Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number 17/94/36. The contractual start date was in January 2019. The draft manuscript began editorial review in January 2023 and was accepted for publication in August 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Tew et al. This work was produced by Tew et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Tew et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Material throughout this chapter has been reproduced from Tew et al. 1

This is an open access article that is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Burden of multimorbidity in older people

Multimorbidity, often defined as the co-existence of two or more chronic medical conditions,2 is a major challenge for health and care systems worldwide and of particular relevance for older adults. In 2015, 54% of people aged 65 years or older in England exhibited multimorbidity; this percentage is projected to increase to 68% by 2035. 3 Multimorbidity is associated with poorer outcomes such as reduced quality of life, impaired functional status, worse physical and mental health and premature death. 4,5 Multimorbidity also increases healthcare utilisation and associated costs. 6,7

Interventions for improving outcomes for people with multimorbidity

There has been limited exploration of the effectiveness of interventions to improve outcomes for people with multimorbidity. A 2021 systematic review identified 16 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with 4753 participants that had evaluated a range of complex interventions for people with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. 8 Eight studies examined multifaceted interventions that targeted the co-ordination of care and healthcare providers while also providing self-management support for patients. Four studies reported on self-management support interventions that did not have a clear link to the patients’ healthcare provision. The other four studies focused primarily on medication management. The results suggested that all intervention types probably make little or no difference to health-related quality of life (HRQoL) or mental health outcomes. Five of the 10 studies with HRQoL outcomes reported EuroQoL 5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) (a generic measure of health utility) scores that could be included in a meta-analysis, with a mean difference (MD) of 0.03 [95% confidence interval (CI) −0.01 to 0.07], consistent with the overall effect suggesting no difference in this outcome. There was also little or no effect on clinical, psychological or medication outcomes or healthcare utilisation. There were mixed effects on function, activity and patient health behaviours, and limited data on costs. There was a low risk of bias overall; however, the evidence for all outcomes was downgraded to low certainty due to serious concerns about inconsistency and imprecision. This review highlighted the need for further research to determine the clinical and cost-effectiveness of interventions that are ideally simple, generalisable and which can address several medical conditions simultaneously. Yoga is a potential candidate intervention.

Yoga as an intervention for improving health and well-being

Yoga originated thousands of years ago in India as an integrated mind–body practice based on ancient Vedic philosophy. During the 20th century, yoga became increasingly recognised outside India, and over the past decades, it has continued to grow in popularity worldwide as a practice for improving health and well-being. While modern yoga often focuses primarily on physical poses and is sometimes thought of as a type of exercise, the practice usually incorporates one or more of the mental or mindful elements that are traditionally part of yoga, such as relaxation, concentration or meditation. There are currently many different styles or schools of yoga, each with a variable emphasis and approach to practice. Research evidence suggests that some of these yoga practices may help to prevent and treat various physical and mental illnesses and improve HRQoL. 9,10

In November 2017, the Cochrane Library published a special collection of 14 systematic reviews that focused on the effectiveness of yoga for improving physical or mental health symptoms and quality of life in a range of health conditions, including musculoskeletal, pulmonary, cancer, cardiovascular, neurological and mental health. A summary of four diverse but pertinent reviews is as follows:

-

Yoga for chronic non-specific low back pain:11 For yoga compared to non-exercise controls (9 trials; 810 participants), there was moderate-certainty evidence that yoga produced small-to-moderate improvements in back-related function [standardised mean difference (SMD) −0.44, 95% CI −0.66 to −0.22] and pain (MD −7.81, 95% CI −13.37 to −2.25) at 6 months. The authors recommended additional high-quality research to improve confidence in estimates of effect and to evaluate long-term outcomes.

-

Yoga for asthma:12 There was some evidence that yoga may improve quality of life (MD in Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire score per item 0.57 units on a 7-point scale, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.77; five studies; n = 375) and symptoms (SMD 0.37, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.65; three studies; n = 243) and reduce medication usage (risk ratio 5.35, 95% CI 1.29 to 22.11; two studies) in people with asthma. The authors concluded that large, high-quality trials are needed to confirm the effects of yoga on asthma.

-

Yoga for improving HRQoL, mental health and cancer-related symptoms in women diagnosed with breast cancer:13 Seventeen studies that compared yoga versus no therapy provided moderate-quality evidence showing that yoga improved HRQoL (SMD 0.22, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.40; 10 studies, n = 675), reduced fatigue (SMD −0.48, 95% CI −0.75 to −0.20; 11 studies, n = 883) and reduced sleep disturbances in the short term (SMD −0.25, 95% CI −0.40 to −0.09; six studies, n = 657). No serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported. Additional research was recommended to assess medium- and longer-term effects.

-

Yoga for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease:14 Yoga was found to produce reductions in diastolic blood pressure (MD −2.90 mmHg) and triglycerides (MD −0.27 mmol/l) and increase high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (MD 0.08 mmol/l). There was no clear evidence of a difference between groups for low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, although there was moderate statistical heterogeneity. Adverse events (AEs), occurrence of type 2 diabetes and costs were not reported in any of the studies. No study reported cardiovascular mortality, all-cause mortality or non-fatal events, and most studies were small and short term.

Elsewhere, studies have sought to determine the effects of yoga in older populations. For example, a 2012 systematic review of 16 studies (n = 649)15 and a more recent trial of 118 participants16 demonstrated that yoga may provide greater improvements in physical functioning and self-reported health status than conventional physical activity interventions in older adults. More recently, a systematic review of six trials (n = 307) of relatively high methodological quality reported that yoga interventions had a small beneficial effect on balance (SMD 0.40, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.65, six trials) and a medium effect on physical mobility (SMD 0.50, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.95, three trials) in people aged 60 and over. 17

In summary, these data offer support for the beneficial effects of yoga in older adults and for several chronic conditions. However, many of the previous studies had limitations, including small sample sizes, a single yoga teacher delivering the programme and short-term follow-up. Robust economic evaluations of yoga are also limited, although a recent systematic review concluded that ‘medical’ yoga is likely to be a cost-effective option for low back pain. 18 Very little research has specifically focused on older people with multimorbidity.

In 2009, the Gentle Years Yoga© (GYY) programme was developed by the Yorkshire Yoga and Therapy Centre to cater specifically to the needs of older adults, including those with conditions common to an older cohort such as osteoarthritis, hypertension and cognitive impairment. As part of the pilot research study conducted at Yorkshire Yoga in 2016, a standardised GYY teacher training programme was manualised with the creation of a quality-assured teacher training course which became the British Wheel of Yoga (BWY) GYY programme that is being delivered by the BWY. British Wheel of Yoga is the National Governing Body of Yoga in Great Britain, with a nationwide network of over 5000 qualified yoga teachers. Gentle Years Yoga is based on standard Hatha Yoga, incorporating traditional physical poses and transitions as well as breathing, concentration and relaxation activities. Adaptations to challenging Hatha Yoga poses have been made so that older adults can participate safely while still obtaining the fitness, health and well-being benefits of yoga. Each programme involves one group-based session per week for 12 weeks (each session includes a 75-minute chair-based yoga class and after-class social time) and promotion of regular self-managed yoga practice at home.

In a pilot trial of the GYY programme,19 82 older adults expressed an interest within a 2-month recruitment period, of which 52 (mean age 75 years) were recruited and randomised. Participants had up to six chronic conditions, the most common of which were osteoarthritis, hypertension and depression. Trial yoga courses were delivered across four community venues by four yoga teachers. Two-thirds of participants had an acceptable attendance of ≥ 80%. The study demonstrated feasibility of evaluating the GYY programme in a fully powered RCT and the potential for a positive clinically important effect on health status [EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) utility index score] at 3 months after randomisation (MD 0.12, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.21).

Consequently, we conducted a larger trial – The GYY Trial – to establish the clinical and cost- effectiveness of the GYY programme in older adults with multimorbidity. If this intervention was shown to be clinically effective and cost-effective, it could be implemented more widely, leading to improved outcomes for this population.

Research aims and objectives

The GYY Trial was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Programme in response to a themed call on complex health and care needs in older people. The aim of the trial was to establish the clinical and cost effectiveness of the GYY programme in addition to usual care versus usual care alone in community-dwelling older adults with multimorbidity.

The primary objective was to establish if the offer of a 12-week GYY programme in addition to usual care is more effective compared with usual care alone in improving HRQoL (EQ-5D-5L utility index score) over 12 months in people aged 65 years or over with multimorbidity.

Secondary objectives were as follows:

-

to explore the effect of the GYY programme on HRQoL, depression, anxiety and loneliness at 3, 6 and 12 months after randomisation

-

to explore the effect of the GYY programme on the incidence of falls over 12 months from randomisation

-

to explore the safety of the GYY programme relative to control in terms of the occurrence of AEs over 12 months after randomisation

-

to assess if the GYY programme is cost-effective, measured using differences in the cost of health resource use between the intervention and usual care groups and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICER) using quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) derived from the EQ-5D-5L measured at 3, 6 and 12 months after randomisation

-

to undertake a qualitative process evaluation to describe the experience of the intervention, explain the determinants of delivery (including treatment fidelity) and identify the optimal implementation strategies for embedding and normalising the GYY programme in preparation for a wider roll-out.

Chapter 2 Methods

Material throughout this chapter has been reproduced from Tew et al. 1

This is an open access article that is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Trial design

This was a multisite, two-arm, parallel-group, superiority, individual RCT comparing an experimental strategy of offering a 12-week GYY programme against a control strategy of no offer of GYY in community-dwelling people aged 65 years or over who had multimorbidity. Both trial arms continued with any usual care provided by primary, secondary, community and social services.

The study also included an internal pilot, economic analysis of cost-effectiveness (see Chapter 4), a qualitative process evaluation (see Chapter 5) and four methodological substudies (see Chapter 6) that addressed the following questions:

-

What is the concurrent validity of the 29-item Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System® (PROMIS-29) against the EQ-5D-5L?

-

Does including £5 and/or a pen in the recruitment pack enhance recruitment?

-

Does sending a pen with a follow-up questionnaire enhance return rates?

-

Does offering a free yoga session to control participants after the 12-month follow-up assessment enhance retention and reduce contamination?

Setting

Participants were recruited from primary care general practices serving nine geographical areas: Harrogate, Hull, Wirral, Kent, Bristol, Oxford, Wantage and Banbury in England and Newport in Wales. The 15 general practitioner (GP) practices that supported recruitment are listed in Report Supplementary Material 1. The yoga courses were delivered either face to face in a non-medical community-based facility (e.g. yoga studio, community hall, leisure centre) or online via video conferencing during periods of social distancing restrictions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic (see Report Supplementary Material 2 for further details).

Eligibility and recruitment

Eligibility criteria for participants

Patients were eligible to join the study if they were aged 65 years or older (both male and female), community-dwelling (including sheltered housing living with support) and had two or more of the following chronic conditions, as derived from a list included in the NHS Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF version 31.0) and following discussions with the Trial Management Group clinical oversight and yoga consultants:

-

arthritis: including osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and history of shoulder, hip or knee arthroplasty for arthritis

-

asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

-

atrial fibrillation

-

bowel problems: including irritable bowel syndrome, diverticulitis and inflammatory bowel disease

-

cancer, diagnosed within the last 5 years

-

cardiovascular disease: including coronary heart disease (includes angina and history of heart attack, bypass surgery or angioplasty), hypertension, heart failure and peripheral arterial disease

-

chronic kidney disease

-

dementia (only if patients have the capacity to provide written informed consent)

-

depression or anxiety

-

diabetes

-

epilepsy

-

fibromyalgia

-

multiple sclerosis

-

osteoporosis or osteopenia

-

Parkinson’s disease

-

sensory conditions: including hearing loss, macular degeneration, cataracts and glaucoma

-

stroke, within the last 5 years.

Patients were ineligible for the study if they met one or more of the following exclusion criteria:

-

inability to attend one of the yoga courses on offer [participants needed to indicate that they would be available to attend at least 9 of the 12 classes on offer for a particular course. In relation to online classes, additional factors that made someone ineligible included: no internet access, unfamiliarity with or inability to use the internet, no suitable device for accessing the online classes (e.g. tablet-size screen or larger; device with camera and microphone), insufficient space at home and no sturdy chair for use in the classes]

-

attended yoga classes twice a month or more in the previous 6 months

-

contraindications to yoga participation (as identified by the patient’s GP)

-

severe mental health problem: Schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder or other psychotic illness (on advice from the Trial Management Group yoga consultants, potential participants with severe mental health problems and learning disabilities were listed as exclusions on the basis that the GYY teacher training programme does not cover how to accommodate these people, who may have specific support needs, and it was thought that this might make the yoga class size of 12–15 difficult to manage)

-

learning disability (on advice from the Trial Management Group yoga consultants, potential participants with severe mental health problems and learning disabilities were listed as exclusions on the basis that the GYY teacher training programme does not cover how to accommodate these people, who may have specific support needs, and it was thought that this might make the yoga class size of 12–15 difficult to manage)

-

unable to read or speak English (potential participants who were unable to read or speak English were listed as exclusions due to the uncertainty of being able to adapt the course delivery and questionnaires to accommodate different languages)

-

unable to provide consent

-

unable to complete and return a valid baseline questionnaire

-

no more than one trial participant per household [no more than one trial participant per household could take part to avoid contamination effects (i.e. if one was allocated to the intervention group and the other to the usual care group)]

-

currently enrolled in another research study for which concurrent participation is deemed inappropriate by their GP or a clinician co-investigator.

All eligibility criteria were assessed by reviewing responses to specific questions posed in a screening questionnaire [see Trial Participant project documents, https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/94/36 (accessed May 2024)] that was self-reported by potential participants either in written format or over the telephone with a researcher. Patients who did not meet the eligibility criteria were notified in writing or via a phone call that they were ineligible, and no further correspondence was sent. Patients who were deemed eligible were required to complete a baseline questionnaire [see Trial Participant project documents, https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/94/36 (accessed May 2024)] either in written format or over the telephone with a researcher. Participants were eligible to be randomised once the study team had received their completed consent form and baseline questionnaire. If a completed baseline questionnaire was not received by the end of the recruitment period, the patient was sent a letter to inform them that recruitment to the trial had closed and that they were unable to participate.

Recruitment of participants

Potential participants were identified by searching the electronic patient databases (SystmOne or EMIS) of 15 general practices. Participating practices ran a custom-built search based on pre-defined read codes, which identified patients with health conditions within the eligibility criteria. A GP then reviewed the resulting list to rule out patients who did not meet the eligibility criteria. Where there were more potentially eligible patients identified than required, practices were asked to order the list of patients by NHS number and select the top required number. Docmail (a third-party information handler) then mailed out a recruitment pack to each of the remaining potentially eligible patients, which included a covering invitation letter, a participant information sheet (PIS) which included a link to an audio version on the trial website, a consent form and a screening questionnaire [see Trial Participant project documents, https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/94/36 (accessed May 2024)] and two prepaid envelopes for returning the completed forms. If the patient was deemed eligible (based on the information provided in the screening questionnaire), a researcher notified the patient’s GP and asked them to confirm the patient’s suitability for participation. Eligible patients were then sent a baseline questionnaire [see Trial Participant project documents, https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/94/36 (accessed May 2024)] to complete and return by a specified date. This questionnaire collected data on sociodemographic measures, primary and secondary outcome measures and preferences/beliefs for the treatments on offer in the trial.

Implementation of an alternative process was required during the COVID-19 pandemic as it was difficult to collect study forms by post, particularly when the trial team was required to work from home. Therefore, participants gave consent electronically by completing an online form and provided screening and baseline questionnaire data via a telephone call with a researcher, who entered these data into an online form during the call.

Identification of trial groups

Participants had to be recruited in groups for the yoga courses, and the courses were run over a period of 29 months. To facilitate identification, each recruitment drive was called a ‘wave’. There were two waves in the internal pilot phase: pilot wave 1 (PPW1) and pilot wave 2 (PPW2) and two waves in the main phase of the trial: main wave 1 (MPW1) and main wave 2 (MPW2). The number of courses run within a wave varied depending on GP practice capacity to recruit and yoga teacher availability.

Consenting participants

As detailed above, potentially eligible patients were posted a recruitment pack, which included a covering invitation letter, an information sheet, a screening questionnaire and a hard copy of (or electronic link to) the consent form.

The information sheet provided a balanced written account of the purpose and design of the trial and also included details of who to contact to ask any questions and how they could access an audio recording of the information sheet on the trial website. Part way through recruitment, we introduced a simple diagram of the trial design to be provided along with the information sheet to facilitate participants’ understanding of the randomisation process and what each group was to receive [see Trial Participant project documents, https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/94/36 (accessed May 2024)].

Participants indicated on the consent form if they also wanted to be considered to take part in the process evaluation interviews. If the participant indicated ‘yes’ and was selected by the process evaluation researcher to take part in the interviews, they were then provided with an information sheet regarding the interviews [see Process evaluation project documents, https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/94/36 (accessed May 2024)]. Additional consent was sought, either via hard copy or electronically, in line with alternative arrangements, from those who agreed to take part [see Process evaluation project documents, https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/94/36 (accessed May 2024)]. Individuals who declined to participate in the trial were able to indicate their willingness to take part in the interviews as a ‘trial decliner’, and additional consent was sought from them, as above.

Eligibility criteria for primary care general practices

The selection of general practices was informed by location (i.e. located close, generally within five miles, to the yoga class venue); local transport routes and teacher recommendations for face-to-face classes; computer system used; patient list size and practice staff availability for conducting recruitment activities.

Recruitment of primary care general practices

General practices that were potentially interested in taking part in the trial were identified with help from the NHS Clinical Research Networks (CRN) in England and the Health and Care Research Wales (HCRW) Support and Delivery Centre. We also worked with NHS Research Scotland (NRS) Primary Care Research Network but did not receive any expressions of interest from invited general practices via this network. Trial coordinators then liaised with key stakeholders at each practice (e.g. practice managers, GPs) to explain the requirements of the study. If a practice agreed to take part, a practice-level agreement form was signed to confirm capacity and capability before any recruitment activity commenced. This initially was the Health Research Authority (HRA) and HCRW Statement of Activities document [see GP practice project documents, https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/94/36 (accessed May 2024)] which was later replaced by the Integrated Research Application System (IRAS) Organisations Information Document [see GP practice project documents, https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/94/36 (accessed May 2024)]. Practice recruitment is represented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

General practice recruitment flowchart.

Eligibility criteria for yoga teachers

To be eligible for inclusion to deliver the intervention programme, yoga teachers needed to have completed the British Wheel of Yoga Qualifications (BWYQ) Level 4 Teaching GYY qualification and have valid BWY membership and insurance. For online courses, teachers also needed to be proficient in remote teaching. The selection of yoga teachers was informed by observations of them leading online non-trial yoga classes, as conducted by the trial’s yoga consultants (LB and JH).

Recruitment of yoga teachers

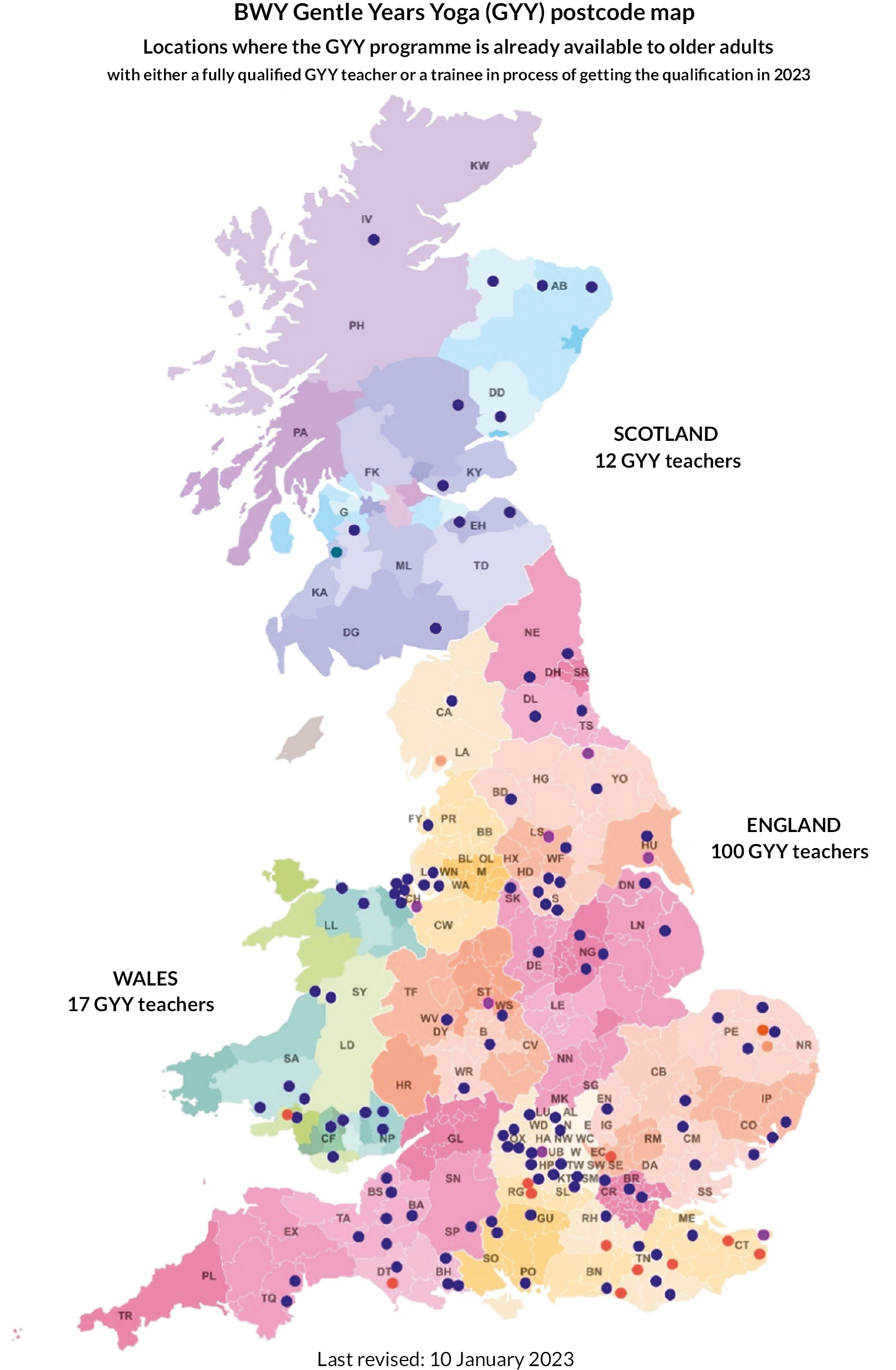

Yoga teachers who were potentially interested in taking part in the trial were identified by the trial’s yoga consultants (LB and JH). The consultants were aware of who had completed the Level 4 GYY teacher training course (because of their work at the awarding organisation BWYQ) and where they were based. The consultants and trial coordinators liaised with potential teachers to explain the requirements of the study. This included both delivery of the courses and provision of backup yoga teachers to cover absence. If a teacher agreed to take part, a contract with the University of York was signed before any trial classes were delivered.

Intervention and comparator conditions

Comparator description

The comparator was usual care alone. Usual care was defined as ‘The wide range of care that is provided in a community, whether it is adequate or not, without a normative judgment’. 20 Throughout the trial, both trial arms continued with any usual care provided by primary care, secondary care, community and social services. This approach reflects the main aim of this pragmatic trial: to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of offering the GYY programme in addition to usual care.

To characterise and quantify usual care, self-reported healthcare resource use (NHS and private care) was collected at baseline and at each follow-up assessment for all participants in both intervention and usual care groups. Prescription data from general practices were also collected for the period between 3 months prior to baseline and up until 12 months after, for a sub-sample of participants in both groups.

The protocol did not restrict access to yoga or any other intervention during the follow-up period. However, to reduce contamination, the trial yoga teachers were asked to only deliver trial classes to the participants who had been randomly allocated to their courses. In the follow-up questionnaires, all participants were asked to report any trial and non-trial, supervised yoga classes and self-managed yoga practice that they had done since the previous study time point.

Intervention description

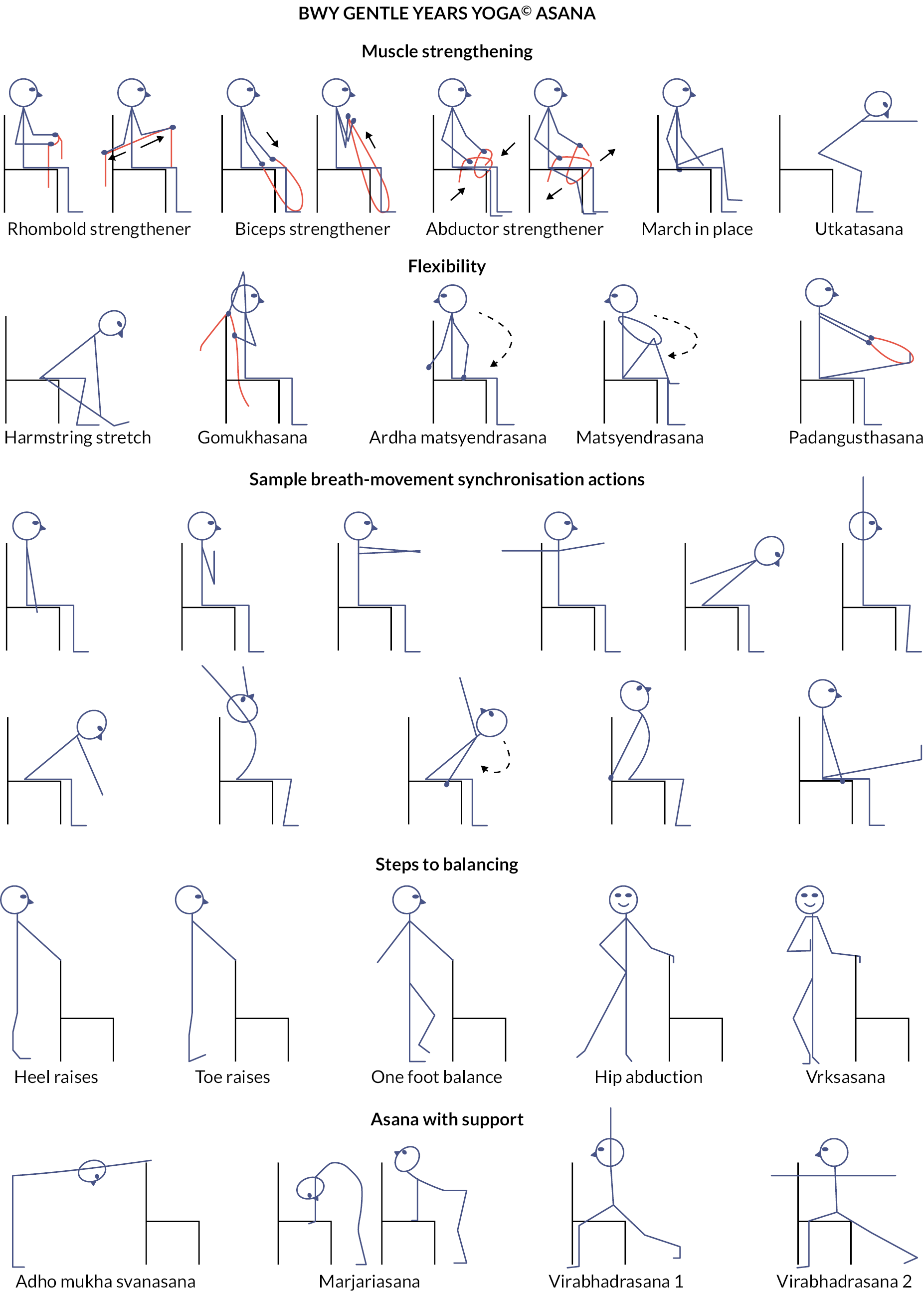

Gentle Years Yoga is a yoga programme for older adults, including those with chronic health conditions. It is based on standard Hatha Yoga and incorporates traditional physical postures and transitions as well as breathing, concentration and relaxation activities. Each class also includes optional, additional time immediately following the class for participants to stay on and socialise. The main aims of the programme are to improve muscle strength, flexibility, balance, mobility and mental and social well-being. Chairs are used for seated exercise and can be used to provide support when standing, although the whole session can be carried out on a chair. Figure 2 shows examples of seated postures that are commonly used. The yoga practices are modified to allow individuals with varying medical conditions and functional abilities to participate safely. Props are also sometimes used to modify some of the postures and concentration activities. A list of props used in the trial is detailed in Table 1. The physical challenge of each posture can be progressed throughout the course as participants become more able and confident. The following summarises how the GYY classes differ from standard Hatha Yoga classes:

| Item | Description | Possible uses |

|---|---|---|

| Resistance bands | Brand: Meglio Material: thermoplastic elastomer Resistance level: extra light, 1–4 lbs Size: 1.2 m Colour: yellow |

Upper and lower body resistance – biceps, triceps, quadriceps; finger/hand mobilisation and dexterity; concentration and focused sensation |

| Scarfs | Brand: TecUnitea/Geeborb/QLOUNIb Material: silk fabric Size: 24 × 24 inches Colour: assorted |

Toss/catch; squeeze hands; finger/hand mobilisation and dexterity; hand-to-hand passing; shoulder mobilisation; breath work, esp. longer exhalation focus; concentration and focused sensation |

| Beanbag | Brand: Prextex/First-Play Material: nylon Covered/Cotton coveredb Size: 10 × 8 cm/15 × 10 cm Weight: 255.15g/110g Colour: assorted |

Toss/catch; squeeze hands; squeeze toes; finger dexterity; foot balance; hand balance; concentration and focused sensation; hand-to-hand/hand-to-foot passing; counting beans meditation |

| Squishy balla | Brand: MIMIEYES Material: polyurethane Size: 2.5 inches Weight: 170g Colour: yellow (with smiley faces) |

Toss/catch; squeeze hands; squeeze toes; roll hands (limited); finger dexterity; foot balance; hand balance; concentration |

| Tennis ballb | Brand: Wilson Material: felt Size: 2.5 inches Weight: 230g Colour: yellow/orange |

Toss/catch and bounce pulse raisers; roll hands; roll feet; foot balance; hand balance; concentration; focused sensation |

| Blockb | Brand: Yoga Studio Material: recycled chip foam Size: 12 × 2 × 8inches Weight: 500g Colour: mottled/multicoloured |

Aligning body in seated Tadasana; use as a platform for exercising toes, feet, ankles, fingers, hands, wrists |

-

For the most part, participants are seated on chairs, and when standing, they use the chair or other aids for support.

-

The classes do not use supine, semi-supine or prone postures; instead, the key elements of traditional supine and prone postures are integrated into seated or standing postures.

-

The classes hold static postures for a shorter length of time, especially those that could cause more pronounced acute increases in blood pressure.

-

The physical set-up of classes has been adapted to suit people with sensory impairments; specifically, participants being relatively close to the teacher; lighting levels being higher; the colour of equipment being in contrast to that of the walls, the floor and the teacher, and no music played during verbal instructions.

-

The pace and overall structure of the class allow greater time for recovery from the more intense activities (e.g. by having a simple breathing practice follow a more-challenging physical posture).

-

If there are individuals with mild cognitive impairment in the group, the teacher will use short, single-subject phrases and pace the instructions to allow time for processing each element of the instructions.

-

The classes have a longer warm-up period and an overall slower pace, making it safer for older adults and at a level where they can work without feeling ‘left behind’ or ‘too old for yoga’ or having their self-confidence eroded.

-

Breathing practices avoid retention, as this is contraindicated for individuals with hypertension.

-

Mobilisation, postures and concentration activities are incorporated that specifically focus on balance and co-ordination.

Participants randomised to the intervention were invited to take part in 12 free-of-charge, 75-minute group-based GYY classes. Each class was immediately followed by an optional 15- to 30-minute period of socialising. All courses commenced within 3 weeks of randomisation. Each course involved one class per week for 12 (mostly) consecutive weeks; however, there was allowance for a gap in delivery for public holidays and unforeseen circumstances. A summary of actual time between randomisation and commencement of a yoga course and between each class, indicating any gaps in delivery, is provided in Report Supplementary Material 3. Before the first class, participants were required to complete and submit a BWY Health Questionnaire to their yoga teacher [see Yoga participant project documents, https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/94/36 (accessed May 2024)]. This questionnaire was needed for BWY teaching insurance purposes and so that the teachers were aware of each participant’s medical conditions and physical activity status.

Each class included: (1) ‘housekeeping’ activities, such as completing the class register and discussing any home practice or health issues (5 minutes); (2) an introduction to the theme and practices of the class, basic breathing and focusing activities (5 minutes); (3) an extended warmup/mobilisation and preparatory postures (30–35 minutes); (4) focused postures and restorative activities (10–15 minutes); (5) breathing exercises (5–10 minutes) and (6) relaxation and concentration activities (5–10 minutes), followed by optional after-class social time (15–30 minutes).

The after-class social time provided an opportunity for participant interaction and building of social networks. The yoga teachers encouraged participants to stay on for this component, but it was not mandatory. The focus of conversations was not standardised; however, the teachers were advised that there was a preference for non-yoga-based discussions. The teacher could still provide general yoga advice to participants if directly asked.

The classes also included instruction on yoga activities that the participants could do at home. Yoga teachers provided participants with a home practice sheet that detailed these activities, which were to be completed at home on non-class days. As the class-based activities became more challenging, students were given new home practice sheets to allow progression of their home yoga routine. Each yoga participant received four home practice sheets in total, covering weeks 1–3, 4–6, 7–9 and 10–12, respectively [see Yoga participant project documents, https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/94/36 (accessed May 2024)]. Each sheet included at least five practices, providing an expected practice time of 10–20 minutes per session.

Towards the end of the course (i.e. classes 11 or 12), the yoga teachers provided participants with general verbal advice about continuing yoga practice and a written or electronic handout [see Yoga participant project documents, https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/94/36 (accessed May 2024)] sign-posting participants to suitable yoga classes (i.e. GYY or similar) in their local community or online, which they could attend on a self-pay basis.

The delivery mode of the trial yoga classes was originally face to face. Online classes were implemented during Pilot Phase Wave 2 (autumn 2020) and addressed the closure of venues during the first national lockdown and, later, the need for social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. The trial classes included intervention participants only (i.e. members of the public could not participate), with each 12-week course having 12 participants allocated if delivered online and up to 15 participants allocated if delivered face to face (see Report Supplementary Material 2). Face-to-face classes were conducted in non-medical community-based facilities (e.g. yoga studio, community hall, leisure centre) following checks for venue suitability by the yoga consultants (LB and JH). Accessibility factors that were considered included close proximity to public transport links, parking facilities and disability access. Online classes were conducted via Zoom, an online livestream platform freely accessible to participants using a computer or tablet. Pre-course contact by the yoga teachers with participants was introduced from the start of Pilot Phase Wave 2. Prior to online classes commencing, the yoga teacher conducted one-to-one Zoom meetings with their participants to optimise the set-up of their equipment and environment and to discuss any health issues or course queries. Prior to face-to-face classes commencing, the yoga teachers conducted one-to-one telephone meetings with their participants to discuss any health issues or course queries.

Yoga teacher training

Nineteen yoga courses were delivered within the trial by 12 yoga teachers (1 teacher delivered 3 courses, 5 teachers delivered 2 courses each and 6 teachers delivered 1 course each). All teachers had the BWYQ Level 4 Teaching GYY qualification, appropriate insurance and experience of working with older adults. They also received specific training about the trial and its procedures from the research team.

The GYY programme is copyrighted by the BWY, and since 2017 they have provided training in GYY to qualified yoga teachers. Training for the regulated level 4 Teaching GYY qualification takes place over approximately 12 months and covers the National Occupational Standards for understanding the principles of adapting physical activity for older adults and the planning, adaptation and delivery of sessions to meet the requirements of participants with specific needs. This includes information on ageing, barriers and motivators to exercise, ethical and legal responsibilities, the physiology of ageing and common chronic conditions and how to modify yoga for different health states. After distance learning modules and face-to-face instruction, the teachers demonstrate their understanding through worksheets, multiple-choice questions, two case studies, designing a GYY programme and being observed and assessed on their teaching of GYY sessions on two occasions.

To minimise inter-teacher variation and enhance fidelity of intervention delivery, the yoga teachers received standardisation training from the research team via a 1-day interactive workshop. The training included background information about the GYY programme and the trial, clarification of standardised class content and structure and practical delivery tips, including intervention progression and provision of home practice sheets. It also stressed the importance of only allowing people in the trial’s intervention group to access the classes and explained trial processes such as AE reporting and class attendance monitoring. To supplement this training day, teachers also received a research training manual (see Report Supplementary Material 4) and feedback from a yoga consultant (JH) on a 12-week course plan that each teacher needed to submit at least 2 weeks before their first trial class. [see Yoga teacher project documents, https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/94/36 (accessed May 2024) for GYY course plan feedback template.] During the intervention delivery period, the yoga teachers were able to contact the yoga consultants (LB and JH, who developed the GYY teacher training course) for advice about the intervention and the trial coordinators for advice about trial processes.

Criteria for discontinuing or modifying allocated interventions

There were no specific criteria for discontinuing or modifying allocated interventions. Participants could decide to stop doing the yoga programme at any point and for any reason.

Strategies to improve adherence to interventions

To optimise and encourage attendance, the teachers were asked to contact participants who missed two consecutive classes without prior notification.

Relevant concomitant care permitted or prohibited during the trial

Participants continued to receive independent, usual care throughout the trial, and this was not prohibited in any way.

Provisions for post-trial care

Towards the end of the course (i.e. classes 11 or 12), the yoga teachers provided intervention participants with general verbal advice about continuing yoga practice and a paper or electronic handout [see Yoga participant project documents, https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/94/36 (accessed May 2024)] sign-posting participants to suitable yoga classes (i.e. GYY or similar) in their local community or online, which they could attend on a self-pay basis. The usual care participants received the same information after completing the final (12-month) follow-up questionnaire. Usual care participants were also randomised into a methodological substudy in which half were offered a GYY class at the end of their 12-month follow-up. They were informed of this offer shortly after randomisation in order to determine whether this improved their retention in the trial. Methods and results of this substudy are detailed in Chapter 6.

Outcomes

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome was the EQ-5D-5L utility index score. 21 The EQ-5D-5L was self-reported by the participant and collected using questionnaires at baseline and at 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation. The primary end point was the overall difference over the 12-month follow-up period. There is currently work ongoing to develop a valuation set for the EQ-5D-5L for England; in the meantime, the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends22 that utility index scores should be calculated using the crosswalk developed by van Hout et al. ;23 hence, they were calculated on this basis.

The EQ-5DTM is a widely used self-reported health utility measure that comprises two parts: the classification of five dimensions of health (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression) and a visual analogue scale (VAS), which records participants’ overall evaluation of their health on a scale from 100 (best imaginable health) to 0 (worst imaginable health). The EQ-5D has been validated in many different patient populations, including those with diabetes, cardiovascular problems, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, chronic pain and rheumatoid arthritis.

There are currently two versions of the instrument that can be used for adults: the original EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L) with five dimensions of health and three response levels of problems and the more recent EQ-5D-5L that has the same five dimensions of health but has five response levels of problems (1 = no problems, 2 = slight problems, 3 = moderate problems, 4 = severe problems and 5 = unable/extreme problems). The EQ-5D-5L helps overcome problems with ceiling effects and has greater sensitivity. 21 It showed evidence of good sensitivity in the pilot trial of the GYY programme19 and has been the primary outcome measure in other primary care-based multimorbidity trials. 24 Responses to the EQ-5D-5L lead to 3125 unique possible combinations of health states where each health state is mapped to a utility index score (on a scale where negative values correspond to a state worse than death, 0 corresponds to a health state equivalent to being dead and 1 corresponds to perfect health) by making use of a valuation set. Participants who die can be given a score of 0 (for both the utility index score and VAS) for any assessment time point following their date of death.

Besides being used as the primary outcome measure in the analysis, the EQ-5D-5L was also used to estimate QALYs for the economic evaluation (see Chapter 4).

Secondary outcomes measures

All secondary outcomes were self-reported by the participant and collected using questionnaires at baseline and during the 12-month follow-up [see Trial Participant project documents, https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/94/36 (accessed May 2024)]. The secondary outcomes were:

-

EQ-5D-5L utility index score at 3, 6 and 12 months after randomisation

-

EQ-5D-5L VAS score at 3, 6 and 12 months and overall

-

HRQoL at 3, 6 and 12 months and overall using the PROMIS-2925

-

depression severity at 3, 6 and 12 months and overall using the Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8)26

-

anxiety severity at 3, 6 and 12 months and overall using the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)27

-

loneliness at 3, 6 and 12 months and overall. Four questions were used to capture different aspects of loneliness. The first three questions were taken from the University of California, Los Angeles 3-item (ULCA-3) loneliness scale. 28 The wording of the UCLA questions and response options was taken from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA). 29 The last was a direct question about how often the respondent feels lonely

-

incidence of falls over 12 months

-

AEs over 12 months

-

healthcare resource use over 12 months (see Chapter 4, Economic Evaluation).

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-29

The PROMIS-29 v2.1 measurement scale consists of seven subscales and a global item. Both a physical and a mental health component summary score can also be generated.

The seven subscales look at the following aspects of HRQoL: physical function, anxiety, depression, fatigue, sleep disturbance, ability to participate in social roles and activities and pain interference. Each of the items in the seven subscales takes an integer-valued response ranging from 1 to 5, where higher-numbered responses indicate a worse quality of life for the anxiety, depression, fatigue, sleep disturbance and pain interference subscales but better for the physical function and ability to participate in social roles and activities subscales. The PROMIS can be scored in multiple ways. Manual scoring: for each of the seven subscales, a raw score is calculated as the sum of the values of the responses for each item in the subscale, and this raw score is converted to a T-score using the conversion tables specified in the PROMIS Adult Profile Scoring Manual (www.healthmeasures.net/images/PROMIS/manuals/Scoring_Manuals_/PROMIS_Adult_Profile_Scoring_Manual.pdf). However, this does not deal with missing data as it uses a ‘complete-case’ approach, where an overall score for a subscale is only calculated if there are no missing responses for any of the items in the subscale. The preferred method of scoring is to use the HealthMeasures Scoring Service (www.assessmentcenter.net/ac_scoringservice). This method of scoring uses responses to each item for each participant (referred to as ‘response pattern scoring’). Response pattern scoring is preferred because it is more accurate than the use of raw score/scale score look-up tables included in the manual. Response pattern scoring is especially useful when there is missing data (i.e. a respondent skipped an item) (text copied and adapted from the PROMIS Profile Scoring Manual). We used the online Assessment Centre scoring in this trial.

The global item asks the participant to rate their pain on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 to 10, where 0 corresponds to ‘no pain at all’ and 10 is ‘worse imaginable pain’.

The mental and physical health component summary scores were calculated as detailed in https://labs.dgsom.ucla.edu/hays/files/view/docs/programs-utilities/prom29/PROMIS29_Scoring_08082018.pdf. A higher score indicates a more favourable outcome.

Each of the PROMIS-29 v2.1 subscales, the physical and mental health component scores (PCS, MCS) and the global item at 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation, as well as overall, were used as secondary outcomes.

Patient Health Questionnaire-8

The eight-item PHQ-8 instrument is used to measure depression severity and asks the participant to indicate how often in the last 2 weeks they have been bothered by eight problems, each scored on the scale 0 = ‘Not at all’, 1 = ‘Several days’, 2 = ‘More than half the days’, and 3 = ‘Nearly every day’. A total score is obtained from summing the eight-item scores. If one item was missing from the score, it was substituted with the average score of the non-missing items (scored pro rata and total score rounded to the nearest integer). 30 Questionnaires with two or more missing values were not scored. A total score of 5–9 represents mild depressive symptoms; 10–14, moderate; 15–19, moderately severe and 20–24, severe.

Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7

The GAD-7 is a seven-item instrument asking the participant to indicate how often over the last 2 weeks they have been bothered by seven problems; each scored 0 = ‘not at all’, 1 = ‘several days’, 2 = ‘more than half the days’ and 3 = ‘nearly every day’. A total score is obtained by summing the seven item scores from 0 to 21. If one item was missing from the score, then it was substituted with the average score of the non-missing items (scored pro rata and total score rounded to the nearest integer). Questionnaires with two or more missing values were not scored. Scores of 5, 10 and 15 represent cut-off points for mild, moderate and severe anxiety, respectively.

Loneliness

The UCLA-3 is a three-item instrument asking the participant to indicate how often they feel they lack companionship, feel left out or feel isolated. The scoring of the three items is as follows: 1 = ‘hardly ever or never’, 2 = ‘some of the time’ and 3 = ‘often’. A summary score is calculated by summing the three item scores, where none of the item responses are missing.

In addition to the UCLA-3 instrument, loneliness was also measured using the ELSA single-item direct loneliness question at each of the follow-up time points, which asks the participant how often they feel lonely with responses: 1 = ‘Never’, 2 = ‘Hardly Ever’, 3 = ‘Occasionally’, 4 = ‘Some of the time’ and 5 = ‘Often or Always’.

Falls

Incidence of falls was measured as the total number of falls experienced by the participant during the 12-month follow-up period. The baseline and 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up questionnaires asked whether the participant fell in the 3 (or 6 on the 12-month questionnaire) months since the last questionnaire, and if so, how many times.

Process evaluation

A qualitative process evaluation was informed by qualitative interviews with trial participants, trial decliners, trial yoga teachers and stakeholders, as well as by observations of standardisation training sessions and yoga classes (see Chapter 5, Process Evaluation).

Intervention fidelity

To ensure the trial yoga courses were delivered in accordance with the GYY teacher training programme and GYY trial guidelines, each yoga teacher underwent an observation of one of their trial classes by one of the yoga consultants (LB and JH). A checklist was completed for each observation [see Yoga teacher project documents, https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/94/36 (accessed May 2024) for the yoga teacher fidelity check assessment template.]. Intervention fidelity was also assessed via class observations and interviews with each yoga teacher as part of the process evaluation.

Other data collected

Sociodemographic measures (age, gender, ethnicity, residential status, employment status, smoking status) and details of health conditions were collected at baseline via the screening and baseline questionnaires. An adapted Bayliss measure of illness burden31 was calculated by summing the amount that each self-reported health condition limits a participant’s daily activities from 1=‘Not at all’ to 5=‘A lot’. Participant beliefs and preferences for the GYY programme and usual care were assessed in the questionnaires at baseline and 12 months. Adherence by participants to the supervised GYY classes was recorded by the yoga teachers using class attendance registers [see Yoga teacher project documents, https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/94/36 (accessed May 2024)]. Participants also self-reported in the follow-up questionnaires any other supervised or self-managed yoga practice that they had done since the previous study time point. Adverse events were recorded (see ‘Adverse event reporting and harms’ below).

Sample size

Original

Walters and Brazier, in a review paper of the EQ-5D-3L,32 found a difference of 0.074 (mean) or 0.081 (median) to be a minimum clinically important difference among a variety of patients, while McClure and colleagues found a minimum clinically important difference of 0.063 (mean) or 0.064 (median) for the EQ-5D-5L using simulated data. 33 To be conservative, we powered the trial to detect the lowest estimate (0.06), assuming a standard deviation (SD) of 0.20. 19 Accounting for loss to follow-up of 20%, we needed to randomise 586 participants to have 90% power with 5% significance (two sided).

Although this was an individually randomised trial, there was the potential for clustering within the intervention arm by yoga class. Assuming an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.04 and average class size of 12 in the intervention arm, with the proposed sample size of 586, we would have still retained 84% power to detect the same magnitude of effect (ceteris paribus). In this calculation, we considered the level of clustering at the yoga class level rather than at the level of the yoga teacher, since we believed this to be the most influential level of clustering. Accounting for potential clustering within the intervention arm only leads to small reductions in power, which could potentially be recovered in the analysis of the repeated measures, adjusting for baseline value, which was not accounted for in the original sample size calculation.

Revised

Trial recruitment commenced prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. The onset of the pandemic caused challenges to recruitment. Considering these challenges, in October 2021, the sample size calculation was revisited. At this point, 454 participants had been randomised (240 intervention; 214 usual care) and the trial team were considering whether to apply for a funded 7-month extension to give extra time to pursue the original recruitment target of 586.

The original calculation did not account for the correlation of outcome with baseline, as this provides the most conservative target. At the start of the trial, there was little to base the estimate of the correlation on, and assuming a correlation that is larger than is eventually observed can lead to an underpowered trial. However, in practice, it was always planned to include the baseline EQ-5D-5L utility index score as a covariate in the primary analysis model, and this provides gains in power.

Assuming all other parameters remained the same, with 454 participants, we would have had 81% power to detect the same effect size. With a higher rate of follow-up that was consistent with what had been observed up until this time (90%), this would have increased the power to 86%. Accounting for a higher rate of follow-up and also correlation of the outcome with baseline of at least 0.35, then we would have retained 90% power. An interim calculation of the correlation between baseline and 12-month EQ-5D-5L utility index score based on data received and processed up to 15 October 2021 (n = 86 observations) was 0.67 (95% CI 0.54 to 0.77), and at that time we had observed a response rate of 90% at 3 months. Therefore, we were confident that we would be able to detect a clinically important difference with close to or greater than 90% power with 454 participants randomised. Hence, it was agreed to cease recruitment at 454 participants and not apply for an extension.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised via a central, computer-based randomisation system designed and managed by York Trials Unit (YTU), University of York. The randomisation was stratified and used varying block sizes and allocation ratios as follows.

When enough patients (ideally 20–30) had provided baseline data and confirmed their availability for a specific GYY course, they were randomised collectively as a ‘batch’ by a member of the research team using the randomisation system. The patients were allocated to either the intervention or usual care group in a ratio that was variable to ensure that each GYY course was full to begin with (12–15 participants randomised to the intervention group for each face-to-face course and 12 participants for each online course, with the remaining participants allocated to usual care). We targeted an overall allocation ratio of 1:1.

Each batch of randomisations was then considered as a ‘site’ (and it is this level of ‘site’ that is included as a random effect in the statistical analysis as detailed later in this chapter), but each site could contain patients from more than one GP practice. One yoga teacher led each GYY course, but some teachers led more than one course.

Since a group of participants were randomised simultaneously, as opposed to participants being randomised one by one, the allocation sequence could not be predicted in advance.

Participants were notified of their group allocation via telephone, letter or e-mail and sent a participant diary to prospectively record their healthcare resource use [see Trial Participant project documents, https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/94/36 (accessed May 2024)] so that they had this to refer to when asked about their healthcare resource use in the follow-up questionnaires. If randomised to the intervention group, they were sent details of the class that they should attend and the name of the yoga teacher.

Following randomisation, the research team at YTU provided the yoga teachers with the names and contact details of those who were going to be attending their classes. They required this information so that they could make appropriate arrangements to support intervention delivery. The randomisation of participants was timed to occur no more than 3 weeks before the start date of the course that had been agreed with the yoga teacher.

For randomisation of participants to the methodological substudies, see Chapter 6.

Blinding

Due to the nature of the intervention, participants and yoga teachers were not blinded to group allocation. Outcome measures were primarily self-reported. Members of the research team collecting the outcome data over the telephone took reasonable steps to ensure that they remained blinded to group allocation.

Although GPs were informed about their patients’ participation in the study, they were not informed about allocation status to reduce the risk of inducing GP behaviour change based on this knowledge. The wider health and social care team were not informed about a participant’s study participation or allocation status.

There were no specific emergency unblinding procedures. A participant’s group allocation could have been revealed to their GP in response to an AE, but there were no instances where this was necessary.

Internal pilot phase

The original overall recruitment target was 586 participants across at least 12 sites over a total of 24 months. Mailouts at different GP practices were staggered. The period covering the first eight sites/courses formed the internal pilot phase.

Internal pilot objectives:

-

to assess whether the provision and acceptability of the intervention met the pre-defined progression criteria thresholds, via the proportion of participants receiving their first yoga session within 3 weeks of randomisation and retention of intervention participants, respectively

-

to assess whether recruitment and 6-month follow-up rates met the pre-defined progression criteria thresholds, measured by recruitment and EQ-5D-5L completion data.

The progression criteria assessed the level of recruitment for each site, follow-up rates and provision and acceptability of the intervention and informed study continuation beyond the internal pilot phase. The progression criteria were assessed using a traffic light system of green (go), amber (review) and red (stop), as follows:

-

intervention provision (assessed 4 months after start of pilot intervention period):

-

green: 3–4 sites offering their first group yoga session within 3 weeks of participant randomisation

-

amber: 1–2 sites offering their first group yoga session within 3 weeks of participant randomisation

-

red: 0 sites offering their first group yoga session within 3 weeks of participant randomisation.

-

-

intervention acceptability (assessed 4 months after start of pilot intervention period):

-

green: ≥80% retention of intervention participants

-

amber: <80% but ≥65% retention of intervention participants

-

red: <65% retention of intervention participants.

-

-

recruitment (assessed at 6 months after start of internal pilot recruitment):

-

green: 3–4 sites recruited ≥20 patients each within 4 months (based on number of participants needed to allow randomisation and formation of a yoga class)

-

amber: 1–2 sites recruited ≥20 patients each within 4 months

-

red: 0 sites recruited ≥20 patients each within 4 months.

-

-

six-month follow-up (assessed at 8 months after start of pilot intervention period):

-

green: ≥80% completion of the EQ-5D-5L

-

amber: <80% but ≥65% completion of the EQ-5D-5L

-

red: <65% completion of the EQ-5D-5L.

-

If any criteria were graded as amber, a rescue plan was to be considered outlining steps to be taken to improve intervention provision, recruitment, retention and/or follow-up (as appropriate) and approved by the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) before submission to the funding body (NIHR HTA). If all the progression criteria were failed (red), then the internal pilot would not have progressed to the main phase of the study. If the TSC deemed that the progression criteria were met to a satisfactory standard by the end of the internal pilot, then the study was to continue, and outcome data from participants in the internal pilot were included in the main study analysis.

Statistical methods

Analyses were conducted once at the end of the trial using Stata version 17. 34 For all outcomes, the analysis population set included all randomised participants with data available for that outcome, and participants were analysed in the group to which they were randomised, irrespective of deviations based on non-compliance, under the principles of intention to treat (ITT). Statistical tests were two sided at the 5% significance level, and two-tailed 95% CIs and p-values were used.

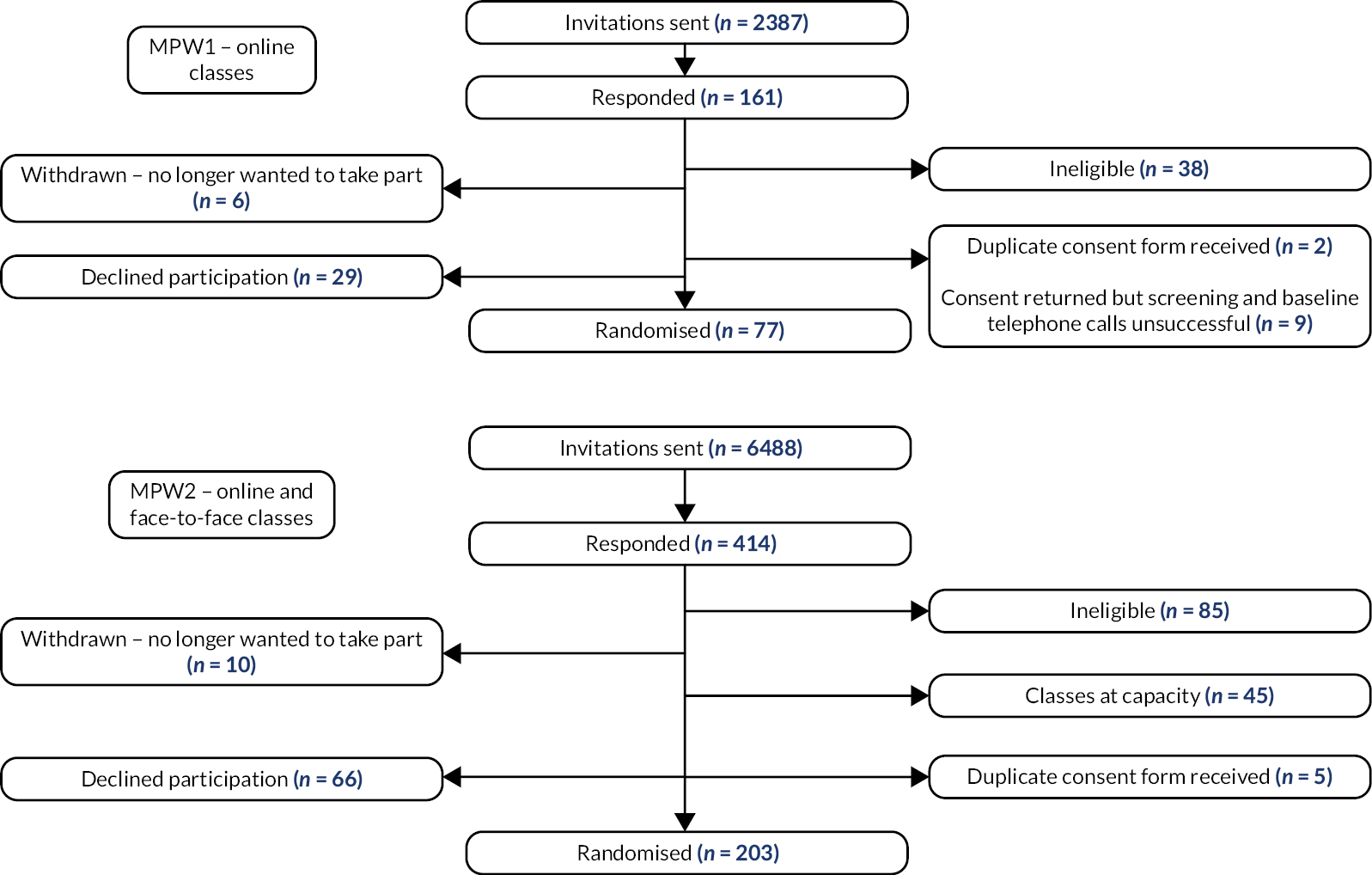

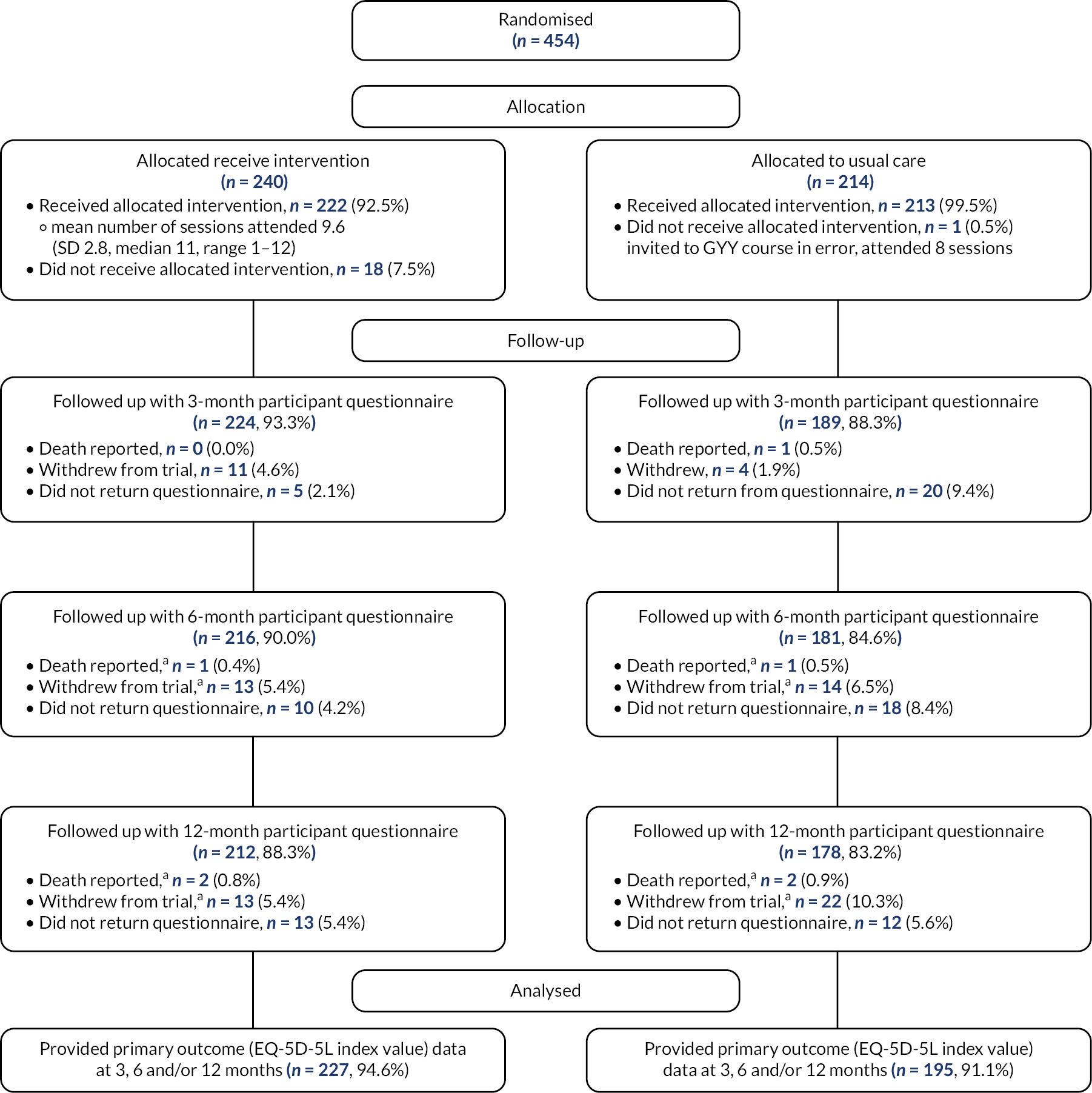

Recruitment

The flow of participants through the trial is detailed in three CONSORT diagrams depicting (1) recruitment of participants in the two pilot phase waves; (2) recruitment of participants in the two main phase waves; and (3) the retention and follow-up of participants post randomisation. The total number of participants approached and randomised are reported, with reasons for non-participation (ineligibility or non-consenting) provided where available.

Baseline characteristics of randomised and analysed participants

All participant baseline data are summarised descriptively by the trial arm, both as randomised and as included in the primary analysis. No formal statistical comparisons were undertaken on baseline data between the arms. Continuous measures are reported as means and SDs (and/or median, interquartile range and range), and categorical data are reported as counts and percentages.

Withdrawals and follow-up

Response rates to the participant questionnaires at 3, 6 and 12 months are presented by the trial arm, and overall, as number expected (i.e. not withdrawn before the time point), they are presented as a percentage of number randomised, number returned (% of expected, % of randomised) and median (interquartile range) time to completion in days from due date. Mode of completion (postal or over the telephone) is summarised for the 6-month time point. Reasons for non-completion are provided where known. Type and timing of withdrawals are presented overall and by the randomised group.

All outcome data are summarised descriptively by the randomised group and overall at each time point.

Interim pilot phase

Descriptive statistics only were used to evaluate the progression criteria for the internal pilot sites. Data from participants in the internal pilot were included in the main study analysis.

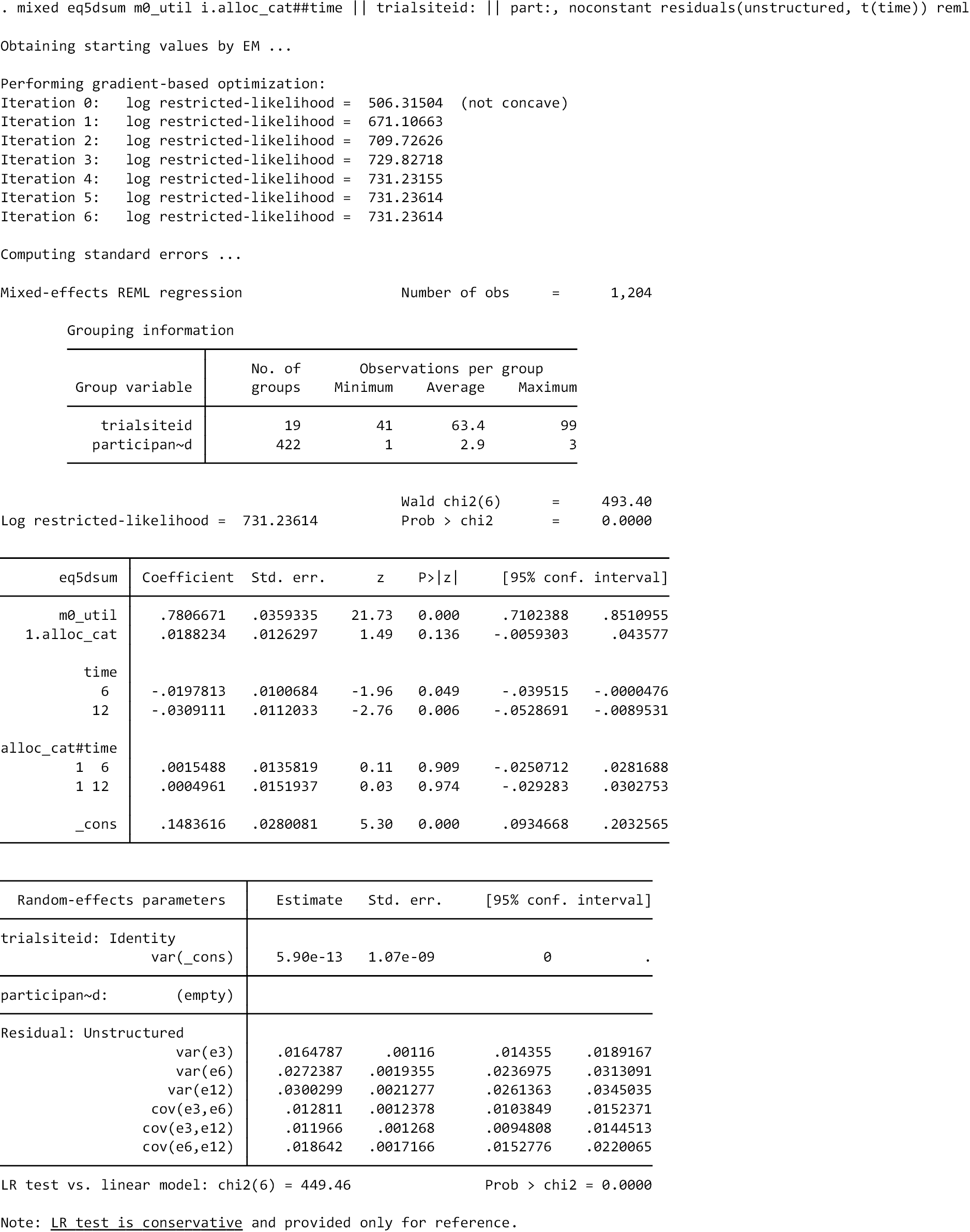

Primary outcome analysis

The EQ-5D-5L utility index score was modelled using a linear mixed-effects model to incorporate the outcome at all post-randomisation time points. The model adjusted for baseline EQ-5D-5L utility index score, time point, trial arm and trial arm by time interaction as fixed effects. Participant and site were included as random effects, to account for the repeated measures of scores by participants over time, and the clustering of participants within sites. The different covariance structures for repeated measurements that are available as part of the analysis software were applied to the model. The most appropriate pattern was used for the final model based on diagnostics, including Akaike’s information criterion (smaller values are preferred). The treatment effect in the form of the adjusted MD in EQ-5D-5L utility index score was extracted with its 95% CI and p-value for each time point and overall. The overall difference between the two groups over the 12 months from randomisation was the primary end point, but differences at each time point were extracted for secondary investigations aimed at determining the potential pattern of improvement. Model coefficients for the covariates with 95% CIs are also presented to aid understanding of the fitted model. Participants were only included in the model if they had full data for the baseline covariates and outcome data for at least one post-randomisation time point; the model assumes any missing data were missing at random (MAR). Model assumptions were checked as follows: the normality of the standardised residuals was checked using Q–Q plot, and homoscedasticity was assessed by means of a scatter plot of the standardised residuals against fitted values.

Sensitivity analyses

Adjusting for other covariates

The primary analysis was repeated, but age, gender and adapted Bayliss score were additionally adjusted for as fixed effects.

Clustering by yoga teacher

Some of the yoga teachers taught more than one course of GYY as part of the trial. Analyses to account for possible clustering by yoga teachers were also undertaken by including the intended yoga teacher as a random effect instead of site.

Compliance with random allocation and treatment received

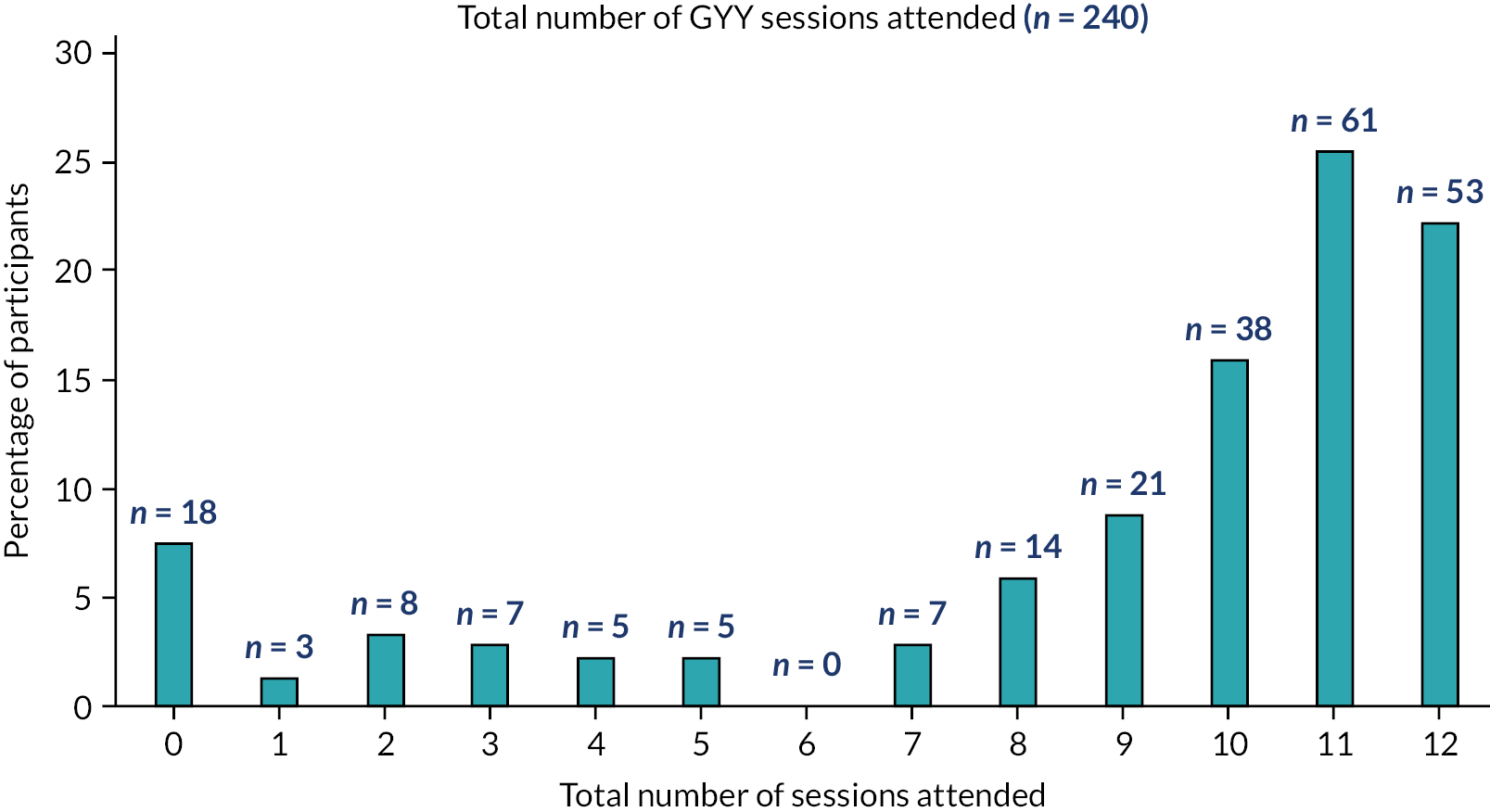

The number of GYY classes attended by participants is summarised. Attendance at GYY classes is presented as the percentage of participants who attended each week, overall and by recruitment wave. The number of participants who attended all 12 of their sessions, at least 9 sessions and at least 6 (including 3 of the first 6) is reported as measures of intervention adherence. We also report the amount of non-GYY yoga conducted by the two groups.

Complier-average causal effect (CACE) analyses for the primary outcome were undertaken to explore the impact of non-compliance on treatment effect estimates. Three analyses were conducted. The first considered participants who are fully compliant, defined as attendance at least three of the first six sessions and at least three other sessions. The second CACE analysis defined compliance as attendance of one yoga session or more (i.e. any compliance), which included participants who were fully and partially compliant. The final CACE analysis considered the number of sessions attended in its continuous form. Two-stage least squares instrumental variable (IV) regression for the EQ-5D-5L at 12 months was used, with randomised group as the IV and robust standard errors to account for clustering within site. The CACE analysis adjusted for gender (in the first stage) since gender was likely to be associated with attendance.

Missing data

The extent of missingness for the primary outcome was investigated and reported. The mixed-effects model incorporated data collected at all post-randomisation time points, and any missing outcome data were assumed to be MAR. We explored patterns of missingness and considered undertaking a sensitivity analysis (SA) to assess departures from the MAR assumption using a pattern mixture model; however this was deemed unnecessary due to the low amount of attrition in the primary analysis model (<10%). The attrition rate here refers to those with only baseline data.

Subgroup analysis

Intended mode of delivery of Gentle Years Yoga

Participants in the first wave of recruitment were randomised in October 2019, and for those allocated to the yoga arm, the classes took place between October 2019 and February 2020. This was before any restrictions were imposed on our daily lives as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and, therefore, the classes were delivered face to face, as initially intended. However, recruitment was paused in mid-March 2020, and once recruitment recommenced, it was decided that yoga classes would be delivered online. Therefore, GYY participants who were randomised between September 2020 and June 2021 had their classes delivered online. Beyond this, up to the end of recruitment in October 2021, some of the sites delivered online and the others face to face.

A subgroup analysis was conducted in which the primary analysis was repeated including, as a fixed effect, an indicator for whether participants were randomised in a site intended for online GYY delivery (as opposed to face to face) and an interaction term between trial arm and intended mode of delivery.

Secondary outcome analyses

Each of the following secondary outcomes was analysed using the same methods as described for the primary outcome, with baseline EQ-5D-5L utility index score swapped as a covariate for baseline value of the outcome:

-

EQ-5D VAS

-

GAD-7 score

-

PHQ-8 score

-

T-scores from each of the seven subscales of the PROMIS-29 v2.1, the PCS and MCS and the global item score

-

UCLA-3 score

-

ELSA single-item direct loneliness question.

The incidence of falls during the 12-month follow-up period was analysed by modelling the number of participant falls over the 12-month follow-up period with a mixed-effect negative binomial regression model, adjusting for the number of falls in the 3 months prior to baseline, and site as a random effect. The model includes an exposure variable for the number of months for which the participant provided falls data. The point estimate for the treatment effect in the form of an incidence rate ratio and its associated 95% CI and p-value is provided.

Adverse events

Adverse events for this trial are summarised descriptively, stratified by whether they are classified as serious or non-serious. Only events deemed at least possibly related to the study are reported. The number, type, outcome, action and relatedness of the events are summarised.

Data collection and management

Participant-completed baseline and follow-up questionnaires were sent from and returned to YTU. A central database at YTU was used to prompt the sending out and return of follow-up questionnaires. Where necessary, participants provided the questionnaire data via a telephone call with a researcher at YTU (e.g. when the research team needed to work from home during the COVID-19 pandemic and thus were unavailable to send and receive postal questionnaires or when participants required assistance). In addition to the data collected at the follow-up time points, some data were collected on an ongoing basis (such as AEs and changes in participant status when a participant requested to be withdrawn). The data collected in this trial, and the timing of its collection, are given in Table 2.

| Assessment | Follow-up time point | Over 12 months | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening/ baseline |

3 months | 6 months | 12 months | ||

| Eligibility and consent | |||||

| Eligibility | X | ||||

| Consent | X | ||||

| Background and follow-up data | |||||

| Demographic data | X | ||||

| Medical history | X | ||||

| Patient expectations and preferences | X | ||||

| EQ-5D-5L | X | X | X | X | |

| PROMIS-29 v2.1 | |||||

| GAD-7 | X | X | X | X | |

| PHQ-8 | X | X | X | X | |

| UCLA | X | X | X | X | |

| Falls | X | X | X | X | |

| Healthcare resource use | X | X | X | X | |

| Prescription usea | X | X | |||

| Ongoing data collection | |||||

| AE reporting | X | ||||

| Change of participant status | X | ||||

Screening and baseline data were collected via postal questionnaires in pilot phase wave 1; however due to the COVID-19 pandemic, data were collected via a telephone call and entered electronically into a Qualtrics® (online survey software, Qualtrics,Provo, Utah, USA) survey by the researcher in pilot phase wave 2 and main phase waves 1 and 2.

Follow-up data were collected via postal questionnaire in all phases of the trial, except for a short period due to COVID-19 restrictions for pilot phase wave 1 (6-month follow-up), where it was collected via a telephone call and entered electronically into a Qualtrics survey by the researcher. If a follow-up questionnaire was not returned to YTU 14 days after it was posted, a reminder questionnaire was sent to the participant. If a follow-up questionnaire was not returned to YTU 14 days after a reminder questionnaire was posted, a researcher contacted the participant via telephone call if the participant had consented to this means of communication. If during the telephone call the participant advised that they were unable to complete the postal questionnaire but agreed to provide the information over the telephone, primary outcome data collection was prioritised and then any other outcome data that the participant was willing to provide was collected. If a questionnaire was returned to YTU incomplete or with errors, a researcher contacted the participant via telephone for clarification or completion of missing data if the participant had consented to this means of communication. Telephone data in this case were entered onto a paper questionnaire by the researcher.

Essential trial documentation, which individually and collectively permits evaluation of the conduct of a clinical trial and the quality of the data produced, was kept in an electronic Trial Master File on a secure file server at the University of York with access restricted to named YTU trial staff. This documentation will be retained for a minimum of 20 years in electronic format in accordance with Good Clinical Practice. Data were handled in accordance with the Data Protection Act 2018, General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) legislation, the latest Directive on Good Clinical Practice and local policy. All paper data records are stored in a secure facility at the University of York in locked filing cabinets in a locked room. The key to the cupboard is held by the data archivist. The paper data records will be archived at an approved off-site location. All electronic data records are stored on a secure file server at the University of York, with access restricted to YTU trial staff. Data entered electronically onto a database will be stored on a private network protected by a firewall at the University of York. Access to the database is restricted to YTU trial staff by login and password. The trial database will be securely archived for a minimum of 10 years on the YTU computer network. Access to the archived data will be restricted to YTU trial staff and named individuals but will be retrievable at the request of the sponsor or investigator. All data will be stored for a minimum of 10 years, in line with the University of York’s policy.

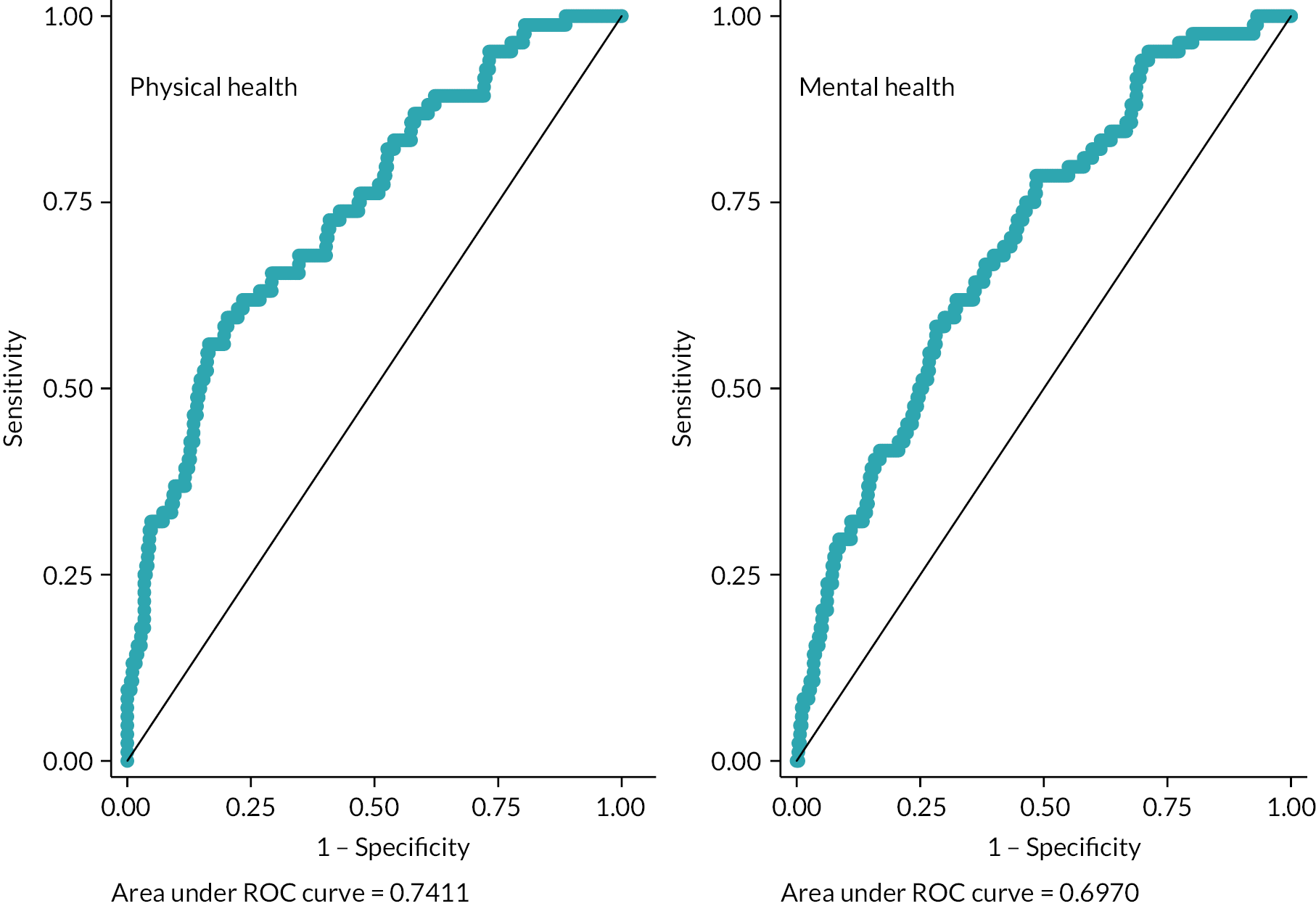

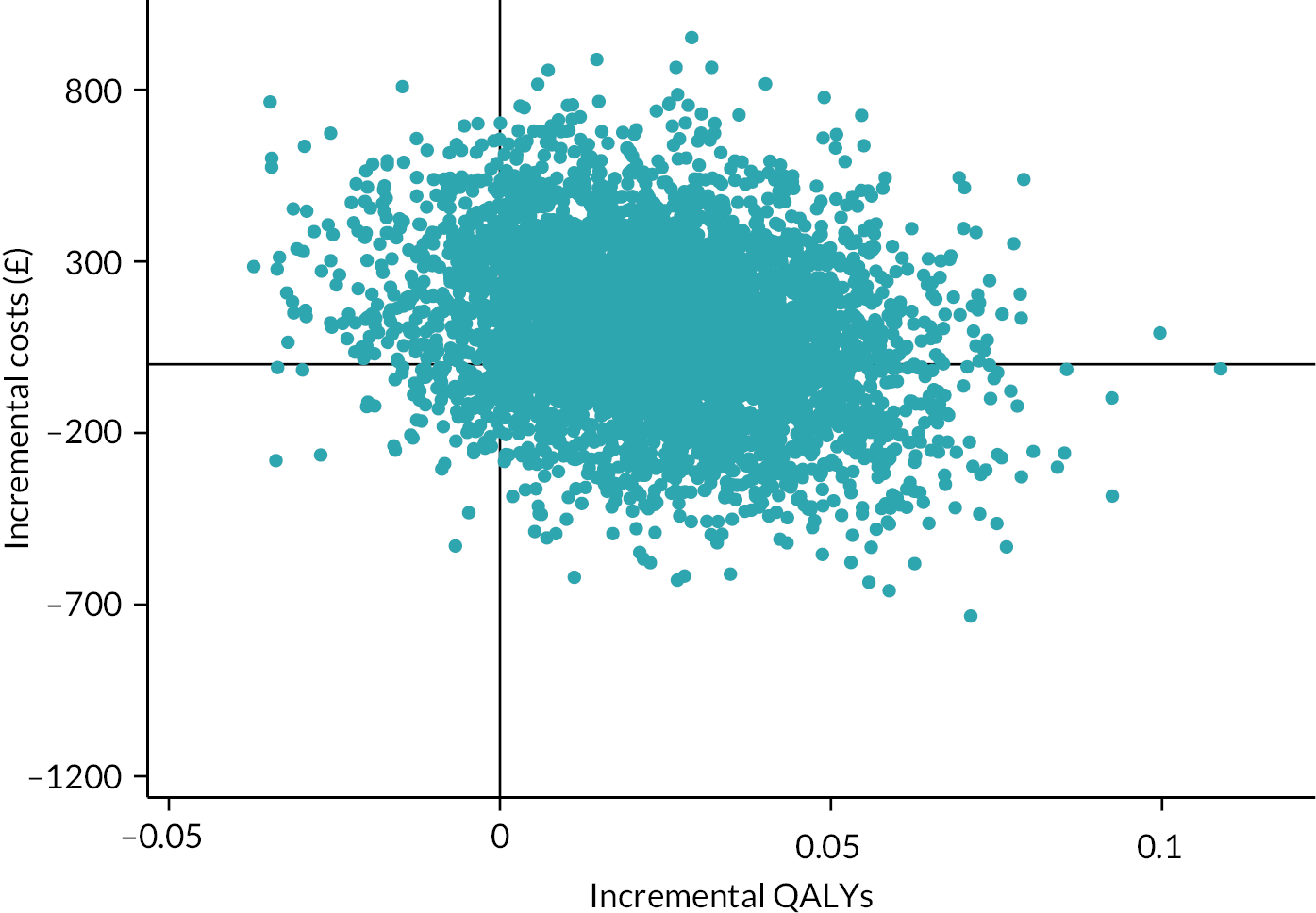

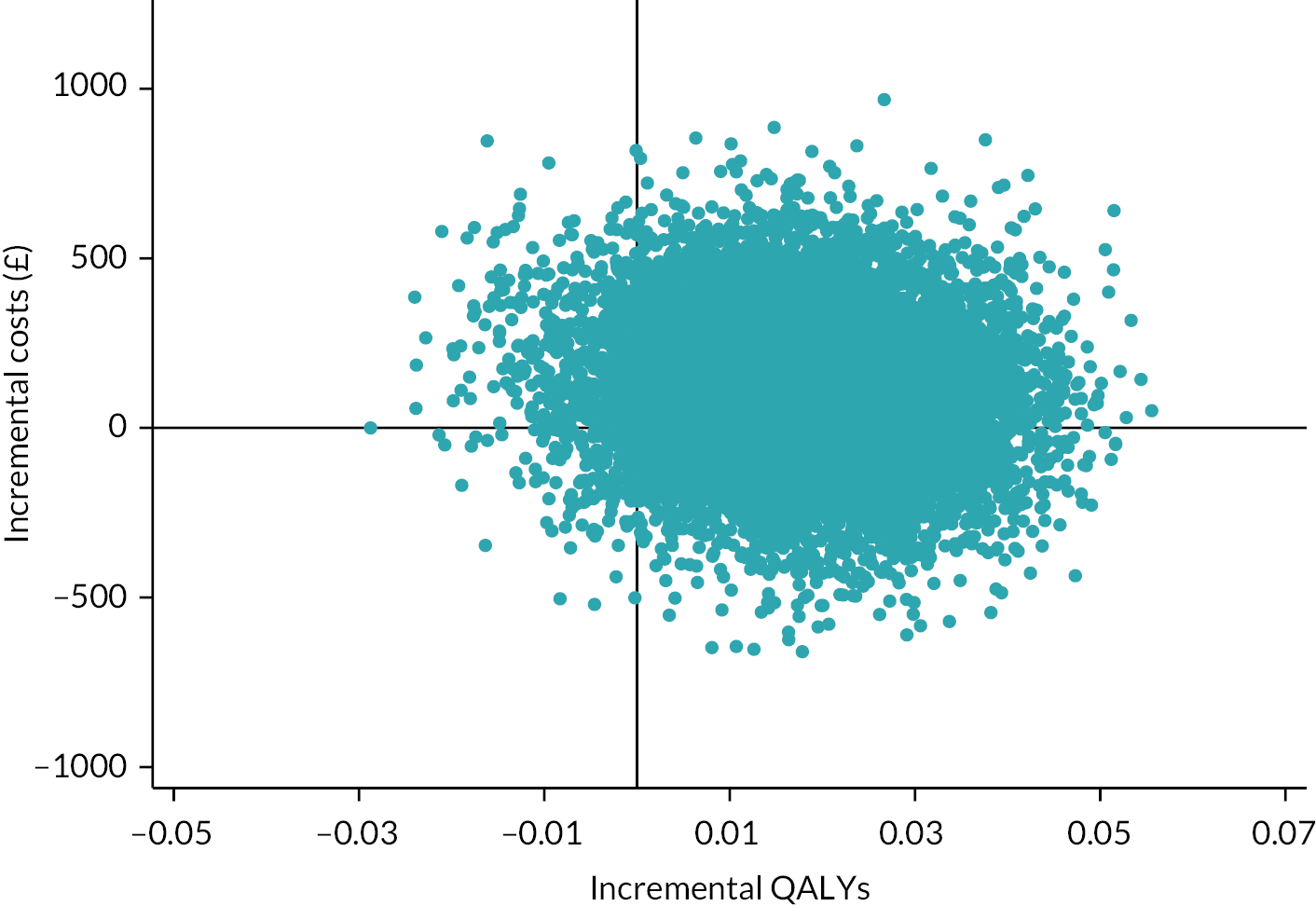

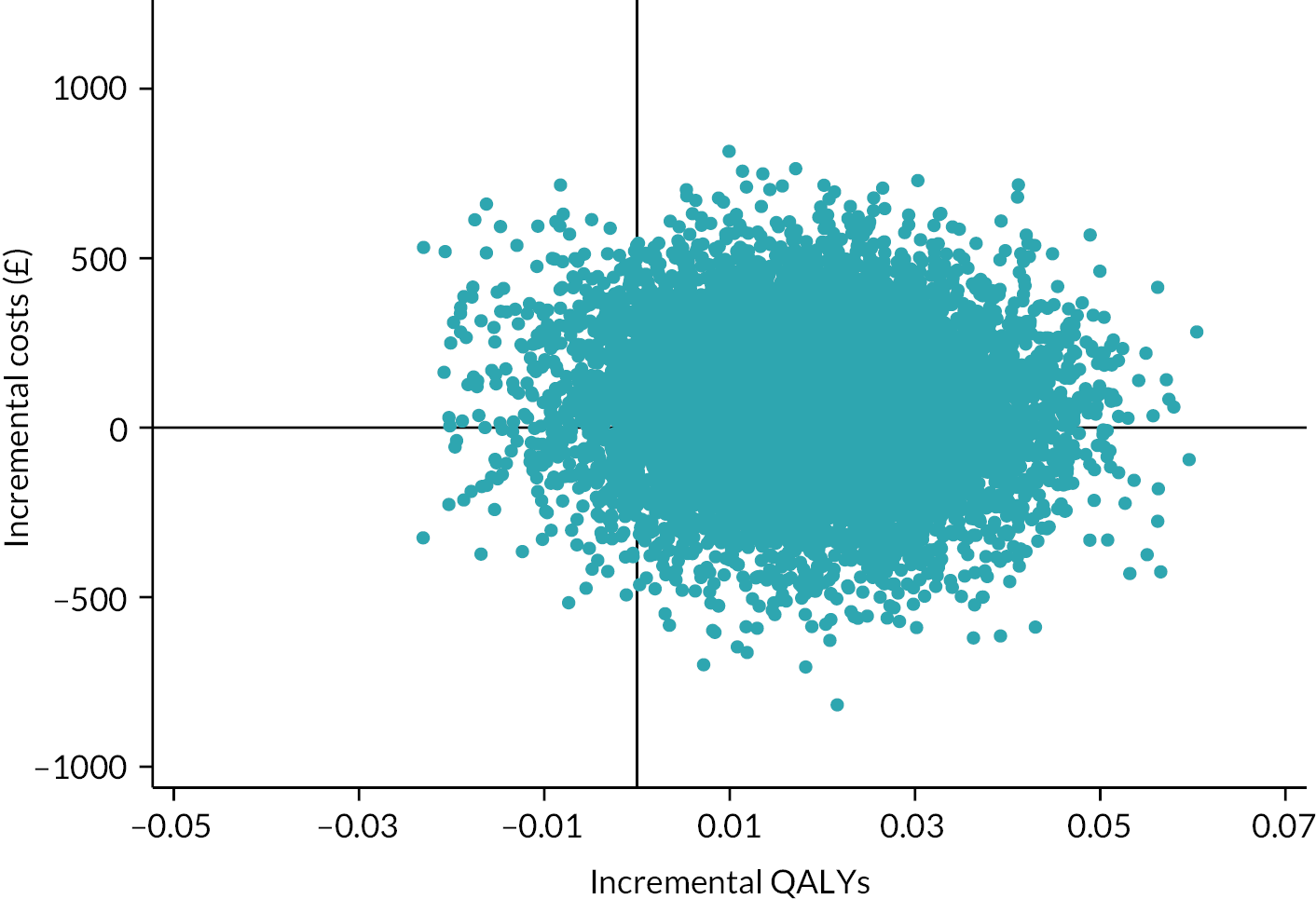

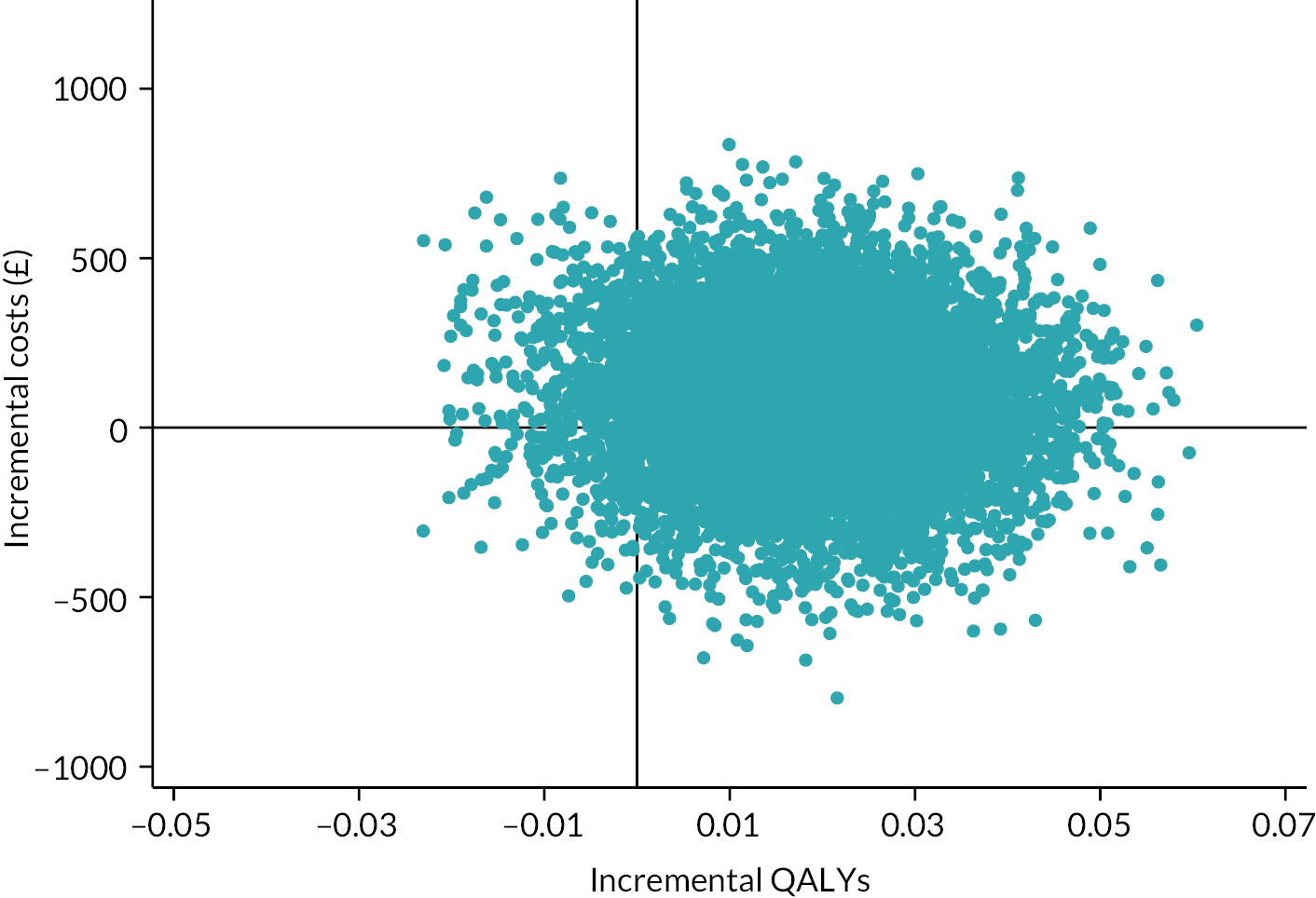

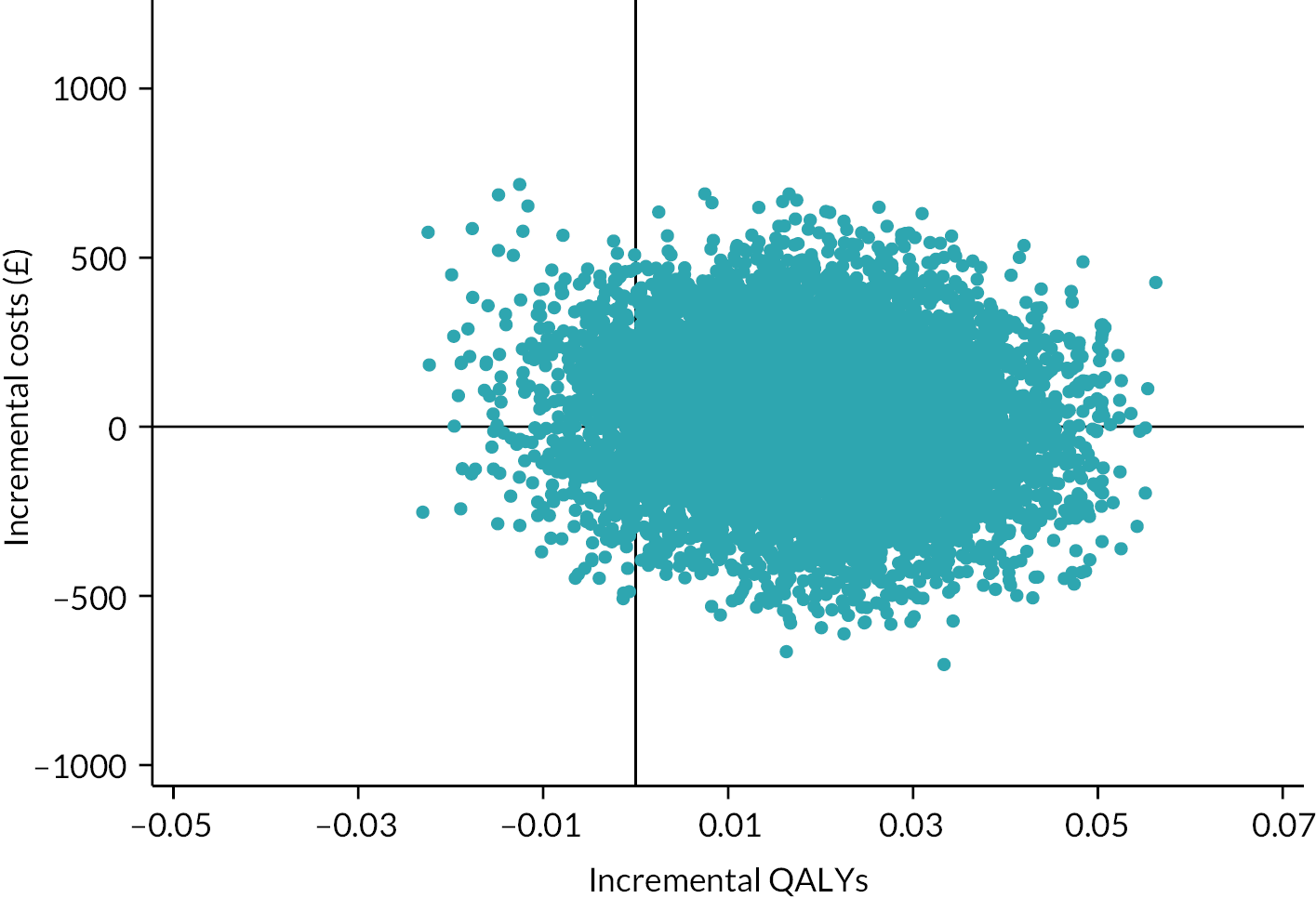

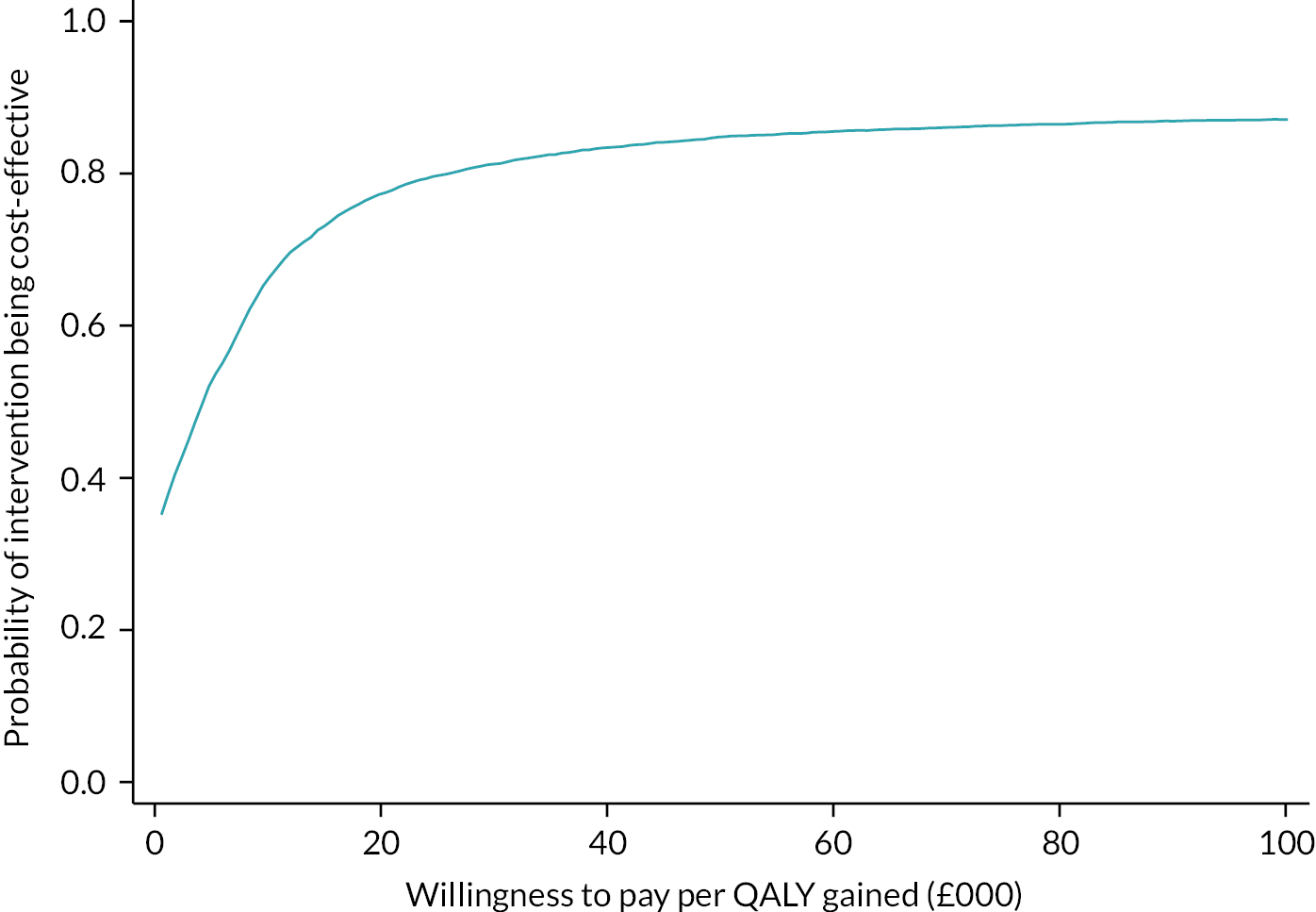

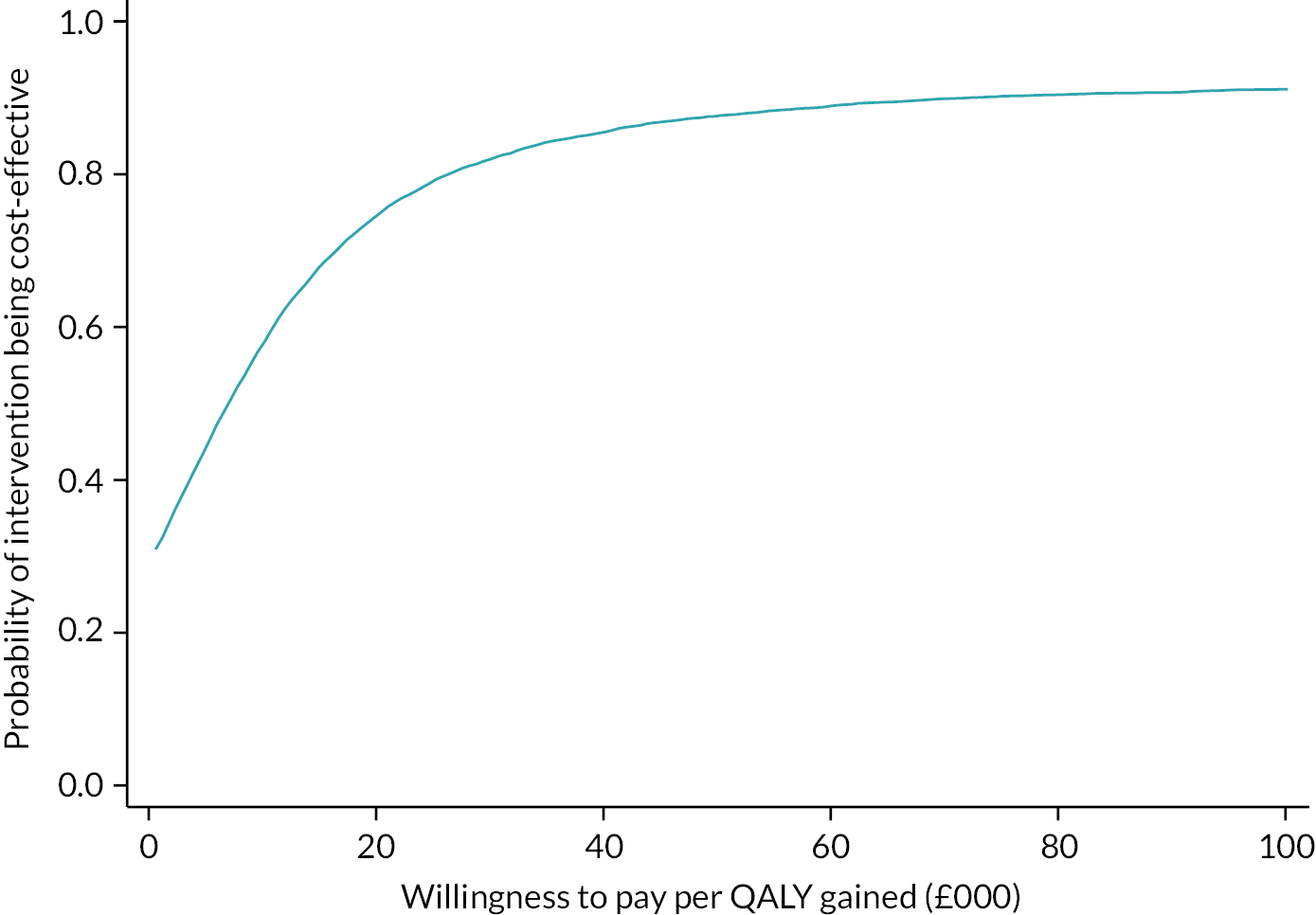

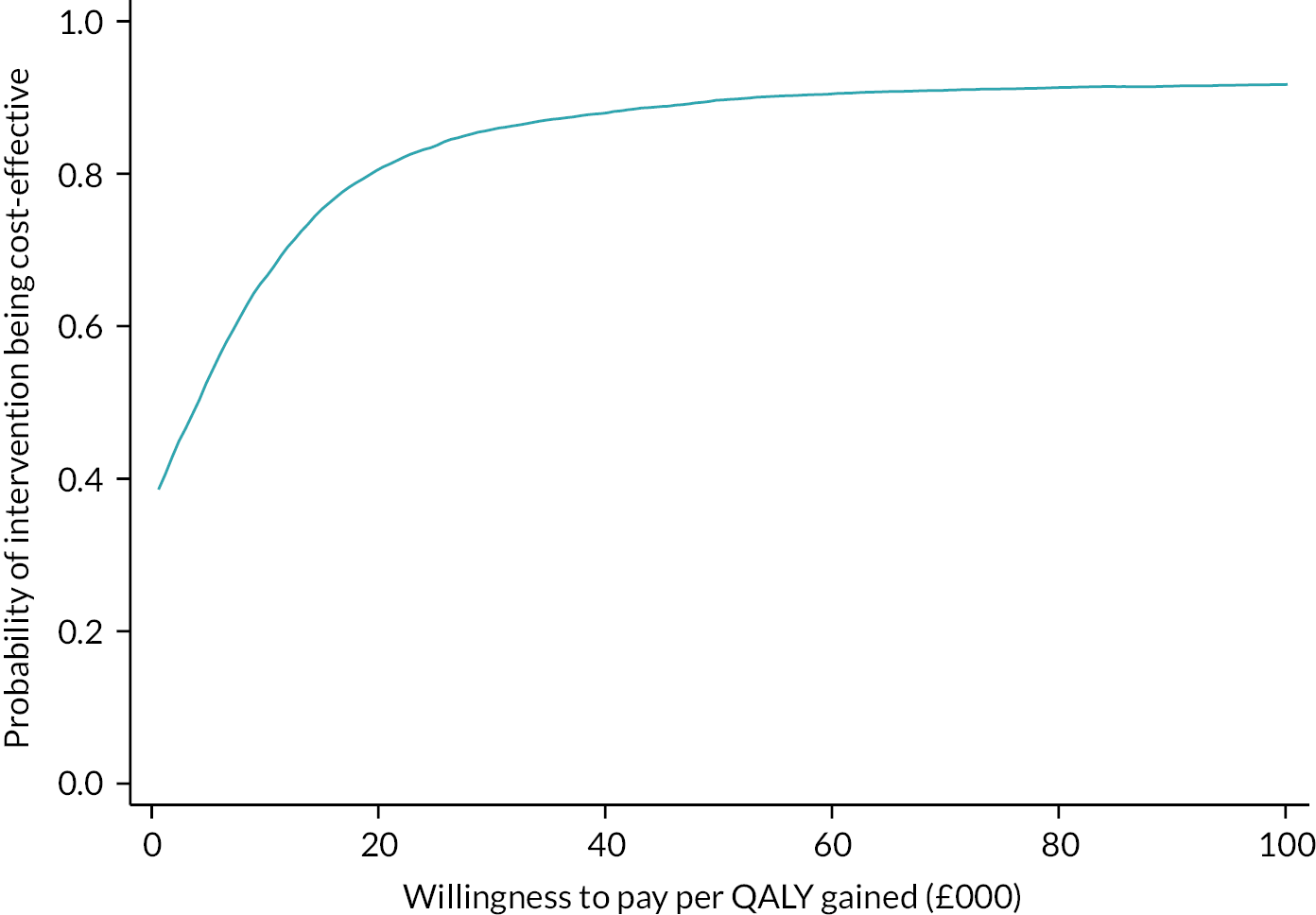

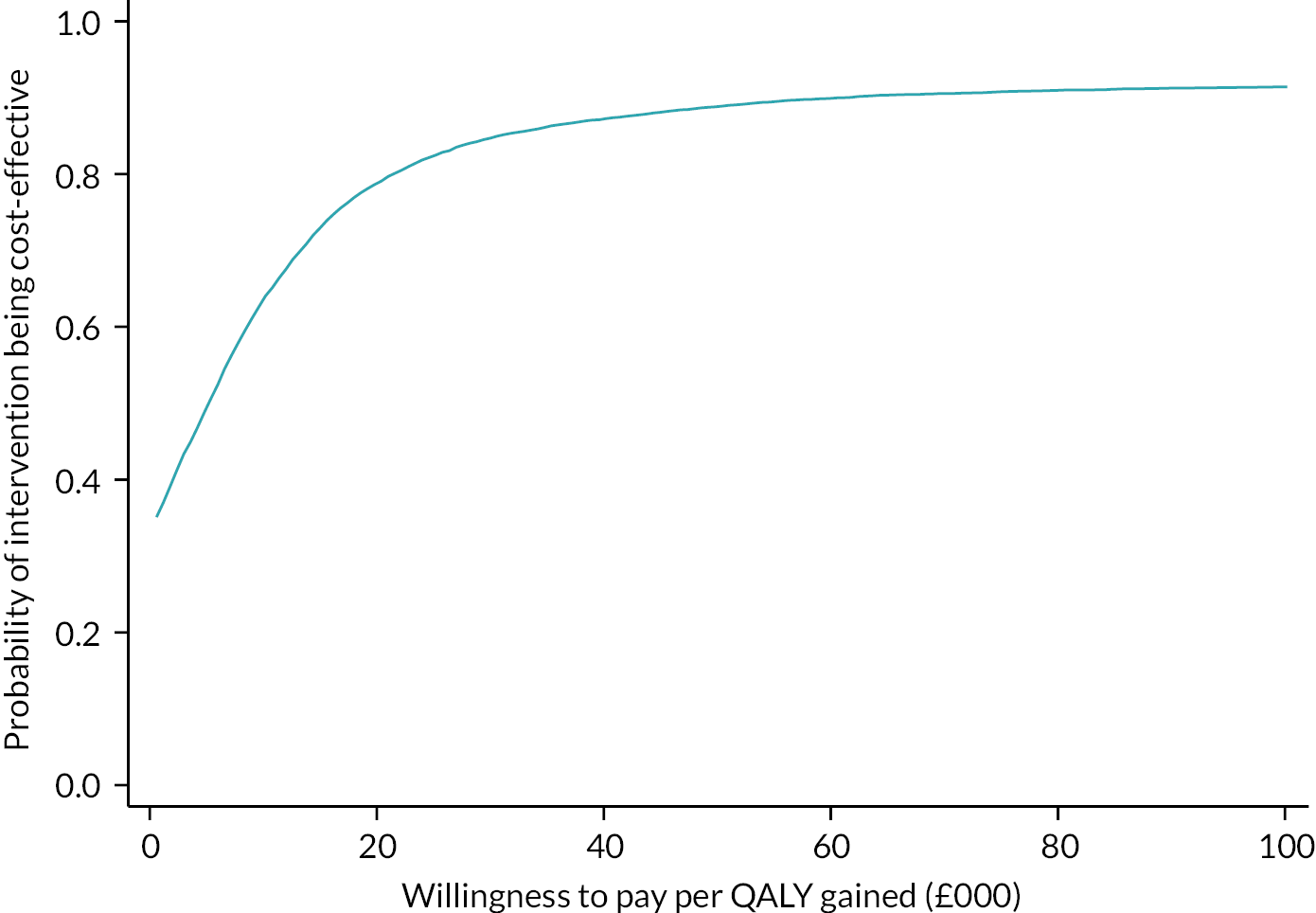

Design and processing of participant questionnaires