Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the Evidence Synthesis Programme on behalf of NICE as project number NIHR131717. The protocol was agreed in November 2020. The assessment report began editorial review in June 2021 and was accepted for publication in April 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Westwood et al. This work was produced by Westwood et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Westwood et al.

Chapter 1 Objective

Sections of this report are reproduced from Westwood et al. 1 © NICE 2020 Diagnostic Assessment Report Commissioned by the NIHR HTA Programme on behalf of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence – Protocol. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/dg44/documents/final-protocol. All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication.

The overall objective of this project was to provide an update to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) diagnostics guidance (DG) on tauroselcholic [75selenium] acid (SeHCAT™) (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) testing for the investigation of diarrhoea among adults with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D) or Crohn’s disease without ileal resection (DG7), published in November 2012. 2 This update report summarises the current evidence on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of SeHCAT for investigating bile acid diarrhoea (BAD) and the measurement of bile acid pool loss in adults referred to secondary care for the investigation of chronic diarrhoea with an unknown cause, functional diarrhoea (FD), or suspected or diagnosed IBS-D (i.e. people with suspected primary BAD). This update also considered SeHCAT for the investigation of possible secondary BAD among adults with chronic diarrhoea and a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, who have not undergone ileal resection.

To address the stated objective, the following research questions were defined.

-

What are the effects of a care pathway that includes a SeHCAT test, compared with no SeHCAT test, in terms of clinical symptoms, other relevant health outcomes and costs among adults with chronic diarrhoea, in the specified populations?

-

Does the result of a SeHCAT test predict response to treatment with bile acid sequestrants (BASs) among adults with chronic diarrhoea, in the specified populations?

-

What is the cost-effectiveness of including a SeHCAT test in the diagnostic pathway for the investigation of chronic diarrhoea, in the specified populations?

Chapter 2 Background and definition of the decision problem

Population

This assessment considers SeHCAT for the assessment of adults referred to secondary care for the investigation of chronic diarrhoea with an unknown cause, FD, or suspected or diagnosed IBS-D (i.e. people with suspected primary BAD).

Bile acid diarrhoea is a form of chronic diarrhoea in which the recycling of bile acids in the body is not functioning properly. Bile acids are produced by the liver and stored in the gallbladder until they are released into the small bowel to aid digestion. Usually, bile acids are reabsorbed into the liver in the final section of the small bowel. If they are not reabsorbed, or the body produces more bile acid than can be reabsorbed, excess amounts of bile travel from the small bowel to the colon, stimulate salt and water secretion and bowel movements, and result in diarrhoea.

Symptoms of BAD may include explosive, smelly or watery diarrhoea, urgency in going to the toilet, abdominal pain, swelling or bloating and faecal incontinence.

The most common form of BAD is caused by overproduction of bile acid in people with no physical damage to the bile acid recycling system. This primary form of BAD is often missed as a cause of chronic diarrhoea. Because of the similarity in symptoms between BAD and both IBS-D and FD, BAD may be misdiagnosed. The actual cause of diarrhoea in up to 30% of people with suspected IBS-D or FD may be BAD. 3

Bile acid diarrhoea can also appear as a secondary condition after the small bowel or another part of the bile acid recycling system has been damaged by disease, surgery or other clinical interventions (e.g. pelvic radiotherapy or chemotherapy).

This assessment also considered SeHCAT for the investigation of possible secondary BAD among adults with chronic diarrhoea and a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, who have not undergone ileal resection.

Intervention technology

Tauroselcholic [75selenium] acid is a radiopharmaceutical capsule that is indicated for use in the investigation of bile acid malabsorption (BAM) and measurement of bile acid pool loss. It may also be used in assessing ileal function, in the investigation of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and chronic diarrhoea and in the study of enterohepatic circulation (these uses are outside the current scope). SeHCAT is manufactured by GE Healthcare.

The SeHCAT test is used to measure how well the body absorbs bile acids. The radiopharmaceutical capsule contains 75selenium (a gamma emitter) and a synthetic bile acid (tauroselcholic acid). When swallowed, SeHCAT is absorbed by the body like a natural bile acid. It can be detected in the body using a gamma camera.

A SeHCAT test involves two outpatient appointments in the nuclear medicine department of a hospital. During the first appointment, the patient swallows a SeHCAT capsule and then waits for up to 3 hours before a baseline scan is taken. A follow-up scan is taken on day 7, after the first appointment. It may be considered reasonable to stop any antidiarrhoeal medication for the duration of the test, as there is a possibility that this may interfere with the test result.

The result of the test is given as the proportion of SeHCAT remaining in the body after 7 days. To calculate the result, the amount of radioactivity detected in the follow-up scan is divided by the amount of radioactivity detected in the baseline scan. A diagnosis of BAD is usually made when ≤ 15% of SeHCAT remains in the body. SeHCAT results are on a continuous scale; hence, the threshold used for a positive result can vary. However, retention values of > 20% are not usually considered to be indicative of BAD, although values of 15–20% may sometimes be considered ‘borderline’ (clinical opinion of specialist committee members). SeHCAT results are also sometimes used to grade the severity of BAD:

-

Retention values from 10% to 15% indicate mild BAD.

-

Retention values from 5% to 10% indicate moderate BAD.

-

Retention values from 0% to 5% indicate severe BAD.

In current clinical practice, the cut-off point for a positive SeHCAT result may vary. A prospective survey, conducted in 2014/15 and published in 2016, of SeHCAT provision and practice in the UK included 38 centres and 1036 patients. Participating NHS centres were recruited through direct mailing and notices on the websites of professional societies; patients referred for a SeHCAT test with a clinical suspicion of BAD because of chronic diarrhoea without a known cause were eligible for inclusion. The survey found that > 50% used their own criteria for defining a positive SeHCAT result. 4

There are no alternative technologies currently in routine use in the NHS in England.

Comparator

The comparators for this technology appraisal are as follows:

-

no SeHCAT testing and no treatment with BAS

-

no SeHCAT testing and trial of treatment with BAS.

Care pathway

Diagnostic assessment

The initial investigation of patients with chronic diarrhoea should involve history-taking, an assessment of clinical symptoms and signs to exclude cancer, as indicated in NICE guideline 12, Suspected Cancer: Recognition and Referral. 5 The initial clinical assessment should also include blood and stool tests to exclude anaemia, coeliac disease, infection and inflammation, as recommended in the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) clinical guidelines. 3 The BSG guidelines position SeHCAT testing as part of secondary clinical assessment, following initial assessment/investigations to exclude coeliac disease (coeliac serology and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and biopsy in people with suspected coeliac disease), common infections (stool examination for Clostridium difficile, ova, cysts and parasites) and colorectal cancer (colonoscopy in people with altered bowel habit and rectal bleeding, and faecal immunochemical testing to guide priority investigations in people with lower gastrointestinal symptoms and no rectal bleeding). 3

The BSG guidelines list BAD among the ‘common disorders’ to be investigated as part of secondary clinical assessment and state that a positive diagnosis of BAD should be made either using SeHCAT testing or by measuring the serum bile acid precursor 7-alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one, depending on local availability. 3 The BSG guidelines also state that ‘there is insufficient evidence to recommend use of an empirical trial of treatment for bile acid diarrhoea rather than making a positive diagnosis’. 3 Referral to secondary care is required for investigation and diagnosis of BAD.

NICE clinical guideline 61, Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Adults: Diagnosis and Management,6 recommends considering a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) for patients with abdominal pain or discomfort that is either relieved by defecation or associated with altered bowel frequency or stool form when the initial investigations are normal and at least two of the following symptoms are present: altered stool passage (straining, urgency, incomplete evacuation); abdominal bloating (more common in women than men), distension, tension or hardness; symptoms worsened by eating; and passage of mucus. The guideline also states that further tests such as colonoscopy or imaging are not necessary to confirm an IBS diagnosis. 6 Investigation of BAD may be useful among patients previously diagnosed with IBS-D; however, NICE clinical guideline 61 does not currently include any recommendations on the investigation of BAD. 6

Investigation of BAD may also be considered when diarrhoea persists, regardless of conventional treatment, in those conditions with which it may appear as a secondary condition. When chronic diarrhoea appears after ileal resection (removal of the terminal part of the small bowel to treat Crohn’s disease), BAD is so common (> 95% of cases)7 that a diagnostic test before treatment may not be considered necessary.

The use of SeHCAT in current clinical practice appears to vary, with some studies indicating that imaging tests and invasive investigations such as colonoscopy are often performed before SeHCAT. 4,8,9 Multiple interactions with different clinicians over many years often take place before BAD is investigated. 10

The manufacturer advises that SeHCAT testing is currently available at 85 hospitals across 74 out of 225 NHS acute trusts in England (data from August 2020). 11 According to the 2018/19 NHS National Cost Collection data,12 the trusts in which SeHCAT testing is available perform about 10,000 SeHCAT tests per year. The number of tests performed across trusts varies widely, ranging from < 50 tests per year to > 500 tests per year.

Management/treatment

The symptoms of BAD are most often controlled with BAS medication. BASs bind to bile acids in the small bowel and prevent them from irritating the colon; they may also slow transit time. The treatment may be long term.

There are currently three BASs available for use in the UK NHS: colestyramine, colestipol and colesevelam. Colestyramine and colestipol come in powder or granule form and colesevelam comes in tablet form. Use of both colestipol and colesevelam for BAD is currently off-label (NICE13). BASs can be difficult to tolerate: constipation and flatulence are commonly reported adverse events, some people find the taste and texture of colestyramine and colestipol very unpleasant and some patients have reported weight gain or weight loss. Increases in dose, addition of antidiarrhoea medication or changes in diet may also be needed to achieve adequate symptom control. Long-term use of colestyramine has been associated with reduced vitamin and folate levels. 14 However, 1–2 years of colestipol use has been reported to have no effect on vitamin A or folic acid levels, and only a small effect on vitamin D levels. 14 Colesevelam was not associated with significant reductions in the absorption of vitamins A, D, E or K in studies of up to 1 year. 14 Guidelines made no recommendation about routine monitoring of fat-soluble vitamins during long-term BAS therapy, while noting that approved product labels recommend supplementation of vitamins A, D and K only if deficiency occurs. 14

In current practice, in some UK secondary care settings (reported by specialist committee members), BAS treatment of BAD is started without a diagnostic test being performed (trial of treatment). The estimated time taken to ascertain the effectiveness of trial of treatment was between 4 and 12 weeks (clinical opinion of specialist committee members).

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

The systematic review methods followed the principles outlined in the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) guidance for undertaking reviews in health care,15 the NICE Diagnostics Assessment Programme manual16 and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy. 17 Data extraction tables for studies included in our previous Diagnostic Assessment Report (DAR),18 conducted to support the development of DG7,2 were used as a starting point for this report. Public input on the definition of the decision problem and research questions was received during the scoping phase of this project, through the lay members of the NICE Diagnostics Advisory Committee and Assessment Subgroup. Stakeholder comments were also sought, through NICE, on the draft and final report.

Systematic review methods

Search strategy

Search strategies used in the original report were updated in line with the NICE final scope. 11 Search strategies were based on target condition and intervention, as recommended in the CRD guidance for undertaking reviews in health care and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy. 15,17,19,20

Searches were undertaken to identify studies of SeHCAT in the diagnosis of BAD. The search strategies combined relevant search terms comprising indexed keywords [e.g. medical subject headings (MeSH) and Emtree] and free-text terms; strategies were developed specifically for each database and the keywords adapted according to the configuration of each database. Only studies conducted with humans were sought. Searches were not limited by language or publication status (unpublished or published). The original 2011 strategies were adapted to incorporate changes to the preferred terminology and search methods for each resource. Owing to the time elapsed, some resources were no longer available, but additional resources were searched to maintain completeness.

Searches for studies on economic evaluations, costs and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) were also conducted (see Chapter 4, Identifying and reviewing published cost-effectiveness studies, for further details). To ensure that no relevant studies were missed, the results of the clinical effectiveness searches were also screened for records relevant to the cost-effectiveness evaluation, and all cost-effectiveness results, including guideline searches, were screened for studies relevant to the clinical effectiveness section.

The following databases were searched for relevant studies from inception:

-

MEDLINE (Ovid) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, and Daily, from 1946 to 30 November 2020

-

EMBASE (Ovid), from 1974 to 25 November 2020

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) (Wiley), up to November 2020, issue 11

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Wiley), up to November 2020, issue 11

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (CRD), up to March 2015

-

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database (CRD), up to March 2018

-

Science Citation Index (SCI) (Web of Science), up to 27 November 2020

-

KSR Evidence (https://ksrevidence.com/), up to 1 December 2020

-

Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS) (https://lilacs.bvsalud.org/en/), up to 27 November 2020

-

National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) HTA programme, up to 26 November 2020

-

PROSPERO (international prospective register of systematic reviews) (www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/), up to 26 November 2020.

Completed and ongoing trials were identified by searches of the following resources:

-

National Institutes of Health Clinical Trials database (www.clinicaltrials.gov/), up to 26 November 2020

-

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/ictrp/en/), up to 2 December 2020

-

EU Clinical Trials Register (www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/), up to 2 December 2020.

Conference abstracts and proceedings were identified in a three-stage approach, conducted as follows:

-

The main Ovid EMBASE search strategy was employed to include conference abstracts and proceedings.

-

A second set of tailored searches was conducted on:

-

Northern Light Life Sciences Conference Abstracts (Ovid), from 2010 to December 2020 week 46

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (CPCI-S) (Web of Science), from 1990 to 30 November 2020

-

-

In addition, the 2020 United European Gastroenterology Week proceedings (not currently covered by EMBASE, Northern Light or CPCI-S) were searched manually.

Additional searches

An additional targeted search for trial of treatment with BASs for IBS/Crohn’s disease was performed on the following databases:

-

MEDLINE (Ovid) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, and Daily, from 1946 to 17 February 2021

-

EMBASE (Ovid), from 1974 to 17 February 2021.

This additional search was conducted with the primary aim of identifying additional studies to inform the cost-effectiveness modelling; search results were screened as part of the main clinical effectiveness searches.

All identified references were downloaded to EndNote X20 software [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA] for further assessment and handling. These references were imported into the existing project library and deduplicated against the 2011 search results. All search results (both clinical effectiveness and economics) were screened for all areas of interest. Rigorous records were maintained as part of the searching process. Individual records within the EndNote reference library were tagged with search information, including the name of the searcher, date searched, database name and host, strategy name and iteration.

The main EMBASE search strategy for each set of searches was independently peer reviewed by a second information specialist, using the evidence based checklist for the peer review of electronic search strategies (PRESS-EBC). 21,22 References in retrieved articles were checked for additional studies. Full search strategies are provided in Appendix 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants

The study populations eligible for inclusion were adults (aged ≥ 18 years) referred to a gastroenterology clinic for the investigation and diagnosis of possible BAD, who had previously undergone primary clinical assessment/investigations (as recommended in the BSG guidelines3) to exclude coeliac disease (coeliac serology and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and biopsy in people with suspected coeliac disease), common infections (stool examination for C. difficile, ova, cysts and parasites) and colorectal cancer (colonoscopy in people with altered bowel habit and rectal bleeding, and faecal immunochemical testing to guide priority investigations in people with lower gastrointestinal symptoms and no rectal bleeding).

Given the paucity of evidence identified, studies that did not fully report prior investigations, or studies in which prior investigations did not match those specified previously, have been included; full details of prior investigations (when reported) are provided in Appendix 2, Table 54.

As detailed previously, this assessment focused on two specific populations:

-

adults presenting with chronic diarrhoea with unknown cause or FD, or suspected or diagnosed IBS-D (i.e. people with suspected primary BAD)

-

adults presenting with chronic diarrhoea and a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, who have not undergone ileal resection (i.e. people with suspected secondary BAD).

Setting

The setting was secondary care.

Intervention (index test)

The intervention was the SeHCAT test.

Comparators

For the purposes of cost-effectiveness modelling, the comparators used in this assessment were as follows:

-

no SeHCAT testing and no treatment with BASs

-

no SeHCAT testing and trial of treatment with BASs.

Outcomes

Studies reporting any of the following outcomes were included:

-

effect of testing on treatment plan (e.g. surgical or medical management, or further testing)

-

effect of testing on clinical outcome (e.g. morbidity and adverse events)

-

effect of testing on adherence to treatment

-

prognosis – the ability of the test (SeHCAT) result to predict clinical outcome (i.e. response to treatment)

-

predictive accuracy – sensitivity and specificity of the SeHCAT test for the prediction of treatment response

-

acceptability of tests to patients, or surrogate measures of acceptability (e.g. waiting time and associated anxiety)

-

adverse events associated with testing (e.g. pain/discomfort experienced during the procedure and waiting times before results)

-

HRQoL.

Study design

The following types of study were eligible for inclusion:

-

randomised controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomised clinical controlled trials (CCTs) or observational comparative studies in which clinical or treatment planning outcomes were compared between participants who received SeHCAT testing and those who did not

-

RCTs, CCTs or observational comparative studies in which all participants received SeHCAT testing and clinical outcomes were compared between treatment decisions based on different definitions of a positive SeHCAT result (different diagnostic thresholds)

-

observational studies in which all participants received SeHCAT testing, and clinical or treatment planning outcomes were compared between patients with positive SeHCAT results and those with negative SeHCAT results

-

observational studies that reported the results of multivariable regression modelling with response to treatment with BAS as the dependent variable and index test result (continuous or categorical) as an independent variable [included studies should control adequately for potential confounders (e.g. age, gender, comorbidities)]

-

predictive accuracy studies that reported sufficient data to support the calculation of the sensitivity and specificity of SeHCAT to predict response to treatment with BAS (i.e. studies that reported the outcome of treatment with BAS for both patients with a positive SeHCAT test and those with a negative SeHCAT test).

Studies using any reported threshold for a positive SeHCAT test and any reported definition of response to treatment were eligible for inclusion.

No new studies, of the higher-level study designs described previously, were identified. Therefore, studies that reported treatment outcome only for those participants with a positive SeHCAT result [i.e. sufficient data to calculate positive predictive value (PPV) only] were included.

Studies that were included in our previous DAR,18 conducted to support the development of DG7,2 and which met the aforementioned inclusion criteria, were also included in this review.

Exclusion criteria

The following study/publication types were excluded:

-

preclinical and animal

-

reviews, editorials and opinion pieces

-

case reports

-

studies reporting only technical aspects of the test, or image quality.

Inclusion screening and data extraction

Two reviewers (MW and ER or Gill Worthy) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all reports identified by searches; any discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus. Full copies of all studies deemed potentially relevant were obtained and the same two reviewers independently assessed these for inclusion; any disagreements were resolved by consensus. Details of studies excluded at the full-text screening stage are presented in Appendix 4, Table 56.

Studies cited in materials provided by the manufacturer of the SeHCAT test (GE Healthcare Ltd) were first checked against the project reference database, in EndNote X20; any studies not already identified by our searches were screened for inclusion following the process described previously.

When available/applicable, data were extracted on the following: study design/details; participant characteristics; previous investigations; details of the application of the SeHCAT test (e.g. threshold used to define a positive test result); details of any treatments received for BAD (e.g. BAS used and dosing regimen, and any concomitant treatments such as diet or loperamide); any information about intolerance to, or discontinuation of, BASs; and the definition of response to treatment, including duration of follow-up and outcomes (as defined in Chapter 4, Identifying and reviewing published cost-effectiveness studies). Data were extracted by one reviewer (MW or ER) using data extraction forms based on those used for the original systematic review,18 which was conducted to support the development of DG7. 2 A second reviewer (MW or ER) checked data extraction and any disagreements were resolved by consensus or discussion with a third reviewer (NA). Full data extraction tables are provided in Appendix 2, Tables 54 and 55.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of included diagnostic accuracy studies was assessed using the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies-2 (QUADAS-2) tool. 23 The methodological quality of observational studies, which reported treatment outcome only for those participants with a positive SeHCAT result, was assessed using a topic-specific adaptation of the quality assessment checklist by Wedlake et al. ,24 as used in our previous DAR,18 conducted to support the development of DG7;2 the use of this tool was carried forward to the current assessment to provide consistency. The results of the quality assessment are used for descriptive purposes to provide an evaluation of the overall quality of the included studies and to inform recommendations for the design of future studies. Quality assessment was undertaken by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer (MW and ER); any disagreements were resolved by consensus or discussion with a third reviewer (NA).

The results of the quality assessments are summarised and presented in tables (see Study quality) and, for QUADAS-2 assessments, are presented in full, by study, in Appendix 3.

Methods of analysis/synthesis

Meta-analysis was considered inappropriate, owing to the small number of test accuracy studies, with varying diagnostic thresholds, and between-study heterogeneity with respect to population (prior investigations), treatment regimen, definition of response, follow-up period and SeHCAT administration; therefore, we employed a narrative synthesis. The clinical effectiveness results section of this report is structured by clinical application (diagnosis of primary BAD and diagnosis of secondary BAD in people with Crohn’s disease who have not undergone ileal resection). A detailed commentary on the major methodological problems or biases that affected the studies is also provided, together with a description of how this may have affected the individual study results.

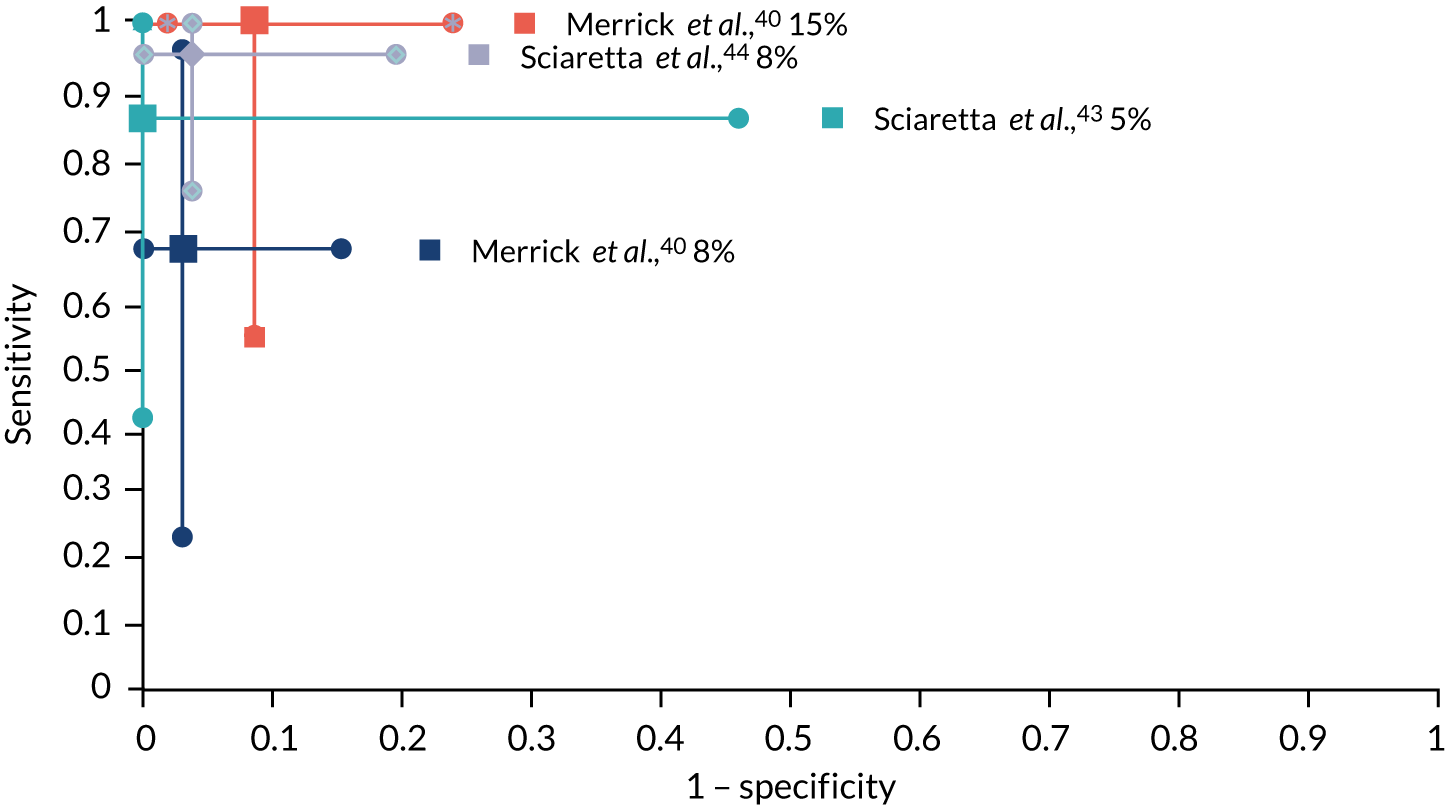

For predictive accuracy studies (studies that reported sufficient data to support the calculation of the sensitivity and specificity of SeHCAT to predict response to treatment with BASs), the absolute numbers of true positive, false negative, false positive and true negative test results of SeHCAT, compared with the reference standard of treatment response, as well as sensitivity and specificity values, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), are presented in Table 4. The results of individual studies were plotted in the receiver operating characteristic plane, with the diagnostic threshold used for the SeHCAT test indicated (see Figure 2).

The results of studies that reported treatment outcome only for those participants with a positive SeHCAT result (i.e. sufficient data to calculate PPV only) are presented in Table 5.

Results of the assessment of clinical effectiveness

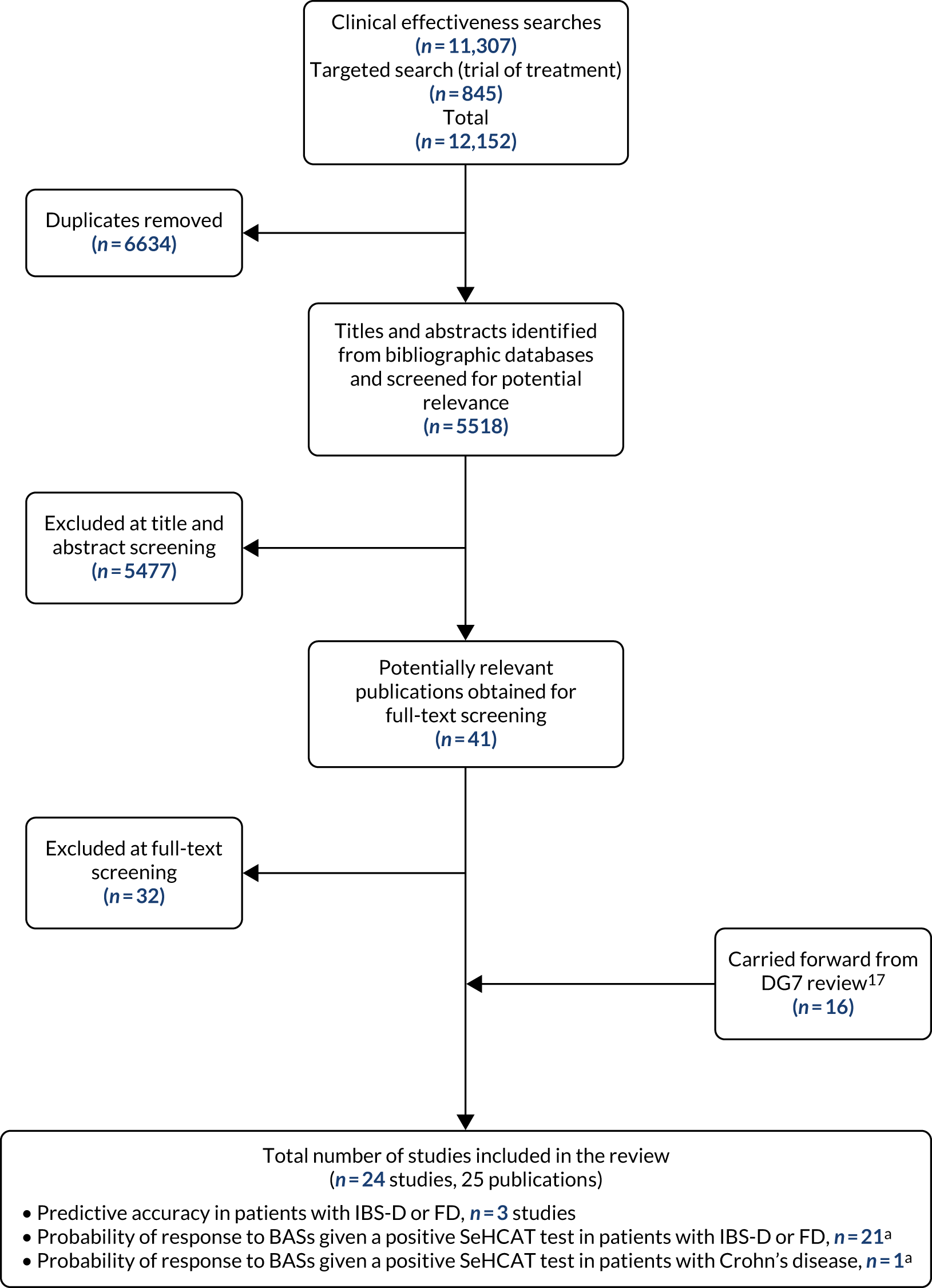

The literature searches of bibliographic databases conducted for this update identified 5518 new references. After initial screening of titles and abstracts, 41 references were considered to be potentially relevant and ordered for full-text screening; of these, nine publications were included in the review. 25–33 In addition, 16 publications, taken from the assessment report conducted for DG7,18 were carried forward and included in this review. 7,34–48 All potentially relevant studies cited in documents supplied by the test manufacturer, GE Healthcare Ltd, had already been identified by bibliographic database searches. Figure 1 shows the flow of studies through the review process. Appendix 4, Table 56, provides details, with reasons for exclusion, of all publications excluded at the full-text screening stage. Six publications49–54 that were included in our previous systematic review18 did not meet the inclusion criteria for this systematic review; these are listed in Appendix 4, Table 57. In all cases, this was because studies included participants with a variety of clinical presentations and did not report separate data for either of the two populations specified in the inclusion criteria for this assessment (see Inclusion and exclusion criteria).

FIGURE 1.

Flow of studies through the review process. a, One study provided data for both populations.

Overview of included studies

Based on the updated searches and inclusion screening described previously, and information taken from the assessment report conducted for DG7,18 a total of 24 studies,7,25–35,37–48 reported in 25 publications,7,25–48 were included in this review; the results section of this report cites studies using the primary publication only.

Fifteen of the included studies were published, in full, in peer-reviewed journals;7,30,34,35,37–45,47,48 eight were published as conference abstracts only;25–29,31–33 and one was an unpublished dissertation. 46 It should be noted that all eight studies that were published as conference abstracts only were new studies, identified during this assessment, that is the majority of the new evidence identified (eight out of nine studies) was not published, in full, in peer-reviewed journals.

No RCTs, CCTs or observational comparative studies were identified that met the inclusion criteria for this review (see Inclusion and exclusion criteria). Similarly, no observational studies were identified that reported the results of multivariable regression modelling with response to treatment with BAS as the dependent variable and index test (SeHCAT) result (continuous or categorical) as one of the independent variables. Finally, no new predictive accuracy studies (studies that reported sufficient data to support the calculation of the sensitivity and specificity of SeHCAT to predict response to treatment with BAS) were identified. All of the nine new studies included in this review25–33 were of the lowest level of evidence eligible for inclusion; these are observational studies that report some outcome data for patients treated with BASs, whereby only those patients with a positive SeHCAT test were offered treatment with BAS.

All 24 included studies provided some data about population 1: adults presenting with chronic diarrhoea with unknown cause, or FD, or suspected or diagnosed IBS-D (i.e. people with suspected primary BAD). Three of these studies,40,43,44 all of which were previously included in the assessment report conducted for DG7,18 provided limited predictive accuracy data for this population. The remaining 21 studies reported only information about the outcome of treatment with BASs for some or all of those participants who had a positive SeHCAT test result. 7,25–35,37–39,41–43,46–48

One study7 also provided data on population 2: adults presenting with chronic diarrhoea and a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease who have not undergone ileal resection (i.e. people with suspected secondary BAD). This study reported only information about the outcome of treatment with BASs for people with Crohn’s disease who had a positive SeHCAT test result, and was previously included in the assessment report conducted for DG7. 18 No new studies meeting the inclusion criteria for population 2 were identified for this assessment report.

All 21 studies for which information on geographic location was reported were conducted in Europe; 10 were conducted in the UK,7,27–30,40,45,46,48 five in Italy,25,33,39,43,44 three in Spain,37,38,41 two in Denmark34,47 and one each in Sweden42 and France. 35

Only three of the included studies provided any information about funding, and only one UK study40 reported receipt of any industry funding [SeHCAT test supplies were provided by Amersham International Ltd (Amersham, UK), which is now part of GE Healthcare]; details of all reported funding sources are provided in Table 1.

| Study | Study details | Objective | FD | IBS-D | Crohn’s disease | Study design and outcome extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bellini 202025 |

|

To determine the prevalence of BAM among IBS-D and FD patients referred to a tertiary gastroenterological centre in Italy, to explore the possible correlation between BAM severity, symptom severity and quality of life, and to explore whether or not the response to colestyramine could be related to BAM severity | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

| aBorghede 201134 |

|

To investigate the frequency of BAM and treatment responses to colestyramine with SeHCAT scanning among patients experiencing chronic watery diarrhoea | ✓ |

|

||

| Farmer 201726 |

|

To compare rates of BAM in Rome III- and Rome IV-defined patients with IBS-D | ✓ |

|

||

| aFellous 199435 |

|

To determine the performance and the clinical significance of a simplified version of the SeHCAT test that measures ileal absorption of bile salt | ✓ |

|

||

| aFernandez-Bañares 200137 and a related publication36 |

|

|

✓ |

|

||

| aFernández-Bañares 200738 |

|

|

✓ | ✓ |

|

|

| aGalatola 199239 |

|

To assess the prevalence of BAM and the efficacy of colestyramine therapy in improving symptoms associated with this condition among patients with IBS-D | ✓ |

|

||

| Holmes 201227 |

|

Unclear | ✓ |

|

||

| Kumar 201329 |

|

To audit sequential patients referred for SeHCAT testing, in order to assess diagnostic value | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

| Kumar 202028 |

|

To investigate whether or not quality of life improves with use of BAS among patients diagnosed with BAD | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

| Lin 201630 |

|

To evaluate the natural history of BAD by examining individuals diagnosed with BAD and determining the use of and response to BASs | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

| aMerrick 198540 |

|

To assess the value of measuring absorption of SeHCAT as a test for the presence of BAM | ✓ |

|

||

| a,cNotta 201141 |

|

To evaluate the utility of the quantification of abdominal retention of SeHCAT as a first-line diagnostic test in the early pathophysiological diagnosis of patients with chronic diarrhoea | ✓ |

|

||

| cNotta 201431 |

|

To evaluate the utility of SeHCAT testing to diagnose BAM and to assess the prevalence of BAM among patients with chronic FD | ✓ |

|

||

| cNotta 201732 |

|

To evaluate the utility of SeHCAT testing to diagnose BAM and to assess the prevalence of BAM in patients with chronic FD | ✓ |

|

||

| aRudberg 199642 |

|

To investigate the usefulness of SeHCAT testing among patients experiencing FD and to document earlier radiological investigations performed in the course of the disease | ✓ |

|

||

| aSciarretta 198643 |

|

To evaluate the diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity and specificity of the SeHCAT test | ✓ |

|

||

| aSciarretta 198744 |

|

To evaluate whether or not BAM, assessed by the SeHCAT test, had a pathogenetic role in functional chronic diarrhoea and to ascertain whether or not the small bowel transit time could be correlated with the SeHCAT test results | ✓ |

|

||

| aSinha 199845 |

|

To identify patients with idiopathic BAM, to describe their clinical features, both qualitatively and quantitatively, and to assess their response to colestyramine treatment | ✓ |

|

||

| aSmith 20007 |

|

To investigate BAM and its response to treatment among patients with chronic continuous or recurrent diarrhoea seen in a district general hospital | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

| aTunney 201146 |

|

To assess the utility of the BSG guidelines for the investigation of chronic diarrhoea, focusing on whether or not SeHCAT should be prioritised in the investigation of chronic diarrhoea, rather than considered as a second-line option | ✓ |

|

||

| aWildt 200347 |

|

To evaluate the usefulness of SeHCAT testing by assessing the extent of BAM and describing the clinical characteristics in a group of patients with chronic diarrhoea. Clinical outcome after treatment with colestyramine was also evaluated | ✓ |

|

||

| aWilliams 199148 |

|

To determine the clinical characteristics of patients with idiopathic BAM and to identify their response to treatment | ✓ |

|

||

| Zanoni 201833 |

|

To present preliminary experience with the use of SeHCAT test | ✓ | ✓ |

|

Further details of the characteristics of study participants and the technical details of the conduct of the index test (SeHCAT) and reference standard (BAS treatment regimen) are provided in Appendix 2.

Study quality

The three studies40,43,44 that provided predictive accuracy data (information on the ability of the SeHCAT test to predict response to treatment with BAS), all of which were previously included in the assessment report conducted for DG7,18 were assessed using the QUADAS-2 tool.

The included predictive accuracy studies were all published > 30 years ago and were generally poorly reported; all three studies were rated as having an ‘unclear’ risk of bias with respect to patient selection and reference standard (no study provided details of whether or not the assessment of response to treatment was conducted blind to the results of SeHCAT testing), and two of the three studies43,44 were also rated as having an ‘unclear’ risk of bias with respect to flow and timing because the duration of follow-up over which response to treatment was assessed was not reported. Merrick et al. 40 was rated as having a ‘high’ risk of bias for the ‘flow and timing’ domain of the QUADAS-2 tool because only patients with positive or equivocal SeHCAT test results received the reference standard (treatment with BAS); patients with a negative SeHCAT test result were managed with unspecified ‘simple conservative treatment’. Sciarretta et al. 43 was rated as having a ‘high’ risk of bias for the ‘index test’ domain of the QUADAS-2 tool because the threshold used to define a positive SeHCAT test result was not prespecified.

All three studies had at least one item of ‘high’ concern regarding applicability to this assessment. In some instances, the applicability issues identified are a consequence of the age of the studies. All three studies were rated as having ‘high’ or ‘unclear’ concerns regarding the applicability of the study population to that specified in the inclusion criteria for this review; all three studies included some participants with prior cholecystectomy and no study reported previous investigations equivalent to those specified in current BSG guidelines for the investigation of chronic diarrhoea. 3 All three studies were also rated as having ‘high’ concerns regarding the applicability of the index test; the age of the studies meant that no study used the current version of the SeHCAT test, manufactured by GE Healthcare, specified in the inclusion criteria for this assessment. Merrick et al. 40 was also rated as having ‘high’ concerns regarding the applicability of the reference standard, because the management of patients with a negative SeHCAT test was not considered likely to provide a reliable indication of whether or not these patients would have responded to treatment with BAS.

The results of the QUADAS-2 assessment are summarised in Table 2 and the full assessments are provided in Appendix 3.

| Study | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient selection | Index test | Reference standard | Flow and timing | Study population | Index test | Reference standard | |

| Merrick 198540 | ? | ✓ | ? | ✗ | ? | ✗ | ✗ |

| Sciarretta 198643 | ? | ✗ | ? | ? | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Sciarretta 198744 | ? | ✓ | ? | ? | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

The methodological quality of studies that reported treatment outcome only for those participants with a positive SeHCAT result (i.e. sufficient data to calculate PPV only) was assessed using a topic-specific adaptation of the quality assessment checklist by Wedlake et al. ,24 as used in our previous DAR. 18 The results of this assessment are summarised in Table 3. These studies represent the lowest level of evidence specified in the inclusion criteria for this assessment (see Inclusion and exclusion criteria) and were generally of poor methodological quality. No study in this group provided full outcome data for patients with a negative SeHCAT test result. Ten7,27,29,30,33,34,45–48 of the 21 studies7,25–35,37–39,41,42,45–48 of this type used a retrospective study design. Eleven studies provided no clear definition of chronic diarrhoea. 7,25,27–29,31–34,41,46 Ten studies did not provide sufficient information about the SeHCAT test used to allow the testing procedure to be reproduced. 25–29,31–33,45,47 Eight studies did not clearly describe how the decision to treat patients with BASs was made. 27,29,33–35,42,46,48 Nine studies provided no or an incomplete description of the BAS treatment provided to patients with a positive SeHCAT test result. 27–29,33–35,41,46,48 Finally, six studies did not report an objective measure of response to treatment. 25,27,29,30,33,46

| Study | Question | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Study design | 2. Diarrhoea | 3. Known cause (n) | 4. SeHCAT test | 5. Cut-off values | 6. Reason for treatment | 7. Negative test | 8. Treatment | 9. Response | |

| Bellini 202025 | Prospective | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| aBorghede 201134 | Retrospective | No |

|

Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Farmer 201726 | Prospective | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| aFellous 199435 | Prospective | Yes |

|

Yes | Yes | No | Yes – some | Yes | Yes |

| aFernandez-Bañares 200137 | Prospective | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| aFernández-Bañares 200738 | Prospective | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| aGalatola 199239 | Prospective | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Holmes 201227 | Retrospective | No |

|

No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Kumar 201329 | Retrospective | No |

|

No | Yes | No | Yes – some | No | No |

| Kumar 202028 | Prospective | No |

|

No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Lin 201630 | Retrospective | Yes |

|

Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| aNotta 201141 | Prospective | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Notta 201431 | Prospective | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Notta 201732 | Prospective | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| aRudberg 199642 | Prospective | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| aSinha 199845 | Retrospective | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| aSmith 20007 | Retrospective | No |

|

Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| aTunney 201146 | Retrospective | No |

|

Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| aWildt 200347 | Retrospective | Yes |

|

No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| aWilliams 199148 | Retrospective | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Zanoni 201833 | Retrospective | No |

|

No | Yes | No | Unclear | No | No |

Performance of the SeHCAT test for predicting response to treatment with bile acid sequestrant among patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome or functional diarrhoea

All 24 included studies provided some data about population 1: adults presenting with chronic diarrhoea with unknown cause, suspected or diagnosed IBS-D, or FD (i.e. people with suspected primary BAD). 7,25–35,37–48

Three of these studies,40,43,44 all of which were previously included in the assessment report conducted for DG7,18 provided limited data on the accuracy of the SeHCAT test for predicting response to treatment with BAS in this population. The results of these studies are summarised in Table 4. All three studies assessed the relationship between the SeHCAT test result and response to treatment with colestyramine.

| Study | Number of participants | Index test (definition of a positive test result) | Reference standard | TP (n) | FN (n) | FP (n) | TN (n) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Tested/treated (n patients) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aMerrick 198540 | 43 (IBS-D) | SeHCAT < 8% | Responseb | 4 | 2 | 1 | 33c | 0.667 (0.223 to 0.957) | 0.971 (0.847 to 0.999) | 3 patients not treated |

| 43 (IBS-D) | SeHCAT ≤ 15% | Responseb | 6 | 0 | 3 | 31c | 1.000 (0.541 to 1.000) | 0.912 (0.763 to 0.981) | 3 patients not treated | |

| aSciarretta 198643 | 13 (group D only, IBS-D and 3 who had a previous cholecystectomy) | SeHCAT < 5%d | Responsee | 6 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 0.857 (0.421 to 0.996) | 1.000 (0.541 to 1.000) | All treated |

| aSciarretta 198744 | 46 (38 with IBS-D and 8 post cholecystectomy) | SeHCAT 8% cut-off value | Responsef | 19 | 1 | 1 | 25 | 0.950 (0.751 to 0.999) | 0.962 (0.804 to 0.999) | All treated |

Merrick et al. 40 reported sufficient data to allow the calculation of the performance of SeHCAT, for predicting treatment response, at two 7-day retention thresholds (< 8% and ≤ 15%). The estimated sensitivity of SeHCAT in predicting a positive response to treatment with colestyramine was 66.7% (95% CI 22.3% to 95.7%) using the < 8% threshold, and 100% (95% CI 54.1% to 100%) using the ≤ 15% threshold. The specificity estimates were 97.1% (95% CI 84.7% to 99.9%) and 91.2% (95% CI 76.3% to 98.1%) using the < 8% and ≤ 15% thresholds, respectively. 40 These results would appear to indicate that the use of the SeHCAT test with a threshold for 7-day retention of ≤ 15% (commonly used in UK clinical practice) could identify patients with IBS-D who may benefit from treatment with BASs. However, it should be noted that, although all 31 patients with a negative SeHCAT test result were classified as true negatives, this assessment was based on long-term follow-up: ‘None of the 31 patients with irritable bowel disease who retained more than 15% at seven days showed any evidence of small bowel disease, and none appeared during a follow up of at least 12, and in some up to 24 months. Simple conservative treatment resolved or eased most symptoms.’40 None of these 31 patients received treatment with colestyramine; therefore, it remains uncertain whether or not any of these patients could have benefited from treatment with BAS. One patient with a SeHCAT test result of < 8% and two with an equivocal result (8–15%) did not receive treatment with colestyramine; these patients were excluded from the analysis. 40 The remaining nine patients were treated with colestyramine; five of these had a SeHCAT test result of < 8%, one of whom did not respond to treatment, and four had an equivocal result (8–15%), two of whom responded to colestyramine and two of whom did not. 40

Sciarretta et al. 43 reported sufficient data to allow the calculation of the performance of SeHCAT, for predicting treatment response, at a threshold reported to be equivalent to a 7-day retention threshold of < 5%. The estimated sensitivity of SeHCAT in predicting a positive response to treatment with colestyramine was 85.7% (95% CI 42.1% to 99.6%) and the specificity was 100% (95% CI 54.1% to 100%). However, only 13 patients were included in this analysis. A subsequent study by Sciarretta et al. 44 estimated the sensitivity of SeHCAT in predicting a positive response to colestyramine as 95.0% (95% CI 75.1% to 99.9%) and the specificity as 96.2% (95% CI 80.4% to 99.9%), using a 7-day retention threshold of < 8% to define a positive SeHCAT test. It should be noted that there may have been overlap between the populations included in these two studies.

Figure 2 illustrates the variation in sensitivity and specificity with SeHCAT threshold, as reported in these three studies. 40,43,44

FIGURE 2.

Accuracy of the SeHCAT test to predict a response to treatment with colestyramine at different thresholds among patients with IBS-D. The centre dots represent the point estimates for sensitivity and specificity of SeHCAT in predicting response to treatment in the three studies at different cut-off values (5%, 8% and 15%). The vertical and horizontal lines represent the 95% CIs for sensitivity and specificity, respectively.

The between-study heterogeneity in these three studies was considerable. The principal diagnosis, method of SeHCAT administration, BAS treatment dose, definition of response to treatment and follow-up period were different between studies. Appendix 2 provides full details of study inclusion and exclusion criteria, participant characteristics, SeHCAT test methods, BAS treatment and definition of treatment response.

The remaining 21 studies7,25–35,37–39,41–43,46–48 reported information about the outcome of treatment with BAS for some or all of those participants who had a positive SeHCAT result only (i.e. sufficient information to estimate PPV), or other descriptive results.

As was the case for the predictive accuracy studies described previously, between-study heterogeneity for these studies was considerable. The principal diagnosis, threshold used to define a positive SeHCAT test, BAS treatment regimen, definition of response to treatment and follow-up period varied between studies. Appendix 2 provides full details of study inclusion and exclusion criteria, participant characteristics, SeHCAT test methods, BAS treatment and definition of treatment response, for the studies that reported this information.

Study design

When information about the BAS treatment was provided, most (13/16) studies reported the use of colestyramine alone. 25,31,32,34,35,37–39,41,42,45,47,48 Four studies reported more than one option for BAS treatment: colestyramine or colesevelam,28 colestyramine or colestipol,7 and colestyramine or colesevelam or colestipol. 30 None of these studies reported either the numbers of patients treated with each drug or the criteria used to select treatment. Eight studies reported the proportion of treated patients who were intolerant of BAS or discontinued treatment for unspecified reasons;25,29–31,34,39,45,46 rates of intolerance/discontinuation were generally high (median 15%, range 4–27%). There was insufficient information to determine whether or not levels of intolerance varied between colestyramine, colestipol and colesevelam. Only three studies reported the proportion of treated patients who were lost to follow-up: 14 out of 56 (25%),39 8 out of 32 (25%)46 and one out of six (17%). 27

Study sizes were generally small; the median number of patients with a positive SeHCAT test (across all thresholds) who received treatment with BAS was 26 (range 6–57), and the proportion of patients who experienced a positive response to treatment varied widely within a given SeHCAT test threshold (Table 5). Most of the included studies evaluated one or more of three 7-day retention thresholds (5%, 10% and 15%) for the SeHCAT test. Table 5 summarises the results for studies in this group.

| Study | Participant details (n) | Positive SeHCAT test threshold | Reference standard | Number with positive/negative test | Number (%) of patients with a positive test treated with BAS | Number (%) of patients with a negative test treated with BAS | Number (%) of patients with a positive SeHCAT test who responded to treatment with BAS (PPV) | Number (%) of responders given a negative SeHCAT test | Number (%) discontinued/intolerant of BAS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bellini 202025 |

All 70 patients with IBS-D and FD |

≤ 5% | Response | 12/58 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| ≤ 10% | 15/55 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||

| ≤ 15% | 31/39 | 22/31 (71%) | 0/39 (0%) | NR | No patients treated | 6/22 (27%) | |||

| aBorghede 201134 |

Subgroup 114 patients with type II BAM |

< 5% | Response | 41/73 | 39/41 (95%) | 18/73 (25%) | 29b/39 (74%) | 14b/18 (78%) | 6/39 (15%) |

| < 10% | 55/59 | 53/55 (96%) | 4/59 (7%) | 41b/53 (77%) | 2b/4 (50%) | 7/53 (13%) | |||

| ≤ 15% | 68/46 | 57/68 (84%) | 0/46 (0%) | 43b/57 (75%) | No patients treated | 8/57 (14%) | |||

| Farmer 210726 | All

|

< 10% | Response | 48/159 | 48/48 (100%) | 0/159 (0%) | 36c/48 (75%) | No patients treated | NR |

| aFellous 199435 |

Subgroup 53 patients with FD |

< 10% | Response | 20/33 | NR | NR | 8d/11 (73%) | 2d/5 (40%) | NR |

| aFernandez-Bañares 200137 |

Subgroup 32 patients with FD |

< 11% | Response | 24/8 | 20/24 (83%) | 0/8 (0%) | 20e/20 (100%) | No patients treated |

|

| aFernández-Bañares 200738 |

All 62 patients with FD or IBS-D |

< 11% | Response | 37/25 | 37/37 (100%) | 0/25 (0%) | 28f,g/37 (76%) | No patients treated | NR |

| aGalatola 199239 |

All 98 patients with IBS-D |

< 11.7% | Response | 56/42 | 56/56 (100%) | 0/42 (0%) | 39h/56 (70%) | No patients treated |

|

| Holmes 201227 |

Subgroup (post test) 8 patients with type 2 BAM |

< 15% | Response | 8/0 | 6/8 (75%) | NA | 3i/6 (50%) | NA | 1/6 (17%) lost to follow-up |

| Kumar 201329 |

Subgroup 57 patients with unexplained symptoms |

< 15% | Response | 24/33 | 23/24 (96%) | Unclear

|

11j/23 (48%) | 1/39 (3%) | 6/23 (26%) intolerant of BAS |

| Kumar 202028 |

Subgroup 20 patients with idiopathic BAD |

NR | Response | 20/0 | 20/20 (100%) | NA | 9k/20 (45%) | NA | NR |

| lLin 201630 |

Subgroup (post test) 29 patients with type 2 BAM, who were contactable at follow-up |

< 10% | Response | 29/0 | 29/29 (100%) | NA | NR | NA |

|

| a,mNotta 201141 |

All 37 patients with chronic diarrhoea |

≤ 10% | Response | 16/21 | 16/16 (100%) | 0/21 (0%) | No patients treated | NR | |

| mNotta 201431 |

All 78 patients with chronic FD |

< 10% | Response | 34/44 | 34/34 (100%) | 0/44 (0%) | No patients treated | 3/34 (9%) discontinued BAS | |

| mNotta 201732 |

All 92 patients with chronic FD |

< 10% | Response | 42/50 | 42/42 (100%) | 0/50 (0%) | No patients treated | NR | |

| aRudberg 199642 |

All (excluding 3 patients who had had a previous cholecystectomy or gastric resection) 17 patients with FD |

≤ 10% | Response | 3/14 | 3/3 (100%) | 8/14 (57%) | 2p/3 (67%) | 4p/8 (50%) | NR |

| ≤ 15% | 8/9 | 7/8 (88%) | 4/9 (44%) | 6p/7 (86%) | 0p/4 (0%) | ||||

| aSinha 199845 |

All 17 patients with a history suggestive of IBS-D |

< 15% | Response | 9/8 | 9/9 (100%) | 0/8 (0%) | 6q/9 (67%) | No patients treated | 2/9 (22%) intolerant of BAS |

| aSmith 20007 |

Subgroup 197 patients with IBS-D |

< 10% | Response | 65/132 | 34/65 (52%) | 0/132 (0%) | 28r/34 (82%) | No patients treated | NR |

| aTunney 201146 |

Subgroup 86 patients with chronic diarrhoea and no known risk factors, who had no endoscopic or histological abnormalities and negative coeliac serology |

< 8 | Response | 20/66 | 20/20 (100%) | 12/66 | 10s/20 (50%) | 2s/12 (17%) |

|

| ≤ 15% | 36/50 | 32/36 (89%) | 0/50 (0%) | 12s/32 (38%) | No patients treated |

|

|||

| aWildt 200347 |

Subgroup 56 patients with possible type 2 BAM |

< 5% | Response | 13/43 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| < 10% | 21/35 | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| < 15% | 24/32 | 17/24 (71%) | 0/32 (0%) | 14t,u/17 (82%) | No patients treated | ||||

| aWilliams 199148 | 181 patients | < 5% | Responsev | 23/158 | 23/23 (100%) | 21/158 (13%) | 23w/23 (100%) | 6/21 (29%) |

|

| < 10% | 39/142 | 36/39 (92%) | 8/142 (6%) | 29w/36 (81%) | 0/8 (0%) | ||||

| < 15% | 60/121 | 42/60 (70%) | 0/121 (0%) | 29w/42 (69%) | No patients treated | ||||

| Zanoni 201833 | 12 patients | < 5% | Response | 2/10 | 2/2 (100%) | 6/10 (60%) | NR | NR | NR |

| ≤ 10% | 6/6 | 6/6 (100%) | 2/6 (33%) | NR | NR | ||||

| ≤ 15% | 7/5 | 7/7 (100%) | 1/5 (20%) | NR | NR | ||||

| ≤ 20% | 8/4 | 8/8 (100%) | 0/4 (0%) | 6x/8 (75%) | No patients treated |

Response to treatment in studies evaluating a single threshold for a positive SeHCAT test

Using a 7-day retention threshold of < 5% to define a positive SeHCAT test, the proportion of test-positive patients who responded positively to treatment with BAS was reported as 74%34 and 100%48 by two studies; the proportion of SeHCAT test-positive patients in these studies who received treatment with BAS was 95%34 and 100%. 48 The equivalent data from the predictive accuracy study by Sciarretta et al. 43 indicated a treatment response rate of 100% among patients with 7-day retention values of < 5%; in this study,43 all patients with SeHCAT test results below the 5% threshold received treatment with colestyramine.

Eleven studies reported information about the rate of positive response to treatment with BAS using a 7-day retention threshold of < 10% or ≤ 10%. 7,26,31,32,34,35,37,38,41,42,48 The median proportion of SeHCAT test-positive patients who received treatment with BAS was 100% (range 52–100%) and the median response rate was 85% (range 67–100%). It should be noted that three studies from the same group31,32,41 may have had overlapping populations. All three of these studies31,32,41 classified response to treatment as complete (normalisation of stool rhythm and consistency) or partial (decrease in stool frequency and/or improvement in stool consistency); the proportion of patients in these studies who achieved a complete response ranged from 50% to 76%, and the proportion that achieved a partial response ranged from 15% to 50%.

Eight studies reported information about the rate of positive response to treatment with BAS using a 7-day retention threshold of < 15% or ≤ 15%. 27,29,34,42,45–48 The median proportion of SeHCAT test-positive patients who received treatment with BAS was 86% (range 70–100%) and the median response rate was 68% (range 38–86%). The equivalent data from the predictive accuracy study by Merrick et al. 40 indicated a treatment response rate of 67% among patients with 7-day retention values of ≤ 15%; in this study, 9 out of 12 (75%) patients with SeHCAT test results below the 15% threshold received treatment with colestyramine.

The results of studies that used other thresholds to define a positive SeHCAT test are summarised in Table 5.

Response to treatment in studies comparing multiple thresholds for a positive SeHCAT test

Four studies reported information about treatment response rates for multiple 7-day SeHCAT retention thresholds. 34,42,46,48 Two studies reported information about treatment response rates for all of the three main thresholds (15%, 10% and 5%). 34,48 In one study,34 there was little variation in the rate of response to treatment across the three thresholds (response rates of 75%, 77% and 74% for threshold values of 15%, 10% and 5%, respectively). By contrast, the second study48 reported increasing response rates as the threshold for a positive SeHCAT test was lowered (response rates of 69%, 81% and 100% for threshold values of 15%, 10% and 5%, respectively). Not all patients with a positive SeHCAT test received treatment with BAS, and the reasons for treatment decisions were not reported. The results of both studies indicated that, if a 5% or 10% threshold were applied, some patients with a negative SeHCAT result (i.e. 7-day retention values of between 5% and 15% or between 10% and 15%), who could be considered to be ‘borderline’ or ‘equivocal’ with respect to a diagnosis of BAM, and who may benefit from treatment with BAS, would be missed. The response rates for patients with 7-day SeHCAT retention values of between 5% and 15% were 14 out of 18 (78%)34 and 6 out of 21 (29%),48 and the response rates for patients with 7-day SeHCAT retention values of between 10% and 15% were two out of four (50%)34 and zero out of eight (0%). 48 Data sets were incomplete (i.e. not all patients received treatment with BAS) for all of these groups. An unpublished dissertation report46 provided information about treatment response rates for patients with a positive SeHCAT result, using two 7-day retention thresholds: 8% and 15%. All patients with 7-day SeHCAT retention values of < 8% received treatment with BAS and 32 out of 36 (89%) patients with 7-day SeHCAT retention values of ≤ 15% received treatment with BAS; response rates were 10 out of 20 (50%) and 12 out of 32 (38%), respectively. 46 The results from this study46 also indicated that, if the lower threshold were applied, some patients with a ‘borderline’ or ‘equivocal’ test result (7-day SeHCAT retention values of between 8% and 15%), who may have benefited from treatment with BAS, would be missed; 12 out of 16 (75%) patients in this group received treatment with BAS and 2 out of 12 (17%) responded positively. 46 It should be noted that no patients in any of these studies34,46,48 who had 7-day SeHCAT retention values of > 15% received treatment with BAS; estimates for the treatment response rate among SeHCAT test-negative patients do not, therefore, represent the complete spectrum of test-negative patients. One further, very small (n = 17), study42 reported results for individual patients, which allowed the calculation of proportions treated and response rates for 7-day retention thresholds of 10% and 15%. In this study,42 all three patients with a 7-day retention value of ≤ 10% received treatment with colestyramine and two out of three (67%) responded positively; seven out of eight (88%) patients with a SeHCAT 7-day retention value of ≤ 15% received treatment with colestyramine, six (86%) of whom responded positively. 42 As with the other studies that assessed multiple SeHCAT test thresholds, the results of this study42 also indicated that, if a 10% threshold were applied, some patients with a negative SeHCAT test result, who may have benefited from treatment with BAS, would be missed: four out of eight (50%) patients with a 7-day SeHCAT retention value of > 10%, who were treated with colestyramine, responded positively to treatment, and zero out of four (0%) patients with a 7-day SeHCAT retention value of > 15%, who were treated with colestyramine, responded positively to treatment. 42 It should be noted that data from Rudberg et al. 42 were incomplete; only 57% of patients who were SeHCAT test negative at the 10% threshold and 44% of patients who were SeHCAT test negative at the 15% threshold received treatment with colestyramine. In summary, few studies reported treatment response rates for multiple SeHCAT test thresholds and data were generally incomplete; hence, the extent to which patients with ‘borderline’ or ‘equivocal’ 7-day SeHCAT retention values could benefit from treatment with BAS remains unclear. The extent to which patients with 7-day retention values of > 15% may benefit from treatment with BAS is unknown.

Bowel symptoms

Three studies reported further results for bowel symptoms, in addition to rates of response to treatment with BAS. 30,37,45 Fernandez-Bañares et al. 37 reported that, among the 20 patients with FD and a 7-day SeHCAT retention value of ≥ 10% who were treated with colestyramine, the median number of daily bowel movements changed from 5 [interquartile range (IQR) 4–8] at baseline to 1 (IQR 1–2) post treatment. A change in stool consistency was also observed across all 20 treated patients; before treatment, all 20 patients had liquid/semi-liquid stools, and after treatment stools were formed/semi-formed across all 20 patients. 37 Urgency disappeared for 13 patients who had this symptom pre treatment. 37 Lin et al. 30 reported that, among 29 patients with type 2 BAM (7-day SeHCAT retention values of < 10%) who were available for follow-up after treatment with BAS, the daily frequency of bowel movements was reduced from a median of 6 (range 3–16) at diagnosis to 3.5 (range 1–16) at follow-up (median time since diagnosis 82 months). Finally, Sinha et al. 45 reported a reduction in stool frequency across all nine patients with 7-day SeHCAT retention values of ≤ 15% who were treated with colestyramine; the median stool frequency pre treatment was five per day, compared with two per day post treatment. One patient did not experience a reduction in stool frequency on treatment, although bowel motion consistency improved and the patient was reported to be happy with this outcome. 45

Health-related quality of life

Two studies also reported very limited results for changes in HRQoL among patients with a positive SeHCAT test result following treatment with BAS. 25,28 Bellini et al. 25 reported that, after 8 weeks of treatment with colestyramine, patients with mild BAM (7-day SeHCAT retention values of between 11% and 15%) showed a significant improvement on the pain domain of the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) (p < 0.05), and patients with severe BAM (7-day SeHCAT retention values of ≤ 5%) showed significant improvements on multiple domains of the SF-36 (emotional problems, energy/fatigue, emotional well-being, social functioning, pain, general health, health change) (p < 0.05). Kumar et al. 28 reported that patients with idiopathic BAD (SeHCAT threshold not reported) showed significant improvements in the activity levels subscore (p = 0.00998) of the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire, following treatment with Questran or colesevelam; the duration of follow-up was not reported.

Performance of the SeHCAT test for predicting response to treatment with bile acid sequestrant among patients with Crohn’s disease, who have not undergone ileal resection

One study7 (results are summarised in Table 6) provided data on population 2: adults presenting with chronic diarrhoea and a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, who have not undergone ileal resection (i.e. people with suspected secondary BAD). This study reported only information about the outcome of treatment with BAS for people who had a positive SeHCAT result, and was included in our previous assessment report, conducted for DG7. 18 No new studies meeting the inclusion criteria for population 2 were identified for this assessment report. The single study that reported information about response to treatment with BAS among patients with Crohn’s disease provided only very limited information about response rates among patients with a positive SeHCAT test result (7-day retention value of < 10%) who were treated with colestyramine or colestipol. 7 Fewer than half (9/24) of the patients with a positive SeHCAT test result received treatment with BAS; the criteria used to decide whether or not to offer BAS were not reported. Most [8/9 (89%)] of the patients treated with BAS responded positively;7 however, the numbers treated with each BAS (colestyramine or colestipol) were not reported.

| Study | Participant details (n) | Positive SeHCAT test threshold | Reference standard | Number with positive/negative test | Number (%) of patients with a positive test treated with BAS | Number (%) of patients with a negative test treated with BAS | Number (%) of responders given a positive SeHCAT test | Number (%) of responders given a negative SeHCAT test | Number (%) discontinued/intolerant of BAS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aSmith 20007 |

Subgroup 44 patients with Crohn’s disease and no prior surgery |

< 10% | Response | 24/20 | 9/24 (38%) | 0/20 (0%) | 8b/9 (89%) | No patients treated | NR |

Appendix 2 provides all reported details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, participant characteristics, SeHCAT test methods, BAS treatment and definition of treatment response, for this study. 7

Pooled estimates of treatment response rates for inclusion in cost-effectiveness modelling

Meta-analysis of test accuracy estimates (i.e. sensitivity and specificity) was considered inappropriate in this assessment, owing to the small number of test accuracy studies, with varying diagnostic thresholds, and between-study heterogeneity with respect to population (prior investigations), treatment regimen, definition of response, follow-up period and SeHCAT administration. However, to provide input parameters for cost-effectiveness modelling, some pooled estimates were calculated using the inverse-variance method on the logit scale, for the probability of testing positive at the 15% threshold (Table 7) and the probability of achieving a positive response to treatment, given a positive test at the 15% threshold (Table 8). The random-effects analysis was chosen because of the high heterogeneity, qualitatively assessed, in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook, section 10.10.4.1. 20

| Study | Number with a positive test | Number tested | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Borghede 201134 | 68 | 114 | 0.60 |

| Holmes 201227 | 8 | 8 | 0.99 |

| Kumar 201329 | 24 | 57 | 0.42 |

| Rudberg 199642 | 8 | 17 | 0.47 |

| Sinha 199845 | 9 | 17 | 0.53 |

| Tunney 201146 | 36 | 86 | 0.42 |

| Wildt 200347 | 24 | 56 | 0.43 |

| Williams 199148 | 60 | 181 | 0.33 |

| Fixed effect, pooled estimate (95% CI) | 0.416 (0.424 to 0.407) | ||

| Random effects, pooled estimate (95% CI) | 0.454 (0.357 to 0.555) | ||

| Study | Number who responded to treatment with BAS | Number with a positive test who received BAS | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Borghede 201134 | 43 | 57 | 0.75 |

| Holmes 201227 | 3 | 6 | 0.50 |

| Kumar 201329 | 11 | 23 | 0.48 |

| Rudberg 199642 | 6 | 7 | 0.86 |

| Sinha 199845 | 6 | 9 | 0.67 |

| Tunney 201146 | 12 | 32 | 0.38 |

| Wildt 200347 | 14 | 17 | 0.82 |

| Williams 199148 | 29 | 42 | 0.69 |

| Fixed effect, pooled estimate (95% CI) | 0.642 (0.615 to 0.668) | ||

| Random effects, pooled estimate (95% CI) | 0.638 (0.495 to 0.760) | ||

Chapter 4 Assessment of cost-effectiveness

This chapter explores the cost-effectiveness of including SeHCAT testing in the diagnostic pathway for investigation of diarrhoea due to BAM among adults with IBS-D or FD and among adults with Crohn’s disease without ileal resection.

Identifying and reviewing published cost-effectiveness studies

A series of literature searches were performed to identify published economic evaluations, cost data and utility studies for diagnostic techniques and procedures used in the investigation of patients with chronic diarrhoea that were not included within the scope of the clinical effectiveness searches. The searches aimed to identify studies that could be used to support the development of a health economic model, to estimate the model input parameters and to answer the research questions of the assessment; the aim was not to perform a systematic review. Searches were therefore pragmatic in design, and date limits were applied when appropriate.

Methodological study design filters were included in the search strategy where relevant. No restrictions on language or publication status were applied. Limits were applied to remove animal studies. The main EMBASE strategy for each search was independently peer-reviewed by a second information specialist, using the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health Peer Review Checklist. 21,22 Identified references were downloaded to EndNote X20 software for further assessment and handling. References in retrieved articles were checked for additional studies. In addition, the EndNote library created for the clinical effectiveness section (see Chapter 3, Search strategy) was also screened to identify potentially relevant economic studies.

Full search strategies are reported in Appendix 1.

The following databases were searched for relevant studies, with no date limits:

-

MEDLINE (Ovid) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily: 1946 to 21 December 2020

-

EMBASE (Ovid): 1974 to 17 January 2021

-

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) (CRD): up to March 2015 (note that, since March 2015, NHS EED has been an archival resource only, and the Wiley Health Economic Evaluations Database searched as part of the original 2011 study is no longer available)

-

EconLit (EBSCOhost): up to 2020/12/22

-

SCI (Web of Science): 1988 to 5 January 2021

-

Research Papers in Economics (RePEc) (http://repec.org/): up to 23 February 2021.

Supplementary searches on SeHCAT, BAD, IBS, Crohn’s disease and chronic diarrhoea were undertaken on the following resources to identify guidelines and guidance (the search was conducted from 2011):

-

Guidelines International Network (www.g-i-n.net): up to 15 December 2020

-

NHS Evidence (www.evidence.nhs.uk): up to 16 December 2020

-

ECRI Guidelines Trust (https://guidelines.ecri.org/): up to 16 December 2020

-

NICE (www.nice.org.uk): up to 15 December 2020

-

Trip database (www.tripdatabase.com/): up to 10 December 2020

-

HTA database (CRD): up to 31 March 2018

-

NIHR HTA programme: up to 16 December 2020.

Note that the National Guidelines Clearinghouse resource included in the 2011 searches is no longer available.

As described by the NICE methods guide, the information process that supports the development of a model is ‘a process of assembling evidence and this reflects an iterative, emergent process of information gathering’. 55 The following additional searches were requested by the health economists as part of this process.

Searches for utility weights for BAD, IBS, Crohn’s disease and chronic diarrhoea were conducted on the following resources:

-

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Registry (https://research.tufts-nemc.org/cear4/Home.aspx): up to 14 January 2021

-

School of Health and Related Research Health Utilities Database (www.scharrhud.org/): up to 23 February 2021.

Additional searches were also requested for HRQoL and cost-effectiveness for both Crohn’s disease and IBS on the following resources:

-

NHS EED (CRD): up to March 2015

-

MEDLINE (Ovid) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily: 1946 to 15 December 2020.

Model structure and methodology

Model structure

Population

The cost-effectiveness of SeHCAT for the assessment of possible BAD was estimated in the two patient populations defined in Chapter 3, Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

-

Adults with chronic diarrhoea with an unknown cause, suspected or diagnosed IBS-D, or FD (i.e. people with suspected primary BAD). This group is referred to as population 1.

-

Adults with chronic diarrhoea and a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, who have not undergone ileal resection. This group is referred to as population 2.

Using the study by Summers et al. ,4 we assumed that the average age in both populations was 50 years, and the ratio of males to females was 35 : 75.

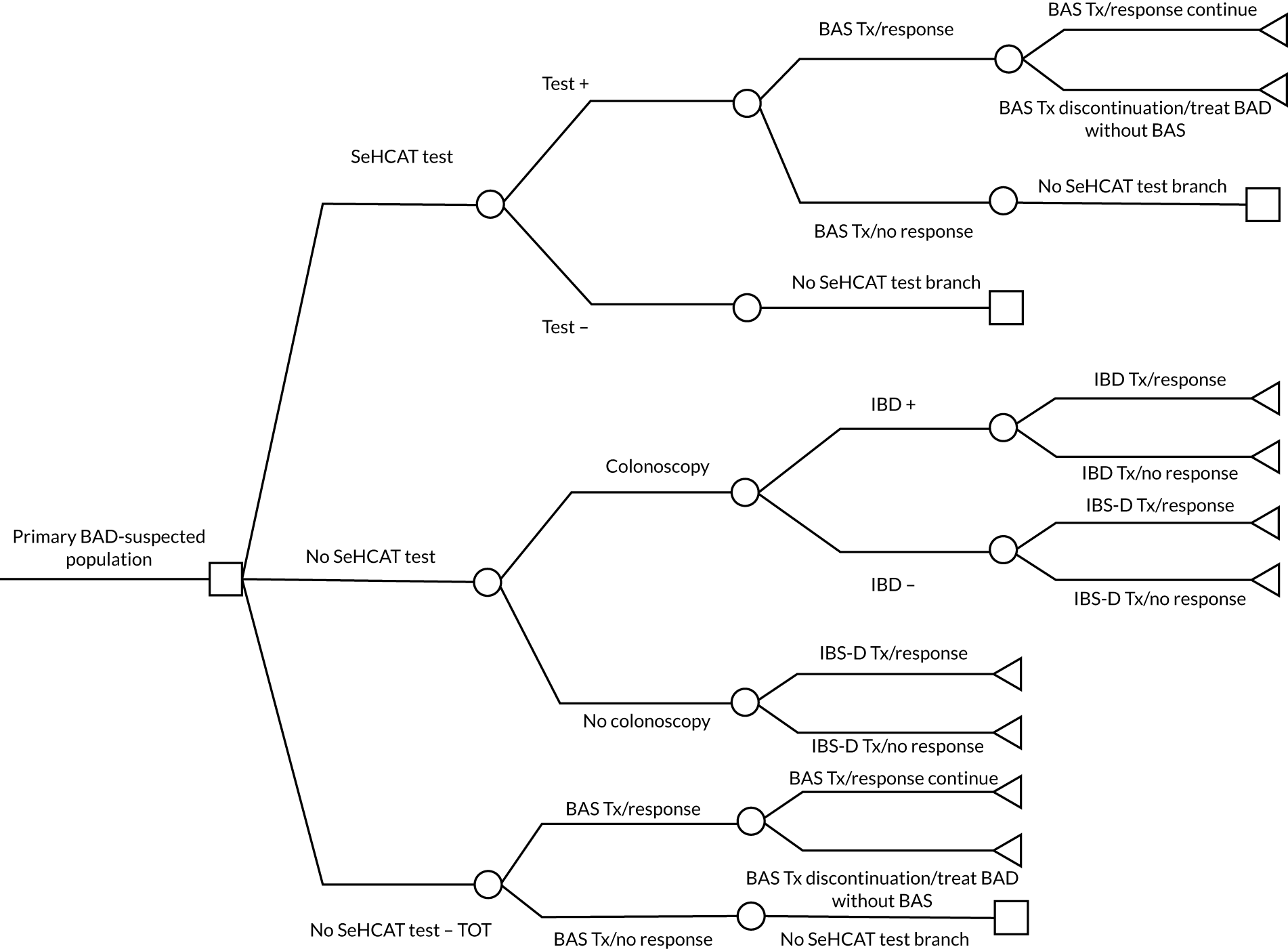

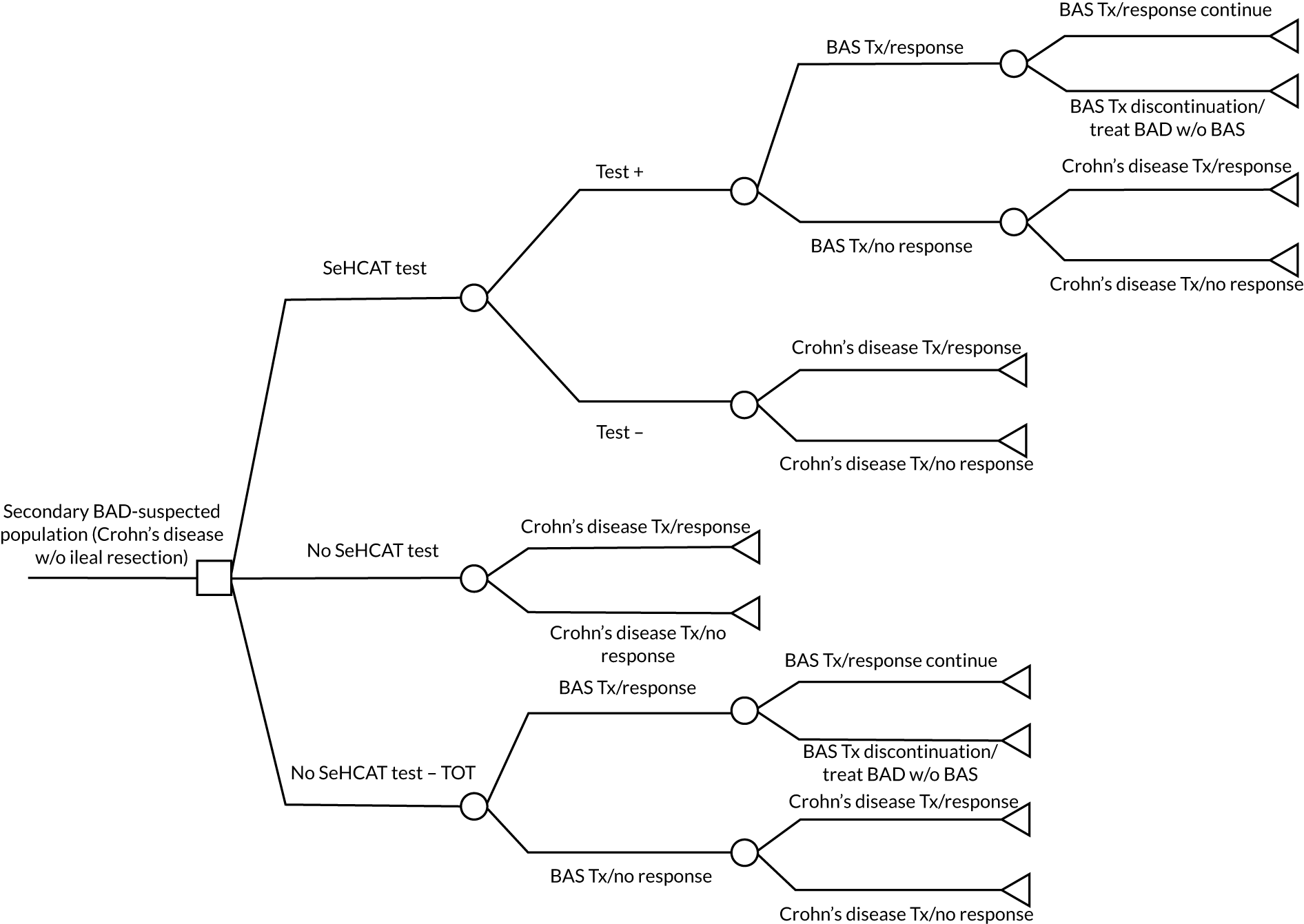

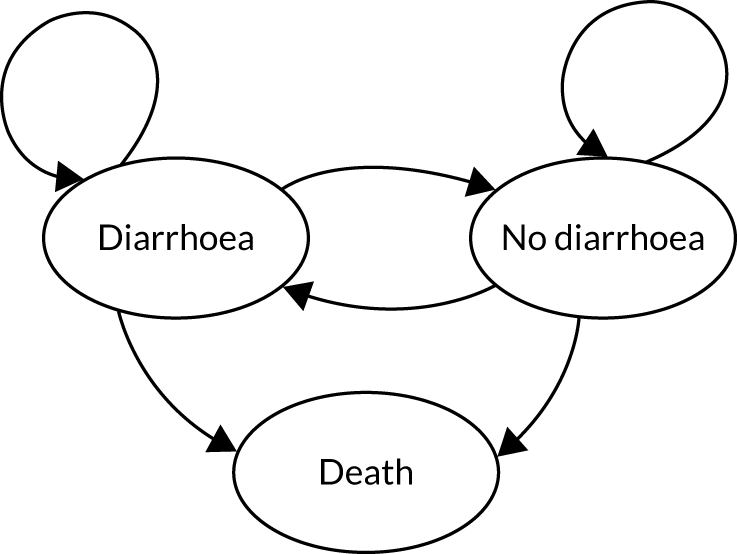

Conceptual model description

The structure of the health economic model is in line with that developed for the previous assessment of SeHCAT. 18 Thus, the model consists of two parts:

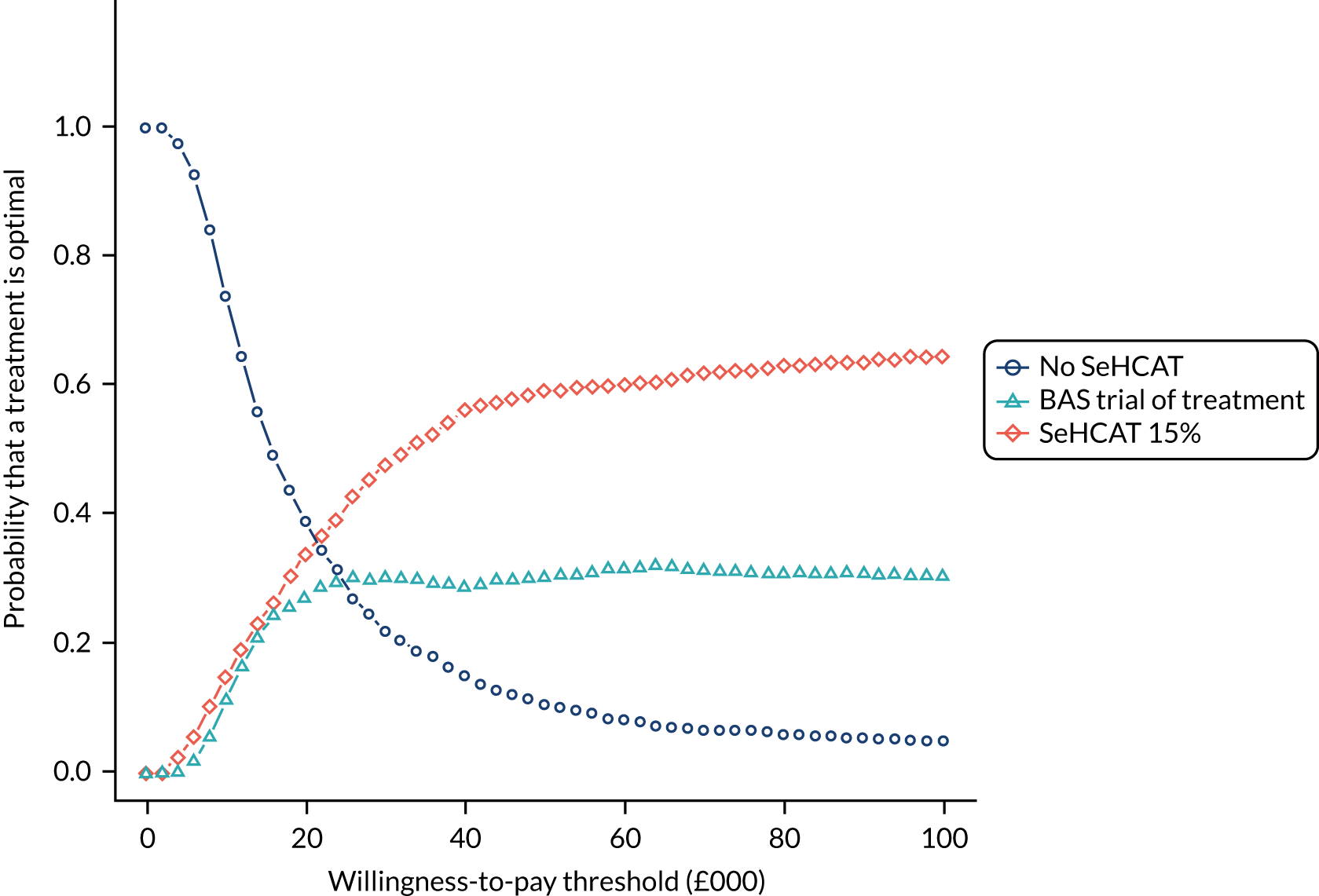

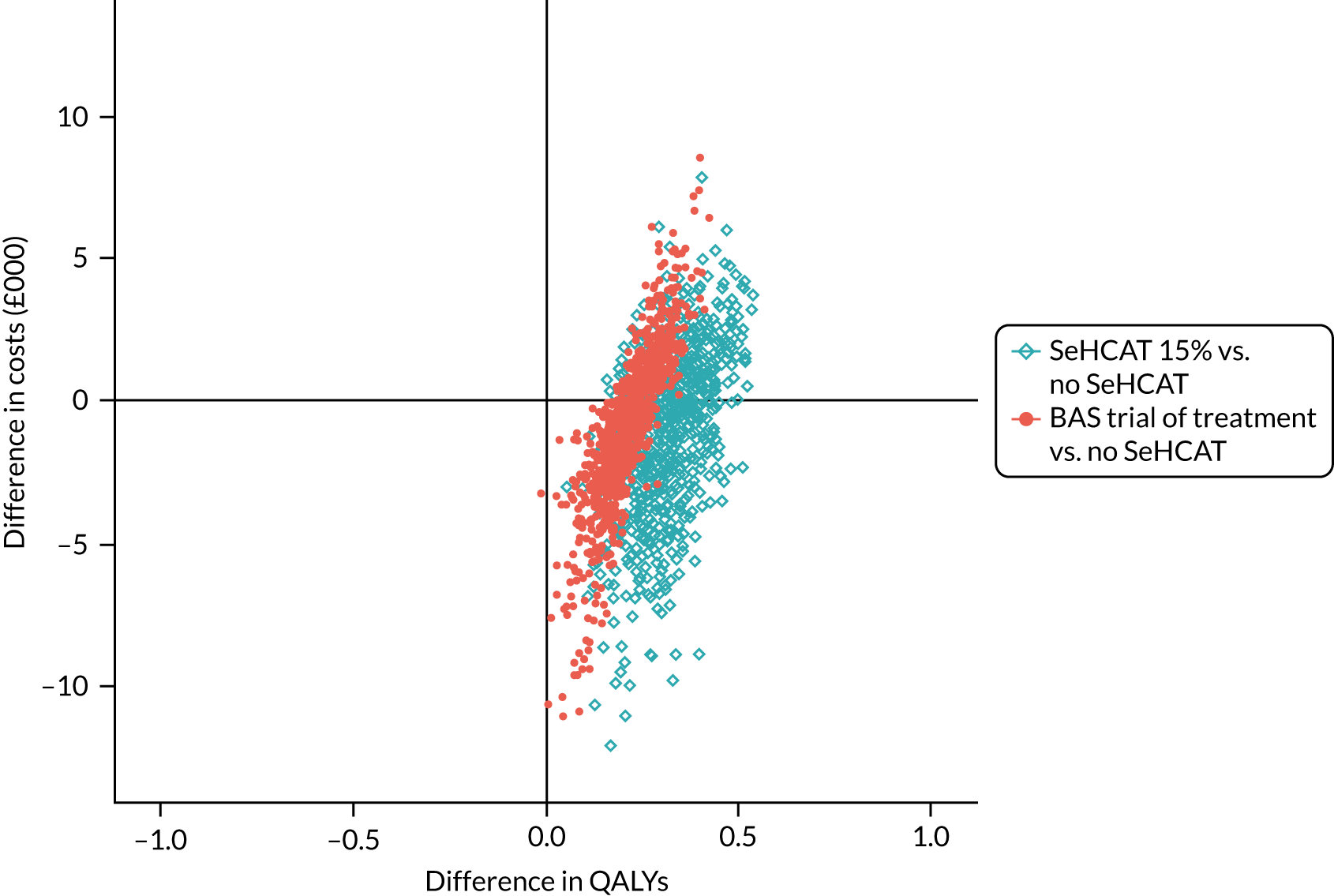

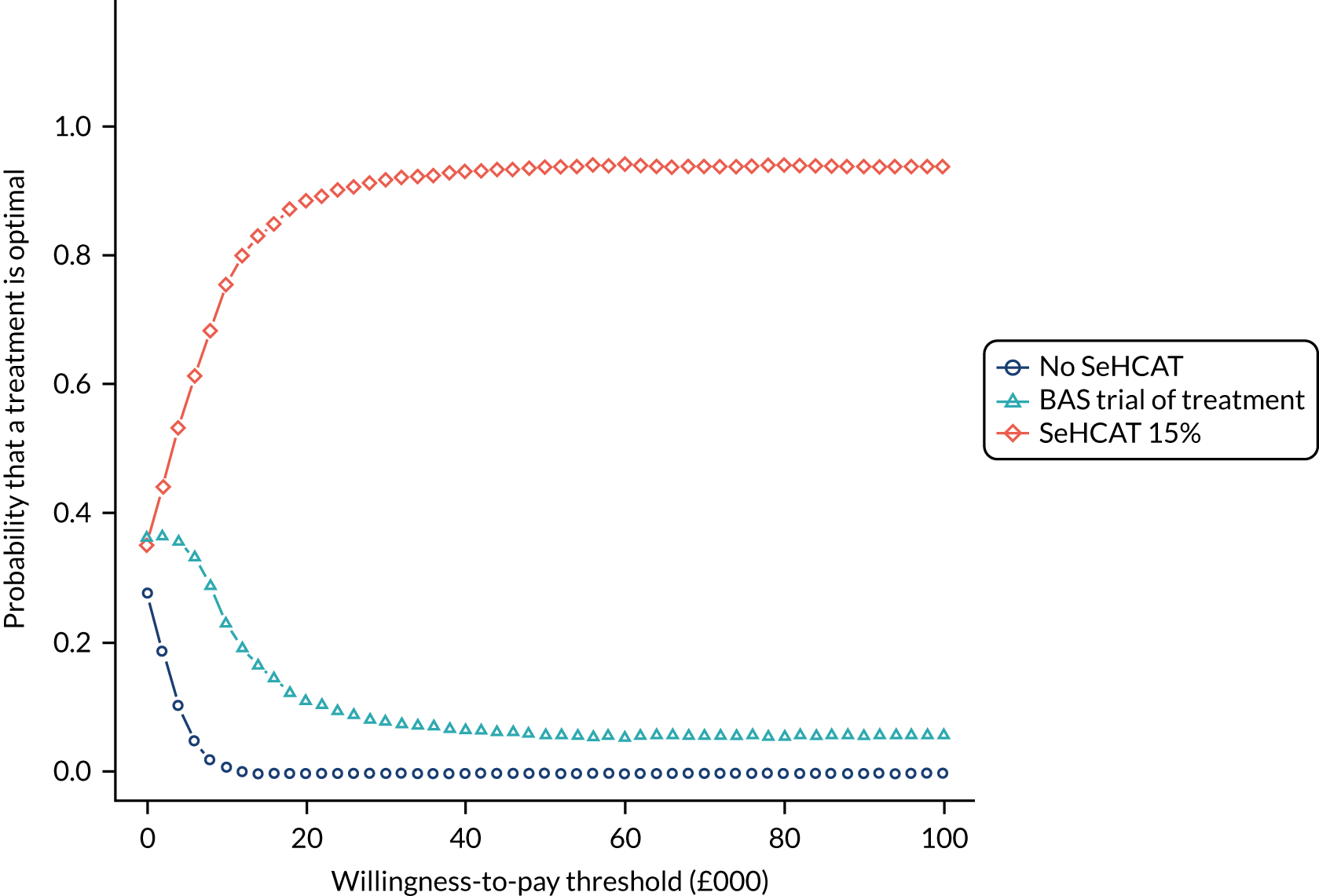

-