Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/35/27. The contractual start date was in November 2013. The draft report began editorial review in April 2021 and was accepted for publication in February 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Goldberg et al. This work was produced by Goldberg et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Goldberg et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Ankle osteoarthritis is a condition in which the cartilage lining the ankle joint has worn away. The cartilage acts as a shock absorber and allows smooth, gliding motion. Absence of the cartilage and the resultant bone spurs that form (bony projections or osteophytes), and calcification and scarring of the capsule, lead to progressive pain and stiffness.

More than 29,000 patients in the UK present to specialists each year with symptomatic ankle osteoarthritis, a condition that causes major disability and has a similar impact on quality of life (QoL) as end-stage cardiac failure1 and end-stage hip arthritis. 2 The current demand incidence of ankle osteoarthritis has been estimated to be 47.7 per 100,000 per year. 3

The most common aetiological factor in the development of osteoarthritis of the ankle is previous trauma, often following fractures or severe sprains of the ankle. 4 The incidence of both of these is rising; hence, post-traumatic osteoarthritis of the ankle is likely to become an increasing health burden. Indeed, ankle sprains are one of the most common reasons for attendance at emergency departments. Other causes of ankle osteoarthritis include long-standing inflammatory arthropathies (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, haemochromatosis and haemophiliac arthropathy).

In the early stages of disease, non-operative measures such as a change in activity levels, weight loss, physiotherapy, painkillers and ankle braces should be used. When these conservative management measures have failed for at least 6 months, and providing the surgeon confirms the diagnosis of osteoarthritis (now termed ‘end-stage osteoarthritis’) on the basis of radiological and clinical evidence (i.e. plain radiographs and unrelenting symptoms, respectively), surgery might then be considered.

Although ankle fusion is the most common surgical treatment for end-stage ankle osteoarthritis, surgeons are increasingly performing total ankle replacement (TAR), also known as arthroplasty, in response to patient demand. TAR started in the 1970s, with initial poor results. However, over the last 50 years, several new generations of implants have been developed with far improved results and its use is increasing globally. At least 4000 patients are treated with ankle fusion or TAR each year in the NHS. 5 Every TAR implanted in England, Wales, Northern Ireland, the Isle of Man and Guernsey is captured on the National Joint Registry, which has revision surgery as its only end point. No comprehensive outcome data are captured for ankle fusion patients. All studies comparing TAR with ankle fusion to date are observational and, to the best of our knowledge, there are no prospective randomised trials.

Many studies have shown that ankle fusion provides good short- and medium-term results. However, in the long term, it poses major risk (> 80%) of the development of adjacent joint arthritis owing to the transfer of stresses and motion to other joints. 6,7 Other complications following ankle fusion include pain, dysfunction, non-union and malalignment. 8

On the other hand, TAR can preserve the functional range of ankle motion, relieve pain and might avoid potential osteoarthritis in the adjacent joints. However, it may also result in revision surgery for aseptic loosening, intraoperative fracture, malalignment, impingement and heterotopic ossification. 9–11

To the best of our knowledge, there is no high-quality study comparing the two procedures, and the literature on this subject does not provide conclusive differentiation of the treatments, with varying length of follow-up, sample size and types of technique and implants. 12–19 The studies use a wide range of patient-reported outcome measures, without consistency of reporting or statistical analysis. Many of them have missing data, which makes the interpretation and comparison of results from individual studies next to impossible.

More recently, Daniels et al. 20 looked at 281 TARs and 107 ankle fusions and found comparable outcome scores between the two surgeries at a mean follow-up of 5.5 years. In their study, which was not randomised, patients who received ankle fusion were younger, more likely to be diabetic, less likely to have inflammatory arthritis and more likely to be smokers than those who received TAR. Veljkovic et al. 21 analysed 88 TARs and 150 ankle fusions at a follow-up of 3.6 years and found comparable clinical outcomes between ankle fusion and TAR in patients with non-deformed end-stage ankle arthritis.

In the National Joint Registry, which covers England, Wales, Northern Ireland, the Isle of Man and Guernsey, the most commonly used ankle replacement implants drastically changed between 2014 and 2019. 22 Prior to 2014, the majority of implants used in the UK were mobile bearing. In 2014, the Mobility™ Total Ankle System (DePuy Synthes Companies, Raynham, MA, USA) was withdrawn from the market. By 2019, the majority of implants used in the UK were fixed bearing. In 2019, the most commonly used implant was the Infinity™ Total Ankle System (Stryker, MI, USA) with the STAR™ (DJO, LLC, Vista, CA, USA) and Box® Total Ankle Replacement (MatOrtho Limited, Leatherhead, UK) implants the second and third most popular, respectively. 22 With regard to ankle fusion, there were a heterogeneity of techniques used to perform the ankle fusion, including arthroscopic and open techniques.

Esparragoza et al. 17 conducted a 2-year follow-up study of 30 patients [ankle fusion, n = 16; TAR with Ankle Evolutive System (AES) prosthesis (Transystème JMT Implants SA, Nîmes, France), n = 14], comparing their QoL before and after the procedure. They showed that the third-generation TAR provided greater improvement in QoL (physical conditions, and perception of general health and QoL) at 2 years post surgery. 17 On the other hand, Krause et al. ,18 in their 3 year-follow up study of 161 patients [ankle fusion, n = 27; TAR with Agility™ (DePuy Synthes Companies), HINTEGRA® (DT MedTech, LLC, TN, USA), STAR or Mobility Total Ankle System implants, n = 114], found no significant difference in the mean improvement between the two groups, although the rate of complication was significantly higher after TAR than after ankle fusion. In another short-term follow-up study, Slobogean et al. 16 assessed QoL 1 year after TAR or ankle fusion in 107 patients and demonstrated that preference-based QoL was improved following TAR and ankle fusion, but the improvement was not significantly different between the two procedures. 16

Two systematic reviews comparing outcomes from TAR with ankle fusion, using second-generation prostheses13 or third-generation three-component meniscal-bearing prostheses,12 showed no significant differences in short-, mid- or long-term outcomes between the two treatments. Haddad et al. 13 reported that ankle fusion resulted in a higher risk of lower limb amputation, although they did not include any studies that directly compared TAR with ankle fusion. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 7942 modern TARs by Zaidi et al. 23 reported that TAR has a positive impact on patients’ lives, with benefits lasting 10 years, as judged by improvement in pain and function, and improved gait and increased range of movement. Zaidi et al. 23 reported an overall survivorship at 10 years of 89%, with an annual failure rate of 1.2% [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.7% to 1.6%]. The same authors reported improvements in clinical scores, although the scores used were heterogeneous and without consistency. Radiolucency was identified in up to 23% of TARs after a mean of 4.4 years (95% CI 2.3 to 9.6 years).

Gougouilas et al. 15 also performed a systematic review of the outcome of seven TAR implants that are currently in use [Agility, STAR, Buechel-Pappas™ (Endotec, Inc., Orlando, FL, USA), HINTEGRA, Salto Talaris® Total Ankle Prosthesis (Integra LifeSciences Corporation, Boston, MA, USA), TNK (Kyocera Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) and Mobility implants] and showed that most patients experienced significant improvement, as assessed by the clinical score. In contrast to Zaidi et al. ,23 Gougouilas et al. 15 suggested that the postoperative improvement in the range of ankle motion was relatively small (0–14°). A decision analysis using a Markov model showed that TAR was a better treatment than ankle fusion, as assessed by the quality well-being index score. 19 These systematic reviews have exposed significant bias and a lack of prospective controlled data for either procedure.

A cost-effectiveness evaluation conducted in the USA concluded that TAR has the potential to be a cost-effective alternative to ankle fusion, but reaffirmed the poor quality of the supporting evidence. 24 To the best of our knowledge, there have been no level 1 RCTs to inform this important subject.

Objectives

The total ankle replacement versus ankle arthrodesis (TARVA) trial was a pragmatic, multicentre, parallel-group, non-blinded randomised controlled trial (RCT) that compared the two existing NHS treatment options: TAR and ankle fusion. The trial compared any current TAR implant with any isolated tibiotalar ankle fusion procedure. As a pragmatic trial should reflect the real-world situation, procedures varied in terms of technique owing to the specific requirements of each case and the preference of the operating surgeon. Thus, no surgical technique or type of ankle fusion was specified, although details were captured. Surgeons performing TAR were free to adopt their usual technique within each treatment arm, allowing the results of the trial to be extrapolated across the NHS. All surgeons included in this trial used implants and prostheses commonly used in the NHS only.

The trial assessed the comparative efficacy of the two main surgical treatments for end-stage ankle osteoarthritis: TAR and ankle fusion. It investigated the clinical effectiveness and complication rates of the two procedures in patients aged 50–85 years, measured through self-reported pain-free function using a standardised questionnaire of walking and standing ability at 52 weeks after the surgical intervention. It also aimed to determine whether or not there was a difference in physical function [measured using the Foot and Ankle Ability Measure – Activities of Daily Living (FAAM-ADL)], QoL [measured using the EuroQol 5-Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)] and range of motion (ROM) at 26 and 52 weeks post surgery. Last, we investigated the cost-effectiveness and cost–utility of TAR and ankle fusion. The adoption of a pragmatic trial design with broad entry criteria for the comparison of the two topical therapies means that the results can be generalised to the large number of patients presenting with ankle osteoarthritis who are treated each year.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter are reproduced from the TARVA trial protocol (Goldberg et al. 25). This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for non-commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Parts of this chapter are also reproduced from the TARVA trial statistical analysis plan (SAP) (Muller et al. 26). This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Design

The TARVA trial was a randomised, multicentre, non-blinded, prospective, parallel-group trial of TAR versus ankle fusion in patients with end-stage ankle osteoarthritis who were aged between 50 and 85 years, comparing clinical outcomes (i.e. pain-free function, QoL, ROM and rate of postoperative complications) and cost-effectiveness.

The trial incorporated an internal feasibility phase to ensure the surgeons’ willingness to randomise and the patients’ willingness to be randomised. The feasibility phase involved four centres and took place over a 6-month period following randomisation of the first patient (24 cumulative months across all centres) to closely monitor eligibility, consent and randomisation rates and ensure that they were adequate. In addition, this provided 5 months’ information on whether or not patients accepted their randomised surgery, and whether or not the surgery took place.

The final protocol has been published previously. 25 All trial analyses were performed in accordance with a predefined SAP. 26

Ethics

London Bloomsbury Research Ethics Committee (REC) reviewed and approved (14/LO/0807) the trial protocol and all material given to prospective participants, including the informed consent forms (ICFs). Subsequent amendments to these documents were submitted for further approval. Before initiation of the trial at each additional clinical site, the same/amended documents were reviewed and approved by local Research and Development.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were involved at all stages of the trial, from the development of the research questions and protocol to the running of the trial. This was important to ensure the salience of the research question and that the methods proposed were acceptable to potential participants, including the frequency of visits and relevance of outcome measures. One patient representative was part of the TARVA Trial Management Group, and one patient and public representative sat on the Trial Steering Committee. We will involve patient organisations and charities such as Versus Arthritis (Chesterfield, UK) and the Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance (London, UK) in the dissemination of the findings to a wider audience, both professionals and patients, through their newsletters, at their annual members’ meetings and on their websites.

Setting

The trial was carried out in 17 UK hospitals, in a mixture of district general hospitals, university teaching hospitals and specialist orthopaedic hospitals (including their adjoining private hospitals) with adequate facilities to carry out the surgical procedures and trial assessments (see Acknowledgements for a list of participating sites).

Participants

The eligibility criteria for participation were patients with end-stage ankle osteoarthritis, aged 50–85 years, who the surgeon believed to be suitable for both TAR and ankle fusion (having considered various patient factors including deformity, stability, bone quality, soft tissue envelope and neurovascular status). The patients had to be able to read and understand the patient information sheet (PIS) and provide written informed consent. Eligible patients were randomised to a surgery type. ‘End-stage’ osteoarthritis is defined as a combination of severe unrelenting symptoms sufficient to make the patient consider surgical intervention, radiological changes consistent with osteoarthritis and failure of at least 6 months of non-operative measures, necessitating a definitive surgical procedure.

Exclusion criteria included patients with previous ipsilateral talonavicular, subtalar or calcaneocuboid fusion or surgery planned within 1 year of index procedure; those with more than four lower-limb joints fused; and those who were unable to undergo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computerised tomography (CT). Those with a history of local bone or joint infection and those who had severe osteoporosis (T-score of < –2.5) with recent fracture (< 12 months previously) were not included in the trial. Patients with any comorbidity that, in the opinion of the investigator, was severe enough to interfere with the patient’s ability to complete the trial assessments or present an unacceptable risk to the patient’s safety were also excluded from the trial.

Interventions

In the UK, two broad types of prostheses are currently used in TAR: a two-component fixed-bearing prosthesis and a three-component mobile-bearing prosthesis. As both are commonly used, no restriction on the type of prosthesis used was stipulated, although data on prosthesis type were captured. The surgical technique followed the standard operative procedure, which involved an anterior approach to the ankle joint, protection of the neurovascular bundle, and talar and tibial preparation according to the prosthesis used and its instrumentation. Intraoperative fluoroscopy was used as required to confirm position, and final implantation used an uncemented technique. Thorough washout was followed by wound closure using the surgeon’s standard technique. Details of the surgeon’s technique were captured on a case report form (CRF). The surgeon’s usual postoperative protocol was followed with respect to method of immobilisation (plaster or walking boot) and weight-bearing status.

Ankle fusion was performed either as an open procedure or arthroscopically, depending on the surgeon’s preference. Tibial and talar joint surfaces were prepared to avoid bleeding from the cancellous bone, any deformity correction was addressed, and the surfaces were opposed and held with screws and/or plates as required to ensure that the foot was plantigrade and appropriately positioned to match the contralateral ankle in axial orientation. If performed arthroscopically, two portals were made, one anteromedially and one anterolaterally, over the ankle joint for access. If arthroscopic access was not favourable, the operation was performed using an open procedure, which involved either a standard anterior approach, two mini anterior incisions or a lateral approach. The surgical technique and implants used were captured on the CRF. The surgeon’s usual postoperative protocol was followed with respect to use of plaster or walking boot and weight-bearing status, and the specific details of these were captured for each patient on the CRF.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Each participant was booked to undergo MRI of the affected ankle, if this had not already been performed as part of routine care, once they had given written informed consent to take part in the trial. If the participant was ineligible for MRI, CT was booked instead. The grade of MRI/CT was determined by an independent radiologist using a methodology published by our group,27 the report of which was sent to the local principal investigator, and a preoperative assessment appointment was scheduled for the participant.

Randomisation

The randomisation process was based on a minimisation algorithm. The algorithm gave an overall chance of 85% of allocating the patient to the treatment arm that was under-represented with respect to three stratifying variables: surgeon, presence of osteoarthritis in subtalar joint and presence of osteoarthritis in talonavicular joint (as determined by preoperative MRI). The research nurse or delegated individual logged on to the Sealed Envelope randomisation service and provided patient information (including information on minimisation variables), and the surgical treatment to be received was supplied immediately. Patients were allocated in a 1 : 1 ratio to the TAR and ankle fusion arms. To protect against allocation bias, the person recruiting the patient to the trial was not aware of the allocation to be assigned prior to contacting the randomisation service. All surgeons were proficient in both surgical procedures, having independently performed ≥ 10 procedures of each type prior to participation.

Blinding

The trial was open (i.e. non-blinded). It was not possible to blind patients, surgeons, radiologists and clinical assessors for the following reasons:

-

Surgeons would have known which procedure they were performing.

-

Radiologists and patients would be able to identify which procedure had taken place from the radiographs.

-

Patients who received ankle fusion would tend to have stiffer ankles and the incisions may also provide clues to the surgery type.

Recruitment and consent

All patients with ankle osteoarthritis who were considering surgery were screened prospectively by principal investigators at 17 UK hospitals. Potentially eligible participants were identified during routine clinic appointments to assess treatment need, or through screening of referral letters/clinic lists. Those identified through screening were sent a study information pack in the post prior to their appointment.

If considered eligible for the TARVA trial, the patient watched a bespoke trial video, and read the PIS and a generic factsheet about ankle arthritis and its treatment options. Participants either consented at that stage or received a follow-up telephone call from the research team to discuss participation. Reasons for non-enrolment in the trial (including lack of equipoise) were recorded. All participants provided written informed consent using an ICF.

Following consent, participants underwent MRI (or, where contraindicated, CT) (if this had not been performed as part of standard care within the previous 6 months), followed by a preoperative assessment 14–30 days prior to surgery. If declared fit for surgery, participants were randomised to one of the two surgical treatments. Participants who were found to be unsuitable for surgery at the preoperative assessment appointment were passed back to their general practitioner (GP) to be re-referred for surgery when they were considered fit.

Baseline visit

Baseline measures were recorded at the point of randomisation, once the participant had been found to be fit for surgery, at their preoperative assessment. Baseline measures included the EQ-5D-5L, MOXFQ, Foot and Ankle Ability Measure (FAAM), Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI), ROM and concomitant medication.

Follow-up assessments and treatment

All participants attended routine follow-up, which consisted of visits at 2, 6, 12, 26 and 52 weeks post surgery. These visits were standard care. Patients underwent routine clinical review at 2 weeks, during which the stitches were removed and plaster casts changed. Trial-specific outcome measures, including adverse events (AEs) and postprocedural complications, were recorded at 6, 12, 26 and 52 weeks. Concomitant medications were recorded from preoperative assessment to the 52-week visit. Participants underwent routine physical examination, as per standard care. Participants completed additional questionnaires (the MOXFQ, EQ-5D-5L and FAAM) at 26- and 52-week routine follow-up visits, with the EQ-5D-5L and CSRI additionally completed at 12 weeks. ROM (total floor to tibial shaft plantarflexion and dorsiflexion) was assessed using a goniometer at the preoperative assessment visit and 52 weeks post surgery. 28

To avoid bias, operating surgeons were not involved in measuring ROM. Preoperative and postoperative hindfoot deformity was measured using weight-bearing anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the ankle and tibia at baseline, and on a postoperative radiograph (between 0 and 26 weeks post surgery) using the methods described by Knupp et al. 29 Plain radiographs were sent to the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital via the NHS Image Exchange Portal (Sectra Ltd, Stevenage, UK) in one batch (containing preoperative and postoperative radiographs) after the second (postoperative) radiograph was taken. Investigators were blinded to participant treatment allocation when reviewing the preoperative radiographs. Each participant was in the trial from consent until the final 52-week follow-up visit, although long-term follow-up at 2, 5 and 10 years post surgery was part of their informed consent.

Safety

All medical device deficiencies, AEs and serious adverse events (SAEs) occurring during the trial that were observed by the investigator or reported by the participant (whether or not they were attributed to the surgery, surgery-related medications, device or other trial-specific procedures) were recorded in the participants’ medical records. Related AEs over and above what would normally be expected after ankle surgery were recorded on the relevant CRFs. SAEs were reported in line with procedures set out in the protocol. 25

The severity of all AEs (serious and non-serious) was graded using the TARVA trial safety management plan for expected AEs, in conjunction with the most recent version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (at the time the protocol was written, this was version 4.030) for other (unexpected) AEs. The ‘expectedness’ was determined by the list of expected events in the TARVA trial safety management plan.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome measure was the absolute difference between the two treatment arms in self-reported pain-free function, as measured by the Manchester–Oxford Foot Questionnaire (MOXFQ) walking/standing domain score at 52 weeks post surgery (0–100, where lower scores are better). 31 The 52-week score was used if it was taken in the window from 48 to 56 weeks post surgery.

The MOXFQ walking/standing domain score has been found to be a valid and responsive measure to evaluate all types of foot and ankle surgery and it has also been shown to be more responsive for the outcomes of foot and ankle surgery patients than generic QoL measures such as the EQ-5D-5L quality-of-life instrument. 32 The MOXFQ walking/standing domain score was selected by patients as the most important outcome measure. 32

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcome measures for the trial were the absolute differences between the two treatment arms in:

-

the MOXFQ walking/standing domain score at 26 weeks post surgery

-

self-reported pain and social interaction, measured using the MOXFQ pain and social interaction domain scores at 26 weeks and 52 weeks post surgery

-

physical function, measured using the FAAM-ADL questionnaire at 26 weeks and 52 weeks post surgery (0–100, higher scores better)

-

physical function for patients involved in sport, measured using the FAAM sport subscale score at 26 weeks and 52 weeks post surgery

-

QoL, assessed using the EQ-5D-5L [EQ-5D-5L index value and EQ-5D-5L visual analogue scale (VAS)] at 26 weeks and 52 weeks post surgery

-

total ROM (degrees plantarflexion and dorsiflexion) at 52 weeks post surgery, assessed using a goniometer

-

the proportion of patients experiencing at least one AE

-

the proportion of patients experiencing at least one SAE

-

the proportion of patients with recorded complications (including revision surgery and reoperations other than revision).

Additional outcomes were also collected for a detailed cost and cost-effectiveness analysis of TAR compared with ankle fusion.

The Manchester–Oxford Foot Questionnaire

Responses to each MOXFQ questionnaire item consist of a five-point Likert scale ranging from no limitation (scoring 0) to maximum limitation (scoring 4). Items are grouped into three domains: walking/standing (seven items), pain (five items), and social interaction (four items). Domain scores are computed by summing the patient’s responses to each item within the domain and converting to a 0–100 metric, where higher scores represent greater severity.

If a single item within any domain is unanswered, it will be imputed with the mean of the respondent’s answers to the other items within that domain. If two or more questions on any domain are unanswered, the overall score for that domain will not be calculated and its value will be set to missing. 33 If the entire questionnaire has not been completed, all MOXFQ domain scores for that visit will be set to missing.

The Foot and Ankle Ability Measure – Activities of Daily Living

Each of the 21 items on the FAAM-ADL is scored from 4 (no difficulty) to 0 (difficulty). 34 The overall FAAM-ADL score is then calculated by summing the responses to each completed item, dividing this by the maximum score achievable based on the number of items completed (e.g. 84 if all 21 items are completed), and then multiplying the resulting fraction by 100 to return a 0–100 metric, where higher scores indicate a higher level of physical function. If an answer for one item is missing, its value will be imputed as the mode of the other items; if more than one item is missing, the overall score will be set to missing.

The FAAM sport subscale score provides a complementary, specific assessment of ability to participate in sports based on eight questionnaire items, each also scored from 0–4. A 0–100 metric is then generated using the same approach as for the FAAM-ADL; higher scores indicate a higher level of ability to participate in sports. Missing items will be handled using the same approach as for the FAAM-ADL.

EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version, quality-of-life instrument

The EQ-5D-5L is a generic measure of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) developed by the EuroQol group in 2009. It was introduced to improve on the sensitivity of its predecessor, the EuroQol 5-Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L). It is a five-dimension, five-level questionnaire scored 1 (no problem) to 5 (extreme problem). The dimensions are mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. It also includes a VAS scored from 0 (worst imaginable health) to 100 (best imaginable health). The EQ-5D-5L was translated into > 130 languages and is available in various modes of administration. 35

The EQ-5D-5L is a descriptive system that defines a unique health state by combining one level from each of the five dimensions. 36 The descriptive system can be converted into a single index value using a value set. 37 The value set was derived from a study that elicited preferences from the general population (n = 3395). 37 The index value can take values from 0 (death) to 1 (perfect health). Currently, a value set is available for the EQ-5D-3L, which was derived directly from the population responses. For the EQ-5D-5L, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends using a ‘crosswalk’ calculator,38 which is a link function that allows researchers to obtain index values using value sets for the EQ-5D-3L. The index values are also used in the calculation of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) in the economic evaluation of health interventions.

Another generic measure of HRQoL is the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36). The SF-36 is a standardised questionnaire comprising 36 items across eight domains. The domains of the SF-36 are physical functioning (10 items), physical role limitations (four items), bodily pain (two items), general health perceptions (five items), energy/vitality (four items), social functioning (two items), emotional role limitations (three items) and mental health (five items). The last item is called ‘self-report health transition’; it is answered by the respondent, but is not included in the scoring system. The SF-36 has a scoring algorithm that generates a score for each of the eight domains and two summary scores (a physical component summary and mental health component summary), but it is not preference based. A study was conducted to create a preference-based measure from the SF-36, which is called the Short Form questionnaire-6 Dimensions (SF-6D). 39 A value set was created by interviewing a representative sample of 611 members of the UK population. There is also a short version of the questionnaire, called the Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12). It is often preferred for routine follow-up. 40

Both measures are widely used in joint replacement registries. 41 The EQ-5D-5L42,43 and SF-3644 were validated to use in patients with osteoarthritis. There are no recommendations as to which one is preferred. 40 There is a mapping function available to convert the SF-12 to EQ-5D-5L index values, which facilitates comparison between the two measures. 45

If any dimension score is missing, the EQ-5D-5L index value will be set to missing. If the entirety of one component of the questionnaire (dimension score or VAS) has not been completed, the associated component score will be set to missing. If the entire questionnaire has not been completed, both the EQ-5D-5L index value and EQ-5D-5L VAS at that visit will be set to missing.

Sample size

The sample size calculation for the primary outcome (change in MOXFQ walking/standing domain score by 52 weeks post surgery) was performed using Stata/IC®, version 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). It was based on achieving 90% power to detect the minimal important difference (MID) in the primary outcome at the 5% level of significance, accounting for expected loss to follow-up.

Dawson et al. 46 previously defined the MID in the MOXFQ when evaluating outcomes following surgery for hallux valgus as the mean change in MOXFQ score of those patients who reported feeling at least ‘slightly better’. They found the MID to be 16, 12 and 24 for the walking/standing, pain and social interaction domains, respectively. 46

A later paper by Dawson et al. 47 discussed the minimal detectable change, which is the smallest change for an individual that is beyond the measurement of error of a given instrument and therefore likely to represent a true change. Although Dawson et al. ’s 2007 paper46 looked at hallux valgus, their later paper47 specifically studied ankle procedures as a subgroup and estimated the MID to be 10.67.

For this trial, we determined that it was important to detect a difference of 12 in the change in the MOXFQ walking/standing domain scores from baseline between the two treatment arms.

The standard deviation (SD) of the MOXFQ walking/standing domain score was estimated to be 27. 46 We took into account an anticipated 10% dropout rate (attrition in orthopaedic trials is about 5–7%, as shown by other similar UK RCTs48). Based on these quantities, the required sample size was estimated to be 118 patients per arm.

However, the trial was multicentre and the outcome was assumed to vary by surgeon, so the sample size was increased to account for clustering by surgeon. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was estimated from the median of 10 previous surgical studies reporting patient-reported disease-specific measures 12 months post surgery,49 and the initial sample size estimate was inflated by a factor of f = 1 + (m – 1) × ICC. Assuming an average cluster size (m) of 14 (patients per surgeon) and an ICC of 0.03, an inflation factor of f = 1.39 was estimated, leading to a final required sample size of 164 patients per arm or 328 patients in total.

Data collection and management

A member of the research team captured data from patients on paper using the TARVA trial CRFs. The data were entered onto the main trial database (MACRO v4.1; Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) by a delegated member of site staff.

The site retained the original paper copies of patient CRFs to allow monitoring and audit by the University College London Comprehensive Clinical Trials Unit (UCL CCTU) trial team. All data queries were resolved prior to trial closure and analysis.

At sites where electronic records were available, the site may have captured some of the data electronically, which were then transcribed onto the paper CRFs to ensure a complete record.

Statistical methods

All trial analyses were performed according to a predefined SAP. 26 All efficacy analyses were conducted following the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle, in which all randomised patients were analysed according to their randomised surgical procedure, irrespective of the type of surgery they received.

In addition, a per-protocol analysis was carried out for the primary outcome, which included only the outcome data that were collected within the protocol-specified time window from patients who underwent surgery according to their randomised surgical procedure, excluding crossover patients.

The baseline characteristics were summarised by randomised treatment arm. The categorical variables were summarised by number and percentage in each category; continuous variables were summarised by mean and SD, or median and interquartile range, as appropriate. No statistical tests of differences in baseline characteristics between arms were undertaken, as in a randomised trial any differences between treatment arms must be due to chance.

Primary outcome analysis

A multilevel repeated-measures linear regression model was used to estimate the difference between the treatment arms in the change in MOXFQ walking/standing domain score from before the operation to 52 weeks post surgery. The model included fixed effects for time, treatment, treatment-by-time interaction, baseline MOXFQ walking/standing domain score and presence of osteoarthritis in each of the two adjacent joints (subtalar and talonavicular). A random patient effect was included to account for clustering by patient. A random surgeon effect was also included to account for clustering by surgeon.

Owing to the heterogeneity of the surgeon cluster sizes, the planned model (which included an additional, random surgeon by-treatment-coefficient) encountered convergence problems. Although randomisation was stratified by surgeon, many of the surgeons treated only a few patients, leading to insufficient data to estimate the random surgeon-by-treatment coefficient. As the primary analysis model failed to converge, the model was refitted after excluding the random surgeon-by-treatment coefficient.

The model used an unstructured covariance structure and was fitted using restricted maximum likelihood. The model makes assumptions about random effects distributions, correlation structure and residuals, which were investigated using appropriate plots.

Secondary outcome analysis: continuous secondary outcomes

Each of the following continuous secondary outcome measures were analysed using a separate multilevel repeated-measures linear regression model:

-

change in MOXFQ pain domain score

-

change in MOXFQ social interaction domain score

-

change in FAAM-ADL

-

change in FAAM sport subscale (for patients involved in sport)

-

change in EQ-5D-5L index value

-

change in EQ-5D-5L VAS

-

change in ROM dorsiflexion

-

change in ROM plantarflexion.

Similar to the primary analysis model, each model included fixed effects for treatment, time, treatment by time, baseline value of the associated score and presence of osteoarthritis in each of the two adjacent joints. A random patient effect and a random surgeon effect were also included in each of the models.

The outcomes ROM dorsiflexion and ROM plantarflexion were measured at baseline and 52 weeks only. Hence, the analyses models included fixed effects for treatment, baseline value of the associated score and presence of osteoarthritis in each of the two adjacent joints, and a random surgeon effect.

Adverse events, serious adverse events and complications

The following absolute differences in proportions were estimated using the treatment coefficient obtained using a binomial regression model with the identity link function:

-

proportion of patients experiencing at least one AE

-

proportion of patients experiencing at least one SAE.

Relative risks were obtained using a binomial regression model with the log link.

The distribution of the AEs and SAEs per patient have also been presented descriptively, but no formal analysis was performed. The descriptive statistics of complications, revisions and reoperations were also presented.

Subgroup analyses

An exploratory subgroup analysis was performed to investigate whether there was any interaction between the effect of treatment and the presence of osteoarthritis in the two adjacent joints on the primary outcome.

The fitted primary analysis model was extended to include the interactions between treatment and presence/absence of osteoarthritis in adjacent joints. As the trial was not powered to detect this, the analysis had limited power and is exploratory.

Further exploratory subgroup analyses were undertaken to investigate whether or not there was any interaction between age and the randomised treatment.

Post hoc analysis

At the time of developing the protocol, only mobile-bearing TAR implants were on the UK market. Between 2014 and 2019, after the study had begun, fixed-bearing implants became the most commonly used implants in the UK. Therefore, a post hoc analysis was carried out as a sensitivity analysis, comparing the most common type of implant in the UK (fixed-bearing TAR) with ankle fusion. The subtypes of TAR patients (those who received fixed-bearing TAR and those who received mobile-bearing TAR) were used as separate groups in the post hoc model and compared with the ankle fusion arm (including both open and arthroscopic ankle fusion patients).

Study oversight

A Trial Steering Committee (TSC) was established, comprising seven independent members, including a patient and public representative, the chief investigator and representatives from among the principal investigators. The trial health economist and senior trial statistician attended meetings as observers. The committee provided advice to the chief investigator, UCL CCTU, the funder and the sponsor on all aspects of the trial.

The UCL CCTU was responsible for the day-to-day management of the trial, with oversight from a Trial Management Group on the design, co-ordination and strategic management of the trial. The Trial Management Group was chaired by the chief investigator.

An Independent Data Monitoring Committee (IDMC) monitored the accumulating data and made recommendations to the TSC on whether or not the trial should continue as planned. The committee consisted of three independent members: a professor of medical statistics, a professor of rehabilitation sciences and a professor of orthopaedic surgery (the chairperson).

All oversight committees had agreed terms of reference.

During the trial, the TSC and IDMC each met six times between August 2014 and July 2019, one of which was a joint meeting of the two committees. The joint meeting led to the abbreviation of the exclusion criteria so that the surgeons’ checklist was shorter. The committees also reviewed the impact of the withdrawal of the Mobility TAR implant, which occurred after the study began but prior to any recruitment. The IDMC and TSC also advised on a recovery plan for slow recruitment, including increasing the number of recruitment sites, extending the recruitment period and a qualitative study to provide insight into recruitment difficulties.

Chapter 3 Trial results

Recruitment

Participants were randomised between 6 March 2015 and 10 January 2019. A total of 1604 patients were screened for eligibility, of whom 303 were randomised: 152 to TAR and 151 to ankle fusion. The numbers of participants recruited and included in the ITT analysis are summarised in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram in Figure 1. Of the 303 patients randomised, 21 withdrew from the trial before receiving surgery, one withdrew before the 26-week follow-up and a further five withdrew/had missing data at week 52. Six of those who received surgery were missing primary outcome measure data at 52 weeks. All patients who received surgery and attended either the 26-week or 52-week visit were included in the ITT analysis. Four patients randomised to arthrodesis did not receive their allocated surgery and crossed over to the TAR arm. All observed outcome data from these patients were analysed according to their randomised surgical procedure.

FIGURE 1.

Trial profile: CONSORT flow diagram.

Of the 282 patients who received surgery, one patient who withdrew before the 26-week follow-up could not contribute data to the primary outcome but was included in the baseline characteristics table. All 281 patients who received surgery and attended at least one follow-up were included in the mixed model for the primary outcome analysis (ITT analysis).

Table 1 lists the 17 sites in order of the date the site opened to recruitment. The first site to open was the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital in December 2014. This site randomised the largest number of patients (24% of the total randomised).

| Site (site identification number) | Date openeda | Number of patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screened | Eligible | Randomised | Per centre per month | ||

| Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital (10) | 23 December 2014 | 287 | 136 | 73 | 1.7 |

| Aintree University Hospital (11) | 10 February 2015 | 109 | 37 | 17 | 0.4 |

| Northern General Hospital (Sheffield) (13) | 13 February 2015 | 101 | 51 | 10 | 0.2 |

| Wrightington Hospital (24) | 21 April 2015 | 147 | 100 | 10 | 0.2 |

| Freeman Hospital (Newcastle) (18) | 19 May 2015 | 116 | 73 | 19 | 0.4 |

| Royal Derby Hospital (28) | 11 June 2015 | 103 | 72 | 30 | 0.7 |

| Royal Surrey County Hospital (27) | 9 July 2015 | 34 | 14 | 12 | 0.3 |

| Cardiff and Vale University Local Health Board (16) | 20 November 2015 | 67 | 27 | 3 | 0.1 |

| Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust (30) | 1 December 2015 | 51 | 36 | 9 | 0.2 |

| Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust (25) | 15 January 2016 | 105 | 73 | 26 | 0.7 |

| Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (19) | 15 January 2016 | 99 | 58 | 11 | 0.3 |

| Robert Jones and Agnes Hunt Orthopaedic Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (21) | 29 January 2016 | 128 | 93 | 23 | 0.6 |

| Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust (26) | 4 March 2016 | 37 | 25 | 18 | 0.5 |

| Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (22) | 3 May 2016 | 32 | 17 | 9 | 0.3 |

| Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust (20) | 20 May 2016 | 75 | 61 | 16 | 0.5 |

| Royal Cornwall Hospitals NHS Trust (33) | 28 September 2016 | 16 | 14 | 1 | 0.0 |

| North Bristol NHS Trust (14) | 23 January 2017 | 97 | 46 | 16 | 0.7 |

| Total | 1604 | 933 | 303 | ||

Table 2 summarises the losses and exclusions after randomisation, with reasons, for each arm. There have been no losses to follow-up in the trial.

| Reasons for withdrawal | Number of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| TAR arm | Ankle fusion arm | |

| Withdrawal pre surgery | 14 | 7 |

| Declined surgery | 9 | 3 |

| Patient experienced medical complication | 2 | 3 |

| Postponed surgery | 3 | 1 |

| Withdrawal post surgery | 2 | 2 |

| Unable to commit to treatment schedule | 1 | 0 |

| Patient experienced SAE | 1 | 0 |

| Patient died | 0 | 1 |

| Reason not given | 0 | 1 |

| Withdrawal after 52 weeks | 1 | 0 |

| Patient died | 1 | 0 |

A total of 21 randomised patients withdrew from the trial prior to surgery – 14 (9%) in the TAR arm and seven (5%) in the ankle fusion arm. Of the patients who received surgery, four (two in each arm) withdrew from the trial prior to the 52-week follow-up. One patient in the TAR arm died after their 52-week follow-up visit.

Baseline characteristics of participants

The baseline characteristics of participants are presented in Table 3.

| Baseline characteristics | TAR arm (N = 138) | Ankle fusion arm (N = 144) | Total (N = 282) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 68.0 (8.1) | 67.7 (8.0) | 67.9 (8.0) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 34 (25) | 47 (33) | 81 (29) |

| Male | 104 (75) | 97 (67) | 201 (71) |

| Height (m), mean (SD) | 1.7 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 85.8 (13.2) | 88.3 (17.4) | 87.1 (15.5) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), n (%) | |||

| < 30 | 87 (64) | 70 (49) | 157 (56) |

| ≥ 30 | 50 (37) | 74 (51) | 124 (44) |

| Smoking status | |||

| Current smoker, n (%) | 5 (4) | 5 (4) | 10 (4) |

| Cigarettes/day, mean (SD) | 5.8 (2.4) | 10.4 (7.4) | 8.1 (5.7) |

| Ex-smoker, n (%) | 53 (38) | 57 (40) | 110 (39) |

| Time since cessation (years), mean (SD) | 25.5 (16.0) | 25.9 (15.6) | 25.7 (15.7) |

| Patients’ treatment preference, n (%) | |||

| No preference expressed | 100 (75) | 112 (79) | 212 (77) |

| TAR | 26 (19) | 20 (14) | 46 (17) |

| Ankle fusion | 8 (6) | 9 (6) | 17 (6) |

| Aetiology of osteoarthritis, n (%) | |||

| Post traumatic | 83 (60) | 73 (50) | 156 (55) |

| Primary | 46 (33) | 56 (38) | 102 (36) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 6 (4) | 7 (5) | 13 (5) |

| Other inflammatory | 2 (2) | 5 (4) | 7 (3) |

| Other | 1 (1) | 4 (3) | 5 (2) |

| Presence/absence of osteoarthritis, n (%) | |||

| Healthy adjacent joint | 81 (59) | 79 (55) | 160 (57) |

| Osteoarthritis in subtalar or talonavicular | 45 (32) | 52 (36) | 97 (34) |

| Osteoarthritis in both adjacent joints | 12 (9) | 13 (9) | 25 (9) |

| User of assistive device, n (%) | |||

| No | 80 (58) | 79 (55) | 159 (56) |

| Yes | 58 (42) | 65 (45) | 123 (44) |

| Assistive device, n (%) | |||

| Crutches | 12 (9) | 14 (10) | 26 (9) |

| Ankle brace | 16 (12) | 7 (5) | 23 (8) |

| Frame | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Wheelchair | 3 (3) | 3 (2) | 6 (2) |

| Stick/cane | 33 (24) | 46 (32) | 79 (28) |

| Wheeled walker | 1 (1) | 4 (3) | 5 (2) |

| Knee scooter | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Other | 8 (6) | 4 (3) | 12 (4) |

| Medical history, n (%) | |||

| Anticoagulants | 24 (17) | 24 (17) | 48 (17) |

| History of cancer | 13 (9) | 20 (14) | 33 (12) |

| Chronic pain | 40 (29) | 46 (32) | 86 (31) |

| Connective tissue disorder | 1 (1) | 4 (3) | 5 (2) |

| Diabetes | 9 (7) | 16 (11) | 25 (9) |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 17 (12) | 22 (15) | 39 (14) |

| Hypertension/hypercholesterolaemia | 61 (44) | 62 (43) | 123 (44) |

| Inflammatory disorder | 8 (6) | 12 (8) | 20 (7) |

| Metabolic disorder | 5 (4) | 3 (2) | 8 (3) |

| Neurological disorder | 2 (2) | 6 (4) | 8 (3) |

| Obesity | 8 (6) | 15 (10) | 23 (8) |

| Peripheral nervous system disorder | 0 (0) | 5 (4) | 5 (2) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 2 (2) | 3 (2) | 5 (2) |

| Renal pathology | 7 (5) | 3 (2) | 10 (4) |

| Respiratory pathology | 12 (9) | 20 (14) | 32 (11) |

| Thromboembolic disease | 7 (5) | 7 (5) | 14 (5) |

| Other condition affecting mobility | 39 (28) | 43 (30) | 82 (29) |

| Degree of deformity, n (%) | |||

| 16–30° varus | 13 (10) | 7 (5) | 20 (7) |

| 5–15° varus | 36 (26) | 43 (30) | 79 (28) |

| Physiological neutral | 47 (34) | 51 (35) | 98 (35) |

| 5–15° valgus | 20 (15) | 18 (13) | 38 (14) |

| 16–30° valgus | 10 (7) | 6 (4) | 16 (6) |

| Not available | 11 (8) | 19 (13) | 30 (11) |

| Fixed flexion deformity of knee, n (%) | 2 (1.4) | 3 (2.1) | 5 (1.8) |

| Fixed equinus, n (%) | 7 (5.1) | 5 (3.5) | 12 (4.3) |

| ROM dorsiflexion (degrees), mean (SD) | 14.3 (9.5) | 14.2 (9.3) | 14.2 (9.4) |

| ROM plantarflexion (degrees), mean (SD) | 25.4 (8.3) | 26.3 (10.5) | 25.9 (9.5) |

| Outcome measures at baseline, mean (SD) | |||

| MOXFQ walking/standing | 81.6 (16.6) | 81.5 (16.8) | 81.5 (16.7) |

| MOXFQ pain | 66.7 (16.8) | 67.6 (17.5) | 67.2 (17.1) |

| MOXFQ social interaction | 54.4 (26.1) | 56.3 (21.7) | 55.4 (24.0) |

| MOXFQ summary indexa | 70.1 (15.4) | 70.9 (14.8) | 70.5 (15.1) |

| FAAM-ADL | 47.0 (16.7) | 44.1 (16.6) | 45.5 (16.7) |

| FAAM sport subscale | 28.3 (19.7) | 25.6 (21.3) | 27.3 (20.2) |

| EQ-5D-5L index value | 0.5 (0.2) | 0.5 (0.2) | 0.5 (0.2) |

| EQ-5D-5L VAS | 72.7 (20.2) | 67.5 (21.4) | 70.0 (21.0) |

The mean (SD) age of the participants was similar in each treatment arm: 68.0 (8.1) years in the TAR arm and 67.7 (8.0) in the ankle fusion arm. In total, 81 (29%) participants were female. The rate of obesity (body mass index of ≥ 30 kg/m2) was 37% in the TAR arm and 51% in the ankle fusion arm.

The proportion of patients with respiratory pathology, diabetes or obesity was lower in the ankle fusion arm than in the TAR arm at baseline. However, there was more deformity in the TAR arm than in the ankle fusion arm (see Table 3). Overall, the two randomised arms were considered generally similar with regard to medical history factors and smoking habits. In terms of American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade (Table 4), there were slightly more ASA grade 3 patients (severe systemic disease) in the ankle fusion arm than in the TAR arm (17.4% vs. 14.5%, respectively).

| Surgery characteristic | TAR arm (N = 138) | Ankle fusion arm (N = 144) | Total (N = 282) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery type,a n (%) | |||

| Mobile-bearing TAR | 65 (47.1) | 1 (25.0)a | 66 (46.5) |

| Fixed-bearing TAR | 73 (52.9) | 3 (75.0)a | 76 (53.5) |

| Arthroscopic ankle fusion | – | 85 (60.7) | – |

| Open ankle fusion | – | 55 (39.3) | – |

| Tourniquet duration (minutes),b mean (SD) | 117 (23.8) | 92 (28.0) | 105 (28.8) |

| Operation duration (minutes), mean (SD) | 121 (31.6) | 103 (36.2) | 112 (35.2) |

| Drain used, n (%) | |||

| No | 125 (92.6) | 139 (98.6) | 264 (95.6) |

| Yes | 10 (7.4) | 2 (1.4) | 12 (4.4) |

| Post surgery weight-bearing recommendation, n (%) | |||

| Full weight-bearing | 9 (6.6) | 1 (0.7) | 10 (3.6) |

| Partial weight-bearing | 17 (12.4) | 6 (4.2) | 23 (8.2) |

| Non-weight-bearing until 2 weeks | 81 (59.1) | 40 (28.0) | 121 (43.2) |

| Non-weight-bearing until 6 weeks | 13 (9.5) | 69 (48.3) | 82 (29.3) |

| Other | 17 (12.4) | 27 (18.9) | 44 (15.7) |

| Immobilisation type, n (%) | |||

| Backslab | 104 (75.9) | 114 (79.2) | 218 (77.6) |

| Walker boot | 11 (8.1) | 13 (9.0) | 24 (8.6) |

| Other | 21 (15.4) | 19 (13.2) | 40 (14.3) |

| ASA grade, n (%) | |||

| Healthy patient | 18 (13.0) | 25 (17.4) | 43 (15.3) |

| Mild systemic disease | 100 (72.5) | 94 (65.3) | 194 (68.8) |

| Severe systemic disease | 20 (14.5) | 25 (17.4) | 45 (16.0) |

| Prior fracture around index joint, n (%) | |||

| No | 87 (63.0) | 111 (77.1) | 198 (70.2) |

| Yes | 45 (32.6) | 28 (19.4) | 73 (25.9) |

| Not available | 6 (4.4) | 5 (3.5) | 11 (3.9) |

| Previous surgery on index joint, n (%) | |||

| None | 92 (66.7) | 92 (63.9) | 184 (65.3) |

| Internal fixation | 22 (16.0) | 18 (12.5) | 40 (14.2) |

| Other | 14 (10.4) | 16 (11.1) | 30 (10.6) |

| Thromboprophylaxis given, n (%) | |||

| None | 2 (1.5) | 3 (2.1) | 5 (1.8) |

| Chemical | 31 (22.5) | 34 (23.6) | 65 (23.1) |

| Mechanical | 2 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.7) |

| Both | 103 (74.6) | 107 (74.3) | 210 (74.5) |

Participants appeared to be equally distributed between treatment arms with regard to the minimisation factors, that is the presence of osteoarthritis in the two adjacent joints (subtalar and talonavicular). A total of 122 patients (34%) had osteoarthritis in the adjacent joints. For 25 (9%) of these patients, the osteoarthritis was in both adjacent joints.

Prior to their surgery, 44% of patients reported that they used assistive devices. The majority of those using an assistive device used a stick or cane. Patients also reported using other forms of assistive devices such as crutches (9%) and ankle braces (8%).

The majority of patients (77%) did not express a treatment preference, 17% of patients stated a preference for TAR and 6% expressed a preference for ankle fusion.

The baseline mean (SD) MOXFQ walking/standing score was 82 (16.6) in TAR and 82 (16.8) in ankle fusion patients. The baseline values for the outcome measures were similar in the two treatment arms.

Surgery details

The duration of the procedure was slightly longer for TAR (121 minutes) than ankle fusion (103 minutes). Patients were immobilised for longer in the ankle fusion arm than in the TAR arm: 26 (19%) patients in the TAR arm compared with seven (5%) in the ankle fusion arm were allowed to weight bear within 2 weeks of the surgery.

The arms were broadly similar in terms of previous surgery, although the TAR arm had slightly more patients who had previously had internal fixation on the index joint than the ankle fusion arm (16% vs. 12.5%, respectively).

For those patients who underwent TAR, 76 (53.5%) had a fixed-bearing TAR and 66 (46.5%) had a mobile-bearing TAR (Table 5). In the ankle fusion arm, 60% of the procedures were performed arthroscopically. For those patients who underwent an open ankle fusion, seven (14%) received a lateral approach (Table 6).

| Type of implant | n (N = 142) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Infinity Total Ankle System | 76 | 53.5 |

| STAR | 24 | 16.9 |

| BOX Total Ankle Replacement | 23 | 16.2 |

| Zenith (Corin Group, Circencester, UK) | 18 | 12.7 |

| Salto Talaris Total Ankle Replacement | 1 | 0.7 |

| Procedure type | n (N = 140) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Arthroscopic | 85 | 60.7 |

| Open anterior/anteromedial | 48 | 34.3 |

| Open lateral | 7 | 5.0 |

The proportion of patients who had an associated procedure was higher in the TAR arm than in the ankle fusion arm (35% vs. 18%, respectively). The most common procedure was Achilles tendon lengthening, which was undertaken in 17 (12.3%) patients in the TAR arm (Table 7). Six patients (4.3%) in the TAR arm required a lateral ligament repair. No patients in the ankle fusion arm underwent ligament repair.

| Procedure | TAR arm (N = 138), n (%) | Ankle fusion arm (N = 144), n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 90 (65.2) | 118 (81.9) | 208 (73.8) |

| Calcaneal osteotomy | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Achilles tendon lengthening | 17 (12.3) | 2 (1.4) | 19 (6.7) |

| Fibula osteotomy | 0 (0.0) | 6 (4.2) | 6 (2.1) |

| Lateral ligament repair | 6 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (2.1) |

| Bone grafting | 2 (1.4) | 5 (3.5) | 7 (2.5) |

| Removal of metalwork | 4 (2.9) | 2 (1.4) | 6 (2.1) |

| Other | 18 (13.0) | 11 (7.6) | 29 (10.3) |

The distribution of procedures by surgeon is shown in Table 8. Recruitment ended at the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital in June 2018, 6 months prior to closure of recruitment.

| Surgeon number | Site | Type of surgery (n) | Total (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAR | Ankle fusion | |||

| 1 | Aintree | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| 2 | Aintree | 4 | 6 | 10 |

| 3 | Brighton | 10 | 8 | 18 |

| 4 | Bristol | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| 5 | Bristol | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 6 | Bristol | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| 7 | Cardiff | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 8 | Cornwalla | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 9 | Derby | 14 | 15 | 29 |

| 10 | Guildford | 5 | 4 | 9 |

| 11 | Hull | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| 12 | Newcastle | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| 13 | Newcastle | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| 14 | Northumbria | 6 | 3 | 9 |

| 15 | Northumbria | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| 16 | Northumbria | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| 17 | Norwich | 2 | 6 | 8 |

| 18 | Norwich | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 19 | Nottingham | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| 20 | Nottingham | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| 21 | Oswestry | 10 | 9 | 19 |

| 22 | Oswestry | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| 23 | Oxford | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| 24 | Oxford | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 25 | Oxford | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 26 | Sheffield | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| 27 | Stanmore | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| 28 | Stanmore | 24 | 24 | 48 |

| 29 | Stanmore | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 30 | Stanmore | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| 31 | Wigan | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 32 | Wigan | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 33 | Wigan | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| 34 | Wigan | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 142 | 140 | 282 | |

Numbers analysed

Owing to the nature of the model used in the analysis of primary and secondary continuous outcomes (i.e. a mixed model), all patients with a baseline visit and at least one follow-up visit were included in the analysis. Therefore, the final primary outcome analysis was based on 281 patients: 137 in TAR and 144 in ankle fusion (Table 9).

| Analysis | TAR arm (N = 138)a | Ankle fusion arm (N = 144) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome (ITT) | 137 | 144 |

| Sensitivity of primary outcome (per protocol) | 135 | 134 |

| Secondary outcome | ||

| MOXFQ pain | 137 | 144 |

| MOXFQ social interaction | 137 | 144 |

| EQ-5D-5L index value | 137 | 144 |

| EQ-5D-5L VAS | 137 | 144 |

| FAAM-ADL | 137 | 143 |

| FAAM sport subscale | 43 | 24 |

| ROM dorsiflexion | 132 | 131 |

| ROM plantarflexion | 132 | 131 |

Primary outcome

Findings for the primary outcome, MOXFQ (walking/standing domain), are presented in Table 10.

| Outcome | TAR arm | Ankle fusion arm | Adjusted difference in change from baseline (95% CI)a | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Value at 52 weeks, mean (SD) | Change from baseline, mean (SD) | n | Value at 52 weeks, mean (SD) | Change from baseline, mean (SD) | |||

| Primary outcome (ITT) | ||||||||

| MOXFQ walking/standing score | 136 | 31.4 (30.4) | –49.9 (30.7) | 140 | 36.8 (30.6) | –44.4 (31.9) | –5.56 (–12.49 to 1.37) | 0.12 |

| Sensitivity analysis of primary outcome (per protocol) | ||||||||

| MOXFQ walking/standing score | 135 | 31.4 (30.5) | –49.9 (30.8) | 134 | 36.4 (30.8) | –45.0 (32.4) | –4.84 (–11.96 to 2.28) | 0.18 |

The mean (SD) MOXFQ walking/standing domain score at 52 weeks was 31 (30.4) in the TAR arm and 37 (30.6) in the ankle fusion arm. The mean (SD) change in scores between pre-surgery baseline and 52 weeks was –50 (30.7) in the TAR arm and –44 (31.9) in the ankle fusion arm. The adjusted difference in change score of –5.56 (95% CI –12.49 to 1.37) suggests that, on average, the improvement in the MOXFQ score from baseline to 52 weeks post surgery was 5.56 points greater in TAR patients than in ankle fusion patients (p = 0.12). The 95% CI for this difference includes both a difference of zero and the MID of 12. The MOXFQ scores improved following surgery in both arms (TAR: mean change –50, 95% CI –55 to –45; ankle fusion: mean change –44, 95% CI –50 to –39), but there was not a statistically significantly greater improvement in the TAR arm than in the ankle fusion arm. The proportion of patients with a reduction in MOXFQ score of at least 12 points from baseline at 52 weeks was very similar in the two arms: 82% of TAR patients compared with 80% of ankle fusion patients.

Four patients crossed over from ankle fusion to TAR after randomisation. Three patients had their 52-week visit outside of the protocol window and an additional five patients had missing 52-week scores. We carried out a per-protocol analysis as a sensitivity analysis for the primary outcome by excluding these 12 patients. The per-protocol analysis did not change the ITT conclusions.

Secondary outcomes

Findings for the secondary outcomes are presented in Table 11.

| Secondary outcomes | TAR arm | Ankle fusion arm | Adjusted difference in change from baseline (95% CI) | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Value at follow-up, mean (SD) | Change from baseline, mean (SD) | n | Value at follow-up, mean (SD) | Change from baseline, mean (SD) | |||

| 52 weeks | ||||||||

| MOXFQ pain | 136 | 26.7 (24.7) | –40.2 (28.0) | 140 | 30.6 (25.7) | –36.7 (24.6) | –4.20 (–9.80 to 1.39) | 0.14 |

| MOXFQ social interaction | 136 | 17.0 (20.1) | –37.0 (30.0) | 140 | 22.4 (24.4) | –33.7 (28.0) | –5.06 (–10.37 to 0.26 | 0.06 |

| MOXFQ summary indexa | 136 | 26.4 (24.5) | –43.7 (26.1) | 140 | 31.2 (25.5) | –39.3 (25.6) | –4.95 (–10.61 to 0.72) | 0.09 |

| FAAM-ADL | 135 | 81.2 (20.5) | 33.8 (22.7) | 141 | 73.8 (20.7) | 29.7 (20.7) | 6.16 (1.54 to 10.78) | 0.01 |

| FAAM sport subscale | 37 | 71.3 (28.8) | 41.9 (31.8) | 22 | 75.6 (23.2) | 52.7 (26.8) | –4.98 (–18.60 to 8.64) | 0.47 |

| EQ-5D-5L index value | 136 | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.3) | 140 | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.02 (–0.02 to 0.07) | 0.32 |

| EQ-5D-5L VAS | 136 | 81.9 (15.2) | 9.1 (19.9) | 141 | 77.0 (17.3) | 9.4 (22.3) | 3.41 (–0.30 to 7.11) | 0.07 |

| ROM dorsiflexion | 132 | 15.3 (7.2) | 1.1 (10.1) | 131 | 9.1 (5.8) | –4.9 (7.9) | 6.09 (4.61 to 7.57) | < 0.001 |

| ROM plantarflexion | 132 | 27.3 (7.9) | 1.9 (9.8) | 131 | 14.4 (7.2) | –11.7 (11.1) | 13.01 (11.24 to 14.77) | < 0.001 |

| 26 weeks | ||||||||

| MOXFQ walking/standing | 134 | 35.8 (29.9) | –45.8 (31.0) | 141 | 44.6 (29.6) | –36.9 (31.2) | –8.21 (–15.14 to –1.27) | 0.02 |

| MOXFQ pain | 134 | 32.9 (24.3) | –33.8 (25.9) | 140 | 36.2 (24.8) | –31.4 (23.8) | –2.45 (–8.06 to 3.16) | 0.39 |

| MOXFQ social interaction | 134 | 22.3 (24.7) | –32.1 (29.5) | 140 | 26.5 (24.4) | –29.6 (26.9) | –3.38 (–8.71 to 1.95) | 0.21 |

| MOXFQ summary indexa | 134 | 31.5 (25.0) | –38.6 (25.6) | 140 | 37.5 (24.9) | –33.2 (24.9) | –5.13 (–10.80 to 0.55) | 0.08 |

| FAAM-ADL | 132 | 77.1 (20.0) | 30.0 (21.4) | 140 | 70.9 (22.1) | 26.8 (21.9) | 4.56 (–0.08 to 9.20) | 0.05 |

| FAAM sport subscale | 39 | 56.6 (28.1) | 27.7 (26.2) | 19 | 62.9 (28.7) | 37.3 (35.7) | –7.17 (–21.11 to 6.76) | 0.31 |

| EQ-5D-5L index value | 134 | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.2) | 141 | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.04 (–0.004 to 0.09) | 0.08 |

| EQ-5D-5L VAS | 134 | 81.3 (14.8) | 8.7 (21.5) | 142 | 76.0 (19.2) | 8.1 (22.2) | 4.14 (0.43 to 7.85) | 0.03 |

On average, patients in both arms reported an improvement in the MOXFQ pain and social interaction domains at 26 weeks, and on all MOXFQ domains at 52 weeks, but improvement was not greater in the TAR arm than in the ankle fusion arm. The difference between the TAR and ankle fusion arms in the change in MOXFQ walking/standing domain score at 26 weeks was statistically significant (p = 0.02).

The difference between the TAR and ankle fusion arms in the change in FAAM-ADL scores at 52 weeks was statistically significant (p = 0.01). There were substantial improvements from baseline in both arms, with a difference of 6.16 (95% CI 1.54 to 10.78) between the two arms.

The change in EQ-5D-5L index values between the two treatment arms was not significantly different at 26 weeks (p = 0.08) or 52 weeks (p = 0.32). The change in EQ-5D-5L VAS was statistically significant at 26 weeks (p = 0.03), but not at 52 weeks (p = 0.07).

Changes from baseline in ROM dorsiflexion and ROM plantarflexion were greater in the ankle fusion arm than in the TAR arm. Although ROM (dorsiflexion and plantarflexion) improved from baseline to 52 weeks in the TAR arm, it decreased in ankle fusion patients and the difference between arms was statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Subgroup analyses

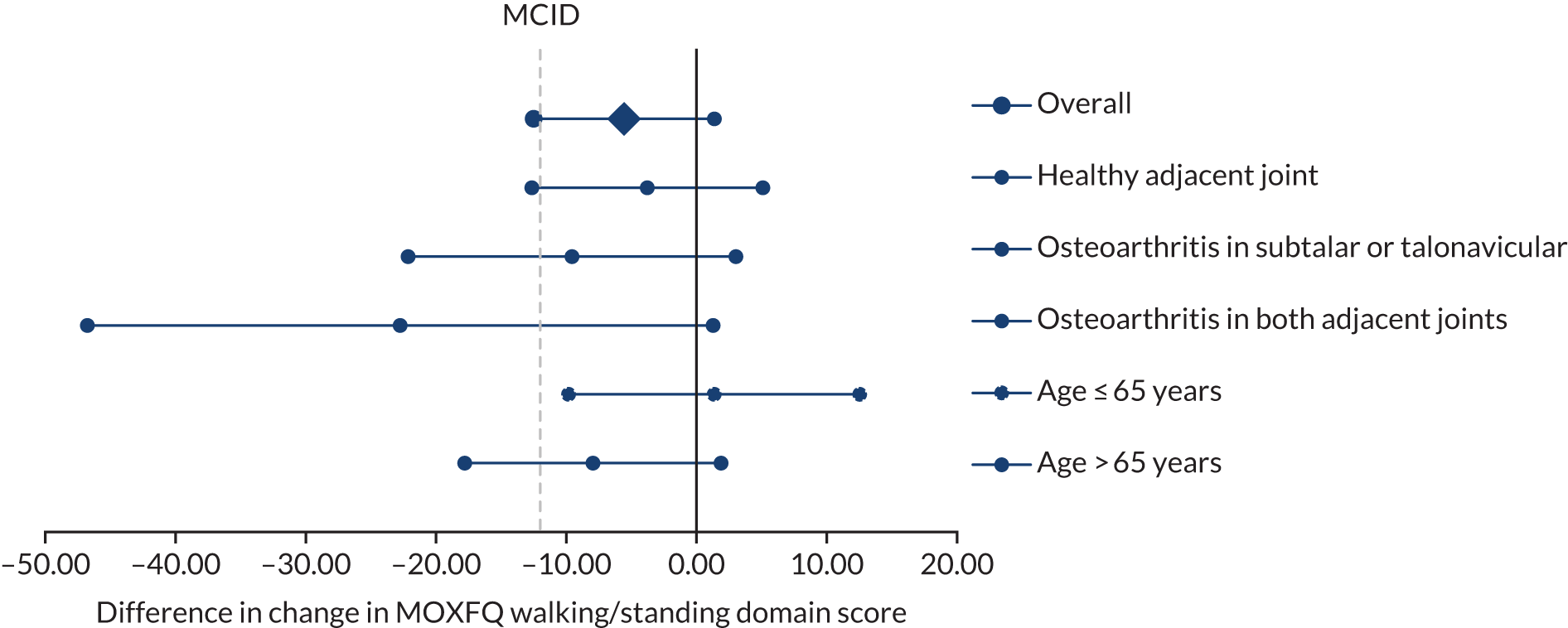

A total of 45 patients (33%) in the TAR arm and 50 (36%) in the ankle fusion arm had osteoarthritis in one adjacent joint at baseline; 11 patients (8%) in the TAR arm and 12 patients (9%) in the ankle fusion arm had osteoarthritis in both the subtalar and talonavicular joints. Adjusted MOXFQ scores were lower in the TAR arm than in the ankle fusion arm at 52 weeks in the subgroup analyses (Table 12). However, we did not find a significant interaction caused by this factor. There was also no evidence to suggest that the effect of treatment was moderated by age. The subgroup analyses are presented in Figure 2.

| Subgroup analyses | TAR arm (n) | Ankle fusion arm (n) | Difference | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in walking/standing score | |||||

| Overall effect | 136 | 140 | –5.56 | –12.49 to 1.37 | 0.12 |

| Age (years) | |||||

| ≤ 65 | 45 | 46 | 1.36 | –9.82 to 12.53 | 0.13 |

| > 65 | 91 | 94 | –7.95 | –17.79 to 1.88 | |

| Adjacent osteoarthritis | |||||

| Healthy adjacent joint | 80 | 78 | –3.78 | –12.64 to 5.09 | |

| Osteoarthritis in subtalar or talonavicular | 45 | 50 | –9.56 | –22.14 to 3.03 | 0.92 |

| Osteoarthritis in both adjacent joints | 11 | 12 | –22.75 | –46.77 to 1.27 | 0.11 |

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot showing subgroup analysis by treatment arm.

Adverse events

A total of 20.8% of randomised patients experienced at least one SAE and 53.5% of patients experienced at least one AE during the course of their trial pathway (Table 13). The risks of patients experiencing a SAE or an AE were not significantly different between the two arms (p = 0.19 and p = 0.84, respectively).

| Event | TAR arm (N = 152) | Ankle fusion arm (N = 151) | Total (N = 303) | Difference in proportion (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) of patients experiencing a SAE | 27 (17.8) | 36 (23.8) | 63 (20.8) | 0.74 (0.48 to 1.16) | 0.19 |

| Total SAEs (n) | 31 | 43 | 75 | ||

| Number (%) of patients experiencing an AE | 82 (54.3) | 80 (52.6) | 162 (53.5) | 1.02 (0.83 to 1.26) | 0.84 |

| Total AEs (n) | 162 | 168 | 330 |

All the AEs and SAEs reported during the trial have been summarised as postoperative complications in Table 14. One patient in the ankle fusion arm died during the follow-up period and one patient in the TAR arm died after the 52-week visit (not presented in Table 14). Both events were unrelated to surgery.

| Complication | TAR arm, n (N = 152) | Ankle fusion arm, n (N = 151) | Total, n (N = 303) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total surgeries (by procedure, not randomisation) | 142 | 140 | 282 |

| Complications (1–11, larger numbers thought to lead to worse outcome) | |||

| 1: Intraoperative bone fracture | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 2: Wound-healing problemsb | 20 | 8 | 28 |

| A: Not requiring antibiotics | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| B: Requiring antibiotics | 17 | 4 | 21 |

| C: Requiring debridement | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 3: Pain undiagnosedc | 17 | 23 | 40 |

| 4: Nerve injuryc | 8 | 1 | 9 |

| 5: Postoperative bone fracture | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 6: Technical error | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7: Reoperation other than revision | 5 | 4 | 9 |

| 8: Bone union issues | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| A: Aseptic loosening for TAR | 0 | – | 0 |

| B: Non-union for ankle fusion | – | 17 | 17 |

| 9: Subsidence | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10: Deep infection | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11: Implant failured | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Not related to implantc | |||

| Medical complication unrelated to implant (including cardiopulmonary) | 73 | 92 | 165 |

| Worsening of pre-existing musculoskeletal issue | 35 | 35 | 70 |

| Death | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Thromboembolic events | |||

| 1: Deep-vein thrombosise | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| 2: Pulmonary embolisme | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Otherc | |||

| Trauma | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Stiffness | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Plaster/immobilisation/mobility issues | 11 | 8 | 19 |

| Tendon complications after surgery | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Swelling | 8 | 7 | 15 |

There were 20 wound-healing problems in 19 (13.4%) patients in the TAR arm and eight wound-healing problems in eight (5.7%) patients in the ankle fusion arm. One patient in the ankle fusion arm and none in the TAR arm required debridement for the infection, although the majority of TAR patients were administered prophylactic antibiotics to treat the superficial wound infections.

There were eight nerve injury events reported in six patients (4.2%) in the TAR arm and one nerve injury event reported in one (< 1%) patient in the ankle fusion arm. Two events were reported twice.

There were 17 non-unions (12.1%) in the ankle fusion arm, which were diagnosed through the presence of a lucent line on plain radiographs at the 52-week follow-up. Of the 17 patients, eight were expected to be revised (47%), two (12%) were symptomatic but not planning to be revised due to serious comorbidities and seven (41%) were completely asymptomatic. Hence, 10 (7.1%) of 140 patients who received ankle fusion went on to symptomatic non-union.

There were 13 thromboembolic events in 11 patients: four (2.9%) patients in the TAR arm and seven (4.9%) in the ankle fusion arm. Two (1.4%) patients in the TAR arm experienced deep-vein thrombosis events and there were five events in four (2.8%) patients in the ankle fusion arm. Two (1.4%) patients experienced pulmonary embolism events in the TAR arm and there were four events in three (2.1%) patients in the ankle fusion arm. None of these events was fatal.

At 52 weeks’ follow-up, nine patients (3.2%) required further unplanned reoperation other than revisions: five in the TAR arm and four in the ankle fusion arm. In the TAR arm, one revision took place within the 52-week window. This was due to a traumatic fall, leading to a fracture and conversion to a tibiotalocalcaneal fusion. We are aware of several other revisions that will take place outside the 52-week window and these data will be reported in the 2-year results. Table 15 lists reoperations and revisions.

| Reoperation/revision | TAR arm (N = 152) | Ankle fusion arm (N = 151) |

|---|---|---|

| Total surgery (n) (by procedure, not randomisation) | 142 | 140 |

| Cases with no reoperations or revision, n (%) | 136 (95.8) | 136 (97.1) |

| Cases with reoperation, n (%) | 5 (3.5) | 4 (2.9) |

| Cases with revision, n (%) | 1 (0.7) | 0 |

| Reoperations/revisions by type (n) | ||

| Type 2: hardware removal | 0 | 2 |

| Type 3: unplanned procedures related to the TAR | 2 | 2 |

| Type 4: debridement of gutters or heterotopic ossification | 3 | 0 |

| Type 5: exchange of polyethylene bearing | 0 | 0 |

| Type 6: debridement of osteolytic cysts | 0 | 0 |

| Type 7: deep infection requiring debridement, no metal component removal | 0 | 0 |

| Type 9: revision of metal components for aseptic loosening, fracture or malposition | 1 | 0 |

| Type 10: revision of metal components secondary to infection | 0 | 0 |

| Type 11: amputation above the level of the ankle | 0 | 0 |

Post hoc analysis

The baseline characteristics of each of the subtypes of TAR (fixed and mobile bearing) and ankle fusion (open and arthroscopic) are reported in Appendix 3. Of those who received TAR, 53.5% received fixed-bearing TAR and 46.5% received mobile-bearing TAR. Of the ankle fusion patients, 61% received arthroscopic ankle fusion and 39% received open ankle fusion. Overall, all four subtypes of patients appeared similar with respect to baseline factors and baseline outcome measures. We carried out a post hoc comparison of each TAR subtype (those who received fixed-bearing TAR and those who received mobile-bearing TAR) with the ankle fusion arm (including both open and arthroscopic ankle fusion patients).

The mean (SD) MOXFQ walking/standing domain score at 52 weeks was 25.9 (28.3) in the fixed-bearing TAR group, compared with 36.8 (30.6) in the ankle fusion arm (Table 16). The adjusted difference of –11.1 (95% CI –19.3 to –2.9) suggests that, on average, the MOXFQ score at 52 weeks post surgery was 11.1 points lower in those who received fixed-bearing TAR than in those who underwent ankle fusion. This difference is statistically significant (p = 0.008). Comparing mobile-bearing TAR patients with ankle fusion patients, the adjusted difference is 2.1 (95% CI –6.6 to 10.8). This difference is not statistically significant (p = 0.64). There was no difference in the change in MOXFQ score at 52 weeks (p = 0.83) between open and arthroscopic patients in the ankle fusion arm (see Appendix 4).

| Ankle fusion arm (n = 136) | TAR arm | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed bearing (n = 75) | Mobile bearing (n = 64) | ||

| Operation duration (minutes), mean (SD) | 103 (36.2) | 121 (30.6) | 122 (32.7) |

| MOXFQ at 52 weeks, mean (SD) | 36.8 (30.6) | 25.9 (28.3) | 38.5 (31.6) |

| Change from baseline at 52 weeks, mean (SD) | –44.4 (31.9) | –55.9 (27.7) | –42.0 (32.1) |

| Adjusted difference in change from baseline (95% CI) | – | –11.1 (–19.3 to –2.9) | 2.1 (–6.6 to 10.8) |

| p-value | – | 0.008 | 0.64 |

The subgroup analyses by subtype of TAR patients (fixed and mobile bearing) compared with ankle fusion patients are shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Forest plots showing subgroup analysis by treatment arm and TAR subtype. (a) Fixed-bearing TAR vs. ankle fusion; and (b) mobile-bearing TAR vs. ankle fusion.

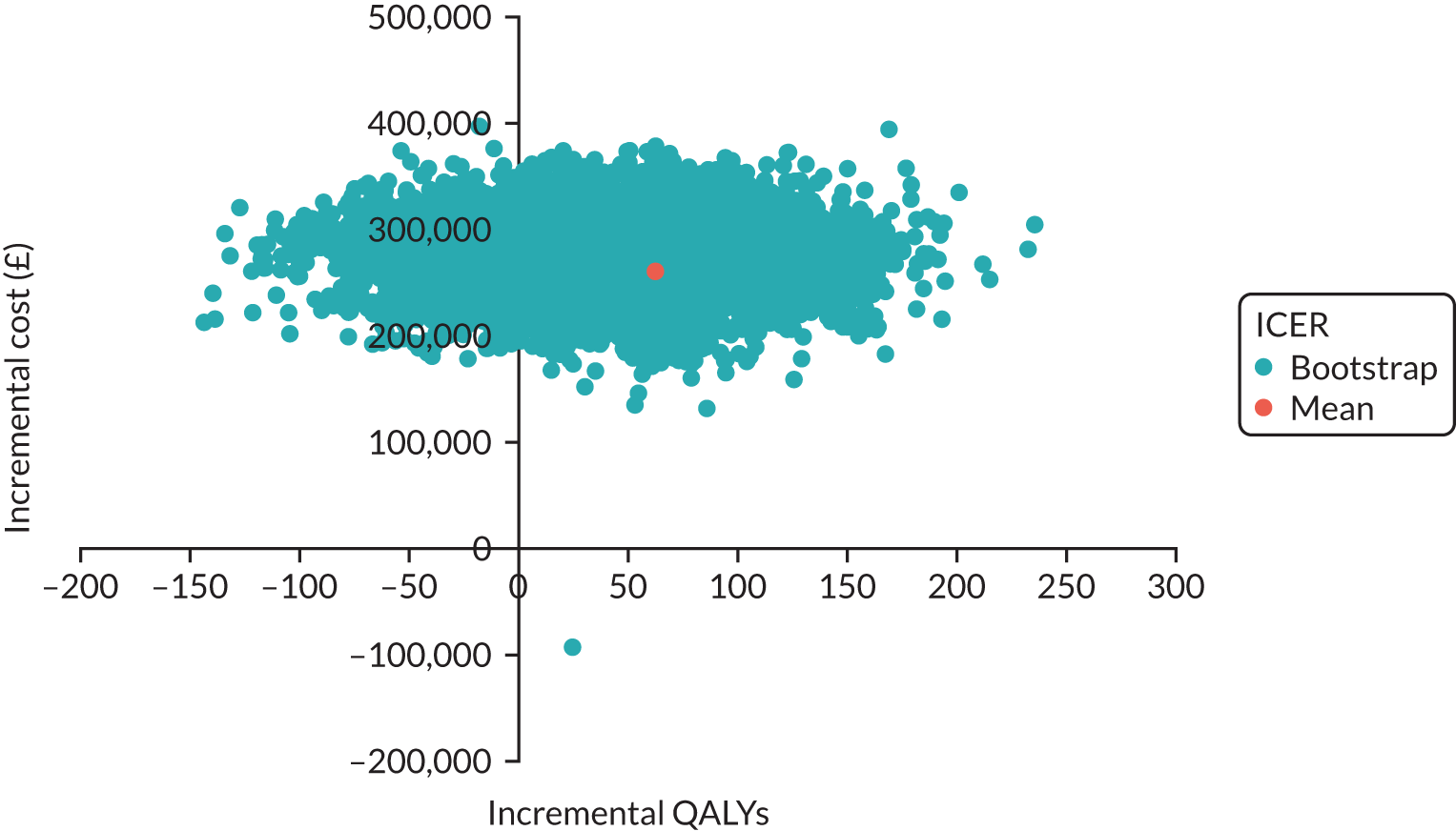

Chapter 4 Economic evaluation

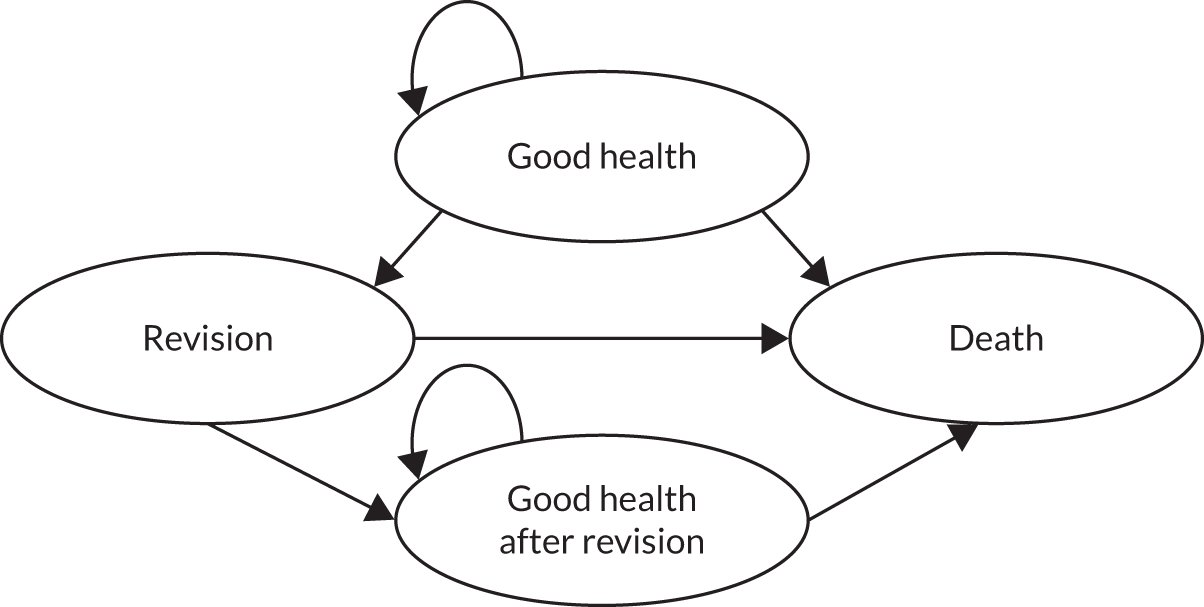

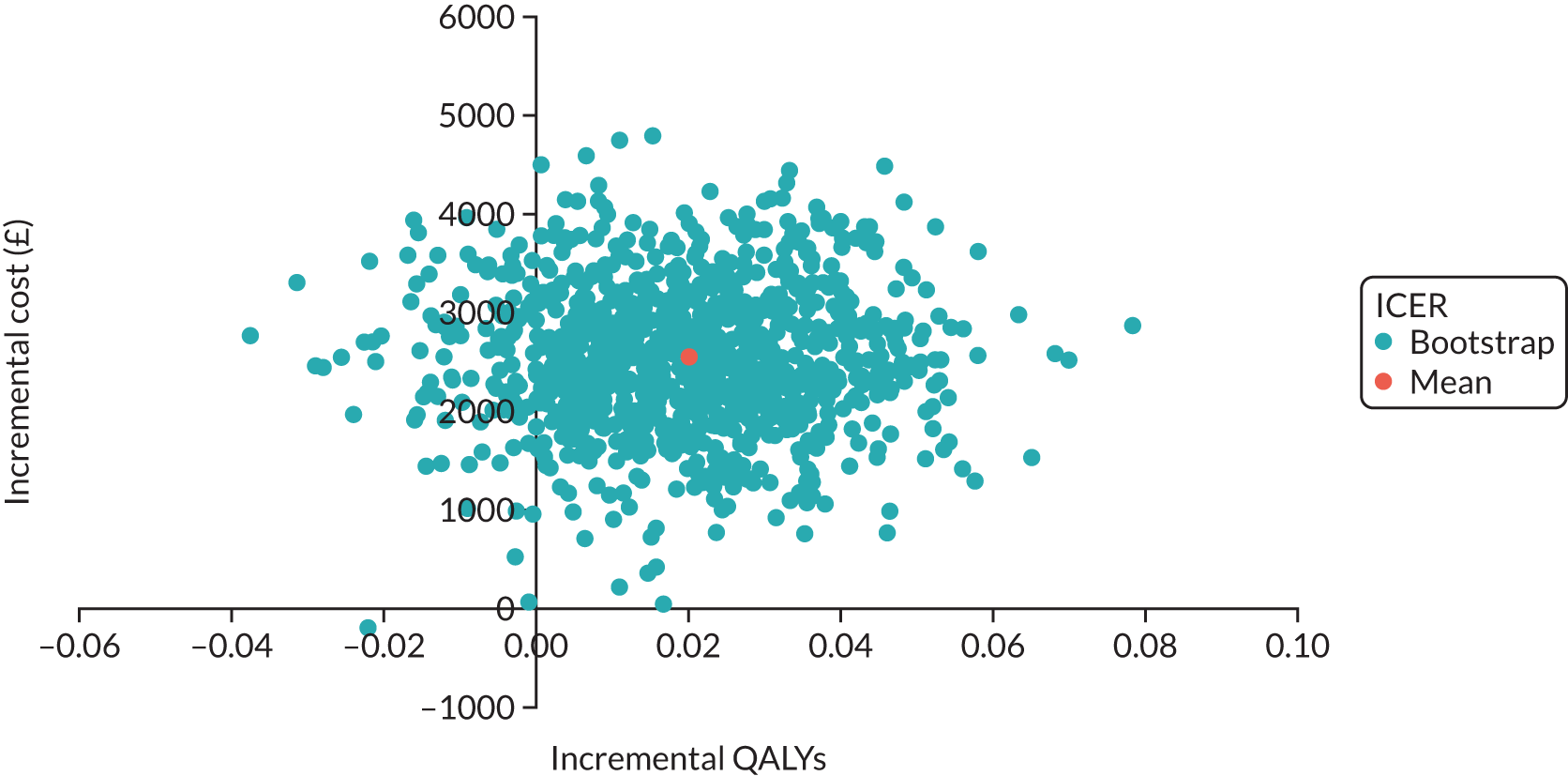

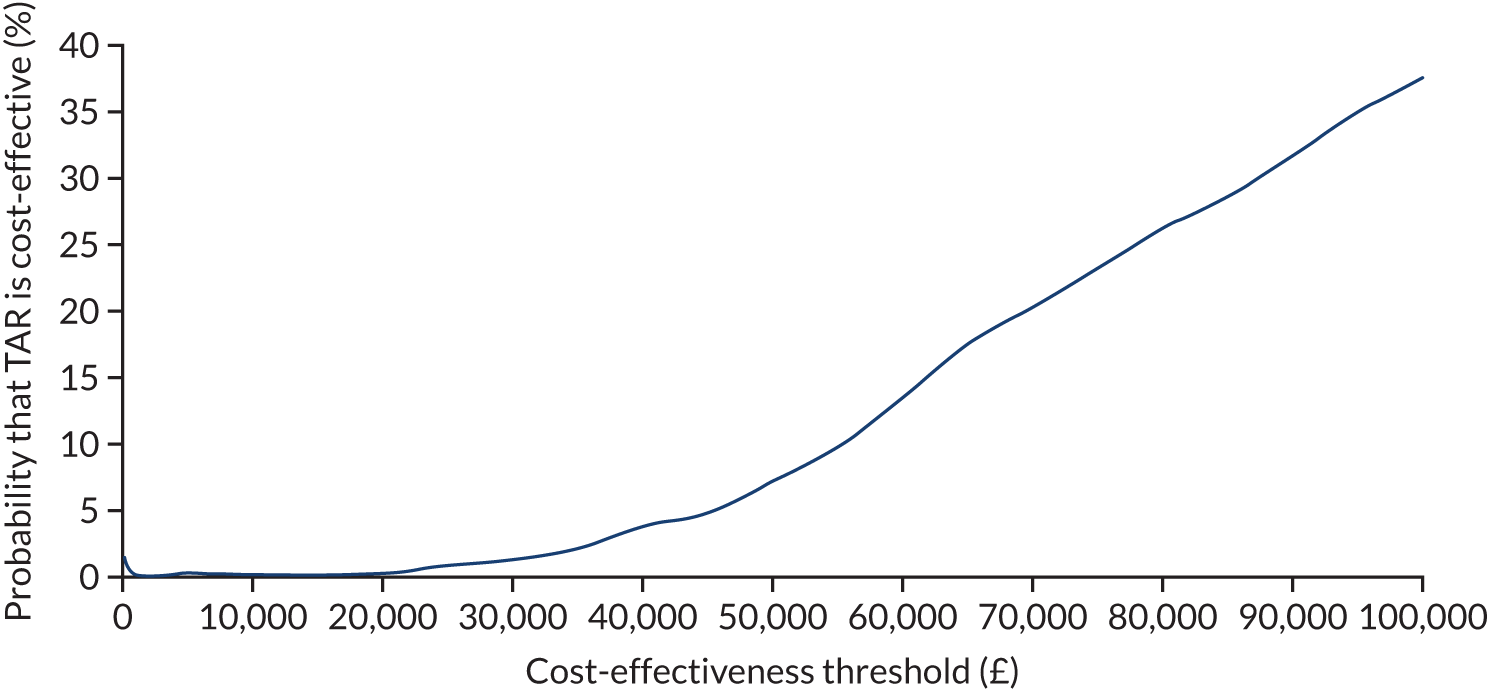

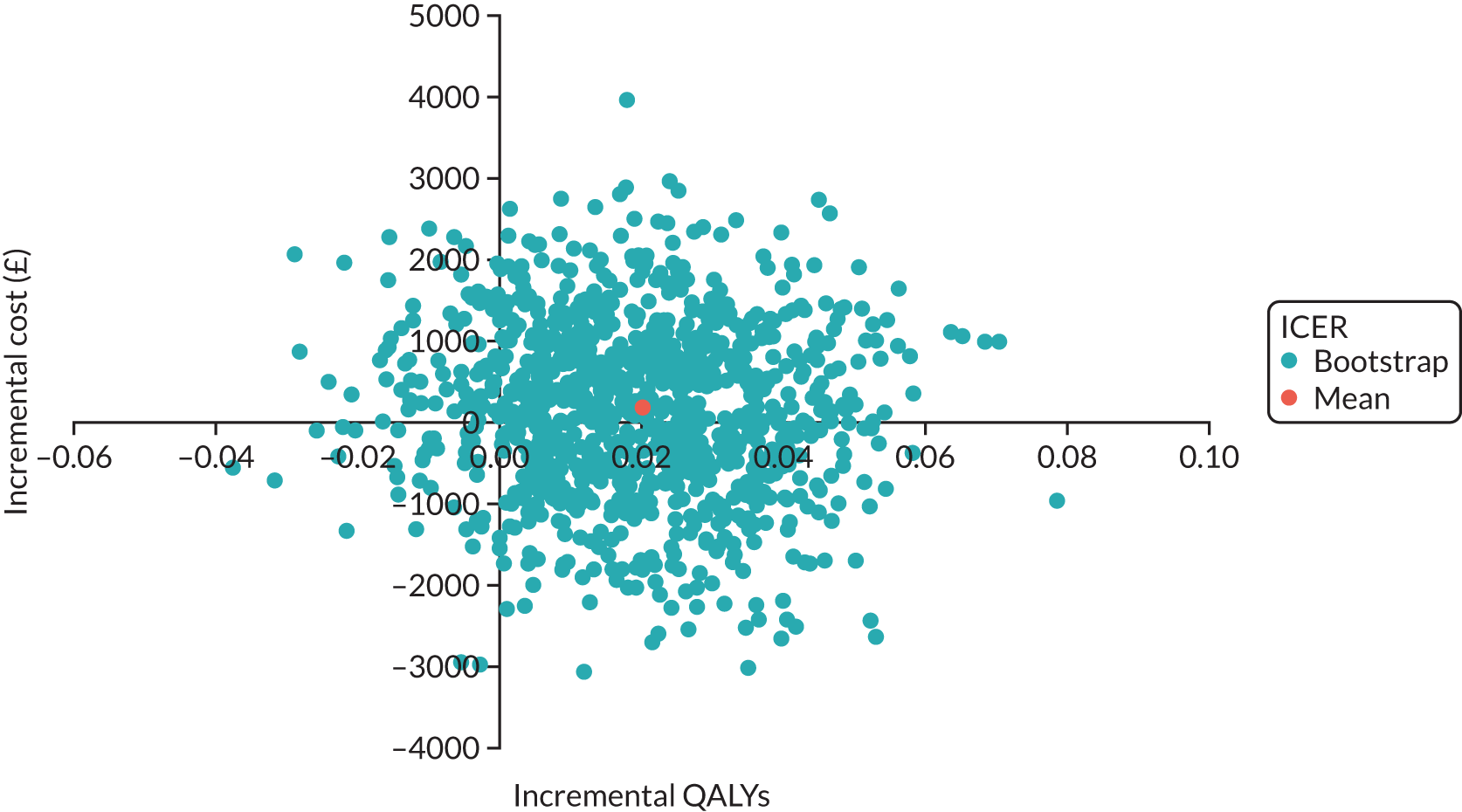

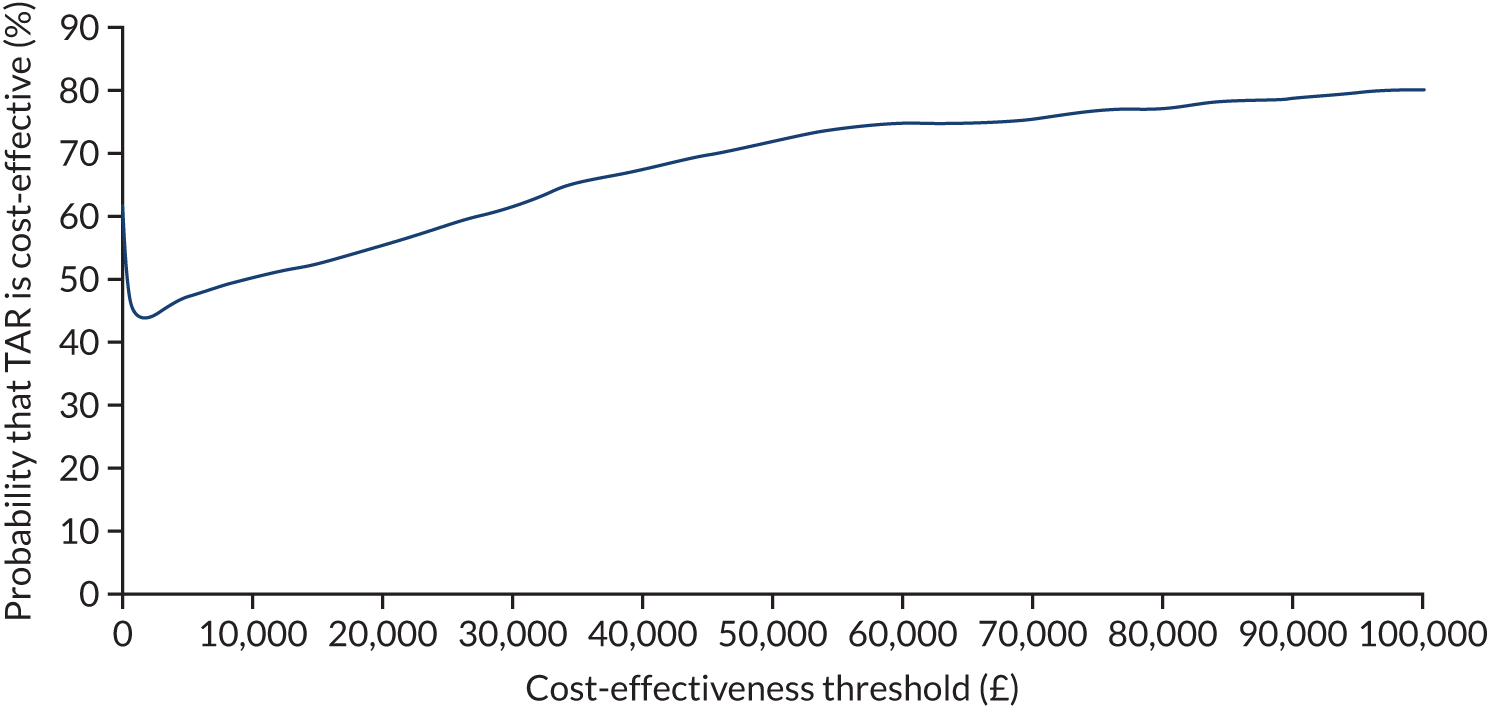

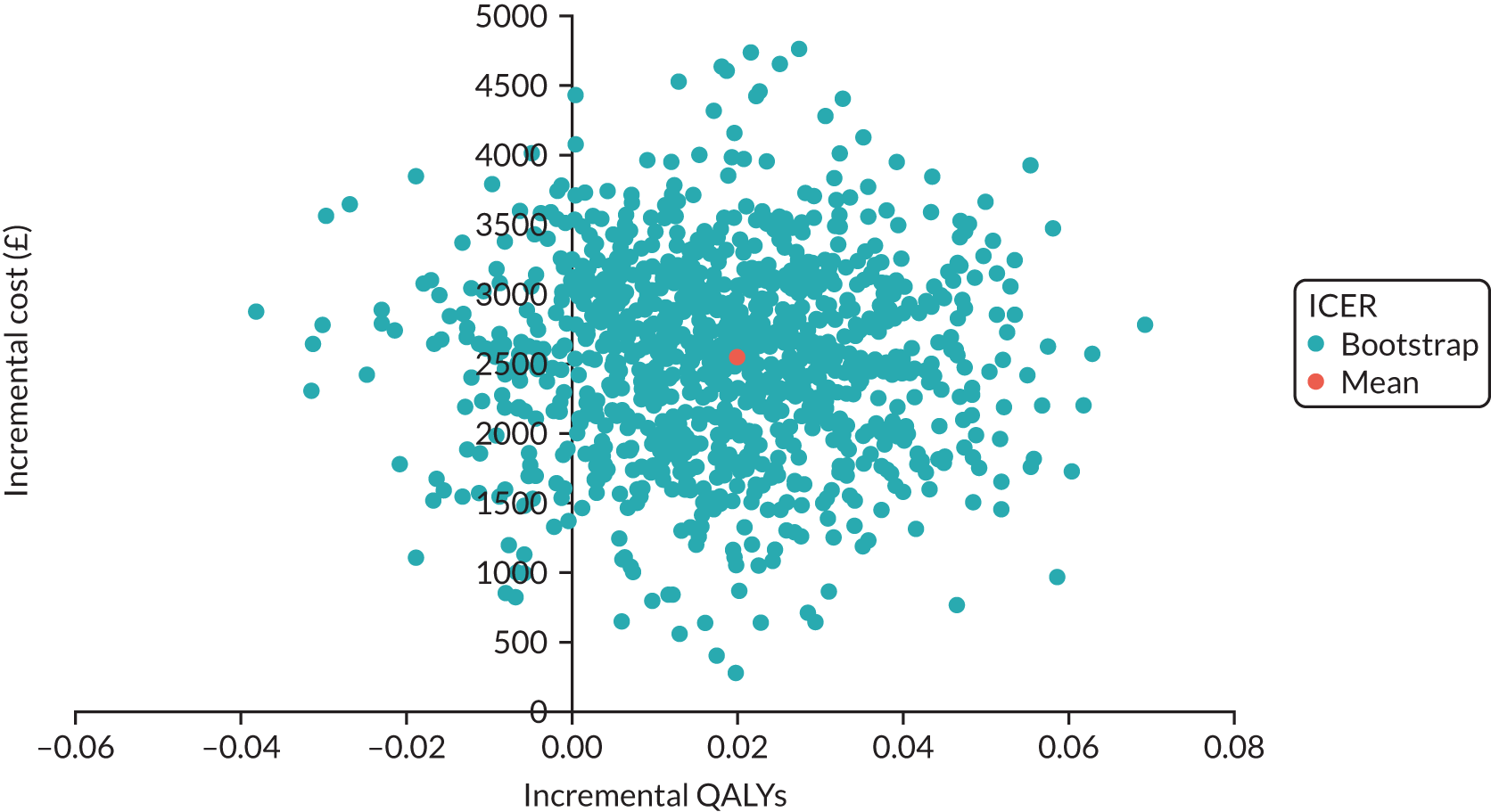

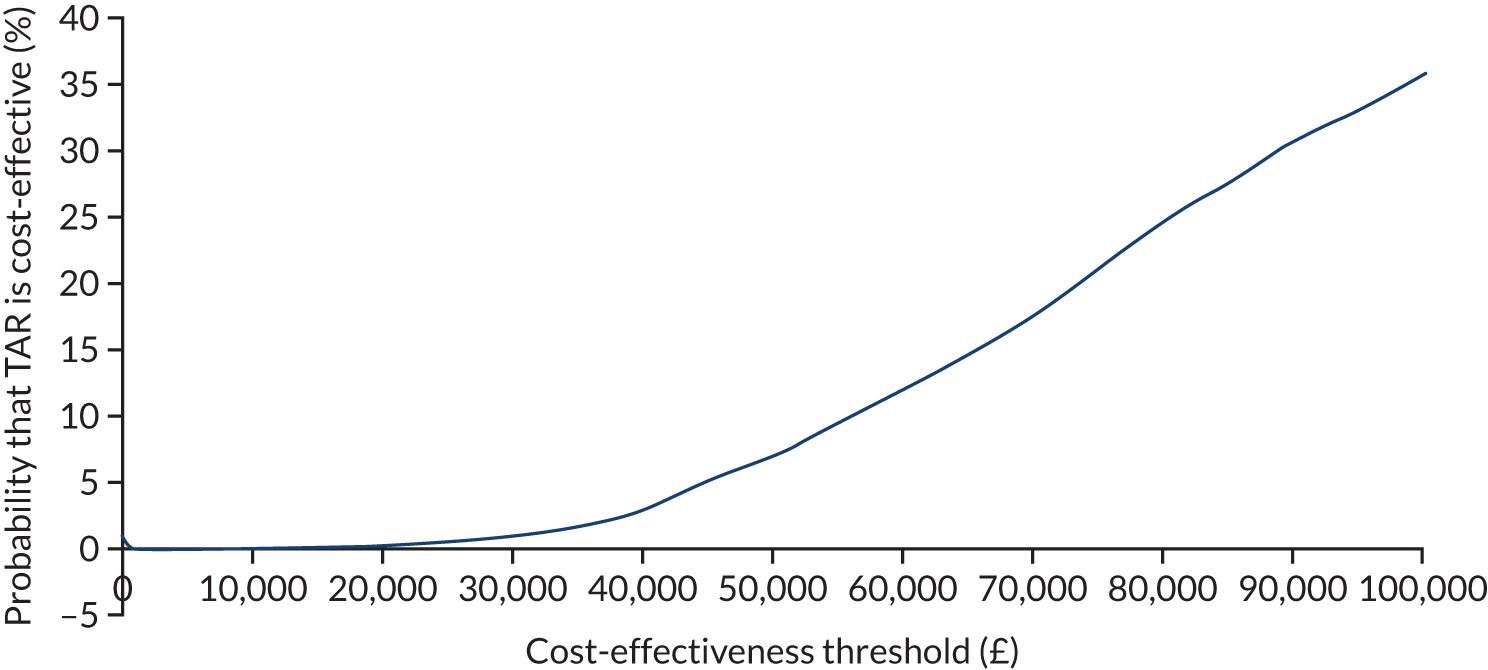

Overview