Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number 14/226/07. The contractual start date was in May 2017. The draft report began editorial review in November 2021 and was accepted for publication in April 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this manuscript.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Carrie et al. This work was produced by Carrie et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Carrie et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

The Nasal AIRway Obstruction Study (NAIROS) addresses the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the operative procedure septoplasty in patients aged > 18 years who have symptoms of nasal obstruction in the presence of a deviated nasal septum. Septoplasty is a commonly performed operation to straighten the mid-line partition between the two nostrils. Within the bony nasal cavities, the lateral aspects (internal sidewalls) each have three nasal turbinates. These are bony structures rich in vascular and glandular tissue projecting into the nasal cavity, which are affected by variable swelling and glandular oversecretion among those with either allergic or non-allergic rhinitis (swelling of nasal cavity lining). The largest and most accessible of those is the inferior turbinate (which is lowest on the sidewall). In addition, when there is a septal deviation, a space is created in the wider nostril, and the inferior turbinate can expand into this space. 1

Many septal operations are combined with reduction of one or both of the inferior turbinates. 2 Turbinate reduction is performed on the assumption that an increase in nasal airway volume will facilitate better functional nasal airflow, which will in turn improve patient symptoms. 3 However, the evidence base for this is limited. In 2007, there were around 95,000 septoplasties performed in Germany4 and around 132,000 turbinate reductions, equating to 1% of all operations in Germany that year. In the USA, > 250,000 septal operations are performed annually. 5 Over a 12-month period in 2019/20, approximately 16,700 septoplasty procedures were performed in England,6 at a cost of £15.9M.

Nasal septal deviation can be either congenital or acquired. 7 Septal deformities may arise in early fetal development. Ruano-Gil et al. 8 noted septal deformities in 4% of 50 fetuses before any intrauterine compressive forces could act, suggesting a possible underlying hereditary factor. Overall, the most common cause of septal deviation is trauma, which can occur at any stage of life. The index injury may not be recollected; for example, in childhood, a fall as a toddler can lead to unrecognised septal trauma. In adulthood, sporting injuries or assault are commonly reported causes of septal deviation. Increasing age and male sex are also associated with a higher prevalence of septal deviation. 9

Septal deflection may cause cosmetic nasal abnormalities. However, the main, functional problems are those related to nasal obstruction: that is, snoring and sleep-disordered breathing. Nasal obstruction is reported in up to 80% of patients and is the nasal symptom most commonly presenting to otolaryngologists. 10 Nasal obstruction was also found to affect one in four of the Swedish population. 11 A significant proportion of nasal obstruction is due to rhinitis, which affects almost 20% of the European population. 12 It is both a poorly understood and poorly characterised symptom: in reality, many patients with a grossly deviated septum do not report symptoms of obstruction, whereas others, with minimal deviation, do. Nasal obstruction has been shown to increase resistance in the upper airways, thus contributing to snoring and sleep apnoea, for which patients, often prompted by their partner, seek treatment. 13 Despite the relationship between nasal obstruction and obstructive sleep apnoea, the impact of surgery in improving nasal patency remains uncertain. 14 In a small randomised controlled trial (RCT), Koutsourelakis et al. 15 found that septoplasty rarely treats obstructive sleep apnoea effectively. In contrast, another small study showed that septoplasty did improve patient-related outcomes concerning difficulty falling asleep and awakening at night. 16

The anterior nasal septum is a cartilaginous structure, never geometrically straight. Researchers have varyingly estimated the prevalence of deviation from 22% to > 70%, reflecting the lack of accepted definition or measurement of what actually constitutes a septal deviation. 7,17 Even estimates from radiological studies range from 20 to > 80%. 18,19 In addition, many nasal conditions other than deviated nasal septum, such as allergic rhinitis and chronic rhinosinusitis, present with a blocked nose. As part of routine clinical assessment of patients with nasal obstruction, these conditions must be excluded. In practice, in the absence of clinical guidelines in the UK, a clinician’s subjective naked-eye assessment of the degree of deviation underpins the decision-making for septoplasty. As a result, decision-making for surgery is subject to great variability and bias.

Studies suggest that anterior septal deviations are more likely to be associated with nasal obstruction than posterior nasal deviations10 (Figure 1). A combination of clinical assessment and fluid dynamic modelling in a 10 year retrospective study showed anterior deflections benefit most from septal surgery. 20 Location is ideally measured with cross-sectional imaging,21 but cost and radiation exposure preclude its routine use. In one cohort, however, computerised tomography scanning was found to alter the surgical plan in 8% of patients. 22 Evidence confirms that the level of the inferior turbinate is the site that determines the sensation of nasal resistance. 23,24 Cole et al. ,25 simulated nasal septal deviations in healthy adults and found that in the majority of adults, the mid and posterior nasal cavities are unresponsive to nasal septal deviation and mucosal changes, but in contrast, that the anterior part of the nose is sensitive to induced septal deviation of as little as 1 mm. The addition of what is called Cottle’s manoeuvre, where the patient pulls the cheek away from the obstructed nostril and derives symptomatic benefit, does not appear to add to the specificity of clinical examination. 26

FIGURE 1.

Typical appearance associated with a deviated nasal septum nasal obstruction, with compensatory enlargement of the inferior turbinate causing nasal obstruction. ©Frances Grierson, 2021.

Headlight illumination allows the first 1–2 cm of septum to be visualised. Septal deviation behind this point requires a nasal endoscopy to assess the mid- and posterior septum and to rule out other pathologies, such as nasal polyps associated with rhinosinusitis. 27 There are fundamental challenges in assessing symptoms of nasal obstruction. In all (except aquatic) mammals under normal circumstances, nasal airflow is greater in one nostril than the other owing to cyclical swelling in the nasal lining (this is known as the ‘nasal cycle’). As a result, over a period of 1–4 hours, each nostril exhibits a periodicity of reducing and then increasing resistance, producing a sensation of alternating blockage in each nostril. Therefore, the sensation of nasal obstruction within each nostril is not a ‘fixed’ phenomenon. 28

Role of the turbinate

Turbinate size has an impact on the volume of the nasal cavity and is influenced by factors such as environmental temperature and humidity, airborne allergens, and respiratory infections such as the common cold. All cyclical swelling within the turbinate contributes to the ‘nasal cycle’. In their classification of turbinate enlargement, Hol and Huizing29 noted compensatory turbinate enlargement in the nostril opposite the side into which the septum is deviated. This so-called compensatory enlargement tends to develop in turbinate tissue exposed to the wider of the two nasal passages30 (see Figure 1). The diagnosis of an enlarged turbinate requires a subjective clinical assessment, and it may simply serve as a diagnosis of exclusion when no other factors are contributing to a blocked nose.

In the UK, patients with nasal obstruction symptoms typically initially self-medicate with nasal decongestants or oral antihistamines. Discussions with pharmacists may lead to the patient commencing a nasal steroid spray. Failure of initial treatments may encourage the patient to seek further options from primary care. Most UK clinical commissioning guidelines will guide general practitioners (GPs) to recommend a trial of intranasal steroid or an alternative steroid medical therapy before considering referral to secondary care for treatment failures, even for those in whom an obviously deviated septum is noted. 31 There is limited scope to undertake visual assessment of the nasal cavity outside secondary care, and there may be alternative or coexistent pathologies, such as allergic rhinitis or chronic rhinosinusitis, contributing to the symptoms of nasal obstruction. Objective assessments of nasal airflow and radiological imaging are rarely undertaken in the UK setting for patients with a deviated nasal septum, although some authorities have long regarded them as useful adjuncts in clinical decision-making. 32,33

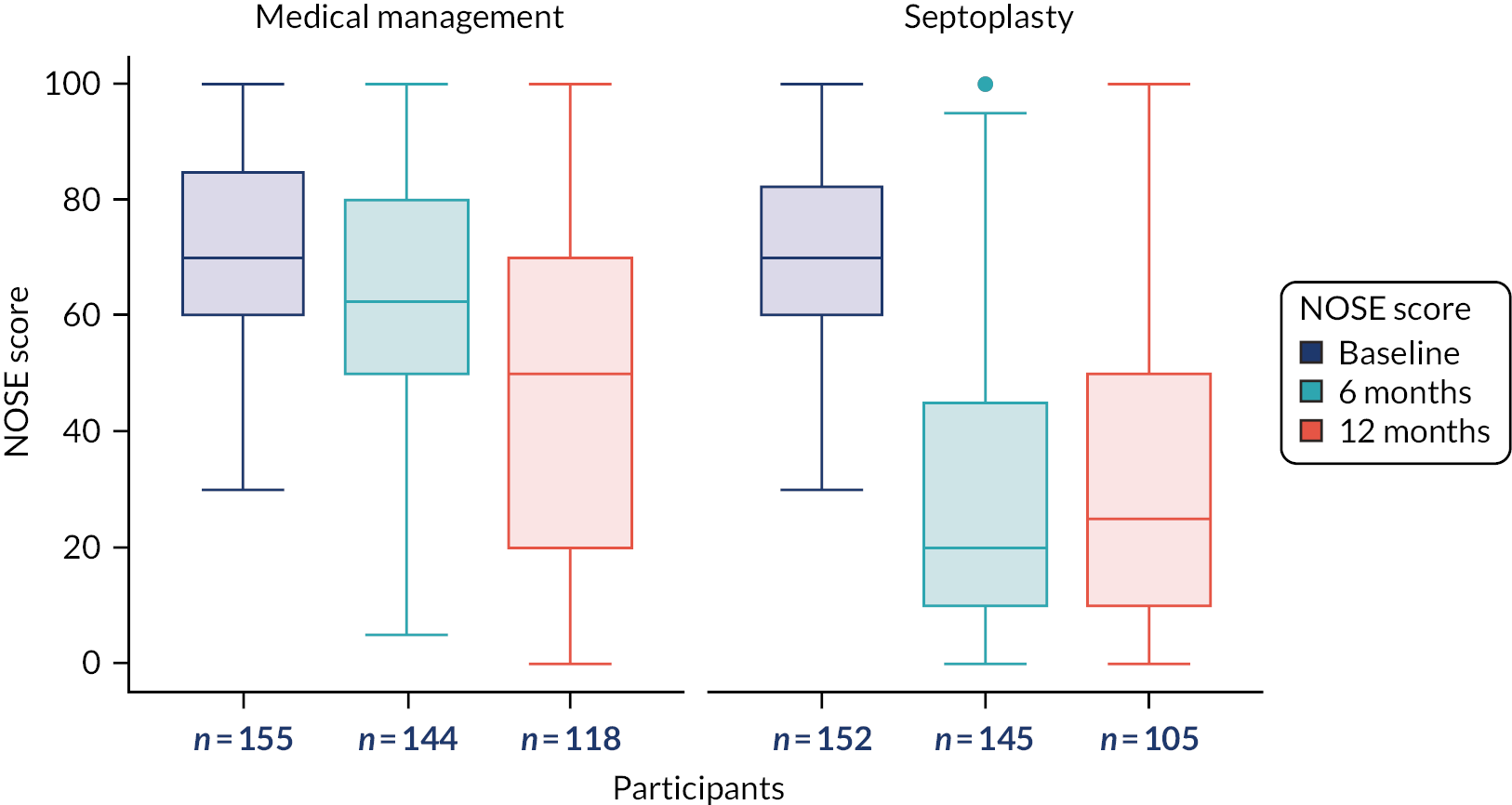

Subjective assessment

The NAIROS used the most commonly employed patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in rhinological practice: the Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) scale and the Sino-nasal Outcome Test-22 items (SNOT-22). The NOSE scale was specifically developed as an outcome tool for septoplasty. 34 The five standard NOSE scale items are scored 0–4, that is the total score equals 20. Conventionally, the score is multiplied by five, such that the maximum possible score is converted to 100. A systematic review of postoperative NOSE scale data of 643 patients undergoing a variety of surgical procedures showed an overall weighted mean change of 42 of 100 scaled points. 35 Lipan and Most36 performed a receiver operating characteristic analysis of NOSE scores obtained in a heterogeneous population of 345 patients undergoing nasal surgery. They defined a NOSE score of < 30 (0–25) as ‘mild’, 30–50 as ‘moderate’, 55–75 as ‘severe’ and 80–100 as ‘extreme’. Only 6% of the study population had mild symptoms. For the NAIROS, we predicted that, as with most interventions, baseline severity is the most important determinant of outcome, that is the effect demonstrated would depend on the severity of disease in the sample studied. On the basis of Lipan and Most’s36 receiver operating characteristic findings, those with a NOSE score of < 30 were considered too mildly affected for inclusion in the NAIROS, as similar NOSE scores are reported by patients who do not have nasal obstruction.

The NAIROS randomisation stratified participants according to baseline severity and gender. The decision to reduce the size of the turbinate in the wider of the two nasal passages (unilateral reduction) in the NAIROS was recorded at baseline and was based on the individual ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgeon’s assessment of the contribution it made, in combination with the septal deviation, to the symptom of obstruction in any given patient. The NAIROS tested, as a secondary statistical analysis, the contribution of turbinate reduction to any improvement in the nasal airway, an outcome on which published results are inconclusive. Indeed, one study concluded that turbinate reduction alone could be superior to operations involving septoplasty. 2 Gender influences patient responses on the SNOT-22. 37 There are more septoplasties among males,38 in part at least because of the circumstances surrounding nasal injury. There are anatomical differences in the size and strength of nasal tissue during growth, which may affect response to surgery. 39 An early study of septoplasty outcome found that only female gender and history of previous nasal surgery were significant predictors of (worse) outcome,40 but the total evidence base is ambiguous. 41

The NAIROS measured the SNOT-22 score at baseline (before treatment), at 6 months and at 12 months, with the 6-month SNOT-22 score reported as the primary outcome measure. The SNOT-22 was first applied to septoplasty in 2003,42 with a mean drop of 16 points from baseline (mean 32 points) 3 months after septal surgery. The SNOT-22 subscale of nasal symptoms reduced from 14 to 7 points, and general health symptoms reduced from 22 to 12 points. A larger study of 126 patients found a smaller reduction of just 4 points at 6 months, perhaps because of a lower starting baseline (mean 22 points). 43

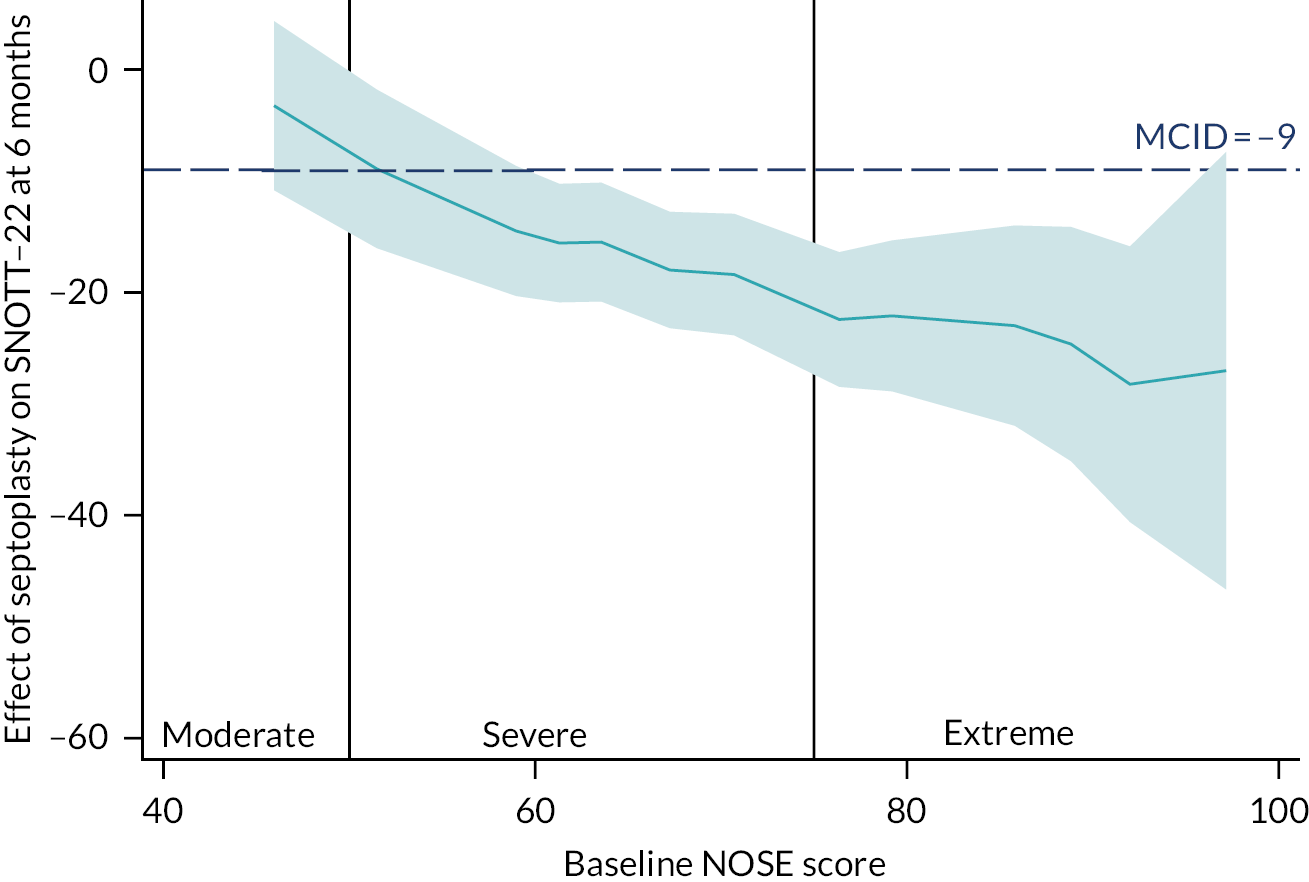

The mean SNOT-22 score in a UK study of > 2000 patients undergoing surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis was (predictably, given its origins) measured > 44 points preoperatively, with a drop of 30 points, on average, postoperatively. 44 The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for the SNOT-22 among patients undergoing surgery for nasal polyposis and chronic rhinosinusitis was 8.9 points. In other words, a change of < 9 points on the SNOT-22 was not judged to be a meaningful improvement by the patient. The NAIROS uses a reduction of 9 points as the MCID for the SNOT-22 primary outcome. 43,45–47

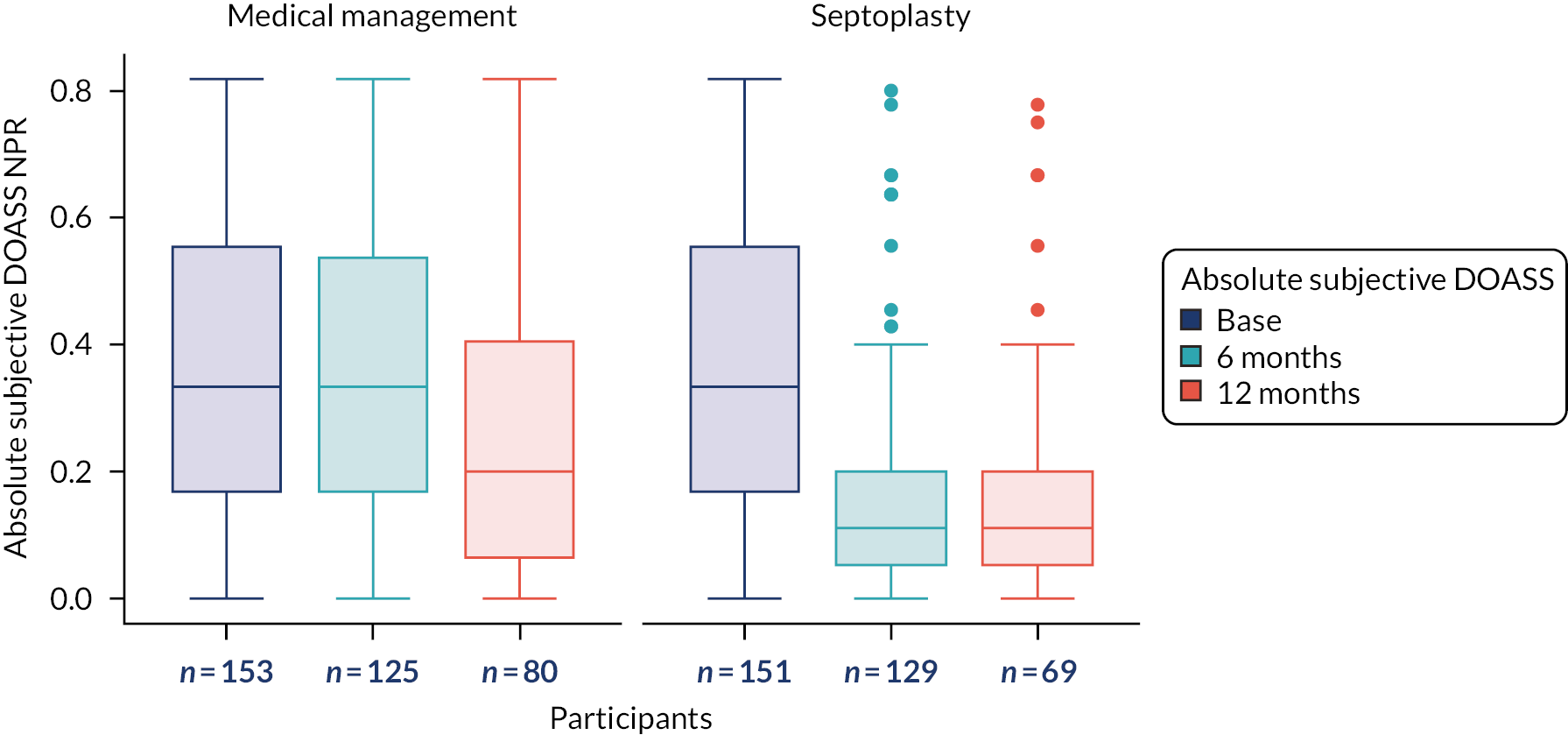

Potentially the most straightforward way of measuring nasal obstruction secondary to a deviated septum is to request that the patient complete a visual analogue scale to quantify the degree of blockage. However, this is a potentially flawed approach, as patients with long-standing septal deviation may become accustomed to breathing with limited nasal airflow. 48 Boyce and Eccles49 developed the Double Ordinal Airway Subjective Scale (DOASS) as an improvement in the subjective assessment of nasal obstruction. The patient rates the nasal airflow through each nostril independently (with the opposite closed) and characterises the amount of flow on a scale of 1–10, on which 1 is complete blockage and 10 is air flowing freely through the nostril. The DOASS was noted to have a sensitivity of 81% and specificity of 61%, the latter being considerably better than an assessment by visual analogue scale of nasal obstruction.

Objective assessment of the nasal airway

A number of tools have been developed to assess nasal airflow. Rhinomanometry, which measures nasal airway resistance as a function of nasal airflow and the pressure required to create that flow, has been described as the gold standard of assessment. 50 However, it is both cumbersome and time-consuming, and thus impractical from a routine clinical perspective. It may have an advantage over subjective sensation, however, when assessing subtle differences between the two nostrils. 51 Acoustic rhinometry calculates the cross-sectional area of the nasal cavity by measuring the reflection of acoustic pulses introduced into the nostril. Although straightforward to use, it has significant limitations related to the inherent challenges of assessing the physical properties of sound transmission of air in a complex chamber such as the nasal cavity. 52

The NAIROS used two objective assessments of nasal airflow: rhinospirometry and peak nasal inspiratory flow (PNIF). Rhinospirometry measures the flow and volume of air through each nostril independently. 53 In the NAIROS, it was used to measure both maximal inhalation volume (MIV) and tidal breathing. Asymmetry of nasal airflow is expressed as a nasal partitioning ratio (NPR), calculated as follows: (VL – VR) / (VL + VR), where VL is left-sided volume and VR is right-sided volume. NPR scores range from −1 (complete left nasal cavity obstruction) to 1 (complete right nasal cavity obstruction), with 0 indicating symmetry of airflow. 54 Cuddihy and Eccles55 measured the NPR of 31 patients before and after corrective surgery for nasal septal deviation. Those patients who had a NPR beyond the normal range had a greater improvement in subjective nasal obstruction. In addition, and as quoted previously, Boyce and Eccles56 identified that the DOASS score correlated well with the NPR values obtained in rhinospirometry. PNIF measures the peak flow rate of air through both nostrils during forced inhalation. PNIF has been shown to respond to septoplasty/turbinectomy and can therefore be used for an overall assessment of nasal airflow impairment. 57

It was expected that, for the NAIROS, a combination of the subjective and objective airway assessments would enable us to construct a robust algorithm for use at baseline to predict which patients were most likely to benefit from septoplasty.

Rationale

The NHS currently purchases 17,000 surgical interventions on the nasal septum across the UK annually, yet the procedure is almost entirely lacking in a suitable evidence base or even adequate guidance. The NHS and personal costs of this practice are considerable and there is an urgent need for evaluation in a substantive study, which, with sufficient sample size and power, has the potential to influence clinical practice, patient choice and NHS commissioning.

Evidence review of septoplasty effectiveness

To our knowledge, van Egmond et al. ,58 published the only RCT on the clinical effectiveness of septoplasty in 2019. This study was based on analysis of septal surgery, compared with non-surgical management, across 206 patients in the Netherlands. They concluded that septoplasty was more effective than non-surgical management for nasal obstruction. Those patients randomised to non-surgical management did not receive a standardised treatment, and they received a variety of medical interventions considered appropriate by the treating clinician. Therefore, it is difficult to conclude whether or not a positive trial is the result of an effective intervention or low-efficacy standard care. 59 Furthermore, the primary outcome measure of the trial, the Glasgow Health Status Inventory, a health-related quality-of-life measure, demonstrated an improved score among those patients undergoing surgery. However, the Glasgow Health Status Inventory is known to have limited sensitivity to septal surgery outcomes,60 and, when compared with the pragmatic medical treatment comparator undertaken by van Egmond et al. ,58 this effect may have been exacerbated. Over 75% of the surgical cohort underwent concomitant inferior turbinate surgery, bilateral in 67% of patients, even though inferior turbinate enlargement was noted in < 50% of patients at baseline. This additional surgery is likely to exaggerate the beneficial impact of turbinate surgery over septoplasty alone. 2 In addition, there was a 30% crossover from the non-surgical to the surgical arm, introducing a further potential element of bias or dilution of the full effect of septoplasty.

In a 2018 systematic review of the evidence for septoplasty with or without inferior turbinate reduction as a treatment for nasal obstruction, van Egmond et al. 61 first compared septoplasty (with or without concurrent turbinate surgery) with non-surgical management and, second, compared septoplasty alone with septoplasty with turbinate surgery. In their review, there were no RCTs comparing septoplasty with non-surgical management, and five RCTs and six controlled trials comparing septoplasty alone with septoplasty with turbinate surgery. Included studies demonstrated substantial heterogeneity in study population, outcomes measured and time points of outcome assessment. The risk of bias was considered high in most reports. However, although subjective and objective assessment improvements did not necessarily mirror one another, studies demonstrated an overall improvement in nasal obstruction symptom. No additional benefit of turbinate surgery was reported in 8 out of 9 studies using subjective assessments, and 5 out of 7 studies using objective measures. Complications were rare, and were reported in only three studies. There were significant limitations related to short follow-up periods, which in some cases were only 9 months.

In a second systematic review of septoplasty alone, Tsang et al. 62 found six studies assessing patient satisfaction; rates varied from 69% to 100% in three studies in which patients were asked if they were satisfied or dissatisfied with outcomes at 6 months. Two studies assessed the degree of patient satisfaction, with one study indicating that 88% of patients were moderately satisfied or better at 1 year post operation, and the other reporting that 50% of patients were satisfied at 5 years post operation. There was significant heterogeneity in the method of assessment of nasal obstruction, which may have led to the finding that, in general, patients with more severe symptoms of nasal obstruction had a better outcome. The authors noted that there were high risks of bias as studies were only observational, with significant variation across multiple categories including patient population, outcome measures and follow-up duration. Overall, the authors concluded that there was insufficient evidence that septoplasty alone had good long-term patient-reported outcomes in the management of septal deviation, based on the heterogeneity of existing data and lack of RCTs. They recommended further research to define which preoperative characteristics are predictive of both subjectively and objectively positive septoplasty outcomes. Neither systematic review undertook a meta-analysis because of the substantial heterogeneity across the studies included.

Benefits and harms of interventions

Surgical

Septoplasty has level III evidence of effectiveness, and observational studies confirm good levels of patient satisfaction. The operation, if successful, requires a single procedure without the requirement of ongoing medical therapy. However, there is variation in criteria for surgery, surgical technique and postoperative follow-up. Selection criteria for surgery variance was discussed previously, but there is also variance in operative techniques among surgeons and the need for patient follow-up postoperatively. In addition, there is no good-quality evidence on either the clinical effectiveness or the cost-effectiveness of such surgery. Septal surgery also carries an economic cost, in terms of time off work or normal duties, and can be associated with side effects or complications that delay recovery and potentially necessitate additional treatment.

Following surgery, it is normal to have some symptoms, lasting between 48 and 72 hours, of minor bleeding, congestion and nasal discomfort. In our own group’s early publication63 of the outcomes among 121 septoplasty patients at 6 weeks, two postoperative complications were noted: septal perforation (1.7%) and nasal septal adhesions (3.3%). A Chinese study of 54 patients reported nasal septal adhesions in > 7% of patients. 64 Adhesions and septal haematoma may necessitate re-admission for corrective surgery. In addition, minor cosmetic change occurs in up to 30% of patients and more major change in > 4% of patients. 65 Dabrowska et al. ,66 in a retrospective series of 5639 patients undergoing septoplasty with or without turbinate reduction, reported excessive bleeding in 3.3%, septal perforation in 2.3%, infection (prolonged healing) in 3.1%, reduced smell acuity in 3.1% and dental anaesthesia in 0.1% of patients.

Septoplasty is routinely performed under general anaesthesia as a day-case procedure. An initial incision is made on one side of the septal lining allowing for the straightening or removal of areas of twisted cartilage and bone. It may not be possible to fully straighten the septum without risking the cosmetic appearance of the nose; therefore, the surgeon must use careful judgement to minimise this risk. The procedure typically takes between 45 and 60 minutes to complete. Nasal packing can be used following surgery; in the NAIROS it was not to be undertaken, if possible, because of the associated discomfort to the patient. Instead, suture repair of the septum was to be performed at the end of the procedure, as this seems to have equal efficacy and fewer disadvantages. 67–69

Medical management

Nasal steroid sprays have potent anti-inflammatory and antiallergic properties, inhibiting the release of inflammatory mediators produced by the nasal lining, thereby reducing swelling and nasal mucus in the nasal passages. Two sprays of 100 μg of mometasone furoate in each nostril twice daily for 6 weeks, followed by 100 μg per day in each nostril, for the remainder of the 6-month treatment period, was chosen based on the maximum recommended standard nasal steroid dose. This spray was identified in patient and public involvement (PPI) discussions with GPs as being restricted by formulary protocols in primary care, and therefore unlikely to have been prescribed previously. Mometasone is licensed for use among patients with reduced nasal airway and has marketing authorisation in the UK.

Medical therapy has the obvious advantage of the avoidance of general anaesthesia and surgery and their associated risks. Nasal steroid sprays are standard treatment for nasal obstruction symptoms and are deliverable in primary care. However, they may not be an effective treatment for patients with a deviated nasal septum70 and, even when they are, patients may require indefinite medical therapy, with its associated costs. Intranasal steroid sprays also have potential risks to the patient: they can cause nasal bleeding (odds ratio 1.56 in a 2020 systematic review, compared with placebo71), crusting, pharyngitis and headache, all of which may affect patient compliance, and there are reports which associate increased intraocular pressure and adrenal suppression with such sprays. Both hypersensitivity and anaphylaxis are rare complications. 72 There are few data comparing different intranasal steroid preparations. 72

Proprietary saline irrigation of the nasal cavity may be performed with either isotonic or hypertonic solutions. 73 These may either be low-positive pressure (from a spray or pump), or gravity-based pressure (using a container with a nasal spout). Saline nasal irrigations have been recommended in the management of various nasal and sinus mucosal disorders such as chronic sinusitis74 and allergic rhinitis,75 although this recommendation is based on mostly low-level evidence. Similarly, saline irrigations have been recommended following endoscopic sinus surgery, but uncertainty remains in the literature around the optimum method of delivery and composition of the saline solution. 73–79 Saline sprays have not been trialled specifically in nasal septal deviation. In consultation with GPs and the PPI group, the Stérimar isotonic spray (Sofibel SAS, Paris, France) was chosen for the NAIROS. Mometasone and Stérimar sprays, in combination with the option of deferred surgery for those in the medical management arm, was noted at initial PPI discussions to be an acceptable alternative to surgery by patients.

Aims and objectives

Primary objectives

The primary objective was to compare the clinical effectiveness of nasal septoplasty (with or without unilateral turbinate reduction) with medical management over a duration of 6 months among adults with a nasal septal deviation who have been referred to otolaryngology outpatient clinics with nasal airway obstruction.

Secondary objectives

The secondary objectives are split into three different aspects: clinical effectiveness, an economic evaluation and a mixed-methods process evaluation.

Clinical effectiveness

We aimed to measure clinical effectiveness according to:

-

subjective self-report rating of nasal airway obstruction

-

heterogeneity of estimated treatment effect, specifically according to severity of obstruction and gender

-

objective measures of nasal patency

-

safety profile recording the number of adverse events (AEs) and additional interventions required.

Measuring clinical effectiveness according to the above standards would enable us to:

-

adjust the estimate of effectiveness in the light of other baseline covariates: severity of self-reported nasal airway obstruction, gender and concomitant turbinate reduction

-

use the results in the surgical arm to explore a possible definition of technical failure in experienced hands, that is experienced surgeons (i.e. consultants or non-consultant career clinicians, but not trainee otolaryngologists)

-

assess to what extent trial participants are representative of the total population of participants referred to ENT clinics with nasal obstruction due to a septal deviation.

Economic evaluation

We conducted our economic evaluation by:

-

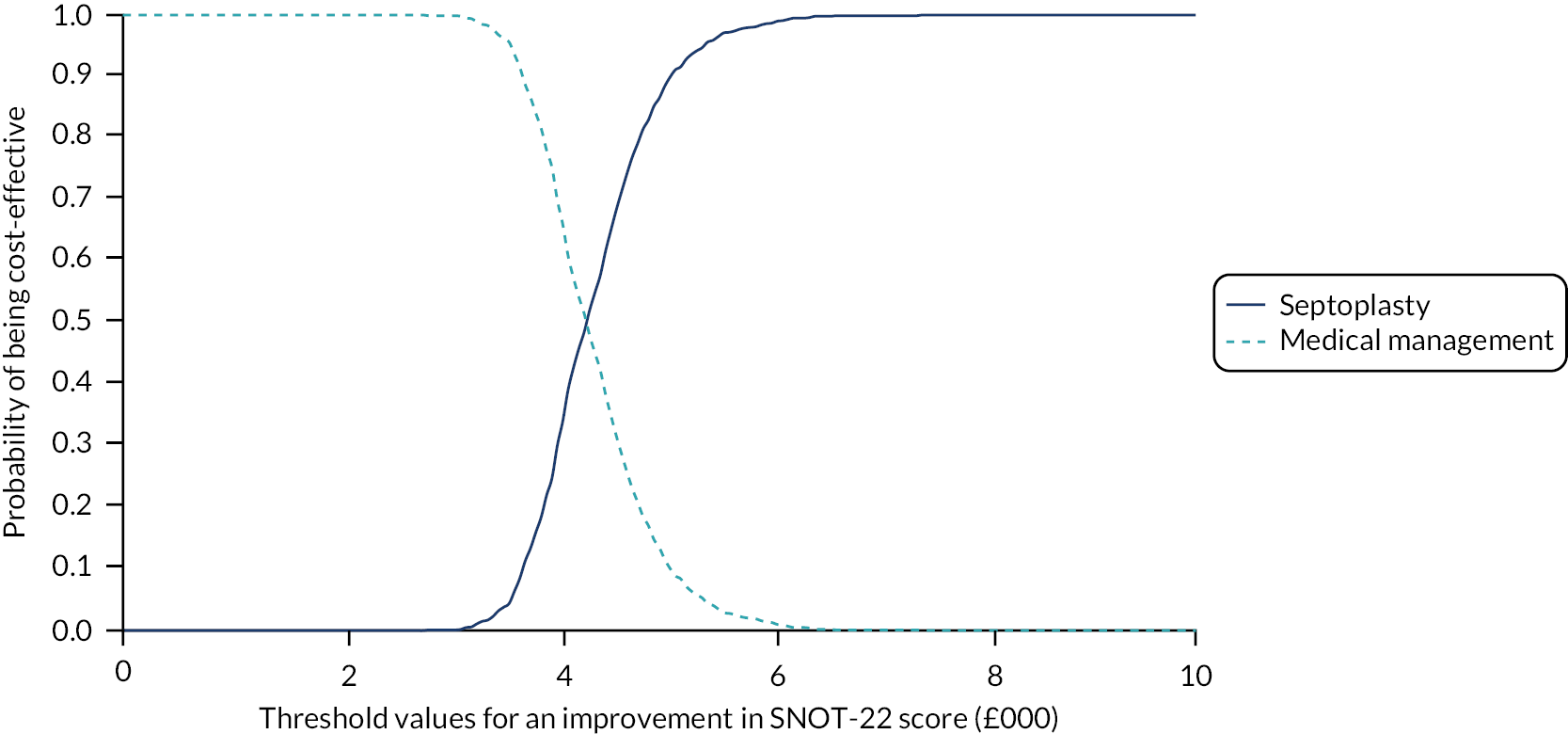

assessing cost-effectiveness measured in terms of the incremental cost per improvement (of ≥ 9 points) in SNOT-22 score and AEs avoided over 12 months

-

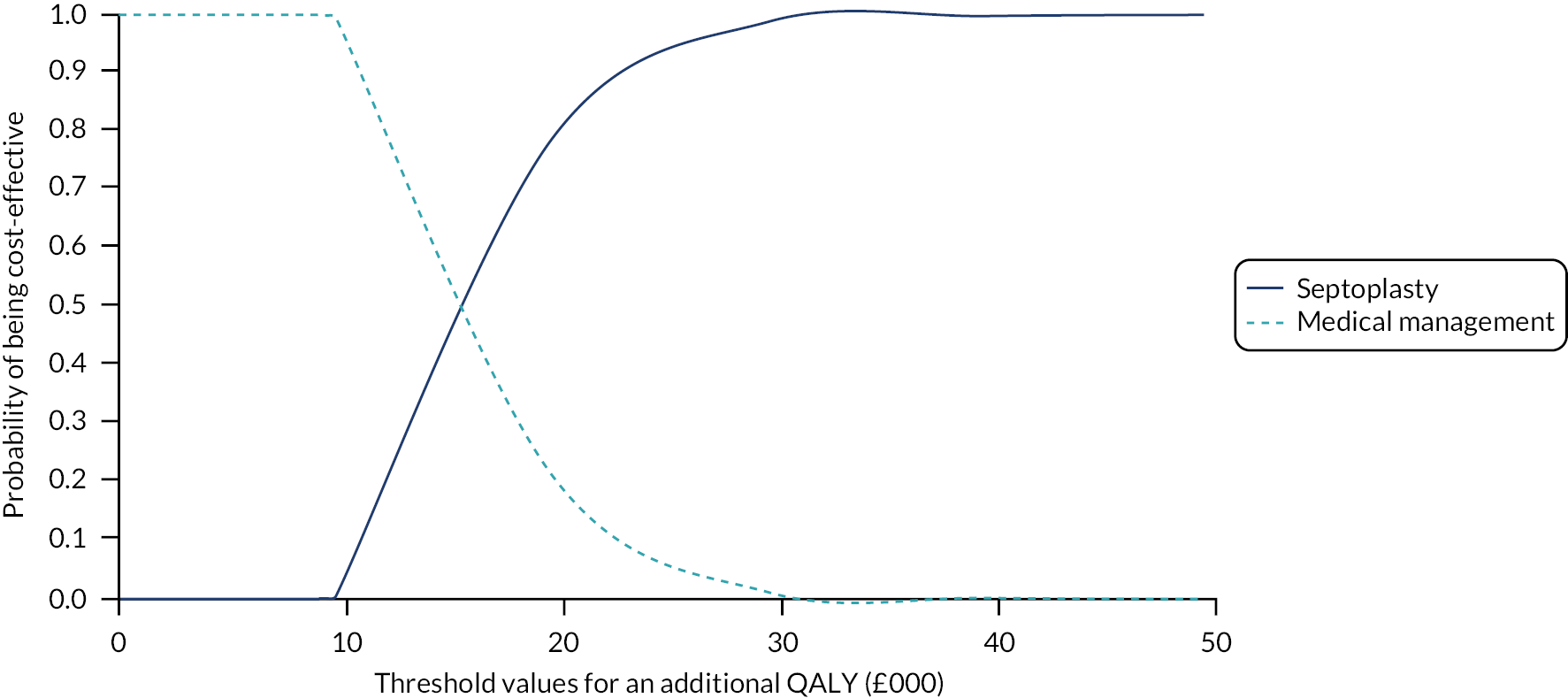

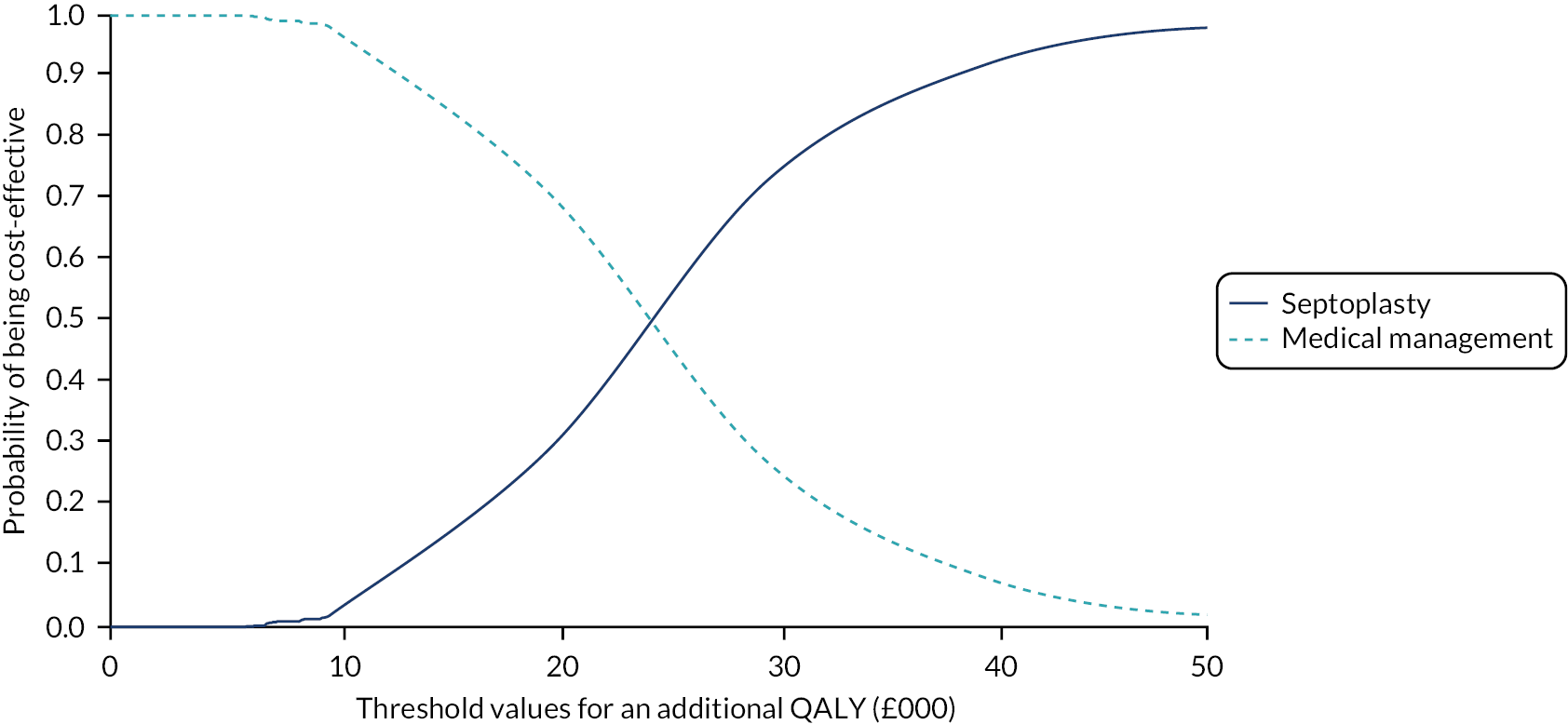

assessing cost-effectiveness measured in terms of incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained [derived from responses to the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) converted to Short Form questionnaire-6 Dimensions (SF-6D) scores] over 12 months

-

designing a longer-term economic model to assess the costs and QALYs beyond the 12-month follow-up period.

Mixed-methods process evaluation of the trial and interventions

Our mixed-methods process evaluation was to identify, describe, understand and address:

-

barriers to optimal recruitment, and potential solutions to address these, through integration of the Qualitative research integrated within Trials (QuinteT) Recruitment Intervention (QRI)

-

participants’ and healthcare professionals’ experiences of trial participation and the interventions under evaluation

-

factors likely to influence wider implementation of trial findings.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter are reproduced from Rennie et al. 80 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Summary of trial design

The NAIROS aimed to establish and inform guidance for the best management strategy for patients with nasal obstruction associated with a deviated septum by comparing a RCT of surgery with medical management.

Adult patients aged ≥ 18 years were identified from referrals to secondary care. Eligible patients who had septal deflection and a NOSE score of ≥ 30 were randomised to the trial. Randomisation occurred on a 1 : 1 basis, and was stratified by gender and severity (i.e. NOSE score) between septoplasty (with or without turbinate reduction), and medical management of combined isotonic saline nasal spray (Stérimar) and mometasone nasal spray.

The target recruitment figure of 378 participants from 17 NHS hospitals was achieved, with recruitment from sites across England, Scotland and Wales. Participants were followed up for 12 months post randomisation. The primary outcome was the total SNOT-22 score measured at 6 months post randomisation.

The trial included a qualitative mixed-methods process evaluation, which included a QRI to optimise recruitment during trial recruitment (see Chapter 5), and a qualitative process evaluation about staff and patient participants’ experiences of the study (see Chapter 6). It also included a full statistical evaluation (see Chapter 3) and an economic evaluation (see Chapter 4). Further details of the study design, clinical outcomes, economic outcomes and recruitment have been described previously. 80

Changes to trial design

Feasibility phase

The NAIROS researchers undertook an extensive assessment of the feasibility of the study by triangulating the views of potential patients, GPs and consultant ENT surgeons. This work assessed the willingness of patients to participate in randomisation, clinicians’ willingness to refer patients and randomly allocate to trial groups and the acceptability of the deferred surgery treatment arm.

Internal pilot

We originally intended for the NAIROS to include a 5-month internal pilot involving 10 sites. However, delays in study set-up expedited an agreement with the funder to remove the internal pilot and open all 17 sites simultaneously.

The pilot objectives of identifying, understanding and addressing any barriers to recruitment, retention or compliance with protocol were incorporated into the main trial, but extended to the full first year of recruitment. Areas for particular scrutiny during this period included patient recruitment, patient discontinuation of allocated treatment and compliance with surgery window. Monitoring of recruitment, retention and compliance with the protocol continued throughout the whole trial.

Collecting primary and secondary outcome measures

All trial interventions had been administered before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. Participants in the trial follow-up were invited to complete the PROMs remotely via e-mail or post [i.e. SNOT-22, NOSE, healthcare utilisation questionnaire (HUQ), time and travel questionnaire and SF-36; see Report Supplementary Material 2, 4, 5 and 6]. The SNOT-22 (primary and secondary outcome measure) could also be completed by participants using a validated online platform hosted by Castor (Castor EDC, Amsterdam, the Netherlands); the method of completion of the SNOT-22 was noted in the database. Owing to suspension of all face-to-face clinic visits from 30 March 2020, no other clinical outcome measure scheduled after this date was collected [i.e. DOASS (see Report Supplementary Material 3), clinical examination, symptoms review, measures of nasal patency]. AEs and concomitant medications were collected remotely over telephone at the 6- and 12-month visits from 30 March 2020 until the end of the trial.

Trial registration and protocol availability

The NAIROS was included in the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network portfolio (study number 35368) and was registered on 24 March 2017 [European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Clinical Trials (EudraCT) number 2017-000893-12, International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number 16168569]. The protocol has been peer reviewed80 (version 5.0, dated 16 January 2019), and the final protocol version (version 8.0, dated 17 December 2020) is available on the project web page [URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/ 1422607#/ (accessed 30 July 2021)].

Ethics approval and research governance

The trial sponsor was the Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (reference number 08302). Favourable ethics opinion was provided by the North East – Newcastle and North Tyneside 2 UK Health Research Authority Research Ethics Committee (REC) on 31 August 2017 (study reference number 17/NE/0239). The trial received approval from the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) (study EudraCT number 2017-000893-12) on 17 August 2017.

Setting

The NAIROS was conducted in the following 17 secondary care hospital trusts in England, Scotland and Wales:

-

NHS Grampian (Aberdeen Royal Infirmary).

-

University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust (Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham).

-

Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Bradford Royal Infirmary).

-

North Cumbria Integrated Care NHS Foundation Trust (Cumberland Infirmary).

-

County Durham and Darlington NHS Foundation Trust (Darlington Memorial Hospital/University Hospital of North Durham).

-

NHS Tayside (Ninewells Hospital).

-

James Paget University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (James Paget University Hospital).

-

NHS Lanarkshire (University Hospital Monklands).

-

Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust (Leeds General Infirmary).

-

Aintree University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Aintree University Hospital).

-

Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust (Guy’s Hospital).

-

Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Freeman Hospital).

-

Aneurin Bevan University Health Board (Royal Gwent Hospital).

-

University Hospitals Plymouth NHS Trust (Derriford Hospital).

-

Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust (Salisbury District Hospital).

-

Stockport NHS Foundation Trust (Stepping Hill Hospital).

-

Wrightington, Wigan and Leigh NHS Foundation Trust (Royal Albert Edward Infirmary).

Participants

We recruited 378 patients who had a deviated septum and reduced nasal airway (as indicated by a NOSE score of ≥ 30) and had been referred by their GP to ENT secondary care outpatient clinics. They were randomised in all 17 participating centres via dedicated research and standard NHS clinics. We also recruited ENT staff to participate in the process evaluation.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

-

Adults aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Baseline NOSE score of ≥ 30.

-

Septal deflection at baseline visible via nasoendoscopy.

-

Capacity to provide informed written consent and to complete trial questionnaires.

Exclusion criteria

-

Any prior septal surgery.

-

Systemic inflammatory disease or the use of oral steroid treatment within the previous 2 weeks.

-

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

-

Nasoendoscopic evidence of unrelated associated pathology, for example adenoid pad, septal perforation, chronic rhinosinusitis indicated by polyposis or pus.

-

Any history of intranasal recreational drug use within the previous 6 months.

-

Breastfeeding, pregnancy or intended pregnancy for duration of involvement in the trial.

-

Bleeding diathesis.

-

Therapeutic anticoagulation (warfarin/novel oral anticoagulant therapy).

-

Clinically significant contraindication to general anaesthesia.

-

Known to be immunocompromised.

-

Presence detected of an external bony deformity likely to make a substantial contribution to the nasal obstruction (determined by clinical opinion).

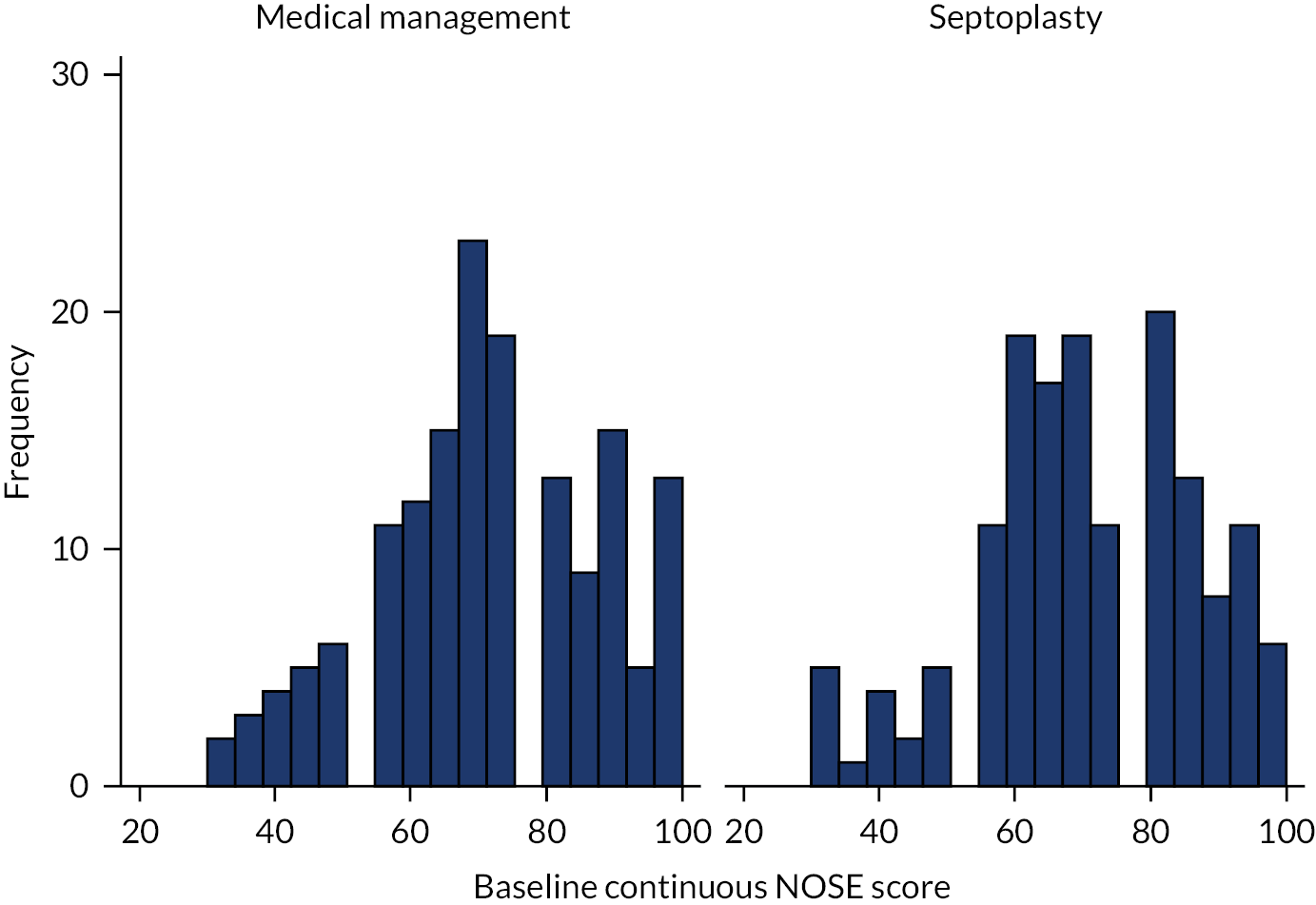

The NOSE score is a validated five-item, unifactorial self-report of nasal-block severity that has been applied in previous research and audit studies. 36,81 The three recognised NOSE-derived categories of baseline severity used were 30–50 (moderate), 55–75 (severe) and 80–100 (extreme). The NAIROS aimed to recruit participants with at least moderate nasal obstruction symptoms.

Intervention

The interventions compared in the RCT were as follows:

-

surgical correction (septoplasty) of the nasal septal deviation, with or without unilateral reduction of the contralateral inferior nasal turbinate

-

medical management consisting of combined use of a nasal steroid spray and an isotonic saline spray for 6 months.

Delivery of the intervention

Septoplasty

Participants randomised to septoplasty received surgery up to 8 weeks (+ 4 weeks) after randomisation. The additional 4-week window was to allow for extenuating circumstances such as pressure on surgical waiting lists or patient cancellation, with reasons for delays to surgery collected and reported. The NAIROS stipulated that experienced surgeons who were not in training should perform the procedure. They had the option to carry out unilateral turbinate surgery on the wider side, according to their assessment of the individual patient airway. As a pragmatic study, the NAIROS did not ask surgeons to change their usual practice in this regard, reflecting the considerable variation in current UK surgical practice. Both the intention to reduce one turbinate prior to randomisation and details of the actual surgery performed were collected.

Clinical Trial of an Investigational Medicinal Product intervention: medical management

Participants randomised to medical management were supplied with 6 months of Stérimar isotonic nasal saline spray and mometasone furoate nasal steroid spray at the time of randomisation. Use of mometasone, an investigational medicinal product, was as indicated by the marketing authorisation. Twice per day for 6 weeks, each participant sprayed a daily metered Stérimar isotonic nasal saline dose into each nostril, followed by a twice-daily dose of mometasone furoate steroid spray. For the remainder of the 6-month period, the same dose of saline spray applied, and the steroid dose was reduced to 100 μg per day; participants could administer this either by spraying either two 50-μg doses into each nostril once daily or one 50-μg dose into each nostril twice daily.

Discontinuation of allocated treatment

Formal crossovers between trial arms were not permitted, but the NAIROS was designed as a pragmatic RCT; therefore, participants could discontinue allocated treatment and explore other options in standard NHS care while remaining in the trial. Medical management arm participants opting for surgical treatment were invited to defer surgery until after the 12-month follow-up visit and received standard non-trial septoplasty in line with current local waiting times (taking into account the time that they had already spent in the medical management arm). Discontinuation of allocated treatment did not constitute withdrawal from the trial.

Participants randomised to the surgical arm, or medical management participants who wished to continue using nasal sprays beyond the initial 6-month intervention period, could be prescribed mometasone furoate nasal spray and Stérimar isotonic spray (or an alternative at the discretion of the clinician) as per standard practice of the local NHS team and without the need for a NAIROS trial prescription.

Participants who wished to discontinue their allocated treatment but remain in the trial were followed up as scheduled for their allocated arm, with data analysed on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis.

Funding of the trial intervention

As the surgical intervention was part of the standard pathway of NHS care for this cohort of patients, it was funded from the standard NHS tariff. The 6-month medical management intervention was categorised as an excess treatment cost and was funded by NHS England, Scotland and Wales.

Outcome measurements

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was defined as patient-reported assessment of nasal and general symptoms assessed using the SNOT-22 at 6 months (−2 weeks/+ 4 weeks). The SNOT-22 is scored from 22 questions with each item scored from 0 to 5. The final total score can range from 0 to 110, with a higher score indicating worse symptoms. The SNOT-22 was also assessed at baseline and 12 months.

Secondary outcomes

-

Objective assessment: nasal airflow was measured using a PNIF meter and an NV1 rhinospirometer (GM Instruments Ltd, Irvine, UK); both rhinospirometry (i.e. tidal volume and MIV) and PNIF measurements were taken at baseline and at 6 and 12 months. Additional exploratory analysis was undertaken using the rhinospirometer.

-

Quality of life was measured using the SF-36 quality-of-life questionnaire (acute/1-week recall) at baseline and at 6 and 12 months.

-

Healthcare resource use (primary and secondary care) was measured using a HUQ at baseline and at 6 and 12 months.

-

Patient-reported outcome measures: subjective – SNOT-22 subscales (rhinologic, sleep, ear/facial pain, psychological) at 12 months, NOSE scale at baseline and at 6 and 12 months, and DOASS at baseline and at 6 and 12 months were used to measure longer-term outcomes.

-

Safety measures: number and characteristics of any AEs and surgical complication/failure and reintervention within 12 months.

-

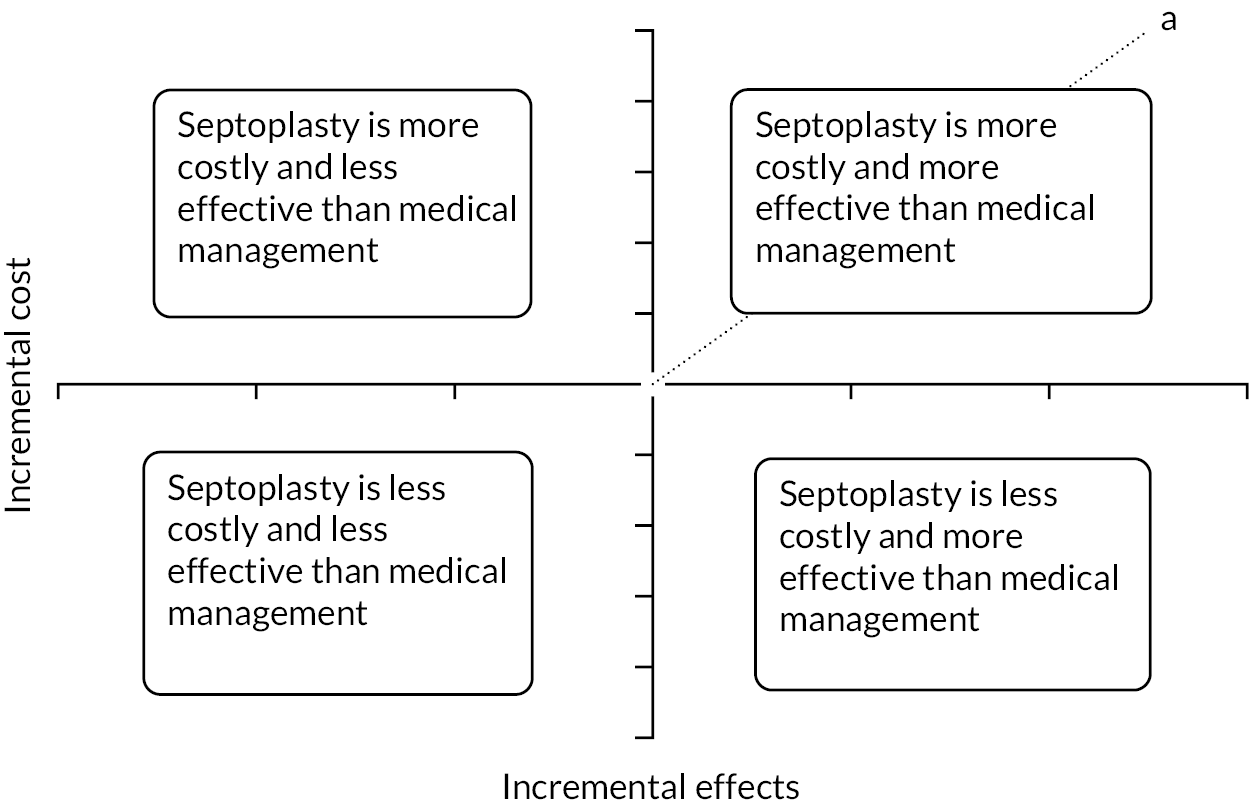

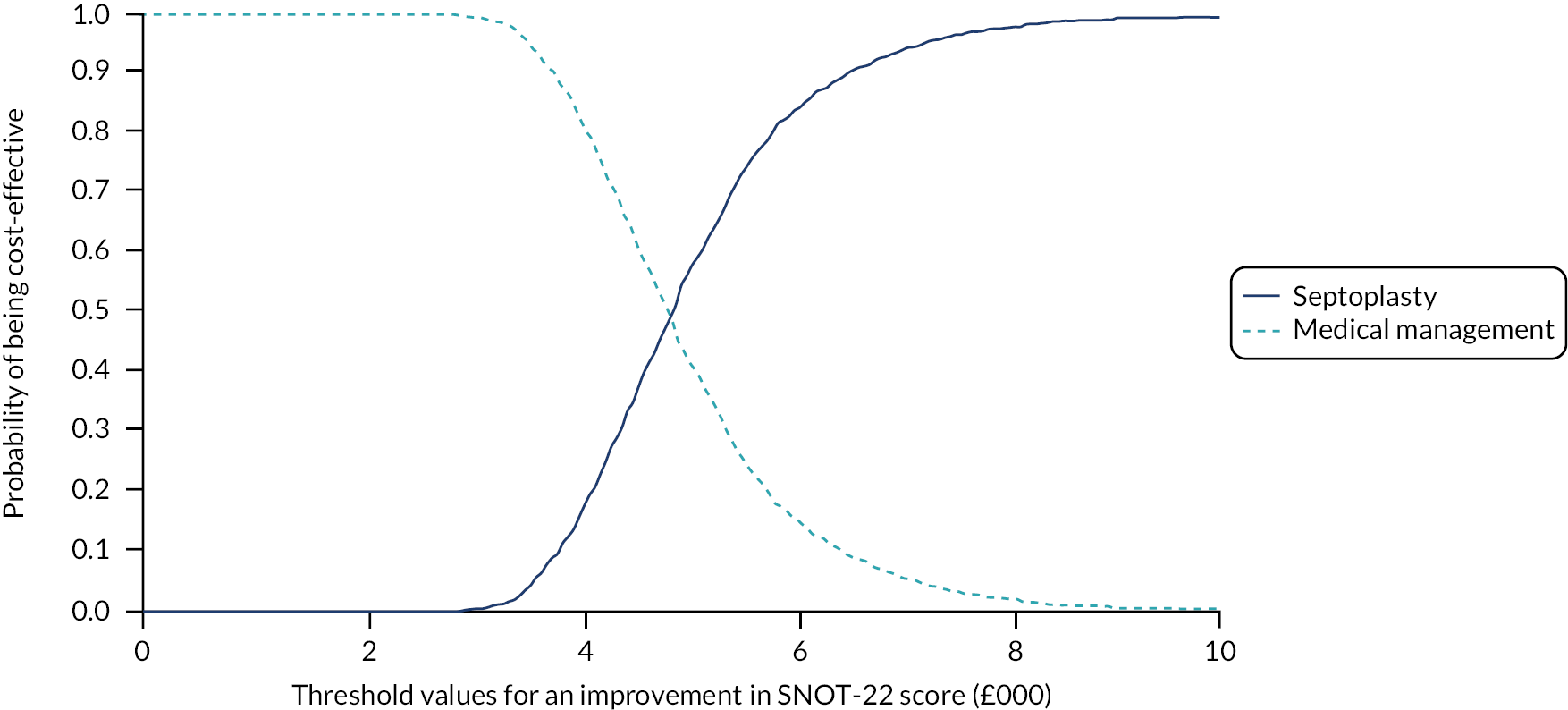

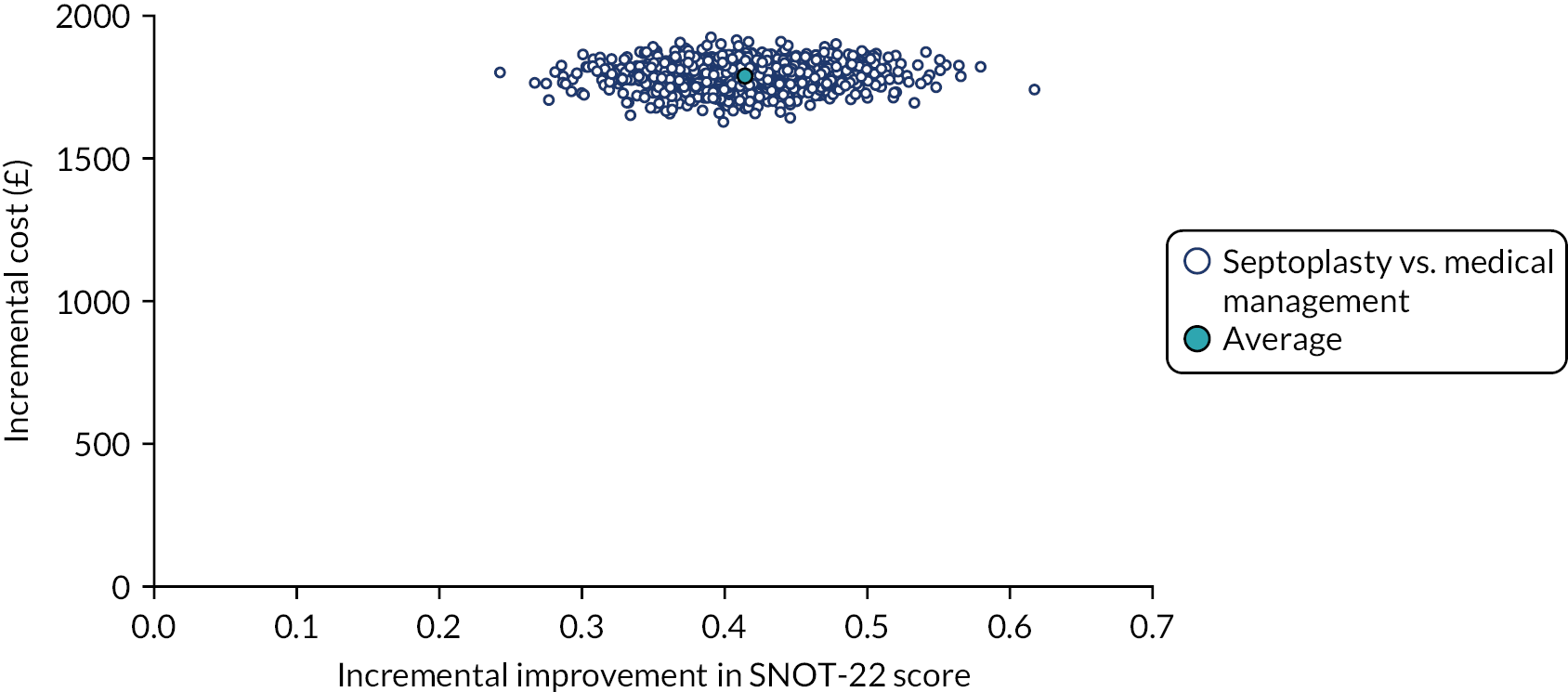

The economic evaluation compared the following between the two intervention arms:

-

costs [the average total cost per participant from the perspective of the NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS)]; sensitivity analyses included participant costs

-

QALYs, based on responses to the SF-36 converted to SF-6D scores, were derived using the area under the curve method82,83

-

improvement (of ≥ 9 points) in SNOT-22 scores

-

number of AEs

-

incremental cost per improvement (of ≥ 9 points) in SNOT-22 score

-

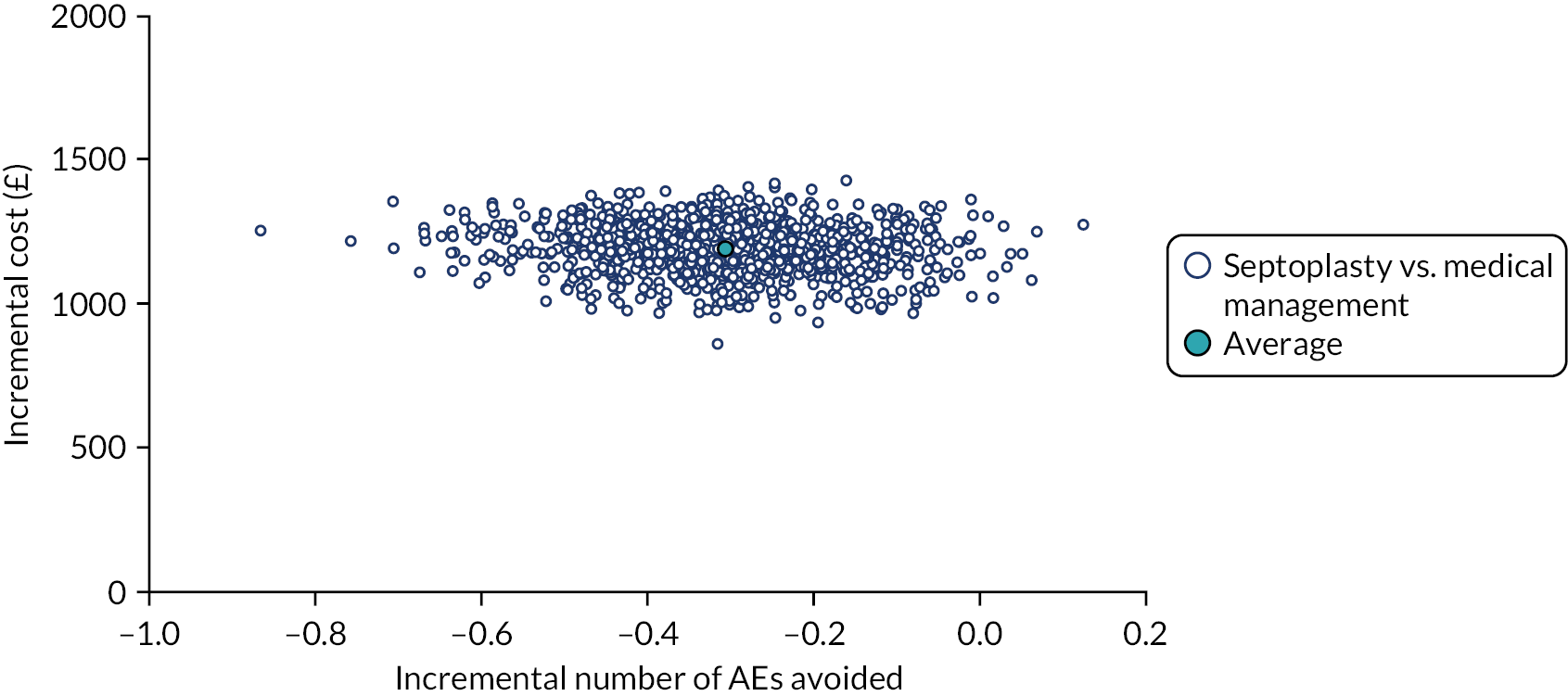

incremental cost in number of AEs avoided

-

incremental cost per QALY gained.

-

-

As part of the economic evaluation, costs and effects were extrapolated beyond 12 months using an economic model.

Economic analysis

The NAIROS economic analysis followed a prespecified health economics analysis plan, which outlined the analysis of the NAIROS trial data and aimed to determine the cost-effectiveness of septoplasty, compared with medical management, over 12 months and over a longer time horizon. Chapter 4 provides detail on the within-trial and longer-term economic models.

Overview of mixed-methods process evaluation

The NAIROS qualitative analysis incorporated the QRI, which aimed to support recruitment and mixed qualitative methods to understand participants’ and healthcare professionals’ experiences of septoplasty and medical management. The QRI took place throughout recruitment to the NAIROS, using qualitative and novel methods to investigate and address recruitment barriers (see Chapter 5). Qualitative interviews and focus groups were conducted throughout the trial to investigate participants’ and site staff members’ experiences of trial procedures, interventions and barriers to implementing findings into practice (see Chapter 6).

Overview of objective outcome measures and analysis

Nasal patency measurement and data collection protocols were devised through review of the scientific literature and the equipment manufacturer’s user information (GM Instruments) (see Report Supplementary Material 1), consultation with the NAIROS Trial Management Group (TMG), and consultation with a representative of the manufacturer.

Site staff were trained in these protocols in person during site initiation visits, were provided with a training video84 and had access to ad hoc support from Northern Medical Physics and Clinical Engineering and GM Instruments.

The NAIROS participants performed two types of objective measures of nasal patency both before and after decongestant: PNIF using a standard device [https://gm-instruments.com/products/nasal-measurements/pnif-meter (accessed 27 August 2021)], and rhinospirometry using an electromechanical/ software rhinospirometer device that measured airflow through each nostril independently [https://gm-instruments.com/products/nasal-measurements/nv1-rhinospirometer (accessed 27 August 2021)]. Rhinospirometry was performed during both MIV and tidal breathing. Measurements of nasal patency took place at all three trial visits (baseline and 6 and 12 months post randomisation). End volume (for the rhinospirometer) and flow (for the PNIF meter) values were read from the devices, recorded onto a case report form and then recorded onto the NAIROS database; these parameters are presented and discussed in Chapter 3.

Four baseline nasal patency parameters were assessed for potential inclusion in the sensitivity analyses (model 3; see Sensitivity analyses).

The four model-3 candidate baseline nasal patency parameters were derived from (1) post-decongestant PNIF and (2) flow rate time series data files saved using the rhinospirometry software, as follows:

-

absolute, post-decongestant, tidal breathing (NPR)

-

the change in absolute NPR following decongestant

-

post-decongestant, tidal breathing tidal volume (both sides combined)

-

post-decongestant, tidal breathing maximum flow rate (both sides combined).

MATLAB® software (version R2019; The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA) was used to analyse rhinospirometry data files and extract the four model-3 candidate parameters. Calculations were validated by comparison to values in the manufacturer’s rhinospirometer software.

The nasal patency protocols and analyses of rhinospirometry data files to produce the four parameters are described in full in a NAIROS nasal patency measurements report (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

Participant timeline

Identification, screening and recruitment of participants

Although primary care clinicians were encouraged to refer patients with a deviated nasal septum directly to nasal research clinics, the majority of eligible patients were proactively identified by researchers from general ENT primary care referrals. Triage of paper referrals and scrutiny of ‘choose and book’ referrals were used to populate research clinics, or alternatively, research slots in general rhinology/ENT clinics. At the majority of sites, clinicians did not have the resources for dedicated research clinics. Nasal septal deviation can be challenging to diagnose in primary care; therefore, the participants selected to attend research clinics were chosen at the clinicians’ judgement.

Screening for study eligibility was maximised by training all staff involved. Potential participants, whenever possible, were sent the participant information sheet (PIS) with their clinic appointment details and were directed to the patient information video available on the trial website. 85 All patients were given a minimum of 24 hours after receiving the PIS to decide whether or not they wished to participate.

Patients were invited to provide written informed consent for the study in three stages, after they had been given sufficient time to consider the trial and had the opportunity to have any questions addressed by the local clinical team.

First, patients were invited to provide consent to undergo screening assessments to determine eligibility for inclusion in the trial.

Eligibility assessments

-

Pre-randomisation NOSE scale.

-

Age.

-

Baseline recording of four core features including endoscopy (without decongestion):

-

the side of the convexity

-

the site of deflection (whether anterior/posterior/upper/lower or all)

-

nasal endoscopy findings to look for evidence of exclusion criteria (e.g. pus/polyps)

-

whether the extent of the observer-rated airway obstruction by the septum was < or > 50% at endoscopy.

-

Second, patients were invited to provide consent for their discussion about the NAIROS trial to be audio-recorded and for their contact details to be shared with qualitative researchers for a potential telephone interview.

Third, eligible patients were invited to provide consent for the main trial. The following assessments were undertaken only once thereafter.

Assessments pre randomisation

-

The SF-36.

-

The SNOT-22.

-

Measurements of nasal patency pre and post decongestion:

-

PNIF (measured by the PNIF meter)

-

rhinospirometry, allowing calculation of NPR

-

the DOASS (post decongestion only).

-

Sites were instructed to use xylometazoline hydrochloride (Otrivine Congestion Relief 0.1% Nasal Spray®; GlaxoSmithKline plc, Brentford, UK) nasal spray as the decongestant.

Eligible patients who declined the main trial

To facilitate baseline analysis of the NAIROS trial participants with eligible patients who declined to participate, those in the latter group were invited to provide written consent to collect the following baseline data:

-

SNOT-22 score

-

NOSE score

-

intention to reduce turbinate

-

baseline recording of four core features including endoscopy (without decongestion) –

-

the side of the convexity (laterality)

-

the site of deflection (whether anterior/posterior/upper/lower or all)

-

endoscopy findings to look for evidence of exclusion criteria (e.g. pus/polyps)

-

whether the extent of the observer-rated airway blockage by the septum was < or > 50% at endoscopy.

-

-

age

-

gender

-

reasons for declining.

Screening data, including the number of participants approached, reasons for ineligibility, those interested in taking part and reasons for declining participation, were collected via a log completed by site staff conducting screening. The intention was to compare the NAIROS trial participants to the total pool of those referred at each participating site.

Randomisation

Participant allocation

At the baseline visit, consenting, eligible patients were randomised on a 1: 1 basis using the centrally administered Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU) web-based system. Randomisation was by random permuted blocks of variable length, stratified by gender and three recognised NOSE-derived categories of baseline severity as defined previously in Eligibility criteria. The treatment allocation was open-label, with the randomisation system providing a unique trial identifier for each participant.

Withdrawal

Participants had the right to withdraw from any element of the RCT at any time without having to give a reason. Participants who withdrew their consent or were withdrawn by the investigator from the trial were not replaced. All data collected until withdrawal were retained for data analysis.

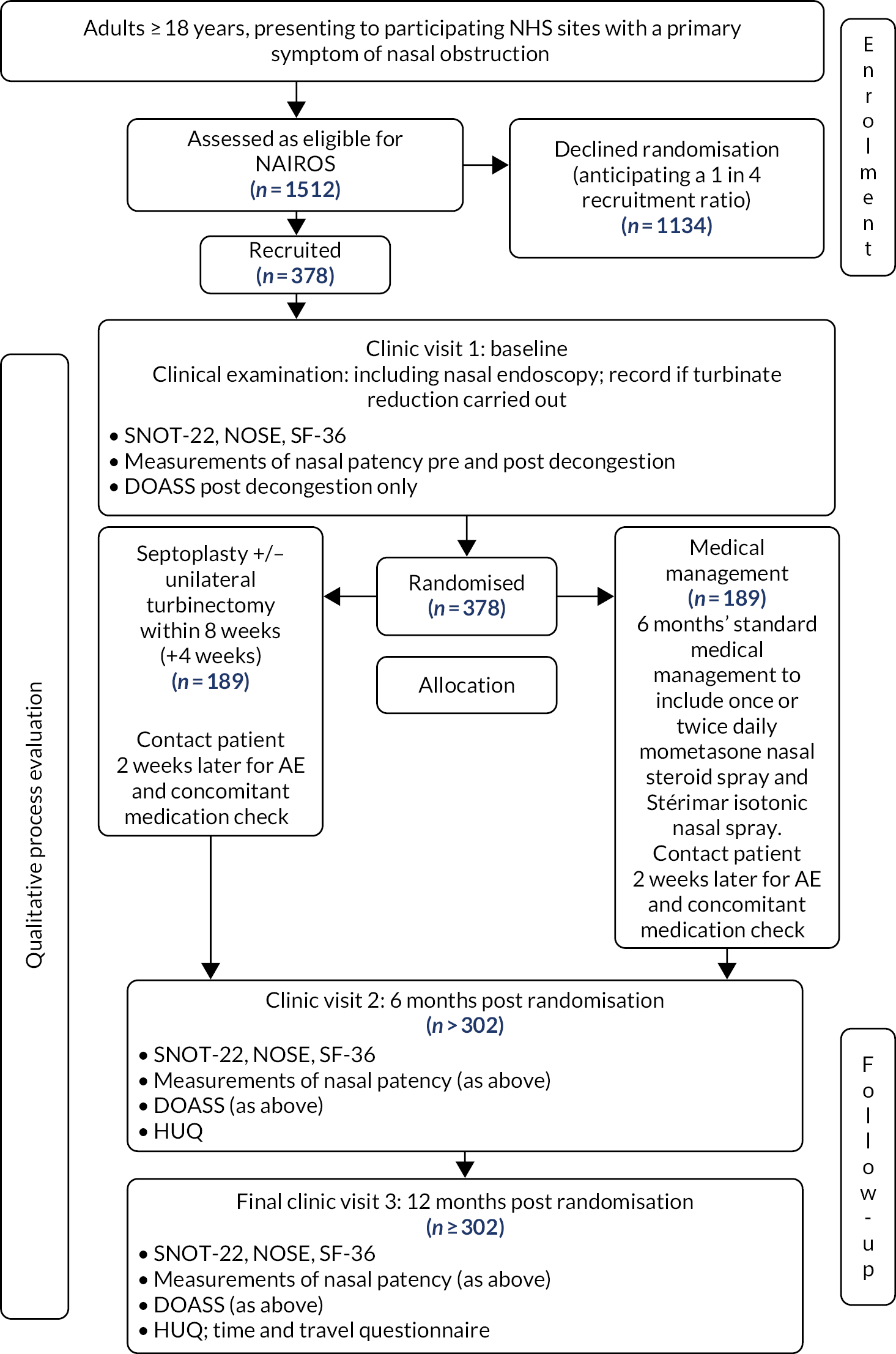

Schedule of events

Participants recruited to the main trial were followed up for 12 months from the point of randomisation (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

The NAIROS participant flow diagram. Reproduced from version 8.0 of the NAIROS protocol (17 December 2020) [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1422607#/ (accessed 30 July 2021)].

Septoplasty participants

The surgeon’s intention to reduce the inferior turbinate was recorded prior to septoplasty and the following information was recorded at the time of surgery:

-

the date of surgery

-

duration in theatre

-

grade of senior surgeon and senior anaesthetist present

-

whether septoplasty, with or without unilateral inferior turbinate reduction, was carried out

-

technical aspects of the surgery

-

discharge medication

-

whether or not any complications occurred

-

whether or not there was any overnight hospital admission.

Medical management participants

As the NAIROS was a pragmatic trial of standard treatment, formal participant compliance with the medical management intervention was not formally assessed. However, quantities of bottles used per participant and reasons for ceasing treatment were recorded.

Follow-up

Participants were contacted by either telephone, e-mail or text 2 weeks after randomisation (medical management) or 2 weeks after their septoplasty, to record any AEs and concomitant medication. Medical management participants were reminded to reduce their dose of mometasone nasal spray at 6 weeks.

Six months after randomisation (− 2 weeks/+ 4 weeks)

Assessments performed are detailed in the trial schedule of events (Table 1). The 6-month follow-up visit was scheduled to allow a minimum of 12 weeks’ recovery from septoplasty surgery.

| Procedures | Pre screening | Screening/consent/pre randomisation (visit 1) | Contact patient 2 weeks after randomisation (± 14 days) | Septoplasty [must occur any time up to 8 weeks (+ 4 weeks) after randomisation] | Contact patient 2 weeks after surgery (± 14 days) | 6 months (− 2 weeks/+ 4 weeks) (visit 2) | 12 months (± 2 weeks) (visit 3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIS given to patients referred to NAIROS clinic when appointment made | ✓ | ||||||

| Eligibility assessment | ✓ Pre randomisation | ||||||

| Demographics (sex and age) | ✓ Pre randomisation | ||||||

| Medical history | ✓ Pre randomisation | ||||||

| Informed consent (must take place prior to any study-specific activities) | ✓ Pre randomisation | ||||||

| Eligibility confirmed | ✓ Post consent and pre randomisation | ||||||

| Clinical examination [includes nasal endoscopy (without decongestion) and baseline recording of four core featuresa] | ✓ Post consent and pre randomisation | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| SNOT-22 | ✓ Post consent and pre randomisation | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| NOSE | ✓ Post consent and pre randomisation | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| DOASS (post decongestion); only for patients consenting to the main trial | ✓ Post consent and pre randomisation | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Measurements of nasal patency (see Report Supplementary Material 1 for further information) (only for patients consenting to the main trial) | ✓ Post consent and pre randomisation | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| SF-36 (only for patients consenting to the main trial) | ✓ Post consent and pre randomisation | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| HUQ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Randomisation (following complete assessments) | ✓ | ||||||

| Medical management arm: dispensing of trial drugs (only if randomised to medical management arm); 6-month supply of Stérimar isotonic spray and mometasone given | ✓ | ||||||

| IMP and Stérimar usage (number of bottles used) | ✓ | ||||||

| Septoplasty arm (must occur any time up to 8 weeks (+ 4 weeksb) after randomisation) | ✓ | ||||||

| Post-surgery CRF | ✓ | ||||||

| Feedback on patient well-being. Contact can be made via telephone, text or e-mail | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Record technical failures from those operations in which widening of the nasal airway has been achieved, yet the patient’s symptoms persist | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| If a participant did not attend the follow-up visit, telephone to remind them to complete/post SNOT-22c | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Time and travel questionnaire | ✓ | ||||||

| AE assessments | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Concomitant medications | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

For participants allocated to the surgical arm, any complications from the septoplasty were recorded.

Twelve months after randomisation (± 2 weeks)

Assessments at the 12-month follow-up visit are detailed in the schedule of events (see Table 1).

At both the 6- and 12-month visits, participants were given the option to discontinue allocated treatment and explore treatment options available within standard local NHS care.

Serious adverse event reporting

Adverse events were recorded from date of randomisation until the end of trial participation (at visit 3, 12 months post randomisation), at every trial visit and during the safety telephone calls described previously. AE severity was assessed by the investigator as mild/moderate/severe and assessed for causality and expectedness by reference to the Reference Safety Information. The Reference Safety Information for surgery (expected AEs) was documented in the protocol. The Reference Safety Information for the medical management arm intervention was section 4.8 of the approved summary of product characteristics for NASONEX® 50 μg/actuation (mometasone furoate) nasal spray (Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., Rahway, NJ, USA). There were no known drug interactions listed in the approved summary of product characteristics.

Serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported to the NCTU and to the sponsor on a trial-specific report within 24 hours of the site becoming aware of the event and followed up until resolution. SAEs were reported until the end of the trial. All SAEs were summarised in the annual development safety update report to the MHRA and in the annual Clinical Trial of an Investigational Medicinal Product (CTIMP) safety report to the relevant REC.

Suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSARs) among participants in both arms underwent expedited reporting to the REC. Only SUSARs in the medical management arm required expedited reporting to the MHRA.

Definition of the end of the trial

The trial end was defined as the collection date of the final participant’s 12-month follow-up data.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement was integrated into the design, conduct and outcome stages of the study. Substantial PPI input was sought in the design of the study. Initially, 21 patients were consulted shortly before undergoing septoplasty and asked about their symptoms, about their willingness to be randomised, and for feedback on the NOSE and SNOT-22. Two-thirds of patients preferred the SNOT-22, which better matched their symptoms (in particular, the NOSE omitted snoring and headache, which were felt to be important).

Of key concern to the patients were details of the treatment received in the medical arm and whether or not randomisation to this arm precluded them from future surgery. This first phase of PPI was used to design a trial outline, which was discussed with a further 18 outpatients with nasal obstruction. During the second phase of the PPI, we were able to adjust the time for which surgery would be deferred in the control arm, and the acceptability of the nature and timing of the outcome measures. Additional input was obtained during the development of patient experience.

On receipt of funding, a PPI panel was convened, with participants recruited via ENT clinics and VOICE (URL: www.voice-global.org). Recruitment materials for the panel outlined details of the study, the expected time commitment and reimbursement for time and expenses. A member of the panel presented a patient perspective on septoplasty and the NAIROS trial, at the NAIROS launch event. Two PPI meetings with five panel members were held during study set-up to obtain input into the development of the recruitment strategy and other study processes (e.g. arrangements for participants who wished to discontinue their allocated treatment); feedback was also obtained on drafts of the PIS, consent form and recruitment video.

Subsequently, PPI panel input regarding specific patient-facing trial materials, including the trial website and the thank-you letter for trial participants, was obtained via e-mail on a more ad hoc basis. At each subsequent contact, before requesting any further input, a short update on trial progress was provided.

The Trial Steering Committee (TSC) included an independent PPI member. The TSC met regularly to review study documentation, including patient-facing documents and lay language text, and to ensure that the trial was conducted in a way that was considerate of the needs and wishes of participants.

Statistical considerations

The trial analysis followed a statistical analysis plan (SAP) (version 2.0, dated 25 March 2021). There was no formal interim analysis, only a single analysis after the database was locked on 29 January 2021. Decisions regarding the continuation of the trial were made at Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) meetings every 6 months.

Analyses are reported according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) recommendations and were conducted in the validated statistical software package Stata®, version 16 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Sample size calculation

The sample size calculation was based on a t-test for superiority assuming equal variance across groups, a conservative approach given the primary analysis was based on adjustment for the baseline values of SNOT-22, which generally increases statistical power. The target recruitment number of 378 participants allowed for a 20% drop-out rate (based on experience from two prior septal surgery audits). 86,87 The remaining 302 participants (151 per arm at completion) would be sufficient to deliver 90% power to detect a 9-point difference in the overall SNOT-22 score between arms. This assumed a 5% type I error rate and a standard deviation (SD) of 24 points. The MCID of 9 units was informed by relevant literature; it was felt to be the most relevant and a change of 8.9 units had been identified as being clinically meaningful. 43,45,46,88,89 The same literature was used to guide assumptions about what would be a reasonable value for the SD for the design parameter. We took a conservative approach as we assumed that the SD would be 24 points, which was the largest value reported. 43,45,46,88,89

Statistical analysis plan

Primary outcome measure

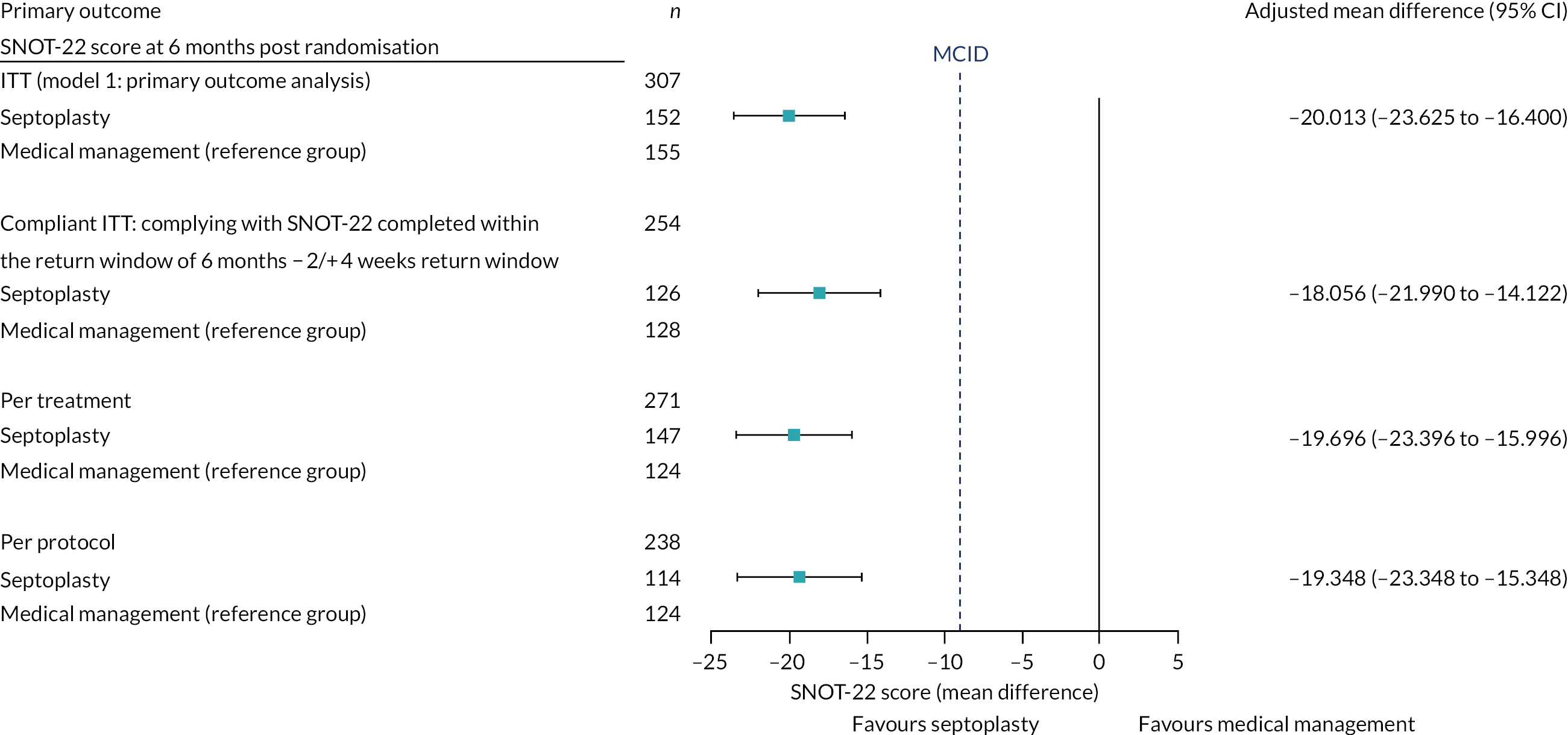

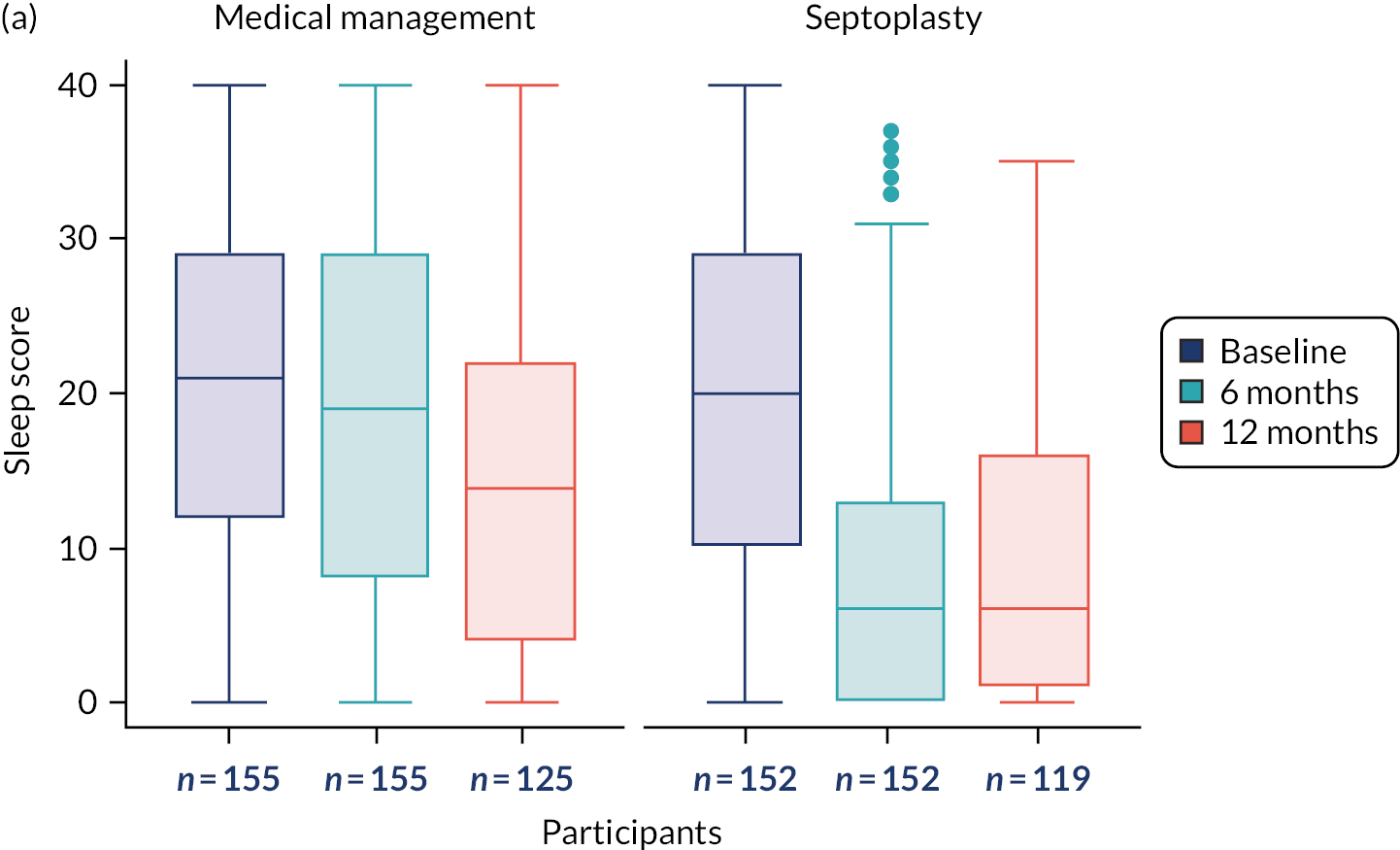

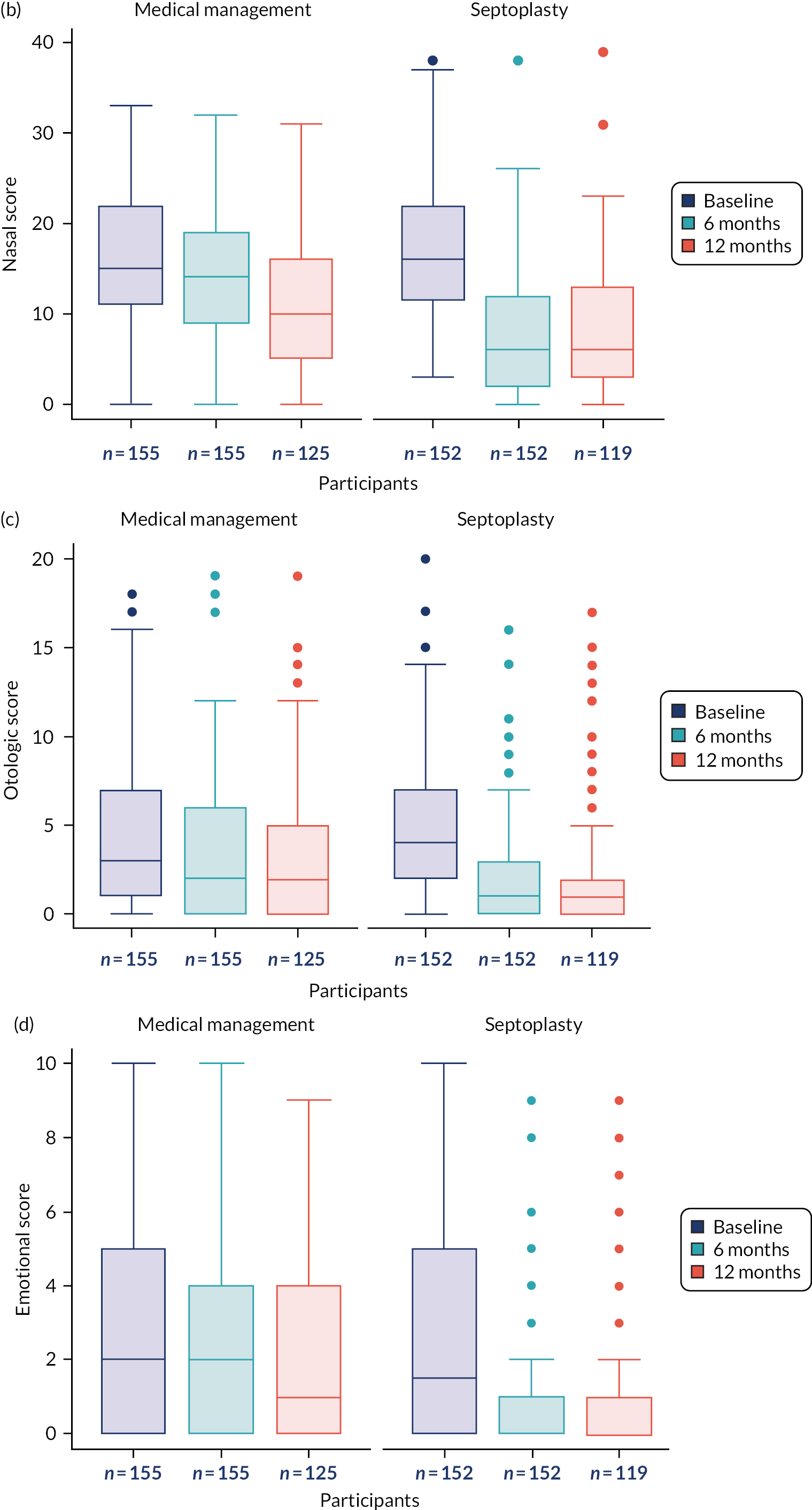

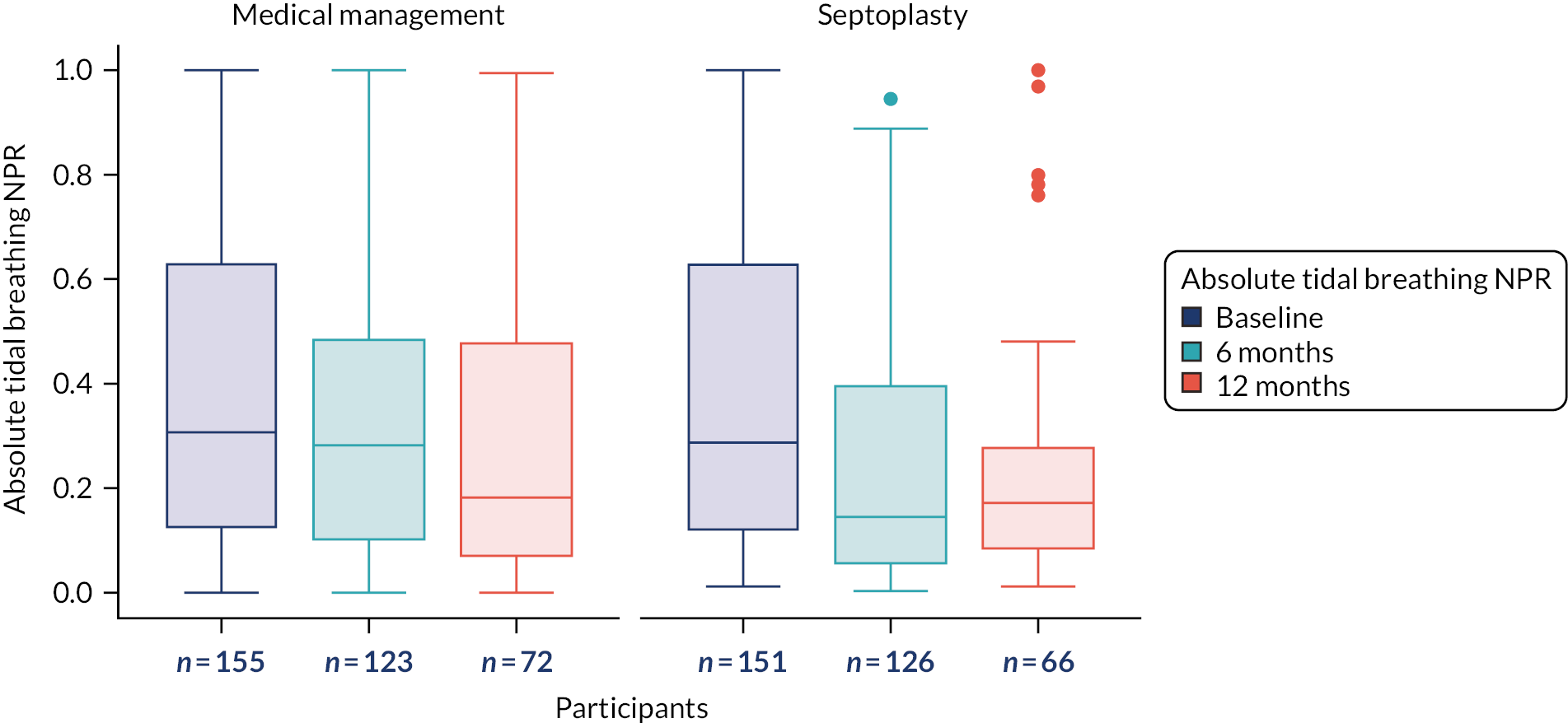

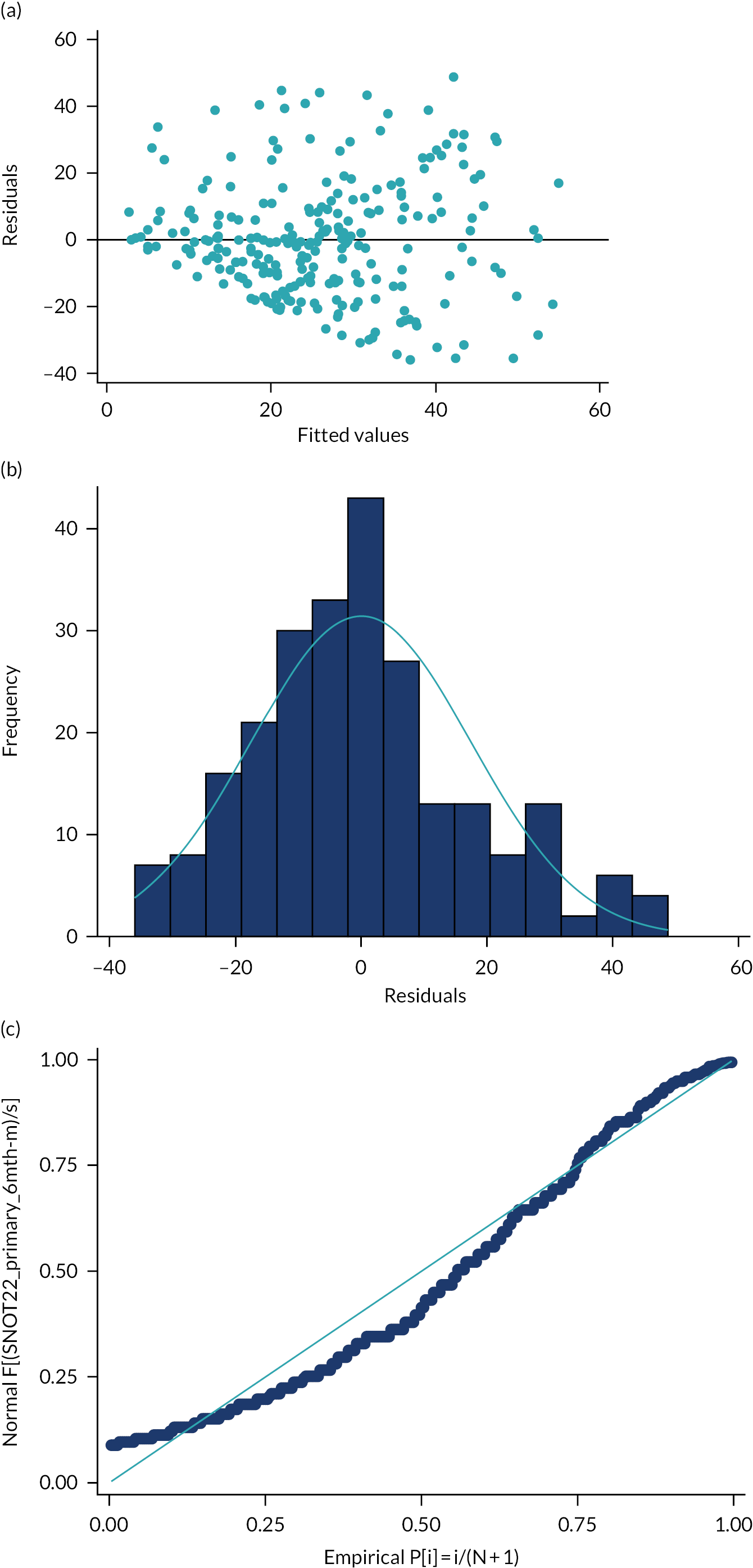

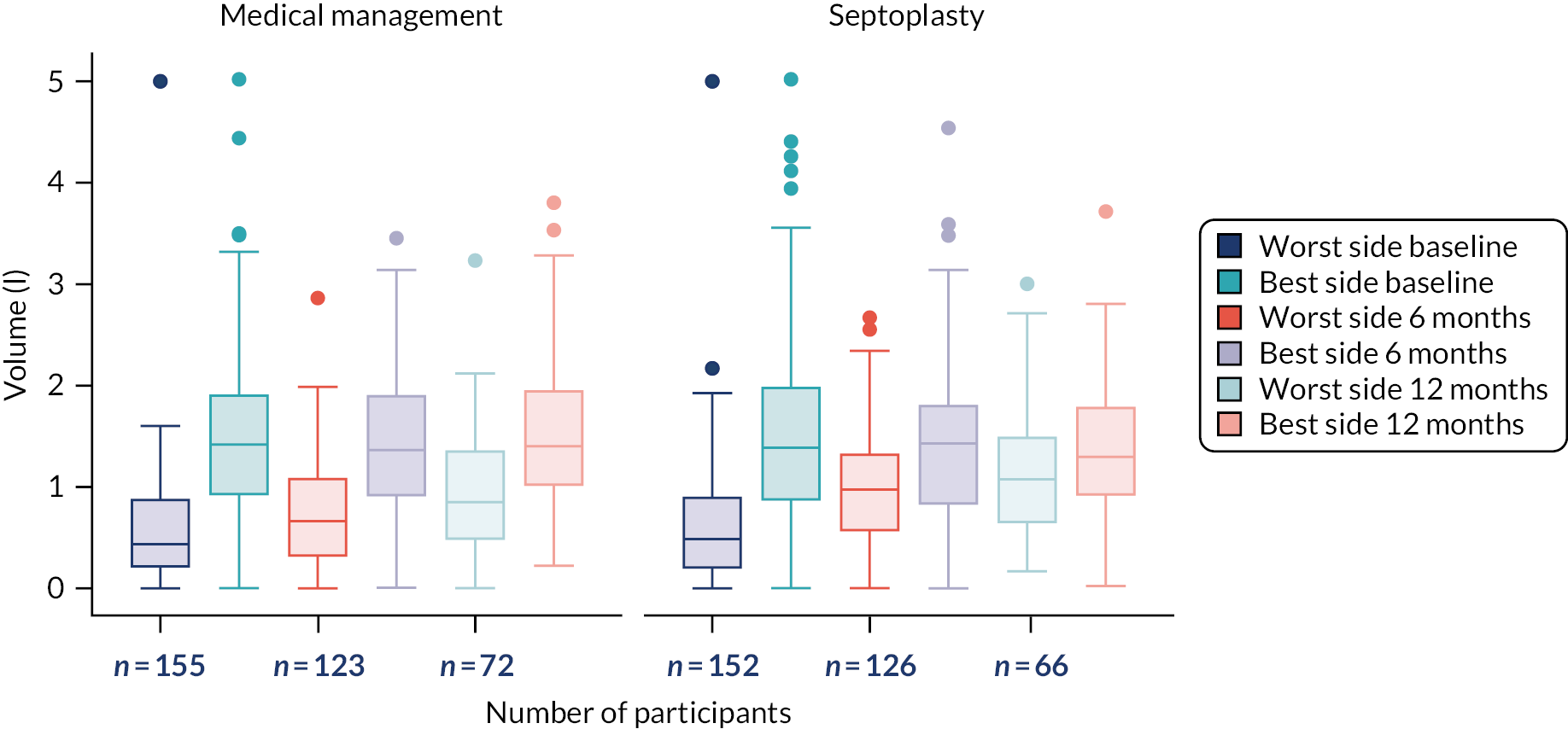

The primary outcome measure was the SNOT-22 score at 6 months. SNOT-22 scores were recorded at baseline and at 6 and 12 months post randomisation. Baseline and follow-up data were summarised using appropriate statistics and graphical summaries. Box plots (e.g. Figure 6) show summary statistics of the measurement they represent. The box represents the middle 50% of the data (lower quartile to upper quartile), the line within the box shows the median (50th percentile), the whiskers show data that fall within 1.5 × the interquartile range (IQR) and the points show data that fall outside these limits. SNOT-22 questionnaires with up to 20% of items missing were imputed, with the average of the completed questions used for missing items.

Summary statistics of overall scores, including means with associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs), are presented by treatment group and overall in Table 6.

Defining the populations for analysis

The following analyses by population were undertaken:

-

Intention-to-treat group – all ineligible and protocol-violator participants included in the analysis on an ITT basis, with participants kept in their randomised treatment group. This included outcome measures completed at any time.

-

Compliant ITT group – all participants in the ITT group, but complying with questionnaires completed within the 6-month (− 2 weeks/+ 4 weeks) return window with no consideration given to septoplasty status.

-

Per-protocol group – all participants who received the treatment they were randomised to and complied with protocol in terms of timings and compliance windows for the surgery and primary end point (6-month visit/SNOT-22 completion). This excluded participants randomised to septoplasty but who did not receive septoplasty within 12 weeks of randomisation, participants randomised to medical management who had actually received standard care septoplasty before the 6-month + 4-week primary end point, and participants whose primary end point was completed outside the compliance window.

-

Per-treatment group – this was similar to the per-protocol group, with some additional participants included. The medical management group was exactly the same as in the per-protocol group. Any participant who was randomised to septoplasty and received their septoplasty at least 10 weeks before the primary end point was included in the septoplasty group. In addition, any participant randomised to medical management but who received septoplasty at least 10 weeks before the primary end point was completed was included in the septoplasty group.

-

Non-randomised group – those eligible to be included in the NAIROS trial but who declined to take part. We planned to compare the non-randomised group with those consenting to take part in the trial; 45 patients agreed to join the non-randomised group and allow their data to be collected and analysed. However, owing to the small number of patients who agreed to join the non-randomised group (only 19 of whom provided NOSE data), a meaningful comparison between this group and those consenting to the trial could not be made and these data were not included in this report.

Analysis of the primary outcome

Primary analysis

The primary analysis was conducted by comparing scores of the two randomised treatment arms (immediate septoplasty and medical management) at 6 months. This analysis used multivariable linear regression.

The associated magnitude and significance of any between-arm differences were calculated in a multivariate regression model (referred to as model 1), adjusting for baseline severity SNOT-22 score as a continuous covariate and stratification factors at randomisation [(1) gender and (2) severity at baseline assessed by the NOSE].

Residual analysis was conducted to assess the goodness of fit of model 1. Model 1 is reported fully (see Chapter 3).

Sensitivity analyses

A number of sensitivity analyses of the primary analyses were conducted. The models for these analyses are outlined below:

-

model 2 – adjusting for continuous baseline NOSE score, rather than the three categories used at baseline, to utilise the full information from the continuous measure

-

model 3 – a series of multivariable analyses to further allow consideration of other important baseline factors in the regression model. This included age, ethnicity, site (as a random effect), smoking history, baseline levels of trial questionnaires (DOASS, endoscopy findings) and the four selected nasal patency variables.

Within the model 3 frame, non-linear relationships with continuous baseline covariates were explored for simple and suitable first order, and more complex fractional polynomial transformations, which were applied when appropriate. Building the optimal model for model 3 was based on a forward selection method (change in −2log likelihood, compared against a chi-squared distribution to assess variable inclusion). Variables were initially assessed using univariable regression against the primary outcome measure before they were included in the forward selection process; any variable with p > 0.1 was included in the forward selection process. The results of this first assessment, of all considered variables along with identified transforms, are presented in Appendix 1, Table 48. Significant variables at 5% level were retained in the final model (p < 0.05). At the end of the forward selection procedures, if any of the included covariates became non-significant (p > 0.05), the impact of removing them from the final model was assessed. Improved model suitability was assessed using Akaike information criterion, which estimates the quality of each model relative to the other models, thereby providing a means for model selection. The aim was to derive the most parsimonious model. The details of the full final model 3 can be found in Appendix 1, Table 48.

Secondary analyses

Secondary analyses of the primary outcome were performed by limiting the analysis to the specific populations: compliant ITT, per protocol and per treatment. Multiple imputation was used to include all patients who consented and were randomised, including those with missing SNOT-22 scores at the primary end point. Missing data were imputed using multiple imputation with the proportion of missing data in each group reported and compared descriptively (see Report Supplementary Material 6). Descriptive statistics of baseline variables are presented by treatment group and missing data status (with and without primary end point data, i.e. SNOT-22 score at 6 months). Baseline variables found to be predictive of missing data status are included in multiple imputation equations.

We used multiple imputation to minimise bias, to maximise use of available information and to obtain appropriate estimates of uncertainty. One thousand multiple imputation data sets were created in Stata 16 using chained equations. The multiple imputation equation includes baseline data on gender; NOSE categories and baseline SNOT-22 score; and predictors of missing data to make the missing-at-random assumption as plausible as possible. A conservative approach was adopted, and treatment group was included in the imputation model.

Secondary outcome measures

The analysis of secondary outcomes followed a broadly similar strategy to the primary outcome measure. Secondary outcomes included data at the 6-month follow-up from the other outcomes [i.e. NOSE, DOASS, PNIF (maximum of three measurements), NPR from MIV (using mean volumes from three measurements) and tidal breathing] and data for all outcomes at the 12-month follow-up. SNOT-22 subscales (rhinologic, sleep, ear/facial pain, psychological) at the three time points are presented.

Summary statistics and graphical representation of subjective scales were tabulated at randomisation and at 6 and 12 months’ follow-up, both by intervention arm and collectively. Multiple regression was used to compare the outcome scores between treatment groups at follow-up time points. Variation between sites was included as a random effect with an assumed normal distribution, with analysis including the stratification factors of baseline severity and gender. Further adjusted analyses included terms for baseline values of the scores and key demographic and clinical covariates.

Adverse events were tabulated according to the World Health Organization Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.03, with the number of severe AEs (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events grade 3, 4 or 5) reported as a proportion of all AEs. The number of participants experiencing at least one severe AE according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events was reported as a proportion of all participants. Surgical complication/failure and reintervention were described and not subjected to statistical testing. Technical failures (defined as occasions when the participant self-reported symptoms remaining the same or worsening, along with surgeon opinion on whether revision surgery was required) from operations in which widening of the nasal airway was achieved were reported. Complications experienced as a result of the septoplasties are also presented in the results chapter.

We carried out a subgroup analysis for participants who were recommended to receive the inferior turbinate reduction. This led to four groups: as randomised, recommended for turbinate reduction or not. This broadly followed the primary analysis, but analysis was carried out separately for each subgroup. Subgroups by gender are also reported.

Subpopulation analyses

The subpopulation treatment effect pattern plot (STEPP) analysis90–93 approach was developed to allow researchers to investigate the heterogeneity of treatment effects on outcomes across values of a (continuously measured) covariate. STEPP is a graphical tool which allows one to visualise treatment differences, and will be useful for guiding patients and clinicians when making decisions regarding treatment choice.

The importance of baseline severity as a continuous distribution of NOSE score at randomisation was further explored graphically by STEPP analysis to display the predicted point estimates of any treatment effect (with 95% CIs) over the range of NOSE values (which ranged from 30–100 among NAIROS participants), with the aim of further informing any patient selection guidance and recommendations. The STEPP analysis was also carried out for overlapping ranges of NOSE score separately by gender.

Data monitoring, quality control and assurance

The NCTU was delegated by the sponsor to monitor trial conduct and data integrity to ensure that the trial was conducted in accordance with the protocol and the latest directive on good clinical practice (2005/28/EC). 94 All final statistical and health economics analyses were reviewed for quality assurance by independent researchers.

Trial management and oversight

The sponsor delegated day-to-day management of the trial to the NCTU and the TMG, which met approximately monthly. External, independent oversight of the trial was provided by an independent DMC and a TSC who reviewed the SAP. Details of these committees and trial monitoring have previously been described in the published protocol paper. 80 Terms of reference and trial oversight charters described roles and responsibilities of individual committees. Members were required to sign the relevant terms of reference or trial oversight charter, declaring any conflict of interest. The TSC met at least annually after the DMC meeting.

Chapter 3 Results

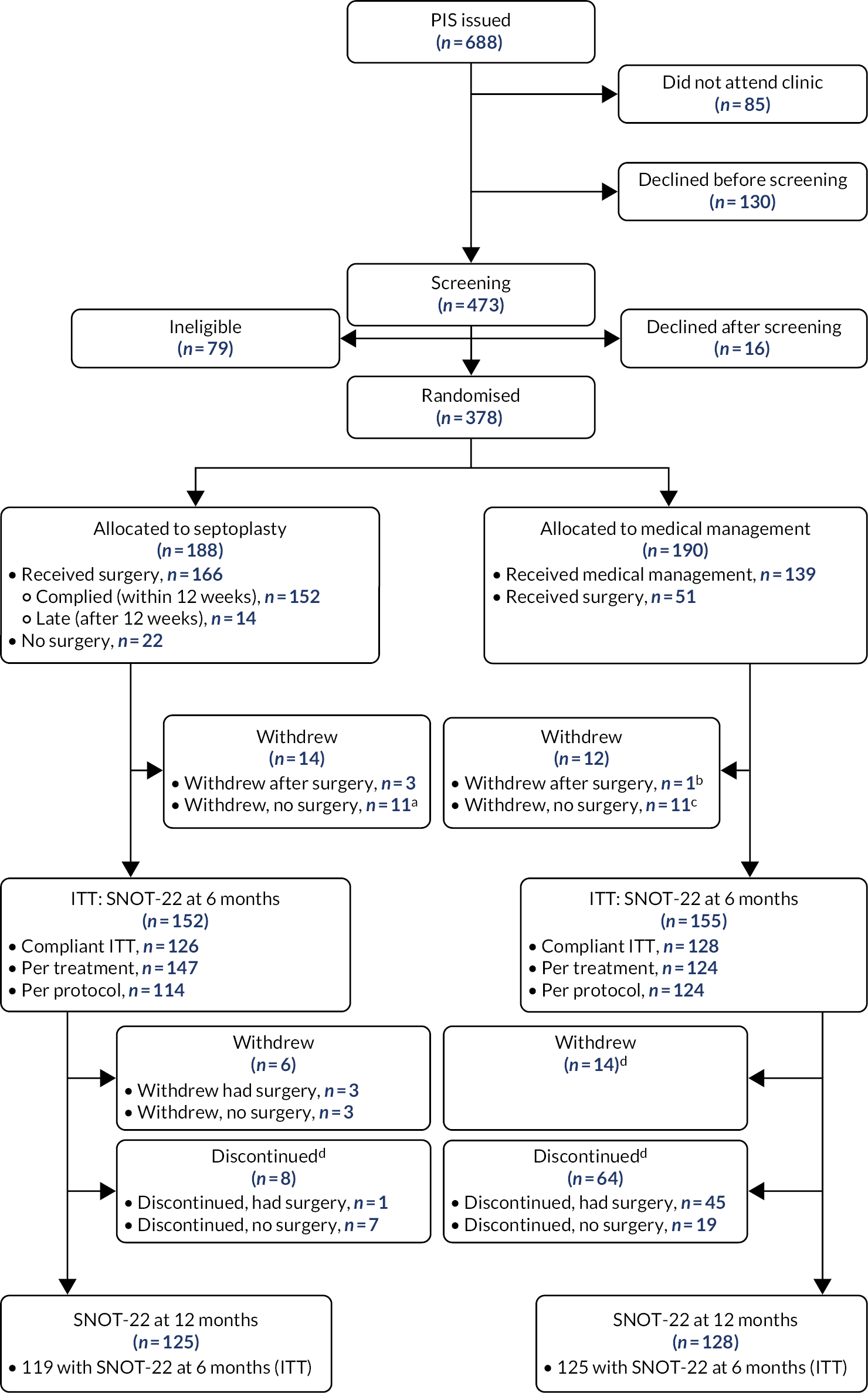

The analysis presented here is reported according to the CONSORT flow diagram (see Figure 3) and is based on the SAP version 2.0 (25 March 2021). SAP version 1.0 (1 February 2021) was approved immediately before data download. A further minor clarification on the definitions of ‘per-protocol’ and ‘per-treated’ analyses populations was required in the SAP following data download; hence, version 2.0 was used for the analysis. The SAP provided guidelines for the analysis of the NAIROS trial data. Any analyses that were not prespecified in the SAP are denoted as ‘unplanned’.

Recruitment

-

Number of sites: 17.

-

Date first site opened: 18 January 2018.

-

Date first participant randomised: 26 January 2018.

-

Total number of participants randomised: 378.

-

Date last participant recruited (consented): 5 December 2019.

-

Date last participant randomised: 5 December 2019.

-

Date of last participant follow-up: 17 December 2020.

-

Date of final data set download: 3 February 2021.

Randomisation and stratification factors

The trial recruited to target. Individual randomisation to the two trial arms was stratified by gender and NOSE category (see Chapter 2). The numbers of participants randomised by strata are presented in Table 2.

| Stratification factor | Trial arm, n (%) | Total (N = 378), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Septoplasty (N = 188) | Medical management (N = 190) | ||

| Moderate/male | 21 (11) | 22 (12) | 43 (11) |

| Moderate/female | 9 (5) | 10 (5) | 19 (5) |

| Severe/male | 60 (32) | 61 (32) | 121 (32) |

| Severe/female | 29 (15) | 28 (15) | 57 (15) |

| Extreme/male | 45 (24) | 44 (23) | 89 (24) |

| Extreme/female | 24 (13) | 25 (13) | 49 (13) |

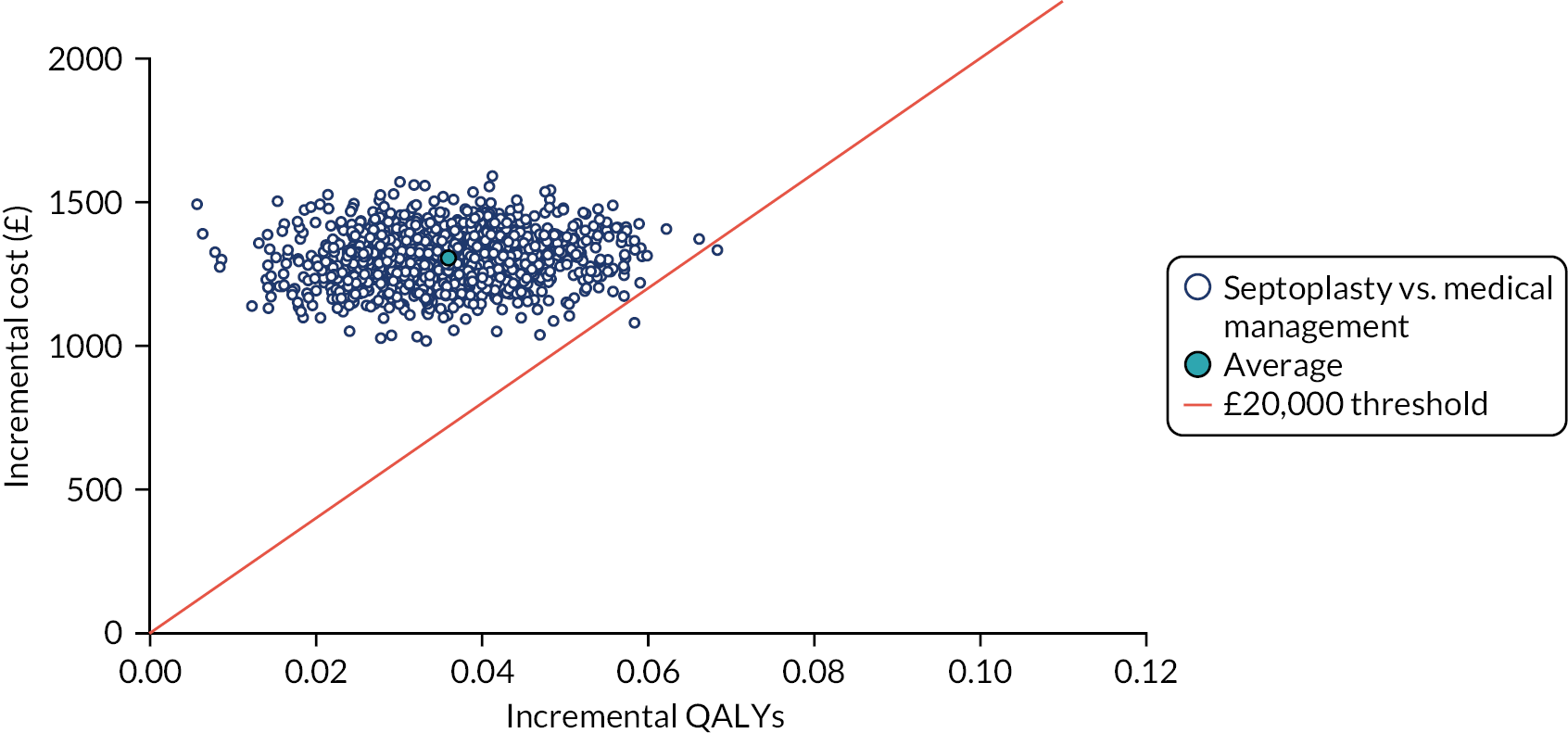

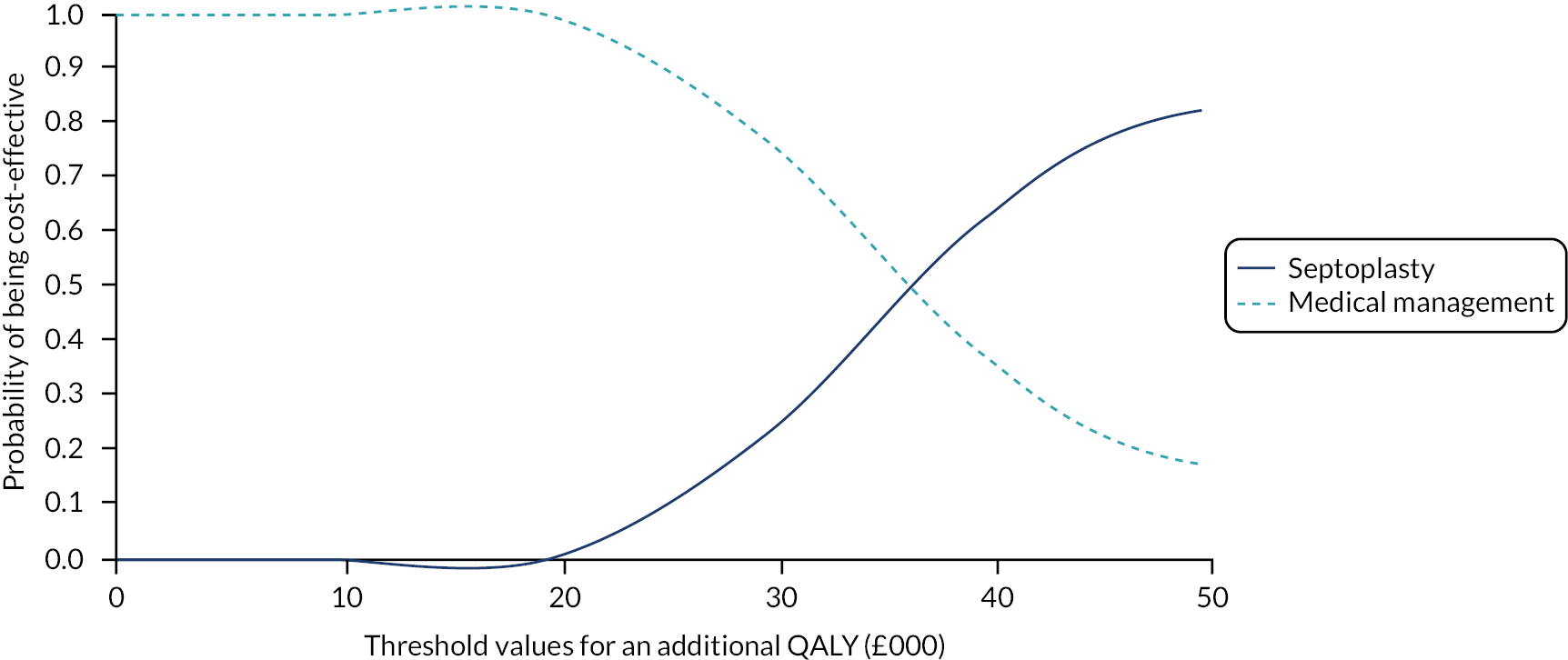

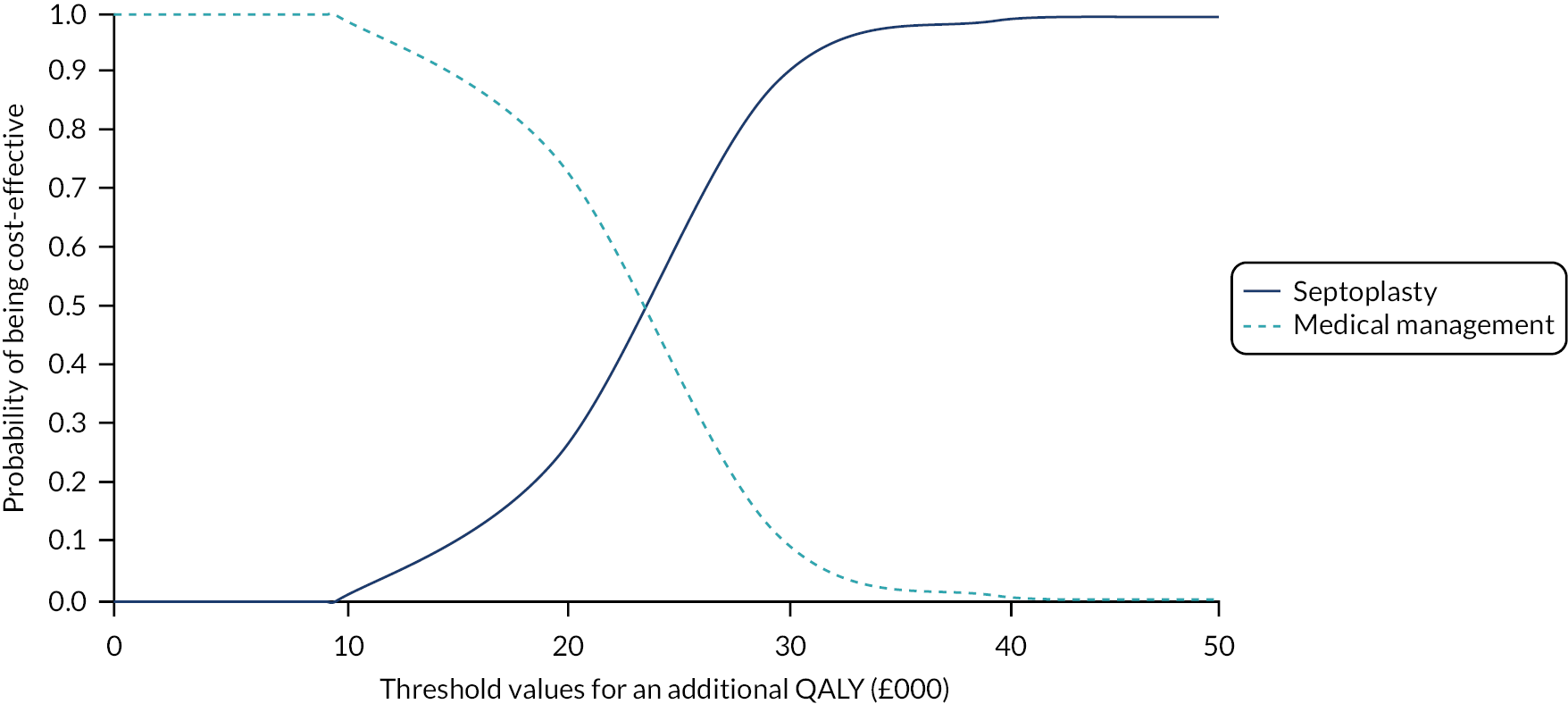

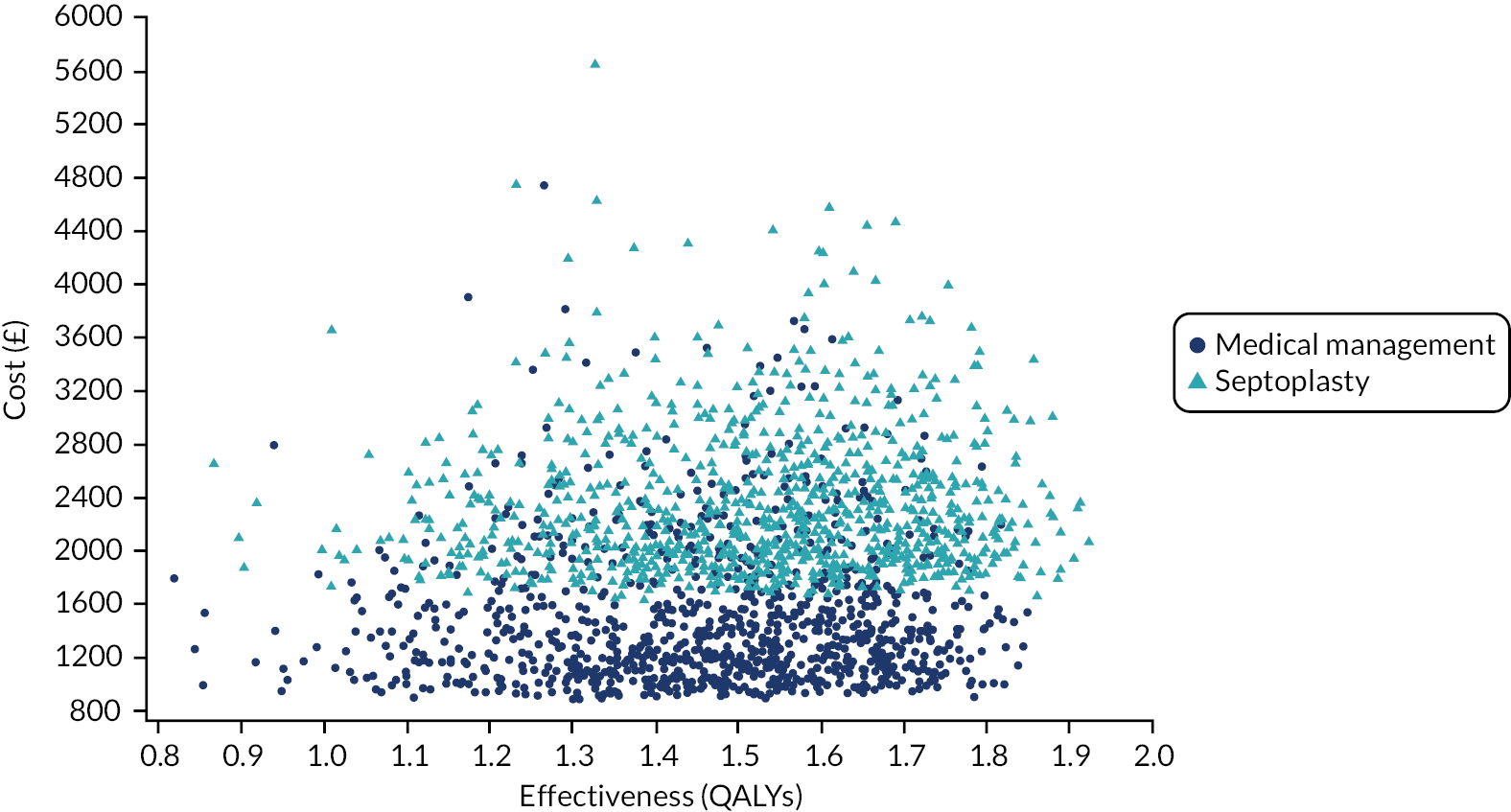

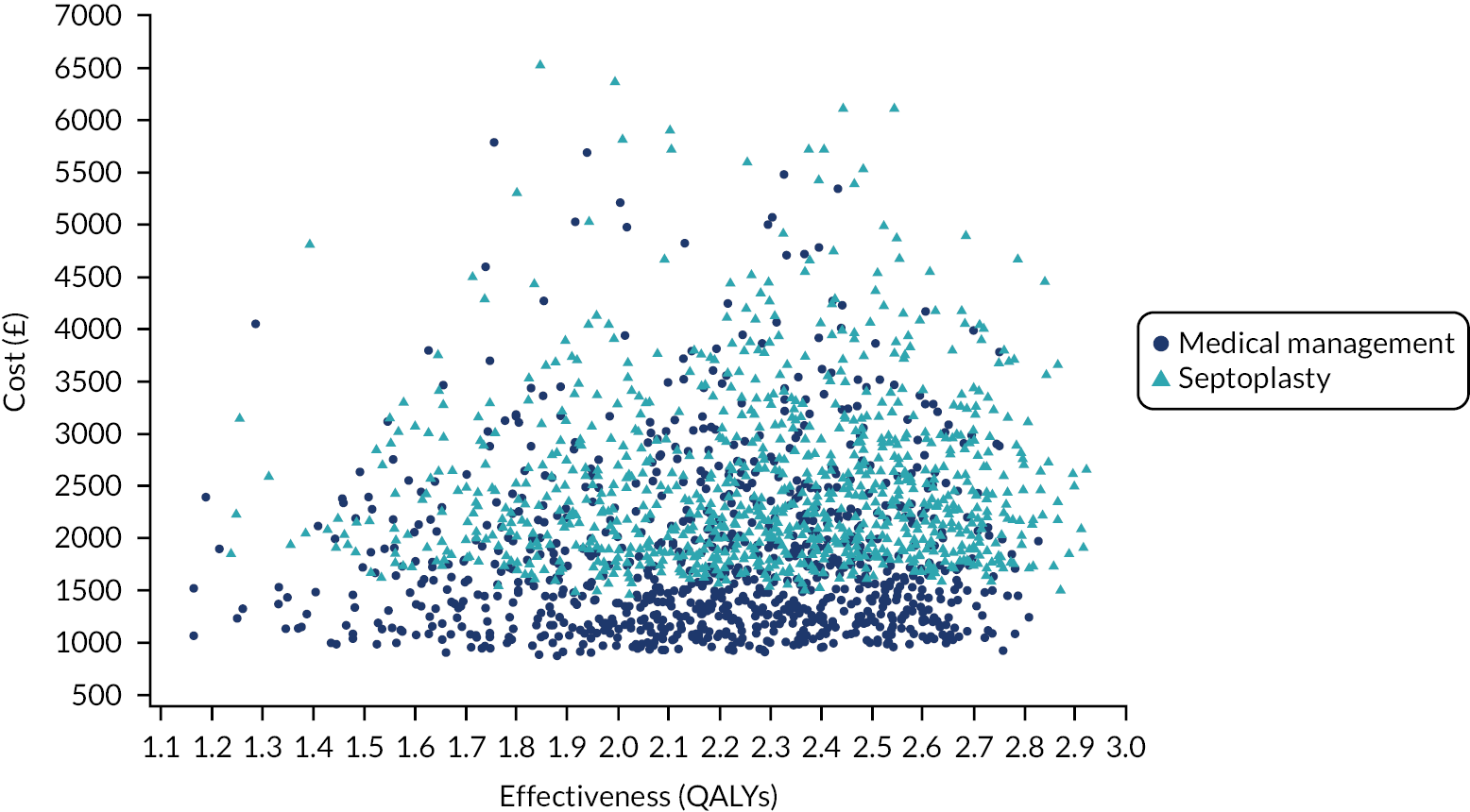

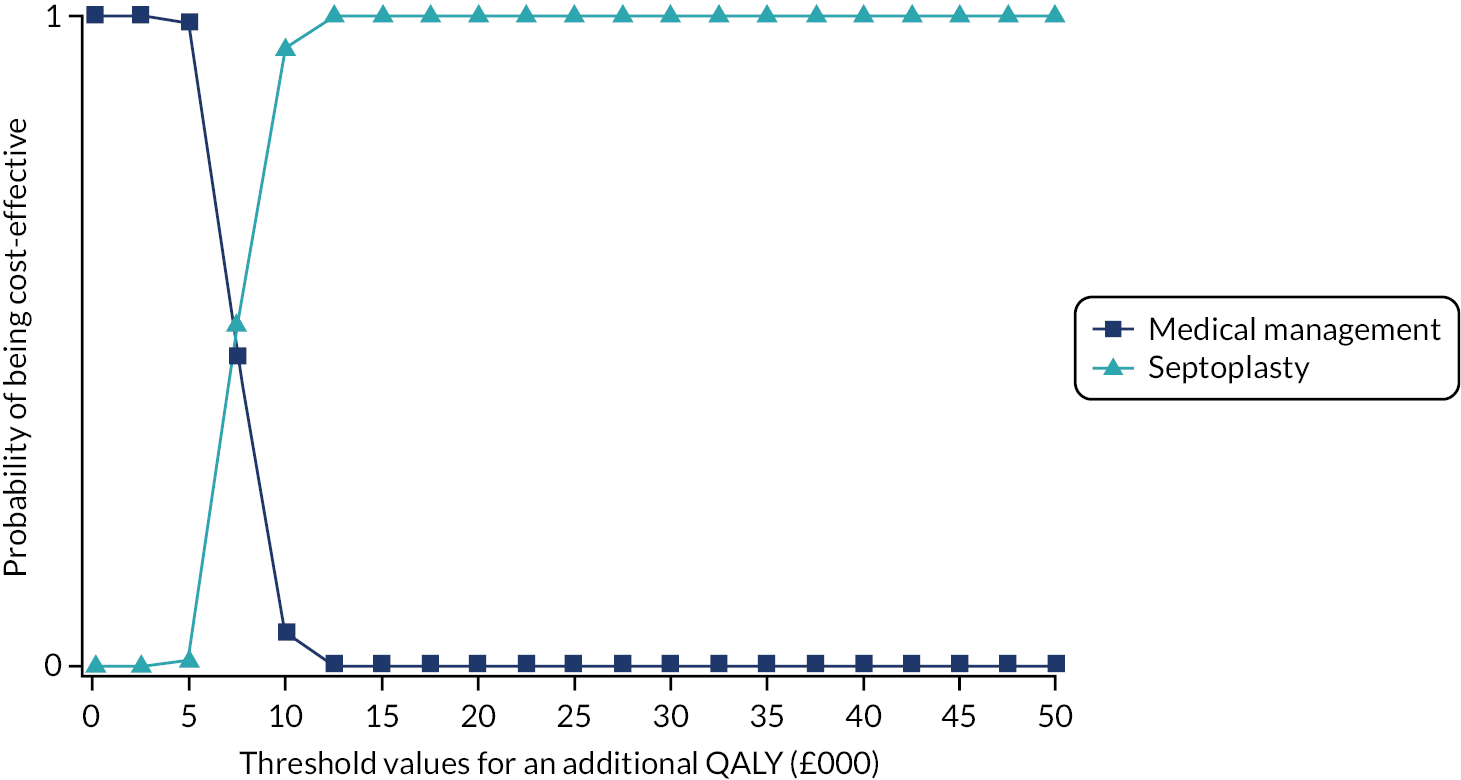

| Total | 188 (100) | 190 (100) | 378 (100) |