Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number NIHR127489. The contractual start date was in January 2020. The draft manuscript began editorial review in April 2022 and was accepted for publication in December 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Rivero-Arias et al. This work was produced by Rivero-Arias et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Rivero-Arias et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

National population screening programmes are implemented in health systems on the advice of screening committees such as the United Kingdom National Screening Committee (UK NSC), which makes independent, evidence-based recommendations to ministers in the four countries of the UK. Antenatal and newborn screening are covered by 6 of the 11 NHS screening programmes, namely fetal anomaly screening, infectious diseases in pregnancy screening, the newborn and infant physical examination, newborn blood spot screening, newborn hearing screening and sickle cell and thalassaemia screening. The recommendation to adopt a screening programme on a national scale is based on the premise that the benefits associated with screening outweigh the harms to all relevant stakeholders once implemented. 1 Harms of screening associated with false-positive and false-negative results include unnecessary additional resources to conduct further investigations, adverse psychological effects and legal claims, as well as decreased trust and confidence in the healthcare system. 2 In antenatal screening, when a decision to continue a pregnancy is made after a true-positive result, a clear screening benefit is the time it offers expectant parents to prepare for the care of a child with a clinical condition. An informed decision to terminate a pregnancy can also follow after a true-positive result. Both outcomes can sometimes lead to long-lasting psychosocial sequelae for women and their partners, affecting their quality of life and their future pregnancy choices. 3–9 The use of whole genome sequencing for newborn screening presents an opportunity to identify and treat or prevent severe health conditions, thus maximising survival and quality of life of the newborn, but is subject to overdiagnosis and over-treatment that need careful evaluation. 10,11

Screening committees require up-to-date evidence of these benefits and harms as well as data demonstrating that the screening programmes represent value for money. 12 The latter is determined using a health economic assessment confirming that the additional costs of implementing a screening programme are justified by the additional benefits achieved, usually through outcome measures such as the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained, where the QALY combines preference-based health-related quality-of-life weights (health utilities) with data on length of time in the health states of interest. 13 This approach to cost-effectiveness assessment mirrors those recommended more broadly by Health Technology Assessment (HTA) agencies in the UK, such as the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in England and the Scottish Medicines Consortium in Scotland. 14,15 It also mirrors the preferred form of cost-effectiveness assessment adopted by HTA, pricing and reimbursement authorities in several other industrialised countries. 16–18 Although there is established guidance on best practices for economic assessment for screening programmes in general, such as in the area of economic modelling,19 such guidance does not address the challenges of how to incorporate the breadth of potentially relevant benefits and harms into a single assessment, and does not specifically focus on antenatal and newborn screening. Guidance in this area, therefore, remains limited. 20

Furthermore, several methodological factors have constrained capacity to evaluate antenatal and newborn screening programmes using the standard incremental cost per QALY gained metric. These include challenges surrounding the valuation of prenatal life when decisions following antenatal screening and diagnostic testing result in the termination of the fetus or unborn child,21,22 the absence of a multi-attribute utility measure validated for use in infancy and through early childhood23 and the challenges surrounding QALY aggregation across the mother, child and potentially other family members. 24 Attributes of relevance to parents, such as the utility derived from information per se or reassurance following a screen-negative test result, and the disutility associated with anxiety from a false-positive test result or over-diagnosis of disease, are likely to be missed, or at least inadequately covered, by standard approaches to health utility measurement, such as available multi-attribute utility measures [e.g. EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D), Short Form 6-Dimension (SF-6D), Health Utilities Index Mark 3]. 25,26 In addition, numerous ethical challenges also compound the technical complexities surrounding economic assessments of antenatal and newborn screening programmes. These emanate from differences in moral perspectives on the status of the fetus or unborn child22 and how society should value disability,27 and differing perspectives on the ownership of genetic information28 and the potential harms of inadequately informed consent processes on parental autonomy. 29 Failure to incorporate all relevant benefits and harms when assessing the cost effectiveness of antenatal and newborn screening programmes may lead screening committees to make decisions based on suboptimal levels of evidence, resulting in a suboptimal allocation of resources.

Previous work has focused on the identification of methodological challenges and the development of good practice guidelines for the purpose of health economic assessments of antenatal and newborn screening programmes. 20,30,31 However, none has specifically focused on the range of benefits and harms incorporated into health economic assessments of antenatal and newborn screening programmes, or the methodological issues surrounding their identification, measurement and valuation.

Objectives

The overall aim of the proposed programme of work was to enhance knowledge about methods for valuing benefits and harms within economic assessments of antenatal and newborn screening and make recommendations about the benefits and harms that should be considered by economic evaluations and the health economic tools that could be employed for this purpose. Our specific objectives were:

-

to systematically identify the benefits and harms adopted by health economic assessments evaluating antenatal and newborn screening programmes, and to assess how they have been measured and valued

-

to identify attributes of relevance to stakeholders (parents/carers, health professionals, other relevant stakeholders) that should be considered for incorporation into future economic assessments using a range of qualitative research methods

-

to make recommendations about approaches for the measurement and valuation of outcomes that should be considered by future economic assessments in these contexts.

A brief explanation of the foundations of health economic assessments for non-health economists.

A note about benefits and harms of screening

The aim of a screening programme is to identify asymptomatic people who may be developing or at a greater risk of developing a condition and offer further investigations and/or treatment. The objective is then to allow individuals to make informed choices and reduce complications in the future. Screening programmes run on a national population scale and every year millions of people in countries with established screening organisations benefit from these programmes. However, no screening test is perfect and when false-negative result (individual with a negative screening result with the target condition) and false-positive result (individual with a positive screening result without the target condition) happen, there is potential to generate harm to the people the programme is intended to help. Consequently, screening programmes are subject to benefits as well as harms. In the UK, the NSC makes recommendations about adding new conditions to the current antenatal and newborn screening programmes based on the premise that the benefits associated with screening outweigh its harms at a population level. Essentially, screening agencies evaluate available evidence about benefits and harms of the screening programme in an attempt to understand whether it does more good than harm to the population.

The benefits of screening are diverse and include better future health for individuals who are identified asymptomatically or at an early onset of the disease, more effective treatment for individuals who are true screen positive, reassurance of women and their families, informed decisions about continuation or end a pregnancy and justifiable allocation of NHS resources to implement the programme. Harms of screening are also diverse and encompass incorrect results and associated anxiety or false reassurance, difficult decisions about continuing or ending a pregnancy, risks associated with treatment or the screening test and over-treatment (people identify with a condition that would never develop into a serious condition over the life course). If harms of screening are not quantified correctly, screening agencies risk that many people could be harmed instead of benefiting from screening.

How these benefits and harms are included in health economic assessments is currently not known and VALENTIA aims to clarify this. In the previous section, we introduce the QALY as an outcome measure widely used in economic evaluation to evaluate the health benefits of screening. We hypothesise in this study that QALYs are a good outcome measure to capture functional and psychological impacts of screening test results for women and their babies in newborn screening, but that present challenges in antenatal screening test results leading ending a pregnancy. Moreover, we also hypothesise that a particular screening result may be seen as a benefit for a group of women and seen as a harm for another group. Whether researchers have attempted to estimate QALYs capturing all these complexities is currently not known.

Organisation of the VALENTIA study

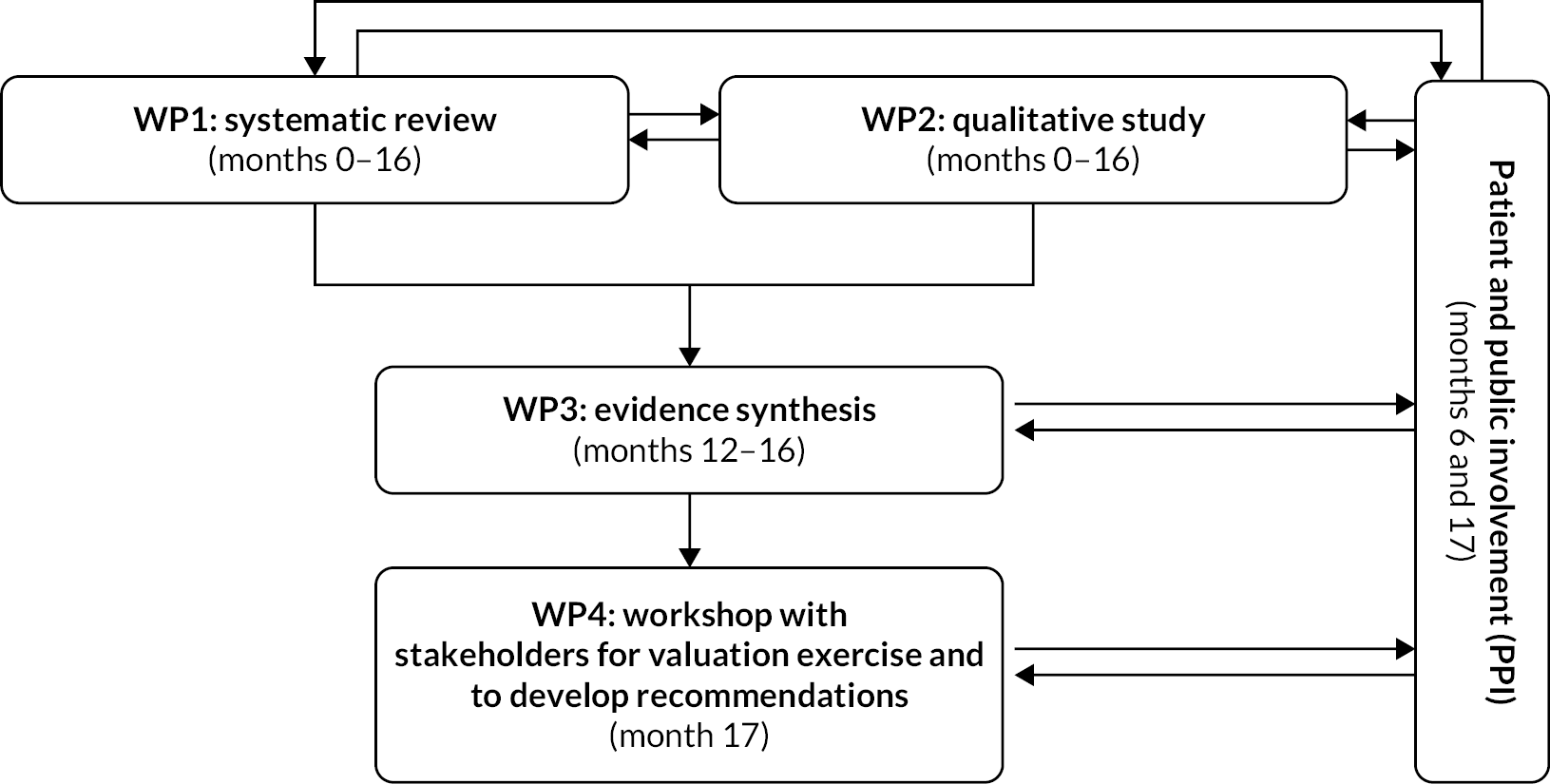

To achieve the objectives set out in Objectives, VALENTIA was organised into four linked work packages (WPs) as described in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of the four linked WPs of the VALENTIA study.

In the first WP1, a systematic review of the published and grey literature identified all health economic assessments evaluating antenatal and newborn screening programmes in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. Information relevant to the screening programmes, complemented by the reporting items contained within the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS), was extracted. This exercise provided a complete picture of the cost-effectiveness evidence assessing antenatal and newborn screening programmes in terms of the clinical areas and the reporting quality of the articles and reports. Chapter 3 describes the methodology of the systematic review with associated results and interpretation. Detailed information about the types of benefits and harms included in each of the studies was also extracted. Using an integrative descriptive analysis, we developed a thematic framework of benefits and harms used in health economic assessments in this area. We applied this thematic framework to the literature identified and discovered that economic evaluations assessing antenatal and newborn screening programmes have generally adopted a narrow range of benefits and harms or ignored important benefits and harms in their evaluations. Our work suggests that there is an immediate need to provide guidance for researchers conducting economic evaluations of antenatal and newborn screening. Our proposed thematic framework of benefits and harms can be used to guide the development of future health economic assessments evaluating antenatal and newborn screening programmes, to prevent exclusion of important potential harms. The development of this framework and its application is presented in Chapter 4.

Work package 2 was a qualitative study conducted using multiple methods to capture stakeholders’ views about the benefits and harms of antenatal and newborn screening that should be incorporated into future economic assessments. The qualitative component of VALENTIA is presented in three separate chapters in this report. Experiences of antenatal screening have been extensively investigated, but newborn screening experiences remained underexplored. Therefore, a meta-ethnography was conducted to better understand what was known about the experiences of newborn bloodspot screening (see Chapter 5). This was followed by secondary analysis of existing individual interviews related to antenatal screening, newborn screening and living with screened-for conditions (see Chapter 6). In this exercise, the goal was to bring together, examine and interpret the findings from disparate qualitative research studies and produce a richer and broader understanding than would be possible by looking at the studies individually. A large body of existing interview data was drawn upon to reflect a range of screening experiences and to better understand how individuals affected by screening discussed their experiences. What emerged was a complex web of individuals, organisations, technologies and discourses that shape the screening landscape. In Chapter 7, a thematic analysis of primary data collected with stakeholders about their experiences with antenatal and newborn screening was carried out. This analysis was conducted with three groups of stakeholders (individuals, charities, professionals working in the field of policy and healthcare professionals) to understand how these groups conceptualised the benefits and harms of screening. This primary data collection further developed the concepts derived from our meta-ethnography and secondary analysis, which developed an understanding of the landscape in which benefits and harms might be conceptualised. By using a range of qualitative methods, the benefits and harms of screening as experienced and perceived by a variety of stakeholders were identified, as well as concepts which did not map neatly onto the harms and benefits identified within existing economic assessments from WP1. The methods and results for each of these pieces of work in individual chapters are presented before summarising critical findings from across components of the qualitative study at the end of Chapter 7.

Work package 3 compared the benefits and harms identified in the quantitative health economics literature (WP1) and the qualitative literature (WP2) using a narrative synthesis exercise. The aim was to understand whether benefits and harms relevant to stakeholders were missing in the health economic assessment conducted in antenatal and newborn screening. In general, we observed good overlap between both types of data, but some gaps were also found. We present this in Chapter 8 and provide a discussion about potential alternatives to incorporate some of the missing benefits and harms in future work.

The final WP4 involved meeting with key stakeholders to discuss potential valuation techniques to value antenatal and newborn screening scenarios following the results from previous WPs and a final meeting to present the results of the study and our recommendations for future work. Although originally planned as face-to-face meetings over 2–3 days with different stakeholders’ groups, this was not possible due to pandemic restrictions at the time of the study. Given this change in format and the challenges of keeping audiences engaged in online settings, we instead conducted two online workshops with participants from our patient and public involvement group where we discussed potential alternative valuation techniques, and a large virtual workshop with the remaining stakeholders to discuss our final results and recommendations. Full details are presented in Chapter 9.

A final set of recommendations for the conduct of economic evaluations assessing antenatal and newborn screening programmes arising from the study is presented in Chapter 10.

An important aspect of the VALENTIA study was our approach to parent and public involvement (PPI). From the design of the study through to delivery, we placed PPI at the centre of our programme of work. Our strategy involved working with our PPI co-investigator to create a group of PPI members at the beginning of the study with different antenatal and newborn screening experiences to support the work carried out in the WPs. We explain this strategy and the areas where we have benefited from input from our PPI members in the next chapter (see Chapter 2).

Chapter 2 Parent and public involvement

Background

The inclusion of the public and patient voice is now widely regarded as an important element of research, ensuring that research is both relevant to the people affected by it and written in a way that is easily understood by the general public. 32 For VALENTIA, it was clear from the conceptualisation of the study that PPI would be fundamental to the identification and interpretation of benefits and harms of screening, since this calls for first-hand experience of antenatal and newborn screening.

There were several key considerations which steered the development of the PPI strategy for the study. Firstly, the many kinds of experiences that a woman and/or her partner may have during their interactions with a screening programme would need to be reviewed to determine how to put together a representative group for the PPI. Secondly, an engagement strategy would be needed since the PPI members would be engaged over a considerable period of time (24 months) and across several of the WPs. Finally, it was crucial that the PPI members were treated sensitively and respectfully, given the potential for traumatic experiences related to screening outcomes. There was particular concern to ensure the emotional well-being of all PPI members, avoiding harm through interactions with other PPI members who may hold different views or have had very different screening experiences.

This chapter describes the development of the PPI strategy, the ‘recruitment’ and characteristics of the group, and reflects on the successes and challenges of the PPI element of the study. Where our PPI members provided input into the specific workstreams, this is expanded in the PPI sections in the relevant chapters. We have reported the methodology and results according to the GRIPP2 guidelines. 33 The GRIPP2 short form table (Table 1) identifies the area(s) in the report where each reporting element can be found.

| Section and topic | Item | Reported on |

|---|---|---|

| 1: Aim | Report the aim of PPI in the study | Chapter 2 |

| 2: Methods | Provide a clear description of the methods used for PPI in the study | Chapter 2 |

| 3: Study results | Outcomes – report the results of PPI in the study, including both positive and negative outcomes | Chapters 2 , 6 , 7 , 9 |

| 4: Discussion and conclusions | Outcomes – comment on the extent to which PPI influenced the study overall. Describe positive and negative effects | Chapters 6 , 7 , 9 |

| 5: Reflections/critical perspective | Comment critically on PPI input in the study, reflecting on the things that went well and those that did not, so others can learn from this experience | Chapter 2 |

Objective

The aim of our PPI was to create a representative group of members of the public with direct experience of the antenatal and newborn screening programmes in the UK. The group was established to help clarify and interpret the study results, the sampling and data collection methods, analysis and synthesis of the results and conclusions of the study. The PPI group was an integral part of the research process, being involved at several stages for input and guidance, and receiving regular study updates.

Methods

In a first step, in collaboration with our PPI co-investigator (JF), the research team mapped out the broad categories of possible antenatal and newborn screening experiences, resulting in 14 different ‘groups’ of experience (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Flow chart of the categories of experience of newborn and antenatal screening.

These groups were shaped and refined according to several factors: whether parents consented or not to the screening, whether the results of the screening tests were positive or negative and whether a condition was diagnosed or not (‘true-’ or ‘false-’ positive or -negative results). Depending on which categories parents’ experiences fall into, their perceptions of the benefits and harms of screening vary. As a result, it was decided that representation across as many of the groups as possible in Figure 2 was needed. We aimed to recruit several members from each category, with the goal of including a minimum number of two members from each experience group, representing 28 potential PPI members. We were also cognisant to include seldom-heard voices within the screening process, including fathers, people with disabilities and those from ethnic minority groups. 34–36 Engaging such a large and diverse group would be a significant undertaking, so early in the study a PPI Coordinator (JSO) joined the study team.

The creation of the PPI group coincided with the start of the global pandemic and affected the PPI element in two ways. Firstly, resources: access to recruitment avenues, and then the available time and energy that potential PPI members had for a study such as this were drastically reduced. Charities with whom we engaged were under resourced and many were not able to support reaching out to their communities in a way we had hoped. Potential PPI members were likely to be parents of young children, some with additional support needs, with dual working from home and child-care responsibilities, which significantly impacted the likelihood of being able to participate. Secondly, restrictions in the UK meant that the planned face-to-face interactions had to take place online, which caused concern over the development of rapport and group cohesion. However, we found that regular communication by e-mail and holding discussions online still provided the depth of response and input we had hoped for.

To begin engaging possible PPI members, we contacted relevant organisations as well as contacts linked to pregnancy, parenting, screened-for conditions and parental support following the diagnosis of a condition, drawing on the networks of our co-investigators. The National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit (NPEU), where several of the research team were based, has long-standing relationships with such organisations. Twenty-eight organisations were identified through these sources and contacted, including several that support parents in socially deprived areas such as Maternity Mates (based in Tower Hamlets). Eleven of the organisations responded to the team’s request to advertise the opportunity to their members. Alongside this, VALENTIA co-investigator JF, who is Director of Antenatal Results and Choices (ARC), a charity that supports parents following the diagnosis of a genetic or physical condition, shared the project with service users, and co-investigator FB identified parents and people with disabilities who had been involved in earlier research relating to screening and who had consented to participate in future research.

These ‘trusted intermediaries’ enabled the team to undertake wide-reaching advertising, which, along with other avenues such as social media posts and snowballing, resulted in 30 PPI members across 9 of the experience groups in Figure 2 volunteering to participate as PPI members. Groups 7, 10, 12, 14 and 15 including those who opted out of NHS screening and either undertook private screening or no screening at all proved more difficult to engage with. Several clinics and privately practising clinicians were contacted for support with reaching those parents who opted for private screening but declined to engage with the study. It was expected that parents opting out of screening would be a harder population to reach,37 given that only a very small number of parents do not have tests. In 2018–9, the NHS reported that 99.1% of eligible parents in England had a fetal anomaly screening test result documented. Of the nine groups that were represented most had between two and four representatives, but it should also be acknowledged that, while parents were ‘assigned’ to a group based on their most recent or prominent experience, many parents had multiple experiences of screening over one or more pregnancies, and therefore members provided a broad and rich depth of perspectives.

To maintain engagement and reflect the value they added to the study, we ensured that all our PPI members were remunerated at a rate consistent with National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Centre for Engagement and Dissemination guidelines. We maintained regular e-mail communication throughout the project, providing updates on progress and signposting when further input may be needed. We also produced training videos to explain the roles of PPI in research, an overview of the study and an overview of qualitative research. There was concern that not being able to hold face-to-face PPI focus groups would be detrimental to the members’ engagement with the project. Careful thought was given to how to recreate the level of interaction and rapport gained through face-to-face discussions using online communication tools. We chose the platform ‘SLACK’ which allowed PPI members to have own anonymised communication though an individual ‘channel’ where a researcher could ask their input, share resources such as training videos or written material, and to respond to questions and discussion points that were posted by the research team either in their own time or over a specified window. This feature was crucial for the accessibility of the PPI strategy, given the competing demands on members’ time, and our desire not to exclude those with limited availability, for example, due to caring responsibilities. In some ways, it was an advantage over face-to-face discussion groups. Towards the end of the study, we also facilitated two smaller online focus group discussions using Zoom conference facilities, which enabled the researchers and PPI members to interact in real time and enabled more free-flowing discussions (see Chapter 9).

Demographics

It took a significant amount of time and resources, from April to September 2020, to reach sufficient numbers of representatives for the group. Thirty members, representing 10 of the 14 experience groups, ultimately consented to take part; however, 1 member withdrew prior to the first interaction session due to personal reasons, resulting in a final group of 29 members. Their characteristics are shown in Table 2.

| Woman, n (%) | 27 (93.1) |

|---|---|

| Mean age, years | 34.8 |

| Range of age, years | 23–41 |

| Disability, n (%) | |

| No | 27 (93.1) |

| Yes | 1 (3.4) |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (3.4) |

| Religious beliefs, n (%) | |

| Christian | 7 (24.1) |

| Hindu | 1 (3.4) |

| None | 20 (69.0) |

| Other/prefer not to say | 1 (3.4) |

| Nationality, n (%) | |

| British | 22 (75.9) |

| Scottish | 1 (3.4) |

| British and American | 1 (3.4) |

| Other/prefer not to say | 5 (17.2) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| White | 20 (69.0) |

| Other white background | 4 (13.8) |

| Black | 1 (3.4) |

| Asian/British Asian | 2 (6.9) |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic background | 2 (6.9) |

| Employment status, n (%) | |

| Full-time | 8 (27.6) |

| Part-time | 10 (34.5) |

| Self-employed | 4 (13.8) |

| Furloughed | 1 (3.4) |

| Unemployed/working with your family/caring | 5 (17.2) |

| Other/prefer not to say | 1 (3.4) |

Despite the unprecedented burdens of child care on this group, we managed to build up the PPI group over several months. The PPI group was demographically diverse, although we acknowledge not nationally representative. The group characteristics included a range of age and socioeconomic status, but it was not as diverse as we had hoped for in terms of ethnicity, religion or disability. Efforts were made to engage with people from minority ethnic backgrounds, such as engaging with ‘Maternity Mates’, sharing widely through charities and social media and using wording which encouraged men and lesser heard voices to participate. With the limited resources available and the pressures on this particular population, it was not possible to achieve representativeness in the group. Perhaps if the timing of the study had been different, it might have been easier to obtain a more representative PPI group, and this is acknowledged as a significant challenge and limitation.

Results

The PPI members provided input at several points over the duration of the project, feeding significantly into WP2 and WP4. They reviewed the sampling strategy of the qualitative WP, and identified additional participant groups to include. They also provided feedback on the wording and screening scenarios that would be used as tools to prompt discussions during focus groups and interviews with participants in the qualitative research, and supported the recruitment of participants to the qualitative WP.

We tracked how many PPI members took part in the interactions over the duration of the study to give us a sense of engagement levels with the study. Ninety-seven per cent (28/29) of PPI members responded to the first task and 76% (22/29) to the second task a few weeks later. By the end of the study, around 15 months after the first task, 41% (12/29) of PPI members were still actively involved with the study and responding to communications. Thirty-five per cent (10/29) participated in the last online focus groups. They represented the following categories: one in group 3 (positive antenatal screening and no further tests); two in group 4 (false-positive antenatal screening); one in group 5 (positive antenatal screening and continue pregnancy); three in group 6 (positive antenatal screening and pregnancy termination); two in group 9 (true-negative newborn screening); and one in group 13 (true-positive newborn screening), representing six of the experience groups. Given the global pandemic, the duration of the study and the fact that PPI members had caring responsibilities, the rate of attrition was unsurprising. However, the focus groups did benefit from the breadth of experiences represented by the PPI members.

Discussion and reflections

Despite the limitation of the representativeness of the PPI group, the study benefitted significantly from its input based on their experiences of screening over the perinatal period. Their input included advising on appropriate language for research participants; reviewing and adding to the list of stakeholders; supporting recruitment of participants into the primary research; and ultimately advising on the appropriateness of employing different health economic methods to value antenatal and newborn screening scenarios. Their input shaped the success of the study by not only enhancing the engagement the research team had with the study participants, but also advising on the feasibility of the recommendations to move forward. Specific examples of PPI input that were taken forward and led to an amendment in the methodology or improvement in interpretation are expanded upon in Chapters 6, 7 and 9.

Having a PPI co-ordinator to manage the group proved crucial due to the numbers involved, the extraordinary circumstances of the pandemic and the length of time members needed to be involved. Some aspects of the engagement strategy were labour-intensive, for example, recruitment, creating the online platform; producing information videos to explain the role of PPI in research and another to explain qualitative research; and producing study progress communications. Another aspect was the involvement of JF as a co-investigator, who was able to provide contacts, champion the involvement of the PPI at the regular project meetings and advice on ways that their input could be helpful. PPI engagement was well-maintained for a significant duration, and the quality of the input was high, with the members providing very insightful and thoughtful input throughout, shaping the progress and recommendations of the study.

Our final interaction with the PPI members involved two smaller online group discussions with the health economics researchers (see Chapter 9). The research team gained very useful input on some of the proposed recommendations of methods for valuing benefits and harms of antenatal and newborn screening. The PPI group and the research team did not get to meet other than these final interactions, due to COVID-19 restrictions. Our experience demonstrates that engaging a large PPI group such as this is possible, that it greatly improves the quality of the research. It also demonstrates that group cohesion does not necessarily rely on face-to-face interactions. However, it does require significant resource commitment, thought and effort on behalf of both the research team and PPI group members.

Chapter 3 Work package 1: systematic review of health economic assessments evaluating antenatal and newborn screening

Sections of this chapter have been previously reported in Png et al. (2021). 38

Introduction

In this chapter, we report our systematic review of health economic assessments evaluating antenatal and newborn screening programmes in developed countries. The systematic review had two distinct purposes. The first was to identify all available evidence in the published and grey literature over the last two decades and understand its main characteristics, the clinical areas and conditions covered and the reporting quality of the contributing studies. The second objective was to extract detailed information about the benefits and harms incorporated into these health economic assessments. This chapter covers the first aim and reports a comprehensive overview, whereas the second aim is presented in Chapter 4.

Methods

We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 checklist39 when reporting the methods and results of the systematic review. The review protocol has been registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020165236) and published on 13 January 2020. This review is based on data available from secondary sources and published materials with no primary data collection required, so ethics committee approval or written informed consent was not required.

Eligibility criteria

The Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome and Study design (PICOS) framework was used to develop the study eligibility criteria (Table 3) and applied to the literature searches. Searches were limited to studies published after 1 January 2000. Studies reporting health economic assessments, such as economic evaluations and studies that use economic frameworks of cost-effectiveness evidence or economic notions of value (e.g. multi-criteria decision analyses, programme budgeting and marginal analyses) of antenatal or newborn screening programmes, were included. Non-English language studies were included, but studies were limited to those conducted in developed countries (defined, for the purposes of this review, as a member of the OECD40).

| Characteristics | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Pregnant women Newborns |

Anyone other than pregnant women or newborns Studies on animals Not conducted in an OECD member countrya |

| Intervention | Antenatal or newborn screening programmeb | Pre-conception screening No screening programme |

| Comparator | No screening or specific form(s) of screening other than experimental intervention(s), as defined by specific conditions | |

| Outcome | Benefits and harms of antenatal or newborn screening that have been identified, measured and valued by economic assessments | |

| Study design | Economic evaluation design:

Economic framework that incorporates cost-effectiveness evidence or economic notion of value (e.g. multi-criteria decision analysis, programme budgeting and marginal analysis) |

Descriptive cost analysis Budget impact analysis Not an economic evaluation |

Other report types:

|

Information sources

Systematic searches of both published and grey literature, including peer-reviewed journal articles controlled by commercial publishers and documents produced by all levels of government, academia, business and industry, were conducted. The following electronic bibliographic databases were searched: MEDLINE (OvidSP) (1946–present), EMBASE (OvidSP) (1974–present), NHS Economic Evaluation Database (via CRDWeb www.crd.york.ac.uk/CRDWeb/) (inception to 31 March 2015), EconLit (Proquest) (1969–present), Science Citation Index, Social Science Citation Index and Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (Web of Science Core Collection) (1945–present), CINAHL (EBSCOhost) (1982–present) and PsycINFO (OvidSP) (1806–present). SCOPUS (Elsevier) was used to run forward and backward citation searches once relevant studies were identified. The academic electronic database searches were supplemented by manual reference searching of bibliographies from studies that were included, contacts with experts in the field and author searching based on experts’ opinion. The first full search of published literature was conducted on 24 April 2020 with a top-up search conducted on 2 July 2020 to include the ‘perinatal’ search term while a refresh search was conducted on 22 January 2021.

The list of grey literature searched was derived from a pool of relevant websites that was informed by a recent systematic review of national policy recommendations on newborn screening that identified websites of national and regional screening organisations with documentation about antenatal and/or newborn screening recommendations. 41 This was widened to cover websites reported by the Health Grey Matters checklist and those for national and regional screening organisations, HTA agencies, paediatrics organisations, and obstetrics and gynaecology societies in OECD countries, as well as international decision-making bodies, such as the World Health Organization, the European Council, European Commission and the European Observer. 41,42 A customised web scraping tool that used the Google search engine was built using Python to directly query the stated websites (see Appendix 1) from 18 to 27 January 2021 using English search terms and from 14 to 17 February 2021 using translated search terms for non-English websites, as well as to automate the data extraction processes.

Search strategy

The search strategies applied to the published literature (see Appendix 2, Tables 21–26) were developed using a combination of medical subject headings (MeSH) and free-text keywords related to health economic assessments of antenatal and newborn screening programmes in collaboration with an information specialist (NR) with expertise in conducting systematic literature reviews in the health sciences. A simplified search strategy derived based on the Cochrane guidelines was applied to the grey literature search. 43 Translation of the simplified search terms for non-English websites was performed by professional translators.

Data management

The results of the literature searches were uploaded into the Endnote software package X9 (Clarivate, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019), a reference management system specifically designed for managing bibliographies and citations, to remove duplicates. Unique records were subsequently imported into Covidence,44 an online software program that facilitates collaboration among reviewers during the screening and data extraction stages. This software allows importation of references and files to be screened and information can be entered into a pre-created data extraction form after removing duplicates. Screening criteria based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria specified in Table 3 were developed and tested. A calibration exercise was undertaken to pilot and refine the screening criteria before the formal screening process started. For non-English language papers, Google Translate (Google, Mountain View, CA, USA) was used to translate relevant documents.

Selection process

For the published literature, two reviewers (MEP and MY) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all retrieved articles and documented the reasons for study exclusion according to the criteria specified in Table 3. Full texts of potentially relevant articles were reviewed independently by the same reviewers (MEP and MY), and study eligibility based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria was assessed. At each stage of the selection process, any disagreement was resolved by discussion and consensus between the two reviewers. When consensus could not be reached, input from the rest of the review team (ORA and SP) was obtained. For the grey literature, only one reviewer (MEP) did the title/abstract and full-text screening of all the retrieved articles, while another reviewer (SR) screened the titles/abstracts of a random sample of at least 10% (13%) of the retrieved articles due to a change and shortage in work force and limited time.

Data collection process

A data extraction form, which was piloted and refined using 10 randomly selected studies identified in the academic electronic databases, was created using Microsoft Excel following recommendations from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 43 As we had anticipated a large number of articles to data extract, after consulting our Independent Oversight Committee members and Information Specialist (NR), a selection of 10% of the articles/reports was extracted independently by two health economists (MEP and MY), followed by a reconciliation process. During this reconciliation process, MEP and MY had to extract the same key information from a random set of conference abstracts, journal articles and reports before they proceeded to extract the other studies independently and this was observed after assessing around 10% of the papers/reports. The rest of the published literature was subsequently divided between the two reviewers (MEP and MY), while data from the grey literature were extracted by one reviewer (MEP) only. Furthermore, any uncertainties related to data extracted by the two independent reviewers (MEP and MY) was discussed with the two senior investigators (ORA and SP) at weekly meetings. The list of variables extracted from each report included at the final stage of the review process was finalised following the piloting and refinement of the data extraction sheet.

The data extraction form consisted of two parts: (1) a section that contained items from the CHEERS checklist,45 modified where applicable to align with our research focus (i.e. benefits and harms within economic assessments) (see Appendix 3). This included bibliographic details; condition(s) screened; approaches for measuring and valuing health outcome measures; the journal impact factor quartile during the year that the article was published, obtained from Clarivate Analytics and SCImago; whether the authors made any policy recommendation based on their economic evaluation evidence; and whether the authors might have had any potential conflicts of interest in promoting their screening programme or mechanism (defined as a study that was funded by an industry sponsor, unless it was an unrestricted grant, and at least one of the authors being clearly employed by the industry sponsor); and (2) a bespoke form (see Appendix 4) created by the research team to extract benefits and harms adopted by economic assessments evaluating antenatal or newborn screening programmes. This form was created de novo as we could not find any previous examples in the published literature. A detailed description of the process to create the bespoke form is described in Chapter 4. This bespoke form contained consequences as reported by authors by screening test outcome (i.e. true positives, false positives, true negatives and false negatives) and type of data (i.e. probability, cost or outcome), which were captured and categorised as either a benefit or a harm. We also recorded the stage of the disease pathway at which the screening test was administered and the phase(s) of the screening programme using categorisations from recent guidance,1 as well as recorded whether the structure of decision-analytical models had been reported, and the consequences associated with treatment where applicable.

Data items

In order to reduce bias from including data from multiple reports of the same study, multiple articles published by the same authors with similar titles and abstracts were treated as linked companion studies (i.e. multiple reports from a single study) and only the most detailed publication was included in our final outputs. Similarly, if conference abstract(s) and a journal article by a similar group of authors had been published on the same topic, only the journal article was included at the full-text screening stage. Since we were interested in the methodological approaches to the measurement and valuation of benefits and harms and how the results were reported, if the article/report title suggested that an economic evaluation was conducted but neither the methods nor the results were presented in the abstract or full text, the article/report was excluded at the screening stage(s). Articles/reports that did not focus specifically on pregnant women or newborns but reported separate results of screening of pregnant women or newborns within broader populations were still included. In addition, authors were not contacted for missing data on individual data items included in our data extraction sheet, which were instead recorded as ‘not stated’.

Assessment of reporting quality of individual studies

Since only aggregated data and no effect sizes were sought, we did not assess the risk of bias or conduct a formal meta-analysis. Instead, the reporting quality of articles and reports (excluding conference abstracts) was assessed using the CHEERS reporting statement. 45 The items were considered as ‘satisfied’ if reported in full or ‘not satisfied’ if not reported or partially reported. The items were not scored as per the guidance in the CHEERS reporting statement. 45

Deviations from protocol

There were a few of deviations from the protocol. First, we used Endnote and Covidence for different components of the systematic review. Endnote was used to record all the studies identified as part of our searches and employed to identify and remove duplicates. Covidence was used as it can better facilitate collaboration among reviewers during the screening and data extraction stages than Endnote. Second, we did not use any risk of bias tools such as Cochrane ROBEQ tool and Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions (ROBINS-I) for different study designs because the aim of the systematic review was to understand the benefits and harms of antenatal and newborn screening and not to extract any quantitative information from the papers. Therefore, we excluded any reference to risk of bias assessment from the final published protocol for the systematic review. For the same reason, we did not explore further the external validity of any of the cost-effectiveness results published in the studies. We have used the CHEERS statement to evaluate the reporting quality of the studies since understanding the reporting quality of these studies was a primary aim of our systematic review as it was good indicator of whether a particular study was going to provide all the information in our bespoke form. Last, data extraction was not conducted independently by the two reviewers and a 10% sample was used because the former was not feasible as we ended up including 336 articles and reports and it was decided given our timelines to change the strategy for the data extraction. All deviations were discussed and approved by our Independent Oversight Committee.

Results

Search results

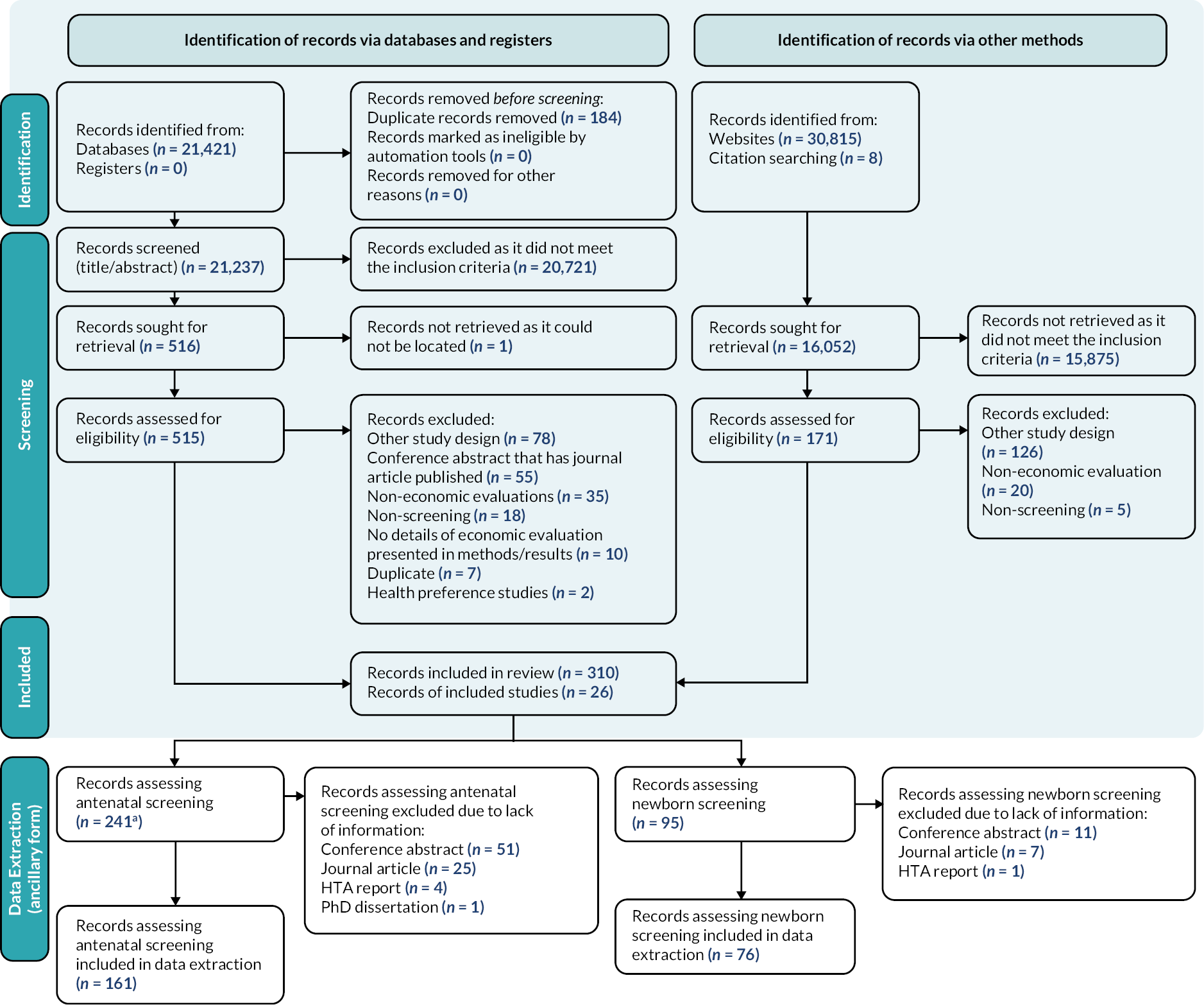

We identified 52,244 articles and reports from the searches of the published and grey literature. Among the 16,052 records that were sought for retrieval based on identification of records via other methods (i.e. grey literature), 7464 records were non-English (46.5%). Thirty-nine studies of the non-English records were assessed for eligibility with five subsequently included in the data extraction phase. A total of 336 records, 310 articles (1.4% of databases) and 26 reports (0.08% of websites), were included in the systematic review. One HTA report included two separate economic evaluations that were separated into two different reports, resulting in 337 outputs. Study selection and reasons for exclusion as well as data extraction of the bespoke form are summarised in the modified PRISMA diagram (Figure 3). The list of studies excluded is summarised in Report Supplementary Material 1.

FIGURE 3.

Modified PRISMA flow diagram. a, One HTA report included two separate economic evaluations that were separated into two different reports, resulting in 242 outputs from the 241 records.

There was no trend in the publication year of the articles and reports (Figure 4). Characteristics of the included articles and reports are presented in Table 4. The majority of the articles and reports included were journal articles (228, 67.7%) and almost half of the studies were conducted in the USA (109, 32.2%) and the UK (43, 12.7%). The majority of the articles and reports also required further information to determine if the authors had potential conflicts of interests (221, 65.6%). Furthermore, the authors did not make any recommendation about the adoption of the screening programme based on the economic evidence generated for the majority of the articles and reports (273, 81.0%). The majority of the articles were published in top quartile medical journals (i.e. quartile one; 129, 38.3%).

FIGURE 4.

Number of articles and reports published from 2000 to January 2021. Note: Dotted lines were used to indicate that only January 2021 was included in this chart.

| Articles and reports assessing antenatal screening (%) (n = 242) |

Articles and reports assessing newborn screening (%) (n = 95) |

Articles and reports assessing either screening type (%) (n = 337) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Publication type | |||

| Journal article | 156 (64.5) | 72 (75.8) | 228 (67.7) |

| Conference abstract | 61 (25.2) | 12 (12.6) | 73 (21.7) |

| HTA report | 24 (9.9) | 11 (11.6) | 35 (10.4) |

| PhD dissertation | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Country of screening programmea | |||

| USA | 82 (33.7) | 27 (28.4) | 109 (32.2) |

| UK | 32 (13.2) | 11 (11.6) | 43 (12.7) |

| Canada | 17 (7) | 15 (15.8) | 32 (9.5) |

| The Netherlands | 12 (4.9) | 9 (9.5) | 21 (6.2) |

| France | 8 (3.3) | 4 (4.2) | 12 (3.6) |

| Australia | 9 (3.7) | 3 (3.2) | 12 (3.6) |

| Spain | 6 (2.5) | 4 (4.2) | 10 (3.0) |

| Colombia | 3 (1.2) | 3 (3.2) | 6 (1.8) |

| Austria | 3 (1.2) | 1 (1.1) | 4 (1.2) |

| Israel | 4 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 4 (1.2) |

| Italy | 3 (1.2) | 1 (1.1) | 4 (1.2) |

| Germany | 1 (0.4) | 2 (2.1) | 3 (0.9) |

| Belgium | 1 (0.4) | 2 (2.1) | 3 (0.9) |

| Finland | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (0.6) |

| Sweden | 1 (0.4) | 3 (3.2) | 4 (1.2) |

| Chile | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Czech Republic | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Denmark | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Ireland | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.6) |

| Japan | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.3) |

| New Zealand | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (0.6) |

| Norway | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.6) |

| Switzerland | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Not stated | 51 (21) | 7 (7.4) | 58 (17.2) |

| Potential conflicts of interest | |||

| No | 70 (28.9) | 38 (40) | 108 (32.0) |

| Yes | 7 (2.9) | 1 (1.1) | 8 (2.4) |

| More information needed to classify | 165 (68.2) | 56 (58.9) | 221 (65.6) |

| Policy recommendation | |||

| No | 194 (80.2) | 79 (83.2) | 273 (81.0) |

| Yes | 48 (19.8) | 16 (16.8) | 64 (19.0) |

| Journal impact factor quartile (articles only) | |||

| First quartile of medical journals | 36 (10.7) | 93 (27.6) | 129 (38.3) |

| Second quartile of medical journals | 17 (5) | 26 (7.7) | 43 (12.8) |

| Third quartile of medical journals | 11 (3.3) | 27 (8) | 38 (11.3) |

| Fourth quartile of medical journals | 3 (0.9) | 7 (2.1) | 10 (3) |

| Not available | 5 (1.5) | 3 (0.9) | 8 (2.4) |

Target population and setting

The characteristics of screening programmes and populations in the included articles and reports are summarised in Table 5. There were 173 (71.5%) studies on antenatal screening and 63 (66.3%) studies on newborn screening that did not state the setting of the screening (236, 70.0%) or the women’s gestational stage at the time of screening (168, 65.4% of the antenatal screening studies). The majority of the studies were targeted at the general population of pregnant women (197, 57.1%) or infants (91, 26.4%). Many studies were investigations at the symptomless stage with pathologically definable change present (303, 89.9%) or involved all phases of the screening programmes (162, 48.1%).

| Articles and reports assessing antenatal screening (%) (n = 242) |

Articles and reports assessing newborn screening (%) (n = 95) |

Articles and reports assessing either screening type (%) (n = 337) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Setting of screeninga | |||

| Home | 0 (0) | 3 (3.2) | 3 (0.9) |

| Primary care | 6 (2.5) | 3 (3.2) | 9 (2.7) |

| Secondary care | 58 (24.0) | 22 (23.2) | 80 (23.7) |

| Primary and secondary care | 5 (2.1) | 4 (4.2) | 9 (2.7) |

| Not stated | 173 (71.5) | 63 (66.3) | 236 (70.0) |

| Populationa | |||

| Healthy pregnancy | 196 (79.0) | 1 (1.0) | 197 (57.1) |

| Pregnant women and their partner/relative | 8 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 8 (2.3) |

| Pregnancy at risk | 37 (14.9) | 1 (1.0) | 38 (11.0) |

| Healthy infant | 7 (2.8) | 84 (86.6) | 91 (26.4) |

| Infant at risk | 0 (0) | 11 (11.3) | 11 (3.2) |

| Gestation stage of pregnant women | |||

| First trimester | 25 (9.7) | 0 (0) | 25 (7.2) |

| First or second trimester | 3 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.9) |

| First and second trimesters | 6 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 6 (1.7) |

| First and third trimesters | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Second trimester | 25 (9.7) | 0 (0) | 25 (7.2) |

| Second and third trimesters | 10 (3.9) | 0 (0) | 10 (2.9) |

| Third trimester | 19 (7.4) | 0 (0) | 19 (5.5) |

| Not stated | 168 (65.4) | 2 (2.2) | 170 (49.0) |

| Not applicable | 0 (0) | 88 (97.8) | 88 (25.4) |

| Stage of disease pathway | |||

| Person at risk but no pathological changes present | 24 (9.9) | 6 (6.3) | 30 (8.9) |

| Symptomless stage with pathologically definable change present | 217 (89.7) | 86 (90.5) | 303 (89.9) |

| Signs and/or symptoms exist but condition undiagnosed | 1 (0.4) | 2 (2.1) | 3 (0.9) |

| Clinical phase | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.3) |

| Phase(s) of screening programme | |||

| Screening and diagnostic | 60 (24.8) | 16 (16.8) | 76 (22.6) |

| Screening and intervention | 59 (24.4) | 10 (10.5) | 69 (20.5) |

| Screening, diagnostic and intervention | 103 (42.6) | 59 (62.1) | 162 (48.1) |

| Not clear | 20 (8.3) | 10 (10.5) | 30 (8.9) |

Medical conditions investigated are summarised in Table 6. Genetic conditions and infectious diseases (153, 63.2%) were the main areas covered by the articles and reports assessing antenatal screening. Metabolic and structural conditions (57, 60.0%) were the main areas covered by health economic assessments evaluating newborn screening programmes.

| Conditions | Articles and reports assessing antenatal screening (%)a (n = 242) |

Articles and reports assessing newborn screening (%)a (n = 95) |

|---|---|---|

| Developmental | 0 (0) | 6 (6.3) |

| Endocrinology | 24 (9.9) | 4 (4.2) |

| Genetic | 77 (31.8) | 12 (12.6) |

| Gestational cardiorenal | 5 (2.1) | 0 (0) |

| Haematology | 18 (7.4) | 12 (12.6) |

| Infection | 76 (31.4) | 3 (3.2) |

| Intrauterine fetal demise/sudden infant death syndrome | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.1) |

| Maternal mental health | 1 (0.4) | 6 (6.3) |

| Metabolic | 0 (0) | 32 (33.7) |

| Neurodevelopment | 1 (0.4) | 3 (3.2) |

| Neurological | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Nutrition | 4 (1.7) | 0 (0) |

| Structural | 36 (14.9) | 25 (26.3) |

| Urology | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) |

The key methodological characteristics of the health economic assessments from the CHEERS checklist are summarised in Table 7 and in the following subsections.

| Articles and reports assessing antenatal screening (%) (n = 242) |

Articles and reports assessing newborn screening (%) (n = 95) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Study design | ||

| Individual patient-level data analysis | 12 (5.0) | 6 (6.4) |

| Cohort | 10 (4.1) | 5 (5.3) |

| Cross-sectional | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Randomised controlled trial | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0) |

| Decision-analytical model | 200 (82.6) | 72 (76.6) |

| Decision tree | 90 (37.2) | 39 (41.5) |

| Decision tree and Markov model | 9 (3.7) | 6 (6.4) |

| Discrete event simulation model | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.1) |

| Markov model | 10 (4.1) | 15 (16.0) |

| Model type not specified | 83 (34.3) | 8 (8.5) |

| Patient-level simulation model | 7 (2.9) | 3 (3.2) |

| Other | 2 (0.8) | 3 (3.2) |

| Not stated | 28 (11.6) | 13 (13.8) |

| Type of economic evaluationa | ||

| Cost–benefit analysis | 18 (7.4) | 5 (5.3) |

| Cost–consequences analysis | 6 (2.5) | 3 (3.2) |

| Cost-effectiveness analysis | 87 (36.0) | 47 (50.0) |

| Cost-minimisation analysis | 2 (0.8) | 3 (3.2) |

| Cost–utility analysis | 129 (53.3) | 38 (40.4) |

| Perspective of costsa | ||

| Health system or payer | 107 (43.5) | 53 (52.5) |

| Societal | 44 (17.9) | 25 (24.8) |

| Not applicableb | 0 (0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Not stated | 95 (38.6) | 22 (21.8) |

| Time horizon of decision-analytical model | ||

| Up to delivery | 9 (4.5) | 0 (0) |

| From delivery to 1 year from delivery | 26 (13.0) | 7 (9.7) |

| Between 1 year to specific time horizon excluding lifetime | 8 (4.0) | 14 (19.4) |

| Lifetime: infant | 52 (26.0) | 37 (51.4) |

| Lifetime: mother | 16 (8.0) | 0 (0) |

| Lifetime: mother and infant | 12 (6.0) | 0 (0) |

| Not stated | 77 (38.5) | 14 (19.4) |

| Sources to inform health benefits | ||

| Primary data collection | 21 (9.7) | 13 (14.1) |

| Evidence synthesis of secondary data | 167 (77.3) | 62 (67.4) |

| Combination of primary and secondary data | 28 (13.0) | 16 (17.4) |

| Expert opinion only | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Main outcome measure used in the economic evaluationa | ||

| Natural units | 187 (59.2) | 73 (65.2) |

| QALYs | 126 (39.9) | 36 (32.1) |

| DALYs | 3 (0.9) | 2 (1.8) |

| Not applicableb | 0 (0) | 1 (0.9) |

| Reporting of preference-based outcomes in cost–utility analysis | ||

| Maternal QALYs/DALYs | 94 (72.9) | 4 (10.5) |

| Infant QALYs/DALYs | 19 (14.7) | 34 (89.5) |

| Maternal and infant QALYs/DALYs | 16 (12.4) | 0 (0) |

Choice and time horizon of model

The most common type of economic evaluation used was ‘cost–utility analysis’, which reports outcomes in terms of QALYS or disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), for antenatal screening (129, 53.3%), and cost-effectiveness analysis for newborn screening (47, 50.0%). Decision-analytical models were employed in 272 (81.0%) of the articles and reports for the economic evaluations – 200 (82.6%) in antenatal screening and 72 (76.6%) in newborn screening. Among these studies, the majority either employed a lifetime horizon (82, 41.0% for antenatal screening and 37, 51.4% in newborn screening) or did not state the time horizon (75, 37.5% for antenatal screening and 14, 19.4% for newborn screening).

Cost perspective

The costing perspective adopted was not stated in 117 (33.7%) articles and reports. Among those that stated a costing perspective, the majority adopted a health system or payer perspective (107, 43.5% for antenatal screening and 53, 52.5% for newborn screening).

Main outcome measures used in the economic evaluations

The source to inform the main outcome measures in the economic evaluations came predominantly from evidence synthesis of secondary data for both antenatal (167, 77.3%) and newborn (62, 67.4%) screening. Natural units such as number of cases averted and number of cases detected were the more commonly reported outcome measure in both antenatal (187, 59.2%) and newborn (73, 65.2%) screening studies. QALYs were used as the main outcome measure in 129 (39.9%) of antenatal screening and 36 (32.1%) of newborn screening studies. The DALY metric (an outcome measure that combines years of life lost due to premature mortality and years lived with a disability) was used in five studies across both types of screening programmes. Maternal preference-based outcomes (QALYs/DALYs) were reported in 94 (72.9%) of the antenatal screening evaluations, whereas infant preference-based outcomes were reported in 34 (89.5%) of the newborn screening evaluations.

Preference-elicitation methods for valuation of outcomes

Thirty out of 162 studies generated QALYs based on preferences for relevant health states using direct valuation exercises or preference-based instruments based on individual patient-level data. Thirteen out of the 65 studies (20%) reported that they had used a standard gamble and/or time trade-off method to obtain preferences directly from individuals within their studies; of which, 10/47 (21.3%) were antenatal screening programme assessments and 3/18 (16.7%) newborn screening programme evaluations. The use of preference-based instrument to describe health-related quality of life outcomes was limited with only 9/47 studies (19.1%) that investigated antenatal screening programmes and 7/18 (38.9%) that investigated newborn screening programmes stating clearly the instrument used and included the EQ-5D, Health Utilities Index 2 (HUI2), HUI3, 16-Dimension (16D) or the Quality of Well-Being Scale (QWB). There were two studies (one each for antenatal and newborn screening programmes) that used mapping of a non-preference-based survey [i.e. Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and Adrenoleukodystrophy-Disability rating scale (ALD-DRS)] onto a generic preference-based measure.

Assessment of reporting quality

Reporting quality assessed using the CHEERS checklist was heterogeneous among the 264 full-length articles and reports (as summarised in Appendix 5). The top five items not satisfied among the studies for antenatal screening programmes were ‘Abstract’ (160, 88.4%), ‘Time horizon’ (153, 84.5%), ‘Choice of model’ (153, 84.5%), ‘Discount rate’ (130, 71.8%) and ‘Study funding, limitation, generalisability, and current knowledge’ (123, 68.0%). Similar results were found among studies assessing newborn screening programmes. The top five items not satisfied among these studies were ‘Abstract’ (69, 83.1%), ‘Time horizon’ (67, 80.7%), ‘Study funding, limitation, generalisability, and current knowledge’ (59, 71.1%), ‘Choice of model’ (55, 66.3%), ‘Discount rate’ (53, 63.9%) and ‘Setting and location’ (53, 63.9%). The majority of these items were partially satisfied as authors failed to justify the rationale of their methodology as required by the CHEERS checklist.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review to synthesise the evidence surrounding the benefits and harms adopted by health economic assessments evaluating antenatal and newborn screening programmes in OECD countries. Almost half of the articles were published in first-quartile journals, indicating interest in the topic by high-impact journals. Most of the economic evidence of antenatal screening programmes focused on screening for genetic conditions or infectious diseases, while that surrounding newborn screening programmes primarily focused on screening for metabolic or structural conditions.

We found clear evidence that decision-analytic models represent the main vehicle for the conduct of these studies, unsurprisingly given the nature of the evidence synthesis needed. Almost half of the articles and reports used standard health economic measures of QALYs or DALYs to measure the health benefits of the screening programmes. Only 30 of the studies using QALYs attempted to estimate preferences for relevant health states using valuation exercises or employing a preference-based instruments or mapping exercise on participant-level data sets. Therefore, the main source of information to inform utility values used in QALY estimations was the published literature.

A key strength of this review includes the focus on a comprehensive set of antenatal and newborn screening programmes across OECD countries. We did not restrict our search to English-only records to avoid language bias and did not restrict to the published literature only to avoid publication bias. However, this study has its limitations. We did not perform dual extraction of data, as currently recommended,43 due to the large amount of information to extract from the final included articles and reports and the timelines to complete the project. For practical purposes and quality assurance, dual data extraction was performed for 10% of the papers after consulting our Independent Oversight Committee and information specialist (NR) using a reconciliation process that ended in a high-level agreement between reviewers. Furthermore, reporting quality was assessed using the original CHEERS checklist and not the CHEERS 2022 checklist that was published after the completion of the systematic review. 46 Arguably, application of the CHEERS 2022 checklist, which includes requirements to report on the use of health economic analysis plans, the contributions of patients and members of the public to study design and reporting, and trade-offs between efficiency and equity concerns, would have led to different assessments of reporting quality.

We found that many of these studies did not adhere to recent reporting guidance for health economic evaluations. Time horizon, choice of model and discount rates were poorly reported in general. Related to time horizon, we observed that authors employed longer time horizons to estimate health benefits than their associated costs counterparts. It was common to observe studies that used a lifetime horizon for the estimation of QALYs but a shorter time frame (e.g. up to delivery or when a case was detected) for the costs included in the model. Current lack of long-term data to inform accurate costs of living with a condition over time partly explains this result,11 but it highlights a serious limitation of these studies. It also indicates that these studies did not adhere to recognised methods guidelines for the conduct of economic evaluations for the purposes of assessing the value for money of screening programmes. 14 This suggests that policy-makers using cost-effectiveness information from these studies to inform local decision-making should read these reports with caution.

Chapter 4 Work package 1: developing a thematic framework of benefits and harms to use in health economics assessments evaluating antenatal and newborn screening programmes

Introduction

The systematic review presented in the previous chapter identified all the health economic assessments evaluating antenatal and newborn screening programmes over the last two decades and described their characteristics and reporting quality. This chapter presents the methodology used to understand the benefits and harms adopted in these studies.

Methods

Development of bespoke form

A rapid review was conducted to identify previous checklists in the area of identification of benefits and harms associated with screening programmes. We evaluated checklists for the conduct of economic evaluations of screening programmes [i.e. Consensus Health Economic Criteria for trial-based studies and International Society of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) checklist for model-based studies], and report of harms in clinical studies [i.e. PRISMA-Harms, PRIO-Harms, McHarm and Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT)-Harm checklists]. This review suggested that no previous checklist was fit-for-purpose to identify benefits and harms associated with screening and adopted by economic evaluations. We therefore developed a de novo bespoke form for this purpose. Our starting point was that benefits and harms can manifest across the screening pathway and that ideally studies should report the following: the stage of the screening pathway; information on different phases of the screening programme such as the screening test, confirmatory diagnosis (if needed) and treatment; and description of consequences included, depending on the outcomes of the screening test (i.e. true positives, false positives, true negatives, false negatives as well as inconsequential conditions that will remain without symptoms during lifetime among the ‘true positives’ and ‘false negatives’) as set out in recent guidance. 1 Therefore, a bespoke form based on the aforementioned was created (see Appendix 3).

Development of the thematic framework

For all the studies included in the systematic review, we attempted to complete the bespoke form. The information captured in the bespoke form was used to create a framework of benefits and harms adopted by health economic assessments using a process of grouping themes derived from the data collected in the bespoke form. 47 An integrative descriptive analysis48 of the collated themes within each category was then conducted, resulting in a taxonomy of benefits and harms consisting of a primary theme and up to four levels of subtheme(s). In the first step, the description of consequences was categorised into specific themes by ST-P. This pool of themes was the starting point of an iterative process where members of the study team (ST-P, MEP, OR-A and SP) merged, separated and refined the wording of themes and subthemes. The iterative process was maintained until consensus was reached among the study team (ST-P, MEP, OR-A and SP). Articles and reports were categorised into themes and subtheme(s) according to the condition and screening type. Bar charts were generated to illustrate the framework across and by medical condition(s).

Results

We identified 86 unique descriptions of consequences across all articles and reports up to January 2021. Our thematic analysis resulted in seven core themes around benefits and harms with each core theme including up to four levels of subtheme(s). An update of the search strategies up to November 2021 identified an additional 18 articles but no new themes on benefits and harms emerged (see Report Supplementary Material 2). An abridged version of the thematic framework with a description of each theme and key examples is presented in Table 8 with the full version up to subtheme level 4 presented in Table 27 (see Appendix 6). All the themes listed are applicable to both antenatal and newborn screening except for theme 6 – pregnancy loss, which is only relevant to antenatal screening programmes.

| Theme no. | Theme | Description | Key selected examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Diagnosis of screened for condition | Related to the process of identifying a condition through screening. For example, cases diagnosed or missed, confirmatory tests (necessary and unnecessary), reduction in infants born with condition through effective treatment, or pregnancy termination | Infants born with condition Confirmatory test and additional tests to reach diagnosis of screened for condition Cases missed at screening Cases diagnosed at screening Screened for condition-related complications Additional screening of partners Additional testing to reach diagnosis in the absence of screening (links to diagnostic odyssey) |

| 2 | Life-years and health status adjustments | Impact of identifying a condition on the health of women, infants and other family members and included, for example, standard health measures such as QALYs, DALYs, life-years or impact of anxiety on parents after a false-positive result | Infant life-years post birth (including QALYs) Maternal life-years (including QALYs) Parental QALYs Psychological (anxiety/disutility from false-positive results, genetic variants of unclear penetrance, or knowledge of disease) |

| 3 | Treatment | Caused by harms of adverse reactions, unnecessary interventions and antibiotic resistance, or benefits of adverse complications averted due to timely interventions | Comparison of earlier treatment after screen detection and later after symptomatic detection Additional health care post diagnosis Hospital stay Missed due to false negative Prevention of screened for condition (infectious) Psychological (counselling about screening/confirmatory test/genetic diagnosis) Screened for condition-related treatment/management Treatment-related harm (disutility/anxiety/adverse reaction/antibiotic resistance) Unnecessary due to false positive |

| 4 | Long-term cost associated with screened for condition | Impact on long-term healthcare and non-healthcare costs related to identifying a condition through screening | Direct healthcare cost Direct non-healthcare cost (education/social care/caregiving) Productivity gains Societal cost |

| 5 | Overdiagnosis | Impact on costs and consequences of detecting a condition that would never develop into symptomatic disease | QALY decrement Unnecessary test/treatment |

| 6 | Pregnancy loss | Caused by treatment or an invasive diagnostic procedure, or an informed decision of termination after a true-positive result | Spontaneous Termination (of unaffected fetus due to false-positive test result/prevent downstream adverse maternal outcomes/psychological consequences) Treatment/test related |

| 7 | Spillover effects | Health and well-being effects to parents and other relevant stakeholders as a direct consequence of the child’s diagnosis | Health impacts to parents and siblings from child’s diagnosis with genetic condition, through knowledge of their own genetic status |

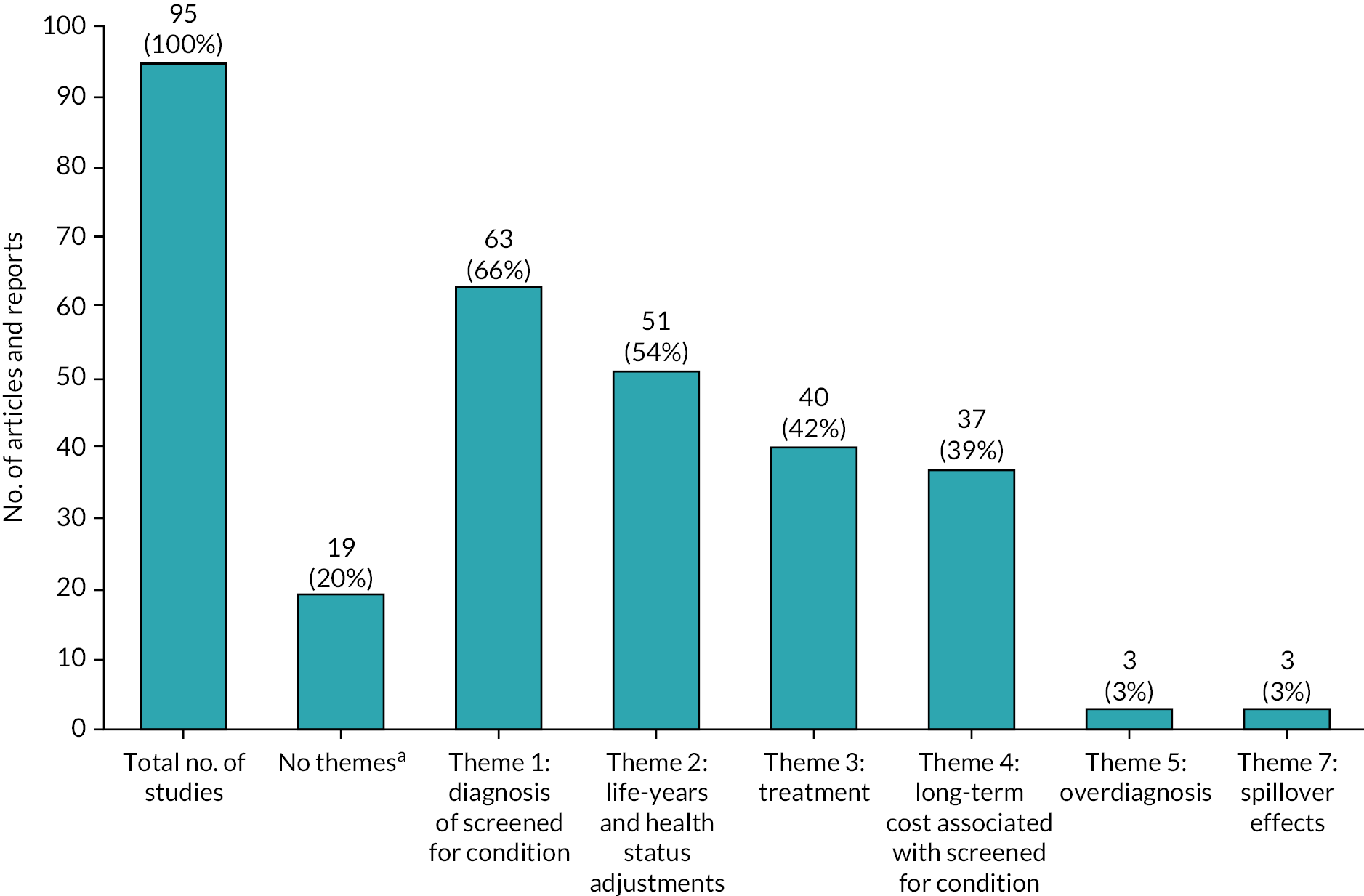

The benefits and harms incorporated within health economic assessments are presented in Figures 5 and 6 by screening type using the thematic framework. Limited information about benefits and harms was provided in 81 (33.5%) out of the 242 antenatal screening evaluations and 19 (20.0%) out of 95 newborn screening evaluations (e.g. conference abstracts). These included 51 (63.0%) antenatal screening evaluations and 11 (57.9%) newborn screening evaluations described in conference abstracts. Across all conditions targeted by antenatal screening, represented in Figure 5 (n = 242), 115 (47.5%) incorporated benefits and harms related to the diagnosis of screened for condition (theme 1). Ninety (37.2%) of the evaluations included benefits and harms related to life-years and health status adjustments (theme 2). Eighty-eight (36.4%) of the antenatal screening evaluations included benefits and harms associated with treatment (theme 3). In general, for antenatal screening, benefits and harms associated with the long-term costs of screened for conditions (theme 4) were only adopted in 68 (28.1%) of the evaluations. Only 21 out of the 242 (8.7%) antenatal screening evaluations adopted benefits and harms from all of themes 1 to 4. The condition in the antenatal screening programmes which reported the widest range of themes was infectious diseases (see Report Supplementary Material 2). Among the 76 antenatal infectious diseases programmes, 22 (28.9%) did not have any themes and the remaining studies reported at least one theme from themes 1 to 6. However, none of them reported any spillover effects (theme 7).

FIGURE 5.

Benefits and harms adopted by health economic assessments evaluating antenatal screening programmes using thematic framework. a, Limited information about benefits and harms could be extracted from 81 (33.5%) out of the 242 antenatal screening evaluations to inform our bespoke form.

FIGURE 6.

Benefits and harms adopted by health economic assessments evaluating newborn screening programmes using thematic framework. a, Limited information about benefits and harms could be extracted from 19 (20.0%) out of 95 newborn screening evaluations to inform our bespoke form.