Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number 16/167/57. The contractual start date was in October 2018. The draft report began editorial review in June 2022 and was accepted for publication in November 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this manuscript.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Cook et al. This work was produced by Cook et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Cook et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale

Pelvic fractures

Pelvic fractures can be life-threatening and people can experience significant problems with mobility following the injury. 1 They are associated with a total inpatient mortality rate of 9% and an all-cause mortality rate within 3 months of fracture of 13%. 2 All-cause mortality following pelvic fracture is approximately 50% at 3 years. 3 Mortality for fragility fractures of the pelvis is reported to be around a third after 1 year. 4

The incidence of pelvic fractures in the UK between 2008 and 2012 in men and women over 50 was 2.0 and 7.4/10,000 person-years (based on a retrospective observational study using data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink, which is shown to be broadly representative of the UK population). 5 People can experience this injury as a result of a high-energy impact such as a road traffic accident or, in the case of older adults (generally 65 years of age and older), as a result of a low-energy fall from a standing height. 1 The UK age-specific incidence of pelvic fractures (based on a single centre) has increased from 39.6/100,000 (95% confidence interval: 31.8 to 48.1) in 1997 to 71.6/100,000 (58.4 to 81.0) in 2007–8 amongst people 65 years and older; 84% of these had pubic rami fractures. 6

Lateral compression type-1 (LC-1) fractures are a common fragility fracture of the pelvis in older adults and are associated with low bone density. 7 They typically involve a fracture of the pubic ramus, which patients experience as groin pain when they mobilise. There is usually also a ‘buckle’ fracture to the sacrum posteriorly, which is felt as low-back or buttock pain when moving the legs. The likelihood of an LC-1 fragility fracture increases with age and is more common in women. 3,8,9

Lateral compression type-1 fractures are often painful, particularly when the patient moves. This leads to reduced mobility, usually over a 1- to 2-month period, although it is estimated that 25% of patients experience pain for up to 5 years following the injury. 10 The ability of patients to mobilise following an LC-1 fragility fracture varies: some can mobilise and walk, albeit with some degree of pain, whereas others struggle to walk due to the pain. Patients who do not manage to get back walking due to ongoing pain are at greater risk of immobility-related complications. 11 These can include respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, pressure sores and venous thromboembolic events such as deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. 11,12 These individuals are also at risk of irreversible muscle wasting (systemic sarcopenia), loss of confidence and permanently decreased levels of independence, often leading to increased care requirements. Inability to return to independent living can result in utilisation of intermediate care or residential facilities. 13,14 Some patients do not regain their pre-injury level of walking or their prior independence with activities of daily living due to their loss of confidence and muscle strength/conditioning. 8,9,15,16 Additionally, individuals with LC-1 fractures have reported emotional stress, family strain, employment and financial difficulty, sleep disturbance and anxiety. 17

The current standard care for lateral compression type-1 fragility fractures

In the UK, standard treatment for LC-1 fractures is to ‘mobilise as pain allows’, prescribing pain relief and getting patients up within a few days of injury with physiotherapy input and getting them to mobilise with an assistive device until the fracture heals. 11,18,19 This is unlike fragility neck of femur fractures (hip fractures), which are usually treated surgically, and there is evidence that early surgery (within 1–2 days) is associated with reduced risk of death and pressure sores. 20 Despite LC-1 fractures being similarly disabling for some patients in terms of pain and immobility, while also occurring in the same patient group as hip fractures, to date, it has not been shown whether or not patients with LC-1 fragility fractures would have a better recovery with surgery than with non-surgical management.

Surgical fixation

Traditional pelvic implants carry poor ‘bite’ or ‘purchase’ in low-quality osteoporotic bone around the pelvis and surgeons have been reluctant to offer surgery to patients with LC-1 fragility fractures. External fixators, consisting of pins inside the pelvis connected to bars and clamps outside of the skin, are cumbersome, poorly tolerated and carry a high incidence of pin-site infections and soft-tissue problems. 21 The alternative is surgical fixation of the back of the pelvis with ilio-sacral screws;9 however, in the majority of elderly patients, these screws carry poor ‘purchase’ in osteoporotic bone, leading to ineffective fracture stabilisation and persistence of pain. 11

A more recent approach is use of an anterior pelvic fixation device that resembles a traditional external fixator, in that it has screws that are secured into the pelvic bone, and these are connected by a metal bar across the front of the patient. This is an internal fixation device (INFIX). Unlike traditional external fixation devices, it is fitted internally, sitting entirely underneath the patient’s skin, with no external metalwork visible. INFIX has two potential benefits over external fixation: it is less cumbersome and less inconvenient to patients, compared with pins, clamps and bars protruding out of the skin. It also does not have pin sites (where the bone pins exit through the skin), which make traditional external fixation very susceptible to local infection. The INFIX technique involves percutaneous placement of screws in the pelvic bone and connects them with a bar under the skin. 22 The pelvic bone where the screws are placed is generally strong and easy to visualise intraoperatively, even in highly osteoporotic bone. Although a proportion of implants need to be removed, this is usually done as a day case procedure. INFIX is used in younger patients with high-energy LC-1 fractures. It is now a well-described technique with a number of peer-reviewed series confirming its safety. 23 It is therefore a widely practiced, rather than ‘novel’, technique and is technically straightforward to carry out.

Existing evidence

A systematic review found no robust evaluations of the effectiveness of internal fixation with INFIX in patients with osteoporotic LC-1 fractures. 24 The review identified five case series, with four being retrospective. Participants were aged 64 or over and most had sustained their injury from a low-energy fall. A variety of fixation techniques were used. Of the 225 patients in the five studies, most had internal devices, with 25 having external fixation; most patients had more than one type of fixation.

In the single series evaluating INFIX alone, 19 of the 29 patients had LC-1 fractures. 25 Six patients had anterior fixation with INFIX alone and the remaining 23 had INFIX with additional internal fixation. Postoperatively, 22 of the 29 (76%) returned to their pre-injury walking ability, and a further 6 patients had some deterioration but could still walk. Complications included chronic pain (n = 3, 10.3%) and painful lateral femoral cutaneous nerve hyperaesthesia (n = 8, 27.5%) and, less commonly, infections, implant loosening, pneumonia and thrombosis.

Our search of clinicaltrials.gov in advance of our study identified an ongoing trial in the USA of surgical versus non-surgical management of patients aged between 18 and 80 with LC-1, LC-2 and LC-3 pelvic fractures in 130 participants. The aim of this trial is to determine which patients would benefit from early surgical stabilisation. 26 There is also a Research for Patient Benefit funded feasibility study of surgical versus non-surgical management of LC-1 pelvic fractures in patients with non-fragility fractures. 27

The existing evidence on the effectiveness of using an INFIX device to stabilise LC-1 fractures is limited to one case study with 29 participants. Surgeons are already carrying out INFIX surgeries in the absence of extensive evidence. There is a need to collect more evidence and there are currently no other clinical trials focusing on the effectiveness of surgical fixation with INFIX in adults with fragility fractures.

Aim and objectives

The aim was to assess the clinical and cost effectiveness of surgical fixation with INFIX compared to non-surgical management of LC-1 fragility fractures in older adults (L1FE trial).

The objectives of the L1FE trial were to:

-

Undertake a 12-month internal pilot to obtain robust estimates of recruitment and confirm trial feasibility.

-

Undertake a parallel group multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT) to assess the effectiveness of surgical fixation with INFIX versus non-surgical management of LC-1 fragility fractures in older adults. The primary outcome is average patient health-related quality of life, over 6 months, assessed by the patient-reported EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) utility index score measured at baseline, 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 6 months.

-

Undertake an economic evaluation to compare the cost effectiveness of surgical fixation compared to non-surgical management, to determine the most efficient provision of future care and to describe the resource impact on the NHS for the two treatment options.

-

Undertake a long-term review of patient well-being (EQ-5D-5L and mortality) 12 months after entering the trial.

The trial closed early due to poor recruitment. This report contains descriptive data from the trial only and focuses on the challenges faced and lessons learnt.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

This study was a multicentre, pragmatic, randomised controlled superiority trial, with a 12-month internal pilot to assess assumptions about recruitment and provide guidance on optimising the trial processes before proceeding to the main trial phase. Participants were randomised between surgical and non-surgical management of LC-1 pelvic fracture with a 1 : 1 allocation ratio. The study also included an economic evaluation.

The internal pilot addressed the question of whether a sufficient number of eligible patients could be identified and recruited in 12 months to make the target sample size for the trial of 600 participants viable within the proposed 36-month recruitment period. We intended to set up a minimum of 19 sites and randomise 148 patients during the pilot. We planned to set up six sites in each of the first two quarters and the final seven sites in the third quarter. Based on data from four centres, we estimated that each centre would see on average 50–60 potentially eligible patients each year. Applying a conversion rate of 50% for potentially eligible patients to be recruited, we aimed to recruit 1 patient per site per month and a total of 148 patients across the 19 sites that would be gradually opened during the 12-month pilot phase. The recruitment progression criterion was set as a minimum average rate of one patient per site per month. A rate of 0.80–0.99 patients per centre per month was set to signify that a decision to progress may be supportable depending on other supplementary information available (e.g. number and characteristics of potential participants not approached, proportion not meeting eligibility criteria and reasons, proportion declining participation and reasons why) and whether any of the factors impeding recruitment could be remedied.

Population

Patients who met all the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria were eligible for the trial. Eligibility was assessed by research nurses/associates and was required to be confirmed by a surgeon or clinician authorised in the trial delegation log prior to recruitment.

Inclusion criteria

-

Patients aged 60 years or older.

-

An LC-1 pelvic fracture, arising from a low-energy fall from standing height or less.

-

Patients unable to mobilise independently to a distance of around 3 m and back due to pelvic pain (or perceived pelvic pain) 72 hours after injury. Use of a walking aid and verbal guidance were permitted; however, physical assistance was not.

Exclusion criteria

-

Unable to perform surgery within 10 days of injury.

-

Surgery was contraindicated due to soft-tissue concerns, or because the patient was not fit for anaesthetic (spinal or general).

-

Patients who were non-ambulatory or required physical assistance to walk, prior to their injury (use of a walking aid was permitted).

-

Concomitant injury or polytrauma that impedes mobilisation.

-

Fracture configurations not amenable to internal fixation using INFIX, with or without ilio-sacral screws.

Due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, and emerging evidence that infection with COVID-19 may increase the risk of mortality in patients undergoing surgery,28 the following exclusion criterion was added when the study reopened following a pause to recruitment: patients who tested positive for COVID-19 within 72 hours of admission (applicable only where testing was standard of care).

Study setting

We intended to undertake the study at 21 NHS Major Trauma Centres (MTCs) across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

In order to participate in the study, sites needed to have surgeons experienced in the INFIX operation or who had the capacity to be trained to perform it. Participating surgeons were required to be familiar with the surgical procedure [have previously conducted 10 or more INFIX procedures or undergo training until the chief investigator (CI) confirmed that they were sufficiently experienced]. Level of experience was recorded, and no grade of surgeon was excluded from performing the procedure. In addition, all surgeons were required to watch a training video and read a summary guidance document.

There were no specific requirements in place on who could deliver the non-surgical rehabilitation. This was delivered in line with routine practice at each participating site.

Recruitment pathway

Patient pathways for LC-1 fractures were diverse, and therefore research staff at sites had to work across departments and teams in order to maximise patient identification. Patients were identified through collaboration with teams such as Orthopaedics, Trauma, Accident and Emergency, Care of the Elderly, as well as through consultation with orthogeriatricians, inpatient therapists and ward lists.

In order to facilitate raising and maintaining awareness of the study in various disciplines, and thus support patient identification and recruitment, the L1FE trial was registered with the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) associate principal investigator (API) scheme from the onset of the study. This scheme provides opportunities for healthcare professionals starting their career, who would not normally have the chance to be involved in clinical research, to gain practical experience with this and be formally recognised for their involvement. Due to difficulties with recruitment, we obtained agreement from NIHR to include more than one API per site, as well as to include consultant-level staff without research experience as APIs.

Informed consent

Once eligibility was confirmed, hospital research staff sought written informed consent from patients who had mental capacity to provide it. This study also included recruitment of patients who lacked capacity, and in this instance, consultee agreement or consent was sought in line with legal requirements. 29,30 Consent or consultee agreement was sought for follow-up beyond the duration of the trial to allow the possibility of future long-term follow-up including the use of routinely collected Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) and Office of National Statistics (ONS) data.

Interventions

Participants were randomised to:

-

Non-surgical management: This is the standard care for LC-1 fragility fractures in this patient population in the UK. Patients were routinely administered pain relief and seen by a physiotherapy team who worked to mobilise the patients as pain allowed.

-

Surgery: INFIX is a type of anterior INFIX; it is fitted underneath the patient’s skin. The technique involves percutaneous placement of long pedicle screws within the pelvic bone. The screws are connected by a metal rod across the front of the patient under the skin. As this was a pragmatic study, surgeons could use their preferred INFIX device. The primary fixation for every patient was INFIX. If the surgeon felt that the fracture configuration in a patient warranted supplementary ilio-sacral screw fixation, this was permissible under the trial protocol, provided adequate intraoperative pelvic imaging could be achieved. Surgery had to be undertaken within 10 days of injury.

Participants in both the non-surgical management and surgery groups received pain relief and physiotherapy as per standard care at the participating site and they were also provided with a trial rehabilitation leaflet. This leaflet detailed suggested exercises to perform and was intended to supplement and not replace advice given by the site physiotherapy team. Instructions stated ‘immediate weight bearing, as pain allows’. For both groups, the goals of physiotherapy were to improve function, strength and range of movement in both legs, while aiming to get patients back to independent mobility as soon as possible.

Participants were followed up for 6 months and completed patient questionnaires at baseline (for the day of baseline data collection and 1 week prior to injury), 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 6 months post-randomisation time points. There was an additional, 12-month follow-up point for those participants who opted it on recruitment and who were recruited early enough in the study to reach this time point within the planned follow-up period.

Outcomes

Table 1 provides a summary of the participant timeline and when measures were collected.

| Time point | Study period | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post allocation | |||||||

| Enrolment/baseline | Randomisation | 2-week | 6-week | 12-weeka | 6-month | 12-monthb | |

| Eligibility screen | ✗ | ||||||

| Informed consent | ✗ | ||||||

| Demographic datac | ✗ | ||||||

| Randomisation | ✗ | ||||||

| Surgical fixation | ✗ | ||||||

| Non-surgical management | ✗ | ||||||

| EQ-5D-5L | ✗d | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| PROMIS (LEF and GMH) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| TUG | ✗ | ||||||

| Pain VAS | ✗e | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| AMTS | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| 4AT | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Mortality | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Resource use data | ✗f | ✗ | ✗g | ✗g | |||

| Imaging | ✗ | ||||||

| Complications | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| COVID-19 statush | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| AE reporting | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Change in status form | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

Primary outcome

The primary outcome measure was originally intended to be the average health-related quality of life (HRQoL), over 6 months, assessed by the patient-reported outcome measure, EQ-5D-5L utility score. However, due to the poor recruitment and the resulting low sample size, the average EQ-5D-5L utility score over the follow-up period was not feasible. Instead, the EQ-5D-5L utility scores were reported descriptively at each follow-up time point.

EQ-5D-5L was collected at baseline [for the day of baseline data collection and 1 week prior to injury (adapted with permission)], 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 6 months post-randomisation time points, as well as at the optional 12-month follow-up point where relevant.

The EQ-D-5L is a validated generic patient-reported outcome measure (www.euroqol.org), including validation in patients with hip fractures and orthopaedic patients with cognitive impairment. The descriptive system has five health domains (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression) with five response options for each domain (no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems and extreme problems/unable to do). In addition, it has a health status visual analogue scale (VAS) which measures self-rated health with endpoints ranging from ‘the best health you can imagine’ to ‘the worst health you can imagine’. The EQ-5D-5L was scored according to the User Guide. 31 The measure is easily completed and can be completed by proxy (which was important for our clinical population), and it can also be scored for those who die during follow-up. EQ-5D-5L data were collected either in patient-completed questionnaires (for participants with capacity) or in proxy questionnaires (for those who lacked capacity). EQ-5D-5L proxy version 2 was used where the caregiver (the proxy) is asked to rate how he or she (the proxy) thinks the patient would rate his or her own HRQoL, if the patient were able to communicate it.

Secondary outcomes

-

Self-rated health using the EQ-5D-5L VAS

The second component of the EQ-5D-5L instrument is scored as a number ranging from 0 to 100 where 0 indicates the worse imaginable health and 100 indicates the best imaginable health. The EQ-5D-5L VAS score was collected from patients at baseline (for the day of baseline data collection and 1 week prior to injury), 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 6 months and (if the patient was followed up at this time) 12 months post randomisation.

-

Physical function using the eight-item Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Information System (PROMIS) lower extremity function (LEF) (mobility) – Short Form. 32

Lower extremity function is an extremely important outcome domain for people with a LC-1 fracture, due to the impact of the injury on ability to mobilise. Measured at baseline, 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 6 months (by proxy where required).

-

Physical function using Timed Up and Go (TUG)

This test, used routinely in clinical practice, assesses walking speed, mobility, balance and fall risk. 33,34 The TUG test involves measuring the time it takes for a patient to rise from a chair, walk 3 m, turn 180 degrees and return to sitting in the chair. The outcome of this test is the time in seconds taken to complete the test and lower times indicate better mobility. In addition, the number and type of walking aids used by the patient to complete the test was recorded. This measure was undertaken at the 12-week follow-up only in the clinic setting (there was no attempt to perform this where a remote visit was undertaken).

-

Global mental health using the PROMIS scale v1.2 – Global Health Mental 2a subscale

This is a two-question subscale on global mental health (GMH). Inclusion of this subscale was highly commended by our patient and public involvement (PPI) group. Measured at baseline, 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 6 months (by proxy where required).

-

Pain experienced from their pelvis using a VAS

A unidimensional measure of pain intensity in adults. 35 This is a validated measure for acute and chronic pain in adults where scores are recorded by the patient placing a handwritten mark on a 10-cm line that represents a continuum from ‘No pain’ to ‘Worst imaginable pain’. 36 This outcome was collected from people with capacity only, at baseline, 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 6 months, and an optional 12-month follow-up for those recruited early within the study.

-

Delirium using the Abbreviated Mental Test Score

Abbreviated Mental Test Score is a short, verbal test widely used in clinical practice to screen for confusion and dementia. 37,38 Recent data confirm its validity in emergency admissions in older adults within UK hospitals. 37 Measured at baseline, 2 weeks and at 12 weeks. Repeat assessment at 12 weeks was to confirm whether delirium was temporary or represented a permanent change.

-

Delirium using the 4AT Rapid Assessment Test for Delirium

4AT Rapid Assessment Test for Delirium is a short, practical instrument validated for detecting delirium, routinely used in clinical practice. 39,40 Postoperative delirium is a known complication for the elderly, particularly those with dementia. Therefore, its use as an outcome measure was to monitor this potential adverse effect of surgery. The strengths of the 4AT Rapid Assessment Test for Delirium are that it can be used on patients who are drowsy or agitated (which is common after surgery), it does not require specialist training and it takes less than 2 minutes to complete. Measured at baseline, 2 weeks and at 12 weeks. Repeat assessment at 12 weeks was to confirm whether delirium was temporary or represented a permanent change.

-

Displacement of the pelvis

A radiological assessment of the pelvis was to be performed at the 12 weeks’ visit for all participants and was to investigate whether there is clinically significant displacement of the pelvic ring; the week 12 investigator case report form (CRF) included a yes/no question asking if there has been clinically significant displacement of the pelvic ring. These X-rays would be standard care for patients undergoing surgical fixation but may be over and above what is routine practice for patients being managed non-surgically. To allow for scheduling around local restrictions and capacity within imaging departments arising from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, the 12-week X-ray could be performed up to 6 months post randomisation.

-

Mortality

Collected at 6 months (and 12 months for those participants who agreed to this additional follow-up).

Complications and adverse events

Lateral cutaneous nerve injury was an adverse event of special interest (AESI), and information on this was collected on an adverse event (AE) form. Patients were also asked about this in the 2-week, 6-week, 12-week and 6-month questionnaires, as well as in the 12-month questionnaires for those who agreed to this additional follow-up.

Information on expected complications, including additional surgery, was collected in hospital at 2 weeks, at 12 weeks and at discharge (if after 2 weeks). Expected complications that were recorded included (but were not limited to): neurological complications, deep wound infection [using Centres for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention definition],41 superficial infection (using CDC definition), rehospitalisation, re-operation (including removal of implant) and skin problems.

We collected data for the AESI and any unexpected AEs that were related to treatment for the original injury. We collected AE data from the point of randomisation up to 6 months post randomisation for all patients and up to 12 months post randomisation for patients that agreed to this additional time point. All AEs were listed on the appropriate AE or serious adverse event (SAE) CRF for routine return to York Trials Unit (YTU).

The planned process for SAEs was that they were entered onto the SAE reporting form and forwarded to YTU within 24 hours of the investigator becoming aware of them. Once received, causality and expectedness were to be confirmed by the CI. SAEs that were deemed to be unexpected and related to the trial were to be notified to the Research Ethics Committee (REC) and sponsor within 15 days and reported to the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) at the soonest meeting.

Resource use

Information on resource use throughout patients’ hospital stays and at discharge was collected to assess the impact on the NHS as part of the economic evaluation. Data collected in CRFs included length of hospital stay, medication, surgery details and details of therapy during rehabilitation. The 2-week and late discharge CRFs also collected details on any aids or adaptations required and any change of place of residence (e.g. own home to residential care home) at discharge relative to baseline. Resource use data were also to be collected in the 12-week patient questionnaire, from patients with capacity only. This included information on any readmittance to hospital, outpatient care received, any additional medications, aids or adaptations since discharge and return to work.

Patient preference data

Patient preference data were collected for patients invited to participate in the study. Patient preference data were collected on the baseline CRF for patients who did consent to the study and on an optional, separate patient preference form for those who did not. The baseline CRF asked which treatment the patient would have preferred or if they had no preference. The patient preference form asked what the patient’s preferred study treatment was: ‘No preference’, ‘Non-operative management’ or ‘Surgical fixation’. The strength of their preference was also assessed on a scale of 1–10 (with 1 corresponding to no preference and 10 corresponding to very strong preference). Also, the patient was asked how effective they thought each treatment would be: ‘Very ineffective’, ‘Fairly ineffective’, ‘Can’t decide’, ‘Fairly effective’, ‘Very effective’. The patient preference form given to patients who did not consent to participate in the study asked them to record their reason for non-consent.

Sample size

It was estimated that 600 participants were required to address the study objectives. The primary outcome was the EQ-5D-5L over 6 months. To be conservative, we took the lowest published estimate of the minimal clinically important differences (MCID) (0.074)42 with an estimated standard deviation (SD) of 0.25 (estimated from the 0.30 reported by Adachi et al. 43 for the 3L version and adjusted down to account for the 5L version’s greater sensitivity). Based on these assumptions we would have needed to analyse 480 participants (240 per group) and, after accounting for loss to follow-up of 20%, we would have needed to recruit and randomise 600 participants for a study with 90% power (2p = 0.05).

Assignment of interventions

Intervention allocation was assigned using a secure, web-based randomisation system developed for the L1FE study by the software development team at YTU. The online L1FE Data Management System was an independent secure randomisation service for sequence allocation hosted by YTU and accessed by site research staff either by telephone or via the internet. Research staff who were delegated the responsibility to randomise patients on their site delegation log were granted access using a personal log in.

Once an eligible patient had consented and their baseline forms had been completed, research staff recorded their information on the L1FE Randomisation System. The system confirmed eligibility and then performed independent and concealed random allocation (1 : 1), using computer-generated permuted blocks of random sizes (4, 6 and 8), stratified by centre. The patient was allocated to either surgical fixation or non-surgical management.

Patients and treating clinicians were informed of the allocation. As with many surgical trials, where the surgical site is clearly visible, it was not feasible to blind patients, surgeons or outcome assessors.

Data collection and management

Paper CRFs were used to record data. Data were collected at recruiting sites by research staff on hospital CRFs and participants completed CRFs by post. For participants who lacked capacity, a proxy version was completed on the participants’ behalf; to be pragmatic, the proxy could be a family member, friend or carer who had regular contact with the participant. All CRFs were returned to YTU for scanning and processing.

To minimise attrition, we used multiple methods to keep in contact with participants. We asked participants for full contact details (including mobile phone number and e-mail address). We also collected alternative contact details of someone who could be contacted if the participant changed address. Participants (or their proxy) could complete the 2- and 12-week questionnaires in clinic when attending in person or they could be completed over the phone. The 6-week, 6-month and 12-month questionnaires were completed either by post or over the phone for the patient’s convenience. Pre-notification letters were sent out before the postal follow-up questionnaires were due, to help prime participants, and a text message reminder was also sent on the day participants were expected to receive the postal questionnaire. This has been shown to significantly reduce time to questionnaire response. 44 Where a participant did not return their follow-up CRF, there were also up to two follow-up postal reminders and a telephone reminder at each time point. The telephone reminder gave participants the option to complete an abridged questionnaire (a minimum of the EQ-5D-5L) by telephone. The study team also called the participant when there were missing data on the primary outcome (and other missing data as feasible) when a postal questionnaire was returned.

Participants were free to fully withdraw from the study at any point; however, it was also possible for them to withdraw from only one aspect of the trial if participation became a burden. For example, participants could continue with clinical visits only, postal questionnaires only or data collection from their hospital records only with no participant involvement. It was anticipated that these options would reduce the need for patients to fully withdraw from the trial and enable some useful data to still be collected.

Data management

An electronic management system was used to track participant recruitment and study status as well as CRF returns. Data from CRFs were processed by administrative personnel at YTU. Data were verified through cross-checking of the data against the hard copy of the CRF. A Validation Plan for the CRFs was written by the trial coordinators and trial statistician in consultation with the YTU Data Manager. The Plan included detailed coding for the CRFs and data query resolution rules/procedures. Quality Control was applied at each stage of data handling to ensure that all data were reliable and processed correctly.

Data were handled in accordance with the Data Protection Act 2018, GDPR legislation, the latest Directive on Good Clinical Practice, and local policy.

All personal information collected about enrolled participants was stored electronically in a secure environment at the University of York, with permissions for access in line with standard operating procedures (SOPs). All paper records containing personal information such as consent forms and consultee declaration forms were stored safely in a separate compartment of a locked cabinet.

Clinical information was only looked at by responsible individuals from the study team, the Sponsor, the NHS Trust or from regulatory authorities, where it was relevant to the patient taking part in this research as he or she agreed to at the time of consent or consultee declaration.

Once randomised, patients were assigned a participant ID number. This was used on all CRFs, and individual participants were only to be referred to by their participant ID number to maintain patient confidentiality. All study data were completely anonymised for any analyses, reports and publications.

Study Within A Trial

Improving retention of participants is important to all RCTs and there is a need to develop and test interventions to improve retention. The L1FE trial acted as a host trial for an embedded trial, referred to as a Study Within A Trial (SWAT). The objective of this SWAT was to evaluate the impact of making a courtesy introductory telephone call to newly recruited trial participants, on response rates to follow-up questionnaires compared with a written card with equivalent information, or nothing. This SWAT was registered on the Medical Research Council (MRC) SWAT Repository. SWAT Ref 114: Effects of telephone calls or postcards to trial participants following enrolment on retention in a randomised trial. Due to recruiting so few participants there are no results to report on this study.

Analysis of internal pilot

The L1FE study was designed with an internal 12-month pilot phase to test assumptions about recruitment and confirm whether the trial is feasible. The target was to set up a minimum of 19 sites during the pilot with the aim of including all interested sites by month 13. Assuming one patient per site per month, 148 patients should be randomised. An average recruitment rate of one patient per centre per month would support a decision to progress to the main trial. An average rate of 0.80–0.99 per centre per month would suggest that a decision to progress may be supportable depending on other supplementary information available (e.g. number and characteristics of potential participants not approached, proportion not meeting eligibility criteria and reasons, proportion declining participation and reasons why) and whether any of the factors impeding recruitment could be remedied.

Data on the number of sites and average number of patients recruited per site per month are presented.

Data on screening, eligibility and recruitment for the trial are presented in Table 2 as frequencies and proportions and at an overall level. The following information on screening, eligibility and recruitment into the trial are reported:

-

number of patients assessed for eligibility

-

number and proportion of patients assessed for eligibility who were found to be eligible

-

number and proportion of eligible patients who were approached for consent

-

number and proportion of patients approached for consent who consented to participation

-

number and proportion of consented patients who were randomised.

A summary of the frequencies for patient preferences and reasons for refusing consent for non-consenting patients are also reported.

A summary of how identified potential patients progress through the trial and their reasons for dropping out are shown in a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram.

Details of all participating surgeons’ prior experience with the INFIX procedure were collected as part of the trial. Equipoise is an essential concept in trials and was covered during the training delivered as part of the site set-up process. The assumption of surgeon equipoise was monitored during recruitment by scanning reasons for exclusion during screening and reasons for crossover following randomisation that may reflect surgeon preferences, as well as during research staff teleconferences where site staff were asked about recruitment progress, as well as barriers and facilitators to recruitment at their site.

Final analysis

All analyses were conducted in STATA v17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Full analyses were detailed in a statistical analysis plan (SAP), which was finalised following patient recruitment prior to the completion of data collection and database lock.

Overview

The originally planned primary analysis was a mixed-effects linear regression model, with EQ-5D-5L scores at 2 weeks’, 6 weeks’, 12 weeks’ and 6 months’ follow-up as the dependent variable, adjusting for baseline EQ-5D-5L, randomised group and other pertinent baseline characteristics as fixed effects. The plan was to control for potential clustering at hospital site level by including it in the model as a random effect and to account for the correlation of scores within patients over time by means of an appropriate covariance structure. The secondary outcomes were to be analysed by similar mixed-effects linear regression models. Mortality was planned to be analysed using a logistic regression model.

Originally, it was intended that statistical analysis would generally be conducted using two-sided hypothesis tests with a 5% significance level. However, due to poor recruitment no formal statistical hypothesis testing has been undertaken, as the achieved sample size is too low for the conclusions of these tests to be meaningful. As a result, all analyses of the primary and secondary outcome measures are descriptive in nature. Analyses are conducted on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis, with patients being analysed in the groups to which they were randomised.

Baseline data

Baseline data of the outcome measures and information on patient characteristics at baseline are presented descriptively by randomised group and overall in a table. For continuous measures, the mean, median, SD, first and third quartiles, minimum and maximum are reported. For categorical outcome measures, the data are presented as outcome measures and percentages.

Primary analysis

Analysis of the EQ-5D-5L utility index, the primary outcome which measures HRQoL, was descriptive in nature with no formal hypothesis testing due to the small sample size. The mean and median of the EQ-5DL-5L utility index score at each follow-up period in the study are reported. In addition to the mean and median, the following summary statistics are reported for the EQ-5D-5L utility index score at follow-up period: SD, first quartile, third quartile, minimum, maximum, number of observations and number of missing observations. All reported summary statistics are given at both a treatment group and overall level.

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses

No sensitivity analyses were undertaken. Originally there was to be a subgroup analysis exploring how patient’s knowledge and experience of their allocated treatment affected the results of their primary outcome measure; this was going to be achieved by including an interaction between patient preference and treatment group in the linear mixed-effects model for EQ-5D-5L utility index score. However, this subgroup analysis was not undertaken, as there was no statistical modelling of the primary outcome.

Secondary outcomes

A descriptive analysis of secondary outcomes was undertaken due to the low sample size. There was no formal hypothesis testing or statistical modelling. All summary statistics are reported on both a treatment arm and overall level for the secondary outcomes. These include mean, SD, median, minimum, maximum for continuous variables and counts and proportions for categorical variables.

Complications and adverse events

Expected complications (expected AEs)

A summary reporting the number and proportion of patients experiencing each expected complication and the number of patients experiencing any expected complication in both treatment arms at 2 weeks, 12 weeks and discharge (if after 2 weeks) will be created. The proportion of patients affected by each type of complication at 2 weeks, 12 weeks and discharge (if after 2 weeks) and the proportion of patients affected by any expected complication at 2 weeks, 12 weeks and discharge (if after 2 weeks) will all be secondary outcome measures.

Adverse events

The number of (all) AEs and the proportion of patients with at least one AE in each treatment arm and overall are reported for both the 6- and 12-month follow-up time points; and broken down by outcome of the AE, the relationship of the AE to the treatment, action taken, seriousness of the AE, severity of the AE and whether the AE was expected. The number of times each reason for classification was used in classifying the AE is reported.

The number of SAEs and the proportion of patients with at least one SAE in each treatment arm are reported for both the 6- and 12-month follow-up time points; and broken down by outcome of the SAE, the relationship of the SAE to the treatment, action taken and whether the SAE was expected. The number of times each reason for classification was used in classifying the SAE is reported.

The number of reported incidents of lateral cutaneous nerve injury in patients in the surgical fixation of INFIX treatment arm since the patient received surgical fixation of the INFIX device and the proportion of patients in this treatment arm who experienced lateral cutaneous nerve injury since they received the INFIX device at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 6 months and 12 months are reported.

Economic evaluation

Due to the trial stopping early, it was not possible to undertake the planned economic evaluation as outlined in the study protocol.

The planned economic evaluation was to be conducted from the recommended NHS and personal social services (PSS) perspective according to NICE guidance. 45 Data were collected on the costs and outcomes of each trial participant. Participants were asked to complete economic resource use questionnaires at 12 weeks and 6 months as well as at the optional 12-month time point. This included hospital (e.g. inpatient, outpatient, A&E) and community and social care resource used; and for the purposes of secondary analysis, costs associated with lost productivity and out-of-pocket costs. Hospital forms were designed to collect information on the cost of surgery (e.g. time in theatre, staff time, consumables and devices, nights in hospital after the procedure), complications, physiotherapy and removal of devices. Relevant UK unit costs, such as NHS Reference costs and Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) costs of health and social care, would have been applied to each resource item to value total resource use in each group.

For the planned economic evaluation, the raw EQ-5D-5L scores at baseline (today and 1 week prior to injury), 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 6 months post randomisation according to domain would have been displayed, in order to examine the movements between levels for each domain according to group. The overall difference in EQ-5D-5L index scores between the two groups would have been examined through regression methods, consistent with the model selected in the statistical analysis. The EQ-5D-5L health states would have been valued using the mapping function developed by van Hout et al. (2012) in accordance with NICE recent recommendation (www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/what-we-do/NICE-guidance/NICE-technology-appraisal-guidance/eq5d5l_nice_position_statement.pdf). Quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) would have been calculated by plotting the utility scores at each of the four time points and estimating the area under the curve. 46 For the analysis, regression methods would have been used to express the incremental cost per QALYs gained. Results would have been presented using incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) generated via non-parametric bootstrapping. The pattern of missing data would have been analysed and handled by means of multiple imputation (MI) methods. 47 A range of sensitivity analyses would have been conducted to test the robustness of the results using different scenarios, including probabilistic sensitivity analysis. We proposed to undertake longer-term modelling if this had been deemed appropriate (i.e. there was a non-dominant situation in the trial-based evaluation). To do this, we would have undertaken a secondary analysis to explore how the differences observed during the trial evolved beyond the study. For this projection, we would have used a decision-modelling approach to extrapolate the cost-effectiveness data observed in the study to a lifetime horizon. The analysis would have been based on a combination of observed in-trial cost and HRQoL and projections of life expectancy.

If the planned economic evaluation had gone ahead, full analyses would have been detailed in a pre-specified health economics analysis plan (HEAP) that would have been signed off by the trial management team and oversight committees.

From the limited data collected, we have provided a descriptive analysis of resource use. Data of resource use during the patient’s stay in hospital up to and including discharge (which encompasses length of hospital stay, medication, rehabilitation and surgery details) and since their discharge from hospital (which includes re-admission to hospital, outpatient care received, any additional medications, aids or adaptions since discharge and return to work) are analysed descriptively by comparing summary statistics from each treatment arm. Descriptive statistics include counts and proportions for categorical variables and mean, SD, median, minimum, maximum for continuous variables (or discrete variables which have a large range of values).

Regulatory approvals and protocol amendments

The L1FE study was given favourable opinion by London – Harrow REC (Ref: 19/LO/0555) on 16 July 2019. The Health Research Authority (HRA) has also given governance approval on 17 July 2019. The study was given approval by Scotland A REC (REF 21/SS/0002), specifically related to the inclusion of patients who lack capacity to consent in Scotland on 12 February 2021.

Written, informed consent to participate was obtained from all participants with capacity. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time and for any reason, and all participants were made aware that withdrawal would not affect their routine care. The study included patients who lack capacity, and, as appropriate, consultee declaration was sought from a personal or nominated consultee (in England, Wales and Northern Ireland) or consent from a guardian, Welfare Attorney or nearest relative (in Scotland). The process for seeking consultee declaration for patients lacking capacity in England, Wales and Northern Ireland has been approved by the REC in England and was in accordance with the Mental Capacity Act 2005 for England and Wales and in accordance with the Mental Capacity Act (NI) 2016 for Northern Ireland. The process for seeking consent for patients without capacity in Scotland was in accordance with the Adults with Incapacity Act (Scotland) 2000 and approved by the REC in Scotland. The Mental Capacity Act 2005, the Mental Capacity Act (NI) 2016 and the Adults with Incapacity Act (Scotland) 2000 establish a framework for the protection of the rights of people who lack the capacity to decide themselves. They are designed to ensure that the interests and rights of people who lack capacity are protected and that their current and previously expressed wishes are respected.

The final version of the protocol is V3.2, dated 22 December 2020, and is available from the funder website. All substantial amendments were submitted to the HRA (and the REC where required) having been agreed with: the funding body, Sponsor, TSC, DMEC and the Trial Management Group (TMG). Minor modifications to the protocol were agreed with the funding body, TMG and Sponsor before submission for approval to the HRA. All amendments are listed in Appendix 1.

Chapter 3 Results

Overview

The internal pilot took place in two separate phases. The trial first opened to recruitment on 2 August 2019 and this first phase of the pilot continued until 19 March 2020, when recruitment was paused for 1 year due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The trial re-opened for recruitment on 15 March 2021 with a revised internal pilot end date of 15 September 2021 agreed with the funder. Recruitment targets were not being met in the first pilot phase and, despite adjustments and mitigations to address the various challenges, the recruitment difficulties were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic during the second phase of the pilot. It became clear before the end of the second phase that the study was not viable at that time and the team proposed to the funder that recruitment should be suspended early rather than waiting for the pilot phase to complete. It was agreed with the funder to stop recruitment on 13 August 2021. Follow-up was completed for all participants (last follow-up was completed in January 2022) and a close-down plan implemented.

Site set-up

Eleven sites in England and Wales were opened during the first phase of the internal pilot (see Appendix 2). Ten of these re-opened following the study pause and one declined to participate further. A further 10 sites, including 3 in Scotland and 1 in Northern Ireland, were interested in participating and were in various stages of set-up prior to closure. The 11 sites were open for a combined total of 92 months.

Eligibility, screening and recruitment of patients

The flow of participants through the trial is reported in the CONSORT flow diagram (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram.

Table 2 provides a summary of potential participants identified for the study. During the internal pilot, 316 patients were assessed for eligibility, of whom 43 were eligible (13.6%). The main reasons for ineligibility were: patient able to mobilise independently or with supervision to 3 m and back (n = 161), concomitant injury or polytrauma that impedes mobilisation (n = 57), surgery contraindicated (n = 40), patient did not have a low-energy LC-1 pelvic fracture (n = 38), unable to schedule surgery within 10 days of injury (n = 34), patient was under 60 years of age (n = 23) and/or the patient was non-ambulatory or required assistance prior to injury (n = 22).

| Number of patients assessed for eligibility, n | 316 |

| Number of eligible patients, n (%) | 43 (13.6) |

| Number of eligible patients approached for consent, n (%) | 36 (83.7) |

| Number of patients approached providing consent, n (%) | 11 (30.6) |

| Number of consenting patients randomised into study, n (%) | 11 (100.0) |

It was predicted that 50% of eligible patients would consent and be recruited to the study. Of the 43 eligible participants, 36 (83.7%) were approached for consent, of whom 11 (30.6%) provided consent. Eleven (100%) of the consenting patients were randomised into the study. The most common reason for eligible patients not consenting to take part were that they were unwilling to be randomised to a treatment (n = 10) (Table 3). Four non-consenting patients completed a patient preference form. All four patients stated they had a preference for surgical fixation with the average strength of this preference being 7.8 (SD 2), indicating a strong preference. All patients could not decide how effective they thought surgical fixation would be. Two patients thought non-surgical management would be fairly effective and two could not decide.

| Reasons for refusing consenta | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Unwilling to participate in research | 3 (12) |

| Unwilling to be randomised to a treatment | 10 (40) |

| Next of kin unavailable | 2 (8) |

| Consultee did not want to complete CRFs | 1 (4) |

| No reason given | 10 (40) |

Recruitment rate

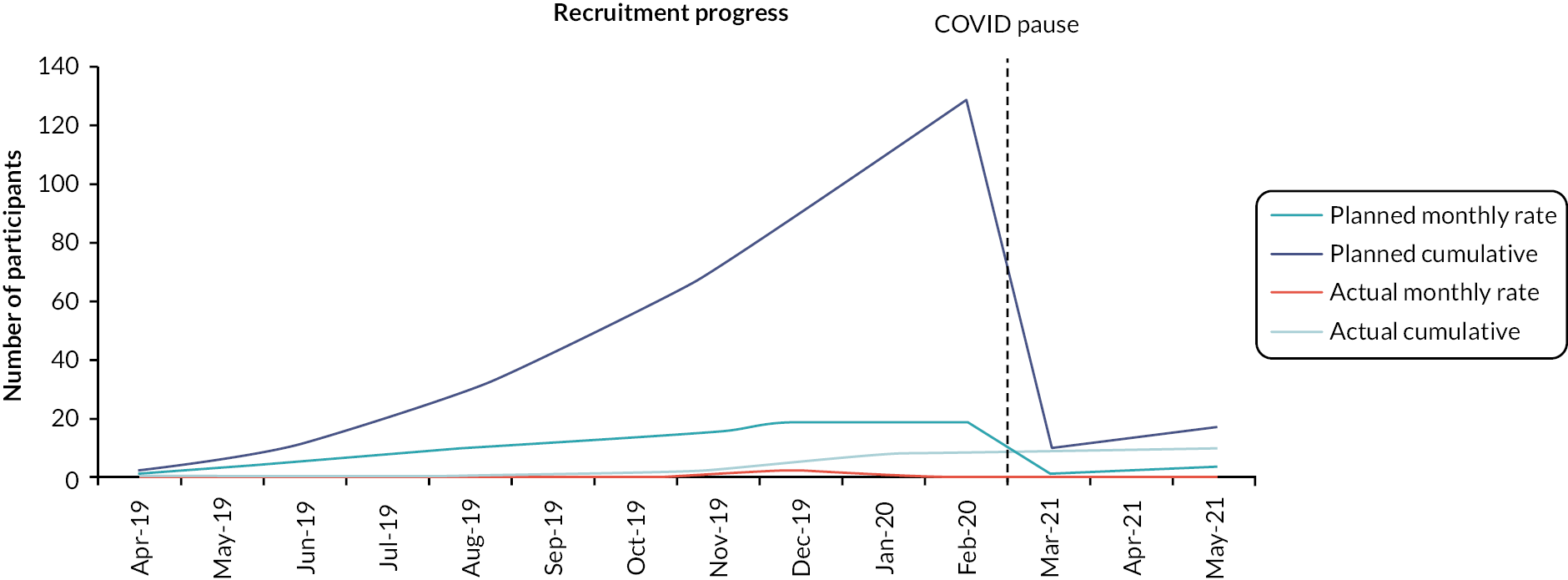

The average recruitment rate per site per month was 0.175. The average recruitment rate was well below the target rate of one patient per site per month. See Figure 2 for predicted and actual recruitment. Table 4 provides a summary of screening and recruitment data by site. The number of patients screened varied greatly between centres and there is not a clear relationship between this and the length of time each centre was open to recruitment. The number of patients randomised varied between sites, with 7 out of the 11 sites not recruiting any participants at all. Of the four sites that did recruit, the CI’s site at Bart’s Health NHS Trust recruited the most successfully, with 8 of the 11 participants randomised from this site. North Bristol NHS Trust, South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust all recruited a single participant.

FIGURE 2.

Predicted and actual recruitment.

| Centre | Centre open (months) | Screened | Eligible | Approached | Randomised |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bart’s Health NHS Trust | 13 | 52 | 21 | 20 | 8 (15) |

| Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 8 | 17 | 1 | 1 | 0 (0) |

| North Bristol NHS Trust | 9 | 89 | 6 | 3 | 1 (1) |

| Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust | 9 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 8 | 25 | 4 | 3 | 1 (4) |

| Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 7 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| Cardiff and Vale University Health Board | 9 | 17 | 2 | 1 | 0 (0) |

| University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| Kings College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | 8 | 23 | 1 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 10 | 22 | 6 | 6 | 1 (5) |

| Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust | 8 | 22 | 2 | 2 | 0 (0) |

| Total | 92 | 316 | 43 | 36 | 11 (3) |

Randomisation and follow-up

Eleven patients were randomised, five to INFIX surgical fixation and six to non-surgical management (see Figure 1). Three participants in the non-surgical management group were withdrawn from the study: one participant died, one participant lost capacity and their family member no longer wanted them to take part in the study, and one participant had sight problems and considered themselves too frail to continue (see Figure 1). Of the five participants randomised to surgical fixation, all received surgery and no one in the non-surgical management group received surgery. All participants in the surgical fixation group completed the 6-month questionnaires (5/5) and the remaining participants in the non-surgical management group provided data at 6 months (3/6). Not all participants were followed up at 12 months.

Demographics and baseline data

Table 5 provides the demographic characteristics and baseline data as randomised. The average age of participants in the trial was 83, with the youngest 72 and oldest 97. Participants were predominantly female (82%), white (82%), non-smokers (82%) and all retired. Of those who responded, none of the participants had a previous fracture or used steroids and 18% reported having diabetes. The average EQ-5D-5L utility score and VAS score 1 week prior to the injury (collected on the day of the baseline assessment) was 0.7 (SD 0.3) and 60 (SD 25) and at baseline was −0.2 (SD 0.3) and 32 (SD 27), respectively. The average PROMIS physical function lower extremity score was 10.5 (SD 5.6) and GMH score was 36.9 (SD 9.6). The average AMTS was 7.1 (SD 3.6) and 4AT score was 1.5 (SD 2.0). The baseline VAS pain score was only completed for six participants and ranged from 9 to 99 with the average being 69 (SD 33) and median 78 (IQR 55–96).

| Control (n = 6) | Intervention (n = 5) | Overall (n = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| N (missing) | 6 (0) | 5 (0) | 11 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 83.3 (8.7) | 83.8 (8.1) | 83.5 (8.0) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 81.5 (79.0, 89.0) | 86.0 (76.0, 88.0) | 83.0 (76.0, 89.0) |

| Min, max | 72.0, 97.0 | 75.0, 94.0 | 72.0, 97.0 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 6 (100.0) | 3 (60.0) | 9 (81.8) |

| Black | 0 (0.0) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (9.1) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (9.1) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 2 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (18.2) |

| Female | 4 (66.7) | 5 (100.0) | 9 (81.8) |

| Current smoking status, n (%) | |||

| Smoker | 1 (16.7) | 1 (20.0) | 2 (18.2) |

| Non-smoker | 5 (83.3) | 4 (80.0) | 9 (81.8) |

| Work status, n (%) | |||

| Retired | 6 (100.0) | 5 (100.0) | 11 (100.0) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 1 (16.7) | 1 (20.0) | 2 (18.2) |

| No | 4 (66.7) | 3 (60.0) | 7 (63.6) |

| Missing | 1 (16.7) | 1 (20.0) | 2 (18.2) |

| Use of steroids, n (%) | |||

| No | 5 (83.3) | 4 (80.0) | 9 (81.8) |

| Missing | 1 (16.7) | 1 (20.0) | 2 (18.2) |

| Previous fracture, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (9.1) |

| No | 5 (83.3) | 3 (60.0) | 8 (72.7) |

| Missing | 1 (16.7) | 1 (20.0) | 2 (18.2) |

| EQ-5D-5L utility score (1 week prior to fall – collected at baseline) | |||

| N (missing) | 5 (1) | 1 (4) | 6 (5) |

| Mean (SD) | 0.7 (0.4) | 0.7 (a) | 0.7 (0.3) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.8 (0.6, 0.8) | 0.7 (0.7, 0.7) | 0.7 (0.6, 0.8) |

| Min, max | 0.1, 1.0 | 0.7, 0.7 | 0.1, 1.0 |

| EQ-5D VAS (1 week prior to fall – collected at baseline) | |||

| N (missing) | 5 (1) | 2 (3) | 7 (4) |

| Mean (SD) | 66 (26) | 45 (21) | 60 (25) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 75 (70, 80) | 45 (30, 60) | 70 (30, 80) |

| Min, max | 20, 85 | 30, 60 | 20, 85 |

| EQ-5D-5L utility score | |||

| N (missing) | 6 (0) | 5 (0) | 11 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | −0.1 (0.4) | −0.2 (0.2) | −0.2 (0.3) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | −0.2 (−0.3, −0.1) | −0.3 (−0.4, −0.2) | −0.3 (−0.4, −0.1) |

| Min, max | −0.6, 0.7 | −0.4, 0.2 | −0.6, 0.7 |

| EQ-5D-5L VAS | |||

| N (missing) | 6 (0) | 5 (0) | 11 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 31 (27) | 34 (31) | 33 (27) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 30 (10, 40) | 30 (9, 60) | 30 (9, 60) |

| Min, max | 0, 75 | 0, 70 | 0, 75 |

| Physical function (lower extremity) | |||

| N (missing) | 6 (0) | 5 (0) | 11 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 8.8 (1.0) | 12.6 (8.1) | 10.5 (5.6) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 8.5 (8.0, 10.0) | 9.0 (8.0, 11.0) | 9.0 (8.0, 10.0) |

| Min, max | 8.0, 10.0 | 8.0, 27.0 | 8.0, 27.0 |

| GMH | |||

| N (missing) | 6 (0) | 5 (0) | 11 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 39.6 (10.7) | 33.8 (8.0) | 36.9 (9.6) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 36.5 (36.5, 44.4) | 36.5 (25.8, 36.5) | 36.5 (25.8, 44.4) |

| Min, max | 25.8, 57.7 | 25.8, 44.4 | 25.8, 57.7 |

| AMTS | |||

| N (missing) | 6 (0) | 4 (1) | 10 (1) |

| Mean (SD) | 7.8 (3.9) | 6.0 (3.3) | 7.1 (3.6) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 9.5 (8.0, 10.0) | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | 8.5 (6.0, 10.0) |

| Min, max | 0.0, 10.0 | 2.0, 10.0 | 0.0, 10.0 |

| 4AT score | |||

| N (missing) | 6 (0) | 4 (1) | 10 (1) |

| Mean (SD) | 0.7 (1.2) | 2.8 (2.5) | 1.5 (2.0) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.0 (0.0, 1.0) | 2.5 (1.0, 4.5) | 0.5 (0.0, 3.0) |

| Min, max | 0.0, 3.0 | 0.0, 6.0 | 0.0, 6.0 |

Patient preference at baseline

Five participants in the non-surgical management group provided data on their preferences at baseline; two had no preference and three had a preference for INFIX surgical fixation.

Primary outcome

Table 6 reports the EQ-5D-5L utility score by intervention group and overall for baseline, 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 6 months and 12 months post randomisation, including the number.

| Control (N = 6) | Intervention (N = 5) | Overall (N = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| N (missing) | 6 (0) | 5 (0) | 11 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | −0.12 (0.43) | −0.21 (0.23) | −0.16 (0.34) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | −0.21 (−0.27, −0.13) | −0.26 (−0.35, −0.17) | −0.26 (−0.35, −0.13) |

| Min, max | −0.59, 0.69 | −0.43, 0.16 | −0.59, 0.69 |

| Perfect health (11111), n (%) | 0, (0.0) | 0, (0.0) | 0, (0.0) |

| Week 2 | |||

| N (missing) | 5 (0) | 4 (0) | 9 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 0.01 (0.35) | 0.12 (0.38) | 0.05 (0.34) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.07 (0.05, 0.22) | 0.14 (−0.17, 0.40) | 0.07 (0.03, 0.26) |

| Min, max | −0.59, 0.28 | −0.36, 0.53 | −0.59, 0.53 |

| Perfect health (11111), n (%) | 0, (0.0) | 0, (0.0) | 0, (0.0) |

| Week 6 | |||

| N (missing) | 3 (0) | 3 (0) | 6 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 0.49 (0.14) | 0.34 (0.22) | 0.42 (0.19) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.44 (0.39, 0.65) | 0.34 (0.12, 0.57) | 0.42 (0.34, 0.57) |

| Min, max | 0.39, 0.65 | 0.12, 0.57 | 0.12, 0.65 |

| Perfect health (11111), n (%) | 0, (0.0) | 0, (0.0) | 0, (0.0) |

| Week 12 | |||

| N (missing) | 2 (0) | 5 (0) | 7 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 0.04 (0.23) | 0.35 (0.24) | 0.26 (0.27) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.04 (−0.13, 0.20) | 0.34 (0.23, 0.34) | 0.23 (0.10, 0.34) |

| Min, max | −0.13, 0.20 | 0.10, 0.74 | −0.13, 0.74 |

| Perfect health (11111), n (%) | 0, (0.0) | 0, (0.0) | 0, (0.0) |

| Month 6 | |||

| N (missing) | 3 (0) | 5 (0) | 8 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 0.39 (0.51) | 0.28 (0.33) | 0.32 (0.37) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.49 (−0.17, 0.84) | 0.27 (0.10, 0.36) | 0.32 (−0.01, 0.63) |

| Min, max | −0.17, 0.84 | −0.12, 0.77 | −0.17, 0.84 |

| Perfect health (11111), n (%) | 0, (0.0) | 0, (0.0) | 0, (0.0) |

| Month 12 | |||

| N (missing) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 2 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 1.00 (a) | −0.20 (a) | 0.40 (0.85) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | −0.20 (−0.20, −0.20) | 0.40 (−0.20, 1.00) |

| Min, max | 1.00, 1.00 | −0.20, −0.20 | −0.20, 1.00 |

| Perfect health (11111), n (%) | 1, (100.0) | 0, (0.0) | 1, (50.0) |

Secondary outcomes

EQ-5D-5L VAS

Table 7 reports the EQ-5D-5L VAS score by intervention group and overall for baseline, 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 6 months and 12 months post randomisation, including the number.

| Control (N = 6) | Intervention (N = 5) | Overall (N = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| N (missing) | 6 (0) | 5 (0) | 11 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 31 (27) | 34 (31) | 32 (27) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 30 (10, 40) | 30 (9, 60) | 30 (9, 60) |

| Min, max | 0, 75 | 0, 70 | 0, 75 |

| Week 2 | |||

| N (missing) | 5 (0) | 4 (0) | 9 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 43 (27) | 53 (21) | 47 (23) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 55 (35, 60) | 55 (40, 65) | 55 (35, 60) |

| Min, max | 0, 65 | 25, 75 | 0, 75 |

| Week 6 | |||

| N (missing) | 3 (0) | 3 (0) | 6 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 65 (27) | 53 (23) | 59 (23) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 55 (45, 95) | 55 (30, 75) | 55 (45, 75) |

| Min, max | 45, 95 | 30, 75 | 30, 95 |

| Week 12 | |||

| N (missing) | 2 (0) | 5 (0) | 7 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 62 (11) | 53 (26) | 56 (22) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 63 (55, 70) | 60 (50, 70) | 60 (50, 70) |

| Min, max | 55, 70 | 10, 75 | 10, 75 |

| Month 6 | |||

| N (missing) | 2 (1) | 5 (0) | 7 (1) |

| Mean (SD) | 63 (25) | 53 (15) | 56 (16) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 63 (45, 80) | 50 (40, 60) | 50 (40, 75) |

| Min, max | 45, 80 | 40, 75 | 40, 80 |

| Month 12 | |||

| N (missing) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 2 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 90 | 0 | 45 (64) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 90 | 0 | 45 (0, 90) |

| Min, max | 90, 90 | 0 | 0, 90 |

PROMIS lower extremity function score

Appendix 3, Table 14 provides details of the number of missing data items for this measure and Table 8 provides a summary of the scores over time.

| Control (N = 6) | Intervention (N = 5) | Overall (N = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| N (missing) | 6 (0) | 5 (0) | 11 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 8.8 (1.0) | 12.6 (8.1) | 10.5 (5.6) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 8.5 (8.0, 10.0) | 9.0 (8.0, 11.0) | 9.0 (8.0, 10.0) |

| Min, max | 8.0, 10.0 | 8.0, 27.0 | 8.0, 27.0 |

| Week 2 | |||

| N (missing) | 4 (1) | 4 (0) | 8 (1) |

| Mean (SD) | 12.3 (4.0) | 11.8 (4.5) | 12.0 (4.0) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 12.0 (9.0, 15.5) | 11.0 (8.0, 15.5) | 12.0 (8.0, 15.5) |

| Min, max | 8.0, 17.0 | 8.0, 17.0 | 8.0, 17.0 |

| Week 6 | |||

| N (missing) | 3 (0) | 2 (1) | 5 (1) |

| Mean (SD) | 22.0 (9.5) | 14.0 (1.4) | 18.8 (8.1) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 17.0 (16.0, 33.0) | 14.0 (13.0, 15.0) | 16.0 (15.0, 17.0) |

| Min, max | 16.0, 33.0 | 13.0, 15.0 | 13.0, 33.0 |

| Week 12 | |||

| N (missing) | 2 (0) | 4 (1) | 6 (1) |

| Mean (SD) | 11.0 (4.2) | 17.8 (8.5) | 15.5 (7.7) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 11.0 (8.0, 14.0) | 16.5 (11.5, 24.0) | 14.0 (9.0, 19.0) |

| Min, max | 8.0, 14.0 | 9.0, 29.0 | 8.0, 29.0 |

| Month 6 | |||

| N (missing) | 3 (0) | 5 (0) | 8 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 20.3 (14.3) | 16.4 (9.2) | 17.9 (10.5) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 17.0 (8.0, 36.0) | 16.0 (8.0, 20.0) | 16.5 (8.0, 25.0) |

| Min, max | 8.0, 36.0 | 8.0, 30.0 | 8.0, 36.0 |

Timed Up and Go test

One participant randomised to the surgical fixation group provided TUG data at week 12. This participant did not use any walking aids and completed the test in 18 seconds.

PROMIS global mental health

Table 9 reports the PROMIS GMH 2a score by intervention group and overall for baseline, 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 6 months post randomisation, including the number.

| Control (N = 6) | Intervention (N = 5) | Overall (N = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| N (missing) | 6 (0) | 5 (0) | 11 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 39.6 (10.7) | 33.8 (8.0) | 36.9 (9.6) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 36.5 (36.5, 44.4) | 36.5 (25.8, 36.5) | 36.5 (25.8, 44.4) |

| Min, max | 25.8, 57.7 | 25.8, 44.4 | 25.8, 57.7 |

| Week 2 | |||

| N (missing) | 4 (1) | 4 (0) | 8 (1) |

| Mean (SD) | 44.4 (14.4) | 40.3 (10.2) | 42.3 (11.8) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 40.5 (34.3, 54.5) | 38.2 (32.0, 48.6) | 40.5 (32.0, 48.6) |

| Min, max | 32.0, 64.6 | 32.0, 52.8 | 32.0, 64.6 |

| Week 6 | |||

| N (missing) | 3 (0) | 2 (1) | 5 (1) |

| Mean (SD) | 47.6 (9.0) | 28.9 (4.4) | 40.1 (12.2) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 44.4 (40.6, 57.7) | 28.9 (25.8, 32.0) | 40.6 (32.0, 44.4) |

| Min, max | 40.6, 57.7 | 25.8, 32.0 | 25.8, 57.7 |

| Week 12 | |||

| N (missing) | 2 (0) | 5 (0) | 7 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 37.2 (16.1) | 39.6 (6.7) | 38.9 (8.7) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 37.2 (25.8, 48.6) | 36.5 (36.5, 44.4) | 36.5 (32.0, 48.6) |

| Min, max | 25.8, 48.6 | 32.0, 48.6 | 25.8, 48.6 |

| Month 6 | |||

| N (missing) | 2 (1) | 5 (0) | 7 (1) |

| Mean (SD) | 48.6 (0.0) | 33.2 (6.8) | 37.6 (9.3) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 48.6 (48.6, 48.6) | 32.0 (32.0, 32.0) | 32.0 (32.0, 48.6) |

| Min, max | 48.6, 48.6 | 25.8, 44.4 | 25.8, 48.6 |

Pain visual analogue scale

One participant in the surgical fixation group recorded the pain VAS score across all time points up to 6 months. The score was 99 (100 = worst imaginable pain) at baseline moving to 52 across weeks 2, 6 and 12 and then reducing to 5 at 6 months. In the non-surgical management group, five participants recorded the pain VAS at baseline, three participants at week 2 and week 6, none at week 12, two participants at month 6 and one participant at month 12. The average scores across time points was 63 (SD 34) at baseline, 54 (SD 10) at week 2, 26 (SD 24) at week 6, one participant rated their pain as 1 and the other 34 at 6 months and at 12 months it was rated as 1 (0 = no pain).

Abbreviated Mental Test Score

Table 10 reports the AMTS by intervention group and overall for baseline, 2 weeks and 12 weeks, including the number.

| Control (N = 6) | Intervention (N = 5) | Overall (N = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| N (missing) | 6 (0) | 4 (1) | 10 (1) |

| Mean (SD) | 7.8 (3.9) | 6.0 (3.3) | 7.1 (3.6) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 9.5 (8.0, 10.0) | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | 8.5 (6.0, 10.0) |

| Min, max | 0.0, 10.0 | 2.0, 10.0 | 0.0, 10.0 |

| Week 2 | |||

| N (missing) | 4 (1) | 3 (2) | 7 (3) |

| Mean (SD) | 7.5 (5.0) | 5.7 (4.5) | 6.7 (4.5) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 10.0 (5.0, 10.0) | 6.0 (1.0, 10.0) | 10.0 (1.0, 10.0) |

| Min, max | 0.0, 10.0 | 1.0, 10.0 | 0.0, 10.0 |

| Week 12 | |||

| N (missing) | 1 (0) | 1 (3) | 2 (3) |

| Mean (SD) | 9.0 (a) | 10.0 (a) | 9.5 (0.7) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 9.0 (9.0, 9.0) | 10.0 (10.0, 10.0) | 9.5 (9.0, 10.0) |

| Min, max | 9.0, 9.0 | 10.0, 10.0 | 9.0, 10.0 |

4AT rapid test for delirium

Table 11 reports the 4AT score for intervention group and overall for baseline, 2 weeks and 12 weeks post randomisation, including the number.

| Control (N = 6) | Intervention (N = 5) | Overall (N = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| N (missing) | 6 (0) | 4 (1) | 10 (1) |

| Mean (SD) | 0.7 (1.2) | 2.8 (2.5) | 1.5 (2.0) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.0 (0.0, 1.0) | 2.5 (1.0, 4.5) | 0.5 (0.0, 3.0) |

| Min, max | 0.0, 3.0 | 0.0, 6.0 | 0.0, 6.0 |

| Week 2 | |||

| N (missing) | 4 (1) | 5 (0) | 9 (1) |

| Mean (SD) | 1.8 (3.5) | 2.2 (2.5) | 2.0 (2.8) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.0 (0.0, 3.5) | 2.0 (0.0, 3.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 3.0) |

| Min, max | 0.0, 7.0 | 0.0, 6.0 | 0.0, 7.0 |

| Week 12 | |||

| N (missing) | 1 (0) | 2 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Mean (SD) | 0.0 (a) | 1.0 (1.4) | 0.7 (1.2) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 1.0 (0.0, 2.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 2.0) |

| Min, max | 0.0, 0.0 | 0.0, 2.0 | 0.0, 2.0 |

Complications and adverse events

There were no recorded clinically significant displacements of the pelvic ring during the trial. There was one participant who died during the trial who was randomised to the non-surgical management group. No responses were received at week 2 for expected complications but 9 of the 11 randomised patients had data at discharge (5 non-surgical management and 4 surgical fixation). Of those nine patients, one person in the surgical group had acute renal failure with no other expected complications noted. At week 12, five responses were received (one non-surgical management and four surgical fixation) and one person in the surgical group had a urinary tract infection and delirium. One participant in the surgical fixation group had a single non-SAE within 6 months of randomisation which was considered unexpected but not related to the trial intervention. Another participant in the surgical fixation group had a lateral cutaneous nerve injury which was an AESI.

Resource use

Appendix 4, Tables 15–21 provide details of resource use during hospital stay in relation to physiotherapy rehabilitation, medication use, surgery, length of hospital stay, walking aids provided on discharge, location of discharge and medication provided to take home. Of those providing data, all participants received a physiotherapy leaflet and therapy. The average number of sessions in the non-surgical management group was 9.2 (SD 5) and in the surgical fixation group was 8.6 (SD 5.4) and for the average session duration was 31.5 (SD 8.2) and 41.3 (SD 5.4) respectively. Most participants received pharmacological venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis across both groups, but no other medication was reported being used during the hospital stay. All five participants randomised to surgery received surgical fixation with INFIX. Most participants received a general anaesthetic and had a local infiltration. In theatre the lead surgeon was a consultant with a registrar/speciality trainee or associate specialist as the first assistant present. In the non-surgical management group two patients had their length of hospital stay recorded and these were 7 and 14 days. In the surgical fixation group three patients had their length of stay recorded and the median was 24 days with a minimum of 23 and maximum of 39 days. No data were returned for the number of walking aids patients were discharged with in the surgical fixation group and in the non-surgical management group one patient was discharged with a walking frame and one with a wheelchair. The discharge location was recorded for one participant in the non-surgical management group (rehabilitation unit) and three participants in the surgical fixation group (live alone, live alone but with support from carers and early supported discharge). All participants with data were discharged with antibiotics (across both groups) and of all those in the surgical fixation group received analgesia and two of the four in the non-surgical management group received analgesia.

Appendix 4, Tables 22–26 provide details of resource use in relation to participants’ pelvic fracture since discharge from hospital, at 12 weeks post randomisation for physiotherapy, outpatient care, community care, private treatment, medication use, walking aids bought or received since discharge and days off work and unpaid activities missed. One participant in the surgical fixation group received five sessions of NHS physiotherapy in the community which lasted on average 15 minutes. One participant in the non-surgical management group received five sessions of private physiotherapy which lasted on average 45 minutes. One participant in the surgical fixation group received two orthopaedic care appointments in relation to their pelvic fracture since discharge from hospital and attended the emergency department once. They also had a single GP home visit and three GP telephone contacts. One participant in the non-surgical management group had a GP telephone contact, a visit from the district nurse and received a four-wheel walker and a shower and sink seat since discharge from hospital, at 12 weeks post randomisation. One participant in the surgical fixation group reported being unable to do unpaid activities (e.g. chores, shopping) for 91 days.

Assessing barriers to recruitment and actions taken to increase enrolment

The study did not have a formal process evaluation. The main barriers to recruitment and actions taken to address them, outlined below, are based on documentation from TMG Meetings, two cross-site meetings with recruitment/research staff from participating centres, individual communications between the trial team and research staff and other trial documentation. We also held a round-table meeting of the central trial team at the end of the study to inform the drafting of this section of the report.

Barriers to recruitment

Patient pathways