Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number HTA 13/146/02. The contractual start date was in April 2016. The draft report began editorial review in November 2021 and was accepted for publication in June 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Sohanpal et al. This work was produced by Sohanpal et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Sohanpal et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common, incurable, but treatable, condition characterised by the progressive reduction in lung function,1 insidious onset of breathlessness, cough and sputum production, along with increasing fatigue. 2–4 The primary cause of COPD in the UK is tobacco smoking and, globally, indoor biomass fuel and air pollution (including occupational) and, therefore, COPD is largely preventable. In addition, reducing exposure (e.g. quitting smoking) slows progression. 2,3 The progressive course of the disabling symptoms is interspersed by acute exacerbations5 (often associated with respiratory infections), which accelerates the deterioration in health. As the condition becomes more severe, exacerbations lead to increasingly frequent hospitalisations,6 and about one-third of people with COPD will die of the condition. 7

Burden of disease

Burden on healthcare systems

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a major public health problem globally, and is associated with socioeconomic deprivation and with high morbidity and mortality. COPD is currently the third leading cause of death worldwide,8 causing in excess of 3 million deaths annually,4 and this number is predicted to increase over the next decade. 9 In the UK, about 1.2 million people have diagnosed COPD, incurring more than 140,000 hospital admissions, over a million bed-days and about 30,000 deaths each year. 10,11 It is estimated that COPD costs the NHS £1.9B each year, with costs attributed mostly to hospital admissions. 12

Burden on individuals

Symptoms start insidiously, but a diagnosis of COPD is rarely made until the symptoms (especially breathlessness) or exacerbations have become troublesome enough to affect day-to-day activities, typically after the age of 40 years. 5,11 As the condition becomes more severe, breathlessness and the other symptoms of productive cough and fatigue increasingly limit activities and reduce quality of life. The negative impact extends to social isolation, loneliness, embarrassment and loss of independence. 13 Inhaled therapy can ease the symptoms, and pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) aims to reverse the vicious circle of reduced activity causing muscle weakness and further reduction in activity levels. 2,3

Multimorbidity and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Multimorbidity is the norm. 14 Smoking-related conditions, such as cardiovascular disease15 and lung cancer,16 are common comorbidities that are responsible for over half the deaths in people with COPD. 7,11,17 COPD is also associated with conditions such as metabolic diseases (including diabetes), obstructive sleep apnoea and osteoporosis (increased by immobility and steroid use), as well as a number of mental health conditions,2,3,9 including an increased suicide risk. 18

Anxiety and depression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

The estimated prevalence of anxiety and depression in people with COPD varies widely, depending on the population screened and the definitions used, with rates of up to 80% associated with more severe disease. 19–21 Even in stable COPD, rates of anxiety and depression of 30–40% are cited. 19 Anxiety and depression often overlap and affect quality of life, even in patients with mild to moderate COPD. 22 Anxiety and/or depression reduce the ability to manage the COPD effectively, reduce physical activity capacity and capability, and make patients susceptible to exacerbations, hospital admissions and re-admissions. 21,23 A recent mixed-methods review has highlighted the need to address psychological and emotional morbidity in addition to physical and social domains in supporting people to live with and manage their COPD. 24

Evidence-based management of anxiety and depression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease guidelines recommend that comorbid anxiety and/or depression should be treated ‘as usual’. 3 Current recommendations for both anxiety and depression include cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) instead of, or as well as, pharmacotherapy. 25,26 In the context of COPD, the potential benefits of physical exercise on mental health morbidity and the importance of promoting PR are specifically highlighted,3 suggesting synergy between these approaches.

Cognitive–behavioural therapy

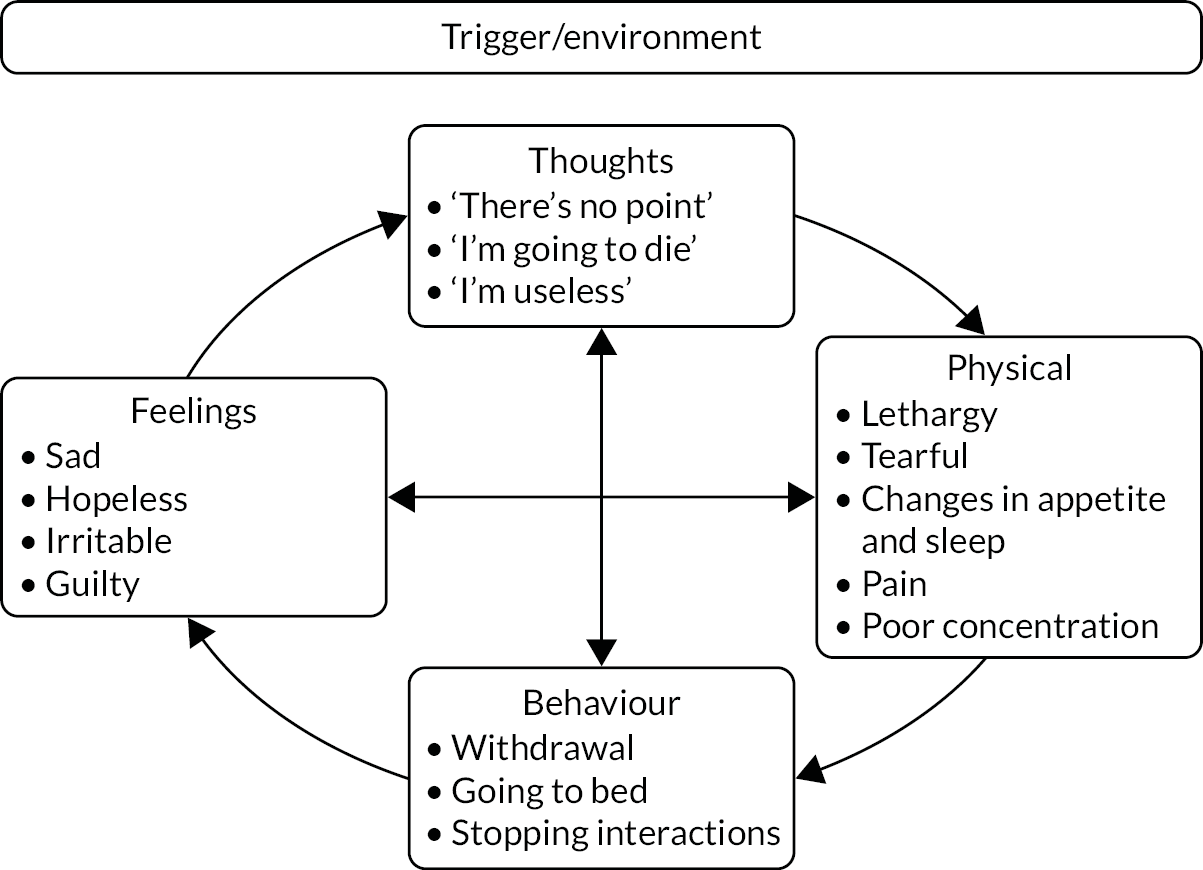

Developed by Beck27 in the 1960s, CBT is based on the principle that given a triggering event or situation, how one thinks and interprets the event/situation will influence physical, behavioural and emotional response to that situation. These interactions are not ‘one-offs’ but can reinforce and impact on each of the other elements unless the cycle is interrupted. In mood disorders, patients are commonly in a pattern of vicious cycles where each element negatively influences the others. Figure 1 uses an exemplar of a depressive cycle of thoughts, symptoms, behaviours and feelings formulated as a ‘hot cross bun’. 28

FIGURE 1.

‘Hot cross bun’ formulation, illustrating a typical cycle of depressive thoughts, symptoms, behaviours and feelings in the context of COPD.

Cognitive–behavioural therapy addresses this unhelpful pattern by working at the level of thoughts, behaviours or symptoms to interrupt and reverse the negative impacts and, hence, improve mood. Low-intensity CBT is focused more around the present than historical events and commonly deals with what are known as negative automatic thoughts (i.e. the constant, sometimes subconscious, internal dialogue that is present for all of us). 29 High-intensity CBT can, however, deal with ingrained thinking patterns, rules for living and schema, which may have evolved at earlier stages of development. Limited in duration, and often delivered by specifically trained healthcare professionals rather than psychologists, low-intensity CBT is usually targeted at people with mild/moderate depression. 29

Cognitive–behavioural therapy improves anxiety and depression

Cognitive–behavioural therapy has been widely evaluated in a broad range of mental health conditions, and it has been adapted and delivered face to face or using a variety of digital health options. (The Cochrane Library lists 168 reviews relating to CBT in anxiety, depression, severe mental illness, substance misuse, self-harming, obsessive compulsive disorders and post-traumatic stress, among many others.) Psychological therapy based on CBT principles for people with anxiety disorders is effective in reducing anxiety, worry and depression symptoms, at least in the short term. 30–34 Similarly, psychological therapy, including CBT, reduced depression scores over the medium/long term35 and, importantly, given the age group affected by COPD, was effective in older patients with depression. 36 On the basis of this evidence, clinical guidelines now recommend CBT (via the internet or face to face) for the treatment of mild to moderate depression25 and generalised anxiety. 26

Benefits of cognitive–behavioural therapy for people with anxiety and/or depression associated with long-term conditions

There is increased recognition of the importance of identifying and treating mental health problems in people with long-term physical conditions. 37,38 Policy initiatives, such as promoting Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services,39 build on systematic review evidence that CBT can reduce symptoms of depression in people with physical conditions (including COPD). 40 Patient selection is important as effects are greater in people with clinically relevant depression at baseline. 40,41 Benefits for symptoms of anxiety have also been demonstrated in people with cardiovascular disease42 and cancer,43 both of which are common comorbidities in people with COPD. A lower-intensity CBT intervention [termed a ‘cognitive–behavioural approach’ (CBA)] delivered by physiotherapists to groups of people with low back pain has also been shown to be effective. 44

A Cochrane review,45 with 13 studies and 1500 participants, and focused on people with COPD, concluded that psychological therapies (using a CBT-based approach) may be effective for treating COPD-related depression. 45 There was a small effect showing the effectiveness of psychological therapies in improving depressive symptoms when compared with no intervention [standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.19, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.05 to 0.33; six studies, 764 participants] or with education alone (SMD 0.23, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.41; three studies, 507 participants).

Pulmonary rehabilitation

Pulmonary rehabilitation is a comprehensive, multidisciplinary and individually tailored exercise and education intervention, which is designed to reduce the symptom burden associated with the deconditioning induced by COPD. 46,47 National and international COPD guidelines2,3,48 recommend offering PR to patients who are functionally disabled by breathlessness [commonly defined as a Medical Research Council (MRC) Dyspnoea Scale grade 3 and above]. 49 PR comprises an individually prescribed physical exercise training programme with at least twice-weekly supervised sessions, augmented by home-based exercise sessions and strategies to manage breathlessness. 3,46,47 Other components include an educational package to support effective self-management, nutritional advice, and social and psychological support.

Benefits of pulmonary rehabilitation

There is robust evidence from a Cochrane review,50 with 65 studies and 3822 participants, that completion of a course of PR significantly improves health-related outcomes, including increased functional exercise capacity, reduced breathlessness and improved quality of life, and this specifically includes an improvement in the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire score for ‘emotional functioning’ (mean difference 0.56, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.78), suggesting benefit for people with both COPD and anxiety/depression. These effects are described as ‘moderately large and clinically significant’. 50

In addition, people with COPD report benefits from attending PR beyond health outcomes, such as having a better understanding of COPD and strategies that can help them live better with COPD, including improvements in social functioning. 51,52 Patients who had experienced these benefits wished that they had had been offered PR early in the course of their disease. 51

Barriers to attending pulmonary rehabilitation

There are well-documented delays in healthcare professionals initiating a referral,53–55 and more than one-third of patients referred do not attend the offered assessment. Likewise, assessment completion rates are persistently low,11,55 especially in people from the most deprived quintile, people who are underweight or very severely obese and people with more severe disease. 56 In addition to limited information about PR, and long delays between referral and starting a course, there are multiple practical barriers (e.g. travel, parking arrangements, timing of classes) that reduce people’s capability to attend and/or complete a course of PR. 57 People who had ‘lost hope’ or whose anxiety about their breathlessness ‘made exercise impossible’ were less likely to attend PR,53 suggesting that a focus on addressing these perceptual barriers could benefit people with COPD and anxiety/depression. Providing information and reassurance, addressing practicalities and maintaining contact while waiting to start the course are suggested as strategies to improve attendance at PR. 53

Strategies to increase uptake and completion of pulmonary rehabilitation

A systematic review of interventions (14 studies) to improve uptake and completion of PR had inconsistent outcomes,58 although uptake was improved when the referral was part of a care plan actively supported by the healthcare team59 or when information about the benefits of attending the course was provided to the patient. 60 Qualitative interviews reinforce the potential benefits of ‘repeated discussions’ to facilitate understanding of PR and its perceived benefits and of addressing any emotional and practical limitations associated with attending. 53 A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative evidence (48 studies) in relation to referral, uptake, attendance and/or completion in PR mapped interventions to aspects of the theoretical domains framework. 61 The domains most mapped were ‘environmental, context and resources’, ‘knowledge’ and ‘beliefs about consequences’, again, emphasising the need to support patients’ understanding of the benefits of PR. Potential practical solutions were also addressed (including provision of transport or parking, offering choice of timing of classes and language provision), along with organisational support to increase service capacity.

Synergies of psychological and physical interventions

Both CBT and PR, therefore, have benefits for improving the mental health of people with COPD and anxiety/depression, raising the potential for synergistic and additive effects.

The National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment brief62 was based on a systematic review and meta-analysis of complex interventions that concluded that psychological interventions combined with exercise training (29 studies in the meta-analysis) resulted in clinically significant improvements in symptoms of anxiety and depression in COPD, compared with CBT alone, which was only minimally effective. 63 This effect applied regardless of the severity of the anxiety and depression, although there was a caveat in that some of the studies recruited people with normal mental health scores at baseline. A more recent Cochrane review45 concluded that a psychological therapy combined with a PR programme reduced depressive symptoms more than a PR programme alone (SMD 0.37, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.74; p = 0.05; two studies, 112 participants).

The TANDEM (Tailored intervention for Anxiety and Depression Management in COPD) intervention was, therefore, designed to provide an intervention based on CBT and linked with a referral to PR for people with moderate to very severe COPD and mild to moderate anxiety and/or depression [see Chapter 2, Step 2: theory-informed intervention outline, for an explanation of how we developed the TANDEM intervention using a COPD-focused, lower-intensity CBT approach that addressed negative automatic thoughts (but did not address more ingrained thinking patterns)].

The potential benefit to carers was of interest and, at the request of the funder, we invited carers (who were nominated by patients recruited to the trial) to participate. 62

Aim

Our aim was to evaluate a tailored psychological CBA intervention (i.e. the TANDEM intervention), which precedes, links into and optimises the benefits of attending an existing PR course, with the intention of reducing mild/moderate anxiety and/or depression symptoms in people with COPD and moderate to very severe airflow limitation. 2,3

Objectives

-

To develop and refine the TANDEM intervention to develop a training programme for healthcare professionals who will deliver the programme, and to document the training programme in a manual (see Chapter 2).

-

To undertake a randomised controlled trial of the TANDEM intervention to examine the effectiveness of the TANDEM intervention on clinical outcomes compared with usual care (i.e. guideline-defined care including the offer of PR2,3) (see Chapter 4).

-

To examine the affect of the TANDEM intervention (which is directed at patients) on carers (where appropriate) (see Chapter 4).

-

To determine the cost effectiveness of the TANDEM intervention from an NHS and PSS perspective (see Chapter 5).

-

To conduct a process evaluation to assist interpretation of findings and inform the implementation of the TANDEM intervention if the trial results are positive (see Chapter 6).

Rationale for our approach

Pooler and Beech23 outlined a virtual model in which a cycle develops, starting with anxiety and/or depression, which leads to increased exacerbations and hospitalisations, which leads to reduced ability to cope, leading back to further increases in anxiety/depression. Figure 2 illustrates our proposed logic model, which shows how we aimed to counteract this cycle. An updated version of the logic model following intervention development is described in Chapter 2.

FIGURE 2.

Proposed logic model. We proposed that by addressing cognitions and behaviours the TANDEM intervention would (1) reduce anxiety and depression, (2) lead to increased participation with PR, (3) result in a decrease in exacerbations and improve quality of life and (4) directly feedback to further reduce anxiety and depression, as well as reducing morbidity and healthcare utilisation.

The TANDEM intervention optimised the potential synergy between the psychological one-to-one intervention and PR. The TANDEM therapy preceded PR and targeted individuals’ cognitions and behaviours associated with anxiety and depression both to decrease psychological morbidity and to increase motivation to attend and complete PR, which in itself has a positive effect on anxiety and depression.

Patient and public involvement in the TANDEM intervention

Aligned with our patient-centred approach, patient and public involvement (PPI) was central throughout the TANDEM project, informing the initial proposal, contributing to development of the intervention, advising on the evaluation and contributing to dissemination.

Further details on how PPI has been used in the TANDEM study are provided in Barradell and Sohanpal. 64

How patients and the public were recruited

Patients with COPD and carer advisors were identified via established patient networks. We had worked with some patients/carers before, whereas other patients/carers were introduced to us by study team members as patients who had previously expressed interest in involvement. In addition, we promoted the TANDEM study on social media, specifically Twitter, now renamed X (URL: www.twitter.com; Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA). We approached potential advisors by letter, e-mail or telephone, or by attending one of their regular meetings and presenting the purpose of study, inviting them to become an advisor to the TANDEM study and giving options for involvement.

Most of the patients who expressed interest were members of support groups affiliated to the Asthma UK (London, UK) and British Lung Foundation (BLF) (London, UK) partnership (e.g. Breathe Easy patient groups in London, an exercise group in the West Midlands and a dedicated hospital-based PPI committee in Leicestershire). One patient responded to the Twitter invitation and we also recruited a patient representative known to a study team member through previous work.

Flexible options for involvement

We were flexible in our approach of involving patients as advisors. Advice was sought in groups (e.g. a discussion group to inform intervention development) or individually (e.g. to provide comments and feedback on intervention handouts). Communication could use any mode of contact (e.g. in person, telephone, e-mail, post).

Remuneration for involvement was discussed with Steven Towndrow (PPI/Engagement and Communications Officer, NIHR Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care North Thames, hosted by Barts Health NHS Trust). Vouchers to the value of £15 or £30 were provided based on involvement activity (i.e. £15 for reading and providing comments on study documents and £30 for attending a meeting).

The research cycle

The research cycle (Figure 3) highlights the contributions of PPI colleagues to the TANDEM study before, during and after the trial. A PPI co-applicant (who eventually withdrew from involvement in the study) had been with us from inception of the study. At grant application stage, the PPI co-applicant contributed to shaping the research question, methods and intervention, and helped write the lay summary. During the trial, the PPI co-applicant attended and contributed to the study team meetings and also attended the Independent Trial Steering Committee.

FIGURE 3.

The contributions of the PPI colleagues throughout the TANDEM study. Reproduced with permission from Kelly et al. 65 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

The nature of involvement from other patient or carer advisors varied, as it depended on the requirements at that stage of the trial. Types of involvement included the following:

-

Providing comments and feedback on patient and carer study documentation (i.e. invitation letter, participant information sheet, consent form, study leaflets, interview topic guide, intervention handouts). Advice was sought on clarity, how easy it was to understand what is proposed and suitability of content and images, as well as suggestions for improvement.

-

Providing comments and feedback on terminology, advising on the best words to describe the intervention.

-

Providing comments and feedback on patient and carer recruitment and participant flow into the study.

-

Providing comments and feedback on intervention content and materials, and intervention delivery processes.

-

Role-playing with researchers to improve the process of approaching patients about the study.

-

Completing the patient and carer questionnaire to assess burden and time of completion.

-

Suggesting preferences for:

-

promotional study materials for study participants

-

an electronic database based on looking at screenshots of two types of electronic database.

-

-

Commenting on dissemination plans.

Ethics approvals and research governance

The trial was sponsored by the Joint Research Management Office for Barts Health NHS Trust and Queen Mary University of London (London, UK). The study was approved by the London – Queen Square Research Ethics Committee (reference 17/LO/0095) and by the local research and development departments in each participating trust. Before commencing recruitment, the trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number Register (reference ISRCTN59537391) and NIHR Clinical Research Network Portfolio (reference 32713).

All study participants gave written informed consent. All participants were aware that they could withdraw from the study at any time and that participating in the study, or withdrawing from it, would have no effect on the medical care they were offered.

The trial was monitored by a Trial Steering Committee and a Data Monitoring Committee.

Chapter 2 Developing the TANDEM intervention

A paper has been published elaborating on the process of intervention development. 66

A five-step approach to intervention development

We used the widely cited MRC framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions,67 guidance and a ‘person-based approach’68 to guide the development of the TANDEM intervention.

At the time of TANDEM development, the MRC framework recommended that intervention development should be evidence based, use theory and model processes and outcomes prior to feasibility testing the intervention before formal evaluation. 67 The person-based approach to intervention development was originally designed for use with digital interventions,69 but has subsequently been applied to a more diverse set of interventions. 68 The person-based approach is based on the premise that a full and in-depth understanding of the target population and their involvement throughout the design process will enhance how the theory and evidence base are used. There are two main elements of this approach: (1) a developmental phase in which users provide information and opinions around the behavioural elements of the intervention and (2) a set of guiding principles are identified that ‘highlight the distinctive ways that the intervention will address key context-specific behavioural issues and provide a guiding framework for the intervention’. 68

In the TANDEM programme of work, these two approaches to intervention development were integrated to inform a five-step process that has been described in detail by Steed et al. 66 The steps were (1) building an expert team, (2) theory-informed intervention outline, (3) developing guiding principles informed by qualitative work, (4) developing a detailed intervention design and (5) pre-piloting and refinement (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Schema of the five-step approach to intervention development as applied to the TANDEM intervention. Reproduced with permission from Steed et al. 66 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

The fit of the TANDEM intervention with the 2021 Medical Research Council guidance for complex interventions

The extended MRC guidance for development and evaluation of complex interventions published in 2021 continues to specify the four key phases: (1) intervention development, (2) feasibility testing, (3) evaluation and (4) implementation. 70 In addition, there are six core elements that should be considered within each phase:

-

How does the intervention interact with its context?

-

What is the underpinning programme theory?

-

How can diverse stakeholder perspectives be included in the research?

-

What are the key uncertainties?

-

How can the intervention be refined?

-

What are the comparative resource and outcome consequences of the intervention?

Although the TANDEM intervention was developed prior to this publication,70 each of these questions was addressed during the course of the developmental work. With regard to how the intervention interacts with its context, consideration was given to where the intervention would be delivered (e.g. within a patient’s home or at a clinic). The programme theory was extensively developed and illustrated in a logic model. Using the person-based approach meant that a full range of stakeholder perspectives were used to inform intervention development from the outset. The pre-pilot identified important uncertainties (e.g. whether or not acceptability and feasibility were influenced by qualification level of the facilitator) and the intervention was refined post pre-pilot. Finally, the TANDEM trial addresses questions of clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness to understand resource implications.

Step 1: building an expert team

The commissioning brief called for an intervention combining psychological therapy and physical retraining tailored to the severity of the patient’s respiratory and mental health. 62 Important outcomes were defined as measures of depression and anxiety, breathlessness, health-related quality of life and acceptability, as well as impact on carers, smoking status, use of healthcare resources and cost effectiveness. 62 As outlined in Chapter 1, Synergies of psychological and physical interventions, we proposed combining two well-established interventions (i.e. CBT and PR) and considered that efficient intervention design would be best served by building on the work of others in the field, rather than ‘re-inventing’ the wheel. Therefore, we sought, from the beginning, to build a multidisciplinary team with particular expertise in CBT for COPD and PR. In addition to leaders in COPD and primary care research (SJCT, HP and RS), we invited colleagues who had developed and demonstrated the effectiveness of a CBT intervention (i.e. The Lung Manual) for individuals with anxiety and COPD (KH-M)71,72 and colleagues who had developed Self-management Programme of Activity, Coping and Education (SPACE) for COPD® (a self-management manual) (SS)73 to join the team. Other team members included a health psychologist (LS), a clinical psychologist (SW), a qualitative research lead (MJK) and our co-applicant with COPD (see Chapter 1 for a detailed description of the contribution of PPI colleagues). Initially, the team aimed to pool resources from the already developed interventions (i.e. The Lung Manual and SPACE for COPD) to provide a starting point that could act as the bedrock for the intervention. The intervention development team subsequently met at key points along the development journey, forming an expert panel to suggest content, consider theory, review resources, provide feedback and agree revisions to the intervention.

Step 2: theory-informed intervention outline

Cognitive–behavioural therapy: a theoretical approach to influencing mood

The brief specified an intervention be designed that combining psychological therapy with physical retraining that was tailored both to the severity of the patient’s COPD (ranging from moderate to severe COPD) and their mental health (ranging from mild to moderate anxiety and/or depression)’. 62 Arguably, the most commonly used and well-proven psychological therapy for people with mood disorders, either with or without physical health conditions, is CBT25,26,38,74 (see Chapter 1 for an overview of CBT). CBT typically addresses unhelpful cognitive interpretations that negatively influence mood and feelings. By working at the levels of thoughts, behaviours or symptoms CBT aims to interrupt and reverse the negative impacts and, hence, improve mood. A CBA has been effective when delivered by healthcare professionals with expertise in the clinical condition and who are trained to provide low-intensity CBT (i.e. focused on dealing with current negative automatic thoughts, rather than ingrained historical thinking patterns29).

The TANDEM intervention and a cognitive–behavioural approach

The CBT model has, therefore, been shown to have relevance75 and has had some efficacy with patients with COPD,45,52,76,77 where interpretations of physical symptoms, such as breathlessness, and consequent coping (e.g. fear avoidance) are key precipitators of anxiety and depression. CBT was, therefore, selected as the psychological therapy of choice in the TANDEM intervention (see Chapter 1). Although the underlying theory was based on CBT, the skill set of the facilitators as experienced respiratory practitioners trained to deliver a brief course of treatment meant that high-intensity CBT intended to be delivered by a mental health practitioner would not be appropriate. 29 Instead, we considered that facilitators would use a CBA, working at the level of lower-intensity CBT and addressing primarily negative automatic thoughts, but not addressing engrained thinking patterns, such as rules or schema.

Linked pulmonary rehabilitation: additional benefits for anxiety and/or depression

Physical retraining delivered through PR is recommended for people with COPD. 2,3,46,78 PR has a strong evidence base and is known to improve both physical and psychosocial outcomes at all levels of COPD severity. 50 Therefore, it seemed appropriate to link the cognitive–behavioural element of the TANDEM intervention with existing PR services. The core aim of PR is to increase exercise so that Bandura’s self-efficacy model,75 which holds that confidence in ability to change behaviour is an important predictor of whether or not behaviour will be undertaken, is a useful theoretical basis. Bandura states that self-efficacy can be enhanced through mastery (i.e. successful performance of a goal), vicarious learning (i.e. seeing similar others perform the behaviour of interest) and persuasion (i.e. encouragement from a significant other). Bandura’s self-efficacy model was the theoretical basis of SPACE for COPD73 and so that alignment with the SPACE for COPD programme was appropriate. The TANDEM intervention, therefore, provided all intervention participants with SPACE for COPD materials.

The TANDEM intervention and supporting pulmonary rehabilitation

A challenge of PR is poor uptake and retention54,55,79,80 (see Chapter 1 for a summary of the main issues). The TANDEM intervention aimed to address the issues of poor uptake and retention by applying behaviour change theory to the intervention. We selected Leventhal and Leventhal’s81 common sense model of illness self-regulation, as this model is designed to help understand the dynamic processes that an individual goes through when understanding and managing illness. Leventhal and Leventhal81 hypothesised that to understand their condition, individuals develop cognitive illness representations, which are beliefs that revolve around the following six conceptual areas: (1) identity (i.e. the label and symptoms that are attributed to the condition), (2) consequences (i.e. the impact the condition will have on physical and psychosocial areas of the person’s life), (3) causes (i.e. what contributed to causing the condition), (4) timeline (i.e. how long the illness is perceived to last), (5) control (i.e. the extent the individual can exert control over the condition) and (6) coherence (i.e. the extent to which the condition makes sense). People also have emotional representations that, together with the illness representations, influence coping procedures. Coping procedures can include behaviours undertaken to manage a condition (e.g. COPD), such as ‘take medications’ or ‘attend PR’, as well as adopting problem-based coping strategies rather than avoidance strategies. Within the common-sense model, the impact of the coping procedures on both illness and emotional outcomes is then appraised with potential to feedback and influence early aspects of the model. Illness representations have been shown to be important in COPD,82,83 and interventions targeting illness representations have been shown to be successful;84 therefore, this theory was seen as relevant for the TANDEM intervention. A recent extension to the model is the inclusion of treatment representations (i.e. beliefs around effectiveness, worries and concerns of the recommended treatment). 85 Given that PR is a specific treatment that we were targeting, we felt it appropriate to include content around the theoretical construct of treatment representations in addition to illness representations.

The theoretical basis of the TANDEM intervention was, therefore, complex because of integration of several models; however, the models were considered to be complementary and such approaches have previously been used. 86

Healthcare professional training

It was recognised at this stage that it would be necessary to train professionals to deliver the intervention. There is a large body of theory relating to training and adult education, one of the most common being the VARK [visual, auditory, read, kinesthetic (i.e. experience or practice, simulated or real)] model of learning. 87 The VARK model was recommended to us by collaborators from Education for Health (Warwick, UK) and was adopted in the professional training element of the TANDEM intervention. The VARK approach to learning suggests that different learners will have preferences for different ways to assimilate knowledge, and these preferences can be categorised as visual or aural information by reading about things or through simulated learning. By incorporating material in a range of formats (e.g. videos, papers for reading, practical exercises), we aimed to embrace each of the possible learning styles.

Step 3: guiding principles

In line with the person-based approach, exploratory qualitative work was conducted with both patients and healthcare professionals from the outset to understand what would be important to include in the intervention and whether or not certain elements were important for both the effectiveness and implementation of the intervention.

Methods for exploratory qualitative work

Recruitment

A maximum variation sample of respiratory healthcare professionals who had an interest in delivery of psychological interventions to patients were recruited through social media and professional networks. The healthcare professionals were invited to participate in either an individual interview (i.e. face to face or telephone) or a focus group, dependent on participant preference. Similarly, two focus groups for people with COPD and carers were arranged (one for individuals with experience of psychological therapies and one for patients without this experience). Patients and carers were recruited for the focus groups via a respiratory support group (‘Breath Easy’). These formal qualitative approaches were in addition to PPI input on, for example, the one-to-one approach, number of sessions and content of intervention booklets (see Chapter 1, Patient and public involvement in the TANDEM intervention, for further description of the whole integrated PPI contribution).

Topic guides and data collection

Interviews/focus groups were conducted by Liz Steed, Ratna Sohanpal and Karen Heslop-Marshall. Topic guides for both patient and professional groups included (1) perspectives on patients’ difficulties with living with COPD, (2) opinions on the proposed intervention (i.e. we described our ideas as outlined in the grant application to participants) and (3) key strategies that would maximise the chance of implementation if the intervention was shown to be successful. Interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded, transcribed and analysed thematically.

Results of the exploratory qualitative study

Participant characteristics

One focus group with respiratory professionals was conducted, comprising a respiratory consultant, three physiotherapists, an occupational therapist and one exercise practitioner. All participants in the focus group were employees at a tertiary care hospital. In addition, seven individual interviews were conducted with healthcare professionals [one general practitioner (GP), four psychologists and two physiotherapists]. These individuals all had experience of working with respiratory patients within the community, primary care or secondary care.

We were able to conduct only one focus group with patient and carers because of time and governance delays at the site where individuals who had previously received CBT were to be recruited. In total, four individuals with COPD, two individuals with other respiratory conditions and two carers participated.

Guiding principles

Table 1 provides a summary of the guiding principles for both the intervention and its implementation.

| Guiding principle | Illustrating quote |

|---|---|

| Intervention | |

| Depression and anxiety are key topics, but could be introduced via breathlessness |

I think they most often talk about symptoms like breathlessness, rather than saying that they’re anxious or depressed

HCP006 physiotherapist Terminology is important such as ‘dealing with’, ‘living with’ Patient focus group discussion … not much focus is given on … knowing how to deal and what to expect when you experience breathlessness Patient focus group participant |

| The intervention should be tailored/flexible to individuals |

It’s just that patients are all different, and therefore present very differently and the intervention has to be tailored individually to what they’re presenting with

HCP003, psychologist Topic suggestions ‘involve family’, ‘concept of acceptance’, ‘coping strategies’ Patient focus group discussion |

| Sessions could be offered at home or in a clinic, but there may be limitations to the latter. Accessibility is key |

So I think having the capacity to start off at home is certainly a good idea. I think just something about accessible locations

HCP002, psychologist |

| Clear expectations and boundaries should be set at the start of the intervention |

So there needs to be quite clear boundaries about what the intervention offers and doesn’t offer

HCP006, physiotherapist |

| Implementation | |

| Delivery by respiratory professionals rather than psychologists is preferable |

It feels important that other members of the healthcare team are being trained up in these approaches. That can only be a good thing …

HCP003, psychologist |

| Some selection and training of facilitators will be needed |

A lot of people would be attracted to this, but it’s not for everyone to deliver

HCP005, physiotherapist What training would this nurse have? Patient focus group participant |

| Supervision of facilitators delivering the intervention is essential and should be ongoing |

I think that’s important [supervision]

HCP005, physiotherapist |

| The intervention must be deliverable and supported by management |

There’s no point evaluating it, if it’s not something that’s going to be deliverable

HCP FG001 doctor |

In general, both patients and healthcare professionals were very positive about the proposed intervention. Patients and healthcare professionals felt that anxiety and depression were important and relevant for individuals with COPD, and that anxiety and depression were closely linked to breathlessness, which might be an acceptable way to introduce the intervention to potential participants. There was recognition that different people would have different needs and, therefore, being able to offer an intervention tailored to the individual with the possibility of home-based sessions would be ideal. There was consensus that, given the physical complexity of these patients, delivery by respiratory professionals would be preferable to psychologists, but training and supervision would be essential. One of the key concerns was around the symptom of breathlessness and its causation (i.e. was breathlessness anxiety related or an indicator of a developing exacerbation?). For anxiety-related breathlessness, some basic distraction and breathing techniques may be appropriate; however, for an acute exacerbation, assessment and treatment by a healthcare professional would be needed. These management options are diametrically opposed. From a safety perspective, it was considered that training respiratory professionals (familiar with COPD and managing acute exacerbations) in psychological techniques would be preferable to training psychology practitioners in respiratory medicine.

Step 4: developing the detailed intervention design

Patient sessions

The topics for the patient-facing intervention were informed by the underlying theory, discussed with the intervention development team and aligned with the guiding principles. Table 2 provides an overview of the TANDEM intervention. The topics to be addressed in the first session were related to illness representations around COPD and, in particular, the symptom of breathlessness and techniques to manage this. At this initial session (and repeated at the final session of the TANDEM intervention), the facilitator administered short questionnaires that are widely used in clinical practice to assess anxiety and depression status. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9) assesses depression88 and the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) measures anxiety. 89 These assessments were intended to guide the intervention, and were not considered as trial outcome measures.

| Session | Topic covered | Content |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction, setting expectations Topic 1: what is COPD? Topic 2: taking control of COPD Topic 3: the patient experience of breathlessness |

Eliciting the patient’s understanding of COPD Identifying and working with illness and treatment beliefs and acceptance Teaching basic breathing control |

| 2 | Feedback from home practice Topic 4: introducing mood and COPD |

Conducting a formulation and presentation of a CBA |

| 3–7 (CBA) | Feedback from home practice Topic 5: managing anxiety and COPD Topic 6: managing depression and COPD Topic 7: applying CBA to other problems (optional) |

Up to four sessions to conduct cognitive–behavioural work on anxiety and/or depression dependent on individual need One further session available to discuss other problems if needed |

| Penultimate session | Feedback from home practice Topic 8: living with COPD day to day |

Self-management approaches to COPD Learning to problem solve and set goals |

| Final session | Feedback from home practice Topic 9: preparing for PR |

Expectations of PR, addressing worries and concerns |

| Linking to PR | Reviewing progress and adjusting goals | Fortnightly telephone calls exploring any worries or concerns delivered between the end of the one to one sessions until the end of PR |

The topic of mood and COPD was introduced in session 2, as the premise of CBT is that thoughts, feelings, symptoms and behaviours interact. By the end of session 2, an initial formulation of the primary presenting problem of the individual patient should have been made (see Figure 1 for an illustration of a ‘hot cross bun’ formulation). Dependent on the presenting problems, sessions 3–6 used a CBA that focused on depression and/or anxiety. The penultimate session addressed self-management techniques and the final session addressed treatment representations around PR. An additional, optional, session was designed to apply CBA skills to a non-COPD problem, if needed, and this reflected recognition that many COPD patients have complex lives and may have issues that affect their psychological well-being that are separate from COPD. To acknowledge the importance of other issues, while maintaining the centrality of the intervention on COPD, session 7 (i.e. ‘applying CBA to other problems’) was added.

All topics were coded as core (i.e. applicable and for delivery to all participants), tailored (i.e. addressing depression and/or anxiety as appropriate) or optional (i.e. used only if applicable). Patient-guided self-completion leaflets were written by a member of the team (LS) and revised by members of the intervention development team. The PPI co-applicant then went through the leaflets in detail to ensure they were accessible to the COPD population. The leaflets were modelled on publicly available self-help leaflets designed by Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK), which had been extensively reviewed by lay people. Leaflets were developed for key topics (e.g. mood and COPD, depression and COPD, anxiety and COPD). Any relevant SPACE leaflets (controlling your breathing, diet and COPD etc.) were reformatted to be consistent with the TANDEM intervention style. In addition, we developed a leaflet for ‘caring for someone with COPD’, as this had been highlighted in focus groups as an important topic. Having developed the key topics and related resources, these were then translated into individual facilitated sessions to be delivered by the healthcare professionals trained as TANDEM facilitators, following a similar model to that of guided lower-intensity sessions by the NHS IAPT programme. 90,91

In addition to the face-to-face sessions, telephone contacts were designed for patients who were going on to PR. The telephone calls were designed to be fortnightly, leading up to and throughout the PR. The aim of the telephone calls was to provide continuity of contact between the conclusion of the face-to-face sessions and PR, and to help patients reflect on their goals for PR and review progress. If participants decided not to participate in PR, or if patients were not considered eligible by the PR service, then they did not receive additional telephone calls.

Facilitator training

Following development of the patient-facing intervention, we devised a training programme for respiratory healthcare professionals to deliver the sessions. The training programme drew on training developed in ‘The Lung Manual’. 73 The Lung Manual, in contrast to the TANDEM intervention, did not specify session content or provide an overview structure, rather the manual, supported by 3 days of training, taught ‘a practical and structured guide to using CBT principles with patients who have been identified as experiencing anxiety, panic, low mood or depression as a result of their physical health problems’. 73

Three-day training

For the TANDEM intervention, a 3-day training programme was proposed. The first 2 days of the training programme were delivered consecutively and were designed to cover background theory, introduction to depression and anxiety, and the basic knowledge and skills to use in the TANDEM CBA for patients with COPD. The training was designed to be delivered in a group by two trainers (a respiratory healthcare professional and either a health or clinical psychologist). Learning was interactive, with practical exercises and opportunities to practise skills with a professional actor who had been briefed on the training aims. This type of learning was informed by medical education curricula that suggests that providing students practice with simulated patients is beneficial to clinical competency. 92

A third day was scheduled 4–6 weeks later. During the interim period, all trainees were asked to apply the skills they had learnt within their clinical practice. On the third training day, trainees presented a case study of a patient to illustrate how they had conducted a formulation and used the skills they had learnt. The case studies presentations were discussed, with any difficulties or problems resolved.

Training manual

A comprehensive training manual was developed, comprising three sections:

-

A detailed outline of content and delivery recommendations for each topic.

-

A guide to skills of cognitive–behavioural and self-management assessment and intervention.

-

Background information on COPD and theoretical underpinnings of behaviour change and CBA for trainees who wished to gain additional knowledge.

All resources, such as patient handouts, were appended at the end of the manual. The aim was to make the manual a comprehensive ‘go-to’ resource for delivery of all TANDEM intervention elements.

Study materials (research and clinical documentation)

Facilitators were provided with all materials required to audio-record the intervention sessions, along with video instructions on how to (1) use the encrypted audio-recorder and (2) securely transfer audio-recordings to the study team. Research documents included a CBA-session contact and delivery log. Clinical documents (not for research purposes) were as follows:

-

A CBA-session case notes and supervision document was used to record detailed clinical information (including personal identifiable details of participant) necessary for intervention delivery for each participant, and to facilitate clinical supervision. The clinical notes were stored securely and separately from the TANDEM research data.

-

A summary letter that was sent to patients’ healthcare professionals (with the participant’s permission) following completion of intervention delivery. The letter included a brief summary about the intervention delivery, the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores (used by the facilitator to assess the mental health status of the patient at the beginning and end of the CBA sessions) and any other information that was important for healthcare professionals to know about the patient in relation to their ongoing care.

Supervisor training

We recognised that TANDEM intervention facilitators would require clinical supervision to ensure safe and effective delivery of the intervention. Supervision has been shown to be an important factor in reducing ‘therapist drift’, particularly with new therapists. 93,94 All supervisors were required to be qualified as either a cognitive–behavioural therapist or a clinical/health psychologist. The supervisors participated in the 3-day TANDEM training programme and had an additional half-day training in the clinical management of COPD and applying TANDEM CBA to COPD-related issues. The supervisors themselves received support through a lead supervisor who was a member of the research team (SW).

Ensuring fidelity

Throughout step 4 of intervention development, the intervention development team considered actions that would enhance intervention fidelity in line with the National Institutes of Health Behaviour Change Consortium framework and recent recommendations. 95,96 Figure 5 summarises the strategies taken to enhance fidelity (see Chapter 6 for greater detail on fidelity assessment).

FIGURE 5.

Strategies used to enhance fidelity.

Important elements to ensure fidelity were provision of a manual for facilitators (with a comprehensive description of the content to cover in each session), reinforcement of the skills taught in the training and background information on the theoretical basis of the intervention. The aim of the manual was to (1) increase facilitator confidence and (2) ensure consistency of delivery between facilitators. Similarly, standardised materials were developed for patients. Patient materials included both information and self-completion exercises to ensure that topics were covered consistently while also allowing tailoring to the individual. All materials were discussed with PPI colleagues to ensure appropriateness for people with COPD.

Step 5: pre-pilot

Having developed the draft patient intervention and facilitator training, a pre-pilot study was conducted. The pre-pilot study allowed delivery of the intervention as a whole and considered how different parts of the intervention worked together. The pre-pilot study was explicitly part of the intervention development (in contrast to feasibility studies, which are typically conducted after the main intervention development phase). Two key questions were asked in the pre-pilot study:

-

Is the TANDEM intervention acceptable and appropriate for patients when delivered by a therapist previously trained and qualified in CBT (when it can be assumed the intervention is delivered with fidelity)?

-

Is the TANDEM intervention acceptable and appropriate when delivered by a facilitator who receives the TANDEM training (i.e. does the TANDEM training provide facilitators with sufficient skills to deliver the intervention appropriately and, therefore, has it potential for implementation)?

To answer these questions, the TANDEM training was delivered to three purposively sampled respiratory healthcare facilitators (one facilitator was a qualified CBT therapist, one facilitator had received a previous 3-day training in CBT and had used the techniques in practice, and one facilitator was a complete novice to CBT). To replicate the group element of the training programme, key members of the research team, including the trial manager, the principal investigators and the qualitative lead, also participated. At the end of each day of training the trainees had a group discussion about strength and weaknesses of the training and what they perceived should change. Each facilitator was then given the task of delivering the TANDEM intervention to two of their patients who fitted TANDEM intervention criteria (i.e. mild/moderate anxiety and or depression and moderate to very severe COPD). Following intervention delivery, the three facilitators and six patients were invited for qualitative interview.

Feedback from the training sessions

The quotations below have been reproduced from Steed et al. 97 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Group members provided constructive feedback at the end of each training day, which highlighted the following themes:

-

A greater need for an overview of the TANDEM intervention at the outset of day 1.

-

A sense that role-play with a professional actor within the first 2 days of training was unhelpful, as participants did not feel confident enough to gain from this role-play at such an early stage and, instead, it was perceived as threatening.

-

A desire for more case study practice to develop formulations of patients’ presenting difficulties.

Two of the three respiratory healthcare professionals went on to deliver the TANDEM intervention. One healthcare professional (the CBT qualified professional) delivered sessions to two patients and one healthcare professional (the briefly CBT-trained professional) delivered sessions to one patient. The complete novice to CBT did not manage to deliver any TANDEM sessions to patients because of governance delays and a change in his work responsibilities, and this facilitator was also not available for interview. Interviews with the facilitators who delivered the TANDEM intervention reported that patients were engaged:

Yeah, I mean the two patients who I had were very, very enthusiastic about all elements of the intervention.

PP-HCP01

This engagement was corroborated by the patients who reported the intervention to be beneficial and acceptable:

And then [facilitator] and I just seemed to get on very well, he’s a likeable chap, very laid back. And so it went from there. And then we started doing the things that you asked in TANDEM. Planning ... They’re just small things, but marvellous.

PP-P01, male participant

The facilitators found that the manual and session materials were too complex at certain points:

I mean section nine, it’s got ‘identifying maintenance factors’, and it talks about ‘safety behaviour’, ‘avoidance and escape’, ‘catastrophic interpretation’, ‘scanning or hypervigilance’, ‘self-fulfilling prophecies’, ‘fear of fear’, ‘reductions’, ‘affectionism’, ‘short-term rewards’. If you’re trying to talk to a patient and remember what it says in the manual you might get yourself a little bit flustered.

PP-HCP02

Recommendations were made to simplify things, with a tool box of techniques for anxiety and depression and crib cards given as examples of additional useful resources:

I feel that people who come away from the training need to have something like a virtual toolbox of techniques that they can refer to ... they expected quite a lot of you ... I made myself a crib sheet type of thing.

PP-HCP01

Adherence to the sessions was good, but one element of the whole intervention that fell below expected levels was use of supervision. Neither facilitator contacted or responded to calls from the supervisor while delivering sessions and this was of concern, as supervision was perceived as a core safety element of the intervention. On further exploration, the facilitators divulged that they did receive supervision but got this from their normal CBT supervisor who worked at their clinical site. As the site supervisor also knew the patients recruited to receive the pre-pilot intervention, a judgement had been made that it was preferable to use the local supervisor rather than the TANDEM supervisor. Although understandable, this highlighted that more focus was needed on the importance of how and when supervision should be received.

Refinements to facilitator training after the pre-pilot study

Table 3 shows the finalised training programme with the amendments made after the pre-pilot study. An additional session on the importance and mechanism of supervision was added. Role-play with an actor was removed from the core training days and, instead, each facilitator conducted an individual video-recorded role-play with a professional actor on day 3. In this role play, the facilitator was asked to conduct an initial interview and formulation with the simulated patient and feed this back to them. This recorded role play served two purposes. First, the role play allowed an assessment of therapeutic competency of the facilitator, which is important for ensuring fidelity in treatment delivery. Second, role play served as a further training opportunity. All facilitators were visited by one of the trainers (LS) who showed them their video-recording and discussed strengths and areas for development. Several of the facilitators commented that although they found this a difficult process it was important for their learning and, in many cases, increased their confidence in the skills they had learnt.

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Introductions aTANDEM overview The patient’s experience of COPD (group exercise) What are depression and anxiety? (group exercise) Depression and anxiety in COPD Introduction to CBA (group exercise) Core therapeutic skills (avideo demonstration) Making an assessment: recognising thoughts, feelings behaviours, symptoms (practical) Sharing ideas with patients (practical) Feedback on worries and concerns after day 1 |

Practical CBA techniques Psychoeducation Breathing control Distraction Monitoring Problem-solving Goal-setting Graded practice/simple behavioural experiments Challenging thoughts (avideo demonstration) aToolbox for anxiety aToolbox for depression Preparation for case studies |

Case study feedback aIndividual practice with actor (videoed) Delivering TANDEM session by session, including: Changing behaviour Preparing for PR (using a photobook) aImportance of supervision Risk assessment Research requirements aProvision of crib cards |

A further innovation designed to support facilitators and to enhance fidelity of delivery was design of TANDEM-specific clinical case notes. TANDEM-specific clinical case notes served the same purpose as routine clinical practice notes, but were designed to guide the facilitators in key things they should consider in formulation and intervention. For example, in early sessions, facilitators were prompted to record a ‘hot cross bun’ formulation. In later sessions, there were prompts for not only recording what intervention was being undertaken, but also why. Therefore, facilitators were encouraged to be reflective in their practice.

Arrangements for facilitator recruitment

To enhance fidelity of facilitator training and delivery we also put in place a recruitment process for the facilitator role. The recruitment process involved a formal job advertisement and job specification. Facilitators were invited to apply for the role by sending the study team their curriculum vitae. Facilitators who met eligibility criteria were invited to a structured telephone interview focused around their engagement with a biopsychosocial model of care, flexibility to deliver TANDEM sessions and respiratory experience.

Iterative refinements to the TANDEM patient-facing intervention

As a result of the pilot, it became apparent that some patients could have exacerbations during the 6- to 8-week delivery period, necessitating a break in the delivery of the intervention. The decision was, therefore, made to allow one additional review session if there had been a gap in delivery, as this would also allow an adjustment to the formulation, if necessary, and intervention techniques, if appropriate.

A practical problem that occurred was if the participant was invited to start PR before completion of the full TANDEM CBA intervention. As delay in attending PR would not represent best clinical care, the decision was taken that topics could be re-ordered to address the beliefs and concerns around PR at an earlier stage if needed. However, it was stipulated that topics 1, 5 and 6 should have been delivered before initiation of PR to allow for a sufficient dose of the TANDEM intervention to be received first.

Final logic model

Following the finalised intervention design, a logic model was specified outlining movement from initial problem to change in outcomes via hypothesised mechanisms (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

The TANDEM logic model. ADL, activities of daily living, HCU, healthcare use.

Chapter 3 Methods: clinical effectiveness study

The trial protocol and statistical analysis plan are published. 98,99

Study design

The TANDEM study was a multicentre pragmatic two-arm individual patient randomised control trial with an internal pilot phase. Following collection of baseline data, participants were randomised with full allocation concealment in a ratio of 1.25 : 1 to the TANDEM intervention (see Chapter 2 for a detailed description of the development) or to usual care. All healthcare providers, including PR teams, outcome assessors and statisticians, were blind to the allocation arm of participants. An economic evaluation (see Chapter 5) and a process evaluation (see Chapter 6) were conducted in parallel.

Research sites

The TANDEM trial was run from what is now the Wolfson Institute of Population Health and Barts, The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London (London, UK) where one of the co-chief investigators, the trial manager, a research assistant and the trial administrator were based. Trial support was provided by the Pragmatic Clinical Trials Unit (PCTU) at Queen Mary University of London.

Research assistants were based alongside co-applicant Investigators in the School of Population Health and Environmental Sciences, King’s College London (London, UK), Centre for Exercise and Disease Science, University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust (Leicester, UK) and Warwick Clinical Trials Unit, Warwick Medical School (Coventry, UK).

As the TANDEM intervention was designed to precede the opportunity to attend routine PR, recruitment sites had to involve a participating PR service(s). Initial recruitment sites were local (London, Leicester and Warwick) to the co-applicant investigators, but a number of sites approached the study team and asked to be involved either through their local Clinical Research Networks or because their local respiratory clinicians were particularly interested in participating in the study.

Recruitment of TANDEM facilitators and cognitive–behavioural therapy supervisors

Facilitators were experienced respiratory healthcare professionals with portfolio careers in respiratory health. Potential TANDEM facilitators were identified via news articles and advertising campaigns across respiratory healthcare networks and associated social media. In addition, TANDEM researchers ran a stall about the study at two successive Primary Care Respiratory Society annual conferences.

To avoid any risk of contamination and to preserve blinding of healthcare providers, TANDEM facilitators were recruited from staff not involved in either the provision of routine COPD care or the delivery of PR for COPD at participating sites while the study was running. Typically, TANDEM facilitators were recruited from neighbouring trusts that were not participating in the study, often from part-time staff who were willing to work an extra day per week for the duration of the study (see Chapter 2 and Steed et al. 66 for a description of screening, training and assessment of TANDEM facilitators).

The co-ordinating supervisor was already involved in the study as a co-applicant (SW). The CBT supervisors were either already known to the study team and invited to join as a supervisor or recruited from an advertisement in the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies’ (Bury, UK) official membership magazine CBT Today (delivered free to over 10,000 members across the UK and Ireland) [URL: https://babcp.com/Membership/Join-Us (accessed 26 October 2022)]. Each facilitator was assigned a supervisor based on matching availability of a day that was mutually convenient for clinical supervision.

Trial training for facilitators and practical considerations

The facilitators were good clinical practice-trained to deliver the research aspects of intervention delivery, and a NHS letter of access was arranged if facilitators were seeing patients outside their usual trust. The facilitators were informed about the concept of blinding and the arrangements in place to prevent the researcher who would be collecting outcome data knowing the allocation of the patient.

The trial manager (RS) delivered training in practical aspects of intervention delivery, provided TANDEM intervention materials and organised brief telephone catch-ups following first patient assignment, and then approximately fortnightly, to resolve any queries or concerns related intervention delivery.

Participant pathway

The TANDEM intervention (see Chapter 2) is a stand-alone intervention designed to precede the opportunity to attend routine PR. There is often a delay between referral to PR and starting a course, and the TANDEM intervention was designed to take place in this hiatus. 46 In 2017, when the study was conceived, the median waiting time form referral was around 11 weeks. 55

A course of PR is always preceded by an assessment of the patient and not all referred patients are deemed eligible to attend a course when assessed by their local PR team. 46,78 Therefore, ‘referral to PR’ is actually ‘referral to assessment for PR’. Assessment of who is fit for PR may vary between sites, depending on the range of courses the sites offer (e.g. some sites may offer the option of seated PR or attendance once a week instead of twice weekly sessions). We included participants who met our eligibility criteria and were eligible for referral for assessment for a course of PR. Some TANDEM intervention patients would, therefore, not be offered subsequent PR. However, as the TANDEM intervention is a stand-alone, talking-based intervention, and our primary outcome was mood, patients still had the opportunity to benefit from the intervention.

At the time of this study, UK national guidelines defined eligibility for PR as:46

-

patients with chronic respiratory disease who are functionally limited because of dyspnoea, including patients with a Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) Dyspnoea score of ≥ 2 and a mMRC score of 1 if they are functionally limited.

The main exclusion criteria were:

-

unstable cardiac disease, locomotor or neurological difficulties precluding exercise (e.g. severe arthritis or peripheral vascular disease)

-

patients in a terminal phase of their illness

-

significant cognitive or psychiatric impairment.

Study participants

People with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

In the internal pilot we included adults with a confirmed diagnosis of COPD and with moderate to severe airflow limitation,2,3 but the recruiting team felt that there were otherwise eligible patients with very severe airflow limitation who were missing out on the opportunity to participate in the study. In the main trial, after discussion with the Trial Management Group and Trial Steering Committee, we extended eligibility to include patients with very severe airflow limitation.

In addition to meeting the eligibility criteria for referral to their local PR service, eligible participants had to have a Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) score at the baseline screening suggestive of mild to moderate anxiety or depression, or both [i.e. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – anxiety (HADS-A) or Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – depression (HADS-D) scores in the range of ≥ 8 to ≤ 15100]. Participants with HADS suggesting severe anxiety or depression were advised (and supported) to seek advice from their GP. Patients who were receiving a psychological intervention, or who had received such an intervention within the preceding 6 months, were excluded; however, patients taking prescribed medication for anxiety or depression remained eligible.

A full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 4.

| Inclusion criterion | Exclusion criterion |

|---|---|

|

|

Carers of people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Recruited participants were asked if they could identify a ‘particular family caregiver or friend who helps them’ whom they would be happy for us to invite to join the study to examine the effect of the patient-directed TANDEM intervention on carers. In this report, we use ‘carers’ as a shorthand to describe this group. Inclusion criteria for carers, identified by a patient participant, were willingness to participate in the study and being sufficiently fluent in English to be able to complete the questionnaires.

Intervention

Chapter 2 provides a detailed description of the TANDEM intervention and its development, and see also Steed et al. 66 In brief, the intervention consisted of a tailored manualised intervention based on CBAs and self-management support delivered one to one by respiratory healthcare professionals (i.e. physiotherapists, occupational therapists, nurses, physiologists or psychologists working in respiratory services) experienced in working with patients with COPD, and trained to deliver the TANDEM intervention as facilitators. A course of therapy lasted six to eight sessions (plus an optional catch-up session if there had been a break in delivery), depending on the needs of the individual participants, and was delivered in patients’ own homes or at a local clinical setting, according to the patient’s choice. Sessions were 40–60 minutes in duration. Facilitators received regular structured telephone supervision from a CBT therapist supervisor throughout intervention delivery who themselves were overseen by a senior clinical psychologist who acted as a co-ordinating supervisor (co-applicant SW).

On recruitment, all intervention and control arm participants were given a BLF DVD on living with COPD and BLF booklets on COPD and PR. At the time of recruitment, these resources were freely available via the BLF website [now the charity Asthma UK + Lung UK URL: https://shop.auk-blf.org.uk/collections/new-shop-hcp (accessed 26 October 2022)]. If local services preferred, then we substituted the BLF PR booklet with local PR resources.

Participants were directed to their usual healthcare providers if they reported that their clinical condition had deteriorated or if they had developed new health problems. In addition, the TANDEM facilitators could (with participants’ permission) discuss with the co-lead applicants (SJCT or HP, both of whom are GPs) any concerns about the participant’s health or social circumstances that may be affecting the participant’s health.

After completing the course of face-to-face sessions, with the participant’s permission, the TANDEM facilitator sent their healthcare providers a brief, structured written case summary documenting progress and highlighting any need for further support. Between completing the face-to-face intervention and up to 2 weeks after completing PR, facilitators also offered brief (15 minutes or less) weekly or less frequent (dependent on participant preference) CBA telephone support.

Usual care

In addition to the BLF materials, participants randomised to the control arm received usual care that followed local arrangements for the provision of guideline-recommended care, including PR. 2 Control participants were eligible for referral to IAPT services or any other psychological or mental health services at the discretion of their usual healthcare providers.

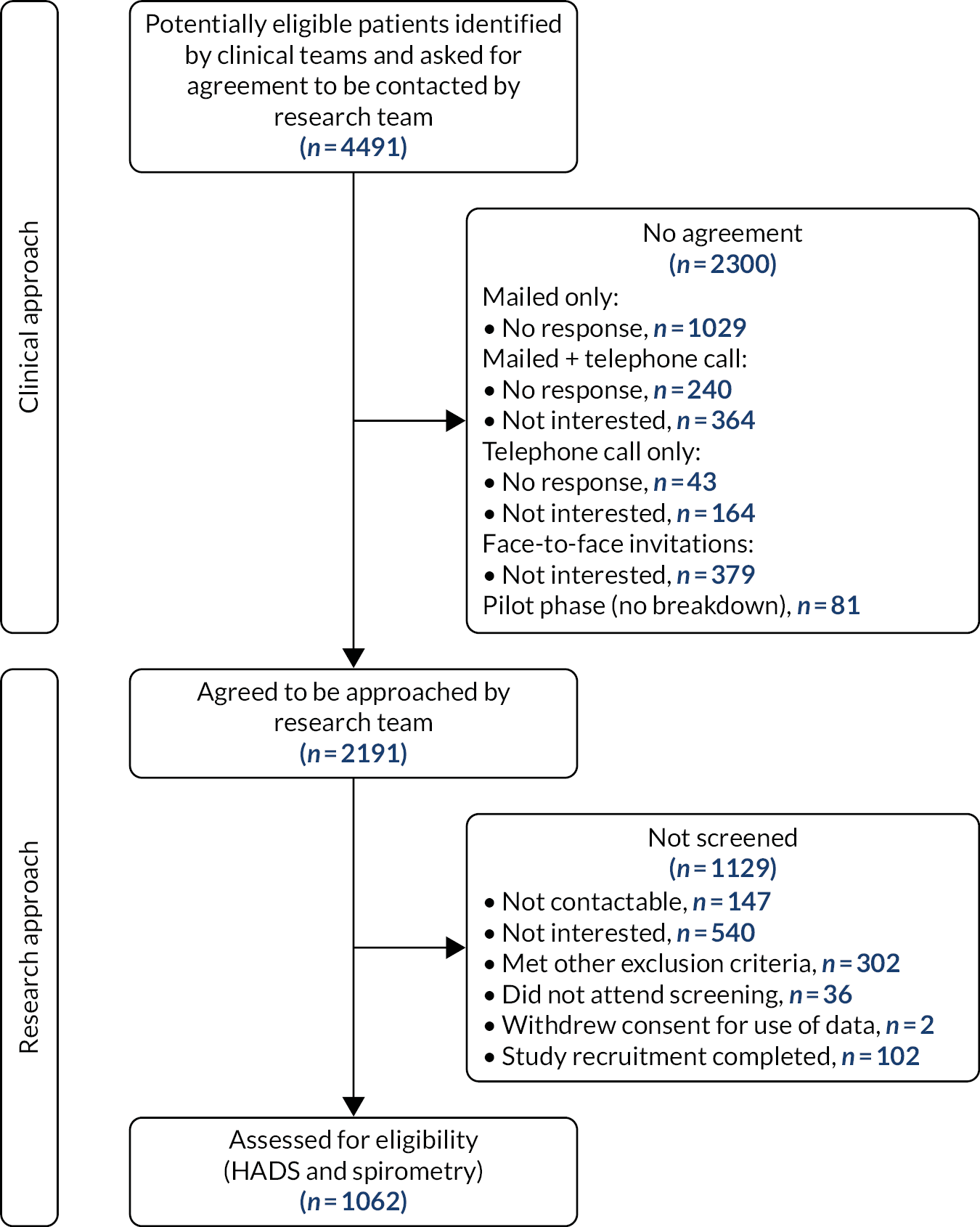

Recruitment of participants with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Potential participants with COPD were recruited from secondary, community and primary care, and from referrals to PR services in participating sites. Advertisements in the form of study leaflets were placed in respiratory clinics and other relevant clinical settings. Potentially eligible people with COPD were asked by their clinicians or clinical research staff if they were interested in being contacted by the study team to learn more about the study and to discuss participation. In addition, primary care teams in participating sites identified potentially eligible participants by searching their primary care COPD registers. The primary care teams wrote to the potentially eligible participants, informing them about the study and inviting them to contact the study team if they might be interested in participating.