Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number NIHR128128. The contractual start date was in January 2020. The draft manuscript began editorial review in November 2022 and was accepted for publication in September 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Hughes et al. This work was produced by Hughes et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Hughes et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Co-occurring serious mental health problems and alcohol/drug use

The focus of the realist evaluation co-occurring (RECO) study is on people who have severe and enduring mental illness (SMI). This group is likely to require support and treatment from secondary mental health services such as inpatient mental health units and/or community mental health services for at least some of their lives, and approximately 30–50% of them have a coexisting alcohol/drug condition. 1,2 SMI includes individuals with psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia, paranoid psychosis, schizoaffective disorders, bipolar affective disorders, and long-term and severe depression. It is also recognised that many people (70–80%) who seek help for drug and alcohol conditions also experience co-occurring mental health problems such as depression, anxiety and personality disorders. However, serious mental health issues are less commonly seen in addictions services with 16–21%3 also having a SMI. 4

Co-occurring severe mental health and alcohol/drug conditions (COSMHAD) are associated with significant negative impacts on health and social outcomes including increased risk of suicide and self-harm,5 violence perpetration and victimisation,6,7 contact with the criminal justice system and forensic mental health,8 and higher overall service costs (as a result of more frequent and longer admissions to hospital) than those with single diagnoses,9 comorbid physical health problems10 and social problems including homelessness. 11 These issues are further compounded by comorbidities going untreated, with a UK study12 observing that over a third of drug users with a comorbid psychiatric disorder received no treatment for their mental health.

Co-occurring severe mental health and alcohol/drug conditions interventions

There is currently very limited evidence to inform the treatment of COSMHAD. The evidence to date comprises evaluations of psychosocial interventions,13,14 integrated treatment models15 and evaluations of workforce training. 16 There remains a lack of definitive evidence to inform how service models and treatments could improve health and other outcomes for this population. One of the challenges of undertaking research with individuals receiving care for COSMHAD is that they are a heterogeneous group. Individuals can differ greatly both in terms of the type of mental health problem(s) and the type and severity of alcohol and/or drug use. Furthermore, those receiving care for COSMHAD often present with a number of other diverse and complex needs, particularly around housing and employment. Research studies often exclude those who are currently mentally unwell (particularly those with SMI) and/or those who face barriers to participation such as homelessness. Consequently, the already limited evidence from the COSMHAD literature is further weakened by the findings potentially representing a very limited subsection of this population.

Co-occurring severe mental health and alcohol/drug conditions policy in the United Kingdom

Co-occurring mental health and alcohol/drug use (encompassing all mental health conditions, not just serious and enduring), which was previously referred to as ‘dual diagnosis’, has received a significant amount of attention from policy-makers. In 2000, the All Party Parliamentary Drugs Misuse Group published a short report outlining the challenges posed. This included people ‘falling between the gaps’ and consequently not receiving support for their mental health or substance use due to the narrow focus and differing philosophies of treatment organisations.

In 2002, the Department of Health published the Dual Diagnosis Good Practice Guide17 which set out the requirements for the treatment of co-occurring mental health and substance use. Central to this guide was the concept of ‘mainstreaming’. This approach advocates that the workforce in relevant services should have the appropriate training and capabilities to offer treatment that addresses and integrates both mental health and substance use issues. Mainstreaming requires clinical leadership roles to offer training and support to implement this at a local level. It was further recommended that care for this group should be integrated, with key agencies working together to develop agreed care pathways to ensure that people get the right help, in the right place, at the right time. However, 5 years after this guidance was released, there was still significant national variation in the provision of care, with 40% of local implementation teams failing to implement an agreed ‘dual diagnosis’ strategy and less than half having assessed the training needs of staff. 18

In 2011, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published clinical guidance on the management of psychosis and substance misuse, to better support the provision of care for COSMHAD. 19 This was followed in 2016 by broader NICE guidance on COSMHAD treatment in community health and social care services, informed by a systematic review of research evidence as well as expert opinion. 19 More recently, Public Health England (PHE) released refreshed policy guidance. 20 This broadly reflects the original principles of mainstreaming (i.e. it’s ‘everyone’s job’, with ‘no wrong door’ for people trying to access help); however, it also broadens its remit to consider the wider health and social care sector including the third sector providers of substance use treatment, and the growth of volunteers and peer support. This broader remit reflects the core elements of the NHS Long Term Plan (LTP) and Community Mental Health Framework (CMHF),21 with the ambitions of these underpinning the unprecedented transformation currently happening within health and social care. Within this, there is a focus on working with multimorbidity, reflected in, for example, the definition of SMI used in the CMHF including multimorbidities such as substance use. Indeed, the CMHF states that ‘In this Framework, close working between professionals in local communities is intended to eliminate exclusions based on a person’s diagnosis or level of complexity’ (p. 5), with complexity noted as being influenced by multiple factors including ‘co-occurring drug and alcohol-use disorders’ (p. 20). Such transformation focuses on a move to integrated working and a focus on addressing health inequalities across the whole system with the creation of 42 Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) in England. Within ICSs sit Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) which have taken on the commissioning responsibilities throughout England, formalised legally by the new Health and Social Care Act that came into force in July 2022. Alongside this, ‘From Harm to Hope’, the 10-year drugs plan,22 was published in December 2021, which reflects commitment to implementing Dame Carol Black’s key recommendations,23 by ‘ensuring better integration of services – making sure that people’s physical and mental health needs are addressed to reduce harm and support recovery’ (p. 8).

Policy in the devolved nations has also called for improvements in the delivery of care for people with COSMHAD. ICSs have been in place in Scotland and Wales since their respective devolutions, with 31 health and social care partnerships across Scotland and 7 regional partnership boards across Wales. In Northern Ireland, substance use policy24 cross-references with mental health strategy and specifically calls for improvements in the delivery of integrated care for people with COSMHAD and specifies the ambition for expert leader posts to be created in every area to ensure that this happens. The Scottish mental health strategy 2017–2725 identifies specifically that people with COSMHAD fall through gaps in services and integration. It sets out that authorities should work jointly to address these gaps in order to provide holistic care. Mental health is briefly mentioned in the Scottish Alcohol and Drug Treatment strategy26 and calls for more integrated work treatment and suicide prevention. The Wales Substance Use Delivery plan 2019–2227 calls for improvements in joint working and mentions co-occurring mental illness as an area for development, particularly that no one should be excluded from mental health services because of a concurrent substance use issue.

However, despite the sustained development of policy related to COSMHAD across the UK, there remains a lack of operational and granular detail as to how to achieve ‘better integration of care’ and ‘prevent people falling through [the] gaps’. There is uncertainty about how care should be delivered, under what contexts it works (or does not work) and whether a range of approaches, rather than a single approach, is required to meet the needs of such a diverse group.

Study aims and outcomes

The aim of this study was to use a realist approach28 to understand COSMHAD treatment models by investigating what works for whom, why, and in what circumstances.

Structure of report

The report is divided into five chapters: Chapter 1 covers the background and aims. Chapter 2 covers the design and procedures for the three work packages (WPs), Chapter 3 covers WP2 mapping and audit findings and Chapter 4 covers the development of initial programme theories (IPTs) (realist synthesis of evidence) and the refinement of the PTs using data from the case study evaluation. Chapter 5 discusses the findings, strengths, limitations and implications for policy, research and practice.

Chapter 2 Design and methods

Overall study design

In order to address the aims of the study, the project was divided into three complementary WPs. The literature mapping and realist synthesis in WP1 provided valuable insights into existing treatment models and practices for COSMHAD, allowing us to develop and refine an overarching PT (explanatory framework) of what works, for who, in which circumstances and why. In WP2 a national mapping exercise and audit identified COSMHAD care provision in the UK, and gathered detail regarding how services function in practice, further refining the PTs developed in WP1 by elucidating the contexts in which COSMHAD treatment is intended to operate. Finally, in WP3, case studies were used to further test and refine the PTs in different models of COSMHAD care using data from people who work in those services and people who use those services (and carers). It is important to note that although the research is described in three distinct phases, the process of conducting realist research is iterative rather than linear, cycling between literature searching and data collection, with constant refinement of, adjudication between, and evidencing of emerging PTs.

Work package 1: developing programme theories

Justification for choice of realist synthesis framework

Realist approaches attend to the ways that interventions (or programmes) may have different effects for different people, depending on the context. An intervention or service for people with COSMHAD is considered to provide resources that alters the context, triggering a change in the reasoning of intervention participants, leading to a particular outcome, that is context + mechanism = outcomes (or CMOs). CMOs are used as explanatory formulae (otherwise referred to as realist PTs), which are then ‘tested’ either through literature (synthesis) or empirical data (evaluation) and refined as the project progresses. They, in effect, postulate potential causal pathways between interventions and impacts. Thus, use of a realist approach was intended to help expose the multiple resources delivered as part of services for COSMHAD, the ways these were employed with different people and how they generated different outcomes. Furthermore, with any service or intervention, implementation can lead to the programme being interpreted and/or utilised differently, with possible impact on outcome. Realist methodologies aid the development of a broader picture of how such combinations of context and underlying causal mechanisms can improve or impair programme fidelity and efficacy. 29 Realist synthesis methods provide valuable insights into ‘literature ideals’ and develop and refine PT(s) of what works, for who and in which circumstances.

Research questions

The research questions identified for the realist synthesis were:

-

What does the existing literature suggest ‘works’ (demonstrated by engagement and other health outcomes) in terms of COSMHAD, for whom and in which circumstances?

-

What are the current range and types of service systems that currently operate in the UK that aim to improve engagement and health outcomes for people with COSMHAD?

-

What are the specific contexts and mechanisms that make COSMHAD models successful (or not), for whom and in which circumstances?

To inform our understanding of the current range and types of service systems, we used a literature mapping approach to map the types of services/models that exist for people with COSMHAD in the UK. From this, a typology of service provision models was developed which was used to further focus the realist synthesis questions and inform the analysis of the national mapping study (WP2).

Methods for literature mapping

Seven health, social sciences and educational databases (Medline, Cochrane, EMBASE, Web of Science, CINAHL, PsycInfo and HMIC) were searched in March 2020. A comprehensive search strategy was developed using a combination of free text and controlled vocabulary terms and adapted for each database. Search terms were drawn from five categories relating to SMI, substance use, co-occurrence, service integration and delivery of health service-related terms. A full search strategy is included in Appendix 1 (see Tables 9 and 10). Database searches were supplemented by searching grey literature, websites related to mental health and substance use, and by checking the reference lists of retrieved articles and COSMHAD-related policy documents.

The searches identified 5099 articles which went through a two-stage title and abstract screening process by two reviewers (JH, TA) using the Covidence (Melbourne, VIC, Australia) review management software. Any conflicts were resolved through discussions with a third reviewer (LJ). In stage 1, an initial corpus of 817 articles focusing on co-occurring SMI and substance use service provision and use was identified. In stage 2, the number of articles was subsequently reduced to 414 which met the screening objectives for the literature mapping.

Studies were included in the literature mapping if they described services for people with COSMHAD aged 18 years and over. We excluded services which specifically integrated COSMHAD with addressing additional conditions/needs (such as HIV or violence/aggression) and those delivered in population specific specialist settings (such as veteran services, prison services and services for homeless populations). Empirical studies, reviews and service description focused articles in practice-based journals were eligible. Full text articles were screened by one researcher and 20% were double-screened by a second researcher (LJ). Due to a wide variety of literature and the contextual differences in delivering COSMHAD services in high-income countries, the decision was made to focus on UK-based studies. These papers were deemed most relevant to the wider aims of the study and best placed to develop a framework for the service mapping exercise.

Formal quality assessment of the articles included in the literature mapping was not undertaken. We used a structured approach to data extraction based on the four domains of the Effective Organisation and Practice of Care (EPOC) taxonomy developed by Cochrane (2015).

Methods for realist synthesis

Our protocol for the realist synthesis was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020168667). In phase 1, we developed and verified potential PTs from the published literature and with stakeholders. In phase 2, we conducted a systematic search of the relevant literature, supplemented by further purposive explorations for evidence, underpinning each PT component. The review followed the five stages identified by Pawson:1 (1) identifying the review question, (2) search for studies, (3) quality appraisal, (4) extract the data and (5) synthesising the data and disseminating the findings.

Identification of programme theory

A classic realist synthesis begins with the identification of opinions and commentaries as a source of PTs for which evidence is then sought. 5 We therefore began by analysing policy documents and articles describing COSHMAD services in practice in the UK. We also held one 2-hour workshop with clinicians, policy-makers, managers and academic experts (n = 14) to gather their views on what worked for COSMHAD services in the UK, for who and in which circumstances. We also attempted to engage with individuals who had experience of COSMHAD; however, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and lockdown restrictions meant that this was not possible in the early stages of the realist synthesis.

The findings from the literature, key policy documents and the workshop were triangulated to develop a sketch of the COSMHAD programme (Figure 1) and 16 draft PTs. This was achieved by extracting if/then statements from the literature, workshop transcript and key policy documents (including from NICE and PHE) which were then grouped. Key concepts that were important to the programme (‘engagement’ and ‘integration’) were explored and defined from the relevant literature. The 16 draft PTs and an initial programme sketch (see Initial programme theories) were reviewed and refined by the entire project team (n = 9). By combining service descriptions from the practice literature and views of stakeholders, we were able to identify underpinning mechanisms by which different programme components achieve their outcomes, as perceived by those actively involved in designing and implementing COSMHAD services. The 16 draft initial PTs are shown below.

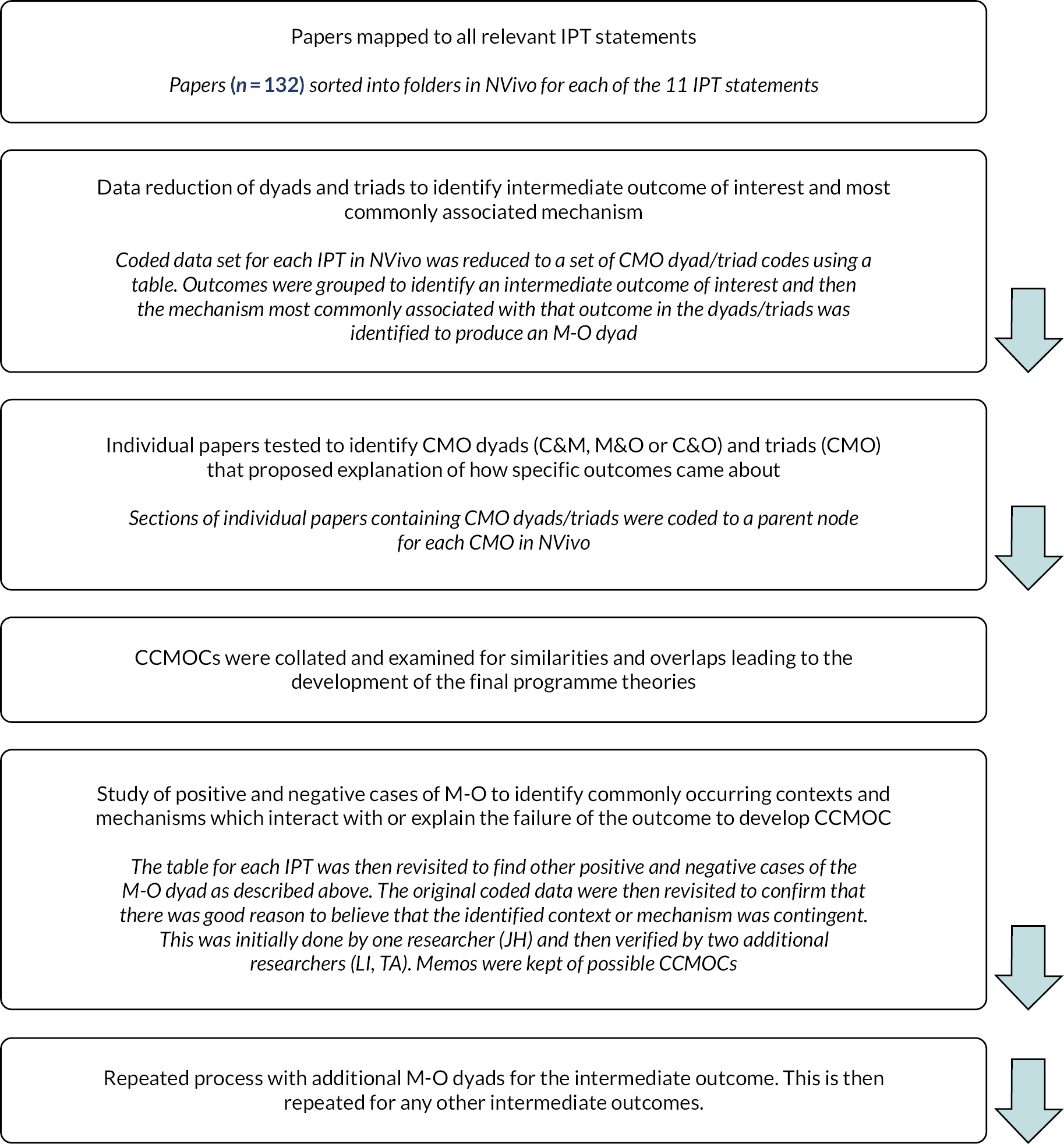

FIGURE 1.

Summary of the data extraction and analysis process for the realist synthesis.

-

‘Everyone’s business’: Recognising that COSMHAD is the responsibility of everyone who comes into contact with these service users will increase their access to mental health and substance use support and reduce exclusion due to crisis or intoxication.

-

Positive attitudes: A shared, empathetic and non-judgemental attitude towards individuals with COSMHAD across all services can reduce stigma, improve engagement and prevent premature discharge from services.

-

Collaboration: Strong and consistent management which promotes understanding of COSMHAD and the benefits of collaboration facilitates collaborative working between services to support multiple and complex needs.

-

Workforce education: Continuous education (from undergraduate/pre-registration onwards) which incorporates the biopsychosocial approach to individuals with COSMHAD will assist staff to deal with the complexities faced by these service users and appropriately employ behaviour change strategies.

-

Workforce support and development: Comprehensive workforce development which includes dual diagnosis training and ongoing supervision and skills development (e.g. shadowing, work-based learning and multiagency meetings) ensures that staff have the right values and skills to assess and respond to the needs of individuals with COSMHAD.

-

Leadership: COSMHAD opinion leaders are needed at the practitioner, operational management and strategies management levels to ensure that the needs of people with COSMHAD are met by driving forward new/modified practices.

-

Care pathways: A formalised collaborative pathway of care with ‘buy-in’ from all key agencies and opportunities for practitioners to meet with each other (e.g. through network) will ensure all teams, services and specialisms have good relationships to collaboratively respond to individuals’ needs.

-

Strategic senior level commitment: Senior managers/commissioners must believe it is right for them to be involved and accountable for COSMHAD service development by putting in place strategic frameworks to improve access to services and reduce health inequalities.

-

Sustaining practice: Continuous training and supervision is needed to sustain COSMHAD service models and allow staff to stay involved in practice.

-

Networks: Multiagency groups or networks for practitioners can increase their awareness of other services and improve service delivery (e.g. through improved referrals and reduced waiting times).

-

Mental health as lead agency for care: Mental health service care co-ordinators should take the lead in developing a care plan and co-ordinating services which will improve people with COSMHAD’s access and engagement with services, response to care, recovery and longer-term outcomes.

-

Commissioning: Strategic commitment to reconcile differing funding and commissioning arrangements is needed to develop an effective, collaborative COSMHAD pathway.

-

Evaluation impact of staff training: Evaluation measures need to be put in place to determine the impact of staff training on outcomes for service users.

-

Evaluation outcomes: Evidence-based quality improvement measures are needed to evaluate the impact of COSMHAD services and capture learning across services.

-

Recruitment and retention: Processes are needed to ensure that staff with the requisite COSMHAD skills, knowledge and values are recruited and retained in services to deliver better care.

Identifying formal theory to inform the initial programme theories

The process of identifying formal theories which assisted in explaining our PTs6 took place iteratively throughout the realist synthesis, mainly over two phases. Searches for theory to help inform the development of the IPTs, described in this section, and searching for theory to inform and develop the final PTs, took place during the data analysis phase.

Following the project team review of the if/then statements, we began working to refine these theories into context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) statements. In some realist synthesis, the intervention under investigation has well-defined boundaries and outcomes and the PT is explicitly stated. However, COSMHAD service models are complex, large scale and ‘messy’,7 requiring transformation and organisational culture change within publicly funded services. 8 As our early work developing draft PTs identified, COSMHAD programmes in the UK were often not a well-defined intervention, rather they were often a set of ideas which had been tried, and not always in a systematic or uniform way. We therefore undertook a purposive search of theories and frameworks that covered the various aspects of the COSMHAD service model. We developed an initial shortlist of 16 substantive theories (at the middle range)30 from the field of COSMHAD, other realist work looking at similar service transformation, and our own expertise in public health, psychology and other relevant fields.

The shortlisted theories were appraised according to the following criteria developed from Shearn et al.’s31 guidance for complex interventions: (1) the level in the social system (offering explanation at the micro, meso or macro level); (2) their fit with our research aim of explaining how COSMHAD services work, for who and in which circumstances; (3) their simplicity in inspiring theory generation; and (4) their compatibility with the realist notion of articulating causation. Four theories were selected which best fitted the criteria and helped explain various aspects of the PTs. Normalisation process theory (NPT)9 was used as an overall framework to inform the generation of the final PTs, with the four sense-making, relational, operational and appraisal domains used to organise the PTs. Three additional theories were used to help refine specific PTs, namely: the Health and Stigma Framework10 (PT 2), the Framework for Action in Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice11 (PT 3) and the Integrated Commissioning for Better Outcomes Framework12 (PT 10). The use of these theories expanded the team’s thinking around specific aspects of the PTs. For example, use of NPT allowed us to consider the relationship between the sense-making, relational, operational and appraisal work required of stakeholders when working to co-ordinate care for people with COSMHAD.

Finalisation of the initial programme theories

Eleven IPTs were developed, which included context, mechanism (including resource and response) and outcome. These PTs were reviewed and refined through consultation with the entire project team. Following development, we searched for empirical evidence to test and refine the IPTs. The decision was made to use the initial corpus of 817 articles identified in the literature mapping as the preliminary starting point for the realist synthesis. This is because, as recommended by Booth et al.,32 the initial search terms had been developed in consultation with the project team who represented a range of stakeholder perspectives and the literature identified through structured searches had been supplemented by literature provided by stakeholders and sampled purposively. These 817 articles provided us with an initial, exhaustive search of examples of service provision which we considered an ‘initial sampling frame of empirical papers’13 (p. 151). However, it is recognised that realist searching is an iterative process, with search criteria often emerging as theories are proposed, tested and refined. We therefore took an iterative approach to literature searching, with additional articles being identified and included through CLUSTER searching to identify sibling studies, citation tracking and named and complementary theory searches as the review progressed. 13

The 817 full texts were screened against criteria made up of the 11 PTs. Articles were selected for inclusion when they provided causal insights into the PTs by: (1) reporting on integration of services for people with COSMHAD; (2) describing features and functions of the integrated service architecture relevant to the PT; and (3) providing data on the outcomes of this integration. All texts were screened by the lead researcher (JH) with two researchers independently screening (TA, LJ) 10% of these articles. The three reviewers met regularly throughout the screening process to discuss their decisions and any disagreements were resolved through discussion. This discussion process was also used to identify potential studies and authors for CLUSTER searching and citation tracking, with additional purposive searches undertaken as a result. In total, 172 articles were selected for inclusion in the realist synthesis.

Quality appraisal

Realist synthesis approaches do not follow more rigid, traditional approaches to quality appraisal. The nature of the data collected by realist reviews is not always necessarily of the ‘highest quality’ in the traditional sense (i.e. they will be of variable trustworthiness). The aim of realist methods is not to arrive at the ‘final truth’ regarding the research topic. 33 Rather, realist reviewers recognise that we can only get as close as possible to a complete understanding. Realists assemble imperfect data into plausible and coherent arguments, but others may disagree with their claims. Quality appraisal in this review therefore considered each article on the basis of whether it was good enough to provide some evidence that would contribute to the synthesis. This was based on two grounds: (1) assessment of relevance and richness and (2) assessment of rigour. In the case of this review, relevance and richness were assessed as to whether the study helped to explain how context shapes the mechanisms through which UK service models for COSMHAD work, for whom, how and in which circumstances. Studies were considered as relevant where they met one of the three inclusion criteria described above and thus relevance was applied to both the topic (COSMHAD) and the PT. 34 Richness was discussed between the researchers, in terms of conceptual richness (conceptual and theoretical development) and thickness (the amount of detail provided). 35 Consideration of the study rigour took into account the plausibility and coherence of the method used to generate data and the limitations of the methods used. However, the decision to include a study in the synthesis was not restricted to a study level, pre-formulated checklist of methodological rigour. The rigour of each fragment of evidence was balanced with its relevance and the extent to which it assisted in explaining the relevant PT. Thus, assessments of a particular piece of evidence (i.e. the trustworthiness of the source) were considered alongside the overall coherence and plausibility of the PT. 36 Assessments of rigour are therefore commented on throughout the findings, at the evidence and theory level.

Data extraction and synthesis

Following this screening process, the articles were re-read and mapped to each of the IPT statements using a data extraction form. This revealed 132 articles that provided causal insights into one or more of the IPT statements. The selected articles were then imported into NVivo (version 12) (QSR International, Warrington, UK), which allowed for an organised and transparent audit trail of decisions related to the data analysis, using the linked memo function. 14 Source folders were created for each IPT and articles were uploaded to each folder based on the mapping exercise. In NVivo, parent nodes were created for each IPT and selected articles coded independently to each IPT. 14 Rather than separately coding the data from the articles into context, mechanism and outcome for each IPT statement, we attempted to identify CMO configurations directly from the literature as either dyads (context–mechanism/mechanism–outcome/context–outcome) or triads (CMO). 15 Following the identification of individual dyads and triads, we followed the process of data reduction described by Byng et al. 37 Firstly, we developed a reduced data set for each IPT by creating a table containing all lower-level codes for CMO dyads and triads. We were then able to group the outcomes (which usually had the least codes) and identify an intermediate outcome of interest for the IPT. We then reviewed the data table to identify the mechanism most associated with this outcome to create a mechanism–outcome (M-O) dyad. We then searched our coded data for positive and negative cases of the M-O to identify consistently occurring contexts and additional mechanisms which interacted or could explain the failure of the outcome which were used to produce ‘conjectured context–mechanism–outcome configurations’ (CCMOC). The CCMOC was checked against the original literature for face validity and the process was then repeated with each additional mechanism associated with the outcome and then any other intermediate outcomes for the IPT. The full process is described in Figure 1.

The process of mapping, extracting and coding data for each CMO dyad/triad was undertaken by one researcher (JH) through reading and re-reading of the data. Using a realist context–mechanism–outcome configurations lens for each outcome identified, the analysis sought to understand what contexts had fired the mechanism and underpinning common mechanisms between studies. After coding possible CMO dyads and triads, the researcher consolidated the data using tables and revisited the literature to develop the possible CCMOCs. The first stage of analysis was read and discussed with two additional researchers (LJ, TA) to ensure reliability and validity and the CCMOCs were refined following these discussions. The CCMO statements were then reviewed, refined and finalised in discussion with the realist methods lead for the project (SD).

Summary of literature mapping

A total of 23 papers met the inclusion criteria, which described 19 UK COSMHAD service models. Service models described in multiple publications were combined into a single entry on the data extraction form. Nine of the studies were delivered by mental health trusts in either community or inpatient settings, four by substance use services (three in the community and one specialist ward), and six studies involved collaboration between multiple service settings either through networks or liaison with specialist workers.

Models of service provision fell into three broad categories: (1) multidisciplinary COSMHAD groups or networks to establish provider relationships and co-ordinate care pathways; (2) placement of specialist COSMHAD link workers within existing mental health or substance use teams; and (3) specialist COSMHAD liaison workers working with mental health and substance use teams from a separate specialist COSMHAD team. These three categories are indicated in the first column of the Table 1, with the allocated colours indicating elements specific to that model.

| How and when care is delivered | |||

| Co-ordination of care among different providers | Multidisciplinary network groups establish provider relationships and co-ordinate pathways | Specialist COSMHAD link workers placed within existing teams | Specialist dual diagnosis liaison workers in a COSMHAD team |

| Group vs. individual interventions | Incorporating COSMHAD into existing provision of combined individual and group interventions. Majority draw on Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and Motivational Interviewing approaches | ||

| Triage | Inclusion of COSMHAD measures into existing assessments | Joint assessment or assessment by COSMHAD worker after referral | |

| Where care is provided and changes to the healthcare environment | |||

| Environment | Within existing service environment | ||

| Outreach | Minimal engagement with assertive outreach teams in majority of models (exception COMPASS) despite recognition of high dual diagnosis prevalence and benefits of proactive engagement | ||

| Site of service delivery | Site of usual provision | Mental health or substance use teams. Majority placed in mental health teams | Additional team providing separate or integrated care |

| Site of organisation | Model coverage usually by geographical area – majority defined by catchment of NHS Mental Health trust (small number by substance use service) | ||

| Who provides care and how the healthcare workforce is managed | |||

| Role expansion or task shifting | All staff have increased awareness of dual diagnosis and are able to co-ordinate care for these service users | Staff specialising in COSMHAD lead on raising awareness and facilitating co-ordinated care for team in

|

Staff specialising in COSMHAD provide time-limited service to raise awareness and support teams in delivering integrated care |

| Pre-licensure education | Range of experience and education among membership provides new perspectives | Challenging to find balance between mental health and substance use expertise, and between level of education and amount of experience in practice | |

| Co-ordination of care and management of the care process | |||

| Care pathways | Establishing and formalising collaborative care pathways for individuals with COSMHAD. Stepwise approach based on the US Integrated Treatment Model (detection, engagement, motivation, active treatment and relapse prevention) | ||

| Case management | Case management remains responsibility of service user’s existing case manager with time-limited specialist joint working, consultation and assessment to assist with this | Case management largely remains responsibility of case manager with support, but in some services the specialist may take over case management in cases with severe complexities or chaotic engagement | |

| Communication between providers | Communication should be transparent and built on mutual trusting relationships. This can be achieved formally through documentation at service and service user level, and informally through multidisciplinary attendance at groups and networks | ||

| Continuity of care, discharge planning and referrals | Discharge and continuity of care should be a key part of joint care plans | ||

| Shared care and decision-making | Shared care and decision-making between mental health and substance use teams (and wider services). Shared care protocols and documentation of care in care plans and referral letters is important | Shared care and decision-making between link/liaison worker and service user’s case manager. Link worker often brokers shared care arrangements with other services | |

| Funding | |||

| Funding | Majority of models operated on no dedicated funding or single source of funding (e.g. from local budgets or research funding) | ||

| Governance arrangements | |||

| Governance arrangements |

|

||

| Implementation strategies | |||

| Organisational culture | Integration means COSMHAD is the responsibility of all staff who encounter these service users. Address:

|

||

| Communities of practice | Formalised to varying degrees but involve groups of practitioners who work with people with COSMHAD meeting regularly for case discussion, sharing experiences and practice, peer support, local supervision and facilitating joint working. Learning then fed back to organisations | ||

| Clinical practice guidance | Resources such as manuals, service directories and local practice guidelines can support link workers and network members to deliver key principles of COSMHAD in their services | ||

| Interprofessional education | Two levels of training identified:

|

||

| Local opinion leaders | Two types of local opinion leader required:

|

||

| Managerial and clinical supervision | Link/liaison workers provide supervision to colleagues to assist them to work with people with COSMHAD but also require supervision from COSMHAD specialists to prevent them becoming isolated in their roles | ||

Work package 2: national mapping and audit of services

Work package 2a: national mapping procedure

The aim of WP2 was to identify the location and types of provision of service models for COSMHAD across the UK. This comprises a general mapping exercise then an audit form for those identified.

For the mapping process, requests for information were sent to organisations across the UK who were likely to be responsible for providing or commissioning COSMHAD care. This included every NHS mental health trust and local authority in the UK, as well as all clinical commissioning groups (CCGs; now recognised to have transitioned to ICBs) and devolved nation equivalents including health and social care NHS trusts and local commissioning groups in Northern Ireland, and health boards in Wales and Scotland. We also contacted Public Health England, the Northern Ireland Department of Health, Public Health Reform Scotland, Health Protection Scotland, Scottish Association for Mental Health, Inspire Wellbeing, Turning Point and Mind. We adopted a broad definition of COSMHAD care to include services. At this stage, our definition of what was included as a service or provision was sufficiently broad to be inclusive, but specific enough to meet the aims of the study in (1) explicitly containing elements of provision for people who meet our inclusion criteria and/or (2) having a written service level agreement or guidance describing what is offered and to whom in relation to COSMHAD.

Requests were sent in the first round by email, and in the second round using Freedom of Information (FOI) requests, asking for the following information (a complete version of the request sent can be seen in Report Supplementary Material 1):

-

Details of the approach/treatment pathway for COSMHAD treatment that the contacted organisation commissioned or was commissioned to provide – particularly whether it was commissioned specifically for COSMHAD.

-

Details of any other COSMHAD services that organisations were aware of operating in their region.

-

The name and contact details of the local COSMHAD/dual diagnosis lead.

The first wave of information requests was sent in March 2020, with a second wave sent in October 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic severely reduced the capacity of many organisations to engage fully with our requests. A third wave of requests was planned to be sent early in 2021; however, with a new national lockdown beginning in January 2021, it was decided that this third wave of requests would have been of limited utility.

Work package 2b: service audit/survey

To gain a deeper understanding of how COSMHAD services across the UK are commissioned and operate, a more detailed service audit was developed with input from the RECO team members, individuals with lived experience, and those involved in commissioning and delivering COSMHAD care. It included closed and open-ended questions on commissioning, provider, models of care and available treatments, managing joint working between mental health and drug and alcohol treatment, and staffing resource health economic data such as staff numbers and resource use (see Report Supplementary Material 2 for full questionnaire).

The RECO group reviewed the mapping data and identified 16 services that had at least one person employed as part of their local response to COSMHAD, and they were invited to complete the audit.

Potential services were first approached by e-mail, describing the RECO project as a whole and the rationale for collecting service provision information, and asking to be put in contact with an individual within the service best situated to provide the necessary information. Once contact was made with this individual, a link to the survey was sent along with instructions of how to complete the survey, including the option to complete the survey over the phone. Participants choosing to complete the survey online were given 2 weeks to complete and return the survey and were contacted by the study team if the survey had not been returned after this time. If a returned survey did not include sufficient detail, respondents were contacted to ask if they would be willing to be contacted by phone to collect missing details. Participants choosing to complete the survey over the phone were made aware of specific questions that may require preparation on their part (e.g. staff numbers dedicated to COSMHAD care) and a date was organised for the survey to be completed. Data from the online survey were downloaded into Statistical Package for Social Science to analyse multiple response sets and descriptive analysis.

Case study procedures

Site selection and setting

A set of six case study sites were chosen from those that completed the online audit. The services were grouped as follows based on the information they provided:

-

specialist worker plus link workers (lead and link)

-

consultancy model (consultancy)

-

network model (network).

From the responses, we chose case studies that represented all three types of models (three lead and link, one consultancy and two network). We also ensured that we included at least one service from a devolved nation. Case studies were specifically defined as the primary COSMHAD service (the mental health service provider) and the relevant partnering agencies. All case studies were complex in that they described a social complex service, but also because substance use treatment services did not neatly configure geographically with the mental health providers.

Staff recruitment

Staff were invited to participate if they worked in mental health and substance use services in the case study locality, including those in dedicated COSMHAD roles. Each case study had a link clinician through which the research team communicated. Initial e-mails were sent to COSMHAD care personnel in each of the six study sites, with individuals wishing to take part contacting the study team directly.

The researcher (JH) liaised with the link clinicians to book dates for staff focus groups at convenient times and undertook all focus groups and interviews for consistency. Each focus group was also co-facilitated by two RECO researchers (EH, AC, EG). Typically, two staff focus groups were required for each site, with relatively small participant numbers in each one to allow space for each person to discuss and contribute. Quotes from service providers in the narrative are indicated using the label SP.

Service user and carer recruitment

The target was to recruit 12 service users and 6 carers at each site. Service user inclusion criteria were broad and inclusive: people with a SMI (including psychosis, bipolar affective disorder, schizophrenia, severe depression, personality disorders) who had accessed local mental health and/or substance use services.

Co-occurring severe mental health and alcohol/drug conditions service users and carers were first approached by staff at case study sites who provided them with details of the study. Posters advertising the study were also placed in treatment centres. Those interested in taking part could contact the study team directly or elect for the treatment centre staff to pass their contact details on to the study team. All participants completed an online consent form prior to taking part in the focus groups, and mobile phone data vouchers were made available to allow access to the study.

The original intention was to conduct the interviews face to face, but due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a need to move data collection to an online format. Realist interviews are quite different to qualitative interviews; rather than taking a constructivist approach which aims to elicit participant narratives, the primary aim of realist interviews is the development, refinement and consolidation of PTs, depending on what stage of the research cycle the interviews are being conducted. 38 In the context of the RECO study, the interviews were intended primarily to facilitate the refinement and consolidation of the PTs developed through the earlier WPs. This entailed asking considered and purposeful questions to elicit specific information regarding PTs, including directly presenting interviewees with PTs in a conversational style, to spark discussion about how well they matched participants’ experiences.

A convenient date and time for the data collection were arranged and an invite to the Microsoft Teams meeting circulated. A topic guide was formulated to guide the focus groups, underpinned by the PTs from the realist review. However, with the constant iteration between testing and refinement of PT, the topics addressed at each focus group were highly dynamic. At the start of each session, participants were asked to respect the confidentiality of the focus group discussion. If during the session a participant became distressed, there was an option for one of the facilitators to meet them in a virtual break-out room. All service user and carer participants were offered an optional debrief call after the focus group. Participants were informed prior to the session that their name would be visible during the focus group, but all data would be anonymised for analysis. All service user and carer participants received a £10 gift voucher to thank them for their time.

The online interviews and focus groups were recorded and auto-transcribed in Microsoft Teams. Quotes from service users and their carers are indicated in the narrative using the label P. Carers are indicated in the quote label.

Costing case study sites

While there was not the scope or remit within this study to undertake an economic evaluation of the services, we costed the case study sites from an NHS perspective following a mix of top-down and bottom-up costing approaches. A generic costing pro forma was developed from the data identified in the service audit (WP2). This included costing categories on staffing resource (direct and indirect), costs directly related to intervention delivery, intervention-related costs, training, equipment and overheads related to delivery or maintaining the service. The costing pro forma was sent to the service leads in each of the six case study sites and followed up via e-mail. Where required, a Teams call was arranged to assist with completion. Where available, actual costs were obtained directly from the case study sites, otherwise NHS pay scales were used. Cost data were entered into Excel and total per annum costs over the financial year 2021–2 were estimated for each site. Recommendations for future health economic research are articulated in the discussion.

Ethics and governance

This study could be considered ‘low risk’ as the main data collection methods were qualitative interviews with staff, people with lived experience and their carers. However, this service user group is deemed by the nature of their mental health and co-occurring substance use to be a ‘vulnerable group’. The main ethical consideration was the potential for the interviews to be upsetting by asking people about their experiences of help-seeking (some of which may have occurred during times of crisis). The other consideration was that someone could disclose information about risk to self and/or others. NHS ethics and HRA approval were obtained on 17 June 2021 (Surrey Research Ethics Committee RE21/LO/0384 IRAS 277924).

Ethics amendments

Five amendments were approved, but most of these were minor administrative changes that did not affect any participants or the design:

-

Amendment one – extend the data collection period to 31 July 2022 (due to COVID delays).

-

Amendments two and three – adding additional sites.

-

Amendment four – changing name of NIHR to National Institute for Health and Social Care Research on the study documents.

-

Amendment five – to add the option to undertake data collection in person as well as online. This was added towards the end of the data collection period in June 2022 as COVID-19 restrictions had lifted and there was an opportunity to meet with a carer group.

Data management

The chief investigator (EH) at the University of Leeds (study sponsor) was the data controller. All RECO data were stored in University of Leeds RECO study Teams site and only the research group had access. Raw data in the form of transcripts were also stored securely at Liverpool John Moores University and analysed in NVivo, before being uploaded to the RECO Teams folder at the University of Leeds. All transcripts were anonymised, and we have removed identifiable information so that individuals cannot be identified. Personal data (such as participant names and contact details used for the purposes of arranging focus groups and interviews) were destroyed after data collection was completed. As well as being used to support the current research, data that have been anonymised may also be used to help with relevant future research and/or training, and this may be shared anonymously with other researchers (subject to relevant research governance processes such as confidentiality and data access agreements). Anonymised data may also be made available indefinitely on a public database so that when research is published, it is clear to everyone what the research process was. When we use anonymised data in this way, the participant will not be identifiable. Anonymised research data will be stored for 10 years and then destroyed in accordance with the University of Leeds’ research data policy.

Public and patient involvement

The proposal ideas were discussed with a group of people with lived experience of mental illness and substance use and they told us how difficult it could be to access services with this type of comorbidity. We had a co-investigator (CW) who has lived experience of SMI and is an author of the report. We engaged with people with lived experience during stakeholder consultation for the development of PTs for the realist synthesis, and also in the development of the protocol for the ethics application. They informed us not to combine data collection with staff and service users in one group, because they felt that service users may feel uncomfortable being honest about their experiences in front of service providers. They also advised on how best to promote participation and ways to make people feel safe during and after the interviews and focus groups. This included having an option for a debrief chat after the event. The PTs were also sense-checked with people with lived experience in a meeting following the analysis. We would have liked to have done much more patient and public involvement (PPI) work, but the COVID-19 pandemic impacted on peoples’ capacity to be involved and online methods did not suit everyone.

Chapter 3 National mapping data and audit

National mapping

Requests were sent to a total of 793 individual organisations between March and October 2020. A total of 311 responses were received, 230 from the first wave of requests and 81 from the second. Of these responses, 188 provided information about services and 42 responded to confirm that this information was not held, that the organisation was not responsible for commissioning or providing COSMHAD care, or that they were unable to deal with our request at that time. Table 2 shows the response rates from each of the organisations contacted.

| Organisation | 1st wave | 2nd wave | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contacted (n) | Responded (n) | Contacted (n) | Responded (n) | |

| Local Authorities | 435 | 75 | 337 | 37 |

| NHS Mental Health Trusts | 57 | 30 | 23 | 6 |

| CCGs | 177 | 48 | 120 | 25 |

| Care Quality Commission and Devolved Nation Equivalents | 5 | 5 | ||

| Health Boards Wales | 7 | 4 | 7 | 2 |

| Health Boards Scotland | 14 | 60 | 9 | 2 |

| Health and Social Care Partnerships Scotland | 31 | 3 | ||

| Alcohol and Drug Partnerships Scotland | 31 | 1 | ||

| Health and Social Care Trusts Northern Ireland | 5 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Local Commissioning Groups Northern Ireland | 5 | 2 | 5 | 0 |

| PHE | 1 | 1 | ||

| NI Department of Health | 1 | 1 | ||

| Public Health Reform Scotland | 1 | 1 | ||

| Scottish Association for Mental Health | 1 | 1 | ||

| Third Sector Drug and Alcohol Treatment Providers | 16 | 2 | ||

| Total | 725 | 230 | 568 | 81 |

Of the 311 responses received, 190 provided sufficient information about the approach to COSMHAD treatment to be categorised. Overall, just under half of the services that responded had a specific COSMHAD service (Table 3).

| Total number of responses | Specific COSMHAD service N (%) | No specific COSMHAD service N (%) | Unclear N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 190 | 88 (46) | 78 (41) | 24 (13) |

| England | 156 | 73 (47) | 68 (44) | 15 (10) |

| Wales | 8 | 6 (75) | 0 | 2 (25) |

| Scotland | 18 | 5 (28) | 7 (39) | 7 (39) |

| NI | 5 | 4 (80) | 2 (40) | 0 |

Sixty-two per cent of responding services reported providing ‘integrated treatment’, with just over half of these not being specifically commissioned COSMHAD services. In England, integrated services were indicated more than twice as frequently than in the other devolved nations (Table 4).

| Number of responses | Integrated treatment N (%) |

Unclear N (%) | Oher N (%) | Integrated but no specific commissioned COSMHAD service N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 190 | 117 (62) | 47 (25) | 66 (35) | 64 (34) |

| England | 156 | 108 (69) | 32 (21) | 46 (29) | 62 (40) |

| Wales | 8 | 2 (25) | 4 (50) | 5 (63) | 0 |

| Scotland | 18 | 6 (33) | 11 (61) | 11 (61) | 2 (11) |

| NI | 5 | 1 (20) | 0 | 4 (80) | 0 |

Service audit

From the mapping responses, areas that had some specifically commissioned service and personnel were selected to receive the audit. Audit responses were returned from 19 respondents representing 16 services. Multiple returns from the same organisation were merged and deleted when cleaning the data.

Most services were commissioned by local authorities (44%) [or via local authorities through PHE (19%)] (63% in total), with only 31% indicating that they were commissioned by the CCG, and even fewer were jointly commissioned. Conversely, services indicated that provision and delivery was primarily through NHS mental health services (50%), followed by substance use services (38%) and joint services (6%). This suggests that the burden for funding of dual diagnosis services falls disproportionately on local government. The majority of services were categorised as lead and link worker (31%). Most services offered a broad range of interventions and modes of delivery, with only two services reporting that they delivered one intervention using only one mode. This result reflects the size of these services. Interventions tended to be delivered one-to-one (81%) and over the phone (69%), likely the reflecting the complexity of cases.

Case study sites

Summary descriptions and costs at each case study site

The six case study sites are described from the information they provided in the audit (Table 5).

| Site | Service model category | Service remit | Service inclusion criteria | Training and supervision | Annual costs (£) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Network | Specialist secondary mental health service provider. No lead clinician in post; link workers are in situ and engage with the dual diagnosis working party | No exclusion criteria if person experiencing a SMI | Clinical supervision and review cases with staff in a group setting | 72,906 |

| B | Consultancy | To support secondary mental health services to deliver integrated treatment for people with dual diagnosis. Nurse practitioners offer assessments and interventions as required but the primary role is to support care co-ordinators with training and supervision to deliver the interventions themselves | A diagnosis of severe mental illness and problematic substance use | Mandatory e-learning package for all staff; 1–2 days training for ward staff; 3 days training for assertive outreach teams. Formal and informal supervision is offered | 444,267 |

| C | Lead and link | We advise on cases and offer training. We encourage mainstreaming and provide staff with support but ideally there will be an integrated approach. There is a consultant nurse lead and champion network across the city | Specialist dual diagnosis training provided to all mental health and substance use treatment services across the city | 111,164 | |

| D | Lead and link | To engage mental health clients with substance use with local treatment services. To begin this engagement process from inpatient admission | All staff have access to dual diagnosis training that is delivered in modules covering all aspects of substance use – offered online and face to face | 167,962 | |

| E | Lead and link | We adopt the dual diagnosis champion model in acute adult inpatient wards and community mental health settings | Training at postgraduate certificate in dual diagnosis or master’s in substance use. Supervision is offered formally and informally to the local champions via clinical lead | 83,070 | |

| F | Lead and link | Delivery of integrated treatment model whereby most service users with mental illness and substance use will have both needs met at the same time, in one setting by one team | A service user who is displaying a severity of mental illness that cannot be managed in primary care or presenting a risk to staff and/or themselves/others as a consequence of mental health symptoms | E-learning for all. Emphasis on experiential learning and ongoing practice development sessions to help embed learning into practice. Tailored learning and support for teams and shadowing opportunities to work alongside dual diagnosis experts. Quarterly dual diagnosis leads development days | 2,394,537 |

Recruitment at case study sites

We recruited a total of 58 staff. Table 6 provides details of the numbers and roles of the staff who participated in the study.

| Staff role | Case study site | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | Total | |

| Mental Health Inpatient | 4 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 14 | ||

| Community Mental Health | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |||

| Community Drug and Alcohol | 5 | 3 | 1 | 9 | |||

| Community Drug and Alcohol (NHS) | 5 | 1 | 6 | ||||

| Early Intervention in Psychosis | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Dual Diagnosis Team | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 9 | ||

| Assertive Outreach | 2 | 3 | 5 | ||||

| Homeless Team | 4 | 1 | 5 | ||||

| Adult Social Care | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Total | 11 | 6 | 16 | 10 | 6 | 9 | 58 |

| Mental Health Staff Nurse | 1 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| Drug and Alcohol Nurse | 3 | 1 | 4 | ||||

| Community Psychiatry Nurse | 3 | 4 | 7 | ||||

| Psychiatry Registrar | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Doctor (Addictions) | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Consultant Psychiatrist | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 10 | ||

| Ward Manager/Matron | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Clinical Service Lead | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Social Worker | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Dual Diagnosis Lead (Nurse Consultant or equivalent) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 6 | ||

| Drug and Alcohol Recovery Worker | 4 | 2 | 6 | ||||

| Drug and Alcohol Assessment Worker | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Well-Being Practitioner | 3 | 3 | |||||

| Team Manager | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| Mental health Advisor | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Occupational Therapist | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Training Lead | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Total | 11 | 6 | 16 | 10 | 6 | 9 | 58 |

In addition, we were able to recruit 25 service users and 12 carers (Table 7). There were challenges to recruiting service users and carers. This covered the period of early 2022 to summer 2022 when restrictions were still in place due to the Omicron surge of winter 2021–2. Initial ethics approval was for online focus groups (due to the requirement for social distancing and stay at home orders), but this method of data collection was not popular with participants who were not always familiar with and in some cases (e.g. those in hostel accommodation) did not have access to sufficient technology. We did offer data vouchers to compensate for the cost of data use on smart phones, but many potential participants were not comfortable with using MS Teams. Only 6 of 25 service user interviews were completed online with 19 participants preferring to speak over the phone. This required an ethics amendment which delayed data collection. Similarly, only 2 carers chose to undertake the data collection online with the remaining 12 taking place over the phone or face to face. In the last 2 months of the project, we were given approval via an amendment to NHS ethics to collect data face to face (which had not been permitted during the pandemic). We undertook a successful carer focus group at Site B in a non-NHS community venue. At this point, there was not sufficient time within the project timescales to get the R&D approval needed from each site to undertake research face to face and so we were limited to non-NHS venues. Many service users mentioned that the groups they had previously attended during the pandemic (e.g. in substance use services) were still not running face to face following the pandemic, and these would have been valuable contact points from which we could have promoted the study. A small number of service users did engage well with online groups [four of the participants who chose to participate online came from a successful online substance use and mental health support group for LGBTQ+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer) people] but they were not popular with all service users or available at all case study sites (e.g. site E). We did attempt to incorporate our data collection into existing online groups at mental health and substance use services (e.g. at site D) but this was not successful due to groups taking place on a secure online portal which created access, data governance and storage issues. Recruitment was done through staff working in services (such as the COSMHAD leads and focus group participants). Many were still working in an extremely pressured post-pandemic environment alongside high demand for services which limited the time staff had for discussing the RECO study with potential participants. Given these significant challenges, the recruitment to the study is to be recognised as a real positive despite not meeting original targets.

| Case study site | Number of service users | Number of carers | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 6 | 3 | 9 |

| B | 3 | 9 | 12 |

| C | 10 | 1 | 11 |

| D | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| E | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| F | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Total | 25 | 13 | 38 |

Chapter 4 Identifying and refining programme theories

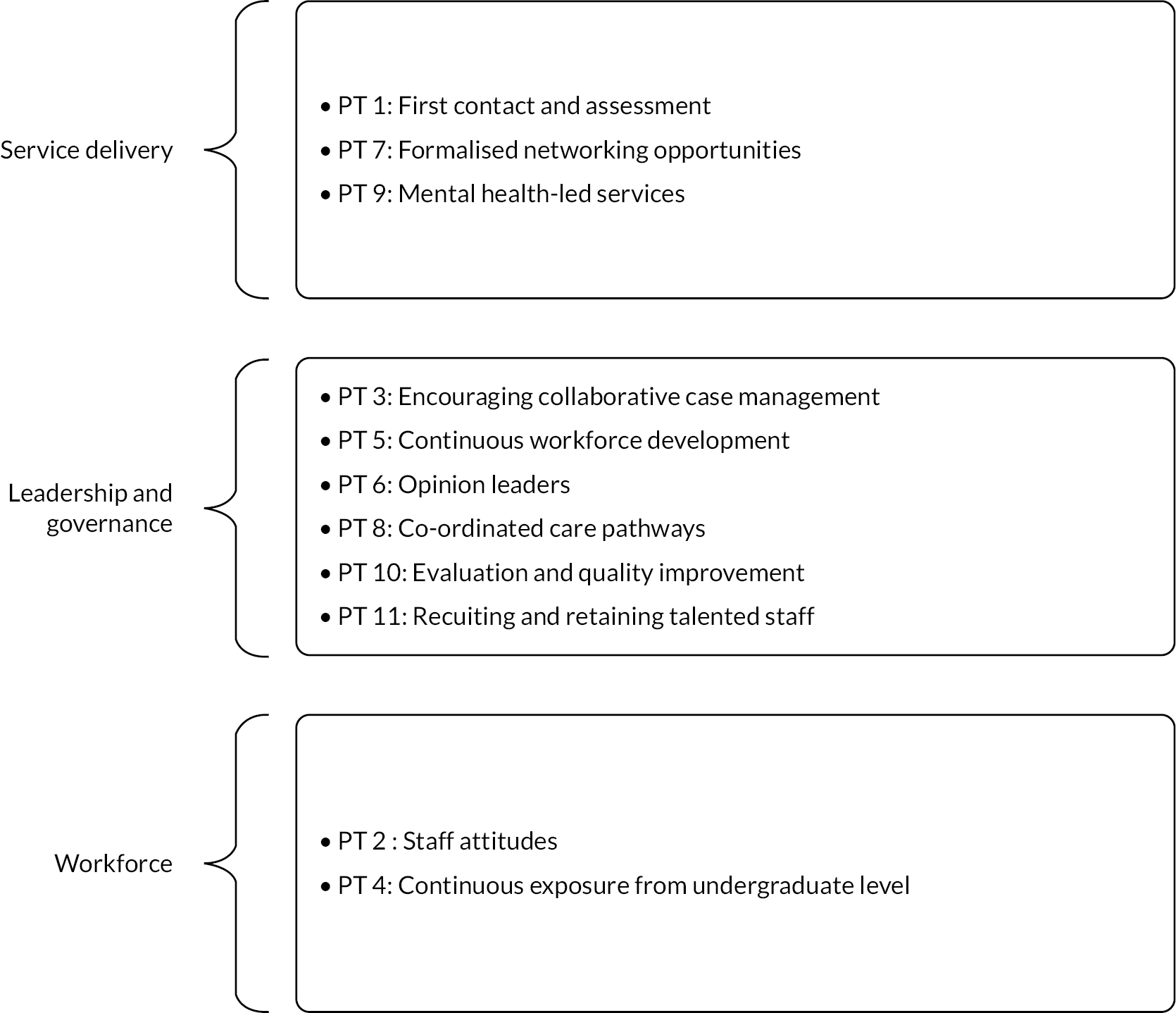

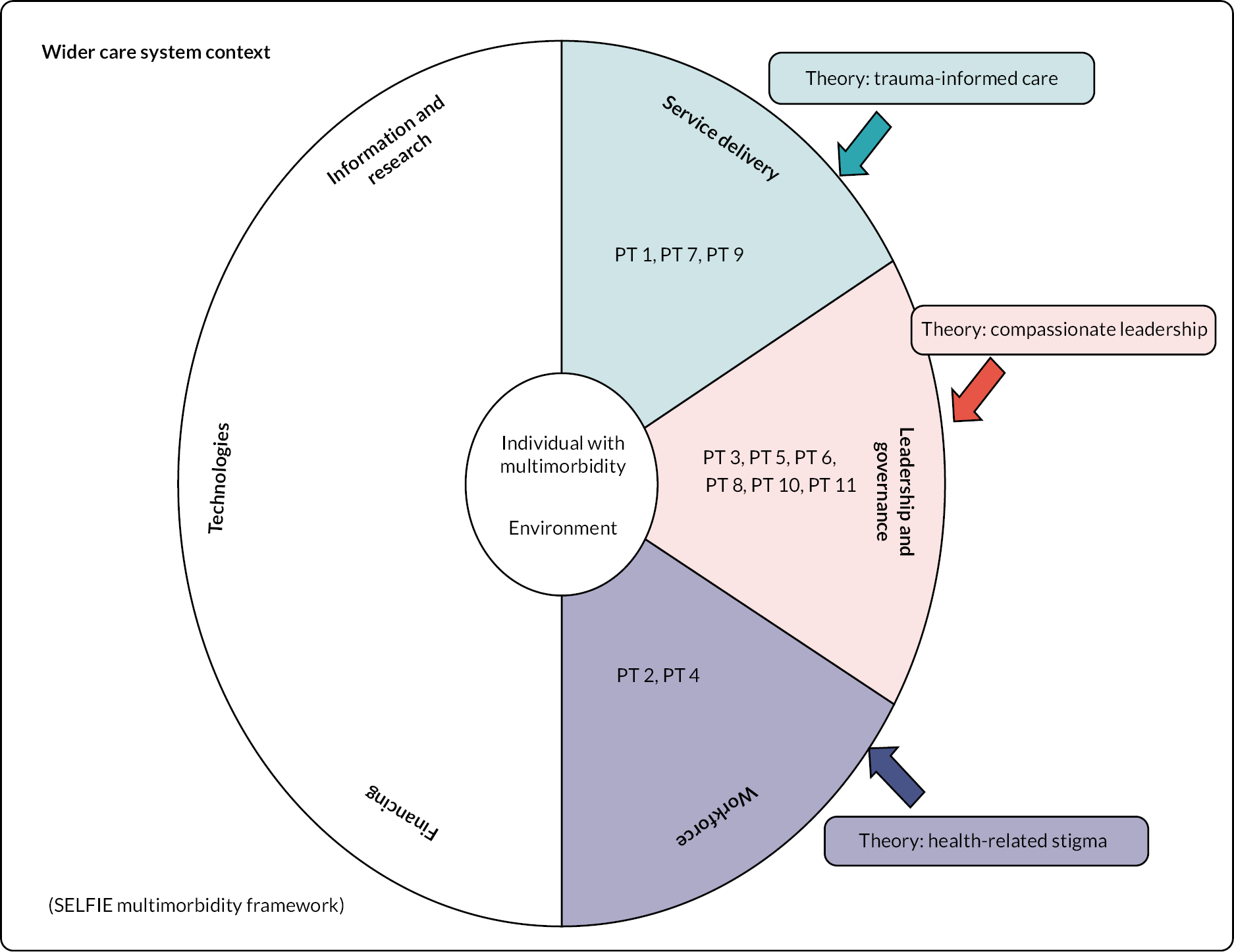

Initial programme theories

Throughout the realist synthesis, substantive theory was used to further understand and refine on the PTs, in line with RAMESES guidelines. 29

Eleven IPTs were developed, which included Context, Mechanism (including resource and response) and Outcome. These PTs were reviewed and refined through consultation with the entire project team (n = 9) through written comments on drafts, and two meetings at which the PTs were presented and discussed in detail. The first meeting took place when the PTs were first developed and the second reviewed the finalised statements following testing in the literature. These final PTs are summarised in Table 8. A full and detailed description of each PT generated in the realist synthesis can be found in Report Supplementary Material 1.

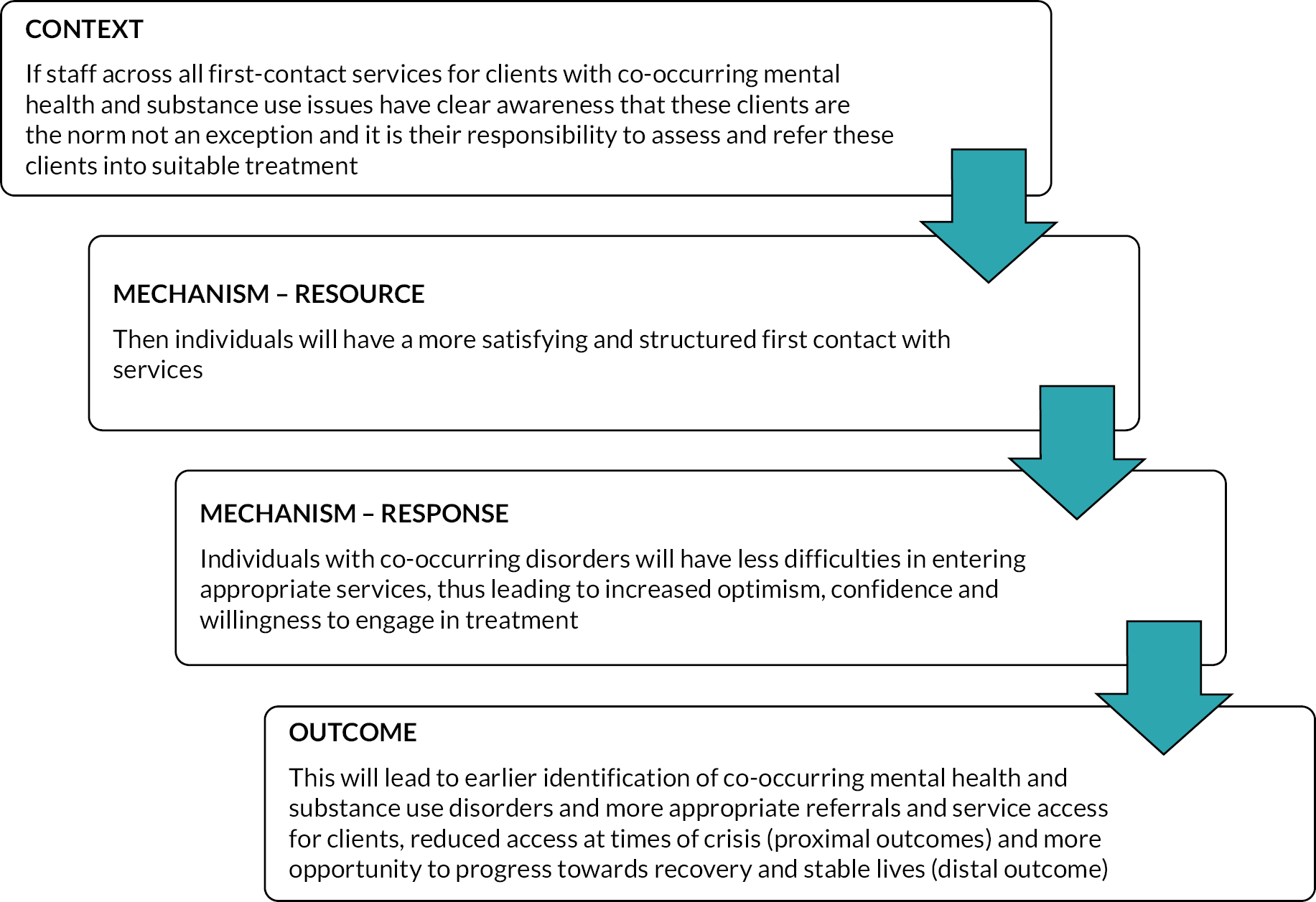

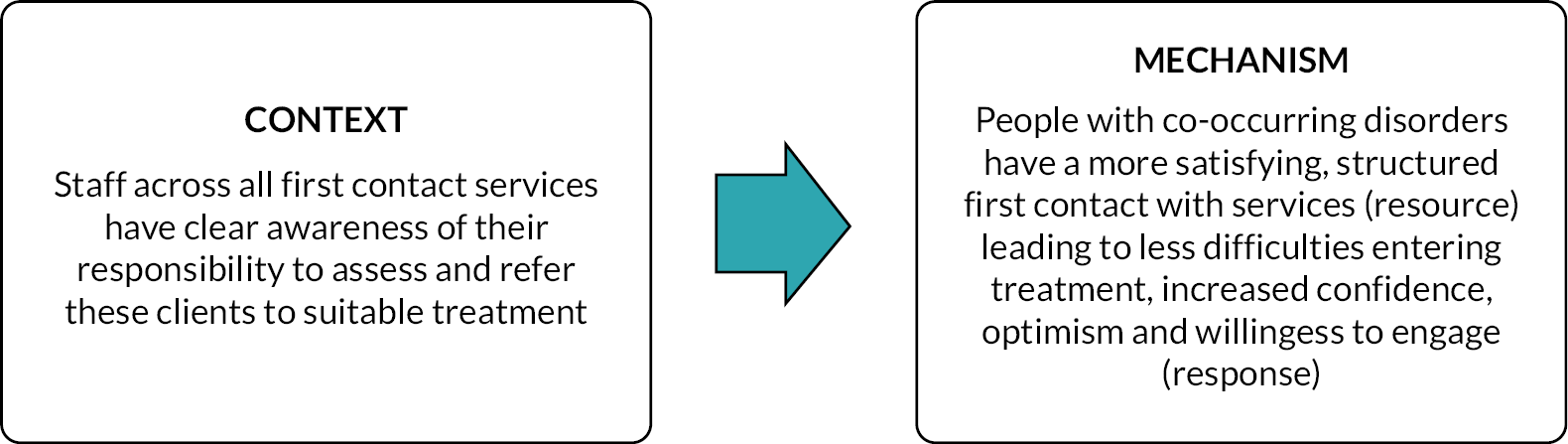

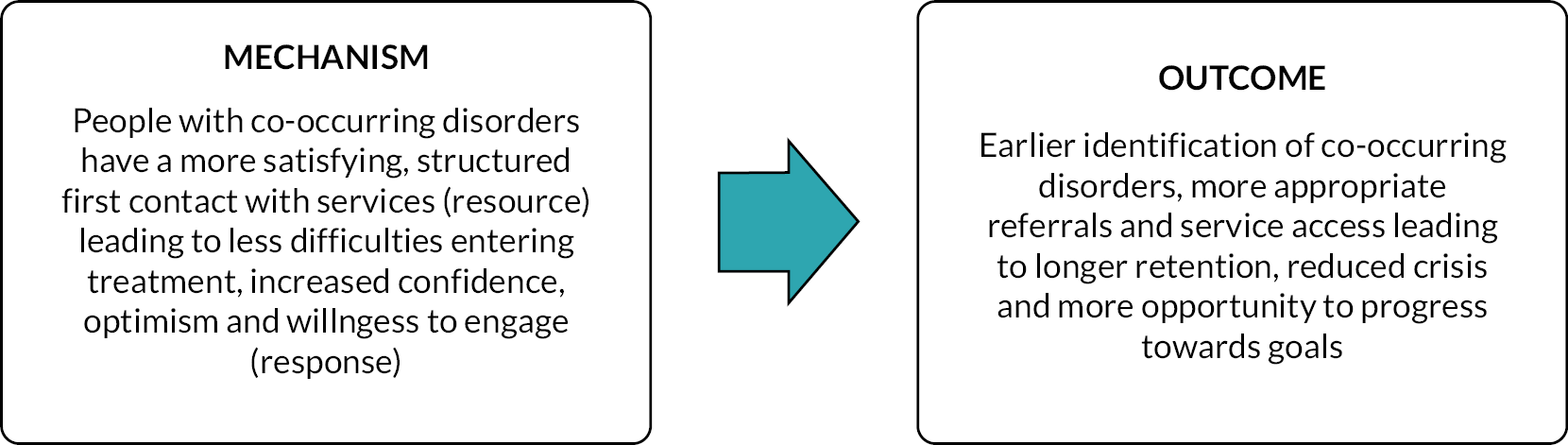

| PT 1: first contact and assessment (‘It’s everyone’s business’) | If staff across all first contact services for people with COSMHAD accept that it is part of their role to work with this group, and that it is their responsibility to assess and refer these service users into suitable treatment (context), then individuals will have a more satisfying and structured first contact with services (mechanism – resource). People with COSMHAD will have less difficulties in entering appropriate services thus leading to increased optimism, confidence and willingness to engage in treatment (mechanism – response). This will lead to earlier identification of COSMHAD and more appropriate referrals and service access for service users, resulting in longer retention, reduced access at times of crisis (proximal outcomes) and more opportunity to progress towards recovery and stable lives (distal outcome) |

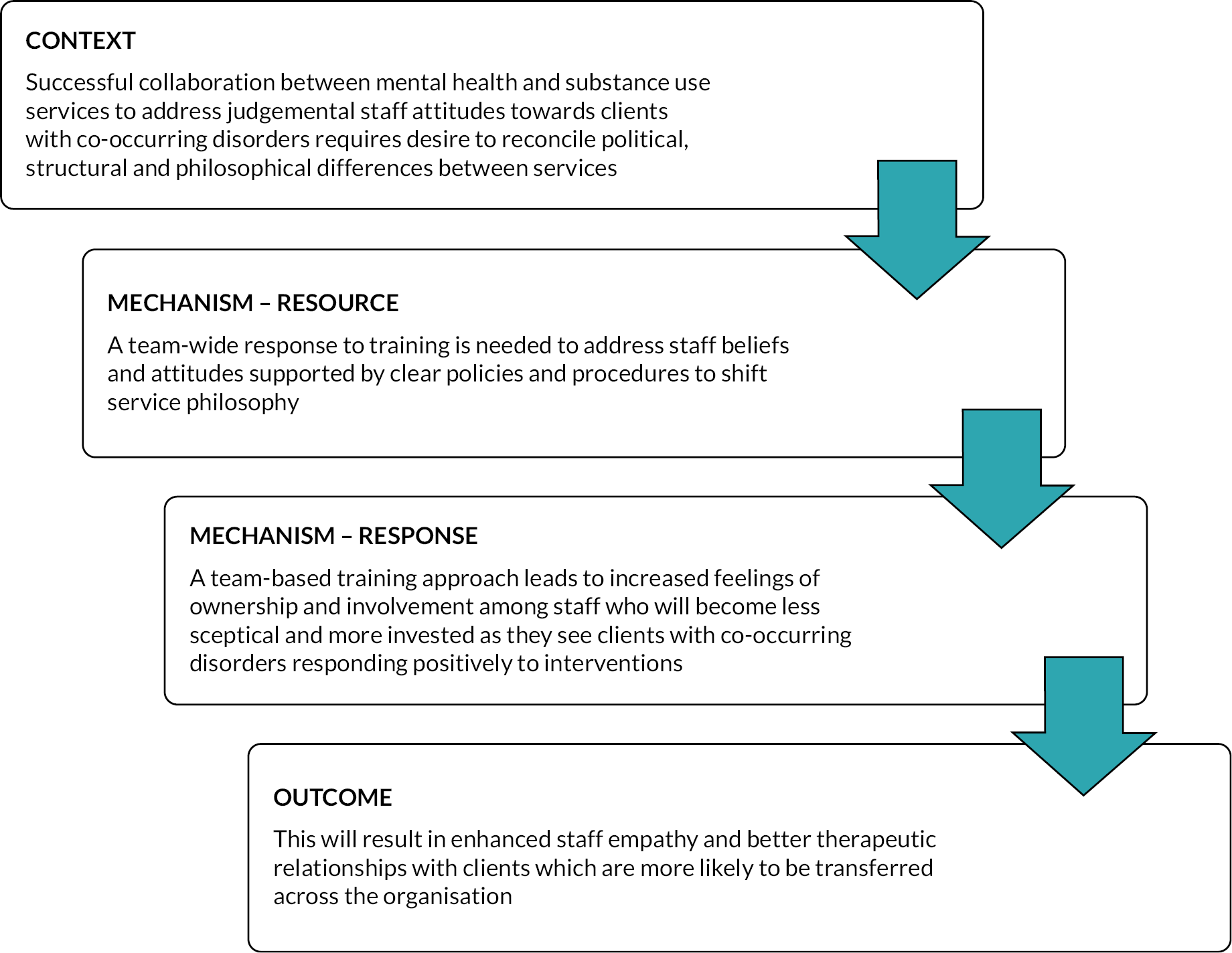

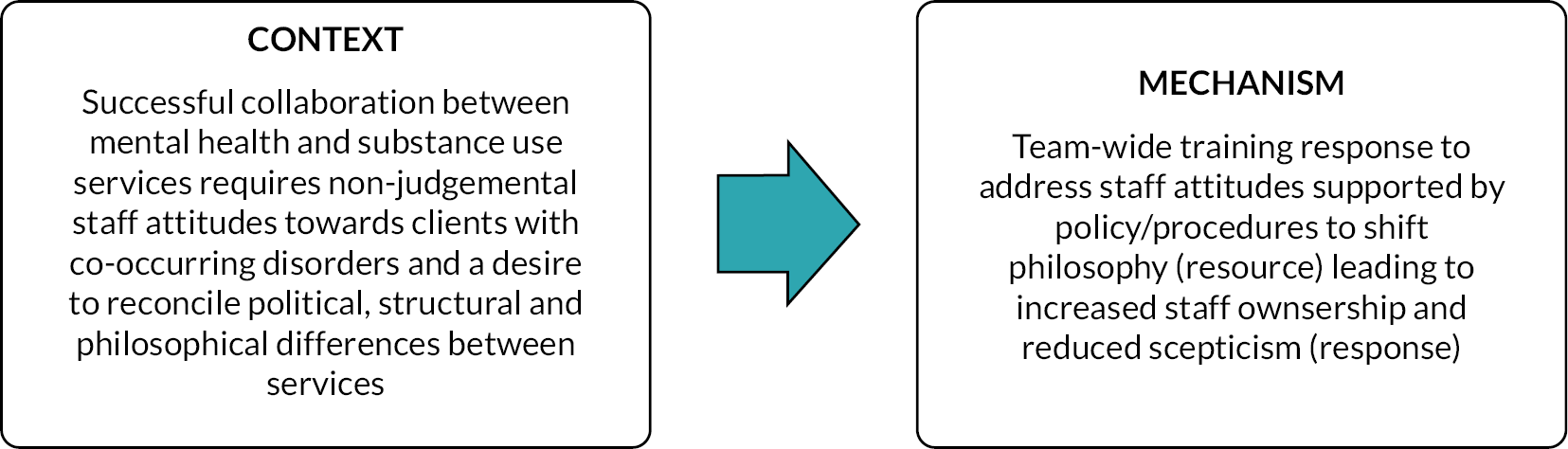

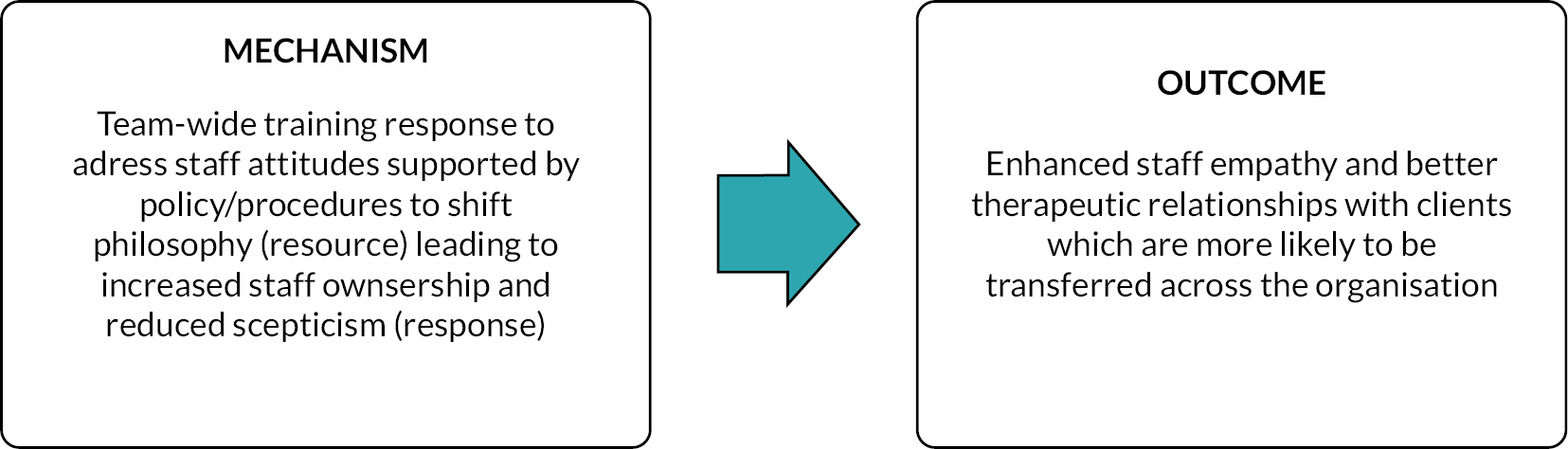

| PT 2: staff attitudes | Successful collaboration between mental health and substance use services requires non-judgemental staff attitudes towards people with COSMHAD and a desire to reconcile political, structural and philosophical differences between services (context). A team-wide response to training is needed to address staff beliefs and attitudes supported by clear policies and procedures to shift service philosophy (mechanism – resource). A team-based training approach leads to increased feelings of ownership and involvement among staff who will become less sceptical and more invested as they see people with COSMHAD responding positively to interventions (mechanism – response). This will result in enhanced staff empathy and better therapeutic relationships with service users which are more likely to be transferred across the organisation (outcome) |

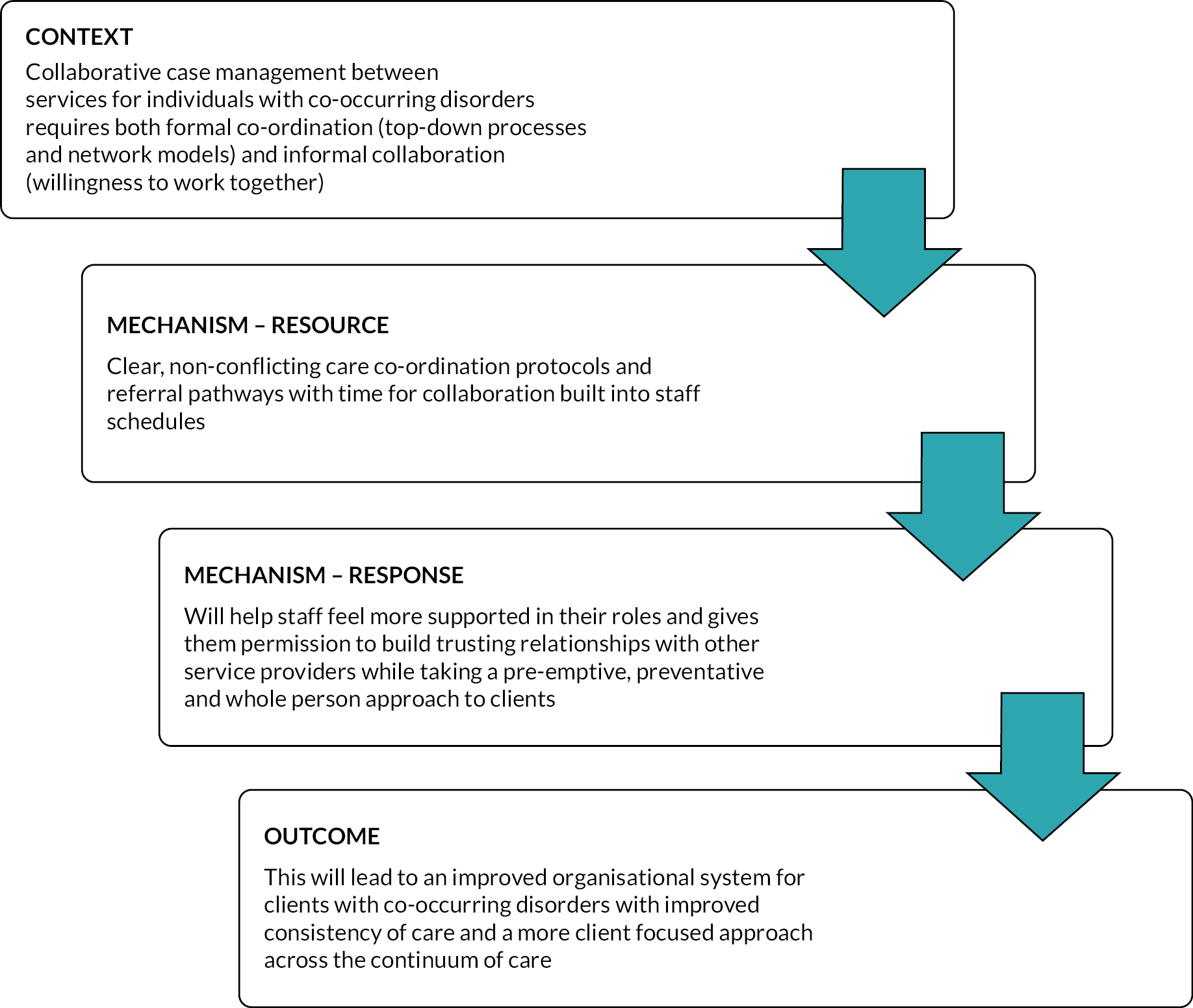

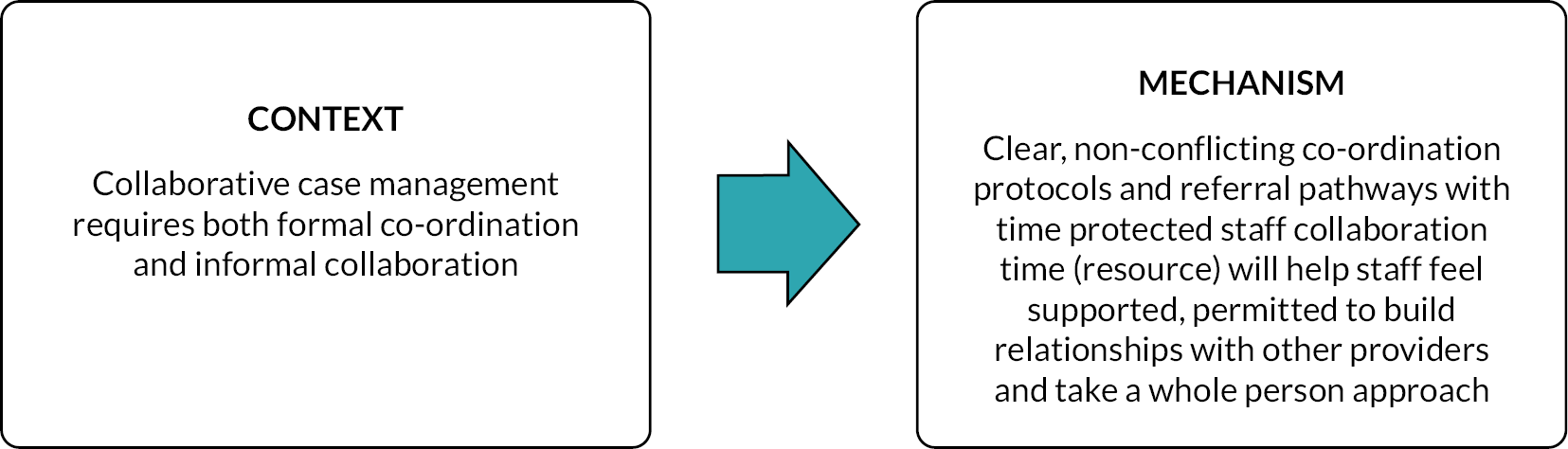

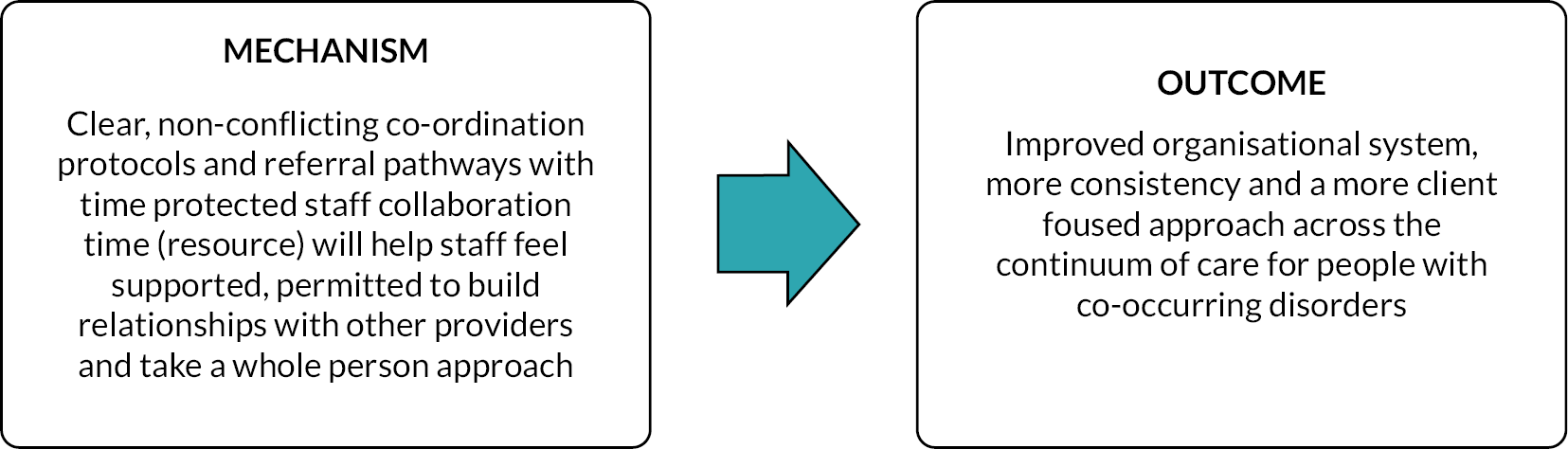

| PT 3: encouraging collaborative case management | Collaborative case management between services for people with COSMHAD requires both formal co-ordination (top-down processes and network models) and informal collaboration (willingness to work together) (context). Clear, non-conflicting care co-ordination protocols and referral pathways with time for collaboration built into staff schedules (mechanism – resource) will help staff feel more supported in their roles and gives them permission to build trusting relationships with other service providers while taking a pre-emptive, preventative and whole person approach (mechanism – response). This will lead to an improved organisational system for people with COSMHAD with improved consistency of care and a more service user focused approach across the continuum of care (outcome) |

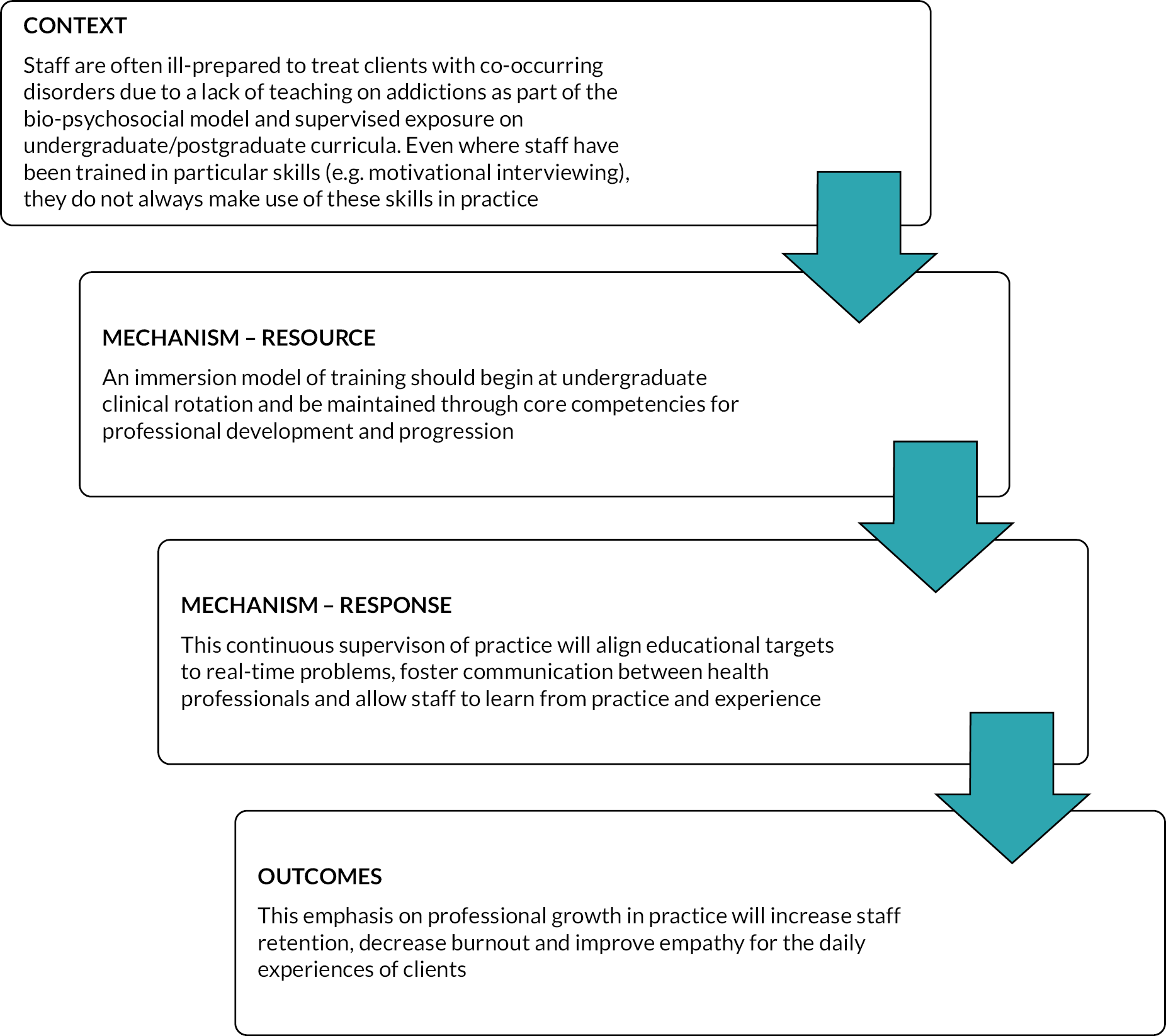

| PT 4: continuous exposure from undergraduate level | Staff are often ill-prepared to treat people with COSMHAD due to a lack of teaching on addictions as part of the biopsychosocial model and supervised exposure on undergraduate/postgraduate curricula. Even where staff have been trained in particular skills (e.g. motivational interviewing), they do not always make use of these skills in practice (context). An immersion model of training should begin at undergraduate clinical rotation and be maintained through core competencies for professional development and progression (mechanism – resource). This continuous supervision of practice will align educational targets to real time problems, foster communication between health professionals and allow staff to learn from practice and experience (mechanism – response). This emphasis on professional growth in practice will increase staff retention, decrease burnout and improve empathy for the daily experiences of service users (outcome) |

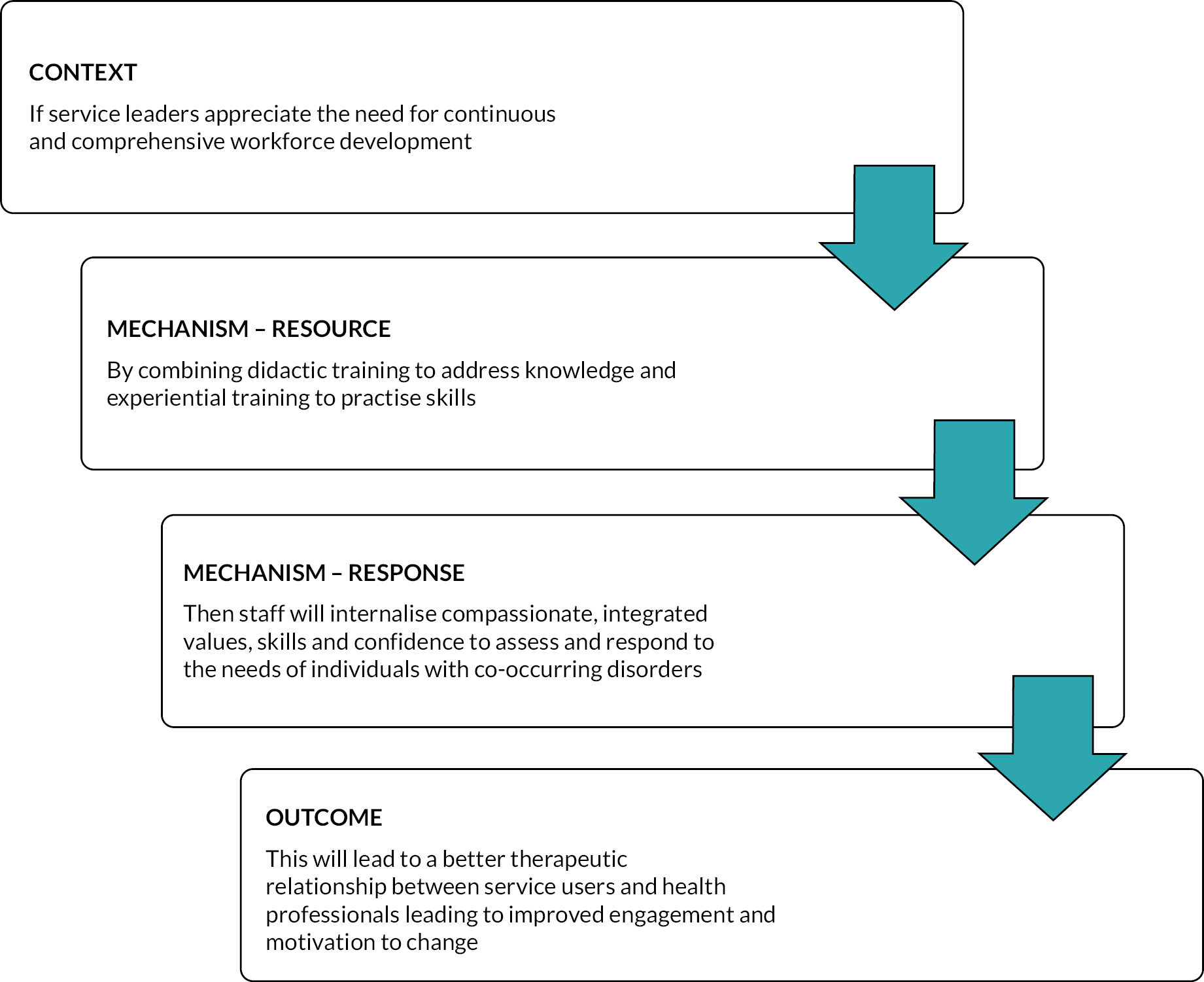

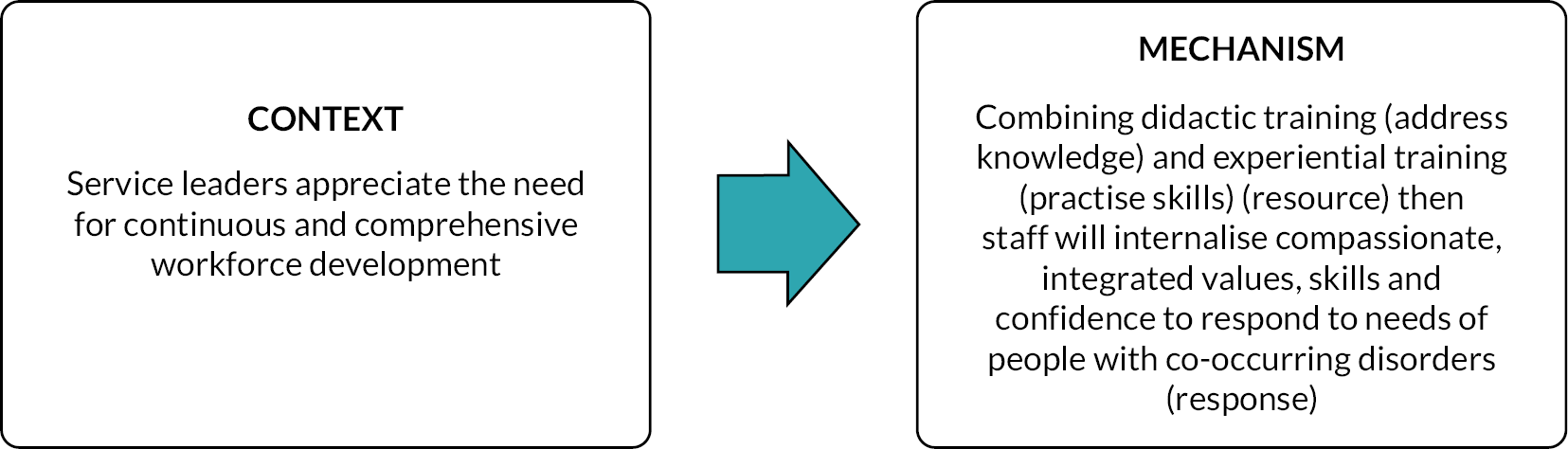

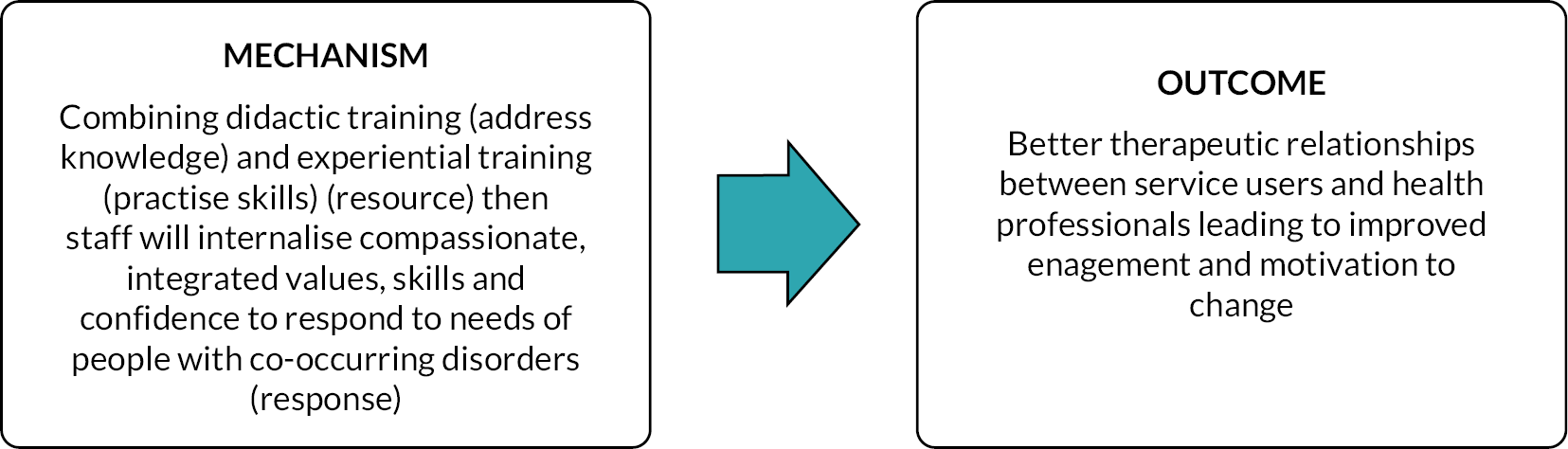

| PT 5: continuous workforce development | If service leaders appreciate the need for continuous and comprehensive workforce development (context) by combining didactic training to address knowledge and experiential training to practise skills (mechanism – resource) then staff will internalise compassionate, integrated values, skills and confidence to assess and respond to the needs of individuals with co-occurring disorders (mechanism – response). This will lead to a better therapeutic relationship between service users and health professionals leading to improved engagement and motivation to change (outcome) |

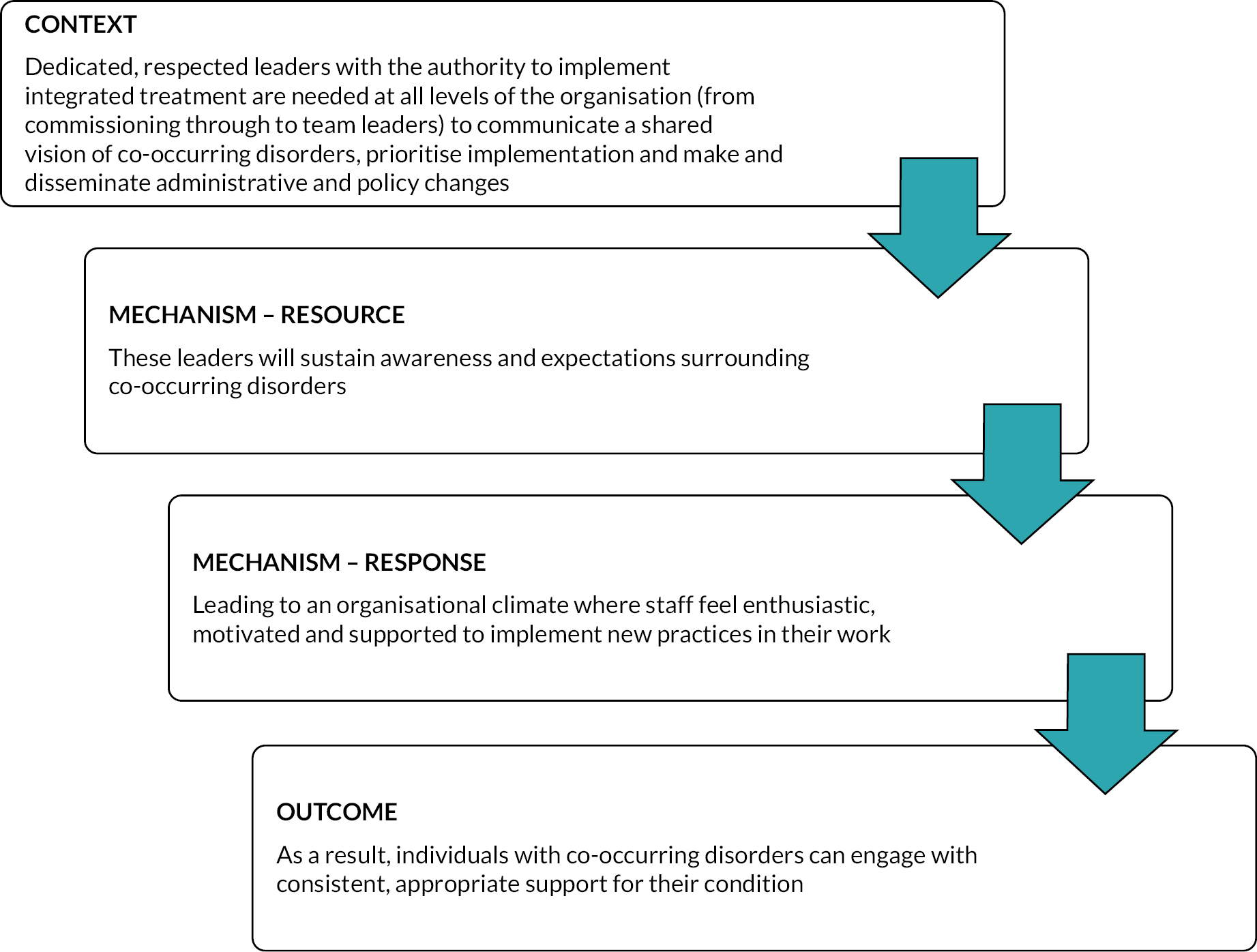

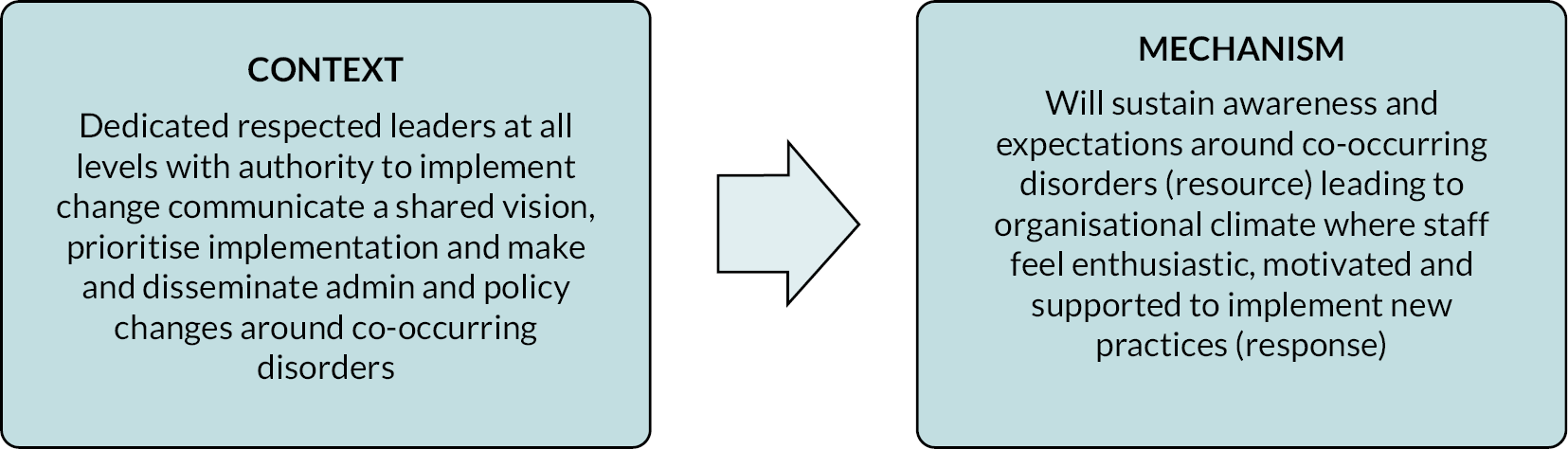

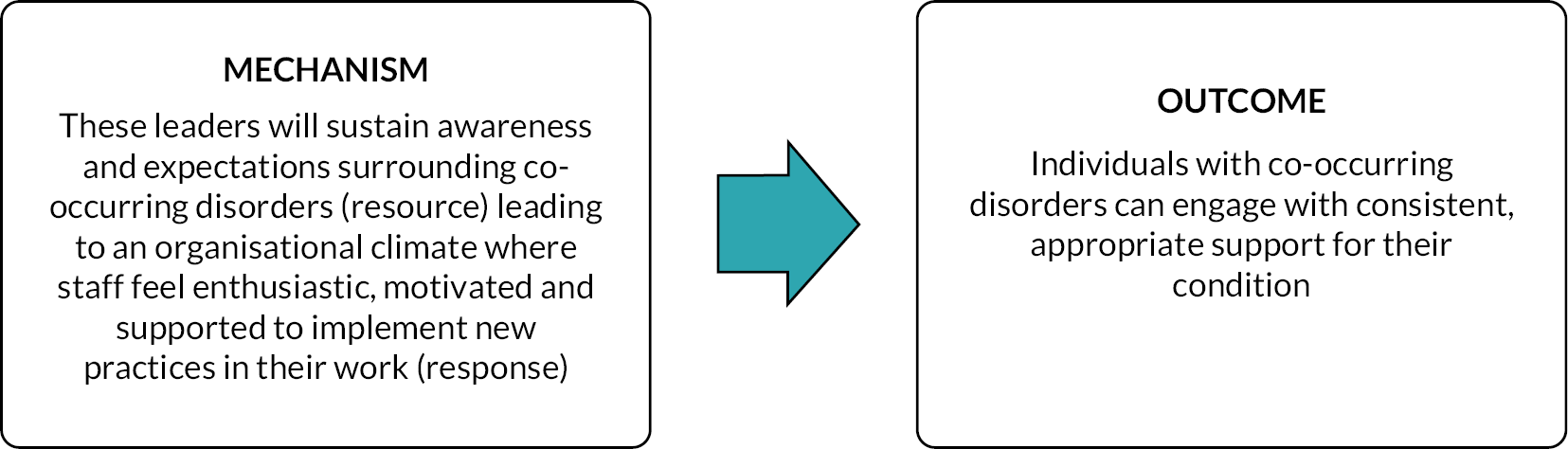

| PT 6: opinion leaders | Dedicated, respected leaders with the authority to implement integrated treatment are needed at all levels of the organisation (from commissioning through to team leaders) to communicate a shared vision of co-occurring disorders, prioritise implementation and make and disseminate administrative and policy changes (context). These leaders will sustain awareness and expectations surrounding co-occurring disorders (mechanism – resource) leading to an organisational climate where staff feel enthusiastic, motivated and supported to implement new practices in their work (mechanism – response). As a result, individuals with co-occurring disorders can engage with consistent, appropriate support for their condition (outcome) |

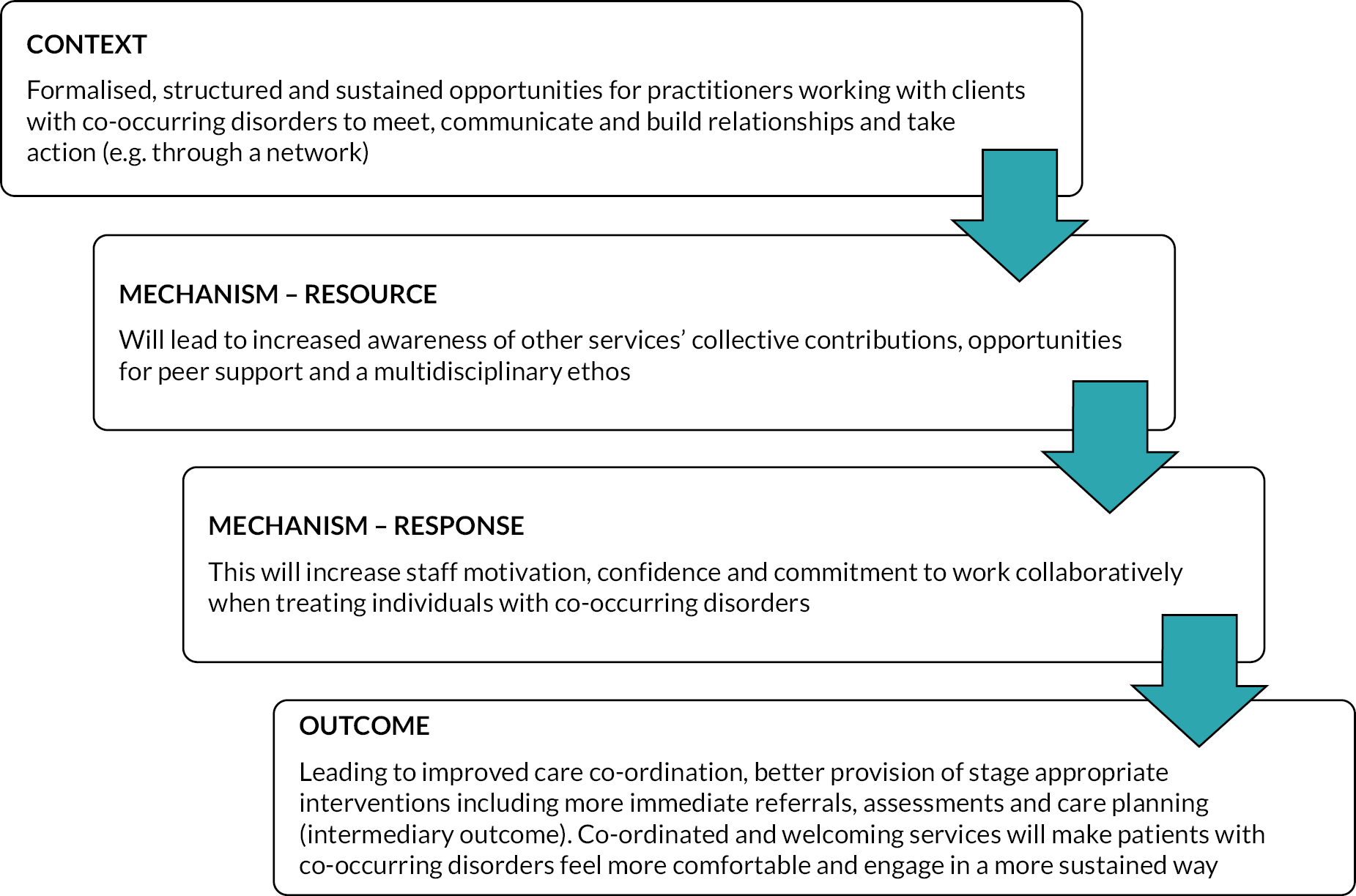

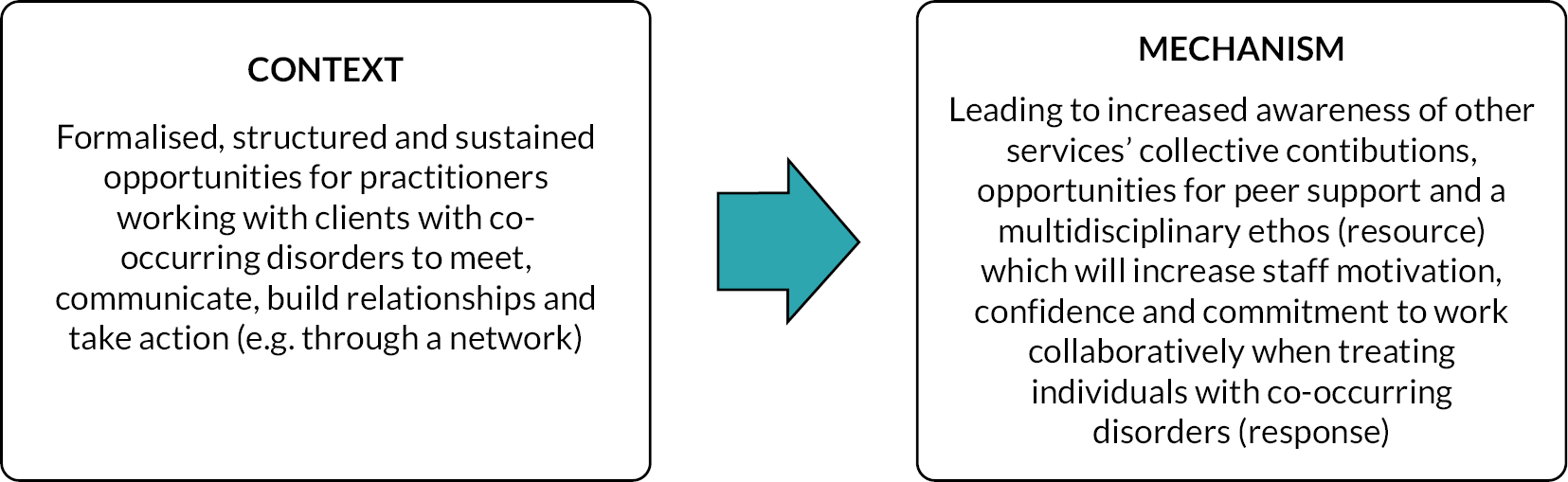

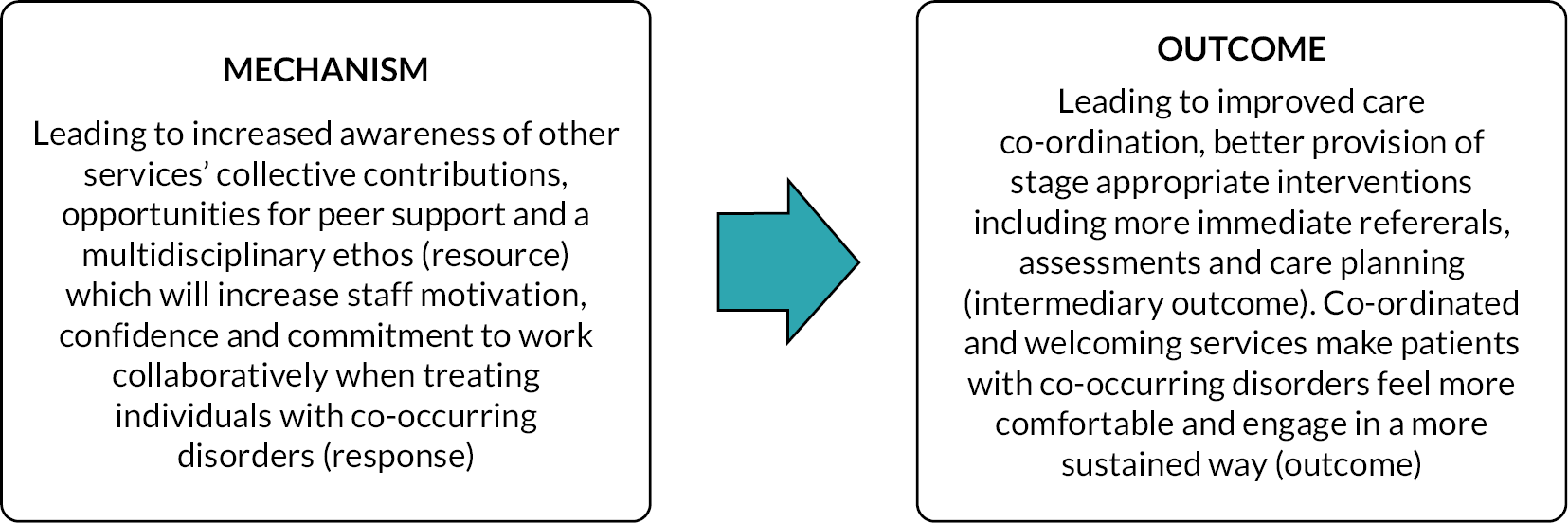

| PT 7: formalised networking opportunities | Formalised, structured and sustained opportunities for practitioners working with people with COSMHAD to meet, communicate and build relationships and take action (e.g. through a network) (context) will lead to increased awareness of other services’ collective contributions, opportunities for peer support and a multidisciplinary ethos (mechanism – resource). This will increase staff motivation, confidence and commitment to work collaboratively when treating people with COSMHAD (mechanism – response) leading to improved care co-ordination and better provision of stage appropriate interventions including more immediate referrals, assessments and care planning (intermediary outcome). Co-ordinated and welcoming services will make patients with co-occurring disorders feel more comfortable and engage in a more sustained way (outcome) |

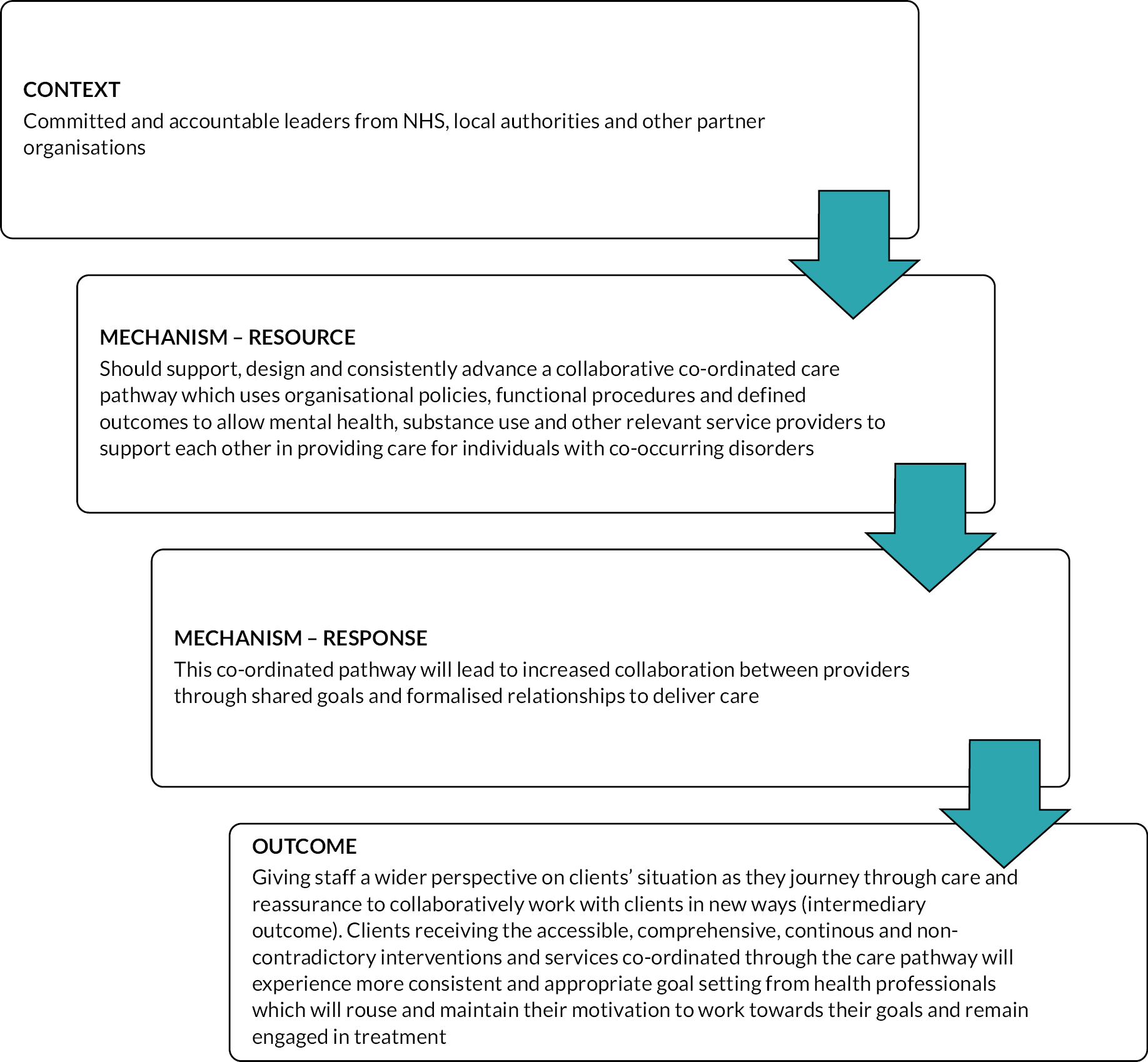

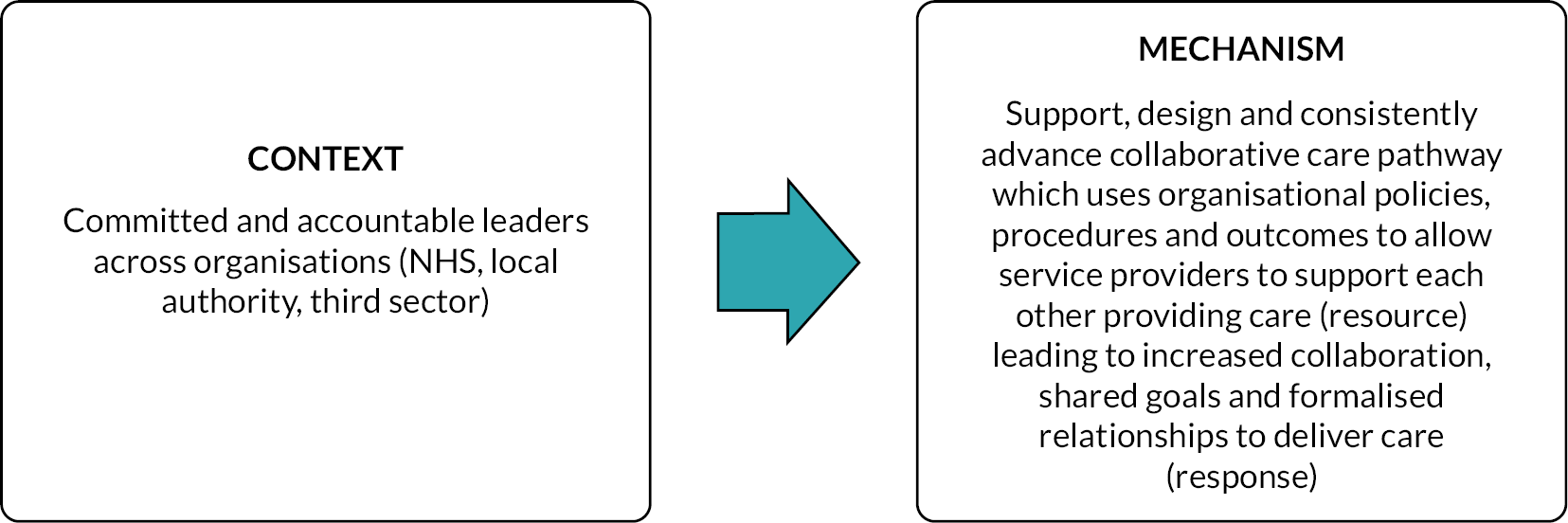

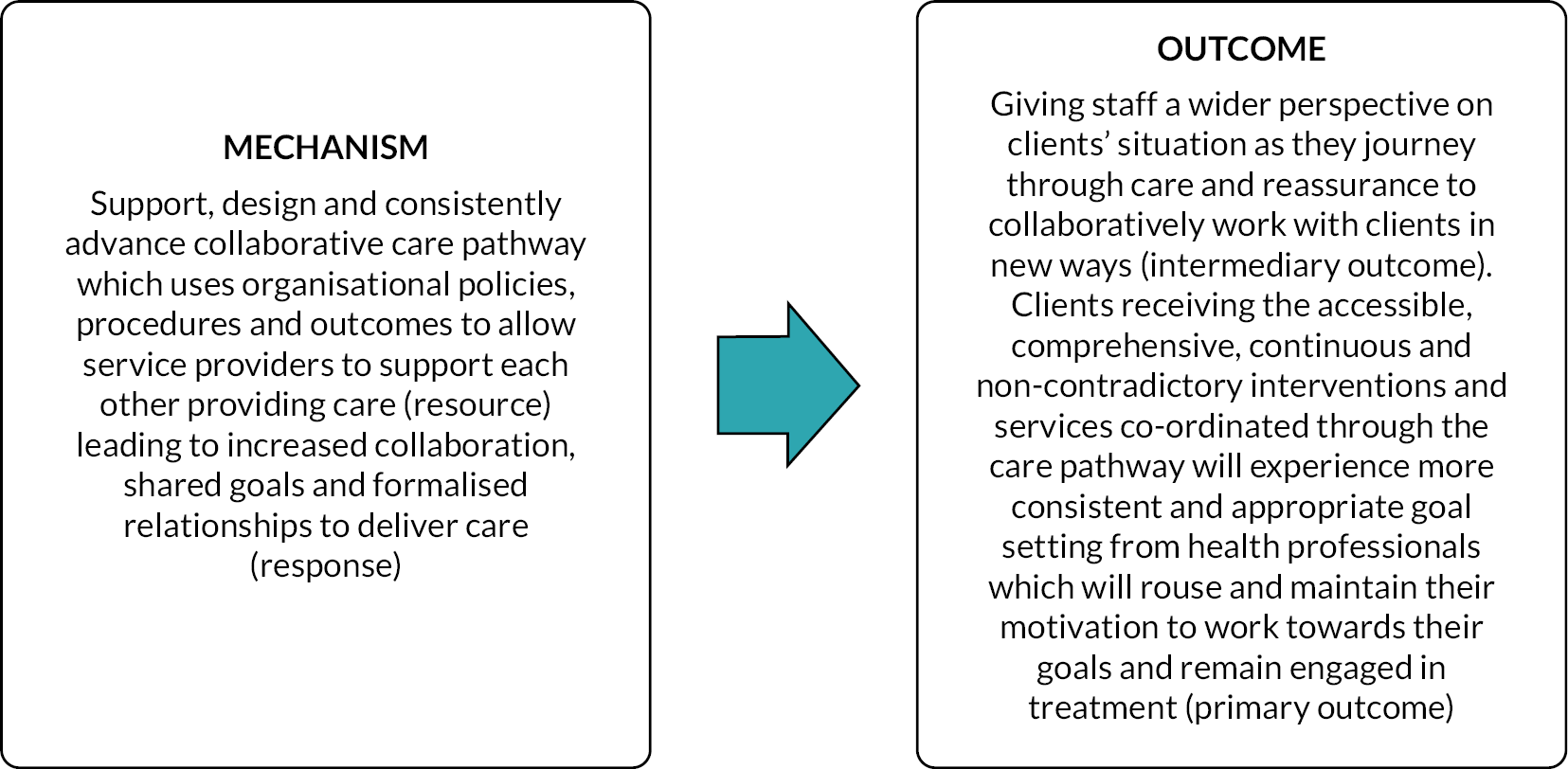

| PT 8: co-ordinated care pathways | Committed and accountable leaders from NHS, local authorities and other partner organisations (context) should support, design and consistently advance a collaborative co-ordinated care pathway which uses organisational policies, functional procedures and defined outcomes to allow mental health, substance use and other relevant service providers to support each other in providing care for individuals with co-occurring disorders (mechanism – resource). This co-ordinated pathway will lead to increased collaboration between providers through shared goals and formalised relationships to deliver care (mechanism – response), giving staff a wider perspective on service users’ situations as they journey through care and reassurance to collaboratively work with service users in new ways (intermediary outcome). Service users receiving the accessible, comprehensive, continuous and non-contradictory interventions and services co-ordinated through the care pathway will experience more consistent and appropriate goal setting from health professionals which will rouse and maintain their motivation to work towards their goals and remain engaged in treatment (outcome) |

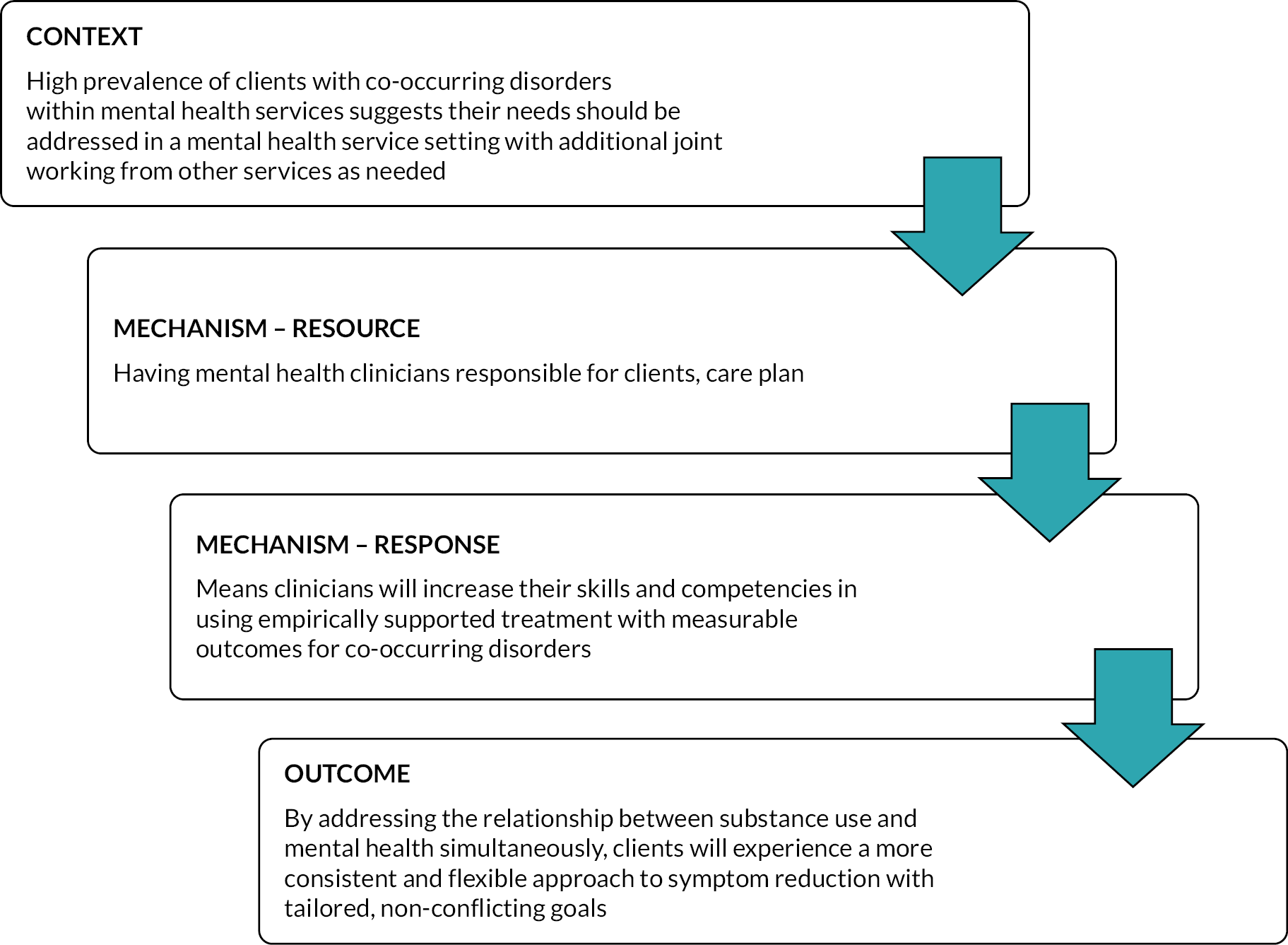

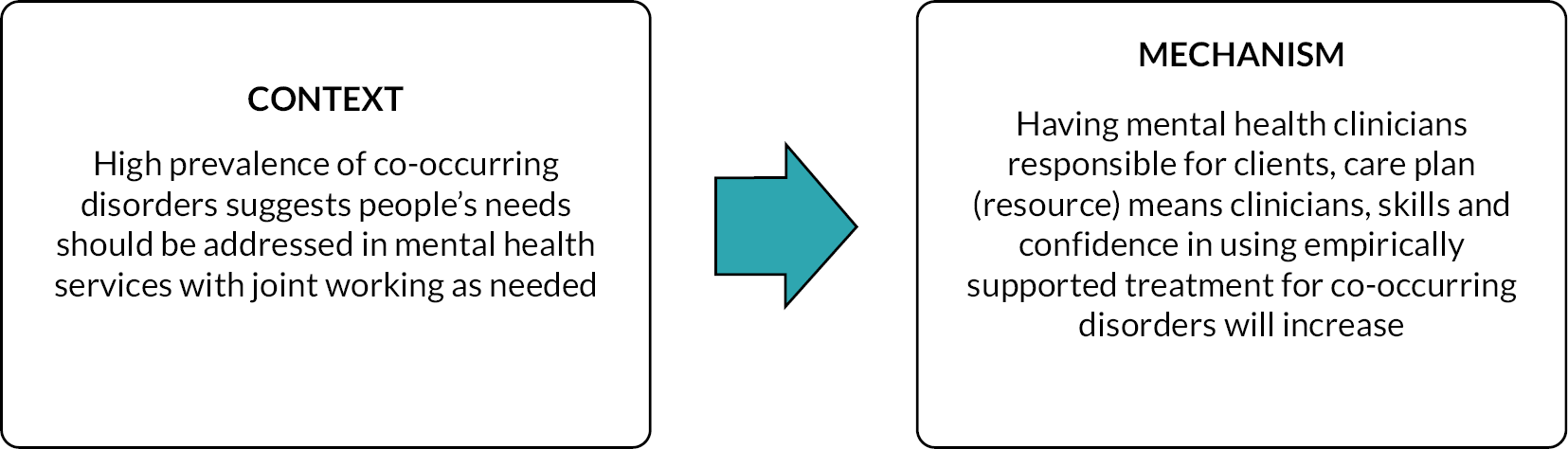

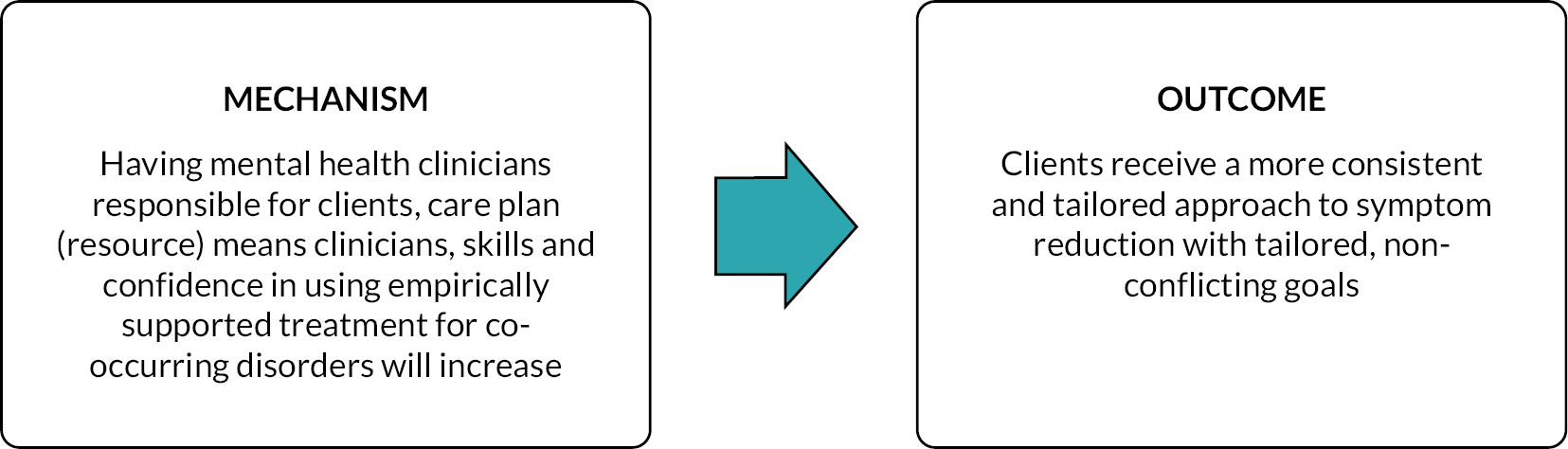

| PT 9: mental health led services | A high prevalence of people with COSMHAD within mental health services suggests their needs should be addressed in a mental health service setting with additional joint working from other services as needed (context). Having mental health clinicians responsible for care planning (mechanism – resource) means clinicians will increase their skills and competencies in using empirically supported treatment with measurable outcomes for COSMHAD (mechanism – response). By addressing the relationship between substance use and mental health simultaneously, service users will experience a more consistent and flexible approach to symptom reduction with tailored, non-conflicting goals (outcome) |

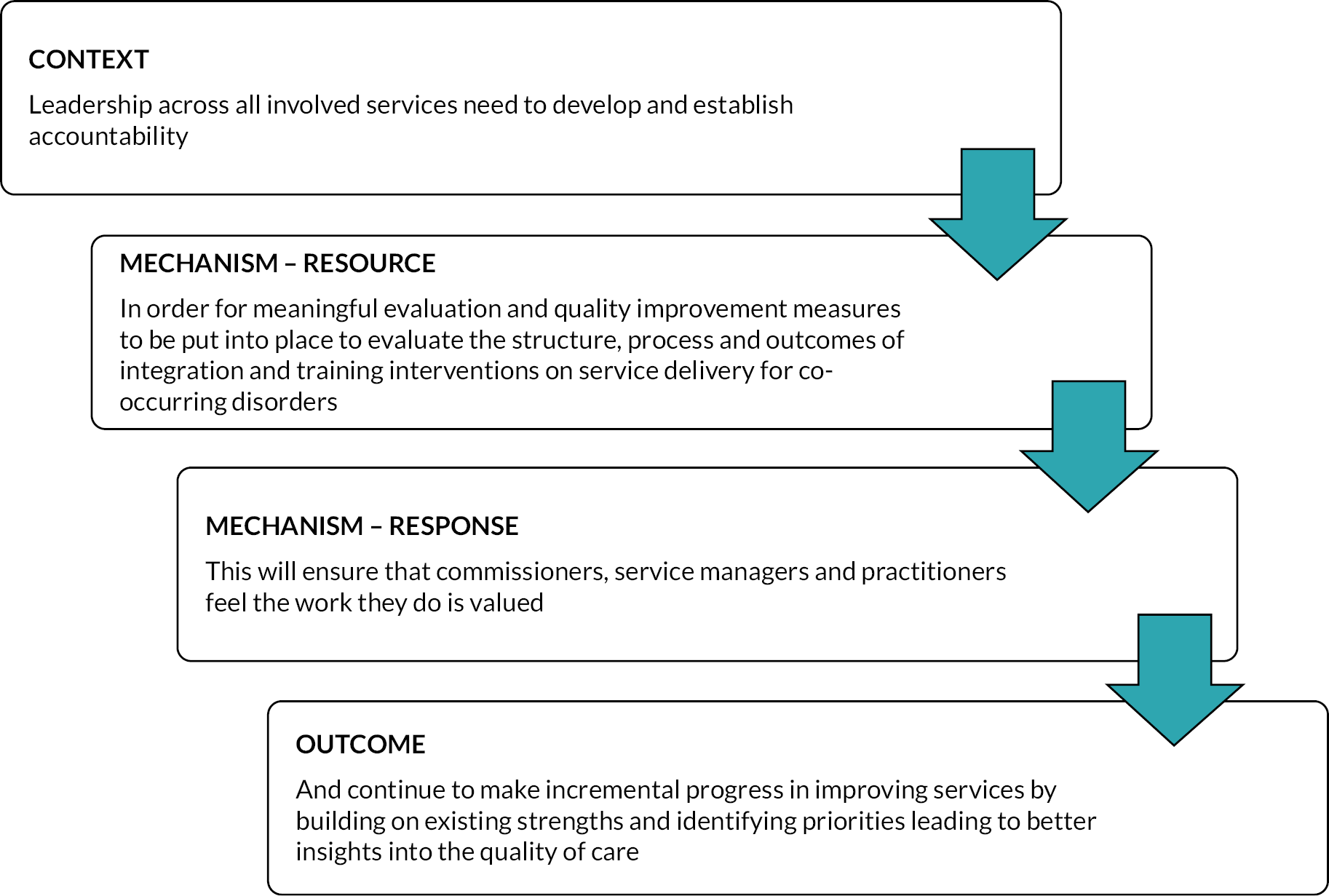

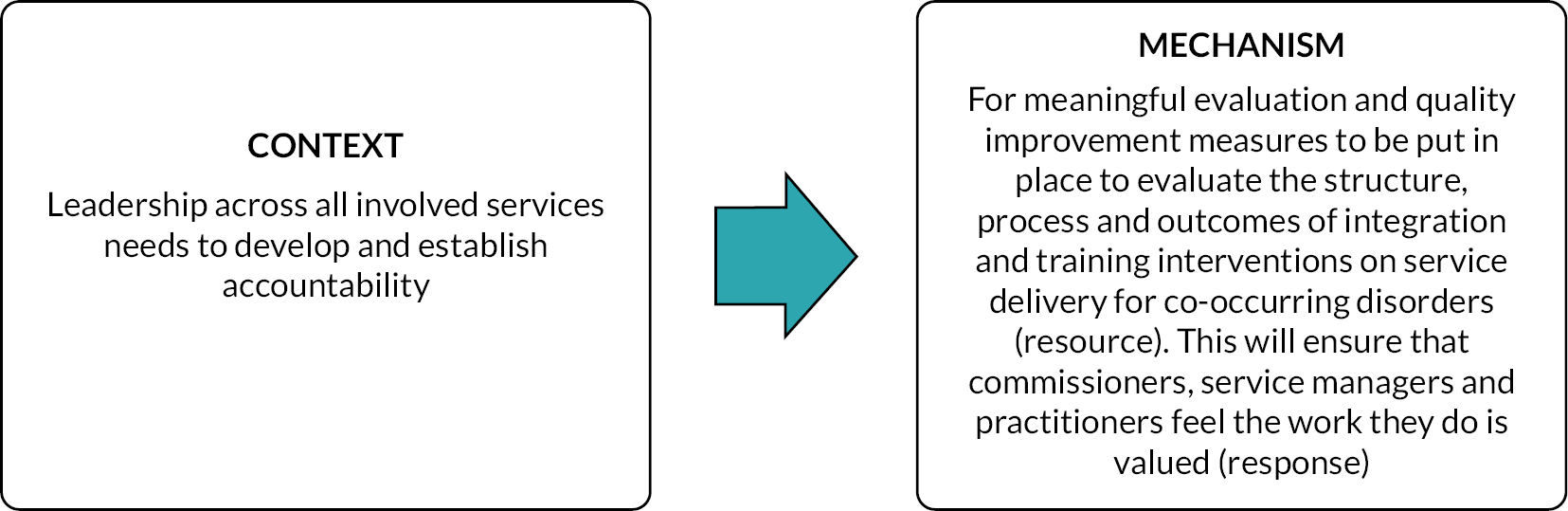

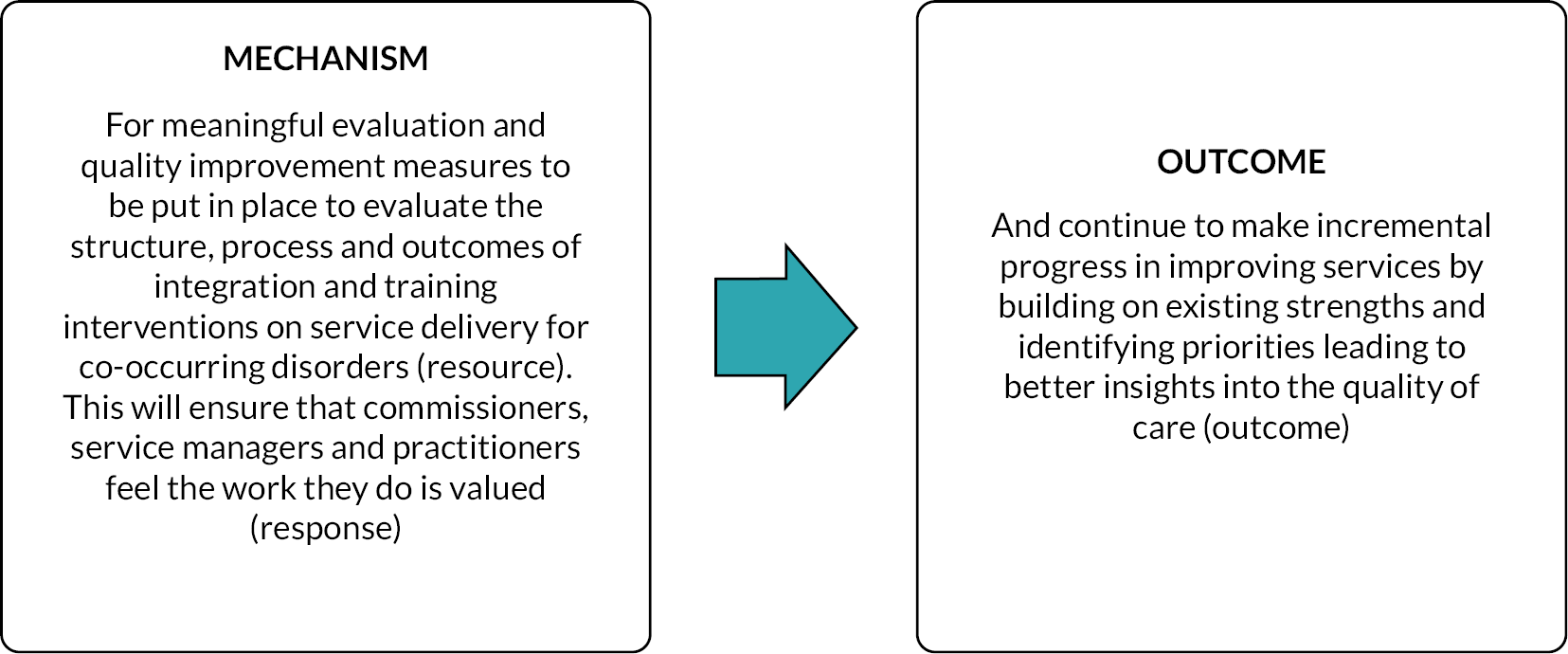

| PT 10: evaluation and quality improvement | Leadership across all involved services need to develop and establish accountability (context) in order for meaningful evaluation and quality improvement measures to be put into place to evaluate the structure, process and outcomes of integration and training interventions on service delivery for co-occurring disorders (mechanism – resource). This will ensure that commissioners, service managers and practitioners feel the work they do is valued (mechanism – response) and continue to make incremental progress in improving services by building on existing strengths and identifying priorities leading to better insights into the quality of care (outcome) |

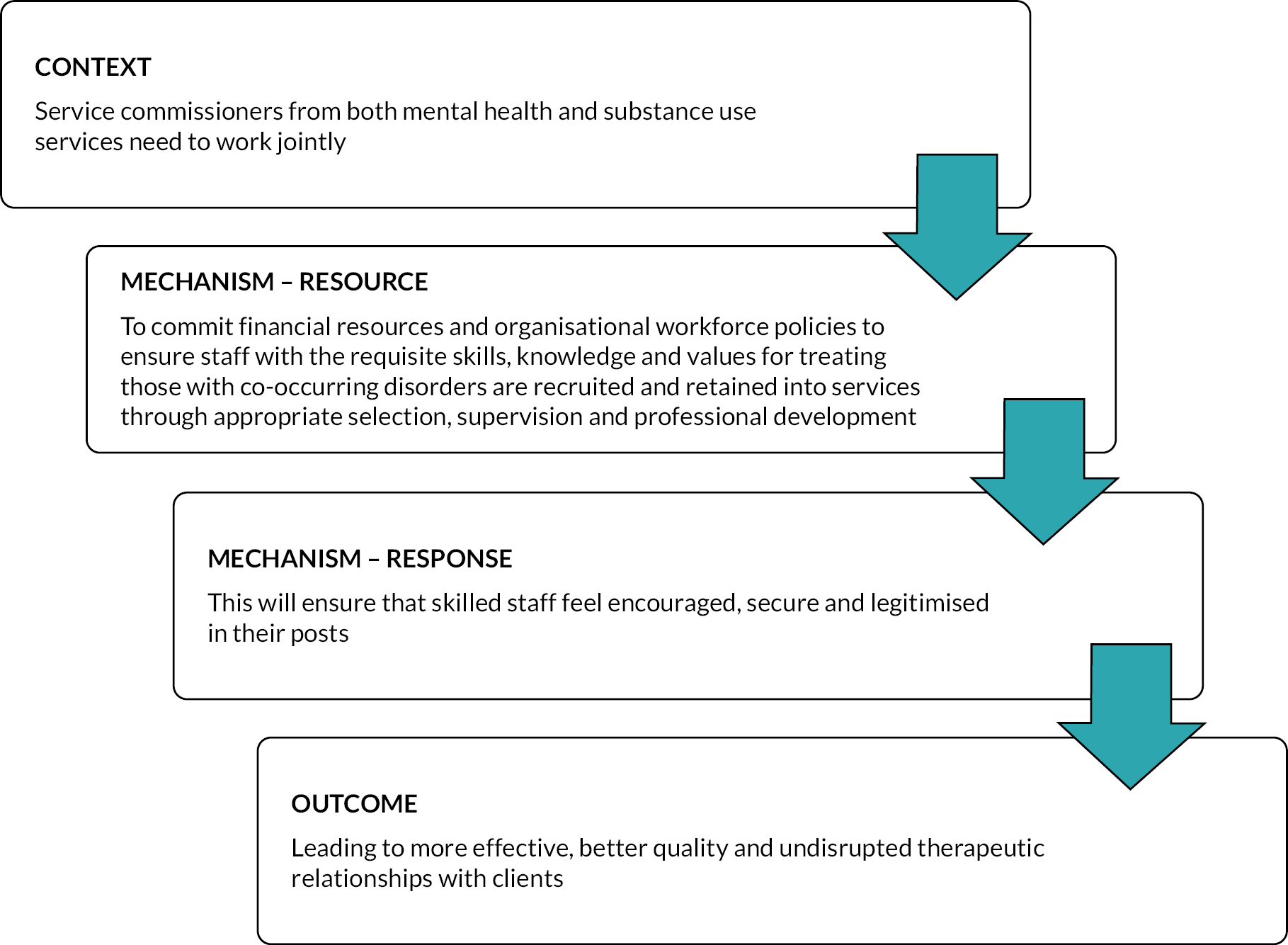

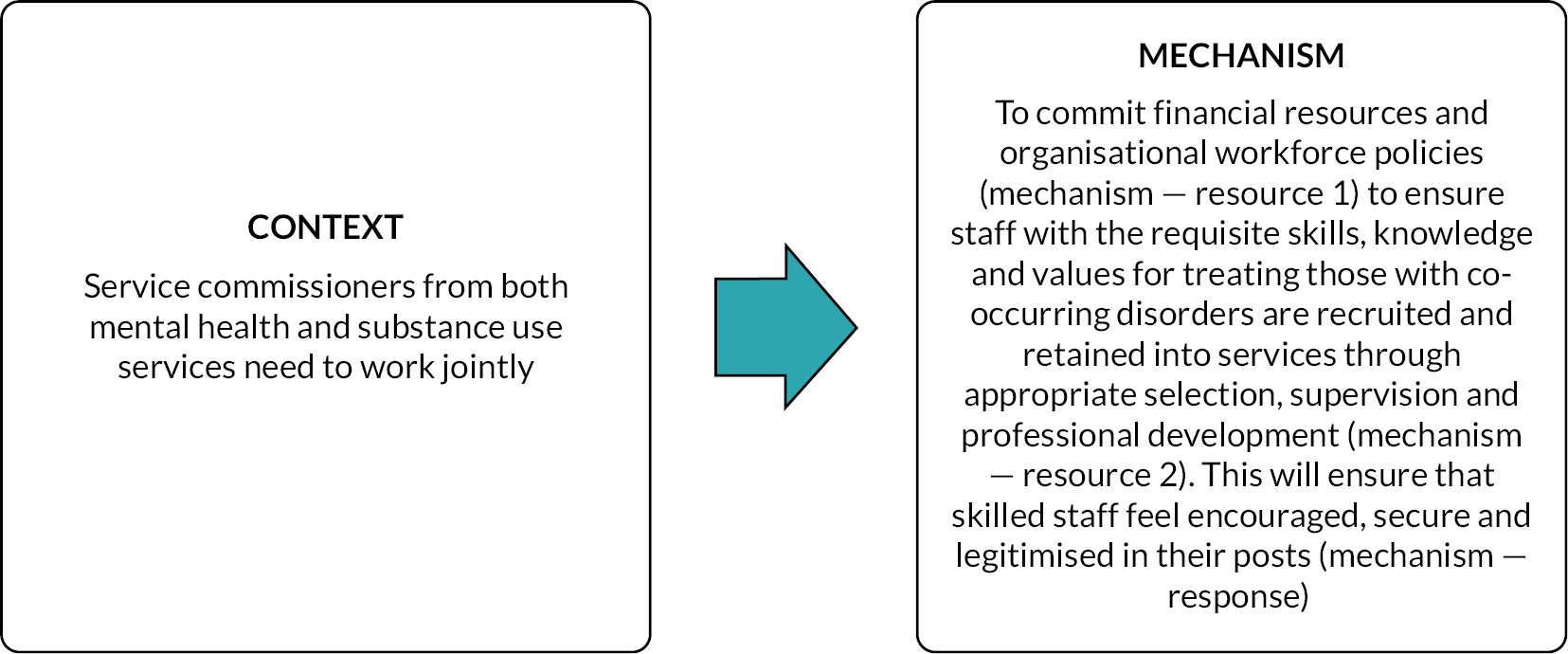

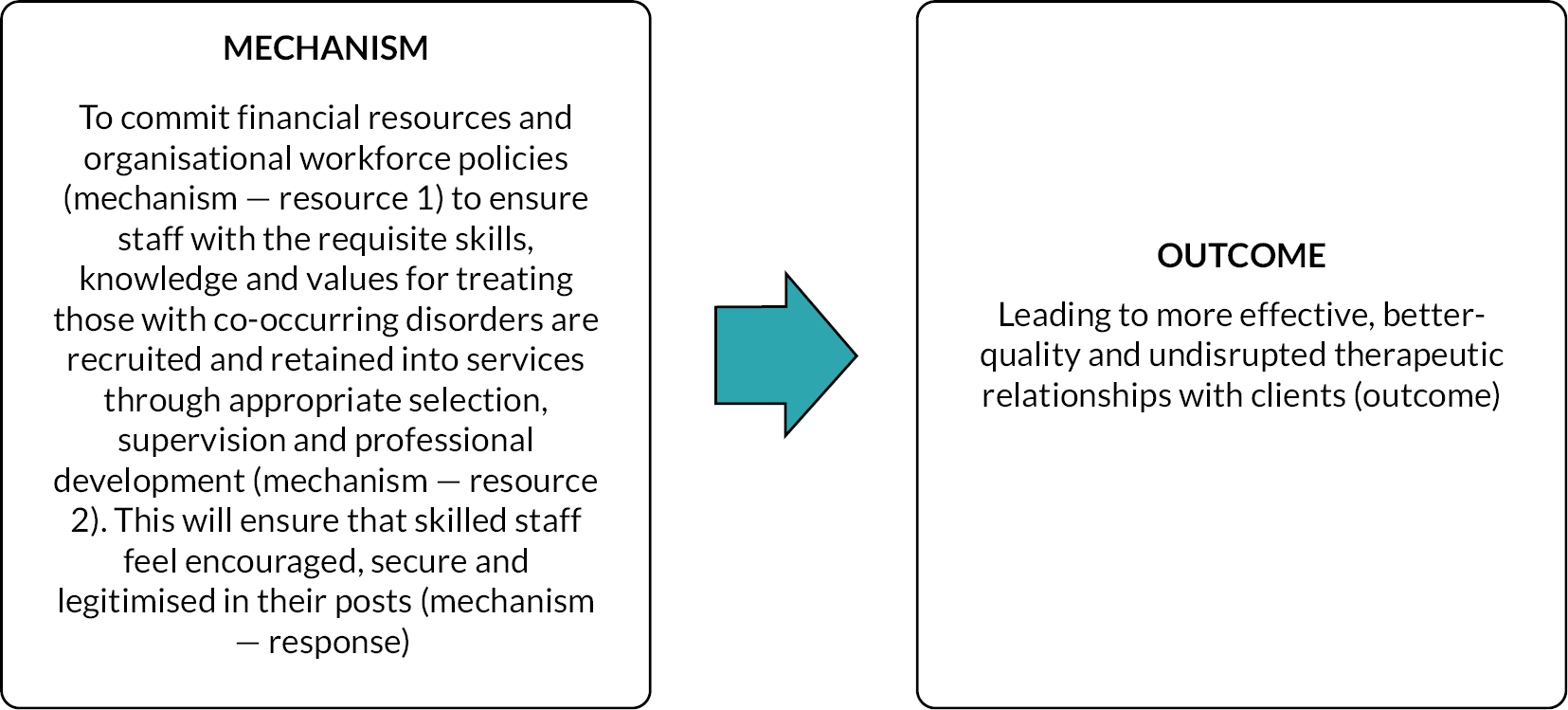

| PT 11: recruiting and retaining talented staff | Service commissioners from both mental health and substance use services need to work jointly (context) to commit financial resources and organisational workforce policies (mechanism – resource 1) to ensure staff with the requisite skills, knowledge and values for treating people with COSMHAD are recruited and retained into services through appropriate selection, supervision and professional development (mechanism – resource 2). This will ensure that skilled staff feel encouraged, secure and legitimised in their posts (mechanism – response) leading to more effective, better quality and undisrupted therapeutic relationships with service users (outcome) |

Finalisation of the programme theories

The aim of the RECO study was to develop, test and refine a set of PTs that identified and described the contexts and associated mechanisms by which engagement and other health outcomes are achieved in service systems for COSMHAD, and for whom these are most effective.

This next section will address how the evidence from the real-world case studies supported the PTs generated from the realist synthesis. The realist review has been accepted for publication at the time of preparing the report. 39 Each PT will be discussed in light of the evidence from the staff, service user and carer perspective and a summary provided at the end of the chapter.

Refined programme theory 1: first contact and assessment (‘It’s everyone’s business’)

Summary of evidence

The concept of ‘everyone’s business’ comes from the position that a significant number of people who use mental health and substance use services have co-occurring disorders and therefore need to be equipped to engage people in treatment and attend to their multiple needs. This PT (Figure 2) describes how this concept can actually be operationalised. A key contextual factor facilitating successful engagement (especially on initial contact) is that staff should recognise that working with COSMHAD is a part of their job. Adams3 describes how ‘professional ambivalence towards comorbidity [context] … may influence the assessment process and subsequent interactions [mechanism–resource]’ (p. 102) and several studies have highlighted the importance of using assessment protocols and screening tools to help the clinician formulate a thorough picture of the client’s life circumstances. 40–44 This in turn allows the clinician to develop a richer understanding of the person’s situation, which promotes compassion. This was also supported by the case study data with staff emphasising the importance of a flexible and non-judgemental approach, that it’s ‘everyone’s business’ and a needs-led holistic approach can be effective in identifying the right care and treatment.

FIGURE 2.

Refined PT 1: first contact and assessment (‘It’s everyone’s business’).