Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number 15/166/08. The contractual start date was in January 2017. The draft manuscript began editorial review in October 2022 and was accepted for publication in May 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Marshman et al. This work was produced by Marshman et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Marshman et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Introduction

The high prevalence and severity of dental caries adversely affect children and young people in the UK, bringing with it an economic burden. Reducing the disease, and therefore its negative impact, is a public health priority. 1–3 Dental caries is largely preventable and there are a number of successful interventions across the UK for young children, including those based on toothbrushing with fluoride toothpaste. 4,5 However, there is a lack of evidence for community-based oral health improvement programmes in older children and young people that target toothbrushing practices. A behaviour change intervention incorporating a school-based lesson together with mobile health (mHealth) technology (through mobile phones) has the potential to have a positive effect on this oral health behaviour and ultimately reduce dental disease and its sequelae.

Prevalence of dental caries in young people

Dental caries is the most prevalent non-communicable condition worldwide, with untreated caries affecting 2.4 billion people. 6 In the UK, there have been reductions in caries experience for young people reflected in the 2003 and, most recent, 2013 Child Dental Health Surveys (CDHS) which cover England, Wales and Northern Ireland. The proportion of children with teeth showing active carious lesions, dental restorations or which had been extracted due to dental caries dropped from 43% to 34% in 12-year-olds and from 56% to 46% in 15-year-olds over the 10-year period. 7 In Scotland, over a similar period, the annual National Dental Inspection Programme (NDIP) reported reductions in obvious caries experience for 12-year-olds, from 47% in 2005 to 27% in 2015, and in the most recent survey carried out in 2019, there has been a further reduction with 20% affected. 8–10

Despite these improvements across the UK, the prevalence of dental caries remains high. The overall reduction in the prevalence is positive, but potentially masks three underlying issues. First, there is a persistence in underlying oral health inequalities. The positive association between living in a deprived area and prevalence of dental caries is seen across the UK11,12 and globally. 6 A variety of indicators are used for measuring deprivation. Using eligibility for free school meals (FSM) as a measure, the 2013 CDHS found that the proportion of children with obvious caries experience was 46% among 12-year-old children eligible for FSM, compared with 30% among those not eligible for FSM. 7 Similarly, for 15-year-olds, this was 59% for those eligible for FSM compared with 43% for those not eligible. 7 In Scotland, the difference in obvious decay experience levels between those living in the most and least deprived areas, was 26.3% in 2009 reducing to 18.6% in 2019. 10

Second, although the overall prevalence has reduced, the disease is severe in those affected. The burden of disease in children can be measured using the mean number of decayed, missing and filled teeth (DMFT) per child. In 2013, for England, Wales and Northern Ireland, for children with obvious decay experience, this was 2.5 teeth per child7 and in Scotland, 2.1 teeth per child. 10

Finally, although there has been a reduction in the prevalence of dental caries in children, there is a high burden of untreated disease. The 2013 CDHS found obvious untreated decay into dentine in 19% of 12-year-olds and in 21% of 15-year-olds. 7 Similarly, in Scotland, in 2019, untreated caries into dentine was found in 8% of 12-year-olds. However, this rose to 40% who had untreated disease, when only the children with carious lesions were included. 10 COVID-19-related challenges with access to dental care will potentially increase the burden from disease for all and widen inequalities. 13,14

Impact of dental caries on young people and their families

The impact of dental caries on the lives of children and young people has been well documented, including pain15 and difficulties with eating and sleeping, with disrupted social activities and absences from school. 12,16 Families report guilt, lack of sleep and taking time off work related to their child’s carious teeth in 5- to 16-year-old children. 17 Following treatment of dental caries, there is a reduction in these impacts for both children up to the age of 16 years and their families. 16–19

In a secondary analysis of data from the 2013 CDHS, 3859 children were included to investigate the relationship between the presence/absence of severe dental caries (e.g. pulp involvement, ulceration, fistula or an abscess in at least one tooth) and seven items from the Family Impact Scale. 20 Three in 10 parents (29.5%) reported that their child’s oral health impacted on their family life. The areas most frequently affected were parents having to take time off work (15.5%), feeling stressed (14.2%), feeling guilty (10.4%) and their child needing more attention (13.4%); the least frequent impacts related to financial difficulties (2.4%), disruption in normal activities (6.1%) and disturbed sleep (7.4%).

For those children waiting for tooth extractions in hospital in the North of England, 67% of parents reported that their child had pain and 38% reported parental sleepless nights. 21 In a national health survey conducted in the USA, dental pain was reported in 32% (n = 7.5 million) of children whose parents stated that they had caries. 22 Around 50% of 12- and 15-year-olds reported toothache and 6% of 12-year-olds and 3% of 15-year-olds reported difficulty with schoolwork because of their teeth and mouth condition over the previous 3 months in the 2013 CDHS. 7

Economic impact of dental caries

Treatment of oral diseases is expensive, with NHS England spending £3.4 billion in 201423 and £3.6 billion in 2021 for adults and children in treatment costs. 24 Dental expenditure in the UK has been estimated to be around £196 per capita. 25 In 2017, hospital admissions (usually for general anaesthetic) in NHS England for tooth extractions due to dental caries, for children aged 0–19 years cost £33.0 million. 1 However, the economic costs when taking into consideration time off work and school are much greater. Worldwide, these indirect costs are estimated to be US$144 billion per year. 26

Aetiology and prevention of dental caries

Dental caries is a biofilm-mediated, diet-modulated, multifactorial, non-communicable, dynamic disease resulting in mineral loss from dental hard tissues. 27 It is determined by biological, behavioural, psychosocial and environmental factors. The main modifying factors in the development of caries are sugar consumption and the use of fluoride. 28 Therefore, prevention of dental caries can be achieved by optimising exposure to fluoride and reducing sugar consumption by improving diet. These changes can be encouraged at an individual level by professional intervention or through community- or population-based public health programmes. 29

Brushing with fluoride toothpaste is one of the most effective measures to prevent caries. 5 The Scottish multicomponent oral health programme targeted at young children has toothbrushing in schools as a major component. It was introduced as a pilot in 2006 and then delivered across all Health Boards in Scotland from 2011. Around 80% of 12- and 15-year-olds stated that they brushed their teeth twice per day in the 2013 CDHS, although this was 82% of those not eligible for FSM and 72% of those who were eligible for FSM. 30 The same survey found that only 25% of 12-year-olds and 32% of 15-year-olds were considered to have good periodontal health (plaque in no more than one sextant, no gingival inflammation, no calculus), which may demonstrate that there is less adherence to oral hygiene practices than reported. 31 This is in line with observational studies that have shown current levels of efficacy, frequency and duration of toothbrushing to be inadequate,32–34 thereby increasing the risk of caries. 35

School-based oral health promotion programmes

Community-based oral health interventions in the UK have been aimed mainly at younger children of pre-school age or in primary education. Few interventions are aimed at reducing dental caries in young people, despite adolescence being a critical transition stage where independence develops, diet begins to become self-managed and oral health behaviours change,36 with irregular toothbrushing associated with reduced fluoride exposure and resultant increased caries risk reported. 37 While national oral health promotion programmes such as Childsmile have been implemented in Scotland, and Designed to Smile has been developed in Wales, these programmes focus mainly on children under 12 years of age. Examples of current community-based interventions to improve the oral health of young people have been categorised into oral health education interventions and more complex interventions involving additional activities such as clinical prevention measures alongside the education component. 38 However, limitations of these existing programmes include the lack of use of behaviour change theory and that these interventions are not embedded as statutory content within the school curriculum, as recommended by the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Health Promoting Schools framework. 38–42

Behaviour change interventions

To reduce caries prevalence and its associated burden, young people need to adopt and/or maintain oral health behaviours, including regular toothbrushing with a fluoride toothpaste and sugar reduction. Successfully intervening to induce behaviour change, whether at an individual or community-based level, requires an understanding of these behaviours in the context of people’s lives and developing interventions to change behaviour. For example, an intervention to improve toothbrushing behaviour may be considered to require education (improving knowledge and understanding) plus persuasion (that the behaviour will produce a positive effect) and training in the necessary skills. The type of intervention required then influences the choice of the delivery method; both the setting where it is delivered, the vehicle(s) used and the timing and frequency. For example, digital interventions are recommended as appropriate vehicles for delivering behaviour change interventions directed at young people. 43

Use of mHealth for delivering health interventions

There has been increasing interest in the development and use of health interventions (including behaviour change interventions) through the vehicle of mobile phones and wearable technologies. 43,44 mHealth has been defined by the WHO45 as ‘a medical and public health practice supported by mobile devices such as mobile phones, patient monitoring devices, personal digital assistants and other devices’. mHealth is a particular category of a wider eHealth area,46 which provides innovative ways of improving the overall health. 47

Short messaging service (SMS), also known as ‘text messages’, are the most widely investigated mHealth interventions and have been used to deliver health education, promote treatment adherence in a range of conditions and in the prevention of communicable diseases. A systematic review of preventive health behaviour change text message interventions found a small but statistically significant positive effect for the impact of text messages both shortly after cessation of the intervention and also after a period of ‘no intervention’ to demonstrate whether the effects can be maintained longer term. 48 Potential moderators of effect size were considered including the duration, tailoring and targeting of the content and how text messages were used, along with other activities such as educational content. It appeared that interventions lasting 6–12 months were associated with greater effects than shorter interventions. The limitations of the component studies included insufficiently powered studies lacking the ability to detect change, short-term follow-up, failure to blind those assessing outcomes and lack of a theoretical framework to inform the behaviour change intervention. 48,49 It has been recommended that future studies ensure the intervention is developed rigorously, the text messages are appropriate for the target population in terms of their age and wording and the messages use the participant’s name.

Most studies in this field have involved adults, although more recently there have been studies involving young people. In the UK, in a 2022 Ofcom report on children’s media use, it was estimated that 9 in 10 children owned their own mobile phone by the time they reached the age of 11, and 97% of 12- to 15-year-olds used a smartphone for texting and making calls. 50 It is perhaps the ubiquity of mobile phones that explains why smartphone ownership among young people does not seem to vary by socioeconomic status,51 suggesting that mHealth interventions may suit this age group.

mHealth interventions to improve oral health

mHealth has gained popularity and has been investigated as a possible vehicle to deliver dental behaviour change interventions. Three recent systematic reviews have evaluated the effectiveness of mHealth. They cover all teledentistry (including mHealth) on oral health promotion and prevention compared with other strategies and in all ages;52 mobile applications and text messages compared with conventional oral hygiene instructions53 in adolescents, adults and mothers of young children; and text messages only in dental patients. 54 Many of the primary studies were included in more than one review.

In the review of all teledentistry, apps and text messages were found to be used most frequently. 52 This review included 18 studies, with 12 involving young people undergoing orthodontic treatment and 4 focusing on prevention. The nine studies that focused on text messaging reminders often had other parts to the intervention (education element before or during, phone calls, etc.). The meta-analysis was carried out on the basis of outcomes for those receiving all mHealth interventions. There was a demonstration of an overall reduction in plaque scores and improvement in gingival health. However, because of the combined delivery formats (apps, texts, etc.), multicomponent interventions and variable intervention delivery times as well as follow-ups, it was not clear what the exact contribution of each of the components, including text message reminders. The second53 included 15 studies with 12 involving text messaging, of which 11 studies included patients undergoing orthodontic treatment and one study of adult patients. Again, an improvement in plaque control and gingival health was found and an improvement in knowledge. This review assessed the interventions on the basis of behaviour change techniques, which were evaluated according to the Michie and colleagues’ taxonomy. 55 Most of the studies that used text messaging combined two behaviour change techniques, prompts and cues, and information about health consequences. Twelve studies involved text messages and were included in the meta-analysis, which showed improvements for the groups that received the mHealth intervention compared to the control groups. However, follow-up times were short, ranging from 4 weeks to 12 months, although the majority (13/15) were 6 months or less. The GRADE evaluation found the quality of evidence to be very low. The third review subgroup analyses again found consistently in favour of the text intervention improving oral hygiene clinical outcomes (plaque index and gingival index). The overall summary statistics were incorrectly calculated with double counting.

Although there are studies investigating text messages, the actual effect of these as individual components within multicomponent interventions is unclear. They are of variable duration and frequency, follow-up times to investigate effect have been short (usually weeks or months), none seem to have investigated dental caries as an outcome, with dental plaque levels and gingival bleeding most commonly used as indicators of behaviour change, and, less frequently, level of knowledge. In addition, few have been delivered as community-based interventions via settings such as schools when compared to interventions delivered in clinical settings to patients. All three systematic reviews found a high degree of heterogeneity, especially in plaque and gingival health outcome measures, as well as variable, short follow-up times and poor reporting quality. Recommendations were made that longer follow-up periods were needed with standardised methodologies and outcome measures.

Community-based behaviour change text message interventions

The first, and so far only, community-based text message intervention aimed at improving toothbrushing was conducted in New Zealand with unemployed people aged 18–24 years. This study investigated the Keep on Brushing (KOB) programme of weekly text messages and provision of free toothbrushes/toothpaste. 56 The intervention was underpinned by the Health Belief Model. 57 One hundred and seventy-one participants were recruited and completed a baseline survey. No important differences were noted between sex, ethnicity or age. Participants then received a series of motivational text messages over 10 weeks. To increase recruitment, participants were also given a pack containing toothpaste and a toothbrush. Self-reported toothbrushing of twice or more per day increased from 51% at baseline to 70% at week 3, 74% at week 6 and 73% at week 9; however, by week 9, only 26% of the original participants were still taking part. The authors concluded that motivational text messages improved the self-reported oral health of this hard-to-reach group and suggested that a randomised controlled trial (RCT) including a longer intervention with tailoring of the messages was needed.

Rationale

This intervention was developed based on the commissioning brief from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR, now known as the National Institute for Health and Care Research) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme (HTA no. 15/166 Interventions to improve oral health in deprived young people). Reducing childhood dental caries remains a public health priority; however, there are limited interventions aimed at preventing dental caries in adolescents. There is strong evidence for the effectiveness of toothbrushing with a fluoride toothpaste in preventing dental caries. The commissioning brief requested an evaluation of a digital behaviour change intervention to promote toothbrushing based on the pilot work of the KOB study. Behaviour change to reduce sugar intake, which is essential to the development of caries, was not included in this intervention. In terms of an appropriate setting for such an intervention, the use of the school setting with an mHealth component could potentially deliver the type of behaviour change needed. Existing interventions have predominantly involved oral health education only, without being underpinned by behaviour change theory or embedded within the school curriculum.

As with any public health investment, the value of the health benefits needs to be balanced against the cost of generating them using economic evaluation. Without convincing economic information, support for any health intervention from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and national public health bodies is unlikely. Consequently, any evaluation of an attempt to change toothbrushing behaviour in young people needs to be combined with a robust economic evaluation.

Aim and objectives

Aim

The aim of the Brushing RemInder 4 Good oral HealTh (BRIGHT) trial is to establish the clinical and cost effectiveness of an intervention for young people from deprived areas, delivered through a short classroom-based session (CBS) embedded in the curriculum and a series of text messages, compared to usual education and no text messages, on dental caries.

Trial objectives

Objectives of the BRIGHT trial:

-

conduct an internal pilot phase with feasibility components to:

-

tailor the intervention to young people

-

test trial processes in schools

-

assess the feasibility of within-school cluster randomisation (by year group)

-

-

investigate the effect of the intervention on caries prevalence

-

investigate the effect of the intervention on twice-daily toothbrushing, oral health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and oral health behaviours

-

investigate the cost effectiveness of the intervention

-

explore implementation, mechanisms of impact and context through a process evaluation

Chapter 2 Methods

The BRIGHT trial was designed (including target group, setting, intervention, comparator and outcomes) based on the details in the commissioning brief (HTA no. 15/166 Interventions to improve oral health in deprived young people).

Trial design

Brushing RemInder 4 Good oral HealTh is a multicentre, school-based, assessor-blinded, two-arm cluster RCT with an internal pilot phase, and embedded health economic and process evaluations. Schools with above the national average proportion of children receiving FSM were targeted to participate. Pupils in Years 7 and 8 (England and Wales) and S1 and S2 (Scotland) (i.e. age 11–12 years) in participating schools were recruited and, within each school, these year groups were randomly allocated using a 1 : 1 randomisation ratio to either the intervention or control group. The trial intervention consisted of a short CBS embedded within the school curriculum on dental health and looking after teeth, followed by twice-daily text messages to remind pupils to brush their teeth. The control arm of the trial was routine education and no text messages. The outcomes (caries prevalence, twice-daily toothbrushing, oral HRQoL and oral health behaviours) were assessed through clinical examination and questionnaires.

The trial protocol for BRIGHT has been published previously. 58,59 Figure 1 presents an overview of the trial design, including the planned follow-up time points (baseline, after the CBS, 12 weeks, 6 months, 1, 2 and 2.5 years following the lesson in the school). Final follow-up was originally planned for 3 years following CBS delivery but was amended to 2.5 years with the funder’s approval. This was to avoid the final clinical examinations coinciding with school exams during the spring/summer when school staff and space are at a premium. Two early follow-ups, at the time of the CBS and 12 weeks later, were only conducted in schools recruited during the internal pilot phase, as these data were to assess the appropriateness of the study design and inform progression to the main phase and were not required in schools that were part of the trial main phase. In addition, data collection at 2 years following CBS delivery was also only carried out in internal pilot schools. This follow-up was removed from the main phase, with the funder’s approval, when the final follow-up was amended to 2.5 years to reduce burden on schools and pupils.

FIGURE 1.

Trial design diagram. CARIES-QC, Caries Impacts and Experiences Questionnaire for Children.

Note, the descriptors of the time points for the assessments (e.g. 2.5 years) reflect the planned follow-up schedule and, in the interests of brevity and consistency, are used throughout the report when referring to the follow-ups. However, some of the actual average time intervals of follow-up varied from that planned (e.g. the actual average length of follow-up at the 2.5-year assessment was closer to 3 years, as this was unexpectedly delayed due to disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic). This is elaborated on in The impact of the COVID-19 on data collection and in Results.

Figure 1 also illustrates the point at which the internal pilot phase progression criteria were reviewed to determine continuation to the main phase of the trial.

The progression criteria that were used to determine trial continuation from the internal pilot phase are listed below. These were developed based on the commissioning brief and guidance from the NIHR HTA and were pre-specified within the protocol.

-

An indication of a positive effect of the intervention on self-reported frequency of toothbrushing at 12 weeks using an 80% one-sided confidence interval (CI) approach.

-

Engagement with 80% of the number of schools required for the main phase of the trial, including obtaining agreement to participate, in principle.

-

Recruited an average of 48 pupils per year group from the 10 schools included in the internal pilot (48 was 80% of our target average recruitment of pupils per year group).

-

Minimum 80% response to questionnaires, completed by pupils.

-

Confirmation of feasibility of embedding the education component within the curriculum through discussion with school head teachers.

-

Confirmation of the feasibility of the outcome data collection methods and time points within the school year.

-

Assessment of contamination in the control group and whether feasible to undertake randomisation within schools (by year group) or whether randomisation at the school level was required, and calculation therefore of the required school sample size.

The independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC), Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) and the funder reviewed the progress of the internal pilot phase against the progression criteria at the relevant time point and determined that the trial should continue without major amendment. 60

Regulatory approvals and research governance

The BRIGHT trial was granted ethical approval by the East of Scotland Research Ethics Service on 14 August 2017 [Research Ethics Committee (REC) reference number 17/ES/0096; the favourable opinion letter is provided on the NIHR BRIGHT project web page]. 59 Approval was also obtained from Research and Development offices at the participating NHS sites, NHS Tayside (on 23 August 2017) and Cardiff and Vale University Health Board (26 September 2017). A summary of amendments made to the protocol is provided in Appendix 1, and a more detailed discussion regarding the changes to the protocol can also be found in Changes to the protocol. All protocol deviations/breaches were reported as necessary and are explained in Appendix 2, Table 22.

The BRIGHT trial was conducted in accordance with the requirements of the HTA programme. A TSC and a DMEC were formed and both were independently chaired. Both the TSC and the DMEC met at least once a year during the trial period. The Trial Management Group (TMG), which consisted of the Chief Investigator, Co-Principal Investigator, Regional Clinical Leads and members of the local research teams (LRTs), as well as team members from York Trials Unit (YTU) (including the Methodological Expert, Health Economist, Statistician, Senior Statistician, Trial Manager, Trial Coordinators and Trial Support Officers) and other study co-investigators, was responsible for the management of the trial and met once a month from initiation until after final data collection. A smaller group from within the TMG met every 1–2 weeks to closely monitor milestones and delivery of the trial.

The study was cosponsored by the University of Dundee and NHS Tayside from the start of the trial until 31 July 2020. From 1 August 2020 until the trial end, the sponsor was Cardiff University as one of the Chief Investigators changed institutions.

The trial was registered with the ‘International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number’ (ISRCTN) Registry on 10 May 2017 (ISRCTN12139369).

School recruitment

Schools in Scotland, England (West Yorkshire and South Yorkshire) and Wales were recruited to take part in this trial. A number of schools were recruited to start the trial in the 2017–8 academic year (i.e. complete pupil recruitment and baseline data collection and commence the intervention) and these formed the population for the internal pilot phase. The remaining schools were recruited to start the trial during the 2018–9 academic year.

Schools were eligible for participation if they met all the following inclusion criteria:

-

located in Scotland, England (South Yorkshire and West Yorkshire) or Wales (Cardiff, Vale of Glamorgan, Rhondda Cynon Taf and Merthyr Tydfil local authority areas)

-

were state-funded

-

had pupils attending the school who were aged 11–16 years old

-

had at least 60 pupils per year group

-

had above the national average percentage (for each devolved nation) of pupils eligible for FSM. The cut-offs used to determine eligibility were 13.2% for schools in England, 14.2% for schools in Scotland and 15.6% for schools in Wales, which were the average percentages of children eligible for FSM in state-funded secondary schools in each devolved nation in 2016 (i.e. the most recent figures available at the start of school recruitment). 61–63

Schools were not eligible to take part in the trial if they were in ‘special measures’ [i.e. judged by the Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted) to be failing, or likely to fail, to provide an acceptable standard of education] or if the school was due to close.

Eligible schools were identified using the Department for Education’s register of educational establishments in England and using school data available from the Scottish and Welsh government websites. 64–66 School recruitment strategies were developed based on consultation with teachers and head teachers (particularly David Cooper from Batley Girls’ High School), researchers with experience of recruiting schools and local authorities. LRTs for each region approached schools using a variety of recruitment strategies, including: engaging with local or national organisations for schools (e.g. School Leaders Scotland and Learn Sheffield); use of professional and personal contacts of the LRT; approaching schools through contacts held by the recruiting universities and public health and education contacts at local councils; approaching academy trust chief executives; involving local school nursing teams; advertising through local authority networks; approaching eligible schools through letter, e-mail or phone call; and through head teachers recommending the trial to other schools.

Members of the LRTs met with interested schools and provided information describing what the school’s participation in the trial would involve, including the procedures for distributing participant information resources, gaining consent, delivering the CBS and collecting data at the baseline and follow-up time points. Interested schools were asked to sign an Agreement to Participate Form and a Data Sharing Agreement to confirm their involvement in the trial. At recruitment, schools were informed that they would receive £500 after baseline testing was completed and £500 after the final follow-up to cover any administrative costs associated with being involved in the trial.

Participant recruitment

Pupils

Pupils from Years 7 and 8 (England and Wales) and S1 and S2 (Scotland) were recruited from participating schools. These year groups were chosen purposefully to minimise disruption to English and Welsh General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) and Scottish Qualifications Authority National 5 exam years; and also to confine final follow-up to within the school setting to avoid the need to follow participants to further education settings.

The LRTs delivered information sessions, typically within assemblies, in each school to pupils in Years 7/S1 and 8/S2. BRIGHT trial information packs were then distributed to the parents/carers of all pupils in participating classes in these year groups (in most cases this was all classes in the year) via post, or by sending them home with pupils. Information packs contained a cover letter signed by the school head teacher, a parent/carer information sheet, parent/carer opt-out form and a copy of the pupil information sheet and consent form. Parents/carers could decline their child’s participation by completing and returning the opt-out form to their child’s school within a 2-week opt-out window. Schools were requested to record which pupils had been opted out on a spreadsheet. If parents/carers did not return an opt-out form within the 2-week window, it was assumed they were happy for their child to decide themselves if they would like to participate. Parents/carers could withdraw their child at any point over the trial.

Eligible pupils, whose parents/carers had not opted them out of the trial, were subsequently invited to consent to take part in the trial. These pupils were provided with a pupil information sheet and were asked to complete a consent form if they were happy to take part. Schools were requested to do this within class or form time in a dedicated consent session and LRTs offered to deliver or facilitate these sessions. As the information session would have taken place at least 2 weeks prior to the consent session (i.e. before the parent/carer opt-out window), pupils were able to consent to take part within the consent session. Schools were requested to make additional pupil information sheets and consent forms available for any pupils who were absent on the day of the consent session or who wanted more time to consider participation.

The school, supported by the LRT, collected and checked completed consent forms and updated their spreadsheet to record which pupils had consented to take part, ensuring that a parent/carer opt-out form had not been received for each consenting pupil. Completed consent forms for pupils whose parents/carers had not opted them out were collected via courier and returned to the YTU where the trial team checked whether all consent forms had been completed correctly.

Pupils were also asked to complete a contact form in order to provide their mobile telephone number and to indicate their text message preference times and preferred name to be used in the text messages should they be in the intervention group. If they did not own their own mobile telephone or could not provide their own mobile telephone number, they were considered ineligible for participation in the trial. For the internal pilot phase, we requested for the contact form to be completed at the consent session and returned with the consent forms; in the main phase of the trial, the contact form was completed at the time of baseline data collection to allow LRTs to provide greater assistance to pupils in the completion of these forms and reduce errors.

Parents/carers of participating pupils

All parents/carers of participating pupils were invited to complete resource use questionnaires59 to provide data for the health economic evaluation. These were either posted to parents’ home addresses or sent home with the pupils from school.

Retention

Schools

Each school was asked to nominate a lead contact and member of administrative staff with whom the LRTs liaised closely throughout the trial to try to pre-empt and troubleshoot any problems and maximise retention. In addition, newsletters were issued on a yearly basis over the trial period. Within the final newsletter, delivered prior to the 2.5-year follow-up, schools were reminded that they could claim £500 at the end of the data collection period to cover any administrative costs associated with being involved in the trial.

Participants

The BRIGHT Youth Forum, run by a charity called Children and Young People’s Empowerment Project (Chilypep) whose lead (Lesley Pollard) was one of the co-applicants for BRIGHT, proposed a variety of methods to optimise retention, response rates and completion rates. These included prize draws for shopping vouchers, trial-branded merchandise or ‘freebies’ (such as pens, stickers and pencils), thank you vouchers, using the school’s house-point system to encourage engagement and having more senior school pupils as Research Champions to provide peer support.

All pupils who completed the baseline questionnaire and dental assessment were given a £10 voucher as a thank you. All pupils who completed the final follow-up questionnaire and dental assessment were given a £5 voucher as a thank you. Pupils received trial-branded merchandise such as pens during data collection activities in the trial.

All parents/carers who completed and returned parent/carer questionnaires were entered into a prize draw with the chance of winning £300 in vouchers (with one annual prize draw each for the internal pilot phase and the main phase).

Withdrawal procedure

Pupils or their parents/carers were able to fully withdraw from the BRIGHT trial (i.e. no longer be involved in any further data collection or receive any further intervention delivery) at any point over the trial by letting a member of either the LRT or dental team know (e.g. when they visited the school), telling their school or via contacting the research team at YTU. For participants who fully withdrew or could no longer be followed up (e.g. due to leaving the school), data already collected were retained and used in the analysis (based on current Health Research Authority guidance in relation to the General Data Protection Regulation).

At each data collection point, if pupils did not want to take part in the dental assessment or complete pupil questionnaires, they did not have to. However, such pupils were only fully withdrawn from BRIGHT if they explicitly stated that they did not want to take part in the trial anymore, otherwise they were approached again at the next data collection time point.

Sample size

Internal pilot phase

For the internal pilot, the sample size was calculated in order to address the following progression criterion:

-

an indication of a positive effect of the intervention on self-reported frequency of toothbrushing at 12 weeks using an 80% one-sided CI approach.

As randomisation for this trial occurred within schools at the year-group level, year groups within schools acted as the ‘clusters’. At least four clusters per arm are recommended for cluster pilot RCTs. 67 It was determined that 1200 pupils from 10 schools [equivalent to approximately 284 young people in an individually randomised trial, assuming 60 recruited pupils per year group, 20% attrition at follow-up and an intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.02 (see justification in next section)] would be sufficient to produce an 80% one-sided CI that excluded a 5% difference in the event of a zero or negative effect of the BRIGHT intervention on self-reported toothbrushing at the 12-week follow-up, assuming 66% reported brushing twice daily in each of the two groups. 68,69 A trial of this size would also allow a participation rate of 50% and a completion rate of 80% to be estimated within a 95% CI of ± 6% and ± 5%, respectively. 70 We therefore aimed to recruit 1200 pupils across 10 schools, an average of 60 pupils per year group (Year 7/S1 and Year 8/S2) per school, into the internal pilot.

Full trial (internal pilot and main phase)

In 2013, the estimated proportion of UK 12-year-olds with caries was 34%. 7 The definition of caries here is described as ‘obvious decay experience’, which incorporates untreated decay into dentine and decay that has previously been subject to restorative treatment (fillings) or tooth extraction. Based on a systematic review of interventions to increase the frequency of toothbrushing for caries prevention, a reduction of caries prevalence of 8% might be expected. 71 An individually randomised trial powered at 90% (5% two-sided α) to detect an 8% absolute reduction, from 34% to 26%, in caries would require 1376 pupils. Few estimates of school-level ICC are available for dental data. In a previous study evaluating a behaviour change programme for preventing dental caries in primary schools, an ICC of 0.01 was used, which was estimated using their own unpublished data. 72 It was agreed that the present trial would use a more conservative ICC of 0.02.

Assuming partial contamination effects (i.e. those contaminated gain half the treatment benefits) for 27% of the control group (based on findings from the internal pilot), this trial required 42 schools in total across the internal pilot and main phase of the trial, assuming within-school (year-group level) randomisation, an average of 60 pupils per year group per school, an ICC of 0.02 and 20% attrition at follow-up. This would give 90% power (5% two-sided α) to detect an 8% absolute difference, from 34% to 26%, in the proportion of pupils with ‘obvious decay experience’. Therefore, this trial aimed to recruit a total of 42 schools and 5040 pupils across the internal pilot and main phase of the trial.

Randomisation

Allocation took place within schools by randomising schools 1 : 1 to one of two regimes: (1) pupils aged 11–12 years (Year 7 in England and Wales/S1 in Scotland) to receive the intervention and pupils aged 12–13 years (Year 8 in England and Wales/S2 in Scotland) to act as the control group; or (2) pupils aged 12–13 years (Year 8 in England and Wales/S2 in Scotland) to receive the intervention and pupils aged 11–12 years (Year 7 in England and Wales/S2 in Scotland) to act as the control group.

An allocation sequence, stratified by school using blocks of size two, was generated by an independent YTU statistician. Once all baseline assessments were complete for a school and the assessment paperwork had been received by YTU, the year groups in that school were randomised by allocating them to the next available block in the sequence in the order Year 7/S1 then Year 8/S2. The statistician then informed the relevant members of the research team of the school’s year group allocation and they disseminated this to the school.

Blinding

Given the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind schools or pupils to their group allocation; however, clinical examinations for the outcome assessments were performed by a trained and calibrated dentist/dental therapist who was blind to the allocation of the pupils, as far as possible. We aimed to minimise the risk of the dental assessors becoming unblinded by asking pupils not to discuss the intervention they received with the assessors. Dental staff were asked to record whether or not they were unblinded to each pupil’s randomisation group during the assessment. Researchers and trial team members, including the trial statistician and health economist, were not blinded to group allocation.

Intervention

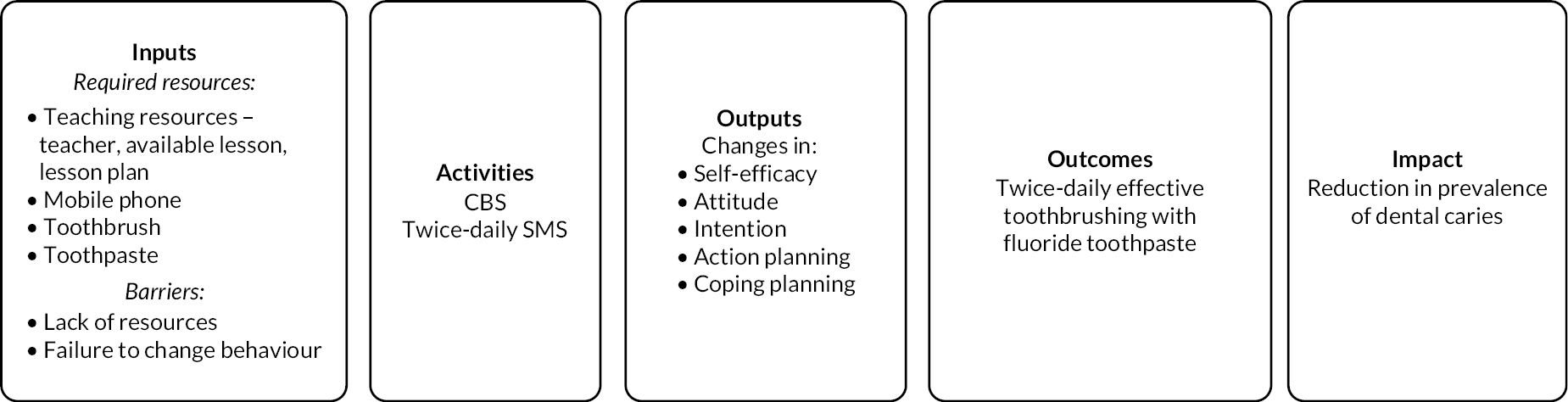

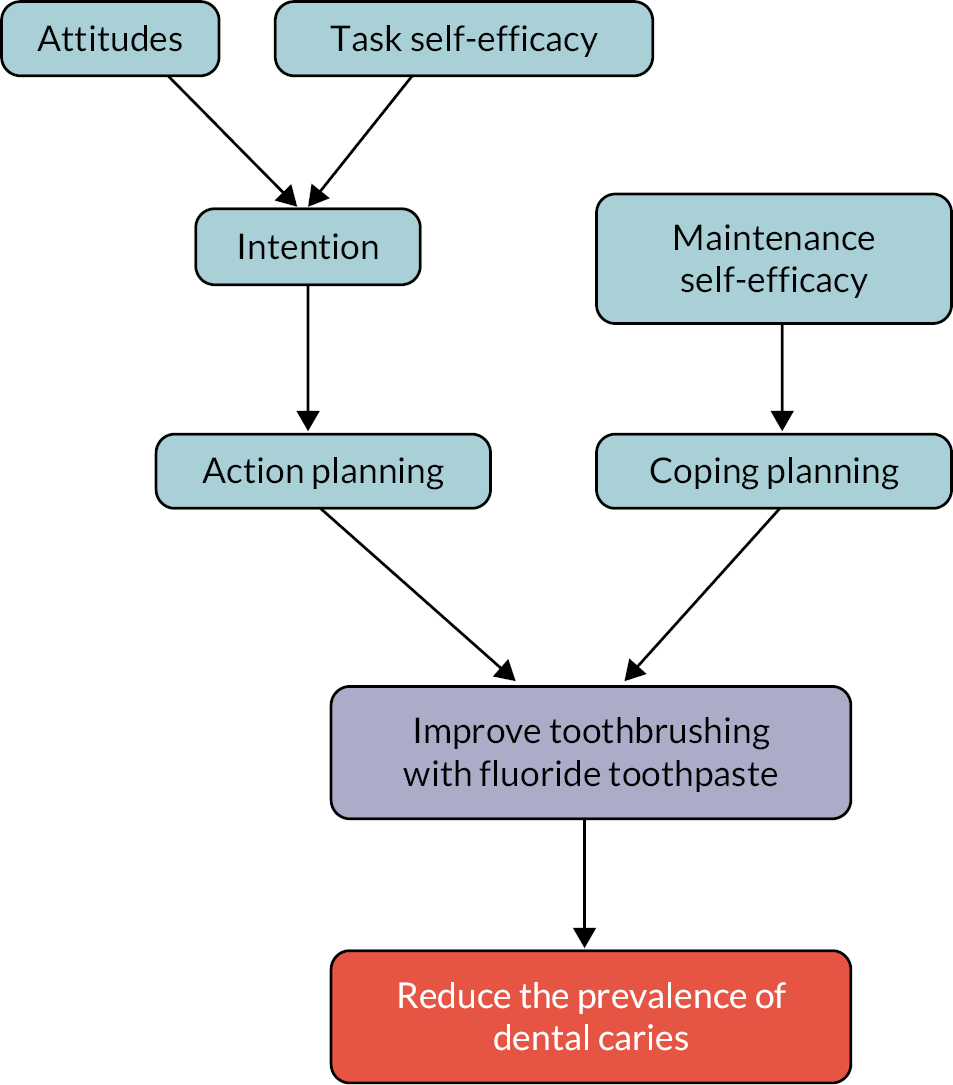

The commissioning brief required a ‘digital behaviour change programme’ and specified a programme which ‘initiates good oral health practice followed by a series of text or other media messages to change behaviour and promote tooth brushing’. The intervention evaluated was developed according to this brief and based on the KOB study described in Chapter 1, which was referenced in the brief. 56 The KOB intervention was refined to strengthen the behaviour change techniques employed and through input from school staff and young people tailored to be appropriate for pupils aged 11–14 years in secondary schools in the UK. The intervention development drew on the Health Action Process Approach and was informed by the Behaviour Change Wheel. 73,74 The intervention consisted of two components: (1) a CBS delivered by teachers and embedded in the school’s curriculum followed by (2) a series of text messages to pupil’s mobile phones. 75 The logic and causal models for the intervention are included in Appendix 3. Further details of the refinement of the intervention are reported elsewhere. 75

Schools were requested to deliver the CBS to all classes in the year group allocated to the intervention arm, regardless of whether the pupils had completed a BRIGHT consent form. Text messages were only sent to pupils in the intervention year group who completed a BRIGHT consent form and were considered as part of the randomised sample. Year groups allocated to the control arm received routine education but neither the CBS nor the text messages.

Classroom-based session

The CBS was developed by the School of Education and Social Work at the University of Dundee and the research team to be appropriate for the curricula as part of personal, social health, and economic education (PSHE) (England) and personal and social education (Scotland and Wales). The lesson plan was developed using the curriculum guidelines for: Science Key Stage 3 (a) and 4 (b);76,77 PSHE study Key Stage 3,78 the Scottish Curriculum for excellence experiences and outcomes for both health and well-being (a) and science (b)79,80 and the Welsh Personal and Social Education framework. 81

Teachers delivered the 50-minute CBS in the school environment. The schools received a lesson plan (which outlined the learning intentions and success criteria for the lesson – see Report Supplementary Material 1) and pupil-facing materials in advance of teaching the lesson. The pupil-facing materials included a young person booklet, an effective toothbrushing video, photographs on PowerPoint slides, post-it notes (not provided by the trial team) and a young person toothbrushing factsheet (see Report Supplementary Materials 2–4). All CBS materials and resources were provided to schools as digital copies only.

The CBS contained the following elements:

-

Helping pupils establish the motivation to brush twice daily for:

-

social reasons – interpersonal considerations of having a ‘fresh and clean feeling’ when interacting with others

-

health reasons – toothbrushing prevents tooth decay and gum disease

-

appearance reasons – to stop teeth looking discoloured.

-

The literature and Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement (PPIE) activities suggested these were key motivating reasons for young people to brush their teeth.

-

Encouraging pupils to ‘own the goal’ of twice-daily toothbrushing so they want to brush twice daily for themselves, not just when parents/carers remind them.

-

Developing pupil’s toothbrushing skills and the intention to brush effectively twice daily with a fluoride toothpaste.

-

Discussing the ‘when’ and ‘where’ of toothbrushing and ways to overcome barriers to toothbrushing.

Text messages

The content of the intervention text messages used young people’s own words developed through the workshops and BRIGHT Youth Forum to remind and reinforce the messages from the CBS. The text messages were delivered to mobile phones via TextApp, a software tool developed by the Health Informatics Centre (HIC), University of Dundee. TextApp has been successfully adopted in a number of behaviour change interventions which targeted alcohol and obesity. 82,83

The message schedule (see Report Supplementary Materials 5 and 6) and any personalisation were programmed into the TextApp delivery system, which also handled replies and delivery monitoring. The minimum data set required was stored, that is, phone number, the preferred name specified by the pupil for text messages to be addressed to, each pupil’s preferred timings for the twice-daily text messages (weekdays: 7 a.m. or 7.30 a.m., and 9 p.m. or 9.30 p.m.; weekends: 8.30 a.m. or 9 a.m., and 9.30 p.m. or 10 p.m.) and any responses a pupil sent to the BRIGHT text messaging intervention number.

Text messages were triggered by YTU using TextApp for participating pupils in the intervention year group in each school shortly after the school had provided confirmation that they had delivered the CBS. When mobile phones first became widely used, people tended to change their number whenever they changed, lost or damaged their phones or switched supplier. However, it is now possible and relatively easy to keep the same number in all these cases and it is much more common for people to have the same number for many years. We therefore anticipated the loss of participants due to changes in mobile phone number being lower than in previous studies. However, to help mitigate this, participants were reminded to inform the research team of any changes to their mobile phone number by texting the dedicated BRIGHT text messaging intervention number. Reminders were also issued through the school at the time of engagement in any trial-related activity such as questionnaires and clinical examinations.

Replies received were monitored by the research team and any updates were managed through the TextApp monitoring website. When pupils wanted to stop receiving text messages, they could text STOP for free at any time. Messages were stopped as soon as reasonably possible. Messages sent to the BRIGHT text messaging intervention number were monitored for safeguarding purposes and messages could be restarted if a participant indicated that this was their wish. For participants who requested text messages to be stopped, we assumed continued participation in the trial (based on original consent and current Health Research Authority guidance in relation to the General Data Protection Regulation); therefore, we retained and used data already collected and continued to collect follow-up data.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

Caries prevalence for obvious decay experience (D4–6MFT) at 2.5 years

Caries assessments were completed using the International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS). 84 The ICDAS was used to evaluate each surface (n = 5; mesial, occlusal, distal, buccal, lingual) of a tooth [up to n = 32, though this includes four third molars (i.e. wisdom teeth) that were unlikely to have erupted in pupils of this age] via a two-digit coding system: a measure of the restorative status of each surface of the tooth (assigned one of nine numbers, 0–8, where 0 indicates a surface that has not been restored or sealed); and a measure of the extent of any carious lesion(s) present on the surface (assigned one of seven numbers, 0–6,84 where 0 indicates no carious activity). There were also four codes that could be assigned for all tooth states: 96, 97, 98 and 99. A full breakdown of the ICDAS scoring codes is provided as an appendix to the trial protocol. 59 The ICDAS scoring system also allows the components of ICDAS to be collapsed to give a DMFT equivalent (ICDAS caries codes 4–6 indicate caries into dentine) score and therefore can be compared with studies using traditional caries indices, which record decay at the level of dentine.

If both primary and permanent teeth were visible at a single site, the assessor was asked to only score the permanent tooth. The primary outcome was the presence of at least one treated or untreated carious lesion in any permanent tooth, measured at the pupil level during the 2.5-year clinical assessment using DICDAS4–6MFT where:

-

Decay was measured as carious lesions extending into dentine – ICDAS levels 4–6,84 that is, on any surface, the caries code was 4, 5 or 6, regardless of the associated restoration code. The surface and/or tooth was counted as decayed if the restoration code was 8 regardless of the caries code.

-

Missing included any tooth extracted due to caries.

-

Filled included any restoration but not an obvious pit or fissure sealant, that is, the restoration code was between 3 and 7 and the caries code was 0, 1, 2 or 3.

This was also considered as a secondary outcome at the 2-year time point for schools that were recruited during the pilot phase only (this assessment could not be conducted for schools recruited in the subsequent academic year as clinical examinations were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic).

Secondary outcomes

Caries prevalence for all carious lesions (DICDAS1–6MFT)

The presence of at least one treated or untreated carious lesion in any permanent tooth, measured using DICDAS1–6MFT where:

-

Decay was measured as any enamel or dentinal caries – ICDAS levels 1−6,4 that is, on any surface, the caries code was 1–6, regardless of the associated restoration code. The surface tooth was also counted as decayed if the restoration code was 8 regardless of the caries code.

-

Missing included any tooth extracted due to caries.

-

Filled included any restoration but not an obvious pit or fissure sealant, that is, the restoration code was between 3 and 7 and the caries code was 0 (only).

This was measured at baseline, 2 years (internal pilot only) and 2.5 years.

Number of carious teeth

The number of permanent DICDAS4–6MFT and DICDAS1–6MFT at 2 years (pilot schools only) and 2.5 years.

Frequency of toothbrushing

Pupils were asked the question ‘How often do you usually brush your teeth?’ on questionnaires at baseline, at the time of the CBS (internal pilot only) and at 12 weeks post CBS (internal pilot only), 6 months, 1 year, 2 years (internal pilot only) and 2.5 years. This is a validated question from the national CDHS 2013. 7 Self-reported toothbrushing is considered to be a reliable measure of toothbrushing behaviour85 in epidemiological studies and was the primary outcome of the KOB study mentioned in the NIHR HTA commissioning brief. 56 Response options were: ‘Never’, ‘Less than once a day’, ‘Once a day’, ‘Twice a day’, ‘Three times a day’ and ‘More than three times a day’. The categories ‘Never’ to ‘Once a day’ were combined, as were the categories ‘Twice a day’ to ‘More than three times a day’, to consider the proportion of pupils who reported brushing their teeth at least twice a day. This categorisation is based on national guidance. 86

In addition to questions on the frequency of toothbrushing, questions were included to examine the determinants of toothbrushing behaviour, specifically the motivational and volitional factors from the causal model, including self-efficacy, attitude (social norms, outcome expectancy and risk perception), intention, coping planning and action planning. Questions were adapted from those used previously in the literature and asked at baseline, 1 year, 2 years (pilot phase only) and 2.5 years. 87,88

Dental plaque and bleeding gingivae

Clinical measurement of levels of dental plaque on teeth and gingivitis followed national protocols established for dental epidemiology. 86 Plaque levels were assessed using the Turesky Modification of the Quigley Hein Plaque Index. 89,90 Plaque scores were given for all buccal (n = 14) and palatal (n = 14) surfaces of the upper arch, and buccal (n = 14) and lingual (n = 14) surfaces of the lower arch. A plaque score for the entire mouth was determined by summing the surface codes (0 = no plaque to 5 = plaque covering two-thirds or more of the crown of the tooth) and dividing this total score by the number of surfaces (a maximum of 4 × 14 = 56 surfaces) examined.

The degree of gingival inflammation was assessed using a modification of the Gingival Index of Löe91 and mean number of bleeding gingival sites per child. The gingival index was recorded using an approach that has been validated in young people as a replacement for full mouth recordings. 92 These clinical measures were carried out at baseline, 2 years (internal pilot only) and 2.5 years.

A gingival bleeding score was recorded using a periodontal probe on the buccal and lingual/palatal sites of each of the eight index teeth (16, 26, 36, 46, 12, 11, 32, 31; maxillary right and mandibular left first molars, maxillary left and mandibular right first premolars and maxillary left and mandibular right central incisors). Each index tooth scored 1 if gingival bleeding was present, 0 if not and X if the index tooth was missing.

A total bleeding score was obtained by adding the individual bleeding scores and dividing by the number of scorable sites (maximum 16, excluding missing teeth). The sum of the number of teeth associated with bleeding gingivae (i.e. bleeding present at one or both sites of the tooth) was also calculated.

These measures of plaque and gingivitis were used as surrogate outcomes to assess the impact of toothbrushing.

Health-related quality of life

Health-related quality of life was pupil reported using the Child Health Utility 9D (CHU9D),93,94 which consists of nine dimensions (worried, sad, pain, tired, annoyed, schoolwork/homework, sleep, daily routine and activities), each represented by a single question with five response options. Each response is associated with its own weighting, with participant responses to all questions combined to produce an overall HRQoL score on a scale anchored on 0 and 1 (which represent ‘death’ and ‘full health’, respectively). 94 The recall period was today/last night. This was measured at baseline, and at 1 year, 2 years (internal pilot only) and 2.5 years.

Oral health-related quality of life

Child oral HRQoL was assessed using the Caries Impacts and Experiences Questionnaire for Children (CARIES-QC),95 a measure of the impact of caries validated in children and young people aged 5–16 years, at baseline, and at years 1, 2 (internal pilot only) and 2.5. CARIES-QC contains 12 items and one global question. The items are scored on a 3-point Likert scale from 0 to 2, with a higher score indicating increased impact (possible total score range, 0–24). As CARIES-QC focuses on attributes which are not directly measurable, the raw score is only indicative of a rank along the scale. In order to use the raw score to accurately measure change, conversion to an interval level scale is required. This can be achieved by transforming the ordinal score to a logit score. 18 Both raw and interval scores were summarised at each time point to allow comparison with other studies; however, only raw scores were used in the hypothesis testing to compare the intervention and control groups at the different time points.

The global item is not included in the calculation of the total score and was summarised separately. A preference-based measure was constructed using five items from the CARIES-QC. The preference weights generated from adolescents were used to calculate quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) anchored on a 0 to 1 scale for the cost-effectiveness analysis. 96

School attendance

Impact on school attendance was measured by asking schools to provide the past and current year’s attendance record for each participating pupil at baseline, 1, 2 (internal pilot only) and 2.5 years post CBS. However, this proved difficult for schools and was only provided by a small number of them; therefore, the decision was made instead to request average school attendance at an aggregate level, by year group, for each academic year that the school had been involved in the trial as this was easier to obtain.

Other data collected

Oral health behaviours

Self-reported oral health behaviours were assessed at baseline within the pupil questionnaire using questions from the national CDHS7,86 on diet, use of dental services and other forms of fluoride use which allowed assessment of confounding.

Participants were asked at baseline to report the frequency they consumed cariogenic foods/drinks [cakes or biscuits, sweets or chocolate, cola or squash (not diet or non-sugar), fruit juices and smoothies and energy (sport) drinks (e.g. Powerade, Lucozade)]. These were scored 0 = ‘Never’ to 5 = ‘Four or more times a day’. A summary cariogenic score was calculated by summing these, dividing by the total possible score N, where N = 5 * the number of completed items, and multiplying by 100.

Availability of toothbrushes and toothpaste

Questions on toothbrush and toothpaste availability were included on pupil questionnaires at baseline and 6 months as part of the pilot phase as these resources were necessary for the implementation of the intervention.

Determinants of toothbrushing behaviours

As per the intervention’s causal model, questions on motivational and volitional factors influencing toothbrushing (self-efficacy, attitude, intention and coping and action planning) were included at all time points. Self-efficacy was assessed by the item ‘I know how to brush my teeth properly’, coping planning by ‘I have a plan of how I will make myself brush when I find myself not brushing properly’ and intention by ‘How often do you want to brush your teeth?’ A scale for attitude was generated by taking the mean of responses to the following six items: ‘If I brush my teeth twice every day, then my teeth will look clean when talking to friends’, ‘If I brush my teeth twice every day, then my teeth will be healthy’, ‘If I brush my teeth twice every day, then my teeth will feel good’, ‘If I don’t brush my teeth twice every day, I risk getting tooth decay’, ‘If I don’t brush my teeth twice every day, I risk my teeth looking dirty’ and ‘If I don’t brush my teeth twice every day, I might have bad breath’. A scale for action planning was generated by taking the mean of the items ‘I know where and when I will brush my teeth in the morning’ and ‘I know where and when I will brush my teeth in the evening’. All items had responses 1 = Not true at all, 2 = Not true, 3 = True and 4 = Definitely true, except for the intention item, which had six responses ranging from ‘Never’ to ‘More than three times a day’.

Contamination

A question, adapted from the national CDHS, was used in the trial to estimate contamination in the control group and was collected from all pupils at 12 weeks and 6 months, during the pilot phase of the trial only. Pupils were asked ‘Have you received helpful information about how to keep your teeth and mouth healthy from any of these places?’ with 10 possible sources listed, including ‘a lesson in school’, ‘friends in another year group’ and ‘text messages’. Data from this question were used to investigate the likely impact of contamination of the intervention in the control group to help determine the feasibility and efficiency of continuing with within-school randomisation for the rest of the trial, rather than switching to randomisation at the level of the school. This was considered as part of the review of progression criteria following completion of the internal pilot (see Appendix 6 for further details).

Orthodontic appliances

As part of the 2.5-year dental assessment, dental teams recorded whether the pupil was wearing a fixed or removable orthodontic appliance. This allowed identification of instances where a fixed orthodontic appliance was worn during the assessment, which may affect the ability to record the ICDAS codes, and confirmed that pupils wearing removable orthodontic appliances were asked to take them out during the examination.

Data collection

Data were collected via dental assessments, pupil-completed questionnaires and parent/carer-completed questionnaires. 59 In addition, schools provided sociodemographic and school attendance data electronically, and information about participating schools was collected from publicly available sources. Procedures for data collection are outlined below. Data collection time points are outlined in the trial design diagram in Figure 1 and in Table 1.

| Baseline | CBS (internal pilot only)a | Between CBS and 12 weeks (internal pilot only)a | 6 months | 1 year | 2 years (internal pilot only) | 2.5 years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dental assessment | |||||||

| Caries (ICDAS) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Dental plaque score | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Gingival bleeding score | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Pupil questionnaire measures | |||||||

| Self-reported toothbrushing frequency and factors influencing toothbrushing behaviour 13 questions |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Oral HRQoL (CARIES-QC) 13 questions |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| HRQoL (CHU9D) 9 questions |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Toothbrush/paste availability 2 questions |

✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Oral health behaviours 5 questions |

✓ | ||||||

| Contamination 1 question |

✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Parent/carer questionnaires | |||||||

| NHS resource use | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Pupil demographics | |||||||

| FSM eligibility | ✓ | ||||||

| Sex | ✓ | ||||||

| School attendance | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Deprivation | ✓ | ||||||

Dental assessments

Dental assessments were carried out in participating schools, under standard dental epidemiological data collection conditions, at baseline, 2 (internal pilot only) and 2.5 years following CBS delivery. LRTs each put together dental teams, consisting of at least a dentist/dental therapist and dental nurse, for each dental assessment time point. Each child’s dental assessment consisted of a caries assessment, taking around 10 minutes, and a plaque and gingivitis assessment, taking around 5 minutes. All dental assessment data were recorded on paper case report forms. 59

Training and calibration

Prior to the start of baseline data collection for the internal pilot, a hands-on training and calibration event was run in a school with an experienced dental epidemiologist for all dental team members. Prior to baseline data collection for the main phase, another training and calibration event was held for new dental team members and update training/recalibration was provided for those who attended the initial training and calibration event. Update training/recalibration was also provided for all dental team members prior to the 2-year follow-up (for the internal pilot) and prior to the 2.5-year follow-up. Details of the training and calibration can be found as an appendix to the trial protocol, and in Appendix 4. 59

Reproducibility

At each dental assessment time point, where time constraints allowed, dental teams completed a second ICDAS assessment for 5% of participating pupils at each school to assess intra- and interexaminer reproducibility. For plaque and gingivitis assessments, the initial examination disturbs plaque and probing and can increase susceptibility to gingival bleeding so, as is standard practice, there was no reproducibility measured for these outcomes.

Pupil questionnaires

The time points for pupil questionnaire completion are given in Table 1. At dental assessment time points [baseline, 2 years (internal pilot only) and 2.5 years post CBS delivery], LRTs requested pupils to complete the pupil questionnaire either before or just after completing their dental assessment and were on hand to encourage questionnaire completion and answer any queries. At other follow-up time points, pupil questionnaires were distributed and collected by school staff or LRTs, and schools were requested to allow pupils approximately 10 minutes of class time for questionnaires to be completed. School staff and LRT members recorded reasons for non-completion of questionnaires. All pupil questionnaires were completed on paper case report forms59 and were returned to YTU via courier.

The measures included within the pupil questionnaire at each time point are summarised in Table 1. More details about the measures are provided in the Outcomes section and copies of each questionnaire can be found on the NIHR project web page. 59

Parent/carer questionnaires

For the health economic evaluation, parents/carers of participating pupils were asked to complete a resource use questionnaire at baseline, 1, 2 (internal pilot only) and 2.5 years post CBS delivery. Parent/carer questionnaires59 were handed to pupils at the time they completed their pupil questionnaire (apart from the baseline time point for the internal pilot) and they were asked to take these home to their parents/carers to complete. The questionnaire was enclosed in an envelope along with a cover letter and a freepost envelope, which parents/carers were requested to use to return the completed questionnaire via post to YTU. Approximately 2 weeks after parent/carer questionnaires were distributed (excluding the baseline time point for the internal pilot), schools were provided with a second copy of the questionnaire to distribute in order to try to maximise response rates. For the internal pilot, baseline parent/carer questionnaires,59 along with a cover letter and freepost envelope, were posted to parents/carers who had returned a consent form and shared their name and address so questionnaires could be posted directly to them.

Sociodemographic characteristics and school attendance data of participants

At baseline, schools were also asked to complete and return an encrypted spreadsheet to YTU, via the University of York DropOff secure data transfer service, in order to provide the following for each consenting pupil: sex, year group, form group, current eligibility for FSM, past and current year’s school attendance, and home postcode [to facilitate data linkage for the economic evaluation and for calculation of Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) scores]. Participating schools were also asked to provide the past or current year’s attendance record for each participating pupil at 1, 2 (internal pilot only) and 2.5 years post CBS. Average year group attendance rates were also requested after final data collection for all previous academic years within which the BRIGHT trial had been active.

School-level data were also captured at recruitment, from publicly available sources, on the proportion of children eligible for FSM. 64,97–99 Publicly available school inspection ratings (i.e. Ofsted for schools in England, Estyn for schools in Wales and Education Scotland for schools in Scotland) were also obtained. 64,100,101

Adverse events, suspected pathology and child safeguarding

Due to the nature of participant involvement, no serious adverse events or adverse events were anticipated that would be unexpected and related to being in the trial. However, a procedure was described in the protocol58 to capture and report any complications associated with the trial raised by participants, parents/carers or dental assessors. Any suspected serious pathologies were also recorded and a procedure put in place to enable a referral to a relevant dental service. A procedure was also established to deal with child safeguarding issues to ensure the young person’s school and parent/carer could be informed and any further action taken.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted in STATA v17 (StataCorp, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, TX). Outcomes were analysed collectively after follow-up had been completed in all schools. Data from pupils recruited during the internal pilot and the main trial phase were combined for analysis. Analyses followed the principles of available case intention to treat (ITT) with participant’s outcomes analysed according to their original, randomised group, where data were available, irrespective of deviations based on non-compliance. Statistical tests were two-sided at the 5% significance level and 95% CIs were used.

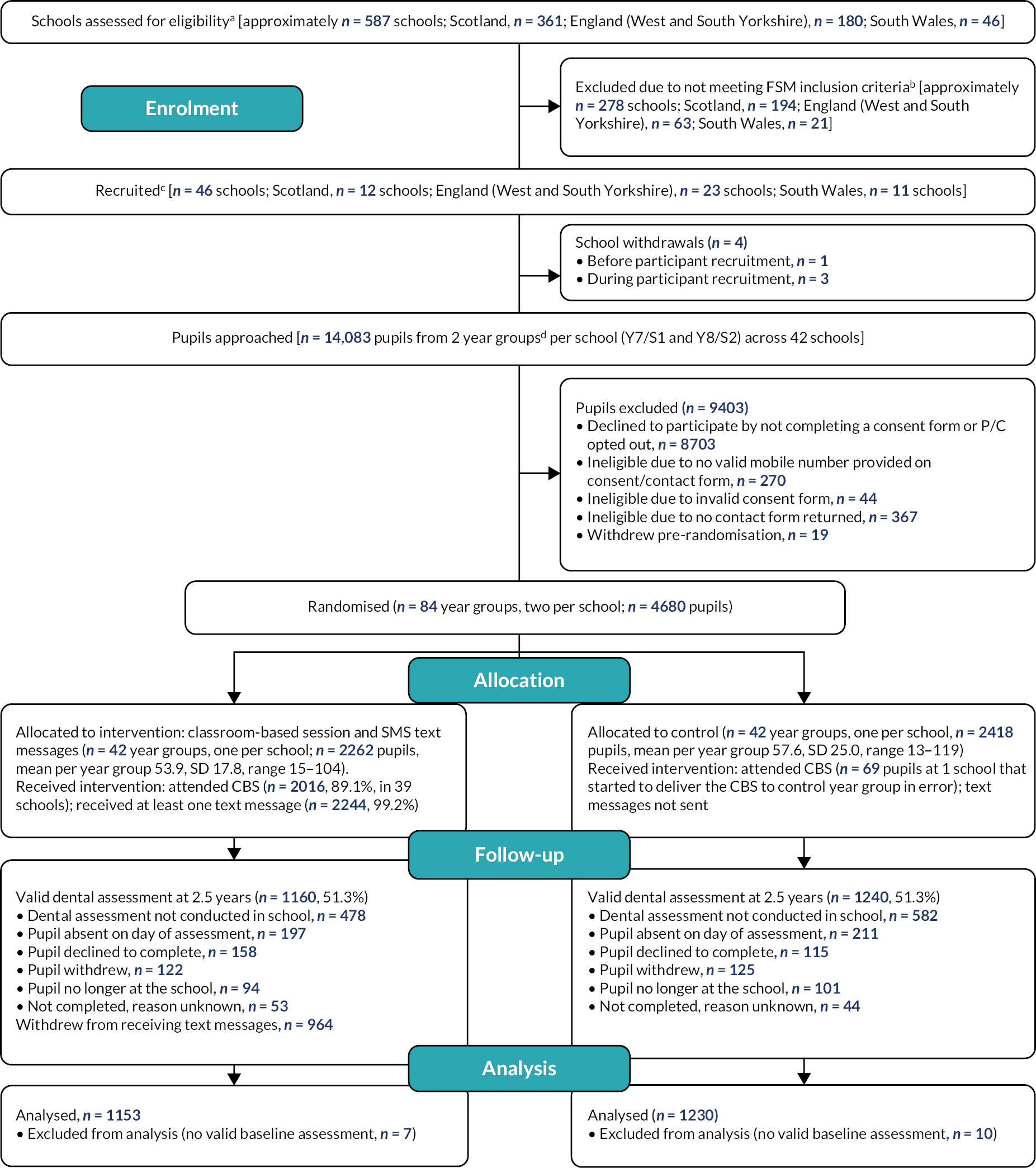

A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram depicts the flow of schools and pupils through the trial. The number of schools and pupils approached, eligible and randomised are presented, with reasons for non-participation at each stage provided where known.

Characteristics of the participating schools are presented to provide the context to the intervention delivery. All participant baseline data are summarised descriptively by randomised group both as randomised and as analysed in the primary analysis (the available case population). No formal statistical comparisons were undertaken on baseline data. Continuous measures are reported as means and standard deviations (SDs) and categorical data as counts and percentages.

Participants were free to withdraw from the intervention (intervention group only) and/or from data collection at any point. For participants in the intervention group, they could request at any time that their text messages cease by replying ‘STOP’. Pupil withdrawals are summarised by type and randomised group.

Intervention implementation is summarised, including whether, when and to whom the schools delivered the CBS and number of text messages sent and delivered. Time to final text message delivered is presented on a Kaplan–Meier curve.

The number and percentage of completed follow-ups are presented by randomised group and according to the time point for each type of follow-up. Reasons for missing follow-up are provided, where known (e.g. absent from school on day of assessment, no longer at the school, declined). The time of the completion of follow-up from the time of the CBS at the school is summarised.

Data summaries

All data collected at follow-up (both dental and from the pupil questionnaires) are summarised by randomised group and overall. This includes the primary and secondary outcomes that were formally analysed, and also data not included in hypothesis tests such as toothbrush/paste availability, influences on toothbrushing and contamination. The following pupil-level dental outcomes are summarised descriptively for each time point:

-

presence of obvious decay experience in at least one permanent tooth as measured by DICDAS4–6MFT

-

total number of permanent teeth assessed

-

total number of DICDAS4–6MFT

-

number of teeth extracted due to caries

-

number of decayed permanent teeth based on ICDAS 4–6 definition, that is, number of teeth whose highest surface caries severity code is 4–6 or restoration code is 8

-

number of filled permanent teeth based on ICDAS 4–6 definition, that is, number of teeth whose lowest surface caries severity code is 0–3 and the restoration code is 3–7

-

presence of decay experience in at least one permanent tooth as measured by DICDAS1–6MFT

-

total number of DICDAS1–6MFT

-

number of decayed permanent teeth based on ICDAS 1–6 definition, that is, number of teeth whose highest surface caries severity code is 1–6 or restoration code is 8

-

number of filled permanent teeth based on ICDAS 1–6 definition, that is, number of teeth whose lowest surface caries severity code is 0 and the restoration code is 3–7

-

dental plaque score

-

gingival bleeding score

-

number of teeth where there were sites with gingival bleeding

-

presence of an orthodontic appliance, by type, and for pupils with a removable orthodontic appliance, whether this was removed during the assessment

-

whether blinding of the dental assessor to the child’s group allocation was maintained.

We also summarise the following, based on comparing baseline and 2.5-year dental assessments:

-

the number (%) of pupils who moved from ‘caries negative’ at baseline to ‘caries positive’ at 2.5 years (for both DICDAS1–6MFT and DICDAS4–6MFT definitions)

-

the number (%) of pupils who developed new carious lesions over this time, defined by an increase in total number of DICDAS1–6MFT/DICDAS4–6MFT

-

mean caries increment using the individual surface scores to do the calculations (dmft_surface_1@2.5 years – dmft_surface_1@baseline), where the individual surface scores are 1 (positive for caries, based on DICDAS1–6MFT/DICDAS4–6MFT definitions) or 0 otherwise. Therefore, increments for each surface can take values of −1, 0 and 1, where −1 indicates reversal from carious to sound, 0 no change in surface status and 1 change from sound to carious surface. A maximum of 120 surfaces were assessed per pupil. The total caries increment was calculated as the sum of these individual increments, treating reversals in the following three different ways:

-

a net caries increment on a surface level – leave the reversals as is when calculating the caries increment

-

a crude caries increment on a surface level – summing only the positive increments and ignoring any reversals

-

consider that the negative reversals have been erroneously coded and replace instances where the total caries increment (all surfaces combined) was negative with a zero increment.

-

Changes from the protocol

In the published trial protocol, the proposed method of analysis of dental outcomes involved regression models that accounted for repeated measures, that is, the dental outcomes at 2 and 2.5 years. Similarly, for self-reported twice-daily toothbrushing, a repeated measures binary logistic model incorporating 6 months, 1, 2 and 2.5 years was planned (not including earlier time points since these were for pilot schools only). However, a subsequent trial amendment removed the 2-year dental assessment for main trial schools, and, at this point, it was clear that very few main trial schools had been able to provide data at 1 year due to school closures caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, a repeated measures approach was deemed no longer appropriate nor necessary, and it was detailed in the statistical analysis plan (SAP) (reviewed and approved by the TMG, TSC and DMEC prior to the 2.5-year data collection) that analyses would largely take the form of separate (cross-sectional) regression models for the outcomes at relevant time points, as detailed below. The principle and output of the two approaches are the same, to provide a comparison of the outcome at a specific time point between groups, so this does not reflect a fundamental change in the primary end-point analysis.

Primary analysis