Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/142/02. The contractual start date was in June 2014. The draft report began editorial review in February 2021 and was accepted for publication in July 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Heer et al. This work was produced by Heer et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Heer et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Tandogdu et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Background

Incidence

Bladder cancer is the most frequently occurring tumour of the urinary system, with > 10,500 new cases diagnosed each year in the UK. 2 Overall, bladder cancer is the 11th most common cancer in the UK, accounting for 3% of all new cancer cases. 2 Histologically, > 90% of bladder cancers are of the transitional cell carcinoma type. Bladder cancer is more common in men than in women (5 : 2 ratio), making it the eighth most common cancer in men and the 16th most common cancer in women. 2 Incidence rates for bladder cancer in the UK are highest in people aged 85–89 years, with 8 in 10 cases occurring in people aged ≥ 65 years. Cigarette smoking is causally related to over one-third of bladder cancer diagnoses and is also a risk factor for progression to cancer-related death. 3,4 Time trends in bladder cancer incidence rates over the past 10–20 years are difficult to interpret because of changes in classification. There is a trend towards a reduction in age-standardised incidence rates, currently 11 cases per 100,000 population, which is predicted to continue to decline at a rate of 1% annually. 5 However, the growth in the ageing population will have a substantial impact on the total number of cases, which is projected to rise at an annual rate of > 1%. 5

Pathology

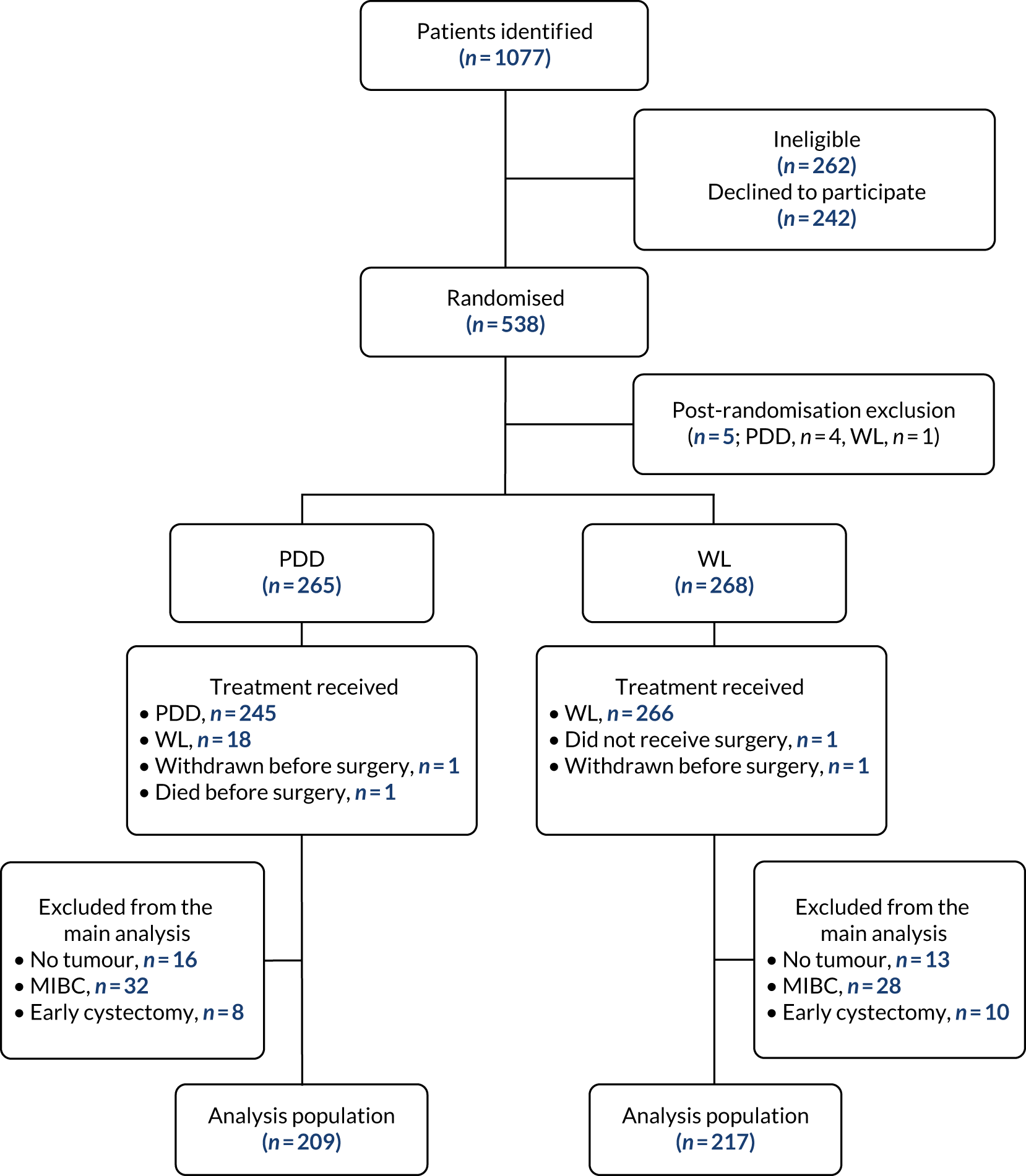

The extent of the spread of cancer is described using the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) tumour node metastasis (TNM) staging system. 6 Tumours confined to the epithelial lining (urothelium) are classified as stage Ta and those invading the lamina propria are classified as stage T1 (Figure 1). Ta and T1 tumours can be easily removed through transurethral resection (TUR) and, therefore, for therapeutic purposes, are grouped together as non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC). NMIBC also includes flat, high-grade tumours that are confined to the epithelium, which are classified as carcinoma in situ (CIS). Grade (microscopic characteristics of the tumour cells) can be used to describe the aggressiveness of cancers, which are characterised as either low grade (relatively benign) or high grade (aggressive). 6

FIGURE 1.

Tumour node metastasis staging of bladder cancer (AJCC TNM staging system). The primary tumour (T) stage shown in this figure is CIS. Node (N) stage and metastasis (M) stage measure cancer spread to local lymph nodes and other parts of the body, respectively.

Presentation and diagnosis of bladder cancer

The most common presentation of bladder cancer is haematuria (presence of blood in the urine), which may be associated with additional symptoms such as dysuria (painful urination), increased frequency/urgency of urination, failed attempts to urinate or urinary tract infections. Haematuria is either visible (frankly blood-stained urine) or non-visible (urine that is clear-looking to the naked eye). Non-visible haematuria is detected by dipstick or microscopic examinations, often included in standard primary care assessments for an NHS Health Check or in the investigation of urinary symptoms. Bladder cancer is detected in approximately 10% of patients with visible haematuria and 3–5% of those with dipstick or microscopic haematuria who are aged > 40 years. 7,8 Therefore, these patients are urgently referred for assessment in rapid-access haematuria clinics in secondary care, where suspected bladder tumours are usually detected by cystoscopy under local anaesthetic or, less frequently, on imaging by ultrasound scanning or computerised tomography (CT). Visual appearances of bladder cancer are confirmed by histological diagnosis using samples taken during cystoscopic transurethral resection of bladder tumour (TURBT), which is conducted as part of the initial management of bladder cancer.

Initial management of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer

About 80% of people with a new diagnosis of bladder cancer will have NMIBC and will initially be treated by TURBT. The subsequent goal in NMIBC management is the prevention of recurrence and/or progression to higher-stage, life-threatening, muscle-invasive disease. It is thought that failure to identify/appreciate tumours is a factor in 20–40% of the recurrent tumours that are overlooked. 9,10 Tumour seeding following resection and urothelium that may be genetically ‘primed’ for new tumours developing are other factors that are considered relevant and will have an impact on recurrence rates independent of the completeness of resection. Recurrence and stage progression to muscle-invasive or metastatic cancer is more likely to occur in those with high-grade tumours with concomitant CIS. In particular, CIS, which is a flat tumour, can be easily missed using conventional white-light (WL) resection. 11

Risk of recurrences and stage progression

Both clinical and histological parameters can be used to estimate individual risk of recurrence and progression of NMIBC into muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). Based on this, the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Genitourinary Group has developed an algorithm that calculates probabilities of recurrence and progression, which are integral to the current European Association of Urology (EAU) guideline on the treatment of NMIBC. 12

These probabilities are based on the number of tumours, tumour size, prior recurrence, histological T stage, presence of CIS and tumour grade. The risks of recurrence and progression 3 years after diagnosis are summarised in Table 1. Patients’ cancer management plans are tailored to the risk categories in terms of the intensity of follow-up and the use of adjuvant therapies.

| Recurrence risk group (score) | Probability of recurrence at 3 years (%) | Progression risk group (score) | Probability of progression at 3 years (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk (0) | 25 | Low risk (0–1) | 0.8 |

| Intermediate risk (1–9) | 40–56 | Intermediate risk (2–6) | 4 |

| High risk (10–17) | 75 | High risk (7–23) | 11–30 |

Strategies to reduce recurrence and progression

Strategy 1: adjuvant therapy

A meta-analysis of seven randomised trials showed that a single instillation of chemotherapy into the bladder [intravesical mitomycin C (MMC), epirubicin or doxorubicin] leads to a decrease of 39% [standard deviation (SD) ± 8%] in the odds of recurrence (odds ratio 0.61; p < 0.0001). 13 For patients with low-risk disease, no further intravesical treatment is required. 14 For patients with intermediate-risk disease, additional courses of either intravesical chemotherapy or intravesical immunotherapy with bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) for a minimum of 1 year is advised based on clinical evidence and EAU guidelines. 13–17 Use of BCG, which has greater toxicity than chemotherapy, tends to be reserved for those with high-risk disease with higher risk of progression. In some instances, immediate cystectomy is recommended following diagnosis, depending on high-risk factors and patient preference. 12 Intravesical adjuvant therapies are associated with treatment morbidity, affect quality of life (QoL) and have associated costs. 16

Strategy 2: surveillance

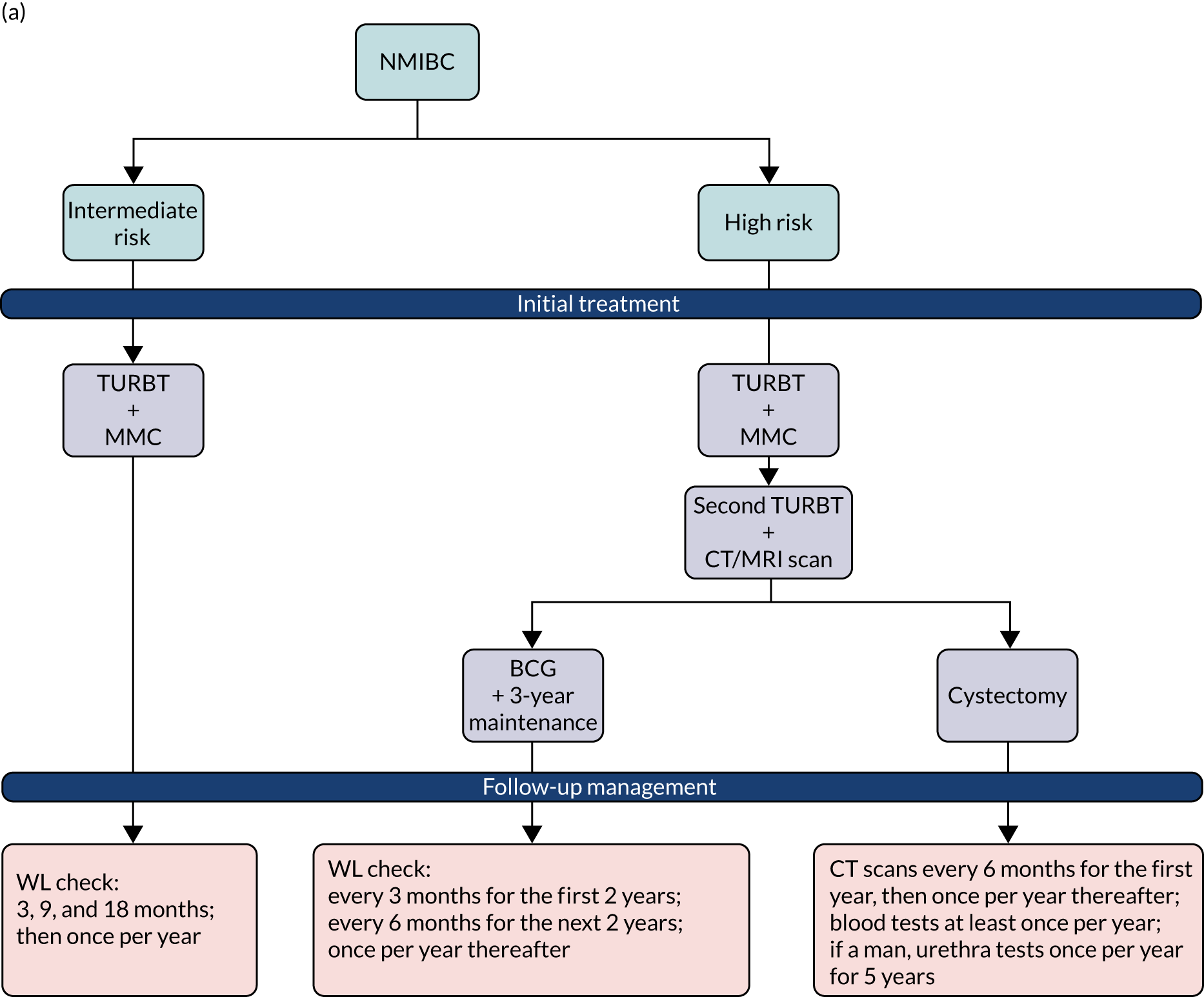

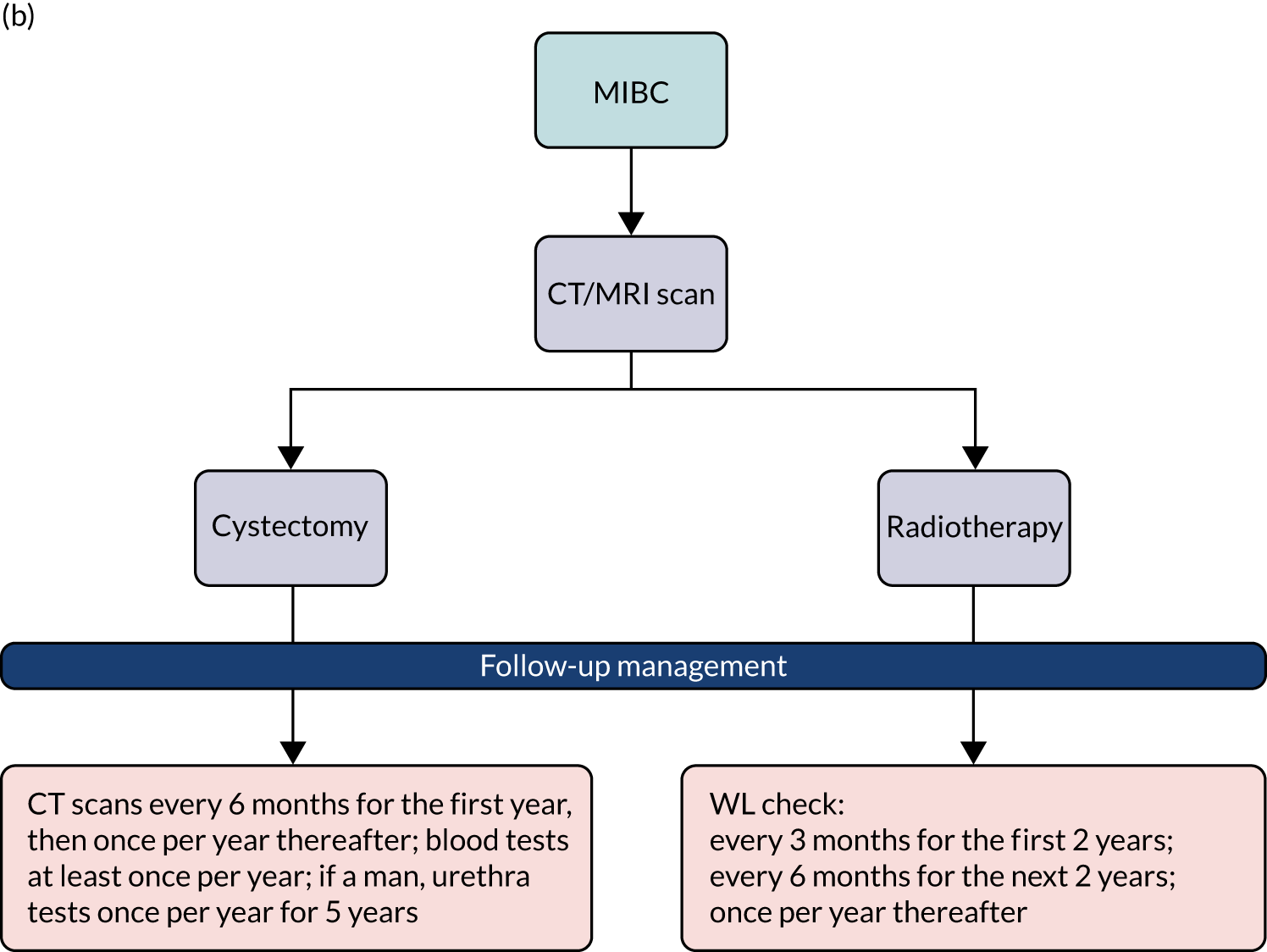

Surveillance of NMIBC is carried out using cystoscopy with the aim of detecting recurrence early and allowing treatment before progression. Clinical guidelines tailor follow-up protocols according to the risk groups described above. 12,18 The advised follow-up of low-risk disease is cystoscopy 3 months after initial TURBT; if this is negative, the next cystoscopy is scheduled 9 months later and patients are then discharged if they are clear at that assessment. 18,19 Patients with high-risk tumours have cystoscopy and urine cytology 3 months after TURBT. If this is negative (according to the guidance in place during this study), cystoscopy is repeated every 3 months for 2 years, then every 6 months until 5 years, and annually thereafter. More recently, this guidance was updated by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) to recommend follow-up cystoscopy every 3 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for the next 2 years and then once per year thereafter. 18 The recommended intensity of cystoscopic follow-up for patients with intermediate risk was not clearly defined when this trial started. It was recommended that follow-up of patients with tumours considered to fall between low and high risk be adapted according to personal and subjective factors. NICE guidance has since been updated to advise that people with intermediate-risk NMIBC undergo cystoscopic follow-up at 3, 9 and 18 months, and once per year thereafter. Those with intermediate-risk NMIBC can be discharged to primary care after 5 years of disease-free follow-up.

Strategy 3: high-quality resection

A high-quality TURBT aims to completely eradicate Ta–T1 tumours and to accurately stage disease at first presentation. The high between-centre variability in recorded 3-month recurrence rates indicates that TURBT can often be incomplete. 10 Training and technology to improve completeness of resection is thought to be one of the most important modifiable factors in reducing recurrence. 10

Health economic impact of managing non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer

Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer is one of the costliest cancers to manage because of its high prevalence and high recurrence rate and the need for adjuvant treatments and long-term cystoscopic surveillance. The total cost of treatment and 5-year follow-up of UK patients with NMIBC increased from £73M to £213M from 2001 to 2012 (inflation corrected). This was due to an ageing population and better-defined adjuvant treatment and surveillance regimens requiring additional therapies, with potential mortality and long-term morbidity (e.g. radical surgery). 20,21 Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is also known to be affected in those receiving morbid treatments for bladder cancer. 22 The cost-effectiveness of NMIBC treatment strategies has not been widely studied.

Rationale for research

Health need

Although many cases of NMIBC are readily treatable with cystoscopic resection, it remains a major health-care burden, for the reasons described above. 11,20 From a patient perspective, there are often considerable anxieties about recurrences, TUR and the impact of adjuvant treatments. 23 TUR is associated with reduced QoL across both mental and physical health domains, although these effects are usually transient. 24 Substantial effects on HRQoL are most likely to result from adjuvant intravesical treatments and radical or palliative treatments for progression. 22 More efficient management strategies to reduce NMIBC recurrence, and hence decrease both the burden to patients and costs to the NHS, are urgently needed. One such approach currently available in the NHS is photodynamic diagnosis (PDD).

Photodynamic diagnosis of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer

Mechanism

Photodynamic diagnosis can enhance tumour detection during the initial cystoscopic diagnosis and TURBT. 11 PDD exploits photosensitising agents with a high selectivity for accumulation within tumour cells. 25 The photosensitiser can then be excited by a specific electromagnetic wavelength and will re-emit light at a different wavelength for detection. Photosensitising agents that can be administered intravesically include 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA), hexaminolevulinate (HAL) and hypericin. Conversion of 5-ALA to HAL by esterification results in a more rapid cellular uptake and, subsequently, the cancer fluoresces more brightly than with 5-ALA. 26

The HAL product Hexvix® (PhotoCure, Oslo, Norway) is the only agent licensed in the European Union (marketed through Ipsen, Boulogne-Billancourt, France) and the USA (as Cysview™) for PDD in NMIBC.

Diagnostic accuracy

A systematic review funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) suggested that PDD offered greater diagnostic accuracy in detecting NMIBC than conventional WLC based on a total of 27 studies enrolling 2949 participants. 11,27 The pooled estimates [95% confidence interval (CI)] for patient-level analysis comparing PDD against WL showed increased diagnostic sensitivity from 71% (49–93%) to 92% (80–100%), but decreased specificity from 72% (47–96%) to 57% (36–79%). In particular, PDD was better than WL in detecting intermediate- and high-risk disease, including CIS that otherwise could be easily missed (sensitivity 83%, 95% CI 41% to 100%, vs. 32%, 95% CI 0% to 83%, respectively). The review also suggested that PDD treatment was no better than WL for patients with low-risk disease. 11

Clinical outcomes

Based on data from four studies, the systematic review also showed that the improved diagnostic accuracy with PDD translated into a reduced recurrence rate. 11 Compared with white-light-guided transurethral resection of bladder tumour (WL-TURBT), photodynamic diagnosis-guided transurethral resection of bladder tumour (PDD-TURBT) was associated with fewer tumours at the 3-month follow-up, with a relative risk of 0.37 (95% CI 0.20 to 0.69). The benefit of PDD resection in reducing tumour recurrence in the longer term (12–24 months) was less clear, with effect estimates favouring PDD, but without statistical significance. Variability in the administration of single-dose adjuvant intravesical chemotherapy within 24 hours of resection across the four randomised controlled trials (RCTs) was an important confounding factor in terms of generalising the possible benefit of PDD. A subsequent large RCTshowed that PDD using 5-ALA did not decrease rates of recurrence-free or progression-free survival at 12 months. 28 However, this result conflicted with previous and subsequent studies from the same group, for which the cohort size was 814 and 551 randomised patients, respectively, which did show a decrease in recurrence rates. 29,30 This discrepancy is most likely to be a reflection of the differences in research protocols, including patient selection and the use of HAL rather than 5-ALA. 29,30 There is, therefore, still substantial uncertainty around any potential patient benefit of PDD, particularly when applied to routine care in a pragmatic NHS setting.

Evaluations of the potential health economic impact of photodynamic diagnosis

The NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) review included economic modelling of the cost-effectiveness of PDD and assessment of the performance of urine biomarkers [e.g. nuclear matrix protein 22 (NMP22) and those detected via fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) and immunocytochemistry (immunoCyt)] and cytology for the detection and follow-up of bladder cancer. 11 Although the differences in outcomes and costs between detection methods appeared to be modest, the decision about which strategy to adopt depended on society’s willingness to pay (WTP) for an additional gain. The HTA review was unable to undertake a cost–utility analysis owing to the lack of relevant health utility data. Therefore, although strategies that replaced WL with PDD resulted in a gain in life-years, it was unclear whether this was sufficient to justify the extra costs. 11 To address this, more details on the long-term outcomes of clinical effectiveness, HRQoL data [as quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs)] and a full assessment of all treatment costs were required.

Aims and objectives

We aimed to undertake a pragmatic, patient-randomised controlled trial to compare outcomes of PDD resection with outcomes of standard WL cystoscopic resection for newly diagnosed intermediate- and high-risk NMIBC. Apart from initial treatment, both groups were scheduled to receive usual care, including single-dose adjuvant intravesical MMC, surveillance according to standard risk-adjusted schedules and further adjuvant therapy as indicated by current practice guidelines. 12,18 With the trial results, we aim to deliver a definitive assessment of the benefits, harms and cost-effectiveness of PDD within the NHS to guide decisions around further adoption and implementation.

Primary objectives

Clinical effectiveness

Time to recurrence was compared for the two treatment strategies, with a principal point of interest at 3 years.

Economic evaluation

A within-trial analysis was conducted over a 3-year follow-up period to determine whether or not, as part of the management of people with suspected intermediate- and high-risk cancers confined to the bladder lining, PDD resection was cost-effective for the NHS compared with resection under WL.

Secondary objectives

Clinical effectiveness

-

The relative rates of disease progression at 3 years were measured; a formal comparison was difficult, as progression is rare. Therefore, modelling was undertaken at 3 years using trial and other published data. A projection over the patient lifetime (15–20 years) was also included.

-

Relative harms and safety complications were measured within 30 days of surgery.

Economic evaluation

A model-based economic analysis was planned to estimate the cost-effectiveness of PDD-TURBT over a patient’s lifetime.

Additional objectives

-

Lay the basis for modelling the safest and most cost-effective cystoscopic follow-up surveillance schedules.

-

Evaluate the learning curve for the procedure to account for its effects on outcomes of both PDD and standard WL resections.

-

Establish a well-characterised cohort of patients with intermediate- and high-risk NMIBC, including clinical data and urine, blood and tumour specimens that would be available for separately funded research of genotypic and phenotypic studies.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Tandogdu et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Study design

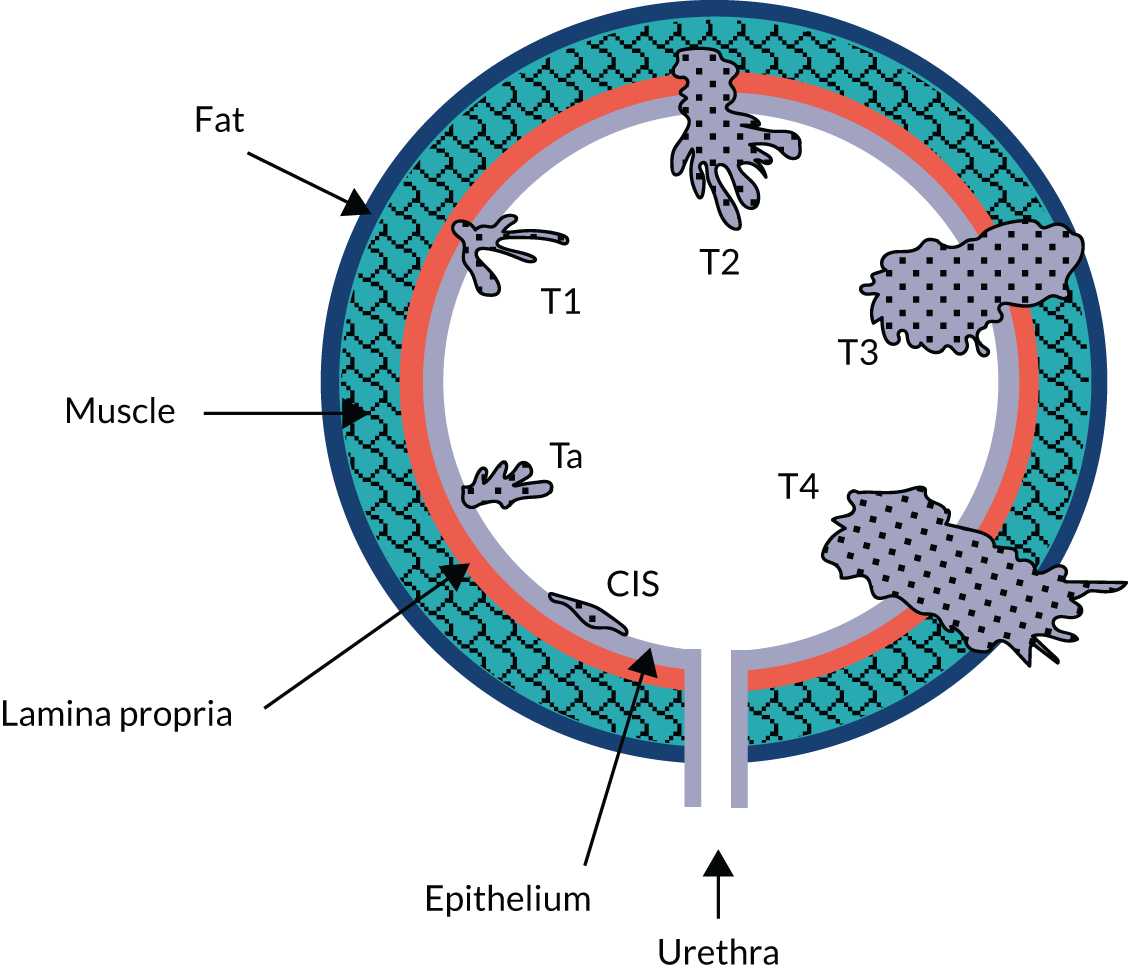

The Photodynamic versus white-light-guided resection of first diagnosis non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (PHOTO) trial was a multicentre, pragmatic, open-label, parallel-group, non-masked, superiority RCTthat compared the intervention of PDD-TURBT with standard WL resection in patients with newly diagnosed intermediate- or high-risk NMIBC. Apart from initial treatment (initial TURBT with or without second TURBT), both groups received standard care as indicated by current practice guidelines,12,18 including single-dose intravesical MMC within 24 hours of initial resection, risk-adjusted adjuvant therapy and surveillance. The target number of participants was 533, with a trial-specific follow-up of at least 36 months per participant. Further details of the study design have been described previously and are shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

The PHOTO trial schema. a, Clinical follow-up scheduled from date of second TURBT, if conducted. CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events. Adapted with permission from Tandogdu et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Ethics approval and research governance

The Newcastle & North Tyneside 2 ethics committee [Research Ethics Committee (REC) reference number 14/NE/1062] provided a favourable ethics opinion for this research in July 2014. The trial was sponsored by The Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and is registered as ISRCTN84013636.

Participants

Adult patients (aged ≥ 16 years) with a suspected new and first diagnosis of intermediate- or high-risk NMIBC were potentially eligible and were recruited from participating secondary care hospitals, mainly at rapid-access haematuria clinics. On visual diagnosis, it is impossible to confidently predict a final risk category of intermediate or high, as the risk calculators require the results of histological parameters that are not perceptible by macroscopic assessment at flexible cystoscopy, that is, primarily, the microscopic features of low-grade, early-stage papillary tumours (pT) (pTa vs. pT1) and primary or concomitant CIS. Separation of high-risk and intermediate-risk disease can be resolved only retrospectively once the resection and pathological assessment of the tissue have occurred; therefore, separation is included as part of our pre-planned analyses after randomisation. Pragmatically, we can confidently remove low-risk disease on visual parameters alone because the finding of a new solitary lesion of < 3 cm in diameter, irrespective of histological details, would score below the threshold of points (measured using the EORTC calculator; EORTC, Brussels, Belgium; URL: www.eortc.be/tools/bladdercalculator/, accessed 14 January 2022) that indicates ‘higher risk’ disease (intermediate or high risk). Therefore, participants were identified based on the preliminary visual assessment of intermediate- or high-risk NMIBC using cystoscopy or imaging, performed as part of standard evaluation for suspected urinary tract malignancy.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

-

Adult men and women aged ≥ 16 years.

-

First suspected diagnosis of bladder cancer.

-

Visual/ultrasound scan (USS)/CT diagnosis of intermediate- to high-risk NMIBC.

-

WL visual appearances of intermediate- or high-risk disease (tumour of ≥ 3 cm in diameter, ≥ 2 tumours or flat velvety erythematous changes giving rise to a clinical suspicion of CIS) or suspicion of papillary bladder tumour of ≥ 3 cm in diameter based on ultrasound or CT scanning (without hydronephrosis).

-

Written informed consent for participation prior to any study-specific procedures.

-

Willing to comply with the following lifestyle guidelines:

-

Female participants must be surgically sterile, be post-menopausal or agree to use effective contraception after joining the study and for 7 days after treatment. (Effective contraception was defined as two forms of contraception, including one barrier method.) Female participants must not breastfeed for 7 days after treatment.

-

Male participants must be surgically sterile or agree to use effective contraception after joining the study and for 7 days after treatment.

-

Exclusion criteria

-

Visual evidence of low-risk NMIBC (solitary tumour of < 3 cm in diameter).

-

Visual evidence of MIBC on preliminary cystoscopy, that is non-papillary or sessile mass (attached directly by its base without a stalk).

-

Imaging evidence of MIBC on CT/USS (including the presence of hydronephrosis).

-

Upper-tract (kidney or ureteric) tumours on imaging.

-

Any other malignancy in the past 2 years [except non-melanomatous skin cancer cured by excision, adequately treated CIS of the cervix, ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)/lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) of the breast, or prostate cancer in patients who have a life expectancy of > 5 years on trial entry].

-

Evidence of metastases.

-

Porphyria or known hypersensitivity to porphyrins.

-

Known pregnancy (based on history and without formal testing, in keeping with day-to-day NHS practice of PDD use).

-

Any other conditions that in the opinion of the local principal investigator (PI) would contraindicate protocol treatment.

-

Unable to provide informed consent.

-

Unable or unwilling to complete follow-up schedule (including HRQoL questionnaires).

Recruitment procedure

An eligibility checklist was completed by the local PI (or a delegate) to assess fulfilment of the entry criteria for all patients considered for the study. Information from the diagnostic cystoscopy was used to assess eligibility.

Informed consent

All potentially eligible patients were provided with an information sheet to explain why they had been approached and the nature of the study. Eligible patients were asked to provide written informed consent to take part in the study only after they had had sufficient time to consider the trial and the opportunity to have any further questions addressed by the local clinical team.

Interventions

The interventions being compared within the PHOTO trial were:

-

PDD-TURBT (experimental group)

-

standard WL-TURBT (control group).

All participants, unless there were clinical contraindications, received intravesical MMC (40 mg in 40 ml of saline), ideally within 6 hours following TURBT, but otherwise in the inpatient setting before discharge.

Technique of photodynamic diagnosis

Photodynamic diagnosis requires the preliminary instillation of the photosensitiser HAL (85 mg in 50 ml of phosphate-buffered saline) into the participant’s bladder through a urethral catheter. Participants were asked not to pass urine for at least 1 hour after instillation. Following operating theatre preparation in accordance with local standard procedures and under appropriate anaesthesia, participants underwent TURBT of their bladder tumour under blue-light illumination of the bladder (wavelength 380–450 nm). A specialised light source, cystoscope, light cables and cameras were required. When using PDD, normal bladder epithelium appears blue, and red areas are considered suspicious and should be resected.

Technique of standard white-light cystoscopy

The control group did not have any preliminary photosensitiser instillation, and standard tumour localisation and resection took place under WL illumination of the bladder (wavelength 400–800 nm).

Second resection

If, in accordance with the EAU guideline,12 the local PI deemed a second TURBT was required, the same method (PDD or WL) was used as that of the participant’s trial treatment allocation.

Adjuvant therapy

Adjuvant therapy was prescribed according to local clinical judgement in accordance with participant characteristics and the EAU guideline. 12

Treatment allocation (randomisation concealment and blinding)

Eligible consenting patients were centrally randomised using either the secure web-based randomisation system or the 24-hour interactive voice-response randomisation system at the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials (CHaRT) in Aberdeen. Minimisation by centre and sex was used to allocate participants 1 : 1 between the control (WL) and experimental (PDD) groups. The minimisation algorithm incorporated a random element to prevent potential deterministic treatment allocation. Participants were randomised by clinical teams at the participating NHS hospitals.

Blinding

Participants reported baseline HRQoL data using self-completed questionnaires before being informed of their randomised allocation. Surgeons and participants could not be blinded to the allocated procedure.

Delivery of the intervention

It was anticipated that allocated treatment would typically occur within the 2 weeks after randomisation to allow reasonable time for planning to meet the NHS 62-day target for cancer treatment. All other aspects of care were left to the discretion of the responsible surgeon.

Outcome measures

The primary clinical outcome measure was the time to recurrence measured as time from the day of randomisation to the day of subsequent biopsy for pathologically proven first recurrence (including progression, cystectomy and death from bladder cancer). The primary objective was to compare the time to recurrence for the two treatment strategies, with a principal point of interest at 3 years.

The primary health economic outcome was to evaluate cost-effectiveness using the incremental cost per recurrence avoided and cost–utility as the incremental cost per QALY gained at 3 years.

Secondary outcome measures

Other clinical outcomes included adverse events (AEs) and complications up to 3 months from initial or second TURBT (as applicable). Direct, surgically related, postoperative events occurring within the 30 days following TURBT were assessed using the Clavien–Dindo classification for surgical complications. 31 Events occurring up to 3 months after TURBT were assessed and recorded using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v4.0 framework. 32

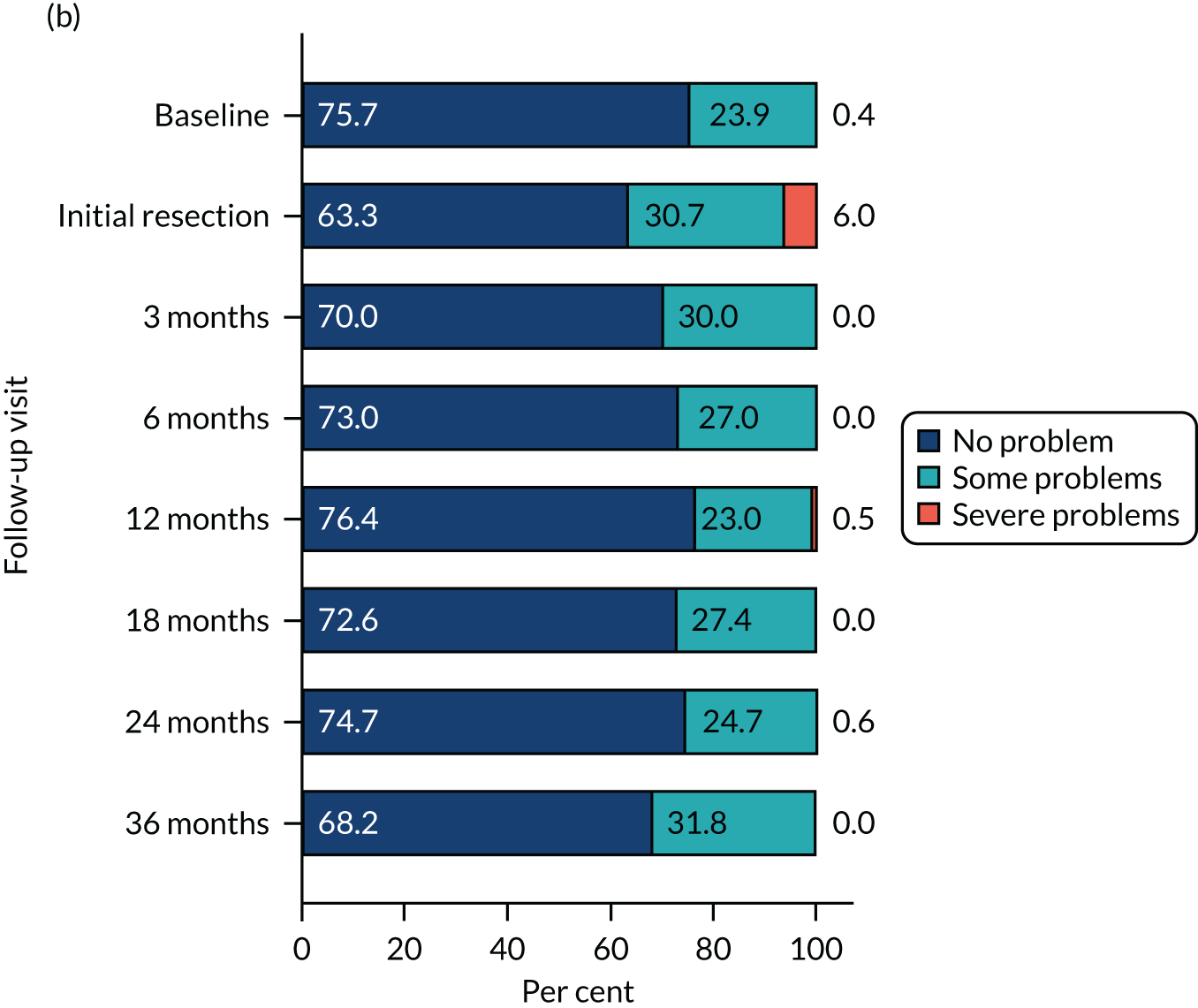

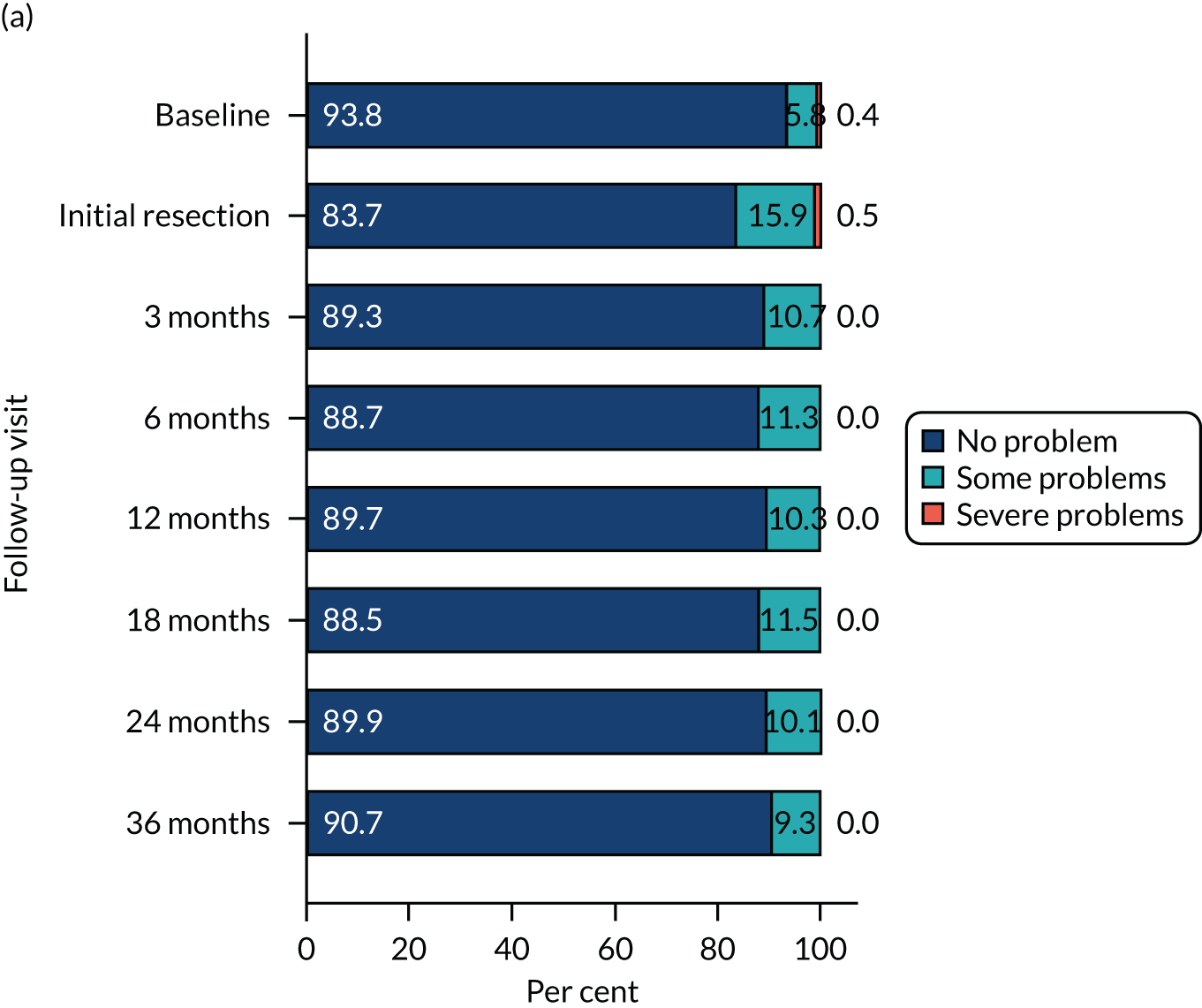

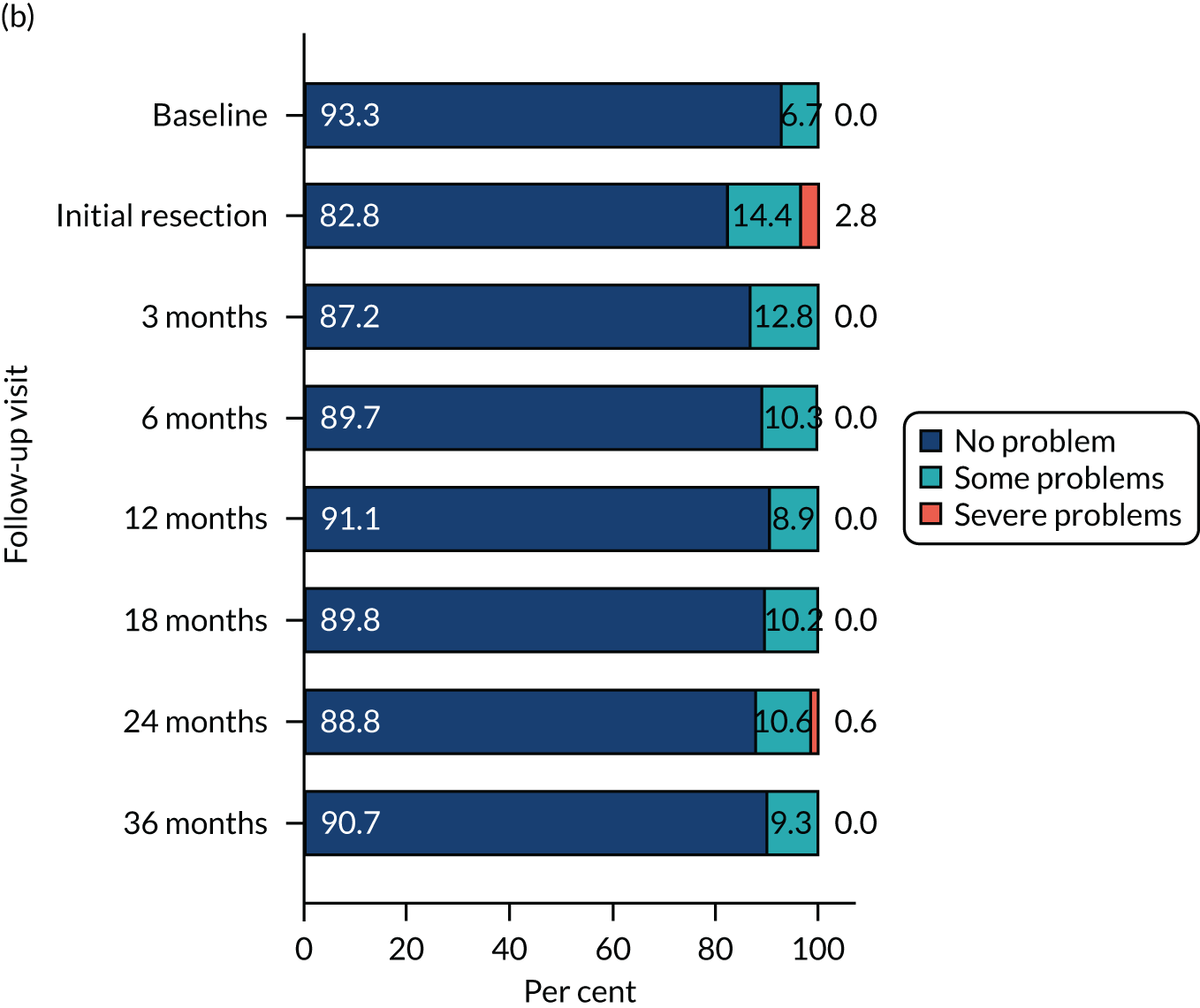

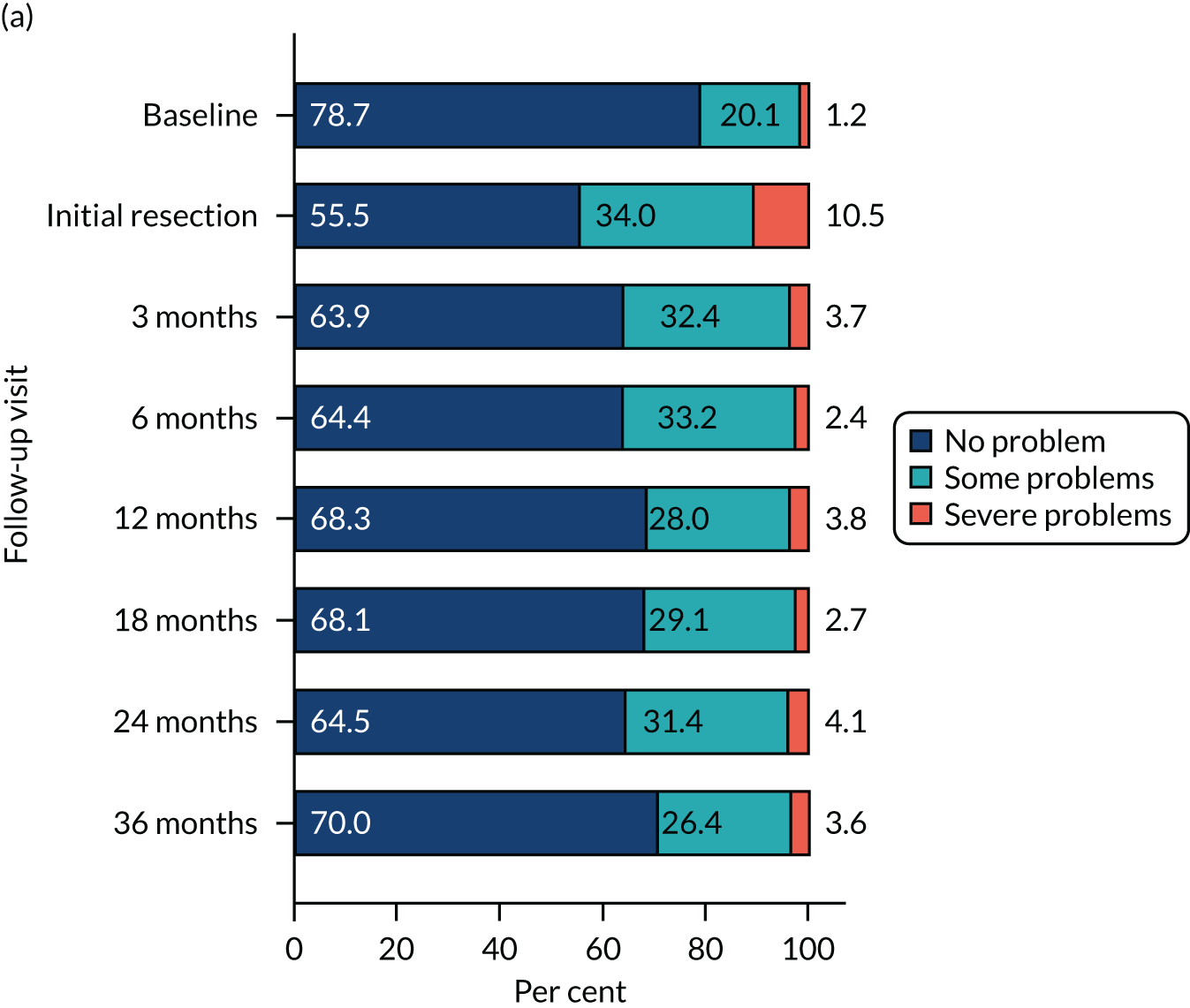

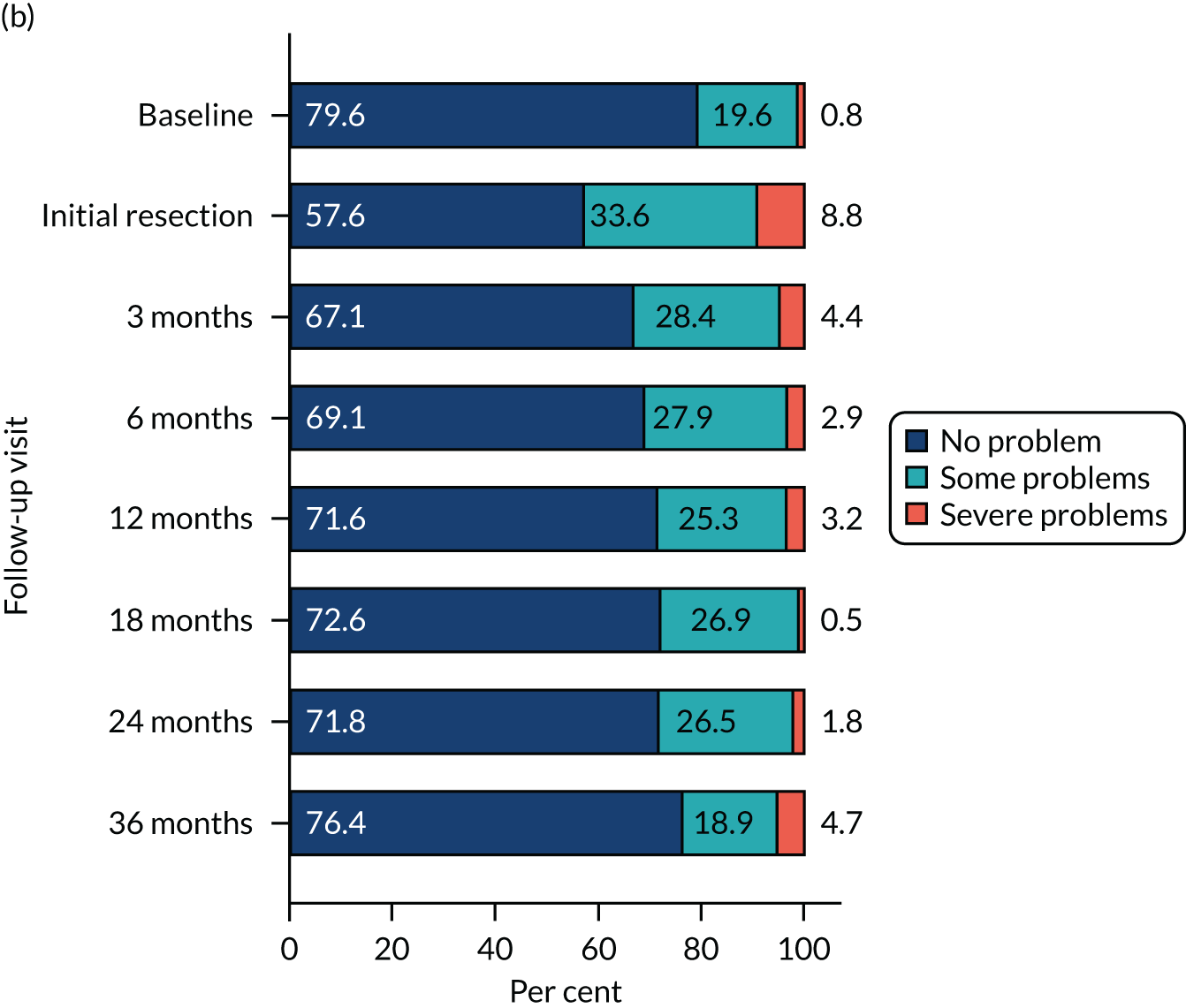

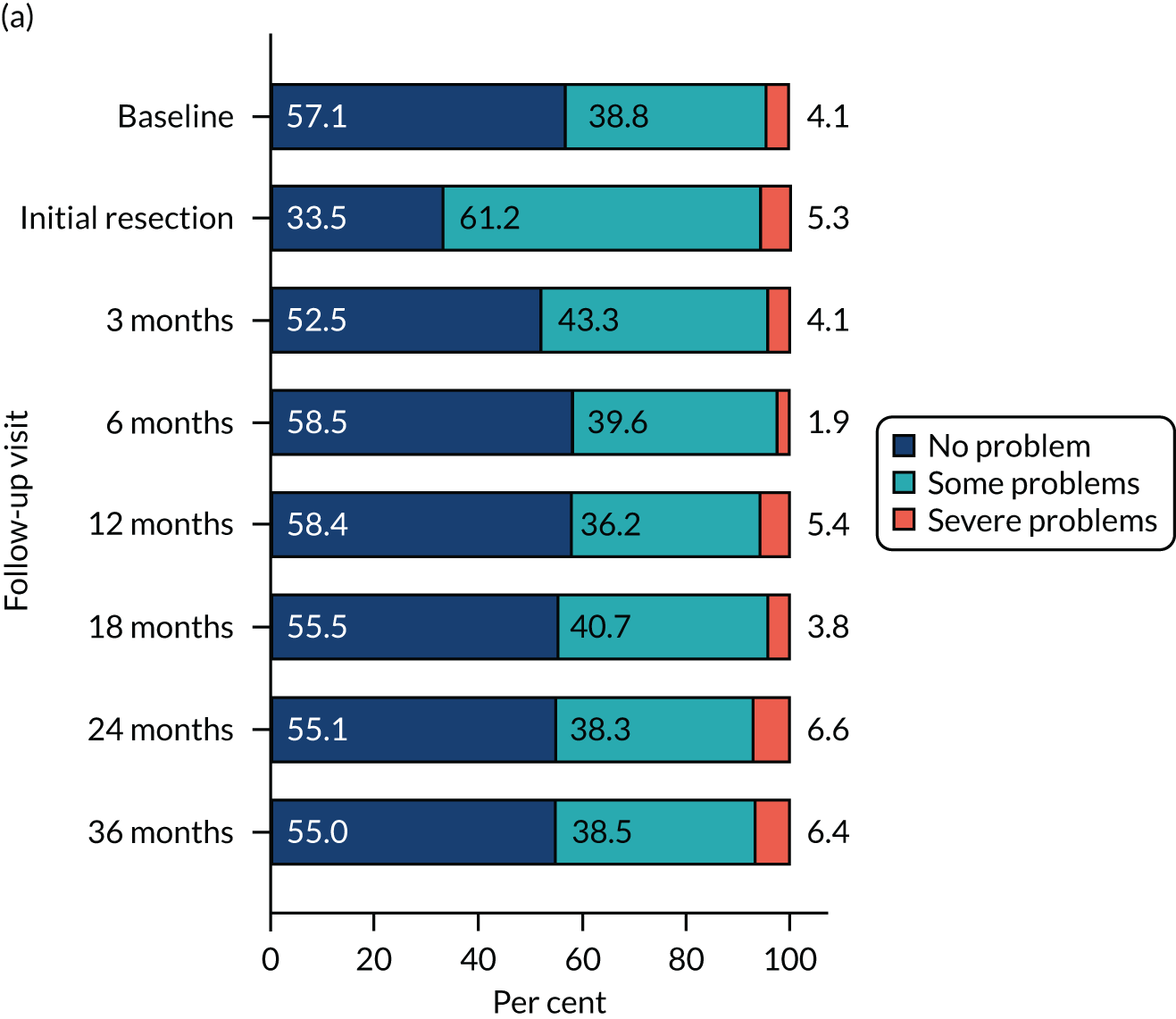

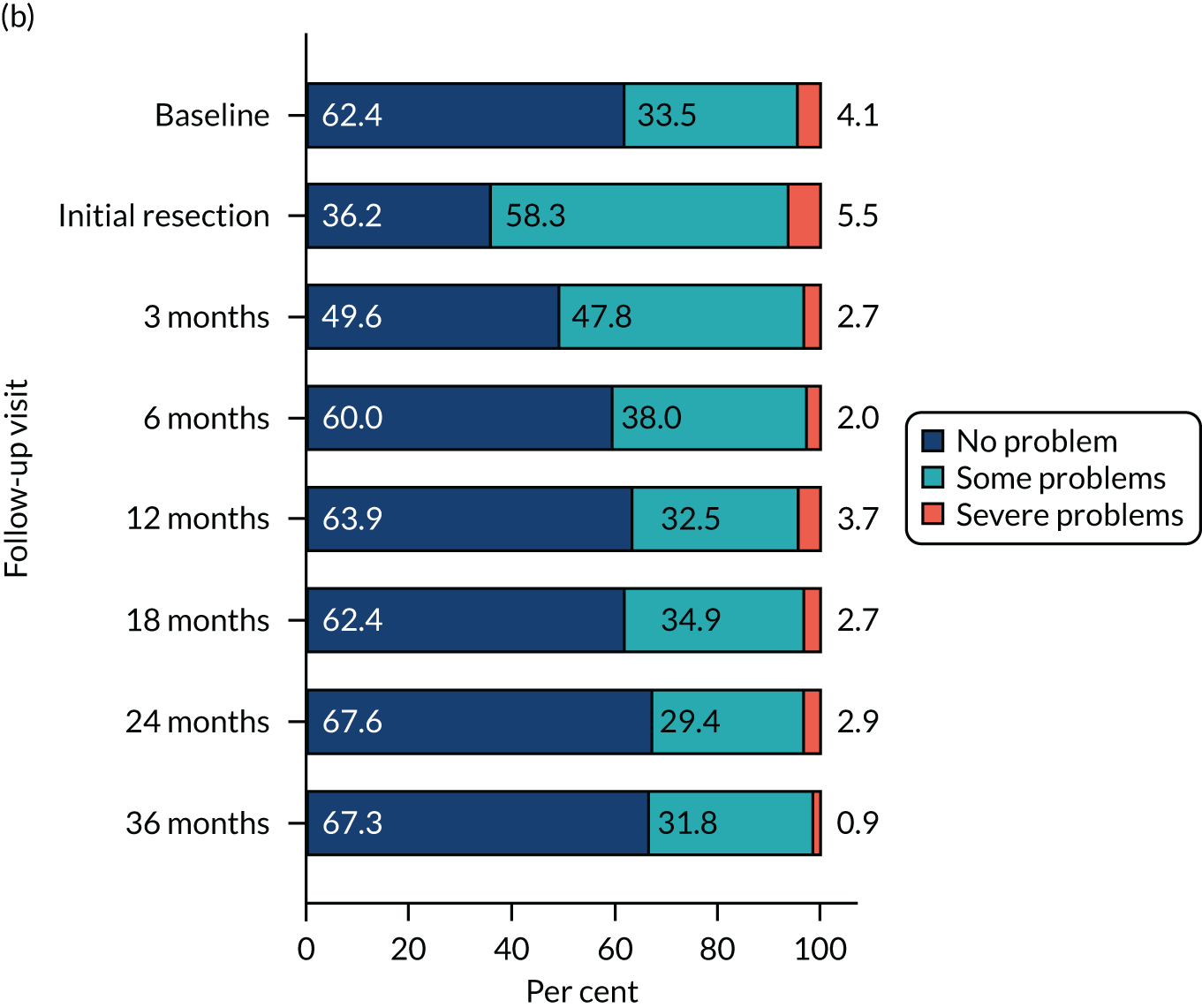

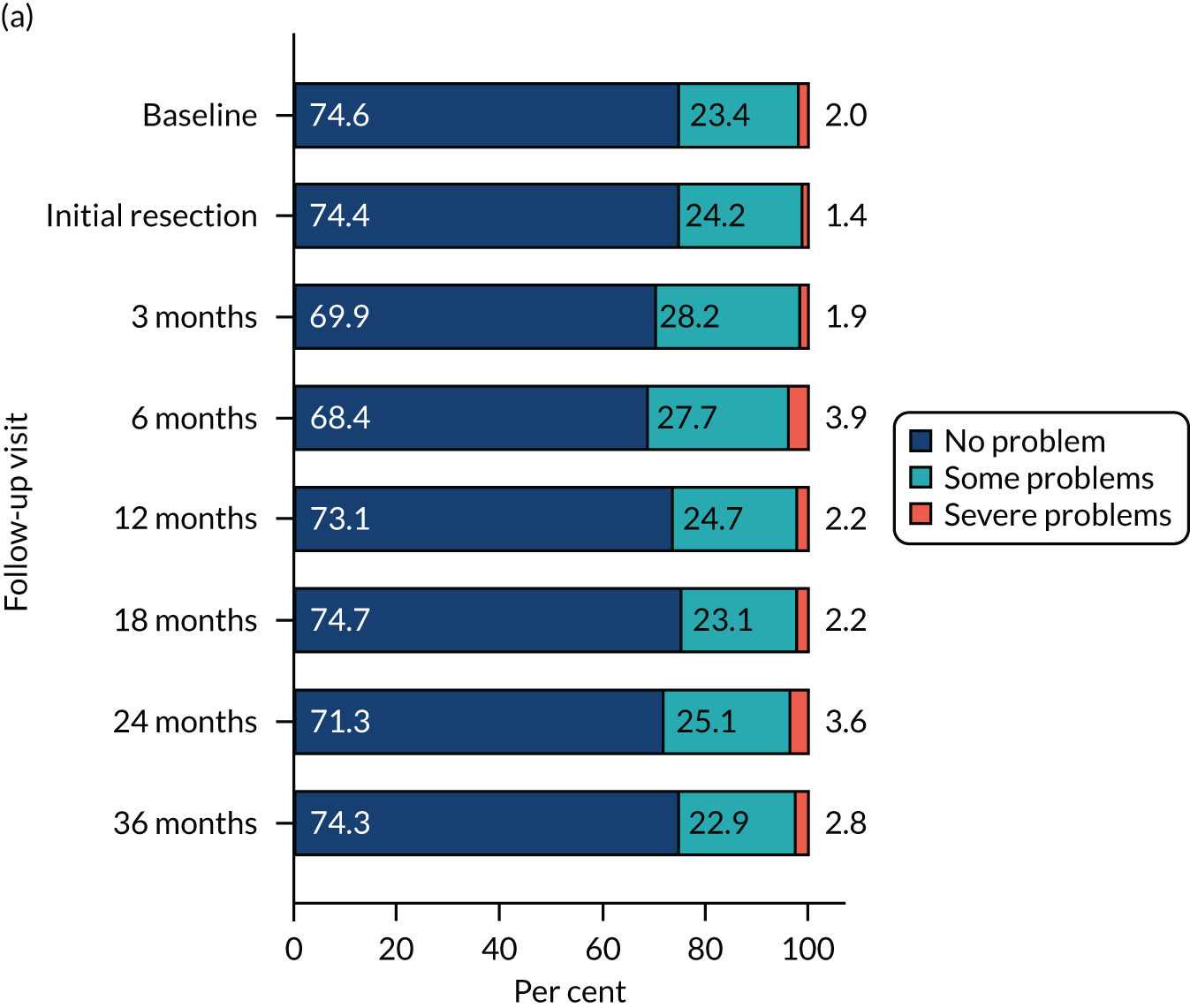

The relative changes in HRQoL resulting from the physical and psychological benefit, together with any harms associated with each strategy and any subsequent necessary cancer treatment, were measured using the generic EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), questionnaire; the cancer-specific European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer – Quality of Life Questionnaire – Core 30 (EORTC-QLQ-C30); and the disease-specific European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer – Quality of Life Questionnaire – Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer – 24 items (EORTC-QLQ-NMIBC-24) questionnaire. These were completed by participants on paper at baseline (prior to knowledge of treatment allocation), following surgery and at 3, 6, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months after randomisation.

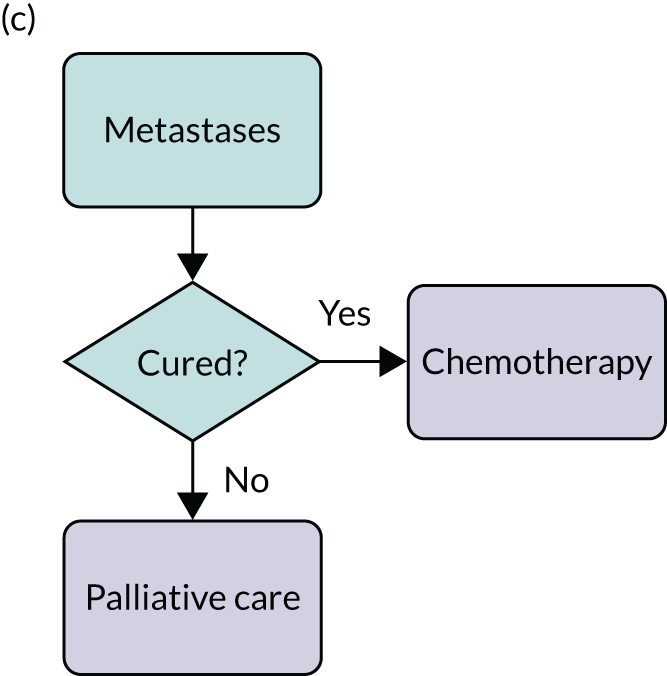

Disease progression was defined as an increase in stage to MIBC or the development of nodal or metastatic disease. In addition, details of intravesical treatment failure (e.g. BCG) were captured. Overall survival and bladder-cancer-specific survival were compared between the two treatment groups.

Other cost-effectiveness outcomes included the estimation of the incremental cost per recurrence avoided using the economic model over the patients’ lifetime and the estimation of the incremental cost per QALY gained using the economic model over the patients’ lifetime.

Additional exploratory objectives

The following objectives were explored:

-

to model the safest and most cost-effective cystoscopic follow-up surveillance schedule using data from within the trial and, if appropriate, from other relevant sources to describe the risk of recurrence at each interval of surveillance cystoscopy (note that this research is not part of this report; see Mowatt et al. 27)

-

to evaluate the learning curve for the PDD procedure and account for its effects on outcomes of both PDD and standard WL resections

-

to establish a well-characterised cohort of patients with intermediate- and high-risk NMIBC, including clinical data and urine, blood and tumour specimens for separately funded genotypic and phenotypic studies [the Photodynamic versus white-light-guided resection of first diagnosis non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer – Translational (PHOTO-T) study; see Appendix 3].

Data collection and management

The PHOTO trial schedule of assessment and investigations is summarised in Table 2. Eligibility was checked during routine attendance for diagnosis and staging of new bladder cancers, which included obtaining medical history. Eligible patients who consented to join the trial completed HRQoL questionnaires prior to initial TURBT and again prior to discharge from hospital. Intraoperative and postoperative data were reported by the local research teams at the time of the initial and second (as applicable) TURBT. At first recurrence, the date of biopsy and confirmatory histological details were reported by the local team. Details of any cystoscopy checks that were carried out were reported by the local research teams from the routine clinic visits at 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months post initial/second TURBT (as applicable), including an assessment of AEs at 3 months. Disease progression was assessed by the local research team using the results of further resection or imaging during follow-up. A short case report form (CRF) was completed annually from routine urology clinic visits following recurrence or progression to collect the disease status (e.g. further recurrence of NMIBC, progression to MIBC or cystectomy) and survival status of participants. The outcome of these assessments for each participant were entered as appropriate by centre staff on electronic CRFs on the central secure database held by CHaRT, where the accruing data were monitored.

| Assessment | Time point | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre randomisation screening | Pre treatment | TURBT | Prior to discharge | Second TURBT (as clinically indicated) | 3 months post treatment | 6 months post treatment | 9 months post treatment | 12 months post treatment | 18 months post treatment | 24 months post treatment | 36 months post treatment | Annually thereafter | At first disease recurrence/progression | |

| Visual diagnosis of intermediate- to high-risk NMIBC | ✗ | In accordance with EAU guideline12 | Treatment in accordance with local practice | |||||||||||

| Medical history | ✗ | In accordance with EAU guideline12 | Treatment in accordance with local practice | |||||||||||

| HRQoL questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | In accordance with EAU guideline12 | Treatment in accordance with local practice | ||||||||||

| TURBT according to treatment allocation, with post treatment MMC instillation | ✗ | In accordance with EAU guideline12 | Treatment in accordance with local practice | |||||||||||

| Second TURBT, if required, according to treatment allocation | ✗ | In accordance with EAU guideline12 | Treatment in accordance with local practice | |||||||||||

| Assessment of AEs (CTCAE and Clavien–Dindo) | ✗ | In accordance with EAU guideline12 | Treatment in accordance with local practice | |||||||||||

| Cystoscopy | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | In accordance with EAU guideline12 | Treatment in accordance with local practice | |||||

| Histological confirmation of recurrence/progression | In accordance with EAU guideline12 | ✗ | ||||||||||||

Costs and changes in HRQoL were collected via self-completed postal questionnaires sent directly to participants by CHaRT at 3, 6, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months post randomisation. In addition, a participant costs questionnaire was administered by post at 30 months post randomisation.

All recruiting surgeons completed a learning curve questionnaire to elicit their WL- and PDD-resection experience prior to their centre commencing recruitment. The subsequent accruing experience of each surgeon was captured on CRFs.

All CRFs and participant questionnaires are available on the NIHR Journals Library project web page (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1114202/#/documentation; accessed 16 November 2021).

Tracking and monitoring adverse events

The CHaRT study office was notified of AEs (CTCAEs, primarily grade ≥ 3) by the local research team on the 3-month cystoscopy CRF. Unrelated AEs were not recorded. In the PHOTO trial, ‘relatedness’ was defined as any untoward medical event that had a reasonable causal relationship with PDD-TURBT, standard WL-TURBT or the intravesical MMC. The following events were potentially expected: anaemia, bladder discomfort/pain, bladder perforation, bleeding resulting in clot retention, constipation, diarrhoea, deep-vein thrombosis (DVT), fever, gout, haematuria, headache, increase in white blood cell count, increased level of bilirubin, insomnia, nausea, postoperative dysuria, prolonged catheterisation, skin rash, ureteric obstruction/hydronephrosis, urethral stricture, urinary frequency, urinary retention, urinary tract infection and vomiting.

Any serious adverse events (SAEs) related to the participants’ TURBT treatment that were not further interventions (e.g. being admitted to hospital for an infection) were recorded on the SAE form. All deaths from any cause (related or otherwise) were recorded on the SAE form.

It was a requirement to report to the sponsor any SAEs that were deemed related and unexpected within 24 hours of receiving the signed SAE notification. Such SAEs were also reported to the main REC within 15 days of the chief investigator becoming aware of the event. All related SAEs were summarised and reported to the appropriate authorities as required.

Trial oversight

The day-to-day management of the trial was provided by the Clinical Trials and Statistics Unit at the Institute of Cancer Research (ICR-CTSU) and CHaRT based within the Health Services Research Unit, University of Aberdeen, with ICR-CTSU leading on trial management and CHaRT coordinating data management and statistics. The trial offices provided day-to-day support for the PIs at recruiting centres. The PIs, supported by dedicated research nurses, were responsible for all aspects of local organisation, including recruitment of participants, delivery of the interventions and notification of any problems or unexpected developments during the study.

A core group, chaired by the chief investigator and comprising key members of CHaRT and ICR-CTSU as well as the Health Economics and Biorepository teams at Newcastle University, met monthly. A Trial Management Group (TMG) was established and included the chief investigator, scientific leads (from ICR-CTSU and CHaRT), a health economist, co-investigators and collaborators, a patient representative, CHaRT’s Senior information technology manager, a trial statistician, and senior project managers and trial managers from ICR-CTSU and CHaRT. PIs and other key study personnel were invited to join the TMG, as appropriate, to ensure that there was representation from a range of centres and professional groups. The TMG met regularly and at least annually, and had operational responsibility for the conduct of the trial. The TMG’s terms of reference, roles and responsibilities were defined in a charter issued by ICR-CTSU. The trial was further overseen by the independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and an independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC). The TSC comprised an independent chairperson and four independent members. The DMC comprised an independent chairperson and two independent members.

Patient and public involvement

A co-investigator (a patient with bladder cancer) provided advice based on the service user perspective and contributed to user-led selection of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). His experiences of the diagnosis and treatment of bladder cancer were taken into consideration in the design of this trial; in particular, this helped inform the use of QoL questionnaires that included emotional, social and physical domains specific to bladder cancer. As a member of the TMG, he also advised on approaches to recruitment, participant information resources and the dissemination of findings.

One of the independent members of the TSC was also a patient representative. The TSC met throughout the trial and reviewed all study documentation, including patient-facing documents. In addition to being an integral part of the study oversight and contributing to the Plain English summary included in this report, he provided feedback on what he felt were the key impacts of the study and the value of his contributions as the patient and public involvement (PPI) representative on the independent TSC:

As a patient who has lived experience of both a white light and a blue light, PDD-TURBT, I was particularly interested in both the outcome and the conduct of this trial from a patient perspective. Equally, in my role as Chair of the charity Action Bladder Cancer UK, I was keen to support much needed research into bladder cancer, and to use social media and speaking opportunities to raise the profile of the trial and promote participant recruitment. I have supported the TSC since its inception in 2014, being an active part of the committee and helping to make the reporting more patient focused. I was alert to recruitment issues early on (common to all bladder cancer trials) and able to ensure that the TMG, including its own PPI, was doing all it could to improve recruitment rates, paying particular attention to patient-facing materials. Overall, the trial has been very well run.

PPI TSC member

Sample size

The trial aimed to detect an absolute reduction in recurrence of 12% at 3 years: from 40% (under the conservative assumption that all of the patients recruited would be intermediate-risk patients with a probability of recurrence of 0.4 at 3 years) to 28% (similar effect sizes of photodynamic therapy have been reported in both intermediate- and high-risk groups27). This is equivalent to a relative reduction of 30%. Power calculations were based on log-rank analysis of time-to-event data, translating an improvement in the fixed time point recurrence-free rate of 60–72% to a target effect size hazard ratio (HR) of 0.64. The recruitment of 533 participants (214 recurrences) would enable the detection of a HR of 0.64 between experimental and control strategies, and would, using the log-rank test, provide 90% power at a two-sided 5% significance level. This calculation assumed 2.5 years of staggered recruitment (with 6%, 13%, 21%, 29% and 31% of the total number of patients recruited within each 6-month period), a minimum of 3 years’ follow-up and cumulative follow-up attrition rates of 0.56% by the end of year 1, 1% at the end of year 2 and 6.4% at end of year 3, based on unpublished data from the Bladder cyclooxygenase 2 Inhibition Trial (BOXIT).

To achieve the recruitment target, we planned to activate 30 secondary care sites that expected to see approximately 4590 new bladder cancer diagnoses over 2.5 years, from which we would exclude patients with MIBC (20%) and, from the remaining NMIBCs, those with low-risk disease (50%). Furthermore, we predicted that only 30% of these patients would be recruited based on willingness to participate or missed opportunities for recruitment.

Statistical methods

The trial analysis followed a statistical analysis plan. There was no interim analysis of clinical effectiveness data, only a single analysis after the database was locked on 2 June 2020. The main analyses for both safety and clinical effectiveness were based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle, that is they were analysed as randomised, regardless of the intervention received. However, after the initial resection, some participants were found to have no tumour, some were found to have MIBC and some had an early cystectomy. These participants were excluded from the ITT population (see Chapter 3 for details). We also used per-protocol analyses restricted to participants who received the treatment to which they were allocated.

Baseline and follow-up data were summarised using appropriate statistics and graphical summaries. All analysis was done using Stata, version 16 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), software.

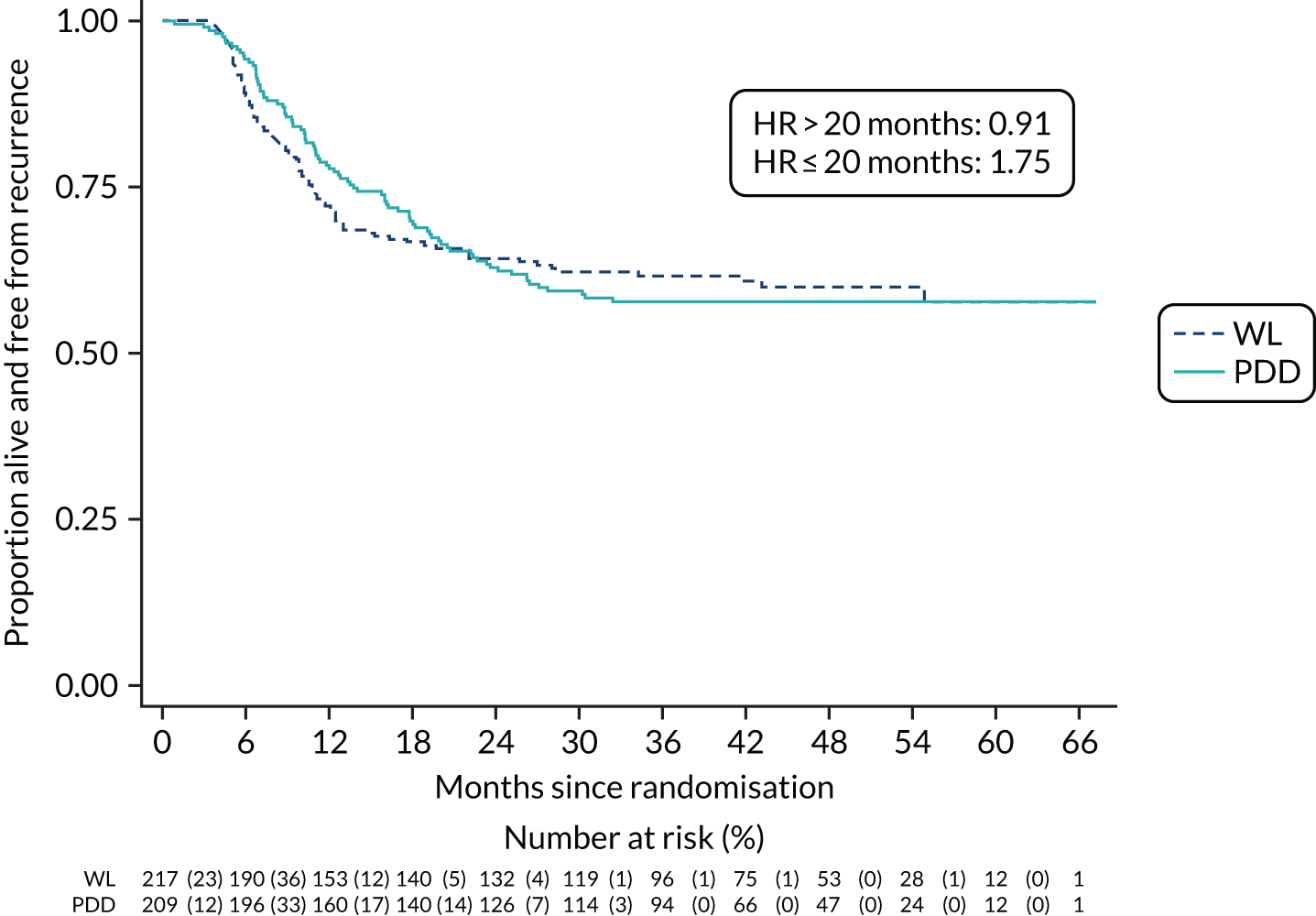

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was time to recurrence of bladder cancer, measured in months from randomisation to recurrence, progression, cystectomy or death due to bladder cancer. The principal time point of interest was 3 years. We used a time-to-event framework to analyse the primary outcome. In the primary analysis, deaths were treated as censored in Cox proportional hazards regression models. The first model adjusted for the minimisation covariate factors of sex and centre (the latter via a random-effects frailty model) and the treatment effect was summarised as a HR with a 95% CI. The second model added the following known prognostic factors: smoking status, risk group, presence or absence of CIS and grade of surgeon (i.e. registrar, non-consultant career grade or consultant). The HRs and 95% CIs for these prognostic factors were given, as was the HR for the treatment effect adjusting for these prognostic factors.

We plotted empirical survival distribution using Kaplan–Meier plots; visually, the proportional hazards assumption was questionable. The proportional hazard assumption was assessed by plotting log [−log (survival)] against log (analysis time). We used accelerated failure time models based on Weibull, exponential, log-logistics, log-normal and generalised gamma distributions, relaxing the proportional hazards assumption. The model with the smallest Akaike information criterion value was considered the best-fitted model and reported.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were analysed using the appropriate generalised linear models as follows:

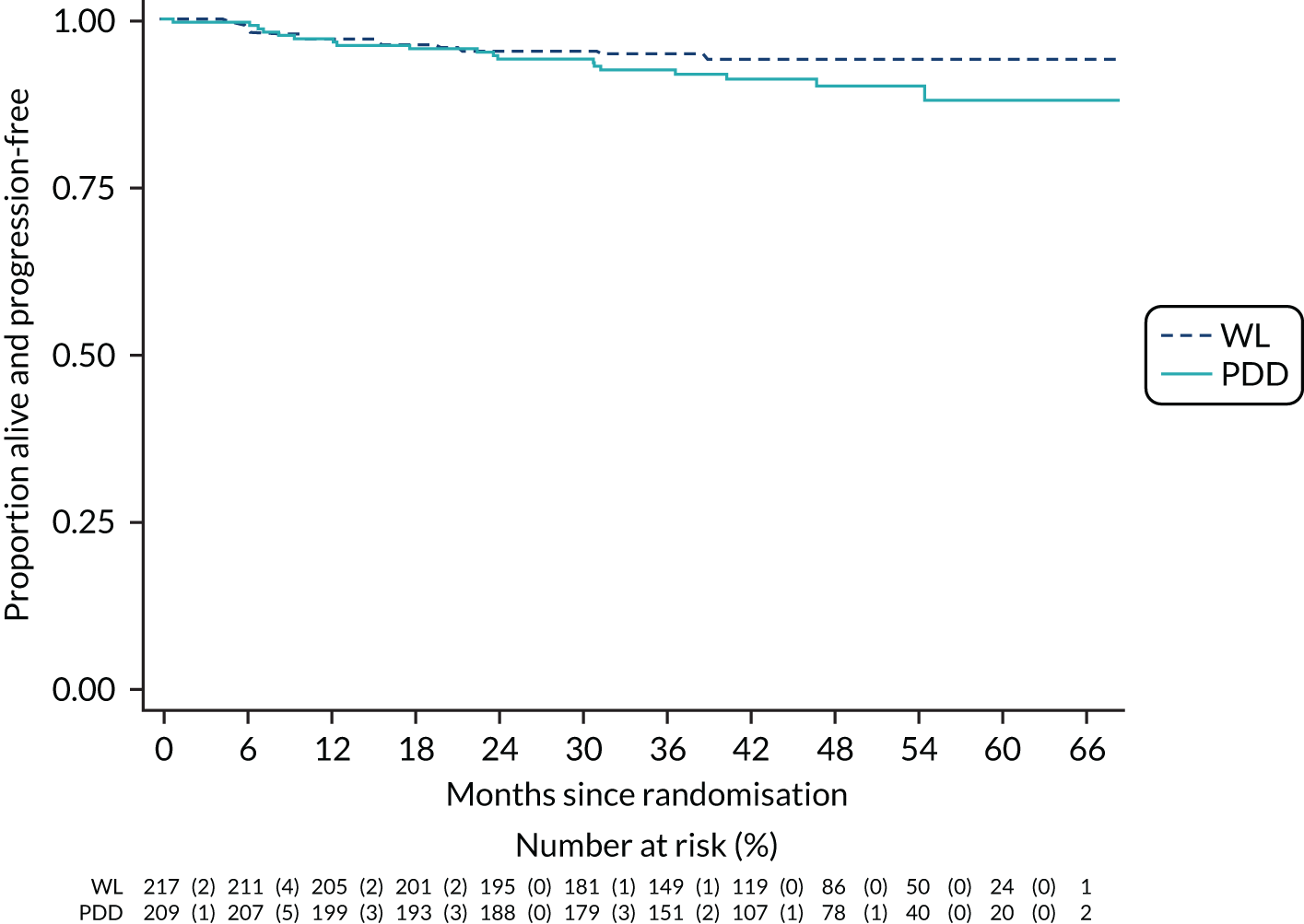

-

Disease progression at 3 years – progression was defined as increased stage to MIBC, development of metastatic disease at other regional sites, development of nodal disease or death due to bladder cancer. The end point was analysed using a time-to-event framework. Analysis was as for the primary outcome.

-

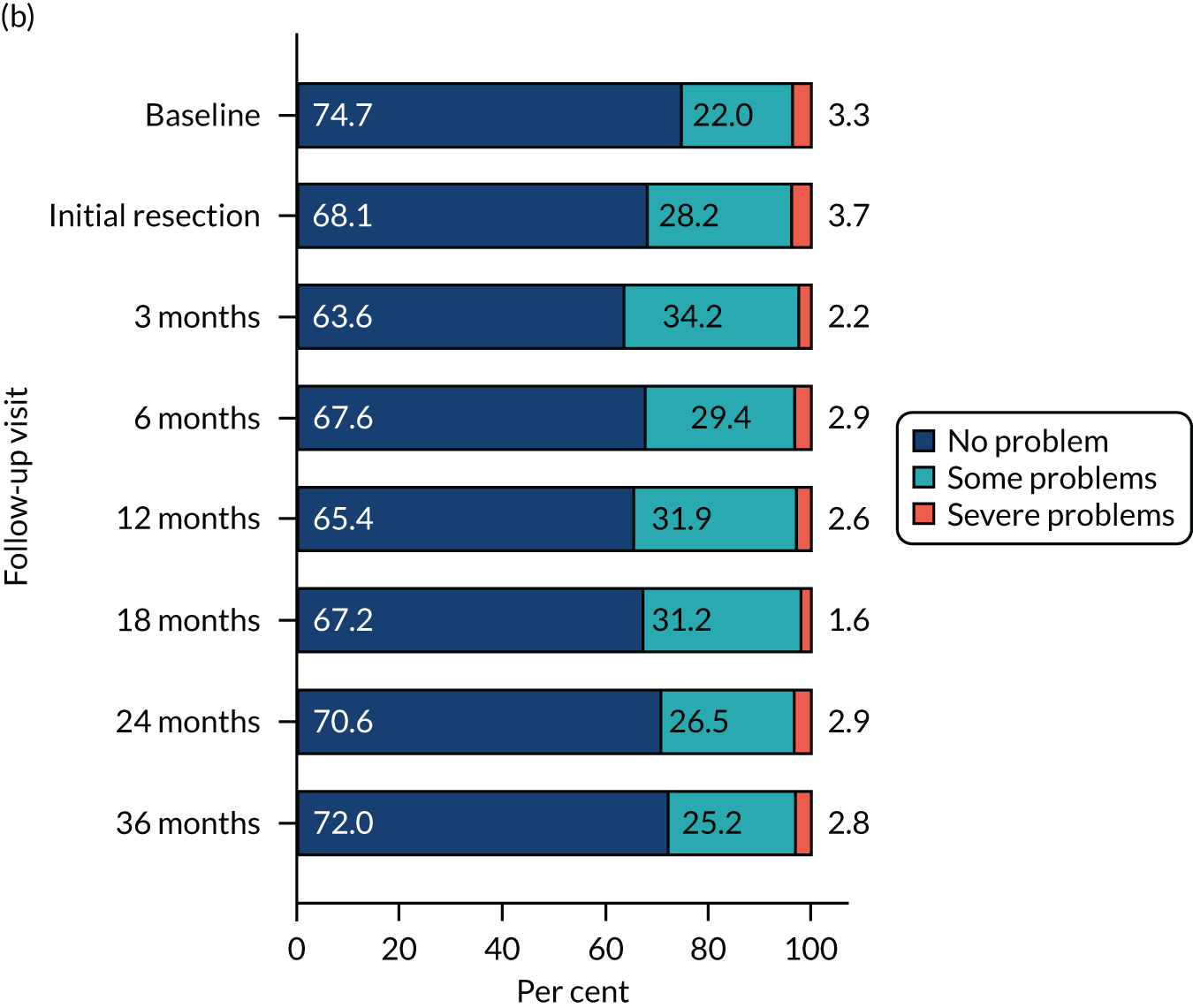

HRQoL – standard measure-specific algorithms were used to derive scores from and handle missing data within each HRQoL outcome. We used a linear mixed model (random effect for centre and participant; fixed effect for nominal time, treatment, sex, smoking status, risk group, presence or absence of CIS and grade of surgeon) to analyse the repeated measures of HRQoL outcomes. Treatment effects at each time were derived from the interaction term for time by treatment. To account for multiple HRQoL outcomes and time points, we report 99% CI around estimates.

-

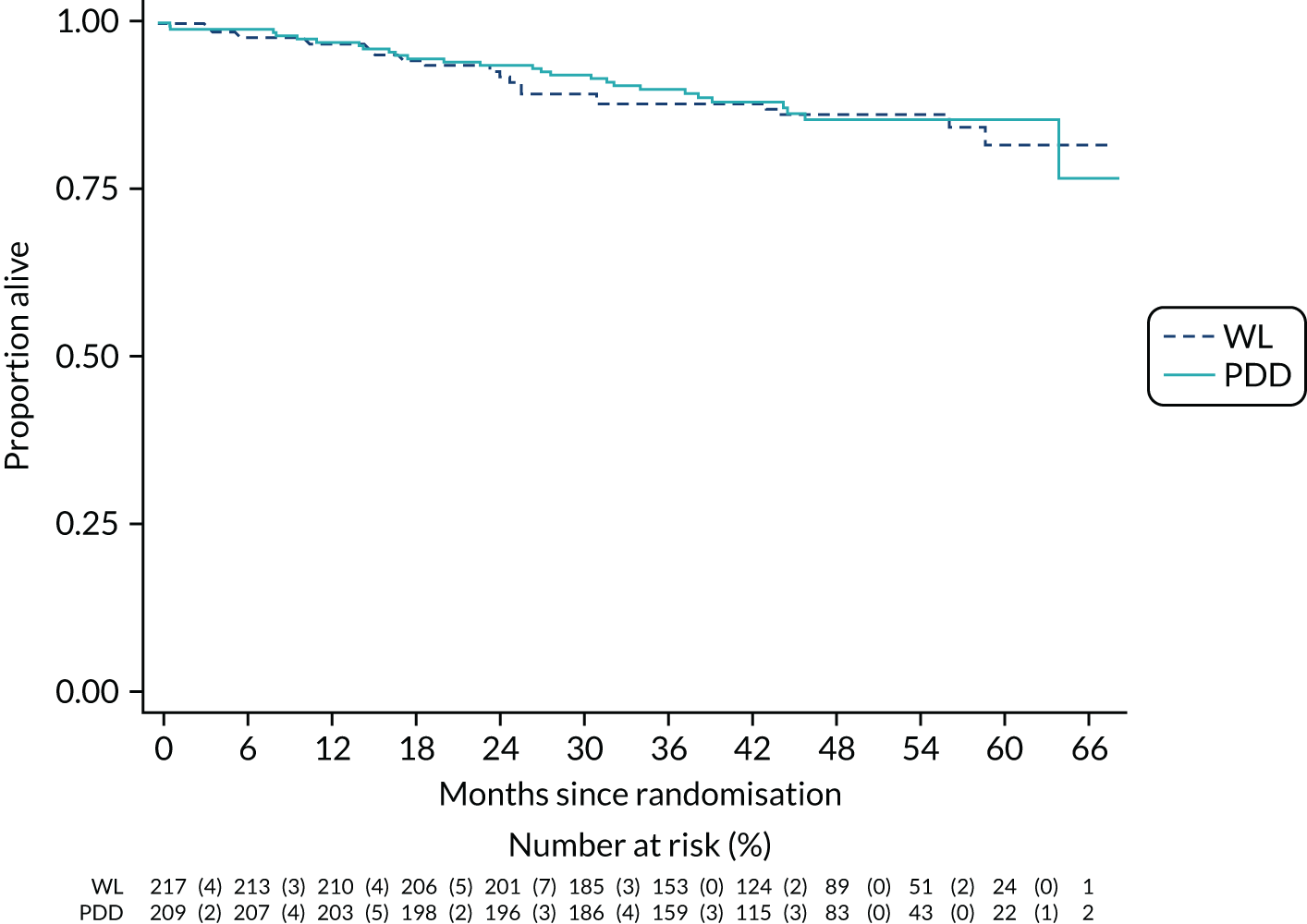

Bladder-cancer-specific survival – the time to bladder-cancer-specific death was analysed using a competing risks approach (based on the Fine and Gray model). 33 Death from other causes was considered a competing risk in the Cox proportional hazards model, instead of assuming non-informative censoring. The first model was adjusted for sex and centre, and the second was adjusted for sex, centre, smoking status, risk group, CIS and surgeon grade.

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis of the primary outcome that treated deaths from non-bladder cancer causes as a competing risk rather than non-informative censoring was performed. We report the subhazard ratio (SHR) for the treatment effect in two models, first adjusted for sex and centre, and then adjusted for sex, centre and prognostic factors as per the primary outcome. We plotted cumulative incidence curves for time to recurrence.

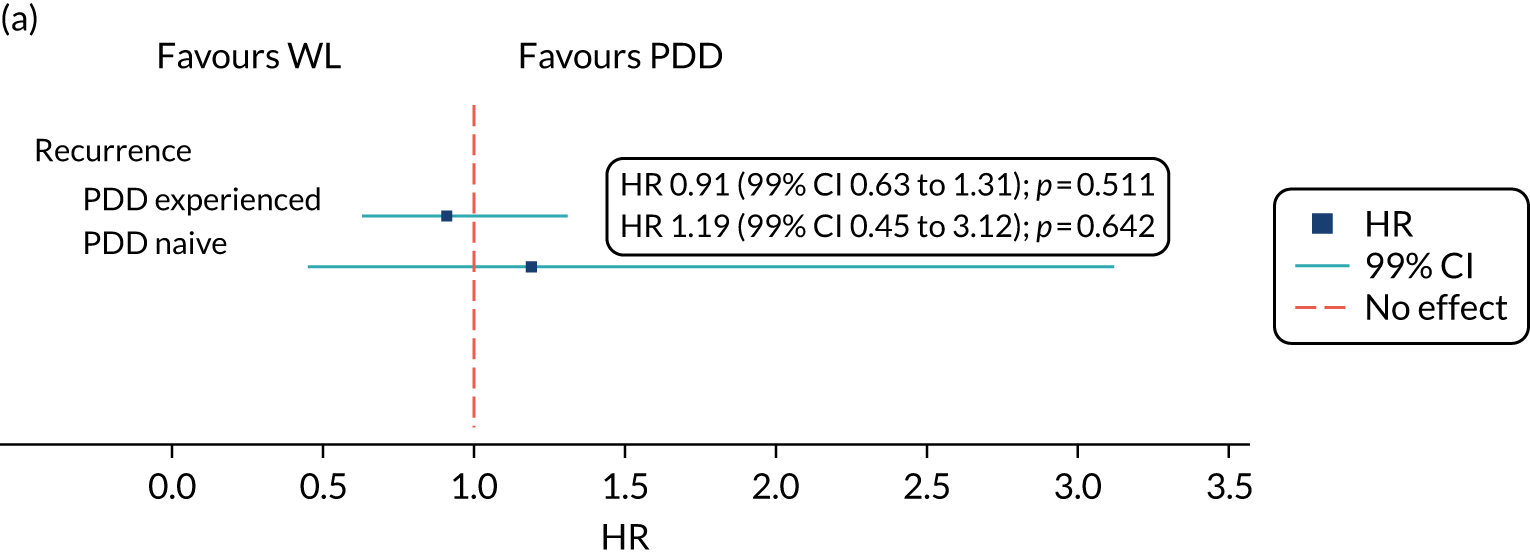

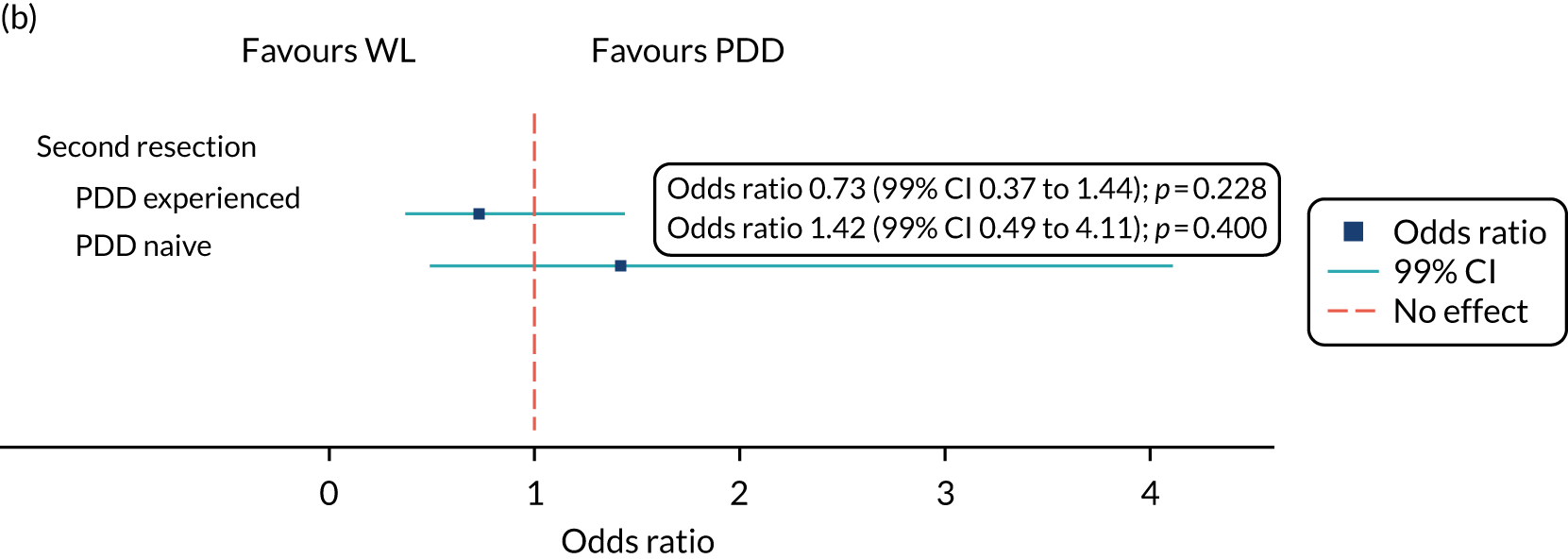

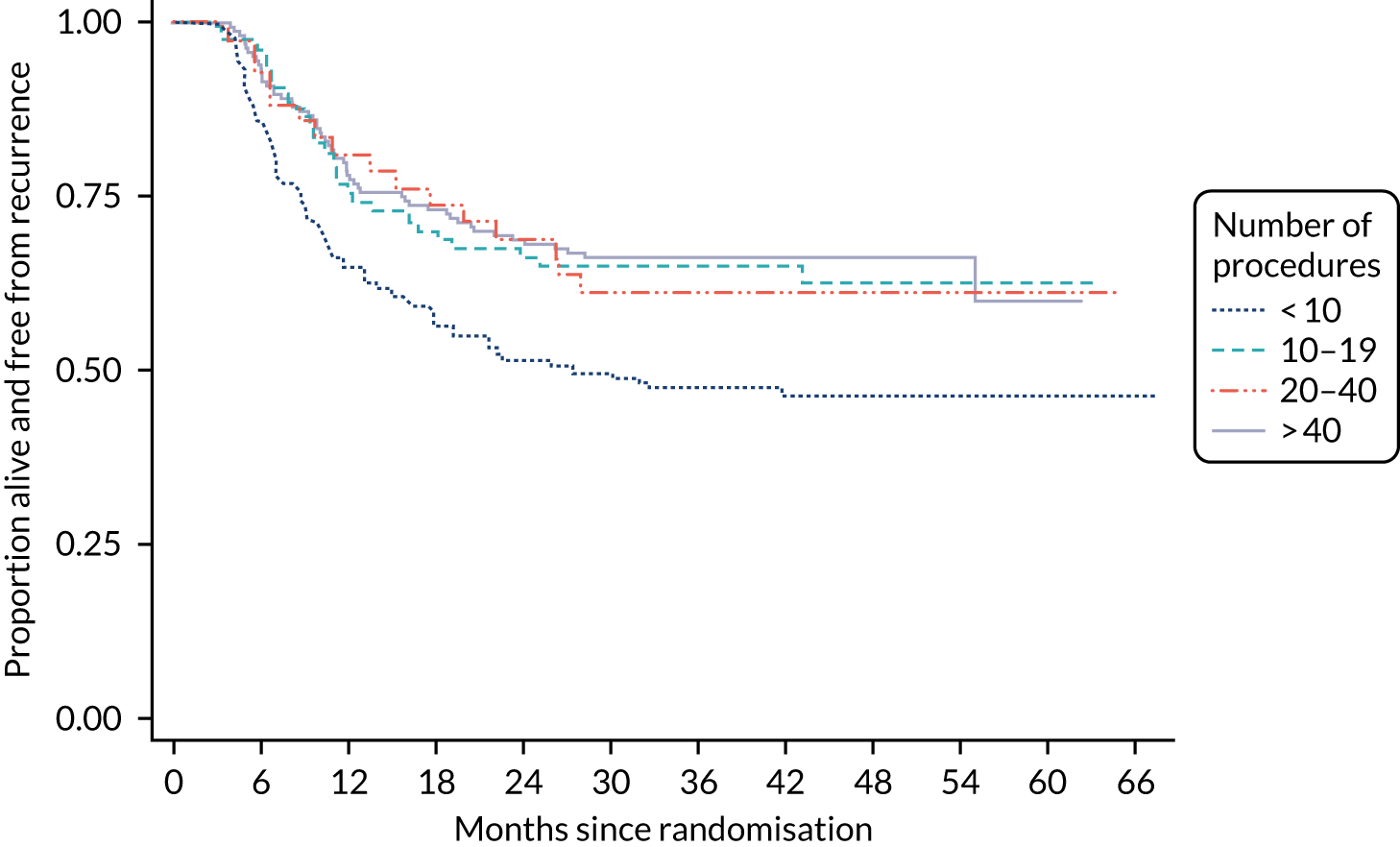

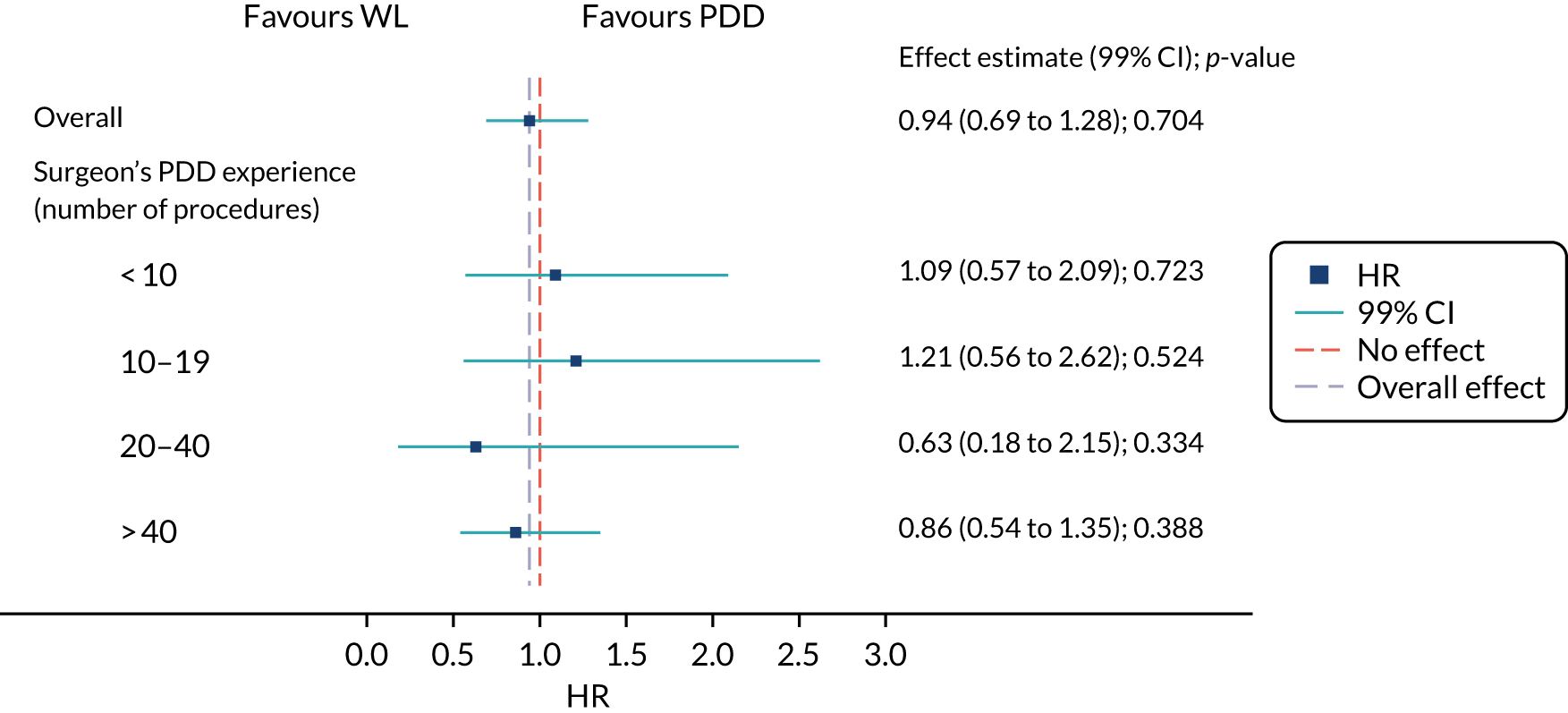

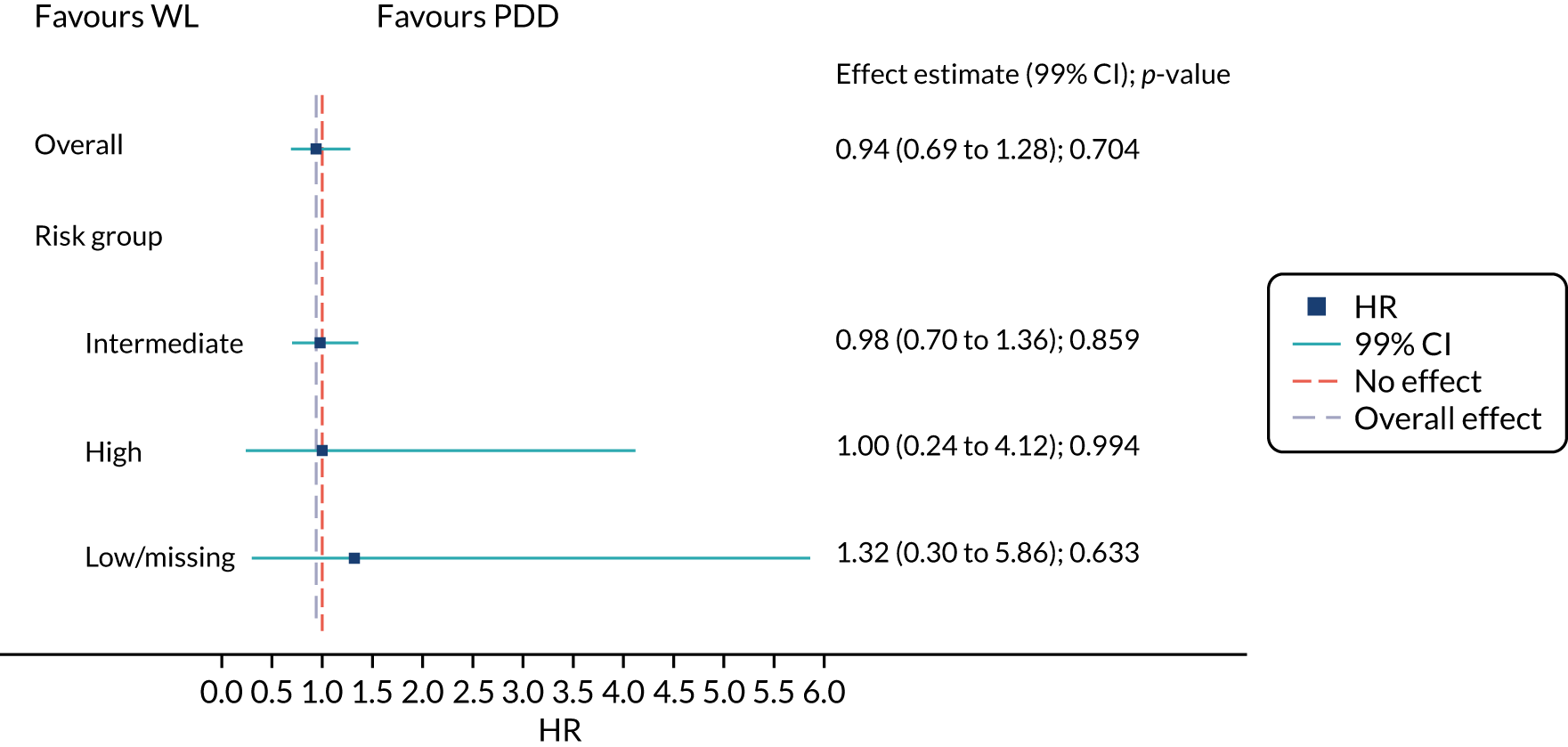

Surgical learning curve

The effect of photodynamic resection experience (learning curve) on clinical effectiveness was examined. Based on the results of a questionnaire completed by participating surgeons prior to centre activation, each centre was classified as PDD experienced or naive.

A subgroup analysis comparing outcomes from experienced or naive centres, including specific PDD- and WL-resection-related outcomes, was used to assess the maximum effect of experience on outcome in an NHS setting. Early recurrence (at 12 weeks) was used as a proxy of incomplete resection. The subsequent accruing experience of each surgeon was captured on a CRF. This allowed each randomised participant to be positioned on an individual surgeon learning curve.

Safety data

The proportion of participants experiencing AEs (CTCAE grade 3 or above) was compared between groups using Poisson regression. The number of AEs by Clavien–Dindo grade was tabulated by group.

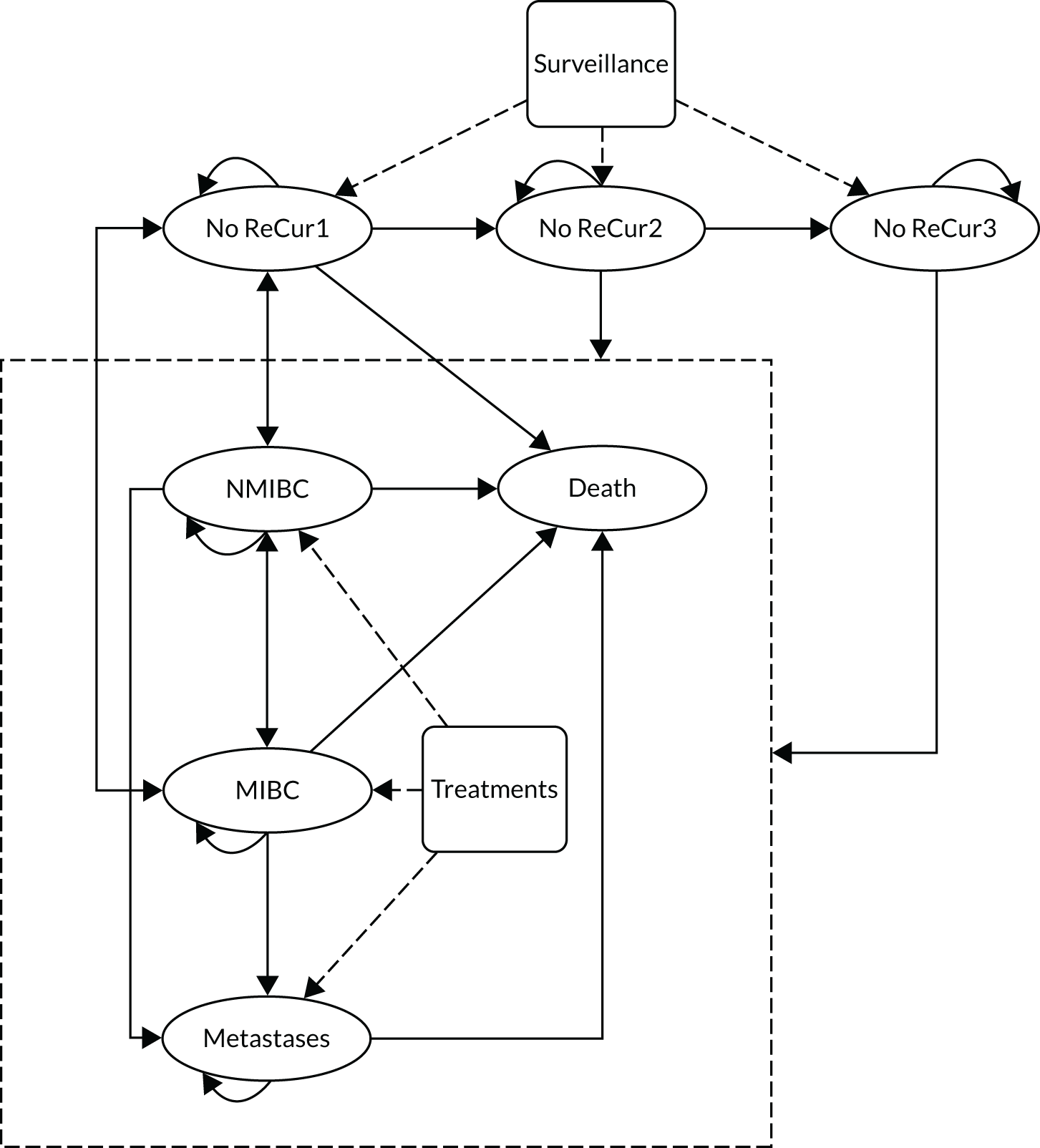

Health economics methods

Economic evaluations are conducted as an aid to decision-making. In the PHOTO trial, the economic evaluation aimed to determine whether or not PDD-TURBT was cost-effective compared with WL-TURBT as part of the management of people with suspected intermediate- and high-risk cancers confined to the bladder lining. For the economic evaluation, both a trial-based and model-based cost–utility analysis was planned. The within-trial analysis considered costs and outcomes over a 3-year follow-up. The model-based analysis was planned to have a lifetime time horizon. The model-based analysis was not conducted as it was judged not to add any additional information for decision-makers. See Appendix 2 for information about the proposed modelling component.

The within-trial economic evaluation took an NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) perspective in line with the NICE reference case. 34 The results were estimated at 3 years following randomisation using the ITT principle. Results are presented in terms of cost, QALYs, incremental cost, incremental QALYs and incremental cost per QALY. The costs and QALYs accruing after the first year and the incremental cost per QALY gained were discounted at a rate of 3.5% per annum.

A time trade-off (TTO) study was commenced to provide estimates of short-term decreases in utility following cystectomy; these data were planned to be used alongside the EQ-5D-3L trial data collected at 6-month intervals. However, the TTO work was paused because of COVID-19 and the nature of the interviews (involving complex instructions, face-to-face contact and lasting approximately 1 hour); it was not feasible to continue this work within COVID-19 restrictions. Eleven patients were recruited, which was substantially short of our target sample size (n = 50) and, hence, meaningful analysis could not be performed. See Appendix 2 for a brief description of the method.

Incremental costs and QALYs were presented as point estimates and 95% CIs using adjusted linear regression. The on-parametric bootstrap approach was also used to produce the cost-effectiveness plane, representing the uncertainty in incremental cost and QALY estimates, and the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC), representing the probability that PDD-TURBT was cost-effective compared with WL-TURBT at different cost-effectiveness thresholds for an incremental cost per QALY gained. 35

The within-trial analysis was conducted in Stata version 16.1. The model-based analysis was to be conducted in TreeAge Pro™ 2020 (TreeAge Software, Inc., Williamstown, MA, USA).

Derivation of NHS resource use

The resource use data collected during the PHOTO trial were used to estimate the individual patient costs over the trial. The analysis included the following categories of NHS resource use:

-

Resource use associated with the hospital episode during which the initial intervention was provided. This also included the length of hospital stay.

-

Resource use of hospital associated with readmissions after the initial index admission (follow-up operations and length of stay in hospital) over the 3 years’ follow-up.

-

Outpatient contacts over the 3 years’ follow-up.

-

Use of primary care services, including outpatient/general practitioner (GP)/doctor/nurse consultations and GP/nurse home visits over the 3 years’ follow-up.

The resource use data were collected on an ongoing basis by the clinical investigators, or were self-reported by trial participants at the initial procedure or during the follow-up period (3, 6, 12, 18, 24, 30 and 36 months post randomisation).

Initial procedure

The resources associated with the initial procedure included all of the resources incurred until discharge. The resource use data required to deliver each intervention were collected prospectively for every participant in the study. The operative details were recorded at the time of surgery (e.g. time in theatre, grade of operating surgeon). These data were captured in the operation details CRF. Costs incurred after the TURBT procedure but before discharge were collected using the initial resection CRF and post-treatment participant questionnaire. These forms contained information on the length of hospital stay for the initial TURBT (based on admission and discharge dates), medical procedures and medical events that could occur during the treatment phase.

Subsequent use of services following discharge for the index procedure

After participants were discharged, their resource use was captured using the health service utilisation questionnaire (HSUQ) completed by participants at 3, 6, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months. The use of the HSUQ allowed us to categorise resource use as either secondary or primary care. This included all secondary care (e.g. WLC, flexible cystoscopy, mitomycin, BCG, CT scan, cystectomy, palliative care, inpatient admissions, day admissions, hospital doctor consultation, outpatient consultations, accident and emergency consultations) and primary care contacts with health professionals (e.g. GP consultations, practice and district nurse consultations, other health professional consultations). Visits with these health professionals could occur at the health-care practice, at the participant’s home or over the telephone. We distinguished between the different types of consultation to account for the different costs associated with each setting.

For our analysis, we assumed that any participant who partially completed the questionnaire had left other responses blank because the questions did not apply to them. For participants who had died during the follow-up period, their resource use was automatically imputed as 0. This could cause an underestimation in our costs as these participants may have used some services during the data collection period before they died.

Unit costs of NHS care

National average unit costs were applied to resource use data to generate the total costs to the health service. The sources of unit costs were the British National Formulary (BNF)36 and the NHS Reference Costs 2018–1937 for secondary care resource use data, and the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU)’s Unit Costs of Health and Social Care for primary care resource use data. 38 See Appendix 2, Table 46, for a list of all unit costs used in the within-trial economic analysis, together with their sources. These costs were reported in 2018–19 Great British pounds (£). For the purpose of inflation, we utilised the Campbell and Cochrane Economics Methods Group Evidence for Policy and Practice Information Centre (CCEMG-EPPI-Centre) Cost Converter, version 1.6 (Campbell and Cochrane Economic Methods Group, London, UK), using International Monetary Fund-reported inflation data. 39

Estimation of NHS costs

For each participant, the total use for each resource was multiplied by the unit cost to calculate the total cost of each resource. For example, the initial length of admission was multiplied by the NHS cost per night for an inpatient stay on a general ward to obtain the cost of hospitalisation for each participant. The cost for each year beyond the first year was discounted at a rate of 3.5% per annum. The total discounted costs from the health services perspective were calculated by summing all intervention treatment and follow-up discounted costs for each participant in the data set.

Participant- and companion-incurred costs and indirect costs

Participant resource utilisation comprised three main elements:

-

costs of accessing and using NHS health services (e.g. petrol, public transport and parking)

-

time costs of accessing and using NHS health services (e.g. time involved away from usual activities or work)

-

indirect costs due to ill health.

Costs of accessing and using NHS health services

The estimation of costs of accessing and using NHS health services required information from participants about the number of visits to, for example, their GP (estimated from health-care utilisation questions in the participant costs questionnaire administered at 30 months) and the unit cost of making a return journey to each type of health-care provider.

Time-off costs of accessing and using NHS health services

The cost of participant time was estimated in a similar manner. The participant was asked, in the participant costs questionnaire, how long they had spent travelling and attending their last visit to each type of health-care provider and if they had been accompanied by a friend or relative (if so, the companion’s time and travel costs were also incorporated into the analysis). These data were recorded in their natural units (e.g. minutes). The unit cost of time lost was obtained from the Department for Transport estimates for the value of work and leisure time. 40 The cost of each visit was then calculated by multiplying the time lost by the time unit cost. The total time cost per patient was then calculated by multiplying the patient’s time cost per visit by the number of health-care contacts obtained from the health-care utilisation questions.

Indirect costs due to ill health

Indirect costs were defined as the production losses when the participant was unable to return to work or was required to take sick leave because of their illness. The cost of days lost was estimated using the UK median gross hourly wage. When a participant’s self-reported costs associated with a specific type of health service visit were missing, the mean cost for that type of visit was imputed. Participants completing the participant costs questionnaire were asked how many days they had been off work in the previous 2 months as a result of health problems. These data were collected using the participant costs questionnaire at the 30-month follow-up point. The data were recorded in their natural units (e.g. days) and multiplied using the unit costs. The total production losses due to time away from work as a result of health problems were estimated and compared between treatment groups.

The data on costs and time-off costs of accessing and using NHS health services and the indirect costs due to ill health were summed to generate a total cost for each participant and their companions. The incremental cost differences between groups from a participant perspective were estimated using the same methods outlined for the NHS perspective (see Health economics methods).

Quality-adjusted life-years

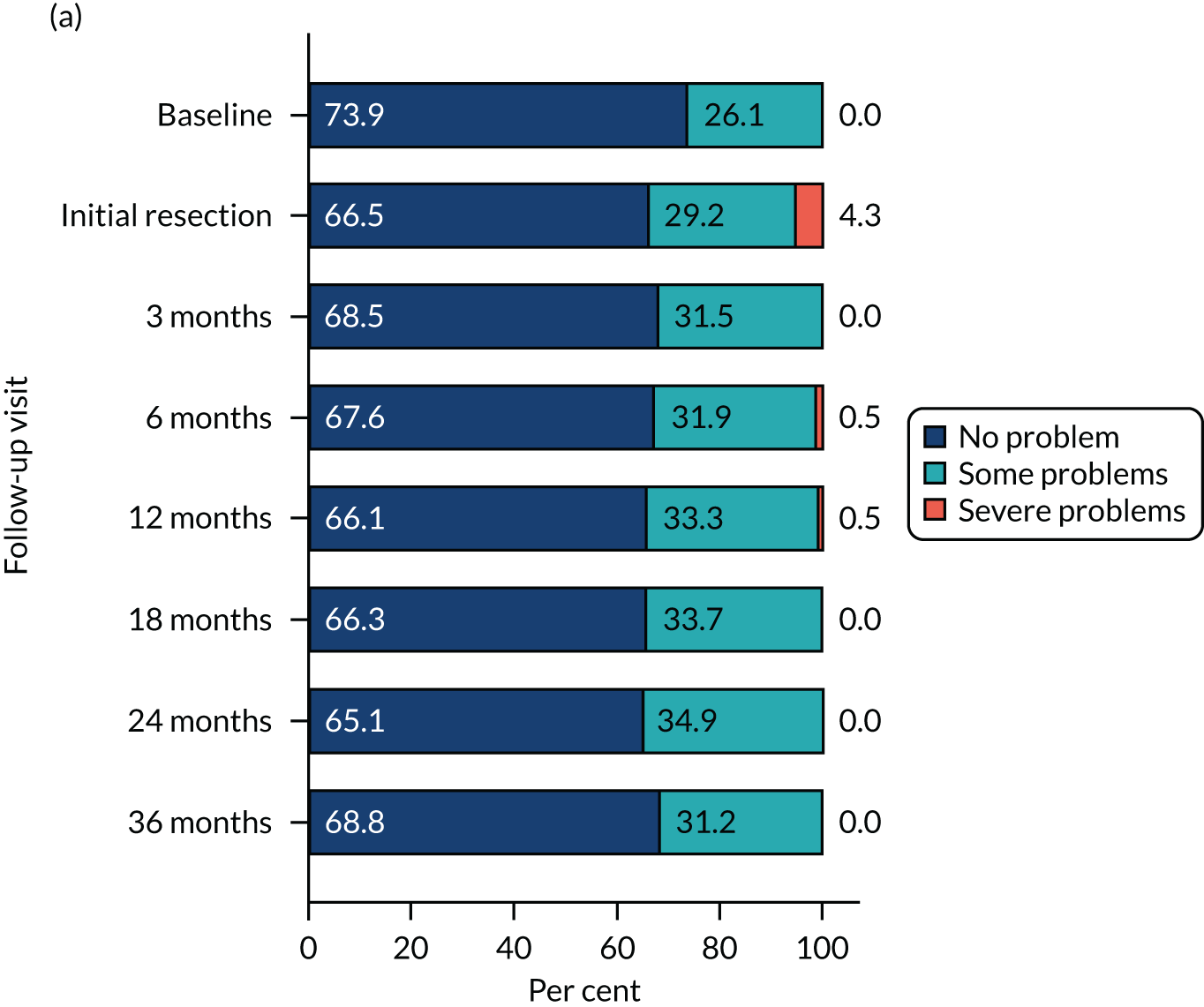

Participants were asked to complete the EQ-5D-3L instrument41 at baseline, discharge and follow-up visits (3, 6, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months). The EQ-5D-3L is a generic instrument used to assess participants’ QoL for the base-case analysis because it is the preferred utility measure of NICE. 34 The EQ-5D-3L measure divides health status into five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression). Each of these dimensions has three levels, so 243 possible combinations of health states exist. Each combination of levels across the dimensions is associated with an EQ-5D-3L index value. 41 Utility value data derived from the EQ-5D-3L were combined with mortality data from the trial under the standard assumption that all patients who have died in the trial will have a utility value of 0 from the date of death to the end of follow-up. The QALY for each year was then calculated based on these assumptions using the area-under-the-curve approach, and assuming linear extrapolation of utility between time points. QALYs for each year beyond the first year were discounted at a rate of 3.5% per annum. The total discounted QALYs for each participant were calculated by summing the discounted QALYs over the trial follow-up period.

Handling missing data

Missing data are a concern in this study because costs or health outcomes in individuals with missing data may be systematically different from those in individuals with no missing data. A substantial proportion of missing data observed in a trial can pose significant problems for data analysis.

The complete-case analysis is inefficient for the PHOTO study because all of the information from individuals with at least one assessment missing is discarded. In addition, the complete-case analysis cannot be considered an ITT analysis because some randomised patients with follow-up data are excluded. 42 Therefore, the imputed data analysis was used as the base-case analysis and the complete-case analysis was conducted as a scenario analysis in the sensitivity analysis. The imputation was undertaken using Stata’s multiple imputation (MI) procedure.

Multiple imputation was used to impute missing EQ-5D-3L utility values and cost values for individuals with data at baseline or at least one follow-up visit. When missing data are ‘missing at random’ (MAR), valid conclusions can be drawn from the available data using the MI approach. 43 Missing values of total follow-up cost and EQ-5D-3L utility values at each time point were imputed using predictive mean matching by treatment allocation group, accounting for the three closest estimates in terms of baseline EORTC recurrence risk group, age at randomisation and sex. Chained equations were used for the imputations. The imputation procedure predicted 50 plausible alternative imputed data sets, which was found to be a sufficient number to provide stable estimates. An analysis of incremental costs and QALYs was undertaken across the 50 imputed data sets and combined to generate one imputed estimate of incremental costs and QALYs. We drew bootstrap samples from each of the 50 imputed data sets.

Estimation of cost-effectiveness

A seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) approach was used to simultaneously estimate the total discounted costs at 3 years and the total discounted QALYs at 3 years, allowing for the likely correlation of costs and effects. 44 For the QALY outcome variables, baseline EORTC recurrence risk group, age at randomisation, sex and baseline EQ-5D-3L utility value were included as covariates. For the cost outcome variables, baseline EORTC recurrence risk group was included as a covariate.

The results are reported as incremental cost per QALY gained for PDD-TURBT relative to WL-TURBT. The incremental cost per QALY was calculated from the coefficient of treatment effect on costs divided by the coefficient of treatment effect on QALYs from the SUR model.

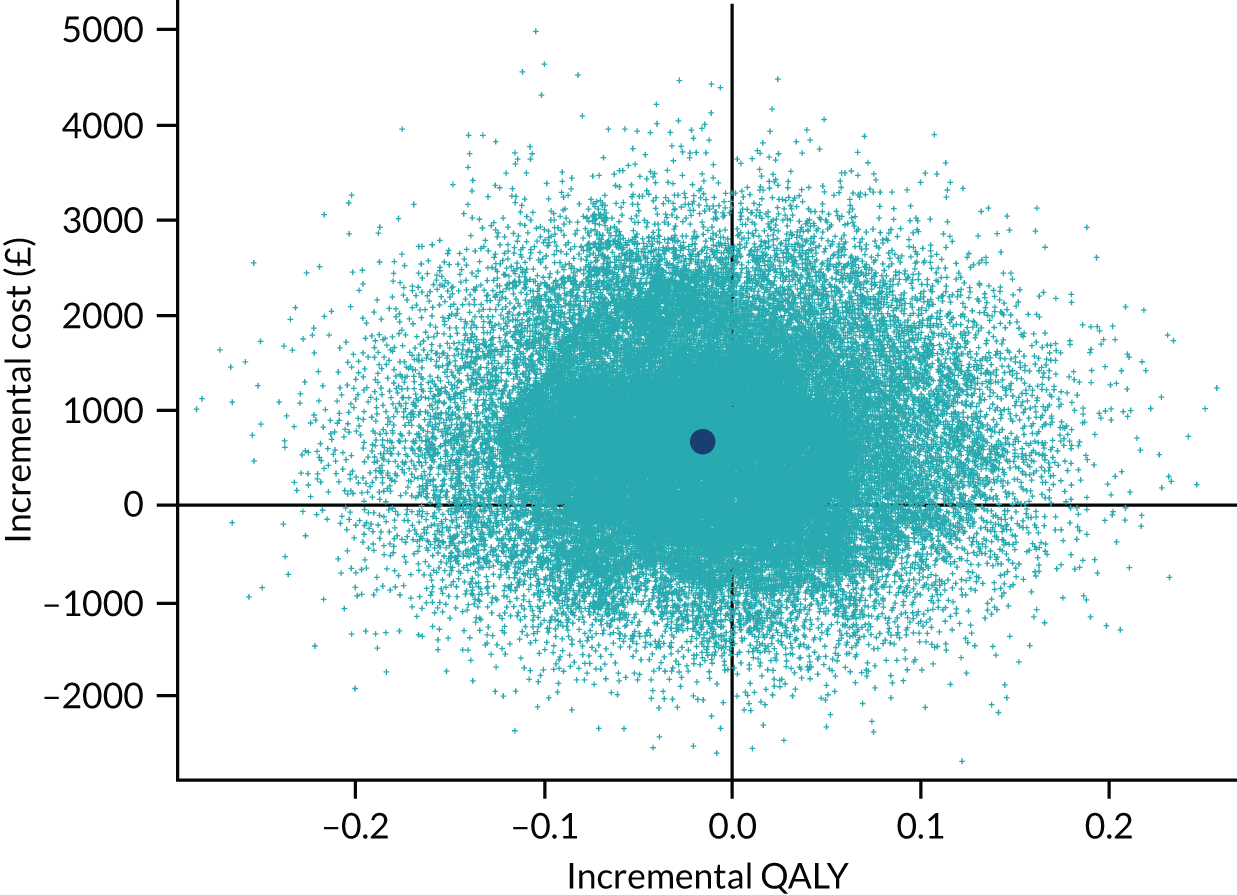

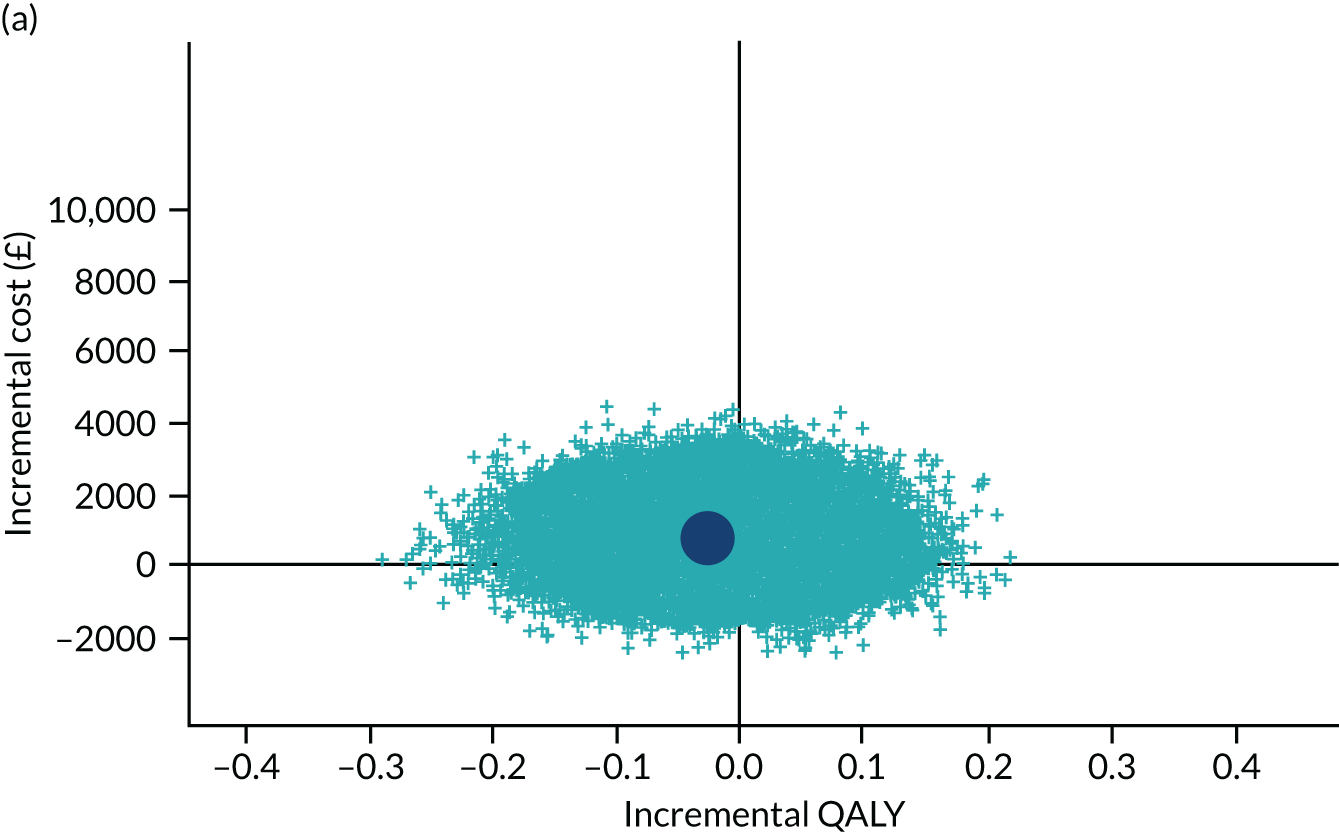

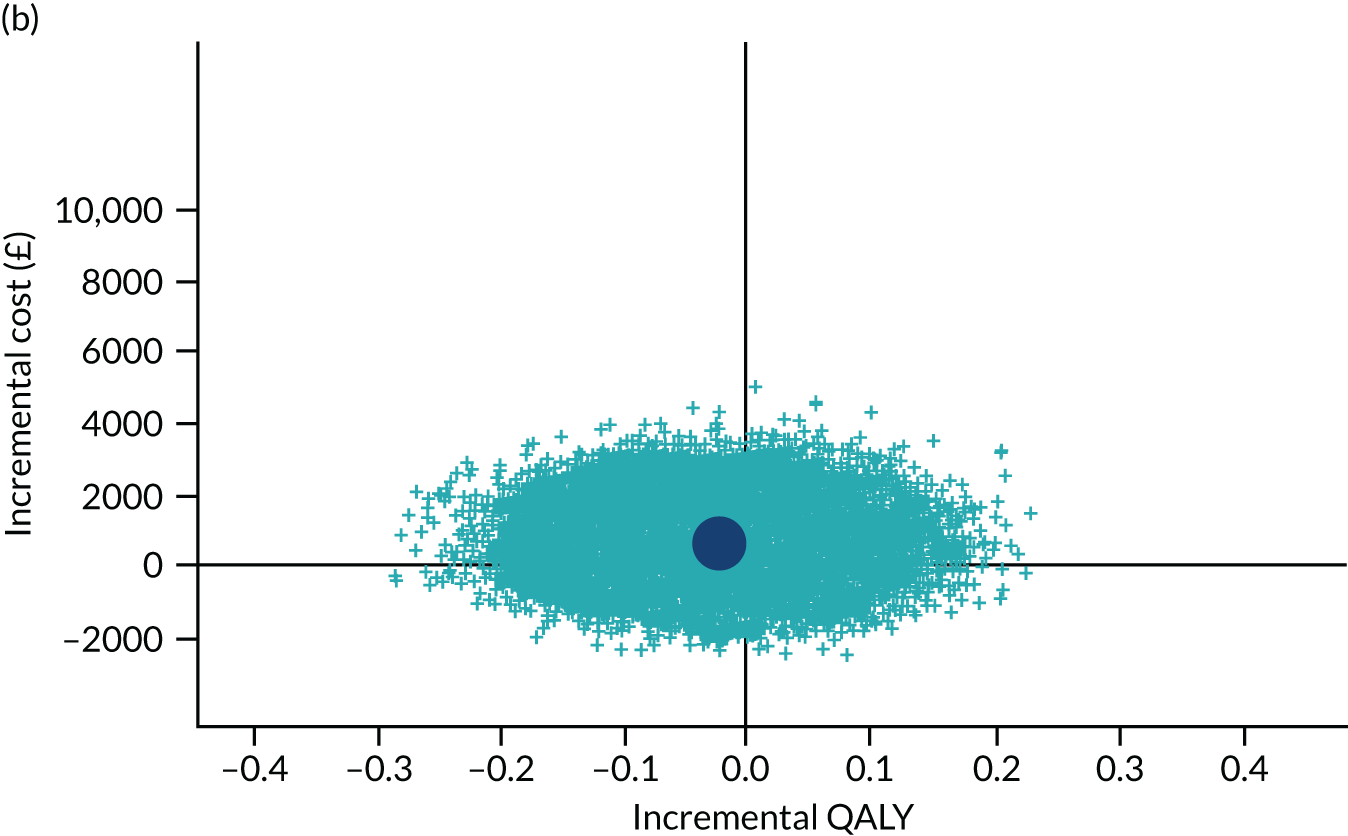

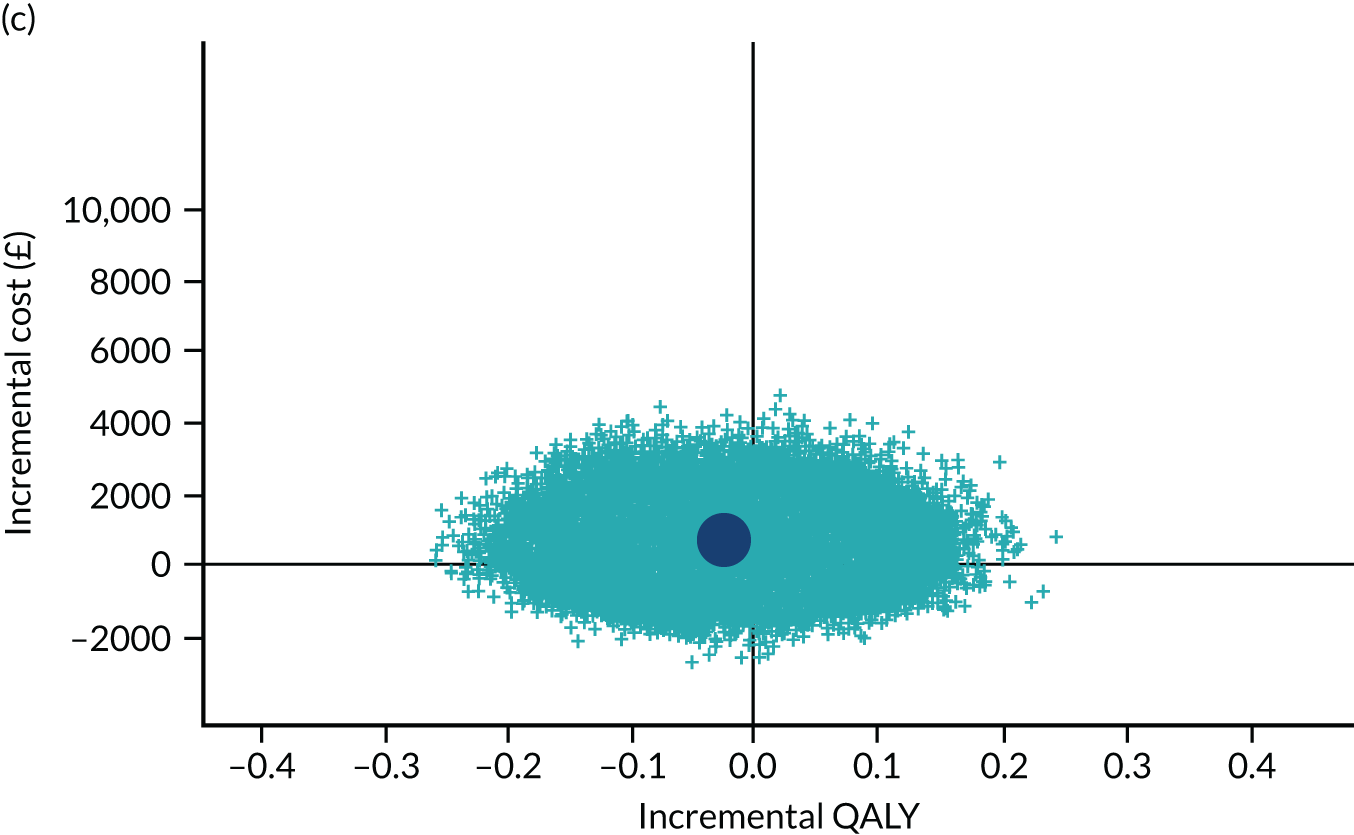

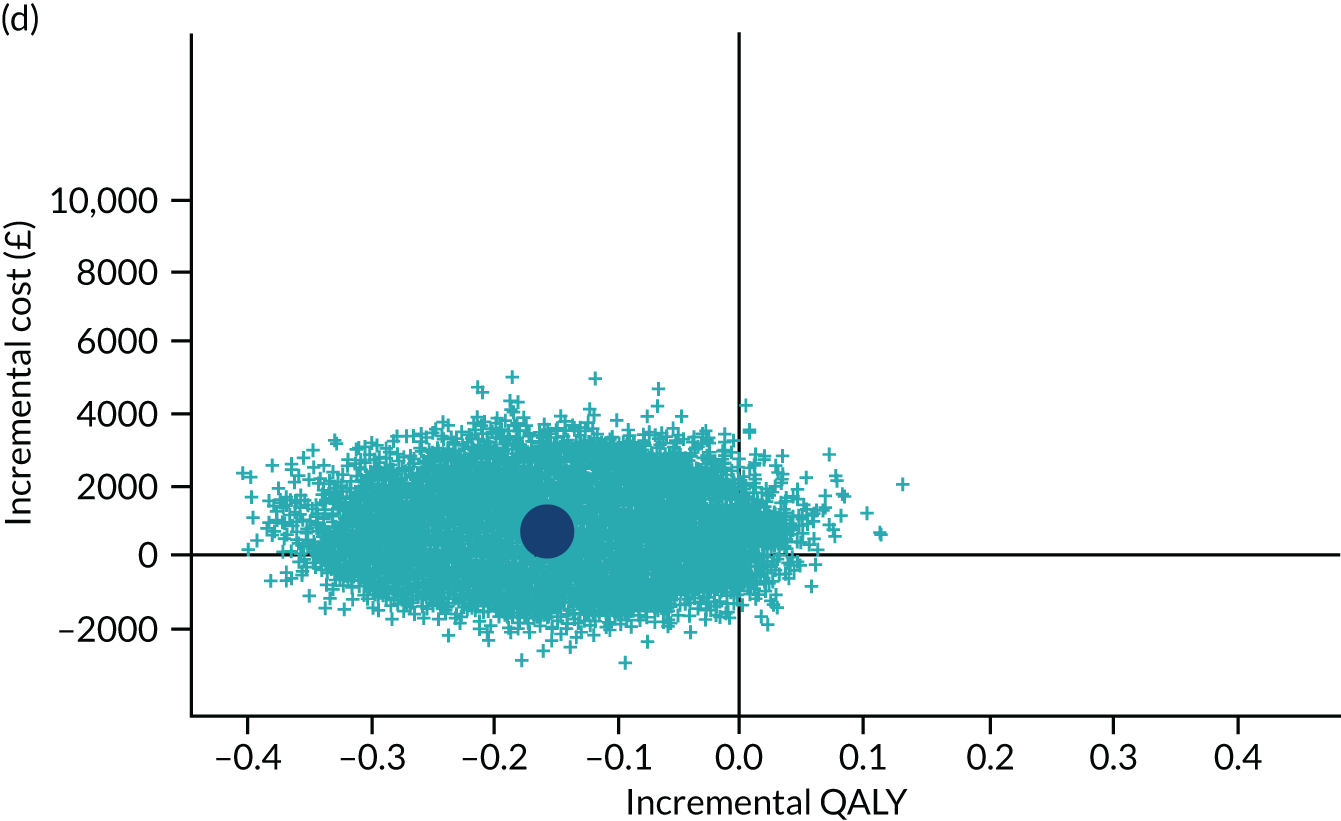

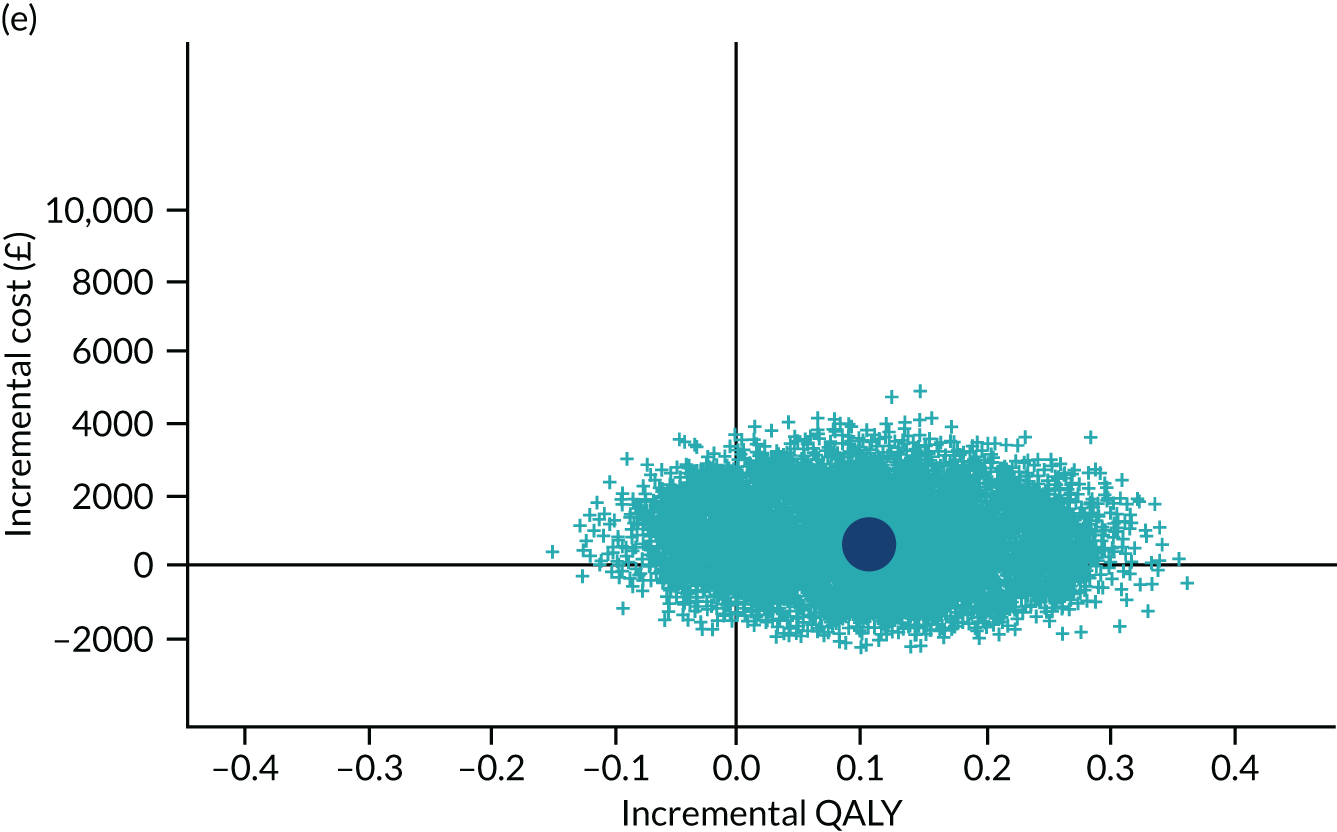

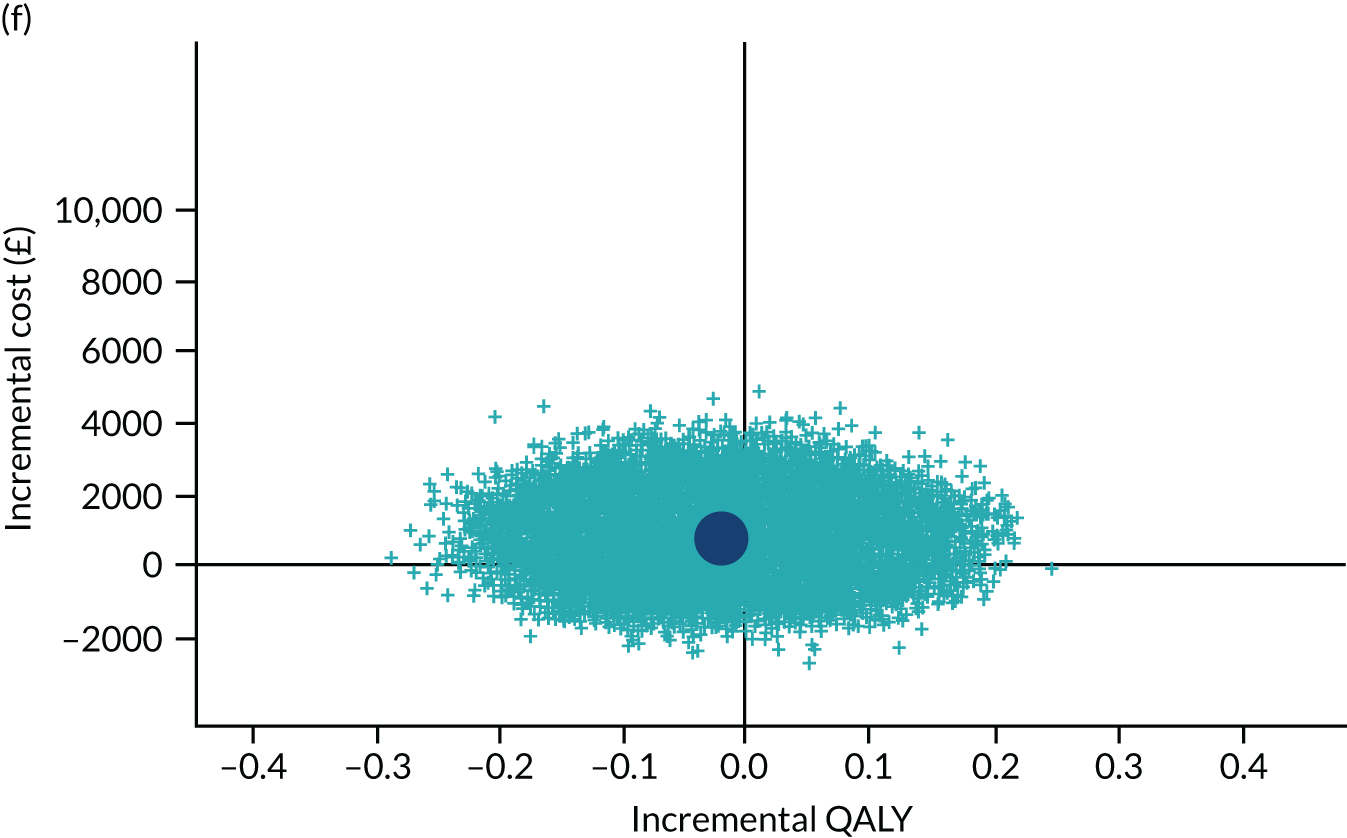

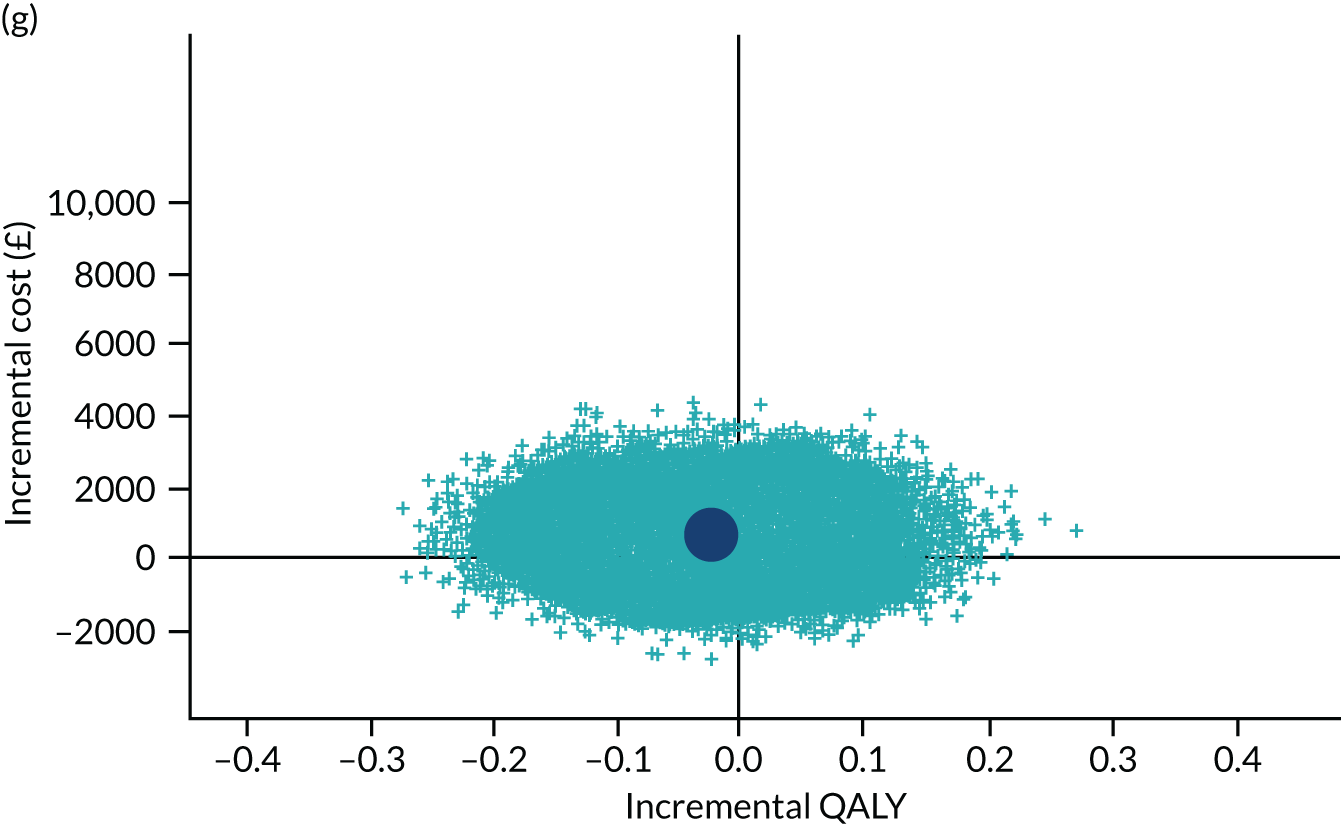

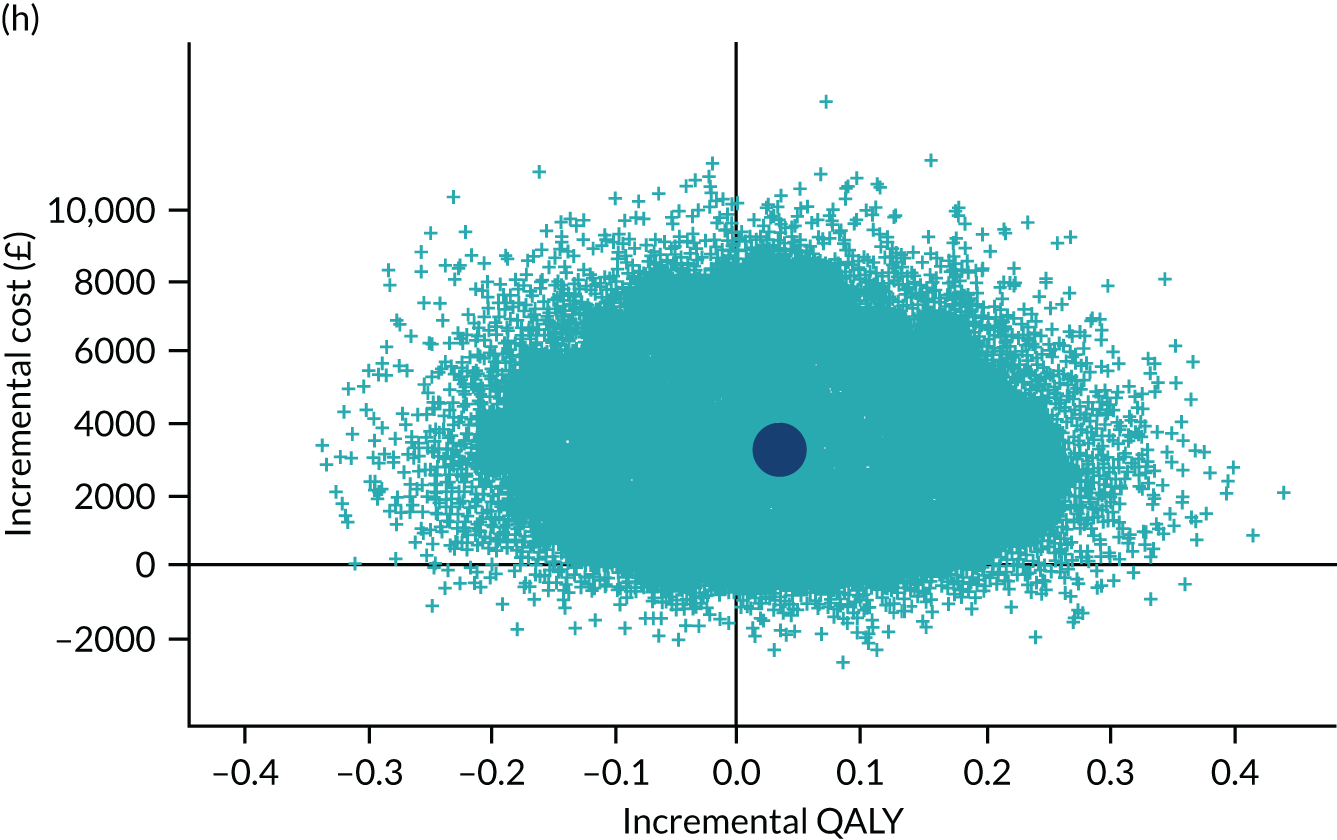

To address the issue of sampling uncertainty in the data, we used non-parametric bootstrapping methods to estimate 95% CIs for the treatment effects on costs and QALYs, using 2000 repetitions. 45 This imprecision was then presented graphically as a cost-effectiveness plane (see Figure 14). This shows the scatterplot of bootstrapped repetitions for incremental costs and incremental QALY pairs for PDD-TURBT compared with WL-TURBT. 46 The scatterplot is divided into four quadrants, each of which represents one of the following scenarios:

-

PDD-TURBT is less costly and more effective than WL-TURBT.

-

PDD-TURBT is more costly and less effective than WL-TURBT.

-

PDD-TURBT is less costly and less effective than WL-TURBT.

-

PDD-TURBT is more costly and more effective than WL-TURBT.

The proportion of the total bootstrap samples that lie in a quadrant represents the probability associated with that scenario.

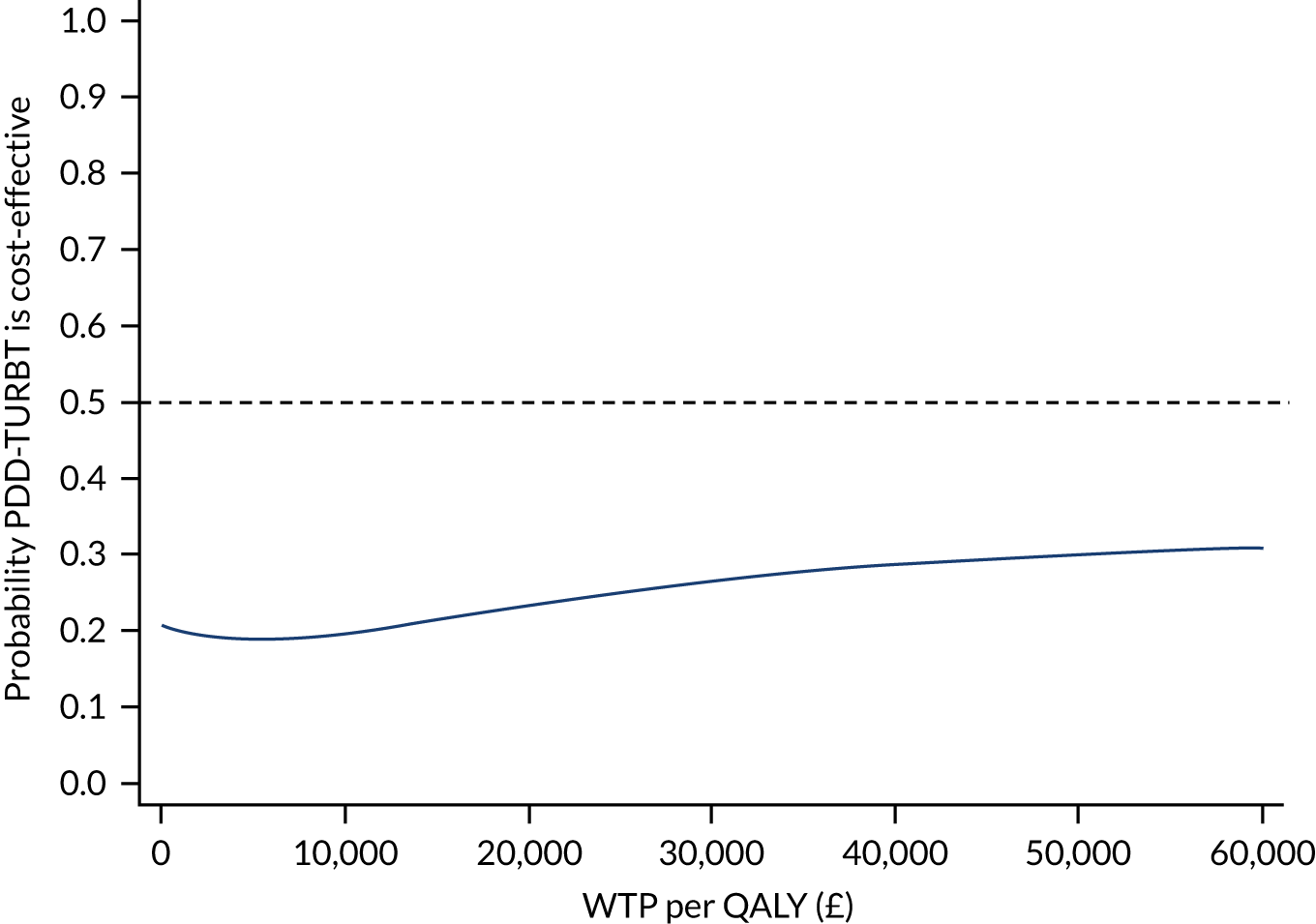

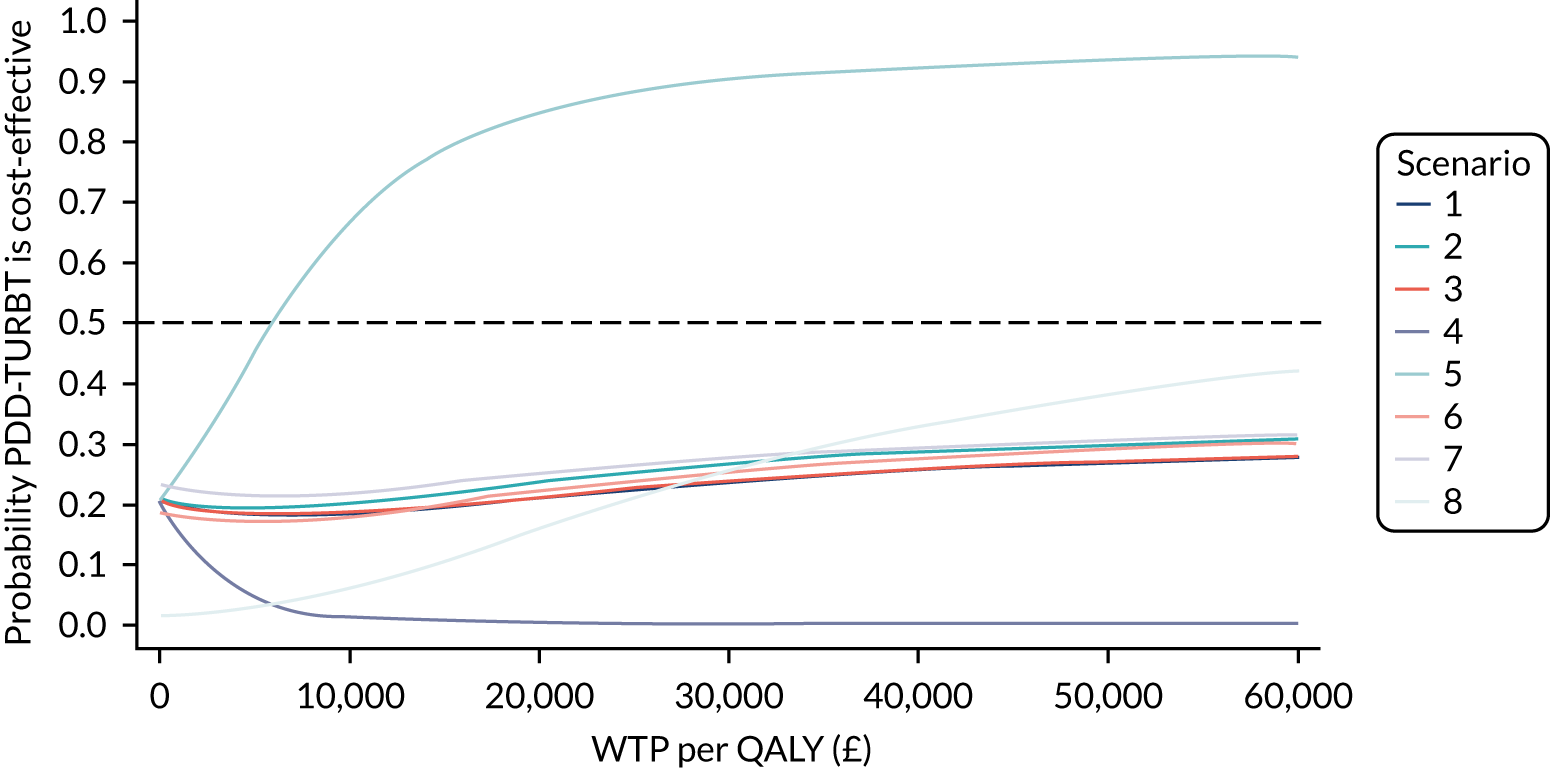

The bootstrapped estimates of costs and QALYs were also used to produce CEACs. 47 CEACs were generated using the net monetary benefit (NMB) approach, where:

‘QALY’ and ‘cost’ are the estimated total QALYs and total costs for a treatment strategy, respectively, and λ is the decision-maker’s cost-effectiveness threshold for a QALY gained.

In this analysis, λ was varied over the range £0–60,000. In the tabular presentation of the analysis, λ is presented at the following thresholds: £0, £20,000, £30,000 and £50,000.

The proportion of bootstrap samples in which the net benefit is positive at a given threshold for cost per QALY represents the probability that the treatment is cost-effective. This was repeated for each MI data set. The probability across all MI data sets was averaged for the threshold values stated above.

Sensitivity analysis

The base-case analysis was conducted under the MAR assumption, using MI to impute the missing cost and HRQoL values. It is, however, recognised that participants who failed to complete an EQ-5D-3L questionnaire at a specific follow-up assessment may have been in relatively poorer health than those who did. This means that the chance of observing HRQoL could depend on their actual utility value, that is data are likely to be missing not at random (MNAR). Therefore, it is important to explore the impact of the missing data mechanism [i.e. missing completely at random (MCAR), MAR and MNAR assumptions] on cost-effectiveness outcomes. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to explore the impact on the results of assuming that the data are MNAR, with scenarios for systematic differences between missing and observed values being examined. The sensitivity analysis also explored whether or not this might have differed between randomised groups.

Because we cannot determine the true missing data mechanism based on the observed data, pattern-mixture models were implemented using MI to assess whether or not conclusions are robust to plausible departures from the MAR assumption in the sensitivity analysis. 48,49 These analyses adjusted the imputed values in the base-case analysis by either adding up to 10% to the imputed QALYs and/or total cost, or subtracting up to 10%. This sensitivity parameter was allowed to differ by group, with up to a 5% difference between the two groups (this reflects that the missing data mechanism may not be the same in the two groups, but that it is unlikely to be perfectly MAR in one group and strongly MNAR in the other). The pattern-mixture approach has been favoured in the context of clinical trial sensitivity analysis. 50,51

To explore structural uncertainty in the base-case analysis, the following scenarios around missing data for cost and QALY outcomes were explored:

-

For patients who failed to complete an EQ-5D-3L questionnaire, we assumed their HRQoL could be up to 10% lower than the MAR setting in both groups.

-

For patients who failed to complete an EQ-5D-3L questionnaire, we assumed that their costs could be up to 10% higher than the MAR setting in both groups.

-

For patients who failed to complete an EQ-5D-3L questionnaire, we assumed their HRQoL could be up to 10% lower and their costs could be up to 10% higher than the MAR setting in both groups.

-

For patients who failed to complete an EQ-5D-3L questionnaire, we assumed their HRQoL could be up to 10% lower than the MAR setting in the PDD group.

-

For patients who failed to complete an EQ-5D-3L questionnaire, we assumed their HRQoL could be up to 10% lower than the MAR setting in the WLC group.

-

For patients who failed to complete an EQ-5D-3L questionnaire, we assumed their costs could be up to 10% higher than the MAR setting in the PDD group.

-

For patients who failed to complete an EQ-5D-3L questionnaire, we assumed their costs could be up to 10% higher than the MAR setting in the WLC group.

-

A complete-case analysis was performed, in which participants with missing data were excluded from analysis.

We also explored the impact of varying the discount rate used for costs and QALYs following NICE best practice recommendations,34 ranging the discount rate from 0% to 6% per annum. Furthermore, a supplementary analysis presents costs from a wider patient/societal perspective.

Chapter 3 Participant baseline characteristics

This chapter describes patient recruitment into the study and baseline characteristics. The subsequent results of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness analyses are reported in Chapters 4 and 5, respectively. Participants were screened and recruited at 22 NHS hospitals (see Appendix 1, Table 29, for the numbers recruited at each centre).

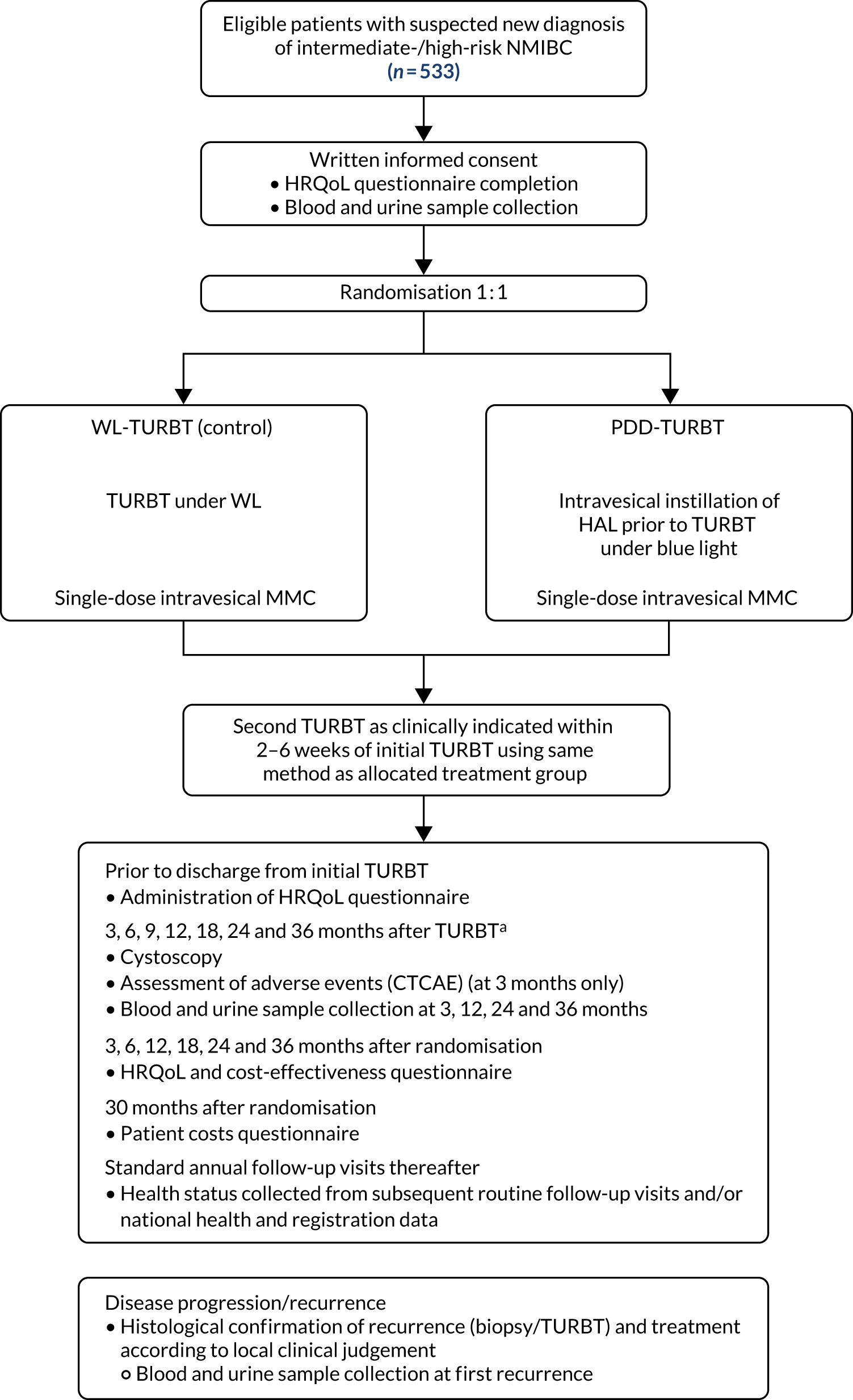

Study recruitment

A total of 538 participants were randomised into the study across the 22 participating centres. Participants were recruited between 11 November 2014 and 6 February 2018, and followed up until 28 August 2020. (See Appendix 1, Table 29, for the centre recruitment figures.) Figure 3 shows the trajectory of the number of participants randomised over the recruitment period.

FIGURE 3.

Recruitment graph.

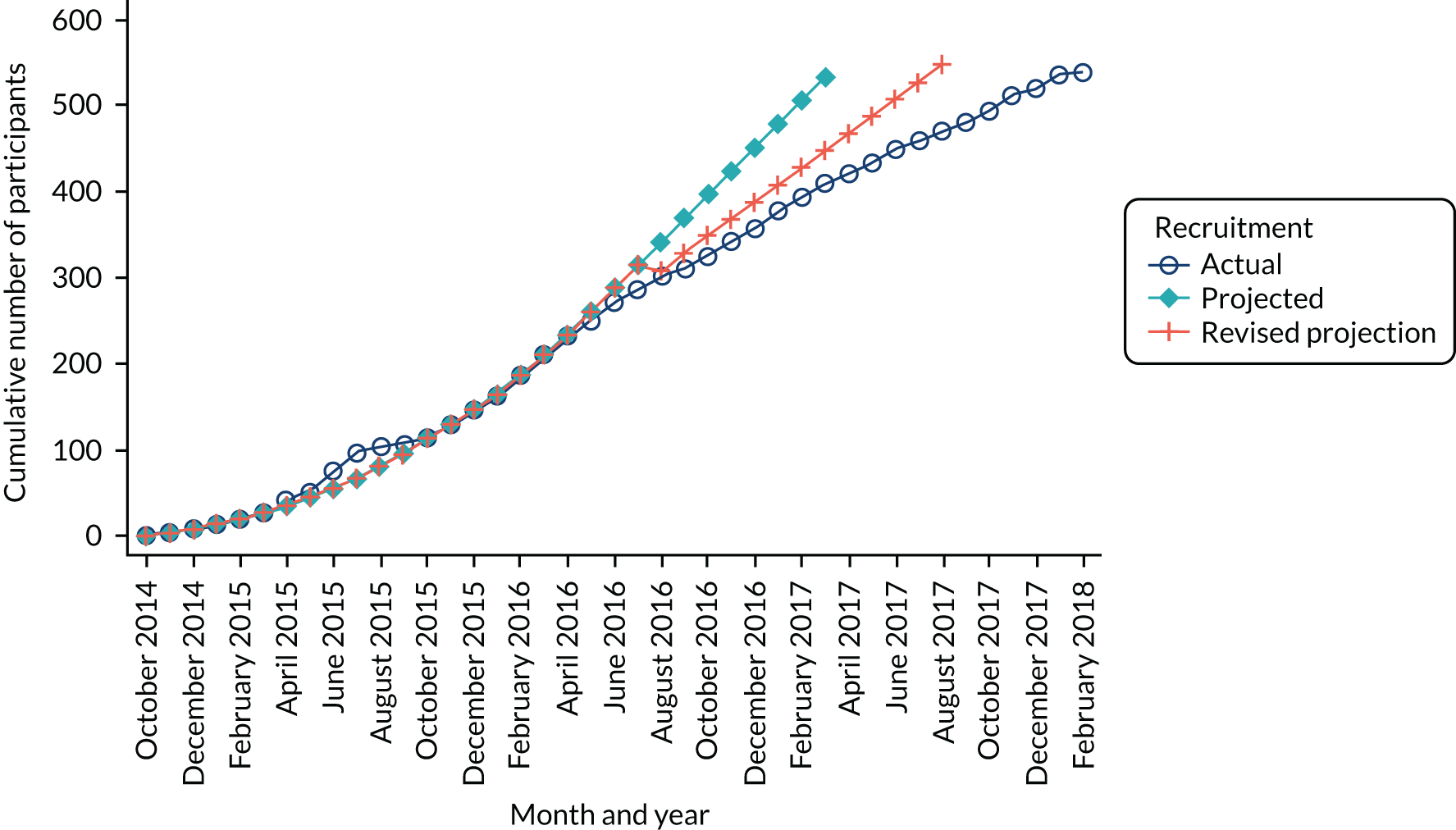

Participant flow

The flow of participants through the trial is summarised in Figure 4, in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement. A total of 1077 patients were reported on ineligible or declined eCRFs and were assessed for eligibility. Of those, 538 were randomised: 269 participants were allocated to PDD and 269 were allocated to WL. There were 226 participants who did not meet the inclusion criteria and 242 who declined to participate in the study. The main reason for ineligibility was visual evidence of low-risk NMIBC (59%) and the most frequent reason for participants declining was because they were not interested in the study (21%). (See Appendix 1, Table 30, for further details of why screened participants were not randomised.)

There were five post-randomisation exclusions, the reasons for which were as follows: participant was consented and randomised and then found to be ineligible; CT report showed left hydronephrosis; CT scans of two patients showed likely MIBC after randomisation; and patients were found to have upper tract disease after randomisation. After the initial TURBT, 29 participants were found to have no histological evidence of tumour, 60 had MIBC and 18 had an early cystectomy. These 107 participants have been excluded from analysis and reporting in the main body of this monograph beyond this point (see Appendix 1 for baseline and follow-up data for these participants). A total of 426 participants (PDD, n = 209; WL, n = 217) were included in the analysis (see Figure 4).

Baseline characteristics

The minimisation variables of centre and sex are shown in Table 3, and participants’ baseline characteristics are shown in Table 4. The groups remain well balanced after the exclusion of participants with MIBC and no tumour. The mean age of the participants was 70 years and the majority were men.

| Minimisation variable | Treatment group, number of participants (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| PDD (N = 209) | WL (N = 217) | |

| Centre | ||

| Newcastle Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Newcastle | 22 (10.5) | 21 (9.7) |

| Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust, Exeter | 15 (7.2) | 17 (7.8) |

| Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford | 12 (5.7) | 9 (4.1) |

| NHS Tayside, Dundee | 5 (2.4) | 4 (1.8) |

| University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London | 2 (0.9) | |

| Cwm Taf Morgannwg University Health Board, Bridgend | 1 (0.5) | |

| Ashford and St Peter’s Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Ashford | 5 (2.4) | 2 (0.9) |

| NHS Lothian, Edinburgh | 34 (16.3) | 38 (17.5) |

| Hull University Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Cottingham | 6 (2.9) | 10 (4.6) |

| Hampshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Basingstoke | 3 (1.4) | 3 (1.4) |

| South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Middlesbrough | 21 (10.0) | 24 (11.1) |

| Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London | 2 (1.0) | 7 (3.2) |

| Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Leeds | 14 (6.7) | 11 (5.1) |

| Swansea Bay University Health Board, Swansea | 13 (6.2) | 12 (5.5) |

| Dartford and Gravesham NHS Trust, Dartford | 20 (9.6) | 26 (12.0) |

| University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, Southampton | 6 (2.9) | 2 (0.9) |

| University Hospitals of North Midlands NHS Trust, Stoke-on-Trent | 10 (4.8) | 10 (4.6) |

| Derby Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Derby | 6 (2.9) | 4 (1.8) |

| Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust, Salisbury | 6 (2.9) | 9 (4.1) |

| NHS Grampian, Aberdeen | 8 (3.8) | 4 (1.8) |

| East and North Hertfordshire NHS Trust, Stevenage | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 167 (79.9) | 172 (79.3) |

| Female | 42 (20.1) | 45 (20.7) |

| Baseline clinical characteristic | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|

| PDD (N = 209) | WL (N = 217) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD); minimum, maximum | 71 (11); 27, 96 | 70 (10); 31, 89 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||

| Current smoker | 33 (15.8) | 30 (13.8) |

| Previous smoker | 117 (56.0) | 123 (56.7) |

| Never | 57 (27.3) | 60 (27.6) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.4) |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| Number of tumours, n (%) | ||

| Single | 66 (31.6) | 81 (37.3) |

| 2–7 | 122 (58.4) | 113 (52.1) |

| ≥ 8 | 17 (8.1) | 21 (9.7) |

| Missing | 4 (1.9) | 2 (0.9) |

| Tumour size at baseline (cm), n (%) | ||

| < 3 | 69 (33.0) | 81 (37.3) |

| ≥ 3 | 133 (63.6) | 129 (59.4) |

| Missing | 7 (3.3) | 7 (3.2) |

| Histological grade at baseline, n (%) | ||

| Grade 1 | 17 (8.1) | 16 (7.4) |

| Grade 2 | 116 (55.5) | 112 (51.6) |

| Grade 3 | 72 (34.4) | 86 (39.6) |

| Missing | 4 (1.9) | 3 (1.4) |

| Histological stage at baseline, n (%) | ||

| pTa | 150 (71.8) | 160 (73.7) |

| pT1 | 64 (30.6) | 66 (30.4) |

| CIS, n (%) | ||

| Present | 27 (12.9) | 24 (11.1) |

| Absent | 180 (86.1) | 190 (87.6) |

| Missing | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.4) |

| EORTC risk group, n (%) | ||

| Low risk (score 0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.9) |

| Intermediate risk (score 1–9) | 184 (88.0) | 190 (87.6) |

| High risk (score 10–17) | 17 (8.1) | 15 (6.9) |

| Not calculable | 8 (3.8) | 10 (4.6) |

| NICE risk group, n (%) | ||

| Low risk | 10 (4.8) | 8 (3.7) |

| Intermediate risk | 100 (47.8) | 96 (44.2) |

| High risk | 96 (45.9) | 107 (49.3) |

| Not calculable | 3 (1.4) | 6 (2.8) |

Participants were categorised into low-, intermediate- and high-risk groups for recurrence based on EORTC and NICE risk tables. 18 Based on the EORTC risk table > 80% of participants in both treatment groups were in the intermediate-risk group. CIS was absent in > 85% of the participants.

Table 5 summarises the characteristics of the surgeons who performed the initial/second resections. Consultants performed > 65% of the surgeries in both groups. Surgeons with experience of > 40 cases of PDD performed 39% of PDD surgeries and 40% of WL surgeries.

| Surgeon characteristics | Treatment group, number of participants (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| PDD (N = 209) | WL (N = 217) | |

| Grade of surgeon | ||

| Registrar/non-consultant career grade | 46 (22.0) | 65 (30.0) |

| Consultant | 160 (76.6) | 148 (68.2) |

| Missing | 3 (1.4) | 4 (1.8) |

| Surgeon’s PDD experience (number of cases) | ||

| < 10 | 43 (20.6) | 50 (23.0) |

| 10–19 | 46 (22.0) | 46 (21.2) |

| 20–40 | 30 (14.4) | 11 (5.1) |

| > 40 | 81 (38.8) | 87 (40.1) |

| Missing | 9 (4.3) | 23 (10.6) |

Health-related quality of life was assessed using three validated questionnaires: the EQ-5D-3L, EORTC-QLQ-C30 and EORTC-QLQ-NMIBC-24. Data are summarised in Table 6. The mean EQ-5D-3L score was 0.83 in the PDD group and 0.84 in the WL group. Across subscales, median scores ranged between 75.0 and 100.0 in both the PDD and WL groups. For symptom subscales, the scores ranged between 0 and 22.2 (the score for fatigue) in the PDD group and between 0 and 11.1 (the score for fatigue) in the WL group.

| Baseline HRQoL | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|

| PDD (N = 209) | WL (N = 217) | |

| EQ-5D-3L | ||

| Total score | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 0.83 (0.20); 189 | 0.84 (0.22); 190 |

| Median (25th, 75th percentile) | 0.85 (0.73, 1.00) | 0.87 (0.73, 1.00) |

| Visual analogue scale | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 75.92 (18.37); 183 | 74.58 (18.25); 184 |

| Median (25th, 75th percentile) | 80 (70, 90) | 80 (65.00, 90) |

| EORTC-QLQ-C30 | ||

| Functioning scalesa | ||

| Physical | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 83.50 (20.26); 191 | 85.55 (17.76); 197 |

| Median (25th, 75th percentile) | 93.33 (73.33, 100) | 93.33 (80, 100) |

| Role | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 85.53 (24.95); 190 | 87.65 (21.94); 197 |

| Median (25th, 75th percentile) | 100 (83.33, 100) | 100 (83.33, 100) |

| Cognitive | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 85.44 (18.58); 190 | 87.48 (18.09); 197 |

| Median (25th, 75th percentile) | 83.33 (83.33, 100) | 100 (83.33, 100) |

| Emotional | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 80.01 (21.18); 188 | 81.63 (19.14); 194 |

| Median (25th, 75th percentile) | 83.33 (66.67, 100) | 83.33 (75.00, 100) |

| Social | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 86.61 (22.26); 188 | 88.46 (21.26); 195 |

| Median (25th, 75th percentile) | 100 (83.33, 100) | 100 (83.33, 100) |

| Global QoL | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 73.36 (19.27); 188 | 73.80 (20.29); 195 |

| Median (25th, 75th percentile) | 75.00 (66.67, 83.33) | 75.00 (66.67, 83.33) |

| Symptom scales and/or itemsb | ||

| Fatigue | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 21.84 (22.81); 189 | 19.51 (20.27); 197 |

| Median (25th, 75th percentile) | 22.22 (0, 33.33) | 11.11 (0, 33.33) |

| Nausea and vomiting | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 3.88 (11.89); 189 | 3.13 (9.23); 197 |