Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number 17/136/10. The contractual start date was in July 2019. The draft report began editorial review in April 2023 and was accepted for publication in August 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Goodacre et al. This work was produced by Goodacre et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Goodacre et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

The problem

Sepsis is a life-threatening reaction to an infection in which the immune system overreacts to infection and causes organ damage. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (sepsis-3) defines sepsis as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection, in which organ dysfunction can be represented by an increase in the Sequential (Sepsis-related) Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score of two points or more, and is associated with an in-hospital mortality > 10%. 1

This definition has recognised limitations. Sepsis is a broad term applied to an incompletely understood process with, as yet, no criteria that uniquely identify a septic patient. In adults, the clinical presentation of infection and new organ damage is often seen in people with long-term conditions where a self-limiting or easily treatable infection is exacerbating underlying comorbidity, rather than causing organ damage through a dysregulated response. 2 In such circumstances, comorbidities or frailty may be the main determinants of mortality. 3,4

Early recognition and treatment of sepsis has the potential to reduce mortality, depending upon the extent to which mortality risk is due to a dysregulated response to infection. Guidelines for sepsis highlight the importance of early recognition and treatment, with treatment recommended within 1 hour of presentation for those at highest risk. 5–9 This can only be achieved if sepsis is recognised and prioritised in the emergency care system.

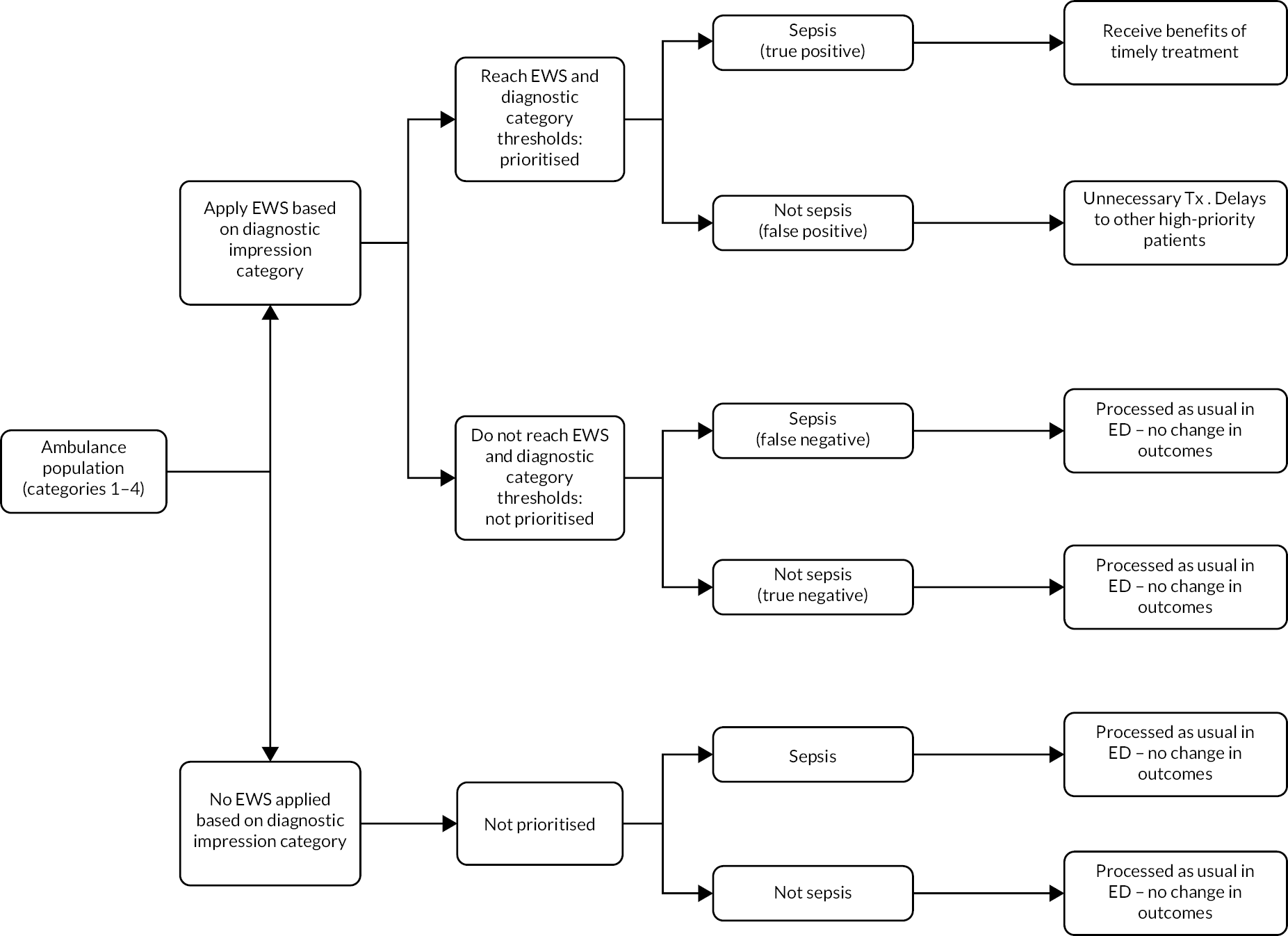

Sepsis can be recognised by identifying clinical features of the host response or organ dysfunction, such as altered mental state, low blood pressure or rapid respiratory rate. Early warning scores use simple measurements to calculate a score, with a higher score indicating a higher risk of serious illness and adverse outcomes. They can be used by prehospital providers, such as ambulance paramedics, to identify people with suspected sepsis who need to be prioritised for treatment. 10 Prioritisation can involve a range of options based around pre-alerting the emergency department (ED), allowing the patient with sepsis to be seen before other patients. This could lead to the patient with sepsis being seen immediately on arrival by a clinician who is able to provide time-critical treatment for sepsis and refer for urgent specialist care. Early warning scores could also be used to select people for prehospital treatment for sepsis, such as intravenous fluids or antibiotic therapy, to further reduce treatment delays.

The recognised limitations of the definition of sepsis and uncertainty around the benefits of early treatment can lead to lack of clarity in determining what an early warning score for sepsis is intended to diagnose or predict. An early warning score could be used to identify patients with a diagnosis of sepsis according to the sepsis-3 definition, to predict patients with the highest risk of adverse outcome from sepsis, or to identify patients most likely to benefit from early treatment or a specific intervention for sepsis.

An effective early warning score needs to be accurate and implemented with an appropriate balance between sensitivity and specificity. High sensitivity is needed to ensure that people with the potential to benefit from urgent treatment are not missed, with consequent delayed treatment and avoidable mortality and morbidity. However, sacrificing specificity to maximise sensitivity can result in overtriage, in which people without sepsis or the potential to benefit from urgent treatment are inappropriately prioritised. This increases the pressure on EDs and impairs their ability to provide rapid treatment to those who require it. It may also result in inappropriate prehospital treatment with associated consequences, especially if prehospital scope of practice for sepsis includes antibiotic therapy.

The problem of overtriage is compounded if early warning scores are applied to an unselected population with a low prevalence of sepsis or a high prevalence of conditions that increase early warning scores in the absence of sepsis. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance advises thinking ‘could this be sepsis?’5 if a person presents with signs or symptoms that indicate possible infection and highlights that people with sepsis may have non-specific, non-localised presentations, and may not have a high temperature. This could result in sepsis being suspected in any patient attended by emergency ambulance for a medical complaint that is not attributable to a clear alternative cause. An early warning score with poor specificity could therefore result in overtriage of a huge number of patients, placing severe pressure on the emergency care system.

Uncertainty and evidence deficit

The NICE Guideline Development Group (GDG) identified a number of early warning scores that are easy to use, only require simple measurements and could therefore be used in the prehospital setting. 5 These are the Simple Triage Scoring System (STSS), Rapid Emergency Medicine Score (REMS) or modified-REMS, the Modified Early Warning score (MEWS) and National Early Warning score (NEWS). 11–14 They were developed through expert consensus or analysis of routine data from hospitalised patients and contain similar measures (heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, blood pressure and conscious level) but differ in their calculation. REMS, MEWS and NEWS have been shown to predict adverse outcome in acute medical admissions, while STSS has been shown to predict mortality in inpatients with suspected infection.

The NICE GDG identified other early warning scores for use in hospital, such as Mortality in the Emergency Department, Sepsis and Predisposition, Infection, Response and Organ dysfunction, but did not recommend them for prehospital use on the basis that they include blood tests that are not currently available in the prehospital setting. 5

A meta-analysis and systematic review of in-hospital studies suggested that early warning scores predicted mortality in sepsis with limited accuracy, based on poor-quality data. 15 A systematic review of early warning scores undertaken for NICE guidance identified 47 relevant studies (including studies of in-hospital scores). All were judged as being of very low quality. There was significant variability in population, outcomes and analysis, so meta-analysis was not possible. No relevant economic evaluations were identified. The guideline recommended that clinicians consider using an early warning score to assess people with suspected sepsis in acute hospital settings and recommended research to determine whether early warning scores can be used to improve the detection of sepsis.

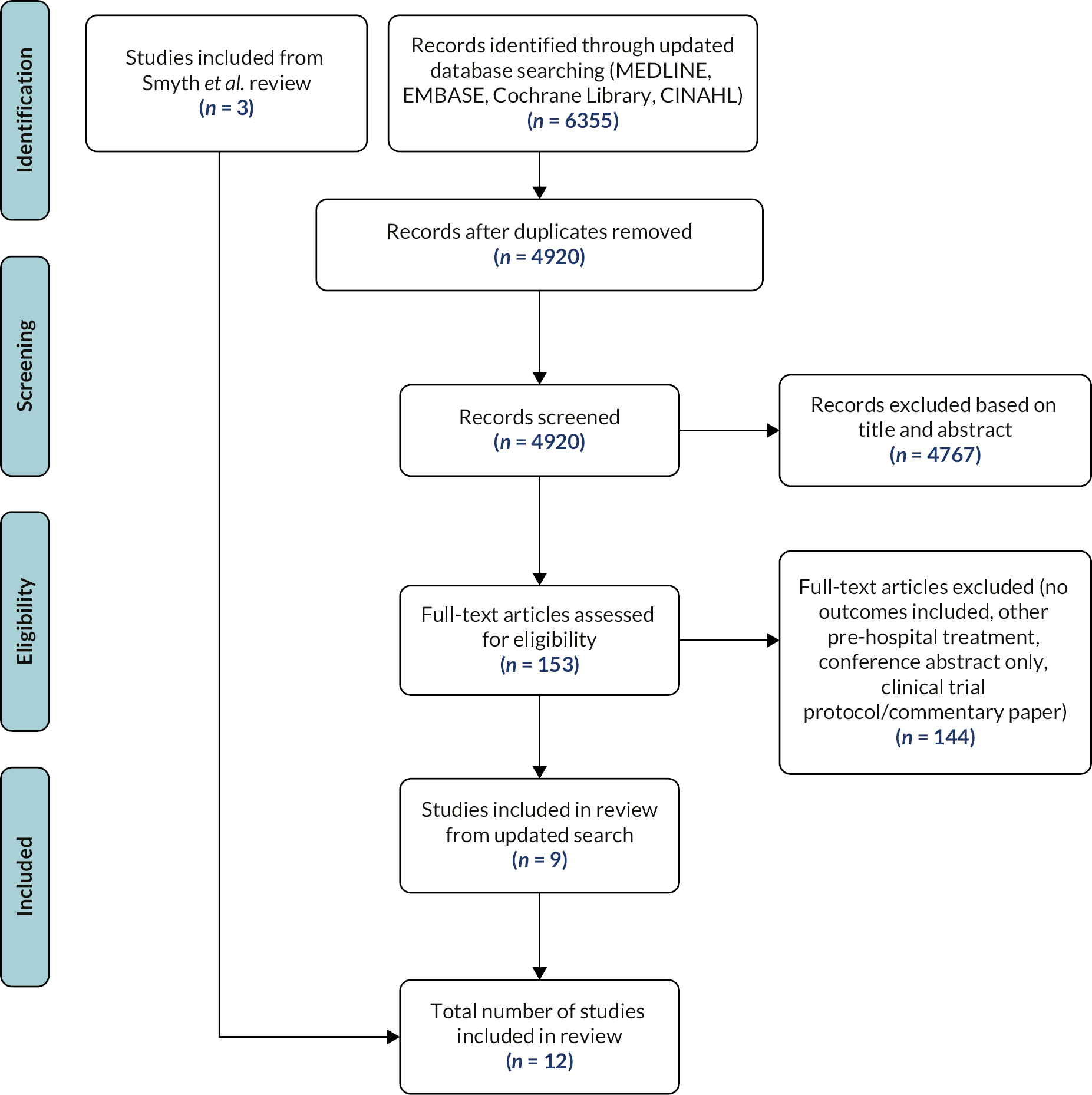

Two systematic reviews of prehospital identification of sepsis also reported limited existing evidence and a need for further research. Smyth et al. reported three studies developing prehospital sepsis screening tools for adults and six studies of paramedic diagnosis of sepsis. 16 Lane et al. reported nine studies of prehospital identification of sepsis. 17 Three of the studies from these systematic reviews evaluated sepsis-specific prehospital scores [Prehospital Early Sepsis Detection (PRESEP), Prehospital Severe Sepsis (PRESS) and the CIS], and the other studies evaluated MEWS, the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) criteria and the Robson tool. 18 Study quality was poor, sensitivity (0.43–0.86) and specificity (0.47–0.87) varied markedly, and none of the screening tools had been validated.

More recently, the qSOFA score has been derived and validated to predict death in hospitalised patients with suspected sepsis and NEWS has been updated to become the National Early Warning Score, version 2 (NEWS2). 19–21 A meta-analysis of 38 recent studies of qSOFA reported pooled sensitivity of 0.61 and pooled specificity of 0.72 for mortality. 22 A systematic review comparing qSOFA and hospital early warning scores for prognosis in suspected sepsis in ED patients suggested that qSOFA has better specificity for predicting adverse outcome at its recommended threshold but NEWS has better sensitivity. 23

Other recent studies have developed scores in the prehospital setting. Smyth et al. derived and validated the Screening to Enhance PrehoSpital Identification of Sepsis (SEPSIS) tool to identify patients with high risk of sepsis in medical cases attended by emergency ambulance with an area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of 0.86, and sensitivity 0.80 and specificity 0.78 at the recommended threshold. 24 Bayer et al. developed the PRESEP score to identify sepsis in prehospital patients with suspected sepsis with area under the ROC curve 0.93, sensitivity 0.85 and specificity 0.86. 25 Polito et al. developed the PRESS score to identify severe sepsis in physiologically abnormal prehospital patients with suspected sepsis with sensitivity 0.86 and specificity 0.47. 26

In developing our research proposal, we searched for studies evaluating the sensitivity and specificity or the effect of implementation of early warning scores for suspected sepsis in a prehospital population. 10 We identified 13 studies evaluating 20 scores. All but one were retrospective studies. The study populations varied from including all medical cases to including only those with presumed or diagnosed sepsis. Definitions of the reference standard included diagnosis (sepsis), prognosis (mortality) or health service use (admission to intensive care). Sensitivity and specificity varied substantially across the scores and studies. The most extensively studied score, qSOFA (studied in 9 of the 13 studies), had sensitivity ranging from 0.16 to 0.86 and specificity ranging from 0.16 to 0.97.

Two single-centre uncontrolled before versus after implementation studies have evaluated the potential effect of a score on practice. Polito et al. showed that implementation of the PRESS score was associated with improved sepsis recognition by prehospital personnel. 26 Borelli et al. showed that implementation of a prehospital sepsis screening tool was associated with improved clinician compliance with Surviving Sepsis Campaign 3-hour sepsis bundle recommendations. 27

Previous studies have important limitations other than the low quality identified in the NICE review:

-

Early warning scores should ideally identify patients who have the greatest potential to benefit from prioritisation and urgent treatment. Studies using mortality as the outcome or reference standard may not achieve this aim. 28 Firstly, patients whose lives are saved by urgent treatment will be categorised as reference standard negative despite having clearly benefited. Secondly, patients with severe pre-existing life-limiting conditions that make life-saving treatment futile or inappropriate will be classified as reference standard positive despite having little potential to benefit. Early warning scores developed to predict adverse outcomes such as mortality may therefore identify those with irreversible mortality while missing those with greatest potential to benefit from urgent treatment.

-

Early warning scores need to be operationalised by using a threshold for decision-making that optimises the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity in terms of the benefits, harms and costs of prioritisation. Existing studies have not explicitly examined the trade-off in these terms and the NICE review identified no relevant economic evaluations. Although the cost of applying an early warning score is small, the potential knock-on costs of overtriage are substantial.

-

Early warning scores should be evaluated in the population in whom the score will be used. REMS, MEWS and NEWS were developed and validated in acute medical inpatients with a range of medical complaints, while STSS and qSOFA were developed in inpatients with suspected sepsis. Inpatient populations, especially those identified as having suspected sepsis by hospital clinicians, are likely to have a higher prevalence of severe sepsis than prehospital populations. Using an early warning score developed for an inpatient population in the prehospital setting could lead to substantial overtriage.

Research therefore needs to use a reference standard or outcome that reflects potential to benefit from urgent treatment, examine the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity in terms of the benefit, harms and costs of using an early warning score to prioritise patients, and evaluate early warning scores in the prehospital population.

Research objectives

We aimed to determine the accuracy, impact and cost-effectiveness of prehospital early warning scores for adults with suspected sepsis. Our specific objectives were:

-

to estimate the accuracy of prehospital early warning scores for identifying sepsis requiring time-critical treatment in adults with possible sepsis who are attended by emergency ambulance

-

to estimate the impact of using prehospital early warning scores to guide key prehospital decisions, in terms of the operational consequences, and the cost-effectiveness of alternative strategies.

We planned two concurrent streams of work to address these objectives:

-

A retrospective cohort study using routine data sources to estimate the accuracy of prehospital early warning scores alongside paramedic diagnostic impression (index test) for identifying sepsis requiring time-critical treatment (reference standard) in adults with possible sepsis who are attended by emergency ambulance (population).

-

Decision-analytic modelling to determine the impact of using prehospital early warning scores to guide two key decisions: (1) alerting the receiving hospital so that the patient is seen immediately on arrival; (2) providing prehospital treatment for sepsis, such as intravenous antibiotics.

We focused on evaluating existing scores rather than developing a new score, because the existing evidence showed that numerous scores have been developed, but with very limited validation.

We limited our study to adults because the presentation and management of sepsis differ markedly between adults and children. The physiological constituents of early warning scores have different normal ranges and associations with outcome in adults and children, the confounding role of comorbidities is more significant in adults, and adults have higher rates of adverse outcome than children, when sepsis is suspected. For these reasons adults and children have separate guidelines for suspected sepsis and are studied in separate research projects.

Chapter 2 Retrospective cohort study

Methods

We used routine sources to collect data from a cohort of patients with possible sepsis who were transported by two ambulance services (Yorkshire and West Midlands) to four acute hospitals (Sheffield Northern General Hospital, Rotherham General Hospital, Barnsley Hospital, and University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire). We calculated early warning scores from routine data recorded on the ambulance service electronic patient-report form (ePRF) and determined the number of cases that would be prioritised using early warning scores alongside paramedic diagnostic impression.

We planned to determine the accuracy of early warning scores and paramedic diagnostic impression against a reference standard of sepsis needing urgent treatment, based on retrospective hospital record review. We planned to use the Data Access Request Service (DARS) from NHS Digital to link ambulance service data to Emergency Care Data Set, Hospital Episodes Statistics and Office for National Statistics mortality data. Hospitals would then be notified of cases with a diagnostic coding for sepsis that would undergo reference standard assessment. However, we were unable to implement this plan (see details below) and had to use an alternative approach, linking data from one ambulance service (Yorkshire) to one hospital (Sheffield Northern General Hospital).

Study population

We used routine ambulance service data to identify all episodes in which Yorkshire or West Midlands Ambulance Service transported adults as an emergency to the participating hospitals over the course of 2019 and a diagnosis of sepsis could have been suspected. We excluded episodes with injury, mental health problems, cardiac arrest or direct transfer to specialist services (including maternity, cardiac or stroke services). We also excluded episodes with no vital signs recorded since vital signs are essential to calculating early warning scores.

The participating ambulance services used an item on the ePRF to record the ambulance clinician diagnostic impression from a range of standardised options. These options differed between the two ambulance services, so clinical experts in the research team grouped the diagnostic impressions into five categories:

-

sepsis

-

infection (excluding sepsis)

-

non-specific diagnostic impression in which sepsis could be suspected

-

other diagnostic impression in which sepsis would not usually be suspected

-

diagnostic impression meets exclusion criteria.

Appendix 1 shows the categorisation of diagnostic impressions in the two ambulance services. We excluded episodes with a diagnostic impression in category 5 or no diagnostic impression recorded. Categories 1–4 were used to evaluate how the accuracy of early warning scores varied according to their application on the basis of diagnostic impression. NICE guidance suggests that sepsis could be suspected in any non-specific presentation but only applying early warning scores to those with suspected sepsis or suspected infection could provide a better balance of sensitivity and specificity.

The ambulance services differed in the way that diagnostic impression was recorded, with Yorkshire Ambulance Service only allowing one diagnosis to be recorded, while West Midlands Ambulance Service allowed multiple diagnoses, with no ranking in order of likelihood or importance. We categorised the West Midlands episodes according to whichever impression was nearest the top of our ranked order. For example, a patient with diagnostic impressions of atrial fibrillation, urinary tract infection and sepsis would be categorised in group 1. The exception was category 5, where any diagnosis meeting the exclusion criteria resulted in exclusion.

This represented a fundamental difference in the way that diagnostic category would be used in principle and in practice alongside an early warning scores. In Yorkshire, patients in category 1 would be those in whom the ambulance clinician considered sepsis to be the most likely diagnosis. In the West Midlands, patients in category 1 would be those in whom sepsis was one of the main differential diagnoses.

We identified patients with multiple episodes recorded so that we could use episode or patient as the unit of analysis. We only used data from the first episodes in analyses involving patient as the unit of analysis.

Prehospital early warning scores for sepsis

We evaluated any early warning scores that could be used by prehospital professionals and calculated from routinely available prehospital data. We included dichotomous scores (i.e. rules) that simply categorise into high- and low-risk groups, but refer collectively to the index test as constituting early warning scores for simplicity.

We searched EMBASE, CINHAL, PubMed, Clinicaltrials.gov, the ISRCTN registry and Research Registry for completed and ongoing studies of early warning scores for suspected sepsis in a prehospital population using the search strategy outlined in Appendix 2.

We planned to convene a group of 10–15 experts from prehospital care, emergency medicine and critical care to review the early warning scores identified by the literature search and select those that could be used in prehospital care and calculated from routinely available prehospital data. However, the COVID-19 pandemic substantially reduced the ability of relevant clinicians to participate in this activity, so we amended the study protocol to allow clinical experts from the research team to review early warning scores for evaluation and reduce the need for the project to draw upon overstretched clinical expertise.

The clinical experts convened over two online meetings and selected early warning scores that fulfilled the following criteria: (1) the variables constituting the score are likely to be measured and recorded in a standard manner; (2) categorisation and allocation of points to form a score follows a logical and intuitive process; and (3) the process of calculating a score is simple and reproducible, with a low risk of error. They also considered whether thresholds used to categorise a continuous measure were based on accepted cut-points, such as accepted normal ranges, but did not exclude scores that failed to meet these criteria.

The clinical experts selected 21 early warning scores that could potentially be used by prehospital professionals and calculated from routine ambulance service data. They determined whether any modification to the score was required to allow it to be calculated from routine data and then specified the modification required. They also specified how the score should be calculated if any elements were missing in routine data. This usually involved assuming that any missing variables were normal or negative. Finally, they identified a decision-making threshold for each score using existing literature or their knowledge of use of the scores in practice.

Public representatives reviewed the early warning scores to determine whether their use was likely to be acceptable to the patient and the public, taking into account whether measuring or recording variables for the score could be intrusive for the patient, and whether the score raises concerns about equity, such as in relation to age, gender, ethnic group or socioeconomic status. Several scores used age as a variable, which was felt to be acceptable given the association between age and risk of adverse outcome, provided use did not result in any age discrimination. None of the scores used gender, ethnic groups or socioeconomic variables. Some concerns were raised about use of residence in a care home as a variable in the PRESS score. This was dropped from the score on the basis of these concerns and lack of ambulance service data to confirm residence.

Table 1 outlines the scores and compares their constituent variables. Appendix 3 provides details of how each score is calculated, any modifications or assumptions in calculating the score from routine data, and the threshold for decision-making. The scores used combinations of age and six physiological measurements (temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, peripheral oxygen saturation, conscious level, and blood pressure), along with a small number of other variables. Conscious level was assessed using either the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) or the alert, confusion, voice, pain, unresponsive (ACVPU) scale. Blood pressure was assessed using either the systolic blood pressure or the mean arterial pressure. Modification of the UK Sepsis Trust (UKST) red-flag criteria involved removing lactate, oliguria and recent chemotherapy from the criteria because these were not routinely recorded and lactate is not routinely measured in the prehospital setting.

| Early warning score | Age | Temperature | Heart rate | Respiratory rate | Oxygen saturation | Conscious level | Blood pressure | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90-30-9029 | X | X | X | |||||

| Borelli27 | X | X | X | X | X | X | Suspected infection | |

| CIS30 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| HEWS31 | X | X | X | X | X | X | Inspired oxygen | |

| MEWS13 | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| NEWS214 | X | X | X | X | X | X | Inspired oxygen | |

| NHS pre-alert32 | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| PHANTASi33 | X | X | X | |||||

| PITSTOP34 | X | X | Paramedic suspicion of infection | |||||

| PreSAT35 | X | X | X | X | ||||

| PRESEP25 | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| PRESS26 | X | X | X | X | Dispatch chief complaint of sick person; nursing home resident | |||

| PSP36 | X | X | X | X | ||||

| REMS12 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| qSOFA19 | X | X | X | |||||

| RST29 | X | X | X | X | Blood glucose | |||

| SEPSIS24 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | Skin appearance |

| Sepsis Alert37 | X | X | X | X | Suspected or documented infection, hypoperfusion | |||

| STSS11 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Suffoletto strategy38 | X | X | ||||||

| UKST red flag39,a | X | X | X | X | X | Skin appearance |

We planned, as part of the expert group work, to use consensus methods to create additional scores for evaluation. However, having reviewed the existing scores, the clinical experts determined that there was little potential to develop an additional score from routinely recorded data that would provide a clinically important improvement on the extensive range of existing scores.

Calculation of the early warning score from electronic patient-report form data

Age, heart rate, respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure, peripheral oxygen saturation, temperature and GCS were recorded on the ePRF. Mean arterial blood pressure was calculated using a formula in which the diastolic blood pressure is doubled and added to systolic blood pressure, and then divided by three. Conscious level and ACVPU were inferred from GCS. We used the first recorded measurement for each variable, if it was recorded multiple times. If the variable was not recorded in the first set of observations, then the first recorded measurement was used from a subsequent set of observations.

Appendix 3 outlines how other variables used in the early warning scores were calculated from the ePRF. Reference standard results were unknown at the time of early warning score calculation.

Use of the early warning score alongside diagnostic impression

The index tests for our evaluation were early warning scores and paramedic diagnostic impression, either used alone or in combination. We evaluated how early warning scores could be used alongside the prehospital diagnostic impression by applying each early warning scores in the following ways:

-

Score applied only to cases in category 1 (sepsis), with cases in categories 2–4 considered index test negative.

-

Score applied only to cases in categories 1 and 2 (sepsis or infection), with cases in categories 3 and 4 considered index test negative.

-

Score applied only to cases in categories 1–3 (sepsis, infection or non-specific), with cases in category 4 considered index test negative.

-

Score applied to all eligible cases, regardless of diagnostic category (i.e. evaluation of the early warning scores alone).

We also evaluated diagnostic category alone as an index test (with no early warning scores) using three different thresholds: (1) category 1 positive, categories 2 to 4 negative; (2) categories 1 and 2 positive, categories 3 and 4 negative; and (3) categories 1 to 3 positive, category 4 negative.

The reference standard: sepsis requiring urgent treatment

The purpose of prehospital early warning scores is to prioritise patients who have potential to benefit from urgent treatment for sepsis. We therefore defined the reference standard as being positive if the patient met the sepsis-3 definition of sepsis and received treatment for sepsis within 4 hours of initial assessment at hospital. This definition recognised that some patients with sepsis have life-limiting conditions (such as metastatic malignancy or end-stage chronic disease) that would make urgent treatment for sepsis futile or run counter their wishes. The reference standard for the primary analysis (treated sepsis) required both diagnosis and treatment. We undertook a secondary analysis using a reference standard that only required the sepsis-3 definition to be met (diagnosed sepsis). The rationale for this approach was that the primary analysis would determine the accuracy for identifying cases most likely to benefit from urgent treatment. The secondary analysis would determine whether accuracy differed when the reference standard included cases that could have benefited from early diagnosis (e.g. to allow prognostication or consideration of treatment options), even though they did not receive urgent treatment for sepsis.

Determining the reference standard involved hospital record review and expert judgement, but we needed a large sample size to detect a sufficient number of cases with a positive reference standard. We therefore used a screening process to select cases for reference standard review that were likely to meet the reference standard definition and avoid review for those unlikely to meet the definition. We used routine hospital data to select those with a primary or secondary International Classification of Disease (ICD) 10 admission code or cause of death compatible with sepsis, or an ED code for sepsis. Research nurses briefly reviewed the ED records of these cases and selected patients for expert review if they had a diagnosis of sepsis or any treatment for sepsis recorded in the ED notes or if sepsis was recorded as an admission diagnosis on the hospital discharge summary. Cases were excluded if there was no evidence of sepsis diagnosis or treatment, or if sepsis developed after hospital admission.

Two experts independently reviewed hospital records for all patients selected by the research nurses and determined whether the following criteria were met: (1) evidence of infection and life-threatening organ dysfunction (as defined by sepsis-3, the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock) within 4 hours of initial assessment; (2) treatment for sepsis was given within 4 hours. Evidence of infection could include microbiology reports identifying organisms, radiology reports identifying infective changes, or consistent markers of infection (elevated white cell count, C-reactive protein and temperature). Organ dysfunction, in accordance with the sepsis-3 definition, was defined as a SOFA score of 2 or more points worse than normal. The SOFA score was estimated using the ED observations chart and first blood results after admission. If arterial blood gas sampling had not been recorded, the arterial partial pressure of oxygen was estimated from the peripheral oxygen saturation. The normal SOFA score was estimated using previous hospital records and blood tests. Elements of the normal SOFA score were assumed to be zero unless there was clear evidence that they would not be normal, such as evidence of pre-existing confusion in patients with dementia or evidence of hypoxia or long-term oxygen therapy in patients with chronic lung disease. Treatment for sepsis usually involved evidence of administration of any antimicrobial that could be used to treat a sepsis-causing organism. Oral antimicrobial therapy was not considered to be treatment for sepsis unless there was a specific reason why intravenous antibiotics were not used (such as delays in gaining intravenous access). The expert reviewers were encouraged to make judgements in all cases, even when information was incomplete, since the potential bias from excluding cases with incomplete information was considered to be greater than the potential bias from misclassification. Index test results were not available to assessors during reference standard review, although assessors were aware of constituent elements of early warning scores recorded in ED notes.

If the two reviewers disagreed on the overall sepsis-3 judgement or whether treatment for sepsis was given, then a consensus decision was reached through discussion, with a third expert available to resolve any cases where consensus could not be reached. Disagreements over an element of the sepsis-3 definition (evidence of infection or change in SOFA score) were left unresolved if they did not affect the overall judgement, that is, if the reviewers agreed that the sepsis-3 definition was not met but disagreed on which criterion was not met.

Data linkage and management

Each ambulance service provided data from all eligible cases transported to one of the participating hospitals over 2019. The ambulance service created a unique study identification number for each case. Two linked databases were created: (1) containing the unique identification, time and date of call, and personal details, which was sent to NHS Digital; (2) containing the unique identification, time and date of call, and all non-personal details, which was sent to the Sheffield Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU).

We planned that NHS Digital would use the personal details from the ambulance data to link each case to the Emergency Care Data Set data for the related ED attendance and any related Hospital Episodes Statistics or Office for National Statistics data from subsequent hospital admissions. They would then send selected de-identified data from the Emergency Care Data Set, Hospital Episodes Statistics and Office for National Statistics data alongside the unique study identification number to the Sheffield CTRU, and would send a data set to a research nurse at each participating hospital consisting of the unique study identification number, personal data and the selected Emergency Care Data Set, Hospital Episodes Statistics and Office for National Statistics data. The research nurses would then undertake the process outlined above to determine the reference standard.

Our initial application to the NHS Digital DARS was rejected on the basis that the data flow process, involving NHS Digital sending personal data to multiple recipients (Sheffield CTRU and the four hospitals), incurred an unacceptable risk to NHS Digital. We therefore amended the data flow process so that NHS Digital would only send data to Sheffield CTRU, who would then send NHS numbers for patients requiring reference standard adjudication to the four hospitals. The regulatory authorities and NHS Digital approved the amended process.

After NHS Digital approved the application and signed a Data-Sharing Agreement with the University of Sheffield there was a prolonged delay in receiving data during which a scheduled date for data release (19 May 2022) passed without receiving any data. In September 2022, after 9 months of waiting for NHS Digital to provide data and no indication of when it would be provided, and with 4 months until the funder had stated that the project had to be completed, we still had not received linked data. At this point, after consultation with the study steering committee and public representatives, and approval from regulatory authorities, we implemented a rescue plan to allow us to collect reference standard data at one of the participating sites. Details of the timeline for seeking linked data from NHS Digital are outlined in Appendix 4.

The rescue plan involved Yorkshire Ambulance Service identifying all eligible cases transported to the Sheffield Northern General Hospital that had an NHS number recorded, excluding cases where the patient had opted out from access to their personal details for research purposes, and then adding NHS numbers to the data sent to Sheffield CTRU. The data were then sent to the Chief Investigator, who works as a clinician at the Sheffield Northern General Hospital. The Chief Investigator shared the data with the Scientific Computing team at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, who searched the hospital information system for any ED attendances or hospital admissions with the same NHS number, occurring within 48 hours of ambulance transport to hospital. The Scientific Computing team informed Sheffield CTRU of any cases that could not be linked or had no coded attendance or admission within 48 hours. These were excluded from the analysis. The Scientific Computing team then provided the Chief Investigator with ED codes and admission ICD10 codes or causes of death for all cases identified as having a coded attendance or admission within 48 hours. The Chief Investigator then identified all cases with an ED code of septicaemia or neutropenic sepsis, or a primary or secondary ICD10 code for sepsis.

As outlined above, the research nurses then screened the ED records and hospital discharge summaries of cases with a code for sepsis and selected for expert review those with a diagnosis of sepsis or treatment for sepsis recorded. Four consultants in emergency medicine who work in the Northern General Hospital ED (SG, KI, SC and GF) undertook expert review, with two independently reviewing each case.

Data analysis

We originally planned to undertake analysis across both ambulance services and all four hospitals, but revised this plan to undertake a separate analysis for each hospital because: (1) inability to use NHS Digital linkage meant that we could only measure the reference standard at Sheffield Northern General Hospital; (2) the two ambulance services used diagnostic impressions in fundamentally different ways, and evaluation of early warning scores alongside diagnostic impression was considered to be crucial.

Descriptive analysis of the ambulance service data for each participating hospital used episode as the unit of analysis to compare the index tests (early warning scores and paramedic diagnostic impressions) in terms of the mean [standard deviation (SD)] number of episodes per day that would be positive (i.e. prioritised or selected for treatment). We also reported the mean total eligible attendances per day and the mean number per day that received a pre-alert from the ambulance service. We then calculated the proportion of eligible attendances that would be prioritised using each index test strategy. This indicated whether each strategy is likely to be manageable and result in meaningful prioritisation, on the basis that prioritisation requires sufficient staff resources, sepsis is one of a number of conditions that might benefit from prioritisation, and prioritisation will not be meaningful if too many attendances are prioritised. We used three categories to indicate whether each strategy was likely to be manageable, based on the opinions of clinicians in the research team:

-

Green: < 5% of the mean daily attendances would be prioritised – likely to be manageable.

-

Amber: 5–10% would be prioritised – uncertain.

-

Red: more than 10% would be prioritised – unlikely to be manageable.

We evaluated each index test based upon using the recommended threshold (see Appendix 3) with the exception of NEWS2 and qSOFA, where we evaluated all potential thresholds. NEWS2 is routinely used in NHS ambulance services and can be implemented at any threshold with minimal additional training, while qSOFA is simple to calculate and recommended in international guidelines. 1 Implementing other scores would require additional training and possibly decision-support tools. We therefore wanted to compare these scores to all NEWS2 thresholds to ensure that superior performance did not just reflect the chosen NEWS2 threshold.

When calculating early warning scores, missing parameters were generally assumed normal (scored zero): details for each score are outlined in Appendix 3. Cases were excluded from analysis of a specific early warning scores if more than half of the variables used to calculate the score were missing.

We used data from a subset of the cohort (patients with NHS numbers who were transported to the Sheffield Northern General Hospital) to estimate the accuracy of each index test compared to the reference standard. We used the patient as the unit of analysis and only included the first eligible episode per patient. Primary analysis used treated sepsis as the reference standard and secondary analysis used diagnosed sepsis (see The reference standard: sepsis requiring urgent treatment). Kappa scores were calculated to determine the agreement between adjudicators for each element of the reference standard, the overall reference standard judgement and the judgement of whether treatment for sepsis was provided.

We constructed ROC curves to evaluate sensitivity and specificity over the range of each score. We calculated the area under the ROC curve and sensitivities and specificities at key cut-points, each with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

In our proposal, we planned to explore whether it is possible to statistically derive a clinically credible new score using multivariable logistic regression. We ultimately did not include this in our statistical analysis plan for the following reasons: (1) the large number of existing scores using the same limited number of available variables suggested that there was little potential to derive a new score with superior accuracy (other than due to overfitting); (2) the limited time available after delays incurred waiting for NHS Digital compelled us to prioritise the core analysis; (3) limitations in the population sample with reference standard adjudication (single site, only those with NHS numbers) undermined the potential applicability of a derived model to other settings.

Selection of strategies for the decision-analytic modelling

We used the results of the primary (treatment) analysis to compare the sensitivity and specificity of each strategy (combination of early warning score and diagnostic impression) to all other strategies and exclude any strategy that had inferior sensitivity and specificity to another strategy (i.e. both parameters inferior or one parameter equivalent and the other inferior). We used the point estimate to three decimal places for this assessment. Clinical experts in the group then reviewed these strategies for inclusion in the decision-analytic modelling. They excluded the strategies that were considered unmanageable due to prioritising > 10% of eligible cases in the analysis of mean daily rates of attendances prioritised. They then excluded strategies that would require additional training for ambulance and ED staff if they did not offer clearly superior accuracy to points on the NEWS2 ROC curve or an alternative rationale for use instead of NEWS2. The rationale for this decision was that NEWS2 is widely used by NHS ambulance services and hospitals, so any alternative strategy requiring additional training would need to offer clearly superior accuracy. We included the accuracy of pre-alert practice in 2019 alongside diagnostic impression as a strategy in this assessment in case it could represent a worthwhile comparator strategy in the modelling.

Sample size

We based our planned sample size estimate on data from Smyth et al. reporting 3.7% prevalence of high-risk sepsis in adults transported to hospital with a non-specific emergency presentation,24 and data from reviews of sepsis by the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD) and the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre (ICNARC). 40,41 NCEPOD identified 3363 adults (≥ 16 years) seen by the Critical Care Outreach Team or admitted directly to critical care with a diagnosis of sepsis across 305 hospitals over a 2-week period. ICNARC reported 22,081 admissions to critical care with septic shock across 205 hospitals over 2012. These studies suggest that the key determinant of sample size is the number of reference standard positive cases (to estimate sensitivity with acceptable precision) and an incidence of around two reference standard positive cases per week at a typical hospital.

Our plan to collect data across four hospitals over 1 year was based on attempting to ensure generalisability across multiple sites and avoid seasonality. Data from Smyth suggested around 23,000 eligible episodes over 1 year at each participating hospital, including around 847 with the reference standard, providing a total sample size of 92,000 across four hospitals with 3388 reference standard positive cases. This would result in an overpowered study with unnecessary and excessive work delivering reference standard validation. We therefore planned to randomly sample cases at each site to achieve a sufficient number of reference standard positive cases.

We estimated that around 2000 episodes would be selected for research nurse review (500 at each site), with around 1000 for expert hospital record review, to identify 200 reference standard positive episodes. This sample size would allow us to estimate the sensitivity of an early warning score with a standard error of 2.1% assuming sensitivity of 90%, and the area under the ROC curve with a standard error of 2% assuming an area under the ROC curve of at least 0.75. 42 The sample size also satisfies the recommendation by Collins et al. that external validation studies be based on a minimum of 100–200 events. 43

Following the failure of NHS Digital to provide linked data and the activation of our rescue plan, we attempted to pragmatically deliver an appropriate sample size within the time and resources available. We decided that random sampling of cases would not be practical and instead used consecutive sampling of cases in time order. In the event we were able to review all available cases across 2019 at the Sheffield site and deliver a sample of reference standard positive cases that exceeded our planned sample size.

Ethical approvals

The study gained initial approval from the London – Stanmore Research Ethics Committee (REC) (reference number 19/LO/1443) on 23 September 2019 and the Health Research Authority (HRA) on 30 January 2020. Due to the use of personal data for record linkage Confidentiality Advisory Group (CAG) approval was sought and granted on 13 January 2020. Over the course of the study, three substantial amendments were submitted to the REC, HRA and CAG. Dates of approval are provided in Table 2 and the resulting changes are outlined in the text below.

| Amendment date | REC approval | HRA approval | CAG approval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substantial amendment 1 | 16 December 2019 | 20 December 2019 | 30 January 2020 | Not required |

| Substantial amendment 2 | 24 May 2021 | 7 June 2021 | 15 June 2021 | 17 June 2021 |

| Substantial amendment 3 | 6 July 2022 | 20 July 2022 | 26 July 2022 | 26 July 2022 |

Substantial amendment 1

A change to the inclusion criteria for the study on the Integrated Research Application System form, lowering the age of inclusion from 18+ to 16+ in order to bring the study inclusion criteria in line with the age the ambulance services consider to be an adult.

Substantial amendment 2

A change to the data flow in order to secure approval from NHS Digital. The initial data flow was rejected by NHS Digital as it involved the provision of data to more than one data processor. The new approach was for NHS Digital to send all data to Sheffield CTRU, who would act as the data processor and controller. Sheffield CTRU would then securely transfer NHS numbers to the appropriate participating hospitals for assessment of the patient for reference standard inclusion.

Substantial amendment 3

The introduction of an alternative data flow to be used in the case that NHS Digital data linkage was not delivered. This involved staff at one participating hospital (Northern General Hospital, Sheffield) using NHS numbers to link data form one ambulance service (Yorkshire) to the hospital data.

Results

Overview of the ambulance service data

There were 178,333 ambulance episodes provided from 2019: 27,564 from West Midlands Ambulance Service and 150,769 from Yorkshire Ambulance Service. The Yorkshire Ambulance Service data set (Doncaster, Sheffield and Rotherham sites) was missing a period of 9 days in February. The West Midlands Ambulance Service data set (Coventry site) was missing data for the second half of each of the last 6 months of the year.

We excluded 83,311 episodes that met study exclusion criteria, had no unique patient identifier or had no data to calculate early warning scores. The analysis set included 95,022 episodes from 71,204 unique patients across the four sites. Table 3 compares the characteristics of the 71,204 first episodes to those of the 23,818 repeat episodes. The repeat episodes involved patients who tended to be older (median age 75 vs. 66 years) and had slightly more abnormal physiological measurements. Diagnostic impressions of sepsis (4.4% vs. 3.8%), infection (9.7% vs. 8.8%) and non-specific presentations (41.8% vs. 37.1%) were slightly more common in the repeat attendances.

| First (N = 71,204) | Repeat (N = 23,818) | Total (N = 95,022) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 61.7 (22.3) | 68.8 (19.8) | 63.5 (21.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 66.0 (44.0–81.0) | 75.0 (56.0–84.0) | 69.0 (47.0–82.0) |

| Range | 16.0–106.0 | 16.0–107.0 | 16.0–107.0 |

| Sex | |||

| Missing | 220 | 49 | 269 |

| Female (%) | 37,588 (53.0) | 12,539 (52.8) | 50,127 (52.9) |

| Male (%) | 33,396 (47.0) | 11,230 (47.2) | 44,626 (47.1) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Missing | 29,005 | 9381 | 38,386 |

| White (%) | 40,045 (94.9) | 13,979 (96.8) | 54,024 (95.4) |

| Asian (%) | 968 (2.3) | 253 (1.8) | 1221 (2.2) |

| Black (%) | 397 (0.9) | 69 (0.5) | 466 (0.8) |

| Mixed (%) | 208 (0.5) | 41 (0.3) | 249 (0.4) |

| Other (%) | 581 (1.4) | 95 (0.7) | 676 (1.2) |

| ACVPU | |||

| Missing | 1944 | 688 | 2632 |

| Alert (%) | 63,059 (91.0) | 20,805 (89.9) | 83,864 (90.8) |

| Confusion (%) | 2371 (3.4) | 991 (4.3) | 3362 (3.6) |

| Pain (%) | 890 (1.3) | 282 (1.2) | 1172 (1.3) |

| Unresponsive (%) | 1029 (1.5) | 282 (1.2) | 1311 (1.4) |

| Voice (%) | 1911 (2.8) | 770 (3.3) | 2681 (2.9) |

| GCS | |||

| Mean (SD) | 14.5 (1.7) | 14.4 (1.7) | 14.5 (1.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 15.0 (15.0–15.0) | 15.0 (15.0–15.0) | 15.0 (15.0–15.0) |

| Range | 3.0–15.0 | 3.0–15.0 | 3.0–15.0 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 82.1 (17.4) | 79.9 (17.3) | 81.6 (17.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 82.0 (71.0–93.0) | 79.0 (68.0–90.0) | 81.0 (70.0–92.0) |

| Range | 0.0–197.0 | 0.0–191.0 | 0.0–197.0 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 140.9 (28.1) | 138.7 (27.8) | 140.3 (28.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 139.0 (122.0–157.0) | 137.0 (120.0–155.0) | 138.0 (122.0–157.0) |

| Range | 32.0–285.0 | 36.0–288.0 | 32.0–288.0 |

| Heart rate (beats/minute) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 90.1 (23.2) | 90.3 (22.5) | 90.2 (23.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 88.0 (74.0–104.0) | 88.0 (74.0–104.0) | 88.0 (74.0–104.0) |

| Range | 0.0–220.0 | 0.0–220.0 | 0.0–220.0 |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 95.7 (5.2) | 94.6 (6.0) | 95.4 (5.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 97.0 (95.0–98.0) | 96.0 (94.0–98.0) | 97.0 (95.0–98.0) |

| Range | 10.0–100.0 | 15.0–100.0 | 10.0–100.0 |

| Supplemental oxygen | |||

| Missing | 7433 | 2005 | 9438 |

| No (%) | 60,228 (94.4) | 20,100 (92.1) | 80,328 (93.9) |

| Yes (%) | 3543 (5.6) | 1713 (7.9) | 5256 (6.1) |

| Respiration (breath/minute) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 20.5 (6.4) | 21.4 (6.9) | 20.7 (6.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 18.0 (16.0–22.0) | 20.0 (18.0–24.0) | 18.0 (16.0–22.0) |

| Range | 0.0–98.0 | 0.0–98.0 | 0.0–98.0 |

| Temp (°C) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 37.0 (1.0) | 37.0 (0.9) | 37.0 (1.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 36.9 (36.4–37.4) | 36.9 (36.4–37.4) | 36.9 (36.4–37.4) |

| Range | 26.0–42.0 | 27.0–41.8 | 26.0–42.0 |

| Glucose (mmol/l) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 7.3 (3.4) | 7.5 (3.7) | 7.4 (3.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 6.4 (5.5–7.9) | 6.5 (5.5–8.1) | 6.4 (5.5–7.9) |

| Range | 0.0–49.0 | 0.6–50.0 | 0.0–50.0 |

| Pre-alerted | |||

| No (%) | 65,736 (92.3) | 22,011 (92.4) | 87,747 (92.3) |

| Yes (%) | 5468 (7.7) | 1807 (7.6) | 7275 (7.7) |

| Impression | |||

| 1 – sepsis (%) | 2700 (3.8) | 1045 (4.4) | 3745 (3.9) |

| 2 – infection (%) | 6293 (8.8) | 2321 (9.7) | 8614 (9.1) |

| 3 – non-specific (%) | 26,393 (37.1) | 9962 (41.8) | 36,355 (38.3) |

| 4 – others (%) | 35,818 (50.3) | 10,490 (44.0) | 46,308 (48.7) |

Table 4 shows the characteristics of the 71,204 patients by hospital site. Patients at the larger hospitals (Sheffield and Coventry) tended to be older and more ethnically diverse. Patients transported to Coventry by West Midlands Ambulance Service were more likely to have a diagnostic impression of sepsis (6.5% vs. 2.5–3.6%), infection (21.4% vs. 3.7–5.5%) or non-specific presentations (40.8% vs. 33.9–38.3%), reflecting the potential for paramedics in West Midlands Ambulance Service to record multiple diagnostic impressions.

| DRI (N = 15,825) | NGH (N = 24,815) | RGH (N = 13,222) | UHCW (N = 17,342) | Total (N = 71,204) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 63.1 (21.7) | 60.9 (22.7) | 62.2 (22.0) | 61.2 (22.2) | 61.7 (22.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 68.0 (47.0–81.0) | 65.0 (42.0–80.0) | 67.0 (45.0–81.0) | 65.0 (44.0–80.0) | 66.0 (44.0–81.0) |

| Range | 16.0–105.0 | 16.0–105.0 | 16.0–106.0 | 16.0–105.0 | 16.0–106.0 |

| Sex | |||||

| Missing | 7 | 22 | 6 | 185 | 220 |

| Female (%) | 8564 (54.1) | 13,087 (52.8) | 7233 (54.7) | 8704 (50.7) | 37,588 (53.0) |

| Male (%) | 7254 (45.9) | 11,706 (47.2) | 5983 (45.3) | 8453 (49.3) | 33,396 (47.0) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Missing | 3095 | 12,115 | 4461 | 9334 | 29,005 |

| White (%) | 12,412 (97.5) | 11,931 (93.9) | 8493 (96.9) | 7209 (90.0) | 40,045 (94.9) |

| Asian (%) | 90 (0.7) | 256 (2.0) | 137 (1.6) | 485 (6.1) | 968 (2.3) |

| Black (%) | 43 (0.3) | 127 (1.0) | 16 (0.2) | 211 (2.6) | 397 (0.9) |

| Mixed (%) | 53 (0.4) | 81 (0.6) | 12 (0.1) | 62 (0.8) | 208 (0.5) |

| Other (%) | 132 (1.0) | 305 (2.4) | 103 (1.2) | 41 (0.5) | 581 (1.4) |

| ACVPU | |||||

| Missing | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1941 | 1944 |

| Alert (%) | 14,497 (91.6) | 22,853 (92.1) | 12,166 (92.0) | 13,543 (87.9) | 63,059 (91.0) |

| Confusion (%) | 456 (2.9) | 724 (2.9) | 417 (3.2) | 774 (5.0) | 2371 (3.4) |

| Pain (%) | 189 (1.2) | 298 (1.2) | 124 (0.9) | 279 (1.8) | 890 (1.3) |

| Unresponsive (%) | 196 (1.2) | 298 (1.2) | 164 (1.2) | 371 (2.4) | 1029 (1.5) |

| Voice (%) | 485 (3.1) | 642 (2.6) | 350 (2.6) | 434 (2.8) | 1911 (2.8) |

| GCS | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 14.5 (1.7) | 14.5 (1.6) | 14.5 (1.6) | 14.4 (1.9) | 14.5 (1.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 15.0 (15.0–15.0) | 15.0 (15.0–15.0) | 15.0 (15.0–15.0) | 15.0 (15.0–15.0) | 15.0 (15.0–15.0) |

| Range | 3.0–15.0 | 3.0–15.0 | 3.0–15.0 | 3.0–15.0 | 3.0–15.0 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 83.3 (18.1) | 82.6 (17.4) | 82.7 (17.3) | 80.0 (16.6) | 82.1 (17.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 83.0 (71.0–94.0) | 82.0 (71.0–93.0) | 83.0 (72.0–93.0) | 79.0 (70.0–89.0) | 82.0 (71.0–93.0) |

| Range | 0.0–197.0 | 0.0–195.0 | 0.0–192.0 | 0.0–196.0 | 0.0–197.0 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 142.7 (28.4) | 140.8 (27.1) | 141.3 (27.2) | 139.0 (30.0) | 140.9 (28.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 141.0 (124.0–159.0) | 139.0 (123.0–156.0) | 140.0 (123.0–156.0) | 137.0 (118.0–158.0) | 139.0 (122.0–157.0) |

| Range | 42.0–260.0 | 43.0–285.0 | 48.0–281.0 | 32.0–271.0 | 32.0–285.0 |

| Heart rate (beats/minute) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 90.1 (23.4) | 89.1 (22.3) | 89.4 (22.4) | 92.2 (24.8) | 90.1 (23.2) |

| Median (IQR) | 88.0 (74.0–103.0) | 86.0 (74.0–102.0) | 87.0 (74.0–102.0) | 90.0 (75.0–106.0) | 88.0 (74.0–104.0) |

| Range | 0.0–220.0 | 0.0–218.0 | 0.0–220.0 | 0.0–220.0 | 0.0–220.0 |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 95.5 (5.5) | 95.8 (4.9) | 95.6 (5.1) | 95.9 (5.3) | 95.7 (5.2) |

| Median (IQR) | 97.0 (95.0–98.0) | 97.0 (95.0–98.0) | 97.0 (95.0–98.0) | 97.0 (95.0–99.0) | 97.0 (95.0–98.0) |

| Range | 13.0–100.0 | 10.0–100.0 | 16.0–100.0 | 17.0–100.0 | 10.0–100.0 |

| Supplemental oxygen | |||||

| Missing | 53 | 45 | 29 | 7306 | 7433 |

| No (%) | 14,756 (93.6) | 23,466 (94.7) | 12,473 (94.5) | 9533 (95.0) | 60,228 (94.4) |

| Yes (%) | 1016 (6.4) | 1304 (5.3) | 720 (5.5) | 503 (5.0) | 3543 (5.6) |

| Respiration (breath/minute) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 20.7 (6.4) | 20.1 (6.0) | 20.6 (6.2) | 20.6 (7.1) | 20.5 (6.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 18.0 (18.0–22.0) | 18.0 (16.0–22.0) | 18.0 (18.0–22.0) | 18.0 (16.0–22.0) | 18.0 (16.0–22.0) |

| Range | 0.0–98.0 | 0.0–93.0 | 0.0–96.0 | 0.0–98.0 | 0.0–98.0 |

| Temp (°C) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 37.0 (1.0) | 36.9 (1.0) | 37.0 (1.0) | 37.0 (1.0) | 37.0 (1.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 36.9 (36.4–37.4) | 36.8 (36.4–37.4) | 36.9 (36.4–37.4) | 36.9 (36.4–37.5) | 36.9 (36.4–37.4) |

| Range | 26.4–41.7 | 26.0–41.8 | 32.0–41.8 | 30.1–42.0 | 26.0–42.0 |

| Glucose (mmol/l) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 7.3 (3.4) | 7.2 (3.3) | 7.3 (3.4) | 7.4 (3.6) | 7.3 (3.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 6.4 (5.5–7.9) | 6.3 (5.5–7.8) | 6.4 (5.5–7.9) | 6.4 (5.6–7.9) | 6.4 (5.5–7.9) |

| Range | 0.1–44.0 | 0.5–49.0 | 0.4–46.0 | 0.0–39.5 | 0.0–49.0 |

| Pre-alert | |||||

| No (%) | 14,584 (92.2) | 23,601 (95.1) | 12,036 (91.0) | 15,515 (89.5) | 65,736 (92.3) |

| Yes (%) | 1241 (7.8) | 1214 (4.9) | 1186 (9.0) | 1827 (10.5) | 5468 (7.7) |

| Impression | |||||

| 1 – sepsis (%) | 477 (3.0) | 623 (2.5) | 472 (3.6) | 1128 (6.5) | 2700 (3.8) |

| 2 – infection (%) | 585 (3.7) | 1377 (5.5) | 613 (4.6) | 3717 (21.4) | 6292 (8.8) |

| 3 – non-specific (%) | 6063 (38.3) | 8413 (33.9) | 4836 (36.6) | 7082 (40.8) | 26,394 (37.1) |

| 4 – other (%) | 8700 (55.0) | 14,402 (58.0) | 7301 (55.2) | 5415 (31.2) | 35,818 (50.3) |

Daily rates of prioritised attendances

Tables 5–8 show, for each hospital, the mean (SD) number of attendances per day that would be prioritised according to each strategy using the threshold in the second column and when applied to the paramedic diagnostic impression(s) in the remaining columns. The first row shows the number of attendances prioritised using paramedic diagnostic impression alone. The second row shows the number of attendances that were recorded as being pre-alerted to the ED in 2019.

| Early warning score | Threshold | Impression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sepsis | Sepsis/infection | Sepsis/infection/non-specific | All | ||

| Impression alone | 1.9 (1.3) | 4.2 (2.2) | 28 (6.8) | 59.5 (10.8) | |

| Pre-alerted | 0.9 (1) | 1 (1) | 2.6 (1.7) | 4.7 (2.4) | |

| NEWS2 | 4 | 1.7 (1.2) | 2.9 (1.8) | 10.9 (4) | 15.1 (4.7) |

| NEWS2 | 6 | 1.5 (1.2) | 2.1 (1.5) | 6.7 (2.9) | 8.4 (3.3) |

| qSOFA | 0 | 1.7 (1.3) | 3.2 (1.9) | 15.6 (4.8) | 25.6 (6.4) |

| qSOFA | 1 | 0.8 (0.9) | 1.1 (1.1) | 3.3 (2) | 4.6 (2.3) |

| 90-30-90 | 0 | 1.3 (1.1) | 2 (1.5) | 8.2 (3.2) | 10.8 (3.6) |

| Borelli | 0 | 1.4 (1.1) | 2.1 (1.5) | 6.6 (3) | 8.4 (3.4) |

| CIS | 0 | 1.8 (1.3) | 4 (2.2) | 25.9 (6.5) | 52.2 (9.9) |

| CIS | 4 | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.5 (0.7) | 1.1 (1.1) | 1.4 (1.2) |

| HEWS | 4 | 1.5 (1.2) | 2.3 (1.5) | 7.9 (3.3) | 11.1 (3.9) |

| MEWS | 4 | 1.4 (1.1) | 1.9 (1.4) | 5.2 (2.5) | 7.1 (3) |

| NHS | 0 | 1.5 (1.1) | 2.3 (1.6) | 9.3 (3.5) | 13.5 (4.1) |

| PHANTASi | 0 | 1.4 (1.1) | 2.2 (1.5) | 5.9 (2.8) | 8.1 (3.4) |

| PITSTOP | 0 | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.4 (0.7) |

| PreSAT | 0 | 1.6 (1.2) | 2.8 (1.7) | 10.6 (3.8) | 15.4 (4.8) |

| PRESEP | 3 | 1.6 (1.2) | 2.8 (1.7) | 8.8 (3.6) | 11.3 (4.2) |

| PRESS | 1 | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.9 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.2) |

| PSP | 1 | 1.7 (1.2) | 2.9 (1.8) | 12.6 (4.2) | 22.3 (5.6) |

| REMS | 2 | 1.8 (1.3) | 3.9 (2.1) | 24.9 (6.4) | 49.1 (9.5) |

| RST | 0 | 1.8 (1.3) | 3.4 (1.9) | 15.2 (4.6) | 25.7 (6.3) |

| SAS | 0 | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.1 (0.4) | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.5 (0.7) |

| SEPSIS | 4 | 0.9 (0.9) | 1.1 (1) | 2.4 (1.7) | 2.7 (1.7) |

| STSS | 1 | 1.4 (1.2) | 2.6 (1.7) | 11.7 (4.1) | 17 (4.9) |

| Suffoletto | 0 | 1.4 (1.2) | 2.4 (1.6) | 7 (3.1) | 9.2 (3.6) |

| UK | 0 | 1.7 (1.3) | 3.1 (1.9) | 14.2 (4.6) | 22.6 (5.7) |

| Early warning score | Threshold | Impression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sepsis | Sepsis/infection | Sepsis/infection/non-specific | All | ||

| Impression alone | 2.5 (1.6) | 8 (3.2) | 41 (8.6) | 93.5 (14.7) | |

| Pre-alerted | 1 (1) | 1.3 (1.1) | 2.9 (1.8) | 4.8 (2.3) | |

| NEWS2 | 4 | 2.2 (1.5) | 5.3 (2.6) | 16.1 (5.1) | 22.7 (6.2) |

| NEWS2 | 6 | 1.9 (1.4) | 3.6 (2.1) | 9.6 (3.5) | 12.3 (3.9) |

| qSOFA | 0 | 2.2 (1.5) | 5.9 (2.7) | 23.1 (6.1) | 39.3 (8.2) |

| qSOFA | 1 | 1.2 (1.1) | 2 (1.5) | 5.1 (2.5) | 7.4 (2.9) |

| 90-30-90 | 0 | 1.6 (1.2) | 3.3 (2) | 11.6 (4) | 15.4 (4.7) |

| Borelli | 0 | 1.9 (1.4) | 3.9 (2.2) | 9.5 (3.7) | 12.4 (4.2) |

| CIS | 0 | 2.5 (1.6) | 7.7 (3.1) | 37.3 (8) | 79 (12.9) |

| CIS | 4 | 0.5 (0.8) | 0.6 (0.8) | 1.5 (1.3) | 1.9 (1.4) |

| HEWS | 4 | 1.9 (1.4) | 4 (2.2) | 11.2 (3.9) | 15.7 (4.7) |

| MEWS | 4 | 1.7 (1.3) | 3.3 (2) | 7.3 (3.1) | 10.1 (3.6) |

| NHS | 0 | 1.8 (1.3) | 3.9 (2.2) | 13.3 (4.4) | 19.7 (5.4) |

| PHANTASi | 0 | 1.8 (1.4) | 4.4 (2.3) | 8.9 (3.6) | 12.7 (4.4) |

| PITSTOP | 0 | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.5 (0.7) | 0.6 (0.8) |

| PreSAT | 0 | 2.2 (1.5) | 5.5 (2.7) | 15.2 (5.1) | 23.1 (6.1) |

| PRESEP | 3 | 2.2 (1.5) | 5.6 (2.7) | 12.9 (4.7) | 16.7 (5.3) |

| PRESS | 1 | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.6 (0.8) | 1.5 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.3) |

| PSP | 1 | 2.3 (1.5) | 5.6 (2.7) | 18.5 (5.1) | 35.1 (7.2) |

| REMS | 2 | 2.4 (1.5) | 7.3 (3) | 35.4 (7.8) | 73.3 (12.3) |

| RST | 0 | 2.4 (1.5) | 6.4 (2.8) | 22.6 (6.1) | 40.2 (8) |

| SAS | 0 | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.6 (0.8) | 0.8 (0.9) |

| SEPSIS | 4 | 1.3 (1.2) | 2 (1.5) | 3.6 (2.1) | 4.1 (2.2) |

| STSS | 1 | 2 (1.4) | 4.8 (2.4) | 17 (5.1) | 25.4 (6.4) |

| Suffoletto | 0 | 2 (1.4) | 5 (2.5) | 10.6 (4) | 14.3 (4.6) |

| UK | 0 | 2.2 (1.5) | 5.5 (2.7) | 21.2 (5.8) | 34.7 (7.8) |

| Early warning score | Threshold | Impression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sepsis | Sepsis/infection | Sepsis/infection/non-specific | All | ||

| Impression alone | 1.9 (1.4) | 4.4 (2.3) | 23.8 (5.3) | 51.3 (8.9) | |

| Pre-alerted | 1 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.1) | 2.8 (1.7) | 4.5 (2.2) | |

| NEWS2 | 4 | 1.8 (1.4) | 3.1 (1.9) | 9.2 (3.5) | 12.5 (3.9) |

| NEWS2 | 6 | 1.5 (1.3) | 2.2 (1.6) | 5.7 (2.7) | 6.9 (2.8) |

| qSOFA | 0 | 1.8 (1.4) | 3.4 (2) | 13.7 (4) | 22.5 (5.2) |

| qSOFA | 1 | 0.9 (1) | 1.3 (1.1) | 3.2 (1.9) | 4.3 (2) |

| 90-30-90 | 0 | 1.2 (1.1) | 2 (1.5) | 6.6 (2.9) | 8.6 (3.2) |

| Borelli | 0 | 1.5 (1.2) | 2.3 (1.6) | 5.6 (2.5) | 7.1 (2.7) |

| CIS | 0 | 1.9 (1.4) | 4.3 (2.2) | 21.7 (5.1) | 43.9 (8.1) |

| CIS | 4 | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.8 (1) | 1 (1) |

| HEWS | 4 | 1.5 (1.3) | 2.3 (1.6) | 6.5 (2.8) | 8.8 (3.1) |

| MEWS | 4 | 1.4 (1.2) | 2 (1.5) | 4.3 (2.2) | 5.8 (2.3) |

| NHS | 0 | 1.5 (1.3) | 2.4 (1.7) | 7.7 (3.1) | 11.1 (3.7) |

| PHANTASi | 0 | 1.5 (1.2) | 2.4 (1.6) | 5.1 (2.5) | 6.9 (2.8) |

| PITSTOP | 0 | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.4 (0.6) |

| PreSAT | 0 | 1.7 (1.3) | 3.1 (1.9) | 8.8 (3.3) | 12.9 (3.9) |

| PRESEP | 3 | 1.7 (1.3) | 3 (1.8) | 7.5 (3.1) | 9.5 (3.5) |

| PRESS | 1 | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.8 (0.9) | 1 (1) |

| PSP | 1 | 1.7 (1.3) | 3.1 (1.9) | 11.1 (3.6) | 19.7 (4.8) |

| REMS | 2 | 1.9 (1.4) | 4.1 (2.2) | 20.7 (4.9) | 41 (7.9) |

| RST | 0 | 1.8 (1.4) | 3.6 (2) | 13.1 (3.8) | 22.2 (5.2) |

| SAS | 0 | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.5 (0.6) |

| SEPSIS | 4 | 0.9 (1) | 1.2 (1.1) | 2.1 (1.6) | 2.3 (1.6) |

| STSS | 1 | 1.5 (1.3) | 2.8 (1.8) | 10 (3.5) | 14.6 (4.2) |

| Suffoletto | 0 | 1.6 (1.3) | 2.7 (1.7) | 6.1 (2.7) | 7.9 (3.1) |

| UK | 0 | 1.7 (1.4) | 3.2 (1.9) | 12.3 (3.8) | 19.5 (4.9) |

| Early warning score | Threshold | Impression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sepsis | Sepsis/infection | Sepsis/infection/non-specific | All | ||

| Impression alone | 5 (2.4) | 21.4 (6) | 52.1 (9.5) | 74 (11) | |

| Pre-alerted | 2.5 (1.7) | 3.3 (1.9) | 4.2 (2.2) | 7.6 (2.8) | |

| NEWS2 | 4 | 4.4 (2.3) | 11.6 (4.2) | 18.1 (5.1) | 23.7 (5.8) |

| NEWS2 | 6 | 3.7 (2) | 7.6 (3.1) | 10.3 (3.7) | 12.9 (4) |

| qSOFA | 0 | 4.5 (2.3) | 14.1 (4.7) | 25.9 (6.2) | 34.9 (7) |

| qSOFA | 1 | 2.2 (1.5) | 4 (2.1) | 6 (2.5) | 7.5 (2.8) |

| 90-30-90 | 0 | 3.1 (1.9) | 6.9 (3.1) | 10.6 (3.8) | 13.2 (4.1) |

| Borelli | 0 | 3.4 (2) | 7.1 (3.1) | 9.3 (3.5) | 11.3 (3.8) |

| CIS | 0 | 4.9 (2.4) | 19.7 (5.7) | 44 (8.6) | 63.1 (10.1) |

| CIS | 4 | 0.8 (0.9) | 1.1 (1.1) | 1.4 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.4) |

| HEWS | 4 | 3.7 (2.1) | 8 (3.3) | 11.7 (4) | 15.4 (4.4) |

| MEWS | 4 | 3.4 (1.9) | 6.7 (3) | 9.2 (3.4) | 11.7 (3.6) |

| NHS | 0 | 3.8 (2) | 8.9 (3.5) | 14.6 (4.4) | 19.2 (4.8) |

| PHANTASi | 0 | 3.1 (1.8) | 7.7 (3.2) | 9.8 (3.6) | 11.5 (3.9) |

| PITSTOP | 0 | 0.5 (0.7) | 0.8 (1) | 0.9 (1) | 0.9 (1) |

| PreSAT | 0 | 4.3 (2.1) | 11.8 (4.3) | 17.9 (5.1) | 22 (5.4) |

| PRESEP | 3 | 3.8 (2.1) | 10.2 (4) | 13.2 (4.4) | 14.8 (4.7) |

| PRESS | 1 | 1 (1) | 1.6 (1.4) | 2.1 (1.6) | 2.4 (1.6) |

| PSP | 1 | 4.2 (2.2) | 13 (4.4) | 26.1 (5.8) | 33.7 (6.5) |

| REMS | 2 | 4.8 (2.4) | 18.6 (5.5) | 40.3 (8.2) | 57.4 (9.4) |

| RST | 0 | 4.6 (2.3) | 15 (4.9) | 27.5 (6.4) | 37 (7.2) |

| SAS | 0 | 0.5 (0.7) | 0.7 (0.8) | 1 (1) | 1.1 (1) |

| SEPSIS | 4 | 1.8 (1.4) | 3.1 (1.9) | 3.5 (2.1) | 3.7 (2.1) |

| STSS | 1 | 3.7 (2.1) | 10.5 (3.8) | 16.5 (4.8) | 21.3 (5.4) |

| Suffoletto | 0 | 3.5 (1.9) | 9 (3.6) | 12.5 (4.2) | 13.9 (4.4) |

| UK | 0 | 4.4 (2.3) | 12.7 (4.3) | 22.2 (5.5) | 30.5 (6.3) |

The colours in Tables 5–8 indicate the proportion of eligible attendances that would be prioritised and thus whether the number of prioritised cases would be manageable. Green indicates that < 5% of the mean daily attendances would be prioritised (likely to be manageable), amber indicates that 5–10% would be prioritised (uncertain) and red indicates that more than 10% would be prioritised (unlikely to be manageable).

The mean (SD) number of daily attendances meeting the study inclusion criteria were 93.5 (14.7) at Sheffield Northern General Hospital, 59.5 (10.8) at Doncaster Royal Infirmary, 51.3 (8.9) at Rotherham General Hospital, and 74 (11) at University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire. The proportion of attendances that the ambulance service pre-alerted to the hospital varied from 5.1% (4.8/93.5) at Sheffield Northern General Hospital to 10.3% (7.6/74) at University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire, with around 1 in 5 of the pre-alerted attendances at the Yorkshire hospitals having a diagnostic impression of sepsis, compared to 1 in 3 in the West Midlands.

The proportions of cases in categories 1 and 2 were higher at University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire because paramedics at West Midlands Ambulance Service can select multiple diagnostic impressions whereas paramedics at Yorkshire Ambulance Service can select only one. As a consequence, the index tests would generally result in more attendances being prioritised at University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire than at the Yorkshire hospitals. The combination of an early warning score with a diagnostic impression of sepsis in the West Midlands would result in a similar proportion of attendances being prioritised as the combination of an early warning score with a diagnostic impression of sepsis or infection in Yorkshire.

Most early warning scores operating at their pre-specified threshold would prioritise a substantial proportion of attendances if they were applied to attendances other than just those with a diagnostic impression of sepsis or infection. The exceptions are qSOFA (threshold > 1), the SEPSIS score, the CIS (threshold > 4), the Paramedic Initiated Treatment of Sepsis Targeting Out-of-hospital Patients clinical trial (PITSTOP) rule, the PRESS score and the sepsis alert criteria. It should be noted that the PITSTOP rule and sepsis alert criteria, along with the Prehospital Sepsis Assessment Tool (PreSAT), Robson and Suffoletto criteria, all specify paramedic suspicion of sepsis or infection as a qualifying criterion, so should only be applied to diagnostic categories 1 and 2.

In summary, to avoid prioritising a substantial proportion of cases, most early warning scores would need to be applied only to attendances with a primary diagnostic impression of sepsis or infection, or with sepsis as one of a number of diagnostic impressions, depending upon how the ambulance service records diagnostic impression.

Data linkage to Sheffield Teaching Hospitals National Health Service Trust

National Health Service numbers were available to link ambulance service to hospital data for 14,050/24,955 (56.3%) patients transported to Sheffield Teaching Hospitals. Table 9 compares the characteristics of the patients with NHS numbers available to those without. The patients with NHS numbers were markedly older (median age 71 vs. 55 years). They were more likely to be female (54.7% vs. 53.0%) and white ethnicity (95.7% vs. 91.8%), although these characteristics may reflect their older age. They were more likely to have a diagnostic impression of sepsis (2.9% vs. 2.0%), infection (6.5% vs. 4.3%) or non-specific presentation (35.3% vs. 32.0%). The difference in median age between the linked and unlinked populations was greatest for those in the ‘other’ diagnostic impression category and was not seen in those with a diagnostic impression of sepsis.

| Not linked (N = 10,905) | Linked (N = 14,050) | Total (N = 24,955) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 55.2 (23.3) | 65.3 (21.2) | 60.9 (22.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 55.0 (34.0–76.0) | 71.0 (51.0–82.0) | 65.0 (42.0–80.0) |

| Range | 16.0–102.0 | 16.0–105.0 | 16.0–105.0 |

| Sex | |||

| Missing | 0 | 22 | 22 |

| Female (%) | 5484 (50.3) | 7672 (54.7) | 13,156 (52.8) |

| Male (%) | 5421 (49.7) | 6356 (45.3) | 11,777 (47.2) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Missing | 5290 | 6880 | 12,170 |

| White (%) | 5153 (91.8) | 6860 (95.7) | 12,013 (94.0) |

| Asian (%) | 136 (2.4) | 122 (1.7) | 258 (2.0) |

| Black (%) | 73 (1.3) | 55 (0.8) | 128 (1.0) |

| Mixed (%) | 49 (0.9) | 32 (0.4) | 81 (0.6) |

| Other (%) | 204 (3.6) | 101 (1.4) | 305 (2.4) |

| ACVPU | |||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Alert (%) | 9754 (89.4) | 13,232 (94.2) | 22,986 (92.1) |

| Confusion (%) | 341 (3.1) | 387 (2.8) | 728 (2.9) |

| Pain (%) | 192 (1.8) | 107 (0.8) | 299 (1.2) |

| Unresponsive (%) | 232 (2.1) | 67 (0.5) | 299 (1.2) |

| Voice (%) | 386 (3.5) | 257 (1.8) | 643 (2.6) |

| GCS | |||

| Mean (SD) | 14.4 (2.0) | 14.7 (1.2) | 14.5 (1.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 15.0 (15.0–15.0) | 15.0 (15.0–15.0) | 15.0 (15.0–15.0) |

| Range | 3.0–15.0 | 3.0–15.0 | 3.0–15.0 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 83.1 (17.5) | 82.1 (17.2) | 82.6 (17.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 83.0 (72.0–94.0) | 82.0 (71.0–93.0) | 82.0 (71.0–93.0) |

| Range | 0.0–190.0 | 5.0–195.0 | 0.0–195.0 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 139.0 (26.5) | 142.1 (27.4) | 140.8 (27.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 138.0 (122.0–153.0) | 140.0 (124.0–158.0) | 139.0 (123.0–156.0) |

| Range | 53.0–257.0 | 43.0–285.0 | 43.0–285.0 |

| Heart rate (beats/minute) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 89.5 (22.8) | 88.7 (21.9) | 89.1 (22.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 87.0 (74.0–103.0) | 86.0 (73.0–102.0) | 86.0 (74.0–102.0) |

| Range | 0.0–218.0 | 0.0–216.0 | 0.0–218.0 |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 96.0 (4.9) | 95.6 (4.9) | 95.8 (4.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 97.0 (95.0–98.0) | 97.0 (95.0–98.0) | 97.0 (95.0–98.0) |

| Range | 18.0–100.0 | 10.0–100.0 | 10.0–100.0 |

| Supplemental oxygen | |||

| Missing | 18 | 27 | 45 |

| No (%) | 10,345 (95.0) | 13,252 (94.5) | 23,597 (94.7) |

| Yes (%) | 542 (5.0) | 771 (5.5) | 1313 (5.3) |

| Respiration (breath/minute) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 19.7 (6.0) | 20.5 (6.1) | 20.1 (6.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 18.0 (16.0–20.0) | 18.0 (16.0–22.0) | 18.0 (16.0–22.0) |

| Range | 0.0–93.0 | 0.0–91.0 | 0.0–93.0 |

| Temp (°C) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 36.8 (1.0) | 37.0 (1.0) | 36.9 (1.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 36.8 (36.2–37.3) | 36.9 (36.4–37.4) | 36.8 (36.4–37.4) |

| Range | 26.0–41.3 | 27.1–41.8 | 26.0–41.8 |

| Glucose (mmol/l) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 7.1 (3.2) | 7.4 (3.4) | 7.2 (3.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 6.2 (5.4–7.6) | 6.4 (5.5–8.0) | 6.3 (5.5–7.8) |

| Range | 0.5–36.6 | 0.9–49.0 | 0.5–49.0 |

| Pre-alerted | |||

| No (%) | 10,307 (94.5) | 13,419 (95.5) | 23,726 (95.1) |

| Yes (%) | 598 (5.5) | 631 (4.5) | 1229 (4.9) |

| Impression | |||

| 1 – sepsis (%) | 222 (2.0) | 407 (2.9) | 629 (2.5) |

| 2 – infection (%) | 471 (4.3) | 912 (6.5) | 1383 (5.5) |

| 3 – non-specific (%) | 3494 (32.0) | 4962 (35.3) | 8456 (33.9) |

| 4 – other (%) | 6718 (61.6) | 7769 (55.3) | 14,487 (58.1) |

| Median (IQR) age by impression | |||

| 1 – sepsis | 76.5 (60.2–84.0) | 75.0 (63.0–83.0) | 75.0 (62.0–83.0) |

| 2 – infection | 71.0 (47.0–82.0) | 76.0 (62.0–84.0) | 74.0 (57.0–83.0) |

| 3 – non-specific | 63.0 (41.0–79.0) | 74.0 (57.0–83.0) | 71.0 (50.0–82.0) |

| 4 – other | 50.0 (31.0–72.8) | 67.0 (45.0–81.0) | 58.0 (37.0–78.0) |

The Scientific Computing department of Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust identified a hospital admission or ED attendance within 48 hours for 12,870 of the 14,050 first episodes with an NHS number transported to the Northern General Hospital (91.6%). The remaining episodes comprised 431 (3.1%) with no data returned for the NHS number and 749 (5.3%) with no admission or attendance within 48 hours. Some 8260 (64.1%) had a hospital admission, of whom 275 (3.3%) had no primary diagnosis code and 347 (4.2%) had no secondary code. Some 10,964 (85.2%) had an ED attendance, of whom 14 (0.1%) had no ED code.

Overall, 684 episodes had a primary or secondary admission diagnosis of sepsis or an ED diagnosis of septicaemia or neutropenic sepsis, and were screened by the research nurses. Of these, 594 had a primary or secondary admission diagnosis of sepsis (315 primary, 322 secondary, 43 both) and 160 had an ED diagnosis of septicaemia or neutropenic sepsis (70 also has an admission primary or secondary diagnosis of sepsis, 90 did not).

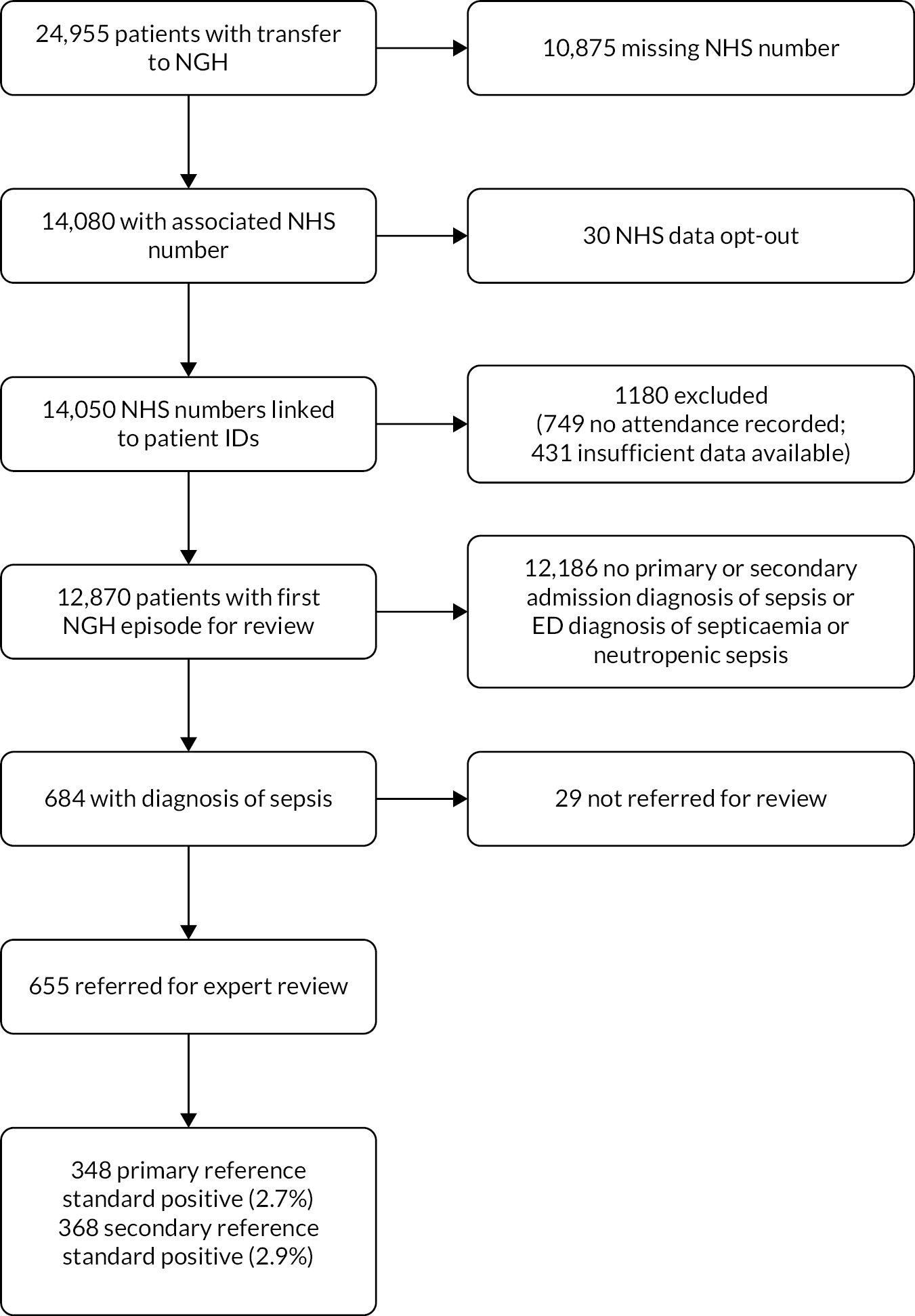

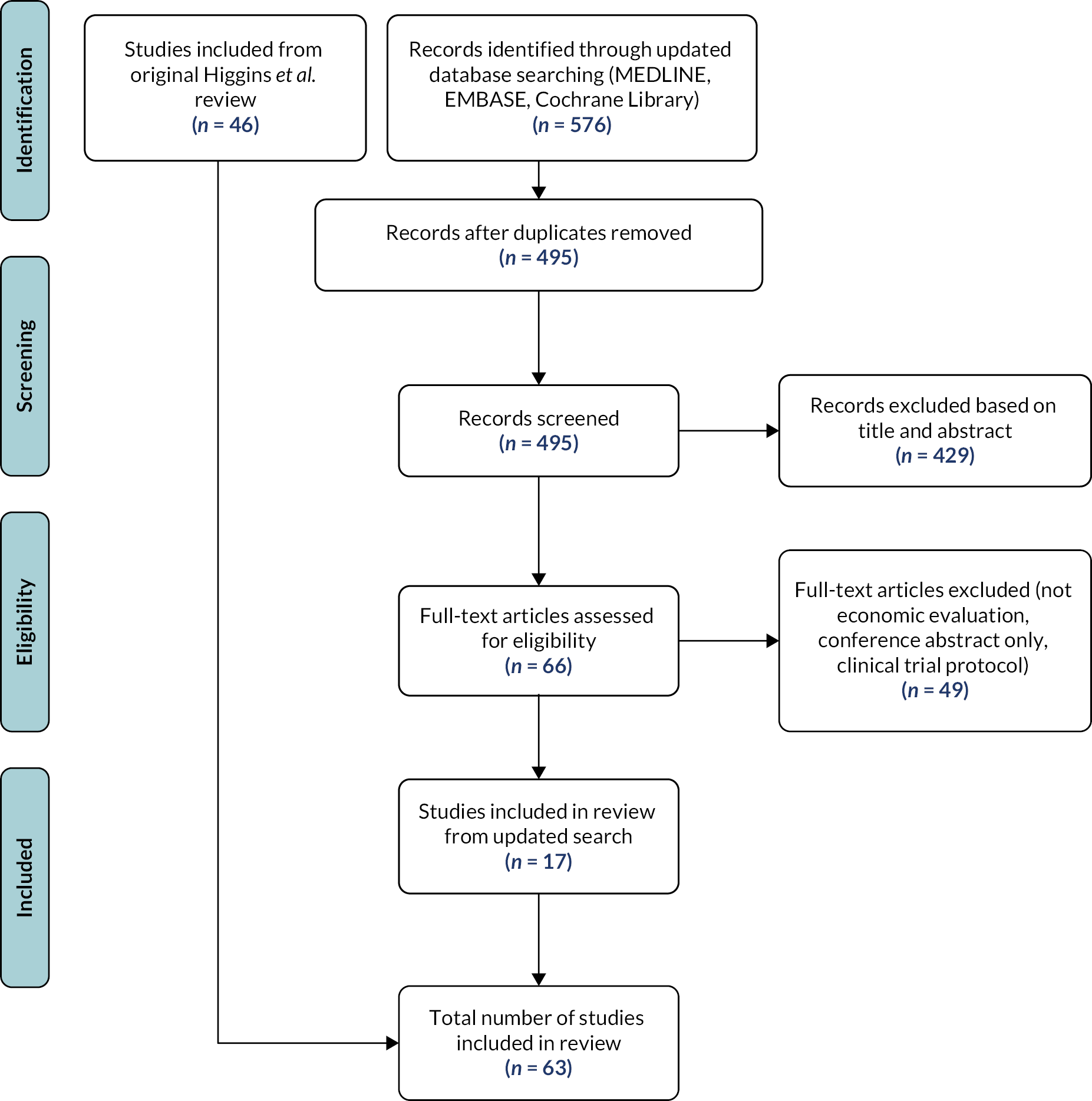

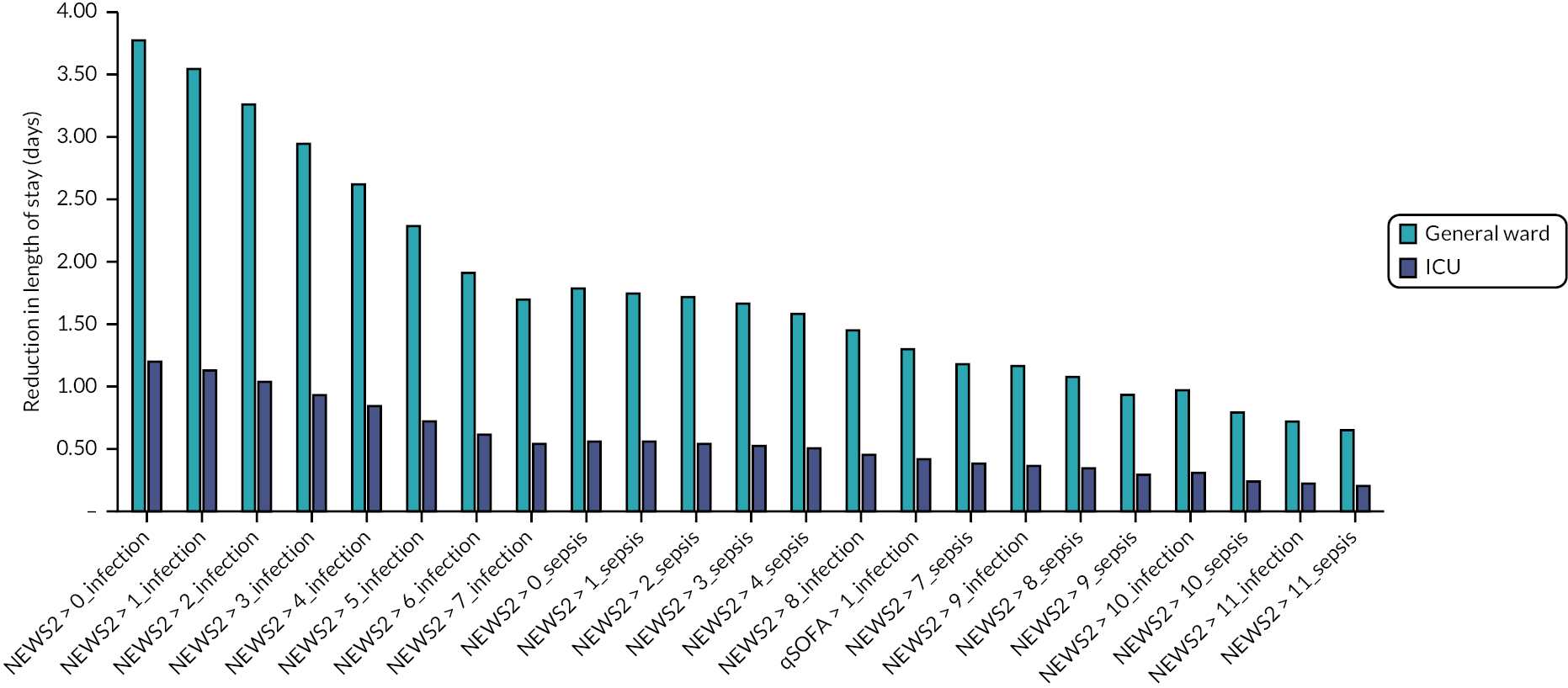

The research nurses referred 655/684 (95.8%) for expert review. The experts judged that 368/655 (56.2%) episodes met the sepsis-3 definition and 348/368 (94.6%) of these received treatment for sepsis. Therefore, out of the 12,870 episodes that were linked with hospital attendance or admission, 684 (5.3%) had a diagnostic code for sepsis, 655 (5.1%) had evidence of sepsis diagnosis or treatment in their ED or admission records, 368 (2.9%) met the secondary (diagnosis) reference standard and 348 (2.7%) met the primary (treatment) reference standard. Figure 1 summarises the flow of cases to create the diagnostic accuracy cohort.

FIGURE 1.

Participant flow to create the Sheffield diagnostic accuracy cohort. NGH, Northern General Hospital.

Adjudication of the reference standard

Table 10 shows the agreement between the two doctors adjudicating the reference standard. Agreement was very good on the two key judgements of whether the case met the sepsis-3 criteria and whether treatment for sepsis was given. Agreement was not as good on whether there was evidence of infection, but the cases in which there was disagreement tended to be those in which the doctors agreed that the SOFA score criterion was not met, so they did not affect overall judgement on the sepsis-3 definition.

| Assessment | Doctor 1 (%) | Doctor 2 (%) | Consensus (%) | Kappa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evidence of infection | 86.0 | 87.6 | 84.7 | 0.62 (0.53 to 0.71) |

| SOFA score 2 + worse than normal | 60.2 | 61.1 | 60.0 | 0.87 (0.83 to 0.91) |

| Patient meets sepsis-3 criteria | 56.0 | 55.0 | 56.2 | 0.89 (0.85 to 0.92) |

| Treatment for sepsis given | 52.5 | 51.5 | 53.3 | 0.87 (0.83 to 0.91) |

There was radiological evidence of infection in 175/348 (50.1%) cases with the primary reference standard, microbiological evidence of infection 171 (49.0%) and other evidence of infection in 328 (94.0%). The site of suspected infection was the chest in 155 (44.4%) urine in 78 (22.3%), biliary in 43 (12.3%), abdominal in 16 (4.6%), skin in 25 (7.2%), other in 6 (1.7%) and unknown in 26 (7.4%). They had a mean clinical frailty score of 5.6 (median 6.0, range 2.0–9.0; 3 missing) and a mean SOFA score of 3.9 (median 3.0, range 2.0 to 14.0; 13 missing). They included 138 (39.5%) who had a Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation decision recorded, of whom 102 (29.2%) were pre-existing and 36 (10.3%) were made on attendance. Some 28 (8.0%) were admitted to critical care and 261 (74.8%) survived to hospital discharge or 30 days after attendance, whichever was sooner.

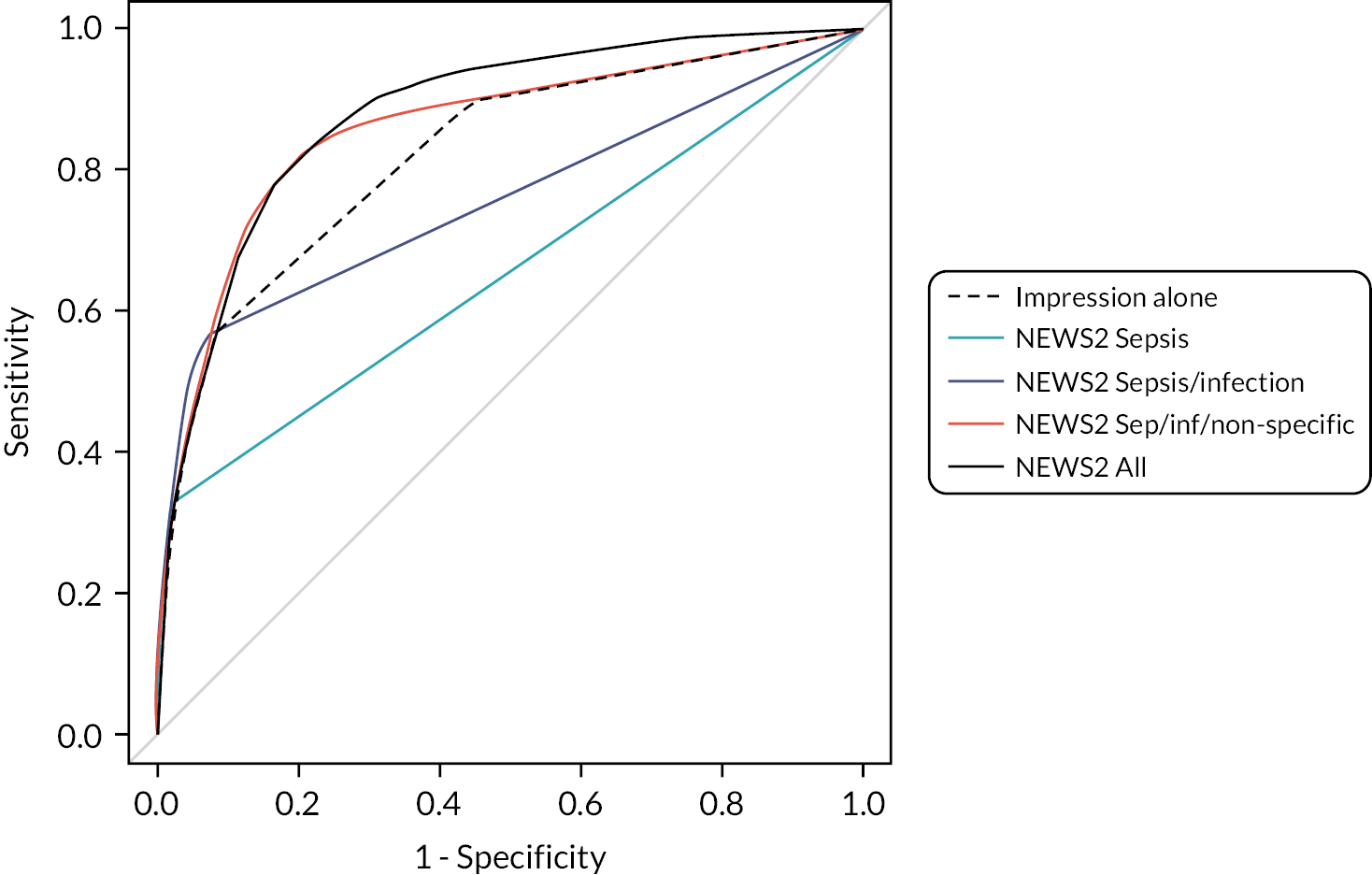

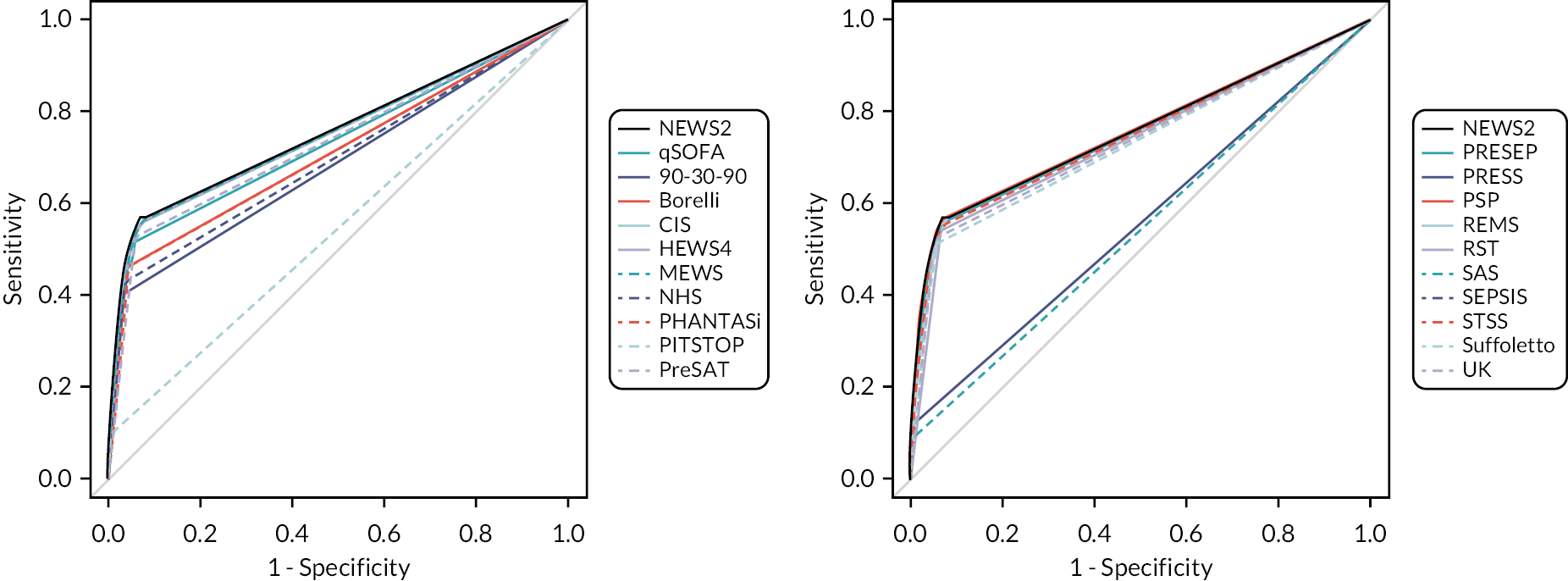

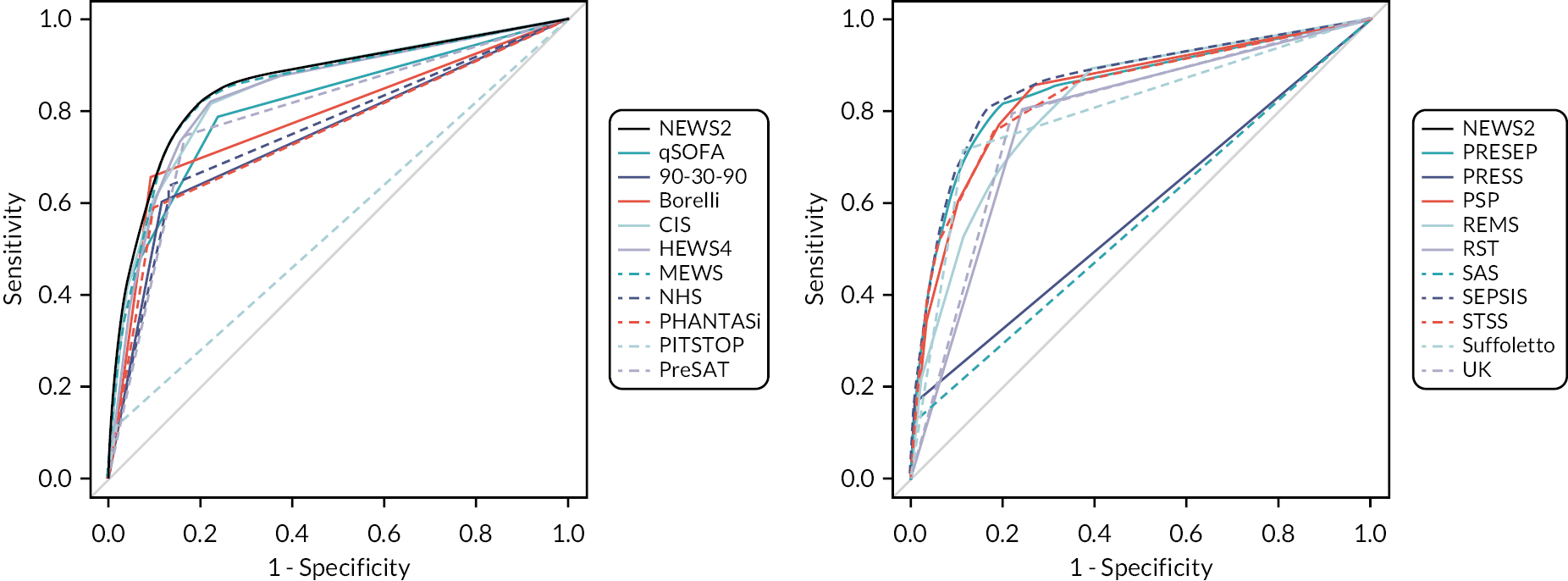

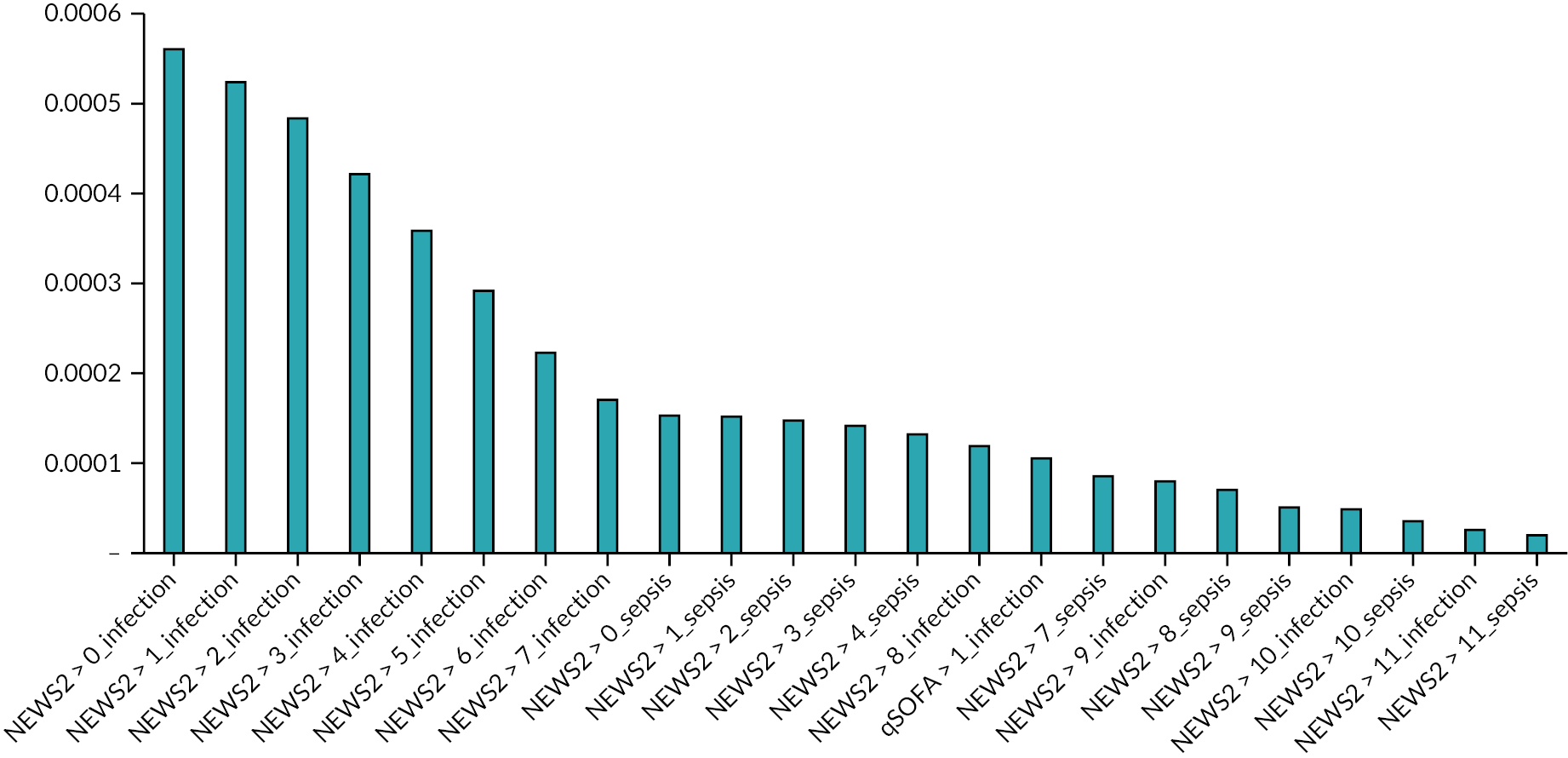

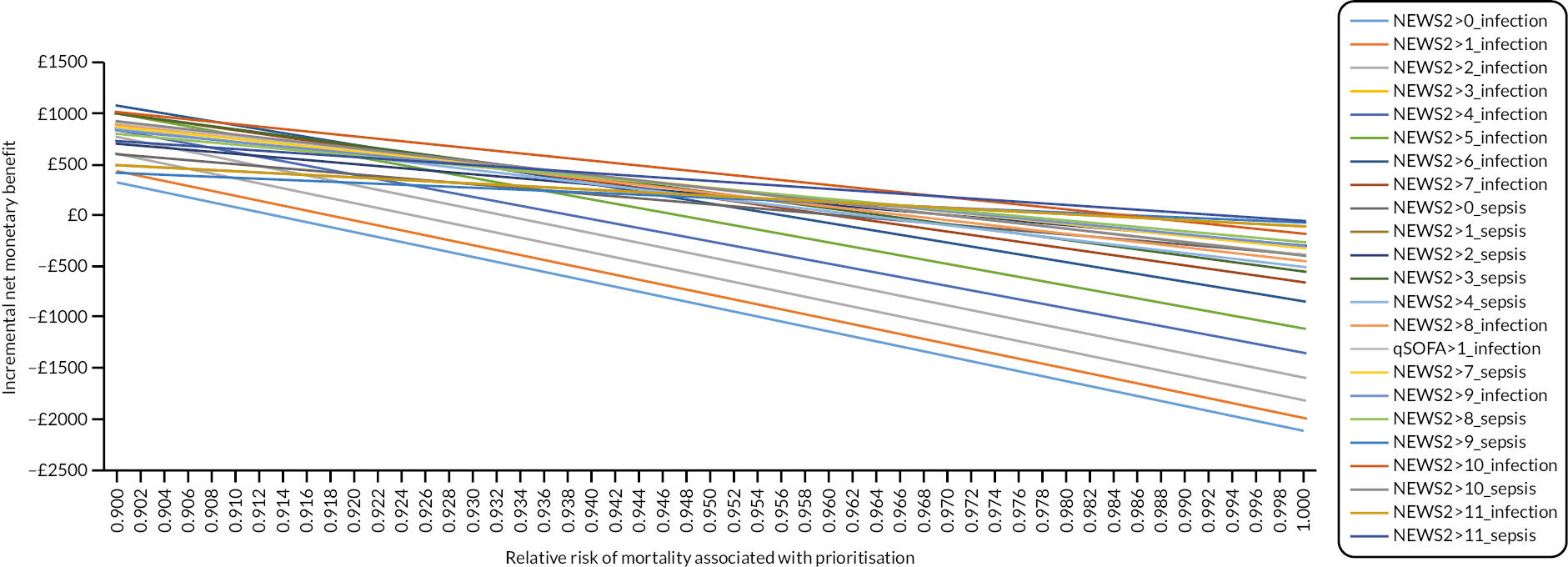

Accuracy for the primary (treatment) reference standard