Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/84/10. The contractual start date was in March 2015. The draft report began editorial review in March 2020 and was accepted for publication in June 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Bruce et al. This work was produced by Bruce et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Bruce et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women in the UK, with over 55,000 new cases diagnosed each year. 1 Breast cancer incidence has increased by 20% since the early 1990s. 1 Despite increasing incidence, survival rates have improved dramatically as a result of advances in early diagnosis and treatment. 1 Breast cancer survival has doubled in the UK over the last 40 years; now, nearly 8 in 10 women (78%) treated for invasive breast cancer survive for ≥ 10 years. 1 Treatments are complex and can be toxic, causing side effects that persist in the long term. There is increased recognition of the benefits of providing supportive care for people living with and beyond cancer treatment. 2

Surgical treatment of breast cancer

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for breast cancer, supplemented with chemotherapy, radiotherapy and biotherapy, with or without reconstruction surgery. 3 Treatment decisions are based on clinical criteria, tumour stage, lymphatic spread and patient preference. Surgery to the breast consists of either mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery (BCS), with newer oncoplastic conserving procedures increasingly being used. 4 Breast-conserving procedures, such as lumpectomy or wide local excision, combined with whole-breast radiotherapy, aim to achieve disease control with minimal morbidity. These breast-conserving treatments have been demonstrated to be as effective as mastectomy in increasing long-term overall survival in patients with early breast cancer. 5,6 Conservative surgery followed by radiation therapy allows for the preservation of the breast, which can improve patient quality of life (QoL) and satisfaction with treatment. 7 Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) has largely replaced axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) for disease staging, and also reduced the need for extensive axillary node clearance (ANC). There is good evidence that 10-year survival among women receiving SLNB only is equivalent to that among women receiving ANC after SLNB. 8,9

Treatment-related side effects

Although largely curative, breast cancer treatments have negative sequelae. Surgery and radiotherapy can affect the upper body, especially the shoulder joint and upper limb, causing restricted shoulder range of movement (ROM), impaired strength and functional limitations. Arm morbidity has been strongly associated with the extent of axillary node surgery. Although arm lymphoedema can affect up to 20% of women, systematic reviews report higher rates of lymphoedema after ALND than after SLNB up to 2 years after surgery [20%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 14% to 28%, n = 18 studies, n = 3599 participants, vs. 6%, 95% CI 4% to 9%, n = 18 studies, n = 3583 participants]. 10,11

A systematic review11 of upper limb problems after surgery and radiotherapy (32 observational studies) reported prevalence estimates for restricted shoulder ROM (up to 67%), arm weakness (< 28%) and shoulder/arm pain (< 68%). Prevalence estimates vary widely, in part because of differences in definitions, methods of measurement and timing of postoperative follow-up. Other common postoperative complications include wound infection, seroma and axillary web syndrome (cording) and chronic pain. 11,12

A nationwide Danish study13 of 2500 women undergoing breast cancer surgery found that over one-third of women reported persistent pain and half reported sensory disturbances up to 7 years after treatment. Persistent upper limb dysfunction and pain are debilitating, affecting sleep quality, QoL and physical and emotional function. These enduring adverse sequelae of cancer treatment are burdensome and associated with increased health-care utilisation.

Risk factors for persistent post-treatment complications

Research has examined patient- and treatment-related risk factors associated with upper body problems after breast cancer treatment. 11,14,15 Women undergoing mastectomy have higher odds of postoperative shoulder restriction than those undergoing BCS [odds ratio (OR) 5.67, 95% CI 1.03 to 31.2]. 11 More invasive axillary surgery is associated with greater impairments of abduction ROM and strength than SLNB, up to 7 years post treatment. 16 Radiotherapy to the axilla or chest wall, compared with no radiotherapy, slightly increases the odds of shoulder ROM restriction (pooled OR 1.67, 95% CI 0.98 to 2.86) and lymphoedema (pooled OR 1.46, 95% CI 1.16 to 1.84). 11 A higher body mass index (BMI) was found to be an independent risk factor for shoulder external rotation problems up to 7 years after treatment. 16 Higher BMI (overweight or obese) is also a known risk factor for lymphoedema10 and for development of chronic post-surgical pain (six studies, pooled OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.67). 17

Evidence for the effect of exercise on shoulder dysfunction

A Cochrane systematic review,12 published in 2010 [24 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), 2132 participants], reported that exercise and/or physiotherapy may help to prevent shoulder and arm morbidity after breast cancer treatment. This review12 found that physiotherapy, compared with usual care or control, improved shoulder flexion only within the first 2 weeks and at 3 and 6 months postoperatively. The timing of starting postoperative physiotherapy may also be important for shoulder ROM and upper limb function. Early exercise, started on the first postoperative day, was beneficial in improving flexion and abduction at 1 week postoperatively, and flexion at 4–6 weeks postoperatively, when compared with delayed exercise (exercise that started after the fourth postoperative day). 12

A more recent systematic review,14 published in 2015 (18 RCTs, 2389 participants), compared different exercise modalities (multifactorial therapy, passive mobilisations, stretching and exercise therapy) and the timing of application. 14 The overall findings were similar, suggesting that early exercise improved upper arm ROM in the short and long term after breast cancer treatment. However, exercising in the first postoperative week also increased the risk of greater wound drainage volume and seroma formation. 14 Regarding physiotherapy modalities, adding stretching to an exercise programme may improve postoperative ROM. 14

Although these reviews suggest that physiotherapy may prevent postoperative shoulder problems, the majority of trials conducted to date are small, methodologically weak and with short-term follow-up. Many trials investigated exercise delay prescription until after completion of adjuvant therapy. 12 Few fully report details of prescribed regimes; hence there is a lack of knowledge regarding the optimum content, frequency, intensity, timing or safety of exercise prescription. Another limitation is the exclusion of patients with existing shoulder problems, the very population who may benefit the most from targeted postoperative support. 18

Rationale for the PRevention Of Shoulder ProblEms tRial

We designed the PRevention Of Shoulder ProblEms tRial (PROSPER) to address the evidence gap and to investigate whether or not an early supervised exercise programme, compared with usual care, could prevent musculoskeletal shoulder conditions in patients undergoing treatment for breast cancer. This research was commissioned in 2013–14 by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme, with specifications to design an exercise intervention for women identified as being at higher risk of developing shoulder problems as a consequence of their breast cancer treatment. At the time of funding, the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommended that all breast cancer patients should be provided with instructions on functional exercises to start doing from the first postoperative day. Each breast cancer centre should have written local guidelines for postoperative physiotherapy, but NICE recommended that patients be referred to physiotherapy services only if they experienced persistent shoulder restrictions after cancer treatment. 3

Literature update

We reviewed literature to identify new trials investigating exercise after breast cancer surgery published since the commissioned call in 2014. We sought RCTs comparing exercise and/or physiotherapy with standard or usual care (i.e. no active intervention), regardless of the type of outcome. Our search strategies were adapted from previous systematic reviews12,14 and applied to MEDLINE (via Ovid), EMBASE (via Ovid), PEDro (Physiotherapy Evidence Database) and LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature). We also searched for trials registered on the World Health Organization (WHO) search portal, the European Union clinical trials register and www.clinicaltrials.gov (US National Library of Medicine). We searched for citations published from 1 January 2014 to 10 December 2019. Of 439 potentially eligible studies identified, after screening titles and abstracts, 12 trials were included, eight of which were published trials and four of which were registered as ongoing. One trial reported ROM and grip strength data across two separate publications. 19,20

Recent evidence: physiotherapy compared with usual care

Of eight published trials, four were pilot RCTs and all studies were single centred with small sample sizes (mean 79 participants), although one trial recruited 153 participants. 21 Type of exercise varied and included aquatic-based,22 aerobic23 and resisted exercises. 19–21,24–26 Interventions were delivered either in the clinic setting19–23,25,26 or using an online interface. 24 Exercise programmes varied widely in terms of duration and frequency, ranging from 3 to 9 months (Table 1). 23,26 Outcomes also varied, but the most commonly reported were health-related quality of life (HRQoL), function and lymphoedema. Five studies reported improvements favouring the intervention group for the majority of outcomes (n = 427 participants). Three studies reported no differences between groups for function19 (n = 59 participants), lymphoedema22 (n = 29 participants) or limb volume25 (n = 35 participants).

| First author | Country (design) | Sample size (n) | Participants | Intervention | Comparison | Primary outcome | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casla23 | Spain (RCT) |

94 I: 47 C: 47 |

Stages I–III breast cancer 1 month to 3 years post completion of RT or chemotherapy |

Resisted and aerobic supervised exercise Frequency Twice per week for 12 weeks plus dietary counselling (three sessions) |

No intervention | Cardiorespiratory capacity: VO2 max at 12 weeks and 6 months |

Improvement in VO2 max at 12 weeks in favour of exercise Only the exercise group reassessed at 6 months: maintained improvements from 12 weeks |

| Galiano-Castillo24 | Spain (RCT) |

81 I: 40 C: 41 |

Stages I–III breast cancer Completed adjuvant therapy |

Tailored exercise programme using an online interface Frequency Three times per week for 8 weeks; 90 minutes for each session |

Information about exercise only | QoL: EORTC QLQ-C30 at 8 weeks and 6 months | Difference in QoL at 8 weeks and 6 months in favour of exercise |

| Ibrahim19,20 | Canada (Pilot RCT) |

59 I: 29 C: 30 |

Stages I-III breast cancer Younger women aged 18–45 years, scheduled for adjuvant therapy |

Progressive exercises Frequency 6 weeks, with an optional additional 6 weeks |

Advice on healthy lifestyle and exercise |

Function: DASH score at 18 months post radiotherapy19 ROM: goniometer at 18 months post radiotherapy20 |

No differences between groups for function19 The intervention group had better ROM at 6 months, but it was not sustained at 12 and 18 months20 |

| Johansson22 | Sweden (pilot RCT) |

29 I: 15 C: 14 |

Unilateral breast cancer and lymphoedema for at least 6 months |

Aquatic physiotherapy Frequency Three times per week for 8 weeks; 30-minute sessions |

Instructions to continue exercises if any | Lymphoedema: volume, bioimpedance and tissue water at end of 8-week intervention | No differences in lymphoedema at 8 weeks |

| Leal25 | Brazil (RCT) |

35 I: 17 C:18 |

Women undergoing breast cancer surgery and RT | Supervised exercise | No intervention | Volume: circumference | No differences observed at 8 weeks post therapy |

| Rafn26 | Canada (Pilot RCT) |

41 I: 21 C: 20 |

Women scheduled for breast surgery |

Patients assessed at 3, 6 and 9 months after surgery. Physiotherapy started because of restricted ROM, weakness or lymphoedema Usual care also provided |

Usual care: three sessions at 3, 6 and 9 months post surgery. Information on nutrition, stress and fatigue management |

Arm morbidity: ROM – goniometer. Strength: hand-held dynamometer and handgrip dynamometer Volume: circumference Function: QuickDASH Pain: NRS QoL: FACT-B4 |

At 12 months, control group had complex arm morbidity compared with intervention group |

| Yuste Sánchez21 | Spain (non-randomised comparative study) |

153 I: 76 C: 77 |

Stages I and II breast cancer, unilateral surgery with ALND |

Exercises plus MLD Frequency Three times per week for 3 weeks, plus information on treatment, morbidity and behavioural change |

Information on treatment, morbidity and behavioural change | QoL: EORTC QLQ-C30 + EORTC QLQ-BR23 at 3 weeks, and 3, 6 and 12 months |

Differences in physical and social dimensions only at 3 and 6 months The intervention group showed greater improvement |

Forthcoming studies: registered trials

At the time of writing, we found four registered trials, all overdue for reporting, from Spain (n = 90 participants27 and n = 84 participants28), Brazil (n = 38 participants29) and the USA (n = 568 participants30) (Table 2). These trials have different primary outcomes and postoperative follow-up points: ROM at 1 month,28 pain and fatigue after 7 weeks of exercise sessions,29 functional capacity at 12 months27 and presence of lymphoedema at 18 months. 30 The American lymphoedema trial30 has provided interim data on the clinicaltrials.gov website suggesting early benefit on lymphoedema outcomes; final results are pending. We present an overview of findings regarding the content and safety of exercise interventions in Chapter 3, which describes the development of the PROSPER exercise intervention.

| First author | Country | Estimated completion date | Target sample size (n) | Participants | Intervention | Comparator | Primary outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| de Santana29 | Brazil | December 2018 | 38 | Women with mastectomy, without drain within 4 months of surgery |

Supervised exercises Frequency Three times per week for 50 minutes, 20 sessions (7 weeks) |

Information leaflet. Patients to have face-to-face sessions once per week, in which the physiotherapist will help patients with exercise and load progression; exercises are performed at home three times per week | Pain (NRS) at 7 weeks |

| Gomez27 | Spain | February 2017 | 90 | Women with breast cancer, completed at least 6 months before, with persistent fatigue | Supervised physiotherapy and information about healthy habits and exercise following breast cancer treatment | Patients instructed to practice exercises of their preference and received information about healthy habits and exercise following breast cancer treatment | Functional capacity: 6-minute walking test at 12 months |

| Paskett30 | USA | December 2018 | 568 |

Stages I–III breast cancer Women, newly diagnosed with or without neoadjuvant, surgery and/or RT |

Supervised physiotherapy and information on lymphoedema | Information on lymphoedema only | Lymphoedema events at 18 months |

| Sánchez28 | Spain | August 2019 | 84 | Women with SLNB | Supervised six sessions of physiotherapy over 4 weeks | Information on adequate recovery | ROM at 4 weeks |

Aims and objectives of PROSPER

The overall aim of PROSPER was to investigate whether or not an early supervised exercise programme compared with best practice usual care was clinically effective and cost-effective for women at high risk of shoulder problems after breast cancer treatment on outcomes of upper limb function, complications and QoL.

The study objectives were to:

-

develop and refine a complex intervention of physiotherapy-led exercises, incorporating behavioural strategies, for women at risk of developing musculoskeletal problems after breast cancer treatment

-

assess the acceptability of the structured exercise programme and outcome measures, to optimise participant recruitment and refine trial processes during a 6-month internal pilot phase

-

use findings from the internal pilot phase to undertake a definitive, full RCT in approximately 15 UK NHS breast cancer centres.

A health economic analysis and a qualitative substudy were embedded within the trial. Qualitative research was undertaken throughout to inform intervention development and gain insight into the experiences of both women and physiotherapists taking part in trial interventions.

Overview of report

The report is structured across seven subsequent chapters. We present the methods and describe intervention development and trial results, followed by separate chapters reporting the qualitative findings and the health economic evaluation. Finally, we present an overarching discussion and conclusion.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design and setting

This trial was a two-arm, pragmatic RCT with an internal pilot study, an embedded qualitative evaluation and a parallel economic analysis. A detailed description of the trial protocol has been published. 31 The trial was undertaken in secondary care settings, in breast cancer centres within NHS trusts across England.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Those eligible to participate were women aged ≥ 18 years who had been diagnosed with primary breast cancer scheduled for surgical excision and were willing and able to comply with the study protocol. All participants provided signed, informed consent. Only patients considered at high risk of developing shoulder problems were eligible to participate, defined in accordance prespecified PROSPER criteria.

Definition of high risk of shoulder problems

We specified high-risk criteria for the purpose of the trial. Participants deemed at higher risk of developing shoulder problems were defined in accordance with one or more of the following criteria: planned ANC, planned radiotherapy to the axilla or supraclavicular nodes, shoulder problems before breast cancer treatment, obesity (defined as a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2) or any subsequent axillary surgery related to the primary surgery. Existing shoulder problems were defined as a history of shoulder surgery, shoulder trauma injury (fracture or shoulder dislocation), frozen shoulder, osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis affecting the shoulder, non-specific shoulder pain, stiffness or decreased function. Decreased function was assessed using simple screening questions: ‘Can you do any of the following without problems? (a) wash your hair, (b) wash your back, (c) reach up to a high shelf?’. Participants who could not undertake one or more of these activities were eligible to be invited to take part in the trial.

Eligibility for late entry (within 6 weeks of surgery)

The decision about the need for radiotherapy is often taken after surgery, after pathological confirmation of tumour size, grade, histology and margin status. Patients who were ineligible at the time of primary surgery but who were later informed of the need for axillary and/or supraclavicular nodes radiotherapy within 6 weeks of surgery were eligible to participate. Six weeks was selected as the cut-off point for commencement of physiotherapy treatment.

Exclusion criteria

Men were excluded, as were women known to be undergoing immediate breast reconstruction surgery at the time of recruitment, women undergoing SLNB without other high-risk criteria, women undergoing bilateral breast surgery and those with known metastatic disease at the time of recruitment.

Participant recruitment and consent

Patients were identified from multidisciplinary cancer team meetings and preoperative oncology and radiotherapy clinics. Screening was undertaken by a member of the clinical team (a specialist breast nurse, surgeon, research nurse or facilitator trained in PROSPER screening and recruitment procedures). Eligible patients were given a patient information sheet while attending an oncology clinic and were given at least 24 hours to consider participation. In the case of those interested and willing to participate, written informed consent was obtained by the delegated site investigator after discussion and clarification of any queries. We sought consent for multiple levels of access to medical data, including medical records and routine data held by NHS Digital. At the time of trial launch, the wording of consent forms was appropriate for access to Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data and approved by the Ethics Committee and relevant monitoring committees.

Trial setting and prespecified requirements

The trial was undertaken in secondary care settings in England, in NHS trusts with specialist breast oncology services. Any centre could take part as long as hospital physiotherapy services had the capacity to treat participants for the trial duration. We specified that a minimum of two physiotherapists per site attend intervention training. Any hospital providing routine preoperative or postoperative physiotherapy for non-reconstructive breast surgery could not take part. We also screened usual-care practices at hospitals expressing an interest in taking part. A specification was the agreement of centres to provide PROSPER usual-care leaflets for all trial participants.

Allocation sequence generation and randomisation

The unit of randomisation was the individual participant. Three stratification variables were used: the centre, whether it was the participant’s first or repeat surgery and whether or not the participant had been informed of the need for radiotherapy within 6 weeks of surgery. These stratification variables accounted for late-entry participants and for those having multiple surgical procedures, which can increase the risk of postoperative complications. We used a computer-generated randomisation algorithm held and controlled centrally within the Warwick Clinical Trials Unit (WCTU) by an independent programmer. Trial participants were registered after screening checks, then randomised to treatment. Treatment allocation was coded and unavailable to the trial management team.

Blinding

We adhered to the Consolidating Standards of Reporting Clinical Trials (CONSORT) statement. 32 Owing to the nature of the exercise intervention, it was not possible to blind participants or physiotherapists delivering the intervention. Data entry staff were unaware of treatment allocation, and we undertook data cleaning blind to treatment allocation. Senior members of the research team and the statistical team were blind to treatment allocation for the duration of the trial. Final statistical analysis was undertaken by a statistician independent of the core trial team.

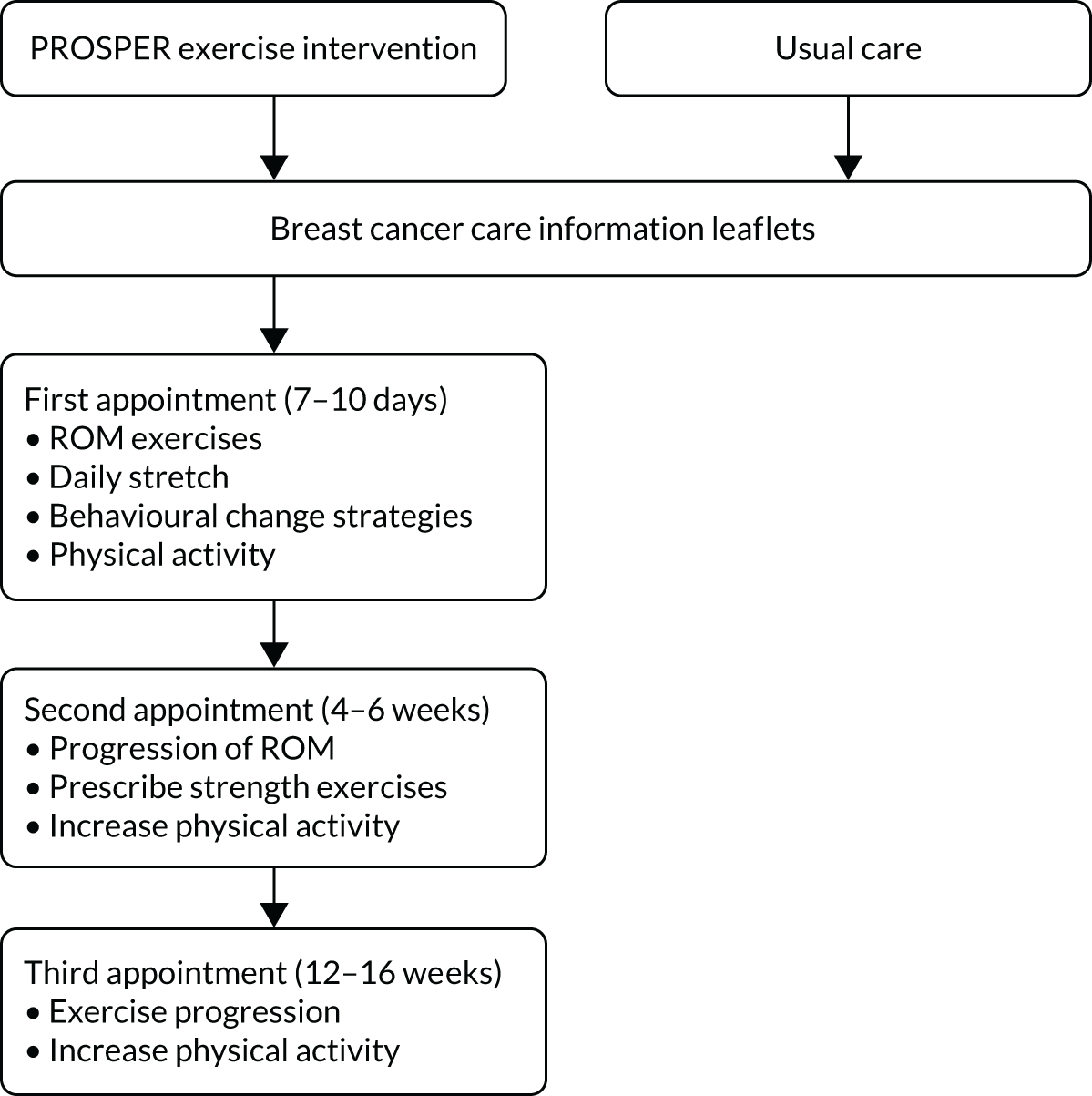

Trial interventions

Full details of trial interventions are described in Chapter 3. In summary, all participants received best-practice usual care consisting of two information leaflets describing postoperative exercises and advice for recovery after surgery. 33,34 The control group participants received no further intervention other than usual clinical care. Participants randomised to the exercise intervention were then referred to physiotherapy. We designed a new exercise programme that was underpinned with evidence and co-developed with cancer rehabilitation specialists and breast cancer survivors. The newly developed intervention was a physiotherapist-led, individualised, structured exercise programme comprising shoulder-specific exercises, behavioural change strategies and physical activity. 35 Three face-to-face appointments with a trained physiotherapist were scheduled at specific postoperative time points, with up to three optional appointments at any time up to 12 months after randomisation. An overview of the PROSPER intervention is detailed in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of trial interventions.

Co-interventions

No restrictions were placed with regard to referral to other health-care providers or private physiotherapy during the trial. At trial closure, participants continued with their usual health care.

Data collection

Baseline data

Baseline data were collected after participants provided informed consent. Baseline questionnaire booklets were given to participants preoperatively either to complete in clinic or to take home and return by post to the study office. Late entry trial participants completed booklets after surgery. Descriptive data included age, height, weight, marital status, education level, employment, handedness, ethnicity and self-reported comorbidity. Questionnaires also included all patient-reported outcome measures, described in Outcomes. We gathered data on planned clinical treatment at recruitment. Follow-up data were collected by postal questionnaire.

Outcomes

Primary outcome: function of upper limb

The primary outcome was upper limb function at 12 months measured using the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) scale. 36 Breast cancer treatments mainly affect the axilla and shoulder region, but can also affect the arm and hand, leading to functional problems with daily activities, such as dressing, writing, opening or closing jars and lifting and/or holding shopping bags. 37 We opted to use the 30-item DASH scale to measure upper limb function rather than the shorter Quick-DASH or a shoulder-specific assessment tool. The DASH scores range from 0 (no disability) to 100 (most severe disability). 36 The DASH questionnaire includes 21 items on function, five items on symptoms (pain, activity-related pain, tingling, stiffness and weakness) and three items on social/role function. There is good evidence that the DASH scale can detect change in function over time and detect clinically important differences between groups. 38 The DASH scale has also been used in observational studies39 and clinical trials of breast cancer populations. 18,40,41 An overview of outcomes is provided in Table 3.

| Outcome | Timing | Instrument, description of outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Function | Baseline, 6 months, 12 months | Primary outcome: upper-limb function – DASH 30 items (no difficulty, mild, moderate, severe difficulty, unable to do). Total score 0 (no difficulty) to 100 (extreme difficulty) |

| Function subscales | Baseline, 6 months, 12 months | Secondary outcomes: AL 17 items, I 6 items and PR 5-item subscale using DASH 30 items,a modified from Dixon et al.42 |

| Wound related | 6 weeks only | Wound healing, self-reported and doctor-diagnosed SSI |

| Pain in breast and armpit (acute, chronic, neuropathic) | Baseline, 6 weeks, 6 months, 12 months | Pain on movement and at rest in last week, NRS. Pain intensity 0 (no pain) to 10 (pain as bad as can imagine). Single NRS at other time points. Neuropathic pain: DN4 – seven-item descriptive scale; score of ≥ 4 indicative of neuropathic pain. FACT-B4. Arm symptom scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). Symptoms: arm swollen or tender, movement is painful, poor range of arm movements, arm numbness, arm stiffness |

| Lymphoedema | Baseline, 6 weeks, 6 months, 12 months | LBCQ: arm feels heavy and arm looks swollen, previous week. Presence of both is indicative of lymphoedema |

| Physical activity | Baseline, 6 weeks, 6 months, 12 months | PASE: two activity items: walking in home or garden and strenuous sport/recreational activity, in the past week. How many hours per day on average |

| Confidence in activity | Baseline, 6 weeks, 6 months, 12 months |

Confidence in return to usual activities and regular physical activity in future NRS: score 0 (not confident at all) to 10 (very confident) |

| HRQoL | Baseline, 6, 12 months |

EQ-5D-5L + VAS: 5-item score converted into a single summary score (–0.594 to 1). A score of 1 indicates maximum HRQoL. VAS numerical 0 to 100, maximum health SF-12: HRQoL: 12 items, score 0 to 100, higher score indicates better HRQoL |

| Health-care resource use | 6, 12 months | Self-report and routine HES data for APC and outpatient activity for years 2015–16, 2016–17, 2017–18 |

Secondary outcomes

DASH subscales (baseline, 6 months and 12 months)

The DASH scale has been used to generate three health outcome subscores for activity limitations, impairment and participation restriction, as per the WHO International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health taxonomy. 42,43 DASH subscores were measured at baseline, at 6 months and at 12 months.

Health-related quality of life (baseline, 6 months and 12 months)

We used the Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12)44 to measure physical function, engagement in usual activities and mental functioning. The physical health composite scale (PCS) and mental health composite scale (MCS) allow comparison with national norms and to cancer populations. We also used the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) questionnaire, a standardised measure of self-reported HRQoL that includes five domains of mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. 45

Acute and chronic postoperative pain (baseline, 6 weeks, 6 months and 12 months)

We measured treatment-related complications, including pain intensity, pain character and neuropathic pain at multiple time points. We measured acute postoperative pain using an 11-point numerical rating scale (NRS) from 0 (no pain) to 10 (pain as bad as you can imagine) for pain at rest and movement-evoked pain at 6 weeks postoperatively, as per recommended international guidance for postoperative pain assessment. 46 A single pain NRS was used to capture chronic pain at 6 and 12 months. We examined proportions with none/mild (0–3 NRS) and moderate/severe intensity pain (≥ 4 NRS). We used the Douleur Neuropathique (DN4)47 seven-item scale, validated for postal use, to capture neuropathic pain at 6 weeks, 6 months and 12 months.

Wound-related outcomes: surgical site infection (6 weeks)

We measured wound-related outcomes, including patient-reported wound healing and surgical site infection (SSI), at 6 weeks: questions included whether or not a doctor or nurse had diagnosed a wound infection, whether or not the participant thought that they had had a wound infection and whether or not the participant had been prescribed antibiotics. Any other postoperative complication could be reported using free text.

Lymphoedema (baseline, 6 weeks, 6 months and 12 months)

We also used the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Breast, version 4 (FACT-B4), five-item subscale48 to capture symptoms of arm disability: higher scores indicate greater arm disability or morbidity (scale range 0–20). We assessed patient-reported symptoms of lymphoedema using the validated Lymphoedema and Breast Cancer Questionnaire (LBCQ). 49 Two items (i.e. arm swelling and arm heaviness) from the full LBCQ are predictive of arm swelling of at least 2 cm change in arm circumference. 49 Objective measurement, such as optoelectronic limb volumeters (perometry), was not available across all NHS breast cancer units and thus was not feasible to use in this multicentre trial. Patient-reported symptoms are more meaningful to patients and these self-reported LBQC items have been used in other large-scale international trials investigating morbidity outcomes after axillary treatment (NIHR-funded POSNOC50 and ATNEC51). Items included ‘my arm feels heavy’ and ‘my arm/hand looks swollen’ on the side on which surgery had been carried out in the previous week. We accepted a positive response to both questions as indicative of self-reported lymphoedema.

Physical activity (baseline, 6 weeks, 6 months and 12 months)

We collected physical activity data using selected items from the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE)52 for activity in the previous week: walking outside the home and sport/recreational activities, with average hours per day for each. The term ‘yard’ was replaced with garden to align with UK terminology.

Health-care resource use (over 12 months)

Health-care resource use was captured for health economic analyses, using self-report. This is described further in Chapter 6. We obtained HES data from NHS Digital for three financial years, from 2015 to 2018. Data sets included admitted patient care and outpatient activity.

Data collection

Follow-up data were collected at 6 weeks, 6 months and 12 months postoperatively. We used postal questionnaires for all patient-reported outcomes with an explanatory cover letter. Questionnaire booklets were professionally printed, in colour, with a freephone number on the front page and a free-text section on the final page. Draft versions were modified after pilot testing and feedback from women treated for breast cancer. Core outcome data were collected by telephone if no response was received after one postal reminder. Clinical data on all surgeries and adjuvant treatment delivered over the study duration were gathered from medical records after completion of the 12-month follow-up.

Process evaluation

We measured a range of process evaluation indicators relating to intervention uptake and delivery. Data included time from randomisation to first appointment, participant uptake of the exercise intervention, number of contacts with physiotherapists and number of quality control (QC) assessments. We defined adherence to or compliance with the prescribed exercise programme as a participant having three or more contacts with the physiotherapist. Those having one or two contacts only were defined as partial compliers. We calculated ‘strength and work capacity’ for ROM and strength exercises, defined as the product of repetitions and sets prescribed at each appointment. The terminology ‘work capacity’ is used throughout to denote ‘strength and work capacity exercises’. For strength exercises, this was calculated using the product of resistance for Therabands [Paterson Medical, Cascade Healthcare Solutions, Tukwila, WA, USA (1.1 kg, 1.7 kg or 2.7 kg)] by repetitions and sets prescribed from the second appointment onwards. Theraband length was standardised, although physiotherapists spent time with each participant to demonstrate how to use the band correctly to ensure that the band length was suitable and to check their technique. If necessary, the bands could be shortened by adjusting the grip.

Monitoring of intervention delivery

Physiotherapists completed treatment logs to record information on attendance, exercise prescription, shoulder ROM, muscle strength, lymphoedema, wound healing, pain intensity and confidence in exercising for every participant. Completed treatment logs were returned to the co-ordinating centre after participants were discharged from physiotherapy. Chapter 3 describes quality assessment procedures for intervention fidelity.

Data management

Questionnaires were entered manually by the research team into a bespoke database, designed by the WCTU programming team. All data were checked for range, outliers, data missingness and date discrepancies. Any identified anomaly was checked against original data sources for rectification.

Data analyses

Sample size calculation

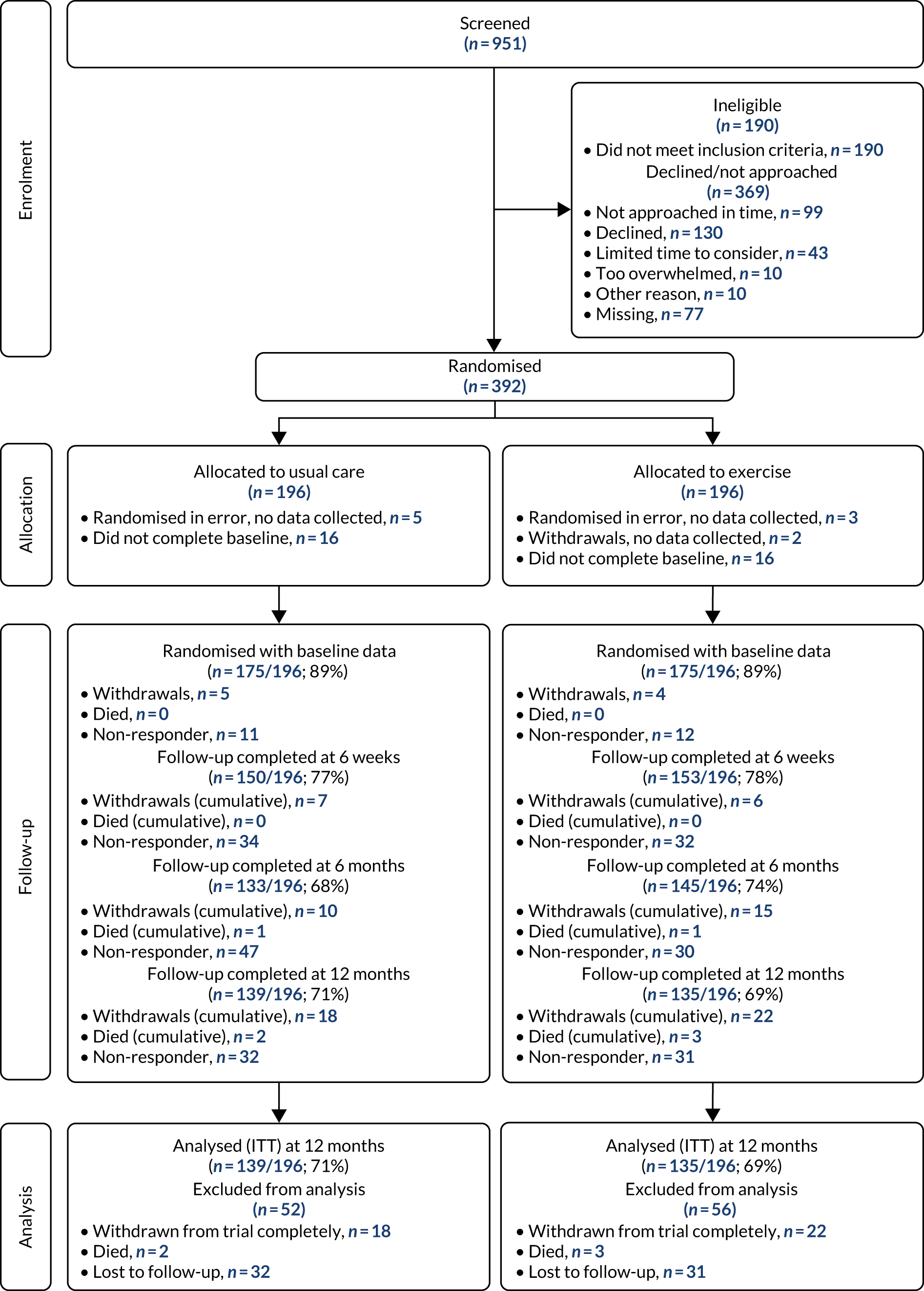

The target sample size for the trial was 350 patients, allocated in a 1 : 1 ratio. This calculation was based on data from a Dutch trial41 comparing the effects of a leaflet only with an exercise intervention, started 2 weeks postoperatively in 30 women having breast surgery and ALND (n = 15 per group). The authors reported a between-group difference of 7 points on the DASH scale at 6 months [mean 21.6 points in the control group; mean 14.6 points in the intervention group; pooled standard deviation (SD) of 19.5 points at baseline and a standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.36 points] after a 3-month exercise intervention. 41 At 80% power and significance level of < 0.05 points, this yielded a target total sample of 242 participants. Accounting for therapist effects, with up to nine patients per therapist in the intervention group, an intracluster coefficient (ICC) of 0.01, yielding a design effect of 1.05, gave a target of 256 patients. The ICC estimate of 0.01 was based on previous experience of exercise interventions in a range of musculoskeletal trials. 53 We anticipated very little therapist effect but, in the eventuality of lower therapist effects, we would have greater power with the given numbers to detect the same difference. We considered a loss to follow-up of 25% because the complexity and challenges of cancer treatment increase the risk of attrition over time. This higher percentage of loss to follow-up allows the detection of smaller effects.

We considered the recommended minimally clinically important difference (MCID) for the DASH scale. 38 Observational studies of rheumatology and orthopaedic populations suggested that the MCID is 10 points (95% CI 5 to 15 points) and that between-group difference for trials using the DASH scale should be set at 10. 38 However, this fails to account for many of the eventualities that occur in pragmatic trials, notably that there is not a no-treatment control, and that some members of the control group may be exposed by serendipity to an intervention of similar intensity, particularly in a high-risk population. Previous studies also used shorter time frames for follow-up, assessing change in function from weeks to several months. 38,41 Therefore, we powered the trial to detect a 7-point difference between groups at 12 months.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out using Stata® version 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). All statistical tests were two-sided and performed at the 5% significance level. We undertook two levels of analysis: using intention to treat (ITT), as per CONSORT guidelines,32 and complier-average causal effect (CACE). 54 We reviewed other examples53,55 of CACE analyses from physiotherapy trials to inform our definition of compliance with exercise. We found variation in the reporting of compliance or adherence with exercise because definitions depend on the content and duration of interventions being evaluated, for example defined as completing half of six recommended sessions53 or exploration of different thresholds. 55 For PROSPER, we defined ‘complete’ compliance with the intervention as three or more sessions with the physiotherapist. This was the specified minimum number of recommended contacts that would ensure that all elements of the exercise programme were introduced and progressed. We defined non-compliance as none or fewer than three physiotherapy sessions.

Descriptive analysis

All baseline demographic and pre-randomisation clinical measures were summarised by treatment allocation. Continuous data were summarised using mean, SD, median and range values. Categorical data were summarised by number and proportion (%) by treatment group. For both types of data, CIs were also specified.

Primary analysis

The primary analysis compared the DASH score at 12 months between usual care and the exercise intervention. The clustering effect was assessed prior to data analysis and was found to be negligible. For this reason, the primary outcome was assessed using ordinary linear regression. In each case, we summarised the mean DASH change score from baseline to 6 and 12 months respectively, by treatment group and for differences between treatment groups using unadjusted and adjusted estimates. We adjusted for baseline scores, age, type of breast surgery (BCS vs. mastectomy), type of axillary surgery (ANC vs. SNLB), radiotherapy (yes/no) and chemotherapy (yes/no). For the primary analyses, a post hoc sensitivity analysis was undertaken to assess the impact of adjusting for age only at baseline, given that participants had not completed adjuvant therapy on recruitment. Mean changes and 95% CIs were plotted graphically to assess change over 12 months.

Missing data

We followed the DASH scoring manual, which specifies that a score cannot be calculated if there are more than three missing items. As a sensitivity analysis, the impact of the missing data was assessed using multiple imputation. Two data sets were used for the statistical analysis, observed and imputed. The observed data set comprised all observed data, including follow-up, with missing values. Impact of data missingness was assessed using multiple imputation. Missing data due to participants or health professionals incorrectly leaving fields blank (invalidly missing) were examined further to assess whether multiple imputation was viable: missing completely at random, missing at random or not missing at random. For normally distributed data, we used multiple imputation methods. 56 These were carried out using the imputation by chained equations (ICE) procedure. 57 The imputed ITT data set was used for sensitivity analyses.

Subgroup analyses

We prespecified subgroup analyses to examine differences in baseline DASH scores depending on previous clinical history. We anticipated that women reporting a history of shoulder problems were more likely to have arm disability than those without a history of shoulder problems, although this would be reflected in DASH scores at baseline. This was explored and reported.

Sensitivity analyses

Various sensitivity analyses were planned: first by comparing high- and low-volume recruiting centres to examine the impact on clustering effect and to analyse high-volume centres to examine therapist effect. We also explored time of follow-up from randomisation. As this was a surgical trial, we anticipated variation in follow-up in relation to timing of surgery. Most participants will have a short time period between randomisation and surgery, except for late-entry participants informed of the need for radiotherapy postoperatively. We assessed differences between date of randomisation and date of surgery by treatment group, but these were negligible. As the clustering effect was also negligible, the first two sensitivity analyses were discarded.

Adverse event reporting

An adverse event (AE) was defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a participant that did not necessarily have a causal relationship with this intervention. We defined serious adverse events (SAEs) as an untoward occurrence that resulted in death, was life-threatening, required hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity, or was considered medically significant. Expected common postoperative AEs included superficial and deep SSIs, seroma, bruising/haematoma and drain site infections. Some muscle soreness was to be expected after stretching and strengthening exercises. We recorded postoperative events, but they were not considered serious unless they arose as a direct consequence of the trial intervention. All AE data were reviewed by independent monitoring committees. We compared the number of AEs and SAEs by treatment group using chi-squared tests or Fisher’s exact test, with odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs.

Withdrawals

There were different levels of withdrawal within the trial: (1) withdrawals from treatment (exercise intervention), (2) withdrawals from postal questionnaires but with permission for all other data collected to be used, (3) withdrawal of approval for access to routine hospital data (HES) and (4) complete withdrawal of all data. The level of withdrawal from follow-up was explored by treatment group.

All planned analyses and template tables were detailed in the statistical analysis plan and reviewed and approved by the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) prior to any final statistical analysis. One amendment was made to the statistical analysis plan after publication of the protocol to adjust analyses for baseline DASH scores.

Pilot study

A 6-month internal pilot was planned in three centres, with a target recruitment of 30 participants. We launched the pilot study in January 2016 in three breast cancer units: Coventry, Oxford and Wolverhampton. We launched the main trial after reaching recruitment targets and satisfying stop/go criteria.

Monitoring and approval

Ethics approval for the trial was granted on 20 July 2015. The first amendment, granted on 16 December 2015, was for modifications to participant materials. Amendments 2 and 3, granted on 4 April and 18 July 2016, respectively, related to the opening of new centres and transfer to Health Research Authority-regulated approvals. Amendment 4, granted on 18 April 2017, amended wording on the 12-month data collection forms. The final amendment was to add qualitative interviews with physiotherapists and was granted on 4 May 2018. We first applied for HES data in October 2017. Approval was granted by the Caldicott Guardian in April 2019 and we received data in October 2019.

Patient and public involvement

Patient representatives were involved at multiple stages throughout the trial, from grant writing and protocol refinement to intervention development and trial oversight. We sought input into the proposed intervention from breast cancer survivors attending a local community support group, described in Chapter 3. Our lead lay applicant passed away in 2017 (CH).

Trial Steering Committee

The Trial Steering Committee (TSC) was responsible for monitoring and supervising PROSPER progress. The TSC comprised independent members with expertise in oncology, physiotherapy, radiotherapy and medical statistics and one lay member (CH).

Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee

The DMEC reviewed trial progress, recruitment, protocol compliance and interim analysis of outcomes. The committee included independent experts with expertise in surgical oncology, health services research and medical statistics.

Chapter 3 Intervention development

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced or adapted with permission from Richmond et al. 35 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

This chapter presents a description of the PROSPER usual-care and exercise interventions. We developed an exercise intervention for the trial following Medical Research Council guidance for the design of complex interventions. 58 We present an overview of the evidence to inform the selection of core components and we describe the final intervention as per the Template for Intervention Development and Replication (TIDieR)59 recommendations and the Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT). 60

Control group: information leaflets

Participants allocated to the control group received best-practice usual care. At the time of trial set-up, usual NHS care was to provide newly diagnosed breast cancer patients with information leaflets describing cancer treatments and advice for postoperative recovery. 61 Specialist breast cancer nurses or oncology teams gave leaflets preoperatively. Patients undergoing non-reconstructive surgery were not routinely referred to physiotherapy services unless for a specific postoperative musculoskeletal problem. In 2005, a review61 of patient materials from 105 UK oncology departments across England was undertaken to identify usual clinical practice for postoperative shoulder mobilisation after breast cancer surgery. This survey61 found that half of the responding centres used materials published by Breast Cancer Care (now Breast Cancer Care/Breast Cancer Now; London, UK). We undertook a scoping survey of information leaflets used in breast cancer units across England and evaluated materials published by breast cancer charities. The content and design of hospital leaflets varied widely, although many were adapted or photocopied from charity materials. Most recommended restricted arm movement in the first postoperative week. We reviewed all materials, in collaboration with patient representatives and clinical rehabilitation experts, to select leaflets for best-practice usual care. We selected two well-designed, colourful leaflets produced by the charity Breast Cancer Care: Exercises After Breast Cancer Surgery33 and Your Operation and Recovery. 34 These leaflets describe exercises to do after breast surgery, lymph node removal and/or radiotherapy. Recommendations were to start upper body exercises from the first postoperative day, with instructions for warm up, basic arm exercises restricted to 90° of shoulder elevation, and a cool-down (BCC633). More advanced exercises, such as wall climbing, arm lifts and elbow pushes, were recommended from the second postoperative week onwards. The surgical recovery leaflet (BCC15134) covered generic postoperative advice and common complications, including wound infection, pain, cording, seroma and lymphoedema. These leaflets were provided to the study team free of charge by Breast Cancer Care. All participants were given a copy of each leaflet on recruitment to the trial; these were given out by the surgical oncology teams.

Overview of exercise intervention development

We designed a new exercise programme specifically for testing within PROSPER. We followed multiple steps to develop and refine the intervention before testing in the main trial. The key stages of development included:

-

an exploratory phase incorporating a literature review to identify evidence of effectiveness and harm from exercise interventions and of behaviour change techniques, a survey of postoperative materials used in the NHS, a patient and public involvement (PPI) focus group with breast cancer survivors and consultation with cancer rehabilitation experts

-

production of a draft intervention protocol for agreement at an intervention development consensus day, hosted by the WCTU, attended by 20 clinical rehabilitation experts and two breast cancer survivors

-

assessment of feasibility and acceptability of the prototype exercise programme with women attending a community-based support group for breast cancer patients, testing the intervention with 15 newly diagnosed breast cancer participants recruited to the internal pilot study from three NHS trusts

-

final refinement of the exercise programme based on patient and therapist feedback during the internal pilot study.

The final PROSPER exercise intervention was a physiotherapist-led, early, progressive, home-based postoperative programme that incorporated three components: shoulder-specific exercises, physical activity and behavioural support strategies to encourage adherence. The PROSPER programme was designed to be adaptable and flexible to allow for prolonged cancer treatment schedules and cancer-related fatigue. The evidence and rationale for inclusion of core components are given below.

Overview of evidence for exercise after breast cancer surgery

We undertook a literature review to identify systematic reviews and clinical trials investigating the effectiveness and potential adverse effects from exercise interventions for breast cancer patients. We also reviewed national and international breast cancer clinical guidelines62–64 and the types of exercises reported to be prescribed within the UK survey of physiotherapy and oncology departments. 61 We considered the content, timing, duration and setting of delivery of exercises.

A Cochrane systematic review,12 published in 2010, investigated the effectiveness of exercise interventions in preventing, minimising or improving upper limb dysfunction due to breast cancer treatment (24 trials; 2132 participants). Exercise type was broadly classified as active, active-assisted, passive, manual stretching and resistance. The review compared interventions on outcomes of ROM, strength, lymphoedema and pain. Subgroup analyses compared the timing of exercise in relation to cancer treatment (10 trials; 1304 participants) and the effect of postoperative exercise to usual care (six trials; 354 participants). Authors defined early exercise as that commencing from days 1 to 3 postoperatively; in contrast ‘delayed’ exercise was defined as starting from day 4 onwards. This definition differed from that used in the UK survey,61 which defined delayed exercise as starting after 1 week. Only one of the 24 trials in the Cochrane review was considered at low risk of bias:65 the remainder were of low to moderate quality and with small sample sizes (mean 44 participants per treatment arm). Included trials were published between 1979 and 2008 and older trials examined rehabilitation after extensive breast surgery, such as modified radical mastectomy. These procedures have since been replaced with less invasive surgeries; therefore, some rehabilitation practices, such as wearing a sling, are no longer indicated.

We summarise findings from the literature review in relation to the core components considered for the PROSPER intervention. The Cochrane review12 informed intervention development, although the findings are now outdated as other trials of exercise interventions have been published or registered since publication of the Cochrane review in 2010. To date, however, only two trials have ever been undertaken in the UK NHS: a small trial examining wound drainage, conducted in 197966 (n = 69 radical mastectomy), and a single-centre trial67 examining lymphoedema after breast surgery with ALND (n = 116).

Evidence for early postoperative exercises

Axillary surgery and radiotherapy increase the risk of shoulder ROM restrictions, in particular flexion, abduction and abduction with external rotation. 14 Breast cancer treatments can damage the lymphatic system, causing secondary lymphoedema. Patients may benefit from ROM exercises as active and active-assisted ROM exercises can improve fluid drainage and lymphatic flow. These exercise modalities activate physiological mechanisms as a result of muscle contraction, and they can also increase blood flow to the joints and soft tissues. 14,68

The Cochrane review12 found some evidence that early ROM exercises were more beneficial than delayed exercise for shoulder flexion ROM in the short term, within 4–6 weeks postoperatively [mean difference (MD) 12.12°, 95% CI 0.35° to 23.88°; I2 = 89%; three studies, 608 participants]. 12 However, there was no evidence of a difference up to 2 years after surgery (MD 3.00°, 95% CI –0.65° to 6.65°; one study, 181 participants). 12 Early exercise was beneficial for shoulder abduction ROM at 1 week (MD 11.65°, 95% CI 2.93° to 20.38°; I2 = 85%, three studies, 677 participants), with meta-analysis suggesting some increased benefit at 6 months compared with delayed exercising (MD 4.31°, 95% CI 1.38° to 7.25°; I2 = 0%; two studies, 549 participants). 12

Evidence for harm or adverse events after early postoperative exercise

Early ROM exercises, when compared with delayed exercises, did not increase the risk of seroma after surgery (OR 1.52, 95% CI 0.82 to 2.82; five studies), delay wound healing (OR 1.30, 95% CI 0.82 to 2.31; four studies), increase the number of wound aspirations (weighted mean difference 0.11, 95% CI –0.23 to 0.45; three studies), increase postoperative pain at 6 months (OR 1.87, 95% CI 0.70 to 4.96; one study) or increase lymphoedema incidence at 6 months (OR 1.24, 95% CI 0.45 to 3.41; three studies). 12 However, early ROM did increase volume of wound drainage (SMD 0.31, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.49; seven studies, 912 participants) and extended duration of wound drainage by 1 day (weighted mean difference 1.15; 95% CI 0.65 to 1.65; five studies, 725 participants) compared with delayed exercises. In a sensitivity analysis excluding older surgical trials published pre 1995, these findings did not change: early ROM increased the volume of postoperative wound drainage. 12

The single-centre UK trial,67 published since the Cochrane review,12 found that introducing ROM exercises limited to 90° shoulder elevation in the first week after ALND did not increase the risk of AEs compared with starting exercises after 1 week. 67 As programmes incorporating ROM exercises were known to be safe, we included shoulder ROM from the first week onwards while recommending restriction of shoulder ROM below 90° in the first postoperative week. Early restriction of shoulder ROM was also recommended in hospital information leaflets and cancer charity materials.

Evidence for stretching exercises

Surgery to the axilla and radiotherapy to the supraclavicular and infraclavicular nodes can lead to structural and functional problems as a result of tissue inflammation and damage. 69 Treatments can lead to tightening and contracture across the shoulder and chest area. 70 Studies report that the pectoralis muscles can atrophy after treatment. 71 Stretching exercises may contribute to remodelling injured connective tissues and may prevent negative physiological adaptations to the muscle spindles. 72,73 Stretching may prevent the shortening of muscle fibres. 74 Few trials provided details of the included exercises, but, in those that did, stretching of the pectoral muscles was most commonly reported. 65,75,76 Although study findings were largely inconclusive in terms of ROM improvement, there was no evidence to suggest that exercise regimes incorporating pectoral muscle stretching increased the risk of arm comorbidity. 65,75 Some studies found evidence of benefit when stretching was combined with other ROM exercises. 14,77 Another consideration was the arm position required for radiotherapy, which requires flexibility and adequate ROM of the shoulder joint. A minimum range of 90° of shoulder abduction and lateral rotation is required for radiotherapy targeting the lateral side of the breast and chest wall. 61 Owing to the pectoralis major insertion on the humerus, a shortened pectoralis will affect the ability to place the arm into the required position for radiotherapy. 78 Given that we aimed to recruit women already considered at risk of shoulder problems, the PROSPER exercise intervention included a daily ‘stretch and hold’ exercise for the pectoralis muscles.

Evidence for strengthening exercises

Patients undergoing cancer treatment are at an increased risk of loss of muscle mass and reduced muscle strength as a consequence of treatment-related pathophysiological changes. 79,80 Older age is also a risk factor for reduced muscle mass and strength. Muscle strength is greatest in our younger years, with maximum strength peaking at age 20–40 years. 81 Breast cancer is more common in women aged > 50 years, when 10% of muscle mass is already lost. The rate of muscle decline then accelerates,81 although this decline is thought to be, in part, due to decreasing levels of physical activity. Strengthening exercises can prevent the loss of muscle and bone mass. 82 The physiological stimulus from strengthening exercises can improve muscle mass and strength even during active treatment, as demonstrated in studies of cancer populations. 82 Targeted strength training can stimulate other changes, including improvements in insulin action, bone density and energy metabolism. 81 One systematic review found some evidence for improved HRQoL in adult cancer survivors participating in resistance training compared with usual care or alternative exercise regimes (SMD –0.17, 95% CI –0.34 to 0.00; I2 = 0%; six studies, 548 participants). 83

Another systematic review84 investigated the impact of low- to moderate-intensity resistance training on outcomes of muscle function, body composition and fatigue in cancer survivors (nine trials, 752 participants). Seven of the nine trials included breast cancer patients. 84 A meta-analysis revealed that resistance training improved upper limb muscle strength up to 1 year after cancer treatment (weighted mean difference ≥ 6.9 kg, 95% CI 4.78 to 9.03 kg; I2 = 79%; nine studies, 752 participants). 84 Improvements in lower limb strength and percentage body fat were also observed, but with weaker evidence of an improvement in cancer-related fatigue [weighted mean difference 1.86 Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Fatigue, 95% CI –0.03 to 3.75; I2 = 0%; four studies, 437 participants]. 84

One trial82 included in the systematic review84 directly compared strengthening exercises to a stretching only programme for breast cancer patients (n = 106). 82 Those randomised to do strengthening exercises three times per week for 1 year maintained their bone and muscle mass throughout cancer treatment, in contrast to those following the stretching-only protocol. 82 Given the evidence for the benefits of strengthening exercises, we included progressive and individually tailored strengthening exercises to the PROSPER intervention. We specified that strengthening exercises should start only after the first postoperative month, to allow time for wound and tissue healing.

Evidence for physical activity

The American Cancer Society recommends that cancer patients should complete at least 150 minutes of moderate activity and at least two sessions of strength training per week. 85 This is in line with Department of Health and Social Care recommendations for physical activity for adults. 86 The American College of Sports Medicine recently recommended that cancer survivors should undertake aerobic and resistance training for approximately 30 minutes, for three sessions per week. 87 Physical activity during and after cancer treatment is safe, and has been associated with improved survival, reduced cancer recurrence and improvement in cancer-related side effects, with some studies reporting beneficial effects on fatigue, anxiety and depression. 83,88,89 Despite these benefits, only a small proportion of people achieve the recommended activity levels. One systematic review90 found that up to 70% of cancer survivors did not achieve the recommended activity targets. Cancer survivors are twice as likely to be physically inactive as the general population. 91

A Cochrane review,92 published since we developed the PROSPER intervention, found moderate-quality evidence that exercise during adjuvant treatment for breast cancer improved physical fitness (SMD 0.42, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.59; 15 studies, 1310 participants) and slightly reduced fatigue (SMD –0.28, 95% CI –0.41 to –0.16; 19 studies, 1698 participants), although there was weaker evidence for physical activity improving cancer-specific QoL or depression. 92 Given international recommendations to increase physical activity and evidence for improved outcomes during cancer treatment, without incurring risk of AEs, we incorporated physical activity guidance as a core component within the PROSPER intervention. 85

Evidence for behavioural change strategies

Early engagement with our lay representatives highlighted the need for a supported self-management approach to rehabilitation. National guidelines93 recommended that behaviour change strategies should be incorporated into any self-management interventions to support adherence and to achieve long-term behaviour change. 93 Adherence to any exercise intervention is essential to achieve the expected positive outcomes. However, there are numerous barriers to adherence and engagement with exercise, particularly during cancer treatment, when symptom burden can be overwhelming. 94 Psychological factors play a key role, particularly fear of cancer recurrence and fear of being active during treatment. 94–96

We referred to the NHS Health Trainer Manual,93,97 which was developed by health psychology experts in behaviour change. This practical guide summarises evidence-based strategies to promote positive health-related behavioural change. We selected the most relevant techniques to meet the needs of our patient population, while also considering demands placed on physiotherapy teams working in NHS clinics. Our aim was to increase motivation to exercise and to encourage adherence to the PROSPER programme. We recommended and trained physiotherapists in the motivational interviewing mode of communication. Motivational interviewing uses techniques to encourage compliance and participation. It has been found to be an effective technique for facilitating change in other lifestyle behaviours leading to improved health outcomes, such as weight loss and increased physical activity, and also for addressing the psychosocial needs of cancer survivors. 98 We incorporated the motivational interviewing approach into the PROSPER programme, along with other evidence-based psychological techniques. These included working with participants to set short- and long-term goals, promoting confidence to exercise, developing strategies to solve problems and reduce barriers and encouraging motivation and sustaining exercise adherence.

Intervention refinement with clinicians and patients

We refined the draft intervention to produce a long menu of exercises after discussion with 20 cancer rehabilitation specialists, upper limb physiotherapists and patient representatives who attended our 1-day consensus event at the WCTU in March 2015. We refined the menu of exercises after the consensus meeting and applied a colour-coded classification framework to each movement direction (e.g. flexion, abduction, external rotation with abduction). We described each exercise using lay-friendly terminology: for example, one shoulder abduction and external rotation movement was named ‘the woodchopper’ exercise. We developed patient manuals using colour photographs with clear instructions for each exercise. Qualitative interviews were held with seven women who had been recently treated for breast cancer and recruited from the lead hospital site, University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire (UHCW) NHS Trust. The women were positive about draft trial materials, preferring photographs to cartoon diagrams commonly used in NHS materials; they also preferred the term ‘physiotherapy’ to ‘exercise’ on patient-facing materials.

We also attended a community-based breast cancer support group for feedback on the almost finalised version of trial intervention materials before testing in the pilot study. This support group was attended by women with a recent breast cancer diagnosis, but also by cancer survivors who had been treated years previously. Feedback on materials was again positive, and the only recommendation was that more information on lymphoedema should be included.

Pilot study

We tested pragmatic implementation of the intervention by testing the PROSPER intervention with the first 15 women with newly diagnosed primary breast cancer recruited from three hospital sites within the pilot study. The qualitative study (see Chapter 5), with feedback from participants and physiotherapists, informed refinement of trial-related procedures and paperwork. Minor edits were made to the wording of participant materials. We reviewed treatment pathways and algorithms for the management of postoperative complications including pain, cording, wound infection, lymphoedema and cancer-related fatigue.

Overview of exercise programme

The aim of the exercise intervention was to prevent shoulder problems, caused by breast cancer treatments, by improving shoulder function through a physiotherapist-led, early, progressive, home-based postoperative exercise programme. It used behavioural strategies to encourage exercise adherence and support participants to be more physically active (see Table 5). Although several of the upper body exercises were familiar to physiotherapists and used in clinical practice, the PROSPER exercise programme was packaged as a new intervention to be prescribed and delivered as a whole. The intervention was delivered by NHS physiotherapists with musculoskeletal expertise.

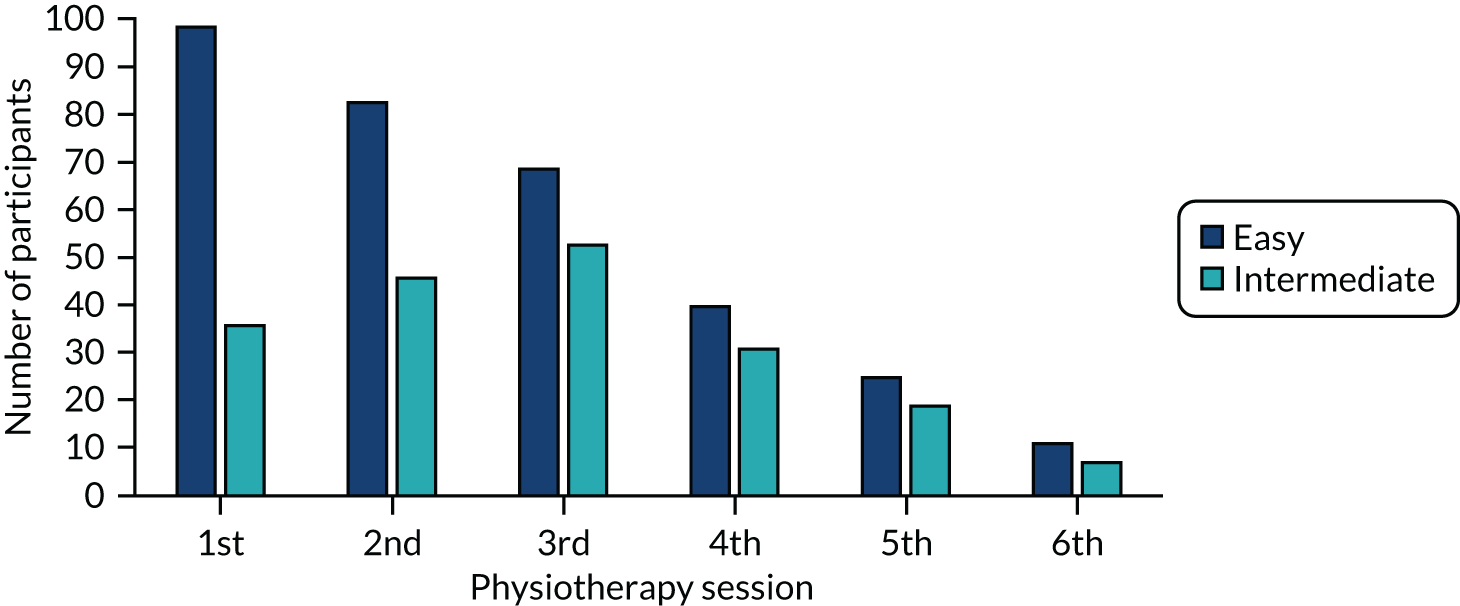

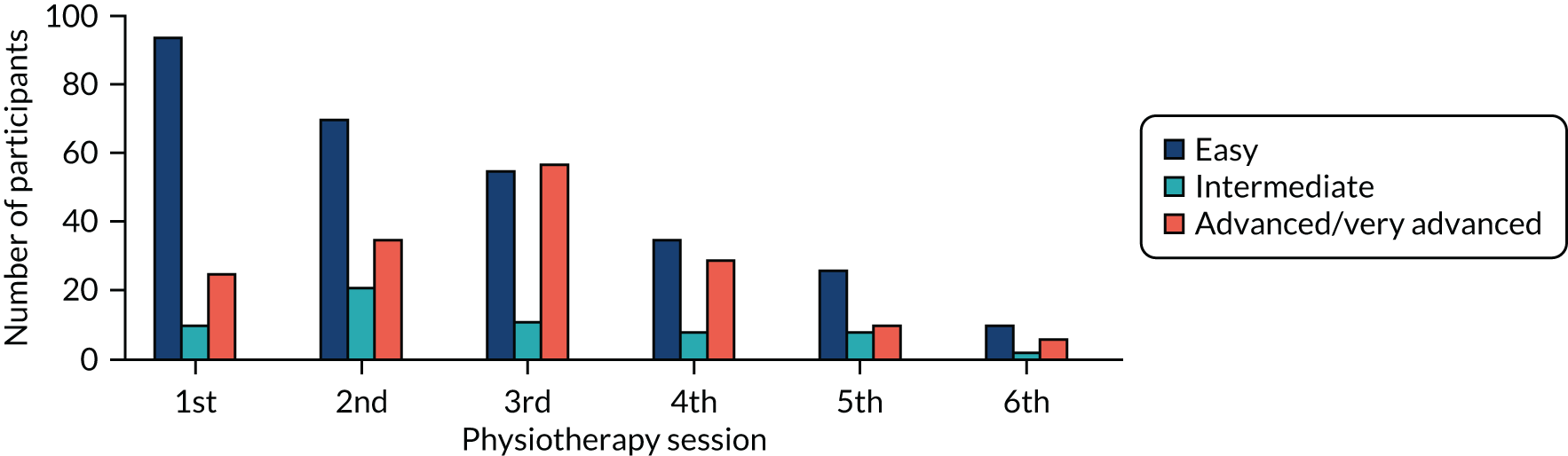

Number and duration of physiotherapy contacts

The trial was designed to be pragmatic rather than explanatory; hence we tested an exercise intervention suitable for delivery in the NHS setting. All participants were advised to follow the Breast Cancer Care leaflets (usual care) in the first postoperative week. 99 For the intervention group, we then recommended a minimum of three face-to-face appointments with the trained PROSPER physiotherapist. These sessions were scheduled at specific time points after surgery: at 7–10 days, 4–6 weeks and 12–16 weeks postoperatively. These timings were selected to broadly fit around the cancer treatment pathway and expected tissue healing. Participants could also have up to three optional appointments, which could be face to face or by telephone. These appointments could be arranged at any time over the 12-month postoperative period, and physiotherapists could provide telephone support as and when needed. A maximum of six physiotherapy contacts were specified.

The first appointment was scheduled for 1 hour, to allow sufficient time for physical assessment, explanation of the programme and to prescribe stretches and ROM exercises. We recommended that the subsequent face-to-face follow-up appointments should be approximately 30-minute appointments.

Discharge from physiotherapy

Participants were discharged from physiotherapy when they had reached their long-term goals or when ROM and muscle strength in relation to their functional needs was achieved. This was determined by the physiotherapist, unless the participant decided that they no longer wanted to attend treatment sessions. We allowed more than six appointments if the services had capacity. After discharge, the participant could still contact their physiotherapist up to 12 months postoperatively.

Participant materials

Each trial participant was given an exercise folder, entitled ‘Your Exercise Folder’, which contained the full menu of exercises with colour pictures and instructions. The folder contained information on self-monitoring for postoperative complications. Each folder contained a supply of exercise diaries to record progression at home.

Recommended content of physiotherapy sessions

Table 435 summarises the initial targeted exercise dosage; all prescription details were recorded in a treatment log. All exercises are illustrated in Figure 1.

| Exercise type/category | Exercise | Frequency | Sets | Repetitions | Hold | Initial load | Progression | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From 7 days after surgery | ||||||||

| Warm-up | Posture check | Twice per day | 1 | 5 | 5 seconds | – | – | |

| Shoulder circles | N/A | |||||||

| Trunk twists (1–4) | 3 seconds | |||||||

| Range of movement | Daily stretch | Daily stretch and hold | Daily | 1 × 10 minutes or 2 × 5 minutes | ||||

| Forward | Clasp hand raise or forward wall slide | Twice per day | 1 | 5 | 3 seconds | – |

Step 1: increase up to 10 repetitions Step 2: if applicable, progress to next level of difficulty for the exercise |

|

| Side | Morning stretch or sideways wall slide | |||||||

| Open chest | Back broom lift or surrender | |||||||

| From 4 weeks after surgery | ||||||||

| Strength | Forward | Forward band lift or rocker (advanced only) | 2–3 times per week | 1 | 10 (minimum 8 repetitions, maximum 12 repetitions) | 3 seconds | Selected so that two repetitions are rated as 5 or 6 on modified Borg scale |

Step 1: maintain 5–6 rating on Borg scale through increasing load (from tan to red to blue Theraband tubing) Step 2: build up to three sets with 1–3 minutes’ rest between sets |

| Side | Sideways band stretch or woodchopper | |||||||

| Open chest | Overhead band stretch or front band stretch or low band row | |||||||

| Physical activity | From day 1 | Gentle | Daily | 3 | 10 minutes | – | – | Build up to 30 minutes continuous |

| From 4 weeks | Moderate | 5 times per week | – | 30 minutes | No restrictions after 12 weeks | |||

| From 12 weeks | Moderate to hard | |||||||

First physiotherapy appointment (7–10 days postoperatively)

Participants followed usual-care leaflets for the first postoperative week. At the first appointment, physiotherapists were asked to complete a short medical history; assess usual physical activity, pain intensity, wound healing, posture and active ROM; and screen for lymphoedema. Short- and long-term goals were discussed, along with barriers to and facilitators of exercise and an assessment of the participant’s confidence in their ability to do the prescribed exercises.

Participants were prescribed stretches and ROM shoulder movements above 90°. We recommended three ROM exercises that targeted the three main shoulder movements affected by breast cancer treatment (i.e. flexion, abduction and abduction with external rotation). One exercise of each movement was selected from a menu of exercises after discussion between the participant and physiotherapist. We encouraged collaborative decision-making rather than didactic prescription of exercise. The ‘daily stretch and hold’ exercise of the pectoralis muscles was also recommended for either 10 minutes once per day or 5 minutes twice per day. Participants were advised to first complete a warm-up comprising an active posture check, shoulder circles and trunk twists. If there were early signs or symptoms of lymphoedema, fist pump exercises were prescribed.

Manual therapy techniques

If the physiotherapist observed any signs of cording, we allowed two manual therapy techniques within the programme: gentle massage techniques, using effleurage and petrissage, and cording release by skin traction. We encouraged physiotherapists to teach participants how to do these techniques at home, either by themselves or with a partner, to promote self-management. We provided training and also laminated guides for physiotherapists on how to do these manual techniques.

Second face-to-face appointment (4–6 weeks postoperatively)

In the second appointment, recommended at 4–6 weeks postoperatively, the physiotherapist monitored progress, assessed wound healing, progressed ROM exercises and introduced strengthening exercises. We asked physiotherapists to repeat physical examinations and screen for postoperative complications, including cording and lymphoedema, and assess pain intensity and wound healing.

Prescription of strength exercises (4–6 weeks postoperatively)

Shoulder ROM was reassessed and isometric muscle strength was tested. Muscle strength was tested using a standardised protocol for glenohumeral flexion, abduction, and internal and external rotation. Both shoulders were assessed and given a score from 3 (can hold position with no resistance) to 5 (can hold position against maximal resistance), according to Kendall’s method. 100 The intervention included seven strengthening exercises: two flexion movements, two abduction movements and three abduction and external rotation movements (see Table 4). Selection of one strengthening exercise for each movement was made after assessment and discussion with the participant. All strengthening exercises, apart from the ‘rocker’ exercise, were performed using resistance bands (Theraband tubing). Each band was cut to 1 m length and provided at 100% elongation resistance of 1.1 kg (tan), 1.7 kg (red) and 2.6 kg (blue).

Third face-to-face appointment (12–16 weeks postoperatively)

The third appointment was scheduled for approximately 3 months after surgery. This time period was selected for exercise progression according to individual ability and final review of surgical wounds, which were expected to be fully healed. We also expected muscle adaptation to stimuli from strengthening exercises by this time. Exercises were progressed according to individual ability. The focus at 3 months was on the return to usual activities and the ability to undertake more demanding functional activities.

Establishing baseline level and progression for exercises

Range of movement and stretch exercises

At all appointments, the ROM of active scapula elevation, protraction and retraction was assessed. In addition, glenohumeral flexion, abduction, and internal and external rotation were assessed. ROM was graded as either ‘full’ or ‘restricted’ by comparing the affected (operated side) with the unaffected arm. ROM exercises could be progressed by increasing the number of sets and repetitions and/or advancing to the next difficulty level for the chosen exercise. The daily stretch was progressed by increasing time spent stretching, if needed.

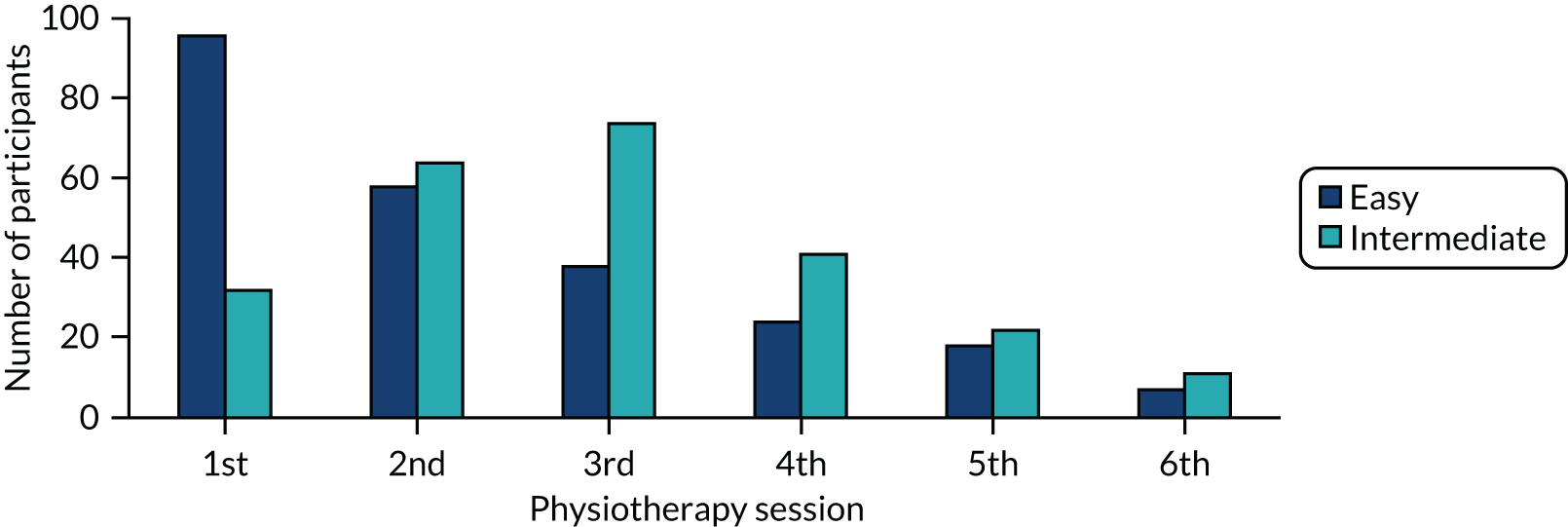

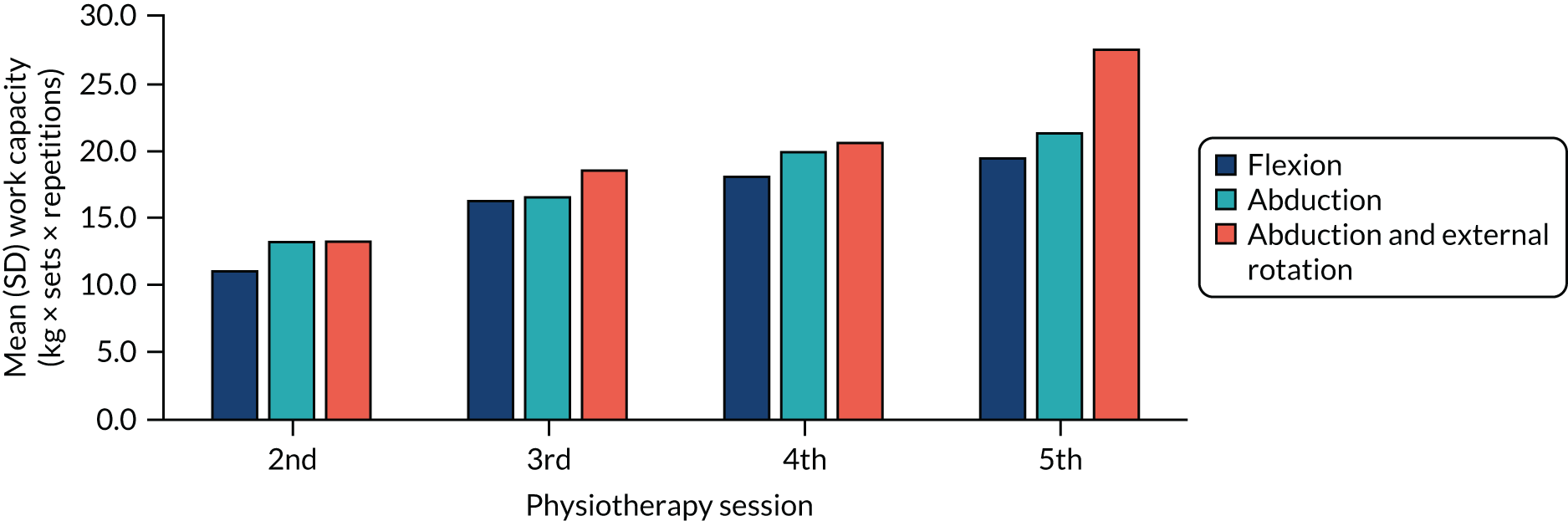

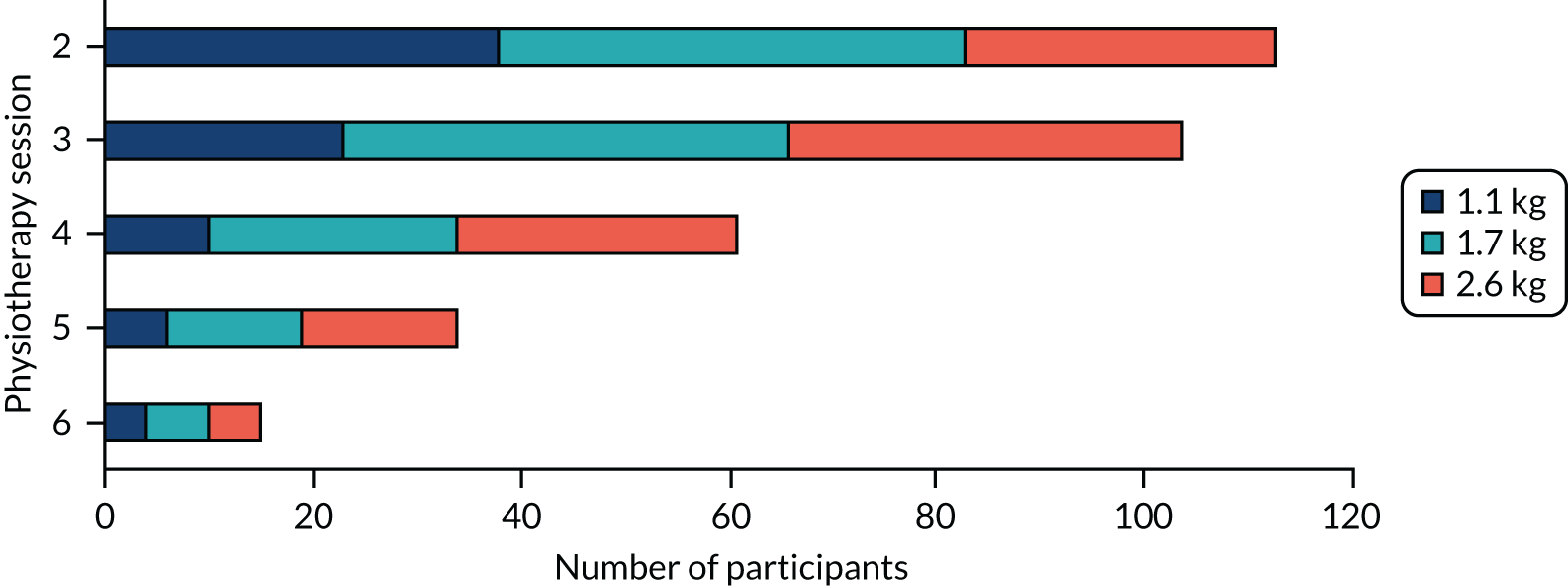

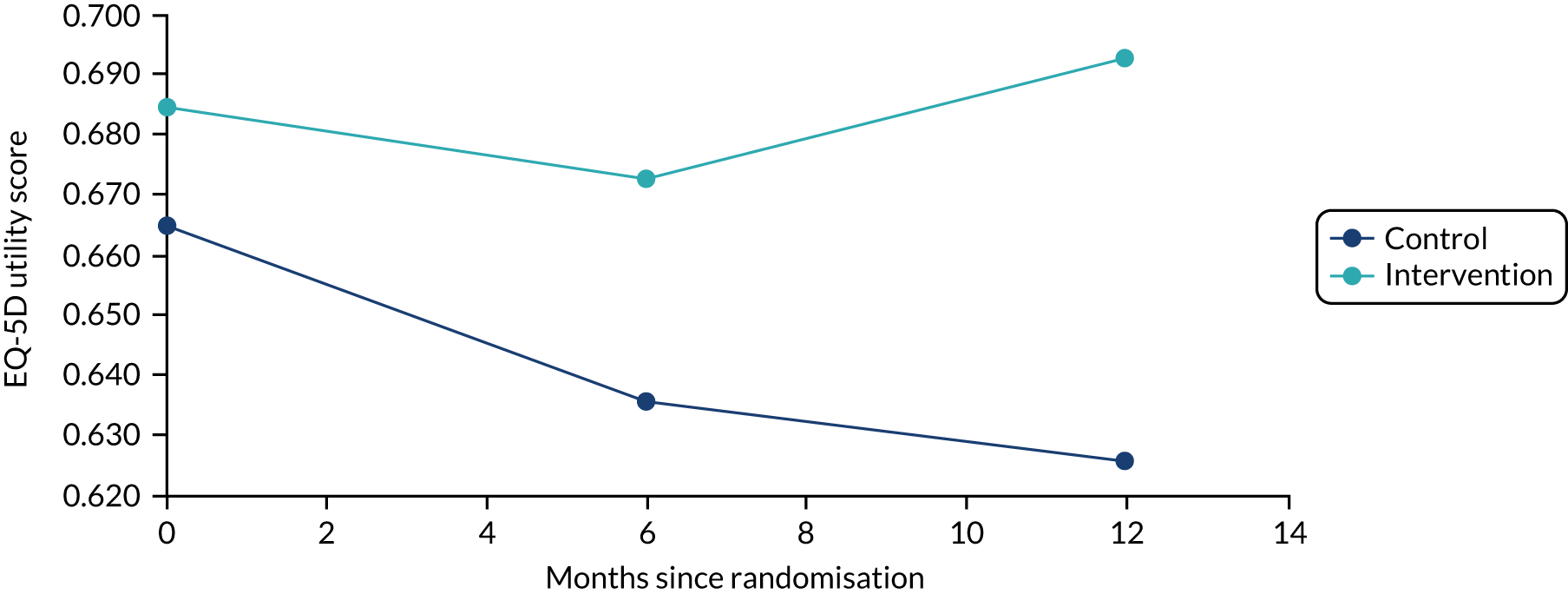

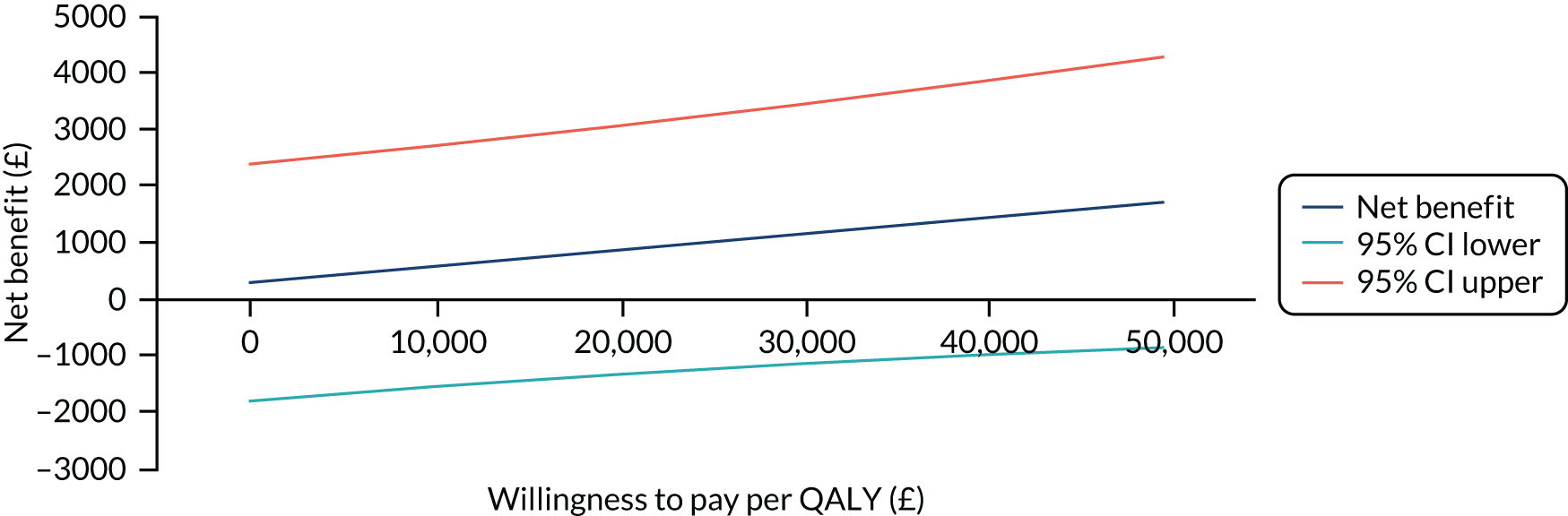

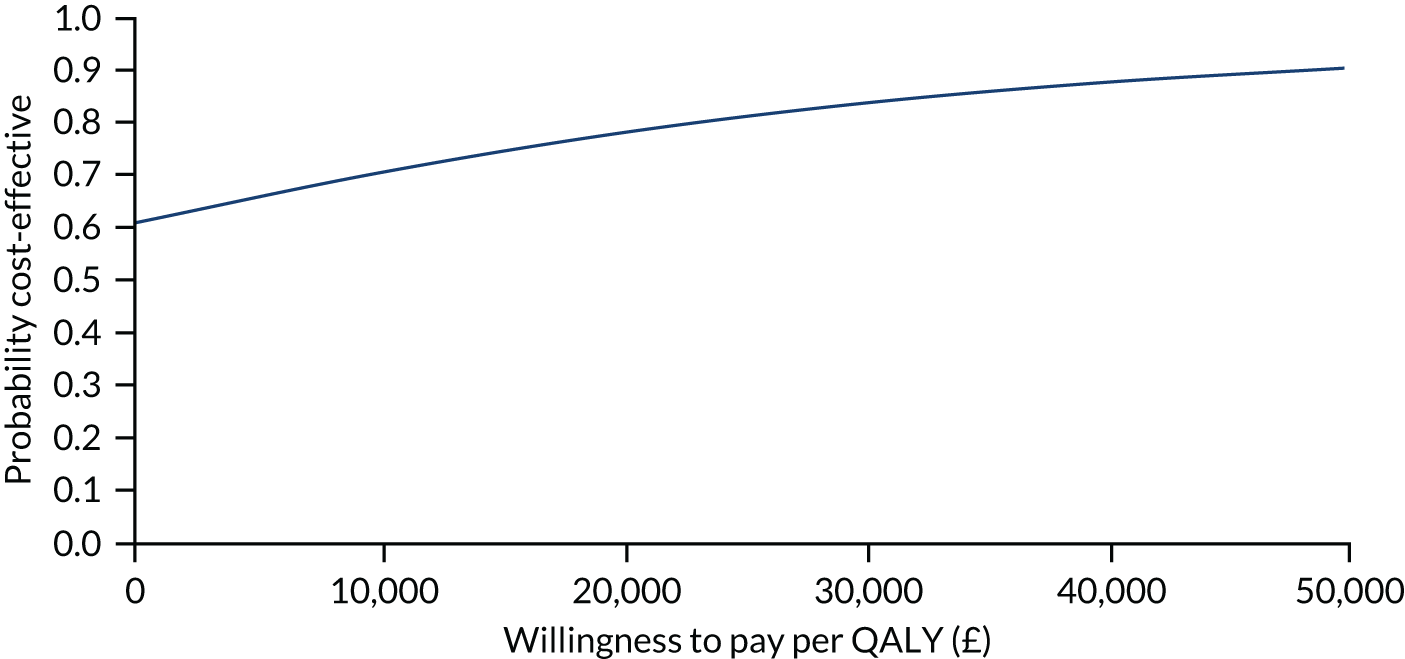

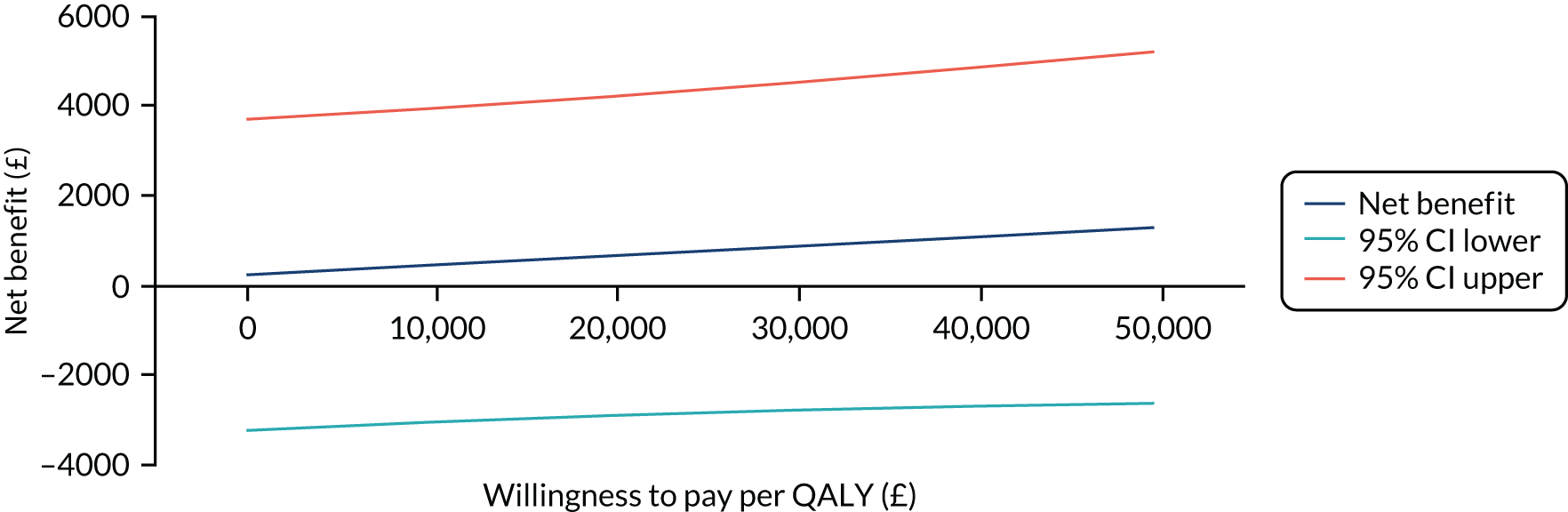

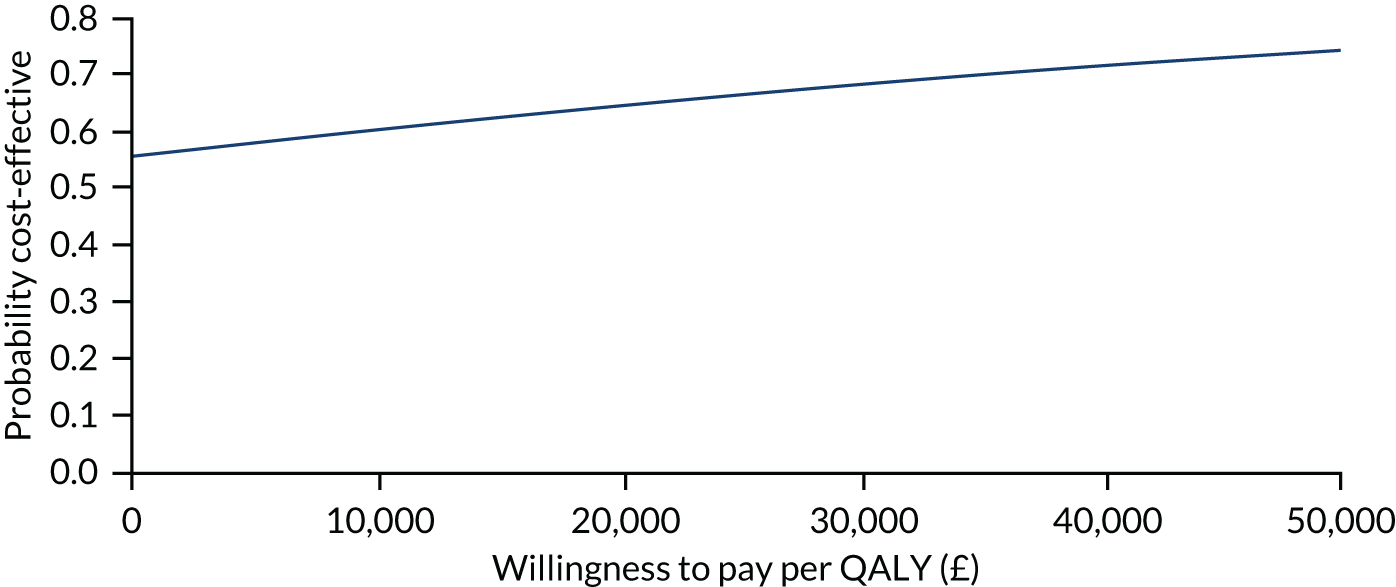

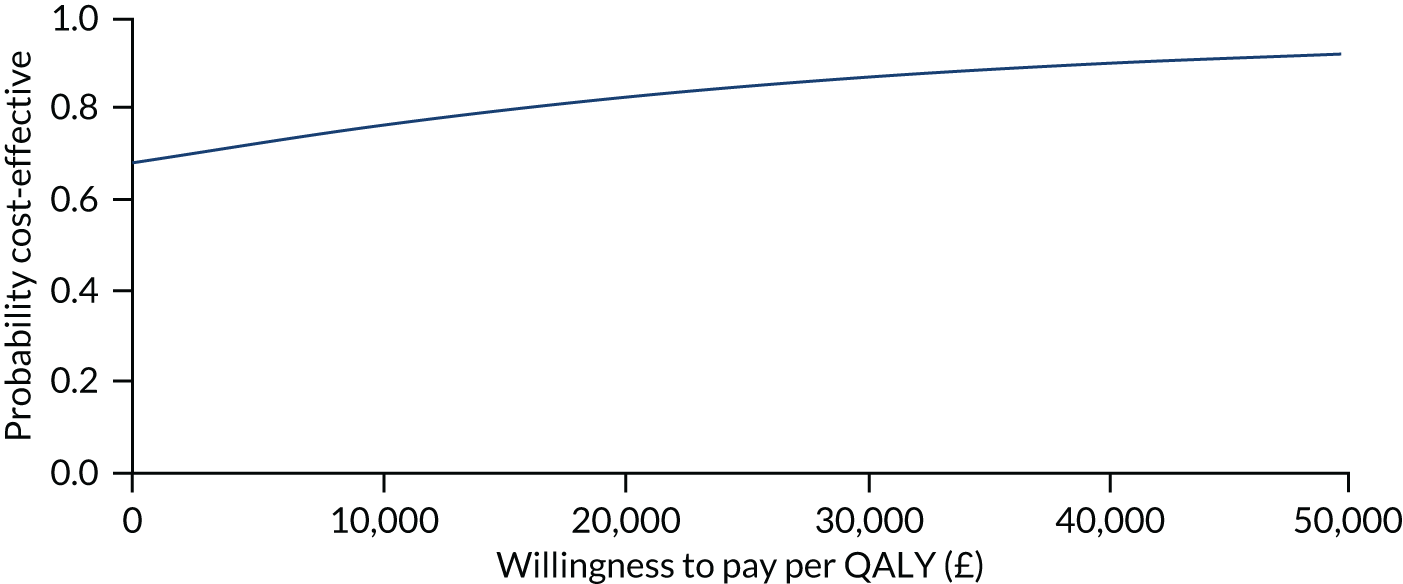

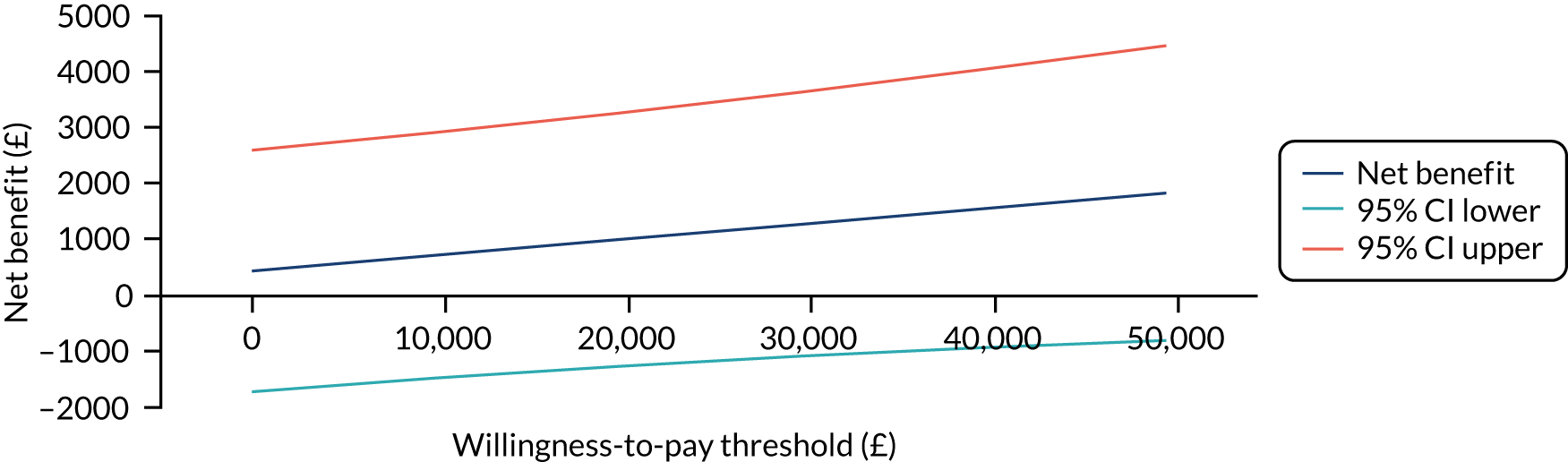

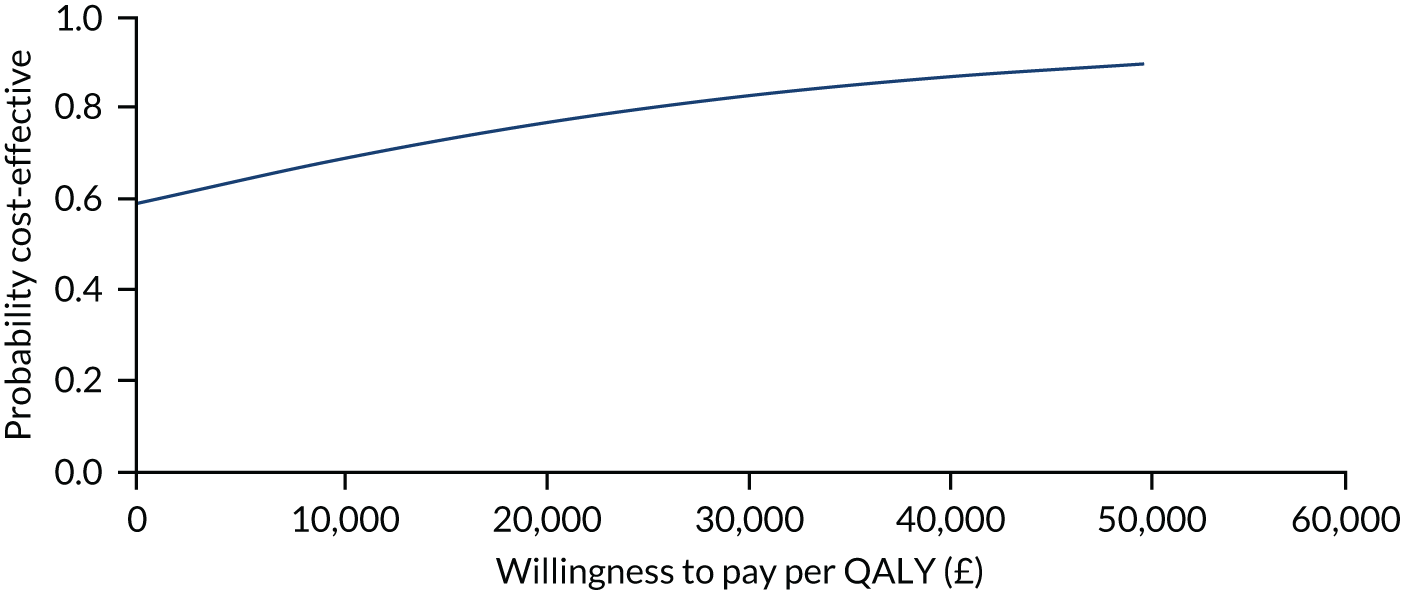

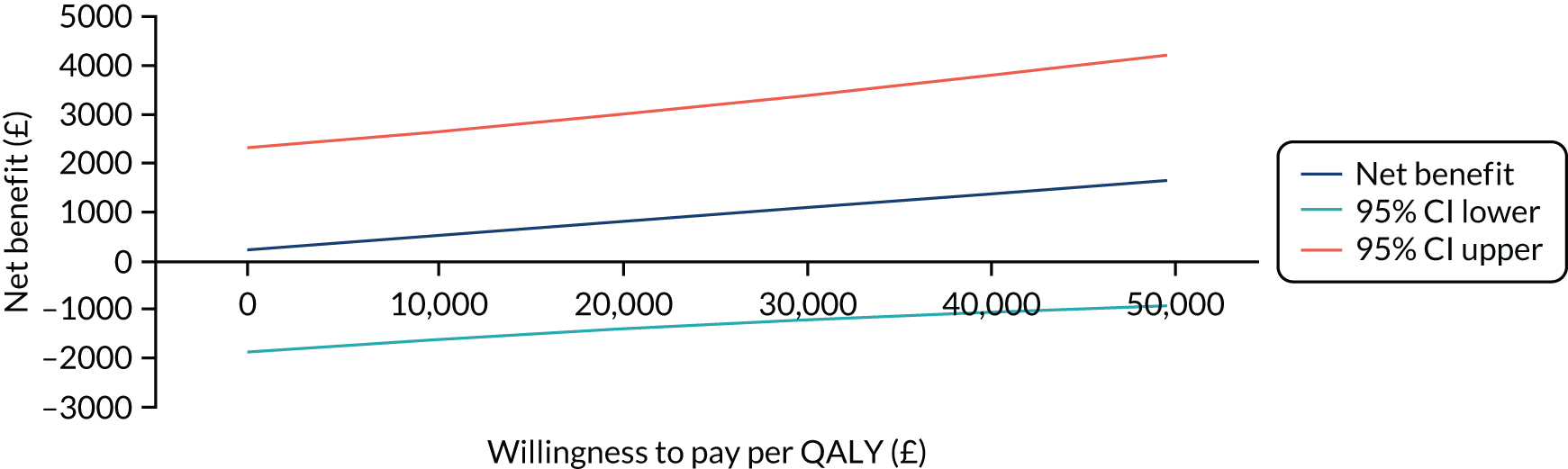

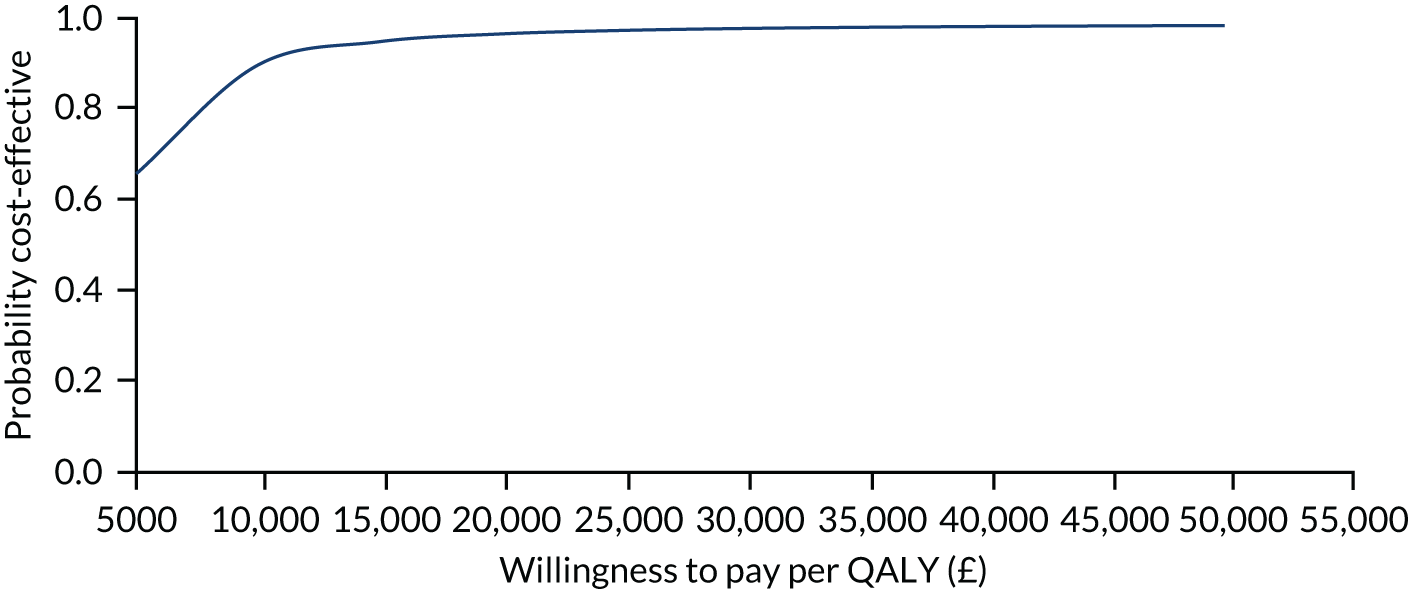

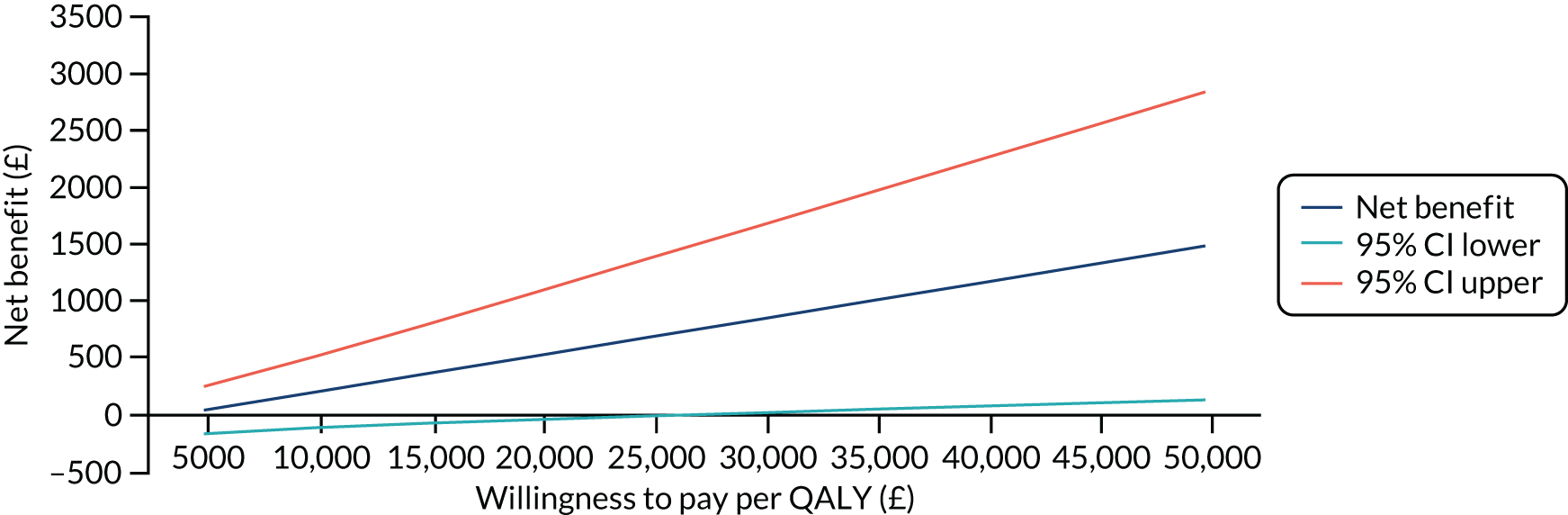

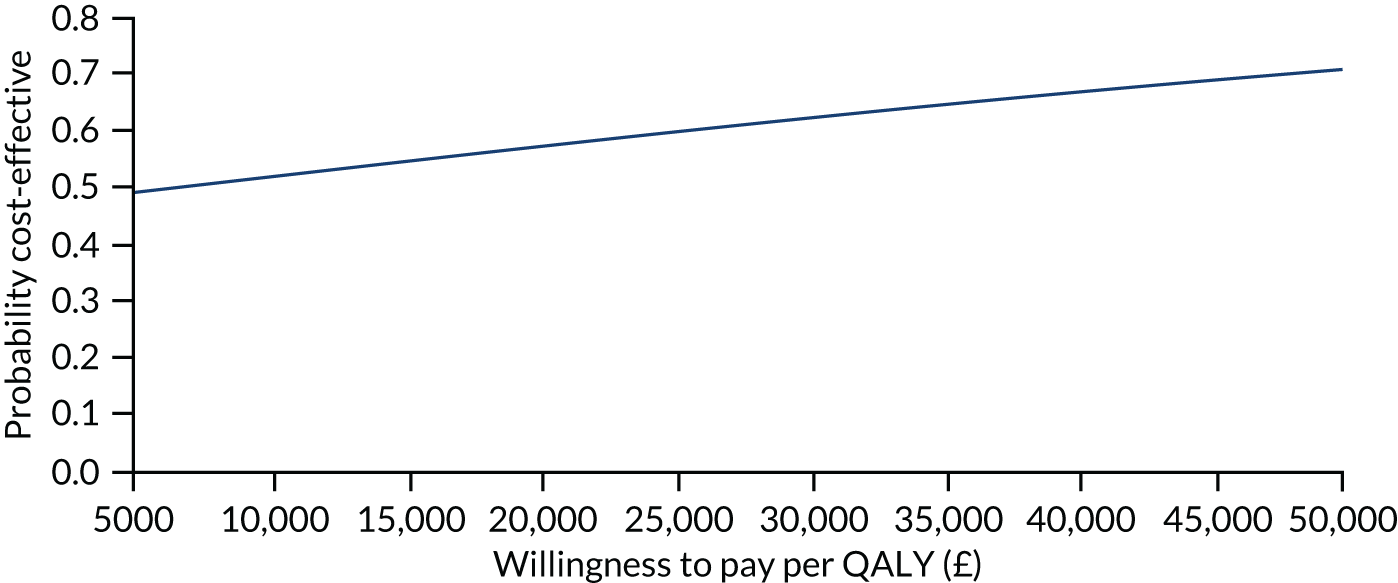

Strength exercises