Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/08/45. The contractual start date was in December 2015. The draft report began editorial review in October 2020 and was accepted for publication in May 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Metwally et al. This work was produced by Metwally et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Metwally et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Burden of fertility treatments

In vitro fertilisation (IVF) is an assisted reproductive technology widely used in women unable to reproduce naturally. IVF (in which the sperm and egg are mixed together in a Petri dish) can be undertaken with or without intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), in which the sperm is directly placed inside the egg; from hereon we refer to IVF, with or without ICSI, as ‘IVF’. In 2018, about 54,000 patients in the UK underwent IVF. 1 Success rates are modest, but have been increasing over recent years, with an overall live birth rate (LBR) of 23% in the UK in 2018. 1 Undergoing IVF takes an emotional and financial toll on couples,2 causing absence from work,3 feelings of distress, lack of control and stigmatisation,4 with repeated failure sometimes invoking subclinical emotional problems. 5 When treatment fails, there is often a desire to try one of a bewildering selection of expensive IVF ‘add-ons’ in order to improve the chances of success,6 despite a lack of high-quality evidence to support their benefits or safety. 2,7,8 One such add-on is the use of local endometrial trauma, also known as endometrial scratch (ES), which can cost up to £325 per procedure and involves ‘scratching’ the lining of the womb (the endometrium) with a pipelle or similar device. 8

Evidence for endometrial scratch

The use of ES to improve implantation rates in women undergoing assisted conception was first described in 2003. 9 Initially, ES was reported to positively affect the outcome of IVF in women with repeated implantation failure. 10 This was later also demonstrated in unselected populations (i.e. women who had undergone any number of previous IVF cycles),11 including in a 2015 Cochrane review,12 which reported a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCTs), finding that ES improves the chances of a live birth when undertaken in this unselected population [relative risk (RR) 1.37, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.05 to 1.79]. However, a more recent systematic review has included subsequent RCTs and highlighted that the evidence for ES improving LBR in this population is unclear (RR of 0.95, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.41). 13 Subsequently, a large high-quality RCT by Lensen et al. 14 in an unselected population found that ES did not result in a higher LBR than ‘usual’ IVF. Despite this, the pros and cons of undertaking ES in an unselected population have been discussed since this publication, with proponents of the procedure arguing that it has low costs and a low level of harms, which, coupled with the possible benefits of taking a tissue sample at the same time as ES, warrant its use in selected populations. 11

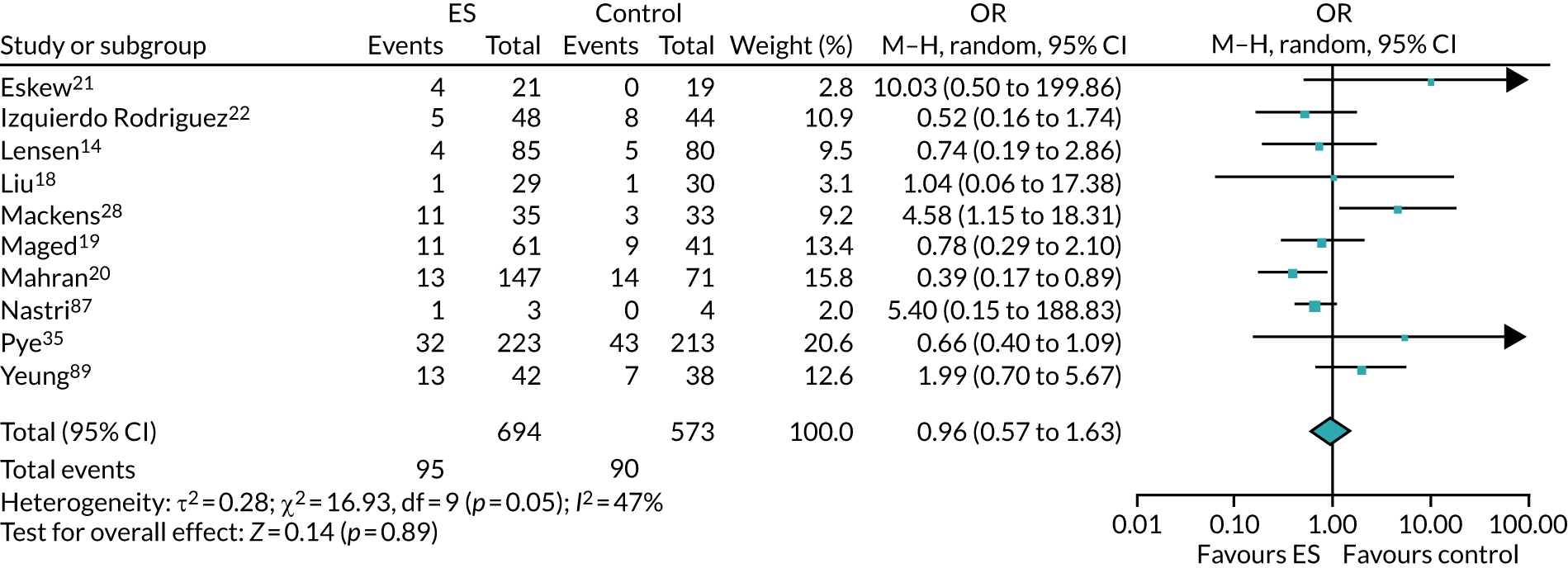

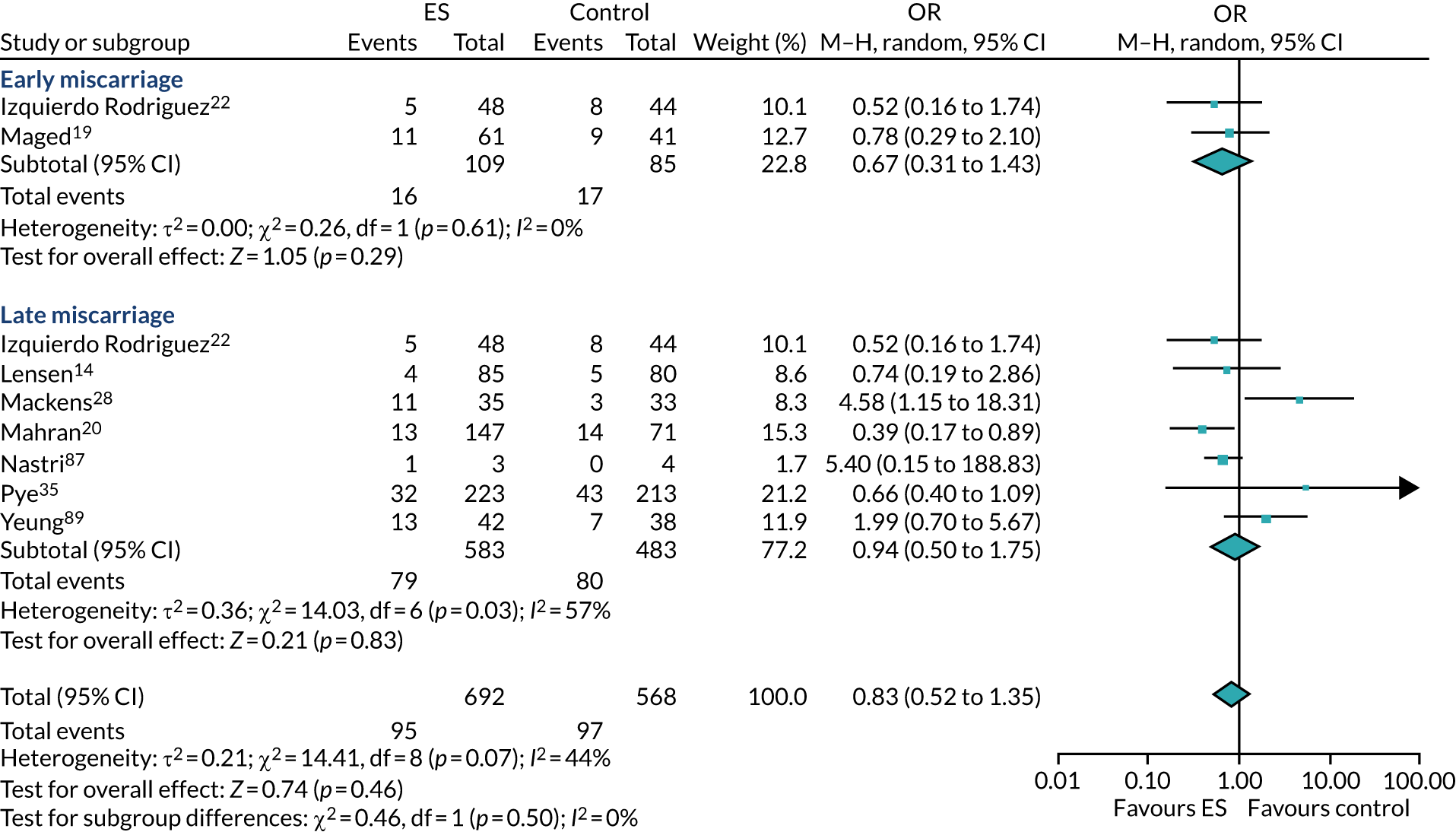

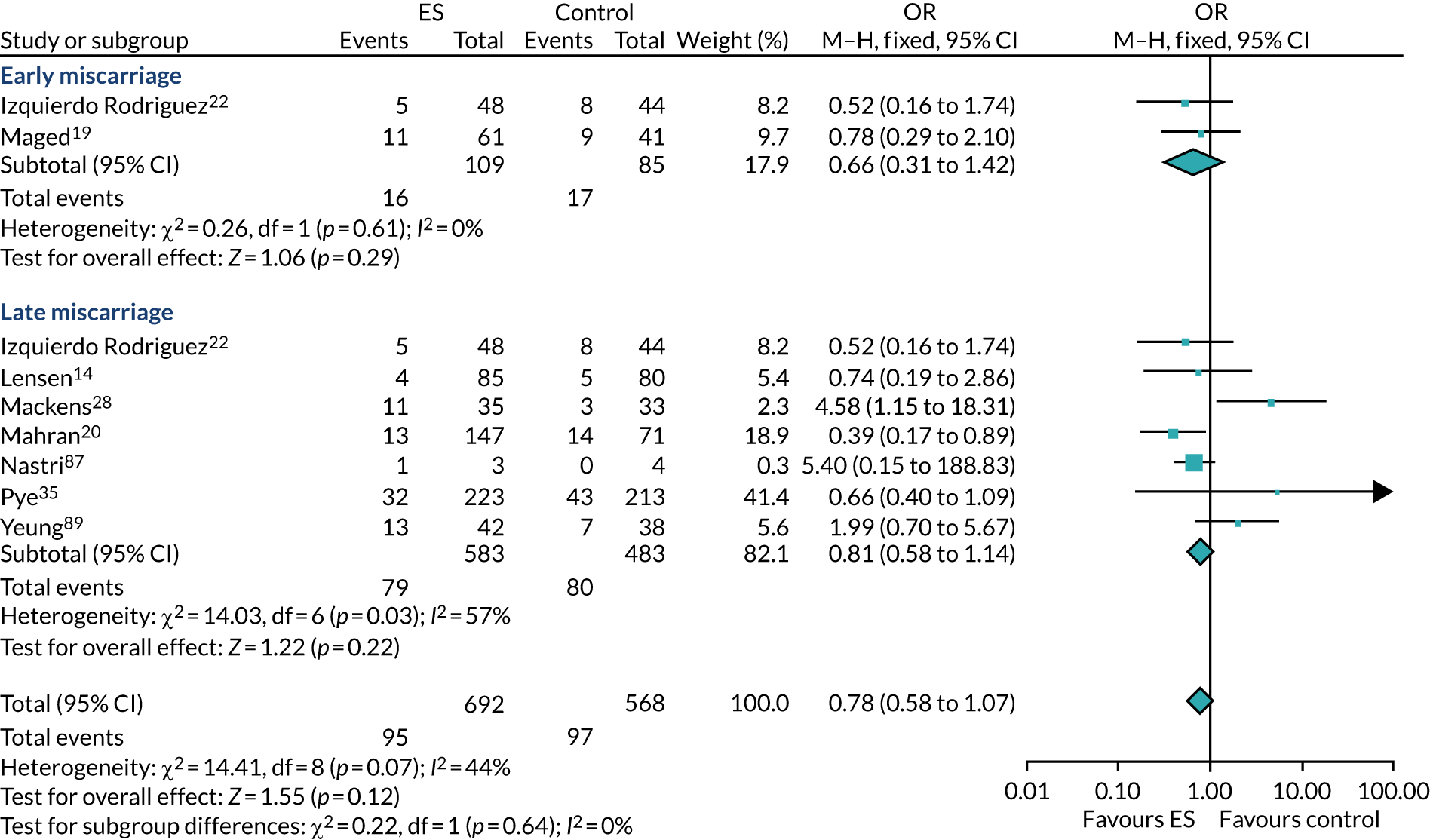

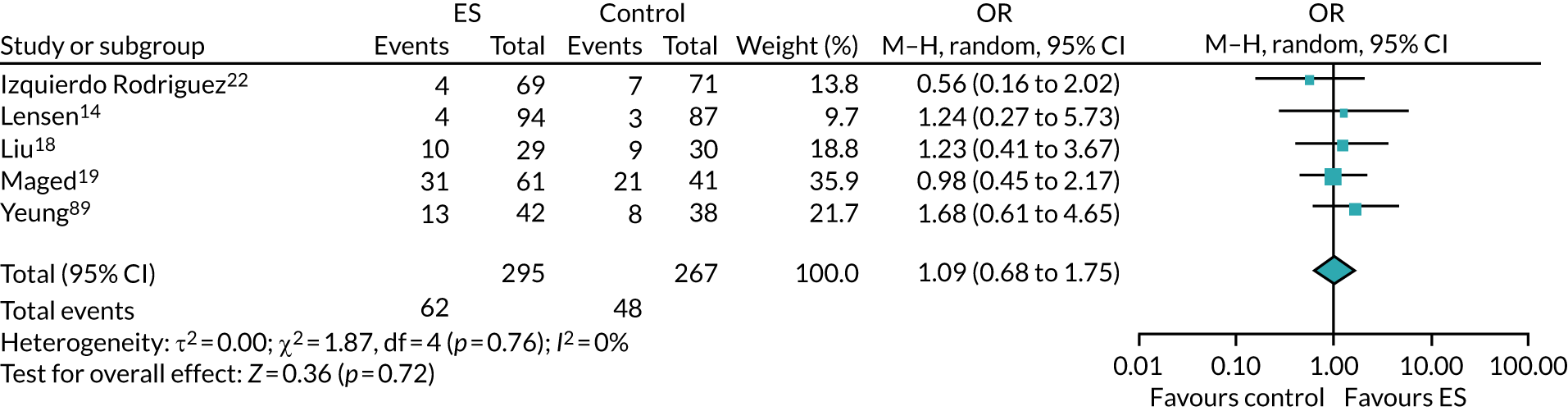

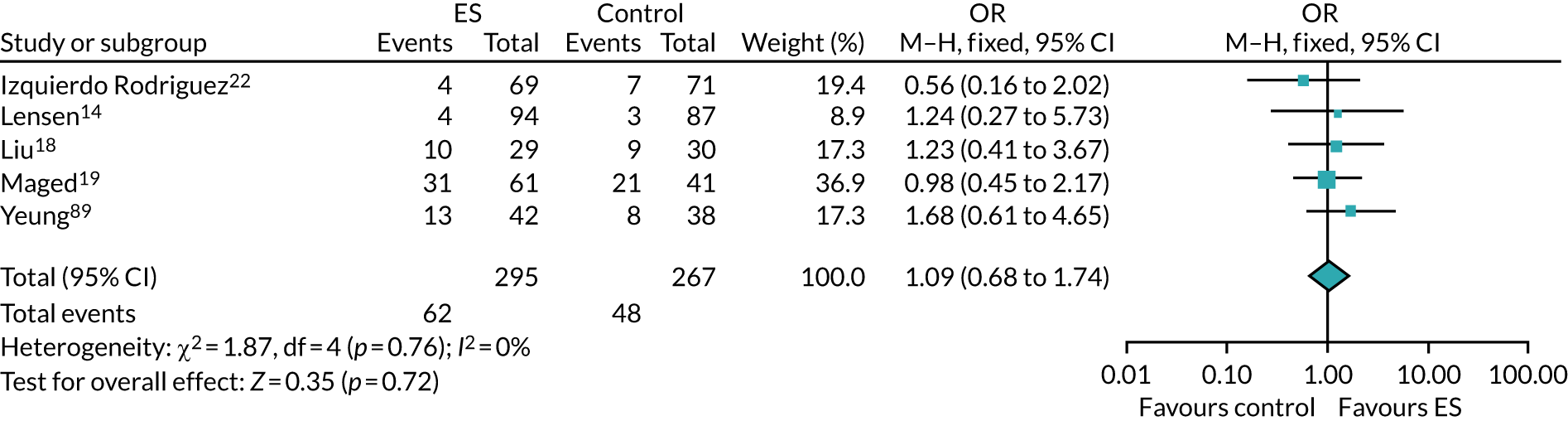

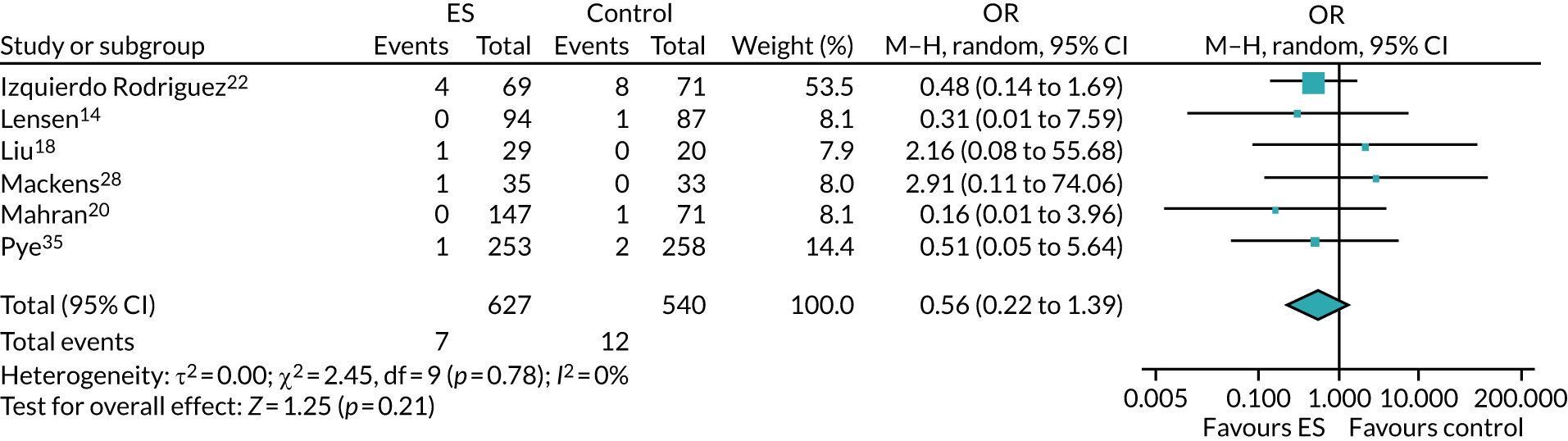

The chances of achieving a live birth decrease with successive cycles of IVF; therefore, the aforementioned evidence from unselected heterogeneous populations, in many cases including women who had undergone a previous IVF cycle, are not necessarily generalisable to the first-cycle population. 15 One systematic review by Vitagliano et al. 16 specifically focused on patients undergoing their first IVF cycle and included seven RCTs; it found that there was no evidence that ES followed by IVF, compared with IVF alone, increased the success of treatment, with a RR of live birth (or ongoing pregnancy if LBR was not reported) of 0.99 (95% CI 0.57 to 1.73; p = 0.97). Secondary outcomes (miscarriage, multiple pregnancy and ectopic pregnancy) were also not significantly altered by undertaking ES. Notably, the small sample sizes of the included studies resulted in uncertainty around the effects of ES in women undergoing their first IVF cycle, and the included trials were at either a high or an unclear risk of bias. Consequently, the authors concluded that a robust and definitive trial is required to assess the effect of ES on the chances of success of the first IVF cycle. 16

Definitive studies of IVF ‘add-ons’ are challenging, as large numbers of patients are required to detect changes in LBRs with sufficient power, therefore making them expensive. 2 Consequently, studies in this first-cycle population have been small and have included heterogeneous populations. 16 To date, four RCTs have specifically focused on assessing ES in women undergoing their first cycle of IVF,17–20 all of which were included in the review undertaken by Vitagliano et al. 16 The two largest trials included 418 and 300 participants, and found significant increases in IVF success in women who received ES;19,20 however, according to the Vitagliano et al. 16 review, in one study20 the risk of bias was deemed to be high and in the other participants were not followed up until delivery. 19 Previous studies have also differed in the timing of the ES procedure, with Karimzade et al. 17 undertaking ES on the day of oocyte retrieval, and the majority of other studies undertaking ES in the menstrual cycle prior to the cycle in which embryo transfer was carried out. Notably, Karimzade et al. 17 identified that undertaking ES on the day of oocyte retrieval (compared with in the menstrual cycle prior to the cycle in which embryo transfer was carried out) resulted in a reduction in clinical pregnancy rates [12.3% vs. 32.9%, respectively; odds ratio (OR) 0.25, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.66; p < 0.004].

Three RCTs published since the Vitgaliano et al. 16 review included heterogeneous unselected populations but were not adequately powered to detect clinically important differences in women undergoing their first cycle. 14,21,22 In all three trials, outcomes for women undergoing their first cycle were not presented. However, for the unselected population, all three trials identified no significant differences in pregnancy rates or LBRs between women who received ES and those who received ‘usual’ IVF. 14,21,22 Of note, one of these trials stopped early following an unplanned futility analysis, as the clinical pregnancy rates between the ES and control (sham procedure followed by ‘usual’ IVF) groups were similar. 21

The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) has set up a ‘traffic-light’ system to inform patients of the evidence supporting a selection of ‘add-ons’ that fertility units frequently offer and charge extra for – according to HFEA, the evidence to support the benefits of ES is currently unclear. 2

Costs to the NHS and patients

Fertility treatment places a significant cost burden on the NHS and patients, with the cost to the NHS estimated to be around £68M per year (based on 2013 costs). 23 The number of first IVF cycles funded by the NHS has been decreasing over recent years; 58% of first cycles were funded by the NHS in 2017, reducing to 52% in 2018. 1 Given that the average patient undergoes three cycles of IVF,1 and a single IVF cycle can cost £5000, the cost of IVF treatment is a significant burden to patients. 8 In addition, loss of productivity due to the emotional and physical effects of IVF treatment has been estimated at £540 (€596, converted in 2020) per woman per IVF cycle in one study. 3 The cost of IVF is increased further if the couple decides to undergo the ES procedure, despite a lack of evidence to suggest that it is effective or safe. ES is estimated to cost £325 per cycle, a cost that does not take into account the potential pain of receiving the procedure and the potential health-care contacts if the procedure is in fact unsafe. Therefore, any increase in LBRs in the first cycle of IVF will prevent patients from receiving subsequent IVF cycles, thereby reducing this burden.

The endometrial scratch intervention

Endometrial scratch is a routinely performed outpatient procedure in which a pipelle or similar device is inserted into the cavity of the uterus; negative pressure is applied by withdrawing the plunger and the sampler is rotated and withdrawn three or four times so that tissue appears in the transparent tube. The rotation and withdrawal of the plunger ‘scratches’ the endometrium. Risks were identified in a previous study when the procedure was undertaken on the day of oocyte retrieval. 17 The procedure is not known to be associated with any particular risks when undertaken in the menstrual cycle preceding that of IVF therapy, apart from pain during and shortly after the procedure. 12 As with any intrauterine procedure, there is a potential for intrauterine infection. However, women attending for fertility treatment are usually screened for serious vaginal infections, such as chlamydia, to minimise the risk of any spread of infection.

The exact mechanism by which ES may improve implantation is not yet known; however, it is known that implantation of the embryo is a complex process involving the release of several inflammatory mediators including uterine natural killer cells, leukaemia inhibitory factor and interleukin 15. 24 ES may lead to the release of inflammatory cells and mediators such as macrophages and dendritic cells, tumour necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 15, growth-regulated oncogene-α and macrophage inflammatory protein 1B. 25 ES has also been shown to cause the modulation of several endometrial genes that may be involved in membrane stability during the process of implantation, such as bladder transmembranal protein and adipose differentiation-related protein and mucin 1. 26

Rationale for research, aims and objectives

In 2016, a survey undertaken by Lensen et al. 27 of clinicians based in the UK, Australia and New Zealand reported that ES was seen as potentially beneficial when undertaken prior to the first cycle of IVF by nine (6.3%) of the 143 surveyed clinicians, with a further 54 (38%) stating that they were neutral regarding its potential effect. Since this survey, a number of RCTs have reported conflicting evidence regarding the effect of ES on the outcome of IVF when undertaken prior to the first cycle of IVF, with both positive and negative results reported. 14,18,19,22,28 Given the conflicting evidence, and the lack of recent data regarding the provision of ES, it is unknown if this procedure is being widely delivered to women undergoing their first IVF cycle. However, anecdotal evidence collected by the Endometrial Scratch Trial team suggests that some fertility units in the UK are still offering this procedure to women undergoing their first cycle of IVF. Given the additional cost to patients of ES (around £325), this represents a significant burden. 8 Given the lack of evidence to support its use, ES may have a negative or unequivocal effect on pregnancy outcomes and may be unsafe or poorly tolerated in this population.

The Human Fertility and Embryology Authority states in its statistical report into multiple births that the risks associated with multiple births are the single biggest health risk associated with fertility treatment. 29 Multiple births carry risks to the health of both the mother and the babies. The birth of a healthy singleton child, born at full term, is therefore the safest outcome of fertility treatment for both mother and child, and this is best achieved through promoting the practice of single embryo transfer (SET). 30 Although SET may be associated with a slightly lower pregnancy rate in an IVF cycle using fresh (rather than frozen) embryos, when a patient has a surplus of embryos generated during the treatment cycle, and hence potentially more attempts at embryo replacement per cycle, the pregnancy rate is the same whether one or two embryos are replaced. 31 For this reason, most strategies of SET are limited to women for whom there is a reasonable chance of having surplus embryos available for cryopreservation. Through improving success rates, the ES procedure could have the potential to increase the uptake and implementation of the practice of SET, which would consequently have a large impact on the risks and costs associated with multiple pregnancies (which is the greatest risk of assisted conception treatment). 32

The main trial aimed to assess the clinical effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness of the ES procedure in women aged between 18 and 37 years (inclusive) undergoing their first IVF cycle, with or without ICSI, using either antagonist or long protocols on the chances of achieving clinical pregnancy and live birth.

The objectives of the Endometrial Scratch Trial were to evaluate the:

-

clinical effectiveness and safety of the ES procedure compared with ‘usual’ IVF treatment, with or without ICSI, in women undergoing their first IVF cycle by undertaking a RCT

-

cost-effectiveness of the ES procedure. This was evaluated by collecting the costs to the NHS and patients of undergoing the intervention, including the cost of IVF care and other health-care contacts.

The secondary objectives were to:

-

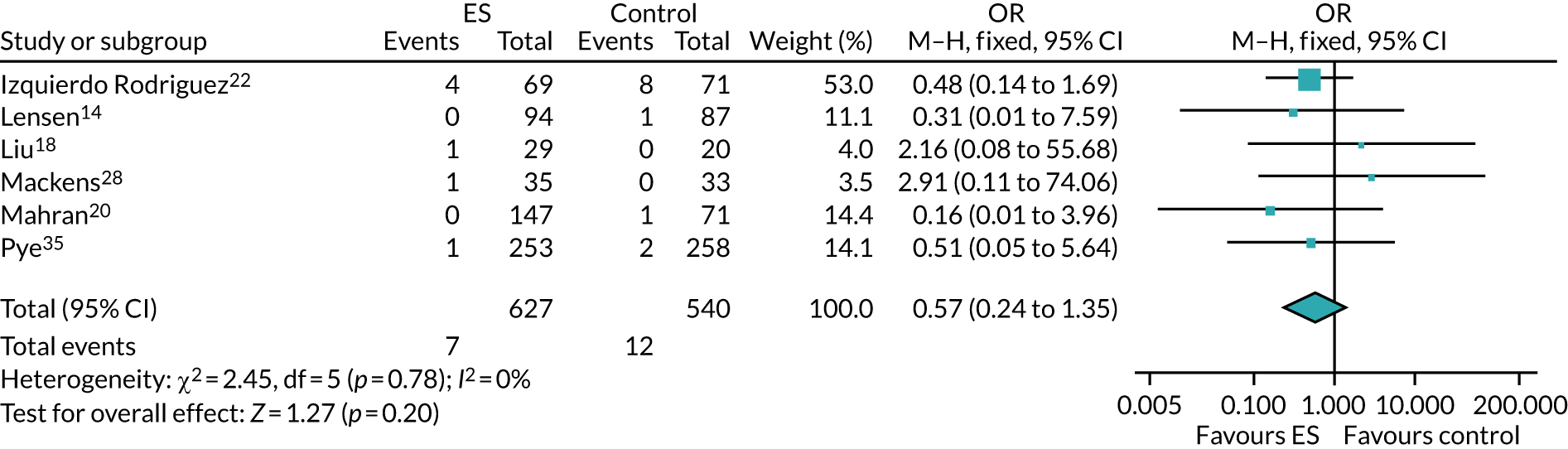

synthesise evidence of the clinical effectiveness and safety of the ES procedure by combining the results of this trial with other similar RCTs in this population

-

understand the experiences of trial participants and fertility unit staff of participating in the trial, including recruitment, receiving/delivering ES, data collection methods and withdrawal from the ES procedure.

Chapter 2 Trial methods

Study design

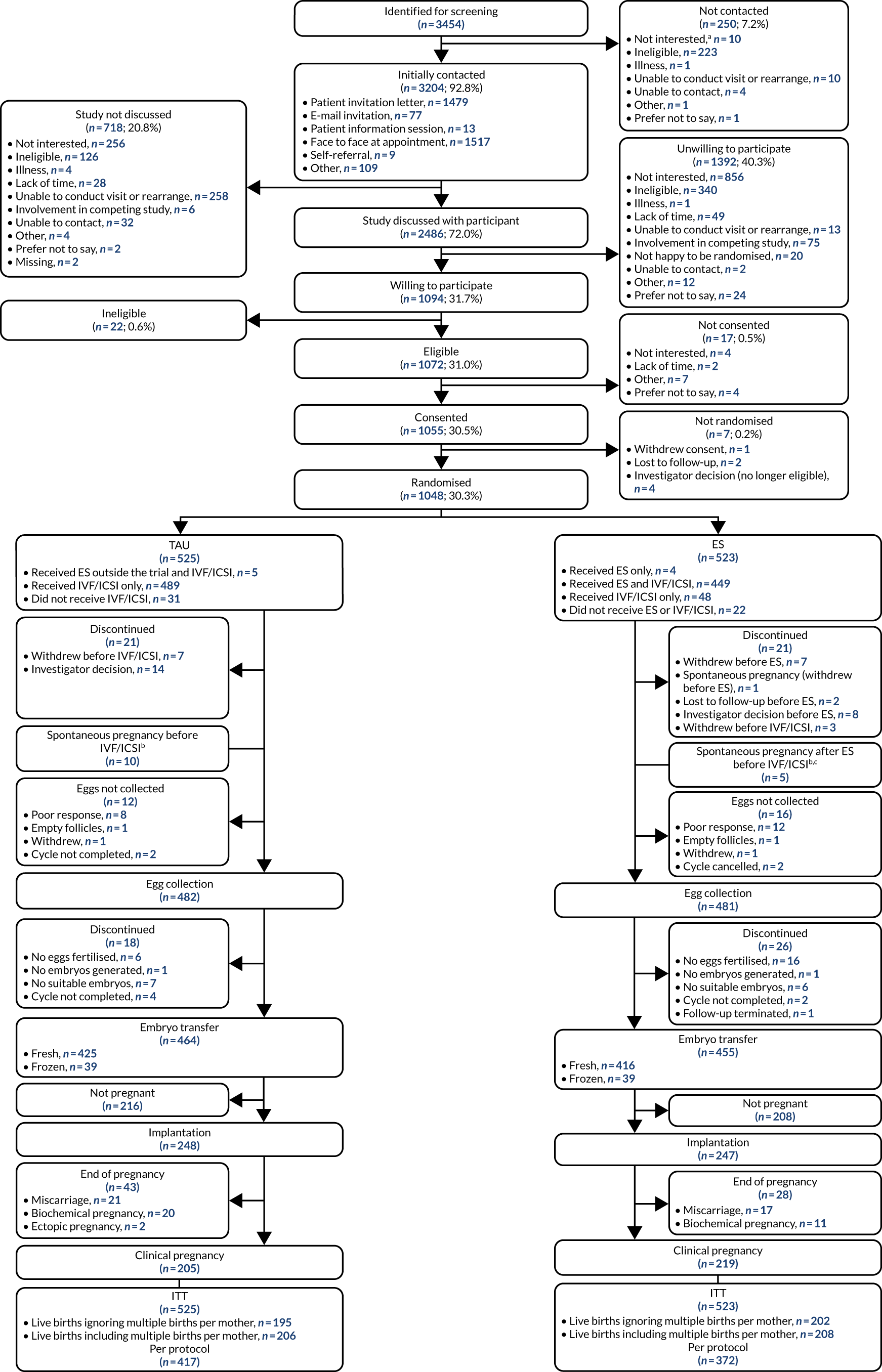

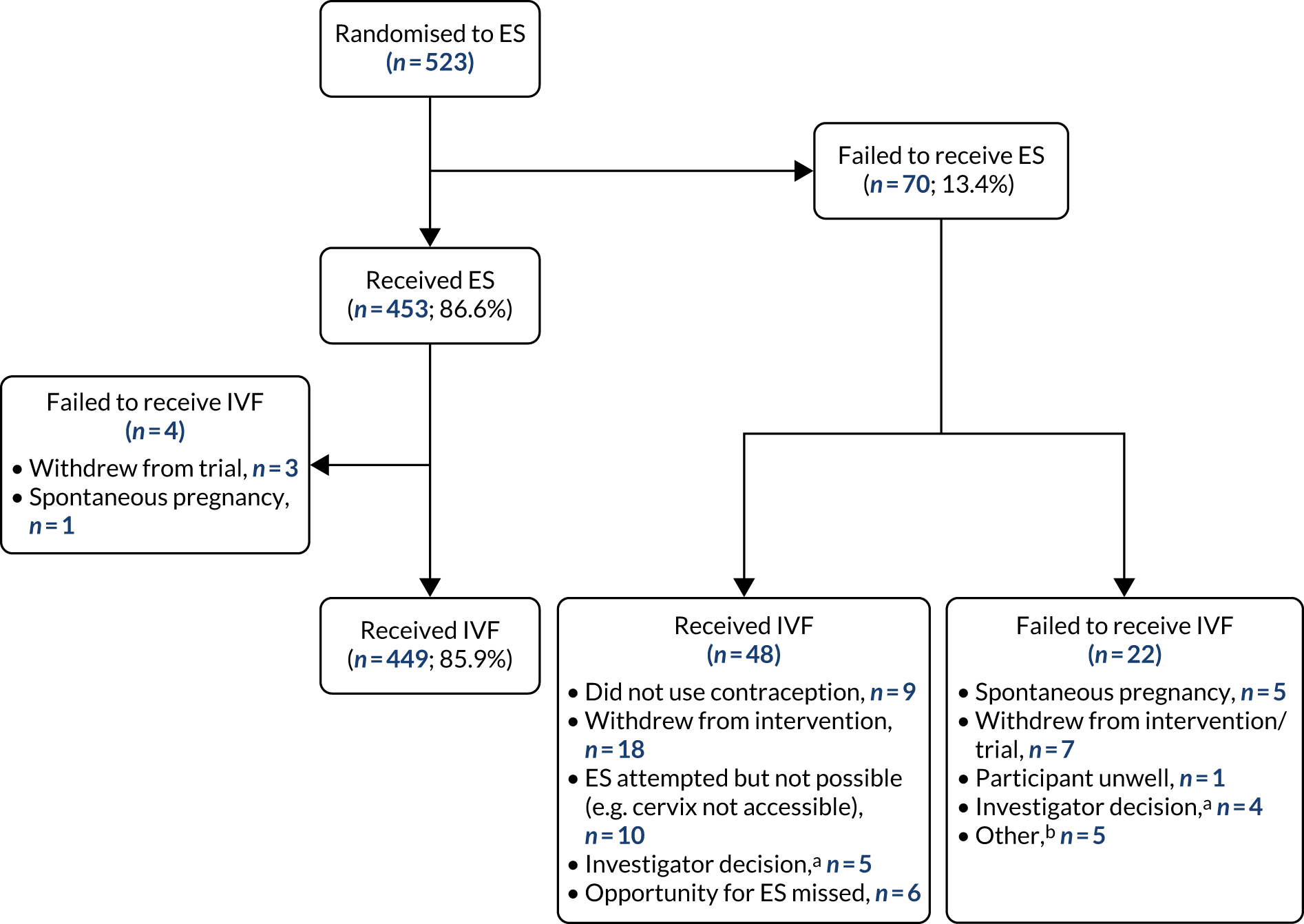

This was a two-arm, pragmatic, individually randomised, superiority, open-label, parallel-group multicentre clinical trial that evaluated the clinical effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness of the ES procedure compared with no ES procedure, followed by usual IVF treatment, with or without ICSI. The pragmatic nature of the trial is explained using the PRagmatic Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary 2 (PRECIS-2) tool (see Appendix 1). 33 Participants were randomised to one of these groups using a 1 : 1 allocation ratio stratified by fertility unit and planned IVF protocol (antagonist or long). Participants were recruited from 16 fertility units across the UK (England and Scotland) and followed up between 4 July 2016 and 24 October 2019.

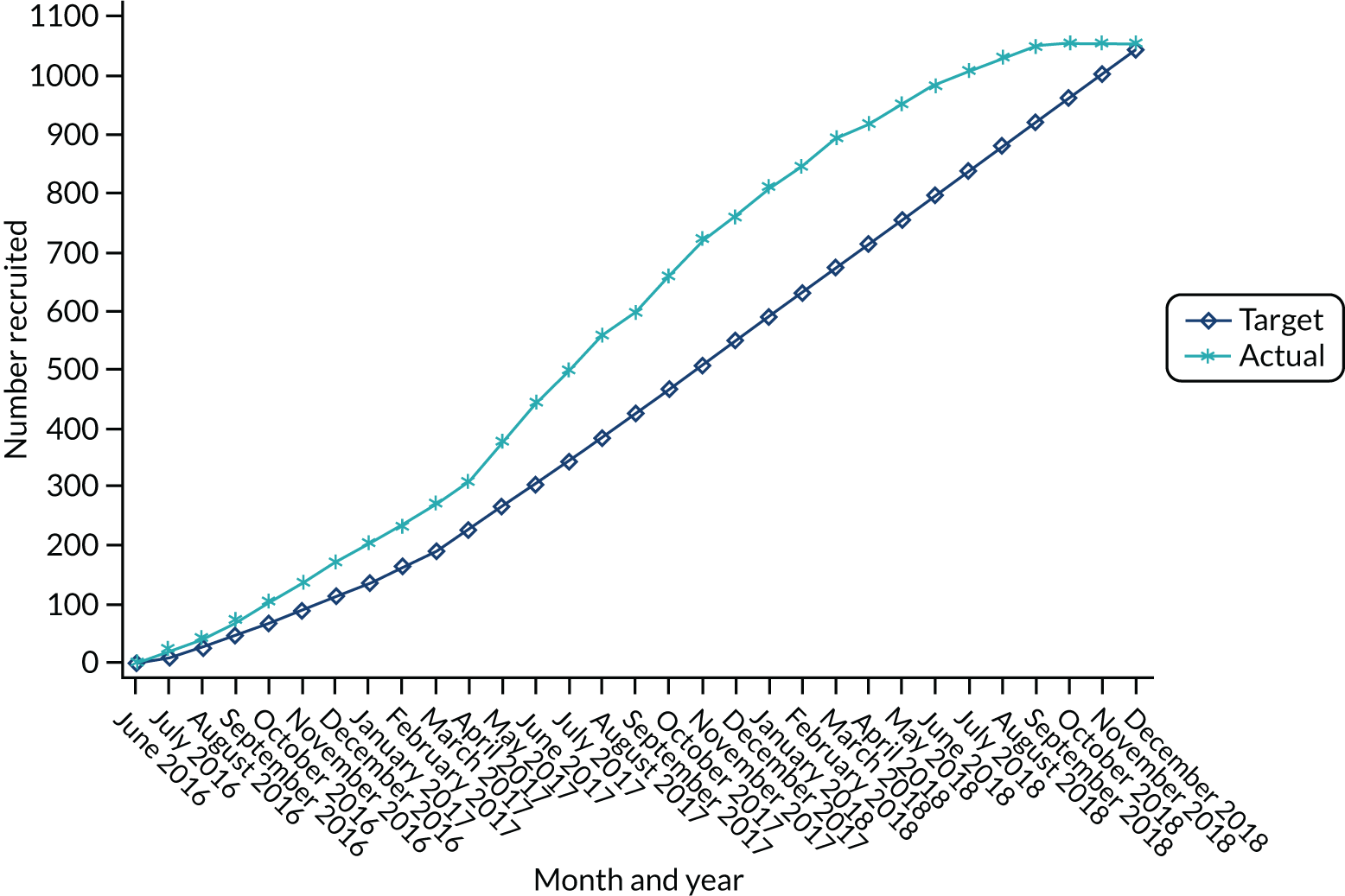

Internal pilot summary

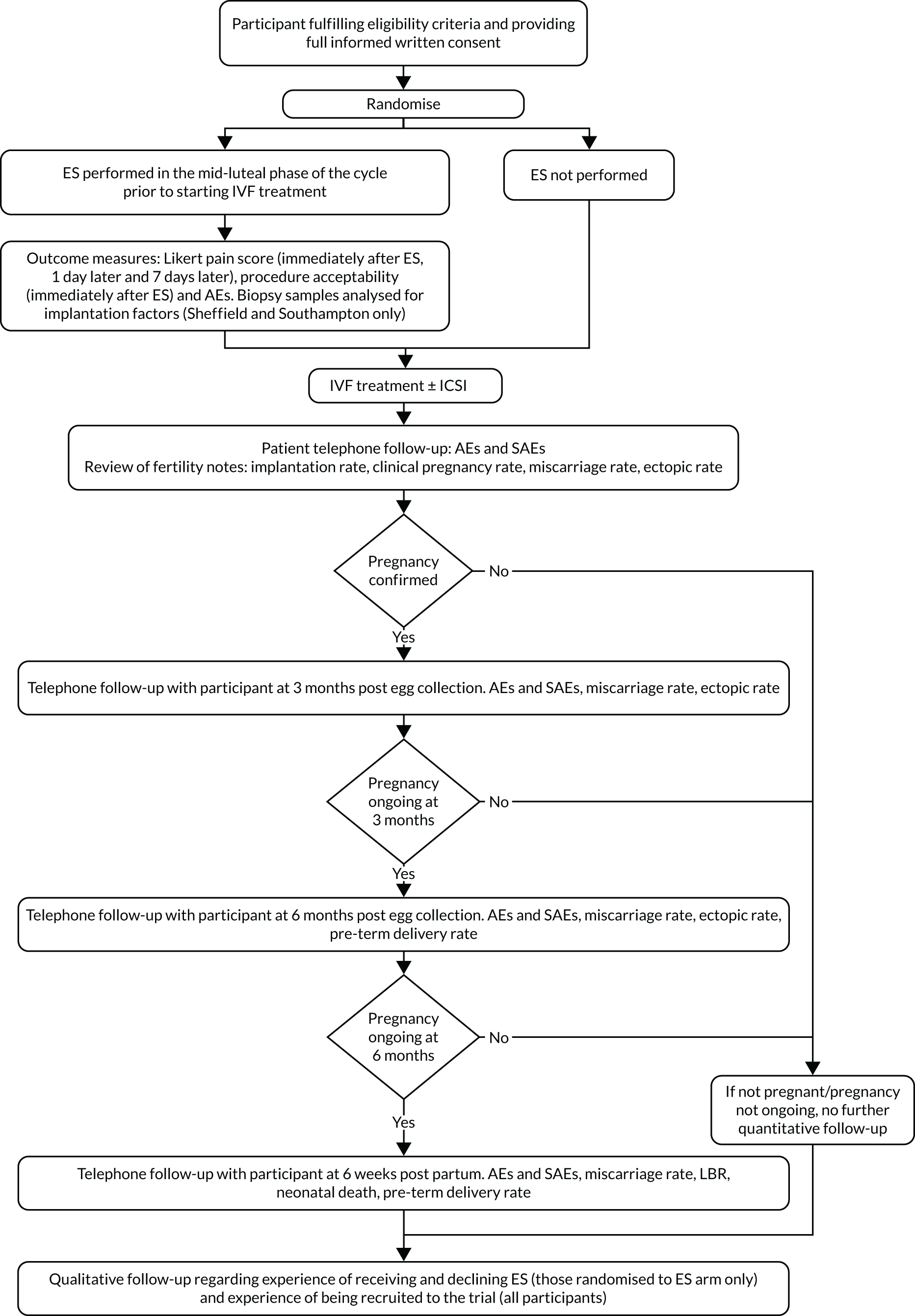

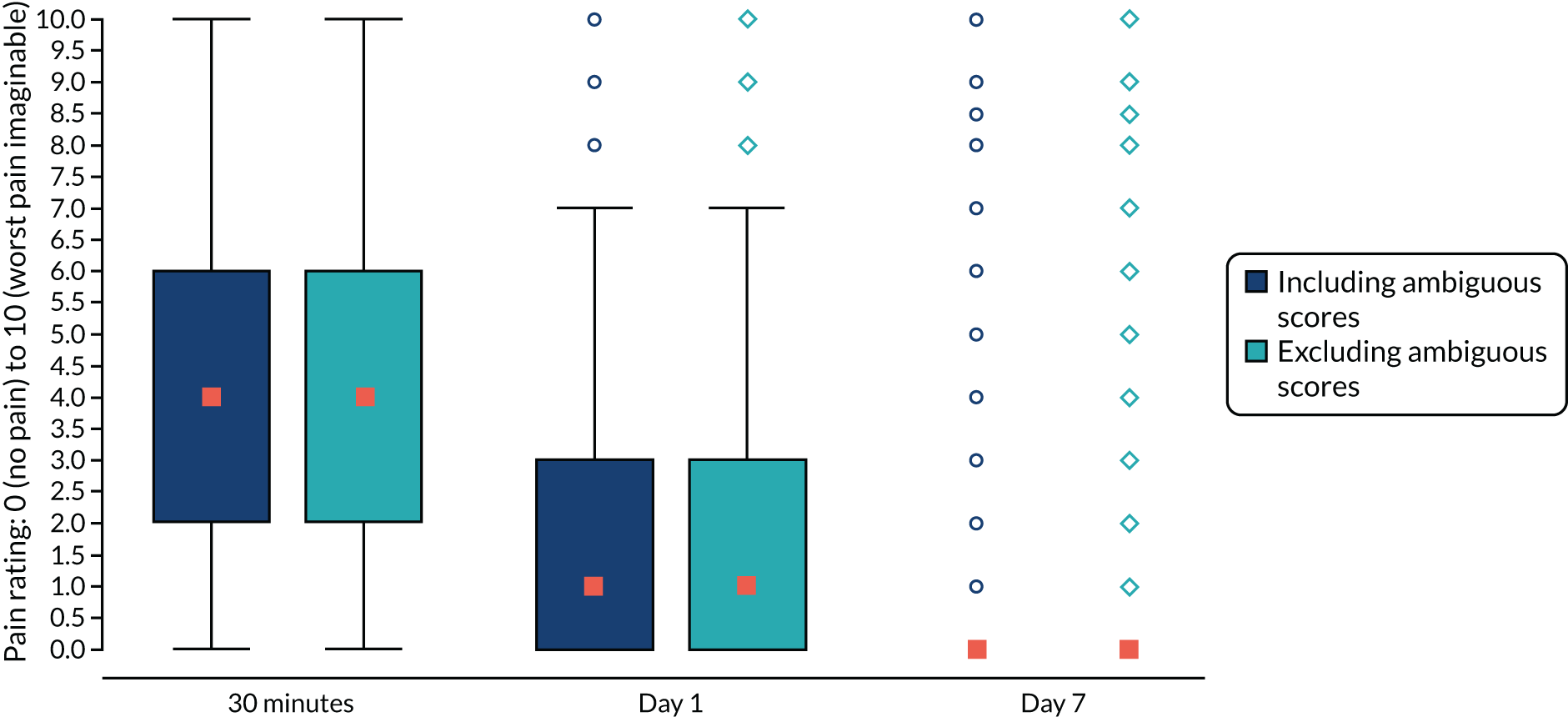

The main trial was designed with an internal pilot phase with stop–go criteria applied after 6 months of recruitment to assess the feasibility of recruitment and delivery of the ES procedure as per the protocol. The trial met the recruitment and intervention delivery outcomes (see Appendix 2), and therefore the trial continued as planned without any modifications to the trial protocol. Participants from the internal pilot phase were included in the final analysis. Figure 1 is a flow chart of the study design.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of the study design. ±, with or without; AEs, adverse events; SAEs, serious adverse events.

Trial registration and ethics

The trial was registered on the ISRCTN registry (ISRCTN23800982) on 31 May 2016. The trial protocol was reviewed and ethics approval was granted by the National Research Ethics Service Berkshire South Central (reference 16/SC/0151). 34 Over the course of the trial, eight amendments were made to the protocol (consisting of seven substantial and one non-substantial amendment), all of which were also approved by the National Research Ethics Service Berkshire South Central (as detailed in Appendix 3).

Participant inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients who met the following criteria were eligible for the trial. Parts of the text have been reproduced with permission from Pye et al. 35 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Inclusion criteria

-

Women who were expected to be aged between 18 and 37 years (inclusive) at the time of egg collection.

-

Women who were undergoing their first cycle of IVF, with or without ICSI treatment, using the antagonist or long protocol only.

-

Women who were expected to receive treatment using fresh embryos.

-

Women who were expected to be good responders to treatment, with:

-

ovulatory menstrual cycle (regular menstrual cycles defined by clinical judgement or with ovulatory levels of mid-luteal serum progesterone as defined by local laboratory protocols)

-

normal uterine cavity (assessed by transvaginal sonography at screening, and no endometrial abnormalities, such as suspected intrauterine adhesions, uterine septa, submucosal fibroids or intramural fibroids exceeding 4 cm in diameter, as assessed by the investigator, that would require treatment to facilitate pregnancy)

-

expected good ovarian reserve, which was assessed clinically, biochemically [follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) < 10 mIU/ml and normal follicular-phase oestradiol levels and/or normal anti-Müllerian hormone] and/or sonographically (antral follicle counts), and no history of previous radiotherapy or chemotherapy (all laboratory/ultrasound standards were based on local normal reference ranges)

-

SET expected.

-

-

Women for whom local procedures were followed to exclude relevant vaginal/uterine infections prior to starting treatment.

-

Women who were willing to use an appropriate method of barrier contraception if randomised to ES in the cycle in which the ES procedure is performed.

-

Women who understood and were willing to comply with the protocol.

Exclusion criteria

The following women were excluded from the trial:

-

women with a history of endometiral trauma or surgery (e.g. resection of submucous fibroid, intrauterine adhesions)

-

women with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 35 kg/m2

-

women with known grade 4 (severe) endometriosis

-

women currently participating in any other fertility study involving medical/surgical intervention

-

women who were expected to receive protocols other than antagonist or long (e.g. ultra-long protocol)

-

women in whom an ES (or similar procedure, e.g. endometrial biopsy for the collection of natural killer cells) was planned (added to version 5 of the protocol, 20 July 2017; see Appendix 3)

-

women previously randomised to this trial.

Participants for whom cycle programming was planned were initially excluded from the trial until 13 June 2016 (version 3 of the protocol), when this exclusion criterion was removed (see Appendix 3).

Recruitment of participants

Settings and locations where participants were recruited

During the internal pilot trial, recruitment took place at six IVF fertility units across England. In the main trial, recruitment sites were expanded to include an additional 10 IVF fertility units across England and Scotland. Two of these 16 fertility units were privately run outside the NHS. Appendix 4 provides a list of sites and their involvement during and after the internal pilot phase.

Identification, screening and first approach

Participants, who were attending the IVF clinic prior to starting their first IVF cycle were identified by site staff [i.e. research nurses (RNs) and clinical trials assistants], who screened clinic lists to identify potential participants for the trial. Those who were identified and met the ‘screening criteria’ (aged 18–37 years inclusive, first IVF cycle, ovulatory menstrual cycle) were added to the screening log. A full ‘eligibility’ check was then undertaken, following consultation with the participants within the clinic, to confirm the remaining eligibility criteria.

Potential participants were approached about the trial by post by including an invitation to participate along with their initial clinic appointment letters, during routine clinic appointments before the start of their IVF or at patient information sessions, or they self-identified themselves after becoming aware of the trial from the trial website, recruitment video or posters that were placed within IVF units. Potential participants were approached at any time prior to the start of their IVF cycle, which was defined as the start of stimulation. Eligible participants were provided with written and verbal explanations about the trial; the participant information sheet (PIS) was provided to the individual either by post or in person, depending on how the participant was first approached. Three different versions of the PIS were used owing to variation in trial procedures across the trial sites: one version for the Sheffield and Southampton sites (because of the tissue substudy at these sites; see Participant information sheet – Sheffield and Southampton sites), one for Dundee (where a postal consent process was used; see Participant information sheet – Dundee) and one for all other sites (see Participant information sheet – all sites, except Dundee, Sheffield and Southampton).

When participants had been approached and information about the trial provided, they were given time to consider their decision. Women were either asked about the trial at a subsequent routine visit to the fertility unit prior to the start of their IVF cycle, or contacted by telephone, e-mail or text message at a later date to ascertain their interest.

Informed consent

Informed consent was taken during a routine appointment prior to the start of the IVF cycle. The need to possibly delay the IVF cycle was discussed with participants, if randomisation was being undertaken close to the start of IVF, such that, if randomised to the ES arm, the IVF cycle would need to be delayed in order for ES to be delivered within the mid-luteal phase of the menstrual cycle prior to IVF. A decision to delay was made and agreed by both the participant and her fertility team prior to randomisation.

A written consent form (see Consent form – all sites except Sheffield and Southampton) was provided to the participant by a member of site staff [either the Principal Investigator (PI) or the RN], and, following the participant’s agreement to participate, was signed by both the person taking consent and the participant. Participants recruited at the Sheffield and Southampton sites had the opportunity to consent to participate in a tissue substudy, in which tissue was collected from the endometrium and stored for future analysis (the results and detailed methods of which are not contained in this report); therefore, a different version of the consent form was used at these two sites (see Consent form – Sheffield and Southampton). Consent for this substudy was sought at the same time as consent for the trial. Participants were able to participate in the main trial without consenting to participate in the substudy, but not vice versa. Participants recruited at the Dundee site had the option to use a postal consent process, to lessen the burden of having to travel long distances to the fertility unit to consent and be randomised to the trial. In such cases, consent was obtained by post using an adapted consent form [see Postal consent form (Dundee only)], followed by consent in person post randomisation at the next routine appointment.

Description of trial arms

Endometrial scratch arm

Participants randomised to the ES arm received ES in the mid-luteal phase (defined as 5–7 days before the expected next period, or 7–9 days after a positive ovulation test) of the menstrual cycle prior to which IVF was being undertaken.

Endometrial scratch is a minor procedure performed in daily clinical practice in an outpatient setting. The procedure, which was already routinely undertaken at many of the fertility units for participants undergoing their second or subsequent IVF cycle, and, in some centres, was already offered to patients undergoing their first cycle of IVF, was undertaken as per local guidelines by a suitably trained doctor or nurse. When undertaking the procedure, a standard operating procedure (SOP) was followed (see Endometrial Scratch Standard Operating Procedure).

The participant was required to use a barrier method of contraception (if necessary) in the menstrual cycle in which the ES was performed. Before ES was undertaken, participants were asked if they had complied with this. If there was a risk of pregnancy (i.e. the participant reported unprotected sexual intercourse prior to ES), the ES was not undertaken and was either rescheduled (and the IVF cycle delayed, as appropriate) or IVF commenced as planned without performing the ES procedure.

Participants were free to withdraw from receiving the ES at any point prior to or during the procedure. Those who did not receive the procedure remained in the trial and were followed up as described in Procedures and assessments.

At two centres (Sheffield and Southampton), endometrial biopsies were taken during the ES procedure (if the participant consented to do so). In order to collect the exact time point of menstruation at which the procedure was undertaken (and the tissue collected), ovulation kits were provided to participants who were randomised to the intervention arm at these centres. Once ovulation was detected [luteinising hormone (LH) surge detected], the participant contacted the fertility unit in order to schedule the ES, and the procedure was undertaken 7–9 days later. The tissue was harvested from the pipelle sampler that was inserted into the uterus to undertake the ES. Samples were collected and stored in formalin-containing specimen pots in the fertility units; the specimen pots will be stored for up to 10 years in liquid nitrogen. The tissue samples were anonymised and coded prior to storage and the liquid nitrogen Dewars were kept locked.

At all other fertility units, participants randomised to receive ES contacted the fertility clinic when their menstrual cycle preceding IVF began; the procedure was then scheduled 5–7 days prior to their next period. Women who failed to contact the site were telephoned by the RN.

To perform ES, a speculum was first inserted into the vagina and the cervix was exposed and cleaned. A pipelle or similar endometrial sampler (as per local procedures) was then inserted into the cavity of the uterus; negative pressure was applied by withdrawal of the plunger. The sampler was then rotated and withdrawn several times so that tissue appeared in the transparent tube. The sampler and speculum were then removed. If no tissue was seen in the transparent sampler, this was an indication that the sampler was not fully inside the uterine cavity and, therefore, the procedure was repeated. In total, the ES procedure took approximately 10–20 minutes. See Appendix 5 for a description of the intervention using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist. 36

Following ES, ‘usual’ IVF treatment was received as per local protocols and no further interventions were performed beyond usual care.

Treatment-as-usual arm

Participants randomised to the treatment-as-usual (TAU) arm received ‘usual’ IVF treatment in accordance with the local protocols at their fertility unit.

Randomisation and concealment

Randomisation was undertaken by a doctor or nurse based at the fertility unit prior to the start of the IVF cycle.

Eligible and consented participants were randomised (1 : 1) to either ES or TAU via a web-based randomisation system hosted by Sheffield Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU) using block randomisation stratified by fertility unit (site) and planned treatment protocol (antagonist or long). Research staff at recruiting sites logged onto the web-based randomisation system to enter participant details, and the treatment allocation was revealed only when randomisation was requested.

Random permuted blocks of size two, four, and six were used to ensure that participants were allocated evenly to each site and in accordance with IVF treatment protocols during the trial. The trial statistician generated the sequence that was retained within the web-based randomisation system, which had restricted access rights, but they did not have access to the generated sequence. Research staff based at the trial sites did not have access to the randomisation sequence. The block sizes were masked to the research team during the trial except for the trial statistician who generated the randomisation sequence but was not involved in the screening and randomisation of participants. The details of block sizes that were disclosed at the reporting stage were documented in a restricted access computer folder. Once a participant was randomised, re-randomisation of the same participant was not permitted under any circumstance.

Blinding and masking

The nature of the ES procedure makes it impracticable to blind participating women, clinicians, research staff and outcome assessors, and therefore this was an open-label RCT. However, the trial uses objective pregnancy outcomes that are unlikely to be affected by the placebo effect or assessment bias; for example, achieving a live birth is a definitive primary end point. Therefore, it was unnecessary to use a sham ES procedure in the TAU group. The trial statisticians and health economist were blinded to the treatment allocation throughout the trial.

Outcome measures

Primary and secondary outcomes

Primary outcome

Live birth was defined as live birth after 24 weeks’ gestation within the 10.5 months post egg collection follow-up period. The denominator for calculating the LBR is the number of women randomised to each treatment group. Multiple live births from a single pregnant woman because of a multiple pregnancy contributed to one live birth in the numerator (i.e. a multiple live birth was counted as one live birth).

Secondary outcomes

-

Acceptability and tolerability of ES procedure:

-

pain rating and tolerability (yes or no) within 30 minutes of the procedure

-

pain rating directly after 24 hours and 7 days post procedure.

-

-

Pain was assessed on a rating scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable) and was self-reported by women who underwent the ES procedure.

-

Implantation, measured based on a positive serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin or by a positive urine pregnancy test on approximately day 14 following egg collection. The denominator for calculating the implantation rate is the number of women randomised to each treatment group.

-

Clinical pregnancy, measured based on an observation of viable intrauterine pregnancy with a positive heart pulsation seen on ultrasound at/after 8 weeks’ gestation.

-

Ectopic pregnancy, measured as a pregnancy outside the normal uterine cavity.

-

Miscarriage, defined as a spontaneous pregnancy loss, including pregnancy of unknown location (PUL) prior to 24 weeks’ gestation within the 10.5 months post egg collection follow-up period.

-

Multiple birth, defined as the birth of more than one living fetus after completed 24 weeks’ gestation.

-

Stillbirth, defined as the delivery of a stillborn fetus showing no signs of life after 24 weeks’ gestation within the 10.5 months post egg collection follow-up period.

-

Preterm delivery, measured by a live birth after 24 weeks before 37 weeks’ gestation within the 10.5 months post egg collection follow-up period.

-

Treatment cycle characteristics detailing the participant’s IVF cycle, including number of eggs retrieved, number of embryos generated 1 day after egg collection, quality of the embryos transferred, number of embryos replaced and day of embryo replacement.

Safety outcomes

Data on adverse events (AEs) were collected up to 6 weeks post partum in participants (see Table 1). In the fetus/baby, data on severe congenital abnormalities (detected both antenatally and postnatally) and neonatal deaths were also collected up to 6 weeks post partum (see Table 1). Definitions of the different events recorded can be found below.

In participating women

-

Adverse events, defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a participant that does not necessarily have a causal relationship with the intervention.

-

Expected AEs, defined as an AE related to pregnancy or IVF treatments that is expected in this patient population (listed in Appendix 6).

-

Unexpected AEs, defined as an AE that does not meet the definition of an expected AE as defined above.

-

Serious adverse event (SAEs), defined as any untoward medical occurrence that results in death; is life-threatening; requires participant hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation (excluding events related to the birth or birth process); results in significant disability/incapacity; is a congenital anomaly/birth defect; or is an important medical event.

-

Expected SAEs, defined as a SAE that is expected in the patient population or is a result of the routine care/treatment of a patient (listed in Appendix 7).

-

Unexpected SAEs, defined as a SAE that does not meet the definition of an expected SAE as defined above. This includes maternal death, stillbirth, and any other SAE that is not foreseeable.

In the fetus/neonate

-

Severe congenital abnormalities, defined as a congenital anomaly detected antenatally or postnatally. Common minor congenital anomalies as defined by the European Monitoring of Congenital Anomalies (EUROCAT)37 minor anomaly exclusion list were excluded as unexpected SAEs. Those anomalies that were excluded were either minor (e.g. skin tags) or expected for the gestation (e.g. patent ductus arteriosus in babies born at < 37 weeks’ gestation).

-

Neonatal deaths, defined as the death of a baby within 6 weeks of life.

-

Preterm delivery, defined as delivery of a live birth of gestational age ≥ 24 weeks and < 37 weeks.

-

Very preterm delivery, defined as delivery of a live birth of gestational age < 24 weeks.

-

Low birthweight, defined as delivery of a live birth with birthweight ≤ 2499 g or < 10th centile for a given gestational age and sex of baby.

-

Very low birthweight, defined as delivery of a live birth with birthweight < 1500 g or < 5th centile for a given gestational age and sex of baby.

-

Small for gestational age, defined as delivery of a live birth with birthweight < 10th centile for a given gestational age and sex of baby.

-

Large for gestational age, defined as delivery of a live birth with birthweight > 95th centile for a given gestational age and sex of baby.

Health economic outcomes

-

Health resource use of the participant measured at baseline and 3 and 10.5 months (or at 6 weeks post partum) post egg collection.

-

Patient costs at 3 months post egg collection.

Both outcomes were collected using a bespoke questionnaire (see Collection of health resource use and patient costs data).

Procedures and assessments

An online database was utilised in order to collect participant data. Data collection proceeded as described in Table 1 (see Figure 1 for a study flow chart).

| Time point | Data type | Data | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (pre randomisation) | Medical history | Alcohol, smoking, drugs | Medical notes |

| Pregnancy and medical history | Participant (in person)/medical notes | ||

| Fertility history | Expected treatment protocol and methods | Medical notes | |

| Ovulation markers | Medical notes | ||

| Fertility history | Medical notes | ||

| Health resource use | Questionnaire | ||

| Eligibility assessment | Participant (in person)/medical notes | ||

| Demographics | Medical notes | ||

| Randomisation | Date and outcome of randomisation | Randomisation system | |

| Intervention | Details of ES procedure | Medications taken prior to procedure | Participant (in person) |

| Day of cycle, reason ES not received (if applicable), instrument used | Medical notes | ||

| Pain and tolerability: within 30 minutes of procedure | Likert scale 0–10 and tolerability (yes/no) | Participant (in person) | |

| Pain: 1 day and 7 days post procedure | Likert scale 0–10 | Participant (SMS message) | |

| Treatment cycle | IVF cycle details | Details of down-regulation, stimulation, egg collection, embryo transfer | Medical notes |

| Approximately 2 weeks post egg collection | Pregnancy test | Test type and results (blood/urine) | Medical notes |

| Approximately 2 weeks post positive pregnancy test | Pregnancy scan | Outcome of scan (fetal heartbeats detected, intrauterine sacs) | Medical notes |

| Pregnancy outcomesa | Medical notes | ||

| Between 2 and 4 weeks post egg collectionb | AEsc | Participant (telephone/in person) | |

| 3 months post egg collection | Pregnancy outcomesa | Participant (telephone) | |

| AEsc | Participant (telephone) | ||

| Health resource use | Questionnaire | ||

| Patient costs | Questionnaire | ||

| 6 months post egg collection | Pregnancy outcomesa | Participant (telephone) | |

| AEsc | Participant (telephone) | ||

| 6 weeks post partum | Pregnancy outcomesa | Participant (telephone) | |

| AEsd | Participant (telephone) | ||

| Weight and gestational age of baby when born | Participant (telephone)/medical notes | ||

| Neonatal death | Participant (telephone) | ||

Baseline data collection and randomisation

Following consent, participants underwent baseline assessments prior to randomisation, which included height/weight, ethnicity, medical history and a fertility assessment, including ovarian reserve assessment.

Randomisation was then undertaken as described in Randomisation and concealment. If randomised to do so, the participant received ES (see Description of trial arms, Endometrial scratch arm), followed by ‘usual’ IVF. If randomised to TAU, ‘usual’ IVF was delivered (see Description of trial arms, Treatment-as-usual arm).

In vitro fertilisation cycle

Following randomisation, and ES (if randomised to this arm), information regarding the received treatment cycle was collected, including information about down-regulation and stimulation phases, egg collection and embryo transfer. During embryo transfer, details of whether the clinician detected fluid on the endometrium or blood on the tip of the catheter were collected. In Newcastle, data regarding fluid on the tip of the catheter could not be collected because ultrasound-guided embryo transfer was not undertaken at this site.

Owing to a perceived lack of equipoise in this patient group, fertility unit staff asked participants randomised to either arm if an ES had been received ‘outside’ the trial.

Embryo grading

The quality of each transferred embryo was recorded. Three stages of embryo development are commonly recognised: morula (day 3 of development), cleavage (day 1, 2 or 3) and blastocyst (day 5 or 6). Embryo grading was undertaken immediately prior to embryo transfer; embryos were subjectively assessed by visual microscopic inspection as per the fertility unit’s protocols and recorded using established grading schemes for cleavage-stage embryos and blastocysts. Sites used either the National External Quality Assessment Service (NEQAS)38 or Gardner blastocyst grading systems,39 in accordance with their normal clinical practice (see Appendix 8 for a list of embryo grading systems used at each trial site). The NEQAS system was updated in April 2017 and, therefore, both systems were used during the trial. 40

For each grading system, we mapped embryo grading to a common quality rating scale created by a principal embryologist, to enable the comparison of embryo quality between treatment groups and sites. A separate quality scale was created for cleavage and blastocyst embryos. Both conversion algorithms can be found in Appendix 9.

For embryo selection at the blastocyst stage, three elements of the blastocyst were graded: the expansion score, trophectoderm and inner cell mass. The conversion algorithm for blastocysts does not take into account expansion score, as blastocysts undergo dynamic expansion, the status of which can change depending on what time on day 5 of development the grading was performed. As fertility units graded blastocysts at different time points and we did not record whether the grades provided were at selection or transfer, or a mixture of the two, it was cleaner to leave out the ‘expansion’ score. Cleavage-stage embryos, which are not rated using the Gardner blastocyst grading system, were rated using a different scale in both old and new NEQAS grading. Morula-stage embryos are not commonly graded.

Intervention delivery and post-intervention pain and tolerability

For those randomised to the ES, the details of the ES procedure were collected when the participant attended the unit to undergo the procedure. Pain was subjectively assessed within 30 minutes post ES, and then at 1 day and 7 days post ES, as described in Outcome measures, Secondary outcomes. This was collected in person directly after the procedure, at which time the participant took part in the pain assessment and was asked if the procedure was tolerable (yes/no) (see Directly post ES pain and tolerability CRF). At the 1- and 7-day post-ES time points, the Likert rating scale was recorded via short message service (SMS) (see One day and seven day pain rating CRF). If the participant failed to respond to the message, a reminder text message was sent. If there was still no response, a member of the fertility unit telephoned or e-mailed the participant to request this information. Part-way through the trial, the wording of the SMS was reviewed and changed because of concerns that participants were misreading the question posed.

Pregnancy test and scan

Pregnancy tests and scans were undertaken as per local procedures and details of these were collected by the fertility units. AE information for the period prior to the pregnancy test was also collected by the fertility unit. In the event that the participant’s IVF cycle had ceased prior to the pregnancy test (i.e. no eggs collected or no embryos generated), the participant was contacted at a similar time point (i.e. 2 weeks post pregnancy test) to collect information on AEs.

Post-treatment cycle follow-up

Participants were followed up for at least 10.5 months post randomisation, or 6 weeks post partum, unless they did not become pregnant following their first IVF cycle (in which case, participants were followed up until the termination of their IVF cycle, e.g. IVF cycle not started, no eggs fertilised or pregnancy not achieved) or their pregnancy ended before full term (e.g. miscarriage or termination). Participants who were randomised to the trial but whose IVF treatment was then delayed were followed up for as long as the study timelines allowed in order to collect information regarding their treatment cycle and outcome, if treatment occurred.

Participants who were randomised to the trial but became spontaneously pregnant prior to embryo transfer were followed up in the same manner. However, the starting point for determining the timing of 3- and 6-month follow-ups was the date of the participant’s last menstrual period, rather than the date of egg collection (which did not go ahead in cases of spontaneous pregnancy).

Participants who underwent frozen embryo transfer (FET) and had received no previous fresh/frozen embryo transfers were followed up until a maximum of 6 weeks post partum, if the timelines of the trial allowed. Participants who commenced the stimulation phase of IVF but did not complete IVF for any reason were classed as having received their first cycle of IVF, and, therefore, their involvement in the trial was complete.

Collection of pregnancy outcome data

Following a positive pregnancy scan, patients were discharged from the fertility unit; therefore, in order to collect information regarding the outcome of the pregnancy, participants were contacted by the fertility unit by telephone at three time points post discharge: 3 months post egg collection, 6 months post egg collection and 6 weeks post partum (in the event of a live birth at any gestation). Pregnancy outcome information (where applicable) and AEs were recorded at each time point.

Collection of health resource use and patient costs data

The health resource use questionnaire (at baseline, 3 months post egg collection and 6 weeks post partum) and patient costs questionnaire (at 3 months post egg collection) were sent to the participant by post or electronically if the pregnancy was ongoing (at 3 months) or if a live birth occurred (at 6 weeks post partum). Questionnaires were not sent in the event of a negative outcome (i.e. miscarriage or stillbirth) to minimise distress, as the questionnaire pertained to events/health-care contacts that occurred during the pregnancy. If a participant did not complete her questionnaire within approximately 1–2 weeks, she was contacted by text message, letter or e-mail to ask her to return the questionnaire. Questionnaires collected information for the preceding 3 months. Resource use included the cost of IVF treatment, visits to the assisted conception unit and, for those who conceived, the cost of antenatal and postnatal visits, delivery costs and any hospital stays not related to birth for both mother and baby. The resource use questionnaire collected information on contacts with the midwife and general practitioner (GP) visits. The resource use questionnaire was designed for this study from data collection tools developed in the School of Health and Related Research (Sheffield, UK) and those collated by the Database for Instruments for Resource Use Measurement – slightly adapted versions were used at the three time points of data collection (see Health resource use questionnaire – baseline, 3 months and 6 weeks post partum). Patients were sent a cost questionnaire 3 months post egg collection and asked to record time taken to travel to appointments and loss of productivity (see Patient costs questionnaire).

Safety outcomes

Adverse events and SAEs were collected at four follow-up time points, and were collected during the post-treatment cycle follow-up phase only if the participant had a positive pregnancy scan. Site staff were delegated the responsibility for recording AEs and SAEs electronically on the case report form (CRF). Unexpected SAEs were logged on the CRF and also sent by e-mail to Sheffield CTRU to expedite reporting.

In the participating women

Safety events (AEs and SAEs) in the participating women were classed as expected or unexpected (see Outcome measures, Safety outcomes). A list of expected AEs and expected SAEs can be found in Appendix 6 and Appendix 7, respectively. The research sites made the assessment regarding whether an event was expected, in addition to recording the relatedness and seriousness of the event. The way in which these events were collected differed; only the presence of expected AEs was collected (i.e. a box was ticked on the CRF to signify that the participant had experienced the AE), whereas a ‘full’ AE report was collected for all other AEs and SAEs. AEs were not formally assessed for relatedness to trial procedures, but SAEs were. The sponsor and CTRU were responsible for reporting to relevant regulatory bodies, where appropriate. In January 2019, the trial protocol was amended to reflect the fact that events related to the birth of a baby or the process of birth were no longer to be classed as AEs or recorded during the trial (see Appendix 3).

In the fetus/neonate

Safety outcomes in the fetus/neonate were entered directly onto the CRF and were not subject to categorisation of seriousness or expectedness. A list of events recorded can be found in Safety outcomes. For outcomes regarding birthweight and size, the site entered gestational age at birth, date of birth, weight and sex into the CRF.

Withdrawal from the trial

Participants could voluntarily withdraw their consent at any time. If a participant was not contactable at a follow-up point, and three attempts to contact her had been made, attempts were made to review AEs in the participant’s fertility notes. Contact was attempted again at the next follow-up point. If the participant could not be contacted at the final follow-up (6 weeks post partum), attempts were made to obtain the outcome of the pregnancy and other related information (sex of baby, birthweight and gestation) from the participant’s medical records.

Sample size

The primary outcome was live birth, defined as a live birth after completing 24 weeks’ gestation within the 10.5-month post egg collection (or 6 weeks’ post partum) follow-up. The denominator for calculating the LBR is the number of women randomised to each treatment group. Available data from HFEA suggest a LBR of 32.8% (women < 35 years) and 27.3% (women aged 35–37 years). We therefore assumed a 30% LBR in the TAU group and that a 10% absolute increase to 40% in the ES group is of clinical and practical importance, which is equivalent to a RR of 1.33. We proposed a large effect size of 10% absolute difference (AD) in LBRs, as it was believed that an effect of such magnitude is needed to change clinical practice. There is a 5% AD in the LBR between women aged under 35 years and women aged 35–37 years, and the proposed effect size is less than that observed in the systematic reviews, in which the RR estimates ranged from 1.83 to 2.2.

To preserve at least 90% power of detecting a 10% AD in LBRs between treatment groups for a 5% two-sided type I error, the trial required 992 women (496 per group) with continuity correction. After adjusting for an expected follow-up dropout rate of 5% (due to anticipated difficulties of follow-up for participants who have been referred from NHS trusts other than the participating fertility unit), the trial required 1044 women (522 per group). It should be noted that a decision was later taken during the statistical analysis plan (SAP) development to include all dropouts in the prespecified primary analysis [see Chapter 3, Analyses of the primary outcome (live birth)] while recruiting the original targeted sample size. 41 This compensated for residual uncertainty in the TAU group around the assumed 30% LBR.

Interim analyses and stopping rules

This was a fixed sample size trial designed without any interim analysis, so no formal stopping rules based on efficacy data were applicable. Final analysis was planned after the recruitment of the target sample size of 1044 participants (522 per group). However, the trial had an internal pilot to assess the feasibility of recruitment and delivery of the ES procedure with stop/go criteria as detailed in Appendix 2. In addition, as part of trial oversight, the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) reviewed ongoing data, as detailed in Trial management and oversight to safeguard the welfare of participants and integrity of the trial.

Patient and public involvement

Service user involvement has been integral to the success of the trial. The patient and public involvement (PPI) co-applicants, patient and public advisory groups and service users have contributed to the development and progression of the trial throughout its course.

The RN leading on public involvement was involved with the trial throughout, including at the outline bid, and sought early engagement from couples waiting to commence IVF treatment. In addition to this, the Reproductive Health Research Public Advisory Panel at the Jessop Wing, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and two service users named as co-applicants also provided input.

Pre-funding preparation

All groups received the project plan and lay summary, and were asked about their perspective on the proposed research plan and research intervention, as well as the physiological and psychological impact of this new intervention on infertility treatment. The Chief Investigator and lead RN attended all meetings and were able to answer questions and resolve queries.

Feedback from PPI influenced the intervention design, data collection protocol and recruitment strategy, but it specifically influenced the follow-up of women who had failed to achieve a pregnancy or who experienced a miscarriage. PPI members felt that it was unreasonable and insensitive to complete questionnaires and be contacted by research staff to collect AE data if there was no ongoing pregnancy.

Post-funding preparatory work

The PPI lead arranged frequent communications with the PPI co-applicants, service users and advisory panel members (by e-mail, teleconference and face-to-face meetings) to develop study protocols and participant documentation. Both PPI co-applicants reviewed participant-related documentation (including, but not limited to, the poster, PIS/consent, questionnaires and patient introduction video). These documents and the patient introduction video were updated in the light of their comments.

In late 2015, the E-Freeze trial42 (funded by the National Institute for Health Research) and the HABSelect trial43 (which had required an extension to its recruitment timeline) were endeavouring to recruit the same patient population in many of the same research sites as was the Endometrial Scratch Trial. The Trial Management Groups (TMGs) of each trial requested input from the Reproductive Health Research Public Advisory Panel (Jessop Wing, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust) to help support a potential way forward to ensure the success of the three trials. The panel recommended the creation of an overarching leaflet for all potential participants to explain, in lay terms, the differences in the three trials in an unbiased manner. This was approved by the regulatory bodies and was used to facilitate recruitment. It was made clear that, at the time of writing this leaflet, no particular study was known to be superior to another in increasing the chances of a live birth.

Throughout progression of the internal pilot trial

Throughout the course of the internal pilot trial, changes to the study protocol and documentation were reviewed by the PPI co-applicants, service users and advisory panel members. Discussions among these groups also included recruitment progress and ideas to improve the process of collecting follow-up data. During the design of the qualitative substudy, PPI members were instrumental in supporting its design by, again, recommending changes to the recruitment techniques and the patient-facing materials, specifically the interview topic guide for participants.

Report writing, academic paper preparation and dissemination

All PPI co-applicants, service users and advisory panel members have been involved in the interpretation of the results, and they recommended that the trial team consider how certain aspects of the results were worded, in order not to provide undue positivity to the results of the trial. The PPI co-applicants, service users and advisory panel members also provided input to the presentation of results and dissemination materials, and the production of the final report to the funder (including preparation of the Plain English summary), and will continue to be involved in dissemination activities and the preparation of academic papers.

Compliance monitoring

Intervention

Compliance with the intervention was ascertained through the record taken by the clinician or nurse of whether or not the participant had attended the clinic for the ES procedure and received the procedure per protocol. Any deviations from the ES procedure were noted and are reported.

Other

Any deviation from the trial protocol or Good Clinical Practice regulations44 was recorded by staff at the site or at the CTRU.

Trial monitoring

Responsibility for trial monitoring was delegated to the CTRU and conducted in accordance with CTRU SOPs, using both on-site and central monitoring approaches.

On-site monitoring was undertaken at all sites at study set-up, after around 10 participants were recruited to the trial and at the mid-point of the recruitment phase. At each visit, the site file and study logs were reviewed for completeness. Source data verification was undertaken for at least 10% of the randomised participants. Fertility notes were reviewed to substantiate participant existence and eligibility. Monitoring reports were issued after each visit detailing the actions required. Study close-out was undertaken remotely.

Central monitoring included point of entry validation, verification of data and post-entry validation checks.

Trial management and oversight

Trial Management Group

The TMG was responsible for the day-to-day management and oversight of the trial, and included the Chief Investigator, clinical co-applicants, a statistician, the trial manager, the lead RN and a PPI representative. The TMG reviewed blinded trial reports without any outcome data during trial management meetings.

Trial Steering Committee

The TSC provided overall oversight of the trial and comprised two independent gynaecologists and an independent statistician. Members of the TMG (including the trial manager and Chief Investigator) also attended meetings, which occurred at least once every 6 months. Blinded reports without any outcome data were provided by the data management team based at the CTRU prior to each meeting.

Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee

The DMEC was responsible for the safety of trial participants and the scientific integrity of the trial, and comprised two independent clinicians (gynaecologists) and one independent statistician. Even though the trial was not designed with formal stopping rules, blinded reports (for open-session discussions) and unblinded reports consisting of safety and outcome data (for closed-door discussions) were provided on a monthly basis and prior to each 6-monthly meeting.

Chapter 3 Statistical methods

This chapter details statistical methods and principles used to analyse outcomes relating only to the clinical effectiveness and safety objectives that are described in Chapter 2, Outcome measures. These methods are detailed in an accessible and approved pre-planned SAP version 2.0 and in the amendments in version 2.1. 41 This SAP also contains a history of amendments and whether or not they were made before or after blinded or/and unblinded review of the trial data. Any unplanned analyses conducted are highlighted in this chapter with the rationale for doing so. All analyses were performed in Stata® (v16.1) (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) software. For quality control, an independent statistician within the Sheffield CTRU reproduced the analyses of the primary and secondary outcomes (including sensitivity analyses) and safety outcomes in R (v3.6.0) (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) software.

Analysis populations

Intention to treat

The primary analysis was based on an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis population that included all randomised participants with informed consent regardless of circumstances after randomisation, except if they withdrew consent and explicitly stated that their data should not be used. Treatment allocation was as randomised even if participants switched treatments or did not receive their randomly allocated treatment. The Clinical effectiveness section of this chapter explains how missing data were addressed under the worst- and best-case scenarios.

Per protocol

The purpose of the per-protocol analysis was to explore the effect of the ES procedure among those women who were viewed to have met key protocol requirements. The per-protocol population included women who complied with key protocol requirements, defined as those who:

-

met the inclusion criteria as stipulated in the protocol

-

received the allocated treatment, that is, excluding those who were allocated to TAU but underwent the ES procedure within or outside the trial, those who were allocated to ES but received only IVF, and those who did not receive any trial intervention

-

did not achieve a spontaneous pregnancy before the delivery of the interventions

-

completed the fertility treatment cycle and successfully generated embryos

-

used contraception before the ES procedure (i.e. excluding those who failed to use contraception before ES and whose procedure could not be rescheduled)

-

received treatment using fresh embryos (i.e. excluding those who underwent FET)

-

were treated using only the antagonist or long protocols (i.e. excludes other protocols such as ultra-long).

Based on the advice of the TMG, since the delivery of the ES procedure is simple and unlikely to vary significantly across fertility units, per-protocol analysis also included women who were randomised to ES but known to have received the ES procedure outside the trial (if applicable).

Complete case

Complete-case analysis was used for sensitivity analysis on the primary analysis of the primary outcome. Complete-case population is the subset of the ITT population that included women with the known live birth outcome.

Safety

The analysis of all safety outcomes on participating women and born babies was based on the safety analysis population, which included randomised women who provided informed consent, and treatment assignment was according to the intervention received rather than the allocated intervention. Thus, women who were randomised to:

-

ES but failed to receive the ES procedure before receiving IVF were reassigned to the TAU group

-

TAU but received the ES procedure (within or outside the trial) before receiving IVF were reassigned to the ES group

-

either intervention but failed to receive any were excluded.

Prespecified subgroups

The following subgroups were prespecified for subgroup analyses with an objective to explore the potential heterogeneity in the effect of the ES procedure across these subgroups:

-

day of embryo transfer (day 2, 3, 4, 5 or 6)

-

fertilisation method (IVF, ICSI or split ICSI)

-

type of protocol (long treatment or antagonist)

-

embryo transfer (single or double)

-

nature of embryo used (frozen or fresh)

-

history of miscarriages (0–2 or ≥ 3)

-

cycle programming (yes/no).

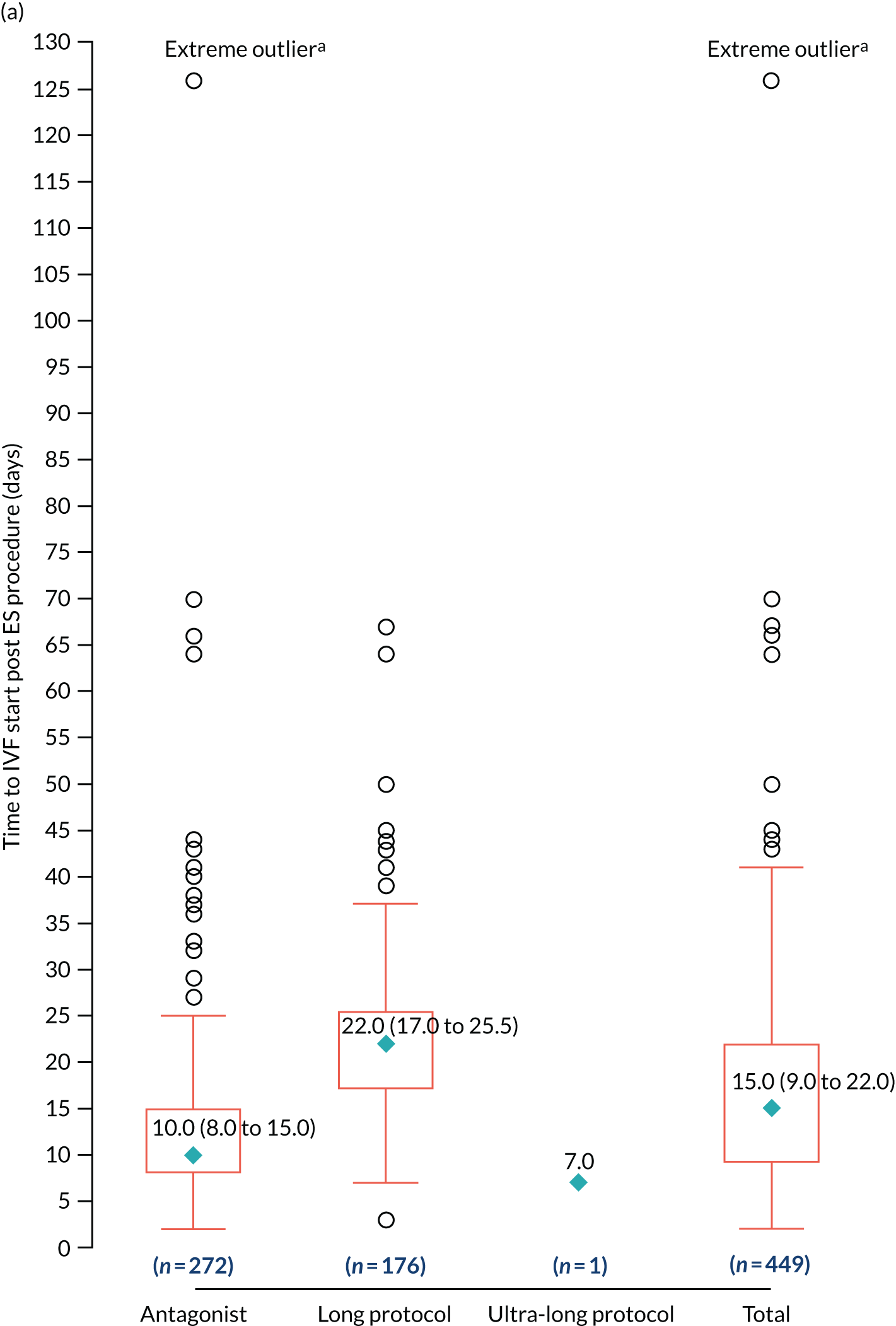

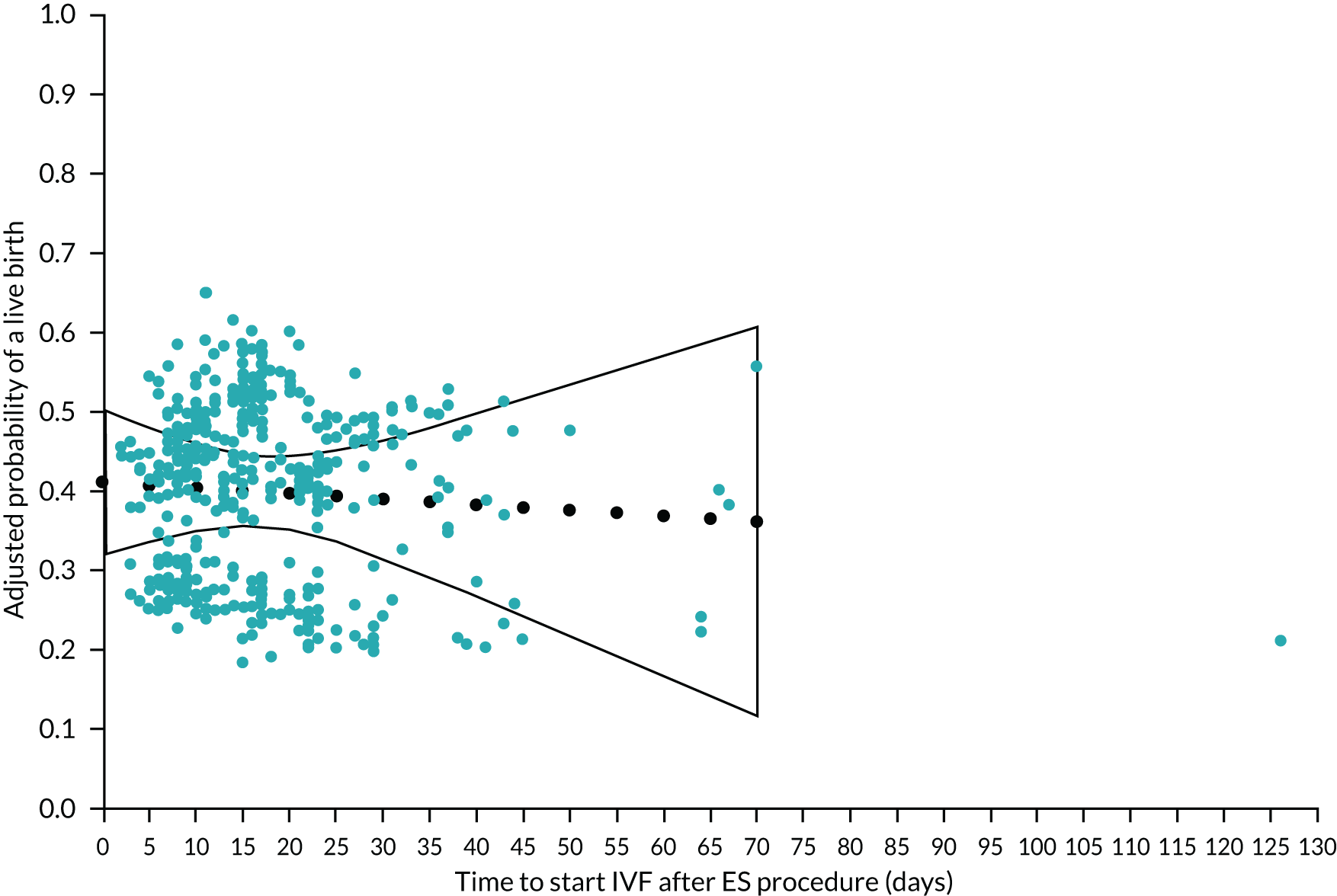

In the ES group only, we also explored whether or not delaying the start of IVF after the ES procedure influences the chances of achieving a live birth.

Descriptive analyses for comparability between treatment groups

The demographics and characteristics of randomised women at baseline and treatment cycle characteristics during the trial were descriptively summarised by treatment group depending on the underlying distribution of variables without any statistical significance testing to assess comparability between the TAU and ES groups. 45–47 The numbers and percentages for categorical variables are reported. For continuous variables, the mean [standard deviation (SD)] and median [interquartile range (IQR)] as well as minimum and maximum values are reported. However, mean (SD) is reported in text for normally distributed variables, whereas the median (IQR) is used for skewed data. Any notable differences between treatment groups are discussed with implications, where applicable, in the results (see Chapter 7).

Clinical effectiveness

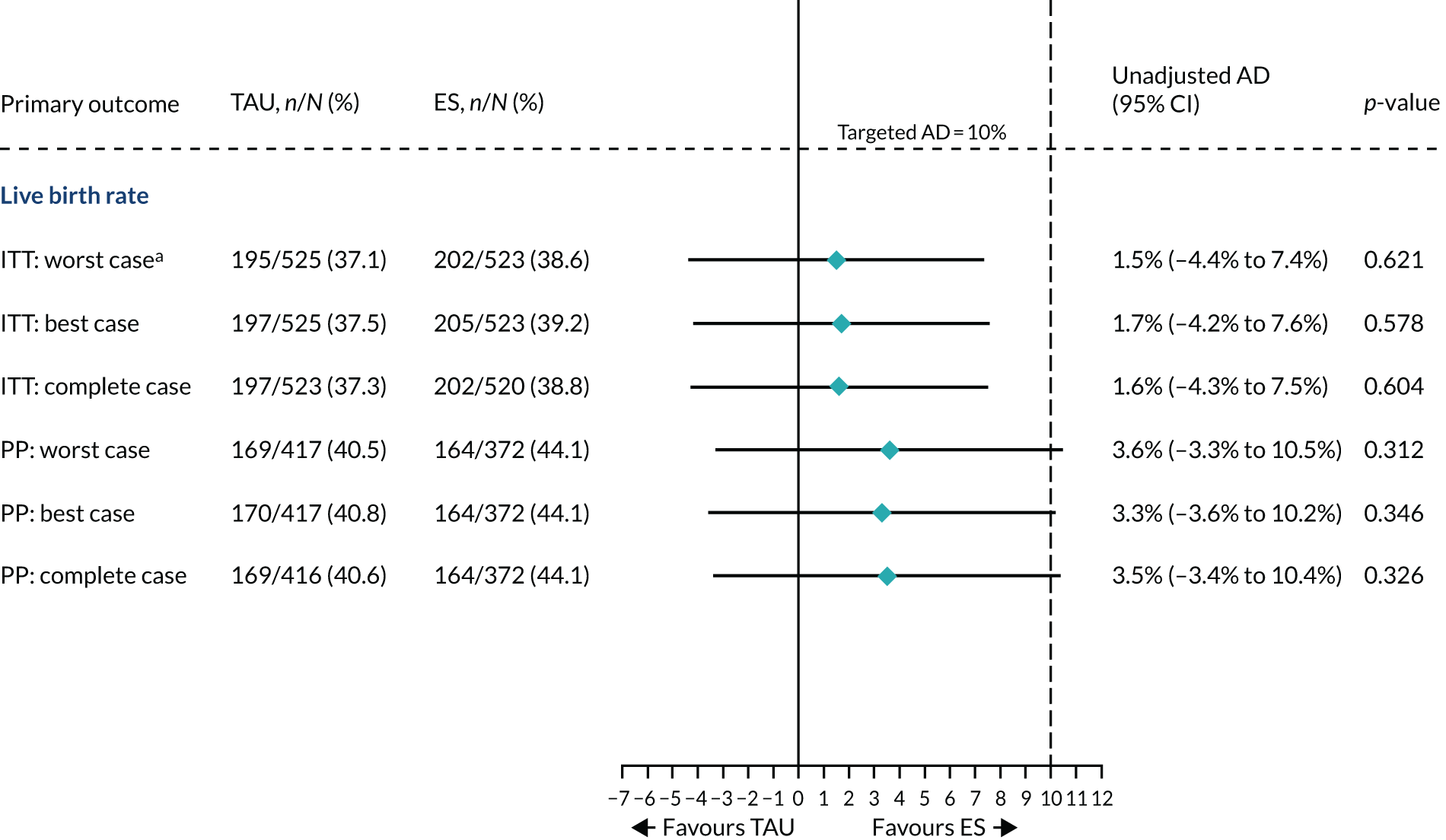

Analyses of the primary outcome (live birth rate)

The AD in LBRs was the primary measure of the treatment effect of interest. In the calculation of LBRs, we treated multiple live births per woman due to multiple pregnancies as a single event and the denominator was the number of women randomised. We estimated the 95% CI around the differences in LBRs using the normal approximation to the binomial distribution and calculated the associated p-value using Pearson’s chi-squared test. A 5% two-sided significance level was used for the hypothesis test. To aid interpretation, in line with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidance,48 we estimated the unadjusted OR with 95% CI using a simple logistic regression (binomial generalised linear model with a logit-link function) and the unadjusted RR with 95% CI using a simple binomial generalised linear model with a log-link function. We performed a sensitivity analysis by adjusting for fixed stratification factors (i.e. site and planned treatment protocol) and potential prognostic factors [i.e. history of pregnancy (yes or no), age, BMI, duration of infertility and smoking status (yes or no)]. The adjusted OR and 95% CI were estimated using a multiple logistic regression model and adjusted RR (95% CI) using a binomial generalised linear model with a log-link function. The adjusted AD and associated 95% CI were post estimated via margins using the delta method after fitting a binomial generalised linear model with a log-link function. 49

The primary approach to deal with missing data used the worst-case scenario by assuming that all women with an unknown live birth outcome, such as ‘lost to follow-up’, failed to achieve a live birth unless it was known otherwise (e.g. obtained from patients’ medical notes). We performed a sensitivity analysis using the best-case scenario by assuming that women without pregnancy and/or live birth outcome data were pregnant and delivered a live birth. Furthermore, we also performed a sensitivity analysis using a complete case that included only women with the known live birth outcome (see Complete case).

Per-protocol analysis on the primary outcome was performed assuming a worst-case scenario using the same methods as described for the primary ITT analysis based on a per-protocol population, as defined in Per protocol. Following the presentation of trial results to the TMG, TSC and DMEC on 18 May 2020, an unplanned analysis was requested to aid the interpretation of the per-protocol results. This involved the estimation of the posterior probability of the treatment effect being at least 10% AD of clinical importance (equivalent to an OR of ≈1.5 given the observed 40.5% LBR in the TAU arm) given the observed data. We fitted an equivalent Bayesian multiple logistic regression model with all covariates that were included in the primary ITT analysis with normal priors on parameters with a mean of 0 and variance of 105. The posterior distribution of the treatment effect was estimated via Markov chain Monte Carlo sampling with a sample size of 200,000 and burn-in of 500.

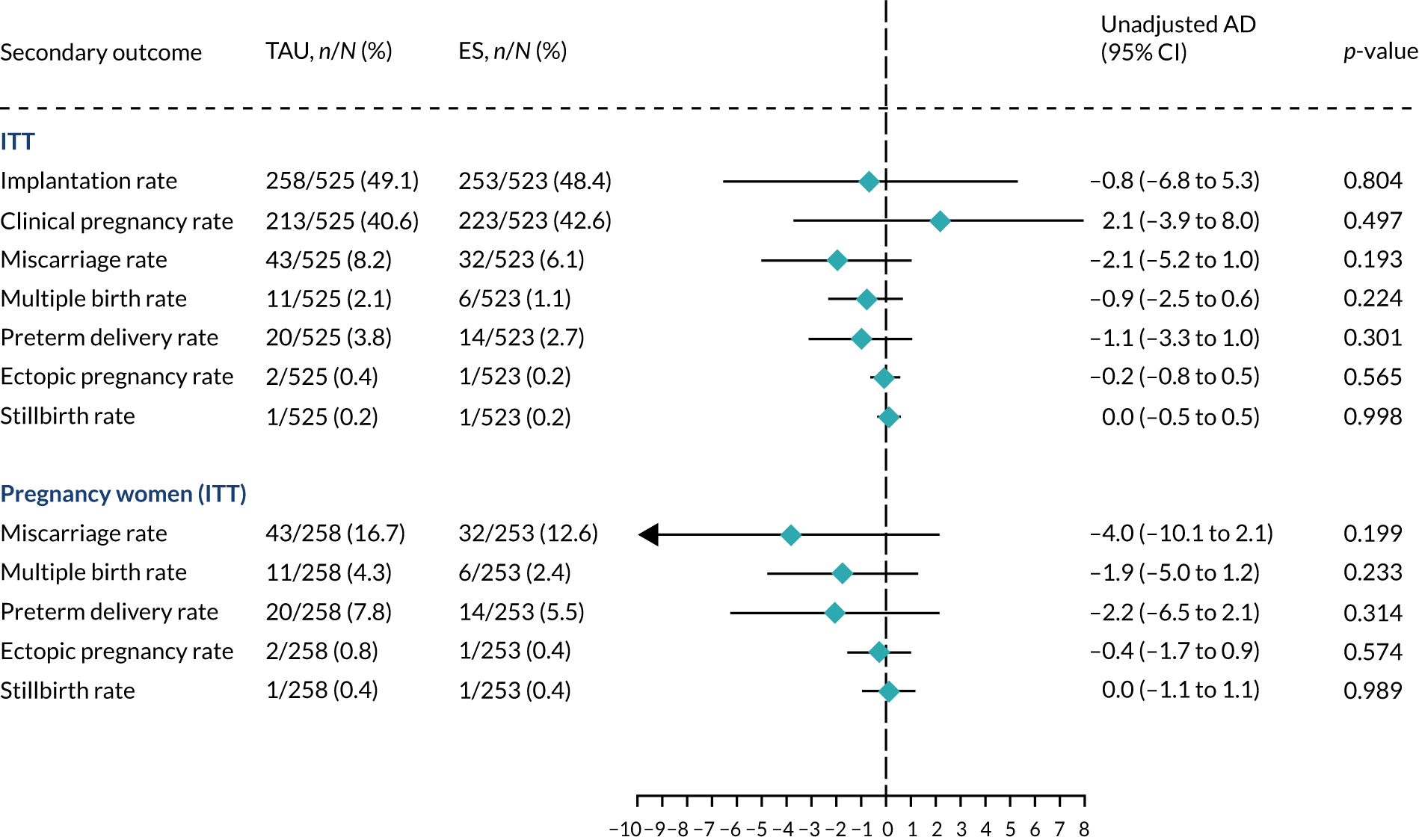

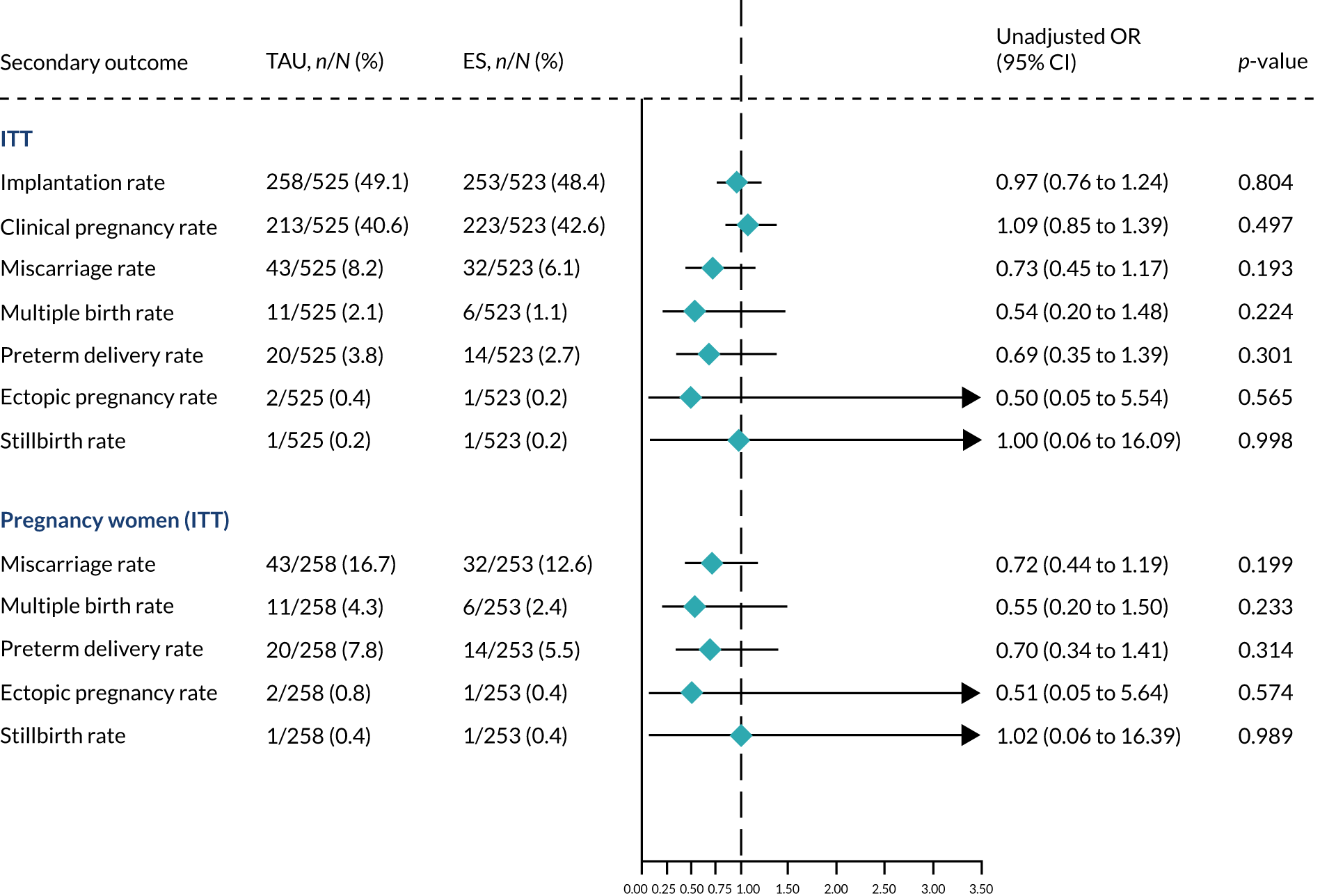

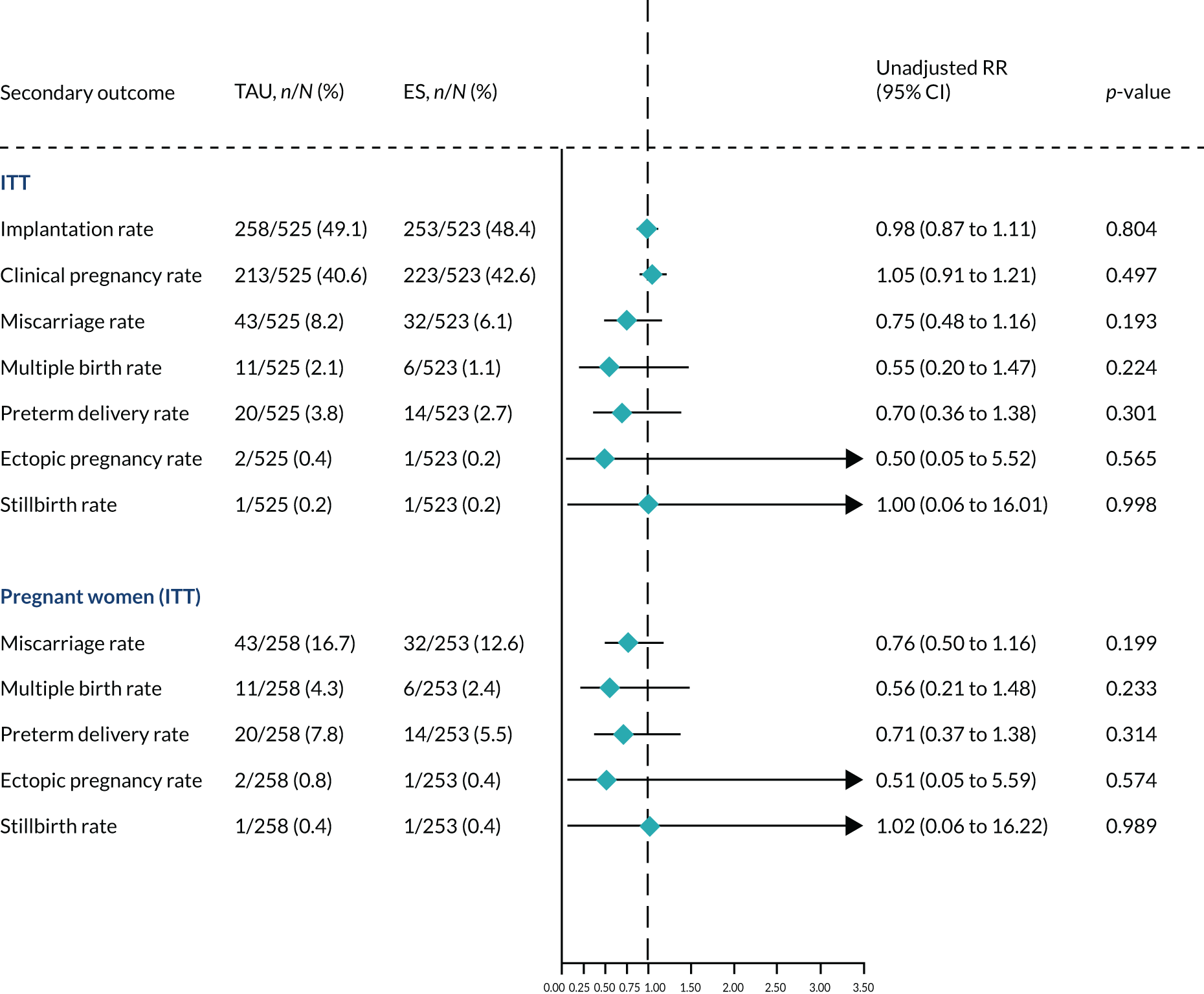

Analyses of secondary outcomes

We performed unadjusted analyses on all secondary clinical outcomes in the same manner as the primary outcome (see Analysis populations). This covered ectopic pregnancy, implantation, clinical pregnancy, miscarriage, multiple birth, preterm delivery and stillbirth. We repeated this analysis on secondary outcomes that also relate to safety signals (except implantation and clinical pregnancy) in women who achieved successful implantation (i.e. with a positive pregnancy test). There was no correction for multiple hypotheses testing, as this was exploratory and all tests were performed at 5% two-sided significance level.

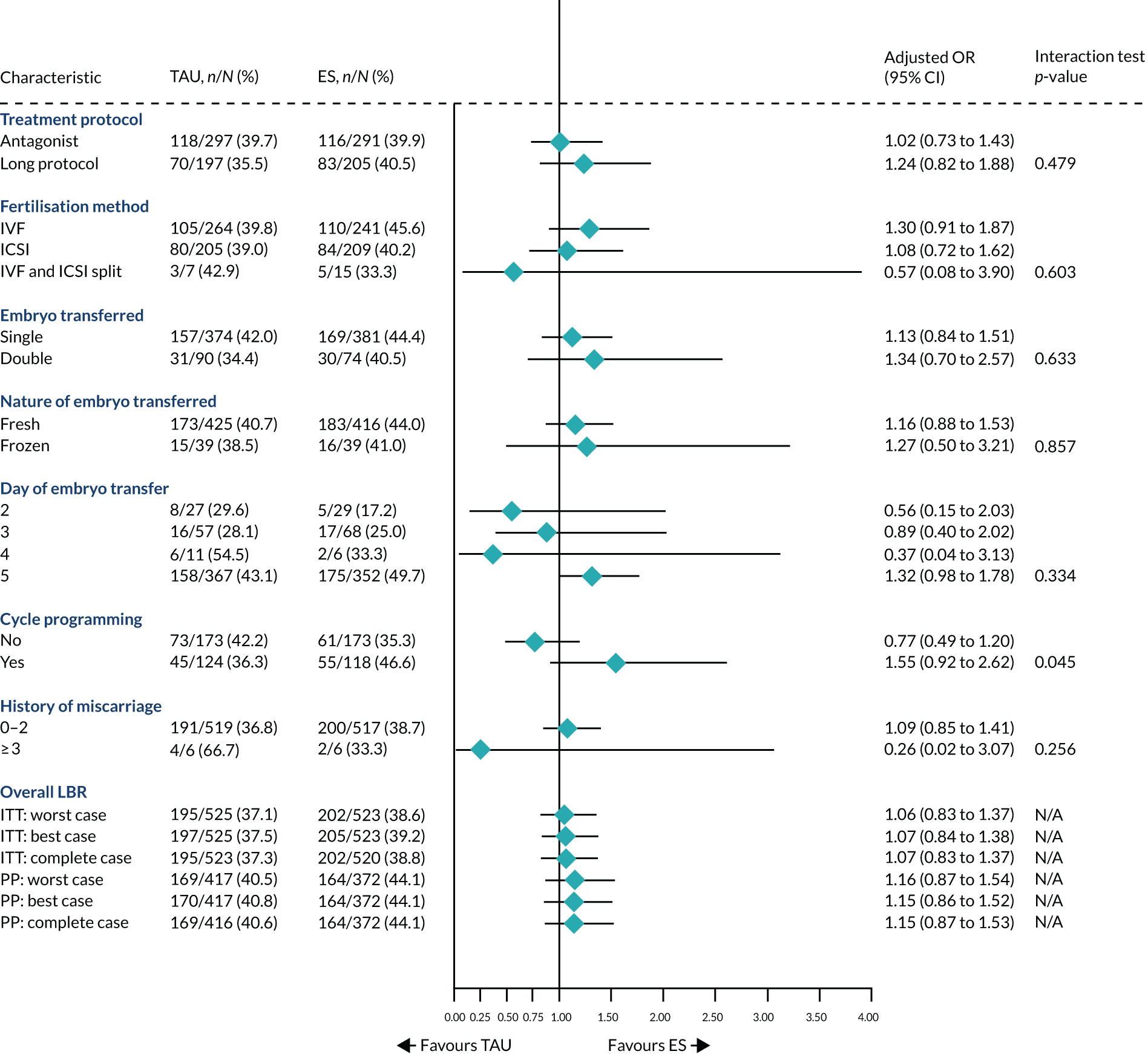

Subgroup analyses: primary and secondary outcomes

The purpose of the subgroup analyses was to explore whether the estimated treatment effects were consistent or there was potential heterogeneity across prespecified subgroups. The adjusted OR with associated 95% CI and interaction p-value were estimated using a multiple logistic regression model that included an interaction term between treatment and subgroup as well as fixed stratification factors (site and planned treatment protocol) and potential prognostic factors [history of pregnancy (yes/no), age, BMI, duration of infertility, smoking status (yes/no)]. However, for subgroups relating to the treatment protocol followed and the history of miscarriage, planned treatment protocol and history of pregnancy were not included as covariates, respectively (because the subgroup and covariate were highly correlated). The same approach to estimate the adjusted RR with associated 95% CI and interaction p-value using a Poisson generalised linear model with log-link function and robust standard errors was used. We did not estimate the adjusted AD with associated 95% CI because the post-estimation of margins using the delta method failed to converge. 49

Subgroup analysis was only performed for the primary outcome (live birth) and selected secondary outcomes (clinical pregnancy and implantation). Other secondary outcomes with very small numbers of events were excluded because statistical models failed to converge; these were ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, multiple birth, preterm delivery and stillbirth.

Safety analyses

Participating women

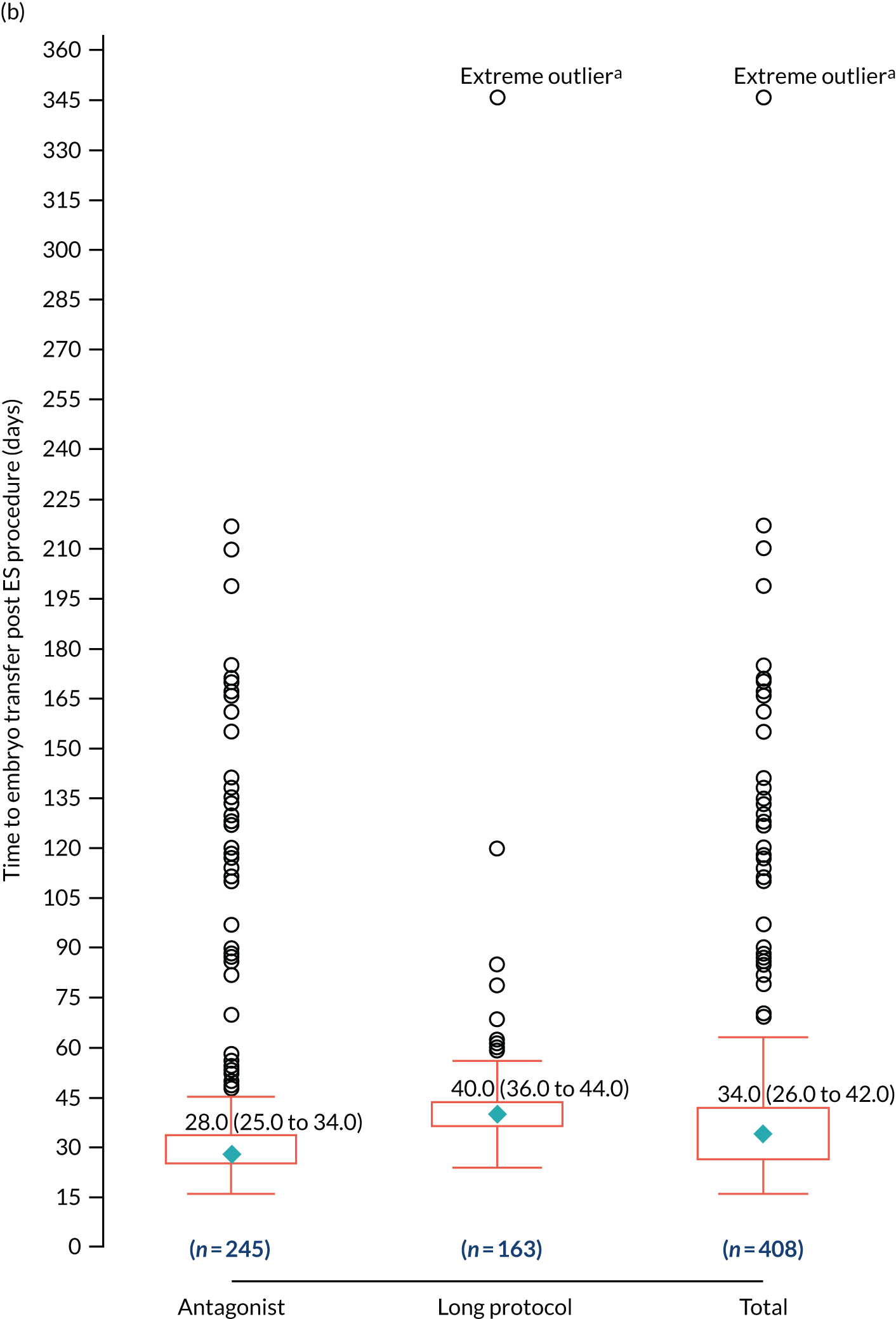

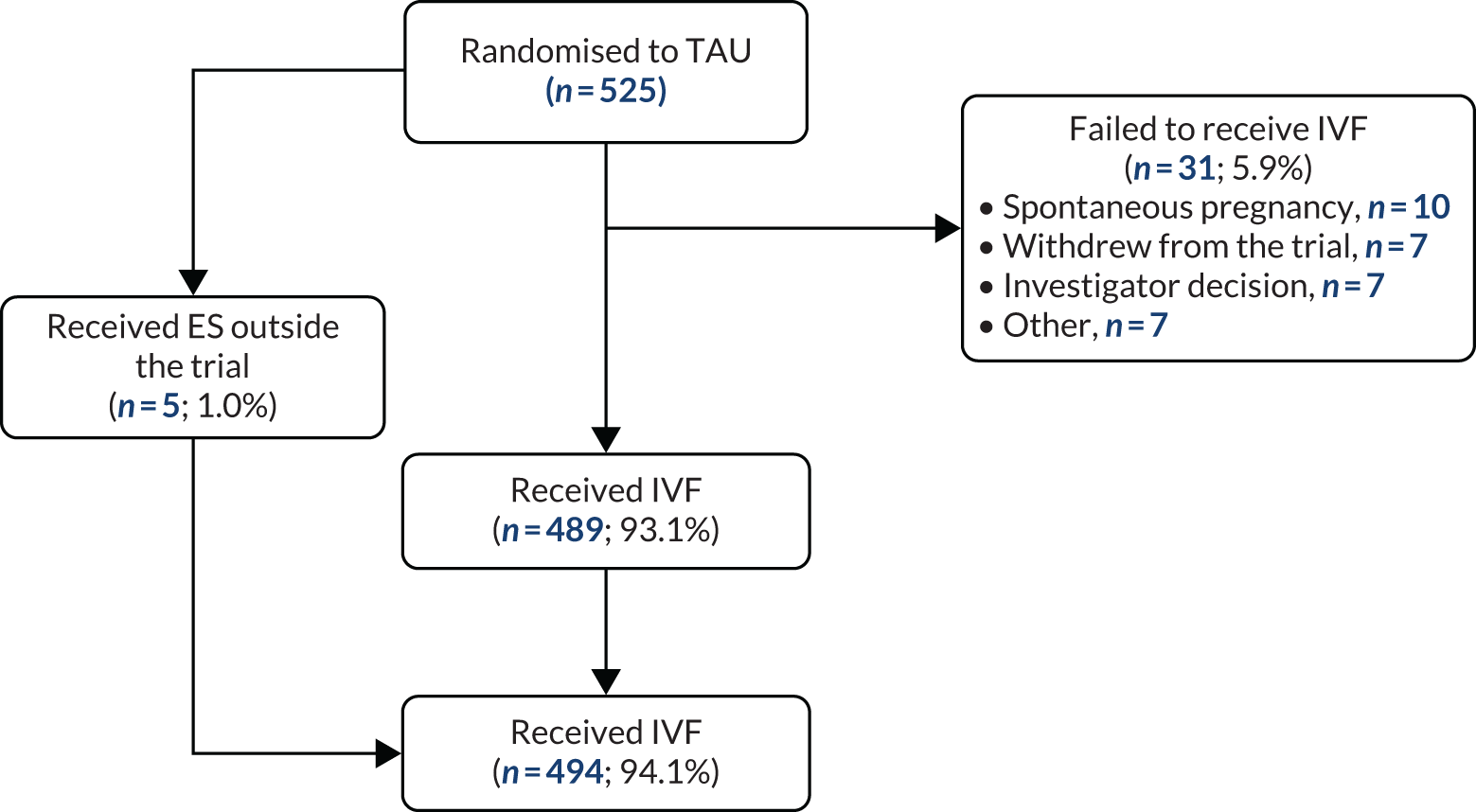

We used the Wilson score method to estimate the 95% CI around the proportion of women who tolerated the ES procedure based only on women with tolerability data. 50 Sensitivity analysis was performed assuming that women who received ES but without tolerability data did not tolerate the ES procedure. The distribution of pain rating scores within 30 minutes and at 1 day and at 7 days was displayed using a multiple box plot and was also summarised using means (SD), median (IQR) and minimum and maximum scores.

The expected AEs that were recorded during the trial were summarised by the treatment group using the numbers and proportions of women who experienced at least one event. Unexpected AEs and SAEs that occurred between receiving the intervention and the end of the trial were summarised by the number and proportion of women who reported at least one event and a total number of repeated events per treatment group. The AE category, frequency, seriousness, intensity, outcome and its relationship with ES procedure (in those who received ES) were summarised in the same manner.

The numbers of repeated events per woman were analysed using a negative binomial regression model (accounting for follow-up period) to estimate the incidence rate (IR) per treatment group and incidence rate ratio (IRR) with associated 95% CI. We also performed a sensitivity analysis by including all unexpected AEs and SAEs reported at any point during the trial. In addition, events that occurred between receiving ES and IVF were also summarised in the ES group only.

Born babies

In women with a positive pregnancy test, safety outcomes experienced by born babies (see Chapter 2, Safety outcomes) were summarised using the numbers and proportions per treatment group as well as the unadjusted AD in proportions between treatment groups with 95% CI estimated using the normal approximation to the binomial distribution.

The UK World Health Organization Neonatal and Infant Close Monitoring Growth Charts51 were used to estimate the centiles of birthweight given gestational age and sex of baby using the hbgd R package [URL: https://hbgdki.github.io/hbgd/#growth-standards (accessed 4 February 2022)]. These centiles were used to classify babies at birth as low birthweight, very low birthweight, small for gestational age and large for gestational age, as described in Chapter 2, Safety outcomes.

Chapter 4 Economic evaluation methods

Another specific objective of the trial was to assess the cost-effectiveness of the ES procedure. This chapter details the methods utilised for the cost-effectiveness analysis, which aimed to compare ES with TAU. The results are presented in Chapter 8 as incremental cost per extra live birth from an NHS and social care prospective. All analyses were undertaken using Stata (v16) software.

Analysis

The primary analysis aimed to present results as cost per extra live birth from an NHS and social care perspective in accordance with NICE guidelines. 52 Unit costs were derived from appropriate national sources and included NHS reference costs,53 Personal Social Service Research Unit costs54 and Office for National Statistics (ONS) data. 55

Resource use

Resource use was collected as described in Chapter 2, Collection of health resource use and patient costs data. Unit costs were for 2018/19 and no discounting was applied as costs were presented over the time frame of the pregnancy, which was less than 1 year.

Primary cost-effectiveness outcome

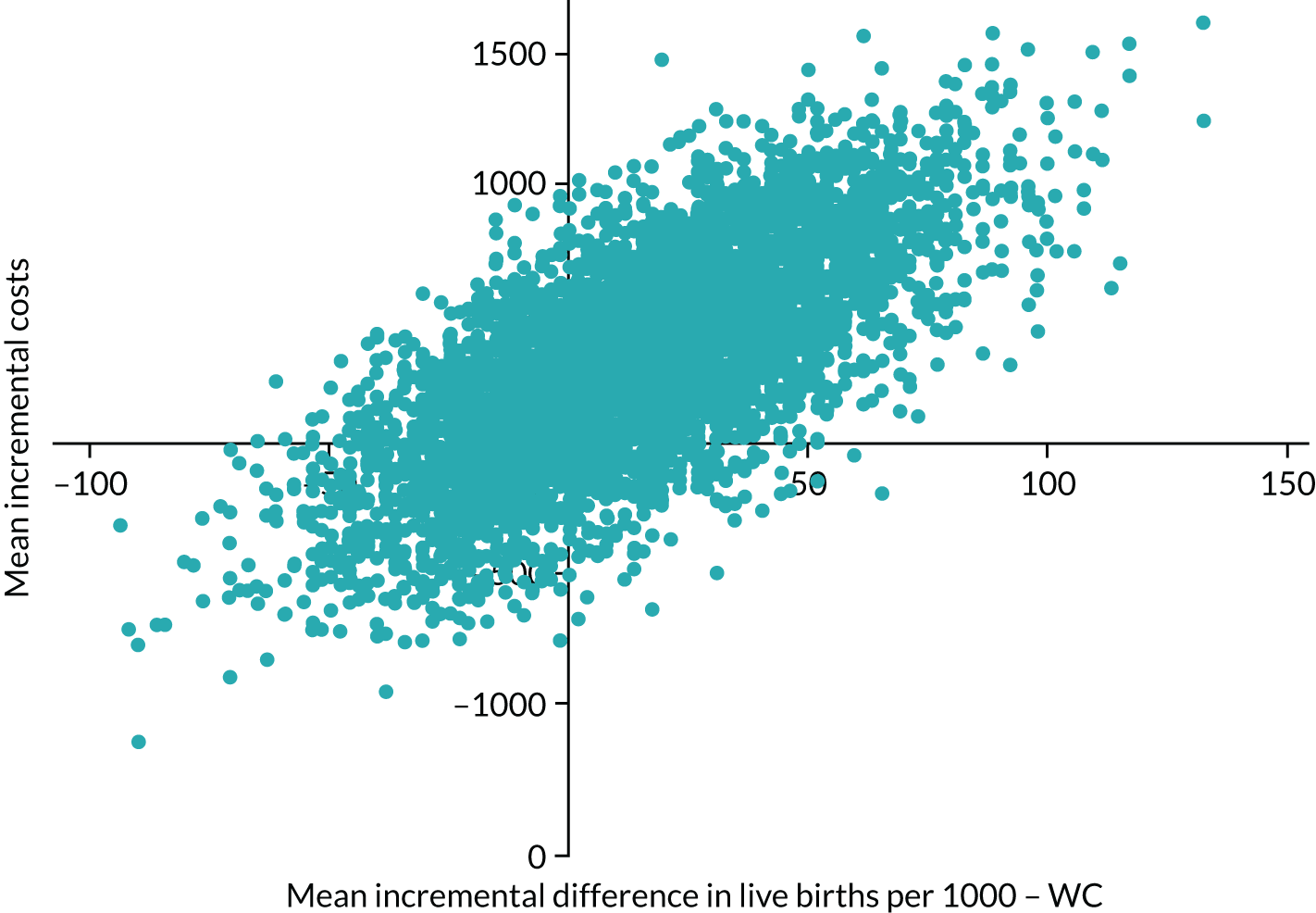

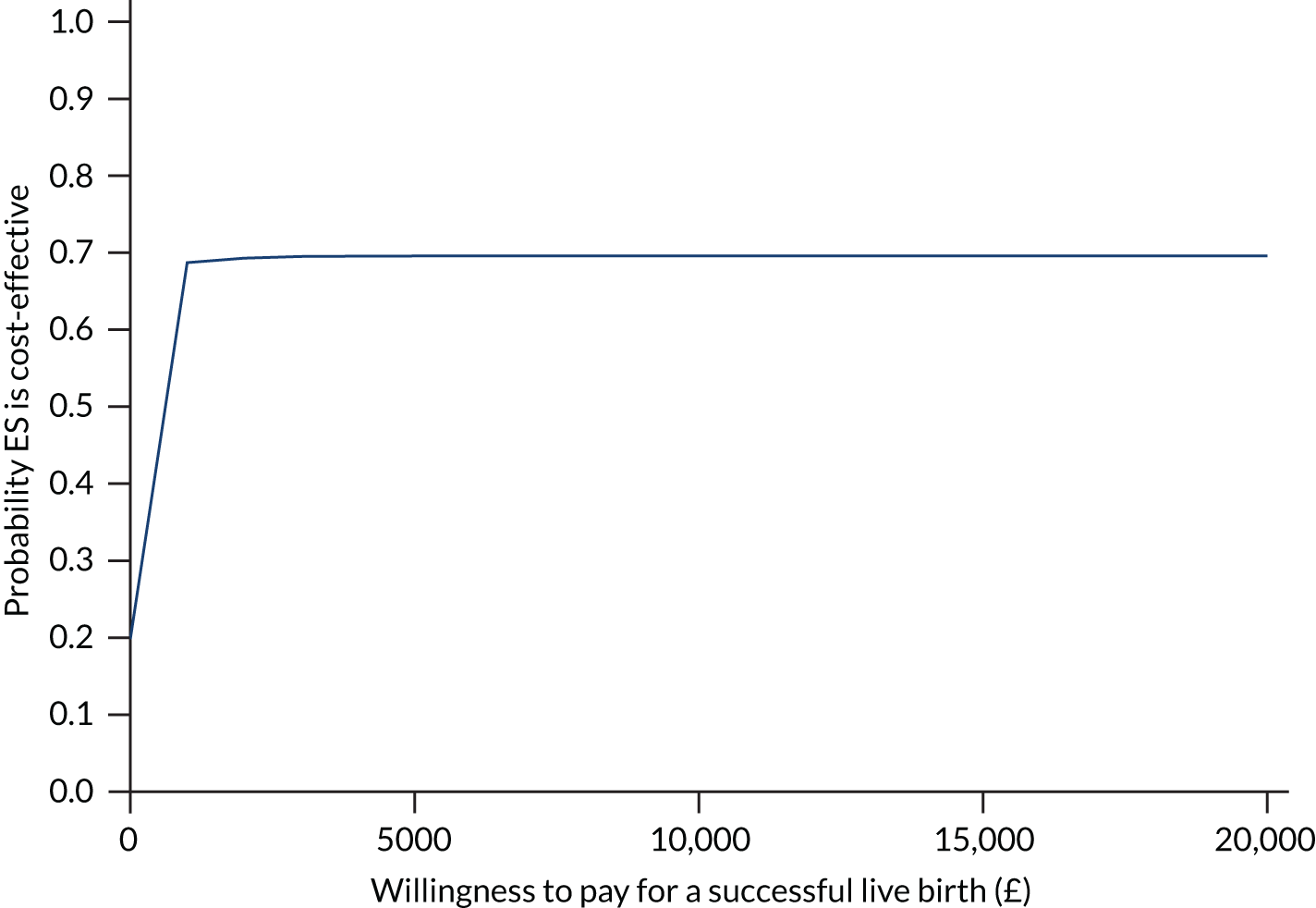

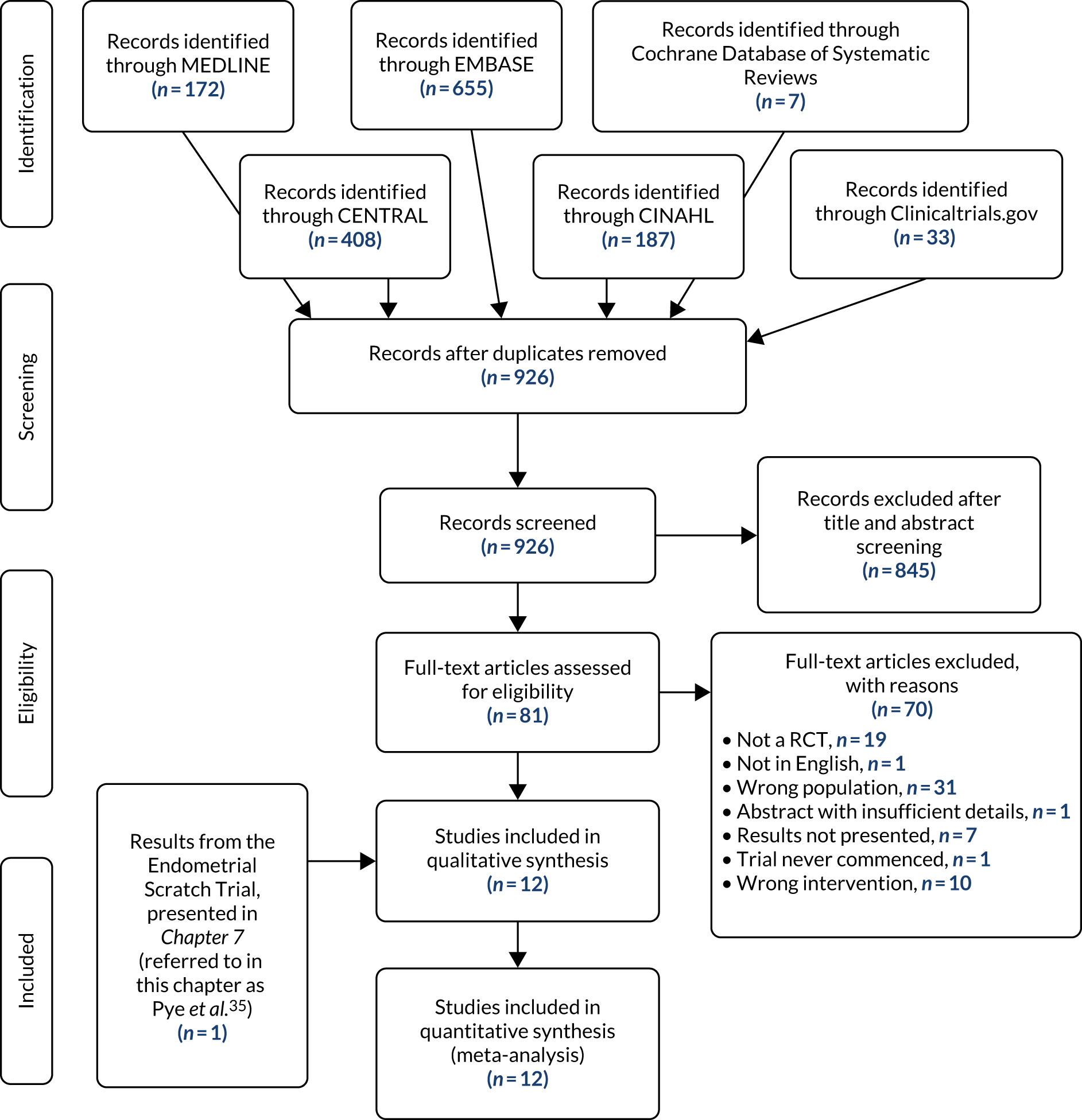

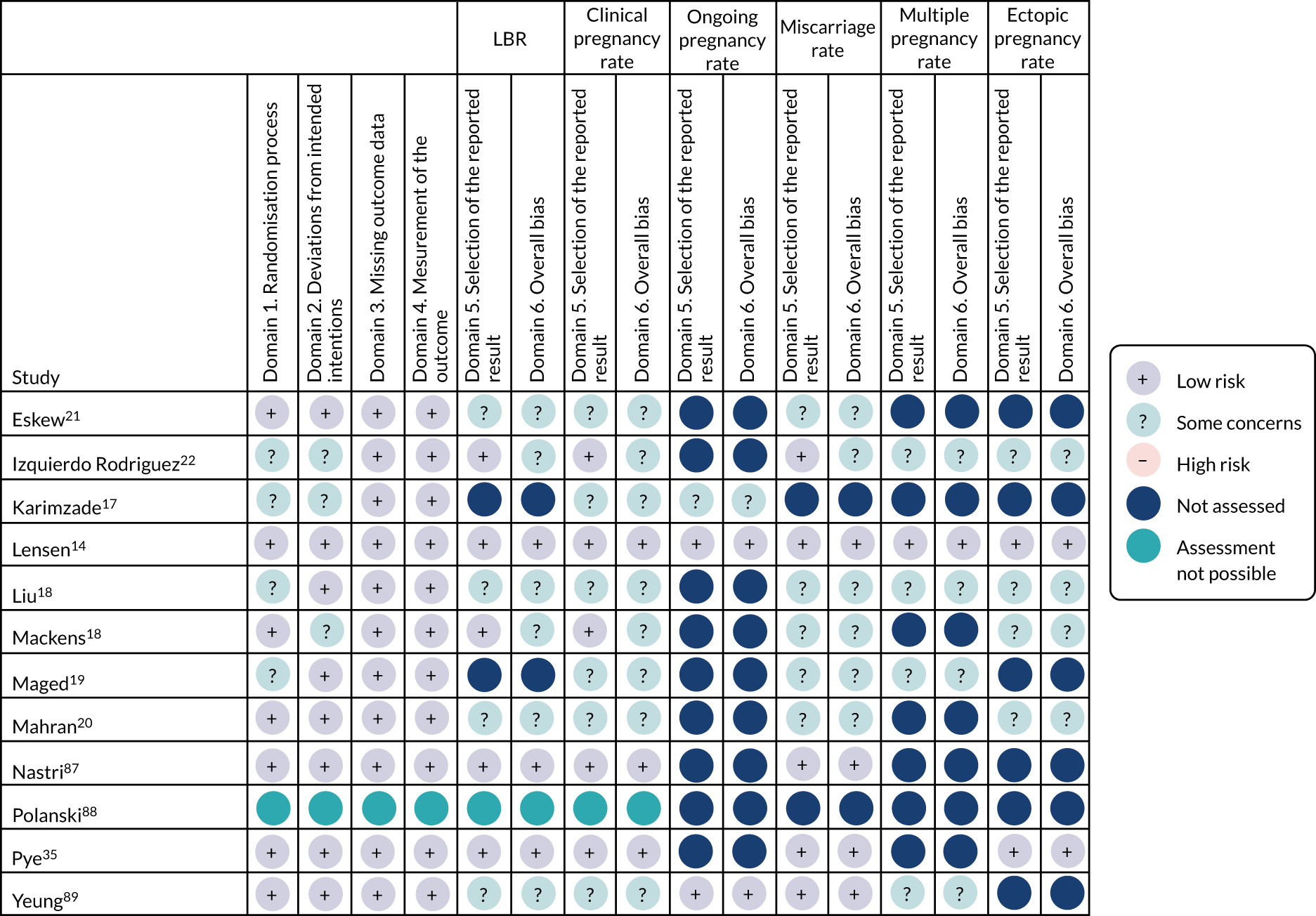

We calculated the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) as cost per percentage of successful pregnancies and the ICER as cost per successful pregnancies per 1000 population. To allow for uncertainty, a resampling method (known as bootstrapping) was used to obtain 95% bias-corrected CI around the ICER. 56 A total of 5000 simulations were used. Results are presented on the cost-effectiveness plane and on the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve.

Secondary cost-effectiveness outcomes

The cost-effectiveness of ES compared with TAU was examined for the following secondary outcomes: cost per clinical pregnancy, cost per ectopic pregnancy avoided, cost per miscarriage avoided, cost per multiple birth, cost per stillbirth avoided, cost per preterm delivery and cost per biochemical pregnancy. Analysis of variance was conducted to see whether or not there were any statistically significant differences in costs between the two treatment groups after allowing for the secondary outcome variable.

Prespecified subgroups

We explored the effectiveness differences in costs for different prespecified subgroups, as detailed in Chapter 3, Prespecified subgroups.

Sensitivity analysis

Resource use was collected at baseline, when participants were asked to recall their resource use over the previous 3 months. Analysis of covariance was undertaken to adjust for baseline costs and the ICER per successful live birth per 1000 population was calculated. A further analysis adjusting for baseline costs and any subgroups was also undertaken, as specified in Prespecified subgroups, and found differences in costs.

Triangulation based on labour and in vitro fertilisation resources reported by participants

The health resource use questionnaire was not designed to collect information on IVF or labour; this was collected directly from sites as part of the CRF. In the health resource use questionnaire, respondents were asked about visits to hospital, and some gave details of their IVF treatment and labour. Not all participants reported labour or IVF in the health resource use questionnaire; thus, if this questionnaire was used alone, without the CRF data, the costs of labour and IVF would be under-reported. We assumed that those who did not report these resources in the questionnaire were also under-reporting other resources that they accessed during the study in the same way. As a sensitivity analysis, a simple triangulation exercise was carried out assuming that the information reported on the CRF was accurate, as it was recorded from patient notes. The percentage of participants who reported undergoing IVF and labour on the patient resource use questionnaire was reported and costs were inflated to reflect this under-reporting.

NHS and wider perspective

As part of the study, participants were asked to complete a patient cost questionnaire that asked them about how they travelled to their last fertility appointment, the cost and time taken to travel and what they would have been doing had they not been at the appointment (lost time/earnings). The questionnaire also asked whether or not a companion accompanied them and about any lost time/earnings to their companion. Respondents indicated if they had travelled to their appointment by car, bus, train, taxi, foot or other mode of transport; they were also asked how far they travelled to their appointment. Respondents supplied details of the cost of car parking and any train, bus or taxi fares. The cost of car journeys was based on the UK Government’s mileage allowance payments for car travel of £0.45 per mile57 and multiplied by distance travelled to obtain a total cost for the journey.

Hourly rates of hours and earnings were taken from the ONS Earnings and Working Hours Survey for 2019. 58 It was assumed that any time away from usual activities had the same value for those in or not in paid employment, and the average hourly rate for the time spent at the appointment was applied to all participants. The cost of travel and time away from other activities was applied across all planned hospital visits plus seven additional visits for those who underwent IVF plus a further visit for those who became pregnant. These costs incurred by participants were added to the NHS costs to present a wider than NHS perspective in a sensitivity analysis.

Chapter 5 Qualitative methods

We undertook a qualitative substudy, within a phenomenological framework, to provide context to the results of the trial and to improve the delivery and patient experience of future reproductive health studies. Qualitative interviews were undertaken with a sample of trial participants and site staff, which included doctors and nurses involved in recruitment and delivery of the trial, to explore their experience of recruitment, delivery of the intervention and delivery of the trial. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist was used when writing this report. 59