Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number 16/82/01. The contractual start date was in November 2017. The draft manuscript began editorial review in March 2022 and was accepted for publication in November 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Bugge et al. This work was produced by Bugge et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Bugge et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background and current evidence base

Pelvic organ prolapse

Pelvic organ prolapse (hereafter prolapse) is the descent of some, or all, of the female pelvic organs from their usual position in the pelvis into the vagina. 1 Prolapse is common, with one UK survey identifying that 8.4% of community-dwelling women report a vaginal lump or bulge2 and up to 50% of women reported to have prolapse on examination. 3 The prevalence of prolapse increases with age and, with the UK population of older adults increasing, it is anticipated that the prevalence of prolapse will also increase. 4

Two large cohort studies identify that prolapse has a multifactorial aetiology. 5,6 Factors that predict prolapse include pregnancy, vaginal delivery, hereditary factors, ageing, menopause, and factors associated with chronically raised intra-abdominal pressure (caused by, e.g., obesity or heavy lifting). 5,7

Women report symptoms of ‘something coming down’ in their vagina, a dragging sensation in their vagina, a bulge coming down from their vagina, and pelvic and back pain. 1 The movement of the pelvic organs into the vagina can also cause urinary, bowel and sexual problems. 1 Women’s quality of life, body image and ability to function in their day-to-day life are negatively affected by their symptoms in general and the extent to which those symptoms are bothersome. 8–11

Current treatment options for pelvic organ prolapse

Women with prolapse can be treated with surgical or conservative options. Approximately 9.5% of women will undergo surgery for prolapse in their lifetime. 12–14 One study estimated the cost of any prolapse surgery in England, in 2005, as €81,030,907. 15

There are several conservative treatment options: lifestyle advice, pelvic floor muscle training, vaginal lubricants (hormonal and non-hormonal) and vaginal pessary use. Lifestyle interventions include features such as weight management or physical activity, each of which has minimal evidence of effect. 16,17 Pelvic floor muscle training has been shown to be effective across several clinical trials. 18,19 Local oestrogen as a treatment for prolapse may need further evidence to guide practice. 20

Few clinical trials have assessed the effectiveness of vaginal pessaries. 1 However, two-thirds of women will opt to try a vaginal pessary when it is offered. 21 The largest UK-based pessary study reported that 86% of women who successfully retain their pessary at 4 weeks will continue to use a pessary at 5 years. 22 However, other studies have reported lower continuation rates, for example 62.1% among women aged 65–74 years and 37.8% among those aged ≥ 75 at 5 years. 23 Reasons for pessary discontinuation include development of complications, dislike of pessary changes (insertion or removal) and inconvenience of attending appointments. 24–27

Care pathways for women who use a vaginal pessary as treatment for prolapse

Vaginal pessaries are a common, and recommended, treatment option in the UK NHS. 3,28 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance recommends that a woman be offered 6-monthly appointments if she is at risk of complications that may make it ‘difficult for them to manage their ongoing pessary care’ (recommendation 1.7.9). 3 The NICE guidance does not offer clear recommendations on self-management; however, joint guidance from the United Kingdom Continence Society and Pelvic, Obstetric and Gynaecological Physiotherapy recommends that women are offered self-management where that option is available. 29

A UK multiprofessional survey found that only 17% of clinicians offered their patients the option of self-managing their pessary, with most pessary care being delivered in clinics. 30 This is a difference in practice from North America, where self-management is offered more routinely. 31 Clinic-based care therefore seems to be the most common way of delivering pessary care in the UK, but alternative models of care delivery do exist.

Evidence for the effectiveness of self-management of vaginal pessaries for prolapse

There are no published trials to date comparing the effectiveness of pessary self-management with that of clinic-based care. 32 One small (n = 88), non-randomised study assessed self-management of vaginal pessaries;33 this study reported gains from self-management, in that women reported higher levels of convenience, ability to access help, support and comfort than those attending clinic. 33 A few observational studies have addressed various features of self-management. For example, Manonai et al. 34 undertook a chart review and found that self-management was a strong predictor of pessary continuation for women in Thailand at 3 years. The observational studies suggest that self-management may be a viable treatment option, but self-management effectiveness has not been tested.

Proposed mechanism of action for why self-management might improve quality of life for women with prolapse

The treatment of prolapse with self-care pessary (TOPSY) trial was developed prior to the publication of the 2021 complex interventions framework35 and therefore draws on the 2008 framework36 and the 2015 process evaluation guidance. 37 We will therefore refer to the mechanism of action of the intervention as opposed to the programme theory.

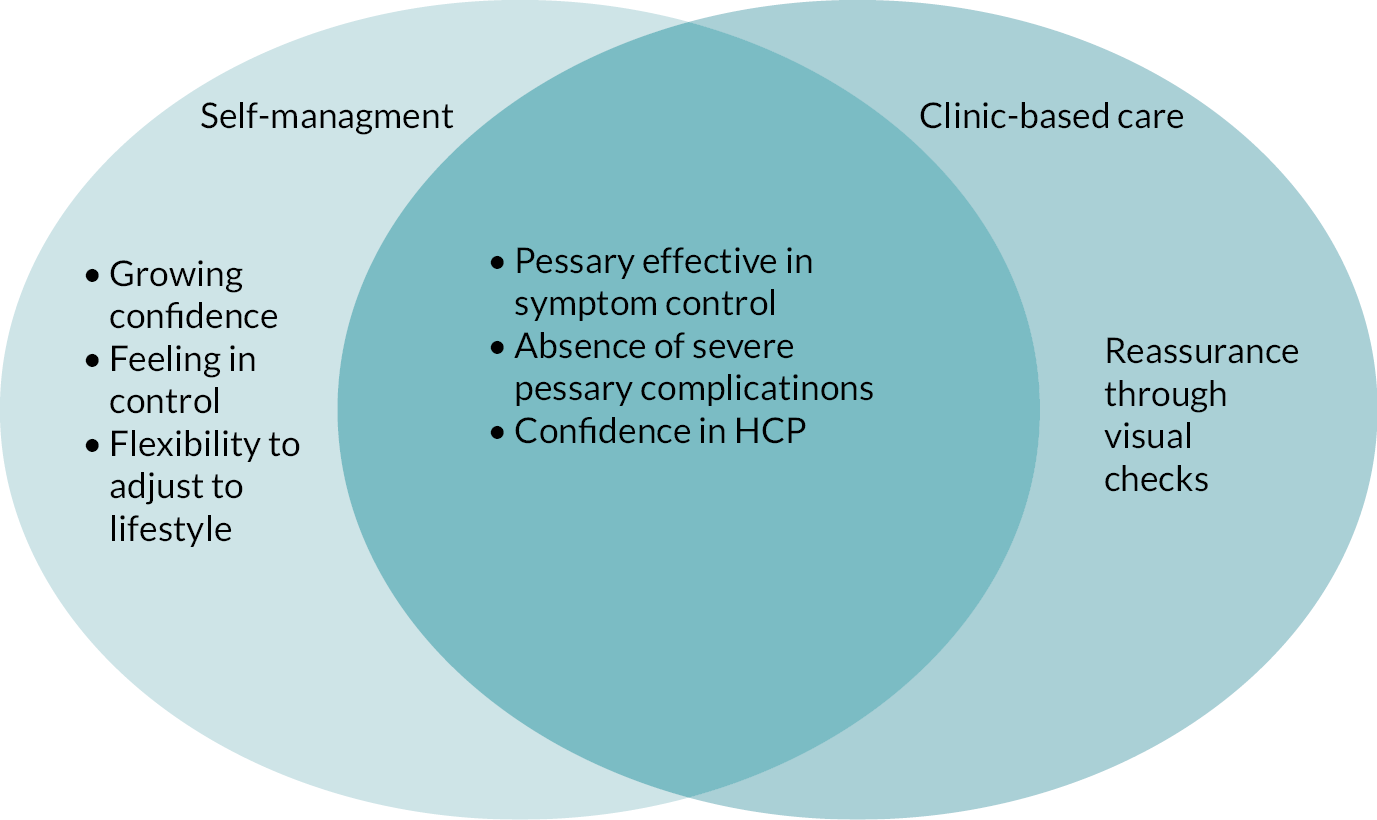

The mechanism of action of the TOPSY self-management intervention is based within self-efficacy theory38 and self-management theory. 39 Self-efficacy has been argued to be the mechanism through which self-management achieves its goals. 39,40 Self-efficacy focuses on an individual’s beliefs in their abilities to achieve goals. 38 Previous service evaluation has suggested that women who self-manage may feel more in control of managing their prolapse than those who receive clinic-based care. 33 Self-management theory posits that three tasks need to be achieved for individuals to self-manage: medical management of the condition, role management and emotional management. 39 Based within these theoretical constructs it was therefore hypothesised that self-management of a vaginal pessary will lead to improved quality of life for women with prolapse because support at service and professional levels, receipt of information and self-management support will lead to women becoming more confident (self-efficacious) about their pessary management; will improve their understanding of and confidence in their role to self-manage; and will enhance their emotional capacity and confidence to cope with their pessary such that their condition-specific quality of life will be improved more than that of those who receive clinic-based care. The details of the intervention are presented in Chapter 2.

Rationale for the research

It is unclear if self-managing a vaginal pessary, rather than receiving care in a clinic, would improve women’s quality of life. Data from non-pelvic health and pelvic health observational studies suggest that self-management interventions have the potential to improve quality of life. Thus, a robust comparison of a theoretically developed self-management intervention with clinic-based care is imperative to understand if alternative clinical models of pelvic health delivery can support better outcomes for women.

Aims and objectives

This research aims to answer the following research questions (RQs):

-

What is the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of self-management of vaginal pessaries to treat pelvic organ prolapse, compared with clinic-based pessary care, on condition-specific quality of life? (RQ1).

-

What are the barriers to and facilitators of intervention acceptability, intervention effectiveness, fidelity to delivery, and adherence for women treated with vaginal pessary and the healthcare professionals (HCPs) who treat them, and how does this differ between randomised groups? (RQ2).

The specific objectives are:

-

to undertake a parallel-group, multicentre, individual randomised controlled trial to test for the superiority of pessary self-management compared with clinic-based pessary care in terms of women’s condition-specific quality of life

-

to undertake an internal pilot study to ensure that the trial can recruit, randomise and retain sufficient numbers of participants while delivering the intervention as planned

-

to undertake a process evaluation in parallel with the trial to maximise recruitment; assess eligible but non-randomised women; understand women’s experience and acceptability of the intervention; assess adherence to allocated trial group; describe fidelity to intervention delivery; and identify contextual factors that may interact with intervention effectiveness

-

to undertake an economic evaluation to establish whether pessary self-management is cost-effective compared with clinic-based pessary care.

The structure of the report

Chapter 2 outlines the study design. It is split into three sections outlining the three component parts of the study: the trial, the process evaluation and the economic evaluation. The pilot study was reported previously and therefore is not included in this report, but it is included as part of the Project Documentation. 41 This Project Documentation, which we refer to throughout this report, is listed in Appendix 1 and available to view on the award website41 [https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/16/82/01 (accessed June 2022)]. Chapters 3–5 present the findings of the trial, process evaluation and cost-effectiveness analysis, respectively. Chapter 6 brings some key points from across the three components together in a synthesis, and Chapter 7 presents the discussion.

Chapter 2 Study design and methods

Sections of this chapter have been reproduced from the TOPSY protocol papers published by the same authorship group,42,43 published under licence CC-BY-4.0, or by re-use of materials available on the project website and listed in Appendix 1.

The design and methods are explained for each part of the TOPSY study: the randomised controlled trial, the process evaluation and the cost-effectiveness evaluation. Appendix 2 is a study flow diagram that provides an overview of the study. Published protocols are available for the trial and cost-effectiveness evaluation42 and process evaluation. 43 The funder-approved protocol is available on the project website. 41

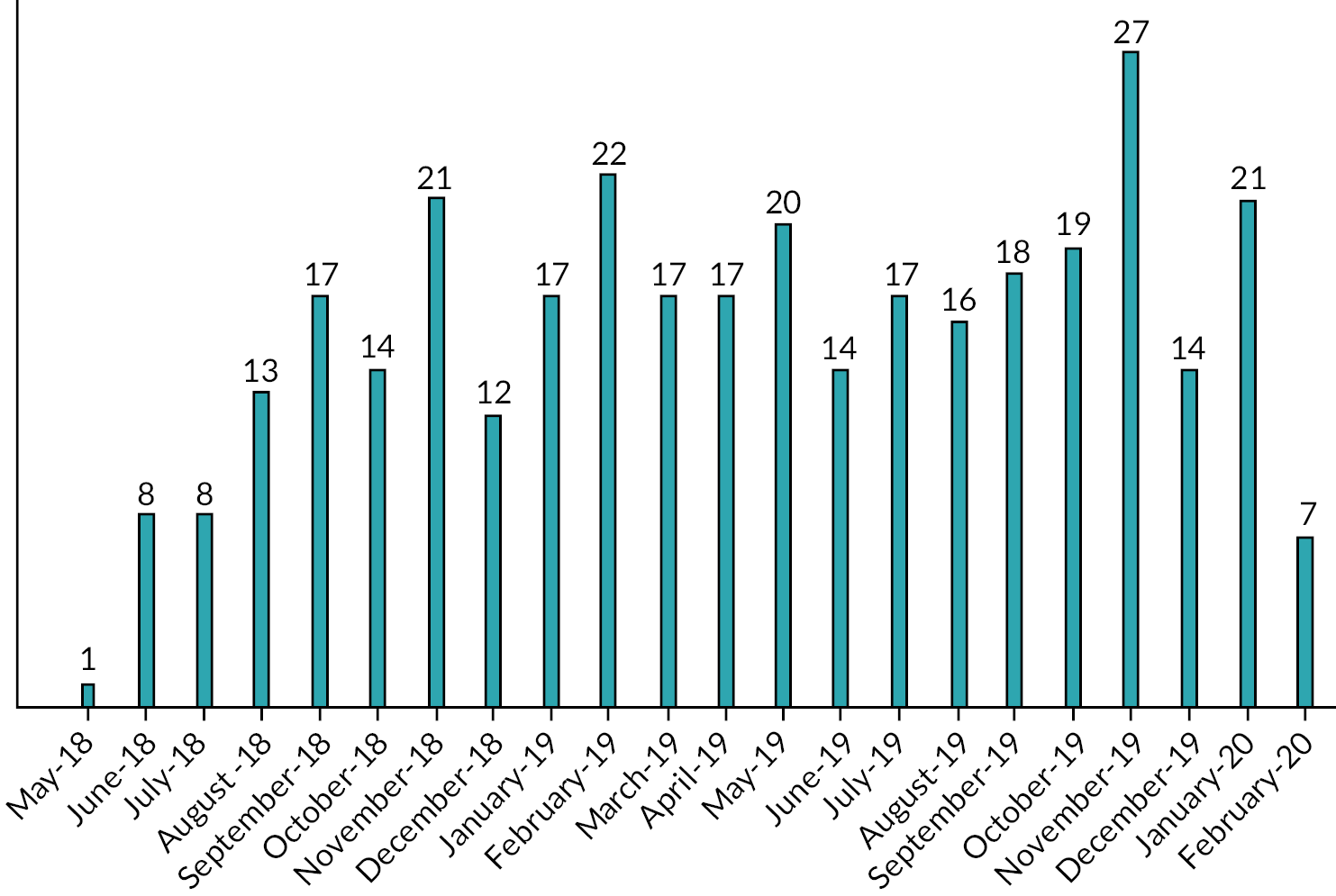

Internal pilot study

The internal pilot study was undertaken to ensure that the trial could recruit, randomise and retain sufficient numbers of participants while delivering the intervention as planned. Stop/go criteria were applied that focused on recruitment and retention. Both of the pilot study targets, namely to recruit 63 women across six centres over 6 months and for 60% of those in the self-management group to be self-managing at the 2-week follow-up telephone call, were achieved. The study therefore continued as planned.

The internal pilot study findings were reported to the funder in January 2019. That report is available as part of the Project Documentation on the project website. 41 Data from non-randomised women heavily influenced our understanding of recruitment processes and their acceptability, and these are reported in detail in the pilot study report. Participant data gathered in the pilot study were the same as the data gathered in the main trial, process evaluation and cost-effectiveness analysis. As a result, the pilot study used the same methods reported here for all parts of the study, and all pilot study data are included in the analysis presented in this report.

The treatment of prolapse with self-care pessary trial

The trial is reported following guidance from the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT)44 and the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR). 45

Design

The TOPSY trial was designed to compare vaginal pessary self-management with clinic-based pessary care for pelvic organ prolapse in order to assess improvement in women’s quality of life. 42 It included a multicentre superiority randomised controlled trial comparing two parallel treatment groups: pessary self-management and clinic-based pessary care (the results can be found in Chapter 3).

Recruitment to the trial was completed on 6 February 2020, before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Follow-up procedures amended due to the pandemic are detailed in this chapter and included in a COVID-19 annex in the funder-approved protocol.

Participants and setting

The trial recruited women who used a vaginal pessary for the management of pelvic organ prolapse from 21 UK hospital-based centres (see Appendix 3, Table 36).

Inclusion criteria

Women were eligible for inclusion if they:

-

were aged ≥ 18 years

-

were using a pessary of any type/material (except shelf, Gellhorn or cube pessaries)

-

had retained the pessary for at least 2 weeks.

Exclusion criteria

Women were ineligible if they:

-

had limited manual dexterity that would affect their ability to remove and replace their pessary

-

were judged by their healthcare team to have a cognitive deficit such that it was not possible for them to provide informed consent or self-manage

-

were pregnant

-

had insufficient understanding of the English language (the self-management teaching was only available in English).

Recruitment procedure

To identify potential participants, local centre staff reviewed patient notes, clinic lists and caseloads to identify women who were currently using a pessary and were suitable to be approached. In addition, women were identified at appointments when attending for pessary review (existing users) or being fitted with a pessary for the first time (new users). If a woman had previously used a pessary but was having a break in pessary use, she was classed as an existing user, as it was believed that her experience would mean she had existing knowledge of pessary use. Women who learned about the TOPSY study themselves (by the website, posters, word of mouth) could approach their centre or the trial office to enquire about participation.

Women were provided with a recruitment pack (either given in person or sent by post) containing an introductory letter, a participant information leaflet, an expression of interest form and a reply-paid envelope. Once women had made their decision regarding participation, they returned the expression of interest form to the local clinical team. On receiving a positive expression of interest form, a member of the local clinical team discussed the study further with the woman in question and screened her for eligibility.

If the woman was a new pessary user (had used a pessary for ≤ 3 months), eligibility screening included a telephone call to confirm that the pessary had been retained for at least 2 weeks. If not, and the woman remained interested in participating, eligibility was reassessed once the pessary had been retained for 2 weeks.

Consent

If a woman was eligible and willing to take part, she attended a baseline clinic appointment where she provided written, informed consent for randomisation. The trial consent form asked participants if they were willing to be contacted about taking part in interviews for the process evaluation, and if they were willing to have their self-management teaching session or 2-week telephone call digitally recorded. They were also asked if they could be contacted about future research.

Women were informed of their right to withdraw at any time from all or part of the study. Any change to women’s participation was recorded in a study change of status form. Women randomised to self-management could opt to change to clinic-based care, and their reasons for choosing to do this were recorded. A woman randomised to clinic-based care could cross over to self-management only if she received formal TOPSY training and was no longer on a regular clinic-based pathway. If a woman discontinued pessary use, she could remain in the study and continue with the data collection elements of the research.

Participant retention

Active measures to minimise loss to follow-up of participants included:

-

Recording women’s e-mail addresses and mobile phone numbers at the outset, their preferred method of contact (for follow-up) and their preferred method of completing questionnaires. Questionnaires could be completed online (via an e-mail link) or on paper and returned by post.

-

Any participant who did not return their questionnaires within 3 weeks was sent a maximum of three reminders, the first two of which were via the participant’s preferred method. The third reminder was a telephone call in which either the researcher reminded the participant to complete and return the questionnaire or the questionnaire was completed during the call.

Response rates to the participant-completed questionnaires were monitored closely to ensure that they remained above 80%.

Randomisation, concealment and blinding

The trial was supported by the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials (CHaRT), a fully registered UK Clinical Research Network clinical trials unit in the Health Services Research Unit, University of Aberdeen. CHaRT developed an internet-based data management system and remote automated computerised randomisation system for the trial.

After informed consent was obtained from a woman, the local clinical staff entered the required information into the data management system to remotely generate the participant’s group allocation. The centralised randomisation of participants after enrolment ensured allocation concealment. The randomisation system assigned women to one of the two trial groups, with an even allocation ratio and naive minimisation by age (< 65/≥ 65 years), pessary user type (new user/existing user) and centre.

Due to the nature of the trial interventions, the trial group to which women were allocated could not be masked from the participants or the centre staff who provided treatment and assessed outcomes after randomisation, and therefore blinding was not possible.

Intervention

Self-management

The self-management of pessary intervention was developed using the Medical Research Council complex intervention framework,36 normalisation process theory46 and self-management theory,39 with the aim of boosting self-efficacy guided by the tasks and skills described by Lorig and Hollman39 as necessary to self-manage a health condition. No previous trials of self-management of pessary had been identified and only one paper outlining a self-management intervention was found. 33 Therefore, informal consensus methodology was used. A draft protocol for pessary self-management support was created by two clinical co-applicants drawing on the sole paper identified during the literature search33 and their own clinical practice. This was subsequently reviewed by clinical and pessary user co-applicants. Feedback was received and reviewed by the co-applicants and changes made accordingly. The protocol was changed to reflect feedback about the language used when discussing the correct positioning of the pessary.

The self-management support documentation was then reviewed by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Women’s Voices panel. Further amendments were made to ensure that the content offered pragmatic and realistic self-management advice that met women’s information needs. This included the addition of further illustrations and details about pessary insertion and removal.

To support a woman to achieve the three tasks needed for self-management, the intervention was directed at three levels:

-

at a service level to facilitate a supportive culture for a self-management treatment pathway

-

at a professional level to ensure that staff had the necessary self-management teaching and support skills

-

at an individual woman level to ensure that women could achieve the necessary tasks to self-manage.

As many different health professional groups deliver pessary care in the UK, a pragmatic approach was taken to who delivered the intervention based on pessary management practice at the hospital or clinic site to ensure that the intervention was only delivered by a HCP who already delivered pessary care as part of their role. This included doctors, nurses (bands 5–8), and physiotherapists.

A clinical co-applicant delivered intervention delivery training before recruitment opened at all sites. The majority of the training was completed face to face. In a few instances, the training was delivered remotely when either a staff member was absent from the initial site initiation visit or a new site staff member came on board during the recruitment phase and needed to be trained to deliver the intervention at the site. The training presentation covered pessary self-management, each aspect of the intervention, why it was necessary and the information to be included. A reference training manual was also provided, which specified the key components of the self-management intervention, facilitating standardisation of the self-management intervention across all centres. During the site visit, the TOPSY team ensured that the intervention was compatible with how pessary self-management was currently taught (if applicable) and could be feasibly delivered. By ensuring that additional training was not onerous and did not conflict with established working, cognitive participation and collective action were secured among clinicians and key stakeholders in intervention delivery. Following the site visit, HCPs who accepted delegated responsibility for intervention delivery were asked to sign a training record confirming that they had received the training and felt confident in delivering self-management support as part of the trial. All those who delivered the self-management intervention received training and signed the training record.

Women allocated to self-management received a self-management teaching appointment, a self-management information leaflet, a 2-week follow-up telephone call, and a telephone helpline number/e-mail address for their local clinical site. The self-management teaching appointment followed the guidance given in the training manual. 41 During the appointment, women were also given a self-management information leaflet containing written information about pessary self-management. The leaflet included diagrams of various pessary types and pelvic floor anatomy and information about common complications and what to do if these were experienced. The same leaflet was used across all centres.

Participants in the self-management group were asked to remove, clean and reinsert their pessary at least once in the 2 weeks following the self-management teaching appointment. They were telephoned 2 weeks after the appointment and asked if they had been successful in removing, cleaning and reinserting their pessary and wanted to discuss any difficulties experienced. If the participant had not changed the pessary, she was asked to try again during the following week, and a subsequent telephone call was completed. If a participant experienced difficulty that necessitated HCP assessment or had not changed the pessary by the time of the second telephone call, she was offered a second self-management teaching appointment. If, after this second appointment, the participant was unable to self-manage or did not wish to do so, she was given the choice to transfer to clinic-based pessary care. Once it was clear that a participant could remove and reinsert the pessary at least once, she was asked to do this at least once every 6 months.

Participants in the self-management group also received a local telephone number and an e-mail address to contact the intervention HCP at their centre if they experienced any pessary-related problems or had questions. Women in the self-management group using a PVC (polyvinyl chloride) pessary received a new pessary by post or by prescription, or they were given two extra pessaries at the baseline visit. Women using silicone pessaries, which are more durable, had the pessary replaced only if required (e.g. if the pessary became damaged).

Clinic-based care

In the clinic-based care group, pessary management appointments were conducted in accordance with each local centre’s policy (commonly every 6–12 months, but sometimes as often as every 4 months for a new pessary user). Care was delivered during these appointments in accordance with the usual local centre protocols.

Data collection, management and storage

Data were gathered from participants and other sources throughout the trial. An overview of the trial data collected is presented in Table 1. Introductory information and instructions in the questionnaire booklet were drawn from previous trials led by the applicant team. 47 All data collection instruments are available on the project website as part of the Project Documentation. 41

| Data collected | Data type (for outcome measures) | Time point | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | 18 months | ||

| Consent and randomisation | N/A | X | |||

| Demographics and medical history | N/A | X | |||

| Primary outcome | |||||

| Condition-specific quality of life (PFIQ-7) | Continuous | X | X | X | X |

| Secondary outcomes (validated) | |||||

| Generic quality of life (EQ-5D-5L) | Continuous | X | X | X | X |

| Pelvic floor symptoms (PFDI-20) | Continuous | X | X | X | X |

| Sexual function (PISQ-IR) | Continuous | X | X | X | X |

| General Self-efficacy Scale | Continuous | X | X | ||

| Patient Global Impression of Improvement | Ordinal | X | X | X | X |

| Secondary outcomes (non-validated) | |||||

| Pessary Complications Questionnaire (to assess complications specific to pessary use) | Continuous | X | X | X | X |

| Pessary Use Questionnaire (to assess pessary use, acceptability and benefit)a | Binary/ordinal | X | X | X | X |

| Pessary Confidence Questionnaire (to measure pessary-specific self-efficacy)a | Continuous | X | X | X | X |

| Health Resource Use Questionnaire (uptake of additional prolapse treatment/support) | Binary | X | X | X | |

| Telephone support log (uptake of telephone support related to pessary use) | Continuous | Continuous data collection | |||

| Adherence to randomised protocol | Binary | Continuous monitoring | |||

| Health of vaginal tissues (vaginal examination in clinic)b | Binary | X | X | ||

| COVID-19 surveyc | N/A | Completed at first clinic visit once services resumed | |||

All participants were given an individual trial identification number, which was used on all trial paperwork. After a participant consented, her demographic and medical history data were collected. Table 1 shows the primary and secondary outcome measures collected at each trial time point, and more detailed information is given in Outcome measures.

At 18 months after randomisation, participants in both groups attended a clinic appointment that included an examination of vaginal tissues. All follow-ups were completed by September 2021.

Participants in both trial groups were asked to complete questionnaires at baseline and at 6, 12 and 18 months. Participants who opted to complete the questionnaires on paper posted these back to the TOPSY office where they were checked for completeness and data were entered into the data management system. Women were sent a £10 voucher with their 18-month questionnaire (whether they returned it or not). For those participants who opted to complete questionnaires online, no further data entry was required but a check for completeness was carried out. If any data were missing, checks were undertaken to see if there was any supporting evidence of what the missing data should be. Self-evident correction was made only if there was evidence to allow this. Detailed information on permitted self-evident corrections was documented in the TOPSY data entry guidelines. If a large part of the questionnaire was missing, attempts were made to contact the participant to obtain the information.

Data return rates were continually monitored by the central team for completeness and timeliness of all data returned. The frequency with which those randomised to self-management reverted to clinic-based care was reviewed at every team meeting (usually fortnightly) and reported to the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC).

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome of condition-specific quality of life at 18 months post randomisation was measured using the participant-completed Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ-7). 48 The PFIQ-7 is a reliable, valid and responsive short-form of the PFIQ that measures condition-specific quality of life in women with pelvic floor disorders including urinary incontinence, prolapse and faecal incontinence. The participant-completed instrument included questions about the effect of bladder, bowel and vaginal symptoms on the woman’s activities, relationships and feelings. There are three subscales (UIQ-7, CRAIQ-7, POPIQ-7), with each subscore ranging from 0 to 100 and the total score ranging from 0 to 300. Data were collected at each time point to allow repeated measures analysis of the PFIQ-7 scores.

Validated secondary outcome measures

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L),49 was used to measure participants’ general health-related quality of life, complementing the primary outcome measure of condition-specific quality of life, and to provide data for the analysis of cost-effectiveness using quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). The EQ-5D-5L is a two-part instrument. The first section, the EQ-5D descriptive system, contains five items: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. The second part, the EQ-5D VAS, is a visual analogue scale. Data were collected at each time point to give a complete profile of QALYs across the trial time points, calculated using an area under the curve method.

The Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory-20 (PFDI-20) measured the severity of pelvic-floor-related symptoms. This was developed and validated in parallel with the PFIQ-7. 48 It comprises 20 questions about the presence of bladder, bowel and prolapse symptoms and how bothersome these are. There are three subscales (Urinary Distress Inventory-6 [UDI-6], ColoRectal Anal Distress Inventory-8 [CRADI-8], Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory-6 [POPDI-6]), with each subscore ranging from 0 to 100 and having a total score of 0–300.

The Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire, IUGA-Revised (PISQ-IR),50 was used to assess female sexual function in women with pelvic floor disorders. It contains 10 subscales, of which six are relevant to women who are sexually active and four are relevant to women who are not sexually active. A psychometrically valid summary score can be created for sexually active women only and is calculated as a mean of scores ranging from 1 to 5. 51 The PISQ-IR is a revision based on the PISQ-12, which was the originally planned measure of sexual function (this was the only change to any of the planned outcome measures).

The General Self-efficacy Scale52 was used to assess general self-efficacy (hypothesised to be a moderator of quality of life). This is a 10-item scale with scores ranging from 10 to 40.

Non-validated secondary outcome measures

Pessary Complications Questionnaire

A new pessary questionnaire (listing 15 possible complications of pessary use), developed based on the literature, women’s experiences and the team’s experiences in a previous service evaluation,33 was used to assess women’s pessary-related complications (e.g. discharge, odour, pain, discomfort, bleeding). The same questionnaire was used in both groups.

Pessary Use Questionnaire

A new questionnaire (of nine questions) developed based on the literature and women’s experiences was used to assess the pattern of women’s pessary use, including perceived acceptability and benefit. This included questions on whether or not women were still using a pessary as treatment for prolapse; when they last removed and reinserted their pessary; the reasons for pessary removal; interference of the pessary with everyday life; and if they found the pessary an acceptable treatment. Also included in the questionnaire was a question adapted from the Patient Global Impression of Improvement that was used to assess perceived benefit of the pessary care regimens being evaluated. The Patient Global Impression of Improvement is a single-item tool that rates the change in a condition since having treatment and has been validated for urogenital prolapse. 53,54 An amended version was used that asked women to describe how they felt about their pessary care since taking part in the TOPSY study. The standard range of response options from very much better to very much worse was used. Patterns of pessary use were used to measure the impact of, adherence to and acceptability of the trial interventions.

Pessary Confidence Questionnaire (to measure pessary-specific self-efficacy)

No suitable condition-specific measure existed; thus, questions were developed relating to pessary self-efficacy based on the guidance from Bandura. 38 These six questions were discussed with and reviewed by patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives, statistical experts, the Project Management Group (PMG) and clinical team members before they were used and assessed in the pilot study. We used both the generic validated measure of self-efficacy (the General Self-efficacy Scale) and the responses to the developed pessary-specific self-efficacy questions to measure self-efficacy and to aid understanding of the influence self-efficacy had as a moderating factor on quality of life.

Uptake of additional treatment for prolapse

As an indicator of intervention effectiveness, the uptake of additional treatment for prolapse since the start of the study, or treatment awaited, was recorded in participant questionnaires (e.g. surgery, pelvic floor muscle training, oestrogen use, lifestyle advice). Participants’ access to professional pessary-related support since starting the study was also recorded [e.g. telephone support, a hospital appointment, a general practitioner (GP) appointment]. These data were collected at all trial time points to maximise reliability as they rely on participants recalling events occurring over a period of months.

Uptake of telephone support related to pessary use

Using a telephone support log form, we asked the intervention HCP to record the frequency and details of all participant calls to the telephone support line. In addition, the pessary complication questionnaire included a question to all women about telephone support they had accessed from their local team.

Adherence to randomised protocol

Adherence to the self-management or clinic-based care protocol was monitored throughout the trial. Monitoring was via multiple data sources: questions in the Pessary Use Questionnaire, telephone support contacts and health records. It included monitoring crossover to the other trial group (i.e. self-management group participants crossing over to clinic-based care). Clinic-based care group participants did not have access to the trial self-management teaching and support intervention and therefore did not cross over. However, individual women may choose (without being trained to do so) to remove and replace their pessary at home, and instances of this were recorded in the Pessary Use Questionnaire.

Health of vaginal tissues

At baseline and 18 months, all women in the trial underwent a vaginal examination by a HCP at the clinic to assess the health of the vaginal tissues and identify any problems associated with pessary use. Information was collected on inflammation of vaginal tissues, ulceration, granulation and any other clinical concerns.

Sample size

The aim was to recruit sufficient participants to detect a 20-point difference between groups in the primary outcome measure, namely PFIQ-7 score at 18 months. The potential range of scores on the PFIQ-7 is 0–300, and, in the absence of robust data on minimal clinically important difference, the clinicians in the research team and the wider Trial Steering Committee (TSC) considered 20 points to be an important clinical difference. A sample size of 330 women (165 per group) was required to provide 90% power to detect a difference of 20 points in the PFIQ-7 score at 18 months, assuming a standard deviation (SD) of 50, which was based on previous studies,55,56 two‐sided alpha of 0.05, and 20% loss to follow-up.

COVID-19: changes to follow-up assessment

This section describes the changes to study processes that were implemented from 21 April 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. As recruitment was complete in February 2020, only follow-up processes were amended.

Clinic-based pessary care during the pandemic

All 21 centres postponed pessary clinics for at least 3 months at the start of and intermittently throughout the pandemic, depending on local lockdown procedures. All centres let women know (by either letter or telephone call) what to do if they had any issues with their pessaries. Some centres implemented a new standard procedure of calling women when they would have been due a follow-up appointment to carry this out a remotely over the telephone. If this happened, the clinical staff completed the telephone support log form that captured the same information that would have been collected at clinic. If centres did not call women as part of their standard care pathway, they were not asked to complete this.

Eighteen-month treatment of prolapse with self-care pessary visit: health of vaginal tissues (COVID-19)

The greatest impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was that participants could not attend their 18-month end-of-study TOPSY visit, which included an examination of the vaginal tissues, if pessary clinics were postponed/cancelled. Therefore, from April 2020, if a woman could not receive her 18-month TOPSY end-of-study assessment in person at the appropriate time, the process was changed to the following:

-

part 1 – a telephone call during which all end-of-study questions were completed

-

part 2 – a clinic visit, when clinics resumed, during which the vaginal examination took place.

Questionnaire completion

A letter providing a COVID-19 update was sent to all TOPSY participants. This letter stated that if a woman wanted to complete her questionnaires online, rather than on paper, she could e-mail the TOPSY office to provide her e-mail address.

A batch of questionnaires were issued at the beginning of March 2020, just before the first lockdown, when the TOPSY trial office team commenced working from home. From 11 May 2020, a member of the TOPSY team was granted access to the trial office every 6 weeks to post out batches of questionnaires. For all batches of questionnaires sent as of this date, reminder 1 (which would usually be sent 3 weeks after the initial questionnaire) was not sent. Reminders could be posted out every 6 weeks (which was previously the time of the second reminder), and then the third reminder, if required, was undertaken over the telephone as described previously.

A short-form questionnaire was developed to ensure that the minimum number of primary outcome and other required data could be gathered when data could only be gathered by telephone.

COVID-19 survey: impact of COVID-19 on how women view their pessary management

We developed a COVID-19 survey to assess the impact of the care delivery disruption, such as cancelled clinic visits, on participants’ views of pessary care/self-management. The survey was completed at the woman’s next clinic visit or alternatively posted to participants who had had a clinic-based care or 18-month appointment cancelled or postponed due to COVID-19.

Statistical analysis

Study analyses were conducted in accordance with a prespecified statistical analysis plan (Project Documentation is available on the project website)41 using Stata version 16 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The primary outcome measure (PFIQ-7) and all secondary outcome measures were presented as summaries of descriptive statistics at each time point, and comparisons between the groups were analysed using general linear models. All analyses were adjusted for minimisation covariates (age, pessary user type and centre) and for baseline scores where applicable. The models used to analyse the continuous outcomes were repeated measures mixed models with a compound symmetry covariance matrix and centre fitted as a random effect. Estimates of treatment effect size were expressed as the fixed-effect solutions in the mixed models and odds ratios in the ordinal regression models. For all estimates, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated and reported.

Planned sensitivity analyses were carried out on the primary outcome measure to investigate the impact of missing data under various assumptions. The first sensitivity analysis was a complete-case analysis that used only cases for which follow-up data were available at the primary end point (18 months). The remaining sensitivity analyses used pattern mixture modelling by increasing and decreasing the imputed PFIQ-7 values in the initial sensitivity analysis by 20 points, equivalent to the minimal clinically important difference. These adjustments were then repeated in one group only and repeated again by applying the adjustments in the other group only. We used 20 points on the PFIQ-7 score as this was the clinically important difference initially assumed and hence a meaningful systematic difference to test in the sensitivity analyses.

A further set of planned sensitivity analyses of the primary outcome measure were conducted to examine crossover, adherence to treatment and the inclusion of previous hysterectomy as a covariate. In addition, a sensitivity analysis of the repeated measures mixed model specification was carried out, applying the constrained longitudinal model57 with the baseline value in the outcome vector, an approach suggested for extension to randomised studies. 58 Finally, a planned sensitivity analysis was carried out to incorporate mode of data collection, which shifted more to electronic submission as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, as it was recognised that the results could be biased if collection method was not addressed in the analysis. 59

Analysis populations

The main analysis was an intention to treat (ITT) analysis, and all participants were analysed as randomised. Two further prespecified per-protocol analyses were conducted. The first analysed all participants, reflecting any change of status resulting in crossovers to the other trial group. The second analysis included only participants defined as ‘on treatment’ at the 18-month follow-up. The definition of ‘on treatment’ is given in the statistical analysis plan and summarised in Intervention adherence.

Missing data

Missing baseline data were not imputed for the reporting of baseline characteristics, but imputation of the primary outcome was carried out prior to the main analysis to improve efficiency. Missing baseline values of the primary outcome were imputed at the overall mean.

Demographic and baseline variables

The baseline characteristics of the participants were tabulated by randomised group. No inferential tests were undertaken when comparing participant baseline characteristics between the trial groups.

Intervention adherence

Intervention adherence was assessed through the definition of ‘on treatment’. The proportions of women adhering to the self-management or clinic-based care protocols for the duration of the 18-month intervention period were reported for each group. Adherence was further analysed as part of the process evaluation (see Chapter 4). Adherence to the intervention was defined in the self-management group as the participant using a pessary for the management of prolapse, the participant having received the TOPSY self-management teaching, and the participant inserting her pessary herself. In the clinic-based care group, adherence was continued use of a pessary and not reporting inserting own pessary.

Analysis of primary outcome measure

The analysis of the primary outcome used a mixed-effects repeated measures model or longitudinal analysis of covariance as described by Twisk. 60 The three follow-up measurements of the outcome variable (PFIQ-7 at 6, 12 and 18 months) were employed as the dependent variable. The analysis adjusted for the baseline value of the dependent variable. The model included ‘time’ (6, 12, 18 months) as a dummy variable because a non-linear development of the outcome over time was anticipated. Interaction effects between treatment (trial group) and time were included in the model. The model also included age group (< 65/≥ 65 years) and pessary user type (new/existing) as fixed effects and participant and recruitment centre as random effects. A random effect of participant was included at the level of the individual to account for the non-independence of observations under repeated measures. In addition, the three PFIQ-7 subscales were each analysed separately using equivalent models.

To assess whether the assumptions behind the mixed-effects model were met, we generated normal quantile plots of residuals and standardised residuals. Where the assumptions of the analysis of covariance appeared to be violated, we explored other modelling strategies such as zero-inflated Poisson models.

Analysis of secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcomes assessed through continuous measures were analysed in a similar way to the primary outcome measure (see previous section). However, the reporting of subscales includes only descriptive summaries. For binary measures, we estimated odds ratios using mixed-effects binary logistic regression, and for ordinal measures, we estimated odds ratios using mixed-effects ordinal logistic regression with odds determined by the logistic cumulative distribution function. Age group and pessary type were included as fixed effects and participant and centre as random effects in the logistic regression models.

From the Pessary Complications Questionnaire, the unweighted proportion of complication types reported was calculated for each participant, with the summary statistic reported being the mean proportion in each group. Only the 13 categories applicable to both clinic-based care and self-management were used in this calculation. For women not sexually active, only the relevant subset of complication types was included in the calculation (questions 11 and 12 were therefore excluded). Individual items were summarised for the two other non-validated questionnaires (pessary use and pessary confidence), but overall scores were not calculated. Between-group comparisons were made for the confidence to remove pessary and insert pessary as specified in the statistical analysis plan, and an additional analysis of the confidence to manage pessary problems was added as post hoc analysis and is listed in the deviations from the statistical analysis plan.

For the uptake of additional support, regression models were used to estimate the mean difference in the number of telephone support and additional clinic appointments between the groups. Both outcomes included the uptake of additional support over the 18-month follow-up period as a single time point.

Subgroup analysis

Prespecified subgroup analyses of the primary outcome were carried out within the following groups identified at baseline:

-

age (< 65/≥ 65 years)

-

pessary user type (new/existing)

-

previous hysterectomy (yes/no).

Adverse events and data and safety monitoring

All women in the TOPSY trial had a vaginal pessary inserted. As a foreign body placed in the vagina, a pessary is recognised as a potential cause of specific symptoms. Expected events arising from pessary treatment are noted below and were not collected as adverse events but were recorded as secondary outcomes if they occurred:

-

granulation of vaginal tissue

-

involuntary expulsion of pessary

-

vaginal smell

-

vaginal discharge

-

bleeding during pessary change.

The questionnaires completed at the 6-, 12- and 18-month follow-ups included a Pessary Complications Questionnaire in which women indicated any complications they experienced. All participants were asked in the questionnaires if they had been admitted to hospital, had any accidents, used any new medicines or changed medication regimens. In the clinic-based care group, the local clinical TOPSY research team asked about the occurrence of adverse events (AEs)/serious adverse events (SAEs) at every pessary follow-up appointment. Women in the self-management group were asked during the teaching appointment and advised in the information leaflet to call the telephone helpline if they experienced any of the symptoms indicative of an SAE/AE. At the end of data capture, a cross-check of the database and the SAE forms was also carried out to ensure that an SAE was recorded for all women who had self-reported in their follow-up questionnaires that they had been admitted to hospital.

Methods for the process evaluation

Research question for the process evaluation

The process evaluation answers the following research question: what are the barriers to and facilitators of intervention acceptability, intervention effectiveness, fidelity to delivery and adherence among women treated with vaginal pessary and the HCPs who treat them, and how does this differ between trial groups?

The process evaluation objectives are:

-

to undertake an internal pilot study to ensure that the trial could recruit, randomise and retain sufficient numbers of participants while delivering the intervention as planned

-

to undertake a process evaluation in parallel with the trial to maximise recruitment; assess eligible but non-randomised women; understand women’s experience and acceptability of the intervention; assess adherence to allocated trial group; describe fidelity to intervention delivery; and identify contextual factors that may interact with intervention effectiveness.

Study design

The process evaluation is a mixed-methods study that was nested within, and operationalised concurrently with, the trial. 43 The process evaluation samples, methods of data collection, including those that were part of the internal pilot study, and analysis are outlined briefly below. Further details of the design are in the published protocol. 41 Table 2 outlines the links between the purposes laid out in the objectives and the methods used.

| Objectives | Audio-recordings recruitment sessions | Audio-recordings self-management teaching and telephone calls | Checklists | Interviews: randomised women | Interviews: non-randomised women | Interviews: HCPs | Open question in outcome measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximise recruitment | |||||||

| Assess non-participating women | |||||||

| Understand women’s experience and acceptability | |||||||

| Assess adherence to group | |||||||

| Describe fidelity | |||||||

| Identify contextual factors linked to effectiveness |

Study methods for recruitment, consent and data collection

The sampling, recruitment and data collection for each method are outlined below. The participant information leaflets and consent forms for each element are part of the Project Documentation on the project website. 41

Audio-recording of recruitment discussions (maximise recruitment)

The target was two or three recruitment sessions in each of the six pilot centres (a total target of 12–18 sessions). If more than one person undertook recruitment at any of the pilot centres, recruitment aimed to sample for diversity of recruiter professional background. Potential participants received a short participant information leaflet from a delegated member of the local TOPSY research team. If a woman was willing to take part, her written consent was obtained prior to audio-recording. If a woman did not want to take part, the recruitment discussion still took place but was not audio-recorded. With the woman’s consent, the recruiter asked to record the discussion using a small, unobtrusive digital recorder.

Audio-recording of self-management teaching appointments and self-management support telephone calls (fidelity)

In the internal pilot study, 5–10 teaching appointments and 5–10 support telephone calls were recorded and analysed. Feedback was given to centres to maximise fidelity to delivery of the self-management protocol. A further 20–25 self-management teaching appointments (total n = 30) and 20–25 telephone calls (total n = 30) were audio-recorded in the main trial, with at least one self-management teaching appointment or one telephone call recorded in each centre. Variation across the sample aimed for diversity in treating HCP (nurse/physiotherapist/doctor) and woman’s age. The main trial participant information leaflet stated that, if the woman was allocated to the self-management group, a self-management teaching appointment or a follow-up call may be recorded with her consent. The main trial consent form asked the woman to indicate ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to these recordings by initialling the relevant box, and her consent was checked verbally prior to the recording. To record the interaction, a small digital recorder was, with the consent of the woman and HCP, placed in the consulting room or attached to the phone.

Checklists (fidelity)

Checklists to assess fidelity were developed to include the key aspects of the intervention content and theory. The checklists were completed by the HCP who delivered the self-management teaching appointment or the 2-week follow-up telephone call for all appointments and all follow-up calls.

Interviews with randomised women (maximise recruitment, women’s experience/acceptability, adherence, contextual factors)

To understand the perspectives of those in receipt of self-management or clinic-based care, a purposive sample of women randomised to the trial were asked to take part in one-to-one, face-to-face, semi-structured interviews. The original aim was to recruit 30 women (10 in the clinic-based care group and 20 in the self-management group). However, early in the trial, the protocol was amended to prevent bias in the trial, so that the same number of women in each group were interviewed. Therefore, the recruitment target was changed to 36 women, 18 in each group. Five women in each group were interviewed as part of the pilot study.

The main trial patient information leaflet advised that some women would be invited to take part in an interview. The trial consent form asked women to tick ‘yes’ or ‘no’ if they were willing to be contacted about the interview. Among those who ticked ‘yes’, women were purposively sampled to achieve variance in centre, age, user status (new/existing) and treating HCP (nurse/physiotherapist/doctor). An interview participant information leaflet was posted to sampled women and a telephone call made a few days later to discuss their possible participation in the interview study. If they consented, an interview study consent form was signed prior to the first interview. Their consent was verbally rechecked prior to the 18-month interview.

Interviews occurred at randomisation and at 18 months post randomisation (the same time point the primary outcome was measured). Interview schedules were developed based on the literature and with guidance from PPI members who were study grant holders or on study committees along with the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists’ Women’s Voices group. Interview schedules explored perspectives on recruitment (baseline); symptoms (baseline)/change in symptoms (18 months); experience and acceptability of clinic-based care or self-management (18 months); adherence to the allocated trial group (18 months); and contextual factors perceived to interact with the effectiveness of the intervention (18 months). Where a woman crossed over to receive treatment offered in the group to which she had not been randomised, her reasons for doing so were explored during the 18-month follow-up interview.

All face-to-face interviews were suspended and changed to telephone interviews after March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent restrictions placed on interactions and travel. The interviewing of women randomised to the self-management group prior to their self-management teaching appointment was not always possible, as the time between randomisation and appointment was short. This short timeline also meant that it was also not always feasible to interview women face to face, and therefore some pre-COVID-19 interviews were also undertaken over the telephone. Interviews were digitally recorded using a small recorder placed discreetly in the room or attached to the phone.

Interviews with women who declined randomisation (assessment of non-randomised women)

To assess women who were not randomised, those who were eligible for the trial and did not consent to randomisation but did consent to taking part in an interview study were interviewed at baseline and 18 months over the telephone using a semistructured interview schedule. Sampling was by convenience as it relied on women responding to the research team. The aim was to recruit 20 women who declined randomisation (approximately five in the internal pilot). Sampling variance was on woman’s age and centre type (outpatient/community/primary care).

Based on ethics committee requirements, only women invited to take part in the trial in the clinic (as opposed to those who had information posted to them), and declined in clinic, were asked to take part. Women who declined trial participation were asked if they were willing to take a recruitment pack for an interview study with non-randomised women. The recruitment pack contained an introductory letter, a participant information leaflet, an expression of interest form, a consent form and two stamped addressed envelopes. Participants opted into this component of the study by returning the expression of interest form. When a completed form was received, the researcher contacted the woman in question to answer any questions she had, go over the consent process and arrange a baseline telephone interview if the woman was willing to consent. Participants were asked to sign and return the consent form prior to the telephone interview.

Interviews focused on reasons for declining to take part in the trial (baseline); symptoms (baseline)/change in symptoms (18 months); treatment received for prolapse (18 months); and contextual factors that may interact with future service implementation (baseline and 18 months).

Qualitative semistructured interviews with healthcare professionals who recruited to the trial and delivered the interventions (maximise recruitment, fidelity, contextual factors)

Interviews with HCPs aimed to increase understanding of the recruitment, fidelity and contextual factors that affected the intervention. The aim was to interview at least two staff involved in the trial at each centre who recruited to the trial and/or delivered the self-management intervention. Sampling aimed for diversity of professional group for both recruitment and delivery.

Consent started at the site initiation visits, where HCPs who were identified as being part of the local TOPSY research team were advised that they may be approached and invited to take part in an interview as part of the TOPSY trial. Contact details for the local TOPSY research team were collected before the centre was opened to recruitment and as part of the delegation log. Interviews with pilot centre recruiters were undertaken during the pilot study; all other interviews took place towards the end of data collection in each centre. The TOPSY process evaluation researcher contacted HCPs to invite them to participate in the interview, sent them a participant information leaflet and consent form and was available to answer any questions. Willing HCPs were asked to return the consent form. Once written consent was obtained, a suitable date and time for a telephone interview was arranged.

Interviews were semistructured, lasted approximately 30 minutes and were undertaken over the telephone. Interviews with recruiters focused on factors that influenced the identification of potential participants and recruitment, including service structures, contributing to maximising recruitment. Interviews with those involved in delivering clinic-based pessary care and/or self-management focused on experiences of delivering self-management/clinic-based care, including variation in delivery and reasons for the variation, and contextual factors that were perceived to impact on delivery. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed.

Secondary outcome measures in questionnaires (experience/acceptability, adherence, contextual factors)

Within the questionnaire booklet at baseline and at 6, 12 and 18 months, women were asked questions about adherence and self-efficacy. In addition, an open question asked women about their experience of their trial group (self-management or clinic-based care). The aim of these questions was to understand the experience and adherence of the wider sample of women involved in the trial.

Data analysis

Recordings of recruitment sessions, teaching sessions and telephone calls and interviews with women were transcribed verbatim and imported into NVivo software (QSR International, Warrington, UK). Each data source was analysed individually in the first instance to reach separate conclusions, and the findings were then synthesised across data sources. Quantitative checklist and coded self-management appointment and follow-up recording data were transferred to Statistical Product and Service Solutions (IBM SPSS Statistics v26, Armonk, NY, USA) for analysis. All analysis was undertaken by the process evaluation subgroup of grant‐holders, which included PPI and clinical representation, with the rest of the team blinded to the analysis.

Analysis process for all interviews and open question in outcome questionnaires

A thematic framework analysis approach61 was applied to interviews and data from the open question. The stages laid out below were applied to each individual data source (randomised interviews, non-randomised interviews, HCP interviews, individual question). The initial level of analysis focused on women’s experience of prolapse and their symptoms at the outset; experience of self-management or clinic-based pessary care; perceptions of prolapse cause; experience of trial processes and participation; perceptions of treatment outcomes; adherence to trial group; and reasons for declining participation in the main trial. At this stage, the aim of the analysis was to identify barriers to and facilitators of adherence to trial group, acceptability of self-management pessary care and acceptability of trial participation (where applicable). The steps are briefly listed below:

-

Based on the research questions, an initial broad thematic framework was developed.

-

Individual transcripts were uploaded into NVivo and read several times so that the content became familiar. Ten per cent of interview transcripts from each data set were coded by a second analyst, and the coding was discussed.

-

Initial framework was applied to all data and iteratively developed as coding progressed.

-

Data extracts for codes were summarised, reviewed and discussed.

-

Preliminary ‘findings’ and case summaries were shared and discussed with the process evaluation management group.

-

Data for each individual source were described and explained.

Interviews with both randomised and non-randomised women were further analysed using a case study approach. Priority was given to complete data sets (cases that had interviews for both time points) during the analysis process. Each case comprised one woman and all of the data gathered about that woman. This is a three-tailed case study, with the tails representing the intervention and control groups of the trial, respectively, plus women who declined participation in the trial but consented to the interview study alone. The analysis approach is briefly summarised below:

-

Case summaries were written for each case. Case summaries were written with a focus on creating an understanding of women’s experience using the key areas of interest driven by the process evaluation analysis plan (see Project Documentation on the project website). 41

-

Additional (to those originally set out) theoretical propositions were developed that were drawn from observations of the data.

-

All of the cases for one group of the interview study (intervention, control, non-randomised) were collected and consistencies/inconsistencies were searched for. The collected data were discussed with the process evaluation group of researchers. The aim of analysis at this stage was to identify the core barriers and facilitators within the trial groups, as well as detailed explanations for them and interactions between them.

-

Study groups were compared. The intervention and control groups of the trial were compared using the theoretical underpinnings of the study. The aim of this part of the analysis was to identify similarities in and differences between the two trial groups. Additionally, cases from the non-randomised interview only group were compared with the trial groups with regard to experiences of treatment and perceptions of treatment outcome.

Self-management teaching sessions and follow-up telephone calls

The self-management teaching sessions and 2-week follow-up telephone calls were transcribed. An a priori analytic grid was developed for the teaching session and 2-week self-management follow-up telephone call. The analytic grid was developed based on the underlying self-management philosophy around which each component part of the intervention was set up, for example to assess if women were offered the practical skills to self-manage. The grid was applied to each transcript from the teaching sessions and 2-week self-management follow-up calls by MD, the primary qualitative researcher. Over 10% transcripts were double coded (by CB) to assess for agreement in coding and discussed with members of the qualitative PMG. Coded data were imported into SPSS and described.

Intervention checklists for self-management teaching session and 2-week telephone call

The HCP-completed checklists for the self-management teaching sessions and 2-week follow-up telephone calls were entered into SPSS. Following the procedures explained in the process evaluation analysis plan, the data were described and analysed.

Methods for the health economic evaluation

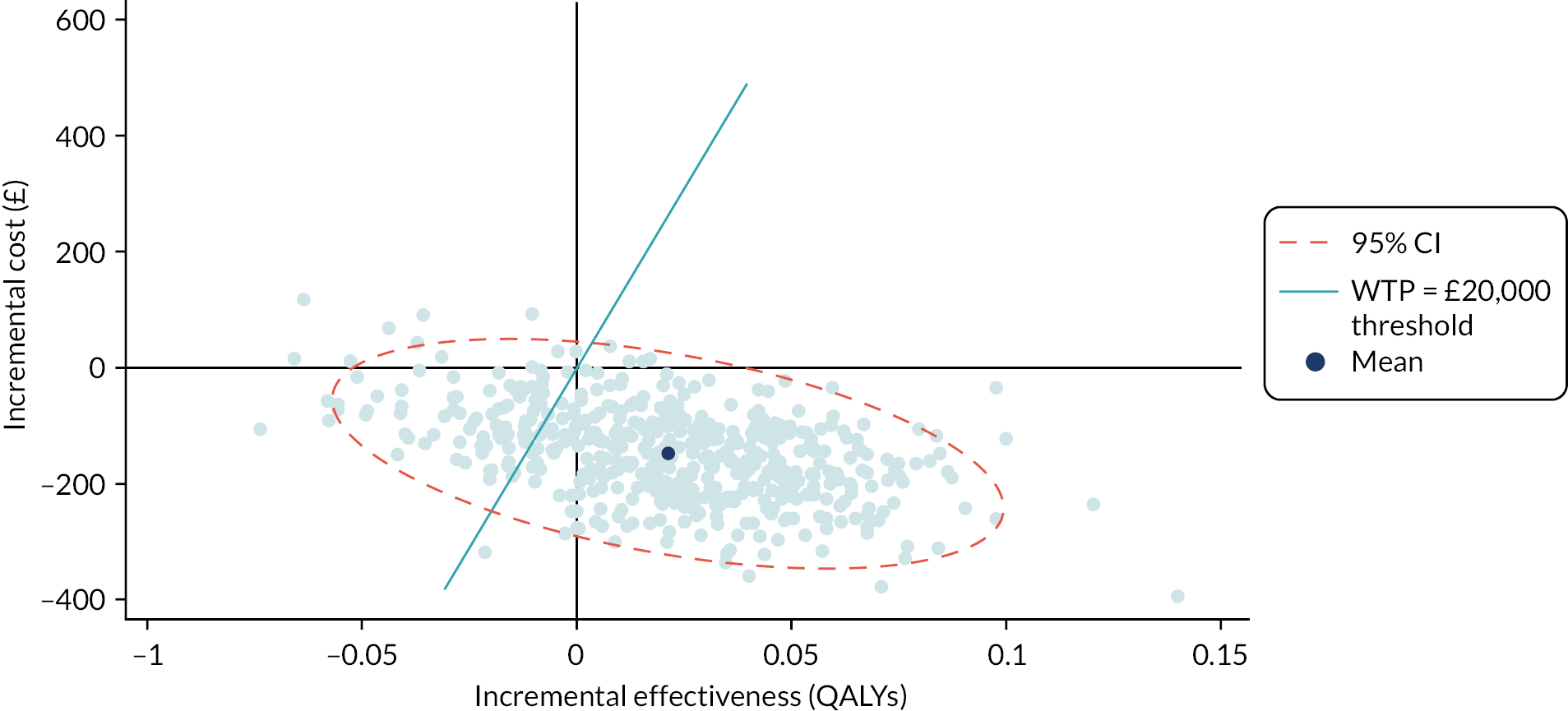

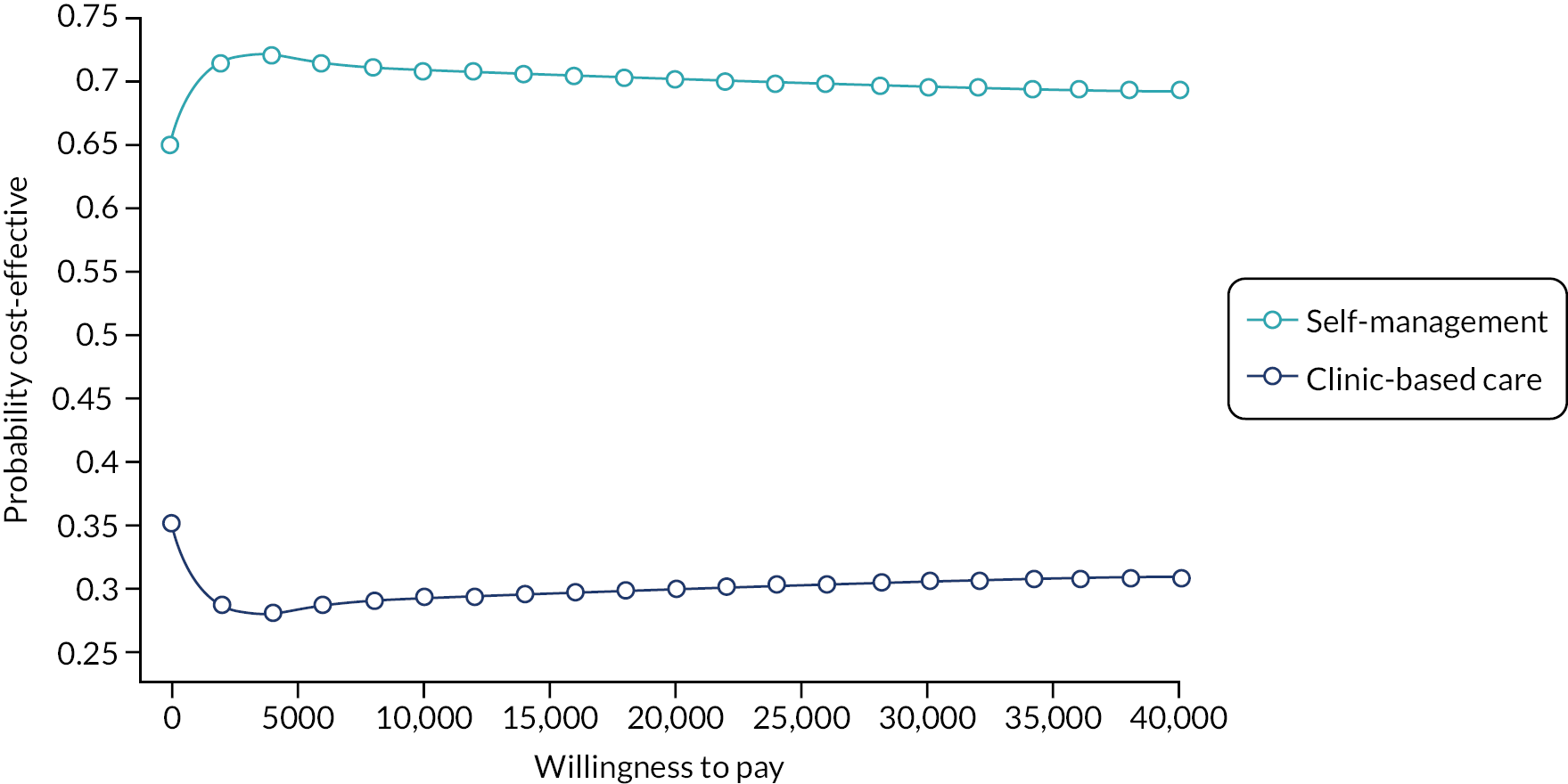

A cost–utility analysis was conducted. In this economic evaluation method, costs are attached to resource use for the delivery of the intervention and comparator treatments as well as all healthcare-related resource use for each patient during the follow-up period. Health outcomes are measured in QALYs. The incremental net monetary benefit (INMB) is calculated for the treatment (self-management) versus the comparator group (clinic-based care). The INMB has been proposed62 as a more informative alternative to the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), especially in situations where the incremental cost or effectiveness is negative. The INMB is calculated by multiplying incremental effectiveness by the policy-maker cost-effectiveness threshold, which in the UK is £20,000 willingness to pay per QALY gained,63 and then subtracting the incremental cost of the treatment. A positive INMB implies that the treatment is cost-effective, whereas a negative INMB suggests that the alternative or existing approach should be adopted.

For both the within-trial analysis and the decision-analytic model, a prospectively agreed health economics analysis plan was followed (see Project Documentation). 41 As reported in Chapter 3, patients in 21 sites across the UK were randomised to either pessary self-management or clinic-based care. Clinic-based care was not standardised across all sites and each site continued with their regular follow-up appointment schedule, although in practice all sites had a standard 6-month follow-up for outpatient appointments. The details of the women recruited into the trial are reported in Chapter 3. The economic analysis follows the same approach as the main statistical analysis by adopting an ITT methodology. Some women in this trial reverted from self-management to clinic-based care, but this analysis is based on status at randomisation.

Perspective

A health sector payer (NHS) perspective was taken for the cost–utility analysis.

Time horizon and discounting

The primary economic analysis compared the costs and benefits of each group over the first 18 months after randomisation. A secondary analysis over a 5-year time horizon was performed using modelling beyond the trial data collection period. A 5-year horizon was chosen as it was assumed that the conditions and characteristics of patients will be broadly the same across the period while still being relevant to NHS funding cycles.

A discount rate of 3.5% was applied to all costs and outcomes over 1 year as recommended by NICE. 63

Health outcomes

Data about health-related quality of life for use in the cost–utility analysis were collected using the EQ-5D-5L. 49 The EQ-5D-5L is a generic measure of health-related quality of life with five domains: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. For each domain, respondents can select one of five levels ranging from ‘no problems’ to ‘unable or extreme’ based on their health today (the full version of the questionnaire is available as part of the Project Documentation). The raw scores from responses to the EQ-5D-5L domains can be used to generate health state utility values that are used to calculate QALYs. The QALY can be described as 1 year in full health and along with costs forms the basis of this economic evaluation. The utility values were calculated using the procedure recommended by NICE using the crosswalk from the UK EQ-5D-3L tariff. 64

The five questions are followed by EQ-VAS, a visual analogue scale on which respondents are asked to rate their health today between 0 (worst imaginable health) and 100 (best imaginable health). The EQ-5D-5L was completed at baseline and at 6, 12 and 18 months post randomisation alongside the primary outcome and other secondary measures reported in Chapter 2.

Resource use and costs

The intervention for the self-management group was additional training from a specialist nurse at a hospital clinic during the first appointment. This consisted of approximately 30 minutes more than clinic-based care with a specialist nurse, physiotherapist or consultant (see Chapter 2 for full details of the intervention). For the women in the self-management group, the regular follow-up clinic appointments were then scheduled for the 18-month time point only.

Healthcare resource use was collected from the clinic visit [case report form (CRF) 07] and the telephone support (CRF08) CRFs and from a participant-completed Resource Use Questionnaire (RUQ) designed for this study (all are part of the Project Documentation available on the project website). Data on outpatient clinic appointments related to pessary management were captured on the clinic CRF, and telephone support appointments were recorded on a telephone log CRF.

The RUQ consisted of six questions related to the use of secondary care services, primary care services and medications (prolapse-related treatments) and for any personal out-of-pocket expenses resulting from experiencing prolapse or having a pessary. For primary care services participants were asked to record the number of GP appointments in person and home visits, nurse appointments in person and home visits, district nurse home visits, community physiotherapy appointments and community dietitian appointments. For secondary care services participants were asked to record the number of outpatient appointments with a doctor, outpatient appointments with a nurse, attendances at accident and emergency (A&E), and inpatient stays including the number of nights. For both primary and secondary care resource use participants were asked to record this in terms of appointments for prolapse-related reasons and any other health-related reason.

The RUQ was completed by participants at the 6-, 12- and 18-month follow-ups; they were asked to report all resource use over the period since the previous questionnaire. Given the long period between follow-up questionnaires, an aide memoire was given to the participants so that they could note down any appointments or medication during the intervening period that could then be transferred to the main questionnaire.

The unit costs attached to each item of resource use are presented in Table 3. Unit costs were identified using Unit Costs of Health and Social Care for staff and British National Formulary for prescribed medication. 65,66 All costs are in Great British pounds (GBP) in 2019/20 prices. To calculate an A&E unit cost, we used the weighted average of all acute outpatient appointments as described in Unit Costs of Health and Social Care (page 87). 65 For hospital episodes, we used the average cost per non-elective inpatient stay (short stays), which is based on national data and described in Unit Costs of Health and Social Care (page 87). 65 Outpatient doctor appointments were costed based on consultant grade. Outpatient nurse appointments were costed based on 1-hour contact with a band 7 nurse. Outpatient physiotherapist appointments were costed based on a 1-hour appointment with a band 6 physiotherapist. In-person appointments with GPs were costed based on a 9-minute contact time for each appointment. Community nurse appointments were costed as 15-minute appointments. Costing of GP and nurse (band 7) home appointments assumes 1 hour of patient contact, which includes travel to the patient’s home. District nurse at home appointments costing assumes 1 hour with a band 6 nurse. Physiotherapy local clinic visits were costed assuming 1 hour of patient contact with a band 7 community (advanced) physiotherapist. Appointments with a dietitian were costed using a band 7 hospital-based dietitian. Clinic visits assume 45 minutes of patient contact, and telephone support calls assume 10 minutes of patient contact with a band 6 specialist nurse. The costing of the initial training appointment was based on patient-level trial data that were costed using Unit Costs of Health and Social Care depending on the grade of the HCP who provided the training. The statistical analysis accounted for the uncertainty in the unit costs by drawing Monte Carlo samples from normal distributions shown in Table 3.

| Service | Mean | SD | Distribution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A&E | 154 | 30.8 | Normal | Curtis and Burns65 |

| Hospital episode | 602 | 102 | Normal | Curtis and Burns65 |

| Outpatient doctor | 135 | 27 | Normal | Curtis and Burns65 |

| Outpatient nurse | 60 | 12 | Normal | Curtis and Burns65 |

| Outpatient physiotherapist | 50 | 10 | Normal | Curtis and Burns65 |

| GP | 33 | 6.6 | Normal | Curtis and Burns65 |

| Community nurse | 9.5 | 1.9 | Normal | Curtis and Burns65 |

| GP @ home | 223 | 44.6 | Normal | Curtis and Burns65 |

| Nurse @ home | 120 | 24 | Normal | Curtis and Burns65 |

| District nurse @ home | 89 | 17.8 | Normal | Curtis and Burns65 |

| Physiotherapist @ local clinic | 58 | 11.6 | Normal | Curtis and Burns65 |

| Dietitian | 60 | 12 | Normal | Curtis and Burns65 |

| Initial training appointment | 29.90 | 12 | Normal | Curtis and Burns65 |

| Clinic visits | 37 | 7.4 | Normal | Curtis and Burns65 |

| Telephone support | 8.3 | 1.7 | Normal | Curtis and Burns65 |

Data analysis

Within-trial cost–utility analysis

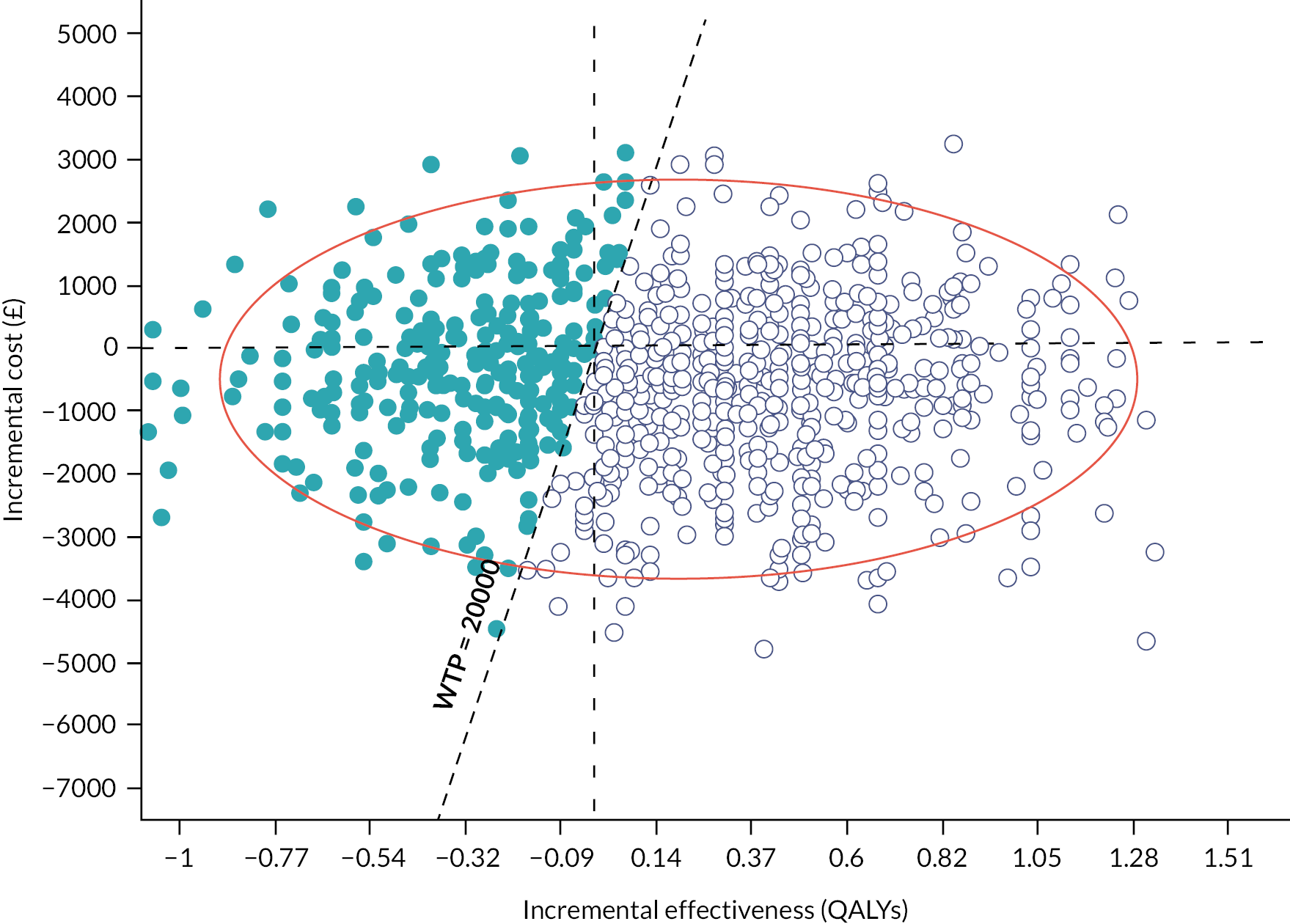

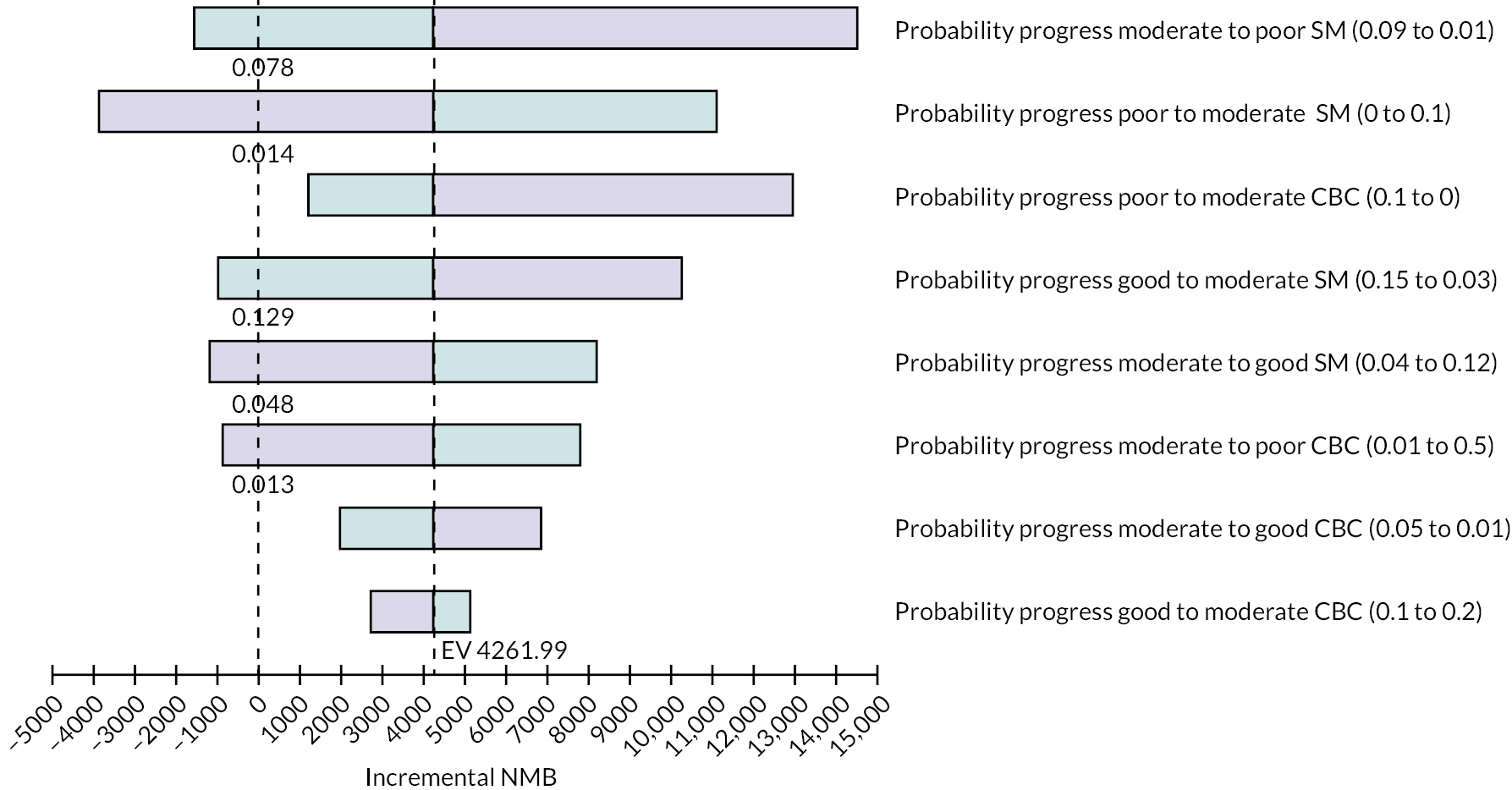

The analysis included all randomised participants based on the definition of ‘on treatment’ for the TOPSY trial, with the results presented based on an ITT sample. Subgroup analysis was not conducted, and no additional adjustments were made to account for how socioeconomic characteristics of participants could impact on the findings.