Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/192/89. The contractual start date was in April 2016. The draft report began editorial review in July 2020 and was accepted for publication in July 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Harris et al. This work was produced by Harris et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Harris et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale of the ADAPTT study

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), a combination of aspirin and clopidogrel, prasugrel or ticagrelor, is recommended for secondary prevention of ischaemic events (i.e. heart attack and stroke) among people with coronary artery disease. Guidelines recommend that patients are treated with DAPT for 6–12 months following myocardial infarction (MI) and coronary interventions [percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)],1–4 and support the use of the more potent antiplatelet inhibitors ticagrelor and prasugrel. 3 Antiplatelet agents reduce the risk of ischaemic events by preventing the formation of clots in atherosclerotic coronary arteries and within stents (following PCI) or grafts (following CABG), but increase the risk of bleeding. 5 Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have shown that adding clopidogrel to aspirin leads to a 1% excess risk of major bleeding (necessitating admission to hospital) compared with aspirin alone. 6,7 Prasugrel and ticagrelor reduce the risk of ischaemic events further, but also further increase the risk of bleeding. 8 Some patients [e.g. those with existing atrial fibrillation (AF), or those who develop AF after PCI, CABG or acute coronary syndrome (ACS)] are prescribed an anticoagulant (e.g. warfarin, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban) in addition to DAPT [known as triple therapy (TT)], which further increases the risk of bleeding.

‘Real-world’ bleeding events that do not require any intervention are likely to be much more frequent than those reported in RCTs, which exclude patients at high risk of bleeding and mainly report only on major bleeding. Bleeding events that do not result in hospitalisation are largely managed in primary care and may have a significant clinical and economic impact. 9 Minor and nuisance bleeding (nose and gum bleeds, bruising and prolonged bleeding from cuts) may also reduce adherence to DAPT, thereby reducing the benefit of DAPT among non-adherent patients,10 who are at increased risk of a secondary ischaemic coronary episode. 11 Only three studies have reported the incidence and consequences of nuisance bleeding after DAPT;12–14 these suggest that nuisance bleeding is common (affecting 29–38% of patients) and affects adherence (11% of patients in one study discontinued clopidogrel13).

The economic impact of bleeding events, particularly minor bleeding events, associated with DAPT is poorly characterised, as is their impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL). 9 This is not surprising given that health economic analyses often lack detailed data on adverse effects of interventions, despite consensus that such effects should be considered. 15,16 To ensure that appropriate decisions are made about which DAPT regimens to use in clinical practice, the health and resource use consequences of minor and major bleeding events should be incorporated into assessments of cost-effectiveness. For DAPT, this entails accounting for uncertainty in the absolute risk of bleeding; the impact of different bleeding events on HRQoL and treatment adherence, and subsequent risk of secondary ischaemic events; and the cost implications of managing these bleeding events.

In the ADAPTT study, we used Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) and the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) databases to conduct three non-randomised studies of interventions to estimate the incidence of all bleeding events occurring among patients prescribed different DAPT or TT regimens after undergoing coronary interventions (i.e. PCI and CABG) and in conservatively managed ACS patients. We used the framework recommended by the Cochrane Bias Methods Group and the Cochrane Non-Randomised Studies for Interventions Methods Group for establishing appropriate patient populations, interventions and follow-up to emulate the following three hypothetical RCTs (hereafter referred to as the target trials):17

-

for patients who have undergone PCI, estimate the effect on bleeding events of assignment to DAPT with aspirin and clopidogrel (AC) (reference), compared with assignment to DAPT with aspirin and prasugrel (AP) or DAPT with aspirin and ticagrelor (AT)

-

for patients who have undergone CABG, estimate the effect on bleeding events of assignment to aspirin (reference), compared with assignment to DAPT with AC

-

for patients who are conservatively managed after presenting with ACS, estimate the effect on bleeding events of assignment to aspirin (reference), compared with assignment to DAPT with AC.

The Cochrane Bias Methods Group and the Cochrane Non-Randomized Studies for Interventions Methods Group17 also recommended that confounders should be specified a priori, using clinician expertise and literature review, although no method of doing this was specified. In the context of ADAPTT, we carried out a literature review, surveys and semistructured interviews with clinicians to identify confounders and relevant co-interventions (medications that a patient might receive with or after starting the antiplatlet regimen, which may both be related to the antiplatelet regimen and be prognostic for bleeding) (see Chapter 2). The confounders identified were taken forward for the analyses of the NRSIs emulating the three target trials (see Chapter 3).We also estimated rates of minor and major bleeding in patients receiving TT (see Chapter 3).We also specified relevant co-interventions, that is medications that a patient might receive with or after starting the antiplatelet regimen, which may both be related to antiplatelet regimen and be prognostic for bleeding. The confounders identified were taken forward for the analyses of the non-randomised studies of interventions emulating the three target trials (see Chapter 2). We also estimated rates of minor and major bleeding among patients receiving TT (see Chapter 3).We conducted a qualitative study exploring patient perspectives on adherence and nuisance bleeding when on DAPT (see Chapter 4). We also conducted a health economic analysis, including a literature review to estimate the deterioration in utility [i.e. quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs)] of patients who have minor or major bleeding events, and a health elicitation study (see Chapter 5). Finally, patient and public involvement was extensive and was used to guide the ADAPTT study (see Chapter 6). Patient and public involvement identified the need for the qualitative study with patients and informed the decision-making process with regard to assembling the target trials from the data sets.

Research objectives

The following objectives were defined in the application for funding:

-

Estimate the rates of major and minor bleeding events with different DAPT (and TT) exposures in each target trial (PCI, CABG, ACS but no procedure).

-

Estimate hazard ratios (HRs) for bleeding for different antiplatelet regimens: for the PCI cohort, we will compare AC with AP or AT; for the CABG and ACS no-procedure cohorts, we will compare aspirin with AC.

-

Review the literature to estimate the deterioration in utility (i.e. QALYs) of patients who have minor or major bleeding events.

-

Revise/extend existing economic models of the cost-effectiveness of different DAPT regimens to include estimates of the incidence of minor and major bleeding events and associated impacts on utility in the general population.

-

Estimate the resources required and associated costs incurred of treating major and minor events of the alternative DAPT (TT) exposures in the three specified patient populations.

-

Understand patients’ perspectives of DAPT, and the factors that influence responses to nuisance bleeding, focusing on adherence and information-seeking.

This last objective was identified through the patient and public involvement work after the start of the ADAPTT study. The patient and public involvement group discussed their own experiences of nuisance bleeding symptoms, prompting the research team to identify this as a topic warranting further investigation.

Changes to the ADAPTT study since the start of the study

We made the following additions/changes to the study that were not specified in the original application for funding:

-

We included a study to identify confounders systematically, as recommended by the Cochrane Bias Methods Group and the Cochrane Non-Randomized Studies for Interventions Methods Group. 17 This involved a systematic review; semistructured interviews with cardiologists, cardiac surgeons and general practitioners (GPs); and a survey to assess the extent to which the confounders identified by the first two methods were considered by different medical practitioners when making prescribing decisions (see Chapter 2).

-

For the PCI target trial, we excluded patients with stable angina undergoing PCI (elective PCI) because > 90% of these patients were prescribed DAPT with AC (see Chapter 3).

-

For the emergency PCI target trial, we conducted two analyses, one including the entire ACS population (for the comparison of DAPT with ticagrelor vs. DAPT with clopidogrel) and another restricted to the ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) population (for the comparison of DAPT with prasugrel vs. DAPT with clopidogrel), as only STEMI patients were prescribed DAPT with AP (see Chapter 3).

-

We did not attempt to estimate HRs for DAPT compared with TT because the number of patients who could be assigned to TT was too small to justify meaningful comparative analyses (see Chapter 3).

-

We conducted a qualitative study with patients to explore patients’ perspectives on adherence and nuisance bleeding (see Chapter 4).

-

We did not revise existing cost-effectiveness models or attempt to build a new model because our estimates for bleeding were at risk of bias and confounding (see Chapter 5).

Chapter 2 Confounders study

This chapter describes the systematic identification of confounders using systematic review and qualitative interviews with clinicians, including a survey of clinicians to describe DAPT prescribing practice in the UK and to assess the extent to which the confounders identified by the first two methods were considered by different medical practitioners when making prescribing decisions.

Systematic review

Methods

Study eligibility criteria

We reasoned that the number of confounders was likely to be limited and that most would be repeated across multiple studies and study designs. We, therefore, took a pragmatic approach and restricted the study designs to RCTs and cohort studies, which we believed would be the most likely to yield confounders. We included all RCTs and cohort studies (prospective or retrospective) that compared different DAPT interventions (or DAPT and anticoagulants) in our populations, regardless of intervention duration, and any prognostic studies that investigated the relationship between DAPT and bleeding.

Search methods for the identification of studies

The search strategy is shown in Appendix 1. Search terms included the population (e.g. ACS, PCI and CABG), the intervention (e.g. DAPT, TT and P2Y12 inhibitor) and a filter for study design (RCT and cohort study). We searched the following electronic databases: MEDLINE (via Ovid), 1950 to 24 August 2016; The Cochrane Library (issue 7, 2016); and EMBASE (via Ovid), 1970 to 24 August 2016.

Study selection

One review author (MP) triaged the titles and abstracts identified by the search and obtained the full text of studies identified as relevant to the review. Because of the large number of relevant studies identified, we included only the studies for which full text was available to download electronically (no attempt was made to obtain the full text of studies without online access or unpublished studies). We considered studies published in the English language only.

Quality assessment

We did not perform a risk-of-bias assessment because the output of the review is descriptive (i.e. a list of confounders and co-interventions) and there are no established criteria for assessing the validity of the methods used by primary researchers to consider potential confounders and co-interventions. It would, therefore, be inappropriate to apply a risk-of-bias tool for studies estimating a treatment effect.

Data extraction and checking

Data on potential confounders and co-interventions were extracted by two researchers (MP and KM) independently. Variables extracted included study characteristics, population characteristics (reported in the tables of baseline characteristics), study design (RCT or cohort study), interventions considered, factors adjusted for in the statistical analyses and factors reported to predict risk of bleeding in our populations. We anticipated that potential confounders would be identified from multiple studies and that the list of potential confounders would reach an asymptote, so it would not be necessary to extract data from all studies identified. We, therefore, used ‘saturation’ as a criterion for discontinuing data extraction, defined as review of the full text of 10 consecutive studies without identifying an additional confounder/co-intervention. Given the large number of studies identified, we initially selected a random sample of 70 studies for data extraction. All identified potential confounders were grouped into demographic factors, medical history, comorbidity, presentation risk factors, biomarkers, procedural risk factors and other factors (for those that did not fit into these categories).

Results

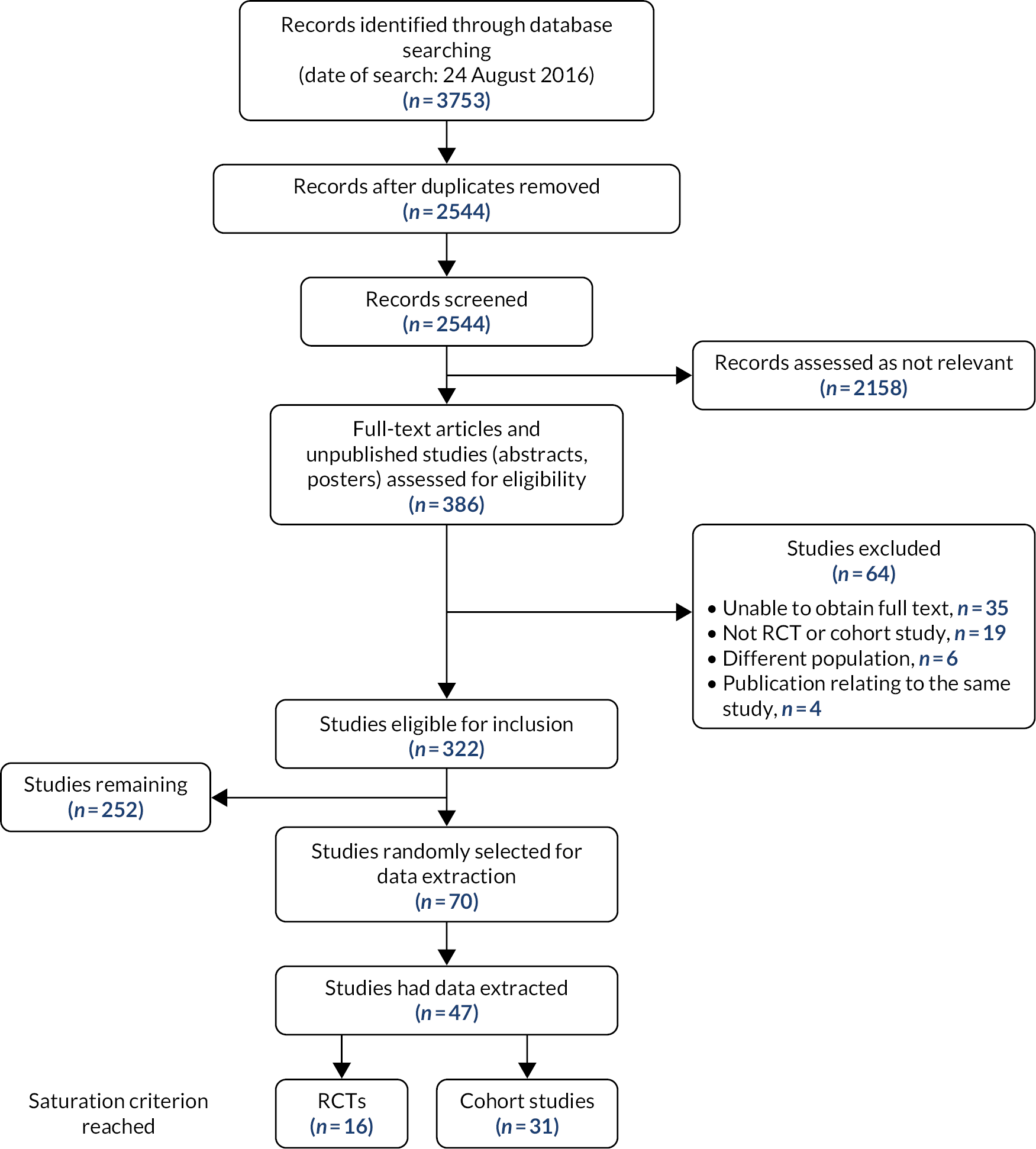

We screened 2544 records, identified 322 studies eligible for inclusion and selected a random sample of 70 for initial data extraction. The saturation criterion (no further new factors identified in 10 consecutive studies) was reached after data extraction from 47 studies (16 RCTs and 31 cohort studies) (Figure 1). We identified 59 potential confounders (seven demography, five medical history, 16 comorbidities, six presentation risk, four risk scores, seven biochemical markers and 14 procedural risk), as shown in Table 1.

| Confounders (N = 59) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demography (n = 7) | Medical history (n = 5) | Comorbidity (n = 16) | Presentation risk (n = 6) | Ischaemic/bleeding risk scores (n = 4) | Biomarkers (n = 7) | Procedural risk (n = 14) | Co-interventions (N = 10) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

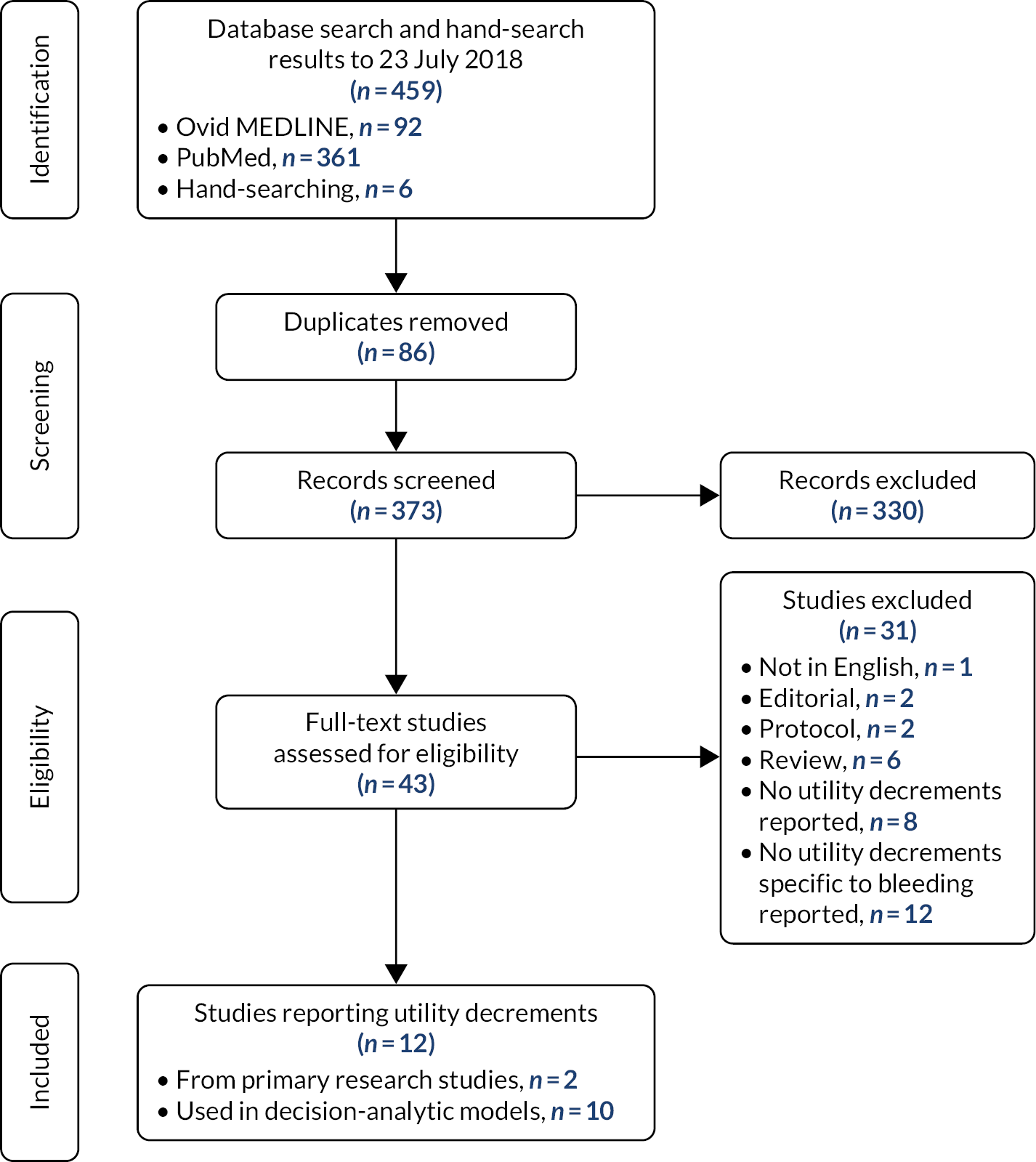

FIGURE 1.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Qualitative study with clinicians

Methods

Recruitment and sampling

Cardiologists, cardiac surgeons and GPs based in one of four UK regions [Bristol (University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust), Gloucestershire (Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust), Oxford (Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust) and Cardiff (Cardiff and Vale University Health Board)] were invited to take part in individual, face-to-face or telephone semistructured interviews. These clinicians are responsible for initiating DAPT or continuing to prescribe DAPT in the light of patients’ experiences and symptoms, in tertiary, secondary or primary care settings. Potential participants were identified by clinicians who were part of the ADAPTT study team, using purposive sampling. The participants selected regularly prescribed DAPT, and practised over a wide geographical area, ensuring that a variety of different practice settings were included. The aim was to recruit six participants from each of the three clinician groups. This number was considered adequate for identifying the range of factors involved in shaping DAPT prescribing decisions. 18,19 Potential participants who expressed an interest in the study when approached by study team members were contacted by the qualitative researcher via e-mail and were provided with a participant information sheet. A suitable date for the interview was arranged if the clinician was still able to participate within the study period.

Data collection

Face-to-face or telephone interviews were conducted between June and October 2017. Face-to-face interviews took place at the Bristol Royal Infirmary and the Bristol Heart Institute. Before each interview, participants signed a consent form or, in the case of telephone interviews, participants had a choice of providing oral informed consent or signing and returning a digital copy. All interviews were audio-recorded.

A clinical vignette-based topic guide was used to guide discussions and elicit clinician prescribing judgements and the range of prescribing decisions when considering prescribing DAPT and/or DAPT and an anticoagulant (TT). 20,21 Four vignettes presenting different clinical scenarios were generated for cardiologist and cardiac surgeon interviews, and three for GP interviews (see Appendix 2). Participants were asked to comment on (1) the clinical decisions that would need to be made for each case vignette; (2) whether they would prescribe DAPT, or DAPT and an anticoagulant, or change the regimen presented; (3) their choice of pharmacotherapeutic agents; and (4) the factors that would influence their decisions (see Appendix 4). Participants were also asked to comment on their use of guidelines and evidence for each case vignette. They were also asked about their links to pharmaceutical companies to ascertain possible conflicts of interest when making prescribing decisions. Vignettes were designed by the ADAPTT study chief investigator and co-investigators, which included a consultant cardiologist; the cardiac surgeon topic guide was piloted with one cardiac surgeon to test the overall structure and relevance of scenarios and questions.

Data analysis

Interview audio-recordings were transcribed by a professional transcription service. All transcripts were checked for accuracy against the original audio-recordings and anonymised. Transcripts were imported into NVivo 11 data management software (QSR International,Warrington, UK) to aid data coding and management. Initially, data were analysed as three separate data sets, using a framework approach. 22 A framework approach was considered to be the most appropriate method for guiding data analysis because:

-

it sits well within pragmatic applied health research in which qualitative methods are used to address a real-life issue, rather than generate theory

-

it allows for analysing data by case (i.e. individual participant or clinician group) and by code using a matrix output, to explore differences or similarities between cases in judgements and views on DAPT.

Initial codes were created representing the clinical vignettes, and the topics of interest under each one: stated prescribing intention, factors considered and sources of information. Transcript data were indexed based on these codes and participants’ responses to each question were deductively mapped to these codes. Open coding (i.e. inductive coding) was then used to extract the individual factors reported by each participant and capture items of interest to the research question emerging from participants’ narratives. Following the coding of the first three transcripts, an analytical framework was developed. When analysis of the three data sets was complete, in-depth coding of the totality of the transcripts as one large data set was carried out to identify a detailed list of factors reported by participants to influence their decision to prescribe, or not prescribe, antiplatelet and anticoagulant medication. Descriptive labels capturing the factors, and clinical or non-clinical indicators linked to these factors (e.g. indicators linked to a patient’s risk profile), were then categorised under higher-order codes to capture broader descriptive categories. Framework matrices were created in NVivo 11 to address specific research questions (e.g. when and why clinicians prescribe DAPT) and to allow for comparisons to be made between and within the three clinician groups in their responses on codes of interest. The analytical framework and findings were presented to the ADAPTT study team at different stages during the analysis to obtain clinical input on the relevance, significance and authenticity of the findings, and to explore clinical concerns arising from these data to guide subsequent analysis and interpretation of data. Findings were also presented to the patient and public involvement group for comments (see Chapter 6).

Results

Eight cardiac surgeons, six cardiologists and eight GPs were initially approached. Six interviews with cardiac surgeons, six with cardiologists and five with GPs were organised. The remainder of the clinicians either did not reply to the researcher’s e-mails or declined to participate, citing lack of time as the reason. Five interviews were conducted face to face and the rest were conducted over the telephone. Interviews lasted between 26 and 45 minutes.

Differences in prescribing decisions between clinician groups

Differences emerged in the prescribing practices between GPs and secondary care specialists. Cardiologists and cardiac surgeons would make independent decisions about whether a patient required DAPT or DAPT and anticoagulant. GPs, on the other hand, were mostly involved in medication regimen management, and would not be independently prescribing or changing specialist medication and regimens without first consulting secondary care specialists:

The only treatment that I would start in primary care is aspirin, so if a change is required, and obviously apixaban for an AF or something like that, so therefore if there was a problem I would probably go back to the specialist rather than change it myself.

GP010

[Bleeding] would be a difficult situation and would almost certainly be left to the specialist in the hospital to agonise over.

GP012

I’m questioning here kind of where the aspirin and ticagrelor’s come from [...] I would [...] probably ring the cardiology on call on the day.

GP010

I would probably again phone the cardiologist to say do I need to keep this patient on aspirin as well and simply give them some gastric prophylaxes and cross my fingers or can I safely have them just on warfarin?

GP012

I wouldn’t [change the prescription] routinely unless the patient was unhappy, we won’t change drugs that have been issued by the hospital. We will stick with what the hospital said.

GP013

General practitioners differed from the other two groups in that they would consider the DAPT regimen in relation to a patient’s other medication and medical history:

When I see a summary printout from the hospital, if I have seen that these drugs are incompatible or there’s a problem with them, then yes, I would go back to the [hospital].

GP010

One always has to consider [patient ischaemic risk and medication history] and look at the list of medication; for example if we see [a patient on DAPT] with a painful ankle and we’re thinking about using an anti-inflammatory, for example, you know, we’d perhaps be a bit more reluctant if we can see that they’re on dual antiplatelet therapy as well.

GP013

The prescribing decisions of each clinician group are reported Table 2. In summary, ticagrelor was the most common choice of cardiologists when prescribing DAPT, whereas clopidogrel was the one routinely used by cardiac surgeons. Clopidogrel was the agent of choice of the majority of participants when it came to prescribing TT, and for patients who were assessed to be at high risk of bleeding. Cardiologists were more likely than cardiac surgeons to prescribe DAPT in all four scenarios, whereas cardiac surgeons were more likely to discontinue DAPT because of bleeding risks if a patient was also on anticoagulant medication, or if the prescription of an anticoagulant agent was being considered.

| Scenario | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Patient, elderly and diabetic, develops unstable angina; initiate DAPT | Patient on long-term anticoagulation undergoing PCI for new-onset angina; initiate DAPT | Patient on DAPT following STEMI; develops AF; initiate anticoagulant | Patient on DAPT with ticagrelor following PCI; presents with nosebleeds and bruising |

| Cardiologists (n = 6) | All participants would initiate DAPT | Five participants would prescribe TT | All would prescribe TT | All would change to clopidogrel |

| Cardiac surgeons (n = 8) | Five participants would initiate DAPT |

|

|

|

| GPs (n = 8) |

|

|

|

|

Table 3 presents the factors that informed clinician prescribing decisions within factor categories, with examples. A detailed report of the factors, along with their constituent indicators, is presented in Appendix 4.

| Patient-related factors | Clinician-related factors | Drug characteristics | Local contexts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient risk profile: | Clinical guidelines and evidence-based medicine | Potency of drug | Commissioning and organisation budget policy |

|

|

|

|

| Previous and planned revascularisation procedures: | Professional opinion and experience | Licensing | Local culture of prescribing |

|

|

||

| Factors specific to the pharmacotherapeutic regimen of the patient: | Local prescribing protocols and decision support tools | ||

|

|||

| Multidisciplinary team-working | |||

|

|||

| Patient views and preferences |

Patient-related factors

Patient bleeding and ischaemic risk profile

The starting point for all clinician groups and all participants was an assessment of ischaemic and bleeding risk. Factors relating to a patient’s clinical presentation and risk profile were the most frequently raised by all participants (a comprehensive list of the indicators emerging from the analysis is presented in Appendix 4). The following excerpt is illustrative of the judgements described by participants:

You are making a balanced judgement between the benefit of anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy in terms of its ischaemia reduction, versus the risk which is bleeding, [...] so you’re looking at the presentation and judging whether it’s a high ischaemic risk presentation such as STEMI or a low ischaemic risk presentation such as stable angina and then the risk of bleeding, which would be low in healthy, young diabetic men, and would be very high in elderly, low body weight, hypertensive females with renal failure, so you’re trying to make a judgment taking all those factors.

Previous and planned revascularisation procedures

The patients’ previous and planned revascularisation procedures influenced prescribing decisions, including the duration of treatment. The most frequently mentioned factors to guide decisions were the stenting procedure and stent attributes. Interviewees considered time since stents were inserted, the types and number of stents inserted, and the success of the revascularisation procedure:

If let’s say [it is] 3 months from the time of the stent, we are a lot safer. For certain stents, even after 6 weeks, you are a lot safer.

Cardiac surgeon 007

The period of time really would depend on the actual procedure performed, how complex it is, how many stents he’s put in and how worried you are about the stent failing over the next few months.

Cardiologist 014

If the patient has had a successful revascularisation, the questions are what should they be restarted on.

Cardiac surgeon 015

I would [consider prescribing a second antiplatelet]. Only on the basis that, presumably, [the patient] is going for revascularisation [...] in preparation for a stenting procedure.

Cardiologist 002

Patient reactions to the pharmacotherapeutic regimen

When deciding to initiate a pharmacotherapeutic agent, or make changes to an existing regimen, interviewees considered factors related to a patient’s medication history, for example presenting with side effects, resistance or allergic reactions to agents:

This is someone who’s already on anticoagulation, so I’d look and see if they were on warfarin already and, [if] they’d had good control, I would carry on with the warfarin. If they were on a NOAC [non-vitamin K oral anticoagulant], I probably would put them onto a reduced dose of the NOAC.

Cardiologist 009

If a patient is having intolerable side effects [...] such as breathing difficulties, which I know is a potential side effect with ticagrelor [then would swap to clopidogrel].

GP 018

We test the patients if they are previously on clopidogrel and they are proven to have high resistance to clopidogrel, then I will swap them to aspirin and ticagrelor.

Cardiac surgeon 007

Risk of non-adherence

Interviewees considered individual patient characteristics that might compromise adherence to the pharmacotherapeutic regimen. They raised concerns for non-adherence more often when explaining their judgements of prescribing anticoagulant agents:

The problem with warfarin is it doesn’t have a fixed dose, so patients need to undergo blood tests [...] you have to consider which patient you have so sometimes you have very old patients, they live alone, it’s difficult for them to have blood tests. Maybe they’ve got very difficult veins to access to do the blood test and in this case it would be much easier to give another anticoagulant drug.

Cardiac surgeon 004

I always [...] ask [patients] ‘are you good at taking tablets? Do you struggle? Do you sometimes miss tablets?’ [...] if they’re telling me that they miss their evening tablets, I’m not going to give them a BD [bis in die (twice a day)] medication, try and give them once a day.

Cardiologist 003

Patient views and preferences

In some instances, interviewees would consider patient preferences in their prescribing decision-making. For example, patient preferences would be taken into account when choosing between anticoagulant agents because of the impact of different regimens on a patient’s lifestyle, and the regimen’s dosage requirements. Some interviewees also reported that they would consider patient views when balancing risk of ischaemia with risk of bleeding, and ways to manage nuisance bleeding:

Warfarin is very much a lifestyle-changing medication and you do need to have that discussion with them and they do need to be on board with attending warfarin clinics and for their prescribing of warfarin, along with modification of their lifestyle, in order to be safe when taking warfarin.

Cardiac surgeon 008

You have to have a discussion with the patient to say ‘I think this is due to the medication we’re on. You’re on it because you’ve got a high risk of recurrent myocardial infarction. How bad are these nosebleeds? What are the consequences of the nosebleeds?’ and then you have to consider the position as to what to do depending on what the patient tells you really.

GP 006

You chat to the patient, you know you talk to them about the risk of a stroke versus the risk of a bleed and they have to help you to make a decision.

Cardiologist 003

Clinician-related factors

Guided by clinical guidelines and evidence-based medicine

Clinical guidelines and evidence-based medicine did not inform decisions for some case vignettes. Several factors influenced the use of guidelines, including awareness of the guidelines and research evidence for specific case vignettes. Several interviewees, in particular cardiac surgeons, commented on the lack of research evidence to inform decisions in some scenarios. Multiple, and sometimes conflicting, sources of evidence could also present challenges:

Clopidogrel would be another [choice] and, again, we wouldn’t use that because I think NICE [National Institute for Health and Care Excellence] guidance suggests ticagrelor as the best treatment option in this scenario.

GP 006

As far as I know, there are no randomised clinical trials that demonstrate clearly that, after elective CABG, dual antiplatelet is better.

Cardiac surgeon 004

You need to have enough evidence, clinical evidence, of the use of the medication [to inform the decision of whether or not to prescribe it].

Cardiac surgeon 007

And the trouble is, you’ve got so much data [...] the more data we get, the more confused we seem to be.

Cardiologist 001

The quality and credibility of guidelines and available evidence and their relevance to complex patient cases also influenced attitudes towards the use of clinical guidelines and evidence-based medicine:

The guidelines and the studies are done on patients maybe up to 70 or 75 years of age. They don’t help you when you have someone who’s 90, there isn’t any data for that and there isn’t data for the patients who are complex, like the ones in hospital, because in the study [they are] not the ones who have dementia, falls, emphysema, all the other problems that you have to try and consider.

Cardiologist 003

What the guidelines and the trials are desperately trying to do, and I’m not sure it’s actually possible, is they’re trying to make all patients the same and give you a simple answer. I personally have always felt that’s a gross oversimplification because all patients are different and all scenarios are different.

Cardiologist 001

[Clinical guidelines] are useful. As a reference point, no doubt about it, and some of them are [...] a general one-size-fits-all approach.

GP010

I read them, I know them, but I don’t always follow them. [...] guidelines are written by committees that may or may not have vested interests about what they’re writing the guidelines about and they may have an inadequate evidence base on which to do it.

Cardiologist 005

The problem, particularly in surgery, is then a lot of those guidelines are based on weak evidence, not on significant sizeable randomised studies.

Cardiac surgeon 015

Other considerations were their clarity and level of complexity:

[...] NICE particularly [...] they’re not necessarily good at helping you weigh two treatments against each other, they’re just saying ‘This is an appropriate treatment to give which you should consider and offer where appropriate’.

Cardiologist 009

[Local guidelines] change a lot and still some people maybe ignore little bits and pieces, but they change and they’re becoming really complicated because of the scenarios [...] [there are] so many boxes you have to follow to go down to tell you what to do.

Cardiologist 003

I think we need risk calculators to predict for specific situations what the best strategy for antiplatelet therapy is. Otherwise it does take quite some time to try to ascertain from the guidelines what should we do with specific cases.

Cardiac surgeon 008

I think sometimes they’re very long and they are difficult to get through.

GP010

Professional opinion

Individual professional opinion was an important determinant of prescribing behaviours when prescribing guidelines and evidence were not thought of as relevant or useful. Clinicians would tend to prescribe agents that they were familiar with and had used in the past:

I think what influences prescribing, certainly in my experience, and I think in lots of surgeons’ experience, is their own practice. [...] Since the guidelines are not very clear or not supported by very strong evidence, often you find individual surgeons will have their own opinion.

Cardiac surgeon 015

There are no clear indications taken by the guidelines [to support DAPT] so, really, if you have, let’s say, 30 years’ good experience with aspirin, maybe you would prefer to continue giving aspirin.

Cardiac surgeon 004

From experience, what you’ve used in other patients in the past [would help decide what agent to prescribe].

GP006

That really comes down to one of comfort and what you’ve been used to and what you use a lot of [...] since sort of late in my training a few years ago I’ve just been using more of apixaban and that’s what you get comfortable with. I’m happy using apixaban because I’ve been prescribing it quite a lot, I’m used to the potential side effects.

Cardiologist 014

Drug characteristics

When choosing between agents, agent potency was an important consideration for managing the risk of bleeding for a patient:

The reason I’m choosing apixaban is it’s the anticoagulant which probably has [...] the lowest bleeding risk, so because you’re also giving a patient two other drugs which cause bleeding, I would go for the drug which has the lowest bleeding risk.

Cardiologist 001

In this case, there really only is the clopidogrel that we would use because we would not want to combine a very potent antiplatelet agent such as ticagrelor or prasugrel with anticoagulation.

Cardiologist 014

Ticagrelor is a very powerful antiplatelet agent, so [...] I would stop the aspirin and see whether, with ticagrelor only, the nose bleeding and the bruising reduced. If it [...] I would stop the ticagrelor and put the patient back on aspirin and clopidogrel.

Cardiac surgeon 015

The licensing of agents for specific clinical scenarios would also influence prescribing:

For any valvular disease, like if you have AF and you have had a mitral valve repair, mitral valve replacement, or aortic valve replacement, you cannot currently use NOACs or apixaban because they are not licensed for it at the moment.

Cardiac surgeon 011

Local contexts

Commissioning and organisation budget policy

Prescribing behaviours were influenced by the local budgets, commissioning decisions and prescribing protocols:

At the moment in the unit, we only [prescribe] clopidogrel, we’re not using ticagrelor.

Cardiac surgeon 015

If you asked me, I would use NOAC or apixaban, not warfarin; however, at the moment, after cardiac surgery, NOACs are not licensed to be used, number one. Number two [...] it’s more expensive, it’s not allowed to be used, I cannot use it.

Cardiac surgeon 011

Clopidogrel is much more [often prescribed] locally and I actually don’t know why. I think it’s an expense issue. I think clopidogrel has been around longer and is now much cheaper.

GP012

When you’re prescribing, there is a software that actually tells you, first of all, it can link you to the guidance and the CCG [Clinical Commissioning Group].

GP006

Guided by local prescribing culture

Prescribing culture would also influence prescribing behaviours, meaning that clinicians would tend to prescribe agents routinely prescribed within the unit. How familiar other clinicians and staff members who were involved in a patient’s care were with specific agents was thought to be important for patient safety and team-working:

Because there’s no clear statement about cardiac surgery for the moment, we stick to clopidogrel, which is a bit more known by clinicians, and known by GPs as well.

Cardiac surgeon 004

Familiarity of the medication in the unit and people who treat the patient, so if you get some that nobody is familiar, they don’t know what to do with it, how rapid is the response and if it is possible to be reversed, especially for cardiac surgery because you may have to take the patient back for bleeding or something.

Cardiac surgeon 007

Interviewees based in one hospital setting reported the importance of standardising prescribing practices in secondary care settings through local prescribing protocols to promote patient safety, improve multidisciplinary team (MDT) communication and support junior doctors and other members of staff in their roles:

In the past, there were 10 surgeons, you had 11 different [prescribing] policies. Now it’s not the case because you want to run things in a simple way and not as confusing as it was in the past, not least for the nurses and the juniors, so generally most units will have protocols which have been agreed by everybody. So I think it makes life easier for everybody concerned.

Cardiac surgeon 015

We have what we call trust protocols or trust guidelines [...] it’s easier; it’s much quicker and easier to read and to understand [than individual guidelines and research evidence].

Cardiac surgeon 004

There’s multiple different antiplatelet regimes and, to some extent, there’s only certain evidence base for them and it’s very confusing for juniors to have a lot of different approaches [...] so reducing variants is sort of one of the tenets of safe care in hospital. [...] So the EC [European Community] guideline approach would say ticagrelor. I think the clinical scenario says ticagrelor and the hospital protocol says ticagrelor, so I’d go ticagrelor.

Cardiologist 005

Interviewees respected colleagues’ clinical decision-making autonomy and were reluctant to change medication prescribed by other clinicians:

I would carry on with aspirin and clopidogrel because I am worried about the stent that might block and the cardiologists are going to be pretty upset if they find that the clopidogrel has been stopped.

Cardiac surgeon 011

If the clinician in the hospital had recommended ticagrelor, I would continue it because I’d be concerned if there was some specific reason why they chose that one.

GP012

Guided by multidisciplinary team opinion

A decision on which regime was the most appropriate would be guided by members of the MDT if the individual clinician felt that they lacked the expertise to make an informed decision. Most interviewees stated that their decisions would be informed by cardiology expert opinion, whereas a minority referred to other members of the MDT:

I would expect my interventional colleagues to be saying, you know, ‘We’ve reviewed the data, we’ve reviewed the international guidelines and then this is how we think they should be interpreted in our settings’.

Cardiologist 009

Haematology can be useful [...] regarding anticoagulation, and pharmacies, pharmacy are very good at being able to guide us regarding evidence.

Cardiac surgeon 008

We try and work as a team, so I might, if I’m in any discomfort about making this decision, I might discuss it with my GP colleagues as well as the patient’s consultant cardiologist. Or actually the prescribing adviser at the CCG [Clinical Commissioning Group] can often be very helpful in producing guidelines and protocols if there are any.

GP018

Conflicts of interest and pharmaceutical company influence

Two interviewees reported being involved in research funded by pharmaceutical companies, and two stated that they made an effort to maintain independence because of their academic roles. Some GPs reported their surgery’s policy to block access of pharmaceutical company representatives to individual doctors. None of the interviewees reported being directly influenced by pharmaceutical companies in what they prescribed, even in the cases of participants reporting direct involvement with pharmaceutical companies through their research activities:

I have to be very careful not to have too many links with pharma in that particular area, otherwise I can’t be involved in that particular kind of, you know [...] reviewing of the evidence and providing the guidelines.

Cardiologist 009

I’ve never held any consultancy with any company. I’ve always refused because I wanted to maintain my independence.

Cardiac surgeon 015

I have a good relationship with companies in terms of looking at data and them funding some of my research occasionally, but I certainly wouldn’t let that affect my prescribing.

Cardiologist 001

I don’t see any drug rep[resentative]s at all. I don’t know if anyone in our practice does. I try not to engage with them, personally.

GP013

Most interviewees described the role of pharmaceutical companies in continuing professional education and dissemination of clinical trial findings. Some believed that this involvement had the potential to indirectly influence prescribing behaviours through the relationships created:

We do a journal club where [...] we also have a rep from one of the pharma companies who is providing the lunch, often telling us about an [research] update [...] Their education support sometimes is [a] double-edged sword that, although it’s supposed to be neutral of a product [...] they’ve gone for subtle forms of influencing [...] It’s making you associate their product with some good feeling so that when you have a choice that’s equal, you think ‘actually here I’m going to use that drug because I feel more confident about it’.

Cardiologist 009

If somebody takes you to a big meeting and you have a great time, then the next time you have to prescribe a drug which is produced by that particular company, willingly or unwillingly, you will be more disposed isn’t it, it’s human nature.

Cardiac surgeon 015

Some interviewees believed that pharmaceutical companies had some influence in the content of guideline recommendations through funding the clinical trials that provided the evidence for the recommendations, promoting individuals who supported their products within key committees and lobbying decision-makers:

By definition, they have a role because if you look at major trials they have done, especially with the new drugs [...]. [Guidelines] are not as much independent, but they are by definition influenced one way or another by the companies and the drug-producing manufacturer.

Cardiac surgeon 007

I think that the pharma companies are trying to target it at a bigger level so they’ve got key opinion leaders that you associate with particular brands [...] They’ve tried to push those people forward so [...] they’re not necessarily directly promoting their drug, but are finding ways to make that person have influence by linking them up with other leaders in the research world or in national or international societies.

Cardiologist 009

They [pharmaceutical companies] produce the drugs and they pay for the trials, so they’re obviously massively important [...] [named pharmaceutical company] basically lobbied government saying, ‘our drug isn’t being prescribed’ and ‘the guidelines say it should and why not?’ so and they started to get very political.

Cardiologist 001

Survey of clinicians

Methods

Two online surveys (one for cardiologists and one for cardiac surgeons) were developed by the study team, including a methodologist with expertise in survey design, a consultant cardiologist and a consultant surgeon. The surveys were designed to do the following:

-

Describe DAPT prescribing practice among various patient subgroups [based on age, type of event (e.g. ACS vs. non-ACS), concomitant anticoagulant use for cardiology patients and type of surgery, anticoagulant use for cardiac surgery patients].

-

Identify the five most important factors that influence the choice of DAPT prescription in each of six separate domains (e.g. demography, comorbidity and procedure related-characteristics) for cardiology patients and two domains (age and comorbidity only) for cardiac surgery patients. The factors included in the survey were those identified from the systematic review (see Table 1) and additional factors identified from the clinician interviews.

-

Identify whether or not the chosen factors influenced prescribing decisions because they increased risk of ischaemia, risk of bleeding or risk of both ischaemia and bleeding.

The factors and their respective domains were those identified from the systematic review and clinician interviews. The surveys were uploaded to SurveyMonkey® (Palo Alto, CA, USA) and the online surveys were piloted among a small group of cardiologists and cardiac surgeons to ensure ease of use and to test face and content validity. An invitation including a link to the survey was disseminated by e-mail via the Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery (cardiac surgeons) and the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (cardiologists) to all individual fellows and members of the societies. The data analysis tools in SurveyMonkey and Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond,WA, USA) were used to calculate descriptive statistics.

Characteristics of survey respondents (cardiologists and cardiac surgeons)

There were 101 cardiologists and 36 cardiac surgeons who initiated the survey. Of these, 22 cardiologists (22%) and five cardiac surgeons (14%) consented to participate (selected the ‘agree’ electronic consent button) but did not complete any survey questions, so they were removed, leaving a total of 79 cardiologist and 31 cardiac surgeon respondents (Table 4). Of the cardiologists, almost two-thirds of respondents were consultant grade and were evenly distributed across years of practice categories, whereas, for cardiac surgeons, the majority of respondents (90%) were consultants and over half of them had practised for > 15 years. Respondents represented all regions of the UK, but the regions most represented were London, the south west and the north west. Just under two-thirds of cardiologist respondents prescribed DAPT daily, and the majority of the remainder prescribed DAPT two or three times per week. The most common guidelines used by both clinician groups were NICE1 and European Society of Cardiology2 guidelines, although just under half of cardiac surgeon respondents (42%) reported using none of the guidelines. Most cardiologists reported that local protocols for DAPT prescribing were available, whereas two-thirds of cardiac surgeons reported that they had no local protocols for antiplatelet prescribing.

| Demographic details | Respondents, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiologists (N = 79) | Cardiac surgeons (N = 31) | |

| Grade | ||

| Consultant | 50 (63) | 28 (90) |

| Fellow/specialist registrar | 25 (32) | 2 (6) |

| Associate specialist/staff grade | 4 (5) | 1 (3) |

| Subspecialty (consultants only) | ||

| Interventional cardiology | 45 (90) | – |

| Heart failure | 4 (8) | – |

| Cardiac imaging | 1 (2) | – |

| Years of practice (consultants only) | N = 28 | |

| < 5 | 12 (24) | 4 (14) |

| 5–10 | 14 (28) | 5 (18) |

| 11–15 | 11 (22) | 4 (14) |

| > 15 | 13 (26) | 15 (54) |

| Location | ||

| North West | 6 (8) | 6 (19) |

| North East | 1 (1) | 1 (3) |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 4 (5) | 1 (3) |

| East Midlands | 5 (6) | 1 (3) |

| West Midlands | 6 (8) | 2 (6) |

| Eastern England | 6 (8) | 1 (3) |

| London | 16 (20) | 5 (16) |

| South East Coastal | 4 (5) | 1 (3) |

| South Central | 6 (8) | 3 (10) |

| South West | 11 (14) | 4 (13) |

| Scotland | 10 (13) | 4 (13) |

| Wales | 2 (3) | 1 (3) |

| Northern Ireland | 2 (3) | 1 (3) |

| How often DAPT is prescribed | ||

| Daily | 48 (61) | – |

| Two or three times per week | 25 (32) | – |

| Less than once per week | 6 (8) | – |

| Guidelines used for DAPT prescribinga | ||

| NICE | 37 (47) | 12 (39) |

| European Society of Cardiology | 64 (81) | 16 (52) |

| American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association | 8 (10) | 9 (29) |

| None of the above | 6 (8) | 13 (42) |

| Are local protocols for DAPT prescribing available? | ||

| Yes | 63 (80) | 12 (39) |

| No | 16 (20) | 19 (61) |

Survey results: cardiologists

Dual antiplatelet therapy prescribing practice for ACS and stable angina patients is shown in Table 5. The default prescribing regimen for ACS STEMI patients was AT (more than two-thirds of respondents, with most prescribing for 12 months). Relatively few STEMI patients were prescribed AP (12% and 5% in those aged ≤ 75 years and > 75 years, respectively).

| Patients, split by age (years), n/N (%) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAPT regimen and duration of treatment | ACS STEMI (PCI) | ACS NSTEMI (PCI) | ACS unstable angina (PCI) | Stable angina (PCI) | ACS (conservatively managed) | |||||||

| ≤ 75 | > 75 | ≤ 75 | > 75 | ≤ 75 | > 75 | ≤ 75 | > 75 | ≤ 75 | > 75 | |||

| AC | 8/68 (12) | 14/64 (22) | 18/68 (22) | 26/64 (41) | 29/67 (43) | 34/64 (53) | 59/67 (88) | 57/63 (90) | 40/71 (56) | 46/67 (69) | ||

| 1 month | 0 | 1/14 (7) | 0 | 0 | 1/29 (3) | 0 | 1/59 (2) | 1/57 (2) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 months | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/26 (4) | 1/29 (3) | 1/34 (3) | 2/59 (3) | 1/57 (2) | 2/46 (5) | 1/46 (2) | ||

| 6 months | 2/8 (25) | 3/14 (21) | 2/18 (11) | 3/26 (12) | 1/29 (3) | 3/34 (9) | 20/59 (34) | 24/57 (42) | 3/46 (8) | 7/46 (15) | ||

| 12 months | 5/8 (63) | 9/14 (64) | 15/18 (83) | 20/26 (77) | 24/29 (83) | 28/34 (82) | 35/59 (59) | 30/57 (53) | 34/46 (85) | 37/46 (80) | ||

| > 12 months | 1/8 (13) | 1/14 (7) | 1/15 (7) | 2/26 (8) | 2/29 (7) | 2/34 (6) | 1/59 (2) | 1/57 (2) | 1/46 (3) | 1/46 (2) | ||

| AP | 8/68 (12) | 3/64 (5) | 4/68 (6) | 2/64 (3) | 2/67 (3) | 1/64 (2) | 1/67 (1) | 1/63 (2) | 2/71 (3) | 1/67 (1) | ||

| 1 month | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/1 (100) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 months | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 6 months | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 12 months | 8/8 (100) | 3/3 (100) | 4/4 (100) | 2/2 (100) | 2/2 (100) | 1/1 (100) | 1/1 (100) | 0 | 2/2 (100) | 1/1 (100) | ||

| > 12 months | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| AT | 52/68 (76) | 47/64 (73) | 46/68 (59) | 36/64 (56) | 36/67 (54) | 29/64 (45) | 7/67 (10) | 5/63 (8) | 29/71 (41) | 20/67 (30) | ||

| 1 month | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 months | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2/29 (7) | 2/20 (10) | ||

| 6 months | 5/52 (10) | 3/47 (6) | 5/46 (11) | 3/36 (8) | 3/36 (8) | 2/29 (7) | 5/7 (71) | 3/5 (60) | 4/29 (14) | 3/20 (15) | ||

| 12 months | 47/52 (90) | 42/47 (89) | 40/46 (87) | 32/36 (89) | 32/36 (89) | 27/29 (93) | 2/7 (29) | 2/5 (40) | 27/29 (79) | 15/20 (75) | ||

| > 12 months | 0 | 2/47 (4) | 1/46 (2) | 1/36 (3) | 1/36 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

Among patients who had a non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), just over half of all respondents prescribed AT for both younger and older patients, whereas, for conservatively managed ACS patients, 41% (for patients aged ≤ 75 years) and 30% (for patients aged > 75 years) of respondents prescribed AT. The use of AP was infrequent, except for STEMI patients aged ≤ 75 years, for whom just over 12% of respondents prescribed this regimen.

Across all ACS groups, approximately 10% of respondents prescribed DAPT for 6 months only (all regimens and age groups), although there was variation in the duration of DAPT treatment in the ACS conservatively managed patient group, with DAPT prescribing ranging from 3 months to > 12 months. Among patients with stable angina undergoing PCI, the default DAPT regimen was AC (for ≈ 90% of patients across both age groups), with variation in duration of treatment ranging from 1 month to > 12 months. Fewer than 10% of stable angina patients were prescribed AT.

Antiplatelet prescribing practice for ACS patients who also need anticoagulants is shown in Table 6. The majority of respondents (63–70%) prescribe TT with AC to ACS patients undergoing PCI (STEMI, NSTEMI and unstable angina patients), with the duration of TT ranging from 1 to 6 months, although 1 month was most frequent. About one-third of respondents prescribe antiplatelet monotherapy, with the majority (80%) prescribing it for 12 months. Most respondents (84%) reported stopping aspirin when stepping down from TT to dual therapy; only 16% reported stopping the P2Y12 inhibitor.

| Patients, n/N (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antiplatelet regimen and duration of treatment | ACS STEMI (PCI) | ACS NSTEMI (PCI) | ACS unstable angina (PCI) | ACS conservatively managed |

| Monotherapy | 16/60 (27) | 20/65 (31) | 20/65 (31) | 36/58 (62) |

| 1 month | 1/16 (6) | 2/20 (10) | 1/20 (5) | 3/36 (8) |

| 3 months | 1/16 (6) | 1/20 (5) | 1/20 (5) | 2/36 (6) |

| 6 months | 0 | 0 | 1/20 (5) | 6/36 (17) |

| 12 months | 13/16 (81) | 16/20 (80) | 16/20 (80) | 24/36 (67) |

| > 12 months | 1/16 (6) | 1/20 (5) | 1/20 (5) | 1/36 (3) |

| AC | 42/60 (70) | 41/65 (63) | 41/65 (63) | 20/58 (34) |

| 1 month | 21/42 (50) | 21/41 (51) | 23/41 (56) | 12/20 (60) |

| 3 months | 16/42 (38) | 15/41 (37) | 13/41 (32) | 5/20 (25) |

| 6 months | 5/42 (12) | 5/41 (12) | 5/41 (12) | 2/20 (10) |

| 12 months | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/20 (5) |

| > 12 months | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 month | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 months | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 months | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 months | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| > 12 months | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AT | 7/60 (12) | 4/65 (6) | 4/65 (6) | 3/58 (5) |

| 1 month | 5/7 (71) | 3/4 (75) | 3/4 (75) | 2/3 (67) |

| 3 months | 1/7 (14) | 1/4 (25) | 0 | 1/3 (33) |

| 6 months | 1/7 (14) | 0 | 1/4 (25) | 0 |

| 12 months | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| > 12 months | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

For patients with conservatively treated ACS, antiplatelet monotherapy was most commonly prescribed (62% of respondents), followed by TT with AC (34% of respondents), mostly prescribed for 1–3 months. None of these patients was prescribed AP.

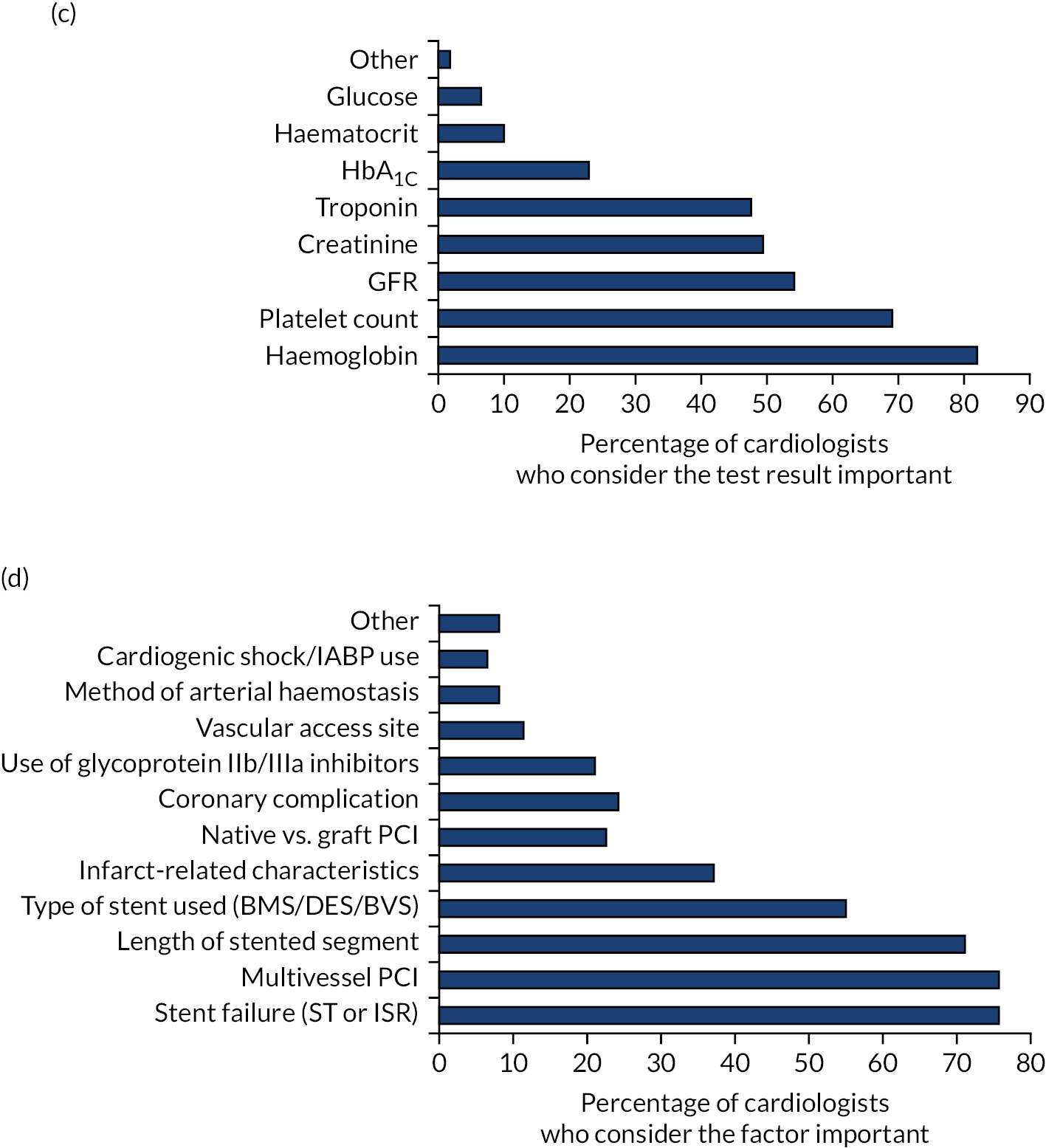

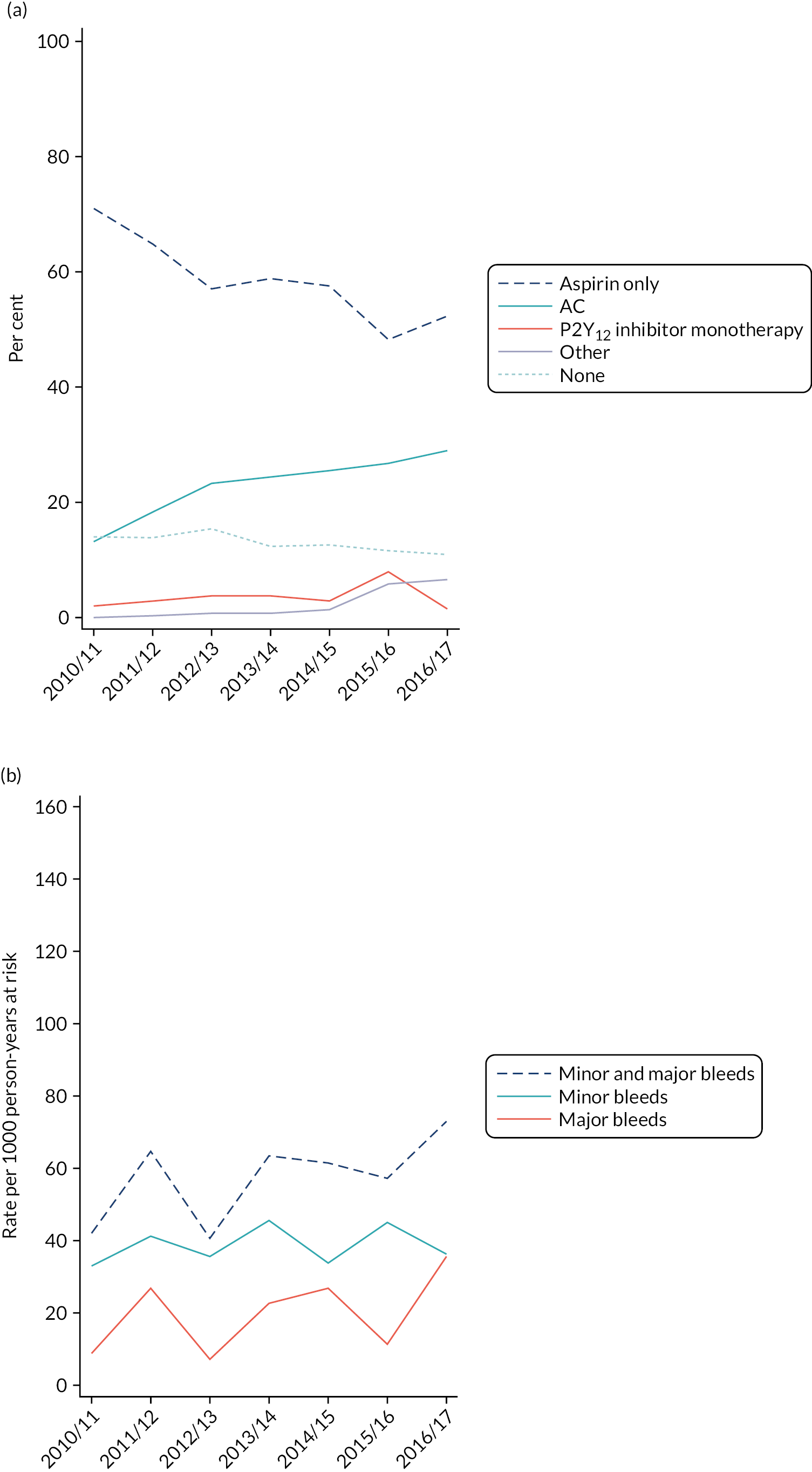

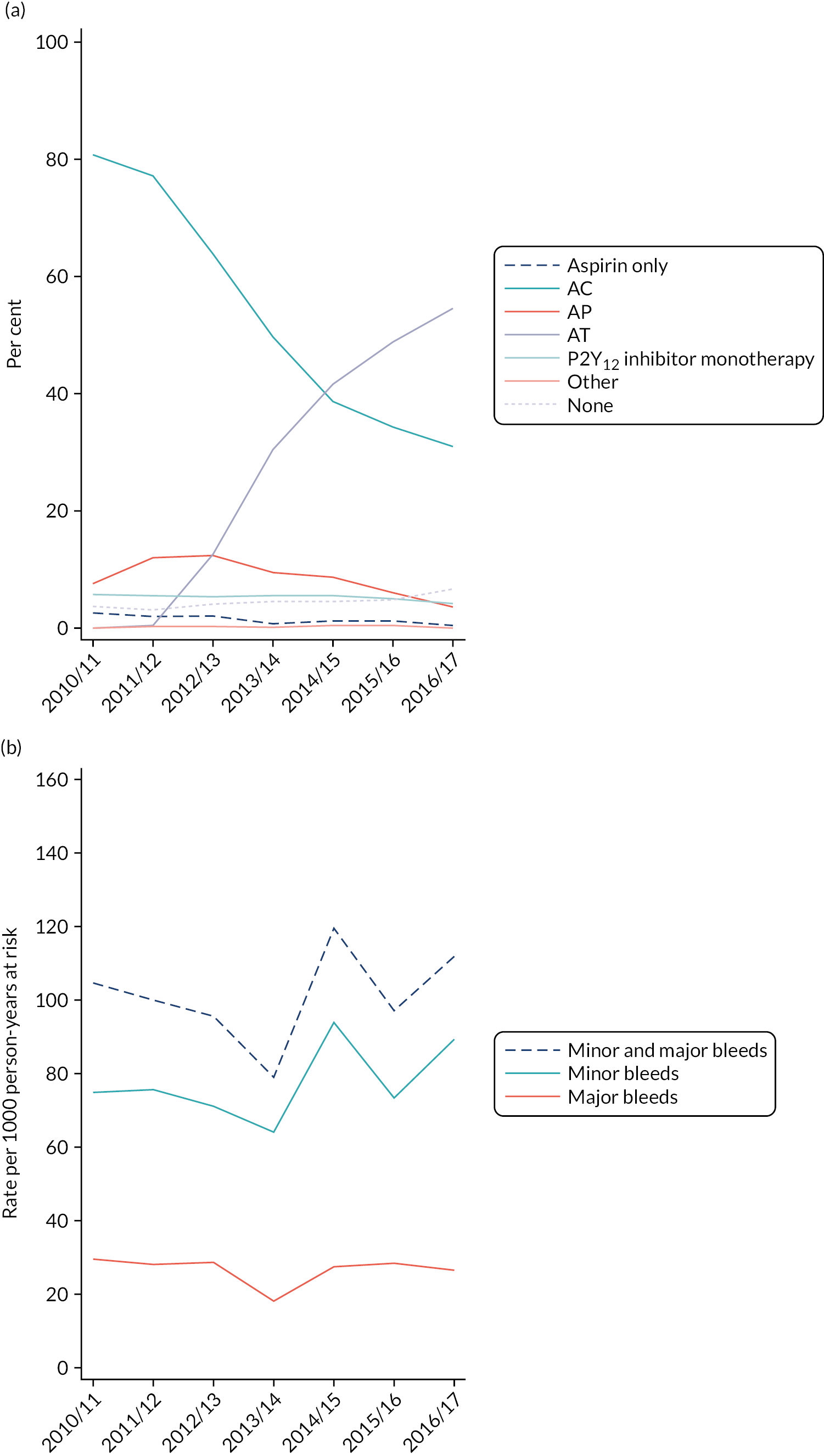

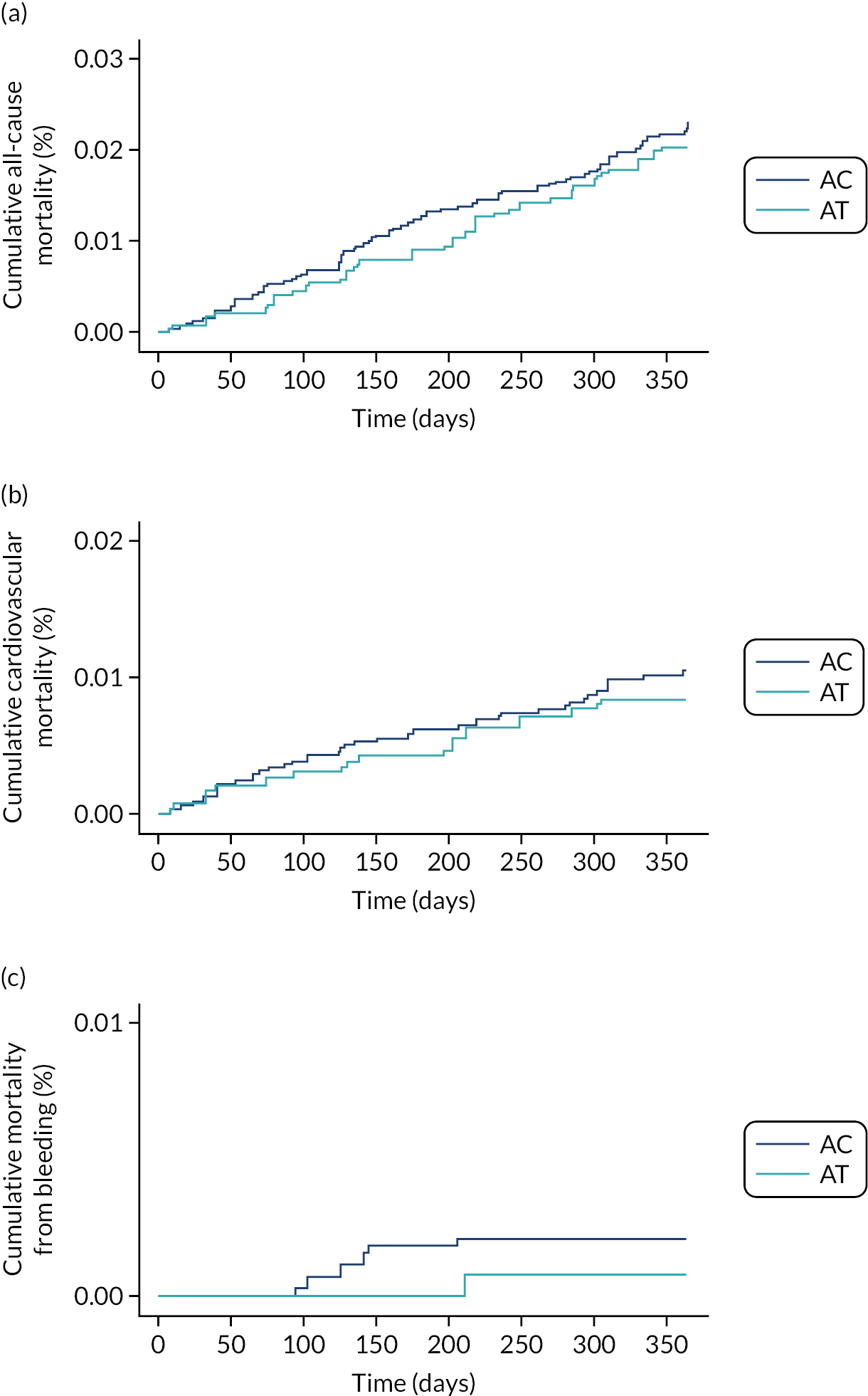

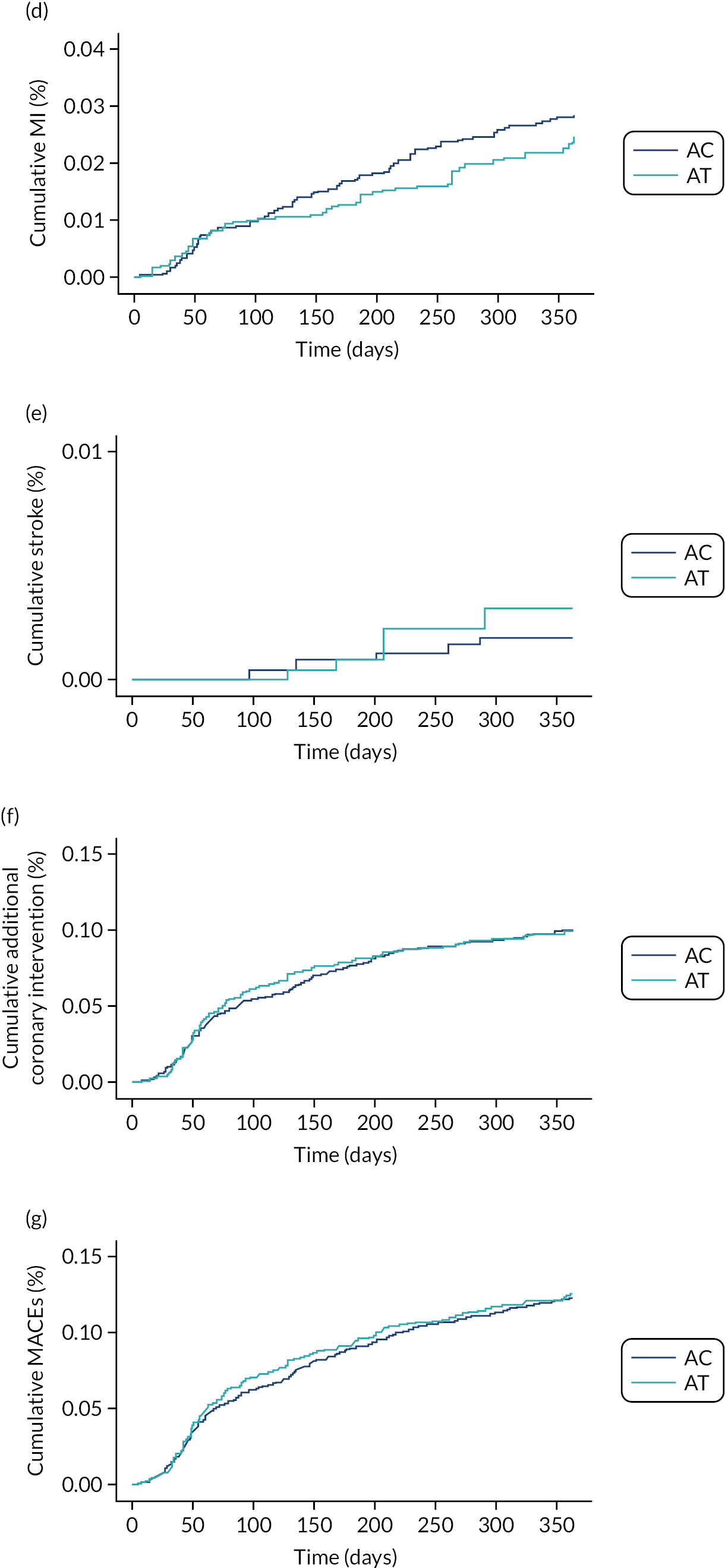

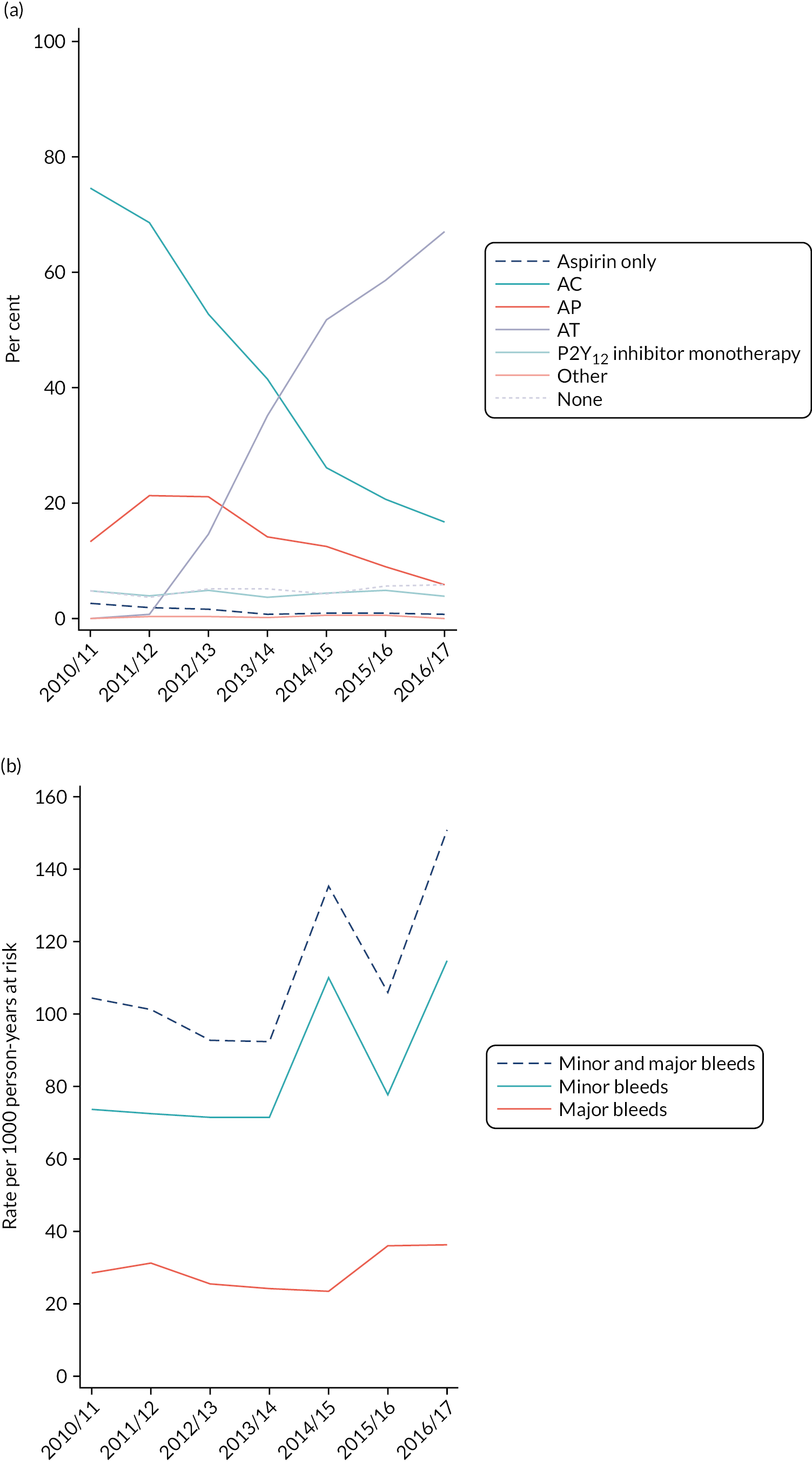

The patient factors that cardiologists take into account when prescribing DAPT are shown in Figure 2a. Patient age, use of concomitant anticoagulation, and whether or not a patient had a current, or had experienced a previous, bleed were considered important by 73%, 72% and 70% of respondents, respectively, followed by disease complexity (40%), anaemia (37%) and renal impairment (33%). About one-quarter considered peptic ulcer diseases, body mass index (BMI), diabetes and ACS risk score as important when prescribing DAPT for their patients.

FIGURE 2.

Patient, procedure- and presentation-related factors and blood test results that cardiologists consider important when prescribing DAPT to their patients. (a) Patient factors; (b) presentation-related factors; (c) blood test results; and (d) procedure-related factors. BMS, bare-metal stent; BVS, bioabsorbable vascular scaffold; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CRUSADE, Can rapid Risk stratification of Unstable angina patients suppress ADverse outcomes with Early implementation of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline; DES, drug-eluting stent; ECG, electrocardiogram; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; HAS-BLED, hypertension, abnormal liver/renal function, stroke history, bleeding history or predisposition, labile international normalised ratio, elderly, drug/alcohol usage; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; ISR, in-stent restenosis; LV, left ventricular; ST, stent thrombosis; SYNTAX, SYNergy between PCI with TAXus and cardiac surgery; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Presentation-related factors and blood test results that cardiologists consider when they prescribe DAPT are shown in Figure 2b and c, respectively. Presenting syndrome (ACS or stable angina) was the single most important presentation-related factor taken into consideration when prescribing DAPT (98% of all respondents). In terms of blood test results, haemoglobin (82%), platelet count (69%), glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (54%), creatinine (49%) and troponin (47.5%) were considered to be important.

Procedure-related factors that influence DAPT prescription are shown in Figure 2d. More than 70% of respondents thought that stent failure (76%), multivessel PCI (76%) and length of stented segment (71%) were important factors that influenced their DAPT prescription; 55% thought that type of stent used was important when prescribing DAPT. Just over one-third (37%) considered infarct-related characteristics, and about one-quarter considered coronary complications or whether a native or graft vessel had been stented.

Respondents were asked to indicate whether or not the factors that influence their decision-making process when prescribing DAPT did so because of their association with ischaemia risk, bleeding risk, or both ischaemia and bleeding risk. Figure 3 shows the contribution of each risk (ischaemia, bleeding or both) to the decision-making process for the most commonly considered factors (i.e. those regarded as important by ≥ 50% of respondents). Figure 2 indicates that cardiologists consider bleeding and ischaemia risks equally when prescribing DAPT. Five of the 12 factors (presenting syndrome, ACS or stable angina, and those related to the PCI procedure) were chosenmainly on the basis that they increase ischaemia risk, 5 of the 12 (concomitant anticoagulation, previous or current bleeding, bleeding risk score, haemoglobin level and platelet count) were chosen mainly on the basis that they increase bleeding risk, and 2 of the 12 (age and GFR) were chosen mainly on the basis that they increase both bleeding and ischaemia risks.

FIGURE 3.

The contribution of each risk (ischaemia, bleeding or both) to the cardiologist decision-making process for the most commonly considered patient, presentation- and procedure-related factors (i.e. those regarded as important by ≥ 50% of respondents).

Survey results: cardiac surgeons

Table 7 shows antiplatelet prescribing for the various patient subgroups. Antiplatelets were commonly prescribed for the following patient subgroups: CABG and recent ACS (81%), CABG with poor vessel/conduit quality (71%) and CABG and previous stent (61%). Relatively few respondents prescribed DAPT as a substitute for vitamin K antagonist prophylaxis for CABG and tissue valve surgery (13%) and post-operative AF (3%).

| Respondents, n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient subgroup | Low-dose aspirin (75–150 mg) | High-dose aspirin (150–300 mg) | Low-dose AC (75 mg once per day) | Low-dose AT (90 mg twice per day) | Low-dose AT (60 mg twice per day) |

| CABG plus recent ACS | 7 (24) | 6 (21) | 15 (52) | 18 (62) | 3 (10) |

| CABG with poor vessel/conduit quality | 0 | 0 | 3 (10) | 4 (14) | 1 (3) |

| Off-pump CABG | 10 (35) | 18 (62) | 8 (28) | 6 (17) | 17 (58) |

| CABG plus tissue valve (as substitute for VKA prophylaxis) | 11 (38) | 4 (14) | 3 (10) | 2 (7) | 6 (21) |

| CABG plus previous stent | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 2 (7) |

| Post-operative AF (as substitute for VKA prophylaxis) | 20 (69) | 2 (7) | 3 (10) | 2 (7) | 2 (7) |

For the CABG with recent ACS, CABG with poor vessel/conduit quality and CABG with previous stent patient subgroups, DAPT was the preferred treatment (76%, 79% and 86%, respectively). DAPT with clopidogrel was most frequently prescribed for the last two patient subgroups, although, for the CABG and recent ACS patient subgroup, respondents were equally likely to prescribe DAPT with ticagrelor. Low-dose aspirin was preferred for patients undergoing off-pump CABG (62% of respondents), patients undergoing CABG and valve surgery (76%) and patients with post-operative AF (76%). Just under two-thirds of respondents (18/29; 62%) never prescribe DAPT after surgery for patients who require thromboprophylaxis with warfarin or a NOAC, whereas the remainder (38%) prescribe DAPT only in very selected patients requiring warfarin or a NOAC.

The patient factors that cardiac surgeons take into account when prescribing DAPT are shown in Figure 4. Previous or current bleeding and previous CABG or PCI were considered important by 59% and 66% of respondents, respectively, followed by age, concomitant anticoagulation and bleeding risk score (48%). About one-third considered previous stroke and peptic ulcer disease, one-quarter considered disease complexity and one-fifth considered resistance to antiplatelet agents to be important.

FIGURE 4.

Patient factors that cardiac surgeons consider important when prescribing antiplatelet agents to their patients. CKD, chronic kidney disease; CRUSADE, Can rapid Risk stratification of Unstable angina patients suppress ADverse outcomes with Early implementation of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; HAS-BLED, hypertension, abnormal liver/renal function, stroke history, bleeding history or predisposition, labile international normalised ratio, elderly, drug/alcohol use; SYNTAX, SYNergy between PCI with TAXus and cardiac surgery; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Respondents were asked to indicate whether or not the factors that influence their decision-making process when prescribing DAPT did so because of their association with ischaemia risk, bleeding risk, or both ischaemia and bleeding risk. Figure 5 shows the contribution of each risk (ischaemia, bleeding or both) to the decision-making process for all patient factors. Both bleeding and ischaemia risks were considered equally in the decision-making process, but concern about bleeding risk featured more prominently in the factors that > 48% of surgeons considered to be important when prescribing (previous or current bleeding, age, concomitant anticoagulation and bleeding risk score).

FIGURE 5.

The contribution of each risk (ischaemia, bleeding or both) to the cardiac surgeon decision-making process for the most commonly considered factors (i.e. those regarded as important by ≥50% of respondents). CKD, chronic kidney disease; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Discussion

We identified 70 factors and 10 co-interventions by systematic review, clinician interview and clinician survey (Table 8). Of the 70 factors identified, 59 (84%) were identified by systematic review, 25 (36%) were identified by clinician interview and 46 (66%) were confirmed by clinician survey. Only 25 (36%) were identified by all three methods. The clinician interviews identified an additional 10 factors (14%) not identified by the systematic review (four were confirmed by clinician survey), including antiplatelet cost considerations, local/international prescribing guidelines, adherence issues among patients, clinician professional opinion and resistance to antiplatelet agents.

| Factors identified | Source | Confounder, cause of exposure, cause of outcome, none | Direction of effect for risk of bleeding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demography (n = 7 ) | |||

| Older age | SR, I, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Female sex | SR, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Decreasing BMI | SR, I, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| South Asian ethnicity | SR | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Smoker | SR, CS | Cause of exposure | – |

| Lower educational level | SR | None | – |

| Family history of IHD | SR | None | – |

| Medical history (n = 5 ) | |||

| Previous MI | SR, I, CS | Cause of exposure | – |

| Previous CABG or PCI | SR, I, CS | Cause of exposure | – |

| Previous bleeding | SR, I, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Dyspnoea | SR, I | None | – |

| Recent surgery | SR, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Comorbidity (n = 16 ) | |||

| IHD | SR, I, CS | Cause of exposure | – |

| Diabetes | SR, I, CS | Confounder | – |

| Hypertension | SR, I, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | SR | Cause of exposure | – |

| Peripheral vascular disease | SR, I, CS | Cause of exposure | – |

| Stroke or TIA | SR, I, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Heart failure | SR, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Peptic ulcer disease | SR, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Chronic kidney disease | SR, I, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Cancer | SR, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Haematological disorder | SR, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| AF/thrombosis/valve disease requiring warfarin or NOAC | SR, I, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Anaemia | SR, I, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Lung disease (e.g. COPD and asthma) | SR | None | – |

| Liver disease (e.g. cirrhosis) | SR, I, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Gout | SR | None | – |

| Presentation risk (n = 6) a | |||

| ACS risk scores | SR, I, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| LV impairment | SR, I, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Cardiogenic shock | SR, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Killip class | SR, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| ECG | SR, I | Cause of exposure | – |

| Median heart rate | SR | None | – |

| Ischaemic/bleeding risk scores (n = 4) a | |||

| SYNTAX | SR, I, CS | Cause of exposure | – |

| CRUSADE | SR, I, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| HAS-BLED | SR, I, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| CHA2DS2-VASc | SR, I | None | – |

| Biochemical markers (proxies of disease) ( n = 7) a | |||

| Troponin (ACS) | SR, I, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Glucose or HbA1c (diabetes) | SR, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Creatinine or GFR (kidney disease) | SR, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Haemoglobin or haematocrit (anaemia) | SR, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Platelet count | SR, I, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| CRP or ESR (inflammation) | SR, CS | Cause of outcome | – |

| Leucocytes (infection, malignancy) | SR | None | – |

| Procedural risk (PCI) (n = 14)a | |||

| IABP use | SR, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Total ischaemic time | SR | None | – |

| Clopidogrel loading dose | SR | Cause of outcome | Increases risk |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor use | SR | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Radial access site | SR | Cause of outcome | Decreases risk |

| Method of arterial haemostasis | SR, CS | Cause of exposure | – |

| Type of stent used (BMS vs. DES) | SR, I | None | – |

| Length of stented segment | SR, I, CS | Cause of exposure | – |

| Stent failure | SR, I, CS | Cause of exposure | – |

| TIMI flow pre/post procedure | SR | None | – |

| Multivessel PCI | SR, I, CS | Cause of exposure | – |

| Native vs. graft PCI | SR, CS | Cause of exposure | – |

| Infarct-related characteristics (no reflow/reduced TIMI flow/MVO) | SR, CS | Cause of exposure | – |

| Coronary complication (perforation, dissection) | SR, CS | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Other (n = 11) a | |||

| Drug potency | I | Confounder | – |

| Drug allergies | I, CS | Cause of exposure | – |

| Resistance to antiplatelet agents | I, CS | Confounder | Decreases risk |

| Adherence to clinical guidelines | I, CS | None | – |

| Commissioning and organisation budget policy | I | Cause of exposure | – |

| Local DAPT prescribing culture | I | Cause of exposure | – |

| MDT opinion | I | Cause of exposure | – |

| Adherence-related factors | I, CS | Confounder | Decreases risk |

| Patient views and preferences | I | Cause of exposure | – |

| Individual clinician professional opinion | I | Cause of exposure | – |

| Conflicts of interest and pharmaceutical company influence | I | Cause of exposure | – |

| Co-interventions (n = 10) | |||

| Statin | SR | None | – |

| Beta-blocker | SR | None | – |

| ACE-I | SR | None | – |

| Calcium channel blocker | SR | None | – |

| Diuretic | SR | None | – |

| RAS | SR | None | – |

| NSAIDs | SR | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Steroids | SR | Confounder | Increases risk |

| Co-intervention | SR | None | – |

| Statin | SR | Confounder | Increases risk |

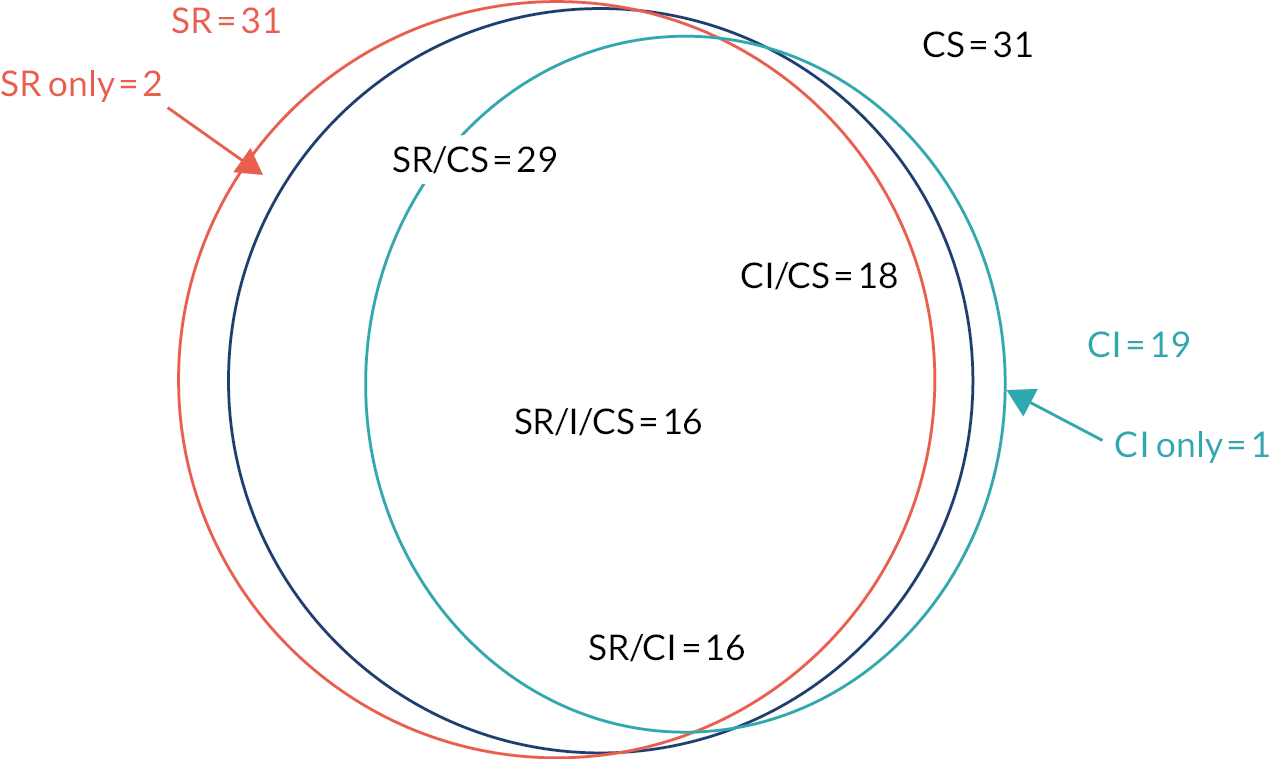

Only 34 out of 70 (49%) of the factors identified were classified as true confounders (factors that influence both DAPT prescribing and risk of bleeding). The decision regarding classification of potential confounders as true confounders was based on survey results and clinician expertise in the research team. The overlap between systematic review, clinician interview and clinician survey is shown in Figure 6. Of the 34 true confounders, no data were available to characterise 17 (50%).We had data to identify all demographic (n = 4), medical history (n = 2) and comorbidity (n = 11) confounders, but not all presentation risk (n = 4), risk score (n = 2), biochemical marker (n = 5) procedural risk (n = 3) and other factor (n = 3) confounders. We also identified 10 co-interventions from the systematic review. Of these, only three (judged to influence both what antiplatelet regimens a patient might receive and bleeding risk) were classified as true confounders.

FIGURE 6.

Overlap of 34 true confounders between those identified by SR, CI and CS. CS, clinician survey; I, interview; SR, systematic review.

We did not attempt to classify the factors we identified as potential confounders into confounding domains, that is domains that can be characterised by measuring one or more of a range of the identified variables. Such an approach is logical and could reduce the number of covariates used for statistical adjustment, given that many of these will be highly correlated. For example, bleeding risk could, in theory, be identified from several factors: previous bleed; increasing age; presence of anaemia; biomarkers such as haemoglobin, haematocrit and platelet count, etc. However, we were not certain if individual variables that might be grouped within a domain such as bleeding risk would generate an equal amount of bias nor if all are equally valid and reliable measures of the bleeding risk confounding domain. Classification into domains would require further input from cardiologists and cardiac surgeons, which was beyond the scope of this project. Nevertheless, we chose not to include biochemical markers as confounders in the statistical models, given that they are proxies of diseases captured through comorbidities.

The process of identifying confounders was systematic. There was good agreement between the three methods used (i.e. systematic review, clinician interviews and clinician surveys). The clinician interviews identified hard-to-measure factors not identified in the systematic review, such as clinician concerns regarding patient adherence; patient preferences; cost; the influence of local protocols and guidelines on prescribing practice; and patient drug allergies or resistance to medication. Some of these factors may influence eligibility criteria in RCTs and lead to the exclusion of certain patients (e.g. those deemed not likely to comply with medication regimen, or those with drug allergies or resistance to antiplatelets).

The inclusion of clinician interviews and surveys alongside the systematic review identified the main factors that influence bleeding risk and confirmed that similar risk factors influence both ischaemic and bleeding risk. Reliance on the literature only may be misleading; for example, in our review, most of the studies used for data extraction had ischaemic end points as their primary outcome [e.g. major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs)]. It is, therefore, plausible that some of the variables reported in the descriptive tables or adjusted for in the statistical analyses of these studies influenced ischaemic outcomes, but not bleeding. This highlights the importance of using multiple sources of information for identifying confounders. The research team included broad expertise (clinical, epidemiological, qualitative methods, survey design), which contributed to the cohesiveness of the study and its findings.

We did not attempt to select factors on the basis of causality/understanding of underlying mechanisms or consideration of clinician behaviour, mainly because we do not have full knowledge of the structure of the causal diagram that relates all covariates to each other and to the DAPT prescription and risk of bleeding. Therefore, we cannot be certain that the covariates we selected as true confounders would be sufficient to control for confounding bias. 23

There is currently no guidance on how to extract data on confounders using literature review, given the variety of study designs potentially eligible for inclusion (e.g. RCTs, prospective/retrospective cohort studies/registries, some descriptive and some comparative, prognostic/risk prediction studies). Non-randomised studies in particular have different designs, different and inconsistent methods of reporting, and often do not justify their rationale for statistical adjustment. 24 Given these issues and the lack of guidance, we took a broad approach to data extraction and included every factor considered by the authors of these studies as a potential confounder for our study.