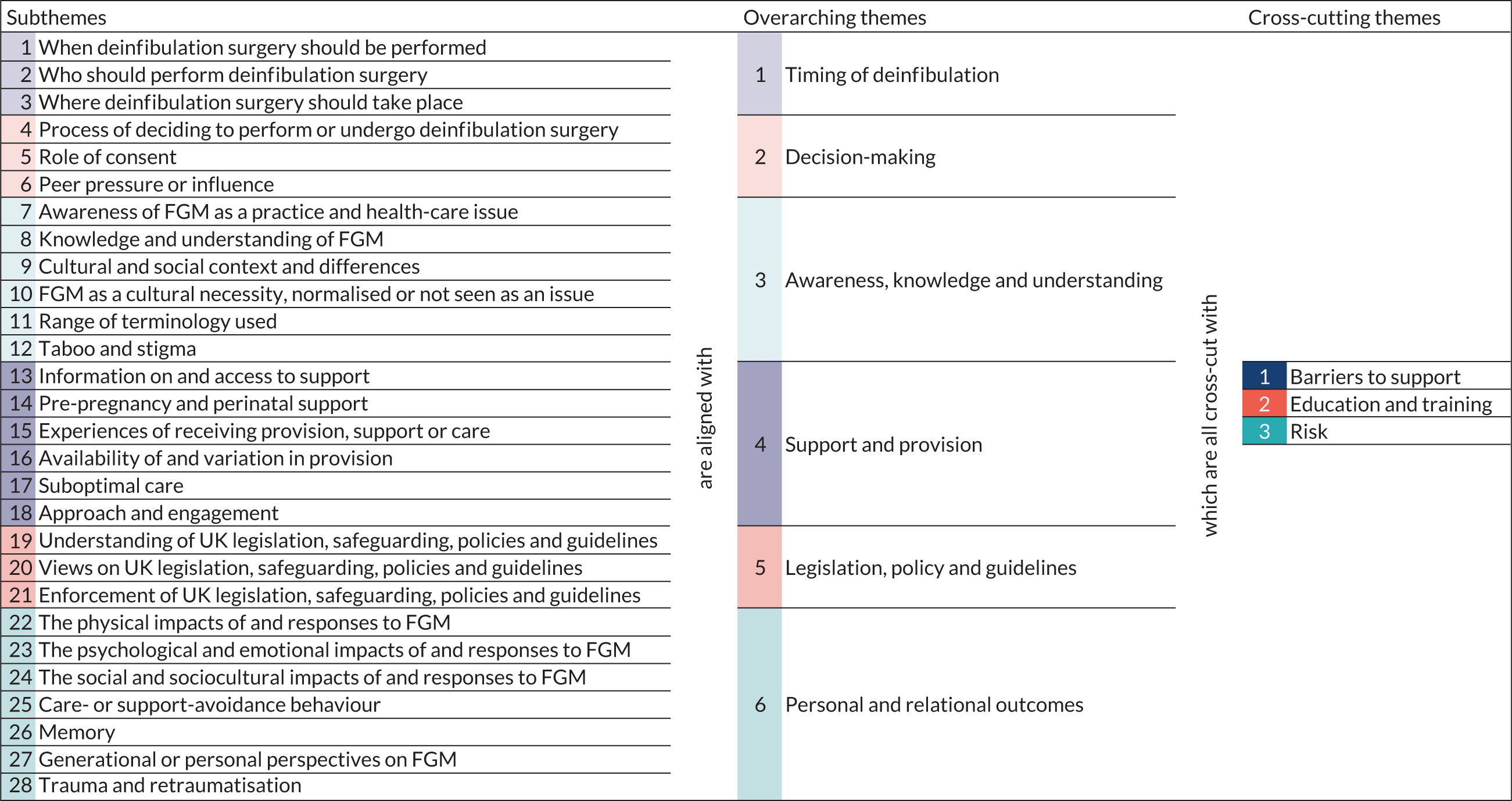

It is important to note that the results chapters (see Chapters 3 and 4) will present overarching themes and silences; there is, in many cases, an intrinsic relationship and cross-over between the themes and silences, although these are interpreted through different theoretical lenses.

Description of quotations used in Chapters 3 and 4

As a qualitative study, the participants’ voices were the cornerstone to the interpreted findings. Quotations used in Chapters 3 and 4 have not been edited to improve the narrative flow and are presented verbatim to ensure that the voices of participants were captured. It was important to capture the voices of the participants to ensure that these were not further silenced as a result of the research, analysis or interpretation. The quotations selected for Chapters 3 and 4 were identified across each of the participant cohorts to reflect our interpretations of the data. This also included deviant cases to ensure that a balanced view was presented.

Quality assurance of interpretation, transcription and translation

It was important to assure the quality of the interpretation and subsequent transcription of interviews undertaken in languages other than English. Therefore, we randomly selected one interview (which was in Arabic) and had the professional interpretation company transcribe and translate the whole interview into English, including what was said by the researcher, interpreter and participant. This provided us with an opportunity to check what had been asked by the researcher and whether or not the interpreter presented the core concepts correctly to the participant (conceptual equivalent interpretation). We were also able to check how the interpreter had presented concepts from the participant back to the researcher. In general, the conceptual equivalence was good. However, we did provide feedback to the interpreters regarding ensuring that they did not summarise what the participant had said in the feedback to the researcher, but that they interpreted all that had been said, and that they provided more regular interpretation, rather than waiting until a large amount of information had been discussed, as this could potentially lead to reduced recall accuracy.

Furthermore, we randomly selected four audio files (two Arabic and two Somali) and identified a 5-minute window in each where the researcher had asked about preferences for deinfibulation. These sections were transcribed and translated by the interpretation company and checked for conceptual equivalence. This process ensured confidence in interpretation and ensured that the voices of participants were not lost during interpretation. We therefore made the decision for the remaining interviews supported by an interpreter that only the English parts of the discussion would be transcribed.

Ethics considerations

The study was sponsored by the University of Birmingham (17-188). It has received a favourable opinion from the North West Greater Manchester East Research Ethics Committee (18/NW/0498) and approval from the Health Research Authority (HRA).

Assessment and management of risk

A detailed risk register was developed and maintained to assess risk(s) and implement actions to mitigate against or reduce risk(s). Risks were rated as red (high), amber (medium) or green (low) based on the likelihood that the risk would occur and the potential impact of the risk on the study. The register was reviewed on a monthly basis by the research team as risks (actual and potential) and the associated rating changed throughout the study period. The risk register was a rolling agenda item for the SMG and SSG meetings. Risks were categorised into three main sections:

-

general (e.g. staffing, ethics/governance approvals, subcontracting, COVID-19, resource constraints, time constraints, engagement of recruiters and stakeholders)

-

participant (e.g. identification, diversity of sample, recruitment, sensitivity of discussions, distress, eligibility, disclose of potential harm/illegal activity, language, availability for interview/events, location of interview/events)

-

researcher (e.g. sensitivity of discussions, distress, disclosure of harm, safeguarding, location and timing of data collection).

Managing distress and safety of the participants and the research team

FGM is a sensitive topic and discussions of FGM may cause distress during interviews with survivors or men. During data collection, the welfare of participants was of paramount importance and was placed ahead of the knowledge gained for the study. To mitigate against any potential or actual distress, a study-specific distress pathway was developed and embedded into the study protocol, aligned with the guidance from Draucker et al. 106 During data collection, when emotionally distressing aspects of the interview/community event occurred, these were dealt with in a sensitive manner and participants were encouraged to seek support from services specific to FGM survivors. Contact details of such services were provided in the PILs.

There was also potential for the research team to be exposed to highly distressing and sensitive information during data collection, including hearing and discussing the participants’ particularly challenging experiences. There was provision for debriefing sessions to support the research team if difficult and/or challenging circumstances arose. All members of the research team had access to senior members of the team to discuss concerns and decisions made in relation to the study.

Researchers also facilitated interviews in participants’ homes and in other ‘safe spaces’ (as defined by the participant). In these circumstances, the researcher was in participants’ homes or other spaces alone. Although it was possible that some participants would be non-English-speaking, interpreters were used to assist with telephone interviews only. The research team operated a ‘buddy system’, whereby another member of the research team was contacted at an agreed time by the researcher conducting the interview on arrival at the participant’s home and then contacted again following departure from the participant’s home. This was in line with the University of Birmingham’s Lone Worker Policy.

Safeguarding and legal aspects of FGM

FGM has been illegal in the UK since 1985. It is an offence under the Female Genital Mutilation Act 200369 to (1) perform FGM in the UK or take a girl abroad to be subjected to FGM, (2) assist in the carrying out of FGM in the UK or abroad, (3) assist, from the UK, a non-UK person to carry out FGM outside the UK on a UK national/permanent UK resident and (4) for someone in the UK to ‘aid, abet, counsel or procure’ FGM outside the UK (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). The Serious Crimes Act 201571 (1) provides ‘anonymity for victims of female genital mutilation’, (2) created a new offence of failure to protect a girl from FGM, (3) introduced ‘FGM protection orders’ and (4) introduced a mandatory reporting duty requiring regulated health and social care professionals and teachers to report known cases of FGM in girls aged < 18 years to the police (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0).

As some members of the research team were regulated HCPs, it was felt that the team had a duty of care to all participants to follow the mandatory reporting guidance that was published by NHS England. 107 Therefore, all members of the team were trained on mandatory recording and reporting procedures, with the remit of implementing appropriate action following a disclosure during data collection. 107 As a research team, we made a conscious choice for our safeguarding protocol to align with mandatory reporting guidance, meaning that if there was disclosure of serious risk of harm, then we would need to break research confidentiality.

We understand that in some contexts it may be possible to truly maintain confidentiality for research participants, but we did not feel that this was the case when there was potential for disclosure of illegal activity and there was mandatory reporting legislation in place. A completely confidential safeguarding protocol within a FGM research study would fail to recognise that FGM is illegal. The reality of this means that if, for example, a woman was to disclose during a research interview that they were planning to have their daughter cut that the research team would do nothing, even though we knew that that child might be at serious risk and as a result might undergo a life-changing event that we could have potentially prevented. As well as considering this both morally and ethically inappropriate, many of the research team hold professional qualifications bound by codes of professional conduct. Within the participant information sheet and the consent form, it was made clear to potential participants that we would maintain their confidentiality unless they disclosed something that the research team thought put them or others at risk. Therefore, participants were aware of this prior to taking part.

During the study, there was one disclosure from a participant that was judged to require mandatory reporting. With the participant’s knowledge, this was reported to the police by the researcher to whom the disclosure was made. The disclosure was investigated, with no further action taken.

Reflexivity

Aligned with good practice in qualitative research, and as highlighted in stage 2 of the SSF, it was important that the research team were aware of how their worldview, preconceived ideas and biases may have influenced the study. In particular, it was important for the team to be reflexive with regard to exploring, identifying and interpreting silences related to their role in the research. Six researchers were involved in interview data collection (i.e. ED, BC, FCS, JC, LJ and LA). Two researchers (i.e. ED and BC) conducted the majority of the interviews. Of the six researchers, five were female and one was male. Two researchers were midwives, one was a philosopher and qualitative researcher and three were applied qualitative health researchers. Five were from non-FGM-affected communities and one was from a county with a history of practising FGM (predominantly type 2). We had a range of ontological views or worldviews. Two researchers (i.e. ED and BC) led the analysis, supported by Laura Jones. The wider research team, including Kate Jolly and Julie Taylor, provided investigator triangulation of the analysis and interpretation. The range of worldviews and lenses through which the data were interpreted provided triangulation and validation of findings. However, all but one of the research team were outsiders to the practice. Therefore, we were particularly mindful to ensure that we recognised that we may hold Western societal views of the practice, and discussed and reflected on this throughout the process.

Study support and management

Patient and public involvement: FGM Sister Study survivor group

In alignment with the SSF,86 active and sustained PPI involvement was central to the delivery of this study. Our approach to patient involvement was aligned with the six UK Standards for Public Involvement108; throughout this section, text in brackets represents the standards (e.g. support and learning, communication) relevant to each aspect of PPI involvement. We initially had a PPI co-applicant who supported the development of the protocol, but was unable to continue in this role after the study started owing to wider commitments.

A collaborative FGM Sister Study survivor group was established through contacts of one of the clinical co-applicants (AB). The survivor group consisted of four members who were type 3 FGM survivors, three of whom had undergone deinfibulation in the UK (inclusive opportunities, working together, communications). Laura Jones (on one occasion supported by ED) met with members of the FGM Sister Study survivor group on five separate occasions during the study. Members were supported to participate where needed (e.g. meeting at times and locations that suited them) and any paperwork was sent in advance in an agreed individual format [e.g. by WhatsApp (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA), e-mail, post] (support and learning, communications).

The survivor groups have provided input to the study, including the design of the logo, the cohorts of participants that it was important to target, recruitment pathways, appropriate language to use around FGM, development of discussion guides and participant-facing materials, identification of solutions when difficulties were encountered (e.g. low recruitment), support of the early interpretation of data, planning for WP2 and the dissemination pathways (opportunities, working together, communications, impact). A summary of the discussions was written to document how the input of the survivor group had shaped the research and was sent to survivors when they requested this, which was not always the case; rather, some preferred that we discussed what was talked about at the previous meeting at the start of the subsequent meeting (impact, governance). We used a survivors’ WhatsApp group to facilitate regular ad hoc contact, rapid feedback on queries and group cohesiveness. Survivor group members were compensated for their input, in line with INVOLVE guidance. 109 Contributions from survivors have been documented and acknowledged (impact) and we have undertaken monitoring and evaluation of survivor involvement in the research, including what has worked well and what we could have changed (impact, governance).

Study management group

The SMG was chaired by the principal investigator (PI) and included all co-applicants and University of Birmingham research staff. The PI and research and study co-ordination staff were responsible for the day-to-day delivery of the study. The wider SMG met with the core research team to discuss all aspects of the study on seven occasions during the study, with additional ad hoc discussions as necessary. The PI met with the research team roughly every 2 weeks throughout the study.

Study Steering Group

The SSG consisted of eight members, comprising women’s health researchers, FGM academics, FGM-specialist clinicians, a FGM survivor and FGM third-sector organisation representatives (see Acknowledgements). The SSG provided independent oversight and overall supervision of the study and met with the PI, members of the SMG and the research team on four occasions during the study, with additional ad hoc discussions between the PI and the chairperson as necessary.

Final study sample and participant characteristics

This section provides a summary of the final study samples for each WP, including participant characteristics, the pathways to recruitment and a breakdown of the language and types of interviews conducted. Data were collected between September 2018 and October 2019 for WP1, in November and December 2019 for WP2a and in January 2020 for WP2b. The total sample was 101 participants for WP1 and 40 participants for WP2; therefore, the total sample size for the study was 141 participants. There was constant monitoring and reflection on sample size adequacy throughout the data collection period. A judgement about sample adequacy and information power was made across the whole cohort and by group. The overall sample and associated data had sufficient information power and adequacy to develop new knowledge in relation to the research question. There was also sample size adequacy for survivor and HCP groups, but not for men.

Work package 1a

A total of 44 survivors participated in interviews in WP1a. Table 1 provides an overview of the WP1a sample, highlighting that the majority of participants were recruited in London, were of Somali origin, were married, were aged < 40 years, reported having type 3 FGM and had been deinfibulated.

| Characteristic | Number of survivors interviewed (%) (n = 44) |

|---|---|

| Region | |

| Birmingham | 13 (30) |

| London | 29 (66) |

| Manchester | 2 (5) |

| Country of origin | |

| Eritrea | 1 (2) |

| Guinea | 5 (11) |