Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number HTA NIHR130177. The contractual start date was in January 2021. The draft manuscript began editorial review in July 2023 and was accepted for publication in November 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Gray et al. This work was produced by Gray et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Gray et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Children and adolescents with learning disabilities are at increased risk of developing mental health problems, including anxiety, compared to their typically developing peers. 1,2 The estimated prevalence of specific phobia in children and adolescents with learning disabilities ranges from 1.9 to 17.5%. 2–4 In contrast, estimates of phobias in children in the general population range from 5 to 9%. 5 In direct comparison studies, children and adolescents with learning disabilities are at least twice as likely to experience specific phobia than their typically developing peers. 2

In typically developing populations, specific phobias usually first present in childhood and are associated with an increased risk of developing lifetime psychiatric disorders, particularly anxiety disorders. 6,7 Despite high rates of specific phobia in children and adolescents with learning disabilities, rates of treatment are low. In one study, only 2.4% of children with learning disabilities and a specific phobia had received treatment for their phobia. 3

Building the Right Support outlines the plan for England to develop better community-based services for people with learning disabilities with mental health difficulties. 8 The service model specifies that all individuals with learning disabilities and/or autism should be offered both mainstream and specialist NHS healthcare services as needed, including mental health treatments. While there are well-developed, evidence-based interventions for the general population, such an evidence base is lacking for children and adolescents with moderate to severe learning disabilities. Our recent review of mental health treatments for people with severe learning disabilities failed to find good evidence for any psychological treatment for anxiety, including specific phobia. 9 Despite significant need, there is a lack of research evidence to guide treatment for children with learning disabilities and specific phobia.

Specific phobias have a significant impact on children and families, resulting in considerable impairment. For example, phobias associated with medical procedures can result in the need for anaesthesia or sedation for routine procedures and check-ups, blood/injury/injection phobias make vaccinations and blood tests difficult and can compromise health care, and dog phobias can result in risky behaviour when dogs are encountered in the community. 10

Only a minority of children and adolescents with learning disabilities and significant mental health difficulties are likely to receive mental health services. 11,12 However, costs are high due to the overall need for more services, and increase when young people also have behaviour and emotional problems. 13–15 Effective early interventions and mental health supports have the potential to reduce longer-term care costs. 13,14

The needs of children and adolescents with learning disabilities have been identified as a research priority and a priority service area by NHS England. 16,17 Psychological interventions for mental health problems in children with learning disabilities have been identified as a top 10 research priority. 18 NHS England19 has also highlighted that research must reduce health inequalities among patients, which is of direct relevance to individuals with moderate to severe learning disabilities who face a double inequality (existing health inequalities coupled with a lack of evidence about how to reduce these).

There is evidence to support the use of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and graded exposure to treat specific phobias in typically developing children and children with autism without learning disabilities. 20–23 These interventions focus on both cognitive and behavioural strategies; require good verbal communication, abstract thinking and affect labelling skills; and, in the case of internet-delivered interventions, require independent learning skills. Depending on associated impairments, individuals with learning disabilities may present with significant communication difficulties, including difficulties in articulation and phonology affecting speech intelligibility; morphosyntax affecting sequencing of ideas in utterance; lexicon affecting vocabulary and understanding for meaning; and discourse and pragmatics affecting social use and function of communication. 24,25 The high prevalence of motor and sensory differences also needs to be taken into account. 26,27 As such, existing interventions focusing on both cognitive and behavioural strategies are typically not appropriate or fully accessible for children and adolescents with moderate to severe learning disabilities.

Although National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance recommends guided exposure for the treatment of specific phobia in people with learning disabilities, NICE found very little high-quality evidence about interventions for mental health problems in children with learning disabilities,28 resulting in a call for more research evidence. Our group has recently completed a systematic review of interventions for mental health problems for children and adults who have severe learning disabilities (including those who are autistic). 9 Very few studies met the eligibility criteria for inclusion, and those evaluating psychological therapies made use of minimal-quality single-case experimental designs – with a resulting poor current evidence base.

Rationale for the current study

The research literature on the treatment of specific phobia consists largely of single-case design studies and small non-controlled trials to treat dog phobia. 10,29–31 There is a clear need for the development and evaluation of interventions for children with moderate to severe learning disabilities and a broad range of specific phobias.

Aims and objectives

This research aimed to develop, and evaluate the feasibility of, an exposure-based intervention for specific phobia in children and adolescents with moderate to severe learning disabilities. This work was undertaken in two phases: (1a) intervention development and (1b) description of treatment as usual (TAU); and (2) evaluation of the feasibility of the proposed intervention.

Phase 1a: intervention development

The objectives were to:

-

establish an Intervention Development Group (IDG), and using coproduction over a series of meetings, develop an intervention for specific phobia for use with children and adolescents who have moderate to severe learning disabilities and a range of specific phobias, with or without autism

-

develop a treatment fidelity checklist to be used alongside the intervention manual

-

appraise and consider several candidate outcome measures of anxiety-related symptoms, and secondary outcomes, and make a recommendation for use within phase 2.

Phase 1b: description of treatment as usual

The objective was to describe the current standard treatment provided for children and adolescents with moderate to severe learning disabilities and specific phobia within the UK.

Phase 2: feasibility study

The objectives were to:

-

explore recruitment pathways

-

evaluate the manualised intervention to determine the acceptability and feasibility for all stakeholders, including children and young people, carers and therapists

-

review the appropriateness of proposed measures of anxiety-related symptomatology, and secondary outcomes, for use within a larger study

-

describe factors that challenge or facilitate the implementation of the intervention (e.g. comorbid behaviour problems, other mental health problems, community resources to support exposure)

-

determine the feasibility and acceptability of consent and associated processes

-

determine the acceptability of randomisation in a future trial

-

describe the parameters of a future study to examine the effectiveness of exposure-based therapy to treat phobias in this population.

Chapter 2 Intervention development

Theoretical framework

Phobias are generally considered to be learned fears, acquired through direct conditioning, vicarious conditioning (fear learned by observing the fear of others) or the transmission of information and/or instructions. 32,33 Fear usually builds up gradually, rather than being the sole consequence of a single traumatic event, and typically develops as a result of repeated frightening experiences and/or through social learning. 34 Behavioural treatment of fears stems largely from the work of Wolpe on systematic desensitisation. 35 It is based on the hypothesis that the fear is learned, and can therefore be unlearned and replaced with more adaptive reactions to the fear stimulus. This is achieved through exposure to the feared object that is graded (gradual). By reversing the desire to escape, withdraw or avoid the phobic stimulus, the person learns that the situation is not dangerous. Graded exposure, combined with positive reinforcement, therefore breaks the cycle of fear and avoidance that maintains the fear symptoms. 34

Cognitive behavioural therapy and graded exposure is the intervention of choice for specific phobia. 36 It is effective in treating specific phobias in typically developing children and adolescents. 37,38 There is evidence to support the use of CBT and graded exposure to treat specific phobias in autistic children without learning disabilities. 20–23 However, these interventions focus on both cognitive and behavioural strategies; require good verbal communication, abstract thinking and affective labelling skills; and, in the case of internet-delivered interventions, require independent learning skills. As such, these interventions are not appropriate or accessible for children and adolescents with moderate to severe learning disabilities.

Although NICE guidance recommends guided exposure for the intervention of specific phobia in people with learning disabilities,28 research in this area is sparse. The research literature on the intervention of specific phobia consists largely of single-case design studies and small non-controlled trials to treat dog phobia. 10,29–31

Co-applicant Williams developed an exposure-based intervention for children with severe learning disabilities and limited communication skills, and through a series of case studies demonstrated successful intervention delivery and outcomes. 10,29 This intervention, which is already designed to accommodate the necessary augmented communication strategies, as well as addressing behavioural, repetitive and sensory difficulties often experienced by this population, informed the development of the first draft manual for the SPIRIT intervention. Together with the IDG, this manual and accompanying materials were then reviewed and revised (phase 1a).

Methods

Recruitment

The IDG comprised six key stakeholders: a representative from the Foundation for People with Learning Disabilities (our PPI partner), two parents of children with learning disabilities and specific phobias, and three clinicians with experience of working with children and young people with learning disabilities and anxiety. Seven members of the research team had a background in psychology; other members had clinical backgrounds in child psychiatry and speech and language therapy. Members of the IDG were recruited by the Foundation for People with Learning Disabilities (PPI partner) and through the clinical networks of the research team.

Design

The IDG worked collaboratively over a series of five meetings over 2 months. Meetings were scheduled every 2 weeks, with the exception of the last two meetings which were 1 week apart. All meetings were online. The aims of the IDG were to:

-

define the needs and problems that are to be addressed for children and adolescents with moderate to severe learning disabilities and specific phobia

-

define the intervention objectives, with reference to likely barriers

-

review and revise proposed manualised intervention

-

develop a logic model

-

develop a fidelity checklist, based on approaches that have been successful in our recent learning disabilities trials within UK NHS settings39

-

advise on recruitment pathways

-

establish how to measure outcomes

-

consider the challenges/barriers to our evaluation plan, including likely solutions.

A draft intervention manual, materials, logic model, therapist training outline and the fidelity checklists were developed prior to the first IDG meeting (see Chapter 3). Three of the five IDG meetings focused on the intervention manual and corresponding materials, one on the fidelity checklists, logic model and therapist training, and one on outcome measures. Table 1 shows a detailed schedule of the IDG meetings.

| Meeting 1 |

|

| Meeting 2 |

|

| Meeting 3 |

|

| Meeting 4 |

|

| Meeting 5 |

|

The materials for each meeting were provided to all members at least 1 week prior to the meeting. Feedback was sought at each meeting, and following reflection, subsequent refinements were made to the manual, logic model, materials and the fidelity checklists by the research team that were then presented to the IDG at the next meeting for discussion. Any disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached. All changes and subsequent actions were recorded in a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet which was shared with the IDG for approval. Feedback was also sought on a range of candidate outcome measures. The IDG were invited to make the final recommendation as to which outcome measures should be used within phase 2 of the study.

Results

Objective 1: SPIRIT intervention development

To develop the initial draft of the SPIRIT intervention manual, we drew on co-applicant Williams’s intervention for dog phobia in adolescents with severe learning disabilities and little to no speech. 10,29

The SPIRIT intervention was designed by the research team to be developmentally appropriate for use with both children and adolescents with moderate to severe learning disabilities, and with phobias related to any specific stimulus, as defined by the DSM-5 (animal, natural environment, blood-injection-injury, situational, other). 40 The intervention also included extended support for communication difficulties. A number of materials were developed to accompany the therapist intervention manual, together with a workbook for parents/carers.

The intervention is parent-mediated, with initial parent skills training and therapist support. The SPIRIT intervention consisted of two parts: (1) two parent/carer skills training group workshops (two half-days); and (2) weekly therapist support sessions with individual parents/carers over 8 weeks.

Following feedback from the IDG, revisions were made to the intervention manual and materials. See Chapter 3 for a detailed description of the SPIRIT intervention and accompanying materials.

Tables 2–8 summarise changes proposed to the intervention manual and materials by the IDG and how they were addressed.

| IDG feedback/suggestions | Action |

|---|---|

| General feedback | |

| Offer parents/carers a choice regarding when they would like to attend the skills training workshop and provide flexibility with timing. | We will consult with parents/carers within the treatment group and find a mutually convenient time. |

| Include regular monthly reviews with the therapist. | Parents/carers will have weekly support sessions with the therapist for 8 weeks following the initial training. |

| Simplify the language in the therapist intervention manual. | We have used vocabulary known to clinicians/therapists working in learning disabilities services. Where applicable we have added definitions in text boxes. |

| Add more definitions to the intervention manual. | Completed. |

| Add real-life examples. | Real-life examples added. More will be added after the study is finished based on experiences/feedback of the participating families and therapists. |

| Recheck the manual for spelling. | Completed. |

| Define vocabulary in tables or thought bubbles. | Completed. |

| Add a page of key terms. | We have added text boxes with definitions throughout the manual. |

| Restructure the manual: 1. general introduction to the problem; 2. the guiding framework/logic model; 3. the intervention itself that operationalises the aspects of the logic model; 4. All supporting concepts and session materials. | Completed. |

| IDG feedback/suggestions | Action |

|---|---|

| Restructure the manual: 1. general introduction to the problem; 2. the guiding framework/logic model; 3. the intervention itself that operationalises the aspects of the logic model; 4. All supporting concepts and session materials. | Completed. |

| Develop a resource bank including materials written in simple language, video materials, images and practical examples. | Completed. |

| Add a section on potential harms resulting from the intervention. | This information is included in the participant information sheet. We considered including this in the manual as well, but we decided it was best suited to the participant information sheet. However, discussion of all potential issues related to the intervention was added to the therapist training workshop. |

| Add a section on how likely it is that a behaviourist approach is going to work for an autistic person. | Explained in the section on theoretical background of the intervention. |

| Add the page explaining the role of the introduction and the theoretical section. | Completed. |

| Add a clear general framework/logic model that is informing the intervention and helping therapists make sense of the approach. | Completed. |

| Develop a script with practical suggestions on relaxation. | Adaptations to the relaxation strategies are included in the session on relaxation and in the parent workbook. This also includes consideration that for some young people traditional relaxation exercises might not be helpful and other strategies should be considered. |

| Emphasise the importance of rapport building and trust building. | Completed. |

| Emphasise the importance of a person-centred approach. | Completed. |

| IDG feedback/suggestions | Action |

|---|---|

| Support the section on reinforcement with practical examples. | Completed. |

| Explain the concepts of differential reinforcement of other behaviour, differential reinforcement of incompatible behaviour, and differential reinforcement of alternative behaviour in more depth and support them with practical examples. | Completed. |

| Rephrase the section on reinforcement effectiveness. | Completed. |

| Consider moving the toolkit to the appendix or add more explanation in the ‘How to use the manual’ section. | Was considered, but decided the toolkit should be part of the main body of the manual to ensure therapists read it. Added additional explanation on how the toolkit fits with the rest of the manual to the ‘How to use the manual’ section. |

| Delete section on active support. | Completed. |

| IDG feedback/suggestions | Action |

|---|---|

| Add more explanation and examples. | Completed. |

| Develop additional training handout with more information on each point covered in the ‘Considerations for working with young people with moderate to severe intellectual disabilities and their parents’ section. | Completed. |

| Rephrase good practice guidelines so that it is expressed as ‘do this’ or ‘do that’ rather than ‘It is important that’. | Was considered; however, felt this wording not appropriate. Revised to further emphasise the importance of the good practice guidance. |

| Specify ‘preferences and needs’. | Completed. |

| Add that it is important that the staff working with the young person know how to use the person’s communication aids effectively. | Completed. |

| Add that it is important to establish how the person communicates ‘stop’, ‘no’, ‘enough’ and requests a break. | Completed. |

| Add that it is important to ensure communication is adapted to the needs of the individual. | Completed. |

| To rephrase ‘keeping well’. | Reviewed and discussed; however, decision made by the IDG to retain this phrase. |

| IDG feedback/suggestions | Action |

|---|---|

| Consider how to communicate the content of the training to parents/carers who are not attending, especially if parents are separated. | Information added. |

| Consider when to introduce the rationale of the intervention (exposure but also indirect work with parents) and how to highlight it in the manual. | The rationale is first introduced in the ‘Intervention structure and rationale’ section and then further discussed in ‘Introduction to exposure therapy’. We have added a brief rationale for upskilling parents/carers in the ‘Introduction’ section. |

| Consider how to address potential anxiety of parents/carers. | Relevant information added. |

| Provide more rationale for upskilling parents/carers rather than doing direct work. | Completed. |

| Consider how to address potential concerns of parents/carers about their role in the treatment (e.g. confidence). Provide space for parents/carers to discuss this together at the beginning of the training and consider any barriers. | Discussed in the ‘Considerations for working with parents’ section. Parents were asked how they feel about their role in the intervention during the introduction section and had ample opportunities to discuss this further in small groups during the remainder of the workshop. |

| Highlight working together to improve family life. | Completed. |

| Add that exposure as a gradual approach is for everybody, not only the child. | Completed. |

| Rethink wording such as ‘neurotypical’ or ‘comorbid’. | As the intervention manual is intended for clinicians, concluded wording is appropriate. Wording not used in the parent/carer materials. |

| Consider adding a content warning to the video on different types of specific phobias. | Completed. |

| Perhaps the video could be a homework task for those who feel comfortable watching it. | Considered; however, decision was made to keep it as an activity completed during the workshop as facilitates discussion if parents/carers have just watched the video. A content warning was added, and parents/carers were asked to watch it on their own devices. |

| Perhaps ask people to watch the video on their own device, instead of showing it to the whole group. | Completed. |

| Consider other ways of illustrating the discussion on types of phobias and their impact for parents/carers who do not want to watch the video. | Parents/carers who do not want to watch the video are encouraged to reflect on situations when they felt afraid. The aim of this activity is to illustrate the impact of the specific phobia on their child and not only on family unit. |

| Rethink phrase ‘faulty thinking’. | Phasing changed. |

| Define specific phobia more clearly – clarify how this differs from being frightened/anxious about something or because of sensory needs or situations where an element of being afraid is ‘expected’. | Completed. |

| Rethink examples of different types of specific phobias (e.g. not animal-related, environmental, dental). | Completed. |

| Consider including a topographical definition of each type of specific phobia. Define what it looks like from a parent/carer point of view. | This is covered in the ‘Symptoms of specific phobia in young people with learning disabilities’ section. |

| Consider adding a clip of parent/carer talking about the impact of specific phobia on their child and family or a case study. | Considered, but not possible due to time and budgetary restrictions. To be considered for future work with the intervention. Parents/carers had opportunities to discuss the impact of their child’s phobia in small groups throughout the workshops. |

| Rethink materials used in the intervention manual and parent workbook to be more inclusive. | Completed. |

| Emphasise the flight concept in anxiety problems. | Completed. |

| Add how to communicate the training content to the parent/carer not attending the training. | Information added. |

| Consider how to communicate content of the training to the school the young person is attending, grandparents and break carers. Talking to parents/carers about who needs to know about the intervention. | Information added to the manual. Created a document called ‘Information Sheet for Other Carers’ that can be passed on to carers, other family members or school. |

| Rethink title of the ‘Motivation’ section (e.g. ‘Reinforcement’). | Name of the section changed to ‘Reinforcement’. Added a section called ‘How phobias develop’. |

| Make the link between reinforcement and preference assessment clearer. | Completed. |

| Emphasise that the exposure plan will be gradual and achievable for the young person so there will be opportunities to use reinforcement. | Completed. |

| Emphasise that the intervention focuses on gradual approximations to the target – so that there is always reinforcement available. | Completed. |

| Mention slow and fast triggers. | Completed. |

| Include a section on the child avoiding an anxiety-provoking event or engaging in other behaviours to reduce anxiety. | Completed. |

| Make distinction between reinforcement and bribery/reward clear. | Completed. |

| Rethink placement of group activity 5. | Considered different placements of this activity, but concluded the current placement works best for the flow of this section. |

| More time might be needed to introduce the preference assessment. | Added an additional 15 minutes to be spent on the ‘Reinforcement’ and ‘How phobias develop’ sections. Changed group activity 6 from practice in pairs to demonstration by the therapist to save time and be helpful to the parents/carers overall. |

| Add an example of the completed preference assessment in the parent workbook. | Completed. |

| Add a text box at the end of the preference assessment form which allows parents/carers to say anything else they would like to mention about their child’s phobia which has not been covered; that is, things which do not fit into the previous questions. It may give a fuller picture or allow them to express their concerns. | Completed. |

| Think about putting each type of reinforcement in the box or presenting it differently so the distinction is clearer. | Completed. |

| Rethink word ‘contrived’. | Wording changed. |

| Emphasise in the manual how parents/carers are supported and what happens if they feel they cannot continue with the intervention. | This is included in the ‘Introduction’, ‘Intervention structure and rationale’ and ‘Implementation plan’ sections. |

| Consider changing ‘reinforcement strategy’ to ‘reinforcement plan’. | Wording changed. |

| Change word ‘aversive’. | Wording changed. |

| Rethink flow of parent handout on reinforcement. | Completed. |

| Consider giving space for the parents/carers to state for what phobia they are collecting data on the ABC chart. | Completed. |

| Mention in aims of activity 7 child’s existing relaxation strategies. | Completed. |

| Add blowing bubbles, fidget things and sensory items as alternatives to standard relaxation exercises. | Already included in the adaptation section. |

| For parents/carers who have smartwatches – it might be worth asking them to track change in heart rate during activity 7. | Information added. |

| Consider introducing grounding in some form. | Information added. |

| Parent workbook – people with literacy difficulties find it much harder to read text in capitals, and lower case tends to be easiest to read. | Text reformatted. |

| Possibly have a video of a person doing the relaxation exercises for parents/carers to access. | Parents/carers were trying the exercises themselves during the workshop, so did not feel the video was needed. Provided a video on grounding as an option. |

| Add visuals for relaxation. | All visuals needed for relaxation exercises are provided in the image bank that comes with the intervention manual. |

| Consider different visuals so children are using visuals they are familiar with. | Used visuals from ‘Easy on the I’ for consistency. Therapists advised to use different visuals if there was a format the child was already familiar with. |

| Look into resources included in the PELICAN pack. (PELICAN resource from Foundation for People with Learning Disabilities41). | Added a hand massage as per the PELICAN materials as alternative to standard relaxation strategies. |

| Add video on visual schedules. | Completed. |

| Some children might only tolerate visual schedule for the morning or the afternoon rather than the whole day. | Revised this section so the visual schedule will be used during exposure tasks only. |

| IDG feedback/suggestions | Action |

|---|---|

| It might be helpful to talk about the fact that exposure therapy may seem a bit strange, but it does work. Ask people how they have overcome their own fears. | Completed. |

| Rethink name of ‘fear ladder’. | Changed to ‘exposure steps’. |

| Possibly consider a different analogy for the exposure steps. Maybe a mountain, thermometer or a horizontal progress to emphasise that steps should not be getting more scary. Possibly providing parents/carers with a few different analogies/templates to choose from. | Completed. |

| Maybe add an example of success of using exposure therapy to give parents/carers some hope. | After the feasibility study is finished, we will draw on information and learnings to develop case examples to include in future SPIRIT work. |

| Add information about the experience of feeling anxiety being also important. | Completed. |

| Emphasise that intervention is done at child’s pace. | Completed. |

| Sitting in the chair might not be appropriate for everybody for completing exposure steps. ‘Position themselves in a way which is comfortable for them’ is better phrasing. | Completed. |

| Emphasise that parents/carers will be working on the steps at slow pace and adding more steps once started. | Completed. |

| Consider adding some strategies parents/carers can use if they feel anxious themselves about any steps or feel like giving up. Just noticing such feelings may be enough. This may be a potential ‘barrier’ in applying the therapy for parents/carers. Some messages about looking after themselves, but also looking out for their own response. | Information added. |

| Add a picture or image on headings of the parent workbook. | Considered this, but the handout looked too busy with additional visuals. We have incorporated plenty of visuals for the parents/carers throughout all intervention materials. |

| Theoretically you do not need to tolerate exposure steps calmly to master them; you only need to be less anxious than before. | Phasing revised. |

| Change ‘fear evoking’ to ‘frightening’. | Completed. |

| Add to activity 12 that parents/carers should include steps that the child can currently tolerate as the first step. | Completed. |

| Mention that the fear ladder will evolve during the intervention and does not need to be perfect from the beginning. | Completed. |

| Add tips on how to break down the exposure steps. | Completed. |

| Consider suggesting online app to help parents/carers organise exposure steps. | Considered this, but did not find an app that was freely available and appropriately structured for the SPIRIT intervention. |

| Consider Post-It® type of board that parents/carers can move things on. | Created a template of a visual schedule that can be used as a fear ladder. |

| It would be helpful to highlight that for different children, different steps might be needed. Parents’/carers’ expertise will be crucial in designing the fear ladder. | Completed. |

| Add more information on practical issues around exposure to the handout on the fear ladder; for example, completing steps at the dentist. | Completed. |

| Possibly consider adding information about when to review the ladder and break down the steps. | The fear ladder is reviewed every week as part of the weekly support sessions. Information on breaking down exposure steps is in the ‘Troubleshooting’ section. |

| Consider changing ‘reaching mastery’ to ‘reaches goals’. | In the context of behavioural treatment, reaching goals is not a synonym for reaching mastery. As this is in a manual for professionals, the expression is considered appropriate. |

| If exposure needs access to specialist situations, for example dogs or dentist, then daily practice will not be possible. | More information added. |

| Consider asking parents/carers to let their child’s school know that their child has a dog phobia, so dogs are not brought to the school when the child is present. | Developed an information sheet for parents to use with school and in other relevant settings. |

| Add examples of organisations that can help with access to dogs: Pets as Therapy, Guide Dogs, Pets as Therapists. | Information added. |

| Consider adding a ‘partially successful try’ rating to the data sheet. | Completed. |

| On the data sheet – write the first step initially, then add the next step when the previous one is mastered in case you need to make amendments. | Information added. |

| Consider having two sample data sheets – one with all steps completed and one with just one step. | Completed. |

| Emphasise that the data sheet should be shared with the therapist during the weekly check-ins. | Completed. |

| Add to the troubleshooting section about checking how much time is spent on talking about exposure without doing it. | Completed. |

| A section is needed on parents/carers who have problems with anxiety themselves. | Discussed in the ‘Considerations for working with parents’ section. |

| Create a separate troubleshooting handout for parents/carers. Acknowledge that parents will already have some troubleshooting strategies they use regularly with their children, so this is an add-on. | Completed. |

| Add suggestion for the therapists to check when the best time is during the day to do exposure with parents/carers. | Completed. |

| Suggest using the same reinforcement scheme as that used at the child’s school. | Completed. |

| Consider if relaxation is being overemphasised. Could we reword this to techniques to cope with stress? Or ‘Relaxation and calming?’ | Reviewed, but concluded not appropriate in the context of exposure therapy. |

| Add more relaxation adaptations. | Completed. |

| Add suggestions on what to do if parents are struggling to get started. | Completed. |

| Consider adding some guidance for therapists and parents/carers about their avoidance as they are fearful of their child’s reaction and how to support parents. | Discussed in the ‘Considerations for working with parents’ section. |

| IDG feedback/suggestions | Action |

|---|---|

| Add review of the data sheet to the session outline. | Completed. |

| Build in more celebration of success and achievements, perhaps by having a document to record it every week. | Completed. |

| Therapist reminding parents/carers how brave their children are to work on exposure. | Completed. |

| Add congratulations for getting this far to the last support sessions. | Completed. |

| The Keeping Well plan should be available to parents/carers as a hard copy and Word document. | Completed. |

| Building more celebration of success and achievements, especially in the therapist handbook. | Completed. |

The cultural appropriateness of the parent workbook was discussed during consultation with a parent of ethnic minority background. The parent was sent the workbook to review, and met with the Study Manager (SM) and Research Assistant (RA) to discuss. The parent felt that the content did not need any adaptations; the sole suggested change was to include more diversity in the pictures used for parent-facing materials.

Logic model and therapist training

A draft logic model was presented to the IDG. Table 9 summarises proposed changes and actions.

| IDG feedback/suggestions | Action |

|---|---|

| Mechanisms should include antecedent interventions. | Added. |

| Define longer-term outcomes (sustained/further reduction in fear). | Added. |

| Specify short, medium and long term; for example, 4 weeks, 8 weeks and 6 months. | Considered; concluded that appropriate to define specific timelines. |

| It might be misinterpreted that children and young people themselves understand that they are at increased risk of developing anxiety. | This point has been rephrased to improve clarity. |

| Specify that anxiety might be incorrectly seen as part of a learning disability. Consider adding in brackets diagnostic overshadowing. | Added. |

| Add more about autism symptomatology without directly referring to autism. Consider adding more about specific difficulties that children and parents/carers might have, their impact on intervention and how to troubleshoot that (social difficulties, rigidity/preference for sameness/neophobia) to the intervention manual. | Added. |

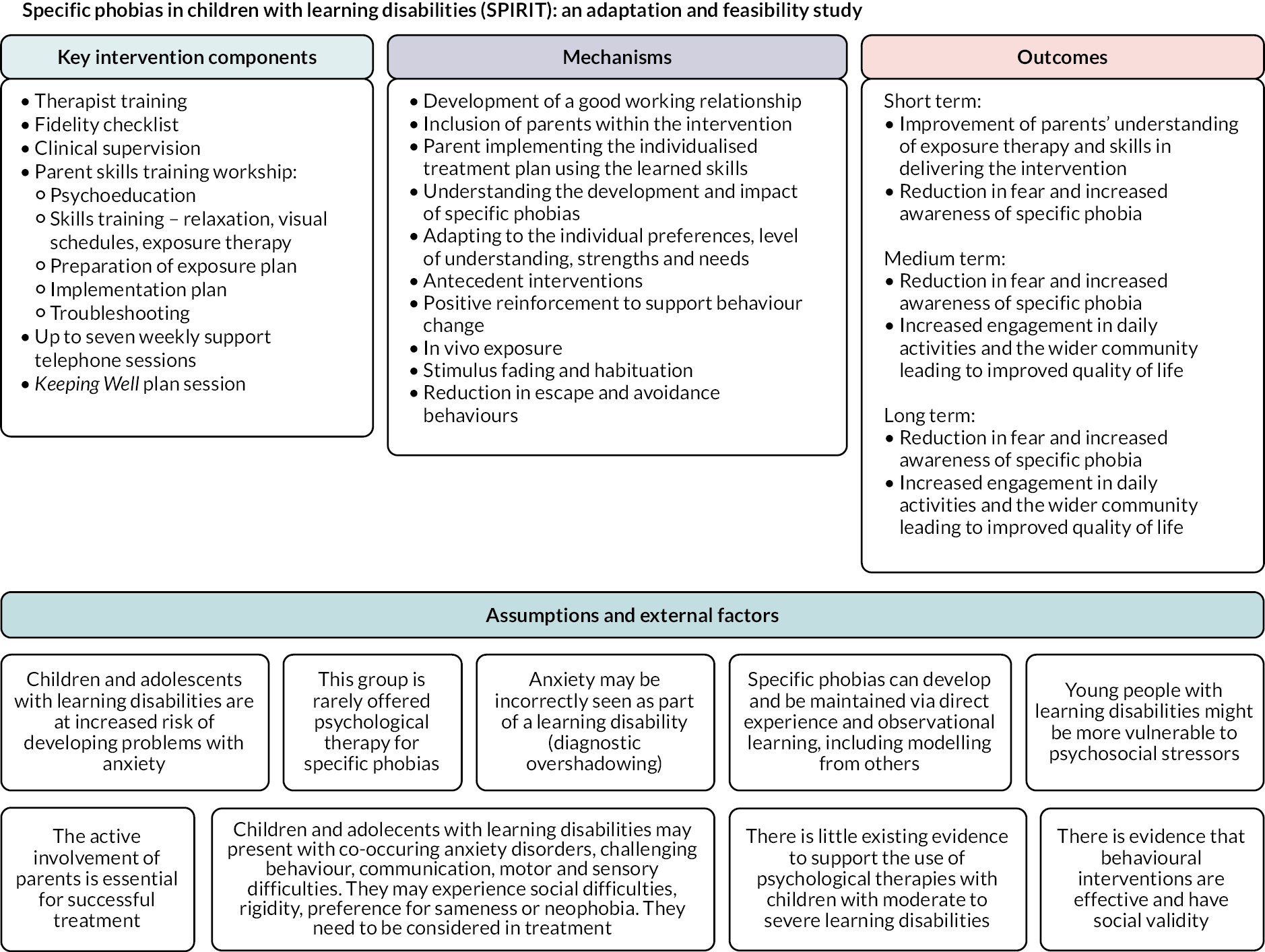

See Figure 1 for the finalised logic model.

FIGURE 1.

SPIRIT intervention logic model.

A draft therapist training plan was presented to the IDG. Table 10 summarises proposed changes and actions.

| IDG feedback/suggestions | Action |

|---|---|

| Training in the intervention might possibly include the behavioural section before the intervention detail. The ‘order’ of training basically might be different to the logical order of the manual itself. | Considered, but concluded important to introduce the intervention before working on specific concepts. |

| Role-plays could work well in breakout rooms if the task is manageable and designed for online format. | Option of role play added. |

| It would be helpful if trainers were role-playing. | Considered; however, parent skills training workshop may be delivered by one trainer so role play may not be possible. Added videos of different techniques instead. |

| Provide longer breaks. | Duration of breaks changed to 15 minutes. |

| Invite parents/carers to the training and ask for their contribution. | Considered; however, not possible to implement due to budgetary restrictions. We will consider inviting parents/carers for future training sessions or making videos with parents to be shown during the training. |

| Add video interview footage of a parent/carer talking about their child’s anxiety and specific phobias. | Considered; however, not possible due to time and budgetary restrictions. Will consider this for future evaluation work. |

| The first part of the toolkit of behavioural strategies is longer than needed but the second part is too short. | First part shortened to 45 minutes and second part extended to 75 minutes. |

| Add a section on possible trauma that parents/carers may experience coping with some extreme phobias their child has. Also, some parents might be hurt physically in managing certain behaviour. | Section on impact added. If indicated, this section will be developed further based on feedback from parents/carers taking part in the study. |

| Give therapists some places they can refer parents/carers for extra support if needed. This should be also added to the intervention manual to ensure that therapists appreciate and recognise that signposting to additional resources and supports may be needed. | Therapists directed to provide signposting information relevant to their service/region. |

| Add trainer-level troubleshooting around what happens if parents/carers are not able to do exposure tasks, cannot fit it in the schedule or are worried into the intervention manual and the training outline. | Information added. |

See Chapter 3 for a detailed description of the therapist training.

Objective 2: develop an intervention fidelity checklist

A fidelity checklist was developed for the SPIRIT intervention, based on checklists used in a previous study. 39 It included seven main sections:

-

general workshop/session preparations

-

coverage of workshop/session plan

-

understanding and accessibility

-

interpersonal effectiveness

-

engaging participants

-

workshop/session content

-

comments.

Checklists were developed for each of the workshops and each of the eight support sessions. Therapists were asked to reflect on the workshop or session and indicate whether they had fulfilled the aims by checking ‘yes’ or ‘no’. See Report Supplementary Material 7 for a sample fidelity checklist and Chapter 3 for a detailed description.

Draft fidelity checklists were prepared and presented to the IDG meeting. Following feedback from the IDG, revisions were made. Table 11 summarises changes proposed by the IDG and how they were addressed.

| IDG feedback/suggestions | Action |

|---|---|

| Add a statement on the top of the checklist that when scoring these items, it is important to think of majority of parents/carers, rather than all. | Statement added. |

| It might be hard to judge impact on parents/carers if the checklist is self-reported – feedback from parents would be needed. | Considered; however, it was felt parents already have sufficient intervention tasks to complete each week. Their experience of the intervention and working with their therapist will be captured during post- intervention interviews. |

| Self-reflection tool needs more work; consider adding a reflection box. | Notes section added to the bottom of each document. |

| Reflection might be difficult for some people – some cross-referencing with parent feedback would be helpful. | Considered; however, it was felt parents already have sufficient intervention tasks to complete each week. Their experience of the intervention and working with their therapist will be captured during post-intervention interviews. |

| Add a section where therapists can reflect on what worked well and what could be better. | Notes section added on the bottom of the document. |

| Therapists should be rating concepts rather than behaviours. | Reviewed and implemented for parts of the checklists; however, concluded it was not appropriate for sections directly relating to session objectives. |

| It might be easier to admit that the criterion was only ‘partially met’ rather than just selecting ‘no’. | Considered; however, concluded a broader scale would not be appropriate for this checklist. Feedback will be sought from the therapists on the fidelity checklist and potential revisions to be made for a future study. |

| The child Improving Access to Psychological Therapies measures include some form of patient-reported session-by-session recording. The Dagnan Confidence Scale42 might also be helpful. | Different checklists were considered. |

| Feedback about parents’ experience is vital. | Considered; however, it was felt parents already have sufficient intervention tasks to complete each week. Their experience of the intervention and working with their therapist will be captured during post-intervention interviews. |

| It might be helpful to think about the role of clinical supervision here. | Considered, but felt it would not be appropriate to include this on the fidelity checklist. This checklist is intended to be used for this specific study, rather than intended for clinical supervision. |

Objective 3: appraise and consider several candidate outcome measures of anxiety-related symptoms, and secondary outcomes, and make a recommendation for use within phase 2

A range of potential outcome measures were considered, including parent/carer questionnaires, interviews, behavioural measures and physiological measures. These included:

Eligibility assessment

Specific phobia

Emotional and behavioural difficulties

Physiological measures

-

Apple Watch® (Apple, Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA)

-

Fitbit® watch (Fitbit, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA)

The IDG was presented with detailed information about the measures, including content/purpose of measure, format, age range, time needed to complete and psychometric properties. They were also given access to all potential outcome measures apart from smartwatches. Following a discussion, the IDG made recommendations about outcome measures to use in phase 2 of the project. Table 12 summarises IDG feedback and actions on the measures reviewed.

| Measure | IDG feedback/suggestions | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Eligibility | ||

| ADIS44 | IDG recommends using this measure. | Measure included in eligibility assessment. |

| Diagnostic checklist for anxiety based on DM-ID-243 | IDG recommends using this measure. | Measure included in eligibility assessment. |

| VABS-345 | IDG recommends using this measure. | Measure included in eligibility assessment. |

| Specific phobia | ||

| Severity Measure for Specific Phobia – Child Age 11–17.46 SPIRIT adaptation for people with little or no language: caregiver version | Add section for additional comments. | Added. |

| Rephrase question 10. | Question rephased. | |

| Consider families that avoid certain situations so might not have had contact with feared stimuli in the last 7 days. An additional text box could be a good solution, so parents/carers can add further details. | Text box added. | |

| Consider how parents/carers can report on children’s emotional states and bodily states that are not easily observable (e.g. racing heart). Consider phrasing such as ‘It looks like your child might be experiencing . . .’ or ‘Did they seem to have . . .’. | Questions rephrased. | |

| Consider how to capture what children communicate. | Text box added. | |

| Add a section on the top of the checklist to ask parents/carers how their child behaves when in the presence of feared stimuli. | This information would be captured by another measure. | |

| Children might not be engaging in avoidance because their families are avoiding situations where they might be exposed to feared stimuli, so they do not have a chance to escape the situation. | Text box added so parents/carers can mention this information. | |

| IDG recommends using this measure with recommended revisions. | Measure added to the baseline and follow-up assessment. | |

| Emotional and behavioural difficulties | ||

| SDQ: Impact supplement.47 SPIRIT adaptation | Consider changing the rating scale. | Only three questions were used from the questionnaire, and therefore felt the scale was appropriate. |

| Question on ‘do the difficulties that upset or distress your child’ seems redundant. | Question deleted. | |

| Add a question about the difficulties getting worse or escalating in the last 12 months. | This information would be captured by another measure. | |

| Add a question on avoidance and level of stress. | This information would be captured by another measure. | |

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder materials might be helpful to capture this information. | Reviewed these but felt the questionnaire captured the necessary information. | |

| The measure could be helpful to assess broad issues and is easy to complete. However, it is not as useful to detect change or capture more specific information. | Feedback noted. | |

| Possibly the scale could be changed to 2 weeks to capture potential change. | Questions referring to specific timescale were not used. | |

| Consider how to capture the effort families put into avoiding specific situations/items. | This information captured by another measure. | |

| Think about further dividing the ‘home life’ and ‘leisure’ categories. | We considered this but decided to proceed with the question in its current form and ask parents/carers for feedback. | |

| Make it clear that the difficulties are in relation to specific phobia. | Clarification provided to parents/carers. | |

| Possibly agree on four most important areas with the parent/carer at the beginning and track change in relation to those. Goal attainment scaling might be helpful to look at. | Reviewed and decided on three main questions that the IDG preferred. | |

| Look at goal-based outcomes measure where individual goals are scored on 0–10 scale to estimate how close parents/carers feel to goal. | Reviewed, but felt not appropriate for this questionnaire. | |

| IDG recommends using this measure with recommended revisions. | Measure added to the baseline and follow-up assessment. | |

| ABC-C48 | IDG does not recommend using this measure due to its length and vocabulary used. | Measure not used. |

| DASH-II49 | IDG does not recommend using this measure due to its length. | Measure not used. |

| DBC2: Parent Form50 | •Good feedback from clinicians but not clear what parents/carers think about it. •Contains preferred language in relation to disability. •IDG recommends using this measure. |

Measure added to the baseline and follow-up assessment. |

| BPI for Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities – Short Form51 | •Good feedback from clinicians and parents/carers. •IDG recommends using this measure. |

Measure added to the baseline and follow-up assessment. |

| Physiological measures | ||

| General feedback on using smartwatches to record heart rate | •There is a risk that the watch becomes associated as a cue that exposure is coming if it is only used for the exposure – would need to be worn more regularly. •A colourful watch might be better tolerated by children. |

Feedback noted; however, it might not be possible for children to wear the watch outside of intervention time due to battery life and risk of damage. |

| Apple Watch | Some watches might be distracting, especially Apple Watch. | Apple Watch excluded. |

| Fitbit watch | •One of the clinicians had experience using Fitbits in research – many devices were lost, damaged or ran out of battery. The solution could be to only use them during exposure tasks. •Most children tolerated the Fitbit. •Could enquire about a discount or donation from Amazon or Fitbit. •Concluded testing the Fitbit was the best option. |

Feedback noted; the watch will be used only during intervention time. |

Chapter 3 SPIRIT intervention description

Description and structure of the intervention

The SPIRIT intervention has been specifically created to meet the needs of children and young people with moderate to severe learning disabilities and specific phobias. It is a parent-mediated approach which uses graded exposure paired with strategies such as reinforcement, visual schedules and communication training to ensure it is accessible to young people with moderate to severe learning disabilities.

With the use of augmentative and alternative communication strategies, visual schedules, and consideration of unusual fears, restricted and repetitive behaviours and sensory aversions, this intervention is also appropriate for autistic young people with moderate to severe learning disabilities. Further specific adaptations for autistic children address difficulties with discourse and pragmatics, understanding and inference. Difficulties with discourse and pragmatics were managed through the use of concrete vocabulary/lexical items (avoidance of abstract concepts and metaphors) and simplified morphosyntax (sequencing of ideas in utterance).

The intervention consists of two half-day parent skills training workshops and eight support sessions (in-person, online or by telephone) with the therapist. Each of the workshops lasts for 4 hours and focuses on specific phobias, behaviour change and graded exposure. Workshops are led by at least two trained therapists and can be delivered online or face to face. Table 13 shows the structure of the workshops.

| Stage | Main focus | Key activities/focus points |

|---|---|---|

| PARENT SKILLS TRAINING WORKSHOP | DAY 1 | |

| Introductions (20 minutes) |

|

|

| Psychoeducation | ||

| Introduction to specific phobias (30 minutes) |

|

|

| How phobias develop (15 minutes) |

|

|

| Intervention overview (10 minutes) |

|

|

| Introduction to exposure therapy (15 minutes) |

|

|

| Skills training | ||

| Reinforcement (50 minutes) |

|

|

| Introduction to the visual schedule (20 minutes) |

|

|

| DAY 2 | ||

| Day 2 check-in (10 minutes) |

|

|

| Introduction to relaxation (40 minutes) |

|

|

| Building the exposure plan | ||

| Building exposure steps (40 minutes) |

|

|

| How to work through exposure steps (20 minutes) |

|

|

| Next steps and troubleshooting | ||

| Exposure plan (20 minutes) |

|

|

| Role of the parent/carer and the therapist (10 minutes) |

|

|

| Troubleshooting (35 minutes) |

|

|

The workshops are designed for groups of up to six parents/carers; however, final group sizes were determined by recruitment at the participating site. The small-group format is advantageous as it provides parents/carers with shared learning experiences in a supportive and safe environment, and direct support is provided by other parents/carers who have had similar experiences. It is also efficient to teach principles and skills involved in the SPIRIT intervention in a group format before providing more tailored, individual support.

Following the two workshops, parents/carers are supported by therapists during weekly support sessions (telephone or online), each lasting approximately 30 minutes, for up to 8 weeks. Therapists are advised to allow for 30 minutes to prepare and write notes after the support session. Whenever possible, the support sessions are led by the same therapist each week. These sessions are designed to check on the well-being of the child and parents/carers, monitor progress, address questions, problem-solve and help to plan the week ahead. Prior to the support session, parents/carers are asked to send a photo of the data sheet to the therapist or share it during the session. Table 14 shows the structure and content of the weekly support sessions.

| Weekly support sessions | |

|---|---|

| Support session 1 (30 minutes) |

|

| Support session 2 (30 minutes) |

|

| Support session 3 (30 minutes) |

|

| Support session 4 (30 minutes) |

|

| Support session 5 (30 minutes) |

|

| Support session 6 (30 minutes) |

|

| Support session 7 (30 minutes) |

|

| Support session 8 (30 minutes) |

|

Both parents/carers are encouraged to attend the workshops and support session. However, if one parent/carer is not available, they can familiarise themselves with the intervention using the parent workbook. See the Materials section for more details on the content of the parent workbook.

Key components

Exposure therapy

Exposure therapy is an integral component of the SPIRIT programme. It is an intervention method that involves gradually exposing the young person to the feared stimulus and pairing it with relaxation techniques. It involves three main steps:

-

teaching deep breathing and relaxation strategies

-

building exposure steps, which are a list of situations, places or things connected to the young person’s feared stimulus ranging from least distressing to most distressing

-

gradually exposing the young person to the steps included in the exposure steps while practising relaxation strategies.

This approach helps the young person to build their tolerance of the feared object or situation at a pace that they are comfortable with. The experience of feeling anxious is an important component of exposure therapy, as children learn how to manage this feeling. The aim is to reduce the young person’s fearful response and help them learn that the feared object or situation may not be as dangerous as they believe. In exposure therapy, regular practice is key. Ideally the young person should work on exposure each day, even if they practise a step only once.

Parents/carers are guided to identify exposure steps during the workshops using the form described in the Materials section. Exposure steps are reviewed during the support sessions and broken down further if needed. Parents/carers are encouraged to include things the child can already tolerate as the first few steps.

Relaxation

Relaxation strategies help to reduce tension in the body and reduce anxiety. When the child experiences feelings of anxiety or fear, their muscles tighten, and it can be difficult for them to feel calm. By introducing relaxation, tension in the body is reduced, which helps them feel calmer. Relaxation strategies are used when the child is feeling anxious or overwhelmed, as well as during exposure tasks. Some examples of relaxation strategies include deep breathing and muscle relaxation.

During the workshops, parents/carers are taught breathing exercises that involve taking a deep breath through the nose, counting to five and exhaling through the mouth while counting to seven. This exercise is repeated five times. For muscle relaxation, parents/carers are asked to inhale through the nose and clench their hands. The breath is held for 5 seconds and released as the hands are relaxed. This exercise is repeated with different body parts – shoulders, back, face, stomach and feet. Parents/carers are also taught how to do a hand massage in case they need to help the child relax when quiet space is not available.

During the workshops, the therapist spends some time discussing children’s existing relaxation strategies with parents/carers, such as sensory play or self-stimulatory behaviours, and identifying new strategies that could be tried. Parents/carers are also guided to explore possible adaptations of traditional relaxation strategies (e.g. deep breathing and muscle relaxation) to meet the needs of their child. This can include:

-

reduced verbal language in instructions

-

reduced number of body areas targeted for muscle relaxation

-

teaching body parts before moving on to the muscle relaxation

-

using modelling to demonstrate the exercises

-

using example and non-example procedure – modelling a ‘relaxed’ and ‘not relaxed’ pose and asking the child to only copy the relaxed pose

-

incorporating child-friendly scenarios and favourite objects or stories into the exercises; for example, bubbles or feathers

-

using physical prompting to teach the child the exercises

-

introducing a visual cue or signal, for example picture card(s), to signal relaxation

-

incorporating relaxation aids like a stress ball, therapeutic putty, dimmed lights or relaxing music.

Reinforcement

Reinforcement is a consequence which follows a behaviour and increases the likelihood the behaviour will occur again in the future. In the SPIRIT intervention, reinforcement is used to teach new skills, such as requesting a break and relaxation, and after completing the exposure tasks. To identify the young person’s reinforcers, parents/carers are asked to complete a preference assessment before starting exposure. A preference assessment is a systematic process that allows the parent/carer to identify six things the young person likes the most. To complete the preference assessment, parents/carers use the ‘What I like and enjoy’ form, which is described in more detail in the Materials section. Parents/carers are asked to review identified reinforcers frequently and redo the preference assessment if needed.

Generalisation and maintenance

Another component of the SPIRIT intervention is generalisation and maintenance. Generalisation is an ability to perform a behaviour learned in one context in a different context. While neurotypical individuals often generalise behaviours themselves by observing others and through indirect learning, people with learning disabilities may need help with generalisation. Therefore, working on the generalisation of acquired behaviours/skills in a systematic and structured way is an essential (and crucial) part of a successful behaviour change. This includes teaching and practising new behaviours:

-

in different environments

-

with different people

-

with varying instructions

-

using different materials.

In terms of ensuring that behaviour change is maintained, a variety of strategies are incorporated, such as:

-

focusing on behaviours that are meaningful to the young person

-

teaching until mastery

-

providing opportunities to practise new behaviours

-

adjusting the level of reinforcement.

Strategies to encourage generalisation and maintenance of new behaviours are incorporated into the intervention. During the last support session, the therapist makes a plan with the parent/carer to support continued work on generalisation and maintenance.

Communication

It was anticipated that a number of young people using the SPIRIT intervention would have communication support needs. Therefore, the intervention includes a number of augmented communication strategies such as visual aids and a visual schedule. These supports were reviewed and expanded by co-applicant Bunning (speech and language therapist), drawing on aided (e.g. using graphics and objects) and unaided (e.g. using manual signs and gestures) options from established augmentative and alternative communication methods. 52

Intervention procedures

Order of intervention activities

The skills training workshops provide parents/carers with an opportunity to learn about specific phobias and all components of the SPIRIT intervention. After both workshops, parents/carers should have:

-

an understanding of how the intervention works, their responsibilities and support available

-

an understanding of their child’s specific phobia – their triggers, behaviours associated with being afraid, and tolerance levels of items or situations related to their specific phobia

-

an understanding of how to teach new skills using modelling and prompting

-

completed the preference assessment

-

completed a relaxation plan and developed an understanding of how to adapt the relaxation strategies

-

an understanding of how to prepare and use the visual schedule

-

an understanding of how to monitor their child’s well-being and how to use the rating scale

-

a complete list of exposure steps

-

an understanding of how to collect monitoring data and work though the exposure steps

-

knowledge of what to do when challenges arise.

After the workshops, parents/carers are asked to work on introducing relaxation, the visual schedule and the rating scale to their child. This work forms the focus of the first support session. After that, parents/carers introduce the first exposure step and start working though the remaining steps. It is important that parents/carers do not start working on exposure before they identify how the child relaxes and ensure that they can request a break or communicate that they want to stop.

Work on exposure continues until the seventh support session, where ending the SPIRIT intervention support sessions is discussed. Parents/carers are asked to reflect on the intervention and the progress so far. During the last support session, the therapist prepares a plan with the parent/carer to support further exposure work if needed and for maintenance and generalisation. This is contained within the Keeping Well plan (see Materials section for more details). We anticipate that 8 weeks might not be enough to complete all exposure steps for some young people. The idea of the SPIRIT intervention is that parents/carers will develop sufficient expertise to continue with the exposure once support from the therapist ends.

We recognise that many young people will have more than one specific phobia. However, for the purposes of the intervention, parents/carers are asked to focus on one phobia at a time. Once the intervention finishes, parents/carers should have sufficient expertise to apply the same procedures to their child’s other phobias.

Implementation of the exposure steps

Parents/carers should have the complete list of exposure steps after attending both workshops; however, the steps should be reviewed during the support sessions and amended if needed. Parents/carers are asked to work on one step at a time and not skip steps. They start with a step that is the least fear-evoking for the young person and initially expose them for a short period of time. The duration is extended in the subsequent steps. Initially, the child should be reinforced for attempting the exposure steps (e.g. by praising them).

Depending on the nature of the relaxation strategies selected, the child should be encouraged to focus on relaxation during the exposure or immediately before and after (if it is not possible to implement them at the same time).

The visual schedule should be prepared and reviewed with the young person before working on exposure (for more information, see the Materials section).

The next exposure step is introduced only when the young person reaches the mastery criterion: three successfully (independently) completed attempts in a row. If the young person is consistently struggling to complete the same step for over a week, the therapist discusses revising the exposure steps with the parent/carer.

Data collection

Parents/carers are asked to collect data after each attempt at the exposure step to help with monitoring progress and making decisions about moving to the next step. Parents/carers learn how to use the data sheet (for more details, see the Materials section) during the workshops. They are asked to record each attempt of an exposure step as correct (completed without help), partially correct (completed with some help) or incorrect (not completed).

Parents/carers are asked to share their data sheet with the therapist during each support session.

Materials

All materials for parents/carers are put together in one folder. The folder was assembled by the research team and posted to parents/carers prior to the first workshop.

Intervention manual

The intervention manual, parent workbook and all materials were developed together with the IDG.

The therapist intervention manual includes both background and a step-by-step guide to treatment for specific phobias for children with moderate to severe learning disabilities. The manual provides therapists with detailed plans for the workshops and the support sessions, as well as general guidelines on working with parents/carers and children with learning disabilities.

Parent workbook

The parent workbook contains eight sections and covers the key information presented during the workshops:

-

introduction to specific phobias

-

introduction to exposure therapy

-

reinforcement

-

visual schedule

-

relaxation

-

exposure steps

-

key points to remember

-

troubleshooting.

The workbook was designed to be accessible and clear for parents/carers to follow. The idea is that parents/carers can refer to the workbook while working on the intervention and can share it with coparents and other carers.

Assessment for parents

Prior to the first workshop, parents/carers are sent the ‘Assessment for parents’ along with the instructions for completion. This assessment asks questions about their child, including what they are like in different environments, and their phobia. Parents/carers are asked to complete the document ahead of time and send it back to the therapist a week before the parent workshop. The assessment helps parents/carers to start thinking about their child’s phobia in preparation for the workshops and also provides the therapist with information to individualise the content of the intervention for each parent/child.

About my child’s phobia

‘About my child’s phobia’ is a worksheet that parents/carers complete during the second workshop. The worksheet summarises information about their child’s phobia, including triggers and associated behaviours, so they can easily refer to it while working on exposure.

My child’s story

Parents/carers are sent the ‘My child’s story’ worksheet prior to the intervention starting and are asked to complete it with their child if possible. The worksheet covers information about their child’s strengths and interests, and their phobia. Parents/carers are asked to use the worksheet to introduce their child to the group during the first workshop.

Rating scale

The rating scale is a tool used by parents/carers to monitor their child’s mood and level of discomfort during exposure work. It can help parents/carers identify when their child is becoming distressed. The rating scale consists of three options: good, OK and bad. These options are accompanied by a corresponding hand signal and colour (green, amber and red).

Relaxation routine

During the second workshop, parents/carers are asked to write down what relaxation strategies they are planning to try with their child, and potential adaptations. This document is updated once the child’s relaxation routine is decided.

Visual schedule

The visual schedule is a visual representation of activities planned for the child. It allows the young person to know what will be happening and provides an opportunity to manage transitions in a more controlled manner. For some children, it might be helpful to use the additional ‘now/next’ board which is embedded in the visual schedule. It helps the young person know what is happening at that moment and what is happening next.

Parents/carers are asked to prepare the visual schedule every time they work on exposure. It is suggested that the young person is involved in this process as much as possible.

What I like and enjoy

The ‘What I like and enjoy’ form guides parents/carers though the preference assessment process. Parents/carers are first asked to identify six potential reinforcers. Then they pair them together to see which ones are preferred by the child. Later, they create a reinforcer ranking which is used during exposure work.

Exposure steps

‘Exposure steps’ is a list of situations, places or things connected to a child’s specific phobia, arranged from least feared or distressing to most feared or distressing. Parents/carers are given a choice of an exposure steps template that they find most suitable. Some of the options include a ladder, stairs and a horizontal or vertical schedule.

Data sheet

The data sheet is used to record progress with the exposure steps. Parents/carers are asked to use it each time they work on exposure to record how the attempt went. They can put a tick on the data sheet to indicate a successful try (completed independently), a dash for a partially successful try (when the young person needed help to complete the step) or a cross for an unsuccessful try (when the young person did not complete the step).

Information sheet for other carers

To help with sharing information about the intervention with the child’s other carers and school, we created the ‘Information sheet for other carers’. This document summarises information about specific phobias and the SPIRIT intervention to help with consistency.

Exposure summary

When preparing for the end of the intervention, parents/carers are asked to complete the exposure summary. The worksheet asks them to reflect on the progress with the intervention: what went well, the impact on the child and their family, and barriers that they overcame. The worksheet helps parents/carers prepare for continued exposure work after the therapist’s support ends.

Keeping Well plan

During the last intervention session, the therapist creates a Keeping Well plan with the parent/carer to help with exposure work after the support ends. This summarises short- and long-term goals and ways in which they will be achieved, as well as strategies to ensure maintenance and generalisation of skills learned.

Therapists and therapist training

The intervention is delivered by a trained therapist, who could be a nurse, clinical psychologist, assistant psychologist, allied health professional or other suitably qualified health professional with experience of working with young people with learning disabilities and their families. Therapists were trained by the Chief Investigator and the SM. Supervision was provided by the clinical supervisors at the therapists’ workplace.

All therapists were required to take part in a one-and-a-half-day training course on the delivery of the intervention. Table 15 lists the content of the therapist training. The training included a mixture of PowerPoint® presentation, whole-group discussions and work in small groups. Training was delivered online by the research team. For small groups of therapists, it is possible to complete the training in 1 day.

| Training day | Focus | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Introduction to the SPIRIT intervention | Welcome and introductions |

| Intervention overview | ||

| How to use the intervention manual | ||

| Intervention structure | ||

| Good practice guidelines | ||

| Background and rationale | ||

| Key concepts and strategies | ||

| Additional strategies | ||

| Considerations for working with young people with moderate to severe learning disabilities and their parents | ||

| Sample parent workshop schedule | ||

| Parent skills training workshop day 1 | Introductions | |

| Introductions to specific phobia | ||

| How phobias develop | ||

| Intervention overview | ||

| Introduction to exposure therapy | ||

| Reinforcement | ||

| Introduction to the visual schedule | ||

| Parent skills training workshop day 2 | Day 2 check-in | |

| Introduction to relaxation | ||

| Day 2 | Building exposure steps | |

| How to work through exposure steps | ||

| Exposure plan | ||

| Role of the parent and the therapist | ||

| Troubleshooting | ||

| Weekly support sessions | ||

| Fidelity checklists |

Therapists received regular supervision as per their existing supervision arrangements; this was at least monthly. Supervisors were given the opportunity to attend the SPIRIT training and received a copy of the intervention manual. The research team was in regular contact with the therapists to check on progress and offer support.

Adherence

Therapist adherence to the intervention manual was measured with fidelity ratings (number of completed session components) after the parent/carer skills training workshop and after each support session.

Patient adherence was defined as attendance of intervention sessions. To meet the adherence criterion, parents/carers needed to attend both workshops and at least 80% of the weekly support sessions, taking into account, for example, holidays and illness.

Fidelity checklist

Therapists completed a self-report fidelity checklist at the end of each parent workshop and after each support session to record intervention adherence. Items on the checklist are organised into seven sections:

-

general workshop/session preparations

-

coverage of workshop/session plan

-

understanding and accessibility

-

interpersonal effectiveness

-

engaging participants

-

workshop content

-

further comments.

Therapists were asked to reflect on all session aims and indicate whether they were completed by circling ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ on the checklist. Supervisors were encouraged to review the fidelity checklist with their supervisees.

Chapter 4 Treatment as usual survey

Objective