Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the Evidence Synthesis Programme on behalf of NICE as award number NIHR135477. The protocol was agreed in May 2022. The draft manuscript began editorial review in December 2022 and was accepted for publication in June 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Llewellyn et al. This work was produced by Llewellyn et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Llewellyn et al.

Chapter 1 Background and definition of the decision problem

Description of health problem

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in men in the UK; it accounts for more than a quarter (27%) of all male cancer diagnoses in 2016–8. 1 It is the second most common cause of cancer death in males in the UK, accounting for 14% of all cancer deaths. The estimated lifetime risk of a PCa diagnosis is one in eight for males born in the UK. 2,3 Over 57,000 new cases were diagnosed in 2018, with an estimated 10-year survival rate of 77.6%. Since the early 1990s, estimates of PCa incidence rates have increased by nearly half (48%) in males in the UK (2016–8) and are projected to rise by 12% between 2014 and 2035, resulting in 233 cases per 100,000 males by 2035. 3

Early-stage diagnosis is associated with improved survival outcomes compared with patients diagnosed at the latest stage of the disease. PCa primarily affects people aged 50 years or more, and the risk of developing PCa increases with age. 3 In England and Wales, 87% of people diagnosed with PCa are aged 60 years or older,4 and on average each year around a third of new cases (34%) were in males aged 75 and older. 2 People from an African family background and individuals with a family history of PCa are at higher risk of PCa. 5,6

Prostate cancer might be suspected if any of the following symptoms cannot be attributed to other health conditions: lower urinary tract symptoms, such as frequency, urgency, hesitancy, terminal dribbling and/or overactive bladder; erectile dysfunction; haematuria; lower back or bone pain; lethargy and weight loss.

The descriptor ‘clinically significant’ (CS) is widely used to differentiate PCa that may lead to morbidity or death from types of PCa that do not. This distinction is important as insignificant PCa that does not cause harm is common. 7 Autopsy studies, in men who died of causes other than PCa, indicate that there is a significant prevalence of non-CS prostate in the general male population, which increases with age. 7 PCa screening may therefore lead to overdiagnosis, by identifying cancers that are not destined to cause morbidity or mortality. Men with these cancers are at risk of being harmed by early detection and unnecessary treatment,8,9 such as radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy with no additional mortality benefit compared to an active surveillance approach, which includes regular monitoring of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels and digital rectal examination (DRE). On the other hand, individuals with undetected cancer or with lesions incorrectly classed as benign may miss out on relevant treatment. Clinical guidelines have focused efforts to address the risk of overtreatment and undertreatment of PCa, notably with recent updates to diagnosis pathways and refinements to risk stratification of cancer lesions. 10–12

Care pathways for the diagnosis and management of prostate cancer

Referral to suspected cancer pathway

There is no screening programme in the UK for PCa, although PSA testing is available for asymptomatic individuals above 50 years of age requesting this test. 13 For people presenting to primary care with certain clinical signs and symptoms that may indicate PCa, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)’s guideline for suspected cancer recognition and referral advises to consider a PSA test and DRE to assess for PCa in men with: any lower urinary tract symptoms (such as nocturia, urinary frequency, hesitancy, urgency or retention) or erectile dysfunction or visible haematuria. 14 The guideline recommends men should be referred using a suspected cancer pathway (for an appointment within 2 weeks) for PCa if their PSA levels are above the age-specific reference range or if their prostate feels malignant (hard, or lumpy) on DRE. The NHS Faster Diagnosis Standard requires that patients are diagnosed or have cancer ruled out within 28 days of being referred urgently by their general practitioner (GP) for suspected cancer,15 and NICE requires that GPs should have direct access to appropriate imaging tests. 16

Figure 1 summarises the EAG’s interpretation of the pathway for the diagnosis and care of individuals with suspected PCa according to NICE guidance (NG) 131 and the NHS timed PCa pathway, which was validated by clinical advisers to the EAG. 12,17

Figure 1.

Diagnostic and care pathway for individuals with suspected prostate cancer. a, per mL of prostate volume. MDT, multidisciplinary team.

Magnetic resonance imaging for suspected cancer

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s guideline for diagnosis and management of PCa advises that, in patients with suspected clinically localised PCa, multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) should be offered as the first-line investigation, but not to those patients who would not be able to have radical treatment. 12 This guidance superseded prior guidance which recommended transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)-guided systematic biopsy as first-line test. Introduced in the 2019 review of the guidelines, the recommendation to offer first-line mpMRI followed the results of PROMIS and PRECISION studies which found a greater negative predictive value (NPV) with mpMRI as first-line diagnostic test compared with the traditional standard-of-care use of TRUS-guided systematic biopsy. 18,19

The results of the MRI can be reported using a 5-point Likert scale as recommended in NICE Guideline 131 (NG131), which estimates the risk that an area seen on the MRI scan may be a cancer or not. The prostate imaging – reporting and data system (PI-RADS) is an alternative to the Likert scale assessment of MRI results. 20–22 Here, each lesion is assigned a score from 1 to 5, with higher scores, usually PI-RADS 4 and 5, indicating a higher likelihood of CS cancer.

Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging and compliance with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance

Uptake of MRI, prior to biopsy in England and Wales, has significantly increased in recent years, from 37% in 2017 to 87% in 2019. Data from 10 of 14 trusts in Scotland also indicate that uptake of a pre-biopsy bi-parametric MRI (bpMRI) or mpMRI as first-line diagnostic ranged from 75% to 100% across centres, although most trusts have not yet met the new NHS Scotland target of 95%. 23,24 TRUS biopsy is still offered as first-line investigation for some patients, although the practice is becoming increasingly rare. 4 Clinical advice to the EAG noted that in some hospitals, patient presenting with an overtly malignant feeling prostate gland (T4) and high PSA may proceed directly to TRUS and biopsy before having MRI to speed up diagnosis. Reasons for deviating from the recent NICE guidance include challenges in meeting waiting targets and the limited availability of mpMRI slots. The COVID-19 pandemic has also disrupted the implementation of the guidance. 23,24

Clinical advisers to the EAG highlighted that bpMRI is sometimes used in current practice where mpMRI is not available. Although the 2019 National Prostate Cancer Audit (NPCA) indicated that 98% of NHS organisations were able to offer mpMRI on site, challenges in meeting the 28-day diagnostic waiting target have been reported. 25 However, there is no evidence that the accuracy of mpMRI and bpMRI differ in treatment-naive patients. 26

Although uptake of mpMRI as first-line diagnostic test has increased in recent years, it is unclear to what extent this is implemented in the NHS, and whether and to what extent other alternative pathways may be followed.

Biopsy

The decision to collect biopsy samples is informed by the MRI, as well as specific risk factors (such as PSA density, family history and ethnicity) and individual clinician preference. One or more prostate biopsies may be performed to rule out or confirm the presence of PCa. Different methods exist for sampling the prostate tissue. The site(s) for biopsy can be targeted for people who have a suspicious lesion identified by the MRI scan. Tissue samples or cores are only collected from the areas identified in the MRI scan as suspicious. The biopsies can also be systematic, where multiple samples are taken in a systematic fashion from different regions of the prostate according to a predefined scheme rather than guided by the MRI results. A systematic only biopsy approach may be taken for instance where clinical suspicion is high but not reflected in the MRI (typically with a LikApplicability of Urostation to KOELISTrinity is unknown.ert/PI-RADS score of 2 or less), although there is regional variation in this practice.

Prostate biopsies may be performed via the transrectal route or the transperineal route. Both routes use a TRUS probe inserted into the anus to generate a live image of the prostate. With TRUS prostate biopsy, a biopsy needle is inserted through the rectal wall via the anus. TRUS biopsies are usually performed under local anaesthesia, although it can also be carried out under general anaesthesia (e.g. if the patient is unlikely to tolerate the procedure otherwise). In a transperineal biopsy (TP), the biopsy needle is inserted through the perineum. Historically, TPs were always conducted under general anaesthesia. However, recent developments in TP techniques have made the procedure more tolerable, and it is now routinely performed under local anaesthesia. 27 NICE draft guidance has recently recommended local anaesthetic transperineal (LATP) prostate biopsy, using the freehand needle positioning devices PrecisionPoint, EZU-PA3U device, Trinity Perine Grid, and UA1232 puncture attachment, as options for diagnosing PCa. 28,29 Furthermore, patients may receive a spinal block prior to the biopsy being taken, although practice will vary between centres. Spinal anaesthesia may be conducted in an outpatient office30 or operating theatre. 31

When a prostate biopsy is performed, tissue cores from the prostate are obtained for histological examination. The number of cores sampled primarily depends on the biopsy technique, but may also vary based on whether the patient has a previous negative biopsy. In a systematic biopsy, the number of cores sampled can range from 6 to 12 or 14. When more samples are obtained, a greater volume of the prostate gland is sampled, potentially increasing the detection rate. Obtaining any further cores is associated with a limited increase in diagnostic yield,32 but an increased risk in the incidence of complications, such as bleeding (haematuria, haematospermia, haemoejaculate, haematochezia or rectal bleeding), infections [e.g. urinary tract infection (UTI)], pain, urinary retention and erectile dysfunction. 33 In MRI-guided biopsies, fewer cores can be obtained, as sampling can be targeted at the areas where there is a high suspicion of cancer. The NICE guidelines do not specify the number of cores that should be obtained from each suspicious area; European guidelines state that multiple (three to five) biopsy cores per lesions should be taken to reduce the chance of missing or under sampling lesions,34 whereas guidance from the American Urological Association and the Society of Abdominal Radiology’s Prostate Cancer Disease-Focused Panel35 notes that at least two target cores per region of interest should be obtained. Clinical advisers to the EAG indicated that a minimum of two cores per targeted lesion were typically taken in NHS practice, and that for most patients, only one lesion (typically the largest) was targeted.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence NG131 recommend that a targeted, MRI-influenced prostate biopsy should be offered to people whose Likert score is 3 or more. 10 Currently, MRI-influenced prostate biopsy may use one of three different approaches:

-

cognitive fusion (CF or visual estimation), in which the operator interprets the MRI imaging before the biopsy and manually targets the area of interest using TRUS as a guide; additional samples are also taken in a systematic way according to a pre-defined protocol

-

software fusion (SF), which automatically overlays the MRI image onto the real-time TRUS therefore allowing for real-time visualisation of the area of interest where targeted samples are taken additional samples are also taken in a systematic way according to a pre-defined protocol

-

in-bore biopsy, or ‘in-gantry’ biopsy, a technique that involves performing the prostate biopsy in the MRI scanner, where the diagnostic MRI is fused with real-time MRI using the MR images taken immediately after each needle placement to guide the biopsy.

Cognitive fusion is the current standard of care (SOC). Clinical advisers to the EAG noted that different versions of SF are currently used in a number of NHS centres. In-bore biopsies, and MRI-fusion software that integrates AI-driven diagnosis of PCa, are not used in standard clinical practice.

Software fusion and CF prostate biopsy can be performed with or without the addition of systematic biopsy. The European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines on PCa recommends combining targeted and systematic biopsy in people with a PI-RADS score of 3 or more who have not had a prior biopsy. 34 In UK clinical practice, after targeting sites of interest for biopsy in eligible people, additional biopsy cores may be taken from the area around the target lesion and a systematic biopsy is performed in addition to the targeted biopsy. Although not strictly recommended by NICE, their guideline on the diagnostic and management of PCa (NG131) notes that most often, MRI-influenced biopsies will be performed in combination with systematic biopsies. 10 However, there is variation in practice dependent on local protocols in terms of whether off-target cores are sampled or not, the number of samples taken and the sampling pattern for the systemic component of combined biopsies. For people whose Likert score is 1 or 2, omitting a prostate biopsy should be considered but only after discussing the risks and benefits with the person and reaching a shared decision. If a person opts to have a biopsy, systematic prostate biopsy (whereby multiple samples are taken in a systematic fashion from different regions of the prostate according to a predefined scheme) is offered. NHS England guidance17 states that people with a Likert or PI-RADS score of 1 or 2 and people with a Likert or PI-RADS score of 3, who also have a PSA density < 0.15 ng (or 0.12 ng in some centres) of PSA per mL of serum per mL of prostate volume may be discharged, taking account of risk factors and patient preferences.

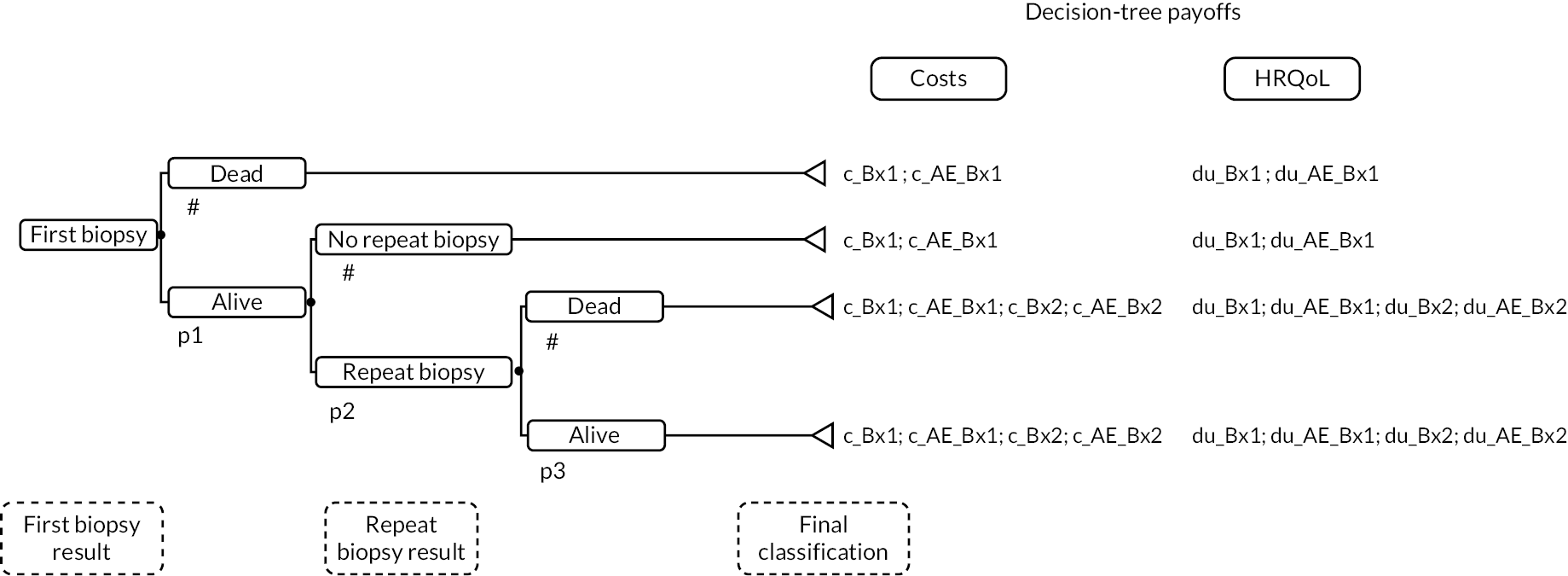

For those patients whose MRI-influenced biopsy is negative, results will be reviewed by a urological cancer multi disciplinary team (MDT), typically including a urologist and a radiologist, and the possibility of significant disease discussed with the patient. However, clinical advice to the EAG noted that in practice, not all hospitals are able to perform a MDT review of all negative MRI-influenced biopsies, in which case results may be sent for individual clinician review. A decision to offer a repeat biopsy is based on individual risk factors, including whether the biopsy showed high-grade prostatic intra-epithelial neoplasia, atypical small acinar proliferation or whether the DRE result was abnormal. 12,17,34 Clinical advice to the EAG noted that factors determining eligibility for, and timing of, repeat biopsy may vary across centres and will depend on individual risk factors, although patients with a negative biopsy and PI-RADS/Likert scores of 4 or 5, larger suspicious lesions on MRI and fitter patients are more likely to undergo repeat biopsy within 12 months. If a repeat biopsy is not offered, patients could instead undergo active surveillance with PSA testing or may be discharged depending on the MRI and histology findings. 17 Patients whose repeat biopsy result is positive may be offered active surveillance or radical treatment, depending on individual patient characteristics and preferences (see Software fusion prostate biopsy). Patients with a negative repeat biopsy may be discharged, or have their PSA levels monitored if cancer is still suspected. Antibiotics, combined with PSA monitoring, may be administered to rule out prostatitis, which may show as false positive on MRI. In some rare cases, further tests such as an additional repeat biopsy, template biopsy, or a positron emission tomography (PET) scan may be conducted to definitely rule out cancer.

Following the biopsy, a pathologist will look at the biopsy samples and assign a Gleason score (GS). The GS is a grading system which estimates the aggressiveness of the PCa, based on the pattern of the cancer cells and the extent of cell differentiation. Gleason grade 1 cells look like normal prostate tissue, and Gleason grade 5 cells have mutated to such an extent that they do not resemble typical prostate cells. A primary grade is given to describe the cells that make up the largest area of the tumour and a secondary grade is given to describe the cells of the next largest area. For example, a GS written as 3 + 4 = 7 indicates that most of the tumour is grade 3 and the next largest section of the tumour is grade 4. The two most common patterns of cells (e.g. Gleason grades 3 and 4) are added together to determine a GS. GSs can range from 2 to 10, with a score of 6 being the lowest grade cancer. To help with outcome prediction and patient communication, GSs ≤ 6, 3 + 4, 4 + 3, 8 and 9–10, respectively, can be reported as five risk groups defined by the International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP), that is, ISUP grades 1–5, respectively. 36

Although the exact definition of CSPCa varies across studies, it commonly refers to organ-confined cancer above a specific GS (or grade) and maximum cancer core length, indicating PCa that may cause excess morbidity or death. 34 European guidelines state that lesions with a GS between 2 and 6 can be considered clinically insignificant. Recent studies have commonly defined CSPCa as above a GS of 7 (3 + 4), some have used a narrower definition, including above 7 (4 + 3). 19,37–39 Some publications provide more than one definition within a single study, reflecting the lack of consensus and difficulty in defining clinical significance. 40,41

People diagnosed with PCa are assigned a Cambridge Prognostic Group (CPG) risk category. The CPG score is assigned based on the person’s PSA levels, the GS of the lesion(s) (based on histological analysis of the biopsy) and the clinical stage of the disease. 10 The EAU guidance states that further tests, such as abdominopelvic imaging and bone scans, may be required to determine clinical stage of the disease when there is suspicion that the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes or the bone marrow. 34 The CPG risk category and definition is described in Table 1.

| CPG | Risk category | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| CPG 1 | Low risk | GS 6 (GG 1) AND PSA < 10 ng/ml AND stages T1–T2 |

| CPG 2 | Favourable intermediate risk | GS 3 + 4 = 7 (GG 2) OR PSA 10–20 ng/ml AND stages T1–T2 |

| CPG 3 | Unfavourable intermediate risk | GS 3 + 4 = 7 (GG 2) AND PSA 10–20 ng/ml AND stages T1–T2 OR GS 4 + 3 = 7 (GG 3) AND stages T1–2 |

| CPG 4 | High risk | One of: GS 8 (GG 4) OR PSA > 20 ng/ml OR Stage T3 |

| CPG 5 | Very high risk | Any combination of: GS 8 (GG 4), PSA > 20ng/ml or Stage T3. OR GS 9–10 (GG 5) OR Stage T4 |

These risk categories, along with the outcome of discussion with patients regarding the benefits and harms of the treatment options, determine which treatment option is chosen. This ranges from active surveillance, for patients with CPG 1 or 2, to radical prostatectomy or radical radiotherapy for people with localised cancer and CPG ≥ 2. Patients with locally advanced PCa and CPG 4 or 5 may also be offered docetaxel (DTX) chemotherapy. The recommendation to use the CPG five-tier risk prediction model was included in the NICE NG131 2021 update10 and superseded a three-tier risk classification model including low-, intermediate- and high-risk/locally advanced groups, which did not differentiate between favourable intermediate risk (CPG 2) and unfavourable intermediate risk (CPG 3). Another important difference between the two classifications is that CPG 1 includes more men than the low-risk group in the previously recommended risk classification; some men who previously would have been in the intermediate-risk group are now classified as CPG 1. This change in risk prediction model aims to reduce under- and over-treatment in people who are at either end of the tiers, following evidence from the NICE’s surveillance programme that indicated that active surveillance may not be appropriate in patients with unfavourable intermediate PCa, and that patients with favourable intermediate risk and lower risk may be over-treated. 10,12,42,43

Software fusion prostate biopsy

Using a digital overlay, SF biopsies allow operators to view a real-time ultrasound image alongside the patient’s MRI. This requires a period of preparation, to obtain and annotate the MRI images prior to biopsy. 44 MRI images are first downloaded onto a dedicated processing software before they are annotated by contouring the edge of the prostate and the regions of interest. Clinical advice to the EAG suggests that, for an experienced practitioner, this contouring can take around 5–7 minutes. The annotated MRI scans are then uploaded onto a fusion software platform and are fused with the real-time ultrasound image. Updates to the fusion software are possible, and, depending on the fusion device, are covered by a service contract or can be purchased with a one-off payment.

Use of SF prostate biopsy systems may potentially improve detection rate of CSPCa compared with CF, while reducing the number of samples taken, potentially reducing pain and risk of sepsis associated with the procedure. It could improve the accuracy of assignment of prognostic scores such as Gleason, which influences subsequent treatment and associated patient outcomes. The technology could reduce the number of repeat biopsies for those patients with a negative index biopsy, avoiding unnecessary travel and anxiety for the person. Some fusion technologies also allow operators to keep records of previous biopsy sites to allow the urologist to return to those areas with greater precision for follow-up or additional testing.

However, the accuracy of a prostate biopsy may be impacted by a number of factors. Movement during the procedure (which could stem from patient pain),45 operator experience,46 difference in bladder size or prostate deformation may impact the accuracy of the biopsy, as the MRI image may not accurately reflect the prostate shape at the point of biopsy. Mechanisms using ‘elastic’ prostate registration, where the MRI image alters to fit the ultrasound image, have been designed to account for prostate deformation and allow for more accurate targeting of the lesions of interest. 47 Errors during the fusion of images, specifically incorrect image registration or discordance between the MRI and ultrasound image planes, especially around the base of the prostate, can lead to biopsy failure. 48

The mechanism by which SF techniques may lead to improved accuracy relates notably to a better targeting of suspicious prostate lesions, including in locations that are more challenging to diagnose, such as anterior and posterior lesions. 49,50 However, evidence for the accuracy of SF biopsy systems compared with CF methods is limited. Watts et al. 51 and Sathianathen et al. 52 found no statistically significant difference between SF and CF in PCa detection, while Bass et al. 53 found no evidence that SF was superior to CF at detecting CSPCas. An older review found that SF biopsies detect more CS cancers, using fewer biopsy cores. 54 Between-study heterogeneity ranged from moderate51 to high,53 although review methods and selection criteria varied.

Prostate cancer management: active surveillance, watchful waiting and radical treatment options

Active surveillance is a monitoring strategy for people with localised PCa for whom radical treatments (such as radical prostatectomy or radical radiotherapy) are suitable; it allows avoiding or deferring these treatments when disease progression is likely to be slow, while maintaining the possibility to initiate timely curative treatment. Current NICE guidance suggests a schedule of active surveillance involving regular monitoring of PSA levels and kinetics, and annual DREs. Reassessment with mpMRI and/or re-biopsy can be triggered if concerns about clinical or PSA changes emerge at any time during active surveillance; a positive result (GS 3 + 4 or above) on re-biopsy would then result in offering radical treatment.

For people with CPG 1, active surveillance is offered (radical treatments can be considered if active surveillance is not suitable or acceptable to the person). For people with CPG 2, a choice between radical radiotherapy with androgen deprivation (anti-hormone therapy), radical prostatectomy or active surveillance is given. For people with CPG 3, localised PCa, radical prostatectomy or radical radiotherapy with androgen deprivation is offered, and active surveillance can be considered for people who choose not to have immediate radical treatment. This recommendation is informed by a randomised trial that found that PCa-specific mortality is low (approximately 1%) at 10 years follow-up and does not differ significantly between active surveillance, prostatectomy or radical radiotherapy in individuals with localised PCa, although surgery and radiotherapy resulted in lower incidences of disease progression and metastatic disease compared with active monitoring. Radical prostatectomy may also be associated with worse urinary and erectile dysfunction outcomes compared with active surveillance and radical radiotherapy at up to 6 years follow-up. 55 People with CPG 4 and 5, localised or locally advanced PCa, should be offered a combination of radical radiotherapy and androgen deprivation. Evidence from an individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis shows that the addition of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) to radiotherapy significantly improves metastasis-free survival. 56 Brachytherapy (a form of radiotherapy where radiation is directly targeted on the tumour by inserting radioactive pellets into the prostate) in combination with external beam radiotherapy should also be considered for people with CPG 2, 3, 4 and 5 localised or locally advanced PCa. 57 Randomised controlled trial (RCT) evidence shows a reduction in biochemical failure (such as local recurrence or distant metastases) associated with the use of low-dose-rate brachytherapy plus external beam radiotherapy at 6.5 years follow-up for people with high-risk (CPG 4 and 5) localised PCa. 58

Radical prostatectomy or radical radiotherapy is offered to people with CPG 4 and 5 localised and locally advanced PCa, when it is likely that the person’s cancer can be controlled in the long term. DTX chemotherapy may also be considered for these patients. This recommendation follows RCT evidence indicating that clinical progression-free survival (PFS) was prolonged in individuals with hormone-sensitive high-risk PCa receiving DTX compared to standard care alone. 59–61

Finally, some patients with metastatic disease, where the cancer has spread outside the prostate may still undergo targeted biopsy to aid decision-making for localised treatment where the patient may receive some symptomatic benefit.

People with localised PCa, who do not wish to undergo potentially curative treatment with radical prostatectomy or radical radiotherapy (or for whom this is not suitable), can be managed with watchful waiting. This is a monitoring strategy that aims to achieve disease control rather than cure. It is less formal and intensive than active surveillance and involves fewer tests (e.g. typically an annual PSA level measurements not leading to a MRI or biopsy10) and is more likely to be offered to older, frailer populations. With watchful waiting, treatment is generally only considered in response to symptoms. Since MRI as first-line test is only recommended for patients fit for radical treatment, only a small subset of patients who received a MRI for suspected prostate lesions, such as those with worsening health since initial investigation and a PCa diagnosis, are expected to undergo watchful waiting in practice. Some patients who are not fit enough or eligible for curative treatment may also be offered a MRI because their lack of eligibility for radical treatment is not identified prior to undergoing imaging.

Description of technologies under assessment

This assessment will evaluate SF technologies matching the following criteria:

-

intended for use in people with suspected PCa

-

available in the UK

-

holds a CE-mark

-

compatible with MRI scanners of 1.5 tesla field strength or above.

This includes; ARTEMIS (InnoMedicus ARTEMIS), BioJet (Healthcare Supply Solutions Ltd), BiopSee (Medcom), bkFusion (BK Medical UK Ltd and MIM Software Inc), Fusion Bx 2.0 (Focal Healthcare), FusionVu (Exact Imaging), iSR’obotTM Mona Lisa (Biobot iSR’obot), KOELIS Trinity (KOELIS and Kebomed) and UroNav Fusion Biopsy System (Phillips). Table 23, Appendix 1, presents a brief summary of the characteristics of these nine technologies.

Software fusion devices can have a variety of different features, which means they vary in the way in which they operate.

-

Positioning of the ultrasound probe: An ultrasound probe can be cradled and held stationary using a device called a stepper which is attached to a workstation (also known as a stabilised approach). It can be supported by a semi-robotic arm, which allows for the ultrasound probe to be manoeuvred, while maintaining a stable pressure on the prostate. The semi-robotic arm can be used as a stepper for stabilised biopsies or can allow complete freedom of movement for use during a freehand biopsy. Finally, the ultrasound probe can be held by hand (using a freehand technique).

-

Core sampling technique: Different techniques can be used to take the cores, especially in the case of transperineal biopsies. First, a grid or template can be used, which is attached to a stepper and placed in front of the perineum. The grid is marked with a number of holes, which correspond to a letter and a number to allow for multiple cores to be taken in a systematic way. Alternatively, a coaxial needle can be used. In this technique, a larger introductory needle is used to puncture the perineum before the biopsy needles is passed through. This biopsy needle can be angled to take multiple biopsies without creating multiple puncture wounds to the perineum. The coaxial needle is used with the freehand technique, where it is attached to the ultrasound probe, or in a double freehand technique, where the needle is held by hand.

-

Image registration: During SF, the mpMRI images are fused with the ultrasound images during the biopsy procedure. The mpMRI image can be fixed (known as rigid registration) and will not move when the prostate is deformed, either by patient movement or by the insertion of a needle; or elastic, which means the mpMRI image adjusts to match the ultrasound image to account for prostate deformation.

A description of the principal features of the technologies is given in Appendix 1.

Other interventions

‘In-bore’ biopsy, or ‘in-gantry’ biopsy, is a technique that involves performing the prostate biopsy in the MRI scanner, using the MR images taken immediately after each needle placement to guide the biopsy. The use of in bore MRI and artificial intelligence (AI)-driven software are beyond the scope of this assessment.

Place of the intervention in the diagnostic and care pathway

Software fusion targeted biopsy, for people with suspected PCa, takes place at the same two points in the diagnostic pathway as targeted CF biopsy, the current SOC.

Patients having a first targeted biopsy

Software fusion biopsy (with or without systematic biopsy) would be offered as an alternative to targeted CF biopsy to people with a Likert/PI-RADS score of 3 or more following a MRI, after having been referred to secondary care with suspected PCa (with PSA levels above the age-specific reference range or those whose prostate is suspicious of malignancy based on rectal examination). Clinical advisers to the EAG indicated that biopsy-naive patients represented the large majority (more than 90%) of patients with suspected PCa undergoing targeted biopsy.

Patients having a repeat targeted biopsy

Patients offered a repeat biopsy, following a prior negative biopsy, could also be offered a SF biopsy as an alternative to targeted CF. As discussed in Care pathways for the diagnosis and management of prostate cancer, NG131 recommends that an MDT decides on whether to offer a repeat biopsy based on individual risk factors, although not all centres may be able to perform a MDT review of all negative MRI-influence biopsies, and eligibility and timing of repeat biopsy may vary in practice. In clinical practice, repeat biopsies are likely to be offered to patients whose mpMRI results were not consistent with the biopsy (i.e. mpMRI of 4–5 and no PCa detected on biopsy). NG131 does not recommend repeat MRI for patients requiring a repeat biopsy; instead a repeat targeted biopsy can be conducted based on the initial MRI report. EAG clinical advisers suggested this subgroup would make up <10% of patients with suspected PCa.

Potential pathway positions out of scope for the current assessment

Although SF may also be used to monitor patients and inform treatment for individuals with a PCa diagnosis in active surveillance, this population is beyond the scope of this assessment.

Relevant comparator

The comparator for this assessment is targeted transperineal or transrectal prostate biopsy using CF with or without systematic biopsy, under local or general anaesthesia, in which the operator interprets the MRI imaging before the biopsy and manually targets the area of interest using TRUS as a guide. Clinical advisers to the EAG highlighted that the expertise of the person performing the biopsy may affect the accuracy and procedure time of CF.

Chapter 2 Aims and objectives

The aim of the study was to assess the clinical and cost-effectiveness of SF biopsy systems in people with suspected localised and locally advanced PCa, by addressing the following protocol-specified objectives:

Clinical effectiveness

-

To perform a systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy and clinical efficacy of nine SF systems compared with CF targeted biopsy and with each other, in people with suspected PCa who have had a MRI scan that indicates a lesion.

-

To compare the diagnostic accuracy of different SF biopsy systems with each other and with CF targeted biopsy in people with suspected PCa who have had a MRI scan that indicates a lesion using meta-analytical methods and to combine the diagnostic accuracy of different SF systems where appropriate.

-

To perform a narrative systematic review of the clinical efficacy, safety and practical implementation of SF targeted biopsy. This includes assessment of intermediate outcomes, mortality and morbidity, patient-centred outcomes, adverse events (AEs), and acceptability to clinicians and patients.

Cost-effectiveness

-

To conduct a systematic review and critical appraisal of relevant cost-effectiveness evidence of the use of SF biopsy systems compared to CF for targeted biopsy in people with suspected PCa who have had a MRI scan indicating a lesion.

-

To develop and validate a decision-analytic model to estimate the cost-effectiveness of SF targeted biopsy systems in people with suspected PCa who have had an MRI scan indicating a lesion compared to targeted biopsy using CF. This will require linking intermediate outcomes, such as the diagnostic accuracy of SF biopsy systems to subsequent management decisions and to final health outcomes including morbidity and mortality associated with alternative treatment options. The analysis will take the perspective of the NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS), consistent with the current manual for health technology evaluations by the NICE. Final health outcomes will be evaluated in terms of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs).

-

To populate the model using the most appropriate available evidence. This evidence is likely to be identified from published literature, routine data sources and potentially using data elicited from relevant clinical experts and companies.

-

To estimate the incremental cost-effectiveness of the SF biopsy systems compared to the current SOC for the population of interest (CF biopsy), based on an assessment of long-term NHS and PSS costs and quality-adjusted survival. The time horizon of the model will be sufficient to capture both the short-term and longer-term outcomes.

-

To characterise the parameter uncertainty in the data used to populate the model and present the resulting uncertainty in the results to decision-makers. To this purpose, we will perform comprehensive (probabilistic and deterministic) sensitivity analyses varying parameter inputs, and structural assumptions of the model, as appropriate.

-

Where possible and applicable, to assess the impact of potential sources of heterogeneity on cost-effectiveness, including subgroup analyses (e.g. patients with previous negative biopsy results within 12 months) and consideration of other factors that may affect diagnostic accuracy.

Chapter 3 Assessment of diagnostic accuracy and clinical effectiveness

This section presents the methods and results of the systematic review of diagnostic accuracy and clinical effectiveness. Systematic review methods (study selection, data extraction, quality assessment) details the systematic review methods, and Data synthesis methods presents the data synthesis methods. Quantity and quality of evidence summarises the quantity and quality of evidence included in the systematic review, Diagnostic accuracy results presents the diagnostic accuracy results of the systematic review and meta-analysis; results for all other outcomes included in the systematic review are presented in Clinical effectiveness results. Diagnostic accuracy and clinical effectiveness: summary and conclusions summarises the key findings from the systematic review, and Additional evidence to inform model structure and parameterisation presents a summary of additional evidence identified to inform the economic model.

Systematic review methods (study selection, data extraction, quality assessment)

Searches

The aim of the literature search was to systematically identify published and unpublished studies of prostate biopsies utilising either SF or CF.

An information specialist (MH) developed a search strategy in Ovid MEDLINE using textword searches of the title and abstracts of database records along with relevant subject heading searches. The search strategy consisted of: (1) terms for PCa AND, (2) terms for MRI AND, (3) terms relating to fusion techniques AND, (4) terms for prostate biopsy. The terms used to describe fusion techniques were found to vary in the literature with some articles lacking any terms for fusion techniques in the title, abstract or subject headings of the database record. Therefore, related terms such as targeted biopsy, focal biopsy or MRI-guided biopsy were added to the strategy along with some proximity searching to capture phrases in the title and abstracts of records around the use of MRI prior to a prostate biopsy. Named SF software and hardware were also included in the strategy (e.g. Fusion Bx, BioJet, KOELIS Trinity, bkFusion).

A date limit was applied (from 2008 onwards), due to the relatively recent nature of the technologies under assessment, and as informed by results of scoping searches and previous systematic reviews. 51,53,62,63 No language or study design restrictions were applied to the searches. The MEDLINE strategy was agreed with the review team and checked by a second information specialist using aspects of the PRESS checklist. 64 The final MEDLINE strategy was adapted for use in all resources searched.

The following databases were searched in May 2022: MEDLINE ALL (Ovid), Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials (Wiley), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Wiley), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (Ebsco), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (CRD databases), EconLit (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database (CRD databases), Health Management Information Consortium (Ovid), International Health Technology Assessment (INAHTA) database, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS) database, NHS Economic Evaluation Database (CRD databases), and Science Citation Index (Web of Science).

Further ongoing and unpublished studies were identified through searches of: ClinicalTrials.gov, Conference Proceedings Citation Index: Science (Web of Science), European Union Clinical Trials Register, Open Access Theses and Dissertations, Proquest Dissertations and Theses A&I, PROSPERO, and World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform portal.

A search for relevant guidelines was carried out via the following websites: NICE, ECRI Guidelines Trust, Guidelines International Network (GIN) international guideline library and the Trip database. Full search strategies for all resources can be found in Appendix 2.

Additionally, company websites were searched to identify relevant publications and other materials relating to the technology, and companies registered with NICE at the time of the protocol submission were contacted for further details about their respective technologies. Reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews were scanned to identify any further potentially relevant studies.

An update search was carried out on 2 August 2022 to capture any recently published studies. The update search was undertaken on the following four databases: MEDLINE ALL (Ovid), Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials (Wiley), Embase (Ovid) and the Science Citation Index (Web of Science). Search results were downloaded from each database and added to the EndNote library of original search results for deduplication.

Selection criteria

All titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers (AL and LB). Full-text papers of any titles and abstracts deemed to be relevant were obtained where possible, and the relevance of each study assessed independently by two reviewers according to the criteria below. Disagreements were resolved by consensus, or where necessary, by consulting a third reviewer. Conference abstracts were considered to be eligible if they provide sufficient information for inclusion, and attempts were made to contact authors for further data. The eligibility criteria that were used to identify relevant studies are listed below.

Population

People with suspected PCa who have had a MRI scan that indicates a significant lesion (Likert or PI-RADS score of 3 or more). This included people who were biopsy naive and those who are referred for a repeat biopsy following a previous negative prostate biopsy. No time limit since the first negative biopsy was set for inclusion of studies including patients with repeat biopsies, although applicability with respect to the scope was considered as part of the quality assessment.

Studies primarily focused on people who do not have a lesion visible on their magnetic resonance image, people on an active surveillance care pathway, and people with relapsing PCa were excluded. Patients who could not have a MRI scan were also excluded. Studies including a small subset of individuals with a Likert or PI-RADS score of 2 or less were included if they provided data primarily for the eligible population; their applicability was assessed during quality assessment.

Interventions

Studies evaluating SF alone or in combination with CF or systematic biopsy, under local or general anaesthesia were eligible. No exclusions were made based on the biopsy route. The included SF technologies are described in Appendix 1. Where applicable, earlier versions of these technologies were also included, and their applicability was accounted for during quality assessment.

Comparators

Eligible comparators were targeted transperineal or transrectal prostate biopsy using CF with or without systematic biopsy, under local or general anaesthesia. Although systematic biopsies and ‘in-bore’ biopsies are outside the scope of this review, studies that evaluate these methods were included if they provide separate data to compare targeted biopsies using SF against CF. Studies evaluating several SF technologies against one another were also eligible for inclusion.

Reference standard

Total cancer cases in diagnostic accuracy studies are commonly identified using a combination of SF, CF and systematic biopsies as ‘reference standard’. 51,53

In those studies, diagnostic accuracy estimates of SF and CF are therefore inherently dependent on the accuracy of mpMRI, TRUS and fusion approaches, as well as the accuracy of the biopsy method, which may vary by type and route. Reference standards that use histopathology from biopsy samples, rather than radical prostatectomy, may also miss positive cases. Reference standards that include results from samples identified by SF and/or CF are at risk of incorporation bias (when results of an index test are used to establish the final diagnosis). Reference standards that use histopathology from radical prostatectomy are usually only reported for those who have been classified as high risk and have had radical prostatectomy. In addition, histopathology, although commonly used as the gold standard test for cancer detection and grading, may also misclassify a small proportion (approximately 2%) of negative PCa cases as positive. 65

Template-guided biopsy, including transperineal template-guided mapping biopsy (TTMB), also called template-guided saturation biopsy (TSB), is seen as a more optimal reference standard, compared with standard 12-core systematic biopsy. TTMB is a transperineal TRUS-guided biopsy of the prostate using a 5-mm brachytherapy grid, with at least one biopsy from each hole. TSB includes 20 or more transperineal or transrectal TRUS-guided biopsies of the prostate performed to comprehensively sample the whole prostate, according to a predefined core distribution pattern. Template-guided biopsies using a uniform grid and taken at 5 mm intervals can technically only miss tumours that are smaller than the distance between the adjacent cores. 66 Although template-guided biopsy is imperfect, notably due to the fact that test accuracy depends on the intensity of cores taken and core trajectory,66 it is superior to standard systematic biopsy as a reference standard as it aims to comprehensively sample all zones of the prostate. However, template-guided biopsies are invasive and may not be used in diagnostic accuracy studies, therefore combinations of reference standards with lower diagnostic accuracy (e.g. CF with SF and systematic biopsies with fewer than 20 cores) were also eligible for inclusion.

A positive biopsy was defined as histopathological confirmation of one of the target conditions within the biopsy cores.

Outcomes

The following intermediate outcomes were eligible:

-

measures of diagnostic accuracy (including sensitivity, specificity, test positive/negative rates)

-

cancer detection rates (number of patients with detected cancer by SF or CF divided by the total number of patients with confirmed cancer)

-

CS cancer detection rates (all definitions)

-

clinically insignificant cancer detection rates (all definitions)

-

cancer detection rates by prognostic score (such as CPG 1 to 5 or other similar classification that can be mapped into the CPG classification) and/or GS

-

biopsy positivity rate (ratio of positive biopsies out of total number of biopsy samples)

-

biopsy sample suitability/quality

-

number of biopsy samples taken

-

procedure completion rates

-

software failure rate

-

time to diagnosis

-

length of hospital stay (emergency department and inpatient stay)

-

time taken for MR image preparation

-

time taken for biopsy procedure

-

number of repeat biopsies within 12 months

-

subsequent PCa management (such as no treatment, active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, radical radiotherapy and hormone therapy).

The following clinical outcomes were eligible:

-

rates of biopsy-related complications and AEs, including infection, sepsis and haematuria, urinary retention, erectile dysfunction, and bowel function

-

hospitalisation events after biopsy

-

survival

-

PFS

-

AEs from treatment.

Patient- and carer-reported outcomes were eligible, including:

-

health-related quality of life (HRQoL)

-

other self-reported outcomes including tolerability, embarrassment and loss of dignity.

The following implementation end points were eligible:

-

operator preferences

-

barriers and facilitators to implementation.

The following cost outcomes were eligible:

-

costs of MRI fusion software and any proprietary hardware (including the workstation, ultrasound systems, probe holders, replacement parts, consumables such as guides, and maintenance)

-

cost of staff time (including MR image interpretation time and biopsy procedure time) and of any associated training

-

medical costs arising from the biopsy such as anaesthetic, sedation, hospital admissions and stays

-

costs related to using intervention (including any time analysing and storing data)

-

costs of histopathology biopsy samples analysis

-

cost of treatment of cancer (including costs of any AEs)

-

costs relating to follow-up

-

costs of subsequent biopsies

-

costs arising from watchful waiting

-

costs arising from active surveillance.

Study designs

Prospective studies comparing SF against CF biopsy that report the results of both SF and CF biopsy separately were considered. Studies including within-patient comparisons (where SF and CF biopsy are compared within the same patient) and between-patient comparisons (where participants receive either SF or CF biopsy) were included.

Where no prospective evidence could be found to inform the diagnostic accuracy of an eligible SF technology, retrospective studies that met all other selection criteria were included.

No restriction by healthcare setting was made.

Indirect evidence

Where the interventions of interests did not form a connected network to allow comparison of each intervention against every other, prospective, within-patient comparisons or RCTs between SF and systematic biopsy, and between CF and systematic biopsy, were also eligible to inform indirect comparisons, provided they reported numbers or rates of patients with no cancer (NC), all PCa and CS cancers for either SF or CF against systematic biopsy or template biopsy, and the combination of software or CF with systematic biopsy or template biopsy.

Data extraction

Information on study details (including study design, sample size), patient characteristics (e.g. age, PSA, PI-RADS/Likert score and version, reason for referral, whether first biopsy, repeat biopsy and lesion location), intervention characteristics (including SF technology type and version, MRI technology and magnet strength, biopsy route (transrectal or transperineal) whether the procedure used fixed/free hand; local/general anaesthetic and was based on biparametric or mpMRI, the use and number of targeted and systematic core biopsy samples, operator experience), outcomes data and definitions of outcomes were extracted by at least one reviewer (AL or LB) using a standardised data extraction form and independently checked by a second reviewer (AL or LB). Discrepancies were resolved by discussion, with involvement of a third reviewer (SD) where necessary.

Where required and appropriate, attempts were made to contact companies for additional information, including unpublished data, missing data, relevant subgroup data and more granular outcome data (e.g. matrices reporting a breakdown of detection rates by cancer prognostic score). Data from relevant studies, with multiple publications, were extracted and reported as a single study. The most recent or most complete publication were used in situations where the possibility of overlapping populations could not be excluded. Where not reported (NR), rates of clinically insignificant cancers were imputed by subtracting the number of CS cancers from the total number of cancers detected (as per Bass, et al.). 53

Critical appraisal

The quality of the diagnostic accuracy studies was assessed using the tools Quality Assessment tool of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS)-2 and QUADAS-C tools. 67,68 The QUADAS-2 tool evaluates both risk of bias (associated with the population selection, index test, reference standard and patient flow) and study applicability (population selection, index test and reference standard) of individual studies to the review question. The QUADAS-C tool is designed to assess risk of bias in test comparisons undertaken in studies that evaluate two or more index tests. QUADAS-C is an extension of QUADAS-2 and includes all domains covered by QUADAS-2. Each QUADAS-C domain is informed by each QUADAS-2 judgement for each test and additional signalling questions that are specific for comparisons to produce a risk of bias judgement for the comparison. The quality assessment focused on the risk of bias and applicability of cancer detection outcomes only. Since the review focused on the relative accuracy of two index tests, QUADAS-2 risk of bias assessments were not presented. All studies were quality assessed and checked by a second reviewer. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. Decisions with rationale for judgements were presented in tables.

Data synthesis methods

Meta-analysis

The meta-analyses aimed to compare four types of prostate biopsy approaches: CF, SF, CF with concomitant systematic biopsies, and SF with systematic biopsies. When relative effects comparing more than one intervention are of interest, a network meta-analysis (NMA) should be conducted to allow comparison of all interventions to each other. 69 NMA is an extension of pairwise (two-treatment) meta-analysis to allow comparisons across more than two treatments by producing relative effects for every pair of treatments in a connected network. Direct evidence from studies comparing two interventions directly is pooled with indirect evidence from studies that have a common comparator thus allowing consistent estimates of relative effects to be produced that account for all relevant evidence and are typically more precise. Common- (fixed-) or random-effects models can be used. 70

Since many studies compared one or more of the four biopsy types of interest to systematic biopsy alone, this biopsy type was also included in the network of interventions in order to allow more comparisons to be made and to increase precision in the estimated relative effects. 69

Network meta-analyses were conducted using a Bayesian framework estimated through Markov chain Monte Carlo methods. In an attempt to minimise bias, only prospective studies reporting within-patient comparisons, or RCTs reporting comparative results for two or more of the interventions of interest (SF, CF, systematic biopsy or a combination of software/CF with systematic biopsy), were included in the synthesis.

Model convergence was assessed by running two independent chains with different starting values looking at history plot and through inspection of Gelman–Rubin diagnostic plots. Due to data sparseness (few studies per comparison and not all studies reporting all outcomes) only fixed-effects models were fit to the data. Model fit was assessed by comparing the mean total residual deviance to the number of independent data points contributing to the analysis. 71

Network plots were drawn in R72 using the netmeta package. 73

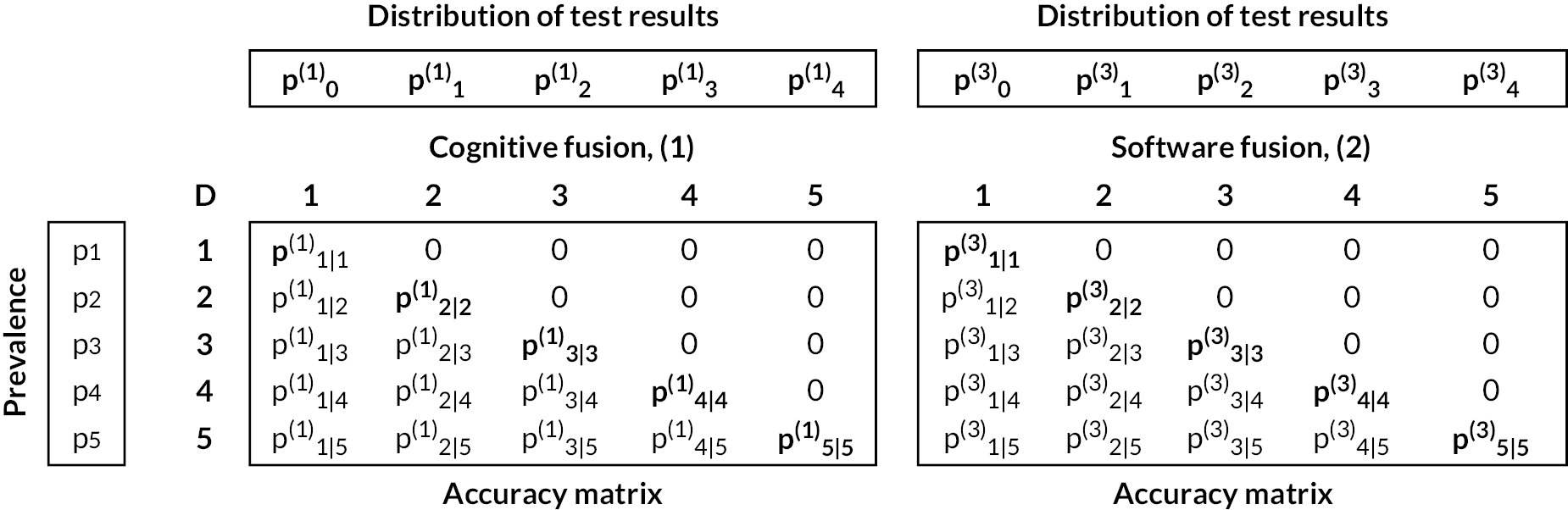

Multinomial synthesis model

To adequately distinguish between the different biopsy methods and SF devices, it is necessary not only to describe how they differ in classifying patients as having PCa or not, but also how they differ in classifying patients as having PCa at different Gleason grades, as that determines further treatment strategies. To inform post-biopsy patient management in the economic model, data are modelled by ISUP grade, where reported.

In order to best describe the differences between biopsy methods for each diagnostic category, a multinomial logistic regression model was fitted where the odds of being categorised in each of the different categories in Table 2 compared to the reference category (no PCa) are allowed to vary by biopsy type. This model is conceptually equivalent to four binomial logistic regressions comparing category r > 1 with category 1 (no PCa), for each different biopsy type compared to the reference, cognitive biopsy.

| Categories | Gleason | ISUP grade |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | – | NCa |

| 2 | 3 + 3 | 1 |

| 3 | 3 + 4 | 2 |

| 4 | 4 + 3 | 3 |

| 5 | 8 – 10 | 4–5 |

The multinomial logistic regression model accounts for the ordered nature of the categories, which is important since a higher or lower detection of higher-grade cancers may have an impact on the cost-effectiveness of each device. However, the model does not take into account that some of the included studies reported results from different biopsies techniques performed on the same patients. 74 The study arms are treated as independent. This is a limitation of this model, which may inflate the uncertainty in the estimates. Models and code that can incorporate non-independent data (measured on the same patients) with ordered categories are not readily available.

Studies that only report the number of individuals in collapsed categories, for example the number of individuals with NC, non-CS cancer (Gleason 3 + 3) and CS cancer (Gleason > 3 + 3) provide information only on the odds ratio of being classified in the first two categories (NC, non-CS cancer). The model has been adapted to allow these studies to be included. However, they provide only limited information to the network compared to studies that report a finer breakdown of GSs.

Models were fitted in WinBUGS 1.4.3. 75 CF prostate biopsy was chosen as the reference intervention, and ‘no cancer’ as the reference category. Full details of the model and WinBUGS code are given in Appendix 3.

The relative effects produced by the model are the odds ratios for being classified in category r, instead of category 1 (‘no cancer’), using intervention X (SF, systematic biopsy or a combination of software/CF with systematic biopsy), compared to cognitive fusion biopsy. Interpretation of these relative effects is complex since it relates to both a reference treatment and reference category. To aid interpretation, absolute probabilities of being classified in each category, using each intervention, are also reported. Details of how these are calculated are given in Appendix 3.

Analyses are presented assuming all SF devices share a common effect, that is they all have the same odds ratio compared to CF biopsy (Model 1a) and assuming individual device effects (Model 1b).

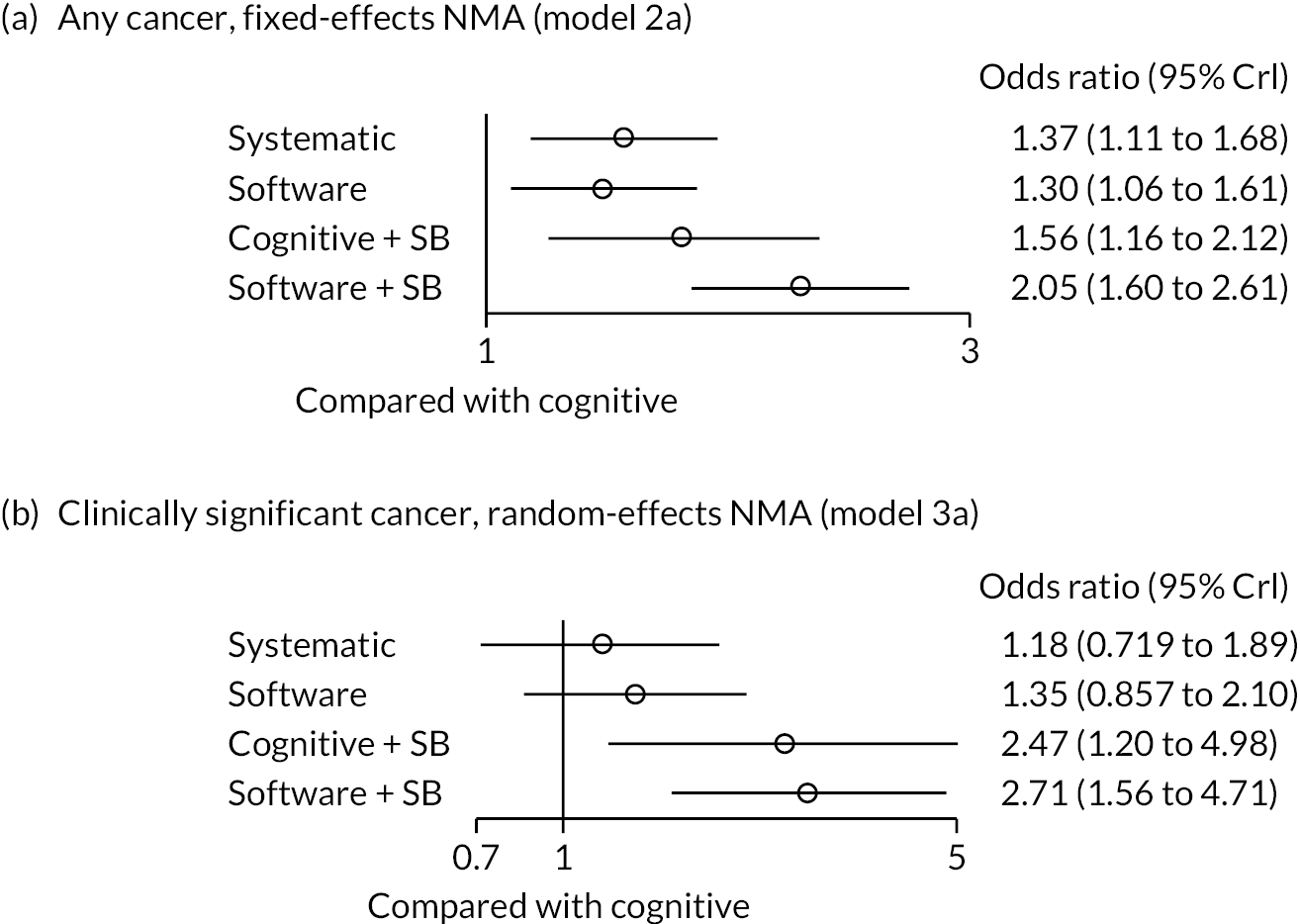

Cancer detection network meta-analysis models

The odds ratios of cancer detection, for different biopsy methods compared to each other, were also pooled. The number of cancers detected were modelled using the NMA model for binomial data with a logit link described in NICE technical support document 2,71 fitted in R72 using the package gemtc. 76

Model convergence was assessed through inspection of Gelman–Rubin diagnostic plots. Both fixed-effect and random-effect models were fitted to the data. Non-informative prior distributions were used for all effect parameters and a Uniform (0,5) prior distribution was selected for the between-study standard deviation (SD) in random-effects models. 71 Model fit was assessed through mean total residual deviance and inspection of residual deviance contribution for each study arm. Heterogeneity was assessed by inspecting the size of the between-study SD and its 95% credible interval (CrI), and by comparing the Deviance Information Criteria (DIC) for fixed-effect and random-effects models. Where DIC differed by < 3 points the simplest model (fixed effect) was chosen. Consistency between direct and indirect evidence was assessed by fitting an unrelated mean effects model and where that suggested potential inconsistency, further investigation of the location of inconsistency was carried out by fitting node-split models. 77

Any cancer detection network meta-analysis

The odds ratios of detecting any PCa (both CS and non-CS, i.e. Gleason ≥ 3 + 3) for different biopsy methods compared to each other were pooled. Analyses are presented assuming all SF devices share a common effect (Model 2a) and for individual device effects (Model 2b).

Clinically significant cancer detection NMA model

The odds ratios of detecting CSPCa (Gleason > 3 + 3), as opposed to NC or Gleason 3 + 3, for different biopsy methods compared to each other were also pooled, for studies that reported it. Analyses are presented assuming all SF devices share a common effect (Model 3a) and for individual device effects (Model 3b).

Narrative synthesis

Results of studies that were not eligible for inclusion in the NMAs, and results of all studies reporting protocol-specified outcomes other than diagnostic accuracy, were synthesised narratively following published guidelines. 78

Outcomes were presented following the order listed in the protocol, then by comparison. Effect estimates, including metrics, measures of variance, statistical significance (at conventional threshold of p = 0.05), and direction of effect were presented narratively and/or in tables at patient-level, unless only data per lesion could be extracted. Studies were grouped based on direction of effect and statistical significance. Where NR, outcomes including detection rates, test positive rates and biopsy positivity rates were imputed. No formal statistical methods were used to assess heterogeneity. Results were narratively compared with the meta-analyses, and limitations of the evidence (e.g. inconsistency, risk of bias) informed findings summaries and conclusions.

Quantity and quality of evidence

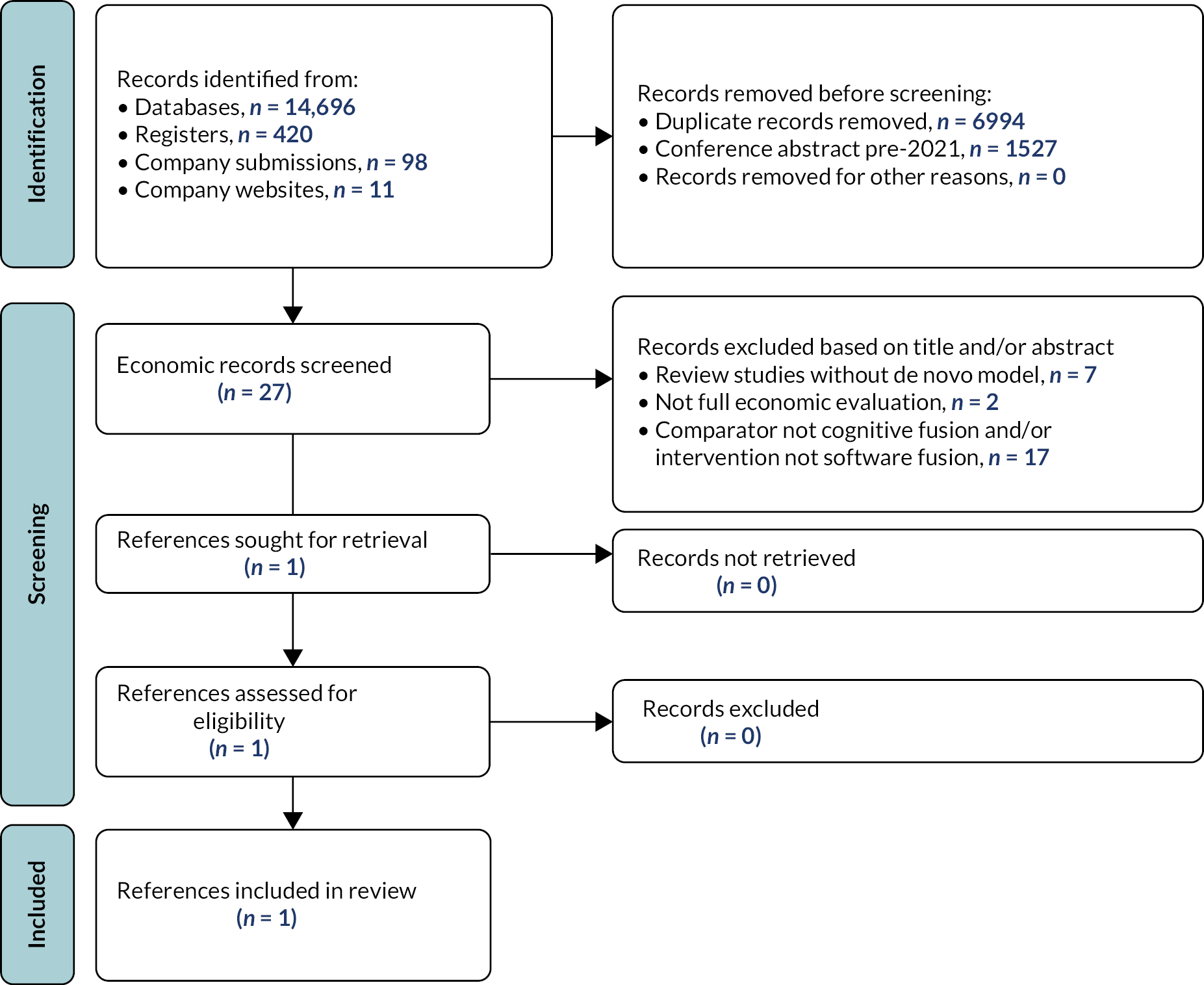

Figure 2 presents an overview of the study selection process in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram. The literature searches identified a total of 6289 unique records. After title and abstract screening, 247 references were retrieved and a total of 23 unique studies were included in the systematic review. 31,79–101 Fourteen studies were included in the quantitative synthesis,31,79,80,82,84,86–88,92–94,96,97,99 while nine studies were included in the narrative synthesis only. 81,83,85,89–91,95,98,100,101

FIGURE 2.

Study selection process (PRISMA flow diagram).

Evidence was included for all SF technologies specified in the scope and protocol (all versions) except for Fusion Bx (Focal Healthcare) and ExactVu (Exact Imaging). Report Supplementary Material 1 presents a summary of the evidence for Fusion Bx and ExactVu that was considered for inclusion and ultimately excluded, and a list of studies excluded from the systematic review, grouped by reason for exclusion.

Description of studies included in the systematic review of diagnostic accuracy and clinical effectiveness

Table 25, Appendix 4, presents the characteristics of the 23 studies included in the systematic review. The majority of studies were conducted in Europe,31,80,81,83,86,89,92–95,98,101 and five studies were conducted in the USA. 87,88,90,96,97

Twelve studies compared SF against CF; of those, three used a within-patient comparison design (where participants underwent biopsy with both SF and CF within the same session),88,93,97 and nine compared separate cohorts who received either SF or CF biopsy (between-patient design). 31,82,85,89,90,95,98,100,101 Three studies compared two or more SF software against one another. 79,86,99 Five studies compared SF against systematic biopsy,80,87,92,94,96 and three studies compared CF with systematic biopsy. 79,86,99

Three RCTs were included; of those, two compared SF against CF,31,82 and one compared three SF devices. 83 All other studies were non-randomised trials or observational; of those, four studies used a retrospective design. 85,90,100,101

The following SF technologies were evaluated: ARTEMIS (five studies),82,84,88,96,97 BioJet (four studies),81,83,84,89 BiopSee (two studies),31,95 BK (two studies, referred to as Predictive Fusion Software in one study85 and MIM fusion software in another),100 iSR’obot Mona Lisa (one study)101 and UroNav (one study). 90 One study evaluated KOELIS Trinity,83 and six studies evaluated, KOELIS Urostation, an earlier version of the software which used a third-party ultrasound. 80,81,92–94,98

Table 26, Appendix 4, maps the evidence by SF technology, biopsy route, anaesthesia method and registration method, and highlights a number of limitations in reporting and gaps in the evidence. Of the 20 studies that evaluated a SF technology, 7 studies used SF for a TP,31,84,85,89,95,100,101 and there was no evidence for ARTEMIS, KOELIS and UroNav used in the context of a TP. BiopSee was only evaluated under general anaesthesia,31,95 and 10 studies did not report their method of anaesthesia. 80,81,89,91–94,96,98,100 Image registration methods (rigid vs. elastic) were NR or could not be inferred in five studies. 84,88,89,95,96

Table 27, Appendix 4, summarises the characteristics of the patients in the included studies. Across all included studies, a total of 3733 patients who received SF and 2154 individuals who underwent CF were analysed and informed estimates of PCa detection. Where reported, the median age ranged from 62 to 73.1 years, median PSA levels ranged from 4.2 ng/mL to 10.7 ng/mL, and all patients had a PI-RADS or Likert score of 3 or more. Seven studies only included biopsy-naive patients,79,81,82,85,88,95,98 four studies only included patients who received a repeat biopsy following one or more prior negative biopsies31,86,94,99 and eight studies included a mix of patients with no prior biopsy and individuals undergoing a repeat biopsy following a prior negative biopsy. 80,83,84,87,89–93,101 Three studies included a subset of patients under active surveillance and reported separate results biopsy naive and/or repeat biopsy with prior negative result. 96,97,100 Where reported, all operators were experienced in biopsy procedures, although levels of expertise varied across the studies. Table 28, Appendix 4, summarises information from the studies on operator experience.

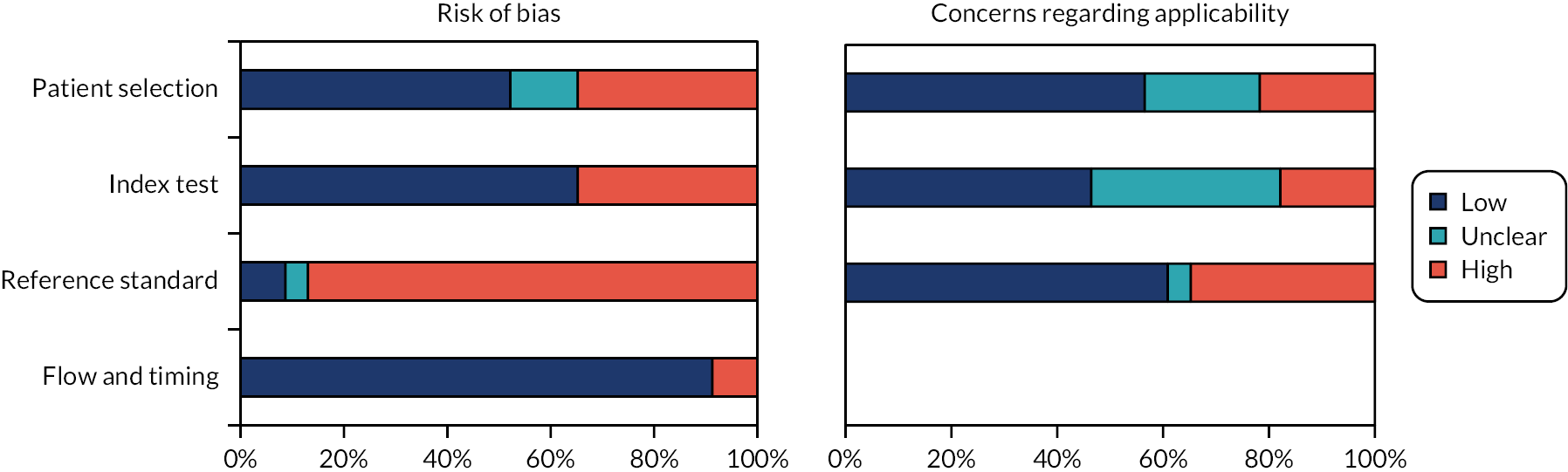

Quality of included studies

Results of the quality and applicability assessment are reported in Figure 3, and further details on the rationale for decisions are reported in Appendix 5. All studies were at high risk of bias for at least one of the following domains: patient selection, index test, reference standard and flow and timing. Eight studies were at high risk of patient selection bias; all were non-randomised comparisons. 81,83,89,90,95,98,100,101 Three studies were at unclear risk of selection bias;31,84,85 including the two RCTs,31,84 and all other studies were at low risk of selection bias. Eight studies had a high risk of bias related to the comparison of index tests,31,81,84,88,89,93,97,101 and all other 15 studies were at low risk of bias for this domain.

FIGURE 3.

Risk of bias and applicability assessment summary of studies included in the systematic review.

Twenty studies were at high risk of bias associated with the reference standard. 31,79–87,89,90,92,94–96,98–101 For between-patient comparisons, this was primarily due to the fact that total cancer positive cases in each study arm or cohort were derived from different biopsy methods; in within-patient comparisons, as all biopsy methods were performed within the same examination, it was not feasible for studies to truly blind operators from tracks of preceding biopsy methods (true blinding would several biopsy sessions per patient, which would be unethical). Participants in all within-patient comparison studies received SF, CF and/or systematic biopsy within the same examination; the order in which the different biopsy methods were implemented varied where reported, therefore the overall direction of bias due to the lack of operator blinding could not be determined.

Of the 15 studies that compared SF with CF or with another SF device,31,81–85,88–90,93,95,97,98,100,101 7 did not use systematic biopsy or include systematic biopsy results as part of a reference standard test. 31,81,83–85,97,101 Of the studies that included systematic biopsy as part of a reference standard test, only one reported blinding the systematic biopsy operator to the MRI report. 88 This is an important design limitation, since knowledge of the MRI report may have influenced the placing of systematic biopsy cores. Clinical advisers to the EAG confirmed that lack of blinding to MRI reports may have improved the accuracy of systematic biopsies relative to targeted biopsies. Therefore, for most of the evidence for systematic biopsy included in this review, there is a risk that the detection of PCa from systematic biopsy may have been overestimated compared with true random, standard systematic biopsy. This said, the lack of blinding to MRI report when using systematic biopsy concomitant with targeted biopsy is reflective of current practice. Blinding of the histopathologists, who analysed the biopsy samples, was generally NR, and none of studies used TTMB. Two studies were at high risk of bias due to missing outcomes data (flow and timing domain),93,95 and all other studies were at low risk of bias for this domain.

Three studies raised no concerns about their applicability to the review question. 79,82,88 Five studies included a population that was deemed not applicable (NA) to the review question (high concern),31,86,90,94,99 and five included a significant proportion (approximately half) of patients undergoing repeat biopsy following a prior negative biopsy. 87,89,92,93,101 Although patients with a prior negative biopsy were eligible in this systematic review, clinical advisers to the EAG noted that they made up only a minority (approximately under 10%) of the total population undergoing targeted biopsy who are not under active surveillance. All other studies included mostly biopsy-naive patients and had a population that was considered broadly representative. Five studies used an intervention that was not considered applicable to the review question,31,84,89,95,101 primarily due to the use of general anaesthesia in all procedures. Clinical advisers to the EAG noted that general anaesthesia is normally only used in a minority of patients, although it may facilitate biopsy targeting due to the lack of patient movement. The applicability of SF was uncertain in 10 studies. 80,81,90,92–94,96,98–100 In four cases, this was due to insufficient reporting about biopsy routes and anaesthesia methods,90,96,99,100 and in six studies, a KOELIS device with no integrated ultrasound was evaluated, and the applicability of their results to KOELIS Trinity was uncertain. 80,81,92–94,98 Following request for further information from the EAG, the company did not clarify or provide evidence that the diagnostic accuracy of older versions of KOELIS was equivalent to KOELIS Trinity. Eight studies raised concerns about the applicability of the reference standard test. 31,81,83–85,95,97,101

Diagnostic accuracy results

This section presents the evidence included in the meta-analyses and structure of the networks of evidence (see Studies included in the meta-analysis and network structure), the results of the NMAs (see Meta-analysis results), and results of studies not included in the meta-analyses (see Narrative synthesis results).

Studies included in the meta-analysis and network structure

Model 1a: multinomial synthesis model (base case)

Thirteen studies, identified by the systematic review, with data suitable for inclusion in the NMA are presented in Table 24, Appendix 3 and form the network in Figure 4. Rabah et al. 84 is excluded as it compared two SF devices, assumed to have identical effects, and therefore does not contribute to the analysis. The multinomial synthesis model was used to synthesise comparative information on the probabilities of being classified at the various ISUP grades of PCa (see Meta-analysis results). Resulting estimates are then used in the base-case economic model.

FIGURE 4.

Network of biopsy types compared, under the assumption of a common effect for different SF devices. Lines represent comparisons made in studies, numbers on the lines show how many studies included that comparison and shaded areas represent multiarm studies. SB, systematic biopsy.

Due to data sparseness, we assumed that there is no difference in relative effects of the various SF biopsy devices compared to cognitive biopsy and only fixed-effect models could be fitted. This assumption is supported by the limited direct evidence comparing different fusion devices and clinical advice to the EAG. However, the different costs of each device will still be taken into account in the economic model. This assumption will be relaxed in an additional analysis (Model 1b: Multinomial synthesis model, individual device effects).

Although the network in Figure 4 is fully connected (there is a path connecting every intervention to every other), not all studies reported the breakdown of cancers detected by ISUP grade (see Appendix 3, Table 24). This resulted in a de facto disconnect in the network for comparisons of CF + SB and SF + SB for ISUP grades > 2. Relative effects comparing disconnected components of the network cannot be estimated and are reported separately.

Calculating absolute probabilities

As noted in Meta-analysis results, odds ratios estimated from this model are hard to interpret. We will therefore also present results on the absolute probability scale to aid interpretation. To calculate the absolute probabilities of being classified in each category using each intervention, we need to assume a set of underlying baseline probabilities of being classified in each category on one of the included interventions. For ease of interpretation, in this section these underlying baseline probabilities will be assumed to be fixed, that is, to have no uncertainty. All other probabilities are then obtained by applying the estimated odds ratios to these probabilities, as described in Appendix 2. These baseline probabilities should be as representative as possible of the population of interest. A targeted review was carried out to determine a good source of evidence on these probabilities (see Review of additional prevalence, test results and diagnostic accuracy evidence and Appendix 8 Distribution of test results obtained with cognitive fusion or software fusion biopsy).

The two studies with the largest sample size that were identified and deemed most representative of NHS practice were considered as a source of evidence for the baseline probabilities: Filson et al. 96 and PAIREDCAP (2019). 88 Two subgroups of patients are of interest: biopsy-naive patients and those undergoing a repeat biopsy after a negative result. Filson (2016)96 reported probabilities for these two subgroups separately and for two interventions of interest, SF using ARTEMIS and combined SF (ARTEMIS) with systematic biopsy, allowing the same source of baseline probabilities to be used for both disconnected components of the network.

However, Filson et al. 96 does not report separate data for ISUP grades 3 and 4–5, as required by the model. We approximated the probabilities of patients being in grade 3 and 4–5 by splitting the combined patients according to the proportions in each category reported in PAIREDCAP (2019)88 (approximately 60/40).

In a sensitivity analysis for the subgroup of biopsy-naive patients, the distribution of test results from PAIREDCAP (2019)88 (which only include biopsy-naive patients) was used to inform the baseline probabilities in the first part of the network. In the absence of other suitable sources of evidence, data on biopsy-naive patients from Filson et al. 96 will continue to inform the baseline probabilities in the combined biopsy (software/CF plus systematic biopsy) network.

Absolute probabilities were therefore reported for:

-

subgroup of biopsy-naive patients (based on Filson et al. 96 biopsy-naive data)

-