Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number NIHR129804. The contractual start date was in January 2021. The draft manuscript began editorial review in August 2023 and was accepted for publication in February 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Langdon et al. This work was produced by Langdon et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Langdon et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Within our report, we recognise that “learning” and “intellectual” disabilities are both used to refer to the same group of people in different parts of the world. In the United Kingdom, we tend to use learning disabilities. We have intentionally used intellectual disabilities in our title, while we have used learning disabilities throughout our report.

Background

There is evidence that ‘talking’ psychological therapies are likely effective for autistic people without learning disabilities and those with mild learning disabilities,1–3 but there is a lack of evidence that these interventions are effective for those with both autism and moderate to severe learning disabilities. 4 While there is substantial evidence that cognitive behavioural therapy is an effective intervention for anxiety disorders in adults,5 the inclusion of cognitive methods within behaviour therapy has been questioned, as there is evidence that these methods do not improve intervention outcomes,6–8 including outcomes following intervention for anxiety disorders. 9–12 There is evidence that behavioural interventions and, specifically, exposure therapy may work just as well as cognitive therapy for many anxiety disorders. 13–15 Considering the difficulties that autistic people with learning disabilities experience with communication, psychological therapies which focus upon behavioural interventions, such as exposure therapy, may be advantageous because of a potential reduced reliance upon verbal communication.

Rosen et al. 16 completed a systematic review of behavioural interventions used for anxiety disorders with autistic people with moderate or severe learning disabilities. Their review included seven studies involving children, adolescents and adults. None of the included studies were randomised control trials; instead, they made use of single-case experimental designs. Within the review, a variety of behavioural interventions with adaptations, such as the inclusion of parents or carers within therapy, were successfully modelled, which included: systematic desensitisation and the use of fear hierarchies,17–19 video modelling and mastery techniques,19 stimulus fading,20 positive reinforcement to support behaviour change19–22 and exposure techniques. 20–23 These studies suggested that behavioural interventions have the potential to be beneficial for anxiety amongst those with autism and moderate to severe learning disabilities. Additionally, we completed a systematic review of interventions for mental health problems for children and adults who have severe learning disabilities (including those with autism). 4 Very few studies met the eligibility criteria for inclusion, and those that evaluated psychological therapies made use of minimal-quality single-case experimental designs, with a resulting poor current evidence base, indicating that better modelling and feasibility studies are initially needed to inform the decision as to whether to proceed to larger studies.

It is clear that autistic people are at increased risk of developing mental health problems, including anxiety disorders, relative to their neurotypical peers. 24–27 Those with autism often present with atypical reactions to sensory stimuli as well as restricted and repetitive interests which are associated with anxiety, including an insistence on sameness and routine. 28,29 Approximately 32–43% of those with autism also have symptoms of anxiety,30,31 while members of our research team have identified that up to 14.3% will have a diagnosis of an anxiety disorder by the age of 27, compared with only 7.1% of the general population. 32 Adapted talking psychological therapies can be used to treat anxiety disorders with autistic people,2,33 and similar interventions can be used with people who have mild learning disabilities. 1,3,34 However, as already mentioned, the evidence to support their use with people who have autism and moderate to severe learning disabilities is sparse. 3

A variety of factors have been associated with the development of emotional disorders in autistic children, adolescents, and adults. It is important that these factors are considered and incorporated within intervention programmes for autistic people, and include:

-

difficulties with social functioning,35 and social skills difficulties,36,37 including social motivation38 and communication39

-

difficulties with friendship quality40 and lack of social support41,42

-

difficulties with the development and use of coping strategies35

-

seeing oneself as dissimilar from others45

-

autistic traits42

-

lack of flexibility and associated executive function difficulties, associated with anxiety47,48

-

difficulties with meta-cognition, associated with depression47

-

restricted and repetitive behaviours,28,49,50 including an insistence on sameness28,29,51–54

-

level of general intellectual functioning,55–58 which has not been consistently associated with emotional disorders in some studies59

-

sensory issues, including atypical sensory over-responsivity and avoidance of sensory input28,29,53,60,61

-

intolerance of uncertainty,28,62–65 which has been shown to mediate the relationship between sensory issues and anxiety, as well as anxiety and insistence on sameness66 and

-

alexithymia. 64

Autistic people with moderate to severe learning disabilities who have anxiety disorders have a high level of need, and this has been recognised by the NHS. In 2015,67 Building the Right Support was published, which was a national plan for England to develop community services for people with learning disabilities and/or autism in an attempt to reduce the need for psychiatric hospital admission. As part of this new national service model for people with learning disabilities and/or autism, all individuals should be offered both mainstream and specialist NHS health care, including mental health interventions, as needed. While there are well-developed evidence-based psychological therapies for the general population, such an evidence base does not exist for autistic people and those with moderate to severe learning disabilities. The results of our systematic review of interventions for mental health problems in individuals with severe learning disabilities, including those who have autism, showed no robust evidence for any psychological interventions for anxiety. 4 Thus, autistic individuals with moderate to severe learning disabilities face an evidence inequity whereby there is a lack of research to guide intervention despite significant levels of need. However, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence does recommend psychological interventions, including relaxation training and exposure therapy, for adults with either autism or learning disabilities who have mental health problems. 68–70

Lifetime care costs for one person with autism and learning disabilities have been estimated at £1.5 million,71 while the literature about the economic benefits of healthcare interventions for autistic people with learning disabilities is scarce. Developing mental health interventions for autistic people was previously identified as the number one priority by stakeholders, including autistic people and their families, in the James Lind Alliance priority-setting exercise (www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/news/answering-the-questions-from-people-with-autism-their-families-and-health-professionals/7681). NHS England have identified autism and learning disabilities as a 10 Year Plan clinical priority for the NHS, while the need to eliminate any potential discrimination against those with a protected characteristic, as defined within the Equality Act, 2010, has been recognised by NHS England72 within their previously published research plan for the NHS. This has also included a recommendation that research must reduce health inequalities amongst patients, which is directly relevant to autistic people with moderate to severe learning disabilities who face a double inequality (existing health inequalities coupled with a lack of evidence about how best to reduce these).

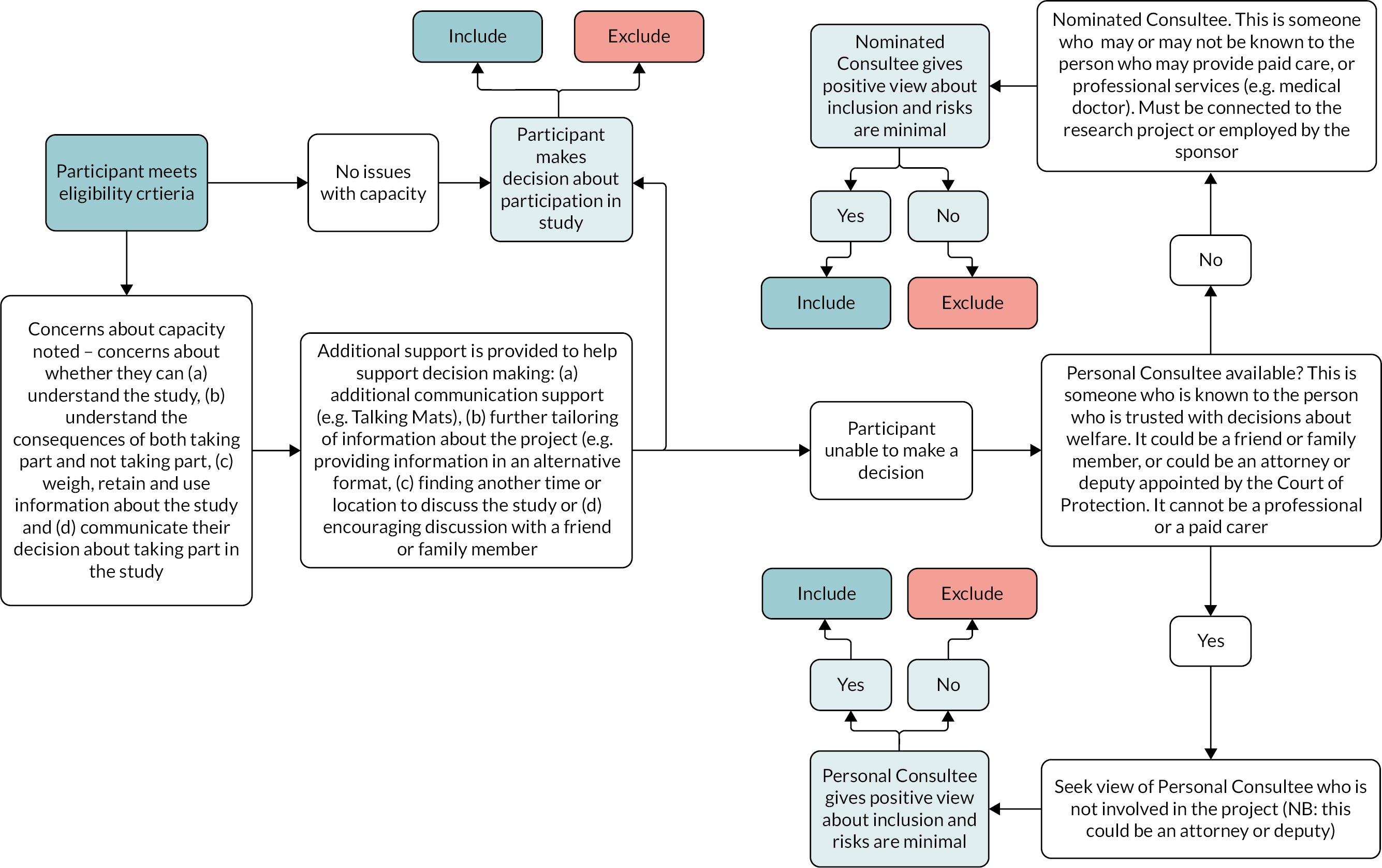

However, developing and testing interventions for this population are associated with several challenges, and feasibility studies are needed to effectively model these challenges and develop effective solutions. First, individuals with autism and learning disabilities have significant communication difficulties. Second, there is an increased prevalence of behaviours that challenge (e.g. aggression, self-injurious behaviour) amongst this population,73,74 which may not be recognised as associated with a mental health problem,75,76 especially in those with more severe learning disabilities,77 but needs to be considered in the context of intervention for anxiety. Third, those with autism present with restricted and repetitive behaviours,28,49,50 an insistence on sameness,28,29,51–54 sensory over-responsivity and avoidance of sensory input,28,29,53,60,61 and rumination,41,46 amongst other difficulties42 which need to be considered within intervention. Fourth, a large proportion of this population are unlikely to have capacity to provide informed consent to take part in research. As such, the provisions of the Mental Capacity Act, 2005, in England and Wales must be followed. Fifth, the measurement of anxiety symptomatology within the context of a future clinical trial requires consideration, including the appropriateness of patient-reported outcome measures in this population and similar proxy-rated outcome measures.

Considering measurement, we previously completed a systematic review of measurement tools for mental health problems with people who have severe or profound learning disabilities, including those who have autism. 78 The measures deemed to be the most robust overall in terms of available data were both broad-based psychopathology tools: the Aberrant Behaviour Checklist (ABC-2)79 and the Diagnostic Assessment for the Severely Handicapped Scale-II (DASH-II). 80 Specific data on the measurement of anxiety in this population were limited. Thus, some work is required to determine the most appropriate measures to use within a clinical trial of behaviour therapy for anxiety in people with autism and moderate to severe learning disabilities.

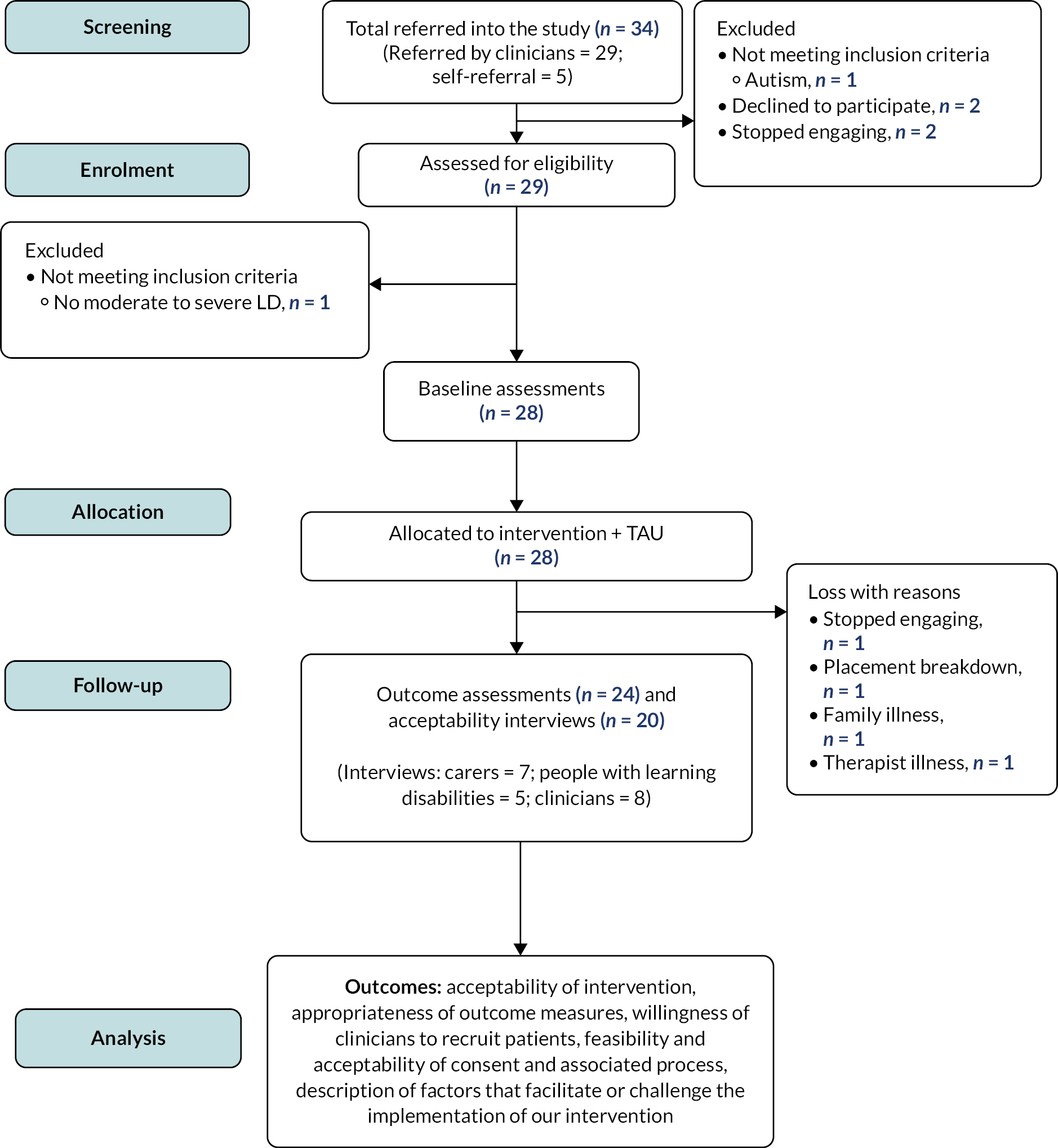

Taking the aforementioned issues together, the current project aimed to adapt and model a manualised intervention for the intervention of anxiety disorders amongst autistic people who have moderate to severe learning disabilities within a feasibility study. We worked with carers, clinicians, and autistic people to adapt an existing intervention programme,81–83 complete a survey of intervention within existing services to characterise treatment-as-usual (TAU), and complete a feasibility study to model the intervention. This project comprised two phases: Phase 1: Intervention Adaptation and Description of Treatment-as-Usual, and Phase 2: a Feasibility Study.

Rationale for the current study

A large number of autistic people with learning disabilities have problems with anxiety and have a high level of need. However, a previous systematic review4 and a recent systematic review incorporating meta-analysis3 found no robust evidence for any psychological intervention approaches for anxiety for adults who have severe learning disabilities (including those who are autistic). To meet the needs of autistic adults with moderate to severe learning disabilities, therapies for anxiety need to be adapted to meet need and successfully modelled before future larger trials can take place to generate evidence about the efficacy.

Aims and objectives

To adapt an existing intervention for use with autistic adults who have moderate to severe learning disabilities and anxiety, investigate the feasibility of implementing the intervention, and characterise TAU by completing a national survey of services.

Phase 1a: intervention adaptation

Our objectives were:

-

to establish an intervention adaptation group (IAG) and, over a series of meetings, adapt an existing intervention used within a previous clinical trial to treat anxiety symptoms in autistic adults81–83 for use with people who also have moderate to severe learning disabilities

-

to develop an intervention fidelity checklist that can be used alongside the intervention manual

-

to appraise and consider several candidate outcome measures of anxiety-related symptoms and social care and make a recommendation for use within Phase 2

-

to develop an intervention logic model.

Phase 1b: description of treatment-as-usual

Our objective was:

-

to complete a national survey of existing interventions for autistic adults with anxiety disorders who have moderate to severe learning disabilities.

Phase 2: feasibility study

Our objectives were:

-

to model the manualised intervention to determine the acceptability and feasibility for all stakeholders, including patients, carers and clinicians, and adjust as required

-

to judge the appropriateness, including response rates, of our measures of anxiety-related symptomatology for use within a larger study

-

to examine the feasibility and acceptability of consent and associated processes

-

to describe factors that facilitate or challenge the implementation of our intervention.

Chapter 2 Phase 1a: intervention adaptation

Methods

Recruitment

We established an IAG of eight stakeholders. This included an autistic collaborator who chaired the meeting, a representative from the National Autistic Society (NAS) [our patient and public involvement (PPI) partner], a sibling of an autistic person with severe learning disability, and five clinicians with experience of working with autistic adults with learning disabilities including those who had additional caring roles. Members of the research team also attended and had a background in clinical psychology or speech and language therapy.

Design

We made use of methods drawn from action research84 by focusing upon collaboration and reflection with practitioners and patient and public involvement and engagement members in order to improve the intervention, logic model and fidelity checklist, and make decisions about candidate outcome measures. This happened over five meetings that lasted at least 2 hours over a 2-month period. Meetings were scheduled every 2 weeks, with the exception of the last two meetings, which were 1 week apart. All meetings were online and were recorded.

The aims of the IAG based upon our Phase 1a aims and objectives were to: (1) define the needs and problems that are to be addressed for autistic people with moderate to severe learning disabilities, (2) define the intervention objectives, with reference to the likely barriers, (3) adapt the existing manualised intervention and associated materials, (4) collaboratively develop the fidelity checklist with the researchers, (5) consider candidate primary and secondary outcome measures, including measures of social care, making a recommendation for use within the feasibility study (Phase 2), (6) consider any additional methods to identify users of the intervention and further development of implementation protocols as needed and (7) give further consideration of any challenges or barriers to our evaluation plan, including likely solutions.

Before the first IAG meeting, we prepared an initial draft of the intervention manual, intervention materials, logic model, therapist training outline and the fidelity checklist. Three of the five meetings focused on the intervention manual and corresponding materials, one on the fidelity checklist, logic model and therapist training, and one on outcome measures. Table 1 details the schedule of the IAG meetings.

| Meeting 1 |

|

| Meeting 2 |

|

| Meeting 3 |

|

| Meeting 4 |

|

| Meeting 5 |

|

Prior to each meeting, documents were circulated to participants. An agenda was set and discussion and reflection were encouraged amongst participants until consensus was reached for each decision. Any disagreements were discussed until the group reached consensus and a recommendation was made. Feedback and reflections were sought from participants about changes and refinements to the manual, logic model, materials, and the fidelity checklist. These changes were then presented to the IAG at the next meeting to ensure that they were enacted as previously recommended and to encourage further reflection. All recommendations were recorded in an Excel spreadsheet, which was shared with the IAG for approval. Feedback was also sought on the range of candidate outcome measures, and several candidate measures were presented to the IAG, which included a review of the items, psychometric properties, and likely ease of use. The IAG were invited to make the final recommendation as to which outcome measures should be used within Phase 2.

Results

Objectives

Objective 1: the adaptation of an existing intervention for anxiety

To develop the initial draft of the intervention manual, we used an existing intervention for anxiety symptoms in autistic adults. 81–83 Importantly, this intervention was developed explicitly for autistic people who did not have learning disability, and was previously evaluated.

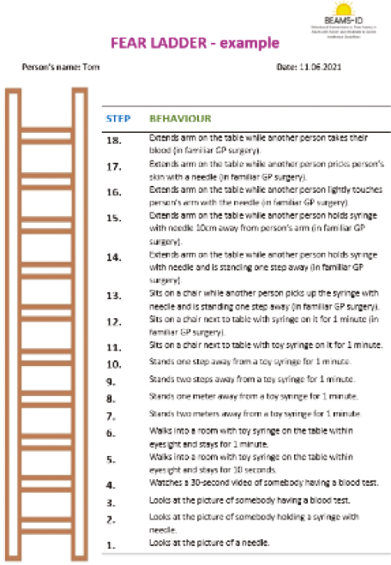

In developing our initial draft of the intervention manual, we focused upon the following modules from our previously developed intervention manual: (1) relaxation training, (2) building fear hierarchies, (3) exposure therapy and systematic desensitisation and (4) behavioural experiments. A description of each of these modules and their associated content is found within Table 2.

| Module | Content |

|---|---|

| Relaxation | Participants are taught about the relationship between relaxation and anxiety. A variety of relaxation techniques are taught and practised, ranging from Jacobson85 muscle relaxation to breathing exercises. Participants are encouraged to try different methods and choose one they consider the most beneficial. Participants are encouraged to practise relaxation out of session and assigned associated homework and record forms. Participants are asked to record the frequency and length of time they took to practise each relaxation episode, along with the associated type, and their emotional state. |

| Building fear hierarchies | Collaboratively, participants work with the therapist to break down anxiety-provoking situations into a number of different components, ranking them from least to most fearful. Multiple fears and associated fear hierarchies can be chosen. The role of safety-seeking behaviours and avoidance is explained and discussed. |

| Exposure therapy and systematic desensitisation | These concepts are explained and the importance of using relaxation techniques while undertaking exposure therapy is discussed. Participants work through their hierarchy of fears, considering each step and how to apply relaxation strategies during exposure work. Initially, exposure techniques using imagery-based methods are used where participants begin with the least fearful step within their fear hierarchy and make use of relaxation techniques. This is repeated, leading to a reduction in anxiety. Participants are asked to practise these skills outside of the session. |

| Introduction to behavioural experiments | Participants review their out-of-session skills practice using their fear hierarchies, and the paradoxical role of safety-seeking and avoidance behaviours is further discussed and considered. In vivo exposure work is introduced, discussed and planned collaboratively with the participants and therapist. Participants are asked to continue to practise imagined exposure and relaxation techniques. |

| Behaviour experiments | Over a series of sessions, the planned in vivo exposure work is carried out based upon the previously created fear hierarchy, working from the least to the most feared situation. Participants are asked to continue to practise these techniques outside of the formal session throughout the week using their fear hierarchies and relaxation techniques. |

The intervention was initially adapted by the research team to be accessible to people with moderate to severe learning disabilities and presented to the IAG over a series of meetings for further adaptation. Our manualised intervention involved 12 sessions that focused upon: (1) building rapport and providing psychoeducation about anxiety, autism and learning disabilities to both carers and autistic people, (2) relaxation training and (3) the development of individualised exposure therapy leading to recommendations for maintenance and generalisation. We made use of a blend of sessions that involved both the carer and the autistic person with a learning disability, as well as carer-only sessions. Carer and participant handbooks were also developed for use during the intervention.

Following feedback from the IAG, a series of changes were made to the intervention manual and materials. See Chapter 3 for detailed description of the intervention and accompanying materials, including the logic model. Table 3 summarises changes proposed to the intervention manual and intervention materials by the IAG and how they were addressed.

| Feedback/suggestions | Action |

|---|---|

| General feedback | |

| To include explanation of safeguarding and the capacity to consent more overtly in the materials. | Completed |

| To replace ‘have’ with ‘may face’ when talking about challenges. | Completed |

| Check spelling throughout the intervention manual. | Completed |

| To consider producing easy-read versions of a future research paper. | To be actioned in the future following the completion of the project. |

| Introduction and intervention structure | |

| To add a section providing additional introduction and further information within the theoretical section. | Completed |

| To ensure the language on theoretical background and introduction is understandable to all staff. | Completed |

| To explain ‘operationalisation’. | Completed |

| To add real-life examples or case studies. | We added more case examples throughout, which could be further strengthened following the completion of Phase 2. |

| To break down the sentence: ‘The behavioural therapist is interested in behavioural contingencies (…)’ and to delete the phrase ‘young person’. | Completed |

| To add a paragraph about identifying a key carer or carers to participate in the intervention. This might be raised with a manager. | Completed |

| Key concepts and strategies | |

| To expand the text box under ‘Antecedent’ in the figure explaining Antecedent-Behaviour-Consequence (ABC). | Completed |

| To rephrase section on effectiveness of reinforcement. | Completed |

| To replace the word ‘satiation’ with another word or provide definition. | Completed |

| To further explain differential reinforcement – DRO, DRI and DrA. | Completed |

| To replace the term ‘attention’ with another term. | Completed |

| To consider how the idea of a ‘break allowance’ would be introduced to clinicians/carers delivering the intervention and how much training on implementing it there will be. | Completed |

| To move the behavioural toolkit section to the appendix or to add more explanation in the ‘How to use the manual’ section. | Completed |

| Delete active support from the manual. | Completed |

| Considerations on care and good practice guidelines | |

| To add more explanation and examples to the section on ‘What to consider when planning care’. | Completed |

| To specify ‘person’s preferences and needs’ in the good practice guidelines. | Completed |

| To add a further explanation about ensuring communication is adapted to the needs of the individual. | Completed |

| Use directive text within the good practice guidelines for therapists. | Changes were made to emphasise the importance of following good practice guidance. |

| To consider obtaining feedback on rapport-building after the study, including exploring whether the initial sessions were sufficient. | This was noted and we included questions about this within our post-intervention interviews with the therapist, carer, and participant when possible. |

| To emphasise the importance of responding to the person’s capacity to understand information and their communication ability. | Completed |

| To include phrases: ‘being conscious of infantilising’, ‘respectful’, ‘person-centred’. | Completed |

| To remove the term ‘age-appropriate’. | Completed |

| To emphasise the importance of treating the person as an adult and talking to and looking at them. | Completed |

| To emphasise the importance of using the same words and tone of voice when prompting. | Completed |

| To add that it is important that the staff working with the person know how to use the person’s communication aids effectively. | Completed |

| To add that it is important to establish how the person communicates ‘stop’, ‘no’, ‘enough’ and requests a break. | Completed |

| Sessions 1–12 | |

| To define vocabulary in tables or thought bubbles across all sections. | Completed |

| To re-structure the manual: (1) General introduction to the problem, (2) The guiding framework/Logic Model, (3) The intervention itself that operationalises the aspects of the Logic Model, (4) All supporting concepts and session materials. | Completed |

| To add a section on potential harms resulting from the intervention. | This information was included in the participant information and included in our training provided to therapists. |

| To add a section on how likely it is that a behavioural approach is going to work for an autistic person. | This was included within our theoretical background section. |

| To replace ‘Velcro’ with ‘loop sided fasteners (e.g. Velcro)’. | Completed |

| To simplify language. | Completed |

| To change 1.5 hours to 90 minutes. | Completed |

| To replace ‘communication aids’ with ‘augmented communication’. | Completed |

| To ask the carer to take photos of the person taking part in the activities they enjoy which could be included in the preference assessment. | Completed |

| To include instructions on the Preference Assessment form. | Completed |

| To replace ‘faulty thinking’ with ‘distorted thoughts’/‘unworkable beliefs’/‘unhelpful thinking’. | Completed |

| To define ‘regular intervals’. | Completed |

| Add description of the ABC chart to the intervention manual. | Completed |

| Emphasise consent when working on exposure and using touch with relaxation. | Completed |

| To replace ‘fear hierarchy’ with ‘fear ladder’. | Completed |

| To replace ‘systematic desensitisation’ with ‘gradual exposure’. | Completed |

| To include recommended frequency for practising exposure outside of the session. Daily if possible. | Completed |

| To add a reminder for the person that they cannot be anxious and relaxed at the same time. | Completed |

| Person and carer handbooks | |

| To change wording in the section on carer’s role. | Completed |

| To consider adding taste and temperature to the list of sensory sensitivities. | Completed |

| To make sure person-first language is used consistently throughout the manual and materials when talking about autistic people. | Completed |

| To add information about alexithymia to the Carer’s Handbook. | Completed |

| To add ‘butterflies in the stomach’ when explaining how anxiety can feel in the Person’s Handbook. | Completed |

| To remove acronyms from Person’s Handbook. | Completed |

| The words ‘anxiety’ and ‘worry’ are being used interchangeably but are arguably separate. Ensure consistency in the handbooks. | Completed |

| To emphasise consent when working on exposure and using touch with relaxation in the Carer’s Handbook. | Completed |

| To add examples that are not phobia-related to the section on Fear Ladders. | Completed |

| To consider asking the carer to take pictures of the person completing steps of the fear ladder to be included as visual representation. | We added that suggestion to the intervention manual and created a Fear Ladder template for visuals. |

| It would be worth looking at the literature on video (self) modelling and replicate some of these ideas in this context. I would hope that the person and carers could video anyway as long as the video is not passed on to anyone else. | We have added this suggestion to the intervention manual; however, questions were raised about whether this would be very time-consuming and it was not included as a core element of the intervention. |

| To replace ‘systematic desensitisation’ with ‘gradual exposure’. | Completed |

| To replace the ‘fear evoking’ phrase for one more appropriate for carers and people with LD. | Completed |

| Materials | |

| To add more space for notes in the Interview for carers. | Completed |

| To change some of the wording in the section in the Interview for carers. | Completed |

| To add a question about sensory triggers to the Interview for carers. | Completed |

| To consider adding a session countdown so the person can tick off each session as it is completed. | Completed |

A further description of our intervention can be found within Chapter 3. Our draft logic model and therapist training plan were also presented to the IAG. Table 4 summarises proposed changes and actions. Our logic model and therapist training are detailed further within Chapter 3, Figure 2.

| Feedback/suggestions | Action |

|---|---|

| Logic model | |

| To change some of the wording to improve understanding. | Completed |

| To add a point about harm and adverse reactions. | We decided that this was more suited for inclusion within the main body of the intervention manual where it was covered in detail. |

| To add a point about ‘Praxis difficulties’. | Completed |

| To add more information about restrictive and repetitive behaviours. | We decided that this should be included within the intervention manual where it was covered in detail. |

| Therapist training | |

| To change the structure to avoid starting with the most difficult concepts, for example, (1) Introduction, (2) Rationale for intervention, (3) Structure of the intervention, and (4) Toolkit of behavioural strategies. | Completed |

| To consider using visuals in PowerPoint presentations, worksheets and activities using different sensory resources. | Completed |

| To consider developing a jam board or a poster with definitions that trainees can refer to if needed. | We developed and included handouts. |

| To include 5-minute mindfulness/relaxation practice during the training. | Completed |

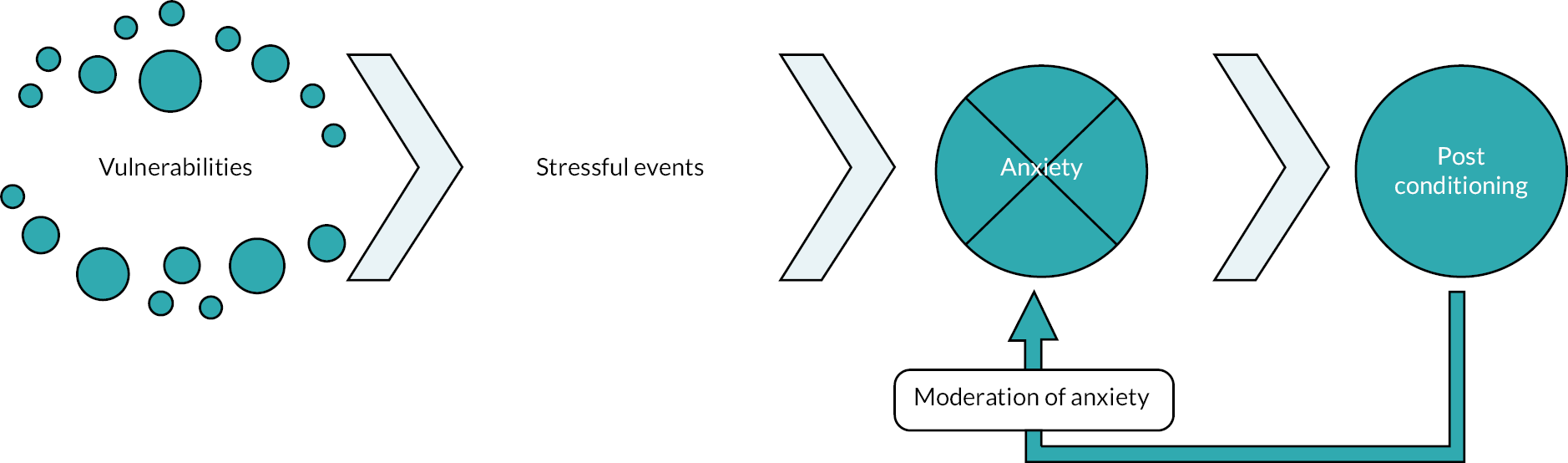

FIGURE 1.

Theory of change: as depicted, contemporary learning theory postulates that anxiety disorders develop as a consequence of direct and vicarious learning experiences which are affected by a variety of factors including pre-existing vulnerabilities, the predictability and controllability of stressful events, and temporal proximity to stressful events. Additional factors, such as sensory sensitivity, learning disability, restricted and repetitive behaviours, and lack of flexibility are markedly relevant for those with autism and moderate to severe learning disability. Further, the experience of anxiety is moderated by events that occur post-learning; for example, the nature and degree of avoidance behaviours, generalisation of anxiety, and additional stimuli which inflate or decrease anxiety, and directly inform interventions, such as exposure therapy.

Objective 2: intervention fidelity checklist

Our fidelity checklist was adapted from that used by Jahoda et al. 86 Eight sections were included as follows:

-

general session preparations

-

coverage of session plan

-

understanding and accessibility

-

interpersonal effectiveness

-

engaging participants

-

session content

-

inter-session tasks

-

further comments.

There were separate checklists for each of the 12 intervention sessions. Therapists were asked to reflect on the sessions and indicate if they have fulfilled the aims by circling yes or no on the checklist. See Appendix 3 for a sample fidelity checklist and Chapter 3 for a detailed description. Our draft fidelity checklist for each of our 12 sessions was prepared and presented to our IAG for discussion. The group accepted the checklist without suggesting any further changes and recommended that it should be used within Phase 2.

Objective 3: appraise and consider several candidate outcome measures of anxiety-related symptoms, and secondary outcomes, and make a recommendation for use within Phase 2

A broad range of potential measures were considered, including parent/carer questionnaires, behavioural measures, and physiological measures. These were initially selected by the research team and included:

Eligibility

Outcome measures

-

a draft version of the Clinical Anxiety Screen for people with Severe to Profound Intellectual Disability (CIASP-ID)90

-

Autism Spectrum Disorders – Assessment Battery for Intellectually Disabled Adults91

-

Aberrant Behaviour Checklist – Community92

-

DASH-II93

-

Developmental Behaviour Checklist-2 Adult (DBC2-A)94

-

the Behaviour Problems Inventory for Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities – Short Form95

-

the Index of Community Involvement96

-

Psychopathology in Autism Checklist (PAC)97

-

Anxiety, Depression and Mood Scale (ADAMS)98

-

Psychological Therapies Outcome Scale – Intellectual Disabilities 2nd Edition (PTOS-II). 99

The IAG was presented with detailed information about each instrument including format, intended age range, time needed to complete, and psychometric properties. Following a discussion, the IAG made recommendations about outcome measures that should be used in Phase 2 of the project. Table 5 summarises the IAG feedback on presented measures.

| Measure | Feedback/suggestions | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Eligibility | ||

| Diagnostic checklist for anxiety based on Diagnostic Manual – Intellectual Disability-2 (National Association for the Dually Diagnosed, 2016) | IAG recommended using this measure | Measure added to the eligibility case report form (CRF) |

| Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales – Third Edition (Sparrow et al., 2016) | IAG recommended using this measure | Measure added to the eligibility CRF |

| Social Responsiveness Scale 2 (Constantino et al., 2003) | IAG recommended using this measure | Measure added to the eligibility CRF |

| Outcome measures | ||

| CIASP-ID | Measure did not consider unexpected changes in person’s life | Not used |

| The group was not sure about validity of this measure | ||

| The group suggested this measure is more helpful for clinical practice rather than research | ||

| The measure was too long to be used repeatedly | ||

| The group did not recommend using this measure | ||

| DBC2-A | The group had questions about how change would be captured considering limited scale | Measure included in the baseline and follow-up CRF |

| The group was unsure if the measure captured communication well | ||

| There was limited evidence around using this measure with adults | ||

| Language was deficit-focused which might not be perceived well by some carers | ||

| The group agreed to include this measure as it is a measure of emotional and behavioural problems suitable for use with this population, noting the limitations | ||

| Autism Spectrum Disorders – Behaviour Problems for Adults | Language was deficit-focused which might not be perceived well by some carers | Not used |

| The group suggested the measure would take too long to complete | ||

| Communication domain was useful and the rating scale was seen as good | ||

| Some wording not helpful, especially for parents | ||

| The group did not recommend using this measure | ||

| Aberrant Behaviour Checklist (ABC-2) | The group felt that some of the language used in this measure was problematic, especially around stimming and special interests | Not used |

| Some people might have relevant conditions but not officially diagnosed which led to questions about the use of this measure | ||

| The group did not recommend using this measure | ||

| The Behaviour Problems Inventory for Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities – Short Form | The measure was user-friendly | Measure included in the baseline and follow-up CRF |

| Used by clinicians in the group and generally accepted | ||

| The group recommended using this measure | ||

| PAC | The rating scale was seen as helpful because you rate whether the person has improved, not changed or worsened | Measure included in the baseline and follow-up CRF |

| The group liked that this measure was short | ||

| Some items might be difficult to score for people with severe communication problems | ||

| The group recommended using this measure | ||

| DASH-II | The group felt that this measure was very deficit-focused | Not used |

| The group felt that this measure can be difficult to complete and was not user friendly | ||

| It might be difficult for carers to remember details about behaviours across so many items | ||

| The group did not recommend using this measure | ||

| ADAMS | It can be used for people regardless of disability and communication needs | Not used |

| Measure would focus on shorter time frame than 6 months | ||

| Questions were raised about carer’s objectivity rating a behaviour as problematic | ||

| Families might have higher threshold so the severity rating might not be accurate | ||

| Group felt that the items are accessible | ||

| Item about fatigue and weight was considered problematic | ||

| The group did not recommend using this measure | ||

| PTOS-II | This was the only measure that can be also completed by the person with learning disabilities | Not used |

| The informant version relies a lot on knowing how the person feels | ||

| Items were considered to be not specific | ||

| The group did not recommend using this measure | ||

| The Index of Community Involvement (Raynes, 1994) | IAG recommends using this measure as seen as short and easy to complete | Measure included in the baseline and follow-up CRF |

Summary

Within Phase 1a, we aimed to adapt an existing intervention for use with autistic adults with moderate to severe learning disabilities who have anxiety, develop a fidelity checklist, select candidate outcome measures for use with Phase 2, and develop an intervention logic model. Collaboratively, with our IAG using methods adapted from action research incorporating methods to develop consensus, a variety of changes were made to our intervention manual, a series of candidate outcome measures were selected, and our logic model was refined. No changes were recommended to the fidelity checklist. Our intervention and associated logic model are further considered within the next chapter.

Chapter 3 Intervention description

Within this chapter, a description of the theoretical framework informing the intervention is provided along with a thorough description of the intervention and associated logic model. Material found within this chapter is reproduced from the protocol for this study which we authored (see: www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/NIHR129804).

Theoretical framework

Contemporary learning theories provide a robust explanation of both the aetiology and intervention of anxiety disorders, through the process of direct and vicarious learning experiences. Integral to these theories is not only the process by which anxiety is learnt (i.e. classical, operant and vicarious conditioning), but also the important role of vulnerabilities to anxiety, such as previous vicarious conditioning, individual genetic differences, previous and future life experience, cultural and familial transmission of fears, controllability, behavioural inhibition, interoceptive conditioning (i.e. internal states becoming a ‘trigger’ for anxiety), and exteroceptive conditioning (i.e. external stimuli becoming a ‘trigger’ for anxiety). 100–104 These factors impact upon the experience of stressful events, which are further moderated by the predictability and perceived controllability of events, and previous direct and vicarious learning experiences. Both interoceptive (e.g. sensory input) and exteroceptive (e.g. external stimuli) conditioned stimuli can moderate stress, leading to an increase or decrease in anxiety and the quality of associated anxiety, including the intensity of any conditioned association. Events that occur post-conditioning moderate anxiety further, and these can include unconditioned stimulus inflation (factors that promote anxiety), and derived relationship responding and stimulus generalisation (where related stimuli become conditioned due to their relationship with other conditioned stimuli). Further, multiple excitatory stimuli occurring within close proximity can lead to summation effects, further increasing anxiety. Other post-conditioning events serve to moderate anxiety through their inhibitory effects, such as safety-seeking behaviours and avoidance, which paradoxically maintain anxiety.

These learning processes will lead to the development of an anxiety disorder in some individuals, as depicted in Figure 1, which was adapted from Mineka and Zinbarg100 to incorporate additional factors relevant to autistic people and those with learning disabilities (e.g. sensory over-responsivity; lack of flexibility; restricted interests; cognitive ability, communication difficulties). Clinical interventions must reflect theory, and, primarily, these interventions are based upon psychological formulations using these models to inform individualised exposure techniques to successfully treat the symptoms of anxiety, making use of strategies, such as systematic desensitisation and fear hierarchies, leading to habituation or, in other words, a reduction in experienced anxiety over time.

There is some evidence drawn from single-case experimental designs that interventions based upon learning theory using exposure-based interventions and associated strategies may be effective for those with autism and learning disabilities. 16 Exposure-based interventions have been shown to be effective for a range of anxiety disorders amongst those without autism and/or learning disabilities including specific phobias, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia, and post-traumatic stress disorder. 5,105 The exclusion of cognitive strategies, which are delivered using verbal communication within ‘talking’ therapy, and a reliance upon exposure-based techniques have been shown to be associated with no reduction in therapy effect size. 5,6,8 Considering this, psychological interventions which are not entirely delivered using verbal communication are likely to be advantageous when used with autistic adults with moderate to severe learning disabilities because it is not possible for many individuals to engage effectively within ‘talking’ psychological therapy due to their difficulties with verbal communication and processing. As a consequence, the delivery of appropriately adapted behavioural interventions for anxiety amongst autistic adults with moderate to severe learning disabilities may be advantageous.

Description and structure of the intervention

The BEAMS-ID intervention was specifically created to meet the needs of autistic adults with moderate to severe learning disabilities. It was further developed collaboratively with the IAG, composed of autistic people, therapists, carers and researchers experienced in working with autistic adults with moderate to severe learning disabilities (see Chapter 2 for more details). Parts of the intervention were originally developed and tested with autistic adults without learning disabilities,82 and then systematically adapted for use with autistic adults with learning disabilities collaboratively with our IAG drawing upon their theoretical and clinical knowledge and personal experiences of providing care to this group.

There are a number of potential challenges that were considered when delivering psychological interventions for anxiety to this group. These include different ways of communicating, behaviours that challenge, problems with recognising mental health issues, restricted or repetitive behaviours, and sensory differences, such as over-responsivity or avoidance of some types of sensory input, amongst others. Keeping these challenges in mind, we collaboratively adapted the intervention to meet the needs of autistic people with moderate to severe learning disabilities. These adaptations included:

-

involving carers or family members in the delivery of intervention

-

focusing on using methods that are less reliant upon verbal communication, including graded exposure, which involves gradually exposing someone to the feared object or situation in a progressive and safe way that is not overwhelming and is coupled with relaxation and reinforcement

-

using a person-centred approach – it is clearly recognised that many with moderate to severe learning disabilities communicate their needs well, while others require support, and this needs to be well understood by the therapist and incorporated into the intervention; this involves working with carers and others to help the therapist understand the needs of the person as an individual and tailor the delivery to their needs

-

performing a preference and functional assessment, and a thorough exploration of the nature of anxiety, avoidance, accommodation, and sensory issues to develop a psychological formulation; and

-

using adapted ways of communicating, such as visual schedules and easier to read materials.

The intervention consisted of 12 sessions that were up to 90 minutes long usually delivered on weekly basis. Three sessions were attended only by the carer to enable the therapist to develop a good understanding of the needs of the participants and to socialise the carer into the intervention. The remaining nine sessions were attended by the autistic person with learning disability and their carer. The intervention focused upon providing relaxation training, leading to the implementation of carefully planned graded exposure associated with delivery of reinforcement. Refer to Table 6 which details the structure of the BEAMS-ID intervention.

| Session | Main focus | Key activities/focus points |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Psychoeducation on behaviour change CARER-ONLY SESSION |

|

| 2 | Building rapport |

|

| 3 | Psychoeducation on anxiety, autism and learning disability |

|

| 4 | Relaxation training |

|

| 5 | Design of individualised Intervention Plan CARER-ONLY SESSION |

|

| 6 | Building Fear Ladders CARER-ONLY SESSION |

|

| 7 | Graded exposure |

|

| 8 | Graded exposure |

|

| 9 | Graded exposure |

|

| 10 | Graded exposure |

|

| 11 | Wrap up |

|

| 12 | Wrap up |

|

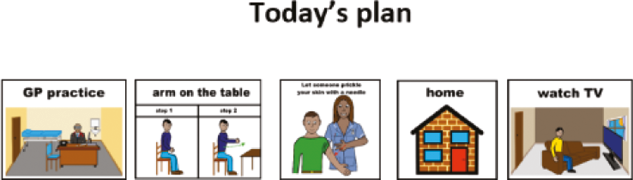

Each session plan was composed of three core elements – objectives, materials and session activities/content. Each session started with an introduction during which the therapist planned the session with the person and their carer using a visual schedule. Session activities usually included a mixture of psychoeducation and practical tasks. Some sessions also included instructions for inter-session tasks that the carer was asked to support outside of the sessions. Sessions ended with a wrap-up, during which the therapist summarised the covered content and reminded the person and their carer of their next session.

To help carers and individuals understand and engage with intervention, they were provided with a variety of resources that were used by the therapist collaboratively with the individual and the carer. This included a Carer’s Handbook which focused upon psychoeducation about anxiety, relaxation, graded exposure, and the principles of behaviour change, including their role within the intervention. A Person’s Handbook with a focus upon explaining autism, learning disability, anxiety, and the intervention, including relaxation was also included and shared. See the Materials section for more details.

Logic model

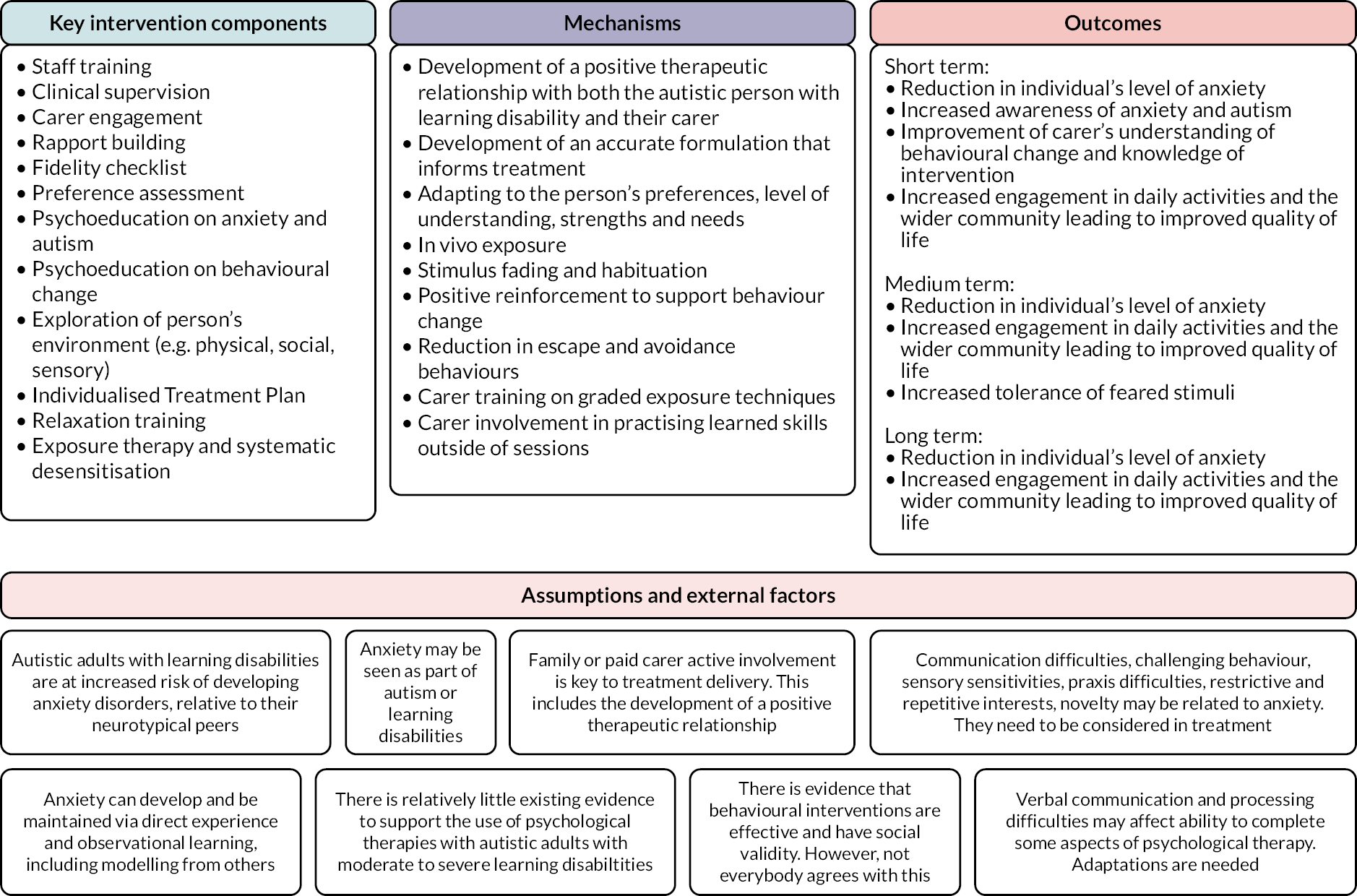

Collaboratively with our IAG, we developed an intervention logic model, based upon our theoretical framework (Figure 2).

Key components

Considering the specialised nature of our intervention, key intervention components included staff training and ongoing supervision. Additional key components included the development of high-quality relationships with the autistic person with a learning disability and their carer, along with the provision of psychoeducation, a good understanding of the autistic person with a learning disability and their needs including any sensory sensitivities, and the development and provision of an individualised intervention plan using relaxation training and exposure therapy paired with reinforcement.

Carers

One of the key components to our intervention is carer engagement. Carers have a markedly important role in the delivery of the intervention because: (1) they know the person well and understand how the person communicates, (2) they have a role in helping to build the psychological formulation and collect data to inform this formulation, (3) they assist with helping to arrange and attend sessions, (4) they need to learn and practice new skills together with the person outside of the session to help promote learning and generalisation and (5) they communicate with other carers who are involved in delivering care to ensure they understand the intervention and are able to assist with inter-session tasks as needed.

Exposure therapy

The intervention involved gradually exposing the person to the feared stimuli and pairing this with relaxation techniques. It involved three main steps:

-

teaching deep breathing and relaxation strategies

-

building a fear ladder (graded hierarchy of fears) which is a list of objects and/or situations related to the feared stimuli ranging from least distressing to most distressing and

-

gradually exposing the person to the steps included in the fear ladder while practising relaxation strategies.

This approach helped the person to build tolerance of the feared object or situation at a comfortable pace. The experience of feeling anxious is an important component of exposure therapy as the individual learns how to manage this feeling coupled with habituation. The aim was to reduce person’s fearful/anxious response and learn that feared objects or situations are not dangerous.

The Fear Ladder was developed in collaboration with the individual with learning disability and their carer to help promote engagement and avoid overwhelming the individual and their carer using the form described in the Materials section. The Fear Ladder was reviewed regularly and broken down further if needed.

Relaxation

Relaxation strategies reduce tension in the body and anxiety. When the individual experiences feelings of anxiety or fear, their muscles tighten, and it can be difficult for them to feel calm. By introducing relaxation, tension in the body reduces and promotes calmer feelings. Relaxation strategies were used when the person was feeling anxious or overwhelmed, as well as during exposure. Some examples of relaxation strategies included deep breathing and muscle relaxation.

During the sessions, the therapist spent time discussing existing relaxation strategies, which may be idiosyncratic, such as sensory activities or self-stimulatory behaviours, and whether the identification of new strategies could be helpful. If deemed appropriate, they were taught breathing exercises that involved taking a deep breath through the nose and exhaling through the mouth. Visual cards were used to support with this task. The therapist could also introduce muscle relaxation, which included clenching and relaxing muscle in different body parts – shoulders, back, hands, face, stomach and feet.

Some of the possible adaptations the therapist was able to consider to meet the needs of the person included:

-

reduced verbal language in instructions

-

reduced number of body areas targeted for muscle relaxation

-

teaching body parts before moving on to the muscle relaxation

-

using modelling to demonstrate the exercises

-

using the example and non-example procedure – modelling a relaxed and not relaxed pose and asking the person to only copy the relaxed pose

-

incorporating favourite objects or stories into the exercises. For example, bubbles or feathers

-

using physical prompting to teach the person the exercises

-

introducing of a visual cue or signal, for example picture card(s) to signal relaxation and

-

incorporating relaxation aids like a stress ball, therapeutic putty, dimmed lights, or relaxing music.

If the person was struggling to engage in deep breathing and muscle relaxation, different strategies were considered, such as the carer performing a hand massage, having a break in a quiet space, using fidgets and sensory equipment and so on.

Reinforcement

Reinforcement is a consequence which follows a behaviour and increases the likelihood the behaviour will occur again in the future. Reinforcement was used to teach new skills, such as requesting a break and relaxation, and after completing the exposure tasks during the intervention. To identify appropriate reinforcers, the therapist completed a preference assessment. A preference assessment is a systematic process that allows the therapist to identify six things the person likes the most. To complete the preference assessment, the therapist uses the Preference Assessment form, which is described in more detail in the Materials section. Identified reinforcers were reviewed frequently. If needed, the preference assessment was redone during the course of the intervention.

Generalisation and maintenance

Another component of the intervention was generalisation and maintenance. Generalisation is an ability to perform a behaviour learnt in one context in a different context. While neurotypical individuals often generalise behaviours themselves by observing others and through indirect learning, autistic people with learning disabilities may need help with generalisation. Therefore, working on the generalisation of acquired behaviours/skills in a systematic and structured way is an essential part of a successful behaviour change. This includes teaching and practising new behaviours:

-

in different environments

-

with different people

-

with varying instructions and

-

using different materials.

To ensure that behaviour change is maintained, a variety of strategies were incorporated, such as:

-

focusing on behaviours that are meaningful to the person

-

teaching until mastery (i.e. fluent in a skill)

-

providing opportunities to practise new behaviours and

-

adjusting the level of reinforcement.

Strategies to encourage generalisation and maintenance of new behaviours were incorporated into the intervention and discussed during the last session.

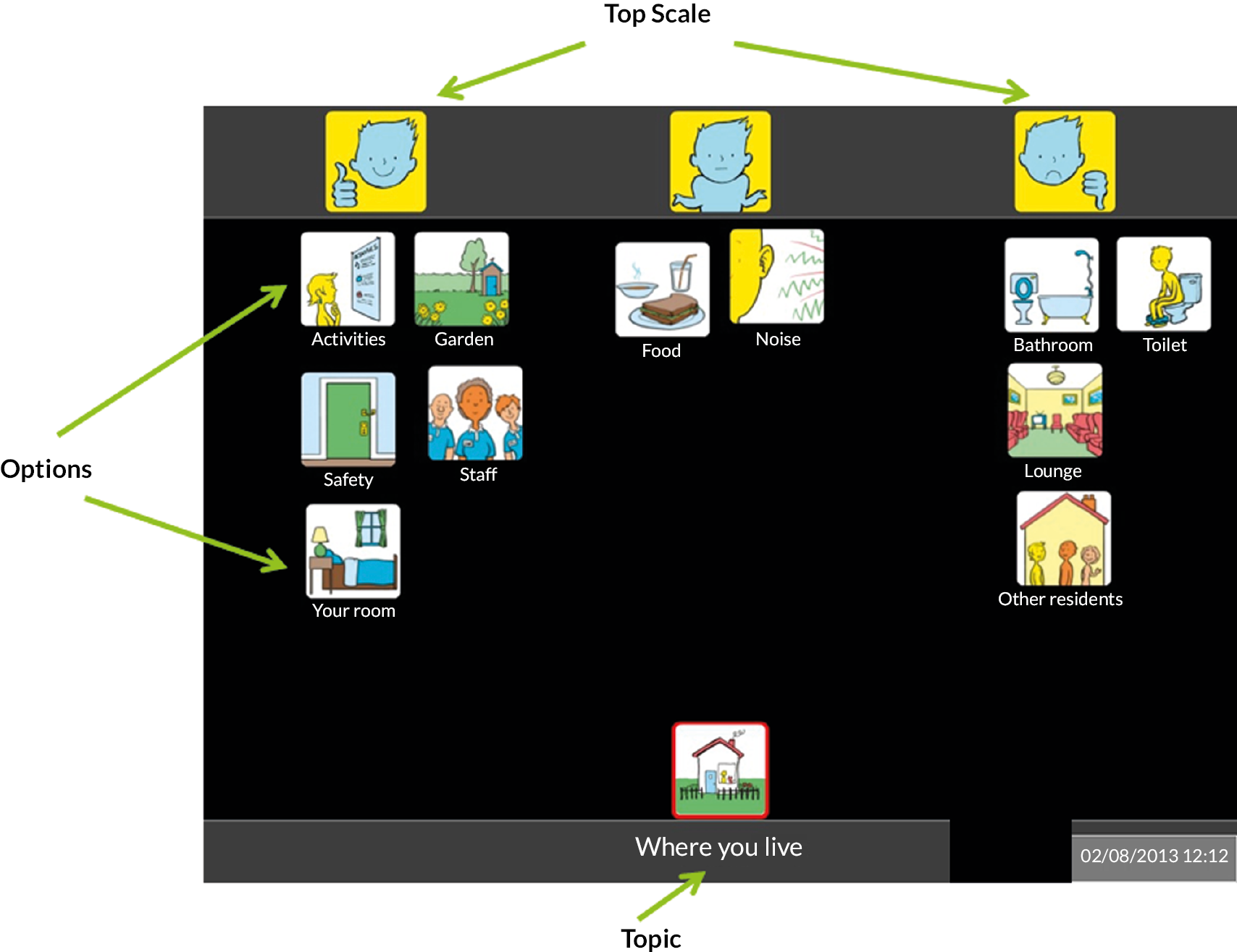

Communication

It was anticipated that all participants would have communication differences. Therefore, the intervention included a number of augmented communication strategies, such as visual aids and a visual schedule. These supports were reviewed and expanded on by a speech and language therapist, drawing on aided (e.g. using graphics and objects) and unaided (e.g. using manual sign and gesture) options from established augmentative and alternative communication methods (e.g. Signalong: www.signalong.org.uk; photosymbols: www.photosymbols.com; Talking Mats: www.talkingmats.com).

Intervention procedures

Order of intervention activities

The first session was a carer-only session focused upon explaining the intervention and included psychoeducation about anxiety while introducing aspects of functional analysis and behaviour change. The second session focused upon completing a preference assessment with the individual and their carer. This is a method that is used to help choose reinforcers that can be used during intervention to help support behaviour change. Session three focused upon psychoeducation about anxiety, routines, and sensory issues, along with teaching new concepts that are to be used later in the intervention. The fourth session focused upon teaching relaxation, while our fifth session was a carer-only session where the therapist worked collaboratively with the carer to help design an Individualised Intervention Plan for the next phase of therapy. This included developing strategies to help manage anxiety, including the use of reinforcement and relaxation. Sessions six and onwards were focused upon developing an individualised Fear Ladder and implementing graded exposure. This continued and within the penultimate session, ending was introduced, with a focus upon next steps. During the final session, strategies and goals for continuing beyond the end of therapy are developed collaboratively with the carer and the individual to encourage maintenance and further generalisation.

Fidelity and adherence

Fidelity to the intervention manual was measured with fidelity ratings (number of completed session components) after each session. This self-report measure was adapted from Jahoda et al. 34 Person and carer adherence was defined as attendance at intervention sessions. To meet the adherence criterion, the person and carer need to attend at least 80% sessions.

Materials

There were three sets of intervention materials developed:

-

materials for the therapist: intervention manual, Antecedent-Behaviour-Consequence (ABC) chart, fear ladder, fidelity checklists, preference assessment document, intervention plan document

-

materials for the carer: Carer handbook, ABC chart, assessment for carers, intervention plan, intervention summary

-

materials for the autistic person with learning disability: Person’s handbook, certificate of completion, rating scale, visual intervention schedule, intervention summary, visual schedule and associated materials.

Intervention manual

The Intervention manual was further developed with the help of the IAG. It included both the background and a step-by-step guide to the intervention of anxiety amongst autistic adults with moderate to severe learning disabilities. The manual provided the therapist with detailed plans for the intervention sessions, as well as general guidelines on working with autistic people with learning disabilities and their carers, which are summarised earlier within this report.

Person’s handbook

The Person’s handbook contained three sections and covered:

-

autism and learning disabilities

-

anxiety

-

relaxation.

Carer handbook

The Carer handbook contained seven sections and covered:

-

role of the carer

-

principles of behaviour and behaviour change

-

autism and learning disabilities

-

anxiety

-

relaxation

-

introduction to fear ladders

-

introduction to graded exposure.

Antecedent–Behaviour–Consequence chart

For the first five sessions, carers were asked to complete ABC charts in between the sessions every time the person with learning disabilities became anxious. The chart guided them through recording what happened immediately before the person became anxious, what they did when anxious, and what happened immediately after. The carer was asked to share completed charts with the therapist for the first five sessions to inform the intervention plan.

Assessment for carers

Prior to the start of the intervention, carers were sent the Assessment for carers along with the instructions for completion and asked to bring it to the first session. This assessment asked questions about the person they were caring for, including what they were like in different environments and their anxiety. Carers were asked to involve the autistic person with learning disability as much as possible in completing this document.

Certificate of completion

After the last session, the therapist was able to issue a Certificate of completion to the autistic person with learning disability to recognise their efforts and mark the end of intervention.

Fear ladder

A Fear ladder is a list of situations, places, or things connected to the person’s anxiety arranged from least feared or distressing to most feared or distressing. Autistic people with moderate to severe learning disabilities and their carers were given a choice of a Fear ladder template that they found most suitable. Some of the options included a ladder, stairs, and a horizontal or vertical schedule.

Fidelity checklist

Therapists used a self-report Fidelity checklist at the end of each session to record the extent to which the content was delivered according to the manual. Therapists were asked to reflect on the aims of each session and indicate if they were completed by circling ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ on the checklist. Supervisors were encouraged to review the Fidelity checklist with their supervisees.

Preference assessment

The Preference assessment form guided therapists though identifying a person’s preferred objects and/or actions. Together with the person and their carer, the therapist started by identifying six potential reinforcers. Then they paired them together to see which ones were preferred by the person. Later they created a reinforcer ranking, identifying preferred reinforcers, which were used during exposure work.

Rating scale

The Rating scale was used by carers to monitor a person’s mood and level of discomfort during exposure work. It helped carers identify when the person became distressed. The Rating scale consisted of three options – good, ok and bad. These options were accompanied by a corresponding hand signal and colour (green, amber and red).

Intervention plan

During the fifth session, the therapist and carer completed the Intervention plan. This document summarised the intervention strategies selected for the person and divided them into green (person’s anxiety is at their baseline), amber (person is becoming anxious) and red (person is anxious and distressed) strategies. This document was developed to allow for easy integration into an existing positive behavioural support plan.

Intervention sessions schedule

To help the person understand how they are progressing though intervention, the therapist was asked to use the Intervention session schedule. This was a visual schedule for the person that included all 12 sessions.

Intervention summary

While preparing for the end of the intervention, the person and their carer were asked to complete the Exposure summary. The worksheet asked them to reflect upon intervention progress – what were their goals, what they have achieved and what they still want to work on.

Visual schedule

The Visual schedule is a visual representation of activities planned for the person. It allowed the person to know what will be happening and provided an opportunity to manage transitions in a more controlled manner. For some autistic people with learning disabilities, it was considered helpful to use an additional ‘Now/Next’ board which was embedded in the Visual schedule. It helped the person know what is happening in that moment and what is happening next.

The Visual schedule was used during all intervention sessions and the carer was encouraged to also use it outside of the sessions.

Therapist training and supervision

The intervention was delivered by a trained therapist, who could be a nurse, clinical psychologist, assistant psychologist, medical doctor, allied health professional, or other suitably qualified health professional with experience of working with autistic people with learning disabilities and their carers.

All therapists were required to take part in a 2-day training course on the delivery of the intervention. Refer to Table 7 which depicts the content of the therapist training. The training included a mixture of PowerPoint presentations, whole group discussions and work in small groups. Training was delivered online by the research team and led by a consultant clinical psychologist, and training in the intervention lasted 1.5 days. The remaining half-day was used by participants to complete their training in good clinical practice (GCP).

| Training day | Activity |

|---|---|

| Day 1 | Welcome and introductions |

| Intervention structure | |

| Theoretical background and rationale | |

| Behavioural approaches to intervention of anxiety | |

| Key behavioural concepts and strategies | |

| Logic model | |

| Considerations for working with autistic adults with moderate to severe learning disabilities | |

| Sessions 1–2 (Intervention structure, Rapport building, Principles and behaviour and behaviour change, Anxiety disorders, ABC chart, Preference assessment) | |

| Sessions 3–5 (Psychoeducation on anxiety, autism and learning disability, Key vocabulary training, Relaxation techniques, Person’s key behaviours and strengths, Individualised Intervention Plan) | |

| Day 2 | Sessions 6–10 (Psychoeducation on Fear Ladders and Graded Exposure, Graded Exposure, Relaxation) |

| Sessions 11–12 (Graded Exposure, Intervention Summary) | |

| Troubleshooting | |

| Fidelity checklists |

Therapists received regular supervision as per their existing supervision arrangements; this was at least monthly. Supervisors were given an opportunity to attend the training and received a copy of the intervention manual. The research team remained in regular contact with the therapists to check on progress and offer support and supervision as required.

Summary

Anxiety disorders develop through a process of direct and vicarious learning experiences, and events that occur post-learning moderate the experience of anxiety. Not all autistic people with moderate to severe learning disabilities develop anxiety disorders, but this group presents with vulnerabilities that increase the probability of anxiety becoming problematic. These vulnerabilities include sensory sensitivities, information-processing difficulties, restricted and repetitive behaviours, and difficulties with flexibility, amongst others. Our intervention was developed with reference to this theoretical framework, and within our logic model we outlined the key intervention components and mechanisms that are considered to lead to a reduction in anxiety and increased community engagement.

Our intervention comprised 12 sessions which were delivered by trained therapists and developed in collaboration with our IAG. Carers attended all sessions, while some of the sessions involved only the carer. Our primary intervention strategies involved psychoeducation, relaxation training, and exposure therapy coupled with reinforcement. Our intervention was accompanied by a fidelity checklist which was also developed in collaboration with our IAG.

Chapter 4 Phase 1b: treatment-as-usual survey

Within this phase, data were collected to characterise interventions that were currently being delivered to autistic people with moderate to severe learning disabilities who have problems with anxiety.

Methods

Participants and recruitment

We recruited health and social care professionals working in services providing care to autistic adults aged 16 years and older with moderate to severe learning disabilities. We asked them to describe interventions for anxiety offered by their service to this population.

Participants were recruited via the Research in Developmental Neuropsychiatry (RADiANT; https://radiant.nhs.uk/) consortium of NHS providers. We also sent e-mail invitations directly to NHS Trust research and development (R&D) departments and charitable organisations which provide care to autistic adults with learning disabilities in the UK. This included information about the survey and an online link to the survey. Information about the survey was also available in the public domain on our website and information was further shared with e-mail distribution lists for professionals working with people with learning disabilities (e.g. British Psychological Society, Faculty for Intellectual Disabilities Listserv).

Ethical opinion

Our survey was granted a favourable ethical opinion by Wales Research Ethics Committee (REC) 6 and had associated NHS Health Research Authority Approval (Ref: 21/WA/0013).

Consent

The participants could choose to complete the survey online via Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA) or in the form of an interview with a member of the research team (via Microsoft Teams or over the telephone). For participants completing the survey online, the Participant Information Sheet (PIS) and Participant Consent Form were embedded in Qualtrics. Participants who opted for an interview were e-mailed the PIS and Participant Consent Form ahead of time and asked to sign it electronically. Participants provided consent to take part in the survey prior to accessing any survey questions.

Withdrawals

Participants had the right to withdraw their consent at any time. Withdrawals were recorded.

Survey questions

The questions for the survey were based upon the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist. 106 Initially, participants were asked if their service offered any interventions for anxiety to autistic adults with moderate to severe learning disabilities (this could include psychological interventions, medication, or any other intervention). If participants indicated that their service offered interventions for anxiety, they were asked a series of questions about the nature of the intervention. See Appendix 1 for the questions included in the survey. At the end of the survey, participants were asked if their service offered any additional interventions for anxiety, apart from the one already described. If yes, participants were asked to answer the same set of questions but in relation to the additional intervention. This cycle repeated until the respondent indicated that their service offered no further interventions for anxiety.

Analysis

We summarised both the quantitative and qualitative data generated. The number of responses to the closed-end survey questions was counted and reported. Responses from the open-end questions were analysed using content analysis107 as our aim was to describe TAU. Initially, a set of codes was identified by one coder by grouping survey responses that shared the same meaning. If the response contained more than one concept, separate codes were generated for each concept. Codes were grouped into subthemes which represented the professional views on the intervention offered for anxiety to autistic adults with learning disabilities. The subthemes were sorted into themes that were determined by each survey question using the TIDieR checklist as an organisational framework.

Two observers independently coded 10% of the responses. The inter-rater reliability agreement was 93% (84 agreements and 6 disagreements). The final codes were discussed by the raters and consensus was reached.

Results

Sites and participant characteristics

Seventy-eight health and social care professionals working in services providing care to autistic adults aged 16 years and older with moderate to severe learning disabilities responded to the survey. Seventy-five participants chose to complete the survey online. One interview was conducted. Not all participants answered all the questions. For some questions, the total number of responses exceeded the number of participants who took part in this study because they could choose more than one answer.

Sixty-three participants provided information on the country in which their service was located: England (n = 59), Scotland (n = 3) and Wales (n = 1). Table 8 shows participants’ roles.

| Participant’s role | Number of responses |

|---|---|

| Nursing or care professional | 24 |

| Allied health professional | 14 |

| Psychology | 11 |

| Medical doctor | 10 |

| Dental professional | 7 |

| Leadership or management staff | 7 |

| Other | 6 |

| Behaviour specialist | 2 |

Sixty-two professionals provided the name of the service within which they worked. Table 9 shows types of services indicated by the participants.

| Type of the service | Number of responses |

|---|---|

| NHS Trust | 54 |

| Local authority service | 3 |

| Private service | 2 |

| Non-NHS community learning disabilities service | 2 |

| Learning disability charity | 1 |

Forty-one participants categorised their service as community-based, 15 as a combination of community and inpatient, 4 as inpatient and 2 as other types of services.

Objectives

Objective 1: complete a national survey of existing interventions for autistic adults with anxiety disorders who have moderate to severe learning disabilities

Sixty-four (out of 78) participants (82.1%) responded to the question asking if their service offered any intervention for anxiety to autistic adults with moderate to severe learning disabilities.

Fifty-nine participants (92.2%) indicated that their service offered a treatment or intervention for anxiety to this population. Five participants (7.8%) stated that their service did not offer any treatment or intervention for anxiety to autistic adults with learning disabilities.

Out of the 59 participants whose service offered the intervention, 21 stated they offered more than 1 type. Refer to Table 10 for the intervention types described in the survey. Participants were able to add more than one intervention option.

| Type of intervention | Number of responses |

|---|---|

| Psychological | 49 |

| Medication | 32 |

| Other (e.g. speech and language therapy, occupational therapy, music therapy) | 12 |

| Physical health support | 4 |

Psychological interventions

Forty-nine participants indicated that their service offered psychological intervention or intervention for anxiety to autistic adults with moderate to severe learning disabilities.

Table 11 summarises responses to the question on the rationale for using psychological intervention.

| Rational for using the intervention | Number of responses |

|---|---|

| Targets anxiety using proactive and reactive strategies | 39 |

| Person-centred | 16 |

| Improves quality of life | 13 |

| Collaborative working | 9 |

| Evidence-informed | 9 |

| Improves engagement in other important interventions | 7 |

| Develops a clinical formulation | 5 |

| Psychoeducation about anxiety or autism | 4 |

| Predictable and consistent | 3 |

| Complies with national guidance | 3 |

| Improved access to psychological intervention | 2 |

| Practical | 1 |

| Goal-oriented | 1 |

| Ethical | 1 |

| Supports staff well-being | 1 |

Refer to Table 12 for key procedures, activities and/or processes of the psychological intervention. A majority of participants indicated that the key procedure used as part of an intervention to treat anxiety was ‘psychological intervention’, which was non-specific. Only five participants indicated that their service offered exposure therapy as a key procedure or activity.

| Key procedures, activities and/or processes | Number of responses |

|---|---|

| Psychological intervention | 34 |

| Biopsychosocial assessment | 21 |

| Formulation | 15 |

| Liaison with other professionals | 12 |

| Skills training in autism and anxiety | 11 |

| Intervention planning and monitoring | 10 |

| Staff support or supervision | 6 |

| Functional analysis | 6 |

| Engagement with the patient | 5 |

| Graded exposure procedures | 5 |

| Reflective practice | 5 |

| Supporting communication | 4 |

| Observation | 4 |

| Carer engagement | 3 |

| As part of dental intervention procedures | 2 |

| Environmental adaptations | 2 |

| Mental Capacity Act procedures | 1 |