Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/162/02. The contractual start date was in June 2017. The draft report began editorial review in June 2022 and was accepted for publication in November 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Ondruskova et al. This work was produced by Ondruskova et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Ondruskova et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders1 describes developmental disabilities as intellectual disabilities, communication disorders, autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and motor disorders. Intellectual disability is a lifelong condition impairing an individual’s intellectual and adaptive functioning, affecting approximately 1.2 million children, young people and adults in England. 1,2 Children with developmental disabilities are approximately three to four times more likely to develop internalising and externalising behaviour problems compared to their non-disabled peers. 3,4 Figures from recent studies in England show that over 40,000 children with intellectual disabilities display behaviour that challenges, otherwise referred to as ‘challenging behaviour’. 5 Although the figures vary due to different methodologies used in the studies, the estimates show that between 10% and 45% of children with intellectual disabilities display behaviours that challenge. 6–11

The Royal College of Psychiatrists12 define behaviours that challenge as behaviours of such an intensity, frequency or duration; they threaten the quality of life and/or the physical safety of the individual or others and are likely to lead to responses that are restrictive, aversive or result in exclusion. These behaviours include self-injury, aggression, destructiveness and stereotypical behaviours, and are described as dangerous and interfere with participation in preschool, educational or adult services and often require special interventions. 1 Behaviours that challenge are reported to be more severe with a higher likelihood of long-standing presentation in children with intellectual disabilities and comorbid ASD, compared to children with intellectual disabilities only. 1,13,14 Multiple factors have been identified as vulnerabilities or risk factors of these behaviours, including underlying sensory problems, genetic syndromes, a higher degree of disability and a lack of communication skills. 4,9,15,16 The behaviours may only appear in specific environments and may be used to create sensory stimulation or to communicate the need for a carer’s attention or help. Poor understanding of behaviours that challenge can lead to the exacerbation and maintenance of such behaviour, and also to poor psychological outcomes in carers. 17 Indeed, a recent study found that early behaviour problems in children with intellectual disabilities were related to increased parenting stress levels and greater child behavioural problems during later childhood. 18

Parents or primary carers of children with intellectual disabilities play a key role in their child’s daily support and usually throughout their lifespan. Parents perform complex care tasks, respond to their child’s needs, manage behaviours that challenge and advocate for services and support for their child. These tasks are demanding and can lead to high levels of stress for the whole family. 18,19 In addition to daily tasks, parents may experience high distress from observing their child self-harming or can experience injuries from their child’s aggressive behaviours. For example, some parents report having bruises from being repeatedly kicked or punched and in some cases even need emergency hospital care. 19 As such, this group is vulnerable and at increased risk of a variety of negative psychological and physical health outcomes compared to the general population. 20,21 Interventions that aim to help parents effectively manage behaviours that challenge can lead to positive outcomes for both children and their parents and to create a more stable family environment. A common approach for children without intellectual or developmental disabilities is an early intervention delivered in groups to families, with children as young as 18 months. 22 Early intervention is recommended as it reduces early-onset child behaviour problems while it also increases parent efficacy in managing the child’s behaviours. 23 Parents learn new ways to manage behaviours that challenge which they can generalise to other areas of life, through positive parenting techniques (e.g. such as descriptive praise, reward charts, clear instructions) and contingency management strategies (e.g. exclusionary timeout, non-exclusionary timeout, logical consequences). 24,25 Many of those interventions, known as parenting programmes, are provided in group settings. The group format allows for the creation of valuable social networks between parents in similar situations, provides space for parents to share ideas, normalises the challenges they face at home and can reduce perceived isolation. 26,27 However, families with children with developmental delays and/or comorbid conditions may find these universal interventions inaccessible or unsuitable for their child’s needs or specific behaviours. Thus, it is essential to tailor universal parenting programmes to fit the needs of the families of children with more complex behaviours.

Several factors need to be considered when developing behaviour-management programmes for families with children with developmental disabilities to ensure they fit their needs. Qualitative research can inform us about what parents of disabled children are looking for from these interventions. For instance, parenting programmes that offer more specific information and education about coping with the child’s disability are seen as more relevant. 26 In a study by McIntyre,28 modifications to a universal parenting programme, the Incredible Years Parent Training, facilitated access and retention by adding content on functional assessment of behaviour problems in children with developmental disabilities. Furthermore, families with children with intellectual disabilities require high flexibility from parenting programmes because of the high likelihood of last-minute cancellations due to child behaviours or unexpected crisis moments. 29 If flexibility is not offered, parents may perceive these programmes as a burden adding to their daily stress levels. 30 The ability of the services to increase flexibility and adapt intervention delivery can facilitate access to families with children with intellectual disabilities. 31 Examples of reasonable adjustments for this population have been reported and include delivery of the programme in easily accessible locations (e.g. local community centres) or remotely, offering multiple times and dates for sessions, and offering catch-up sessions. 29,32,33 Another factor considered to be important is providing on-call support for parents (e.g. by regular practitioner−parent contact). 29 As such, early intervention is essential and needs to be delivered according to the child’s needs to ensure relevance and positive outcomes.

One of the most widely available parenting programmes to support parents of children with intellectual and socio-emotional disabilities and with sufficient evidence for efficacy is the Level 4 Stepping Stones Triple P (SSTP). SSTP is an adaptation of the Triple P Positive Parenting Programme (see www.triplep.uk.net/uken/home/) and was developed for families with children with intellectual disabilities who display behaviours that challenge. This programme combines psycho-educational and behavioural components and is designed for parents of children aged 2–8 years.

Stepping Stones Triple P aims to improve parental confidence and skills by promoting a positive parent–child relationship. The theoretical basis of this intervention is embedded in the social learning model, which emphasises the bidirectional and reciprocal nature of the parent–child interactions that surround behaviours that challenge. 34 The intervention encourages parents to develop skills to use in everyday situations, such as during mealtimes, bathing or dressing, rather than through artificial training scenarios. As such, SSTP aims to teach parents positive child management skills contrary to coercive parenting strategies.

Studies have shown that SSTP is effective, acceptable to parents, reduces problem behaviours and improves parenting styles. 25,35–38 While available to be delivered in the UK, it has yet to be tested in a randomised controlled trial. Following a research recommendation of the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE guideline 11),39 which recognised the paucity of available interventions for children with more severe intellectual or developmental delay, a randomised controlled trial to evaluate the SSTP in the UK was conducted. The current study provides a clinical and cost evaluation of SSTP to address behaviours that challenge in preschool children with intellectual disabilities (EPICC-ID). 40 The trial’s main objective was to assess whether SSTP reduces behaviours that challenge displayed by children with moderate and severe intellectual disabilities aged 3–5 years (30–59 months) when assessed at a 12-month follow-up.

Study aims and objectives

The study aimed to evaluate the clinical and cost-effectiveness of level 4 SSTP designed to reduce behaviours that challenge in preschool children with moderate to severe intellectual disability. The primary objective was to undertake a pragmatic randomised controlled trial to evaluate level 4 group SSTP in addition to treatment as usual (TAU). The secondary objective was to undertake an economic evaluation to assess the cost-effectiveness of the intervention compared to TAU.

Research questions

-

Does the addition of level 4 SSTP to TAU reduce behaviours that challenge displayed by children with moderate to severe intellectual disabilities aged 30–59 months at 12 months post randomisation compared to TAU alone?

-

Does SSTP reduce behaviours that challenge at 12 months post randomisation in blind-rated observations and caregiver/teacher questionnaire measures?

-

Is SSTP more cost-effective compared to TAU?

Chapter 2 Method

Some text in this chapter has been reproduced from Farris et al. 40 This is an Open Access article distributed following the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Trial design and setting

Study design

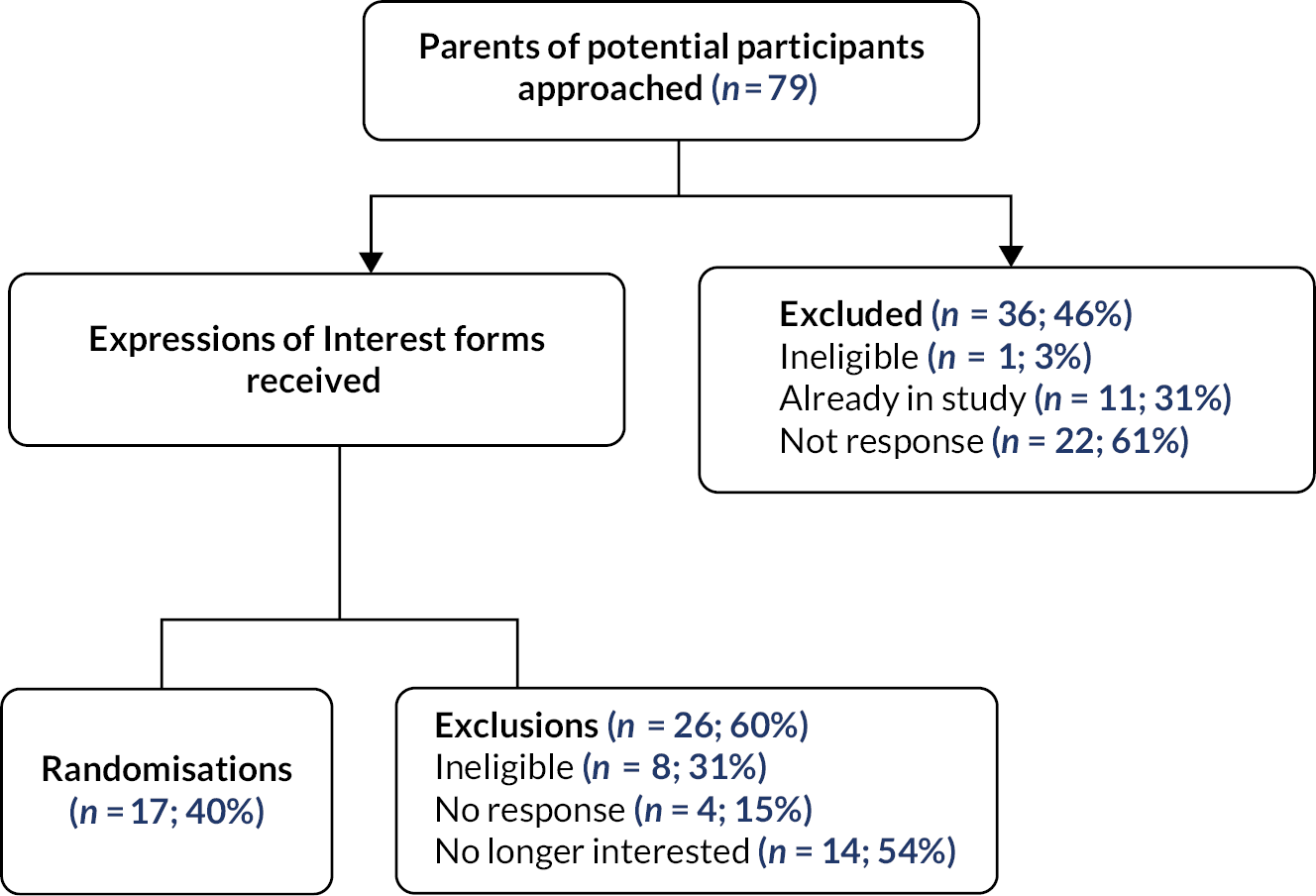

A parallel two-armed pragmatic multisite single-blind randomised control trial (RCT) was conducted with blinding of outcome assessors. A process evaluation was also included utilising parent and service manager qualitative interviews to enhance understanding of the appropriateness and feasibility of the intervention. The study was planned and implemented following the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) extension to compare the cost-effectiveness of the combination of SSTP plus TAU, versus TAU alone in reducing behaviours that challenge at 12 months post randomisation. The trial design is summarised in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The CONSORT flow diagram for the EPICC-ID RCT.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised into the intervention arm using the 3 : 2 ratio (SSTP vs. TAU) using randomly permuted blocks of different block sizes and stratification by site and the level of intellectual disability (moderate and severe). Eligible participants were allocated online to the next available treatment code in the relevant randomisation list. All randomisation and data management were provided by an internet-based site called Sealed Envelope.

Allocation concealment and implementation

At the end of the baseline assessment, the researchers entered the results on a web-based case report form (CRF) form. Parents and therapists were informed about the allocation status and arranged the commencing of the group sessions. Researchers were based in a different location from the staff involved in the delivery of the level 4 SSTP. Therapists were not involved in any treatment of the families that were allocated to TAU.

Blinding

Since parents and therapists were aware of the treatment allocation, it was not possible to ensure a completely blind trial. All research assistants who were collecting the data remained blinded to treatment allocation throughout the study. Parents were reminded not to disclose any information about their treatment allocation to the research assistant during assessments.

The researcher entered the results of all study assessments on web-based electronic case report forms (eCRFs). They did not have access to eCRFs that may pose a risk of unblinding them [e.g. Child and Adolescent Service Use Schedule (CA-SUS) at 4 and 12 months, Client Satisfaction Questionnaire, serious adverse event (SAE) form]. During coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), CA-SUS forms were collected remotely, and the question relating to parenting groups was omitted and collected later.

The lead study statistician remained blinded to arm allocation throughout and the subsidiary trial statistician attended the Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB) meetings. The lead statistician attended the Trial Management Group (TMG) and Trial Steering Committee (TSC) meetings during the study.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

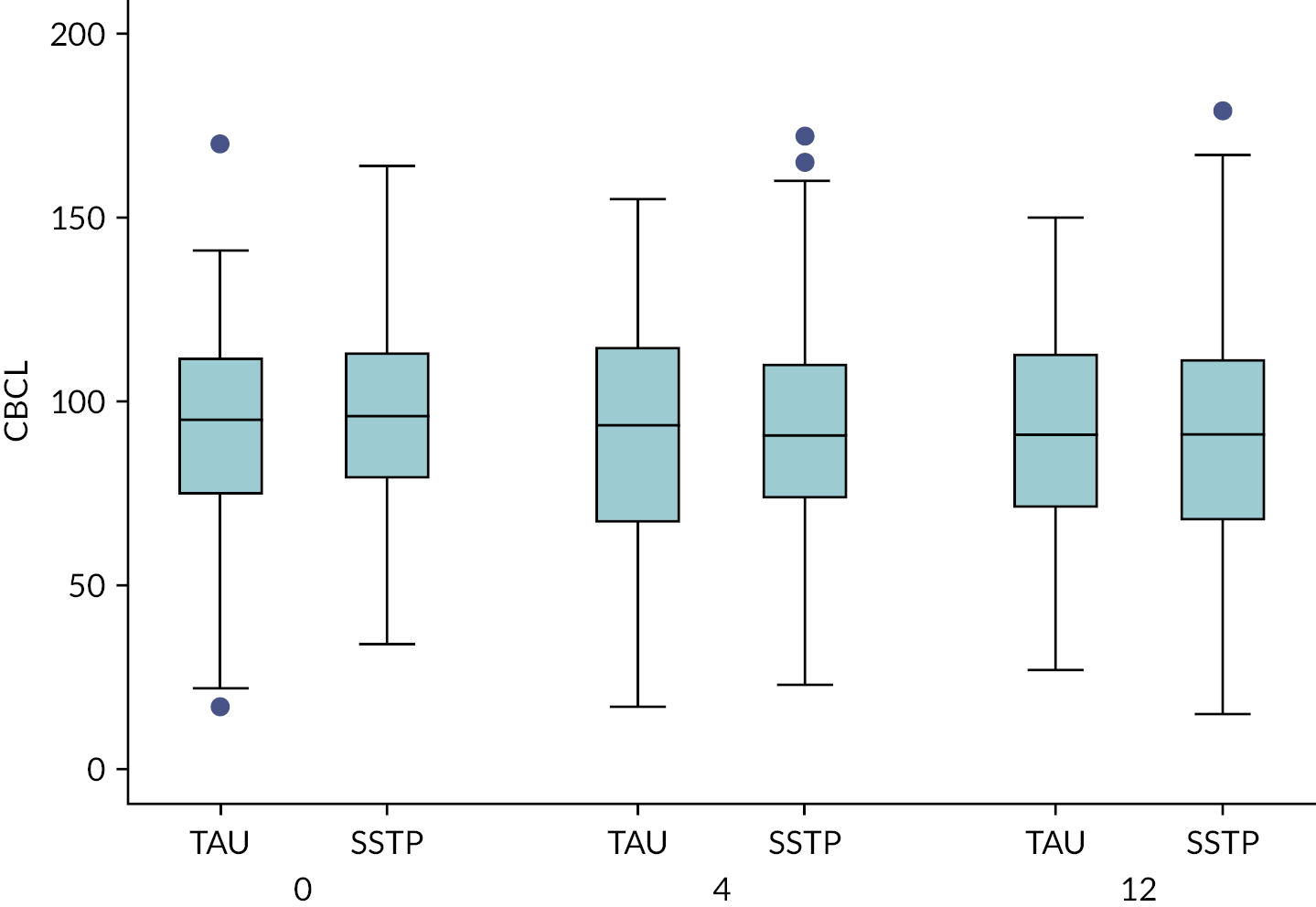

Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL)41

The primary outcome was parent-reported child’s behaviours that challenge at 12 months post randomisation. The severity of behaviours that challenge was measured by the preschool version of the CBCL. The CBCL is widely used in clinical trials and epidemiological studies assessing children with intellectual disabilities. 42,43 This version of the CBCL is used for children aged 1½–5 years. It measures behaviour on a 3-point Likert scale (0 – not true; 1 – somewhat/sometimes true; 2 – very/often true) over a period of 2 months. The 99 items measure emotional and behavioural problems. Respondents are also asked to provide more details for certain items and are asked open-ended questions at the end to describe the child’s illnesses and disabilities as well as their biggest concerns about the child and what the child does best. Items are grouped into seven subscales: (1) Emotionally Reactive, (2) Anxious/Depressed, (3) Somatic Complaints, (4) Withdrawn, (5) Sleep Problems, (6) Attention Problems and (7) Aggressive Behaviour. Subscale scores can also be grouped into two broader categories, Internalising Behaviours (problems that occur mainly within oneself) and Externalising Behaviours (involves conflicts with other people and their expectations for the child). The total raw score for each subscale is computed by summing the scores of 1 and 2 for all items of that subscale. A scoring algorithm is used to determine a T-score for the internalising and externalising behaviours and an overall T-score for the child’s Total Problem Behaviours. Children with a T-score of 60–63 are in the borderline clinical range and a T-score of 64 and above indicates clinically significant difficulties. A participant is excluded from the analysis if 8 or more items are missing. See Achenbach and Rescorla41 for validity studies.

Secondary outcomes

Revised Family Observation Schedule (FOS-RIII)

Direct observations were carried out by researchers using the FOS-RIII, a measure of parent–child interaction. 44 This measure is commonly used in studies that investigate SSTP. Parents are asked to interact with their child while being filmed for 20 minutes carrying out various activities that reflect tasks that likely happen in their daily life at home. Overall, there are four 5-minute tasks: (1) child’s free play; (2) a structured block task; (3) parent and child in the same room but each involved in separate activities; and (4) cleaning up after play. The FOS-RIII codes 10-second segments and computes four scores that indicate positive and negative child behaviours, and positive and negative parent behaviours (see Table 1 for further details). A senior developmental psychologist scored the video observations. The FOS-RIII has demonstrated reliability and discriminant validity and is sensitive to the effects of behavioural interventions. 45

| Child behaviours | ||

|---|---|---|

| Parent behaviours | ||

| Positive | Engaged activity | Any interval with no negative behaviours and with no intelligible verbalisation or vocalisation |

| Appropriate verbal activity | Any interval with no negative behaviours and in which intelligible speech/verbalisation/vocalisation occurs | |

| Affection | Any verbal or non-verbal affection directed towards the parent | |

| Negative | Non-compliance | When a child does not follow an instruction given by a parent or another adult |

| Complaint | Any instance of whining, crying, screaming, shouting, grizzling, intelligible vocal protests or displays of temper | |

| Physical negative | Any actual or threatened physical attack on an object or another person | |

| Interrupt | Child interrupts when parent is talking, in an intrusive, loud, annoying, abrupt or disruptive way | |

| Oppositional | Any inappropriate behaviour that cannot be categorised into any other negative behaviour category | |

| Positive | Praise | Any praise comment directed to the child about a specific behaviour or child characteristic |

| Positive physical contact | Parent initiated or parent maintained (e.g. hug, kiss) | |

| Positive instruction | Direct or indirect verbal commands that are used to initiate change in the child’s behaviour, with no anger, sarcasm or harsh tone | |

| Positive social attention | Any verbal or non-verbal attention not scored in other categories (e.g. look up to monitor child) and not aversive | |

| Affection | Any affectionate words or affectionate physical contact | |

| Negative | Negative physical contact | Contact that could cause pain or discomfort |

| Negative instruction | Direct or indirect commands in a harsh, angry, abrupt or annoyed tone of voice | |

| Negative social attention | Comments in unpleasant, sarcastic or abrupt voice tone or criticism of child | |

Child Behaviour Checklist Caregiver−Teacher Report Form (C-TRF)

We measured caregiver-reported child behaviour to allow additional perspective on the child’s behaviour outside of the home setting. 46 This measure was completed by caregivers other than parents (e.g. teachers, teaching assistants, grandparents). Teachers were asked questions about child’s behaviours that can be observed in a school setting, such as defiance, hyperactivity, destructiveness or social skill deficits. The behaviours are divided into two subscales, internalising and externalising problems. The preschool C-TRF measure is associated with other measures of child behaviour problems (see Achenbach and Rescorla46 for review of validity studies).

Caregiving Problem Checklist – difficult child behaviour

Frequency of the child’s behaviours that challenge during care-giving tasks was measured on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always). 47 The behaviour is assessed in seven care-giving areas, such as direct care, in-home therapy tasks, involvement in leisure activities and other. The total score is the sum of all items, whereby higher scores indicate a higher frequency of problematic behaviour.

General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12)

Parent psychiatric morbidity was measured by the commonly used 12-item GHQ measure, following the recommendations by the Department of Health to include such measures in this type of study. The questionnaire assesses the severity of a mental problem over the past few weeks on a 4-point scale (from 0 to 3). The total score is the sum of all items. Validity studies report high internal consistency values (from α = 0.79 to 0.91). 48,49

Questionnaire on Resources and Stress (QRS-F short form)

This measure is used to assess parental stress in caregivers of children that are chronically ill or have intellectual disabilities. 50 It is a 31-item questionnaire with ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ response options.

Parenting Sense of Competence Scale (PSOC)

Parents rated their perceived competence in the areas of satisfaction and efficacy as a parent. 51 The measure comprises 17 items that are rated on a 6-point scale ranging from 6 (strongly disagree) to 1 (strongly agree). Studies report good internal consistency for this scale (α = 0.8)52

Child and Adolescent Service Use Schedule (CA-SUS)

A child’s health and social care service use was measured on a modified version of the CA-SUS form. 53 The CA-SUS collects information on the child’s use of a range of services for the 4 or 6 months preceding assessment. The form contains questions on contacts with primary and secondary healthcare services, social services, voluntary organisations and medication use.

Pediatric Quality of Life (PedsQLTM)

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was measured using the PedsQL™ covering four domains, including Physical, Emotional, Social and School Functioning. 54 The current study uses this measure to derive the quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) for the health economic evaluation. Validity and reliability studies show high internal consistency values (α = 0.9). 55

Euro-Qol-5D (EQ-5D)

Health-related quality of life in the parent/other caregiver was assessed using a self-completed EQ-5D questionnaire. 56 These data will be used in the economic evaluation.

Other measures

Mullen Scales of Early Learning

The Mullen Scales of Early Learning was used to measure a child’s level of disability at baseline. 57 It is a developmentally integrated system that assesses language, motor skills and perceptual abilities. This assessment was only used during face-to-face assessments.

Case report form (CRF)

Parent’s and child’s sociodemographic and clinical information about comorbidities were collected using the CRF.

Client Satisfaction Questionnaire

Parent intervention acceptability was measured using the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire. 23 This allowed parents to provide feedback about the intervention during the 4-month follow-up by commenting on their satisfaction with and experience of SSTP. This questionnaire was specifically created for use in research investigating SSTP and has high internal consistency (α = 0.92).

Schedule of assessment visits

Table 2 presents the schedule of assessment visits and measures used during each visit throughout the study.

| Visit number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tasks | Screening | Baselinea | 4-month follow-up | 12-month follow-up |

| Allowed deviation window | N/A | ± 4 weeks | ± 4 weeks | ± 4 weeks |

| Informed consent (screening) | x | |||

| Assessment of eligibility criteria | x | x | ||

| ABAS (< 69) | x | |||

| Research assessments minimum 1 week, maximum 4 weeks after screening | ||||

| Informed consent (research) | x | |||

| Mullen Scales of Early Learning | x | |||

| CRF | x | |||

| Preschool CBCL | x | x | x | |

| Parent–child observation and FOS-RIII | x | x | x | |

| C-TRF | x | x | x | |

| GHQ-12 | x | x | x | |

| QRS-F short form | x | x | x | |

| Caregiving Problem Checklist | x | x | x | |

| PSOC | x | x | x | |

| CA-SUS | x | x | x | |

| Client Satisfaction Questionnaire | x | |||

| Peds-QL | x | x | x | |

| EQ-5D | x | x | x | |

Participants

Sample size

The original sample size calculation required a sample of 258 children in an allocation ratio of 3 : 2 (155 vs. 103) to detect a low to a moderate (standardised) effect size of 0.40 for the primary outcome CBCL at 12 months at the 5% significance level with 90% power; the equivalent to detecting a clinically important difference of 8 points, assuming a standard deviation (SD) of 20. This was calculated as follows: A standard calculation based on analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) leads to a sample size of 99 children per arm, assuming a correlation of 0.5 between baseline and follow-up measurements. An equivalent calculation (same power) based on an allocation ratio of 1.15 : 1 gives group sizes of 107 and 93. Increasing the SSTP arm (only) to allow for therapist clustering leads to 139 children in the SSTP arm, assuming an intraclass correlation of 0.05 and an average therapist group size of 7 (design effect = 1.3). An adjustment for the anticipated dropout of 10% leads to 155 children in the SSTP group and 103 in the control group.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows:

-

parents aged 18 years or over;

-

child aged 30–59 months at identification;

-

child had a moderate to severe intellectual disability, measured by parent-reported Adaptive Behaviour Assessment Schedule (ABAS) General Adaptive Functioning score between 40 and 69;

-

reported child’s behaviours that challenge over a 6-month period prior to the study, but no less than 2 months;

-

obtain a written consent by parent/caregiver.

Exclusion criteria

Participants were not included in the study if:

-

child had a mild, profound or no intellectual disability on parent-reported ABAS form;

-

parent/carer had insufficient English language skills to complete the study questionnaires;

-

another sibling was taking part in the study.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited from various community services including Participant Identification Centres (PIC) in four main areas in England: Blackpool (and surrounding areas; Site 1), North London (Site 2), South London (Site 3) and Newcastle (and surrounding areas; Site 4). The services included National Health Services (NHS) settings (e.g. Child Development Teams), Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS), education (e.g. nursery, preschool) and third sector (e.g. caregiver groups). Health or social care professionals identified eligible participants through new referrals or existing cases. Children were assessed for developmental delay through the Healthy Child Programme, which aims to identify families that require further support with their children, and children aged 0–5 years who are at risk of ‘poor outcomes’. Flyers were put up at local parent groups, nurseries, special schools and general practitioners (GPs) to promote the study among families. We followed a multisource referral strategy facilitated by the clinical research networks, our national, clinical and third-sector contacts and social media. We opened five PIC adjacent to Site 4, three PIC sites adjacent to Site 2 and two PIC sites adjacent to Site 3 to reach our planned recruitment target at the sites. Several recruitment difficulties were addressed throughout the study. This included parents declining or not being eligible to take part in the study due to various reasons, such as time commitments, child-care issues, health problems, language barriers or parents not thinking that child has an intellectual disability or behaviours that challenge. Table 3 presents the overview of recruitment at each study site.

| Site | EOIs received | Participants randomised | EOI to randomisation rate (%) | 4-month follow-ups completed (%) | 12-month follow-ups completed (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | 91 | 64 | 70 | 61/64 (95) | 55/64 (86) |

| Site 2 | 212 | 56 | 26 | 45/56 (80) | 44/56 (79) |

| Site 3 | 181 | 74 | 41 | 66/74 (89) | 61/74 (82) |

| Site 4 | 99 | 67 | 68 | 57/67 (85) | 53/67 (79) |

| Total | 583 | 261 | 229/261 (88) | 213/261 (82) |

Allocation arms

Intervention arm

SSTP is part of Triple P (Positive Parenting Program), a psycho-educational parenting and family intervention developed for families who have children with behavioural or emotional problems. 58 SSTP was adapted specifically for parents of children with intellectual disabilities. This trial provided the SSTP level 4 manualised course, which offers six group sessions and three individual telephone or face-to-face contacts with the parent over a period of 9 weeks. Each group session lasted approximately 2.5 hours and individual sessions took about 30 minutes. The combination of group and individual sessions allowed parents to share experiences and build on skills gained while providing personalised support. The group sessions aimed to educate and actively train parents in skills and behaviour management. The individual consultations aimed to facilitate independent problem-solving and allowed parents to pick strategies most relevant to their child’s difficulties. All parents also received a course book that covered topics from each session. Those who missed a session were contacted by the therapist to discuss their progress and were encouraged to attend the next sessions. The group sessions were delivered in person until March 2020. Afterwards, all group sessions were delivered online via Zoom or Microsoft Teams. Table 4 provides the outline of the SSTP sessions.

| Group sessions | |

|---|---|

| Telephone sessions | |

| Session 1 | Positive Parenting |

| Session 2 | Promoting Children’s Development |

| Session 3 | Teaching New skills and Behaviours |

| Session 4 | Managing Misbehaviour and Parenting Routines |

| Session 5 | Planning Ahead |

| Session 6 | Implementing Parenting Routines 1 |

| Session 7 | Implementing Parenting Routines 2 |

| Session 8 | Implementing Parenting Routines 3 |

| Session 9 | Program Close |

Treatment as usual arm

Treatment as usual was available to participants in both arms of the trial. Parents allocated to both arms also received a list of national resources and the Contact charity’s guide for managing behaviours that challenge with recommendations about social and health care support. We identified a variety of services and support offered to families with children with intellectual disabilities and autism in each of the study’s local areas. This included individual help from speech and language therapists, occupational therapists, child psychotherapists, clinical psychologists, child psychiatrists and family therapists. There were numerous children’s centres offering support with parenting advice, local child-care options and access to specialist services for families and their children with intellectual disabilities and parenting classes (e.g. Camden MOSAIC centre in Site 2; SLAM Child and Family Service in Site 3, etc.). Parenting programmes were available in each of the study local areas (N = 3 in Site1; N = 8 in Site 2; N = 9 in Site 3; N = 9 in Site 4). For example, the Early Bird parenting programme was available in all four study areas. This is a 3-month programme for parents providing general information about autism and advice about looking after children with autism. It combines group training sessions for parents with individual home visits where video feedback is used to help parents apply what they have learnt with their child. Parenting programmes that focus on conduct problems in children without an intellectual disability were also available, such as The Incredible Years (Site 2, Site 3 and Site 4), The Family Links Course (Site 2) and Triple P (Site 3). Other support included third-sector organisations, which provided wide-ranging help through workshops, home visits, child care, information and advice and time-limited interventions. Most of the available programmes focused on autism awareness and general information for parents about autism or intellectual disabilities, providing limited advice on parenting strategies and techniques for addressing behaviours that challenge displayed by disabled children.

Process evaluation

A process evaluation is an essential part of a trial that reviews the implementation of an intervention and supports the interpretation of trial results and outcomes. 59 We conducted a process evaluation using a mixed-methods approach, including exploring the views and experiences of participants in the study, looking at contextual components and monitoring the intervention fidelity, dose and reach.

Treatment fidelity

To assess treatment adherence, therapists completed a session checklist after each session and other paperwork detailing the content covered in sessions. To assess the therapists’ competence in delivering SSTP, we videotaped all group sessions and 10% were rated by an independent assessor and specialist in delivering SSTP.

Study procedures and assessments

Participant identification

The study population was parents of preschool children with moderate to severe intellectual disability, who were concerned about their child’s behaviour living in the community in the four study sites. We excluded children with mild intellectual disabilities, as they are likely to access other interventions more suitable for their needs. Similarly, children with profound intellectual disabilities were excluded as they were unlikely to be able to follow the observation tasks and the psychometric assessments. Eligible participants were identified by local community paediatric or CAMHS teams through new referrals or existing cases. Members of the clinical teams screened and reviewed identifiable personal information of potential participants. Parents who were approached by a member of clinical staff or a clinical study officer were given a description of the study, the study Patient Information Sheet and an Expression of Interest form to complete. Those who were eligible and interested in taking part completed the ‘Expression of Interest’ form, which was passed to the researchers, who then contacted the parents for further screening.

Screening process

The eligibility of each participant was confirmed during the screening assessment with a member of the research team. During the screening, the parent rated the child’s level of functional abilities on the ABAS form. Children who had a General Adaptive Functioning score between 40 and 69 were considered to have moderate to severe intellectual disability, and thus were eligible to participate. Parents also had to confirm that their child displayed behaviours that challenge continually over the 2 months prior to the screening assessment. If the result of the screening assessment indicated the child’s adaptive functioning to be outside of our inclusion criteria, parents were given the reason for non-inclusion, were thanked for their cooperation and time, and no further contact was made with the family. Those who were eligible after the screening assessment were contacted to schedule the baseline assessment. Following this, the participants were randomised into the intervention arm (SSTP plus TAU) or TAU.

Informed consent procedure

Informed consent was taken in two stages. First, the person who had parental responsibility for the child completed the consent form at the beginning of the screening assessment prior to completing the ABAS form. Second, if the child was eligible, the family was invited to enter the study and complete the consent form prior to their randomisation. Parents were given a minimum of 24 hours to decide whether they wanted to enter the study and were given contact details of the research assistant to ask further questions. For both stages, parents provided written or audio-recorded verbal informed consent. The right to withdraw at any time without giving a reason or affecting further treatment was explained to each participant. Each participant was given a copy of their informed consent form, and the signed original was retained at the study site.

The researchers were inducted into the study procedures about obtaining informed consent and completed the online Good Clinical Practice (GCP) course.

For the process evaluation, parents signed a consent form and were provided with a copy to keep if interviews were done in person. For telephone interviews, the consent process was audio-recorded and stored securely in Data Safe Haven (DSH), a secure online platform to store confidential data at University College London (UCL).

Participant safety

Reports of SAEs were collected by the trial manager who reported the information via the eCRF within 24 hours of becoming aware of the event. SAE was defined as any event that:

-

resulted in the death of the participant;

-

was life-threatening;

-

required hospitalisation or prolonged existing hospitalisation;

-

resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity;

-

consisted of a congenital anomaly or birth defect;

-

was otherwise considered medically significant by the investigator.

All reports of SAEs were reviewed by the Chief Investigators (CI) or Principal Investigators (PI) within 2 days of receiving the report and the review outcome was recorded in the eCRF. Each SAE was assessed to determine if the event was related to the intervention (e.g. resulted from the administration of the research procedures or SSTP) and if the event was unexpected (e.g. the type of event was not listed in the protocol as an expected occurrence).

Serious adverse events that were related and unexpected would have been reported to the Research Ethics Committee (REC) that approved the trial, and to the PRIMENT Clinical Trials Unit using the SAE report form within 15 days of the CI becoming aware of the event. These would also have been reported to the Joint Research Office at UCL.

Data management

Data collection methods and handling

Data management in this study complied with the UK Data Protection Act 1998, PRIMENT Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) and GCP. Researchers uploaded and stored all data into DSH, which is a secure system for storing sensitive information. Audio and video recordings were uploaded to the system, and researchers deleted all other versions of the data from digital machines where they were originally recorded.

The investigator was responsible for ensuring the accuracy of all data entered in the CRFs. Data verification checks were completed on 100% of CBCLs (primary outcome measure), and 10% of all secondary outcome measures. The original application stipulated that 5% of all secondary outcome measures would be checked, but due to researcher turnover, it was deemed necessary to carry out a higher percentage of checks for quality assurance in three study sites (Site 2, 3 and 4), where 10% checks were carried out. All study staff were also reminded of the importance of careful data entry to minimise errors.

Confidentiality

All personal data collected about the participant was managed following the PRIMENT SOP for Managing Personal Data. Each participant was given a unique identification number at randomisation. The participant’s initials, date of birth and unique randomisation number were used for identification. All other personal or identifiable information about the participants was stored separately and securely in the UCL DSH system. The CRFs did not contain identifiable information. We used a delegation log to track personnel responsible for data management.

Trial database

All data from the participants were entered into an online clinical data management system called Sealed Envelope. PRIMENT approved the quality management, software development and security of this system. The original paper forms of outcome measures were stored in secured locked cabinets in the office at each trial site. PRIMENT SOP Database Lock, Unlock and Closure was followed at the end of the trial.

Data entry

Baseline data for 261 randomised participants from all four sites were entered into the Sealed Envelope database. The primary outcome measure (CBCL) was available in the database for 261 participants and the CRFs for Source Data Verification (SDV) checking were available for all participants.

Four-month follow-up data for 229 participants from four sites have been entered into the database. The primary outcome measure was available for 223 participants.

Ethics

Approval

Approval for the study was given by the London – Camden and Kings Cross REC (reference: 17/LO/0659).

Substantial amendments

Ethics and Health Research Authority (HRA) approval for the study was given on 19 May 2017. Overall, there were six substantial amendments approved by the REC as well as nine non-substantial amendments to the study protocol.

-

Substantial amendment 1: added participant recruitment via third-sector organisations, such as ‘Contact’ (co-applicant) and added PIC sites to the study.

-

Substantial amendment 2: extended the screening and baseline visit window from 2 to 4 weeks, approved giving the brochure and list of resources to all participants in both arms of the trial.

-

Substantial amendment 3: included minor updates to the participant information sheets and the study poster, created treatment allocation letters for the participants and created a letter for clinicians, teachers or third-sector organisations to send the study information sheet and expression of interest form to potential participants.

-

Substantial amendment 4: added an independent reviewer to code the video interviews, included the possibility of verbal consent and the possibility of conducting qualitative interviews for process evaluation over the phone, and added sections of the transparency wording from the HRA website in line with the new General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), added intervention survey, created a letter for parents from the intervention group that did not attend any of the sessions, provided minor amendments to information sheets, consent forms and topic guide for interviewing service managers.

-

Substantial amendment 5: approval to invite parents not taking part in the study to attend the SSTP groups to ensure viable group sizes, created a ‘Thank you’ card for parents to boost attendance at follow-up assessments, added a minor update to the information sheet.

-

Substantial amendment 6: approved use of external transcription service to transcribe recorded audio files and to include some participants from the TAU group in qualitative interviews, including information regarding the 10-month costed extension approved by the study funders.

Deviations from the study protocol

There were 37 protocol deviations at 4 sites. Most of these deviations concerned baseline or follow-up assessments being completed outside of the assessment window as specified in the protocol. The assessment window between screening and baseline was extended to 4 weeks as part of substantial amendment 2. Other deviations included issues with the consent forms (e.g. a participant signed a consent form with the wrong site logo). These consent forms were corrected, or the correct forms were completed retrospectively. Protocol deviations relating to the COVID-19 pandemic are described later in the report under the heading ‘COVID-19 Adaptations’.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic had a substantial impact on the study. Three non-substantial amendments (7, 8 and 9) were drafted to enable study changes to ensure participant and researcher safety and adherence to social distancing government regulations. These amendments allowed researchers to complete all assessments over the telephone and for the therapy to be conducted remotely. These amendments also included the addition of a COVID-19 parent survey to assess the impact of the pandemic on families (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Parents from the Parent Advisory Group (PAG) provided their views at the start of the pandemic, stating the situation was very stressful and families may need time to settle and find a routine before they can allocate time to the study.

We also discussed how to mitigate risks imposed on the conduct of the trial regarding the safety of participants and researchers, treatment delivery and adherence, data quality and completion, and statistical considerations with the Clinical Trials Unit and the Trial Oversight Committee.

Recruitment during the COVID-19 pandemic

In total, 51 out of 261 families in the trial were randomised on or after 16 March 2020. The non-substantial amendments also simplified the process for Clinical Study Officers to pass on expressions of interest to the study team and updated the study protocol to reflect all changes. Study recruitment was halted between 18 March 2020 and 18 May 2020, and the timescale for re-opening was determined independently by each site. Sites reopened gradually between May and August 2020. Study follow-ups continued throughout this period, although child−parent observations and cognitive neuropsychological assessments (i.e. Mullen Scales of Early Learning)57 that required face-to-face contact were omitted from the study, as we were unable to find alternative ways to conduct the assessments (max n = 51). Wet signatures for logs were replaced with online signatures, and verbal recorded consent was obtained rather than written consent.

Observing government guidance on the spread of COVID-19 led to the study team working remotely. Before the pandemic, the CA-SUS forms at 4 and 12 months were completed by parents during visits and then handed to the Trial Manager for data entry. As this was no longer possible, research assistants completed the CA-SUS assessment over the phone but did not ask questions about attendance at parenting groups that would unblind them. These data were collected once the participant had completed the final follow-up. Moreover, the issues associated with the pandemic caused further difficulties with completing the study assessments with participants. For example, some parents found it challenging to find the time to complete all questionnaires over the phone, therefore many only completed the primary outcome measure (CBCL). Since all work, appointments, therapies and school responsibilities became remote, many assessments were re-scheduled and this increased the number of missing assessments and those completed outside of the assessment window.

The restrictions from the COVID-19 pandemic caused difficulties with obtaining the secondary outcome measure (C-TRF), which was meant to be completed by the child’s teacher. Most of the schools were closed and many parents did not have other relatives or people who would know their child’s behaviours well enough to complete this measure.

Parents from the PAG reflected on their own experiences during the pandemic, including big routine changes, which could affect the availability of parents to complete assessments. In particular, single parents may not have had the time to dedicate to the study. One parent reflected that during the pandemic situation, it was difficult to make phone calls without interruptions, but as the situation progressed, the family started to settle into a routine and this increased their capacity to take phone calls and allocate time to more responsibilities. They said this may also be similar for other parents. Another parent from the PAG noted that many of these families may not have education health care plans yet, which was allowing children to continue attending school during lockdowns. For those without a plan, routines are being disrupted, which may have been extremely difficult for both children and their families. Overall, the COVID-19 pandemic brought challenges not only to the delivery of SSTP and other services in TAU but also to the daily lives of every individual. This likely resulted in a deterioration in children’s behaviour patterns, increased parental stress and poorer parental ability to manage behaviours. These disruptions likely challenged many parents’ ability to comply with study directives.

Treatment as usual during the COVID-19 pandemic

Treatment as usual could not have been delivered in the conventional way as most of the services available in local areas were interrupted or completely suspended from March 2020. As such, families that were recruited in this study from this time had little to no help or support available to them.

During the qualitative interviews conducted for the process evaluation, parents shared their views about the COVID-19 pandemic and the national lockdowns. They described this time as extremely challenging as the children’s challenging behaviours worsened due to lack of routine and limited access to school. Parents were trying to balance working from home and caring for their child with no additional support from services or school. As such, parents felt even more abandoned during the times when they felt the most need to be supported.

The behaviour during the three months of lockdown took its toll. It escalated to where it was, like, unmanageable most days. Um, but there wasn’t a lot we could do about that.

One of the biggest challenges I’ve ever had to face is being in three months lockdown with a child with needs … It was really, really unfair to do I think, what they done originally, was said children who have EHCP plans would be taken care of. We’d be taken into consideration, the needs, and it wasn’t.

Stepping Stones Triple P delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic

From March 2020, the intervention was adapted to follow the COVID-19 safety precautions and regulations. At the start of the pandemic, no online version of SSTP was available from the Triple P group. The therapists continued with the same session plans and content that was delivered before the COVID-19 pandemic and delivered this remotely. The final group combined participants from all sites to ensure a sufficient group size. The Triple P held a panel discussion on remote delivery in practice on 21 July 2020. This was attended by the Trial Manager. The Triple P developers granted permission for us to share the advice provided in this session, including:

-

Using video conferencing software, which allows for better participation than the telephone as parents can see the therapist when skills are being demonstrated.

-

Allowing space for discussing progress and being able to problem-solve technical challenges.

-

Acknowledging the stressors parents are facing and normalising the feelings they are experiencing. Offer hope that with the plans and strategies to be discussed, they will feel more confident in how to tackle this new normal, reduce stress and enjoy their parent–child interaction.

-

Maintain contact with fellow Triple P practitioners, including Peer-Assisted Supervision and Support (PASS) sessions, to support each other in learning this new format and maintain fidelity.

-

For parents with children at home, consider proposing that parents use a Planned Activities Routine to occupy the children so parents can participate fully in the session.

-

Consider sending parents text reminders of their upcoming session.

-

Resources can be available to pick up from an office (if open) or mailed to families.

-

Consider planning how to use behavioural rehearsal based on your chosen delivery format (on videoconference platforms, it can be done as usual).

-

When parents or practitioners are stressed or anxious, it may be more difficult to come up with ideas. Practitioners may need to think about giving more examples or offering more specific prompts sooner if they realise that parents are struggling with idea generation.

-

Provide an opportunity for informal communication between parents before or after the sessions.

-

Show DVDs by sharing your screen or demonstrate live the strategies. The DVD could also be played in the background, sharing the audio only (additional commentary may be required), or therapists should read the relevant section of the Positive Parenting Booklet.

-

Consider if the parent has safe activities for the children while they are taking part in the intervention.

-

Content can be fully delivered remotely, and the process/strategies should not change.

Data on attendance at parenting groups were collected once the participant has completed the study. Forms were sent to the Trial Manager for data entry.

Statistical analysis plan

Unmasking of the data and analysis was initiated after the last participant had completed their 12-month follow-up. All relevant data had been entered, checked and locked, and the analysis plan had been finalised and approved (see Report Supplementary Material 2 for the full Statistical Analysis Plan). Before the analysis was conducted, data were checked for quality. Incomplete or inconsistent data included missing data, data outside the expected range and other inconsistencies between variables (e.g. on the dates the questionnaires were completed). Any inconsistencies that were found were checked with the researchers, corrected and documented by the trial statistician. The primary analysis was performed independently by two statisticians (CQ and GA) to ensure its accuracy. For the primary analysis, we analysed participants with outcome data (CBCL) at 12 months according to their original assigned groups. The secondary analyses were carried out by one statistician (CQ) and checked by the lead statistician (GA). All the statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 15 (or above) and R version 3.5.0 (or above).

Assessment of baseline characteristics

Summary measures for the baseline characteristics of each group are presented as mean and SDs for continuous, symmetric variables, medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous, skewed variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. We compared baseline characteristics visually to assess whether the balance had been achieved. Any notable imbalances prompted additional adjusted analyses (see later).

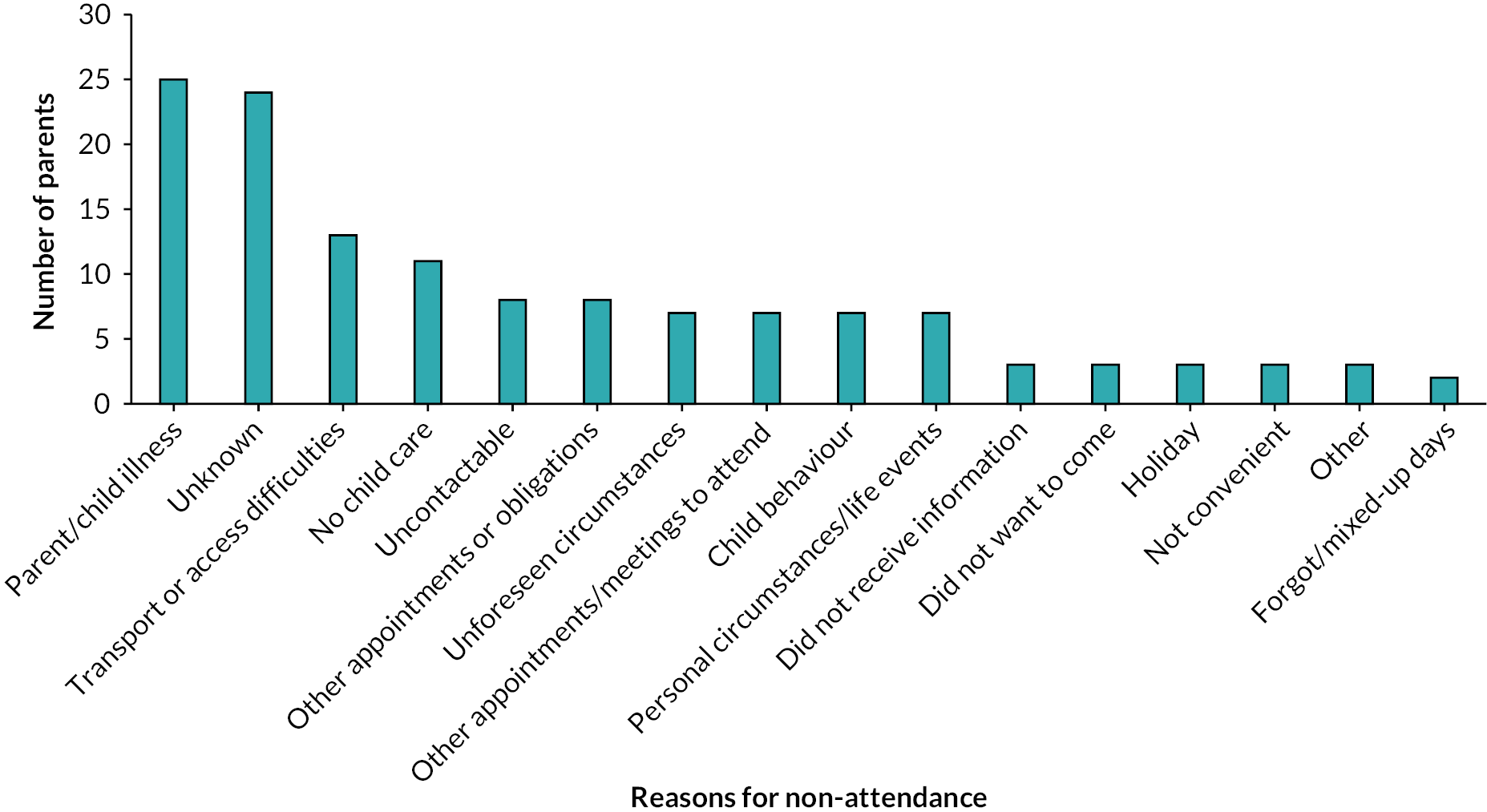

Adherence to allocated programme and attrition

Some loss to follow-up was expected over 12 months. The proportion of participants missing was summarised for each outcome measure, in each arm, and at each time point. Potential bias due to missing data was initially investigated by comparing the baseline characteristics of the trial participants who have (analysable) primary outcome data to those who do not, using descriptive comparisons, t-tests, chi-squared tests and Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. Reasons for withdrawal from the programme were summarised. Participants’ adherence with SSTP is defined as attendance to most of the planned group and individual sessions, that is participation in at least 4 (out of 6) group sessions and 2 (out of 3) individual sessions. Participants who engaged with SSTP were compared descriptively with those who did not in terms of their baseline characteristics.

Analysis of primary outcome

The primary outcome is the CBCL total score at 12 months. The primary analysis used mixed models to perform an individual-level analysis and followed Roberts and Roberts60 in adjusting for therapist clustering in the intervention arm only (random coefficient model). This model also adjusted for baseline total CBCL score and randomisation stratification factors (centre, level of intellectual disability) using fixed effects. This was a complete case analysis. The only ‘imputation’ performed was done by following guidance from the CBCL scoring manual. That is, missing values for CBCL were scored as zero unless more than eight items were missing, in which case the participant was excluded. The presentation of all findings is in accordance with the latest CONSORT statement. The model assumes that the residuals are normally distributed and homoscedastic, which was checked using residual plots (e.g. normal Q−Q plots). Where substantial departures from normality occurred, a transformation of the outcome variable was considered.

Analysis of the secondary and other outcomes

In addition to the analysis of the total CBCL score, we analysed the internal and external scores separately using the same approach. In addition, analyses were performed for each of the secondary outcomes. Continuous outcomes were analysed using the same approach as that described for the primary outcome. For binary outcomes, we used analogous logistic mixed models,61 although without adjustment for baseline outcome scores. All analyses of secondary and other outcomes should be considered supportive analyses. Missing values in the outcomes were handled, where possible, using guidance from the corresponding manual.

Sensitivity analysis

The following additional sensitivity analyses were performed. We repeated the primary analysis with additional adjustments to see if any notable baseline imbalances were encountered (due to chance or missing data). We used a mixed model to analyse both the 4- and 12-month CBCL outcomes simultaneously. We repeated the primary analysis after imputing outcome data using multiple imputations using chained equations. Specifically, we imputed component items of the CBCL score (i.e. not the total score) using item information from the baseline, 4- and 12-month CBCL scores and other variables (as appropriate). Missing baseline data were imputed using single imputation methods where multiple imputation was not successful. Per-protocol and complier-average causal effect (CACE) analyses were performed as participant adherence was relatively low.

Coronavirus disease 2019 considerations and additional analyses

The following analyses were carried out to explore the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the trial findings. The baseline characteristics of children and parents were summarised by randomised group before and after 16 March 2020. In addition, adherence to the programme, attrition and adverse events were summarised before and after this time point. We performed a subgroup analysis to investigate whether the intervention effect differed depending on whether recruitment was before or after 16 March 2020. This was achieved using the primary analysis model with additional indicator and interaction terms. Finally, we considered whether the effect of the intervention depended on the size of session groups. Separate analyses considered: (1) the overall group size and (2) the average group size in sessions attended. These analyses were achieved using the primary analysis model with additional indicator and interaction terms. Similar health economics analyses were performed to assess whether the cost of the intervention was affected when intervention sessions were moved online. We also assessed whether the COVID-19 pandemic had an impact on children and carers’ mental health and HRQoL during this period.

Health economics analysis

The economic evaluation aimed to assess the cost-effectiveness of delivering the level 4 SSTP intervention from the NHS, personal social services (PSS) and parents’/caregivers’ perspectives (please see Report Supplementary Material 3 for the full Health Economics Analysis Plan).

Valuation of economic outcomes

The primary economic outcome measure was the QALYs derived from utility scores obtained using the PedsQL™ General Core Scales (GCS). Mapped EQ-5D-Y utility scores algorithm62 provided an empirical basis for estimating health utilities. For parents/caregivers utility scores were derived from responses to the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) using valuations obtained from an English population. 63 These were used to form QALYs over the 12-month period, adjusting for any imbalances in baseline scores. 64 Measurements have been recorded at baseline, 4 and 12 months.

Valuation of resource use

Study records of the number of therapists attending training sessions were used to track resources used in the delivery of the training programmes including trainee and trainer time (and preparation time), travel costs, attendance incentives and course materials to calculate the fixed cost of training. For the intervention delivery, we recorded the number of sessions delivered, the time each therapist spent with a family, and also any materials provided to parents/caregivers.

For the NHS and PSS analysis, data were collected on the use of health services in primary and community care, investigations and prescribed medication, hospital admission and outpatient attendance, ambulance use and social care. Data on health and social care resource use were collected at baseline (for the past 6 months), 4 months (for the past 4 months) and 12 months (for the past 6 months) post intervention.

For the analysis from the parent/caregiver perspective, we additionally collected data on out-of-pocket expenses. Expenditure on private use of treatments and therapies was captured in the CA-SUS.

Health and social care resource use was costed using unit costs from the most recent Unit Costs of Health and Social Care published by the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU)65 and NHS reference costs. The costs of medications were estimated from the British National Formulary. The cost of each resource item was calculated by multiplying the number of resource units used by the unit cost. The total cost for each participant was estimated as the sum of the cost of resource use items consumed. The primary analysis included only health and social care data collected as part of the trial and hence covered only 10 months of the trial (missing months 4–6). We have projected costs from 4- and 12-month follow-ups to estimate the 12-month health and social care resource use as part of sensitivity analyses. All costs are reported in 2019–20 Great British pounds. No discounts were applied, as trial follow-up did not exceed 12 months.

The overall economic evaluation

All analyses were conducted using intention-to-treat (ITT) principles, comparing the two groups as randomised and including all participants in the analysis. Analyses were compliant with the accepted economic evaluation methods. 66

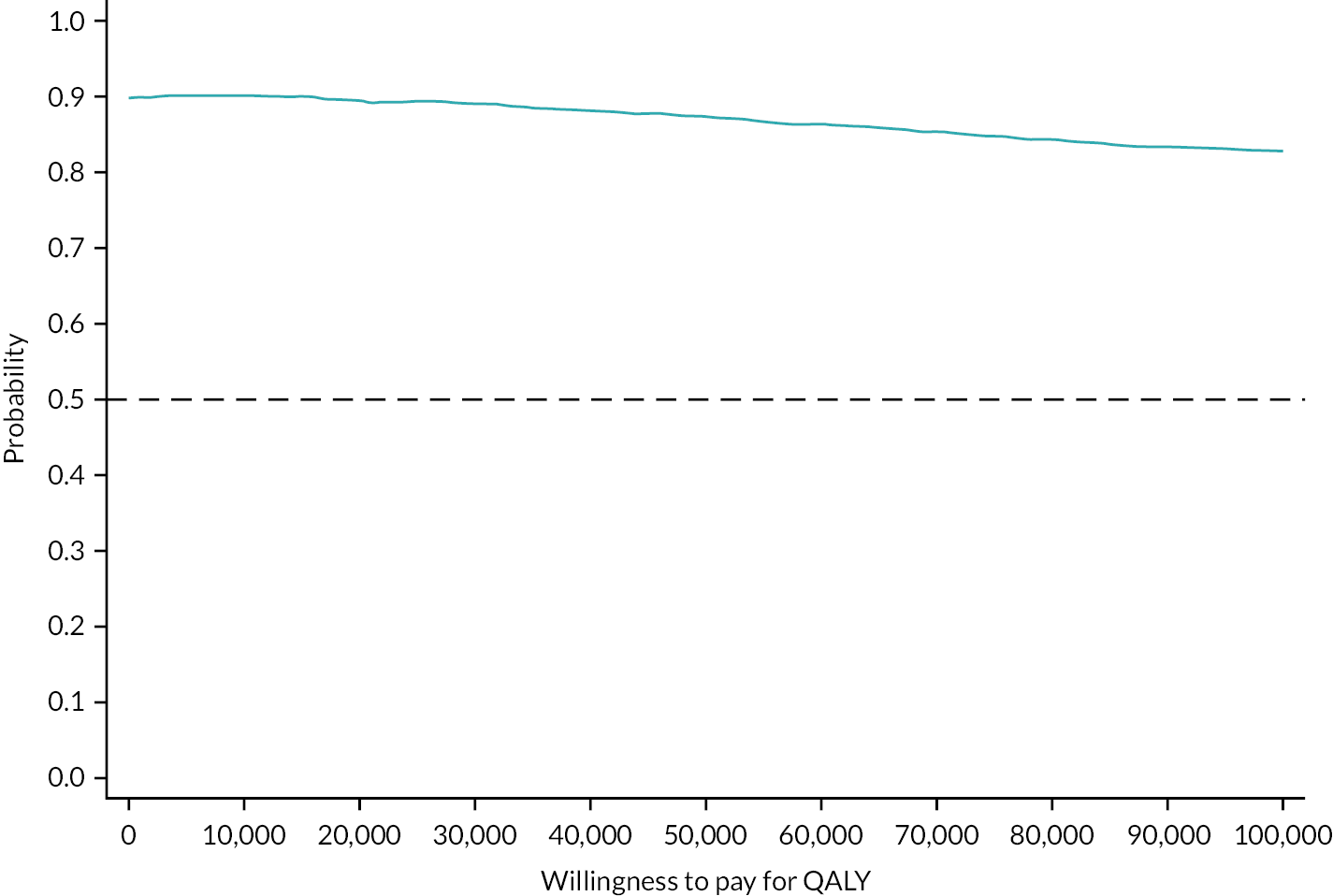

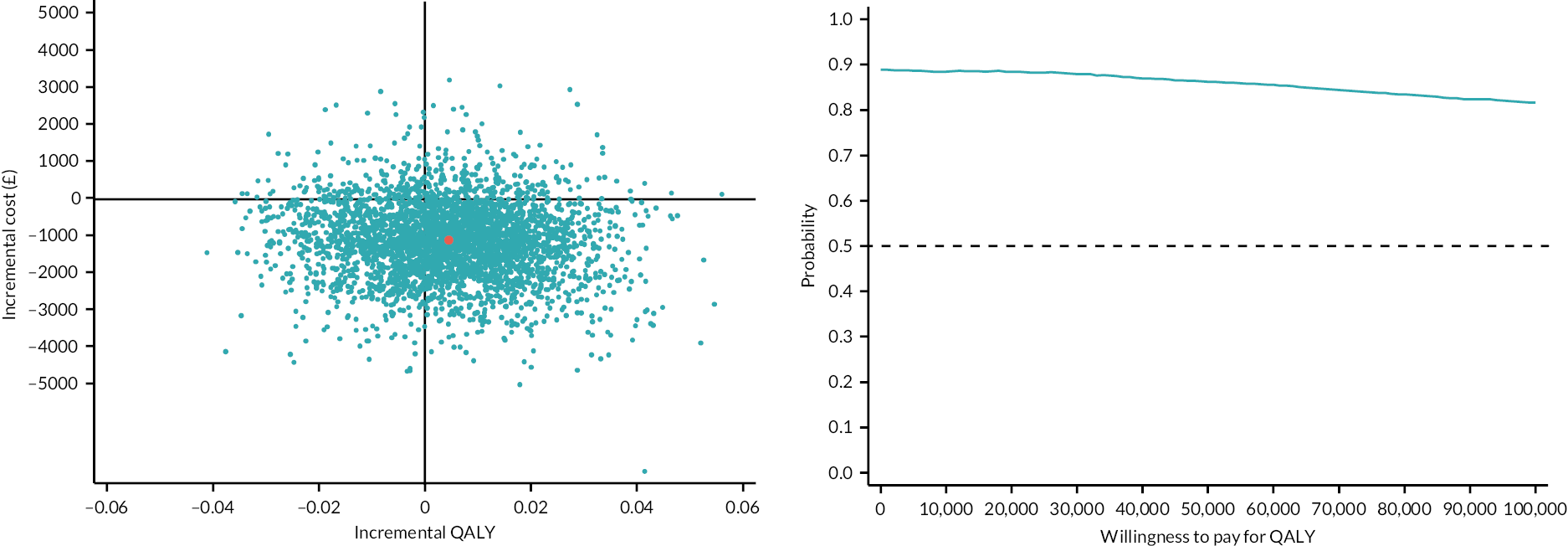

-

Cost-effectiveness analysis: mean incremental cost from the NHS and PSS perspective per change in CBCL. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICER) were reported, and uncertainty was explored using cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs). 67,68

-

Exploratory analysis of quality of life using PedsQL™ to predict utility scores. The mean cost per participant for the intervention and TAU was reported by type of service use. We calculated the mean cost per QALY using the mapped EQ-5D-Y. Mean QALY per participant was calculated as the area under the curve for the duration of the trial, adjusting for baseline values.

Cost−benefit analysis of the impact on the parents/caregivers: Responses to EQ-5D-5L were used to calculate QALYs in a standard format and valued as willingness to pay (WTP) for a QALY gained. We calculated the mean cost (including out-of-pocket expenditure) per QALYs. Mean QALY per participant was calculated as the area under the curve for the duration of the trial, adjusting for baseline values.

Missing data

Missing data were explored to determine any patterns, extent and association with participant characteristics. The primary analysis included all participants using multiple imputation to predict missing costs and outcomes. 69

Analysis of relative costs and outcomes

Cost and QALY data were combined to calculate an ICER. Uncertainty in the point estimate of the cost per QALY was quantified using bootstrapping methods to calculate confidence intervals around the ICER.

The results of the non-parametric bootstrap are presented on a cost-effectiveness plane (CEP). CEACs, showing the percentage of cases where the intervention is cost-effective, over a range of values of WTP for a QALY gained, were constructed using the bootstrap data from a range of values of WTP for a QALY gained for each different costing perspective and for the different methods of calculating QALYs. The probability that the intervention is cost-effective compared to TAU at a WTP for a QALY gained of £20,000 and £30,000, and £13,000 as a measure of opportunity cost were reported. 70

Sensitivity analyses

One-way sensitivity analyses were used to judge the potential impact of sources of uncertainty:

-

complete case analysis;

-

given that training costs may differ between the trial and implementation of the intervention due to learning or being delivered to a larger patient group, we tested the impact of varying training costs (particularly because of larger patient numbers per staff member trained) on the mean incremental cost per QALY gained.

Chapter 3 Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI) in this trial was defined as research carried out with members of the public at every stage of the project. 71 This included helping to identify research priorities, forming an advisory group, reviewing study documentation, problem-solving challenges and supporting dissemination strategies. This level of involvement is similar to other comparable trials within this population. 72

Ms Una Summerson, the Head of Policy and Public Affairs for the charity Contact, is one of the study’s co-applicants. Ms Summerson was involved with study design, recruitment strategies, documentation review and study dissemination. The research team produced a newsletter twice a year to provide study updates. This was shared with study participants and local investigators.

Parents of children with intellectual disabilities and behaviours that challenge were recruited from the Camden Special Needs Forum (CSNF) to assist in the development of the study proposal. Eight parents were originally invited to form the PAG. These parents were recruited through a national charity called Contact and meetings were facilitated by the Head of Policy and Public Affairs at Contact (Una Summerson). Three parent members regularly attended a meeting every 3 months to assist in overseeing the trial, discussing study progress and helping with materials. These parents were all mothers and were each based at different trial sites. After the first seven PAG meetings, it was agreed that from September 2019 onwards, the PAG meetings would be merged with the TMG meetings, and so, all PAG members were invited to attend every subsequent TMG meeting. Altogether, parents attended seven PAG meetings and 19 combined TMG and PAG meetings. The TMG meetings were held every month until January 2021 and it was then decided that meetings would be held every 2 months. All meetings were held face to face before March 2020. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, all meetings after this time were held online via MS Teams.

Parents from the PAG group worked alongside researchers on tasks to oversee the successful running of the project. Parents were involved in the following tasks:

Study design

Parents from the CSNF helped us to develop the study proposal. The PI met with six parents for a discussion about the study and another five parents were contacted to provide views about the study application. Some of these parents continued to be involved once funding for the study was received. Parents felt there was a real need for the study and were complementary of the behavioural approach which they saw as a critical ingredient. ‘If we had the right strategies to use earlier, I could of gone back to work and the school wouldn’t be ringing me all the time’. We discussed the number and type of assessments, randomisation and the lay summary, and asked about any issues they considered as challenging. They said that research would be helpful even for the control group as it allows time to think about the child and their needs and has a positive impact on both groups. The parents we consulted with argued that there would be short and medium term benefits from providing the resource and even suggested a summary of the research assessment to be shared with the parent who took part in the study. They were also interested in potentially adding to collection of data on other variables that may be associated with challenging behaviour including food items.

We held two face-to-face meetings with CSNF parents from diverse ethnic backgrounds on 13 January 2016 (for the outline) and 19 April 2016 for the main application. We also had extensive e-mail correspondence and discussions with the CSNF group leaders and with our co-applicants Contact regarding the best way to involve parents. This helped to formalise a plan for the PAG group and its role throughout the study.

The PAG members assisted in training the research assistants (a topic mentioned was how to talk to the parents without the latter feeling blamed), examining the study parent information materials and consent forms, assisting with drawing up topic guides and in the process evaluation, attending TMG meetings, helping to format feedback to parents and interpreting and disseminating the findings.

Feedback on newsletters and study documents

Parents made suggestions on how to make the study documentation more accessible and comprehensible for families, including comments on study posters, information sheets, etc. For example, feedback was provided on the study poster, and it was suggested that pictures of children with various disabilities be included to make it more welcoming to families who have children with less common disabilities.

Improvements to recruitment strategies

The PAG proposed many strategies to support recruitment and overcome challenges that arose over the course of the study. At the beginning of the study, parents suggested the trial be promoted in parent forums and that the study poster be given to parents at meetings of local parent groups. This led to parents from London sites being invited to attend a parent meet and greet morning where two parents from the PAG group talked about the study. Parents were provided with study information and expression of interest forms at this meeting and were asked to share the information with other parents. This helped to increase recruitment rates at the London sites.

Towards the end of the study, we experienced challenges reaching parents for the 12-month follow-up assessments. The PAG members suggested we provide e-mails or a newsletter to explain the importance of the study and what will happen with the results and outcomes of the research. The idea with this was to try and increase parents’ motivation to complete the final study follow-up. This information was included as part of the study’s Christmas newsletter.

Problem-solving challenges

To improve attendance at the SSTP group meetings, it was suggested to offer an incentive to parents, such as providing food or snacks at the intervention group each week. This was appraised by parents who attended the groups and who said the hospitality during sessions created a welcoming atmosphere.

Providing lived-experience perspectives and insight throughout the course of the study

Parents taking part in the study often expressed their gratitude to research assistants for the opportunity to be a part of the study and to be able to talk to someone who is interested in hearing about their child. The parents from the PAG agreed and shared personal experiences of feeling that often parents only get little time to speak about their child and being appreciative of the time they get to talk to a professional.

The parents also discussed the need for and utility of group interventions. It was discussed that usually, the main carer receives all the training, and this may leave the other parent or another carer feeling helpless. It would relieve the pressure and burden if all the family could receive the training/intervention. As a result of these discussions, we enabled additional caregivers to attend intervention sessions.

Publication and involvement with research outputs

The PAG were involved in reviewing the full study report and dissemination plan. The parents have also provided commentaries and reflections that have been included in our study publications. The PAG provided the following commentary for the qualitative study results (publication being drafted for submission):

Intellectual disabilities occur in all racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic group/ lifestyles. Although its specific causes are still unknown, we do know one thing, the rate is increasing. Treatments and interventions are offered in brick and mortar centres, community providers, and by in-home therapists; derived from parent’s enticement of therapies that promise to do everything. Unfortunately, parents only escape from the confusing unforgiving treatment’s business is the NHS, which often through little fault of its own is stalled by unavoidable hurdles. The services are not efficient, and it often feels like parents know more than the professionals and are constantly teaching them rather than professionals providing support to parents. This makes parents lose trust and faith in the system. So, where does our support come from? The described points in this paper are concise and relevant, however parent’s feeling of loneliness and exclusion also come from the overwhelming and confusing online information overload, which can take years to declutter, to select the credible resources and build supportive and convenient entourage. An arduous job for parents, specially under time pressure to find and implement necessary early intervention for the child.

The behaviour during the three months of lockdown took its toll. It escalated to where it was, like, unmanageable most days. But there wasn’t a lot we could do about that.’ This quote highlights the striking reality that postcode often defines the level of lockdown discomfort and opportunities. Actually, all parents want is a consistent professional proficient support that is able to comprehensively listen to them and work collaboratively toward a better life quality for the child. The quotes in the paper were about appreciating talking, listening, understanding, talking through, and sharing ideas, opinions, and techniques. The caring role is a very lonely journey that parents shouldn’t have to take alone.

One parent from the PAG commented on their involvement with a publication of a case study:

I was part of the BMJ article writing a case study and doing a podcast. I believe having real parents on the panel helped the project understand real life problems that we face as families daily, including why we can’t always make appointments at last minute and as much as we need/want the support offered, just the situation we can find ourselves in can be so chaotic that we can’t always take part every time.

The three parents described their involvement with the study and experience of being part of the PAG:

Parent 1

As a parent of two children with additional needs that have very challenging behaviour, I was so excited to be part of this project to give the voices of parents who had genuine lived experience. I also had the benefit of being part of a large network, had opportunity to ask direct questions and got feedback from others. We were included in every part of the project. The information we gave as parents was always respected and included and we felt very much a part of the team. The professionals on the trial always listened to our opinions and genuinely wanted the support that we gave on the parent panel. I would definitely love to be part of any future projects like this and the whole team at UCL and NHS England treated us with respect and as a colleague with experience rather than just having to have us there as part of guidelines for the project. I found the face to face meetings beneficial as we all felt part of a wider team and network and they weren’t as daunting as online meetings. I think having face-to-face meetings before the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in better working when we had no alternatives than working online as relationships had already been formed. I am extremely proud of this project and how they altered as much as possible to meet the COVID-19 requirements. I hope that it results in helping families struggling with their children and would have benefitted from it when my children were that age.

Parent 2