Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number 14/192/71. The contractual start date was in April 2016. The draft manuscript began editorial review in April 2022 and was accepted for publication in February 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Innes et al. This work was produced by Innes et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Innes et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter are reproduced with permission from Ahmed et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

Gallstone disease (cholelithiasis) is one of the most common gastrointestinal disorders in industrialised societies. The prevalence of gallstones in the adult population is approximately 10–15%. 2–6 Gallstones are more common in women and people over the age of 40 years.

Clinical surveys conducted in Europe, North and South America, and Asia indicate that prevalence rates for gallstone disease range from 5.9% to 25% and tend to increase with age. 7–10 A clinical ultrasound survey conducted in the UK reported prevalence rates of 12% among men and 22% among women over 60 years of age. 9 A multicentre population-based study conducted in Italy has reported an annual incidence of gallstone disease of 0.66% in men and 0.81% in women. 11

In the UK and North America, the number of surgical procedures for gallstone disease increased steadily between the 1950s and 1990s, reflecting the rise in prevalence of identified gallstone disease and the use of cholecystectomy as the treatment of choice. Rates of surgical procedures stabilised in these countries towards the end of the twentieth century. 6

The natural course of gallstones is benign, with most people being asymptomatic and with relatively low progression from asymptomatic disease to symptomatic disease. 12 In an Italian population-based study, the overall frequency of symptom development in asymptomatic people was around 20% over a long follow-up period (mean 8.7 years). 12 Similarly, a systematic review published in 2007 reported that the progression of asymptomatic to symptomatic disease ranged from 10% to 25% in studies that followed up patients after their initial diagnosis (up to 15 years of follow-up). 13 The annual risk of developing symptoms has been estimated to be around 2–4%. 12

Most people with symptomatic uncomplicated gallstone disease probably do not develop complications; the annual rates of developing gallstone-related complications (e.g. acute cholecystitis, acute pancreatitis, acute cholangitis obstructive jaundice) have been reported to be as low as 1–3%. 14–16 The Italian Group for the Epidemiology and Prevention of Cholelithiasis study reported an annual incidence of complications of 0.7% for symptomatic patients. 17

Mortality from gallstone disease is rare, with typically < 1% of people dying from gallstone-related causes. 12,17,18

From a patient’s perspective, the defining symptom of gallstone disease is severe and lasting (i.e. > 30 minutes) abdominal pain. 19,20 Commonly, general abdominal symptoms intensify over a period and become regular pain attacks (biliary colic) and may require medical attention.

A recent large prospective study conducted in the UK (8909 participants) has shown that 10.8% of people experienced complications 30 days after surgery. 21 Furthermore, a proportion of people (up to 40%) may continue to experience pain and abdominal symptoms after surgery. 22 In particular, persistent pain similar to that experienced preoperatively has been reported in about 20% of people after cholecystectomy23,24 and de novo pain has been reported in up to 14% of people. 25

The term ‘postcholecystectomy syndrome’ is an umbrella term widely used to describe the range of symptoms that occur after cholecystectomy. 26 The term ‘persistent postcholecystectomy symptoms’ has been suggested as a more accurate description of these symptoms. 27 Symptoms include biliary and non-biliary abdominal pain, dyspepsia, heartburn, nausea, vomiting and jaundice. Persistent diarrhoea or constipation is often reported after cholecystectomy, and flatulence may arise de novo after surgery. 25 There is no consistent pathophysiological explanation for persistent postcholecystectomy symptoms and, in about 5% of people, the reason for constant abdominal pain remains unknown. 28,29

The rationale for the trial

Current clinical guidelines recommend expectant treatment for asymptomatic gallstones and hence laparoscopic cholecystectomy is considered for biliary pain or acute cholecystitis with radiological evidence of gallstones (i.e. symptomatic gallstones). 30 As per most of the international guidelines, cholecystectomy is the default option for people with symptomatic gallstone disease,30 and one of the most common and, in terms of total costs, costly elective surgical procedures performed in the NHS in the UK. Some 74,373 cholecystectomies were performed in England in 2019 at an average cost of £3581 per procedure31 (61,584 of these following elective admissions). 32 These figures indicate that although some patients are operated on in the acute hospital setting, many people with uncomplicated symptomatic gallstone disease are put on a waiting list and operated on electively after several months. Mean waiting time varies according to available resources; in the UK pre-COVID it has been reported to be around 12 months. 33

Observation and relief of symptoms, delivered mainly in primary care, may be a valid therapeutic option in people presenting with uncomplicated disease, depending on their age, clinical presentation and evolution of symptoms over time. Symptom management includes the prescription of analgesics alongside dietary advice and, when necessary, anti-inflammatory drugs or antibiotics. Moreover, as symptoms of uncomplicated gallstones are usually not urgent, it may be reasonable to consider a conservative option first, which could save a considerable amount of NHS resources.

Early natural history studies, and more recent observational and population-based studies, have suggested that a proportion of people with symptomatic gallstone disease no longer experience biliary pain after the onset of symptoms. 12,17,18,22,34 Larsen et al. 22 found that 45% of symptomatic people on watchful waiting were relieved from symptoms during a 1-year observation period. Similarly, Festi et al. observed that 58% of people with initially mild symptoms, and 52% of those with more severe symptoms, did not experience further pain episodes during a follow-up period of 10 years, or an increase in disease severity over time. 12 If about half of the people treated conservatively were likely to be symptom-free, up to 30,000 cholecystectomies per year could potentially be avoided with a likely saving for the NHS of around £68 million/year.

A National Institute of Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) found that, on average, cholecystectomy is more costly but more effective than observation/conservative treatment for symptomatic gallstones or cholecystitis. 35 Nevertheless, half of the people treated conservatively were symptom-free and did not require surgery in the long term (14-year follow-up) indicating that there is probably a proportion of patients with uncomplicated symptomatic gallstone disease who could benefit from a conservative approach. The specific results were that participants randomised to observation/conservative treatment were significantly more likely to experience gallstone-related complications [risk ratio (RR) 6.69; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.57 to 28.51; p = 0.01], in particular acute cholecystitis (RR 9.55; 95% CI 1.25 to 73.27; p = 0.03), but less likely to undergo surgery (RR 0.50; 95% CI 0.34 to 0.73; p = 0.0004) and experience surgery-related complications (RR 0.36; 95% CI 0.16 to 0.81; p = 0.01) than those randomised to receive surgery. Fifty-five per cent of people randomised to observation/conservative treatment did not require an operation during the 14-year follow-up period, and 12% of people randomised to cholecystectomy did not undergo the scheduled surgical operation. These results were subject to major uncertainties in the reported economic model. Even when cholecystectomy occurred after conservative management, a conservative management strategy had between 40% and 60% chance of being cost-effective for alternative values of willingness to pay for an additional quality-adjusted life-year (QALY).

Furthermore, results were strongly influenced by the proportion of individuals initially treated conservatively who subsequently required surgery. Due to the limited evidence available and the current lack of UK NHS data, the C-GALL Research Group highlighted the need for a well-designed trial assessing the effects and safety of observation/conservative treatment compared with cholecystectomy.

Aims and objectives

The primary aim of the study is to assess the clinical and cost-effectiveness of observation/conservative management with laparoscopic cholecystectomy for preventing recurrent symptoms and complications in adults presenting with uncomplicated symptomatic gallstones in a secondary care setting.

The primary patient objective is to compare observation/conservative management with laparoscopic cholecystectomy in terms of participants’ quality of life (QoL) using the Short Form-36 items (SF-36) health survey bodily pain domain at up to 18 months after randomisation.

The primary economic objective is to assess the cost-effectiveness of observation/conservative management versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy in terms of the incremental cost per QALY.

The secondary objectives are to compare observation/conservative management with laparoscopic cholecystectomy in terms of condition-specific quality of life (CSQ); SF-36 domains (excluding bodily pain domain); complications; need for further treatment; persistent symptoms; healthcare resource use (HCRU); and costs. Secondary outcomes are assessed at 18 and 24 months after randomisation. The bodily pain domain of the SF-36 health survey will also be assessed up to 24 months after randomisation.

The null hypothesis being tested is that there is no difference between observation/conservative management and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The alternative hypothesis is that laparoscopic cholecystectomy is superior.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Parts of this chapter are reproduced with permission from Ahmed et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

The study was prospectively registered on a publicly available website on 27 May 2016 as International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) 55215960.

Trial design

The study protocol has been published in an Open Access journal. 1 The study protocol and study paperwork will be available on the project webpage at https://www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/14/192/71 (accessed January 2024).

C-GALL was a pragmatic, multicentre parallel-group patient randomised superiority trial (with internal pilot phase) to test if the strategy of laparoscopic cholecystectomy is more (cost-) effective than observation/conservative management at 18 months post randomisation. The aim was to recruit 430 adults with symptomatic uncomplicated gallstone disease (biliary pain), who were electively referred to a secondary care setting and considered suitable for cholecystectomy, to assess the clinical and cost-effectiveness of observation/conservative management with laparoscopic cholecystectomy for preventing recurrent symptoms and complications.

The trial design is summarised in Figure 1. Patients were recruited to the trial, and all were followed up to at least 24 months post randomisation and every 6 months thereafter to the end of the trial.

FIGURE 1.

C-GALL trial design. CRF, case report form.

The primary patient objective was to compare observation/conservative management with laparoscopic cholecystectomy in terms of participants’ QoL using the SF-36 bodily pain domain at up to 18 months after randomisation.

The primary economic objective was to assess the cost-effectiveness of observation/conservative management versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy in terms of the incremental cost per QALY. This information was collected at each follow-up time point (3, 9, 12, 18 months and 6 months thereafter post randomisation till end of trial).

Embedded process evaluation

An embedded process evaluation was incorporated into the study design to identify challenges relating to trial design and/or conduct that could be addressed and modified. The process evaluation component included, where necessary: analysis of participant flow data; audio recording of recruitment consultations with potential trial participants; and semistructured telephone interviews with patients and trial participants [trial consenters, trial non-consenters, those who crossed over trial groups, those who returned questionnaires (returners) and those who did not (non-returners)], and in-depth semistructured telephone interviews with clinical site staff. The trial process evaluation is described in more detail in Chapter 6.

Participants

Participants were adults with symptomatic uncomplicated gallstone disease (biliary pain from previous biliary colic or acute cholecystitis) who were electively referred to a secondary care setting and considered suitable for cholecystectomy. Adult patients with diagnosed gallstone disease electively referred to a secondary care setting via general practitioner (GP) referral, accident and emergency (A&E) department or elsewhere, not requiring emergency surgical or endoscopic intervention were approached by the research teams. The following inclusion criteria were used to identify eligible participants.

Inclusion criteria

All adult patients with confirmed symptomatic gallstones electively referred to a secondary care setting for consultation. Clinical diagnosis of gallstone disease was confirmed by imaging. Transabdominal ultrasonography was the standard imaging technique for the diagnosis of gallbladder stones, but diagnosis by any imaging technique was acceptable.

Exclusion criteria

-

Unable to consent.

-

Medically unfit for surgery.

-

Current pregnancy.

-

Previous open major upper abdominal surgery.

-

Gallstones in common bile duct or evidence of previous choledocholithiasis.

-

A history of acute pancreatitis.

-

Evidence of obstructive jaundice.

-

Evidence of empyema of the gallbladder with sepsis.

-

Suspicion of gallbladder cancer.

-

Perforated gallbladder (recent or old perforation detected on imaging).

-

Haemolytic disease.

Identification

Potential participants were recruited from secondary care hospitals across the UK. Participants were identified by the local research team at these participating centres. Following identification of potential participants, an invitation letter and patient information leaflet (PIL) detailing the trial were sent out, inviting them to attend a hospital outpatient clinic visit, where the trial and their treatment would be discussed. Potential participants not identified prior to a clinic visit, or at sites that were unable to send the PIL in advance, were given the PIL at their outpatient clinic visit. The PIL also highlighted that the clinical consultation might be audio-recorded; in sites who had agreed to do this, participants were asked to consent to do so.

At the hospital outpatient clinic visit, the local research team outlined the trial and asked the patient if they were willing to discuss participation and have their conversation audio-recorded. If the patient did not wish to have their conversation audio-recorded the consultation went ahead as normal, and the patient still had the choice to take part in the trial. For those patients who were happy to discuss the trial, a member of the local research team completed a trial screening form using information from the prospective participant and from the clinical record to document fulfilment of entry criteria. Eligibility criteria were then cross-checked with the patients’ clinical records. If the patient was eligible and in provisional agreement, a local research team member met with the patient immediately in the clinic. Eligible participants who expressed an interest in participating had the study explained to them by local research staff and were asked if they had any questions or concerns about participating in the trial. If they agreed to take part, they gave written consent to be randomised.

Recruitment and consent

All staff involved in recruitment and consent had evidence of up-to-date good clinical practice (GCP) training. Written informed consent was sought from those patients interested in participating in the trial. Patients were given sufficient time to accept or decline involvement and were free to leave the study at any time. Patients made the decision to participate during the initial consultation, during a subsequent visit to hospital, or alternatively at home. If the patient decided to take part during the initial consultation, this became the baseline visit. For patients who decided to take part during a subsequent visit to hospital, this became the baseline visit. If the patient agreed to be contacted at home, they received a telephone call from the local research nurse (RN) to discuss any queries. Patients who decided to participate following telephone counselling could either send their completed documents (consent form and baseline questionnaire) through the post to the local team at their treating hospital or bring it with them if they were returning to hospital for another consultation.

Randomisation/treatment allocation

Eligible participants consenting to the trial were randomised to receive either laparoscopic cholecystectomy or observation/conservative management in a 1: 1 allocation ratio, using the randomisation application at the trial office at the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials (CHaRT). The randomisation application was available via a 24-hour telephone Interactive Voice Response randomisation system or a web-based application. The minimisation algorithm used recruitment site, gender (male/female) and age (< 35; 35–64; ≥ 65 years) as minimisation covariates to allocate treatment. A random element (20% chance) was incorporated into the minimisation algorithm.

For patients who consented to take part in the trial at their initial consultation, randomisation happened during this visit, and they were informed of their allocated treatment group immediately. If the patients were not present in the clinic, they were contacted by the research teams to inform them of the allocated treatment group.

Interventions evaluated

-

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (surgical management): the current standard surgical procedure for the management of symptomatic gallstone disease. The gallbladder is removed with the stones within it using keyhole techniques (laparoscopy). The procedure is undertaken under a general anaesthetic. It usually involves three to four small incisions in the abdomen, which allow the surgeon to dissect the gallbladder from its attachments and safely divide the key anatomical structures (the cystic duct and artery) that link it to the main bile ducts. The gallbladder is then separated from the under surface of the liver. Usually the gallbladder (containing the stones) is removed within a retrieval bag via one of the small incisions. The operation takes between 45 and 120 minutes, and many patients are admitted for one night, although day-case laparoscopic cholecystectomy is safely undertaken in otherwise fit patients with appropriate social support. All surgical cases are initially started laparoscopically (keyhole) with an intention to remove the gallbladder. Occasionally it might have to be converted to open surgery either to deal with a complication or due to difficulty in progressing safely. Moreover, an alternative procedure may be performed if there is anticipated difficulty in removing gallbladder safely (i.e. drainage of the gallbladder, subtotal cholecystectomy, etc.).

-

Observation/conservative management: in the context of gallstone disease, this involves the prescription of analgesics to relieve the biliary pain, if and when required. Typical therapy includes paracetamol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (e.g. ibuprofen), narcotic analgesics (e.g. opiates), antispasmodics (e.g. Buscopan), together with generic healthy lifestyle advice. In the longer term, observation/conservative management may involve strategies for symptom control (e.g. analgesia and antispasmodics) alongside the advice to follow a healthy diet and eat regular meals.

Participants who were randomised to the observation/conservative management group of the study were also given a copy of the medical management PIL which provided them with information about what to do if they had a flare-up of their condition and advice on diet.

Blinding of personnel in the study

Baseline data were reported by study participants before randomisation using self-completed questionnaires. Blinding was not possible due to the interventions.

Data collection

The patient-reported outcomes SF-36, CSQ and HCRU were collected at recruitment [baseline (before surgery), except HCRU] and then at 3, 9, 12, 18 and 24 months (post randomisation) and 6 monthly thereafter until the end of trial, December 2021. An additional questionnaire, participant costs, was issued at 18 months. Case report forms (CRFs) were completed after gallstone surgery had taken place (with details of operative procedures), complications, and resource use in hospital. A RN completed a CRF at 24 months for all participants to confirm if they had received any gallbladder-related surgery, and if so the type of procedure and the date it was received.

The schedule for data collection is outlined in Table 1.

| Outcome measure | Baseline | Surgery | 3 months | 9 months | 12 months | 18 months | 24 months | 6-monthly thereafter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-36 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| CSQ | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| CRF | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| HCRU | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Participant costs questionnaire | X |

Baseline

For each participant two CRFs were completed at baseline: participant details and baseline. The participant details CRF recorded name and full contact details, date of birth, gender and ethnicity. The baseline CRF recorded clinical information (including height, weight, information about the gallbladder, confirmation of diabetes and hypertension). The data from the CRFs were entered into the study website.

At baseline, participants completed the baseline questionnaire: SF-36 and CSQ. At the end of the baseline consultation, a reminder card was given to all participants to record information about any surgery they went on to have for their gallstones. Participants were asked to return this to the trial office in a prepaid envelope.

Follow-up

Participants were followed up by questionnaire (issued by post, e-mail or telephone) which collected patient-reported outcomes (SF-36; CSQ; HCRU) at 3, 9, 12, 18 and 24 months (post randomisation) and 6 monthly thereafter until the end of trial. If participants did not respond to the first issue of the questionnaire, a reminder was sent 3 weeks later. If no response was received after 3 weeks, then this was followed up with a telephone call, and if no contact could be made a final questionnaire for this time point was issued. In addition, at 18 months an additional questionnaire, participant costs, was issued to collect information on participant costs in using health services.

Where data were collected by telephone, participants were offered the option of only completing the responses required to capture the primary outcome, safety and surgery data.

A participant newsletter was issued in August 2019 in an attempt to encourage questionnaire response. This included personalised information about their stage in the trial, how many questionnaires were left to complete and, more generally, trial progress.

A RN completed CRFs after any gallstone surgery had taken place, providing details of the operative procedures, complications and resource use in hospital. Costs of the initial intervention procedures were estimated from resource use data recorded on the CRFs coupled with routine unit cost data. Costs associated with subsequent contacts with primary and secondary care (due to symptomatic gallstones) were estimated from patient questionnaires at 3, 9, 12,18 and 24 months (post randomisation) and 6-monthly thereafter until the end of trial and checked at source. QALYs were estimated from patients’ responses to the SF-36.

Where completed follow-up questionnaires identified that a participant had received an operation to remove their gallbladder or received a further treatment or surgery to treat their gallstone symptoms, this was followed up with the site RN to complete the appropriate CRFs.

A RN completed a CRF at 24 months for all participants to confirm if they had received any gallbladder-related surgery, and if so the type of procedure and the date it was received. If participants had been found to have had a surgery, the relevant CRFs were then completed.

Data processing

Research nurses at each of the participating centres entered both baseline and CRF data for their participants onto the study website through an online portal. Follow-up questionnaire data, which were sent from the participant directly to the trial office, were entered into the study website by trial office staff.

As part of the trial’s monitoring plan, the trial office carried out data accuracy checks on a sample of baseline data entered by each site. No data accuracy checks were carried out on the data entered by trial office staff upon receipt of follow-up questionnaires.

Participant withdrawal

Participants remained in the trial unless they chose to withdraw consent or if they were unable to continue for a clinical reason. All changes in status (with the exception of complete withdrawal of consent) meant the participant was followed up for all trial outcomes wherever possible. All data collected up to the point of complete withdrawal were retained and used in the analysis.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary patient outcome measure was QoL. This was measured by area under the curve (AUC) at up to 18 months post randomisation using the SF-36 bodily pain domain (AUC measures at 3, 9, 12 and 18 months).

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were measured at both 18 and 24 months post randomisation. These were:

-

AUC up to 24 months post randomisation for SF-36 bodily pain

-

CSQ

-

SF-36 domains (excluding bodily pain domain)

-

complications (defined as any presurgery, intraoperative or postoperative complications)

-

need for further treatment (patient reported)

-

persistent symptoms [patient reported and consisted of two sections (pain and dyspepsia) of the CSQ]

-

HCRU

-

costs.

Safety and breaches

Adverse events

An adverse event (AE) is defined as any untoward medical event affecting a clinical trial participant. Each AE will be considered for severity, causality and expectedness and may be reclassified as a serious event based on prevailing circumstances.

In the C-GALL trial, AEs were anticipated to occur during or after any type of surgery and while in observation/conservative management. In this trial, the following events were expected.

Adverse events during or after laparoscopic cholecystectomy

Intraoperative complications:

-

bleeding > 500 millilitres (ml)

-

injury to abdominal viscera, including liver tear or laceration

-

anaesthetic complications (including hypersensitivity to the general anaesthesia and/or any of the medications or material used)

-

injury to the bile duct

-

bile leak from the bile duct, hepatic duct or ducts at the base of the liver or bile spillage from the gallbladder

-

bile/stone spillage from the gallbladder.

Immediate postoperative complications:

-

postoperative bleeding > 500 ml

-

injury to the abdominal viscera, including liver tear or laceration

-

injury to bile duct

-

bowel obstruction

-

wound infection

-

pain requiring additional analgesia

-

bile leak

-

thrombosis (deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism)

-

urinary retention

-

infection (sepsis, septicaemia, abscess)

-

retained/missed common bile duct stone.

Late postoperative complications:

-

incisional/port site hernia

-

chronic wound pain

-

infection (sepsis, septicaemia, abscess)

-

biliary pain (right upper quadrant pain)

-

non-specific abdominal pain

-

post cholecystectomy jaundice.

Potential adverse events during observation/conservative management/presurgery

The anticipated risk of developing a potential AE in the conservative management group that might require further surgery or endoscopic treatment was 0.7%/year. 35 The following were expected:

-

acute cholecystitis

-

empyema/mucocele

-

gallbladder perforation

-

acute pancreatitis

-

common bile duct stone

-

obstructive jaundice

-

gallstone ileus.

Adverse events that met the criteria for ‘serious’ were reviewed in order to determine whether or not the event was ‘related’. Within C-GALL, ‘related’ was defined as an event that occurred as a result of a procedure required by the protocol, whether or not it was either (1) the specific intervention allocated at randomisation or (2) it was administered as an additional intervention as part of normal care.

All serious adverse events (SAEs) that were considered to be ‘related’ were recorded on a trial-specific SAE form. SAEs are described as complications or need for further treatment in Chapter 3. SAEs that were not related were not recorded. Deaths were also recorded on this SAE form.

A SAE is any AE that:

-

results in death

-

is life-threatening (i.e. the subject was at risk of death at the time of the event; it does not refer to an event which hypothetically might have caused death if it were more severe)

-

requires hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

is a congenital anomaly or birth defect

-

is otherwise considered medically significant by the investigator.

All AEs and SAEs that met the criteria for recording within C-GALL were recorded from the time a participant consented to join the trial until the end of the trial.

Breaches

Sites were asked to report potential breaches of trial protocol or GCP to the trial office. Trial office staff could also report potential breaches. There were two breaches recorded within the study and these are summarised in Appendix 1, Table 36. Both breaches were assessed by the Chief Investigator and the Sponsor as non-serious.

Ground rules for statistical analysis

The trial analysis followed a statistical analysis plan (SAP), which was agreed by the Project Management Group (PMG) and Trial Steering Committee (TSC) before analysis was started. Apart from the trial statistician, all other authors were blinded to the data when agreeing the SAP. The main analyses were based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle (i.e. analysed as randomised irrespective of non-compliance or crossover) and took place after the 24-month follow-up was completed for all participants. Baseline and follow-up data were summarised using appropriate statistics and graphical summaries. Statistical significance was at the two-sided 5% level with corresponding 95% CIs derived. All analyses were carried out using Stata 16. 36

Sample size

The primary outcome was AUC measured from SF-36 bodily pain up to 18 months. To detect a 0.33 standard deviation (SD) difference, with 90% power and alpha at 5%, 194 participants per group (388 in total) were required. A 0.33 difference in generic health status is considered clinically relevant and in terms of treatment effect size, in the small to medium ranges as observed in other clinical studies. We allowed for 10% of participants to have completely missing outcome data, with no AUC calculable, inflating the sample size to 430 participants in total.

Primary outcome analysis

The primary outcome, AUC SF-36 bodily pain up to 18 months, was analysed using a mixed effects regression model with adjustment for the minimisation covariates gender (male, female), age (< 35; 35–64; ≥ 65 years) and including centre as a random effect. The AUC for each participant was generated by the trapezium rule using baseline, 3-, 9-, 12- and 18-month time points. Missing SF-36 bodily pain baseline values were imputed using centre-specific baseline mean. Our primary analysis included all participants who had at least one time point up to 30 months post randomisation. For participants with missing data at 18 months, multiple imputation (MI) using Rubin’s rule under a missing at random assumption was used to impute their SF-36 bodily pain score at 18 months only. Variables included in the imputation model were SF-36 bodily pain at follow-up time points up to 30 months as well as baseline characteristics. The number of imputations used was the proportion of missing data. If participants were missing SF-36 bodily pain at other time points (apart from 18 months), then the AUC was calculated using the time points available only. Secondary analysis of the primary outcome was performed for participants who had an 18-month score. A sensitivity analysis was performed including all participants who had at least one time point up to 18 months with MI being used for missing 18 months’ data.

Secondary outcome analysis

Short Form-36 bodily pain AUC up to 24 months post randomisation was analysed in a similar way to the primary outcome analysis. CSQ, SF-36 (excluding bodily pain) and persistent symptoms were analysed using repeated-measures mixed-effects regression model correcting for baseline score, minimisation covariates gender (male, female), age (< 35; 35–64; ≥ 65 years) and time as a fixed effect. The repeated measures were assessed at 3, 9, 12, 18 and 24 months with treatment effects estimates from time-by-treatment interactions at each time point. This approach uses participant data from all time points and incorporates a random effect for centre and participant. Data missing at baseline were reported as such. For the analysis, missing baseline data were imputed using the centre-specific mean of that variable. Complications and need for further treatment were analysed using a Poisson model adjusting for minimisation covariates gender (male, female), age (< 35; 35–64; ≥ 65 years) and including a random effect for centre using robust error variance. 37 This allows results to efficiently calculate adjusted relative risk. Analysis was performed separately for data up to 18 months and data up to 24 months.

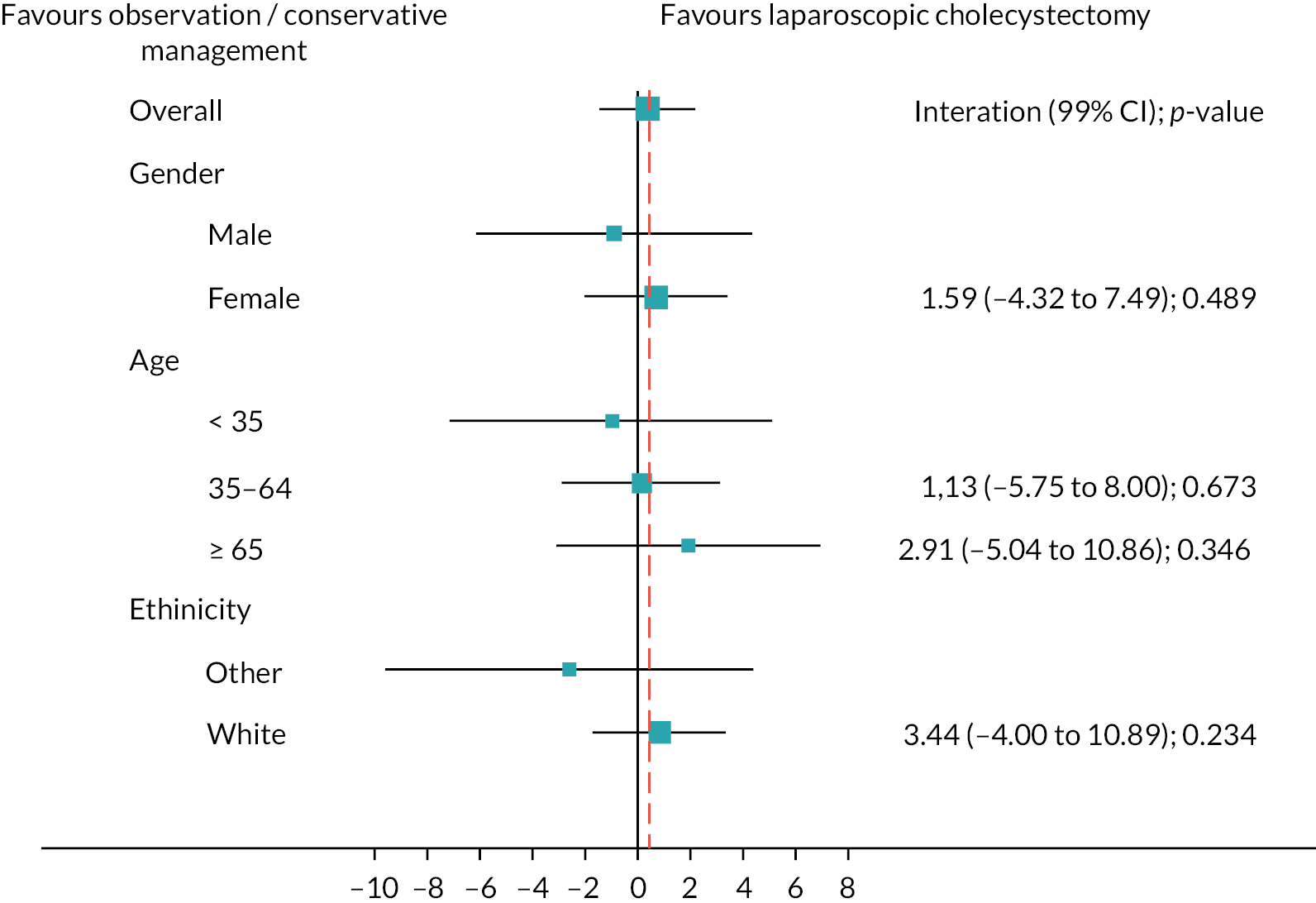

Subgroup analysis

Planned subgroup analyses explored the potential treatment effect moderation of gender (male, female), age (< 35; 35–64; ≥ 65 years) and ethnicity on the primary outcome. For ethnicity, we planned to use the UK census ethnic groupings; however, due to limited numbers in certain categories we categorised ethnicity as white or other than white. The subgroup-by-treatment interaction was assessed by including interaction terms in the models outlined above. We used a stricter level of significance (two-sided 1% significance level) and 99% CIs to reflect the exploratory nature of these analyses.

Compliance analysis

We explored the influence of compliance by undertaking a complier-adjusted causal estimation analysis. Compliance was defined as participants who received their allocated treatment within 24 months. For the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group, participants who received emergency cholecystectomy were defined as non-compliant. For the complier-adjusted causal estimation analysis, an instrumental variable two-stage least squares regression model with compliance instrumented by random allocation was used adjusting for baseline score, minimisation covariates gender (male, female), age (< 35; 35–64; ≥ 65 years) and adjusting for centre using cluster robust variance.

Coronavirus disease 2019

The impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was assessed by looking at the AUC for the subset of data pre-COVID-19 defined as before 11 March 202038 using the same analysis as described in the primary outcome analysis.

Criteria for the termination of the trial

Due to the staggered nature of recruitment and, therefore, the measurement of the primary outcome at 18 months, there were no planned interim analyses for futility or benefit. We proposed one main effectiveness analysis at the end of the trial. During the trial, safety and other data were monitored by reports prepared for the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC).

Differences between the statistical analysis plan and the published protocol

In the published protocol,1 we did not include ethnicity in the subgroup analysis. This was because when writing the SAP, we highlighted the need to look at the effect of different ethnic groups on the primary outcome. Also, we stated we would look at a per-protocol analysis; however, we decided to do a compliance analysis as it does not exclude participants who did not receive their allocated intervention.

Economic evaluation

Within this study both a ‘within-trial’ and a model-based economic evaluation were conducted. These are described in detail in Chapters 4 and 5.

Ethics approval and monitoring

C-GALL received favourable ethics opinion from North of Scotland Research Ethics Committee (REC) A, on 23 May 2016 (REC reference number 16/NS/0053).

Sponsorship

The University of Aberdeen and NHS Grampian co-sponsored the trial.

Management of the trial

The trial management team (consisting of the Trial Manager, Data Coordinator and the Co-Chief Investigators), based within CHaRT, University of Aberdeen, provided day-to-day support for the recruiting centres. Recruiting centres were led by a local Principal Investigator (PI). The PIs in most cases were supported by RNs, trial co-ordinators or dedicated staff, who were responsible for all aspects of the local organisation, including recruitment of participants, delivery of the interventions and notification of any problems or unexpected developments during the study period. The study was supervised by the PMG, which consisted of representatives from the study office and grant holders.

Oversight of the study

Project Management Group

The PMG was responsible for overseeing the management of the trial. This group consisted of the representatives from the study office, and grant holders which included a grant holder who was the patient and public involvement (PPI) representative and a senior programmer. Members of the PMG are listed in the Acknowledgements.

Trial Steering Committee

The TSC was responsible for monitoring and supervising the progress of the C-GALL study. The committee met nine times between August 2016 and September 2021 at agreed intervals. The TSC consisted of independent experts, patient representative, the Co-Chief Investigators and key members of the PMG. Members of the TSC are listed in the Acknowledgements.

One of the independent members of the TSC was a patient representative who contributed their individual perspectives of gallstone disease and the perspectives of gallstone disease of the wider community. Our grant holder PPI representative also provided us with perspectives of gallstone disease from the wider community. The TSC reviewed and commented on the study design, protocol and all study documentation, including patient-facing documents that were sent to potential and recruited participants in the C-GALL study. In addition, the PPI partners (grant holder PPI representative and TSC patient representative) also contributed to regular funder progress reports.

Patient and public involvement

The PPI partners were actively involved in discussions of the study results with the TSC and the trial investigators and contributed to the preparation of the plain language summary. They continue to be involved in developing dissemination materials for participants and contribute to academic papers. The PPI partner on the TSC will comment on the participant results letter. At the end of the study, the PPI partners reflected on their input and made suggestions for future research, which is included in the discussion.

Participants who took part in the focus group for the core outcome set (COS), described in Chapter 7, have remained involved with the C-GALL study as members of the C-GALL PPI group. The PPI group were actively involved in discussions of the study results with the PPI partners and contributed to the review of the Plain language summary. They continue to be involved in the review of dissemination materials for participants.

Data Monitoring Committee

The DMC was independent of the trial and was responsible for monitoring safety and data integrity. The DMC met nine times between October 2016 and November 2021 at agreed intervals. The trial statistician provided the data and analyses requested by the DMC prior to each meeting. The committee consisted of three independent experts. Members of the DMC are listed in the Acknowledgements.

Protocol amendments

There were 10 protocol amendments, and these are summarised in Appendix 2, Table 37. All were minor clarifications within the protocol. All were reviewed by the sponsor and the study funder before being submitted to, and then approved by, the REC.

Important changes to the methods after trial commencement

Extension to recruitment

Slower than anticipated recruitment and longer than anticipated waiting lists for surgery meant an 18-month recruitment extension was required to achieve full sample size and the opportunity for more participants to receive surgery. The 24-month time point, as an outcome, was added as part of this extension. Due to the staggered recruitment of participants, when the later randomised participants reached 24 months, earlier participants would have reached a longer follow-up time point. Therefore, it was decided to carry on collecting data, as it was deemed this would be useful in the analysis and any long-term follow-up plans.

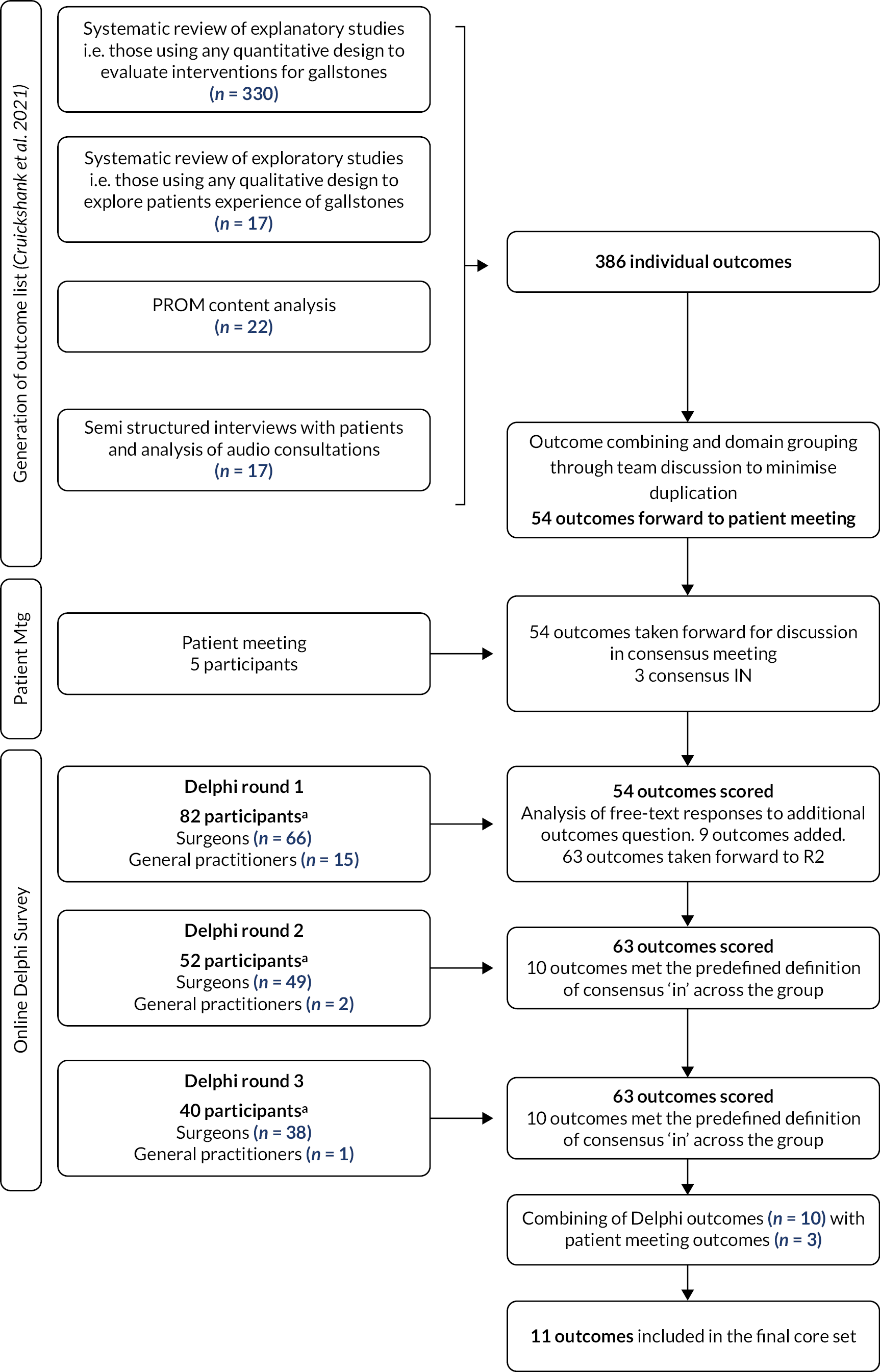

Core outcome set

A COS for uncomplicated symptomatic gallstones was developed and is described in more detail in Chapter 7.

Study Within A Trial

The C-GALL study was involved in the Christmas Card Study Within A Trial (SWAT). 39 Full details of the methods and results can be accessed in the associated publication. 40

In brief participants receiving postal questionnaires in eight host studies (including C-GALL) were randomised to receive a Christmas card or no Christmas card. The primary outcome of the SWAT was response to the next postal questionnaire that was due. The results of the SWAT showed that sending a Christmas card did not increase response rates compared to not sending a Christmas card.

The C-GALL study was also involved in the STICKER SWAT. 41 Participants receiving postal questionnaires in two studies (including C-GALL) are randomised to have a sticker with the trial logo included on the outgoing envelope or a plain envelope. This SWAT is ongoing and, as such, results are not yet available but will be reported in the future.

Chapter 3 Baseline, trial results and clinical effectiveness

Recruitment to the C-GALL trial

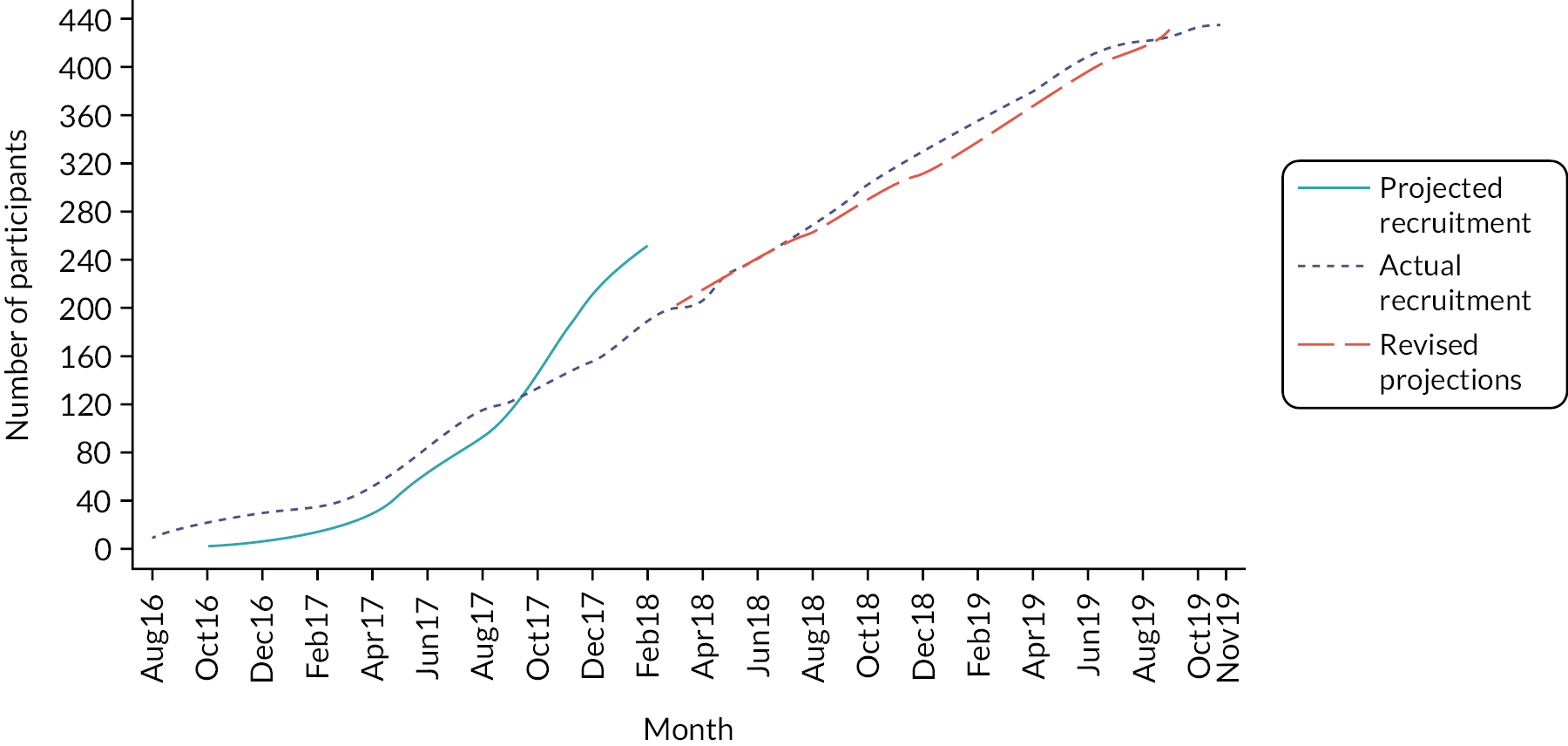

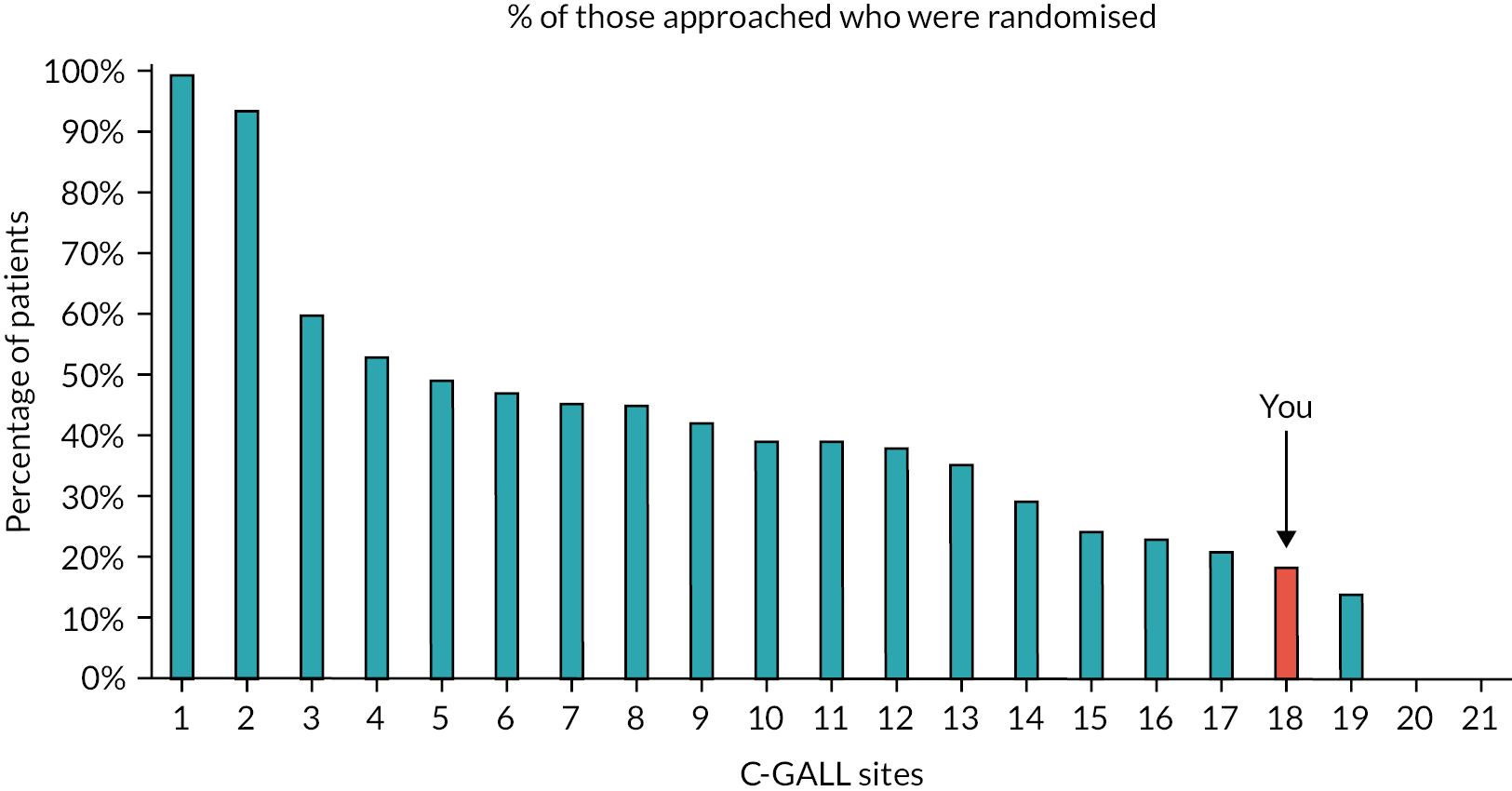

Participants were recruited to the C-GALL trial between August 2016 and November 2019. In total, 436 participants were randomised from 20 centres within the UK (Table 2), 218 to each group. The trajectory of recruitment from all centres is shown in Figure 2. Initial recruitment was limited to four pilot centres (Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Nottingham City Hospital, Musgrove Park Hospital, Taunton and Royal Free Hospital, London). Roll-out to other centres began in April 2017. Recruitment was slower than originally projected and an 18-month extension to recruitment was requested and approved. A revised recruitment projection was initiated in March 2018 (see long dashed line in Figure 2).

| Centre | Observation/conservative management, N = 218 | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, N = 218 | Overall, N = 436 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aberdeen Royal Infirmary | 48 (22.0) | 45 (20.6) | 93 (21.3) |

| Nottingham City Hospital | 24 (11.0) | 24 (11.0) | 48 (11.0) |

| Coventry University Hospital | 23 (10.6) | 21 (9.6) | 44 (10.1) |

| Musgrove Park Hospital, Taunton | 18 (8.3) | 16 (7.3) | 34 (7.8) |

| Birmingham Heartlands Hospital | 15 (6.9) | 15 (6.9) | 30 (6.9) |

| North Tees University Hospital | 13 (6.0) | 15 (6.9) | 28 (6.4) |

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham | 13 (6.0) | 14 (6.4) | 27 (6.2) |

| Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, Glasgow | 11 (5.0) | 12 (5.5) | 23 (5.3) |

| University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff | 10 (4.6) | 11 (5.0) | 21 (4.8) |

| Sandwell Medical Research Unit | 9 (4.1) | 9 (4.1) | 18 (4.1) |

| University Hospital North Durham | 9 (4.1) | 6 (2.8) | 15 (3.4) |

| Royal Free Hospital, London | 4 (1.8) | 10 (4.6) | 14 (3.2) |

| Royal Gwent Hospital, Newport | 5 (2.3) | 7 (3.2) | 12 (2.8) |

| Warwick Hospital | 4 (1.8) | 4 (1.8) | 8 (1.8) |

| Yeovil District Hospital | 4 (1.8) | 4 (1.8) | 8 (1.8) |

| Bedford Hospital NHS Trust | 3 (1.4) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (0.9) |

| Victoria Hospital, Fife | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.9) | 3 (0.7) |

| Royal Liverpool University Hospital | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (0.7) |

| Borders General Hospital | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) |

| Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment over time.

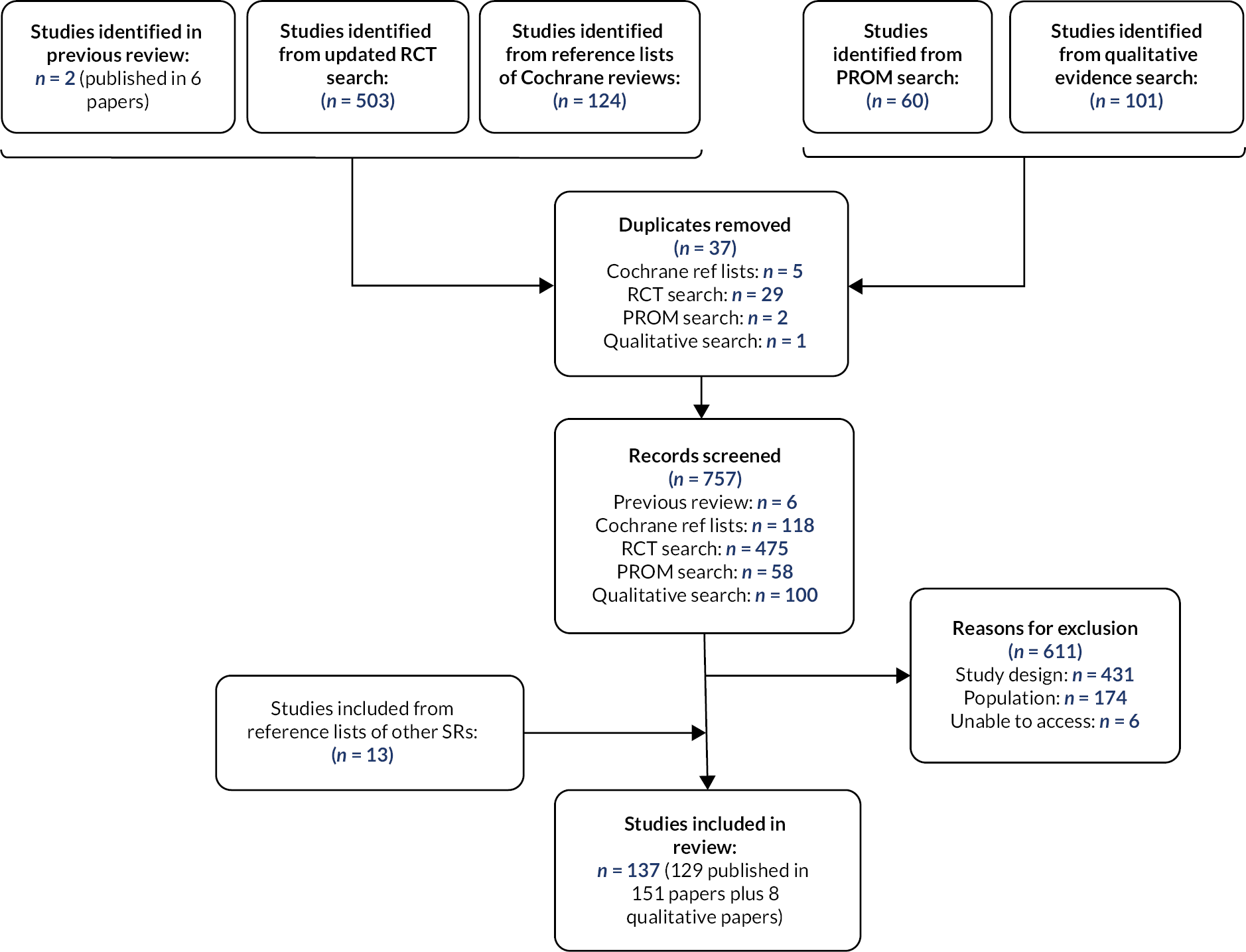

Participant flow

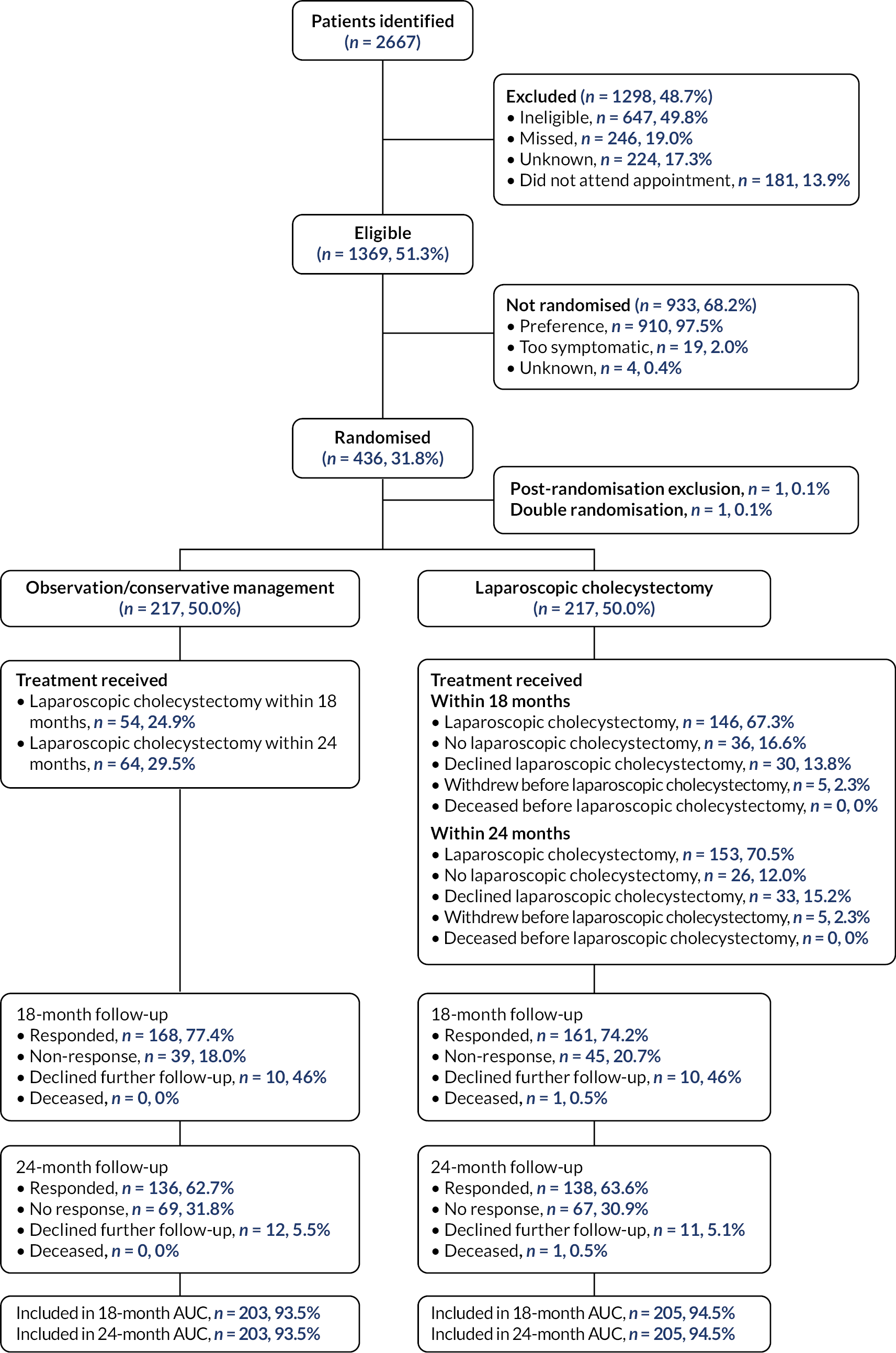

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram for the C-GALL trial is shown in Figure 3. There were 2667 patients identified to be potentially eligible for inclusion into the trial, of which 1298 were excluded. The main reasons for patients’ exclusion were that they were ineligible (647/1298, 49.9%). Ineligibility was due to unconfirmed symptomatic gallstones (233/647, 36.0%), clinical diagnosis of symptomatic gallstone disease not confirmed by imaging (144/647, 22.3%) and being medically unfit for surgery (105/647, 16.2%). Of the 1369 eligible patients, 933 were not randomised with 910/933 (97.5%) having a preference. Main preference reasons were participants preferred laparoscopic cholecystectomy (538/910, 59.1%), observation/conservative management (167/910, 18.4%) and did not want to be randomised (91/910, 10.0%). Further details on reasons why patients were excluded and not randomised are shown in Appendix 3, Table 38.

FIGURE 3.

Participant flow (CONSORT) diagram.

Of the 436 participants randomised, one participant was a post-randomisation exclusion in the observation/conservative management group due to the participant immediately withdrawing from the study due to a previously unstated preference for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. One participant was randomised twice in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group through error. At 24 months, in the observation/conservative management group, 136 (62.1%) participants responded to participant questionnaires (PQs) and 12 (5.5%) had declined further follow-up. In the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group, 138 (63.6%) participants responded to PQs and 11 (5.1%) had declined further follow-up and one participant had died. Appendix 3, Table 39 shows the response rates for each of the follow-up time points.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 3. Overall, the randomised groups were well balanced in baseline characteristics. The mean age of participants was approximately 50 years, over 78% were female and over 85% were white. In the observation/conservative management group, 60.4% had a normal gallbladder wall confirmed by transabdominal ultrasonography or another imaging technique compared with 55.3% in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group. The mean SF-36 norm-based bodily pain score was 44.5 (SD 11.7) in the observation/conservative management group and 43.3 (SD 11.1) in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group.

| Participant characteristics | Observation/conservative management, N = 217 | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, N = 217 |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) – mean (SD); n | 50.4 (15.1); 217 | 50.5 (15.3); 217 |

| Sex – n (%) | ||

| Male | 46 (21.2) | 47 (21.7) |

| Female | 171 (78.8) | 170 (78.3) |

| Ethnicity – n (%) | ||

| White | 185 (85.3) | 188 (86.6) |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic groups | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.5) |

| Asian/Asian British | 15 (6.9) | 15 (6.9) |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British | 7 (3.2) | 5 (2.3) |

| Arab | – | 2 (0.9) |

| Other | 7 (3.2) | 6 (2.8) |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) | – |

| BMI (kg/m2) – mean (SD); n | 32.0 (7.0); 215 | 31.5 (7.1); 217 |

| Diagnosed with diabetes – n (%) | ||

| No | 200 (92.2) | 203 (93.5) |

| Type 1 | – | 2 (0.9) |

| Type 2 | 17 (7.8) | 12 (5.5) |

| Gallbladder walla – n (%) | ||

| Normal | 131 (60.4) | 120 (55.3) |

| Thick | 27 (12.4) | 30 (13.8) |

| Not recorded | 59 (27.2) | 67 (30.9) |

| Thickness of gallbladder wall if thicka (mm) – mean (SD); n | 5.3 (2.1); 10 | 5.9 (3.4); 15 |

| Hypertension – n (%) | ||

| No | 173 (79.7) | 182 (83.9) |

| Yes | 43 (19.8) | 35 (16.1) |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) | – |

| SF-36 norm-based scores – mean (SD); n | ||

| Bodily pain | 44.5 (11.7); 215 | 43.3 (11.1); 216 |

| Physical functioning | 48.2 (10.6); 214 | 47.3 (10.9); 216 |

| Role physical | 47.7 (10.3); 215 | 46.4 (11.4); 216 |

| General health | 45.0 (9.3); 213 | 43.3 (10.4); 216 |

| Vitality | 46.7 (10.0); 213 | 44.7 (10.9); 216 |

| Social functioning | 45.6 (11.7); 213 | 43.9 (12.5); 216 |

| Role emotional | 45.9 (12.4); 215 | 44.7 (13.3); 216 |

| Mental health | 47.7 (10.4); 213 | 46.1 (11.1); 216 |

| PCS | 46.7 (9.3); 213 | 45.6 (9.7); 216 |

| MCS | 46.4 (11.5); 213 | 44.72 (12.1); 216 |

| Otago gallstones CSQ – mean (SD); n | 33.2 (19.9); 210 | 35.4 (20.6); 211 |

| Persistent symptoms scoreb – mean (SD); n | 43.0 (20.9); 213 | 44.6 (22.8); 215 |

Non-responders to questionnaires tended to be younger (mean 46 vs. 52 years), have worse SF-36 bodily pain (mean 41.8 vs. 46.6) and worse disease-specific measures at baseline compared to responders.

Treatment received

At 18 months, 54 (24.9%) in the observation/conservative management group and 146 (67.3%) in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group received surgery. Further surgery details up to 18 months are provided in Appendix 3, Table 40. At 24 months, 64 (29.5%) in the observation/conservative management group, and 153 (70.5%) in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group received surgery with a median time to surgery of 9.0 months (IQR 5.6–15.0) and 4.7 months (IQR 2.6–7.9), respectively. The majority of the surgical operations were elective in both groups, and over 95% were performed laparoscopically. In the observation/conservative management group, surgery was straightforward for 36/64 (56.3%) compared with 94 (61.4%) in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group. In the observation/conservative management group, 54/64 (84.4%) did not have a normal gallbladder and of these 44 (81.5%) had chronic cholecystitis. In the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group, 143/153 (93.5%) did not have a normal gallbladder and of these 130 (90.9%) had chronic cholecystitis. Further surgery details at 24 months are shown in Table 4.

| Surgery details | Observation/conservative management, N = 217 | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, N = 217 |

|---|---|---|

| Received surgery | ||

| Yes | 64 (29.5) | 153 (70.5) |

| No | 153 (70.5) | 64 (29.5) |

| Received surgery, N = 64 | Received surgery, N = 153 | |

| Time to surgery (months) – median (IQR); n | 9.0 (5.6–15.0); 63 | 4.7 (2.6–7.9); 153 |

| Time between surgery and 24 months follow-up (months) – median (IQR); n | 15.0 (9.0–18.4); 63 | 19.3 (16.1–21.4); 153 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) – median (IQR); n | 1 (0–1); 61 | 0 (0–1); 150 |

| Operation time (minutes) – median (IQR); n | 65 (50.0–101.5); 56 | 61 (50.0–85.0); 139 |

| Elective surgery | ||

| Yes | 56 (87.5) | 149 (97.4) |

| No | 6 (9.4) | 2 (1.3) |

| Missing | 2 (3.1) | 2 (1.3) |

| Procedure type | ||

| Laparoscopic | 61 (95.3) | 149 (97.4) |

| Open | 1 (1.6) | 1 (0.7) |

| Laparoscopic converted to open | 1 (1.6) | 1 (0.7) |

| Missing | 1 (1.6) | 2 (1.3) |

| Grade of operating surgeon | ||

| Consultant | 37 (57.8) | 100 (65.4) |

| Consultant supervised by another consultant | 7 (10.9) | 7 (4.6) |

| Registrar | 2 (3.1) | 6 (3.9) |

| Registrar supervised by a consultant | 7 (10.9) | 19 (12.4) |

| Specialty (specialty and associate specialist grade) supervised by a consultant | 2 (3.1) | – |

| Senior House Officer supervised by a consultant | 1 (1.6) | 3 (2.0) |

| Specialist trainee | – | 2 (1.3) |

| Specialist trainee supervised by a consultant | 1 (1.6) | 4 (2.6) |

| Other | – | 2 (1.3) |

| Other supervised by a consultant | 2 (3.1) | 6 (3.9) |

| Unknown operating surgeon but supervised by a consultant | – | 1 (0.7) |

| Missing | 5 (7.8) | 3 (2.0) |

| Prophylactic antibiotic used in the operation | ||

| Yes | 35 (54.7) | 81 (52.9) |

| No | 23 (35.9) | 64 (41.8) |

| Missing | 6 (9.4) | 8 (5.2) |

| Difficulty of surgerya | ||

| Straightforward | 36 (56.3) | 94 (61.4) |

| Mildly difficult | 5 (7.8) | 12 (7.8) |

| Moderately difficult | 4 (6.3) | 16 (10.5) |

| Extremely difficult | 3 (4.7) | 1 (0.7) |

| Missing | 16 (25.0) | 30 (19.6) |

| Admitted to ICU or HDU | ||

| No | 58 (90.6) | 145 (94.8) |

| ICU | – | 2 (1.3) |

| HDU | 1 (1.6) | – |

| Missing | 5 (7.8) | 6 (3.9) |

| Time in ICU (hours) – median (IQR); n | – | 30 (24–36); 2 |

| Time if HDU (hours) – value; n | 47; 1 | – |

| Required additional pain relief predischargeb | 12 (18.8) | 31 (20.3) |

| Histopathology | ||

| Normal gallbladder | ||

| Yes | 6 (9.4) | 7 (4.6) |

| No | 54 (84.4) | 143 (93.5) |

| Missing | 4 (6.3) | 3 (3.0) |

| Cholecystitis in abnormal gallbladder | ||

| No | 4 (7.4) | 7 (4.9) |

| Acute | 5 (9.3) | 5 (3.5) |

| Chronic | 44 (81.5) | 130 (90.9) |

| Missing | 1 (1.9) | 1 (0.7) |

| Incidental biliary cancer | ||

| No | 59 (92.2) | 149 (97.4) |

| Yes | – | – |

| Missing | 5 (7.8) | 4 (2.6) |

For those who had not had surgery by 24 months (Table 5), 15 (6.9%) were on a waiting list and 7 (3.2%) declined any further follow-up from hospital records in the observation/conservative management group; 13 (6.0%) and 5 (2.3%) in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group.

| Status | Observation/conservative management, N = 217 | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, N = 217 |

|---|---|---|

| Gallbladder removed | ||

| Yes | 64 (29.5) | 153 (70.5) |

| No | 153 (70.5) | 64 (29.5) |

| If no, status of participant | ||

| Participant is on surgical waiting list | 15 (6.9) | 13 (6.0) |

| Participant not on surgical waiting list | 131 (60.4) | 13 (6.0) |

| Withdrew before 24 months | 7 (3.2) | 5 (2.3) |

| Declined laparoscopic cholecystectomy | – | 33 (15.2) |

Primary outcome

Figure 4 shows the mean of SF-36 norm-based bodily pain score. At 18 months, the mean SF-36 norm-based bodily pain score was 49.4 (SD 11.7) in the observation/conservative management group and 50.4 (SD 11.6) in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group (Table 6). For the primary analysis, the mean AUC over 18 months was 46.8 for both groups with no difference: MD –0.0, 95% CI (–1.7 to 1.7); p-value 0.996.

FIGURE 4.

Mean SF-36 norm-based bodily pain score up to 24 months. Higher score indicates better quality of life. Bars represent ± SD.

| Primary outcome | Observation/conservative management, N = 217 | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, N = 217 | Observation/conservative management, N = 217 | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, N = 217 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITT | ITT | Complieda | Not-compliedb | Compliedc | Not-compliedd | |

| Primary analysis | ||||||

| Summary measures based on available data | ||||||

| Baseline | 44.5 (11.7); 202 | 43.4 (11.2); 205 | 46.3 (11.1); 142 | 40.3 (11.8); 60 | 43.1 (11.1); 147 | 44.1 (11.7); 58 |

| 3 months | 44.6 (11.5); 176 | 42.6 (11.0); 174 | 46.4 (10.8); 124 | 40.1 (12.0); 52 | 42.0 (11.0); 126 | 44.2 (10.7); 48 |

| 9 months | 46.6 (11.4); 144 | 47.9 (12.7); 160 | 46.0 (10.8); 103 | 48.1 (12.9); 41 | 48.7 (12.5); 119 | 45.6 (13.1); 41 |

| 12 months | 48.6 (11.6); 156 | 49.0 (11.4); 149 | 47.8 (11.0); 118 | 50.8 (13.3); 38 | 50.0 (10.6); 112 | 45.9 (13.1); 37 |

| 18 months | 49.4 (11.7); 167 | 50.4 (11.6); 161 | 48.9 (11.6); 121 | 50.6 (11.8); 46 | 51.5 (11.1); 119 | 47.3 (12.3); 42 |

| 24 months | 48.0 (12.0); 135 | 49.1 (12.3); 138 | 46.8 (11.9); 102 | 51.9 (11.7); 33 | 49.9 (11.5); 100 | 47.1 (14.1); 38 |

| AUC over 18 monthse | 46.8 (8.8); 203 | 46.8 (8.7); 205 | 47.2 (8.6); 143 | 45.8 (9.0); 60 | 47.2 (8.2); 147 | 45.6 (9.8); 58 |

| MD, 95% CI; p-value | –0.0 | (–1.7 to 1.7); 0.996 | –0.0 | (–5.1 to 5.1); 0.997 | ||

Sensitivity and complete case analyses are shown in Appendix 3, Table 41.

Compliance analysis

Figure 5 shows the mean of SF-36 norm-based bodily pain score by compliance, where compliance was defined as participants receiving their allocated treatment within 24 months (excluding those two participants in the cholecystectomy group where surgery was done as an emergency case). For the compliance analysis of AUC over 18 months, there was no evidence of a difference: MD –0.0, 95% CI (–5.1 to 5.1); p-value 0.997 (see Table 6).

FIGURE 5.

Mean SF-36 norm-based bodily pain score up to 24 months by compliance. Higher score indicates better quality of life. Compliance was defined as participants who received their allocated treatment within 24 months (apart from the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group if surgery was an emergency).

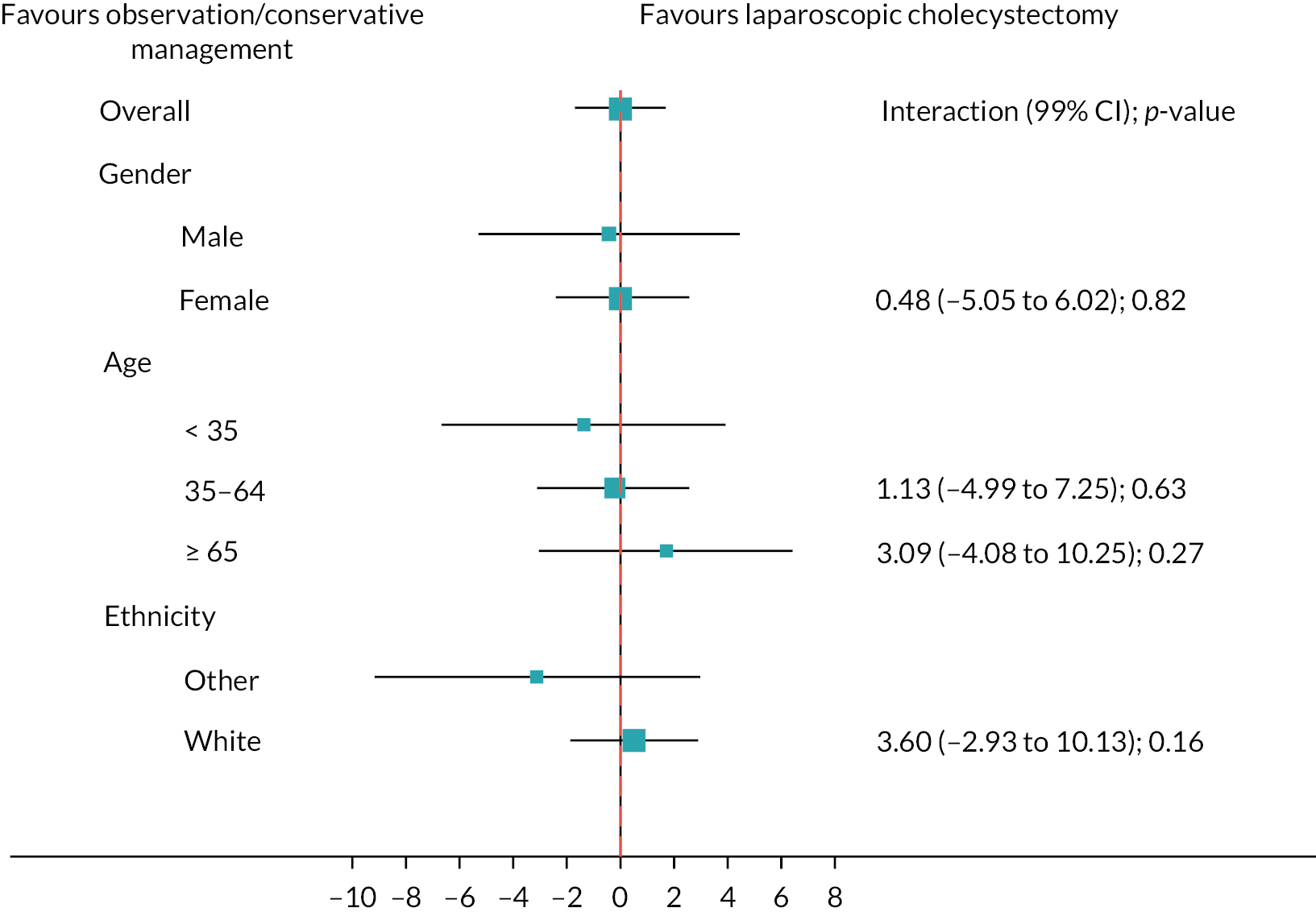

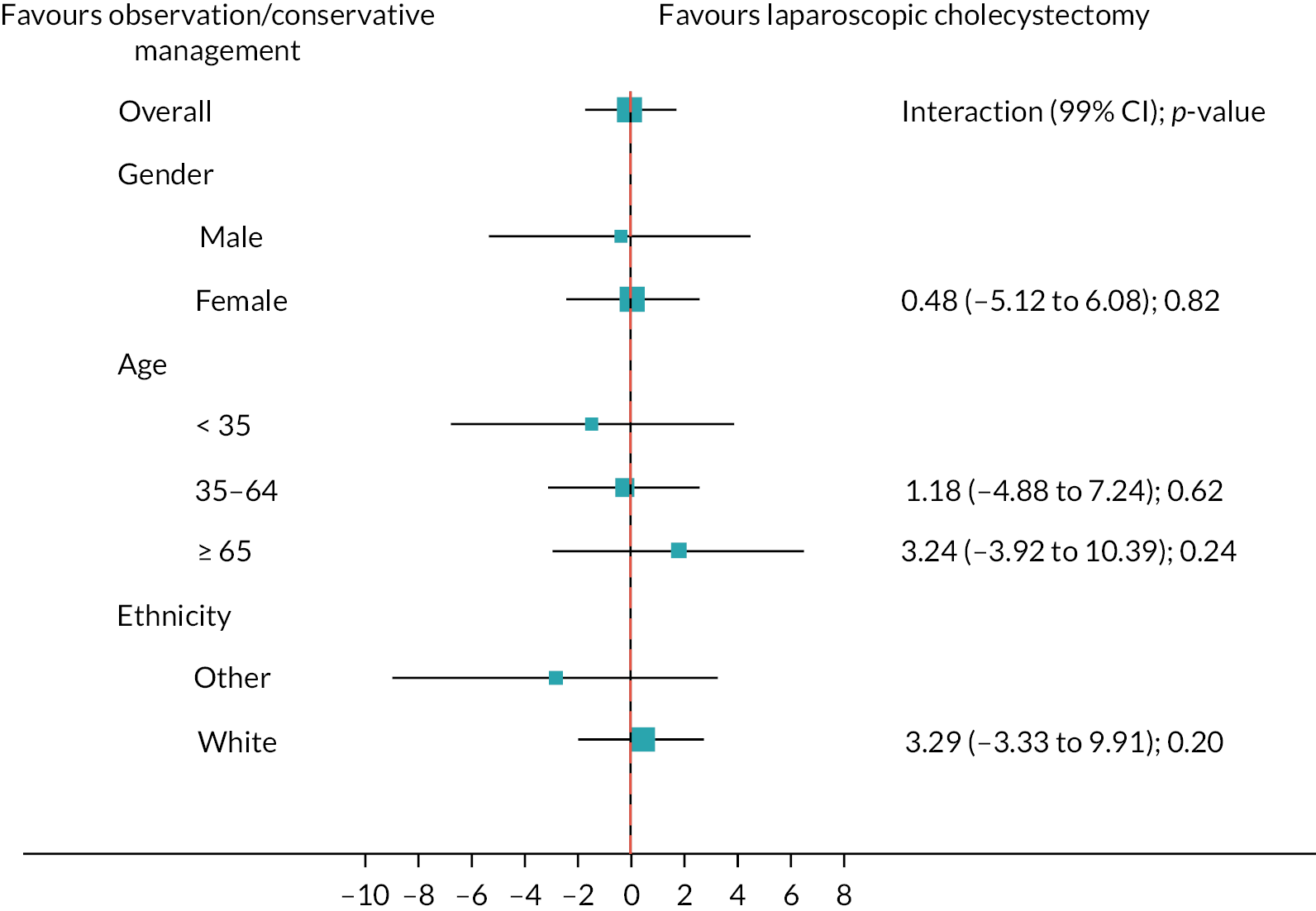

Subgroup analyses

Figure 6 shows the prespecified subgroup analyses for AUC SF-36 norm-based bodily pain score, gender, age (< 35, 35–64, ≥ 65 years) and ethnicity (white vs. other) at 18 months (primary outcome). Overall, there was no evidence that the treatment effect was moderated by any subgroups. Appendix 3, Figures 18 and 19 show the subgroup analyses for the sensitivity and complete case analyses.

FIGURE 6.

Subgroups for observation/conservative management vs. laparoscopic cholecystectomy up to 18 months for AUC SF-36 bodily pain primary analysis. Boxes represent differences in AUC and lines are confidence intervals.

Secondary outcomes

Patient-reported quality of life

The mean AUC SF-36 norm-based bodily pain score over 24 months was 47.2 (SD 8.6) in the observation/conservative management group and 47.3 (SD 8.7) in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group and with no evidence of a difference for the primary analysis: MD –0.1, 95% CI (–1.8 to 1.7); p-value 0.948. Sensitivity and complete case analyses are shown in Appendix 3, Table 42.

For the SF-36 norm-based scores (apart from bodily pain), some small differences were observed as statistically significant at 18 months, but these disappeared at 24 months (Table 7). None of the observed effect sizes were clinically important.

| Patient-reported secondary outcome | Observation/conservative management, N = 217 | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, N = 217 | MD | 95% CI; p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-36 norm-based score | ||||

| Physical functioning | ||||

| Baseline | 48.2 (10.6); 214 | 47.3 (10.9); 216 | ||

| 3 months | 47.3 (11.0); 161 | 46.6 (11.1); 155 | 0.5 | (–1.3 to 2.3) |

| 9 months | 46.5 (11.6); 131 | 47.4 (11.6); 143 | –1.4 | (–3.3 to 0.4) |

| 12 months | 47.7 (10.6); 127 | 48.2 (11.1); 125 | –0.4 | (–2.3 to 1.5) |

| 18 months | 47.8 (10.4); 120 | 49.6 (10.0); 114 | –2.1 | (–4.0 to –0.1); 0.04 |

| 24 months | 47.7 (10.4); 103 | 49.1 (10.9); 99 | –1.8 | (–3.9 to 0.2); 0.08 |

| Role physical | ||||

| Baseline | 47.7 (10.3); 215 | 46.4 (11.4); 216 | ||

| 3 months | 46.8 (10.9); 161 | 44.8 (11.5); 152 | 2.1 | (0.07 to 4.14) |

| 9 months | 46.1 (11.5); 130 | 46.1 (12.5); 138 | –0.5 | (–2.63 to 1.70) |

| 12 months | 46.7 (11.8); 126 | 48.8 (10.9); 121 | –1.6 | (–3.80 to 0.67) |

| 18 months | 47.7 (10.7); 121 | 48.5 (11.0); 114 | –1.1 | (–3.3 to 1.2); 0.36 |

| 24 months | 46.5 (11.0); 103 | 47.8 (11.9); 99 | –2.0 | (–4.5 to 0.4); 0.10 |

| General health | ||||

| Baseline | 45.0 (9.3); 213 | 43.3 (10.4); 216 | ||

| 3 months | 43.1 (10.8); 160 | 42.3 (10.3); 155 | 0.0 | (–1.7 to 1.8) |

| 9 months | 43.8 (10.7); 130 | 44.6 (10.8); 139 | –1.5 | (–3.3 to 0.4) |

| 12 months | 44.5 (10.6); 127 | 45.2 (10.6); 125 | –1.7 | (–3.5 to 0.2) |

| 18 months | 44.3 (10.9); 121 | 46.6 (11.0); 111 | –2.0 | (–3.9 to –0.1); 0.04 |

| 24 months | 44.9 (10.5); 103 | 44.8 (11.3); 99 | –0.9 | (–2.9 to 1.1); 0.40 |

| Vitality | ||||

| Baseline | 46.7 (10.0); 213 | 44.7 (10.9); 216 | ||

| 3 months | 44.8 (10.8); 160 | 44.2 (10.5); 156 | –0.6 | (–2.5 to 1.3) |

| 9 months | 44.9 (10.9); 130 | 46.3 (11.3); 139 | –2.9 | (–5.0 to –0.9) |

| 12 months | 45.9 (11.5); 127 | 46.7 (11.2); 125 | –2.1 | (–4.2 to 0.0) |

| 18 months | 45.6 (11.2); 121 | 48.8 (11.4); 113 | –3.9 | (–6.0 to –1.7); < 0.001 |

| 24 months | 46.3 (11.2); 102 | 47.0 (11.3); 99 | –2.2 | (–4.5 to 0.0); 0.06 |

| Social functioning | ||||

| Baseline | 45.6 (11.7); 213 | 43.9 (12.5); 216 | ||

| 3 months | 43.9 (11.9); 161 | 42.5 (12.4); 155 | 0.8 | (–1.4 to 3.1) |

| 9 months | 44.1 (11.6); 129 | 46.1 (12.4); 140 | –2.4 | (–4.8 to 0.0) |

| 12 months | 44.5 (13.0); 126 | 46.2 (12.2); 124 | –1.5 | (–4.0 to 1.0) |

| 18 months | 46.2 (11.3); 119 | 47.8 (12.0); 111 | –1.2 | (–3.8 to 1.3); 0.34 |

| 24 months | 45.9 (12.5); 101 | 45.0 (12.5); 97 | 0.6 | (–2.1 to 3.3); 0.68 |

| Role emotional | ||||

| Baseline | 45.9 (12.4); 215 | 44.7 (13.3); 216 | ||

| 3 months | 44.5 (12.6); 160 | 42.7 (12.8); 152 | 1.8 | (–0.5 to 4.1) |

| 9 months | 44.2 (12.7); 129 | 44.6 (13.6); 138 | –1.5 | (–4.0 to 1.0) |

| 12 months | 44.7 (12.8); 124 | 46.3 (12.4); 121 | –1.7 | (–4.2 to 0.9) |

| 18 months | 44.1 (12.7); 121 | 46.4 (12.5); 114 | –3.2 | (–5.8 to –0.6); 0.015 |

| 24 months | 45.6 (12.0); 103 | 44.8 (12.9); 99 | –0.5 | (–3.3 to 2.2); 0.71 |

| Mental health | ||||

| Baseline | 47.7 (10.4); 213 | 46.1 (11.1); 216 | ||

| 3 months | 44.9 (11.4); 160 | 45.1 (11.4); 156 | –0.7 | (–2.8 to 1.3) |

| 9 months | 45.2 (11.4); 130 | 47.2 (11.2); 139 | –2.8 | (–4.9 to –0.6) |

| 12 months | 46.4 (12.4); 127 | 47.1 (11.6); 125 | –1.6 | (–3.8 to 0.6) |

| 18 months | 45.9 (11.0); 121 | 48.1 (11.0); 112 | –2.4 | (–4.6 to –0.1); 0.040 |

| 24 months | 46.6 (11.5); 103 | 45.3 (11.4); 99 | –0.0 | (-2.4, 2.3); 0.98 |

| Physical component summary – PCS | ||||

| Baseline | 46.7 (9.3); 213 | 45.6 (9.7); 216 | ||

| 3 months | 46.3 (10.1); 157 | 44.8 (10.2); 150 | 1.4 | (–0.4 to 3.2) |

| 9 months | 46.4 (10.4); 127 | 46.9 (11.7); 136 | –0.8 | (–2.7 to 1.1) |

| 12 months | 47.4 (10.8); 123 | 48.4 (10.5); 119 | –0.8 | (–2.7 to 1.2) |

| 18 months | 47.8 (10.3); 117 | 49.3 (10.2); 108 | –1.2 | (–3.2 to 0.8); 0.24 |

| 24 months | 47.2 (10.9); 100 | 48.7 (11.4); 97 | –1.9 | (–4.0 to 0.1); 0.07 |

| Mental component summary – MCS | ||||

| Baseline | 46.4 (11.5); 213 | 44.7 (12.1); 216 | ||

| 3 months | 43.9 (12.3); 157 | 43.2 (12.4); 150 | –0.1 | (–2.3 to 2.1) |

| 9 months | 44.2 (12.4); 127 | 46.0 (11.7); 136 | –2.8 | (–5.1 to –0.5) |

| 12 months | 45.1 (13.3); 123 | 46.1 (11.9); 119 | –1.8 | (–4.2 to 0.6) |

| 18 months | 44.9 (12.6); 117 | 47.8 (11.7); 108 | –2.9 | (–5.4 to –0.5); 0.020 |

| 24 months | 45.9 (12.1); 100 | 44.4 (12.6); 97 | 0.2 | (–2.3 to 2.8); 0.85 |

| CSQ total | ||||

| Baseline | 33.2 (19.9); 210 | 35.4 (20.6); 211 | ||

| 3 months | 29.5 (23.4); 148 | 30.9 (22.6); 147 | –0.8 | (–4.9 to 3.4) |

| 9 months | 26.6 (22.5); 122 | 23.6 (22.4); 132 | 4.4 | (–0.0 to 8.8) |

| 12 months | 21.7 (22.1); 119 | 18.4 (19.4); 120 | 4.7 | (0.2 to 9.2) |

| 18 months | 21.3 (21.0); 113 | 15.8 (19.7); 101 | 6.6 | (1.9 to 11.3); 0.006 |

| 24 months | 20.7 (20.1); 98 | 14.0 (17.0); 91 | 9.0 | (4.1 to 14.0); < 0.001 |

| Persistent symptoms scoreb | ||||

| Baseline | 43.0 (20.9); 213 | 44.6 (22.8); 215 | ||

| 3 months | 32.9 (26.6); 156 | 34.6 (24.7); 153 | –1.4 | (–6.4 to 3.5) |

| 9 months | 31.1 (26.5); 128 | 26.7 (26.1); 139 | 5.5 | (0.3 to 10.8) |

| 12 months | 23.4 (24.2); 125 | 20.2 (23.1); 121 | 4.6 | (–0.9 to 10.0) |

| 18 months | 23.1 (24.1); 117 | 17.4 (22.2); 106 | 6.7 | (1.0 to 12.3); 0.02 |

| 24 months | 23.1 (23.0); 101 | 15.1 (18.4); 95 | 10.1 | (4.2 to 16.0); 0.001 |

The mean CSQ at 18 months was 21.3 (SD 21.0) for the observation/conservative management group and 15.8 (19.7) for the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group and showed evidence of a difference in favour of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: MD 6.6, 95% CI (1.9 to 11.3); p-value 0.006. At 24 months, again there was evidence of a difference in favour of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: MD 9.0, 95% CI (4.1 to 14.0), p < 0.001. There was a similar pattern for the persistent symptoms score.

Complications

At 18 months, 32 (10.1%) participants in the observation/conservative management group had had a complication compared with 44 (25.3%) participants in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group, with no evidence of a difference between groups: RR 0.72, 95% CI (0.46 to 1.14); p-value 0.17 (further details are shown in Appendix 3, Table 43). At 24 months, there were two additional complications in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group with no evidence of a difference between groups: RR 0.69, 95% CI (0.44 to 1.09); p-value 0.11. Details of the complications are shown in Table 8. In regard to complications that occurred before laparoscopic cholecystectomy (including in participants who did not have a laparoscopic cholecystectomy), they occurred in 25 (11.5%) participants in the observation/conservative management group and 11 (5.1%) in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group, with the majority of the complications being either cholecystitis or biliary colic. For intraoperative complications, 9 participants (4.1%) had a complication in the observation/conservative management group and 24 (11.1%) in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group with the majority being bile/stone spillage from the gallbladder. For postoperative complications, there were 7 (4.1%) and 24 (11.1%) participants, respectively, with bile/stone spillage from gallbladder as the main complication. For postsurgery complications, there were 2 (0.9%) and 3 participants (1.4%), respectively, within 30 days of discharge, and 1 participant (0.5%) after 30 days in both groups. There was one cardiovascular-related death in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group (myocardial infarction). By treatment received at 18 months, there were 8/234 participants (3.4%) who had a complication in the observation/conservative management group and 68/200 (34.0%) in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group. At 24 months, there were 7/217 (3.2%) and 71/217 (32.7%) participants who had a complication, respectively (see Appendix 3, Tables 44 and 45 for further details).

| Clinical secondary outcome | Observation/conservative management, N = 217 | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, N = 217 |

|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 32 (14.7) | 46 (21.2) |

| RR (95% CI); p-value | 0.69 | 95% CI (0.44 to 1.09); p-value 0.11 |

| Number of complications | ||

| 1 | 18 | 32 |

| 2 | 8 | 5 |

| 3 | 4 | 8 |

| 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Presurgery complications | ||

| Number of participants | 25 (11.5) | 11 (5.1) |

| Number of complications | ||

| 1 | 20 | 9 |

| 2 | 4 | |

| 3 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | 1 | |

| Details of presurgery complications | ||

| Cholecystitis | 14 | 8 |

| Biliary colic | 8 | 2 |

| Pancreatitis | 2 | 3 |

| Choledocholithiasis | 2 | – |

| Cholecystitis and jaundice | 1 | – |

| Choledocholithiasis and pancreatitis | 1 | – |

| Cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis and jaundice | – | 1 |

| Cholecystitis and pancreatitis | 1 | – |

| Bouveret syndromea | 1 | – |

| Cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis and pancreatitis | – | 1 |

| Jaundice | – | 1 |

| Right upper quadrant pain | 1 | – |

| Intraoperative complications | ||

| Number of participants | 9 (4.1) | 24 (11.1) |

| Number of complications | ||

| 1 | 8 | 23 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Details of intraoperative complications | ||

| Bile/stone spillage from gallbladder | 6 | 16 |

| Injury to abdominal viscera (including liver tear or laceration) | 1 | 5 |

| Bleeding > 500 ml | 1 | 2 |

| Bile leak from the bile duct, hepatic duct or ducts at base of liver | 1 | 1 |

| Injury to bile duct | 1 | – |

| Ruptured empyema | – | 1 |

| Postoperative complications | ||

| Number of participants | 7 (3.2) | 16 (7.4) |

| Number of complications | ||

| 1 | 5 | 10 |

| 2 | 1 | 4 |

| 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Details of postoperative complications | ||

| Bleeding > 500 ml | 1 | 2 |

| Bile leak that required no treatment | 2 | 3 |

| Bowel obstruction requiring no treatment | 1 | 4 |

| Bowel obstruction requiring surgery | – | 1 |

| Wound infection | 2 | 2 |

| Intraperitoneal – collection/abscess requiring no treatment | 1 | 4 |

| Intraperitoneal – collection/abscess requiring precutaneous drainage | 1 | – |

| Vomiting | – | 3 |

| Dizziness and hypotension | 1 | – |

| Haematoma | – | 1 |

| Missed stone in the bile duct | – | 1 |

| Renal failure | – | 1 |

| Residual gallbladder inflamed | 1 | – |

| Wound dehiscence | – | 1 |

| Postsurgery complications within 30 days of discharge | ||

| Number of participants | 2 (0.9) | 3 (1.4) |

| Number of complications | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Details of postsurgery complications within 30 days of discharge | ||

| Cholangitis | – | 1 |

| Surgical site infection | 1 | 1 |

| Bile leak | – | 1 |

| Postcholecystectomy syndromeb | 1 | – |

| Postsurgery complications after 30 days of discharge | ||

| Number of participants | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| Details of postsurgery complications after 30 days of discharge | ||

| Right upper quadrant pain | – | 1 |

| Incisional hernia | 1 | – |

| Death – cardiovascular event | ||

| Number of participants | – | 1 (0.5) |

Need for further treatment

At 18 months, there were 9/202 (4.5%) participants in the observation/conservative management group who had had a further treatment and 12/203 (5.9%) in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group with no evidence of a difference: RR 0.75, 95% CI (0.31 to 1.78); p-value 0.509 (further details are shown in Appendix 3, Table 46). At 24 months, there were 10/202 (5.0%) participants in the observation/conservative management group who had further treatment and 16/203 (7.9%) in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group with no evidence of a difference: RR 0.62, 95% CI (0.28 to 1.38); p-value 0.242 (Table 9). The main treatments were additional pain relief, antibiotics and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

| Clinical secondary outcome | Observation/conservative management, N = 217 | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, N = 217 |

|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 10/201 (5.0) | 16/203 (7.9) |

| RR (95% CI); p-value | 0.62 | 95% CI (0.28 to 1.38); p-value 0.242 |

| Number of treatments | ||

| 1 | 8 | 10 |

| 2 | 2 | 4 |

| 3 | – | 1 |

| 4 | – | 1 |

| Details of the further treatment | ||

| Pain relief | 3 | 12 |

| Antibiotics | 2 | 5 |

| ERCP | 3 | 4 |

| Antisickness | 1 | – |

| Bloating | 1 | – |

| Urinary catheter for retention | – | 2 |

| Bowel | – | 1 |

| Colostomy | 1 | – |

| Blood transfusion | – | 1 |

| Laparotomy washout and haemostasis | – | 1 |

| Fluids | – | 1 |

| Pancreatitis management | – | 1 |

| Unknown | 1 | – |

Appointments with health professionals, medications prescribed and further investigations

Details of appointments with health professionals, medications prescribed and further investigations related to their gallstones by 18 months are shown in Appendix 3, Table 47. By 24 months (Table 10), 108/202 (53.5%) of participants in the observation/conservative management group and 127/203 (62.6%) in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group required appointments with healthcare professionals with the majority visiting their GP, or an NHS hospital A&E or referred to outpatient department. Further medication for their gallstones was prescribed to 67/202 (33.2%) participants in the observation/conservative management group and 59/203 (29.1%), respectively, and further investigation was required in 11/202 (5.4%) participants in the observation/conservative management group and 10/203 (4.9%) in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group.

| Details | Observation/conservative management, N = 217 | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, N = 217 |

|---|---|---|

| Professional appointments | ||

| Number of participants who required appointments | 108/202 (53.5) | 127/203 (62.6) |

| Details of the appointments | ||

| GP | 73 | 91 |

| District nurse | 3 | 8 |

| Practice nurse | 15 | 34 |

| NHS hospital outpatients | 54 | 64 |

| NHS hospital A&E | 39 | 33 |

| Private healthcare | 2 | 3 |

| Appointment with other care provider | 8 | 1 |

| Consultant | 5 | – |

| Physiotherapist | 2 | – |

| Paramedics | 1 | – |

| Medications prescribed | ||

| Number of participants who were prescribed and taken medication | 67/202 (33.2) | 59/203 (29.1) |

| Details of medicationa | ||

| Pain relief | 100 | 69 |

| Paracetamol | 36 | 23 |

| Dihydrocodeine | 33 | 24 |

| Ibuprofen | 21 | 18 |

| Tramadol | 7 | 3 |

| Other pain medication | 3 | 1 |

| Antispasmodic | 25 | 20 |

| Antisickness | – | 1 |

| Antibiotic | – | 3 |

| Antireflux | 20 | 22 |

| Antidiarrhoea | – | 1 |

| Other | 3 | 7 |

| Bile salts | 1 | 5 |

| Iron | 2 | 2 |

| Further investigation | ||

| Number of participants | 11/202 (5.4) | 10/203 (4.9) |

| Number of investigations | ||

| 1 | 9 | 9 |

| 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Details | ||

| MRI | 4 | 2 |

| Ultrasound scan | 3 | 5 |

| CT | 1 | 1 |

| Endoscopy | 2 | 1 |

| SeHCAT test | 1 | 2 |

| Unknown | 2 | – |

Impact of coronavirus disease 2019

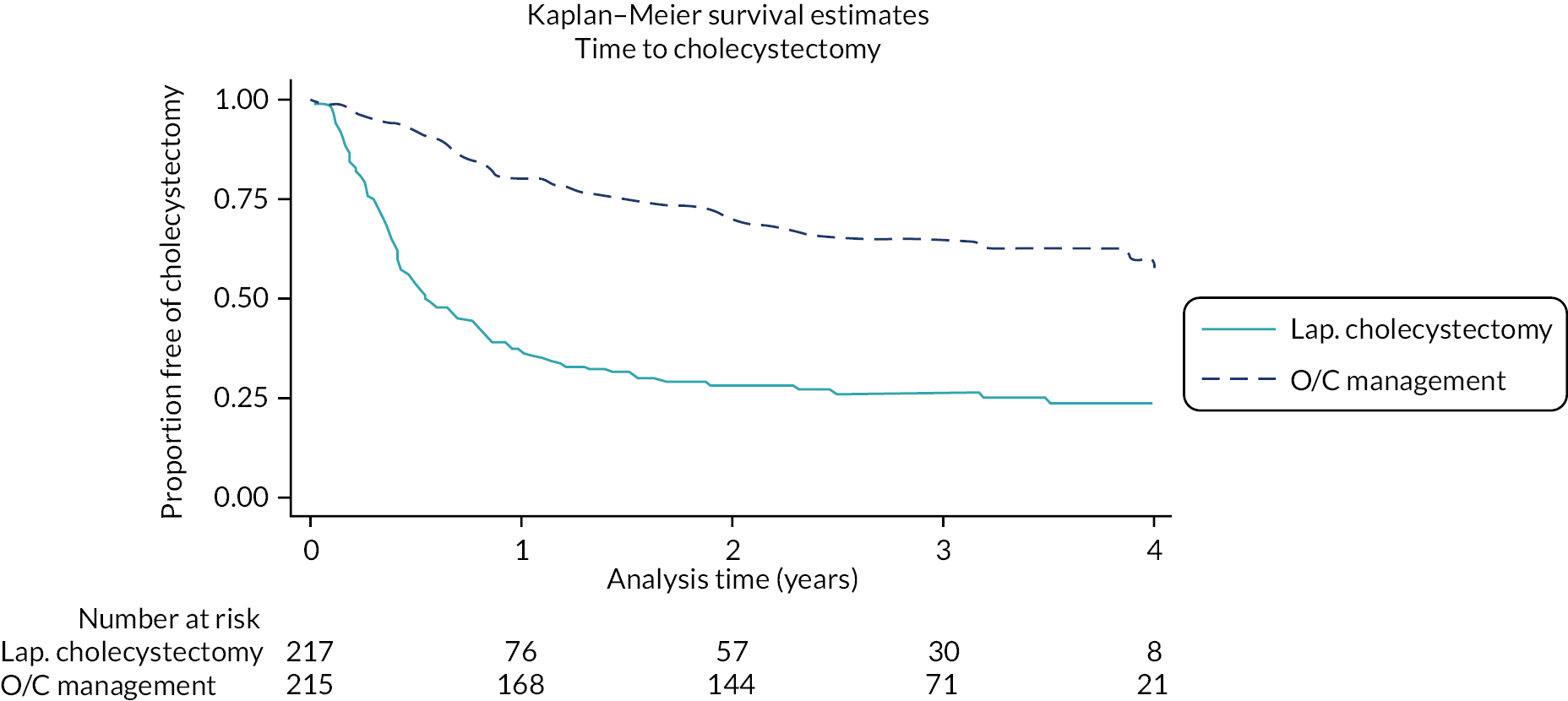

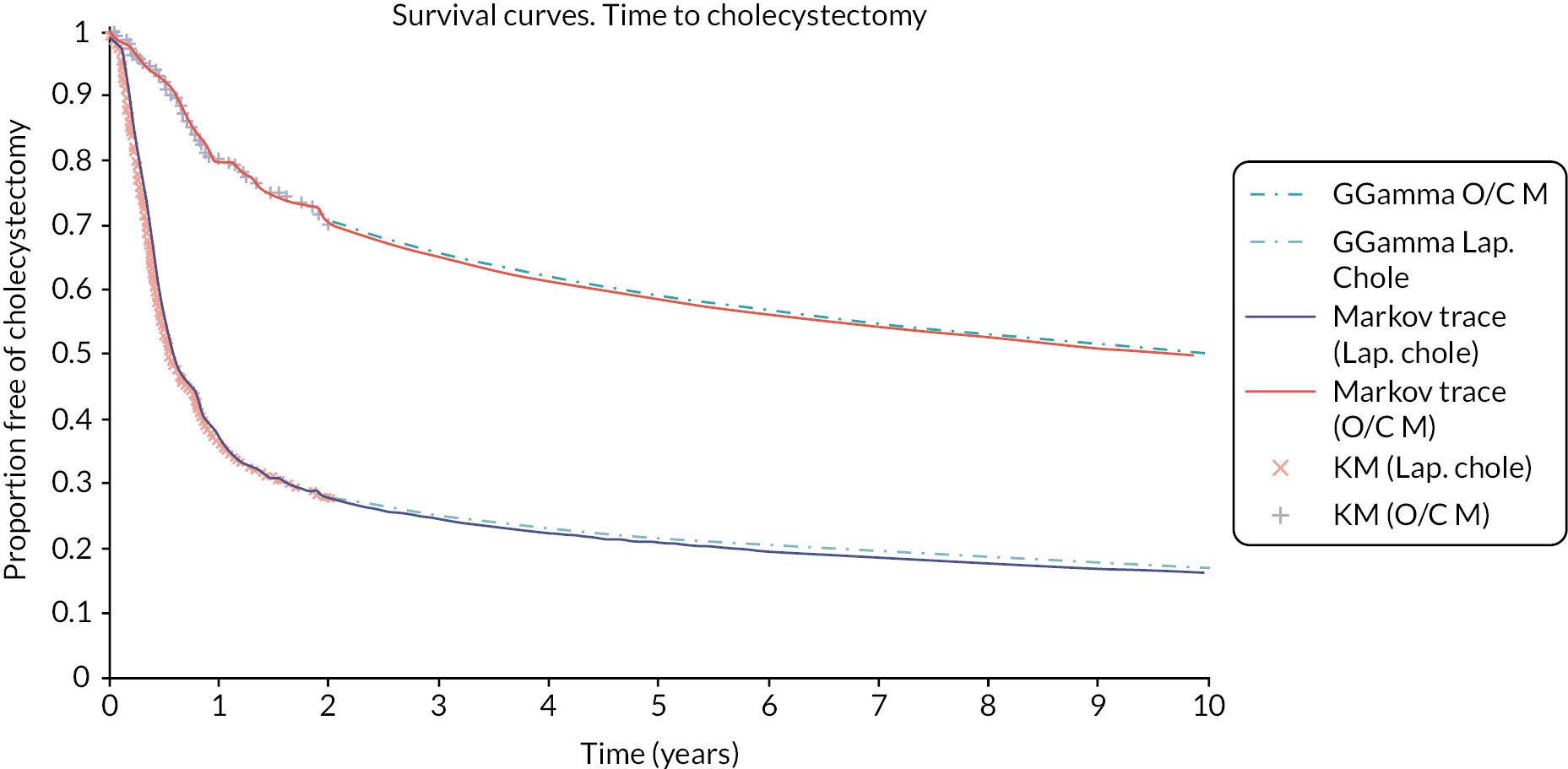

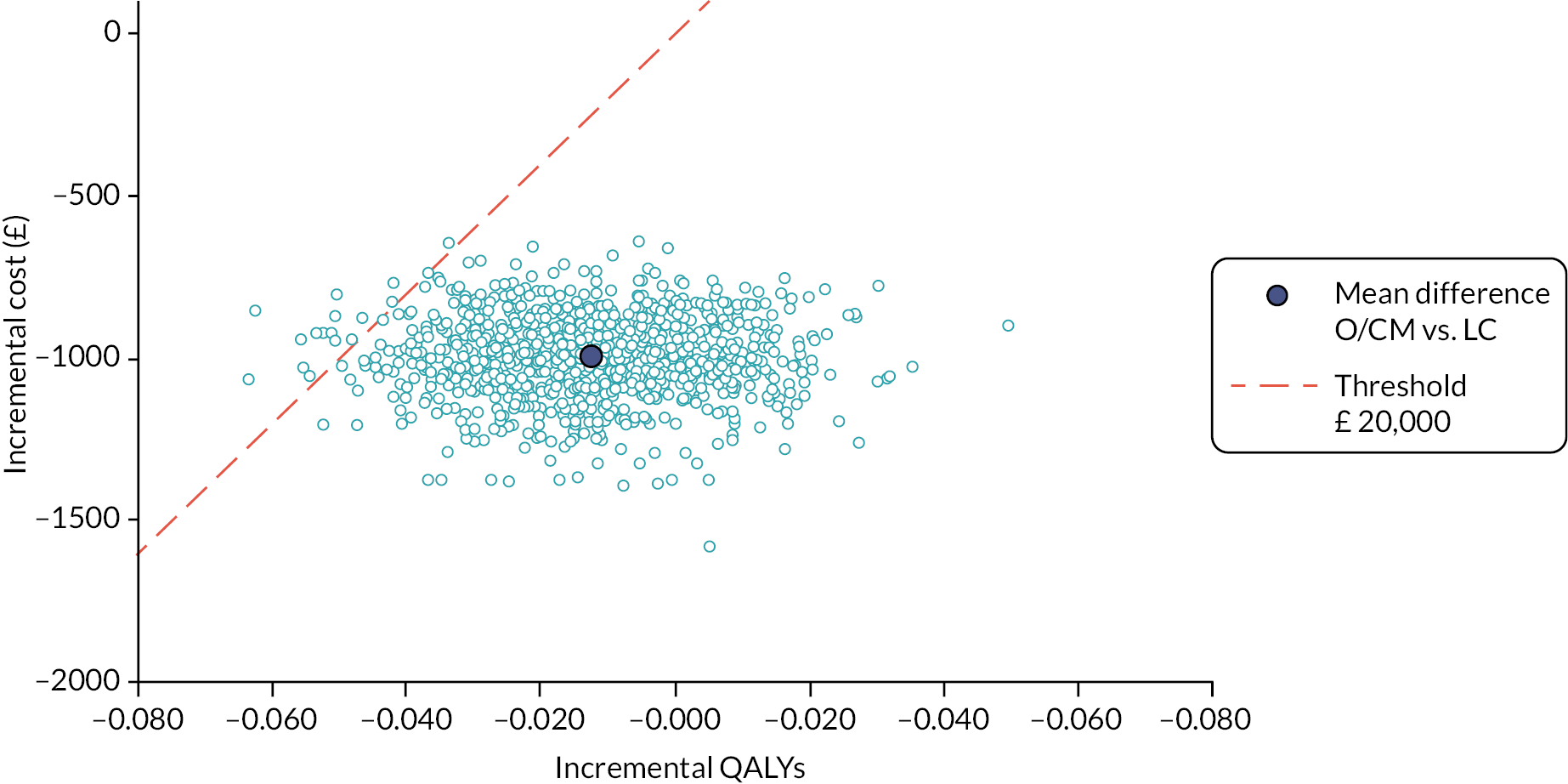

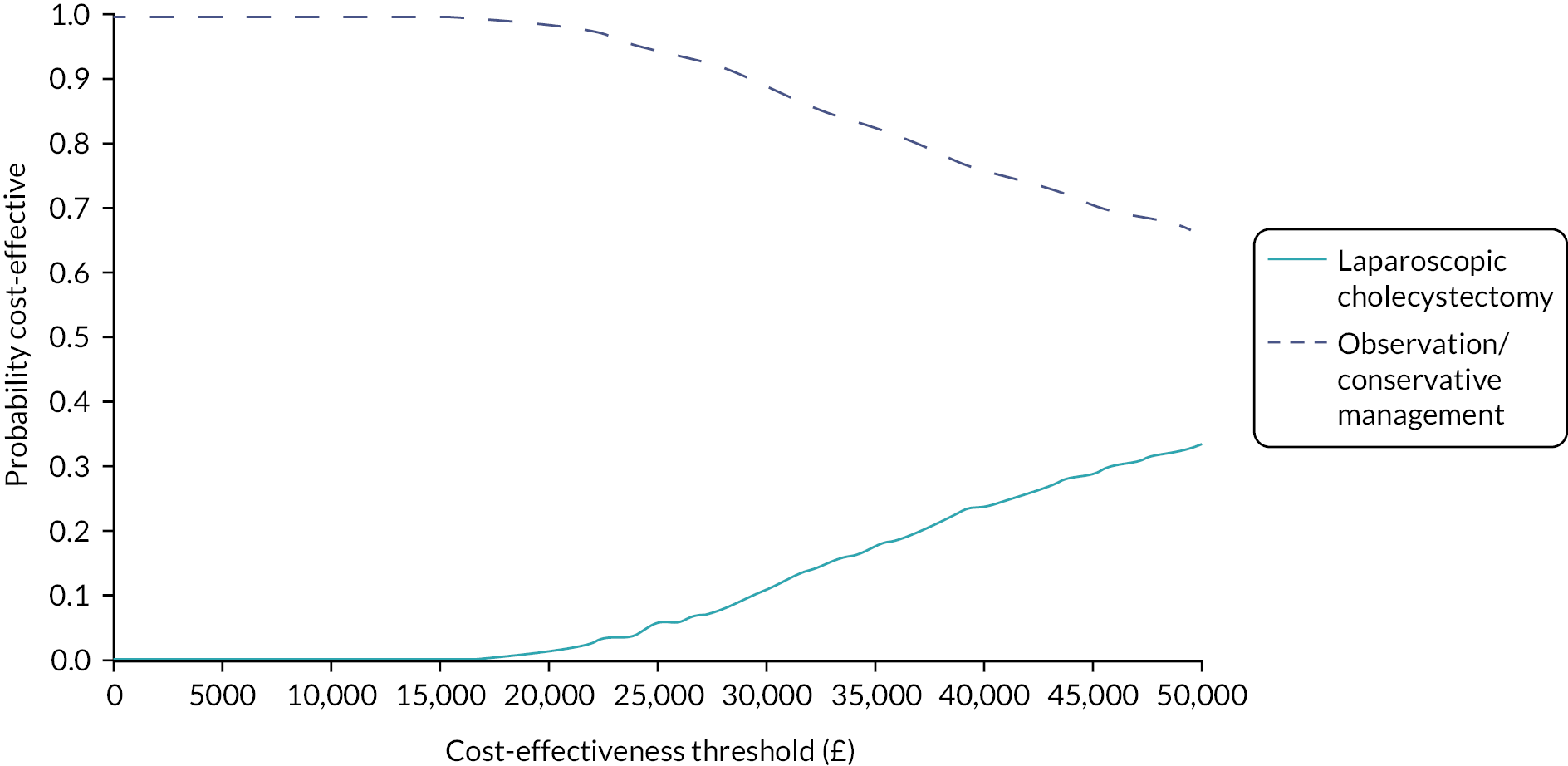

All randomised participants reached the 3-month follow-up time point before the COVID-19 pandemic began (defined as 11 March 2020 by the WHO). 38 In addition, 97/167 (58.1%) in the observation/conservative management group and 102/161 (63.4%) in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group had completed their 18 months of follow-up before this date (see Appendix 3, Table 48). The AUC difference for the SF-36 norm-based bodily pain score by 18 months was MD –0.1, 95% CI (–1.8 to 1.6); p-value 0.94 in the subset of data pre-COVID-19. There was no evidence that this differed from the intention-to-treat (ITT) estimate.