Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number NIHR128996. The contractual start date was in February 2020. The draft manuscript began editorial review in January 2023 and was accepted for publication in August 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Beese et al. This work was produced by Beese et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Beese et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a condition in which the heart does not pump blood properly around the body, limiting an individual’s quality of life (QoL) and reducing length of life. This chapter describes the definition, epidemiology, causes, classification and management of HF.

Definition and classification of heart failure

HF has been defined both as a ‘syndrome recognised clinically by a constellation of symptoms and signs produced by complex circulatory and neurohormonal responses to cardiac dysfunction’ and as ‘a disease characterised by a decline in the heart’s ability to pump blood around a person’s body at normal filling pressures to meet its metabolic needs.’1 These definitions describe the clinical presentation as well as the pathophysiological process. 2 Symptoms of HF typically include shortness of breath during exertion and/or fatigue, signs of fluid retention, such as ankle swelling, and fluid in the lungs. Some patients with HF also suffer from heart rhythm abnormalities that can result in sudden death. Over time, most patients with HF experience deterioration in symptoms and hence require hospital treatment, despite medications.

In advanced stages, patients may suffer from shortness of breath at rest or minimal exertion, cachexia and muscular deconditioning, refractory fluid overload and even kidney and liver failure, a condition sometimes known as end-stage or advanced HF (AHF). 3 For consistency in this report, we will use the term AHF to describe this condition of severe HF symptoms despite conventional HF medications. The New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification system is widely used to classify the severity of symptoms related to HF. The NYHA classification has four levels of increasing severity from Class I to IV (Table 1). Patients with AHF suffer from NYHA Class III or IV symptoms.

| NYHA class | Description |

|---|---|

| I | No limitation of physical activity. Ordinary physical activity does not cause undue fatigue, palpitation or dyspnoea. |

| II | Slight limitation of physical activity. Comfortable at rest, but ordinary physical activity results in fatigue, palpitation or dyspnoea. |

| III | Marked limitation of physical activity. Comfortable at rest, but less than ordinary activity results in fatigue, palpitation or dyspnoea. |

| IV | Unable to carry on any physical activity without discomfort. Symptoms at rest. If any physical activity is undertaken, discomfort is increased. |

Patients with HF have severely reduced QoL, especially AHF based on a number of questionnaires that measure QoL [EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D), Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12), Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36), Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ), Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ)]. 4,5 QoL can be improved by medical therapy that improves HF. 6–16

Epidemiology of heart failure

Heart failure prevalence varies widely depending on definitions from an estimated 23 million people worldwide (USA 6 million, Europe 15 million). 17,18 It affects between 1% and 2% of adults in industrialised populations. 19 In the UK, as many as 920,000 people are living with HF with an incidence of 37.5 and 23 per 100,000 person-years for men and women, respectively. 20 The prevalence increases with age (Table 2), almost doubling with each decade after 65 years. The calculated lifetime risk of developing HF is 20%. 21 HF-related hospital admission rates in England have increased by 5% over the last 10 years and are estimated to increase by about 50% in the next 25 years. Nearly half of the patients admitted with HF had severe symptoms (NYHA Class III or IV). Despite advances in medical therapy, 1-year mortality remains high at about 32% in patients admitted with HF. 22

| Age bracket (years) | Prevalence |

|---|---|

| 65–74 | 1 in 35 |

| 75–84 | 1 in 15 |

| > 85 | 1 in 7 |

Data on the prevalence of AHF in the UK are lacking. A survey of European countries suggested that about 10% of all patients with HF may meet the criteria for AHF. 23 The Olmsted County (MN, USA) cohort study showed that about 14% of patients with HF met the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) criteria for AHF with an annual rate of about 33 per 100,000 and 420 per 100,000 for the under 65 and 65–79 age groups, respectively. 24

Aetiology and pathophysiology of heart failure

Any structural or physiological conditions that affect the ventricular function can cause HF. In the UK, ischaemic heart disease is the major cause of HF, but other causes include dilated cardiomyopathy, which may be familial (genetic) or caused by myocarditis, cardiotoxic drugs or hypertension and valvular heart disease. 25

Historically, descriptions of HF pathophysiology have centred on the left ventricle (LV) as this heart chamber is the most commonly affected, particularly in ischaemic heart disease. Myocardial injury results in a drop in LV function and activation of the neurohormonal system. The latter contributes to salt and water retention and progressive remodelling of the heart. Fibrosis, muscle wall thinning and increased sphericity associated with LV remodelling, often accompanied by functional mitral regurgitation, further compromise myocardial efficiency and drive the downward spiral towards end-stage or advanced AHF. Myocardial fibrosis and remodelling provide the substrate for both atrial and ventricular arrhythmias, which may worsen HF symptoms and result in sudden death.

Diagnosis of heart failure and advanced heart failure

Heart failure is a clinical diagnosis, based on patient history, physical examination and investigations, such as electrocardiography, measurement of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and echocardiography. The echocardiogram is used to assess heart function [by measuring ejection fraction (EF)] and also to identify possible causes or associated features, such as mitral regurgitation. Other investigations, such as chest radiography, may also detect features to support the diagnosis of cardiomegaly, pulmonary congestion and pleural fluid accumulation, but may also exclude other differential diagnoses. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging is increasingly used to assess the heart and identify the cause of HF. In general, BNP and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-pro-BNP) are raised in patients with HF and the concentrations increases with the severity of symptoms. 26

The ESC first defined AHF in a statement in 2007. 27 The position statement was updated in 2018 and the criteria for AHF were defined. The American College of Cardiology and Heart Failure Society of America have also defined AHF (Table 3). These definitions of AHF are conceptually very similar – severe symptoms in association with signs of congestion, poor perfusion and hospitalisations attributable to severe cardiac dysfunction despite medical therapy. One-year mortality in patients with AHF may be close to 50% in patients with all the characteristics of AHF. 24

| All the following criteria must be present despite optimal guideline-directed treatment |

|---|

|

Recognising the significant heterogeneity in patients with AHF, the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) profiles were introduced to better describe the clinical characteristics in patients with NYHA Class III and IV HF (Table 4). The INTERMACS profiles have been widely adopted to describe the characteristics of patients with AHF undergoing assessment of heart transplantation or left ventricular assist device (LVAD) therapy.

| NYHA class III/IV | INTERMACS class | Description |

|---|---|---|

| IV | 1 | Crash and burn (cardiogenic shock) |

| IV | 2 | Deteriorating on inotropes |

| IV | 3 | Stable IVI inotropes dependent |

| IV | 4 | At home resting symptoms on oral therapy |

| IV | 5 | Comfortable at rest but symptoms with minimal activities of daily living (housebound) |

| III | 6 | Walking wounded with activities of daily living possible but meaningful activity hampered |

| III | 7 | Advanced class III |

Health economics

Currency and inflation adjusted cost for hospitalisation is highest in the USA ($125,000/patient/year), while in Europe HF inpatient costs vary from $5000 to $18,000 (2016 prices) with most costs (50–90%) derived from hospitalisations. 28,29 It usually accounts for 1–2% of a nation’s health budget. 29 Health economics indicate that the cost to the NHS is £0.75B annually (approximately 4% of the NHS budget) and continues to rise, largely related to the high prevalence of cardiovascular diseases in older age groups coupled with ageing of the population. Newer medications (angiotensin receptor blocker-neprilysin inhibitors and sodium-glucose cotransporter inhibitors) and interventions (ablations, mitral valve interventions and implantable pulmonary artery pressure monitors) add to the increasing costs of HF therapy.

Medical and electrical device therapy of heart failure

Left ventricular ejection fraction has been a central inclusion criterion over the many decades of clinical trials in HF and has shaped clinical guidelines to this day. Largely based on the LVEF thresholds used in the trials, HF has been categorised into three categories: HF with reduced EF (HfrEF), HF with mid-range EF (HfmrEF) and HF with preserved EF (HfpEF) (Table 5). This review will focus on HfrEF, as LVADs are generally not recommended in patients with HfmrEF or HfpEF.

| HfrEF | HfmrEF | HfpEF |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms ± signs LVEF ≤ 40% |

Symptoms ± signs LVEF 41–49% |

Symptoms ± signs LVEF ≥ 50% Objective evidence of cardiac abnormalities |

Neurohormonal antagonists, beta-blockers and mineralocorticoid antagonists have well-established benefits in patients with HfrEF and remain the first-line therapy in this group of patients. More recently, the sodium-glucose cotransporter inhibitors have also proven to benefit patients with HfrEF and are likely to form another pillar of HF therapy. Other drugs of benefit in some patients with HfrEF are ivabradine and hydralazine-nitrate combination (Figure 1). Loop and thiazide diuretics are routinely used to control congestive symptoms. Treatment options in HfpEF are limited.

FIGURE 1.

European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of patients with HfrEF. ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; ARNI, angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor; BB, Beta blockers; BTC, bridge to candidacy; BTT, bridge to transplantation; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CRT-P/D, cardiac resynchronization therapy with pacemaker/defibrillator; LBBB, left bundle branch block; MCS, mechanical circulatory support; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; MV, mitral valve; PVI, pulmonary vein isolation; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor; SR, sinus rhythm; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation; TEE, transesophageal echocardiography.

Progression in HF is associated with deterioration in kidney function, low blood pressure and fluid overload, often necessitating a dose reduction in HF medications and an escalation in diuretic doses. Low cardiac output is also common at this stage, and inotropes such as dobutamine are used. These are features of AHF that herald HF prioritisation and death.

Implantable electrical devices such as implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) and biventricular pacemakers [also known as cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT)] are commonly used in patients with HfrEF. The latter benefit a specific subset of patients with HfrEF and left bundle branch block, with no benefit or even detrimental effect in patients with narrower QRS complexes. ICDs reduce the risk of sudden arrhythmic deaths, but do not prevent deterioration in cardiac function and death from pump failure in AHF. Shocks from ICDs are recognised indicators of poor prognosis in patients with HF. Heart transplantation or a LVAD may be considered in selected patients in whom these therapies fail.

Heart transplantation

Access to heart transplantation is limited by the shortage of suitable organ donors. In the last 10 years, the number of heart transplants (HTs) performed in the UK has dropped from a peak of almost 200 per year in 2016–8 to about 160 per year in the 2020–1 financial year, even with the adoption of donation after circulatory death heart transplantation. 30 This shortage of suitable donor organs has led to the selection of potential recipients who are most likely to benefit from transplantation based on a range of criteria including age and comorbidities. In selected patients, heart transplantation is a very effective treatment. In the UK, the median survival from heart transplantation now exceeds 10 years. However, the rigorous selection process effectively excludes the majority of patients with AHF.

Mechanical circulatory support devices

Mechanical circulatory support devices (MCSDs) have increasingly been used in the last decade to support patients with worsening HF. These MCSDs may be categorised into temporary (or short-term) and durable (or long-term) devices. The former are largely extracorporeal devices and patients are managed in hospital (often in a high-dependency or intensive care environment), while patients with the latter may be discharged home on the device. Most of the durable MCSDs used in the UK are LVADs. Total artificial hearts and biventricular assist devices will not be discussed in this review.

The terminology in left ventricular assist device therapy

Historically, the nomenclature of LVAD therapy is closely linked to candidacy or eligibility for heart transplantation and treatment intent:

-

Bridge to candidacy (BTC) refers to LVAD therapy in patients with a contraindication to heart transplantation that is potentially reversible with LVAD therapy, such as renal dysfunction or pulmonary hypertension due to left heart disease. Patients would be expected to become candidates for heart transplantation following reversal of the contraindication by LVAD therapy. Thus, the intention of LVAD therapy is to reverse the contraindication to allow heart transplantation.

-

Bridge to transplantation (BTT) refers to LVAD therapy in patients who are eligible candidates for heart transplantation but may be deteriorating on medical therapy on the waiting lists. Progression of HF while on the waiting list may result in multiorgan failure to the extent that they may no longer be suitable candidates for heart transplantation. This may result in death. The treatment objectives of BTT are to stabilise and prevent death in patients on the waiting list for heart transplantation and optimise the outcome of heart transplantation.

-

Destination therapy (DT) refers to LVAD therapy in patients who are not eligible for heart transplantation due to established contraindication(s) that are not amenable to correction by LVAD. The objective of the LVAD as DT is to provide symptomatic and prognostic benefits to patients with AHF who are at high risk of mortality on medical therapy and not suitable for heart transplantation. In an INTERMACS report, contraindications to heart transplantation included advanced age, renal dysfunction, chronic lung disease or high body mass index (BMI). Despite the initial treatment intent, approximately 10% of patients originally considered unsuitable for heart transplantation and selected for DT subsequently improved sufficiently (e.g. improvement in frailty) to undergo transplantation after 2 years of LVAD therapy. 31

Evolution of left ventricular assist devices

Left ventricular assist devices have evolved considerably over the last few decades. The first generation of LVADs were pulsatile devices. These pulsatile devices were large devices due to the need for pumping chambers. The poor durability of first-generation pulsatile devices limited longer-term outcomes, with survival limited to < 2 years in the majority of patients. The high device failure rates led to the development of non-pulsatile continuous flow LVADs.

The second-generation LVADs are non-pulsatile axial flow devices. These axial flow LVADs are significantly smaller than the first-generation pulsatile pumps, which simplified device implantation considerably. In addition to the reduction in implant-related morbidity, axial flow LVADs were also associated with improved durability and significantly improved longer-term outcomes. One of the most commonly used axial flow LVADs was the HeartMate II™ LVAD (Abbott, Chicago, IL, USA). These improvements led to greater adoption and acceptance of LVAD therapy. In the USA, LVAD implant rates increased exponentially with the introduction of the second-generation axial flow LVADs. Despite the improved durability, pump thrombosis and bleeding complicated longer-term support with second-generation LVADs.

The third-generation LVADs are centrifugal flow devices. The HeartWare™ ventricular assist device (HVAD™, Medtronic, Dublin, Republic of Ireland) is a small intrapericardial centrifugal flow pump. Promising early results led to approval for clinical use, although pump thrombosis and neurological complications were concerning. The risks of neurological complications and device failure became increasingly evident with widespread use and the device was withdrawn worldwide in June 2021. 32 At present, there are no new implants of the HeartWare HVAD, although some patients continue to be supported in the UK.

The HeartMate 3™ (HM3) LVAD (Abbott, Chicago, IL, USA) was introduced in 2015 in the UK. The HM3 LVAD is a centrifugal flow device with a number of design features to improve ‘haemocompatibility’ and reduce the risk of complications such as pump thrombosis. Clinical studies confirmed a significantly lower risk of pump thrombosis compared to HeartMate II, and an ongoing randomised trial is evaluating reduced antithrombotic therapy with HM3. 33 HM3 is now the only LVAD in use in the UK following the withdrawal of the HeartWare HVAD.

Description of continuous flow left ventricular assist devices

Continuous flow devices are so called because they generate flow throughout the cardiac cycle. In centrifugal devices, blood is drawn via the inflow cannula in the LV by an impeller within the pump and delivers the blood into the aorta via the outflow graft. The outflow of the pump is arranged perpendicularly to the inflow cannula. Flow can be changed by adjusting the pump speed (revolutions per minute) via the system controller. Pump speed must be carefully balanced as excessive pump speed could compromise right ventricular function. 34 The device is connected to a power source or a pair of batteries via an externalised drive line.

Complications of left ventricular assist device therapy

Various complications can be attributed to the abnormal interaction between the LVAD and the biological circulation, so-called haemocompatibility-related adverse events (HRAEs). Device-related haemolysis, pump thrombosis and systemic embolism, stroke, intracranial bleeding and gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding (GIB) are major HRAEs that compromise long-term outcomes of LVAD therapy. These HRAEs occur in both axial and centrifugal flow devices, but the HM3 LVAD has been associated with a lower burden of HRAEs compared to HeartMate II. 35

The LVAD supports the LV but often at the expense of the right. Right heart failure (RHF) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Studies have identified several risk factors for RHF post-LVAD implant, including pre-implant measures of right ventricular function and severity of HF and organ dysfunction; however, the ability to predict post-LVAD RHF remains challenging. 36 Severe RHF is associated with higher mortality. Timely deployment of a temporary right ventricular assist device (RVAD) may mitigate this risk. 37 Late RHF is increasingly recognised and may limit long-term QoL.

The continuous emptying of the LV and delivery of blood into the aorta pressurises the aorta and reduces left ventricular stroke volume in patients with LVADs. The aortic valve may not open if the LV fails to generate sufficient pressure to overcome the aortic pressure, with consequent loss of arterial pulsatility. Over time, the reduction in aortic valve opening may lead to degenerative changes of the valve and aortic regurgitation (AR). A competent aortic valve is a prerequisite of LVAD function. Severe AR results in the recurrence of HF symptoms and adversely affects long-term survival in patients with LVADs. 38

As with any implantable devices, LVADs are susceptible to infection. Infection in patients with LVADs may not be attributable to the device. Infections related to the device may be localised, related to the driveline (most common) or more severe bloodstream infection related to the pump or endocarditis. The latter may be associated with neurological complications and increased mortality. 39

Current service provision and patient pathway

In the UK, LVADs are currently commissioned in the six HT centres for the purpose of BTC and BTT. Referrals to these centres follow existing pathways in the HT service. As a BTC and BTT service, LVADs are only offered to patients who are eligible for heart transplantation. Despite the intention to bridge patients to heart transplantation, the heart allocation policy does not prioritise candidates with LVADs for transplantation.

In the most recent iteration of the heart allocation policy in the UK, patients with LVADs without complications are offered listing on the ‘non-urgent’ waiting list, the lowest priority of the three tiers (the other two tiers are ‘urgent’ and ‘super urgent’). Patients with LVAD-related complications may be upgraded to the ‘urgent’ list following approval by an adjudication panel, consisting of representatives from each of the HT centres. Paradoxically, prioritisation and transplantation only when patients develop LVAD-related complications is associated with poorer outcomes, which is inconsistent with the original concept of BTT – to optimise the outcome of heart transplantation. In effect, most patients without LVAD-related complications would continue on long-term LVAD support, simultaneously BTT (by intent) and DT (in practice).

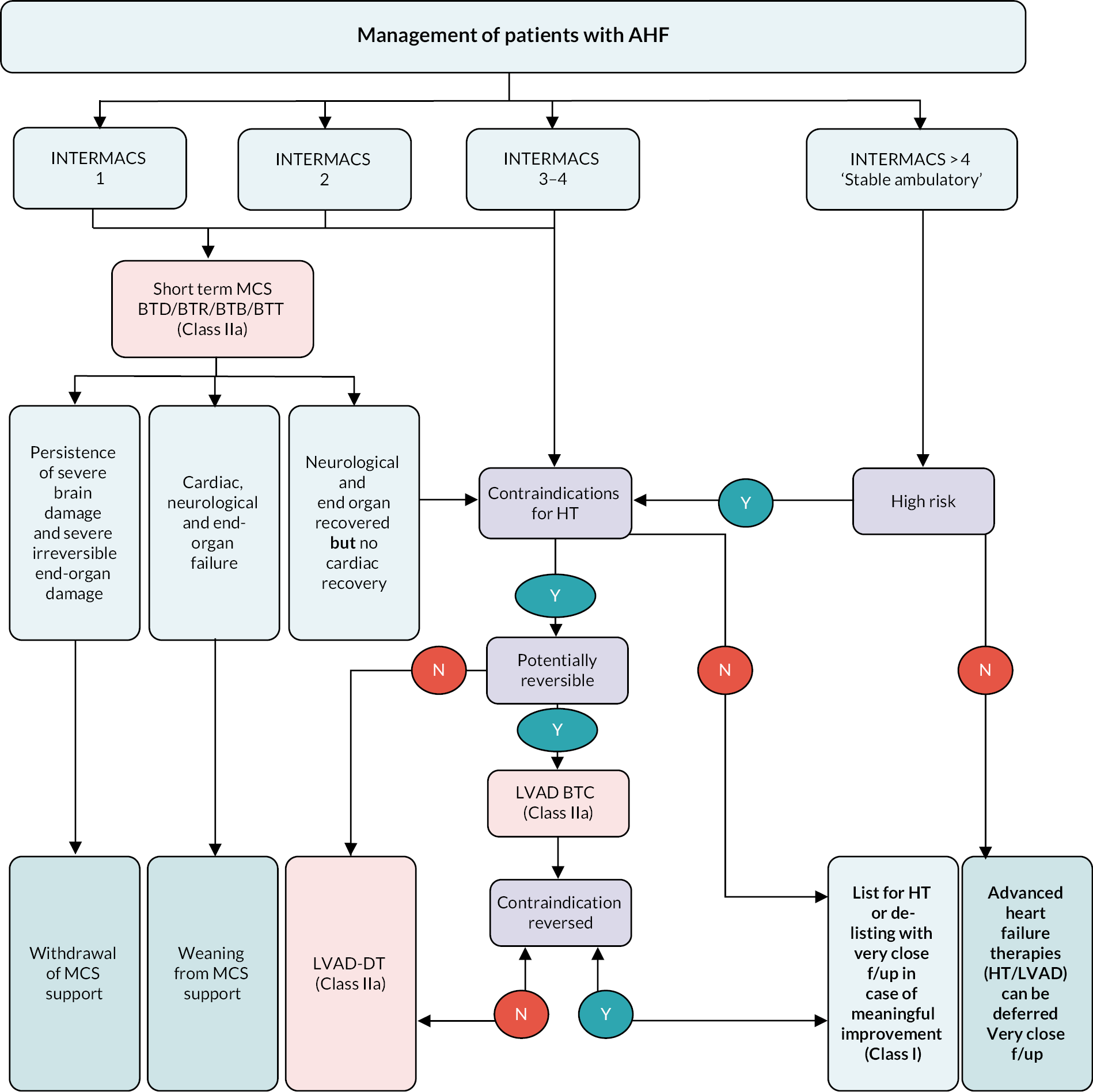

In the most recent iteration of the ESC Guidelines, a LVAD has been recommended in patients with INTERMACS 3 or 4 AHF with contraindications for heart transplantation (Figure 2). Available solely as a bridging therapy, the rate of LVAD implantation in the UK is low compared to other European countries, especially in countries where DT is established. According to a recent study, the UK has one of the lowest LVAD implant per million population at 0.6, compared to a number of European countries (e.g. Hungary 1.0, Portugal 2.4, Spain 3.3, Belgium 4.1 and Germany 13.9) (Figure 3). 23

FIGURE 2.

European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of patients with AHF. BTB, bridge to bridge; BTD, bridge to decision; BTR, bridge to recovery.

FIGURE 3.

Hospitals implanting LVAD per million people (left) and number of LVAD implantations per million people (right). Reproduced from Serefovic et al. 23 with permission from John Wiley & Sons.

In summary

Heart failure is an increasingly common problem with significant impact on individual patient’s QoL and longevity as well as population health economics. Advanced heart failure that fails to respond to medical management (MM) may be treated by LVAD implantation and/or heart transplantation. In the UK, LVAD implantation has been commissioned as a bridging therapy to transplantation. In other countries with different healthcare delivery systems, the majority of LVADs are implanted as DT in patients ineligible for heart transplantation. In the UK, a LVAD for such patients is not currently commissioned. The lack of economic evidence is a key reason that NHS England has not recommended a LVAD for DT.

Chapter 2 Aims

To make an informed decision on the use of LVADs for patients with AHF that fail to respond adequately to MM and who are ineligible for a HT, robust evidence on clinical and cost-effectiveness is required.

The aim of the research documented in this report was to address the question: What is the clinical and cost-effectiveness of a LVAD compared to MM for AHF patients ineligible for heart transplantation (DT)?

The specific objectives to address this aim were to undertake:

-

– a systematic review of available evidence on the clinical effectiveness of a LVAD as DT, including a network meta-analysis (NMA) to provide an indirect estimate of the relative effectiveness of currently available LVADs compared to MM (see Chapter 3);

-

– a systematic review of available economic evidence on the use of a LVAD as DT (see Chapter 4); and

-

– the development of an economic model to estimate the cost-effectiveness of a LVAD compared to MM from the UK NHS/personal social services (PSS) perspective (see Chapter 5).

Sources of information used in undertaking this research include trials, observational studies, economic evaluations, reports from registries, guidance from LVAD recipients and their families, clinical experts, those commissioning healthcare services and companies supplying LVADs.

An exploration of the ability of accessible data sets to provide further data relevant to LVADs as DT was also undertaken (see Appendix 1).

When this research was commissioned and begun, there were two predominantly available LVADs in the UK used for AHF patients. As outlined in ‘Evolution of left ventricular assist devices’, the HeartWare device was withdrawn in 2021. Therefore, this report, while still considering evidence from research on all LVADs for DT in part and where relevant, focuses on the remaining device, HM3. The HM3 is the only device used for AHF patients in the UK at this time.

Chapter 3 Clinical effectiveness of left ventricular assist devices compared to medical management as destination therapy in advanced heart failure patients

Introduction

Left ventricular assist device DT strategy is not currently common practice in the UK. This chapter aimed to systematically review all of the available evidence on the clinical effectiveness of LVADs as DT; including a NMA to provide an indirect estimate of the relative effectiveness of currently available LVADs compared to MM. This was also used to inform the development of the economic model in Chapter 5.

Methods

This systematic review was prepared according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines. 40 The review is registered on PROSPERO (CRD42020158987). 41

Eligibility criteria

Population

Patients (age > 16 years) with AHF who received a LVAD as DT and were ineligible for a HT or potential candidacy at the time of the LVAD implantation. Studies with mixed LVAD populations were also included where DT data were reported separately or could be easily acquired. Eligibility for heart transplantation is defined by individual centres based on international guidelines, but there may be variations in practice.

Intervention

There were no restrictions placed on the type of LVAD, either by flow design or by generational evolution (e.g. first-generation pulsatile pump, second-generation continuous axial flow or third-generation continuous centrifugal flow). All devices were included, regardless of current availability, for completeness of information and for use in the NMA. Studies of participants with biventricular assist devices, or RVADs were not eligible for inclusion.

On 3 June 2021, midway through conducting this project, one of the current third-generation continuous flow centrifugal LVADs, the HeartWare HVAD (used extensively throughout North America, UK and Europe) was withdrawn from the market. While studies on HVAD were included, the analysis focuses on the currently available device (HM3), which reflects the availability to patients as it is the only device currently available in the UK.

Comparator

Medical management or different generation or type of devices or no comparator.

Outcomes

All relevant key outcomes were considered. Outcomes were categorised in accordance with categories established for parameters in the economic model. These were survival, hospitalisations, major events (e.g. stroke, RHF), complications [e.g. GIB, driveline infection (DI), arrhythmias], any report of QoL and functional status (e.g. six-minute walk test). The outcomes are further defined in the data extraction details.

Types of study

Any clinical trial whether randomised, non-randomised or single-arm was included, as well as all observational studies including cohort, case-controls and case series designs. This also included any reports from patient registries of MCSDs (such as INTERMACS, etc.). Studies were eligible only where they included ≥ 50 or more DT patients. A threshold was required, given the large volume of small studies with likely limited value overall to the review. The threshold was based on calculations to determine the likely volume of missed evidence when excluding studies based on various sample size cut-offs. This was carried out by taking a sample of 200 relevant full-text articles and calculating what proportion of patients we would miss by excluding studies based on different sample size cut-offs. Excluding studies with a sample size of < 50 DT patients resulted in an estimated 4.8% of patients excluded across the evidence base. As a result, it was decided to only include studies with at least 50 participants. Systematic reviews were included to identify any additional potentially relevant primary studies.

Searches

The following databases were searched initially from inception until 20 May 2020: Cochrane Library (CENTRAL), MEDLINE and EMBASE via Ovid. For any relevant systematic reviews Epistemonikos, the Cochrane Library of Systematic Reviews and MEDLINE and EMBASE were searched. Searches incorporated free text and index terms related to population and intervention, with no restriction by study design. All database search strategies are available (see Appendix 2). The search term combinations in the example search strategy applied to the bibliographic databases were formulated in the standard way for a review and then augmented to ensure the strategy was sensitive to capturing studies known to the reviewers while keeping the yield to manageable numbers of records.

There was no restriction by date or language of publication on searches. Reference lists of relevant systematic reviews and included primary studies were checked for additional primary studies. Grey literature (e.g. institutional reports) was sought from key organisations. Conference abstracts were included if published within the previous 3 years of the search date. Ongoing and recently completed trials were searched using the World Health Organization (WHO) clinical trials portal.

Data and reports published from relevant registries were also identified from our searches. Further targeted searching was performed to identify publications that were not found during the searches.

Search updates were carried out from April 2020 until 11 January 2022. Searches for registry reports via relevant website lists (e.g. www.uab.edu/medicine/intermacs/research/publications) were undertaken at the same time as the database searches.

Study selection

All records received from the literature searches were initially entered into EndNote X9 (Clarivate Analytics) to facilitate removal of duplicates. 42 Records were entered into Covidence for screening and selection. 43 Title and abstracts were screened for potential relevance using the study eligibility criteria.

Where it was not clear if DT patients were included in the study or if any DT data were reported from the abstract alone, the full text of the study was sought. Full texts were retrieved for any potentially relevant records and checked for eligibility.

All stages of the study selection were undertaken by two reviewers independently and disagreements were resolved by third reviewer or consensus. Reasons for exclusions were recorded via Covidence and within an Excel spreadsheet.

Search results for both the cost and clinical effectiveness reviews were combined within the same EndNote and Covidence databases. During screening and selection, appropriate tags were assigned to potentially relevant records to identify them as either relevant for the clinical or cost-effectiveness review, or both.

Data extraction

Intervention studies

Data extraction of intervention studies was carried out using a predefined data extraction form, which was piloted on two included trials. Extraction was carried out by one reviewer and checked by a second with any discrepancies discussed to reach consensus.

The following data were extracted:

-

Study characteristics: including study design, setting, start and end dates, follow-up length, inclusion/exclusion criteria, number of participants who accepted, were randomised (where applicable) and completed the study, drop out and reasons.

-

Participant characteristics: including summary statistics for age, sex, ethnicity, INTERMACS score, NYHA class, comorbidities, cause of HF, current RVAD and any medications and BMI.

-

Intervention and comparator characteristics: including device type and name, number with each device, implantation details, MM dose and frequency.

-

Statistical analysis information such as methods of analysis.

-

Outcome data: survival, hospitalisation (initial length of stay, number of re-admissions), QoL (any assessment tool), major clinical events [stroke, transient ischaemic attack (TIA), RHF, RHF managed with a RVAD, myocardial infarction, pump exchange (PE)], complications (bleeding, infections, device-related infections, arrhythmias, pump thrombosis, device malfunction, hepatic dysfunction, haemolysis, hypertensions, sepsis), and functional status (any assessment tool). Outcome data were extracted at all time points reported in all measures.

Registries

Key data on all LVAD outcomes were extracted from registry reports to use alongside the trial data as trial populations were not included in the INTERMACS registry database. The following data were extracted:

-

Basic cohort characteristics: including population, age, INTERMACS scores (where reported), any subgroups analysed and device data (understanding that this information was often limited in registry reports).

-

Outcome data: survival, hospitalisation (initial length of stay, number of re-admissions), QoL (any assessment tool), major clinical events (stroke, TIA, RHF, RHF managed with a RVAD, myocardial infarction, PE), complications (bleeding, infections, device-related infections, arrhythmias, pump thrombosis, device malfunction, hepatic dysfunction, haemolysis, hypertensions, sepsis) and functional status (any assessment tool). Outcome data were extracted at all time points reported for all measures.

Single/multicentre observational studies

Data were extracted (as above) from all single/multicentre observational studies recruiting participants not included in any registries to supplement the data from trials and registries. Some of these studies were important in providing data from outside the USA. Single/multicentre observational studies that also contributed patient data to the INTERMACS database [and therefore International Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulation (IMACs)] were only used if they reported key data missing from the previous evidence (such as survival, QoL and major events).

Risk-of-bias assessment

Risk-of-bias assessment was carried out by one reviewer and checked by a second. Tools appropriate for study design were used to assess risk of bias. For RCTs and non-RCTs, version 2 of the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool was used. 44 The randomisation domain was not applicable for non-randomised trials, and it was acknowledged that blinding is not possible in most surgery trials. Risk-of-bias assessment was carried out for the key outcomes of survival and QoL. These were considered as key outcomes as they were consistently reported across trials of this type and were important outcomes for the economic evaluation. Results of the risk of bias were presented in tabular format.

Data synthesis

Consideration, data extraction and reporting of the evidence were based on a hierarchical approach. RCTs and controlled non-randomised trials were considered in the first instance. Registry reports and uncontrolled observational studies were used to supplement findings where gaps were evident. Inclusion of studies with overlapping patient data was avoided where possible. However, all studies, regardless of design, were included and reported in the review.

Clinical trial participants are not eligible to be included in LVAD registries (such as INTERMACS and IMACS). To assess whether patients in trials differed from those in registries, exploratory analyses were undertaken comparing key population differences between the two. This was carried out where the data were available for key outcomes including survival and QoL. Additionally, changes over time in each population were assessed.

Overlap of participants between single, multicentre observational studies and registries was also considered. Many of these centres in the USA also contribute data to registries, including INTERMACS and by default, IMACS. To avoid overlap of participant data reported, data were only considered from studies that clearly did not contribute to the INTERMACS registry (as defined by the list of participating centres on the INTERMACS website www.uab.edu/medicine/intermacs/pedimacs/participating-centers-pedimacs).

Data were tabulated and analysed in a narrative approach in the first instance, firstly with comparative data stratified by device (e.g. HM3) and INTERMACS scores (where available), and then by outcome within this. Following this, non-comparative data were presented stratified by device type and INTERMACS scores (where available), and by outcome within this.

Due to large clinical and methodological heterogeneity expected in the data, no meta-analyses were performed.

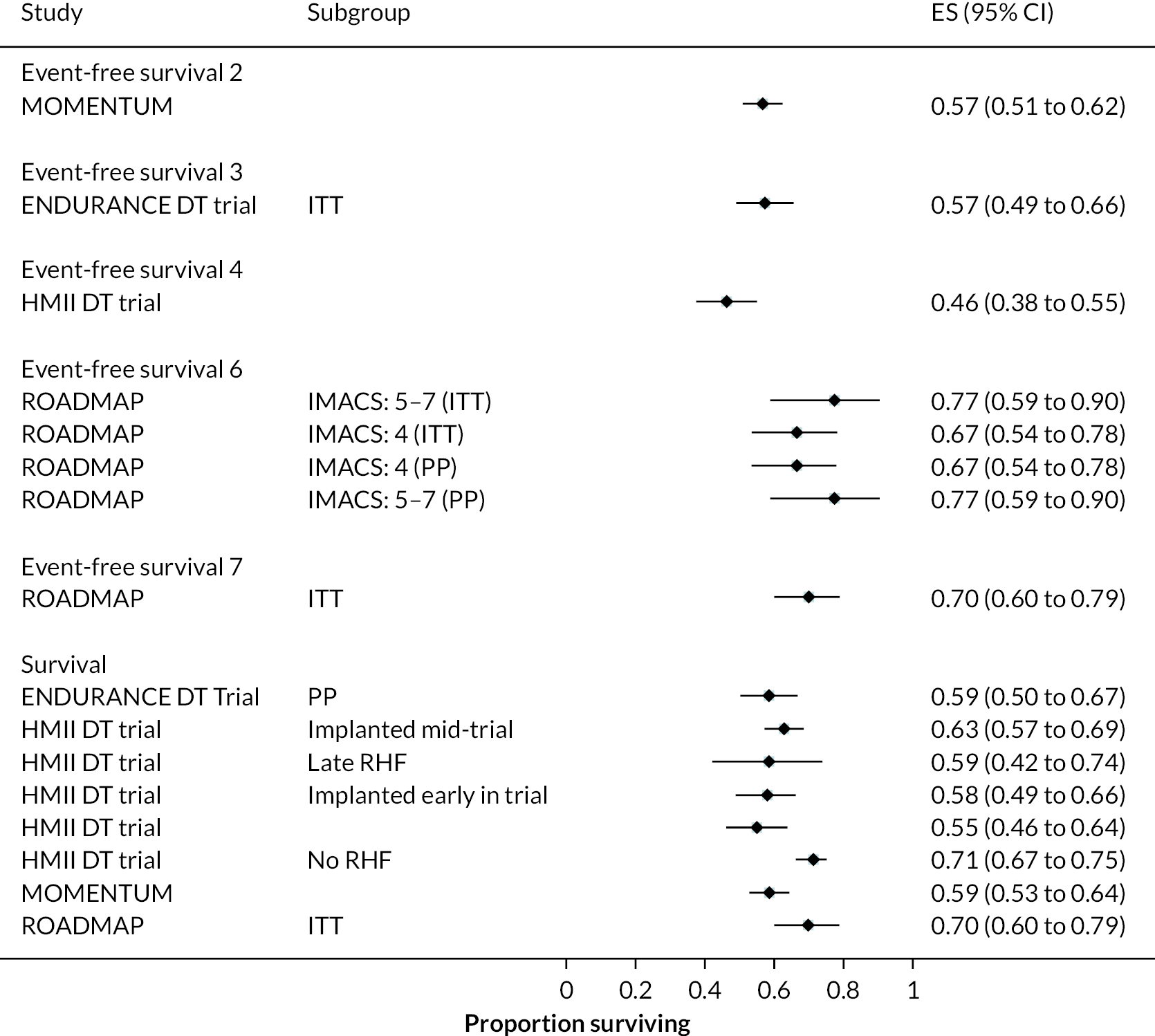

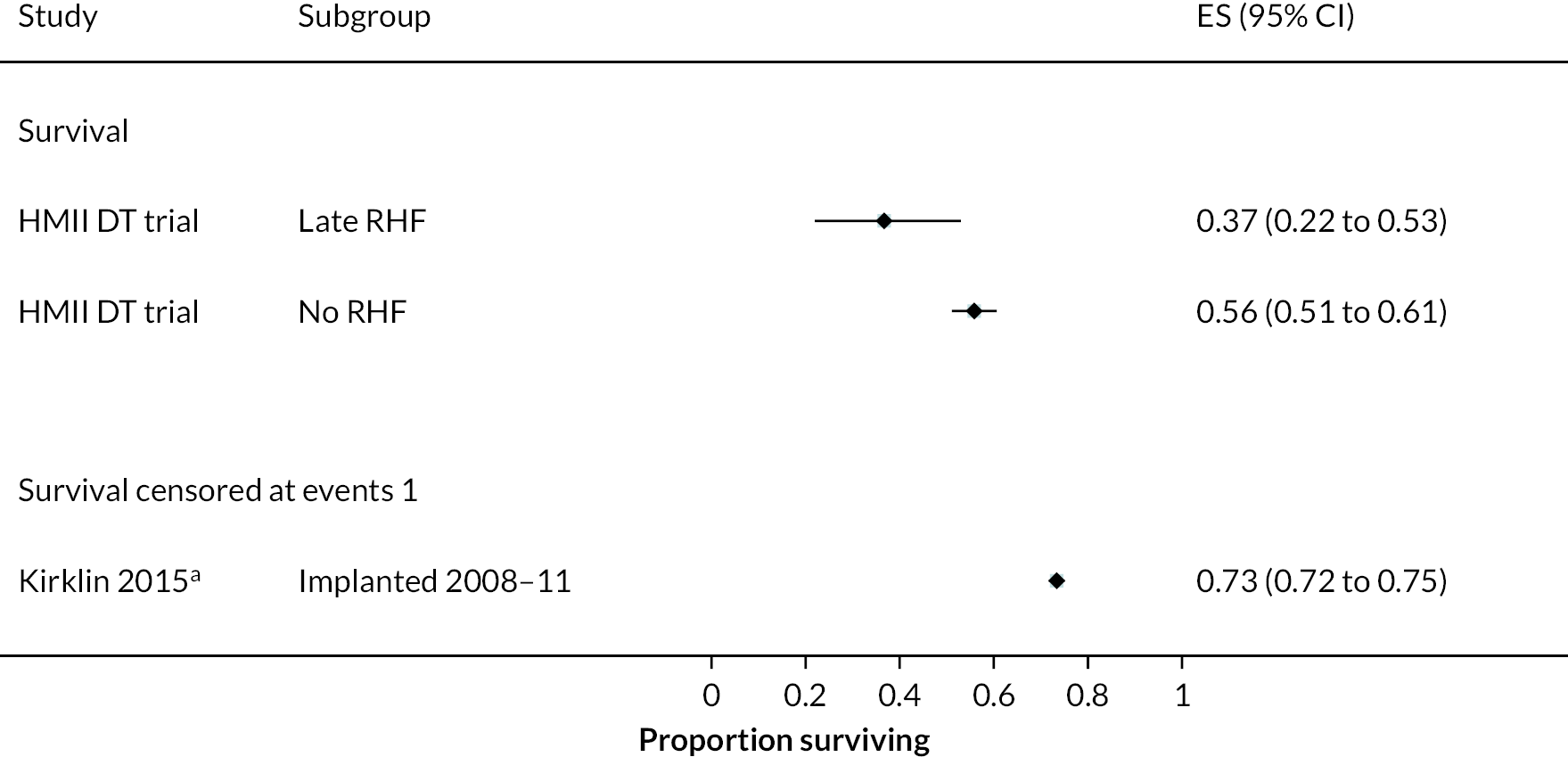

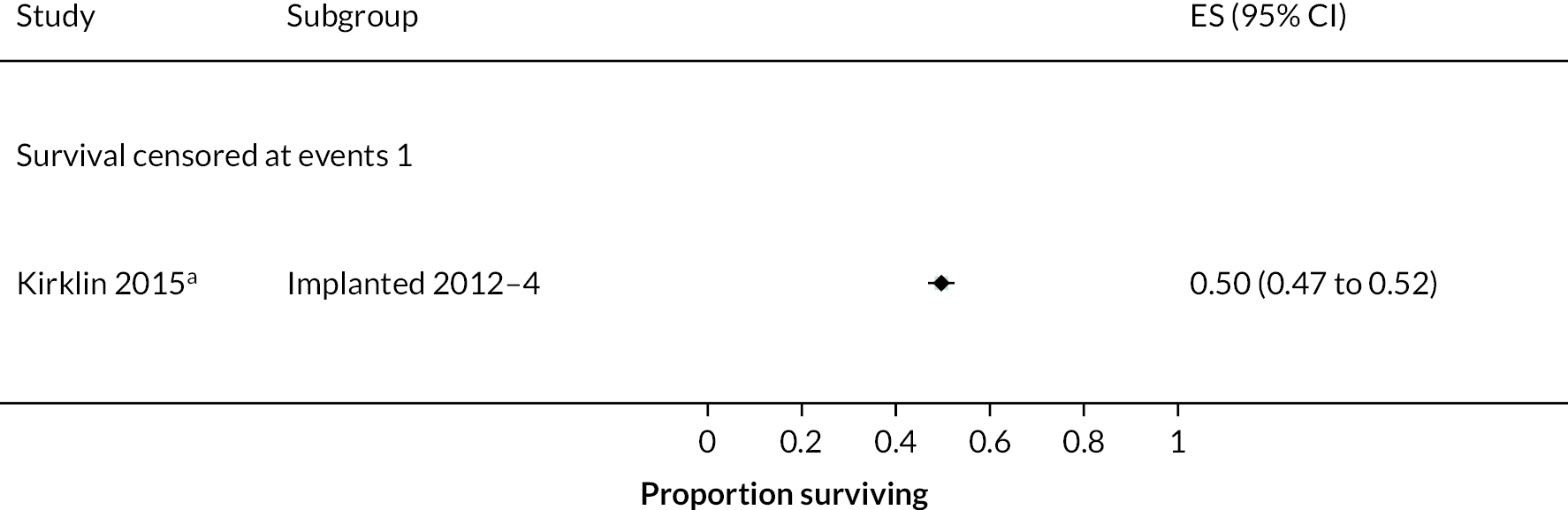

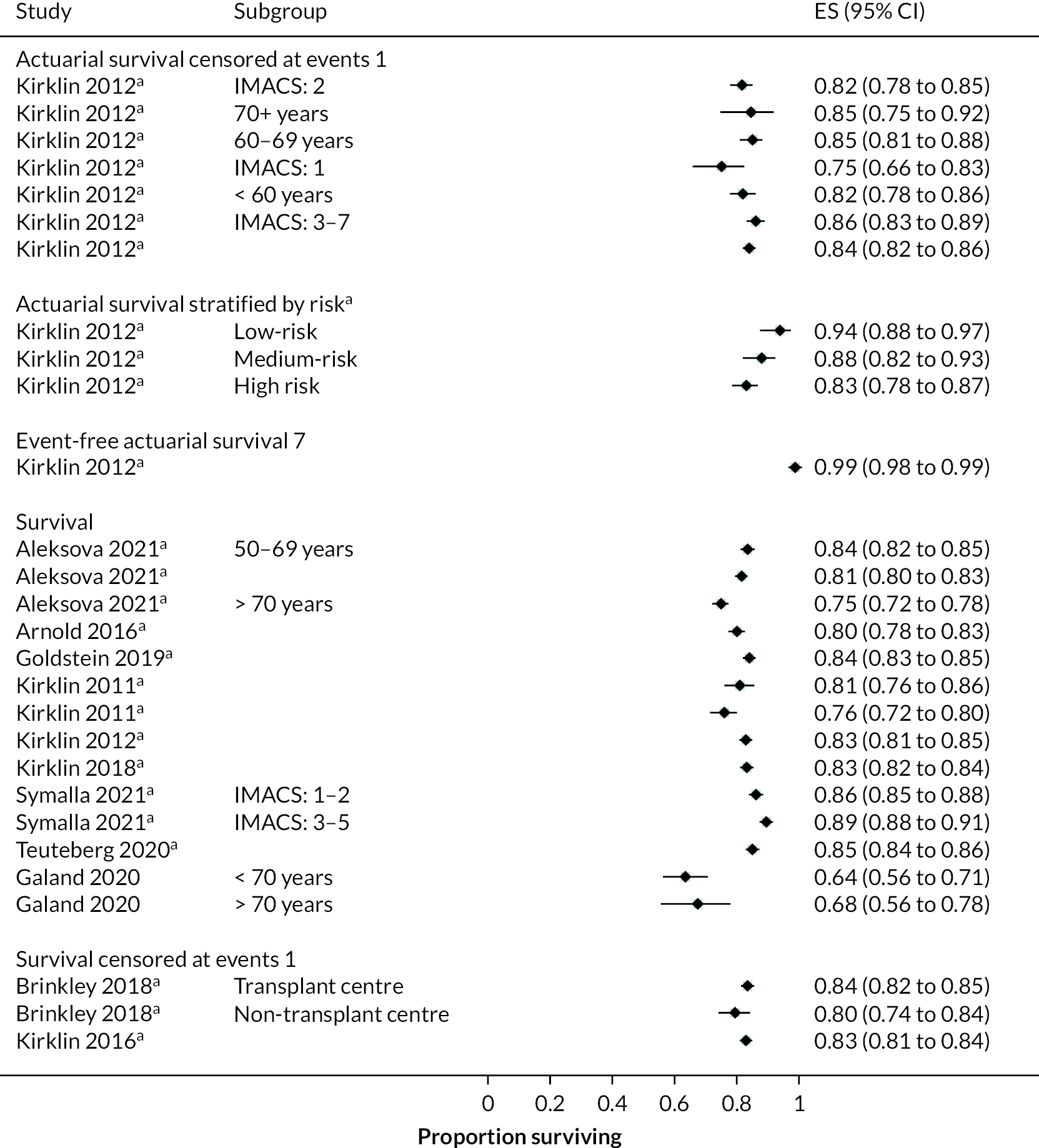

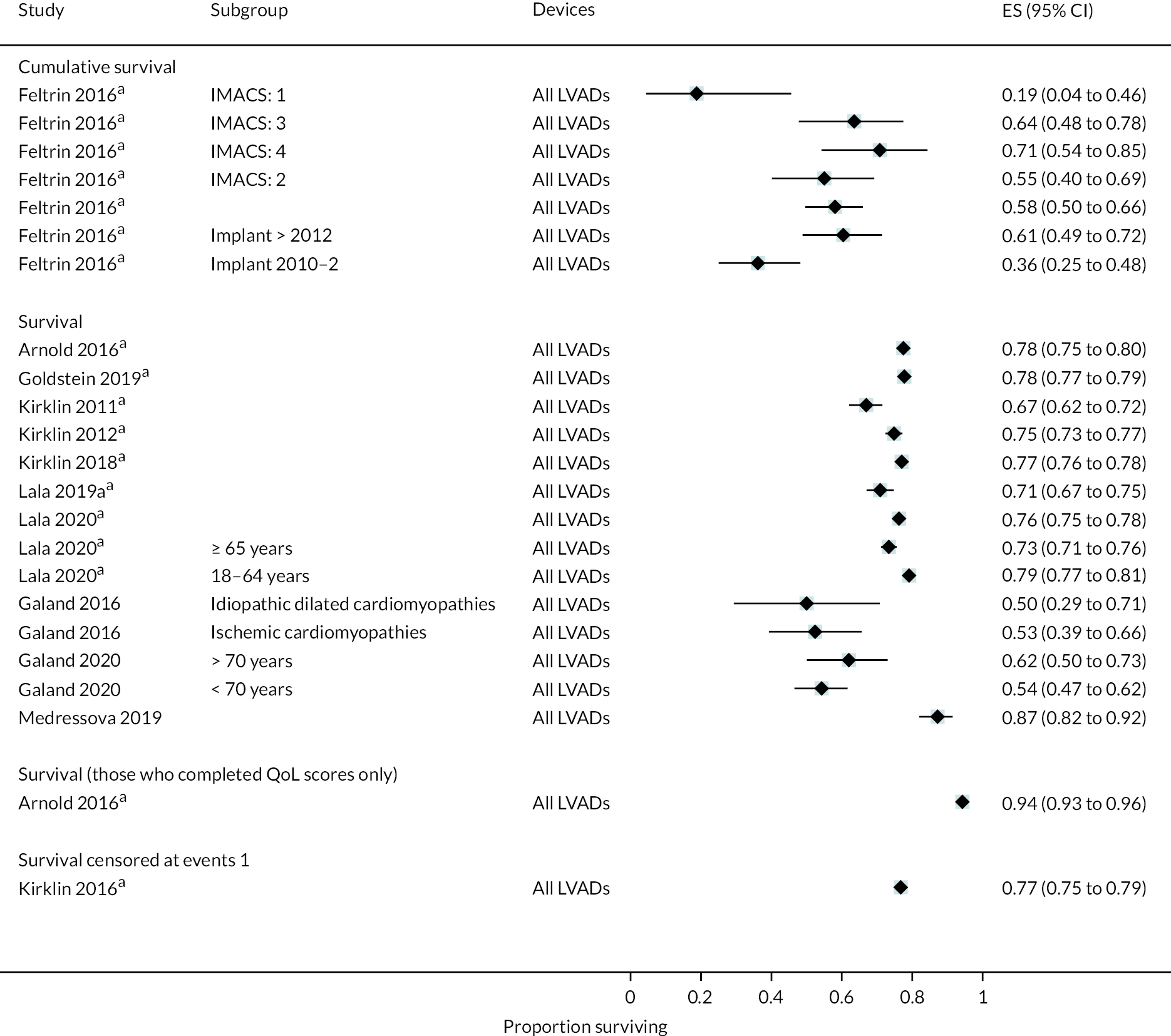

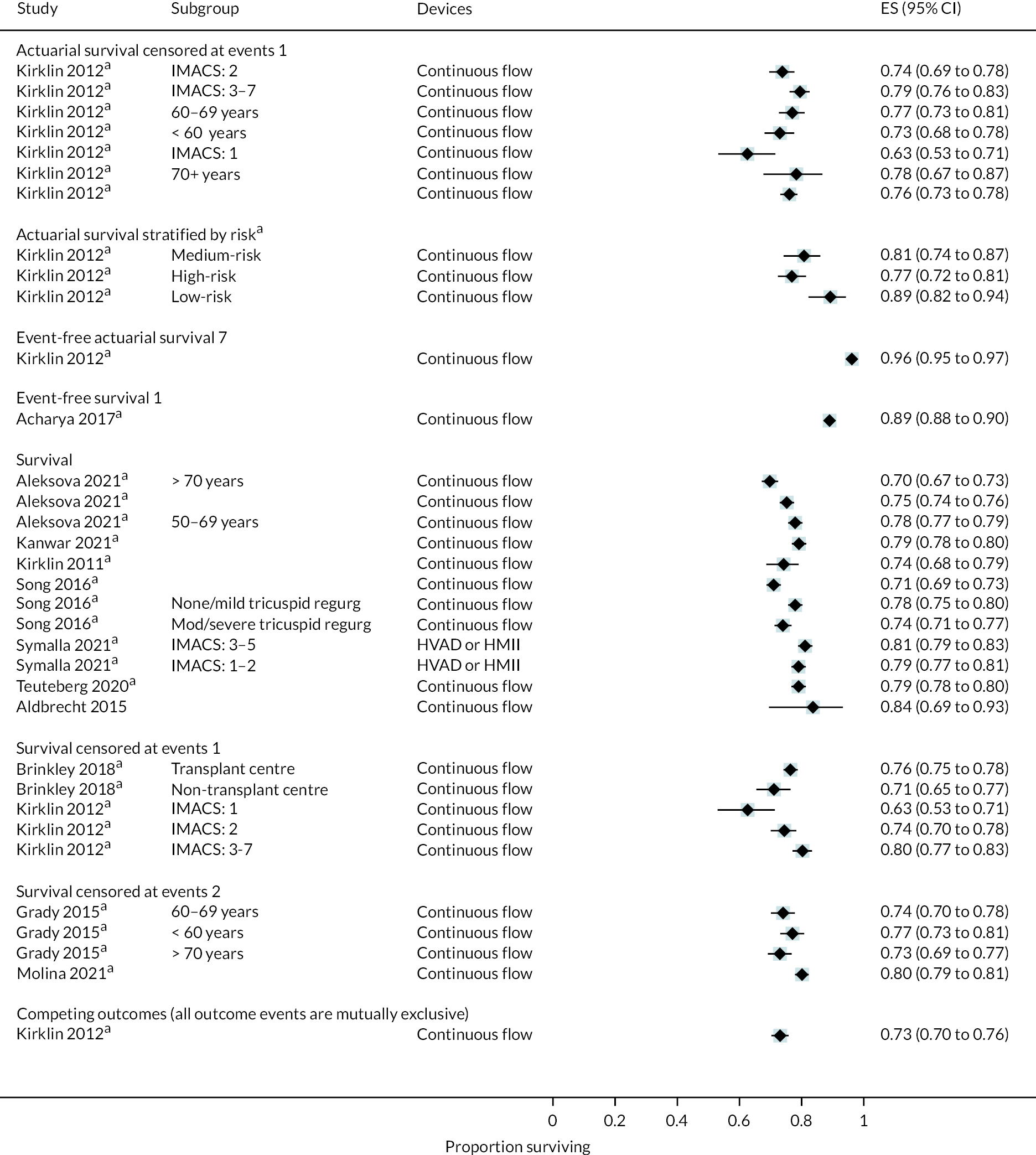

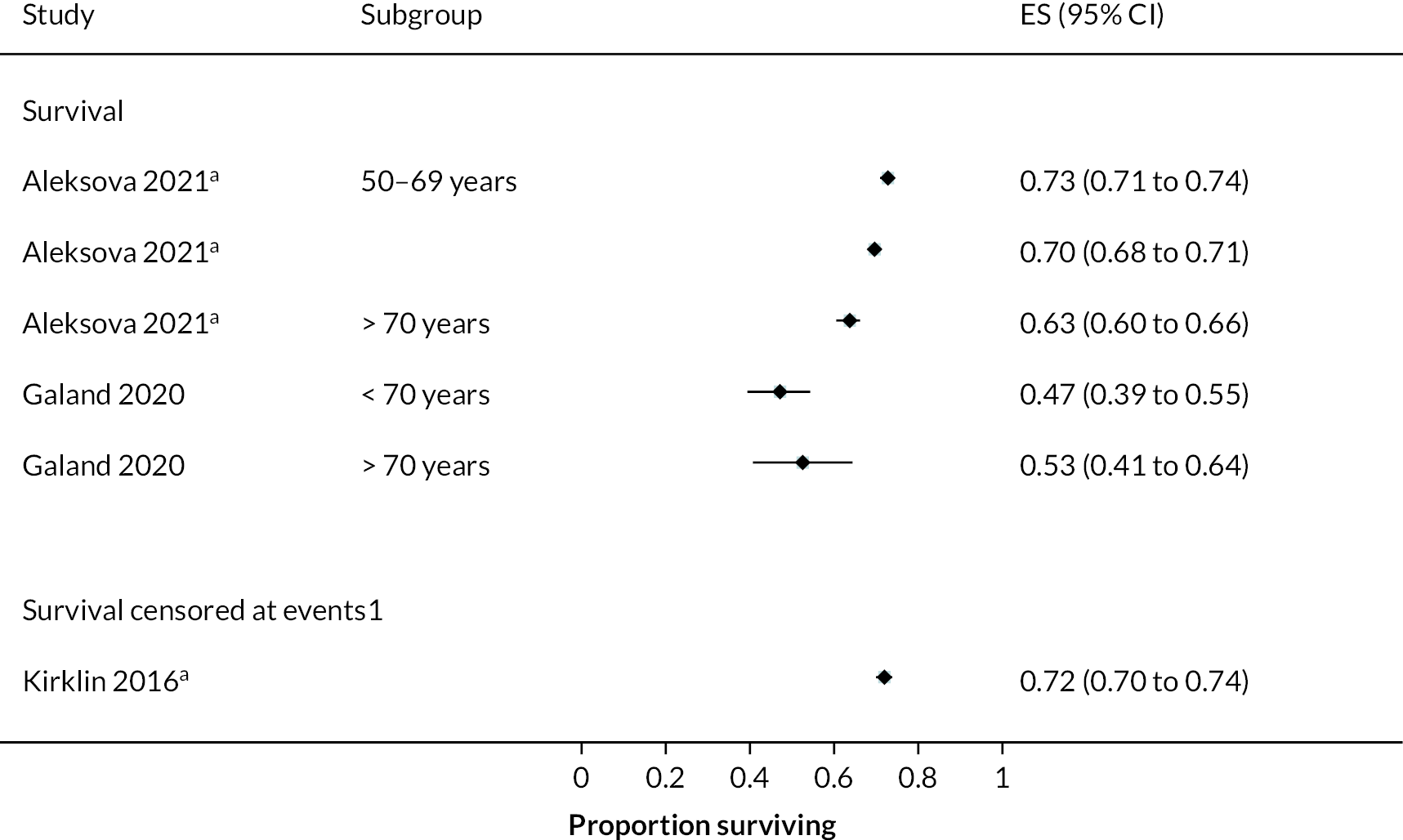

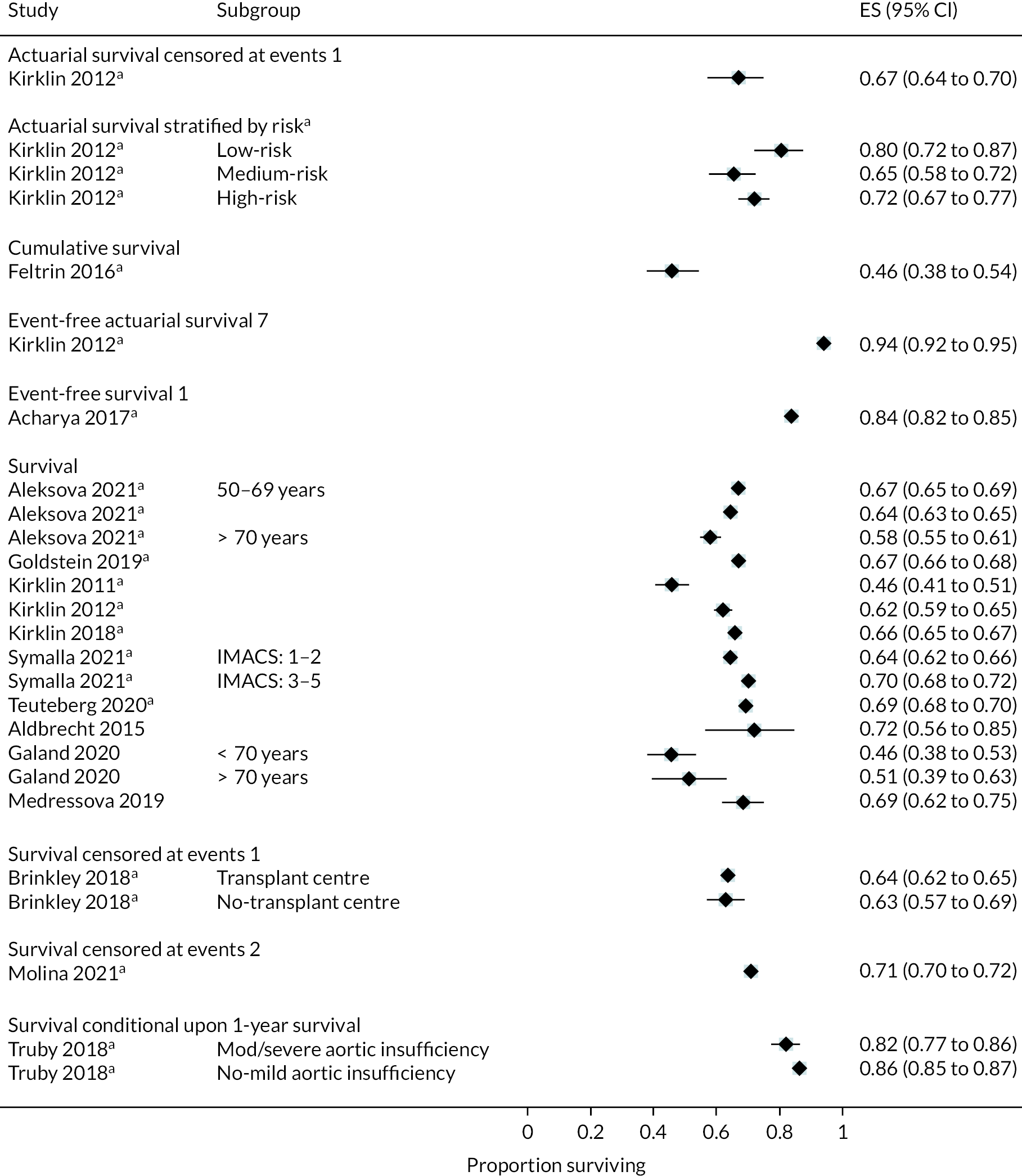

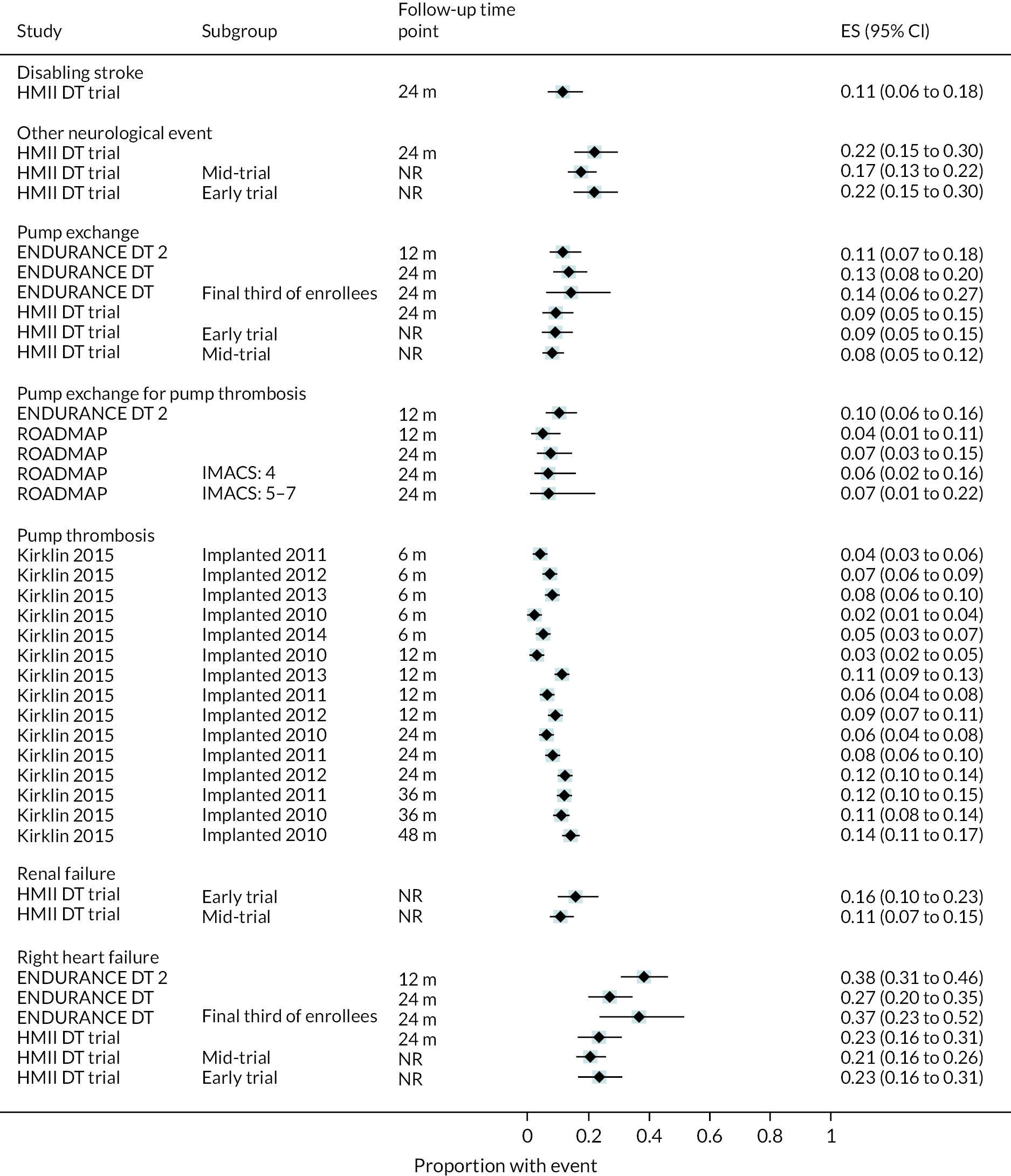

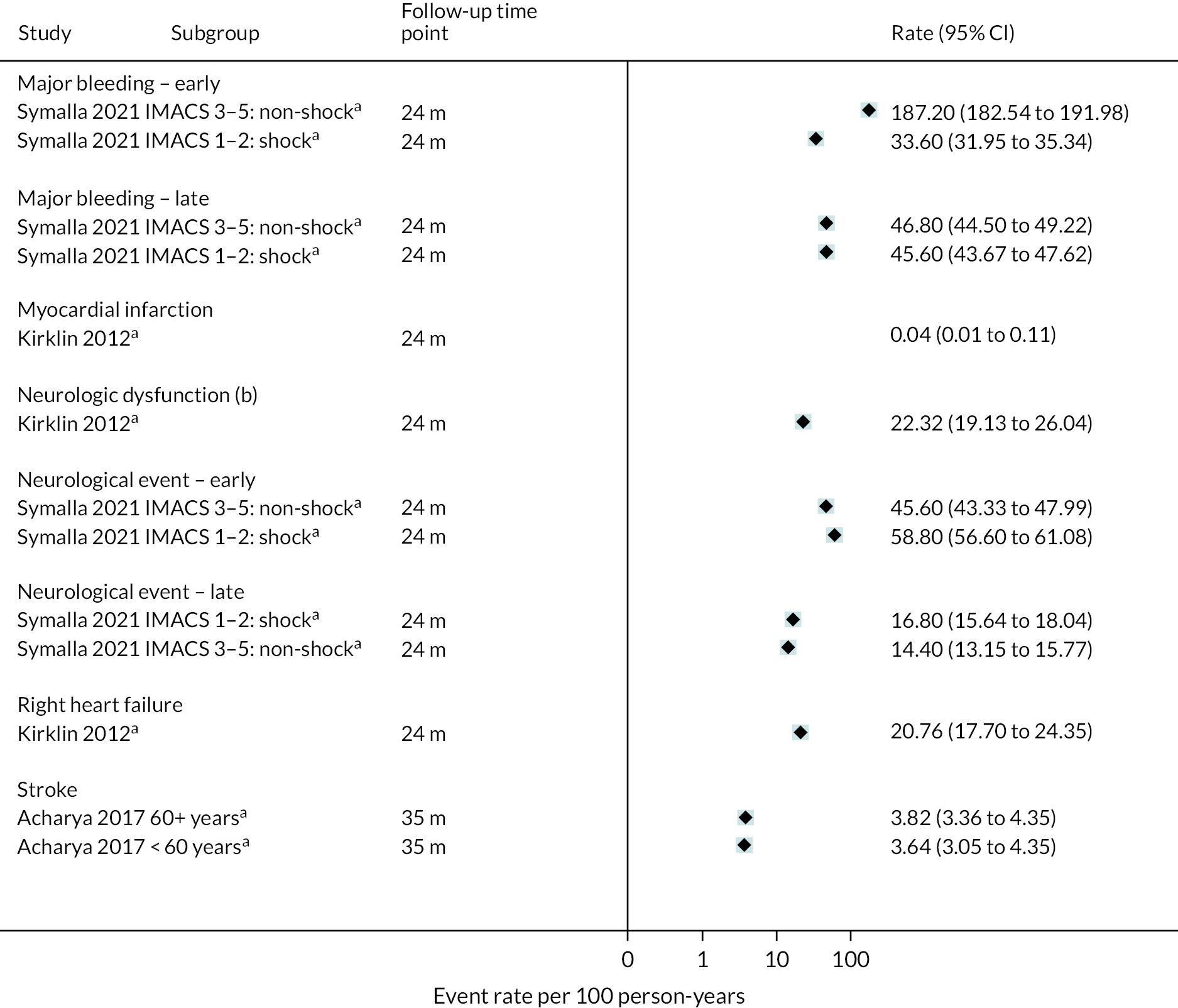

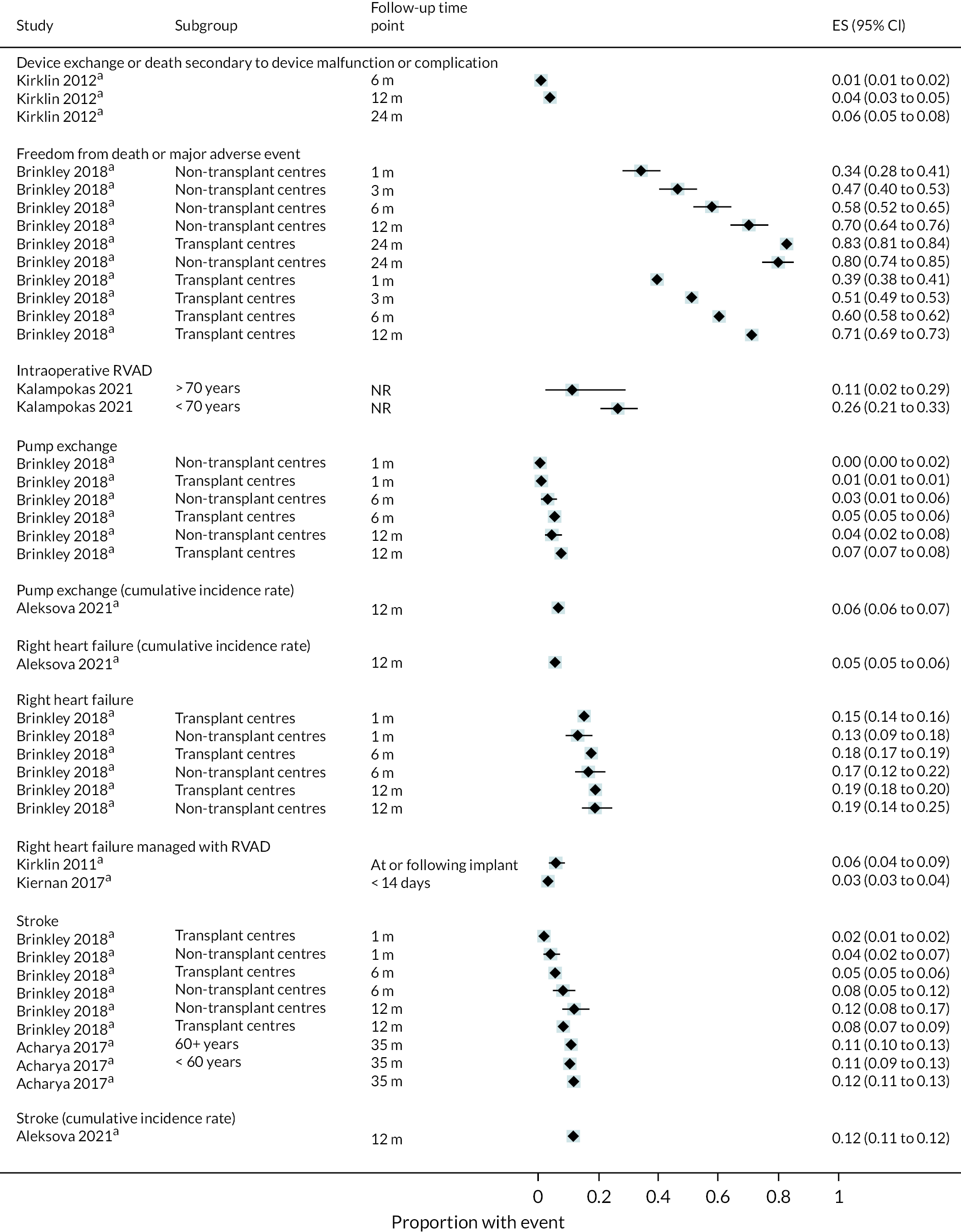

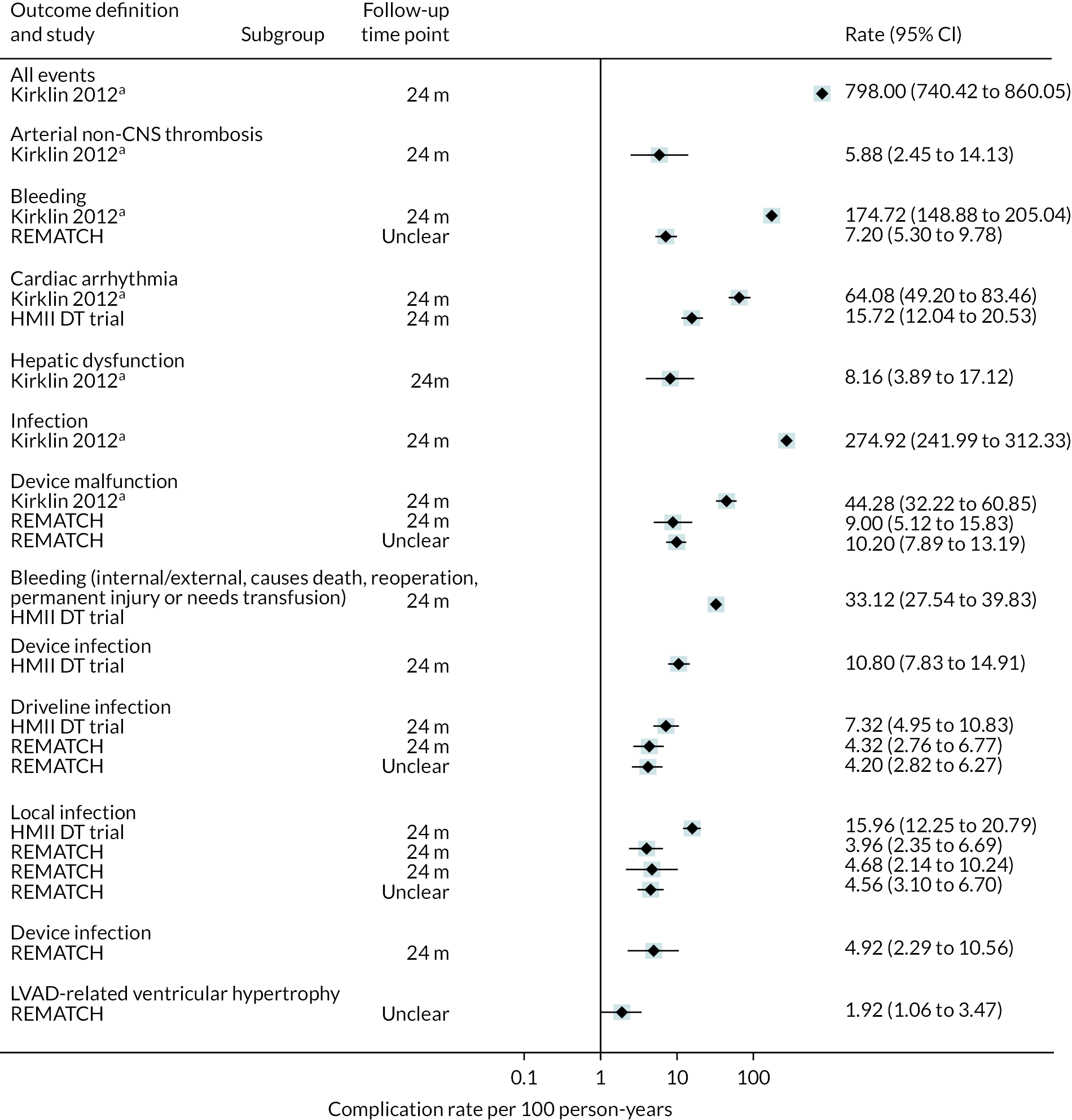

Forest plots without pooled estimates were created for all data stratified by device type for each outcome category (survival, QoL, hospitalisations, major events and complications).

While all recent devices (e.g. HeartMate XVE™, HeartMate II, HeartWare HVAD, HM3) were included and analysed, priority was given to the HM3 device given the availability of devices in the UK and the recent withdrawal of the HeartWare HVAD device in June 2021.

Statistical analysis

Outcomes of mortality, hospitalisation, major events and complications

Potentially relevant data for these outcomes were reported in a variety of different forms. These included:

-

rate per participant, rate per participant-year, rate per 100 participant-years;

-

total number of events, mean number of events per participant, number of participants who had at least one event, proportion of participants who had at least one event, proportion of participants who were event free; and

-

total follow-up time in person-years, average study follow-up time, overall study follow-up time.

Where possible, these data were used to estimate (1) the proportion of participants who had an event, and (2) the event rate per 100 person-years. For each of these statistics a hierarchical approach was used to calculate the sufficient statistics for each study with preference given to those approaches that made the fewest assumptions:

Where possible, these proportions and their 95% CIs were estimated using exact binomial distribution and the results are presented in forest plots. Estimation of the number of participants with the event was as follows:

-

The number of participants with an event is reported by the study report and this number is extracted.

-

The number of participants in the study group together with the proportion of participants with the event are reported. Multiplication of these two quantities rounded to the nearest integer is used.

Where calculable, event rates per 100 participant-years follow-up were reported together with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and these are displayed on forest plots. To estimate the standard errors and CIs it was assumed that patient events over the whole participant group followed a Poisson process and that the sampling distribution on the log-rate scale was normal.

Estimation of total study follow-up time in each group:

-

The total follow-up time was reported for each group and these numbers were extracted.

-

If the total number of events and the rate of events per patient-year (or 100 patient-years, etc.) were reported, these were multiplied together (after a suitable linear transformation if required).

-

If the follow-up time for the study and the number of participants in the study were reported, then these were multiplied together.

Estimating event rate per 100 patient-years follow-up:

-

The number of events per patient-year (or 100 patient-years etc.) was reported, then an appropriate linear transformation was used if required.

-

The total number of admissions divided by the total person-years follow for the patient group if these were both either reported or calculable as described above.

Estimating the number of events occurring in each study.

-

The total number of events for the patient group is reported by the study.

-

If the number of events per participant-year and the total follow-up time were reported or could be estimated as described above, then these were multiplied.

-

If the mean number of events per participant and the total number of participants was reported for each group these were multiplied together and rounded to the nearest integer.

Network meta-analysis

Indirect comparisons between all nodes in the network together with standard errors were calculated using the Butcher method (chained over indirect comparisons as required) on natural log relative risk (RR) scale. 45 As there was no closed loop evidence, no checks for evidence consistency were possible. As there was only one trial for each comparison a fixed effects model was used, and no estimates of heterogeneity were calculable.

Subgroup analysis

Key subgroups were considered following input from the steering group. This included reporting of data from participants with different INTERMACS profiles (indicating severity of HF) as well as different age categories. Subgroup analysis was considered where relevant data were available. While meta-analysis of subgroups was not possible due to a lack of data or differences in definitions, subgroup data were presented in forest plots without summary points.

Results

Selection

Searches for both clinical and cost-effectiveness studies identified 12,153 articles. Following removal of duplicates, 9006 articles remained. There were 982 articles found to be potentially relevant following title and abstract screening, and full texts were sought and checked against the eligibility criteria. Following this, 240 articles from 134 studies met the criteria for the clinical effectiveness review and were included.

There were 6 trials (1 non-randomised, 5 RCTs), 86 observational studies, reports from 5 registries, 5 ongoing studies and 32 systematic reviews (included for citation checking). It should be noted that some of these studies were from the same centres and reports from the same registries were considered as one single study. There were 24 relevant articles included following citation checking, 21 of which were relevant to the clinical effectiveness review. Seven full-text articles could not be retrieved. A summary of the selection process is given in Figure 4. A list of full-text articles excluded with reasons is available in Appendix 3.

FIGURE 4.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram showing selection of studies. a, Only studies considered for the clinical effectivenessreview were excluded based on sample size.

Types of included studies

Studies included in the review were categorised as comparative trials, registry reports or single and multicentre observational studies.

Devices

Several LVADs have been used in the care of end-stage HF patients and these are detailed in Table 6. The pulsatile HeartMate XVE is no longer in clinical use and was replaced by the HeartMate II device. The HeartWare HVAD was withdrawn from the market in June 2021 due to concerns over increased stroke risk and pump thrombosis compared to alternative devices. 32 The HM3 device is currently the most implanted device in the USA, having been approved for clinical use by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for DT in 2019. 46

| Device | Type | Weight | Size | Circulatory support (RPM, flow l/min) |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HeartMate XVE | Vented electric device, pulsatile flow | 1255 g | Diameter: 11.2 cm Nominal height (excluding ports) 5.8 cm (The size of the device requires patients to have a body surface area of more than 1.5 m2) |

4–10 l/minute | Thoratec Inc., Ann Arbor, MI, USA |

| HeartMate II | Axial-flow pump (continuous flow) |

350 g | Diameter: 4 cm Length: 7 cm |

10 l/minute at RPM ranging from 8000 to 15,000 | Thoratec Inc., Ann Arbor, MI, USA |

| HeartMate 3 | Fully magnetically levitated centrifugal-flow pump (continuous flow) |

200 g | Diameter: 50.3 mm Height: 55.8 mm (includes inflow cannula), 33.8 mm (excludes inflow cannula) |

10 l/minute RPM ranging from 3000 to 9000 |

Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL, USA |

| HeartWare HVAD | Centrifugal-flow pump (non-magnetic) (continuous flow) |

145 g | Diameter: 4 cm Length: < 2 cm |

10 l/minute at RPM ranging from 1800 to 3000 | Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA (formerly HeartWare Inc., Framingham, MA, USA) |

| EVAHEART 2 (EVA2) | Centrifugal-flow pump, hydraulically levitated impeller for retained pulsatility | NR | NR | 7–8 l/minute up to 2200 RPM | Evaheart Inc., Houston, TX, USA |

Table 6 also details the EVAHEART 2 (Evaheart Inc., Houston, TX, USA) LVAD, described as a centrifugal hydraulically levitated ‘open vane’ impeller that supports blood circulation and high peak flows for retained native pulsatility. The device is currently being trialled in a large RCT in the USA under a FDA-approved investigational device exemption and being compared to the HM3 device with completion estimated for 2024. 47 At the time of the report’s writing, no results or data have been published pertaining to the EVAHEART 2.

HeartMate 3 data

The HM3 is currently the only option for LVAD-eligible patients in the UK following the withdrawal of the HeartWare HVAD. This section will describe the available data pertaining to the HM3 device.

Trial data

There was one RCT (MOMENTUM 3) undertaken in the USA that compared the HM3 device to the older HeartMate II device. There were 1028 participants included in the study: 515 randomised to the HM3 (317 of these DT) and 505 randomised to the HeartMate II (307 DT). The mean age for all included DT patients was 63 (SD 12) and the majority of included participants were INTERMACS level 3 (Table 1). The following section reports data by outcome from this RCT.

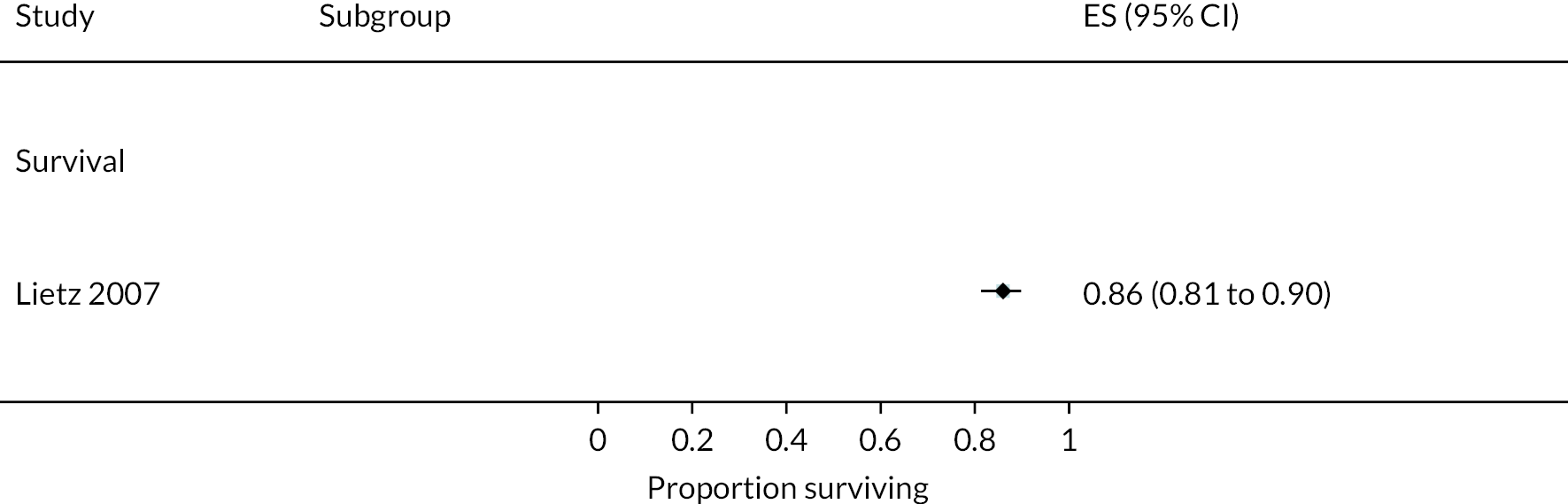

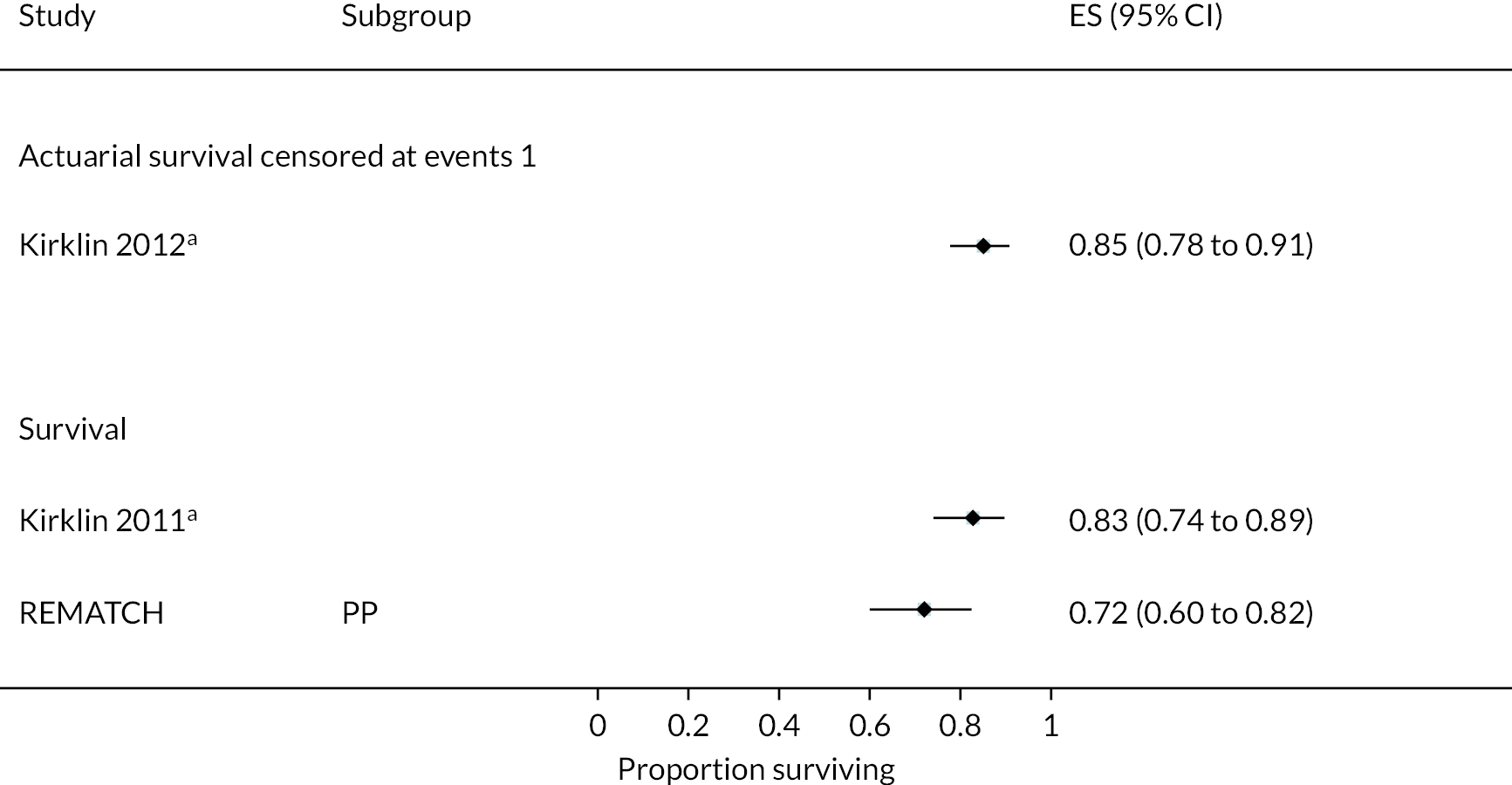

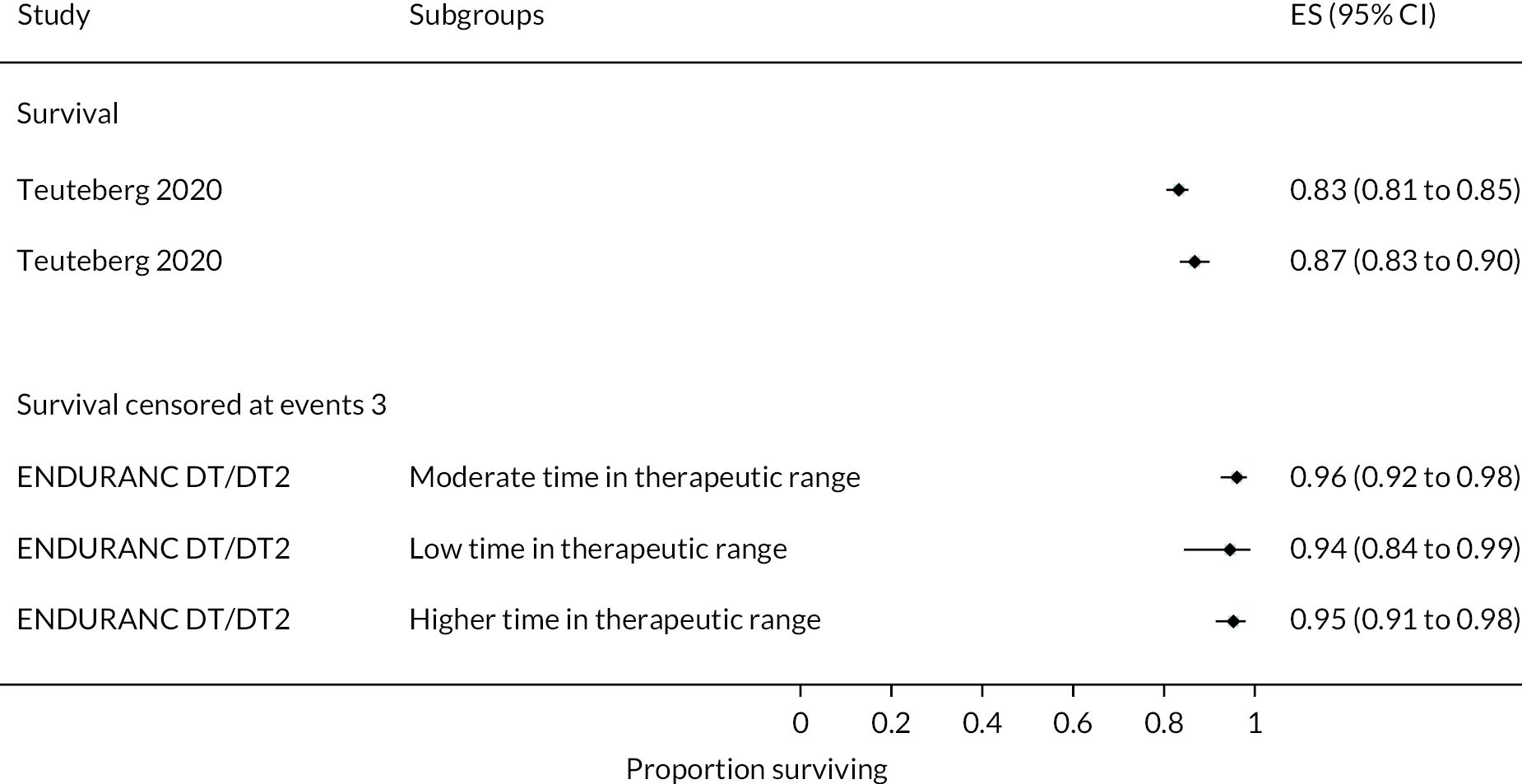

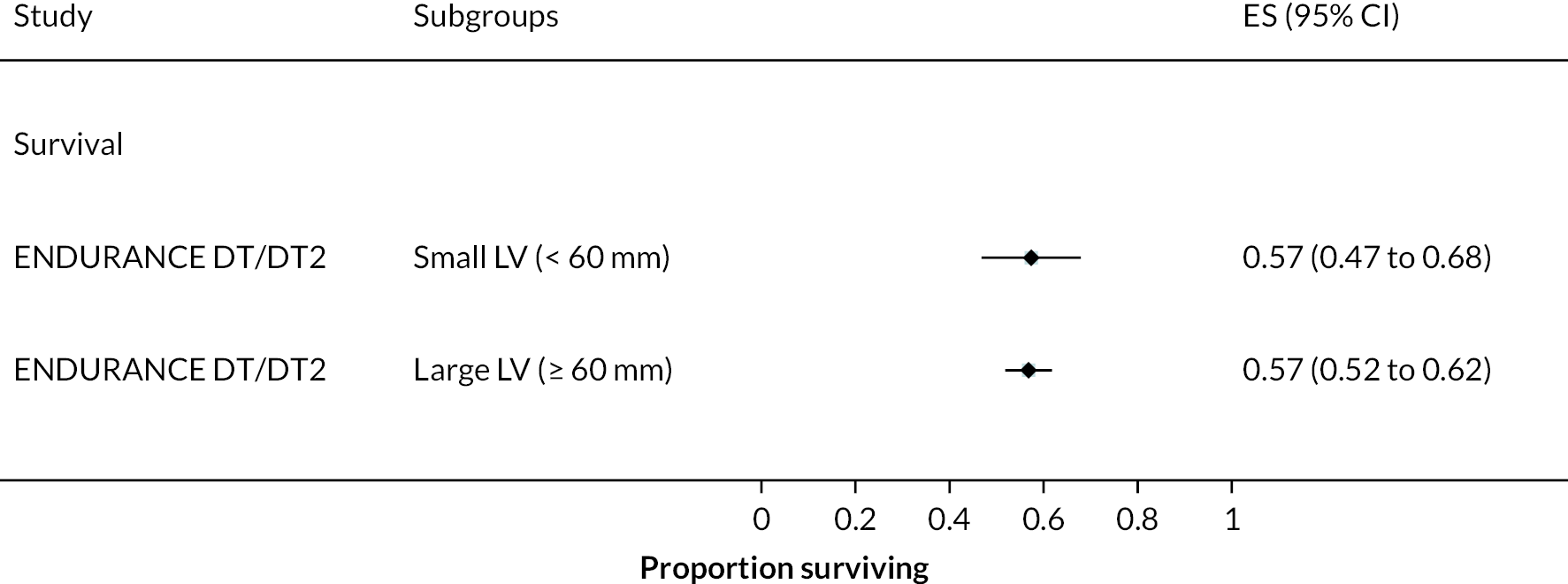

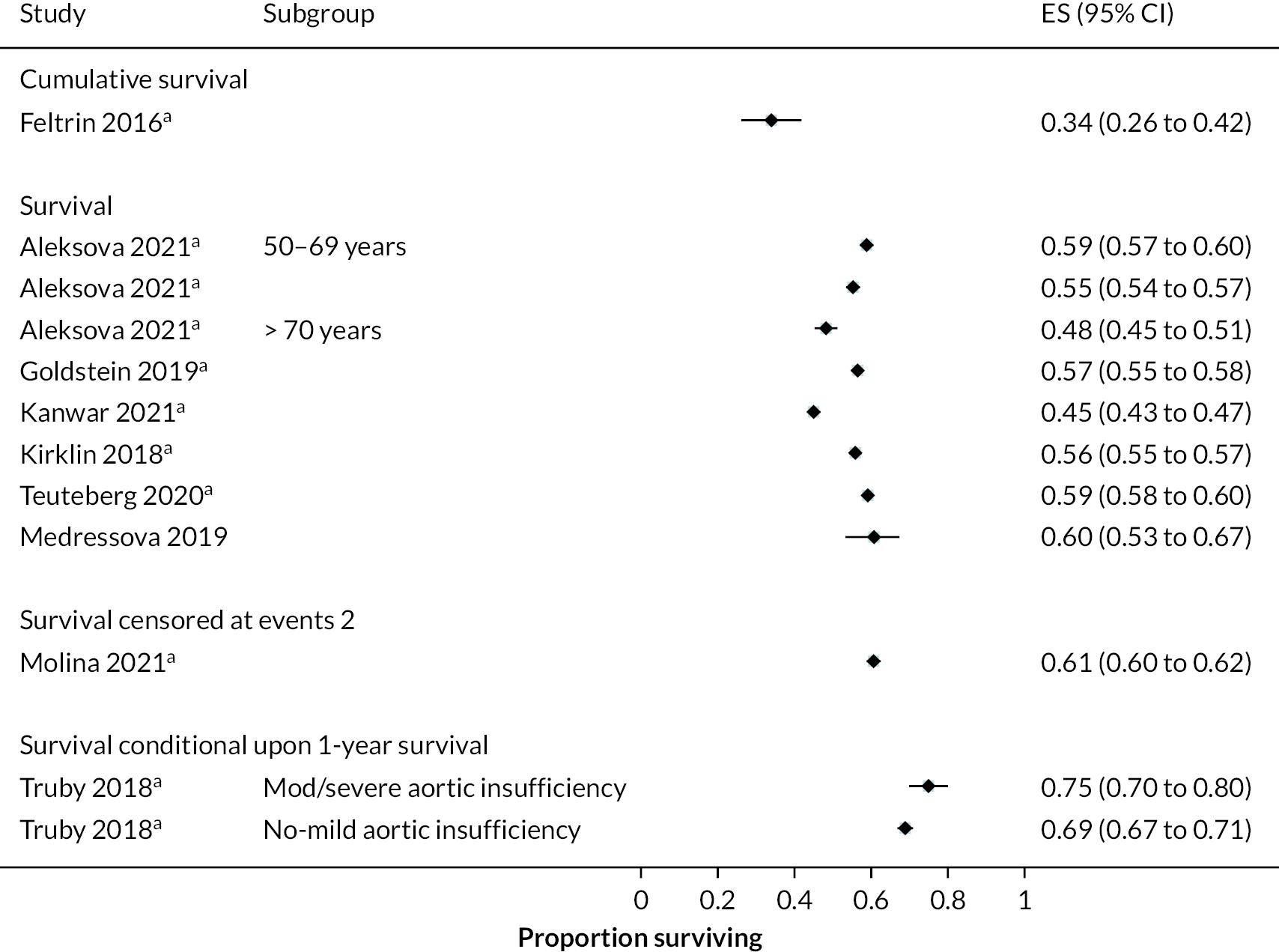

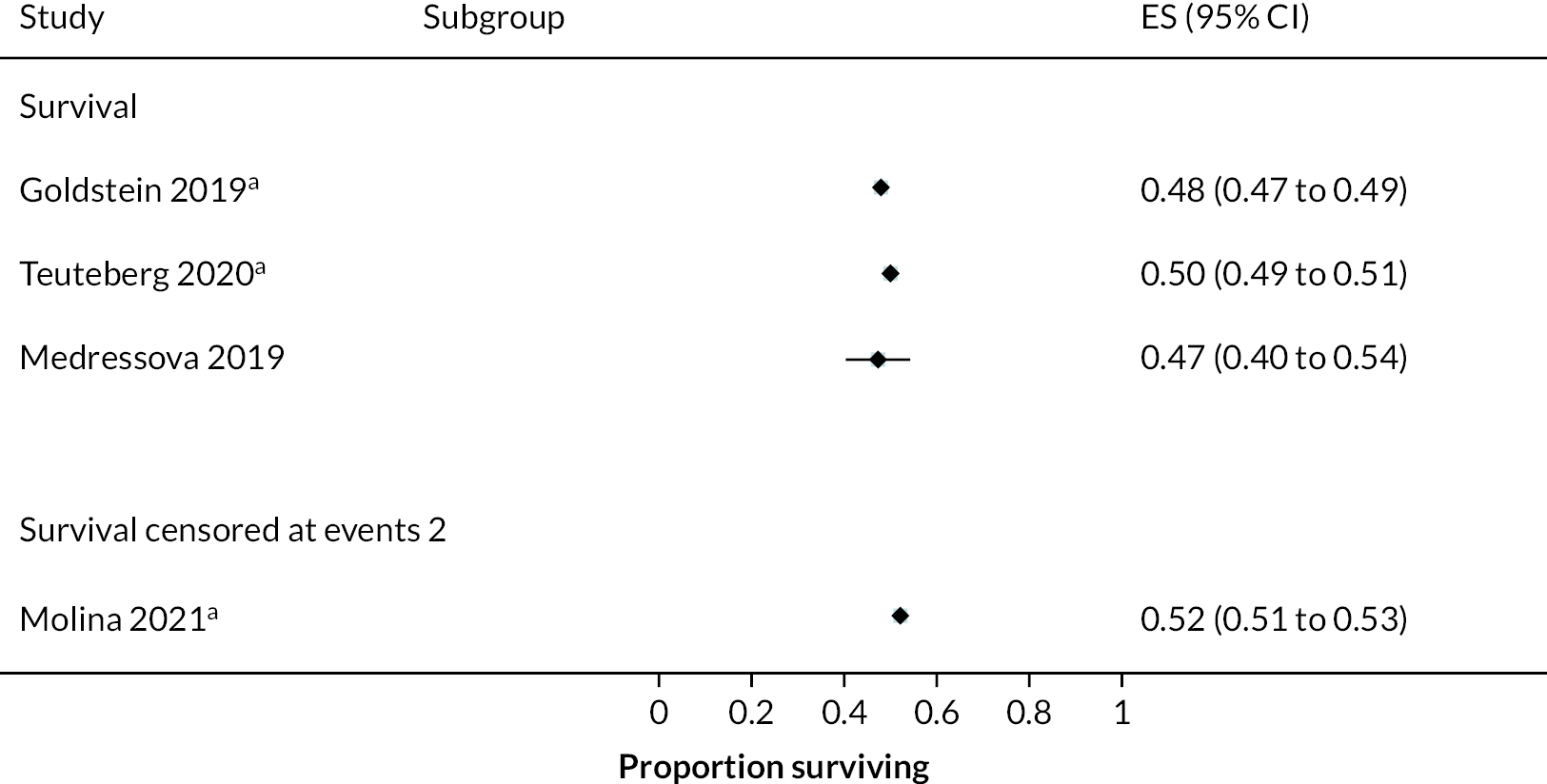

Survival

Survival in DT patients implanted with the HM3 device was 84% at 12 months and 77% at 24 months of follow-up (Figure 5). This is higher than any previously reported survival data in earlier generation devices at 24 months (see Appendix 5). Survival in HM3 DT patients was higher than the HeartMate II patients in the MOMENTUM study at 24 months (77% vs. 59%, respectively) with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.87 (95% CI 0.63 to 1.2), though this was not considered a statistically significant difference. However, survival free of disabling stroke or reoperation to replace or remove a malfunctioning device at 24 months was significantly higher in patients in the HM3 group compared to the HeartMate II group (73% vs. 57%), with a HR of 0.61 (95% CI 0.46 to 0.81).

FIGURE 5.

Survival data in the HeartMate 3 at all reported follow-up time points.

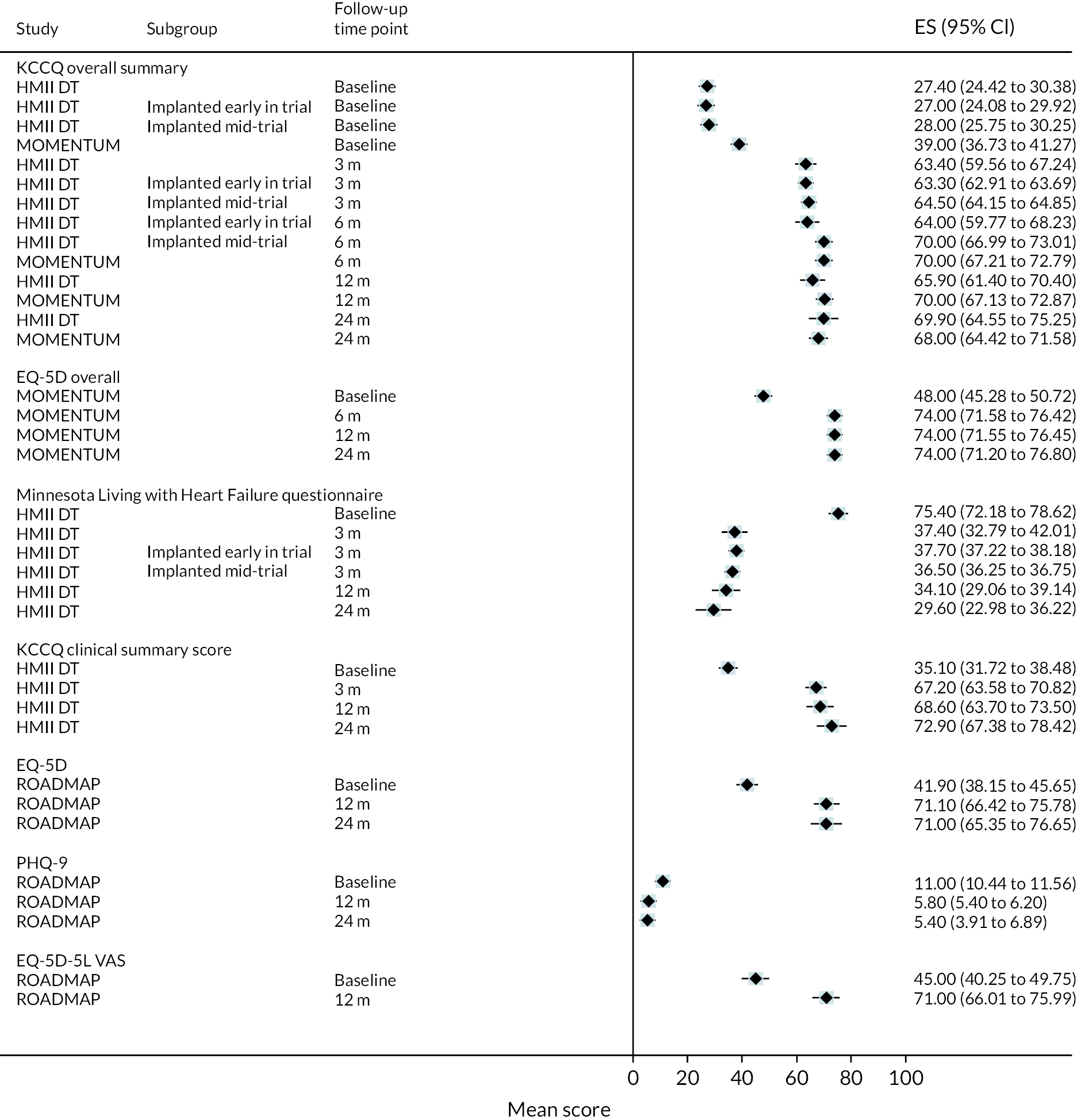

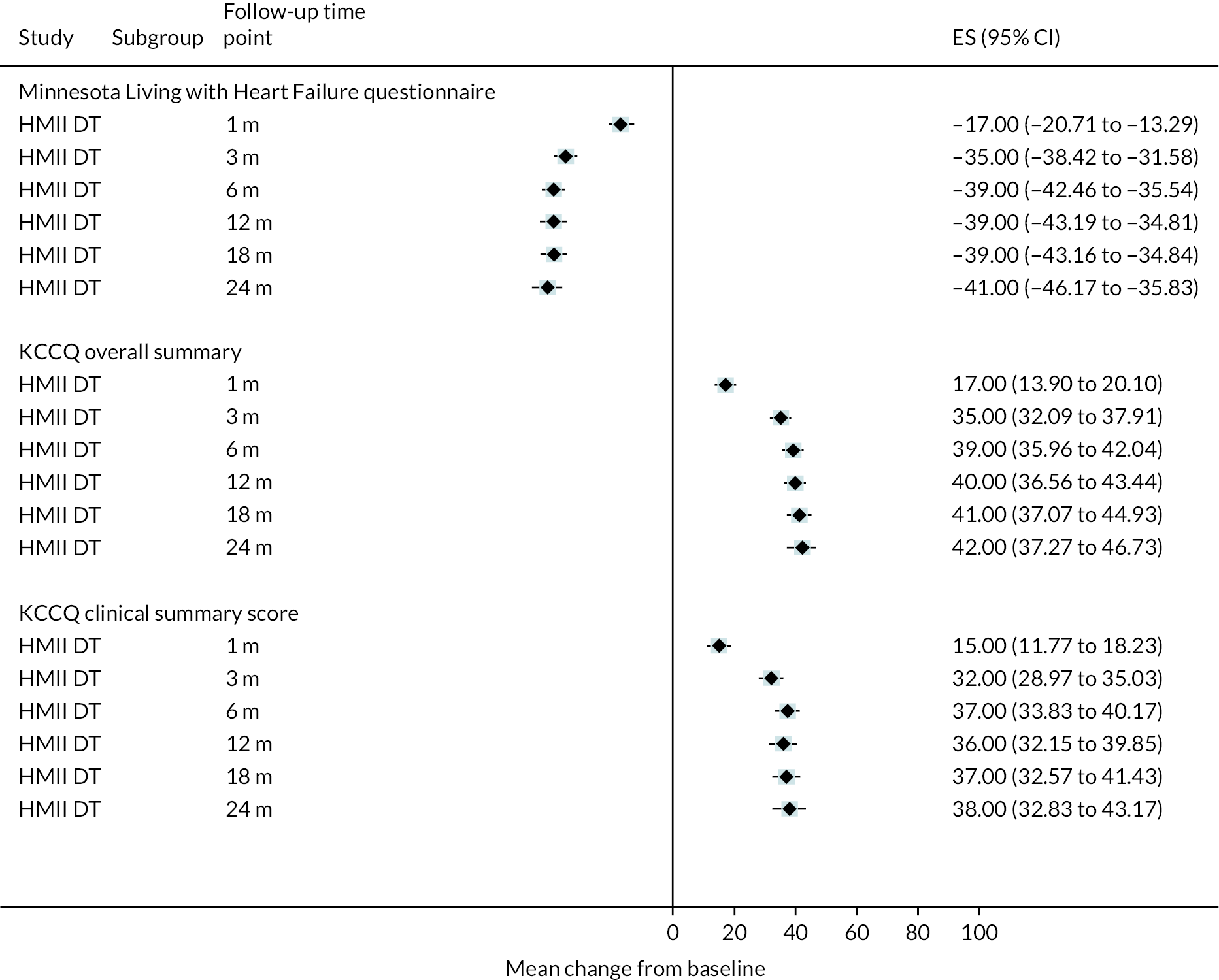

Quality of life

While clear improvements in QoL were reported in DT patients with the HM3 device in both the KCCQ and the EQ-5D at 12 and 24 months compared to baseline, similar QoL improvements were also seen in the HeartMate II group. The mean visual analogue scale (VAS) summary score for the KCCQ improved from 40 at baseline to 69 at both 12 and 24 months in the HM3 group (Figure 6), compared to 39 at baseline increasing to 70 at 12 months and 68 at 24 months in the HeartMate II group. Furthermore, the EQ-5D VAS score improved from 48 at baseline in the HeartMate II group to 74 at both 12 and 24 months (compared to an increase from 51 at baseline to 77 at 24 months in HM3). Improvements in QoL appeared to peak at 12 months and remain stable at 24 months. Scores remained similar to those at 24 months at the end of study follow-up.

FIGURE 6.

Mean QoL scores in the HeartMate 3 at all reported follow-up time points.

Hospitalisations

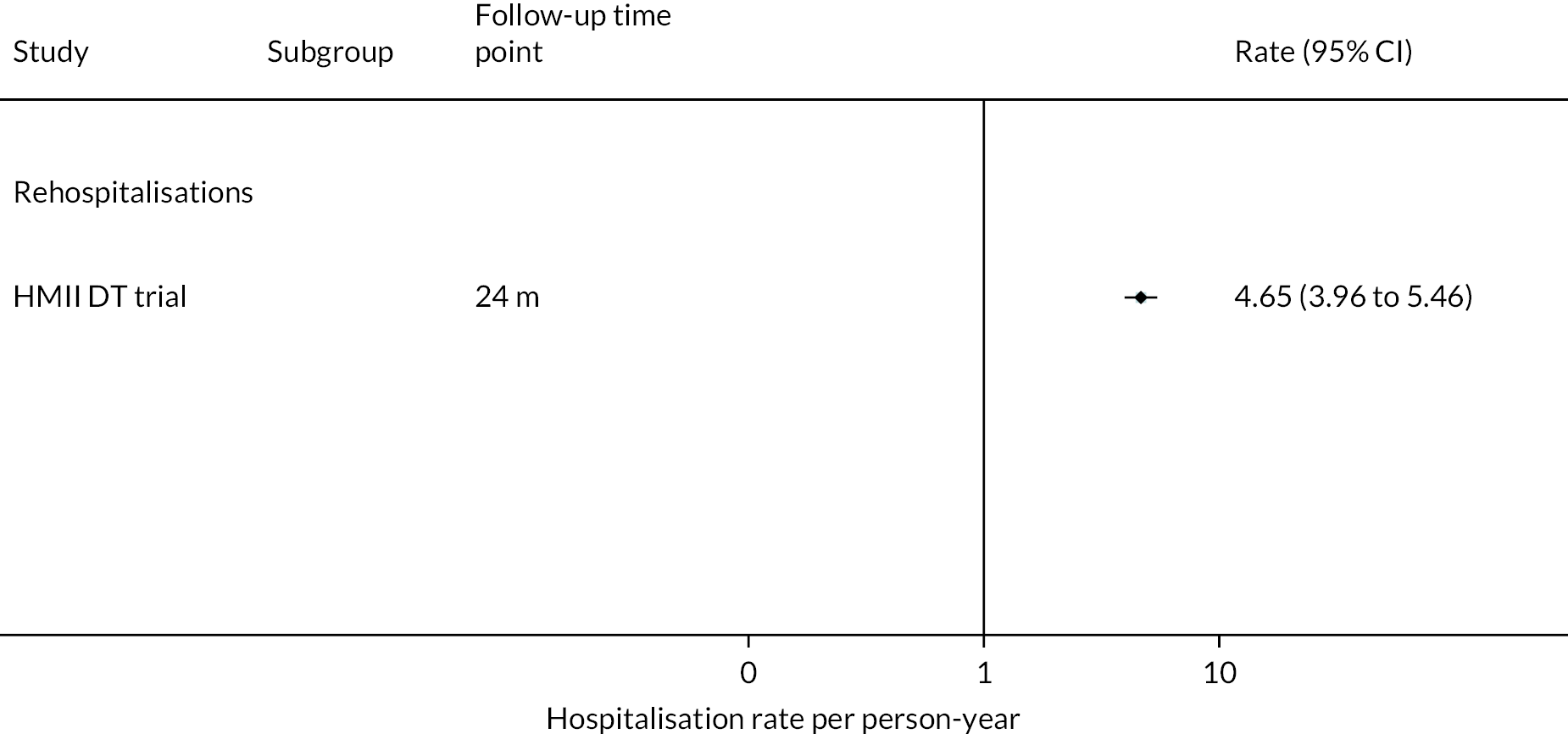

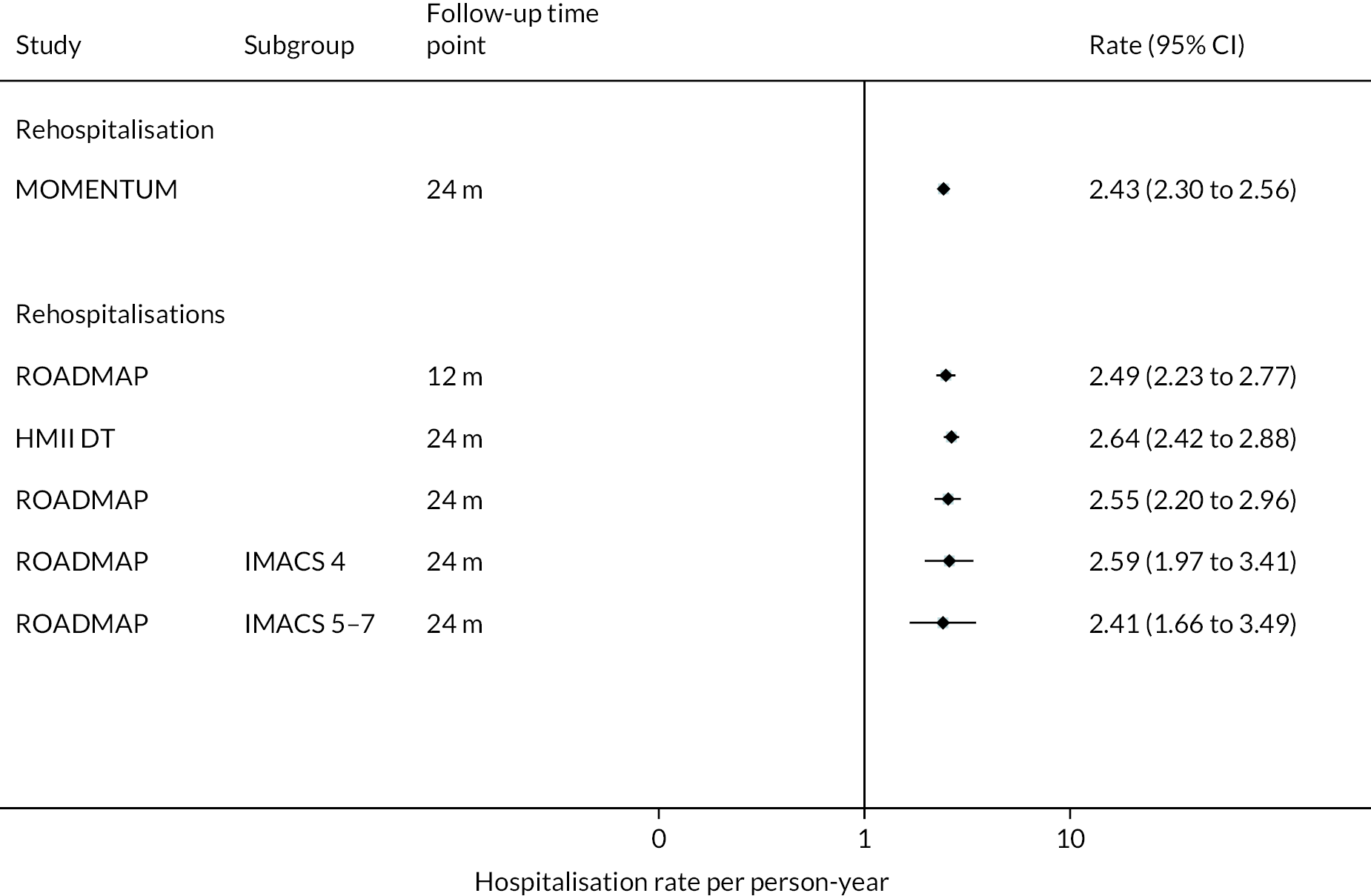

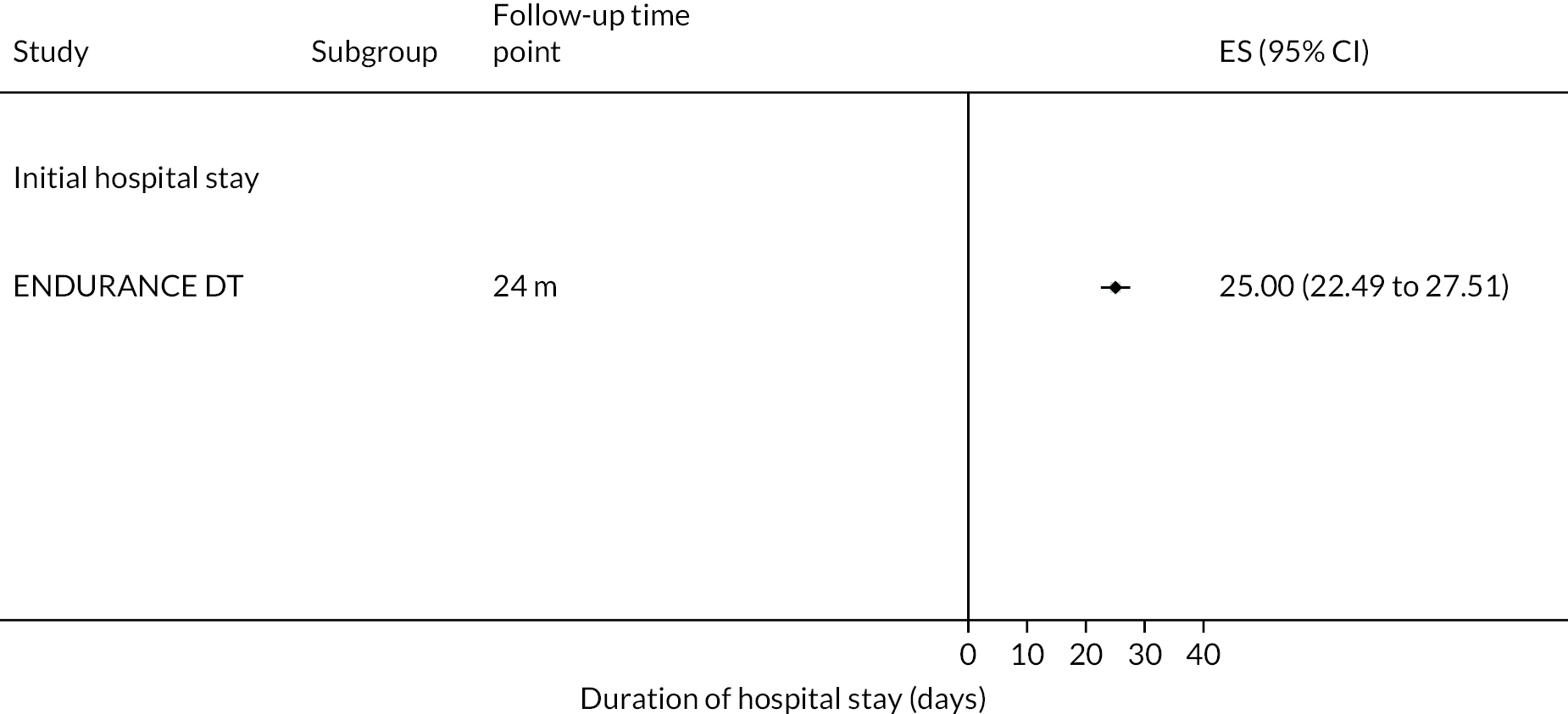

Rehospitalisation days were reported to be fewer in HM3 patients compared to those with the HeartMate II device (median duration 15 vs. 22 days) over 24 months. The event rate of rehospitalisation per 100 patient-years was found to be significantly lower in the HM3 group versus the HeartMate II group (212 vs. 243, HR 0.88 95% CI 0.81 to 0.96, Figure 7 Hospitalisation rate per person-year in the HeartMate 3 at 24 months follow-up).

FIGURE 7.

Hospitalisation rate per person-year in the HeartMate 3 at 24 months follow-up.

Major events

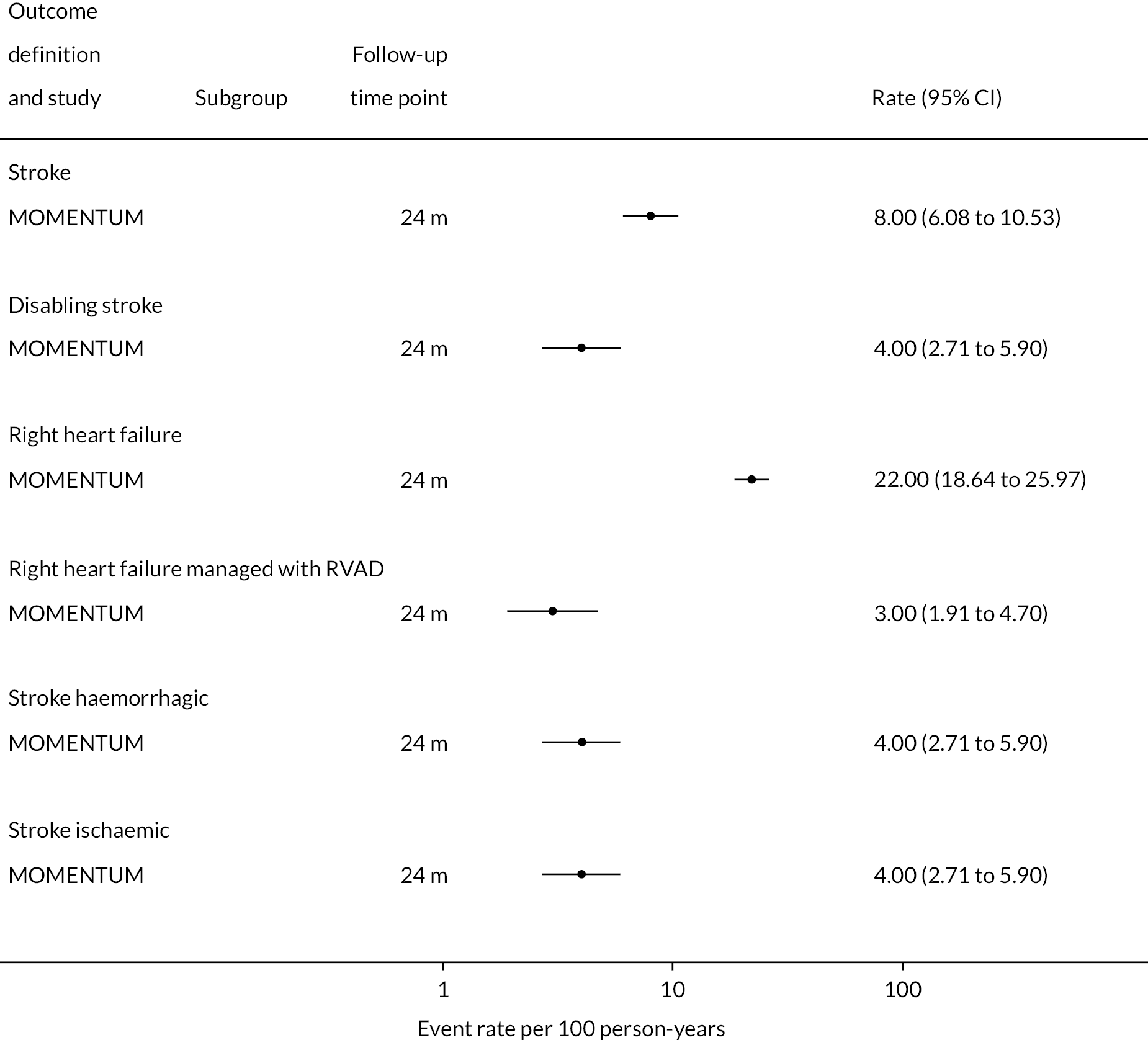

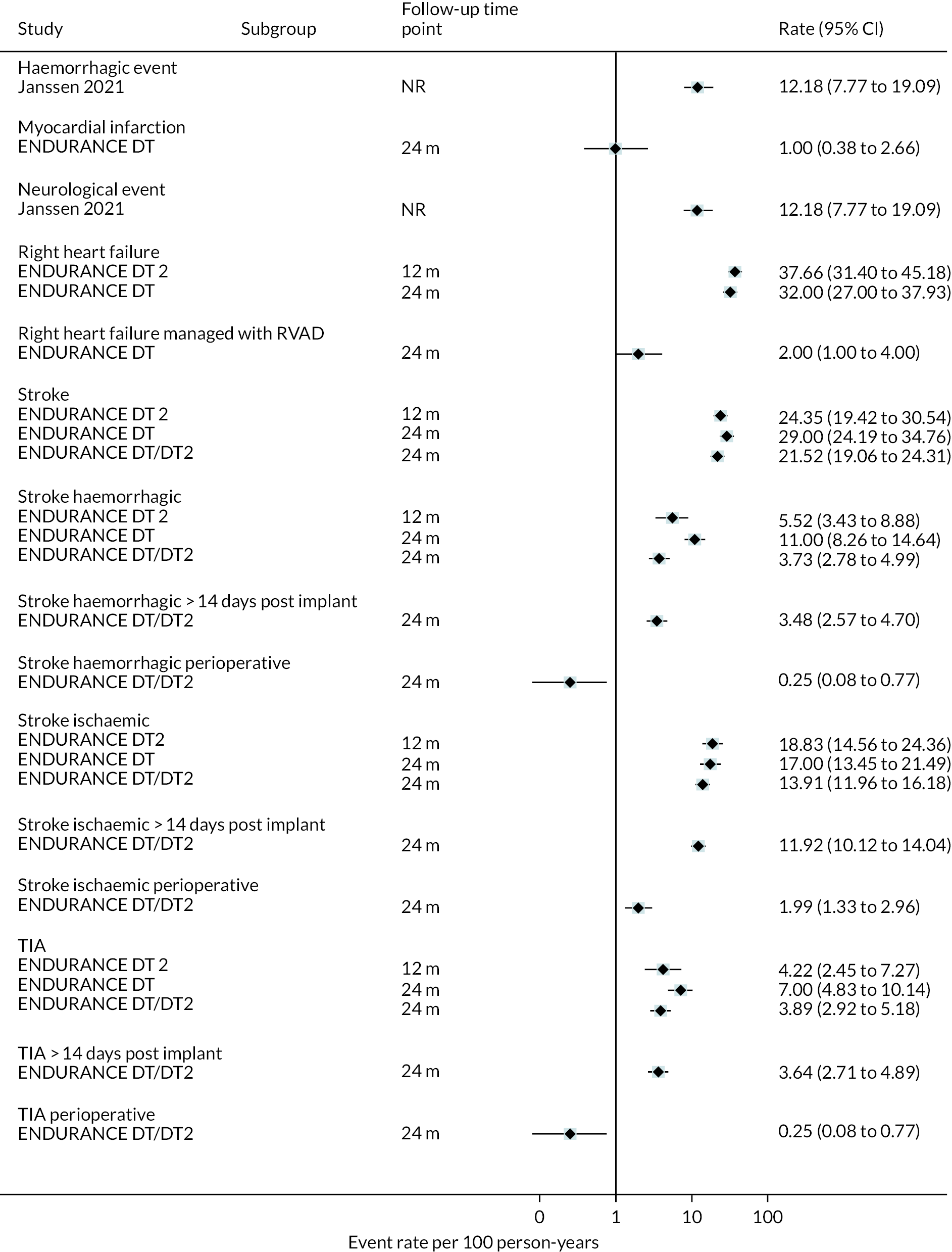

Stroke rates were reported to be lower than seen in the literature previously in the HM3 and lower than the HeartMate II group over 24 months. Regarding any stroke, there were 8 events per 100 patient-years in the HM3 group (Figure 8) (11% had a stroke at 24 months, Figure 9) compared to 19 events in the HeartMate II group (RR 0.42 95% CI 0.29 to 0.62). This was similar for disabling stroke: 4 events per 100 patient-years for HM3 versus 7 events per 100 patient-years for HeartMate II with a RR of 0.59 (95% CI 0.34 to 1.03). There were no significant differences in rates of RHF or RHF requiring RVAD between the device groups.

FIGURE 8.

Event rate per 100 person-years in the HeartMate 3 at 24 months follow-up.

FIGURE 9.

Proportion of patients with major events in the HeartMate 3 at all reported follow-up time points.

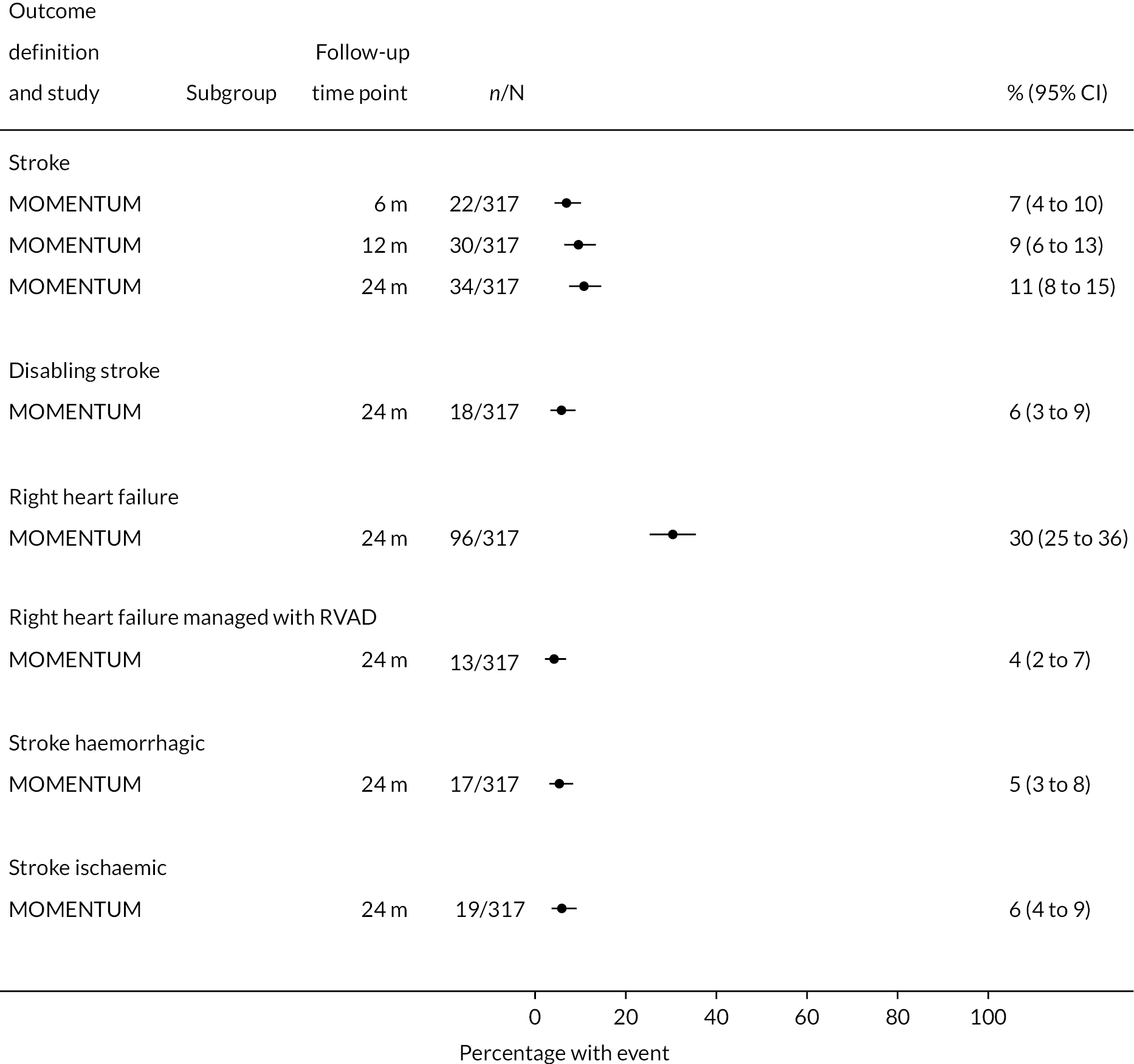

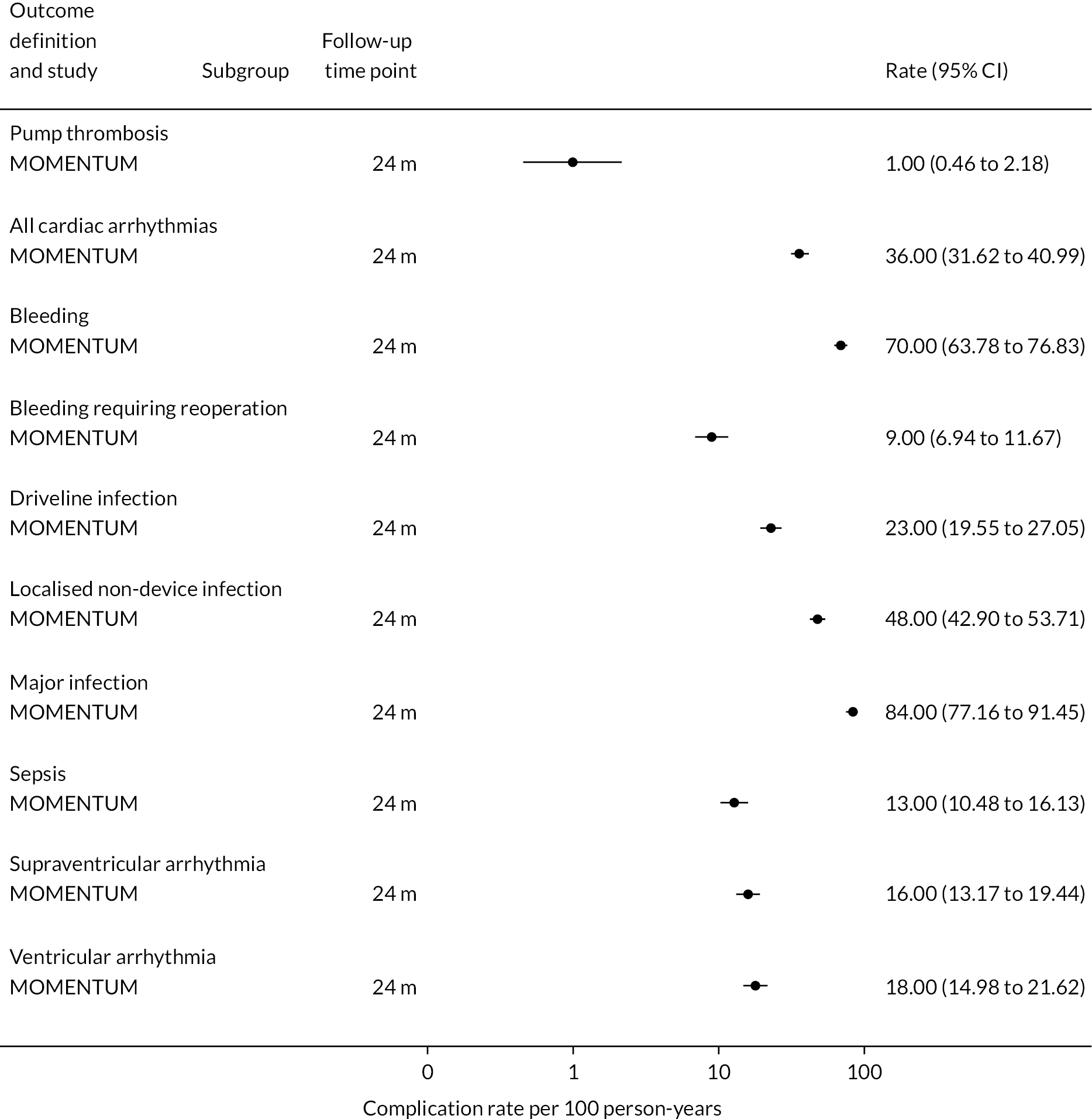

Complications

Rates of pump thrombosis were found to be significantly lower in the HM3 group compared to the HeartMate II group with 1 event versus 12 events per 100 patient-years, respectively, and a RR of 0.1 (95% CI 0.04 to 0.24). On the other hand, DIs were common and not found to be different between the two arms.

While bleeding events were still an issue in MOMENTUM 3, they occurred less frequently in patients implanted with the HM3 compared to the HeartMate II (70 events vs. 103 events per 100 patient-years) with a RR of 0.68 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.78). More specifically, bleeding requiring surgery and GIB rates were both significantly lower in the HM3 group. The proportion of patients with complications and the complication rate are shown in Figures 10 and 11.

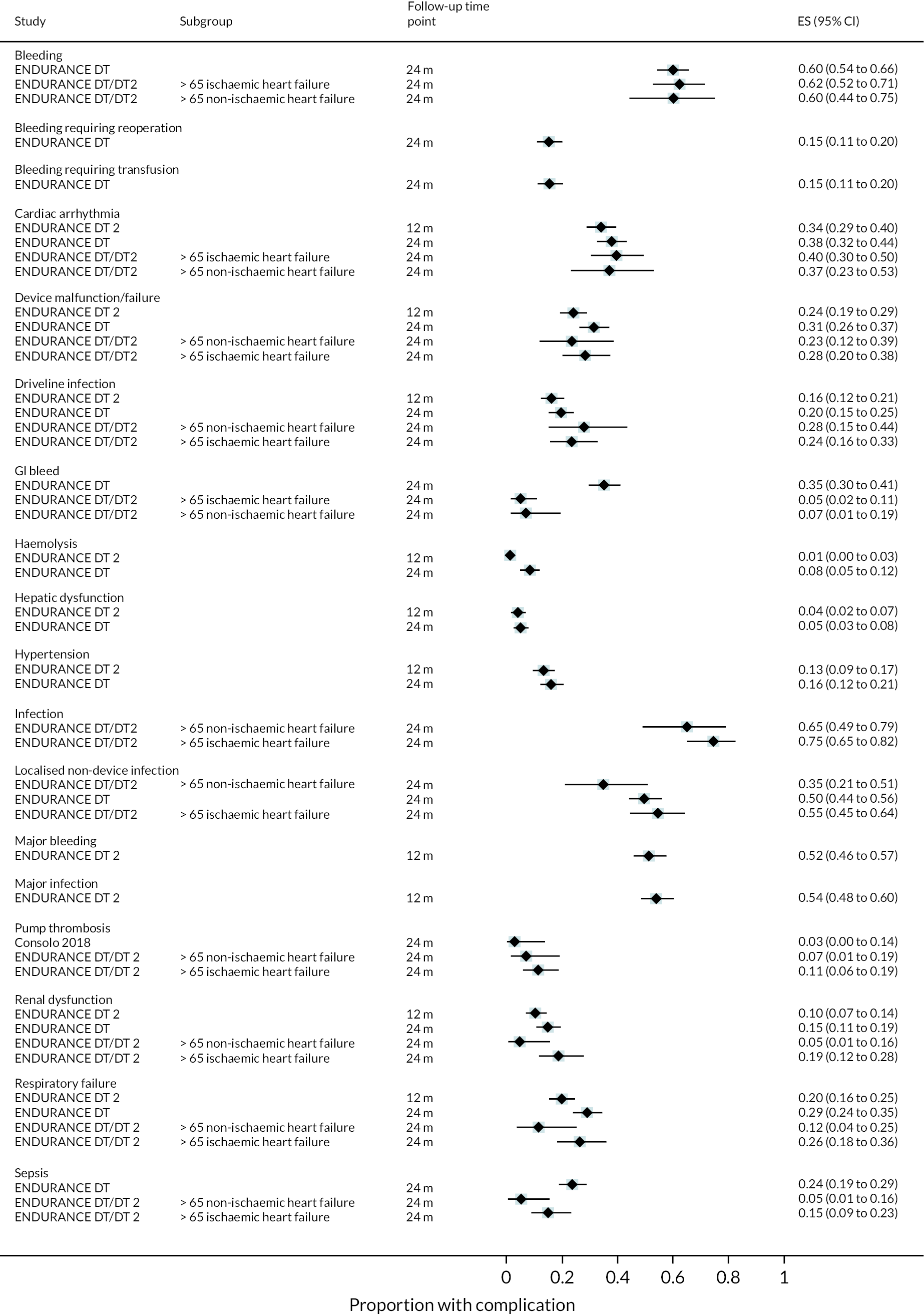

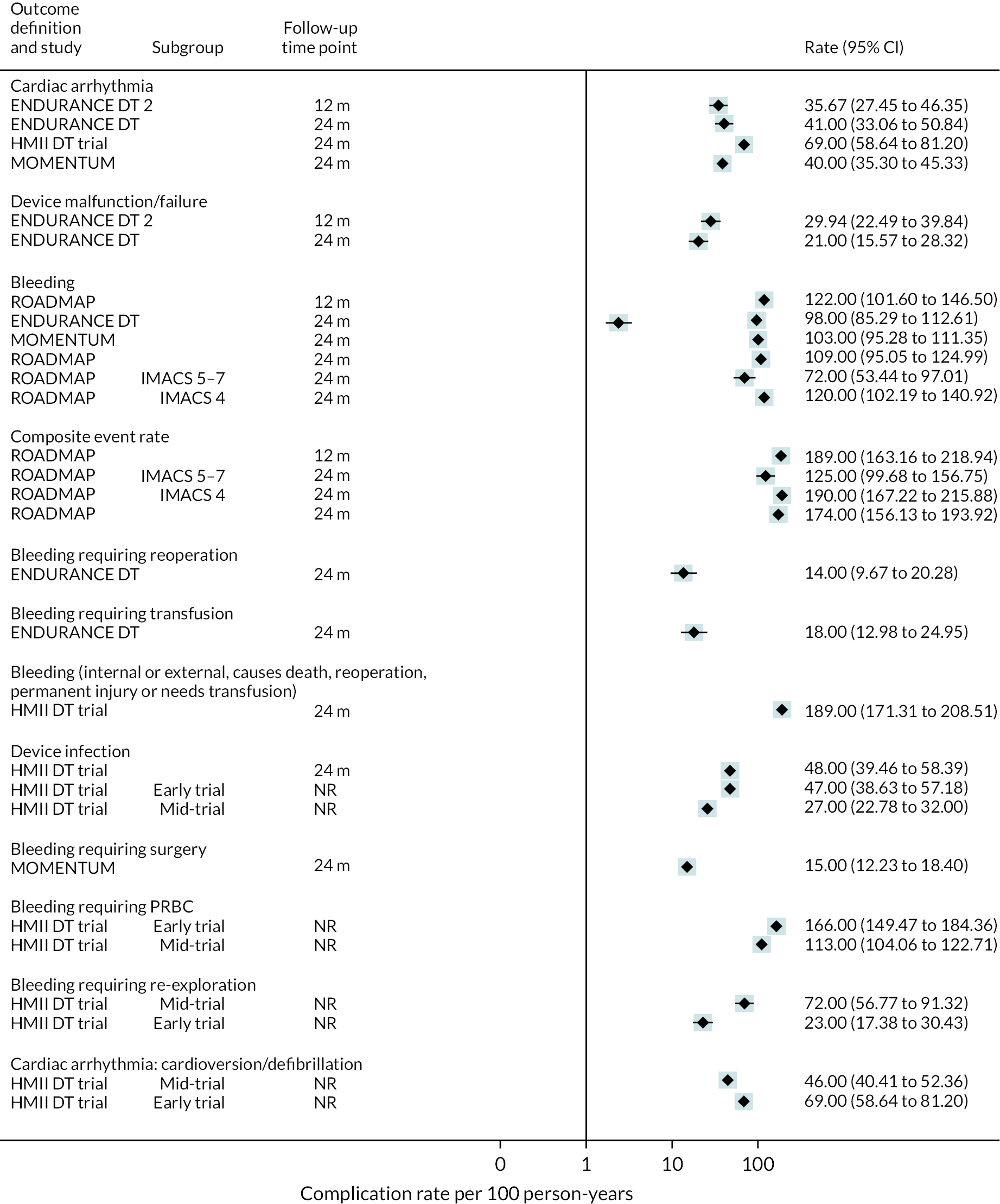

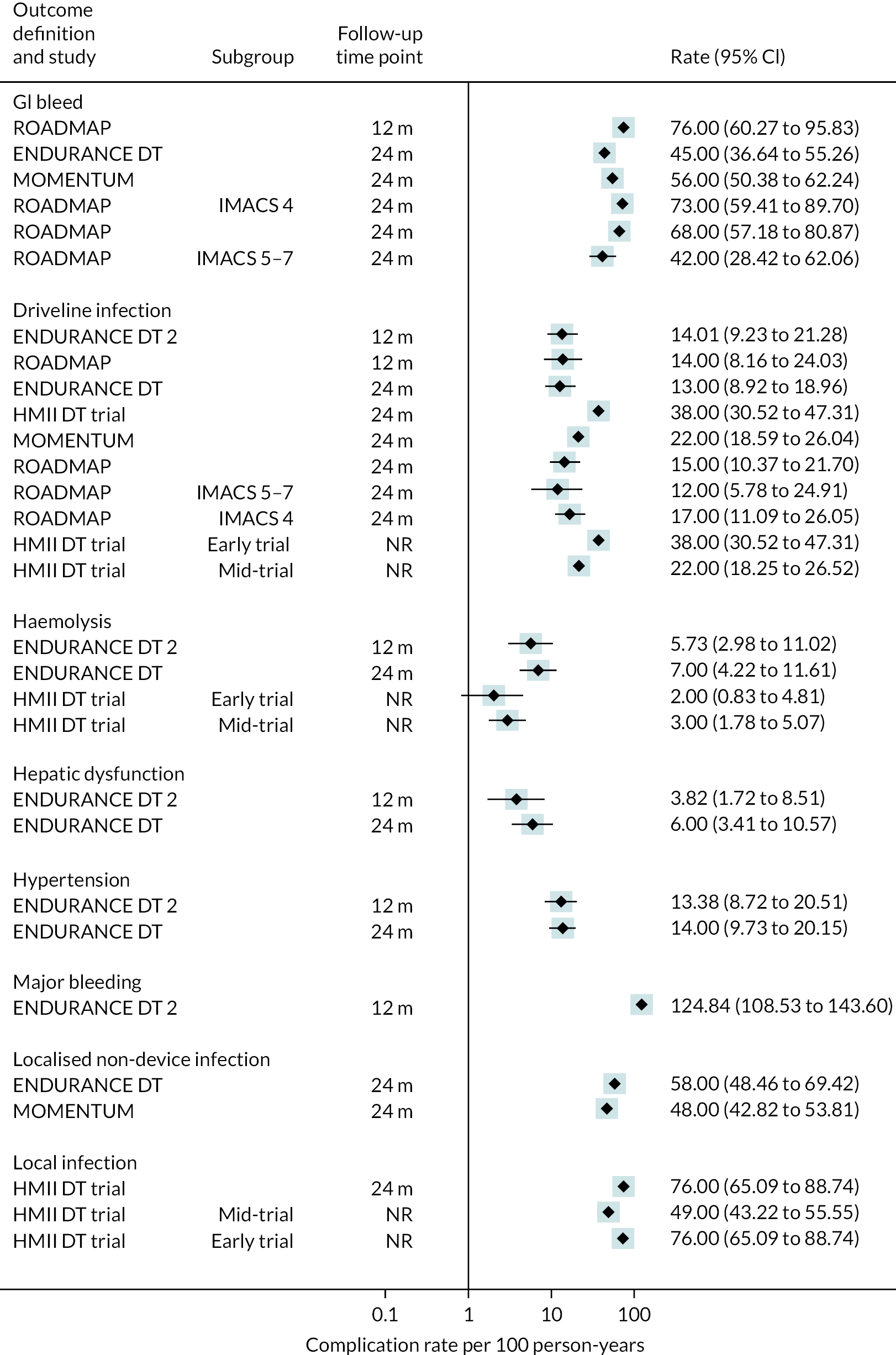

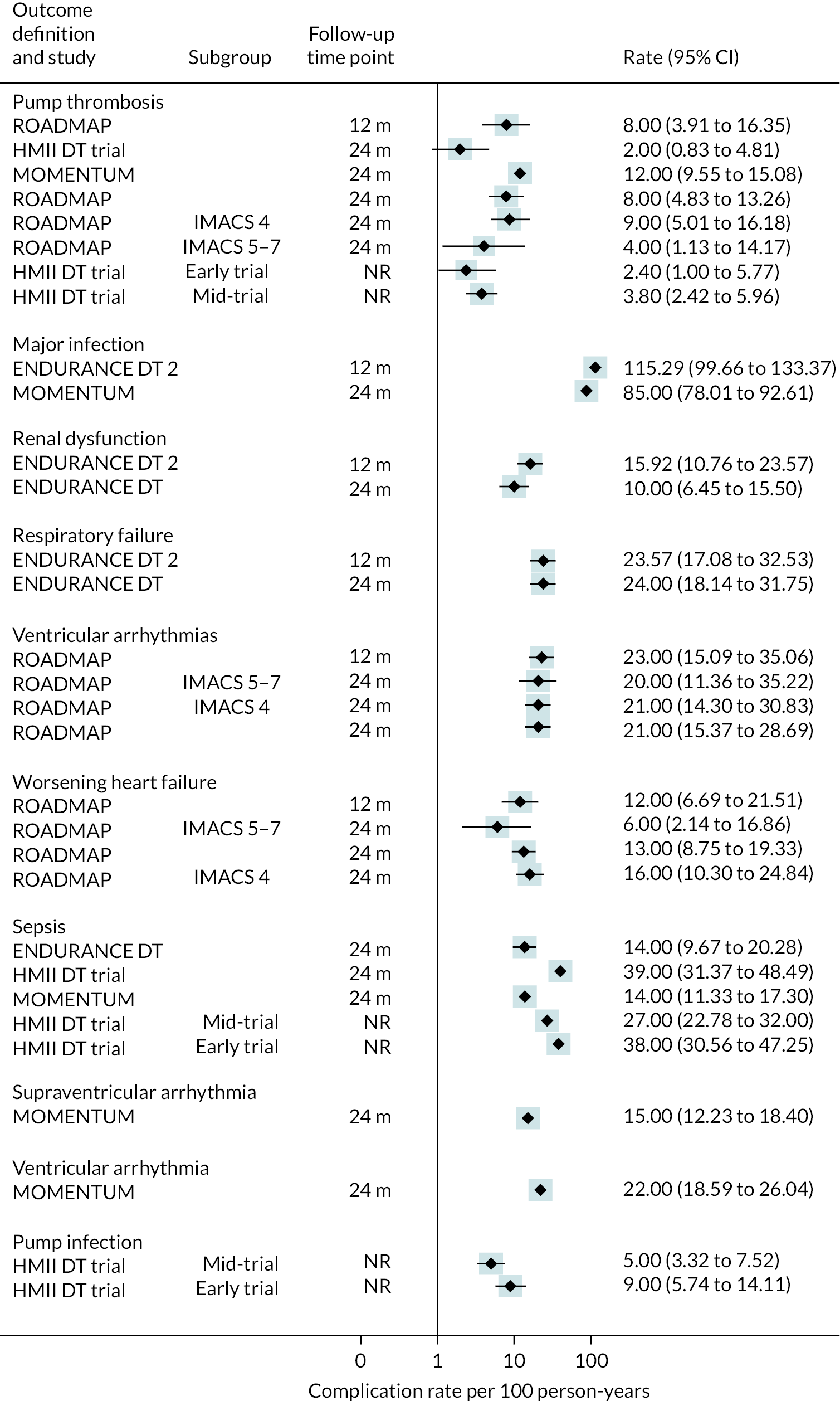

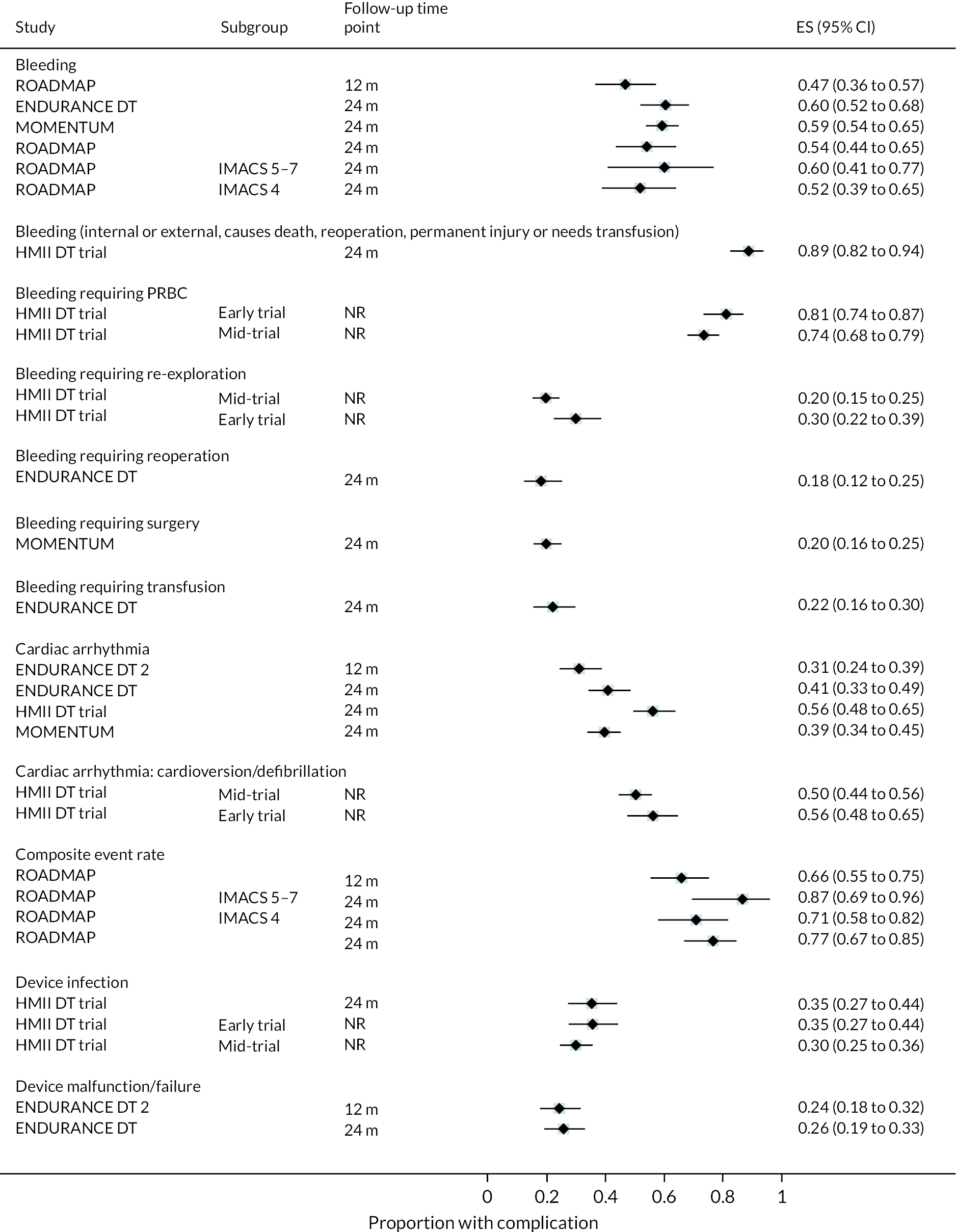

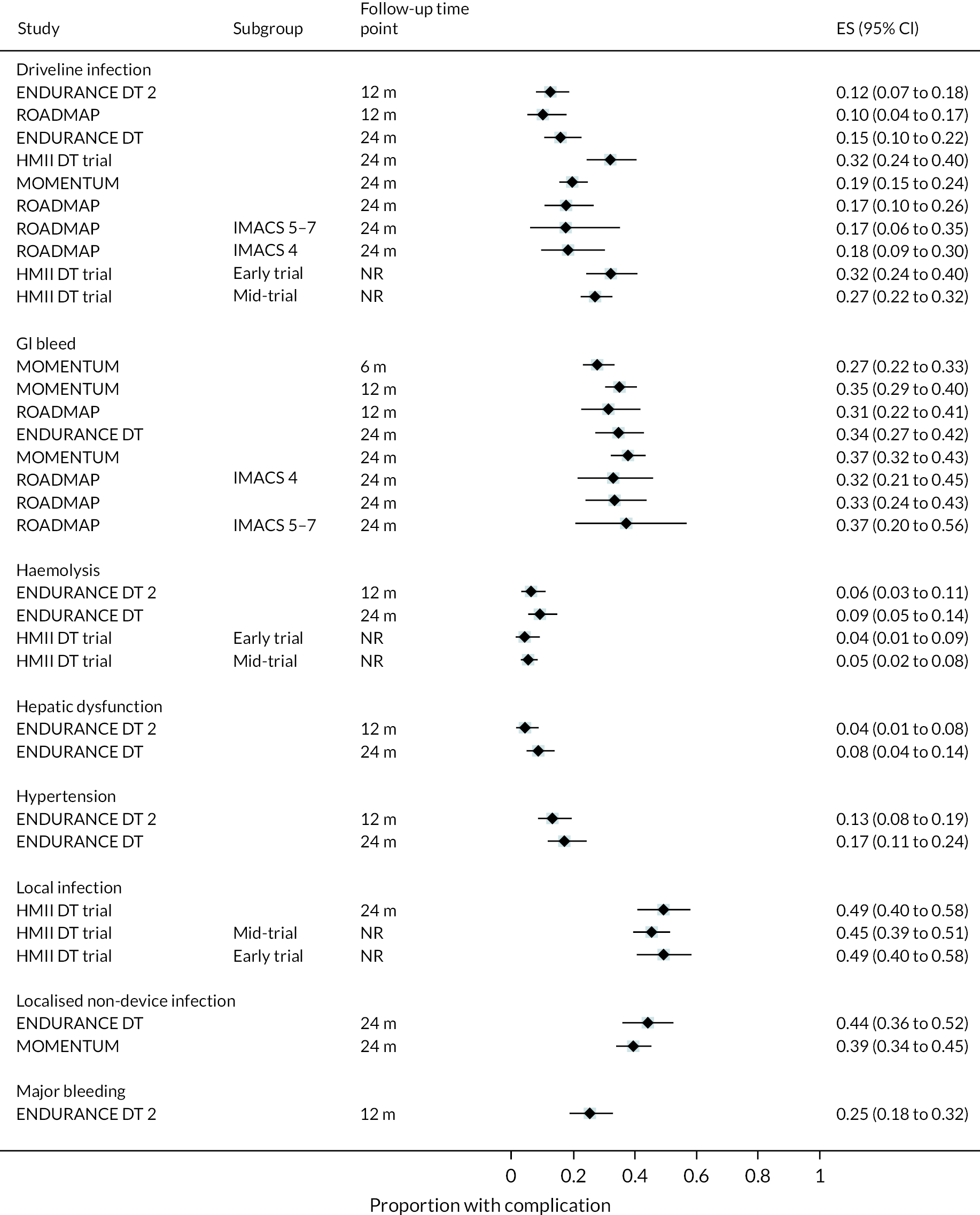

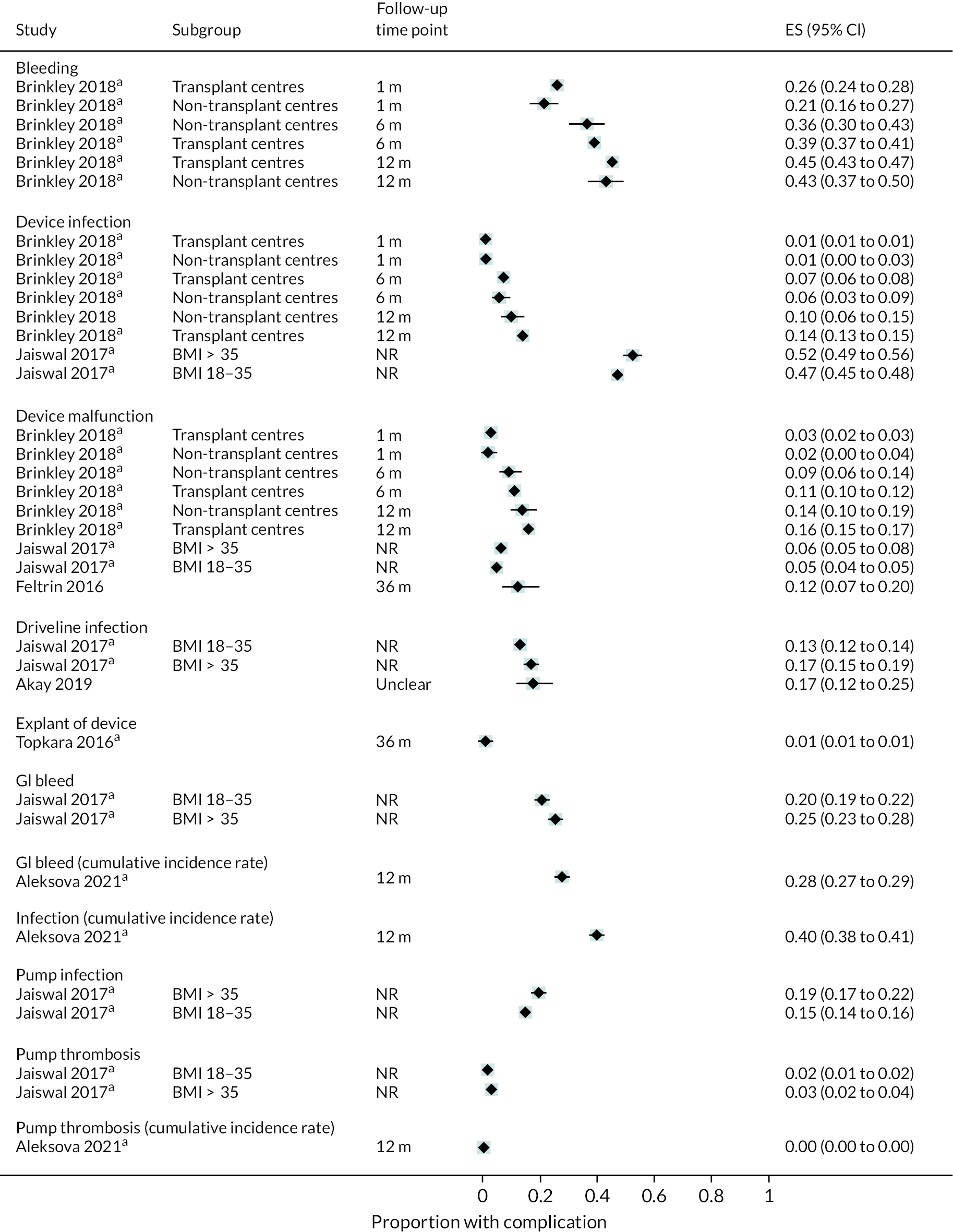

FIGURE 10.

Complication rate per 100 person-years in the HeartMate 3 at all reported follow-up time points.

FIGURE 11.

Proportion of patients with complications in the HeartMate 3 at all reported follow-up time points.

Functional status

The mean six-minute walking distance increased in HM3 patients in MOMENTUM from 137 m at baseline to 320 m at 24 months. However, the proportion of patients with NYHA Class I or II remained similar at baseline (78%) and 24 months (78%).

Ongoing trials

Currently, there are no completed trials comparing the HM3 to any other current LVADs. In addition to the ongoing North American trial of the HM3 versus the EVAHEART device, there is an ongoing Swedish RCT comparing the HM3 to MM, and this trial is expected to be completed in 2023. 47,48 Information on this study and other ongoing trials can be found in Table 7. The Jarvik 2000® is an older-generation device of which data have not been included in this report as it is considered out of date. However, a long-standing trial record established in 2012, which did not appear to have progressed for a long period of time, was updated during the later stages of this report to indicate that the trial of the Jarvik 2000 versus HeartMate II was ongoing, with completion due in December 2023. Therefore, this should be considered in the future.

| Study | Study design | Population | No. participants (no. DT) | Intervention | Comparator | Primary outcome | Length of follow-up (months) | Estimated completion date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swedish evaluation of LVAD as permanent treatment in end-stage HF (SweVAD)49 | RCT | End-stage HF population ineligible for cardiac transplantation | Estimated enrolment 80 participants | HeartMate 3 | Optimal medical management | Survival at 2 years | 24 months minimum (up to 5 years) | December 2023 | Sweden NCT02592499 |

| Sustaining QoL of the aged: heart transplant or mechanical support?50 | Prospective observational | Older (60–80 years) AHF patients undergoing heart transplant or LVAD as permanent therapy | Estimated enrolment: 800 participants | Mechanical circulatory support | Heart transplant | Non-inferior change in patient HRQoL at 2 years | 24 months | March 2022 | USA NCT02568930 |

| Prospective multicentre randomised study for evaluating the EVAHEART®2 left ventricular assist system (COMPETENCE)47 |

RCT | Adult (> 18 years old), AHF NYHA Class IV patients who are refractory to AHF management and meet study inclusion/exclusion criteria will be enrolled | Estimated enrolment: 399 participants, no. DT unclear | EVA2 | HeartMate 3 | Survival to cardiac transplant or device explant for recovery free from disabling stroke (Modified Rankin score > 3) or predefined severe RHF at 6 months after implantation of the originally implanted device | 24 months | March 2024 | USA NCT01187368 |

| LVAD vs. GDMT in ambulatory AHF patients (AMBU-VAD)51 | RCT | Ambulatory AHF patients ≥ 18 years | Estimated enrolment: 92 participants, no. DT unclear | HeartMate 3 | Guideline directed medical therapy | All-cause mortality rate | 24 months | February 2025 | France, NCT04768322 |

| Evaluation of the Jarvik 2000 left ventricular assist system with post-auricular connector--DT Study52 | RCT | End-stage HF patients who are ineligible for transplant | Estimated enrolment: 350 participants, all DT | Jarvik 2000 VAS | HeartMate II | Non-inferiority to control group | 24 months | December 2023 | USA, NCT01627821 |

Additional registry data

Available registries and data

Data from INTERMACS and other registry reports (including IMACS and ITAMACS) were analysed and compared to trial data. Participants enrolled in trials were not eligible for registry inclusion in North America, which means that the populations of these two categories may differ.

Of the 37 registry reports that were included in the review, 29 were from the INTERMACS registry, 2 from IMACS, 2 from ITAMACS, 2 from ELEVATE and 2 from the Thoratec® (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) DT registry (now redundant). DT-specific patient data were limited and were mostly not reported by device type, meaning most of the data were reported across multiple LVADs or sometimes by continuous flow only or pulsatile flow types only. However, INTERMACS and IMACS reports also held the longest follow-up data, reporting up to 60 months for outcomes such as survival, major events and complications in DT patients.

INTERMACS reports contain data from sites in the USA that have agreed to supply anonymous data on registered LVAD patients at their centre. Data are entered at implant where possible, and are then entered over time for events, complications and QoL scores until death or removal/transplant. Only devices that are FDA approved are eligible for INTERMACS inclusion.

IMACS is an international registry that includes all countries and hospitals willing to participate. Currently, this also includes data from INTERMACS, European Registry for Patients with Mechanical Circulatory Support (EUROMACS), J-MACS and the UK registry. Not all of the contributing countries have a DT programme, therefore contributing DT data are limited to countries such as the USA, France and Kazakhstan.

ITAMACS is an Italian registry reporting the vast majority of LVADs and mechanical assist devices implanted in Italy.

ELEVATE is a registry that studies and reports the long-term outcomes of patients on the HM3 device following CE-mark approval in Europe and the Middle East. To date, few DT-specific data have been reported from this registry, though this may be important in the future.

HeartMate 3 data

No usable data specifically for the HM3 device from any registries were available. Patients who are involved in clinical trials are not able to register for INTERMACS, meaning that patients with the HM3 were not likely to enter the registry until after the trial had finished. While some of the later registry reports may include data from HM3 patients, these were not reported separately from other device data. Data were often reported by device type (e.g. centrifugal flow, axial flow), meaning that different devices could not be further distinguished.

Non-INTERMACS observational studies

To supplement findings from trials and registry reports, single and multicentre observational studies that were judged unlikely to overlap with any registry data (i.e. centres did not contribute data to a registry that was known) were analysed. These studies are detailed in Table 8.

| Study ID | Centre | Implant years | Total no. patients (no. DT) | INTERMACS profiles (n, %) | Mean age (SD) | Male (n, %) | Device types (n, %) | Subgroups analysed | Outcomes reported | DT data reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmed 2018 | University of Florida | 1 January 2008–31 December 2015 | 111 (61) | 1–2 (52, 46.8); 3–7 (59, 53.2) |

57.6 (range 19–80) | 92 (82.8) | NR | Low/high socioeconomic status | 1-year survival, re-admission within 30 days, length of stay, aggregate VAD complications | Implant strategy was not found to significantly impact the primary outcomes |

| Aissaoui 2013 | Clinic for Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery of Bad Oeynhausen (Germany) | 2001–April 2011 | 488 (LVAD with temporary RVAD 45, DT 10; LVAD alone 443, DT 115) | NR | LVAD with temporary RVAD 53 (82) LVAD alone 56 (13) |

LVAD with temporary RVAD 37 (82) LVAD alone 289 (65) |

LVAD with temporary RVAD: 9 HeartMate XVE, 9 HeartMate II, 13 HeartWare, 5 VentrAssist, 5 DuraHeart, 4 Novacor. LVAD alone: 50 HeartMate XVE, 111 HeartMate II, 75 HeartWare, 47 VentrAssist, 74 DuraHeart, 53 Novacor, 18 CorAide, 9 LionHeart, 4 Incor, 2 DeBakey VADs |

LVAD with temporary RVAD/LVAD alone | Complications: renal failure, sepsis, adverse cerebral events, reoperation for bleeding, pump malfunction, and arrhythmia Cerebral complications included cerebral haemorrhage, transient ischemia, and cerebral vascular accident |

DT was univariate risk factor for death: odds ratio 7.39 (95% CI 4.09 to 13.4) |

| Akay 2019 | Unclear | May 2012–July 2016 | 222 (144) | 1–2 (124, 56) 3–4 (98, 44) |

54 (12) | 178 (80) | HeartMate II 164 (74), HeartWare HVAD 52 (23), HeartMate 3 6 (3) | Patients who developed DI/patients with no DI | Associations with DI | No. DT patients who had DI 25 |

| Aldbrecht 2015 | Medical University of Vienna | 1997–2012 | 118 (All DT) | Conservative treatment median 3 (IQR 3–3) Pulsatile flow VAD median 3 (IQR 2–3) Continuous flow VAD 3 (IQR 2–4) Patients with INTERMACS 1 were excluded |

Conservative treatment 57 (9) Pulsatile flow VAD 57 (10) Continuous flow VAD 57 (10) |

Conservative treatment 46 (92) Pulsatile flow VAD 22 (88) Continuous flow VAD 38 (88) |

Pulsatile flow VAD 25 (21) Continuous flow VAD 43 (36) |

Conservative treatment (medial therapy) Pulsatile flow VAD Continuous flow VAD |

Survival, cause of death, hospitalisations, heart transplants | All outcomes |

| Baudry 2021 | 19 French Centres | February 2006–December 2016 | 652 (303 of which are INTERMACS 4–7 and focus of analysis, 132 DT) | All patients were INTERMACS 4–7 | 61 (9.9) | 263 (86.8) | HeartMate II 224 (73.9), HeartWare HVAD 52 (17.2), Jarvik 2000 27 (8.9) | N/A | Operative and postoperative outcomes, survival, risk factors for mortality | DT as a risk factor for mortality |

| Bugetti 2016 (CA) | Italy | June 2008–December 2015 | 178 (All DT) | At implant average level was 3 (1.2) | NR | NR | Jarvik 2000 Flowmaker | N/A | Survival, QoL | 12 m survival 82%, 24 m 60%, 36 m 54% |

| Chen 2021 | 19 French centres | 2006–16 | 652 (247 DT, 38) | NR | LVAD implanted < 30 days after cardiomyopathy median 55.2 (IQR 46.9–61.4) LVAD implanted > 30 days after cardiomyopathy median 60.7 (IQR 53.3–66.9) |

561 (86) | HMII 475 (73) HVAD 127 (19) Jarvik 2000 50 (8) |

LVAD implanted < 30 days after cardiomyopathy vs. > 30 days after cardiomyopathy | All-cause mortality, cardiovascular/non-cardiac cause of death, heart transplant, complications (thrombosis, stroke, bleeding, LVAD malfunction) | No. alive at 30 days post implant, DT as a predictor of mortality |

| Consolo 2018 | San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Milan, Italy | March 2015–June 2017 | 68 (All DT) | 1 (20, 30) 2 (17, 25) 3 (15, 22) 4 (15, 22) |

64.7 (7.8) | 64 (94) | HeartMate II 15 (22), HeartWare HVAD 38 (56), HeartMate 3 15 (22) | N/A | Association between platelet activation and the development of thromboembolic events | Incidence of thromboembolic events (patients with events: stroke 4, pump thrombosis 2) |

| Cruz Rodriguez 2020 | NR | January 2008–February 2017 | 204 (77) | Inotrope use < 14 days: 1 (32, 37.2) 2 (44, 51.2) 3 (9, 10.5) 4 (1, 1.2) Inotrope use ≥ 14 days: 1 (49, 41.9) 2 (56, 47.9) 3 (10, 8.5) 4 (2, 1.7) |

Inotrope use < 14 days 51.8 (25th–75th percentile, 38.9–63) Inotrope use ≥ 14 days 56.4 (25th–75th percentile, 48.4–62.7) |

Inotrope use < 14 days 70 (81.4) Inotrope use ≥ 14 days 90 (76.9) |

Only HeartMate II and HeartWare HVAD, numbers not reported | Those on inotropes for < 14 days after implant and those on inotropes for ≥ 14 days after implant | Mortality of LVAD patient on prolonged inotropes, risk factors for early inotrope use, association of prolonged inotrope use and clinical events | Survival for DT compared to BTT HR 1.23 (95% CI 0.72 to 2.11) in a multivariate model |

| Drakos 2010 | NR | 1993–2008 | 175 (74) | NR | RVF 58.2 (12.9) No RVF 56.5 (14.4) |

RVF 61 (79) No RVF 85 (87) |

HeartMate XVE 82 (47), HeartMate VE 42 (24), HeartMate 1000 IP 17 (10), HeartMate II 25 (14), Novacor 9 (5) | RVF vs. no RVF | Survival (not by DT), predictors of RVF | DT as a predictor of RVF in a multivariate model: odds ratio 3.31 (p = 0.005) |

| Galand 2016 (CA) | Multicentre, France | 2008–16 | 223 (160 ICM, 59 DT; 63 DCM, 24 DT) | NR | ICM 60.8 (9.3) DCM 61 (13.3) |

ICM 145 (90.5) DCM 55 (86.9) |

ICM: HeartMate II 107 (66.9), HeartWare HVAD 40 (25), Jarvik 2000 12 (7.5), Ventrassist 1 (0.6) DCM: HerrtMate II |

ICM or idiopathic DCM | Survival, adverse events | 24 m DT survival: ICM 52% DCM 50% No difference between ICM/DCM or by indication |

| Galand 2020 (Same sample of patients as Chen 2021) |

19 French centres | 2006–16 | 652 (247 DT, 38) | NR | Patients aged ≥ 70 years median 71.7 (IQR 70.7–72.8) Patients aged < 70 years median 58.2 (IQR 50.0–64.7) |

561 (86) | HMII 475 (73) HVAD 127 (19) Jarvik 2000 50 (8) |

Patients aged ≥ 70 and patients aged < 70 years | All-cause mortality, cardiovascular/non-cardiac cause of death, heart transplant, complications (thrombosis, stroke, bleeding, LVAD malfunction) | Survival in DT patients ≥ 70 and < 70 presented in survival curve |

| Jaganathan 2019 (CA) | Multicentre USA | NR | 186 (53) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | QoL in a new LVAD QoL tool as well as already established tools | DT vs. BTT: there was no statistical difference in emotional domain (p = 0.11) Social functioning was higher in DT vs. BTT (p = 0.04) No significant difference in PHQ-9 scores between DT and BTT (p = 0.43) |

| Janssen 2021 (CA) | Single centre, the Netherlands | 2010–20 | 63 | NR | Median 63 (range 29–72) | 50 (79) | All HeartWare HVAD | Time in therapeutic range INR < and ≥ 60% | Death, and thromboembolic, neurologic and haemorrhagic events | 13 thromboembolic, 19 haemorrhagic, 19 neurologic events and 34 deaths occurred |

| Kalampokas 2021 (CA) | German centre | January 2010–May 2020 | 227 (27 Age ≥ 70, 200 < 70) | Age ≥ 70 11 (40.7) INTERMACS 4 Age < 70 45 (22.5) INTERMCAS 4 |

Age ≥ 70 73.1 (2.55) Age < 70 55.3 (10.59) |

Age ≥ 70 22 (81.5) Age < 70 174 (87) |

NR | Age ≥ 70 and age < 70 | Peri-procedural complications, mortality | All outcomes, 30 day mortality Age ≥ 70 14.8%, Age < 70 12%. Mid-term mortality (mean 2.5 years) Age ≥ 70 55.6%, Age < 70 32.5% |

| Kapuria 2016 (CA) | NR | 2010–4 | 79 (DT NR) | NR | NR | 58 (73) | NR | N/A | Incidence of GIB, predictors of GIB | DT recipients 6 times more likely to bleed as compared to BTT recipients (OR 6.32, p = 0.032) |

| Loforte 2018 | S. Orsola University Hospital in Bologna and S. Camillo Hospital in Rome | January 2006–December 2017 | Isolated LVADs 170 (30 in derivation cohort, 9 in validation cohort) Unplanned BVAD 88 (32 in derivation cohort, 7 in validation cohort) |

Isolated LVAD: Derivation cohort: 1 (4, 2.9) 2–3 (102, 75.5) 4 (29, 21.4) Validation cohort: 1 (2, 5.7) 2–3 (25, 71.4) 4 (8, 22.8) Unplanned BVAD: derivation cohort: 2–3 (58, 81.6) 4 (13, 18.3) Validation cohort: 2–3 (11, 64.7) 4 (4, 23.5) |

Isolated LVAD: Derivation cohort 54.1 (1.6) Validation cohort 53.1 (1.7) Unplanned BVAD: Derivation cohort 57.3 (2.6)Validation cohort 56.1 (1.4) |

Isolated LVAD: Derivation cohort 120 (88.9) Validation cohort 26 (74.2) Unplanned BVAD: Derivation cohort 51 (69.9) Validation cohort 11 (64.8) |

Isolated LVAD HeartMate II 56 (32.9), HeartWare HVAD 51 (30), CentriMag 35 (20.6), HeartMate 3 19 (11.2), Jarvik 2000 6 (3.5), Heart Assist 5 1 (0.59), Berlin heart Incor 1 (0.59) Unplanned BVAD CentriMag 44 (50); HeartMate II 27 (30.6) HeartWare HVAD 15 (17) HeartMate 3 2 (2.3) |

Include both isolated LVADs and unplanned BVADs | Severe RVF within 30 days of LVAD implantation, all-cause mortality | DT as a predictor of BVAD requirement in multivariate model: HR 2.0 (95% CI 1.7 to 3.9) |

| Loforte 2018 (× 2 CAs reporting results of the same study) | Italy | 2006–16 | 215 LVAD 143, BVAD 72 (DT NR) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Predictors of BVAD need | DT was a major predictor for the need for BVAD (HR 2.0, 95% CI 1.7 to 3.9) |

| Medressova 2019 (CA) | Khazakstan | 2011–8 | 207 (all listed as DT though unclear as they include BTT on long-term support) | NR | 49 (13) | 188 (88) | HeartMate II, HeartWare HVAD or HeartMate 3 | NR | Survival, survival by distance from hospital | Kaplan-Meier survival 12 m 87.3%, 24 m 68.8%, 36 m 60.6%, 48 m 47.2% |

| Papathanasiou 2017 | West German Heart and Vascular Center | December 2010–June 2016 | 112 (77) | 1 (31, 27.7) 2 (18, 16.1) 3 (25, 22.3) 4 (35, 31.3) 5 (3, 2.7) |

58.4 (10.9) | 91 (81.3) | All HeartWare HVAD | Those who underwent resternotomy and those who did not have resternotomy | Prognostic significance of resternotomy, hospitalisations, infection rates, survival | DT as predictor of mortality compared to BTT HR 2.83 (95% CI 1.207 to 6.649) |

Of the 86 included observational studies, 21 were judged unlikely to overlap with registry data. Of these, 2 were carried out in the USA, 13 in Europe, 1 in Kazakhstan and 4 were unclear.

HeartMate 3 data

As with data from registry reports, there were few studies that included patients implanted with HM3 and only one of these reported device-specific data for DT patients. One trial53 reported zero pump thrombosis events in the 15 HM3 patients included in their centre over 24 months of follow-up. No further observational studies reported HM3 data specifically. Often these studies had limited numbers of HM3 patients, likely because the majority of these patients would have been in the MOMENTUM trial when the device was first approved for DT.

HeartMate 3 versus medical management

The key aim of this review is to determine the effectiveness of LVADs compared to MM in DT patients (though the HM3 is currently the only available device on the UK market). However, there are no published studies, randomised or observational in nature, comparing HM3 to MM. However, one ongoing RCT will be important in addressing this question in more detail in the future. This section of the report will detail the available HM3 versus MM data and the methods explored to indirectly compare these interventions in the absence of direct comparisons.

SweVAD study

The SweVAD study (‘Swedish evaluation of left ventricular assist device as permanent treatment in end-stage HF’) is an ongoing RCT comparing the HM3 to ‘optimal medical management’ in those ineligible for a HT. 48 The study aims to recruit 80 participants and follow them up for up to 5 years. The estimated completion date is December 2023 and it will report outcomes for survival, functional capacity, QoL and adverse events. The study is being carried out in seven University Hospitals with implantations being performed at five sites. Given that data are not expected from this study in the immediate future, methods to indirectly compare the HM3 to MM were considered.

Indirect comparison of HeartMate 3 versus medical management through randomised controlled trials

As described in the methods, NMA was considered, where possible, to allow for the indirect comparison of HM3 and MM. This involved sequential indirect comparisons of data through previous RCTs (HM3 vs. HeartMate II, HeartMate II vs. HeartMate XVE and finally HeartMate XVE vs. MM) to ultimately compare the HM3 and MM. To achieve this, data from all previous LVAD trials were extracted and analysed as required. These data are summarised below, in the first instance, to allow for background understanding of the trials and what they assessed and found.

Other trial data

There were five RCTs included in the review (including the HM3 MOMENTUM trial) as well as one non-randomised intervention study (ROADMAP). Generally, the studies compared to either MM (REMATCH and ROADMAP) or an alternative device. Table 2 details the characteristics of the included trials. The most recent and relevant device, the HM3, was compared only to the HeartMate II device. No trials have been completed that compare the HM3 to MM, though ongoing studies are currently exploring this as previously described.

INTERMACS profiles were reported at baseline in all but two of the trials. Most patients were INTERMACS level 3 in ENDURANCE studies across both study groups. Conversely, the ROADMAP study included only patients who were INTERMACS level 4–7.

The mean age did not appear to differ greatly amongst the trials and the intervention groups within each trial, ranging from 62 (HeartMate II DT) to 68 (REMATCH). However, it should be noted that age was reported for different groups of participants in each study. For example, MOMENTUM 3 reported the mean age for all DT patients included, regardless of assigned intervention, whereas most other trials reported the mean age for each arm. The ROADMAP study only reported median age, though this was similar to the other studies, even with the inclusion of participants with INTERMACS profiles 4–7 only.

It is important to note that all of these trials took place in the USA, and that currently no trial data are available in the UK or Europe, though SweVAD may be useful once completed.

HeartWare ventricular assist device

Two RCTs assessed the HeartWare HVAD device. The HVAD was compared to the HeartMate II device in both trials: ENDURANCE DT and ENDURANCE DT Supplemental Trial (an extended study of the HVAD looking at stroke outcomes). The HVAD has now been withdrawn from the market and reporting of results from this device will be of limited value.

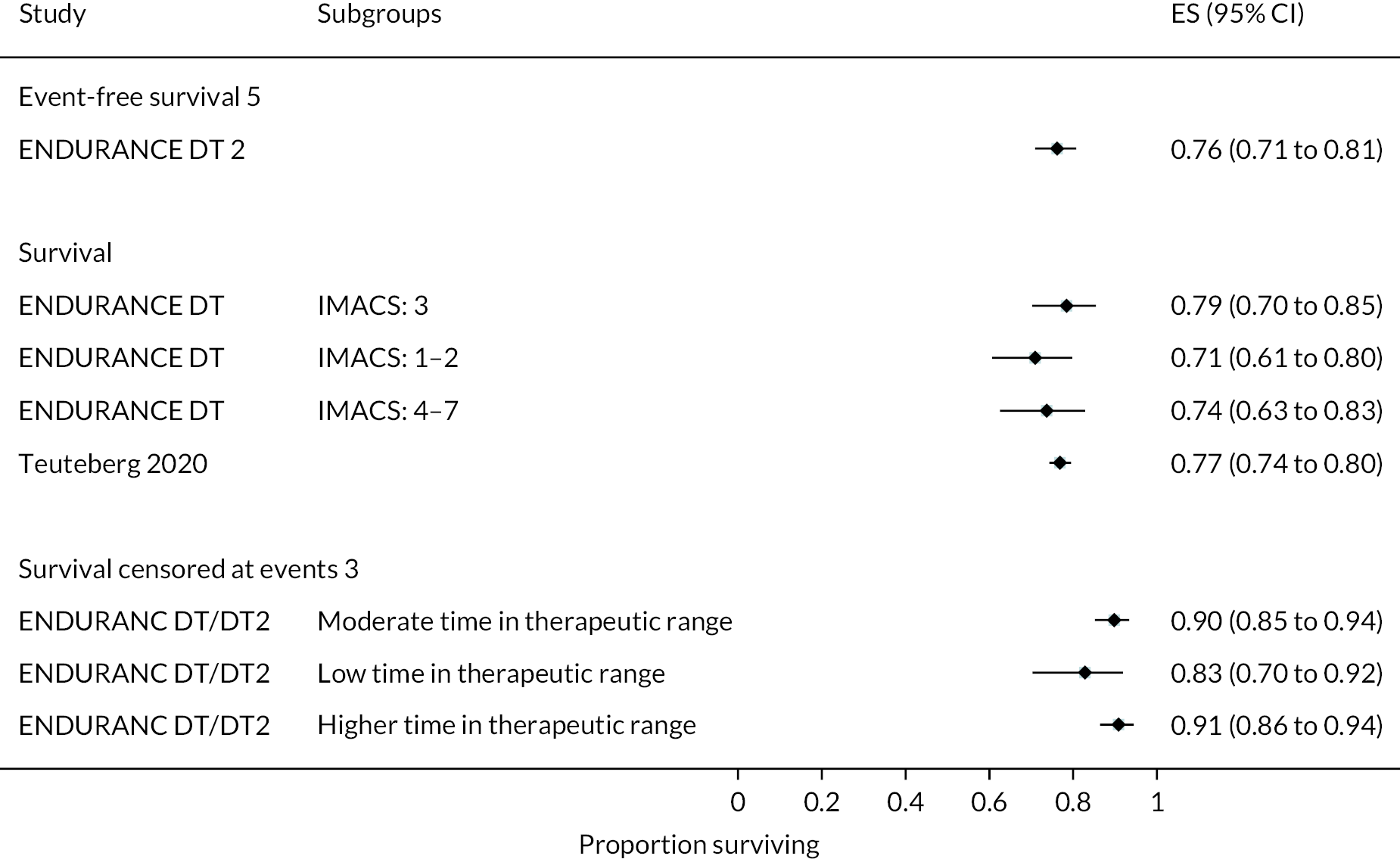

Outcomes

Event-free survival (free of death, disabling stroke and device malfunction and/or failure requiring exchange, explantation or urgent transplantation) was higher in the HVAD compared to the HeartMate II arm, reaching 76% at 12 months in the ENDURANCE Supplemental Trial (compared to 67% in the HeartMate II arm). In the original ENDURANCE trial, the same outcome was 55% at 24 months in the HVAD group and 57% in the HeartMate II group. However, stroke rates were higher in the HVAD device arm, often occurring in the first 6 months. Rates of other events and complications were similar between the HVAD and HeartMate II arms, including major bleeding, cardiac arrhythmias and DIs. In both trials, QoL improved significantly in the HVAD group and was maintained at 12 and 24 months; however, this was also evident in the HeartMate II group.

HeartMate II

The HeartMate II device has been studied in four trials in total. Firstly, as the intervention in the HeartMate II DT RCT (vs. the HeartMate XVE) and the ROADMAP study (a non-randomised comparative trial vs. MM). It was also compared to newer devices in MOMENTUM 3 and ENDURANCE DT. The HeartMate II is currently the most widely studied LVAD.

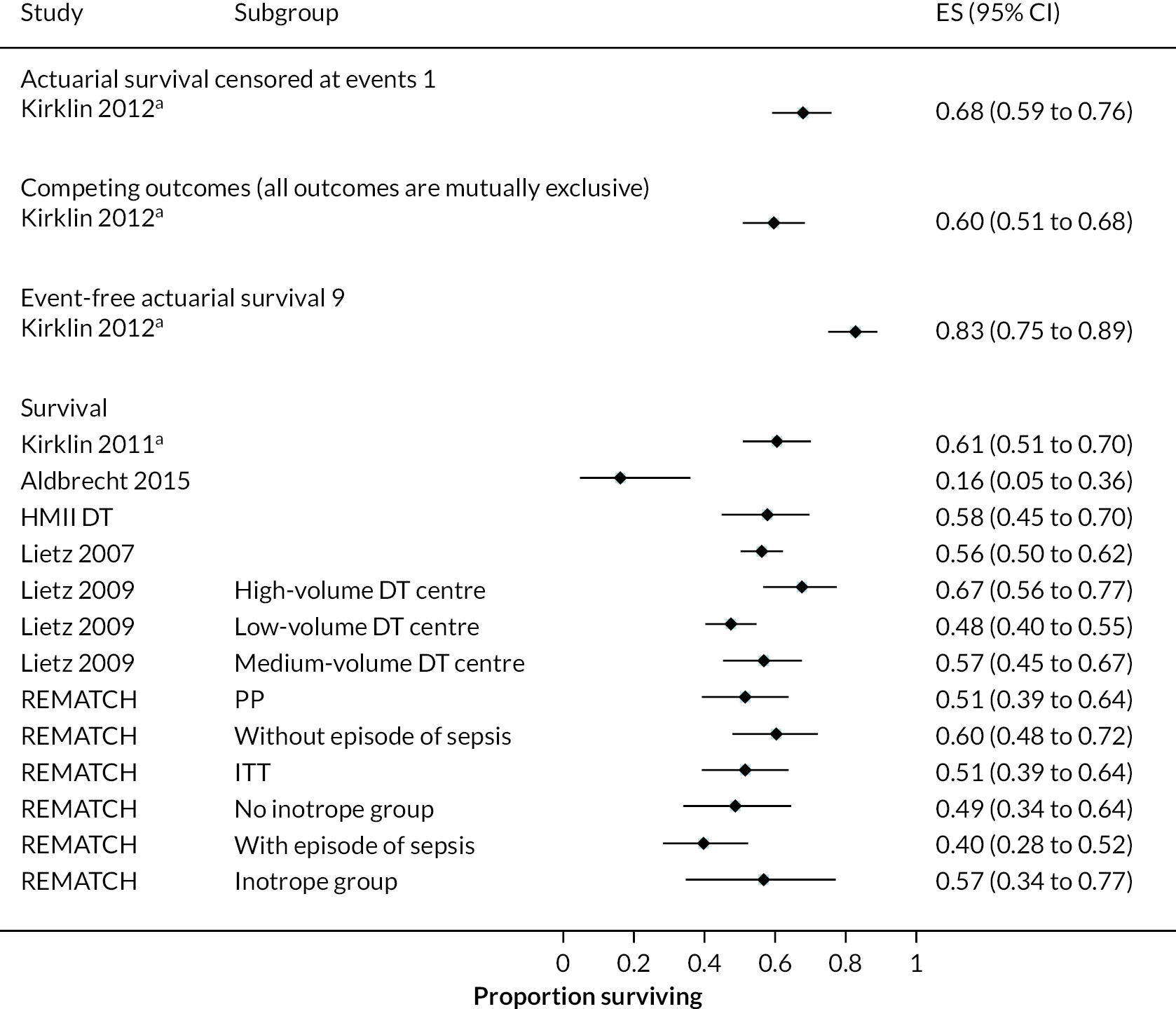

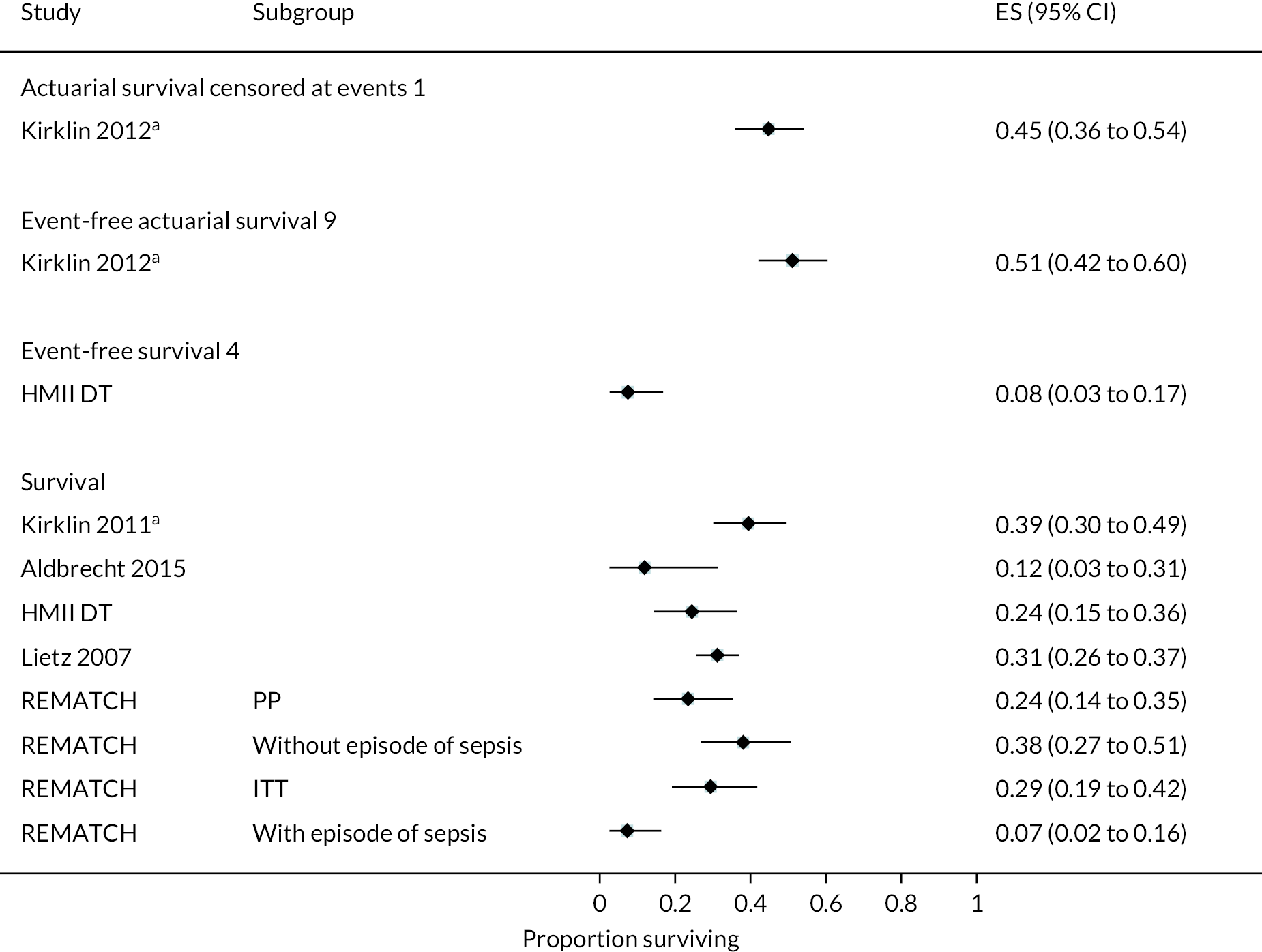

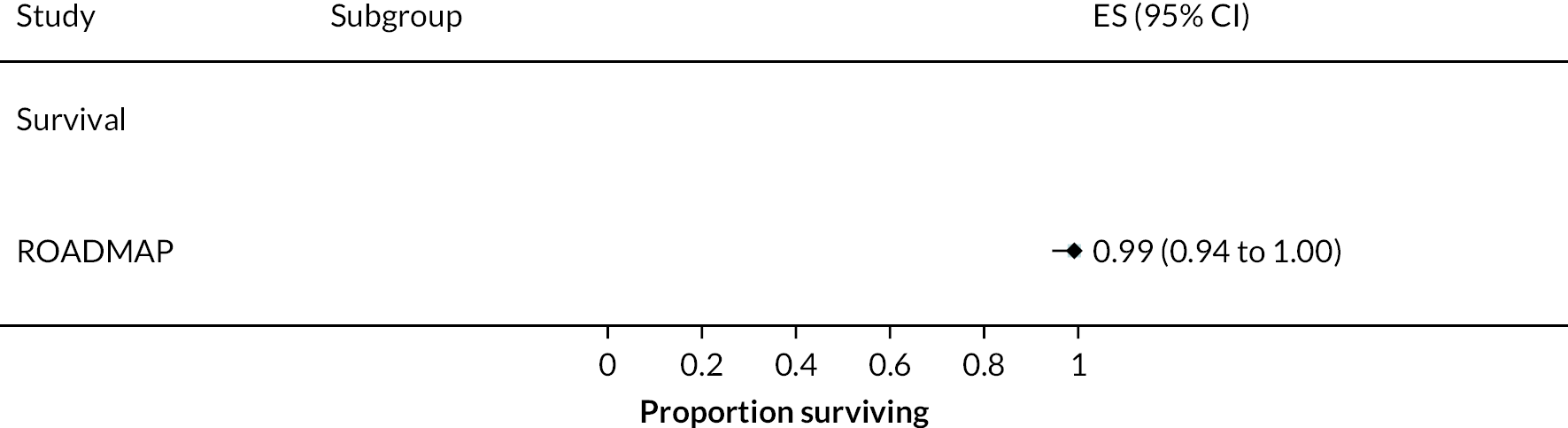

Outcomes

In the HeartMate II DT trial survival was reported to be 68% at 12 months and 55% at 24 months in the HeartMate II group. This was superior to the HeartMate XVE (survival 58% and 24% at 12 and 24 months, respectively). The HeartMate II event-free survival was 82% at 12 months in the more recent ROADMAP study and 70% at 24 months. Events such as haemorrhagic stroke, bleeding and DIs were significantly reduced in the HeartMate II patients compared to the HeartMate XVE patients in the HeartMate II DT trial. Strokes occurred at a rate of 12 events per 100 patient-years, pump replacements 6 events per 100 patient-years and RHF requiring RVAD 2 events per 100 patient-years over 24 months. Strokes in the HeartMate II group at 24 months in the ROADMAP trial were reported at a rate of 9 events per 100 patient-years. Improvements in HeartMate II device outcomes were seen over time in different trials. QoL improved from baseline at 12 and 24 months after the HeartMate II implant in both the ROADMAP and HeartMate II DT trials using the KCCQ and EQ-5D. However, similar improvements were also seen in the control groups in these trials (MM and HeartMate XVE, respectively).

HeartMate XVE

The pulsatile-flow HeartMate XVE was the first LVAD developed in the series of HeartMate devices. It was phased out of clinical use in 2010 in favour of the continuous flow HeartMate II. Outcome data for the HeartMate XVE device can be seen in Appendix 5.

Indirect comparison of HeartMate 3 and medical management – survival

This section discusses the results of the NMA carried out to indirectly compare HM3 and MM for survival. Direct comparison data were taken from several of the RCTs described above (MOMENTUM, HeartMate II DT and REMATCH). The network diagram Figure 12 illustrates the comparisons available to enable the NMA.

FIGURE 12.

Network diagram.

Assessment of the transitivity assumption

Baseline patient characteristics in the three RCTs included in the NMA are shown in Table 9. While most patient and treatment characteristics appeared similar, it shows that IV inotropic drugs (and INTERMACs 1–3) were required by 68% in REMATCH, compared to 87% in MOMENTUM with HeartMate II in the middle at 79%. If the baseline INTERMACS level is an effect modifier for any of the comparisons made in the network, then this would break the transitivity assumption and introduce bias.

| Study ID (no. publications) | Study design | No. participants (no. DT) | Intervention | Comparator | Mean age (SD) | Sex (n, % male) | INTERMACS Profile (n, %) | Length of follow-up (months) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REMATCH 200154 (10) |

RCT | 129 (All DT) | HeartMate XVE LVAD (n = 68) | Medical management (n = 61) | HeartMate 3 66 ± 9.1 Medical management 68 ± 8.2 |

HeartMate 53 (78) Medical management 50 (82) |

NR | 24 months (1 patient in LVAD group still alive at 30 months) | |

| HMII DT 200955 (10) |

RCT | 200 (All DT) | HMII LVAD (n = 134) | HeartMate XVE LVAD (n = 66) | HMII 62 ± 12 HeartMate XVE 63 ± 12 |

HMII 108 (81) HeartMate XVE 61 (92) |

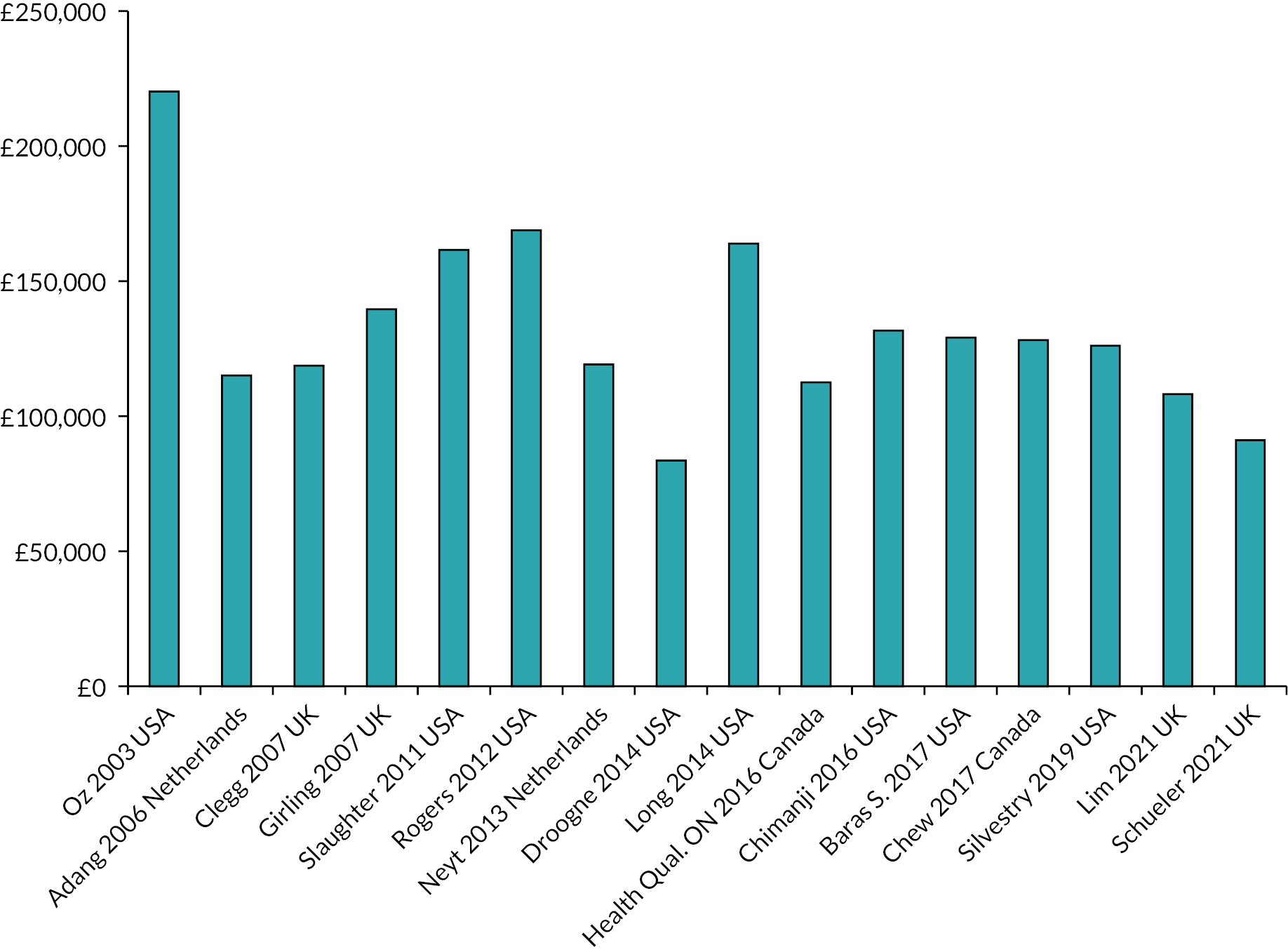

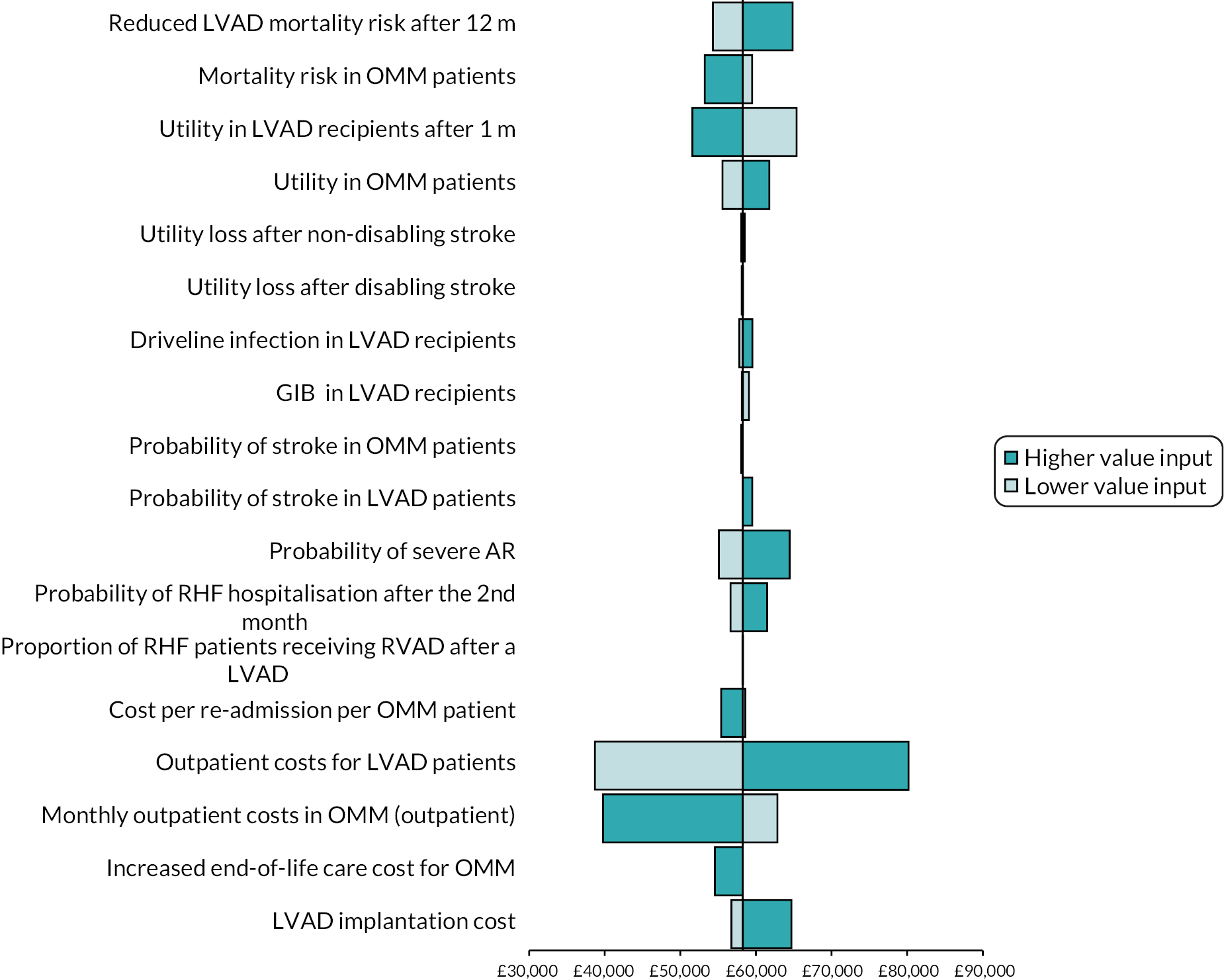

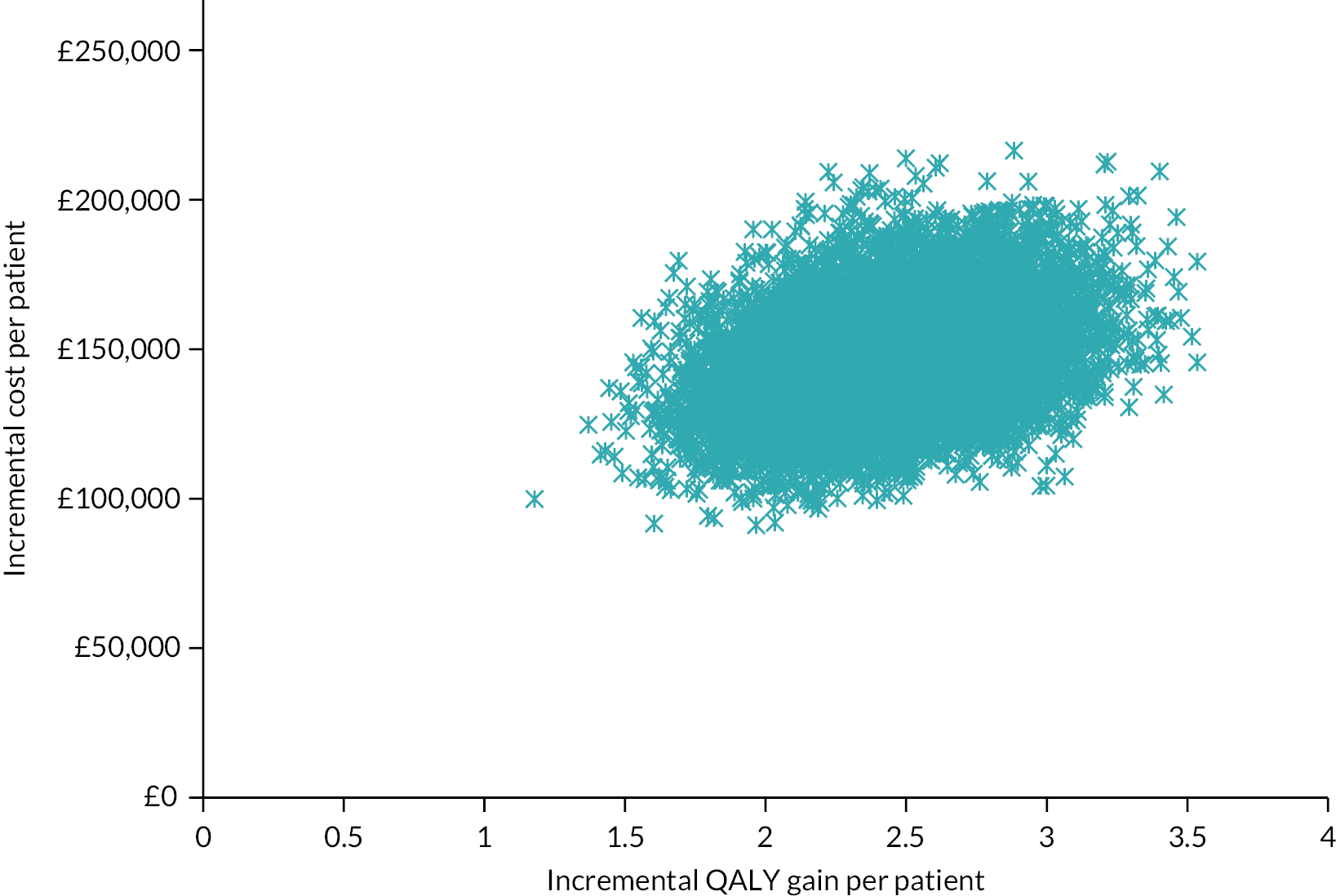

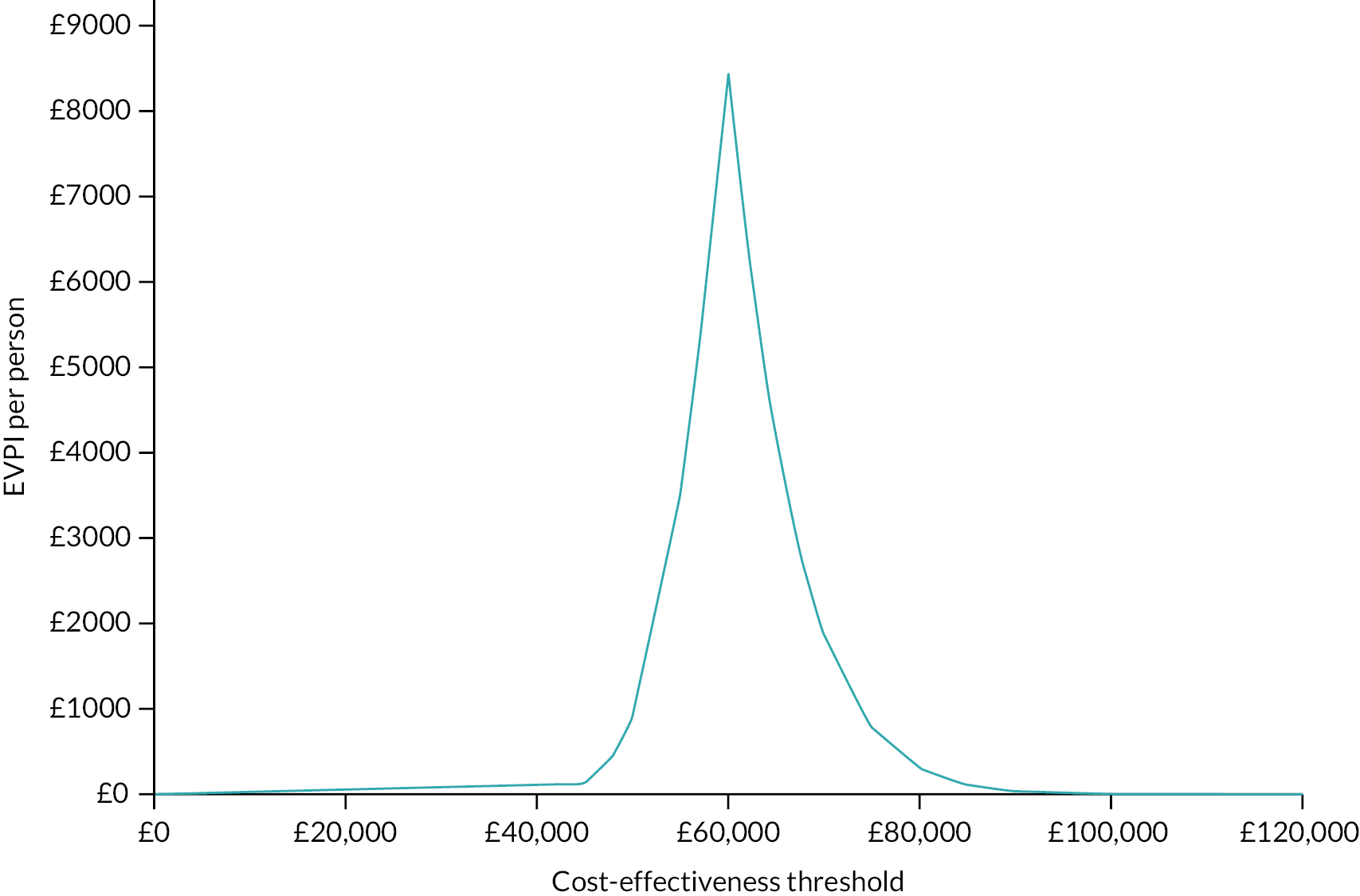

NR | 24 months | Seven papers are retrospective analyses of both the HMII DT and BTT trials and include HMII single arm only |